R E G I S T E R E D B 1 A U S T R A L I A P O S T P U B L I C A T I O N NO. V B P 2121

i N T E It. V I E W S

JOCELYN M O OR H OUSE TALKS A B O U T 'P R O O F ' BLAKE E D W A R D S : 'S C A LLIE K H O U R I : ' T H E L f t§ | S P E C f A L

fill-

IN D E P E N D E N T t t i l B I T I O N A N WSMi

D I S T R I B U T I O N IN A U S T R A L I A R E P O R T A N D IN T E R V IE W S iM g flP v j t

HE A F ^ n D

FFC R E S P O N D

A L L - T I M E F A V O U R I T E F IL M S N D R E J T A R K O V S K Y / LEE RE

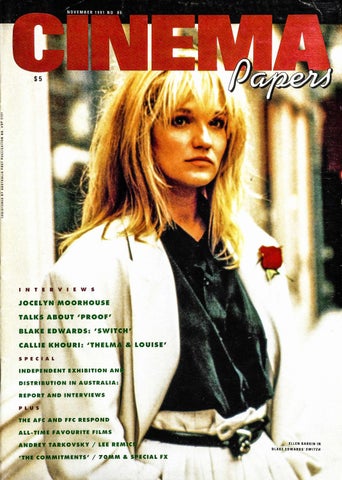

.ELLEN BA RK IN IN BLAKE. E D W A R D S ’ SWITCH