R E G I S T E R E D BY A U S T R A L I A P OST P U B L I C A T I O N NO. VBP 2121

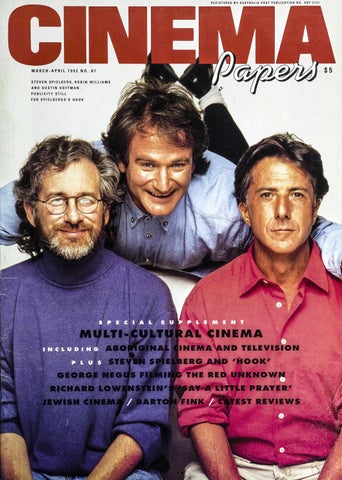

MARCH A P R I L 1 992 NO. 87 S T E V E N S P I E L B E R G . ROBI N W I L L I A M S AND DUS T I N HOF FMAN. PUBLICITY STILL FOR S P I E L B E R G S ' S HOOK

ilÜM

lAVCINEMA

;

I N E M A 'A N D t e l e v i s i o n 8E R C J L N P 'H O O K '

3

S t HE r e d

( O W N -,

(W A V *

'R A V E R /

IjH IS C T É j& T

R E V IE W S