Fi 2 0 9 9 4

April 1979

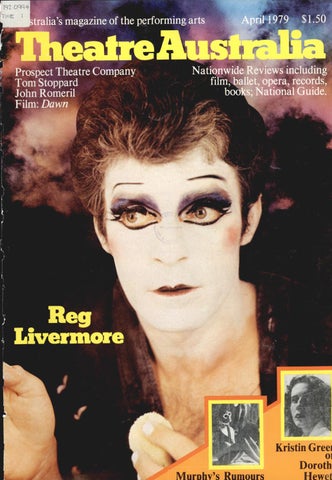

tralia’s magazine of the performing arts

$1.50

Theatre Australia Prospect Theatre Company Tom Stoppard John Romeril Film: Dawn

Nationwide Reviews including film, ballet, opera, records, books: National Guide.

’i t l l

f

Livermore

I

«

Kristin Greei

01

Muruhv’s Rumours

Doroth Hewet