agazine o f the perform ing arts.

February 1981 $1.95*

I

ADELAIDE DANCE T il LATRI 1 EXPANDING J THEIR O PER A TI!« WHERE IS OP READING IN THE EIGHTIEI

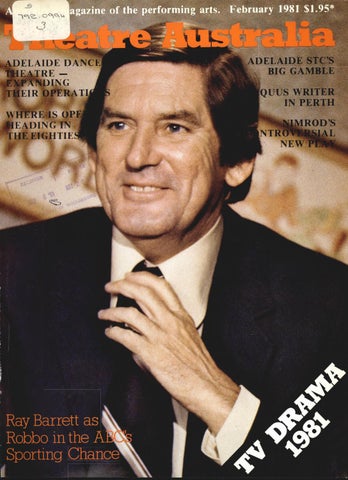

Ray Barrett as Robbo in the A Sporting Chance1

*

T

DELAIDE STC S BIG GAMBLE UUS WRITER IN PERTH ^ N I M ROD’S N T R O T lSiLSI A L L NEW P o l i i