7 minute read

The Other Hawaii-the Enormous Volcanos on the Big Island Written By: Robert Mills

When most people think of the Hawaii Islands, they are likely to imagine warm beaches and palm trees swaying in tropical breezes, not enormous volcanoes with winter snow, and red-hot lava oozing from their slopes. But the Big Island of Hawaii has all of this.

Advertisement

Volcanoes Gave Birth to All of Hawaii

The Hawaiian Islands were formed by volcanic activity above a mysterious magma source called the “Hawaii hotspot”. This spot is a porous opening in the earth’s crust in the middle of the Pacific Plate, the moving tectonic plate beneath the Pacific Ocean. By a strange geologic process, still not understood by geologists, as the Pacific Plate moved northwest, the hotspot remained stationary. Hot magma flowed up through the hot spot to form volcanoes on the ocean floor. These grew into undersea mountains, called seamounts, and as they continued to grow taller, they eventually became islands and burst above the ocean’s surface. As the volcanoes grew taller and hot lava poured out of their summits and outlets on their slopes, the islands grew higher and larger. Then, as if on a conveyor belt, after each island was formed, it rode northwest on the Pacific Tectonic Plate, away from the hotspot. This, in turn, allowed new Hawaiian Islands to form over the hotspot. Eventually, this amazing process created all of the Hawaiian Islands we see today. The Long Chain

Hawaii is usually pictured as the state’s eight largest islands, of which only five are commonly visited by tourists. But Hawaii also includes within its borders an archipelago of 137 islands that sprawl over 1500 miles northwest, from the Big Island of Hawaii to the remote Kure Atoll. These far northwest islands rode the Pacific Plate for hundreds of millions of years while be-ing eroded by rain and weather to the point where many are now underwater or barely above the waterline. The many atolls, reefs, shallow banks, shoals, and seamounts in the northwest portion of this chain are now included in the Papahanaunmokuakea Marine National Monument, the largest protected area in the U.S. and the third largest in the world. This vast, mostly underwater U.S. National Monument is bigger in area than all of the other U.S. National Parks and Monuments combined.

The newer southeastern islands, because they have not been subjected to millions of years of weather erosion, are higher and bigger. The newest, southeastern most island, the Big Island of Hawaii, is the highest and biggest of them all.

But it, too, has continued to ride northwest on the Pacific Plate. The summit caldera of Mauna Loa, the second highest volcano on Hawaii after Mauna Kea, has now moved 50 miles northwest of the center of the stationary hotspot. This porous hole in the earth’s crust continues to spew up hot magma thru the sea floor creating new seamounts which will eventually become islands.

The latest and biggest such seamount is called Loihi, which rises about 3,000 feet over its base on the undersea flank of Mauna Loa. It is estimated that as early as 10,000 years from now, Loihi’s summit will emerge from the sea and become the newest Hawaiian Island.

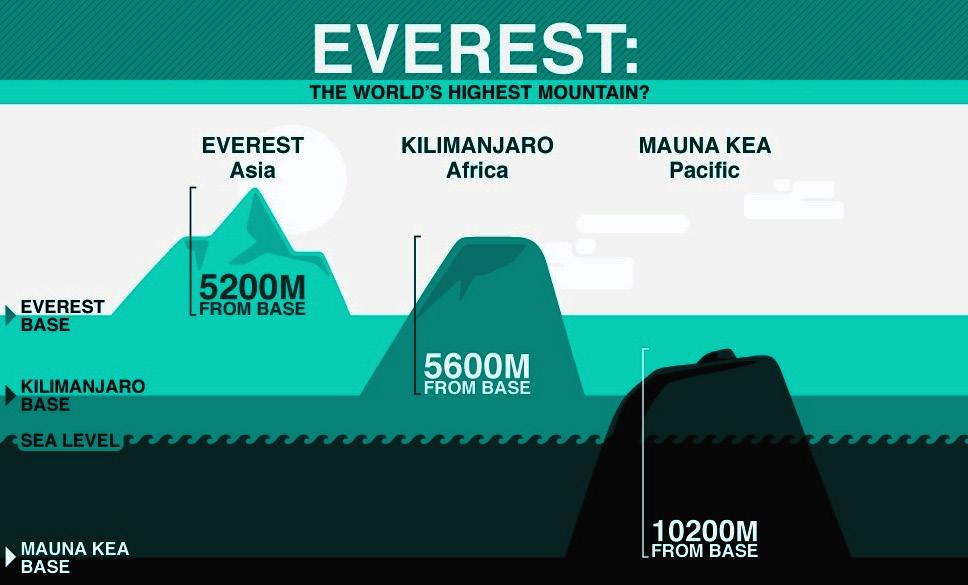

One of the most important attributes of any mountain is its “prominence”, which is the technical term for its “bigness”, the difference in height between its bottom, or base, and summit.

A mountain’s prominence should not be confused with its summit’s elevation above sea level, sometimes referred to as how “high” the mountain is. For example: Mt. Whitney, whose summit is 14,505 feet above sea level, is the highest mountain in the continental United States (the lower 48). But Mt. Whitney rises from its base on a high desert plateau of 4,425 feet, so its prominence above its surroundings is only 10,080 feet. In contrast, the Mauna Kea, the volcano on the Island of Hawaii, is not on a plateau or high plain.

Instead, it rises directly up from the sea to a height of 13,803 feet, so its prominence is the same 13,803 feet as its height, making it significantly “bigger” than Mt. Whitney. Indeed, Mauna Kea is the bigger, and more prominent, than any mountain in the continental US, and is the second most prominent peak, after Mt. McKinley in Alaska, in the entire US.

Unlike mountains whose bases are on land, Mauna Kea rises up in a roughly conical shape from the ocean floor to its summit. Measuring the difference between Mauna Kea’s base on the deep ocean floor to its summit gives it a gigantic prominence of 33,496 feet, making it, by far, the biggest mountain in the world. Weather on Hawaii’s Highest Mountains

Worldwide, with every thousand feet increase in elevation, the temperature decreases roughly three degrees Fahrenheit, a bit less in humid conditions or in direct sunlight. Thus, the average daily high and low temperature in January in humid Kona, at sea level on the Big Island, are 79 and 71F, while the high and low at the arid Mauna Kea Observatory, at 13,780 feet, are 42 and 26F. In between, around the Island of Hawaii, are an incredible 10 of the Earth’s 14 climates, ranging from lush rain forest, with nearly the highest rainfall in the entire U.S., to barren rock in the near-polar summit climate zone.

Snow in Hawaii

Mauna Kea means “the white mountain” in Hawaiian. The natives gave it this name due to the snow which blankets its summit area during the winter. In earlier eras, actual glaciers covered the summit area of Mauna Kea, and the marks of these ice sheets are still evident today. The glaciers have melted, but snow is still common in the highest areas of both Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa throughout the winter.

Astronomical Observatories

Most of the clouds that form around and near the island of Hawaii are mid to low-level stratus or cumulous clouds which, except in big storms, rarely rise above 12,000 feet. This makes for extremely low humidity and unusually clear skies in the summit areas of Hawaii’s highest peaks. At nearly 14,000 feet, these summits are above 40% of the earth’s atmosphere, which can cause haze and distortions. Hawaii’s highest peaks are also far from urban centers, and distant from even the few, small towns on the island itself. As a result, the summit region is free of both the urban light and air pollution that now hinders astronomers at many observatories.

These uniquely ideal conditions on the top of Hawaii’s highest peaks, along with low winds, moderate temperatures, and relative proximity to civilization, have long drawn the attention of the world’s astronomers. Today, 13 of the world’s largest telescopes funded by 11 countries, have been built on the summit of Mauna Kea, making it the largest center for astronomical research on earth. The TMT and Native Protests

On January 7, 1610, Galileo Galilei was the first man to point a telescope to the sky where he discovered the moons of Jupiter and craters on the moon. Even since, astronomers have been in technological race to build more powerful telescopes. In the early 21st century, technological breakthroughs made it possible to create a new generation of extremely large telescopes allowing us to observe cosmic objects with previously unimaginable sensitivity.

In 2008, dozens of nations and universities around the world joined hands to create a non-profit international partnership, the TMT LLC, to utilize new technology to build a gigantic new telescope with a mirror the equivalent of an incredible 30 meters in diameter. It is called the Thirty Meter Telescope, or TMT, will cost an estimated $1.5 billion, and render images 12 times sharper than even the Hubble Space Telescope. In 2009, after carefully searching around the world for the ideal location, the summit of Mauna Kea was selected as the site for the TMT.

After 10 years of hearings, approvals, and appeals, the various authorities with jurisdiction over the summit of Mauna Kea approved the construction of the TMT. Unfortunately, a number of local native Hawaiians consider the summit area of Mauna Kea, for centuries a burial ground, as sacred and “kapu”, meaning forbidden. They view the construction of yet another (the 14th) major observatory to be a sacrilege. As a result, local protesters have mounted enormous, sustained protests which have, since August 2019, blocked the construction of the TMT.

Two thirds of native ethnic Hawaiians support building the TMT on Mauna Kea, but its future is unclear as of now. The TMT partnership is currently researching the selection of an alternate site, a “Plan B”, if it ultimately proves unfeasible to build the TMT on Mauna Kea.