11 minute read

The Battle of Saratoga-How a Stunning, Upset Victory In the New York Forest Written By: Robert Mills

The Battle of Saratoga, how a stunning, upset victory in the New York forest saved the American Revolution

Advertisement

Hinge Points in History – Instances Where One Man, or a Single Event, Changed the Course of History

There have been moments in history where a single determined person, battle, or natural event, forced destiny down one path instead of another, an event which forever changed what occurred afterward. This article, the fourth in a series exclusively for "The Next Taste", explores another example of these history shaping phenomena.

The Battle of Saratoga -- the Hinge Point for the Success or Failure of the American Revolution.

In this article we explore one of the most fascinating hinge points in history: How the surprising defeat of the British by the American Continental Army in the relatively obscure Battle of Saratoga, in 1777, saved the faltering American Revolution, precipitated the massive French intervention, and ultimately led to one of the most consequential events in human history, the creation of the United States of America.

I. Without Foreign Help, The American Revolution Had Little Prospect of Success on its Own.

It is not generally appreciated today how dismal the Colonists’ prospects were when they began their revolt against Great Britain, then the mightiest nation on earth. The Americans’ relatively meager military and economic resources were wholly inadequate and unsuited to pursue the protracted conflict they initiated against the world’s most powerful military. The 13 Colonies had only one quarter the population of England, no factories or industry to speak of, no trained army and, crucially, no navy.

Great Britain had more than enough military might to ultimately suppress the revolt and hang its leaders. King George III was determined to do just that. Most historians believe there is little doubt that without the massive French military assistance – and even then, with no small amount of luck -- the American Revolution would almost certainly have ended in ignominious defeat.

As soon as King George’s military re-inforcements began to arrive in early 1777, the tide of war turned sharply against the Colonist. During that year, the Americans suffered defeat after humiliating defeat. By the fall of 1777, the rebel cause was dire and faltering. The Colonies’ most populous city, Philadelphia, humiliatingly fell to British occupiers in September, forcing the Continental Army to flee to Valley Forge. There, as the winter approached, the volunteer soldiers in Washington’s army, whose enlistment commitments were expiring, begin leaving in droves. With little to show for the immense sacrifice, support for the revolt and funding for Washington’s Army, began to wither.

By the onset of the winter of 1777-8, the Continental Army begun to suffer food shortages, did not have enough blankets for its troops at Valley Forge and was forced to forage for straw instead. Few had coats sufficient to protect against the nearly constant rain and snow, and fully a third did not have adequate shoes.

At this point, what the desperate and failing cause of American independence needed was a near miracle, a military victory of such a decisive, immense scale that it would convince the French that the Americans had the right stuff and that they could actually win. Such a victory appeared to be a completely out of reach dream.

Then, somehow, in October 1777, in the dense woods near the village of Saratoga, New York, that miracle happened.

It Changed Everything.

II. The Battle of Saratoga. How Ragtag Volunteers Shocked the World by Defeating and Capturing an Entire Army of British Regulars.

An upset of this magnitude usually has multiple causes, and such was the case in this instance. Here is how the Americans won this crucial battle that they appeared to have no chance of winning.

From the outset, in 1775, the British strategic plan for defeating the revolution was simple: cut the Colonies in half. With the strongholds of the insurrection in New England separated from the rest of the colonies, the revolt could be easily crushed.

Nature had provided an obvious way to divide the colonies. A waterway stretches from New York City up the Hudson and then, by way of Lake George and Lake Champlain, to Canada. The British began the execution of their plan by sending two armies to act as pincers; one to the south to move north, and one to the north to move south.

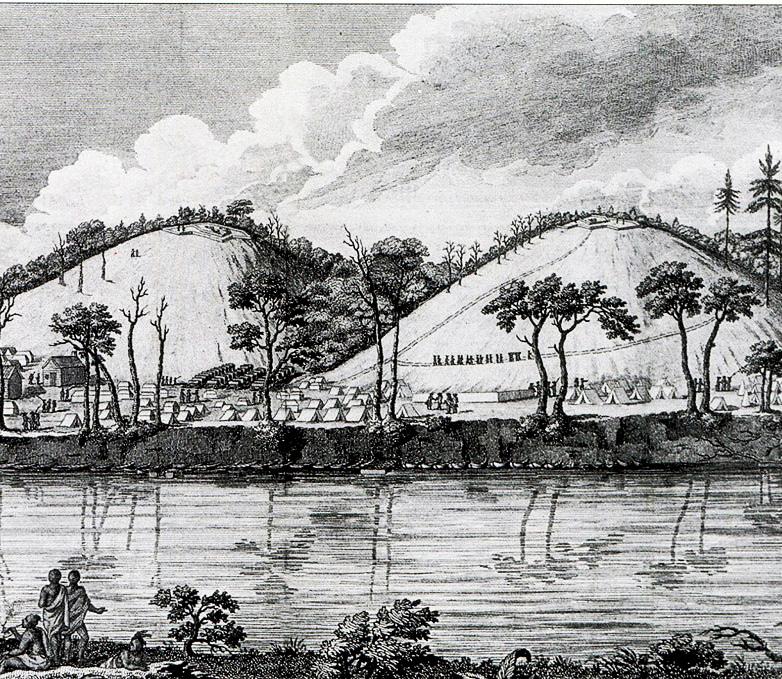

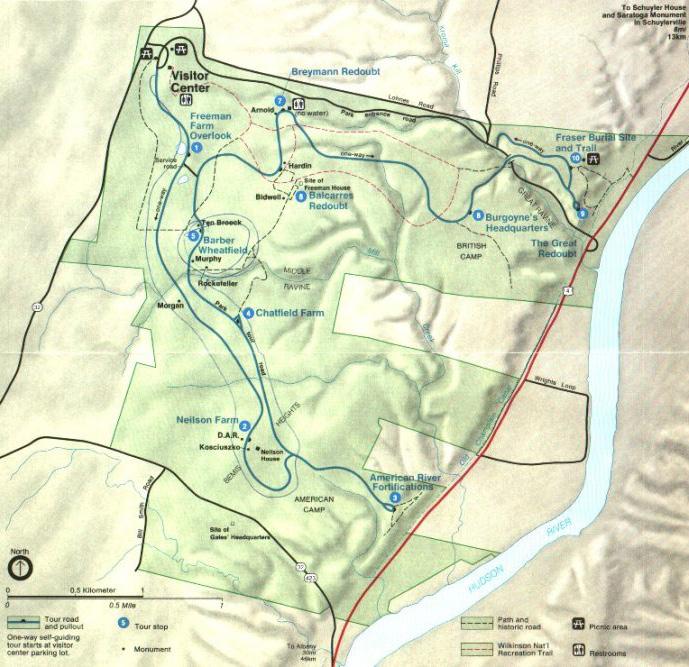

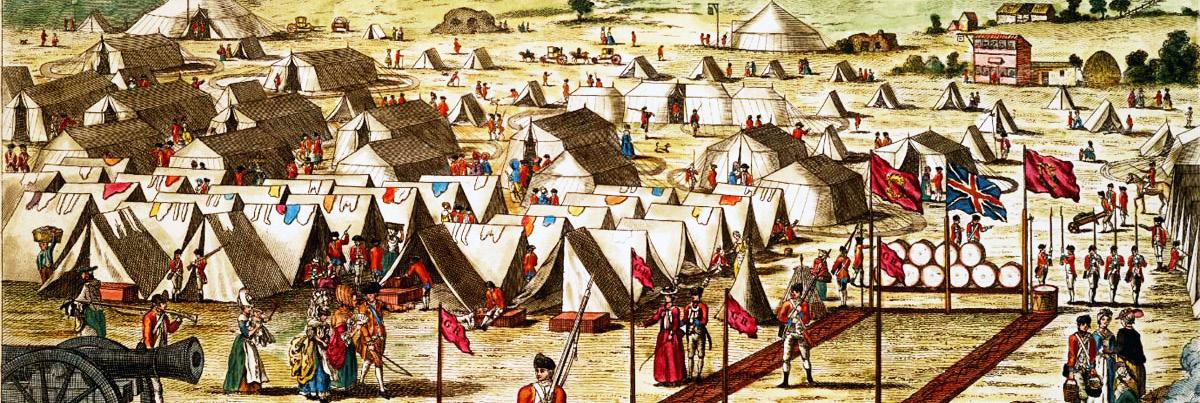

The British failed to complete this maneuver during 1776. During the winter, General Carleton, who led the northern force, was replaced by General John Burgoyne who eagerly renewed the campaign early, so that by June 1777, he had already advanced southward to the northern end of Lake Champlain. There Burgoyne assembled a powerful force of 7,850 men which he used to attack and decisively defeat the 3,000 Americans defending Fort Ticonderoga, a bitter shock to the Americans. With the Continental Army amassing an evergrowing list of defeats, many people now began to predict a quick end to the American Revolution.

With victory in sight, and every strategic advantage in their favor, General Burgoyne and the British forces then made a series of epic blunders.

First, Burgoyne inexplicably choose the wrong way to the Hudson, leading his army through 23 miles of a wilderness of dense forest and ravines. The Americans, in their natural element, energetically seized on this error. As Burgoyne’s army slowly hacked their way thru the deep nearly impenetrable woods, the Americans subjected them daily to deadly and effective guerilla attacks. It took Burgoyne three long, bloody weeks to reach the Hudson, leaving a virtual trail of blood as he lost men every step of the way to American riflemen.

Then things got worse. Two days before Burgoyne reached the Hudson, a party of marauding Native American auxiliaries under his command shot two women prisoners and brutally scalped one of them. Ironically, one of the young victims was engaged to an officer in Burgoyne’s army. Despite that, the American patriots skillfully broadcast lurid and highly inflammatory accounts of this incident far and wide throughout New England and New York, knowing the incredibly potent effect it would have on the populace.

As reports of these outrages circulated, enraged locals, squirrel guns slung over their shoulders, poured out of the farms and villages by the thousands, surging into the Continental Army camps, swelling the rebel army’s manpower by the hour. In the meantime, Burgoyne’s army, now isolated in the deep forests and cut off from food and reinforcements, shrank daily from disease and the ceaseless ambushes.

Burgoyne’s predicament grew suddenly more dire when, less than a week later, he received the horrifying news that General Howe was not on his way up from the south to join forces with him, as planned. Instead, as a result of unimaginable carelessness, the order for Howe to join up with Burgoyne was misplaced and not delivered, and the major British force, which Burgoyne was desperately counting on, had disappeared from the campaign.

Now nearly out of food and supplies, Burgoyne sent out large raids seeking to pillage provisions from nearby farms and towns, but they defeated in skirmishes with Continental soldiers. Burgoyne’s soldiers returned empty handed. A relief party sent from Canada, also turned back after battles with the Continental Army.

Isolated and cut off from help, the British general knew that his only chance now lay in the possibility of defeating his enemy in battle. Burgoyne moved his dwindling army – now down to 6,000 men -resolutely forward toward a fateful engagement with the growing and now 7,000 strong American army under General Gates.

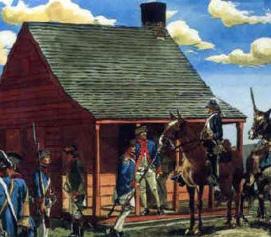

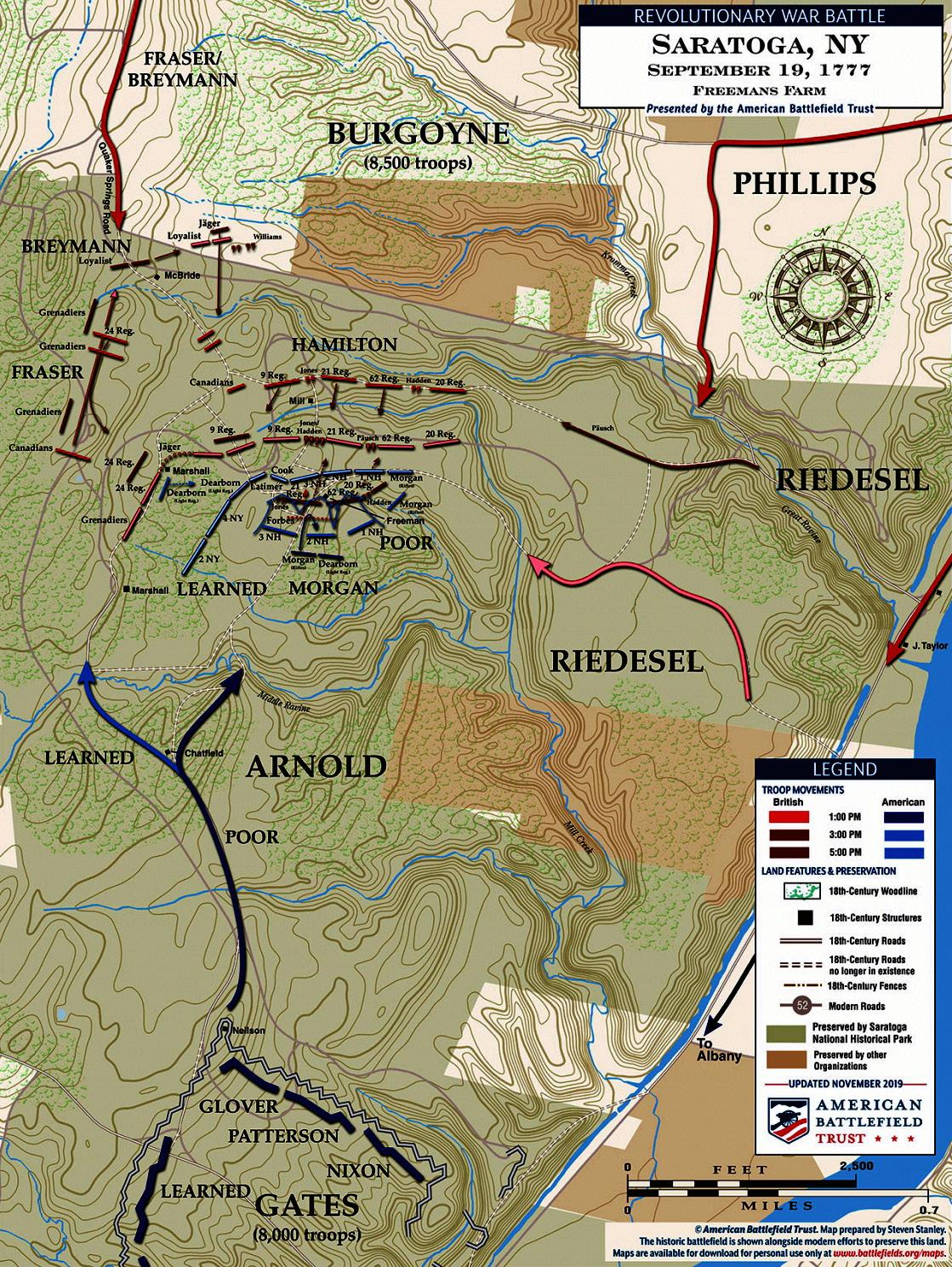

On the morning of September 19, 1777, near the tiny village of Saratoga, New York, the two armies clashed in a furious, desperate, bitter struggle. The battle lines surged back and forth. After only a few hours, the Americans withdrew with the British still holding the field, but only after inflicting heavy losses on the British – 600 men killed, wounded or captured, versus only 300 for the American side.

At this point, General Clinton left New York City leading an army north to come to Burgoyne’s aid, but with only 4,000 men, it was far too little too late to break through and arrive in time to help Burgoyne at Saratoga.

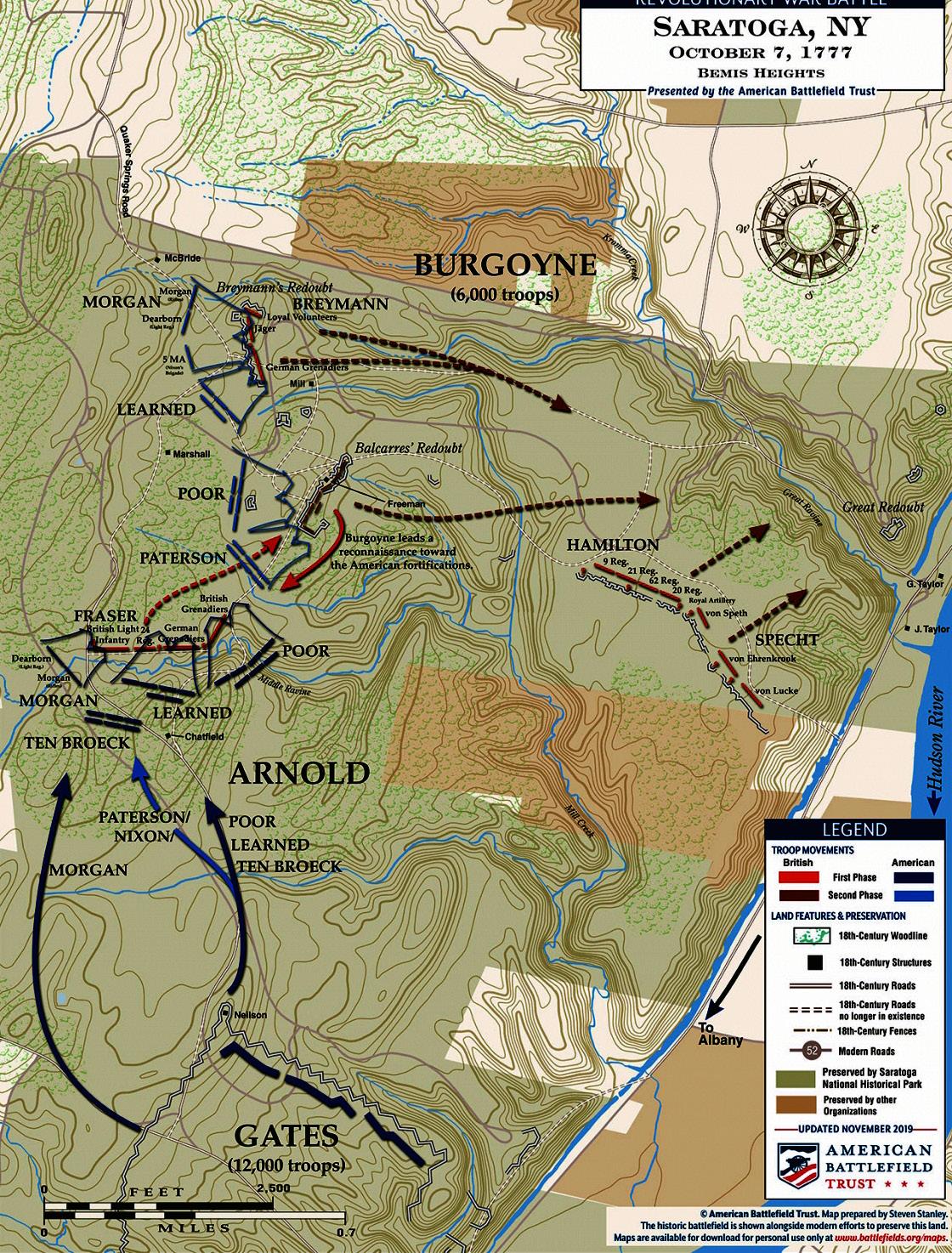

With volunteers flocking into General Gate’s camp, along with tons of fresh supplies and French-sent war material pouring into the rebels’ hands, time was not on General Burgoyne’s side. Still, he waited in vain for three long weeks for Clinton’s promised rescue. It never came. With his men now on half rations, and only 5,000 soldiers fit for duty, the valiant British General at last took the only option left to him and courageously led his men into battle against General Gates’ surging American army, now numbering 11,000 men.

The two determined armies again clashed in a ferocious and savage struggle on a hillside near Saratoga. Finally, at darkness, the Americans gained a position where they could encircle the British. At this point, General Burgoyne expertly withdrew his army to the heights above the nearby river. The British had again lost 600 men, versus only 150 for the Americans.

At this point, the veteran Burgoyne, his men exhausted and starving, his army trapped, and soon to be surrounded and destroyed by the resurgent Americans, knew that all was lost. He quickly moved his army north to the village of Saratoga and there surrendered his entire compliment of 5,700 officers and men to the Americans.

It is hard to overstate the shock waves this development sent throughout the world. Nowhere did this news have bigger consequences than in the French Court of Louis XVI at Versailles.

III. The Massive French Intervention

The immense victory by General Gates at Saratoga was exactly the news the French had been longing to hear. With all Paris cheering him, Franklin raced to Versailles to again plead with the King and his advisors for French intervention. This time, the answer was a decisive “yes”! Saratoga made all the difference, and the French wasted no time in acting on it. On February 6, 1778 the French and the Americans signed the pivotal “Treaty of Alliance” as well as a “Treaty of Amity and Commerce”.

France then declared war on Great Britain. This momentous decision by the French, in turn, persuaded Spain to join France in this new campaign against its ancient rival Britain, and these decisions, in turn, played a key role in Holland declaring war on England as well.

Most Americans today have little grasp of the immense scale of the French intervention in, and sacrifice for, the American Revolution.

From the outset, the French had been supplying limited military provisions and cash, but now they leaped into the conflict with everything they had, providing not only huge sums of cash and credit to the American cause, but also committed 63 warships, 22,000 sailors and 12,000 soldiers. In the end they paid a high price for helping America gain its independence; 7,000 French soldiers and sailors died and another 8,000 were wounded or permanently incapacitated. More Frenchmen died in overall conflict than Americans – only 6,800 Continental Army soldiers died, 6,100 were wounded. By the time of the climactic Battle of Yorktown, there were roughly an equal number of French and American ground soldiers fighting together. At this point the war was for all practical purposes a joint campaign and was depicted as such by contemporary American painters.

The key to the ultimate defeat of the British at Yorktown was the French Navy. Under the command of the Comte de Grasse, the French defeated the British fleet in the famous Battle of the Chesapeake. This victory prevented the British navy from evacuating the trapped General Cornwallis and his army from Yorktown, thus enabling the Franco-American army to force the complete surrender of General Cornwallis and his entire 8,000-man army. This cataclysmic defeat led the British to give up and accept the independence of the new nation, the United States of America.

The Battle of Saratoga was the hinge point of destiny that made this seemingly impossible outcome a reality. But for the Americans’ surprise success in that battle deep in the wild hardwood forest in what is now eastern New York state, there would in all likelihood be no United States of America.

Next Adventure with Robert Mills!