Volume Two December 2024

Volume Two December 2024

Donate Now and Keep the Magazine Live in 2025

Live Encounters is a not-for-profit free online magazine that was founded in 2009 in Bali, Indonesia. It showcases some of the best writing from around the world. Poets, writers, academics, civil & human/animal rights activists, academics, environmentalists, social workers, photographers and more have contributed their time and knowledge for the benefit of the readers of:

Live Encounters Magazine (2010), Live Encounters Poetry & Writing (2016), Live Encounters Young Poets & Writers (2019) and now, Live Encounters Books (August 2020).

We are appealing for donations to pay for the administrative and technical aspects of the publication. Please help by donating any amount for this just cause as events are threatening the very future of Live Encounters.

Om Shanti Shanti Shanti Om

Mark Ulyseas

Publisher/Editor

markulyseas@liveencounters.net

All articles and photographs are the copyright of www.liveencounters.net and its contributors. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the explicit written permission of www. liveencounters.net. Offenders will be criminally prosecuted to the full extent of the law prevailing in their home country and/or elsewhere.

Volume Two December 2024

Dr. Father Ivo Coelho - Guest Editorial

Mark Ulyseas

Percy Aaron

José Truda Palazzo Jr

Dr Greta Sykes

Gopika Nath

Katie Costello

Jill Gocher

Lynda Tavakoli

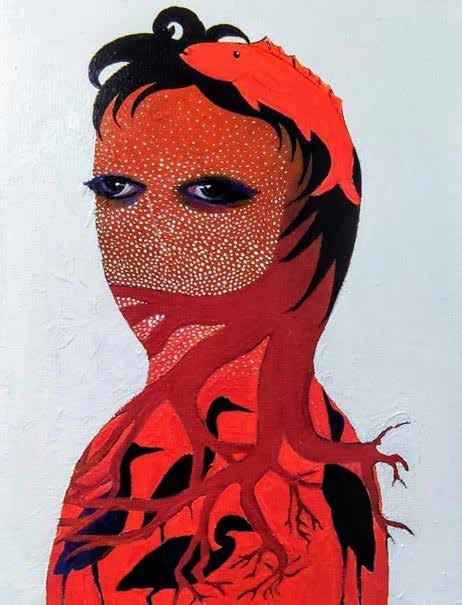

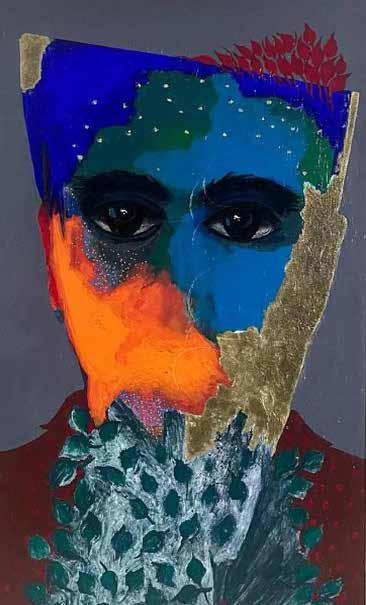

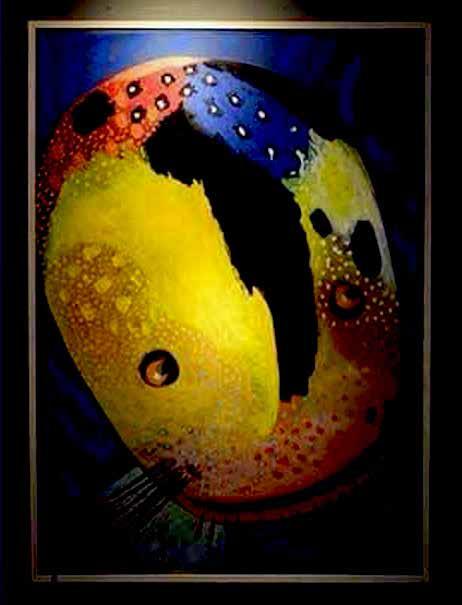

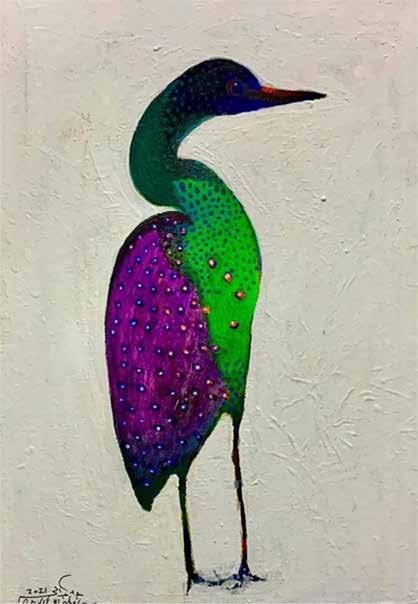

Abdel Wahab Al Abdel Mohsen

Fr Ivo Coelho is a Catholic priest belonging to the Salesian Society of Don Bosco. He was born in Mumbai in 1958 and schooled in Mumbai and Lonavla. He studied under the Indologist Richard De Smet at Jnana Deepa, Pune, and later specialized in the hermeneutical thought of the Canadian philosopher, theologian and economist Bernard Lonergan, earning a PhD in philosophy at the Gregorian University – Rome, for his work on “The Development of the Notion of the Universal Viewpoint in Bernard Lonergan: From Insight to Method in Theology” (1994). He was principal of Divyadaan: Salesian Institute of Philosophy (1988-90) and Reader in Gnoseology and Metaphysics. He was also rector at Divyadaan (1994-2002), secretary of the Association of Christian Philosophers of India (2000-02), and provincial of the Mumbai province of the Salesians of Don Bosco (2002-08). Since 2014 he is based in Rome where he is in charge of the training and formation sector of the Salesians of Don Bosco. He is the author of Hermeneutics and Method: The ‘Universal Viewpoint’ in Bernard Lonergan (Toronto, 2001) and a number of articles. He has also been editing the writings of Richard De Smet (1916-1997), with the following having been published so far: Brahman and Person: Essays by Richard De Smet (Delhi 2010); Understanding Śaṅkara: Essays by Richard De Smet (Delhi 2013); and Richard De Smet, Guidelines in Indian Philosophy (Delhi 2022). Till 2019 he was editor of Divyadaan: Journal of Philosophy and Education.

Life “after” death is something that intrigues me. It was something that intrigued also the great theologian Joseph Ratzinger, who went on to become Pope Benedict XVI. Ratzinger spoke, of course, within a Christian context, and so he talked of “eternal life” rather than of “life after death”. But I think the questions he asked could be of interest to everyone.

First, it helps to think that eternal life is neither spatial nor temporal. It is not a place, a “somewhere”, and it is not something that is “after.”

Perhaps we could think of eternal life as “now”, as somehow simultaneous with the now of our temporal and spatial existence.

Even better, it might help to think of “quality” rather than “quantity”. Eternal life is a quality of life.

Would it make sense to say that we have little experiences of eternal life already in this life? I think there are moments when eternal life bursts into the now of this life.

Let’s quote Ratzinger himself:

“Eternal life is not an endless sequence of instants, in which one should try to overcome boredom and the fear of what cannot have an end. Eternal life is that new quality of existence, in which everything flows into the here and now of love, into the new quality of being, which is freed from the fragmentation of existence in the passing away of instants....

“With this, it also becomes clear that eternal life is not simply what comes later and of which we now have no idea. Since it is a quality of existence, it can already be present in the midst of earthly life and its fleeting temporality, as the new, the other and the more, even if only in a fragmentary and incomplete form.”

I find this position bold, courageous, powerful, inspiring. Of course, I can only speak as a Christian. But I do believe that the kind of reflections offered by Ratzinger cross boundaries and speak to the people of our time.

God is a God of surprises. When thinking about eternal life or life after death, it would be only right to expect more surprises.

Perhaps we could even say that the parallel lines will meet – the parallel lines representing those who think there is no after life, and those who believe in eternal life.

All this involves, of course, a great purification of our images and imagination.

One of the great Christian images is that “heaven” or “eternal life” consists of a being-with-God that includes the whole of humanity – a communion with God that is at once a communion with the whole of humanity, brothers and sisters united in one family. It is a challenging vision. And it is something towards which we can work already in this life. The little or great experiences of human beings going out of themselves to reach out to their brothers and sisters, whatever their race, colour or creed, is, I believe, an experience of eternal life already in the now of this life.

All of us have our little tribal loyalties that sometimes transform into great conflagrations, as the history of the world unfortunately shows, even as I write. But every now and then, we are privileged to witness something beautiful and translucent that attracts us all at the core of our being.

For me one such instance is that of Christian de Chergé and his brother monks who were murdered in Tibhirine, Algeria, in 1996. I consider Chergé’s Last Testament one of the fundamental spiritual texts of our times. Anticipating his death, this human being was able to call his murderer “the friend of my final moment”:

“I should like, when the time comes, to have a clear space that would allow me... to forgive with all my heart the one who would strike me down.... And you also, the friend of my final moment, who would not be aware of what you were doing. Yes, for you also I wish this ‘thank you’—and this adieu—to commend you to the God whose face I see in yours. And may we find each other, happy ‘good thieves,’ in Paradise, if it pleases God, the Father of us both. Amen.”

Jean-Marie Rouart of the Académie Française puts it wonderfully:

“Their example makes us trust in man precisely when we lose hope in him. Believers or not, the example of these monks who died for what is believed to be nothing, but which is perhaps everything – that is, belief in values higher than life – inspires a respect and admiration that for an instant amaze us, as it happens every time we see man, often miserable, surpass himself in greatness.”

I believe sincerely that we all have little or great experiences of eternal life, moments of eternity that break through into time and leave us with gifts of peace, joy, love, even if only for a moment. Perhaps we are not always able to name them. Does it matter? What matters is the quality of our lives.

“Eternal life is present in the centre of time…. Like a great love, it can no longer be taken away from us by any circumstance or situation, but is an indestructible centre from which comes the courage and joy to go on, even if things around us are painful and difficult” (Ratzinger).

Don’t break your heads about what comes after, the Buddha could tell us. Live fully in the now. Live with karuna – compassion.

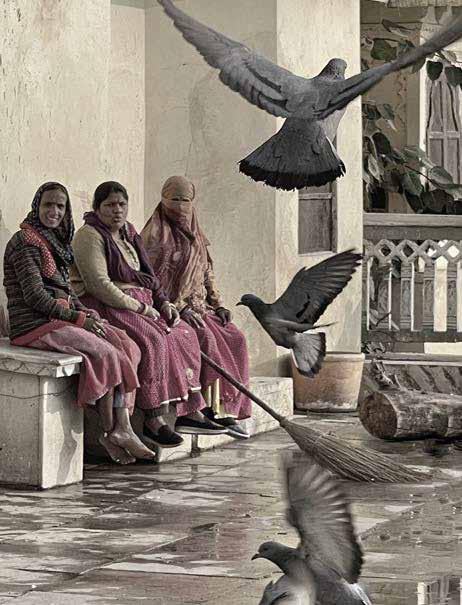

Mark Ulyseas has served time in advertising as copywriter and creative director selling people things they didn’t need, a ghost writer for some years, columnist of a newspaper, a freelance journalist and photo-grapher. In 2009 he created Live Encounters Magazine, in Bali, Indonesia. It is a not for profit (adfree) free online magazine featuring leading academics, writers, poets, activists of all hues etc. from around the world. March 2016 saw the launch of its sister publication Live Encounters Poetry, which was relaunched as Live Encounters Poetry & Writing in March 2017. In February 2019 the third publication was launched, LE Children Poetry & Writing (now renamed Live Encounters Young Poets & Writers). In August 2020 the fourth publication, Live Encounters Books, was launched. He has edited, designed and produced all Live Encounters’ 300 publications. Mark’s philosophy is that knowledge must be free and shared freely to empower all towards enlightenment. He is the author of three books: RAINY – My friend & Philosopher, Seductive Avatars of Maya – Anthology of Dystopian Lives and In Gethsemane: Transcripts of a Journey. https://liveencounters.net/mark-ulyseas-publisher-editor-of-live-encounters-magazines/ https://www.amazon.com/Mark-Ulyseas/

This essay was written and published in 2008. Since then I have updated it every year. It is a reminder to us that the inhumanity of humanity has not changed. In fact, it appears to be growing in intensity.

This year is grinding to a close, so what will it be in 2025?

More wars for religious or commercial purposes or perceived historical lands?

More bombings of civilians, children, hospitals and schools under the garb of fighting terrorism?

Cultural genocide... like the deconstruction of indigenous cultures for homogenisation by a godless State?

Child abuse?

Human slavery?

Theft of human organs?

More public stabbings of innocent people?

And is our dead better than their dead? Do we continue killing them?

All this talk of saving the world is pointless. Everything is done half-heartedly. Let’s make a resolution for the New Year to decimate the planet. Destroy all our natural resources, pollute the rivers and farm the seas to extinction. At least we would be doing one thing properly.

Is there another Mass Extinction in the making, perhaps the Palestinians, followed closely by the rest of humanity?

Are there more insidious revelations that expose the all-pervasive criminality of governments, international politics and sections of the Media?

Is the UN still a coffee shop for the rich and powerful to hang out and where honour still exists among thieves?

And are the medusa-like social media barons still lords of the manor? Do they control our hearts and minds and our freedom of speech? Or is the rise of artificial intelligence taking the baton from them to continue the relay race to the lobotomisation of humanity?

And are the pharma and armaments companies increasing their profits as the body count grows?

And is tourism fast becoming online voyeurism? Or, has the tourist flood gates opened to the peddlers of obscenity?

And is the ether now the domain of roaming viral vitriolic mindsets looking for any cause?

And is liberalism the bastard offspring of fascism?

And has exceptionalism and wokism become a fundamental right?

There is so much to choose from. It’s like a supermarket out there with all kinds of man-made disasters available on the shelves, one has simply to reach out and grab one. 2024 is ending on a note of negotiated delusions with the Climate Change Conference in Baku. What happened to the good old days when we used a blanket instead of a heater? All this talk of saving the world is pointless. Everything is done half-heartedly. Let’s make a resolution for the New Year to decimate the planet. Destroy all our natural resources, pollute the rivers and farm the seas to extinction. At least we would be doing one thing properly.

Statistics are essential in war zones. They can always be rearranged to suit one’s perceived objectives. The little numbers represent people, mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, relatives and friends. A neat way to manage these numbers is to write in pencil so that an eraser can be used judiciously. And as the death toll in war ravaged countries rises, a hysterical caucus threatens a host of other countries for deviating from the ‘the international rules based order’ like illegally invading countries on trumped up charges and bombing innocent folk back to the stone age. The ‘rules based order’ are, perhaps, former colonial masters and their former colonies in their death throes.

On one hand we talk of peace, love and no war. On the other hand, we bomb, rape, pillage, annex and subdue nations with money, military power and warped religiosity.

For instance, let’s take a quick look at Afghanistan. The British couldn’t control the tribes in the 19th century, the Russians failed miserably and the Americans with their assorted comrades in arms, poor souls, were being killed along with thousands of faceless unarmed Afghan civilians. I suppose life is cheaper by the dozen. After a twodecade war the invaders have left the country in the hands of the great unwashed. Afghan women and children are now at the mercy of these pathological misogynistic aberrations of humanity. Will the ordinary Afghan civilians ever get to live in peace?

And what about that European country presently being devastated by a war that has been created and funded by those countries whose mantra is ‘rules based international order’. Has it become the testing ground for newly developed killing machines? And when the killings subside will groups of loving hands at home descend on the land to make money from donations in the name of one fraud or another?

What about certain parts of the Middle East, areas that have become mass open-air abattoirs for the mindless slaughter of innocent people? Do you think they will run out of people considering the number of killings that are taking place? Education there is history – like the slaughter of unarmed civilians, including children, by an army from God. It stems from the barrel of a gun. The pen is for signing death certificates.

Statistics are essential in war zones. They can always be rearranged to suit one’s perceived objectives. The little numbers represent people, mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, relatives and friends. A neat way to manage these numbers is to write in pencil so that an eraser can be used judiciously. And as the death toll in war ravaged countries rises, a hysterical caucus threatens a host of other countries for deviating from the ‘the international rules based order’ like illegally invading countries on trumped up charges and bombing innocent folk back to the stone age. The ‘rules based order’ are, perhaps, former colonial masters and their former colonies in their death throes.

Africa, the Dark Continent, what can one say about its peoples and their ancient civilizations that have slowly been corrupted by large corporations and foreign governments meddling in the affairs of the states: Buying and selling governments on mammoth proportions? Oh, for the days of the Rwandan blood bath. Perhaps the genocide in Sudan has its moments of glory?

Are these the same countries that accuse China of ruthlessly dismantling the vibrant ancient Uighur culture, brainwashing and incarcerating the Uighurs in re-education camps whilst the Islamic countries appear deaf, blind and dumb to the slaughter of their fellow brethren?

Is Tibet now lost forever in the dragon’s jaws of modernisation?

And will Taiwan become just another killing field for jingoists in 2025?

This dragon, which had unleashed a terrible virus (a natural phenomenon?) on the world, killing millions, shutting down tourism and all but destroying economies, has quickly recovered from the scourge and is now selling merchandise in the millions across the world. Is this the soul of Profit & Loss - where people continue to get poorer while the rich get richer, like in democracies?

And is the much-peddled term of democracy actually the mask of plutocracy, where the rich get to be elected and poor are fed promises? And are democracies now avatars of fascism?

Africa, the Dark Continent, what can one say about its peoples and their ancient civilizations that have slowly been corrupted by large corporations and foreign governments meddling in the affairs of the states: Buying and selling governments on mammoth proportions? Oh, for the days of the Rwandan blood bath. Perhaps the genocide in Sudan has its moments of glory?

Everything is quiet now, no excitement and drama except for bloody popular uprisings, theft of natural resources and other inconsequential happenings like the sudden spread of highly infectious diseases and mass kidnapping of school children for forced marriage and conversion…and the continuing practice of female genital mutilation, which appears to be a thriving business across the world where doting parents in western countries take their little girls on ‘vacation’ cuts while their governments lecture Africans on the scourge of female genital mutilation.

Now let’s see who is left on the black board? Hmmm…the indigenous people of the Amazon are still fighting a losing battle with the powers that be to stop the plunder of their home, the rain forest, the green lung of mother earth. South America appears to be lost in translation. We never seem to get a lot of news from there except for soccer, drug lords, plunder of the marine world and the continued exploitation of the poor and defenceless by rapacious governments sponsored by those from the North and elsewhere. It has become the battle ground of powerful countries that use the common folk as cannon fodder.

What about the sub-continent, India? Do they still abort female foetuses or do they bury them alive, now? Burn women who don’t bring enough dowry? Is rape intrinsic to the male mindset? Do they continue to decimate wildlife? Persevere in the destruction of the environment? And do millions still exist on the threshold of life and death? And is the arrogant Indian Middle Class growing to newer levels of self-indulgence?

And is protection of the holy cow more important than feeding millions of people living below the poverty line? And are politicians continuing to feed off the socio-economicreligious insecurities of its people? And are sections of its media turning into manic performing artists, deliberately taking sides in political dramas and creating news for ratings?

Forgive me… I missed that little country to the west of India, the homeland of terrorists and an illicit nuclear arsenal – Pakistan, an army that has a country. Poor chaps they’ve had such a tiresome year with the constant ebb and flow of political violence and religious fundamentalism peppered with suicide bombers that probably the common folk want to migrate to the West… can’t really blame them. Their government is its armed forces’ ventriloquist doll. The common folks’ only desire is to live in peace to pray, work and procreate. Meanwhile, their government has been switching debtors from the West to China to the Middle East, countries that in turn have commercially colonised this country bleeding it by a thousand loans and assorted ventures like the supply of weapons to countries at war.

Now let’s see who is left on the black board? Hmmm…the indigenous people of the Amazon are still fighting a losing battle with the powers that be to stop the plunder of their home, the rain forest, the green lung of mother earth. South America appears to be lost in translation. We never seem to get a lot of news from there except for soccer, drug lords, plunder of the marine world and the continued exploitation of the poor and defenceless by rapacious governments sponsored by those from the North and elsewhere. It has become the battle ground of powerful countries that use the common folk as cannon fodder.

There are many countries that lecture China on its human rights. Wonder who has a perfect track record…The world’s last self-proclaimed superpower? A superpower that continues to interfere in the affairs of other nations by supplying state of the art weapons that are often used against civilians living a hand to mouth existence. I suppose the term ‘collateral damage’ is more palatable than the term… murder. There is a killing to be made on the sale of armaments but little or no desire to urgently help its own people devastated by natural disasters like massive fires and super storms and joblessness and crumbling infrastructure.

Let’s leave all this violence for some tuna, shark fin, whale, and dolphin meat. The Japanese and an assortment of other ‘civilised’ countries, Norway in particular, are so considerate to the world at large. For countries that pride themselves on rejecting nuclear weapons they have a rather odd way of showing their respect for the environment. I am referring to the mass killing of whales, dolphins and other sea creatures on an industrial scale. Actually, you must admire their concern. Ever considered the fact that they maybe ridding the oceans of monsters that take up so much space and are a serious health hazard to humanity? Will we see further progress of this mindless massacre with the mammoth 93,000 brand new whaling ship?

However, the dumping of radioactive waste into the ocean by Japan is its main contribution to preserving the environment in 2024.

I think Japan’s neighbour China has the right approach. It has dispensed with the cumbersome concept of human rights and its implementation. In its place totalitarianism with a large dose of plutocracy has been suitably installed. It uses its economic power and loan shark activities to threaten countries that do not kowtow its line.

There are many countries that lecture China on its human rights. Wonder who has a perfect track record…The world’s last self-proclaimed superpower? A superpower that continues to interfere in the affairs of other nations by supplying state of the art weapons that are often used against civilians living a hand to mouth existence. I suppose the term ‘collateral damage’ is more palatable than the term… murder. There is a killing to be made on the sale of armaments but little or no desire to urgently help its own people devastated by natural disasters like massive fires and super storms and joblessness and crumbling infrastructure.

Civil liberties are essential for the survival of a nation and so is the health of its people. In some areas of society where common sense has been the victim, Nature has found a way of retaliating with diseases like Ebola, AIDS, Swine Flu and Zika, infecting millions and helping to keep the population in check: Of course, with a little assistance from the scientific community who often test drugs on unsuspecting illiterate folk and other living beings, in the holy name of finding new cures, while making a profit.

And once again, as we have done in the past, this Christmas and New Year we shall all sit down to sumptuous meals, drink whatever fancies our taste buds, shop till we drop and pamper our overweight children and pets. It’s the season of happiness, love and family especially for the homeless, injured and maimed children of wars, missing people in Gaza, Ukraine, Russia, Afghanistan, Syria, Xinjiang (Uighur), Tibet, Yemen, and elsewhere; asylum seekers, political detainees and the fringe folk of the planet. They will surely be very happy and content with what they see, hear, feel and touch this festive season.

But Nature has a conscience. It has distanced itself from the prevailing pestilence, COVID-19… a deadly virus that originated from the den of the dragon…a Biblical-like plague not from God, but from the godless. A virus that has receded into the realms of laboratories after killing millions and making huge profits for pharma companies. There is now excited discussions and expectations for upcoming newer more deadly viruses like XEC, a new strain of COVID that has appeared in Germany and spread rapidly to other parts of Europe. Meanwhile, humanity is susceptible to dangerous new strains of super bacteria resistant to antibiotics.

As 2024 downs its shutters the price of human body parts has gone up. Human trafficking, organ trafficking and harvesting around the world (transplant tourism), including the ‘civilised’ nations, is now second only to drug peddling in revenue. Profiteers forecast a higher income in 2025, thanks to continuing wars, growing poverty, disease and transmigration of people (illegal migrants?).

And once again, as we have done in the past, this Christmas and New Year we shall all sit down to sumptuous meals, drink whatever fancies our taste buds, shop till we drop and pamper our overweight children and pets. It’s the season of happiness, love and family especially for the homeless, injured and maimed children of wars, missing people in Gaza, Ukraine, Russia, Afghanistan, Syria, Xinjiang (Uighur), Tibet, Yemen, and elsewhere; asylum seekers, political detainees and the fringe folk of the planet. They will surely be very happy and content with what they see, hear, feel and touch this festive season.

From genocide to environmental disasters to devastating civil wars it has been a roller coaster ride through many countries and peoples and cultures and religions. This journey will end only when we truly comprehend the reason as to why we have been put on this planet by a power far greater than we can ever imagine.

Merry Christmas and a peaceful New Year to you.

Om Shanti Shanti Shanti Om

Percy Aaron is an ESL teacher at Vientiane College in the Lao PDR and a freelance editor for a number of international organisations. He has had published a number of short stories, edited three books and was editor of Champa Holidays, the Lao Airlines in-flight magazine and Oh! – a Southeast Asia-centric travel and culture publication. As lead writer for the Lao Business Forum, he was also on the World Bank’s panel of editors. Before unleashing his ignorance on his students, he was an entrepreneur, a director with Omega and Swatch in their India operations and an architectural draughtsman. He has answers to most of the world’s problems and is the epitome of the ‘Argumentative Indian’. He can be contacted at percy.aaron@gmail.com

Marie Catherine Dungmaly (03.07.1930 - 12.01.22) was surely a saint.

I first met Sr Catherine, as I knew her, when a colleague asked if I would be willing to help a seventy-year-old Catholic nun improve her English. He was going back to Australia for medical treatment and didn’t know when he would be back.

I had been getting up early on Sunday mornings to teach disadvantaged children at a temple in a distant suburb but dropped out after a few weeks when it seemed obvious that the project was more about proselytization than altruism.

So, when Steve asked me to teach this nun, I wanted to know first if she was into conversions. She wasn’t he assured me, and since he was as averse to religion as I was, I agreed to meet her.

Sr Catherine was tiny bubbly nun in her early 70s. ‘Steve!’ she exclaimed, a beam across her face. Steve, a burly Vietnam-war vet bent down and gave her a big hug.

After the introductions, he told me what I had to do. And what to not do. ‘Don’t let her push you around,’ he advised. ‘She’s a stubborn old b@%!h. Give her a kick up the a@!e, when she deserves it.’ Steve was the archetypical abrasive Australian, as diplomatic as a derailed locomotive. I’d heard him swear at everybody but was taken aback that he was saying this to her face. Sr Catherine laughed, crouched in a karate position, then swung her hands to deliver a mock chop. Towering above her, he bent down and gave her another big hug. Twenty years younger than the nun, he was clearly under her spell.

Soon I was visiting Nazareth House, the home for girls aged 9 to 20 that she had founded many years before. Very quickly it became apparent that though English was her fifth language, she needed no help with it. She was fluent in Vietnamese, French, Lao and Thai and also spoke with considerable facility, Hmong and Khmu, two of Laos’s ethnic languages.

Like Steve, I was falling under Sr Catherine’s spell. Gradually my twohours-once-a-week lessons became 3-4 hour-sessions every couple of days. The English lessons were forgotten as we chatted politics and poverty, classical music and church doctrine, culture and Communism. and a host of other subjects in between. A voracious reader, she devoured the books I borrowed for her. The French classics she lent me were way above my interest and comprehension levels and after keeping them for a few weeks unopened, I’d give them back deftly avoiding any discussions.

Her fondness for certain kinds of French cheese – she always gave me half when she received gifts – was the result of the years she had spent in France, I thought. But then her tastes in music and literature, her ability with languages and her sophisticated mannerisms, betrayed the Mandarin influence from her mother’s side. She once told me that she was distantly related to Bảo Đại, the last emperor of Vietnam but didn’t want to discuss him further.

Sr Catherine would squeal with laughter every time, I told her an anti-clergy joke. ‘I must tell this one to the bishop,’ she’d often say. When she said that she belonged to the Sisters of Charity of Saint Jeanne-Antide Thouret, I teased her that even God didn’t know how many orders of nuns there were. She was rather tickled at that comment.

As our friendship developed, I admitted to her my initial misgivings about her being into religious conversions. ‘Poverty knows no religion,’ she replied sadly. ‘Most of the girls here are from the ethnic groups. And they are mainly animists.’ Later, I would observe that it was she, who educated them about their culture and traditions.

As our friendship developed, I admitted to her my initial misgivings about her being into religious conversions. ‘Poverty knows no religion,’ she replied sadly. ‘Most of the girls here are from the ethnic groups. And they are mainly animists.’ Later, I would observe that it was she, who educated them about their culture and traditions.

Sr Catherine looked forward to my visits, she told me. I took her mind off the daily problems she faced finding food and finances for the fifty-five children and the twenty or so nuns and lay helpers at Nazareth House. I admitted that I too looked forward to seeing her as she had become my caffeine fix.

Slowly, our roles changed as she became my teacher: brushing up my French and helping me learn Lao. Her profound insights into various Southeast Asian cultures and her experience with the children definitely informed my teaching practices.

In the large kitchen where the meals were prepared, she showed me how to make spring rolls and vegetable soups. Often, I’d stay for lunch, sitting opposite her, while she taught me how to wrap lettuce around certain food without splattering the contents over my shirt, or how to cut fruit efficiently. I couldn’t help but notice how deftly and daintily she handled the cutlery. After a while the bland diet for octogenarians (at seventy-four, she was one of the younger nuns) soon had me making all sorts of excuses to avoid meals there.

When I asked for help with my garden, she dropped by to make an assessment. She looked around, suggested what should be planted and where and then started pulling out weeds and tossing broken flower pots into the centre of the garden. Days later, she returned with her gardener, in a dilapidated Toyota pickup filled with saplings and flower pots. She instructed the young man to chop down a large tree to its stump and seeing my expression, explained that the tree was diseased and needed to ‘breathe’. Plants were uprooted and the soil prepared. On subsequent visits more saplings were planted, flower pots arranged and the pond drained and cleaned. Three large lotuses were floated in it and orchids hung at the entrance. Within a couple of weeks, my garden was transformed into a mini rainforest.

When I gifted her half a dozen guitars so that the children could learn the instrument, she picked up one and started strumming a few chords. I would sometimes find her in the chapel playing Bach or Vivaldi or singing one of her favourite choral pieces. Then I knew that something was troubling her and would sit quietly in the last pew until she had finished. Steve had introduced me to the music of Palestrina and I recorded some for her. Soon this 16th century composer became one of her favourites.

It wasn’t only in languages, or gardening, or cooking that Sr Catherine’s all-round abilities amazed me. When I gifted her half a dozen guitars so that the children could learn the instrument, she picked up one and started strumming a few chords. I would sometimes find her in the chapel playing Bach or Vivaldi or singing one of her favourite choral pieces. Then I knew that something was troubling her and would sit quietly in the last pew until she had finished. Steve had introduced me to the music of Palestrina and I recorded some for her. Soon this 16th century composer became one of her favourites.

She sketched, painted water colours and did embroidery.

Early one morning, Sr Catherine telephoned. She had never called at such an early hour. ‘Percy, please be here for breakfast at 7.30.’ It was almost an order. I showered, dressed and rushed to Nazareth House wondering what the matter was. The children should have already left for school but they were all assembled in front of the main building, dressed in their school uniforms. The doors to the chapel were wide open and there were flowers everywhere. Had one of the nuns passed away? Inside the chapel, the older nuns were sitting in the front pews.

As usual, she was in the centre of everything, supervising a dozen things. Then a motorcade drove up and five men emerged, dressed in black soutanes, two of them with red zucchettos or skullcaps. From the last car four men in ill-fitting light blue suits climbed out. Sr Catherine shook hands with all of them, then introduced some of us. I didn’t catch any names. After mass, we had breakfast in the refectory and I gathered that the cleric sitting next to me was an Italian monsignor. The men in the blue suits stood in the doorways, one of them clicking the occasional photograph.

After the motorcade drove off, there were so many questions for Sr Catherine. She apologized for the short notice, then said that one of the men was the apostolic nuncio, or papal ambassador, to Thailand. The others were emissaries from John Paul II. The Vatican had sent a high-level delegation to negotiate with the government on granting greater religious freedom. And who were the men in the blue suits? They were the secret police, she answered. I was not too pleased about my photographs ending up in the files of the Ministry of Public Security.

But her attitude to the Communists changed the day her father was put in a bamboo cage just high enough for him to crouch and displayed in the village square. He lay in the hot sun deprived of food and water. When she ran to him with a mug of water, one of the men knocked it out of her hand.

Sr Catherine was implacably anti-Communist. As a young girl in her native Vietnam, she was awe-struck seeing giants for the first time: huge Africans from the French colonies, packed into trucks. She mentioned the troop movements in the village and the headman told her to be careful but report everything back to him. This she found very exciting. But her attitude to the Communists changed the day her father was put in a bamboo cage just high enough for him to crouch and displayed in the village square. He lay in the hot sun deprived of food and water. When she ran to him with a mug of water, one of the men knocked it out of her hand.

The villagers were called upon to denounce him but they refused insisting that he was a good man, ever ready to help others till their lands. For two days he lay there before being released. Later she learned that her father had complained to the headman about the excesses of the Viet Minh who would arrive at night to squeeze the villagers for their meagre stocks of rice and vegetables. That her father was a staunch Catholic, was another reason, she strongly felt. More than sixty years later, her lips would quiver when talking about that incident. Catholic good, Communist bad, was her simple philosophy. President Ngo Dinh Diem, the former South Vietnam dictator was a good man, she always insisted.

Her animosity towards Communism was not directed at individuals. She admitted openly that her work in the country was possible only because of closet Catholics and other sympathetic people in authority.

During the very difficult post-independence years, she was always ensured a steady supply of military uniforms to sew. Though there were no cash payments for the work, the rations she received in compensation were adequate to feed her nuns and others.

In 2006, at the government’s request, she opened the Luang Prabang Deaf and Dumb Centre. During one particularly heavy monsoon, the mountainous roads were blocked due to landslides and food supplies were running low. She went to see a very high official in the national airline to plead for a discount in the air-freight. The man told her furiously that the airline was not his private business and tossed the letter back at her.

Her animosity towards Communism was not directed at individuals. She admitted openly that her work in the country was possible only because of closet Catholics and other sympathetic people in authority.

During the very difficult post-independence years, she was always ensured a steady supply of military uniforms to sew. Though there were no cash payments for the work, the rations she received in compensation were adequate to feed her nuns and others.

She was out of the building when she noticed the red stamp on the paper with his signature: the 200 kg of rice and other supplies were to be flown to Luang Prabang absolutely free of charge. Once in Sydney, the check-in staff at the Thai counter allowed me an additional 45 kg over my allowance at no additional charge, when I mentioned that I was carrying clothes and toys for an orphanage in Vientiane.

‘I really worry when the younger girls, or older nuns fall sick late at night’, she once said. ‘They can’t wait till the morning and admitting them to a hospital at night is a big problem.’ I mentioned this to a friend who had been a professional nurse back in her country. Before the end of the week, my friend had collected medical supplies to run workshops in first aid for the younger nuns, though she insisted that they call her at any time of the day or night. Catherine, she added, handled the syringes and the IV tubes like a trained medic. Later, I learned that my friend was bringing in medical supplies in her embassy’s diplomatic bag, with the full permission of the ambassador.

Sr Catherine seemed to work her little miracles on me too. Every now and again, she would ask me to fix her desktop. My knowledge of computer hardware is limited to a little more than the ON/OFF switch. I’d tell her that I would bring in an expert on my next visit but she’d insist that I first give it a try. The problem would be solved and when asked what I had done, I had absolutely no idea. She’d dictate letters to me in French and despite my basic knowledge, there would be very few mistakes when she’d proofread.

The younger children, when not at school, were always hanging around and the five or six dogs she had adopted were like a security detail. She had to pet or talk to them before they went off wagging their trails. When we walked near the enclosure where the cows grazed, the animals would walk along the fence until she had stroked their snouts and said some words to them. Then they’d twitch their ears and trot off.

Sr Catherine wanted to attend her grandnephew’s ordination in Los Angeles and asked my help in applying for her US visa. Late one evening after work I went to Nazareth House and started the tedious job of filling in a form designed by some brain-dead bureaucrats. She sat beside me, as I read out the questions and typed her answers. Had she ever been a member of the Nazi party?

Once a month I would travel approximately six hours to Thakhek, about 350 km away, to see her. After a night’s stay, I’d visit her for an hour or two the next morning, then catch another dilapidated bus back to Vientiane. The return journeys were even longer as the driver and his helper stopped to smoke, drink, stuff passengers into standing position in the aisle and even load motorbikes on to the roof of the bus. Each time, I swore that it would be my last trip down south. But Sr Catherine was waiting for my visits and the books that I would carry there. Later, it made more sense to save my shoulder from injury by buying her a Kindle and loading up about 200 books at a time to keep her occupied for a month or so.

No. At another question I quickly clicked ‘No’ without reading it to her but she wanted to see what it was. If a septuagenarian nun’s laugh could be described as a guffaw, then that is what she did at being asked if “she was seeking to enter the United States to work as a prostitute or procurer”. At the embassy interview, the visa officer couldn’t understand why she wanted to travel all the way to Los Angeles for just one day: It would take her longer than that to make the round trip, he tried to make her understand.

Sr Catherine was so integral to Nazareth House, that thinking about what would happen to everything when she passed, depressed me immensely. But when the government asked her to set up the centre in Luang Prabang for children with hearing and speech disabilities, she willingly accepted, feeling that her work in Vientiane was complete.

For various reasons, my worst fears, soon came to pass. Stories of what was happening at Nazareth House after her departure upset her so much that she never set foot again in that place. Years later, when she was moved to the retirement home for nuns in Thakhek, her eyes would moisten, when anybody mentioned what they had seen there. I myself, never went back to Nazareth House again, after one such visit.

Once a month I would travel approximately six hours to Thakhek, about 350 km away, to see her. After a night’s stay, I’d visit her for an hour or two the next morning, then catch another dilapidated bus back to Vientiane. The return journeys were even longer as the driver and his helper stopped to smoke, drink, stuff passengers into standing position in the aisle and even load motorbikes on to the roof of the bus. Each time, I swore that it would be my last trip down south. But Sr Catherine was waiting for my visits and the books that I would carry there. Later, it made more sense to save my shoulder from injury by buying her a Kindle and loading up about 200 books at a time to keep her occupied for a month or so.

The pleurisy and other health problems didn’t slow her down and eventually the nuns got her a portable oxygen cylinder to drag along when she couldn’t sit still. Even then she was always thinking of others. She asked me for a knitting machine and endless supplies of wool so thar she could knit warm clothes for poor people to sell for an income.

One January day, I received word that she was deteriorating fast. By the time I arrived in Thakhek, she was slipping in and out of consciousness. Everybody seemed to be waiting for me and a couple of them shouted into her ear in Lao and French that I had arrived - as if that was going to revive her. I sat next to her bedside and rested my hand on her forehead, then held her right hand in both mine. As her life was ebbing away, many memories floated past. And a thought - I had had many times before - came back to me: that I had been truly privileged to have actually known a saint.

But her inability to keep working for the poor was beginning to get her down. ‘I’m ready to go,’ she’d always say, on each visit. ‘When will the Lord call me?’

One January day, I received word that she was deteriorating fast. By the time I arrived in Thakhek, she was slipping in and out of consciousness. Everybody seemed to be waiting for me and a couple of them shouted into her ear in Lao and French that I had arrived - as if that was going to revive her. I sat next to her bedside and rested my hand on her forehead, then held her right hand in both mine. As her life was ebbing away, many memories floated past. And a thought - I had had many times before - came back to me: that I had been truly privileged to have actually known a saint.

Shortly after midnight, her Lord called her.

José Truda Palazzo Jr. is a wildlife gardener, environmental consultant and writer with a career spanning 46 years and 14 books published as author or co-author. He served for almost two decades in government delegations to international conservation treaties and is a co-founder of many conservation organizations around Brazil and South America, having led successful campaigns for the establishment of several Marine Protected Areas in his home country. José is also a Member of the IUCN (World Conservation Union) Task Force on Marine Mammals and Protected Areas and its Tourism and Protected Areas Specialist Group, a Life Member of the Australian Conservation Foundation, and a Board Member of the Brazilian Humpback Whale Institute, having received in 2023 the Animal Action Award of the International Fund for Animal Welfare for his lifelong efforts to protect whales around the world.

Atop a windy cliff bordering the wild shores of Península Valdés, in Patagonia, lies a rusty old folding chair that once lived inside a small, corrugated tin hut with ample windows opening towards the sea – now long gone after being blown away by one of the legendary windstorms which ravage these latitudes from time to time. The lonely chair, however, is still there, defying time and the elements.

This chair once belonged – or will eternally belong, rather – to a friend of mine. Dr. Roger S. Payne, one of the greatest geniuses of our time, and founder of modern non-lethal whale research. Together with his first wife Katy, Roger was the first to understand that humpback whales not only produced aleatory sounds, but created veritable songs, with themes that were repeated by several individuals in the same population during mating season, and which varied over time and between breeding areas, eerie and harmonious melodies which helped save not only their species, but all great whales, from extinction by the greed of whaling fleet barons. Roger’s recordings of humpback whale songs reached millions of people around the world, including on long-play records issued from 1970 onwards and in a flexible one inserted in a special edition of National Geographic magazine in 1979, right in time to fan the flames of a growing global movement against whaling. Thanks in no small part to his efforts, commercial whaling was banned in most of the world’s seas in 1986, and whales started to walk back from the brink.

It had been a while since I’ve been to Camp 39, and in my most recent visit, climbing the path to the top of the cliff, finding the empty chair and looking down on the frolicking right whales in the calm clear waters of the gulf, I had to contend with conflicting feelings. On one hand, I was trapped in a deep sense of loneliness and loss watching that scene, as if contemplating a full orchestra without its maestro; on another, which fortunately replaced those thoughts quite soon, a sense of wonder, gratitude and fulfillment of having been blessed both with Roger’s presence in my life and the legacy he left for me and all of us, of these magnificent whales multiplying slowly but steadily down there in the gulf, of our enhanced awareness about our lives being so interconnected with these still mysterious but no longer distant creatures.

Roger also realized from his early studies in the Caribbean that humpback whales could be individually set apart by the rather distinctive patterns of black and white (and long-lasting scars) in their tails, veritable “fingerprints” which helped, once you had these markings photographed and catalogued, figure out whether they frequented the same breeding grounds over time, where they migrated for food, how they interacted, which calves were born from whom, and other very important traits that helped understand their biology and behavior. Before these findings, “whale research” was basically done by jumping aboard a whaling vessel, measuring, weighing and making notes on dead whales and their organs.

Individual markings on whales were not exclusive to humpbacks, though. In the early 1970’s, Roger moved with his young family to Península Valdés in Argentina, a portion of the Patagonian semidesert that juts out to sea nearly halfway between Buenos Aires and Tierra del Fuego, to study a much rarer species, the southern right whale, which survived in a still numerous breeding ground in the two gulfs encircling the peninsula and its high fossil-laden cliffs. Round, black, docile and easily approachable, right whales could be told apart by a different set of markings: the callosities in their heads, covered in yellowish or whitish cyamids, a small crustacean also called whale lice. His favored research area, named Camp 39, overlooked San José Gulf and is teeming with whales every winter and spring. Here, Roger built his tin hut by the tall cliff from where he spent countless happy hours studying “his” whales, and laid the foundations of longterm cetacean studies that would influence two generations of scientists and marine conservation initiatives across the globe.

I was fortunate enough to have met Roger at an International Whaling Commission conference in Buenos Aires in 1984. By that time my little group of volunteers had just rediscovered the surviving population of right whales off Southern Brazil, and he was immediately excited by the prospect of collaborating with us. In 1985 he would invite us over to Península Valdés, where my brain swelled with knowledge and insights, and our friendship flourished. Over time, I would meet Roger here and there, from Massachusetts to South Africa to Buenos Aires, and there would always be many laughs and an inordinate flow of information and ideas.

It had been a while since I’ve been to Camp 39, and in my most recent visit, climbing the path to the top of the cliff, finding the empty chair and looking down on the frolicking right whales in the calm clear waters of the gulf, I had to contend with conflicting feelings. On one hand, I was trapped in a deep sense of loneliness and loss watching that scene, as if contemplating a full orchestra without its maestro; on another, which fortunately replaced those thoughts quite soon, a sense of wonder, gratitude and fulfillment of having been blessed both with Roger’s presence in my life and the legacy he left for me and all of us, of these magnificent whales multiplying slowly but steadily down there in the gulf, of our enhanced awareness about our lives being so interconnected with these still mysterious but no longer distant creatures.

Roger Payne is likely a good example of the special friends that transit through one’s life with enough power (light) (energy) (meaning) (choose one or many!) to change it profoundly. I have always been a person of very few true friends, perhaps a symptom of growing up interested in books and Nature in a country where most people – regardless of social and economic status - are illiterate and only care about soccer or celebrity gossips, and couldn’t give a damn about our planet and its woes. But walking through life over the last six decades has been a journey molded by friendships with those rare individuals who see beyond the soccer field (or, in most recent times, the cellphone screen). But how do you find and develop these special friendships that help define one’s character and, ultimately, one’s destiny?

I wouldn’t want to enter into the swampy realm of the old dichotomy of nurture versus nature. Perhaps our genes do have a major say in who we will become, culturally speaking; perhaps not that much. In my particular case nurturing had a lot to do with it. My father was my first great friend and maybe a good example of that too. An economist by profession, he had the blessing of going to school to learn with some of the very last scientist-priests of Brazil in the 1930’s and 40’s, mostly naturalists who took advantage of the liberty given by the Jesuit order to roam the country, explore and write. When in my teen years I started to show an acute interest in environmental activism, the young student who had walked the wilds of southern Brazil with his enthusiastic teachers in numerous excursions, seeking an understanding of the exuberant Nature all around, came out from the heart of the old bank director to guide me in my life-defining path.

My father, already in his 70’s, would take me to conservation groups’ meetings, buy me an enormity of Nature-related books which were both expensive and rare at that time, and drive me around to meet conservation icons, and eventually to Patagonia, which would somehow become a prelude to my meeting with Roger Payne.

Being so young when I met these special friends who were much older than me meant that I was at an optimum time to absorb their teachings and, to a great extent, their views on life and our duty towards other species. But it also meant that empty chairs would become a constant in my history of friendships. And all of these empty chairs have taken hold in my mind with the dual nature of an atomic particle, sometimes hurting for the missing presence of these special people, and other times filling me with joy for having partaken in their company and wisdom. And these empty chairs take many, many forms. A walk along the Guaíba lake in Porto Alegre (get your Googlemaps ready for this part!) watching the portentous native fig trees by the road reminds me of Augusto Carneiro, who pioneered most of the fight for urban flora and fauna in Southern Brazil and got me into the global campaign against whaling (thereby leading later to the meeting with Roger Payne).

A trip to the hills of Santa Teresa in Espírito Santo led me to the trail ending by a waterfall where Augusto Ruschi, a celebrated hummingbird researcher, is buried, and who befriended me in 1979 right around the time when he was doing press conferences carrying a shotgun and daring the corrupt State authorities of the time to come and cut down his forest sanctuary as they were threatening to do for a “development”(they never did and the forest and its hummingbirds are still there). Strolling down to the foot of Leme hill framing the limit of famous Copacabana beach in Rio de Janeiro, my mind floats to the many memorable chats with Admiral Ibsen Câmara, former deputy Chief of Staff of our Armed Forces Command and staunch opponent of Japanese whaling interests in Brazil, and a strong advocate of national parks and protected areas.

Names and places, deeds and ideas, shared bonds which somehow have become who I am and also become a long-lasting legacy through the parks I helped create and the species I was able to help save from oblivion.

Not all chairs are empty though.

Roger Payne’s chair by the cliff is in fact surrounded by others which are full of both himself and other unique minds. In the same trip that I mourned Roger’s physical absence and celebrated his permanence in the whales and people he touched with his mind (sensu Leonard Cohen), I reunited with Claudio Campagna and Guillermo Harris, two intellectual giants whose contribution to Patagonian conservation cannot be adequately described in words; with larger-than-life Rodolfo Werner, who leads the Latin American charge for the protection of Antarctica, the planet’s vital and fragile regulator; with Adalberto ‘Peke’ Sosa, who first led Roger to see the right whales up close in his small boat and, now in his eighties, continues to lead the family who built the longest-running whale watching company in the world (please read more about in my article printed in the July 2021 issue of Live Encounters).

Back at Peke’s family home I hastily send some whale photos over to Dan Morast in the United States, who “adopted” me early in my activist career and helped me and many other developing country folks rock the Whaling Commission and defeat the whalers’ misdeeds. I think of my recent bouts with cancer and hope for our chairs to not be vacant anytime soon so I can keep drinking on their friendship fountain and aspire to they enjoying mine too.

Far down the line of chairs by the cliff of life are the younger friends who also mean so much for one’s spirit. From Márcia Engel who valiantly led the Brazilian Humpback Whale Project for almost three decades and against all odds made it become the foundation for the largest and longest-running whale research and conservation program on Earth, to the Project interns that bring inquisitive vitality to our work with their never-ending (I hope) quest for a better world; to the new generation that continued Roger Payne’s work at the Whales Conservation Institute in Argentina; all the way to my closest friend and ally Nalu, my wife and dive buddy.

Why so many names in an article to be read by people who may never get to know them better? Because by thinking and writing them here and elsewhere, be their chairs empty or full, every time one thinks about how past and present friends make us who we are, I think they all become alive and closer, and somehow receive the best energies of those reading their names and learning about their importance for the world.

Because of that, of the way that we remember our friends, Roger’s chair is no longer empty now, and perhaps my younger friends will one day make my own chair by the cliff to be filled with their thoughts and actions - inspired, I would wish, by my own legacy.

Find your empty chairs by the cliff and celebrate them. Visit your friends’ chairs which are still in use, either in presence or mentally, more often. The world is in great need of more people who are not islands in the void, but constantly and endlessly built by the presence, the ideas and the warmth of others – and it needs it right now.

Greta Sykes’ third novel called ‘Eve meets Dante’ is coming out this autumn with Pegasus. It is a story weaving together the fates of extraordinary women from antiquity to the Renaissance. Her other novels also cover the story of women. Her 2016 novel of a family’s life during the rise and fall of the Weimar Republic was followed in 2020 by her story of Mesopotamia and the Goddess Inanna. Greta’s poems have been published in numerous anthologies, the latest is called ‘Under Siege’, available at the British Library. Greta’s essays are accessible at academia.edu and liveencounters.net.

I spent a week in Verona to study Italian. While walking above the river Adige I discovered a Dante exhibition in the castle San Pietro overlooking the town. It was entitled ‘Paradiso – Dante Profeta di Speranza’ (Paradise – Dante the prophet of hope). It was the third part, the previous two having been ‘inferno’ and purgatory’, of an initiative by L’Associazione Rivela. It made use of artwork from a new edition of the Divine Comedy by the publisher Mondadori with art work by Gabriele Dell’Otto and a commentary by Franco Nembrini. Many young volunteers were brought together to study the text and explore its meaning for themselves.

The exhibition’s aim was to use Dante’s poems as a point of reference and support for the participants human, cultural and spiritual growth. Each of them was able to bring their own existential questions, their search for the fullness and meaning of life to the poems. They engaged with visitors to the exhibition to explore how they understood Dante’s thoughts and open their eyes to the present-day relevance of them. The great poet became the prophet of hope, that is, a credible and contemporary interlocutor, whose words and concrete experiences of love, pain and suffering can help young people to become capable of facing life’s journey with hope and courage:

Canto 1

To soar beyond the human cannot be described In words. Let the example be enough to one For whom grace holds this experience in store. (L70-73)

For the past three years I have been working on my third novel ‘Eve meets Dante’ (to be published in 2024). I became inspired by the Divine Comedy and the journey Dante (born 1265) undertook to overcome the suffering that threw his life into disarray and poverty. He was exiled from Florence due to political intrigues never return to his hometown or face certain death. He remained a forever traveller, homeless and suffering severe poverty. His ability to transcend a bad luck story into one of extreme beauty remains unique in literature and, perhaps, can only be compared to Friedrich Nietzsche’s transmutation of suffering into insight. Dante positions the adventures of his travels through hell, guided by Vergil, against the backdrop of his love for Beatrice, a young woman he met as a nine-year-old and could never forget. He only saw her a couple of times but was smitten. When at the age of twenty-one the now married Beatrice fell ill and died, Dante was heartbroken for weeks. His poet friends had to persuade him to leave sorrow behind and seek refuge in his poetry. It is likely that Dante’s exile led him to develop the intense and passionate focus to write a book in verse that speaks to all humans looking to find sense, truth and meaning in a chaotic world.

One may think that medieval times did not have the advantage of modern science and technology. Yet the belief that such knowledge should lead to our world being a better place, or ought to be a better place, was already shattered during two world wars. Extraordinary as it seems we still face similar problems to life in Florence seven hundred years ago, such as homelessness, poverty, wars and elites that care little about making any genuine change by creating more equality. The belief in technological fixes, AI and the power of science is being misconstrued into a toxic fog of narratives that are created by wealthy companies, spun by the media into daily repetitions and regurgitated by government staff.

Dante was thirty years of age when he was elected one of the city’s six priors. He held office from 15th June to 14 August 1300. As one of the priors he had to join a guild. He joined the Physicians and Apothecaries who also accepted poets. The priorate was the highest office in the Republic of Florence. The position only brought me trouble, Dante later said. The quarrels between the aristocracy or grandis and the rising merchant classes represented by the guilds were a constant issue which widened into political turmoil.

Dante fell victim to these struggles between different factions that even involved pope Bonifacios. He was condemned to death by being burnt on the stake. He spent the rest of his life being a traveller in the regions of northern Italy such as Emilia Romana, Piemont and the Veneto. His most famous work The Divine Comedy written at the time of Chaucer, but in a language still spoken by Italians today, remains the cornerstone of the Italian cultural tradition. The experience of seeing it presented by young people engaging with it using their own perspective illustrates the work’s 700-year relevance.

The divine comedy is written in three parts, the inferno, purgatory and paradise. In a poetic form called terzo rhima made of a verse of three lines it delves into the punishments for people Dante considered bad and pleasures for those who he considered good. It is deeply embedded in the Christian tradition, the concepts of heaven and hell and the seven deadly sins. With this work of poetry, Dante transcended his pain of lost love, loneliness and suffering into a work of art. Dante’s divine comedy influenced many British poets and writers to engage with the themes he raises. Chaucer mentions it in the Canterbury Tales. John Keats, Shelley and Byron as well as TS Eliot made references to Dante in their work.

Seven hundred years after Dante’s God was declared dead by several philosophers, such as Schopenhauer, Heidegger and philosophy tutors at the universities of Cambridge and Oxford. They were challenging the whole notion of philosophy having anything to do with morality. Imbued with ideas of logical positivism developed by the Vienna school. Freddy Ayers declared moral judgements to be mere expressions of personal preferences. Jean Paul Sartre’s existentialism saw the modern person’s mode of perceiving themselves as ‘thrown into existence with nothing to hold on to’ at a time when two world wars had left Europe devastated. Yet, another poet who lived in exile only a couple of decades earlier also struggled with the notion of the loneliness of existence and a turning away from the established Christian church. In the 1880s Nietzsche had left behind his love affair with Richard Wagner and his wife Cosima after they had moved to Bayreuth. Nietzsche moved to Turin and fell in love with the town. It fulfilled his need for a classical and majestic environment.

© Greta Sykes

He returned to the Renaissance to rediscover his spiritual soul. ‘Also sprach Zarathustra’ is followed by ‘Beyond good and evil’, both works around the same set of ideas that were on his mind. Nietzsche who was struggling with a number of illnesses embraced the Italian environment in Turin where he often went to hear Verdi’s music. Verdi’s music spoke to him in a lighter spirit and a natural joyfulness which he found lacking in Wagner’s darker, mystical and romantic music. Nietzsche had moved from romanticism to embrace the Renaissance, containing for him powerful aspects of modernity, like liberation of thought, disdain for authority, and the triumph of education over arrogance. His philosophy under the influence of Verdi and a return to Immanuel Kant moved towards a longing for a joyous perspective for all of humanity. In ‘A prelude of the future’, the subtitle of ‘Beyond good and evil’ he demolishes human pretensions, lies and judgmentalism. Similar to Dante’s evocations of peoples’ suffering in inferno to sharply outline wrongdoing, Nietzsche exposes falseness with gusto only to celebrate a way forward that can free humans from the nausea of pettiness, prejudice, and envy. Lonely and antisocial as he lived his life now in his writing he expressed the deepest love for humanity. He wished a person to be ‘superhuman’ in their ability to overcome negativity, depression and nihilism and instead to develop the strength to feel enjoyment and fulfilment. Written in poetic aphorisms show him struggling to find a way to embrace Christian values and ideals without endorsing its institutions.

Pier Paolo Pasolini

Like Dante and Nietzsche, Pasolini was first and foremost a poet. Growing up during the rise of Fascism in Italy, he was born in Bologna in 1922 and began early in his life to agitate against Mussolini. He stood by his mother who was treated badly by her fascist husband. He wrote poetry in the Friolean local dialect which, like other local dialects, was forbidden by Mussolini. After the war Pasolini moved to Rome. While making his movie ‘Erotic stories from 1001 nights’ he witnessed the destruction of the old town of Sanaa to make room for a new town development. This event had a marked influence on him. It confirmed for him the suspicion that global consumerism was the new fascism in that it worked to eradicate traditions, local culture, language and uprooted people from their belonging.

Pasolini saw himself as a Marxist who understood tradition and culture as lived by ordinary people in their villages as providing the background and inspiration for progress and a better life for all. ‘I act more modern than all those who want to modernise, by searching for our brothers and sisters who are not with us anymore.’

‘The real intolerance comes from consumerism, which is, with its apparent generosity of the multitude of goods the worst, evil, cunning, coldest, and unforgiving form of intolerance. It bears the mask of tolerance and through its very falseness affects people on a deeper level than the fascism of the Mussolini type which was open and in your face violence.’ Yet the mask of the consumerist fascism comes off immediately whenever those in power see it as necessary. The mask of tolerance can be withdrawn, as it is in the case of Julian Assange, Edward Snowden and thousands of others who have suffered at the hands of the elite.

Pasolini sees the consumer society as a dictatorial civilisation. It has realised the old fascism successfully by making it look ant fascistic, liberal, benign. Modern so-called antifascists only support the mask of liberalism and are therefore happily embraced by the elite who will send the police to support them. The writer Ignazio Silone saw what was happening and prophesised:

‘When fascism returns it is not going to say ‘I am fascism’. It will say ‘I am antifascism’. The totalitarianism of our consumer society cannot allow any perspective outside itself. It must dominate totally. Social networks must be censored, if they permit alternative views. Views that manage to become public are quickly condemned and cast into abomination by calling them conspiratorial or antisemitic. Bit by bit a world view is put together that tells us that truth is a lie, that we need to go to war to create peace, that men can be women and women can be men. The sacred is absent from this world. Dante, Nietzsche and Pasolini, all deeply spiritual poets, viewed the Sacred as a deep sense of belonging in nature through love and embracing tradition and ritual as they naturally evolved through human history. Otherwise only the abyss is left. All three poets and philosophers spent a lifetime of their philosophical thinking on finding and comprehending the Sacred or the Divine. They recognised that without it a human society will fall apart, become bereft of meaning and purpose, other than making money.

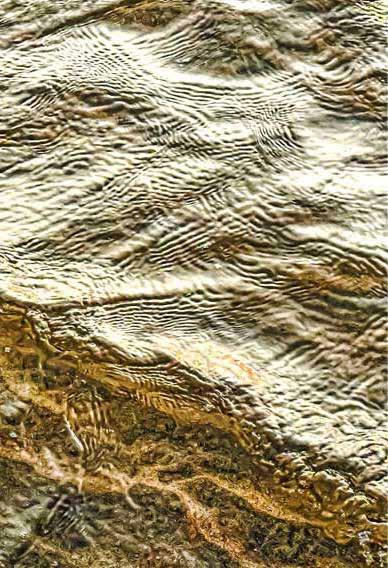

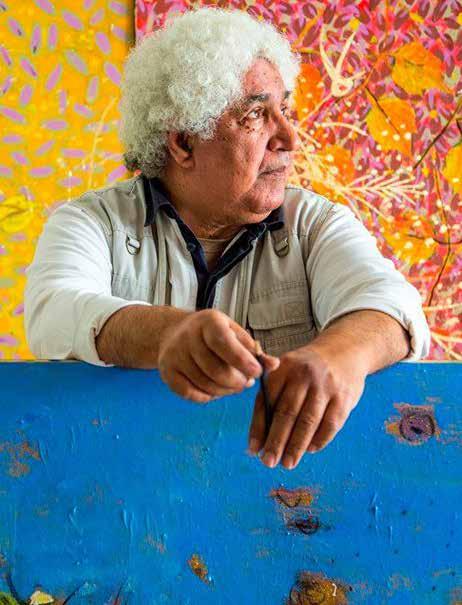

Gopika Nath is a textile artist-craftsman who stitches and writes, threading her syllables into poetry, creative non-fiction and art reviews, where her art practice provides a mirror to the self. Using nature as a catalyst to go within and re-look at her life and human nature with a renewed perspective - deeply inspired by her observations of life along the western coastline of the Arabian Sea. A photography enthusiast and avid photographer, the camera in an important tool in her art practice and the photographed image an adjunct to art works that are crocheted, knitted and embroidered. https://gopikanath.co.in/ A Fulbright Scholar, alumnus of Central St. Martins School of Art and Design [UK], Gopika lives and works in Goa, India.

“The sea is emotion incarnate. It loves, hates, and weeps. It defies all attempts to capture it with words…... No matter what you say about it, there is always that which you can’t.”

― Christopher Paolini, Eragon

Walking along the coastline, observing facets of the Arabian sea, I have felt a parallel in the proclivity of her tendencies and human nature. Where, the visual seascape presents intangible nuances, more evocative than words can describe.

Water is an essential component of the human body and of the planet. The sea, as a dynamic force of this element inspires Robinson Jeffers to suggest “The tides are in our veins” and John Masfield says “I must go down to the seas again, for the call of the running tide/Is a wild call…that may not be denied…”. Thus, proposing that the sea isn’t extraneous, but integral to our being, alluding to the idea that emotions disturbing the ‘water’ within, must echo the tides weaving in and out of the shore. Churning within skin, organs and bones– generating and reflecting feelings.

Emotional geography studies sentiments that arise in response to geographical locales. However, I have creatively interpreted this to express the topography of human emotions.

The philosopher Seneca compared emotions to the rampage of a sea storm - evoking anger, revenge, doubt and uncertainty. I see subtler nuances of the same feelings, in the gentler waves that kiss the shores. In these images, I present a few that simulate quiet intensity, restrained rage and apprehension.

Katie Costello was born and raised in Hubbard, Ohio, USA. Her greatest passion in life has always been to help animals. She is lucky enough to be a licensed veterinary technician and owner of The Canine Campus Training and Wellness Center and The Canine Campus Bed and Biscuit Inn, where she helps animals through behavior work, does training of all types including aggression, fear, and service dog work. A vegetarian since she was 6 years old and a vegan for the last 15 years, she currently has 7 dogs, 5 cats, 7 chickens, 3 roosters, 1 very special turkey and 2 farm pigs that are amongst her dearest friends. She is founder of 2 non-profit organizations, K-9’s for Compassion (Co-founded with her father), a therapy animal group and The Together 3 Journey, a service dog organization. She has been on the board of many animal organizations throughout her life, including Happy Trails Farm Animal Sanctuary and C.H.A.I.N. (Community Helping Animals In Need) and SVBT (Society of Veterinary Behavior Technicians) She enjoys freelance writing about (mostly) animals for different magazines, with her favorite being Live Encounters! https://thecaninecampustraining.com/

The barrier island of Assateague is a 37-mile-long island that spans the coast of Maryland and Virginia in The United States of America. Much of the area is marsh land. The entire island, in both states, is considered Assateague Island. However, the National Park system in each state is different. Maryland (About 2/3 of the island) is known as Assateague National Park, and the Virginia side (about 1/3 of the island) is known as Chincoteague National Park.

When I was a little girl, I loved to read. One of my favorite books was Misty by Marguerite Henry. This book was magical to me as a child, and I waited my entire childhood to grow up and be able to see this magical place for myself.

My first visit was in 1994. It was as magical as I had read about. Feral (wild) horses running free on the island. I went to both the Maryland and Virginia side in that first trip, and fell in love. Over endless visits since, and falling more in love with the location than the little girl’s version of Misty, my thoughts and ideas have changed in so many ways.

On the Maryland side the horses are “owned” by the National Park System. These horses are truly living wild. They do not offer veterinary care, or food during harsh winters. Veterinary care normally only comes in the form of an animal who has been severely injured and is determined to need to be euthanized.

On the Virginia Side the horses are owned by the Volunteer Fire Department. They offer extra food through harsh winters, they do veterinary care twice a year (which is done through stressful roundups) and then they have their annual pony penning, where horses are forced to swim under stressful conditions and sent to an auction. There is also a fall auction. These horses are determined by humans on which side they should live and which mares they will get. These horses are living pseudo wild lives. I also think the pony penning is an archaic and horrible event. Yearly horses die from the stress they are asked to endure, and then they are paraded down the streets of Chincoteague in celebration. It is a complete disconnect between people and horses.

Now let me be clear. I am not anti-fire department by any means. I also am not against offering food during really harsh winters. On the surface much of what they do doesn’t sound awful. However, the definition of freedom is: “The power or right to act, speak or change without hindrance or restraint” and “Absence of constraint: The state of being free from necessity, coercion, or constraint in choice or action.” So, freedom is about choice. Having choices to decide things in your own life. To decide what you like and what you don’t. This is, in my world, true of every single animal I work with, 2 legged or 4. To deny an animal a right to choose is such a violation of ethics.

I love the idea of the freedom, and after witnessing these horses in their true “wild” state is amazing. Their eyes shine differently, they hold their heads differently, their strong familial ties unwavering. I am in awe of them.

In the book Misty, the plot revolves around the “pony penning” that the Virginia Chincoteague side does yearly. The book, thought of solely through the eyes of a human, are troubling to me at this point. I boycott the idea that these families are ripped apart yearly for their auction. Salt water cowboys round the horses up, and auction off mostly the foals. The stress these horses endure during this is horrific. Google Pony Penning in Chincoteague, and you will be witness to the horses in their own body language showing you exactly how stressed they are. I think of those horse families prematurely torn apart. The loss of the wildness, which is all they know. I don’t think of the person who is getting a new horse to keep in their barn.

All too often we have 1 sided relationships with animals. While on the surface, the Chincoteague way may feel kinder. But the more you can open yourself up to understanding that other animals also have a right to freedom, you start to see things very differently. In America a lot of focus is put onto “Land of the Free” and the importance of freedom. Unfortunately thought only extends through humans.

To many, those animals that are caught and auctioned are “lucky” to have a family to love them. Such a human way to think, or justify. I fully believe if we were to give those horses the options, they would choose their moms and dads EVERY time over the barn where they lose most of their choices in their life and are asked to endure “training”, which in the horse world is all too often harsh punishment-based treatment.

I spend most of my time on the Assateague side of the island. I love all things wild. There aren’t houses on the Maryland side of the island. You can camp there, but that is the best you are going to get. The closest town to the island is Berlin, and Ocean City isn’t far. But it is a desolate kind of location where wild things live, and nothing else does.