February 2025

Support Live Encounters.

Donate Now and Keep the Magazine Live in 2025

Live Encounters is a not-for-profit free online magazine that was founded in 2009 in Bali, Indonesia. It showcases some of the best writing from around the world. Poets, writers, academics, civil & human/animal rights activists, academics, environmentalists, social workers, photographers and more have contributed their time and knowledge for the benefit of the readers of:

Live Encounters Magazine (2010), Live Encounters Poetry & Writing (2016), Live Encounters Young Poets & Writers (2019) and now, Live Encounters Books (August 2020).

We are appealing for donations to pay for the administrative and technical aspects of the publication. Please help by donating any amount for this just cause as events are threatening the very future of Live Encounters.

Om Shanti Shanti Shanti Om

Mark Ulyseas Publisher/Editor

All articles and photographs are the copyright of www.liveencounters.net and its contributors. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the explicit written permission of www.liveencounters.net. Offenders will be criminally prosecuted to the full extent of the law prevailing in their home country and/or elsewhere.

Contributors

Mark Tredinnick

Audrey Molloy

Noel Monahan

Magdalena Ball

Brian Kirk

Eugen Bacon

Esther Ottaway

Alex Skovron

Eileen Sheehan

Peter Boyle

Bernadette Gallagher

Neil Leadbeater

Dominique Hecq

Dr Arthur Broom Field

Hedy Habra

Richard W Halperin

Maria Castro Dominguez

Jonathan Cant

february 2025

Enda Coyle-Greene

James Deahl

Claudine Nash

Thaddeus Rutkowski

Elsa Korneti

David Graham

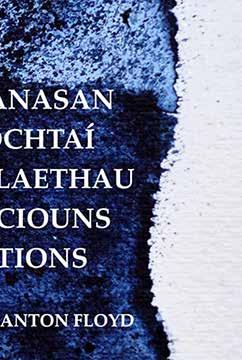

Anton Floyd

–Depositions , book review by Hayden Murphy

Katherine L Gordon -After Midnight, book review by Steven Xu

John Liddy and Jim Burke

– Slipstreaming (In the West Of Ireland) book review by Anton Floyd

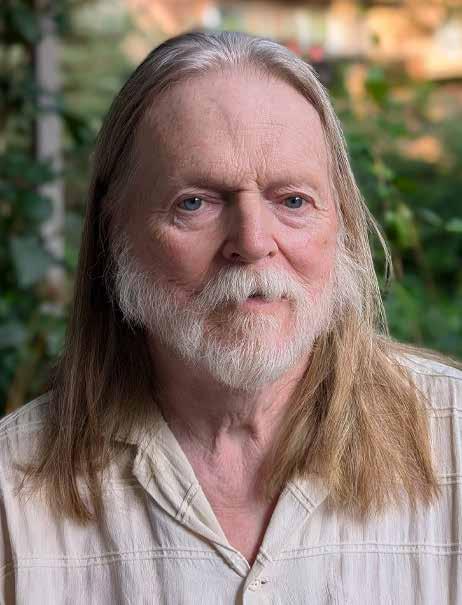

Mark Tredinnick, the author of twenty-five celebrated works of poetry and prose, is the author, most recently, of House of Thieves, One Hundred Poems. His books on the writing craft have touched the lives and works of many. He runs What the Light Tells, an online poetry masterclass, and teaches at the University of Sydney. His edited collection of essays for Robert Gray, Bright Crockery Days, is just out from 5 Islands Press, whose managing editor he is. Mark lives and works southwest of Sydney on Gundungurra Country.

Notwithstanding

Meantime, though, life is the same miraculous gift it always was.

The Lenten air is in, and the last two mornings have been cold.

I love it like this: the humidity almost spent, the days wider open

than summer windows, the nights a meadow of broken-down stars,

each dawn, a down, a life you feel now just about worthy to claim.

From Heaven Back

One day last year they took down one hundred years of poplars along the railway line in town.

This May, one morning in calm bright weather—a High run aground overheard and the Southern Ocean streaming quietly in along the isobars—I stand where the trees had till last year stood, and I look across the new car park and the old tracks at the thin amber palisade abandoned there. The poplars, a skeleton staff, have put out a deeper yellow this year (to stand in, I guess, for all the yellow that will not ever constellate the eastern flank again), and I am a thousand phantom cyan limbs.

Lombardy poplars thin, I notice, from the top down, and when my time comes, may I, too, leave so well,

falling down from heaven back to earth. Each day, less time, more space. More light, Less shade. Each night, more sky. From one hour to the next, less here about me, and more there, and only small good sunlit phrases left to say. Each syllable one more dying star.

And …

… autumn, in the morning, had put up a city of light, and now the one grey cottage that had thought itself out of the woods was a buckle in the mortgage belt, an outer suburb ringed by amber roads, the morning a high urgency of tone. Through which I drove early, to buy you, I recall, a tie from the school shop to replace the one your brother, that prodigal, had bartered or burgled or lost, and the suddenness of the season, waking up by falling fast toward its close, seemed a passing comment on these middle moments of one’s days. And then, as I took the bend

at Osborne, there was the currawong who flew upside down across my sightline and hung by the tips of the fingers of a peppermint limb (the one green note in all the yellowness of things), and I guess it sipped there on scarlet blooms a second, while I pulled over to get some of this down, or else just showered brightly in the light blue rain that had deigned at last to fall. Love always was our best idea, I think— and always just a bit too big for us. But still the (spinning) world goes on showing us, if we’re lucky, how love’s done.

Hunger

For Phil Harmer

Standing on the stilts of her other life, as if she meant to extenuate the depth of the darkness that saturates the shallows she divines, the blue heron bunches her blue shoulders and bundles her slender daylight form inside the soft carapace of her night-time self. Her hunger is the stillness of a sleepwalking stream. And waking is a wrinkle in the fabric of the tide, above where a brown bass on the gravel bed has no idea he’s making ready to become breakfast.

Pinoak Days

After Christmas, the days lose their shape; The numbers fall from the calendar.

One year’s almost as good as the next, And this particular year, Tuesday Morning—if, as it claims, it’s Tuesday— Grows bulky and true as the pinoak,

Which leafs out where, for two lives at least Of women and men, generations

Of hours, it’s held its form and waited.

Audrey Molloy grew up in Ireland and has lived in Sydney since 1998. Her debut collection, The Important Things (The Gallery Press, 2021), won the Anne Elder Award and was shortlisted for the Seamus Heaney First Collection Poetry Prize. The Blue Cocktail was published by The Gallery Press and Pitt Street Poetry in 2023. She has an MA in Creative Writing from Manchester Metropolitan University and is the recipient of a Literature Bursary Award from The Arts Council of Ireland. She is co-editor of The Marrow International Poetry. https://www.themarrowpoetry.com/

Redemption, Redleaf Pool

sunrise

From his pylon, the cormorant watches me, as he once watched Eve in the Garden. He rents the sky’s white silk, holds his breath longer than me, dives deeper. He doesn’t name the fish, as I do, doesn’t know what he has taught me about God. When he unpacks his wings in weak sunlight he looks like an emblem, a fallen angel.

midday

Gulls, gulls. The graceless calls of them. Two children take their chances, spilling from the whispering shade. They barely make a shadow on the sand. The younger child inspects a jellyfish, immortal, but for its errant ways. The older one impales it with a stick— this high-tide line is not for sissies.

sunset

More fish than I can count at Redleaf Pool. On the teak pontoon, a woman and a man, barely clad, practising tai chi; one squats, the other rises in waning intervals until, at last, aligned. Scarlet light fades to lavender. Renouncing gravity, a pelican lifts off.

Noel Monahan is a native of Granard, Co. Longford, now living in Cavan. He has published seven collections of poetry with Salmon Poetry. An eight collection, Celui Qui Porte Un Veau, a selection of French translations of his work was published in France by Alidades, in 2014. A selection of Italian translations of his poetry was published in Milan by Guanda in November 2015: “Tra Una Vita E L’Altra”. His poetry was prescribed text for the Leaving Certificate English, 2011- 2012. His play: “Broken Cups” won the RTE P.J. O’Connor award in 2001and Chalk Dust, a long poem of his, was adapted for stage and directed by Padraic McIntyre, Ramor Theatre, 2019. During the Covid-19 lockdown, Noel had to reinvent his poetry readings and he produced a selection of Short Films: “Isolation & Creativity” , “Still Life”, “Tolle Lege” and A Poetry Day Ireland Reading for Cavan Library,2021. Recently, he edited “Chasing Shadows”, a miscellany of poetry for Creative Ireland. His ninth poetry collection, “Journey Upstream” was published by Salmon Poetry in April 2024.

"I had the Pacemaker implanted in the Mater Private Hospital, Dublin on Friday 10th. January 2025.”

Pacemaker

Tea and toast before we set out For The Mater Hospital. Pleroma of snowflakes falling Winter sun lights up the morning.

It’s back to a world of Slippers and dressing gowns, Back to supporting pillows, Back to one’s heart missing the beat, Back to Rainbow Bibles And the colour of tenderness In a nurse’s smile.

At times like this I become spiritual. My mind strays back To forgotten times, books I’ve read About the Dead Sea Scrolls, The Book of Enoch, Enoch was the father of Methuselah, Great Grand Father of Noah (As if that matters ! )

The sacred geometry of Pythagoras

Flows through my veins

Metal heart beats strike symbols into words ( How can I explain this? )

It’s like my heart has moved to another planet, An alien planet of codes: iPhone passwords: “ Ask for bleep 8206

Shifting patterns of vibration dots Old and new conflicts, Prayers from far-off times and places Echo

Words flowing in and out of each other: You Need A New Pacemaker Installed: NOW

continued overleaf...

Cardiac Care Team gather round

Drip in my arms

Local anaesthetic to numb the skin

The Surgical Magician

Creates a small purse below the collar bone

To fit the pacemaker in Pacemaker leads

To restart the heart if it stops.

My pacemaker has fallen Into place Now it’s back to making poetry

Poetry

More closely connected To the heart.

Magdalena Ball is a novelist, poet, reviewer, interviewer, Vice President of Flying Island, and managing editor of Compulsive Reader. Her work has appeared in an extensive list of journals and anthologies, and has won or shortlisted in many local and international awards, including, in 2023, the Melbourne Poets Union International Poetry Competition, the SCWC Poetry Award, the Liquid Amber Press poetry prize, the University of Canberra Vice-Chancellor’s international poetry prize, and the Woollahra Digital Literary Award, as well as shortlisting for a Red Room Poetry Fellowship. She is the author of several novels and poetry books, most recently, Bobish, a verse-memoir published by Puncher & Wattmann in 2023.

Flowers and Feathers

The boa room was a pop-art camphor closet. Fifty strips of turkey Maribou hung next to Chandelle, hand-sewn ostrich, single and double thickness. Iridescent Coque shimmered under a fluorescent strip. Detangling and fluffing the boas was first job of the day, a finger comb-through, grouping colours into clusters of ROYGBIV, the rainbow of possibility. The Coque was the most expensive, but dreams could be purchased in vivid pink down for twelve dollars a strip or three for thirty. The room always elicited a gasp, the camphor a headache, especially if you were inside for more than an hour. If it was quiet, I could tidy flowers, practice Spanish or read, subversively, under the counter. It wasn’t often quiet. Except on Saturday morning when I counted pheasant feathers, predicting stock versus sales. I never thought about the birds. Plucked alive, starved in feedlots across South Africa, hooded and held. Slaughterhouses, formaldehyde dyes, miles travelled on carbon-belching ships. The pretty room was a lie, draped on bare shoulders, kicked up by the Rockettes, paraded down main street, built on an industry a long way from home. The shop is long closed. The garment industry gets it flowers and feathers elsewhere, imported from overseas factories of slave labour. Flattened feathers and non-biodegradable flowers are rotting in a cellar somewhere. Back then, a poor student, I moved apartment frequently. My mail was delivered to the shop. Maybe it still goes to that repurposed building, piled high in a dusty corner.

In dreams I collect neglected stacks of old mail thirty years of waste.

Breadcrumbs for Pigeons

Black glass is a mirror sunlight on grey tarmac, pigeons.

There are over three hundred species including the flightless Mauritius non-bird we called the Dodo a fatal acquiescence, lesson unheeded

Lazarus on the boil, ready to return shameful as hothouse Earth.

Take the Passenger imagine what it was like

shooting the last one dark blood mingling with the blush of its broken neck. Transgression.

Luckily there are still homing pigeons, who always find their way, gleaming bodies against a mottled grey sky, war-bird

drawn to the nest, unlike me my homing instinct watered lifted by wind a woman stripped of labels swearing to forget the boundaries I’ve crossed my role as commodity or how I might not be capable of all that needs doing.

Patterns of Energy

Intelligence isn’t what it used to be.

We are little more than light, chemicals, temperature tied together with invisible string no one falls alone. Watching from my position on the floor waste products cycling through organs.

If we make it past the contractions

transition to transmission we will become something different connective filaments like bees collective flight patterns against the absence of all those species

sipping nectar, dying slowly as if we had all the time.

Brian Kirk has published two collections with Salmon Poetry, After The Fall (2017) and Hare’s Breath (2023). His poem “Birthday” won Irish Poem of the Year at the Irish Book Awards 2018. His chapbook It’s Not Me, It’s You won the Southword Fiction Chapbook Competition, published by Southword Editions in 2019. His novel Riverrun was chosen as a winner of the IWC Novel Fair 2022. www.briankirkwriter.com

Corpus Christi

The weather was always good but you had to dress up in your Sunday best and parade around town behind the priest who held up the host trapped in a golden cross like it was a photo of Jesus. All the houses had small altars set up at their doors – carnations, chrysanthemums – holy statues balanced on lace covered tables. The Children of Mary carried a banner that said something that made no sense but nobody seemed to notice. Everyone was in good form, sang along with the hymns: Soul of my Saviour, Faith of our Fathers…

The First Communion girls gave their white dresses another outing and the boys wore their suits one more time. It went on for ages. The priest told us to think about what it all meant, but I knew already. It meant summer, time to get in the sea for a swim.

Slap

When I was seven Mrs. Smith slapped me on the face at First Communion practice because I looked along the line in expectation of the ersatz host. Her red painted nails matched my face, which was scarlet on two counts, first from the slap and second on account of the embarrassment I felt in front of my classmates. I couldn’t understand it. You see, the teachers never hit me so I didn’t know how to take it like a man. I couldn’t shrug it off the way the others did. When I was twelve the bishop slapped us lightly on the cheek after Confirmation. Is that how we were marked with the sign of faith? I held my breath, expecting one of the tougher kids to give him what for.

Halloween

No one could afford a proper costume so we wore one of our father’s railway coats and plastic false faces. We wandered around in the dark, waiting to jump out at unsuspecting passers-by, but no one ever passed where we lived, trapped between two one-horse towns. We half-drowned ducking for apples, choked on rings secreted in barmbrack before we headed out into the dark again. We had to make do with scaring one another and somehow we succeeded, whipped up into a frenzy by whispered stories of the walking dead or devil worshippers who hunted down the family cat and nailed it to a telephone pole. It’s not the dead ye should be worried about, my mother said, it’s the living.

Christmas

It should have been the happiest time of the year but it wasn’t. Maybe we were trying too hard what with the tree and the lights and all the food and the sweets. And nobody minded that Santy had replaced Baby Jesus in our minds, because we were only kids and it was all for the kids really, wasn’t it?

I felt sorry for the baby in the crib in our barn of a church. He looked cold and had to wait ages for the wise men to appear. I knew he was just filling in for the real thing, like the fake Santys in the shops who patted your head and asked what you wanted for Christmas. What was the point of telling them, they couldn’t make it happen? I cried as I queued with my mother in Clerys Department Store, but then I thought about Baby Jesus –the real one – and the real Santy, and after a while I felt better.

Eugen Bacon is an African Australian author. She’s a British Fantasy and Foreword Indies Award winner, a twice World Fantasy Award finalist, and a finalist in the Shirley Jackson, Philip K. Dick Award, and the Nommo Awards for speculative fiction by Africans. Eugen was announced in the honor list of the Otherwise Fellowships for ‘doing exciting work in gender and speculative fiction’. Danged Black Thing made the Otherwise Award Honor List as a ‘sharp collection of Afro-Surrealist work’. Visit her at https://eugenbacon.com/blog/

A Hundred Words

Her world is ending. She feels her body eat itself. Her life is a code she can’t read.

It’s a menace. It runs like a dog, the direction unclear. If only she could catch glimpse of a sign listing destination right here: bright-eyed planet. But nothing is bright-eyed about Earth. She’s spinning in lava that’s a calamity of failed loves. If only she could die in peace.

But she worries if she’s damned to eternity in a museum of apocalypses, dioramas of flood, earthquakes, heatwaves, pandemics, hate, intolerance, poverty, misjudgements and bushfires.

Here’s a selfie with the angels of death.

Esther Ottaway is a Tasmanian/lutruwita poet, editor and mentor whose poetry has won or been shortlisted for many international and Australian prizes, including the Tom Collins, Woorilla, MPU International, Bridport, Montreal, and Mslexia. Her second book, Intimate, Low-voiced, Delicate Things, won both the $25,000 poetry prize and the People’s Choice prize in the 2022 Tasmanian Literary Awards. Her new books are She Doesn’t Seem Autistic and a landmark anthology of Australian disability writing, Raging Grace (co-edited with Andy Jackson and Kerri Shying).

Sonnet for a white dress

Broderie anglaise, billows in sleeve and tier, it makes of me a vision, cool and sweet. I am a cloud now, crisp as twilight rain. I am a fair woman photographed on a beach, I hold the noble reins of a white horse, we are equally improbable. How my mind enjoys the dress’ ideals, its smooth denial of life’s insistent mess. How I long to live this way. Not for me Earth’s detritus and entropy – I will not sit on the half-mud beach, perspire; I’ll hold no babies, eat no picnic. Ah, how doomed, how false our embroidered fantasies. See, here comes the beetroot flying.

Alex Skovron was born in Poland, lived briefly in Israel, and emigrated to Australia as a boy. His family settled in Sydney, where he grew up and completed his studies. From the early 1970s he worked as an editor for book publishers in Sydney and (after 1980) Melbourne. His poetry has appeared widely in Australia and overseas, and he has received a number of major awards for his work. His most recent collection is Letters from the Periphery (2021); his previous book, Towards the Equator: New & Selected Poems (2014), was shortlisted in the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards. Skovron’s collection of short stories The Man who Took to his Bed (2017), and his novella The Poet (2005), have been published in Czech translations; The Attic, a selection of his poetry translated into French, was published in 2013, and a bilingual volume of Chinese translations, Water Music, in 2017. His work has also appeared in Dutch, Macedonian, Polish and Spanish. The numerous public readings he has given have included appearances in China, Serbia, India, Ireland and Portugal. In 2023 Alex Skovron was honoured with the Patrick White Literary Award for his contribution to Australian literature.

http://sydneyreviewofbooks.com/towards-the-equator-alex-skovron/ https://compulsivereader.com/2022/03/12/a-review-of-letters-from-the-periphery-by-alex-skovron/

Antique Photographs

Screen flickers and jumps when I release the saver, but at last a document attains focus. An email clicked last evening but still unread, and along the bottom a row of coloured icons gazing philosophic, perhaps expectant, out into the book-laminated room. I discover myself

staring blankly back into the message, thinking if I should read it or open the attachment, blue there among the other symbols, reminding me that I had almost begun the article I had almost turned down, when the editor knocked back maybe for an answer. No, I’ll return to Sarajevo

later, more research first, more questions to be answered, asked, like why is the paling fence on our north boundary sagging in the wind, when I had it repaired just last year? And how is it that the Titanic museum we visited on the drive out from Cork keeps swimming

before my eyes? Maybe I should dump 1914 —who needs another plug for the centenary?— and focus on 1912, throw in the Lusitania, who came to grief off the same Irish coast. And why Ireland anyway? Something I must have dreamt, to bring back those godforsaken faces so starkly,

sadly—but then, I always was hopelessly seduced by antique photos. Yes, I have a perfect mind to call it a morning, revisit that other museum, close to home, where the walls gaze out, where every face flickers, a saved unsaved screen in and out of focus, alternately light and dark.

Eileen Sheehan is from County Kerry, Ireland. Her most recent collection is, The Narrow Way of Souls (Salmon Poetry). A bi-lingual selection from this collection, Duet of Lakes: Eastern-Western Poets in Sympathy, is published by Junpa Books, with Japanese translations by Maki Starfield. She is widely published in journals and anthologies, including; “Days Of Clear Light – A Festschrift in Honour Of Jessie Lendennie And In Celebration Of 40 Years Of Salmon Poetry”( Arlen House/ edited by Alan Hayes & Nessa O’Mahony); TEXT: A Transition Year English Reader (editor Niall MacMonagle / The Celtic Press);The Deep Heart’s Core: Irish Poets Revisit a Touchstone Poem (editors Eugene O’Connell & Pat Boran/ Dedalus Press); and Blackjack, with translations into Romanian by Oana Lungu (editors Dorina Șișu and Viorel Ploeșteanu / Singur Publishing). She has read at festivals in Ireland and abroad including The Shanghai Literary Festival; an ACIS Conference in USA; The Cork International Poetry Festival and Listowel Writers’ Week.

January Morning

Nothing on TV but the spectacle of politics and war. I switch channels and the members of the Dáil

are on their feet, shouting each other down: like a classroom when a teacher has forfeited control. On every other channel, faces of children, children dead, children dying. Overwhelmed by the sadness of it all. Small.

Small in the face of it all, I do the only thing I can. I switch it off and go outside to make the garden

ready for the high winds to come. Tonight I will curl into a tight ball, with all my spines protruding, hoping no tree falls on us. Willing the storm not to sunder the globe from corner to corner.

Saint Brigid’s Eve

Sundown to sunrise marks the time of her travel, with her white cow beside her and her mantel of stars.

Every house in the land has the door on the latch with green rushes spread on the flagstone outside.

While the people inside await the arrival of the Goddess of Springtime; the Keeper of Light.

She blesses the bright squares of cotton laid out on the bushes granting good health to the wearers all year.

Three loud knocks declare she is present to dispense her protection against lightning and storm.

Three loud knocks and her mantra repeating, Open your door, open your eyes, open your hearts, let Brigid come in.

St Brigid’s Cross. Triskele (three-armed) cross (N.M.I. Collection - F:1945.3). https://www.museum.ie/

Peter Boyle has published eleven books of poetry, including Ghostspeaking (Vagabond, 2016) and Enfolded in the Wings of a Great Darkness (Vagabond, 2019). His most recent collection is Companions, Ancestors, Inscriptions (Vagabond, 2024). His awards include the New South Wales Premier’s Prize, the Queensland Premier’s Prize and the South Australian Festival Award. He is a translator of poetry from French and Spanish with nine books of translation published, including poetry by José Kozer, Marosa Di Giorgio, Olga Orozco and Eugenio Montejo. He has published two collaborative books with Queensland poet MTC Cronin, most recently Who Was (Puncher and Wattmann, 2023). After many years working as a teacher with TAFE, he completed a Doctorate of Creative Arts at Western Sydney University. Peter lives and works on Dharug land

Responses 27

A light bulb in an empty warehouse

Two children entering the deep calm of a mountain lake

The metal crutch you use for walking

The clear space between a crowd of people that leads your eyes to a tangle of saltbush gathering light

A shop sign in red and white against the brilliance of midday

Keys dropped accidentally, still there in a neon-lit carpark

A beloved face that takes in all your being, enfolding your body in the stillness of time dissolved

A pair of freshly polished boots beside a crumpled bed

Eyes that hold you, then turn away

A spoon left unused on a restaurant table

Winter light playing along the surface of a parked car

The dotted lines at the end of a lease and the empty spaces in a marriage contract

Milk bottles in a long ago school playground

Tinned sardines and a can opener

Everything that shines is saying farewell.[1]

[1] Héctor Hernández Montecinos, Teoría de la ficción <my translation>, p 52

Responses 42

It is slipping by, the day that was his life, among papers and anxieties, the blossoming wounds of last night’s sky, and close by, somehow intuited, invisible uncles, Melchior and Baltasar, mumbling on the front porch, penniless as stars.

It slips by, the endless childhood hours, mother’s elegant earrings, father’s silences, girls whose soft faces translated the sea

and the bright yellow alertness of flowers in window vases or the stretch of all that unfolded so inexplicably beyond the ever opening sequence of windows.

A clear measure of sweetness trembles on the kitchen counter -warm tea.

Having long since given up on waiting for speech to come he steps out into the extraordinary height and depth of a single moment.

True being is everywhere an ideal goal, a task. [2]

[2] Edmund Husserl, The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology, p.

Responses 57

In the cool room of crystals a woman stoops to tap a scalpel against the brimming water. Outside, a cobbled street takes you by the hand down through a twilight maze of old warehouses to the harbour’s swaying presence. White scratch marks on a stone marker record the last spring tide’s date and time.

Who will plunge into these cold waters to surface freed of their past?

The ocean filters so much of our lives away yet the grit at our core goes on hardening into a small semi-precious stone. Out of the infinite paucity of human language we might call it sadness. Nevertheless, and ever so precariously, it glows. Dislodged slightly from the dogmatist’s web of this or that, of fixed becoming -not fate but a kind of fête, a celebration[3].

[3] Vladimir Jankélévich, Music and the Ineffable, p. 66

Bernadette Gallagher is the author of The Risen Tree (Revival Press, 2024), her debut poetry collection. Further details on https://bernadettegallagher.blogspot.com/.

Your Head on a Plate

But my people would not listen to me; Israel would not obey me. Psalm 81:11

The seeds are sown, the harvest is bountiful. Fires can be seen years hence as the stars still flicker in the sky, as a father cradles his dead son and a mother no longer a mother.

Is there an end to this story?

Today is your birthday

yesterday I cut away briars rambling through blackcurrant bushes and raspberry canes they clung to my jeans, to my jumper — I carefully prised them away placed them in little heaps letting them fall back into themselves

Elia

Blue eyes staring mouth open an angel with news from beyond you let me forget all but this breath your gurgle your soft skin against my aged cloak.

Viridian

Her face was beautiful. It was one of those faces that, once seen, was never forgotten. When the team of divers found her, they brushed their hands over her eyes and cheekbones marvelling at her texture. How had she come to be here, miles from anywhere, deep in the arms of the Atlantic?

The next day, the divers dropped anchor in the same spot and went to search for her again. It was almost as if this beautiful bronze sculpture was drawing them to her. Perhaps she was Salacia, the goddess of saltwater or Amphitrite of the wind and waves? (They had already in their minds raised her status to that of a goddess). When they finally reached her they saw that her mouth was slightly open. They had not noticed this before but now it was very obvious because, to their wonderment, a shoal of mackerel came out of it. They were the most beautiful fish they had ever seen. It was a most extra-ordinary sight. To witness all these tiny fish funnelling out of her lips was strangely compelling and almost beyond their comprehension. It was as if she was birthing them through her mouth. Each one was perfectly formed and seemed to be at ease in their watery element. She nourished them in numbers past all counting.

If she really was Amphitrite, wife of Poseidon, queen of the seas, they should not have been surprised by this phenomenon. She was, after all, the mother of many sea creatures, sea nymph child of the gods. After a few days of mulling things over, the team decided to give her a name. She had become so real to them, and they had become so attached to her, that she needed to be given a form of identity. After careful thought, they named her ‘Viridian’ on account of the colour that the sea had bestowed upon her: a bright shade of spring green that was somewhere between green and teal on the colour wheel or, to the artist’s eye, a kind of tertiary blue-green. The name stood for tranquillity and renewal. It symbolised balance and harmony and it evoked feelings of peace and stability.

* Neil Leadbeater is an author, essayist, poet and critic living in Edinburgh, Scotland. His work has been published widely in anthologies and journals both at home and abroad. His latest publications are ‘Falling Rain’ and ‘Cityscapes and Other Poems’ (both published by Cyberwit.net, Allahabad, India, 2023). Other publications include ‘Librettos for the Black Madonna’ (White Adder Press, 2011); ‘The Loveliest Vein of Our Lives’ (Poetry Space, 2014); ‘The Fragility of Moths’ (editura pim, Iași, Romania, 2014); ‘Sleeve Notes’ (editura pim, Iași, Romania, 2016); and an e-book, ‘Grease-banding The Apple Trees’ (Rafaelli Editore, Rimini, Italy, 2015). His work has been translated into French, Dutch, Nepali, Romanian, Spanish and Swedish.

continued overleaf...

Musing over her name, one of the divers recalled how he first came across the word ‘viridian’. It had not come to him from a dictionary but from a piece of music. A few years ago he had heard a composition on the radio by the Australian composer Richard Meale. The work was called ‘Viridian’ and, for Meale, it proved to be something of a turning point in his musical thinking. Described as evoking an imagined world of luxuriant greenness with its lush orchestration, it quickly gained favour further afield setting Meale off in a new direction enabling him to delve deeper into his own musical persona.

*

The divers in a sudden moment of colourful thinking wanted to bring her to the surface in a chariot drawn by sea-horses. On a practical level, they saw merit in returning her to her original beauty by removing all the toxic copper salts that were clinging to her body. They wanted to restore her to the life she used to lead but none of them, of course, had any idea about what that life might have been. One of the team, who lived on Bryher, the island of hills, wild rugged and almost untamed, thought it might be good to have her restored and placed in his garden but another of the team set his heart on bringing her to the wonderful Abbey Gardens on Tresco. He could just picture her on the East Rockery below the Abbey itself or in that part of the garden called Mexico where giant borages from Madeira and the Canary Isles flower in many brilliant shades of blue. After giving it some thought, the team of divers finally settled on placing her at the southern end of the garden among the carved figureheads from the many ships that had been wrecked around the rocky coasts of the Isles of Scilly.

It took months of preparation to make the necessary arrangements for her to be lifted safely out of the water. It all had to be done professionally and with a great deal of patience because they did not want to run the risk of having her fall apart. The day they saw her being hoisted into the sunlight was unforgettable. At first, sea water poured off her surface features in torrents but later, while she was still being suspended, everything thinned to a stream of droplets. Once she was on land, the cleaning process began. They had to seek specialist help in finding the right kind of materials to use in order to avoid causing any damage.

As soon as she was on land and placed into position her bronzed textures acquired the most beautiful blue-green patina that shone with a warm glow. The glaze on her features was out of this world. It seemed to alternate continually between Tiffany blue and Persian green, cerulean blue and myrtle green, vivid sky blue and sea green. It was no wonder that potters, sculptors and all kinds of people who were creative with their hands were drawn towards her. She had the capacity to inspire them all.

Every time one of the diving team visited her they would be met with the most amazing spectacle. Butterflies would emerge from her mouth. Not just one or two, but a whole swathe of them. One of the divers described it as a flight or a flutter but the best collective noun of all that they came across that day was a kaleidoscope due to the many changing beautiful colours. The butterflies caused a stir as they slowly rose into the air, eager to visit every flower in the garden. Lepidopterists came from afar to see the phenomenon and to do counts on the different types of butterfly that emerged from her mouth. There were red admirals, common blues, speckled woods, painted ladies, tortoiseshells, commas, small coppers, gatekeepers and meadow browns. The variety was simply amazing. Some thought that they were the souls of the drowned glad to feel the warmth of the sun again after all those years beneath the waves.

Halfpenny Green Aerodrome

Breaking in through a gap in the fence we were two tearaways on a runway to adventure. Testing our wings we cried ‘Chocks away!’ and ran like the wind arms outstretched hoping a gust at gale force eight would sweep us off our feet. ‘Any moment,’ you said, ‘we could be airborne on a journey to the stars’ but gravity grounded us in the disused space. Cool, calm and collected, we were unflappable trying and trying and trying again until sense left us standing on our own two feet.

Ormes Lane

Coming home from school on the Bella Viva 40-seater we always looked forward to that perilous 1 in 4 gradient on the tight hairpin bend which our driver took with ease. If he couldn’t turn left at the junction but had to wait on the cusp of the precipice until it was safe to proceed we’d hear the hiss of the air brakes before the long way down.

We’d watch his hands on the steering wheel that rapid swing to the left how did he know how far to let it correct itself as it spun so lightly like a flock of birds flying beneath his hands?

Dominique Hecq is a widely anthologised and award-winning poet, fiction writer, essayist and translator. She lives and works on Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung land (Naarm/Melbourne). Hecq writes in English and French. Her creative works comprise a novel, six collections of short stories and seventeen books of poetry. Together with Volte Face and Otopos her bilingual sequence, Pistes de rêve appeared in 2024.

Unnamed

You listen to the black dog in your sleep speaking of dreamscapes of peril. It lists litanies of murderous melodies that make your blood boil. The is a fist of kindling scraping your veins running away from blood clots and/ or fleeing the nightmare’s crumbling teeth that cripple your mouth. You wake tight-jawed to a wagging of no no no that’s all there is to contain time.

You limp through murderous alleys, each step marking night’s forgotten scars down to the underpass where the dog turns to wolf. Cinder rain pours from eye-sockets. Coats inaudible words.

Your feet walk you past numbered urns to the back of the graveyard where garbage collectors, roofers and hooligans wild as the new weather stand next to tiny white crosses with scattered dates from memory lane. Sleeves rolled up, they tell you how the dead were born from their blood and bones.

Qué calor la vida. The stink of it.

Now you can see it, the wall. It is crimson and dripping.

Between wolf and dog

Night of furphies. Possums hiss like cats. We tear from the brutalities of language, machines, protocols, corollaries, sorority, synchronicity. Flee human letters and litters, their heady smells, flotsam and jetsam. I feel not terror but elation. Writhe in my skin. Revert to my wolf instincts. Howl at the giant moth ball masquerading as moon. Unlike Ginsberg, I have no teeth. I feed on dust. My saturnian eyes defy geography. I pound the ground, dog in tow. We’re off the beaten track. Prowl the parched wetlands by the obsidian necklace once creek. I give my dog silence biscuits so he doesn’t starve. The trees people their bare bones with leathery flesh. They yawn as the morning star peeps through the clouds’ curls. Bow their heads to distant thunder. Hum a wordless tune under their breath. Let them remake language without us.

The dark quenches our thirst for unbridled companionship. Trees blaze, thrumming around. Hair spiky as an echidna’s ancient coat spread all over my body, unsettling all idea of time and place. We reach the lake/ water hole together. A ripple of nausea surges into my/ her body. I/ she shakes. Pronouns drop to their knees. Dog, come back, they rasp. And throw up.

Familiar smell of bat shit on the breeze. I close my eyes on the waning moon. Come, boy, come, I open my arms wide. The caked mud crackles under my feet. Dog materialises at my side. Says we must talk about sticks.

The air’s so muggy its clings. The dog runs his slobbery tongue on my calves. Let’s go, he says. I’m rooted to the ground.

Leaving. Setting sail for the unknown. We’ve been in leaving mode since we disembarked in this dead-end world. Leaving without a tour operator. No craze for nomadism which, in its current forms, is nothing more than sedentarism in motion. None of this gallivanting that extends its networks of freewheeling sightings and vacuities of escapades across continents and seas.

Leaving is something else entirely. It’s jumping in/ out, exiling yourself. Exsul mentis domusque. Deprived of reason and its home. Where the prose poem begins.

The dog sits, obdurate as a rock, as if to say agency is a weird word. He’s anchored in time when I’m already dead. It’s a very strange feeling. I allow the dead to emerge and again and again, coming back. The revenants. In this body, these thoughts, this language. I is a clearing teeming with ghosts, including those who arise from the future. I is a threshold, portal, a porous space where spectres cross.

Arthur Broomfield is a poet, Beckett scholar and short story writer from County Laois, Ireland. His collection of short stories is due out in April.

A night in Portallen

‘I never seen a worse night,’ Charlie said, as his gaze swung from the wicked night sky to Drover’s stretched figure on the couch. The rain was hitting the cobbled alley behind Charlie Murphy’s pub like balls bouncing off the table in a ping pong game.

‘We’ll have to lift him into the back,’ Tommy said. It was a Saturday night, round eleven in Portallen, one December week in the 1960s. Tommy, Charlie and I were planning to get the comatose Martin Delany, known as Drover, into my car.

‘Poor Martin got bad whiskey up town,’ Charlie said. Tommy’s shoulder nudged me.

I’d been in Mollassa’s chip shop, next door to Charie’s pub, polishing off a feed of chicken and chips, when Tommy came in, all in a hurry. Christ, I thought, he’s looking for his money.

‘I’ve got a job for you,’ he said, ‘there’ll be a few quid in it.’

‘OK, sure we’ll have to get him home anyway,’ I said, when Tommy told me. Tommy was a small-time huckster of dubiously acquired tools and accoutrements useful to farmers and cattle jobbers.

‘Drover sold his bullocks on Wednesday,’ Tommy said.

I steered my ten-year-old Ford Consul down the ally, relieved Tommy hadn’t mentioned the fifty quid I owed him. Charlie directed me to a yard good for turning, stopped me at the back door of the pub. Inside, Drover was black out along a battered settee in a back room, all six foot three and sixteen stone, of him. A middle-aged woman sat in the room with him.

‘I‘d have brought him, but I’d never manage a man as heavy as poor Drover,’ she was saying to Charlie.

‘This is young men’s job, Margaret.’ Charlie said.

‘Oh good evening, Mrs McGurk,’ Tommy said.’ It looks like we’ll be passing your gate!’

‘We’ll not delay now, lads,’ Charlie said. We got hold of each side of him and tightened our grip on his belted overcoat. Charley kept a look out, exhorting us with

‘Bring him on now, the coast is clear,’ and ‘careful lads, careful, his oul heart’s not the best.’ Tommy and I had him on his feet.

Tommy’s grip slipped on The Drover’s coat, and he stumbled, cursing under his breath as I tried to keep the body upright. So we held him propped between us, Charlie holding open the passenger side back door while Drover’s hobnail boots slushed through the pools of water and stale urine.

‘I’ll get in first and drag him while you shove him across towards me,’ Tommy said. Drover’s head flopped; his breath rattled like rats escaping on broken glass. Tommy shot a cautious glance towards me. Charlie was saying things like

‘Yes, yes Tommy, get him in safe, ‘and looking round him and back behind him towards the pub, ‘and keep him upright while you’ re driving.’

‘Call in tomorrow night… for a drink,’ Charlie said as we were ready to head out the alley onto the main street.

‘The fucker didn’t wash since Easter,’ Tommy said. He didn’t have to tell me, the car reeked of silage and cowshit. We were driving down Main St. People were filtering out of Campions and Harry’s pubs, a few were standing in the laneway to Reagen’s undertakers, beside Browne’s chipper. as we passed on.

‘The widow McGurk’s his neighbour,’ Tommy said.

‘We just got him out in time,’ he said ‘Drive on past O’Dwyer Park and stop for a while… I’ll have to get out for air before I throw up.’

‘Pull in up here,’ Tommy said, as we approached a half-concealed entrance on the left.

‘It’s the widow’s McGurk’s place.’ A five-bar field gate closed on a potholed lane that led to a cottage a couple of hundred yards away. A dull light shone from one window. I backed in, beside a strip of bare land on the passenger side, a low wall shrouded in overgrown hawthorn beyond it. As Tommy slid towards the car door Drover’s limp body fell towards him.

‘Fuck him,’ Tommy said, ‘I’ll straighten him when I come back.’ I opened the front door.

The rain was more like wolves hunting in packs than cats and dogs. Tommy had crouched under the hawthorn, his back to the wall, puffing on a fag. I was relieved to take the rain with the clean air.

‘Did you have any dealings with this oul lady Tommy?’

‘I sold her a wardrobe and spare wheel… only last week.’

‘Cash deal?’ I said. ‘Ho! ho! cash and kind’, he said. Business is business. I left it at that.

We chatted on for a while till Tommy remarked,

‘Hey Robert, it’s not getting any drier, now, is it?’ We headed back to the car, refreshed.

‘The Channelle seems to have lost its potency.’ I said. Tommy was stooped over Drover, struggling, which was now stretched across the back seat of the Consul.

‘Give me a hand while I straighten him,’ Tommy said. Where’s the money in this lifting, I was thinking.

’Right,’ Tommy shouted, ‘heave.’ The heavy scents of farmyard odours rose again from Drover’s functional attire. I got into the driver’s seat and closed the door.

‘Are you right so Tommy, ‘

‘Hold on…hold on…’ he said. I looked back. Drover was now in an upright position. Tommy was picking stuff from the seat beside him and cramming it into his pocket.

‘He’s loaded,’ he said, as he began to go through the breast pocket of his jacket.

‘Christ, here’s another bundle.’

‘W’ed better get out of here, that oul lady could spot the lights in the car.’ I said.

‘She’ll hang on in Charlie’s till closing time,’ Tommy said. ‘W’ell have to count this.’

‘I think we should move out of here,’ I said. Tommy had moved into the bench seat. He pulled bundles of notes from two of his pockets and laid them down, between us.

‘There’s serious loot. He must have drawn all the mart money,’ he said.

‘Yeah’, I said. ‘What’s she like,’ nodding towards the cottage.

‘It’s not for nothing they call her the merry widow … ‘But she’s got a big mouth.’

‘Which pocket was the money in.’ I said.

‘I can’t remember.’

‘What do you mean, you can’t remember?’ I was wishing I was still in Mollassa’s.

‘Not a problem. It won’t see the lining of that pocket again,’ he said. My gut was tightening.

‘He may be drunk, and have personal hygiene issues, but his father brought his cows to my father’s Shorthorn bull,’ I said.

‘Listen, will you, there’s a thousand quid there,’ he said. ‘It’s a chance of a lifetime.’

‘Yes’, I said, ‘a lifetime in Mountjoy.’

‘And, not that I’d put you under pressure, no way, you always paid your way…We’ll be evens… once we get things sorted,’ Tommy said.

‘I’ve never robbed a sweet shop,’ I said.

‘He’ll drink every penny of it,’ Tommy said.

‘What makes you think we’ll get away with it?’ I said. I heard the car coming.

‘Christ, its herself, I know the Morris Minor,’ Tommy said. ‘Here, hide this before she sees it.’ I stuffed the wad into my jacket pocket. The Morris minor pulled up beside me, the widow’s smiling face was looking at me through the lowered window. I lowered mine. The rain was blowing my way. Tommy reached over me,

‘Begor, and we got home ahead of you,’ Tommy said, ‘and what could have kept a decent woman out late, on a bad night?’

‘Is that a woman you have… in the back, there, with ye?’ she said.

‘It’s not Margaret, as bad luck would have it. It’s Drover, still with us. We stopped for fresh air.’ Tommy said. She peered out her window and leaned closer…

‘How’s Drover now,’ she said. After silence from the back seat,

‘He’s out dead... It’s harder on him those times,’ she said. She sniffed a few times.

’I’ve washed them cleaner for Peter Reagen.’ Tommy’s elbow hit my ribs a sharp jab.

‘We’ll head off Margaret. Put on the kettle, we’ll be back in jig time.’

‘Aye, aye. It’s more than tea ye boyos ‘ill be wantin.’ I wound up my window.

‘It’s only a mile of ground,’ Tommy said. I drove on up the narrow road, a deepish drain on our left.

‘Pull into the yard,’ Tommy said. The place was pitch dark.

‘The oul lad must be rambling,’ Tommy said. We opened the back doors. Drover was laid flat out across the seat. Tommy reached in to straighten him.

‘Mother of God’ he shouted, ‘He’s out cold.’ The blood drained from my head; I was going dizzy. My stomach was thinking of wretching.

‘And there’s not a whisper from his rotten breath.’

‘Let me check his pulse,’ I said. My hands shook, I couldn’t summon a suggestion of spittle to moisten my dry mouth. I fumbled for the radial artery on his wrist.

‘Not a beat. he’s…he’.. gone.’

‘He’s dead… you mean…dead…?’ Tommy crouched over, his arms tight across his stomach.

‘We’ll get the blame for this’, he said. ‘The guards have it in for me already. ’We’ll bring him to the hospital, pretend he’s alive,’ I said.

‘No! no! They’ll have to report it…We’ll be dragged in for questioning.’ He stood up, looked me in the eye.

‘The fucking widow knew he was dead. She’ll squeal.’

‘We’re totally fucked,’ he said. We stared at the body. Tommy shuffled his foot in the gravel on the yard, kicked a few stones, inhaled deep breaths, walked out to the road. He nodded to an open, galvanised porch of sorts.

‘If we leave him in that it’ll make it look worse,’ he said, when he came back. He paced up and down the yard. I was stooped over the car bonnet, holding on.

‘Drive out a bit, and keep her to the right,’ he said as we got back into the car. I was half numb by this stage.

‘Pull up here.’ I pulled in close to the drain. Tommy jumped into the back, beside Drover. Before I could make sense of what was happening he had opened the far door. I was looking ahead, watching for oncoming car lights. Tommy was heaving and breathing heavily in the back.

‘Got him,’ Tommy said. That’s when I heard the splash.

‘Jesus Christ,’ I shouted. It was more than a splash, more than the surge of water hitting the side of the car and landing on the back seat. It was the hollow, gurgling sound rising from the drain. It was the silence that followed as the water subsided. A memory flashed across my mind. It was of the mother at the funeral of two of her children. They’d died in a house fire while the parents had been at a party in the local hotel. It was like she’d had gone further than mere grieving. Her eyes were blank, her hand was ice cold, as I stuttered out my sympathy. Nothing Tommy would do now could be undone, nor could I be freed of responsibility to it.

‘The flood ‘ll save us. Drive on your best,’ Tommy said. I drove on. I was looking into the dark prison cell, its barred window, its steel-clad door, my name written on it. A prison warder checking me through the spy hole. I didn’t have a choice. My brain was full-numb by now. Then a thought broke through.

‘Are you forgetting the widow?’ I said. Her gate was a couple of hundred yards ahead.

‘She left the gate open for us.’ Tommy said, ‘drive on up…The kettle ’ill be boiling.’ My jacket was soaked. I was shivering. My nausea returned with vengeance.

The widow was standing at her open door as we pulled in.

‘Get in outa that night,’ she said. Three mugs and a plate of biscuits decorated the kitchen table.

‘Your coat’s wringing,’ she said to me. ‘Here give it to me and let me dry it for you.’ She helped me off with it and hung it on the back of a chair, beside a Calor gas stove.

‘The kettle ‘ill be boiled in a few minutes,’ she said, ‘and, oh, Tommy, I need your hand to move a wardrobe in here.’

‘I hope it’s not too heavy…I’ve had my share of lifting tonight, ‘he said.

‘It’ll be a clean lift, but it’ll need two,’ she said,

‘Nothing’s ever that clean,’ he said.

‘Come on’ she said, ‘It’s in this way.’

Tommy followed the widow towards the room, opening the buckle on his trouser belt on the way. He glanced back at me with a broad grin across his mouth. But just as he was about to turn a shaft of light, like a steel blade reflecting winter sun, hit his eyes.

As I expected, sounds of what I presumed to be furniture of some sort followed, after some instructions from the widow.

‘That’s as far as it’ll go,’ she was saying. Tommy’s responses, in the chit chat and chuckles genre, didn’t move me such was the level of my capacity to absorb shock, nor did the merry widow’ s feigned protests disgust me. She was, after all, an innocent party. The kettle began to sing.

‘Oh Robert, young man,’ would you ever wet the tea. This wardrobe’s not right yet.’ Tea, I wondered, where was the teapot? Ah, there it was, on the edge of the table.

‘Sure, Ma’am,’ I had to raise my voice above the din from the kettle. I busied myself, the clink of the teapot against the table, the jangle of the teaspoon against the metal of the teapot, helping to shield me from the goings on behind the door. My hands shook as I poured the water, spilling some on the table.

That was until Tommy’s raised voice

‘But you did know… you said it,’ rang truer of the man who had dumped Drover’s body in the drain. The widows voice crackled

‘I don’t know what you’re talking about.’

‘What’s that…’ the widow’s voice quivered. Tommy’s response came in grunts and heavy breathing, a soft sounding thud, followed by a woman’s muffled scream. Silence. Then Tommy’s voice:

‘That’ll put an end to your talking. . .’

It was Tommy’s plan; I kept telling myself. After a minute or so Tommy, buckling his trouser belt, rushed from the room. He grabbed the gas heater and cylinder and dragged them towards the open room’s door.

‘Get out, start the car,’ he screamed. I did what I was told. I waited in the car, the engine running. Tommy flew out the of the house, slamming the door just ahead of a pall of black smoke. I sat in the driver’s seat, the steering wheel was in my hands, the car was on auto pilot. ‘We’ll be as safe as houses, Robert, he was saying.’

‘Safe as houses. I heard my voice repeat. Safe when I acted dumb, when my eyes looked away from Drover’s gurgling body, safe as I drove at breakneck speed from the widow’s flame engulfed body? But they were no more than words. By now I was more robot than human.

‘And we’ve got the money,’ Tommy was saying.

‘The money?’ I asked

‘Yes, you’ve got the money…haven’t you?’

‘No,’ I said.

‘What do you mean... no?’ He said.

‘It’s in my jacket,’ I said. We drove on in silence till I got to Tommy’s house.

‘Mum’s the word…This is between the two of us’ …will you be heading straight home now?’ he said.

Hedy Habra’s fourth poetry collection, Or Did You Ever See The Other Side? (Press 53 2023), won the 2024 International Poetry Book Awards and was a finalist for the Eric Hoffer Award and the USA Best Book Award; The Taste of the Earth won the Silver Nautilus Book Award and Honorable Mention for the Eric Hoffer Award and was a finalist for the USA Best Book Award; Tea in Heliopolis won the USA Best Book Award, and was a finalist for the International Book Awards; Under Brushstrokes was a finalist for the International Poetry Book Award. Her story collection, Flying Carpets, won the Arab American Book Award’s Honorable Mention. Her book of criticism is Mundos alternos y artísticos en Vargas Llosa. She is a twenty-two-time nominee for the Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net. https://www.hedyhabra.com/

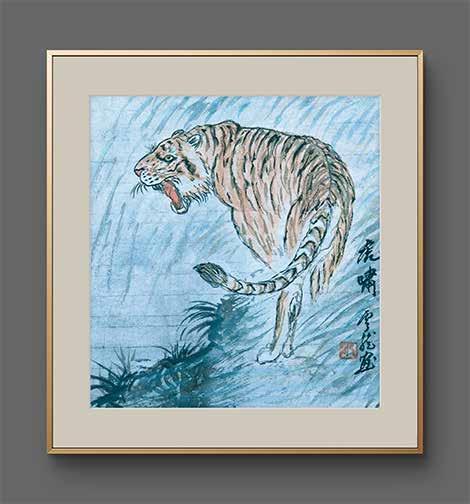

Entering a Chinese Ink Brush Painting

On my daily drive to the rehab center, I linger on the snowy road lined with thick woods. In this arctic cold, deer crossing signs seem obsolete; they must be resting over mounds of fallen leaves, leaning against tree trunks, or under spruces’ lower branches.

Heaven and earth seem to merge into an opalescent jade dome, its walls covered with intricate calligraphic signs drawn by naked twigs and branches, their dark strokes rising in silent stillness.

I drive slowly, entering a Chinese ink brush painting, gliding over rice paper, integrating the black and white landscape since I no longer wear makeup. I become a blank sheet waiting for the words that elude me and the brush marks I long to create. The stillness echoes my emptiness, my enduring inability to write or paint.

A Boat Ride Over the Vltava River

was a must to enjoy the sunset, or so everyone said, and there was still time before the poetry reading. The minute I stepped into the small wooden boat, helped by a slender Senegalese, and handed my ticket to a grey-eyed Albanian tour guide, it felt like entering a spacetime bubble as I was seated next to an Indian couple expressing their hostility against Pakistani, a Mexican family disciplining their children and two British women, each speaking a different tongue interspersed with Prague’s landmarks’ adulterated names. The tour guide’s lulling voice put me to sleep as I enjoyed a tall pivo, the only Czech word I could pronounce. The boat swayed under the soft breeze, and waters shone like polished silver in the twilight as the sun set over Charles Bridge, its statues like huge birds resting their wings, a procession of silhouettes moving back and forth like giant ants, the ship of fools swayed on the murky waters filled with centuries-old whispers and drowned secrets.

Photograph courtesy https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vltava#/media/

Richard W. Halperin’s is a U.S.-Irish dual national living in Paris. His collections are published by Salmon (four to date since 2010) and Lapwing (18 to date since 2014). In March 2025, Salmon will bring out Selected & New Poems, Introduction by Joseph Woods, drawing upon these collections and including thirty new poems. Mr Halperin’s work is part of University College Dublin’s Irish Poetry Reading Archive. He reads frequently in Ireland; his most recent reading (on YouTube now) was at the Heinrich Böll Memorial Weekend, Achill, Co. Mayo, last May.