Lincoln Jaques The Energy of Connection

It’s around 11am on a bright Saturday morning and I’m strolling down Pollen Street in the enclave of Grahamstown, the beating heart of Thames. The markets are buzzing with booksellers, herb growers, astrologers, palm readers, aging hippie tie-dyers, second-hand vinyl dealers, speciality bread-makers, coffee roasters, organic fruit stalls, spirit-conjurers.

Thames is the gateway to the wild Coromandel and was once a gold mining town that bulged at the seams with prospectors who gravitated here from all over Aotearoa and the world. Many of the colonial buildings from that time still exist, crumbling in a stalwart sort of way which gives the impression of permanence in a town which was never really built to last. In those prospector days the area was a scatter of sod-built whare filled with cholera and dysentery and syphilis mixed with normalised daily violence which echoes still through the many potholed mining shafts that litter the surrounding mountains.

We often take the trip down from Tamaki Auckland to visit an artist friend who has a studio in a collective workshop out the back of the Thames Organic Shop. But I also love coming here for the book stalls. I once picked up a first edition of Allen Curnow’s Trees, Effigies, Moving Objects, one of only 500 copies in existence. An early well-thumbed paperback copy of Leonard Cohen’s The Energy of Slaves (yes, I did steal the idea for the editorial).

On this particular Saturday morning book-hunting, I stumble across a trestle table filled with ‘poetry bricks’. The stall is owned by the well-known and much-loved David Merritt, and these aren’t bricks in the traditional sense, but individual poems printed on A3 sheets and folded with the eye of an origami artist. These are then inserted into a bespoke cover. The covers are meticulously upcycled from old Chiquita banana boxes or discarded hardbacks (like that set of Encyclopaedia Britannica from your childhood). The words are produced on preloved inkjet printers resuscitated from the junkyard. Better still, all the poems are written by David himself.

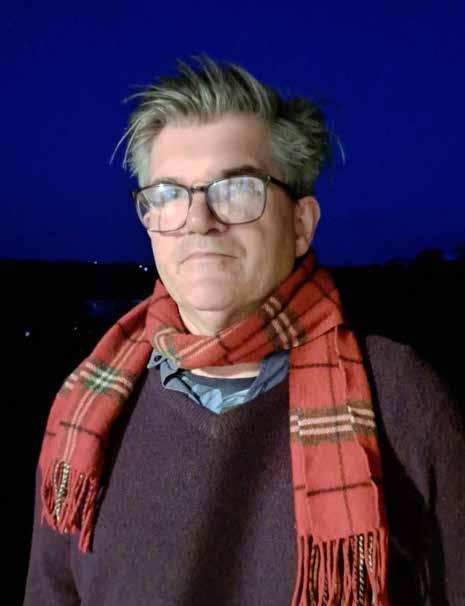

A vintage 1970s Land Rover sits angle parked in the bay behind him. In fact, he runs ‘Landrover Farm Press’, his homebase for his operation. As I browse through the wonderful assortment on offer, we strike up some small talk (neither of us are good at it). Pretty soon my artist friend loudly announces to David that “Lincoln’s a bit of a poet himself” and in my textbook introverted way I shrink back in horror. David is an unassuming character. A full grey beard hides a weatherbeaten but wise face. He wears a woolly beanie, almost his signature look, and behind his spectacles his eyes light up when I’m announced as a fellow bard.

“Ah! Our paths will cross again, you can bet on it,” he says. I laugh and pick up one of his volumes. It’s called Hiatus, and unfolding it was like opening a scroll from the lost Atlantis. Here’s a stanza that captivated me:

I saw people as stick insects through the Windows of a Newmarket commuter bus, I conceived a child called Lola and became The second owner of a dog called Jessie, Who tonight, I can hear breathing in the Heater glow distance.

I instantly purchased it, for a cool six bucks. He date-stamped (with an archaic springloaded stamper similar to those once used in libraries to indicate the return date) and signed the back. “Remember, I’ll see you again,” he said as he handed it to me. David travels the country in his Land Rover in what’s known as ‘The David Merritt Poetry Experience’. He chats to people, generates a connection all the while handmaking a poetry brick as he’s drawing you in. He’s one of those rare poets you can see regularly, get to talk to about writing with no judgement involved. In his own unique style he works diligently every day to bring poetry to the streets, to the people.

I know quite a few poets personally, some now close friends, but it’s taken me many years to build these relationships. We’re a funny, private, guarded lot. Perhaps it’s a mortal fear of rejection (rejection being at the core of our everyday reality). Edith Sitwell said that ‘All great poetry is dipped in the dyes of the heart.’ Perhaps we all write too close to our own hearts...or each other’s. There are numerous poets that I feel connected to, despite never meeting face-to-face. This is the beauty of poetry. It has the power to draw us together through the toughest of times, simply because we instinctively know we hold that deep connection. Poetry helps us make sense of a senseless world. And we are certainly living through troubling times, where we need poetry to take our hand more than ever. When we read and are moved by a poem, it’s usually because we can say “We’re not alone”. We don’t feel the need to explain any further. The words and experience have talked for themselves. Knowing you’re not the only one that sees the world in a particular way gives a sense of comfort, of belonging. I’ve looked at the state of the world and I see things in this way or that way, and I can share that experience. Poets find connections through their sense of justice, however fragile that justice is becoming.

Reading poems to a crowd also gives an exhilarating sense of connection. I’ve had the privilege of being asked twice as guest poet at Auckland’s legendary Poetry Live! held at The Thirsty Dog in Karangahape Road (recently shifted to Bamboo Tiger, more recently to Café 39 – we poets also need to be adaptive, going with whoever will take us in). Both times were a truly frightening experience, but I discovered the amazing support shown to all of us brave enough to take the mic. You are up there baring your soul, and the audience is just as frightened as you, for you, and because of this there’s an instant connection and understanding between us. The room buzzes an electric warmth. We’re a strange bunch, yes, but we’re a nurturing bunch.

In this 2024 edition of Live Encounters Aotearoa Poets and Writers I’ve included work from those seasoned and emerging, previously published and those appearing for the first time, toe-dippers and those who fearlessly butterfly and backstroke out into the great floodwaters of words. There’s Kate Mahony, author of Secrets of the Land , recently appearing on the Whitcoulls Top 100 list (not a small feat, seeing only a handful of New Zealand authors are on this list). There’s Isla Huia’s in the blood, a devastatingly haunting spiral towards our own mortality, where:

when i meet the great beyond i’m gonna give it a whole pōwhiri i’m gonna make sure it mihis to the ringawera

Our societal problems thread through this collection also, especially in Daren Kamali’s Blue-Tooth thing, where he exposes the crisis of crystal meth in his homeland:

Methamphetamine pandemicOn the rise –In the Isles of Smiles Now Isles of crime and sickness.

Our island facesA rapid spread of HIV and AIDS –Highest in Asia-Pacific.

Syringes and needlesFound on streets –In community centres and village gardens.

Our island facesA rapid spread of HIV and AIDS –Highest in Asia-Pacific.

Syringes and needlesFound on streets –In community centres and village gardens.

And in Kate Kelly’s People like me we witness the loss of identity and the prevalence of suicide, especially in our youth, as she chants ‘Continuing to pretend that nothing has happened’, as if we can push it from our minds.

Included are some translations too—one from Alexander Balm who writes in both English and her native Romanian—and some offerings in Te Reo Māori from Trevor Landers and Pasha Mahuto’a Clothier.

Despite his humble bio, I’ve included the powerhouse poet Michael Steven, previous winner of the Kathleen Grattan prize and author of the breathtaking Night School collection; and Michael Giacon, also a winner of the Kathleen Grattan who has recently published his first collection undressing in slow motion, which on its release zoomed to number one on the New Zealand bestseller list. Honoured, also, to be able to include new work from Khadro Mohamed, winner of the 2023 Ockham Book Awards for a debut poetry collection, not to mention a piece by photographer and visual artist Raymond Sagapolutele.

I hope you enjoy this year’s Aotearoa Poets and Writers Special Edition. I also hope it helps to connect us all, to bring us out of our darkened midnight spaces, at least to give us a glimpse at the light, at hope.

Oh! and Mr Merritt – you were right, our paths did indeed cross again.

Nāku iti nei, nā

Lincoln

Alexandra Balm

Alexandra writes poems, short stories, and literary studies. She has received several awards and fellowships, including the Kate Edger Postdoctoral Award (Waipapa Taumata Rau, University of Auckland, 2016). Her work has been published in Aotearoa New Zealand and overseas. She has taught at the Universities of Cluj and Otago. Garry Forrester called her the “mother of metamodernism” in his 2014 memoir. She lives in South Auckland, where she teaches high school English.

Poems in English and Romanian.

Three ages

To DD

I smiled when you told me that you had a meeting to go to in the dead of night, in the middle of our holidays away, while waves were crashing against shelly shores in Vama Veche.

I followed you and saw you stop by the sea, a bridge of silver at your feet, the moon at the other end, thousands of noctiluca scintillans in between.

We stood in silence you ‒ watching the mirage, me ‒ wondering about the very first person in my life in love with a satellite.

In winter, when you caressed furry magnolia buds and spoke of the flowers to come: pink, purple, magenta ‒the colour of the soul, you insisted ‒ I scoffed, for I didn’t speak your language yet.

continued overleaf...

Then, when we walked in the dark by the river Somes you whispered, ‘Bear with me: I’ll stop here, sit on a bench moist with dusk dew and talk with my gods for a while in silence,’ I laughed and went about my drifting.

*

Despite all the affection, I smiled, scoffed, and laughed when you talked with me.

Now that you don’t anymore, I stand by dark waters on subtropical nights; I look at the moon and try to distinguish a possible interlocutor there.

While stroking wispy magnolia branches, I pray to your gods to share their light and keep me company.

Trei vârste

Lui DD

Am zâmbit când mi-ai spus că ai o întrevedere în toiul nopții, în mijlocul vacanței pe litoral, în timp ce valurile se loveau de țărmul plin de scoici sparte de la Vama Veche.

Te-am urmat și te-am văzut oprindu-te lângă mare, un pod de argint la picioarele tale, luna la celălalt capăt, mii de noctiluca scintillans între voi.

Am stat în tăcere tu ‒ privind mirajul, eu ‒ minunându-mă de prima persoană din viața mea îndrăgostită de un satelit.

Iarna, când mângâiai muguri de magnolie pufoși și vorbeai despre florile ce vor veni: roz, violet, magenta ‒culoarea sufletului, insistai ‒ am râs, căci încă nu vorbeam limba ta.

Apoi, când ne plimbam pe întuneric pe malul Someșului ai șoptit: “Asteaptă un pic: m-opresc aici să mă așez pe o bancă umedă de roua amurgului ca să vorbesc cu zeii în tăcere.”

Am râs și apoi mi-am continuat deriva.

În ciuda afecțiunii dintre noi, am zâmbit, te-am zeflemisit și am râs când vorbeai cu mine.

Acum că n-o mai faci, stau lângă ape întunecate în nopți subtropicale; mă uit la lună și încerc să disting un interlocutor posibil.

În timp ce mângâi mlădițe zvelte de magnolie, mă rog zeilor tăi să-și împărtășească lumina și să-mi țină companie.

ANZAC Day

to VS

I can feel your light on my face, to the left, hums the highway that we didn’t notice when we first viewed the house.

It was a quiet Sunday morning, when most were at church ‒ a good time to look at a place merely 50 meters away from a national artery.

There are shrubs and clouds beyond the closed eyelids; to the right persistent wind bothers neighbours’ avocado and cabbage trees ordinarily dressed for autumn this day of restless rest.

We commemorate weeks, months, years of strife and death ‒ pointless, salutary, redeeming (?) Violence is never the solution, always the problem, people say But life without freedom is no life, I tell my students bound by countless servitudes gladly internalised.

Your light still flickers ‒ a reminder of the task you’ve set for me: a clutch of poems, to which I added: a couple of stories For, if we don’t tell our stories who will? Your radiance in my eyes.

Ziua ANZAC

lui VS

Îți simt lumina pe față, la stânga, zumzetul autostrăzii pe care nu am observat-o când am văzut prima dată casa.

Era o dimineață liniștită de duminică, când majoritatea erau la biserică ‒ un moment bun pentru a vizita o locuință la doar 50 de metri distanță de o arteră națională.

Dincolo de pleoapele închise sunt arbuști și nori; la dreapta, în curtea vecinilor, vântul persist și enervează palmierii și copacul de avocado îmbrăcați de toamnă în această zi de odihnă neliniștită.

Comemorăm săptămâni, luni, ani de conflicte și moarte ‒ inutile, salutare, izbăvitoare (?)

Violența nu e niciodată o soluție, Întotdeauna ‒ o problemă, oamenii spun Dar viața fără libertate nu este viață, convenim cu cei din jur, limitați de nenumărate servituți interiorizate în tăcere.

Lumina ta încă pâlpâie

‒ o reamintire a sarcinii pe care mi-ai dat-o: un grupaj de poezii, la care am adăugat: câteva povești Pentru că, dacă nu ne spunem propriile povești, cine o va face? Strălucirea ta în ochii mei.

Alexandra Fraser

Alexandra Fraser lives in the west of the beautiful Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, surrounded by kauri and tree-fern. She has been published in magazines and anthologies in Aotearoa and internationally, and has been highly placed in many poetry competitions. Alexandra is a member of the Isthmus creative and critique group of poets, whom she met while completing the Master Creative Writing at AUT. She’s published two poetry collections through Steele Roberts Conversation by Owl-Light (2014), Star Trails (2019), and is working on two more – one on history and ecology, the other on networks.

A Rhipidura fuliginosa good enough just as it is

Let the fantail be just a bird a thing of bones and feathers striving for a mate a nest food for its young don’t require it to bear the burden of a human soul so that you can feel watched over connected to your lost let the bird be only a bird good enough just as it is seizing insects from the air that you have disturbed as you pass remembering your grandmother

Every day I love someone new

I loved the taxi driver for 25 minutes today He said my daughter works for a big finance firm you will know it very famous He said the name I didn’t but yes I said well done her He said the prime minister of India is bad such bad things in my country He said there is my house pointing as we travel down Great North Road

For four and a half hours I love the young Polish woman who packed up my kitchen She said we like to take very good care She said all your glasses I will wrap like this Be careful when you undo She said this beach is great for my kids they love it here I make sure they are bilingual I say dziękuję which I had just googled

I loved the arborist for a whole day Right he said Good he said That’ll do it as he swung from a high branch then switched on his chainsaw He said do you want the manuka for firewood?

Later I ask how was school today? learn anything new? You teenagegrunt me You politely adjust your earbud try not to let your eyes return to your screen

Every day I love someone new Every day I love you again and again

© Alexandra Fraser

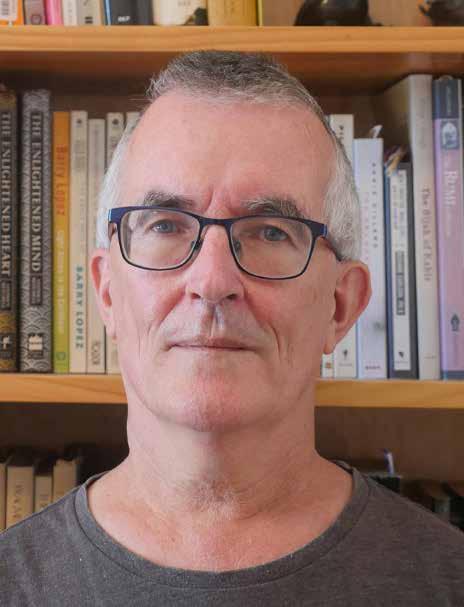

Photograph by Lincoln Jaques.

©Lincoln Jaques

Andy Fey

Andy Fey (he/they) is a queer, disabled Pākehā working in the tertiary education sector, with professional and research interests in access, inclusion and belonging. Andy is an activist and educator, using poetry and zines as a mechanism to connect with people. Their recent performance piece in collaboration with Shasha Ali, ‘Are you meant to be here?’ explored workplace exclusion, and was performed at Waipapa Taumata Rau, the University of Auckland ASPIRE Conference in 2024.

Misplaced concern

“What have you done to yourself?” Have you considered what this question does? You make my mobility aid feel like a consequence. Done- that’s how I feel. My body shouldn’t need an explanation. To exist, crippled yet uninterrogated, would be a relief. Examine Yourself- why does seeing my disability bother you so much?

Joy | Resistance

Joy as a form of resistanceIn a world that would see us crushed The most radical thing you can be is happy.

I have felt loved most by my community When they have shown up for meResistance as a source of joy.

Pneumonia, 2024

‘Productive cough’

A wonderful medical euphemismIt’ll be the only ‘productive’ thing about me.

The first time I caught pneumonia I taught myself embroidery

Each dip into delirium Marked upon my fingers

Second time around, hospitalised

Anaphylaxis, fish-gasping, word slurring Antibiotics harming, not healing.

Third time

Fatigue ever present

Dull siphoning saps

Stealing moments of lucidity

Hours counted in cracked foil packets

Measures to address fever, pain, nausea

Nobody tells you how boring it is

To be bedridden

Even the radio dissolves into static Crackle and buzz bone-weary

“Oh, I wish I could laze around all day.” Come over here and tell me that …after I can move again.

Arthur Amon

Arthur lives in Sandspit, near Warkworth with his wife Miriam and step-dog Lottie. He has been writing poetry sporadically for nearly 4 decades, fitting it around his mathematical modelling job and his sculpting. This has resulted in two books; the most recent of which, safety matches, was published in 2003 – a veritable publishing phenomenon, and his website hasn’t been updated much since then either! Thank goodness for Instagram, where you can find him (and some of his poems) – @amon.arthur

Parnell rose garden

all in their neat patches like rival gangs

bristling with organised intent all bite

the bark lies crushed in immaculate undergirdingno weed stains that sterile bed, so civilised and virginal

it’s a floral zoo; these lame animals need no cages they mutter against the breeze rage in their genteel ghetto

so it is that he approaches:

inserts his nose into Dame Cath Tizard or the Princess of Wales and the sudden jerk from plaisir to jouissance

an epiphany of danger, ecstatic rant against order

right there in that climactic odour everything else fades away all that glisters is on hold

he noses another:

continued overleaf...

from throughout history every sensual caress slaps him sideways give them an inch and they’ll take your family farm in broad daylight these hustlers blaspheme the orthodox sedation of their pens burning down the house

smirking leafy at the mown suburb

I was anxious enough to be quadruplets

when you left, I feared being alone when you didn’t call, I worried by the telephone your slender legs twitched my arachnophobia your catty comments furred up my ailurophobia you took away your embracesit gave me a horror of open spaces

a fear of birds, metaphorical brought me these questions, heretical my neuroses of frogs and dogs and logarithms and night-clubbing handbags and man-bags and sandbags and flooding

I emailed you regarding my deep affection you shunned me; I grew nervous of auto-correction

after several grammar-fuelled catastrophes

I developed a terror of possessive apostrophes when you woke me in the morning with a loud noise it alarmed me you brandished the kitchen knife and disarmed me you left and turned out all the lights; now I dread the dark you demanded your money back with interest, igniting my fear of the shark

but the thing you gave me that put me into a frothy panic was your frankly terrifying love of rhyming couplets… “I’m not so much a cat person myself” (a report from the house-sitting coalface)

continued overleaf...

I do not miss Miss Brodie’s brood White Cat, Minx (the Manx), and Tabby Cat

there was a lot of action when I was therecat action

I kept certain doors shut to avoid confrontations

(don’t open the portholes – you’ll let the tide in! it was a ‘them versus me’ situation).

Tabby, a stately gentleman, left his mark in the bathroom several times, otherwise avoided me; White Cat and Minx were more personable

the owner wrote me a note: ‘water pistol on kitchen table if White Cat should get on the bench’

imagine her: gun in hand, after her cats, her child substitutes (the little squirts)

© Arthur Amon

Miss Chutney Mary. Photograph by Mark Ulyseas.

©Mark Ulyseas

Barbara Peterson

Barbs Peterson lives in the suburb of Māngere Bridge, on the cusp of South Auckland, where much of her poetry has been inspired by the beautiful, diverse surroundings. She has been published in the Auckland Writers anthologies Tales of the Domain and Tales from Dominion Road as well as Ramble On: A celebration of walking in New Zealand by Z.R. Southcombe. Her writing aims to encompass an introspective journey through the experiences of loss, love, heartbreak, joy, bleakness, whimsy and hope.

Vision One

Today isn’t a day of motivation to get things done. Today is a drinkcoffee-in-bed, play games on your phone until 1pm, languish in comfortable pyjamas under a cave of comfortable blankets sort of day. I remember when my cat used to nudge her way under said blankets, more than two winters ago, and curl up in warm ecstasy, paws twitching in blissful dreaming. The “cave of warm sits”, I used to call it. Her cave is one of cold, contemplative sits now. I buried her on a windswept beachfront where she could observe the beauty of the sunset night after night. (A strange concept, for with what eyes do we see once we’re dead and buried? Finally-wide-open ones, I like to think. We can finally see the world and everything in it as it is, aloft a wave of perpetual rest and well-being; our reward for having lived at all.)

So, then, today is also a day to contemplate loss in all her beautiful forms. Loss appears to me today as a lithe young woman in a dress, smiling, flirting, dancing the night away, but never to be mine. She’s my disappeared youth in which I spent too much time trying to understand trauma and not enough time loving the traumatised person who was me. She’s a slender future in which tough choices need to be made, and yet it is tougher to even make them. She’s the regret of a relationship I tried to hold onto that would not hold still for me, like ribbon slipping through my fingers. I no longer curse the bane of feeling unloved. She smiles at me, Loss, and it’s not unkind. She knows how things really are, and most importantly, how they need to be. And I stand, and I understand, but she also says, in that singular glance, that if I should collapse on this dance floor, if I should fail to hold myself upright, I’ll be understood. I’ll be forgiven, if I can’t bring myself to see underneath the skin of things, deep down to the pulse.

In my head sometimes is still the child clutching blankets, fearing the vision of the red monster in front of her terrified eyes, longing for a relief that would never come until the discovery of the magical cassette-tape player; for music soothes the savage beast, as surely as King David played the harp to quell the evil spirit tormenting Saul. In those days the fear crippled me as surely as a net cast over a fragile moth that might crumble to dark dust, but these days it’s welcome to sit in my virtual living room, next to my virtual turntable which circles and circles endlessly playing the same song.

“Why are you here?” I ask. “What do you have to tell me?”

Fear is a storyteller after all, a dramatic mouthpiece to tell us what’s killing us by not being released; the tamped-down poisonous gas that silently steals our years, if not literally then metaphorically.

Fear perches at the end of my bed, gargoyle-style. Fear is a misjudged protector. He’s the pet companion of Loss and trails her everywhere, afraid to let go. We keep him on his leash, afraid of what might happen if he were let loose. The only place he roams at liberty is our dreams.

And yet, and yet... If we released him he might finally find his peace. And so, I do. I unfetter him from his tight collar. Be free, I say. Free in my mind, free in my writing, free in my heart and soul. In your freedom, I find mine from you.

And I let him go, like an exhale.

He leaves me as if he was a tightly pulled-back catapult, flinging himself away to roam the world and come back to me with mind broadened, with stories of open hearts and survival.

He comes back in my sleep, refreshed. Whispers in my ear: “You don’t have to be perfect.”

Snuggles in, sleeps beside my neck, like my cat once slept in the Cave of Warm Sits.

It is easy to be fearless inside the Warm Sits, but it is harder to be fearless on a windswept coast, buried beneath sand and rocks, where the ground might be cold and the stars might feel too far away to care.

And it’s there that I know I’ll find my fearlessness as I watch Loss dance out among the waves and beyond.

And so I lift up the blankets, lift up my legs and step out of the bed and into the world again at last.

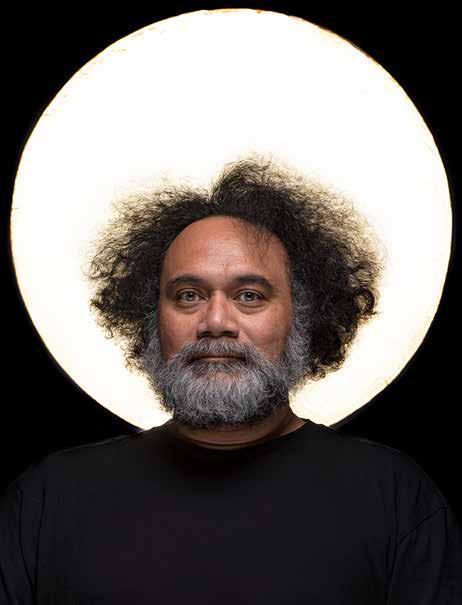

Daren Kamali

‘DKpoet’ or Daren Kamali is a multidisciplinary artist/poet and musician of 25 years in AotearoaNZ and overseas. Fijian – Wallis – Futunan – Samoan – Scottish. He has Viti (Fiji) and Moana Nui a Kiwa at the heart of all his writing and creations.

“This performance poem, Blue Tooth-thing is close to my heart, drawn from recent visits home to Viti and experiencing firsthand the effects of drug consumption and methods of injecting and transferring blood with Crystal Meth which is a damaging rising pandemic and killer, as a result has caused the highest HIV virus and death rate in Asia-Pacific due to the practice of Bluetooththing. I am saddened by what it is doing to my people especially our youth and women. It is and has broken up loving families and communities in a once united society.”

Blue-Tooth-thing

For Viti

I only heard of Bluetooth as hot spot –To share mobile data.

Bluetooth-thing is a thing –A wordplay for needle sharing –Blood extraction and Transmission –From one person to anotherShooting crystal meth - to get high.

Methamphetamine pandemicOn the rise –In the Isles of Smiles Now Isles of crime and sickness.

Our island facesA rapid spread of HIV and AIDS –Highest in Asia-Pacific.

Syringes and needlesFound on streets –In community centres and village gardens.

Outside parliament grounds –They shoot-up –Into the arms of lost onesSmile on their faces with vacant eyes –No one home.

An island nation filled with zombies.

continued overleaf...

Their love is not for each other –It is for this horrific drug –Encouraged by elders –Pushed by parents.

Committed to theft, rape and murder –All suffering together from mental health –The new norm is to inject till death –They can’t help themselves. 10-11-12 year olds – dyingWomen’s minds frying –Turning tricks to get that next fix –They will do anything, and I mean anything.

Men - smashing down doors –Snatching our kids –Loitering the streets –With nothing to eat.

Their sermons so profound –Even in churches they can be foundChoir of fallen angels’ voices echoes –From the underground.

A situation so dire –The United Nations respond –To an urgent call for help –In Oceania’s crossroads.

Isa lei noqu Viti –

You’re like a disobedient child –Beaten to the pulp –Dragging yourself through the mud.

Suva looks so sick and tiredOld and worn –Your people are torn –Between reality and a dark place.

It’s like you don’t have a mother –You’re not part of the human raceOne pandemic – after another –Nor a father to guide you through –The gates of hope. What a struggle to see you suffer.

We must work together to acknowledge this topic –To rid ourselves of this great evil –That has over-shadowed the tropics.

Work together to dig ourselves out –Of this bottomless pit –

To get rid of dealers trafficking P from overseas –Pushing Ice to our off springs.

Rid ourselves of this Blue Tooth-thingContaminating our youths’ veins.

We must rebuild our young bodies –Get rid of this Bluetooth-thingClear our minds and revitalize our children’s brains –Rebuild love and compassion into this nation again.

To re-educate our people on the effects of crack –Knowing that HIV and AIDS can be cured –And to realize that our Pacific nation –Need to get back on track –To the old way –

The way the world should be.

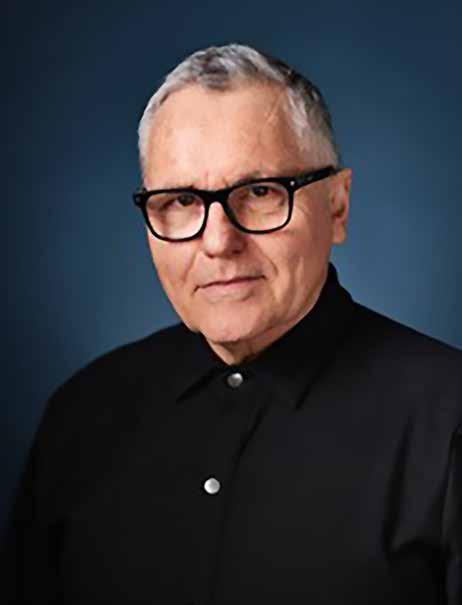

David Eggleton

David Eggleton was the New Zealand Poet Laureate 2019 - 2022. He is former Editor of Landfall as well as the Phantom Billstickers Café Reader. His The Conch Trumpet won the 2016 Ockham New Zealand Book Award for Poetry. In 2016 he also received the Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement in Poetry.

Burning Man

He’s driving a moon module to Burning Man, he’s a hybrid mystic with a Five Year Plan. No words, only lip-synching to silence, and why doesn’t anyone mention his violence? His eyelids flicker, like he heard that snicker. If he’s loving his life, then how about you?

Life’s good, just saying, and we all got guns. He’s doing more navel-gazing these days.

She’s taking the algebra notes from her bra. Who has the audacity to claim they are woke, when everyone else confesses they’re broke?

You’re just another fabulous nobody, admit it, until you get your name engraved on a bullet, so give me another spontaneous high-five, if only to make sure that I’m still alive.

There’s a big white cross shining on my lawn. There are twelve shades of bronze to my medal. Can you tell me what is it about whataboutery? Then can you stick a fork in me, because I’m done. We are what we are, where we are, as you do you, from designated driver to burnt-out survivor, at just random dudes venting in a pious way, though advisory has given me my final warning. Who brought pretzel-logic, who brought bagels, who brought the weed and the loaf of Vogels? You better go back to writing with a twig, a twig dipped in mud stained with blood.

A Place to Stand

I stand with the day-dreamer, with the vagabond, with the boulevardier, with the underachiever, with the poor student, with the impractical inventor, with the underworld denizen, with the beggar, with the unpublished poet, with the café philosopher.

I stand with the wandering muso, with the charlatan, with the fairground chancer, with the resting actor, with the unsuccessful business-person, with the misfit, with the try-hard die-hard, with the circus performer, with those stranded in the world of analogue.

I stand with the ruminator, with the star-gazer, I stand with everyone gone to the mute button, I stand with the sooth-sayer, with the wraiths in hoodies, I stand with those bound for Vallambrosa, I stand with those who build driftwood altars.

I stand with the dissident, with the at-a-loss peace-keeper, I stand with the techno-Buddhists across the road, who blip their sound-system to chanted mantras all night long, I stand with the outer circle, I stand with the old-school o-g, I stand with those loyal to the bitter end.

Tipping Point

Here, at the tipping point, you tip over in a flash. There’s much trial and error, but no more cash. It’s all on plastic, gone belly-up in the ocean. Wind’s time and motion asks who owns the brand? There’s so much exhaustion in breathing exhaust, as the netherworld’s vapour begins to ripsnort. Each rainbow’s oily in the drizzle of more rain, and bubbles are swirled up the food-chain. They sound the retreat where three rivers meet, but to no avail, as if on the list expected to fail. They bring all the fire that’s fit to sink in a gyre. Someone’s upselling smoke of utility vehicles. The divine entablature’s written in digital smog. In heaven skulks God; nought’s right with the world.

David Merritt

Poet David Merritt has a broad, strong back, well suited for gardening, driving old Landrovers and reinventing the economics of poetry. He makes bespoke publications of poems from recycled Readers Digest Condensed book covers and banana box cardboards, often in public places on a footpath bench seat or at a market from the back of his car. Using a stamp pad alphabet set, a stapler, some glue sticks, a photocopier and a copyleft intellectual property model, Landroverfarm Press has now published over 110 distinct titles from unique single page A3 publications to collections, boxsets, #poetryracks, #poetrybricks and anthologies. During this time he has also taken the David Merritt Poetry Experience to all parts far north and south of New Zealand

Shadow banned

I tab from site to site, looking, reading, watching this, downloading that, taking screenshots, doing giant inter-web searches inside of encrypted browser windows.

My various feeds are non-linear, they are abstract and varied and none of them are mainstream in any way;

all offer me information, data, news, analysis, perspectives, boots on the ground viewpoints, opinions, theories and facts.

I watch as tiny homesteaders in Arkansas dig big gardens and I follow a woman stalking a bear in Alaska, I read about a Nun talking about death in London and in Pakistan, the diesel mechanics just roll up their sleeves, everyday.

I track currencies. I track commodities. I track atrocities. I track test cricket scores.

I follow the unknown and marginalised. I keep an eye on the censored and I seek out those that have been shadow banned.

The bus

I had to catch that bus at 7.15am or I was sunk, destined for detention, late for school.

I was 13 years old with a big brain, facing 3 long hours a day on a bus, five days a week. The year is 1972.

I was already nerdy, already geeky, verging on left wing, flirting with hippy and

I liked libraries, Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Ransom, Biggles, Tolkien. Chairman Mao, the Little Red School Book, the Pentagon Papers, the end of Nixon. I was Shadbolt, Kirk and the Labour Party.

Anyway. That bus ground its way up and down the Great South Road through 34 sets of traffic lights, often all of them red.

The Auckland suburbs of Otara, Otahuhu Penrose, Green Lane, Epsom, Newmarket and Khyber Pass rolled on past the fogged up windows, often in the rain.

I reckon there were also 42 bus stops all told, most of them requiring another stop and a start to pick up or drop off a passenger.

Up past the freezing works, the industrial zones of various descriptions, the 5 volcanic cones, the office and factory workers, other kids destined for all the other schools along the way - Otahuhu, Kings, Penrose, Dilworth, St Peters.

That bus journey was tortuous and lasted forever in all directions so aged 12, I started to visit libraries in town and Epsom and Mangere and Onehunga and Otara.

A year or two later, by now aged 16, I’m reading books about UFO’s, the assassination of the Kennedy brothers, MLK, the illegalness of Vietnam and the bombing of Laos and Cambodia, Whole Earth Catalogs, Mushroom magazine, the newsletters of HART and CAFCINZ.

I protested against injustice and I protested against secrecy and misinformation and propaganda.

I raged against US cultural imperialism, against home racism and apartheid. I raged against the rich and powerful figures who ruled our landscapes in every possible direction.

Flash forward 50 years to the here and now, this spring morning and I don’t need to tell you that the names might have changed yet some things, strangely, have remained the same.

Worry

I worry about my future now, so much has changed and I suspect that its the tip of the iceberg yet.

I worry about extended supply chains, logistics, food scarcity. I worry about the Ukraine and Palestine and Taiwan. I worry about the agendas of the governments worldwide.

I know a lot more about the AI singularity that is now upon us. I’ve watched and read a zillion words and images trying to make sense of a world gone mad, orchestrated globally.

Blackrock and Vanguard own everything.

“It’s a free country” is a sham in most democracies and these are the most interesting times we were warned about.

WW3 is being fought out in the cognitive space between our ears, through screens and devices.

And don’t get me started about the Internet of Bodies because the Internet of Things is bad enough.

I miss 2018 a lot.

Photograph by Lincoln Jaques.

©Lincoln Jaques

Erica Stretton

Erica Stretton has a Master of Creative Writing (First Class Honours) from the University of Auckland. Her short fiction and poetry can be found at Headland, takahē, Mayhem, Flash Frontier, and others. She is a freelance editor and book reviewer, and is currently working as editor for Kete Books

dinner

the house gives up midnight for morning but holds onto the thousandmoon shimmer. every shade of emotion poured into the stolid and boring bricks. we slap on purple and pink to the walls, stardust splatter, with a brush that barely has any bristles. she dances as if the world might end and her feet twinkle with glitter. ‘More,’ she demands, ‘more night stars,’ and you deem it more important than every other never-ending task. the washing waits. the vacuuming, too. the cacti lean toward her spiky and difficult. we paint them into canvas. wispy feathery stripes into blossoms, silky flesh. this is a masterpiece. the brush presses into her face; she spins and spins until it’s time for marshmallows in the bath. he comes home and she is delivered a bundle into his arms. he doesn’t appreciate her brilliance and he will sigh. mostly under his breath. even though she is clean and clean and smiling and filled with dancing bubbles. sigh and ask what’s for dinner. will it be ready soon.

Planting for Spring

hovering over the tray, you touch your biggest babies with subtle fingers they lift their heads, unfurling cotyledons, tiny leaves bead buds stories spill from eager lips as you stroke leaves

we sprinkle life giving crystals trapped in drops I separate the seeded lovers their roots tangling frail, freed from saturated soil save them, lest you weep

you are the glee for my day the eagerly-given grin I am your life preserver

my care is all for your face a panorama of floating dreams clear of tears and broken capillaries I lock your hurt in my weak hands

banish tears

but you yank out the smallest plants take the fragile stems between your fingers, snap them a curt sound

the rain is thin like paper, tissue-soft and moulded to form twice smudge myself in amongst the lines

follow and fall, spiralling through the mall filled with folk shedding skins in the controlled temperature

the screeching lights radiating down the back of a thousand pimply necks i slapped on another face for this mall, undirtied tramping boots

rivers rumble on, dank mustiness underground, aboveground spilling licking concrete, swallowing asphalt, leaving plenty fee-free

the news boils, feet quiver to scuttle, a thousand sideways spiders onto wheels my toes touch seeping water – be reight, stop ya beefin’ –

squinting eye beams facing into boots, gridlocked windscreen wipers thrash ineffectively I have a cupped hand of dirty water and I wonder on concrete trying to contain all the soil beneath it

Gillian Roach

Napier poet Gillian Roach won the NEW VOICES – Emerging Poets Competition 2018 and was awarded runner-up in the The Kathleen Grattan Prize for a Sequence of Poems in 2018 and 2019. She has been published in Landfall, Takahē and the Poetry Aotearoa Yearbook.

We are the art in the art museum

At the entrance to Teshima Art Museum we scatter like muffled marbles. Two people sit dead centre uniform in crisp white shirts black cropped pants. Fraternal twins? Mirror lovers? Each watch a different pool at the opposite end of the sphere. They look photoshopped. A glob of water holds tension at my feet. A hanging thread stirs. An ant writes black across the smooth concrete. Kevin finds action. Quick droplets that coalesce and run to a natural depression. Yah! A child enters and is summarily hushed. His grandfather walks through a puddle and time ceases until puzzled he shakes his socked foot. Two girls in lace, linked at the elbows, dance across a patch of sun.

Crashing laughter dies away to the ubiquity of birdsong. The space fits the top of my skull exactly. I grow around it I take it away. The art museum is the art in me. Ant, thread, twins. Ideas nudge closer to a pool. A man tramples through surprised by sensation.

Greendreaming

Cycle all night in deep bush ponga ferns startlegreen against heavy sky filtered sunlight filigree velvet moss lanes cutthrough by isolated men in harsh conditions for extraction

Tumble on repeat alone on a track beyond my skill level humblebruised no option to quit like progressing down a birth canal reborn vulnerable and pure threshed and flayed

Fall from the bike all night wheel trapped in sandy rut boggy moraine cartwheeling slow back over stalled front boltawake at cliff edge or tree looming adrenaline singing doom singing failure and pain until the return to now feather pillow fresh washed sheets eyelids shuttering

All the greens beyond capture to memory or phone dreaming to be seen before this land brownshrivels in coming centuries of heat

Isla Huia

Isla Huia (Te Āti Haunui a-Pāpārangi, Uenuku) is a te reo Māori teacher and kaituhi from Ōtautahi. Her work has been published in journals such as Catalyst, Takahē, PŪHIA and Awa Wāhine, and she has performed at numerous events, competitions and festivals around Aotearoa. Her debut collection of poetry, Talia, was released in May 2023 by Dead Bird Books, and was shortlisted for the Mary and Peter Biggs Award for Poetry at the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards 2024. The books opening poem, ‘Wetlands’, was chosen for the Ōrongohau Best New Zealand Poems 2023.

in the blood

i.

after i’ve gone to the dirt bellied up and crossed the jordan dropped the body, freed the horses

i’m gonna be an enigma i’m gonna get the eternal choir doing nei rā te kaupapa, but gospel

i want it to sound like giving a mouthpiece to sundown.

ii.

my kui only believed she was being sent for abraham’s bosom when it started raining through the roof

we sang fish are jumping, cotton is high made ourselves into rhinoceros with the rose thorns forgot the flooded carpet, turned the lights out.

continued overleaf...

iii.

when i meet the great beyond i’m gonna give it a whole pōwhiri i’m gonna make sure it mihis to the ringawera

i’m gonna share my hakari with the dogs i’m gonna say auē, e moko, and moko’s gonna say nanny, can you teach me how to fly?

or how to not put anything smaller than my elbow in my ear canal?

or how to drink ensure while talking about peace and clarinets and bronchial asthma and spa baths?

when i’ve given up the ghost i hope he’s whāngai’d out

when i meet the vast majority i hope they’re brown i hope we’re in a valley i hope my hair has grown back

that the jaws are too weak to bite down that the GPS says calculating route home.

iv.

makers, make me a machine or at least, the kind of tīpuna who can predict a set of twins, who has the lullabys on lock who has both hands on the wheel and tikanga on the post-its

this is the kaupapa of forever i’m gonna massage out the comedowns i’m gonna clap til the genes settle in i’m gonna tell you about the government

i’m gonna give you an unpopular opinion and i’m gonna pluck the guitar string in the middle of the night

watch it vibrate notice the kererū admire its fat.

v.

i’m gonna be cctv on the wrong side of the grass watching out for all your gold

your mānuka hearts the blood i gave you the tohu i always will

e moko, all you’ve gotta do is open your arms.

i’ll be waiting in the wings.

Ivy Alvarez

Ivy Alvarez is the author of The Everyday English Dictionary (London: Paekakariki Press, 2016), Disturbance (Wales: Seren, 2013), and Mortal. Her latest poetry collection is Diaspora: Volume L (Paloma Press, 2019). A five-time Pushcart Prize nominee for poetry and fiction, her work is widely published and anthologised, including appearances in Best Australian Poems (2009, and 2013). Several of her poems are translated into Russian, Spanish, Japanese, Korean, and Filipino. Born in the Philippines, she has lived in Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and New Zealand, before returning to Australia in 2024. www.ivyalvarez.com

Spell it backwards

You hear the Porsche gunning against the green light, and irritation crinkles your brows, and your stance, relaxed, tenses up. Tires lay black rubber in extravagant cursive, an infernal wedding invitation perhaps. Licence plate NUR5321. But no, here’s the car’s bonnet pinning your hips against the traffic pole, obscene lover, everyone can see. Count it down. Ah, it doesn’t seem to matter now. The choice is gone. Taken in a manifold instant. No more needing money to pay the rent, o dwindling budget for necessities, thy joys deleted from thine bucket list. For ‘twas here the bucket stood, underfoot, and someone kicked it for you. Time to rest. Let’s give thanks. Hallelujah.

Jack Ross

Jack Ross is the author of six poetry collections, four novels, and five books of short fiction, most recently Haunts (2024). He was the managing editor of Poetry New Zealand from 2014-2020, and has edited numerous other books, anthologies, and literary journals. He retired from his job teaching creative writing at Massey University at the end of 2021, and lives with his wife, crafter and artwriter Bronwyn Lloyd, in Mairangi Bay on Auckland’s North Shore. He blogs at http://mairangibay.blogspot.com/.

Nice

She was still crying when I walked into the Tourist Information office

on the Square in Christchurch what’s wrong? I asked

– that man who was in here before he came in and I asked if I could help he didn’t answer just waited for my European colleague to be free – we’re not all like that was all I could find to say to the young Asian woman another colleague hurried in what’s wrong?

she outlined again what had happened as the colleague fixed on me

a nuclear stare not him he’s nice no another man he’s gone I didn’t know what else to say or do just repeated we’re not all like that

Kimono

It’s called the Kimono shop by those of us who frequent it

a warehouse-sized emporium in Penrose full of every Japanese garment and trinket imaginable in long serried rows

some the wedding kimono for instance are priced steeply others $5 or less I bought some old postcards and a guide to Japan from 1966 the date of some of those old paperback novels I love to read

Kōbō Abe Osamu Dazai Shūshako Endō

it felt like an out-of-body experience getting there a labyrinth of twists and turns guided by Kylie our Australian-accented cyborg street-guide voice and then the dusty perfumed smell of the kimono where do they come from?

hand-sewn each one unique retrieved from dumps and skips apparently exotic ambassadors spreading their own delight

Soft

We’re always on the lookout for book-troughs and bookends for my growing collection this time it was a revolving bookcase one metre high 70 centimetres in diameter I know because the shopkeeper made me measure it with her own tape-measure in the middle she prompted not the side this was to see if it’d fit into the car the consensus was it wouldn’t

I wasn’t quite so sure it didn’t after that she got the owner on the phone

are you going up to Auckland anytime soon? yes he’s already bought it

I hadn’t but I wanted to so he needs to have it delivered we settled on next Sunday

they think you’re soft confided Bronwyn as we drove away – what do you mean?

the way she told you tilt it this way not that way as we tried to wrestle it in

the fact she didn’t think you could back into that parking space outside the shop

come to think of it

I did notice a bit of a village-idiot vibe in the way they spoke to me

am I soft? if so it doesn’t worry me more interested in dreaming of all the books

I can squeeze into those shelves

Kate Kelly

Kate Kelly is half a century. Poetry is a mode of expression of choice as it is concrete and feels powerful in a very subtle way. To share a viewpoint that is individual and unique is a real privilege.

People like me

The taking of my authority – crawl to sleep

Called a swamp monster in the morning

Bleeding

Bruised

Frightened

Walking for 2 ½ hours to get home, uphill

Cannot walk properly

Looked at as if disgusting

Continuing to pretend that nothing has happened

Continuing to pretend that nothing has happened

Continuing to pretend that nothing has happened

Eating dinner

Continuing to pretend that nothing has happened

I have changed

I no longer have healthy boundaries

I cannot ask for help

I believe that I don’t deserve assistance

I sleep with anyone without protection

I have suicidal ideation but do not recognise this

I cannot play music anymore

I cannot focus on schoolwork

I am kicked out of school

Continuing to pretend that nothing has happened

Crawl to sleep

The taking of my authority

Crawl to sleep

In emergency, sleep

Crawl to sleep. In emergency, sleep, sleep.

Mercury, aspects of normal

We are not just elements

We are not static

We do not fit on the table

We cannot be held in the palm and turned

I am not zinc – not completely

My son is not Argon – not completely

You are not Iron – not completely

You are not Iron – not completely anyway

Everyone takes fish oil pills these days don’t they

Long, translucent, sticky

Don’t burp on someone

We are not static

Dolly Parton played Glastonbury today

Sunny

Dry

Midriff top about strong shoulders – working 9 to 5 –

She, resplendent in skin-tight white jumpsuit with sequins

“I’ve played big shows, but not this big”

Yet a Pakistani couple, married in secret, were beheaded by the husband’s family

Same day

We are not static

I am not Iron – not completely

I will not fit on that table

The news is full of contrasts

Newsreaders still poker faced

They were be-headed

Dolly, huge boobs and blond hair strode around

“I’ve always wanted to do this” – we are not static.

I can’t believe I’m still bleeding

I can’t believe I’m still bleeding

I can’t believe I’m still bleeding

I can’t believe I’m still bleeding

I’m sure I notice it more

Am more self-conscious

It just seems so absurd.

No vomiting for hours now

No passing out at school.

No FLOODING.

No lack of painkillers

Only sleep could cure pain

And pot.

But really…

I can’t believe that I’m still bleeding

Married Corrections Officer thinks I’m 48 and should have more children

He must assume that Yes…I’m still bleeding.

Kate Mahony

Kate Mahony’s short fiction has been widely published in New Zealand and internationally and been shortlisted and longlisted in international competitions. Her short stories have appeared in literary journals and anthologies including Litro New York (United States), Meniscus (Australia) Blue Nib (Ireland) Fiction Kitchen (Berlin), Fictive Dream (United Kingdom) and in New Zealand in takahē, Blackmail Press, Best New Zealand Fiction Vol 6, Bonsai: Best small stories from Aotearoa New Zealand 2018, Flash Frontier and Mayhem. She has an MA in Creative Writing from the International Institute of Modern Letters at Te Herenga Waka – Victoria University of Wellington. Her novel, Secrets of the Land, published by Cloud Ink Press, was voted number 21 in the Whitcoulls Top 100 books, 2024-2025 www.katemahonyauthor.com

The Good Deed

It had begun to rain and a southerly wind was already whirling down the main street of the city. It was 9.45pm and the electronic bus timetable showed Anna and Tom’s bus due to arrive any minute. It was then Anna saw the slightly built Japanese girl. She was almost hidden in her black puffer coat in the darkness of the shelter. She had two bags – one a large suitcase, the other a carry bag that looked almost as big as her.

Anna looked back at the electronic timetable expecting to see a notice for the airport bus which went directly through the suburbs to the airport. But there was nothing in the long list of destinations. Perhaps it did not stop there. Or it had been cancelled.

Their bus pulled in and the door opened. Anna paused at the entrance and looked across at the girl. ‘Where are you wanting to go?’

‘The airport,’ the girl said in hesitant English.

This bus did go near the airport but Anna and Tom’ s stop was well before that. Would the girl know where to get off? She turned to the driver. ‘Can you let her know when you reach the stop for the airport?’

The man shrugged. The airport was some distance away and she began to doubt he would remember the girl was on the bus by then. It was pitch black outside and the girl couldn’t stay here. This bus would have to do. She gestured for the girl to get on the bus with them.

The girl picked up her heavy bags and followed Anna and Tom onto the bus and sat in the space for wheelchairs and suitcases at the front.

Anna turned to a woman behind her. The other passenger was wearing headphones which she took off. ‘Are you going to Southgate?’ It was the final destination after the airport.

‘Yes,’ the other said.

‘Can you let this passenger know when to get off for the airport?’

The woman said she could.

Her duty done, Anna relaxed in her seat. They had left the city’s main shopping area and were heading to Anna and Tom’s stop. She had a sudden thought. It was already past 10 pm. Domestic planes didn’t leave through the night at the airport. The last plane out was well before 10 pm. Perhaps the girl was taking an international flight. She had no idea when they stopped.

She got up from her seat and went over to the girl. ‘What time is your flight?’ She had to repeat this several times before the other understood her.

‘Eight am. To Christchurch.’

Anna had seen the big notices on the front doors of the airport which stated that the airport building closed between 3 and 5 am. The girl couldn’t wait inside the airport and it would be cold and dark outside. Dangerous even.

She tried to explain this to the girl. Some of the other nearby passengers joined in, agreeing with her.

‘You will need to stay in a motel.’ Anna looked at the girl to see if she understood. Other passengers began calling out the names of motels that were near the airport but none of these were really within walking distance of the bus and Anna could imagine this girl – with her poor understanding of English – getting lost, trying to lug her heavy luggage along badly lit streets.

Tom meanwhile had been looking up a hotel within the airport vicinity itself – there was one, right next door to the departure area. He held up his phone for the girl to look at. ‘One hundred and eighty-seven dollars,’ he said.

The girl blanched. She looked downcast. Clearly the price was too much.

Anna tried to think what to do. Should they offer to pay the cost of the room at the hotel? For a girl they had never met before today. A stranger? What would Tom say if she suggested this?

‘No rooms available,’ Tom said, while she was still deciding. She felt herself relax. They had done what they could. Surely.

A woman sitting opposite them leaned towards Anna. ‘My friend lives in your street,’ she said. ‘We see your husband walking your dog.’

The streets around their house were often busy with walkers. People did a particular route which took them to the rise at the top of the hill and then back along another street. Walking Oscar was Tom’s job. Anna looked at him.

‘Oh, yes?’

Anna suspected he had no idea who the woman was.

‘My friend has a little white dog,’ the woman said.

‘Oh, yes, ‘Tom said. ‘I know the one.’ Perhaps he did. Anna was sometimes surprised at the number of people he seemed to recognise on the street.

The woman now spoke to the young girl. She said something in what Anna assumed was Japanese. The girl responded.

Anna looked enquiringly at the other woman.

‘I learned a little Japanese back home in the Philippines,’ the woman said. ‘Not much, but I told her she can stay at my house.’

That was amazing, Anna thought. Problem solved. She felt so relieved. She did not have to worry about the girl any further. They were nearing her stop. A man in his sixties in a faded blue anorak and wearing a black beanie, who was seated nearby said, ‘I thought of offering the same, but…’

Quite, Anna thought. It would not have been at all suitable for him to suggest this.

She stood up as their stop came closer. ‘You will be ok with this lady,’ she said to the girl. ‘She says her friend lives on our street. She’s a good person.’

Well, she hoped the woman was. Too late to worry about this now, anyway.

Their stop came. Their house was at the top of a small sharp incline, a short walk away. She was pleased she had not invited the girl to stay. It would have meant her dragging those heavy bags all the way up the hill in the dark.

Later, in bed, the evening still on her mind, she remembered another time long ago. In London, late at night also, on a near empty street. Two young men with Scottish accents stopping her to ask if she knew any B and B accommodation nearby. They had got lost. The streets with B and Bs were back some distance behind them, a long walk. She didn’t know what to suggest. Then, unbidden, the thought came to her. ‘I live nearby,’ she said. ‘You can stay at mine.’

She shared a comfortable flat in a former city council apartment block with two flatmates, one of whom had gone to a musical festival, the other was staying over at her boyfriend’s. As she opened the door, the flat suddenly felt too large and empty. She ushered the boys in and showed them the two small couches in the living room they could sleep on. She made tea for them all.

They told her they were both hairdressers in Edinburgh, down to London to sightsee and hoping to spot some celebrities in Notting Hill Gate or Camden. The boys were gossipy and fun. She found some blankets and they set themselves up on the couches. It was getting even later and she had her part-time weekend job at the local florist’s to go to in the morning. They said their good nights amicably.

She had brushed her teeth and removed her make up in the bathroom and then gone into her bedroom. She had got into her own bed. She had been unprepared for the cold harsh fear she would feel once she had pulled the cover up to her face.

What if they attacked her? What if they murdered her? For most of the night, she lay awake.

The night stuttered on until eventually it was morning. The two lads made their farewells presenting her with an array of mini sample hair-dressing products. They were immensely grateful. They both pecked her on the cheek. She went back to bed after they left, slept for a time, and was late for work. She lied to the florist. Her lie was long and involved but she could not face explaining she had let two unknown young men sleep on couches in her flat for an entire night and because of this had been unable to sleep. The craziness of it.

Now as she recalled this event from her long ago past, she felt guilty. She had allowed an unknown girl to stay with a kind woman who she also didn’t know. The girl could have done something to the woman. Murdered her in the dead of night. She knew neither of their names.

She kept an eye on the news for the next few days. Nothing.

Two weeks passed. It had rained heavily but had now stopped and she and Tom went out for a walk with Oscar on the Saturday afternoon. Two women with a little white dog approached them from further down the hill, one waving excitedly. It was the woman from the bus. She was happy and smiling and very much alive. She told them about taking the girl back to her house that night. It was very late and her mother-in-law, who lived with her and her husband, had been astonished to see her arrive with a stranger. They offered the girl a futon to sleep on. She was delighted to see it, the woman said.

The woman’s mother-in-law had made the girl a hot chocolate drink and they had all talked a while. The girl explained she had travelled to Auckland for a job but it hadn’t worked out. She was intending to go back to Christchurch where she had previously lived. She was 31 years of age. Not the ten years younger she had looked at the bus shelter. The woman from the bus was pleased to share all this.

Not only that, but in the morning, the husband offered to drive the girl to the nearby airport. He needed to fill up with petrol anyway, he had said. The girl had handed him some cash for petrol, as a thanks when he dropped her off.

Anna was silent. She wasn’t sure what to say. She thought of “All’s well that ends well.” Instead, she said to the woman that she had done a good deed. ‘You are a good person.’ ‘No.’ the woman said looking steadily at Anna. ‘I did it, because once I was stranded at Sydney airport and no one helped me. So I knew what it was like for her.’

Anna opened her mouth. She would tell the other woman about what had happened in London, how she, too, had reached out late at night, also to help strangers. They were not so different, she could say. But Oscar saw another dog coming towards them and started straining at his leech and the little white dog became agitated.

It occurred to her as they walked away from the women that she was now a different more cautious person. And she wasn’t sure she liked her.

© Kate Mahony

Photograph by Lincoln Jaques.

©Lincoln Jaques

Khadro Mohamed

Khadro Mohamed is a writer and poet from Wellington. Her debut poetry collection We’re All Made of Lightning won the 2023 Ockham Award for Best New Book of Poetry. She is passionate about the beach and the colour purple.

Taste:

i think my tongue was born here because i can taste the stillness of the winter the way it cuts through my skin

i can taste the sunset the budding of the kowhai the redness of the wilting roses in the garden beds of the botanics the sharp sand of karaka bay that rips my sole’s wide open & leaves remnants to be washed away

i think if i ever lost myself i could taste my way back

notes from my old self

that time you ate so much at iftar that you could hear the fluid in your stomach move when you stood up. it made this sound, like the ocean.

that time in summer, when you sat on the grass at mcallister park and the smell of freshly cut grass filled the air & washed away the stickiness of nostalgia.

that time you thought about swimming in the harbour as the wind thrashed the waves, but you were too afraid to move from the concrete sidewalk of oriental parade.

that time you sat at home while mum went shopping and you thought about packing your bags and starting a new life in a far away land.

that time you looked for a large tree to hide underneath as the summer rain burst from the clouds. you were somewhere in denmark. you thought it wasn’t going to rain when you checked your app, but you forgot to change the location from wellington.

that time you promised to commit your pain, your mundane and your thoughtless moments into poetry because it was kind of fun to beautify yourself.

that time you wanted to take scissors and cut your hair off because it hurt too much when mum braided it. it’s kind of funny to think about now, in a sad kind of way.

that time you memorised your father’s lineage, the names of your forefathers linked together like a daisy chain, looped around your five year old neck.

that time you went to egypt and saw spectacular sunsets, day after day. only to later learn that the bright oranges and deep reds were from pollution. you still thought they were beautiful anyway.

Kit Willett

The purpose of life

When we look back on a life well-lived, what do we hope to find?

Solace, that our dear beloved one made something of themselves, someone to applaud and thank? Or perhaps it is a self-comfort we seek— that when we rest at close of day, we, too, will be remembered.

You frolicked in a field once; I can picture you at any age, on a summer’s day, delighting in the breeze and birdsong and shape of the clouds. You swam in the ocean and rejoiced at the salt on your skin as it washed away your worries. You lived in those worries; I can see you, still, at the dimly lit kitchen table, brows furrowed. And you burned when you felt the evils of the world. And you laughed when the world turned and showed you its good side.

When I think about a life well-lived, a life full of joy, and rage, and worry, I think of you, and I cry, and I cry— and in these tears, I find the very purpose of life, and in these tears, I find you.

Kit Willett is a bisexual poet, English teacher, and executive editor of the Aotearoa poetry journal Tarot. His debut poetry collection, Dying of the Light, was published by Wipf and Stock imprint Resource Publications in 2022.

Winter

Often, in the small days of winter, I get a terrible cold: a reminder to drink litres of Earl Grey and watch recordings of Mary Oliver reading aloud. I remember the comfort of sweatpants and the importance of rest (lessons I am eager to forget). I play the piano without singing while the soup boils on the stove, and the cats keep me company by attempting to sleep (on my face).

I think winter must be a good time to be a cat— though they sometimes sneeze, too— for they sprawl languidly in front of the fire or nest in the tossed blankets on the couch, and they get their favourite kind of attention when parading in after an outside visit in a storm: a recoiling hand and an “Oh, you poor thing.”

Haiku

My pen has grown stale— Perhaps it is time at last for a new notebook

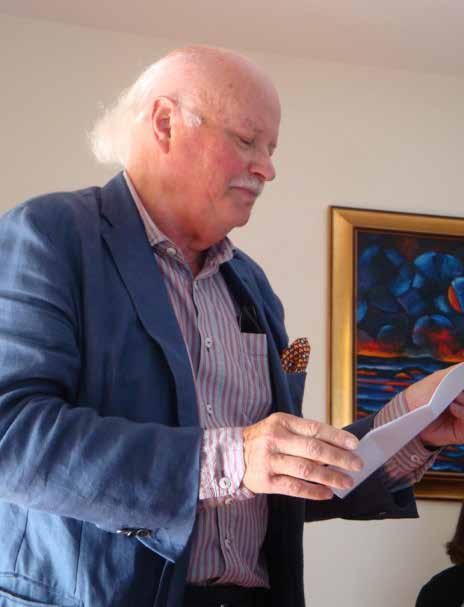

Maris O’Rourke

Maris O’Rourke describes herself as a poet and peregrina, a writer and walker. She has been writing for 10 years and published 10 books – a memoir Zigzags and Leapfrogs; a family history; two poetry collections Singing with Both Throats and Paradox; and six children’s books (two in Te Reo). She lives in Mt Eden with her whānau and regularly retreats to Whaingaroa/Raglan to write and walk.

Will we make a place for them?

Big mammals, nearly extinct, names lost from Te Reo, appear again at Rakiura, Otago Peninsula, The Caitlins. Once a sacred Māori taonga – it’s like the Moa returning or a mythical selkie materialising in Scottish mist.

Sea lions are coming home – after 300 years of exile.

In the subantarctic islands females struggle, make deeper dives for less food, drown as by-catch in the nets of squid-trawlers. Pups wait – pine, starve. Marauding bulls harass, disease decimates.

Deep ancestral memory, of safe breeding, birthing, feeding places – calls – across 500 kilometres.

Hauling-up on mainland beaches – huge, social, inquisitive, adrenaline-producing – their gruff demeanours evoking distrust, resentment, panic, fear.

Preyed upon by dogs – run over, stabbed, gunned down by us.

Sifnos/

awake early crosswise

bats swoop home dusky pink shades the lemon horizon shot-silk sea metamorphs turquoise aqua azure

Blue that solid Greek blue of shutters doors tables panagia-domes windmills plastic-bags bottle-tops chairs gates fences eyes

Blue like job lots of God’s paint spread spilled into every crevice and gene

Blue set against hard bright white wash of blocks buildings piled everywhere as if by a manic child.

Blue

I visualise myself in a full-skirted swirl of brilliant blue browse markets scour shops ferret outlets but I never find that

Blue.

Mark Laurent

Mark Laurent is a professional musician and writer. He’s recorded over 20 albums, worked as a recording producer and session musician, as well as touring NZ, Australia and the UK for several decades. Mark has published 4 collections of poetry, an illustrated children’s book, and has written numerous articles and reviews for New Zealand and international magazines. He is currently putting the finishing touches on an anthology of poetry and short prose, as well as a candid memoir of the 1970s hippie scene in Aotearoa. He lives in Auckland.

Acid Freak

I can’t remember how I met Brian S. Our scene was fluid and people flowed in and out of the circle all the time. Brian had curly blonde hair, looked a bit like Roger Daltry from The Who, and was an easy-going guy. We got along well and I was with him the first time he took acid. We were invited to a party at a big, rambling house in Arthur Street, a short walk from Collingwood. A row of votive candles in sand-filled paper bags led up the path from the gate, and coloured lights had been fitted to chandeliers and lampshades. There were a lot of people, and probably a lot of drugs.

“Ah this is so cool!” exclaimed Brian, standing in the hallway and turning in slow circles. I had to gently steer him to get out of the way of the people coming in and out.

“See you later man, I’m gonna mingle and soak up the vibes.” And he was off.

I didn’t really know anybody else at that party, and had no idea whose place it was, so I found a chair in the room with the stereo and listened to music.

At some point I became aware that something strange was going on. People seemed to be leaving and I could hear agitated voices - one in particular. It was Brian. I got up and followed the voices to a big dining room where three or four people huddled at one end. Brian stood alone in the middle of the room, raving quite incoherently.

“What’s happening?” I asked.

“This guy’s really out of it and he’s acting aggressive.”

“Oh, well he’s a sort-of friend of mine - he came to the party with me. He took a tab of acid earlier. It’s his first time - maybe a bad trip. I’ll try to calm him down.”

But I was nervous. Now Brian was striding around the room. He’d picked up a broom from somewhere and was sweeping glasses and plates off the dining table. Out of the corner of my eye I saw someone climbing out a window as Brian was between them and the door.

“Brian. Brian, you need to calm down man! This isn’t cool.”

“Everything is cool man. If I say everything is cool then everything is cool, because it’s all under my control!”

“I think we need to go now man, the party’s over and we should go home.”

“No, no, the party’s only just begun! I have special powers. If I think it, it will be. This is a great party!”

“Everybody’s gone Brian - it’s just you and me. You know you took some acid tonight and it’s making you imagine things.”

“Oh I’m not imagining anything. It’s all real, more real than you people can possibly know.”

“What do you mean?”

“I’ve had a revelation tonight. You see, I am God.”

“No man, none of us is God. I know dope can make you feel that way...”

“SILENCE! I am God and you must do whatever I command you. And I command you to push down this wall!”

He pointed with the broom handle at one of the walls.

“Man I can’t do that. You know I can’t.”

“If I command you then you must do it. You cannot disobey GOD!”

I put my hands against the wall and gave a push. Of course nothing happened.

“No, see, I’m too weak. Since you are God you’ll need to show me how it’s done...”

Brian was still brandishing the broom and he suddenly made a lunge, aiming it like a spear. I leapt aside and it hit the wall, plaster splinters flying. He stood there for a long moment, contemplating the wall, and then struck it several times with the handle, shouting “FALL! FALL!”

I was terrified that he’d turn back on me, but his addled attention seemed to have shifted to the house itself. He strode to one of the sash windows and smashed the broom against if, shattering panes. He moved to the next window and did the same. His back was now completely to me so I slipped out the back door, stumbled down a short flight of steps onto the lawn and made my way shakily around the house in the dark as fast as I could, hearing Brian’s voice and crashing sounds and half-expecting him to come after me. When I got to the street I ran all the way home and locked the front door.

The next day we heard that Brian had been arrested - he’d even made it into the papers. Before leaving Arthur Street he stripped naked and then walked up to Ponsonby Road. He tried to wave down several cars but no-one was stopping for a raving, nude hippie. On his way he relieved himself in the front garden of one of the houses, which happened to be the home of an off-duty cop. Before the paddy wagon arrived Brian had reached the corner of Richmond Road where a taxi was standing at the red light. Brian leapt on the roof of the cab, thumping on it with his fist, yelling, “GESTAPO! OPEN UP!”

Apparently it took four cops to wrestle him into the paddy wagon.

A couple of months later Brian, who’d spent a minimal time in jail and was on parole, turned up at Collingwood Street. He had no memory at all of what had happened, or so he said, and he seemed his old self. We went for a walk together and I thought he’d come through unscathed until we came to a power box - one of those big steel cabinets that stand near some street corners, where transformers, relay switches and other electricity department stuff live.

Brian knelt down and placed his ear against the box. “Listen man, can you hear them?” “No. What? I can hear the humming.”

“It’s the aliens man, they talk to us through these portals. Listen. I listen to them all the time. They’ve got messages for humanity.”

Michael Giacon

Michael Giacon is a Tāmaki Auckland-based writer. He released his first book of poetry undressing in slow motion in May 2024.

Reason and Belief

I know who Frank is/was, but I didn’t know him exactly, his name on a $1 Easy As Instant Kiwi Christmas gift card, a bookmark within The Mind of God* retrieved from the Help Yourself! box in the Staff Resource Room WT1006. The precise scratching reveals a DNA of hope, two $10,000 panels but no trifecta, the festive token wedged between pages 20-21 of Chapter 1, subtitled The Scientific Miracle.

Whether the thwarted flirtation with fortune darkened Frank’s Christmas and because ‘when it comes to addressing the really deep issues of existence ... there is a strong temptation to retreat into unreasoned belief’ (p.20) whoever bought the book could be presumed to have been interested in a higher holy roller game.

‘Yet why this should be so remains a tantalizing mystery’ (p.20) as evidenced in a question mark, three arrows and five underlined pieces from page 19 forward [innate; leitmotif; determinism; retrodict; relative probabilities of the different states are still determined] that suggest the book was only read to page 31 ten lines shy of the sub-chapter Metaphysics: Who needs it?

I don’t know if I’ll get beyond the Contents although the final chapter, THE MYSTERY AT THE END OF THE UNIVERSE, is only ten pages. The mind-boggled title set in Penguin Books orange amid a treatise on linguistic acculturation and shunned grammar and usage tomes prompted my rescue bid and gave breath to this poem. I plan to split its provenance: a Christmas gift for a friend who would believe, and the scratchy stored in a keepsake box to be disposed of when I am by whoever sorts me over and out. Why did he keep all this? they might wonder, who was/is Frank?

‘It does not deny a meaning beyond existence’ (p.21).

* All quotations from Chapter 1 in Davies, P. (1992). The Mind of God. Penguin Books.

Michael Steven

To My Haters

after Villon

I have found your place of worship. I know the very pew where your knees bend in supplication bothering that bogus god.

My patience is long and merciless. I will wait for the perfect afternoon, the right hour to exact my hit. I know where you hide your train sets.

The last thing you will ever hear: the sound of twin hammers popping. I will empty clips of ‘platonic models’ into your hollow chests.

Muzzle flashes. Powder burns. Forensics will mention shell casings hitting the ground like syllables. I won’t even wear a mask and hoodie.

Michael Steven is a poet from Tāmaki Makaurau.

Earthwork for T

Do not ask me where I went: you know. Hell is anywhere. It is any place where you are not.

Often I wake in the wrong hours because my mind is a district of overloading circuits, darkening alleys and doorways. I cannot handle returning to an intolerable, interminable dream where I am muted, where my hands are busted and bloodied from digging through all this rubble backfilled by loss. I am scarredup and shaken.

I am living here again to love you. I am here to read your body by heart, by heat.

There is dirt and gravel and scoria in my mouth. Listen, baby: I am singing to you.

Dropped Pin: Cashmere, Christchurch

for Chris Holdaway

No gods or scrub fires on the hills today. Only black cloud, formidable threats of rain. The cold endures in a blood continuum, in this helix of hard, damaged genomes. Winter is perpetual in ancestor city where only the broken help the broken.

My dead grandfather slides through wards of white plaster, polished kauri floors— still bathing; still dressing, feeding, drugging shell-shocked returned servicemen. His face mirrors the spooked, the shook. An inheritance he passes down to his children.

There are spaces in the drug safe of time. Missing bottles of amphetamine, barbiturates. There are question marks on case folders locked away in a cop shop filing cabinet where our faces are supposed to be. Genomes in a helix, in a blood continuum.

Pasha Mahuto’a Clothier