Donate Now and Keep the Magazine Live in 2025

Live Encounters is a not-for-profit free online magazine that was founded in 2009 in Bali, Indonesia. It showcases some of the best writing from around the world. Poets, writers, academics, civil & human/animal rights activists, academics, environmentalists, social workers, photographers and more have contributed their time and knowledge for the benefit of the readers of:

Live Encounters Magazine (2010), Live Encounters Poetry & Writing (2016), Live Encounters Young Poets & Writers (2019) and now, Live Encounters Books (August 2020).

We are appealing for donations to pay for the administrative and technical aspects of the publication. Please help by donating any amount for this just cause as events are threatening the very future of Live Encounters.

Om Shanti Shanti Shanti Om

Mark Ulyseas

Publisher/Editor

All articles and photographs are the copyright of www.liveencounters.net and its contributors. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the explicit written permission of www.liveencounters.net. Offenders will be criminally prosecuted to the full extent of the law prevailing in their home country and/or elsewhere.

Volume Two November-December 2024

Thomas McCarthy – Guest Editorial

Anton Floyd

Barbara Crooker

Bob Shakeshaft

Caterina Mastroianni

Charlotte Innes

Damen O’Brien

David Oliveira

Elif Sezen

Finbar Lennon

Fotoula Reynolds

Gary Fincke

Jean O’Brien

Joe Kidd

Kevin Cowdall

Louis Efron

Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozábal

Magdalena Ball

Mandy Beattie

Michael Farry

Michael Minassian

Nessa O’Mahony

Peter Boyle

Ray Whitaker

Shanta Acharya

Stephen Haven

Thad Rutkowski

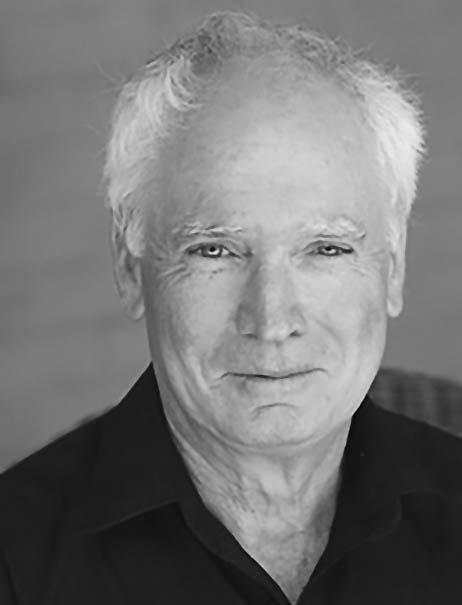

Thomas McCarthy was born at Cappoquin, Co. Waterford in 1954 and educated locally and at University College Cork. He was an Honorary Fellow of the International Writing programme, University of Iowa in 1978/79. He has published The First Convention (1978), The Sorrow Garden (1981), The Lost Province (1996), Merchant Prince (2005) and The Last Geraldine Officer (2009) as well as a number of other collections. He has also published two novels and a memoir. He has won the Patrick Kavanagh Award, the Alice Hunt Bartlett Prize and the O’Shaughnessy Prize for Poetry as well as the Ireland Funds Annual Literary Award. He worked for many years at Cork City Libraries, retiring in 2014 to write fulltime. He was International Professor of English at Macalester College, Minnesota, in 1994/95. He is a former Editor of Poetry Ireland Review and The Cork Review. He has also conducted poetry workshops at Listowel Writers’ Week, Molly Keane House, Arvon Foundation and Portlaoise Prison (Provisional IRA Wing). He is a member of Aosdana. His collections Pandemonium and Prophecy, were published by Carcanet in 2016 and 2019. Last year Gallery Press, Ireland, published his sold-out journals, Poetry, Memory and the Party. Gallery Press published his essays Questioning Ireland in September of this year.; and Carcanet will publish a new collection, Plenitude, in 2025.

These are bad times. These are bad times for the sensitive and for the poet. These are bad times for the innocent. If the 24-hour news cycle – CNN, Al Jazeera, BBC News – with its terrible images of Gaza slaughter, its terrible images of kidnapped young Israelis, its terrible images of occupation in Ukraine, its terrible images of wholesale hidden slaughter in Sudan, has not sent us into a tailspin of despair, then we must be heartless or idiots, or both. Our souls are blood-stained and the soul of mankind is diminished. This is the terrible world we live in. All the moral authority of the UN seems to mean nothing anymore: no tyrant gives a damn about UN Resolutions or Security Council observations. Anarchy is let loose upon the world. Only the Arms Industry is smiling and munitions factories across the world have gone into frantic over-drive. This has to be the wrong kind of Roaring Twenties that we’ve inherited. It is everything we did not expect as the Waterford crystal ball fell on the night of December 31st 2019. We didn’t deserve this, the world didn’t deserve this. If the 1920s descended into Fascism then our 2020s have descended into an unimaginable, heartless brutality.

On that December night of 2019 I dusted down my copy of ‘Cocktails: How to Mix Them’ by ‘Robert’ of the Embassy Club, published by Herbert Jenkins in 1922. It had been a gift to me from Brigadier FitzGerald’s housekeeper at his apartment in Stack House, Ebury Street. I was checking the recipe for ‘SideCar’ a lovely cocktail of Cointreau, Cognac and lemon juice, a mix that had been introduced to London by the barman McGarry at the Buck’s Club. Earlier that that year I’d had a sample of that drink mixed perfectly at the ‘Monte Carlo’ in Minneapolis, Minnesota, where I was dining with that true Irish-American friend of Ireland, Peg Flanagan. Peg, a graduate of Macalester College, was the proud possessor of several ‘Republican Bonds’ that her grandfather had bought in Michigan in the very early Twenties.

So we were kind of celebrating a revolutionary Centenary in our luxury, untroubled American manner. At that luncheon we were confident that the Twenties would be marvellous, a feeling that I’d shared earlier with poets Lani O’Hanlon and Virginia Brownlow in the drawing-room of Molly Keane’s house in Ardmore, Co. Waterford. At that house in that summer we’d been trying to anticipate the kind of celebratory, affirmative poems we might begin to write.

But now we are back in the bad times: our Twenties are shattered with little hope that any of us will see an end to this shattering of the world. An adjustment is no doubt required in the world of poetry. A new kind of poetry is wanted, or at least a more alert poetry. Where should poets look for new mentors? Should we now be ‘refusing to sanction/ The irresponsible lyricism in which sense impressions/ Are employed to substitute ecstasy for information,/ Knowing that feeling, warm heart-felt feeling,/ Is always banal and futile’ as the Scottish poet Hugh MacDiarmid once wrote. For McDiarmid (1892-1978), a committed Communist, son of a country-postman, there was no escape from the responsibilities of poetry. Thought implied commitment and conscience demanded Communism. He continues with that provocative, challenging poem ‘The Kind of Poetry I Want’ in this manner:

‘Only the irritations and icy ecstasies

Of the artist’s corrupted nervous system

Are artistic – the very gift of style, of form and expression, Is nothing else than this cool and fastidious attitude Towards humanity. The artist is happiest With an idea which can become All emotion, and an emotion all idea.

A poetry that takes its polish from a conflict

Between discipline at its most strenuous And feeling at its highest – wherein abrasive surfaces Are turned upon one another like millstones, And instead of generating chaos

Refine the grist of experience between them.

‘Grist’ is such an interesting word here, ‘grist’ meaning grain that has been ground between stones; hence the ‘grist-mill’ marked on so many ancient maps. What is broken down, what is harrowing, must be turned to flour. Bread has to be made out of suffering, this is MacDiarmid’s key message. A new poetry can emerge from a harrowing, abrasive disorder. In Ireland, as in Asia, we are far away from the destruction of Gaza. But we are not a disinterested party, not in Ireland anyway, because we’ve sent a battalion or half battalion of troops each year for forty years to man the ‘Blue Zone’ between Lebanon and Israel. This constant UN deployment of Irish troops has given Irish people a sense of belonging to a conflict elsewhere, a sense of being responsible, however tangentially. This is why Ireland must seem weirdly ‘interfering,’ this silly little country as small and ineffective as a bunch of poets assembled in front of a battletank. I mean, what can you do, what can anyone do? But powerlessness propels us into urgent poetry. Poetry abhors suffering, it rages without power against suffering. The long suffering of the industrial working-class of Glasgow was what really enraged the Communist Hugh MacDiarmid; the long suffering of Gaza is what enrages all sentient beings, not just Muslims throughout the world. But I would go further than this, it is human suffering, even more than political injustice, that makes the blood of poetry boil. Poetry gets close, really close, to the human experience. In this it is like nothing else. It is not a political programme, it is more: more holistic, intimate, humane. Poetry holds hands in a pitiful, Zen-like gesture. Its power, though, is in its ability to witness. As witness, it is unbeatable.

I was reminded of the unbeatable witness of poetry this year as I watched powerful literary work being published about the ‘conflict’ in Gaza, a heart-rending poetry that describes HE blast-bombs, ruined hospitals, dead doctors, murdered aid-workers, heroic ambulance drivers, resourceful, starving mothers. In all of this year, two poems from the Irish anthology of pity stand out for me, two immortal poems that are the bread of life from the grist-mill of Gaza. The first of these poems is simply called ‘Gaza’ published as the Saturday feature poem in the Irish Times on June 29th this year. I can’t quote it all because I don’t have the poet’s permission to do so. The poet is Eoin McNamee, now Director of the Oscar Wilde Centre at Trinity College, Dublin, a poet whose novel, The Bureau, will be published in March 2025.

The poem is about the slaughter of the innocents, but at its core is a local Irish Saint, St. Eunan, who lived in the Seventh Century. This saint belonged to the poet’s townland and the poet, watching the suffering of Gaza, is reminded that his local saint is most famous for an important Seventh Century text Lex Innocentium. St. Eunan had walked the battlefield after a great slaughter in Ireland and saw a dead child attached to its dead mother’s breast ‘White milk on one cheek, blood on another.’ The sight of this horror stimulated the old saint to write a famous Gaelic law, The Law of the Innocents:

‘This witness led him to set forfeits

For the killing of women and children in war. This witness led him to set law about them.

The well water is black at sunset this time of year

In this country of the west, of gull and kestrel.

In this cold country of eel and swan

This is the saint’s well which is for all time law.’

(Eoin McNamee)

The whole is an astonishing poem, and to come upon it casually in the Saturday page of a daily newspaper while I sat drinking coffee in a shopping-mall was to be restored to an immortal humanity. The whole moral force of the world folded itself about me and lifted me up. This text made my soul soar to the heavens, it seemed to make the dead walk across the café floor. The second Gaza poem is, I can say with confidence, a poem in two thousand. It is the winner of the Seán Dunne Poetry Prize organised this year by the Lafcadio Hearn Gardens in Ardmore, Co. Waterford. I was the sole judge of this competition where I read nearly two thousand poems submitted from all over Ireland. There were many fine poems submitted to this competition; and indeed an impressive number of Gaza poems some of which made it into to the Commended and Highly Commended categories. This winning poem is called ‘Seeds are not Numbers’ and it was written by poet Giada Gelli, an Italian poet writing in English, a librarian who has lived in Ireland for many years.

A woman holds the body of a Palestinian child killed in Israeli strikes at Al-Aqsa Martyrs Hospital in Deir el-Balah in the central Gaza Strip [Ramadan Abed/Reuters] - Photo link: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/10/8/israeli-strikes-kill-dozens-in-gaza-as-grisly-anniversary-passes

The poem is written in memory of the Palestinian poet and Professor Dr. Refaat Alareer who was murdered along with his family in the Gaza bombings. After the young poet quotes the Palestinian activist Arrigoni ‘Gaza, Stay Human: Restiamo Umani’ she continues:

‘Kind Rafaat, lend us your knowledge of context and history, of poetry and literature, of how power oft strives to be rid of the likes of us, but forgets that we are seeds and, sure enough, seeds will always sprout back.’

The poem is filled with resilience and pride, and the hope that one day the poet Rafaat may rise again, and that his strawberry fields, too, may fruit again someday. Here the direct humanity of poetry is at play, poetry as witness, poetry as memory-keeper and poetry as fortune-teller. For, the poet implies, everything will be as it once was if Palestinians hold their humanity: restiamo humani.

But let us remain human. The suffering that poetry abhors is everywhere, universal and merciless. Poetry does demand the entirety of the witness, this is poetry’s imperative and it can sometimes be awkward and inconvenient. Nearly six months before Eoin McNamee published his wonderful Gaza poem in the Irish Times and seven months before I read Giada Gelli’s masterpiece, I was sitting in another café, on New York’s Upper Westside where a light snow had begun to pepper down. The snow was falling on all these posters, posted everywhere, with the word KIDNAPPED boldly printed above an assemblage of tiny photographs of beautiful young people. The young people in the photographs were missing Israelis, youngsters who’d gone to a Music Festival and been kidnapped by Hamas that very October. These youngsters stared in the window at me as I drank my coffee and tried to read the New York Times. That evening I was alone in my hostel room listening to the frantic piano-playing of a young person in a room next door. At six am the following morning the same frantic keyboard-piano playing began again, for two and a half hours. The playing was interspersed with tense phone conversations; a young woman was obviously getting last-minute coaching over the phone. The hostel I was staying in was quite close to the famous Juilliard School. It occurred to me that the pianist must be practising for an audition, perhaps an audition for entry to Juilliard. As I listened to her playing I wrote this poem:

Perhaps a candidate with hopes of Juilliard, A girl called Tamar, or Sapir, or Noa,

Each with a place in a New York conservatoire. I stand transfixed at this coffee-stall

On West 80th, wanting more than anything To bring them home. Is there anything

More loving than music, anything more Lovely than a festival in the sun. Remember

Pearled Sheila Goldberg holding the piano hands Of Mr. Charles Lynch, her loving kindness?

When you think unbearably of the young Detained in small rooms, no room service

At this hour in a strange place, the sound Of a piano coming through from another room;

The full round bowls of ivory notes Shuffled against the dawn like so many

Glasses snapped against a silver rack In that Irish bar last night. We are so close

To Juilliard it must be a young woman practising For her third audition. I can feel the anxiety

In her fingers. Just imagine a daughter repeating Scales, a proud father, an anxious mother.

The poem came at once: ‘a proud father, an anxious mother’ was the phrase that came to me first, but I put it at the end of the page in my notebook, knowing that there were words to come before that. By the time I’d made a fresh coffee and found a discarded half-bagel from Zabar’s Café, I had all the other words. I got up and went outside and walked along Columbus Avenue, the one street in New York that still can’t make up its mind. I kept wandering and the light snow kept falling as I turned cross-town, eventually walking down Madison Avenue where I stopped at a gallery window where a magnificent Chagall watercolour was displayed on an easel. I remained so long staring at the artwork and its almost equally impressive golden frame, that an elderly gallery employee came outside and invited me in to take a closer look. We soon fell into conversation, about Norah McGuinness and Jack B. Yeats, both of whose works the gallery had sold during the year. I admitted I couldn’t afford a Chagall, but the curator invited me to the back of his shop, to see the other Chagall lithographs, the Sean Scully oils, the de Kooning prints that lay on the floor against a wall lined with hessian. Inevitably, via Chagall and Avigdor Arikha, we discussed Ireland and Irish life, and Ireland and Israel. The gentleman had bought and read David Marcus’s A Land Not Theirs in the mid 1980s, so he was aware of Ireland’s small Jewish community, made famous in the literary world by the character of James Joyce’s Leopold Bloom. And we regretted then that none of these things seemed to matter anymore as relations have become so bad between Ireland and Israel. We shook hands as I left the gallery and I walked away and marvelled at the sadness of this world that divides people; marvelled too at how frail cultural connections really are.

Days later I returned to Ireland from New York. It was like returning from Israel to Gaza: mentally it was that stark. I was returning to an Irish city, Cork, that had been burned to the ground by British Crown Forces in December 1920 in an act of revenge and grand military looting by the forces of Occupation. The Irish government and the entire Irish population were by then traumatised and depressed by the wanton destruction of Gaza. About a fortnight after I’d returned to Ireland, the Hostages and Missing Persons Forum in Israel revealed that a young art student at the University of Haifa had been murdered in captivity. She had been kidnapped by Hamas at that Supernova Music Festival on October 7th.

Almost immediately, sitting in a Costa café by the banks of the river Lee in Cork I wrote this other small poem:

I’m thinking only of you, darling Inbar Haiman, Of the visual things you must have kept Inside: how you would have communicated Suffering in the poetry of your images. This dated Report of your passing brings home the inept Powers of being beautiful and being young –You just twenty-eight, long hair turned to the sun, Your heart so in love with Israel. Dear child, Dear much-loved one, rubble closes over you In bloody terror on this night of a harvest moon.

Where do you go with such texts? Why do they get written when more direct and urgently political poetry is what this ruined world needs? Poets live in a parallel permanence, sometimes they are elsewhere. I have no doubt about this, yet I am not interested in a mere ‘faults on both sides’ idea of this Mid East conflict, any more than committed activists are interested in such observations. The conflict is too a-symmetrical. It occurs to me now that I might just as easily and spontaneously have written such a poem for the dead poet Dr. Refaat Alareer. My feeling for the tragedy of both deaths is equal. In hell there is no pecking order and in the persistent hell of this conflict there is no one loss more important than another. My poems of Palestine will come too, of that I’ve no doubt, but they may never be the equal of what Eoin McNamee and Giada Gelli have already written. You are not ready to write until you are ready to write from the heart. And I will yet write such poems from the heart too, as McNamee and Gelli have done. A feeling of love attaches us to all victims and such attachment is a powerful virtue in every work of literature. What do poets want, then? I mean what do poets want in the current situation of which we are all fully informed witnesses? For certain, we must remain steadfast as attached witnesses, as Saint Eunan was a witness to the grief of a silenced battlefield in ancient Ireland. What a poet should want, therefore, is very simple. Simple: Hamas hand over those hostages, Israel stop the bombings. Is that not simple? Yes. Yes, it is. Truly, for now and for the future, this is the kind of poetry I want.

Anton Floyd was born in Cairo, Egypt, a Levantine mix of Irish, Maltese, English and French Lebanese. Raised in Cyprus, he lived through the struggle for independence and the island remains close to his heart. Educated in Ireland, he studied English at Trinity College, Dublin and University College Cork. He has lived and worked in the Eastern Mediterranean. Now retired from teaching, he lives in West Cork. Poems published and forthcoming in Ireland and elsewhere. Poetry films selected for the Cadence Poetry Film Festival (Seattle, 2023) and the Bloomsday Film Festival (James Joyce Centre 2023), another, Woman Life Freedom, dedicated to the women of Iran, was commissioned by IUAES. Several times prize-winner of the Irish Haiku Society International Competitions; runner-up in Snapshot Press Haiku Calendar Competition. Awarded the DS Arts Foundation Prize for Poetry (Scotland 2019). Poetry collections, Falling into Place (Revival Press, 2018) and Depositions (Doire Press, 2022); a special edition of Depositions translated into Irish, Scots Gaelic, Welsh, and Scots with an introduction by Professor Seosamh Watson (Gloír, 2024). New collections On the Edge of Invisibility and Singed to Blue are in preparation. Newly appointed UNESCO - RILA affiliate artist at the University of Glasgow.

for James Harpur

Hey Richard Culmer Puritan divine, iconoclast, hater of painted glass, say, if you want white light, go outside. A stand of broad oaks can be your cathedral. Or would you there shed summer leaves and sever branches make nature bend its knee, conform to your austere worship?

for Joe and Anne Creedon

The mountains are in command. They solemnise the dusk. They wear a vestment of heather, the hues accented by slants of purple light in the evening sky. The waters round Gougane’s holy island brim with winter. Stop here with me. There in the treetops, where mist clings to the branches like a lacy surplice the breeze might be the sound of ghost-brothers chanting vespers, and here, the lakewater’s shoreline whisper the antiphon, O Rex Gentium.

A small island somewhere beckonsa world of rock and fields and secret trees, where the eye is drawn seaward, and the weather daily changes habit.

A life beckons where of an evening islanders stop to chat or empathise. The murmur of voices is something foraging bees might understand.

On the mainland we live pressed, governed by crude formalities and skewed agendas like hard winters break into our sentences.

So yes, I could forgo the city with its gaudy rumours of fame. In crowds like a shifting gloom the Muse is stifled and barely audible.

Barbara Crooker is the author of ten full-length books of poetry, including Some Glad Morning (Pitt Poetry Series), which was longlisted for the Julie Suk award and Slow Wreckage (Grayson Books, 2024). Radiance, her first book, won the 2005 Word Press First Book Award and was finalist for the 2006 Paterson Poetry Prize; Line Dance, her second book, won the 2009 Paterson Award for Excellence in Literature; and The Book of Kells won the Best Poetry Book of 2019 Award from Writing by the Sea. Her writing has received a number of awards, including the WB Yeats Society of New York Award, the Thomas Merton Poetry of the Sacred Award, and three Pennsylvania Council on the Arts Creative Writing Fellowships. Her work appears in literary journals and anthologies, including Common Wealth: Contemporary Poets on Pennsylvania and The Bedford Introduction to Literature. She has been a fellow at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, the Moulin à Nef, Auvillar, France, and The Tyrone Guthrie Centre, Annaghmakerrig, Ireland. Garrison Keillor has read her poems on The Writer’s Almanac, and she has read her poetry all over the country, including The Geraldine R. Dodge Poetry Festival and the Library of Congress.

I found that I could say things with color and shapes that I couldn’t say any other way—things I had no words for.

O’Keeffe

Over my single bed, a print of Van Gogh’s Starry Night Over the Rhone, while just to the right, the wooden window frames the exact scene O’Keeffe painted: midnight blue lake, splotchy stars, globes of the dock lights shining like tiny beacons. It’s both serene and ominous, a reduction of shape and color, the dark shoulders of the Adirondacks rising behind. I’m not sure what lesson I’ve come here to learn as I shift from my ordinary routine, only that stillness permeates this wilderness, punctuated by the round notes of loons, and every breath restores my equilibrium.

* Georgia O’Keeffe, oil on canvas

A steamy day. Deep green. Blue lake. The susurrus of wind in the leaves as cirrus clouds drift by. Thrum of tires on the road. The water, stirred by a motorboat, its ruffled wake. Deep waters, hidden pike and perch. Mountains enclose us; beyond their green boundaries, the busy world hums on. The then pitch of a cicada rises.

Hemerocallis, “beauty for a day”

Deep in the throat of summer, daylilies open to the sun, to the humming bees. Some are fire-engine red with yellow centers; others are duplicates of goldfinches in flight. Buttered Popcorn, Stella d’Oro, Mauna Loa, Firecracker. A riot of color in high summer, when everything else browns up. Each blossom only lasts one day, the briefest of beauty. Velvet claret, vintage pink, sun yellow, fox red. They tango in the hot wind. Oh, so quietly, the multiply in the dark.

Bob Shakeshaft has been a regular reader on the Dublin open-mic. scene since 2004. Poems appear in Riposte Broadsheet 2004/20015/ also Census Anthology 2009/2010. Agamemnon Dead 2014. New Ulster 2016/2017. NY. Lit. Magazine 2016. Live Encounters online forum 2016/2021. Bob is a member of the Ardgillan Creative Writers. His debut collection Auld Rope Published by Revival Press June 2021. Is also available from the aforementioned Press. Presently Bob is working on his second Manuscript: Minutes winged.

J.B.Yeats. National Gallery Ireland.[14,8,2021]

Pouring splashing abhorrence of war let there be no more apocalyptic rider rising aloft an angry mob amid aggressive gestures a beaten old man bloody-blood seep-soaking pouring hands trembling a mother arm-covers her son protectively protecting a smallness of hope that violence wont dwell in his life

J.B.Yeats. National Gallery Ireland.14/8/2021

Slumbering shoulders knees in veneration his token of respect a torn-bunch of grass strewed a fresh grave bearing simple cross of throwaway branch criss-crossed-tight embellishing impoverished he adorns his love now as he trails into a distance of sorrows

J.B.Yeats. National Gallery Ireland.14/8/2021

Slumbering shoulders knees in veneration his token of respect a torn-bunch of grass strewed a fresh grave bearing simple cross of throwaway branch criss-crossed-tight embellishing impoverished he adorns his love now as he trails into a distance of sorrows

Caterina Mastroianni is a poet and educator living in Sydney on the land of the Cadigal and Wangal people of the Eora nation. She has published poetry in various literary magazines and five Australian anthologies, including Australian Mosaic, and most recently in the Rochford Street Press anthology.

I asked the thunder dragon for a diamond as it slapped its’ tail and bared its’ teeth at the gateway I squeezed through like a careful contortionist.

At the school in Khuruthang, the children’s morning meditations ambled but their tree and snow leopard stories leapt around me while I slept.

What if the takin animal could bring me at least one diamond on its back? There was no lightning bolt reply, only the village dogs barking all night.

I searched in a Gasa village, until a landslide kept me there overnight, and there I dreamed of a diamond tumbling down into my hands but at first light I saw a black butterfly.

Perhaps, a monkey stole one of the diamonds and tossed it into the jungle by mistake. I lumbered across steep rice paddies, to the wilderness but I found a bag of rice.

I hiked on and up to the temple summit where I marvelled at everything in the valley. I sat in my humid thoughts, slowing down with each breath, until I felt close to nothing.

continued overleaf...

Clouds hung over the mountain peaks like thick dragons’ breath. Glaciers melted down the cliff face and I shuddered with each drop.

I stayed so still, as still as a rock, not asking, not looking around and I heard the thunder dragon asking me to bow to what is.

When the traffic snarls, I leave a mountain behind. A new patience smiles.

My device flashes. City gulls cut skies in half. Sun peeks over me.

Entering the house, dust unbalances my poise. I embrace you, love.

How long can I hold the rice grain on my necklace, hold it from slipping?

Charlotte Innes is the author of a book of poems, Descanso Drive (Kelsay Books, 2017) and three poetry chapbooks, most recently Twenty Pandemicals (Kelsay Books, 2021). Her poems have appeared in many publications in the U.S. and the U.K. including Agenda (online), The High Window, The Hudson Review, Rattle, The Sewanee Review, Tampa Review and Valparaiso Poetry Review. Her poetry has also appeared in several anthologies, including The Best American Spiritual Writing for 2006 (Houghton Mifflin, 2006). She has been a featured reader for poetry readings in the U.S. and the U.K., and for Rant & Rave, the live storytelling series produced by Rogue Machine Theatre in Los Angeles. She was recently interviewed and videotaped for the long-running series Poetry.LA. A former newspaper reporter, freelance writer and teacher, she has written on books and the arts for many publications, including The Nation and the Los Angeles Times. Originally from England, Charlotte Innes now lives in Los Angeles.

Elegant in bearing and expensive clothes, small and light, almost pretty, with a smile that seemed to exhibit the warmth, the inner glow of a Noguchi lamp, my grandmother often collapsed into angry accusations of betrayal that seemed to me as a child, and as an adult, overly harsh, frightening in that sudden shift from smiles to screaming: warmth transformed into fifty acres of fire. How could one thing become another so fast?

Noguchi said that in his work he tried to explore dichotomies. Akari lamps combine an ancient craft with modern art— the bamboo frame, the washi paper shade recast as twisting towers, a ballooning sun— once lit with candles, now with electric bulbs.

He saw the value in a negative space, positive too, often in combination— the empty center of a shade, the sudden shift to vessel, the rich cargo of light.

My grandmother died before I grappled with this melding in her—her natural joie de vivre holding hands with losses. As a child in Galicia, she lost her parents to an early death (I don’t know why—she never spoke of them).

continued overleaf...

At fourteen: her grandfather, killed by Cossacks, her grandmother fleeing, dying in Romania. In Germany, the Nazis took away her husband, her home. She escaped to Switzerland and then to London—which, to my grandmother, was never home, prompting her return to the city where, she said, she’d been most happy, Berlin, to live her last few years alone in a small hotel—our final meeting place.

Beautifully coiffed, dressed in a tailored suit, she screams across a table at my father whose raw, shouted responses she ignores— moments after the hugs, and the warm smile that seems as genuine as the gentle light, the resilience of a Noguchi lamp, whose lightly glued, almost transparent shade, retains the rough texture of the mulberry’s inner bark.

More and more, I swim towards a rock that moves away from me, and what I say

seems less real to me than the sparrow pecking and scraping at my kitchen screen today.

But after we talked, you and I—or rather, I let rip and you replied with a spare yes or no at just the right moment— a gentleness settled in that I might compare with fresh green leaves dipping softly outside my window in the late afternoon breeze,

except that once you said I mention trees too often in my poems. It doesn’t matter.

Maybe trees are a kind of touchstone for me, like that poet whose poems are full of horses, grazing steadily, even as they die. If only tenderness could be stored. I could always turn you into a tree—in a poem, I mean—a noble cedar, shedding needles but evergreen, rooted in words to read in the bitter cold or after the darkest dream.

Too late for lost loves—we all carry the stone of unforgiving anger, all unconquerable, like Callery pears stealing space and nutrients from native species.

Good that other seeds unfurl— inside this child. I ask about her games and toys. I listen. She hugs me. I think she wants to know she matters. I think I’m blessed.

Sometimes goodness can place a hold on hurt, charge rage, change laws, can offer hope or aid— doctors mending limbs, musicians, souls, poets, our battered spirits.

O human ingenuity.

Along my street, houses nestle under palms and cedars, uncrushed by quakes, unharmed by fire or flood, unbombed—

unlike that place where soldiers bulldoze schools, children screaming, parents pulling them through the windows.

My friend, we’ve known each other years. Seated at my table, we talk of those who think they’re in control. My word for them, cartoonish. You say, Doesn’t that diminish evil?

A shadow flickers briefly. True, I fear the worst and maybe we must to save ourselves from sorrow but—

Sometimes they seem ridiculous, I say. We laugh. It’s hard not to.

And here, with sunlight on the floor, the table set for lunch, danger seems a far cry from coffee, coffee cake, good friendship, talk.

By six, the October sun has gone. I clear the plates.

Beneath my window, a sound repeats, click… click-click… click… I pause. On the sidewalk, a small boy is pointing a large, clear-plastic water-gun, red light flashing atop its bulbous body, chasing a girl in a white dress dotted with tiny red flowers.

As the street darkens, the children race around each other, shrieking with laughter. The boy points the gun: click… click-click-click… click…

Damen O’Brien is a multi-award-winning Australian poet. Damen’s prizes include The Moth Poetry Prize, the Peter Porter Poetry Prize, the New Millennium Writing Award and the Café Writer’s International Poetry Competition. In 2024 he won the Ware Poets Open Poetry Competition, the Fingal Poetry Prize, the Ros Spencer Poetry Prize and the Grieve Hunter Writer’s Centre Prize. His poems have been published in the journals of seven countries including Aesthetica, Arc Poetry Journal, New Ohio Review, Southword and Overland. Damen’s poems have been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and highly commended in the Forward Prizes. His latest book of poetry is Walking the Boundary (Pitt Street Poetry, 2024).

after a postcard of Moroccan goats perched in Argan trees

That other goat has not earnt his branch, nothing goes through the brain of that old fool that hasn’t first brewed in his gut. That goat has no grasp of the major philosophers, nor that other goat, or that goat. None have earnt their vantage. They probably think Kant is just refusal, or Spinoza an Italian pasta. Not this goat. It was not all for Argan kernels that first time I climbed this tree, it was for a principle and these other goats followed, sheep that they are. So now the farmers raise us up with cranes and cherry-pickers and tether us to branches so that wide-eyed tourists can rumble up in dusty buses and buy postcards and believe that we each made our climb here for a purpose. But only this goat had a purpose, pure as the white horizon: the demonstration of a principle. Something ineffable which I’ve quite forgotten. But my bondage here is also the illustration of an eternal rule that governs all goatkind: if a host of angels mustered for the first time here beneath this tree, proclaiming the return of some hairy goat-footed God, you can bet the farmers would clip their wings and spike their feet and stop them from leaving, and they’d put a kiosk just around the corner near the shed. That’s goats for you, and none of these other goats here and there amongst the scrawny branches would have anything clever to say about it. Only this goat. I would crap refined Argon oil upon their heads, for that is the essence of philosophy and truth.

Have I written this before?

This morning’s sun has plagiarised the sky and each second’s pinching seconds from itself. Every bird’s a parrot of the birds that came before it, nothing’s new. The cats that stalk them, copy other cats. So what if there’s a pattern to it all: some grand colour scheme of the universe’s design, some unified theory that will explain why every cockroach resembles other cockroaches, why when I kill them, they never seem to die, how men and women are ceaselessly engaged in producing poor facsimiles of themselves, why this morning’s sunset is ripping off Van Goh? I wonder have I written this before?

Witchfinders, old lady sleuths, inquisitors, I’d beat their analytics, cheat their clues: the man who matches times, who compares Facebook photos, who saw a burly viking man racking up a personal best in a woman’s race; and even that bloke, that reattributed the poet’s ‘centos’ to their authors. I’d settle into the victory lap like Rosie Ruiz, scant metres from the finish not out of breath, without a sweat, having run the Boston Marathon in near record time. What was she thinking? Make it look hard, improve gradually, or nobble all the field, work hard at not putting in the work, crawl to the end, come third at first – that’s what will fool witchfinders, old lady sleuths, inquisitors.

If I’d have run the race I could have run, I’d have Ben Johnson’s bulging thighs and Marion Jones’ husband and his syringes, I’d ask for Maradona’s hand and Cronje’s balls, Lance Armstrong’s manifest destiny, Mike Tyson’s teeth, Tonya Harding’s friends, Fred Lonz’ chutzpah and his chauffeur, all the pantheon of sport’s superstars, but most of all, I’d ask for the presence of mind that encouraged the Spanish Paralympic Team to steal a gold with able bodied men. Things are done within the fog of war, or just a fog, like reining back a horse in Louisiana’s Delta Downs to re-join with fresher legs and win by two laps. I’d win that too, if I’d have run the race I could have run.

I’m repainting the Old Masters, not for fame nor immortality, nor as the restoration of Ecco Homo by someone’s mom looks like Jesus done in crayon. I’ve glossed with ancient arsenic and older canvases to put the extra syllables in verisimilitude but I’d bung the whole lot from the back of a van, as easily as hang it on a wall for cash. My Picasso for your Vermeer, my enigmatic Mona Lisa won’t tell you where she’s been or if she’s real and why should she? She’s a lady. It’s the ones that get away with it that I live for, sold in Sotheby’s and Christies with a certificate, that simpering fools will walk past and praise. I’ll be long dead but my frauds will still be hanging, so I’m repainting the Old Masters, not for fame.

I’ve let my mirror copy me, and more: I’ve successfully passed myself off as me, but older, and though I thought I muffed a line or two, I mostly got away with it. It wasn’t jealousy or desire that made me cheat, nor base reproduction we call a life or pointless end or flattery though that accusation’s often said. I just wanted to trace the same lines down, take the same footsteps, experience the same moments that briefly made other men and women seem like gods. There aren’t miracles for such as me. You can line them up, and though they look the same, the firstborn always gets to be the king.

I always knew I’d be flung out of heaven for a fraud, so I’ve let my mirror copy me and more.

It’s always possible I’ve written this before.

A cicada steps out of itself to sing. This is its trick: it shells itself like lace edamame, pinches each branch with bladed legs and soars across the stave. The sound climbs out of the cicada and with soft skin, makes each sine and cosine rub up against each other.

On the occasion of the anniversary of an arbitrary date, day dies into day and we do not mark it. So cicadas abandon their body, like rusty Holdens driven into a culvert, lacquer soldiers shucked from battered suits of armour to peel back the spine of themselves for faith. The day is sacred, cracked in two.

We have finished counting to midnight, but cicadas are prising from their packets, shaking out twelve years of empty drums to pour themselves a solid sheet of sound, thunderous fireworks to mark the edge of one day keened from the next, unzipping the back of their old life, celebrating with wet lungs, new moments wrung from new days.

David Oliveira is an American poet, originally from California, living in Cambodia for 22 years. He is retired from teaching, academia, and IT. Along the way, he has been a publisher, editor, and poetry advocate. He has published three full length poetry collections, the most recent being Still Life with Coffee (Brandenburg Press, 2022). He is included in several important anthologies, among them California Poetry: From the Gold Rush to the Present (Santa Clara University/Heyday Books, 2004); The Gávea-Brown Book of Portuguese American Poetry (Brown University, 2012); and How Much Earth: The Fresno Poets (Heyday Books, 2001), which he coedited with poets Christopher Buckley and M.L. Williams. He lives and writes on the banks of the Mekong River near Phnom Penh.

Someone asks about weather—common question, not unexpected.

Here, it’s the throes of the rainy season, but it’s also morning and hours from any rain. An easy breeze riffles through trees. Thursday is high clouds and welcome cool shade. Because rains come each day, landscapes dress in a hundred hues of green; everything that blooms, blooms. After midsummer’s day, hot temperatures soften. Life takes a breath. Sure, sometimes parts of the year invite heated complaint. Just like a quick turn of seasons, weather can be tough.

Later, when rain comes, you go outside to walk in it, reveling in sky’s blessing, in Earth’s endless largesse. The kindness of being here does not come cheap. It requires sacrifices on behalf of those for whom you care and beneficence to those you meet on the uneven road ahead. The ultimate price exacted is the body.

You know rough seasons. It’s not possible to be human and not be scarred by lashes and cuts to your fragile flesh.

Each person arrives to where they come, at first, oblivious. That place turns out to be loved or hated or roundly ignored, depending on experiences, disposition, and inclination for travel. In whatever place a person settles, well-being requires others, something that must be pursued with blinded optimism, oblivious of the odds for snowballs in sultry weather.

It’s nearly 7, and I overslept this morning. That doesn’t happen often, even on nights I have trouble sleeping, head swirling in world sorrows. My four granddaughters line up at the door to get money for school, each in uniform, each a smiling facet of the other’s beauty. They are sent off with hand kisses, silent hopes for a future desperate for hope.

I resolve to make something of my day (less taxing than making something of myself), skipping the usual check on the day’s news to go for a walk in the neighborhood. I’m socially awkward, separated from neighbors by lifelong shyness and inability to learn more than a toddler’s vocabulary of their language. We smile at each other and because their culture is ancient and generous, I am forgiven.

To get to the road I must step on the spot where my husband burned, where I will burn. This isn’t something I allow myself to think often or I would never make it out of the yard. Walking through the village, I’m in awe to be in this singular place with these people, so different from where I come, and yet, not all that different. Here, people live in the present tense, working through one day to be present for the next, and not troubled about more or less than that. Important questions are pursuits for the leisure class, none of whom have settled in the shade of any trees along this road.

These are beleaguered stretches of days, maybe no more troubled, no more challenging than any other stretch of days, except these fall on us, so they hit especially hard. If the golden light of fortune shines over us, we will overcome these hardships, as have millions of ancestors who gave rise to us. Their resilience points to our survival.

I am an American grandfather, sending four granddaughters to English class because I haven’t learned their language. When the granddaughters return from school, I ask them to stand by me on the balcony, to look at the Mekong, how the river’s blood moves as a constant flow of water.

I can’t tell them what they will only learn after the world breaks their hearts, but the entirety of knowing lies before them, spoken in the undulating syllables washing stones away to time. For eons, sages have said that no one ever sees the same river twice, not twice in one lifetime, not twice in all lifetimes.

He didn’t get here on the strength of intellect. He doesn’t even know where here is. Nothing ever came to him out of a plan but pain, some of his making, to be sure, as he stumbled through every step from childhood until now, with no sense of direction, a mind free of strategies. Without trying, he grew to his age overnight, an age called old in every jurisdiction he knew, and not a thing he could do about that.

His story isn’t unusual, nor is it complicated. It is most common, in fact. Simplicity itself. He’s sure each day doesn’t have to be important, so he goes about unimportant business, letting sunlight wrap him in blankets of warmth, listening to Earth’s music sweep through the air. He felt these were important enough.

Having completed his tasks, not knowing where to go next or why, he did as many others. He waited for someone to tell him. This wait can sometimes be short, though mostly, it’s very, very long. This day, it was short. As luck would have it, his teacher found him quickly, waiting beside the self-same road he had picked. Before sending him off, the teacher cautioned to keep to the right and not leave rubbish behind. In homage to the many who passed here before, he kept to the right and cleared the trash as he went.

Elif Sezen is a Australian/Turkish multidisciplinary artist, bilingual poet/writer, translator. Her poetry collection A Little Book of Unspoken History was published by Puncher & Wattmann (2018), Universal Mother by Gloria SMH Press (2016). She translated Ilya Kaminsky’s acclaimed collection ‘Dancing in Odessa’ into Turkish, published in 2013 by Artshop Press. She received the YTB Turkish Literary Awards 2021 – First prize in Poetry and was shortlisted for the Born Writers Award 2023. Elif’s book A Little Book of Unspoken History was awarded Distinguished Favorite in NYC Big Book Award 2024 – Poetry. Her poems appeared in national and international journals and anthologies. She holds a PhD from Monash University, and currently lives and works in Melbourne. Elif’s website: https://www.elifsezen.com/

Seven sisters gazed at seven stars from seven pyramids and became the stars. But where is she, where is she now? Wind-woman whose breath flows from the North, the lost sister who dreams herself into a holographic earth every nightfall, every chase of Orion, Thursdays, mornings … Ice maiden, the Oceanid who keeps disappearing on an unbelievable world. She sucked her sisters’ longing into her lungs and lived for them.

But she woke one morning as a baby, impeccable grievously, purified from a distance of 444 light years She was given a name, a cuddle, a clock, everything she ever asked for A random girl was all she wanted to be, watching shooting stars from the balcony, as Pleiades threw not-so-powerful gods toward earth.

She finally loved herself and all is well now And one morning she was a speck of something floating above the iron sea.

Finbar Lennon is a retired surgeon. He lives in Collon, County Louth in Ireland. He is the author of three collections of poetry published by Lapwing Publications, Belfast(2021/2022). He is a member of the Bealtaine Writing Group and has had poems published online in Live Encounters, Planet Earth Poetry and Viewless Wings. Two of his poems have recently been published in a new Anthology “When The Lapwing Takes Flight” edited by Amos Greig. Some of his early poems including ‘teenage poems’ appear in his late wife’s memoir “The Heavens are all Blue” that he co-authored and was published by Hachette Ireland in 2020.

Long days of rain for tap-on-chat frozen time in mild-most clime how to figure future tropes young to old a stepping stone first breaking then awakening next settling before final calling two curves that never cross best now if old comes first what wise advice will calm the waves that pound the shore?

Cling to hierarchy and compliance directive advice will save your life as will childhood lessons learned self-doubt nagging – friends gone a small pebble can hide forever unturned it sits much longer master’s locker lined with guilt no escape from scrapes of life carry more to grave than care admit each of us no more than just about.

Seventeen singles is the count of sinners in the nave enter quietly stand behind to add one more to brave we hardly raise a stir the place and space so vast am wrapt to pray must stay ‘til end of mass faithful few did not faze him happens every day though not young, priest spoke and moved like one homily for us a short enlightening presentation for once perfect microphone ensured a conversation nods in nave - mass moved on but not a hurry his call to share sign of peace to wake the life in us vacant smiles, gestures strained and laboured single wave was once enough to ‘love thy neighbour’ chance to make amends on way to altar rails shared communion flakes apiece to leave a trail costume of society was once the church and mass give due he conjured up a remnant from the past could not resist in final blessing the day that’s 31 “Halloween - enjoy the fireworks before November 1”.

Empty hearse at gates a cue this time more on view mass to bid goodbye to teacher with an earnest eye renaissance man met with open arms that day scores aplenty in the nave the faithful out to pray more who knew man at rest along to wish him best church full of life an organ/chorister in full throat priest two weeks older on his mettle full of quotes spoke first of life of Brian consoled those left behind songs of praise, call to angels to watch and mind lulls to sigh and gaze at timeless beauty of the place stucco ceiling – paintings high and safe from thieves not even passing Dorian Gray could prize them free homily on times of loss and gain, self-giving too life’s labour just a still – what a work of art can do asks what Monet’s “water lily” paintings mean what garden pond below the bridge concealed congregation rapt in silent moments nigh long communion sums respect for one who died.

Don’t rush to judgement on first visit –looks deceive doctor’s eagle eye can oft miss wood from trees head shots from behind tell age but don’t tell all empty space and pews a mark of missing footfall second visit patient seems improved numbers rise death and music reason why – edifice is past its time blighted souls no longer sure faith is future-proof despite how well we do last rites- where lies truth!

(After ‘My Life’ by Rainer Maria Rilke)

The Selected Poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke

Well what can one say about his life in absence? a hiccup on a train that caught your eye not the sound, the heave of chest on top of dome that held his heart in thin-cupped space a life of to and fro endless in the present but when you look beyond at dreamers in the queue the wonders in the waves that keeps the core alive to fill with tender love and songs of earthly praise

“It’s beautiful.”

Fotoula Reynolds is a writer of poetry, born in Australia of Greek heritage. She is the author of four poetry collections and is published widely in journals, reviews and magazines. She has been anthologised multiple times in Australia and internationally. Fotoula was nominated for the Pushcart Prize in 2019.

in a wordless moment softness in her breath she looked to the sky the sun held her eyes her freedom unlocked no longer displaced

with a long purposeful stare she looked straight through me and found my soul ‘What does it look like?’ I asked ‘like an enduring flower a gift from God,’ she said

i’ve never been told this before i didn’t know how to receive these words

i am not a gardener but in my garden’s heart i planted the seed of humility and accepted the giving of her compliment

the big hard sun won’t leave me alone with you inside my mind thoughts bleed like a bruised plum dripping, trailing on this road i walk the hours it takes to make a garden grow the moon shows up like a brand new friend fearless in the dark

the patch is bare my heart lays low without seeds to sow no vegetables will grow all seasons purple as I long for that warm september glow

for the sake of love I hold you in new truths upon a time, the bones of once told, old stories die and I hear them in the now in the desert as plain as salt where souls freefall in sound

your affection falls on gravel fragmented and displaced i am broken alongside you we are forever dreamers travel companions in life braided by air and sky guarded along the way

Gary Fincke’s newest collection of poetry For Now, We Have Been Spared will be published by Slant Books in early 2025. In May, Press 53 will publish The Necessary Going On: Selected Poems. Among Gary’s fifteen collections are ones that won what is Now the

and

1

One morning, as if fifteen years of grief had disoriented him, my father failed to locate my mother’s grave, and I, silenced by sympathy, allowed him time to search, the wind swirling spring flurries that created a vast, damp pointillism for where neither of us had walked.

2

A colleague confided that she practiced “feeling” to prepare for the trauma of failing students. For months, she had been rehearsing for her mother’s passing. To calculate the extent of sorrow after her own death, she remembered herself in the third person omniscient.

3

Giraffes, until lately, considered mute, have had their voices recorded in a Viennese zoo. They hum to each other at night, the frequency so low that no one had suspected. For comfort, the zookeeper guessed, admitting uncertainty about their sense of place.

continued overleaf...

4

When, at last, my father set flowers beside my mother’s etched name, he stumbled into silence, the moment filled by the hum of devotion just out of reach, a melody for the present while I bowed my head and waited for the necessary words to embrace.

5

This has been a week when mosquitoes have swarmed, their numbers swollen by record rain, a presence that has prompted my colleague to say that these pests choose mates who harmonize perfectly with them, enhancing the couplings that bring some small equivalent of joy.

6

Our nerves, I once learned, produce the greatest pleasure when stroked four to five centimeters per second, knowledge I repeated to my wife, mentioning distance and location, the body’s mathematics of ecstasy, the encouragement of desire.

7

The old phrases clasp their hands and lower their heads. They recall my mother’s mouth repeating them throughout each day, how she relied upon them like selective memory. Shuffling in place, they say: This language or none, for you will have no other.

How my mother described men who failed, allowing for promise or small achievement-a car engine resuscitated in a driveway, a radio repaired, a furnace revived. Her father, for instance, a handyman who could, despite devotion to alcohol, reopen a swollen door, patch a porch, or smoothly lay a coat of paint as failure swamped the living room. Loss, she said, is hard, but the more difficult is going on, the melody of “making do” sung solo.

For months, I’d understood she meant for me to examine myself. Underfoot, my promises were coughing up dust as rust-colored as our slag-surfaced driveway, “fixing” forgotten, or likely, not yet learned. For sure, she was trying to alter the angle of my downhill slide, my decisions, lately, equations for loss, something exclusive to men so indiscreet with their advantages they apologized with home improvements.

At last, she covered the kitchen table with a map of our township so enlarged that our house was a rectangle among hundreds more, where we lived geometry. Our neighborhood seemed to have died, those shapes chalked where they’d fallen like victims of carelessness and neglect, the largest, nearly square, the hotel that housed men, for economy, by the month.

“Somebody you know lives there,” she said, her finger circling as if it could coil and hiss a warning about awakening, each morning, closeted under nothing but a ceiling bulb, lying where you have never imagined you could live -- a small, rented room furnished only with silence, the odor of clothes thrown over the chair, the sheets in the third week of their one-month cycle, someone moaning early through the wall, one bathroom six doors down the hall, the line at the door shoulders and elbows that have taught you how to hold it. The return trip is all uphill to lament, the rest of the day, as limitless as hell.

Last night, explosion in a neighbor’s garage, The fire consuming the bulk of their house Before hoses were unspooled. This morning, The damage visible from our upstairs windows. Sometimes, we manage weeks without thinking That what we are is temporary. Have you Ever sheltered in place, ominous clouds Tinted bruise-green, the wind carrying what Has been forecasted as a ruin of heavy rain? I’m talking about a place where the highway In and out of danger floods so often that River sediment seems its surface. Where, Falling asleep during downpours is like Leaving active flames in your fireplace Like my father did, trusting the cheap grate. There is a story my worst students loved. A father and son travel by boat to an island Exposed by low tide. The small skiff, secured Improperly by the boy, drifts away. Nothing Can save them, yet none of the students Ever blamed the boy for his fatal error. What they loved to talk about was how The father lifted the boy to his shoulders And steeled himself as the ocean water rose. The students, seventeen and often sullen, Waved their hands to volunteer stories Of their own about making terrible mistakes. In that town, years before, a family had made A fortune manufacturing Jello. Even then, Two of the dead eyes of its factory windows Remained unbroken. None of the boys would Admit to liking Jello, but among those students

Were many children and grandchildren Of men and women who had once believed In the longevity of their work with sugar, Powder, and dye. Even then, years before The factory became unmoored, they would Tell themselves that inevitability had not Already begun. What they made so cheap And colorful that it would always be boxed For delivery within their neighborhood.

Now, a museum for what the town has lost Is housed across from that high school, As proximate as the fire-ruined house, Its owners unmoored so catastrophically That they chorus, “Who could ever imagine?” As if stupefied, sounding like my father, The widower, who, for decades, was stunned To be living alone. Each time I visited, He sank more deeply into the only chair He ever used, his eyes sweeping the walls Of the small living room as he murmured, “Who would have thought?” Something I said Aloud, just before sunrise this morning, As I walked, uneasy, by my neighbors’ yard Into a dedicated, half hour of solitude. Though, when I returned home, the low sun, From a cloudless sky, cast the shadow Of the undamaged, next-door house over The scattered debris, accidental as What remained of the impossible.

Jean O’Brien is an award winning poet with six collections to her name, her latest being Stars Burn Regardless, (2022 Salmon Publishing). She was poet in residence in the Centre Culturel Irelandais in Paris in 2021. She has won, been places and highly commended in many competitions, coming first in the Arvon International UK and the Fish Internation and amongst others has been Highly commended in the Forward Single poem prize (UK) Twice Highly commended for the Bridport prize (UK) and was awarded a Catherine & Patrick Kavanagh fellowship and various Arts Council awards including a travel and training grant to Texas (USA). Her work has been broadcast and has appeared in many anthologies and in Poems on the Dart (Ireland’s Rapid Rail System). In 2023 her celebrated poem Skinny Dippying was set to music and voice by composer Elaine Agnew and sung by New Dublin Voices at the inagural launch in Trinity College, Dublin. She has collaborated with the artists Dixie Friend Gay (USA) and With Ray Murphy and Irene Uhlemann (Irl). She holds an M. Phil in cw/poetry from Trinity College, Dublin and tutors in same in places as diverse as Prisons, Community Centre, Schools, Travellers Centres, the Irish Writers Centre and at post graduate level.www.jeanobrienpoet.ie

Long ago I slept beneath the stone feet of the Lions at Delos. Night was broken by the noise of cicadas, bats, the tooting of an unseen owl. The shush of sea as the tide changed seemed to make stars ignite the black of sky, a scimitar of moon sliced the dark.

The blackness of the sea is frightening. In daylight it sparkles in the sun, now it cloaks everything.

Fathoms down fish and creatures of the deep go about their business; here on this floating island I feel a minor peace among the weathered marble lions facing a sacred lake.

Now of an age to become an oracle, have I gained the wisdom or the foresight to guide anyone in what to do? The huge marble paws are pucked and pitted, rough under my touch. How little I know.

Night is slipping fast, a hint of horizon shows like an entrance to another world. There are no answers. The lions and gods no longer roar and here, we live as castaways.

She picks the puzzle pieces confidently, small finger dexterously sorting lines and corners and colours. I lag behind, my brain trying to create a synapsis between shapes and shade, trying to see the bigger picture while her fresh eyes freewheel over Peppa Pig’s half snout and the smithereened leaves of trees seperated by sea.

She doesn’t look for a coherent pattern, doesn’t confine herself to the lariat of logic. I, with so many years on my shoulders have fashioned a Gordian knot for myself and cannot see the jigsaw in splintered pieces in front of me.

How quickly the extinguished candles multiply. C.P. Cavafy.

As much to escape the daze of heat and sit for a few minutes in the cool, quiet, I entered the Orthodox church in a small square in Chania’s Old Town.

Inside in amber light two women, perhaps not much older than me, sit guard dressed all in black and almost asleep on hard bench seats.

I palm them some money and one offers me tapered candles, I light them like a charm against the dark and place them upright in a dish of sifted sand.

I think of my recent dead, news of a friend’s death pinged my phone as I boarded the plane for Crete, and an ever open wound, my explorer young newphew whose face I see manning the tourist boat in the harbour. I sit amongst the garish icons, light splintering through mullioned windows

striking gaudy glass chandeliers, mirroring off the silver gilt and gold statues and watch as the candles gutter. How quickly the dark surges in.

Joe Kidd is a working, poet/songwriter/artist. In 2020, published The Invisible Waterhole, a collection of spiritual and sensual verse. Awarded by the Michigan Governor’s Office and the United States House of Representatives. Joe was Beat Poet Laureate State of Michigan 2022-2024, and Official Poet of the Government of Birland North Africa. He holds an Honorary Doctorate from International Union Peace Federation. With Sheila Burke he has toured Europe, North America, & Caribbean Islands. He has been featured in international anthologies, magazines, websites, festivals, and other personal appearances. Joe is a member of National & International Beat Poet Foundation, 100 Thousand Poets For Change, Society of Classical Poets, Michigan Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame.

if we do this right, they will never notice slowly, silently, one step at a time we shall fill the room with smoke, fragrant and dark the amphibians, the insects, will be ready to begin the burden of knowledge, the power of the wand undeniable and undetectable in the spinning world

the sparrow knows when to nest the sorcerer knows when to appear the dervish knows when to dance

mother, mother, are you out there now show me your hand, the one with the ring this darkness is a pillow upon which I rest my head and open the door that leads to you

the dreamer knows when to sleep moonflower knows when to bloom the dervish knows when to dance

the wind rises up out from the east the flag of freedom has met its match how does the cobra find its mate beautiful fangs, and venom sweet “get out of my way, you torturous sun” let the night fall to its knees at my tired and blistered feet

the stars know when to remove their clothes the wood knows when to become a pipe the dervish knows when to dance

Like Adam before you, you rise from the dust free and unrestrained by the burden of history the floor of the planet where the footprints are cast to the future we step together in time with the stars that light the night sky in a land abandoned where innocence, tolerance, and mercy may flourish a population of immigrants, and refugees home of the homeless, a dark paradise

Let the rain fall to soften the path of the courageous who meditate upon a peaceful future

Let your crops grow tall and green in their splendor May your cattle grow fat in the warmth of the sun

A land of future Kings and living Queens equatorial Eden once forgotten your constitution is justice and a generous hand now resurrected, a nation without peer your capital city, the heart of man

Kevin Cowdall was born in Liverpool, England, where he still lives and works. In all, over 300 of Kevin’s poems have been published in journals, magazines, and anthologies, and on web sites, in the UK and Ireland, across Europe, Australia, Hong Kong, India, Canada, and the USA, and broadcast on BBC Radio, RTÉ Radio, Ireland, and local radio stations across the UK. His 2016 retrospective collection, Assorted Bric-à-brac brought together the best from three previous collections (The Reflective Image, Monochrome Leaves, and A Walk in the Park) with a selection of newer poems). His most recent collection, Natural Inclinations, features fifty poems with a common theme of the natural world. His poem for children, The Land of Dreams, was published on the Letterpress Project website, wonderfully illustrated by Chris Riddell, and is available on YouTube

Bamboo

The bamboo stands tall against the raging tempest and cannot be bowed.

Chrysanthemum

Symbol of long life: daily rejuvenation begins with each dawn.

Gorilla

So contemplative. With inscrutable wisdom it makes no comment.

Sandalwood

The air is fragrant –its lingering aroma carried on the breeze.

Louis Efron is a Pushcart nominated and award-winning writer and poet who has been featured in Forbes, Huffington Post, Chicago Tribune, North Dakota Quarterly, Ginosko, Jasper’s Folly, Lothlorien Poetry Journal, A New Ulster, Flapper Press Poetry Café, PentaCat Press, Words and Whispers, Bourgeon, The Deronda Review, Young Ravens Literary Review, The Ravens Perch, POETiCA REViEW, The Orchards Poetry Journal, Academy of the Heart and Mind, Literary Yard, New Reader Magazine and over 100 other national and global publications. He is also the author of five books, including The Unempty Spaces Between (winner of the 2023 NYC Big Book Award for poetry), How to Find a Job, Career and Life You Love; Purpose Meets Execution; Beyond the Ink; as well as the children’s book What Kind of Bee Can I Be?.

through the gaping jaws of glass jar candles eager ghost-like serpents stretch, swirl and snap dispersing into the heavens leaving barely lingering warmth from the slowly fading light of recently extinguished wicks our still-puckered lips withdraw from last kisses blown onto the twisted thread like the contorted blurred faces of our departed loved ones once held in the flame still haunting us even after new light replaces old

in their charcoal-colored glass marble eyes glued into shallow stitched beige pouches we see our trapped reflections below golden yarn meant to be caressed

like their fixed expressions we refuse to cry to show weakness when thrown against a wall careful not to make a mark where whiskey bottle shards scent a favorite beating spot

worn cloth bodies without energy to move from harm’s way outside a bolt of lightning snaps at the earth like the knuckles of a drunken father reminding us of the power above to deliver justice with a stern hand from those we love

raindrops tap on dollhouse-style roofs like a chorus of tiny scrambling kitten paws bringing calm to our now empty rooms were we rest our dented faces in dark corners until daylight cracks window shades awakening those meant to hug us

once a starry-eyed child at play at the feet of nonbelievers never losing sight of an unattainable moon forever dreaming of a world seen through tinted gold visors topping marvelous marshmallow suits we glance back at Earth like a newborn untethered from its young mother floating our exposed legs planted in thrift store silver rhinestone buckled boots resting on cracked asphalt below bourbon and urine-drenched curbs like rotting tree branches stuck in ice on a bitter celestial night about to break when trying to stand with gravity pulling us down yet again

relit discarded cigarette butts pressed to our blistered lips dropping ash on our stained white T-shirts like asteroids imprinting scars on the surface of our own moons

between earth and sunrise darkness momentarily fills our space until shadows of our cardboard crafts approach our grey cratered faces removed from the warmth we should call home

around the fringes of broken wings we celebrate our distant touchdowns on what we believe to be

heavenly dust

Born in Mexico, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozábal lives in California and works in Los Angeles. He is the author of Raw Materials (Pygmy Forest Press), Make the Water Laugh (Rogue Wolf Press), and Peering into the Sun (Poet’s Democracy). His recent poetry has been featured in Blue Collar Review, Live Encounters, Mad Swirl, Oddball Magazine, and Unlikely Stories

Distant night sky pearls in vain I try to reach you. Do you exist if you are dead in the vast canvas?

I would like you closer. I want to move to the moon. I could see you closer. I could hold you in my hands.

I have gazed at you for years from my bed out my window. Your flickering lights, how I want to make you mine.

I sit in silence and marvel at your eternal spirit. I shudder at the thought that you are dead, motionless.

These days I chase lazy afternoons and I drink them up with cocoa and milk. I eat them like grapes and dream I am overseas. An outline of the moon can be seen in the sky. Night is far away as are the glimmering lights. I do not join the afternoon cult. I change my names and go by pseudonyms, mostly Latin names. My fragile eyes well up. But I am fine. I think of an old love. I have a bad habit, which does me no favors. The old love is gone and these lazy afternoons will never leave me behind. I put on my shades. I play the part of the poet. My office is outside, where I spend my days chasing lazy afternoons.

Carved out of rock, sculpted into a heart of stone, it never felt love.

Like far away clouds it remained.

Blind to tenderness, still as the stone it was. When thrown, it caused great pain.

Magdalena Ball is a novelist, poet, reviewer, interviewer, Sustainability Manager, Vice President of Flying Island Poetry Community and Managing Editor of Compulsive Reader, one of Australia’s most respected online review sites, which has been publishing high quality book reviews since 1997. Her work has appeared in an extensive list of journals and anthologies, and has won or listed in many local and international awards, including, in 2023/24, the QRAA Ekphrasis Challenge, the Melbourne Poets Union International Poetry Competition, the SCWC Poetry Award, the Liquid Amber Press poetry prize, the University of Canberra Vice-Chancellor’s international poetry prize, and the Woollahra Digital Literary Award, as well as shortlisting for a Red Room Poetry Fellowship. She is the author of several novels and poetry books, most recently, Bobish, a verse-memoir published by Puncher & Wattmann in 2023.

What did you rebel against, father eyes shut, turning slowly like a falconer, letting the bird go.

Every day something new is lost a pendulum you set in motion years ago, when you first walked away feet gliding across the asphalt bitumen and stone aggregate sidewalk not looking back.

Tracking your decline as you dropped gloves, perches, hoods, the detritus of attachment, the way you sloughed off your roots so insistently emancipation playing across your lips while you pretended to fight, burying anarchy with its true name fear under the growing flowers

Impatiens, Marigolds, Zinnias of your new home, a life somewhere else, pretty and languid

continued overleaf...

a scaffold to disguise the predator you wouldn’t name so I couldn’t ask. Annuals returning year on year easy conversation flowering above a recurring dream about something you cannot find.

Not everything comes back your intolerance for crowds the harsh chant, desire tradition, connection, inheritance and time, always time that nasty trick twisting its body round yours, promising freedom all the while turning a cage. You spent your time away the long line of abandoned children playing with weeds in concrete cracks

waiting for the call the rising windstorm, a penny a dime, a birthday card

like a long vowel held till breath ran out a phoneme, negation, uprising. Everything you gathered

as rogue growth without you rising in spite of neglect.

Do you remember anything? Can you still smell cordite on my hands, those crayoned placards

do-it-yourself tear gas burning the eyes torn flag, a renunciation, insurrection marching against an absence you failed to fill.

You wore the t-shirt of flawed ideology green letters across the chest Those days are gone. History is gone but

I’m still here, on the cracked pavement waiting for the return, listening for falcon’s wings, after all these years.

Note: “Free Association” was a finalist in the Mercedes Webb-Pullman Poetry Award (it remains unpublished).

I have given away every artefact, every leather-bound book you left me.

Your silver kiddish cup the brass mezuzah with its Deuteronomy scroll.

How many times have I tried to ring the doorbell, waiting in the cold too young for our imagined conversation lipstick staining your teeth.

Your cello is now in someone else’s drawing room, peacock

feathers and light laminex tiles, moth-riddled spices death in three quarter time.

I wait for you to resolve after all this time to finally buzz me in

smiling with the forgiveness of absence, laughing come in come in it’s all true.

Devotion as great as yours cannot be bound parcelled out as absolution from a wealthy guru

yellow wattles flowering an offering

leaning into astringent air the weight of need heavy on your lips.

Everything changes. a childhood home a body broken into its constituents.

We’re all equal in the end shrine, petals branching in formation a spiral distribution of seeds

both of you are gone now master and disciple the ghastly pink lotus and rolls royces outlived you both.

Maybe it ended with nirvana maybe just ashes.

Mandy Beattie’s poetry appears in, Live Encounters, Poets Republic, Drawn to The Light, Lothlorien Poetry, WordPeace, Crowstep, Full House Literary, Federation of Writers Scotland Anthology, 5 Words, Abridged, Orphic Review, Lunares Zine, Big Girl’s Village Lockdown Showcase, House of Commons, Poetry Super Highway, Knee Brace Press and many more. Winner of Words with Seagulls and City of Poets Competitions. Poets Choice, Marble Poetry. Shortlisted: Creative Future Writer’s Award; 10th International Five Words and Black Box Competitions. Best of Net nominee, 2024. Short Story in Howl New Irish Writing. Forthcoming publications in, Dreich’s swan-song edition, The Banyan Review, Verse-Virtual and Gyroscope Review.

Cypress tree gnarls are kin to speckled knuckles after years of yarns in rib, waffle, stockinette stitches: knitting needles a clacking metronome. On the grapevine-couch your mama’s namesake a snowdrop after ebony: her, comfort’s shoulder-yoke

Somewhere underneath were truffles but the canopy above the tree-line closed ranks as tree rings became stunted for too much salt lack of watering, blackout blinds. What else was there to talk about? Yet, still his name was mute.

If you find me not within you, you will never find me For I have been with you, from the beginning of me - Rumi

learning to let high noon fall away used to be stubborn as jonquil — settling into stillness, a twitchy infusion of nettle tea — even though she knows there is no need to rummage in sand for pearls, resistance was bindweed — as if running to stand stationary before that deep dive inside felt like ivy before vine — sometimes she ambles down aorta’s-ladder at spate of falling snow thirsty for serenity and celestial music — each rung nudges away cement-mistrals and keys lost in blackberry brambles — now after every life-morsel there is a need’s-must deep as middle earth to escape clashing cymbal-crowds to the safe space of silence — she slides inwards quicker than sliding down a fireman’s pole — trusts the plumb line — holds onto its sliver of silver thread — follows its course

to an oxbow heart-loch — to demist milk-opal lenses she leaves everything behind at that open door — nothing

can ambush her here in this inner sanctuary of all that is — bones melt as she floats away in a dandelion puff

through the thin veil to where time stands still — shushes to hush faster than a cheetah — arrives at the Universe’s