LONGWOOD CHIMES 307

Summer 2023

Longwood Gardens is the living legacy of Pierre S. du Pont bringing joy and inspiration to everyone through the beauty of nature, conservation, and learning.

Longwood Gardens

P.O. Box 501 Kennett Square, PA 19348

longwoodgardens.org

“In every department, it involves years of putting ideas together and making them happen. It’s why we’re here, it’s what we do.”

Director of Performing Arts Tom Warner on the process of developing a new idea like Drones & Fountains Shows at Longwood

In Brief

4

10

12

Seed Savers

We are dedicated to orchid conservation not only to build upon our own world-class orchid collection, but to advance orchid conservation globally.

By Katie Mobley

Features

18

To Infinity and Beyond

A whole new way to have fun in the sky.

By Lynn Schuessler

Combating a Treacherous Pest

Tackling Emerald Ash Borer takes expertise and experimentation.

By Rachel Schnaitman

22

Rooted in Science

Science has always played a key role in creating our beauty. A new, refocused strategy aims to make an impact far beyond our Gardens.

By Kate Santos, Ph.D.

Brain Waves

Longwood becomes a living laboratory for innovative research via a flourishing partnership with Drexel University.

By Jourdan Cole

30

East of Eden

In 1967, Longwood embarked on a modernist design trend that was a dramatic departure from previous conservatory construction, along with a new emphasis on educational landscapes.

By Colvin Randall

End Notes

42

A Milestone Moment

Joining together to save a cultural landscape.

By Patricia Evans

Horticulture is both an art and a science. While the esthetic beauty of Longwood is easily seen every day, the foundation of that beauty—our scientific research and work—is perhaps less well known. In this issue of Chimes, we go into the labs and out into the fields to take a look at our scientific pursuits and their role in creating the beauty we share and the impact we make in our global garden.

1 No. 307

In Brief

It takes a variety of tools to make orchid conservation happen in the lab. Shown here are some of the tools the team uses—from specialized spatulas to surgical-grade scalpels—to transfer tiny, difficult-tohandle orchid seeds from their filters to petri dishes.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

Our

Seed Savers

Conservation

By Katie Mobley

Opposite: Associate Director, Conservation Horticulture and Plant Breeding Peter Zale, Ph.D. assesses the flowers of the globally rare Kentucky lady’s slipper (Cypripedium kentuckiense) for pollination. The plants in this image were started from seeds in 2015 and were among the first to be propagated through our Orchid Conservation Program. Photo by Daniel Traub.

Right: In order to ensure seed development, we often find it necessary to hand-pollinate flowers of some orchids, especially lady’s slipper orchids. This image shows the process of carefully removing the pollinium (concentrated mass of pollen) for transfer to the stigmatic surface to complete the pollination process. In the wild this process would be done by native bees and different types of flies, but many orchids are pollinator-limited. Photo by Daniel Traub.

5

Orchid

Program not only builds upon our own world-class orchid collection, but also serves to advance orchid conservation on a global scale.

Sustainability

Opposite: Dr. Peter Zale inspects orchid seedlings growing in test tubes in growth chambers where environmental settings are tailored to the specific conditions native orchids need to grow. Some orchids need only a few months in this environment before planting in the greenhouse, while others can take over a year. Photo by Daniel Traub.

At the heart of plant conservation are core activities essential to the survival of rare species—the simple act of collecting seeds is counted among them. For plants that are globally rare, such as orchids, seed collection often represents the first step of ex situ conservation, where there is concerted effort to identify, collect, and cultivate rare species and determine what it takes to grow them outside of their native habitat. At Longwood, our work to conserve orchids takes place in the fields and forests of Pennsylvania, in far-reaching locations around the globe through our plant exploration, and through specialized research in our laboratory. We are dedicated to this work not only to build upon our own world-class orchid collection, but to advance orchid conservation on a global scale, as we advocate for the conservation of plant resources and collections in our own backyard and worldwide.

Orchids inhabit every continent but Antarctica and make up an extremely impactful 8 to 10 percent of the total diversity of all plants. Yet, despite their global prevalence, all orchids are considered endangered as their populations are generally rare and declining in the wild—an alarming occurrence, as orchids are critically important in determining the overall health of ecosystems worldwide due to their complex ecological interactions with fungi, pollinators, and associated species.

Through our Orchid Conservation Program—which was formalized in 2015 but really dates back to when our founders purchased their first native orchid in 1923— we have used original research to develop innovative and sustainable techniques to grow large seedling populations of native orchids for several reasons: to restore orchid populations native to Pennsylvania, the mid-Atlantic region, and across the country; to continue to build a beautiful, hardy, and genetically diverse orchid collection here at Longwood; and to share techniques for growing orchids in the lab with other gardens and institutions around the world so they may grow and repopulate their own native species.

Among our work in saving and restoring orchid populations native to Pennsylvania is our focus on the fringed or bog orchids of the genus Platanthera Among the most beautiful orchids native to our state, some of these orchids, such as the state endangered Platanthera blephariglottis, are relatively easy to propagate in our laboratory. Others, however, such as the threatened Platanthera peramoena, are among the most difficult native orchids to propagate.

Working with the North Branch Land Trust, an organization that works to conserve the natural, working, and scenic landscapes in northeastern Pennsylvania, we’re currently leading a study in how to most effectively propagate native orchids to both safeguard

To support this study—among many others—Senior Research Specialist Ashley Clayton has established an orchid mycorrhizal fungus bank, containing fungi from several orchid taxa, extracted from the roots of wild adult orchid plants, grown in the laboratory, and maintained in vitro for later use. Here, Clayton uses a microscope to count the number of orchid seeds that have germinated in a Petri dish to compare how sowing the seeds asymbiotically and symbiotically affect orchid seedling development.

7

Photo by Daniel Traub.

them and understand how they grow from seed. Using Platanthera as a model, we’re examining how the art and science of horticulture can contribute to conservation, and we’re seeking to answer this basic question: Can they be grown?

To help answer this question, Longwood Laboratory Technician Kevin Allen, who is working on his master’s degree in plant and soil science from Texas Tech University, is conducting the laboratory portion of this study here at Longwood. Through regular visits to northeastern Pennsylvania, Allen has helped collect seeds of these orchids from the field and has sown 257 Platanthera seed capsules into 352 Petri dishes in our laboratory—which equates to hundreds of thousands of dust-like seeds. With the final seeds sown in November 2022, Allen is currently leading the data collection for related germination efforts, observing each dish under a microscope once per month to assess the seeds’ stages of development, and embarking upon statistical analysis through the end of 2023.

Seeds of almost all orchids depend on mycorrhizal fungi to induce their germination in the wild. Mycorrhiza, which means “fungus roots,” is an association

between a fungus and a plant’s roots. Allen’s research builds upon our work establishing an orchid mycorrhizal fungus bank. Led by Longwood Senior Research Specialist Ashley Clayton, this bank contains fungi from 10 taxa of orchids (and growing), extracted from the roots of wild adult orchid plants (without harming them), grown in the laboratory, and maintained in vitro for later use.

In some cases, the relationship between a plant and a fungus is mutualistic—or symbiotic—in that the plant and fungus obtain something from one another. In the case of orchids, however, the plants actually parasitize the fungi and use them as a food source both while the seedlings are developing and as adult plants. Through this study, we are working to better understand these relationships and apply them to the cultivation and conservation of native orchids. Part of our exploration is whether or not there is an advantage to germinating Platanthera symbiotically as immature seeds—or those extracted from a green seed capsule before it opens up and browns—compared to mature seeds.

In general, immature seeds are typically easier to germinate as they don’t have the

same dormancy factors as mature seeds. Through our Platanthera collection and propagation work, we’re also examining if there’s an advantage to growing these seeds symbiotically, which historically has resulted in a higher germination percentage for mature seeds. Using Clayton’s research, we are examining if growing fungi in a certain way results in successful symbiotic germination, as our ability to grow these fungi will increase our ability to grow the orchid seeds.

Rare native orchids are notoriously difficult to germinate—and symbiotic germination is a very multi-layered process. Perhaps a symbiotic approach, working with immature seeds, may be the way to unlock the secret behind getting them to grow—and conserving them.

Conclusions from this multi-year, multilayered effort remain to be seen. What we do know now is that keeping the orchid’s habitat intact is at the core of conservation efforts. However, if the northeastern Pennsylvania habitat from which we collect these Platanthera seeds were to one day become compromised or inhospitable to these orchids, our growing these native plants outside of their native environment would help ensure they’re here to stay.

Opposite: Conducting the laboratory portion of the Platanthera study, Laboratory Technician Kevin Allen leads the data collection for related germination efforts, which involves hundreds of thousands of dust-like seeds. Here, Allen prepares filters for disinfecting the orchid seeds prior to sowing them in Petri dishes; the seeds are disinfected with a bleach solution and then strained through the paper filters. Photo by Daniel Traub.

8

Below, left to right: Platanthera × bicolor Photo by Peter Zale, Ph.D.; Calopogon tuberosus

Photo by Ashley Clayton; Spiranthes arcisepala Photo by Ashley Clayton.

9

Combating a Treacherous Pest

Tackling Emerald Ash

Borer takes expertise and experimentation.

By Rachel Schnaitman

10

Horticulture

Maintaining the plant health care program throughout Longwood’s greenhouses, conservatories, and outdoor gardens is undoubtedly crucial to our Gardens … and, thankfully, our Integrated Pest Management (IPM) team is up to the task each and every day. This small-but-mighty team of four full-time staff serves as entomologists, plant pathologists, biologists, virologists, and general problem solvers—and, for many years now, they have been wearing all of those hats while working to solve the problem of Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis), or EAB.

A green buprestid or jewel beetle that feeds on ash species, EAB—native to China, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and eastern Russia—was first found in the United States in southeastern Michigan in 2002 and is believed to have arrived in wood-packing materials. Since that first US sighting, EAB has spread to 35 states and has decimated tens of millions of ash trees. It was first found in Pennsylvania in 2007 and is now in every county in the state. It arrived at Longwood in 2019.

Here at Longwood, our IPM approach does not only lie in addressing pests already seen on property—much of our approach pertains to developing strategies and tactics for tackling potential pests that may arrive in the future. While we did not see our first EAB in the Gardens until 2019, we had started planning for EAB in 2010. That year, staff evaluated ash species in our Gardens for their structural integrity, aesthetic quality, significance to Longwood, and interpretive value. We knew it was just a matter of time before we saw this pest in our Gardens; in preparation, we wanted to understand where we were most susceptible and begin to devise a strategy to mitigate EAB impact.

There are currently 16 species of ash tree that are susceptible to EAB, as well as the white fringe-tree (Chionanthus virginicus). The most common species we have at Longwood is Fraxinus americana, the white ash. We have more than 30 specimens in the Gardens proper that we are monitoring for EAB and over 65 in the natural areas. Signs

Opposite: (REF. #1) View of EAB tunnels (S-shaped galleries) and exit holes. Photo by Cliff Sadof, Purdue University; (REF. #2) Bolt preloaded with EAB larvae parasitized with Tetrastichus planipennisi. This larvae parasitoid comes inside of

and symptoms of EAB include yellowing, thin, or wilted foliage, heavy woodpecker activity, D-shaped exit holes, suckering from the base of the tree, and S-shaped galleries under the bark. As infestation increases, the tree’s canopy will thin, advanced dieback will be seen and eventually, trees will die after 3 to 4 years of heavy infestation.

When developing the strategy around any of our pest management plans, our overarching goal is to define and minimize the negative impact of pest organisms on plants, infrastructure, and people—while holding to our strategy of using the “least toxic, yet most effective” means possible to ensure the safety of the environment, staff, and guests. Our IPM team considers several different treatment options that fall in the following categories: chemical treatment, biological control, mechanical control, or cultural modifications. For EAB, chemical, biological, and mechanical control are advised by industry experts. When developing our EAB management plan, we knew we needed to identify select trees for treatment, research available biological controls, and understand that eventually we might need to remove trees once they became affected by EAB.

Our initial survey in 2010 identified the ash trees that we wanted to protect from EAB’s eventual arrival. We began our chemical injection treatments for EAB in 2012 and have continued treating select trees—currently totaling 48 trees throughout our Gardens—every three years. In conjunction with those treatments, we continue to survey our trees with help from our arborist team, who were instrumental in finding our first adult EAB in 2019. Knowing that infested ash is weakened, we have also completed targeted ash removals near paths and roadways.

We’re not stopping there when it comes to our efforts to combat EAB in our Gardens. In addition to our chemical treatments, we continually monitor the latest research and science around emerging ways to mitigate EAB. As a result, this past year we introduced a new tactic to our management plan— biological control, by way of actually

a wood ‘bolt’ prepared on a small ash tree. This temporary bolt is used as a home for the larvae predator of EAB. Once we receive this bolt, we can expect an adult Tetrastichus to emerge in a few weeks.

releasing EAB parasitoid wasps into our Gardens. In the summer of 2022, we partnered with the US Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service to release three species of these wasps: Spathius galinae, Tetrastichus planipennisi and Oobius agrili. These parasitoids are very small, the adult insect is similar to the size of a mosquito. But don’t be alarmed, they are only targeting EAB and will not sting humans.

When we choose our release sites—such as the area in which we released the EAB parasitoid wasps—we take into account a number of factors. We chose release-site trees that were not being chemically treated for EAB and trees that were not in serious decline as we wanted to give the EAB parasitoids several years to become established. Releasing them on declining trees would mean that there could be a potential for the tree to deteriorate before the parasitoids could reproduce. We also released the wasps in different life stages. The S. galinae are released as adults. The O. agrili are released on EAB eggs that they have parasitized. The parasitoids take a few weeks to emerge then they begin their journey to find EAB eggs in the gardens that they can parasitize. Finally, we released wood bolts that have been infested with EAB larvae parasitized with T. planipennisi These parasitoids are natural enemies of EAB and have shown promise in reducing infestations in environments where they have been introduced. We’re hoping that these parasitoids will establish healthy population levels in the next three years and help to diminish EAB throughout our forested areas. IPM is a multi-faceted process rooted in longevity. Going forward, we will continue to survey and scout our ash trees for EAB. Each year, staff from our IPM, arborist, and Land Stewardship and Ecology teams will inspect our trees and decide if any should be added to our chemical treatment schedule, or if a tree should be evaluated for removal. We will also closely watch the parasitoid wasps introduced into our Gardens to determine how quickly they establish as we continue our fight against the Emerald Ash Borer.

Borer exit hole found in 2019, indicating the pest had arrived at Longwood; (REF. #4) Release of EAB parasitoid Spathius galinae, summer 2022. Photo by Becca Manning; (REF. #5) EAB parasitoid release, summer 2022. All three parasitoids are

released together using different methods. This allows multiple predators to attack each life stage of the EAB. In this picture you see the adult wasps released in plastic cups and the larvae predator is inside the wood bolt at far left. Photo by Becca Manning.

11

Photo by Becca Manning; (REF. #3) An Emerald Ash

12

Brain Waves

By Jourdan Cole

Immersion in nature ignites all of the senses—inspiring feelings of awe, wonder, and appreciation. But how can we truly measure the impact nature has on us? That is the question a budding partnership with Drexel University seeks to answer.

Opposite: Drexel University Ph.D. student Kevin Ramirez Chavez navigating a digitized approximation of Longwood using a virtual reality headset on a treadmill equipped with wearable brain imaging and physiological sensors at the Neuroergonomics and Neuroengineering for Brain Health and Performance Research Lab, at the Cognitive Neuroengineering and Experimental Research Collaborative of Drexel University. This page: Postdoctoral Fellow Dr. Adrian Curtin and Ph.D. student Saqer Alshehri, members of the research team, setting up the experimental configuration for virtual scenarios.

Our relationship with Drexel began when Longwood President and CEO Paul B. Redman joined the Drexel Solutions Institute Advisory Board, as part of our ongoing commitment to connect with communities beyond our Gardens. That connection sparked an initial collaboration in 2020 to bring the beauty of Longwood to those who couldn’t easily visit during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, Drexel set out to use virtual reality (VR) to create an immersive, virtual experience of our conservatories, fountains, and more. Since then, that work has blossomed into a far-reaching partnership that has encompassed more than 100 students in seven schools and colleges. Our immersive settings have become a living lab, classroom, and project base for students to study real-world problems and embark on cutting-edge research.

One emerging field that industry and academic researchers have focused on through this work is neuroergonomics, which seeks to study the brain’s

performance in a variety of environments— including how the brain responds to nature. Led by Hasan Ayaz, Ph.D., associate professor at Drexel’s School of Biomedical Engineering, Science and Health Systems and at the College of Arts and Sciences, Drexel began an innovative study to measure the degree to which our brains respond to natural settings. Using mobile neuroimaging technology in the form of high-tech headwear, Ayaz and his team moved their work out of the lab and into our Gardens. They collected and recorded brain activity and physiological data, such as heart rate and electrical properties of the skin, not only as participants walked around Longwood in person, but also as they experienced the Gardens through VR.

“We want to understand human brain function in everyday life,” shares Ayaz. “With wearable neuroimaging, we have this remarkable capability to capture and gather useful information on brain function and cognitive tasks in a variety of realistic and real task environments to learn about neural correlates of complex behavior, and to use that information to improve procedures and tools.”

Also in partnership with Drexel, we’re leveraging new technology and digital assets to provide unexplored insights into the

13

Longwood becomes a living laboratory for innovative research via a flourishing partnership with Drexel University.

Education

Photos by Daniel Traub.

history of the Peirce-du Pont House. With some sections nearly 300 years old, we imagine the walls of the house have many stories to tell. Built by Joshua Peirce in 1730, the house is the oldest structure at Longwood. Given the fact that in 1798, Samuel and Joshua Peirce began planting an arboretum—now known as Peirce’s Woods—in such close proximity to the house, it’s clear the home’s residents throughout time shared a common appreciation of the beauty found in nature. Between expansions and upgrades throughout the years, the house has more than doubled in size.

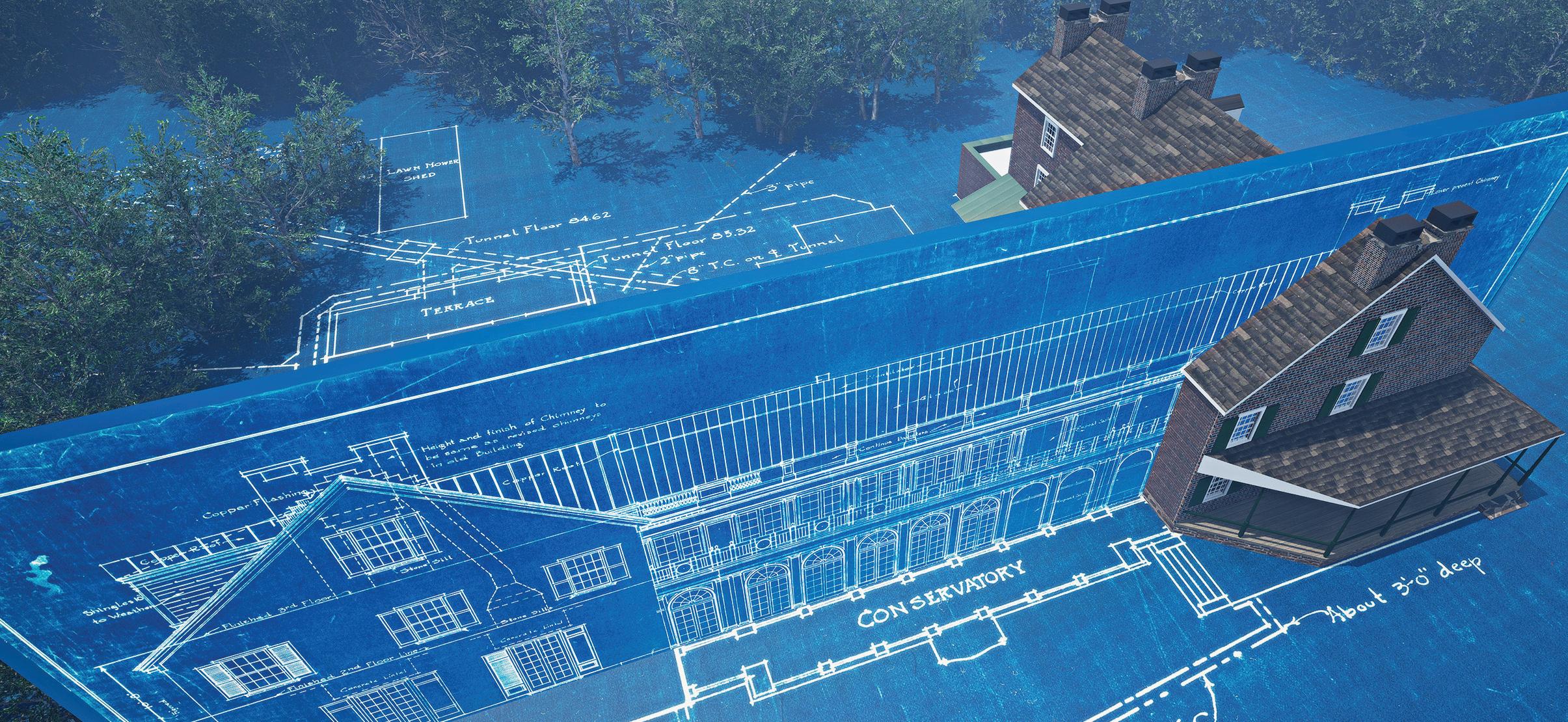

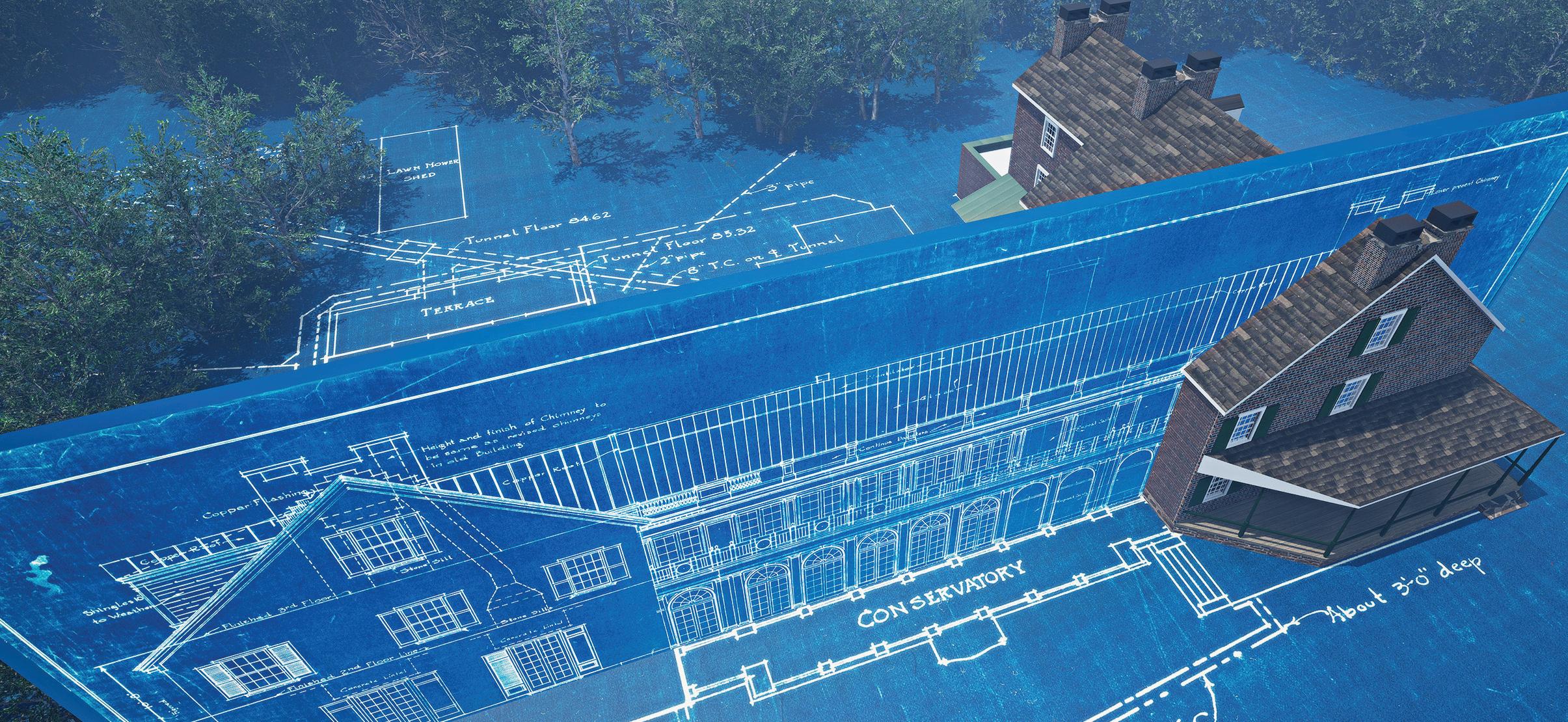

Building on an initial historic evaluation that was completed by John Milner Architects, Inc., we can now paint a more accurate portrait of how the house evolved over time. In partnership with Drexel, a new animation-based video is being created for the Peirce-du Pont House’s Heritage Exhibit, which explores the house’s architectural history and its modifications and additions over the years. The base structure for the animated 3D model was created using LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) scans of the house. The completed video is expected to be on view in the house in 2024.

“We are telling a broader narrative than was originally on display, and it is fun to explore the work of forensic preservationist architects to not only show what we know, but identify what is still in question,” shares Longwood’s Associate Director of Interpretation & Exhibitions Dottie Miles.

The neuroergonomics study and animation-based video for the Peirce-du Pont House serve as just two examples of our multi-faceted and far-reaching relationship with Drexel.

“The collaboration between Drexel and Longwood highlights how multidimensional

work provides students with a variety of opportunities to bridge classroom theory with rich, hands-on learning experiences that address real-world problems and can lead to discovery and innovation,” says Rajneesh Suri, Drexel’s Senior Vice Provost for Academic Industry Partnerships.

For one, using data collected during the neuroergonomics study, Ayaz and the Drexel team recently published a paper in the 2023 Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics Proceedings, and also presented their findings at the 2023 Northeast Bioengineering Conference, confirming the positive benefits of nature on one’s well-being and sharing plans for future research. The initial VR experience Drexel created of the Conservatory and Gardens was used by Drexel students to develop a learning module for our K-12 programming. Additionally, Drexel students from the Westphal College of Media Arts and Design created two horticulturally inspired gowns for our 2022 A Longwood Christmas display; students in the culinary arts program were tasked with creating dishes using produce grown at Longwood; and students in Drexel’s Metaverse in the Real World course explored using augmented and VR tools to engage and elevate the visitor experience in the Peirce-du Pont House.

“Our partnership with Drexel has been an exploration of inspiring ideas and opportunities,” says Longwood’s Associate Director of Land Stewardship and Ecology Lea Johnson, Ph.D., who chairs the crossdepartmental committee that oversees the collaboration. “We are excited to be expanding the partnership to include fresh approaches to interpretation, display, hospitality, visitor experience, and more.”

And we can’t wait to see what comes next.

Clockwise from top left: Ph.D. student

Yigit Topoglu and Postdoctoral Fellow Dr. Adrian Curtin conducting a setup test in Longwood’s Conservatory; Immersed in nature, a participant enjoying a view of Longwood’s Meadow Garden; Associate Professor Dr. Hasan Ayaz overseeing the experimental setup for a Ph.D. student participant; Researchers at Drexel’s School of Biomedical Engineering, Science, and Health Systems working on virtual task scenarios and integrating wearable neuroimaging. From left to right are Master student Felix Maldonado Osorio, Postdoc Dr. Adrian Curtin and Ph.D. student Kevin

Ramirez Chavez; Participant prepared and set up for the study, getting ready to navigate the Conservatory; Dr. Hasan Ayaz describing the experimental procedure to students; Participant undertaking a wayfinding task with wearable sensors, accompanied by researchers; After a successful day of field tests, part of the Drexel-Longwood team gather together. From left to right are Postdoctoral Fellow Dr. Adrian Curtin, Drexel undergraduate student Lynelle Martin, Ph.D. student Saqer Alshehri, Longwood’s Dottie Miles, undergrad student Michael Woodburn, Ph.D. student Yigit Topoglu and Associate Professor Dr. Hasan Ayaz.

Photos courtesy Drexel University

14

15

Features

Detail view of a carbon-fiber Verge Aero X1 drone during setup for the inaugural Drones & Fountains Show To Infinity and Beyond Photo by Hank Davis.

Detail view of a carbon-fiber Verge Aero X1 drone during setup for the inaugural Drones & Fountains Show To Infinity and Beyond Photo by Hank Davis.

To Infinity and BEYOND

18

Photo by Hank Davis.

By Lynn Schuessler

19

A whole new way to have fun in the sky.

The Arts

As illuminated fountains get ready to romp, a grid of more than 150 Verge Aero X1 drones, poised on the Chimes Tower lawn, rises up like a marching band in flight. Then the formation breaks. Each drone is now a single LED pixel, carrying its own program, executing its own orders, blithely unaware of its mates. And yet, like a murmuration, the drones flow from one breathtaking pattern to another.

With explosive fireworks on hold during the Longwood Reimagined project, Director of Performing Arts Tom Warner couldn’t ignore the tech explosion in popular culture, of which drone entertainment is a growing part—from halftime shows to COVID tributes to the 2020 celebration of a winning presidential campaign, practically in Longwood’s backyard.

That victory show was staged by a young hungry company called Verge Aero, which would later go on to receive Simon Cowell’s

golden buzzer on America’s Got Talent: Extreme Warner reached out. And when Nils Thorjussen, one of four Verge Aero cofounders, first saw our iconic fountains against an open canvas of night sky, you might say he was Thunderstruck “I just knew we had to fly drones there!” he says. Meanwhile, Arthur Rozzi Pyrotechnics, the Ohio company responsible for Longwood’s Fireworks & Fountains Shows since 2010, recently partnered with Verge Aero, buying their design software and a fleet of drones. Cincinnati-raised Shop Manager Eric Diehl has been doing fireworks with Arthur Rozzi for 20 years … and is now finding that drones are a whole new way to have fun in the sky. But first, it starts with the soundtrack. Longwood fountain designers Nate Hart and Tim Martin know that their playlists—June’s To Infinity and Beyond and September’s Put Me In, Coach —must stand alone as fountain shows when the

drones go home. They consider music, mood, lighting, color, and fountain effects, choreographing every split second on the Syncronorm computer.

Verge Aero, with input from the team at Arthur Rozzi, will build drone effects around the fountain shows. “We’re exploring new territory here,” says Thorjussen. “A drone show coordinated with fountains has never been done before.” Fountain and drone designers can share renderings—and ideas—in a cooperative and iterative process that blends singular artistic elements into “something exponentially spectacular.”

The Verge Aero Design Studio uses splines—curves made up of pieces, which can be turned at their transition points—to approximate a smooth continuous image, and then assigns drones to create the design in the sky, while ensuring the drones never collide.

The program can factor in windspeed (X1 drones can fly in winds up to 25 mph); the

20

This page: The Arthur Rozzi Pyrotechnics team setting up for the evening Drones & Fountains Show. Photos by Hank Davis.

height of Longwood’s tallest fountain (175 feet); and the safe distance needed from viewers. And Verge Aero’s software can talk to Longwood’s Navigator system, which runs our fountain shows.

Each 2.75-pound carbon-fiber X1 drone has four propellors, four motors, and four RGBW LED lights, bright as a headlight and visible for miles. GPS provides 10 cm precision. Max flight time is about 15 minutes, limited by battery life. To accommodate Longwood’s 30-minute shows, drones will fly in separate fleets.

FAA waivers are required to allow a show pilot to fly more than one drone at a time and to fly at night without anticollision lights. Diehl says he’ll have all four of his certified drone pilots on site to fly the shows. But the thing that keeps him up at night? A geographic anomaly— if President Biden comes home for the weekend, well … Longwood’s backyard becomes presidential airspace.

A dress rehearsal is tricky, but each company can do its own testing. “Once we script a drone show, we can fly it in my backyard,” says Diehl. “My neighbors love it!” But he’s not divulging any secrets. “It’s such an immersive artform. When you see it live, your brain doesn’t even know how to process it.” For Diehl, it’s all about the illusion—and entertaining the audience. “When the crowd cheers, you know they’ve had a good time.”

The legacy and vision of Longwood Gardens has always pushed the limits of beauty and innovation, making drone shows both an inevitable fit and a delightful surprise. “In every department, it involves years of putting ideas together and making them happen,” says Warner. “It’s why we’re here, it’s what we do.”

“This industry is in its Model T era,” says Thorjussen. “Guests are lucky to be in on the start of something new. The technology and the artform are still evolving—we’ve only just begun!”

21

“This industry is in its Model T era. Guests are lucky to be in on the start of something new. The technology and the artform are still evolving—we’ve only just begun!”

Above: A spectacular moment during the inaugural Drones & Fountains Show To Infinity and Beyond Photo by Hank Davis.

ROOTED in SCIENCE

22

Chemistry, biology, and art combine together to produce Longwood compost. Made annually by our Soils and Compost team, it provides us with a sustainable amendment used throughout the Gardens to enrich and improve the quality and health of our soils.

By

By

Horticulture

Science has always played a key role in creating our beauty. A new, refocused strategy aims to make an impact far beyond our Gardens.

Kate Santos, Ph.D.

23

Photo by Daniel Traub.

24

Opposite: Conservation is rooted in Longwood’s legacy, starting with Pierre S. du Pont’s act to conserve the trees in Peirce’s Allée. These trees remain a testament to the continued importance Longwood places on conservation and science. Almost 100 years later, the Longwood Science Leadership team meets here to review key accomplishments and priorities for the upcoming week. From left to right, Associate Director of Land Stewardship & Ecology

Dr. Lea Johnson; Land Stewardship Manager Joe Thomas; Associate Director Conservation Horticulture & Plant Breeding Dr. Peter Zale; Director of the Science Division Dr. Kate Santos; Associate Director of Floriculture Production Diana Shull; Floriculture Manager Betsy Beltz; Floriculture Manager Kevin Murphy; Associate Director of Collections Tony Aiello; and Soils and Compost Manager Erik Stefferud.

Longwood is a wonderful manifestation of beauty in all forms. The foundation for that beauty lies in a commitment to scientific endeavors that spans more than half a century. From plant exploration trips around the globe, to plant breeding and introductions, to land stewardship and conservation efforts, our scientific work lays the groundwork for discoveries that expand our understanding of the natural world and help perpetuate and celebrate its beauty for generations to come.

This is not a small undertaking, and we recognize that we are part of something bigger than ourselves. That’s why we have recently realigned our work under a single Science division, allowing us to better coordinate initiatives, resources, and partnerships, and in turn, expand our impact. Our approach weaves together the scientific disciplines of horticulture, ecology, and agriculture with art, stewardship, conservation, and sustainability, offering us the unique opportunity to demonstrate how cultivation and nature can not only coexist but thrive in the future.

The Science division, which includes full-time and part-time staff as well as volunteers and students, works to achieve our goal to be both a beacon for scientific contributions and a collaborative partner with institutions from around the world. Our intent is for the impact of our work to reach far beyond our garden walls. To accomplish this challenge, the division is divided into four disciplines: Conservation Horticulture and Collections; Land Stewardship and Ecology; Floriculture

Conservation Horticulture and Collections represents an opportunity for us to demonstrate how conservation and cultivation can coexist through the bridge of horticulture. Horticulture is often the missing piece in plant conservation and, as one of the great gardens of the world, we have some of the best horticultural scientists dedicated to celebrating and conserving plants. Our team is focused on conducting research projects that bridge gaps and contribute to solutions to conserve plant species. The Conservation Horticulture and Collections team comprises two integral tenets of our work: the conservation of species found both locally and internationally through plant exploration, horticulture research, and plant breeding; and the curation of collections that serve to preserve and share the importance of these key species with the world.

Our current research is focused on systemic, interdisciplinary approaches to plant discovery, conservation, and recovery in the wild and in the gardens. We start in the laboratory to understand factors affecting seed germination and cultivation, and as we learn (and the plants grow) our work extends into the greenhouses, field trials, our Gardens, and our natural lands and/or native populations. The impact of our work contributes to preventing loss of plant diversity locally and globally, conducting original conservation horticulture research, building ex situ collections, introducing new plants of ornamental interest, and

Right: Our plant trials program serves as a resource to evaluate and promote a diversity of plants. Our goal is to address outstanding questions from the horticulture team and to introduce them to plants not commonly used but will be well adapted to our current and future climate. Associate Director of Collections Tony Aiello and Research Specialist Jameson Coopman pictured here in our lath house trials area evaluating rare, heritage Rhododendron cultivars.

by Daniel Traub.

25

Production; and Agriculture, Soils, and Compost.

Photo

Photo by Daniel Traub.

establishing a conservation network of collaborators. Key benchmarks include expanding our plant conservation efforts beyond orchids to other rare and endangered plants in the state of Pennsylvania (see p. 5 for more on this topic), such as Polemonium vanbruntiae, developing a strategic approach to increasing our capacity to support seed banking of rare and endangered plants, collaborating with the National Herbarium in Tanzania on terrestrial orchid population assessments and conservation, and planting trees such as Quercus virginiana (Southern live oak) in the gardens to evaluate climate resilience.

Mindful stewardship of our natural lands is a responsibility we take very seriously. Our Land Stewardship and Ecology team’s approach is science-driven stewardship, layering incremental changes that build towards the realization of a long-term vision for our natural lands to be a refuge for native plants and wildlife, and that advance understanding of our changing ecosystems and serve as a model for others to follow. Rooted in the landscape of Longwood’s natural lands, we engage in collaborative research to solve ecological problems at landscape to global scales.

Building on decades of work in land stewardship, our high-level management priorities for our natural areas are to protect and maintain our old-growth forests, shade our streams and improve water quality in the three watersheds that intersect our land,

enhance biodiversity and species preservation, and continue our calculated efforts to reduce invasive species across all of our plant communities. In 2022 alone, we enriched our natural lands by planting more than 2,000 diverse native herbaceous and woody plants. In 2023 we will continue the momentum, planting trees and shrubs to help cool and clean streams, increase native biodiversity, enhance climate resilience, and improve habitats for wildlife.

To understand how our ecosystems respond to both management techniques and broader environmental change, we are setting an ecological baseline to serve as the foundation for measurement. In its first year, our baseline vegetation study mapped 216 distinct plant communities and we are establishing long-term ecological research plots in all of them. At the same time, our research specialists are evaluating different experimental reforestation techniques to help inform future larger-scale reforestation strategies and determining the effectiveness of invasive plant management considering costs, benefits, and long-term outcomes.

Agriculture, Soils, and Compost specializes in repurposing the greens, brush, soil, and woody debris generated by the Gardens to produce high-quality materials such as compost and mulch for the garden and local community. Our program focuses on setting the standard for sustainability and serving as a model for material circularity. Each year we work

to close the gap between the amount of materials collected and the complete utilization of the subsequent materials we manufacture. On an annual basis, we are recirculating and transforming more than 9,500 yards of materials into compost and aged mulch. In addition, we continue to refine our product specifications to meet evolving garden expectations and standards; improve our facility design and infrastructure to support manufacturing, processing, and storage capabilities; elevate our community impact through material donations; and define new ways for materials to be used. Earlier this year our compost was STA certified by the US Composting Council, and is now available for purchase in The Garden Shop.

Longwood also maintains 150 acres of agricultural fields where we work collaboratively with Jamie Hicks. Owneroperator of Hicks IV, Hicks is the 2022 Chester County Farmer of the Year, recognized in the agricultural community for his sustainable farming practices. Our goal is to be a leader in regenerative agriculture practices through the implementation of innovative research that provides sustainable models for the agricultural community.

Floriculture Production epitomizes the combination of art and science in horticulture by bringing innovation and ingenuity to growing plants for our indoor and outdoor displays in novel, surprising,

26

Precision meets scale with this highly trained Soils and Compost team effortlessly manipulating the specialized equipment needed to produce compost along with a number of other bulk materials used in the Gardens. Left to right, Senior Equipment Operator Phil Watts and Soils and Compost Manager Erik Stefferud load compost for delivery to the gardens.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

Euphorbia purpurea is a Critically Imperiled (S1) species in the state of Pennsylvania. The Longwood Science team is part of a collaboration with the Pennsylvania Plant Conservation Alliance to innovate ways to propagate the state’s rare plants to help increase the abundance of this (and other) rare species. Pictured here from left to right, Research Specialist Kristie Lane Anderson, Senior Ecology Technician Pandora Young, and Associate Director of Land Stewardship & Ecology Dr. Lea Johnson inspect a recently planted Euphorbia purpurea near the Meadow Garden. Photo by Daniel Traub.

Management of healthy wildlife populations enables us to advance ecological science, inspire people with the beauty of native plants and landscapes and enrich the diversity across our Gardens. Habitat conservation is one element of this approach. Ecology Technician Ryan Pardue is pictured here monitoring one of more than 200 nest boxes found across the natural lands areas of the Gardens. Together with volunteers, our Land Stewardship & Ecology team works to preserve and restore habitats for species like the Eastern bluebird. Photo by Daniel Traub.

27

and inspiring ways. Each year we are cultivating and training more than 100,000 plants for our seasonal displays, spanning 1,300 taxa from around the world. The sophistication of our facilities reflects the complexity of our program. Growing plants from around the world requires a variety of different growing conditions that we simulate in our greenhouses.

Our facilities and techniques have evolved to be incredibly specialized so that we can come as close as possible to mirroring the ideal growing conditions for every plant we produce so that they are at peak when put on display. Additionally, the multiple growing zones affords us the unique opportunity to grow plants with a wide variety of cultural requirements simultaneously. Few, if any, other gardens are able to do this in the same way. Our team of horticultural specialists are often only limited by their imaginations and their continued perseverance to innovate and inspire. Their experience, intuition, and understanding of how plants grow and develop is respected throughout our industry, with our colleagues often seeking advice to improve their own efforts. This expertise informs our approach to growing new plants, forms, and designs. Each year we surpass the last.

Our current projects include upgrading our crop culture and planning database, which is targeted for integration this fall. This upgraded system will enable us to capture and track critical milestones throughout our crop-production processes, making it both a real-time tool for decision making alongside a historical archive for reference and training. Additionally, we are actively trialing and evaluating new plants of interest for upcoming displays, alongside candidates for the new West Conservatory.

These are just a few of the many activities undertaken each year by our science team. and we are just getting started. Science is woven throughout our founding legacy, forming the bedrock for the prominence of our garden collections, research, sustainable production, conservation, and stewardship. It extends to teams across the Gardens and has grown to support our surrounding community and international network of collaborators. These connections ensure our work can contribute to finding solutions for some of the bigger challenges we cannot solve alone, such as climate change and protecting plant biodiversity, land, and water. We strive, through our work, to leave the world better than we found it, with the hope that it inspires others to do the same.

28

Our team of horticulture specialists in Floriculture Production are often only limited by their imaginations and their continued perseverance to innovate and inspire. Their intuition and understanding of plant growth and development, informs our approach to

growing new plants, product forms, and designs—each year surpassing the previous year. Horticulture Specialty Grower Jason Simpson demonstrating the embodiment of this symbiotic balancing of art and science in horticulture. Photo by Meghan Newberry.

29

East of Eden

In 1967, Longwood embarked on a modernist design trend that was a dramatic departure from previous conservatory construction, along with a new emphasis on educational landscapes.

By Colvin Randall

By Colvin Randall

The new Azalea House opened in April 1973 with beds of cymbidium orchids surrounded by azaleas. The building was renamed the East Conservatory in 1982. It was about 216 feet long and 105 feet wide, excluding an open air entrance vestibule at the east end. The pool design for the fountain in the distance was suggested by landscape architect Thomas Church.

30

A Century of Floral Sun Parlors: Part Eight

31

In 1967, the architectural firm of Richard Phillips Fox, AIA, Inc., from Newark, Delaware, was retained to improve Longwood’s facilities, especially the Maintenance Department offices and the 1928 Azalea House, then in poor repair. Richard Fox (1926–1972) earned his architectural degree from the University of Virginia, served as an architect with the DuPont Company from 1951 to 1961, then founded his own firm. His work included the Louviers Country Club in Newark, the expanded fieldhouse at the University of Delaware, and the Education and Humanities Center at Delaware State College in Dover. While with DuPont, Fox consulted with the plastics department to develop a prismatic Lucite™ glazing material that reduced the need for shading during the summer.

Preliminary estimates indicated $1.5 million for a new building versus $250,000 to rehab the existing structure. After additional design proposals, it was decided to proceed

with a lamella arch roof “as an exciting departure from the more conventional greenhouse construction used previously here at Longwood. The potential for display should closely parallel those now possible in the Orangerie and Exhibition Hall.” Such a roof is made up of crisscrossing parallel arches forming a diamond pattern. New holding houses for the existing plants were built east of the Experimental Greenhouse. Construction was to begin in 1969 by the Rupert Construction Company with hopes of finishing by late 1970, but progress was slowed by what was later calculated to be 551 days of delays. The old Azalea House was partially demolished during the fall of 1969. The east wall was first removed to permit the Horticulture Department to relocate about 225 rhododendrons and azaleas to newly built holding houses. Then additional roof was opened to allow moving the largest rhododendron and a huge camphor tree to a temporary house

adjoining the Boiler Room. Foundation excavation continued during the winter under the protection of the remaining roof. By the end of 1969, 50 tons of reinforcing steel had been placed and 430 cubic yards of concrete poured for the substructure, which had to be massive to isolate it from the existing building foundations on three sides.

By early 1970, the old house was essentially gone and new main columns were under construction, but then a 46-day strike by the laborers’ union forced a delay. About 150 blue Lucite roof panels were formed, but it was discovered that the color was too dark, so clear Lucite was ordered instead. Sandblasting of the concrete produced an exposed aggregate finish that blended with the existing Earley finish of the adjoining buildings.

In 1971, errors were discovered in the shape of the roof structural steel, which had to be sent back to St. Louis for modification.

32

Left: The 1928 Azalea House, May 1967. It was 188 feet long by 105 feet wide (excluding the south house sheltering today’s Garden Path).

Below: Emptying the original Azalea House, September 1969.

33

Below: Removing the roof of the original Azalea House, October 1969.

Right: Building the structural columns adjoining the Exhibition Hall and Ballroom, August 1970. Because of the innovative design, many unforeseen, interacting problems had to be solved during the building process.

Photo by Eugene L. DiOrio, Longwood Gardens Library & Archives (gift of Eugene L. DiOrio).

Right: Longwood carpenter Roy Simmers built a tub around a huge camphor tree (Cinnamomum camphora) prior to its 1969 relocation to a temporary greenhouse by the Boiler Room. Photo by William Pierson.

Then the cement finishers went on strike for 134 days. By July some work resumed. The steel lamella arch was nearing completion, and installation of the Lucite glazing began, although some 200 units had dimensional variation that required a return to the manufacturer for adjustment. Roof glazing was finished by March 1972. Problems then arose with the vent operators, and five panels were blown off during Hurricane Agnes. By late 1972, additional problems challenged both engineers and contractors, especially roof leaks. But the conservatory was sufficiently completed for a grand opening with 1,100 guests on April 4, 1973. The total cost was at least $2.3 million (about $15.7 million in today’s dollars), including ancillary storage and greenhouse buildings needed to support the Azalea House.

In August 1972, Longwood’s Advisory Committee reviewed the proposed planting scheme of what was termed “Burle Marx sweeps of color.” It was noted that “the

design portrayed in these displays should express modern trends in horticultural expression and should avoid the classical design most frequently used in the older conservatories.” Later that year, Landon Scarlett was hired to coordinate the Azalea House displays for then-assistant director Everitt Miller. She had worked previously at Longwood starting in 1969, then spent a year at the famed Hilliers Nursery in the U.K. On her return as Longwood’s Design Coordinator, her first job was to decide where to replant specimens that had been held over from the old house. Scarlett coordinated design at Longwood for the next 17 years.

In 1975, the Engineering Societies in the Delaware Valley presented Longwood with a certificate of achievement “for their successful challenge to the engineering profession to produce a Display Conservatory of extraordinary beauty with unique humidity and temperature requirements. The sophisticated mathematics of statically

Opposite: The Azalea House in 1982, when it was renamed the East Conservatory. Three sinuous, overlapping pools and large holly trees were added to the center hourglass in 1977. The hollies were replaced by nine tall Washington palms in 1989.

indeterminate structures was employed to produce a thin membered roof which transmits maximum natural light and is of spectacular beauty.” Longwood director Russell Seibert was pleased, noting that “there is a definite trend for engineers to recognize the value of esthetics along with function.”

Learning by Example

Themed model gardens indoors were a new concept for Longwood in the 1960s. One available location was the rectangular plot between the 1928 Azalea House and the 1921 fruit houses where the seasonal Acacia Path was mounted every year (today’s Garden Path). The first attempt was a Japanese garden in 1965, followed by a southern “Charleston” garden in 1967. Apparently these were more decorative than educational.

When the new Azalea House opened six years later, four small Example Gardens were simultaneously unveiled

34

Azalea House interior, March 1972.

Construction of the lamella arch roof of the Azalea House, August 1971.

on the same plot to show what amateur gardeners could achieve outdoors on a small scale for a typical home landscape. The gardens were designed by invited landscape architects and executed by Longwood staff.

The first year, 1973, featured four small gardens, on the theme “Welcome to the Home—An Entryway.”

In 1974, the theme was “A Service Area,” an outdoor work center serving as a convenient passageway to the rear or secondary entrance of a house.

In 1975, two larger “Patio Gardens” were presented in the previous four allotted spaces.

For the bicentennial year, 1976, one large garden entitled “A Colonial Garden in the Twentieth Century” by prominent restoration architect Robert Raley filled the entire space.

The 1978 theme, “Balcony Gardens,” was suggested by director Seibert after a trip to Italy, where he and wife Deni were

impressed with the planted window boxes and balconies that enlivened Mediterranean cityscapes. Architect for Longwood’s elevated display was Don Homsey from Victorine and Samuel Homsey, Inc., Wilmington, DE. Construction and planting were done, as usual, by Longwood’s craftsmen and horticulturists.

Two years passed before the next exhibit debuted in 1980. “Living with Plants” was set in one half of a simulated turn-of-thecentury brick duplex. Don Homsey was again the architect. Gardening with limited light was a main theme.

The “Weekend Gardener” was the final effort at Example Gardens in the Conservatory. It was constructed in 1984 with two landscapes—a city vista and a country vista— designed around garden rooms. Armistead Browning, Jr., from West Chester, PA, was the landscape architect.

By the mid-1980s, the concept of mostly outdoor gardens indoors had run its course, and imaginative ideas for the conservatories

were proposed instead under the leadership of a new director, Fred Roberts. The next two decades would be an incredibly fertile chapter in Longwood’s history.

35

A Century of Floral Sun Parlors: Part Nine will appear in the next issue of Longwood Chimes

Themed indoor model gardens were a new concept for Longwood in the 1960s. To implement the concept, an available rectangular plot, located between the 1928 Azalea House and the 1921 fruit houses, was employed. On the following pages is an overview of every concept staged, from the introductory foray in 1965 until the display was discontinued in the mid-1980s.

The first attempt at a themed model garden at Longwood was this Japanese garden (above) in 1965, followed by a southern style “Charleston garden” (left) in 1967. These were the precursors to the Example Gardens that followed.

1965: Themed Model Gardens

1965: Themed Model Gardens

36

1973: Welcome to the Home—An Entryway

“Welcome to the Home—An Entryway” was the theme for four small gardens in 1973. The four gardens (clockwise from top left) were designed respectively by: Edward Bachle, Wilmington DE; Frederic Blau, Delaware Valley College; Conrad Hamerman, Philadelphia, PA (Hamerman would later go on to design the Cascade Garden at Longwood in collaboration with Roberto Burle Marx); and William Favand, York, PA.

Example Gardens 1973

37

“A Service Area” was the theme for 1974, which focused on schemes for an outdoor work center that could serve as an extension or passageway to a secondary home entrance. The gardens were designed respectively by (above, clockwise from top left): Richard Harris, Jr., Hockessin, DE; George Patton, Philadelphia, PA; Laurence Paglia, Newtown Square, PA; and Donald Knox, Inc., Greenville, DE.

38 Example Gardens 1974–1975

1974: A Service Area

1975: Patio Gardens

“Patio Gardens” was the theme for 1975. Respective designers (from left to right) were: Allan Ferver, Heritage Gardens, Chadds Ford, PA; Richard Vogel, Kling Partnership, Philadelphia, PA.

39 Example Gardens 1976–1977

1976: A Colonial Garden in the Twentieth Century “A Colonial Garden in the Twentieth Century” was an appropriate theme for the bicentennial year, 1976. The singular installation, which filled the entire space, was designed by prominent restoration architect Robert Raley, Wilmington, DE.

1977: A Quiet Spot Featuring a Bench “A Quiet Spot Featuring a Bench” was the contemplative theme for 1977.

Respective designers (clockwise from upper left) were: Andropogon Associates, Philadelphia, PA; James Reed Fulton, Baltimore, MD; Thomas Kummer, Newark, DE; and Allan Haskell, New Bedford, MA.

“Balcony

was the theme for 1978, an idea that was suggested by Director

after he and his

impressed

1978 40

Example Gardens

1978: Balcony Gardens

Gardens”

Russell Seibert

wife Deni were

with the planted window boxes and balconies they experienced during a trip to Italy. The architect for this elevated display was Don Homsey (Victorine and Samuel Homsey, Inc., Wilmington, DE). Construction and planting were done, as usual, by Longwood’s craftsmen and horticulturists. Upper rows, clockwise from top left: Gardener’s Balcony; Dining ‘Al Fresco’; Victorian Moods; City Form; and Balcony for All Seasons. Lower rows, clockwise from top left: Gardening Under Lights; Window Gardening; and Window Gardening.

1980: Living with Plants

“Living with Plants” was the theme for 1980, a concept centered around gardening with limited light that was set in one half of a turn-of-the-century brick duplex. Don Homsey was again the architect. Upper quadrant, clockwise from top left: Entrance; Porch with Containers and Baskets; Window Greenhouse; and Kitchen Patio Garden. Lower quadrant, clockwise from top left: Kitchen and Solar Greenhouse; Kitchen; Dining Room; and Living Room.

1984: Weekend Gardener

“Weekend Gardener” was the final effort at Example Gardens in the Conservatory. It was constructed in 1984 with two landscapes—a city and a country vista—designed around garden rooms. The designer was Armistead Browning, Jr., West Chester, PA. From top to bottom: Townhouse Garden Room; Townhouse Garden; Meadow and Country Garden Room; and Meadow Pool.

1980–1985 41

Example Gardens

A Milestone Moment

Joining together to save a cultural landscape.

By Patricia Evans

It is said that history often repeats itself. That was certainly the case on February 2, 2023, when Longwood joined with other cultural institutions to preserve the iconic landscape of Granogue, a 505-acre estate situated in New Castle County, DE, just eight miles from Longwood Gardens.

“Our Gardens began with Pierre S. du Pont’s act of preservation to save a 202-acre arboretum that was important to the region and community,” Longwood President and CEO Paul B. Redman said in a statement announcing the preservation. “Today, we are honoring the legacy of Longwood through an act of conservation to protect another landscape and add another open space that is important to our region and community.”

The acquisition, which is expected to close by year end, is being funded by the generous philanthropic leadership of Mt. Cuba Center and the Longwood Foundation. In addition, du Pont family members have generously contributed funds to establish a permanent endowment for the vision and future operations of Granogue. While Longwood Gardens will own and operate Granogue, we did not contribute funds for the initial purchase of the property.

One of the last remaining pieces of unprotected open space in the Brandywine River Corridor, discussions about the future of the property began in 2016 between Granogue Reserve, LTD., LLC (GRLLC), the legal entity that owns the property; Longwood Gardens; and The Conservation Fund. While we have made no final determination on how the property will evolve, our commitment for Granogue to remain a pastoral cultural landscape is at the forefront.

Our commitment to our mission of conservation and the generous support of our community is what has enabled us to take this bold act. We invite you to join us in support of our ongoing work to preserve our global garden, just as our founder did 117 years ago.

End Notes

42

Photos by Jim Graham

There are many ways you can join with us in support of our ongoing efforts such as making a donation, including Longwood Gardens in your estate planning, or becoming a Longwood Innovator. To learn more please contact Melissa Canoni, Director of Development at mcanoni@longwoodgardens. org or at 610.388.5216.

43

No. 307 Summer 2023

Front Cover

Sr. Graphic Designer Morgan Cichewicz gamely tries out the brain imaging headgear during a photoshoot at the Neuroergonomics and Neuroengineering for Brain Health and Performance Research Lab at Drexel University. In the background, Ph.D. student Saqer Alshehri (left) and Dr. Adrian Curtin make minute adjustments to the sensors. Photo by Daniel Traub.

Back Cover

The Longwood ’L’ hovers over the Main Fountain Garden during the inaugural Drones & Fountains Show To Infinity and Beyond

Photo by Hank Davis.

Inside Front Cover

Ph.D. student Kevin Ramirez Chavez uses a virtual reality headset while on a treadmill equipped with wearable brain imaging and physiological sensors at the Drexel University Neuroergonomics and Neuroengineering for Brain Health and Performance Research Lab. Photo by Daniel Traub.

Inside Back Cover

A dynamic series of visualizations created by our partners at Drexel University for a short film in development about the evolution of the Peirce-du Pont House.

Almost 300 years old, the house is one of the most significant artifacts on our property and a focal point for the nascence of the Longwood story. This project started in 2018 when our partners at John Milner Architects, Inc. developed a historical summary report of the house. The report evaluated and documented architectural findings and detailed a new understanding of the significant periods in the evolution of the house. Our partners at Drexel are collaborating with Longwood to bring these findings to life with skilled artists and cutting-edge technology to create compelling visualizations and storytelling about this critical artifact at Longwood.

The final film will interpret our new understanding of how we believe the house was built over time and will eventually be on display in the Heritage Exhibit.

Editorial Board

Sarah Cathcart

Jourdan Cole

Nick D’Addezio

Patricia Evans

Steve Fenton

Julie Landgrebe

Katie Mobley

Colvin Randall

James S. Sutton

Kristina Wilson

Contributors This Issue

Longwood Staff and Volunteer Contributors

Kristina Aguilar Plant Records Manager

Morgan Cichewicz

Sr. Graphic Designer

Hank Davis

Volunteer Photographer

Kate Santos, Ph.D. Director, Science

Rachel Schnaitman

Associate Director, Horticultural Operations

Other Contributors

Jim Graham Photographer

Lynn Schuessler

Copyeditor

Daniel Traub Photographer

Distribution

Longwood Chimes is mailed to Longwood Gardens Staff, Pensioners, Volunteers, Gardens Preferred and Premium Level Members, and Innovators and is available electronically to all Longwood Gardens Members via longwoodgardens.org.

Longwood Chimes is produced twice annually by and for Longwood Gardens, Inc.

Contact

As we went to print, every effort was made to ensure the accuracy of all information contained within this publication. Contact us at chimes@longwoodgardens.org.

© 2023 Longwood Gardens. All rights reserved.

Longwood Chimes 44

Longwood Gardens P.O. Box 501 Kennett Square, PA 19348 longwoodgardens.org Deliver to: Non-Profit Organization US Postage PAID West Chester, PA Permit No. 474 Protecting our Global Garden We are committed to ensuring our Global Garden thrives. As part of our sustainable practices, the Longwood Chimes is now delivered to you in this removable wrap made from 100% recycled paper. Summer 2023

LONGWOOD CHIMES 307

Photo by Daniel Traub.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

Detail view of a carbon-fiber Verge Aero X1 drone during setup for the inaugural Drones & Fountains Show To Infinity and Beyond Photo by Hank Davis.

Detail view of a carbon-fiber Verge Aero X1 drone during setup for the inaugural Drones & Fountains Show To Infinity and Beyond Photo by Hank Davis.

By

By

By Colvin Randall

By Colvin Randall

1965: Themed Model Gardens

1965: Themed Model Gardens