LONGWOOD CHIMES 305

Autumn 2022

Longwood Gardens is a place of beauty and so much more. It’s the workplace for more than 700 employees; a complex campus of buildings and infrastructure; a pillar and supporter of its community; and of course, a welcoming place for more than 1.5 million guests each year. In this issue, we take you behind the scenes and share what it takes to make the business of our Gardens run so our mission can continue to be realized. From the meticulous planning of our horticulture displays that began with our founder, to a look at the diversity of jobs and skills required to operate the Gardens each and every day, to the people who visit and support us, join us for a look at the business of beauty.

In

Features

6 Be Our Guest

A look at who is entering our garden gates, experiencing our Performing Arts, and learning with us through our Continuing Education classes.

By Katie Mobley

16 Green Thumbs

Longwood’s Conservatory was the special jewel of Pierre and Alice du Pont. Together, they and their employees had the greenest thumbs around.

By Colvin Randall 48

A Cut Above

A new addition to our mower fleet offers an efficient and safer option for challenging terrain.

8 Planning for Plants

At the heart of every seasonal display is a document called the Crop List.

By Lynn Schuessler

26

A Day in the Life From sunup to sundown, experience a day in the life of our Gardens and all those behind its beauty.

12

On a Mission for Greater Impact

Our new mission and 2030 Strategic Plan highlight the work we do that extends beyond our garden gates.

By Patricia Evans

End Notes

Brief No. 305 3

In Brief

A plethora of plant materials on display in the Terracotta room, in preparation for a Continuing Education handson workshop featuring internationally renowned floral designer Tim Farrel.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

Legacy Be Our Guest

Our Gardens exist to share with our guests. From our 78,000 Member households—hailing from nearly every US state and as far away as Australia—to our newest Innovators, to our single ticket buyers who travel here from around the globe, here’s a current look at who is entering our garden gates, experiencing our Performing Arts, and learning with us through our Continuing Education classes.

By Katie Mobley

our Members come from every US state

While most of our Member households are located within a two-hour drive of our Gardens, and Puerto Rico, as well as from Australia, Canada, The Netherlands, and the United Kingdom.

10+YRs Longwood Innovators,

Approximately 11,000 Member households have held Longwood memberships for 10 years or more.

a new community of donors, comprise 75 households (and growing!) from 8 states.*

COLORADO/CONNECTICUT/DELAWARE/ FLORIDA/MARYLAND/NEW JERSEY/ OHIO/PENNSYLVANIA

On average, each Member household visited five times in the last year, with Festival of Fountains being the most often visited season for our Members.

6

*

Season Winter Wonder Spring Blooms Festival of Fountains Chrysanthemum Festival A Longwood Christmas Household Visits 2.05 1.72 3.05 1.98 2.25

*

When it comes to our single ticket buyers, guests visited our Gardens from all over the world—32 countries, to be exact—last year.

Angola / Argentina / Australia / Austria / Bangladesh / Bermuda / Brazil / Canada / Cayman Islands / China / Colombia / Costa Rica / Denmark / Ecuador /

El Salvador / Finland / France / Germany / Indonesia / Israel / Italy / Japan /

Mexico / The Netherlands / Norway / Russia / Saudi Arabia / South Korea / Switzerland / Thailand / United Kingdom / United States

In the last year, we welcomed guests from nine countries (Bermuda, Canada, Chile, Denmark, Georgia, Germany, Mexico, the United Kingdom, and the United States) for Performing Arts concerts.

(INCLUDING GUESTS FROM EVERY US STATE, EXCEPT IDAHO, IOWA, KANSAS, LOUISIANA, NEBRASKA, NORTH DAKOTA, OREGON, AND WISCONSIN)

Also in the last year, learners from six countries— Canada, Cayman Islands, China, South Korea, the United Kingdom, and the United States*—joined us for online and onsite Continuing Education offerings.

*FOR THOSE JOINING US FROM THE UNITED STATES, ALL STATES EXCEPT ALASKA, ARKANSAS, LOUISIANA, MISSISSIPPI, MONTANA, NEBRASKA, NEVADA, NORTH DAKOTA, SOUTH DAKOTA, AND WYOMING WERE REPRESENTED.

We also welcome guests to our Gardens via a number of community programs and accessibility initiatives, including Museums for All—a national program that allows those receiving food assistance to receive discounted access to our Gardens.

Through our participation in that program, we welcomed 71,872 guests in 2021 and 27,166 guests from January 1, 2022 through mid-July, 2022.

7

* * * * * * ** * * * * * * * * * ** * * * * * * * * * * * * *

ADMIT ONE

Planning for Plants

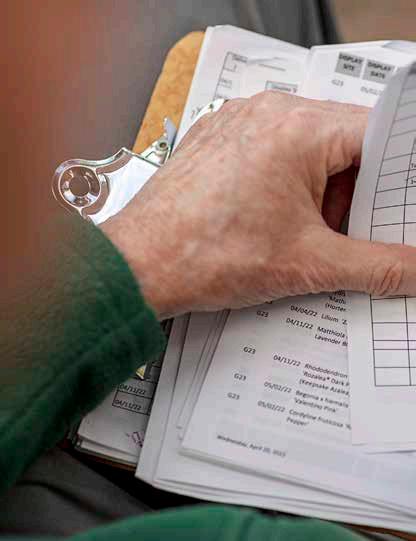

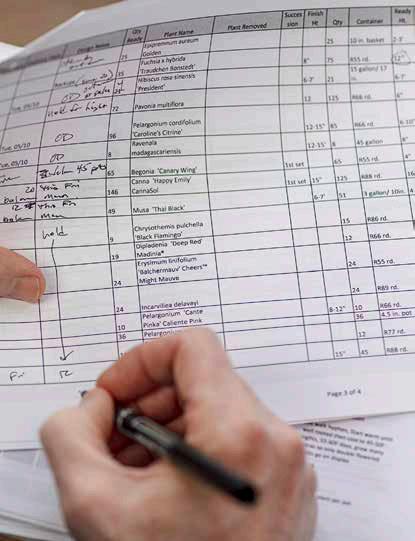

At the heart of every seasonal display is a document called the Crop List.

By Lynn Schuessler

By Lynn Schuessler

Above: Professional Horticulture student Elizabeth Ciskanik installs plants in the Main Conservatory.

Right: Senior Horticulturist Joyce Rondinella (left) and Floriculture Manager Betsy Beltz at the Crop Review team meeting.

Horticulture

Photos by Daniel Traub

8

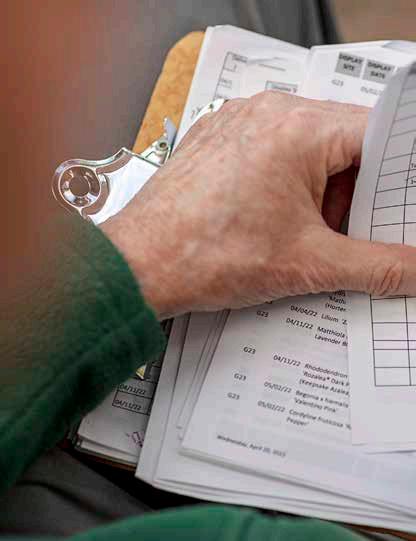

Opposite: At the weekly Crop Review meeting horticulture staff discuss the status of crops for the upcoming indoor displays.

From left: Senior Horticulturist Joyce Rondinella; Floriculture Manager Betsy Beltz; East Conservatory Manager Karl Gercens; Assistant Director, Display Design Jim Sutton; Production Manager Jon Webb; Floriculture Manager Kevin Murphy; Administrative Assistant Mary Askew; and Senior Horticulturist Lauren Hill.

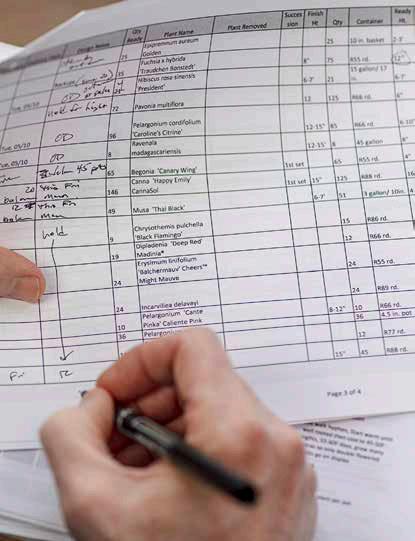

Above: Jon Webb makes notes and revises the Crop List based on feedback from the Crop Review team meeting.

Jon Webb, who started with Longwood in 2006 and is retiring this fall, reviews crops in production with Floriculture Manager Kevin Murphy.

After the Crop Review meeting, Jon Webb and Jim Sutton do a Conservatory walk-through to discuss upcoming plants in the rotation and their placement.

Professional Horticulture students Rowan Nygard (standing) and Kyle Post install crops in the Main Conservatory.

9

At Longwood Gardens, plants don’t just happen. From the hint of spring skies in blue-poppies, to the festive tradition of poinsettias at Christmas, plants are our business—and nobody grows a plant like Longwood.

Behind all that beauty is a culture of planning that traces back more than a century, when founder Pierre S. du Pont carefully designed gardens both indoors and out and filled them with flowers. This attention to detail continues today, embodied in a tool that is key to the planning of horticulture at Longwood— our crop list.

Planning our seasonal Conservatory displays begins a year or more in advance with the inspiration of , Associate Director, Display Design Jim Sutton. Once Sutton creates a design, he passes his “wish list” of plant cultivars, sizes, quantities, and colors to Production Manager Jonathan Webb—aka “Keeper of the Crop List.”

If Sutton’s job is aesthetics, Webb’s is logistics. Will we buy the plant? Which vendor? If one of the 70% of crops grown here: Which grower? Which greenhouse? What finished height and width? It’s all captured in the crop list. “Jon does the essential work of making sure there are no empty beds at Longwood,” says Sutton.

For 40 years, Webb has been figuring out what makes plants thrive. From a

30-acre commercial greenhouse producing thousands of plants for mass-market consumers, where time is money and every touch of the plant drives up its cost, he came to Longwood in 2006, where, he says, “every crop is a specimen, and plants are individually nurtured.”

But as much as he loves growing plants, perhaps Webb’s greatest contribution to Longwood has been growing the crop list. What was once a simple Excel spreadsheet is now an Access database with 27 tables and 15 years of historical content.

Its highly detailed reports make it a powerful communication tool across departments: telling the purchaser what plants to buy, the growers what seeds to sow, the display team what plants are ready to use.

But the best kept secret of the crop list? The thing that sets Longwood plants apart? “The 4,400 schedules,” says Webb, without missing a beat. “The secret of every greenhouse is its growing schedule … that’s the part we hold on to.”

Embodied in the crop list are all the trials, evaluations, and adjustments made from year to year for each and every cultivar, including factors like light, temperature, humidity, and so much more.

“We have eyes on every crop all the time, constantly working out problems as far ahead as possible,” says Webb. “And then we record it so we can do it again,

hopefully even better next time.”

“The crop list is a brilliant, living document,” agrees Sutton. “And yet, it doesn’t replace the skill of the hand and the careful attention of the growers.”

Floriculture Manager Kevin Murphy has been tending plants at Longwood for 24 years, and now leads a team of eight full-time and six part-time growers in our new Nursery Production Greenhouse. He and Webb walk the facility weekly, “to pick each other’s brains, refine growing schedules, and maximize the use of space”—aided by the greenhouse maps Webb has created in Excel.

Murphy makes notes on the Crop Availability Report—a weekly snapshot of reality that tells the Conservatory team exactly what plants they have to work with—from “100% flowering” to “not ready,” or anywhere in between. “Do we need to speed up a crop or slow it down for the display team? Or make a note to plant that Digitalis a month earlier next year?”

Even a state-of-the-art greenhouse can force a change in plan. Murphy admits to a year-long learning curve after the new facility opened in late 2020, with its higher light levels and computer systems that regulate everything from vents and shade curtains to mist irrigation and bench heat, requiring adjustments in growing schedules even for plants we’re familiar with.

Total number of pots used in 2022, of which are composted or recycled

10

1,210Fun Facts from the Crop List 102,344 100 % One of our newest Conservatory crops is Pavonia multiflora (summer 2022) Different taxa in 2022

“In commercial growing I never saw the plants once they left the greenhouse. One of the best parts of working here is seeing greenhouse-grown plants reach their full potential in our displays.”

—Production Manager Jon Webb

“There is a history of greenhouse production at Longwood, a tradition of crops passed down year after year,” says Murphy. “We’ve learned different techniques and refined them along the way. I feel a responsibility to carry on that quality, that tradition.”

To that end, the crop list is the heirloom seed that not only preserves the knowledge of how we grow plants, but also passes on that legacy by putting it into practice.

Floriculture Manager Betsy Beltz loves a challenge, and came to Longwood in 2015 for the sheer diversity of the plants. Her success with a troubled crop, Kohleria, highlights the importance of preserving institutional know-how in yet another resource that Webb maintains—the cultural database—which growers can both consult and edit as their experience grows.

Beltz’s team of four full-time and five part-time growers are responsible for large hanging baskets, poinsettias, orchids, and plant propagation. “The crop list is a comprehensive list of what and when,” says Beltz, “but you still have to react to the variables. Greenhouses all have their idiosyncrasies—the shady spot, the wind through an open door, the perimeter heat where things dry out.”

“The crop list and cultural database are guideposts. But behind all that beauty? People time and people energy.”

For Director, Floriculture and Conservatories Jim Harbage, there is yet another practical aspect to the crop list. It’s a critical budget tool, able to generate a multi-year history that compares plans and costs. He credits Webb with adding so many dimensions to the crop list over the years that it’s become the most important document at Longwood.

“So much time, energy, and brain power go into the crop list,” says Harbage. “It embodies everything from design imagination to ultimately creating beauty in a display. We try to be transparent, so we share growing information with other gardens—but that’s just a piece of the puzzle. What is impossible to share is the years of learning the plants well enough— timing, size, color, texture—to precisely choreograph the look of a display.”

The crop list is a topography of the Gardens, made 3-dimensional by the designers, growers, and horticulturists who bring it to life. “They match or surpass Jim’s vision,” says Harbage. “And the culture of the institution supports all the pieces of the process, so guests can enjoy plants they’d otherwise never see” …

… until the crop list becomes so much more than its 27 tables and 4,400 schedules—elevated from the planning of plants to the realm of beauty that is Longwood Gardens.

11

Average data points per crop: (including plant name, container details, soil info, etc.) Longest crop to grow: Lantana Standards 9,180 About 100 4 Years Number of mums grown for our 2022 Chrysanthemum Festival Number of poinsettias grown for A Longwood Christmas 3,500 1,000 Longwood grown Most Complex Query Maximizing use of greenhouse space for each week of the year purchased This fall 2011 image of Salvia elegans ‘Golden Delicious’ on Flower Garden Drive greets Webb every time he opens the Crop List. Photo by Jon Webb.

On a Mission for Greater Impact

Pierre S. du Pont was a multi-faceted man. His business acumen was revered; his scientific knowledge formidable; his love for the performing arts and horticulture was expressed on an incomparable scale; and his generous philanthropic efforts were well documented. Perhaps less well documented, but none the less impactful, was his generosity with his personal time and talent. Mr. du Pont served on countless committees and boards, on a local, state, and national level, because he understood the importance of civic service.

In the nearly seven decades since his passing, we have continued this legacy of service and community engagement. Our dedication to those efforts is an integral part of our newly adopted 2030 Strategic Plan, which includes a new emphasis on spreading our mission more widely and measuring, articulating, and sharing the story of our impact.

“Our Gardens are intrinsically tied to the communities in which we live and work,” shares Longwood Gardens President and CEO Paul B. Redman, “and our new strategic plan and mission reflect that.” “The idea that a rising tide raises all boats is absolutely true, and we work to ensure that our community and our Gardens grow stronger together.”

Our Gardens and the work of our staff have both quantifiable economic impacts and intangible impacts on the communities we serve, and some of the ways we are serving those communities and the impact we are making may be surprising.

When we think about how we serve our world and the impact we make, we frame it in reference to four main ideas: how we bring people closer to beauty; how we steward our environment; how we share knowledge; and how we strengthen our communities.

Bringing people closer to beauty encompasses everything from the 1.5 million guests we welcome to the Gardens each year (see p. 4 of this issue for more about

our guests) to the more intangible ideas of how guests feel after a visit … do they feel happier, more connected to nature, motivated to try gardening, or inspired to learn more about plants?

Stewarding our environment encompasses the best practices we implement on our nearly 1,100 acres to ensure our ecosystems thrive. Our focus on stewardship encompasses the cleanliness of our water to our use of green-sourced energy to our land management practices and phenology research, but it also extends beyond our physical location and includes such initiatives as our work to save endangered orchids native to Pennsylvania, and our global plant exploration efforts (which to date have amassed 83 trips to 43 countries).

Perhaps our greatest influence on global horticulture has been through our immersive education and training programs. Since their inception more than 60 years ago, our programs have populated the world with more than 3,000 professionally trained, green collar professionals stewarding our global garden. In addition, we have worked to share the wonder and importance of plants with our youngest guests, from grades K-12, with both onsite and online programs designed to spark an interest in horticulture and inspire them to be a part of this vital industry. Each year we welcome nearly 45,000 students to experience our Gardens and programs onsite or online.

While we are proud of our growing global impact that spans many disciplines, audiences, and geographies, our impact in our local community is just as far-reaching.

Closest to home, our staff give of their talents and time on behalf of Longwood to serve many organizations at work in Kennett Square. From Kennett Collaborative to the Kennett Library, to the Anson B. Nixon Park, to the YMCA, to the Longwood Rotary, and more, we are committed to helping our

Legacy

Pierre S. du Pont in the Rose Garden, June 1948. Photo by Gottlieb Hampfler.

12

By Patricia Evans

hometown be as beautiful and welcoming as our Gardens.

“Longwood Gardens’ impact on Kennett Square is enormous,” explains Kennett Collaborative Executive Director Bo Wright, whose organization’s mission is to make Kennett the most beautiful town in America … where everyone can belong and prosper. “Longwood serves as an inspiration of excellence, a major asset for the community by bringing thousands of visitors to the Kennett area to support our small businesses, and as a community partner. They have been a major supporter of Kennett Collaborative’s placemaking initiatives, such as Kennett Blooms and Christmas in Kennett. Our vital work to make Kennett thrive would not be possible without the support of Longwood Gardens,” Wright continues. Christmas in Kennett, offers free shuttle service each

only support local businesses, but to entice guests to experience the community beyond our Gardens.

Longwood also strives to support milestone moments in our community, such as the construction of a new library and resource center in Kennett Square. Steeped in the idea that great communities build great libraries, we are proud to have played a role in bringing this communitywide vision to fruition with representatives serving on the library board and the capital campaign committee, as well as contributing $250,000 to the building effort and hosting additional fundraiser events at the Gardens.

We value the history of our region and the evolution of our land and its role in that history. From the indigenous peoples to William Penn, to the Progressive Quakers,

of organizations and efforts to bolster the health of the local economy.

One such organization is the Southern Chester County Chamber of Commerce, of which Longwood is one of the longest standing members in its 90-year history.

“Strong communities are critical,” explains SCCCC President and CEO Cheryl Kuhn.

“Longwood Gardens is the perfect example of an organization that embodies community spirit, leadership, and giving back. Their deep-rooted friendship, commitment, and support of the Southern Chester County Chamber of Commerce empowers us to do so much more than we would otherwise be in a position to do.”

Longwood Gardens is the living legacy of Pierre S. du Pont bringing joy and inspiration to everyone through the beauty of nature, conservation, and learning. —Mission Statement, adopted in August 2022

We are forever mindful of the well-being provided by connecting with nature and the importance of open spaces in a community. In that effort, we are working with the Kennett Trails Alliance to support an initiative to physically connect disparate parts of our community to each other and to Longwood Gardens through a series of pedestrian paths and biking trails. Feasibility studies are underway to further explore this beneficial project.

Saturday during A Longwood Christmas from downtown Kennett Square to our Gardens. Guests can enjoy the ambiance of the town decked out for the holidays and visit local merchants prior to or after their visit to the Gardens.

Our Community Club program, founded in 2014, helps support local businesses, encompassing a network of more than 70 businesses and counting, including retail, restaurants, lodging, attractions, and other services, that provide year-round discounts or special offers to our more than 78,000 Member households. It is a way to not

there are rich stories to share. In that effort, we are working closely with the local nonprofit Voices Underground to share the important legacy of the Underground Railroad in our community and to elevate the rich African American history found in southeastern Pennsylvania.

Economic vitality is another important ingredient to a thriving community. Outside of the thousands of jobs created and sustained both directly at Longwood Gardens and indirectly through tourism and large-scale construction projects, Longwood has been a longtime supporter

These vital initiatives are just a few of the many ways we work to make an impact. Just like an ecosystem in nature, our work in the community is one part of an interconnected system that needs many participants, all playing an important role, to ensure that the whole community flourishes and thrives. We are proud to be doing our part and will continue to evaluate and explore ways to do more for our community in a meaningful way.

To learn more about our 2030 Strategic Plan, visit: longwoodgardens.org/strategic-plan

Continuing a legacy of service initiated by founder Pierre S. du Pont, our new mission and 2030 Strategic Plan highlight the work we do— and will continue to expand—that extends beyond our garden gates.

13

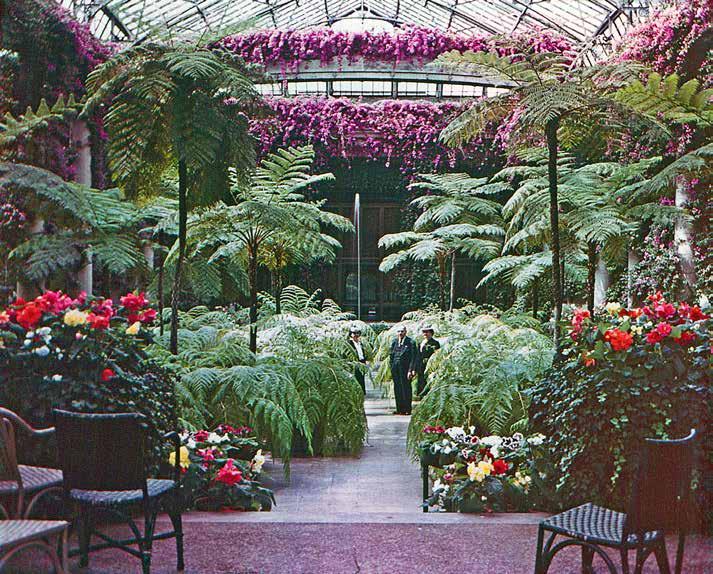

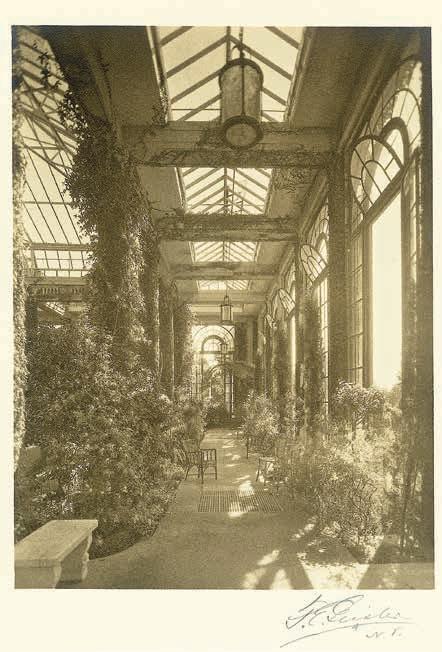

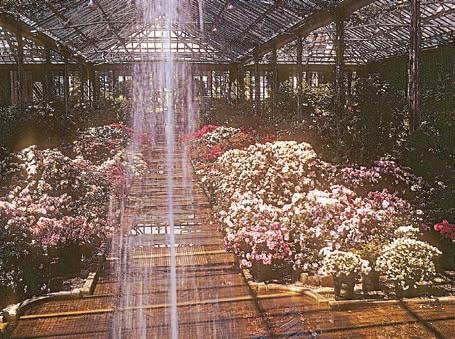

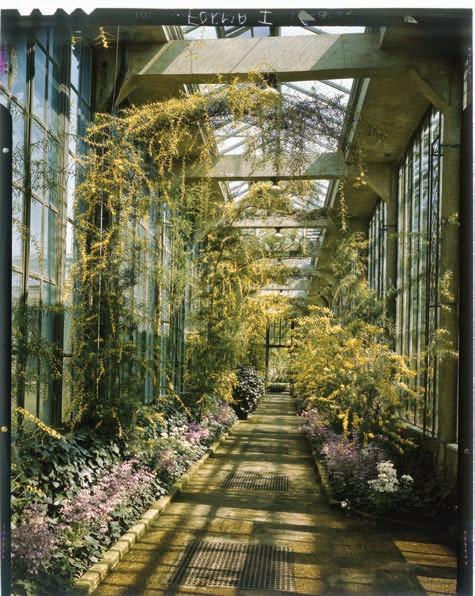

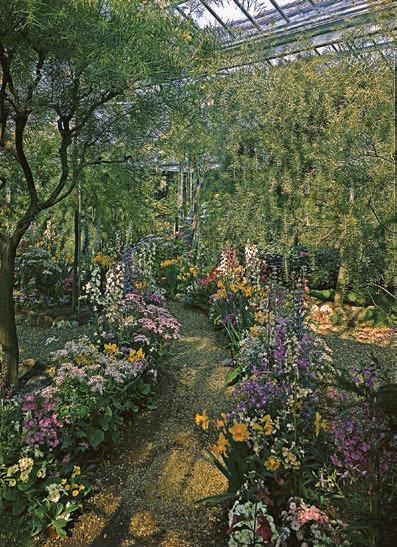

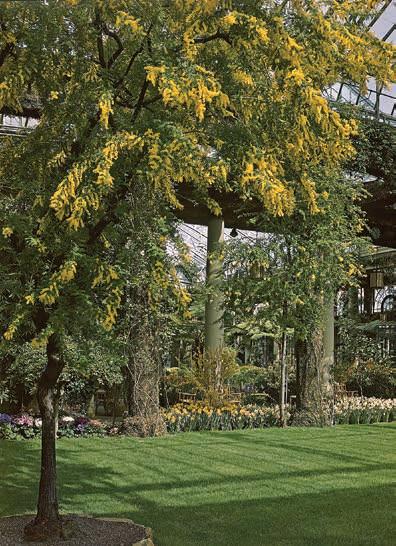

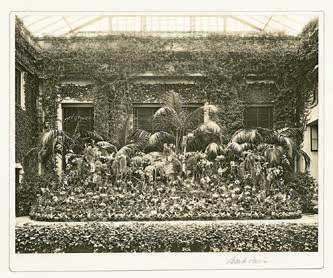

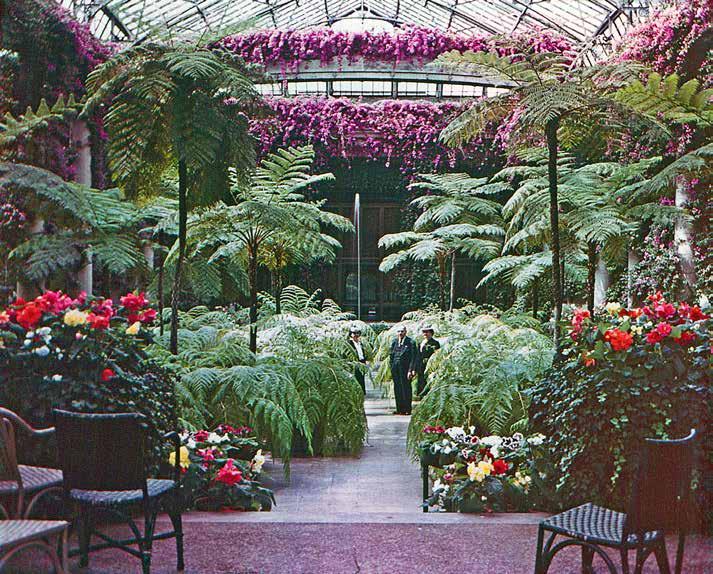

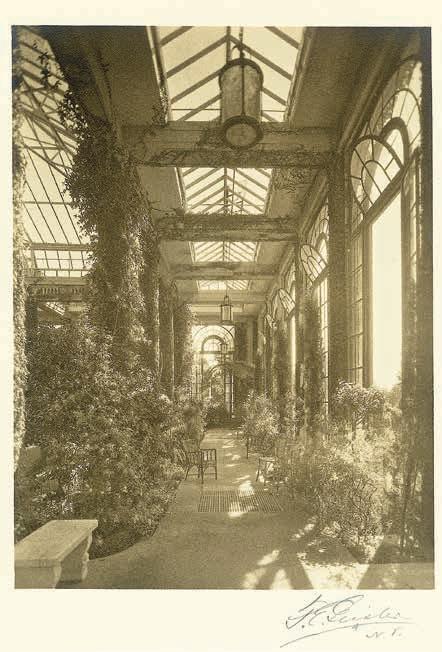

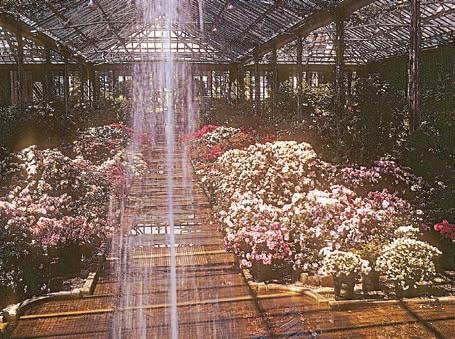

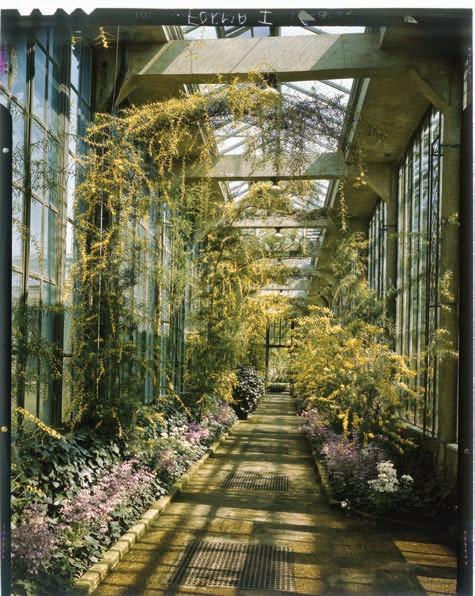

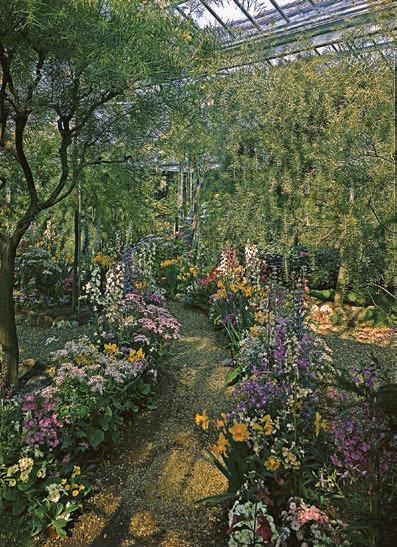

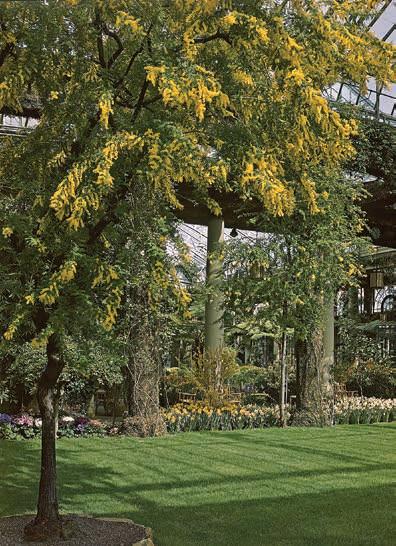

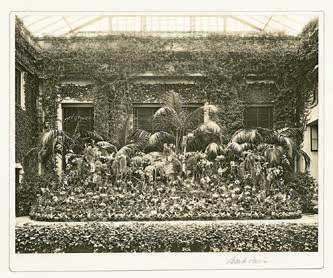

A typical springtime display in the Exhibition Hall, 1947.

For more about Longwood horticulture during Pierre and Alice du Pont’s stewardship, see Green Thumbs starting on page 14. Photo by GottschoSchleisner, Inc.

Features

Green Thumbs

Longwood’s Conservatory was the special jewel of Pierre and Alice du Pont. Together, they and their skilled employees had the greenest thumbs around.

By Colvin Randall

Pierre’s plan was carefully reasoned, just like all his endeavors. First, he wanted the best head gardener he could find, noting in 1915, “…he would have charge of about two acres of flower garden, including roses and perennial borders; and about fifteen acres of wooded park, including the care of rhododendrons, azaleas, etc.; also greenhouses sufficient to furnish plants for a conservatory, and a small grapery. To this glass I propose adding, but definite plans will depend largely on the ability of the man I select. If a man can be found to take charge of the items already enumerated and, in addition, look after indoor roses, orchids or other hothouse products, I will add to my equipment; but the essential is to find a man to take care of the outdoor work and the excess glass. I must have a man who can work well with others, supervise the efforts of six to eight undermen (the number of the latter depending on the requirements of the work). I must have a man who will take an interest in his work and who will be willing to stay indefinitely, preferably a married man between thirty and forty. He must have an ambition to ‘get along’.”

Philadelphia’s Andorra Nurseries and Thomas Meehan & Sons both recommended William Mulliss, then at the Hill School in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, but previously at

Compton, the John and Lydia Morris estate that today is the Morris Arboretum. Frank Gould, Compton’s superintendent and Mulliss’ former boss, gave him the highest recommendation, and Lydia Morris herself replied that Mulliss “was of good character and agreeable personality and satisfactory to us in the position he held.”

Mulliss summarized his qualifications to Pierre, writing on November 26, 1915, from the Hill School: “My experience in greenhouse work, plants and flowers covers nearly twenty years. I was born in England thirty six years ago, and worked on several large estates in that country, in the greenhouses, flower gardens, etc. About six years ago I went to Canada and worked in nurseries there for about two years, afterwards coming to Philadelphia. I worked for the late Mr. J. T. Morris, for over three years at ‘Compton’, Chestnut Hill, Phila in greenhouses etc. and for the last three and a half years, have been in charge of the grounds here. This place is made up mostly of athletic fields and I would like to take up a position where horticulture is more generally carried on …. I feel confident in my ability to fill the position and give you every satisfaction if we could come to terms …. I am a total abstainer and unmarried.”

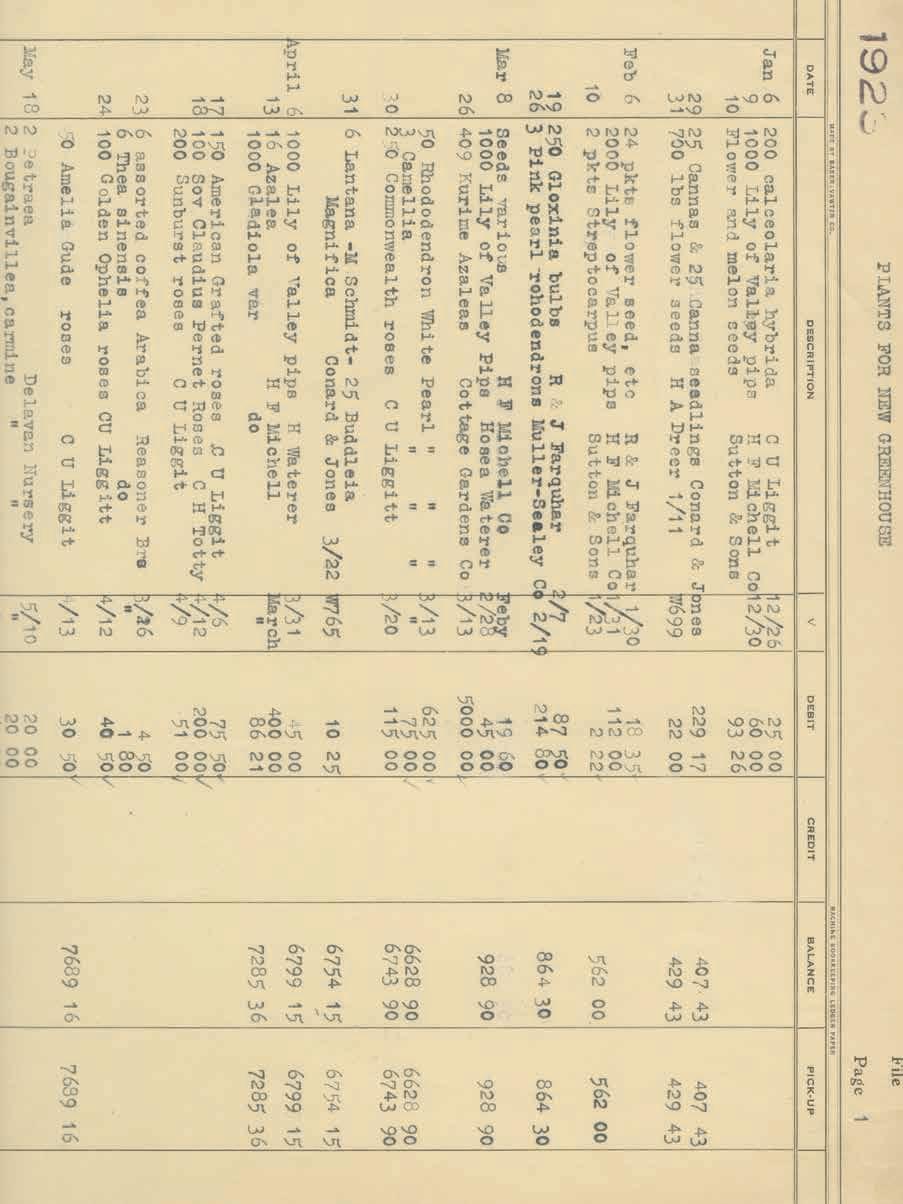

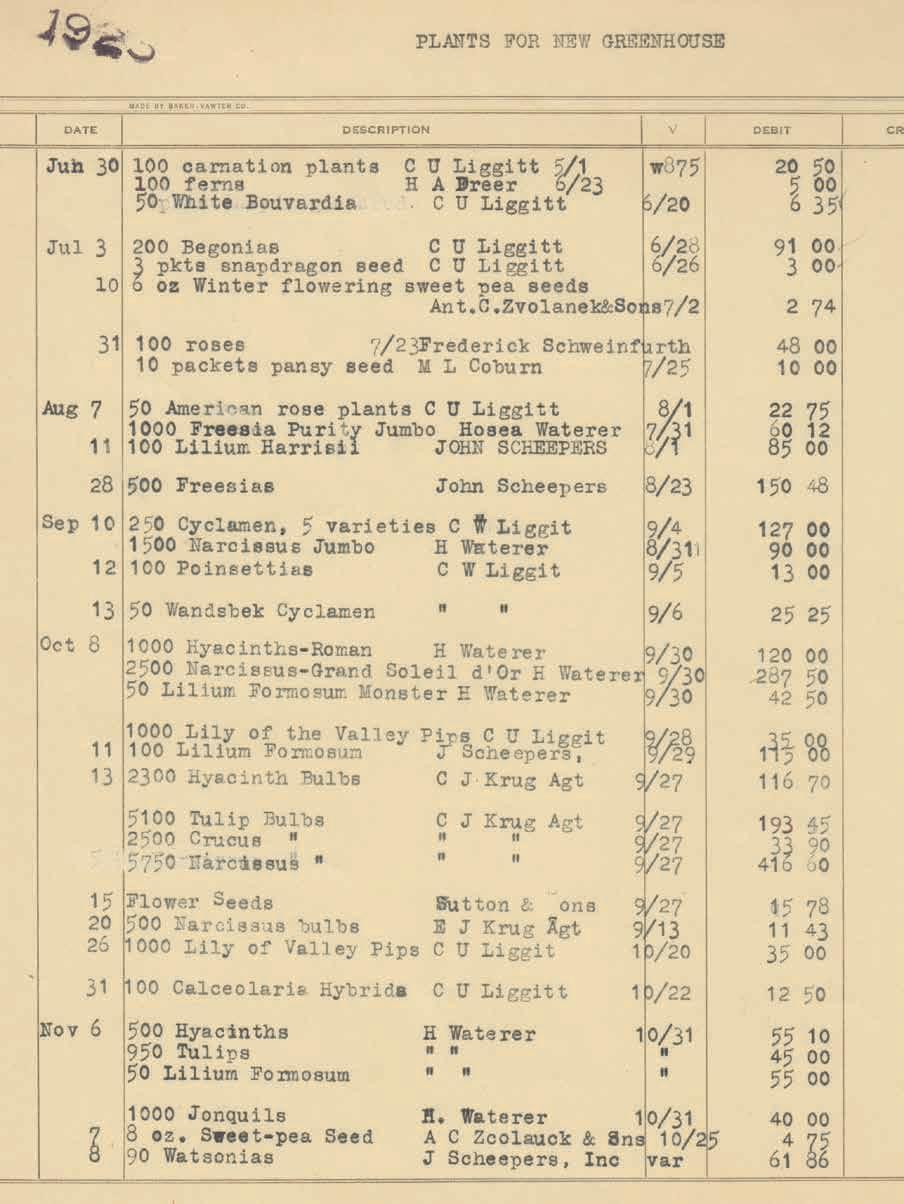

Family friend Gertrude Brinklé assembled this cut-and-pasted caricature of Pierre “on the bowling green at Longwood” for a scrapbook she prepared for Alice, c. 1920. In the background are two of the thousands of ledger cards on which Pierre’s Wilmington staff recorded every expense at Longwood down to the penny. Courtesy Hagley Museum and Library.

Pierre apparently interviewed William at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia on Tuesday, December 7, 1915, then invited him to Longwood on Sunday, January 2, 1916, “to go over my proposition with you and a decision could be reached between us. I do not care to make an offer until you have looked over the ground and are perfectly satisfied that you can fill requirements.” Mulliss started at Longwood in February 1916.

Bill Mulliss obviously fulfilled Pierre’s expectations, giving Pierre impetus to construct the massive Conservatory complex. The initial plantings were described in Issue 303 of the Longwood Chimes, and huge orders and extravagant plantings continued for years, especially a boxcar load again from The City and Kentia Nurseries of Santa Barbara in 1928 with 32 Italian cypress, 20 four-foot-high tree ferns, 12 costal redwoods, 12 giant sequoia, 24 rhododendrons, 24 daphnes, and 10 camellias.

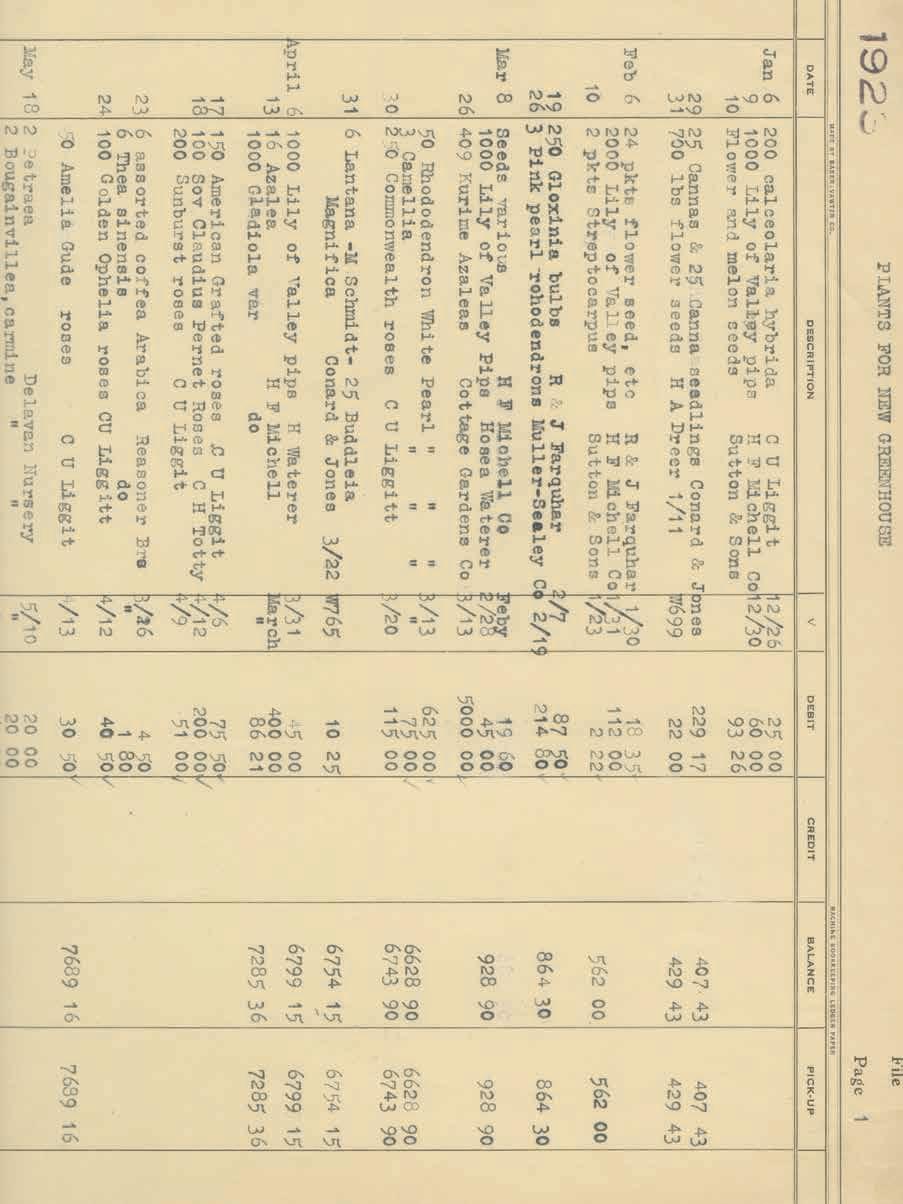

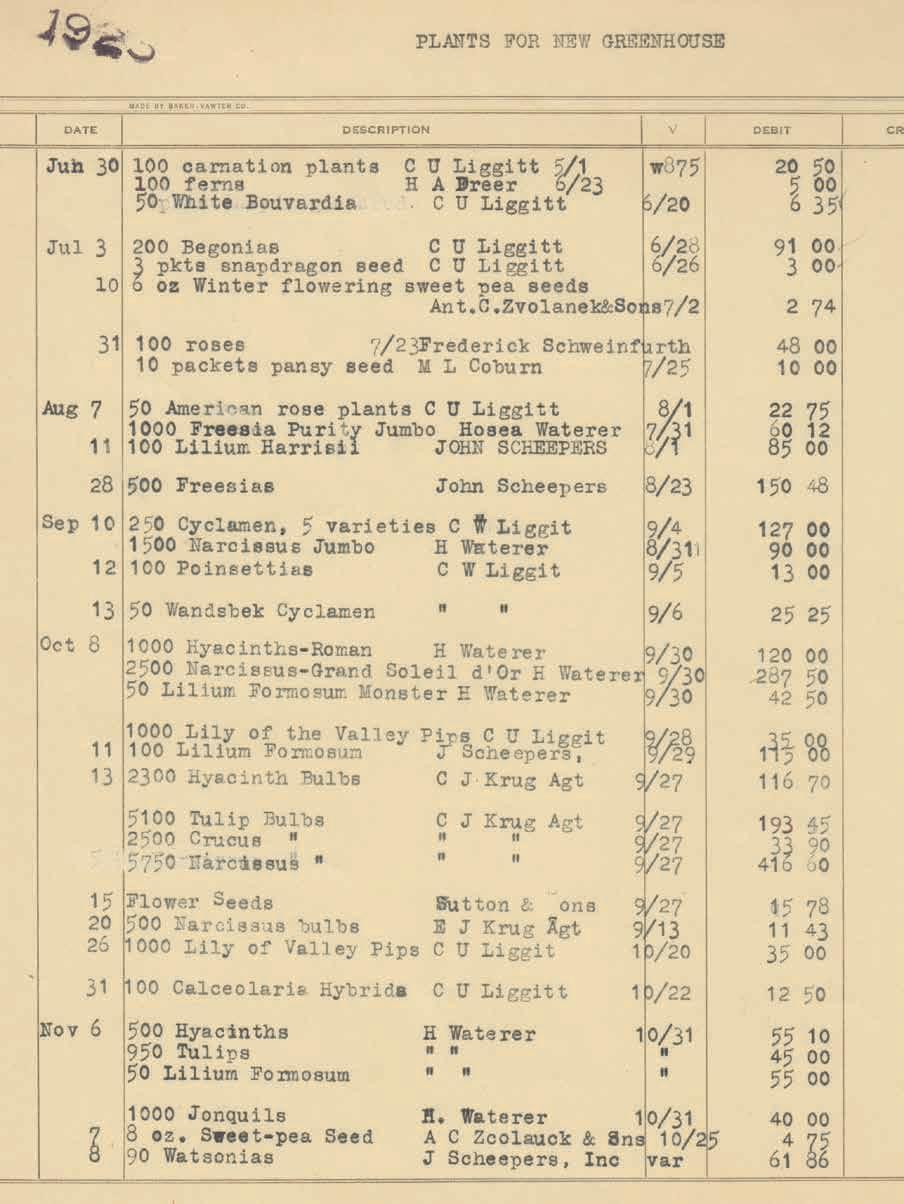

Flowering plants grown from seed were a surefire if relatively inexpensive way of filling the greenhouses. A favorite supplier was Sutton & Sons from Reading, England. In 1923, for example, Pierre ordered 128 packets of their calceolaria, cineraria, and melon seed; in 1924, 129 assorted packets;

16

A Century of Floral Sun Parlors: Part Six

and in 1928 he imported 271 packets of their baby blue-eyes, balsam, begonia, cineraria, dahlia, feverfew, forget-me-not, gerbera, melon, and primrose seed. Domestic suppliers provided not only seed but thousands of bulbs and young greenhouse plants. Poinsettias were procured from Julius Roehrs as early as 1919 and would become a holiday embellishment in the Fern Passage for decades. But while Mulliss cultivated a floral encyclopedia from a to z, Pierre was most passionate about, and devoted the most time to, acquiring rhododendrons, camellias, acacias, and, with Alice, orchids.

Pierre’s importation of 40 massive, potted indica hybrid azaleas from Belgium in 1919 was one of his greatest successes. But following import restrictions imposed that same year, he tried again and again to get United States Department of Agriculture permits, which were issued but only for small, bare-root plants without soil. He complained bitterly to lawmakers and nurserymen about the ban

18

The Conservatory in May, 1924, photographed by William Spruance.

Head Gardener William Mulliss (1880–1945).

Bill Mulliss obviously fulfilled Pierre’s expectations, giving Pierre impetus to construct the massive Conservatory complex.

The Exhibition Hall, circa the late 1940s.

that did not differentiate between an unscrupulous importer and a careful plantsman: “…certain plants may be imported, but without earth about the roots. They might as well require that each plant be boiled to rid it of insects. The whole procedure seems to still further prove the inefficiency of Government operated projects,” he lamented. He even asked the USDA if plants could be imported from Europe to Canada in soil, moved across the border bare root, then immediately repotted in American soil—sorry, no!

He purchased dozens of rhododendrons from domestic suppliers, but through his friendship with Charles Sprague Sargent (1841–1927), founding director (1872–1927) of Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum, Pierre was finally able to import three small plants each of 30 species of rhododendrons from Sunningdale Nurseries, Surrey, England, at a cost of $200. The 90 plants, bare root but packed in damp excelsior, arrived in

April 1927. Sargent’s endorsement likely greased the wheels at the USDA.

Pierre probably made Sargent’s acquaintance through Henry Algernon du Pont (1838–1926) of Winterthur fame. Sargent visited Longwood as early as 1922, if not before, and was genuinely impressed with Pierre’s horticultural aspirations, sending him many rare treasures, including rhododendron seed in 1925. Pierre wrote, “You are a most prompt person in your thought of others. No sooner do I express a wish for plants than I have a letter stating that they have already been shipped. Many thanks for your continued kindness.” Even Alice got involved. Sargent noted that she was expected in Boston in December 1926 “in the interest of [Longwood’s] new Rhododendron house. I wish that you could come with her as it would give us an opportunity to talk over several subjects.” Pierre was equally supportive of the Arnold

Arboretum. Sargent thanked him for a “very generous” contribution in 1922, which Pierre had increased to $11,000 by 1931 (equivalent to $212,000 in 2022).

Ernest H. Wilson (1876–1930), celebrated plant explorer, visited Longwood and what he called its “wonderful Orangery” for the first time in 1926. He was named Keeper of the Arnold Arboretum following Sargent’s death in 1927, and he then supervised the transfer to Longwood of up to 18 rhododendrons, 100 azaleas, 24 clivias, 200 nerines, and two 10-foot-tall starjasmines from Sargent’s former private collection. In 1928, Wilson offered Pierre 41 tender Himalayan and western China rhododendrons of 13 species raised by Charles Dexter (1862–1943) from seed procured by the Arboretum. “They are just the thing for your conservatory,” noted Wilson, and Dexter added that they “ought to make very good plants for your glass garden.” Pierre was also able to import 116

19

Left: Despite Pierre’s abhorrence of plant importation restrictions, Longwood was affected by introduced pests. This photo from 1928 is interesting because the open Orangery windows lack screens. Pierre noted in 1928 that because of Japanese beetles he had screened the Fruit Houses and would next do the Melon and Fig Houses

but at that time was not planning to screen the Orangery or Rose House. He was going to order beetle traps and wanted advice about spraying. Screens everywhere were soon forthcoming. (Japanese beetles arrived in this country as grubs in imported azalea root balls in Burlington County, New Jersey, in 1916.)

small bare-root rhododendrons of 29 mostly hybrids and 50 plants of 22 mostly hybrids from two English nurseries in 1931.

Camellias were another great love. Pierre had imported more than 100 from France and Belgium in 1919 but then had to rely on domestic sources, and he purchased aggressively, especially from Georgia. Sargent, too, helped build the collection, sending two rare specimens, Chinese Camellia reticulata and C. japonica ‘Mrs. Sanders’. From a Virginia nursery, Pierre learned of Guichard Soeurs, a grower in Nantes, France, with plants unobtainable in the US. Pierre was allowed to import 345 small, bare-root plants in 1928 for $287 (about $5,000 today); he noted in 1935 that about 75% had survived.

Acacias were another favorite, which Pierre remembered from his trip to the south of France in 1913. He was not allowed to import them from abroad, but he built quite a collection from domestic sources

20

Photo by Frank E. Geisler.

Above: The Azalea House in 1940 looking west toward the Exhibition Hall. Photo by Phil Brewer.

Left: The original 1921 Camellia House at the east end of the front range was connected northward to the 1928 Azalea House and the camellia planting was extended. This 1947 view looks toward the northeast back corner of the Azalea House.

and from estate and flower show sales, some specimens having originated in Europe before the ban. Acacias were grown permanently in Longwood’s Acacia Passage, sometimes planted in the Orangery and Exhibition Hall, and each year massed in an Acacia Path between the Azalea House and the East Fruit House— today that area is the indoor Garden Path.

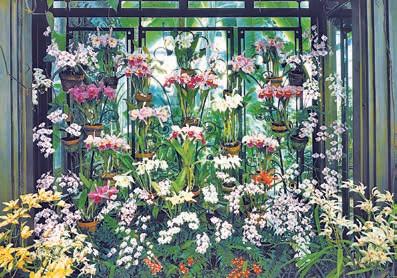

An Orchid House as part of the Conservatory complex was mentioned as early as 1917 and appeared on surviving blueprints beginning in 1919 in various locations in the western half. The current house was designated originally for “display,” without mention of orchids. It is one of two pavilions that bookend the pergola feel of the longer, lower connecting houses branching off from the Orangery; the matching Camellia House is at the opposite eastern end.

Once word that the Conservatory was under construction, Pierre was offered

huge orchid collections from estate sales (3,400 plants, 15,000 plants, etc.) but he declined, noting the houses were still being built.

Copper magnate Albert Burrage (1859–1931) of Boston was the country’s leading orchid collector and president of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society and the new American Orchid Society. On June 18, 1921, Pierre wrote to Burrage, “Since visiting your orchid house, Mrs. du Pont and I have frequently commented on the beauty of the flowers and the careful attention that is given them in order to obtain perfect results.” Burrage suggested that the du Ponts become life members of the American Orchid Society, loosely organized on March 26, 1920, and formally organized on April 7, 1921. Pierre noted, “I am not yet a grower of orchids but, as one interested in horticulture in general, I shall be glad to join,” sending on July 11, 1921, $100 each for himself and Alice as life members. In 1924, some space was finally set

aside at Longwood for orchids. In 1927, Pierre commended Burrage for sparking their interest: “Mrs. du Pont and I wish to thank you for your enthusiasm for orchids, which has led us to start a small collection.” Alice was elected a vice-president of the American Orchid Society in 1924 and continued until her passing in 1944, whereupon Pierre took her place and served as an honorary VP until 1949 when he resigned as an honorary officer.

Alice and Pierre started ordering orchids in quantity in 1924. By 1925, Pierre had figured out how to work smoothly with the USDA to import epiphytic, soil-less orchids from abroad, and he and Alice ordered hundreds from the United Kingdom, Belgium, France, India, Siam, the Caribbean, Brazil, and Canada. Sometimes the plants were suggested by sister-in-law Mrs. William K. (Ethel) du Pont during her travels to foreign growers. In 1945, Pierre modestly noted that Longwood’s collection was assembled largely by Alice, but he was totally

Right: The Acacia Passage, 1947. Photo by GottschoSchleisner, Inc.

21

Above, left to right: Acacias on the Orangery lawn, and the Acacia Path, in 1947.

Photos by GottschoSchleisner, Inc.

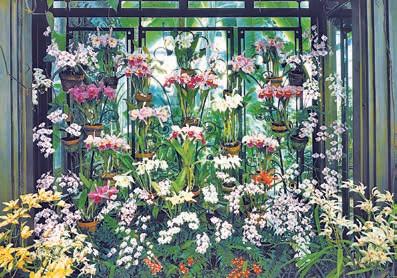

The left Orchid Display case in 1947.

22

Opposite: The American Orchid Society’s Fifth National Orchid Show (May 5–7, 1933) in the Exhibition Hall.

Right: The American Orchid Society’s Sixth Show (October 12–14, 1934) in the Exhibition Hall. This show, as well as the Society’s Fifth National Show (shown opposite), featured plants mostly from eastern US collectors.

involved with the ordering and importation paperwork, aided by his secretary Titus Geesey, Alice’s secretary Victor Thomas, and by Longwood orchid grower Louis Jacoby.

Three non-public orchid growing houses were built in the late 1920s, along with the bronze Orchid Display Case in 1929 in the present Orchid House, which marked the beginning of a dedicated legacy display of blooming orchids indoors. The cases were repositioned in 1983 to expand the orchid area, reducing the banana display on the south side. In 2022, the rearranged Orchid House reopened to visitors after a complete renovation.

By 1931, Longwood had 2,977 orchid plants. From 1928 to 1951, Longwood recorded a grand total of 47,711 spikes of bloom and 164,824 individual flowers (cattleyas and cymbidiums). In 1933 and 1934, Pierre and Alice hosted the Fifth and Sixth National Orchid Shows at Longwood, with the Exhibition Hall filled with gorgeous displays.

After Mrs. W. K. du Pont’s death in 1951, her family asked that Longwood take her collection (and orchid grower). A detailed inventory from January 1952 listed 2,783 plants in Pierre and Alice’s collection and 2,314 plants in Ethel’s collection,

totaling 5,097 orchids at Longwood.

In July 1920, Pierre was asked to join the National Association of Gardeners, an organization supported by many of the wealthiest estate owners in the country— Coe, Cutting, Dodge, Duke, Frick, Guggenheim, Havemeyer, Kahn, Mellon, Morgan, Sloan, Untermyer, Whitney, and the like. Its purpose was “to elevate the profession of gardening by eliminating those from it who do not possess the qualifications, either in ability or trustworthiness, to entitle them to the calling of gardener. It aims to protect the country estate owners as well as the worthy men of the profession which it represents.” Because of the personnel losses of World War I, particularly in the United Kingdom, “we can no longer look to Europe to supply the demand. We must attempt to interest the young men of this country to meet the future demand” for gardeners.

Pierre was intrigued. He had already opened a reconstruction center at Longwood in 1919, where war veterans could rest and rehabilitate with medical supervision. Patients could be trained in and paid for gardening tasks, construction, and virtually all trades during their stay if they wished. Pierre noted that the new

23

Alice and Pierre started ordering orchids in quantity in 1924. By 1925, Pierre had figured out how to work smoothly with the USDA to import epiphytic, soil-less orchids from abroad, and he and Alice ordered hundreds from the UK, Belgium, France, India, Siam, the Caribbean, Brazil, and Canada.

Conservatory would be an ideal training ground for future gardeners, who could live in the Service Building, then under construction. But delays in finishing the complex and subsequent hiring precluded meaningful participation. However, it was through the Association that John Marx (1889–1973) came to be interviewed at Longwood in May 1921. In June he started as Mulliss’ assistant, and over the next 24 years they together perfected the “Longwood style.”

William Mulliss passed away suddenly during a card game with Pierre and two fellow employees on February 17, 1945. Pierre wrote to the Mulliss siblings in England that Bill was “instrumental in building up the well-known horticultural establishment at Longwood. He was the soul of the enterprise, loved and admired by everybody.” John Marx was then named Superintendent and managed the Horticulture Department until his retirement in 1959.

Of course, these two did not work in a vacuum. They built an outstanding indoor staff of ultimately about two dozen

gardeners, most of whom specialized in seasonal crops or cared for themed greenhouses.

World War II slowed Longwood down quite a bit. “We are having very few visitors these days, practically none. The place seems deserted and less like a public park,” noted Pierre in 1942. That same year he wrote to a plant collector in London about a possible scarcity of fuel: “If our greenhouses at Longwood should be abandoned ‘for the duration’, I doubt if they would ever be reopened or replanted. Personally I do not think that I should try to reassemble the necessary force of men to look after the property, and I am sure the present force would be so disbanded as to be impossible of reassembly.” But by April 1945, with the war coming to a close, he was more optimistic, noting “…we have been able to keep ‘Longwood’ in fairly good condition. The display of flowers at the greenhouse is not quite as large or as good as formerly, due to economizing in fuel and labor. Of course some of our young men who could qualify have gone into service of some kind. Fortunately, however, some of

our best employees are those who have been at Longwood a long time and are now much above the service age. In fact, we have three old pensioners back and all doing fine work and glad to be active.” Pre- and post-war purchases for greenhouse flora were relatively consistent: $5,865 in 1938 (today $122,000) versus $6,304 in 1945 ($102,000 today), rising to $7,856 in 1947 ($103,000 today).

Even in his twilight years, Pierre’s achievements excited plant aficionados. In 1947, Henry McLaren (1879–1953), 2nd Baron Aberconway and proprietor of the celebrated Bodnant in Wales, visited Longwood. He offered Pierre his new yellow Clivia kewense (now known as the hybrid Clivia ‘Bodnant Yellow’), red J.C. Williams camellia, and, at Pierre’s request, Viburnum × bodnantense, for which import permits were issued by the USDA in 1948. Aberconway noted that “it is a very great pleasure to me to send any little plants to add to that wonderful collection that you grow, and which twice has given me such pleasure—thanks to your hospitable reception of me.” In 1951, Longwood

Longwood gardeners in the 1930s, most assigned to the greenhouses. Standing outside the Orchid/Banana House, from left:

Roy Johnson, Ben Davis, George Stevens, George Nash, George Ford, Pete Hanway, Louis Jacoby, Carl Bausch, Marshall

Peterson, Chaney Carter, Germino (Jimmy) Franceschini. Seated, from left: Whitey Cloud, Frank Littleton, Clarence

Deckman, Horace Smith, Fred May, Wayne Coyle, George Hartigan. At least three greenhouse men missed this photo opportunity.

24

received a Jasminum polyanthum from Bodnant via the University of California Botanical Garden at Berkeley, and by 1952 it was making “quite a show with its fragrant flowers,” so wrote Pierre to Lord Aberconway. He replied, “The visit to your wonderful greenhouses, which are the best ever, will always remain in my memory as an unforgettable experience.” That same year, Peter Barber from the Exbury Estate in the UK visited and tried to describe “Mr. Pierre’s fountains and his incredible conservatories” to owner Edmund de Rothschild “but it is quite impossible to give a verbal description of their beauty.” Pierre was rewarded with a 1953 shipment of 12 rhododendrons, six azaleas, and six camellias from that celebrated English showplace.

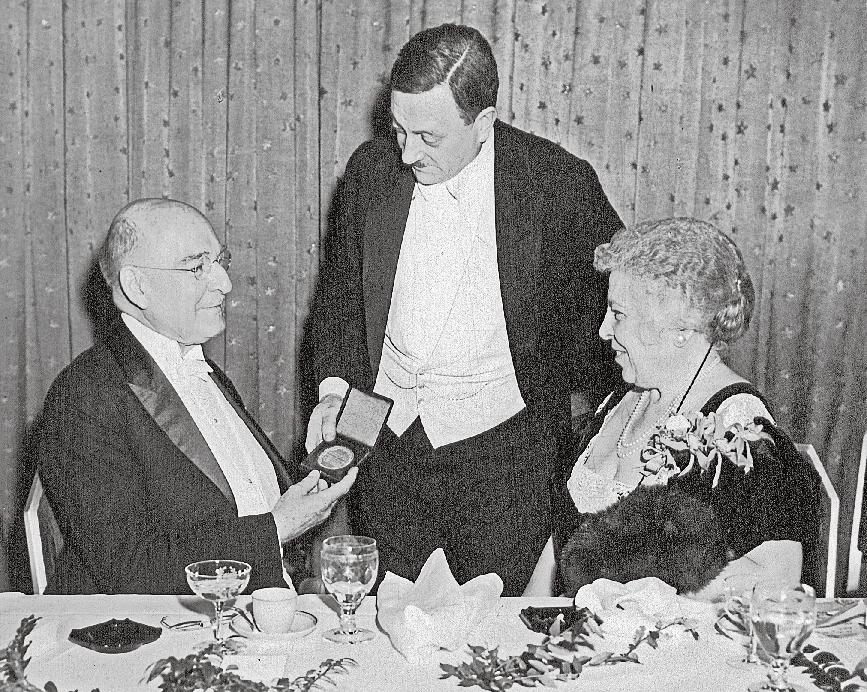

Pierre and Alice du Pont received numerous awards for their gardening efforts. Pierre was given the George Robert White Medal of Honor in August 1926 by the Massachusetts Horticultural Society for “his remarkable work in popularizing horticulture, in extending a love for flowers, and for the establishment of a great winter

garden at Longwood….” The awards committee was chaired by none other than C. S. Sargent.

The Pennsylvania Horticultural Society awarded the du Ponts the Centenary Gold Medal in October 1931 “in recognition to their unique service to the cause of Horticulture.” Pierre noted that he and Alice were “hardly deserving of this honor, but will accept it with the greatest pleasure in the hope that the future of Longwood and our efforts there will justify your decision.”

A decade later, Pierre received the Gold Medal of the Horticultural Society of New York on March 12, 1940, for his “beautiful estate and the sharing of it with so many gardeners.”

But Pierre and Alice’s greatest reward came from the millions of visitors who have enjoyed, and continue to enjoy, the results of the du Ponts’ “green thumbs.”

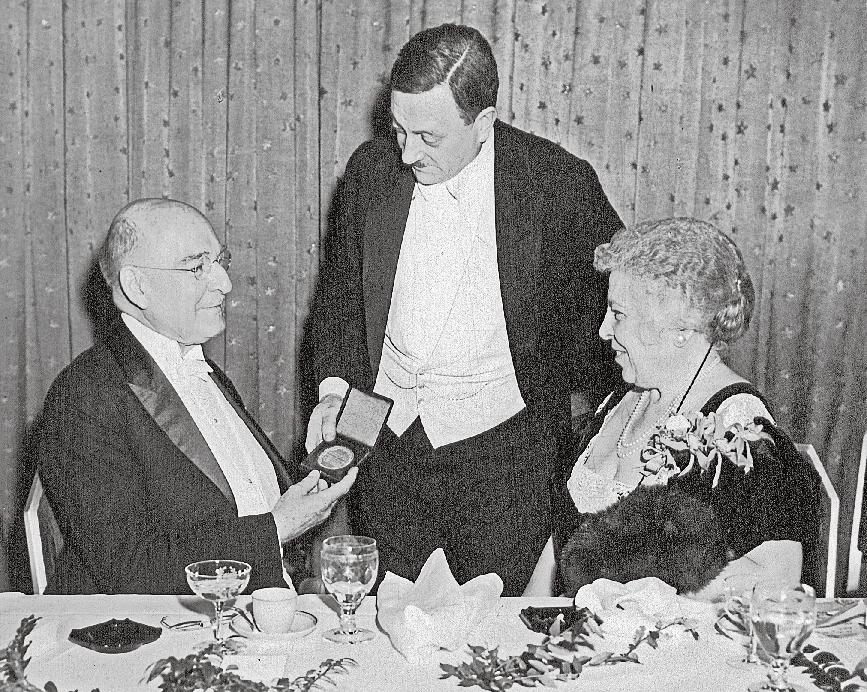

Pierre received the Gold Medal of the Horticultural Society of New York from Richardson Wright on May 12, 1940, at the annual

A Century of Floral Sun Parlors: Part Seven will appear in the next issue of Longwood Chimes

dinner in the Waldorf-Astoria celebrating the International Flower Show held at Grand Central Palace. Alice du Pont beams her approval.

25

Horticulture Department Superintendent John Marx (1889–1973) in 1951.

Pierre received the Gold Medal of the Horticulture Society of New York for his “beautiful estate and the sharing of it with so many gardeners.”

26

The Arts

From sunup to sundown, experience a day in the life of our Gardens and all those behind its beauty.

A DAY in the LIFE

Public Safety Officer Robert Detweiler takes a quiet moment to unlock the Visitor Center Entrance Gate at 5:30 am, while a flurry of activity happens inside to ready the Gardens for that day’s guests. Photo by Daniel Traub.

27

Plumber David Tunstall and Senior Plumber Jason Young adjust the robotic fountain nozzles in the Main Fountain Garden’s Rectangular Basin as part of the fountains’ daily start-up routine. Beneath the basin sits a network of underground pump rooms and 1,400 feet of underground tunnels that together house the garden’s state-of-the-art plumbing and electrical infrastructure. Photo by Daniel Traub.

Opposite: From left to right, Turfgrass Technician Matt Huskey, Turfgrass Manager Mike Raign, and Senior Turfgrass Technician Jack Rude perform edging work along the path at Flower Garden Drive. Photo by Daniel Traub.

28

At the Nursery Production Greenhouse, Floriculture Manager Kevin Murphy, Greenhouse Grower Patti Stefanick, Grower Emily Coghlan, and Senior Grower Michelle Hagerty load up carts with plants headed for display in the Gardens.

Here at Longwood, we grow an average of 1,300 (and growing!) types of plants each year for seasonal displays in the Conservatory and our outdoor gardens.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

30

It takes many hands (and waders) to keep the Oval Basin pristine. Here, a team from our Teen Volunteer program, under the direction of Senior Horticulturist Lauren Hill, collect fallen plant material from the central water feature in the East Conservatory. They also perform pruning and grooming of the lower level plant material that is easier accessed via the pools.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

31

Above: Each morning, before our garden gates open to guests, our Guest Services team gathers for the Daily Morning Line-up meeting to review the day’s events and programs, what’s in bloom, the weather forecast, and other information to assist guests during their visit.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

Opposite Top: Event Operations Manager Brad Dolan leads a weekly crossdepartmental Operations team meeting to review upcoming events throughout the Gardens. Representatives from Guest Services, Performing Arts, The Garden Shop, Security, Operational Services,

Facilities, Horticulture, Restaurant Associates, Event Operations, Engagement & Learning, and Marketing and Communications attend to review logistics and to ensure everyone is prepared for upcoming classes, performances, special programs, and other events.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

Opposite Bottom: Director, Learning and Development Veronica Chase leads a new staff orientation session—part of Longwood’s multi-faceted onboarding program—in the Visitor Center Auditorium.

Photo by Meghan Newberry.

32

33

Undertaking the most ambitious expansion, reimagination, and preservation of our Conservatory and surrounding landscape in a century takes a lot of behindthe-scenes planning. Here, our Longwood Reimagined project team of Longwood and Bancroft Construction Company staff holds one of its weekly progress meetings.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

34

Assistant Project Manager Jennifer Perilli, Bancroft Senior Superintendent Craig Cannelongo, Associate Director, Construction Management Gina Sinovich, and Project Manager Douglas Boyer meet near the new Administration building on the Longwood Reimagined project site to discuss the day’s scheduled activities.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

35

Docent Ingrid Fischer assists guests in the Gardens. In all, we have more than 100 docents serving on six different teams that share stories about our plants, history, and garden design with our guests.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

36

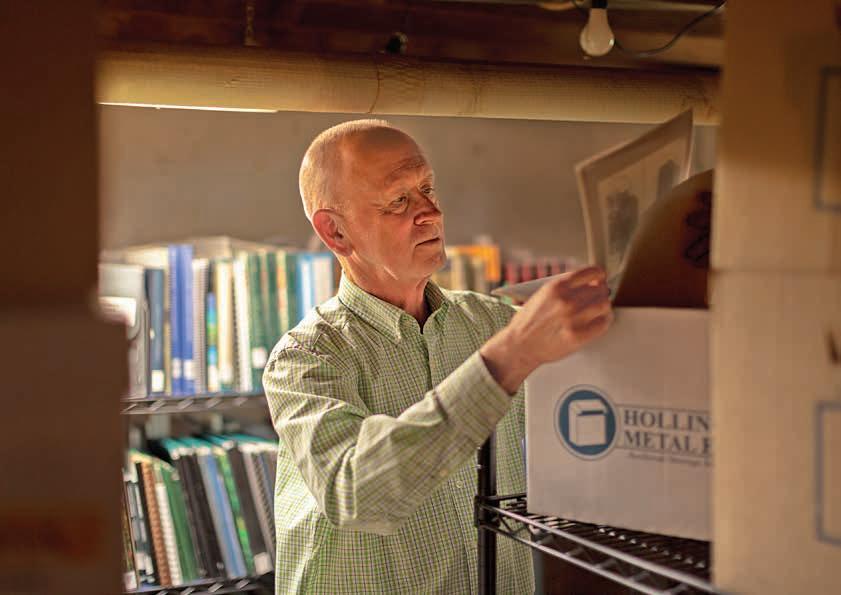

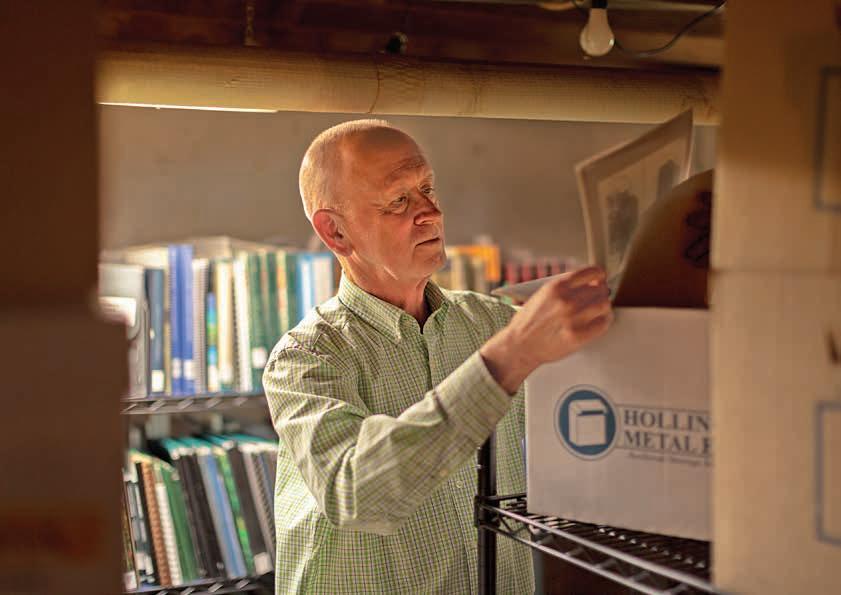

Longwood P.S. du Pont Fellow Colvin Randall, who has authored six books about Longwood, does research in our temporary Library & Archives for his upcoming book, Garden of Music, about our performing arts and musical instruments.

37

Photo by Daniel Traub.

Soil Technician Aldo Gaspari checks the temperature of the mulch rows at our soils and composting facility, where each year we transform 4,000 to 5,000 cubic yards of waste material into usable mulch and compost. These products are used in planting beds across the entire garden.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

38

Above: Research Intern Cole Geissler has been learning the basics of plant tissue culture to support ongoing research and maintenance of laboratorybased projects. Here he can be seen cleaning and transferring cannas that will one day be on display in the Conservatory. Photo by Daniel Traub.

Above: In addition to his daily responsibilities supplying tissue culture laboratory needs, Laboratory Technician Kevin Allen is also remotely attending graduate school at Texas Tech University. His laboratory-based research project is being undertaken at Longwood where he is optimizing cutting-edge native orchid seed propagation techniques to support orchid conservation locally and across the country.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

39

Top: Server Pat Colven is one of 20 front-of-house staff who deliver the extraordinary dining experience for which 1906 is known.

Bottom: Chef Adam Kapa and team expertly prepare a variety of palate-pleasing dishes in 1906. On average, 239 guests each day visit 1906 to enjoy a delicious lunch or dinner.

Photos by Becca Mathias.

40

Above and left:

The Garden Shop offers a fun shopping experience.

Guests peruse an eclectic selection of plants, books, home goods, and Longwood signature merchandise, many created by local artisans.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

In May 2021, we brought the management and merchandise curation of The Garden Shop in-house, introducing new product lines such as our Grown at Longwood plant collection.

Photo by Becca Mathias.

41

Associate Director of Investments and Taxation Lee Sausen and Associate Vice President, Accounting and Finance Eileen Perpiglia meet in the Pierce-du Pont House.

Photo by Meghan Newberry.

42

Right and below: Internationally renowned floral designer Tim Farrell leads a hands-on workshop on rhythm in floral design during a Continuing Education class at Longwood.

Photos by Daniel Traub.

Photos by Daniel Traub.

43

Multimedia Designer and Drone Pilot Carol Gross (left) captures this image of her and Longwood Volunteer Photographer Hank Davis as they document the beauty of SOS, one of Bruce Munro’s Light installations. Photo by Carol Gross.

Above: All of the Illuminated Fountain Performances in the Main Fountain Garden are monitored by our control room operators. They keep a close watch on the health of the pumps, reservoir tank water levels, and the operation of the robotics, nozzles, and flame jet systems. Lead Performance Technician Joseph Whitney monitors a daytime fountain performance from the lower level control room beneath the Main Fountain Garden.

Photo by Becca Mathias.

Opposite: Caring for our plants continues long after our Gardens close for the day. Our night gardeners look after our living collection after the sun sets and through the night, managing the environmental controls for everything under glass, including our Conservatory, Peirce-du Pont House, greenhouses, and nursery.

Night Gardener Danny Taylor is seen here making the evening rounds in the Conservatory after closing, around 11 pm. Photo by Daniel Traub.

46

A Cut Above

A new addition to our mower fleet offers an efficient and safer option for challenging terrain.

At first glance, you may mistake it for a remote-control toy car. But the Husqvarna 435X All-Wheel Drive Automower is far from child’s play. In June 2022 we purchased two automowers, which use GPS and a boundary wire to automatically map and mow sections of turf. Think of it like a Roomba vacuum, but for mowing grass.

“We demoed various models of these mowers in the past but wanted to wait until they refined some of the features before adding them to our mower fleet,” explains Turfgrass Manager Michael Raign.

The automowers are used to cut the Visitor Center berm, an area they are perfectly suited to handle because of its imposing 35-degree slope. While a traditional mower and operator could cut the berm, it is far safer and more efficient to leave the task to the automower.

“With the area having such a steep slope we need the grass to be completely dry before we could safely allow a traditional mower on it,” explains Raign. “Often, by the time the morning dew dries off the turf, we are open to guests, making mowing more challenging and compromising the guests’ experience,” he explains.

Each automower is powered by a rechargeable battery. When the mower detects its battery power is low it will find its way back to its docking station, recharge its battery, and go back out to mow.

Through an app on a mobile phone, our staff can adjust the height of the cut; create the mowing schedule; download data about mowing time, acreage, battery status; and more. The mower also boasts a number of safety features, including sensors that will slow or stop the mower if it gets too close to an object and shut off the blades if the device is touched or lifted. Equipped with lights and very quiet, the mowers can run day and night and currently run overnight on weekdays to keep the berm looking beautiful.

End Notes

Photos

by

Hank

Davis 48

47

Front Cover

Intern Augustin Espinosa and Associate Director, Network Operations Dwight Effinger connect a new storage array in Longwood’s main server room. Photo by Daniel Traub.

Back Cover

Anatomy of a plant ID tag: Top line (in bold) is the full name of the plant.

Display Site is where the plant will end up in the Gardens. Here, Flower Garden Walk, Brick Walk, Bed 3.

Quantity is the number of pots requested. The display team wants 200 of these pots.

SD is the Start Date, indicating when the seed was sown.

PD is Pot Date, indicating when the plant should be potted in order to be ready in time for the DD or Display Date, the exact date when the plant needs to be ready for display.

Grower is who is going to grow the plant and also designates the growing house location. In this case, the grower is Floriculture Manager Kevin Murphy and the location is the Nursery Production Greenhouse (G70).

Ht and Wd is the Height and Width of the plant. Often, horticulturists request a specific height and width for the plant and then the growers do their best to grow the plant to these specifications.

Lastly is the Acc. #. This number helps Plant Records keep track of the plants that are on display.

See Planning for Plants article starting on page 6 for more information about our plant growing process.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

2022

Inside Front and Back Covers

Two of the thousands of ledger cards on which Pierre S. du Pont’s Wilmington staff recorded every expense at Longwood down to the penny. Courtesy Hagley Museum and Library.

Editorial Board

Marnie Conley Patricia Evans Steve Fenton

Julie Landgrebe Sarah Masterton Katie Mobley Colvin Randall James S. Sutton

Contributors This Issue

Longwood Staff and Volunteer Contributors

Kristina Aguilar Plant Records Manager Hank Davis Volunteer Photographer Carol Gross Multimedia Designer Meghan Newberry Volunteer Photographer

Other Contributors

Lynn Schuessler

Copyeditor

Becca Mathias Photographer Daniel Traub Photographer

Distribution

Longwood Chimes is mailed to Longwood Gardens Staff, Pensioners, Volunteers, Gardens Preferred and Premium Level Members, and Innovators and is available electronically to all Longwood Gardens Members via longwoodgardens.org.

Longwood Chimes is produced twice annually by and for Longwood Gardens, Inc.

Contact

As we went to print, every effort was made to ensure the accuracy of all information contained within this publication. Contact us at chimes@longwoodgardens.org.

© 2022 Longwood Gardens. All rights reserved.

Longwood Chimes

50

No. 305 Autumn

Longwood Gardens is the living legacy of Pierre S. du Pont bringing joy and inspiration to everyone through the beauty of nature, conservation, and learning.

Longwood Gardens P.O. Box 501 Kennett Square, PA 19348

longwoodgardens.org

“It’s exciting to be part of a passionate team where everyone’s going for it— that’s pretty cool.”

—Production Manager Jon Webb

Photo by Daniel Traub.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

By Lynn Schuessler

By Lynn Schuessler

Photo by Daniel Traub.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

Photos by Daniel Traub.

Photos by Daniel Traub.