5 minute read

of Arts in Medicine By Rajam Ramamurthy, MD

Physician! Rise to the Heights of Rhythm: The Significance of Arts in Medicine

By Rajam Ramamurthy, MD

Advertisement

Asoft voice singing in an unknown language distracted my attention from documenting my day’s work on medical records. Drawn towards the voice, I stepped into an alcove of the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit where four babies were housed. The light was dim, something the nurses did to provide some calm. Shironi, I recognized her instantly from her long straight black hair and beautiful golden skin, was seated by her baby’s incubator, one port slightly open. She was singing a native Indian lullaby. I glanced at the baby who was moving her hands and feet; did I notice a facial grimace? Instinctively I looked at the monitor, the baby’s heart rate, respiration, oxygen saturation and blood pressure were perfectly within normal limits. I have heard many parents mention that their presence and talking or reading to the baby made the oxygen saturation remain stable. Think of the role a lullaby has played in our lives. These days the recorded voice of the parent and music is not an uncommon sound in the nurseries.

Being a dancer trained in Indian classical dance and a lover of all genera of music, I was a witness for over a 40-year period to the arts creeping into the sterile stark grey and green corridors of hospitals. Now, the purchase of paintings is a line-item budget when a hospital is being built. True, but the arts becoming a part of medical education takes quite another dimension.

In early 2000, Humanities departments were established in several medical schools. In reading about it, this sentence stuck in my mind, and I quote, “The main concern of medical humanities education is teaching professionalism; one important aspect that has emerged is the goal of nurturing emotion through reflexivity.” I spent several minutes

looking up the meaning of reflexivity − the fact of someone being able to examine their own feelings, reactions and motives (reasons for acting), and how these influence what they do or think in a situation. Professionalism, on the other hand, I thought I knew. During my prime in medical school, a role model for professionalism could be described as a male physician, in a stiff starched long white coat, buttoned, with a tie. He always examined the patient thoroughly. He would keep his gaze on the patient’s face, kept a firm hand on the patient’s shoulder and explained his findings in the patient’s language if he could, and his last question always was, “what would make you happy in the hospital.” The wide-eyed patient’s expression was one of having seen the divine. We medical students wanted to emulate this mentor. Today the power of observation and mindfulness when interacting with patients is rediscovered. Would a painting or a sculpture fulfill the role of a mentor?

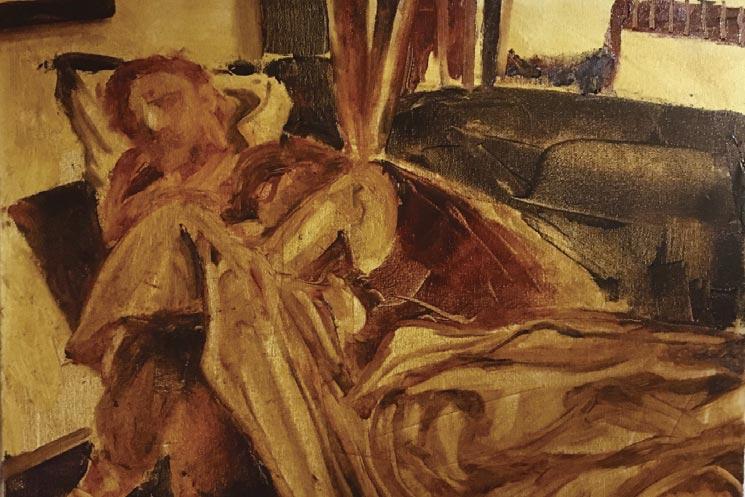

Leonardo da Vinci dissected cadavers to understand the human anatomy. Medicine has used paintings, models and simulations in teaching for decades. However, witnessing a group of medical students touring a museum is a novel endeavor. Dr. David Muller, Chairman of Medical Education at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, mentions how important and underrated the art of looking is to the practice of medicine. He says, "To make a better doctor means to me − and I can't speak for everyone − one who sees the person and not just the patient… not just an organ system that is screwed up.”

In 2001, an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) said that looking at paintings and sculptures can improve medical students' observational abilities. If a student can observe a patient mindfully, notice the patient’s body language, and listen to them with all their attention instead of looking at a screen and typing; with heightened observational skills there will be fewer errors in diagnosis, and fewer reasons to do blood tests and x-rays.

Some schools like UT Health in San Antonio have established centers for Humanities and Ethics that bring prize-winning authors, poets, Nobel laureates and philosophers from the liberal arts into the world of medicine. Generally, in these programs students are not graded, and so it is hard to tell whether their art appreciation was improving their diagnostic skills. However, the students’ narratives indicate that their attention to the patient has improved, and they perceive an emotional response to the patient’s condition. Reflexivity is perceived. By integrating Arts and Humanities throughout medical education, trainees and physicians can learn to be better observers and interpreters; build empathy, communication, teamwork skills and more. In 1999, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) implemented general competencies, applicable to every specialty, that need to be imparted during residency or fellowship training. One of these six competencies is professionalism. Around the same time in 2002, the professionalism charter was published that included the primacy of patient welfare, patient autonomy and social justice.

ACGME through the initiative FRAHME (Fundamental Role of Arts and Humanities in Medical Education) provides resources to help medical educators start, develop and/or improve the use of arts and humanities in their teaching.

A student entering medical school is perceived usually to have a heightened level of altruism, and the experiences of the four years in medical school seem to undermine that. Researchers have shown that medical students finishing medical school have more cynicism than nursing students finishing nursing school. Detaching oneself from the patient, loss of reflection and a turning to rote actions based on expectations have been observed. The arts including painting, sculpture, performing arts like dance and music as well as art appreciation should be encouraged. The practice of these is akin to meditation, keeping one’s attention on a singular endeavor. “Mindful of that particular moment” gives the needed respite to the mind, body and intellect complex that prevents burnout.

In his farewell address as president of the Association of American Medical Colleges, Jordan Cohen, MD, made this statement: “The physician professional is defined not only by what he or she must know and do, but most importantly by a profound sense of what the physician must be.” References 1. Progress integrating medical humanities into medical education: a global overview, Stefani Pfeiffer, Yuchia Chen, and Duujian Tsai.

Curr Opin Psychiatry 2016, 29:298–301. www.co-psychiatry.com

Volume 29 _ Number 5 _ September 2016. 2. Epstein RM, and Hundert EM (2002). Defining and assessing professional competence. J. Am. Med. Association (JAMA) 287(2):226235.

Rajam Ramamurthy, MD is Professor Emeritus of Pediatrics and Neonatology at UT Health San Antonio. Dr. Ramamurthy is an active member of the BCMS Publications Committee.