Designing for Economic Resilience

DESIGN INVESTIGATIONS

In a changing world, shocks and stressors to our established systems can result in incalculable human and environmental damage. The economic impact of a disaster or unforeseen event, however, can be quantified. Factors include the amount required to rebuild damaged infrastructure; the amount of downtime (lost wages, lost revenue, and supply chain disruptions); the need for shelter, search and rescue, and emergency services for displaced people; the short- and long-term cost of health impacts (injuries, deaths, and PTSD); and even insurance payments and losses. Some economic impacts may be immediately evident, such as the cost to repair property damage in the wake of a tornado. Others may emerge over time, such as the post-pandemic decline in office occupancies and the economic ripple effects on downtowns.

While planners and designers can’t prevent or predict specific disasters, we do have an important role to play in mitigating harm. We can guide our clients and communities towards wise planning, design, and construction strategies; navigate interconnected systems to enable positive outcomes; and design with best practices for development, site, durability, redundancy, and flexibility. Proactive investments in resilient design can yield huge dividends in both safety and economy in the wake of a disruptive event.

resilient design can yield huge dividends

Defining Economic Resilience

Economic resilience refers to the ability to withstand and recover from both immediate shocks and slow-moving stressors, at the household (microeconomic) as well as the community (macroeconomic) scale. According to the World Bank, microeconomic resilience is dependent on both individual wealth and on broader mechanisms that help share risk across a population such as insurance and social protection systems. Macroeconomic resilience is both Instantaneous (the ability to withstand and limit immediate losses) and dynamic (the capacity to fund long-term investments in resilience.)i McKinsey & Company defines resilience as “the ability to deal with adversity, withstand shocks, and continuously adapt and accelerate as disruptions and crises arise over time.”ii

From the individual to the national and global scales, resilience depends largely on the built and natural environment's ability to withstand extreme events. Design strategies which can help to minimize damage and downtime while protecting inhabitants are proving to be wise investments, and the business case for upfront investments in resilience is strong.

The Business Case for Resilient Design

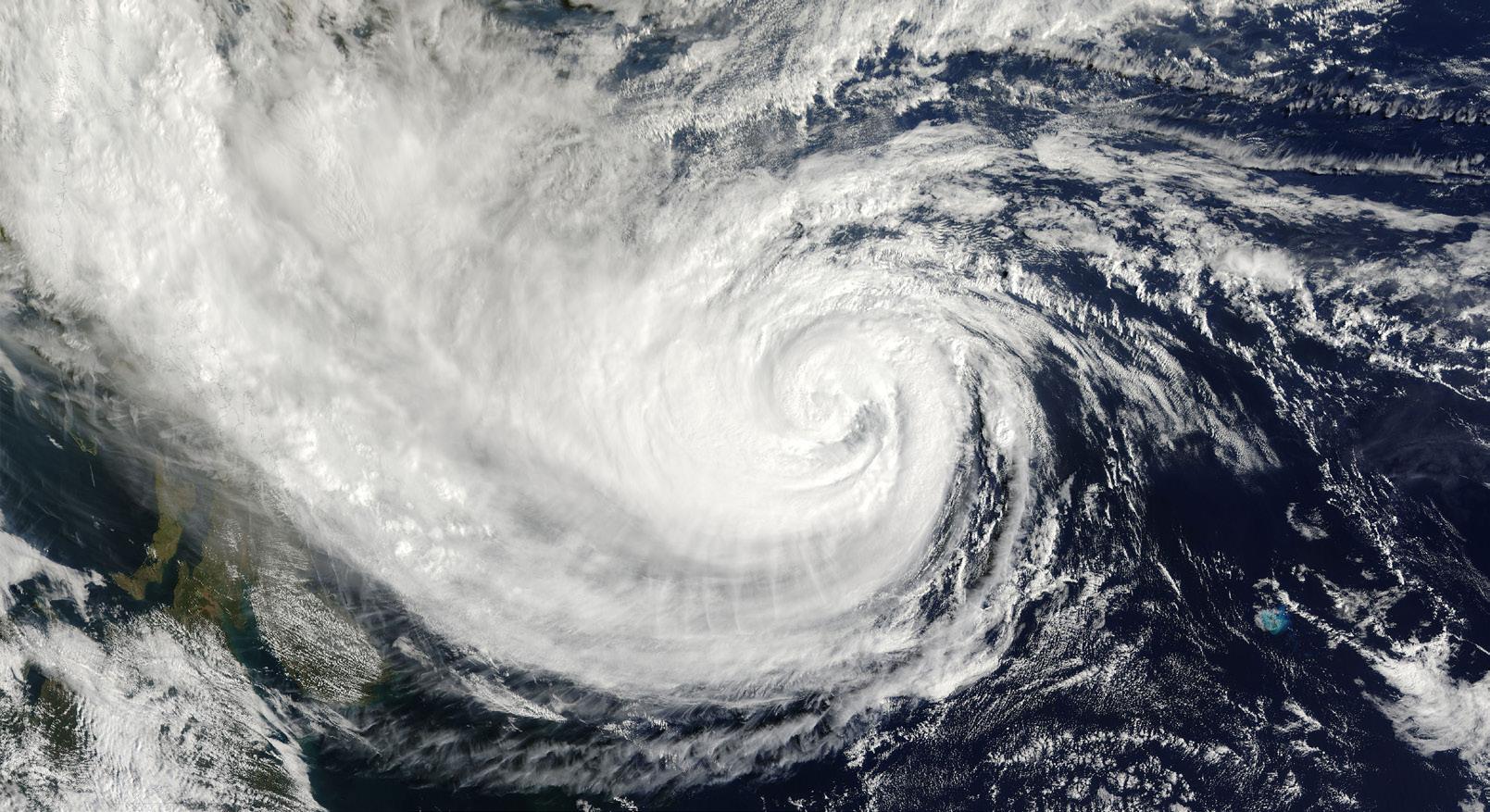

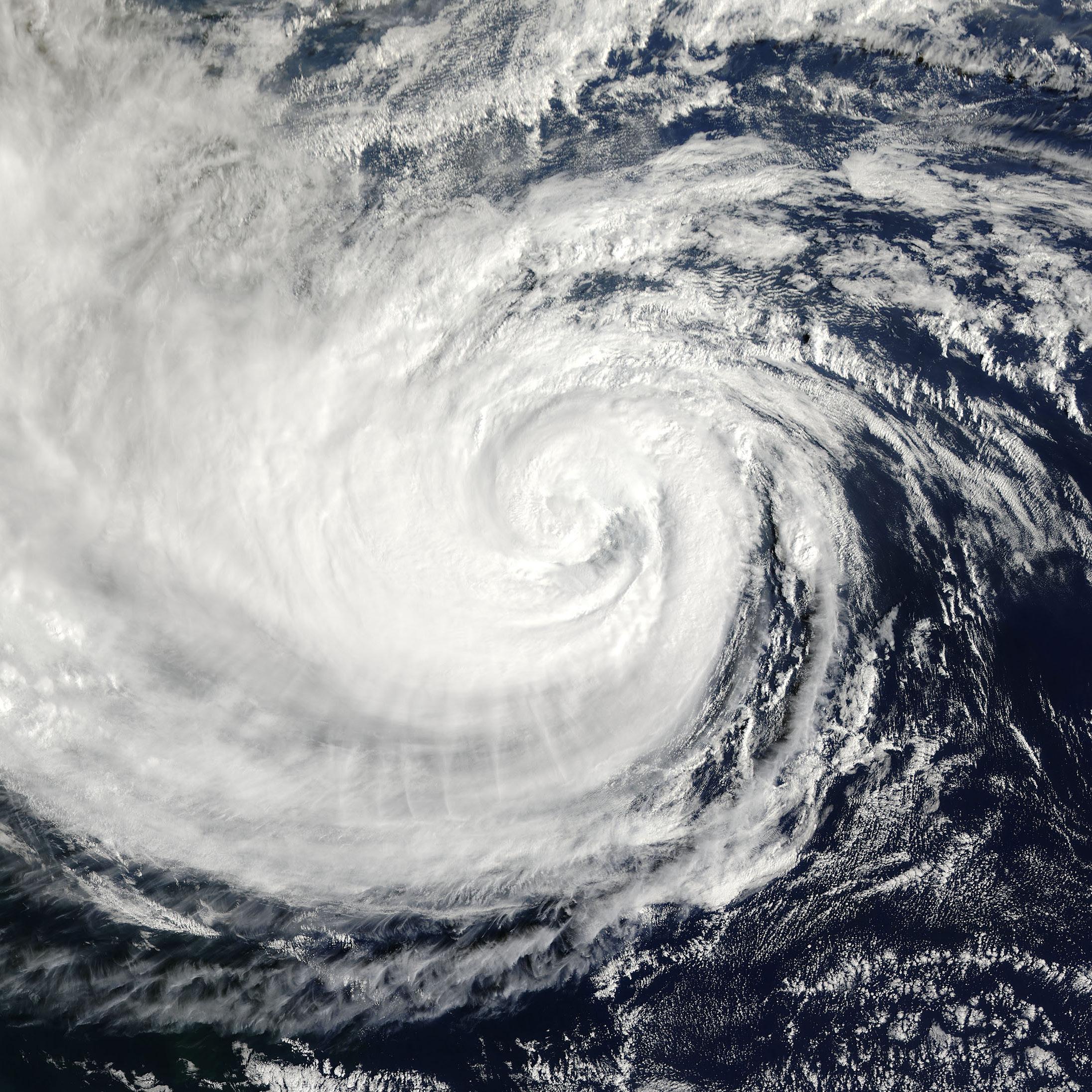

The increasing frequency and severity of climate-driven events are evident in the economic data. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) tracks disasters resulting in a billion dollars or more in damage (adjusting for current costs).iii In the 1980s, the average time between billion-dollar events was 82 days. Today, it’s 18 days, straining resources for disaster relief and recovery. Eighteen events in the US in 2022 resulted in $165 billion in damages caused by extreme cold, wildfires, tornadoes, flooding, hurricanes, and hail. As this data only includes billion-dollar disasters, the actual total is significantly higher. The 2023 total is 28 billion-dollar disasters in the US, the highest so far in a calendar year.iv

The National Institute for Building Science has quantified the return on investment for various strategies for resilience, and the numbers are clear: investments in resilience are worth the up-front costs. The 2019 “Mitigation Saves” reportv found that every $1 spent on adopting current building codes saves $11 in disaster losses. Every $1 spent on above-code designs, private-sector building retrofits, and “lifeline” retrofits (telecommunications, power, water, and other critical infrastructure) saves an additional $4 in disaster costs. Every $1 spent on FEMA, EDA, and HUD ultimately saves the public $6

The Urban Land Institute has also documented the human impacts of resilience strategies: “Just implementing above-code design for one year and carrying out the last 23 years of federally supported mitigation grants will ultimately prevent 600 deaths, 1 million nonfatal injuries, and 4,000 cases of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the long term.”vi Using proven design and construction methods, we can mitigate the human, environmental, and economic costs of a disaster with the tools we already have.

Resilient design principles will be critical in preparing our communities for future storms. Architects are familiar with the advice ‘think like a raindrop.’ We do, but we must also think like a Category 5 hurricane. Designing our buildings to withstand severe weather is far less expensive than repairing avoidable damage; remember that a $500 roof leak exits a building as a $500,000 mold & mildew abatement contract. An investment in civil engineering and durable construction can reap significant dividends by minimizing repair costs and days a building is uninhabitable after a storm.

For site design, raising the finish floor grade is far less expensive than remediating a wet building. The cost of an additional 2’ of fill is minimal compared to the cost of demolishing gyp board walls, replacing flooring, or taking a public school or civic building out of commission during repairs.

- Charles Boney, FAIA Senior Project Manager

”

“

Planning for Economic Resilience at the Community Scale

Structuring communities for economic resilience begins with a proactive approach, and a resilient economy depends on both business and social resilience. Long before disaster strikes, planners and designers can analyze vulnerabilities and invest in resilient systems. McKinsey’s resilience reportvii underscores the need for communities to “prepare, perceive, and propel” in building resilience. Preparing for disruptions involves investing in flexibility, redundancy, and collaborative networks. Perceiving threats means building early warning systems and testing response options. Propelling the community out of a crisis involves deploying established immediate and long-range responses.

McKinsey also identifies seven major themes impacting economic resilience. Of these themes, architects and planners can have the greatest impact on the first: climate, food and energy, which comes with a mandate to “protect people and assets” and “reduce carbon and vulnerabilities.” Other themes include people, education, and organizational resilience; healthcare; sustainable economic development; trade and supply chain; digital resilience, trust, and inclusion; and finance and risk capacity.

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recommends a five-step strategy to assist civic leaders and business and property owners in planning for a climate-resilient economy.viii

Step 1: Organize (establish assessment team, define the community of interest, set objectives)

Step 2: Evaluate projected climate change impacts and hazards (select climate change scenarios, assess hazards, select a method for spatial analysis)

Step 3: Identify community assets and vulnerability (develop assessment methodology, identify assets at risk, define/apply local vulnerability scale, assess potential impacts on economic activity)

Step 4: Analyze overall economic implications

Step 5: Explore and pursue options to enhance resilience (raise public awareness and garner support, identify actions and pursue opportunities)

Each step is critical in building a holistic community response to economic resilience; however, architects and planners may be most effective in evaluating vulnerabilities and proposing solutions for a more resilient built environment. Pre-disaster recovery planning and safeguarding buildings and infrastructure ahead of a disaster means better public safety, less damage, and less downtime in the aftermath of a crisis. Resilient communities, businesses, and property owners may be able to avoid significant impacts altogether, or they may be able to return to normal as quickly as possible to minimize economic impacts.ix

Encouraging Targeted Development

While the causes of economic disruptions vary widely by region, understanding the potential risks for each community is key to preparedness. The public response to a hurricane requires different resources from the response to extreme heat or wildfires, and even within a single community, risks might vary greatly by location. Across the board, however, good urban design contributes to economic resilience (and more inclusive communities). In its 2016 guidebook “Planning Framework for a Climate-Resilient Community,”x the EPA advocates for smart growth: “Where and how communities develop profoundly affects their resilience to extreme events. Smart growth strategies, which promote compact, mixed-use, walkable communities that protect ecologically and economically valuable open space and offer housing and transportation options, can help communities develop in ways that also make them better prepared for climate change.”

A rapidly changing climate means that some areas are increasingly vulnerable to disasters like flooding or wildfires. Assuming the risk of property damage and recovery is becoming prohibitively expensive, to the extent that many insurers are pulling out of states like California, Florida, and Texas.xi This change is likely to slow new development in affected areas, but it leaves many property owners in a financially precarious position. Communities are facing difficult decisions regarding continuous repair and rebuilding vs. strategic retreat. Future development will need to weigh the cost and feasibility of maintaining

infrastructure in sensitive areas; anticipating public safety needs such as evacuation routes and search and rescue efforts; and mandating codes and ordinances that mitigate, rather than exacerbate, potential damage.

Architects and planners are uniquely qualified to advocate for smart growth at all scales, from individual buildings to city plans. Solving development challenges will require multidisciplinary teams of designers, public officials, developers, clients, and community stakeholders to create resilient places that will endure.

Sharing Hope

Confidential Client Headquarters

Clemson University Business School Sirrine Hall

Live Oak Headquarters

Riverlights Art & Events Pavilion

Strategic Site Design

Ideally, planning for economic resilience starts with site selection and design; this applies to both individual buildings and larger-scale development. Any initial site discussions should include an assessment of potential climate impacts over the life of the building, especially in areas already prone to extreme conditions such as high winds, flooding, or heat. FEMA’s National Risk Indexxii provides granular risk data for 18 different natural emergencies; NOAA’s Climate Explorer toolxiii provides information on predicted heating and cooling degree days and high tide flooding for various carbon scenarios.

Strategies will vary by site and condition, but considerations will include:

Multimodal Circulation

Access to public transit and EV infrastructure will provide lowercarbon transit options and better accessibility by the public; multiple access points to the site will be critical in a flooding situation.

Stormwater Management

Understanding site hydrology will be important for both site and building design. Stormwater best management practices must be implemented to handle water on site, bearing in mind that warmer air holds more water so rainfall totals from a storm may be much higher than historic averages. Where a low-lying site is the only or best option, buildings can be designed to accommodate ground-floor flooding.

Greenspace

Strategic greenspaces integrated into the project in the form of green buffers, pocket parks, and even frequent parking lot tree wells can help to reduce pervious paving for stormwater management and minimize the heat island effect. Greenspace contributes to health and wellness and, when strategically programmed, can be a tool for building community resilience and outdoor respite spaces that will be critical in the wake of a disaster.

Long-term Economic Viability

In some cases, walking away from a potential site may be the wisest option. Repair and rebuilding costs are important considerations, but so are operational costs: what is the business, personal, or public health impact of prolonged downtime? Even minor events such as sunny-day flooding can have major financial repercussions to a business which is inaccessible to customers. (An oceanfront hotel may come with stunning views, for example, but what are the costs of a pool frequently flooded with salt water or a parking lot guests can’t access?) The cost or availability of insurance for vulnerable areas will also be a major factor.

Adaptive Reuse Opportunities

Remember that adaptive reuse of an existing property or urban infill may be more sustainable and desirable than building from the ground up on a greenfield site. Additionally, financial implications could include tax incentives for reclaiming a brownfield site or rehabilitating an existing building.

Legacy Place Masterplan

Grace Church

Legacy Place Masterplan

Grace Church

South Park Grill

South Park Grill

Investments in Durability

Designing for durability not only helps a building weather a storm; it also supports a longer useful life for the investment. Well-designed, wellconstructed buildings are easier and less expensive to maintain, and easier to adapt to changing needs. Many municipalities are using outdated building codes, so simply updating to the most current code standards would result in stronger buildings with lower operational costs due to improved efficiency. Designing above code minimums yields a fourfold return on investment when accounting for disaster and recovery costs.xiv

Durable construction is vital for critical infrastructure including emergency operations, first responders, healthcare providers, and emergency shelters.

Safeguarding these facilities requires careful attention to site selection (elevation and access), materiality, and detailing. Though specific design interventions will be informed by potential threats, strategies may include screening for mechanical systems (preferably located above flood levels), blast resistant glass, and backup generators. Anti Terrorism Force Protection (ATFP) design standards may provide additional guidance for hurricane zones prone to airborne debris or for buildings which may be targeted in the event of civil unrest.

The practice of Designing for Deconstruction (DFD) also allows for easier recovery and repair, along with maximizing the value of materials and products during normal cycles of construction and renovation. Buildings with modular components, mechanical fasteners instead of adhesives, and demountable walls instead of hard construction minimize environmental impacts, allow for long-term flexibility of use, and make it easier to repair and recover from damage through strategic replacement of selected components.

Investments in Passive Survivability

Passive survivability refers to the ability to occupy a building if a disaster incapacitates mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems. Operational windows, shade structures, and an orientation that allows daylighting while minimizing solar heat gain in summer or harvests solar heat in winter can help occupants weather an emergency until help arrives or systems are restored. Rainwater storage may help to meet emergency water needs. Net zero designs which minimize energy use and provide power through onsite renewable energy sources such as solar panels or wind turbines may be able to remain operational during a prolonged outage, minimizing downtime while safeguarding building users.

Case Study

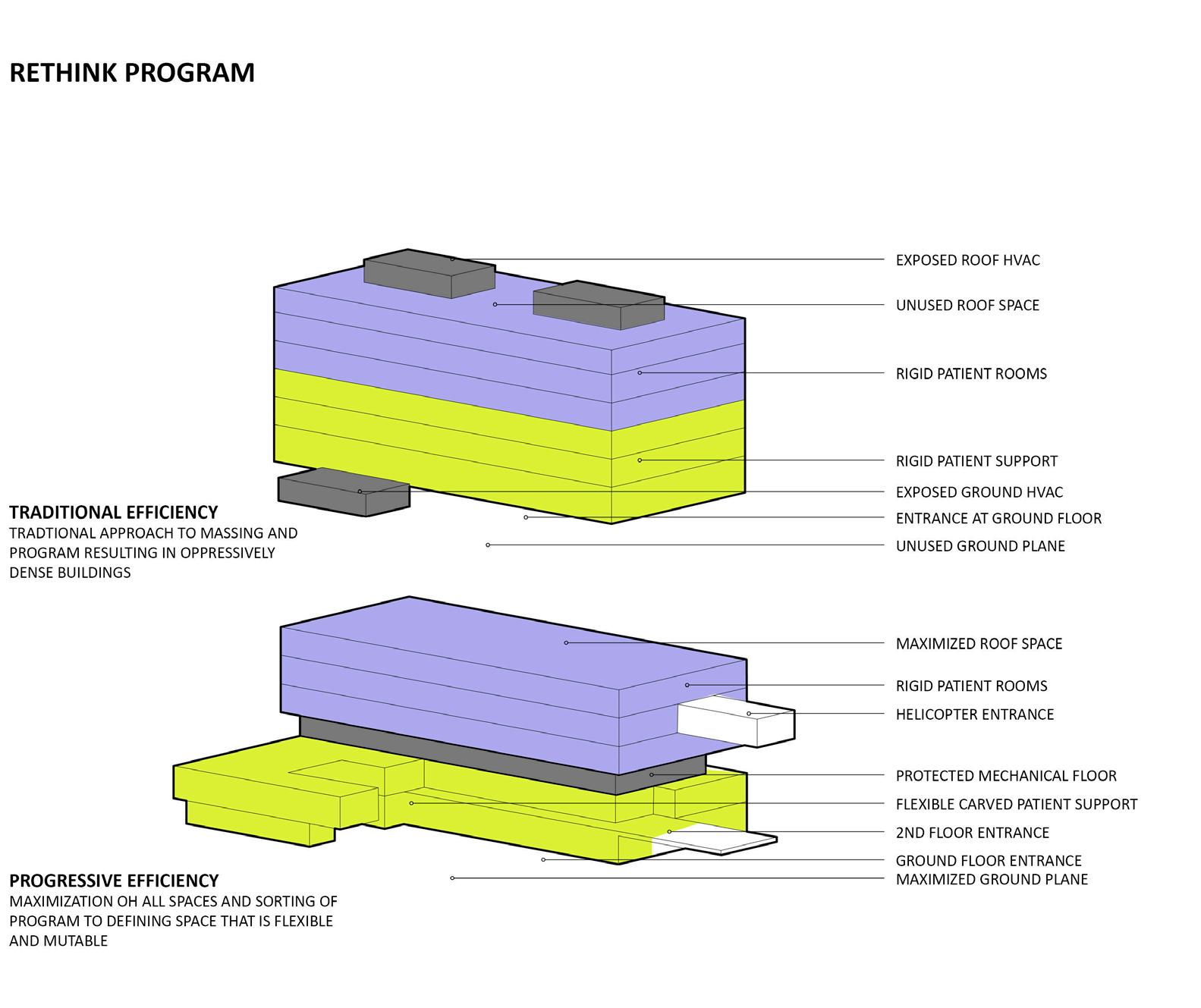

Hurricane Resilient Hospital

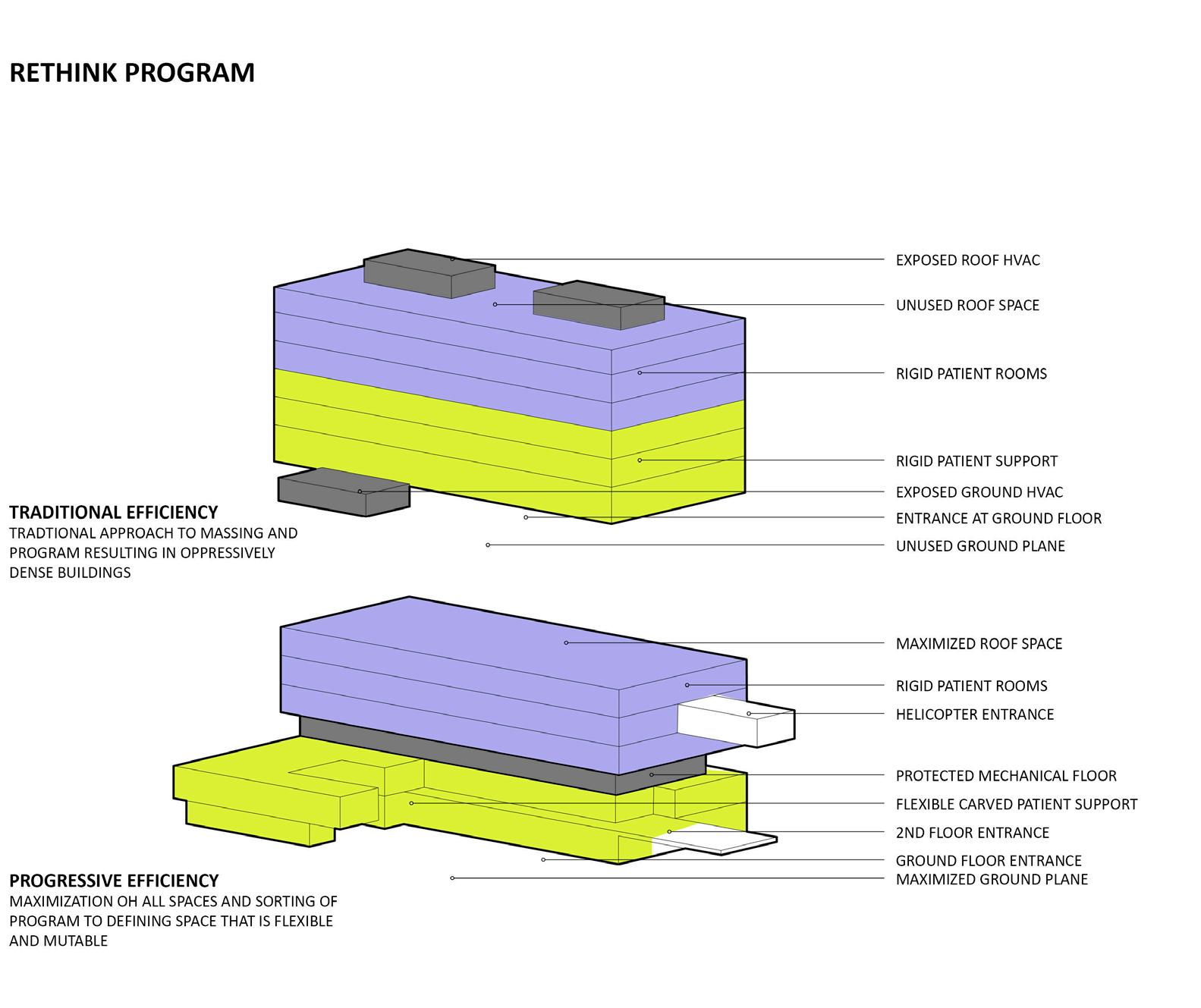

Healthcare facilities, particularly those in coastal areas, are among the most vulnerable typologies in terms of safeguarding patients and facilities at all acuity levels while maintaining access during an emergency.

During Hurricane Florence, Wilmington, NC was isolated from surrounding areas for over a week. With the city effectively an island due to flooding, the only way in or out was by boat or helicopter. In the wake of this disaster, a large regional healthcare system commissioned an in-depth study on resilient hospital design. Its purpose was to better understand inherent challenges and opportunities and to explore innovative concepts to inform future design and construction. The study explores what it means to design and build coastal resilient healthcare facilities not just in NC, but in coastal and low-lying communities everywhere.

In high performance sustainable design, every building element must serve multiple purposes. In the case of this resilient hospital concept, elements that support a more resilient building also create energy efficiency and a better patient experience. Strategies for hardening the structure and maintaining emergency access in severe weather included perforated metal panels, which protect the building from projectiles up to 200 MPH while allowing filtered natural light into the patient spaces; nonessential spaces positioned at lower levels with patient floors elevated above potential flood levels; a rooftop solar array which allows the building to operate if the power grid goes

down; three entry points at ground level, the second-story bridge, and the helipad; and greatly reduced energy loads, which allow the building to operate much longer on solar power than a typical hospital could. High performance, right-sized mechanical systems are located on a protected floor instead of exposed on a rooftop. The resulting concept allows 50% more natural light and reduces energy use by 50% over a typical hospital design.

In addition to being impact resistant, the façade doubles as a key strategy for energy performance, identity, and patient experience. The perforated screen functions in various configurations supporting green roofs, fritted glazing, recessed glazing, and R-40 wall construction depending on location. The screens also support privacy, control glare, provide a connection to nature, and eliminate the need for blinds.

In terms of patient experience, the concept incorporates biophilic design principles to establish views and connections to nature. From the initial approach to the building, the design reduces patient stress through attractive native landscaping, sheltered exterior spaces, uninhibited views in and out of the building, soft edges, and a beautiful façade for visual interest. Patient rooms are designed for optimal efficiency for providers and better healing for patients. The building form supports the necessary choreographed rigidity for critical spaces while allowing flexibility and creative massing in public, communal, and patient support spaces.

This holistic approach to resilient design creates the potential for better places for healing, safer access during disasters, and better building performance both in significant weather events and for year-round use.

Investment in Redundancy

Redundant systems may be the crucial difference between catastrophic damage with prolonged downtime and minimal damage with a quick return to building operations. Some redundancy is written into building codes for safety; however, strategic investments in redundant structure, redundant connections, and even redundant telecommunications systems may yield significant savings over time. Wiredscore, a thirdparty rating system which evaluates building-level connectivity, reports that the business cost of an internet outage for 98% of its customers is upwards of $100,000 per hourxv, so time and money spent securing systems is time and money well spent if it reduces downtime.

Achieving the right level of redundancy will depend upon the threats most likely to occur for any given site. Where possible, a good rule of thumb is to make sure that every building element does more than one thing. Shading structures which mitigate solar heat gain, for example, might drive project aesthetics and provide additional structural bracing, while secondary access points might double as desirable building amenities such as outdoor dining areas that command higher lease rates for tenant spaces.

Achieving the right level of redundancy will depend upon the threats most likely to occur for any given site.

Case Study

Resilient by Design

The New Hanover County Regional Medical Center Inpatient Addition is focused on patient-centered care. A “neighborhood” layout supports efficiency for caregivers, and patient rooms have family spaces and hallways designed for gentle exercise post-procedure.

In order to build in resiliency to keep this coastal building operational in the event of a storm, the design team studied airflow patterns extensively with the use of computational fluid dynamic modeling. An enclosed mechanical level protects AHUs and equipment, and a louvered wall system at this level has motorized dampers that open and close based on pressurization relationships of the intake and exhaust airflow. MER spaces can be conditioned year-round with excess return air. The facility also features a ventilation system that can be manually switched for individual rooms to provide flexibility and rapid response in the event of a pandemic or other isolation needs.

Investment in Flexibility

Economic resilience doesn’t just apply to disasters. Cities change over time; so do campuses, businesses, and neighborhoods. Planning and designing for maximum flexibility allows the built environment to respond to shifting populations or new building functions. Examples include the constantly changing typologies of the office building and significant changes in how people work; evolving teaching methodologies and fluctuations in student enrollment growth; or industrial facilities continuously retooling for new processes, products, or technologies. Downtowns, too, shift as cities grow and change. Durable, timeless buildings with flexible and adaptable floor plates will adapt to new chapters of use better than trendy buildings targeting a short-term investment.

Long-range plans can become dated quickly in the face of rapid change. Architects and planners can work with civic leaders, clients, and other stakeholders to design for probable outcomes while building in flexibility for uncertainty. Designers also bring the tools and vision to reinterpret “what is” in the built environment and help pave the way for “what will be.” Vacant buildings with good bones can be transformed into thriving neighborhood anchors, go-to destinations, and catalysts for community growth. Making use of existing building stock preserves embodied carbon and can save budget and time over new construction, and impacts to the local economy can be significant. When the need for one building function evaporates, other possibilities arise.

Case Study

Changing with the Times

This 60,000 SF headquarters for tech company BoomTown transformed a vacant warehouse in an underutilized neighborhood into a thriving destination. To accommodate changing economic needs over time, this adaptive reuse of an existing brick warehouse created a mix of open offices and enclosed meeting rooms to support a variety of contemporary work models. BoomTown anchors Pacific Box and Crate, a mixed-use development on an industrial site with a rich history.

The original structure featured expansive high-bay space but offered little visual or spatial definition. A weathering steel and corrugated metal exterior, galvanized steel canopy, and edgy balance of sleek and gritty materials integrate with exposed structure to create a contemporary workplace vibe. Large curtainwall inserts and skylights bring natural light deep into the interior, while punches of color and whimsical wallcoverings add visual interest to the space. `Custom furnishings made from reclaimed docks and barns, refurbished white metal lamps, and artwork tailored to the space all contribute to the company’s unique energy. A light filled sunken living room serves as a multiuse space for relaxation or meetings, and a company bar is a popular late-day meeting spot. Outdoor amenities include a beer garden, dog run, great lawn, and courtyards.

Reimagining the vacant warehouse as a modern workspace within an mixed-use destination has updated the structure and site for a new chapter of use, catalyzing change and economic growth in its neighborhood.

Funding Resilience

Though most strategies for resilient design and construction come with an upfront investment, many sources of public and private funding can help meet this need. Recent legislation including the Infrastructure Law, Inflation Reduction Act, and CHIPS ACT may help defray the cost of resilience-related work. Grant funding, public/private partnerships, or local government entities may also provide support. The U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit provides information on an array of possible funding sources; the optimal solution will vary by project. xvi

Building a More Resilient World

Designing for resilience is a multifaceted endeavor, and economics are a key element. When we build the business case for investing in resilient design strategies, we are better able to achieve consensus across diverse stakeholder groups and mitigate damage long before a disaster strikes. The interconnected strategies that encourage economic resilience also yield better human and environmental outcomes; working at all scales and across disciplines, we are better prepared to safeguard resources and prepare for future uncertainties.

Works Cited

i. Hallegatte, Stephanie. 2014. ”Economic Resilience Definition and Measurement.” https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/ en/350411468149663792/pdf/WPS6852.pdf .

ii. Brende, Borge and Sternfels, Bob. June 7, 2022. ”Resilience for Sustainable, Inclusive Growth.” https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/ risk-and-resilience/our-insights/resilience-for-sustainable-inclusive-growth.

iii. Smith, Adam. January 10, 2023. “2022 U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters in Historical Context.” https://www.climate. gov/news-features/blogs/2022-us-billion-dollar-weather-and-climate-disasters-historical-context#:~:text=Damages%20from%20 the%202022%20disasters,Heat%20Wave%20(%2422.1%20billion) .

iv. NOAA. January 9, 2024. “ U.S. Struck with Historic Number of Billion-Dollar Disasters in 2023.” https://www.noaa.gov/news/us-struckwith-historic-number-of-billion-dollar-disasters-in-2023 .

v. National Institute of Building Sciences. 2020. "Mitigation Saves.” https://www.nibs.org/files/pdfs/ms_v4_overview.pdf .

vi. Marshall, Sarene and McCormick, Kathleen. 2015. “Returns on Resilience: The Business Case.” https://uli.org/wp-content/uploads/ ULI-Documents/Returns-on-Resilience-The-Business-Case.pdf

vii. Brende, Borge and Sternfels, Bob. June 7, 2022. ”Resilience for Sustainable, Inclusive Growth.” https://www.mckinsey.com/ capabilities/risk-and-resilience/our-insights/resilience-for-sustainable-inclusive-growth.

viii. US Environmental Protection Agency. April 2016. ”Planning Framework for a Climate Resilient Economy.” https://www.epa.gov/ sites/default/files/2016-05/documents/planning-framework-climate-resilient-economy-508.pdf .

ix. EDA. N.d. “Economic Resilience.” Accessed January 24, 2024. Economic Resilience | U.S. Economic Development Administration (eda. gov)

x. US #nvironmental Protection Agency. April 2016. ”Planning Framework for a Climate Resilient Economy.” https://www.epa.gov/sites/ default/files/2016-05/documents/planning-framework-climate-resilient-economy-508.pdf .

xi. Freedman, Andrew and Bomey, Nathan. June 6, 2023. Uninsurable America: Climate Change Hits the Insurance Industry.” https:// www.axios.com/2023/06/06/climate-change-homeowners-insurance-state-farm-california-florida .

xii. FFEMA. n.d. “National Risk Index.” Accessed July 18, 2023. https://hazards.fema.gov/nri/map .

xiii. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. n.d. “The Climate Explorer.” Accessed July 18, 2023. https://crt-climate-explorer. nemac.org/ .

xiv. National Institute of Building Sciences. 2020. "Mitigation Saves.” https://www.nibs.org/files/pdfs/ms_v4_overview.pdf .

xv. Wiredscore. January 24, 2020. “How to Minimize the Risk of Internet Outage.” https://wiredscore.com/fr/blog/2020/01/24/ how-to-minimize-the-risk-of-internet-outage/.

xvi. U.S. Climate Resilience Tookit. N.d. “Funding Opportunities.” Accessed January 24, 2024. https://toolkit.climate.gov/content/ funding-opportunities

Legacy Place Masterplan

Grace Church

Legacy Place Masterplan

Grace Church

South Park Grill

South Park Grill