President’s Message

Hello IHM Members

I sincerely hope our members had a happy, healthy, and safe Festive Season with whatever celebrations you enjoyed. The most important celebration is with your family and good friends. Of course, we wish everyone a very Happy New Year for 2023. We hope the new year will bring positive progress with the various challenges we have faced and will be a healthy, safe year for everyone.

A new year gives us a reason to reflect on the past year, and IHM is no exception. First and foremost, we had our in-person Annual Educational Conference in Niagara Falls after two years when we were unable to gather for an in-person event. This gave everyone the opportunity to learn from the excellent program and to see friends and colleagues once again. We also had our third Annual Golf Tournament, where everyone who had registered came to play in the snow and freezing temperatures. It was undoubtedly a challenge that day but after many hot chocolates and our parkas, we made it.

Our membership grew in numbers, the number of students participating in our various educational programs was terrific, those members who graduated and became accredited members continued to grow, we embarked on the development of new Accreditation Program for the Co-op Sector, and our monthly Chat Room Sessions were very well attended with an average of 60-70 participants each month, and the topics have been well received. We are excited about our programs for 2023. We also started launching chapters in various areas of Ontario. The first one created is in South Western Ontario, and so far, the results are very encouraging.

We will be holding our Annual Educational Conference a little later this year, May 11th and 12th, in Grimsby. The Conference Committee is well on its way to confirming the program with many topics identified and our keynote speaker in place. I am hopeful that, being a couple of weeks later than usual, our Fourth Annual Golf Tournament will be in somewhat warmer weather conditions. We are looking at several courses in the Hamilton area. I have also investigated Whirlpool again, as it isn’t that far from Grimsby. Watch for the announcements.

The work has begun with rewriting the manuals for the Co-op Accreditation Program, and we are hopeful the first course will be available this year to students. We are very excited about this new opportunity being offered to an entirely new market. We are confident this will increase our membership and the participation in IHM.

In my first message of every new year, I leave these comments to the end as I want those reading to leave this page with my thoughts. I am honored to be the President of IHM and work with a very active and professional Board of Directors and staff. Our Board works very hard (and on a volunteer basis), and I am most thankful for their efforts and dedication to IHM. Our staff at Association Concepts is fantastic and takes care of all the administration needs, from the education programs to the Chat Room Sessions and everything else we need. Thanks to Deborah Filice for her tireless efforts as our Education Director.

Let us all be optimistic and hope 2023 will be an excellent year for everyone.

Jimmy Mellor, FIHM IHM President

Radon-Induced Lung Cancer – Prevention –What Property Managers need to know…

By Robert Maccarrone Radon Specialist Canada Radon

By Robert Maccarrone Radon Specialist Canada Radon

There are simple ways that Canadians look after their health, choosing healthy foods, regular exercise and a good night sleep. These are healthy habits that are engrained in our minds, we need to add proper and regular radon testing to our list.

Why?

o Long-term exposure to high levels of radon gas is the leading cause of lung cancer in non-smokers, and the second-leading cause of lung cancer after smoking.

o Radon is a naturally occurring, radioactive gas that can build up in ANY building, regardless of the building’s location, age, size, design or upkeep.

o Despite being a preventable cancer, more than 3,000 Canadians are dying per year from radon related lung cancer.

o The latest numbers released by StatsCan this October show that 56% of Canadians (52% of Ontarians) have heard of radon, yet less than 9% of the population has tested their home for radon.

o Radon can be up to 8x more harmful to smokers than non-smokers, and up to 10x more harmful to children than adults.

o Radon-related lung cancer is responsible for more Canadian deaths per year than motor vehicle collisions, house fires, carbon monoxide poisonings, and accidental drowning combined.

o A recent study found that people who act quickly to reduce their radon exposure could reduce their lifetime risk of lung cancer by as much as 40%.

o In contrast, the study found “extreme cases” where those who did nothing to mitigate high radon levels endured decades of “exposure to radiation levels exceeding those normally only seen after a nuclear accident”.

What Is Radon and Where Does It Come From?

Radon is present, in varying concentrations, in every region of Canada – every

building has a potential to have elevated radon levels.

Because radon gas is colourless, odourless and tasteless, the ONLY way to know if radon is present in dangerous levels is to have your building tested.

Radon gas is released during the decay of uranium in rocks and soils. It is generated naturally by the bedrock below our buildings all across Ontario and Canada.

In Canada, radon levels are measured in the units of Becquerels per cubic meter (Bq/m3). Concentrations in the outside air we breathe are considered non-hazardous and typically in the range of 5-30 Bq/m3. Radon becomes a health hazard at higher levels.

While Health Canada recommends radon mitigation at radon levels of 200 Bq/m3, the US EPA recommends 150 Bq/m3 while the World Health Organi-

zation (WHO) recommends a level of 100 Bq/m3.

Regardless of these guidelines, no amount of radon is healthy, and radon levels should be kept as low as practically possible.

How Does Radon Get Into A Building?

Radon can enter buildings through cracks and openings in floors, leading to higher levels, especially in basements and lower floors. Over time, exposure to radon increases the risk of developing lung cancer. Health Canada estimates that over 3,000 Canadians die each year due to radon gas exposure.

For most of the year, the air pressure inside your building is lower than the pressure in the soil surrounding your foundation. This difference in pressure can draw air and other gases in the soil, including radon, into the house.

Gas containing radon can enter your building at any opening where it contacts the soil. These openings can be present even in well-built and new dwellings.

Potential entry routes for radon in buildings with poured concrete foundations include cracks, areas with exposed soil or rocks, openings for utility fixtures or hollow objects such as support posts.

Because radon is an inert, monatomic gas that is much smaller than a water molecule, it can find its way into a building’s basement or ‘on-grade’ floor by several different routes:

• Open cracks, seams or gaps in the floor slab, foundation walls, windows, plumbing, or conduit entering the building below grade

• Open sump wells, floor drains, and crawlspaces

• Through our water taps and shower heads

The air pressure inside your building is usually lower than in the soil surrounding the foundation. This difference in pressure draws air and other gases, including radon, from the soil into your building.

Because newer buildings are generally more airtight, even with the use of heat recovery ventilation, radon can accumulate to hazardous levels indoors.

The air pressure inside your home is usually lower than in the soil surrounding the foundation. This difference in pressure draws air and other gases, including radon, from the soil into your home.

Because newer homes are generally more airtight, even with the use of heat recovery ventilation, radon can accumulate to hazardous levels indoors2

2 https://evictradon.org/news/dr-goodarzi-interview-the-impact-of-radon-on-dna/

Which Buildings Might Have A Problem?

Almost all buildings have some radon. The levels can vary dramatically even between similar buildings located next to each other. The amount of radon in a building will depend on many factors including:

• Geology: Radon comes from the decay of naturally occurring uranium in the bedrock beneath our homes, daycares, schools and workplaces. If such a deposit exists, radon gas will be generated and can find its way through the soil and into dwellings above the source. Uranium containing bedrock has been mapped across Canada as an indicator of “Relative Radon Hazard” (source: Radon Environmental)

• Soil Characteristics: Radon concentrations can vary significantly depending on the uranium content of the soil. As well, radon flows more easily through some soils than others, for example sand versus clay.

• Construction Type: The type of building and its design affect the amount of contact with the soil and the number and size of entry points for radon.

• Foundation Condition: Foundations with numerous cracks and openings have more potential entry points for radon.

• Occupant Lifestyle: The use of exhaust fans, windows and fireplaces, for example, influences the pressure difference between the house and the soil. This pressure difference can draw radon indoors and influences the rate of exchange of outdoor and indoor air.

• Weather: Variations in weather (e.g., temperature, wind, barometric pressure, precipitation, etc.) can affect the amount of radon that enters a building.

Because there are so many factors, it is not possible to predict the radon level in a building; the only way to know for sure is to test.

What’s Involved In Radon Measurement?

Health Canada recommends conducting a long-term radon test for a minimum of 91 days, ideally during the heating months (typically November through April) to obtain an accurate average radon level in a given building.

This test should be conducted every 2 years on the lowest ‘occupiable’ level of the building using a Health Canada approved radon measurement device or continuous radon monitor. One of the most common and reliable, Health Canada approved radon measurement devices is the “Alpha-Track Detector”, shown below:

Short-term tests should be avoided as they can indicate low radon levels when in fact average annual radon levels are high.

A recent study found that those who concluded from a single test that the property’s radon levels were low, did not intend to test again. Since radon levels are constantly changing, this behavior could result in long-term exposure to elevated radon levels.

For Property Managers, it may be necessary to demonstrate both due diligence and neutrality when conducting radon tests on their properties and wish to hire a certified and insured radon professional.

If a building is found to have high levels of radon, a certified radon professional can help determine the best course of action for reducing radon levels. Typically, this will involve installing a mitigation system which effectively reduces radon levels inside the building. Costs for radon mitigation vary but are often comparable to replacing a furnace or installing central air conditioning.

Why work with a Professional?

The Canadian National Radon Proficiency Program (C-NRPP) is a Health Canada approved certification program that establishes guidelines and provides training and resources for the provision of radon services by professionals.

C-NRPP Certified professionals must maintain a valid license, re-qualify every 2 years, and are certified to work in every province and territory in Canada. C-NRPP certified professionals must comply with recognized standards of practice to protect public health and safety and are subject to a formal C-NRPP complaint review process.

Case Law and Municipal Authority to “Take Action On Radon”

Provinces and territories have laws that specify that a landlord must provide housing that is safe and in good repair.40 In In Ontario and Quebec tribunals have found that these clauses give tenants the right to have elevated radon addressed.41 Tenants will also be protected by Occupiers Liability law, which gives a right to sue for

damages where injuries such as lung cancer are caused by unsafe premises.42 (all references taken from the Health Canada publication cited below).

In July 2017, a 78 year old tenant in Ontario undergoing cancer treatment argued that he had experienced harm to his health as a result of the condition of the unit and claimed several repair issues including radon (see section 15 on in the link). A 100% rent abatement was warranted until repairs were complete, including ensuring that radon gas average concentrations were mitigated as per Health Canada guidelines (<200 Bq/m3). https://www.canlii.org/en/ on/onltb/doc/2017/2017canlii60362/ 2017canlii60362.html

In July 2022, Health Canada released their handbook entitled “Radon Action In Municipal Law – Understanding the legal powers of cities and towns in Canada”. Among other topics, it provides insight into the ability of municipal government to effect changes that address radon health risks, landlord-tenant law, low radon requirements for public spaces and standards of maintenance/ housing standards across Canada.

Highlights include:

- Municipalities can take action on ra-

don including rules covering rental accommodation, even when higher orders of government have not yet done so. For instance, Kelowna, BC’s Official Community Plan (OCP) (2011) objectives include “Support the creation of affordable and safe rental, non-market and/ or special needs housing”. Radon action is an obvious addendum to these strategies and easily fits into their mandate.

- Many publicly owned housing corporations have taken steps to address radon at both the provincial43 and municipal level.44

- In some cases, provincial housing authorities incorporate radon protection into their Design Guidelines. For instance, Manitoba Housing’s Design Guidelines for Multi-Unit Affordable and Social Housing (2017) include provisions for radon control.45

- “Clean Air” or “Health” bylaws could be expanded to include rules requiring testing and necessary mitigation of radon in public indoor spaces.

- municipalities could expand clean air/health bylaws or create new radon bylaws on the basis of the very general powers to pass health related regulations (or, in some cases, general environmental powers).

What’s Next?

There is a growing case for Property Management policies to include radon testing and mitigation as part of the due diligence process.

The latest StatsCan results, released Oct 2022, show that only 42% of Canadians (38% of Ontarians) have heard of radon and said it is a health hazard and less than 9% of Canadians (<7% of Ontarians) have tested their radon levels. Public awareness is growing, but still low. Government and advocacy groups are working hard to raise radon awareness.

At a time when climate change initiatives put heightened emphasis on building retrofits to improve insulation and energy efficiency, tighter building envelopes can lead to higher radon levels unless properly addressed.

In parallel, municipalities are under tremendous pressure to preserve and improve physical and mental health to avoid overburdening our medical system.

With proper testing, early detection and prompt mitigation of elevated radon levels, radon-induced lung cancer is a very preventable home/school/ workplace health hazard that can be eliminated reliably, quickly and affordably.

For more information, please contact:

Robert Maccarrone

Radon Specialist

(C-NRPP# CRT-202521)

430 McNeilly Rd, Unit 106

Stoney Creek, ON L8E 5E3

Direct: 905.516.1367

Robert.Maccarrone@CanadaRadon. com

A Healthy Home Is A Happy Home … Why Risk it? u

Annual General Meeting

In conjunction with the 2023 IHM Conference

May 11, 2023 | 1:15 pm

Casablanca Hotel, Grimsby, Ontario

We are pleased to advise that the Annual General Meeting (AGM) of the Institute of Housing Management will be held on Thursday, May 11, 2023 at 1:15 pm at the Casablanca Hotel, Grimsby, ON.

The AGM will take place in conjunction with the 2023 Annual Educational Conference “Professional Development - Here’s Looking At You”, which is scheduled for May 11-12, 2023.

We hope you will be able to attend the AGM. If you cannot attend, we hope that you will put forward your proxy and comments directly to the IHM Office so they can be included in the decision making process.

Available Documentation: Notice of Meeting

Call for Nominations

Proxy

IHM Program Completion Certificate

in Property Management

Fernando Garcia

Bernardo Navarro

Katherine Phillips

Jonathan Schwartz

Melissa Warrington

Course Completions in Property Management

Administration

Penny Boileau

Kimberley Bourne

Krista Rempel

Courtney Young

Grace Zhao

uuu

Human Relations

Margarita Navarrete de Garcia

Eva Obi

Jonathan Schwartz

Inna Smirnova

Darren Talbot

uuu

Maintenance

Debbie Craig

Godofredo Corrales

Clinton Davis

Lisa Moshonas

Frank Prospero

Matthew Solomon

Darren Talbot uuu

Finance

Ryan O’Hearn

Jonathan Schwartz

uuu

Tenancy Law

Kimberley Bourne

Jen Kroh

Slobodanka-Boba Popovic

Jacqueline Smith

Vanessa Walsh

Jesse Whalley

uuu

Sheri Adam, AIHM

Elizabeth Black, AIHM

Tracy Geddes, AIHM

Richard Persaud, AIHM

Mold Prevention – Tip Sheet

By Ed Cipriani, FIHM Director, Facility Operations Mohawk College

Mold continues to be an issue for property owners and managers. Property Management Professionals must understand how to prevent and respond to mold growth. Below is information to help you better assess and battle mold in your communities.

1. Mold damages building materials, affecting the look, smell, and possibly, concerning wood-framed buildings, affecting the structural integrity of the buildings.

2. If you suspect Mold has damaged building integrity, consult a structural engineer or professional with the appropriate expertise.

3. When excessive moisture or water accumulates indoors, mold growth often occurs, particularly if the moisture problem remains uncorrected.

4. Mold needs only a viable seed (spore), a nutrient source, moisture, and the right temperature to multiply - this explains why mold infestation is often found in damp, dark, hidden spaces as light and air circulation dry areas out, making them less hospitable for Mold. The Mold spores travel throughout the air and are being breathed in, especially affecting those with underlying breathing problems.

5. When assessing for mold, remember that mold requires MOISTURE, WARMTH, & FOOD. All

three conditions are necessary for growth, with the most likely growing places: bathroom, basement, & kitchens.

6. Moisture or high relative humidity of 60-70% for an extended period will generate mold growth. Temperatures below 21 C or 70 F degrees are best for prevention. Air movement aids in evaporation and decreases moisture. Stagnant air supports mold growth.

7. Regular unit inspections identify mold, as living habits can affect mold’s ability to grow. Look for stains or discolouration on floors, walls, window panes, ceiling tiles, fabrics and carpets. Look for obvious signs of leaks, condensation, flooding, or a musty odour. Immediate action is important.

8. Finding the cause is very important.

a. Inspection of ductwork

b. What is introducing moisture into your environment and stop it

c. Remove the excess moisture

d. Mop, sponge, vacuum and squeegee standing water out of the area

e. The affected area must be protected from people and not entered without PPE.

f. Suspected Mold can be tested and identified.

9. During a site review, look for the following potential issues as they contribute to mold growth.

a. Defective construction materials

b. Leaking material joints/improper flashing or caulking

c. Dirty environments

d. Bug and rodent feces

e. Poor drainage

f. Flood damaged buildings

g. Roof leaks and downspouts that direct water into or under a building

h. Grading drainage should be away from the foundation

i. Unvented combustion appliances.

10. Actions to help prevent mold

a. Reducing the humidity in buildings

b. When practical, increase ventilation or air movement by opening doors and/or windows

c. Use fans as needed

d. Increase air temperatures

e. Cover cold surfaces, such as cold water pipes, with insulation

f. Rust is an indicator that condensation occurs on drainpipes – insulate to prevent condensation

g. Building occupants should report all plumbing leaks and moisture problems immediately

h. Moisture control is the key to mold control. When water leaks or spills occur indoors –act promptly. Any initial water infiltration should be stopped and cleaned promptly. A prompt response (within 24-48 hours) and thorough clean-up, drying, and/or removal of water-damaged materials will prevent or limit mold growth

i. Repairing plumbing leaks and leaks in the building structure as soon as possible

j. Preventing moisture from condensing by increasing surface temperature or reducing the moisture level in the air (humidity)

k. Keeping HVAC drip pans clean, flowing properly, and unobstructed

l. Performing scheduled building / HVAC inspections and maintenance, including filter changes

m. Maintaining indoor relative humidity below 70% (25 - 60%, if possible)

n. Education of residents, remind them to advise the Property Manager

o. Indoor Air Quality Assessment tests for contaminants in the air.

p. Use Mold & Mildew Resistant Sealant Caulk.

11. Government Links

a. https://www.ontario.ca/ page/alert-mould-workplace-buildings#:~:text=If%20mould%20contamination%20is%20extensive,the%20 health%20effects%20of%20mould

b. https://www.canada.ca/en/ health-canada/services/publications/ healthy-living/addressing-moisturemould-your-home.html u

UPCOMING IHM EVENT

February 13, 2023 - February 17, 2023 | 09:00 AM - 04:30 PM (Daily) via Zoom

Monday - Thursday: 9:00 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. - Zoom Session

Monday - Thursday: 1:00 p.m. to 4:00 p.m. - Asynchronous Learning

Details and to Register

Student will be required to self-study from 1:00 - 4:00 pm each day and prepare for the following day of Review.

Friday: 9:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. - Exam

Visit our website’s Events Page for information and updates on all IHM Events

Canadian Housing Affordability Hurts

A DOUBLING OF SOCIAL HOUSING STOCK COULD HELP THOSE IN GREATEST NEED

By Rebekah Young, Scotia Bank Economics• Home prices are cooling in an elevated interest rate environment in Canada, but housing affordability remains elusive. Imbalances persist across the housing continuum as a result of pervasive policy coordination failures.

• Fixing the broader housing supply issue remains an imperative and is still the firstbest option. Signs that we are on this path are not promising. The recent uptick in housing starts is welcome but insufficient to restore affordability.

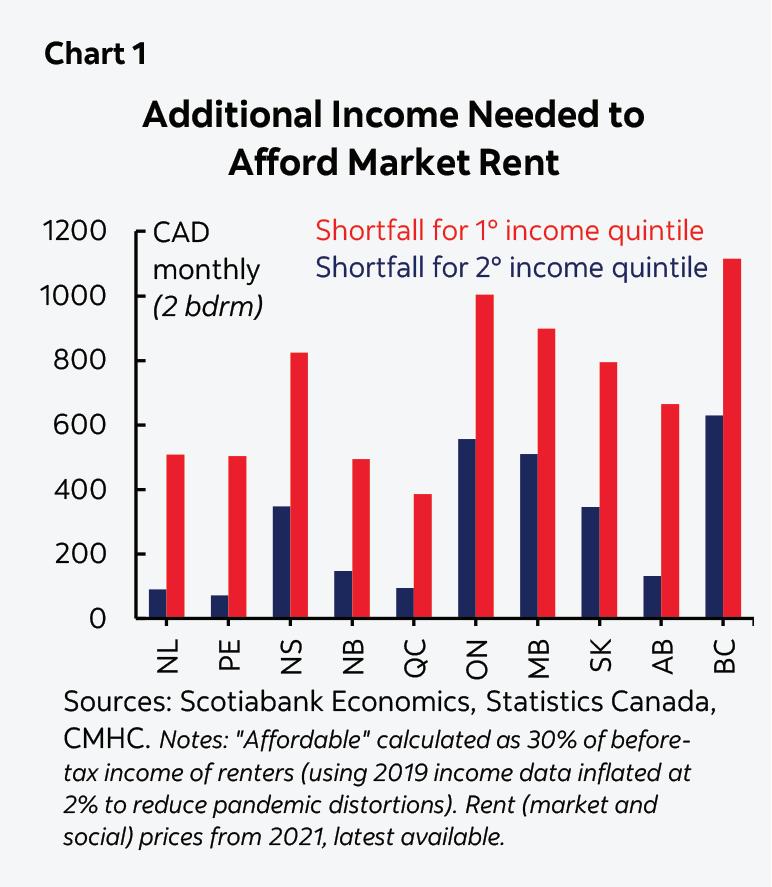

• For most Canadians, rising shelter costs will come at a hefty opportunity cost. For low income Canadians, it represents an impossible dilemma. Market-priced housing will likely never be affordable for a serious share of households—and easily those in the lowest income quintile—based on current trajectories (chart 1).

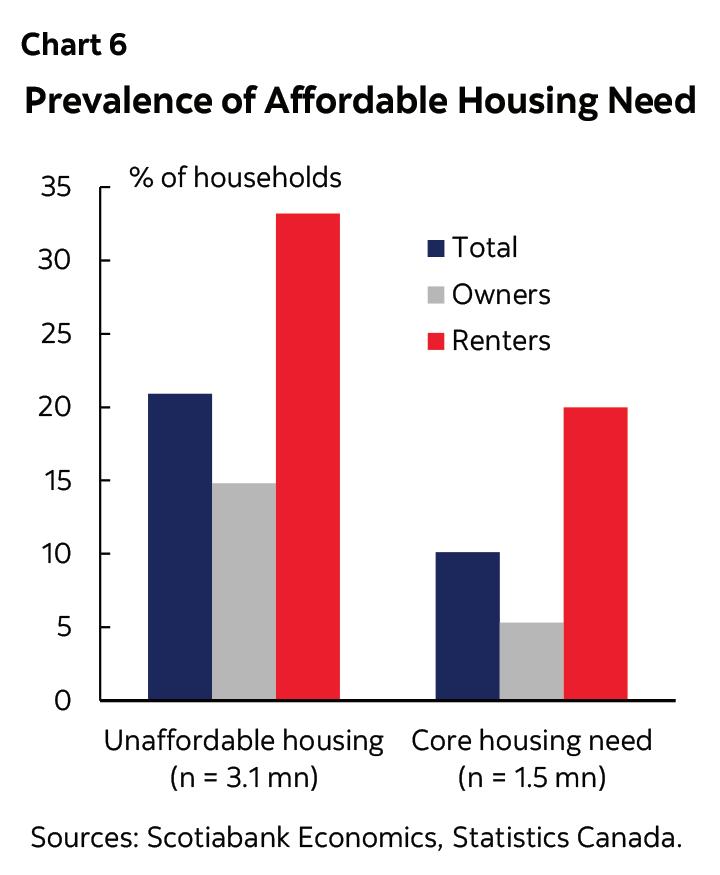

• Over 10% of Canadian households (or 1.5 mn) were in ‘core housing need’ according to the 2021 census. By definition, they have nowhere else to go in the marketplace. Another near-quarter of a million Canadians are homeless.

• The infrastructure to support these most vulnerable Canadians is stark: Canada’s stock of social housing represents just 3.5% (655 k) of its total housing stock, while wait-lists are years long. The moral case to urgently build out Canada’s anemic stock of social housing has never been stronger.

• The economic case is equally compelling. Governments are attempting to alleviate the strain on lower income households with a host of transfers, but the cost to do so will continue to escalate as shelter costs rise, market income provides little offset, and policy failures persist.

• A modest start would be doubling Canada’s stock of social housing to bring it in line with peers in the context of a coherent and well-resourced strategy (chart 2). This would not plug the gap, but it would be a start.

• Such an approach may be more responsive to the needs of Canada’s most vulnerable households and more cost-efficient for governments in the long run.

NO PLACE LIKE HOME

The national housing crisis is well-established. Burgeoning demand against lacklustre growth in supply has driven prices up over time. Scotia Economics elevated the dialogue on mounting structural imbalances last year flagging a per capita housing stock that seriously lags peers. The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) has pegged the shortfall at 3.5 mn additional units beyond a business-as-usual build to help restore affordability by 2030. It projects Canada’s housing stock needs to rise to 22 mn by then (from about 17 mn at the end of 2022).

Policymakers have made some headway in recent years, but ambition meets reality. While the National Housing Strategy has provided an important framework to anchor actions, its $78.5 bn funding pales in comparison to Canada’s housing stock at $3.8 tn (or 2% which doesn’t even keep pace with annual depreciation). Major fault lines in execution have also been exposed in a recent report by the Office of the Auditor General (OAG). There has been some traction around last year’s Ontario Housing Affordability Task Force, but tangible results will take time. These and other developments have also reinforced that the political economy of housing in Canada is far from straightforward.

Meanwhile, housing affordability has deteriorated substantially. The Bank of Canada’s Housing Affordability Index—a measure of homeownership versus broader shelter affordability—has spiked over the course of the pandemic (chart 3). The average cost of a home in Canada is 7 times the average annual household disposable income despite the recent cyclical softening in prices against rising interest rates. This crude measure of home price valuation has doubled in the past two decades, accelerating at twice the clip of the OECD average in recent years. The national benchmark also masks extreme price valuations in some parts of the country, for example, Ontario and British Columbia where the multiple sits at 11.5 and 12, respectively.

Not surprisingly, Canadians are increasingly priced out of homeownership. It is not only home prices steering these shifts, but also mortgage (and more broadly debt) payments as a share of income with macroprudential rules acting as a ceiling for some. Both structural and cyclical factors are behind rising costs of (financed) home ownership (chart 4).

Recent 2021 census data confirm the trend decline in the home ownership rate—at 66.5%—after peaking at 69.0% in 2011 (chart 5). Growth in renting has outpaced ownership at twice the rate over the last decade with about 1 in 3 of Canada’s 15 mn households now renting.

OUT OF THE FRYING PAN INTO THE FIRE

Renting hardly provides reprieve. Shelter costs—a more encompassing measure of accommodation expenses including direct homeownership and/ or rental fees, as well utilities and municipal services—grew by 17.6% for renters versus 9.7% for homeowners between the last two censuses. Keep in mind that rental costs really only took off after census polling in the Spring of 2021. National average rent, for example, was up by over 12% y/y—and approaching 25% y/y in major markets like Toronto and Vancouver—in November 2022, according to rental. ca. (This source measures the market rate of all vacant units versus CMHC’s lagged stock measurement of primary, purpose-built rental units).

Housing affordability is even more acute for renters. Accommodation— whether owned or rented—is considered ‘unaffordable’ in Canada if shelter costs amount to 30% or more of a household’s before-tax income (also known as the shelter-to-income ratio, STIR).

Admittedly, this threshold is somewhat arbitrary and higher income households can likely shoulder higher burdens, but it provides one barometer of affordability. Over 1 in 5 Canadian households (3.1 mn of 14.9 mn) exceeded this benchmark in the 2021 census. For renters, that number is 1 in 3 (or 1.6 mn households). And this count already reflects subsidized housing support that 12% of renting households received at the time.

Renters are also disproportionally likely to be living in ‘core housing need’. Core housing need refers to whether one’s housing falls below at least one of the thresholds for adequacy, affordability or suitability, and the

median rent of alternative local housing would exceed 30% of before-tax income (versus actual spending measured by the STIR). Put bluntly, there are no affordable market-based alternatives for those in core housing need.

In 2021, 1.5 mn households (10.1%) met this definition with affordability the primary criterion for over threequarters of this population (though other gauges are indirectly linked to affordability). The prevalence among renters is 20% versus 5% for homeowners (chart 6).

REMOVING THE ROSE-TINTED GLASSES

Today’s count for core housing need is likely higher. The 2.6 ppt improvement registered in the 2021 tally relative to the 2016 census should likely be faded for a host of reasons. Pandemic supports temporarily boosted incomes disproportionately at the lower end of the income spectrum in earlier phases of the pandemic with a 30% y/y uptick in disposable income in 2020 for the lowest income quintile households, for example, versus 9% for all households, according to Statistics Canada. The timing of polling would also not fully capture the aforementioned double-digit growth in rental prices disproportionally affecting lower income households.

Temporarily-halted immigration also likely masks underlying trends. Canada’s borders had effectively been shut for over a year when census polling took place in the Spring of 2021. Arrivals have surged since then. Immigration (i.e., permanent residents) grew by 6.3% in 2022 (to 431 k) on the heels of border re-opening effects that drove a 2021 expansion in the order of 160%. There has also been a rapid uptick in international student arrivals with study permit holders up by 75% in 2021 and holding through 2022 (at about 440 k). Lagged data shows net temporary residents were up three-fold in the first three quarters of 2022 relative to 2021 (to 411 k). These are a mix of stock and flow markers, but they no doubt underpin demand for affordable housing.

This rapid ramp-up in new arrivals could reasonably push core housing

needs higher with newcomers and temporary residents disproportionally impacted by housing affordability. While core housing data does not yet provide a breakdown according to immigration status, about 35% of Canadian households in core housing need were immigrants in the 2016 count. Over a quarter of those arriving within the five years prior were in core housing need.

Often, cited housing affordability metrics may also fail to fully capture broader hardships stemming from high shelter costs for lower income Canadians. CMHC had launched a new Housing Hardship Measure just prior the onset of the pandemic taking a residual approach (i.e., whether households can still cover basic needs after paying for housing expenses). The methodology accounts for different household structures and geographies that affect these expenditures (and incomes). Such an approach holds promise for shedding more light on housing-induced hardship, but data has not been updated since its launch in early 2020. It is nevertheless reasonable to assume that the picture has deteriorated given the cost of housing and other core essentials (and pretty much everything else) has skyrocketed since then.

THE MISSING MARKET

While there may not be high precision to the numbers—or even the definition—of those facing serious housing hardship, even a ballpark number stands in sharp contrast to housing infrastructure to support these households. Canada’s current stock of social housing—defined as subsidized rental units—is among the lowest across OECD peers at just 3.5% of total dwellings (chart 2 again). By CMHC’s count, there are about 655 k social housing units in Canada, the bulk of which are government-owned (at 58%), trailed by nonprofit and coop ownership models at 26% and 10%, respectively. Average

rent at $613/mos for a 2-bedroom unit is about 50% of market pricing across the stock of primary rental units (e.g., CMHC’s measure) and just 30% of the going market rate for current vacancies (e.g., rental.ca’s measure). Multi-year wait lists across the country for this limited supply suggest that this is not a conscious policy decision to focus on alternative supports.

There are enormous shortfalls between market pricing and ‘affordability’ for low income households across the country. Renters in the lowest income (after-tax) quintile would exceed the 30% (before-tax) income threshold even paying the average social housing rental rate for a 2-bedroom unit (and before incorporating other shelter expenses as per the norm) in all provinces except Alberta and Prince Edward Island. Renters in the second income quintile would exceed this affordability threshold at market rates across all provinces (chart 7). Put another way, the average renter in the bottom income quintile would need another $670 monthly to afford a 2-bedroom rental at 2021 prices without exceeding the affordability threshold. In British Columbia and Ontario, this figure exceeds $1000 per month. The average monthly shortfall for those in the second income quintile is about $260 across the country and more than double that in BC and ON (chart 1 again).

Efforts to crowd in private capital further underscore the enormity of the affordability gap. CMHC’s National Housing Co-Investment Fund provides concessional financing to build or repair ‘affordable’ housing units under a condition that rent is less than 80% of the median market rate. The aforementioned OAG report found that typical rent for units approved so far under the initiative are priced at about 63% of the median market rate. The report rightly points out, however, that even at this substantial discount, rent is still unaffordable for lower income Canadians. This is arguably less a design-flaw in the program, rather concretises the magnitude of the government policy failures—and challenges ahead.

Government efforts to alleviate housing affordability pressures through targeted housing transfers are largely trivial relative to the scale of the gaps. The recently tweaked and topped-up Canada Housing Benefit is expected to provide a one-time $500 payment to 1.8 mn low-income renter households (with a $20 k threshold for individuals and $35 k for families whose rent exceeds 30% of household income) at a cost of $1.2 bn. There is also a patchwork of targeted housing supports across the country at lower levels of government with little line of sight on the final tally, but the earlier formulation of the Canada Housing Benefit allocated $4.3 bn (with provinces) over six years to FY28 (that would very approximately translate into $300 annually for 1.8 mn households).

Limited market income exacerbates affordability challenges among lowest income households. The average household income (before tax) for a renter in the bottom (after-tax) income quintile was just $15.2 k in 2019 (prior to distortionary effects of temporary pandemic measures) according to CMHC data. This is not substantially higher than the maximum income

available through welfare programs across the country as tallied by the Maytree Foundation. The lift in market income (and broader sources of net wealth including housing equity itself) consequently provides less of an offset for lowest income Canadians against rising shelter costs.

At the extreme end of the spectrum, the number of unhoused Canadians remains highly uncertain. The last point-in-time count registered 235 k Canadians experiencing homelessness, but most experts believe this seriously underrepresents the number since it misses ‘hidden’ homelessness. Signs of progress are unclear despite Canada enshrining the right to housing into legislation in 2019. Moral and legal obligations aside, there is a growing body of evidence that a Housing First principle pays off in the long run. A recent counterfactual study by the Mental Health Commission of Canada estimated that every $10 invested in supportive housing resulted in an average savings of almost $22 through costs avoided on top of social returns (chart 8).

challenges, setting targets, and even crafting some solutions to this end. But tangible results will take time and, importantly, face serious implementation risk with some cracks already exposed. Meanwhile, the situation is deteriorating, particularly for those most vulnerable, fueling a growing polarization around the public versus private provision of affordable housing in Canada. The enormity of the challenge requires both.

The first-best solution is still to unlock greater supply across the continuum of housing. Shortages in one segment will have—and are having—spillovers across the continuum. For example, as homeownership increasingly becomes unattainable for most, demand for marketbased rental alternatives are coming under increasing pressure, in turn pricing out lower income households, putting even more demand on social housing and exacerbating housing hardship. That is not to say that there are not market imperfections, but broadly speaking, it is not a zero-sum game: unlocking greater supply across segments should relieve price pressures across the system.

But it increasingly looks like we won’t achieve scale in new supply in meaningful timeframes that would dramatically shift the affordability landscape anytime soon. There has been a material uptick in housing with new-builds running in the range of 275 k starts (annualised) since the onset of the pandemic versus a pre-pandemic annual average closer to 200 k (chart 9). This falls well-short of the very approximate 600 k+ annual units that would be required to close CMHC’s estimated housing shortfall by 2030.

TACKLING THE IMPORTANT AND THE URGENT

Addressing broad-based housing affordability challenges remains as urgent as ever. Policymakers and partners have made some headway in identifying the

There is a case to critically consider next-best approach(es) to non-market housing across the country. There are many learnings to be leveraged from crowding private capital into affordable housing and there is still much more to

be done in that ‘middle market’. This is essential but insufficient. The largely scathing OAG report on basic access to housing suggests we have neither adequate governance frameworks nor the tools at present to address the magnitude of the challenges at the acute end of the housing continuum.

Canada needs a more ambitious, ur-

gent and well-resourced strategy to expand its social housing infrastructure. Aims to double the stock of social housing across the country could be a start. This would bring Canada just in line with OECD (and G7) averages, but wellbelow some European and Nordic markets. There is no particular magic behind this number: bringing the stock to 1.3 mn dwellings would not fully close gaps. But it signals far more ambition than the 150 k incremental units targeted under the National Housing Strategy with the bulk of its efforts focused on keeping the current count whole.

A target should not necessarily imply new builds—in fact governments may not be best-placed to do so. It should encompass a broader approach that contains optionality to build, buy, renovate, or retrofit units to add incremental supply to the social housing sector. The toolkit would also involve much higher rates of concessionality (including

greater grant-based approaches) in partnering with other actors, while avoiding conflating the potentially distinct roles around building/renovating, operating, owning, and funding the expansion of supply. It will take private, public and non-profit sectors together to revitalise Canada’s social housing sector.

Such an approach may be more cost-efficient for governments in the long run and more responsive to those most vulnerable to Canada’s housing crisis in the near term.

Reprinted from Scotia Bank Global Economics - INSIGHTS & VIEWS, January 18, 2023

Contributor - Rebekah Young

VP & Head of Inclusion and Resilience Economics, Scotiabank Economics 416.862.3876

rebekah.young@scotiabank.com u

Moderator:

Jim Mellor, FIHM, IHM President

Presenters:

James Barker, B.E.S, CRSP, Barker Environmental Consulting Inc., President

Stacey Sanelli, Precision Property Management Inc., Property Manager

Join Us for the 2023 IHM Conference

May 11- 12, 2023

Casablanca Hotel, Grimsby, Ontario

Over 1.5 days, IHM provides an intimate setting of approximately 100 attendees from across Canada to learn of new strategies to help make their jobs easier in property management.

Make new connections and learn from not only the presenters, but the attendees themselves as they are encouraged to share stories and help each other with solutions. The 2023 conference will focus on relationship management with all parties involved in property management. Sessions will cover dispute resolution, handling mental health matters with tenants, internal work relationships within a staff shortage, and relationships with suppliers and support systems that can make the job a little easier.

We hope you can join us!

Thank you to Our Current Sponsors

Platinum Sponsors

Gold Sponsors

Bronze Sponsors

Laundry Concession ContractsThings to Consider

By Kevin McCann, FIHM Vice President

Many multi-unit building owners engage laundry concessionaires to provide laundry services in their buildings as opposed to owning and operating the equipment themselves. Laundry concessions can provide a favourable and dependable revenue source for the building in addition to providing a significant convenience for the residents. Often, the building manager will approach a laundry company and ask for a quote, accepting all of the details in the submission along with the revenue proposal. This can lead to a one-sided contract that does not necessarily benefit the residents or the owner. When inviting bids from laundry contractors, the property manager should prepare a specification that clearly defines requirements that will not only elicit a favourable bid, but also ensure that the residents and owner are protected and well serviced.

Some contracts have automatic renewal clauses. Where these clauses exist, it is important for the building manager to ensure that proper notice is given, to enable a new contract to be negotiated. Any new contracts should not be permitted to have automatic renewal clauses.

All machines should be new, commercially rated and energy efficient. The efficiency rating can be as simple as stating that the machines need to have an “Energy Star” rating or a specific “Energuide” rating. Typically, front

loading machines are the most efficient. As getting the laundry in and out of front-loading machines can be difficult for seniors or handicapped individuals, the manager may want to specify that the machines (or a portion of them) be mounted on pedestals.

Where possible, dryers should be gas fired as opposed to electric. Electric dryers use a lot of electricity and with “time of use” metering, can be expensive to operate.

Clauses should be incorporated in the contract to ensure that the vendor complies with standard accounting practices and allows the owner to conduct periodic audits. The machines should have non-resettable coin counters to ensure audit results are accurate.

Insurance requirements should be stipulated clearly and include a specified amount for commercial general liability insurance, including bodily injury and property damage, product liability, contractual liability, water damage and legal liability. The contract should include a clause that indemnifies the building against personal injury claims and other lawsuits that may arise due to the vendor’s negligence, omissions, intentional acts, etc. Proof of insurance must be provided.

Details should be included that clearly stipulate response times for machine

failures, the communication methods to be used, timelines for compliance and allow the owner to terminate the contract for “non-performance”.

In order for the bidders to be able to put forward their best offer, it is important that the bidder knows some essential details about the building i.e. number/ size of units, tenant/member type (seniors, family, mixed) and historical information about the number of wash/ dry cycles that the laundry room has generated in the past. The cost per wash/dry cycle should be reviewed each time a new contract is being negotiated to ensure that the rates used are attractive to the residents while providing a reasonable return to the owner. Typically, longer term contracts produce the best revenues for the building owner, as the successful bidder can depreciate the value of the machines over a longer period of time. Most laundry concession contracts run between five and ten years.

In many buildings, the laundry room can be a social gathering place for the residents. Building managers should ensure that laundry rooms are well lit, safe, clean and furnished with enough seating to accommodate those who would like to stay in the laundry room while they wait for their laundry to be finished. u

IHM Corporate Members

Thank you to Appollo Pest Management, 2023 Event Sponsor and Corporate Member.

Thank you to all IHM Corporate Members.