Lietuva ir Lenkija 1791 m. k onstitucijos epochoje O DOBRO OJCZYZNY Litwa i p o L ska w epoce k onstytucji 3 maja TO KEEP THE HOMELAND ALIVE Lithuania and p o L and in the e poch of the 1791 c onstitution

O DOBRO OJCZYZNY

Litwa i Po L ska w e P oce k onstytucji 3 maja

TO KEEP THE HOMELAND ALIVE

Lithuania and Po L and in the eP och of the 1791 c onstitution

Lietuva ir Lenkija 1791 m. k onstitucijos e P ochoje

Lietuvos didžiųjų kunigaikščių rūmų parodų katalogai, XXXII tomas

Katalogi Pałacu Wielkich Książąt Litewskich, tom XXXII

Exhibition catalogues of the Palace of the Grand Dukes, Volume XXXII

Parodos organizatorius / Organizator wystawy / Exhibition organiser

Parodos bendraorganizatoriai / Współorganizatorzy wystawy / Exhibition co-organisers

Parodos partneriai / Partnerzy wystawy / Exhibition partners

Lietuvos Respublikos ambasada Lenkijos Respublikoje Ambasada Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej w Republice Litewskiej

Parodos rėmėjai / Sponsorzy / Exhibition sponsors

Informaciniai rėmėjai / Patronat medialny / Media sponsors

Iš dalies finansuojama Lenkijos Respublikos kultūros, nacionalinio paveldo ir sporto ministerijos lėšomis

Dofinansowano ze środków Ministerstwa Kultury, Dziedzictwa Narodowego i Sportu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej

Co-financed by the Ministry of Culture, National Heritage and Sport of the Republic of Poland

Viršelyje / Na okładce / On the cover

Lenkijos karaliaus ir Lietuvos didžiojo kunigaikščio Stanislovo Augusto Poniatovskio portretinė miniatiūra su klepsidra.

Vincentas Friderikas de Leseras (1745–1813) pagal Marčelą Bačarelį (1731–1818), po 1793

Król polski i wielki książę litewski Stanisław August Poniatowski z klepsydrą – portret miniatura.

Wincenty Fryderyk de Lesseur (1745–1813) według Marcella Bacciarellego (1731–1818), po 1793

Miniature portrait of the King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania Stanislaus Augustus Poniatowski with a clepsydra. Wincenty Fryderyk de Lesseur (1745–1813) after Marcello Bacciarelli (1731–1818), after 1793

Zamek Królewski w Warszawie – Muzeum, ZKW/5141/ab

© Nacionalinis muziejus Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės valdovų rūmai, 2022

Bibliografinė informacija pateikiama Lietuvos integralios bibliotekų informacinės sistemos (LIBIS) portale ibiblioteka.lt

ISSN 2351-7115

ISBN 978-609-8061-75-8

Lietuva ir Lenkija 1791 m. k onstitucijos e P ochoje

O DOBRO OJCZYZNY

Litwa i Po L ska w e P oce k onstytucji 3 maja

TO KEEP THE HOMELAND ALIVE

Lithuania and Po L and in the eP och of the 1791 c onstitution

Paroda, skirta abiejų tautų respublikos

1791 m. gegužės 3 d. konstitucijos ir tarpusavio įžado 230-osioms metinėms

wystawa poświęcona 230. rocznicy uchwalenia konstytucji 3 maja i Zaręczenia wzajemnego obojga narodów

exhibition dedicated to mark the 230th anniversary of the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth constitution of 3 may 1791 and the mutual assurance of the two nations

Tarptautinės parodos katalogas Katalog międzynarodowej wystawy International exhibition catalogue

2021 m. spalio 19 d. – 2022 m. sausio 16 d.

19 października 2021 – 16 stycznia 2022

19 October 2021 – 16 January 2022

Nacionalinis muziejus Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės valdovų rūmai Muzeum Narodowe – Pałac Wielkich Książąt Litewskich National Museum – Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania

Katalogo sudarytojos / Opracowanie katalogu / Catalogue compilers Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė, Gintarė Džiaugytė-Burbulienė

Vilnius 2022

Parodos globėjai / Patronat wystawy / Exhibition Patrons

Lietuvos Respublikos Prezidentas Lenkijos Respublikos Prezidentas

Prezydent Republiki Litewskiej Prezydent Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej President of the Republic of Lithuania President of the Republic of Poland

GITANAS NAUSĖDA

ANDRZEJ DUDA

Parodos organizatorius / Organizator wystawy / Exhibition organiser

Nacionalinis muziejus Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės valdovų rūmai

Muzeum Narodowe – Pałac Wielkich Książąt Litewskich

National Museum – Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania

Bendraorganizatoriai / Współorganizatorzy / Co-organisers

Instytut Adama Mickiewicza, Polska

Zamek Królewski w Warszawie – Muzeum, Polska

Parodos kuratorė / Kurator wystawy / Exhibition curator

Dr. Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė

Parodos koncepcijos ir ekspozicijos plano autoriai / Koncepcja wystawy i plan ekspozycji / Exhibition concept and plan authors

Dr. Vydas Dolinskas, dr. Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė, Marijus Uzorka

Parodos koordinatoriai / Koordynatorzy wystawy / Exhibition coordinators

Marijus Uzorka, Gintarė Džiaugytė-Burbulienė, Gintarė Tadarovska, Dalius Avižinis

Parodos leidybos koordinatorės / Koordynacja publikacji towarzyszących wystawie / Exhibition publishing coordinators

Dr. Živilė Mikailienė, Gintarė Džiaugytė-Burbulienė

Parodos restauracinės priežiūros koordinatoriai / Nadzór konserwatorski / Exhibition restoration maintenance coordinators

Mantvidas Mieliauskas, Dainius Šavelis, Deimantė Baubaitė, Jurgita Kalėjienė, Andrius Salys

Parodos mokslinės ir kultūrinės programos koordinatoriai / Koordynatorzy programu naukowego i kulturalnego / Exhibition scientific and cultural program coordinators

Dr. Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė, Vytautas Gailevičius

Parodos edukacinės programos koordinatorės / Koordynatorzy programu edukacyjnego / Exhibition educational program coordinators Lirija Steponavičienė, dr. Nelija Kostinienė

Parodos rinkodaros ir informacijos koordinatoriai / Koordynacja działań promocyjnych i informacyjnych / Exhibition marketing and information coordinators

Mindaugas Puidokas, Monika Petrulienė

Parodos techninio įrengimo koordinatoriai / Nadzór techniczny / Exhibition technical installation coordinators

Kęstutis Karla, Aurimas Ramelis, Saulius Marteckas

Parodos eksponatų savininkai / Właściciele eksponatów / Exhibits owned by Anykščių sakralinio meno centras, Anykščių menų centras; Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych w Warszawie, Polska; Bažnytinio paveldo muziejus; Biblioteka Książąt Czartoryskich, Oddział Muzeum Narodowego w Krakowie, Polska; Biblioteka Narodowa w Warszawie, Polska; Biblioteka Naukowa PAU i PAN w Krakowie, Polska; Biblioteka Uniwersytecka w Warszawie, Polska; Fundacja Zbiorów im. Ciechanowieckich, Zamek Królewski w Warszawie – Muzeum, Polska; Jonavos Šv. apaštalo Jokūbo parapija; Kauno arkivyskupijos kurija; Lietuvos istorijos institutas; Lietuvos mokslų akademijos Vrublevskių biblioteka; Lietuvos nacionalinė Martyno Mažvydo biblioteka; Lietuvos nacionalinis dailės muziejus; Lietuvos nacionalinis muziejus; Lietuvos valstybės istorijos archyvas; Muzeum Historyczne w Sanoku, Polska; Muzeum Książąt Czartoryskich – Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie, Polska; Muzeum Książąt Lubomirskich w Zakładzie Narodowym im. Ossolińskich we Wrocławiu, Polska; Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie, Polska; Muzeum Narodowe w Poznaniu, Polska; Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie, Polska; Nacionalinis M. K. Čiurlionio dailės muziejus; Nacionalinis muziejus Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės valdovų rūmai; Panevėžio vyskupijos kurija; Parafia pw. Niepokalanego Poczęcia Najświętszej Maryi Panny w Wigrach, Polska; Raguvos Švč. Mergelės Marijos Ėmimo į dangų parapija; Šiaulių „Aušros“ muziejus; Trakų istorijos muziejus; Turgelių Švč. Mergelės Marijos Ėmimo į dangų parapija; Vilniaus arkivyskupijos kurija; Vilniaus universiteto biblioteka; Vytauto Didžiojo karo muziejus; Zamek Królewski na Wawelu – Państwowe Zbiory Sztuki, Polska; Zamek Królewski w Warszawie – Muzeum, Polska; Львівська національна галерея мистецтв імені Бориса Возницького, Україна; Львівський історичний музей, Україна; Нацыянальны мастацкі музей Рэспублікі Беларусь; Prof.JanK. Ostrowski; Kunigaikštis Motiejus Radvila / Książę Maciej Radziwiłł / Prince Maciej Radziwiłł; Vilius Kavaliauskas

Katalogo sudarytojos / Opracowanie katalogu / Catalogue compilers

Dr. Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė, Gintarė Džiaugytė-Burbulienė

Tekstų autoriai / Autorzy tekstów / Texts by Dr. Vydas Dolinskas, dr. Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė

Leidybos koordinatorės / Koordynator wydawnictwa / Publishing coordinator

Gintarė Džiaugytė-Burbulienė, dr. Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė

Redaktorė / Redakcja katalogu / Copy editor

Liuda Skripkienė

Vertimas į lietuvių kalbą / Tłumaczenie na język litewski / Lithuanian translation

Gintarė Džiaugytė-Burbulienė

Vertimas į lenkų kalbą / Tłumaczenie na język polski / Polish translation

Beata Piasecka, Regina Jakubėnas, Teresa Dalecka

Vertimas į anglų kalbą / Tłumaczenie na język angielski / English translation

Albina Strunga

Katalogo dizainas ir maketavimas / Opracowanie graficzne katalogu / Catalogue design by UAB „Savas takas“ ir ko, dizainerė Laima Zulonė

Fotografijų autoriai / Autorzy fotografii / Picture credits

Vytautas Abramauskas, Irena Aleksienė, Vaidotas Aukštaitis, Maciej Bronarski, Marek H. Dytkowski, Zbigniew Doliński, Mindaugas Kaminskas, Piotr Ligier, Antanas Lukšėnas, Jakub Płoszaj, Zbigniew Reszka, Alvydas Staniūnaitis, Krzysztof Wilczyński

Katalogo iliustracijų savininkai / Ilustracji użyczyły / Illustration lending institutions

Anykščių sakralinio meno centras, Anykščių menų centras; Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych w Warszawie, Polska; Bažnytinio paveldo muziejus; Biblioteka Narodowa w Warszawie, Polska; Biblioteka Naukowa PAU i PAN w Krakowie, Polska; Biblioteka Uniwersytecka w Warszawie, Polska; Lietuvos mokslų akademijos Vrublevskių biblioteka; Lietuvos nacionalinio dailės muziejaus skaitmeninis archyvas; Lietuvos nacionalinis muziejus; Lietuvos valstybės istorijos archyvas; Muzeum Historyczne w Sanoku, Polska; Pracownia Fotograficzna Muzeum Narodowego w Krakowie, Polska; Muzeum Książąt Lubomirskich w Zakładzie Narodowym im. Ossolińskich we Wrocławiu, Polska; Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie, Polska; Muzeum Narodowe w Poznaniu, Polska; Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, Polska; Kolekcja Muzeum Narodowego w Warszawie, Polska; Nacionalinis M. K. Čiurlionio dailės muziejus; Nacionalinis muziejus Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės valdovų rūmai; Šiaulių „Aušros“ muziejus; Trakų istorijos muziejus; Vilniaus universiteto biblioteka; Vytauto Didžiojo karo muziejus; Zamek Królewski na Wawelu – Państwowe Zbiory Sztuki, Polska; Zamek Królewski w Warszawie – Muzeum, Polska; Львівська національна галерея мистецтв імені Бориса Возницького, Україна; Львівський історичний музей, Україна; Нацыянальны мастацкі музей Рэспублікі Беларусь; Prof. Jan K. Ostrowski; Kunigaikštis Motiejus Radvila / Książę Maciej Radziwiłł / Prince Maciej Radziwiłł

Turinys / Spis Tresci / Contents

Parodos globėjai / Patronat wystawy / Exhibition Patrons

10 Lietuvos Respublikos Prezidento Gitano Nausėdos sveikinimo žodis per tarptautinės parodos „Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų. Lietuva ir Lenkija 1791 m. konstitucijos epochoje“ bei konferencijos, skirtų Abiejų Tautų Respublikos 1791 m. gegužės 3 d. konstitucijos ir Tarpusavio įžado 230-osioms metinėms, atidarymą

12 Słowo powitalne Prezydenta Republiki Litewskiej Gitanasa Nausėdy podczas otwarcia międzynarodowej wystawy „O dobro Ojczyzny. Litwa i Polska w epoce Konstytucji 3 Maja” oraz konferencji naukowej poświęconej 230. rocznicy uchwalenia Konstytucji 3 Maja i Zaręczenia Wzajemnego Obojga Narodów

14 Welcoming speech made by the President of the Republic of Lithuania, Gitanas Nausėda , at the opening of the international exhibition To Keep The Homeland Alive. Lithuania and Poland in the Epoch of the 1791 Constitution, and the conference, dedicated to mark the 230th anniversary of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth’s Constitution of 3 May 1791 and the Mutual Assurance of the Two Nations

16 Lenkijos Respublikos Prezidento Andrzejaus Dudos kalba per tarptautinės parodos „Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų. Lietuva ir Lenkija 1791 m. konstitucijos epochoje“, skirtos Abiejų Tautų Respublikos 1791 m. gegužės 3 d. konstitucijos ir Tarpusavio įžado 230-osioms metinėms, atidarymą

18 Wystąpienie Prezydenta Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, Andrzeja Dudy, podczas otwarcia międzynarodowej wystawy „O dobro Ojczyzny. Litwa i Polska w epoce Konstytucji 3 Maja” poświęconej 230. rocznicy uchwalenia Konstytucji 3 Maja i Zaręczenia Wzajemnego Obojga Narodów

20 Welcoming speech made by the President of the Republic of Poland, Andrzej Duda , at the opening of the international exhibition To Keep The Homeland Alive. Lithuania and Poland in the Epoch of the 1791 Constitution, dedicated to mark the 230th anniversary of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth's Constitution of 3 May 1791 and the Mutual Assurance of the Two Nations

Vydas Dolinskas

22 Parodoje permąstytos laisvės vilties idėjos ir skaudžios valstybės sunaikinimo pamokos

32 Wystawa skłaniająca do refleksji nad nadzieją na odzyskanie wolności i przypominająca nauki płynące z utraty państwa

40 This exhibition rethinks ideas for the hope of freedom and the painful lessons of the destruction of the state

Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė

48 Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų. Lietuva ir Lenkija 1791 m. konstitucijos epochoje

95 O dobro Ojczyzny. Litwa i Polska w epoce Konstytucji 3 Maja

116 To Keep The Homeland Alive. Lithuania and Poland in the epoch of the 1791 Constitution

KATALOGAS / KATALOG / CATALOGUE

139 Proloquium

148 I. Valdovas ir tauta / Władca i naród / The Ruler and the Nation

198 II. Tėvynės labui / W imię Ojczyzny / In the Name of the Homeland

262 III. Reformų seimas / Sejm Wielki / The Great Sejm

342 IV. Švelnioji revoliucija / Łagodna rewolucja / The Gentle Revolution

402 V. Konstitucija ir Lietuva / Konstytucja i Litwa / The Constitution and Lithuania

450 VI. Tarp išdavystės ir lojalumo / Między zdradą a lojalnością / Between Treason and Loyalty

498 VII. Kova už laisvę. Valstybingumo idėjos tęstinumas / Walka o wolność. Trwałość idei Konstytucji / The Fight for Freedom. Continuity of the Idea of Statehood

588 Bibliografija / Bibliografia / Bibliography

599 Katalogo tekstų autoriai / Autorzy opisów katalogowych / Catalogue text authors

Parodos globėjai

Patronat wystawy

Exhibition Patrons

8 Valdovas ir tauta / Władca i naród / The Ruler and the Nation

Dr. Vydas Dolinskas Nacionalinio muziejaus

Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės valdovų rūmų direktorius

PARODOJE PERMĄSTYTOS LAISVĖS

VILTIES IDĖJOS IR SKAUDŽIOS VALSTYBĖS SUNAIKINIMO PAMOKOS

2021 m. gegužės 5 d. Valdovų rūmų muziejuje vyko renginys „Tėvynės ir laisvių tvirtovė“, skirtas Gegužės 3 d. konstitucijos įsigaliojimo 230-osioms metinėms. Apskritojo stalo diskusijoje dalyvavo (iš kairės į dešinę): jos moderatoriai Valdovų rūmų muziejaus direktoriaus pavaduotoja kultūrai ir mokslui dr. Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė ir istorikas, žurnalistas Virginijus Savukynas, Lenkijos Respublikos Senato vicemaršalka Bogdanas Borusevičius, Lenkijos Respublikos Senato Ekonomikos ir inovacijų komisijos pirmininkė Marija Koc, Lietuvos Respublikos Aukščiausiosios Tarybos-Atkuriamojo Seimo Pirmininkas, pirmasis atkurtos nepriklausomos Lietuvos valstybės vadovas profesorius Vytautas Landsbergis, poetas, eseistas, publicistas, Jeilio universiteto (JAV) profesorius Tomas Venclova, Vilniaus universiteto docentas dr. Mindaugas Kvietkauskas, Europos humanitarinio universiteto Komunikacijos ir plėtros skyriaus vadovas Maksimas Milta, istorikas, Lietuvos istorijos instituto direktorius habil. dr. Alvydas Nikžentaitis ir anuometinis Lietuvos Respublikos Seimo Užsienio reikalų komiteto pirmininkas Žygimantas Pavilionis.

5 maja 2021 r. w Pałacu Wielkich Książąt Litewskich odbyła się dyskusja okrągłego stołu poświęcona 230. rocznicy formalnego wpisania Konstytucji 3 Maja do akt grodzkich. W dyskusji wzięli udział (od lewej): moderatorzy: dr Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė – zastępca dyrektora Muzeum Narodowego – Pałacu Wielkich Książąt Litewskich ds. kultury i nauki oraz Virginijus Savukynas – historyk, dziennikarz, Bogdan Borusewicz – Wicemarszałek Senatu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej; Maria Koc – Przewodnicząca Senackiej Komisji Gospodarki Narodowej i Innowacyjności, prof. Vytautas Landsbergis – Przewodniczący Rady Najwyższej Republiki Litewskiej, pierwszy przywódca niepodległego państwa litewskiego, Tomas Venclova – poeta, eseista, publicysta, profesor Uniwersytetu Yale (USA), dr Mindaugas Kvietkauskas – docent Uniwersytetu Wileńskiego; Maksimas Milta – kierownik Wydziału Komunikacji i Rozwoju Europejskiego Uniwersytetu Humanistycznego, dr hab. Alvydas Nikžentaitis – historyk, dyrektor Instytutu Historii Litwy i Žygimantas Pavilionis – ówczesny Przewodniczący Komisji Spraw Zagranicznych Sejmu Republiki Litewskiej.

An event titled Fortress of the Homeland and Liberties was held at the National Museum – Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania on 5 May 2021, to commemorate the 230th anniversary of the enactment of the Constitution of 3 May. Participants of the round table discussion (from left to right) included: moderators Deputy Director for Culture and Science at the National Museum – Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania Dr Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė and historian and journalist Virginijus Savukynas, also Deputy Marshal of the Senate of the Republic of Poland Bogdan Borusewicz, chair of the National Economy and Innovativeness Committee of the Senate of the Republic of Poland Maria Koc, Chairman of the Supreme Council – Reconstituent Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania, the first head of the restored independent Lithuanian state, Prof. Vytautas Landsbergis, poet, essayist, publicist, Yale University (USA) Professor Tomas Venclova, Vilnius University Associate Professor Dr Mindaugas Kvietkauskas, head of the Communications and Development Unit at the European Humanities University Maksimas Milta, historian and Lithuanian Institute of History Director Dr habil. Alvydas Nikžentaitis and the then chair of the Seimas Committee on Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Lithuania Žygimantas Pavilionis.

22 Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų / O dobro Ojczyzny / To Keep The Homeland Alive

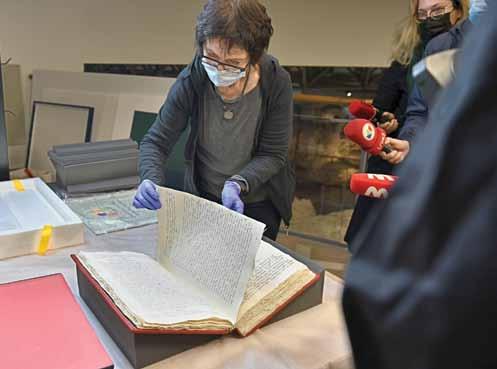

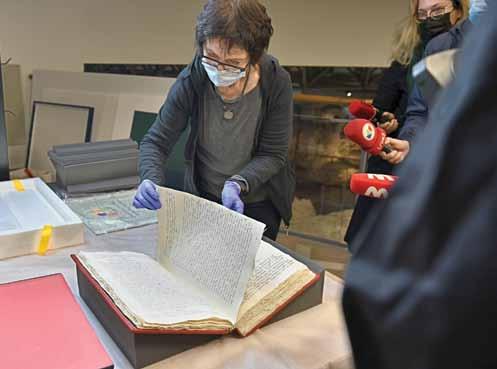

Tinkamas dokumentų ir spaudinių paruošimas eksponuoti –ilgas ir atsakingas, daug kruopštumo reikalaujantis darbas. Mažieji muziejaus lankytojai išvydo paprastai užkulisiuose liekantį muziejininkų darbą – Restauravimo skyriaus vyresnysis restauratorius Andrius Salys ruošia eksponuoti mažiausią parodos spaudinį – 1771 ir 1772 m. Vilniaus kalendorių (lenk. Kalendarz Wileński na rok 1771 ir Kalendarz Wileński na rok 1772).

Właściwe przygotowanie dokumentów i druków do ekspozycji na wystawie to długa i odpowiedzialna praca, która wymaga dużej staranności. Najmłodsi goście muzeum zapoznali się z pracą muzealników, która zazwyczaj jest niewidzialna: Andrius Salys –starszy konserwator Działu Konserwacji Zabytków przygotowuje się do eksponowania najmniejszych druków: Kalendarza Wileńskiego na rok 1771 i Kalendarza Wileńskiego na rok 1772.

The proper preparation of documents and prints ahead of their display is a long and responsible task requiring great diligence. Younger visitors to the museum witnessed the work staff do that usually remains behind the scenes – chief restorer at the Restoration Department Andrius Salys prepares the smallest printed material in the exhibition for display – the 1771 and 1772 Vilnius Calendar (Kalendarz Wilenski na rok 1771 ir Kalendarz Wilenski na rok 1772).

Tarptautinės parodos „Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų. Lietuva ir Lenkija 1791 m. Konstitucijos epochoje“ atidaryme 2021 m. spalio 19 d. vakarą skambėjo Valstybinio M. K. Čiurlionio kvarteto atliekamas Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės paskutiniojo didžiojo iždininko kunigaikščio Mykolo Kleopo Oginskio sukurtas legendinis polonezas a-moll „Atsisveikinimas su Tėvyne“, laikomas tarsi liūdną Abiejų Tautų Respublikos likimą primenančiu himnu. Ši melancholiška, nors vietomis ir viltingai nuteikianti melodija, išlydėdavo kiekvieną lankytoją ir iš paskutinės parodos salės. Skambantis polonezas „Atsisveikinimas su Tėvyne“ kaskart priverčia susimąstyti apie istorinę jungtinės Lenkijos ir Lietuvos valstybės lemtį, XVIII a. antroje pusėje sužibusią tautų ir valstybės atgimimo viltį bei tragišką baigtį, nulemtą išimtinai agresyvių kaimynų kėslų ir interesų.

2021-aisiais sukako 230 metų, kai buvo paskelbta Gegužės 3 d. konstitucija ir patvirtintas Abiejų Tautų tarpusavio įsipareigojimo įstatymas, arba Tarpusavio įžado aktas. Kiekvienas jubiliejus suteikia progą ir paakina atidžiau pažvelgti į praeitin nugrimzdusius istorijos faktus, susimąstyti apie anuometinių įvykių prasmes, priežastis ir pasekmes, istorinių asmenybių pasirinkimus kritiniais momentais, aktualizuoti pakilias ar skaudžias istorijos pamokas nūdienai. Taip ir ši sukaktis –ji priminė Gegužės 3 d. konstitucijos bei Abiejų Tautų tarpusavio įsipareigojimo įstatymo sužadintas viltis ir tragišką Lenkijos bei Lietuvos valstybingumo raidos atomazgą. Istorinės pergalės, vedusios į pakilimą ir ilgalaikį klestėjimą, paprastai prisimenamos su malonumu ir pasididžiavimu, o trumpalaikiai laimėjimai, po kurių sekė nuopuoliai, visada kelia dvejopus jausmus ir verčia susimąstyti apie galimai padarytas klaidas, galbūt parodytą nepakankamą ryžtą ar nuovoką, politinio ir diplomatinio įžvalgumo stoką, neįvertintas išorines aplinkybes. Dar svarbiau, kad tokie vilties spinduliai ir dramatiškos pasekmės verčia bent jau teoriškai mokytis iš istorijos, daryti adekvačias išvadas, aktualias tiek dabarčiai, tiek ir ateičiai. Tarptautinė paroda „Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų. Lietuva ir Lenkija 1791 m. konstitucijos epochoje“, vykusi Nacionaliniame muziejuje Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės valdovų rūmuose 2021 m. spalio 19 d. – 2022 m. sausio 16 d., kaip tik ir kvietė permąstyti sudėtingus XVIII a. Abiejų Tautų Respublikos raidos vingius, pasisemti istorinės patirties ir išminties nūdienai. Verta pabrėžti, kad moderniojoje Lietuvoje apskritai Gegužės 3 d. konstitucijos ir Tarpusavio įžado sukaktis taip plačiai ir valstybiniu mastu 2021 m. iš esmės buvo paminėta pirmą kartą, nes šie dokumentai ilgai laikyti „svetimais“, neigiamai paveikusiais Lietuvos valstybingumo raidą. Valdovų rūmų muziejus greta šios monumentalios parodos, kaip jubiliejinių metų minėjimo kulminacijos, 2021 m. pasiūlė ištisą renginių programą, kuria kvietė prisiminti esminių istorinių dokumentų sukaktį ir jų reikšmę, o kartu suaktualinti daugiau nei prieš du amžius besirutuliojusią istoriją, sužadinti istorinę atmintį.

Gegužės 3 d. konstitucijos ir Tarpusavio įžado sukaktį Valdovų rūmų muziejus minėti pradėjo parengdamas specialią programą „Tėvynės ir laisvių tvirtovė“, kuri buvo įgyvendinta jau 2021 m. gegužės 5 d. rūmų Didžiojoje renesansinėje menėje. Šią valstybinio minėjimo programą globojo ir sveikinimo žodžius tarė Lietuvos Respublikos Seimo Pirmininkė Viktorija Čmilytė-Nielsen, Lenkijos Respublikos Senato Maršalka profesorius Tomašas Grodzkis (Tomasz Grodzki) ir Lenkijos Respublikos Seimo Maršalka Elžbieta Vitek (Elżbieta Witek), nors ji pati į renginį atvykti negalėjo, tad jos sveikinimą perskaitė Lenkijos Respublikos ambasadorė Lietuvos Respublikoje Uršula Doroševska (Urszula Doroszewska).

23 Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų / O dobro Ojczyzny / To Keep The Homeland Alive

Valdovų rūmų muziejaus Restauravimo skyriaus vedėjas

Mantvidas Mieliauskas su kolege Julija Riškute iš Lietuvos nacionalinio muziejaus tikrina Leono Gorskio portreto iš Lietuvos nacionalinio muziejaus būklę prieš rėminant ir eksponuojant.

Mantvidas Mieliauskas – kierownik Działu Konserwacji Zabytków Muzeum Narodowego – Pałacu Wielkich Książąt Litewskich i koleżanka Julija Riškutė z Litewskiego Muzeum Narodowego sprawdzają stan portretu Leona Gorskiego z Litewskiego Muzeum Narodowego przed oprawieniem go i wystawieniem.

Head of the Restoration Department at the National Museum –Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania Mantvidas Mieliauskas and his colleague Julija Riškutė from the National Museum of Lithuania examine the condition of the portrait of Leon Gorski from the National Museum of Lithuania before it is framed and exhibited.

Gegužės 5 d. renginio pradžioje taip pat buvo pristatyta vieno šedevro, papuošusio Didžiąją renesansinę menę, paroda. Tas išskirtinis kūrinys – tai paskutiniojo Lenkijos karaliaus ir Lietuvos didžiojo kunigaikščio Stanislovo Augusto Poniatovskio (1732/1764–1795/1798) visafigūris reprezentacinis portretas, 1783 m. sukurtas kunigaikščių Radvilų rūmų dailininko Juozapo Ksavero Heskio (Józef Xawery Hesk, apie 1740 – apie 1810) ir ilgą laiką puošęs Nesvyžiaus rezidenciją. Su portrete vaizduojamu valdovu pagrįstai siejamos bemaž visos XVIII a. antros pusės valstybės reformų iniciatyvos, taip pat ir Gegužės 3 d. konstitucija. Šiandien Baltarusios Respublikos nacionaliniame dailės muziejuje saugomas valdovo portretas dailininko buvo sukurtas, matyt, patarus kunigaikščiams Radviloms. Ant stalelio greta Lenkijos karaliaus karūnos pavaizduota ir Lietuvos didžiojo kunigaikščio kepurė. Taip pabrėžiamas federacinės Abiejų Tautų Respublikos dualizmas ir Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės valstybinis statusas.

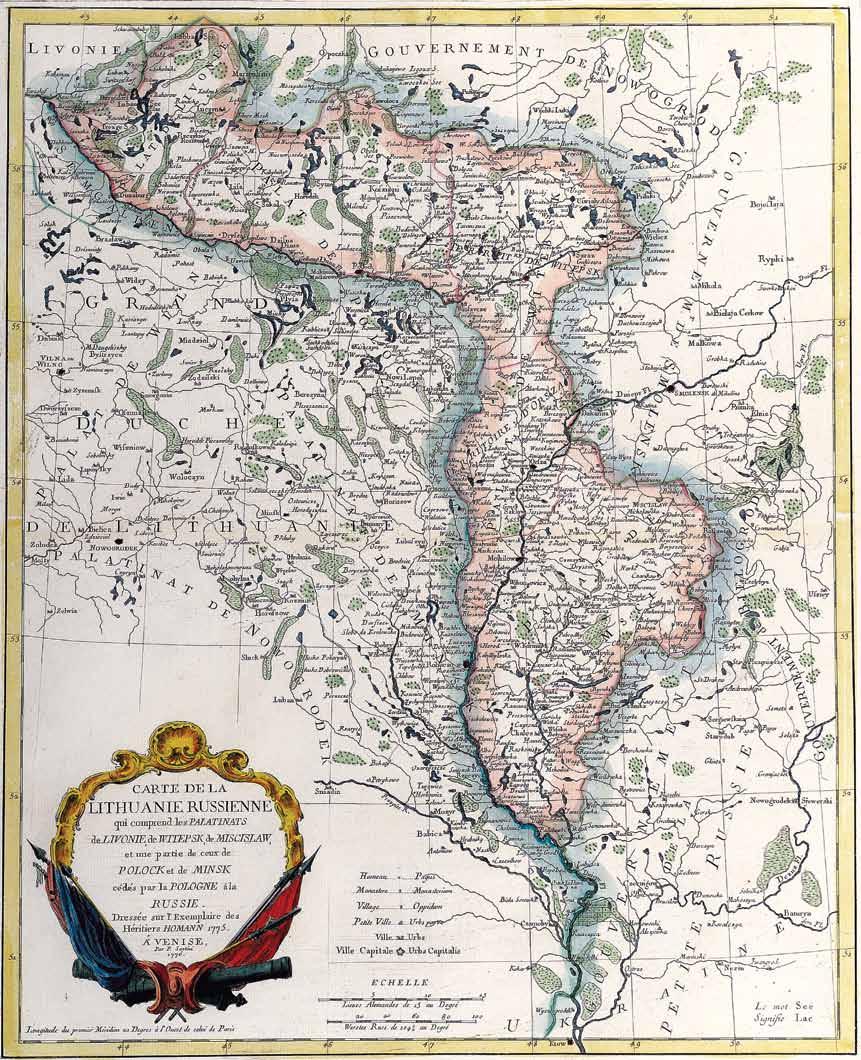

Prieš eksponatams patenkant į jiems numatytas vietas parodoje, jų būklė kruopščiai patikrinama. Gegužės 3 d. konstitucijos originalą iš Varšuvos senųjų aktų archyvo žurnalistams pristatė archyvo darbuotoja Ana Čaika. Zanim eksponaty trafiły na wyznaczone miejsca na wystawie, ich stan był dokładnie sprawdzany. Pracownica Archiwum Anna Czajka zaprezentowała dziennikarzom oryginał Konstytucji 3 Maja udostępniony przez Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych w Warszawie.

Before the exhibits are put out on display, their condition is carefully checked. Anna Czajka from the Main Archive of Old Acts (Archiwum Główne Act Dawnych) in Warsaw presented the original Constitution of 3 May to journalists.

Vėliau, gegužės 5 d. vakare, vyko apskritojo stalo diskusija, kurioje dalyvavo iškilūs Abiejų Tautų Respublikos tradicijos tęsėjų – lenkų, lietuvių, ukrainiečių ir baltarusių – valstybės, visuomenės, mokslo ir kultūros atstovai: politikas, muzikologas, Lietuvos Respublikos Aukščiausiosios Tarybos-Atkuriamojo Seimo Pirmininkas, t. y. pirmasis atkurtos nepriklausomos Lietuvos valstybės vadovas profesorius Vytautas Landsbergis; iš Vilniaus krašto kilęs istorikas, politikas, vienas Lenkijos „Solidarumo“ kūrėjų ir lyderių, Lenkijos Respublikos Senato vicemaršalka Bogdanas Borusevičius (Bogdan Borusewicz); kultūros antropologijos specialistė, politikė, Lenkijos Respublikos Senato Ekonomikos ir inovacijų komisijos pirmininkė Marija Koc (Maria Koc); poetas, eseistas, publicistas, literatūros tyrinėtojas, disidentas, vienas Lietuvos Helsinkio grupės kūrėjų, Jeilio universiteto (JAV) profesorius Tomas Venclova; Lenkijos teisės istorikas, Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės santvarkos ir teisės tyrinėtojas, Varšuvos universiteto profesorius Andžejus B. Zakževskis (Andrzej B. Zakrzewski); istorikas, Abiejų Tautų Respublikos XVIII a. istorijos tyrinėtojas, Londono universiteto koledžo Slavistikos ir Rytų Europos studijų centro profesorius Ričardas Batervikas-Pavlikovskis (Richard ButterwickPawlikowski); ilgesnį laiką Baltarusioje gyvenęs kultūros paveldo ir politikos mokslų specialistas, Europos humanitarinio universiteto Komunikacijos ir plėtros skyriaus vadovas Maksimas Milta; Ukrainos kultūrologas, vertėjas, politologas, vienas iš Ukrainos nacionalinio atgimimo judėjimo „Ruch“ kūrėjų, Lvivo nacionalinės Boryso Voznyckio dailės galerijos generalinis direktorius Tarasas Vozniakas (Taras Voznyak); Lietuvos literatūrologas, kultūros istorikas, poetas, buvęs Lietuvos Respublikos kultūros ministras, Vilniaus universiteto docentas dr. Mindaugas Kvietkauskas; istorikas, Lietuvos istorijos instituto direktorius habil. dr. Alvydas Nikžentaitis; lietuvių diplomatas, ambasadorius, anuometinis Lietuvos Respublikos Seimo Užsienio reikalų komiteto pirmininkas Žygimantas Pavilionis. Diskusiją moderavo žinoma XVIII a. istorijos tyrinėtoja, Valdovų rūmų muziejaus direktoriaus pavaduotoja dr. Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė ir istorikas, įžvalgus publicistas bei garsus žurnalistas Virginijus Savukynas.

24 Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų / O dobro Ojczyzny / To Keep The Homeland Alive

Pagrindinis parodos akcentas – Gegužės 3 d. konstitucijos originalas iš Varšuvos senųjų aktų archyvo – įrengiant parodą sulaukė daugiausia dėmesio. Momentą, kai originalas buvo dedamas į jam eksponuoti skirtą vitriną, fiksavo keletas reporterių.

Główny akcent wystawy – oryginał Konstytucji 3 Maja z Archiwum

Głównego Akt Dawnych w Warszawie, któremu podczas przygotowania wystawy poświęcono najwięcej uwagi. Kilku reporterów uchwyciło moment umieszczenia oryginału w gablocie. The main accent of this exhibition – the original copy of the Constitution of 3 May from the Main Archive of Old Acts in Warsaw – received the most attention when installing the exhibition. Several reporters captured the moment when the original was being placed into its display case.

Jubiliejinio minėjimo programą 2021 m. gegužės 5 d. vakare užbaigė 1791 m. Ketverių metų seimo ir Konstitucijos epochos muzikos koncertas, kuriame Mykolo Kleopo Oginskio, Volfgango Amadėjaus Mocarto (Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart), Džoakino Rosinio (Gioacchino Rossini) kūrinius atliko garsi lietuvių operos solistė Joana Gedmintaitė (sopranas) ir žinoma pianistė Šviesė Čepliauskaitė.

Kadangi tuo metu dėl pandemijos renginiuose dar buvo ribojamas dalyvių skaičius, Valdovų rūmų Didžiojoje renesansinėje menėje galėjo dalyvauti tik nedidelis būrys lankytojų. Tačiau visa programa buvo įrašoma visuomeninio transliuotojo LRT ir rodoma socialiniuose tinkluose bei interneto svetainėse. Greta LRT renginio informacinė rėmėja buvo ir „Lietuvos ryto“ žiniasklaidos grupė. Oficialaus minėjimo programą rengė Nacionalinis muziejus Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės valdovų rūmai, o programos partneriai buvo Lietuvos Respublikos Seimas, Lenkijos institutas Vilniuje, Lenkijos Respublikos ambasada Lietuvos Respublikoje, Lietuvos Respublikos ambasada Lenkijos Respublikoje ir Lietuvos istorijos institutas.

Šis kelių dalių šventinis įvadinis renginys Valdovų rūmų muziejuje įvyko 1791 m. gegužės 3 d. konstitucijos įsigaliojimo 230-ųjų metinių dieną – gegužės 5-ąją, o pagrindiniai jubiliejaus paminėjimo Vilniuje akcentai su didele tarptautine paroda priešakyje buvo nukelti į rudenį, spalio pabaigą, siekiant prisiminti ir specialiai pažymėti Abiejų Tautų tarpusavio įsipareigojimo įstatymo (Tarpusavio įžado), itin aktualaus Lietuvos valstybingumo raidai, patvirtinimo 230 metų sukaktį. Taip jubiliejinius renginius išdėstyti per visus metus skatino ne tik siekis atminti tiek Konstituciją, tiek ir Tarpusavio įžadą, bet ir aplinkybė, kad Konstitucijos epochai skirtą didelę parodą gegužės pradžioje planavo surengti Varšuvos karališkoji pilis, tad Valdovų rūmų muziejus panašią parodą su iš dalies pasikartojančiais eksponatais galėjo surengti tik vėliau ir atverti ją Abiejų Tautų tarpusavio įsipareigojimo įstatymo priėmimo sukakties proga.

2021 m. spalio 19-os vakarą, Garantijų įstatymo patvirtinimo Ketverių metų seime 1791 m. spalio 20 d. 230-ųjų metinių išvakarėse, Valdovų rūmų muziejus kartu su bendraorganizatoriais –Adomo Mickevičiaus institutu (Varšuva) ir Varšuvos karališkąja pilimi – Muziejumi – Vilniaus kultūrinę visuomenę ir svečius pakvietė į iškilmingą tarptautinės parodos „Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų. Lietuva ir Lenkija 1791 m. konstitucijos epochoje“ atidarymą. Kartu su parodos atidarymu įvyko ir tarptautinės mokslinės konferencijos „Tėvynės laisvės aušra – 1791 m. gegužės 3 d. konstitucija: genezė, turinys, reikšmė“ inauguracija. Išskirtinėse iškilmėse dalyvavo ir sveikinimo žodžius tarė parodos ir konferencijos globėjai – Lietuvos Respublikos Prezidentas Gitanas Nausėda ir Lenkijos Respublikos Prezidentas Andžejus Duda (Andrzej Duda). Lietuvos ir Lenkijos valstybių – Abiejų Tautų Respublikos valstybingumo tradicijų tęsėjų – vadovų dalyvavimas ir globa suteikė renginiui ypatingą statusą ir pabrėžė viso regiono istorinių ryšių gyvybingumą bei aktualumą. Po prezidentų sveikinimų žodį tarė vienas parodos bendraorganizatorių – Varšuvos karališkosios pilies direktorius profesorius Voicechas Falkovskis (Wojciech Fałkowski). Kito parodos bendraorganizatorio –Adomo Mickevičiaus instituto – direktorės Barbaros Schabovskos (Barbara Schabowska), kuri dėl pandemijos paūmėjimo negalėjo atvykti į Vilnių, vardu kalbėjo šio instituto projektų vadovė Aneta Prasal-Višnevska (Aneta Prasał-Wiśniewska).

25 Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų / O dobro Ojczyzny / To Keep The Homeland Alive

Parodos atidarymo rytą svarbiomis įžvalgomis apie Gegužės 3 d. konstituciją ir pasirengimą parodai dalijosi spaudos konferencijos dalyviai – parodos organizatoriai, bendraorganizatoriai ir pagrindinių eksponatus skolinusių įstaigų vadovai (iš kairės į dešinę): Valdovų rūmų muziejaus komunikacijos vadovė Monika Petrulienė, direktoriaus pavaduotoja kultūrai ir mokslui, parodos kuratorė dr. Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė, Vilniaus universiteto bibliotekos generalinė direktorė Irena Krivienė, Varšuvos karališkosios pilies – Muziejaus direktorius profesorius hab. dr. Voicechas Falkovskis, Valdovų rūmų muziejaus direktorius dr. Vydas Dolinskas, Adomo Mickevičiaus instituto projektų vadovė Aneta Prasal-Višnevska ir vertėja Julija Levandovska.

W dniu otwarcia wystawy ważnymi spostrzeżeniami o Konstytucji 3 Maja i o przygotowaniach wystawy podzielili się uczestnicy konferencji prasowej – organizatorzy wystawy, współorganizatorzy i szefowie głównych instytucji, które wypożyczyły eksponaty (od lewej): Monika Petrulienė – kierownik ds. komunikacji Muzeum

Pałacu Wielkich Książąt Litewskich, dr Ramunė ŠmigelskytėStukienė – zastępca dyrektora ds. kultury i nauki Muzeum

Narodowego – Pałacu Wielkich Książąt Litewskich, kurator wystawy, Irena Krivienė – dyrektor Biblioteki Uniwersytetu Wileńskiego, prof. hab. Wojciech Fałkowski – dyrektor Zamku Królewskiego w Warszawie – Muzeum, dr. Vydas Dolinskas –dyrektor Muzeum Narodowego – Pałacu Wielkich Książąt Litewskich, Aneta Prasał-Wiśniewska – kierownik ds. projektów Instytutu Adama Mickiewicza i tłumaczka Julia Lewandowska.

On the morning of the exhibition’s opening, participants at the press conference shared their most important insights about the 3 May Constitution and their preparation for the exhibition – these included the exhibition’s organisers, co-organisers and the heads of institutions that loaned the main exhibits (from left to right): Communications

Director at the National Museum – Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania Monika Petrulienė, Deputy Director for Culture and Science, and the exhibition’s curator Dr Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė, General Director of the Vilnius University Library Irena Krivienė, Director of the Warsaw Royal Castle – Museum Prof. hab. Dr Wojciech Fałkowski, Director of the National Museum – Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania Dr Vydas Dolinskas, Project Director at the Adam Mickiewicz Institute Aneta Prasał-Wiśniewska and interpreter Julia Lewandowska.

Malonu pabrėžti, kad parodos atidarymo iškilmėse dalyvavo ir kitų svarbių Valdovų rūmų muziejaus tarptautinių partnerių iš Lenkijos vadovai: Krokuvos Vavelio karališkosios pilies direktorius profesorius Andžejus Betlejus (Andrzej Betlej) ir Malborko pilies muziejaus direktorius profesorius Janušas Trupinda (Janusz Trupinda).

Parodos ir konferencijos sumanymą, pagrindines idėjas ir turinio akcentus atidarymo renginyje pristatė parodos kuratorė ir konferencijos organizacinės kolegijos vadovė dr. Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė – Valdovų rūmų muziejaus direktoriaus pavaduotoja kultūrai ir mokslui, Lietuvos istorijos instituto mokslo darbuotoja.

Didelėje tarptautinėje parodoje „Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų. Lietuva ir Lenkija 1791 m. konstitucijos epochoje“ buvo eksponuojama ir jos kataloge iš viso pristatoma daugiau nei 200 eksponatų, atkeliavusių net iš 42 atminties institucijų (muziejų, archyvų, bibliotekų, bažnyčių, vienuolynų, fondų) ir privačių rinkinių Lietuvoje, Lenkijoje, Ukrainoje ir Baltarusioje. Rengiant temines parodas ir siekiant atskleisti tam tikrus pasirinktos temos aspektus, visada tenka aktualius eksponatus atsirinkti iš daugelio po kelias šalis pasklidusių kolekcijų. Parodos pasakojimas, kuriame dominavo istorinių asmenybių portretai ir su svarbiausiais įvykiais susiję autentiški dokumentai, buvo struktūruotas į kelias dalis.

Pirmojoje dalyje „Valdovas ir tauta“ apžvelgta Apšvietos (Švietimo, Šviečiamosios) epochos idėjų sklaida, pristatyti valstybės ir visuomenės reformų planai Abiejų Tautų Respublikoje, paskutinio tarpuvaldžio kandidatai į Lenkijos ir Lietuvos valdovo sostą bei pirmieji bandymai realizuoti reformas, Lenkijos karaliumi ir Lietuvos didžiuoju kunigaikščiu tapus Stanislovui Augustui Poniatovskiui, taip pat vadinamosios Baro konfederacijos judėjimas ir jo pasekmės.

Antrojoje parodos dalyje „Tėvynės labui“ stengtasi atskleisti, kaip Lietuva sureagavo į pirmojo padalijimo faktinį ir psichologinį smūgį, kokių tiek valstybinių reformų (pvz., Edukacinės komisijos ir Nuolatinės tarybos įsteigimas), tiek asmeninių permainų iniciatyvų (pvz., Lietuvos rūmų iždininko Antano Tyzenhauzo, Lietuvos didžiojo etmono Mykolo Kazimiero Oginskio, Vilniaus vyskupo Ignoto Jokūbo Masalskio, Lietuvos referendoriaus ir Vilniaus prelato Povilo Ksavero Bžostovskio bei kt. projektai) buvo imtasi norint modernizuoti ir sustiprinti Abiejų Tautų Respubliką iki pat Ketverių metų seimo pradžios.

Trečiojoje parodos dalyje apibūdinta Ketverių metų seimo veikla ir svarbiausios reformų kryptys (pvz., valstybės valdymo, kariuomenės, miestų, diplomatinės tarnybos ir kt.), pristatyti aktyviausi to meto Respublikos valstybininkai (pvz., Vilniaus vaivada kunigaikštis Karolis Stanislovas Radvila, Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės pasiuntinių Seime telkėjas ir vadinamojo „Radvilų klubo“ Varšuvoje įkūrėjas, Lietuvos artilerijos generolas Kazimieras Nestoras Sapiega, vienas Konstitucijos projekto autorių, Livonijos pasiuntinys Seime Julianas Ursinas Nemcevičius, diplomatas, vėlesnis Lietuvos didysis iždininkas Mykolas Kleopas Oginskis ir kt.).

26 Kad Tėvynė

/ O

/ To Keep The Homeland Alive

gyvuotų

dobro Ojczyzny

Parodos atidarymo iškilmėse dalyvavo ir sveikinimo

žodžius tarė parodos bei konferencijos globėjai – Lietuvos

Respublikos Prezidentas Gitanas Nausėda ir Lenkijos

Respublikos Prezidentas Andžejus Duda. Kartu su Lenkijos

Respublikos nepaprastąja ir įgaliotąja ambasadore Lietuvos

Respublikoje Uršula Doroševska jie pirmieji išvydo parodą. Ją pristatė Valdovų rūmų muziejaus direktorius dr. Vydas Dolinskas.

W ceremonii otwarcia wystawy wzięli udział oraz zabrali głos

Prezydenci Republiki Litewskiej i Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej Gitanas

Nausėda i Andrzej Duda. Prezydenci wraz z Ambasadorem

Nadzwyczajnym i Pełnomocnym Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej w

Republice Litewskiej Urszulą Doroszewską jako pierwsi obejrzeli ekspozycję, którą zaprezentował dr Vydas Dolinskas – dyrektor

Muzeum Narodowego – Pałacu Wielkich Książąt Litewskich.

The patrons of the exhibition and conference were present at the exhibition opening ceremony and shared their words of welcome –President of the Republic of Lithuania Gitanas Nausėda and President of the Republic of Poland Andrzej Duda. They, along with the Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Urszula Doroszewska, were the first to see the exhibition. It was presented by Dr Vydas Dolinskas, Director of the National Museum – Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania.

Ketvirtojoje parodos dalyje „Švelnioji revoliucija“ atskleisti svarbiausi Ketverių metų seimo kulminacijos – 1791 m. gegužės 3 d. konstitucijos turinio akcentai: valdymo reforma ir paveldimos konstitucinės monarchijos įvedimas, šalies gynybos užtikrinimas ryškiai padidinant ir modernizuojant kariuomenę, teisingumo užtikrinimas ir modernios tautos kūrimas švelninant baudžiavą ir niveliuojant luominius barjerus. Svarbiausias šios dalies ir bene visos parodos akcentas – iš Varšuvos senųjų aktų archyvo atvežtas autentiškas Gegužės 3 d. konstitucijos dokumentas.

Penktosios parodos dalies „Konstitucija ir Lietuva“ centre buvo rodomas originalus 1791 m. spalio 20 d. Abiejų Tautų tarpusavio įsipareigojimo įstatymo (Tarpusavio įžado) aktas, itin svarbus dokumentas Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės valstybingumo raidai, pakoregavęs, patikslinęs, papildęs Konstituciją, atnaujinęs Liublino uniją ir garantavęs Lietuvai paritetines teises Lenkijos atžvilgiu Abiejų Tautų Respublikoje. Konstitucija buvo lietuvių kompromisas lenkų atžvilgiu, o Tarpusavio įžadas – lenkų nuolaida lietuviams. Abiejų konstitucinės reikšmės dokumentų priėmimo istorija yra puikus politinio kompromiso dėl bendros gerovės, kiekvienos šalies labui pavyzdys.

Šeštojoje parodos dalyje „Tarp išdavystės ir lojalumo“ siekta trumpai pristatyti Ketverių metų seimo reformų ir ypač Gegužės 3 d. konstitucijos oponentus Lenkijoje ir Lietuvoje, taip pat abejotinus jų veiksmus Abiejų Tautų Respublikoje bei tarptautinėje politikoje, naiviai tikintis nesuinteresuotos Rusijos paramos kovoje su politiniais vidaus priešininkais. Daugelio vadinamosios Targovicos konfederacijos atstovų veiksmai priminė atvirą kolaboravimą su priešu ir Tėvynės išdavimą.

27 Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų / O dobro Ojczyzny / To Keep The Homeland Alive

Apžiūrėję parodą, jos globėjai Lietuvos Respublikos

Prezidentas Gitanas Nausėda ir Lenkijos Respublikos

Prezidentas Andžejus Duda pasirašė Valdovų rūmų muziejaus svečių knygoje. Tai jau ne pirma Valdovų rūmų paroda, globojama Lietuvos ir Lenkijos vadovų. Paskutinė tokia –2020–2021 m. rūmuose vykusi paroda – buvo skirta Radvilų giminei.

Patronujący wystawie Prezydenci Republiki Litewskiej i

Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej Gitanas Nausėda i Andrzej Duda Po obejrzeniu ekspozycji wpisali się do księgi pamiątkowej Muzeum

Narodowego – Pałacu Wielkich Książąt Litewskich. To nie pierwsza wystawa organizowana przez Muzeum Narodowe – Pałac Wielkich Książąt Litewskich odbywająca się pod patronatem Prezydentów Litwy i Polski. Ostatnia taka wystawa odbyła się w latach 2020–2021 i była poświęcona Radziwiłłom.

Having inspected the exhibition, its patrons President of the Republic of Lithuania Gitanas Nausėda and President of the Republic of Poland Andrzej Duda signed the National Museum – Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania guest book. This is not the first exhibition held here to enjoy the patronage of the leaders of Lithuania and Poland. The previous one, held at the Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania in 2020 and 2021, was dedicated to the Radziwill family.

Paskutinėje, septintojoje, parodos dalyje „Kova už laisvę“ akcentuota bendros lenkų ir lietuvių kovos už laisvę ir nepriklausomybę istorija, atskleisti bandymai išgelbėti Abiejų Tautų Respublikos kariuomenės ginklo garbę 1794 m. sukilimo, vadovaujamo generolų Tado Kosciuškos ir Jokūbo Jasinskio, bei Napoleono kovų laikais. Taip buvo primenama 1791 m. gegužės 3 d. konstitucijos bei 1794 m. herojiškos kovos atminties tradicija, neišblėsusi visą šimtmetį ir teikusi kūrybinių galių poetui Adomui Mickevičiui, taip pat jėgų ir pergalės viltį XIX a. sukilėliams. Salės centre rodyta dar viena ypatinga istorinė relikvija – XVIII a. pabaigoje ar XIX a. pradžioje sukurtas Gegužės 3 d. konstitucijos vertimas į lietuvių kalbą, liudijantis modernios lietuvių tautos ir jos kalbos atgimimo priešaušrį, poreikį nešti Konstitucijos žinią į kiekvieno raštingo lietuvio trobą.

Lietuvos ir Lenkijos Prezidentams Gitanui Nausėdai ir Andžejui Dudai 2021 m. spalio 19-os vakarą ne tik iškilmingai atidarius parodą, bet ir inauguravus tarptautinę mokslinę konferenciją „Tėvynės laisvės aušra – 1791 m. gegužės 3 d. konstitucija: genezė, turinys, reikšmė“, šios darbiniai posėdžiai prasidėjo jau kitos dienos rytą ir truko iki spalio 21-os vakaro. Konferencijos organizatoriai buvo Nacionalinis muziejus Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės valdovų rūmai, Lietuvos istorijos institutas ir Vytauto Didžiojo universitetas. Partneriai – Lenkijos institutas Vilniuje, Lietuvos Respublikos ambasada Lenkijos Respublikoje, Lenkijos Respublikos ambasada Lietuvos Respublikoje, Didžiojo seimo palikuonių draugija ir Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės institutas. Konferencijoje per dvi dienas pristatyti 27 turiningi moksliniai pranešimai, o jų autoriai atstovavo penkioms Europos šalims.

Po iškilmingos parodos „Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų. Lietuva ir Lenkija 1791 m. gegužės 3 d. konstitucijos epochoje“ atidarymo ceremonijos svečiai turėjo galimybę pirmieji išvysti naująją parodą.

Po uroczystym otwarciu wystawy „O dobro Ojczyzny. Litwa i Polska w epoce Konstytucji 3 Maja” goście mieli okazję jako pierwsi obejrzeć nową ekspozycję.

After the ceremonial opening of the exhibition To Keep The Homeland Alive. Lithuania and Poland in the Epoch of the 1791 Constitution, guests had the first chance to see the new exhibition.

Tarptautinė mokslinė konferencija „Tėvynės laisvės aušra –1791 m. gegužės 3 d. konstitucija: genezė, turinys, reikšmė“ kartu tapo ir pirmuoju tarptautinės parodos „Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų. Lietuva ir Lenkija 1791 m. konstitucijos epochoje“ mokslinės, kultūrinės ir edukacinės programos renginiu bei itin svarbiu akcentu. Šioje programoje dar buvo surengta diskusija apie Gegužės 3 d. konstituciją ir jos vertinimą Lietuvoje, perskaitytos dvi viešos paskaitos (prelegentės dr. Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė ir dr. Lina Balaišytė), taip pat surengti du senosios muzikos koncertai ir du spektakliai. Didelė dalis renginių buvo pasiekiama ir virtualiems lankytojams. Buvo parengtos ir dvi edukacinių užsiėmimų temos, suorganizuotos keturios ekskursijos pavieniams lankytojams su parodos kuratoriumi.

28 Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų / O dobro Ojczyzny / To Keep The Homeland Alive

Parodos „Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų. Lietuva ir Lenkija 1791 m. gegužės 3 d. konstitucijos epochoje“ globėjai Lietuvos Respublikos Prezidentas Gitanas Nausėda ir Lenkijos Respublikos Prezidentas Andžejus Duda parodoje įsiamžino ir prie dar vieno simbolinio eksponato – paveikslo „Bajorai, vilkintys vaivadijų mundurus“ iš Krokuvos nacionalinio muziejaus, kuriame vaizduojami pasiuntiniai į 1776 m. Seimą, Didžiosios bei Mažosios Lenkijos ir Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės delegatai. Antrame plane matoma maršalkos palapinė, ant kurios plevėsuoja vėliavos su Lenkijos Ereliu ir Lietuvos Vyčiu.

Patronujący wystawie „O dobro Ojczyzny. Litwa i Polska w epoce Konstytucji 3 Maja” Prezydenci Republiki Litewskiej i Rzeczypospolitej

Polskiej Gitanas Nausėda i Andrzej Duda, sfotografowani przy symbolicznym eksponacie – obrazie „Szlachta w mundurach wojewódzkich” udostępnionym przez Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie, na którym zostali przedstawieni posłowie na Sejm 1776 r., delegaci z prowincji wielkopolskiej, małopolskiej i Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego. W tle widoczny namiot marszałkowski, na którym powiewają sztandary z polskim Orłem i litewską Pogonią.

Patrons of the exhibition To Keep The Homeland Alive. Lithuania and Poland in the Epoch of the 1791 Constitution President of the Republic of Lithuania Gitanas Nausėda and President of the Republic of Lithuania Andrzej Duda were memorialised at the exhibition next to another symbolic exhibit – the painting Nobles dressed in voivodeship mundur costumes from the National Museum of Krakow, depicting envoys to the 1776 Sejm, delegates from Greater and Lesser Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In the background is a marshal’s tent, above which flags with the Polish Eagle and the Lithuanian Vytis are flying.

Per beveik tris tarptautinės parodos „Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų. Lietuva ir Lenkija 1791 m. konstitucijos epochoje“ vyksmo mėnesius (nuo 2021 m. spalio 19 d. iki 2022 m. sausio 16 d.), nepaisant pandemijos paūmėjimo bangų, joje gyvai apsilankė bemaž 19 tūkst. lankytojų, o dar beveik 10 tūkst. interesantų domėjosi paroda virtualiai. Taigi, bendras parodos ir jos renginių aplankymų skaičius pasiekė bemaž 30 tūkst., o tai yra geras parodos lankomumo rezultatas netgi vertinant ikipandeminiais mastais. Beje, jau 2021 m. spalio 20 d. parodą aplankė gausi Lietuvos ir Lenkijos bendro paveldo aktualizavimo komisija, vadovaujama abiejų šalių kultūros viceministrų Rimanto Mikaičio ir Jaroslavo Selino (Jarosław Sellin).

Parodos bei konferencijos organizatoriai vylėsi, kad tiek mokslinis forumas, tiek tris mėnesius trukusi paroda bei plati jos mokslinė, kultūrinė ir edukacinė programa turėtų leisti sustiprinti istorinę atmintį, griauti stereotipus, giliau pažinti ir objektyviau vertinti XVIII a. antros pusės Lietuvos ir Lenkijos istoriją, susipažinti su svarbiausiomis to meto idėjomis ir žmonėmis, valstybės modernizavimo iniciatyvomis, pilietinės visuomenės kūrimo realijomis ir jų karūnacija – 1791 m. gegužės 3 d. konstitucija. Šis dokumentas Lietuvoje vis dar per mažai žinomas, dažnai vertinamas kontroversiškai. Norint suvokti Konstitucijos epochą ir jos reikšmę Lietuvai labai svarbus platesnis kontekstas. Todėl parodoje ir konferencijoje daug dėmesio buvo skirta ir 1791 m. spalio 20 d. Abiejų Tautų tarpusavio įsipareigojimo įstatymui, kuris, kaip minėta, papildė, patikslino Konstituciją, naujai, paritetiniais pagrindais, sureguliavo Lietuvos ir Lenkijos santykius ir prilygo tarpvalstybinio 1569 m. Liublino unijos akto atnaujinimui.

Parodos atpažinimo ženklu neatsitiktinai buvo pasirinktas vienas iš paskutinio Abiejų Tautų Respublikos valdovo – Lenkijos karaliaus ir Lietuvos didžiojo kunigaikščio – Stanislovo Augusto Poniatovskio vėlyvųjų portretų, kuriame jis pavaizduotas su bėgančio laiko simboliu – klepsidra. Visos epochos reformos vienaip ar kitaip buvo susijusios su šio valdovo vardu. Gaila, kad jam valdant buvo prieita prie Abiejų Tautų Respublikos – Lenkijos Karalystės ir Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės –sunaikinimo ar užkariavimo (ne žlugimo). Ši XVIII a. pabaigos istorijos pamoka turėtų mus visus ir šiandien priversti susimąstyti (kaip matome susimąsčiusį portrete valdovą) apie bėgantį laiką, pastangas keisti gyvenimą, siekti gerovės ir klestėjimo, stiprinti visuomenių ir broliškų tautų, sudariusių Abiejų Tautų Respubliką, vienybę, sutarti tarpusavyje, pasitikėti tik savo jėgomis, patiems ir visiems kartu rūpintis bendru gėriu, saugumu ir jokiomis aplinkybėmis netikėti nesavanaudiška priešų pagalba, nepasikliauti svetimais pažadais, nepasiduoti kurstymams, nebūti naiviems.

29 Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų / O dobro Ojczyzny / To Keep The Homeland Alive

Kitą dieną po parodos atidarymo – spalio 20-ąją – prasidėjo dvi dienas trukusi tarptautinė konferencija „Tėvynės laisvės aušra – 1791 m. gegužės 3 d. konstitucija: genezė, turinys, reikšmė“. Joje per dvi dienas buvo perskaityti 27 moksliniai pranešimai, kuriuos pristatė mokslininkai iš penkių šalių. Fotografijoje užfiksuoti jos dalyviai: Varšuvos universiteto profesorius habil. dr. Andžejus B. Zakževskis, Lietuvos istorijos instituto Archeografijos skyriaus vedėjas, Vytauto Didžiojo universiteto docentas dr. Robertas Jurgaitis, Čenstakavos Jono Dlugošo universiteto profesorius habil. dr. Andžejus Stroinovskis ir konferencijos organizacinio komiteto pirmininkė, Valdovų rūmų direktoriaus pavaduotoja kultūrai ir mokslui dr. Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė.

Dzień po otwarciu wystawy – 20 października – rozpoczęła się dwudniowa międzynarodowa konferencja „Świt wolności ojczyzny“ –Konstytucja 3 Maja. Geneza. Treść. Znaczenie”. Podczas dwudniowych obrad prelegenci z 5 krajów europejskich zaprezentowali 27 referatów naukowych. Na zdjęciu uczestnicy konferencji: Andrzej B. Zakrzewski –profesor Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego; doc. dr Robertas Jurgaitis –kierownik Zakładu Archeografii Instytutu Historii Litwy, docent Uniwersytetu Witolda Wielkiego; dr Andrzej Stroynowski – profesor Uniwersytetu Humanistyczno-Przyrodniczego im. Jana Długosza w Częstochowie i dr Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė – przewodnicząca komitetu organizacyjnego konferencji, zastępca dyrektora ds. kultury i nauki Muzeum Narodowego – Pałacu Wielkich Książąt Litewskich.

The day after the exhibition’s opening, on October 20, a two-day international conference began: Dawn of the Homeland’s Freedom –the 3 May 1791 Constitution: Genesis, Contents, Significance. Over the course of two days, 27 scientific papers were presented by researchers from five countries. Some participants appear in the photograph: Warsaw University Professor habil. Dr Andrzej

B. Zakrzewski, Head of the Department of Archeography at the Lithuanian Institute of History and Associate Professor at Vytautas Magnus University Dr Robertas Jurgaitis, Professor habil. Dr Andrzej Stroynowski from the Jan Dlugosz University in Czestochowa and the chair of the conference organising committee, Deputy Director for Culture and Science at the National Museum – Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania Dr Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė.

Taigi, 1791 m. gegužės 3 d. konstitucijos ir Abiejų Tautų tarpusavio įsipareigojimo (Tarpusavio įžado) įstatymo epocha gali būti aktuali ir nūdienos santykiams tarp Lietuvos ir Lenkijos, taip pat ir tarp kitų regiono šalių –Abiejų Tautų Respublikos tradicijos įpėdinių. Istorinės Konstitucijos reikšmės ir jos ilgalaikės prasmės suvokimą bei vertę akivaizdžiai paliudijo Lietuvos ir Lenkijos valstybių vadovų dėmesys jubiliejiniams Konstitucijos ir Tarpusavio įžado renginiams. Kol buvo rengiamas tarptautinės parodos „Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų. Lietuva ir Lenkija 1791 m. konstitucijos epochoje“ katalogas, prasidėjusi žiauri Maskolijos agresija prieš Ukrainą – vieną istorinių Abiejų Tautų Respublikos kraštų – tik paryškino 1791 m. gegužės 3 d. konstitucijos epochos pamokas ir akivaizdžiai paliudijo, kad agresyvios Maskolijos veikimo būdai šimtmečiais nesikeičia. Ši orda nepakenčia laisvės ir padoraus gyvenimo, ji nepaiso teisės, ji skleidžia įžūlaus melo nuodus. Ir tik bendromis pastangomis galima įveikti šią Rytų barbarybę, kuri gerai pažįstama šio Europos regiono tautoms, pirmiausiai lenkams, lietuviams, ukrainiečiams, baltarusiams. Todėl lenkai ir lietuviai taip giliai jaučia ir supranta ukrainiečių kančią, aktyviai remia jų laisvės ir tiesos kovą prieš patį blogio įsikūnijimą. Negalima leisti pasikartoti 1795 m. įvykiams, kai Abiejų Tautų Respublika buvo ištrinta iš Europos žemėlapio. Džiugu, kad šiandien dauguma Europos šalių yra Ukrainos pusėje, o ne siekia dalyvauti jos dalybose. Pasaulis per pastaruosius du šimtmečius pasikeitė, bet ne ta jo dalis, kurią vienija Maskolija...

Tarptautinės parodos „Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų. Lietuva ir Lenkija 1791 m. konstitucijos epochoje“ ir jos katalogo rengėjų vardu nuoširdžiausiai dėkoju visiems, vienaip ar kitaip prisidėjusiems organizuojant šią parodą. Ypač dėkui muziejams, bibliotekoms, archyvams, fondams, bažnyčioms ir vienuolynams, privatiems asmenimis, skolinusiems esminius parodos objektus – vertingus eksponatus. Galima sugalvoti gražią parodą ir patrauklų jos turinį, tačiau be parodos idėjos, koncepcijos, struktūros ir, svarbiausia, be autentiškų ir kalbančių eksponatų, parodos nebūtų.

Tad labai ačiū svarbiausiems ir patiems dosniausiems parodos eksponatų skolintojams: Vyriausiajam senųjų aktų archyvui (AGAD) Varšuvoje, Lenkijos mokslų ir menų akademijos bibliotekai Krokuvoje, Varšuvos karališkajai piliai – Muziejui, Varšuvos nacionaliniam muziejui, Lietuvos nacionaliniam muziejui, Lietuvos nacionaliniam dailės muziejui, Nacionaliniam M. K. Čiurlionio dailės muziejui, Vilniaus universiteto bibliotekai, Lietuvos mokslų akademijos Vrublevskių bibliotekai, Lietuvos valstybės istorijos archyvui, Lietuvos nacionalinei Martyno Mažvydo bibliotekai, Bažnytinio paveldo muziejui, taip pat šių institucijų vadovams ir specialistams. Dėkui Vilniaus, Kauno ir Panevėžio vyskupijų ganytojams už leidimą pasiskolinti bažnyčiose esančias vertybes. Nuoširdžiai ačiū ir privatiems eksponatų skolintojams –kunigaikščiui Motiejui Radvilai (Maciej Radziwiłł, Varšuva), profesoriui Janui Ostrovskiui (Jan Ostrowski, Krokuva) ir Viliui Kavaliauskui (Vilnius). Parodos turinį ir jos grožį nulėmė visų institucijų, išvardytų katalogo pradžioje, ir privačių asmenų skolinti eksponatai, o parodos organizatoriai tas vertybes tiesiog logiškai sudėliojo ir, jų manymu, tinkamai apšvietė.

30 Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų / O dobro Ojczyzny / To Keep The Homeland Alive

Parodą lydėjo renginių, skirtų 1791 m. gegužės 3 d. konstitucijai, ciklas. Vienas jų – diskusija „Sava ar svetima? 1791 m. gegužės 3 d. konstitucija ir Lietuva“, kurios metu (iš kairės į dešinę) renginio moderatorė dr. Ramunė ŠmigelskytėStukienė ir jos dalyviai profesorius Valdas Rakutis, akademikė dr. (hp) Rūta Janonienė, profesorius Tomas Venclova ir docentas dr. Mindaugas Kvietkauskas diskutavo apie tai, kokį pėdsaką paliko Konstitucijos epocha Lietuvos istorijoje, ar Konstitucija užkirto kelius lietuvių tautinės tapatybės išsaugojimui, ar priešingai – atvėrė naujas politinės ir kultūrinės raidos perspektyvas, taip pat apie tai, ar lietuvių sąmonė „prisijaukino“ Gegužės 3 d. konstituciją.

Wystawie towarzyszył cykl wydarzeń poświęconych Konstytucji 3

Maja. Jednym z nich była dyskusja „Własna czy obca? Konstytucja 3

Maja i Litwa”, podczas której (od lewej) moderator dyskusji dr Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė i jej uczestnicy: prof. Valdas Rakutis, akademik dr Rūta Janonienė, profesor Tomas Venclova i doc. dr Mindaugas Kvietkauskas zastanawiali się nad tym, jaki ślad w historii Litwy pozostawiła epoka Konstytucji: czy Konstytucja zaszkodziła zachowaniu litewskiej tożsamości narodowej, czy wręcz przeciwnie – otworzyła nowe perspektywy rozwoju politycznego i kulturalnego, a także nad tym, czy Litwini traktują Konstytucję 3 Maja jako własną.

The exhibition was accompanied by a cycle of events dedicated to the Constitution of 3 May 1791. One was a discussion “Ours or Theirs?

The Constitution of 3 May 1971 and Lithuania, during which (from left to right) the event moderator Dr Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė and participants Prof. Valdas Rakutis, academic Dr (hp) Rūta Janonienė, Prof. Tomas Venclova and Assoc. Prof. Dr Mindaugas Kvietkauskas discussed the following questions: what mark the Constitution epoch leave on Lithuania’s history, did the Constitution block the safeguarding of the Lithuanian national identity, or conversely, did it open up new perspectives in political and cultural development, also, did the Lithuanian consciousness “warm up to” the Constitution of 3 May?

Šį temiškai pagrįstą eksponatų sudėliojimą organizavo ir daugiausiai triūso rengiant parodą bei katalogą įdėjo žymiausia XVIII a. antros pusės tyrinėtoja Lietuvoje, parodos kuratorė ir katalogo sudarytoja, įvadinio teksto ir nemažos dalies eksponatų aprašų autorė dr. Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė, jai talkino kiti išvardyti katalogo objektų aprašų autoriai, taip pat parodos koordinatoriai – muziejaus specialistai Marijus Uzorka, Gintarė Džiaugytė-Burbulienė, Gintarė Tadarovska, dr. Živilė Mikailienė, Kęstučio Karlos vadovaujama parodų įrengimo grupė ir Mantvido Mieliausko sutelkta restauratorių grupė. Prie parodos prisidėjo ir kur kas daugiau muziejaus darbuotojų, jie taip pat išvardyti parodos katalogo pradžioje. Visoms ir visiems labai ačiū. Už kolegišką bendradarbiavimą ir pagalbą rengiant parodą Vilniuje ypač dėkoju Varšuvos karališkosios pilies – Muziejaus direktoriui profesoriui Voicechui Falkovskiui (Wojciech Fałkowski) ir direktoriaus pavaduotojui Zemovitui Kozminskiui (Ziemowit Koźmiński), panašaus turinio parodą surengusiems Varšuvos karališkojoje pilyje ir iš esmės talkinusiems rengiant parodą Valdovų rūmų muziejuje Vilniuje.

Taip pat širdingai ačiū ir supratingiems rėmėjams, be kurių pagalbos krizės metais tokią didelę parodą surengti būtų buvę labai sudėtinga. Tad dėkojame Lenkijos Respublikos kultūros ir nacionalinio paveldo ministerijai, Adomo Mickevičiaus institutui, Lietuvos Respublikos kultūros ministerijai, Lietuvos kultūros tarybai, taip pat ilgametei Valdovų rūmų muziejaus parodinių ir kitų projektų rėmėjai bei partnerei – draudimo bendrovei „BTA. Vienna Insurance Group“ ir jos vadovui Tadeušui Podvorskiui. Informacinį lauką su savo paroda ir konferencija užvaldyti tradiciškai padėjo ištikimi Valdovų rūmų muziejaus informaciniai rėmėjai: nacionalinis transliuotojas LRT (generalinė direktorė Monika Garbačiauskaitė-Budrienė), dienraštis „Lietuvos rytas“ (vyriausiasis redaktorius Gedvydas Vainauskas), tinklalapis „Lrytas.lt“ (vadovas Tautvydas Mikalajūnas), reklamos įmonė „JCDecaux“ (vadovė Žaneta Fomova), žurnalas „Legendos“ (akcininkas Tomas Balžekas).

Į rankas įduodamo turiningo ir estetiško tarptautinės parodos „Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų. Lietuva ir Lenkija 1791 m. konstitucijos epochoje“ katalogo, kaip akivaizdaus parodos atminimo dokumento, vartytojams ir skaitytojams visų jo rengėjų ir autorių vardu norėtųsi tradiciškai palinkėti estetinių potyrių gėrintis įspūdingomis parodos vertybėmis, mūsų bendros praeities, jos lūžinių momentų ir herojų pažinimo džiaugsmo, taip pat – puoselėti istorinę atmintį ir apmąstyti istorinę patirtį – tiesiog pasimokyti iš viltingos ir dramatiškos mūsų istorijos bei paveldo.

31 Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų / O dobro Ojczyzny / To Keep The Homeland Alive

Dr. Vydas Dolinskas

Dyrektor Muzeum Narodowego –Pałacu Wielkich Książąt Litewskich

WYSTAWA SKŁANIAJĄCA DO REFLEKSJI

NAD NADZIEJĄ NA ODZYSKANIE WOLNOSCI I PRZYPOMINAJĄCA NAUKI PŁYNĄCE Z UTRATY PANSTWA

Podczas otwarcia międzynarodowej wystawy „O dobro Ojczyzny. Litwa i Polska w epoce Konstytucji 3 Maja” w dniu 19 października 2021 r. w wykonaniu litewskiego Kwartetu Smyczkowego im. M.K. Čiurlionisa zabrzmiał legendarny polonez a-moll „Pożegnanie Ojczyzny” uważany za swoisty hymn przypominający o smutnym losie Rzeczypospolitej Obojga Narodów, który został skomponowany przez ostatniego podskarbiego wielkiego litewskiego księcia Michała Kleofasa Ogińskiego. Ta melancholijna, choć czasem pełna nadziei melodia, żegnała każdego zwiedzającego opuszczającego ostatnią salę wystawy. Polonez „Pożegnanie Ojczyzny” za każdym razem skłania nas do refleksji nad losem Rzeczypospolitej Obojga Narodów, nad iskrą nadziei na odrodzenie narodów i państwa, która zabłysła w drugiej połowie XVIII wieku, nad tragicznym końcem, do którego doprowadziły wyłącznie agresywne intencje i interesy sąsiadów.

W 2021 r. obchodzimy 230. rocznicę uchwalenia Konstytucji 3 Maja i aktu „Zaręczenia Wzajemnego Obojga Narodów”. Każda rocznica jest okazją i zachętą do bliższego przyjrzenia się faktom historycznym z dawnej przeszłości, do zastanowienia się nad znaczeniem, przyczynami i konsekwencjami dawnych wydarzeń, wyborami ich uczestników w momentach krytycznych, do wyciągnięcia wniosków z bolesnych lekcji historii. Również ta rocznica przypomniała o nadziei rozbudzonej przez Konstytucję 3 Maja i Zaręczenie Wzajemne Obojga Narodów oraz o tragicznym upadku państwowości Rzeczypospolitej. Historyczne zwycięstwa, które prowadzą do rozkwitu gospodarczego i trwałego dobrobytu, zwykle są wspominane z przyjemnością i dumą, podczas gdy zwycięstwa, po których następuje upadek, zawsze wywołują sprzeczne uczucia i zmuszają do zastanowienia się nad błędami, które mogły wynikać z braku determinacji lub przezorności, niedostatku dalekowzroczności politycznej i dyplomatycznej czy niedoceniania okoliczności zewnętrznych. Co najważniejsze, takie promyki nadziei i dramatyczne konsekwencje zmuszają nas do przynajmniej teoretycznego wyciągania z historii wniosków istotnych zarówno dla teraźniejszości, jak i przyszłości. Międzynarodowa wystawa „O dobro Ojczyzny. Litwa i Polska w epoce Konstytucji 3 Maja” zorganizowana w Muzeum Narodowym – Pałacu Wielkich Książąt Litewskich w dniach od 19 października 2021 roku do 16 stycznia 2022 roku, skłaniała do refleksji nad skomplikowanymi dziejami Rzeczypospolitej Obojga Narodów w XVIII wieku, do czerpania mądrości z doświadczeń historycznych. Warto zaznaczyć, że na Litwie rocznica uchwalenia Konstytucji 3 Maja i Zaręczenia Wzajemnego Obojga Narodów na poziomie państwowym była obchodzona po raz pierwszy w 2021 roku, ponieważ dokumenty te przez długi czas uważano za „obce”, negatywnie wpływające na rozwój państwowości litewskiej. W 2021 roku Muzeum Narodowe - Pałac Wielkich Książąt Litewskich oprócz tej monumentalnej wystawy, będącej zwieńczeniem obchodów roku jubileuszowego, zorganizowało cały cykl wydarzeń, których celem było upamiętnienie rocznicy ważnych dokumentów historycznych i ich znaczenia, oraz współczesna refleksja nad historią sprzed ponad dwóch wieków i rozbudzenie pamięci historycznej.

32 Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų / O dobro Ojczyzny / To Keep The Homeland Alive

Obchody rocznicy Konstytucji 3 Maja i Zaręczenia Wzajemnego Obojga Narodów w Muzeum Narodowym – Pałacu Wielkich Książąt Litewskich zainaugurowała specjalna uroczystość „Twierdza Ojczyzny i Swobód Naszych”, która odbyła się w dniu 5 maja 2021 roku w Wielkiej Sali Renesansowej. Patronat honorowy nad tym programem obchodów objęli Viktorija Čmilytė-Nielsen – Marszałek Sejmu Republiki Litewskiej, prof. Tomasz Grodzki – Marszałek Senatu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, którzy wygłosili słowa powitania oraz Elżbieta Witek – Marszałek Sejmu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, która nie mogła wziąć udziału w tym wydarzeniu, a jej powitanie odczytała Urszula Doroszewska – Ambasador Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej w Republice Litewskiej. W dniu 5 maja obchody rozpoczęto od zaprezentowania w Wielkiej Sali Renesansowej wystawy jednego arcydzieła – pełnowymiarowego portretu reprezentacyjnego ostatniego króla Polski i wielkiego księcia litewskiego Stanisława Augusta Poniatowskiego (1732/1764–1795/1798), datowanego na rok 1783, pędzla Józefa Ksawerego Heskiego (ok. 1740-ok. 1810) – nadwornego malarza Radziwiłłów. Portret ten przez długi czas zdobił rezydencję w Nieświeżu. Z monarchą przedstawionym na portrecie słusznie kojarzą się inicjatywy prawie wszystkich reform państwowych z drugiej połowy XVIII wieku oraz Konstytucja 3 Maja. Portret monarchy, który obecnie jest przechowywany w Narodowym Muzeum Sztuki Republiki Białorusi, prawdopodobnie powstał z inicjatywy książąt Radziwiłłów. Na stoliku obok korony króla Polski została przedstawiona mitra wielkiego księcia litewskiego. W ten sposób został podkreślony federacyjny charakter Rzeczypospolitej Obojga Narodów i podmiotowość Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego jako państwa. Później, 5 maja wieczorem odbyła się dyskusja okrągłego stołu, w której uczestniczyli kontynuatorzy tradycji Rzeczypospolitej Obojga Narodów – Polacy, Litwini, Ukraińcy i Białorusini – wybitni działacze polityczni, społeczni, przedstawiciele nauki i kultury: prof. Vytautas Landsbergis – polityk, muzykolog, przewodniczący Rady Najwyższej Republiki Litewskiej, czyli pierwszy przywódca niepodległego państwa litewskiego; Bogdan Borusewicz – wywodzący się z Wileńszczyzny historyk, polityk, współzałożyciel „Solidarności” i jeden z jej liderów, wicemarszałek Senatu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej; Maria Koc – antropolog kultury, polityk, Przewodnicząca Senackiej Komisji Gospodarki Narodowej i Innowacyjności; Tomas Venclova –poeta, eseista, publicysta, badacz literatury, dysydent, jeden z założycieli Litewskiej Grupy Helsińskiej, profesor Uniwersytetu Yale (USA); Andrzej B. Zakrzewski – polski historyk prawa, badacz ustroju i prawa Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego, profesor Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego; prof. Richard Butterwick-Pawlikowski –badacz osiemnastowiecznej historii Rzeczypospolitej Obojga Narodów, profesor w Centrum Studiów Slawistycznych i Studiów Wschodnioeuropejskich na Uniwersytecie Londyńskim (UCL); Maksimas Milta –specjalista ds. dziedzictwa kulturowego, politolog, kierownik Wydziału Komunikacji i Rozwoju Europejskiego Uniwersytetu Humanistycznego, który sporo lat spędził na Białorusi; Taras Voznyak – ukraiński kulturolog, tłumacz, politolog, współtwórca ukraińskiego ruchu odrodzenia narodowego „Ruch”, dyrektor Lwowskiej Narodowej Galerii Sztuki im. Borysa Woźnickiego; dr Mindaugas Kvietkauskas – litewski literaturoznawca, historyk kultury, poeta, były minister kultury Republiki Litewskiej, docent Uniwersytetu Wileńskiego; dr hab. Alvydas Nikžentaitis – historyk, dyrektor Instytutu Historii Litwy; Žygimantas Pavilionis – litewski dyplomata, ambasador, były przewodniczący Komisji Spraw Zagranicznych Sejmu Republiki Litewskiej. Dyskusję moderowali: dr Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė – znana badaczka historii osiemnastowiecznej, zastępca dyrektora Muzeum Narodowego – Pałacu Wielkich Książąt Litewskich i Virginijus Savukynas –historyk, wnikliwy publicysta i znany dziennikarz.

Zwieńczeniem programu obchodów rocznicy był koncert muzyki grywanej w czasach Sejmu Wielkiego i Konstytucji 3 Maja, który się odbył w dniu 5 maja. Słynna litewska solistka operowa Joana Gedmintaitė (sopran) i znana pianistka Šviesė Čepliauskaitė wykonały utwory Michała Kleofasa Ogińskiego, Wolfganga Amadeusza Mozarta, Gioacchina Rossiniego.

33 Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų / O dobro Ojczyzny / To Keep The Homeland Alive

Ze względu na obowiązujące wówczas ograniczenia dotyczące organizacji imprez w czasie pandemii w Wielkiej Sali Renesansowej Pałacu Wielkich Książąt Litewskich mogła być obecna tylko niewielka liczba uczestników. Cały program był nagrywany przez Litewskiego Nadawcę Publicznego LRT i transmitowany na portalach społecznościowych i stronach internetowych. Oprócz LRT, patronem medialnym była grupa medialna „Lietuvos rytas”. Organizatorem programu obchodów było Muzeum Narodowe – Pałac Wielkich Książąt Litewskich, zaś partnerami programu – Sejm Republiki Litewskiej, Instytut Polski w Wilnie, Ambasada Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej w Republice Litewskiej, Ambasada Republiki Litewskiej w Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej oraz Instytut Historii Litwy.

Ta wieloczęściowa uroczystość inaugurująca obchody odbyła się w Muzeum Narodowym – Pałacu Wielkich Książąt Litewskich w dniu 5 maja, czyli w 230. rocznicę wejścia w życie Konstytucji 3 Maja, główne zaś obchody w Wilnie, przede wszystkim duża wystawa międzynarodowa, zostały przesunięte na koniec października w celu upamiętnienia 230. rocznicy uchwalenia Zaręczenia Wzajemnego Obojga Narodów –niezwykle istotnego dla rozwoju państwowości Litwy. Taki sposób organizacji obchodów wynikał nie tylko z chęci upamiętnienia Konstytucji oraz Zaręczenia Wzajemnego Obojga Narodów, ale również z okoliczności zewnętrznych: Zamek Królewski w Warszawie planował zorganizowanie dużej wystawy poświęconej epoce Konstytucji na początku maja, dlatego też podobna wystawa wykorzystująca po części te same eksponaty mogła być zorganizwana w Pałacu Wielkich Książąt Litewskich dopiero później i otwarta z okazji rocznicy uchwalenia Zaręczenia Wzajemnego Obojga Narodów.

19 października 2021 roku wieczorem – w przeddzień 230. rocznicy uchwalenia przez Sejm Czteroletni Zaręczenia Wzajemnego Obojga Narodów, które miało miejsce w dniu 20 października 1791 r. –Pałac Wielkich Książąt Litewskich wraz ze współorganizatorami – Instytutem Adama Mickiewicza (Warszawa) i Zamkiem Królewskim w Warszawie zaprosił przedstawicieli kultury Wilna i gości na uroczyste otwarcie międzynarodowej wystawy „O dobro Ojczyzny. Litwa i Polska w epoce Konstytucji 3 Maja”. Wraz z otwarciem wystawy odbyła się inauguracja międzynarodowej konferencji naukowej „Świt wolności ojczyzny” –Konstytucja 3 Maja Geneza. Treść. Znaczenie“. W uroczystych obchodach wzięli udział oraz przemówienia wygłosili patroni honorowi wystawy i konferencji – Prezydent Republiki Litewskiej Gitanas Nausėda oraz Prezydent Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej Andrzej Duda. Udział i patronat przywódców państwa litewskiego i polskiego – spadkobierców tradycji państwowych Rzeczypospolitej Obojga Narodów – nadały wydarzeniu szczególny status i podkreśliły żywotność i aktualność historycznych więzi całego regionu. Po przemówieniach Prezydentów zabrał głos prof. Wojciech Fałkowski – Dyrektor Zamku Królewskiego w Warszawie, jeden ze współorganizatorów wystawy. W imieniu Instytutu Adama Mickiewicza – drugiego współorganizatora wystawy – przemawiała Aneta Prasał-Wiśniewska. Dyrektor Instytutu Barbara Schabowska nie mogła przyjechać do Wilna z powodu pandemii. Miło jest podkreślić, że w ceremonii otwarcia wystawy uczestniczyli także szefowie innych polskich instytucji – ważnych partnerów międzynarodowych Pałacu Wielkich Książąt Litewskich: prof. Andrzej Betlej – dyrektor Zamku Królewskiego na Wawelu (Kraków) oraz prof. Janusz Trupinda – dyrektor Muzeum Zamkowego w Malborku. Dr Ramunė Šmigelskytė-Stukienė – kurator wystawy i Przewodnicząca Komitetu Organizacyjnego Konferencji, wicedyrektor Pałacu Wielkich Książąt Litewskich, pracownik naukowy Instytutu Historii Litwy – przedstawiła główne idee wystawy oraz jej najważniejsze akcenty.

34 Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų / O dobro Ojczyzny / To Keep The Homeland Alive

Na obszernej międzynarodowej wystawie „O dobro Ojczyzny. Litwa i Polska w epoce Konstytucji 3 Maja” oraz w jej katalogu łącznie zostało zaprezentowanych ponad 200 eksponatów, pochodzących aż z 42 instytucji (muzeów, archiwów, bibliotek, fundacji, kościołów i klasztorów) oraz ze zbiorów prywatnych z Litwy, Polski, Ukrainy i Białorusi. Podczas przygotowwywania wystawy tematycznej, by odsłonić pewne aspekty wybranego tematu, zawsze konieczne jest wybranie odpowiednich eksponatów z wielu kolekcji rozsianych po kilku krajach. Narracja wystawy, zdominowana przez portrety postaci historycznych i autentyczne dokumenty związane z najważniejszymi wydarzeniami, została podzielona na kilka części.

Pierwsza część „Władca i naród” przedstawiała rozprzestrzenianie się idei epoki Oświecenia (wieku świateł) oraz program reform państwa i budowy nowoczesnego społeczeństwa Rzeczypospolitej Obojga Narodów, kandydatów do tronu Rzeczypospolitej w okresie ostatniego bezkrólewia i pierwsze próby przeprowadzenia reform przez Stanisława Augusta Poniatowskiego po objęciu władzy, a także konfederację barską i jej konsekwencje.

Druga część wystawy zatytułowanej „O dobro Ojczyzny” przedstawiała jak Litwa zareagowała na wstrząs spowodowany I rozbiorem. W tej części wystawy pokazano, jakie inicjatywy zostały podjęte przed Sejmem Czteroletnim w celu modernizacji i wzmocnienia Rzeczypospolitej Obojga Narodów w zakresie reformy państwa (np. powołanie Komisji Edukacji Narodowej i Rady Nieustającej) oraz projekty prywatne (m.in. podskarbiego litewskiego Antoniego Tyzenhauza, hetmana wielkiego litewskiego Michała Kazimierza Ogińskiego, biskupa wileńskiego księcia Ignacego Jakuba Massalskiego, prałata wileńskiego i referendarza litewskiego Pawła Ksawerego Brzostowskiego i inne).

W trzeciej części wystawy została ukazana działalność Sejmu Czteroletniego i najważniejsze kierunki reform (m.in. w zakresie zarządzania państwem, wojska, miast, służby dyplomatycznej, itp.) oraz przywołani główni przywódcy stronnictw politycznych ówczesnej Rzeczypospolitej (m.in. wojewoda wileński książę Karol Stanisław Radziwiłł – założyciel tzw. stronnictwa radziwiłłowskiego w Warszawie, który próbował jednoczyć posłów z Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego, Kazimierz Nestor Sapieha – generał artylerii litewskiej, jeden z twórców Konstytucji, Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz – poseł inflancki w czasach Sejmu Wielkiego, Michał Kleofas Ogiński – dyplomata, późniejszy podskarbi wielki litewski i inni).

W czwartej części wystawy „Łagodna rewolucja” przedstawiono kulminacje Sejmu Czteroletniego –najważniejsze założenia Konstytucji 3 Maja: reformę ustrojową i ustanowienie monarchii dziedzicznej, poprawy stanu obronności państwa poprzez zwiększenie liczebności armii i jej modernizację, zapewnienie ochrony praw chłopów i budowanie nowoczesnego narodu poprzez łagodzenie nadużyć pańszczyzny i uznanie chłopów za pełnoprawnych obywateli. Zapewne najważniejszym eksponatem tej części i całej wystawy był oryginalny egzemplarz Konstytucji z 1791 r. sprowadzony z Archiwum Głównego Akt Dawnych w Warszawie. Centralnym punktem piątej części wystawy „Konstytucja i Litwa” był oryginalny egzemplarz aktu Zaręczenia Wzajemnego Obojga Narodów z dnia 20 października 1791 roku – dokumentu niezwykle ważnego dla rozwoju państwowości Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego, który uściślił i uzupełnił Ustawę Rządową, odnowił akt unii lubelskiej oraz zapewnił Litwie równorzędną z Koroną pozycję prawnoustrojową w ramach Rzeczypospolitej Obojga Narodów. Jeśli zatwierdzenie Konstytucji 3 Maja było ustępstwem Litwy wobec Polski, to Zaręczenie Wzajemne Obojga Narodów było już ustępstwem Polski wobec Litwy. Historia uchwalenia obu aktów prawnych jest zatem doskonałym przykładem kompromisu politycznego, którego celem jest dobro wspólne i dobro poszczególnych państw.

35 Kad Tėvynė gyvuotų / O dobro Ojczyzny / To Keep The Homeland Alive

W szóstej części wystawy zatytułowanej „Między zdradą a lojalnością” pokrótce zostali przedstawieni przeciwnicy reform Sejmu Czteroletniego w Polsce i na Litwie, a zwłaszcza przeciwnicy Ustawy Rządowej, którzy naiwnie liczyli na bezinteresowne wsparcie Rosji w walce z przeciwnikami politycznymi w kraju oraz ich wątpliwa działalność w Rzeczypospolitej Obojga Narodów i polityka zagraniczna. Działania wielu tzw. targowiczan świadczyły raczej o otwartej kolaboracji z wrogiem i o zdradzie Ojczyzny.

W ostatniej, siódmej, części wystawy zatytułowanej „Walka o wolność” została ukazana historia wspólnej walki Litwinów i Polaków o wolność i niepodległość, próby ratowania honoru wojsk Rzeczypospolitej Obojga Narodów podczas insurekcji kościuszkowskiej pod przywództwem generałów Tadeusza Kościuszki i Jakuba Jasińskiego oraz w okresie wojen napoleońskich. W ten sposób w pamięci została utrwalona tradycja Konstytucji 3 Maja i heroicznych walk podczas insurekcji kościuszkowskiej, która przetrwała przez wieki i zainspirowała poetę Adama Mickiewicza, zaś powstańcom dodała sił i dała nadzieję na zwycięstwo. Pośrodku sali wyeksponowano inny szczególny relikt – unikatowy egzemplarz przekładu tekstu Konstytucji 3 Maja na język litewski, wykonany na przełomie XVIII i XIX wieku, świadczący o początkach kształtowania się współczesnego narodu litewskiego i jego języka oraz o potrzebie niesienia przesłania Konstytucji do każdego Litwina umiejącego czytać.