Master

Architecture and Structure Energy Material

Head of Master Course

Peter Althaus

Design Studios

Didier Balissat

Céline Bessire

Luca Deon

Steffen Hägele

Joni Kaçani

Tina Küng

Annika Seifert

Matthias Winter Assistants

Qendrim Gashi

Shehrie Islamaj

Andrew Mackintosh

João Moreira

Modules

Alberto Alessi

Nitin Bathla

Marcel Bächtiger

Heike Biechteler

Oliver Dufner

Torsten Lange

Davide Spina

Caroline Ting

further Professors, Lecturers and Guests

Jürg Conzett

Oliver Lütjens

Ludovica Molo

Johannes Käferstein

Thomas Kohlhammer

Felix Wettstein

Die Tourismusindustrie ist einer der grössten Arbeitgeber in Luzern und trägt als solcher massgeblich zur Produktion von physischen Räumen als konsumierbaren Gütern bei. Gebäude wie das KKL wurden spezifisch als Spektakel in einer Erlebnisökonomie entworfen und gebaut. Der Fokus Architektur & Struktur verschiebt das Blickfeld weg von ihren spektakulären und vielfotografierten Vorderbühnen. Um das unsichtbare Wechselspiel von sozialen und räumlichen Aspekten in diesen Architekturen offenzulegen, werden in ethnographischen Feldrecherchen die (räumlichen) Arbeitsbedingungen die ihre Spektakel (re-)produzieren analysiert und ihr Akteursnetzwerk kartiert. Der Fokus auf diese Sehenswürdigkeiten als Räume der Arbeit soll sie demystifizieren und sozial-räumlich neubewerten. Die Studierenden werden die neu-aufgedeckten (sozialen) Realitäten der analysierten Gebäude materialisieren und verräumlichen indem sie deren Rückseiten umbauen und dabei die moderne Unterteilung in dienende und bediente Räume, oder front- und backstages de-konstruieren.

In unmittelbarer Nähe zum touristischen Zentrum von Luzern liegt Emmen als post-industrielle Nachbarin, stellvertretend für die suburbane Wirklichkeit der gesamten Schweiz. Swiss Suburbia mit seiner hektischen Abfolge heterogener Programme karikiert latent das eigentliche Ziel von Zonenplänen: die Schaffung homogener, einheitlicher Bedingungen innerhalb einer Zone. Doch aufgrund der Fragmentierung ist das abrupte Aufeinandertreffen widersprüchlicher Nachbarn die Regel.

Auf der Suche nach einer neuen Sichtweise schauen wir im Fokus Architektur & Material zwischen singuläre Interessen und über isolierte Objekte hinaus, welche als bizarre Konsequenz von Zonierung, Eigentum und Real Estate Wirklichkeit geworden sind.

Ausgehend vom Wohnen entwerfen wir alternative Wohnszenarien und Formen des Zusammenlebens, die sich das programmatische Aufeinandertreffen an der Rändern von Zonen zu eigen machen. Die direkte Konfrontation und Korrelation mit anderen Massstäben und Morphologien verunreinigt das generische suburbane Wohnkonzept und verknüpft es so mit seiner spezifischen Umgebung.

Im Spiel mit dem Begriff der Metamorphose, μεταμόρφωσις, wie er aus Mythologie und Kunst, Zoologie oder Geologie bekannt ist, untersucht das Studio Architektur & Energie die Architektur in der Abfolge verschiedener Lebensphasen und Funktionen und fragt, wie wir typologische Transformationen von Beginn an mitentwerfen können.

In der Tessiner Grenzgemeinde Chiasso ist der Pendlerverkehr eine planerische Herausforderung, die derzeit noch grossen Bedarf an Parkplätzen mit sich bringt. Als Alternative zur absehbar obsoleten Tiefgarage will das Studio Strukturen entwickeln, die zunächst als oberirdische Parkhäuser dienen und gleichzeitig ihre typologische Transformation in eine zweite Nutzungsphase entwerfen: Wohnen und öffentliches Programm. Innerhalb des Narrativs der Metamorphose und im Experiment eines simultanen Entwurfsprozesses werden die Projekte versuchen, die Lebensspanne eines Gebäudes neu zu definieren.

Zusätzlich zu diesen drei Projektmodulen, von denen die Studierenden eines auswählen, werden fünf umfangreiche Module im Regelsemester entlang des Berufsbildes angeboten. Sie bedingen notwendige Vertiefungen in die eigentliche Materie und fragen verschiedene Kompetenzen zwischen fachlichen, methodischen und sozialen Fähigkeiten ab. Ein interdisziplinäres Lehrteam führt durch die unterschiedlichen Module.

The tourism industry is a major employer in Lucerne and as such it contributes to the production of physical spaces as consumable goods. Buildings like the KKL are specifically constructed to be spectacles performing in an experience economy. The Focus Architecture & Structure studio aims at shifting the perspective away from their spectacular frontstage. To reveal the invisible interplay of social and spatial aspects in these architectures the studio will perform an ethnographic analysis of the labour conditions that (re- )produce their spectacle and map their actor networks. Focusing on these sights as spaces of labour allows the studio to demystify and reevaluate them. Students will materialize and redesign the unveiled social realities by constructively transforming the backstages of the analyzed buildings, de-constructing the modern separation of serving and served spaces i.e. front- and backstages.

In direct vicinity to the touristic Lucerne lies Emmen the post-industrial neighbour that epitomises the suburban condition of all Switzerland. Swiss suburbia with its frantic succession of heterogenous programmes constantly caricatures the main aim of zoning: to generate homogenous, equal conditions within a zone. But due to fragmentation, the rule is the unexpected clash of completely different neighbours. In search of another perspective, Focus Architecture & Material takes a look beyond singular interests and the isolated object as the bizarre consequence of zoning, property and real estate. Addressing housing, the semester proposes alternative scenarios of habitation and forms of co-existence that embrace the programmatic collisions at the edges of zones. Here, the direct confrontation with and correlation to other scales and morphologies contaminates the generic suburban housing scheme and links it to the specific urban landscape.

Playing with the term of μεταμόρφωσις, metamorphosis, as known from mythology and art, zoology or geology, the studio Architecture & Energy explores architecture as a sequence of different life phases and functions and asks how we can anticipate typological transformations from the outset of a design.

In the Ticino border community of Chiasso, commuter traffic is a planning challenge, that currently still brings with it the need for parking spaces. As an alternative to the foreseeably obsolete underground parking, the studio seeks to develop a structure that can initially serve as an above-ground car parking, while simultaneously designing its typological transformation into a second phase of use: housing and public programming. Within the narrative of metamorphosis and experimenting with a simultaneous design process projects will attempt the redefinition of a building‘s lifespan.

In addition to these three project modules, of which students select one, five extensive modules are offered during the regular semester that trace the picture of the architectural profession. They require more intense work on specific topics and call for the application of knowledge, methodological and social skills. An interdisciplinary team of lecturers guides the students through the various modules.

«Tourism, human circulation considered as consumption, a by-product of the circulation of commodities, is fundamentally nothing more than the leisure of going to see what has become banal. The economic organization of visits to different places is already in itself the guarantee of their equivalence. The same modernization that removed time from the voyage also removed from it the reality of space.»

Veranstaltungen Events

Donnerstag

Atelier F400

Thursdays

Atelier F400

Ethnographische Exkursionen

Ethnographic Field Trips

Literatur-Workshops

Literature Workshops

Sprache Language

Deutsch / Englisch

German / English

Bewertung Assessment

Benotete Projektarbeiten

12 ECTS

Marked project work

12 ECTS

Architecture & Structure Spaces of Labour

Tourismus in Luzern

Jeder elfte in der Stadt Luzern erwirtschaftete Franken ist direkt mit dem Tourismus verbunden. Damit liegt die Tourismusintensität Luzerns viermal über dem schweizerischen Durchschnitt und im internationalen Vergleich mit 145 alpinen Tourismusdestinationen auf dem dritten Platz. Jeder achte Arbeitsplatz ist unmittelbar mit der Tourismusbranche verknüpft.1 Zählt man jene Arbeitsplätze hinzu, die für die «zur Leistungserstellung verwendeten Vorleistungen» benötigt werden oder Beschäftigte in «regionale[n] Unternehmen[, die] als Zulieferer in regionale touristische Wertschöpfungsketten eingebunden sind» wie «Reinigungsunternehmen [oder eine] Sicherheitsfirma für ein Museum» dann fällt diese Zahl weitaus höher aus.2

All diese Arbeitenden produzieren Güter, die touristisch verwertbar sind, also von Reisenden konsumiert werden können. Um was für Güter handelt es sich? Der Soziologe Andreas Reckwitz attestiert der postindustriellen Gesellschaft eine immer grössere Abwendung weg von funktionalen Gütern mit Verwendungszweck, hin zu Gütern, die «kulturelle Qualitäten und einen kulturellen Wert haben und zugleich einen Anspruch auf Einzigartigkeit (Authentizität, Originalität etc.) erheben. […] Diese Güter können den Charakter von Dingen und Objekten haben, mehr und mehr handelt es sich aber um Ereignisse».3 Doch was hat das mit Architektur zu tun?

One in eleven Swiss francs earned in the city of Lucerne is directly linked to tourism. This places the tourism intensity of Lucerne four times higher than the Swiss average and in third place when compared with 145 tourist destinations in the Alps. Every eighth job is directly connected to the tourism industry.1 Considering all the jobs that ‘produce the basis for the services’ provided to tourists and with the employees in ‘regional companies that are involved as suppliers in regional tourism value chains’, such as ‘cleaning companies or a security service for a museum’, renders this figure much higher.2

All these workers produce goods that can be touristically exploited, that is, that can be consumed by travellers. What kind of goods are we talking about? The sociologist Andreas Reckwitz claims that the post-industrial society is increasingly turning away from functional goods with a purpose of use towards commodities that ‘possess primarily cultural qualities and value. At the same time they also make a claim to being unique (authentic, original, etc.). [...] Goods of this sort can have the character of things and objects, but they tend more and more to be events’.3 But how does this relate to architecture?

Luzern, Jean Nouvel, 19932000. https://www.businessdestinations.com/relax/hotels/perfect-harmony/

Kuturalisierung der Güter The

Culturalization of Goods

Die touristische Wertschöpfung beschränkt sich heute nicht nur auf Zweige, die auf die Abfertigung von Touristen spezialisiert sind wie Gastronomie oder Hotellerie. Auch «traditionsreiche Dienstleistungen […] verlassen immer mehr die alte Logik der Massenproduktion funktionaler Güter zugunsten der postindustriellen Logik der kulturellen Singularitätsgüter; sie gewinnen zunehmend ihr Profil beispielsweise über […] Designobjekte, solitäre Architektur [mit Authentizitätsanspruch], gastronomische Originalität, […]»4 Reckwitz identifiziert die creative economy, zu der er auch die Architektur zählt, als eine der treibenden Kräfte, die diese Veränderung der (Produktions-)Art von Gütern und deren Konsum vorantreibt, insbesondere auch im Tourismus.5

Die Tourismusindustrie bringt Bauten hervor, die nicht mehr nach rein technischfunktionellen Kriterien erstellt werden, sondern durch architektonische Konzepte auch als einzigartige Bauwerke mit besonderem kulturellem Wert beschreibbar sind. In diesem Prozess, den Reckwitz Kulturalisierung der Güter6 nennt, erfüllen Gebäude wie das KKL eine weitere Funktion, nämlich «den Reisenden für eine gewisse Zeit mit Ereignissen zu versorgen, die als affektiv befriedigend erlebt werden. Ereignisse sind […] keine funktionalen, sondern kulturelle Güter: Sie werden von den Konsumenten nicht gesucht, um sie zu benutzen, sondern um sie (im Moment) zu genießen. Ereignisse sind kulturelle Affektgüter par excellence». 7 Die Architektur geht in diesem Kontext wie die grosse Teile der creative economy in eine experience economy über.8 Diese produziert nach der Architektin Anna Klingmann keine Gebäude mehr, welche funktionellen physischen needs zugewandt sind, sondern vor allem Architektur als Destinationen des desire 9

Today, the value creation in tourism is not limited to branches that specialize in directly catering to tourists, such as restaurants or hotels. Even ‘traditional services [...] have been shedding the old logic of mass-produced functional goods in favor of the post-industrial logic of singular cultural goods. More and more their profiles consist of such things as organic products with claim to authenticity [...] design objects, unique architecture, gastronomic originality’.4 Reckwitz identifies the creative economy – of which, according to him, the field of architecture also forms a part – as one of the driving forces behind this change in the type (of production) of goods as well as their consumption. This is especially true in the case of tourism.5

Buildings are also amongst the products of the tourism industry. But today they are no longer developed according to purely technical-functional criteria. Through utilizing architectural concepts they can furthermore be described as unique structures with a special cultural value. In this process, which Reckwitz calls the culturalization of goods6, buildings like the Lucerne Culture and Conference Centre (KKL) fulfil yet another purpose, namely in ‘providing travellers with short-term, emotionally satisfying events[…]. [E]vents are not functional but, rather, cultural goods. They are not sought out by consumers to be used but, instead, to be enjoyed in the moment. Events are cultural affect goods par excellence.’ 7 In this context, architecture, like large parts of the creative economy, is turning into an experience economy 8 According to the architect Anna Klingmann, this economy no longer produces buildings that only comply with functional and physical needs but, instead, it brings about architecture as destinations of desire 9

«And since society in the sense of “good society” comprehended those parts of the population which disposed not only of wealth but of leisure time, that is, of time to be devoted to “culture” […]. In this process, cultural values were treated like any other values, they were what values always have been, exchange values; and in passing from hand to hand they were worn down like old coins.»

Kulturökonomisierung Cultural Economization

Die experience economy produziert jedoch nur eine geringe Anzahl neuer singulärer Architekturen. Nicht nur bieten historische Städte kaum Platz für Neubauten, man riskiert ausserdem, dass sich in unserem Fall Luzern als Destination einer Städtereise als «unauthentisch [erweist], wenn dem Ort die erhoffte Eigentümlichkeit fehlt und er sich als Ansammlung von Lokalen und Straßenzügen herausstellt, wie es sie überall gibt.»10. Gebäude, «die in der Vergangenheit hergestellt wurden, kommen ab einem gewissen Alter natürlicherweise nur in begrenzter Zahl vor» und eignen sich somit hervorragend, um als einzigartig und authentisch wahrgenommen zu werden.11 Viele dieser Gebäude «stammen aus der Sphäre der Kultur selbst – allerdings der vorökonomischen, der nichtmarktförmigen. […] Ihre Ökonomisierung und Verwandlung in merkantible Güter bedeutet gewiss eine Kommerzialisierung. […] Indem sie nämlich aus ihrem lokalen und historischen Entstehungskontext herausgelöst und in eine translokale und transhistorische Zirkulation [dem Tourismus] eingespeist werden, wird dem Rezipienten ihre qualitative Andersheit gegenüber anderen kulturellen Objekten und Praktiken erst sichtbar. […] Aus der Sicht einer globalen Hyperkultur-Ökonomie ist damit buchstäblich die ganze Welt, die Geschichte und Gegenwart sämtlicher Lebensformen aller Zeiten und Räume zu einer kulturellen Ressource geworden –einer Ressource für die Generierung von Singularitätsgütern.»12

Dieser Prozess der Kulturökonomisierung wird erst durch Arbeitsformen, die als immaterielle Arbeit bezeichnet werden, möglich. Sie beschreibt weniger die Arbeit an materiellen Gütern selbst als an ihrer Kommunikation durch Zeichen und Affekte, einem sogenannten doing culture 13 Vor diesem Hintergrund gewinnen (denkmalpflegerische) Instandhaltungs- und Instandsetzungsmassnahmen historischer Bauten wie der Jesuitenkirche aber auch Umnutzungen vormals funktionaler Gebäude wie des Neubads an Bedeutung. Architekt:innen planen die physische Arbeit, welche an diesen Gebäuden als kulturelle Ressource geleistet werden muss, um «mit Hilfe einer entsprechenden narrativ-ästhetischen Einbettung»14 durch Werbe- oder Eventagenturen singularisiert zu werden. Dabei entstehen Singularisierungsgüter15 wie Konzerte mit Alpenpanorama auf der Pilatus Bergstation.

The experience economy, however, produces only a small number of new singular architectures. Historic cities not only offer little space for new buildings –additionally there is always the risk that, as in our case, Lucerne as a destination for city trips might seem ‘an inauthentic travel destination if it lacks an anticipated degree of uniqueness and seems to have the same types of stores and streets as everywhere else.’10 Furthermore the existing building stock can be of service, as buildings that ‘were produced in the past only remain available in a limited number’ and are thus ideally suited to be perceived as unique and authentic 11 Many of these buildings ‘stem from the sphere of culture itself, though from its pre-economic and non-market-based form culture. […] These were once exclusively embedded in particular local and historical practices and were then removed from this context to become globally circulating cultural goods [for tourism] that now compete with other goods […] in multiple contexts. […] In today’s hyperculture, potentially everything – from high to low culture, from today or the past, or from any place whatsoever – can acquire the value of culture. In hyperculture, any good can be freed from its original context and circulate from place to place around the globe; any good can be regarded as singular on account of its difference from other goods and be reappropriated in different contexts.’12

This process, that Reckwitz calls cultural economization, transforms material things, in our case buildings, into cultural resources (for the generation of singular goods) by commodifying them through work known as immaterial labour It refers to the communication of material things by means of signs and emotions rather than physically processing material things themselves, a production process Reckwitz refers to as doing culture 13 Against this backdrop, new light is shed on the maintenance and renovation of historical buildings (in accordance with a sound historical preservation), such as the Jesuitenkirche, as well as conversions of formerly functional structures, such as the Neubad. Architects take part in designing the physical labour that has to be performed on these buildings as cultural resources in order for them to be singularized ‘with the help of a narrative–aesthetic twist’ by advertising or event agencies.14 This process produces singular goods15, such as concerts with an Alpine panorama at the top station of the Mount Pilatus funicular.

Abeit an/in/mit

Architektur

Work on/in/with Architecture

Solche Singularisierungsprozesse verwandeln die Räume der Tourismusarchitektur – auch wenn sie vordergründig als Infrastruktur oder Museum entworfen wurden, oder vormals dem Gebet oder Sport gedient haben – in spätmoderne Produktionsstätten, oder wie der Ethnologe Gerd Spittler sie bezeichnet: Arbeitswelten 16 Die Tatsache, dass die Tourismusbranche der «grösste und expansivste Zweig der globalen creative economy»17 ist, verleiht den Räumen, in denen die beschriebene Produktion stattfindet, neue Bedeutung.

Es gilt jedoch den Trugschluss zu vermeiden, dass die Produktion nur hochqualifizierte Tätigkeiten der creative economy beinhaltet. Diese «bildet zwar das expansive Zentrum der spätmodernen Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft, aber daneben existieren weiterhin alte und auch neue Branchen, die einer industriellen Logik folgen und standardisierte Güter und Dienste produzieren: zum einen das trotz der Entindustrialisierung weiterbestehende, klassisch industrielle Segment der Förderung und Fertigung von Investitionsgütern (Maschinen etc.) und Rohstoffen; zum anderen die alten und vor allem neuen routinisierten und funktionalen Dienstleistungen (zum Beispiel Reinigung, Transport, Sicherheit). Das Verhältnis zwischen der Kulturökonomie und der Industrieproduktion beziehungsweise den funktionalen Dienstleistungen ist eines der Komplementarität zwischen einer Ökonomie des Besonderen und einer Ökonomie des Standardisierten. Die Ökonomie des Standardisierten bildet gewissermaßen die notwendige Infrastruktur im Hintergrund, damit der Kulturkapitalismus mit seinen Singularitätsgütern im öffentlichkeitswirksamen Vordergrund florieren kann.»18

«Auch Arbeitsplätze sind Gegenstand der Gestaltung. Wir meinen damit nicht, daß am Arbeitsplatz die Stühle besser gestaltet oder die Tapeten etwas freundlicher sein könnten und Topfpflanzen aufgestellt werden müssten. […] Auch Arbeitsplätze sind gestaltet, nicht nur im traditionell-designerischen Sinne, sondern in der Art, wie sie Teilarbeit aus der Gesamtarbeit ausscheiden, ihr Kompetenzen zuteilen oder wegnehmen und Zusammenarbeit erzeugen oder verhindern.»

Such singularization processes transform the spaces in the architecture of tourism into late-modern production facilities – even though they were primarily designed as infrastructures or museums, or formerly housed prayers or sport-competitions – or as the ethnologist Gerd Spittler calls them:‘Arbeitswelten’ 16, which would literally translate into ‘worlds of labour’. The fact that the tourism industry is ‘one of the largest and most expansive branches of the creative economy’ injects new meaning to the spaces in which this kind of production takes place.17

It would be wrong, however, to assume that this production only includes the highly qualified activities of the creative economy. Although the creative economy ‘may represent the expansive center of the late-modern economy and late-modern society, […] it coexists with old and also new branches that follow an industrial logic [that] produce standardized goods and services. On the one hand, and despite industrialization, there still exists a traditional industrial sector devoted to the production of capital goods (machines, etc.) and raw materials. On the other hand, there also exists an old, but newly routinized set of services, which includes such things as cleaning, transportation, and public safety). […]. The relationship between the culture economy and industrial production or functional services is a complementary relationship between an economy of the particular and an economy of the standardized. To an extent, the economy of the standardized provides the necessary background infrastructure so that cultural capitalism, with its singular goods, can flourish in the foreground.’ 18

Rückseiten Backstages

Diese Komplementarität ist auch räumlich. Hinter den vielfotografierten Kulissen der architektonischen Ikonen von Luzern existieren Räume, in denen die hintergründige Arbeit (etwa die Logistik oder das Kuratieren von Ausstellungen) stattfindet und die der Soziologe Erving Goffmann als Back-Regions19 bezeichnet. Er definiert sie als jene Räume, in die man sich zurückzieht, um sich auf die (soziale) Performance in den Front-Regions vorzubereiten, analog zur Hinterbühne in einem Theater. Der Theatervergleich erweist sich als besonders fruchtbar, wenn Reckwitz dem Erbringen der Arbeitsleistung in der Spätmoderne immer mehr performative Züge im Sinne von Darbietungen vor einem Publikum zuschreibt und weniger als Performance im Sinne von Leistung.20

Diese Back-Regions von Gebäuden wie dem Verkehrshaus oder dem Bourbaki Panorama bilden den architektonischen Schauplatz dieses Studios. Ein Blick auf ihre Rückseiten lässt uns die räumlichen Arbeitsbedingungen, welche die architektonischen Spektakel produzieren, bzw. deren Produktion ermöglichen erkennen. Ausgehend von der Annahme, dass Arbeitsbedingungen immer auch gesellschaftliche Strukturen (re-)produzieren erschliesst eine Auseinandersetzung mit den Back-Regions also auch die Rolle, die diese Meilensteine der Architekturgeschichte in der lokalen Bevölkerung einnehmen, jenseits ihrer kulturhistorischen Bedeutung oder Performanz in der experience economy.

This complementarity is also spatial. Behind the much-photographed scenery of Lucerne’s architectural icons, there are also spaces for the hidden labour that builds the basis for the previously described singularization processes (such as logistics or curating exhibitions). The sociologist Erving Goffmann would refer to such spaces as back regions 19 Analogous to the backstage in a theatre, he defines them as the intimate or concealed spaces where people (or actors) prepare for (social) performances in the front regions. This comparison to the theatre proves particularly fruitful when Reckwitz ascribes more and more performative traits to work performance in late modernism in the sense of performances before an audience and less as performance in the sense of productive output.20

The back regions of buildings such as the Museum of Transport or the Bourbaki Panorama form the architectural setting of this design studio. Looking at their backstages reveals the spatial labour conditions that on the one hand are produced by these architectural spectacles and that on the other hand produce them. Based on the assumption that working conditions always (re)produce social structures, an investigation into the back regions also reveals the role that these milestones of architectural history play in the local population, beyond their cultural-historical significance or performance in the experience economy

How does this building work? How is this building made to work?

Ethnografische Feldstudien in den Archtitekturattraktionen Luzerns bilden die Basis für zeichnerische Darstellungen der sichtbaren und unsichtbaren Arbeitsprozesse, die kartographisch mit den Bestandesplänen überlagert werden. Dies eröffnet eine Perspektive für die kollektiven (Co-)Existenzen der sozial-räumlichen Beziehungen von Produzent:in–Konsument:in, Museumsbesucher:in–Reinigungskraft, Konzertbesucher:in–Eventmanager:in, … die allesamt Teil der architektonischen Realität Erfahrung sind.

Denn «[w]enn Arbeit als Interaktion statt als einseitige Aktion konzipiert wird, dann sind die Objekte, auf die sich die Arbeit richtet, mehr als passive Gegenstände, die nach Belieben bearbeitet werden können [sondern treten] [b]eim Spiel, beim Kampf, beim Dienst oder der Pflege quasi als Akteure gegenüber: Sie besitzen Eigenständigkeit, Eigenwillen oder Eigensinn.»21 Ähnlich wie Spittler im vorangestellten Zitat und in seinen weiteren Ausführungen, dass «über die Arbeitskooperation hinaus hier immer auch ein Netz von sozialen Beziehungen [besteht, die] Teil einer Lebens- nicht nur einer Arbeitswelt [sind]»22 die Dichotomie der Beziehung der Arbeitenden zu deren Arbeitsräumen in Frage stellt, hinterfragt auch die Soziologin Albena Yaneva den Gegensatz von Architektur und der Gesellschaft, die sie hervorbringt.23 Wie sie fragen auch wir: «how does this building work? How [is] this building made to work?»24, und bilden so die Grundlage für den Entwurf der Back-Regions der betrachteten Gebäude, also den Umbau ihrer Arbeitswelten durch konstruktive Eingriffe in ihre Rückseiten.

| „Hinter dem Titanium und den Kunstwerken versteckt sich sich das Arbeitsprekariat“

Parole für den 285 Tage Streik der Reinigungskräfte 2021, Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao, Frank O. Gehry, 1997

‘Hidden behind the titanium and the art works lies the precariousness of labour‘

Parole for the 285 days cleaning workers strike 2021, Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao, Frank O. Gehry, 1997

Ethnographic field studies of the architectural attractions of Lucerne form the basis for developing graphic representations of the visible and invisible labour processes and interactions within them. These drawings will then be mapped on plans of the analyzed buildings. The aim is to put the collective (co-)existences of the socio-spatial relations of producer–consumer, museum visitor–cleaner, concertgoer–event manager, ... in perspective, the relations that all form the architectural experience.

The visualization and the underlying understanding of these relations questions the dichotomy of labour and the space where it is performed, or in our case also the (architectural) space on which it is performed. As Spittler conceives labour as interaction rather than unilateral action, he also attributes the objects (in our case the spaces) on which and with which it is performed not only the role of passive resources that can be processed but the role of actors, in play, contest, service or care.21 These spaces as Arbeitswelten are not only the vessel of cooperative working relationships and therefore not simply working environments. Beyond that they also mediate social relations that are not directly related to the production process and become living environments that simultaneously serve production and consumption purposes or house labour and leisure activities.22 In the same vein, the sociologist Albena Yaneva also questions viewing architecture and the society that produces it as well as the society that is produced by it as opposites.23 Like her, we ask: ‘How [is] this building made to work?24 In this way we will build the basis for the design of the back regions of the buildings under consideration, that is, the reconstruction of their working environments (Arbeitswelten) through constructive interventions in their ‘backstage’ spaces.

«I argue for a nonrepresentational way of tackling buildings. Here, we open buildings to the experience, to the course of events that make and consume architecture.»

Durch die Darstellungen der Arbeit an/in/mit der Architektur lassen sich die Luzerner Architekturikonen prozesshaft als nicht-menschliche Akteure in einem gleichermassen sozio-ökonomischen sowie sozio-technologischen Netzwerk verstehen. Sie enden räumlich nicht an der Fassade, sind nicht mit deren Eröffnung vollendet und produzieren soziale Beziehungen jenseits der offensichtlichen Nutzer:innen. Dieser Blick ermöglicht uns, die untersuchten Bauten unabhängig vom Baujahr als zeitgenössische Phänomene zu betrachten, die zeitgenössischer räumlich-konstruktiver Eingriffe bedürfen, um fernab von denkmalpflegerischem Konservatismus oder akademisch-bildhafter Rhetorik auf die Fragen unserer Zeit zu reagieren. Der Umbau ihrer Rückseiten entmystifiziert dabei die Meisterwerke der Architektur, bewertet sie durch physische Eingriffe neu und konstruiert so neue soziale, ökonomische, technische und somit räumliche Realitäten. Dieses Hinterfragen der Hierarchien und Beziehungen von Front- und Back-Region eröffnet dabei alternative Handlungsfelder für Architekt:innen in unserer spätmodernen Gesellschaft der Singularitäten.

Through the graphic presentations of labour on/in/with architecture, Lucerne’s architectural icons can be understood, at a processual level, as non-human actors in an equally socio-economic and socio-technological network. Spatially they do not end with their façade, they are not completed when inaugurated and produce social relationships beyond their obvious users. This vantage point enables us to consider these buildings, regardless of their year of construction, as contemporary phenomena that require contemporary spatial-constructive interventions in order to respond to the issues of our time, far removed from conservatism or (visual) academic rhetoric. These masterpieces of architecture are thus demystified by the reconstruction of their backstages. These physical interventions reevaluate them and construct new social, economic, technical and spatial realities. This spatial and social de-construction of the hierarchies and relationships of front and back regions opens up alternative fields of action for architects in our society of singularities.

«Buildings can only be understood through meticulous studies of their specific ways of working, the worlds they generate and the worlds that set them to work […]. [This] is the method that captures the continuous flow of events that a building always is.»

Omnia mutantur, nihil interit.

Alles verändert sich nur, nichts stirbt. Everything changes, nothing dies.

Publius Ovidius Naso (Ovid), 43-17v. Chr., Metamorphosen

Veranstaltungen Events

Donnerstag

Fokus–Veranstaltungen: Foyer Mäder Saal / Zoom

Tischkritiken: Atelier F400

Thursdays

Focus – Events: Foyer Mäder Saal / Zoom

Table crit: Atelier F400

Sprache Language

Deutsch / Englisch

German / English

Bewertung Assessment

Benotete Projektarbeiten

12 ECTS

Marked project work

12 ECTS

Architecture & Energy Metamorphosis Design for Transformation

Modulverantwortung Module Leader Prof. Annika Seifert, Prof. Luca Deon Dozierende Lecturers Prof. Annika Seifert, Prof. Luca Deon Experten Experts Jürg Conzett Assistent Assistant Qendrim Gashi

Einführung

Metamorphose altgriechisch μεταμόρφωσις metamórphosis, „Umgestaltung“ von μετά metá, „um-“ (als Präfix), und μόρφωσις mórphōsis „Gestaltung“.

In seiner einflussreichen Dichtung Metamorphosen reiht der römische Dichter Ovid hunderte Erzählungen mythischer Verwandlungen aneinander und erzählt durch sie die Geschichte der Welt als eine Geschichte fortwährender Transformation. Können wir auch die scheinbar auf Permanenz ausgerichtete Disziplin der Architektur als Schauplatz unterschiedlicher Lebensphasen und Nutzungen begreifen, ja diese typologische Transformationen bereits von Anfang an entwerferisch antizipieren?

In der Tessiner Grenzgemeinde Chiasso ist der Pendlerverkehr durch die italienischen Frontalieri eine planerische Herausforderung. Doch die für das Ortszentrum geforderten unterirdischen Parkhäuser stellen einen Typus dar, der für die momentane Situation zwar noch unabdingbar scheint, aber durch die voraussehbare Veränderung unserer Mobilität schon bald obsolet sein wird. Als Alternative wollen wir eine Ausgangsstruktur entwickeln, die heute als oberirdisches Parkhaus dienen kann, gleichzeitig aber bereits dessen typologische Transformation in eine zweite Nutzungsphase mitentwerfen, in der Wohnen und öffentliches Programm vorgesehen sind. Damit erproben wir einen simultanen Entwurfsprozess zwischen Flexibiltät und Spezifizität, der den städtischen Kontext, die Trag- und Raumstruktur, und nicht zuletzt Konstruktion und Bauprozess simultan für verschiedene Situationen vorausdenkt, um die Lebensdauer des Gebäudes neu zu definieren.

Introduction

Metamorphosis from Ancient Greek μεταμόρφωσις, „transformation“, from μετα metá, „after“ and μορφή morphḗ, „form“.

In his magnum opus Metamorphoses, the Roman poet Ovid strings together hundreds of narratives of mythical transformations and through them tells the story of the world as a sequence of perpetual transformation. Can we also understand the seemingly permanent discipline of architecture as a sequence of different life phases and functions? Can we even anticipate these typological transformations from the outset?

In the Ticino border community of Chiasso, commuter traffic through the Italian Frontalieri is a challenge for planners. However, the new underground car parkings currently demanded for the town centre represent a building type, that still seems indispensable for the current situation, but will soon be obsolete due to the foreseeable changes in our mobility. As an alternative, we want to develop a structure that can initially serve as an above-ground car parking; at the same time, we will already design its typological transformation into a second phase of use: housing and public programming. In this way, we’ll experiment with a simultaneous design process – between flexibility and specificity, considering the changing urban situation, the load-bearing and spatial structure, and last but not least, the construction and building process – in order to redefine the building‘s lifespan.

Transformation und Graue Energie Transformation and Embodied Energy

Metamorphose

In der Zoologie beschreibt der Begriff der Metamorphose «die Umwandlung der Larvenform zum Adultstadium, dem geschlechtsreifen, erwachsenen Tier (Gestaltwandel). Der Begriff bezieht sich speziell auf Tiere, deren Jugendstadien in Gestalt und Lebensweise vom Adultzustand abweichen.»1 – Raupe zu Schmetterling, Kaulquappe zu Frosch etc. In der Geologie ist Metamorphose «die Umwandlung der mineralogischen Zusammensetzung eines Gesteins durch Steigerung von Temperatur und/oder Druck. Dabei entsteht aus dem Ausgangsgestein […] ein metamorphes Gestein.»2 In beiden Fällen findet eine erhebliche «Umgestaltung» statt, die im Wesentlichen durch Zuführung von Energie aber auf Basis einer vorhandenen physischen Masse stattfindet.

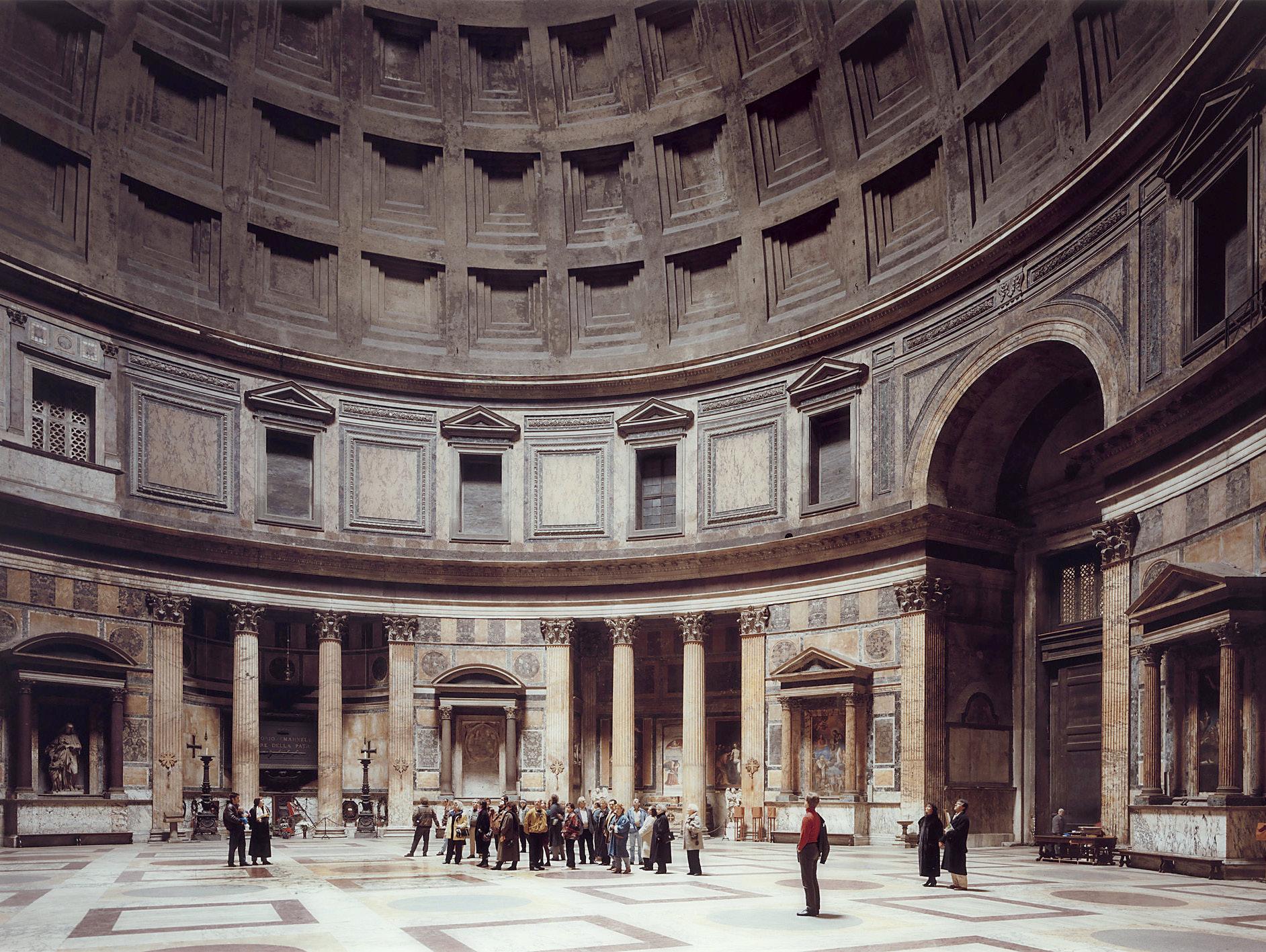

In der europäischen Kulturgeschichte wird gebaute Architektur oft als Gegenpol zur Vergänglichkeit und fortwährenden Selbsterneuerung der Natur dargestellt. Bei genauer Betrachtung sind jedoch auch scheinbar permanente Bauzeugnisse fortwährender Wandlung unterworfen. Vor allem Funktion und Nutzung wechseln über die Lebensdauer von Gebäuden und bedingen Anpassungen und Überformungen. Das aktuelle Thema der Umnutzung ist damit keine Erfindung unserer Zeit. Was uns heute angesichts von Ressourcenknappheit aber auch von Energieund Emissionsproblemen als neuer Imperativ erscheint, ist hinlänglich aus der Geschichte bekannt: Die typologische Überformung bestehender Gebäudestrukturen zur Umnutzung unter veränderten Bedürfnissen oder mit gänzlich neuem Programm. Nichtsdestotrotz können wir in Mitteleuropa seit geraumer Zeit beobachten, wie strukturell intakte Gebäude bereits wenige Jahrzehnte nach ihrer Fertigstellung abgerissen und durch Neubauten ersetzt werden – lang bevor sich die in den Bau investierte Graue Energie amortisiert hat. Die Schweizer Architektengruppe Countdown 2030 schreibt dazu: «Heute fallen beim Bau eines neuen Gebäudes durchschnittlich so viel Energieverbrauch und Treibhausgas-Emissionen an, wie während 50 Jahren im Betrieb. Lösungsansätze für dieses Problem liegen im Erhalt, im Umbau und in der Umnutzung bestehender Gebäude. Abrisse und Ersatzneubauten sollten […] nicht länger als erste und beste Option gelten.»3

Provide for change of use: The Aquatics Centre is designed with an inherent flexibility to accommodate 17,500 spectators for the London 2012 Games in ‘Olympic’ mode while also providing the optimum spectator capacity of 2000 for use in ‘Legacy’ mode after the Games.

Doch auch wenn sich das Bewusstsein um die energetische Relevanz des gebauten Bestandes zunehmend durchsetzt, bleibt die Frage: Warum wird der Abriss dem Erhalt und der Umnutzung von Gebäuden so oft vorgezogen? Und: Was macht eine Architektur aus, der eine lange Lebenspanne zu Teil wird?

Flexibilität

Das Credo der Moderne, form follows function, fordert den Zuschnitt der Architektur auf eine bestimmte Funktion und deren spezifische Anforderungen. Doch selbst bei gleichbleibender Nutzung bedeuten gesellschaftliche, wirtschaftliche, technische Veränderungen immer auch eine Änderung der funktionellen Abläufe und Ansprüche. Je eindeutiger ein Bauwerk auf eine spezifische Funktion zugeschnitten ist, desto aufwändiger eine Adaption. Je flexibler es - strukturell, räumlich, ja sogar im Ausdruck - konzipiert ist, also je transformierbarer es gedacht ist, desto wahrscheinlicher ist eine lange Lebensspanne.

Systemtrennung

Unterschiedliche Bauteile haben eine unterschiedliche Lebensdauer. Die Primärstruktur eines Hauses ist in der Regel langlebiger als seine Fassadenteile. Besonders schnell überholt sind Innenausbau und Gebäudetechnik. Wenn Elemente mit unterschiedlicher Lebenserwartung im Bau systematisch getrennt werden, können schneller alternde Teile repariert und ersetzt werden, ohne das gesamte Gebäude zu tangieren.

Gültigkeit

Städtische Setzung, Volumetrie und Ausdruck von Gebäuden prägen unweigerlich den öffentlichen Raum. Ihr Beitrag zu einem qualitätvollen Ort ist entscheidend für die Akzeptanz eines Gebäudes. Dem praktischen Anspruch and Flexibilität und Transformierbarkeit steht daher gleichzeitig ein Bedürfnis nach Identität und Permanenz gegenüber, die über das Individuelle, Zwischenzeitliche der Nutzung und der Nutzenden hinausreichen und der Architektur ihre Daseinsberechtigung und Relevanz im Kontext geben.

Metamorphosis

In zoology, the term metamorphosis describes „the transformation of the larval form to the adult stage, the sexually mature adult animal (shape change). The term refers specifically to animals whose juvenile stages differ in shape and lifestyle from the adult state.“1 – Caterpillar to butterfly, tadpole to frog, etc. In geology, metamorphism is „the transformation of the mineralogical composition of a rock by increasing temperature and/or pressure. In the process, a metamorphic rock is formed from existing rock [...].“2 In both cases, a significant „Re-Formation“ takes place, essentially through the addition of energy but on the basis of an existing physical mass.

In European cultural history, built architecture is often understood as the antithesis of nature‘s transience and perpetual self-renewal. On closer inspection, however, even seemingly permanent built fabric is subject to continual change. More than anything, it is function and use, which change over the life span of buildings and require adaptations and transformations. The discourse around adaptive reuse of buildings is therefore not an invention of our time. What today, in view of the scarcity of resources, of energy crisis and greenhouse gas emissions, appears to be a new imperative is well known from history: The typological transformation of existing architecture for re-use under changed needs or with a completely new programme.

Nevertheless, for some time in Central Europe we have been observing how structurally intact buildings are being demolished and replaced by new buildings just a few decades after their completion - long before the invested embodied energy has paid for itself. The Swiss architects‘ group Countdown 2030 writes: „Today, the construction of a new building produces on average as much energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions as it does during 50 years of operation. Possible solutions to this problem lie in the preservation, conversion and re-use of existing buildings. Demolition and replacement of new buildings should [...] no longer be considered the first and best option“.3 But even if awareness of existing buildings as an important (energy) resource is on the rise, the question remains: Why is demolition so often preferred to the preservation and conversion of buildings? And: What defines architecture that has a long life span?

1 S ource : https:// de.wikipedia.org/ wiki/Metamorphose_(Zoologie)

2 S ource : https:// de.wikipedia.org/ wiki/Metamorphose_(Geologie)

3 S ee : www.abrissatlas.ch

Lasting spatial and structural qualities in Urban Context

Piazza Navonas in Rome, Italy is dervied originally from the Stadium of Domitian, built in the 1st century AD. Since the foundations and partly the outer walls of the stadium continued to be used for the medieval houses, however, the shape of the arena has been preserved to this day.

Images: G. B. Nolli, ‚Extract of ‚La Pianta grande di Roma‘ (1748), bottom right. Current photo of the Piazza Navona, top left. Present aerial view with a reconstructed Stadium of Domitian, turismoroma.it, i. right.

Flexibility

The modernist credo, form follows function, demands that architecture be tailored to a specific function and its specific requirements. But even if the use remains the same, social, economic and technical changes always mean a change in functional processes and demands. The more clearly a building is tailored to a specific function, the more difficult it is to adapt. The more flexible it is designed to be - structurally, spatially, even in expression - i.e. the more transformable it is intended to be, the more likely it is to have a long life span.

System separation

Different components have different lifespans. The primary structure of a house is usually more durable than its façade components. Interior fittings and building technology become obsolete particularly quickly. If elements with different life expectancies are systematically separated in the building, ageing parts can be repaired and replaced more quickly without affecting the entire building.

Validity

The urban setting, volumetry and architectural expression of buildings inevitably shape public space. Their contribution to a sense of place is decisive for the acceptance of a building. The practical demand for flexibility and transformability is therefore simultaneously matched by a need for identity and permanence that go beyond the individual, transient nature of the use and the users and give architecture its raison d‘être and relevance in its context.

Chiasso

Chiasso – Transit und Station

Die Entwicklung von Chiasso ist stark von seiner besonderen Lage als südlichster Ort der Schweiz geprägt und in ihrer strategischen Bedeutung für den Transitverkehr auf Schiene und Strasse. Bereits im 16 Jh. war Chiasso als Durchgangsort bekannt. Regionale Bedeutung erhielt die Stadt Chiasso allerdings mit dem Aufkommen des Eisenbahnverkehrs und der Erschliessung der Bahnlinie Chiasso-Lugano (1874) sowie nach Como (1876). Der Bahnhof (1874) und der Grenzhandel mit späterem Zollfreilager (1925) führten bald zum wirtschaftlichen und demografischen Aufschwung Chiassos die ab den 1980er Jahren abflachte. Mit der neuen Gotthard-Bahnachse verlor auch der Bahnhof in Chiasso Anfang des 21. Jahrhunderts an Bedeutung.4 Konträr zum rückläufigen Stellenwert der internationalen Bahnverbindung für die Region nahm in den letzten 25 Jahren der Grenzgängerverkehr deutlich zu. Inzwischen pendeln knapp 75‘000 Personen aus Italien täglich zur Arbeit ins Tessin. Transit, Migration und der binationale Arbeitsmarkt sind im Tessin ein politisches und wirtschaftliches Dauerthema.

Concept plan for the Urban development

5 w i T h T he expre SS way T haT run S alon G i T in T he norT h an D T hrou G h T he bor D er - cro SS in G poin T

6 i T i S T herefore no T aT all S urpriS in G T haT a fe D eral a S ylum cen T re i S S i T uaT e D T here . T he S ol D ini D i ST ric T , a former wor K er S ’ hou S in G e STaT e in T he proximi T y of T he cen T ral railway STaT ion , canno T D i SG ui S e T he fra G menTary ST ruc T ure

7 o n T he curren T

S paT ial ST raT e G y S ee ‘ e S brauch T D a S e n G a G emen T aller

– r aumplanun G im T e SS in ’, werk , bauen + wo H nen (5/2018):

Interview: Michele Arnaboldi, Ivo Durisch and Riccardo De Gottardi as well as Ludovica Molo in discussion with Tibor Joanelly and Daniel Kurz.

Zwischen Fluss und Trassee

Die Stadt Chiasso wird städtebaulich wesentlich vom Eisenbahnnetz und der nach Italien führenden Durchgangsstrasse der Corso S. Gottardo nach Como geprägt. Sind die Peripherie von Chiasso durch die Flüsse Breggia5 und Faloppia natürlich begrenzt, ist es die von Westen nach Osten verlaufende Bahnstrecke die den innerstädtischen Raum zweiteilt. Die Segregation zeigt sich auch in der Nutzung, während im Norden der Bahnstrecke das städtische Gefüge eine gelebte Dichte mit Wohnvierteln, Geschäften und kulturellen Institutionen bietet, ist der Grossraum südlich der Geleise ein Nicht-Ort, ein Ort vorbehalten für die internationale Logistik, Freizeitanlagen und Verwaltungsbauten der Stadt.6

Die Stadt Chiasso hat ausgehend auf einer territorialen Raumstrategie7 seit 2017 den kommunalen Aktionsplan PAC für eine städtische Vision in Planung gegeben. Insbesondere die Steigerung der Wohnqualität, die innerstädtische Vernetzung und die Aufwertung / Bereitstellung von Freiräumen sind Ziele des PAC, die auch den südwestlichen Gemeindeteil einbeziehen.

Warte-Raum

Unser Standort befindet sich im Osten vom Quartier Soldini. An der Strasse Via C. Cattaneo liegt ein heutiger Parkplatz. Das Gelände schliesst auch ein Remisebau, ein heutiges Judo Studio, mit ein. Wir nehmen die Fläche zum Anlass, auch zukünftig ein Angebot für das Abstellen von Motorfahrzeugen, zumindest für die nächsten 20 Jahre anzubieten. Die eigene Mobilität bleibt im Tessin auch vorerst beliebt. Der Standort ermöglicht einerseits die innerstädtische Nachfrage nach geeigneten Parkierungsmöglichkeiten zu bedienen. Anderseits bietet das Parkhaus als regionaler HUB eine Chance Grenzgängern und Pendlern aus Italien wie auch Schweizern eine Umsteigemöglichkeit als Park & Ride auf das ÖV-Netz in Nähe des Bahnhofs zu ermöglichen.

Chiasso – Transit and Station

The development of Chiasso is strongly influenced by its particular location as the southernmost town in Switzerland and in its strategic importance for transit traffic by rail and road. Chiasso was already known as a transit town in the 16th century. However, the town of Chiasso gained regional importance with the advent of railway traffic and when the Chiasso–Lugano railway line was opened in 1874 and to Como in 1876. The railway station (1874) and border trade with the later duty-free warehouse (1925) soon led to Chiasso‘s economic and demographic upswing, which levelled off from the 1980s onwards. With the new Gotthard railway axis, the railway station in Chiasso also lost importance at the beginning of the 21st century.4 In contrast to the declining importance of the international railway connection for the region, cross-border traffic has increased significantly in the last 25 years. Today, almost 75,000 people commute daily from Italy to work in Ticino. Transit, migration and the binational labour market are an ongoing political and economic issue in Ticino.

Between River and Railway Line

In terms of urban development, the city of Chiasso is essentially shaped by the railway network and the Corso S. Gottardo through road to Como, which leads to Italy. While the periphery of Chiasso is naturally bounded by the Breggia5 and Faloppia rivers, the railway line running from west to east divides the inner-city space in two. The segregation is also evident in the use to which it is put. While to the north of the railway line the urban fabric offers a living density with residential areas, shops and cultural institutions, the large area to the south of the tracks is a non-place, a place reserved for international logistics, leisure facilities and administrative buildings of the city.6

Since 2017, the city of Chiasso has been planning the municipal action plan PAC7 for an urban vision, based on a territorial spatial strategy. In particular, the objectives of the PAC are to improve residential quality and inner-city networking and upgrade / provide open spaces, which will also be the case for the south-western part of the municipality.

Waiting Space

Our location is in the east of the Soldini district. Via C. Cattaneo is a street with a car park at present. The site also includes a non-residential outbuilding and, currently, also a judo studio. We are using this area as an opportunity to offer parking for motor vehicles in the future, at least for the next 20 years. Personal mobility will remain popular in Ticino for the time being. On the one hand, the location makes it possible to meet the inner-city demand for suitable parking facilities. On the other, as a regional HUB, the car park offers those crossing the border and commuters from Italy as well as Swiss citizens the opportunity to transfer to the public transport network as a park-and-ride system near the station.

Aufgabenstellung

Noch heute wird die Vielzahl aller Parkings unterirdisch gebaut. Das spart auf den ersten Blick Platz - Im besten Fall, um Freiraum zu schaffen. Doch wie sieht es mit der CO2 Bilanz aus? Nicht nur wird teures Volumen, auch wird wertvolle Energie verbaut. Und für was werden die unterirdischen Flächen gebraucht, sollten wir dereinst uns von einer individuellen Beförderung verabschieden?

Wenn aus der Logik ein anderer Umgang gefordert ist, feiert das oberirdische Parkhaus gerade ein Revival? Was wenn Strukturen angeboten werden, die mit den Bedürfnissen der Zeit mitgehen und über die Zeit transformierbar sind? Bietet nicht eine offene und weite Stützenstruktur, im Typus von Park- und Lagerhäusern angelegt, die Flexibilität für künftige Nutzungsveränderungen? Erste aktuellen Beispiele zeigen das Parkhäuser mehr sein können als die Summe ihrer Abstellflächen. Ein Gebäude als ein Regal, das sich mit Nutzungen wie Wohnen füllen lässt, diese Idee ergründen wir in der Aufgabe für Chiasso.

Even today, the majority of all parking facilities are built underground. At first glance, this saves space – at best, it creates free space. But what about the carbon balance? Underground parking is not only very costly in volume, but also uses a large amount of valuable energy. And what will the underground space be used for if we should say goodbye to individual transport in the future?

If logic demands a different approach, is the above-ground car park currently experiencing a revival? What if we offer structures that keep pace with changing demands over time and can be transformed accordingly? Doesn‘t an open and wide support structure, designed in the type of parking and storage buildings, offer the flexibility for future changes in use?

Initial examples currently show that multi-storey car parks can be more than the sum of their parking spaces. A building as a shelf of sorts that can be filled with uses such as dwelling, this is the approach we are exploring in the task for Chiasso.

Nutzungsphase 1:

Raumprogramm

Oberirdisches Parking – Anzahl Parkplätze: 450 - 600PP für PKW. Gebäudehöhe bis 30m. – Mobilitätskonzept mit ergänzenden Angeboten (Car-Sharing, Velos, etc.).

Vorgaben an Fahrwege- und Parkierungsgeometrie nach neuer VSS Norm VSS 40 291 Parkieren. Brandabschnitte sowie Flucht- und Rettungswege nach gültigen VKF-Brandschutzvorschriften. Anforderungen an Technische Anlagen (Schranken, RWA, Sprinkleranlage, , etc.) sind nur konzeptionell zu berücksichtigen.

Nutzungsphase 2:

Wohnen

Transformation des projektierten Parkhauses für Wohnzwecke.

Wohnungsspiegel (Small, Medium, Large) und Wohnform (Familien- und Alterswohnen, Wohnen und Arbeiten, Wohncluster, Rohbau zum Selbstausbau, etc.) projektspezifisch.

Zusatznutzung

– Grossmassstäbliche Zusatzfunktion (Markt, Sport, Versammlung, Kultur, etc.) für halböffentliche bis öffentliche Nutzung, projektspezifisch.

Spatial programme

Stage of use 1:

Above-ground parking

– Parking spaces for cars: 450 – 600. Height of the building up to 30m. – Mobility concept with supplementary offers (car sharing, bicycles, etc.).

Requirements for driving lanes and ramps and parking geometry according to the new VSS standard VSS 40 291 for parking [VSS Norm VSS 40 291]. Fire compartmentalization for fire protection as well as escape and emergency routes according to valid VKF fire protection regulations [VKF-Brandschutzvorschriften]. Requirements for technical systems (barriers, SHEVS, sprinkler systems, etc.) are only to be taken into account conceptually.

Stage of use 2:

Dwelling

Transformation of the projected parking house for residential purposes.

Residential units (small, medium, large) and housing type (family and retirement living, residential and working, housing cluster, shell for self-development, etc.), project-specific.

Complementary function

– Large-scale additional function (market, sports, assembly, culture, etc.) for semi-public to public use, project-specific.

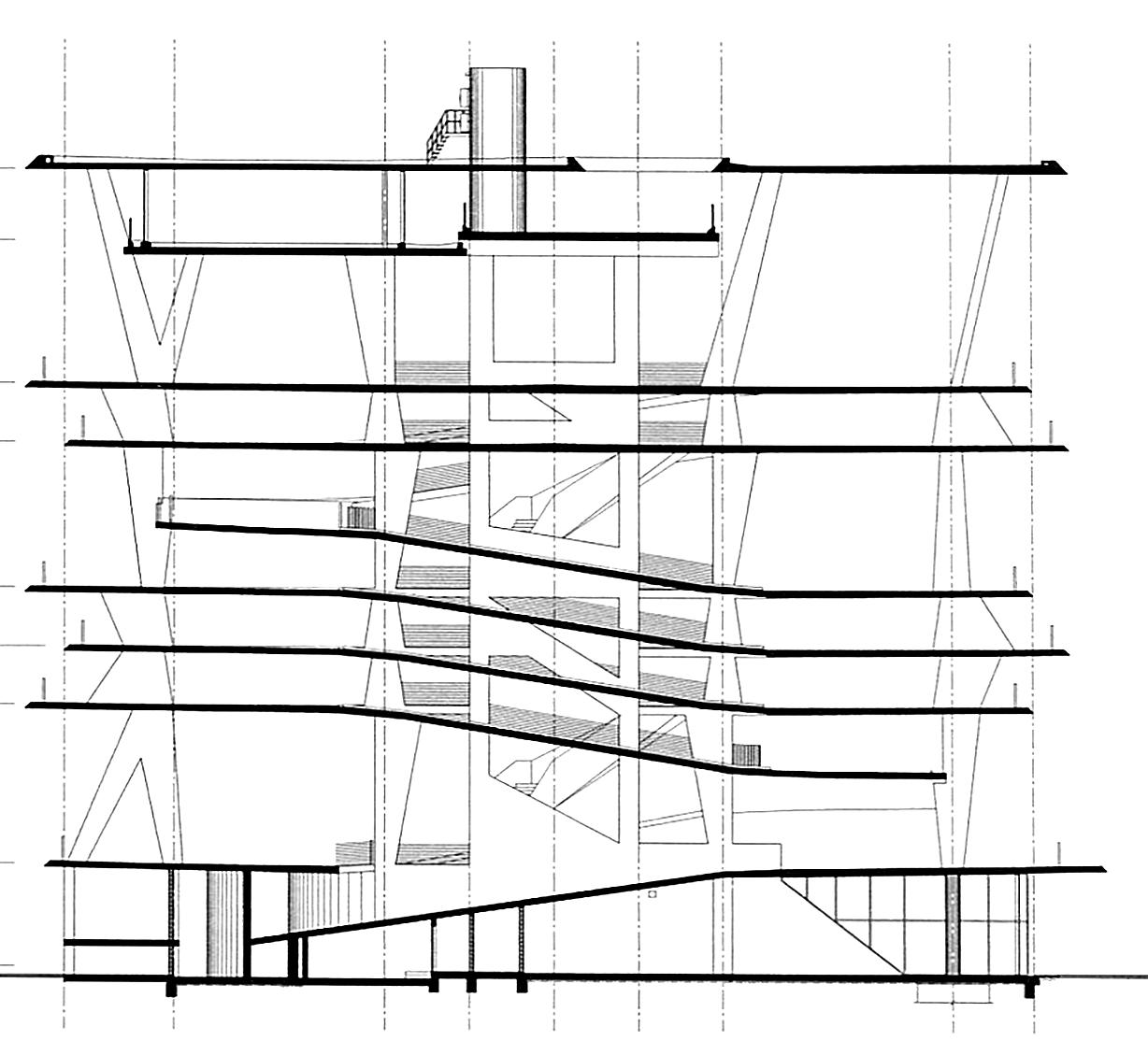

Simultanes Entwerfen

Entscheidend für eine erfolgreiche Metamorphose ist, dass beide Nutzungsphasen und ihre Funktionen simultan entworfen werden. Im Umgang mit der Metamorphose entscheiden sich die Studierenden frühzeitig im Semester für eine Strategie, die ihnen durch sorgfältige Analyse funktionaler und architektonischer Qualitäten und unter folgender Aspekte geboten erscheint:

– Strategie Erhalt, Transformation, Umbau, Aufstockung, Teilrückbau, Ergänzung

Programm, Typologie und Statik Adaptierbarkeit, Wirtschaftlichkeit, Rückführbarkeit (Design for Disassembly), Erweiterbarkeit

Wahl der Konstruktion (Tragkonstruktion + Gebäudehülle)

Holz <> Stahl/Alu <> Beton/Stein; Hybride Werke sind zulässig.

Systemtrennung und Fügung Tragstruktur, Raumstruktur, Infrastruktur, Tektonik

Die synoptische Übersicht15 mittels Aufriss einfacher Konzepte der obigen Aspekte, hilft uns frühzeitig die Weichen für die Ausarbeitung des Projekts in beiden Nutzungsphasen zu stellen und in kurzer Zeit Fragen der Strategie, Typologie, Struktur, Energie und Konstruktion in ihrer Angemessenheit und Nachvollziehbarkeit abzuwägen und auszuarbeiten.

Simultaneous design

Crucial for a successful metamorphosis is that both phases of use and their functions are designed simultaneously. In dealing with the metamorphosis, the students decide early in the semester on a strategy that seems appropriate to them by carefully analysing the functional and architectural qualities and under the following aspects:

– Strategy

Preservation, transformation, conversion, adding storeys, partial deconstruction, additions

– Programme, typology and statics

Adaptability, economic efficiency, dismantling options (design for disassembly), expandability

– Choice of construction (supporting structure + building envelope)

Wood <> steel/aluminium <> concrete/stone; hybrid constructions are allo wed.

– System separation and joining Load-bearing structure, spatial structure, infrastructure, tectonics

The synoptic outline , by means of breaking down the above aspects into simple concepts, helps us, at an early stage, to set the course for the elaboration of the project in both phases of use and to weigh and work out solutions to the problems of strategy, typology, structure, energy and construction that are appropriate and comprehensible – and do this in a relatively short time.

Semesterstruktur Semester Structure

Die Arbeit im Semesterentwurf ist begleitet durch regelmässige Tischkritiken. Vorübung, Workshops zur gemeinsamen Wissensaneignung und Zwischenkritik sind wichtige Etappen im Semester; ergänzt durch die Inputs von externen Experten schaffen sie ein Fachverständnis und vertiefte Auseinandersetzung im Entwurf. Wir üben so, die eigene Entwurfshaltung zu formulieren und durch kritische Reflexion laufend zu präzisieren. Regelmässige Präsentationen in Wort, Bild und Modell zeichnen den eigenen Entwurfsprozess ab, fördern die Selbstreflexion und mit ihr die Entwurfssicherheit.

The work in the semester project is accompanied by regular desk critiques. Preliminary exercises, workshops for the mutual acquisition of knowledge and interim critiques are important steps in the semester course. Supplemented by the input from external experts, they foster a professional understanding and in-depth critical analysis of the design. In this way, we practise developing our own design approach and continually refine it through critical reflection. Regular presentations in words, images and models record each student’s design process, promote self-reflection and, with it, confidence in designing.

Veranstaltungen Events

Donnerstag

Atelier F400

Thursdays

Atelier F400

Sprache Language

Deutsch / Englisch

German / English

Bewertung Assessment

Benotete Projektarbeiten

12 ECTS

Marked project work

12 ECTS

AFTER ALIFE AHEAD

Case Studies for the 21st Century

«I‘m talking about drawing a line in the sand, Dude, across this line YOU DO NOT...»1

Das Baurecht verspricht Vorhersehbarkeit und Eigentumsschutz; in Wirklichkeit entstehen durch die Parzellierung an den Rändern aber unablässig Restflächen. Wenn das Erstellen von Gebäuden und ihrer Umgebung an einzelne Akteur*innen mit isolierten Interessen delegiert wird, verkümmert das Unbebaute zur Pufferzone. Swiss Suburbia mit seiner hektischen Abfolge heterogener Programme karikiert so latent das eigentliche Ziel der Zoneneinteilung: die Schaffung homogener, gleicher Bedingungen innerhalb einer Zone. Denn aufgrund der Fragmentierung ist das abrupte Aufeinandertreffen widersprüchlicher Nachbarn die Regel: Zonierung hat alles in Ordnung gebracht, aber ein Stakkato von Irgendwas erzeugt.

Im Semester suchen wir neue Perspektiven: Wir verlagern den Fokus auf die Peripherie des Grundstücks, wo verschiedene Massstäbe, Programme, Eigenschaften und Interessen aufeinanderprallen. Wir blicken zwischen singuläre Interessen und isolierte Objekte, welche als Konsequenz von Zonierung, Eigentum und Bauboom Wirklichkeit geworden sind.

Das Entwurfsstudio kehrt die Grundsätze des Architekturprojektes um: Vom singulären Werk zum situierten Netzwerk, vom monolithischen Objekt zum porösen Dazwischen, von der Abgrenzung zur Assoziation, von der Flächenziffer zum Boden, von Real Estate zu unterschiedlichen Seinszuständen, von gebauter Dichte zu wechselnden Intensitäten, vom Bewegen von Material zur Anreicherung von Bedeutung, von Tabula rasa zum möglichen Anfang von etwas, das bereits da war.

In Anlehnung an Pierre Huyghe und seine gleichnamige Installation plädiert AFTER ALIFE AHEAD für alternative Wohnformen im scheinbar alternativlosen Schweizer Kontext. Wir hinterfragen gängige Vorstellungen von Wohnen, um es in all seinen Facetten und hin zu einer erweiterten Zeitlichkeit, neu zu denken.

Die Entwürfe werden als unvollendet choreographiert und im Laufe des Semesters in mehreren Iterationen umgewandelt. Mittels Modellbildern und spekulativen Detailzeichnungen werden Projekte entwickelt, die ein breites Spektrum architektonischer Alternativen generieren. Das Semester findet in Emmen statt, eine Agglomeration, die symptomatisch für die ganze Schweiz steht. Luzerns Vorposten ist in seinen Widersprüchen hyper-schweizerisch und verkörpert den totalen helvetischen Durchschnitt.

In theory, building law establishes predictability and protection of ownership. In reality, parcellation relentlessly produces leftover areas on the fringes. As the realization of buildings and their surroundings is delegated to individual stakeholders with isolated interests, the unbuilt areas are degraded into buffer zones. Swiss suburbia with its frantic succession of heterogenous programmes constantly caricatures the main aim of zoning: to generate homogenous, equal conditions within a zone. But due to fragmentation, the rule is the sudden clash of contradicting neighbours: Zoning has put an order into everything, but it created a staccato of anything.

This semester we are in search of another perspective. Shifting the focus to the very periphery of the plot where different scales, programmes, properties and interests collide, forces us to take a stance from multiple grounds. We look beyond singular interests and the isolated object as the bizarre consequence of zoning, property and real estate.

The design studio inverts the paradigm of the architectural project from the singular work to the situated network, from the monolithic object to the porous in-between, from distinction to association, from surface to ground, from real estate to different states of being, from built density to occurring intensities, from moving matter to accumulating meaning, from tabula rasa to the possible beginning of something that was already there.

Borrowing from Pierre Huyghe and his eponymous installation, AFTER ALIFE AHEAD makes a case for alternative forms of living in the Swiss context that appears to be without alternative. We look behind the preconceived notion of housing to rethink it in all its facets and towards an extended temporality.

Projects will be choreographed as unfinished, hence transformed in several iterations over the course of the semester. Projects will be developed by means of model images and speculative detail drawings generating a spectrum of architectural alternatives. The location is Emmen, an agglomeration that is emblematic of all of Switzerland. Hyper-Swiss in its contradictions, this outpost of Luzern represents the total Helvetian average.

I. Collage Suburbia: Siteseeing Emmen

Emmen als Betrachtungsperimeter steht stellvertretend für die suburbane Wirklichkeit der gesamten Schweiz. Flussabwärts und abgekoppelt von den idyllischen Qualitäten des Vierwaldstättersees trägt Emmen das Stigma des Hinterhofs der repräsentativen und touristisch attraktiven Stadt Luzern. In einer Volksabstimmung lehnte es die Gemeinde 2012 ab, sich der Stadt Luzern anzuschließen und blieb damit zwar unabhängig, aber auch peripher. Bestehend aus den beiden Ortsteilen Emmen und Emmenbrücke, liegt ersterer im Reusstal, letzterer grösstenteils auf einem den Alpen zugewandten Plateau. Die Lage am Zusammenfluss der beiden Flüsse Emme und Reuss und der entsprechende Name vermögen jedoch nicht darüber hinwegzutäuschen, dass ein Bezug des Bebauungsteppichs zur Geologie oder zum Territorium kaum noch erkennbar ist. Das heutige Erscheinungsbild ist von menschengemachten Kräften geprägt; das ausufernde Autobahnkreuz, das Wachstum und der Niedergang der Schwerindustrie und das Sperrgebiet des Militärflughafens mit seinen Einrichtungen. Parallel dazu verklumpen heterogene Erweiterungen und ausufernde Gebäudecluster zu einem baulichen Flickenteppich. Dieser ist an jedem Ort spezifisch und dennoch beispielhaft in seiner komprimierten Abfolge unterschiedlicher Gebäude und Restflächen. Im Zonenplan zeigt sich die zügellose Kompression von Programmen und eines rücksichtslosen Fläschenverbrauchs: Der grösste Teil der Gemeindefläche wurde im vergangenen Jahrhundert überbaut. Wie eine endlose Collage legt Emmen in dichter Folge alle möglichen urbanen Phänomene und Identitäten des autozentrierten Jahrhunderts frei. Nur der Plan für Gefahrenzonen wie Überschwemmungen und dergleichen, lenkt das Wachstum und hegt es ein. Emmen repräsentiert die Hyper-Schweiz.

Derzeit durchläuft die Agglomeration eine Überarbeitung der Bauvorschriften und Zonierungen und es stellt sich die Frage, ob Emmen in der Lage ist, seine Stadtentwicklung neu auszurichten, oder ob am Ende die nächste Schicht premium mediocracyTM hinzugefügt wird.

Im Gegensatz zu Verschönerung und analogen Strategien nähern wir uns Emmen mittels „Siteseeing“: Wie können die verschiedenen Schichten eines Ortes und seiner Nachbarschaft auf produktive Weise aktiviert werden? Was lässt sich aus Baugesetzen, wirtschaftlichen Gegebenheiten, bestehenden Prozessen und Abläufen vor Ort ableiten? Was schlummert unter dem komprimierten Zeitrahmen der Totalen Gegenwart?

Addressing the suburban conditions of all of Switzerland, the location for the semester is in Emmen in direct vicinity to Lucerne. Downstream and disconnected from the pastoral qualities of Lake Lucerne, Emmen has been stigmatized as the back yard of the imposing city that is attractive to tourists; Emmen is striving for recognition in its post-industrial phase.

The municipality refused to join the city of Lucerne in a referendum in 2012. It therefore remained independent, but also peripheral. Consisting of the two districts of Emmen and Emmenbrücke, the former is located in the Reuss Valley, the latter mostly on an undulating plateau facing the Alps. Its location at the confluence of the rivers Emme and Reuss and the corresponding name cannot hide the fact that a geological or territorial relation to its urban fabric is hardly recognizable. On the contrary, its current appearance is shaped by man-made forces like the impact of a highway junction, the growth and decline of heavy industries or the prohibited area of the military airport and facilities.

In parallel, a sprawling accumulation of heterogenous expansions and building clusters lead to a patchwork that is specific in each location, yet exemplary

in its compressed succession of different buildings and left-over spaces. The zoning plan becomes the magnifier of a compression of programmes and a reckless squandering of ground: Most of the municipality’s area has been built over in the past century. Collage-like in essence, Emmen presents all sorts of urban phenomena and identities of a car-oriented epoch in close succession. It is only tamed by plans for danger zones – floodings and the like. Emmen represents hyper-Switzerland.

Currently undergoing a revision of its building regulations and zoning, the question is wether Emmen is able to redirect its urban development or if it ends up adding another layer of premium mediocracyTM

As opposed to embellishment and analogue strategies, we approach Emmen by means of Siteseeing: How can the various strata of a site and its neighbourhood be activated in a productive way? What can be adopted from building laws, economic realities, existing processes and procedures on site? What lies dormant beneath the compressed time frame of the total presence?

Robert Venturis bahnbrechendes “behutsames Manifest” für eine “Beziehungsreiche Architektur” aus dem Jahr 1966 legte die Sackgasse der heroischen modernen Architektur offen und reintegrierte Kriterien wie Komplexität, Inkonsistenz, Mehrdeutigkeit oder das Paradoxe im Bereich der Architektur, indem es für Reichtum an Bedeutung im Gegensatz zu Vereinfachung und Bildhaftigkeit plädierte. Eine solche Architektur “muss die schwierige Einheit der Inklusion verkörpern und nicht die einfache Einheit der Exklusion”.

Heute erkennen wir resigniert, dass Vereinfachung und Bildhaftigkeit die gebaute Umwelt der Schweizer Vorstädte dominieren. Die Immobilienbranche stellte sich als resistent heraus gegenüber Venturis Ruf. Nur an den äussersten Rändern der ausgewiesenen Bauzonen zerfällt die anspruchslose Einheit. Hier erscheinen Komplexität und Widerspruch als roher Zustand zwischen den unzusammenhängend kollidierenden Einheiten.

Im Unterschied zum Inneren der programmatisch homogenen Zonen existieren Dichte und Intensität entlang der Grenzen a priori. Hier birgt das zufällige Gegenüber heterogener Programme und Morphologien Potenziale für alternative Formen von Mehrdeutigkeit und Reichtum. Ohne die Spannungen des aktuellen Rohzustands zu nivellieren, versuchen wir diese mit Hilfe der Architektur ausschöpfen: Komplexität und Widerspruch in der Zonierung.

Robert Venturi’s seminal ‘gentle manifesto’ of ‘Nonstraightforward Architecture’ from 1966 laid bare the dead ends of heroic modern architecture and re-established criteria like complexity, inconsistency, ambiguity or the paradoxical in the sphere of architecture, advocating for a richness of meaning as opposed to simplification and picturesqueness. Such an architecture ‘must embody the difficult unity of inclusion rather than the easy unity of exclusion’.

Today we must recognize that simplification and picturesqueness dominate the built environment of Swiss Suburbia. Real estate turned out to be renitent to Venturi’s call. Undemanding unity crumbles only at the very fringes – with complexity and contradiction appearing as a raw state in the collision of unrelated entities.

Along the borders density and intensity exist a priori – as opposed to the interiority of programmatically homogenous zones. Therefore, the coincidental vis-à-vis of heterogenous programmes and morphologies bears potential for alternative forms of ambiguity and richness. Without levelling out the inherent tensions of the current raw state we exploit it by means of architecture: Complexity and Contradiction in Zoning.

II. Komplexität und Widerspruch im Zonenplan

Complexity and Contradiction in Zoning

Explanatory sketches for the measurement and calculation methods according to the Swiss Planning and Building Act (PBG) and General Building Ordinance (ABV), fig. 7.11 (“Spacing to boundaries, buildings, forests and streams”)

Plan of Cappella dei Re Magi, Francesco Borromini, detail (ca. 1660)

III. Jenseits der Zonierung: von der begrenzten Fläche zur gefalteten Linie

Beyond Zoning: from a fixed limit to folds and foldings

Das Baurecht hat das Schweizer Land in verschiedene programmatische Zonen unterteilt, die jeweils durch explizite Grenzen gefasst sind. Diese Unterteilungen führen zu isolierten Funktionen und Resträumen am Rand jeder Zone. An der Konvergenz dieser Grenzen, die durch physische Kontakte entstehen, verbindet und trennt jeder Punkt gleichzeitig. Das ist das Paradoxon der Grenze: Verbindung und Trennung sind hier ein und dasselbe.

Ein Perspektivenwechsel lenkt unseren Fokus von der Bestimmung einer klaren Funktionskante hin zur peristaltischen Linie, die zwischen mindestens zwei unterschiedlichen Funktionen, Interessen, Eigentümer*innen und Massstäben vermittelt. Die Zugehörigkeit der Grenze zu keinem der beiden Gebiete führt zu einer neuen Sichtweise. Wir schlagen eine Abkehr von der konventionellen Zoneneinteilung vor, bei der Zusammenstösse unproduktiv sind, hin zur Nutzung des latenten Potenzials von Grenzlinien.

Diese Linien überschreiten die Bedeutung blosser Grenzen; sie sind Übergänge, die sich zwischen verschiedenen programmatischen Zonen verweben. Die Mehrdeutigkeit der Grenze entwickelt sich zu ihrer Stärke - ein Raum für Aushandlung und Konfliktlösung. Durch den Übergang von Flächen zu gefalteten Linien, von Segregation zu Assoziation fördern wir eine dynamische Architektur, die Inklusivität und Austausch und damit die direkte Demokratie verkörpert.

«The outside is not a fixed limit but a moving matter animated by peristaltic movements, folds and foldings that together make up an inside: they are not something other than the outside, but precisely the inside of the outside.» 2

Common building law has traditionally cut up Swiss land into distinct programmatic zones (Zonenplan), each bounded by distinct borders. These divisions tend to isolate functions and generate residual spaces on the periphery of each zone. At the convergence of these borders, created through physical contacts, each point simultaneously connects and separates. This is the paradox of the border: Connection and division are here one and the same.

A shift in perspective redirects our focus away from determining a clear, functional edge towards the peristaltic line, which mediates between at least two different functions, interests, owners, and scales. The border‘s affiliation with neither territory prompts a novel viewpoint. We propose a departure from conventional zoning, where clashes are unproductive, towards embracing the latent potential of borderlines.

These parcellation lines transcend mere limits; they signify transitions that weave between diverse programmatic zones. The border‘s ambiguity evolves into its strength – a space for latent negotiation and conflict resolution. Shifting from limited surfaces to foldings of lines, from segregation to association, we foster a dynamic architecture that embodies inclusivity and exchange, hence democracy.

IV. Von Trennung zu Koexistenz

From division to co-existence

Der Akt der Grenzziehung ist doppelter Natur. Obwohl Architektur in erster Linie trennt – das Zeichnen einer Linie kommt stets einer Abgrenzung gleich, die Raum ein- oder ausschliesst – propagieren wir eine Architektur die versucht, Grenzen räumlich zu unterwandern und als Schnittstelle Räume verbindet und erweitert. Das Auflösen und Verwischen von Grenzen ist nicht gleichbedeutend mit der Absenz von Material und Substanz; es ist also kein rein subtraktiver Prozess. Vielmehr kann das Dazwischen als Überlagerung verschiedener Ordnungen und Systeme verstanden werden: Als Raum, in dem sich zwei Welten begegnen und durchdringen, verdichten sich hier die Ereignisse.

Im Sinne der Transparenz, der gleichzeitigen Wahrnehmung unterschiedlicher Raumordnungen, eröffnet der hybride Raum unterschiedliche Lesarten und eine Vielzahl von Beziehungen. Ambivalenz wird zum Potential.

«Transparency implies more than an optical characteristic, it implies a broader spatial order. Transparency means a simultaneous perception of different spatial locations. Space not only recedes but fluctuates in a continuous activity. The position of the transparent figures has equivocal meaning as one sees each figure now as the closer now as the further one.» 3

The act of delineation has a dual nature. Although architecture primarily separates – drawing lines is always like drawing a border that includes or excludes space – we are advocating an architecture that strives to undermine borders spatially and as an interface, to connect and extend spaces. Dissolving and blurring boundaries is not the same as the absence of material and substance; it is not a purely subtractive process. Rather, the in-between can be understood as a superimposition of different orders and systems: space in which two worlds meet and interpenetrate concetrates events.

Through the prism of transparency, where distinct spatial configurations are simultaneously apprehensible, this hybrid expanse unveils diverse interpretations and an array of connections. Here, ambiguity metamorphoses into latent potential.

V. Vom Objekt zum verorteten Netzwerk

In der Architektur bahnt sich ein Wandel an, der die Projektentwicklung von Grund auf neu zu denken versucht. Das singuläre Objekt hinter sich lassend, plädiert AFTER ALIFE AHEAD für einen Übergang zu komplexen Netzwerken, die aus vielfältigen und durchlässigen Elementen bestehen. Diese Transformation betont die Koaktivität und stellt die Vorstellung von Architektur als unabhängige Disziplin in Frage. In dieser Evolution werden Projekte zu einem Netz verwoben und reichen über die Grenzen von in sich geschlossenen Einheiten hinaus.

Anstelle des Entwerfens vereinzelter Objekte tritt das immersive, situative Orchestrieren. Dynamische Situationen ähneln Konstellationen von Koordinaten, die offen sind für Veränderungen in Massstab und Zeit, anstatt sich an lineare Zwänge und Konzepte zu halten. Dieser Ansatz ermöglicht eine Vielfalt verschiedener Szenarien, bereit, sich zu entfalten.