URBANISATION & CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION

1 SPRING THESIS STUDIO 2021

Gent, Belgium Master (of Science) Human Settlements & Master (of Science) of Urbanism, Landscape and Planning Faculty of Engineering and Department of Architecture Teaching Team: Raquel Colacios (UIC), Carmen Van Maercke (Architecture Workroom) with Bruno De Meulder, Kelly Shannon Academic Year 2020 - 2021

© Copyright KU Leuven

Without written permission of the thesis supervisors and the authors it is forbidden to reproduce or adapt in any form or by any means any part of this publication. Requests for obtaining the right to reproduce or utilize parts of this publication should be addressed to Faculty of Engineer ing and Department of Architecture, Kasteelpark Arenberg 1 box 2431, B-3001 Heverlee.

A written permission of the thesis supervisors is also required to use the methods, products, schematics and programs described in this work for industrial or commercial use, and for submitting this publication in sci entific contests.

2

3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

4

Articulating Wondelgem’s In-Betweens

Daniela Cobo, Agnese Marcigliano, Lethlabile Shubane, Lucie Van Meerbeeck

Rosambeek, Duivebeek and Oude Leie

Yidnekachew Yilma Seleshi , Md Rafiqul Islam, Cecilia Alejandra Quiroga Zelaya

Weaving Ecotones of Sint Amadsberg

Imraan Begg, Cécile Houpert , Raya Rizk, Jennifer Saad

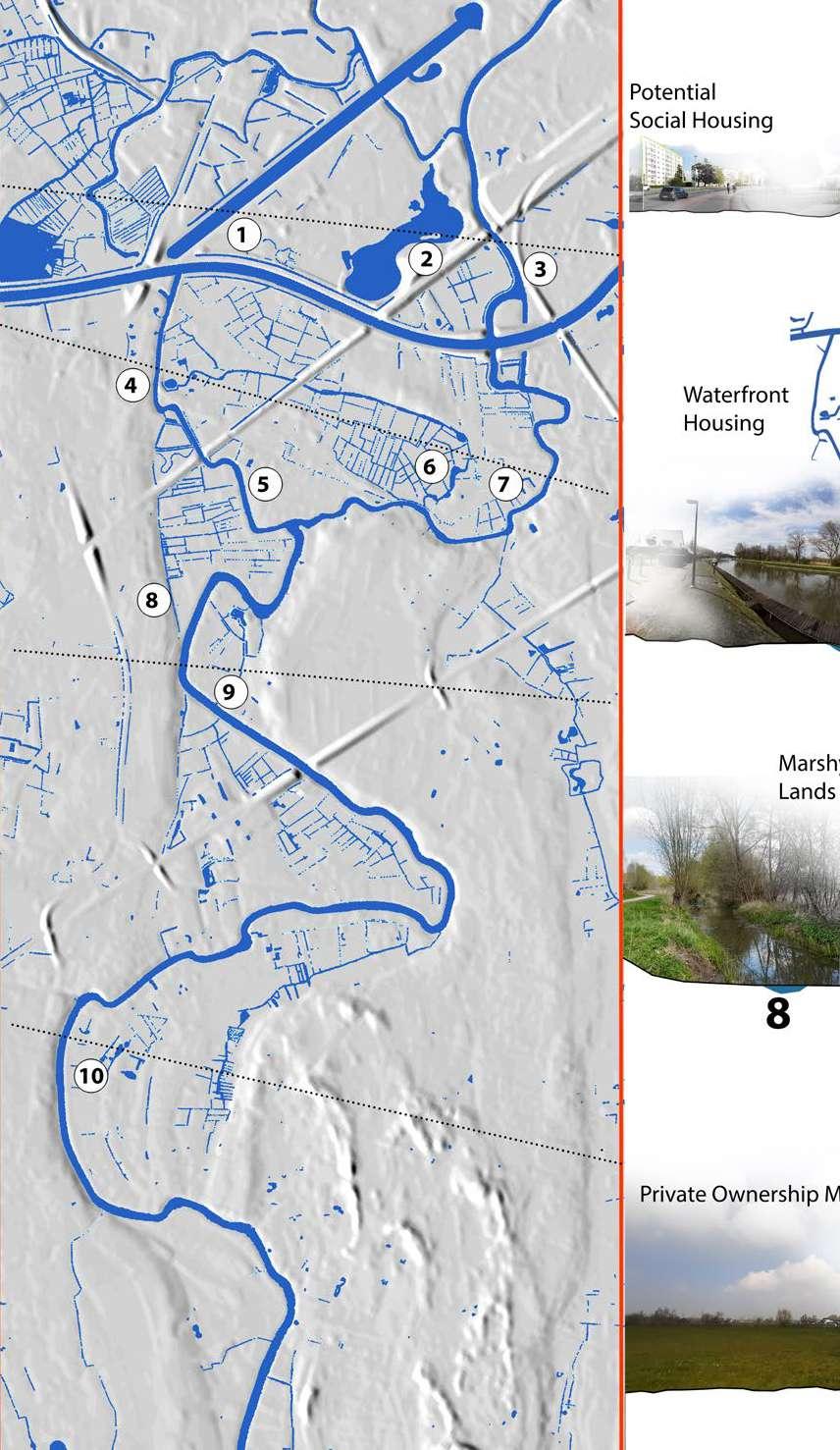

Revealing the Marshland: Shaping Urban-Floodplain Interfaces Along the Schelde

Ermioni Chatzimichail, Carlos Morales Dávila, Sebastián Oviedo Castelnuovo, Tien Huu Traan Camille Hendlisz, Haifa Wajeeh Saleh, Véronique de Pauw, Yentl Wulteputte

Kanaaldorpen: Towards a Cyclical-Ecological Mesh

5 06 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

01 STUDIO CHALLENGE 03 STRATEGIC PROJECTS 02 STUDIO VISION 06 12 18 396 20 114 168 242 338

STUDIO

7 01

CHALLENGE

STUDIO CHALLENGE GENT, BELGIUM

Association) was established in 2009 as a group of enthusiasts looking for ways to reduce the impact on the climate. Gent Climate City outlines an ambition of climate neutrality by 2050.

Gent is growing, and is expected to keep doing so. The spatial policy plan of the city makes a distinction between the (historical) inner city (binnenstad), the central city (kernstand) i.e. roughly the 19th century belt, the growing city (groeistad) i.e. roughly the 20th century belt, and the outer area (buitengebied). As the name suggests, the growing city is the area where the rising number of inhabitants are to be settled, while the focus in the outer area is to preserve unbuilt space.

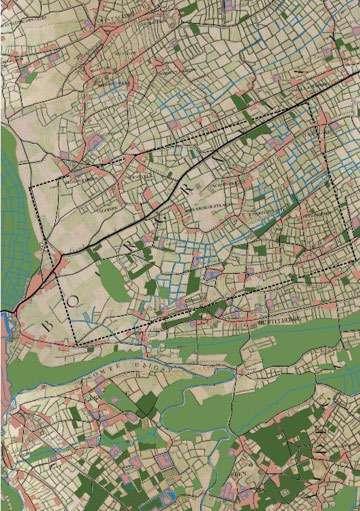

Gent is a major Flemish city, with a rich history dating from the Middle Ages and a tumultuous development during the Industrial Revolution. Gent originated as an archipelago of settlements in and around the confluence of the Leie and Scheldt Rivers. Still today, Gent can be understood as a complex patchwork of domains, particular spatial entities, often delimited by water and mostly with their own centralities.

Over the recent decades, Gent is steadily reorienting and redefining itself into a diverse and dynamic university city of the 21st century. Since the structure planning of the 1980s, the recalibration and reconstitution of its ecological structure is on the agenda, as well as the elaboration of a complementary soft mobility network. However, the economic success and growth of the city over the last decade(s) led to harsh pressure on the housing and land markets. At the same time, climate change is forcing the city to radically strengthen and rebuild its strong natural structure. In short, both the city and nature require a lot more space. Hence, Gent, as so many cities, needs to define a new equilibrium between (an intensified) built and natural environment.

Recent planning policy and strategic projects of the city focused on the city center and the notorious 19th century belt generated in the wake of the Industrial Revolution. Today, the 20th century belt requires attention. This periphery, half urbanised, half open, neither fully untouched nor fully consolidated, is the evident front to test new balances between nature and the built environment while simultaneously absorbing the predicted growth of the city. The urban periphery is an ideal site to rearticulate the poly-nuclear identity of Gent.

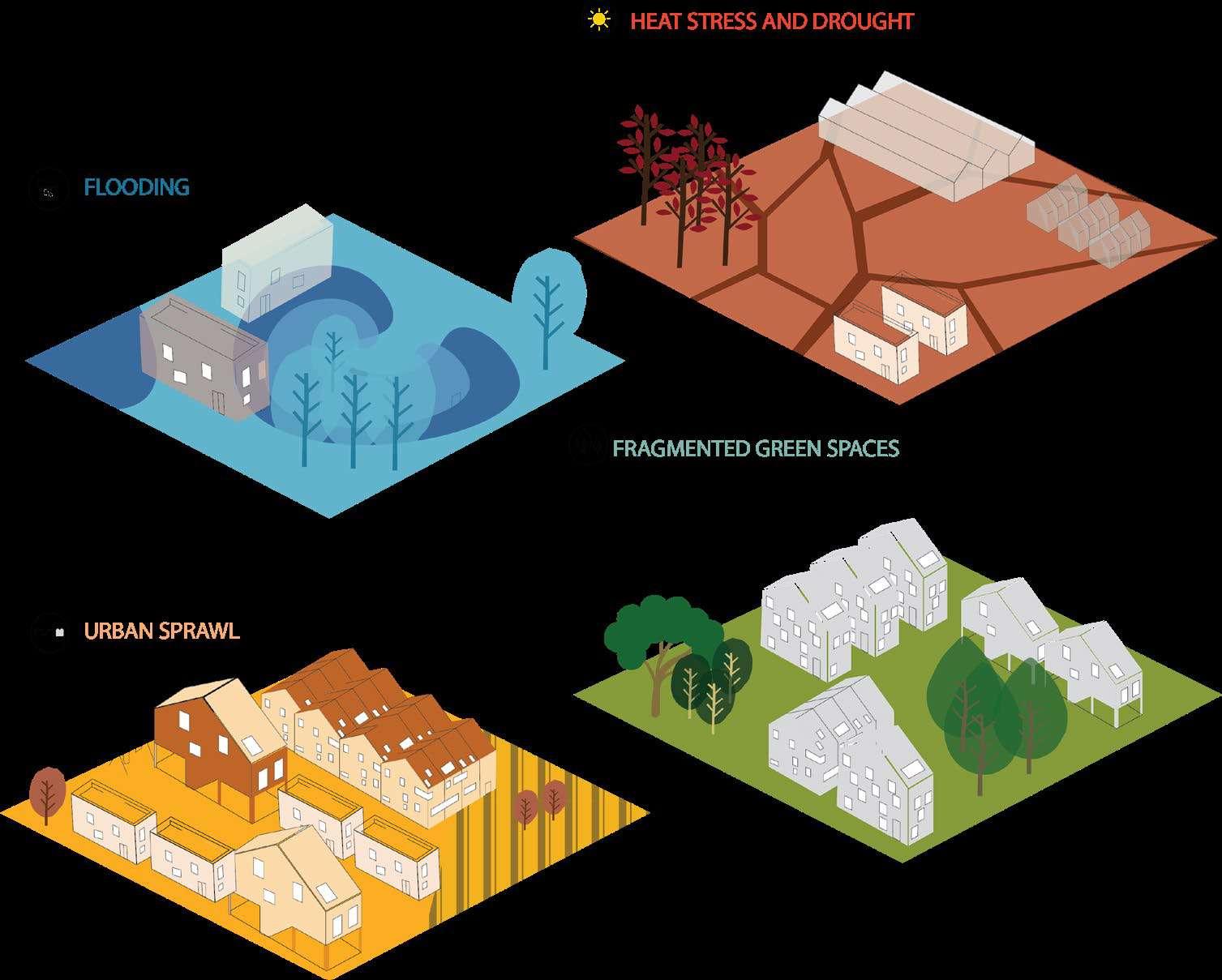

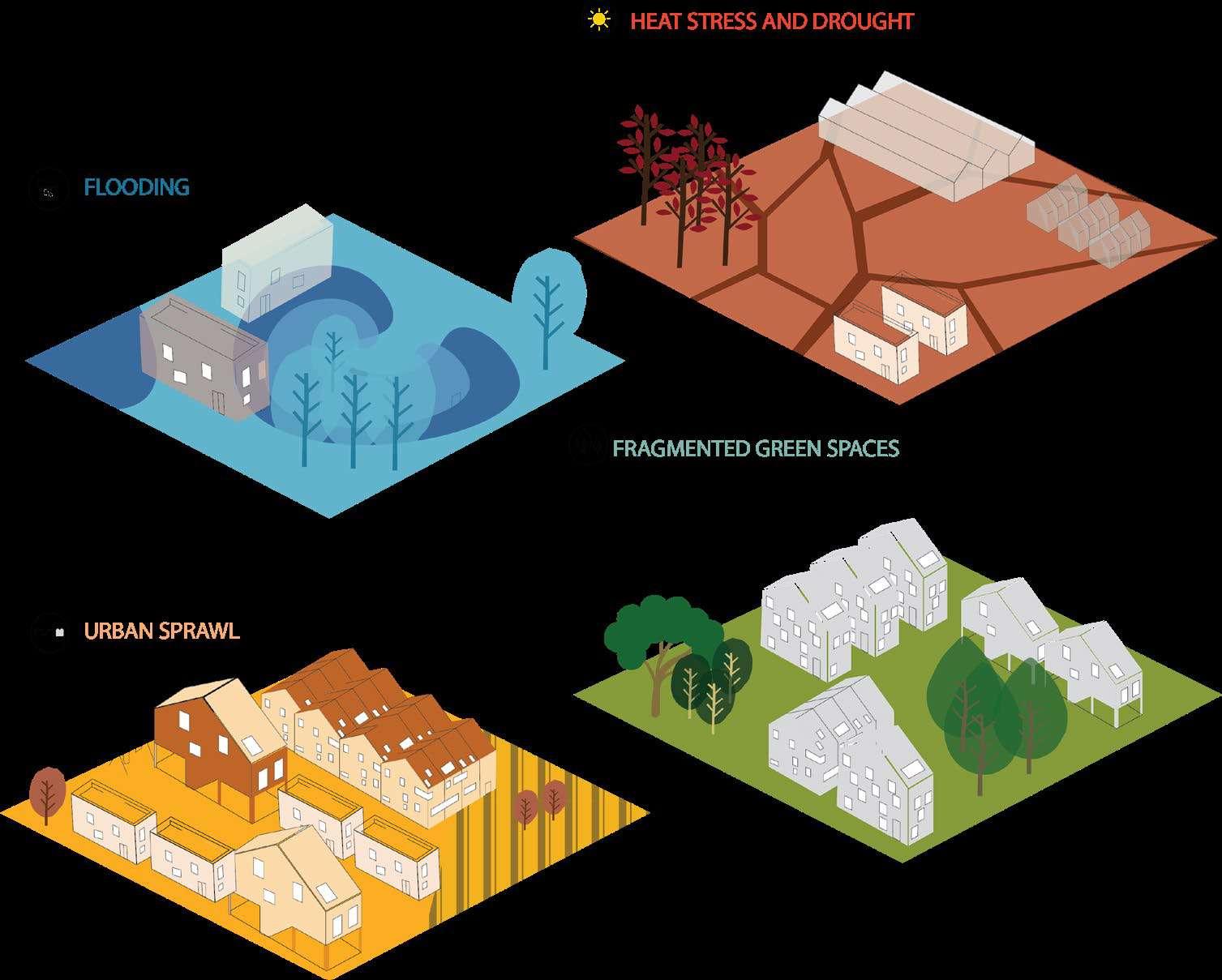

In the case of Gent, climate change impacts are very evident, particularly in the water system. The city and surroundings are significantly affected by both flooding and droughts, disrupting not only water distribution and access, but also other related systems including agriculture, open spaces, industry, housing etc. The urban heat island is as well a challenge. In terms of governance and spatial experimentation, Gent is a pioneer of climate policy in Flanders. Already 1996, city signed onto the Climate Alliance, a commitment between European cities to achieve a 50% CO2 reduction by 2010. The Gents Klimaatverbond (Climate

Although the relatively low densities of the 20th century belt suggest a potential for densification, in practice both the existing urban fabric and the housing market are not very accommodating to this effort. The predominant mode of densification is through the development the few open spaces left in these neighbourhoods, at a slightly higher density than the surrounding residential areas. In the outer area, the existing urban fabric is consolidated. For places with good access to amenities, such as the Leie Valley south of the city, this means restricting new development, while for places with little access, this means trying to reframe the meaning of a village in the 21st century. Whether talking about the growing city or the outer areas, development originated within a local landscape structure, steering clear of valleys and floodable marshes (where agriculture took place), and instead settling on (even slightly) elevated places, such as ridges and hillocks, for example on so-called donken (i.e. an old name for a sandy elevation in a marsh, which often became part of village names).

Today’s urban landscape has mostly lost this direct link between settlement patterns and the underlying landscape. However, with climate change at the forefront of urban challenges, even more so in a growing city (or more precisely, in the growing parts of a city), the reconnection of the two has become a pressing design challenge.

The studio focused on innovative ways of thinking—and designing—for climate change adaptation and urban growth. There is a need to develop housing handin-hand with socio-ecological justice. The studio investigated 1) strategies to address climate change adaptation at a systemic level and across scales; 2) new urban tissues that respond to the need for new ways of settling, meeting, working, moving and recreating. There was a focus on developing new natural, human and non-human ecologies while addressing issues of inclusion and the development of just environments.

Students worked on innovative re-definitions of the interrelations of the systems operating in the region at a landscape scale and zoomed in to de-compose the complex ecosystem re-definition while defining new inclusive housing strategies that (re) articulate vibrant urban tissues embedded in a balanced environment with ample open spaces. To do so, students were divided into five groups, each one working on a different site of the city. The sites are all anchored to important landscape armatures and systems of open spaces. The studio worked on the premise of accommodating an additional 30,000 inhabitants (+/- 12500 households) by 2030: each site should work with adding 2500 houses in each of the five areas.

8

9

10

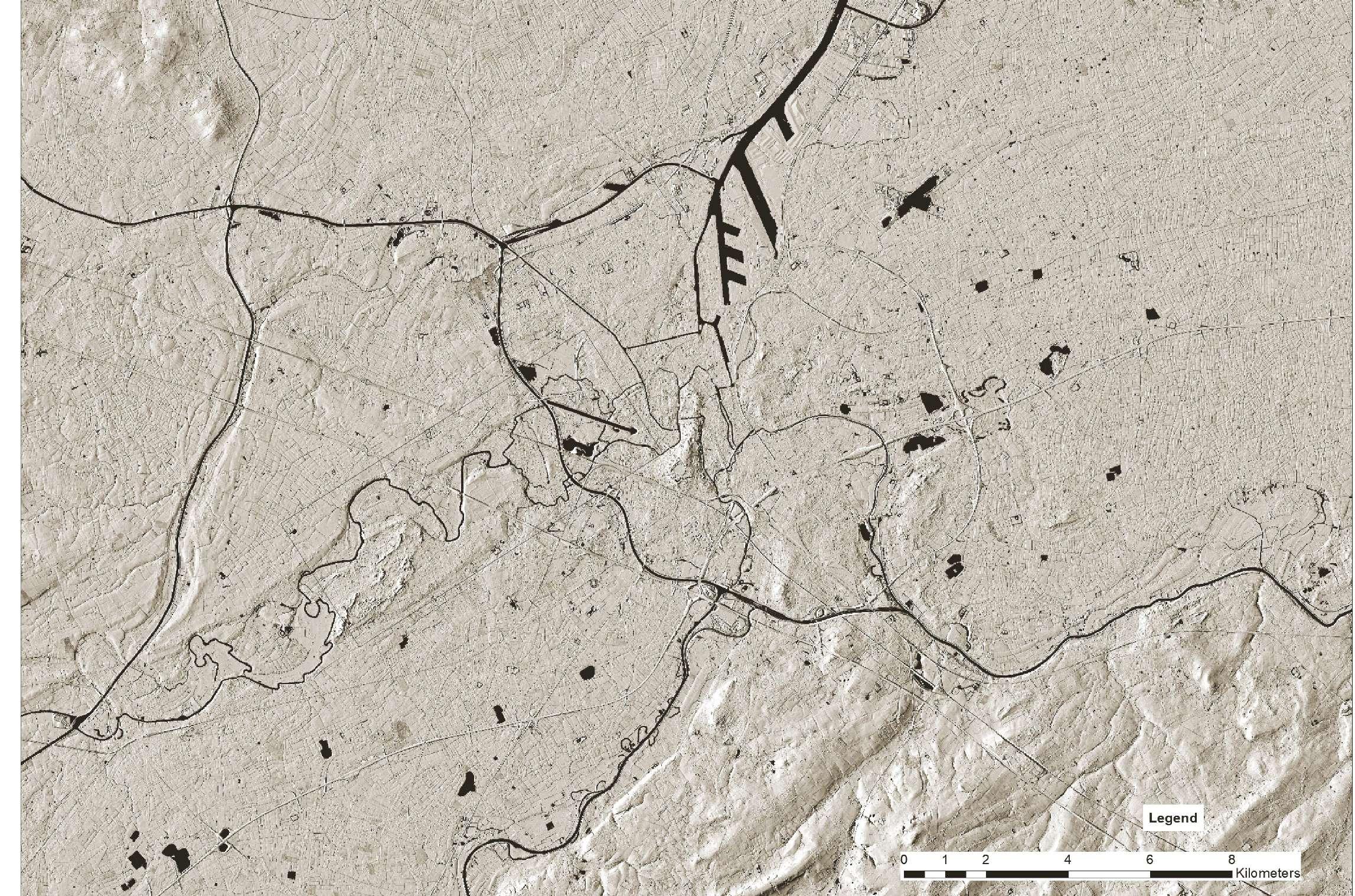

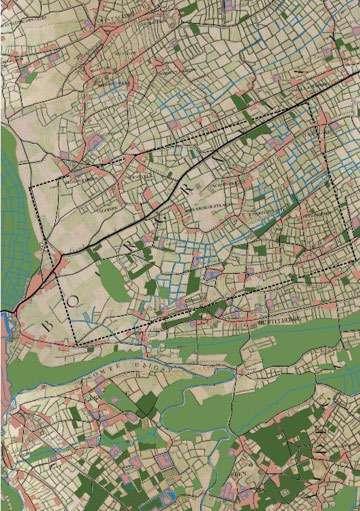

Ferraris map Ghent and surroudings - 1779

Still today, Gent can be understood as a complex patchwork of domains, particular spatial entities, often delimited by water and mostly with their own centralities. Since the structure planning of the 1980s, the recalibration and reconstitution of its ecological structure is on the agenda, as well as the elaboration of a complementary soft mobility network. However, the economic success and growth of the city over the last decade(s) led to harsh pressure on the housing and land markets. At the same time, climate change is forcing the city to radically strengthen and rebuild its strong natural structure.

In short, both the city and nature require a lot more space.

Gent, as so many cities, needs to define a new equilibrium between (an intensified) built and natural environment. Recent planning policy and strategic projects of the city focused on the city center and the notorious 19th century belt generated in the wake of the Industrial Revolution. Today, the 20th century belt requires attention.

This periphery is the evident front to test new balances between nature and the built environment while simultaneously absorbing the predicted growth of the city.

In the case of Gent, climate change impacts are very evident, particularly in the water system. The city and surroundings are significantly affected by both flooding and droughts, disrupting not only water distribution and access, but also other related systems including agriculture, open spaces, industry, housing etc. The urban heat island is aswell a challenge.

Gent is growing, and is expected to keep doing so. The spatial policy plan of the city makes a distinction between the (historical) inner city (binnenstad), the central city (kernstand) i.e. roughly the 19th century belt, the growing city (groeistad) i.e. roughly the 20th century belt, and the outer area (buitengebied). As the name

suggests, the growing city is the area where the rising number of inhabitants are to be settled, while the focus in the outer area is to preserve unbuilt space.

The predominant mode of densification is through the development the few open spaces left in these neighbourhoods, at a slightly higher density than the surrounding residential areas. In the outer area, the existing urban fabric is consolidated. For places with good access to amenities, such as the Leie Valley south of the city, this means restricting new development, while for places with little access, this means trying to reframe the meaning of a village in the 21st century. Whether talking about the growing city or the outer areas, development originated within a local landscape structure, steering clear of valleys and floodable marshes (where agriculture took place), and instead settling on (even slightly) elevated places, such as ridges and hillocks, for example on so-called donken (i.e. an old name for a sandy elevation in a marsh, which often became part of village names).

Today’s urban landscape has mostly lost this direct link between settlement patterns and the underlying landscape.

However, with climate change at the forefront of urban challenges, even more so in a growing city, the reconnection of the two has become a pressing design challenge.

The studio focused on innovative ways of thinking—and designing—for climate change adaptation and urban growth. There is a need to develop housing hand-inhand with socio-ecological justice. The studio investigated 1) strategies to address climate change adaptation at a systemic level and across scales; 2) new urban tissues that respond to the need for new ways of settling, meeting, working, moving and recreating. Focusing on developing new natural, human and non-human ecologies while addressing issues of inclusion and the development of just environments.

11

13 02 STUDIO VISION

14

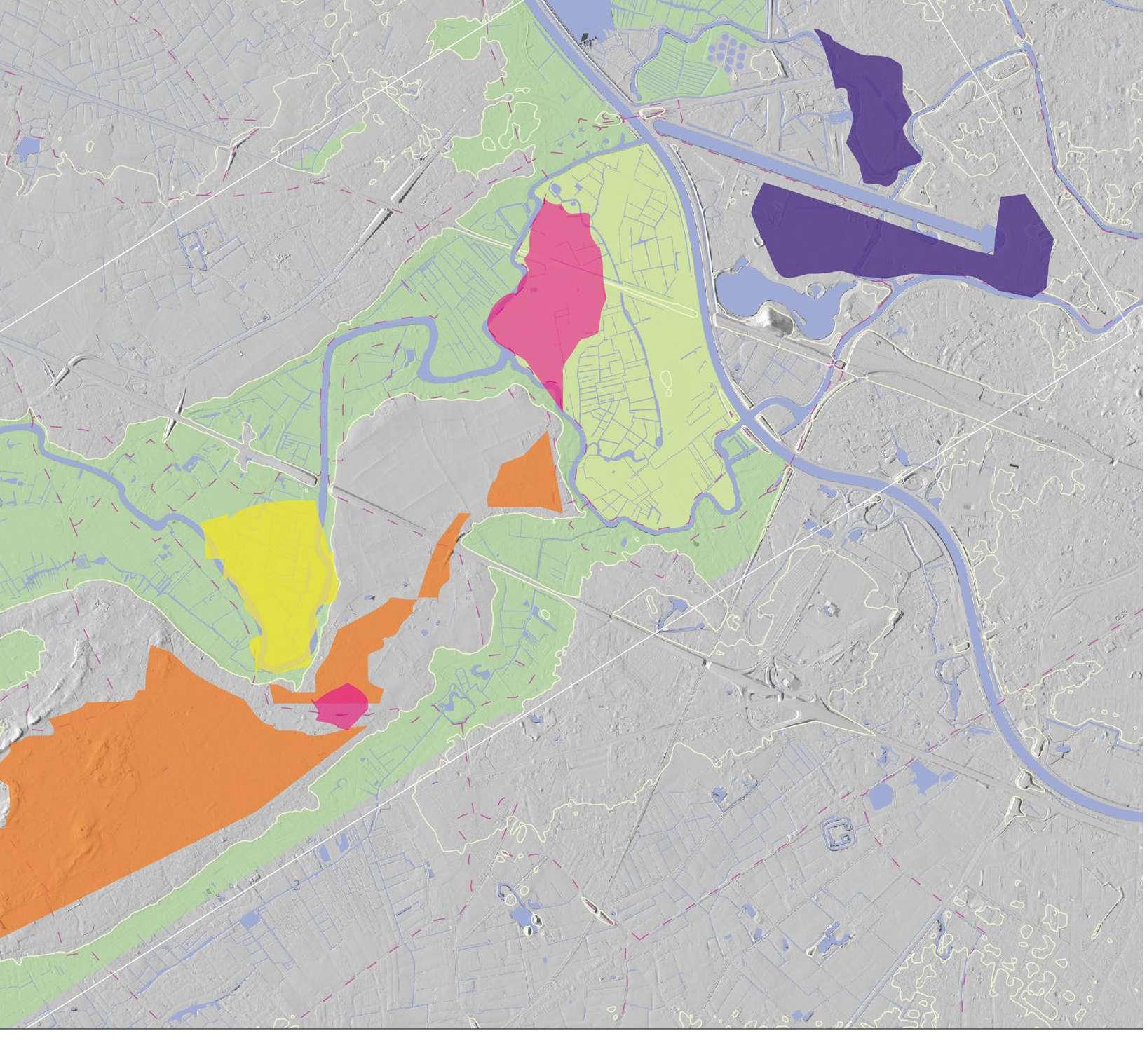

Vision Ghent 2100

Existing Urban areas

New Ribbon settlements

New archipelagos settlements

New desealed public space

New Social infrastructures

Railway system

Soft mobility

Desealed streets

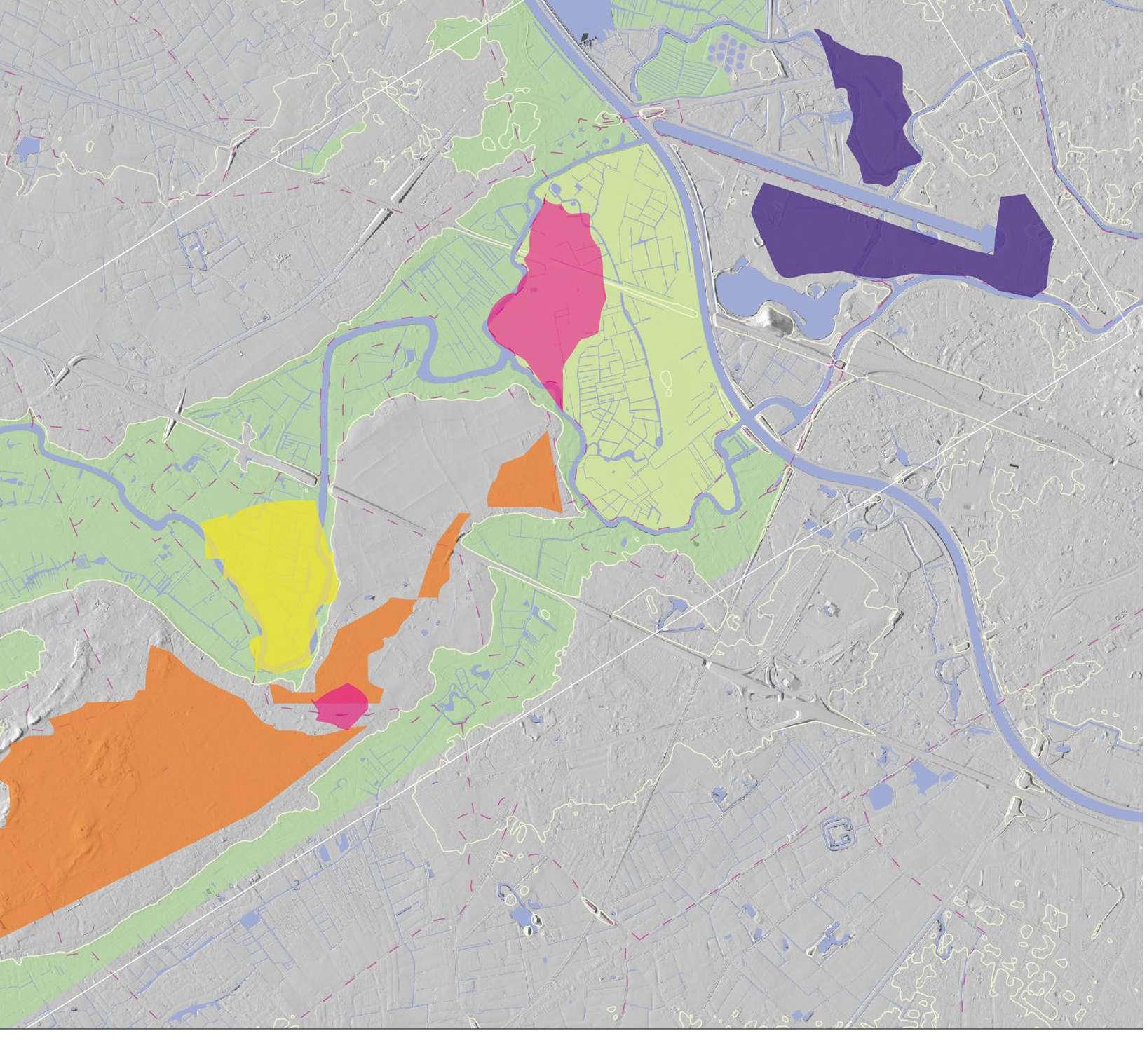

During the last decades the city of Ghent focused in recovering the ecological structure of the City landscape to contrast the urgent flooding and drought issues the City is facing, especially affecting the water presence and management within the city and in particular in its surroundings (Blondia et al. 2021, 2).

Recent projects have focused mainly on the city centre and the 19th century belt, but what we are considering here in this exercise is the role of the 20th century belt into the consolidating process of urban horizontal polycentric expansion of the City (Blondia et al. 2021, 2).

Today, the opportunity to reshape and articulate the relationship between the City and its natural environment lays in the periphery’s rural-urban interplay, which ac commodates future urban growth, while respecting and recovering the fragmented existing landscape.

The restructured and consolidated forest figures form now an intricate system of wild dry and wet natural public spaces, shaping the territory of the Ghent Metro politan Park and reclaiming space for nature and water.

In 2021, water was viewed more as a commodity that as a structuring element of the landscape. In this scenario 2100, however, extended de-sealing strategies are applied at the metropolitan and local scale to increase the presence of water within the neighborhoods.

Particular focus is given to the recovery of the ecological value of the Marshlands environments, which are part of the landscape heritage of the territory and the main preserved natural system. Rainwater is stocked for everyday use in systems of water retention ponds and capillary channels, which are implemented through out the new settlements and integrated within the different water environments.

Meanwhile, water-cleaning cycles are activated in proximity of each new settle ments to reach the maximum level of autonomy.

WATER

Existing waterbodies

New waterbodies

New water management system

Recovered marshlands

NATURAL ENVIRONMENT

Existing Agriculture

Grassland

Agriculture fields (monoculture)

New agriculture

Agroforestry

New Orchards

Existing Vegetation

Existing forest Gardens

New green areas

New Dry Forest

Ne Wet Forest

New green roods

Noew bioremediation fields

New Reclaimed green publice spaces

New tree line

The reconfiguration and naturalisation of the fluvial environments of the two riv ers, the Leie and the Scheldt, leave space for the biodiversity to thrive in protected or semi-accessible areas, which are created to avoid an excessive touristic pressure on these fragile areas.

Users’ affluence is re-directed towards more public water spaces in proximity to new expansions projects, re-activating the banks of the rivers, which were once ruptures in the landscape and now are elements of conjunctions and encounters.

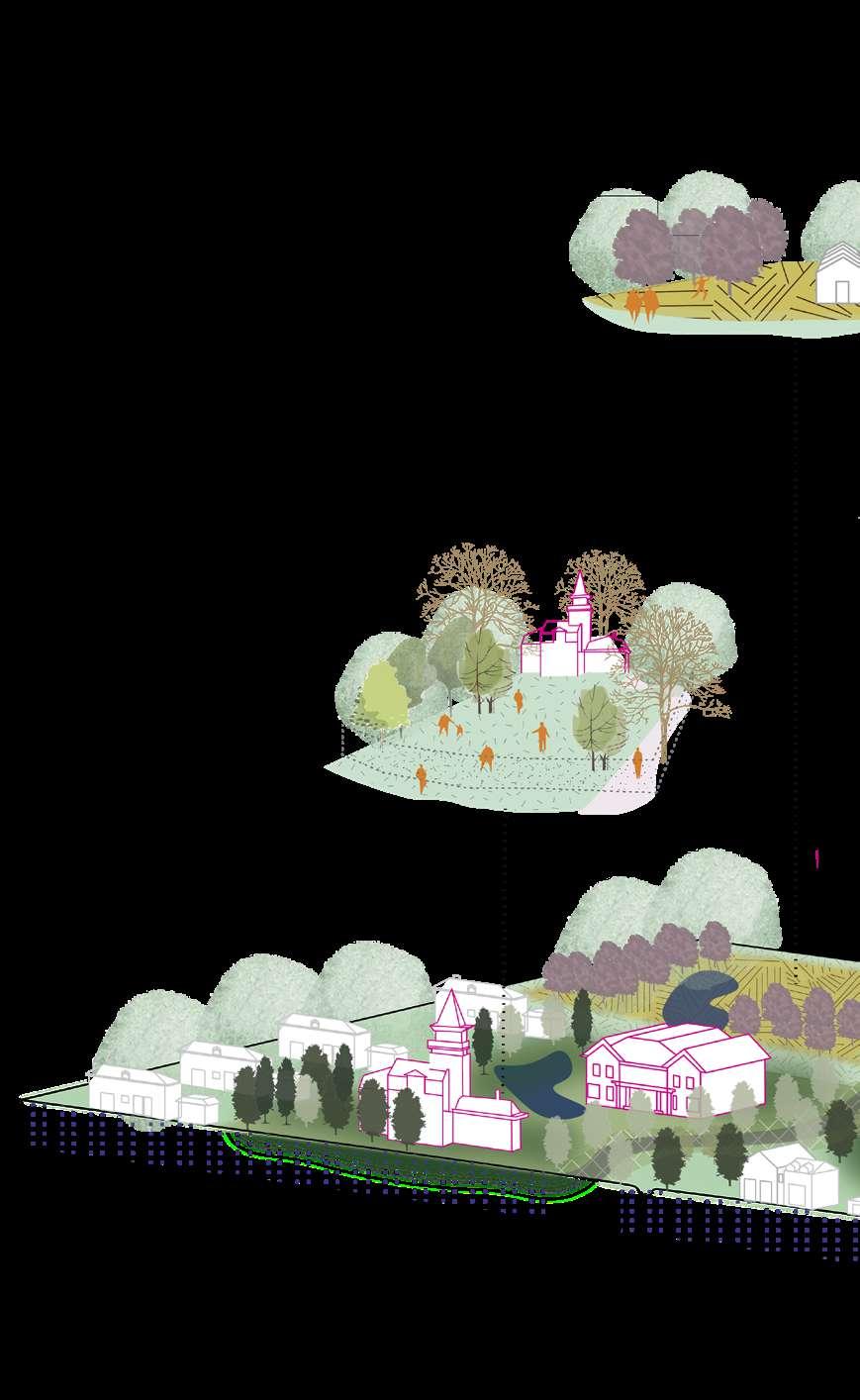

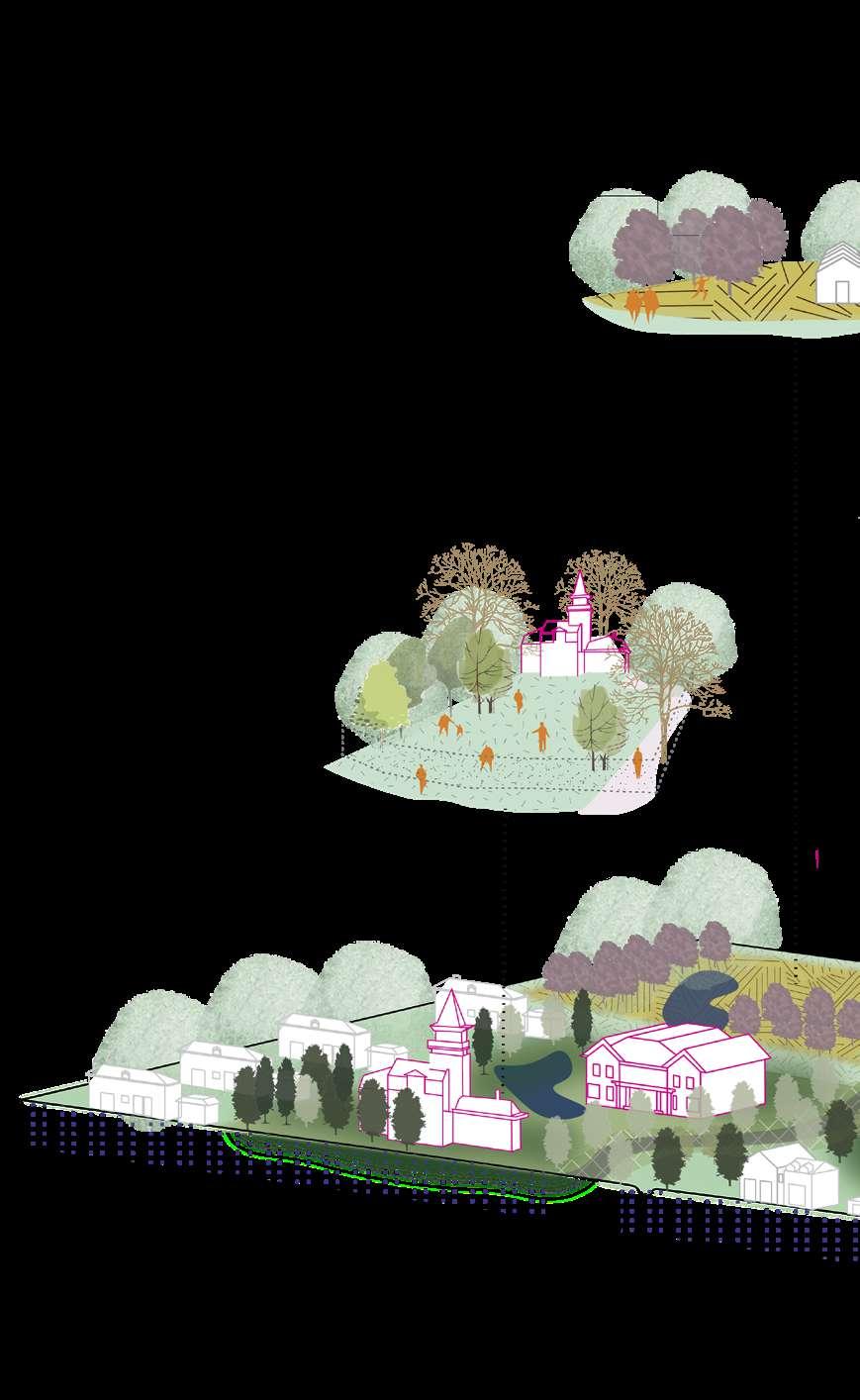

The vision for Ghent 2100 is therefore driven by following principles - restructuring water and forest - healing the productive landscape -navigating the archipelagos -expanding the public realm

Author: Agnese Marcigliano

15

Ghent 2100

Landscape as a driver for social change

Facing in an active way the current climate challenges is a fundamental step towards designing more liveable and inclusive cities, but on top of the already established future environmental issues, the Covid-19 crisis is showing the limitations and deficits of our cities support systems and infrastructures. Moreover, the pressuring economic and social issues currently emerging during the pandemic, urge us to put at the centre of the International debate the evolution of our inhabiting culture and the necessary transformations of our urban environments. These transformations are more than ever neces sary in the peripheries of European cities, which are too often forgotten and left out of the local territorial dynamics.

In this Studio Vision for the Horizon 2100, Ghent establishes itself as a polycentric horizontal system of metropolitan parks in which the outskirts of the City are not anymore the unregulated background of the urban tis sue but its new active front. By unveiling the possibilities that this future model has to offer in term of new living common practices and renovated ecologies, we, as young practitioners and researchers, accept its challenging not-urban nature, engaging ourselves in a quest for alternative urbanism practices that “dismantle the ideological bias of the urbanism of compact ness. In the context of planetary urbanization, it is more urgent than ever to think urbanization beyond the polarity of center vs. periphery, compact vs. distributed, nuclear vs. decentralized”. (Dehaene 2018, 280)

At the Horizon 2100, the City is everything and everything is the city.

16

Navigating the archipelagos. Author: Agnese Marcigliano

Healing the productive landscape. Author: Agnese Marcigliano

17

STRATEGIC PROJECTS

19 03

21 03.01 Articulating Wondelgem’s in-betweens DANIELA COBO AGNESE MARCIGLIANO, LETLHABILE SHUBANE LUCIE VAN MEERBEECK

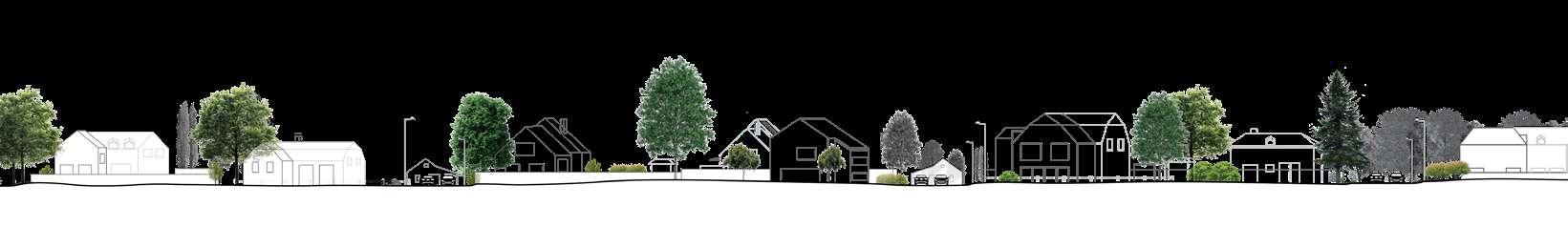

Wondelgem

From ghost town to suburban periphery

"In historical terms, Wondelgem is a redeveloped ghost town; it is found on documents from the 10th century, but after pillaging in the 17th century, inhabitants fled towards the city, leaving the village uninhabited for many years.

It regained some appeal during the 18th and 19th century as an area for summer estates of the Ghent aristocracy, with villas and small ‘castles’ dotting the agricultural landscape. The vicinity of the Oude Kale river, but also a number of brooks (Schipgracht, Lievegracht, Rietgracht) also meant this area had many marshes.

Today, Botestraat is the main axis of Wondelgem, which runs on a slightly elevated ridge parallel to the Oude Kale. Along this street, some of the old estates still remain, leaving green space between the thousands of detached single-family houses. Few open spaces remain, and even those are being eyed on for future developments. Densification of the existing tissue, however, is not happening, due to a combination of high value and high demand for the predominant housing typology.

1970s Wondelgem

The landscape was radically transformed through industrialisation; a canal was dug between Ghent and Terneuzen, two railways were built connecting Ghent to Eeklo and Zelzate (the latter of which has largely disappeared, partly due to a widening of the canal in the ‘60s), industries soon followed, as well as a modest urban development.

However, it wasn’t until the second half of the 20th century that Wondelgem expanded into the suburban area it is today, with the creation of the Ring canal, and –later on – the existing Industrieweg becoming part of a large ring around Ghent, and the extension of the tram network into Wondelgem.

The main question is how this rather consolidated suburban tissue can be re imagined and re-developed to drastically increase the density, without losing the high living quality for inhabitants, but rather by introducing new qualities through this transformation."

(Blondia et al. 2021, 10)

22

Introduction

©

Seleshi, Tran 2021,

1

Historic Axis( Botestraat )

Present Wondelgem

Wondelgem area

Ghent N

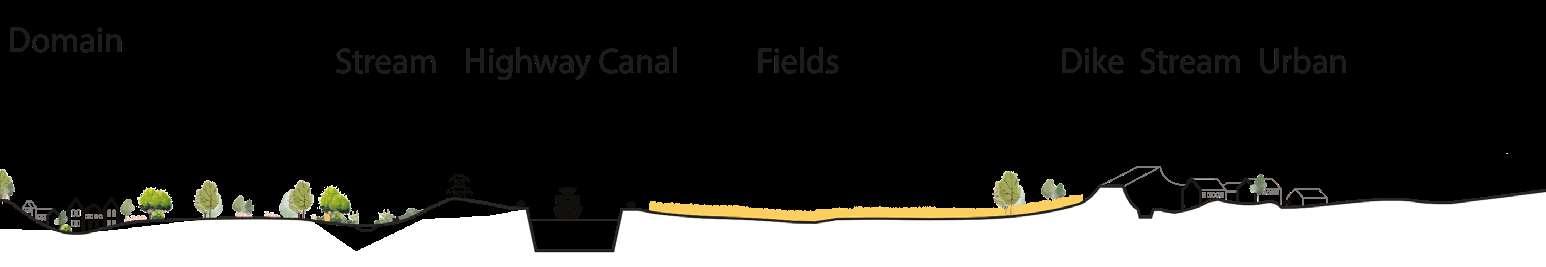

Wondelgem's landscape transformed by industrialization and suburbanization.

23

© Google Earth 2021

24

25 1.0 ANALYSIS

26

Reading & Interpretive Analysis

1.1

Inspiration

BRINGING THE HARVARD YARDS TO THE RIVER

Busquets, Joan; Correa, Felipe. 2004

Cambridge (MA, United States) Harvard University

"Joan Busquets’ mapping methodology (Busquets, Correa 2004) analysed the evolution of the Cambridge area, Harvard university, and the river’s edge over time (1680 – 2004)."

Based on those reflections and sequences, this series of mapping analysis for Wondelgem, a suburban area located North of Ghent’s city centre, guides us to understand the development of the site through time in relation with the landscape, the urban structure and the water.

The mapping analysis of Wondelgem is founded on an array of historical and recent maps in 4 different periods (1777, 1840, 1971, and 2020).

By consecutively overlapping the site’s elements and highlighting the existing and new interventions in each period, the maps show the transformation of the site through time by focusing on the expansion of the urban area, the transformation of the water ways and the alteration of the landscape.

28

Assignment by Jennifer Saad and Raya Rizk

© Busquets, Joan; Correa, Felipe . 2004. Bringing the Harvard Yards to the river, 64-65.

Harvard University. Felipe Correa & Luis Valenzuela (ed).

Interpretation

WONDELGEM: FROM PASTURES TO PORTS DOCKS

Assignment by Jennifer Saad and Raya Rizk Ferraris 1777

Assignment by Jennifer Saad and Raya Rizk Ferraris 1777

Located in-between the two canals that link Ghent to Bruges, Terneuzen and the marshlands of Oude Kale river, the elevated plateau attracted the development of a series of domains for aristocrat families in the 18th century. These domains form a necklace along the Botestraat, strategically located on the ridgeline elevated from the wet lands. Following industrialization, the construction of the railway and the new canal in the marshland, the area has been drastically transformed.

The topography has been manipulated, reducing the difference in levels between the wetland and the plateau.

The urbanization has expanded beyond the limits of the dry area, while the industrial area sits within the marshland."

(Saad, Rizk 2021, 1)

29

© Geopunt.be

Roads Old Roads New

Water Rails Old Rails New Bridges Old Bridges New

Roads Old Roads New

Urban Old Urban New Domains Old Domains New Pastures Port

Water Rails Old Rails New Bridges Old Bridges New

Roads Old Roads New

Urban Old Urban New Domains Old Domains New Pastures Port

Water Rails Old Rails New Bridges Old Bridges New

Water Rails Old Rails New Bridges Old Bridges New

Roads Old Roads New Water Rails Old Rails New Bridges Old Bridges New

Urban Old Urban New Domains Old Domains New Pastures Port

Roads Old Roads New Water Rails Old Rails New Bridges Old Bridges New

Urban Old Urban New Domains Old Domains New Pastures Port

Roads Old Roads New

Urban Old Urban New Domains Old Domains New Pastures Port

Roads Old Roads New

"This methodology pinpoints the principles on which past settlements were established, inhabiting the limit of dry and wetlands, and eliminating the risk of flooding. These principles have long been forgotten with the expansion of urban structure and the manipulation of the landscape. The predicted flooding undeniably show that past inhabitants had a great understanding of the land, lessons we need to bring back to our modern world."

(Saad, Rizk 2021, 1)

Water Rails Old Rails New Bridges Old Bridges New

Roads Old Roads New Water Rails Old Rails New Bridges Old Bridges New

Roads Old Roads New

Urban Old Urban New Domains Old Domains New Pastures Port

Water Rails Old Rails New Bridges Old Bridges New

Urban Old Urban New Domains Old Domains New Pastures Port

Urban Old Urban New Domains Old Domains New Pastures Port

Water Rails Old Rails New Bridges Old Bridges New

Roads Old Roads New

Urban Old Urban New Domains Old Domains New Pastures Port

Water Rails Old Rails New Bridges Old Bridges New

Roads Old Roads New

Urban Old Urban New Domains Old Domains New Pastures Port

Water Rails Old Rails New Bridges Old Bridges New

Roads Old Roads New

Urban Old Urban New Domains Old Domains New Pastures Port

Water Rails Old Rails New Bridges Old Bridges New

Roads Old Roads New

Urban Old Urban New Domains Old Domains New Pastures Port

Urban Old Urban New Domains Old Domains New Pastures Port

30

©

Geopunt.be

31 © Saad & Rizk, 2021 2100 Flood Prediction

Inspiration

Amsterdam als stedelijk bouwwerk een morfologische analyse

Van Der Hoeven, Casper; Louwe, Jos. 2003.

"The mapping of the reference used, by Casper Van Der Hoeven and Jos Louwe, uses building blocks to examine the transformation of the grid layout system and its resulting new formations that constitute the urban fabric and its axes. It highlights features and axes created and enhanced as a result. It also analyses the transformation of urban spaces and urbanization through time in forming the current existing environment."

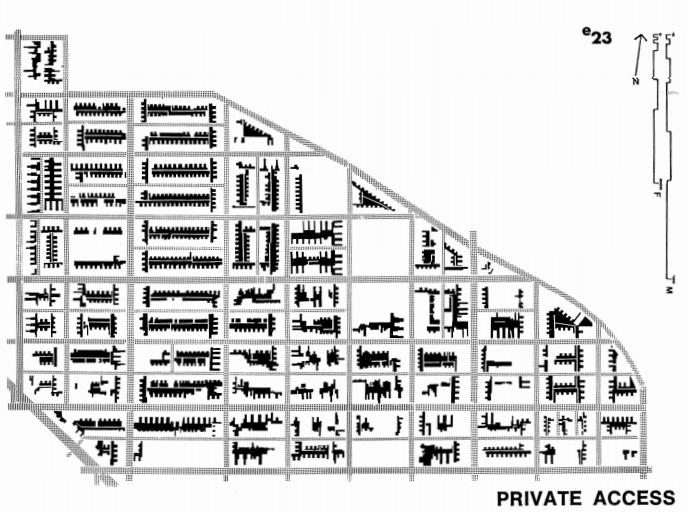

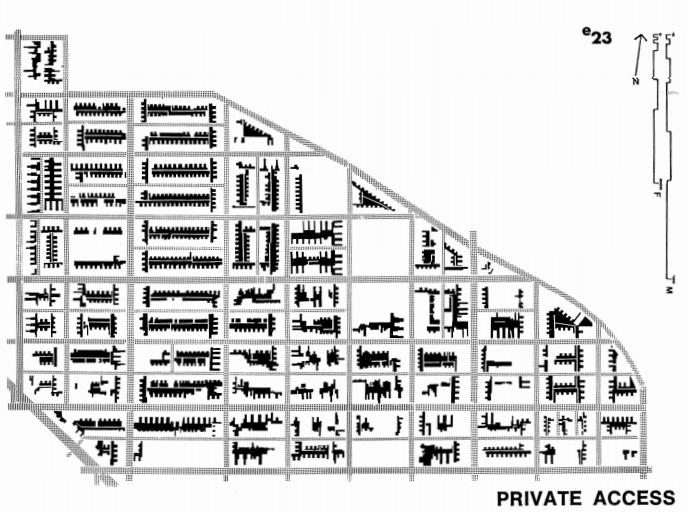

"Wondelgem is a suburbanized and industrialized area. Both the industrialization and suburbanization are seen in two major features of the site, the Ring canal and the historic access ‘Botestraat’ respectively.

The methodology from the reference is used similarly as it was used for Amsterdam to show the urbanization in relation to the historic access where large historic estates and old accesses seem

32

Assignment by Tien Huu Tran & Yidnekachew Seleshi

Meppel (Netherlands): SUN Publishers

©

Van Der Hoeven, Louwe. 2003.

A

msterdam als stedelijk bouwwerk een morfologische analyse

,

61.

Meppel (Netherlands): SUN Publishers

© Van Der Hoeven, Louwe. 2003. A msterdam als stedelijk bouwwerk een morfologische analyse

,

83. Meppel (Netherlands): SUN Publishers

Interpretation

Coiling: Development of Settlement Morphology

33

Assignment by Tien Huu Tran & Yidnekachew Seleshi

Wondelgem morphology 2021

to regulate the building blocks of detached single family houses coming in between. Simultaneously, the introduction of the Ring canal has initiated industrialization on what used to be marshy land alongside Oude Kale river.

In such a method of mapping, change is clearly readable. The use of building blocks with time frames to analyse the existing trend and historic evolution is helpful to see transformations and its players in regulating it.

Such methods can be utilized to formulate and understand major factors for the urbanization process of the existing urban fabric and, with an overview capacity, it provides potentials and challenges of a study site will be easily explored and synthesized for which future schemes and projection will take base at."

(Saleshi, Tran 2021, 1)

34

Scattered Ribbon Settlement

Block expansions

Historic Axis( Botestraat

) Historic Axis Access Tree line Tree line Tree line Canal Tree Large estate

Oude Kale river

&

marshes

1777

Ferraris

1970s Wondelgem

Present Wondelgem

N

Wondelgem area

Ghent N

Scattered Ribbon Settlement

Historic Axis( Botestraat )

Historic Axis Access Tree line Tree line Tree line Canal Tree Large estate Oude

Kale river

&

marshes

1777 Ferraris

1970s Wondelgem

Present Wondelgem

N

Wondelgem area

Ghent N

Block expansions

35

Scattered Ribbon Settlement

Urban Coiling on the existing axis Cul-de-sac Densi cation Historic Axis( Botestraat ) Historic Axis Access Tree line Tree line Tree line Canal Canal Canal Tree Stream Stream Tree Tree Historic Axis Historic Axis Large estate Large estate Large estate Oude Kale river & marshes 1970s Wondelgem

Present

Wondelgem Creation of the Ring Canal Canal Expansion and Industrialization Industrialization 200m100m 0200m100m 0 N N

36

Fieldwork

1.2

38

39

© Agnese Marcigliano 2021

40

© Daniela Cobo 2021

41 ©

Agnese Marcigliano

2021

42

43 ©

Daniela Cobo 2021

44 ©

Agnese Marcigliano

2021

45

©

Letlhabile Shubane 2021

46 ©

Agnese Marcigliano

2021

47 © Lucie_Van

Meerbeeck

2021

48

© Daniela Cobo 2021

49

© Agnese Marcigliano 2021

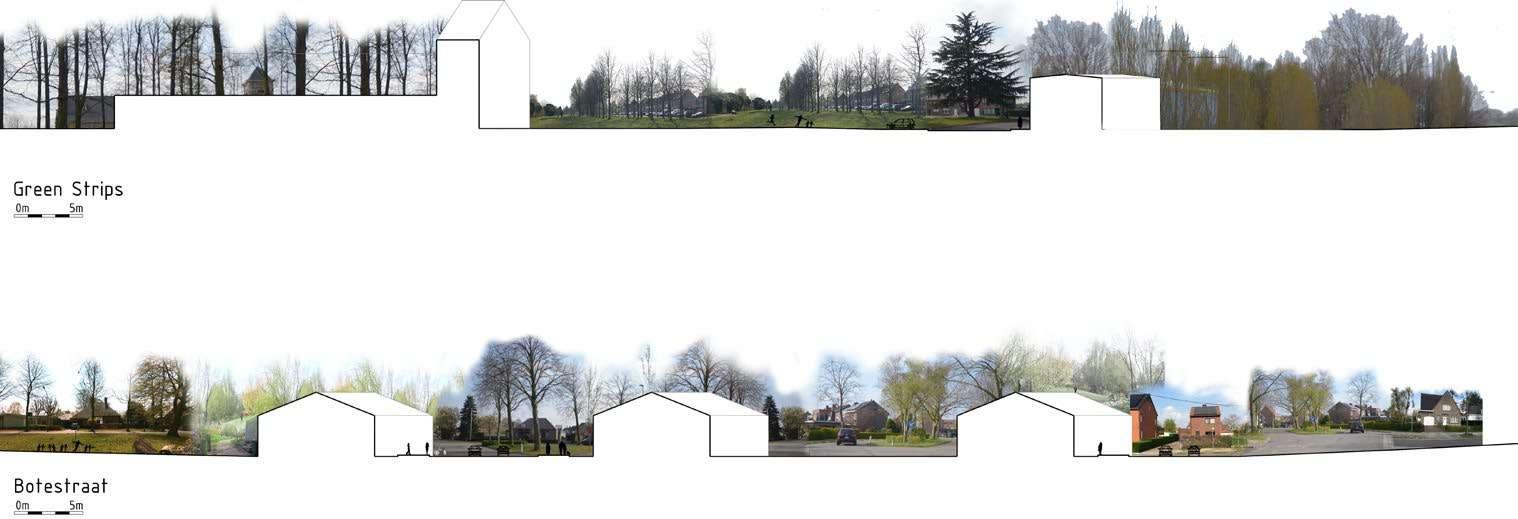

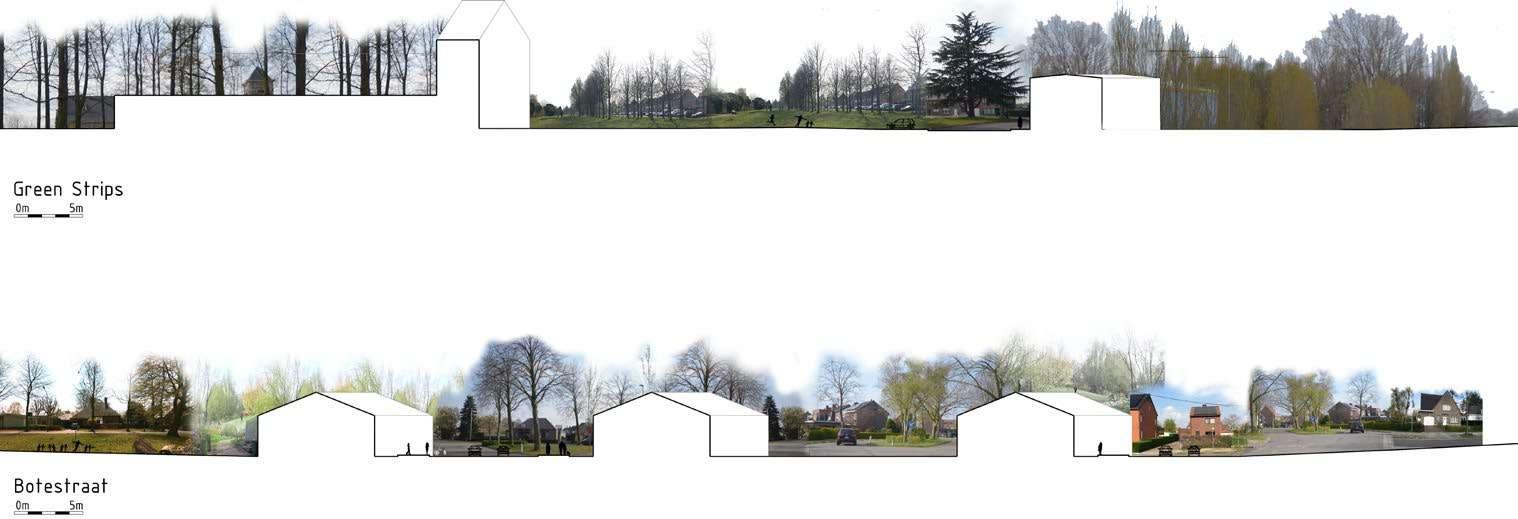

Articulating Wondelgem’s in-betweens

First impressions

This collage illustrates our fieldwork first impressions of the site. Originally Wondelgem's landscape was dominated by marshlands and fertile lands, nowadays the suburbanisation encroaches on what remains of the landscape and water and nature have being relegated to the background, becoming a commodity.

The site is characterised by a consolidated urban tissue, formed by detached-single family houses and punctuated by ancient pri vate domains.

Cycling through the district what we found most interesting was the presence of some leftover green spaces in-between the neighbourhoods, which became the base of our design.

50

Fieldwork Poster

Wondelgem presents a fragmented landscape, where inbetweens/residual spaces continue to exist despite the intense urban speculation.

We found several green strips that accommodate different uses and users; some are playgrounds, some are places for contemplation, and others are occupied by weeds and vegetation.

The Botestraat is one of the main axes on our site. Domains stand out along the street with their castles and large gardens. A few of them are publicly accessible, while the others remain private. All

along the street we found neighbourhoods where cul de sac and in-betweens spaces (rotondes, parterres, etc.) offer opportunities for desealing and articulation.

Along the canal industrial and commercial activities take place. The canal docks are dominated by gigantic infrastructures, buildings, and windmills, and act as an island in the urban tissue of the district.

51

Qualitative information maps

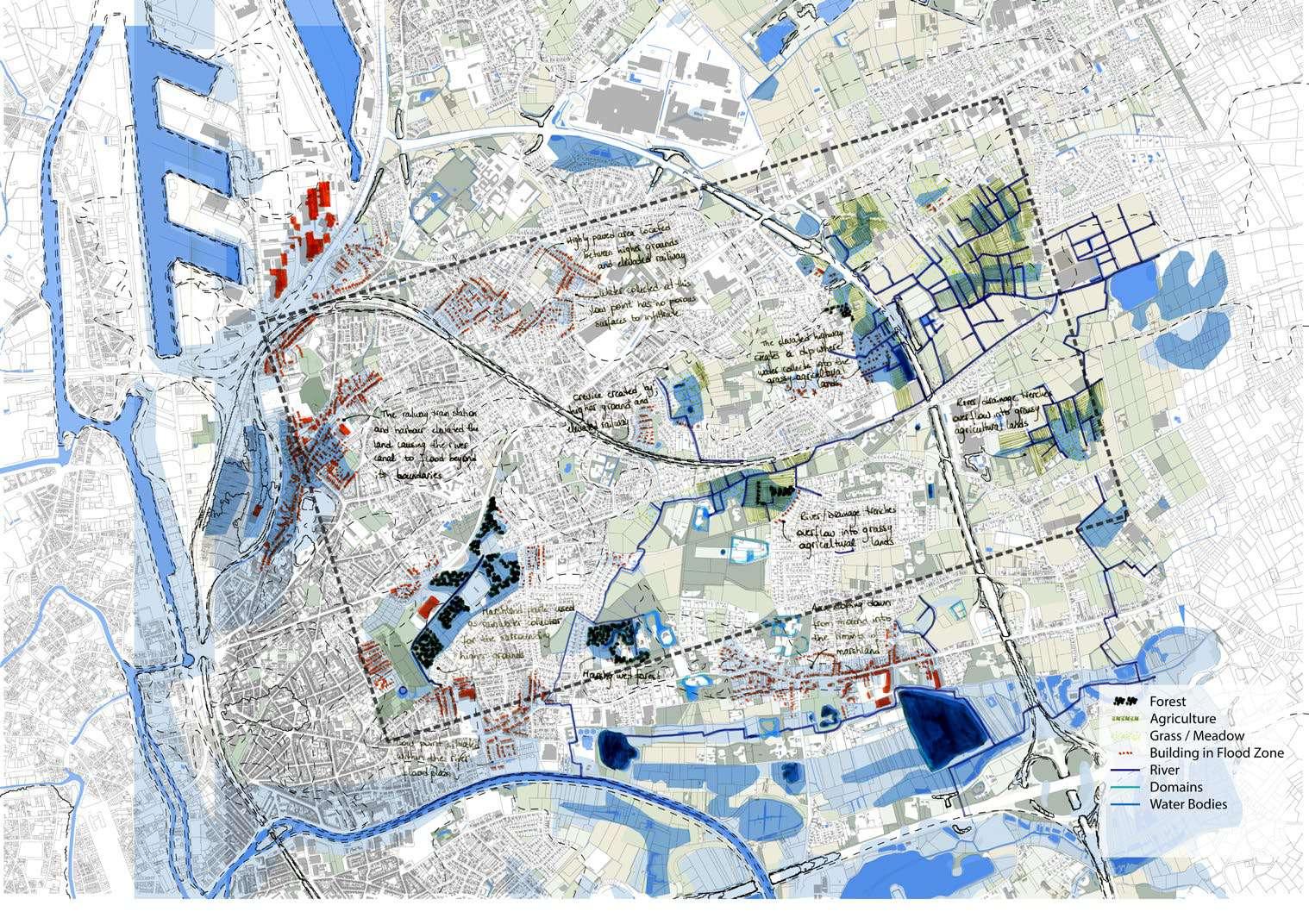

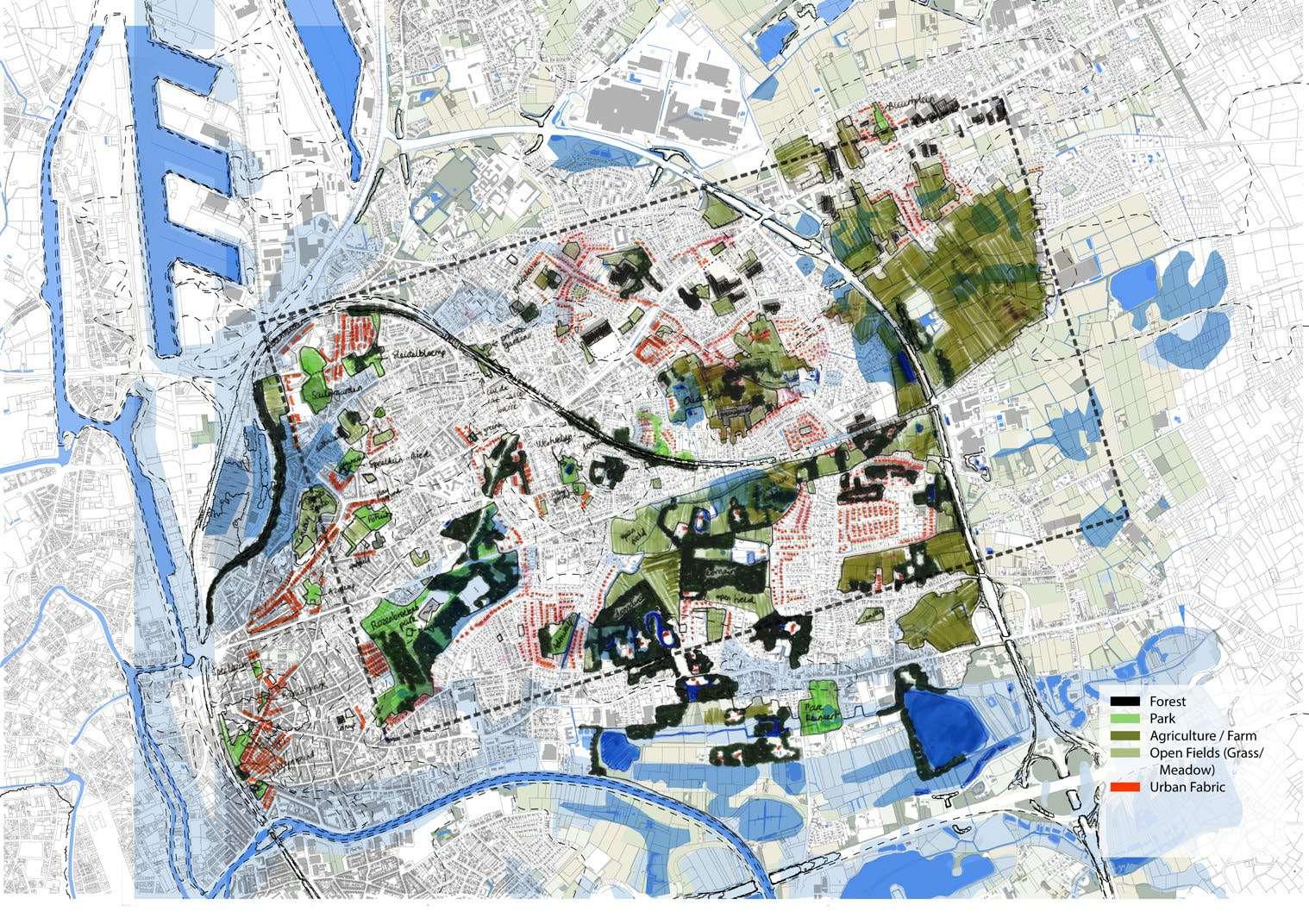

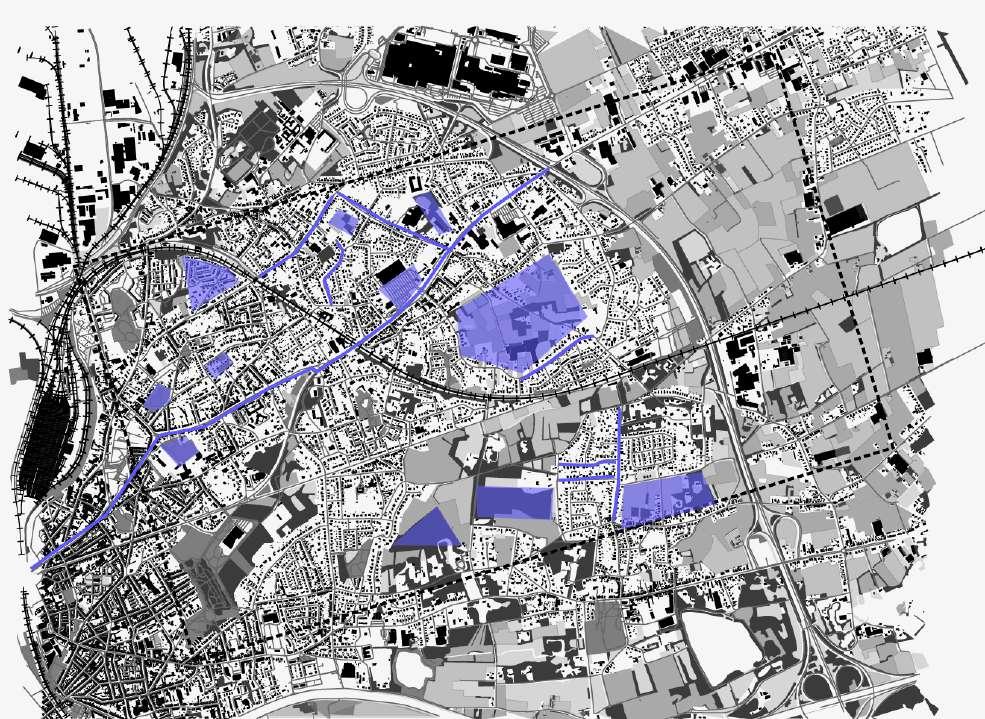

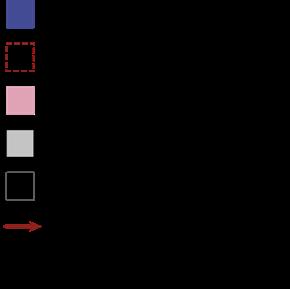

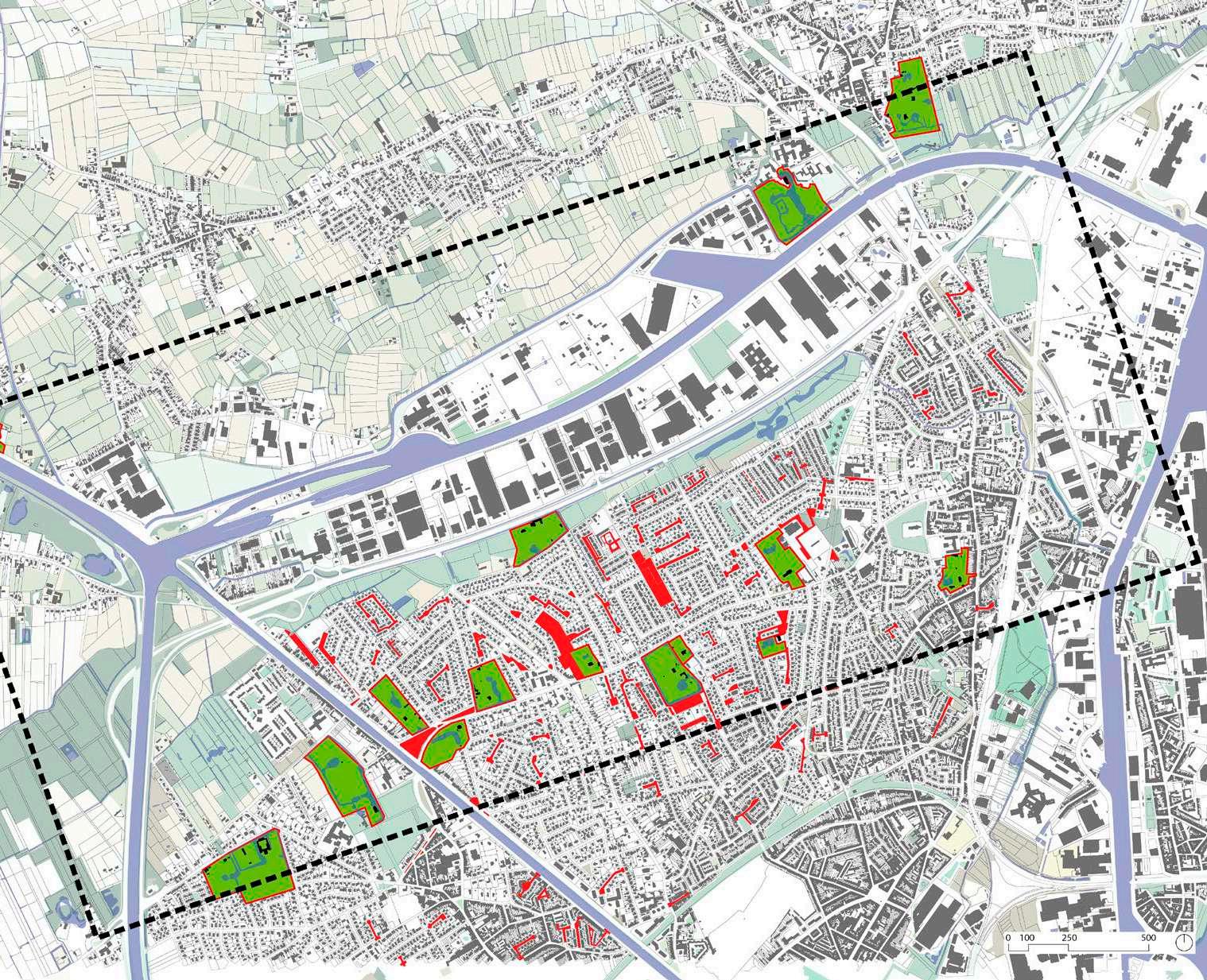

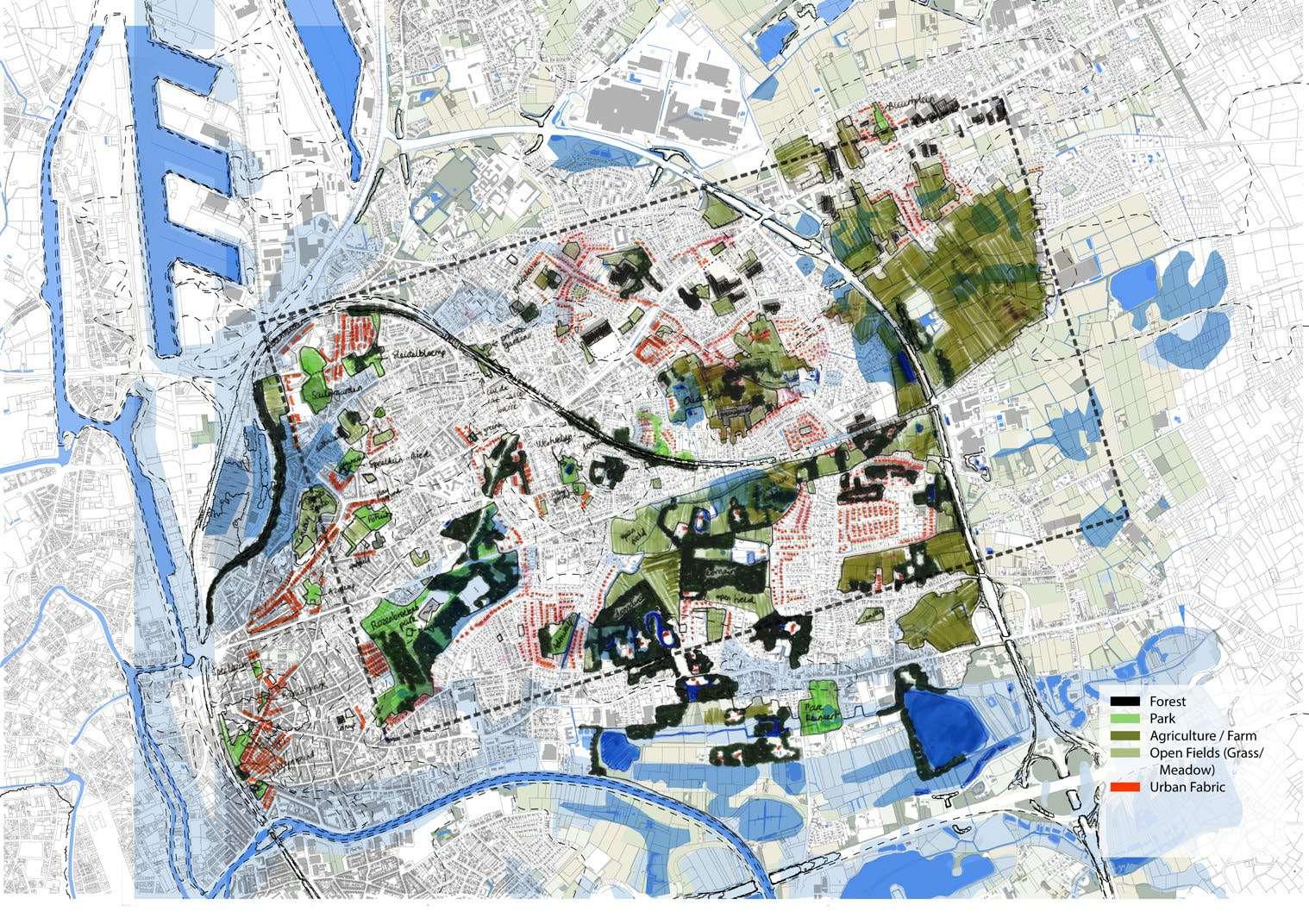

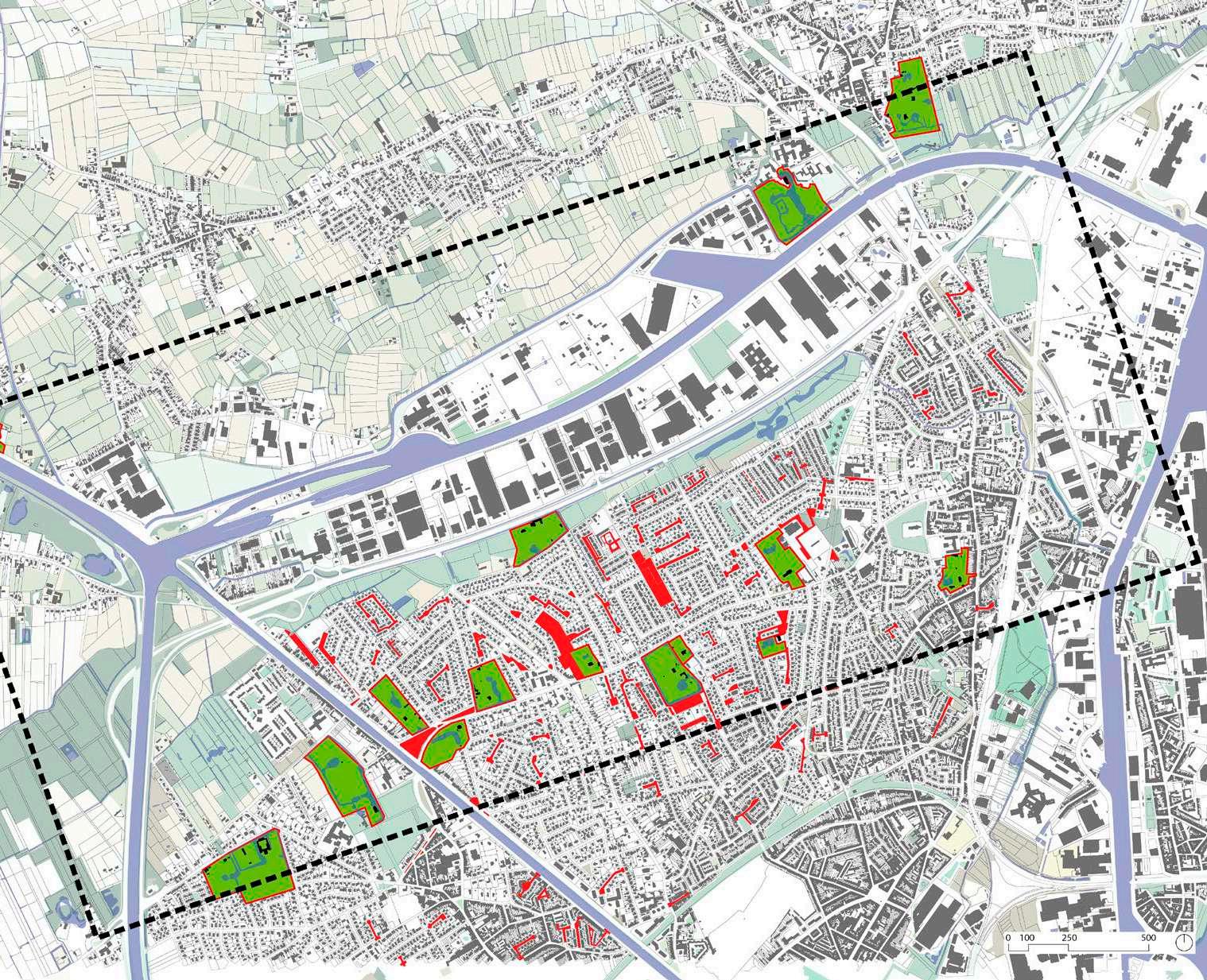

Types of territory: green and blue landscape systems

The map shows the green and blue systems scattered around Wondelgem. North of the industrial canal, the green system consists mainly of agricultural fields, which define the more rural identity of the Northern area. The industry concentrated around the canal forms a clear void in terms of green space, and the little green strips developed around the canal and highway serve as (noise) barriers and are not publicly accessible. This enhances the secluded character of the industrial strip. Additionally, at the southern edge of the industry, a landscaped park serves as both a noise barrier as a place for leisure.

The urbanised area north of the city of Ghent is characterized by a network of informal green spaces surrounded by roads and big domains (mainly privately owned). The way in which many of the informal green spaces are almost strangled by oversized roads emphasizes the leading role of the built environment. The oversized road network and strangled green spaces, however, form places of opportunity to start rethinking the outdated urban practices.

Wondelgem’s blue system is strongly marked by the presence of industrial canals. These canals divide the area in several islands, and are often not publicly accessible. Additionally, the Lieve, which used to be the main industrial route before industrialization, runs through Wondelgem. Contrary to its previous function, it now forms a green and blue axis which provides a place for ecology, movement and recreation.

On a smaller scale, the blue system consists of several ponds inside of the domains, and artificial wetlands constructed in the landscaped parks along the highway. The ponds and wetlands are mainly used for leisure and fishing activities.

52

Green strips next to highway

Isolated

Opportunity for green connections

Inaccessible unmaintained green area

Inaccessible + Untouched

Biological valuable + Hidden

Little green islands strangled by roads

- Eaten by roads and concrete

Scattered around the site

Opportunity for desealing

Opportunity for social encounter

53

-

+

-

+

+

+

+

Qualitative information maps

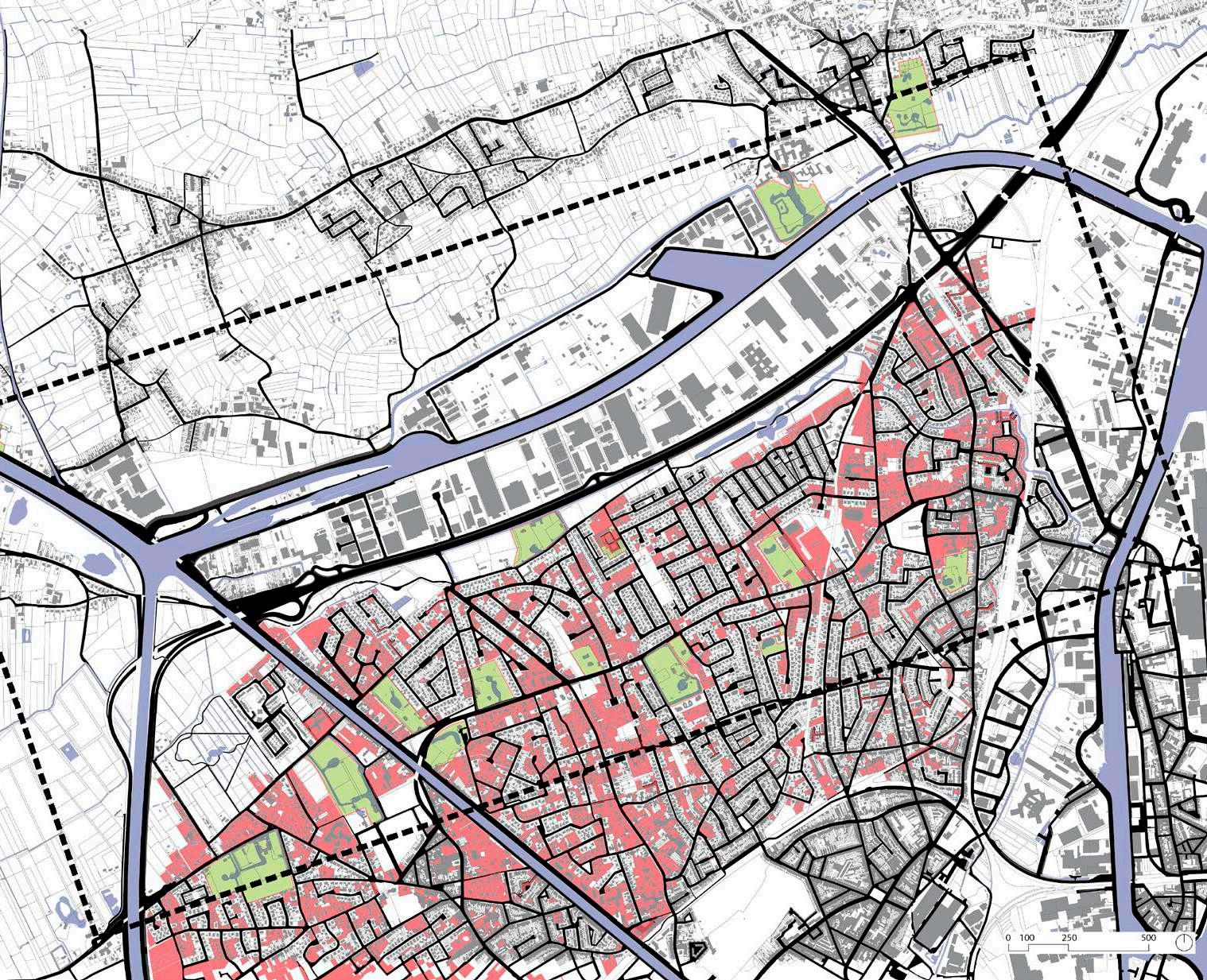

Built Environment: Housing typologies

This map represents the opportunities, challenges and conflicts of the built environment of our site, with a particular focus on the existing structure of the urban tissue.

We observed that the main circulation network and the water element of the canal fragment the tissue into a series of urban islands. Some of these islands constitute satellite communities around Wondelgem, some are formed by large industrial or economical surfaces, and the latter in particular creates a barrier between the main urban core of the district and the green surfaces up north of the site.

At the local scale the main housing typologies already present on site have been identified, in particular the ones standing out of the more basic logic of the urban sprawl or representing a social or physical conflict between systems.

54

55

56

Argumentation & Strategy

1.3

How have the different landscape systems been a guiding element for urbanization?

The three elements that have structured the site have been water, topography, and agricultural parcellation.

The canalisation of the area during the industrial period, prompted the growth of industry, and urbanisation. The canal was built at the lowest points of the topography, where the marshlands once were, so since the 16th century urbanisation has primarily developed on higher and driest ground as a result of (of the territory’s conformation) topography and water.

Following the construction of the canal, the marshy land surrounding the area has been sealed and used for industrial development. The sealing of the wetlands allowed for a growth in the urban area south of the canal.

The highway was built alongside the ring canal, and the main axis route of the suburb, Botestraat, runs in parallel to the ring canal, but with few connections to it.

Plots that were once agricultural plots, have since become

58

© Ferraris Map 1777, Geopunt.be

residential plots, and so their geometry has dictated the urban growth of Wondelgem. These old parcels, intended for agriculture, have resulted in various types of leftover spaces, and less efficient housing typologies.

59 Site 1 Settlement Water Roads Legend Site 1 Settlement Water Roads Legend © Ferraris Map 1777, Geopunt.be ©

Geopunt.be

1 2 5 km

60

61 Wondelgem 1777 Wondelgem 1845 Wondelgem 1969 Wondelgem 2021

The primary conflict that exists is the barriers to accessibility prevalent in the area.

On the larger scale, the ring canal and the industrial edges around it act as a barrier between the suburb, and the satellite communities to the north of the city.

This containment may be a positive attribute, preventing urban sprawl, however, it does act as a wedge, preventing interaction across it. The highway and railway tracks further enforce this

barrier.

The landscape figure of the canal, on which urban structure is formed, is not accessible or present in the environment of the Wondelgem community. This lack of access to the water edge is another point of conflict, but also of opportunity.

62

Which conflicts and future challenges exist from the linkages among the systems?

On a neighbourhood scale, due to the nature of the parcels, a large number of the streets end in cul-de-sacs, providing no thoroughfare, and making pedestrian access very complex or almost impossible between the neighbourhoods. The leftover spaces created by the cul-de-sacs are a point of conflict, thus, opportunities for intervention.

63

The second conflict can be identified in the relationship between public and private green spaces. The majority of the green surfaces left in the area are private domains, therefore inaccessible to the larger public, while smaller green spaces are shrank in between an oversized circulation network.

A few of these domains have been transformed in public spaces, but the rest remains at the mercy of private developers and the real estate market. The qualitative green voids present in the urbanised environment should be preserved, while others can become spaces of opportunity for transformation.

64

A third conflict has to do with climate change and its consequences. As industrialisation and urbanisation took place on the marshy land, flooding but specially droughts issues will be present in the coming decades on the site. This map shows the areas where we can take advantage of floodplains to cope with future drought. De-sealing will be necessary in some cases.

65

The Lieve, which was the main connection to the coast from Ghent during the middle ages, has been subverted as a landscape figure, and now the Westbekesluis is the main waterway through the site, forming part of the ring canal. Industry dominates the water edge, and access to the water from the wider community is therefore limited. Fishing activities, as well as hiking and cycling take place in the few public parks manages by the City of Ghent, where inhabitants can interact with the water and nature.

The large domains, historically owned by wealthier Ghent residents, punctuate the suburban tissue of the district.

These parcels and the rest of the leftover green spaces are at the mercy of real estate private developers, responding with low quality projects to the intense urban growth of the area.

66

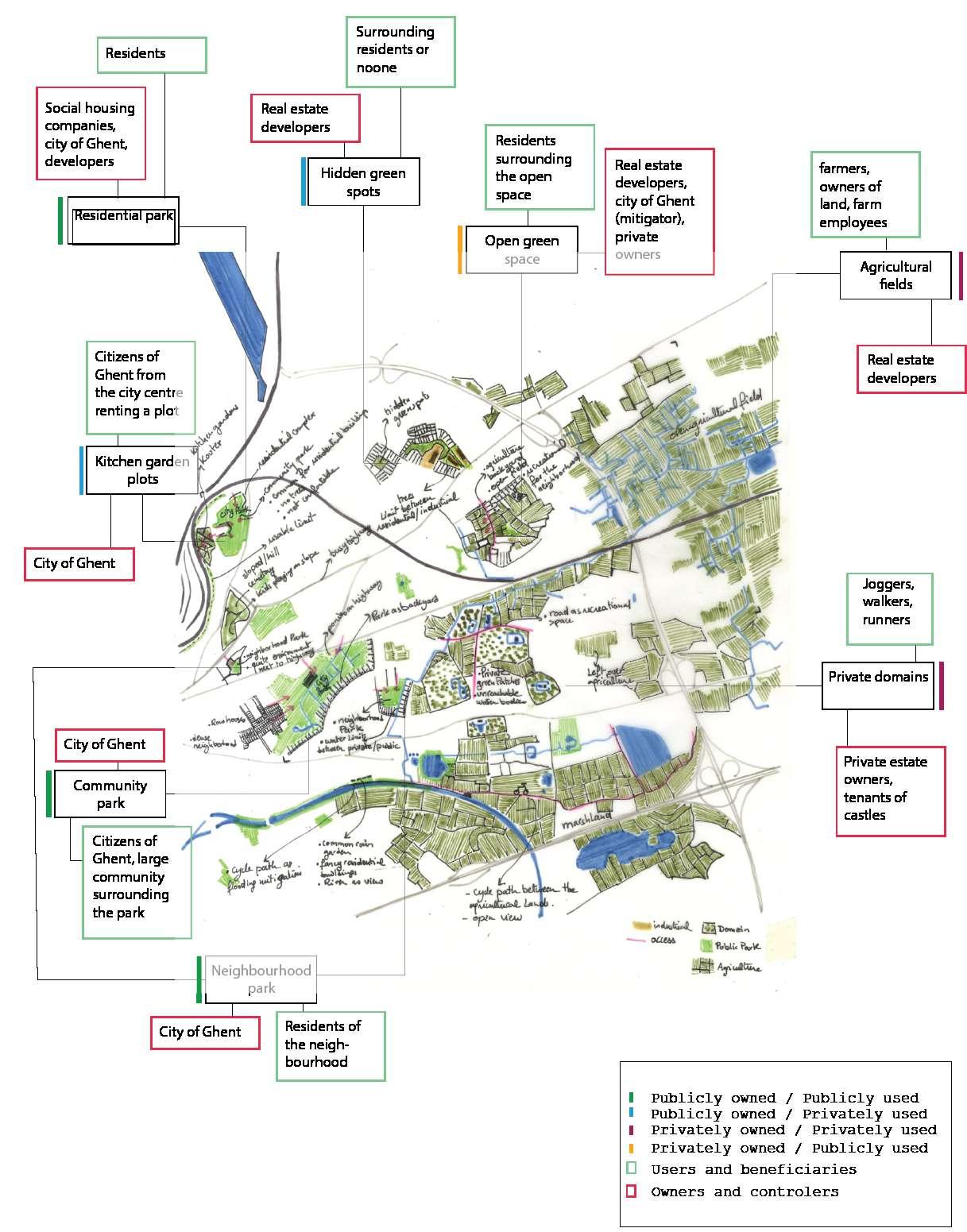

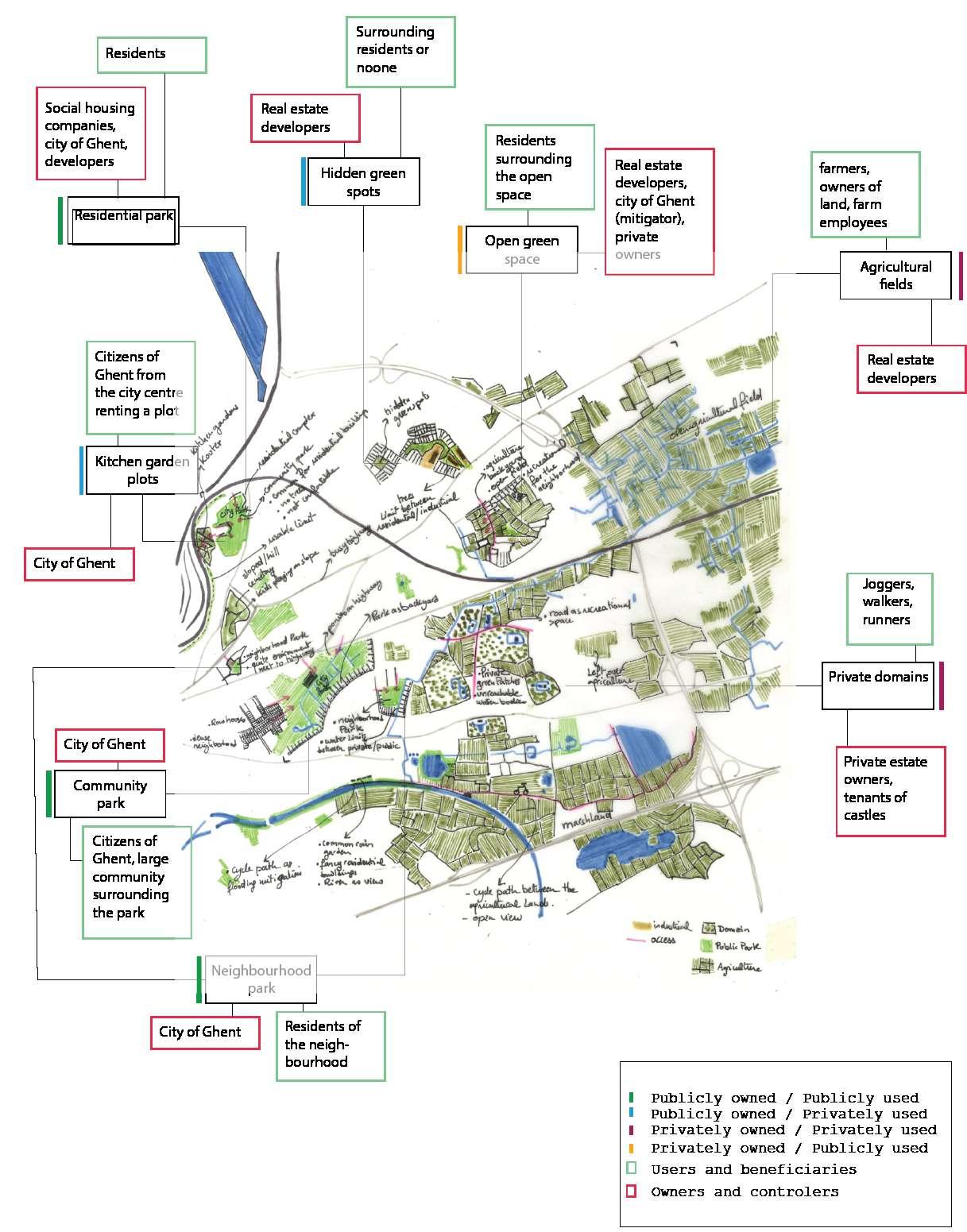

Who is excluded from the system, who controls it, and who is benefitting from it?

Economical barrier

Contrasting housing typologies

67

Research Questions

1. How can the transformation of the economic strip play a role in the restoration of the ecological continuity in the large scale landscape systems in Wondelgem?

2. How can the in-between spaces be articulated to enhance the small scale local green network, recover the marshy land and tackle future droughts?

3. How to contrast the local suburbanisation dynamics and transform the conformation of the urban fabric to reclaim space for more common living practices?

68

69

70

71 2.0 DESIGN

72

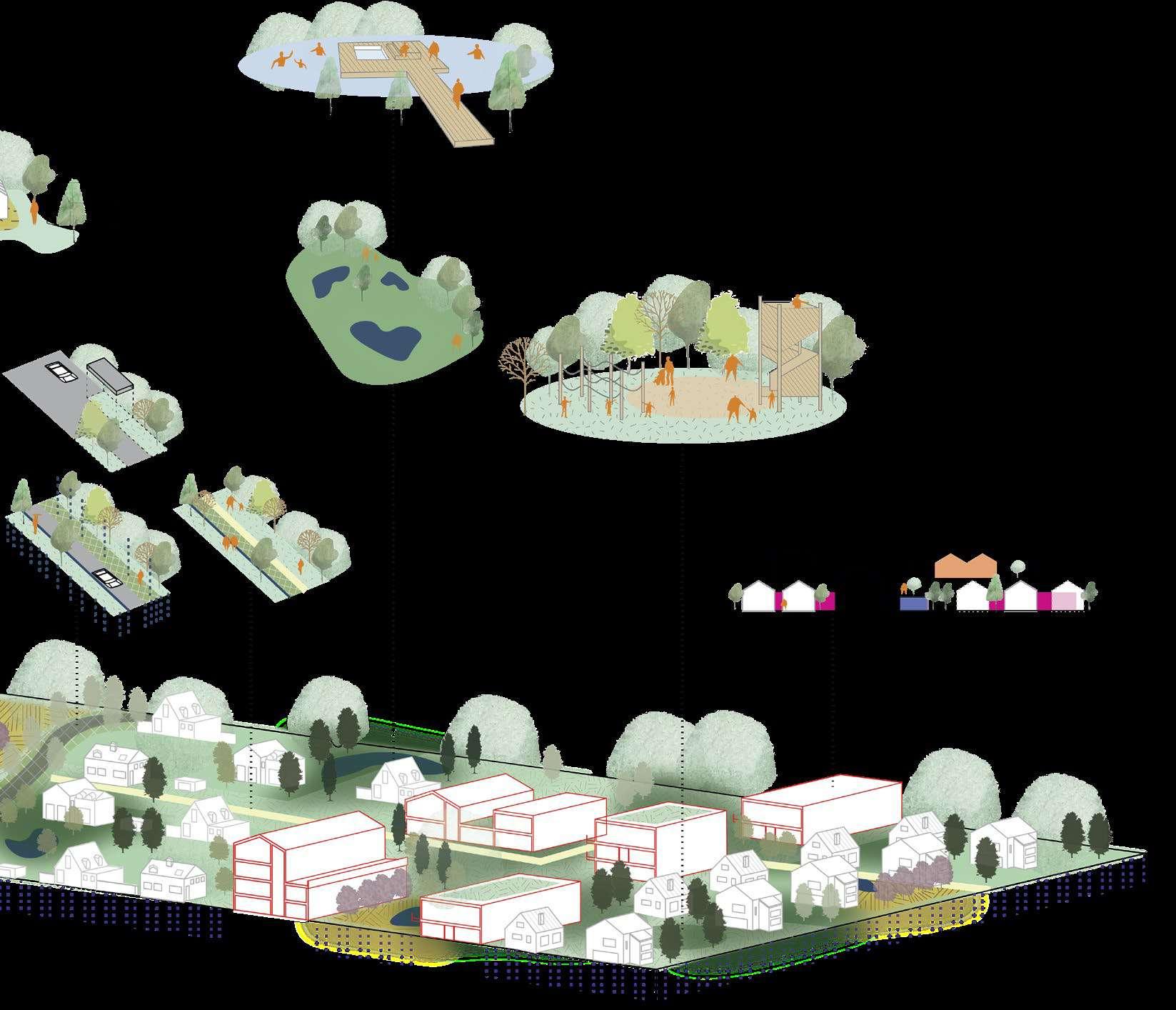

Eco-Systemic Visions

2.1

Reading the Territory

CHALLENGES & STRATEGIES

Flooding / drought

De-sealing

We identified several conflicts and challenges marking the site. The first has to do with climate change and its consequences. Due to industrialization and intensive urbanization covering the marshy land over the years, flooding and droughts issues will worsen in the coming decades.

The map shows the floodable areas and the severity of drought in 2100. By interpreting this map, it becomes clear where we can take advantage of floodplains to cope with future drought. It also indicates where is needed to apply afforestation strategies.

The schemes on the left, indicate the different strategies that could be applied on the site to tackle these challenges.

By combining strategies as desealing, water-management, and the creation of a green-blue network throughout the site, a more climate resilient environment will be created.

Infiltrating

Recovering marshlands

74

Green & blue networks

75

Challenges & strategies

Domains, leftover green spaces, voids, cul-de sac

As shown in the map, the second conflict has to do with the privatization of land and leftover green spaces. The site presents a series of historic domains and castles, traces of the ancient feudal tradition.

A few of these heritage sites have been transformed into public parks, but the rest remains private or at the mercy of the real estate market.

Due to intensive suburbanisation the site is characterized by a scattered network of green voids and leftover spaces, while the dense nature of the parcel system has a major influence on the street network configuration leaving a large number of streets terminating in cul-de-sacs, providing no thoroughfare.

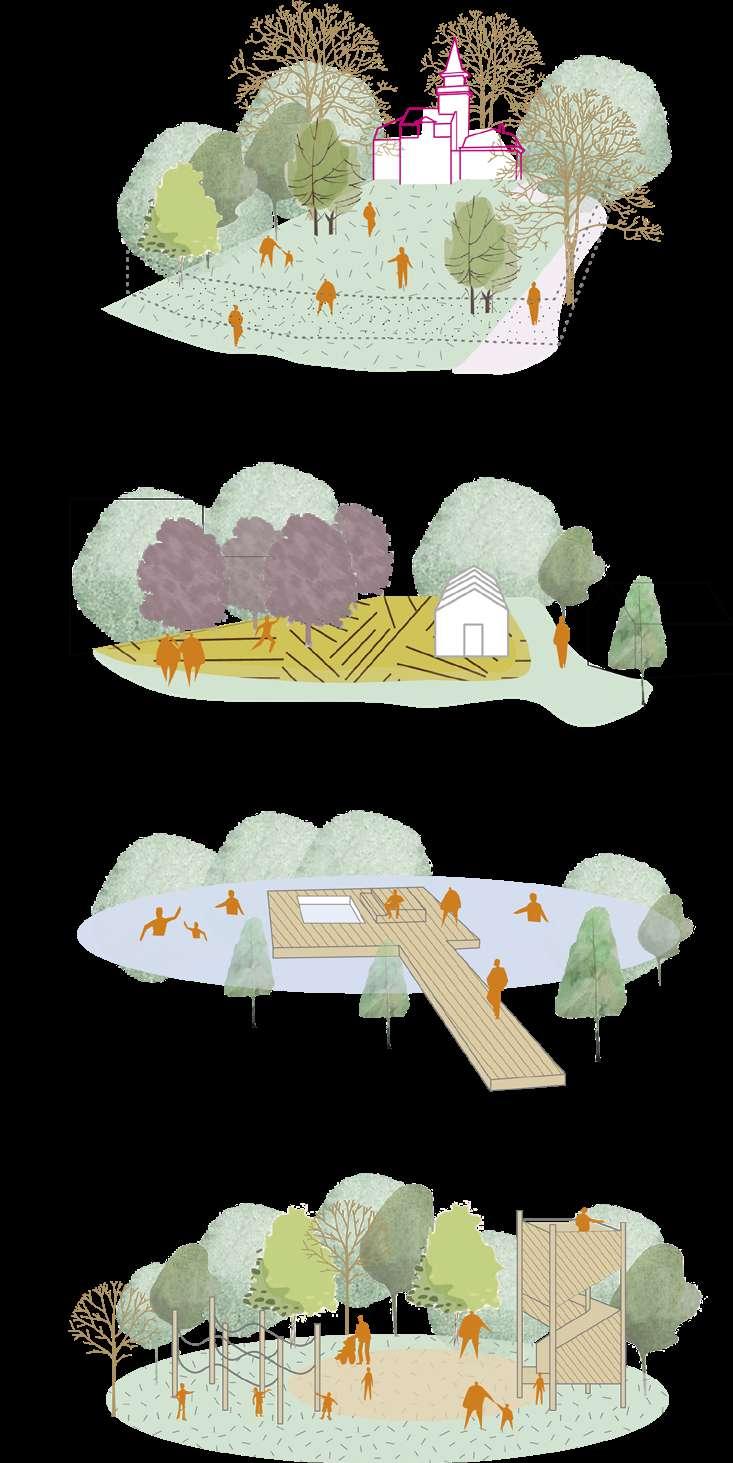

Our strategies expand and recreate an accessible network of various green and blue commons by providing access to the domains, requalifying the leftover voids and transforming the asphalted culde-sacs into communal gardens, community orchards and play forests.

Desealed spaces are given back to the community as new public spaces, improving the living conditions of the district.

Reclaiming heritage

Community orchards

New water spaces

76

Play forest

77

Challenges & strategies

Oversized street network, oversized plots, urban growth

A third conflict has to do with the oversized street network, the oversized plots, and the intensive urban growth. The streets are out of scale in relation to the car space needed for these residential neighborhoods, leaving the remaining green spaces strangled between them. Besides, the existing residential plots are organized following the single-friendly family house notion, including extensive private gardens.

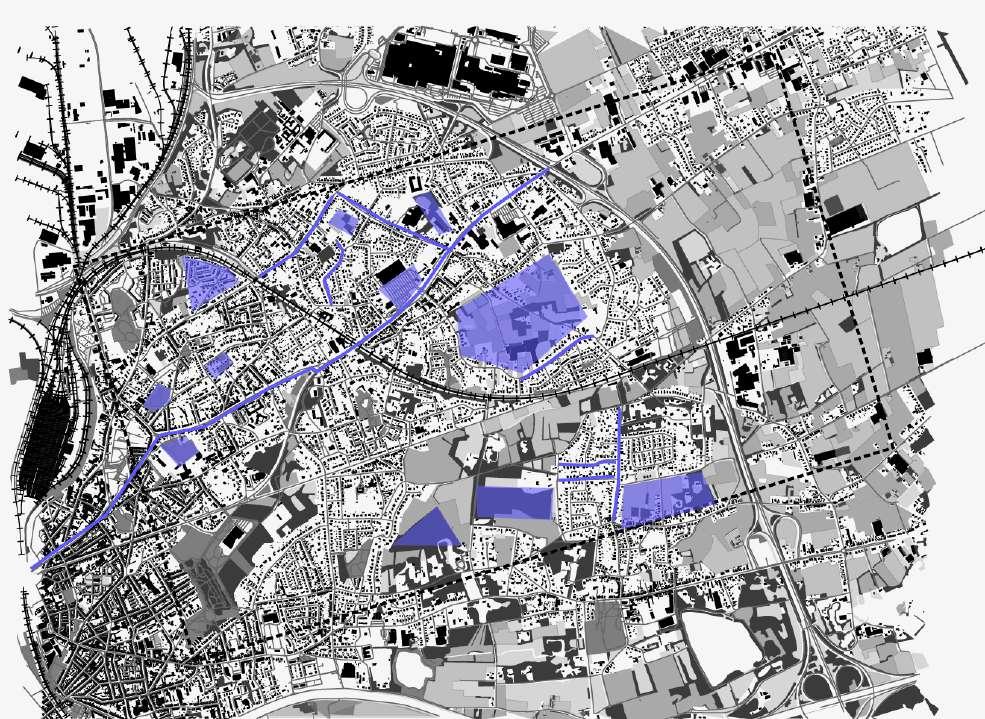

Therefore in our vision, the street network will be transformed into a soft mobility network, leaving just strategic streets accessible to cars.

Furthermore, our approach for densification is to reconfigure the standalone typology housing plots. We have focused on the thoroughfare of the east-west direction, maximizing sunlight and breaking the north-south repetitive pattern. We propose mixed-use, high-rise density, more efficient neighborhoods, and a plot configuration favoring more communal arrangements.

Soft mobility network

Mixed building typologies

Climatic building adaptation

78

Green & blue networks

79

80

Design Proposal & Typologies

2.2

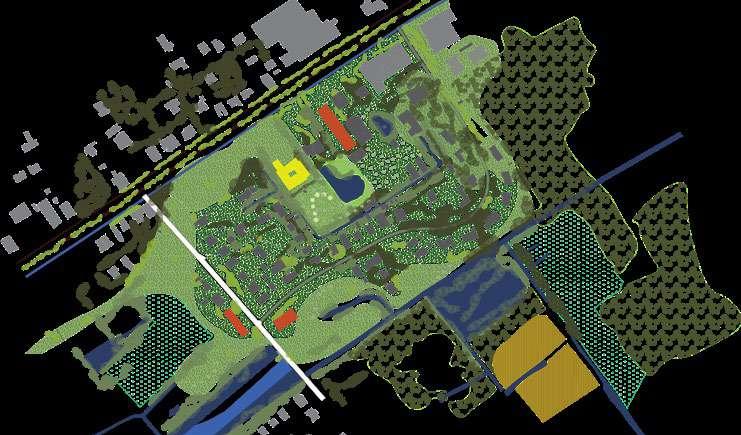

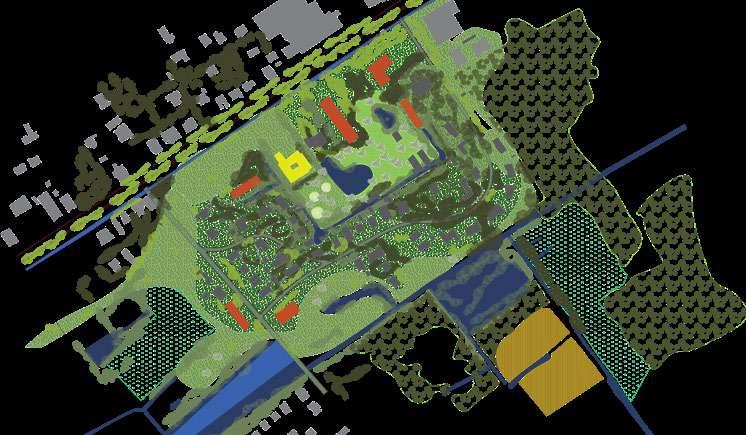

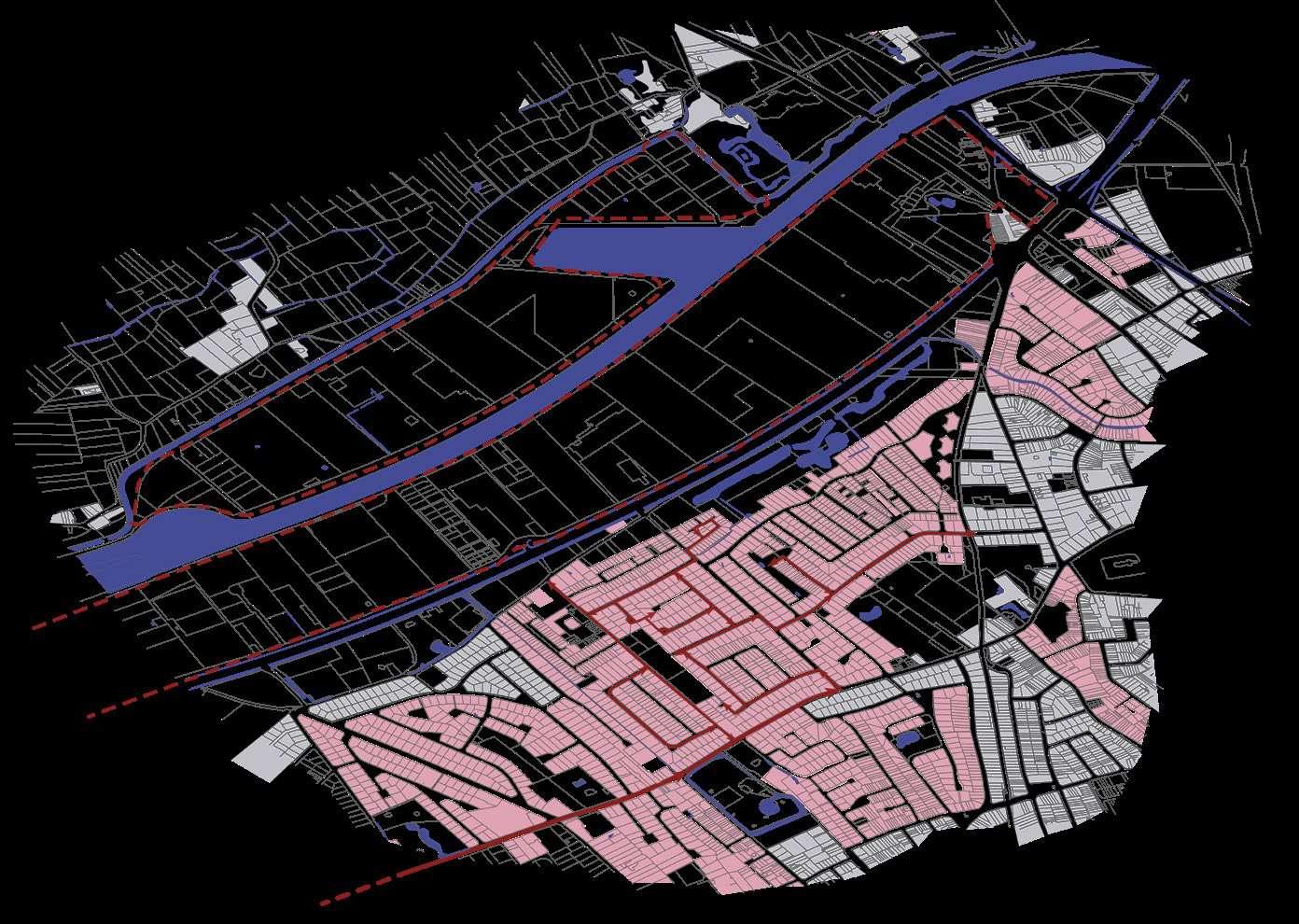

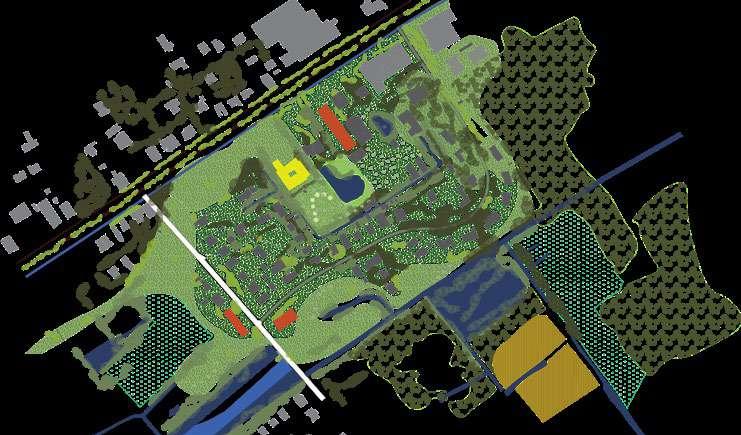

Wondelgem 2100

DESIGN PROPOSAL

Redefining Suburbia

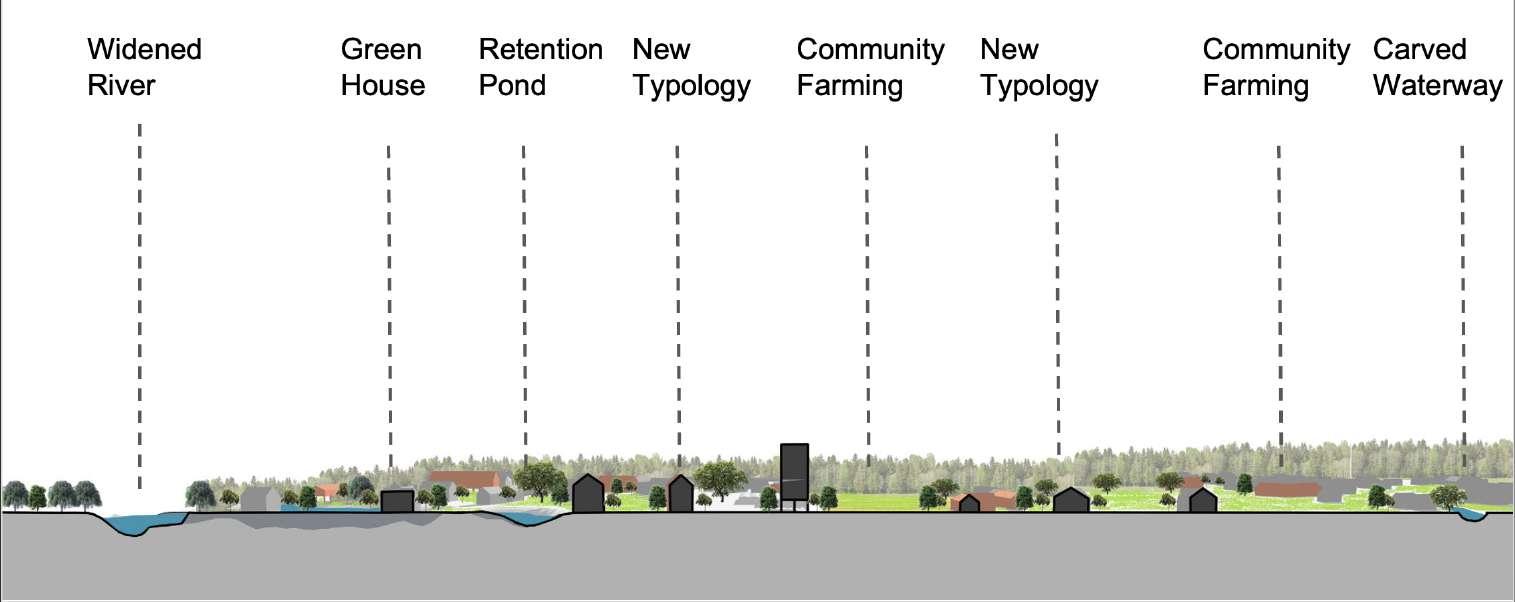

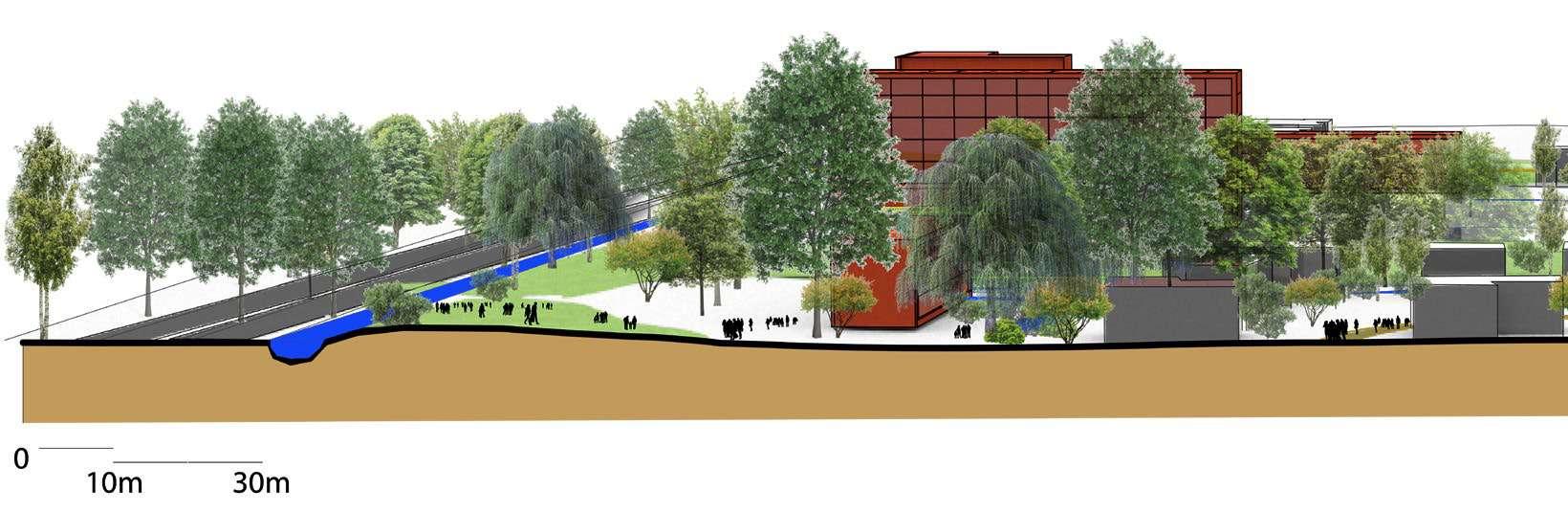

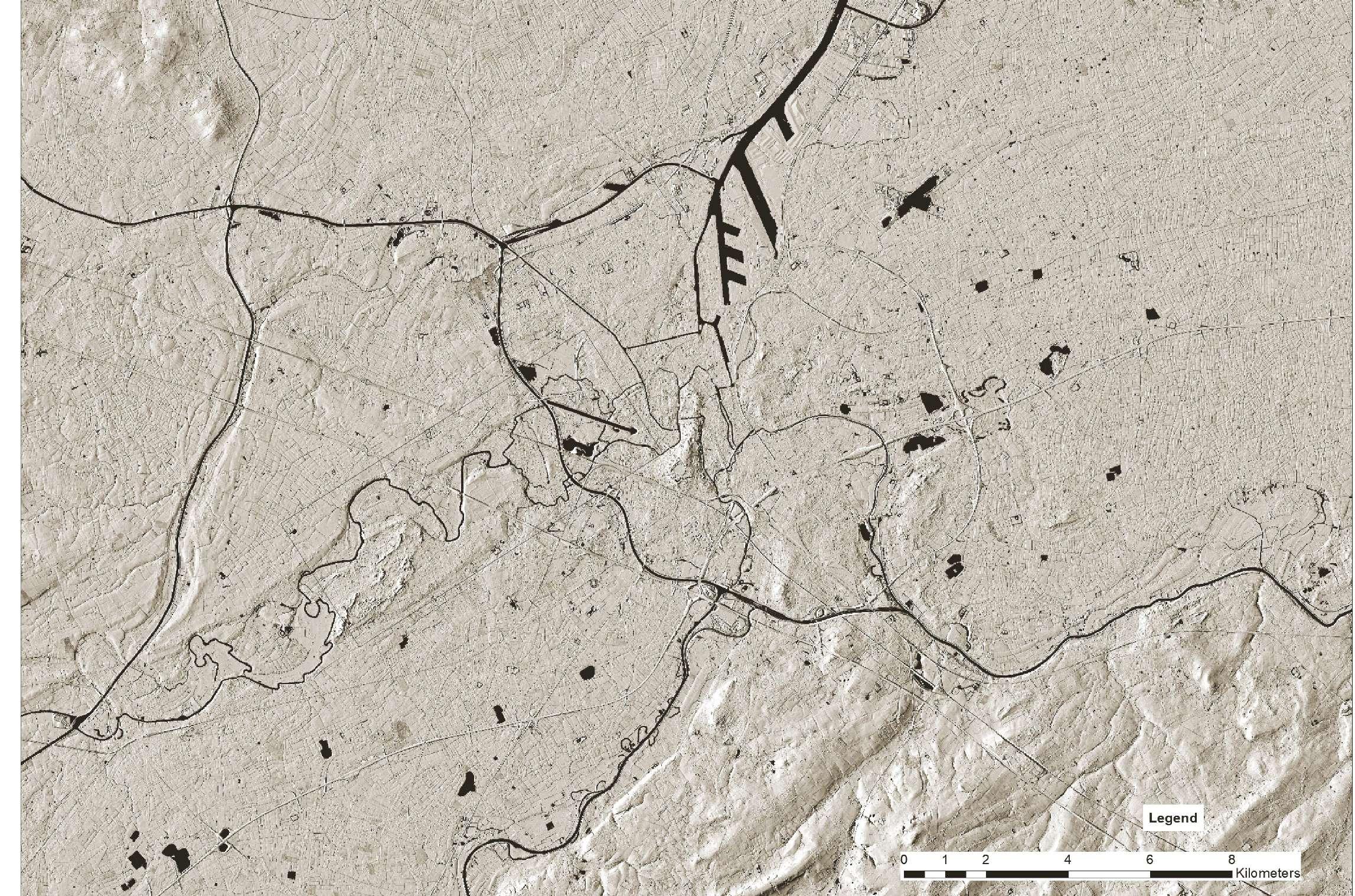

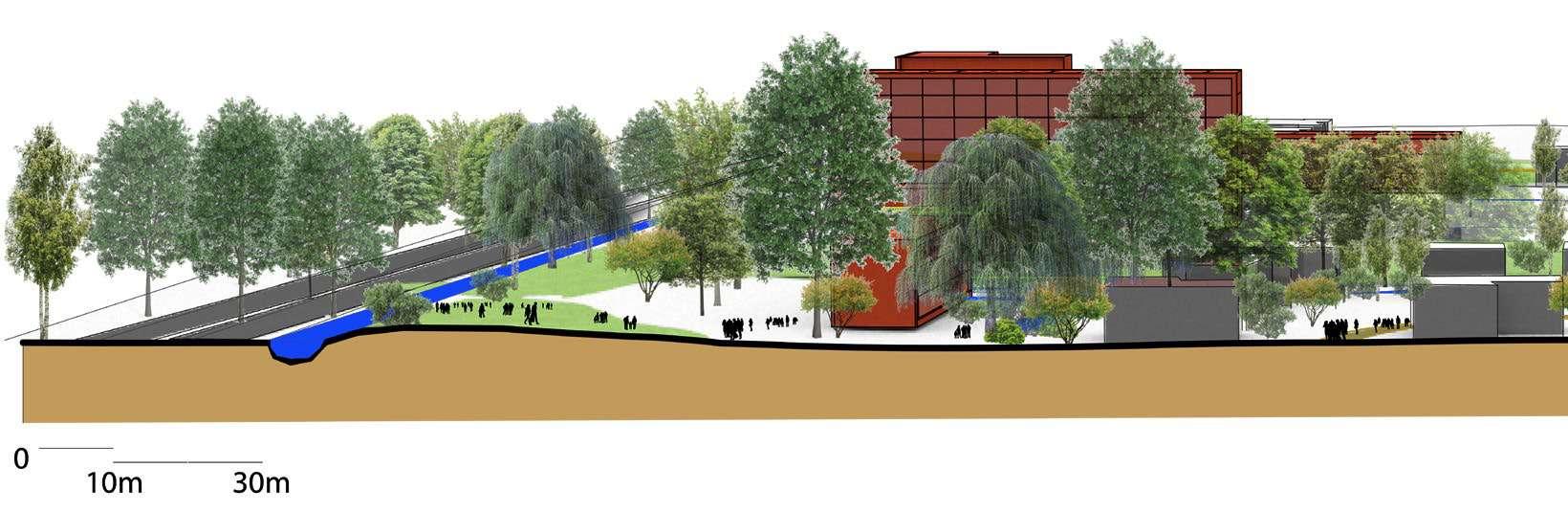

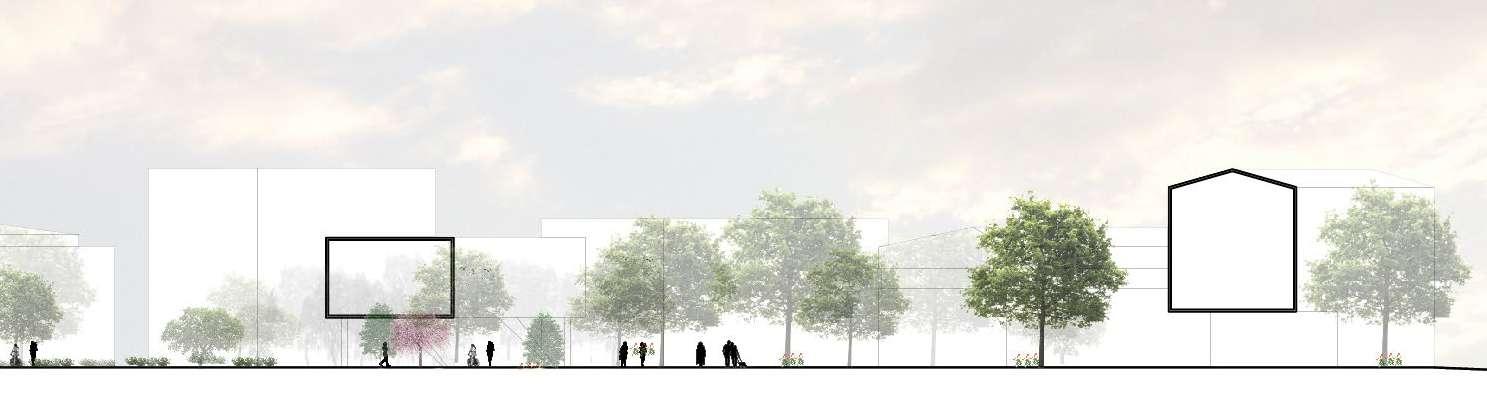

The vision plan and the section summarize our main design strategies to address the challenges in Wondelgem to the year 2100.

By redefining and desealing the existing streets, opening up the domains and leftover green voids a green an blue system is created throughout the site. The new densification pattern integrates respectfully this system re-activating the territory at the local scale,

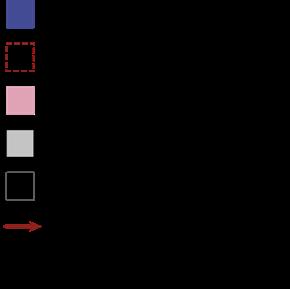

LEGEND

82

83

Challenging the car-driven culture

DESIGN STRATEGIES

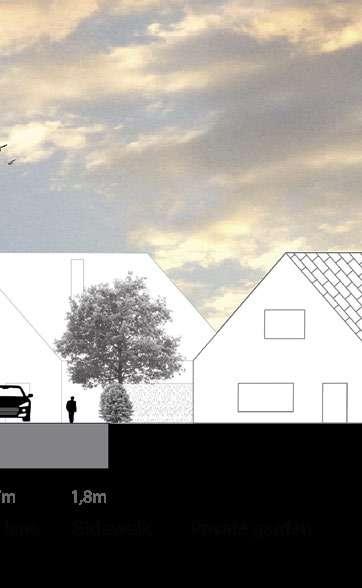

A de-sealed mobility system

The oversized street network transformation is based on a careful assessment of the existing circulation network characteristics, fluxes and hierarchies.

The main circulation axes, like for example the Botestraat, continue to be car-oriented, but are redesigned to accommodate communal re-naturalised spaces. Secondary circulation roads giving access to the main residential areas are reduced to one car lane, providing extra space for pedestrians and the soft mobility network. In both cases the reclaimed public space is extensively de-sealed and complemented by water permeable surfaces and tree lines to increase water infiltration in the soil as a flooding prevention measure. Streets serving only local circulation are transformed into pedestrian trails and slow roads with limited access for residents, which integrate the global green-blue network thanks to the dense presence of natural elements and surfaces. The roads are now included in the neighborhoods dynamics, hosting informal activities and becoming lively places of encounter and exchange, instead of being only axes of circulation.

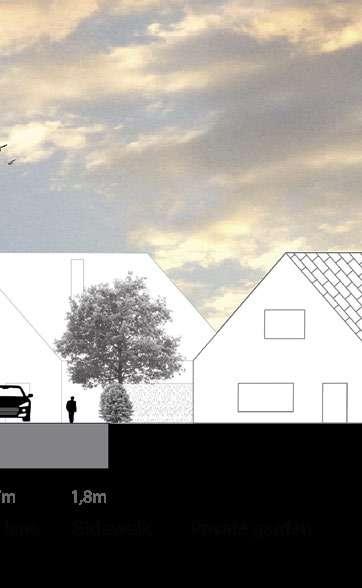

Desealed main circulation (two car lanes)2100

84

Botestraat 2021 Main circulation

Desealed

(one car

Secondary circulation

Katwilgenstraat Welpengang

85

secondary circulation

lane) Local circulation Local pedestrian and slow circulation

Breaking the public/private boundary

DESIGN STRATEGIES

Reclaiming the heritage

Today the private domains present in Wondelgem act as islands in the suburban development pattern of the site. These sites are the few remaining green large spaces in the district, therefore their social and ecological value has to be preserved and protected from further speculation.

To rupture the elitist boundary between private and public property, we suggest that the City of Ghent reclaims the domains that are still private, and open them to the general public.

The conversion of the domains gardens in public parks will be the occasion to organize temporary activities on the premises, such as local markets, concerts or open-air events during the summer season, while some areas will be destined for permanent recreative areas, responding to the necessities of the neighborhoods.

In some cases, the castles will be restored and transformed in social infrastructures for the inhabitants.

The landscape and architecture heritage of the domains is integrated in the general blue and green system, creating a constellation of large scale public spaces going from the canal and culminating in the historic dries at the end of the Botestraat axe.

86

2021 2100

Private green island in the suburbanisation pattern

87

Re-activated landscape heritage in relation with the surrounding environment

Contrasting Climate change through Landscape

DESIGN STRATEGIES

A nature oriented response

Our design approach was built following the flood and drought predictions for the horizon 2100. We classified the different areas of interventions and assigned to each level of drought and flood sensitivity a specific type of vegetation or public space, to implement tailor-made solutions based on the climatic characteristics and challenges of the site.

88

89

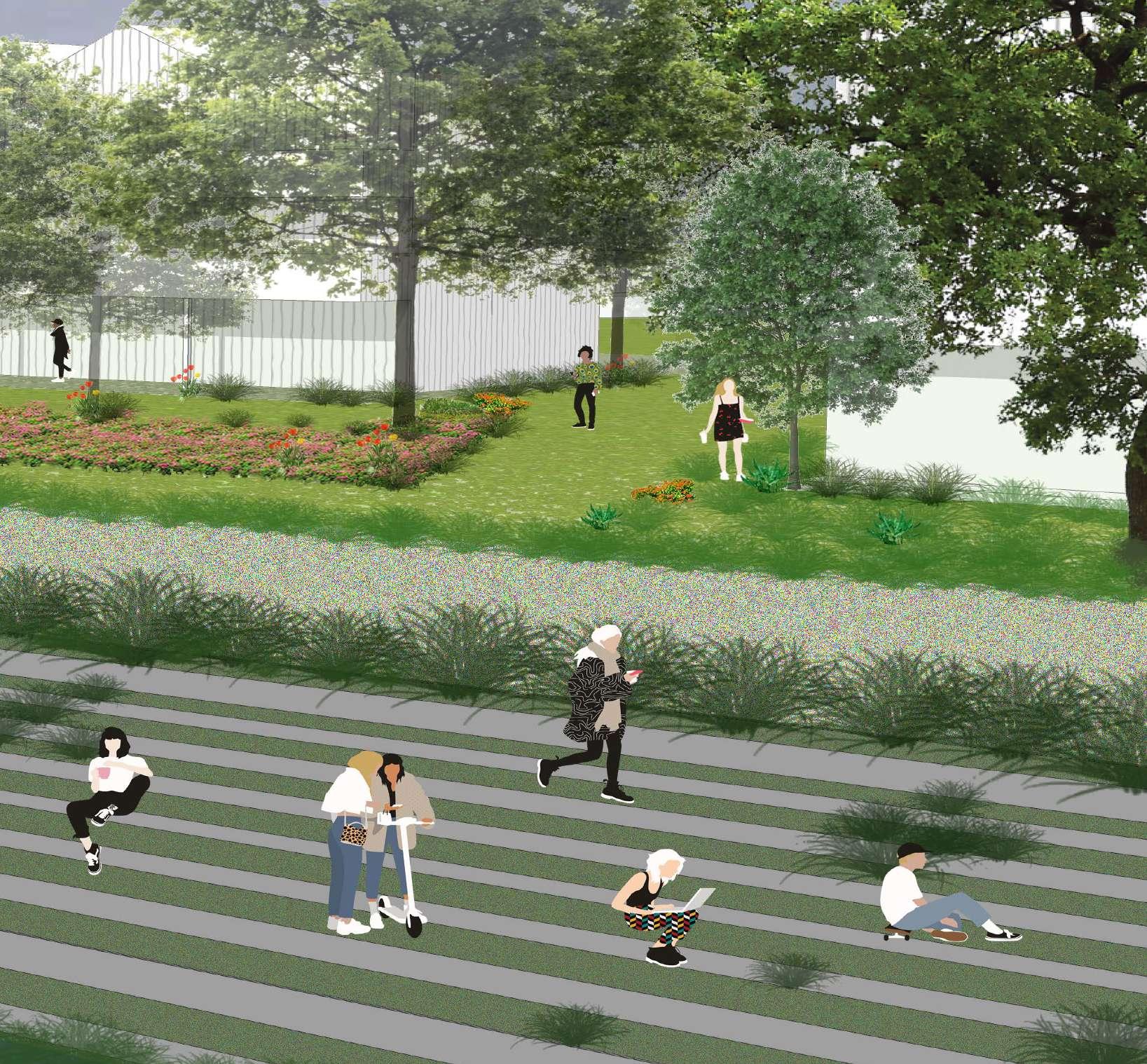

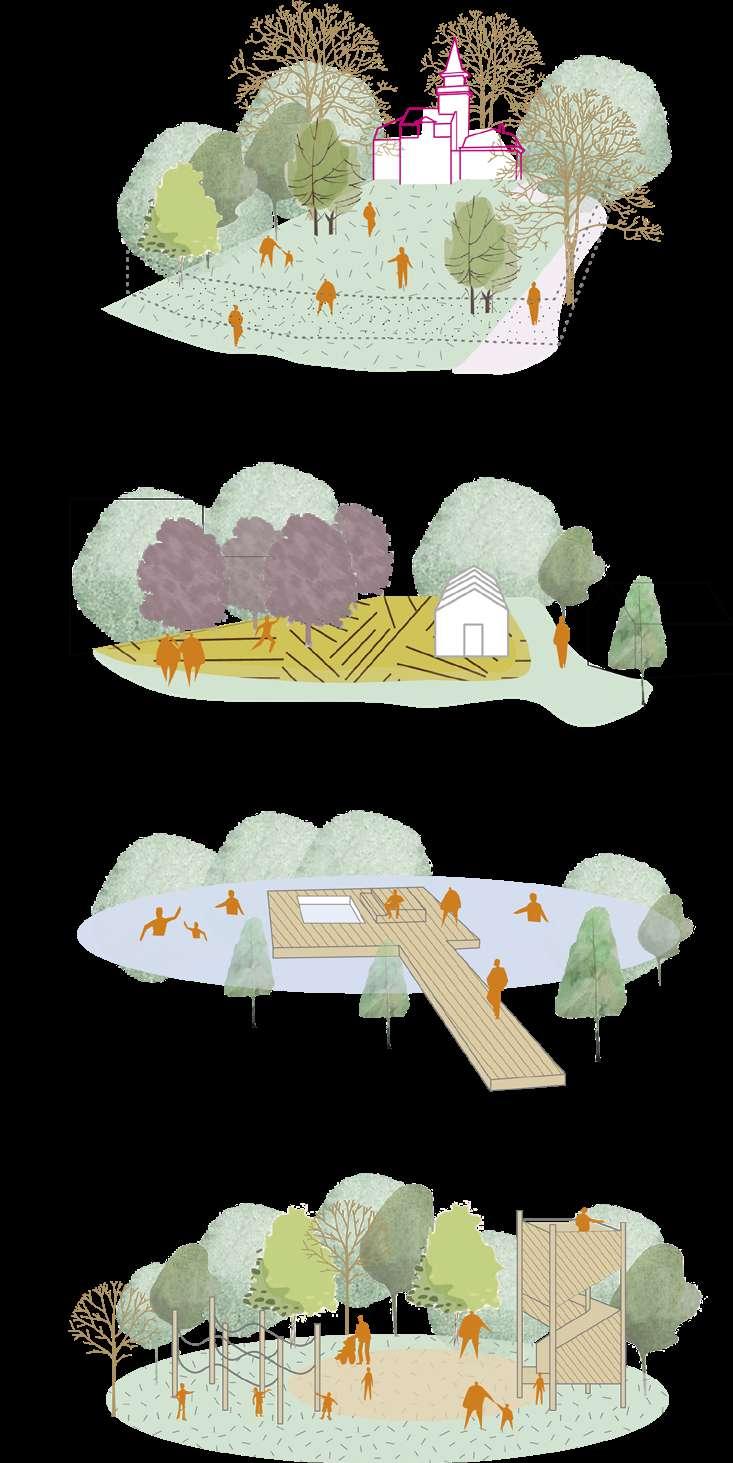

DESIGN STRATEGIES

New green and blue commons

The leftover green spaces and cul-de-sac “plazas” previously identified are requalified and transformed in pedestrianized open spaces of encounter and activities for the community, as part of the green and blue system.

We propose a series of possible configurations including re-wilded public gardens, playgrounds and communal orchards, with the aim of restructuring the human dimension of the neighborhoods.

All these green spaces are complemented with water retention ponds, for daily use and agricultural purposes, and permeable surfaces.

Reclaiming space for the community 2021

The implementation of orchards in particular is a response to an already existing tradition of informal local agriculture, present throughout the district. By promoting small scale agriculture and re-wilded spaces we encourage the citizens to reconnect with their territory, following the changing of the seasons, and to build a renewed common identity for the community.

90

2100

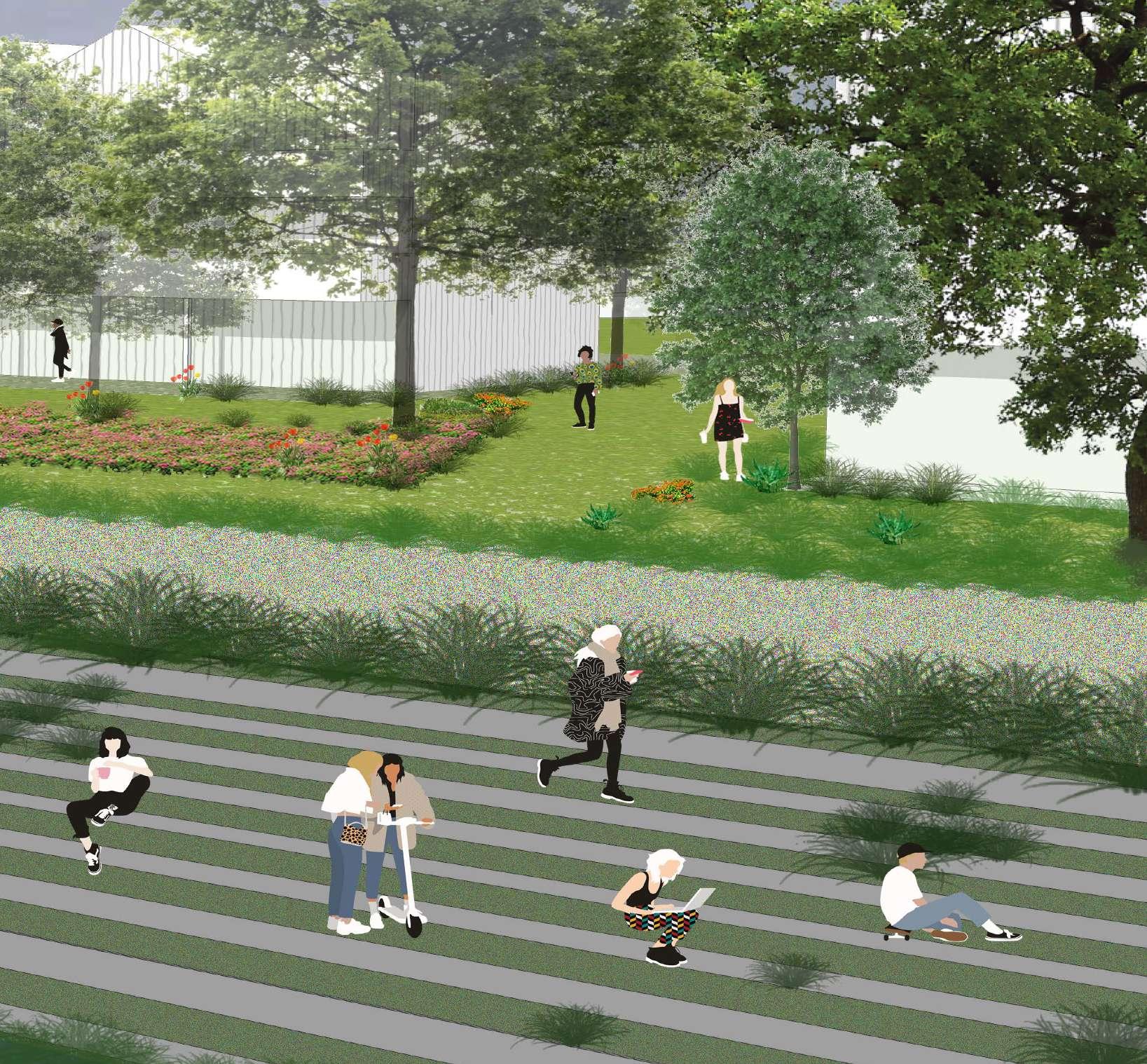

91 2100 2100 Car centered public space Re-wilded public garden Community orchard Play Forest and blue spaces © Source

Reconfiguring the suburban

DESIGN STRATEGIES

Improved typologies and social dynamics

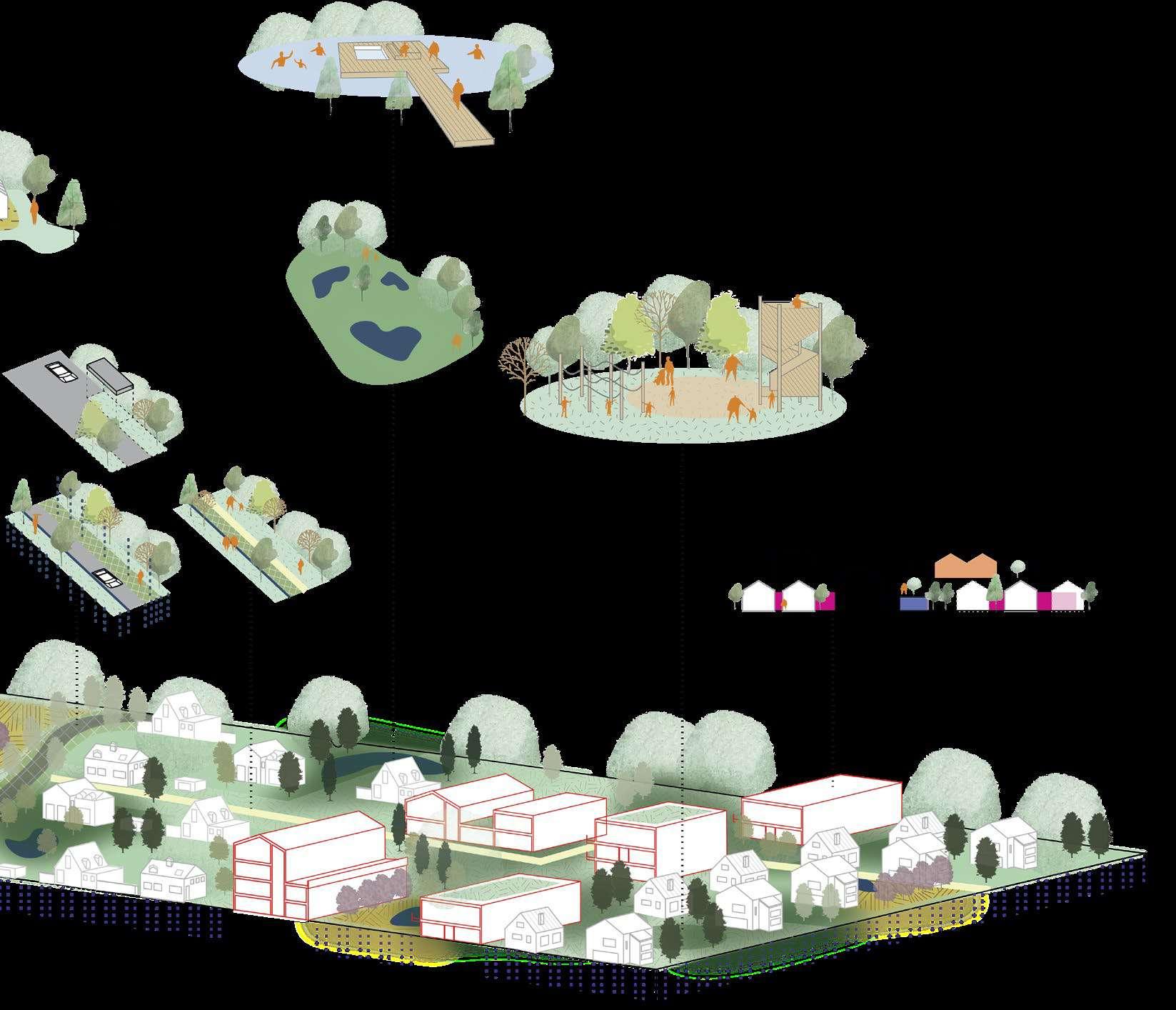

To respond to Wondelgem’s intensive urban growth it was necessary to rethink the model of the stand-alone single family house and design new typologies of housing based on more communal living practices.

We have focused on the thoroughfare of the east west direction, maximizing sunlight exposure and breaking the North/South repetitive suburban pattern of the district. The new developments don’t acknowledge the existing circulation network, but rather favour the continuity of the green and blue network and the connections between the larger public parks.

Our design includes mixed use, more efficient housing neighborhoods, with public outdoor spaces, where once stood private gardens. The new typologies favour intragenerational relationships and focus on improving the living conditions of the most fragile population groups. Ground and top floors are activated by new social infrastructures or communal spaces to diversify and decentralized services and commercial activities throughout the neighborhoods.

92

2100 2021

new neighbourhood with activated ground floors

93 2100North/South suburban pattern New East/West development Mixed

94

95

Transforming urban tissues

DESIGN STRATEGIES

New synergies and collectivities

As previously mentioned our strategies respond to necessities and challenges associated with 4 specific elements of the site : the private domains, the standalone home, the leftover green space and the oversized street network. All of these elements are equally affected by present and future climatic issues, which remain our primary focus in the context of this exercise, as well as the future urban growth.

The ensemble of our punctual interventions create a system that adapt to the characteristics of the site, improving the nature/ human/non-human relationship both at the local and larger scale. The new neighborhoods act as auto sufficient clusters, integrated in the general green-blue system, contributing to the construction of a recovered inhabited natural environment.

96

97

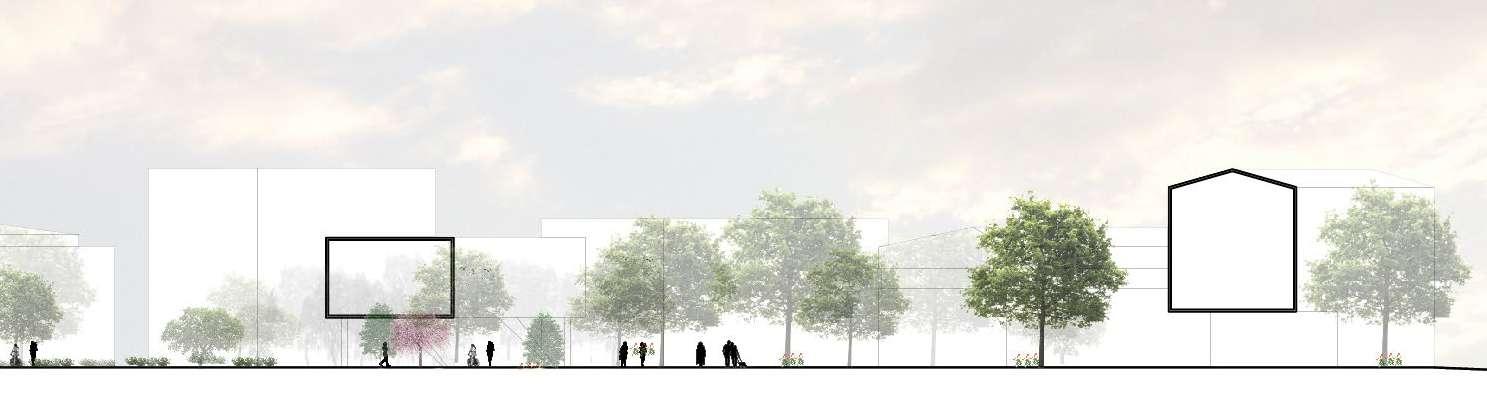

Sequencing the blue and green commons

DESIGN PROPOSAL

Collective living in a recovered landscape

In the following pages we focus on one of our densification areas. On the left the housing scheme explicit the characteristics of the typologies specifically implemented in this area. Our design strategy emphasize the recovered green-blue system with a sequence of public common spaces in-between the housing blocs. In this neighborhood we find small pockets of playground spaces, pick up gardens, community orchards and common areas always in close relationship with the activated ground floors of the new buildings. The green system is complemented by new patches of forest, linking the neighborhood with afforestation strategies applied at the larger scale. The water management network is strengthen by a series of new retention ponds, for daily and agricultural use, and capillary channels longing the streets network. In the north part of the area the original marshland

98

99

100 2021

Fragmented existing suburban pattern

Sequence of open spaces and new relations

101

DESIGN PROPOSAL

Collective living in a recovered landscape

Environment is recovered and enhanced, linking this larger space to the pre-existing linear park and providing new water commons for the community.

The overall housing block system slowly decreases in hight towards the marshlands, to reconnect the inhabitants with their surrounding environment. Cleaning water cycles are implemented near each housing block as to reach the maximum level of autonomy.

Following our de-sealing strategies the street network and all mineralized surfaces are heavily de-sealed throughout the neighborhood, while the circulation hierarchy shift in favour of pedestrian and soft mobility infrastructures.

The neighborhood social dynamics move from today’s individualistic society to a model favoring communitarian life, building common memories at a slower pace and in respect of nature and biodiversity.

102

103

Living along the canal

DESIGN PROPOSAL

A new common relationship with water

The second zoom shows our densification strategy along the canal. Due to the presence of the water and the busy national road next to the canal, this densification strategy forms an exception in our design.

We introduce the L-shaped mixed neighbourhood, which has a facade that opens up towards the water.

In addition, the national road gets transformed by introducing more trees and paths for slow mobility. By doing so the heavy car oriented traffic is tamed.

Further inland, the new buildings are surrounded by new green public areas, that allow for a connection with the urban tissue located further away from the canal.

The building infrastructure becomes the backdrop to the vegetation carpet and canal at the fore. The urban commons becoming the main agenda, even when creating private housing. .

104

105

106

Public waterfront Reconfigured road Public space opening up towards the waterfront

Commercial New densification

107 Canal 2100 Canal 2021 densification typology Passage Co-working space Communal gardens New densification typology

DESIGN PROPOSAL

A new common relationship with water

Indeed, as shown in the collage, the waterfront has been opened up and has thus become a publicly accessible space. Additionally, the busy street and heavy traffic that used to dominate the waterside has been tamed by the presence of pedestrians and cyclists.

Due to the large presence of gardens and de-sealed surfaces, water can easily infiltrate and flooding and drought problems are mediated.

The collage also shows how the newly built typologies open up to the landscape thus allowing to rethink the relationship with the water.

108

109

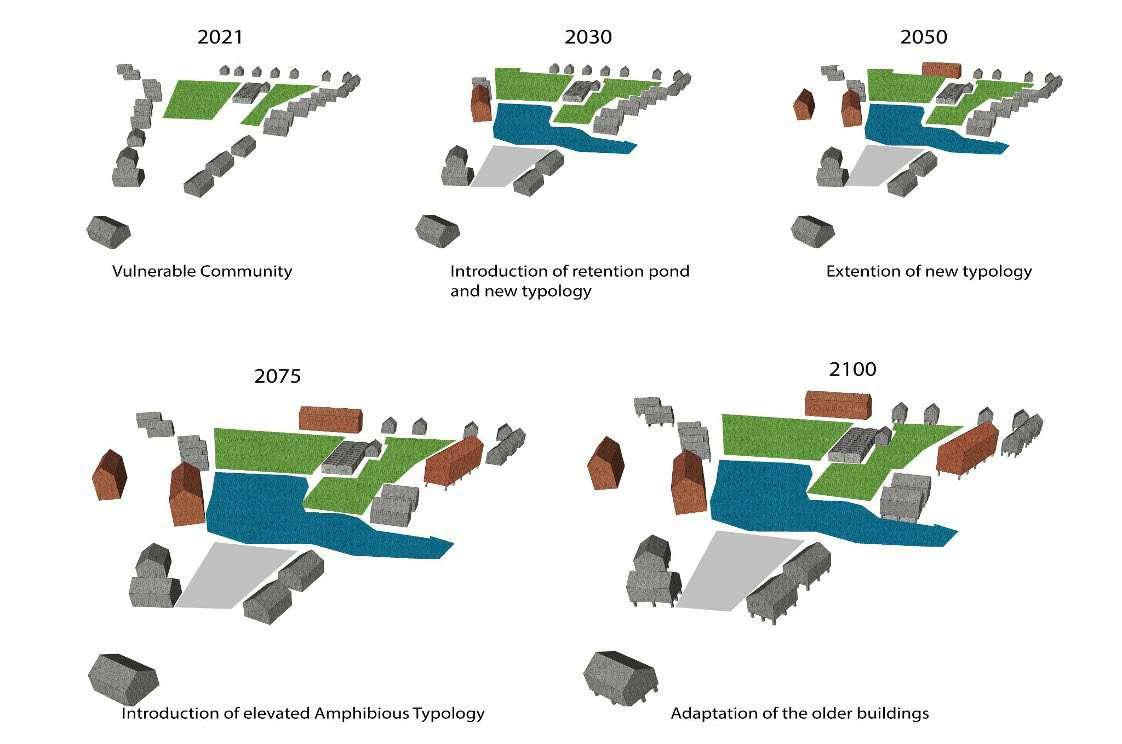

Phasing and timeline

Timeline

The timeline shows our main strategies and their phasing. By consequently de-sealing, the total area of mineralized space re duces, while the new green network expands. Together with this de-sealing strategy, new forest will be planted to tackle future heat and drought problems. Flooding problems will be mediated by strategically constructing new ponds and wetlands. Finally, additional housing will be built around the newly created green and blue network. Additional singular buildings of each densification strategy will be annexed over the years.

Phasing

Our intervention starts on the entire site, but with minimal ele ments, to achieve our vision in the next one hundred years. With the de-sealing happening initially, and over time, the linking of networks, and the realisation of the density clusters as second ary agendas.

110

2021 2030 New greeN Networks wet

Forest orchards

PoNdiNg MiNeralized

sPaces

2030: PoNdiNg aNd begiNNiNg to de seal.

housiNg iNFrastructure

2050: siNgular coNN

dry Forest

111 buildiNgs oF each cluster, with NNectiNg Pathways 2050 2070 2100 de sealiNg

2070: liNkiNg oF greeN Network 2100: reMaiNder oF buildiNg blocks

112

113

and

115 03.02 Rosdambeek, Duivebeek

Oude Leie YIDNEKACHEW YILMA SELESHI MD RAFIQUL ISLAM CECILIA QUIROGA ZELAYA

Oude Leie-Sint Martens Latem

Public and Private Waterfronts

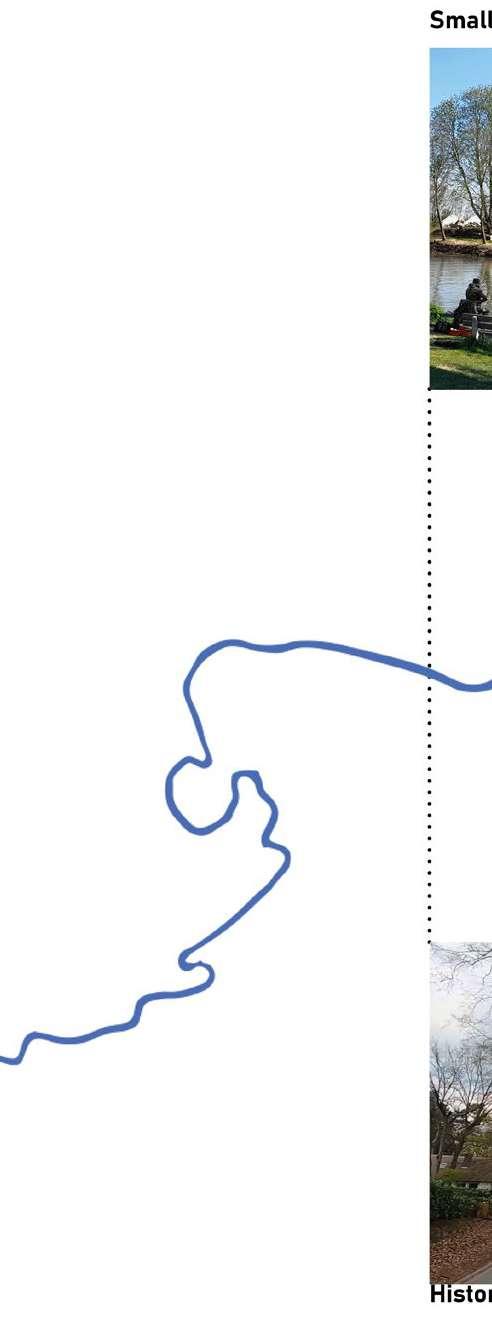

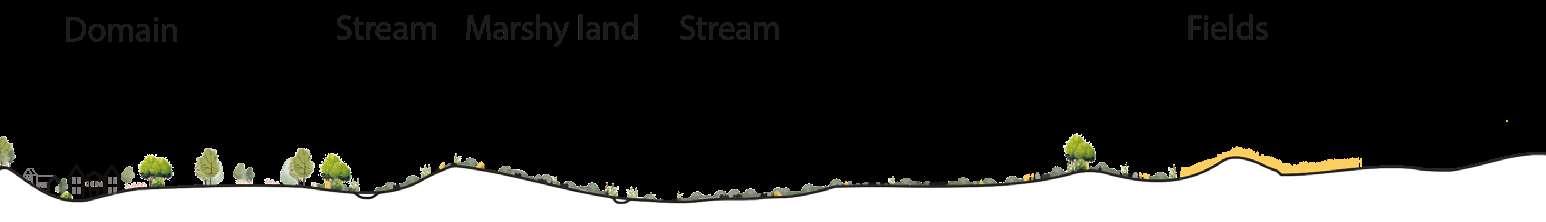

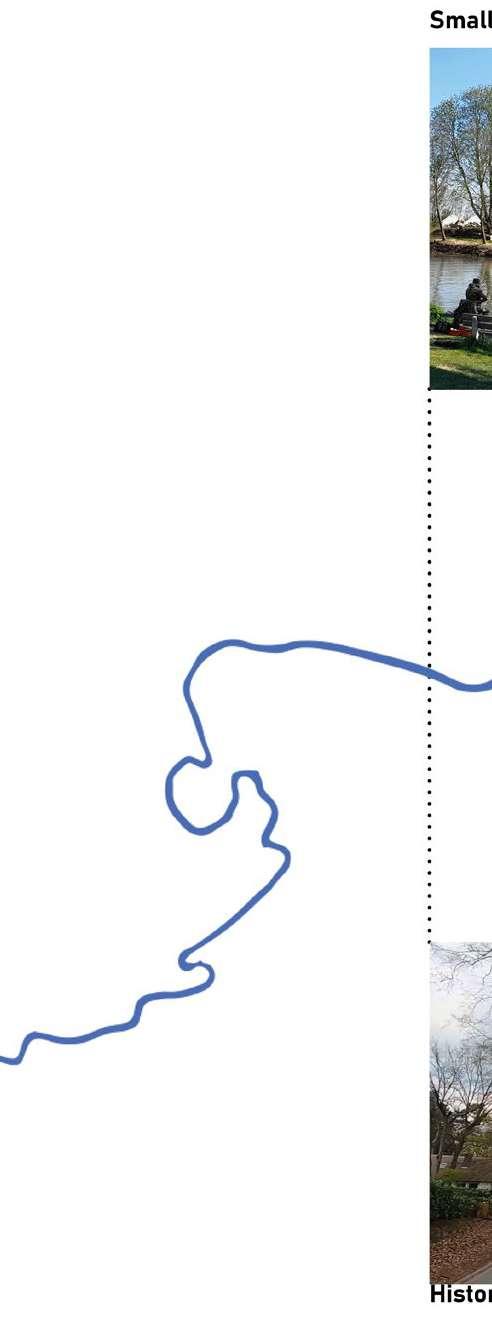

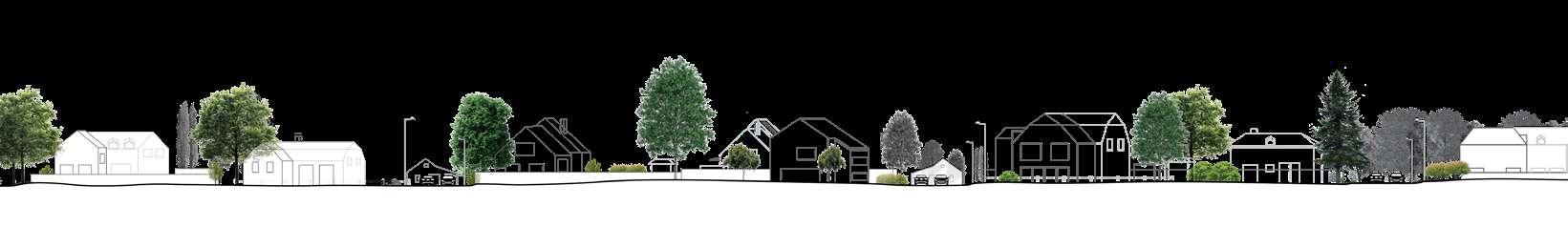

The broad marshes surrounding today’s Leie River, reveal the – quite literally – meandering history of the river. On both riverbanks, there is an intricate system of floodplains, brooks and cut-off river branches. On the east side of the Leie, the main structuring waterways are Rosdam beek, Duivenbeek and Oude Leie.

On the small island defined by Leie, Oude Leie and the Ring Canal of Gent (on this segment also formerly a branch of the Leie), the ‘Assels’ are situated. Since medieval times, the area was predominately agricul tural (the name refers to hazel trees), with farms located on the sandy hillocks (donk) between floodable fields. Relatively isolated, the island remained completely undeveloped, until the early 20th century, when a new bridge triggered the development of small recreational (summer, due to floods in winter) houses. After the Ring Canal was dug, certain parts of the Assels became less prone to flooding, which led to more recreational development, and in time, their transformation into proper residential areas. Development has been halted in the last decades, with a focus on preserving the Assels as a habitat for meadow and wetland birds.

Further south, urban development concentrated on the (slightly) elevat ed ridge between the valleys of the Leie and the Duivebeek/Rosdam beek, again avoiding the floodplains surrounding the river and brooks. Sint-Denijs-Westrem, Sint-Martens-Latem, and (closer to the border of the Leie) Deurle are all part of this system, with the current N43 as a connector, which follows the exact trajectory of the historical connec tion between Ghent and Kortrijk. Here as well, the marshes between the settlements and the Leie River are conserved for their ecological value, with the (very prosperous) towns of Deurle and Sint-Martens-Latem also valorise the visual quality of this landscape.

On the other side of the N43, around the Rosdambeek and Duivebeek, the open space has been transformed over the last decades into the Parkbos (Park Forest), one of the main (soft) recreational greenspaces surrounding the city. The Parkbos is built around a number of existing and new park and forest areas, and uses linear structures in the agricul tural landscape to connect them into one large recreational space.

116

Valerius de Saedeleer. 1867-1941. Le rideau d’arbres - Landscape with floating oil on canvas 65.7 x 75.8 cm, signed lower right and painted around 1907

117

118

119 1.0 ANALYSIS

120

Reading & Interpretive Analysis

1.1

Inspiration

Assignment by Md Rafiqul Islam & Carlos Morales Dávila

STRUCTURING FIGURES

Desvigne, Michel. 2003 Issoudun Territoire

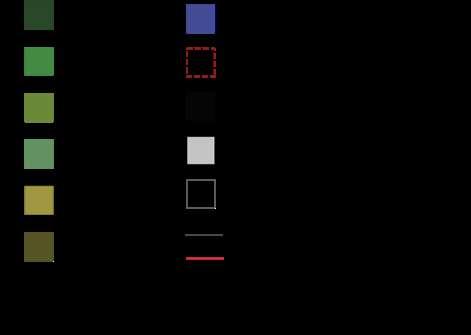

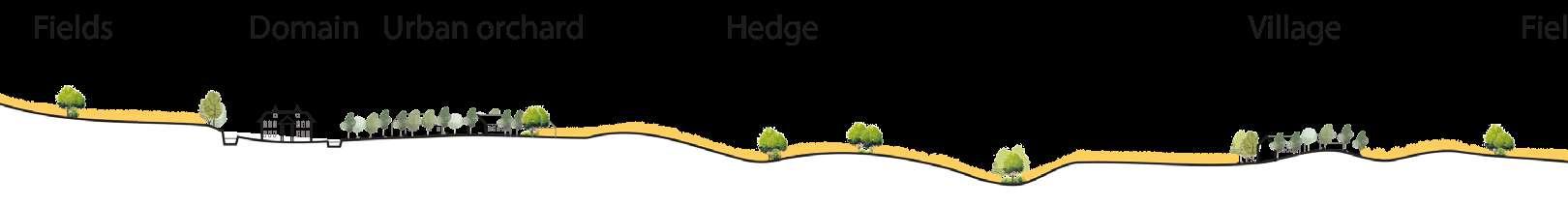

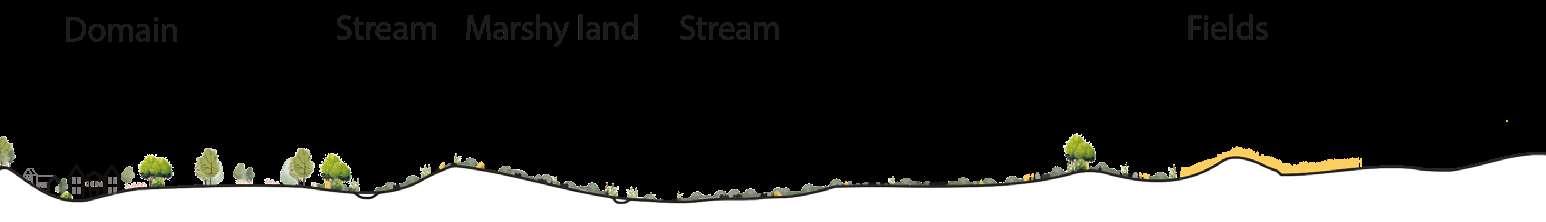

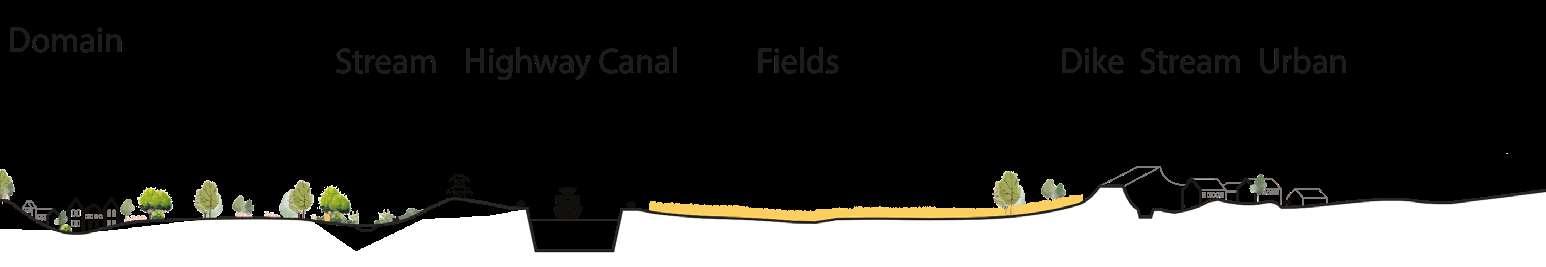

The Valley of Rosdambeek, Duivebeek, Oude Leie located in the South-West area of the city of Gent, a predominantly flat valley with some mounds, structured by bodies of water and agricultural lots that are intertwined with the urban fabric, crossed by large water and mobility infrastructures.

To analyse the valley, we use the graphic methodology of Michel Desvigne in the Issoudun Territorie project (2003), through which we seek to understand which are the structuring figures of the

landscape, the directionality of the different tissues that compose it, as well as the intensity and / or density of the urban grain that surrounds it.

In the case of our site, after a systematic analysis of the different landscape structures (water, green, mobility, urbanization, topography), we could identify that the spatial organization pattern responds to two different logics: one related to the hydraulic landscape and the other related to urbanization.

122

© Busquets, Joan; Correa, Felipe . 2004. Bringing the Harvard Yards to the river, 64-65.

Harvard University. Felipe Correa & Luis Valenzuela (ed).

Interpretation

Assignment by Md Rafiqul Islam & Carlos Morales Dávila

UNDERSTANDING THE SETTLEMENT LOGICS OF THE VALLEY OF ROSDAMBEEK, DUIVEBEEK AND OUDE LEIE.

Ferraris 1777

Ferraris 1777

Regarding the logic related to the hydraulic landscape (specifically to the Leie and Ringvaart rivers), it is possible to identify that the pattern of human settlement occurs perpendicular to them over almost their entire length, while at the back of them (intermediate spaces generated in meanders) the directional pattern changes to a perpendicular or rotated state in relation to the river (see Image 1).

Regarding the logic related to urbanization, the pattern and directionality of urban growth in the area are traced, which are taking place in different patterns. Though the directionality is sometimes dominated by street patterns, an obvious influence of the existing landscape mosaic is evident. There is small but dense linear urban growth in the residential areas where there is not much risk of flood. Then there is some dispersed growth shown with dots

123 (Source: Edited by the authors 2020)

Landscape lines - Directionalities along the river and agricultural land

Urbanisation lines - Directionalities and patterns in the in-between spaces and the industrial growth is more in blocks. Then the directionality of landscape and urban fabric are overlapped together to see how the two systems are intertwining and creating an interdependent relationship where they are both actively affecting each other.

124

125

Holistic interpretation of the logics of the different settlement patterns of the Valley of Rosdambeek, Duivebeek and Oude Leie.

126

Fieldwork

1.2

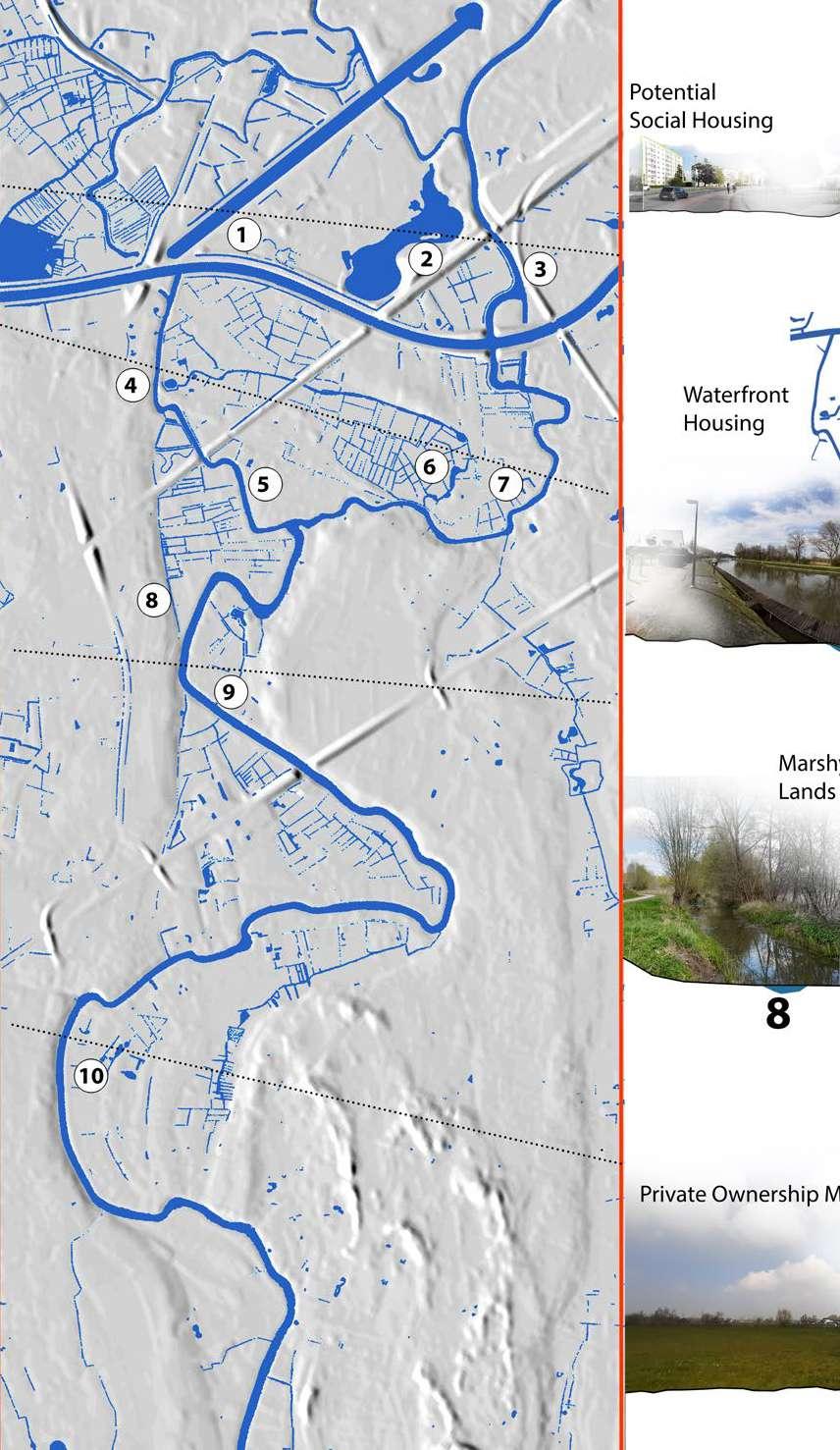

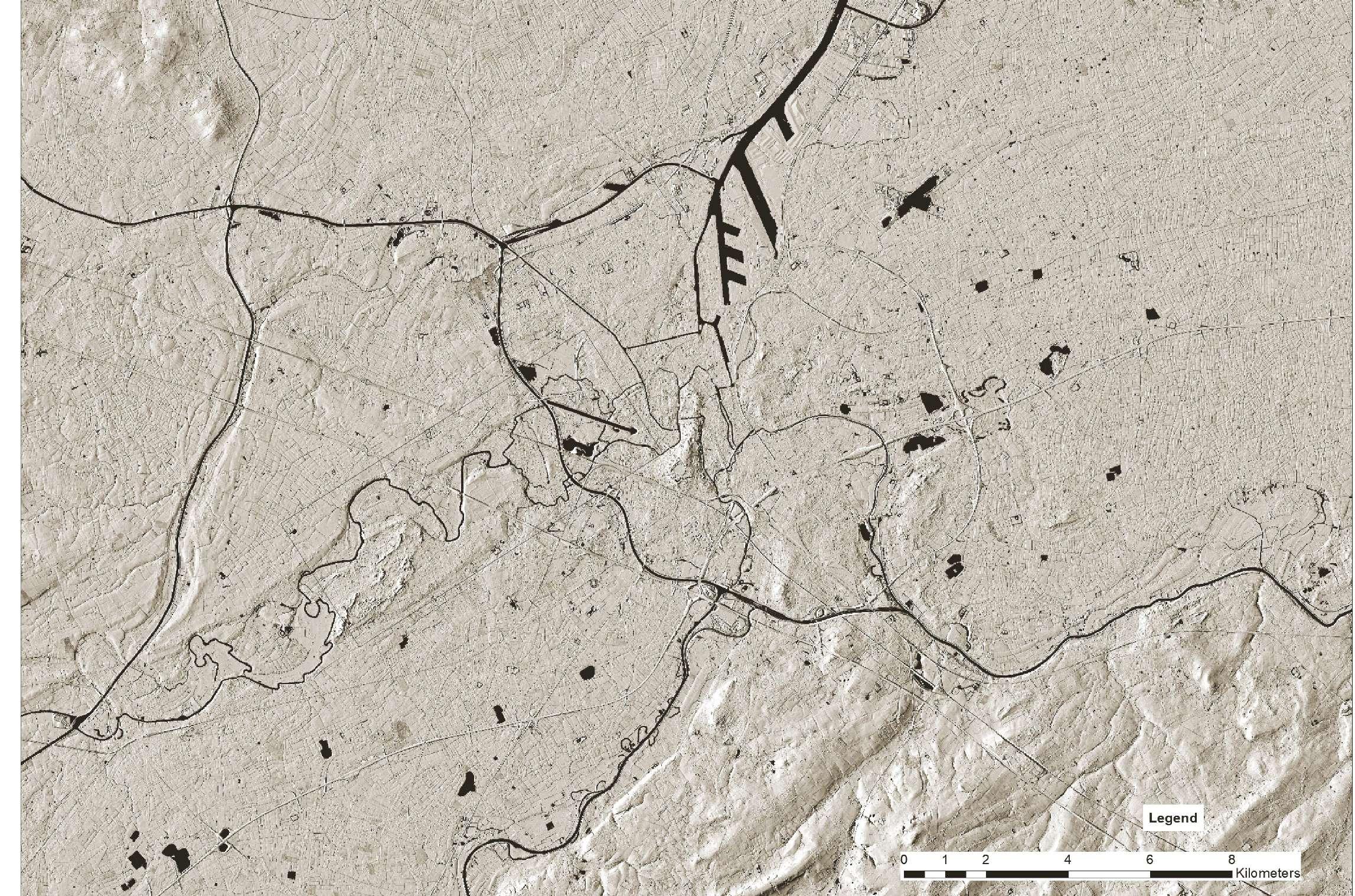

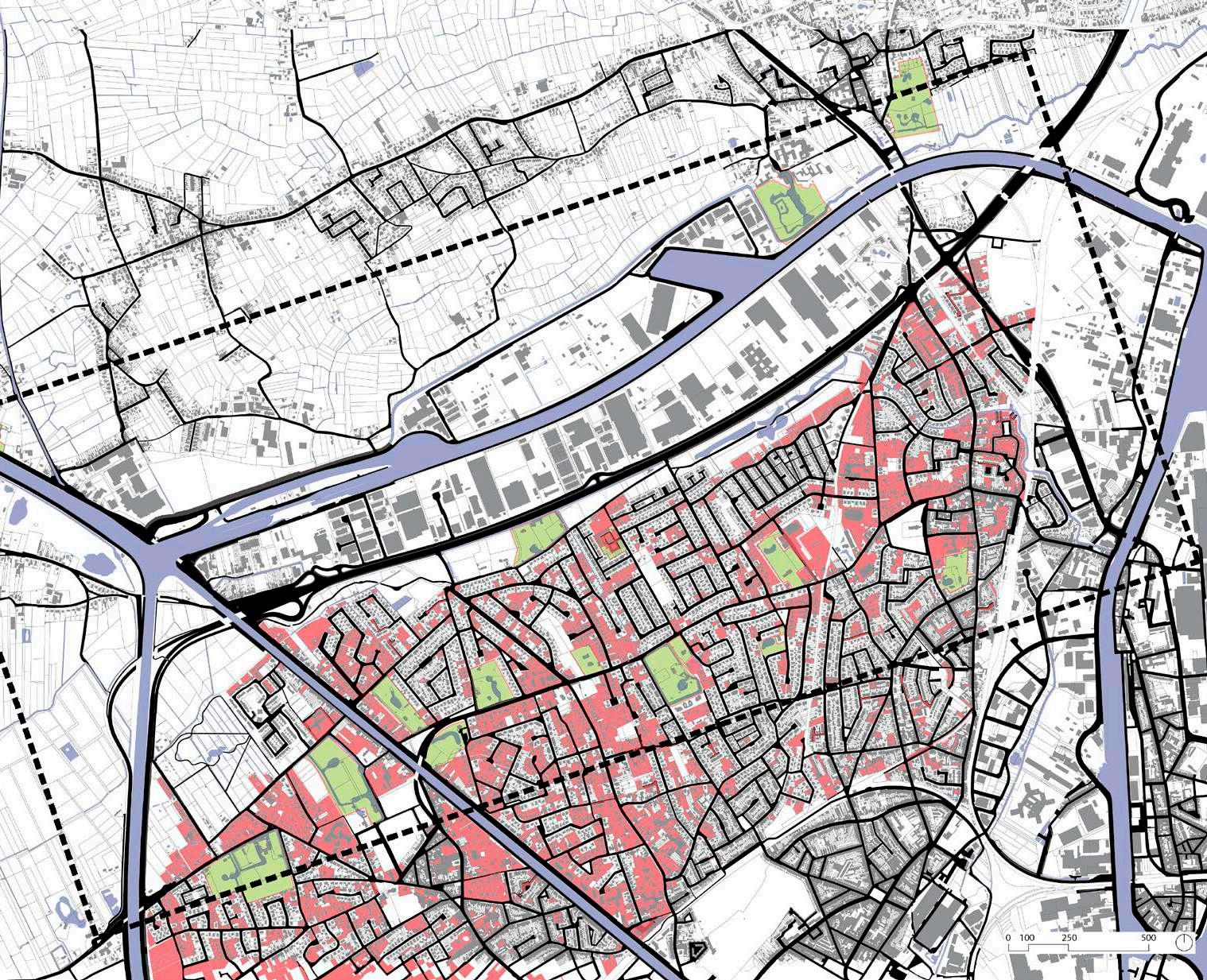

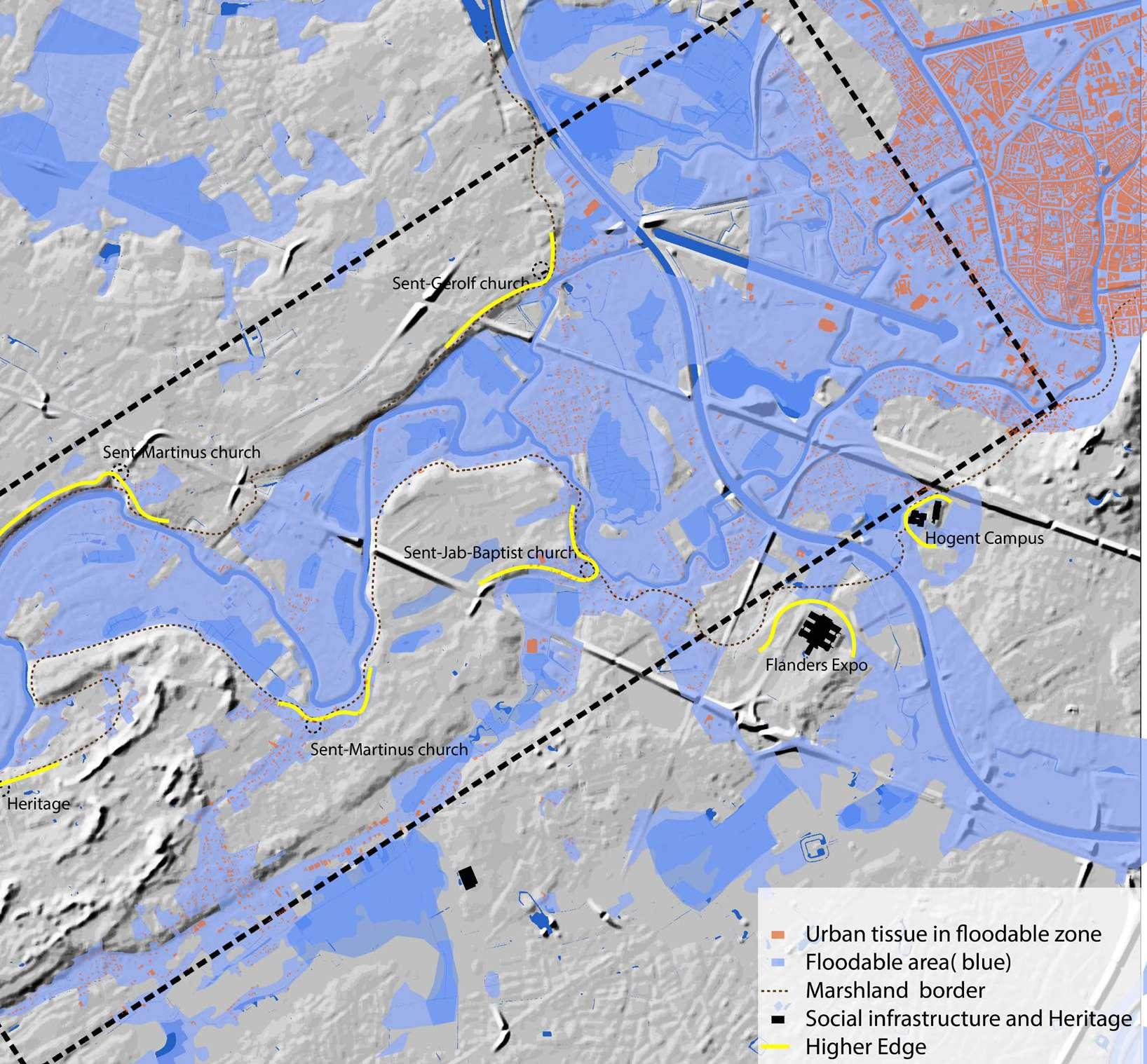

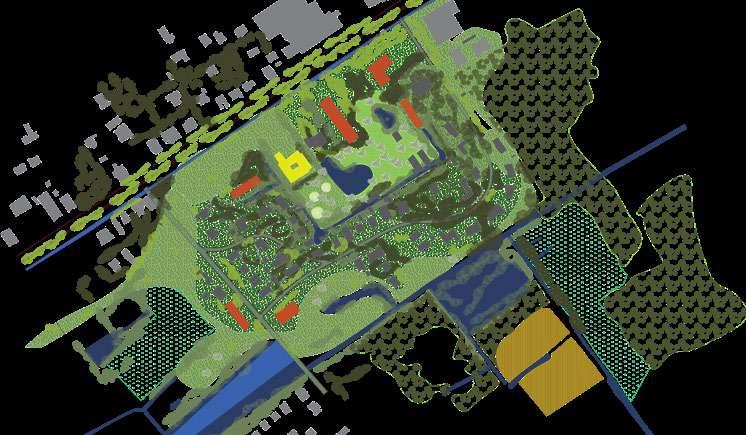

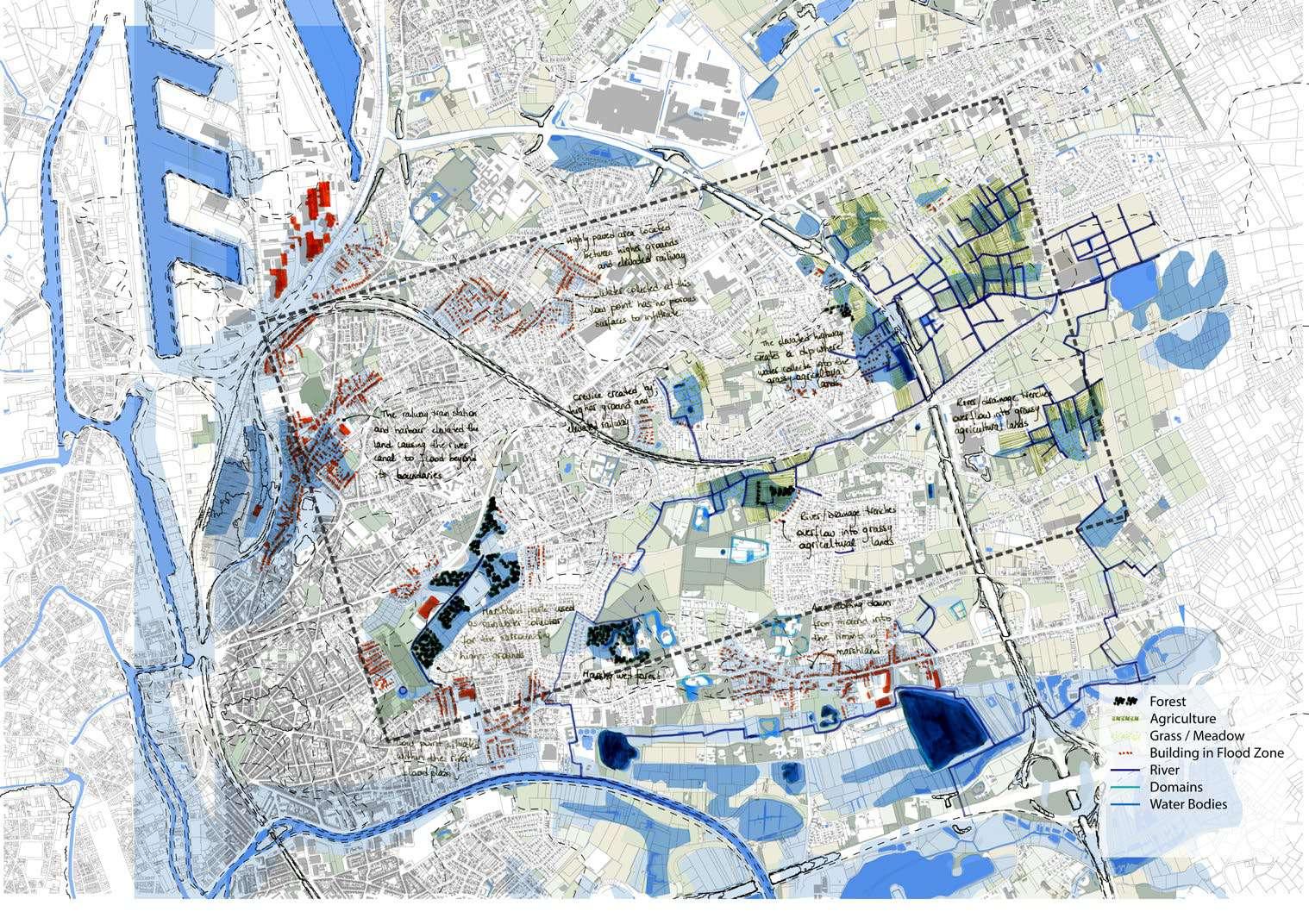

Floodmap for Latem Sint Martens

Map shows the urbanization at risk for flooding in 2100 and the area of focus for the design in tervention in light blue

128

The existing characteristics of the meanders of the Leie within the scope of our site

The site is known for its heritage landscapes and landmarks

129

Characteristics of the water features on the site

130

131

The Assel

132

The quality of the marshlands in the Oude Leie flood plains

These marshes or meersen served as a common grazing space for sheep and cattle. Today they are recognized as heritage landscapes.

133

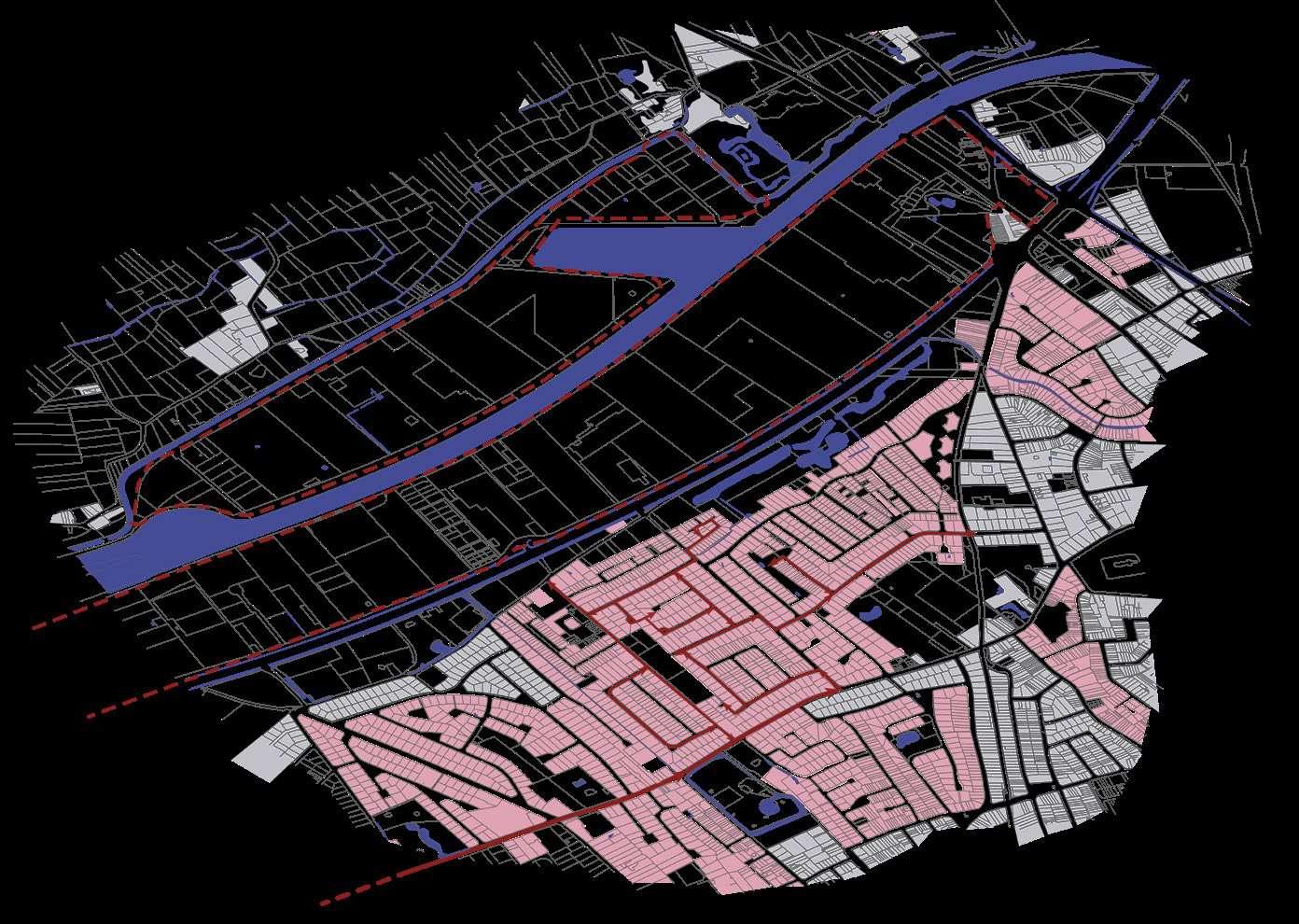

Qualitative information maps

Topographic understanding, Urban tissue & flood planes

Legend

Floodable area

floodable area 2100 River

134

Growth

135

Qualitative information maps

Public, Private and Historical Scenes in Latem

136

Historic Landmark

Detached Luxury Villa Exclusive Waterfronts

Boat Promenade

Public Beach Public Waterbahn

Boat parking

Social Housing

Historic grazing space

Hedge features

137

Soil map at the city scale

This map helped identify the different conditions found on the two banks of the Leie river. On the north side dry sandy loam and on the south side moist sand. This determined the area of the agropark and where we would make the alluvial forest archipelago

138

139 0 2 4 6 81 Kilometers Legend AllForestTerritorial RecentFloodMap Wet Sandy Loam Dry Sandy Loam LandDune Drysand Anthropogenic Damp Sandy Loam Moist Sand

140

Argumentation & Strategy

1.3

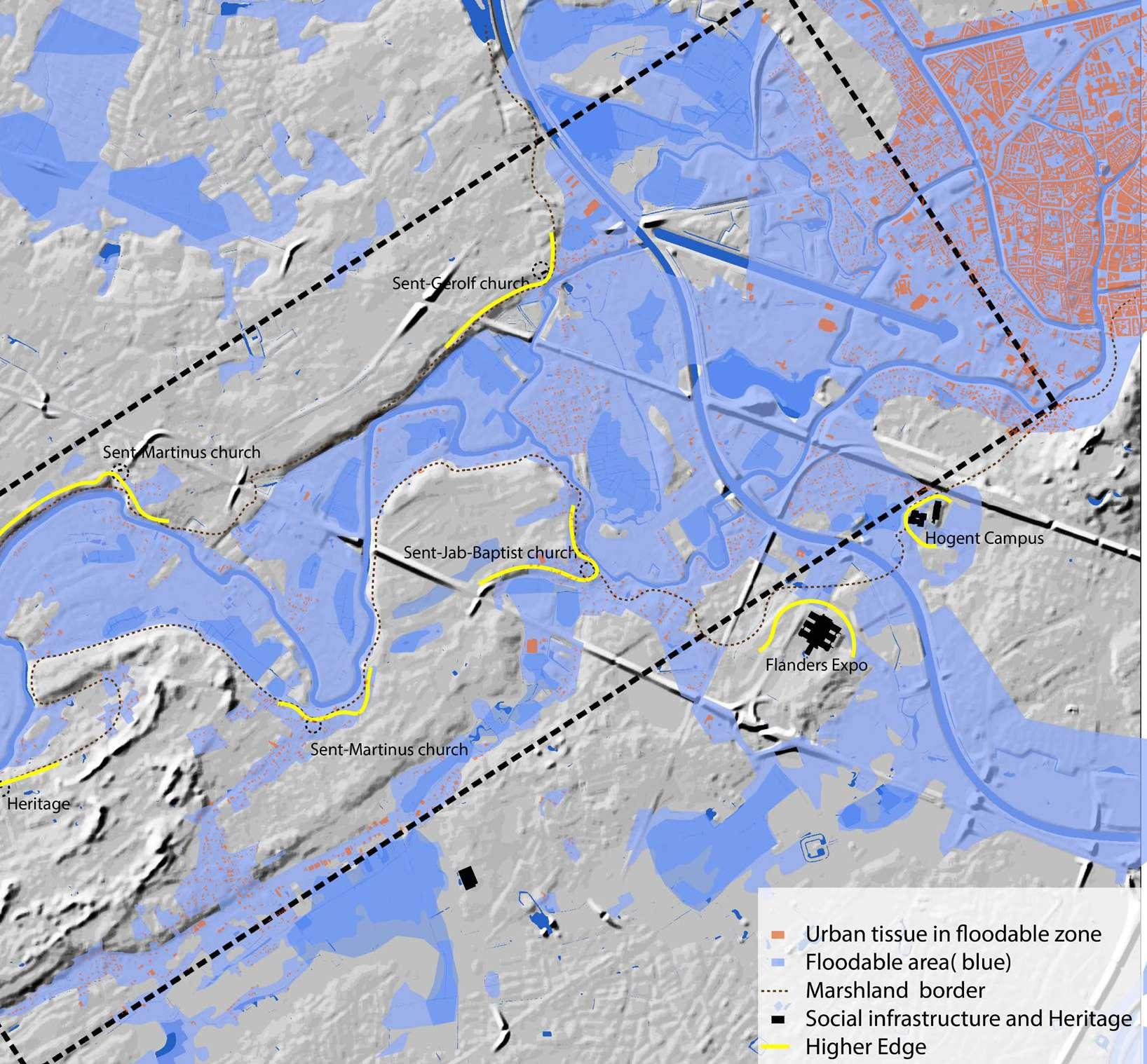

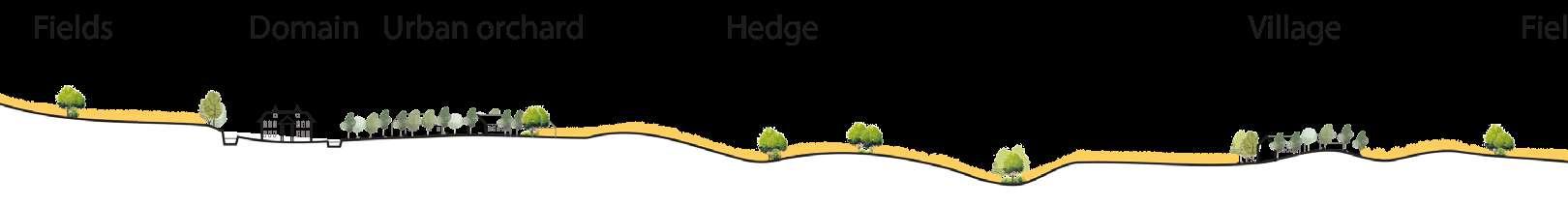

How the landscape shaped settlement patterns in the floodplain of the Leie?

Photo Essay

Drainage in the assel as part of the Drongense Meersen

Drainage canals lined with willow trees is one way that the Flemish people historically managed water

Settlement around the Leie River in Sint Martens Latem and Drongen has been shaped by the floodplain of the Leie River and its con comitant sandy hills. These sandy hills are locally known as ‘donks’ have provided places for housing as well as other productive infra structure such as windmills for grinding wheat into flour. The settlement pattern in this area, has for the most part paid attention to the existing topography. The one historical exception is the Assel, which is an old meander of the river which is currently a marshy meadow land. As suburbanization grows, more agricultural land and more marshy meadows are being engulfed by urban growth.

142

The site contains various scales of water catchment and retention. This is a highly urbanized area of the site which would be flooded were it not for the large scale water retention. Below: a typical privatized waterfront characteristic of the Leie as one moves away from the city.

The wetlands surrounding the Leie river are managed by setting up retaining walls made from tree trunks around the river’s edge pre venting the erosion of the sandy mounds. Canals are carved along perpendicular to the river to assist in the drainage of the habitable land. Trees are planted along the riverside to hold the landscape together. These techniques have created scenic waterfronts which over time has become luxury and exclusive housing. These houses sit on the ‘water boulevard’ of the Leie and showcase privately owned water mobility with some small public areas dispersed along the mostly privatized waterfront. Closer to the urban core of Ghent flooding has been managed by the creation of large recreational water elements. These large and constructed water retention el ements provide leisure and recreational space for the citizens of Ghent, while at the same time mitigating the flood risk.

143

Privatization of waterfronts and landscape heritage on the flood plain of the Oude Leie

Farmland is becoming inaccessible to small farmers. Commercial scale agricultural production is degrading the soil quality.

The Leie valley is naturally rich area, mostly covered with meadow, the flood plains are extensive and home for wet land bird habi tat. The sub urbanization in some areas encroach to this low lands and also claim water fronts. Though the river Leie has gradually changed it use to mostly recreational aspect of its nature, most of the riparian zones are privatized ,some are open yet not accessi ble. The amount of public spaces and accessible riparian area is to a limited amount. For last few years, there has been a significant change in the land ownership pattern in the Latem region. This area has caught the attention of the big investors and they are willing to buy big amount of lands. Due to privatization a lot of riv erfront areas has become inaccessible for the public. A big portion of land are under the ownership of the elite and noble families. But in recent times it is being noticed that some of the big investors and business owners are considering the farmlands of Lathem as a money making machine.

144

Who’s excluded from the system, who controls it, and who is benefitting from it?

Above and Below: One anomaly of agricultural production onsite is the De Goedinge community supported agriculture

Legend

Accessible water front Growth floodable area 2100

Open water front Edge of the marsh lands

Private water front

Public water front

Parks

open public space

Urban tissue

Urban tissue in floodable zone

Floodable area

An analysis of the water fronts revealed that currently the waterfront is only 5% publicly available 47% is unbuilt, or 'open,' and 48% is privatized with private housing blocking the waterfront from any public use or ac cess. Seeing as how the Leie is one of the few remaining rivers in Belgium that still has its historical meanders, the 'commoning' of the meanders as well as designing for flood mitigation became our strategic focus.

145

146

147 2.0 DESIGN

148

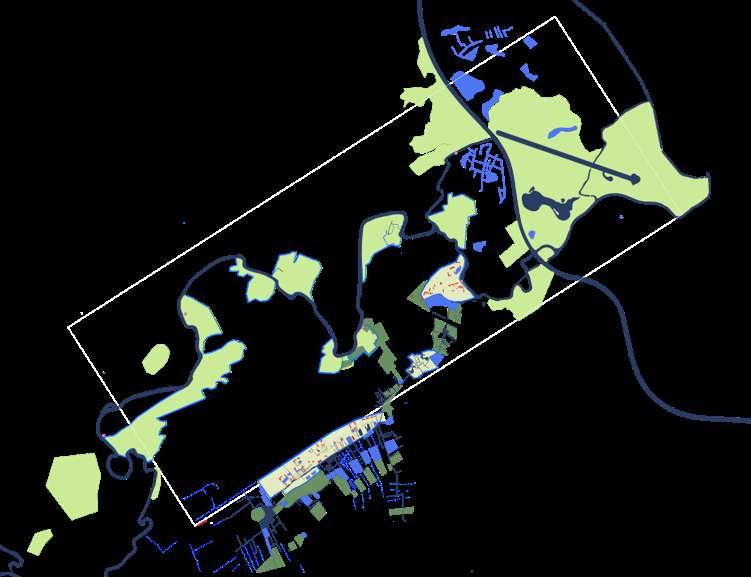

Eco-Systemic Visions

2.1

Eco-systemic visions

150

Commoning the Meanders of the Leie

This proposed vision is to addresses the increasing privatization and inaccessibil ity of the Leie Waterfront. From this common vision we continued to develop the design idea at both the landscape and urban fabric scales .

151

Heritage Buildings to be protected & buildings to be phased out

Doing an analysis of the existing buildings on the site we found that the meanders of the leie contained many heritage sites. Considering heritage as a way that a popula tion constructs its collective identity, it was not only the buildings that are selected but their respective contexts in the case where they existed within consolidated neighbourhoods.

152

Heritage Wetland Archipelago on the Leie

The inhabited park portions of the flood plain are the existing heritage sites which will be maintained to 2100, as they have already been designated to be of a cultural value and heritage is a part of building the collective identity.

Know for and recognised by art works of famous artists for its extraordinary land scape features

153

The agro park, commercial processing of locally produced goods

The CSA meander with a proposal to expand the existing CSA project on the mean der

The small community gardens and greenhouses integrated into the new typology adjacent to the CSA.

154

155

156

Design Proposal & Typologies

2.2

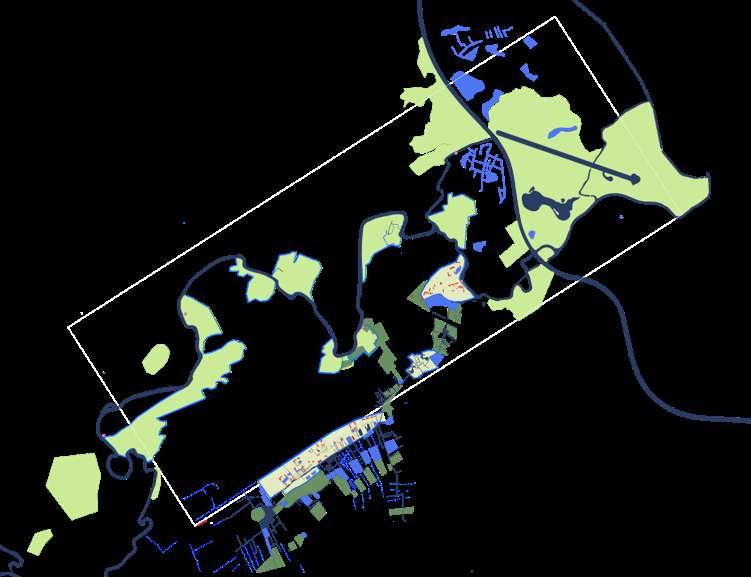

Urban Archipelago Wetland on the Rosdambeek

Existing settlement pattern of creating small islands is extend ed to the neighborhood scale, creating an archipelago with two urbanized islands and one heritage island connected through the rosenbeek.

158

159

New public plaza created at the intersection of a new alluvial forest corridor connection of the two archipelago systems

The Urban Archipelago

160

Agro Island

161

162

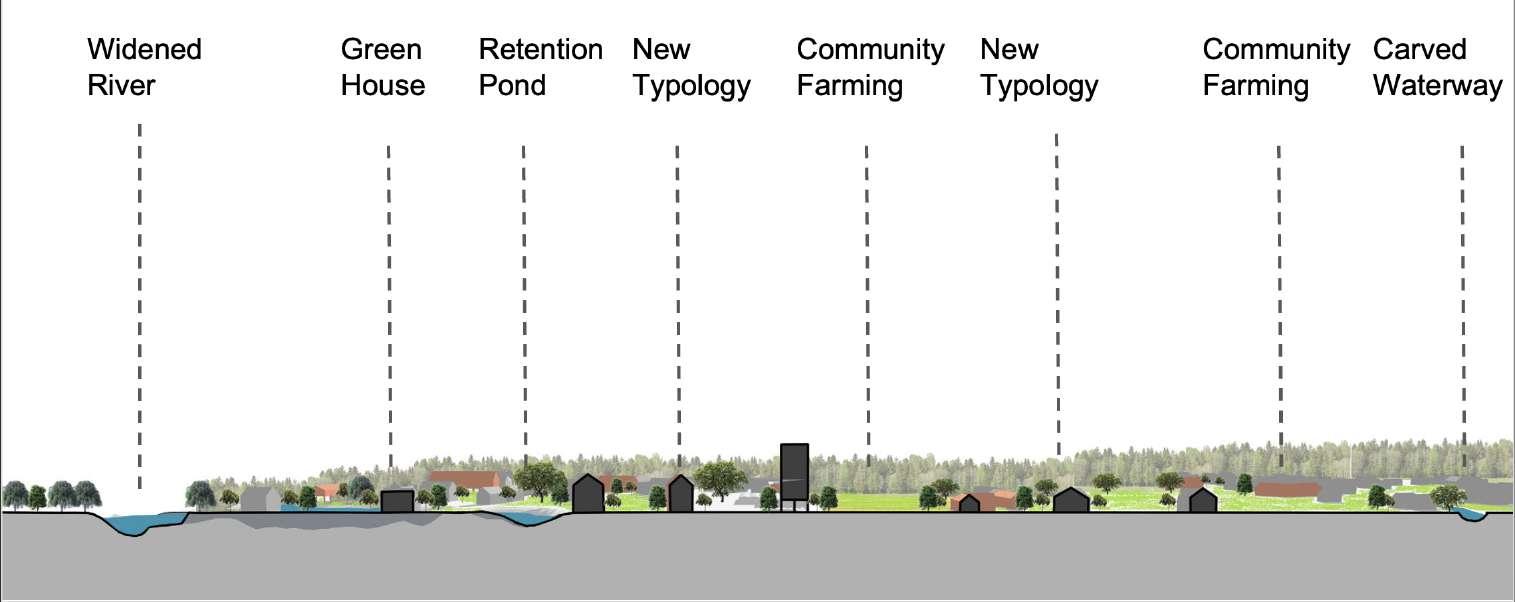

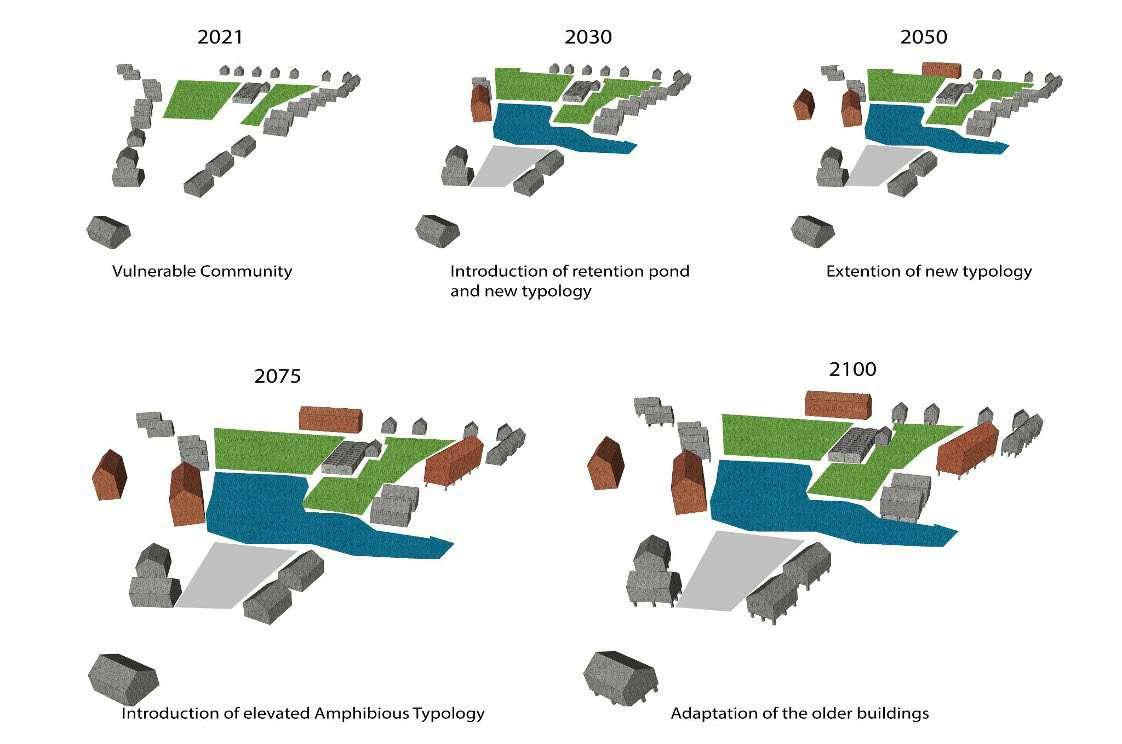

163 Transformation timeline

New Front : Development of new land form ,Urbanism and place for water

Urban tissue scale intervention

164

1

Transformation

Transformation

As part of a larger vision of developing and accentuating a new water system with the goal of making water more accessible and giving it place and diverting attention away from the Leie River floodplains, The area along Rosdambeek, one of the site's struc tural waterways, to the north of the alluvial woodlands has been developed as a strategic location for the development of water front urbanism and a new front towards nature.

Landscape elements transformation is to take place in the recent future with other developments in order to tackle the challenges on the site and also function as a structuring component in the process.

Transformation

165

The new water system along Rosdambeek and zoom in location

2030

2050

2070

section 1:1

As a consequence, a new land form is introduced which will serve as a new public front and also delineate places for water. In doing so, the cut and fill provides regions for water and regions where a protected community with extended natural front with low rise duplexes and mid-height apartment typologies is created.

The new land form will be the stage and the new front; structuring urbanization with features on the Rosdambeek and its waterway.

166

with enhanced water

167

Weaving ecotones

169 03.03

of Sint Amandsberg IMRAAN BEGG CÉCILE HOUPERT RAYA RIZK JENNIFER SAAD

Sint Amandsberg

IntroductionWhen leaving the city center of Ghent, Sint-Amandsberg starts out as a bustling multicultural neighbourhood. However, after these first few streets, suburban development (detached and semi-detached houses on their private plot of land) start to dominate. This goes on well beyond the borders of the territory of Ghent, as this tissue extends into neighbouring Destelbergen and Lochristi as well.

The historic structure of this formerly agricultural landscape, dotted with a number of estates, is hardly discernable anymore. However, a few smaller (estate parks) and larger (agricultural fields) open spaces remain. They manage to give an illusion of rurality in neighbourhoods that are very much part of the urban tissue, and because of that, initiatives to develop some of these areas (at least the ones that are assigned for residential development on land use maps) are systematically being counteracted against by the inhabitants, with concerns of livability and mobility impact as main arguments. The biggest of these remaining open spaces is Oude Bareel, where plans to develop have existed and evolved for years, so far with no success of getting a building permit. So, for now, this patch of unbuilt landscape remains. The density of new developments has been gradually but systematically increasing over the last years, first by shrinking plot size, then by going from detached to semi detached to short rows of houses, etc. By doing so, the qualities that are attributed

to the suburban model have diminished accordingly. However, a few exceptions in the area show the possibility of a more qualitative rethinking of the model, such as Zeemanstuin & Lijnmolenpark.

Not all open space is under pressure to be built: central in SintAmandsberg, is the Rozebroekenpark, a former marsh-turned-landfillturned-park. The park has an emphasis on playing and sporting (with a playground, the city’s biggest pool and other facilities on site), and functions for the whole of Sint-Amandsberg as the main recreational space.

One of the bigger projects that is currently under consideration, is the redevelopment of the Sint-Bernadette neighbourhood. This social housing was built in the 1920’s according to garden city principles, and as such has heritage value, but the current dilapidated state is beyond repair. Demolition is unavoidable, and there is consensus on the ambition to re-imagine the garden city principles into a contemporary model. What that means, however, is to be researched and designed. The larger open spaces that are remaining in this area are obviously being eyed as potential sites for densification. Current proposals are merely continuing the existing suburban model (at a slightly higher density). Can an alternative be proposed for this, either by introducing a new model, or by absorbing all growth within the existing tissue?

170

171 © Google Earth 2021

172

173 1.0 ANALYSIS

174

Reading & Interpretive Analysis

1.1

Inspiration

Assignment by Agnese Marcigliano and Lucie Van Meerbeeck

UNOPEN SPACES

Plunz, Richard and Jhon Cowder. 1970.

© Busquets, Joan; Correa, Felipe . 2004. Bringing the Harvard Yards to the river, 64-65.

Located South-east of the Ghent docks, Sint-Amandsberg begins as a peripheral, dense neighbourhood, while going eastward the municipality gradually becomes more suburban.In this analysis we apply the precise methodology developed by Architect Richard Plunz in the analysis of the Mantua Primer District (NY) , to decorticate the structure of a portion of Sint-Amandsberg’s urban tissue, an area surrounding one of the main green open spaces of the site, the Oude Bareel.

The layering by Plunz of the different components of the district of Mantua has being adapted to the Flemish site, but with the intention of creating two main documents, combining multiple information. The methodology well adjust to urban environments, however, it was challenging working with only grey scales and textures, since it requires much more detail and nuances then working with colour. Following Plunz methodology and grey scales graphic we primarily analyse the built environment, identifying the variety

176

Harvard University. Felipe Correa & Luis Valenzuela (ed).

Interpretation

Assignment by Agnese Marcigliano and Lucie Van Meerbeeck

BUILT AND UN-BUILT ENVIRONMENT’ TYPOLOGIES AND ACCESSIBILITY IN SINT-AMANDSBERG

of neighbourhood configurations and housing typologies, characteristic of the urban tissue. An historic analysis helps us identify which areas could be suitable for transformation, as to prevent further speculation on the rare green surfaces.

The large public retail surfaces seem to be the main source of social interaction between the inhabitants, but it remains challenging to determine specific internal neighbourhood dynamics at this scale

of observation.

Inspired by Plunz analysis on private and public accessibility of space, a closer study of the un-built environment has been conducted. At a smaller scale the urbanised area reveals a patchwork of private mineralised surfaces and gardens, often enclosed by barriers of different nature following the limits of properties.

At the larger scale, the physical continuity of the landscape system

177

of agricultural fields and green spaces is ruptured by the main large infrastructures, and also in this case the open spaces are not clearly accessible to the residents. Due to the future population growth, these open spaces and the urban tissue models are under pressure. It is evident from this analysis that the existing living practices enhance privatisation and contribute to the landscape fragmentation. The area lacks of qualitative communitarian public spaces and the predominant car-driven culture leaves little space for pedestrians or soft mobility users. Therefore, keeping in mind the city’s environmental

goals, questions on how to enhance the value and structure of the existing green and productive spaces should be complemented by a reflexion on new common living practices.

178

179

180

Fieldwork

1.2

182

Sint Amandsberg's existing conditions and context

"When leaving the city center of Ghent, Sint-Amandsberg starts out as a bustling multicultural neighbourhood. How ever, after these first few streets, suburban development (detached and semi-detached houses on their private plot of land) start to dominate. This goes on well beyond the borders of the territory of Ghent, as this tissue extends into neighbouring Destelbergen and Lochristi as well.

The historic structure of this formerly agricultural landscape, dotted with a number of estates, is hardly discernible anymore. However, a few smaller (estate parks) and larger (agricultural fields) open spaces remain. They manage to give an illusion of rurality in neighbourhoods that are very much part of the urban tissue, and because of that, initiatives to develop some of these areas (at least the ones that are assigned for residential development on land use maps) are systematically being counteracted against by the inhabitants, with concerns of liveability and mobility impact as main arguments.

The biggest of these remaining open spaces is Oude Bareel, where plans to develop have existed and evolved for years, so far with no success of getting a building permit. So, for now, this patch of unbuilt landscape remains. The density of new developments has been gradually but systematically increasing over the last years, first by shrinking plot size, then by going from detached to semi detached to short rows of houses, etc. By doing so, the qualities that are attributed to the suburban model have diminished accordingly. However, a few exceptions in the area show the possibility of a more qualitative rethinking of the model, such as Zeemanstuin & Lijnmolenpark. Not all open space is under pressure to be built: central in Sint-Amandsberg, is the Rozebroekenpark, a former marsh-turnedlandfill- turned-park. The park has an emphasis on playing and sporting (with a playground, the city’s biggest pool and other facilities on site), and func tions for the whole of Sint-Amandsberg as the main recreational space.

One of the bigger projects that is currently under consideration, is the redevelopment of the Sint-Bernadette neigh bourhood. This social housing was built in the 1920’s according to garden city principles, and as such has heritage value, but the current dilapidated state is beyond repair. Demolition is unavoidable, and there is consensus on the ambition to re-imagine the garden city principles into a contemporary model. What that means, however, is to be re searched and designed.

The larger open spaces that are remaining in this area are obviously being eyed as potential sites for densification.

Current proposals are merely continuing the existing suburban model (at a slightly higher density). Can an alternative be proposed for this, either by introducing a new model, or by absorbing all growth within the existing tissue?"

Source: Blondia, Mattias, Colacios, Raquel, Van Maercke, Carmen and Peter Vanden Abeele. 2021. “URBANISATION & CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION: Ghent Design Studio”, studio introductory booklet, 46 [Accessed June 14, 2021]. https://app.box.com/file/792684804737.

183

Sint Amandsberg's historical analysis