STUDIO UNIVERCITY

SPRING STUDIO 2022 - MODULE 1

Dijle Valley, Leuven, Belgium Master (of Science) Human Settlements & Master (of Science) of Urbanism, Landscape and Planning Faculty of Engineering and Department of Architecture Teaching Team: Bruno De Meulder, Kelly Shannon, Pieter Van den Broeck Guest Teachers from Practice: Annelies De Nijs (Atelier Horizon), Mircea Munteanu

(Metapolis), Thomas Willemse (Studio Thomas Willemse)

©

Copyright KU Leuven

Without written permission of the thesis supervisors and the authors it is forbid den to reproduce or adapt in any form or by any means any part of this publication. Requests for obtaining the right to reproduce or utilize parts of this publication should be addressed to Faculty of Engineering and Department of Architecture, Kasteelpark Arenberg 1 box 2431, B-3001 Heverlee.

A written permission of the thesis supervisors is also required to use the methods, products, schematics and programs described in this work for industrial or com mercial use, and for submitting this publication in scientific contests.

2

3

4

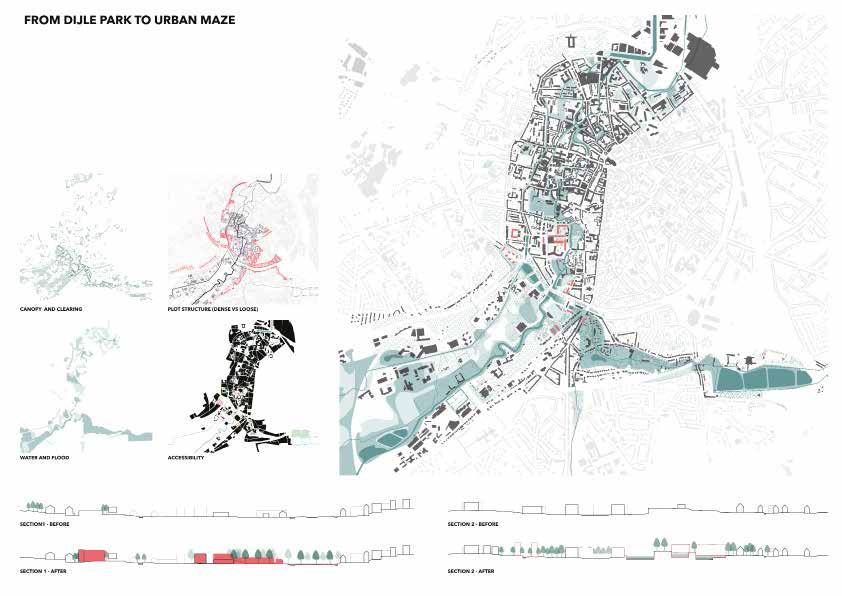

04 URBAN

01 STUDIO

03 HOUSING

06 STAKEHOLDERS 07 STRATEGIC

08 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 05 MIDWAY

02 INTERPRETATIVE MAP 06 16 98 354 362 474 260 334

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ANALYSIS

CHALLENGE

ANALYSIS

PROJECTS

PROJECT VISION

5

7 01

STUDIO CHALLENGE

© Ellen De Wolf

STUDIO CHALLENGE

UniverCity

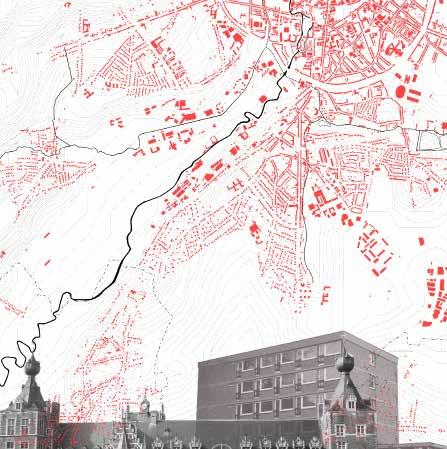

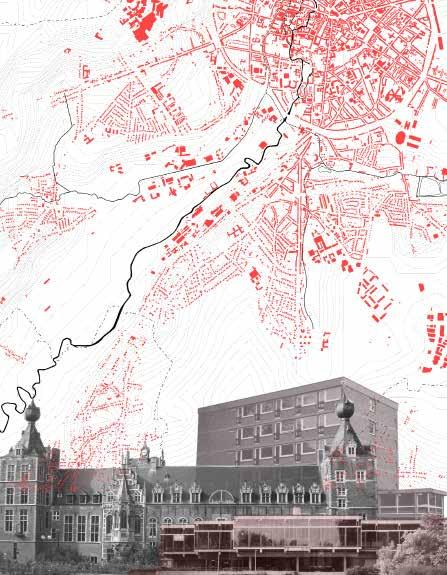

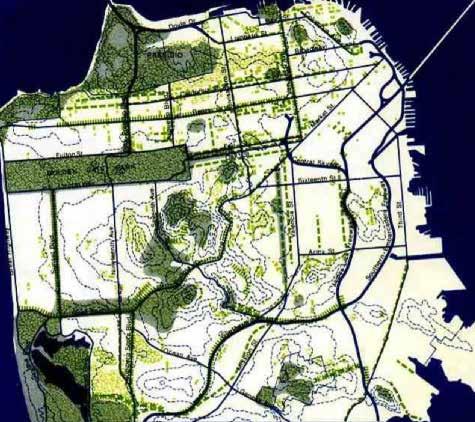

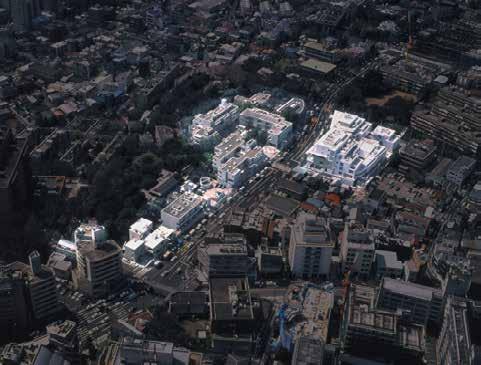

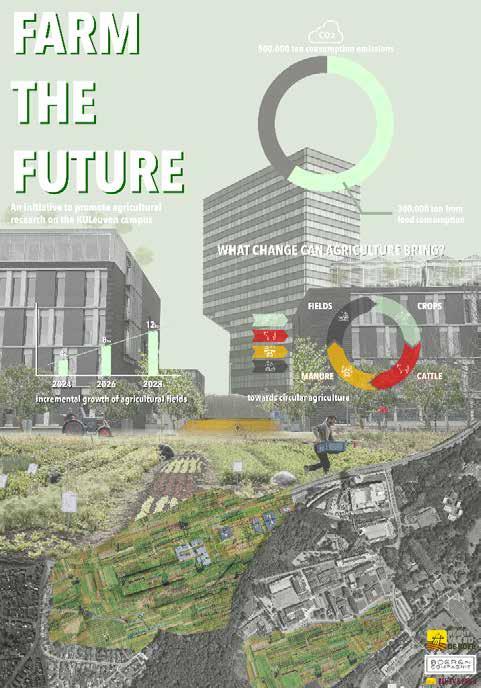

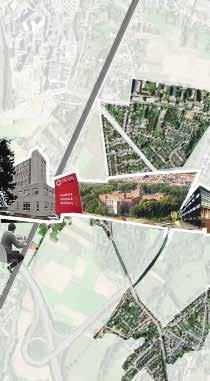

The first studio module investigates the Arenberg Park in Heverlee, home of a large university campus and links it to the inner-city university grounds. It fundamentally questions the Leuven campus model of the 1960s that created a mono-functional and exclusionary enclave and explores contemporary universitymodelsthatacknowledgetheintenseinteractionandintertwinement of universities and cities. The studio’s hypothesis is that sterile campuses can mutate into vibrant urban environments and that universities can imbue a unique form of urbanism into cities. It is understood that respecting heritage and restoring ecologies is high on the agenda, as well is the transition to carfree mobility. The Arenberg Park is seen as the first step-stone for the bikedominant transport mode in the Dijle Valley. Complex and mixed urban tissues are proposed on‘university land’(and other public land) on the slopes of the valley and the studio elaborates innovative development models that do not solely depend on the real estate market, but give way to shared economies, cooperatives, and commons. Greenfield development is banned. Land is recuperated from unnecessary parking, infrastructure, and restructured building tissue.

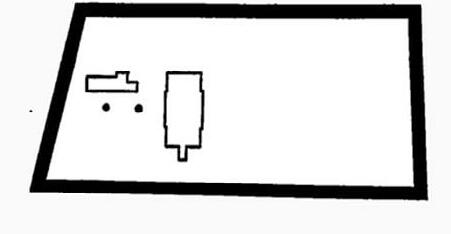

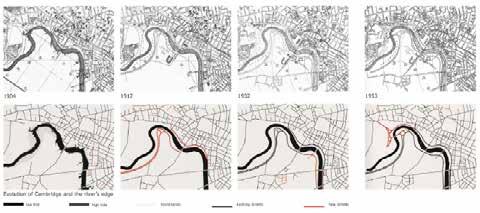

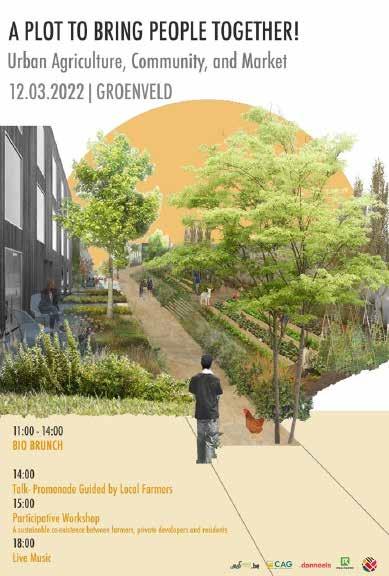

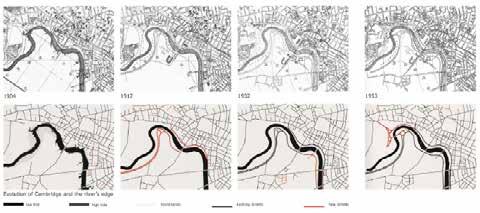

1. University campus and city throughout the decades

In the 1960s, when the university grew so exponentially that spatial ex pansion was required, a master plan was developed. It is basically a plan for three campuses: a campus of the human sciences within the historical inner city and two others outside the city, in Heverlee: a campus for exact sciences in the Arenberg Castle Park and a campus with academic hospital for the medical sciences on Gasthuisberg.

Surprisingly enough, until recently the 1960 masterplan remained the

self-evident reference for the university’s spatial development. Conse quently, the university developed in exclusive enclaves.

Humanities remained in the city, embedded within the urban fabric. De facto, the university retreats into evermore introvert building complexes and clusters that hardly interact with their urban environment.

Since, the congested inner city and further development of the hospital and faculty proved impossible, a new campus was developed. In the best functionalist tradition, the monumental Gasthuisberg was sacrificed to accommodate the medical campus. Without any break since the 1970s, an endless megastructure is under construction. The monstruous building complex surely no longer only provides beneficial economies of scale.

The castle domain of Arenberg has, since WWI, been completely devel oped as a university campus. A series of investment waves since the last quarter of the 20th century (including the extensions for IMEC, science park, etc.) have pushed development limits; heritage as well as ecological values of the domain severely overstressed.

There are numerous reasons to question the current spatial development model of the university, that simultaneously defines the relation between the university and the city. The university as well as city have developed dramatically during the last half of a century. The university not only grew enormously, but it also functions very differently than it did in the 1960s. Universities are more than ever research-oriented and generate numerous spin-offs. The university of Leuven has been the first in Belgium to system atically valorise research through spin-offs. At the same time, educational

8

programs evolved and doctoral studies expanded dramatically. Strange ly enough, an old, land use-based masterplan of the 1960s continued to spatially steer the fundamental development dynamics of the university. This land use planning continued a rigid functional zoning that is at odds with the interweaving of contemporary university and societal activities. This is economically surely the case with spin-offs and contract research, but as well socially and culturally. Since quite some time, universities no longer operate in isolation. On the contrary,throughout the world, plenty of university expansions are on the outlook for new creative and research laboratories.They take initiatives in situ, engage themselves where develop ment questions arise or where societal issues manifest themselves.

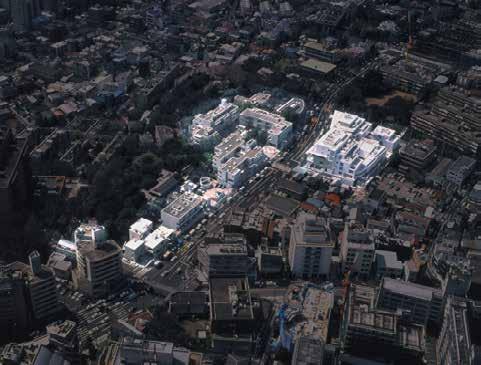

Prominent universities are role models in urban development and create new development models. In short, universities today are on the outlook for the city, they no longer isolate themselves. Interweaving universities in living cities enriches the universities and vice versa. For decades al ready, zoning is no longer considered a legitimate planning concept. Many university campuses belong in that sense (besides heavy industry) to the last relicts of a planning principle proven wrong. Leuven seems to be part of the club. An unease with this fact resonates in recent initiatives such as “Living Campus”, but isn’t that rather a fight against symptoms? In 2018, the KULeuven undertook the initiative to update the campus Arenberg masterplan. In parallel, a first “University City / City University” studio took place in MaHS/ MaULP. The interwoven process resulted in inter esting conclusions for the weaving of the university campus, the city and the valley landscapes. In the meantime, the university finalized their new masterplan, a roadmap for the future campus.

At the same time, the city underwent a metamorphosis over the last half a century. It has evolved away from traditional industries, redeveloped brownfields and dramatically transformed the station area. As well, the popular neighbourhoods were subject to gentrification. The university, spin-offs, and research institutes like IMEC and the university hospital are shaping the renewed economic structure of the city. Like other university cities that evolve successfully towards an ‘education/medical economy’, it evolves towards an exclusive city. Leuven has become the most expen sive city in Flanders with regards to the housing prices. By now this has become very tangible as an issue. Which percentage of the nursing and support personnel of the university hospital can afford to live in Leuven? How many of the administrators, never mind technical staff and grounds’ workers can live with their families in the city? While the population, along with the university and economy continues to grow significantly, the available space stays the same, and therefore the development offerings shrink drastically. Even though the city looks full and complete, it cannot answer to all the current (housing) needs. Many of the improvised actions today are not sufficient answers to the spatial needs—from the socio-eco nomic and ecological justice perspective.

2. Developing spatial visions for a university city and city university

There is clearly the necessity to rethink the current spatial development model. The interplay between university and city is one of the necessary starting points. In spatial terms, they are intertwined systems. After half a century of persistent direction through functional zoning policies, the spatial vision of the development of the university (and its interaction with the city) needs to be revisited. The recently developed masterplan of the

9

university will therefore be critically evaluated. Scenarios will be developed to re-balance the needs of the growing university and evolving city. Their interactions need to be strongly rechoreographed.

The main question therefore is threefold:

Which type of spatial developments will allow the flourishing of a contemporary university?

Which type of spatial developments will allow for the balanced ecological, economical, and social development of the city?

How can the spatial interaction between the contemporary city and university be orchestrated in a most interesting and interdependent way?

Answering these questions means developing a vision for university, city, and their field(s) of interaction. This unavoidably demands a research by design process: design as research and research feeding design. The pro jective process will navigate between different scales: from the building to the region and all scales in between. This design research will also involve the different stakeholders from the city and the university throughout the process. A specific stakeholder exercise will allow for a deeper dive into the understanding of the interactions, interests and involvement.

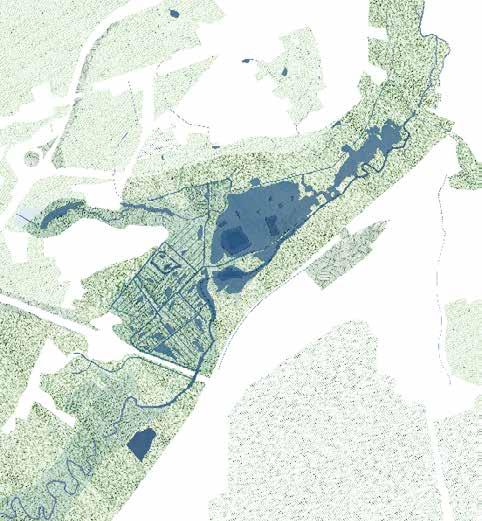

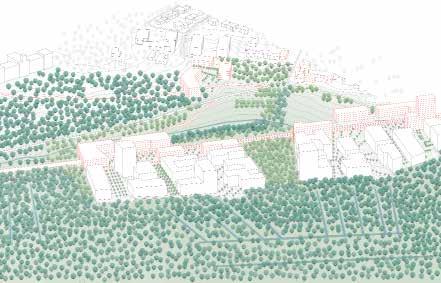

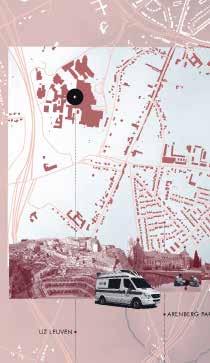

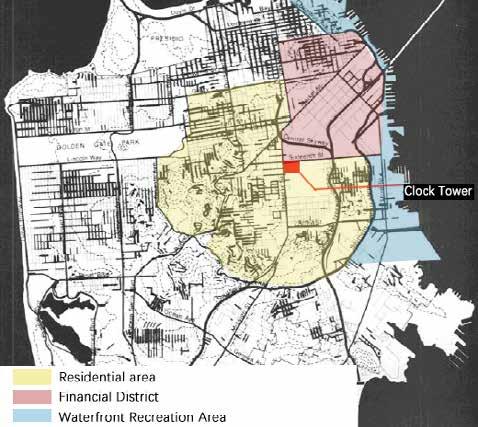

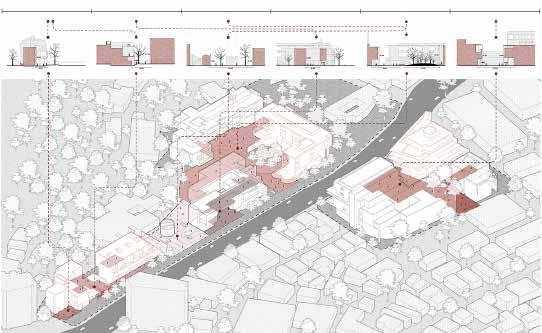

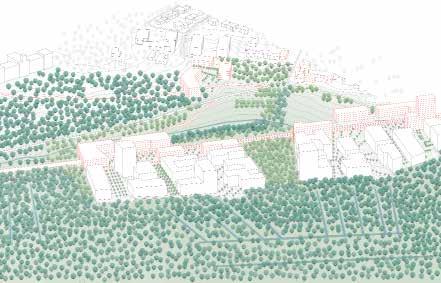

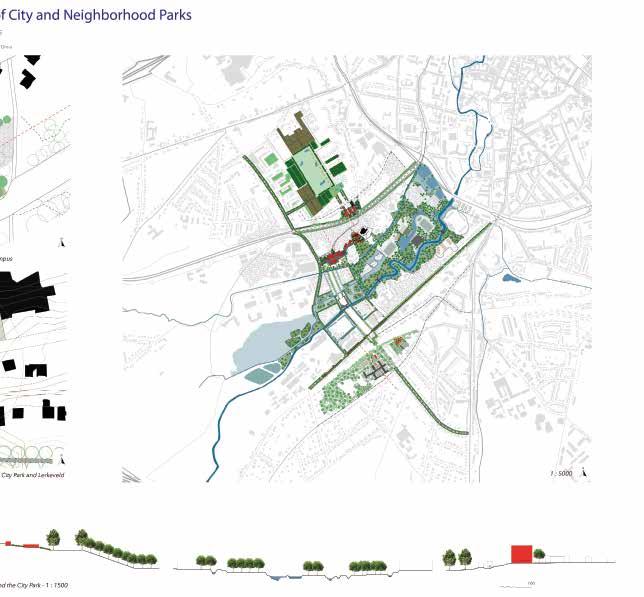

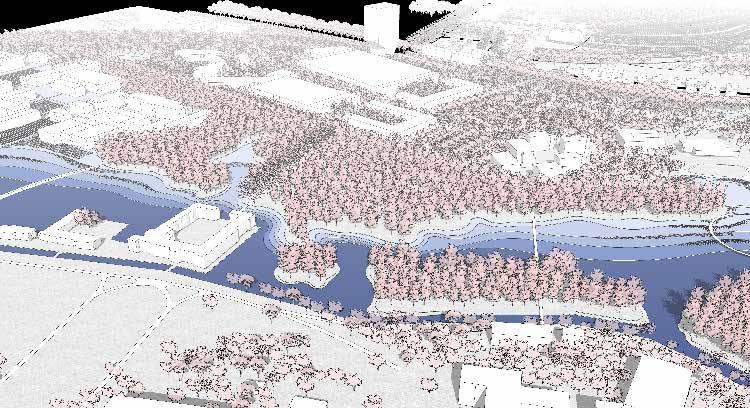

3. The site: university grounds around the valley

The studio will investigate the Dijle Valley as a specific spatial figure that has led to very particular forms of urbanism since the Middle Ages: valley urbanism.

bridges across rivers, on river islands and on riparian slopes. The marshy lands along rivers were usually only developed later because foundations required capital intensive interventions. Hence, the river cities were first places for resourceful institutions as convents, hospitals, schools, be guinages or for industries (starting with mills and breweries). It explains why these buildings are the most public part of the city with the highest concentration of collective services and common spaces. Before the In dustrial Revolution, the unbuilt (convent gardens and orchards, bleaching fields) dominates over the built. The valley city combined the greatest density (through large building complexes) and vast openness.

It is hence not accidental that the university expanded in the 20th century upstream in the castle domain of Arenberg that is embedded in the Dijle Valley to the south of the city. However, it cannot be said that this ex pansion led to a valuable form of valley urbanism. Elaborating a valuable valley urbanism is therefore one of the targets of the studio.

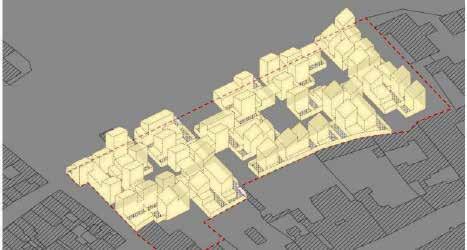

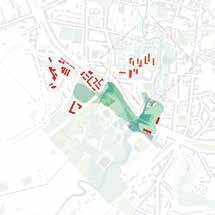

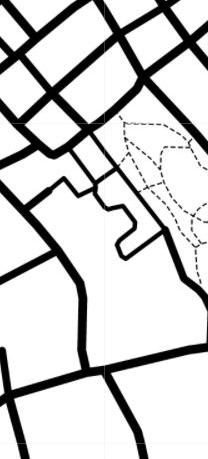

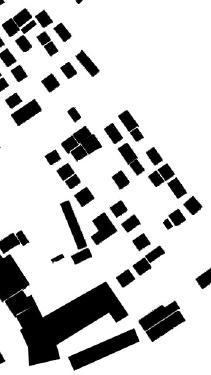

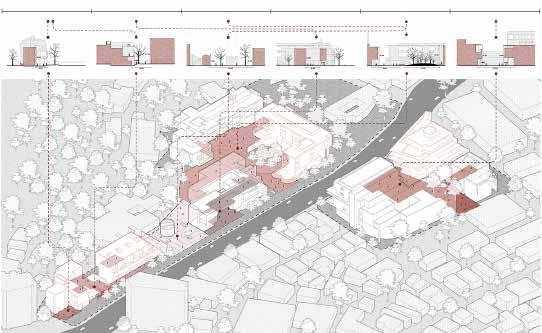

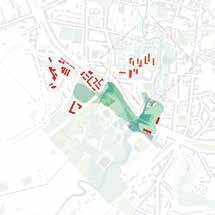

The site is situated around the Dijle Valley from Egenhoven in the south of Leuven untillthe Brusselsestraat in the historical center. The Kasteel park Arenberg with the current Arenberg campus is embedded within this segment. The site will be subdivided in three strips stretching over the valley and including both banks and the lower valley grounds. Each strip includes interesting university properties as well as large infrastructures and landscape figures. All have planned areas for densification.

4. The studio organization

Cities in the Lowlands were historically i river cities and developed as

10

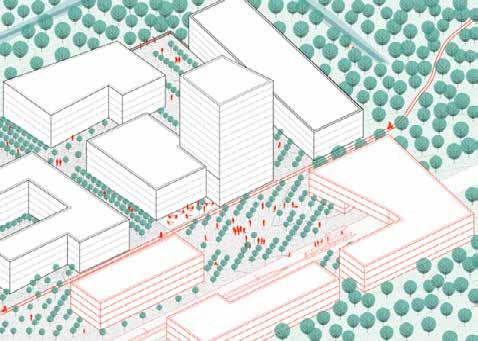

The studio will function as three “offices”, which each responsible for developing a strategic vision for the entire site. Within each of the offices, three groups (of 4 students each) will work on the different strips. They are responsible as a small group to develop a vision for the strip, but at the same time formulate a design hypothesis on the scale of the full site.

Within the strips, each student will develop a particular focus (urban tis sue or landscape urbanism). Specific sites and assignments will be formu lated for each of these specific design exercises.

The goal of the studio is to be able to work across scales and within differ ent group sizes, all with the goal to reach a coherent vision for the inter twined university and city tissue within the Dijle Valley.

5. Design hypothesis & approaches

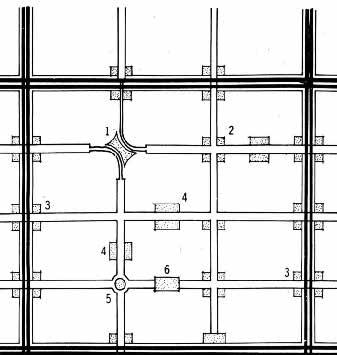

Mobility

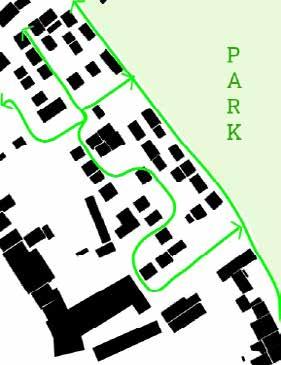

One of the starting points is a car-free university city in the Dijle Valley, consequently the following can be considered as givens:

• decommissioning oversized heavy infrastructures: downsizing the Koning Boudewijnlaan (actually a highway) in the south and Kolonel Begaultaan in the north; decommissioning Celestijnenlaan that cuts the Arenbergpark, downsizing ring road, car and parking infrastruc tures in the valley section of the urban territory; .

• cars are to be stopped at the edge of the valley; they are no longer allowed to penetrate it. The Dijle Valley is to be transformed into a car-free city initiating the global mobility transition. The edge is to be

equipped (for the time being) with hubs for new mobility-systems and (in the end recuperable) parking (as part of the transition).

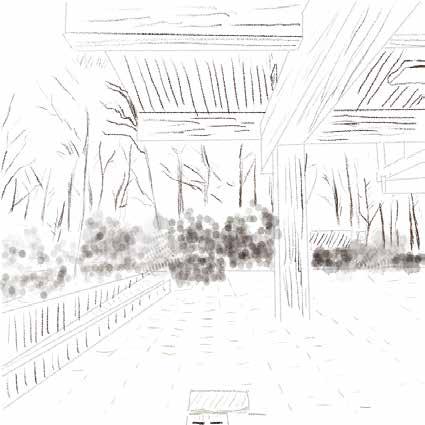

• transition to a car-free university city means making place for other forms of mobility: eliminating and changing (car-)lanes. The valley should become accessible and movement in the valley should become smooth and abundant. Crossing the valley, however, (with cars, etc.) is not considered beneficial and should be limited to the absolute neces sary minimal. In this way, the valley can become the spine of the new (carless) urbanity. Crossing points (ring road, Brusselsestraat, etc. can be articulated as bridges across the valley

• in the valley, place should be made for soft and public transport of the 21st century: autonomous mobility, sharing-economy in mobility (e-bike, e-cars, ...) and new e-public transport forms (from offer to demand oriented, from rigid to flexible, from 9-5 to 24/24 etc.)

Development models

The largest part of the site is university property, public property (public institutions, as schools, etc.) or can be acquired as public land/university property. This is a major asset and can be made use of to develop a comple mentary, cooperative and non-speculative model of urban development. The collective domain can be expanded with land-banking mechanisms, transfer of development rights, etc.– approaches that the private market is looked for.

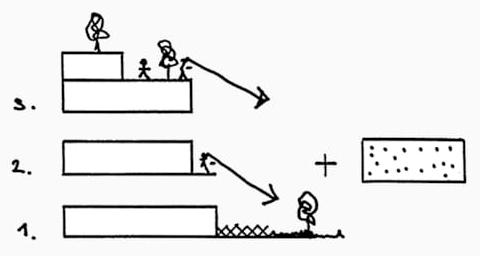

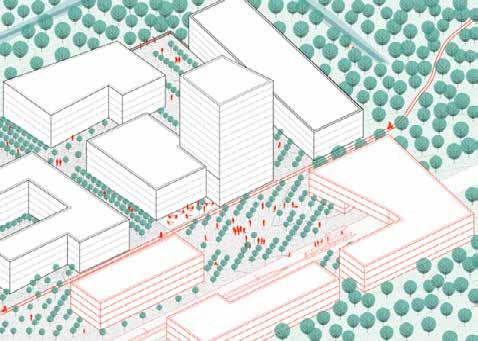

University-city/city-university

From zoned and exclusive over mixed development and living campus towards inclusive and integrated university city development

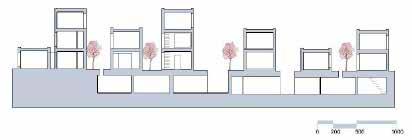

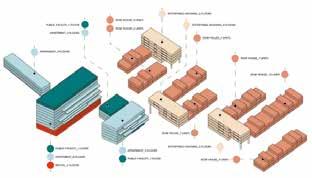

• Hyper density: accommodate half of the growth of Leuven (10,000 inhabitants in a decade) within the Dijle Valley

11

• From economy of scale to scales of economy: from massive production of monofunctional programs to mixture, from office to co-work, from factories on industrial zones to productive city tissues

• Housing fabric forms the city: inclusive urban dwelling forms for the 21st century in a dynamic university context.

• Housing complexes without garages or car parking space, but with e-bike facilities embedded and shared mobility systems

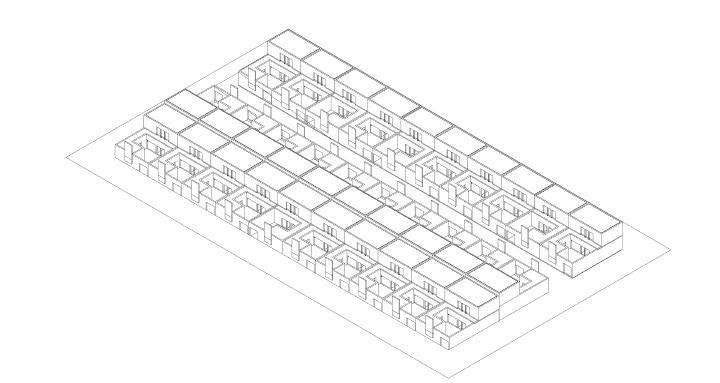

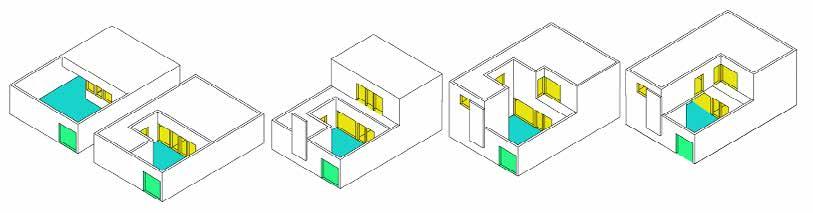

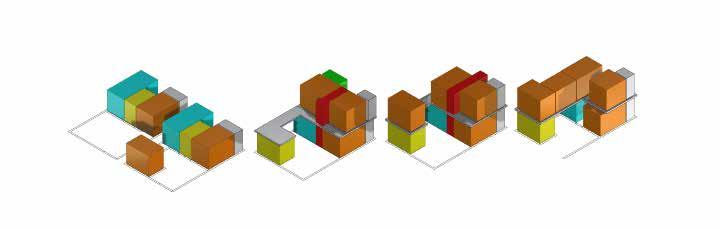

• Uncertainty/unpredictability: fixed frame and flexible infill

Valley Urbanism

• Being inspired by the Middle Ages, but in a 21st century way: build ing density in an ecologically sensitive river valley and compensating dense urban development with even vaster openness (shrinking foot prints, expanding ecologies, space for water, forest, ecology).

• Building a new urban tissue and structure that intertwines with ecolo gy (instead of erasing it by occupation).

• From planning structures on a tabula rasa to a metamorphosis by restructuring: systematic reuse of buildings, limiting demolition, with exception of:

1. some oversized & decommissioned infrastructure,

2. parking space (at least 60% given back to nature),

3. supermarkets (Colruyt, Delhaize, Carrefour) and other nonvaluable, extensive space consuming structures.

• Residential densification projects (on the condition that resulting foot print decreases and natural space increases)

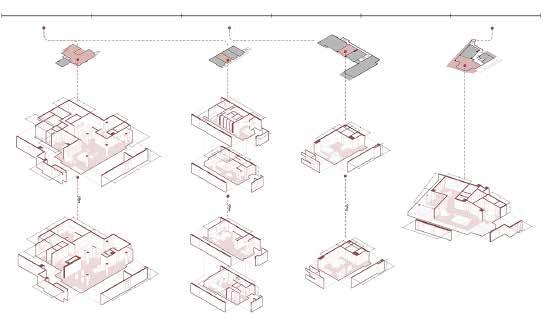

6. Testing sites

The territorial vision of each strip will be put to the test on two particular sites. The program definition for each testing site - finding the specific mix of functions and type of urbanity - is part of the research assignment. The minimum ambition is nevertheless to add at least 400 new housing units per site apart from the other proposed new functions. The existing build ings and programs that are taken out should also be compensated.

Specific challenges per site:

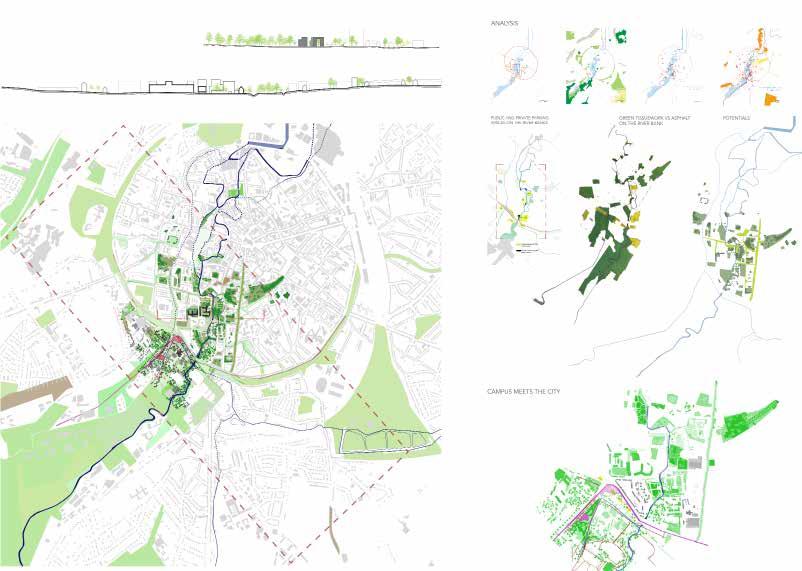

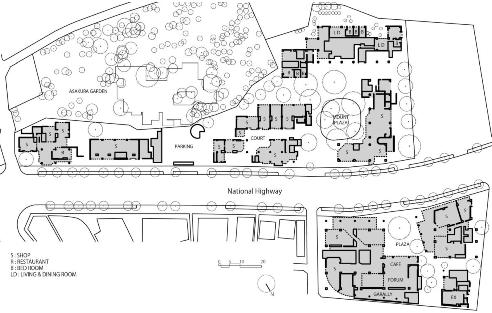

A. Valley meets City - lower valley strip Landscape urbanism challenges

• confontation of the valley and the inner-city tissue

• confluence of the Dijle and the Molenbeek

• how to make room for more nature in the city and therefore creating opportunities for ecosystem services

A.1. Redingenhof-island

1. bringing the campus into the city

2. mediating between a multiplicity of tissues, scales and pasts

3. several (overscaled) infrastructures become potential project sites, in direct interaction with the Dijle and its island in the low city tissue

4. relation has to be sought for with the heritage around the site, e.g. the Beguinage

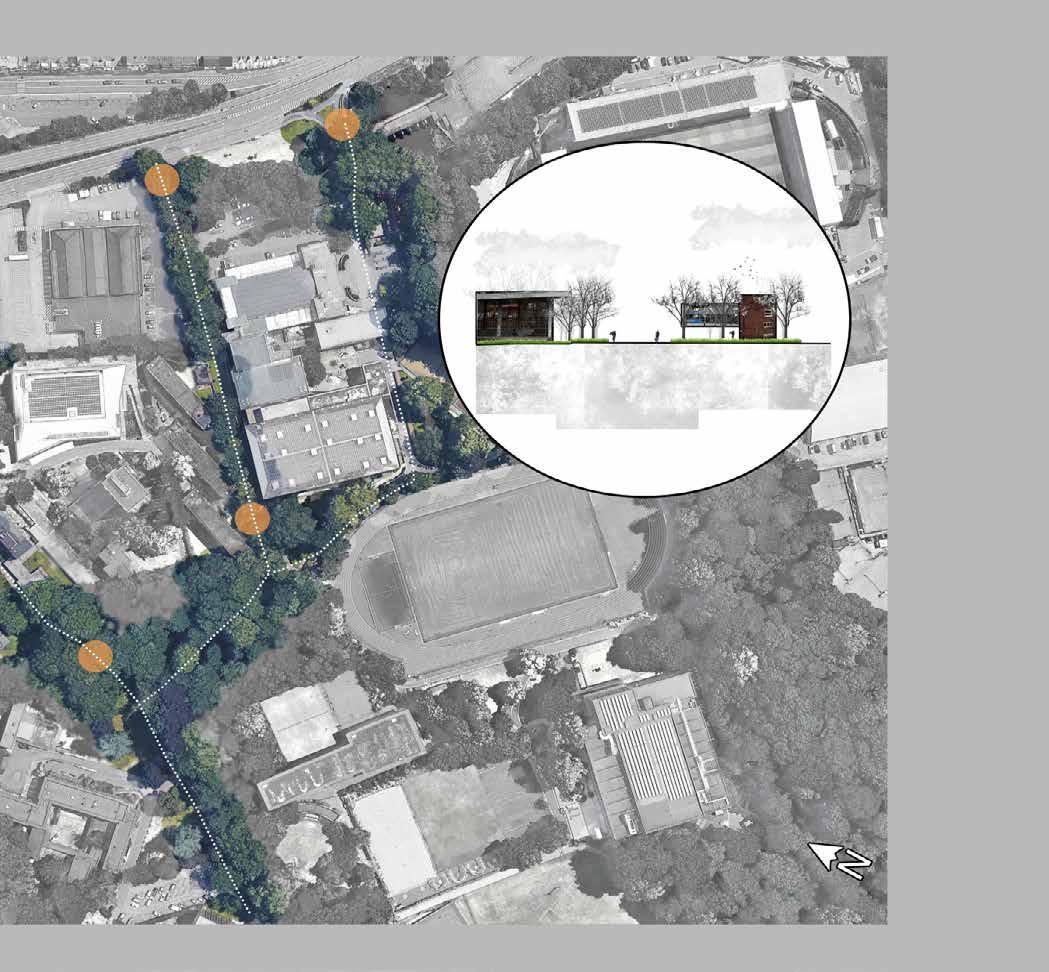

A.2. Bodart-junction

• a gate to the city, a gate to Arenberg

• opening up the collective sports functions to the city

• turning the challenges of an infrastructural node into opportunities for

12

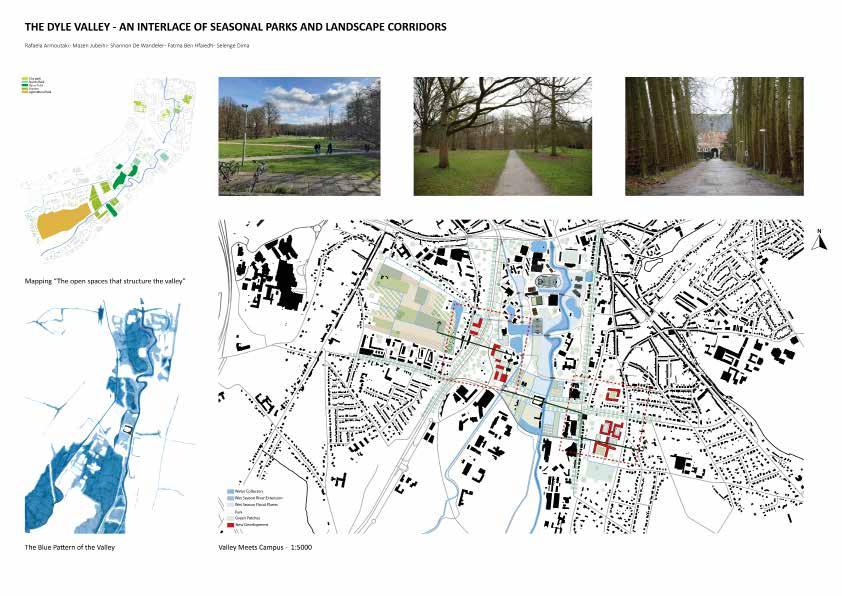

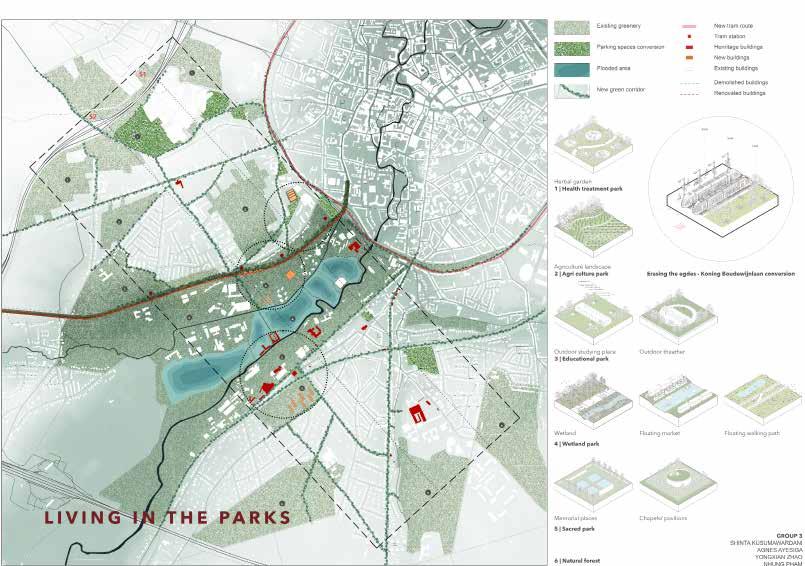

B. Valley meets Campus – middle valley strip

• Landscape urbanism challenges

• Confrontation of the valley and the campus facilities

• Parallel water streams of the Voer – Dijle – Molenbeek to choreograph through the tissue

• How can the valley landscape become even more of an asset to the tis sue? How can the campus park of Arenberg be structured by and along this water landscape?

• How to put the higher banks in relation with the lower lying valley?

B.1. Alma-edge

• creating synergies between functions

• addressing the monofunctionality of the campus

• Making use of the Koning Boudewijnlaan as a katalyst for strategic weaving between campus and residential tissue

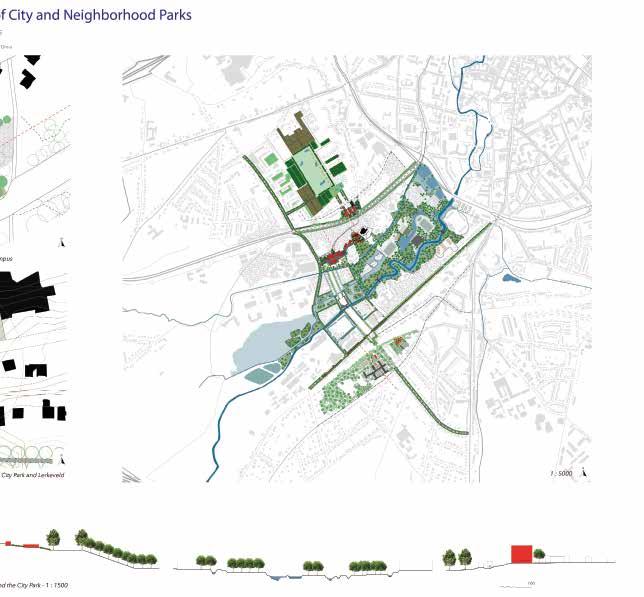

B.2. Lerkeveld-domain

• requalifying underused but built-up backyards

• revisiting the cloister typology/ the domain in the neighbourhood. Seeking opportunities to reinterpret the urban and architectural mono lithic figure

• acting on the hinge campus-suburb

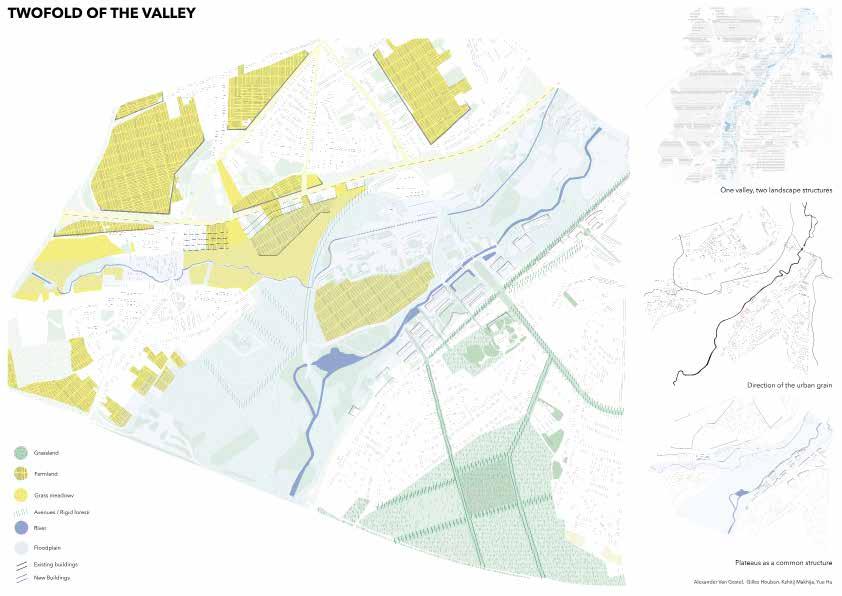

C. Valley meets Fringe – higher valley strip

Landscape urbanism challenges

• Confrontation of the valley and the open and more rural landscapes

• Upstream water management challenges for the Dijle Valley

• Embedding the campus/city in the valley system while precisely valu

ing its landscape logics and systems

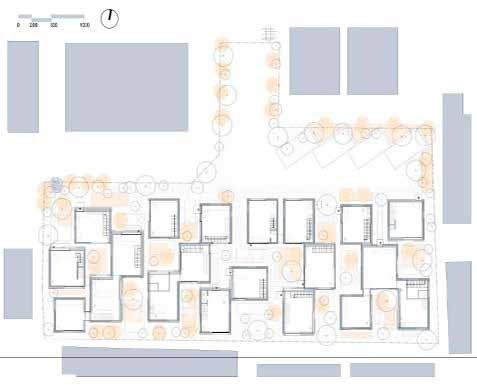

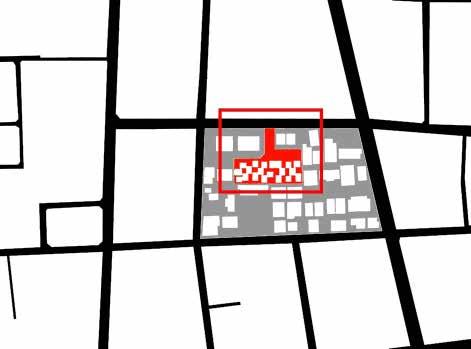

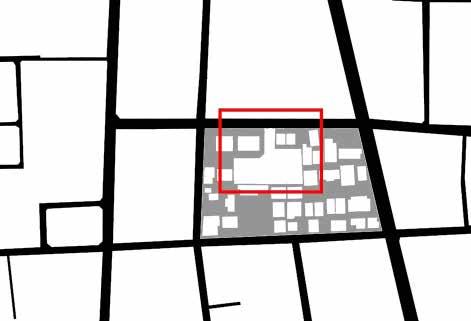

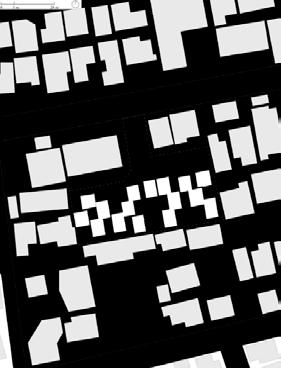

C.1. Arenberg II-patchwork

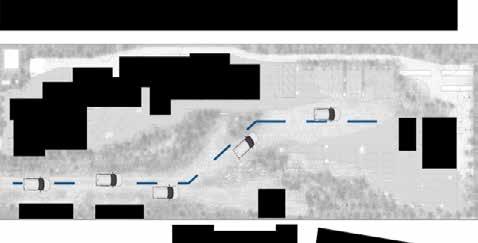

• Moving away from a car –centric, monifunctional and enclaved envi ronment

• Transforming a dead-end into a destination within the urban and cam pus tissue

C.2. Koning Boudewijnlaan-strip

• downgrading of infrastructures and stitching its sides

• moving away from a car centric environment

• designing the edge of the fringe

• searching for a link with the surrounding residential neighbourhoods and the former Jesuit domain

13

an innovative city-university development case

GUEST LECTURES

Perspective of the City of Leuven on the Campus Daan Van Tassel, Wiet Vandaele, City Planning Depart ment Leuven

History of the Domain of Arenberg Cato Leuraers, KULeuven

Water in the Southern Dijle Valley Jan Pauwels, Vlaamse Milieumaatschappij

14

INSPIRATIONAL PROJECT VISITS

Louvain-la-Neuve Cati Vilquin, KULeuven

Centrale Werkplaatsen Leuven Tom Boogaerts, Bogdan & Van Broeck

La Vignette Leuven Guido Geenen, WIT architecten

15

© Ermias Tessema Beyene © Arthur Van Lint © Arthur Van Lint

17 02

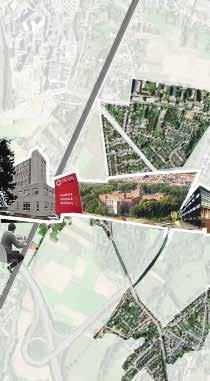

MAP © Axelle Haekens

INTERPRETATIVE

18

19

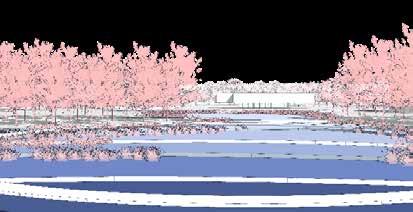

Proximity to water

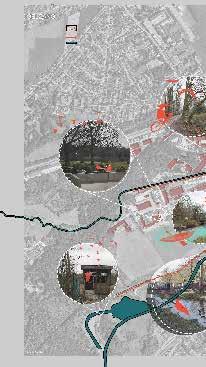

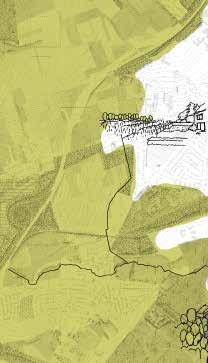

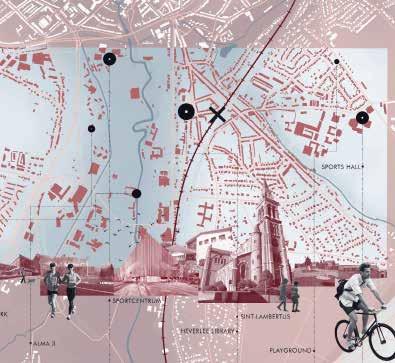

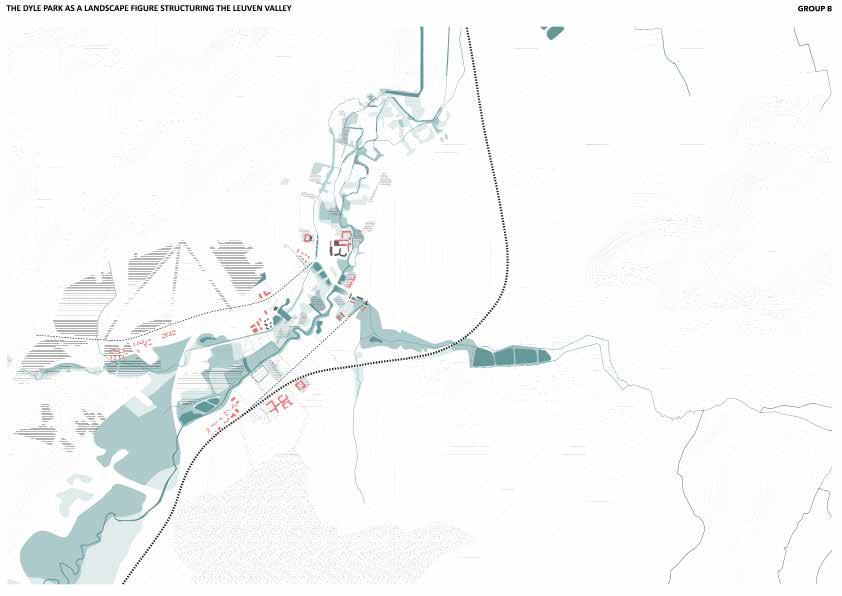

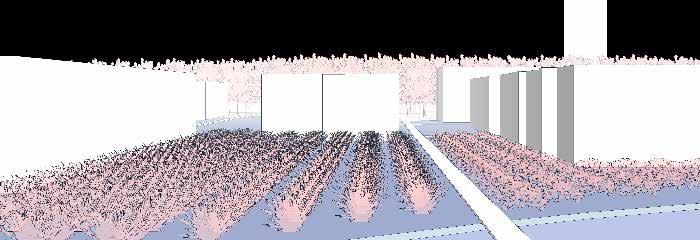

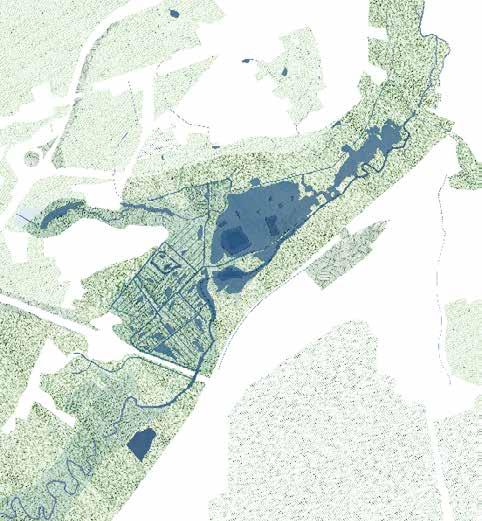

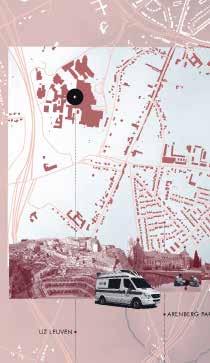

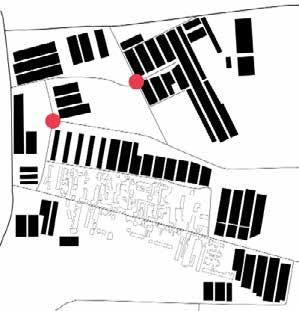

Valley meets campus - Heverlee, Leuven

Yasmine Baamal

The canal and the Dijle are important elements that frame the campus land scape. Yet, there are very few spaces that take advantage of its potential and that create a proximity between humans and nature. In this map, existing and potential spaces of proximity to water are identified, in order to reveal fields of opportunities.

Ponctual users of space Linear users of space Water

20

21

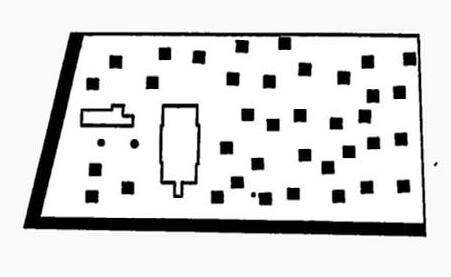

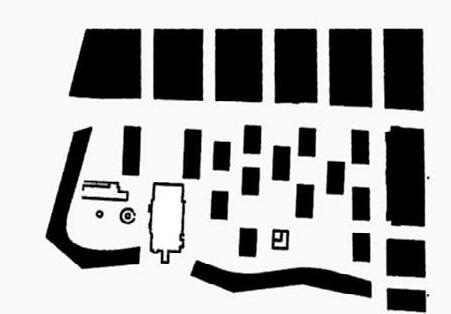

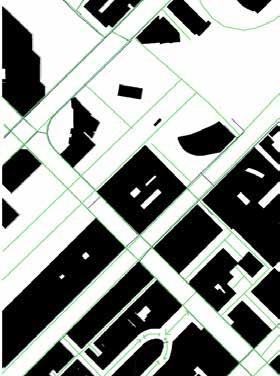

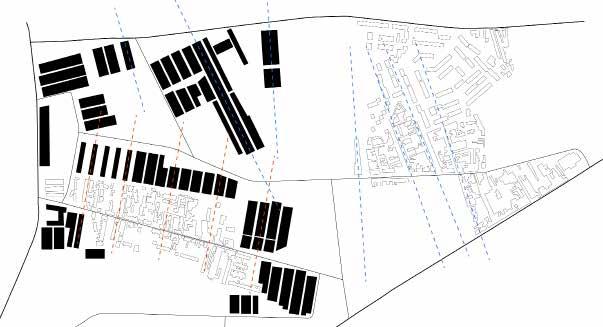

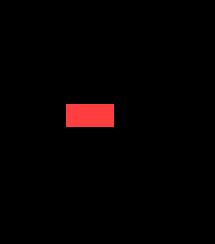

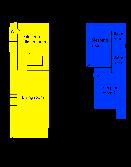

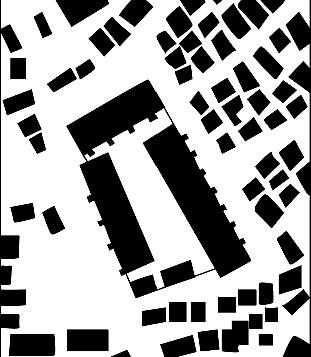

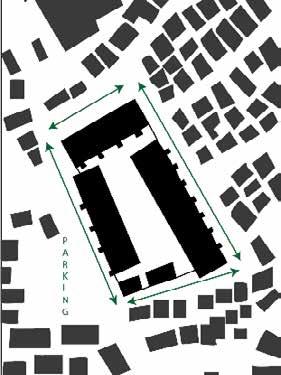

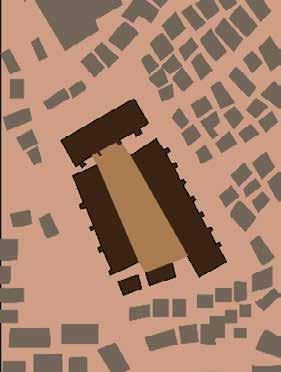

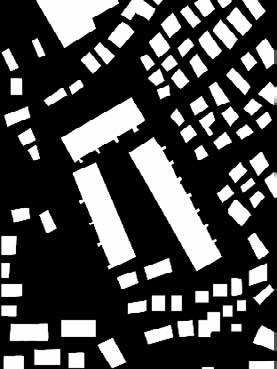

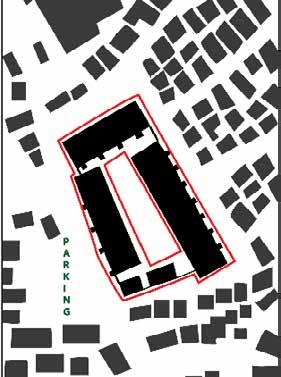

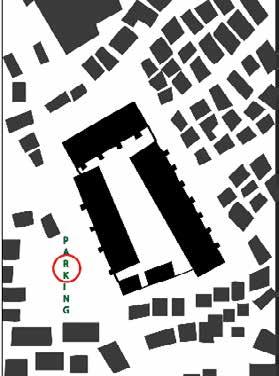

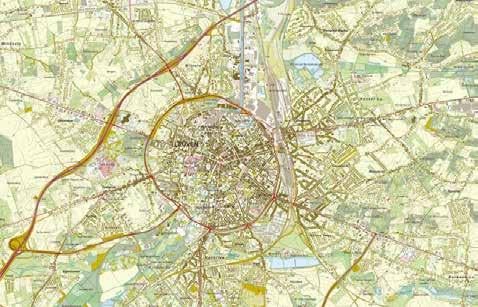

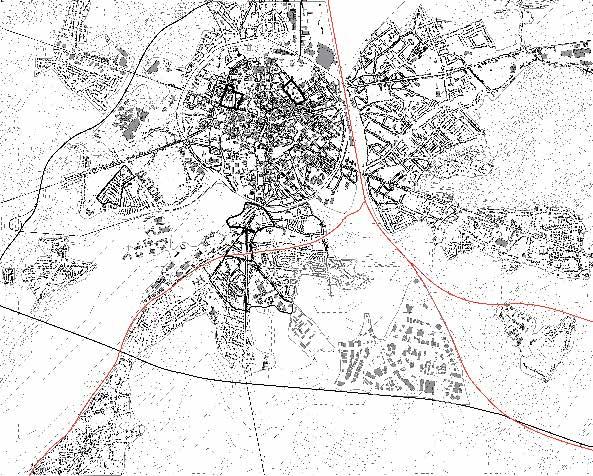

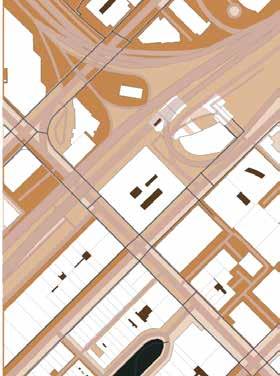

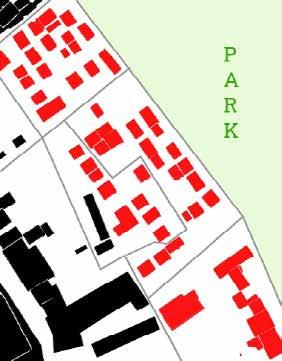

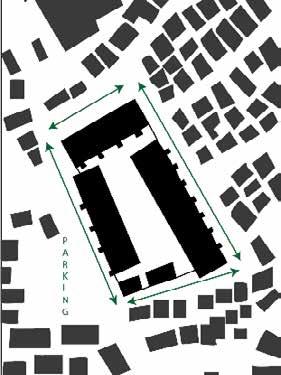

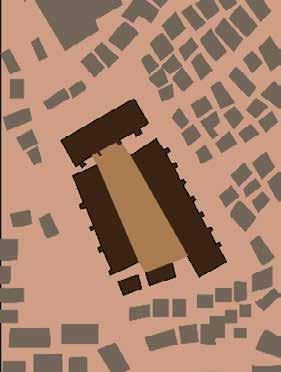

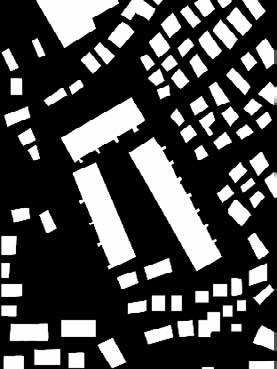

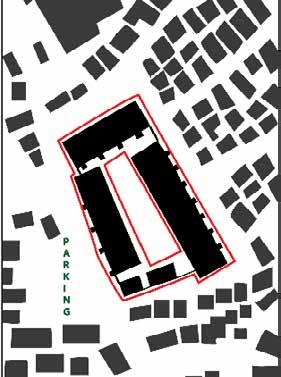

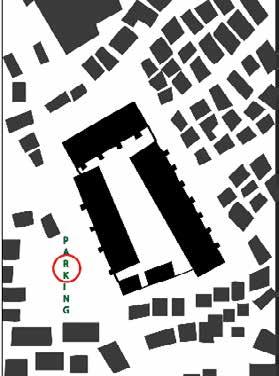

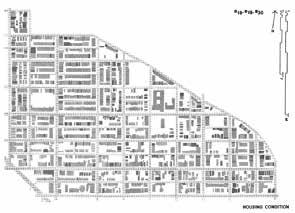

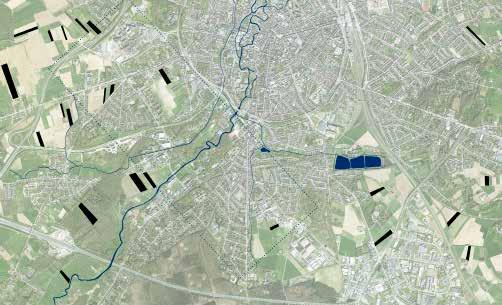

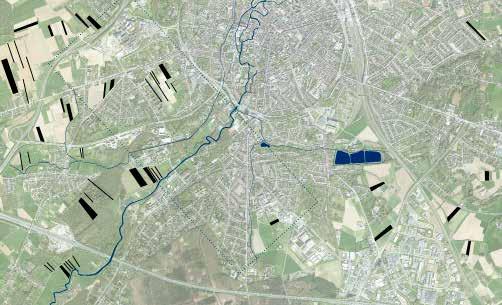

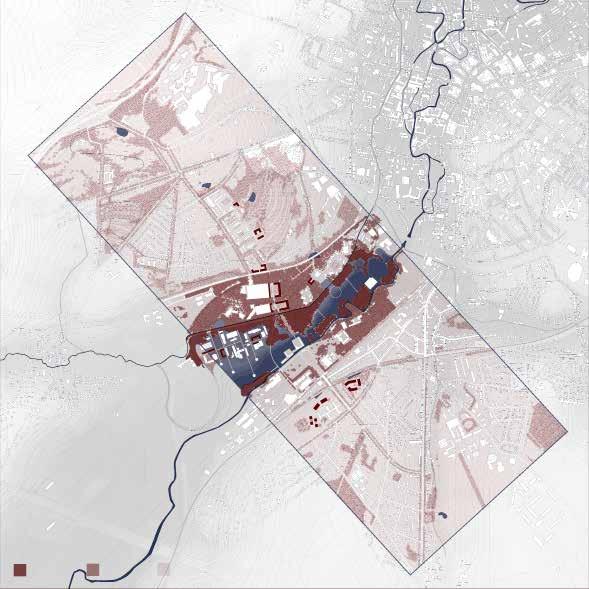

Parking area and urban parcels

Leuven

Tzu-Chun Lin

This analysis map marks the location of the parking spaces(ground parking, underground parking and parking tower) and reveals that all parking spaces can be divided into three types. The first serving a specific cluster of public fa cilities, the second serving a specific functional massing, and the third serving a large residential community. Through the distribution of parking spaces, it can also be found that some specific parcels of land in the site have a certain degree of independence and can be considered as specific areas in the city. In addition, with the mapping of soft mobility, it is possible to explore how different parts of the city are connected except of the vehicular movement.

22

UZ Leuven campus

Supermarkets

Science park Campus area

Industrial area

ground parking undrground parking parking building

Sports center

Abbey and park

Stadium and residential area

23

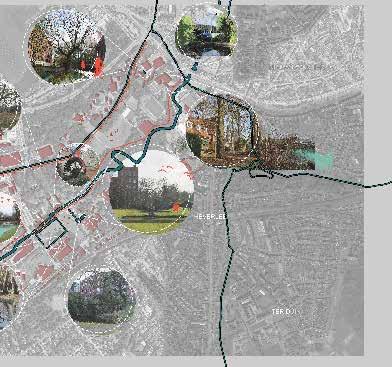

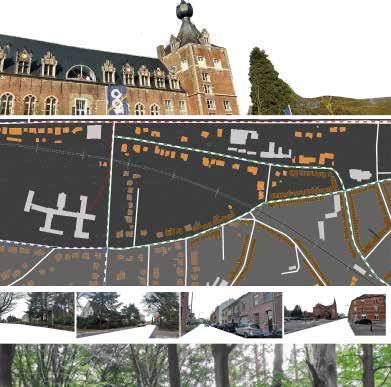

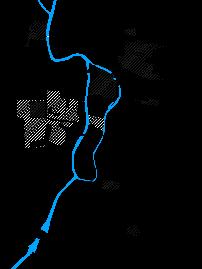

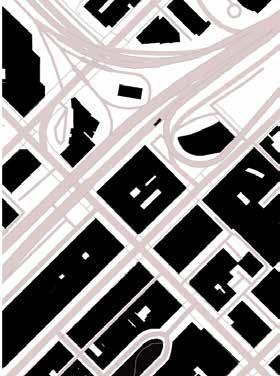

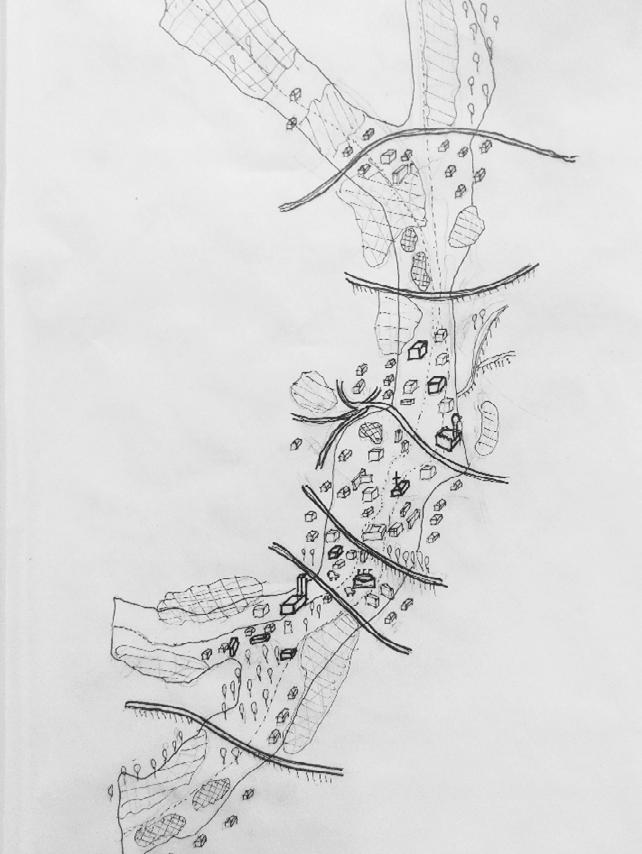

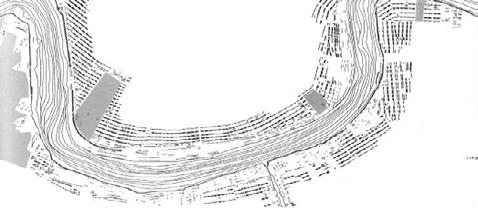

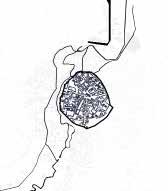

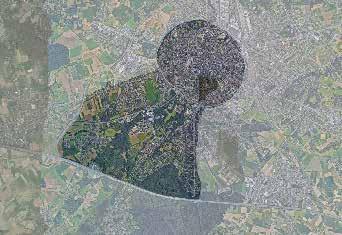

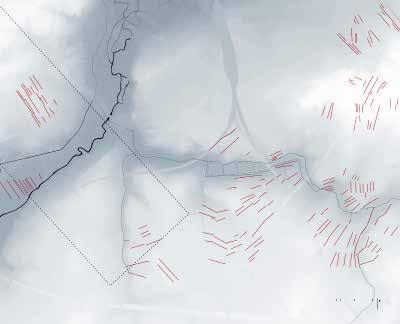

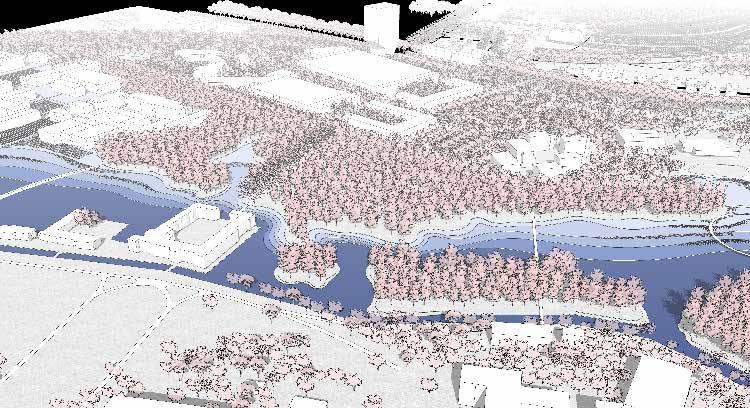

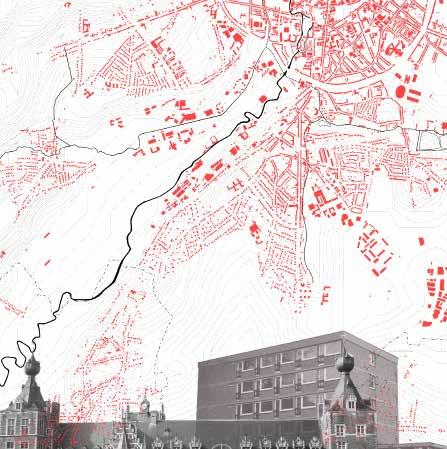

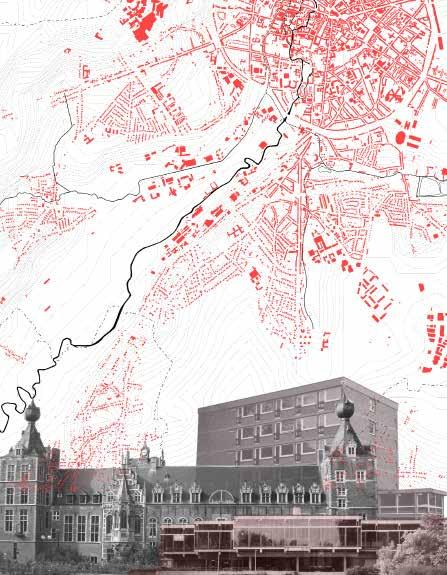

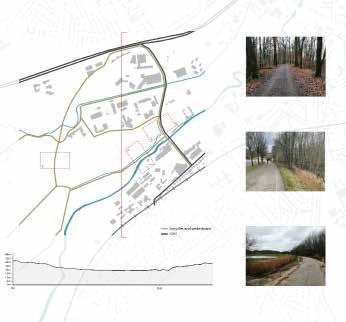

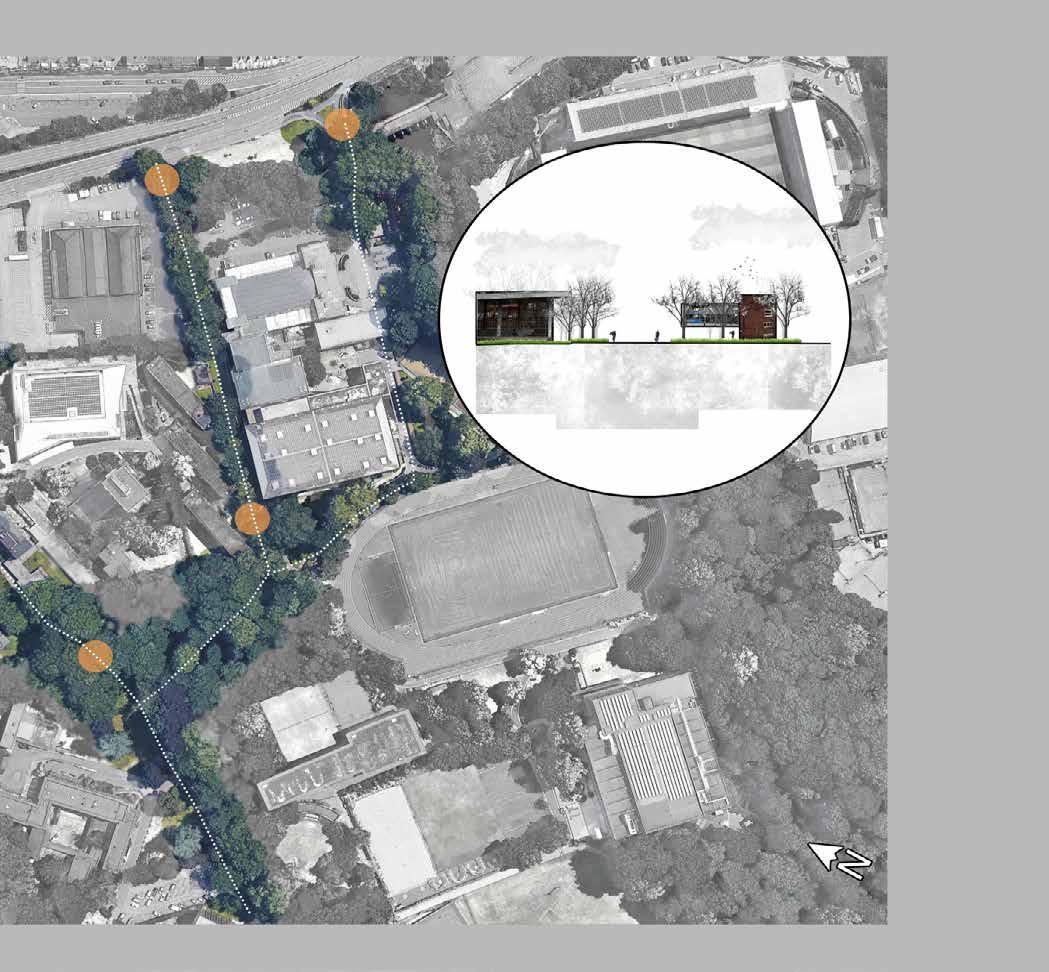

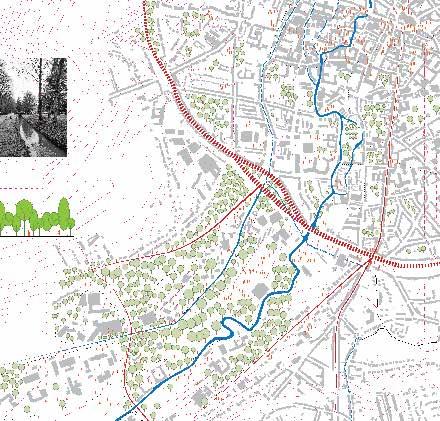

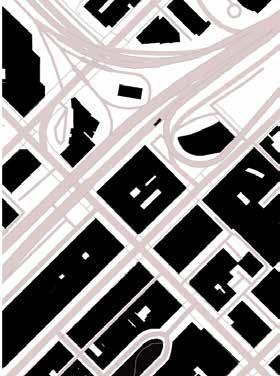

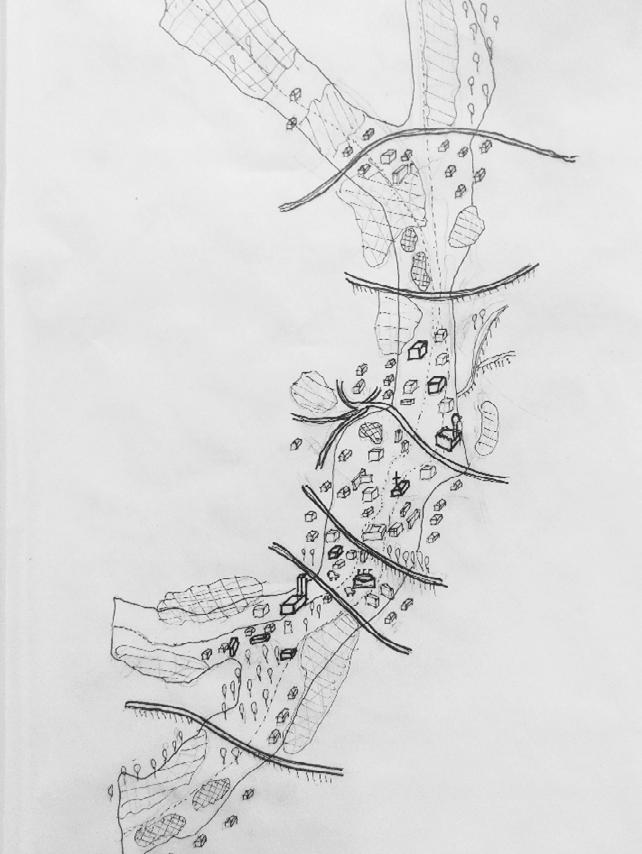

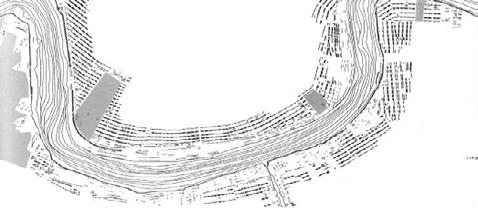

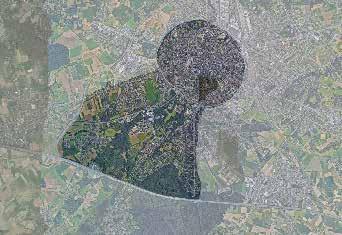

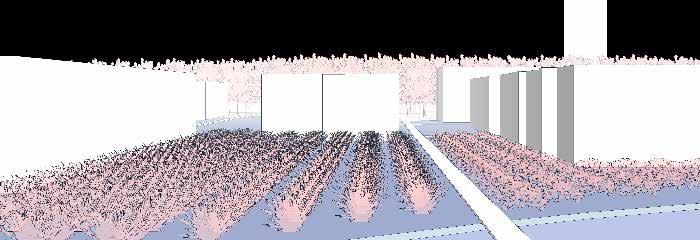

Campus in a valley

Arenberg campus Heverlee

Axelle Haekens

Axelle Haekens

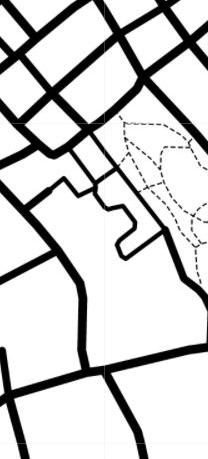

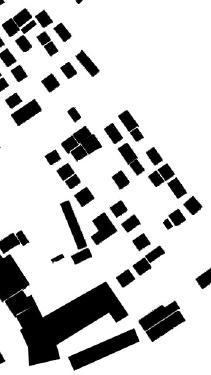

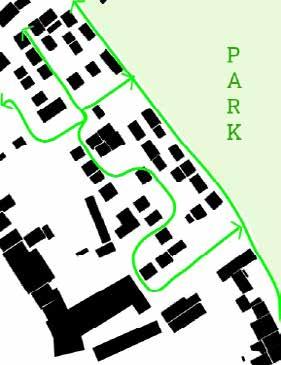

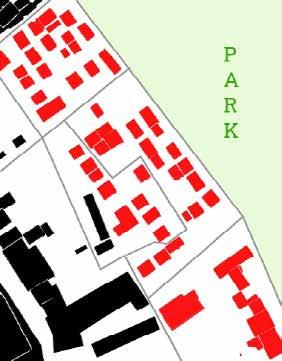

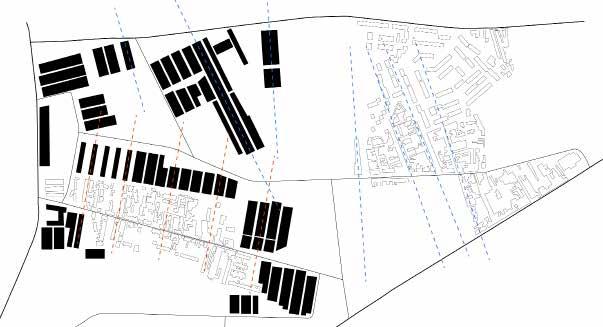

The Arenberg campus in Heverlee consists of multiple ‘islands’ in the Dijle val ley. The Celestijnenlaan and the forest path are the only connections between the various campus domains that lie on either side of the floodable valley. Therefore, there is little interaction between the campus and the valley. If this is the case, how can we enhance the relation between the Arenberg campus and the Dijle valley?

24

25

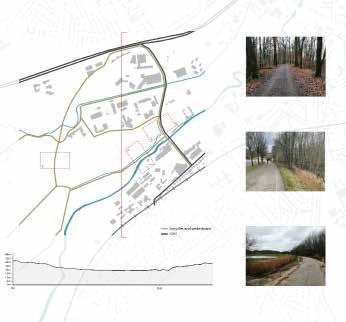

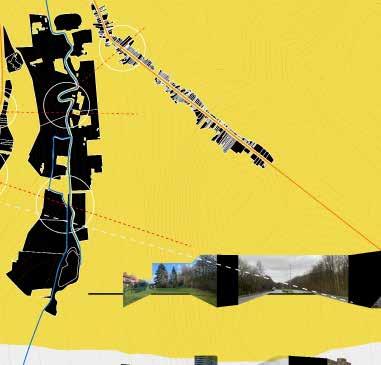

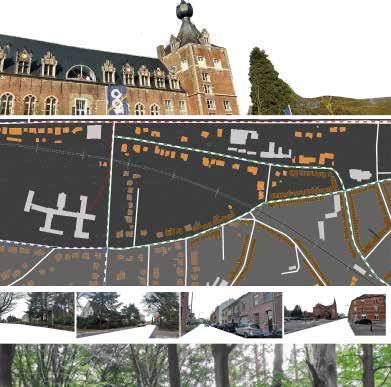

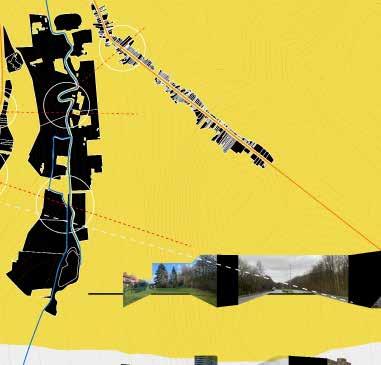

Experience of road

Valley meets fringe

Peiyang Huo

This map describes 5 paths that are important to students and residents, some of which have the potential to better serve users in the future. Such as the forest path connecting Egenhoven and Arenberg III, and the flooding area between the two campuses. But at present the three aspects of terrain, scenery and connec tivity make these 5 routes have different experiences, the map tries to find opportunities and challenges to improve the road experience.

26 37.1m 24.2m 36.5m 32.1m

sense of boundary

32.1m 36.5m 33.5m 24m 35.3m 48.6m 4.0km 3.6km 3.2km 2.8km

0 0.5km 1.0km 1.5km 2.4km 2.0km 1.6km 1.2km 0.8km 0.4km 51.6m 23.9m 54.4m different pavement segmentation by railway segmentation by highway

28

29

Permeability in the valley

Valley Urbanism

Shuting Li

Leuven is surrounded by so many green space (grass, agriculture,forest ect),how to build a new urban tissue and structure that interwines with ecology(instead of erasing it by occupation)?

30

31

3 Different Domains on their own Island

Heverlee, Leuven

Heverlee, Leuven

Evangelical

Sites currently located in urbanized areas by residences for which they do not interact with their sorroundings, they are in the middle and center of a com munity but at the same time, isolated. Due to their green area potential, they could be used to make these lots a private/semi public area for the use of community residents. At the same time, in one way or another create spaces where the different communities could interact wothou the need to sectorize public spaces, which i what is happening today. There are 3 neighborhoods with different urbn morphologies through which a connection and relationship between them could be carried throught design.

osofisch

Zusters

Zusters

32

Ana Veronica Martinez Fil

angelical Theo l ogical lt

osofisch en Theo l ogischCollege vzw(Jezuïetenhuis Heverle e)

Zusters MissionarissenJaDecht, Cult es

33

The Transitions

Noviantari

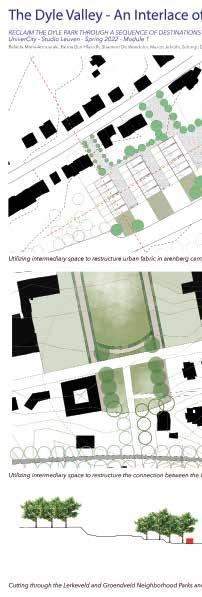

meets campus - Alma and Lerkeveld

The stretch of the Arenberg campus landscape is interpreted as a transition from the city(ness) to the natural/rural landscape or vice versa. Gasthuisberg hospital bridges the transition with the city at the top north and Dijle marsh bridge the transition with the natural forest at the south. With the historical Arenberg Castle and its relation to the Dijle river at the heart of the forest campus, the Alma and Lerkeveld bridge transition to the adjacent suburb housing neighbourhoods and agricultural lands. In that transition, landscapes are in shift, necessities are in conjunction, and infrastructures are intertwined. Spaces of transition represent dialogues with the shift and criss-cross. How and what kind of dialogues mostly occur in accommodating the transition?

34

Valley

Suburb housing & agriculture

National Park Forest

agriculture lands

Tunnel

Carpark, loading dock, and elephant paths at the back of Alma

Parapet wall with steps, pathway, and bike park in between Alma and grass lawn

35

Gasthuisberg

Dijle marsh and bird watching lookout

Wide streetscape of Celestijnenlaan Lerkeveld with grass lawn and forest grove garden

of highway and grassbank leading pedestrians and cycllists from back of Alma to grocery market and adjacent suburban neighbourhood

Planting bank with elephant paths towards housing neighbourhoods

Lerkeveld

Arenberg Castle

Alma

Dijle

Elevated grass lawn with play tools in between highway, carpark, and housing neighbourhood

Stormwater infrastructure and carpark between Gasthuisberg and housing neighbourhood

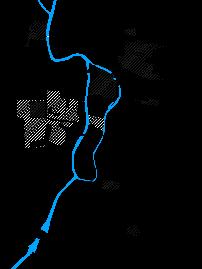

Water Nexus

The river Dijle flows into the city of Leuven from the suburbs of the city, through the campus and then to the center. In accordance with changing landscapes over this large stretch of the river there are several ways in which infrastructure such as tunnels, bridges, highways and canals plays a role in connecting the two banks of the river. How can these spaces be transformed in order to make them more interactive, taking advantage of the existing situation and transforming them into catalysts that bridge the two edges and also provide recreation and interaction for people?

36

Anagha Pandit

Dijle Valley meets Campus, South Leuven

37

38

39

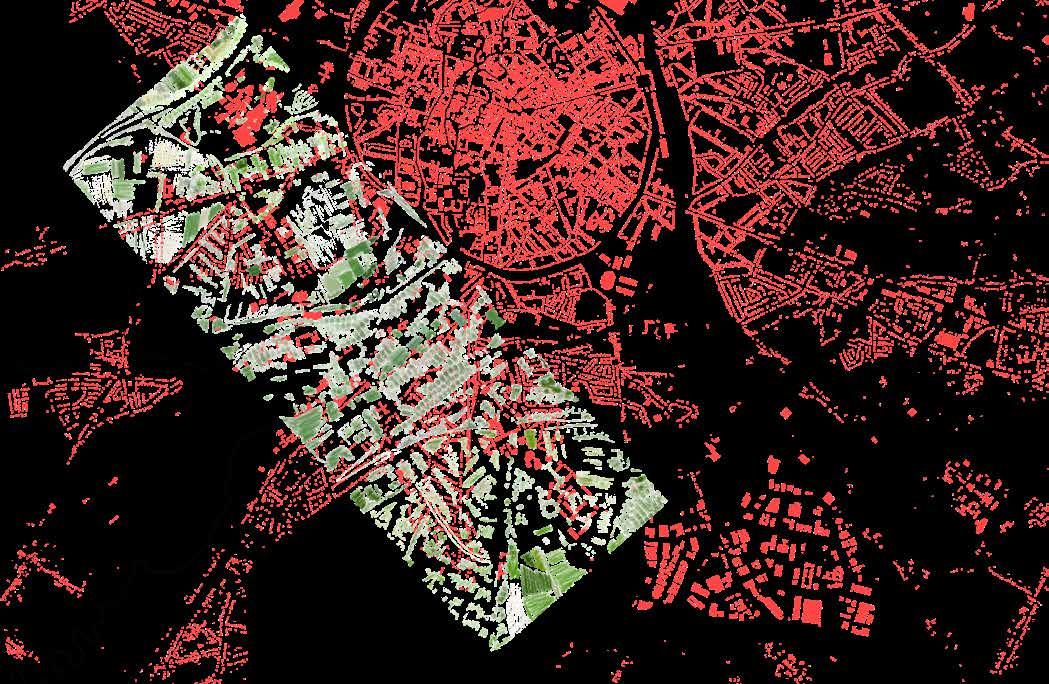

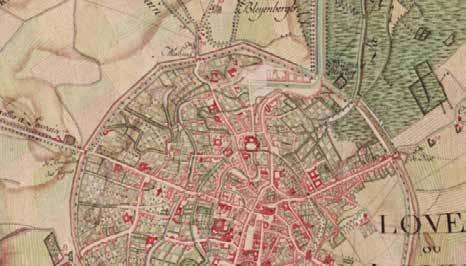

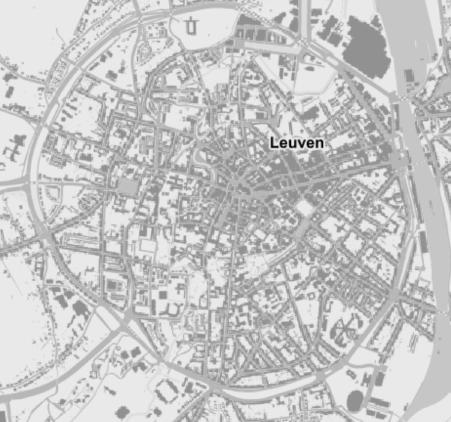

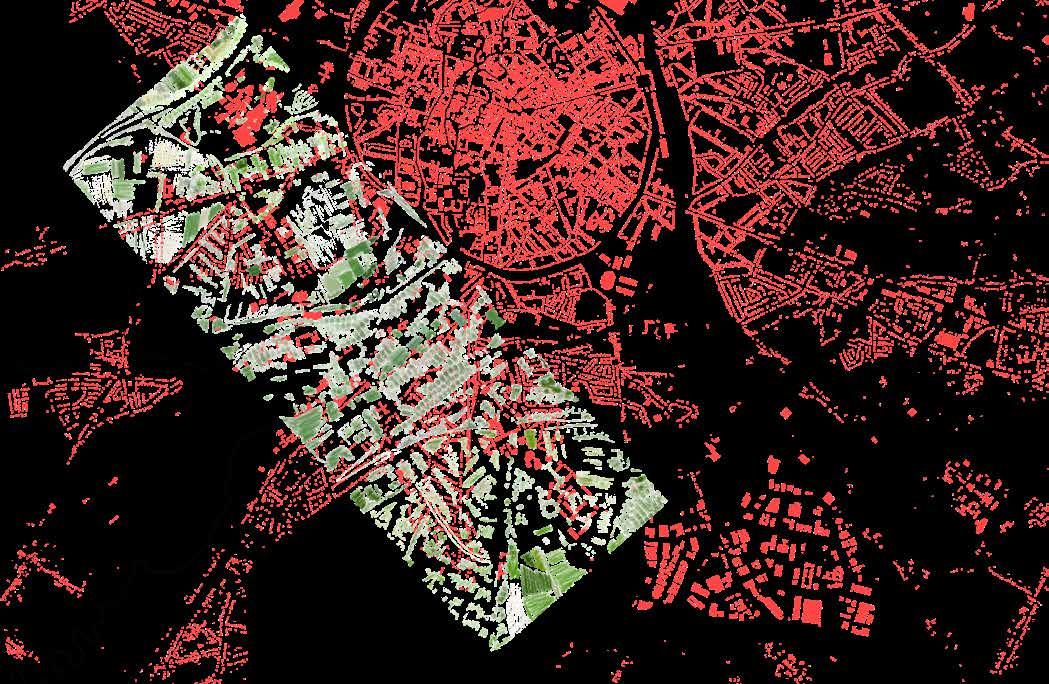

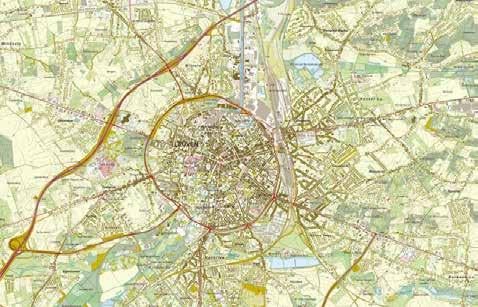

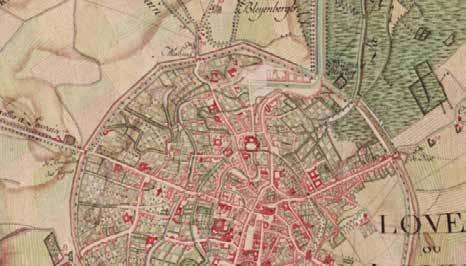

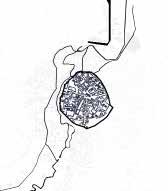

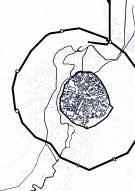

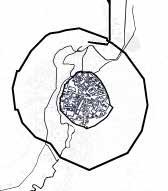

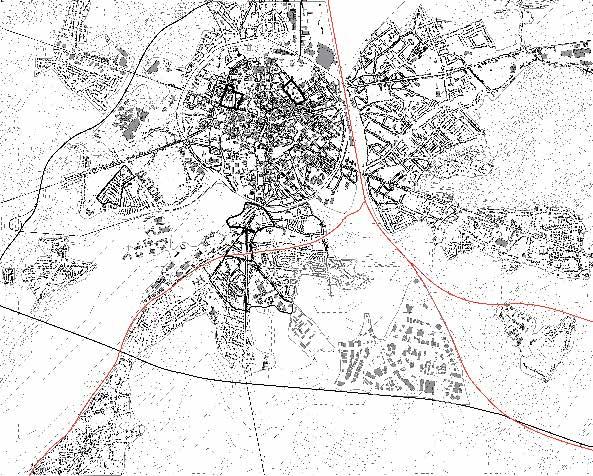

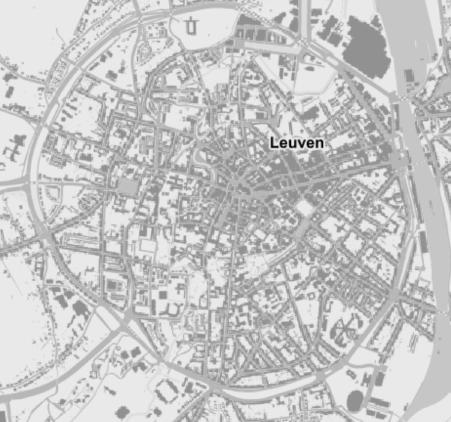

Radial city

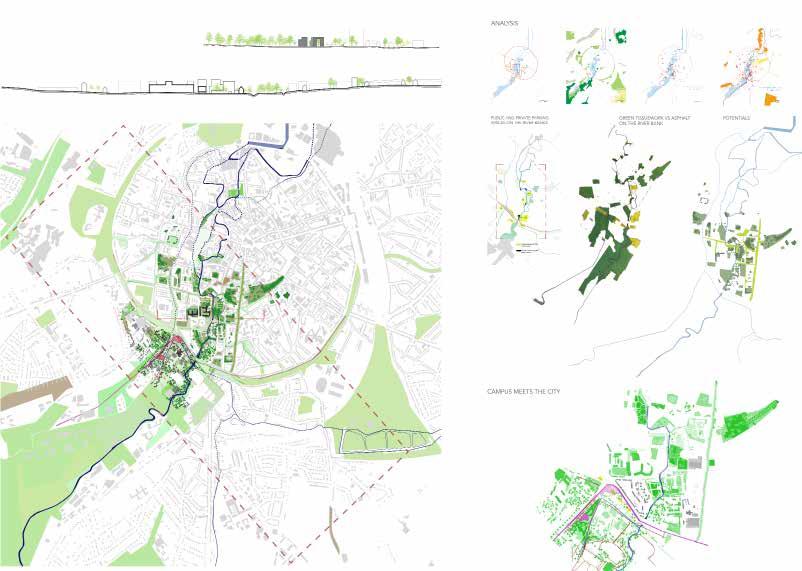

University Meets the City

Taki Tahmid Saurav

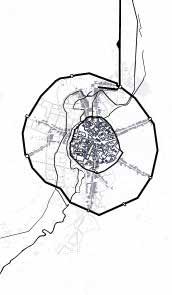

Throughout the morphological growth of Lueven city, radial expansion can be observed within the protective circle and beyond. After the circular protection wall demolision the inclusivity remained still creating a exclusive centrum for the city and the furthur expansions as puzzles plugged in to the centrum. Does rethinking the Leuven city without the strong barrier still replicate the radial expansion of the city’s tradition?

40

41

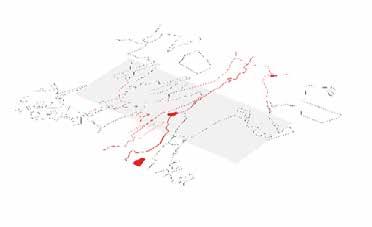

Patches and Edges

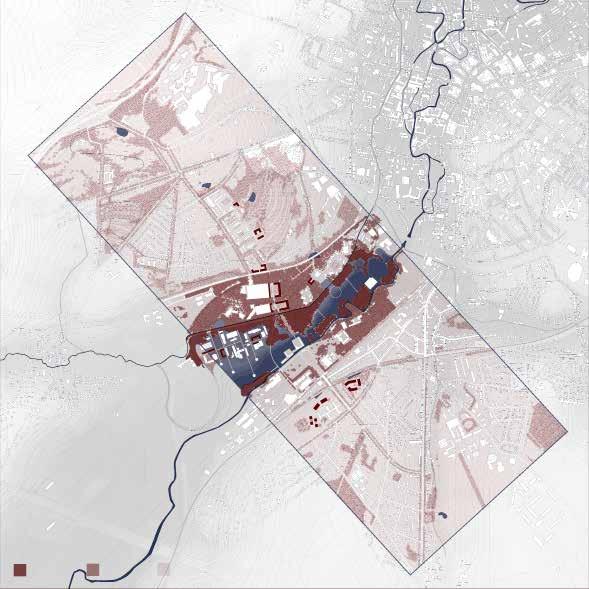

Dijle Valley meets Campus

Aliki Tzouvara

Contrasting and disconnected spaces are scattered as different urban patches in the area. Industrial, agricultural, educational, residential, forest spatialities co exist. The edges in-between vary, rarely in accordance to each function. How would the re-design of the boundaries help the connection and re-appropriation of public space and uses?

42

43

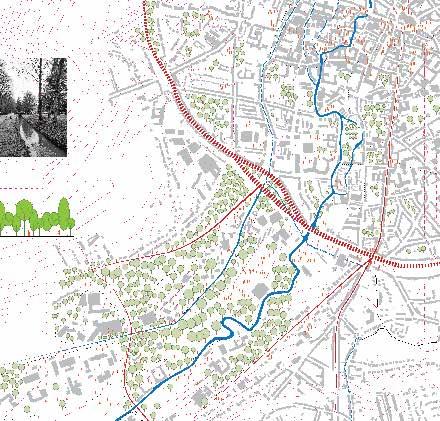

Reconnecting Landscape

University Meets the City

Zhongyan Zhang

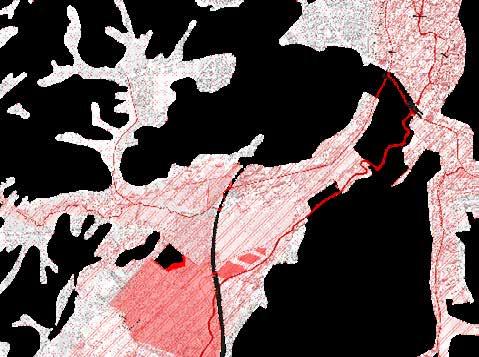

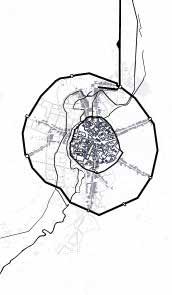

The map demonstrates that the landscape in the urbanised areas consists of three essential elements, the city ring as the primary infrastructure, the river with its tributaries as the dominance of the valley, and the scattered green space and buffer area. However, the city ring plays as a defensive barrier, while the green space is fragmented except for the greenery buffer along the fast road. More importantly, the rivers tend to be ‘invisible’ in both the city and the campus. The accessibility is influenced due to the development occupying the surface of the city and the loss of functions for the waterfront in the university. How can the invisibility of the water landscape be addressed, and therefore facilitate the integration of the city and the university?

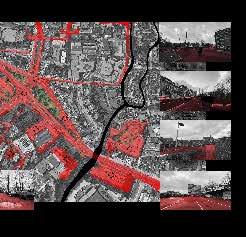

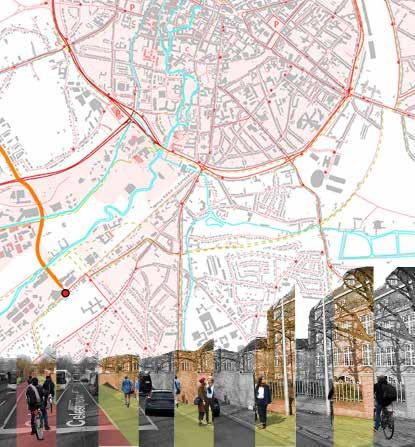

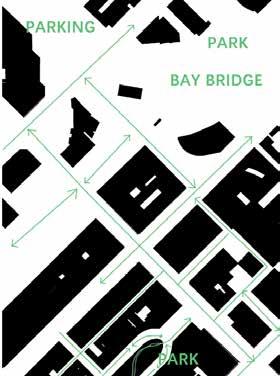

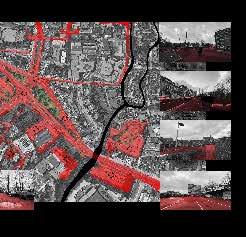

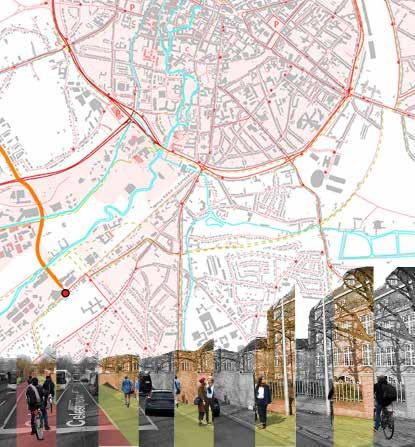

Jun(c)tion or Jun(k)tion?

Valley Meets City - Bodart

Samantha Arbotante

Samantha Arbotante

After the entire bike tour, I was drawn in interest at the two separations at the Bodart area. With the daily routine of entering and exiting the campus through this junction, the blinding lack of identity and character of the area is due to the massive gray infrastructure built in the middle. At its sides, “junk” spaces or areas with flat concrete and permanent boundaries are found dominating the gateways of the sites. How can we use these existing opportunities and recreate a new landscape image to welcome the students and residents?

46

47 1 3 4 5 6 6 7 7 8 8 9 9

Entrance paths of the campus

The ring complex

Rafaela Maria Armoutaki

How could more conndcting poles between the campus and the ring can be integrated to enhace accessibili

48

49

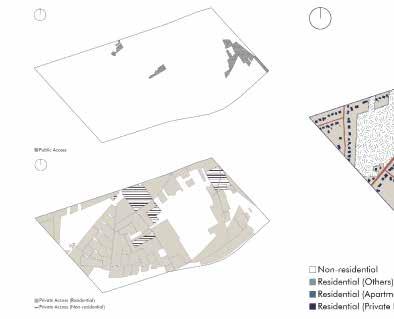

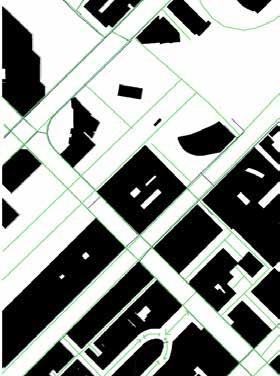

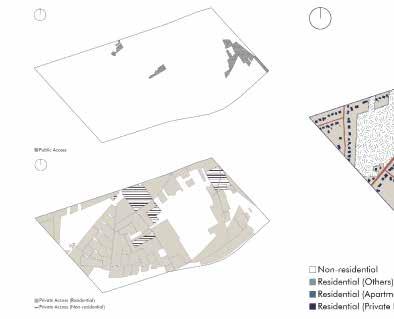

Built and Open space Private and collective spaces

BODART

Frank BAGENZI

MASS AND VOID or BUILT AND OPEN SPACE Analysis is an impor tant feature of the site due to the fact that the dense residential area are created based on the topography. The built environment near the water stream are not too dense comparing to the upper slope built envornment . Not only that but also the plot patterns and porosity reduces as you go away from water stream. How can spacial qualities of the built and non built environment/open spaces help to bridge the gap or connect the city and the university ?

campus Tissue

Elastic tissue campus Tissue

campus Tissue

50

51

Static Tissue-Residentialss

Suburbia Between the Castle and the Forest

Heverlee

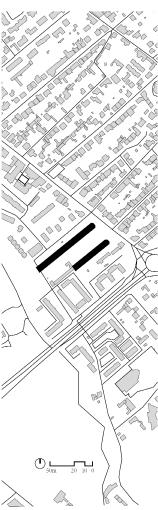

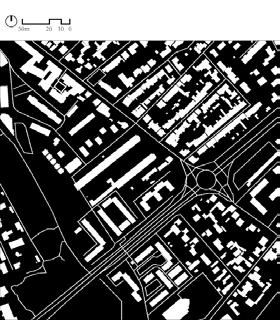

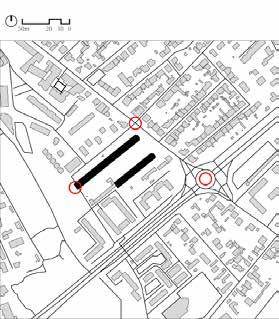

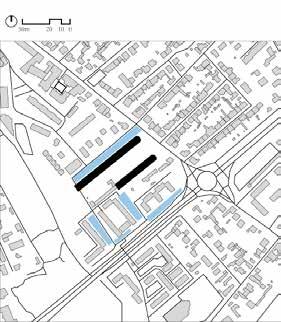

Fatma Ben Hfaiedh

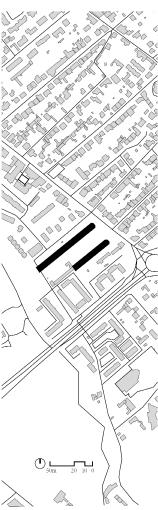

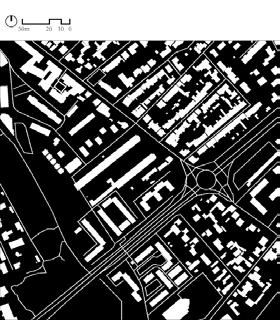

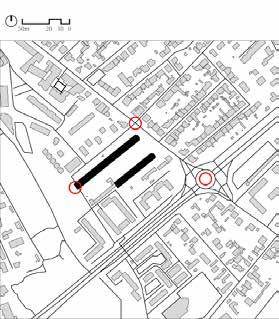

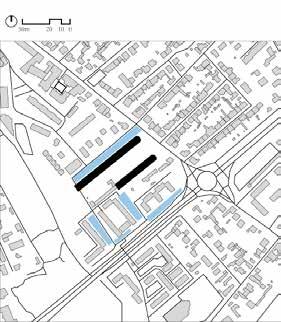

Rich urban fabrics, Hidden mobility, Social interaction, A suburbia within a suburbia. On the sides of the railway crossing Heverlee there is a rich mixity of urban fabric (Residential, Education, Religious, parks) that could be seen as a suburbia within a suburbia?

52

53

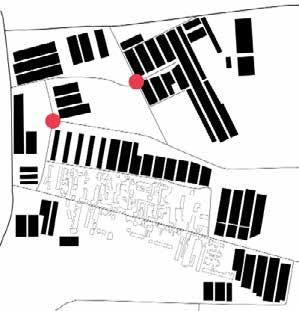

Inherited ENCLAVES

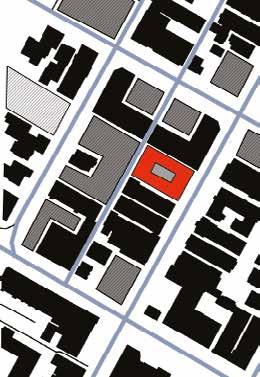

Site A - Lower Valley Strip

Ermias Tessema Beyene

Walls have been a prominent feature of Leuven since medieval times. Maps from the 16th century show that the city had two inner and outer walls. The traces are still noticeable; particularly the outer wall which is now replaced with a wall of ringroad.

Hence, the current Leuven and the University can be read as a system of en claves, territories defined by physical means of barrier, allowing a controlled access. The walls take different forms; fence walls, buildings serving as walls, water walls, hedge walls, highway walls, etc. The controlled access takes a form gate, bridge, and underpass.

Arenberg Castle, Graf Zjef Vanuytsel, Begijnhof, UCLL Groep Lerareno pleiding are currently delineated by brick fences which are remnants of Leu ven’s past. Buildings also create an enclave when they are closely spaced next to each other, which is also a typical character observed in central Leuven. A combination of water walls, highway walls, and brick walls demarcate and partition the Heverlee Campus while bridges, gates, and underpasses link the enclave with the surroundings and within.

54

55

The banks of the Dyle

Leuven

Jules Descampe

Since the beginning of Leuven, the hydrographic structure of the Dyle has influenced the urban fabric. The river and its tributaries cross the city and its different typologies. The nature of the watercourse evolves according to these layers to propose a wide spectrum of spatial relations with its surroundings. These relationships are reflected in the width of the watercourse, the buildings that border it, its accessibility, and the public or private facilities. Its penetrating landscape status places the watercourse as an opportunity for the fabrication of continuities or sequences throughout the city.

Therefore, can the direct relationship of the city to the water not be a means of creating new urban logics at the scale of the city?

56

Replace this box with your collage. The interpretative map is one integrated image.

57

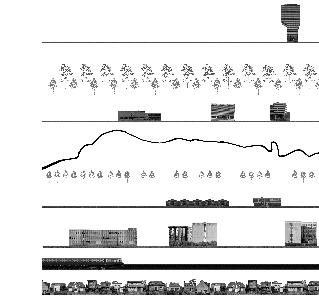

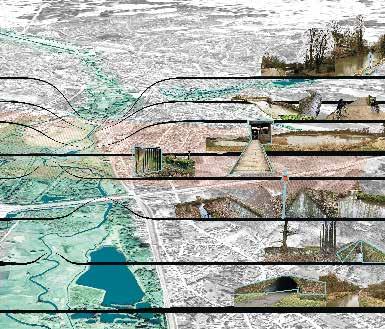

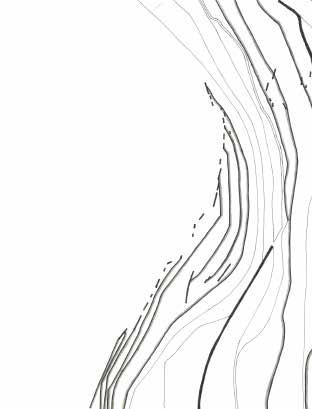

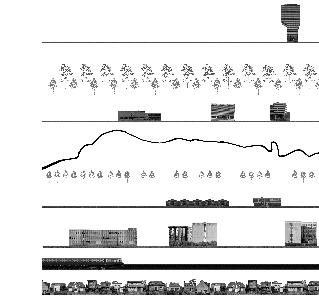

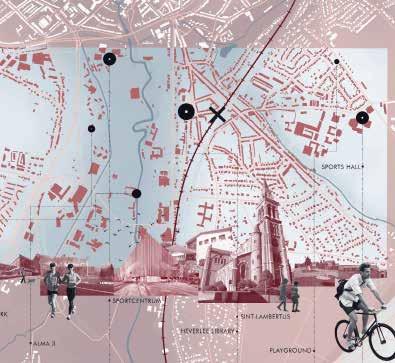

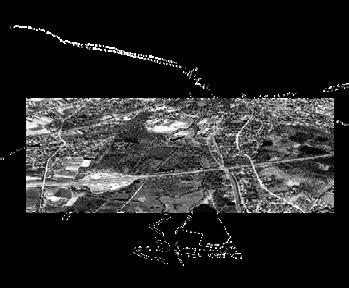

The Valley Unfolded

Valley meets Campus

Shannon De Wandeler

How does the valley unfold itself in relation to water, typography and the campus?

58

59

The line between landscape and urbanism

Selenge Dima

During the site visits there were times where the green fields could not eas ily be accessed and the hard lines between the landscape and the urbanism became apparent. Can blurring the line between landscape and urbanism

60

Valley meets Campus - middle valley strip

contribute to a valuable valley urbanism?

61

Layers of landscape

Heverlee

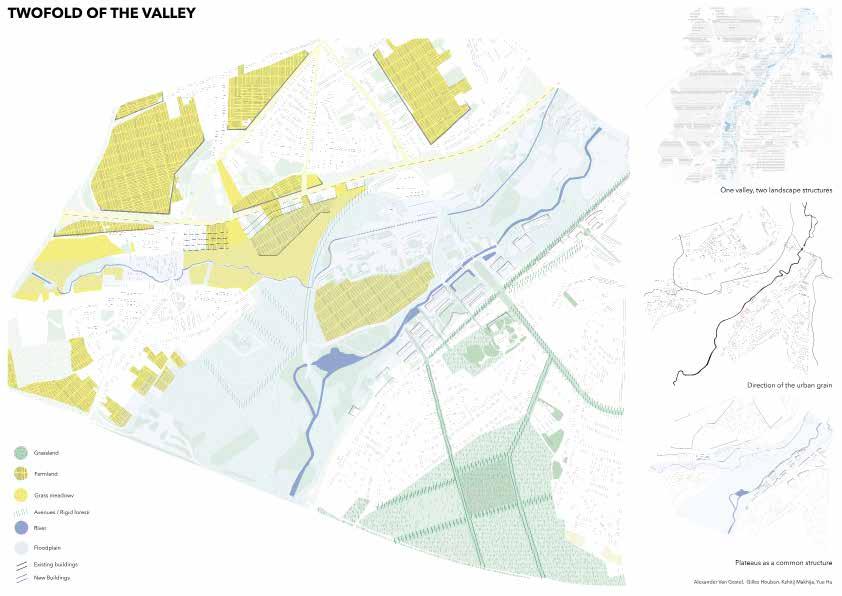

Gilles Houben

Arriving by train to Leuven alongside the Dijle valley, the topography allows us to see glimpses of landscape, framed by the tall facades of the campus Arenberg.

62

63

Zone function and landscape streamline

Yue Hu

Heverlee’s architectural and landscape functions are arranged in an orderly fashion, with roads and train tracks running through the landscape and Di jle Valley. There are scattered campuses and concentrated residential areas on the site, as well as embedded green space.

BUILDING

64

Heverlee OFFICE

BUILDING RESIDENCE ZONE CAMPUS

65

Border Conditions

Valley Meets Campus

Mazen Jubeihi

Valley Meets Campus

Mazen Jubeihi

66

How are the disparate edge conditions reflected in typological differences along the borders?

67

Green vs Grey

Valley meets fringe

Kshitij Makhija

How can more houses be built beside the roadway or railway to make it more usable?

68

69

Green tissue edges

Valley meets fringe

Alexander Van Gestel

The Dijle valley is surrounded by large green networks consisting of forests, agriculture… where a combination of these forms of greenery is noticeable within the valley itself, accompanied by the Dijle. When approaching the university complex of Heverlee and the city centre of Leuven, a fragmentation of these tissues appears across the whole territory, forming fragments or steppingstones of the larger green networks. But how can these various fragments create a new territorial coherence of various tissues and (re)tell a story generated by geography?

TREES AGRICULTURE

RIVER STREAM AND WATER BODIES VALLEY STRUCTURE

70

71

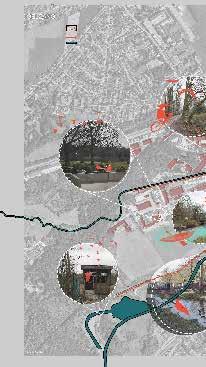

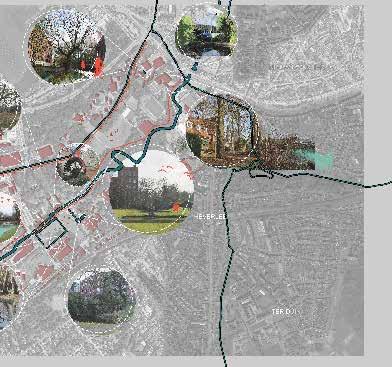

Accessibility

Dijle Valley, South Leuven

Arthur Van Lint

Arthur Van Lint

Where the Dijle flows into the city of Leuven from the south, the river is sur rounded by a series of diverse open spaces. These potentially valuable spaces are often tucked away and exclusively accessible to specific users and/or on a part-time basis, resulting in a landscape of fences and barriers. How can these open spaces around the Dijle be connected to each other, to the river and to the rest of the city to become stimulators for interaction between different users of the city?

72

1 2 3 4 5 6

73 7 8 9 10 11 12

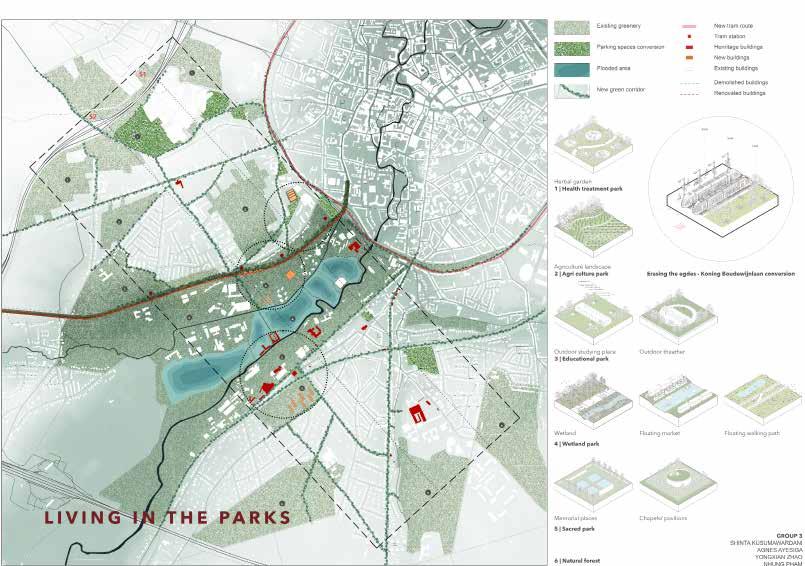

Defining housing qualities

Valley meets Campus- Middle valley strip

Agnes Ayesiga

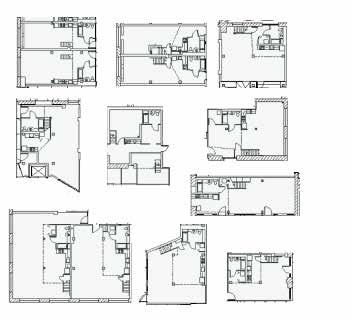

The Djile valley is home to a variety of housing typologies. what are the defining qualities of the different dwellings that exit here?And what can we borrow from the different urban hosuing qualities on the site to inform the design of a new urban vibrant environment.

74

75

Leuven Hidden Terminals

Valley meets City

Beshtawi

76

Basel

77

Levels Of Seperation

Valley meets Fringe - Higher Valley Strip

Majd El Achkar

As we trailed the site the previous days, we noticed the level of separation among areas. It was noticeable that the levels of separation increased at spe cific locations. There is man-made infrastructure such as train tracks and roads throughout the site. There is a disconnect between the characters in the neighborhood due to the natural infrastructure of canals and topogra phy. What can we do to reconnect the characters as a whole, and bring back those connections?

78

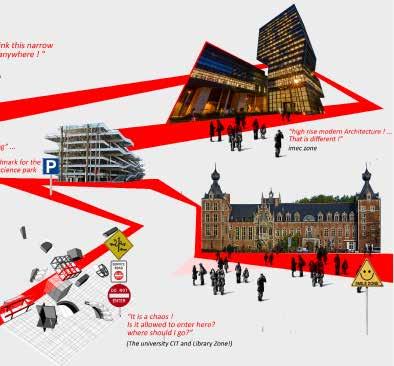

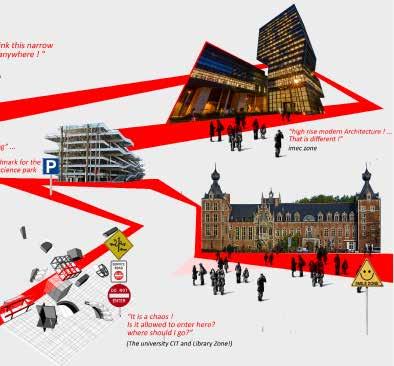

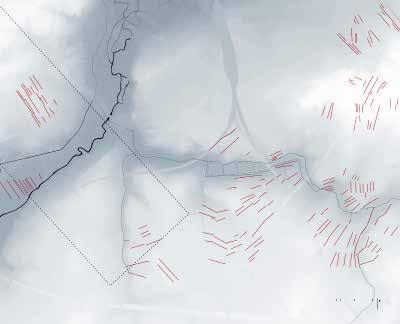

“Psychogeographical” Map

Valley meets Fringe- higher valley strip

Rula Elkhalili

The “ physchogeorgraphical” map is developed based on the emotions, the feelings and the impressions of the user while walking through the city. It rep resents how the city is perceived and what is the message the city is sending to its users. In the sense, the map is highlighting parts of the city that stands out in the memory and the experience of the user, representing how the user feel and read the city.

And from here a question arises: What are the tangible urban and natural elements or configurations that formulate the intangible feeling towards the city while moving through it?

80

81

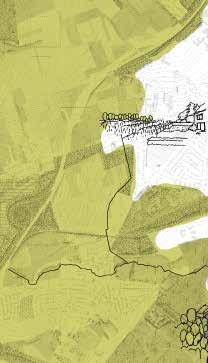

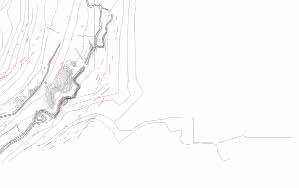

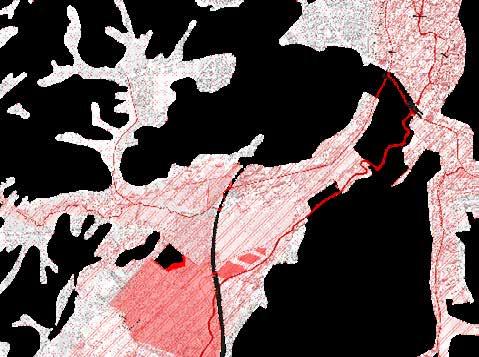

Inside vs. outside the valley

Upstream valley strip

Ellen De Wolf

Ellen De Wolf

The edges of the Dijle valley are represented in the landscape in multiple ways, avoiding different parts of the area to integrate or connect. When considering mobility in the whole strip, the edges of the valley are clearly tangible. It divides the area in the inside and outside of the Dijle valley. The inner part consists mainly of a network of soft mobility, connecting important functions such as the Arenberg campus and the forest. In contrast, the outside of the valley is a car-based area of urban sprawl. How can a rethinking of mobility throughout the strip result in a shift from the car-oriented urban fabric to an integrated and accessible landscape?

82

83

Amenities Re-visited

Valley meets Campus - Middle Valley Strip

Shinta Kusumawardani

Public amenities define the quality of an area’s social infrastructure. In the middle valley strip, a variety of amenities are interwoven within its fabric, either plainly exhibiting themselves with their gigantic structures such as the case of UZ Leuven hospital and public parking lots, or easily go unnoticed due to its lack of spatial quality and camouflaged access such as the case of the designated playgrounds and sports halls. How can these existing spaces be utilized to their maximum potentialities and help contribute to fostering a rich interaction between residents? How can both those said spaces and new spaces be created to make up for a lack of high-quality public amenities in the area?

84

85

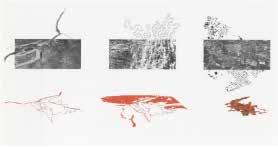

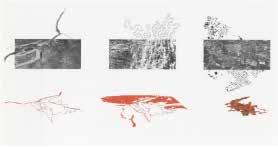

Broken nature

Valley meets campus

Nhung Pham

The landscape of the middle strip is fragmented by different reasons and factors - the roads, the buildings and human selfishness in landuse. This painted a bro ken picture of the nature in Djile Valley transition area - where there should’ve been a comprehensive biological mosaic of nature and non-nature. During the fieldtrip throughout the area, we can feel different atmospheres with sudden changes in landscape types and neighborhood areas, which demonstrated the isolation of city patches - agriculture land, the forest, the residential area, the university. The question is from this status, how to use landscape as the main element to reconnect these fragmented patches? How to reconnect city to university, local residents to students and staffs? In the broadest manner, how to reconnect nature to univercity life?

86

87

route 0 250 500

Fieldtrip biking

Urban Calendar

Valley meets city

Chloé Poisseroux

This map shows a clear difference of “calendar”, in the city centre, many facil-ities are still open after 9 pm. It creates a warm and safe atmosphere for pedes-trians to walk at night. However, once moving away from the city cen tre and entering the campus, open space after 9 pm gets really rare. This map shows also the student residences owned by KU Leuven, a majority is located on the campus resulting in major vacant housing during summertime and weekends.

Wouldn’t it be interesting to mix the functions in the campus part of Leuven with the city centre in order to keep an active environment at different moments of the day, the week and even the year?

88

89

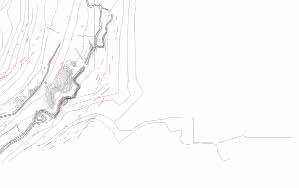

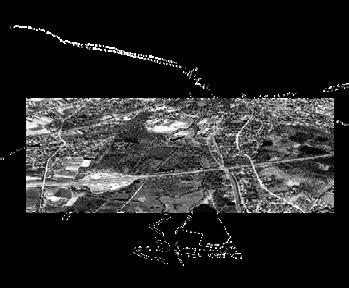

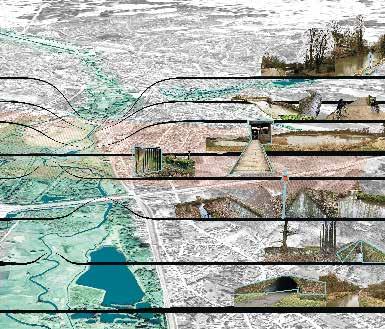

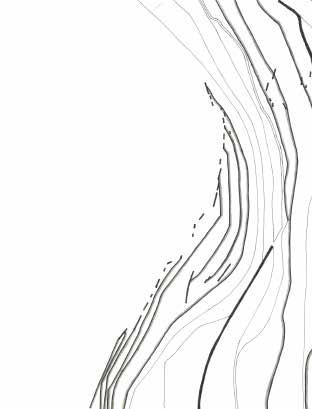

Water Landscape and Management

Valley meets Fringe — higher valley strip

Han Qin

The morphology of the Dijle river in the upstream area is more diverse and natural, and more vital as for the flooding control of Leuven. How to adjust, enrich and strengthen the functional value of the valley as both a comprehensivly strategic water management system also ecological natural landscape?

90

91

The ring - A bridge or a barrier

Redingenhof- Bodart

Lakshiminaraayanan Sudhakar

The hard infrastructure - the ring, divides the urban fabric of the city and the university campus dramatically, creating a disconnect from the nature and ecology. The movement of people and their activities is centralised to the city centre and this gives way for the static nature of the campus through many times of the year. How can an urban intervention help in creating a framework where the city and it’s people co-exist with the blue-green networks that also activates the social fabric of the campus throughout the year?

92

93

Elusive Connection

Redingenhof- Bodart

Michelle Valladares

The fragmentation between the valley and the city is enhanced by over scaled infrastructure. The Dyle river connects these two spaces, but the connection to the river itself is also filled with barriers, abandoned or undefined spaces. These connections can also be reinterpreted to inject some life into the sites in a more permanent way. How can the relation between nature and built be approached to reestructure the urban landscape while connecting and activating spaces permanently?

94

95

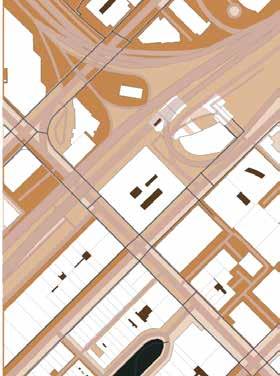

Connection and Transfer

Middle Valley Strip

The Celestijnenlaan has brought structural influence to the whole Arenburg campus, and the motor traffic covered by it has brought potential instability and insecurity. At the same time, it is an obstacle to the realization of the car free mobility. Whether it will be one of the feasible strategies to transfer the original motor traffic.

96

Yongxian Zhao

97

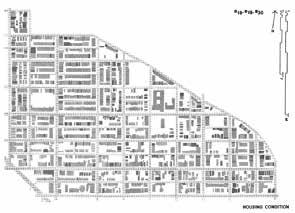

HOUSING ANALYSIS

99 03

© Gilles Houben

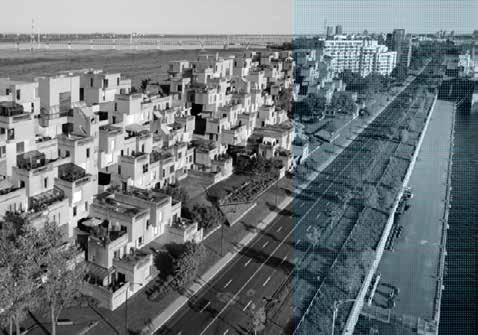

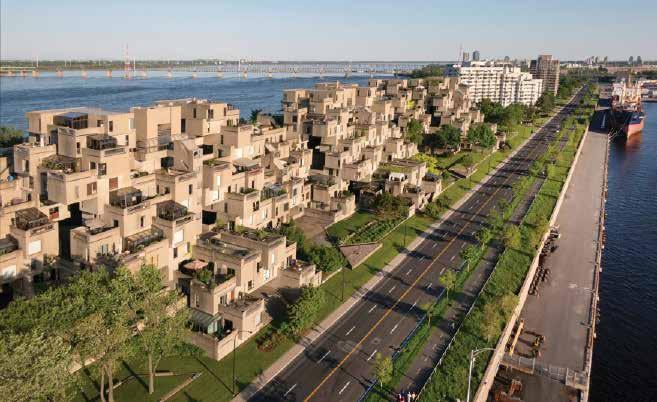

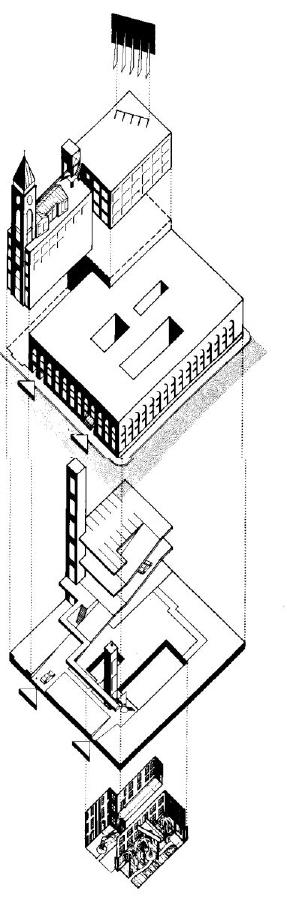

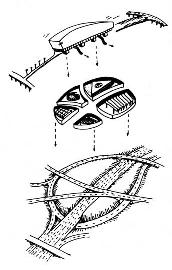

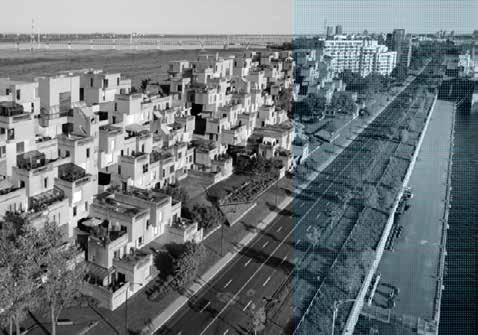

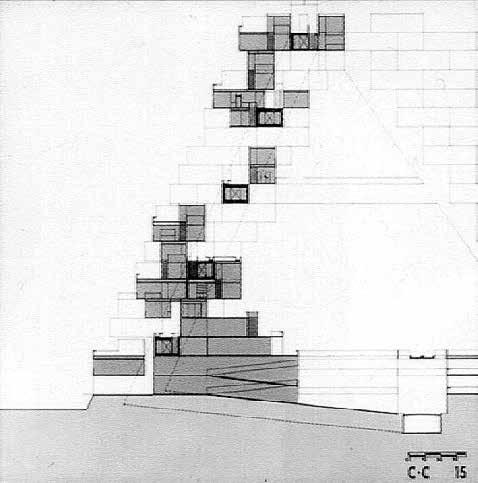

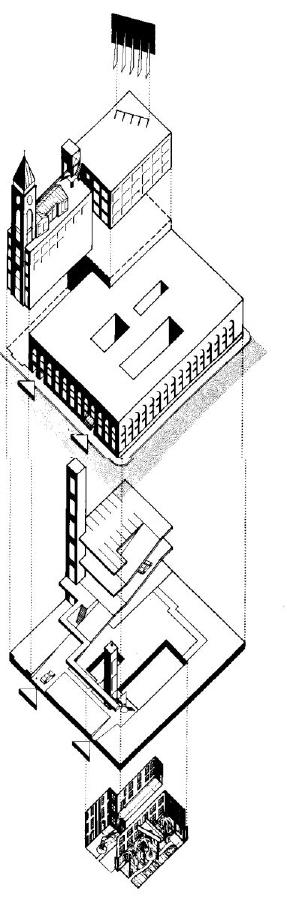

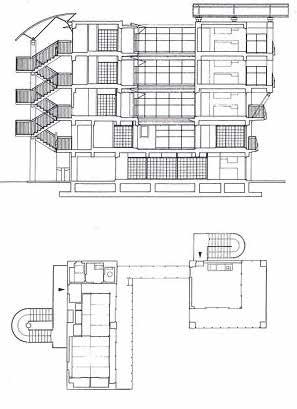

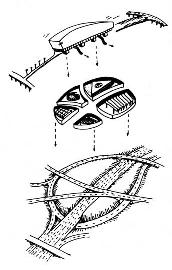

Habitat Expo ‘67

Moshe Safdie

SITE

DESCRIPTION

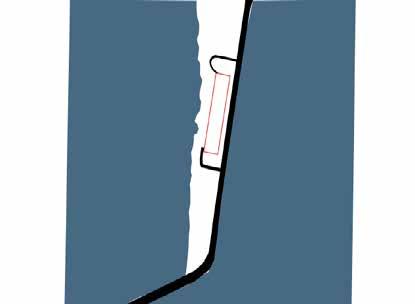

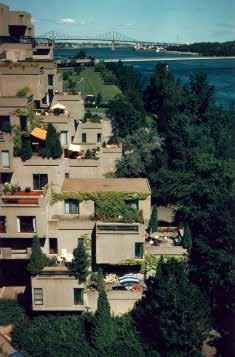

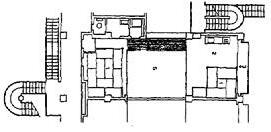

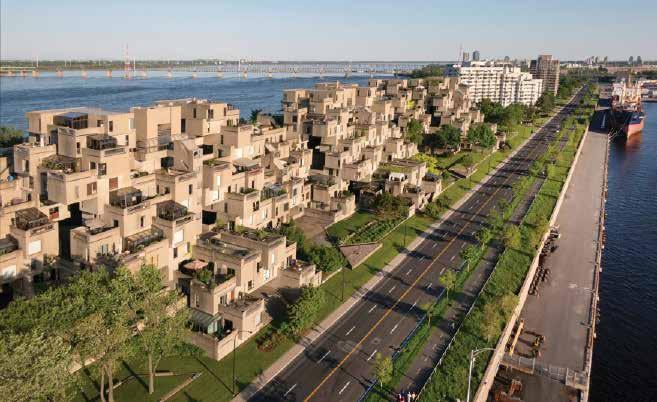

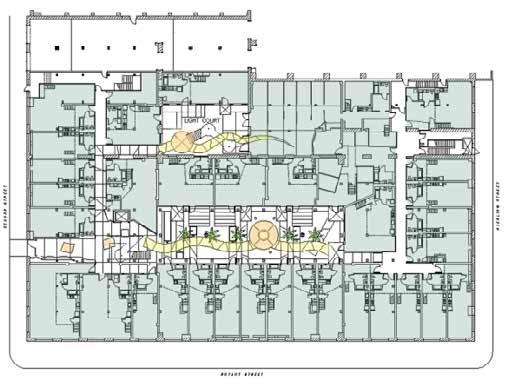

The site for this extraordinary experimental housing complex designed for the great Montreal Expo of 1967 was the Marc-Drouin Quay on the Saint Law rence River.15 in Montreal, Canada. The project is located at the end of the pier, furthest from the city by road but closest in terms of view allowing it to be a centre of display of urban density from the centre of old Montreal.

EVALUATION

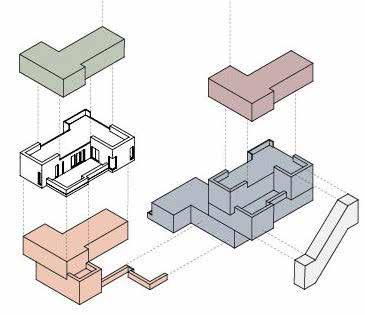

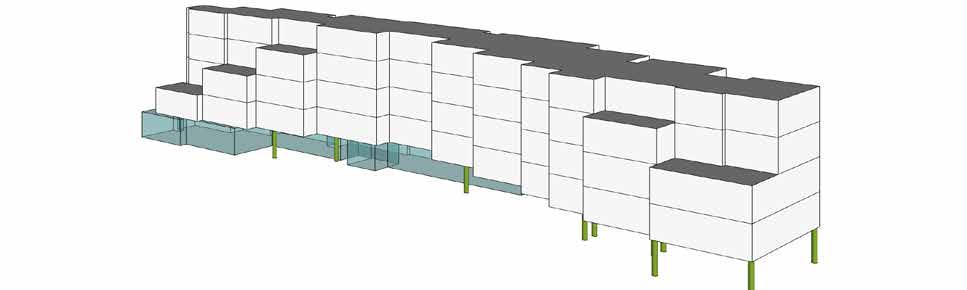

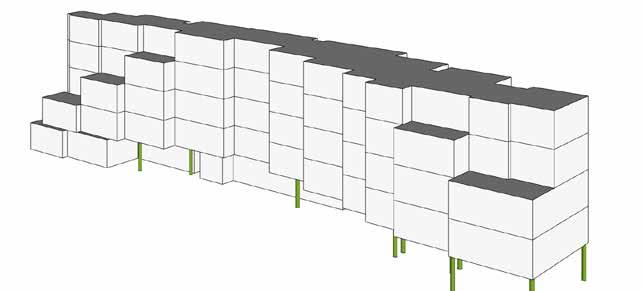

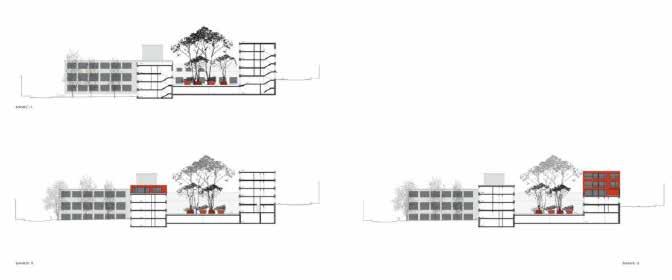

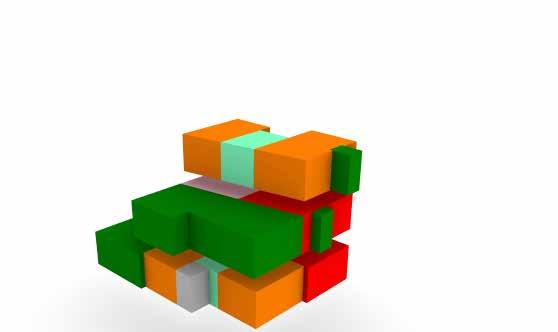

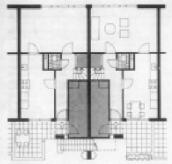

The experimental model is a radical hybrid of the suburban single-family home and the urban apartment building. 365 prefabricated concrete modules are stacked asymmetrically in dense geometric piles whose interlocking forms give rise to a wide variety of typologies. The different types and sizes of apartments range from 600 square foot one-bedroom units to 1,800 square foot four-bedroom units. The project is a demostration of how individuality can be achieved in dense developments

100

Montreal, Canada

Marc-Drouin Quay, Montreal

Satelite image. Source: Google Earth 2022

Satelite image. Source: Google Earth 2022 Habitat 67, Montreal. Source: Karrie Jacobs. Architect 2015. https://www. architectmagazine.com/awards/moshe-safdie-and-the-revival-of-habitat-67_o

CONCEPT

• High quality housing design in dense urban environments through explor ing a combination of surburban living and apartment building.

• Densification to reduce building unit cost. Rethinking apartment design.

• Prefabrication of modules to ensure economies of scale. New housing ty pology.

minimal building footprint on the pier due to densification

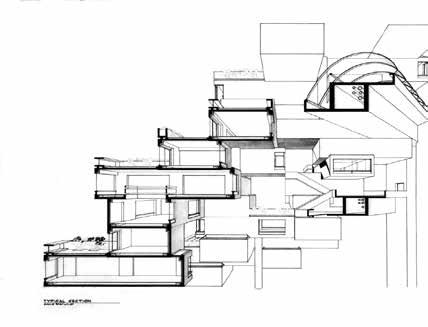

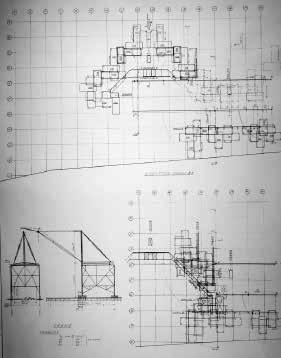

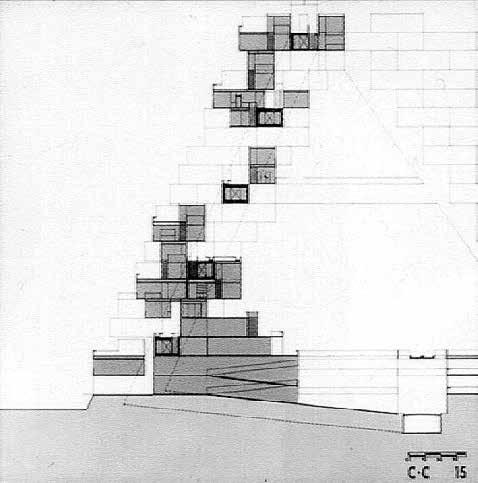

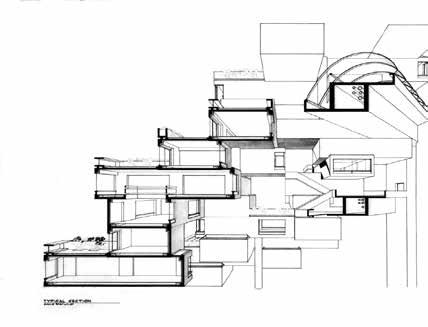

Section showing the irregular stacking of the modules. Source: Dezeen 2014. https://www.dezeen.com/2014/09/11/brutalist-buildings-habitat-67-montrealmoshe-safdie/

Facade of Projections, Habitat ‘67. Source: Archdaily 2018.

101

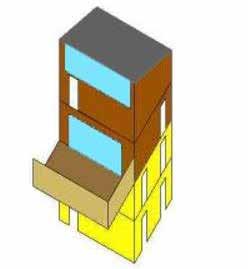

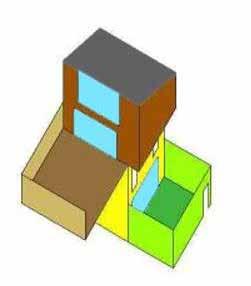

Morphology

Staggered modules

SPECIFIC: DENSIFICATION AND INDIVIDUALITY

102

Interlocking forms and a variety of typologies allows for individuality in a high density development. Source: Jesse Kaplan. Architect 2015. https://www.architectmagazine.com/awards/ moshe-safdie-and-the-revival-of-habitat-67_o

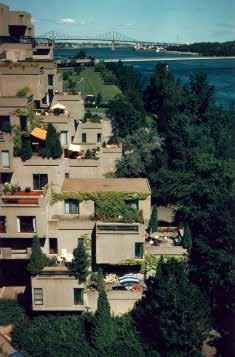

The irregular stacking of the forms ensures each dwelling enjoys natural lighting and views of the St Lawrence River and the City. Source: Loveyousomat. Tumbler 2015. https://loveyousomat.tumblr.com/post/21368893808

SPECIFIC: TYPOLOGY

103

The basic modules are combined are rotated in order to create unique extterior conditions

Massing of various typologies

BUILDING

DESCRIPTION

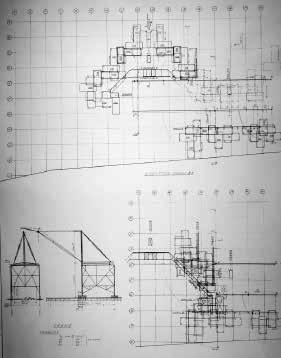

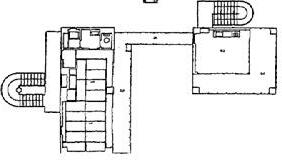

The building constructed with precast concrete boxes each measuring 11.8m long, 5.3m wide and 3m high has three central double cores and four further lift cores. The array of blocks are stacked agaisnt these cores creating a series of courtyards. The blocks themselves are also partially load bearing. This inno vation in structural system and prefabrication of the modules was in response to the focus of the 1967 Montreal Expo which was a testing grounds for new building technologies.

EVALUATION

Canada is a surburban nation with an abundance of cheap lands. Planning policies in the country are also not restrictive on urban sprawl, thus 67% of its population live in sururban areas. Moshe Safdie’s project therefore does not address suburban drift in canada. However the project explores how apart ment buildings can operate in a suburban setting whilst having high densities. The project creates a benchmark for luxury-high rises

104

Roof garden terraces of Habitat 67. Source: Sam Tata. Dezeen 2014

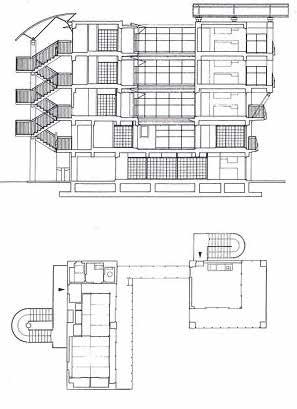

Floor Plans and sections of Habitat ‘67. Source: Archdaily 2018.

SPECIFIC: TYPOLOGY

Building Typology

Section. Source: Dezeen 2014. buildings-habitat-67-montreal-moshe-safdie/https://www.dezeen.com/2014/09/11/brutalist-

Section showing various typologies. Source: Loveyousomat. Tumblr 2015. https:// loveyousomat.tumblr.com/post/21368893808

105

DWELLING

DESCRIPTION

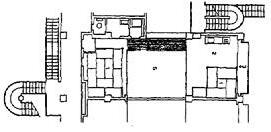

The prefabricated modules originally created 158 dwelling units with 14 different apartment configuarations. The residences range from 600 square feet(one bedroom) to 180 square feet (four bedroom). Three elevator cores, stopping at each fourth floor gives residents access to the footpath which link the dwellings.

EVALUATION

The Architects successfuly achieves individuality for each unit despite the high density of the building through a complex variation of geometry. This allows tenants benefits of suburban housing; light, privacy and views of the St Law rence River and the City.

106

Floor plans of one bedroom unit

Interior View of Habitat ‘67. Source: James Britain. The Architectural Reveiw 2018. https://www.architectural-review.com/buildings/revisit-habitat-67-montreal-canada-bymoshe-safdie

Floor plans of two bedroom unit

Floor plans of three bedroom unit

Floor plans of four bedroom unit (Drawn by Author)

Section

SPECIFIC: TYPOLOGY

Unit typologies. Source: Brianna Ssviano. Wordpress 2014. https://modulatingruin.wordpress.com/2014/06/16/593/

Habitat ‘67; A balance of cold geometry against living, breathing nature. Source: The Guardian 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/ cities/2015/may/13/habitat-67-montreal-expo-moshe-safdie-history-cities-50-buildings-day-35

107

The SIX disabled veteran housing

Brooks +Scarpa

Yasmine Baamal

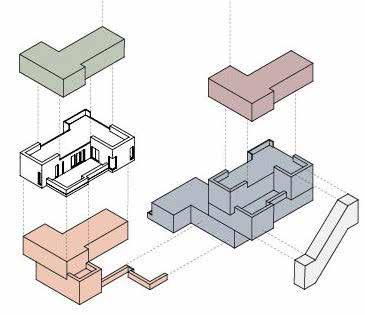

DESCRIPTION

The neighborhood of MacArthur Park is one of the highest density neigh borhoods not only in Los Angeles, but also in the US. The project responds to one of the most important challenges that is facing the city : to provide a home and a shelter for homeless veterans. The project integrates 52 affordable units dedicated to homeless people, in which public and public spaces interact together to create a sense of community, bridging between the street and the housing units.

EVALUATION

The project disrupts the classic distinction between private and public spac es. Indeed, the transition from the neighborhood scale to the studios scale is progressive and blurry, with no strict separation, and a continuous visual connection.

108

Los Angeles, California, USA

Location: Central © Wujcik, Tara. “The Six project main façade, Los Angeles”. [Digital image]. www.brooksscarpa.com. Accessed February 19, 2022. https://brooksscar pa.com/the-six

SITE ©

Google Earth Pro

7.3.4. (14/12/2015). Location

of The Six project.

© Google Earth Pro 7.3.4. (14/12/2015). Location of The Six project.

CONCEPT

• Providing shelter to homeless people within the city.

• Exploring the interrelation between public and private spaces.

• Solving a social problem through an architectural project that empowers individuals

• Promoting a community-oriented way of living

© Brooks+Scarpa. “Concept sketch”. [Digital image]. www.brooksscarpa. com. Accessed February 19, 2022. https://brooksscarpa.com/the-six

The facade becomes a space, connecting the street to the units.

© Wujcik, Tara. “Project integration”. [Digital image]. www.brookss carpa.com. Accessed February 19, 2022. https://brooksscarpa.com/ the-six

© Adapted from Brooks+Scarpa. “Project implementation”. [Digital image]. www.brooksscarpa.com. Accessed February 19, 2022. https://brooksscarpa. com/the-six

109

SPECIFIC: COURTYARD + OPENINGS

Reyes, Alejandro. Moy, Martin. “Section”. In: Arch 202 XL Sharing. “THE SIX, BROOKS + SCARPA | ALEJANDRO & MARTIN” February 8, 2021. video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K9iDkrhWMJA

110

The courtyard structuring the inner circulation.

The project Built form Parking lots Vacant space

Section showing the central courtyard

New typology in the urban fabric

© Wujcik, Tara. “The courtyard”. [Digital image]. www.brooksscarpa.com. Ac cessed February 19, 2022. https://brooksscarpa.com/the-six

© Baamal, Yasmine. “”. [Map]. February 19, 2022.

SPECIFIC: PASSIVE DESIGN STRATEGIES

Passive design strategies

© Brooks+Scarpa. “Project implementation”. [Digital image]. www.brooksscarpa.com. Accessed February 19, 2022. https://brooksscarpa.com/the-six

111

BUILDING

DESCRIPTION

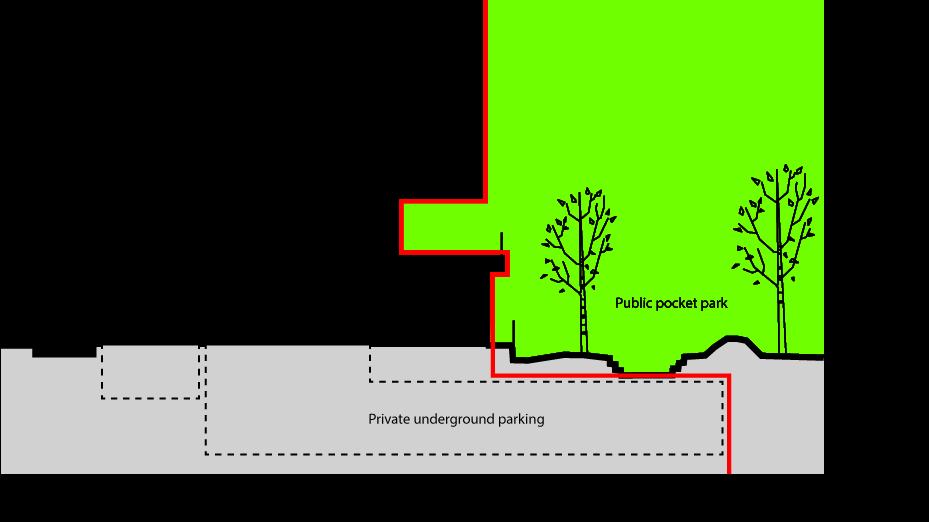

The volume of the building is pierced with big openings in order to maximize natural ventilation and daylight while creating large public areas. The parking space for cars and bikes is on the ground floor, half embedded in the ground, allowing the optimization of space within a dense urban fabric. The inner cir culation is organized around the courtyard in order to serve the private units, while keeping connection with public areas.

EVALUATION

The implementation of the courtyard allows a fluid circulation while illus trating the community-driven aspect of the design. The mixity of functions within the building, including the community space and the support facilities, gives space for the inhabitants to engage with each other and create a sense of community.

Brooks+Scarpa. “Project implementation”. [Digital image]. www.brooksscarpa.com. Accessed February 19, 2022. https://brooksscarpa.com/the-six

112

©

SPECIFIC: TYPOLOGY

Reyes, Alejandro. Moy, Martin. “Analysis”. In: Arch 202 XL Sharing. “THE SIX, BROOKS + SCARPA | ALEJANDRO & MARTIN” February 8, 2021. video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K9iDkrhWMJA

113

Inner circulation Private/public entanglement

DESCRIPTION

The access to the dwelling units is organized by the central courtyard, ensuring a qualitative air flow circulation, and a continuous visual connection inside the building. The Six project is composed mostly of studios, which are equipped with essential furniture and individual bathrooms, providing good housing quality for an affordable cost. Each floor has one appartement besides the studios.

EVALUATION

In addition to giving a material shelter to a vulnerable population, the project provides a symbolic shelter, a place to call home. The circulation around the semi-public areas, connected to the community space ensures a favorable en vironment for the engagement of dwellers.

DWELLING Private units

Circulation

© Wujcik, Tara. “The courtyard”. [Digital image]. www.brookss carpa.com. Accessed February 19, 2022. https://brooksscar pa.com/the-six

© Adapted from Brooks+Scarpa. “Third floor (Right) and fifth floor (left) plans”. [Digital image]. www.brookss carpa.com. Accessed February 19, 2022. https://brooksscarpa.com/the-six

114

SPECIFIC: TYPOLOGY

© Wujcik, Tara. “Private units cconnected to the courtyard”. [Digital image]. www. brooksscarpa.com. Accessed February 19, 2022. https://brooksscarpa.com/the-six

© Wujcik, Tara. “Public area inside the building”. [Digital image]. www.brooksscar pa.com. Accessed February 19, 2022. https://brooksscarpa.com/the-six

Accessed

© Wujcik, Tara. “Community space”. [Digital im age].

Febru ary 19, 2022. https://brooksscarpa.com/the-six

www.brooksscarpa.com.

© Adapted from Brooks+Scarpa. “Second floor plan”. [Digital image]. www.brooksscarpa.com. Accessed February 19, 2022. https://brooksscarpa.com/the-six

115

Private units Circulation Community space

Donnybrook Quarter

Peter Barber

Peiyang Huo

Peter Barber

Peiyang Huo

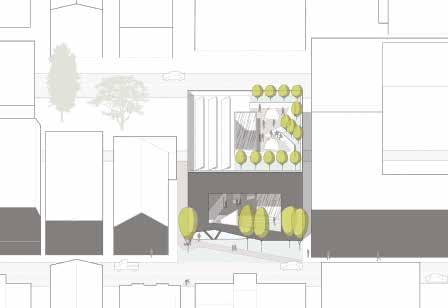

DESCRIPTION

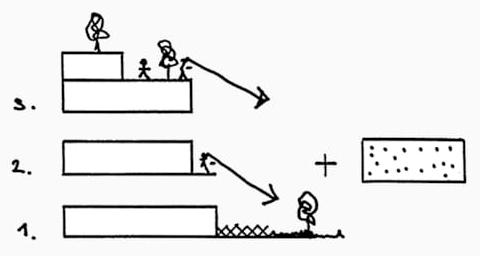

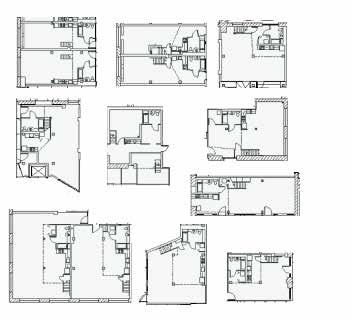

The project is a high-density mixed housing project located on a street corner in a poor neighborhood. The designers intervened in the urban tissue by re arranging the row houses to form new streets and squares. At the heart of the project is the reactivation of street life by removing the semi-open space at the door of the house

EVALUATION

The project brings new vitality to street life and rethinks the relationship be tween urban life and the building environment, revolutionizing the principle of housing design. After the project is completed, there are more people can be accommodated than the previous high-rise nursing home.

116

London, UK

Donnybrook Quarter, Bow (© Source: Google Map)

Donnybrook Quarter, Bow (© Source: architizer, accessed on Feb. 20. 2022, https://architizer-prod. imgix.net/mediadata/projects/482010/0572ad4f.jpg )

Location: close to the center

SITE

Victoria Park

Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park

CONCEPT

• Remodelling the street layout, increasing public space;

• Strong visual relationship between street and building

• back of pavement terrace (no semi-public space)

• sense of community

• Irregular white facade and simple decoration (Le Corbusier)

• Emphasize spatial perception over architectural structure (Adolf Loos)

0m

15m 0m

section

section

(© Source: architizer, section, accessed on Feb.02.2022, https://architizer.com/projects/donny brook-quarter/)

draw by author (© Source: Digimap) draw by author (© Source: Digimap) block model (© Source : architizer, accessed on Feb. 20. 2022, https://architizer-prod.imgix.net/ mediadata/projects/482010/add5abc0.jpg)

117

5m 10m

25m now

• Raumplan (Adolf Loos) figure

1990s

ground plan

SPECIFIC: REINVIGORATING STREET LIFE

terraced houses where the front door opens right onto the street (draw by author )

flow (draw by author )

Create a sense of community (© Source: Peter Barber Architects, accessed on Feb.02.2022., http://www. peterbarberarchitects.com/donnybrook-quarter)

118

25m 0m 25m

0m

commercial space private space

building semi-public space

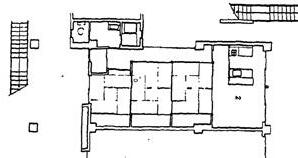

BUILDING

DESCRIPTION

The row houses are arranged to form three built-up fields framing two polygonal street zones that expand into a square. The entrance of the house is directly connected to the street, replacing the semi-public space at the entrance of the terrace house. The residents of the upper floor enter the first floor from the stairs facing the street. The facade of the building adopts a white minimalist style, which contrasts with the traditional British terrace house. Bay windows, small balconies, and oriels offer good views of the public space. The building adapts to this corner plot by changing its shape.

EVALUATION

The removal of semi-public spaces increases private space, enhances the dy namism of the street and strengthens the street as the main engine of social and economic development. The strong visual conflict makes the street more active. The T-shaped layout redesigns the urban tissue and creates more public space. Compared to high-rise apartments, complex house arrangements allow more space to be used for living.space. Compared to high-rise apartments, complex house arrangements allow more space to be used for living.

119

(white facade, © Source: Peter Barber Architects, accessed on Feb.02.2022., http:// www.peterbarberarchitects.com/donnybrook-quarter)

interaction between street and house (source: Ibid.) new community road (source: Ibid.)

THE FIVE POINTS OF ARCHITECTURE

© Source: https://www.archdaily.com/84524/ ad-classics-villa-savoye-le-corbusier

© Source: http://www.peterbarberarchitects. com/donnybrook-quarter

120

Flat roof terrace Open plan Ribbon windows Free facade

Villa Savoye by Le Corbusier Donnybrook quarter by Peter Barber

Pilotis

SPECIFIC: INFLUENCER

SPECIFIC: TYPOLOGY

121

(draw by author )

DWELLING

DESCRIPTION

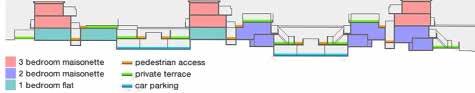

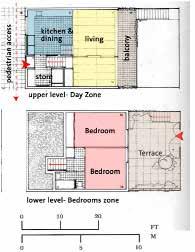

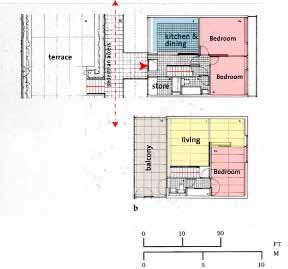

The project emphasizes inclusivity, with 25% as social housing. The double unit in Donnybrook comprises a two-bedroomed masionette at upper ground and first floor and a two-bedroom flat at lower ground floor. The configuration as a ‘notched’ terrace maintains good levels of privacy and amenity to every dwelling

EVALUATION

Each unit has increased living space and enjoys the private space. Space is continuous and interconnected, embodying the Raumplan of Adolf Loos. Different window sizes create different atmospheres, large windows enhance daylight, other small windows ensure “eyes on street” and also make the street view more friendly.

indoor view (© Source: architizer, accessed on Feb.02.2022, https://ar chitizer.com/projects/donnybrook-quarter/)

indoor function ( © Source: architizer, accessed on Feb.02.2022, https:// architizer.com/projects/donnybrook-quarter/)

122

SPECIFIC: RAUMPLAN

“My architecture is not conceived in plans, but in spaces (cubes). I do not design floor plans, facades, sections. I design spaces. For me, there is no ground floor, first floor etc…” by Adolf Loos

123

(draw by author )

balcony bedroom bathroom View

Family space private space Living space storage Kithch living room

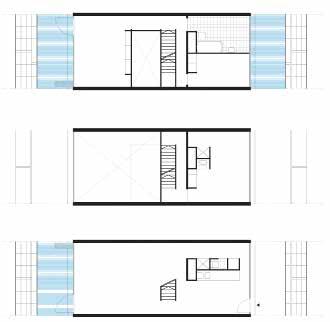

Haarlemmer Houttuinen

Herman Hertzberger

Edwin Kabugi Karanja

DESCRIPTION

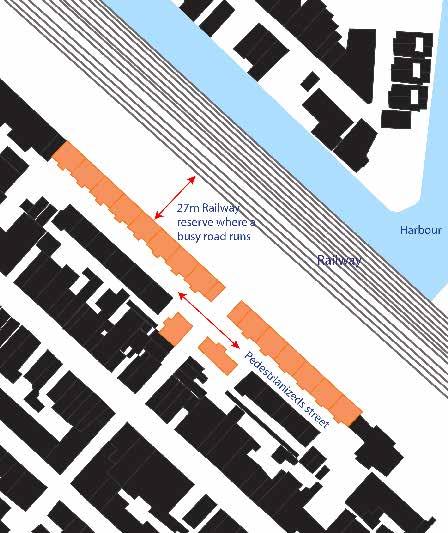

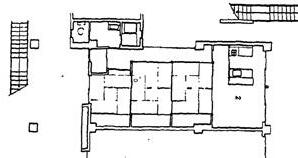

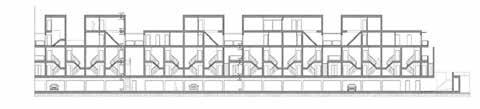

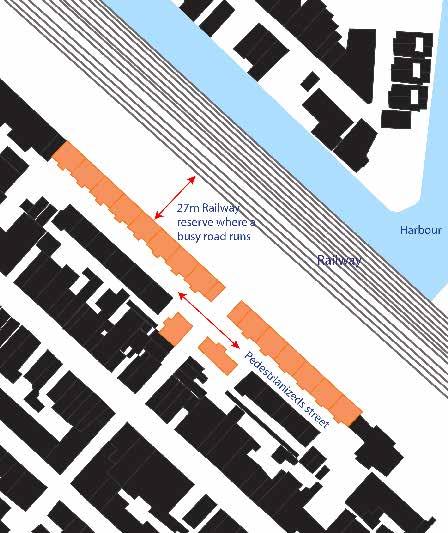

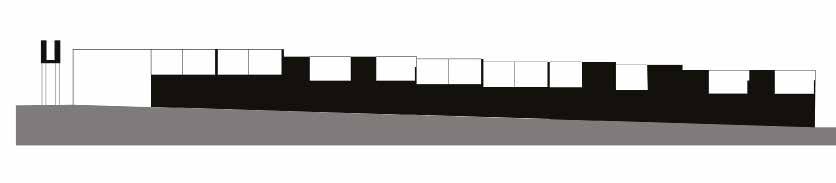

The Haarlemmer Houttuiner Housing project, designed and implemented in 1978 - 1987, lies almost at the centre of Amsterdam city’s urban fabric in the Netherlands. It is an urban renewal project that provides housing for 75 households (homes). Owing to its location along a major transporta tion corridor with a busy road and a railway, the project is linearly designed to utilize the least space possible without encroaching the reserves of this transport corridor. The project also aimed at achieving a street with mini mum vehicular interference and maximum pedestrian freedom.

EVALUATION

Provision of housing and requalification of street use as a new form of pub lic realm was successful in turning the project site a lively community area, despite the compactness of the space within which it is located.

Removal of conflicts between vehicles and pedestrians through separation has created a new profile of public, semi public and private space in the area.

124

Amsterdam, Netherlands

Nieuwe Houttuinen, Amsterdam

Google

2022 Google Earth, 2022

Location: Central SITE Google Earth, 2022

Earth,

• Providing housing while reserving a 27m railway reserve. For this, hous es are built to provide shelter from the busy road and railway behind it. The back side of the buildings act as a rear wall. • Change of residential street use from being thoroughfares and reinstat ing them to a streets as places/spaces where local residents can meet without interferance of vehicular traffic.

125

CONCEPT

inclusive and

strengthening

Side: Acts as a rear wall of the houses. Wager, Hans. 2013. “Nieuwe Houttuinen, Amsterdam –Architekten buro Hans Wagner.” 2013. https://hanswagner.nl/prt/nieuwe-houttuin en-amsterdam/. Accessed 20th Feb 2022 Wager, Hans. 2013. “Nieuwe Houttuinen, Amsterdam –Architekten buro Hans Wagner.” 2013. https://hanswagner.nl/prt/nieuwe-houttuin en-amsterdam/. Accessed 20th Feb 2022 Van Der Vlugt, Ger. 2019. “Haarlemmer

Housing.” 2019. EUMiesAward (miesarch.com). Accessed

Feb 2022

Side: Has all the entrances and the balconies to the houses.

Southern block on the left, requalified street

the middle and Nothern block on the Right.

• The urban infill with an

accumulative

efect. Back

Houttuinen

20th

Front

Section:

in

Source: Author

SPECIFIC: OPEN SPACE STRUCTURE

126

Inversed Figure Ground

Gradient: Public (light) - Private (dark)

Porosity

Source: Author

Source: Author

Source: Author

127

SPECIFIC: CIRCULATION SCHEME

Vehicle Traffic Pedestrian Traffic Points of Superposition

The pedestrianized street only allows for delivery vehicles and car parking lots for local residents.

Source: Author

Source: Author Source: Author

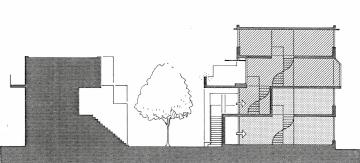

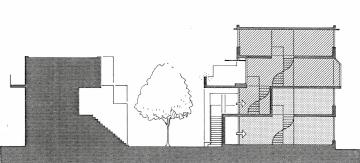

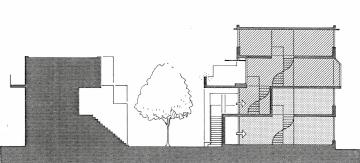

BUILDING

DESCRIPTION

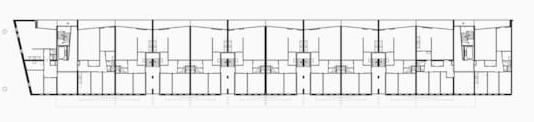

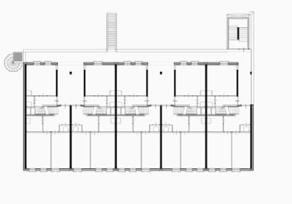

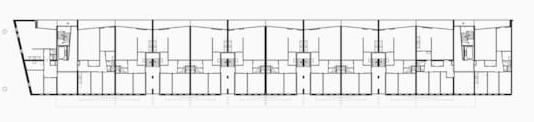

The housing is organized in two blocks adjacent to one another but run ning linearly along the transport corridor. Architect Herman Hertzberg er designed the northern block while Architects Van Herk & Nagelkerke designed the southern block later. They are differentiated in height by one floor. Between them is a 7m street dedicated to pedestrians. The front of the northern block (4 storeys) is characterized with big windows and pro truding piers each of which is an entrance to four maisonnetes at grade and holds the balconies of the upper units.

EVALUATION

While the protruding piers give a systemic rythm to the pedestrianized steet, the street is a lively community area as it no longer acts as a thorough fare. This separation of traffic (street is closed to general motorized traffic) has turned the street to a semi-public space only accessed by local residents of the buildings. This is evident in the way children use it to play when they are out of their houses while their parents could also sit or stand outside in the beautiful balconies to watch them or even to enjoy the space.

Adapted and modified fromVan Der Vlugt, Ger. 2019. “Haar lemmer Houttuinen Housing.” 2019. EUMiesAward (miesarch. com). Accessed 20th Feb 2022

Wager, Hans. 2013. “Nieuwe Houttuinen, Amsterdam –Architekten buro Hans Wagner.” 2013. https://hanswagner.nl/prt/nieuwe-houttuin en-amsterdam/. Accessed 20th Feb 2022

Wager, Hans. 2013. “Nieuwe Houttuinen, Amsterdam –Architekten buro Hans Wagner.” 2013. https://hanswagner.nl/prt/nieuwe-houttuin en-amsterdam/. Accessed 20th Feb 2022

128

Southern block is one storey lower to allow sushine to the street

South block

Protruding Piers

External stairs with a front garden

Entry through stairs to higher floors with shared landing areas.

North block

SPECIFIC: TYPOLOGY

129

Building Typology

Source: Author Source: Author Source: Author

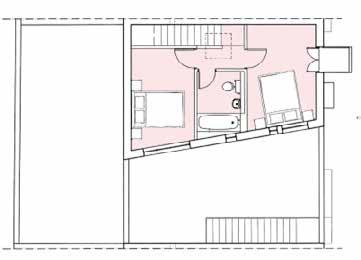

DWELLING

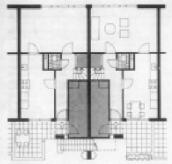

DESCRIPTION

The dwellings accommodate 75 homes with each dwelling being a 1 or 2 bedroomed apartment with a kitchen, toilet and bathroom, sitting room nice balcony overlooking the street, providing a different layer of semi-pub lic space above grade.

EVALUATION

The project’s dwelling design offered good standards of collective housing within Amsterdam City. The buildings are well lit and aerated by natural light as all sides have pretty big windows.

The rear side of the buildings act as the city edge/ city wall where there is no room for gardens. The wall is brought to live by differently sized bay windows (some of which protrude externally from the building), giving the residents a view of the abutting transportation corridor.

130

Protruding bay windows on the ‘city wall’. Plan: Level one Plan: Ground Floor Contextualization Flat roof apartment builing: Front, side and back wall Wager, Hans. 2013. “Nieuwe Houttuinen, Amsterdam –Architektenburo Hans Wagner.” 2013. https://hanswagner.nl/prt/nieuwe-houttuinen-amsterdam/. Accessed 20th Feb 2022 Google Earth, 2022

Accessed

Source: Author Van Der Vlugt, Ger. 2019. “Haarlemmer Houttuinen Housing.” 2019. EUMiesAward (miesarch.com).

20th Feb 2022

131

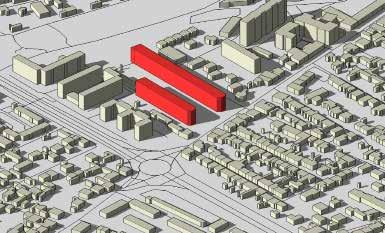

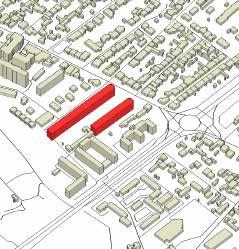

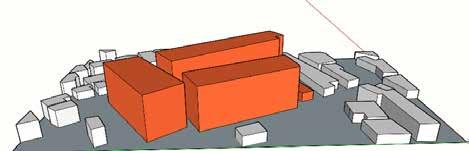

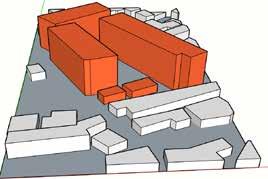

GWL Terrein

KCAP

KCAP

DESCRIPTION

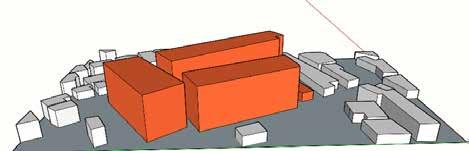

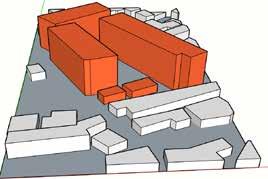

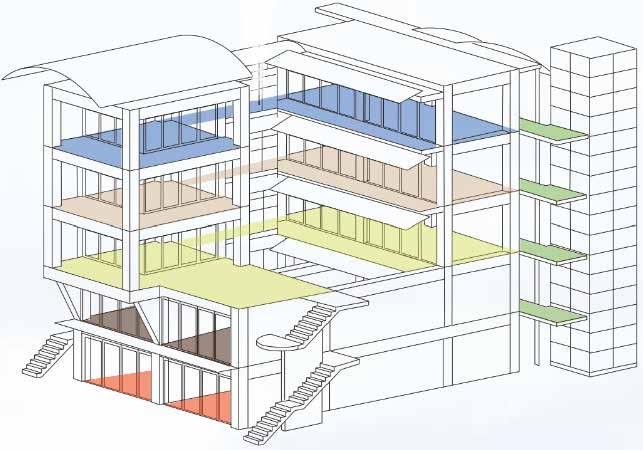

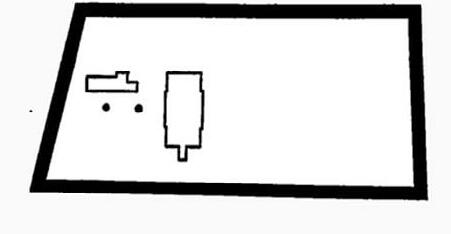

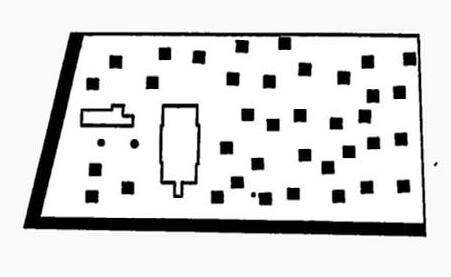

A residential area of GWL Terrein is built at the former site of the municipal drinking-water company (‘GWL’). The 6 hectares site is located in the highdensity urban centre of Amsterdam with a strong cohesion characteristic (KCAP, n.d). It is a residential block that marks the edge of the traditional housing neighbourhood of Staatslieden to its east and the business and industry to the west. The site was developed after an appeal for a car-free eco-district by the inhabitants (gwl terrein, n.d). The construction was completed in 1998 for 600 residential units of 29.000 m2

EVALUATION

The GWL Terrein residential block is well responding to the context of the site for being in between the traditional housing blocks and the busy business and industry area. The singularity of its building blocks protects the residential neighbourhood as well as provide openness to its green open spaces.

132

Noviantari

Amsterdam, Netherland

(Source: https://www.kcap.eu/projects/25/gwl-terrein)

SITE

GWL Terrein, Westerpark

(Source: Google Earth)

Location: Central

CONCEPT

• Eco-friendly (concerning four elements of water, energy, waste, and vegetation; aim to reduce water and energy consumption, separate garbage system, use environmentally-conscious building material) and car-free residential area (discourage car ownership and use by ensuring good public transport, optimal attention for cyclists, and the right selection of inhabitants)

• Preserving strong cohesion and high density character while presents as a single, large-scale urban element in its surroundings; preserving historical features of the site

• Open zone with residential blocks in the midst of greenery - an oasis of calm in the metropolitan chaos.

• Access and ownership to gardens and public spaces

Sources: https://gwl-terrein.nl/bezoekers/gwl-terrain-an-urban-eco-area/; https://www.kcap.eu/projects/25/gwl-terrein.

133

After completion of the urban plan in 1993, 10 Architects were appointed including KCAP and Adriaan Geuze from West 8 for the layout design (gwl terrein, n.d). The layout preserves a tower and a few of the historical buildings of the formerly GWL water company. Sketches of final building plans were completed in June 1994 through participatory design with the inhabitants.

The building layout to emphasize accessibility and proximity to the green open spaces.

OPEN SPACE STRUCTURE

Canal

Haarlemmerweg

Public open spaces

Staatslieden neighbourhood

The figure-ground (above left) shows the openness to the green open spaces inside the GWL Ter rein residential block. It also provides flow and direct centrality to the preserved historical buildings and GWL tower as the landmark of the site.

The open spaces correspond with adjacent neighbourhoods and functions (above right). The open spaces take form as public amenities and allotment gardens with proximities and ownership in response to the housing unit typology. The concentrated car park only at the west of the site with shared space prioritizing pedestrians and cyclists at its access is to realize the car-free urban neigh bourhood.

Private owned allotment garden

Car park Community owned allotment garden

134

Staatslieden neighbourhood

garden

space

court public open space

space

Westerpark

Businesses and industry Businesses and industry Allotment

Car park and shared

Sport

Public gathering

Sources: https://www.kcap.eu/projects/25/gwl-terrein.

BUILDING

DESCRIPTION

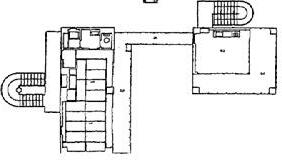

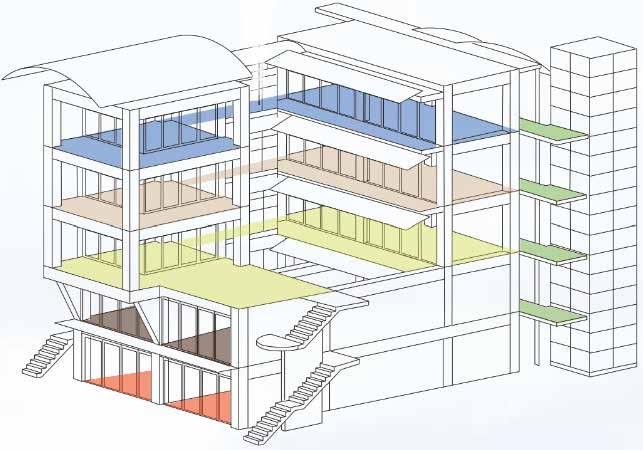

The GWL Terrein residential block in general consists of three building typologies with a density of 100 dwellings per hectare (KCAP, n.d). The meandering residential blocks that climb up from four storeys building at the south-west to nine storeys building at the north-east, and four to five storeys building that form a park-like setting. The meandering blocks provide nearly 57% of the dwelling and protection to the residential site from the business and industrial activities, the noise of the Haarlemmerweg road, and wind from the west. The building blocks also consist of multi-functionalities such as communal housing, live/work dwelling, community centre and public amenities.

EVALUATION

The multi-functionalities of the building blocks invite diverse communities and allow changing activities through time. It provides an opportunity to make the best use of the space and develop cohesion from the communities.

Sources: https://gwl-terrein.nl/bezoekers/gwl-terrain-an-urban-eco-area/; https://www.kcap.eu/projects/25/gwl-terrein.

135

DWELLING

DESCRIPTION

GWL residential blocks consist of various dwelling units that targeted different audiences with different prices. The range of audiences was agreed in accordance with the vision of a car-free and eco-friendly neighbourhood. The diversity of the unit is also related to the ownership of the garden. The ground floor (level 01) dwelling units mostly has direct proximity and ownership to an allotment garden. The upper floor consists of smaller dwelling units with visual proximity and communal ownership to the allotment gardens. Attention is also given to accessibility via street door as well as an upper-level corridor (KCAP, n.d).

EVALUATION

Careful and coherent attention is given to the dwelling unit design to realize the eco-friendly neighbourhood vision. The luxury of access and ownership to the garden for some units does not neglect an equal provision of public amenities and access to other units’ owners.

1st floor 2nd floor 3rd floor 4th floor 5th floor 6th floor 7th floor 8th floor 9th floor

North elevation

Level 01 plan Level 03 plan Level 07 plan

136

5th floor

4th floor

3rd floor

2nd floor

1st floor

137

Sources:

Block 11 cross section Block 11 and 13 cross section Block 11 level 01 plan Block 13 cross section Block 13 level 01 plan Block 13 level 03 plan

https://www.kcap.eu/projects/25/gwl-terrein.

SPECIFIC: NURTURING SOCIAL COHESION AND ECO-FRIENDLY NEIGHBOURHOOD

Proximity to gardens and public amenities in daily life sustains the eco-friendly neighbourhood with cohesion throughout the generation. Sources:

138

https://www.kcap.eu/projects/25/gwl-terrein.

REFERENCES

gwl terrain. n.d. “GWL terrain: an urban eco area.” Accessed February 21, 2022. https://gwl-terrein.nl/bezoekers/gwl-terrain-an-urban-eco-area/

KCAP. n.d. “GWL-Terrein, Amasterdam.” Accessed February 21, 2022. http:// www.kcap.eu/project/25/gwl-terrein.

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

Crest Apartments

Michael Maltzan

Samantha Arbotante

DESCRIPTION

Located in between busy freeways of Los Angeles Valley, the Crest Apartments was created as a new typology of housing in the sea of commercial districts. With its accessible distance to public transportation, the residents of the com plex also have easy linkages to various resources while enjoying the integrated on-site features designed to be a socially sustainable project of its own. (https:// www.swagroup.com/projects/crest-apartments/)

HOMELESS TO PERMANENT ADDRESS

Designed for homeless individuals and disabled veterans, the multi-layered landscape provides a stable space with flexible opportunities for its residents to gather in their own community spaces. The introduction of bioswales in the open areas such as the parking, permeable pavers, rainwater systems, and drought resistant plants and trees had promoted its features towards achieving the LEED Platinum award. (https://www.morleybuilders.com/project-experience/ crest-apartments/)

164

© Jonnu Singleton, n.d.

SITE

© Google Earth, 2022

© Google Earth, 2022

Los Angeles, California, United States

CONCEPT

BREAKING THE EXISTING URBAN TISSUE

Among the rows of commercial establishments with massive portions alloted for parking areas (1), the Crest Apartments provides new access for a break through to the main road for the dwellers living behind the project. The com plex provides ample green spaces for usage.

CHANGE OF VOLUMES

This project distinguishes itself from the rest with its volumetric design, a new sight against the common two to three floor heights of buildings in the area (2).

INSIDE COMMUNITY

Through the length of the project, various accessible spaces found in the ground floor were introduced to create a supportive environment for its users (3).

165

(1) Surrounded with parking areas in light gray shade

View

© Adapted from Google Earth, 2022 © Google Earth, 2022 (3)

from the side of the complex (2) View from the front of the complex © Cooper Hewitt, 2022

SITE

HOLDING DENSITY OF PEOPLE AND WATER

Porosity throughout the entire site is one of the main features of this project. Due to its location and events of frequent drought, the designers of the project had opted to enhance the entire landscape through use of permeable pavers, drought resistant trees and plants, and the introduction of two bioswales. Not only does this project contain the load of its residents but also retain and sus tain the lack of water in the site.

EVALUATION

Empowering the softscape in the site had made this project standout from the rest of housing apartments in the site. Allowing nature to be the main driver of light, ventilation, and movement had improved the quality of the environ ment.

166

© Michael Maltzan Architecture, 2016 © Michael Maltzan Architecture, 2016 Bioswales Softscape Vehicle Traffic Flow Pedestrian Traffic Flow Porosity of whole site

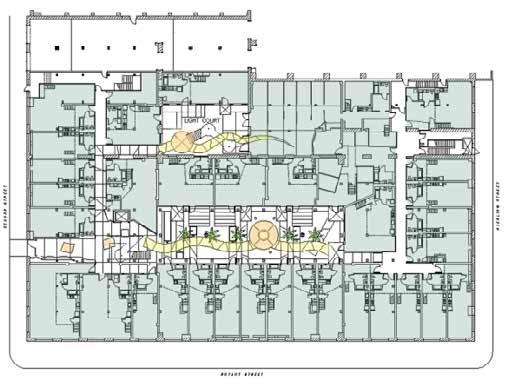

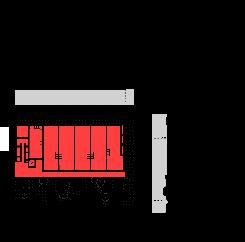

BUILDING

BALANCE OF PRIVATE AND PUBLIC

The long corridor of the Crest Apartments divides multiple of spaces for the residents and visitors. Public spaces such as the sheltered courtyard with tiered terraces, residents’ lounge (2), community kitchen (5), laundry room (8), con ference room (7), social service offices (12), health clinic (11), and an outdoor community garden (18) are shared to the building occupants.

EVALUATION

Comparing with the general housing projects which are either private owned buildings or by the government, the Crest Apartments had an image of sus tainable as a community of its own because of the numerous spaces alloted in the design.

167

Adapted from Maltzan Architecture, 2016

© David Lloyd, n.d.

Public Spaces Private Spaces Building Typology: Spaces Ground Floor Plan (Not to scale)

INCLUSIVITY IN UNITS

In the four levels of the apartments, a total of 64 units were allotted for the beneficiaries. Since the project is located in a postwar area and dedicated also for disabled veterans, special units were specifically designed to cater these people; among these are 6 accessible units, 4 units for people with mobility problems, and 2 units designed for people with hearing/vision problems.

EVALUATION

Providing healthy homes is one of the main goals of the designers. As most of the units are located at the southern part, this inhibits privacy to its users. It is also seen that Inclusive Design was part of the concepts of the studios as seen through the various designs and options. Along with these features, natural lighting, large windows, natural and cross ventilation, and views of the city were projected in the design to make the space more liveable.

168

Roof

All plans adapted from Maltzan

2022 © Michael Maltzan Architecture, 2016 Top: Studio 1, Bottom: Studio 2

DWELLING Second Floor Plan (Studio 1: Green shade and Studio 2: Light Green shade) Third Floor Plan Fourth Floor Plan Fifth Floor Plan

Plan

Architecture,

169

Typology: Studio 1, Studio 2, and Manager’s Studio

Studio 2 Studio 1 Manager’s Studio Studio 1 Building Typology: Volumes All plans adapted from Maltzan Architecture, 2022 Studio 2 Studio 1 Studio 1

SPECIFIC: TYPOLOGY Dwelling

Pilotis

Housing Development and Remodeling Pflegi-Areal

Gigon / Guyer Architects

Frank BAGENZI

SITE

DESCRIPTION