1 SPRING STUDIO 2022 STUDIO

(of Science) Human Settlements OR Master (of Science) Urbanism, Landscape and Planning Faculty of Engineering and Department of Architecture

Academic Year 2021 - 2022 © Noviantari / Samantha / Wim?

LISBON, THE TRANCÃO FLOODPLAIN Lisbon, Portugal Master

Studio Teachers: Ana Beja da Costa (School of Architecture, University of Lisbon), Wim Wambecq (KU Leuven)

© Copyright KU Leuven

Without written permission of the editors and contributors it is forbidden to repro duce or adapt in any form or by any means any part of this publication. Requests for obtaining the right to reproduce or utilize parts of this publication should be addressed to Faculty of Engineering and Department of Architecture, Kasteelpark Arenberg 1 box 2431, B-3001 Heverlee.

A written permission of the editors and contributors is also required to use the methods, products, schematics and programs described in this work for industrial or commercial use, and for submitting this publication in scientific contests.

2

ISBN 9789464447248

3

4 TABLE

01 STUDIO CHALLENGE 03 STRATEGIC PROJECTS 02 MAPPING THE FUTURE 05 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 04 CASE STUDY ANALYSIS 07 25 41 365 215

OF CONTENTS

03.01 Foz do Trancão / Expo '98

Noviantari, Samantha Arbotante, Jules Descampe, Gilles Houben 65 03.02 Sacavém

Maria Rafaela Armoutaki, Aliki Tsouvara, Lakshiminaraayanan Sudhakar 95 03.03 São João da Talha

03.04 Frielas

Edwin Kabugi Karanja, Arthur Van Lint, Océane Vé-Réveillac

03.05 Infantado

Kshitij Makhija, Anagha Pandit, Michelle Estefania Valladares Vaca

03.06 Santo Antão do Tojal

Fatma Ben Hfaiedh, Ana Veronica Martinez Reyna, Kenneth An-Khuong Nguyen 147 163 195

Yasmine Baamal, Albert John (AJ) Mallari, Taki Tahmid Saurav

5

43

STUDIO CHALLENGE

7 01

© Wim Wambecq

THE METROPOLITAN CONTEXT

The Tagus estuary is the largest estuary in Europe and its vast water body is at the center of the Lisbon Metropolitan Area (LMA). It is the common ground that originated many (urban) settlements with distinct genesis, settlement fabrics, interwoven economic activities and social structures, supported by its ecological richness and by its sheltered geography that favored the port development and associated activities. Lisbon, the millenary capital city, sits on the north bank, but many more urban centers integrate the LMA, with many of them punctuating the margins of the estuary.

Throughout the 20th century, shifts in economic activities, abundant rural-urban migration and car-oriented expansion resulted in an increased disconnection from this geography with urbanization dispersing development away from the estuarine dynamics. In sprawling territories, facing considerable problems of ecological fragmentation, urban dispersion and inefficient mobility, such as those found around Lisbon’s municipal boundary, there is the need to articulate various systems and to promote a better-balanced, resilient and qualified serviced living space. Particularly in transitional territories faced with physical barriers, heavy infrastructures and splintered urban fabrics, coherently shaped synergic, continuous and connected networks, such as green infrastructure, transport and urban amenities, are fundamental to address emerging challenges of more open and adaptable living spaces, environmental resilience to water-related phenomena, low-carbon mobility and territorial cohesion.

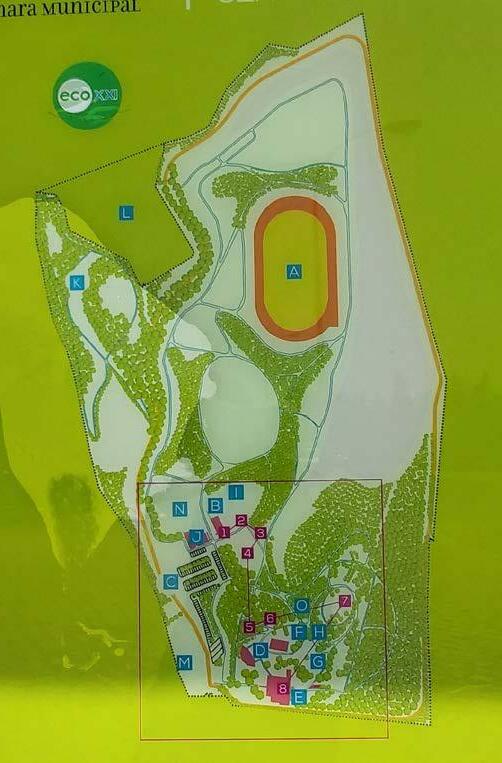

throughout the Loures Municipality (as in other municipalities within the LMA), there is a strong acknowledgment of high potential regarding territorial regeneration based on the inherent richness and resourcefulness of the landscape and its natural and cultural heritage, diverse and active human capital and introduction of new fields of economic development (tourism, nautical uses, sports, new economic sectors, ecological services) (Santos, 2021).

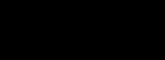

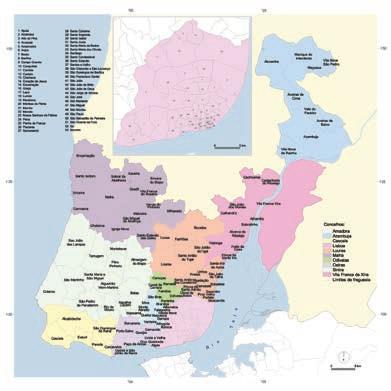

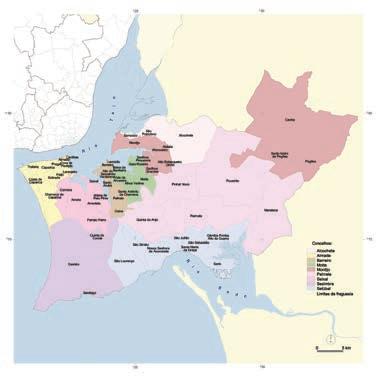

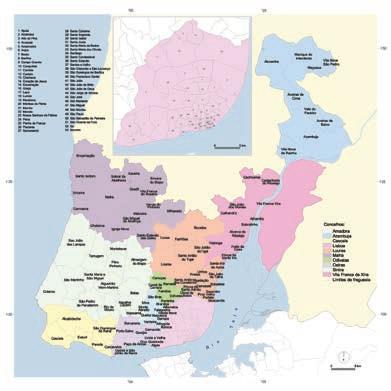

The LMA was created in 1991 to establish strategic spatial and social cohesion for the Lisbon metropolis. It includes 18 municipalities and houses 3 million inhabitants (a number that is still increasing), correspondent to almost 30% of Portugal’s population. It concentrates around 25% of Portugal’s active population, 30% of the national companies and contributes to more than 36% of the gross domestic income.

The LMA has an Atlantic coast with 150km and a riverfront with approximately 200Km. with a varied landscape morphology and abundant natural richness with particular environmental, landscape, economic and leisure qualities whose potential can be further exploited, while it is an absolute and evident priority to preserve and enhance the mentioned landscape qualities. It encompasses two major estuaries; the Tagus and the Sado, and five protected areas which are integrated in the Natura 2000 European network. It also encompasses two main ports: Lisbon and Setúbal, and three medium scale fishing ports: Sesimbra, Cascais and Ericeira. The main ports are having an increasingly relevant role due to its hinge position between northern Europe, the Mediterranean and Africa.

The development process of Lisbon’s Metropolitan Area in the second half of the 20th century is commonly regarded as highly fragmented, and disruptive in terms of infrastructural provision, morphological coherence and open space/ecological continuity. This process left significant problems for which specific spatial responses are required, namely post-industrial sites, splintered patches of open space, substandard and fragmented urban fabrics, badly integrated and car-dependent mobility, monofunctional and poorly equipped living spaces. On the other hand, and

Lisbon’s Metropolitan Area aims at affirming itself as a competitive touristic destination, based on the wide range of resources for which there is an increased international demand, such as ‘city-breaks’, cultural tourism, conference tourism and cruises. In the future, it aims, as all metropolitan areas internationally, also at gaining relevance as an innovation and technological development hub, with a specialized tertiary sector growth. The ports modernization, the logistic platforms expansion, a

8

new international airport, the link to the high speed railway European network are forthcoming challenges as well as opportunities. (AML, 2022)

Studio Lisbon investigates near future scenarios for the Lisbon Metropolitan Area. At the metropolitan scale, it investigates the estuary’s adaptive role in the face of current urban challenges that can contribute to the resilience and environmental robustness of the territory; to a sustainable and low-carbon mobility network; and for inclusion and territorial cohesion, exploring strategies to tackle the climate change crisis (Santos and Matos Silva, 2019), which in Lisbon´s context aims at responding to the need of adaptation facing extreme climate events challenges, such as more frequent heat waves, droughts, and overall changes in the water dynamics, with more frequent flash floods episodes, and subsequent erosion, landslides and soil loss. The expected sea level rise scenario, more frequently combined episodes of high tides and sudden precipitation can cause significant impacts on the urbanized areas of the LMA (CEDRU, 2019).

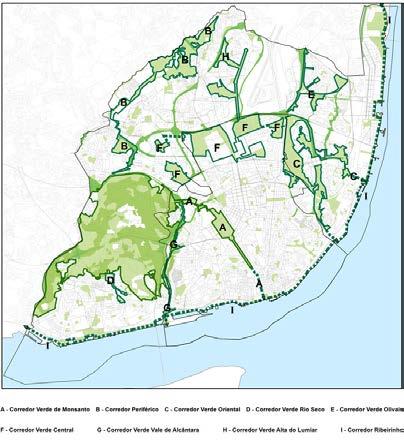

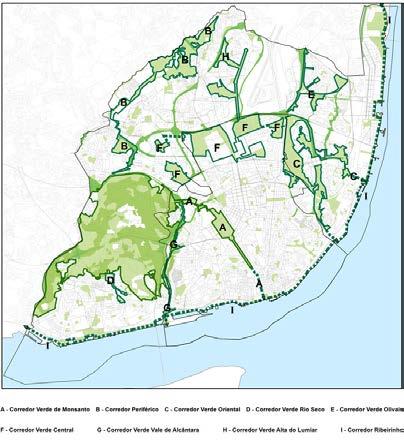

In this context, green and blue infrastructure, walkability and active mobility, and neighborhoods connection and cohesion are layers that altogether reflect upon possibilities for the sustainable development of Lisbon’s metropolitan area, both from an ecological perspective and as place of inhabitation. The studio therefore does not limit itself to the estuary and its shores but includes a tributary of the Tagus - the Trancão river and its floodplain - as main landscape entity that defines (part of) the systemic functioning of the metropolis.

9

© Atlas da Area Metropolitana de Lisboa, 2003

Divisão administrativa da AML

2000

Lisbon Metropolitan Area

Sul.

INSTITUTIONAL COLLABORATION

The studio is developed under the framework ‘MetroPublicNet - Building the foundations of a Metropolitan Public Space Network to support the robust, lowcarbon and cohesive city: Projects, lessons and prospects in Lisbon’ research project, of the School of Architecture of the University of Lisbon in partnership with the Lisbon Metropolitan Area Authority, that is running between 2021-2024 (https:// metropublicnet.fa.ulisboa.pt/).

Its main goal is to map, decode, assess and discuss the combined result of public space improvements in Lisbon Metropolitan Area (1998-2020). The research project builds upon the hypothesis that a public space network at a metropolitan scale can offer possibilities to interconnect and integrate various fields in search for synergic responses to today’s societal and urban challenges (Santos and Matos Silva, 2019). The studio also integrates findings of former and ongoing research projects, essays, literature and design exercises that investigate the relation between the Lisbon Metropolitan Area (or parts) and the Tagus estuary. In sequence, Studio Lisbon will also pay particular attention to public space networks that can be sustained and/or proposed by the studio’s design strategies.

DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE

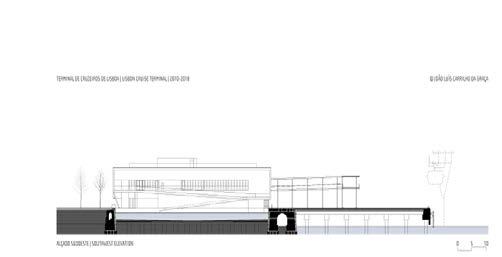

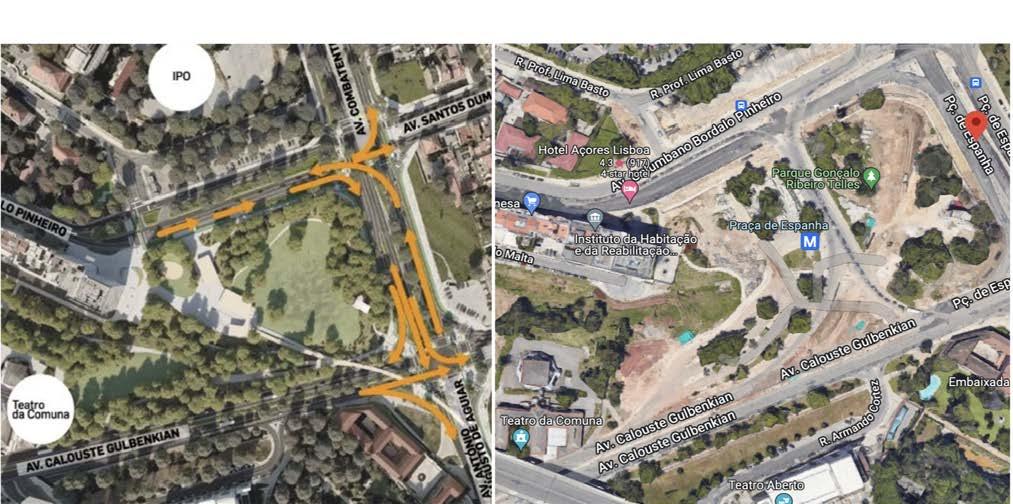

1. MetroPublicNet: overview of case study identification of public space projects between 1998 - 2020. 2. Lisbon case studies: Ajuda, Lisbon waterfront, eixo central 3.

Soft mobility case studies in Cascais. 4. Vila Franca de Xira case studies. 5. Setúbal case studies. 6.

Ajuda case study: public space interventions; landmarks; porosity of groundfloor; public transport;

FCT, Portugal. Project reference: PTDC/ART-DAQ/0919/2020

10

MASTER OF HUMAN SETTLEMENTS MASTER OF URBANISM, LANDSCAPE AND PLANNING

FACULTY OF ENGINEERING SCIENCES

5. © MetroPublicNet, 2022

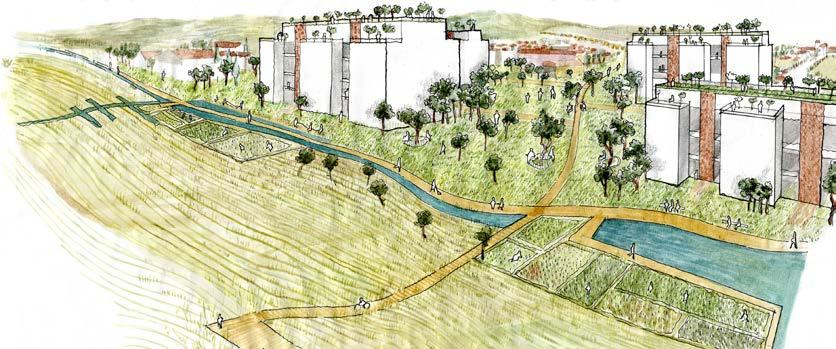

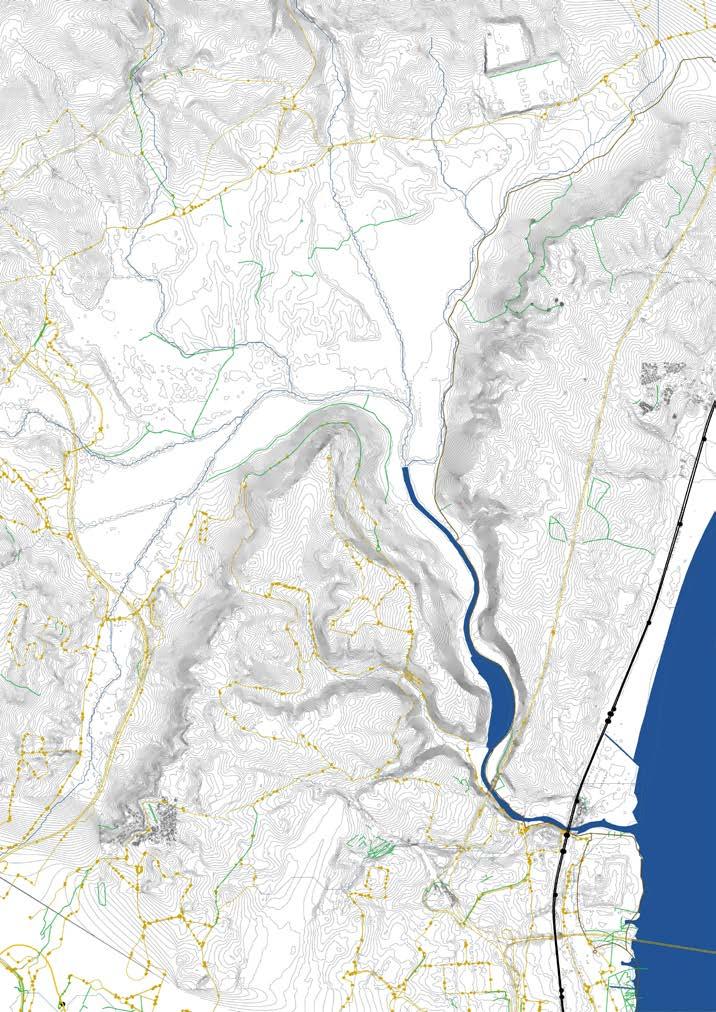

TRANCÃO FLOODPLAINS & LOURES

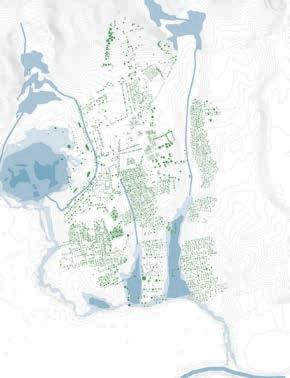

The design studio will investigate the territory through design on the scale of the Trancão river and its floodplain, a tributary of Tagus, and the surrounding urban patchwork as an outstanding landscape entity and ecological corridor. The studio seeks to explore networks, flows and inhabitation modes that are to become coherent with the specificity of its context within the LMA, and embedded in the broader resilient and dynamic estuarine landscape systems. It aims at combining critical survey / interpretive mapping, complex thinking, and a strategic approach to large scale public space networking and tactical urban design to reimagine this territorial entity as (part of) the systemic functioning of the metropolis.

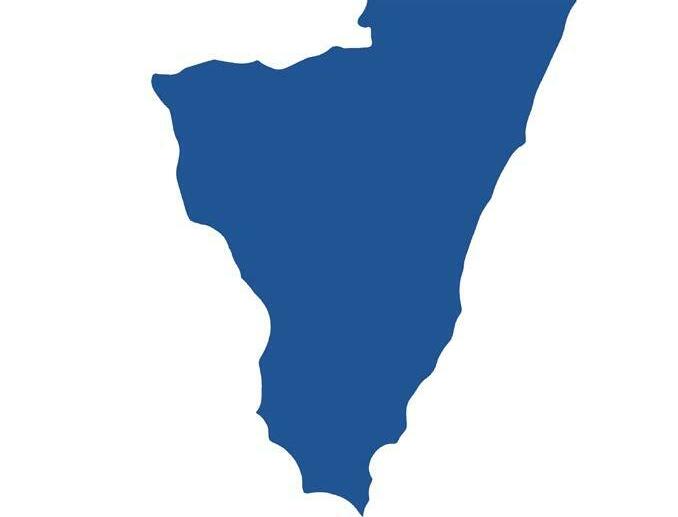

Loures Municipality, within the District of Lisbon, is located in the Greater Lisbon region (NUT II), in Lisbon (NUT III), 7 Km away from the core of Lisbon. It borders with the Municipalities of Vila Franca de Xira on the east, Sintra and Mafra on the west, Lisbon and Odivelas in the south an Arruda dos Vinhos in the north. It encompasses an area of 167,9 Km2 and 18 parishes.

Economy

The secondary and tertiary sectors dominate today the region’s economic activity. Machinery and transportation material production, clothing, pottery and chemical products are the main industries. Commerce related to the industrial activity also has a relevant weight. Agriculture as an economic activity still has relevance, namely in what concerns horticultural production for international export.

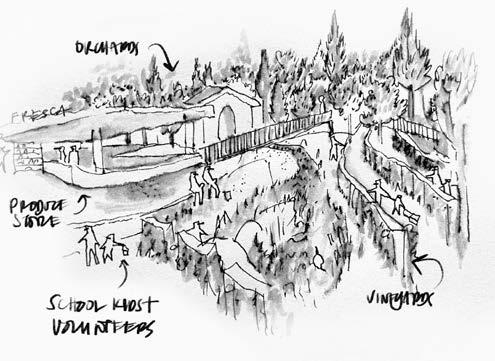

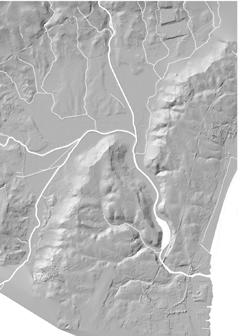

Landscape

The Trancão river floodplain (Várzea de Loures) is considered a ‘secondary structuring area of the metropolitan ecological network’, and is located in the right margin of the Tagus Estuary, in the south-central area of the Loures Municipality, expanding towards the southeast limit of the Vila Franca de Xira Municipality. Its area is not only relevant for environmental preservation of soil and water resources, but also as excellent areas for agricultural production, taking advantage of the Loures hydraulic resources. As such an agro-ecological balance should be enhanced.

Historic background

Loures historical center was formed around the Igreja Matriz (Rua Fria) and gradually expanded towards the Alvogas hillsides, the river margins and its old dock near the Loures river bridge. In 1179, Loures is mentioned in the independence charter granted to Lisbon. Within Lisbon’s boundaries, Loures had an important role throughout the centuries, as a region that supplied agricultural products to the capital city. Since the 18th century, there are records from salt pans on the Loures floodplains, and of intense commercial activity centered on the agriculture and horticulture products coming from the ‘saloia’ region (from Mafra and Arruda dos Vinhos), using the navigable section of the Trancão river.

Its landscape is characterized by an extensive agricultural plain in the alluvial terrains of the Trancão river, which is influenced by salt water coming from the Tagus estuary tidal influence. The steep rocky hillsides – the ‘costeiras’ - are covered by dense shrubbery cover of Mediterranean species. There are also areas with reeds and intertidal sediments, which are important habitats for several aquatic bird species. The ‘Paul das Caniceiras’ is a floodable area with 14,6 ha by the Santo Antão do Tojal historical center. Besides the presence of several bird species, it is one of the last remaining habitats for the ‘boga de Lisboa’ fish, whose presence is limited to the Trancão river and the Rio Maior stream (CCDR-LVT, 2018).

12

CASE STUDY - TRANCÃO FLOODPLAINS

13 © Wikipedia, 2022 Trancão Watershed

TRANCÃO FLOODPLAINS

The Trancão floodplain forms a distinguishable and valuable landscape figure in the Lisbon metropolitan area. Its hydrology is the structural element that lies at the base of its unique natural features, its productive landscapes, its urban morphology…

Current crisis has shown the potential of, and threats to the Trancão floodplains. Since COVID-19 emerged, the floodplains have been sought by an increasing number of people. Non-crowded, aerated, low intensity, and low programmed green spaces have gained a shared interest from the surrounding population, with farmers that before were suspicious about visitors entering their fields, being more welcoming to their temporary visitors. The scale and character of this rural piece, almost at the heart of the Lisbon metropolitan area, is remarkable.

For decades’ urbanization turned its back to the industrialized and consequently polluted floodplain, also prone to extreme flood episodes, such as the devastating ones that took place in 1967. Currently, and with special decontamination efforts around the Expo 98 construction period, soils and water have generally been remediated. Nevertheless, climate change is likely to exacerbate flooding, in combination with the possibility for extreme high tides that enter the Trancão floodplain. At the same time drought – as in this past winter – might be even more problematic as needs for water render the natural wetlands dry, pushing unique fish and plant species towards extinction.

Many challenges lie ahead.

14

© Arquivo Municipal de Lisboa

1967 Floods of the Trancão river

15

© Google Earth image

The very distinguishable Trancão floodplains

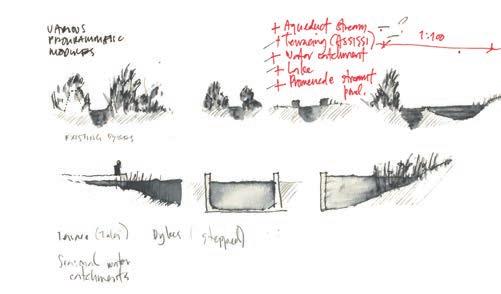

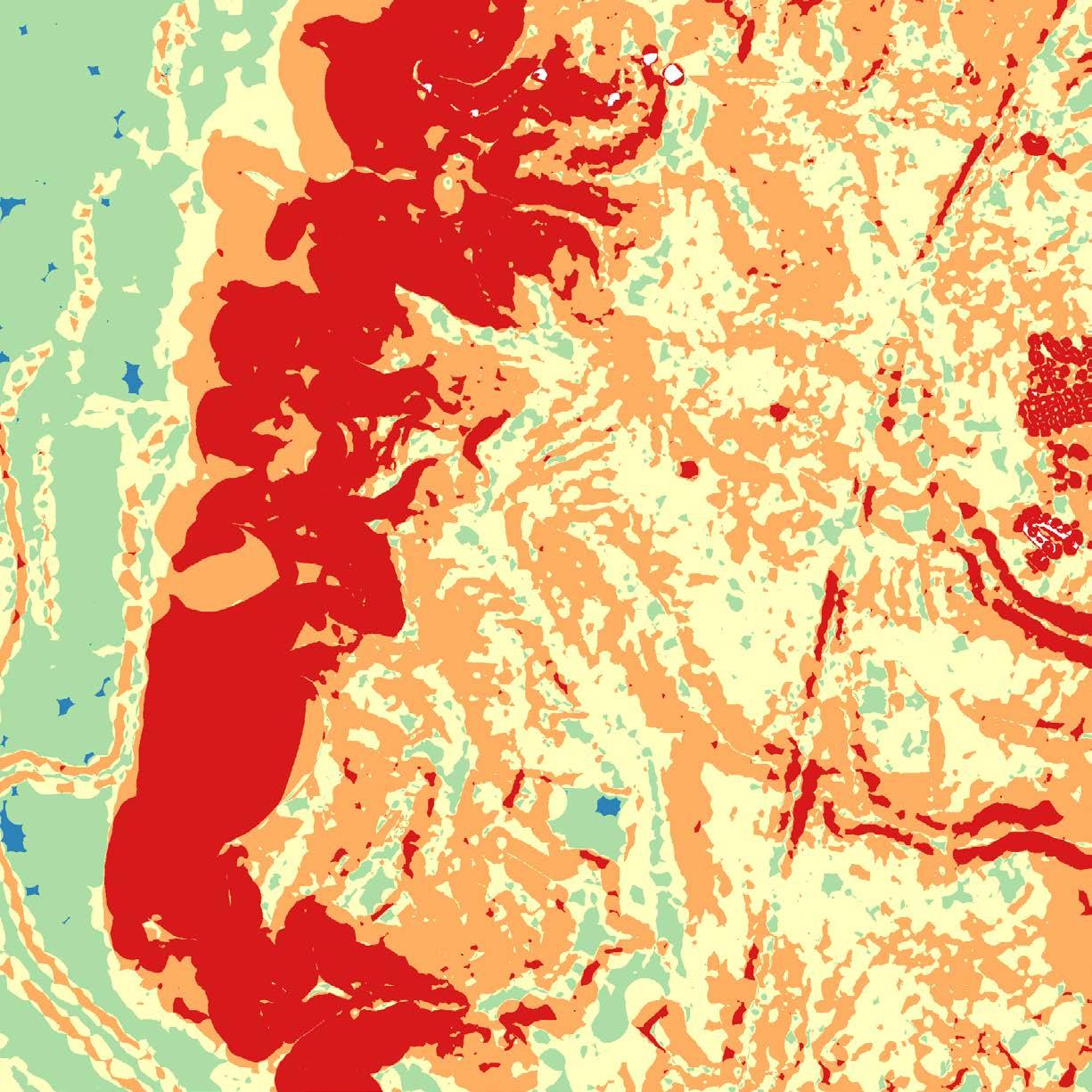

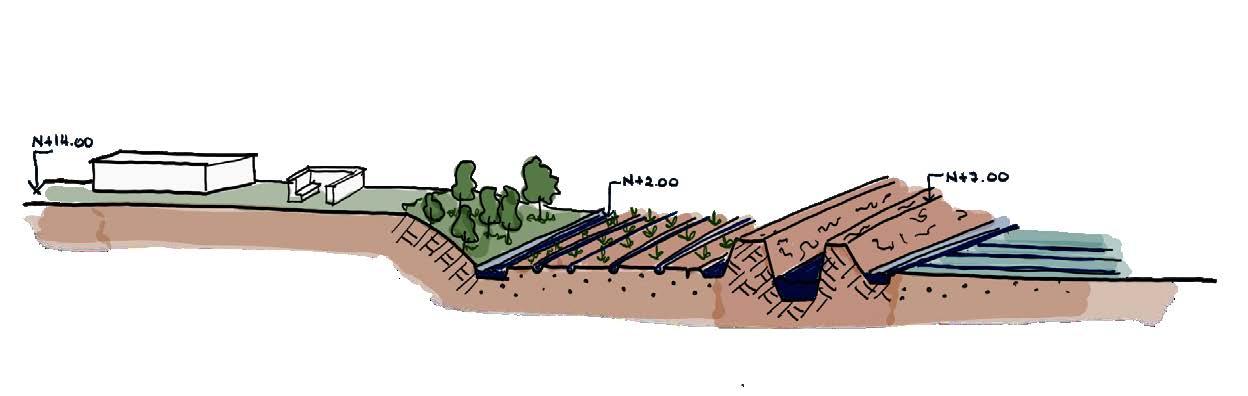

CHALLENGE 1

RESILIENCE AND ENVIRONMENTAL ROBUSTNESS

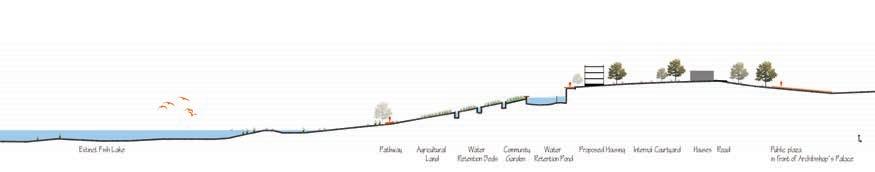

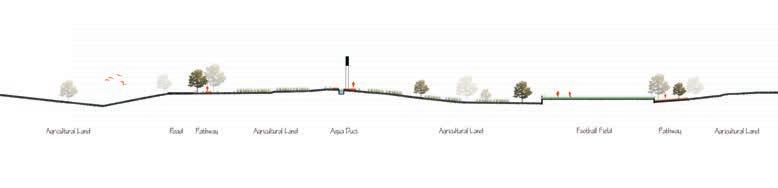

The water cycle for the Trancão floodplains needs to be recalibrated. The high embankments push water directly towards the Tagus, while it might be more productive to hold and store water as high up as possible. Natural and productive water needs should find a balance through the landscape systems and the rational use of water, but also by optimizing agricultural production, compatible with an optimized water regime and crop choices in relation to soil suitability. The reuse of cleaned sewage water in the two main sewage treatment plants (ETAR) can contribute to this.

The main land use is and will continue be agricultural production. The floodplain is divided into private parcels owned by local farmers. Without their collaboration, the floodplain will not change. Nevertheless, the demand for productive space results in a very narrow natural strip along the main water courses, with steep embankments that are contradictory to the ecological processes of the alluvial plains.

How can a recalibration of a multifunctional landscape allow for the strengthening of ecological processes and biodiversity, the remediation of climate change impact as floods and drought, while maintaining the identity of a rural, productive landscape with strong ecological assets? How can urban development be combined within this landscape and its rural character?

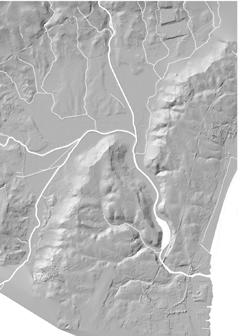

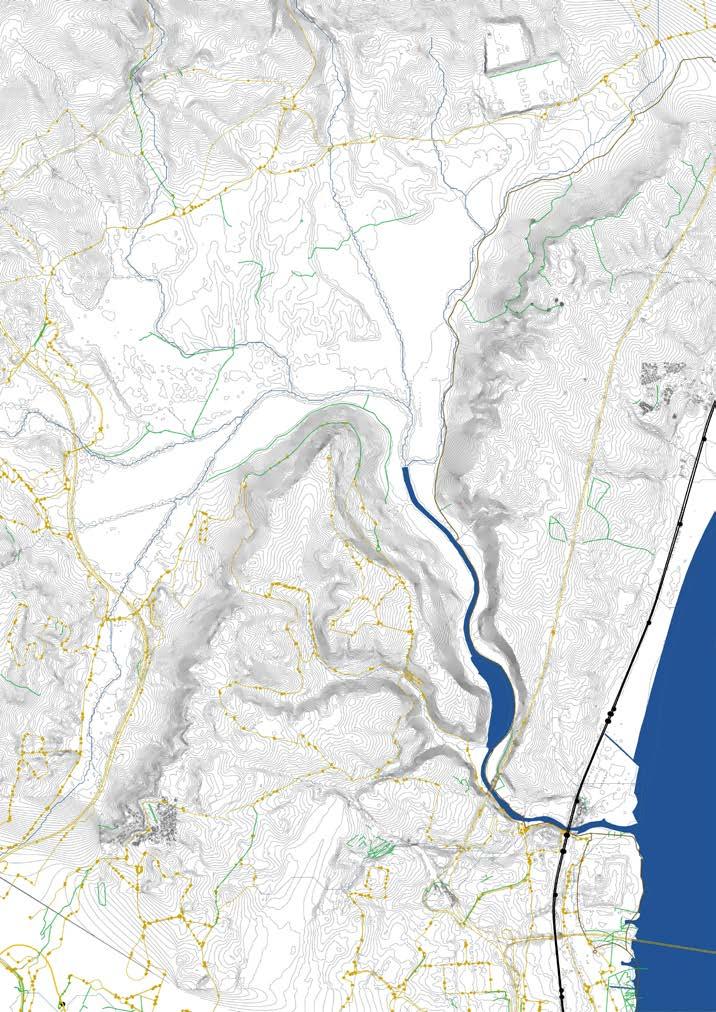

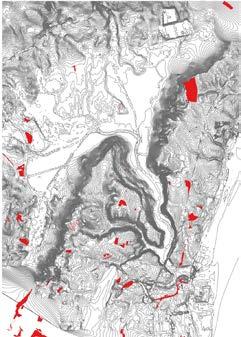

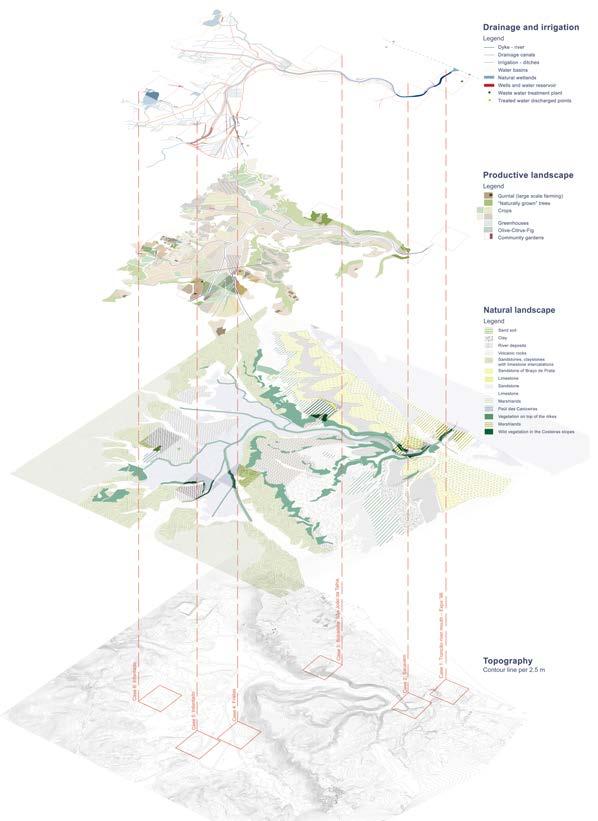

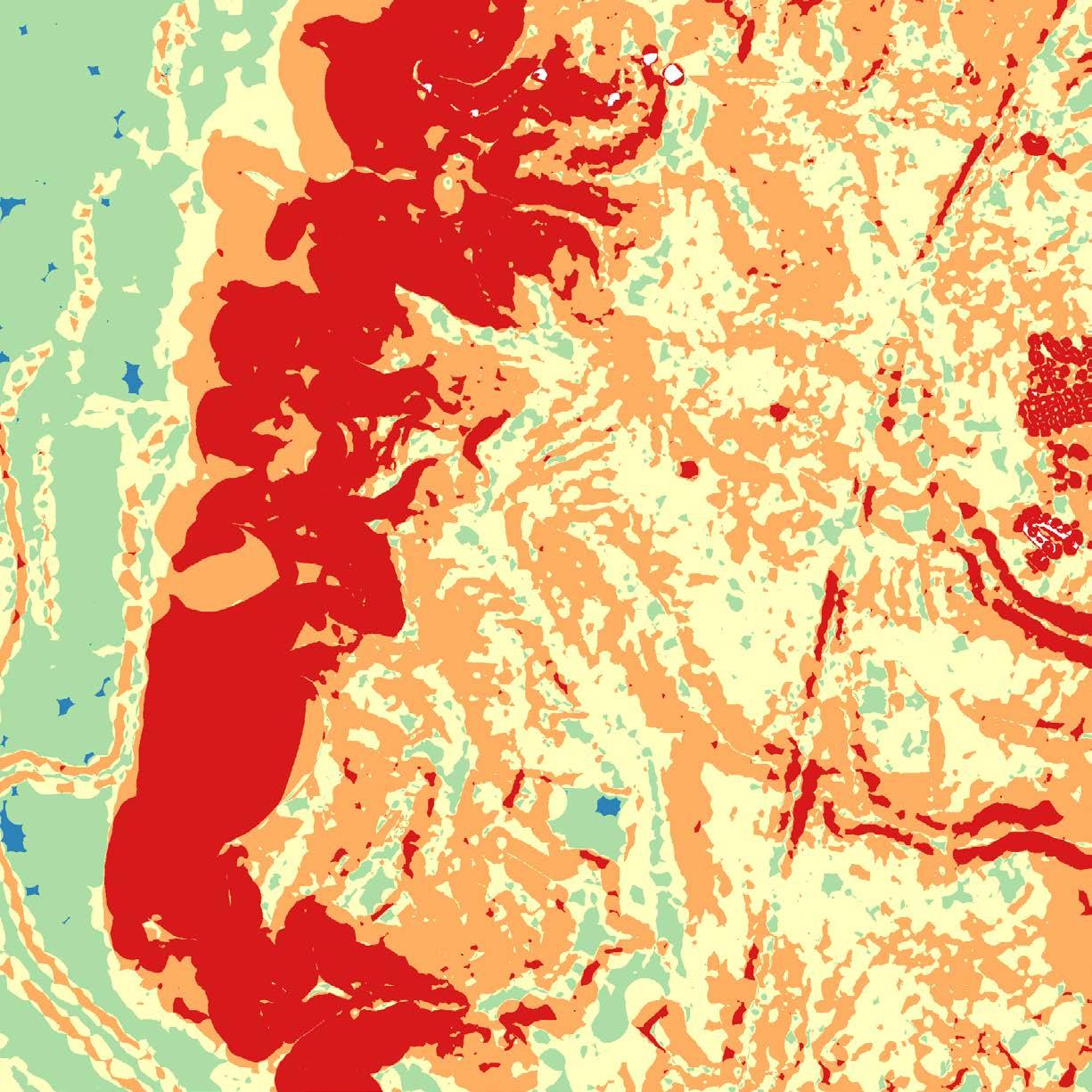

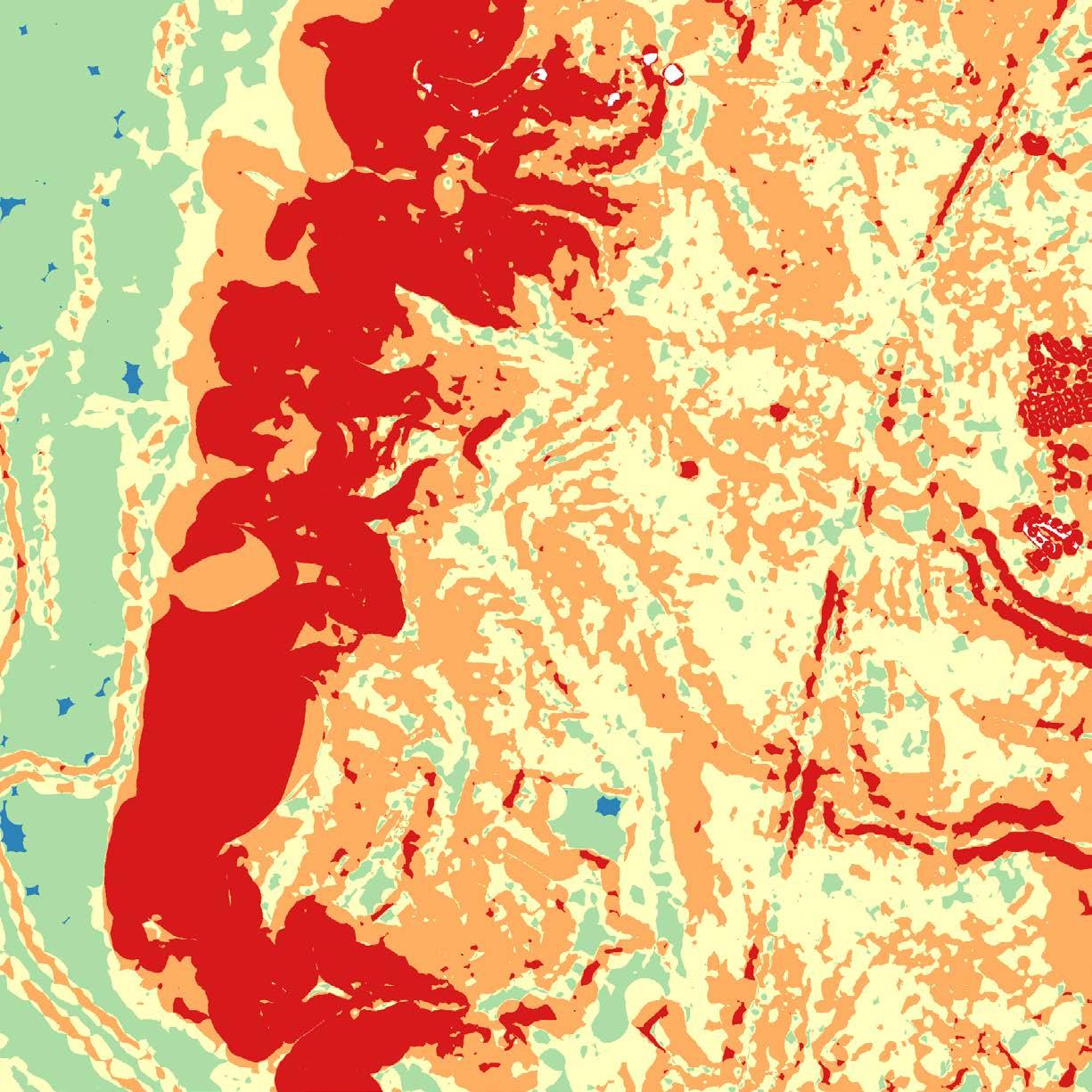

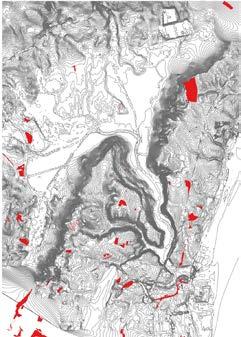

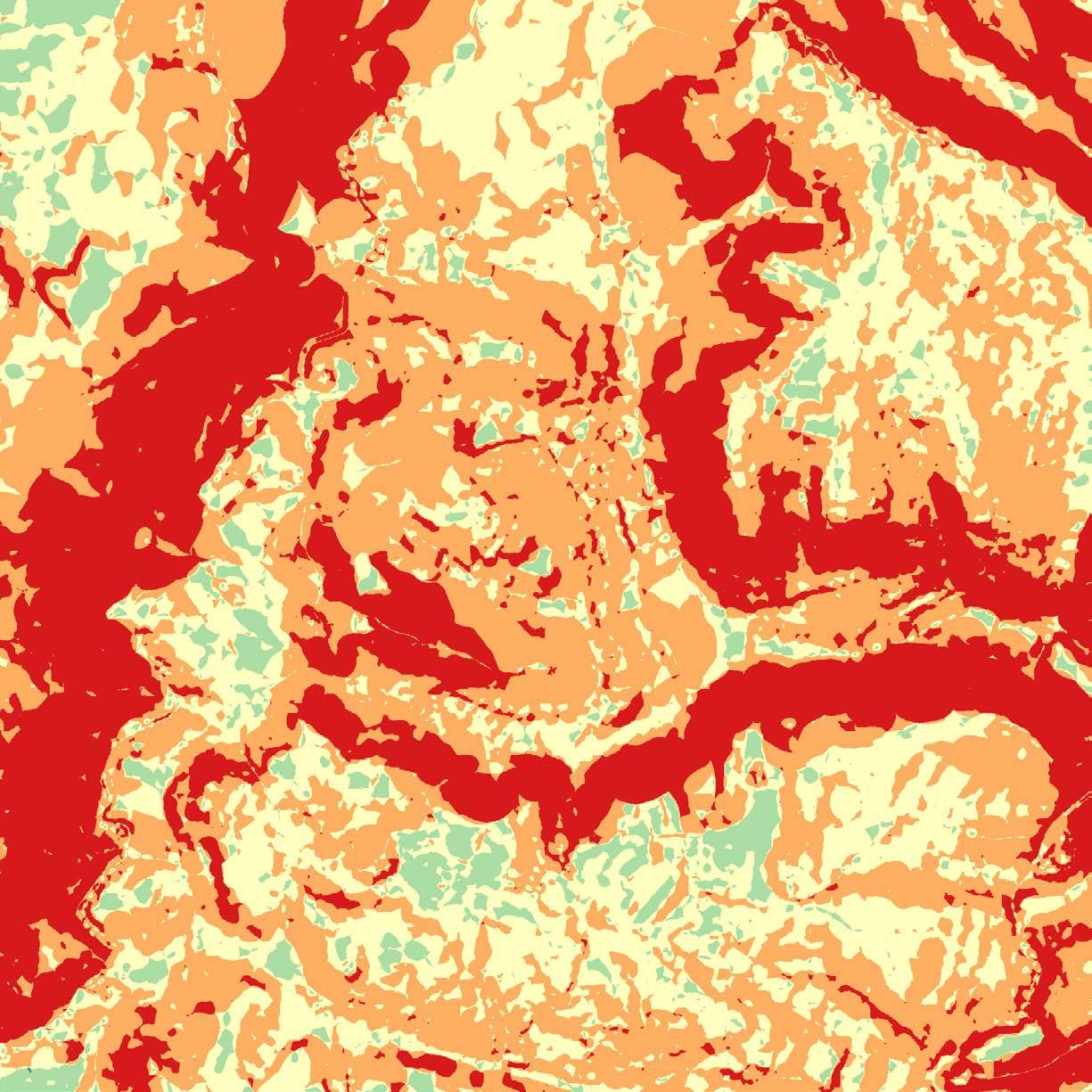

16 © Studio Lisbon Mapping

1. Topography / 2. Hillshade / 3. Slope

1. 2. 3.

Water / Streams / River Flood / Tidal movement

17

100 Year storm flood scenario - also future SLR scenario? © Studio Lisbon Mapping

CHALLENGE 2

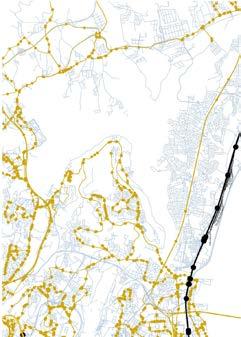

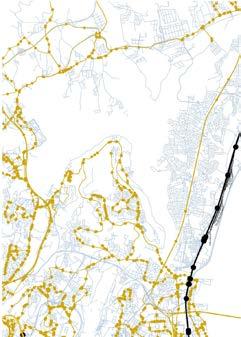

SUSTAINABLE AND LOW-CARBON MOBILITY

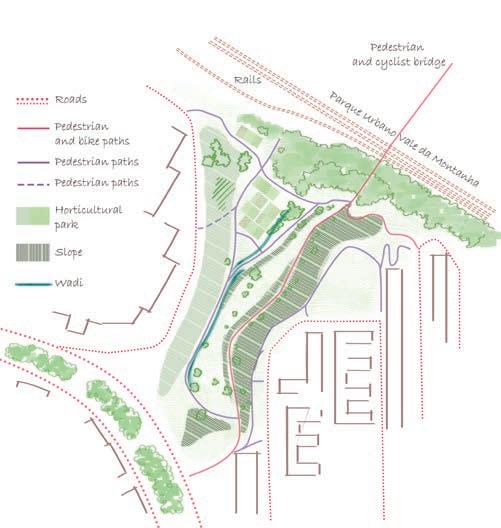

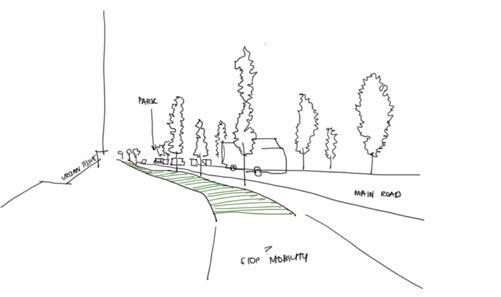

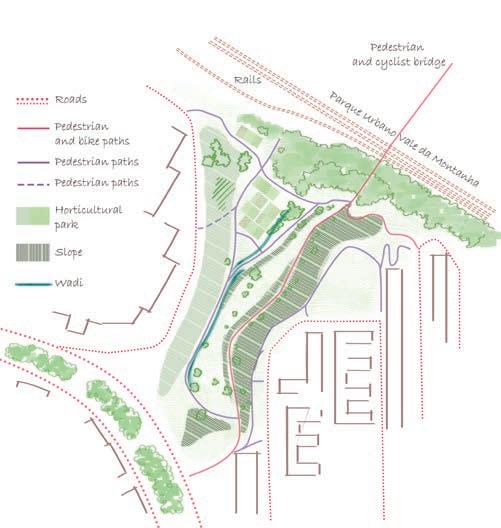

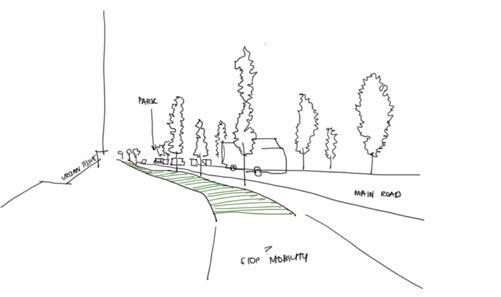

To activate the floodplains as a valuable space of connection between the surrounding urban cores, an efficient soft mobility network is needed, that can act as a sustainable alternative to the existing road network that surrounds the floodplain. An important bike connection between Sacavém and Santo Antão do Tojal has been drafted, but has encountered completion delays due to the opposition of some local farmers, as its management requires careful attention. The light metro line that will reach Infantado neighbourhood and São João do Tojal – also still on the drawing table - can introduce a new logic of the mobility network, through new hierarchies or new circulation patchworks.

What would a consistent soft mobility network look like, stretched between the light metro in Loures and the train station in Sacavém? Is there space for a return to some kind of boat transport as before?

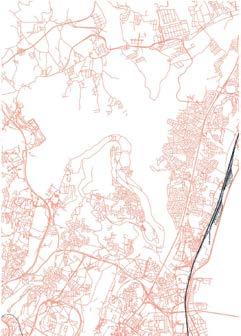

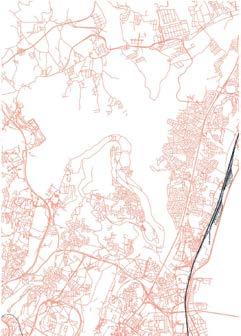

1. Road / 2. Soft mobility irt topography 3. Public transport (train, metro, bus...)

18 © Studio Lisbon Mapping

1. 2. 3.

Walking paths

Bike paths

Train line / train stop / Metro stop

Bus line / stop

19

Existing

©

mobility network

Studio Lisbon Mapping

CHALLENGE 3

SOCIAL INCLUSION & TERRITORIAL COHESION

The urban tissue in the most vulnerable areas around the floodplains, and on the hillsides resulted mainly from vernacular / informal urbanization processes. Some urbanized areas became formal (legal) throughout the years, while others lack urban structure and qualitative minimum characteristics for its legalization within the current possible legal frameworks.

Its urban reconfiguration implies finding valuable features that improve neighborhood connectivity and urban cohesion by: -Connecting isolated urban tissues and its wider scale context;

-Providing public infrastructures / public amenities; -Promoting multi-functionality of the urban tissue;

-Public spaces, -its access and setting within the landscape and/or the realization of a new piece of urban tissue that can become strategies to create interfaces to tackle this problematic.

How can urban regeneration be a motor for identity creation? What are the interventions needed – of public space, urban development… - to improve urban cohesion and neighborhood connectivity?

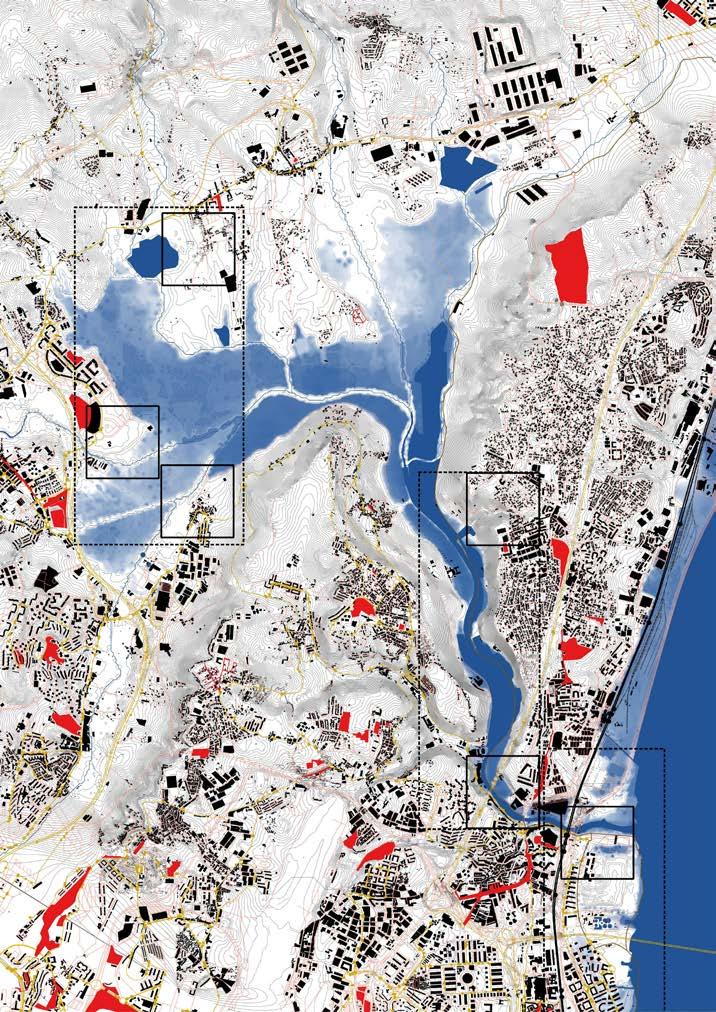

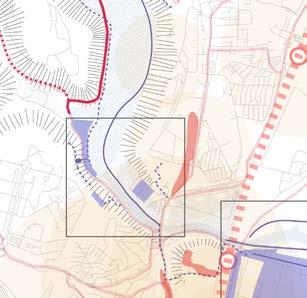

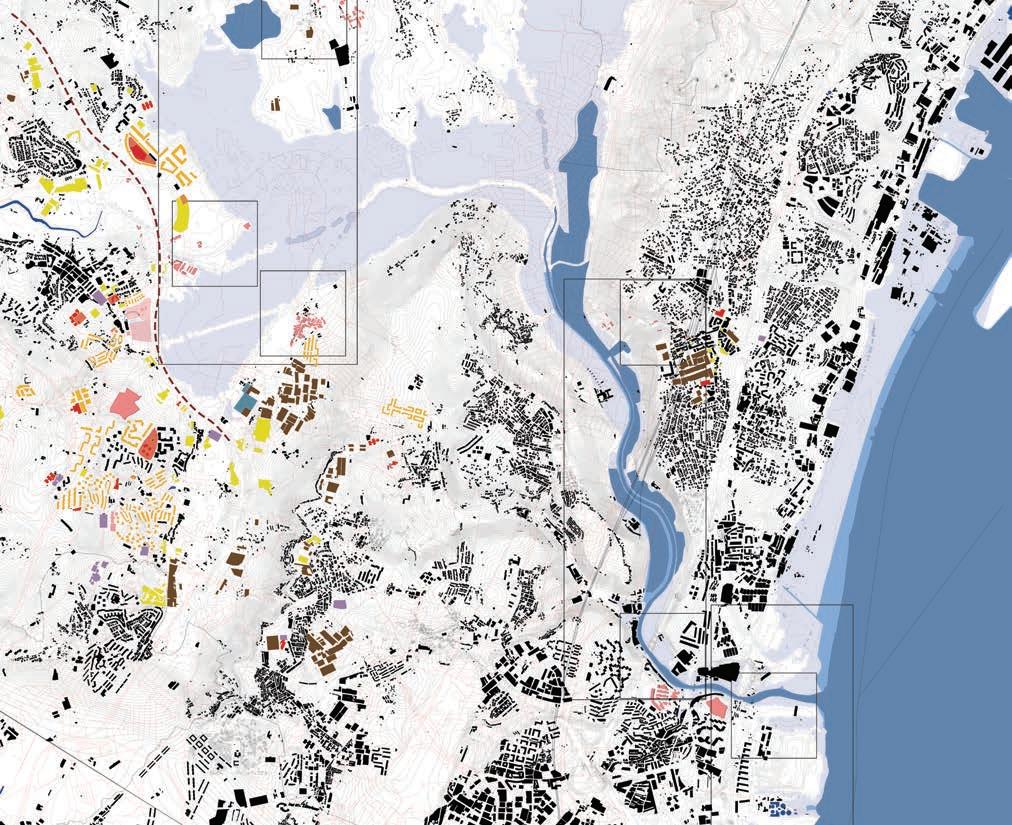

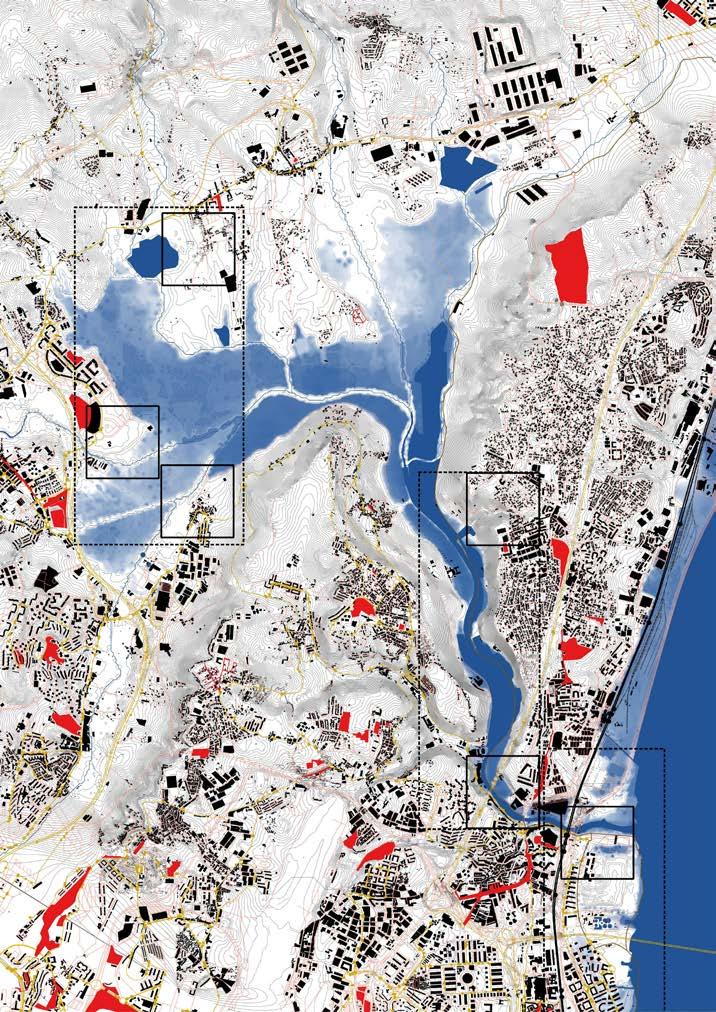

20 © Studio Lisbon Mapping

1. Built + Topography / 2. Road 3. MetroPublicNet + Topography 1. 2. 3.

21 Urbanization and public spaces MetroPublicNet © Studio Lisbon Mapping

Infrastructure Buildings Selected projects MetroPublicNet

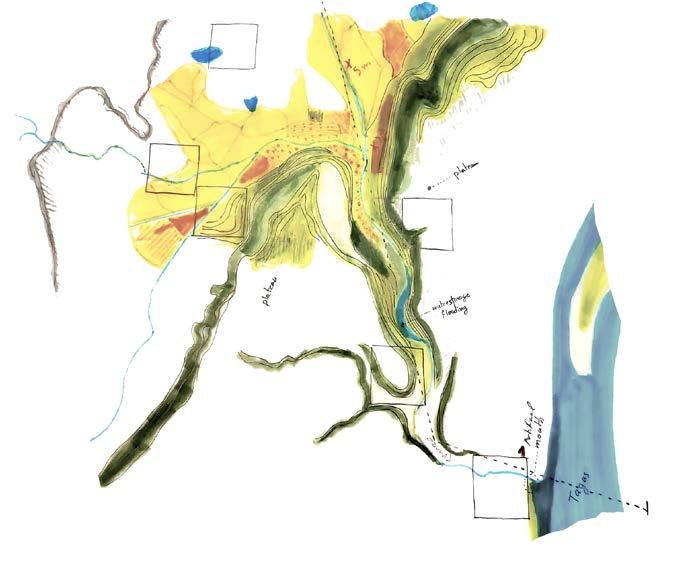

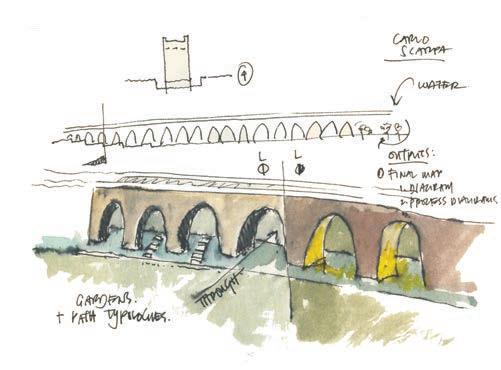

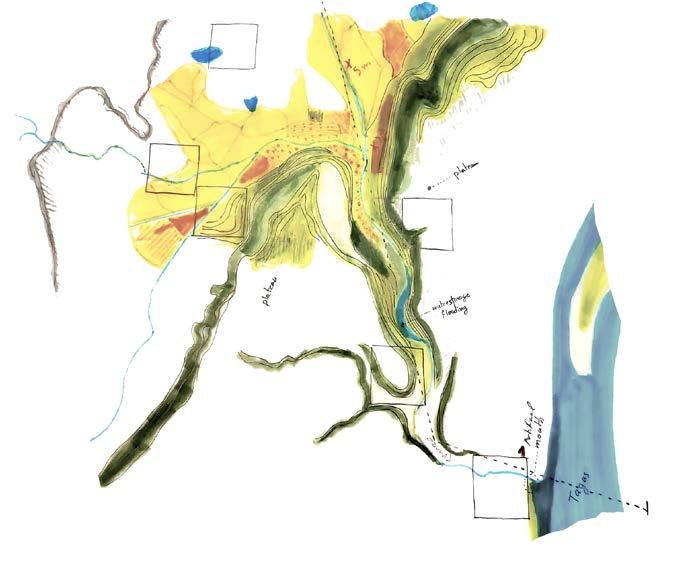

GEOMORPHOLOGICAL FEATURES & CASES

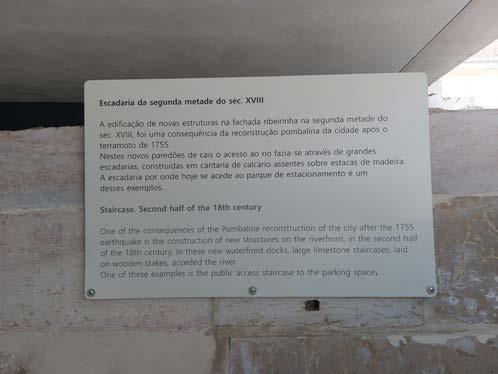

Geomorphological feature 1: the river mouth

The Trancão river mouth arrives into the Tagus river estuary on the transition between Lisbon and Vila Franca de Xira. The river mouth has been avoided for decades as part of the city due to its poor water quality and industrial connotation, just as the whole stretch of the Tagus embankment north and south of the river mouth. Expo 98 was a fundamental turning point. Post-industrial brownfields made way to a new piece of the city of Lisbon. The Expo masterplan was based on its remediation strategy, that defined areas for different uses. The development of the pavilions of the Expo 98 world fair went hand in hand with a mid-term urban renewal project, a new train station, the second bridge over the Tagus estuary –ponte Vasco da Gama -, and the park along the Tagus river. Development was done in parallel with the remediation of the waterfront, envisioned to reach up to the Trancão river mouth. This area of the city is a proven successful case study for urban regeneration. Nevertheless, the pollution of the former industrial activities was stored and sealed in the last land stretch before arriving to the Trancão river, and the project of Expo 98 remains unfinished at its end for more than two decades. The intertidal marshland system of the Tagus estuary, north of the Trancão river, is becoming more accessible, woven together by stretches of bike / pedestrian connections. In the near future, a final piece of the soft connection that forms the missing link between the various stretches (and between the municipalities of Lisbon, Loures and Vila Franca de Xira), will soon include a soft mobility bridge crossing the Trancão river. The design investigation of this case aims to develop a project in continuation ofand as the end of? – expo ’98 urban developments, to improve its connectivity to Loures and Vila Franca de Xira, north of Trancão river; to envision an integrated solution for the sealed contaminated soils of the Expo ‘98 developments; and, finally, a project that enables the connection towards the Sacavém train station and that forms the entrance to the Trancão river floodplain.

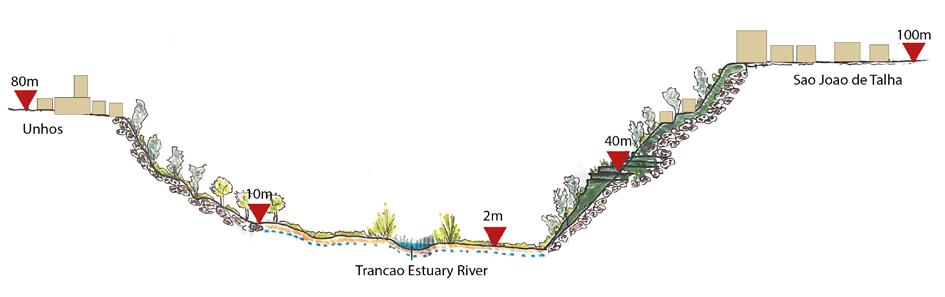

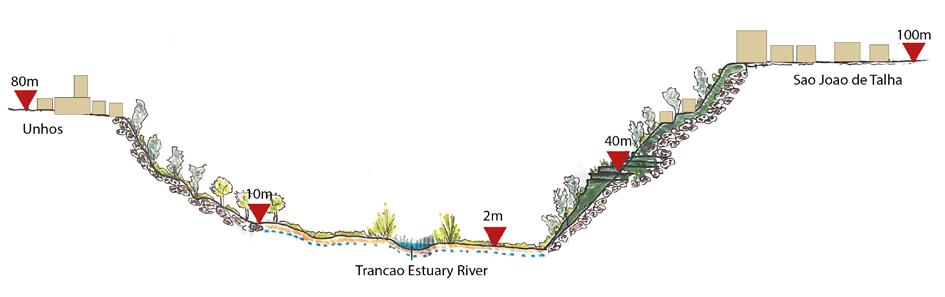

Geomorphological feature 2: the hillsides (costeiras)

The Trancão river reaches the Tagus through a narrow breach of a higher plateau along the Tagus. The strong topographic difference – an average of 75m difference, with a peak of 130m – characterizes this transitional geography between the river mouth downstream and the wide floodplain upstream. The high plateaus,

the hillsides and the low, narrow valley form distinct entities with different uses associated to it.

The narrow valley seems mono-functionally zoned: it is almost completely occupied by industry, or belongs partially to one of the few large farming estates (“quintas”) along the river. The high plateaus are generally urbanized as “edge of the territory”. Due to the strong hillsides, urbanization turns its back at these edges. The hillsides are “spacers” in between both. Precarious informal urbanization has been removed gradually as the slopes are an imminant danger for landslides under heavy rain, and fire propagation in dry conditions. Here and there, the hillside softens allowing a movement between valley and plateau. In these sporadic moments, a functional relation can exist between floodplain and plateau. How can the few connections between plateau and floodplain become meaningful places for the reclamation of the Trancão floodplains?

What kind of urban regeneration would be expected for these “fringe” urbanizations as Bobadela, São João da Talha and Quinta do Mocho / Terraços da Ponte? What role does the “Estrada Militar” play as a collector of fringes?

Geomorphological feature 3: the floodplain

Water and sediments accumulate in this wide floodplain that receives water from 180° directions before finding its way through the narrow passage towards the Tagus.

It is the most fertile landscape for the local ‘saloia region’ agriculture production. Urbanization has generally respected the outline of extreme flooding events –with the floods of 1967 as an imperative reminder. Nevertheless, the distinction between what is floodplain, valley and then where urbanization is located, is not as straightforward as in the other geomorphological features. Urbanization appears in a more dispersed and unstructured way which reduces the readability and functioning of the floodplain.

All aspects of the water cycle come together here: water treatment plants and reuse of treated water; natural wetlands with unique species and qualities (Paul das Caniçeiras); new wetland projects, former salt pans…

22

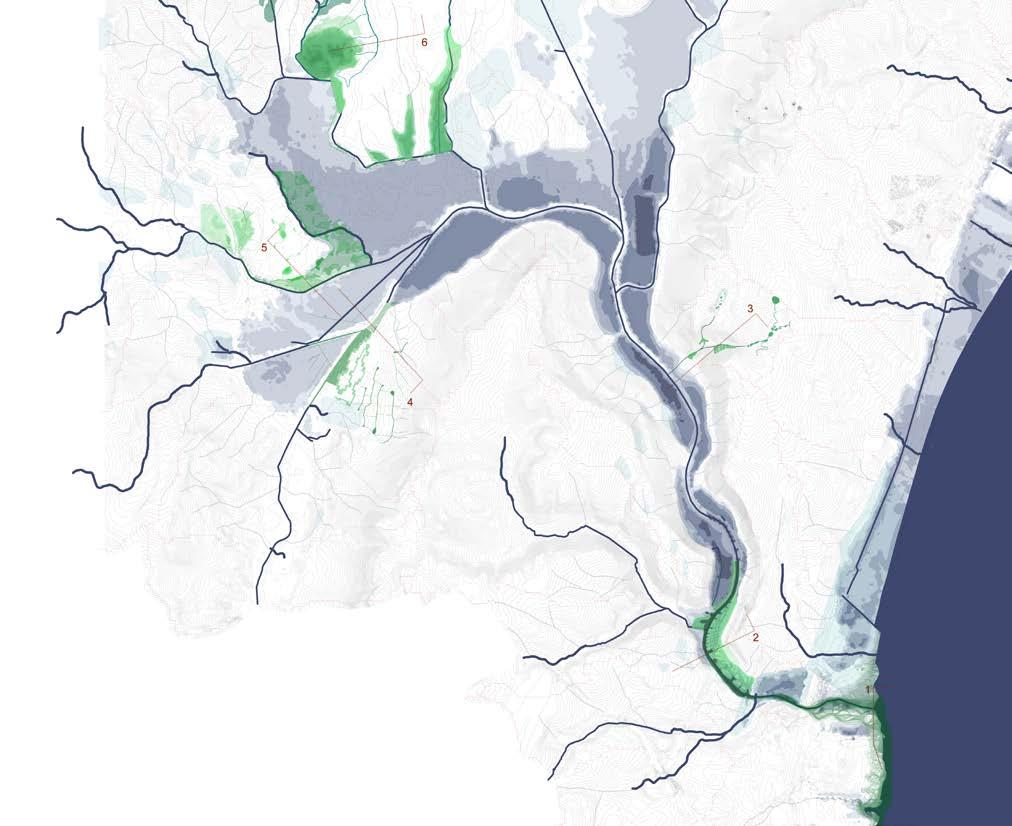

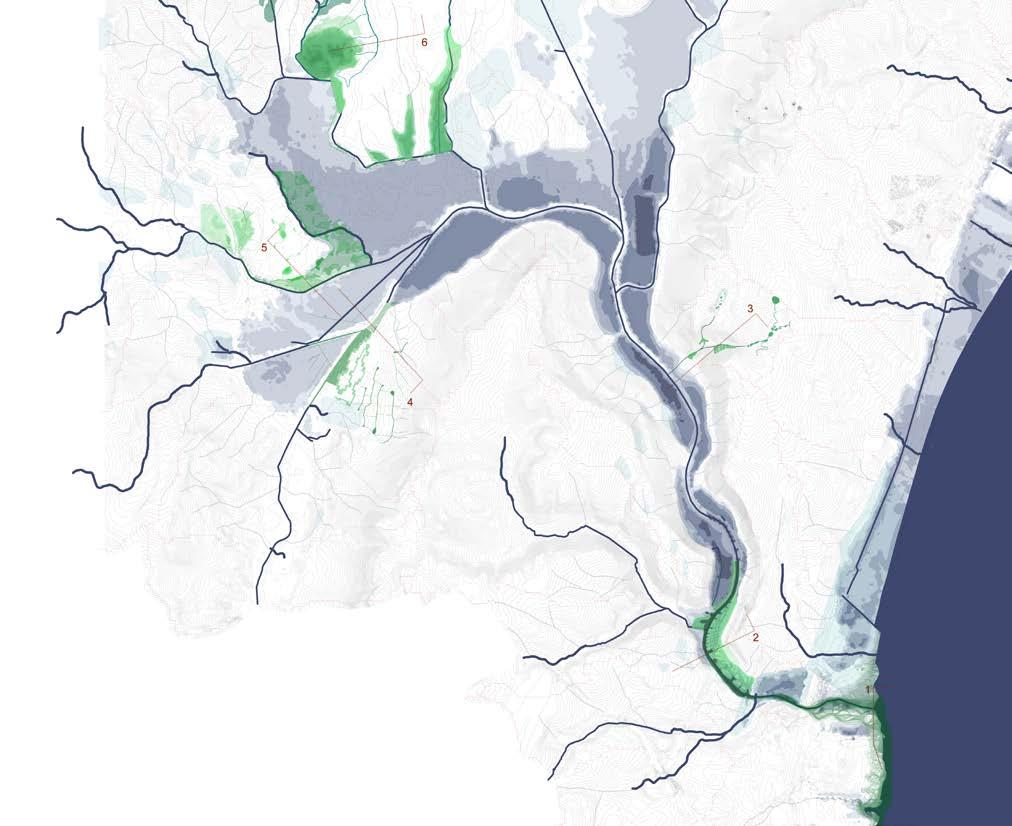

23 Trancão river mouth / Tejo confluence 1. 2. 3. Trancão Hillslides (costeiras) Trancão Floodplain 4. 5. 6.

© Studio Lisbon Mapping

Bike

Train

Bus

Indication of cases in relation to the geomorphological features of the Trancão floodplains.

Infrastructure Buildings Selected projects MetroPublicNet Walking paths

paths

line / train stop / Metro stop

line / stop Water / Streams / River Flood / Tidal movement

24

MAPPING THE FUTURE

25 02

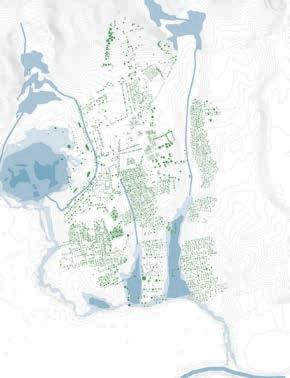

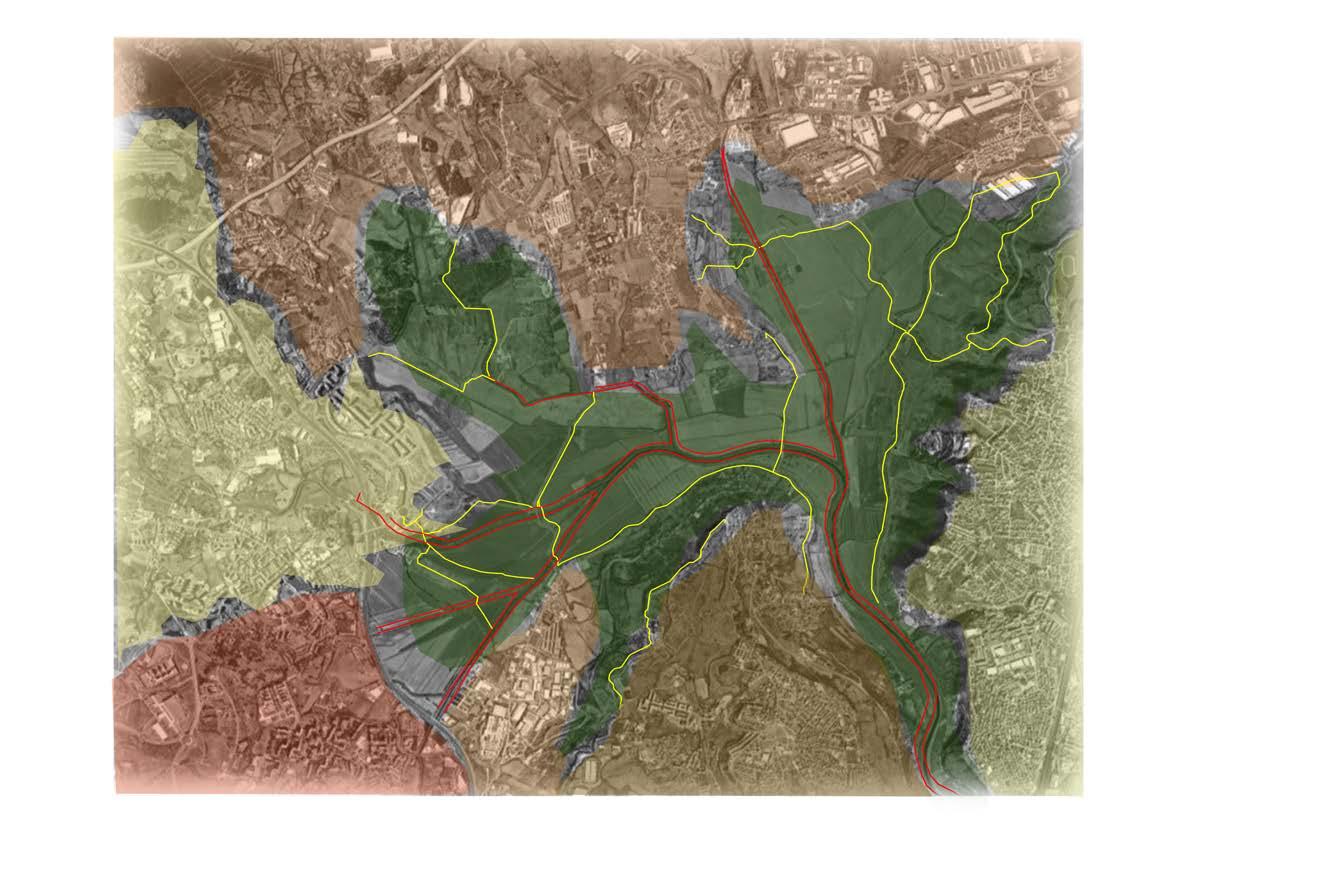

Trancão in the Tagus Estuary

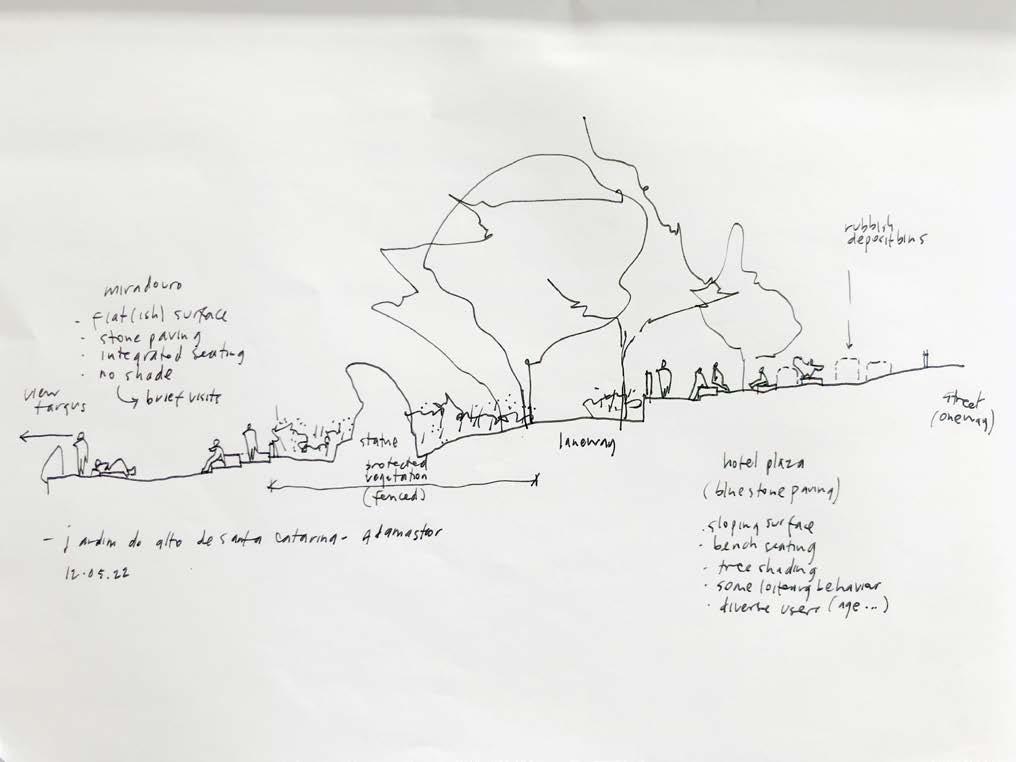

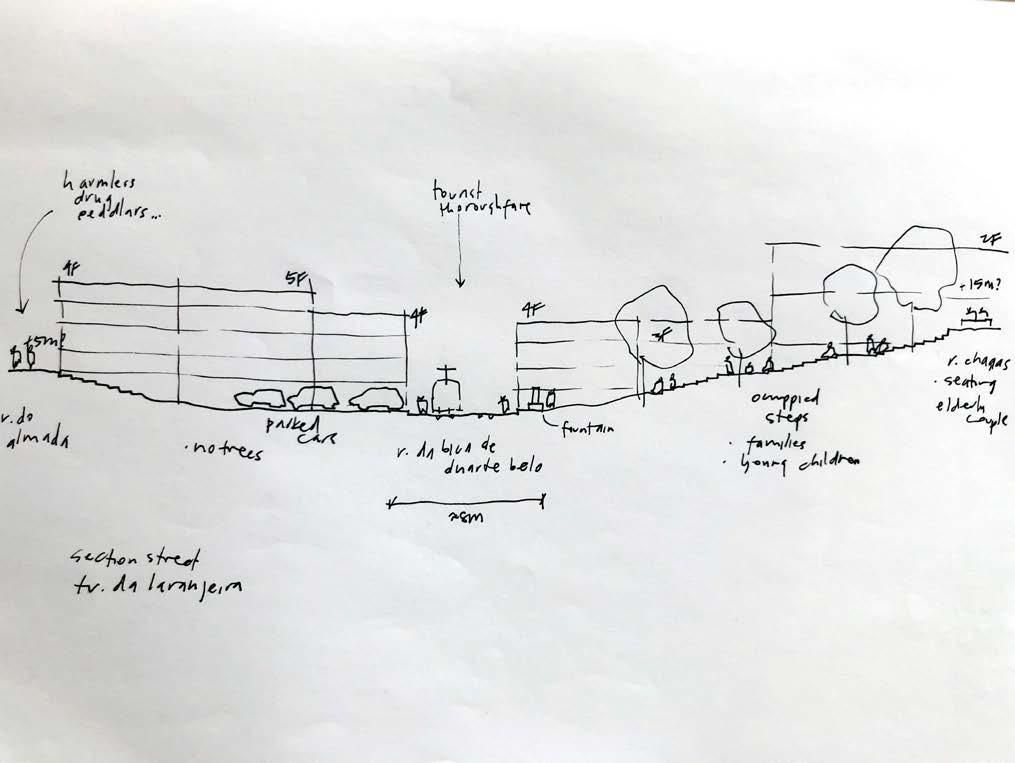

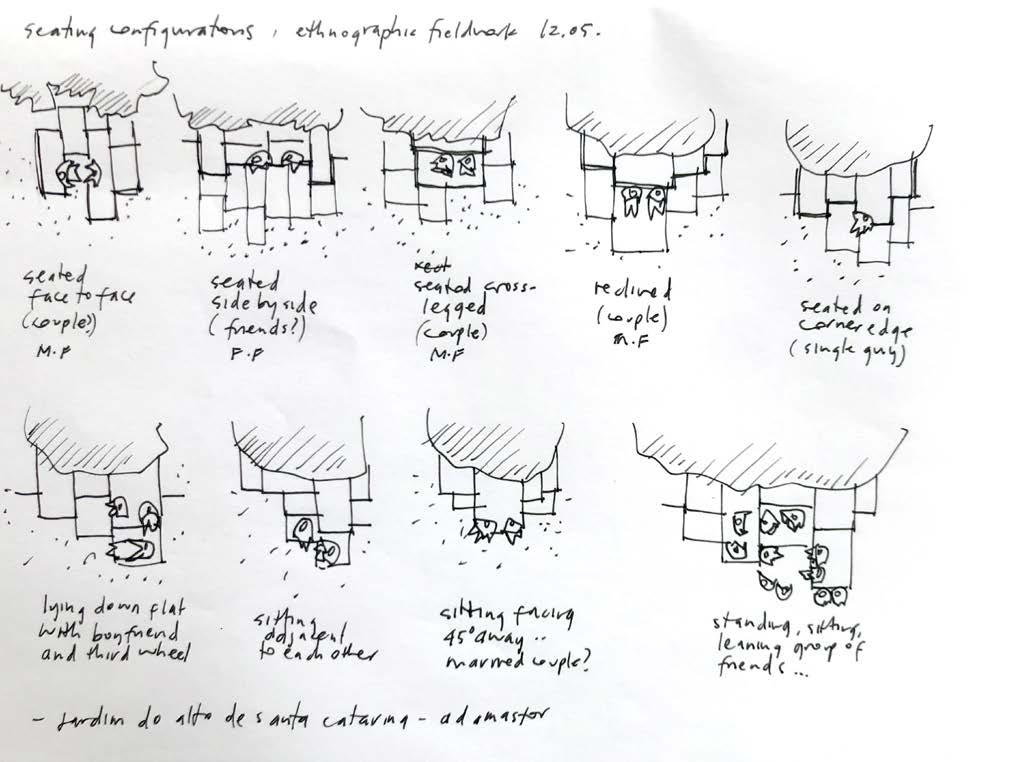

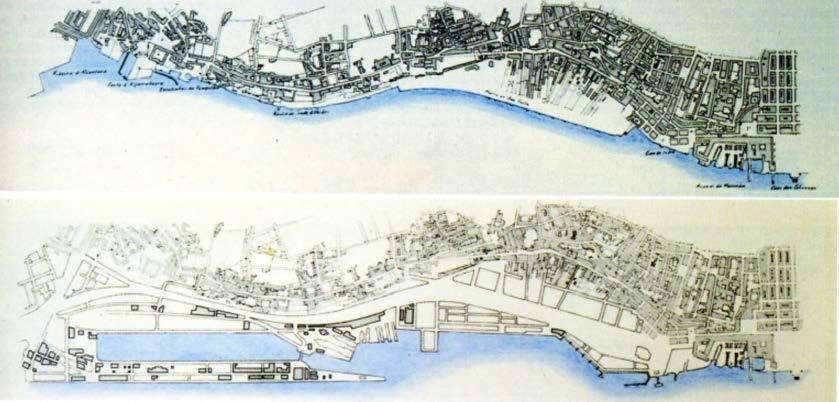

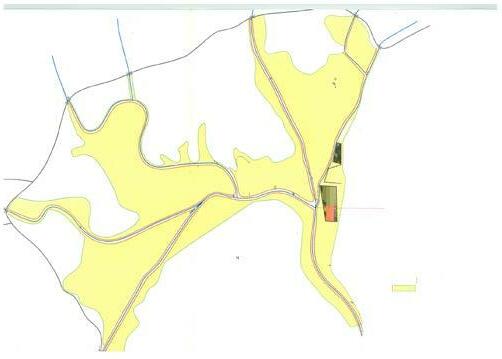

The Trancão floodplain is part of the Tagus Estuary. It is as if the estuary turns land inwards at Trancão. In earlier maps, Trancão was rep resented as such. Tidal movement was said to arrive up to Santo Antão do Tojal. Nowadays - and probably under the influence of the dykes and altered water system, the tidal movement does not reach so far anymore. Trancão needs to be rethought in relation to the estuary. With SLR, the estuary will anyways invade the floodplain again. Let's anticipate and image ho the norherns waterfront of the Tagus turns inwards along the floodplain of Trancão. With new estuarian (leisure) ports, maybe?

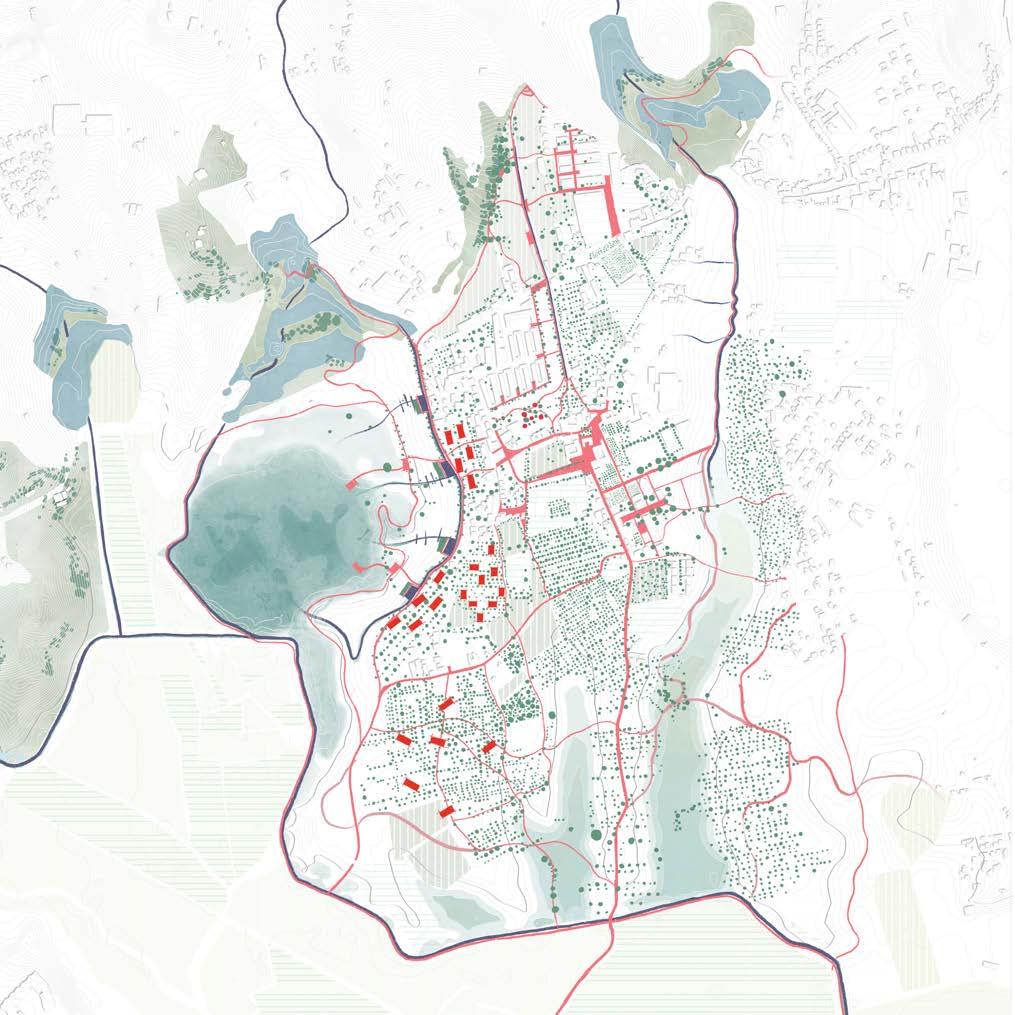

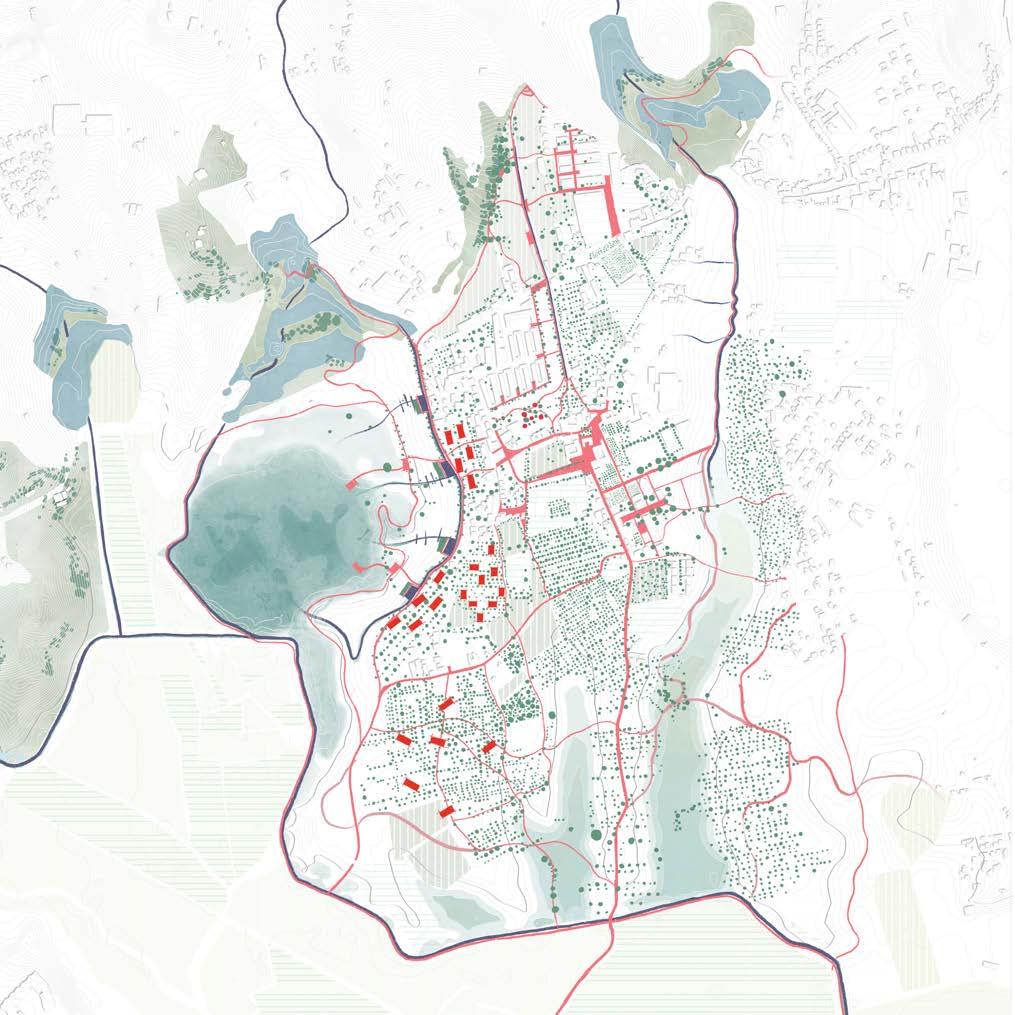

26 © SamanthaArbotante

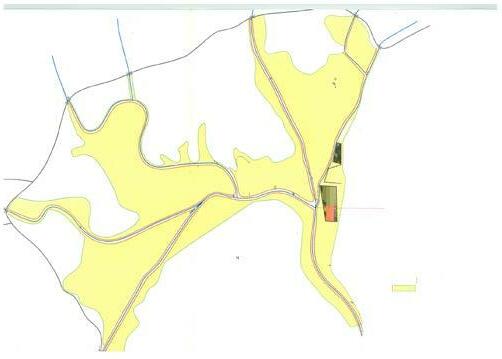

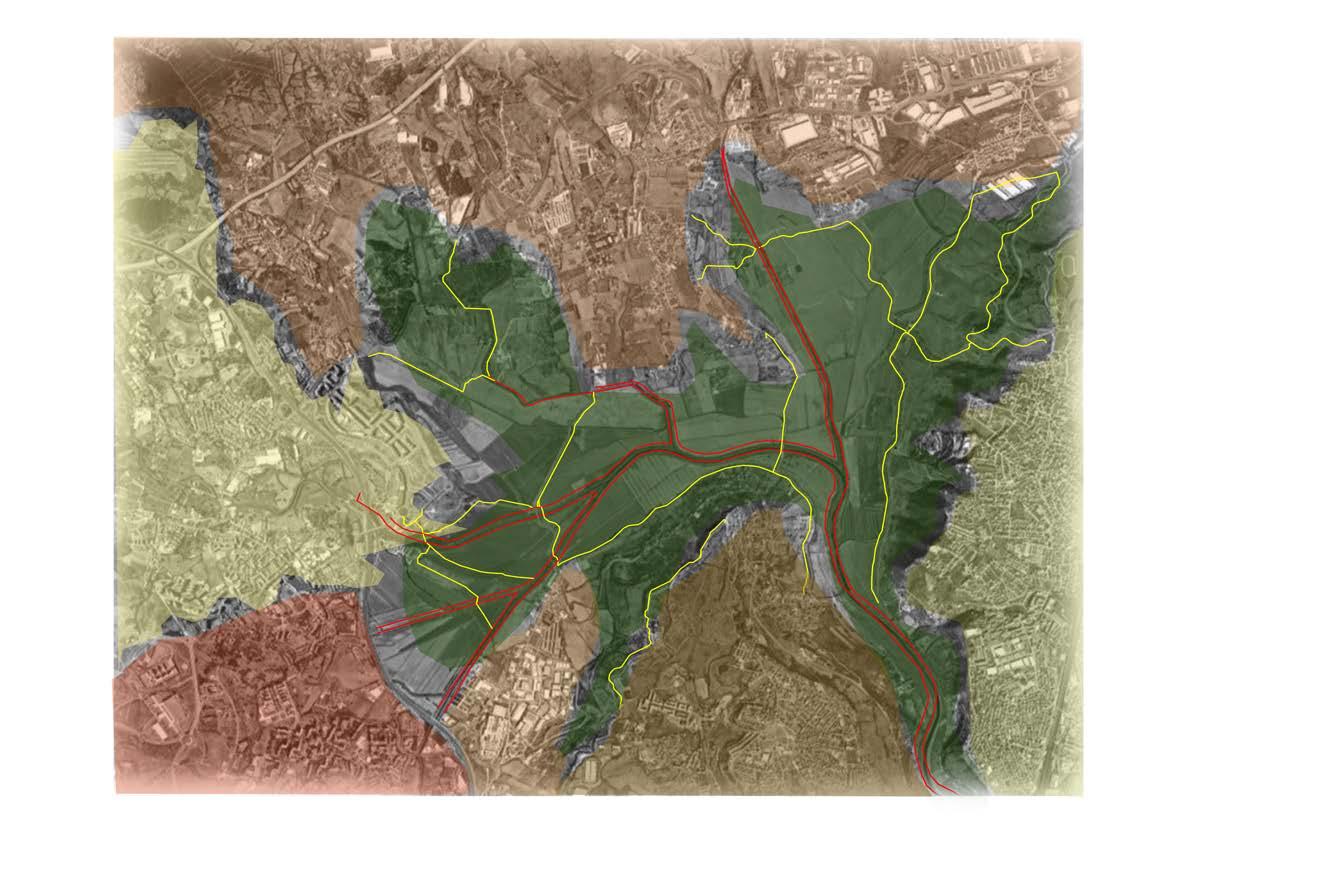

Map showing Loures, Frielas... and the straightening of the river courses (canalization).

1934 project for the recuperation of fertile land for cultivation, against flooding - dyke construction.

Trancão floodplain in time

Topographic map end of 19th, beginning of 20th Century, wetlands and salt marhes/production

The floodplain was gradually transformed from a natural wetland that flooded frequently and extensively into a dry floodplain for agri culture, first by straightening and canalizing the rivers, then by building high dykes to prevent flooding. Contradictorily, water needs to be captured from the rivers, run off of (partially) cleaned wastewater and eventually the formal water network of the city. A middle term between space for production and space to hold and store water is inexistent.

27

© Catalogo de Cartas Antigas, IGEO

© Campos de Loures, JAOHA, 1941

© Catalogo de Cartas Antigas, IGEO

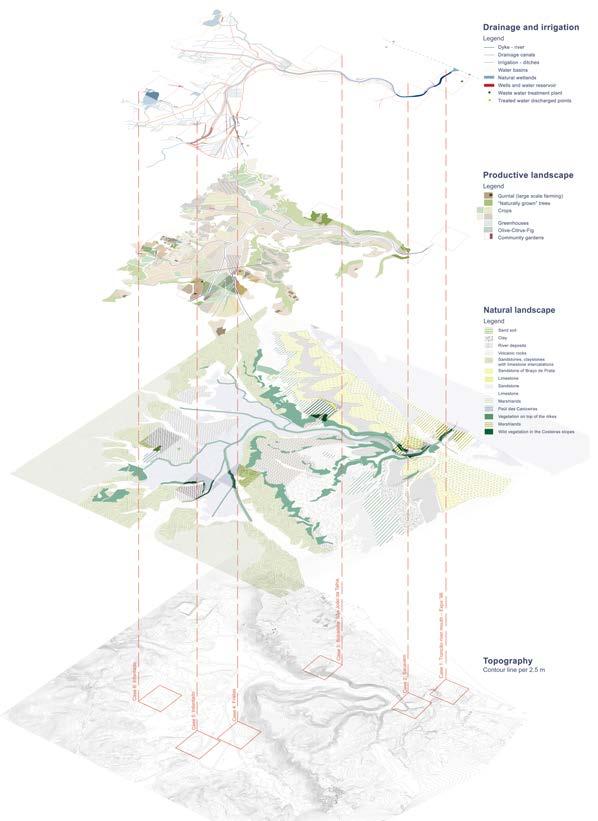

Dyke - River

Drainage Canals

Irrigation - Ditches

Water Basins

Natural Wetlands

Wells & Water Reservoirs

Waste Water Treatment Plant

Treated Water Discharge Points

28

Smallest draining ditches

Drainage Canals Dyke - River

Water Basins Irrigation - Ditches

Natural Wetlands Wells & Water Reservoirs Waste Water Treatment Plant Treated Water Discharge Points

Largest dyked rivers Drainage/irrigation canals + natural wetlands + treated wastewater + water basins

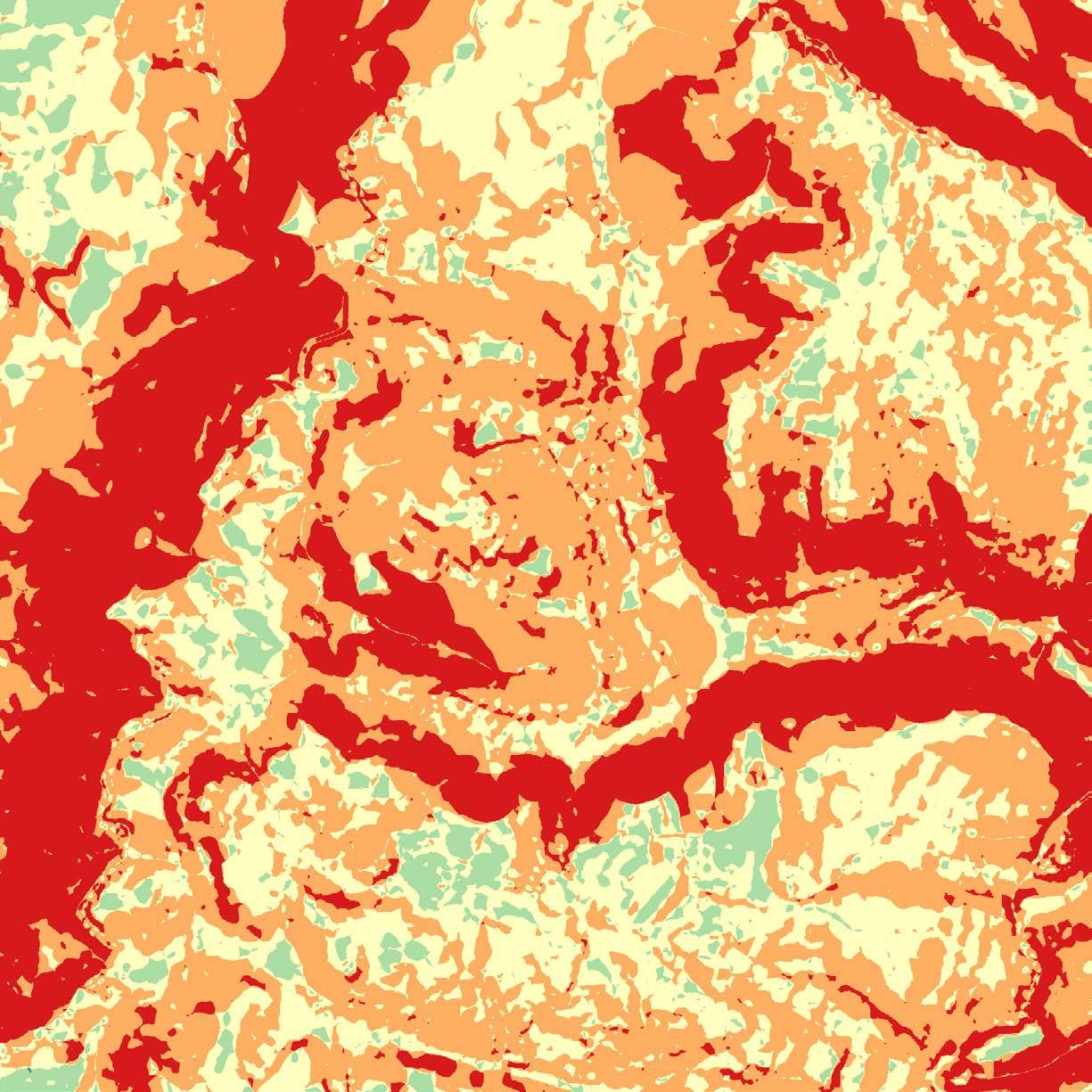

The water system

The water system consists of different types that either blend together as one system, or are designed to function as separate systems. In between the largest and the smallest hierarchies of water - the small drainage ditches and the rivers -, lies an extensive network of drainge canals that make the transition between the systems: the rivers that drain away upstream water; the ditches that drain the fields; the collector of treated wastewater; the provider of irrigation water; the controller of natural wetlands. They define drainage basins or entities that can be connected or disconnected to and from different systems.

29

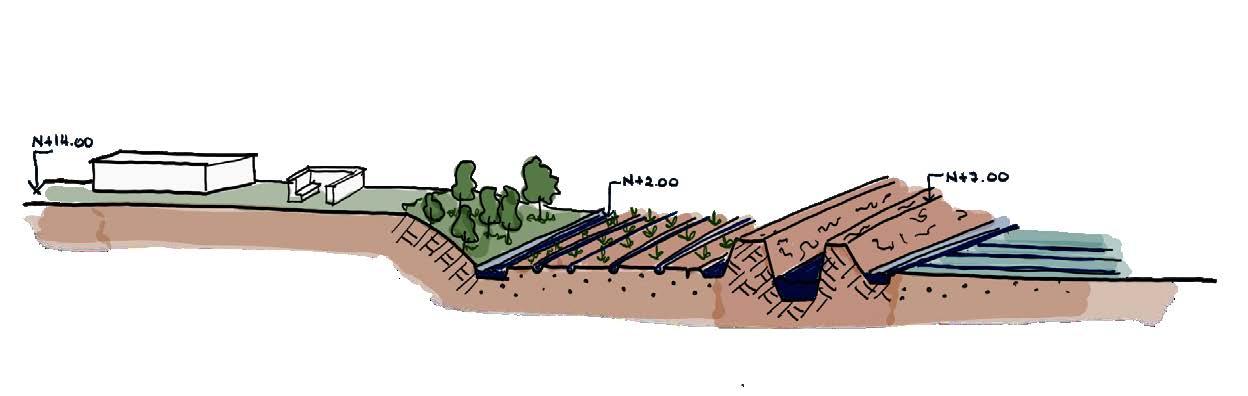

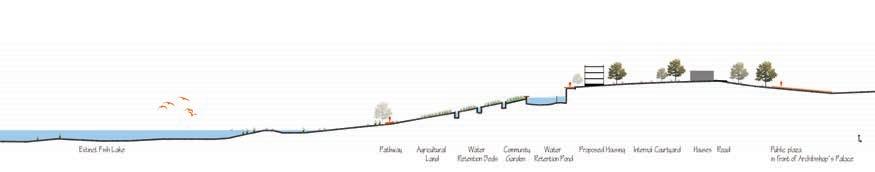

The existing water cycle / dyke the rivers

100yr storm / +4,5m

+7m terrestrial +2m

0m terrestrial -2,08m / 0m maritime

STRONG HILLSIDES

WATER TREATMENT PLANT / WATER FACTORY

SOFT HILLSIDES

AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION

LOW PRODUCTIVE FIELDS DRAINAGE SYSTEM

DYKED LOURES RIVER

XL INTENSIVE AGRICULTURE DRAINAGE SYSTEM

The proposed water cycle / protect the fields

+7m terrestrial +2m 100yr storm / < +4m

0m terrestrial -2,08m / 0m maritime

WATER TREATMENT PLANT /WATER FACTORY CONSTRUCTED WETLAND POST-TREATMENT

UPSTREAM WATER CAPTION SWALES / INFILTRATION

UPSTREAM - SPONGE

AGRICULTURAL

XL INTENSIVE AGRICULTURE DRAINAGE SYSTEM

STRONG HILLSIDES

SOFT HILLSIDES

WATER CAPTION SWALES / INFILTRATION

The existing water cycle / dyke the rivers

CONSTRUCTED AND NATURAL WETLANDS WATER TABLE REPLENISHING

LOURES RIVER REINSERTED IN NATURAL DYNAMIC

The existing water cycle is organized as a monofunctional system with the sole purpose to guide water from upstream quickly to the Tagus river and to drain the agricultural fields. High dykes run through the floodplain and define the water cycle as its experience as a landscape.

30

PRODUCTION

XO

XL INTENSIVE AGRICULTURE DRAINAGE SYSTEM

AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION

PRODUCTION

XL INTENSIVE AGRICULTURE DRAINAGE SYSTEM

DYKED RIBEIRA DA PÓVOA / TRANCÃO RIVERS RIBEIRA DA PÓVOA / TRANCÃO RIVERS REINSERTED IN NATURAL DYNAMIC

LOW PRODUCTIVE FIELDS DRAINAGE SYSTEM CAMINHO DE FÁTIMA CAMINHO DE FÁTIMA

UPSTREAM WATER CAPTION SWALES / INFILTRATION

DOWNSTREAM - TIDAL

EROSION LANDSCAPE

TIDAL LANDSCAPE PRODUCTIVE TIDAL LANDSCAPE

The proposed water cycle / protect the fields

TAGUS RIVER TAGUS RIVER

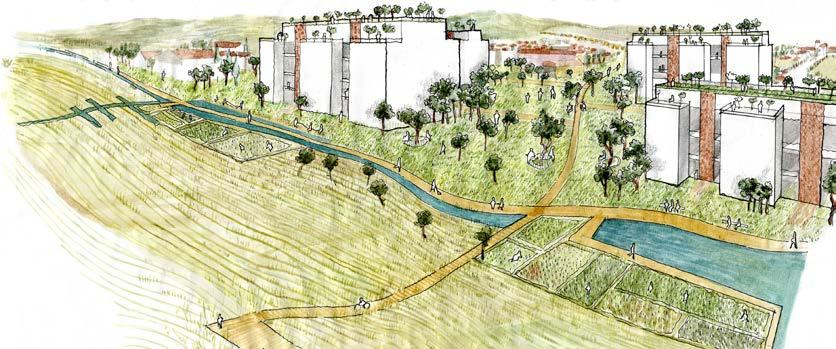

dyking the rivers protect the fields sponge tidal

A new water cycle defines a project for the floodplains of the river Trancão. Agricultural production is largely safeguarded by keeping some dykes that protect the fields. Many dykes are removed to be able to keep and store water on the higher parts of the floodplain (the sponge), an action that is demanded by climate change and increased drought. Also the tidal landscape is strengthened by this action, allowing to anticipate SLR and valorize its landscape (even as productive landscape). A monofunctional landscapes unfolds into three overlapping, interlacing and thus mutually enriching landscapes that strongly supports a more ecological future.

31

OX

New water landscapes (green)

The systemic approach to store water (sponge) and allow tidal movement (tidal) creates new large-scale water landscapes that partially restores the vocation of Trancão valley, yet with a form coherent with the diverse urban conditions and lifestyles.

32 © Studio Lisbon

33

Vegetation systems

The vegetation results from the systemic interplay between soil, topography, water availability. A reconfiguration based on a stronger tie with urban systems, and informed by the new water cycle, will allow for a more varied and richer vegetation, namely following geographic consistencies: the productive core, the sponge made out of natural and constructed wetlands, community gardens

34

© Studio Lisbon

Sand Clay River deposit

Vulcanic rocks

Sandstone, claystone with limestone intercalation

Sandstone of Braço de Prata

Limestone

Sandstone Limestone Marshland

Paul das Caniceiras Dyke heightening

Vegetation on slopes

Quinta (large farming estate)

Vegetation on slopes

Horticulture crops

Greenhouses

Olive-Citrus_fig trees

Community gardens

Trancão river mouth

Sacavém

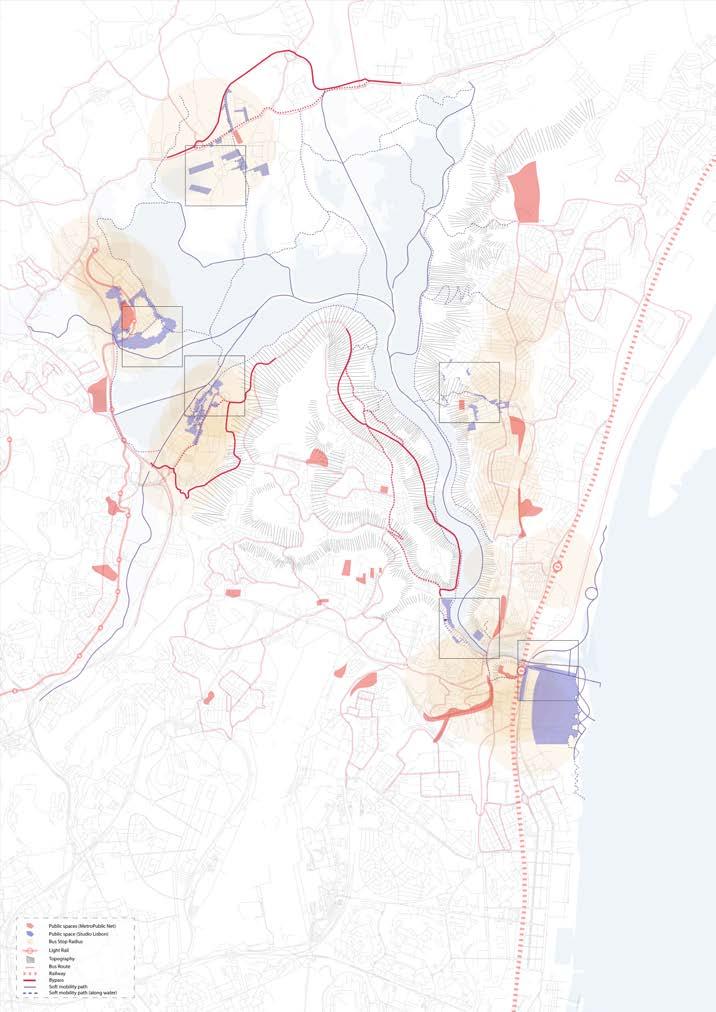

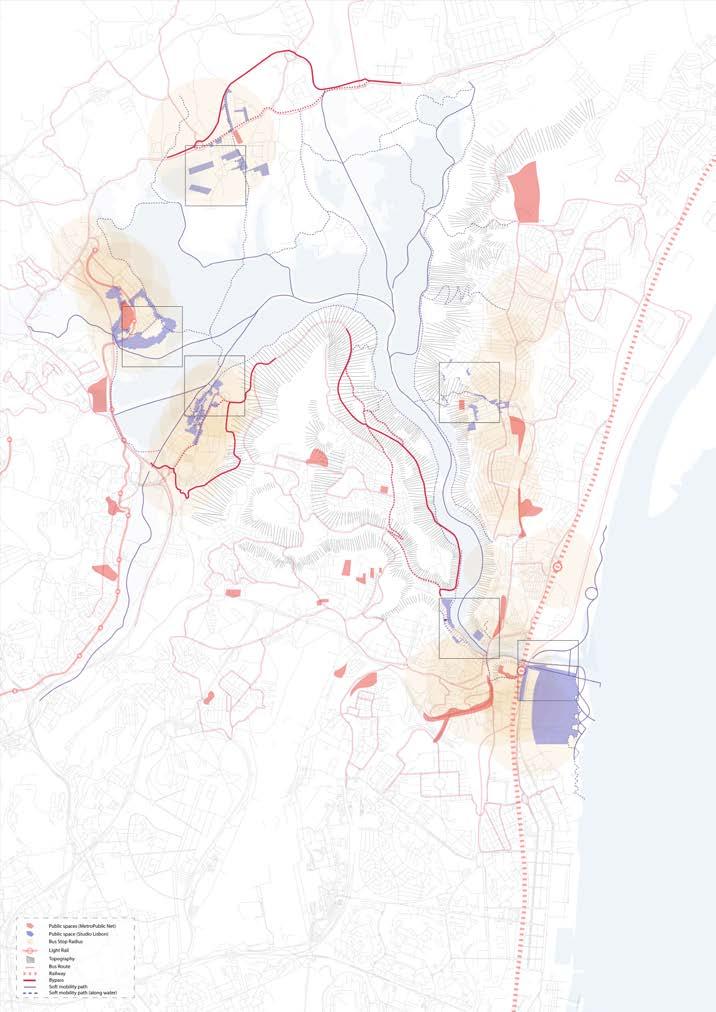

Public spaces MetroPublicNet

Proposed public spaces

Bus stop

Light rail

Topography

Bus route

Railway

Bypass

Soft mobility path

Soft mobility path along water

36

São

da Talha

João

A new mobility network

The mobility in and around the Trancão floodplain was rethought as two separate but well-connected networks. Within the floodplain, a soft mobility network of hike and bicycle paths provide leisure opportunities and safe direct connections in between the surrounding villages. Around the floodplain, fast through traffic is pulled out of the village centres through bypasses. Busses and occasional cars become mere guests in the pedestrian-friendly centres, which are carefully connected to the soft mobility network through diverse strategic interventions that vary depending on the specific circumstances (topography, distance to river...) of each surrounding village.

37

Frielas

Infantado

Santo Antão do Tojal © Arthur Van Lint

Hikers on top of one of the dykes along the Trancão river branch

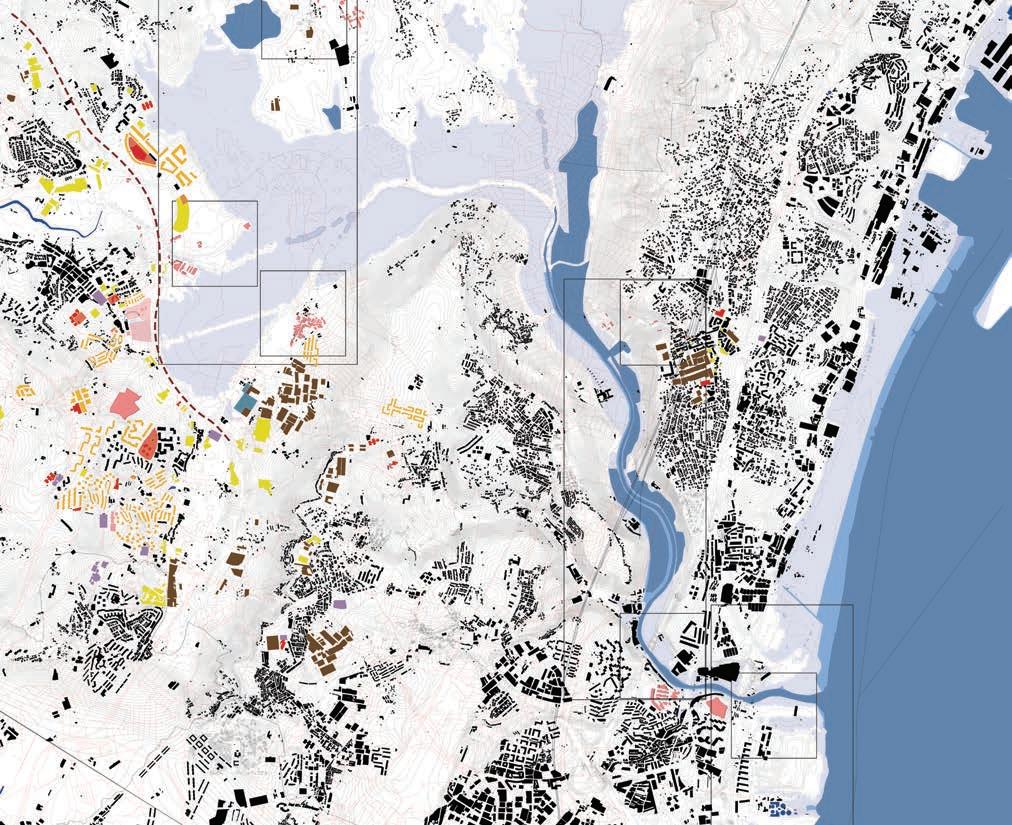

Historical settlements Collective housing ensembles Industrial Water related services Commercial Sports Education Health - hospital Cultural spaces

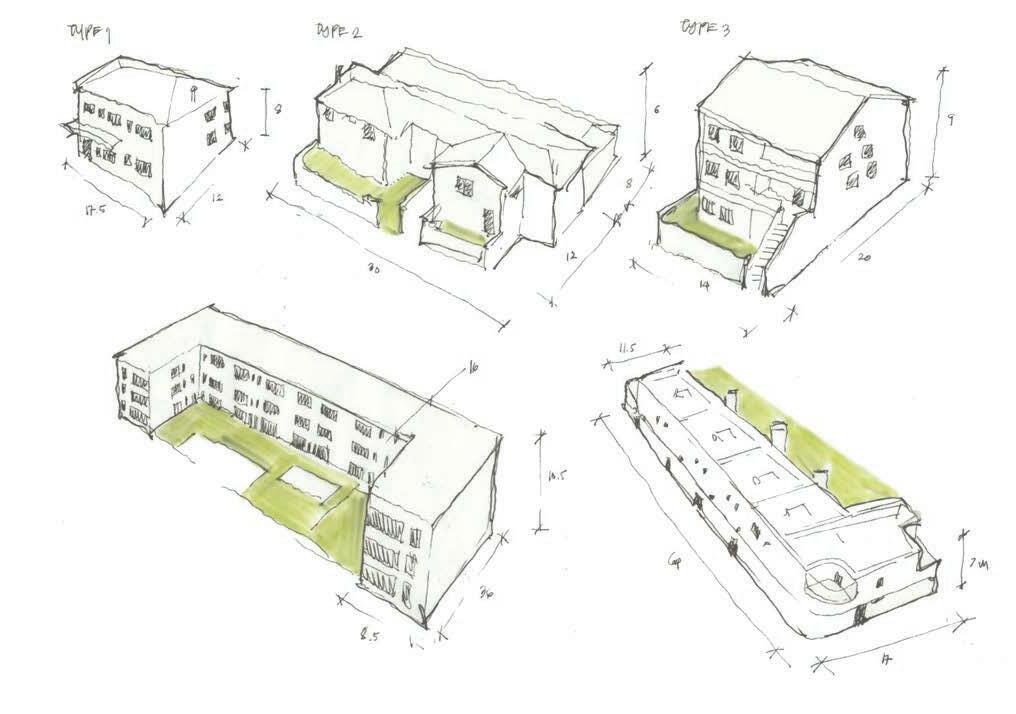

A way of living: services and typologies

The access to a wide range of services is generally difficulted due to the lack of efficiënt means of transport, and the lack of services in general. A formalization process is often ongoing, with the gradual, yet slow, provision of services. A wide range of typologies exist along the floodplain, suggesting a social mixity. Yet, there is a unequal spatial distribution. New often high end, large houses are built close to well-services urban centres, while almost no affordable housing is foreseen in good locations. The need for more balance is evident.

38

Trancão Floodplain Trancão Rivermouth

QUINTA DO PINTO, FRIELAS

Trancão Hillslides

BAIRRO NOSSA SENHORA DA SAUDE

BOBADELA

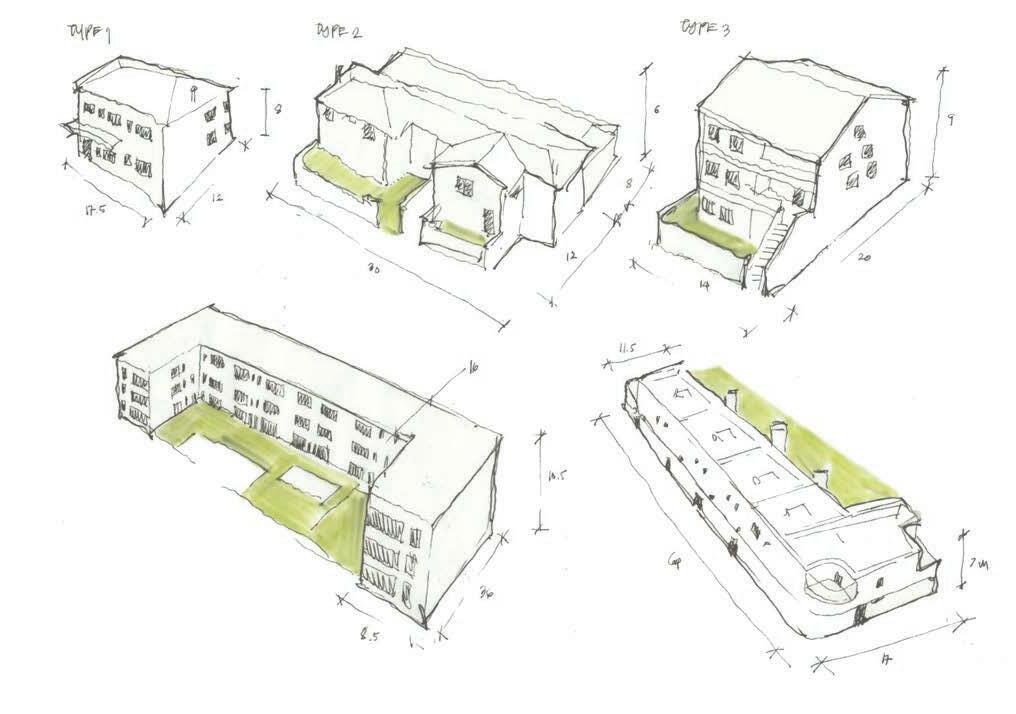

collective housing / floodplain soft slope / 3-5 storeys

SAN ANTAO DO TOJAL

single family, row house, collective housing / hillside steep slope, 2-4 storeys / 50 dwellings/ Ha / 200 m2

BAIRRO DA QUINTA DO MOCHO

single family house / waterfront river mouth / 2 storeys / 40 dwellings /Ha / 120 m2

QUINTA DA PARREIRINHA

single family house, row house / floodplain soft slope

FRIELAS

single family, row house, collective housing / floodplain soft slope / 1-4 storeys / 50

INFANTADO

collective housing / on hillsides plateau / 4 storeys / 96 dwellings/ Ha / 100 m2

BAIRRO QUINTA DA FONTE

collective housing / on hillsides plateau / 5 storeys / 144 dwellings/ Ha / 140 m2

PARQUE DAS NAÇÕES

collective housing / on floodplain plateau / 8 storeys / 150 dwellings /Ha / 160 m2

collective housing / floodplain plateau / 6 storeys / 170 dwellings /Ha / 85 m2

SÃO JOÃO DA

collective housing and single family house / hillside plateau / 1-4 storeys / 35 dwellings / Ha / 220 m2

collective housing / waterfront river mouth / 9 storeys / 130 dwellings/ Ha / 150 m2

SACAVÉM

collective housing / hillside plateau / 6-8 storeys / 96 dwellings /Ha / 120 m2

39

40 Trancão river mouth Tejo confluence / Expo '98 1. 2. 3. Trancão Hillslides (costeiras) Trancão Floodplain 4. 5. 6.

STRATEGIC PROJECTS

41 03

STRATEGIC PROJECT Case 1 - Foz do Trancão / Expo '98

43

NOVIANTARI SAMANTHA

GILLES

JULES

03.01

ARBOTANTE

HOUBEN

DESCAMPE

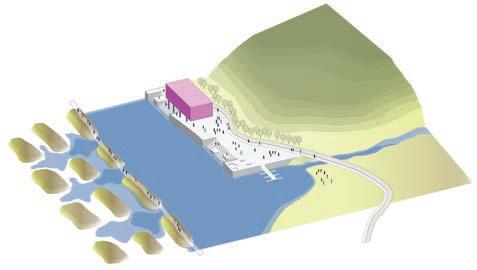

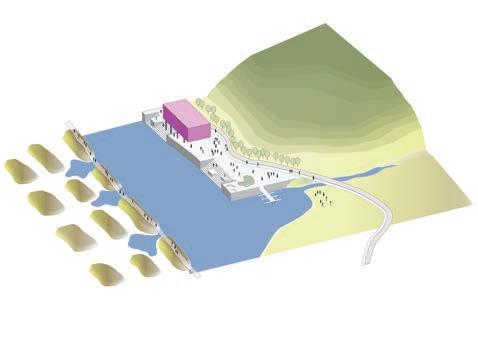

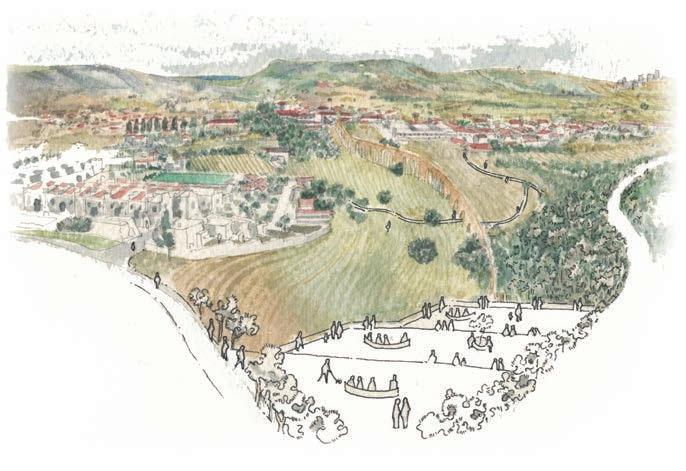

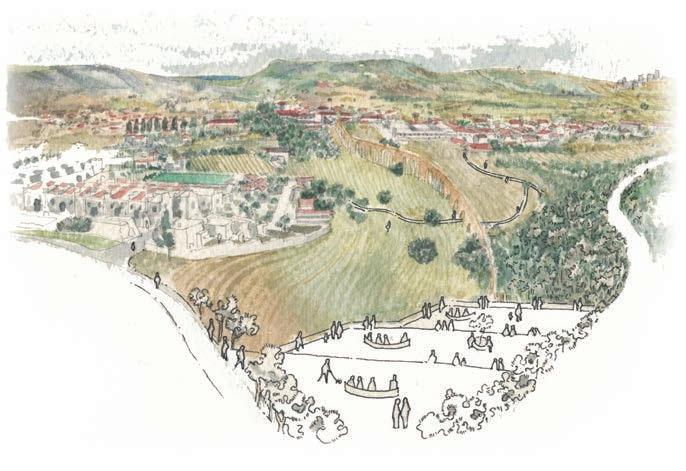

FOZ DO TRANCÃO: THE MEETING POINT

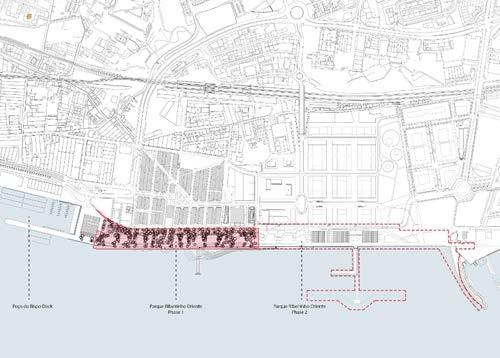

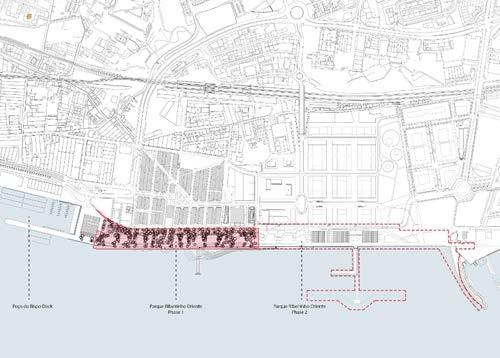

Foz do Trancão (the river mouth of Trancão River) is a conjunction between the developed side of Expo 1998 (Expo ’98), natural marshland, and the rest of the industrial site along the Tagus River coastline. The site is part of the waterfront public park of Expo ‘98. At the end of the park, a bridge was designated to connect the marshland on both sides of the river. As a remark of Expo ‘98, the waterfront development shifted the orientation from treating the water as a backyard to ap preciating water as a front place of urban life. Expo ‘98 is also a milestone for public spaces expansion in Lisbon Metropolitan Area (LMA). The construction of the bridge crossing the Trancão river has been initiated today. Later than the Expo ’98, the project of Loures River Front, suggests a continuation of accessibility along the marshland of Tagus river in Loures municipality and towards Vila Franca de Xira.

Nonetheless, the site remains as the unfinished leftover of Expo ’98. A wastewa ter treatment plant act as a transition between the fully developed Expo ’98 and the Trancão river mouth site. A landfill mound covering domestic and industrial wastes from post-industrial activities is predominant. A flowering meadow has now grown on top of the waste seal. A recent urban infill to the site is a sequence of apartment buildings and a public school. From the west edge, the infill initiates a dialogue to the previous development of the Expo ’98 with roads, railway, and Sacavem train station on the west side of the site. However, looking back to the remark of the Expo ’98, the latest infill seems reluctant to carry on the substantial impact from the shift.

1 The edge of Expo 1998, the Trancao river mouth, and the initiation of the bridge over the Trancao river potentially con nect marshland along the Tagus estuary.

2 Landfill mound with the flowering meadow, marshland of Tagus estuary, and soft mobility pathway in between.

44

Noviantari

1 2 3 © Noviantari

4 Sediment deposit and marshland as the evidence of upstream flow and tidal movement define the site along the east and north; view towards the road that define the site at the north

5 Sacavem train station and hillslope towards historical fort

6 The porosity underneath the road and railway connects the site

Tidal movement and upstream flow of Tagus to Trancao and vice versa define the space along the east and north of the site. Meanwhile, a strong line of the terraced hillslope, roads, and railway delineate the west side of the site. These strong lines of hillslope and heavy infrastructure have set the site apart from the Sacavém neigh bourhood on the west side of the railway. However, Sacavém train station halfway up the slope equips connectivity of the site to the territorial scale of LMA. Further more, a view of the historical Sacavém fort on the highest point of the topography set a vague relation between the site and the urban fabric on the west. Compared to the separation of east and west by the railway throughout the Expo '98, the giv en proximity to the train station and the fort might offer a chance of porosity to stitch cohesion between the neighbourhoods of Sacavem and the river mouth site. Too, topography differences from the upstream to the river mouth site could be an opportunity to weave the landscape of Trancão’s valley, floodplain, and marshland.

45

©

4 6 7 5

Noviantari

The valley and floodplain from upper stream Trancão to the marshland is a contin uous hydro-geomorphological and ecological system with the river mouth site as a critical meeting point for the fresh and saltwater of Trancão and Tagus rivers. The marshland ecosystem is formed by upstream flood, tidal movement, and different nutrient content in the water. It is a potentially biodiversity-rich environment that serves as a varying habitat and a defence from high tide or sea-level rise. Neverthe less, it is a vulnerable environment since the ecosystem is dictated by nutrient com position from the upper stream and the frequency and magnitude of the flood and tidal movement. Taking the waste landfill as consideration, the ecosystem might gain vulnerability from the contaminated soil while anticipating sea level rise. In that sense, awareness of the continuation of the Trancão floodplain's hydro-geo morphological system and promotion of better soil management is crucial to sus taining the marshland and its ecosystem services.

Apart from its ecological potential, the Trancão floodplain has a long history of being utilized as a productive landscape as we can see today in the upstream val ley and floodplain. Going downstream, the rural landscape shift into peri-urban settlements and industrial landscapes with fragments of community gardens. Compared to the coastline of the centre of Lisbon, the Trancão river mouth has a defining role in shifting the waterfront from a hard coastline to a soft meeting of green and blue. Taking disconnected urban cohesion and marshland ecosystem as the underlying starting point, the Trancão river mouth site is awaiting to be associated with the proposition for crisscrossing urban and ecological potential and challenges.

46

8 Modified floodplain to support agriculture in the upper stream Trancao 9 Community garden and social housing in the middle segment © Noviantari 8 9 10 11

Layers of biodiversity on the marshland

47 12

12 13 ©

Noviantari

Mobility in Foz do Trancão

Samantha Arbotante

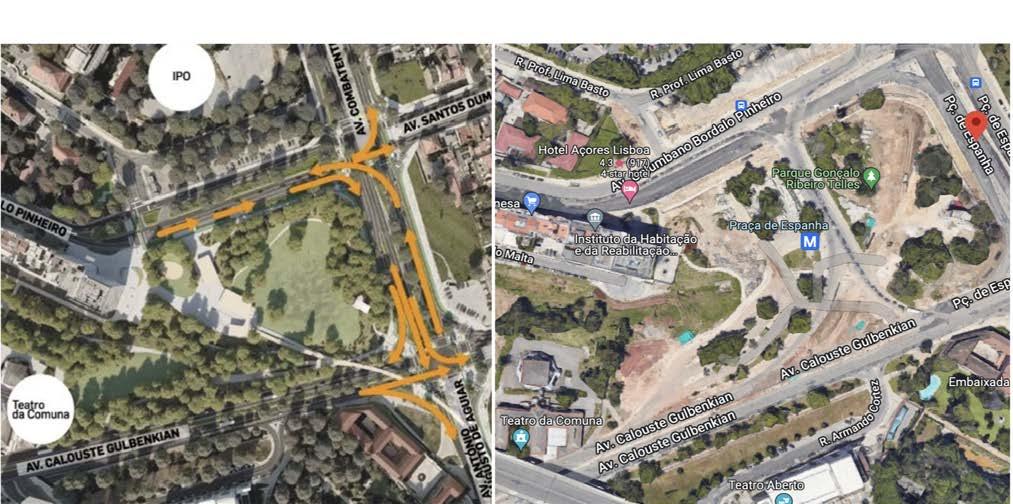

The massive investment of Expo 98 had provided a remarkable history due to the exquisite production of different urban infrastructures designed by star architects such as Santiago Calatrava, Alvaro Siza, and more in Lisbon. One of its planned projects, the Parque Tejo-Trancão, was conceptualized as a reclamation project in volving a post-industrial landscape. Focusing on the extension of the park on the south side below the Ponte Vasco de Gama, the neglected park development of the river mouth to connect the municipal districts of Lisbon and Loures on the other side known as the Foz do Trancão (Loures and Panagopoulos 2010). To un derstand the context, a series of fieldwork was conducted to identify the existing roles and gaps in the connectivity conditions of the assigned site and examine its accessibility from various multimodal transportation alternatives in detail.

In a macroscale view, the site encompasses potential through sequences of des tinations. In the north, the Trancão river has an ongoing project of a soft mobil ity bridge connecting to an envisioned Loures riverfront. At the east, the existing footpath on marshland provides a link with water as it faces the largest estuary, the Tagus river. From the south, the Jardim do Passeio dos Herois do Mar is a walkable distance leading visitors to enter the Expo 98 complex. On the other hand, a main transverse highway of A30 (Fig.1) and the train railway situated on the hilly west of the site block access to significant historical areas such as the Forte de Sacavém, Sacavém Ceramic Museum and the Sacavem Train Station. Currently, the A30 highway may seem to connect logistics to the industrial areas of the Loures river front. However, this line only loops around and serves as a supplementary road to the main highway. These infrastructures are the causes of the gap across the urban fabric from the north and the river mouth.

Looking closer at the existing soft mobility, even if the site is relatively flat, cycle paths were provided in limited ranges restricting smooth transition from Sacavém towards the area of the Expo. The Colégio Pedro Arrupe, a private educational school along with the housing blocks of the Urbanização Parque do Rio, provided wide pavements to easily walk and safely move from school to the commercial spaces. Meanwhile, with poor circulation, absence of direct entry points, and pe destrian paths from the housing areas in Sacavém disallowed direct walk as inter ested buyers must navigate around the hill. This option takes a longer period due to the travel distance despite the fact these are adjacently close on the map. One pos sible impact of this condition is the fast turnover or decrease of commercial renters due to the location’s inaccessibility. renters due to the location’s inaccessibility.

Towards the location, impervious parking spaces dominate the area encouraging private transport usage. Locals were observed parking their cars at the nearby park ing area below the A30 before entering the marshlands of the river mouth where they follow footpaths to go near the water. For multimodal options, the public can

In line with the Move Lisboa: Strategic Vision for Mobility 2030, new strategies are to be implemented to develop and pursue reliable mobility and urban accessibility. The first is to rethink the existing impervious roads and repurpose the A30 into soft mobility options to provide new entry points through the highway. Also, in spired by the prevalent usage of walk bridges around Lisbon (Fig.3), installing new footbridges aiming to connect the Sacavém Fort, train station, and housing areas will provide more alternatives to direct access. Second, by collectively emphasizing the potential of the Trancão river mouth and its neighbourhood, we can reactivate potential points to be recognized as a series of destinations by developing new cy cle routes and pathways to relate the parks, link one historical landmark to another, and to reach the site to Loures riverfront. These will allow locals and visitors to encounter smooth transitions from various environments. In this way, we enhance the potential of being a new waterfront destination for more active and educational activities and a new sustainable tourist development incorporating the site to the entire vision of Expo 98.

Lastly, by using the network of the Tagus River and Trancão as the city’s infra structure, providing waterway options and new leisure activities such as jogging, strolling, and kayaking will allow new experiences while reliving the historical us age of the river to transport from one place to another and redirect focus back on the water.

Fig.1: Main Transverse A30 Highway

48

49

Fig.2: Existing location of bus signages on poles and discontinued cycle paths

© Samantha Arbotante

Fig.3: Taking inspiration from existing walk bridge near the site

Fig.4: Using the Tagus River and Trancao as city's infrastructure for new activities

© Samantha Arbotante

© Samantha Arbotante

Urban cohesion in Foz do Trancão Jules

Descampe

A critical position in the territory.

Located at the confluence of the Tagus and Trancao rivers, site number 1 constitutes a small portion of the coast of metropolitan Lisbon. It shares its thickness, pinched between the railroad and the Tagus coast, with numerous ensembles forming the river front of the Capital and its periphery.

Once there, it takes a moment to understand that the immense scale of the few buildings and the expanses inked in its landscape. These represent the legacy of the large plans imagined in 1998 for the Park of Nations of which it is part. While the planted park of the Expo 98 complex constitutes one of the most frequented parks in Lisbon for its rich biodiversity and public facilities, it is interrupted by the wastewater treatment building at the edge of our site. This boundary, formed by the set of infrastructure and buildings closed to the public, marks the beginning of what was designed as the second part of the park: the former public dump. Nowadays, this huge sealed surface covered by a vast landscape of high grass constituting more than half of the vegetal park is made inaccessible due to the pollution of its soil. Its topography, its enclosed condition, its polluted status and the lack of biological diversity of this old dump creates a caesura beyond which, a huge deserted parking lot testifies to an unfinished plan still marked by its industrial harbor past.

In spite of this broken north-south sequence, a delicate path at the edge of the marshland keeps the different parts of the site together. Following this path from the center of the park of nations, we end up on this large desert surface facing the

50

In spite of this broken north-south sequence, a delicate path at the edge of the marshland keeps the different parts of the site together. Following this path from the center of the park of nations, we end up on this large desert surface facing the Trancao, its marshland and in the distance, the coast of the Lisbon metropolitan area bending to let the possibility of apprehending it in its whole. Heading towards the east of the site we come up against the brutality of the wide topographic and infrastructural barrier formed by the 8 bands of the highway and the railroad. This thick limit makes impossible the contact with Sacavem so much physically, audibly that visually, isolates completely the end of the park of the expo 98 of the rest of the basin of the Trancao.

The whole land is then shared between many issues at the landscape, ecological, urban, mobility, topographic, programmatic and land form levels.

- First of all, this situation requires special attention to the encounter of the Tagus and the Trancao River. This meeting must be understood as the contact of two major territorial figures: the Trancao basin and the Lisbon riverfront and its prefecture. Each of these figures has its own biological, hydrological, urban and topographical characteristics that must be treated on a currently deserted, mineralized, enclosed and polluted site in order to restore the authenticity of the territory.

- Secondly, the connection of the first interventions aiming at developing the connections of the localities and the zones of interest by soft mobility along the coast while developing its unique landscape qualities constitutes a second important stake of the site.

- Thirdly, reconnecting the site to the Park of Nations, finishing the park while succeeding in offering a transition with the marshland located north of the Trancao constitutes a major challenge to affirm the identity of the site and its location in the great territorial figure of the Waterfront.

- Finally, it is important to increase the permeability of the park with the Trancao basin and the innerland communities. To do this, the barrier constituted by the highway must be redefined and the railroad crossings rethought.

51

Urban cohesion in Foz do Trancão

Gilles Houben

Gilles Houben

A Site of Limits and Beginnings

At first glance, the site that evolves along the south waterfront of the Trancão river mouth seems to be restrained by clear limits. The Trancão and the Tagus clearly define the northern and eastern borders, while large mobility infrastructures such as the railway and the large A30 road run alongside the east. Even politically, the site is located at the very limit between Lisbon and Loures municipalities. But standing at such a crossroads of urban and landscape structures implies not only to consider these as limits, but also as beginnings, stepping stones, to a much larger scale. Indeed, the Trancão river mouth in Sacavém can be seen as the start of the river’s floodplains, the Tagus waterfront relates to the large waterbody between Vila Franca de Xira and Alcochete, and the mobility infrastructures insure connectivity to distanced urban areas.

In that sense, this territory is regarded as a multi-scale entity around which the urban and the landscape unfolds into large structures. This intermingling of water and city is understood as a key identitary feature for

Identity and Neighborhood, an Urban Cohesion

The whole portion of territory here considered is part of the Park of Nations, and form its northern edge. The large sealed surfaces attest the intentions of the master plan established more than 20 years ago, and have patiently waited to be built ever since. The housing towers have gradually spawned since 2004, and following the 1998 master plan, still remains the constructions of shops and various amenities. The college Pedro Arrupe was constructed early in the 2010s although formerly not included in the intentions of the Expo ’98 master plan.

52

The bridge that is set to be soon built over the Trancão river will carry intertwined changes for the site. The main goal is to extend the Park of Nations further up north, to include the raw land alongside the Tagus waterfront. But by doing so, it also requalifies the here-considered site, which will switch from being the edge of the Park of Nations to being another step.

While it is quite self-evident that the site has a lot to benefit from the cultural heritage of the ’98 Expo, it has to be noted that such an enormous urban project lead us to investigate how can a neighborhood and a community can evolve in this environment of “big buildings”. Indeed, stepping off the train at the small Sacavém station and strolling towards the site, it becomes striking how everything starts drifting away from human scale, from the roads infrastructures to the large unbuilt sealed surfaces.

On the other hand, when strolling between the housing towers and through the commercial street, where more localized settings such as playgrounds and terraces do exist, they lose their ambiance of “place for the community” in endless large rectilinear streets, and fifteen storeys high buildings. Also, the identical architecture style of the numerous housing towers as well as the repetitive parking lots leave no room for anomalies in the network of public spaces. Pedestrian then wander around similar spaces that are neither complementary nor hierarchized.

The argument here is to express how the recent cultural heritage from the Expo and the water landscapes mentioned before can set foundation to formulate a “sense of place”, while acknowledging that individually, they are not sufficient to truly generate the identity of a neighborhood. For example, while walking near the housing towers, you lose the bond to the Trancão river, as well as the Tagus water front, and vice versa. This area then sets up an unwelcoming scene for curious pedestrians, and it seems like the strong cultural appeal from the core of the expo district, filled with amenities, doesn’t radiate enough to reach this part of the park.

53

The site then sits in a mixed context. Too far to actually benefit from the cultural heritage of the ’98 Expo, while also still having built surfaces and volumes that kept its scale. This ambiguity hinders the establishment of a “sense of place”, a “sense of local community”. It might be timely to start strengthening the interactions between the culture heritage, the buildings and the landscape features to create this sense of place, to then define a distinctive identity and a more local character of the neighborhood.

54

55

Reclaiming the river mouth

Noviantari Samantha Arbotante Gilles Houben Jules Descampe

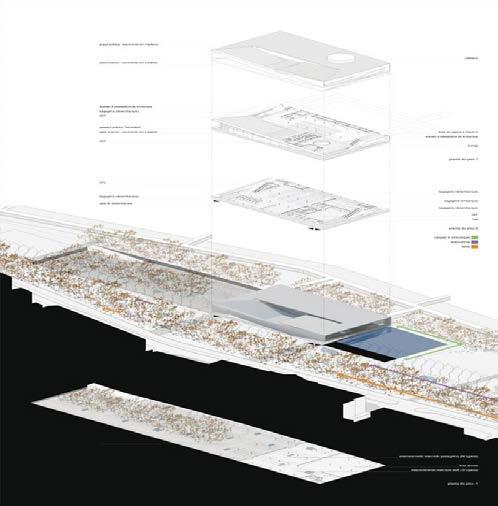

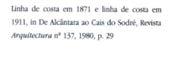

The narrative of the project is introduced by a very present and defining figure in the urban structure of Lisbon. This figure highlights the thickness pinched between the continuous line set by the railway, and the more angulous line formed by the waterfront.

Like many major settlements that grew alongside main territorial estuaries, the development of Lisbon was greatly influenced by the industrial sector. Thus, it becomes quite evident that this thickness has had its land use dominantly occupied by industries, punctuated by railway stations and harbors. Even today, this layer is still marked by this industrial heritage, making it impermeable and generating distance between the waterfront and the citizens.

That is why in recent history, the city of Lisbon has put efforts into making this thickness more pervious. With the Praça do Comércio being the oldest public space directly connected to the riverfront, the Expo ’40 of Belém initiated the reconquest of the waterfronts by public spaces. The whole Expo ’98 district, the here-considered case study, thereby fits into this story.

By mapping the green spaces and interventions that aim at reclaiming the waterfront, we see that they are fragmented along the figure. This fragmentation evidently implies a fragmented soft mobility network, and we then understand that they work as individual interventions that step by step, we ease up the establishment of the desired continuity. Closing this introduction and arriving at our site, we quickly acknowledge that it stands at a crucial location in this urban figure. Indeed, the meeting of the Trancão and the Tagus entail the waterfront to bend and create a deeper interaction with the inner lands. This phenomenon is quite unique, as it is the very last confluence of the Tagus, before joining the ocean. The potentials of reconquering the waterfront are quite substantial here, as we address two different but interconnected waterbodies. Zooming in on the case study, we observe : - an oversized hard mobility infrastructure, that cuts the marshland and makes the thickness even more impermeable

The project that we’re about to present tackles these potentials with the aim of fitting in the story of reclaiming the waterfronts of Lisbon.

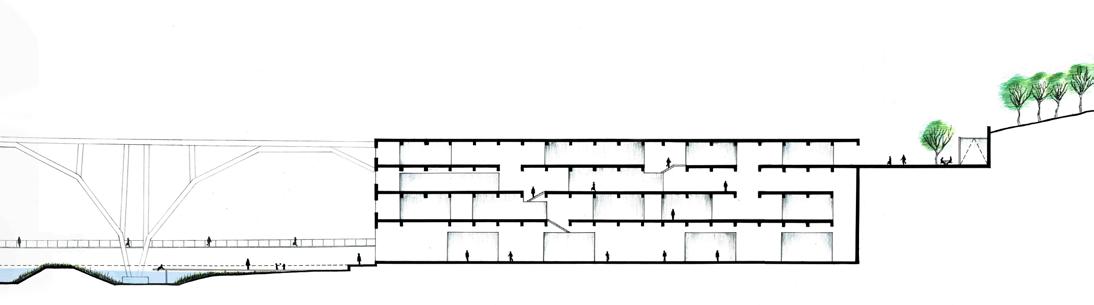

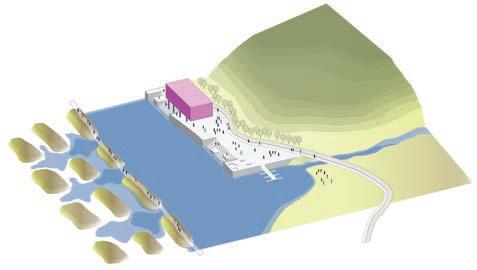

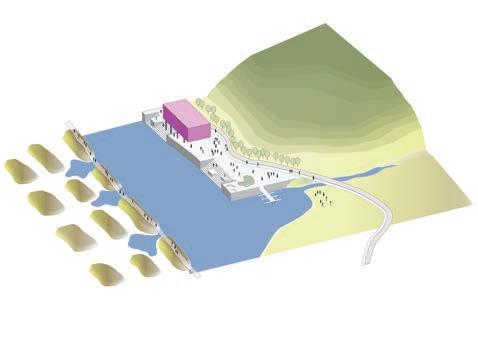

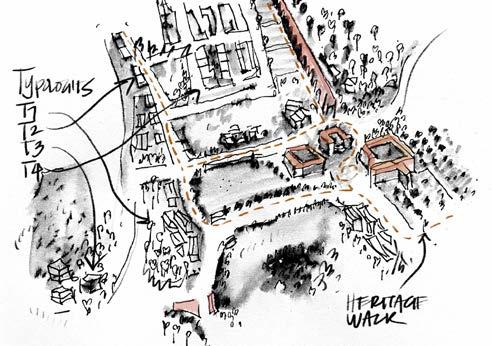

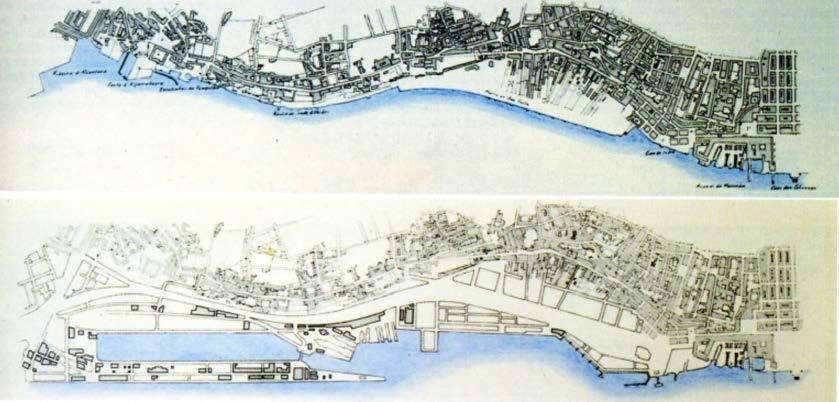

To start things off, we remove a portion of the road, by only keeping the lanes that are valuable connections between th e Sacavém and Bobadela neighborhoods. What we remove is nothing else but an oversized and poorly used infrastructure. Doing so will unify the marshlands between the railway and the waterfront, give more space to the new Topiaris project that is set to settle there, and finally, it will enable new connections between the Expo ’98 and Sacavém, across what we envision as a requalified urban boulevard.

Then, we emphasize the presence of the marshland. Doing so will bring a strong and recognizable identity to the site, standing at the very corner shaped by the meeting of the two waterbodies. This objective is achieve by two different interventions. On one hand, desealing the large mineral surface will grant the Trancão more freedom to evolve through its erosion process. On the other hand, we suggest various topographic displacements of the waste land site, mainly a cut and fill to give more space to the marshland and create few mounts on top of the hill, that repeat the iconic shape of “teardrops” of the smaller mounts already present in the Park of Nations. Additionally, we propose to add new clean soil on top of these mounts, so they can welcome vegetation, to turn it into a habitable park.

We finally make two interventions on both side of this mount. On the south side, we suggest to decluster the water treatment plant, by revealing the adjacent former water stream and reorganizing its various components. On the north side, a single urban intervention works as a stitching line for all the components of the site, such as the fort and railway station of Sacavém, an enclosed college, the park as well as a new neighborhood that is set to end the housing figure of the Expo ’98 district. At the same time, various water related arrangements such as piers and outside pools evolve alongside this linear structure. All of these proposals have the strong intention to restitute the true landscape of the riverfront to a strategic site, currently a true no man’s land leftover from the Expo ’98 master plan, while increasing its accessibility and its social cohesion.

56

Territorial figure of the Tagus Estuary Permeable & green margins of the Tagus Estuary

Fragmented network of water mobility

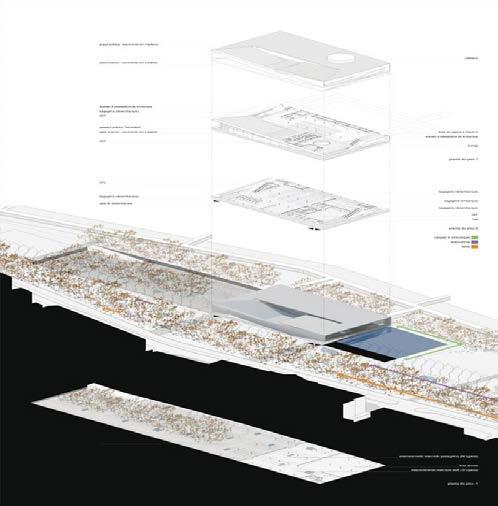

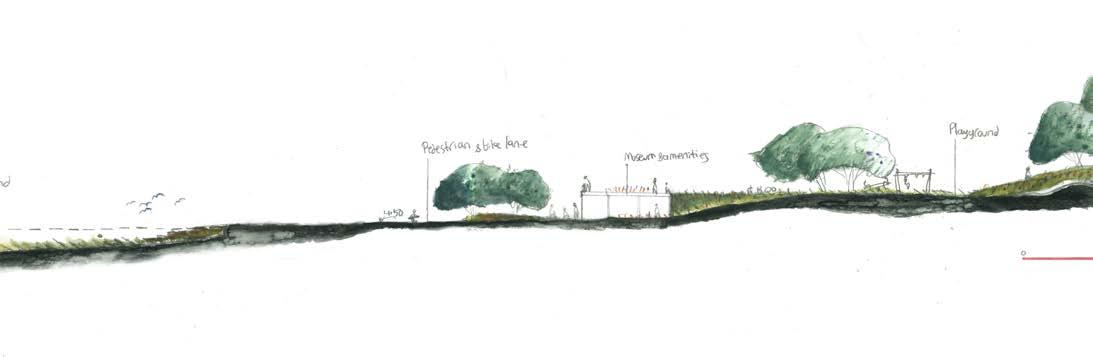

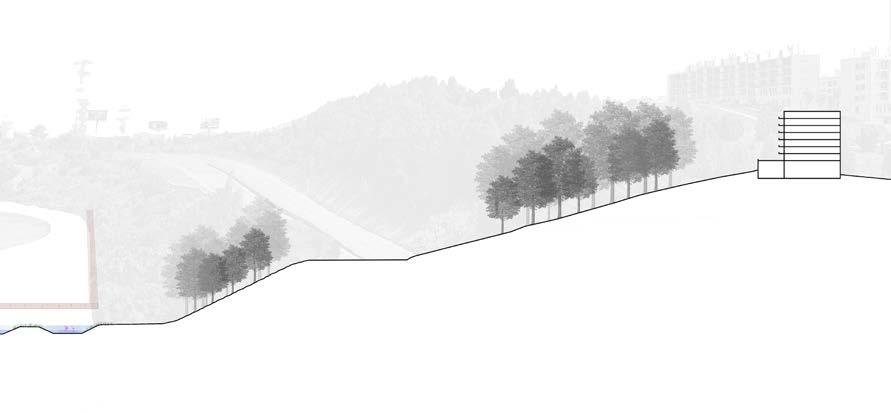

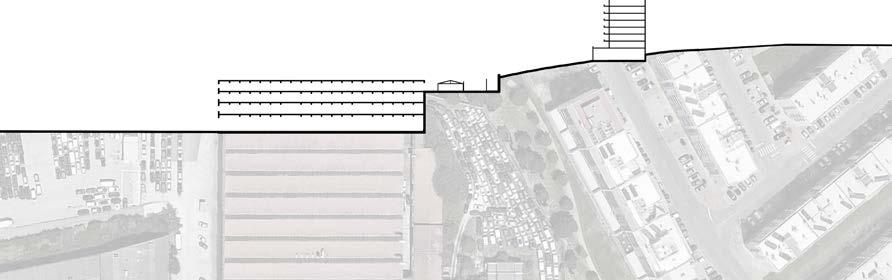

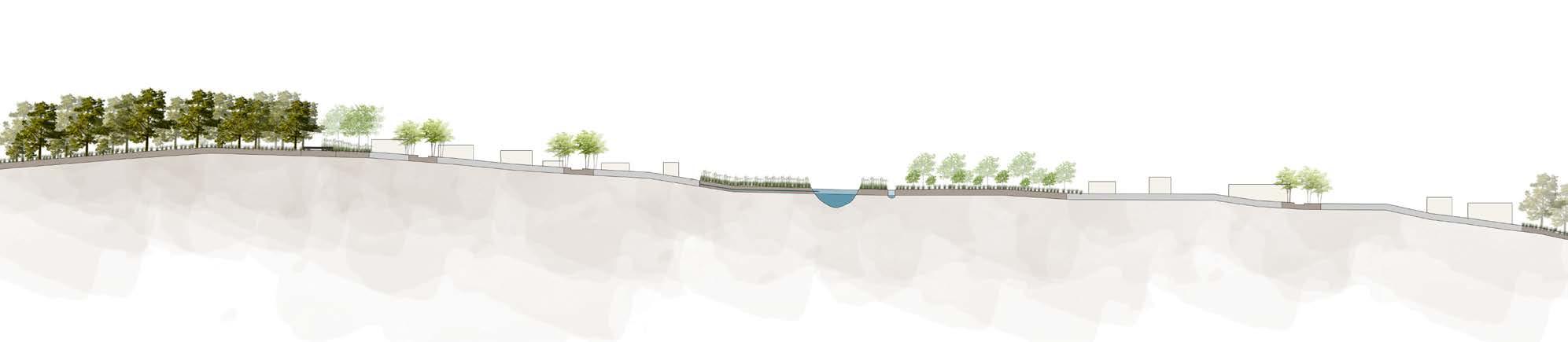

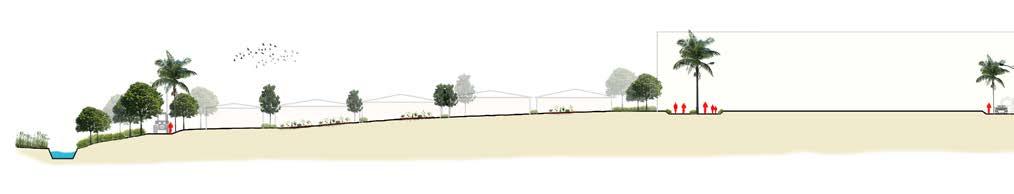

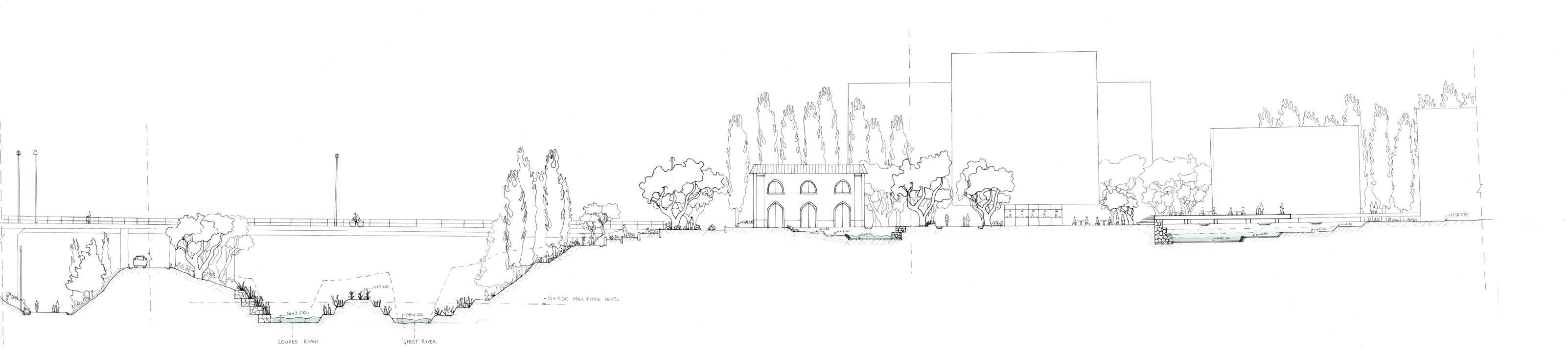

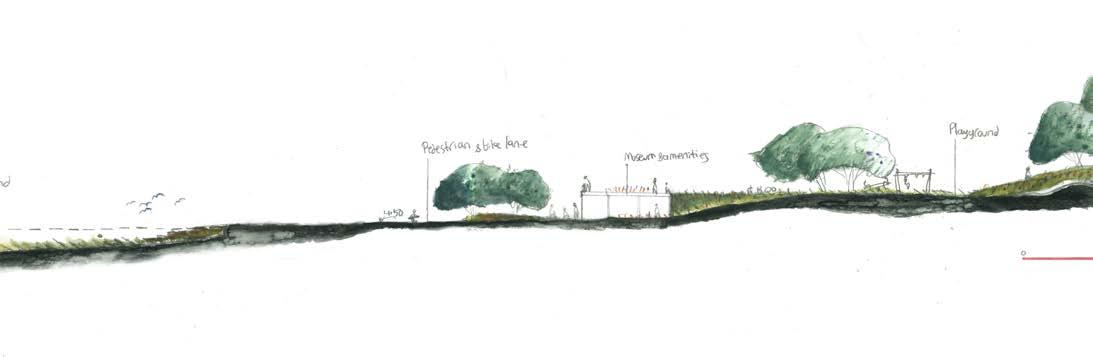

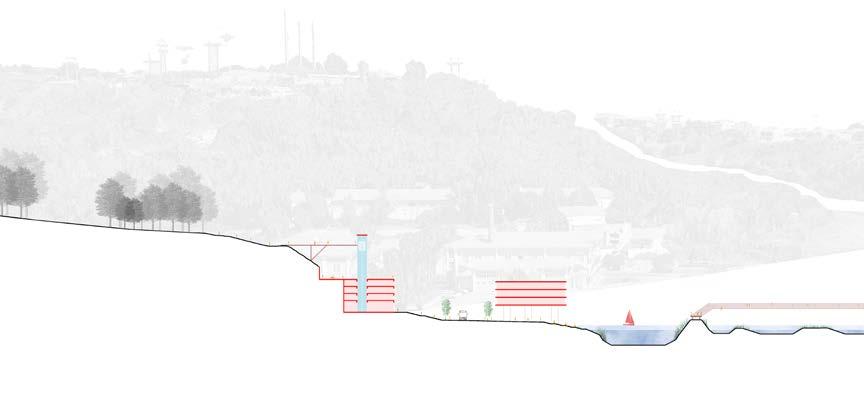

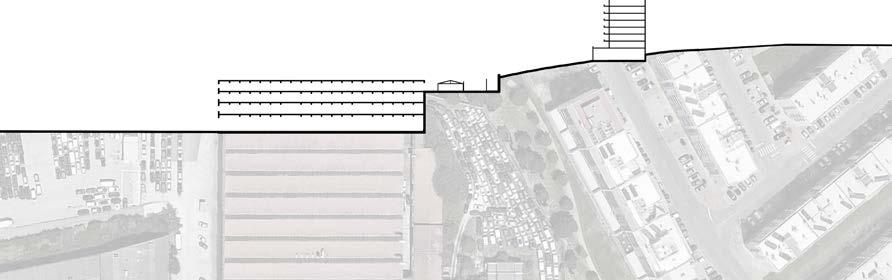

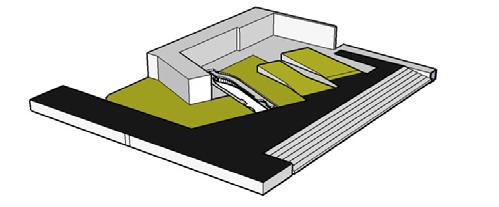

Section through the hilly park

Aerial picture of existing

58

Proposed design

60

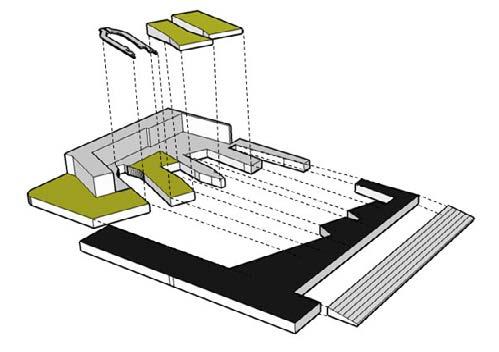

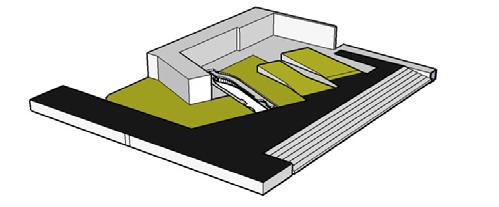

Park atop the sealed waste landfill

Marshland expansion

Trancão river

Reopening of water stream

The water factory - waste water plant

Expo '98

Park atop the sealed waste landfill New interface

61

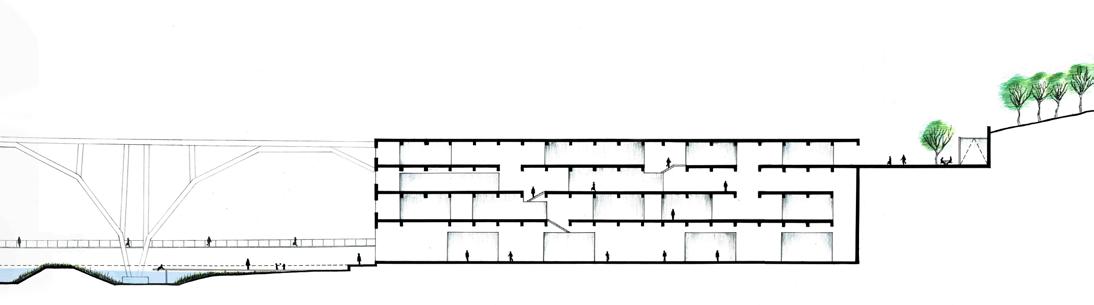

Urban tissue section

62

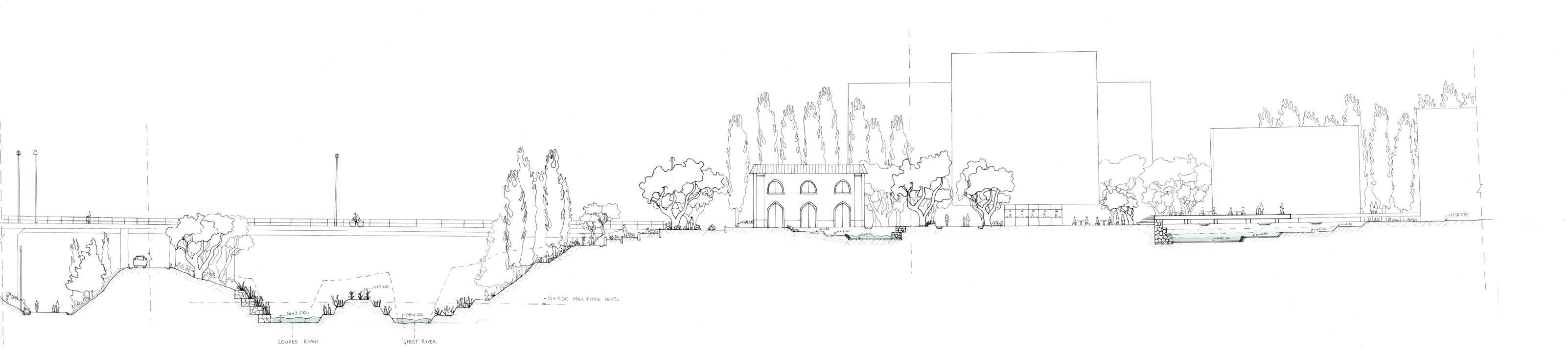

A binding linear architectural structure Ground floor map

63 structure Topographic connections throughout the site Axonometric view Connection section

STRATEGIC

PROJECT

Case 2 - Sacavém

65 ALIKI TZOUVARA LAKSHIMINARAAYANAN SUDHAKAR RAFAELA ARMOUTAKI

03.02

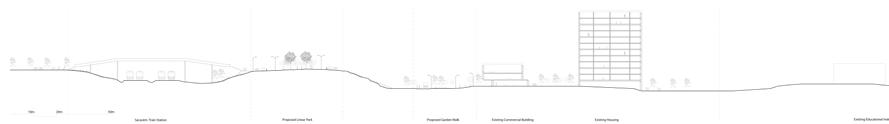

Decoding and declogging Sacavém

Sacavém is located in the eastern part of Loures municipality, Lisbon District, Portugal. There is the Tagus River to the east and the Trancão River (formerly known as Sacavém River) to the north, separating Sacavém from Bobadela. Sacavém was an important settlement during periods in Portuguese History owing to its strategic location near several north and east-bound roads connecting to Lisbon, with some evidence dating back to pre-history. Given its strategic location, a bundle of infrastructure crosses the Trancão river at this point, starting from national roads to water pipelines.

The site has two distinct characters – one that is along Trancão river, the lower part and the other on top of the plateaus. These two parts are completely disconnected from each other and there is no easy access to reach the upper Sacavém from the lower Sacavém. This has also resulted in the region being heavily dependent on cars, even though buses connect to some areas of the site that are not frequent. Parking spaces, commercial establishments and industries have taken over the flood plains of the river. It has changed the character of the landscape of what used to be predominantly marshlands. There is no relation to the river and most of these built forms turn their back to the river.

Antigo Quartel de Sacavém is an abandoned military barrack, which has not been in use for more than a decade. It was sold to a private buyer – still waiting for a new development to take place. This can be used for housing or other amenities that the community now lacks. Repurposing the massive industrial building at the bottom of Bobadela, on the floodplain's edge, gives a significant chance to establish a market/mixed use facility.

66

Figure 1. Caminho do Tejo along the Trancão river, the pilgrimage path to Fátima

© Lakshiminaraayanan

Sudhakar

Lakshiminaraayanan Sudhakar

67

Figure 3. Large impermeable surfaces clogging the flood plain. Commercial and industiral urban fabric becomes the face of Sacavém. Multi story upscale housing occupying the plateaus.

© Lakshiminaraayanan Sudhakar

© Lakshiminaraayanan Sudhakar

Figure 2. Sacavém is at the junction of multiple infrastructures, with an industrial character.

Sacavém does not have much of productive landscape/ agricultural fields. Very few pockets of urban gardens exists in some parts of the neighbourhood. Untamed natural landscape has taken over large portions of the site, most of which are on steep hills.

The challenge lies in how we can bring the different parts of the site together and create a closely-knit community. Can this be done by establishing a network of green that weaves through the different parts of the neighborhood? Can it help in tying them together and bring them closer? Soft mobility can also be used to connect the different terrains by navigating topographical variations and making use of existing urban fabric, some of which is already plugged into the steep slopes. A connection can also be established across the river, to bring Sacavém and Bodabela together.

The commercial establishments on and near the flood plain that have large landscape parcels have no connection to the water and are physically and visually isolated. How can we make use of the water margins to enrich the built fabric's character? The built fabric should also coexist with water and embrace it, instead of blocking it.

How to improve the relationship of these neighborhoods with water rather than just using floodplains for parking? The huge parking spaces clogging the valley can be removed to give more room for the water and create a regenerative landscape system.

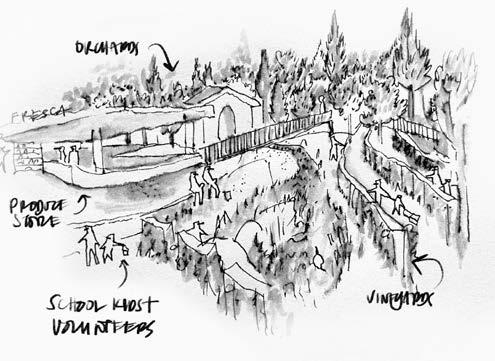

Can the untamed landscape parcels be used for creating urban community gardens or productive landscapes, as well as creating a sense of community among the neighbours?

68

© Lakshiminaraayanan Sudhakar

© Lakshiminaraayanan Sudhakar

Figure 4. New multi-story residential buildings lack enough public spaces and green spaces. Cars and their infrastructure are given importance.

Figure 5. River streams are canalized below hard surfaces to make place for industrial buildings and services.

69

Figure 7. Bus terminus, industries, parking spaces occupying the flood plains, that once used to be marshlands.

Figure 6. There are a few community gardens at the bottom of steep slopes, along the floodplain.

© Lakshiminaraayanan Sudhakar

© Lakshiminaraayanan Sudhakar

Mobility in Sacavém

Aliki Tzouvara

Sacavém, located in the eastern part of the Loures municipality, lies between the mouth of Tagus River and the Trancão River. The site is divided into two areas, one lying in a narrow strip of land along the riverbed and the valley and the other climbed on the plateaus that oversee it.

Walking along the banks of Trancão one can observe fractured continuities of in dustrial uses along with scattered landscape pieces, mostly inaccessible from both the water and the land. These create the image of a multifunctional site, a bundle of urban infrastructure accommodating different uses that seek a way to form the edges and boundaries (or connections?) between them.

The presence of the car is highly intense in both the valley and the plateaus of Sa cavém. While the car industry and commerce occupy most of the banks’ area, the intense topography and the poor public transport connections leading up the hills result in the intensification of private transport. Three highways of different speeds and locality are imposed on the landscape, crossing the river and affecting visually and acoustically the landscape, in the course of only a kilometer.

The increasing urbanization pressure has resulted in a fragmented urban fabric. The residential areas lie mostly on the plateaus and are occupied by big, multi-sto ries housing blocks with different characteristics. While most of them are social housing, the ones on the edges of the hills are new apartment complexes, that over view the floodplain but have no connection to it. The public space seems to lack or be present in scatters along the roads and in between the housing blocks. The edges of the plateaus are largely isolated and inaccessible, due to various reasons; a mix of privately owned land with uncertain use, plots that turn their backs on the river, the highways that divide the landscape and shatter the connection and the large industrial sites that creep against the topography, constraining physical and visual access.

So what is the character of Sacavém? From a historical settlement with traces back to the prehistoric and Roman times is now a passing between larger urban centers. Do we need to make it a destination? What are the possibilities of this place?

Sacavém is relatively easily connected to the wider area of Lisbon by the train sta

tion that lies at the entrance of it, right next to the Tagus estuary.

Sacavém de Baixo, the lower part of Sacavém, near the bank of the Trancão River, is a node of public transport, with 4 bus stops existing in a radius of 50 meters, and the bus terminal located in close proximity. However, they mostly move trans versely to the river or travel towards the center of Lisbon, leaving the residents of the highlands dependent on individual private transport. This is visually evident in the landscape as well. As one climbs over the hills the few free open spaces are dominated by parked cars.

The banks of the river are frequently used recreationally by hikers and cyclists de spite the poor existing infrastructure. The Caminho de Fatima follows the river through the whole extent of Sacavém, creating a peculiar co-existence between the car industry and the users of the fragmented public space. Despite the path being next to the water, the connection to it is non-existent. Water mobility is also pres ent in the site, with kayakers enjoying the opportunities offered by the river, despite the lack of proper infrastructure.

So how could we stitch the spatial ruptures along the floodplain? What are the possibilities of the existing hard infrastructure as future public infrastructure? The river and the banks lying along it could form a new spine of mobility and public space, providing a new multi-functional space of different character than the ex isting one; one that will not only enhance neighbourhood and intra-municipality connectivity but will also create recreational opportunities for both locals and vis itors and will redefine the meaning of mobility for public space.

What potential do we have for new systems of mobility that can directly connect the hills and their edges to the floodplain? The abandoned or with no use complex es that creep against the steep slopes offer opportunities for a middle level between the plateaus and the river. The former military facilities lie unused, occupying an enormous part of land, available for different urban uses.

A new, innovative system of mobility here has the potential to impact the scattered character of the area and contribute to natural, economic and social coherence.

70

The north residential plateau opening up to the valley

Mild topography allows the access through walking paths that end abruptly on private property. Semi-public space in front of high-rise housing complexes, restrained by hard boundaries that forbid further relation to the valley.

71

A messy urban environment

The valley is occupied by impermeable surfaces and private, industrial uses that clog the floodplain, restrain the flow of the water and block the access to it.

72

A bundle of infrastructure

The historical Caminho de Fatima squeezed between the river and the car industry, only allowing one cyclist or pedestrian to pass at a time.

73

Marginal mobility

Water mobility present in the valley, despite the absence of proper infrastructure. The current equip ment is accommodated in a container on the south bank.

74

404, public space not found

The car dominates the streets and the scatters of public space that exist among the social housing neighborhoods.

75

Urban cohesion in Sacavém

Maria Rafaela Armoutaki

The city of Sacavem can be found north-east close to Portugal’s capital, Lisbon. Sacavem is located a stone’s throw from “Foz do Trancao” (river mouth of Tran cao) and the Tagus and it is a former civic parish in the suburban municipality of Loures, Lisbon District. Both the city and the river Trancao have great historical significance for Portugal, especially during the 19th century. However, Loures mu nicipality, so as Sacavem, belongs to a massive construction movement mid of the ’70s with a selection of interventions occupying most of its region. Trancao is of vi tal importance and is distinguishable through Lisbon’s Metropolitan Area but also for Sacavem. The latest can be reflected through history. Nowadays, most of the river basin is influenced by agricultural and industrial exploitation, while heavy urbanization has dichotomized the river's ecological value. The natural collorary of these human-scale interventions was the soil and water contamination which, in turn, greatly decreased the river's merit through the years. In parallel, this spatial fragmentation, together with the climate change brought many flood risks into the whole valley of the river's region as is Sacavem.

A consequence of a natural border: River and Landscape

On both sides of the river’s narrative, huge masses of slopes appeared. These stiff slopes create a hard typology of the valley and topography of the landscape. Τhe dominance of socio-economic behavior of its region shows a landscape under con struction without a specific character with a set of conditions, trying to keep it maintained. Furthermore, the penetration of the urban infrastructure modified the landscape the recent years. The territorial presence of the lower Sacavem (Sa cavém de Baixo) has been occupied by a continuous line of hard urban edges via buildings that serve for housing, trade, or industrial purposes whilst the feeder lines of the river have been eliminated. The current condition makes clear that the river is not a destination for the people but only a natural border that provides visually and technically water to the area most of the time. With the river pushing through the slopes, it is clear that the area is not prosperous for many applications along its way apart from the bridges to connect the two sides. The imbalance of ar tificial and natural systems allows some clusters of open spaces mostly for passing purposes and less for leisure. Private transport has a meaningful character behind human presence and inhabitants rarely use the region. However, the only part that enhances the human presence in the natural area is the path parallel to the river,

which leads into a narrow landscape together with the urban pressure made clear the problematic areas from different scopes. It is important to be mentioned, that a small portion of people take advantage of the natural trail that the area provides, known as the Camino de Fatima which connects Lisbon and Porto.

Though the observations, it was obvious that the fragment fringes of the area, can be identified mostly into the disconnected patches of urban fabric. These frag ments seems a routine part of Sacavem’s urban experience socially but also spatial ly. Most of urbanized land gathered into plateaus with old and new infrastructure. Due to stiff slopes and the river, these areas created different experiences from the military barracks, to new urban developments, and the social housings. Moreover, the transport interventions, such as the highway and the bridges, are an integral part of the area, which enhances the issue. Notwithstanding, these projects at tempt to decrease the gap between the two stories of slopes through perpendicu lar but sporadic connections, and provide connectivity for passing though private transportation, only, as a main priority. Also, along the river the agglomeration of industrialization doesn’t give space to water by downgrading its presence. With a cursory glance across the existing condition in terms of urban cohesion, it can be seen that the geomorphological characteristics of Sacavem organize the incitement of site’s urban structure. More specifically, the three crucial artificial borders (bridges and highways) along with the heavy industrialization and the nat ural borders of the river and the stiff slopes, are incitements of urban’s structure.

The territorial and social cohesion creates patches with asymmetries. A tangible example are the contrasts of the new urban development and the social housings appear in the same urban section. There are two main clusters of new urban devel opment. These are collective housings which are located into the hilltops on both sides of the river. The construction pattern follows multi-storey houses up to 4-6 levels residence by “upper-class" with small pieces of public spaces. Apart from the lack of open public spaces are also easy to notice many parking plots. Regards to the densely populated part of Sacavem, it is clear that the social structures are one of the vulnerabilities of the area. More specifically, the most of the social housings are in poor condition while public space is does not exist at all. There are some clusters with some public space amenities however they are in poor maintance such as playgrounds or courts.

76

North residential site and its fragments

Between the landscape and the new urban development, it is clear that the access to the site is limited by artificial boundaries which make it difficult to interact with nature and the river.

77

Experiences though the military barracks.

In contrast to the densely populated Sacavém, inside the camp the experiences and impressions are different.

78

© Rafaela Maria Armoutaki

Social Housing and gardens

The narrow confines of the residential Sacavém have created the need to develop public spaces and gardens.

79

The social housing effect of Sacavém

The area surrounding the social housing concentrates high percentages of parked cars while public amenities such as pavements or benches are difficult to locate. Public space beyond its narrow boundaries is also non-existent.

80

© Rafaela Maria Armoutaki

81

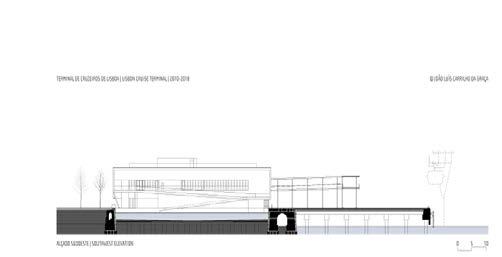

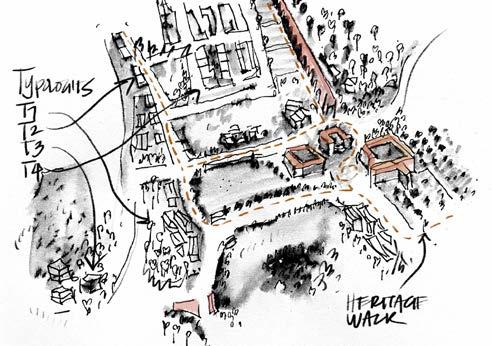

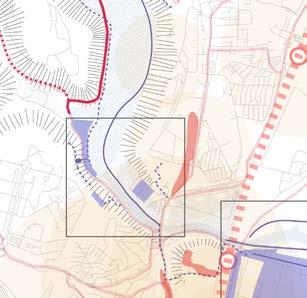

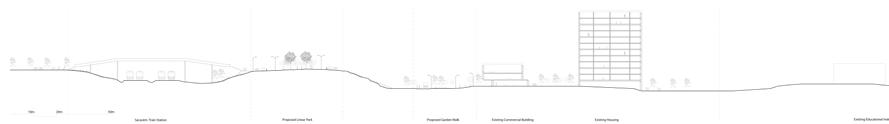

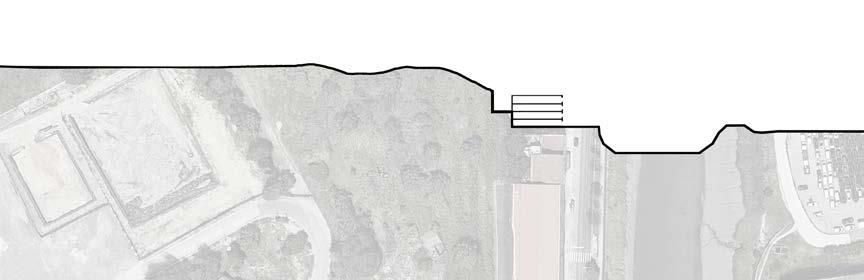

Plan 1:2000

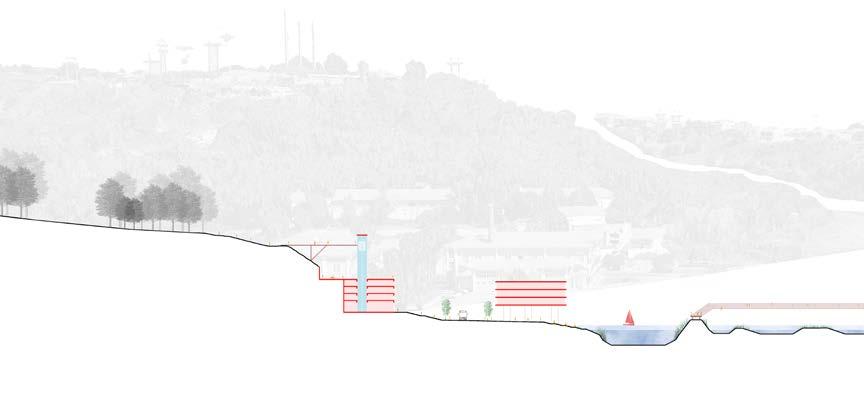

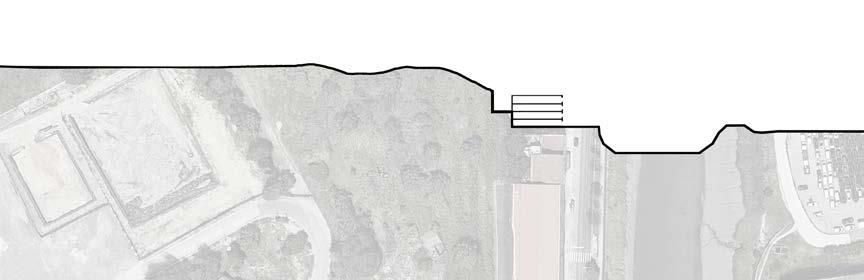

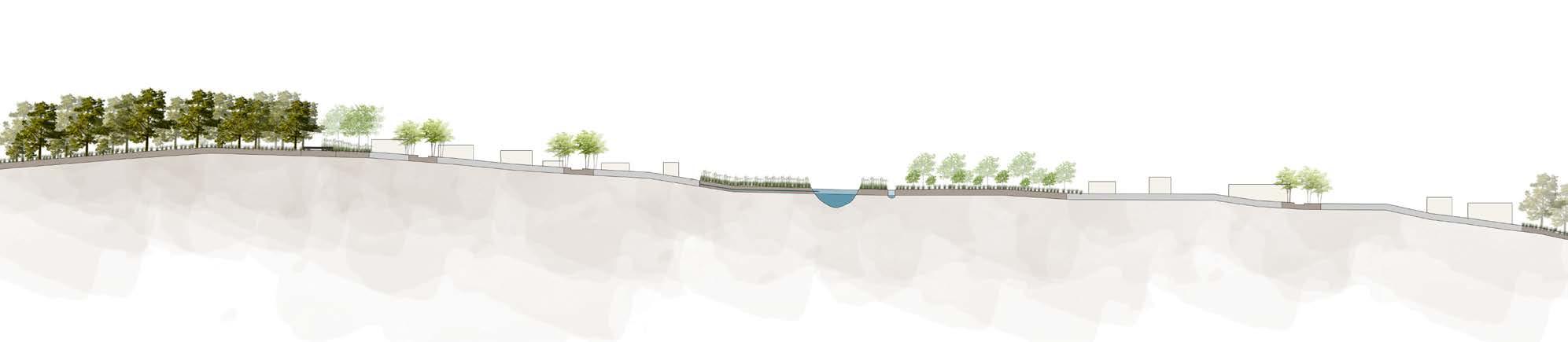

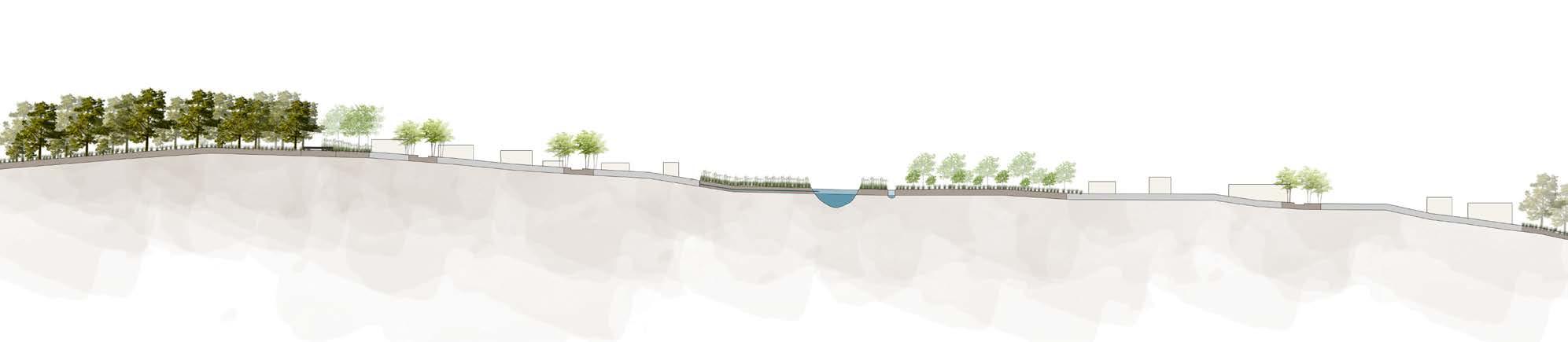

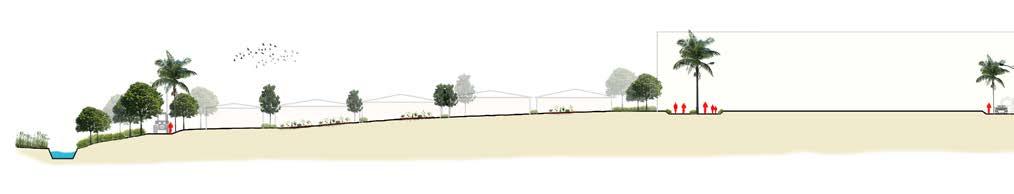

Reclaiming the valley

Aliki Tsouvara Lakshiminaraayanan Sudhakar Maria Rafaela Armoutaki

Aliki Tsouvara Lakshiminaraayanan Sudhakar Maria Rafaela Armoutaki

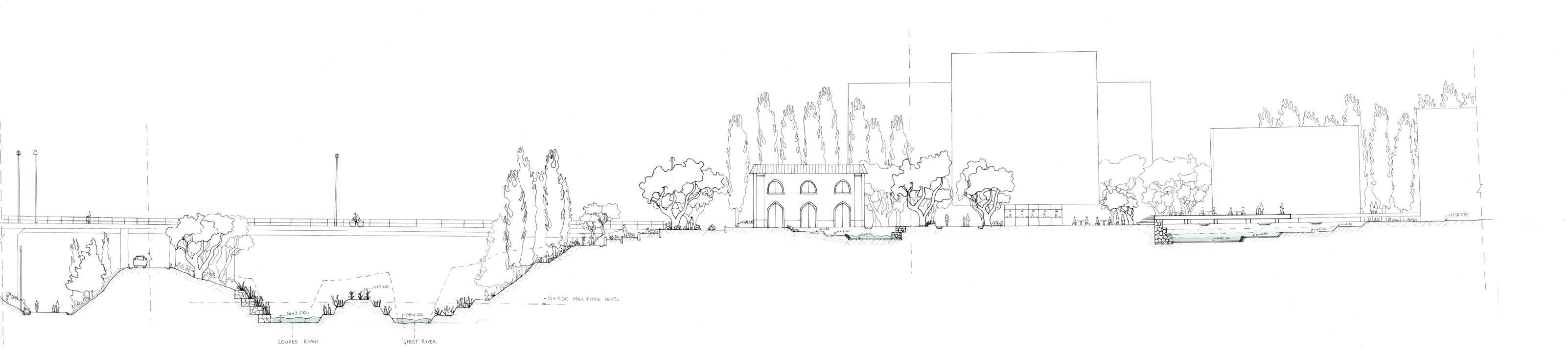

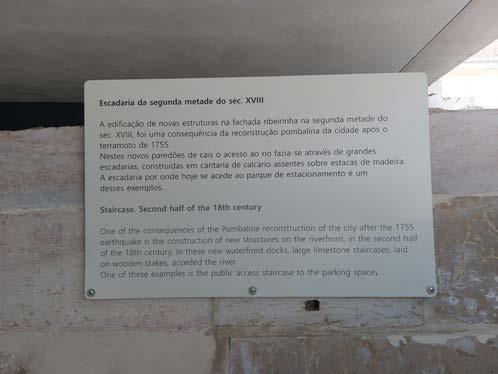

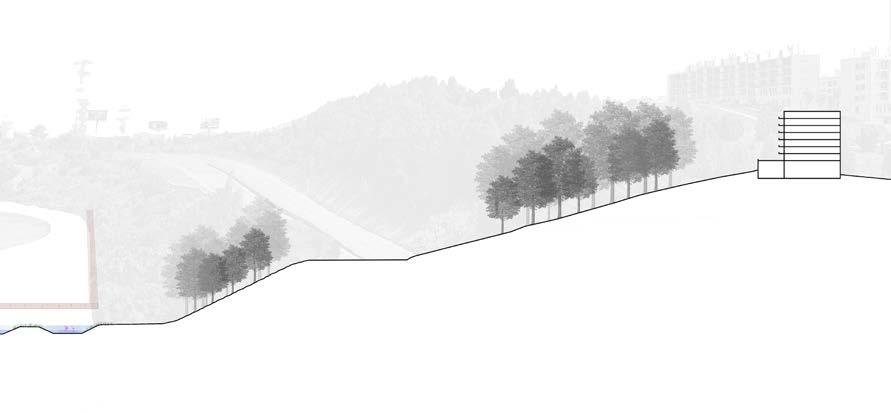

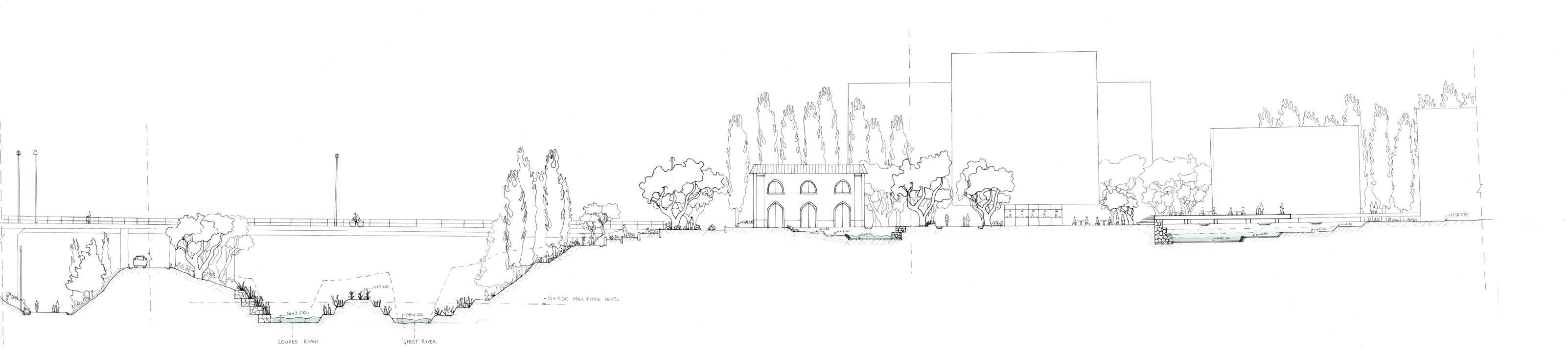

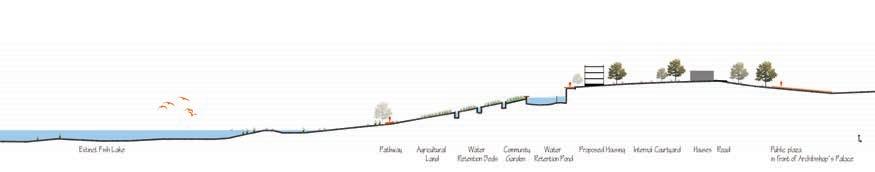

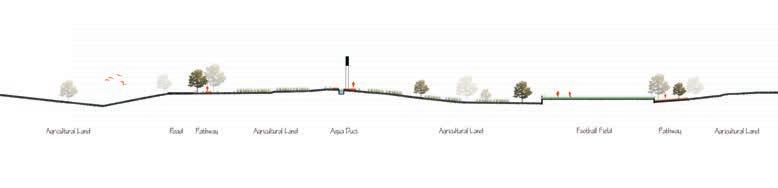

The floodplain is given back to the water. As in the past, the western bank retains the urban feel it had - a hard edge, enriched by expanded urban public spaces that step down to the water, enhancing the relationship with it. The eastern bank is re naturalised, by a dual system of breaking the dykes and excavating the floodplain to create longitudinal profiles for the water to enter and erode the land, reclaiming the space it once had. Existing infrastructure and abandoned mid-levels embedded on the slopes are re-designed into new public spaces and connection points that allow the movements between the isolated plateaus and the valley. In one such movement, an elevator is incorporated to enable efficient and quick movement of people from the lower to the upper levels.

The historical path of caminho de Fatima is reappropriated to allow comfortable movement of pedestrians and cyclists, both for the purposes of everyday life and recreation. It is retained on top of the existing dyke, facilitating soft mobility in the floodplain. The connection between the two sides of the river is made through a suspended bridge that is inserted within the existing structural framework under neath the highway. The former monofunctional industrial building on the east ern edge that once acted as a barrier between the river and the neighborhood is transformed into a multifunctional, porous communal space that promotes public movement through it. Picking up cues from the traces of the small community gardens that existed on site, a sequence of large community gardens are developed on the flood plain. By combining the new community gardens with the multi functional communal space, social cohesion is enhanced. A small dock located on the hard edge of the river encourages water mobility, restoring the character that Sacavém once had.

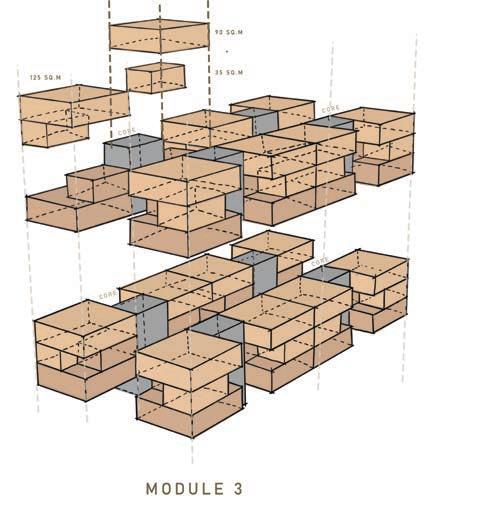

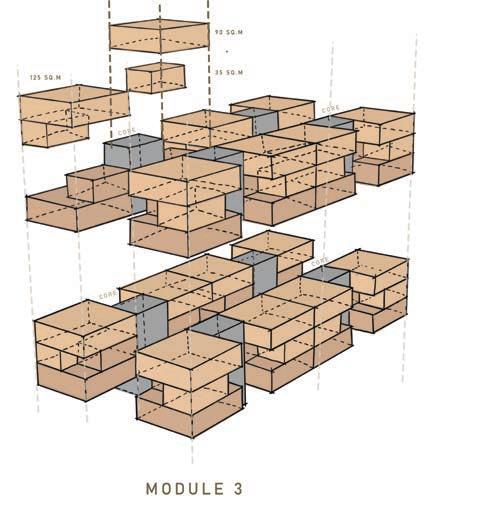

Now moving up from the floodplain to the plateaus, the former military quartel is transformed from an obsolete infrastructure to a vibrant low-rise neighbor hood, with gardens and public pathways that cross it starting from the main road. The vacant plot next to it now accommodates new dense urban tissue, with 400 units varying from 60-90 sq.m. The corridors connecting the different typologies of the buildings are envisioned as wide streets, allowing sunlight to enter and air to circulate within those. Some housing blocks have an open ground floor, giving the complex a public character and allowing pedestrians to circulate between the various public spaces within the community and the newly-forested area between the buildings.

83

buildings removed from the flood plain flood plain impermeable surfaces in the flood plain existing built form

The banks of the river occupied by car industry and warehouses, creating a confusing and messy urban environment with no relation to the water. Hard, impermeable surfaces constraining what once was a wide riverscape.

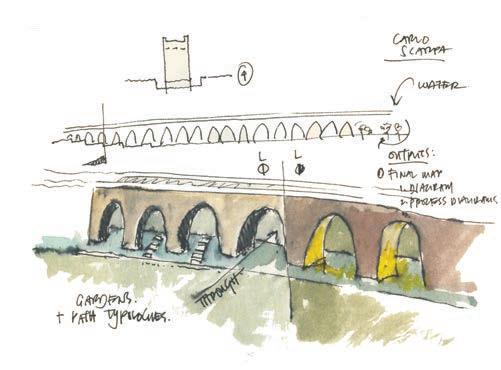

84

plateaus - valley connecting routes