Maitland Regional Art Gallery acknowledges the Wonnarua People, the traditional custodians and owners of the land. We acknowledge the unbroken connection to country, culture and community and we extend this respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who visit and engage with the Gallery.

MICHAEL BELL

SCOTT BEVAN

JENINE BOEREE

SALLY BOURKE

OSVALDO BUDET

WANJUN CARPENTER

TOBY CEDAR

NICOLE CHAFFEY

LOTTIE CONSALVO

TALLULAH CUNNINGHAM

VIRGINIA CUPPAIDGE

DAVID DARCY

JAMES DRINKWATER

PENNY DUNSTAN

SARETTA FIELDING

LISS FINNEY

TODD FULLER

PETER GARDINER

LUCAS GROGAN

NICOLA HENSEL

GEORGIA HILL

HANNA KAY

CHRIS LANGLOIS

RYAN LEE

ZOË LONERGAN

MITCH MAHONEY

DANI MARTI

CLAIRE MARTIN

HOLLY MACDONALD

BRETT MCMAHON

NIGEL MILSOM

NICOLE MONKS

JOHN MORRIS

BRONTË NAYLOR

NELL

KEN O’REGAN

JAIME PRITCHARD

REBECCA RATH

UNA REY

ALESSIA SAKOFF

LESLEY SALEM

BRADDON SNAPE

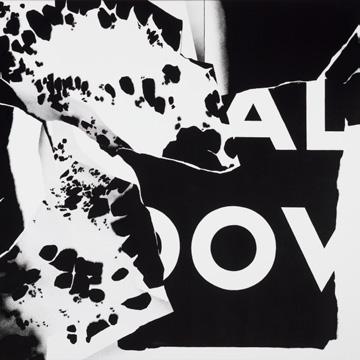

RICHARD TIPPING

SHONAH TRESCOTT

JOHN TURIER

SHAN TURNER-CARROLL

GAVIN VITULLO

TRAVIS DE VRIES

CLARE WEEKS

TREVOR WEEKES

GRAHAM WILSON

VERA ZULUMOVSKI

The Mayan

The river that runs through Wonnarua Country (the Hunter River) was known here in the Maitland region as Mayan and written in historical records ‘My.an’. In the language of the Wonnarua, Kuukuyn/kukuyn translates as ‘water’.

AUNTY SHARON EDGAR-JONES

Commissioned by Maitland Regional Art Gallery for exhibition Upriver Downriver, 2023 (detail on pages 4-5 & 108-109)

The Source, 2023, acrylic on hand-carved birch plywood, 240 × 488cm

GRAHAM WILSON

UPRIVER DOWNRIVER was an expansive opportunity to showcase the creative energy along the banks of the mighty river that flows from a small brook in the Mount Royal Range through Wonnarua Country of the Upper Hunter and Maitland and down to the Port of Newcastle.

The Mayan, the Coquun, the Hunter. This river flows with all the paradox filled philosophy of Heraclitus who said around 2,500 years ago ‘No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.’

Both poetic and pragmatic, this sentiment is embedded in the shifting form of a river and the shaping of communities. It was fascinating to see the ideas emerge in the development of this exhibition with artists inadvertently forming clusters of shared themes and ideas of place from the deeply personal reflections of home to the political and environmental realities of a region in transition.

This mighty river became a way of traversing terrain and drawing in artists who work across this remarkable region. The work presented in Upriver Downriver is not an exhaustive representation of creatives working in the Hunter, a region brimming with artists. This is, rather, a geographic snapshot curated with passion and deep respect by Kim Blunt reflecting a diversity of practices, forms, ideas and methods of making art throughout this place we call home.

Maitland Regional Art Gallery’s collection continues to grow with a strong representation of Hunter based artists and we are proud to share a number of these works in Upriver Downriver. We would like to thank all the artists who shared their work with our audience for this exhibition and extend a very special thankyou to longstanding patrons and supporters Bob and Paula Cameron who through generous funding, provided a commissioning opportunity for the creation of new work for artists Graham Wilson and Brontë Naylor.

We hope you enjoy this complete takeover of MRAG with art that reflects our region in an all-encompassing celebration of place.

DR GERRY BOBSIEN

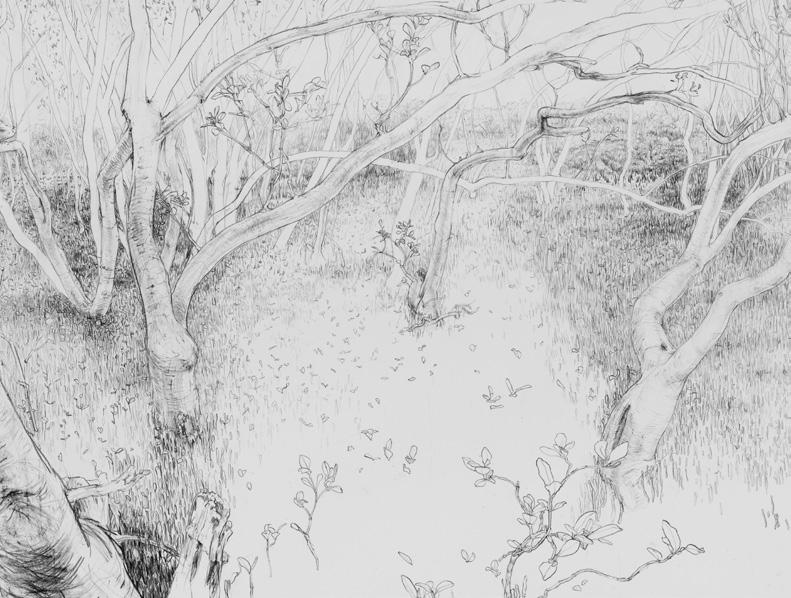

Architecture 3 , 2020, Falls, 2015, ink and acrylic on hand-made paper, 76 × 56cm each

Collection, purchased by Maitland Regional Art Gallery, 2021

RYAN LEE Wonnarua, 2020, dual-channel video, 2:01 mins

NICOLE MONKS & JENINE BOEREE

Thalanara Yalimanha (making kangaroo skin blankets), 2022, kangaroo skin, printed blanket, dimensions variable

Into the Woods (detail), 2023, oils and tempera on rice paper, 150 × 70cm each

HANNA KAY

Photo: Leslie Wand

Commissioned by Maitland Regional Art Gallery for exhibition Upriver Downriver, 2023. Image supplied by artist

Study for Muscle Memory, 2023, aluminium, aluminium composite, metal primer, acrylic paint, acrylic exterior house paint. 240 × 500cm

BRONT Ë NAYLOR

Documentation of movement experiment on Hunter River with skateboarders Adam Tabone & Connor Reeve

VERA ZULUMOVSKI

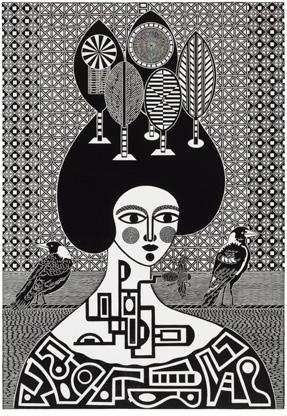

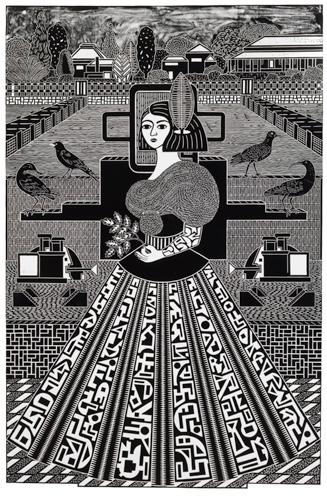

The trees are now silent , 2023, 95 × 66cm, The trees fall silent everywhere , 2023, 144 × 75cm, linocut on paper

Collection, purchased by Maitland Regional Art Gallery, 2021

I stirred the sea to see if it was alive , 2019, single-channel video, 5:45 mins

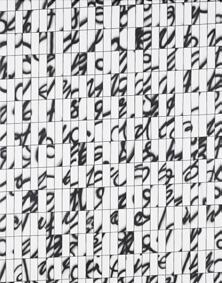

NIGEL MILSOM Judo house part 7 (the white light), 2017, ink on paper, 44 x 34m each

Photo: Nick de Lorenzo

Collection, donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program by Virginia Cuppaidge, 2022

VIRGINIA CUPPAIDGE Lilium, 1975, acrylic on canvas, 106.5 × 183cm

OSVALDO BUDET

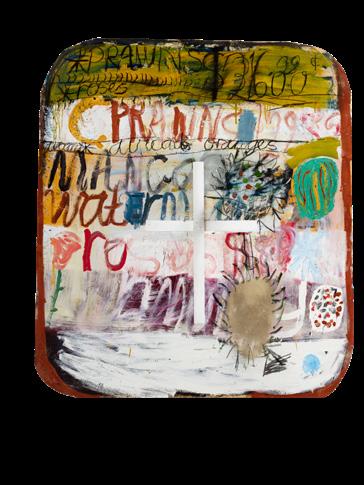

The over-representation of Indigenous Australians in prisons is one of the most pressing human rights issues in Australia... (detail), 2021 acrylic on panel, 120 × 90cm

KEN O’REGAN Fractured Sanctuary, 2023, recycled plastic items, bread crates, LED lights, timber, 250 × 350xm

Photo: Ken O’Regan

Hawkesbury River Marker, 2021, oil on linen, 60 × 60cm, Morning Light and Mist, 2021, oil on linen, 60 × 60cm

JOHN MORRIS Morning Light and Mist on the Hawkesbury, 2022, oil on canvas , 137 × 137cm

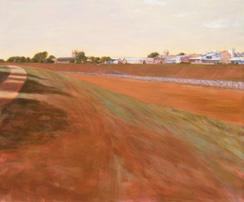

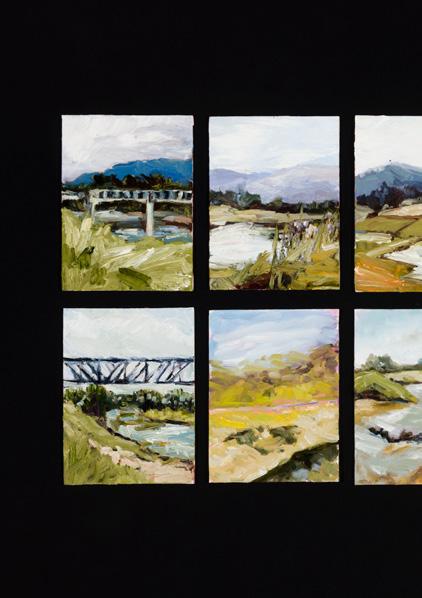

Upriver Downriver, Hunter Valley, 2023, oil on wood and canvas panels, 20 × 15cm each

Collection, donated under the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program by Todd Fuller, 2020

TODD FULLER Railway Overpass, 2018, acrylic, chalk and charcoal on paper, 57 × 75cm

CHRIS LANGLOIS

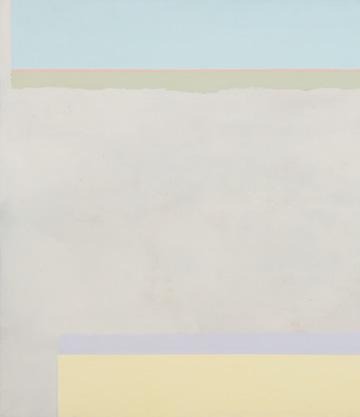

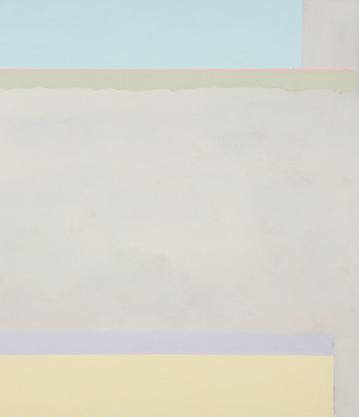

Nocturne part 1 , 2023, Nocturne part 2 , 2023 , oil on linen, 153 × 168cm each

Photo: Chris Langlois

SHAN

TURNER-CARROLL

The snake, the rock and the river , 2021, mixed media, dimensions variable

Photo: Zan

Wimberley

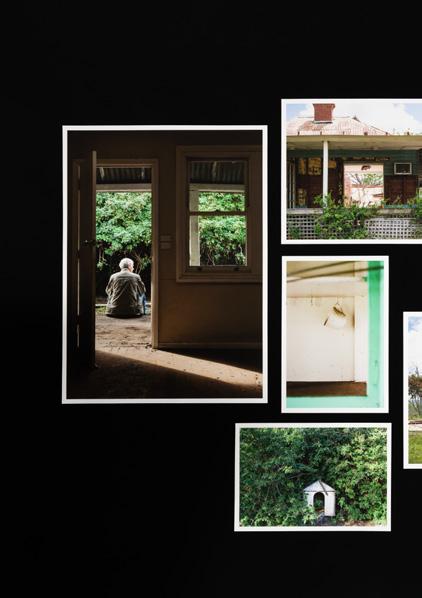

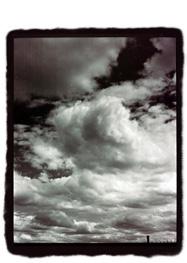

SEEING THE RIVER A kayaking journey along the Hunter

Photography

CHRIS LANGLOIS

WE stand together by the Hunter River, Chris and I, but we see our surroundings with different perspectives.

I’m looking at the river. It looks restless, having gorged on the rain that has been falling. Soon that restless river will cradle us, as we paddle our kayaks for two days from Stanhope, downstream from Elderslie Bridge, to Morpeth, a journey of about 55 kilometres.

While I’m staring at the water, Chris seems to be staring into the distance.

I’m not surprised. After all, if his paintings are a reflection of how he looks at the world, Chris often takes the long, wide view.

Chris Langlois is a gifted landscape and seascape artist. Through his meticulous yet mystical work, Chris often places us on a shore and takes our vision far out to sea, until the swell touches the sky, or he gently puts us in a paddock and encourages us to look up at the trees. A Langlois painting doesn’t just depict the water, land and sky. It seems to be infused with their qualities. Light and shapes shift subtly, almost imperceptibly, across the canvas. Langlois is an artistic water diviner, locating what our souls crave and drawing beauty to the surface with his brushes.

So when you stand before a Chris Langlois artwork, you’re at the beginning of an insightful journey.

And so it is when Chris and I stand together by the Hunter, preparing to paddle the river that feeds, flows through and defines the region where we have both lived and grown.

SCOTT BEVAN

AT the spot where we are launching our kayaks, the river shows off its scars and tattoos collected when the water was not just restless but raging.

Debris is clumped in the shallows, and the corpses of riparian vegetation rot in the mud. Trees along the banks have been pushed over, while others are left standing as shorn and decapitated trunks.

This is the legacy of the July 2022 flood.

The Hunter is synonymous with floods. What this river gives to all who live and work along its banks, it takes at will. In good times, for instance, the water nourishes the soil that provides a living to a farmer and helps feed a region; in disastrous times, the water tears the soil away, dumping it downstream. But that dumped soil provides the foundation on which to rebuild. Along the Hunter, people aren’t dirt poor; their lives are richer because of the dirt.

Where we have camped at Stanhope, the dirt clings to us. The owner of this farm, Jamie Pittman, tells us our campsite would have been under water in July, with the river rising many metres above where it is flowing now. It is hard to imagine the river that high. Then again, that is a gift of water. It encourages and impels you to reimagine, to think differently. My paddling buddy knows that better than most.

Which is why Chris is keeping his eyes and mind open for this journey. ‘With all the trips I’ve been on, I’ve had in my mind what

I’m going to find, but in the end, I end up finding something else,’ he says.

On this quest to find ‘something else’, Chris has brought not paints and brushes but a camera. Chris is an accomplished photographer, and the camera is a key tool in how he views the world and approaches his art. ‘The good thing about the camera is that it moves you one step back, and you see things differently,’ he explains.

Decent rain (as long as it isn’t too much) is not just a farmer’s friend, but a kayaker’s. The river is skipping along at a couple of knots. So we’re not just going with the flow, we’re being carried by it. Yet the quicker pace doesn’t lessen our opportunities to observe the world we’re passing through.

And so much of what we’re seeing we see through the eyes of artists. For both of us, art is as much a reference as the river itself. After all, the landscape helps artists to see, and then the artists help the rest of us see our land.

Distant hills with gums smudged along the ridgelines look like a Fred Williams painting.

In the middle of the stream at Dalwood and Gosforth are the ruins of low-level bridges. The wooden pylons defying time and successive floods are reminiscent of the figures of explorers wading through a river in an Albert Tucker painting, or the totem posts carved and painted by Tiwi Islander artists.

In a conical hill on a bend near Gosforth we see reflections of the Pulpit Rock paintings of Arthur Boyd, who found his muse in another river, the Shoalhaven.

SCOTT BEVAN

That other river bubbles into my mind while paddling along one of the Hunter’s long reaches. The chocolatey water snaking its way through the valley and flanked by tones of green and dun scumbled into the vegetation by the floods remind me of Margaret Preston’s extraordinary work, Flying over the Shoalhaven River.

In the early morning, a Clarice Beckett mistiness softens the river and the landscape, in the late afternoon light, the gums along the banks are burnished and gilded like trees in a Streeton, and at night, with a half-moon suspended above us, the shapes of flood-tossed debris and shadows on the silvered water look as though Dorrit Black could have painted the scene.

Even the tree branches that have fallen into the water and are tormented by the flow to incessantly flap and tap out a rhythm on the river’s surface conjure comparisons to artworks.

‘I think of Ken Unsworth installations,’ says Chris. ‘He always has something playful that goes “Whack!”.’

The river not only determines our course, it marks where it has been. The legacy of the July 2022 flood accompanies us on the journey. The river has created its own sculptures, piling up wood and the detritus of daily lives like pyres on ghats along the Ganges. Products of modern life are also entangled high in the trees along the banks, tossed there by the flood waters, and,

in places, soil has been dumped onto the crowns of torn-out trees, so it looks as though the natural world has been turned upside down by the river. The natural world often seems to be pushed aside by the incursions of other lives and places. Sounds of the world beyond the river often sneak over the banks: distant trains carrying coal to the river’s mouth to be exported; the thrum of road traffic; tractors trundling through cattle-punctuated paddocks that crouch close to the water. Then the river bestows respite, with stretches where there is no sight or sound of the 21st century.

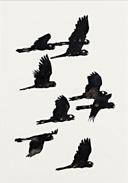

The air is occasionally sprinkled with nothing but birdsong, or the bank is cloaked in not willows or other weeds but native trees, providing a glimpse of how this place must have been before the Europeans arrived with their axes and ambitions to build empires. Above the bridge ruins at Dalwood, a pair of wedge-tailed eagles performs a pas de deux in the currents of air. The eagles are as graceful as Chris and I are graceless in the current of water.

At the start of our journey, Chris mentioned how every tree told a story, but he would be looking for those telling a special story to photograph. At the Dalwood bridge ruins, he found such a tree speaking to him. It is an aged casuarina bent over by the force of the floods but ‘it has not entirely relented to the river’. The story of resilience is told in the bent trunk.

‘This shape is so beautiful,’ murmurs Chris, with one of his eyes buried in the camera’s viewfinder.

SCOTT BEVAN

SEEING THE RIVER A kayaking journey along the Hunter

Photography CHRIS LANGLOIS

WATER wipes away any sense of time from itself. When you’re in the embrace of water, the past, the future, is meaningless; there is only this moment.

Yet water marks moments past on the landscape, from the raw wounds of erosion on outside bends to the layers of soil on the river flats, which bloom with produce that sustain us. The past is also sprinkled along the Hunter’s banks, including majestic colonial homes, such as Aberglasslyn House, with its wide-eyed windows staring upstream. There are also shards of the past lying like mines in the river. The pieces of anti-erosion structures that have failed to stop the banks from being eaten by the river are now but bits of iron and concrete in the stream, just waiting to tear open a kayak’s hull.

The art references keep bobbing up along the journey. We pass more Albert Tucker figures/ totem posts/old pylons as we approach the present-day Melville Ford Bridge. We hear the bridge before we see it.

The wooden deck beats out a syncopated clickety-clack as vehicles run over it. Downstream are the ruins of another bridge. Chris sees a rusting iron brace that has taken on the demeanour of a sculpture and declares, ‘Woah! Robert Klippel!’ Nearby is a sandbank, and on it rests a dumped filing cabinet. Parts of the metal structure are crushed, other pieces look as though they have been inflated, and it is electric blue in colour. ‘Woah!,’ I shout. ‘Braddon Snape!’

The river broadens along a long reach approaching Maitland, and the water seems

to slow. More and more of the left bank is entombed under concrete slabs as housing progressively colonises the land near Bolwarra while on the opposite side, at Oakhampton, the dead rest in river-soaked soil. We land and tread through long grass to view the colonial graves in Oakhampton Cemetery, including a headstone memorialising members of a family that has fed us for generations – Arnott.

A biscuit-baking empire was born on the banks of the Hunter, at Maitland and Morpeth, before founder William Arnott moved downstream to Newcastle. It seems this historic cemetery has a guardian. A red-bellied black snake raises its head. We encourage the snake to move off, but then it encourages us to move.

‘It’s coming at you!,’ says Chris with just enough urgency to make me sprint.

We lull our elevated heart rates by returning to the river. We drift under Belmore Bridge and pass the main business area of Maitland. This city was put on the map because of the river and, particularly during the disastrous 1955 flood, it has faced the threat of being wiped off the map by the river. Maitland neighbours the river, relies on the river, and yet it remains constantly wary of the river, with the city huddling behind a rock wall and levee. As a result, from the water, Maitland’s CBD looks something like it would, if a flooding Hunter River were to inundate it. The tops of buildings and trees float past the top of the levee. We see a solitary streetlight poking above the levee’s lawn-covered slope. It looks like a scene from a Jeffrey Smart painting.

SCOTT BEVAN

We paddle on, past Horseshoe Bend and Pitnacree, gliding by somnolent cattle and market gardens and the severe geometry of floodgates, as we ride the anguine twists of the river towards Morpeth.

‘The light is golden, the air still; it’s like a dream,’ notes Chris.

Then a jetski rounds a bend, slicing across the surface and slashing the dream into foam. Morpeth gradually pops its head up in the distance. A reminder that Morpeth was once a bustling river port, carrying the agricultural wealth of a valley out into the world, is embedded in the bank below the town.

The remains of a wharf are pressed into the mud. If that doesn’t express how important Morpeth was to the colony, and to international trade, then the stonemasonry in the town’s cemetery does. Among the headstones are those for sailors from across the seas, including Germany and Sweden. They had drowned in the river. They now lie in the earth on the fringe of Morpeth, far from their homelands.

We are nearing out destination. Reflecting on the paddle, Chris says he has found that ‘something else’. He is surprised by the amount of flood damage along the river.

Yet in the destruction, there’s also been beauty – and fascinating subjects to photograph.

Chris and I land at Morpeth’s Queens Wharf. Our kayaking journey has ended. But our relationship with the river never will. The Hunter courses through us, through how we see ourselves and our place in the world, as surely as the river flows through the valley to the sea.

We stand together, Chris and I, with a river in our eyes.

SCOTT BEVAN

Scott Bevan is a Novocastrian but lays claim to being almost a Maitland boy (his parents grew up in East Maitland). Scott’s book about the river he loves, The Hunter, formed the basis of an ABC documentary of the same name, and it is now being reprinted, along with the story of a new kayaking adventure, in his latest publication, Return To The Hunter.

First published in 2023 by Maitland Regional Art Gallery

230 High Street, Maitland, NSW, 2320

to accompany the exhibition Upriver Downriver

Exhibition dates: 10 June — 13 August 2023

Gallery Director: Dr Gerry Bobsien

Gallery Deputy Director: Courtney Novak

Exhibition Curator: Kim Blunt

Curatorial Assistant: Belle Beasley

Exhibition Officer: Linden Pomaré

Foreword: Gerry Bobsien

Contributors: Aunty Sharon Edgar-Jones, Scott Bevan

Editing: Cheryl Farrell, Gerry Bobsien, Kim Blunt, Courtney Novak

Graphic Design: Clare Hodgins

Photography: Clare Hodgins, Bryce Doudle (unless otherwise noted)

© Maitland Regional Art Gallery | All images copyright of the artist

ISBN: 978-0-6487348-8-8

Catalogue proudly printed in Australia by Jennings Print Group.

Maitland Regional Art Gallery is a service of Maitland City Council and is supported by the NSW Government through Create NSW.

Works commissioned for this exhibition were made possible through the generosity of Bob and Paula Cameron.

1 River: Australian documentary narrated by William Dafoe, writer Robert MacFarlane and Jen Peedom, 2022.

RIVERS GIVE US SO MUCH MORE THAN WATER, THEY FLOW THROUGH OUR LIVES AS SURELY AS THEY FLOW THROUGH A PLACE1

UPRIVER DOWNRIVER was a project embarked upon with a simple idea – to create one exhibition across all the gallery spaces in collaboration with a selection of artists who have a relationship with the Hunter region – creatives living and working across Wonnarua, Awabakal and Worimi Country. We don’t often have an opportunity to hand the gallery over to one exhibition and this is one that could not have happened without 52 artists saying yes!

Upriver Downriver is not a survey exhibition of Hunter artists but more a snapshot of a region through a creative lens at a particular time. With private benefaction from Bob and Paula Cameron, MRAG commissioned artists Graham Wilson and Brontë Naylor. A big shout out to Graham, who literally put his body on the line carving metres of birch plywood across several months with the heart of the Hunter river on his mind. Thank you Bob and Paula, Graham and Brontë for all saying yes!

Next, we selected artwork from the MRAG collection which featured artists from the region. It is always a joy to delve into the MRAG collection and bring together artworks to speak in new conversations.

For the text in this publication and throughout the exhibition, we approached Hunter based writer Scott Bevan. Scott embraced the project wholeheartedly by taking a paddle on the river with artist and friend Chris Langlois. Together, as the weather cooled earlier this year, these two creative friends spent a few days paddling, camping and talking as they kayaked down the river. Thank you Chris and Scott for saying yes!

For the rest, our approach to each artist was loose – and this resulted in thrilling outcomes. One on one conversations were had with each artist as we moved towards the exhibition’s various deadlines. These conversations revealed remarkable connections and universal themes. The river, the ocean and coal where all there – not wholly unexpected. But the soundtrack of a region appeared as a strong element to the exhibition – the universal clank, shunt and screech of the coal trains with its dark cargo traversing the region from the Upper Hunter down to the Port of Newcastle.

There was a lot of trust given by the sponsors and artists in this exhibition and MRAG is forever grateful for the unbridled way in which everyone so wholeheartedly dived in. We say thank you for saying yes!

KIM BLUNT