WE ACKNOWLEDGE THE SOVEREIGNTY OF THE TRADITIONAL CUSTODIANS ON WHOSE COUNTRY THIS EXHIBITION IS STAGED –THE WONNARUA PEOPLE.

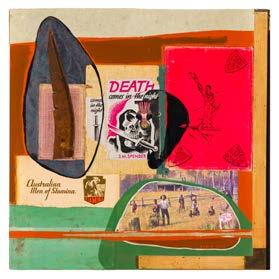

No fairy tales just grimm truths, 2023 mixed media, 40.5 × 64.5cm (detail page 10–11)

Foreword

CrownLand began as a conversation between artists. A conversation that shifted and turned a few times moving between issues that punctuate public and private life consistently. They all came back to the idea of life in an unreconciled nation. In conversations where truth and history remain shadowy. Not quite told. But there. Highlighting the absurdity of what now seems like a fading claim to a ‘black armband’ view of history.

The immense privilege of being born into power is a curious thing for us as subjects to ponder and the work of the artists in CrownLand remind us of our place as subordinates within its structure, or as Dr Lisa Slade reminds us in her essay, in our place where there is no common wealth.

As we walk through the exhibition, its corridors wallpapered with the terrifying images of Andrew Quilty’s Cronulla riots reportage, we face the grim reality of what can be done when a flag, an idea of nationhood is used for ugly and dangerous purposes. This exhibition is filled with complex conversations that are as nuanced and idiosyncratic as the communities we live in. It is also filled with affectionate humour and grim irony. This exhibition was conceived long before a referendum for The Voice was announced and we have no doubt it will be a lightning rod for discussions centred on this. Our aim therefore will be to try as hard as we can to keep community safe in this process.

We would like to extend a very dear thank you to Vincent Namatjira and Ben Quilty for their role in kickstarting this project with relish and to Karla Dickens who made a new body of work for this exhibition along with a powerful project honouring the Wonnarua Elders and Queens of the Mindaribba Local Aboriginal Land Council women’s group. A very warm thank you to all the women who took part in this and to Tara Dever for her trust in us with this project.

We invite you to step into the corridors of CrownLand and move within its complex world.

Karla Dickens

Maitland Regional Art Gallery

When planning began for the exhibition CrownLand, the reign of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II seemed eternal. Just months on, and there’s a new monarch and a new wave of conversations about Australia’s place in the Commonwealth. CrownLand animates these critical discussions, making explicit the aphorism that art is often the very best conduit for difficult conversations.

The ABC television commentary that preceded the Coronation of King Charles III in May 2023 unsettled the Australian Monarchists to the extent that, at the time of writing, legal action was threatened.i Claiming bias against the royal family, the monarchist groups fail to understand that there is no common wealth, that First Nations people in this Country and across the ‘Kingdom’ (the former British Empire) remain the most incarcerated and impoverished peoples on the planet.

Wiradjuri man Stan Grant, author of The Queen is Dead and an ABC coronation coverage panellist, was the target of racial vilification in the wake of the coverage. Recently Grant stood down from his media commitments. Grant’s concurrent offering of a conceptual and cultural

framework for understanding grief via Yindyamarra (the Wiradjuri ideation for respect and a call for justice and respectful dialogue ii) has been ignored, much like every offer of reciprocity made by Indigenous Australians since the first invasive incursions on this land more than 250 years ago.

As Grant elaborates:

My people have a word, Yindyamarra – its meaning escapes English translation. It is a philosophy – a way of living – grounded in a deep respect. I have sought to show Yindyamarra to those for whom this moment is profound. This is their ‘sorry business’ and I respect that. But it will pass. For Indigenous people, our sorry business is without end.iii

In CrownLand, contemporary artists have initiated a conversation that is long overdue. This dialogue begins with acknowledging the sovereignty of the traditional custodians on whose Country the exhibition is staged – the Wonnarua people. The weight of the colonial crown is subverted in a project led by Wiradjuri artist Karla Dickens, who poses the seemingly simple question of ‘who wears a crown?’ to the women of the Mindaribba Local Aboriginal Land Council. The answer is a dramatic series of performative photographs, in which local Elders, including those young and emerging, are adorned by self-made crowns that carry Country. Shells, feathers, seeds and string assert a new/ancient sovereignty and supplant the stolen gemstones of Commonwealth crowns. Dickens, as both artist and teacher says: Let’s rewrite the Royal Fairytale, by adding adornments of culture, power and truth telling of my peoples. The First Nation peoples of Australia [who] will not be owned or ruled by a bunch of out-of-date bullies. I hope you enjoy working on your tiaras –embodying your personal stories of power and culture – as each of you [is] the power of this country, of your ancestors and your families futures.iv

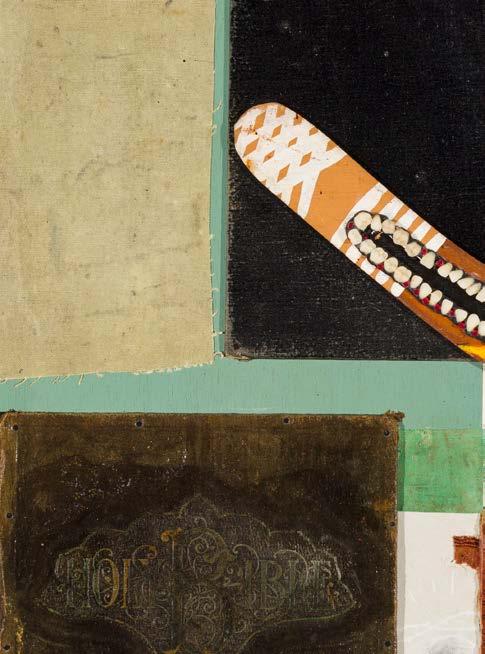

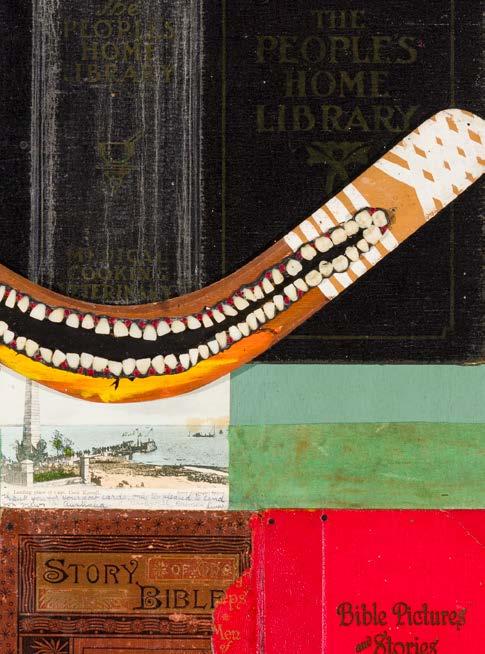

In the series of table-top sculptures made for the CrownLand exhibition, Dickens reclaims ‘Australiana’ – the laughing kookaburra, the souvenir teaspoon, sporting miniaturised fauna, and the carved emu egg – to create dioramas of death and dispossession. ‘Deadly’ humour is never far away for Dickens, who reminds us that ‘she is not happy Jan’. Dickens belongs to a lineage of feminist and First Nations political artists and through her assemblages she draws upon the carnivalesque. For Dickens, this is both literal – represented as a series of miniatures theatres or carnivals – and philosophical, with Dickens mobilising the folkloric to challenge dominant society,

Dr Lisa Sladean approach best articulated by literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin in his discussion of the carnivalesque as a subversive power.

Vincent Namatjira, the great-grandson of famed artist Albert Namatjira, knows too well the ambivalence of the crown for First Nations peoples. On the day the Queen died Vincent released the following statement: Queen Elizabeth met my great-grandfather Albert Namatjira in 1954 and she awarded him the Queen’s Coronation medal. This connection between my Family and the British Royal is the reason why I’ve made so many paintings of the Queen and the royal family. When I heard the news today I was pretty shocked – I’ve been reflecting on the fact that the Queen lived to 96, while my great grandfather passed away when he was only 57. Personally I’d like to see Indigenous leaders and heroes past and present have the same level of recognition and respect that the royal family does. I might retire from painting the Queen, let her rest in peace the poor thing … but I’ll definitely be busy painting King Charles!V

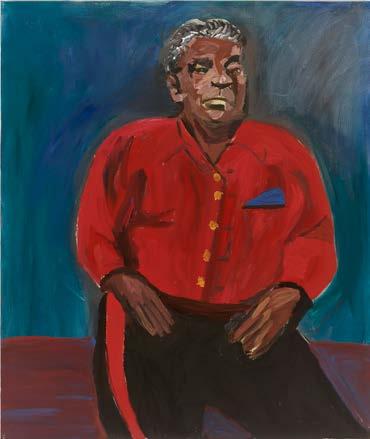

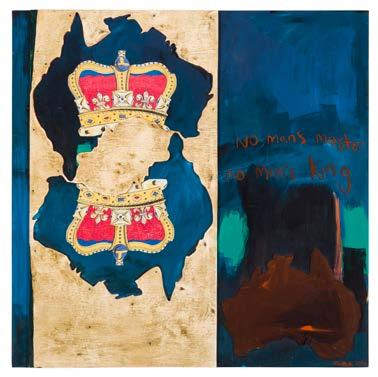

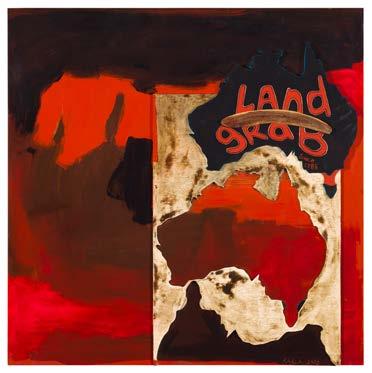

In the days following the Queen’s death, Vincent Namatjira found himself in Ben Quilty’s Southern Highlands studio on Gundungarra land, more than 2000 kilometres from his home in South Australia’s Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands. Not surprisingly, the two artists, both celebrated as contemporary chroniclers, took to paint and canvas to make sense of the event. For Vincent this was his first extended experience using oil paints, and what emerged from the impromptu residency is a series of history paintings, whereby the new King, Albert, Vincent and even a royal corgi (which shares a strong resemblance to Vincent’s own corgi camp dog called ‘Dingo’) are regaled. They are all made royal, crowned by Vincent’s brush, thereby extending his abiding practice of inverting the power base. As he explains:

For me, the canvas is a setting where I can combine the past, present and possible futures, and I can put myself – as a proud Aboriginal man – at the front and centre of a situation where we would usually be out of sight. In my paintings I’m on equal footing with the royals. I’m part of their royal balcony photo shoots, I climb on top of the Queen’s carriage, I share a cuppa tea in the palace and I return the favour by offering the Queen some bush tucker – maku (witchetty grubs) and tjala (honey ants). I’m still waiting on my invitation to visit Buckingham Palace for real though.vi

Where crown land is traditionally defined as a territorial area belonging to the monarch – who in turn personifies the Crown – Vincent’s Aboriginal sitters represent the real ‘royal domain’ in an approach that embodies what Stan Grant calls ‘speaking back to the world in our language’.

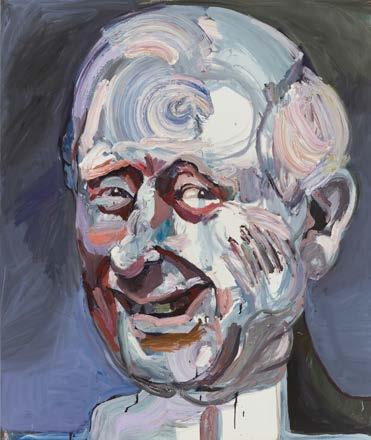

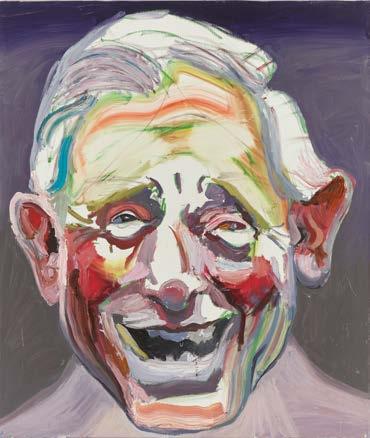

Quilty has focused on Charles, the new sovereign, who in spite of decades of preparation seems astonished and slightly bemused in the face of his new fate. Lavender-coloured supersized heads appear as a row of laughing clowns, with the new King absurdly beseeching his royal subjects. This series by Quilty, and Namatjira’s royal portraits, are in conversation with a collaborative canvas made by the two painters in a call and response during their final hours together in the studio. Namatjira’s monumental head, a self-portrait, emerges from a Quilty Rorschach, a double portrait that could well be Quilty himself. With its violent figuration, this self-portrait resembles a scream, much like that of Edvard Munch, who in paint was able to conjure a human expression so doleful that it carries the quality of sound. Quilty and Namatjira’s painted ensigns – James Cook’s bicorne or double-horned headpiece and Ned Kelly’s helmet – appear on the canvas like the heraldic symbols found on a flag. Meanwhile, a pair of skulls – one for each shoulder – can be read as epaulettes of dispossession in this colossal collaboration.

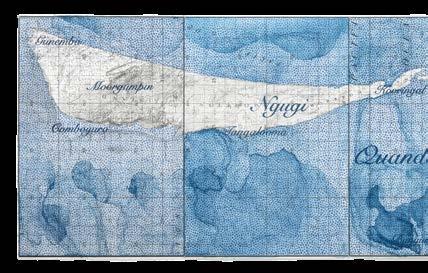

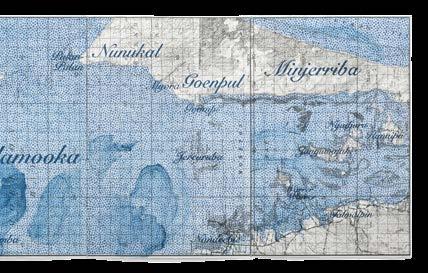

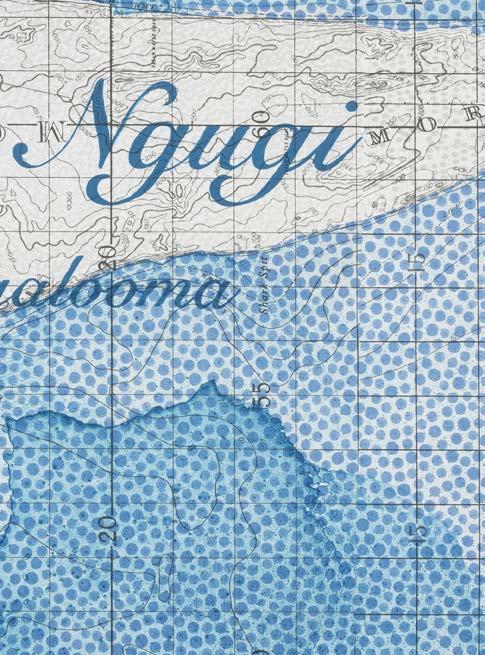

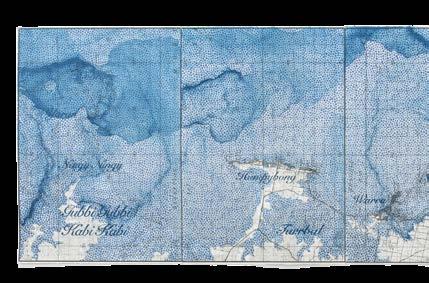

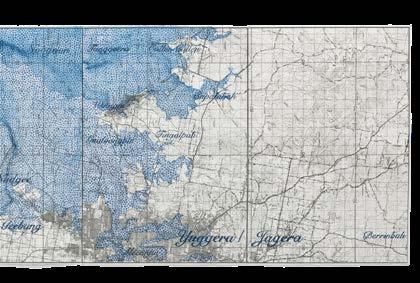

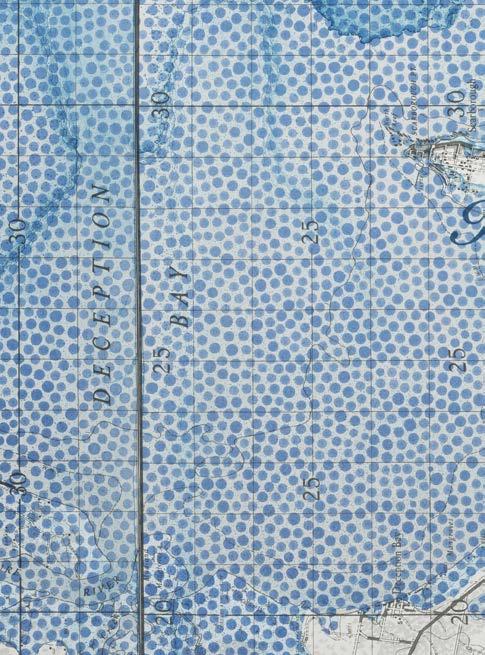

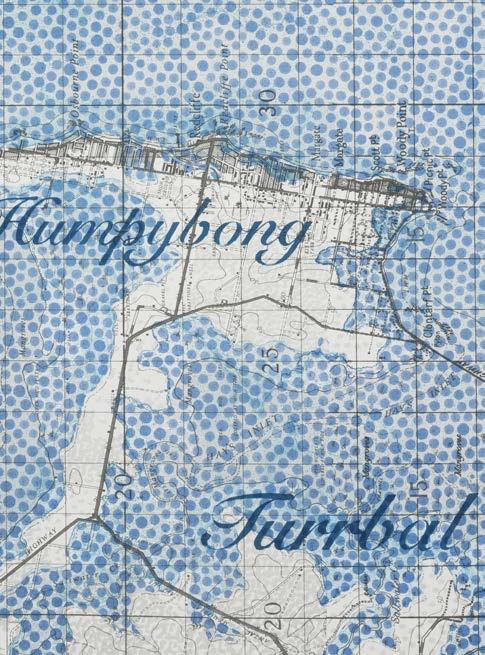

Just as Dickens, Quilty and Namatjira all remake militaria, Quandamooka artist Megan Cope erases the language of colonisers marked across her Country in her work Yarabindja Budjurung, translated as ‘beautiful sea country’. In Yarabindja Budjurung, Cope starts with printed maps of her ancestral Country near Stradbroke Island and its surrounds, using a nineteenth-century typeface to replace colonial names. The irony is not lost on her that these maps were made out of fear during wartime – in the event of a possible attack by Russians or Japanese – while in effect they are the very maps of invasion. As Cope articulates: Being a saltwater woman and growing up with these sorts of cultural foundations it’s very important to our identity and our sense of being with ourselves and then to each other and the land is very much informed by a specific location. That being Moreton Bay at large but more specifically North Stradbroke Island, where we have long lineage of many, many relatives coming from the same place. Multiple shared histories, multiple experiences, but [there is] something about that specific Country that really gives us our sense of self and it also informs the way we see the world.vii

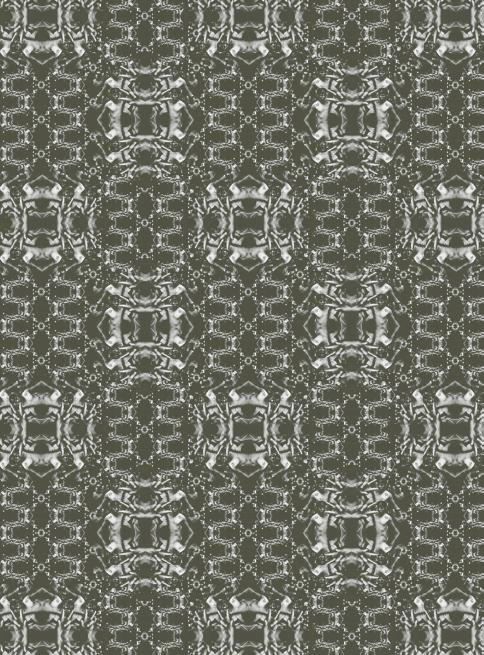

Celebrated as a war photographer, Andrew Quilty maps a critical moment in Australia’s history – the 2005 Cronulla race riots in his work Cronulla, 2005. Presented as a claustrophobic cacophony of images, made by digitally replicating his original black-and-white photographs

Dr Lisa Sladeof the event into an architecturally scaled ‘screen saver’, Quilty speaks to the ongoing and pervasive nature of racism and hints at its multiplication via media. A quarter of a million text messages helped to mobilise the violence that targeted people of ‘Middle Eastern appearance’, with the Australian flag, dominated by the Union Jack, emerging again and again in the photographs by the then twenty-fouryear old artist. Quilty’s photographs documenting home-grown terrorism challenge us to consider whether indeed anything at all has changed. British artist Jake Chapman ‘terrorises’ imperial currency in his series Pity is Treason, 2022, reminding us of the proximity of humour to horror. Following the death of Queen Elizabeth II in 2022, Chapman revisited a body of work from 2007 involving the defacing of legal tender. The late Queen’s demise materialises across each banknote, with the value of each note similarly in decline. In a perverse reversal, the addition of necrotic features and the Sabbath Black font (a typeface associated with royalty from the Middle Ages) escalates the exchange value of each defaced note as they become sought-after collectibles. The series title is a tribute to a quote by Robespierre, the French lawyer and revolutionary who played a role in the fall of the French monarchy in the late eighteenth century. Robespierre’s quote aligns sympathy with betrayal reminding us that when we believe so unquestioningly in a power that is above us, as subjects, as individualsfear follows. Chapman’s Pity is treason calls for an engagement with radical negativity. In his words, ‘nothing impedes the theology of optimism’. The crime of betraying one’s country, the very definition of treason, is precisely what is at stake in contemporary Australiaa reality keenly felt by the artists selected. Here in the south, sovereignty has never been ceded and the exhibition CrownLand is an ensign of self-determination that just cannot be ignored.

i Guests included Stan Grant, co-chair of the republican movement; Craig Foster, monarchist; Julian Leeser, Liberal MP; writer Kathy Lette; lawyer, writer and Wiradjuri and Wailwan woman Teela Reid; 2023 Australian Local Hero of the Year Amar Singh; Youth Advocate Angelica Ojinnaka; Constitutional Law Professor Anne Twomey; and Juliet Rieden from The Australian Women’s Weekly.

ii https://theconversation.com/the-power-of-yindyamarra-how-we-can-bring-respect-to-australiandemocracy-192164

iii https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-09-18/queen-death-indigenous-australia-colonisation-empire/101445508

iv Provided to MRAG by Karla Dickens

v Iwantja Arts Instagram post 8 September 2022

vi Quote from forthcoming publication Vincent Namatjira by Thames & Hudson

vii https://www.megancope.com.au/works/yarabindja-budjurung

CrownLand

Queen Elizabeth met my Great Grandfather Albert Namatjira in 1954 and awarded him the Queen’s Coronation Medal. This connection between my family history and the British Royal family is the reason why l’ve made so many paintings of the Queen and the royal family. When the Queen passed away I spent a lot of time reflecting on her connection to my family, especially the fact that she lived to 96, while my great-grandfather passed away when he was only 57. Personally I’d like to see Indigenous leaders and heroes past and present have the same level of recognition and respect that the royal family does.

Maitland Regional Art Gallery

Vincent Namatjira and Ben Quilty

The Crown, 2022 oil on linen, 202 × 265cm

Photo: Mim Stirling (detail page 32–33)

Maitland Regional Art Gallery

Vincent Namatjira and Ben Quilty

The Crown, 2022 oil on linen, 202 × 265cm

Photo: Mim Stirling (detail page 32–33)

A few days after Queen Elizabeth II died, Vinnie came to my studio. We’d been planning to make paintings together since before Covid. As he walked through the door, he told me he wouldn’t be needing to paint the Queen anymore “Never again,” he said. “Now we’ll paint the King.”

We spent a week discussing the world, what the Queen’s death meant and how we both fit into modern day Australia, a country we both call home. We made paintings, ate, slept, and made paintings again and again. Vincent told me stories of his life, filled with humour but often cloaked in sadness. He worked from 7am every morning, coffee and a cigarette beside him, exploring a brand-new era of a regal dynasty on the other side of the planet; paintings about a family that had indirectly wrought a profound impact on the trajectory of Vincent’s own family. We laughed about his dog, a “desert corgi” and talked about his Grandfather and the legacy that old man left after he died, a few years older than I am now. We discussed how our art allowed us to have a voice in big discussions.

Most of my ancestors were Irish convicts, victims of the potato famine of 180 years ago. I’ve often wondered what they’d make of us subjects, still subjected to an English monarch. Both Vinnie and I mined the internet for images to make paintings about. It’s a bit hard to get your own pic of anything royal from this side of the planet. In a peaceful paradise it would be easy to envisage that an artist, like Vincent, in the 21st century would make simple and beautiful works. The more social harmony, the less urgency to rail against a system that is successfully stabilising your town. But Vincent’s town has been smashed and with humour and satire he allows us to walk down his street. Namatjira Street is troubled. And the King of that realm is working hard to bring peace to his street. The notion that Vincent Namatjira is a ‘subject’ of a King on the other side of the planet is hilariously and utterly absurd.

Maitland Regional Art Gallery

Vincent Namatjira The New King, 2022 oil on linen, 132.5 × 112cm Photo: Mim Stirling

Yarabindja Budjurung II, 2021 lithograph on BFK rives paper, 5 panels: 105 × 75cm each, 105 × 365cm overall. Edition of 10 plus 2 artist’s proofs.

Carl Warner. Courtesy the Artist and Milani Gallery (detail page 48–49)

Maitland Regional Art Gallery

Megan Cope Photo:

Yarabindja Budjurung I, 2021 lithograph on BFK rives paper, 5 panels: 105 × 75cm each, 105 × 365cm overall. Edition of 10 plus 2 artist’s proofs.

Carl Warner. Courtesy the Artist and Milani Gallery (detail page 52–53)

Maitland Regional Art Gallery

Megan Cope Photo:

Maitland Regional Art Gallery

Jake Chapman Pity is Treason (series), 2022 ink and watercolour on used currency 14.6 × 7.7 cm each Photo: Sahlan Hayes

Maitland Regional Art Gallery

Jake Chapman Pity is Treason (series), 2022 ink and watercolour on used currency 14.6 × 7.7 cm each Photo: Sahlan Hayes

Maitland Regional Art Gallery

Jake Chapman Pity is Treason (series), 2022 ink and watercolour on used currency 14.6 × 7.7 cm each Photo: Sahlan Hayes

Maitland Regional Art Gallery

Jake Chapman Pity is Treason (series), 2022 ink and watercolour on used currency 14.6 × 7.7 cm each Photo: Sahlan Hayes

Maitland Regional Art Gallery

Jake Chapman Pity is Treason (series), 2022 ink and watercolour on used currency 14.6 × 7.7 cm each Photo: Sahlan Hayes

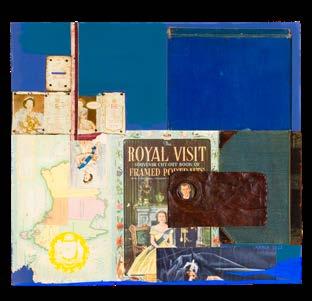

The Blues I, 2022 mixed media, 65 × 71cm

Bound with no Binding II, 2022 mixed media, 65 × 65cm

Bound with no Binding I, 2022 mixed media, 65 × 65cm

Maitland Regional Art Gallery Karla Dickens

Maitland Regional Art Gallery

Karla Dickens

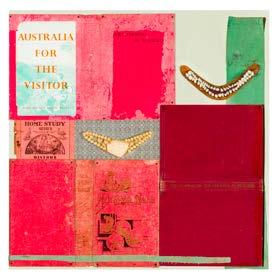

Silver spoons and genocide, 2023 mixed media, 35 × 64.5cm

Hit the road Jack, 2023 mixed media, 47 × 64.3cm (detail page 70–71)

Maitland Regional Art Gallery

Karla Dickens

Silver spoons and genocide, 2023 mixed media, 35 × 64.5cm

Hit the road Jack, 2023 mixed media, 47 × 64.3cm (detail page 70–71)

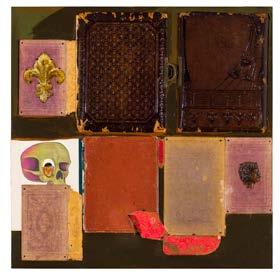

Keep smiling IV, 2022 mixed media, 65 × 65cm (detail page 74–75)

Keep smiling V, 2022 mixed media, 65 × 65cm

Keep off the Grass, 2022 mixed media, 65 × 65cm

Maitland Regional Art Gallery

Karla Dickens

Karla Dickens

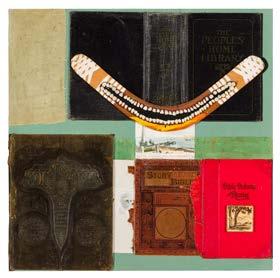

Terror nullis, 2023 mixed media, 41 × 64.5cm

The kings of the bush aren't laughing, 2023 mixed media, 40 × 64.5cm (detail overleaf)

Karla Dickens

Terror nullis, 2023 mixed media, 41 × 64.5cm

The kings of the bush aren't laughing, 2023 mixed media, 40 × 64.5cm (detail overleaf)

CrownLand

Karla Dickens

Soldiering On, 2022 mixed media, 125 × 125cm

Home Sweet Home, 2023 mixed media, 125 × 125cm

CrownLand

Karla Dickens

Soldiering On, 2022 mixed media, 125 × 125cm

Home Sweet Home, 2023 mixed media, 125 × 125cm

First published in 2023 by Maitland Regional Art Gallery

230 High Street, Maitland, NSW, 2320

to accompany the exhibition CrownLand

Exhibition dates: 26 August — 05 November 2023

Gallery Director: Dr Gerry Bobsien

Gallery Deputy Director: Courtney Novak

Exhibition Curators: Dr Gerry Bobsien and Kim Blunt

Exhibition Lead: Holly Farrell

Foreword: Dr Gerry Bobsien

Essay: Dr Lisa Slade

Editing: Dr Gerry Bobsien, Kim Blunt, Courtney Novak, Holly Farrell

Graphic Design: Clare Hodgins

Photography: Clare Hodgins, Bryce Doudle (unless otherwise noted)

© Maitland Regional Art Gallery | All images copyright of the artists

ISBN: 978-0-6487348-9-5

Catalogue proudly printed in Australia by Who Printing, Newcastle.

Maitland Regional Art Gallery is a service of Maitland City Council and is supported by the NSW Government through Create NSW.

Ben Quilty is represented by Jan Murphy Gallery, Meeanjin (Fortitude Valley), Queensland, Australia

Tolarno Galleries, Naarm (Melbourne), Victoria, Australia

Arndt Art Agency, Berlin, London

Karla Dickens is represented by Station Gallery Naarm (Melbourne), Victoria, Australia

Gadigal (Sydney), New South Wales, Australia

Megan Cope is represented by Milani Gallery, Meeanjin (Brisbane), Queensland, Australia

Vincent Namatjira is represented by Iwantja Arts, APY Lands, Northern Territory, Australia

Yavuz Gallery Gadigal (Sydney), New South Wales, Australia

Acknowledgements

Maitland Regional Art Gallery

Maitland Regional Art Gallery (MRAG) warmly extends their gratitude to the artists, creatives and writers who have come together to create this important and timely exhibition;

Ben Quilty for being the starting point of this exhibition and being so flexible and fluid when important and relevant situations presented themselves; as well as introducing Vincent Namatjira to Maitland.

Vincent Namatjira, an established subversive and witty portraitist who will no longer have to paint the Queen – thank you Vincent for allowing these new portraits to be shown first at MRAG.

Megan Cope for lending important work to the exhibition which speaks directly to the importance of Indigenous knowledge and memory.

Karla Dickens for your generosity with your time connecting with us and our community in Maitland, reimaging a new vision of the Crown and extending that vison to the Queens of Wonnarua Country

Tara Dever and the highly respected Elders and First Nations women from, or living on, Wonnarua Lands. MRAG is especially honoured to have Aunty Marge Weastell at the centre of a series of portraits newly created under the artistic direction of Karla Dickens and MRAG photographer Clare Hodgins

Andrew Quilty for allowing MRAG to use important documentary images taken from a dark time in Australia’s recent history; reminding us that almost two decades after these images were taken, we are not far removed from a shocking underbelly of Australia’s wider culture.

Mirra Whale for re-imagining Andrew Quilty's manacing imagery into the sublime for both the exhibition design and this publication.

Jake Chapman, UK artist who is undertaking his own critique of the Crown from the land of the crown and what it means to him living in the ‘home country’.

Jeremy Robinson and Gerry Bobsien for forging the series of steel crowns for the Queens of Wonnarua.

Dr Lisa Slade for her important and powerful words and for bringing the exhibition together with significance and thoughtful consideration.

MRAG would also thank the artists galleries and studio teams involved in supporting this important exhibition.

With thanks: Kim Blunt

CrownLand

CrownLand