EARN CME CREDIT WITH THIS ISSUE. SEE PAGE 10.

a

Hypophosphatasia (HPP) is a metabolic disorder characterized by LOW Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) activity1

Patients with HPP may experience unpredictable, devastating, and life-limiting consequences, including:1

Patients with any of these key signs/symptoms and LOW ALP should be evaluated for HPP1

Example cutoff from Abbott Laboratories; adult ALP ranges are lab specific and may vary.

References: 1. Bishop N, et al. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101(6):514-515. 2. Alkaline phosphatase [package insert]. Abbott Park, IL: Abbott Laboratories; 2007. 3. Offiah AC, et al. Pediatr Radiol. 2019;49(1):3-22. 4. Colantonio DA, et al. Clin Chem. 2012;58(5):854-868.

0-14d15d-<1y1-<10y10-<13y13-<15y15-<17y17-<19y 0-14d15d-<1y1-<10y10-<13y13-<15y15-<17y17-<19y Adults a

NOTE: Graph adapted from the Canadian Laboratory Initiative on Pediatric Reference Intervals (CALIPER) project. 2 Caliper samples from 1072 male and 1116 female participants (newborn to 18 years) were used to calculate age- and sex-specific reference intervals. No variation in ALP based on ethnic differences was observed. Reference intervals shown were established on the Abbott ARCHITECT c8000 analyzer. a Adult interval provided by the Abbott ARCHITECT ALP product information sheet is for females >15 and males >20 years of age. For younger ages, Abbott does not provide lower limits of normal. 3

LOW Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) is hallmark of Hypophosphatasia.1 To learn more, please visit www.hypophosphatasia.com

LOW Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) may not be flagged if your laboratory does not use age- and sex-adjusted reference intervals in children when testing ALP activity1

BOARD CHAIR John Burroughs, MD (Kansas City)

PRESIDENT Kara Mayes, MD, FAAFP (St. Louis)

PRESIDENT-ELECT Afsheen Patel, MD (Kansas City)

VICE-PRESIDENT Natalie Long, MD (Columbia)

SECRETARY/TREASURER Lisa Mayes, DO (Macon)

DISTRICT 1 DIRECTOR Arihant Jain, MD (Cameron)

ALTERNATE Vacant

DISTRICT 2 DIRECTOR Robert Schneider, DO, FAAFP (Kirksville)

ALTERNATE Eric Lesh, DO (Kirksville)

DISTRICT 3 DIRECTOR Emily Doucette, MD, FAAFP (St. Louis) DIRECTOR Dawn Davis, MD (St. Louis)

ALTERNATE Lauren Wilfling, DO (St. Louis)

DISTRICT 4 DIRECTOR Jennifer Scheer, MD, FAAFP (Gerald)

ALTERNATE Jennifer Allen, MD (Hermann)

DISTRICT 5 DIRECTOR Amanda Shipp, MD (Versailles)

ALTERNATE Vacant

DISTRICT 6 DIRECTOR David Pulliam, DO, FAAFP (Higginsville)

ALTERNATE Justin Cramer, MD, FAAFP (Marshall)

DISTRICT 7 DIRECTOR Beth Rosemergey, DO, FAAFP (Kansas City) DIRECTOR Jacob Shepherd, MD, FAAFP (Lee’s Summit)

ALTERNATE Ed Kraemer, MD (Lee’s Summit)

DISTRICT 8 DIRECTOR Andi Selby, DO (Branson)

ALTERNATE Barbara Miller, MD (Neosho)

DISTRICT 9 DIRECTOR Douglas Crase, MD (Licking)

ALTERNATE Vacant

DISTRICT 10 DIRECTOR Gordon Jones, MD (Sikeston)

ALTERNATE Jenny Eichhorn, MD (Jackson)

DIRECTOR AT LARGE Wael Mourad, MD, FAAFP (Kansas City) Krishna Syamala, MD, FAAFP (St. Louis)

Wesley Goodrich, DO, MPH, UMKC

Kelly Dougherty, MD, Mercy (Alternate)

STUDENT DIRECTORS

Karstan Luchini, KCU Joplin

Abby Crede, UMKC (Alternate)

Kate Lichtenberg, DO, MPH, FAAFP, Delegate

Peter Koopman, MD, FAAFP, Delegate

Sarah Cole, DO, FAAFP, Alternate Delegate

Jamie Ulbrich, MD, FAAFP, Alternate Delegate

MAFP STAFF

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Kathy Pabst, MBA, CAE

ASSISTANT EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Bill Plank, CAE

MEMBER COMMUNICATIONS AND ENGAGEMENT Brittany Bussey

The information contained in Missouri Family Physician is for informational purposes only. The Missouri Academy of Family Physicians assumes no liability or responsibility for any inaccurate, delayed, or incomplete information, nor for any actions taken in reliance thereon. The information contained has been provided by the individual/organization stated. The opinions expressed in each article are the opinions of its author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of MAFP. Therefore, Missouri Family Physician carries no respsonsibility for the opinion expressed thereon.

Missouri Academy of Family Physicians, 722 West High Street

Jefferson City, MO 65101 • p. 573.635.0830 • f. 573.635.0148

Website: mo-afp.org

• Email: office@mo-afp.org

Population Health Through Immunizations

Using Motivational Interviewing to Discuss Vaccine Hesitancy

Vaccine Hesitancy: Something Old, Something New

AAFP Vaccine Science Fellowship

Family Medicine Transition Conference for Residents and Students

To Incentivize or Not: Does Paying to get Vaccinated Work?

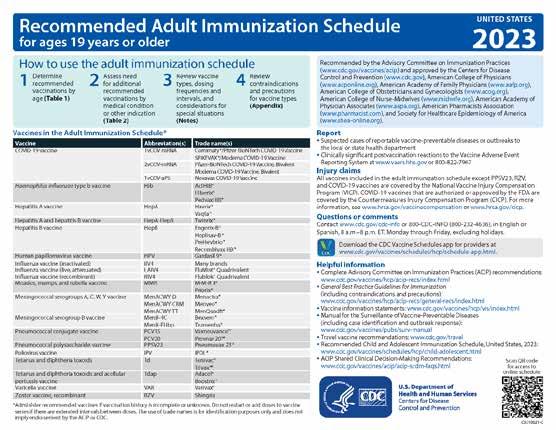

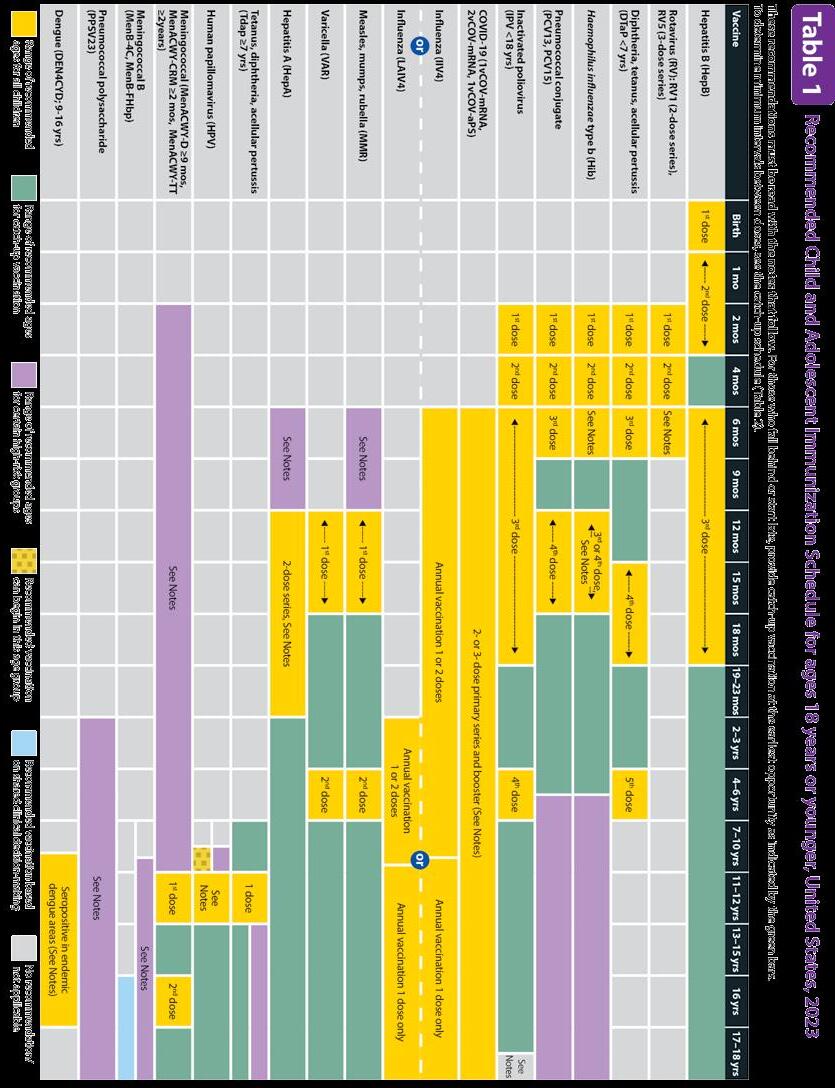

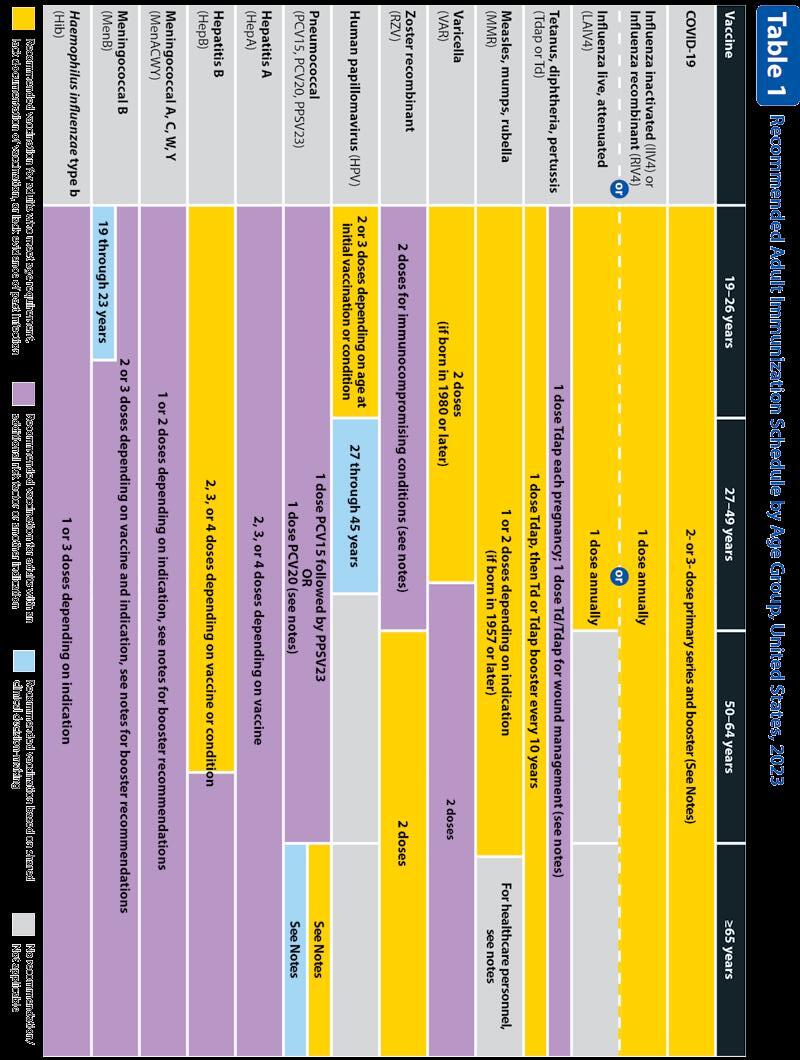

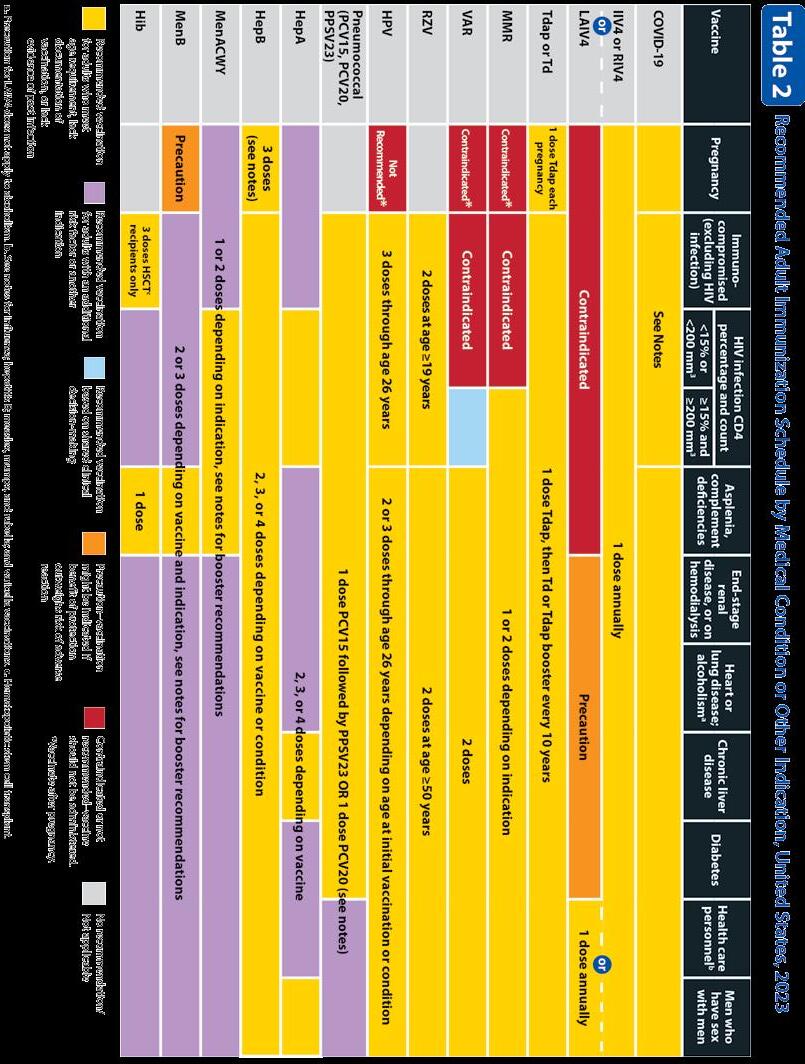

2023 Recommended Vaccination Schedules

Advocacy + Day = Impact

MAFP Priority Issues

Multi State Forum is Back

Shaffer Candidate for AAFP President-Elect

April 27

Virtual CME: Adolescent Care

https://www.mo-afp.org/cme-events/virtual-cme/

May 25

Virtual CME: Nutrition and Obesity

https://www.mo-afp.org/cme-events/virtual-cme/

June 9-10

Transition to Practice Conference for Residents and StudentsCourtyard by Marriott, Jefferson City, MO

https://www.mo-afp.org/transition-to-practice/

October 20-22

Physician Wellness Seminar - Margaritaville at Lake of the Ozarks

https://www.maops.org/general/custom.asp?page=wellnessseminar

November 10-11

31st Annual Fall Conference - Big Cedar Lodge, Ridgedale, MO https://www.mo-afp.org/cme-events/afc/

February 26-27

MAFP Advocacy Day 2024 - Courtyard Marriott, Jefferson City, MO https://www.mo-afp.org/advocacy/advocacy-day/

Welcome to the Missouri Family Physician Vaccination issue! Our staff and wonderful physician contributors have assembled an informative and provocative publication.

Inside this issue, you will find up-to-date information from the CDC regarding vaccination schedules that we hope will be a helpful resource for you, your office staff, and your patients. It is more important than ever for family physicians to have clear, sound information on vaccine schedules and safety in order to have the greatest impact on our patient’s journey to take full advantage of available vaccinations. This is critical for not only their individual health but the health of their families, friends, and communities as well.

Acquiring the proper vaccinations at the appropriate time has become less common across our state and nation. This has worsened since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. As noted in several of the articles in this issue, across the state of Missouri, <93% of children have received the full series of the MMR vaccine by the time they enter kindergarten. This falls below the 95% threshold for herd immunity. What a frightening thought!

I completed my residency training in Salt Lake City in the late…well, a long time ago, and unfortunately saw children (whose parents had religious objections to vaccinations) hospitalized with measles. In medical school in North Carolina, I actually saw a patient in true tetany! And I

Mission Statement:

The

am also old enough to have cared for patients with post-polio syndrome. At that time, I hoped these would be interesting stories to tell but not diseases I would see again in practice.

That brings us to vaccine hesitancy, the subject of many articles in this issue. Our authors explore the causes and options to combat vaccine hesitancy in our practices and communities. This hesitancy was heightened during the COVID-19 pandemic as fear and distrust of vaccinations (and those who encouraged their use) were stoked by easily accessible misinformation. Trust in vaccine manufacturers and our public health agencies have fallen to disturbingly low levels, but fortunately, trust in you, our family physicians remains high.

How do we use this platform of trust to engage those patients and family members making medical decisions for our patients, to have a truly open conversation without closing the door to more conversations? I think you will find helpful advice in the pages of this magazine! Thank you for all that you do in your communities to encourage vaccinations. We need you more than ever. And thank you for your activity with the Missouri Academy of Family Physicians. Feel free to contact our staff for more information on vaccines and any issues that may arise in your practice. They are such a helpful group of caring people. And remember to take care of yourselves while you care for others. We need you!

Missouri Academy of Family Physicians is dedicated to optimizing the health of the patients, families and communities of Missouri by supporting family physicians in providing patient care, advocacy, education and research.

THANK YOU FOR ALL THAT YOU DO IN YOUR COMMUNITIES TO ENCOURAGE VACCINATIONS. WE NEED YOU MORE THAN EVER.

For over 500 years, and perhaps much longer, humans have recognized immunization as an effective way to prevent disease and death. In fact, vaccinations have saved more lives in human history than any other single medical intervention.1 The storied history of smallpox vaccination is one resounding example of the success of immunization - from inoculating healthy individuals with smallpox in the 15th century, to discovering the improved safety of cowpox inoculation in 1796, to the global eradication of smallpox in 1980.1 In the last century, as with many medical interventions, we have seen enormous growth in our understanding and application of immunization technology. The major success of public health and vaccination efforts has afforded those in developed countries the opportunity to live in a state of unawareness about the once-devastating nature of some diseases.2

Unfortunately, while vaccines continue to save millions of lives each year, they face growing resistance.3 One of the most well-known and well-publicized exhibitions of the anti-vaccine movement began with a paper published in 1998, where the author claimed a link between the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine and the development of childhood autism.4 The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the variability of vaccine hesitancy amongst different groups - including religion, race, gender, age, geographic location, political affiliation, socioeconomic status, and level of education.5 Vaccine skepticism is not a new dilemma6 but is exponentially more difficult to tackle in a society with instant access to information (whether true or false), vast social media influence, history, and at the heart of it all - human nature.

As healthcare providers, we are tasked with navigating the complicated and sometimes uncomfortable conversations around individuals’ vaccine uncertainties. Because most healthcare professionals are pro-vaccination, it may be difficult to understand or sympathize

with our patients who harbor concerns with immunizations for themselves or their family members. However, there are techniques to guide us in these conversations, which may ultimately strengthen the provider-patient relationship as well as improve health outcomes.

Multiple studies have evaluated the efficacy of education in improving a parent’s intention to vaccinate their child. The evidence is not clear that education alone has a major effect on vaccine hesitancy if the beliefs of the parent are not considered.7 Increasing education may be more helpful if the major barrier to vaccine acceptance is unawareness, however more studies are needed in the future to further tease out these nuances.

In particularly hesitant individuals, pro-vaccination messaging does not seem to function as intended. One randomized controlled trial evaluated parental intent to vaccinate children for MMR and the effect of pro-vaccine messaging on these parents. In this study, as with others, parental intent to vaccinate was not affected by providing reliable information about the safety of MMR vaccination and the dangers of measles, mumps, and rubella, nor by showing images or telling detailed stories of children affected by measles, mumps, or rubella.8 Addressing all vaccinehesitant individuals with a blanket pro-vaccine message is unlikely to be effective in a majority of those targeted, and in particular those who lean towards the more hesitant viewpoint may further cling to false beliefs about immunization when pushed to consider alternative information.8 Focusing solely on “myth-busting” may even emphasize the myth itself and reinforce false beliefs rather than facts, while attempting to harness fear of preventable diseases may actually increase fear in vaccine side effects.

When approaching difficult conversations, it is important to remain curious and allow the patient or family member to voice their concerns while listening in order to understand rather than respond. In that vein, the initial portion of the conversation can be spent asking questions relating to what the patient says and avoiding giving advice or personal interpretations of the other party’s feelings.9 Sometimes, functioning as a sounding board and allowing a person to think aloud rather than immediately offering advice can result in the individual coming to a positive conclusion on their own.

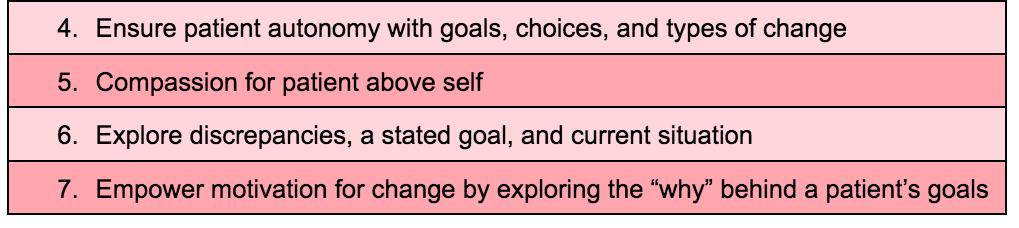

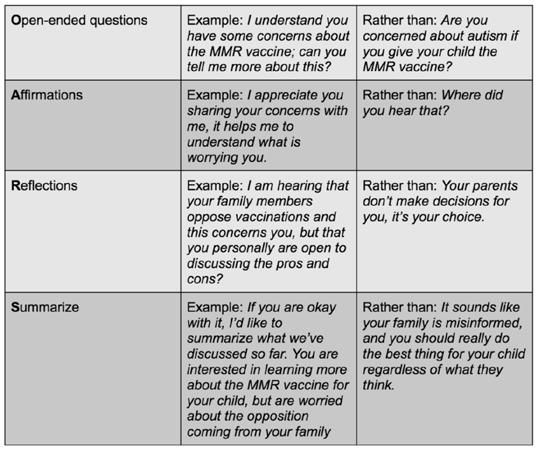

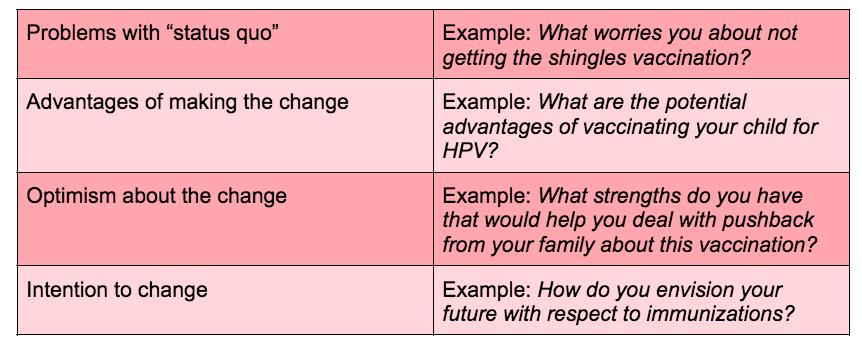

Motivational interviewing is another concept that combines tenets of cognitive and social psychology, and which initially began in the arena of addiction medicine.10 The basic concept is that motivational interviewing is a person-centered, goal-oriented communication technique whereby the goal is to increase an individual’s drive and commitment to achieving a certain positive outcome, while especially focusing on that individual’s circumstances and reasons for change. This should be done in a safe space, where we offer acceptance and empathy regardless of our own personal hangups.10 As physicians, our role in this conversation is to guide the patient and to allow for personal reflection and discovery (Table 1).

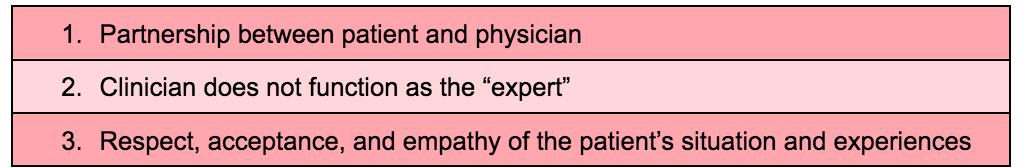

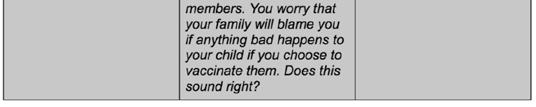

So, how does motivational interviewing work? There are two phases; the first involves building a person’s motivation to change, and the second reinforces that decision and commitment to continue a change. When building motivation to make a change, we can consider the OARS approach (Table 2) by starting with asking open-ended questions, affirming and reflecting upon answers to those questions, and summarizing the conversation back to the patient without judgment.12

Engaging in open and reflective conversations like this can help the provider determine where their patient falls along the continuum of “readiness to change” (Figure 1). If a patient is unprepared for change, a provider may intervene by raising the patient’s awareness of potential doubts or risks of their current behavior and to provide harm reduction strategies. In the case of vaccine hesitancy, an example would be to reflect on the patient’s risks for harm without immunization(s), and to provide strategies for avoiding exposure to vaccine-preventable conditions. In the contemplative stage, providers can discuss risks and benefits of immunization, and once a patient is ready to change, we can help in setting clear goals. For example, outlining a timeline for vaccinations over several visits and providing contact information if the patient has questions or experiences side effects. Finally, once a patient has made a change - in this case, accepting recommended immunizations - it is important to maintain the change and prevent relapse. This may be in the form of encouraging follow up visits for booster doses and ongoing conversations about newly recommended immunizations. Relapses are not unexpected, so encouragement without demoralization is important to sustain positive changes long-term.12

Once a patient has made a commitment to change, we can further strengthen that commitment by discussing what are the issues with “status quo,” what are the advantages of making this change over time, and what level of optimism and intention that patient has for making a change (Table 3).12 Overall, we can reinforce a patient’s decision to make a long-lasting positive change by empowering patient autonomy and self-efficacy.

After a more in-depth discussion outlining the effects of sustained change, providers and patients can put together a patient-directed plan of change. In the specific scenario of vaccine hesitancy, we may describe which vaccinations are recommended, inquire about which immunizations a patient may or may not be hesitant about, describe how a timeline for administering vaccinations might look, and relay how we can be available to the

patient going forward, all with the goal of allowing for patientmotivated and patient-directed care plans.

There are certainly barriers for providers trying to implement motivational interviewing into routine practice when discussing immunizations and other medical problems. These include time constraints, lack of professional development to improve motivational interviewing skills, the default nature of many providers to provide quick advice and expertise, and sometimes a patient’s desire for an immediate fix to a difficult problem, among others.12 A few ways to overcome these issues include incorporating dedicated training for motivational interviewing, for example with educational videos or role-playing, systemsupported professional development of these skills, as well as determining how to incorporate motivational interviewing within the limited time providers have for patient consultations.14 This could include pre-visit questionnaires with more in-depth inperson discussions, as well as extending the conversation over multiple visits, or using telemedicine to allow for more flexibility.

In summary, vaccine hesitancy is a real issue with real consequences, and may be difficult to address for a variety

of reasons. Healthcare providers are tasked with navigating conversations around vaccine hesitancy and encouraging patients to make the best decisions for positive outcomes. Research has shown that education alone does not often change the mind of vaccine-hesitant patients, and in some cases may actually strengthen anti-vaccine sentiment. However, we may be more successful by approaching these conversations with the goal to motivate and empower patients to consider the factors contributing to their hesitancy, reflect upon these factors, examine the pros and cons of decisions surrounding immunization, and plan for sustained change. Motivational interviewing requires restraint on the part of the practitioner to hold back on offering advice or judgment, to educate if/when needed, and to allow and respect patient autonomy. Using this technique, we can become more comfortable and successful in discussing vaccine hesitancy. In order to combat barriers to utilizing motivation interviewing, it is important to incorporate training and practice as well as tailoring this practice to fit with individual provider styles and time limitations.

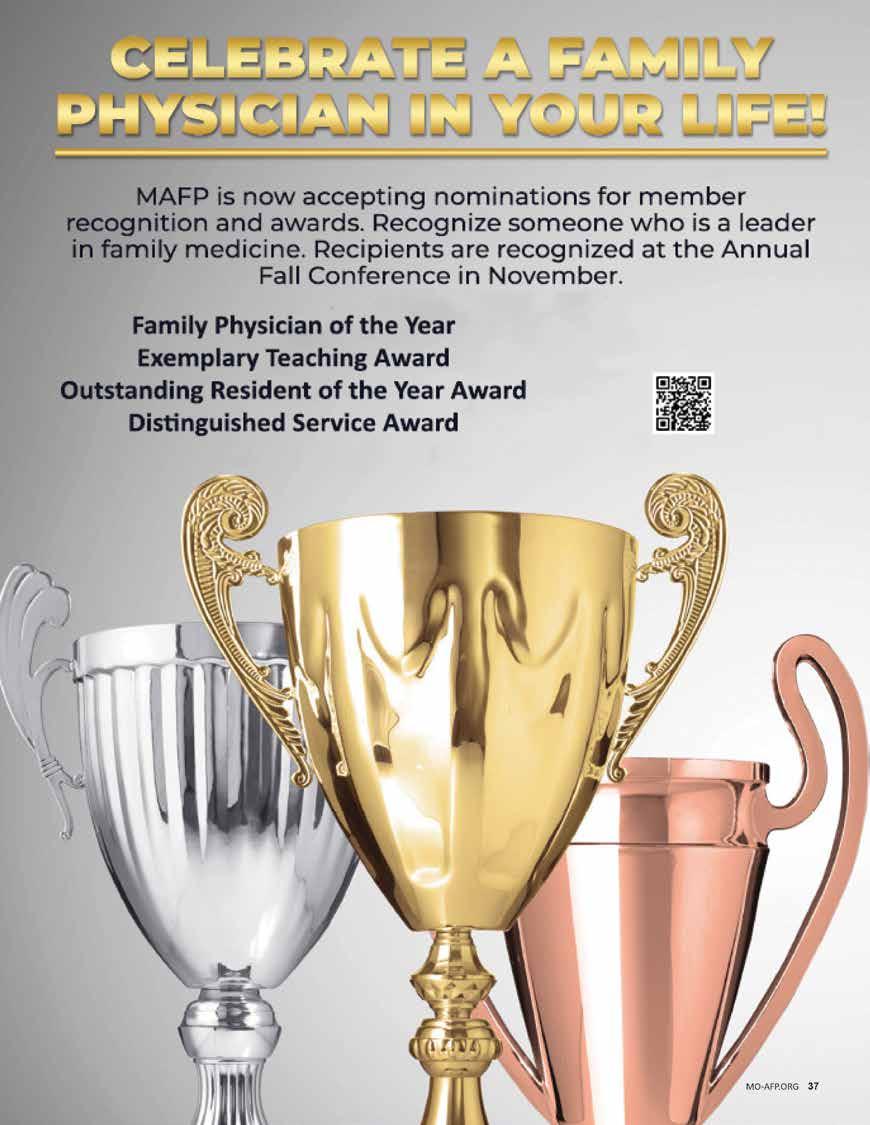

The MAFP Board of Directors recently approved an adjustment of registration fees for the Annual Fall Conference (AFC) to address increasing conference costs. These adjustments are the first increase in registration fees since 2010. The active member conference registration fee is $425 or $375 for the early bird rate. Most other registration fees are increasing by $50. Exhibitors will also pay an increased fee beginning in 2023. Visit our Annual Fall Conference page at https://www.mo-afp.org/cme-events/afc/ for more details, to register, and stay updated on conference developments.

In response to a proposed increase in lodging costs of more than double attendee’s previous rates, the MAFP Board decided to move the conference location beginning in 2024. We appreciate three decades of hospitality at Big Cedar and are looking forward to the 2024 Annual Fall Conference at the Intercontinental Kansas City at the Plaza, November 8-9, 2024. Additional details will be shared closer to the event.

Please reach out to MAFP Assistant Executive Director, Bill Plank, CAE, at bplank@mo-afp.org or submit a Call for Presentations available at https://www.mo-afp.org/cme-events/call-for-presentations/ if interested in presenting CME.

Since the early 20th century, physicians have recommended vaccines to prevent and, in some cases, eradicate disease. Starting with recommendations for smallpox, diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis, our list of modern vaccines has bloomed to cover a multitude of illnesses. As the advancement of this science and modern healthcare pushed vaccine-preventable infections out of society’s collective memory, hesitancy has increased among patients and providers.

When public trust drops in vaccines, avoidable diseases reemerge. (https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/ volumes/72/wr/mm7202a2.htm?s_cid=mm7202a2_w) In the 2021-22 school year, completion of vaccines among kindergartners dropped nearly 1% from the year prior and 2% from the year before the pandemic started.1 Missouri reports 2021-2022 kindergarten coverage of Measles, Mumps, Rubella (MMR) vaccine at 92.6%, well below the target of 95% to ensure suppression of a measles outbreak.2 In 2019, the world experienced the most individual cases of measles since 1992, mostly in under-vaccinated areas, the same year that the World Health Organization named vaccine hesitancy as one of the top 10 threats to global health—prior to the emergence of a global pandemic!3

For as long as vaccines have existed, so has vaccine hesitancy.

Our goal as physicians and healthcare providers is to promote the belief that vaccines work, are safe, and are trustworthy, also known as vaccine confidence. Multiple factors can undermine vaccine confidence, leading some patients, and healthcare workers, to delay or refuse vaccination. Understanding why patients and healthcare workers choose not to get vaccinated is the first step to moving hesitance toward acceptance. Vaccines are a victim of their own success, as most Americans have never witnessed the devastating effects of vaccine-preventable diseases such as polio or diphtheria. Belief systems that prioritize personal choice over group benefit also contribute. On an individual level, many doubts arise from a few basic tenets, including concerns about “purity” or “keeping natural,” distrust in science or government institutions, concerns about bodily autonomy, religion, and disproportionate fear of side effects.4

Fears and myths have been amplified by the use of the internet and social media. Popular media outlets give voices to prominent anti-vaccine figures, validating and intensifying common fears about vaccination. Sensational and inflammatory headlines generate the most online engagement, leading even readers who may generally support vaccination to click into a story filled with false claims. Social media algorithms also help perpetuate the online “echo chamber,” often silencing views that differ. A 2022 Kaiser Family Foundation survey asked over 1,500 adults whether they had encountered false statements about COVID-19 vaccines on the internet or social media. A striking 78% had seen at least one of eight

Reiana Mahan, MD

University of Missouri Columbia Dept. of Family & Community Medicine

Reiana Mahan, MD

University of Missouri Columbia Dept. of Family & Community Medicine

false statements and either believed them to be true or were unsure, while 32% believed or were unsure about four (or more) of the eight. The belief in misinformation correlated strongly with COVID-19 vaccination status, as 64% of unvaccinated respondents believed or were unsure about at least half of the false statements.5

Public concerns about individual vaccines can affect vaccination rates more broadly. In Denmark, studies showed that the introduction of the Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) vaccine for females increased completion of MMR in girls but not young boys. When negative media coverage about HPV ran throughout the country, MMR vaccination rates subsequently dropped in both boys and girls.6

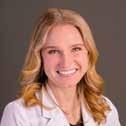

Media posts that support the anti-vaccine movement can be convincing. Quasi-Science can be difficult for both patients and providers to identify, and these sources often use emotional appeals to make their case. Countering misinformation by presenting facts and figures may help some patients understand the science behind vaccines, but this evidence-driven approach does not address vaccine hesitancy fueled by political or religious beliefs or disproportionate fears about side effects. In a randomized study examining the effect of directed messaging on influenza vaccine refusal, correcting inaccurate beliefs improved patients’ knowledge but not their intent to vaccinate.7 Family physicians are in a unique position to engage with our patients and leverage our doctor-patient relationship to recommend, reassure, and provide vaccinations. We are present in under-resourced places where healthcare access is not equitable to provide stable, trusted clinical information. Despite the charged atmosphere of the COVID-19 pandemic, people across education levels and regardless of political views continue to list healthcare professionals as their most trusted source of information about vaccine safety.8,9

Not everyone who declines vaccinations is staunchly anti-vaccine. Sentiments can range across a continuum from full acceptance to hesitancy to full opposition. So how should a family physician approach those who are questioning?

Patients trust their physicians and healthcare providers, and provider attitudes on vaccinations are often conveyed to the community. Endorsing

vaccines publicly helps promote use among patients along with colleagues. Having a good relationship with coworkers and patients allows for open dialogue to occur.10

But how do you have that dialogue? Multiple approaches utilizing familiar principles of motivational interviewing have been proposed to address vaccination with patients, including the C.A.S.E. (Autism science foundation) and A.S.K. (Approaches to families questioning vaccines) tools.11

• Corroborate with patients to find points of agreement while acknowledging their concerns

• About me, discuss how you are qualified to make this recommendation

• Science, review the data.

• Explain/advise patients on your recommendations.

• Acknowledge concerns

• Steer the conversation to refute myths and have open dialogue

• Knowledge, provide a strong recommendation

All approaches endorse a need to validate and discuss concerns and discuss benefits and support science in patient-friendly language. Most importantly, make clear, strong recommendations. “It’s time to get your flu shot” lends more weight than “are you interested in getting a flu shot?” This presumptive language normalizes vaccines as part of the accepted healthcare routine.

One tactic known as “conversion messaging” has shown impact on patients’ degree of vaccine-hesitancy.13 Similar to the approaches used in political or religious settings, hearing a personal story of transformation from vaccine-hesitant to vaccine-acceptance can move a hesitant patient toward acceptance. The messenger matters: this effect is mediated by perceived trustworthiness. Consider sharing conversion stories of community leaders, staff, or others using accessible social media platforms.

It’s impossible to discuss vaccines without mentioning the effect the COVID-19 pandemic has had on preventative healthcare. Since the development of the COVID-19 vaccine, increase in acceptance rates have increased slowly, but some demographics are lagging. A systematic review of 65 studies showed high predictors of vaccine acceptance, including male sex and individuals with a college degree or higher. The lowest rates were found among non-Hispanic Blacks. Those from low-income backgrounds were also found to have particularly low vaccination rates. Age of >45 years and known chronic illnesses were linked to increased acceptance of the vaccine among participants.14

Healthcare workers are not immune to vaccine hesitancy. An international review of 35 studies focusing on healthcare workers across a spectrum of education levels and job titles found hesitancy rates between 4.3% to 72%, with an average of 22.5%. The main listed reasons for avoiding vaccination among healthcare professionals included concerns about safety, efficacy, and side effects. Other reasons reported were insufficient knowledge, rate of vaccine development, and misinformation/mistrust.15

Over time, healthcare workers’ vaccine confidence related to COVID-19 has improved. In a 2022 survey of attitudes about COVID-19 vaccine across 23 countries, healthcare workers reported less than 5% hesitancy rates, with non-licensed healthcare workers reporting the highest hesitancy at 7.6%.16

Most vaccines used today are inactivated, conjugate, or toxoid vaccines. Since there is no live infectious component, they cannot transfer the disease they are meant to prevent. They can cause acute side effects that are often signs of an immune reaction. Since patients cannot distinguish a fever caused by an infection from that caused by cytokines in response to immune system stimulation, a natural conclusion is that they were “sick” in the hours or days following a shot. Many vaccines are given around cold and flu season, and a patient who was recently vaccinated may simply be symptomatic from another infection not targeted by their vaccine.

Sharing the anticipated side effects with patients can alleviate their concerns when side effects do arise. Consider sharing your personal experience with vaccination to acknowledge further that you understand and have shared a similar event but still recommend vaccination.

Vaccines may contain adjuvant metals, preservatives, or other substances that have toxic potential if encountered in large quantities but are instead utilized in tightly regulated, minuscule amounts. In the case of vaccines and any other substance, dose is key to understanding if an ingredient causes concern. Conservatively low Minimum Risk Levels (MRLs) of ingredients in vaccines and other medications are monitored closely.

Two substances commonly questioned are aluminum and formaldehyde.

Aluminum is used as an adjuvant to boost the immune system’s response to the vaccine. MRLs are set at 1mg/kg/day.17 The average amount of aluminum given during a 6mo well child check would only add up to 1.4mg, meaning the toddler would have to weigh less than 1 kilogram before aluminum exposure approaches a minimum risk level! Aluminum is also found in everything from the soil we walk on to deodorants, cereal, and even breast milk and infant formula. While an infant will receive a small bolus of aluminum on the day they are vaccinated, a much larger amount of aluminum exposure occurs from food over their lifetime.18 While most aluminum ingested is simply excreted, even the small amount absorbed will surpass that from vaccines. Aluminum is processed and has a 24-hour halflife. Blood specimens tested for aluminum are indistinguishable between vaccinated and unvaccinated patients.19

Formaldehyde is used to help inactivate viruses during the vaccine manufacturing process, making them safer to use. It is diluted to leave only trace amounts following the vaccine manufacturing process.20 MRLs for formaldehyde are 0.3mg/kg/day, and those same 6mo vaccinations contain only about 0.2mg total.17 (Safe for another 1 kg toddler). Formaldehyde is also commonly found in the environment, and we even make it in our own bodies in small amounts since it is essential for DNA synthesis.

The human body is amazing, but all patients and their network of immune responses are not created equal. Non-immunocompromised patients will mount some degree of response to a novel infectious agent, but the human immune system functions best when primed. The elderly, infants and those with compromised immune systems cannot rely on generating their own “natural” protection when obtaining it comes at the price of being exposed to an infectious disease. Even healthy adults can suffer significant morbidity during and even years after acute, preventable illnesses. Observational data from 2010 through 2016 showed that of all children who died in the United States from influenza, about half of them had no medical conditions prior to diagnosis.21

Since the implementation of vaccines for routine childhood illness, mortality rates in children <5 years have dramatically declined—children no longer needlessly die in order for society to develop immunity. Immunity after vaccination is just as “natural” as that following infection, but the safety profile is significantly better! Modern vaccines that expose a patient to an antigen, such as a viral protein, also eliminate the possibility of further disease transmission during the process of developing immunity.

Sharing stories about unfortunate patients who experienced a vaccinepreventable illness and suffered consequences makes an impact when data become overwhelming or fall on deaf ears. We cannot predict who may have a life-altering effect from a “natural” disease.

There is no limit to the number of vaccines your body can tolerate at once. (CDC) Humans expose our immune system to innumerable antigens every day—every time we take a breath, take a bite, or touch our mucus membranes! The immune system is not overwhelmed or overpowered

by these exposures, nor by the micrograms of vaccine antigens. The infant vaccine schedule includes multiple vaccines at the same time because they are the population at highest risk, lacking previous exposure to pathogens. Immune-compromised adults will also receive considerably more vaccinations, since a weaker response to previous vaccination may leave them vulnerable, with potentially impaired responses of their innate immunity as well. There is no evidence that vaccinating against the most common antigens of serious bacterial and viral diseases creates any risk for infections not targeted by vaccines.22

Normalizing acceptance of the recommended vaccine schedule can go a long way. Many parents are under the impression that vaccines come “a la carte” and they should pick and choose, but hearing that the vast majority of children receive timely complete vaccinations goes a long way toward convincing the worried caregiver.

The reason very few United States medical school graduates have seen a patient with diphtheria or measles, and many parents don’t recognize the classic rash of chickenpox, is because of vaccinations!

Smallpox was eradicated due to a worldwide vaccination effort, but with other diseases, political barriers, vaccine misconceptions, and poor health systems slow global progress.23 Polio may have been eliminated in the US, but in other countries, including Pakistan, Nigeria, and Afghanistan, it remains endemic. In an era of nearly unlimited international travel, there are still risks of transmission from country to country. In under-vaccinated areas, diseases like measles and mumps have been seeing increased rates and can have life-long side effects. Vaccines have been a victim to their own success, a feature of well-resourced countries where patients have the luxury of living without encountering life-threatening infectious diseases.

Recent news of measles outbreaks and even sporadic vaccine-type polio (originated from oral vaccine poliovirus but has mutated and circulates in unvaccinated populations) diagnosed in the United States can influence a parent who hesitates to accept routine vaccinations.24 “Not around here” is no longer a guarantee!

Herd immunity protects everyone, including those who do not have an adequate immune system or can’t get vaccinated themselves, and many vaccine-preventable diseases are transmissible before symptoms are present. Vaccine hesitancy not only leads to increased illness, but also increased economic burden. Between losses from doctor visits, hospitalizations, and lost income, the economic burden that can be attributed to vaccine-preventable diseases among US adults yearly has been estimated to be in the billions.25

A sense of responsibility to their community and the need to safely care for at-risk loved ones are some of the reasons cited by patients who came to accept COVID-19 vaccines. These principles apply to annual influenza vaccination as well. Remind patients that transmission of infections, though inadvertent, does occur pre-symptomatically. By reducing the number of infections, and infectious particles, vaccination decreases the likelihood of sharing illness among your household or workplace.26

7. There isn’t enough evidence

The data about vaccine safety are monumental. Many concerns are derived from the recent COVID-19 vaccine being produced too quickly or cutting corners. mRNA vaccines have been in development for years and were being tested for multiple other viruses at the start of 2020.

Years prior to the pandemic, articles were published discussing the clinical and preclinical reports showing optimism about the continued use of mRNA vaccine technologies. By 2018, Moderna had raised almost US$2 billion in capital with plans to move forward with mRNA-based therapies. At the time, they were targeting influenza, CMV, Zika, and other common viruses.27 Vaccine development accelerated during the pandemic due to the influx of money and grants, which are usually a limiting factor in the implementation of vaccine research and development.

The current attention on COVID-19 vaccine development and anxiety about its rollout takes away from the previously vetted and proven vaccines given routinely in the United States. Decades of safety monitoring and published, transparent research reassures us that not only have vaccines been tested for efficacy, but they have also been conclusively shown to be safer than the diseases they prevent.28

In 1998 a study was published that connected bowel issues in children with autism to the MMR vaccine.29 This infamously flawed and biased study included only 12 children, and since then, large population-based studies have been unable to replicate these findings. The ingredient of concern at that time was thimerosal, a preservative to allow for safe use of vaccines in multi-dose vials. Thimerosal is metabolized into ethylmercury. Ethylmercury should be distinguished from methylmercury, a substance that is found in certain kinds of fish and can be toxic to people at high levels. Since the 1930s, thimerosal, and ethylmercury have been subject to numerous studies that have shown no ill effects outside of minor local injection site reactions.30 In 1999, thiomersal, out of an abundance of precaution and public pressure, was removed from routine vaccinations.

Dr. Mahan is a Clinical Instructor and current Academic Fellow in the Department of Family & Community Medicine at MU Health Care.

Dr. Morris is a Professor of Family & Community Medicine and Associate Chief Medical Officer for Ambulatory Care at MU Health Care. She completed an American Academy of Family Physicians Vaccine Science Fellowship in 2019 and co-leads her institutional COVID-19 and Influenza vaccine committees.

order to claim your CME Credit, please take the quiz

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) is encouraging members to apply for the Vaccine Science Fellowship Program in 2024. The fellowship, now in its 14th year, is a significant leadership opportunity for family physicians interested in working with mentors and other clinicians to better understand vaccine science and the challenges of related policies. Two positions are anticipated to be available for the fellowship next year, which is made possible through financial support from Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. Watch for application details in early 2024.

During the year-long program, fellows will build extensive knowledge about vaccines, as well as practical, hands-on experience from meetings with public health officials, policymakers, manufacturers, and others.

Selected applicants will gain education and practical hands-on experience through meetings with experts in public health and immunization, federal and state vaccine policy groups, and vaccine manufacturers.

This fellowship creates a group of family physicians interested in the science of vaccine development, production, and policy. This program is designed for those who are mid-career in their professional development. The awards are granted to two fellows annually. Each fellow will work with mentors with experience in immunization policy and issues.

The fellowship is for one year with the commitment from their institution and/or department chair that they will allow the time to complete the fellowship. Anticipated 2024-2025 dates are from May 1, 2024–April 30, 2025.

Each fellow will devote approximately 10% FTE for one year (22 days), including travel to fellowship activities. A nominal stipend will be provided. Mentors will guide and assist with education-related vaccine science, policy and family medicine.

Fellows will participate on monthly calls to discuss immunization policies, recommendations, barriers, trends, shortages, concerns, etc.

Fellows will develop a self-study project. This project could be poster presentations, articles, research projects, education outreach, etc. The project will be disseminated to the AAFP membership, public health officials, other immunization organizations, etc.

Fellows are required to travel for vaccine-related meetings. View the travel schedule at: (https://www.aafp.org/content/dam/AAFP/documents/ patient_care/immunizations/2023-vaccine-science-fellowship-travelschedule.pdf). Travel costs will be covered under the fellowship.

Note: Fellows are required to attend one of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices meetings during their fellowship year. Two meetings are typically held – one each in Summer and Autumn.

For more information on the AAFP Vaccine Science Fellowship, please contact Pamela Carter-Smith, MPA at Pcarter@aafp.org, or visit https:// www.aafp.org/family-physician/patient-care/prevention-wellness/ immunizations-vaccines/aafp-vaccine-science-fellowship.html.

“The Vaccine Science Fellowship is a positive, career-altering experience,” Carlos O’Bryan-Becerra, M.D., a 20222023 Vaccine Science Fellow and a core faculty member at the Ventura County Family Medical Center Family Medicine Residency in Ventura, Calif., told AAFP News. “By having protected time to focus on vaccine science, I have been able to learn so much, to the point where I am now much more confident formally teaching medical students, residents and even faculty on vaccines.”

“The Vaccine Science Fellowship provides something unique for a practicing clinician: time to explore and deepen one’s fund of knowledge,” added James Bigham, M.D., M.P.H., also a 2022-2023 Vaccine Science Fellow, and a clinical associate professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, in Madison.”

Missouri family medicine residents and students are invited to the Missouri Academy of Family Physicians Transition to Practice Conference Courtyard by Marriott in Jefferson City. networking, and relaxing! students interested in family they begin residency or their will leave the conference to become a Missouri family legislative hearing at the

All MAFP resident and student members are invited to attend at no cost. Registration is supported by the Family

Dinner at Arris’

Dinner at Arris’

There have always been patients who decline immunizations despite our counseling and incentives are one method that has been used in an effort to increase vaccination rates. Hesitancy when COVID vaccines first became available resulted in many novel programs trying to get Americans to get a first dose.

Finding ways to encourage vaccinations is taking on ever more urgency. In January 2023, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that vaccination rates continued to drop rather than rebound after an initial drop in the first year of the pandemic.1 Children entering kindergarten with all required vaccines dropped to 93% for the 2021-22 school year. This is well below the 95% threshold needed to achieve herd immunity.

There has been concern among academics that incentives could have negative unintended consequences.2 For example, people may feel that there is no moral imperative to become vaccinated for the good of society. Studies have shown that incentives may not produce much of an increase in vaccine rates. Providing money or another incentive may be seen as coercive.2 This may be especially prevalent in communities that are already struggling financially. Incentives might also be seen as a reward or even a bribe for a behavior that might be considered undesired or risky. An attitude may develop where people expect to be paid for getting additional vaccines or even other screening measures.

There have also been studies looking at whether financial incentives actually work and if there is a certain subset of individuals where this might work best. Andresen et al looked at the impact of a hypothetical program that would pay $600 or $1200 incentives for getting vaccinated.3 Results showed that 26.89% of the 364 vaccine hesitant participants would get the vaccine if offered $600 and 30.06% would get it for the $1,200 incentive. Since this was a hypothetical scenario, it is difficult to know if the numbers would be the same if the money was actually available.

In July 2021, Missouri Governor Mike Parson announced drawings with $10,000 prizes in an effort to get Missourians to get at least one dose of a COVID vaccine.4 This was done in partnership with the Missouri Lottery. In addition, there were federal funds for local health departments to provide $25 incentives to anyone getting vaccinated.

A total of 656,259 Missourians entered the lottery.5 However, only 57,117 residents were vaccinated after the lottery was

announced. More than 91% of the entries were from residents who had already received at least one dose of a vaccine. The under 18 population had a total of 39,309 entries that included those who had both received and not received a first dose before the announcement.

Only 20 out of 115 eligible local health departments participated in the program to give out gift cards. This was after Missouri received permission from the federal government to increase the incentive to $100. According to the Missouri Independent, Greene County was the most successful in the program giving away nearly 1,000 gift cards.6 The program had been geared toward adults, but those gift cards mostly went to children between the ages of 5-11 since it coincided with vaccine approval for that age group.

Of the health departments that did not opt in to the program, many cited the additional administrative burden it would entail to run the program. Some Missouri residents thought of the gift cards as a bribe and the health departments were concerned about losing credibility with the population they served.6 The low uptake even with incentives was not unique in Missouri. Other states reported similar results.

In January 2023, Schneider, et al published their results showing that vaccination incentives do not have negative unintended consequences.7 Their study revealed that an ~$24 incentive did not have a negative impact in a group of 5,019 Swedish residents. The incentive was paid for taking a first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine and increased uptake by 4 percentage points.

There were “no negative impacts on morals, sense of civic responsibility, trust in vaccination providers, safety and efficacy perceptions of vaccines, attitudes toward financial incentives, and feelings of self-determination and coercion.”7

They also looked at a study in the US of a general population sample from 12 states that implemented vaccine incentive programs, including Missouri. The results again showed no negative impacts on the feelings and attitudes described above. There was no comment from the authors on the differences in incentives among states and whether incentives were available to anyone being vaccinated or only to those in a lottery type program.

There was little to no information on the degree of vaccine hesitancy and even less on the disparities that are commonly seen in the US healthcare system. The arguments for and against the use of incentives remain unresolved and the experience in Missouri indicate that incentives did very little to increase rates. More research is needed to better understand the pros and cons of incentive use not only for vaccines but also for other services including annual wellness exams, colonoscopies, and other screening measures.

Dr. Lichtenberg works in value-based care in St. Louis, MO. She has a special interest in population health, public health, and quality improvement.

We are pleased to work with the CDC to provide you with the immunization charts on the next few pages. We encourage you to tear them out of the magazine and use for quick reference. Full charts with complete information can be accessed using the QR codes.

Photos top to bottom

1. MAFP members across the state gather at Advocacy Day. L to R, Brea Lombardo, MD; Madeline McFarland, Student; Elizabeth Keegan-Garrett, MD; Natalie Long, MD; Misty Todd, MD; Kelly Dougherty, MD, Resident; Amanda Shipp, MD

2. L to R, Lisa Mayes, DO; Kara Mayes, MD; Jordan Grimmett, Student; Mitchell Mahan, Student; ride the trolley to the Capitol to meet with their legislators.

3. The Kansas City area is well represented at Advocacy Day. L to R, John Burroughs, MD; Jordan Grimmett, Student; Mitchell Mahan, Student; Noah Brown, Student; Wesley Goodrich, DO, Resident; and Ed Kraemer, MD.

Drawing over 40 family physicians, residents, and students, this year’s Advocacy Day successfully addressed legislation that impacts your practice and patients. Attendees spent Valentine’s Day visiting with legislators and their staff sharing their love for family medicine and stressing the importance of primary care. The issues and legislation discussed can be found on pages 24-25. Members unable to attend Advocacy Day participated by submitting a Speak Out message to their legislators. This year’s messages focused on GME expansion, DEI/Do No Harm Act, and Scope of Practice.

Scope of practice continues to recur each session, and this year was no exception. The Missouri Board of Nursing’s Annual Workforce report confirms what we already knew, that nurse practitioners do not go to rural areas.

The 2022 report shows that 5.3% of nurse practitioners work in rural areas. And, when analyzing the data from 2018 through 2022, it shows that modifying the collaborative practice requirements for mileage from a 50-mile radius to 75 miles, and changing the number of nurse practitioners a physician can collaborate with, did not increase the number of nurse practitioners in rural areas.

Another issue addressed is legislation that would increase graduate medical education residency spots in primary care with state funding. Based on a 2021 MAFP survey of family medicine residencies, we estimate existing programs can increase their residency spots pending ACGME approval and funding. Sarah Cole, DO, FAAFP, Mercy Family Medicine Residency, met with Senate and House appropriation committee chairs on funding for primary care residency spot expansion.

Then, she, along with Misty Todd, MD, Bothwell Family Medicine Residency, presented testimony in support of a state program and funding for GME expansion. Negotiations are ongoing, and we will keep you updated in the weekly legislative report.

Another issue important to medical schools and residency programs is legislation, HB 489/ SB 410, the “Do No Harm Act,” that would prohibit the incorporation of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in admissions requirements and curriculum. Banning the discussion on DEI, which includes social determinants of health and their impact on diseases and treatments, will negatively impact the Missouri healthcare community. We do not support legislative limitations on specific educational content due to the various settings in which family physicians practice. In addition, the ACGME requires that DEI be incorporated into the curriculum. This legislation would force residency programs to choose between funding and accreditation.

Family physicians do not get to select their patients and need to be educated to care for the population in their communities. Family physicians are uniquely positioned to address social determinants of health as a factor that affects the health and safety of our patients.

Photos top to bottom

1. Rep. Jonathan Patterson (right) meets with MAFP members, L to R, Wesley Goodrich, DO, Resident; and Ed Kraemer, MD

2. John Burroughs, MD, MAFP Board Chair (chair), and Arihant Jain, MD, Board Member, collaborate between legislator meetings.

3. Members meeting with Senator Tracy McCreery, L to R, Katie Liu, MD; Catherine Baker, MD, Resident; Lauren Wilfing, DO; Senator Tracy McCreery; Josephine Glaser, MD; and Kelly Dougherty, MD, Resident

Photos top to bottom

1. Rep. Jonathan Patterson (right) meets with MAFP members, L to R, Wesley Goodrich, DO, Resident; and Ed Kraemer, MD

2. John Burroughs, MD, MAFP Board Chair (chair), and Arihant Jain, MD, Board Member, collaborate between legislator meetings.

3. Members meeting with Senator Tracy McCreery, L to R, Katie Liu, MD; Catherine Baker, MD, Resident; Lauren Wilfing, DO; Senator Tracy McCreery; Josephine Glaser, MD; and Kelly Dougherty, MD, Resident

OPPOSE HB 69 (Dinkins), HB 271 (Riley), HB 284 (Lewis), HB 329 (Cook), HB 330 (Cook), SB 27 (Brown), SB 79 (Schroer), SB 157 (Black)

• MAFP believes the physician-led team approach delivers the best and most cost-effective care to Missourians and that APRNs, PAs, and APs are dedicated, skilled members of the health care team.

• 4 out of 5 patients prefer a physician-led health care team (AMA 2018 Survey)

• A 2022 National Bureau of Economic Research study found that independently practicing NPs within the US Dept. of Veterans Affairs increased the patient’s length of stay, raised the cost of emergency department care, raised the 30-day preventable hospitalizations, decreased opioid prescriptions, and increased antibiotic prescriptions.

• Due to extenuating circumstances, the MAFP would support an arbitration board to mediate requests to create special arrangements within the collaborative practice requirements that would be overseen by the arbitration board.

• A new nurse practitioner received 3-10% (500 – 1,000 hours) of the clinical training of a family physician (15,000 hours.)

(Source: Primary Care Coalition)

• Data from states with independent practice for mid-level providers clearly show that this does not resolve the health care workforce shortage. Mid-level providers practice primarily in the higher population geographic areas with fewer in health professional shortage areas (HPSA). The 2022 Missouri Board of Nursing Workforce reports shows that 5.3% of APRNs practice in a rural area.

• A standardized curriculum from the Association of American Medical Colleges and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education ensures all physicians are trained on the best practices, research, and advancements across the continuum of medical education. APRN programs are not required to maintain a standardized curriculum and most content is taught online.

• Considering the physician shortage, geographic APRN location data, and the proliferation of APRN online courses, it is imperative

to increase the number of primary care physicians. This will not only meet today’s demand for physicians, but will also ensure there is a qualified workforce in the future for Missourians.

• The MAFP supports expanded primary care residency slots to meet the demand for primary care physicians. Missouri has the capacity to add 17 family physician residency slots per year.

• Funding: Regular and dedicated state appropriations are needed to incentivize Missouri medical students to choose primary care residencies. Missouri has 4,555 medical students for 1,257 primary care residency slots (over 3 years). Research shows that resident physicians will set up their clinical practice within 60100 miles of the location where they complete residency.

A patient’s physician has access to the patient’s full history and medical record. A physician is best equipped to assess conditions in the context of the whole patient, recommend, order, and interpret diagnostic tests and imaging studies, and refer to other healthcare professionals as needed. Physicians also have undergone the extensive training required to assess the need for pharmacological treatment and to prescribe medications as may be indicated and appropriate for the patient.

• OPPOSE HB 710 (Buchheit-Courtway), SB 418 (Brown) – A physician and patient relationship is not established through a questionnaire. This is a useful tool in assessing an existing patient and for minor issues. It is important to interview the patient, take a medical history, and perform a physical exam.

• OPPOSE HB 99 (Davidson), HB 115 (Shields), HB 144 (Doll), SB 51 (Eslinger), SB 205 (Moon) –Physical therapists should work with a referring physician to ensure proper diagnosis and treatment of the patient.

• OPPOSE HB 249 (Busick), SB 270 (Roberts) – Dentists focus on oral health and treatment and do not have a patient’s full medical history. Dentists administering vaccines further fragments the patient and physician relationship by adding another provider of care.

• OPPOSE HB 331 (Cook), SB 41 (Thompson Rehder) –The pharmacist and physician work collaboratively so their combined expertise is used to optimize the therapeutic effect of pharmaceutical agents in patient care. When vaccines are administered elsewhere, the information should be transmitted back to the patient’s primary care physician and their state registry to assure continuity of the patient’s medical record. The physician’s knowledge of the patient history could minimize a potential adverse reaction to the vaccine.

• OPPOSE SB 322 (Mosley) – Naturopathic education does not prepare practitioners to properly and accurately diagnose or provide appropriate treatment, safely or effectively prescribe medications, perform physicals, or perform surgical procedures.

• NEUTRAL HB 163 (Seitz), HB 818 (Titus), HB 838 (Lewis), SB 62 (Razer), SB 108 (Arthur), SB 160 (Schroer), SB 356 (Moon), SB 453 (Moon), SB 491 (Cierpiot), SJR 8 (Eigel), SJR 19 (Moon) – Family physicians provide reproductive health and education to their patients as needed. The MAFP supports evidence-based practice of medicine, patient-physician relationship, and the delivery of safe, timely, and comprehensive care. Physicians should not be criminalized for the health care provided to Missourians. We respect each member’s view and ultimately have not taken a position on abortion to reflect the broad span of opinions of family physicians across the state.

• MAFP supports immunizations to protect Missouri’s infants, children, adolescents, adults, and seniors.

• The MAFP supports local health agencies to develop public health policies and plans that could mitigate the impact of the epidemic on their communities. We support evidence-based decisions to ensure the safety and health of communities in ordinary times and in a state of emergency.

• OPPOSE HB 445 (Schnelting), SB 159 (Schroer), SB 99 (Eigel), SB 201 (Brattin) SB 232 (Carter) – Immunizations are among the most cost-effective and successful public health interventions. Without vaccines, diseases such as measles and pertussis are becoming more common in the United States.

• We understand recent public apprehension about vaccines due to policies put in place during the pandemic. Routine vaccines prevent and eradicate preventable diseases such as measles, mumps, and polio. These immunizations are a vital component for better public health.

• The MAFP believes that all Missourians should have access to essential health care services, regardless of social, economic,

or political status, race, religion, gender, or sexual orientation. We support measures that increase Medicaid coverage to Missourians who lack affordable health care.

• SUPPORT HB 254 (Pollitt), HB 286 (Lewis), HB 328 (Bosley), SB 90 (McCreery) which extends the current coverage of pregnant women receiving MO HealthNet pregnancy-related and postpartum benefits

• SUPPORT HB 354 (Davidson), SB 45 (Gannon), SB 183 (Arthur) which extends Show-Me Healthy Babies Program benefits from 60 days to one year following the last day of their pregnancy.

• SUPPORT SB 183 (Arthur) which changes MoHealthNet’s eligibility re-verification and renewal process to follow federal regulations.

• OPPOSE SB 289 (Moon) – This bill repeals the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) passed by the legislature in 2021. The MAFP supports the use of the PDMP as a strategy to combat the prescription drug epidemic.

• OPPOSE HB 757 (Mayhew) – Medical school trains students to become residents, not physicians. Residency provides graduated responsibility, oversight, and progressive duties to many different patients (chronic and complex conditions), pathologies, practice settings, and undifferentiated signs and symptoms which require critical thinking and differential diagnosis. Although this measure includes educational requirements for licensure, there are issues with the requirements of third-party credentialling organizations.

• SUPPORT HB 285 (Lewis), HB 348 (Coleman), HB 407 (Doll), SB 393 (Bernskoetter) – With the expansion of telehealth and the workforce shortage, we support the need to join the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact based on the Missouri Board for Registration of the Healing Arts oversight. Board certification should not be required for physician participation or licensure. The MAFP will continue to monitor these bills to ensure appropriate language is utilized.

• OPPOSE HB 489 (Baker) SB 410 (Koenig) – The guidelines for curriculum and accreditation for medical schools and residencies have been developed based upon clinical practices that support people and healthy communities. We oppose curriculum mandates on medical education as well as any specific continuing medical education topics for licensure. Diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) have been included in the medical school and residency curriculum for over 30 years and ensures Missourians have the support needed to overcome social determinants of health. Family physicians provide care based on the patient’s needs, not on DEI ideology.

The Missouri Academy of Family Physicians developed a syllabus to guide and teach family medicine residents about advocacy at the local, state, and national levels. This Advocacy Syllabus for Family Medicine Residents is a 50-hour commitment but can be modified to meet the specific needs of the residency program. With the upcoming changes to the ACGME requirements for family medicine residencies, we want to support future planning to enhance further and expand the advocacy efforts of our residents. The MAFP Board of Directors felt strongly about this initiative and included the development of this syllabus in their 2023-2025 strategic plan. It was created in collaboration with Lincoln University (Jefferson City), Mercy Family Medicine Residency (St. Louis), and the MAFP. Building a strong collaboration among family physicians, residents, legislators, and policymakers will ensure our voices will be heard as we shape the future of family medicine in Missouri.

The annual Multi-State Forum was held in February, with MAFP leadership and team attending the two-day conference in Dallas, Texas. This Forum is always an excellent opportunity for learning and networking among peers.

MAFP delegates this year were Kara Mayes, MD, President; Afsheen Patel, MD, President-Elect; Natalie Long, MD, VicePresident; and Todd Shaffer, MD, AAFP Board Director. Kathy Pabst, Executive Director, and Bill Plank, Assistant Executive Director, also attended the event. State chapters participating in this regional event are Missouri, Arkansas, Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas, Illinois, Colorado, Texas, California, Arizona, Oklahoma, and Montana.

Tochi Iroku-Malize, MD, AAFP President, shared an inspirational story about her journey and equity challenges as an African American patient. We had an opportunity to ask Shawn Martin, AAFP EVP/CEO questions about AAFP and its strategic direction, followed by an advocacy update by David Tulley, AAFP Vice President of Government Relations.

Attendees had an opportunity to discuss topics about GME, prior authorization, workforce issues, and other topics in small groups. Gary LeRoy, MD, ABFM Senior Vice President of Diplomate Experience, provided an update on changes occurring at the ABFM. Federal and state drug pricing was an insightful session, followed by chapter governance restructuring. Kathy Pabst presented a session on the need, process, and results of the survey of Missouri residency expansion and barriers.

Missouri delegates at this year’s 2023 Multi-State Forum: Todd Shaffer, MD; Bill Plank, CAE; Afsheen Patel, MD; Natalie Long, MD; Kara Mayes, MD, and Kathy Pabst, MBA, CAE.

The MAFP Board of Directors is pleased to announce that Todd Shaffer, MD, MBA, FAAFP, is a candidate for the AAFP PresidentElect position. The election will occur during the 2023 Congress of Delegates, October 25-27, in Chicago, IL. Other candidates for this position are Jennifer Brull, MD, Kansas, and Mary Campagnolo, MD, New Jersey.

Dr. Shaffer has served as a director on the AAFP board since 2020. The President-elect will serve as Chair of the board’s Subcommittee on Strategic Planning and Development, and as a member of the board screening subcommittee, in addition to presiding at meetings in the absence of the President. The President-elect will also represent the Academy at chapter meetings, with external groups, at AAFP conferences, on the Commission on Finance and Insurance, and before legislative bodies. The President-elect assumes the office of President following the term as President-elect.

The 2023 National Residency Match Program (NRMP) had the most family medicine positions available in history marking the 14th straight year of growth in positions offered. Family medicine offered 5,107 positions, 172 more than in 2022, and 13.6% of positions offered in all specialties.

A total of 4,530 medical students and graduates matched to family medicine residency program this year. Here’s a breakdown of those matches:

• 1,514 osteopathic medical school (DO) seniors

• 1,499 U.S. allopathic medical school (MD) seniors

• 793 U.S. international medical graduates (IMGs)

• 562 foreign IMGs

• 91 previous graduates of U.S. MD-granting schools

• 70 previous graduates of DO-granting schools

• 1 classified by the NRMP as “other”

The Missouri Academy of Family Physicians is excited to support medical students entering Missouri family medicine residency programs and would like to extend a warm welcome to those coming from out-of-state schools. Congratulations to all!

Data from nrmp.org and aafp.org.

1. “I matched at my #1 choice for Family Medicine at CoxHealth in Springfield, MO! So thankful for all of the constant love and support I’ve received from family, friends, and mentors throughout this journey. Excited to start the next chapter!” - Cerena Stinogel

2. MAFP member Noah Brown matched at Mercy’s Family Medicine Residency Program.

3. MAFP Student Director Karstan Luchini matched at UKC’s Family Medicine Residency Program.

4. “Super excited that I matched at my dream program and will be staying in Kansas City for residency. Grateful to be joining the amazing field of Family Medicine. Cannot wait to be someone’s PCP and advocate for my community” - Deborah Rivera-Hernandez, MAFP Student Member

Todd Shaffer, MD, MBA, FAAFP, participated in activities in 2022 for the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) individual and school-based exams and United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE). Dr. Shaffer served on the USMLE Test Material Development Committee which was charged with developing and reviewing the test questions and cases that form the USMLE.

Individuals who contribute to NBME exams and the USMLE program support the design and development of the highest quality assessments of competencies relevant to health professions practice in the US and around the world. These assessments provide information to individuals, schools, programs and, in the case of licensure for practice, state regulatory boards.

Dr. Shaffer is MAFP Past President and current AAFP board member. He is employed by University Health in Kansas City.

Missouri Academy of Family Physicians (MAFP) Members are invited to make a recommendation to the MAFP Board of Directors to consider a resolution to be submitted on behalf of our members at this year’s AAFP Congress of Delegates, October 25-27, 2023, in Chicago.

The MAFP considers many issues that are important to our members. The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) Congress of Delegates (COD) meets annually to develop and set policy for the AAFP and to elect its officers and the AAFP Board of Directors (BOD).

More information about submitting a resolution can be found on our website https://www.mo-afp.org/about/ congress-of-delegates/.

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) recently established the Osteopathic Family Physician Project Advisory Group or DO-PAG. The DO-PAG is being convened to assist the AAFP in attaining insights regarding the professional and practice needs of Osteopathic Family Physicians.

Dr. Sterling Ransone, AAFP Board Chair, selected six members to serve on the advisory group, including representatives from each chapter size (small-extra large), a new physician, and a resident. MAFP Resident Director Wesley Goodrich, DO, MPH, was selected as the resident member. Dr. Goodrich is a PGY-2 at the University of Missouri – Kansas City’s Family Medicine Residency Program.

pages 6-9

1. A Brief History of Vaccination (who.int) (https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ history-of-vaccination/a-brief-history-of-vaccination)

2. McAteer J, Yildirim I, Chahroudi A. The VACCINES Act: Deciphering Vaccine Hesitancy in the Time of COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):703-705. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa433

3. Larson, H. J., Gakidou, E., & Murray, C. J. L. (2022). The Vaccine-Hesitant Moment. The New England journal of medicine, 387(1), 58–65. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra2106441

4. DeStefano F, Thompson WW. MMR vaccine and autism: an update of the scientific evidence. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2004;3(1):19-22. doi:10.1586/14760584.3.1.19

5. Yasmin F, Najeeb H, Moeed A, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in the United States: A Systematic Review. Front Public Health. 2021;9:770985. Published 2021 Nov 23. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.770985

6. Gillray J. The cow-pock, or, The wonderful effects of the new inoculation (satirical cartoon), by James Gillray; H. Humphrey St. James’s Street (pub), 1802. Available at: https:// collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-101455847-img

7. Kaufman J, Ryan R, Walsh L, et al. Face-to-face interventions for informing or educating parents about early childhood vaccination. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5(5):CD010038. Published 2018 May 8. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010038.pub3

8. Brendan Nyhan, Jason Reifler, Sean Richey, Gary L. Freed; Effective Messages in Vaccine Promotion: A Randomized Trial. Pediatrics April 2014; 133 (4): e835–e842. 10.1542/ peds.2013-2365

9. Launer J. Effective clinical conversations: the art of curiosity. Postgraduate Medical Journal 2021;97:339-340.

10. Bischof G, Bischof A, Rumpf HJ. Motivational Interviewing: An Evidence-Based Approach for Use in Medical Practice. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2021;118(7):109-115. doi:10.3238/arztebl. m2021.0014

11. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivierende Gesprächsführung Motivational Interviewing: 3rd edition des Standardwerks in Deutsch. Freiburg im Breisgau: Lambertus. 2015

12. Hall, K., Gibbie, T., & Lubman, D. I. (2012). Motivational interviewing techniques Facilitating behaviour change in the general practice setting. Australian Family Physician, 41(9).

13. Prochaska J, DiClemente C. Towards a comprehensive model of change. In: Miller WR, Heather N, editors. Treating addictive behaviours: processes of change. New York: Pergamon, 1986.

14. Boom SM, Oberink R, Zonneveld AJE, van Dijk N, Visser MRM. Implementation of motivational interviewing in the general practice setting: a qualitative study. BMC Prim Care. 2022;23(1):21. Published 2022 Jan 28. doi:10.1186/s12875-022-01623-z

pages 10-13

1. Seither R, Calhoun K, Yusuf OB, et al. Vaccination Coverage with Selected Vaccines and Exemption Rates Among Children in Kindergarten United States, 2021–22 School Year. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023;72:26–32. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr. mm7202a2

2. Vaccination Coverage and Exemptions Among Kindergarteners (Missouri). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/ schoolvaxview/data-reports/index.html Updated May 14, 2021. Accessed Feb 22, 2023.

3. Larson, H. J., Gakidou, E., & Murray, C. J. L. (2022). The Vaccine-Hesitant Moment. The New England journal of medicine, 387(1), 58–65. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra2106441

4. Rodrigues CMC, Plotkin SA. Impact of Vaccines; Health, Economic and Social Perspectives. Front Microbiol. 2020 Jul 14;11:1526.

5. Hamel L,Lopes L, Kirzinger A, Sparks G, Stokes M, Brodie M. KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: Media and Misinformation. Published online Nov 8, 2021. https://www. kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-media-andmisinformation/

6. Gørtz, M., Brewer, N. T., Hansen, P. R., & Ejrnæs, M. (2020). The contagious nature of a vaccine scare: How the introduction of HPV vaccination lifted and eroded MMR vaccination in Denmark. Vaccine, 38(28), 4432–4439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.04.055

7. Nyhan B, Reifler J. Does correcting myths about the flu vaccine work? An experimental evaluation of the effects of corrective information. Vaccine.Volume 33, Issue 3, 2015, Pages 459-464. ISSN 0264-410X. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.11.017

8. Nielsen RK, Fletcher R, Newman N, Brennen JS, Howard PN. Misinformation, Science, and Media. Navigating the Infodemic: How People in Six Countries Access and Rate News and Information about Coronavirus. April 2020. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/ sites/default/files/2020-04/Navigating%20the%20Coronavirus%20Infodemic%20FINAL. pdf

9. Edelman. 2022 Edelman Trust Barometer Special Report: Trust and Health. https://www. edelman.com/trust/22/special-report-trust-in-health

10. Paterson, P., Meurice, F., Stanberry, L. R., Glismann, S., Rosenthal, S. L., & Larson, H. J. (2016). Vaccine hesitancy and healthcare providers. Vaccine, 34(52), 6700–6706. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.042

11. Morgana, T., & Pringle, J. (2010, October). Approaches to families questioning vaccines— the ASK approach for effective immunization communication. In 48th Annual Meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, Vancouver, BC.

12. Autism Science Foundation. Making the CASE for Vaccines: a new model for talking to parents about vaccines. https://autismsciencefoundation.org/wp-content/ uploads/2015/12/Making-the-CASE-for-Vaccines-Guide_final.pdf 2017. Accessed Feb 22, 2023.

13. Conlin J, Baker M, Zhang B, Shoenberger H, Shen F (2022) Facing the Strain: The Persuasive Effects of Conversion Messages on COVID-19 Vaccination Attitudes and Behavioral

Intentions, Health Communication, DOI: 10.1080/10410236.2022.2065747

14. Yasmin F, Najeeb H, Moeed A, Naeem U, Asghar MS, Chughtai NU, Yousaf Z, Seboka BT, Ullah I, Lin CY, Pakpour AH. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in the United States: A Systematic Review. Front Public Health. 2021 Nov 23;9:770985. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.770985. PMID: 34888288; PMCID: PMC8650625.

15. Biswas, N., Mustapha, T., Khubchandani, J., & Price, J. H. (2021). The Nature and Extent of COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy in Healthcare Workers. Journal of community health, 46(6), 1244–1251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-021-00984-3

16. Lazarus, J.V., Wyka, K., White, T.M. et al. A survey of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance across 23 countries in 2022. Nat Med 29, 366–375 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-02202185-4.

17. Minimal Risk Levels (MRLs) for Hazardous Substances. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/TSP/MRLS/mrlsListing.aspx Updated Feb 9, 2023. Accessed Feb 22, 2023.

18. Vaccine Ingredients. Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.https://www.chop.edu/centersprograms/vaccine-education-center/vaccine-ingredients/aluminum. Reviewed Dec 22, 2022. Accessed Feb 20, 2022.

19. Goullé JP, Grangeot-Keros L. Aluminum and vaccines: Current state of knowledge. Med Mal Infect 2020 Feb;50:16-21.

20. Mitkus RJ, Hess MA, Schwartz SL. Pharmacokinetic modeling as an approach to assessing the safety of residual formaldehyde in infant vaccines. Vaccine 2013;31:2738-2743.

21. Shang, M., Blanton, L., Brammer, L., Olsen, S. J., & Fry, A. M. (2018). Influenza-Associated Pediatric Deaths in the United States, 2010-2016. Pediatrics, 141(4), e20172918. https:// doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-2918

22. Glanz, J. M., Newcomer, S. R., Daley, M. F., DeStefano, F., Groom, H. C., Jackson, M. L., Lewin, B. J., McCarthy, N. L., McClure, D. L., Narwaney, K. J., Nordin, J. D., & Zerbo, O. (2018). Association Between Estimated Cumulative Vaccine Antigen Exposure Through the First 23 Months of Life and Non-Vaccine-Targeted Infections From 24 Through 47 Months of Age. JAMA, 319(9), 906–913. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.0708

23. Shah, S. Z., Saad, M., Rahman Khattak, M. H., Rizwan, M., Haidari, A., & Idrees, F. (2016). “Why we could not eradicate polio from pakistan and how can we?”. Journal of Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad : JAMC, 28(2), 423–425.

24. Willingham E. Everything you need to know about polio in the U.S. Scientific American. Sept 29, 2022. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/everything-you-need-toknow-about-polio-in-the-u-s/#:~:text=Wild%20poliovirus%20causes%20polio%20 unrelated,country%20at%20all%20since%201993.