A DOZEN PLAYGROUNDS

“A

Dozen Playgrounds”

This project was made possible by a grant from Alan and Cynthia Reavis Berkshire at Taubman College at the University of Michigan

Principal Research Investigators:

Assistant Professor María Arquero de Alarcón, Taubman College

Assistant Professor Jennifer Maigret, Taubman College

Clinical Profesor R. Charles Dershimer , School of Education

Design Team

Maria Capota, Caileigh MacKellar, Andrew Wolking

Research Assistants

Christopher Bennett, Cara Ciaglo, Leigh Davis, Joseph Fillepelli, Zachary Gong, Jordan Johnson, Justin Meyer, John Monnat, Jeff Nader, Yt Oh, Anna Schaefferkoetter, Catherine Truong, Wen Zhong

“A Dozen Playgrounds” proposes to recuperate playgrounds as space for children, central to the living fabric of the city. Through the development of design strategies that balance prototypical desires with site specificity, similar to Aldo van Eyck’s playgrounds of postwar Amsterdam, this project takes a polycentric, interstitial approach towards Detroit’s network of communities and potential play spaces. Building on the tradition of a neighborhoodcentric approach to learning and playing, the project recognizes the importance of Detroit’s K-6 schools as sites where the city’s ambitions for education, community, and citizenship share common ground.

Four schools were identified as sites for prototypical playgrounds; the iterative designs for these sites examine three different approaches towards designing interfaces between landscape and urbanism, overlaid with a concern for the natural environment. Through a collaborative partnership and interaction with the Detroit Public Schools, the project imagines two outcomes: a series of proofof-concept designs that illustrate innovative ways to bring education, community, and water together in a playground; and short, intensive, design-thinking play sessions to introduce the students to design careers and to gain feedback from children about what makes playgrounds vibrant to them.

“A Dozen Playgrounds”

“It is the supreme seriousness of play that gives it its educational importance. Play seen from the inside, as the child sees it, is the most serious thing in life. Play builds the child. It is part of nature’s law of growth… Play is thus the essential part of education.”

Joseph Lee

Building on the tradition of a neighborhood centric approach to learning and playing, A Dozen Playgrounds positions the grounds of Detroit’s Elementary Public Schools (EPS) as key nodes of social infrastructure where the city’s ambitions for education, community and citizenship overlap. This study presents a visual catalog of the evolution and current state of the Elementary Public School Playgrounds and renders the fragile condition of the built environment that constructs children’s imagination at such early ages The extended operative inventory, compiled in a GIS database, informs the initial design decisions to better sustain the dynamic relationship of neighborhood’s children and playgrounds.

The consideration of the physical relationship between schools and the communities they serve traces back to the origins of democracy in the United States. Historically, public schools in Detroit were identified as sites to provide essential facilities. Furthermore, the placement of schools was carefully considered in order to meet the social and recreational needs of communities of children and adults traveling by foot.

The 1951 Master Plan of Detroit sought to tie together community, schools, and playgrounds,

within a city structured by transportation lines and industry. To meet this aim, the master plan incorporated the concept of the “Neighborhood Unit” first applied by Clarence Perry in New York, and sited schools and play fields within a walkable, quarter mile radius of residential fabric. The physical description of the school grounds, towards this end, was quite specific. Elementary school grounds measured five to seven acres and included a central playground and smaller playgrounds for young children.

The reality of the Public Schools System in Detroit is one of shifting grounds and uncertainty. Once positioned as social and cultural nodes of the thriving neighborhoods in the city, the loss of population and the resulting shrinking tax base threatens today the very sustainability of the system. With 69,616 enrolled students, and capacity for 30,000 more seats, the system is continually “closing, consolidating and merging” schools in order to gain financial stability. In the midst of discussions on the right-sizing strategies for the city to fight vacancy and blight, the consideration of these public grounds as catalytic anchors for protection and community stabilization is not capturing the imagination of the municipality and the local CDCs in their fight against vacancy.

The early establishment of play

The first playground, dated from 1886 (Sapora and Mitchel, 1948), counted with little design, and positioned physical activity and running off energy as main activities to be played by the kids. These “outdoor gymnasiums” were equipped with exercise apparatus, tracks and space for games (Frost, 1987).

Urban playgrounds are microcosms of complex land politics and civic aspirations. Simultaneously loci for exuberance and measured control, the location, design and construction of playgrounds are powerful place-making tools. The history of the urban playgrounds is also intrinsically linked to the communities and cities that host them, as they sustain similar civic values. When urban neighborhoods started a slow decline in many American Cities in the early 1970s, playgrounds soon followed the same fate. The urban playground, a small world of its own to nurture imagination, spontaneity and socialization in

children at early ages (Dattner, Design for play, 1969), became more concerned about safety regulations and less and less about creativity.

In the case of Detroit, long-term partnerships established among schools, neighborhoods and the municipality broke down and playgrounds were caught at the center of resource mismanagement and a lack of imagination and care. Today, Detroit’s urban, elementary public school playgrounds continue to reveal an ongoing absence of planning for the cities’ most vulnerable population—its children.

The consideration of the physical relationship between schools and the communities they serve traces back to the origins of democracy in the United States as described in the Land Ordinance of 1785 wherein “the section, number sixteen, in every township, [...] shall be granted to the inhabitants of such township for the use of schools.” The reservation of land for public schools was further reinforced by the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. This law provided land in the Great Lakes and the Ohio Valley regions for settlement and, and is described in Article 3 as follows: “Religion, morality, and knowledge

being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged.”

The playground movement for children was unofficially “initiated” in the United States when a group of mothers, referred to as “sand garden matrons”, constructed and oversaw the use of a series of sand courts in the Charlesbank area of Boston in the 1880’s. The efforts of these mothers coincided with a larger, national turn towards active recreation as a means to address emerging problems of delinquency of children in cities. The first playgrounds were conceived of as “outdoor gymnasiums” equipped with exercise apparatus and space for games in order for children to burn off their energy (Frost, 1987).

In 1924, President Coolidge called a National Conference on Outdoor Recreation and initiated a nation wide park survey. In the foreword to the study, Coolidge wrote, “Play for the child, sport for youth and recreation for adults are essentials of normal life. It is becoming generally recognized that the creation and maintenance of outdoor recreation facilities is a community duty in order that the whole public might participate in their enjoyment.”

This conference led to the initiation of a National Survey of Municipal and County parks led by L.H. Weir. Co-sponsored by the Playground and Recreation Association of America and the American Institute of Park Executives, the charge Land Ordinance, 1785

of this study was to survey the active recreation opportunities present in every city in excess of 25,000 population across the United States. This initiative also spurred a series of studies on tendencies in public recreation (Pangburn, 1926), many of which noted that school grounds were critical sites to provide public space for outdoor recreation within a cities’ neighborhoods. Building momentum, a number of new types of recreation spaces emerged throughout the country including playgrounds, playfields, neighborhood recreation parks, and swimming

pools. Playgrounds, in particular, were seen as a solution to child automobile fatalities occurring as a result of children playing in streets. By the end of the decade, this work was formalized when the National Recreation Association Guidelines outlined the play equipment that elementary school playgrounds should provide, including a horizontal ladder, a balance beam, a giant stride, six swings on a frame twelve feet high, a slide eight feet high with a chute sixteen feet long and a horizontal bar.

Images of playgrounds in Detroit in the 1920s.

At the time of the study’s conclusion, Detroit was noted as having one acre of park land for every 266 inhabitants, a ratio closely comparable to St Louis, Boston and Philadelphia. Perhaps even more influential than the studies overall findings was the appointment of C.E. Brewer, Commissioner of Recreation of Detroit’s Department of Recreation, to the research team along with representatives from thirteen other cities. Within a year, organized labor as well as a

federal committee on education were taking an active interest in the committee’s work relative to opportunities “necessary to counteract the effects of the modern city and also in relation to future developments of community life.” (LH Weir, Park recreation areas in the United States, May, 1928, p. 2) In October of 1926, an annual convention was held in Detroit, where the following resolution was unanimously adopted: “The growth in the movement for the provision

of adequate means for supervised recreation in towns and cities is significant of an increasing concern for the health of the people. Since the cities are the product of the aggregation of great economic forces, it is but fair that they should put forth every effort to overcome any disadvantage to the freedom of movement and the conditions of health which their very existence entails.”

While it was unanimously agreed that active recreation was a civic issue to be addressed by municipalities, ongoing discussions surrounding how this was to be put in place and supported over time were contentious. In Detroit, this discussion addressed whether the Parks Department or the Board of Education should be held accountable for providing and servicing playgrounds and other active recreation areas. The Board of Education was quick to state “[we are] not interested in those who do not attend school” (Recreation, Volume 16. P. 219) and supported this argument with census data that showed Detroit’s school-aged population to constitute only 15% of the total population. In time, it was determined that a separate city department be created to oversee the recreation matters.

In 1926, Detroit’s Department of Recreation conducted a study of fatal accidents before, and then after the opening of several playgrounds. This study documented 86 fatalities occurring in 5 study areas during the 1925-1926 school year as compared to only 14 during the following

summer session, after over 50 new playgrounds had been opened. For the entire city, the study counted an attendance of 2,128,723 children across the 126 playgrounds operated by the Department of Recreation in 1926, an indication of a quantified commitment to the playground as a space of safety within the dangerous streets of the city.

The period from the late 1890’s and mid 1920’s saw rapid investment in and growth of active park spaces, yet struggled with issues of authority and maintenance of these new recreational services. This was also a time of rapid growth in the city; during the period of 1910 to 1930 the population increased from 465,700 to 993,700 residents, and the city annexed surrounding land therein establishing the extents of its city boundary as recognized today. With this physical and social expansion came a frantic production of housing and other facilities as schools, and libraries, and important urban services as sewers and electrical lines. During this time, the city was growing without any selfregulating instrument beyond a series of studies conducted by Olmsted in 1905 (requested by the Board of Commerce) and 1916 (for the City Plan and Improvement Commission), Eduard H. Bennet (preliminary plan for Detroit for the City Plan and Improvement Commission, 1915), and the initial studies for the Highways in the metropolitan region in the mid-1920s. The Detroit City Plan Commission was finally created in 1919.

Neighborhood Planning

The 1920’s also bore city planning ideas that gained broad influence on the American Planning Profession through the work of Clarence Perry on the Neighborhood Planning Unit (NPU). Leading up to this, Perry produced a number of lesser-known writings on the role of recreation, and specifically the school, as factors in neighborhood development.

Eventually, the ideas he was developing through these writings evolved into the definition of a neighborhood planning unit with the school at its center. Perhaps Perry’s most influential idea was to inscribe basic design standards to the neighborhood unit and to quantify the facilities and institutions necessary to support it. This concept sought to re-establish the

Communities absorbed by Detroit. In “Proposed generalized land use plan: an explanation of a basic plan designed to make Detroit a better place in which to live and work,” the City Plan Commission in 1947.

importance of a civic building serving at the core of each neighborhood: elementary schools were identified as the buildings that could serve this role owing to both pragmatism, that they were the most ubiquitous of local institutions, and optimism, that these played an important role in educating future, democratic citizens. Two results emerged out of this: first, that the programmatic requirements for a community center became the standard basis for elementary school design, and, second, that this relationship became clarified and further reinforced through Clarence Perry’s published work on neighborhood units (Mumford, 1954, p. 261).

Perry’s ideas were influenced, in part, by his

experience as a resident of New York’s Forest Hills Gardens and by his employment with the Russel Sage Foundation. The Russel Sage Foundation was founded in 1907 with the express intent of improving the social and living conditions in the United States. It continues to serve as the principal American foundation devoted to research in the social sciences and at the time of Perry’s employment was investing heavily in opening pubic schools for neighborhood cultural, recreational and social activities. He also clarified his own opinions through the consideration of the influential ideas of his contemporaries, including Ebenezer Howard’s garden cities and Clarence Stein and Henry Wright’s neighborhood ideas as expressed in the construction of several planned

Neighborhood Unit Concept assimilated in Detroit: (left) Neighborhood Unit Perry’s concept, (right) Proposed generalized land use plan: an explanation of a basic plan designed to make Detroit a better place in which to live and work (City Plan Commission, 1947).

communities, including Sunnyside Gardens. The resulting neighborhood unit definition included six principles: (1) each neighborhood should be large enough to support an elementary school; (2) neighborhood boundaries should be composed of arterial streets to discourage cut-through traffic; (3) each neighborhood should have a central gathering place and small scattered parks; (4) schools and other institutions serving the neighborhood should be located at the center of the neighborhood; (5) local shops should be located at the periphery of the neighborhood; (6) the internal neighborhood street system should be designed to discourage through traffic.

By the 1960’s roughly 80% of professional planners and eighteen professional and governmental organizations made use of Planning the Neighborhood, the manual that placed the Neighborhood Unit as its central idea (Solow et.al. 1969). Despite the widespread acceptance and use of this planning concept, there were also strong detractors who pointed towards the tendency of this planning tool to result in homogenous pockets of segregated residents. Reginald Isaac’s work focused on trends in Chicago and built a case that the neighborhood unit formula was used to discriminate against black and low-income households. His work, however, was largely dismissed or ignored until recently, and had little influence to dissuade the wholesale acceptance of this planning concept.

Urban Playgrounds in the modernization of the City

A confluence of factors led Detroit to move from the formation of a City Plan Commission in 1919 towards the completion of its first master plan in 1951. One of the most powerful triggers for the development of planning initiatives in cities across the United States was the federal Works Public Administration program. In order to compete for the financial support of municipal projects, cities were required to produce plans to demonstrate their capacity to manage and allocate the federal funds. In Detroit, the first master plan emerged out of two studies conducted in the 1940’s: “Post-War Improvements to make your Detroit a finer City in which to live and work”, and “The Detroit Plan: a program for blight elimination.” It was also influenced by a manual completed in 1948 by the American Public Health Association called “Planning the Neighborhood,” which built directly on Perry’s definitions of the neighborhood planning unit and described specific details to be considered when implementing these ideas.

The adoption of the neighborhood unit concept was one important contribution in the first master plan of the city of Detroit, approved in 1951. Other cities had initiated similar approaches to improve the living conditions for the working classes. Starting in the mid-1930s, under the tenure of Moses as City Park Commissioner, New York received massive federal funds for

the implementation of an ambitious recreational program including improvements in parks, playgrounds, swimming pools, and vacant lots. Moses also promoted the school-park plan model in which small parks and playgrounds were located near public schools and other urban facilities in working class communities.

The case of Philadelphia, under the longterm leadership of Edmund Bacon, represents another important example in the investment of planning to envision a new model of a better city.

In preparation for the 1947 Better Philadelphia Exhibition, Bacon and Stonorov went to a series of schools and introduced the students the discipline of planning, and invited classes to participate in the incoming exhibition with their ideas for the city. Younger children designed the

perfect playground with clay and pipe cleaners, while older students on ideas to reinvent the neighborhoods across the city. The exhibition, visited by thousands of people, captured public imagination, and among the many components under display were the models and drawings made by the students from elementary to technical high school.

During this same period, the Department of Public Works in the City of Amsterdam was initiating an ambitious program to implement hundreds of playgrounds across the geography of the city, which was almost completely destroyed in WWII. Under the leadership of Aldo Van Eyck, and following an interstitial and polycentric approach, the initiative changed the look of the city through the eyes of its children.

Images form the “Better Philadelphia Exhibition, 1947”. (“Better Philadelphia Exhibition: What City Planning Means to You,” official brochure of the exhibition (1947).

Aldo van Eyck and the City as Playground

Aldo Van Eyck, an active member of the Dutch Team 10, would present his work in 1956, as “The Child in the City: The Problem of Lost Identity.” This exhibit described the playgrounds as neighborhood cores and extensions of the domestic doorstep. Across his tenure Aldo van Eyck contributed to the design and implementation of over 770 playgrounds. Implemented over 20 years, the playground program represented an important shift in the planning practice of the time because it invited participatory processes in the shaping of space.

The minimal design of the playgrounds aimed to stimulate the imagination of the users, and trigger an endless capacity for interpretation and use of the space.

The Neighborhood Unit legacy in the Detroit’s Master Plans

In 1951, on the occasion of Detroit’s 250th anniversary, Mayor Albert E. Cobo and the Detroit City Plan Commission published the city’s first official Master Plan, building on previous planning efforts conducted during

Detroit Neighborhood Unit pattern (above) and plan of schools (right). First Official Master Plan of Detroit, 1951

the 1940s. Since then, there have been three other Master Plans adopted in 1973, 1992 and in 2009. Detroit is currently undergoing a new planning effort under the Detroit Works Long Term initiative.

The introduction of the 1951 Master Plan recognized the importance of a city-wide vision for the future growth and organization of the city. The Introduction to the master plan describes the importance of the use of the neighborhood unit as a minimum planning unit and states, “The plan marks the recognition

that if a given number of families are going to live in a given neighborhood, they need certain public buildings, lands and services and they need equally to be protected from other aspects of city life which, quite necessary in their place, become nuisances when injected into a living area” (DMP, 1951). The report also states that the extent of the neighborhood will be determined in consideration of the service area of an elementary school as influenced by other physical barriers including topography or transportation infrastructure. The provision of

schools, recreational areas, and other public service facilities would be adequate to the needs of all neighborhoods and communities. Through the quantification of population demand, the report determined that a neighborhood population should typically fall within a range between 2,000 and 8,000 persons, with an optimal size of about 5,000 persons. From a geographic standpoint, the manual assumes a ¼ mile walkable radius from the elementary school and therefore estimates a maximum neighborhood size of 125 acres.

Both the language and concepts expressed in the introduction, and later developed in a series of chapters, are strongly aligned if not borrowing directly from Planning the Neighborhood, the American Public Health Association (APHA) manual published in 1948. As does the Detroit Master Plan, the APHA manual acknowledges that there is general agreement that the neighborhood is the minimum planning unit that has been accepted and that it is a physical concept that can be delineated through design guidelines. Finally, the APHA plan makes explicit that as a central organizing resource for the community, the elementary school should also play a role in the neighborhood relative to recreation. “Recreation space is usually best provided by combining the elementary school and neighborhood playground. (p. 45)”

In comparison, Detroit’s 1951 master plan also positions elementary schools as the social and

physical “heart” of a neighborhood, “For the purpose of designating residential areas in the city, the City Plan Commission uses the term neighborhood for the area, usually a square mile or less, which serves as an elementary school district.” At the scale of the city of Detroit, the 1951 Master Plan called for 150 neighborhoods and elementary schools with an additional 600 small playgrounds throughout the city to support a population with 150,000 to 210,000 elementary school aged children of whom, 80% attend the city’s public schools. This system ensured an equitable service provision to residential areas across the city; the cluster of six to twelve neighborhood units into sixteen communities served as a basis for the delivery of other basic services requiring more population base.

The importance of this consideration brought a close collaboration with the Detroit Board of Education, carefully planning the requirements of improvement, demolition, or new construction in each neighborhood. At the time of the master plan, the Board of Education operated 192 elementary schools, all of which were working towards the integration of education, playgrounds and community services. In defining the city this way, the provision of education and recreation for the city’s children was at the very core of its value system.

The plan also noted the agreement among the Board of Education and the Department of Parks and Recreation to maximize the use of

schools and grounds for recreational purposes. The plan identified existing, proposed, and to be discontinued playgrounds. At the time of the master plan, the Board of Education operated 192 elementary schools mostly covering six years in a 6-3-3 grade system. The plan suggested the integration of elementary school, playground and community center for economy, convenience, and for a more effective focus to the social life of the neighborhood. The playground around the school “should be large enough for active play and a landscape

area with picnic tables and benches”. Within the grounds of each school, the Master plan goes into further detail regarding the role of playgrounds. “Schools and playgrounds to be used by small children must be accessible within the distance they can walk in reasonable safety.” It goes on to specify that each elementary school should host a five to seven acre central playground and that, furthermore, there should be an additional four, smaller playgrounds within the four quadrants of each neighborhood. The playground was defined as an area designed

Playground Plan. First Official Master Plan of Detroit, 1951

and maintained primarily for recreation for children from 5 to 14 years of age. It identified two types of playgrounds among the required recreation facilities in each neighborhood: (1) a junior playground, 2-4 acres in size, in a ¼ mile travel distance, and (2) a central playground, 5-7 acres, in a ½ mile travel distance. The junior playground may contain such equipment as slides, spray pools, sand boxes or shuffle board, swings, horizontal bars and jungle gyms. It should have shade trees and landscaping for lawn games, free play and storytelling. It should also have benches or a shaded sitting out area for mothers who accompany their children. The central playground is intended to serve

the outdoor recreational needs of children of elementary school age both during school and after school hours. For this reason, it includes the facilities of the junior playground and space for more active and competitive games for older children. This playground may have places for softball, volley ball, handball, paddle, tennis, badminton, horseshoes, and skating. It should have quiet areas suitable for group singing, and other musical activities, dramatics, storytelling, painting, drawing, handicrafts, nature study and gardening.

Renewal and decentralization

The 1960s were the heyday in the history of the American urban playground through the theoretical and applied work of Lady Allen, Dattner and Friedberg, building on the early work of Isamu Noguchi. The fluid transitions of concepts between Europe and the US, and the productive partnership of architects artists, landscape architects, and public officials made possible some of the finest examples in playground design. Part recreation, part education and part community builder, the playground became a central element in city making.

In Detroit, the lower residential densities in most parts of the city fabric removed the constraints that designers faced in highly dense urban cores. The neighborhood unit concept would co-exist in the city with the urban renewal plans to eliminate residential blight fueled by the Detroit Neighborhood Unit concept. Master Plan of Detroit, 1973

Title I of the Housing Act in 1949. Two other two federal initiatives would further amplify the displacement of residents and initial decay of the residential fabric in the city. On one side, the Federal 1956 Interstate Highway Act facilitated the construction of transportation corridors to the very heart of the city, mostly disrupting and displacing low income neighborhoods. Adding to the impact of this policy, the Federal Housing Authority together with the Home Owners Loan Corporation, triggered the suburban flight with very favorable conditions for residential ownership beyond the limits of the city. These practices were segmented by race, ethnic

and class prejudices and initiated the black ghettoization of the city. The lack of loans and subsidies to inner neighborhoods, due to abusive redlining practices, accelerated the decay of some of the residential areas with a majority of black population without resources to keep up with improvements. Between 1950 and 1970, one third of the 1.8 million Detroit residents left the city. With them, their property taxes left too, and the capacity of the city to keep up with services and maintenance started to suffer. Play and playgrounds started to struggle, as basic service provision became compromised.

Following the civil rebellion of 1967, the second

Early playground studies, Isamu Noguchi.

master plan of the city was adopted in 1973. The plan recognized acute recreation needs for facilities close to people’s homes and available for everyday use. The plan called for more playgrounds and playfields together, and maintained similar standards to the previous 1951 master plan: “a minimum of 13 acres of playgrounds for a square mile neighborhood plus one acre for each 800 dwelling units when population exceeds 10,000 people per square mile.” The master plan also set up the standards for combined schools and recreation sites under article 305, jointly defined by the Department of Parks and Recreation, the Board of Education, and the City Plan Commission.

The master plan also noticed the initiative to promote the decentralization of School district approved under Act 244 of Public Acts of 1969 by

the Michigan Legislature. Under this regulatory framework, the City would be divided in 7 to 11 Regional School Districts with 25,000 – 50,000 students, and freedom regarding curriculum design. This initial move for the decentralization of functions was predicated on the desire of giving more community control over local area school operations. At this time, however, the definition of school districts became a contentious matter in a highly segregated city. The peak of the racial tension in the city in 1967 was the manifestation of decades of frustration and lack of equal opportunities for the black population. The Public School System was not a neutral ground, and many voices demanded a better share of resources in schools serving disadvantaged urban dwelers.

One of the most relevant initiatives voicing

Inventory of recreationsl facilities in the community of Fitzgerald (above), Studies on Children’s fatalities in the Geography of Children of Detroit (right), DGEI, Detroit, 1960s

the need of the black population to gain more control over civic matters was the Detroit Geographical Expedition and Institute (DGEI) led by urban geographer William Bunge. Bunge approached Detroit from inside, and moved to the Fitzgerald neighborhood in the late 1960s. His contentious work would involve the community, under institutional support from the University of Michigan first, and Michigan State afterwards.

Part of the mission of the DGEI implied not

only working with the community, but ensuring the delivery of basic tools for the residents to participate in the decisions relevant to their future. He also brought students and colleagues to participate in a series of studies and proposals in close collaboration with the residents. From the studies that emerged from this initiative, two reports would directly engage children as main matter of concern: “A report to the parents of Detroit on School Decentralization” in 1969, and “The Geography of Children of Detroit”.

Under the first report, the group tackled the plans of decentralization of schools, with a goal of empowering black leadership within the school system. The study used geographical methods for socially just ends (Hovarth, Antipode 3,1, 1971), and the results proved more effective than the formal plans developed by the Board of Education. The second study unveiled the harsh reality that shaped the childhood of low-income black children living in neighborhoods across the city. The document provides a glimpse

of the daily life of children, the spaces where they were playing and learning and the many risks they confronted for survival. It describes a hostile environment rife with hunger and death, and portrays a city that has forgotten about nurturing its children and future generations.

These and other initiatives formed a part of an emerging paradigm towards a participatory, community-centered approach to problem solving in Detroit. During the 1970s the community

Webster Elementary school grounds in Southwestern Detroit

groups started playing a more central role in the re-development of their neighborhoods. The Community Development Block Grant program was one of the federal initiatives to stimulate public and private investment on the City, and targeted the physical, social and economic needs of the different areas. However, during the 1980s the city witnessed the highest unemployment rates in the country, increased poverty and crime. The suburban exodus from previous decades left behind a landscape of

aged infrastructure, a deteriorated downtown, and a poorly maintained housing stock.

By 1992, Detroit’s Master plan called for the re-establishment of coordination between City government and Board of Education in the use of school facilities. For the first time, the master plan recognizes aging and deterioration of the built environment as a major cause of concern, and its policies urge “sensitivity to varying levels of deterioration and differing strategies of development”. (Master plan of policies, 1992).

Acconci Studio. Land of Boats, Saint Aubin Park, Detroit, 1987-91.

CHANGE IN THE ELEMENTARY PUBLIC SCHOOLS

1951-1978

CHANGE IN THE ELEMENTARY PUBLIC SCHOOLS

School choice, neighborhood detachment

The dwindling cooperation between the city of Detroit and the Detroit Public School system was further exacerbated when the right to school choice was voted into law in 1994. This had the unintended consequence of putting the city’s schools at odds with its local residents since neighborhood children still looked to local schools for the use of playgrounds while schools perceived residents who no longer attended neighborhood schools to be a drain on already strained resources. Also approved in 1994, the 1994 $1.5 Billion Bond Program fmade possible the construction of 3 new high schools, renovations in 2 others, and the construction of 16 other new school buildings. The initiative also provided over $600 million in

capital improvements to 175 schools within the district.

During the decade of 1990s Detroit and its neighborhoods also attracted a good amount of national attention. In 1994, through the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Detroit was designated as one of the 7 Empowerment Zones nationwide, “to create economic opportunity for its residents, restore and upgrade neighborhoods, and sustain competent, healthy and safe families”. In addition, the creation of the Detroit Renaissance Zone program in 1997, and the Cities of Promise Program in 2005 both tackled the distressed economic and social conditions of the residents in the City. The physical expression of these initiatives has resulted in a piecemeal approach

School choice advocates and photo of a neighborhood with high vacancy rates

to the stabilization of monofuntional residential areas, and the progressive suburbanization of the residential pattern (Ryan, 2012). In addition, residential vacancy has become a formidable burden for the city with increased expenditures going to a massive demolition program. The Neighborhood Stabilization Plans that came as a federal response to the national foreclosure crisis in 2008 also reached Detroit. With some 67,000 foreclosed properties reported, 65% of them vacant, demolition got an initial 30% of the available funds under this initiative, and has only grown over time.

The resulting vacancy after abandonment also challenged the capacity to maintain a healthy recreational system. In 2006, the City of Detroit Recreation Department approved a Strategic Master Plan with an inventory of all the existing facilities. The overabundance of open space, and the dwindling resources in the city resulted in the “repositioning” of some of the parks, and sustained efforts to engage the community to keep up with the maintenance of the facilities.

Little changes in this respect have been introduced in successive planning efforts in Detroit, and the most recent Master Plan of Policies, adopted by the City Council in 2009, continues to call for support and participation through a collaborative, community-based process to coordinate neighborhood development plans with school, recreation and library development plans. The neighborhood,

however, is no longer defined in terms of what it could or should be as much as how it is defined by the residents living there.

The continued economic decline and depopulation have severely diminished the capacity of the City to coordinate efforts with the Public School System. The struggles in the DPS system, with many underperforming schools and loss of students to private facilities and charter schools, has distracted the attention from the school grounds and the importance of play in the early education of children.

In November 2009, Detroit voters approved Proposal S to enable the district to access $500.5 million for school capital improvement projects, including eight new and ten modernized buildings. This stage marked the transition to the “universal PreK-8 school model”, a consolidated school model that creates “academic centers” within a single school/ campus. The centers cluster administration, PreK–5, academic support (media center, resource rooms), Arts and Athletics, and 6–8 into separate but contiguous areas. So far, the Proposal S bond program has focused on the development of 5 new and 5 renovated PreK-8 schools. Under this model of physical consolidation and geographical choice, the intimate relationship of the surrounding residents has dramatically changed, and the school does not perform any longer as the community core.

Mason Elementary School was first established in 1927 on the site of Outer Drive, Harned, Lantz, and Mitchell Streets, with one temporary building. The first permanent building opened in 1931.

year 2012-2013

Study of Mason Elementary Public School, building closing in the academic

Children under 15 geographical distribution per census tract (left and above); etroit Works Long Term Planning studies of the distribution of city-wide vacancy (right).

Moving forward

The reality of the Public Schools System in Detroit is one of shifting grounds and uncertainty. Once positioned as social and cultural nodes of the thriving neighborhoods in the city, the loss of population and the resulting shrinking tax base threatens today the very sustainability of the system. With 69,616 enrolled students, and capacity for 30,000 more seats, the system is continually “closing, consolidating and merging” schools in order to gain financial stability.

As a response to the need of a visioning

framework to guide Detroit’s future, the City embarked in a new planning initiative in 2010 with the overarching goal of “improving the quality of life and business in Detroit in the next five to twenty years”. The process has required significant research to update the information on existing and projected conditions, and has brought the expertise of consulting technical teams to join efforts with the city officials, residents and businesses to create the Strategic Framework Plan.

In the midst of discussions on the right-sizing strategies for the city to fight vacancy and blight, the consideration of these public grounds as catalytic anchors for civic engagement and community stabilization is not developed at its full capacity. It is in this spirit that our research defies the current sense of emergency driving urban design in the city, and reclaims the ground for small designs, anchored in the most valued social institutions, as an opportunity for the resurgence of the city.

Building on the interest in the social and cultural manifestations of community ties to Detroit, we have initiated an operative inventory of elementary schools and their grounds as a design tool to facilitate social integration and land stewardship. We propose the recuperation of playgrounds as space for children, central to the living fabric of the city, and intrinsically related to the school grounds and the surrounding community. We see the school playground as a unique opportunity to foster a synergy among community engagement, education and design in the Detroit of 2012 and beyond. Despite the massive decommission of public elementary schools and playgrounds due to urban contraction, this study proposes an optimistic approach to preserving space for children’s imaginative play. Revisiting the role of the schoolyard playground as an anchor for the neighborhood, the study selects four sites on which to develop an iterative process of design.

The following pages present a visual catalog of the elementary public school system attending to the physical characteristics of existing outdoor spaces, playgrounds, and their use, and access. This initial set of conditions is further examined in relationship to a set of additional neighborhood characteristics including building structures, land use patterns, ownership, rates of vacancy and other geophysical layers. The study renders the fragile condition of the built environment that constructs children’s imagination at such early ages, and unveils opportunities for its improvement. The extended operative inventory, compiled in a GIS database, informs the initial design decisions to better sustain the dynamic relationship of neighborhood’s children and playgrounds.

If Design is ‘‘the area of human experience, skill and understanding that reflects our . . . appreciation and adaptation of our surroundings in light of our material and spiritual needs’’ then we all naturally engage in design. Since we all use tools and materials purposefully in trying to adapt our communities and environment to one that suits our needs, the capacity for design must be a fundamental human aptitude (Roberts, 1995). And, as children’s ‘‘play’’ incorporates many of the characteristics of ‘‘designerly’’ activity, design-based activities have the potential, to address how the needs of children should return to the heart of planning for our future cities.

Bibliographic Sources

City of Detroit. 1947. The Detroit Plan for Blight Elimination. Detroit, Mich.: City Plan Commission.

City of Detroit. 1951. The Detroit Master Plan. The Official Comprehensive Plan for the Development and Improvement of Detroit as approved by the Mayor and the Common Council. City Plan Commission. Detroit, MI.

City of Detroit. 1973. The Detroit Master Plan as amended to October 1973. City Plan Commission. Detroit, MI.

City of Detroit. 1992. City Plan Commission. Detroit, MI.

Current Master Plan, adopted by City Council in July of 2009. City of Detroit Master Plan of Policies. Detroit City Plan Commission. Detroit, MI.

Detroit Public Schools website, accessed from March 2012 to October 2012

http://detroitk12.org/content/2012/02/08/dps-emergencymanager-roy-roberts-announces-school-changesacademic-initiatives-key-dates-and-timelines-for-parentsfor-the-2012-13-school-year/

http://www.dpsschoolconstruction.org/

Detroit Recreation Department, 2006. Strategic Master Plan, Final Draft for Detroit City Council Review. (1967). Histories of the Public Schools of Detroit. [Detroit].

(1967). Histories of the Public Schools of Detroit. [Detroit].

(1970).A report to the parents of Detroit on school decentralization.[Detroit: Detroit Geographical Expedition and Institute.

(1971).The geography of the children of Detroit.[Detroit: Detroit Geographical Expedition and Institute.

Frost, J. (1988). Child Development and playgrounds, in Play spaces for children: a new beginning. Improving our elementary school playgrounds. Volume II

Lefaivre, L. (2002).Aldo van Eyck: the playgrounds and the city. Amsterdam: Stedelijk Museum.

Solomon, S. G. (2005).American playgrounds: revitalizing community space. Hanover [N.H.]: University Press of New England.

School Playgrounds: Their Surfacing, Administration, Use, and Care. T. C. Holy and William E. Arnold, Review of Educational Research, Vol. 5, No. 4, The School Plant (Oct., 1935), pp. 364-369, American Educational Research Association Historical Maps and Aerial Imagery Sources

Note. The maps and diagrams have been generated in ArcMap with the cartographic base of SEMCOG 2009/2011,

Historical Aerial Image Collection of Detroit from 1949 to 1997, Wayne University, through donation by DTE.

Bagley Elementary School

Beckham, William J. Academy

Bennett Elementary School

Brown, Ronald Academy

School

Carleton

Marshall, Thurgood Elementary School

Maybury Elementary School

Neinas Elementary School

Elementary Public Schools

Pasteur Elementary School

Thirkell Elementary School

Vernor Elementary School

Wayne Elementary School

Wright, Charles School

Young, Coleman A. Elementary

Blackwell Institute Bow Elementary-Middle School

Brewer Elementary-Middle School

Bunche Elementary-Middle School

Burton International School

Carstens

Carver Elementary-Middle School

Clark, J.E. Preparatory Academy

Clippert Academy

Davison Elementary-Middle School

Detroit International Academy for Young Women

Dixon Educational Learning Academy

Dossin Elementary-Middle School

Durfee Elementary-Middle School

Earhart Elementary-Middle School

Edward

Field, Moses

Elementary - Middle

Middle Public Schools

High Public Schools

Aisha Shule/W.E.B. DuBois Preparatory School, 6 –12

Andrew Young Early College Academy, 6 –8

Capstone Academy Charter School, 6 –12

Center for Literacy and Creativity, K8

Covenant House Academy Central, 912

Covenant House Academy East, 912

Covenant House Academy Southwest, 912

David Ellis Academy, K6

EMAN Hamilton Academy, K8

GEE Edmonson Academy, PreK7

GEE White Academy, PreK8

International Preparatory Academy –MacDowell Campus, PreK7

Martin Luther King, Jr. Education Center, K -8

New Paradigm Glazer Academy, PreK6

New Paradigm Loving Academy, PreK6

Ross-Hill Academy, K8

Rutherford Winans Academy, PreK5

Brenda Scott Elementary/Middle

Timbuktu Academy of Science and Technology, K6 & 712 Education Achievement

Burns Elementary/Middle

Law

Self-Governing Schools

DETROIT PUBLIC ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS INVENTORY

“The common belief that play is a waste of time is perhaps the single most restrictive factor in providing good play environments. The contemporary elementary school playground is designed as though playground activity contributes nothing to thinking, relating and creating.” (Frost, 1987)

23 Public Elementary Schools

11,239 children from Pre-K to 6

1. Bagley Elementary School

2. Beckham, William J. Academy

3. Bennett Elementary School

4. Brown, Ronald Academy

5. Carleton Elementary School

6. Chrysler Elementary School

7. Clemente, Roberto Academy

8. Cooke Elementary School

9. Edison Elementary School

10. Fisher Magnet Lower Academy

11. Gardner Elementary School

12. Harms Elementary School

13. Mann Elementary School

14. Marshall, Thurgood Elementary School

15. Maybury Elementary School

16. Neinas Elementary School

17. Oakman Elementary - Orthopedic School

18. Pasteur Elementary School

19. Thirkell Elementary School

20. Vernor Elementary School

21. Wayne Elementary School

22. Wright, Charles School

23. Young, Coleman A. Elementary

1 BAGLEY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

8100 Curtis Street.

2 BECKHAM, WILLIAM J. ACADEMY

9860 Park Drive.

3 BENNETT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

2111 Mullane Street

BROWN, RONALD ACADEMY

11530 E. Outer Drive

5 CARLETON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

11724 Casino Street

6 CHRYSLER ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

1445 E. Lafayette Street

7 CLEMENTE, ROBERTO ACADEMY

1551 Beard Street

8 COOKE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

18800 Puritan Street

9 EDISON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

17045 Grand River Avenue

11 GARDNER ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

6528 Mansfield Street

12 HARMS ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

2400 Central Street

13 MANN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

19625 Elmira Street

14 MARSHALL, THURGOOD ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

15531 Linwood Street

15 MAYBURY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

4410 Porter Street

16 NEINAS ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

6021 McMillan Street

17 OAKMAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

12920 Wadsworth Street

18 PASTEUR ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

19811 Stoepel Street

19 THIRKELL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

7724 14th Street

20 VERNOR ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

13726 Pembroke Avenue

21 WAYNE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

10633 Courville Street

22 WRIGHT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

19299 Berg Road

23 YOUNG ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

15771 Hubbell Street

4 TIMES 3:

DESIGN ITERATIONS OF PLAY

“Play is the vehicle for knowing”. (Piaget, 1962)

CONSTRUCTED GROUND STUDIES :: formal manipulations

“Play is a necessary part of culture. Culture arises in the form of play”. (Huizinga, 1950)

The design decisions that shape our built environment are critical indicators of our cultural engagement with the city. The design of children’s play area is a unique opportunity to foster a synergy between community engagement, education and design. Through our collaborative partnership and interaction with the Detroit Public Schools, we intend two outcomes: (1) a series of concept designs that illustrate innovative ways to bring education, community and water together in a playground and (2) short, intensive design-thinking play sessions to share with the students an introduction to design careers and to gain feedback from children about what makes playgrounds vibrant to them.

In A Dozen Playgrounds, understanding how water moves over constructed ground is leveraged as a playful way to recuperate playgrounds as public spaces. Our approach to playgrounds is prototypical, scalable, durable, colorful and lively. The design of multiple iterations of each of four grounds for play (Vernor Elementary, Chrysler Elementary, Carleton Elementary and Gardner Elementary) is central to an ambition to develop variations within similar sets of constraints considering materiality and use. Here we understand the scalar importance of the work to have resonance at the city level as a polycentric, interstitial approach towards Detroit’s network of communities and potential play spaces.

Hiding/Crawling

AGE APPROPRIATE EQUIPMENT

MATERIALITY

APPROPRIATE EQUIPMENT

Toddler — Ages 6-23 months

Climbing equipment under 32” High

Ramps

Single file step ladders

Slides

Spiral slides less than 3 0°

Toddler — Ages 6-23 months

Spring rockers

Climbing equipment under 32” High

Stairways

Ramps

AGE APPROPRIATE EQUIPMENT

Preschool — Ages 2-5 years

Certain climbers

Horizontal ladders less than or equal to 60” high for ages 4 and 5

Merry-go-rounds

Ramps

Preschool — Ages 2-5 years

Certain climbers

Toddler — Ages 6-23 months

Swings with full bucket seats

Single file step ladders

Slides

Climbing equipment under 32” High

Ramps

Spiral slides less than 3 0°

Spring rockers

AGE APPROPRIATE EQUIPMENT

Stairways

Rung ladders

Single file step ladders

Grade School— Ages 5-12 years

Arch climbers

Chain or cable walks

Free standing climbing events with flexible parts

Fulcrum seesaws

Ladders – Horizontal, Rung, & Step

Grade School— Ages 5-12 years

Arch climbers

Overhead rings

Merry-go-rounds

Merry-go-rounds

Single file step ladders

Slides

Toddler — Ages 6-23 months

Swings with full bucket seats

Ramps

Ramps

Rung ladders

Spiral slides less than 3 0°

Spring rockers

Stairways

Single file step ladders

MATERIALITY

Slides

Preschool — Ages 2-5 years

Slides*

Certain climbers

Spiral slides up to 3 0°

Horizontal ladders less than or equal to 60” high for ages 4 and 5

Spring rockers

Chain or cable walks

Grade School— Ages 5-12 years

Ramps

Free standing climbing events with flexible parts

Horizontal ladders less than or equal to 60” high for ages 4 and 5

Fulcrum seesaws

Stairways

Merry-go-rounds

Single file step ladders

Climbing equipment under 32” High

Slides*

Arch climbers

Ring treks

Chain or cable walks

Slides

Ladders – Horizontal, Rung, & Step

Free standing climbing events with flexible parts

Spiral slides more than one 360° turn

Fulcrum seesaws

Ramps

Preschool — Ages 2-5 years

Certain climbers

Swings – belt, full bucket seats (2-4 years) & rotating tire

Rung ladders

Spiral slides up to 3 0°

Swings with full bucket seats

Spring rockers

Spiral slides less than 3 0°

Spring rockers

Stairways

Swings with full bucket seats

Single file step ladders

Horizontal ladders less than or equal to 60” high for ages 4 and 5

Stairways

Slides*

Merry-go-rounds

Ramps

Spiral slides up to 3 0° Spring rockers

Swings – belt, full bucket seats (2-4 years) & rotating tire

Rung ladders

Stairways

Single file step ladders

Slides*

Overhead rings

Merry-go-rounds

Ramps

Stairways

Grade School— Ages 5-12 years

Arch climbers

Ring treks

Slides

Ladders – Horizontal, Rung, & Step

Swings – belt & rotating tire

Overhead rings

Track rides

Chain or cable walks

Merry-go-rounds

Vertical sliding poles

Ramps

Free standing climbing events with flexible parts

Fulcrum seesaws

Stairways

Spiral slides up to 3 0° Spring rockers

Stairways

Swings – belt, full bucket seats (2-4 years) & rotating tire

Spiral slides more than one 360° turn

Ring treks

Slides

Ladders – Horizontal, Rung, & Step

Swings – belt & rotating tire

Swings – belt, full bucket seats (2-4 years) & rotating tire

Overhead rings

Track rides

Spiral slides more than one 360° turn

Merry-go-rounds

Stairways

Preschool — Ages 2-5 years

Certain

Toddler — Ages 6-23 months

Certain

Vertical sliding poles

Ramps

Ring treks

Slides

Swings – belt & rotating tire

Track rides

Vertical sliding poles

Spiral slides more than one 360° turn

Stairways

Swings – belt & rotating tire

Track rides

Vertical sliding poles

Grade School— Ages 5-12 years

Arch

Free

Fulcrum

Ladders

Overhead

Preschool — Ages 2-5 years

Ring

Horizontal

Rung

by Linda Cain Ruth Auburn University, 2008

Population under age 14 Units of

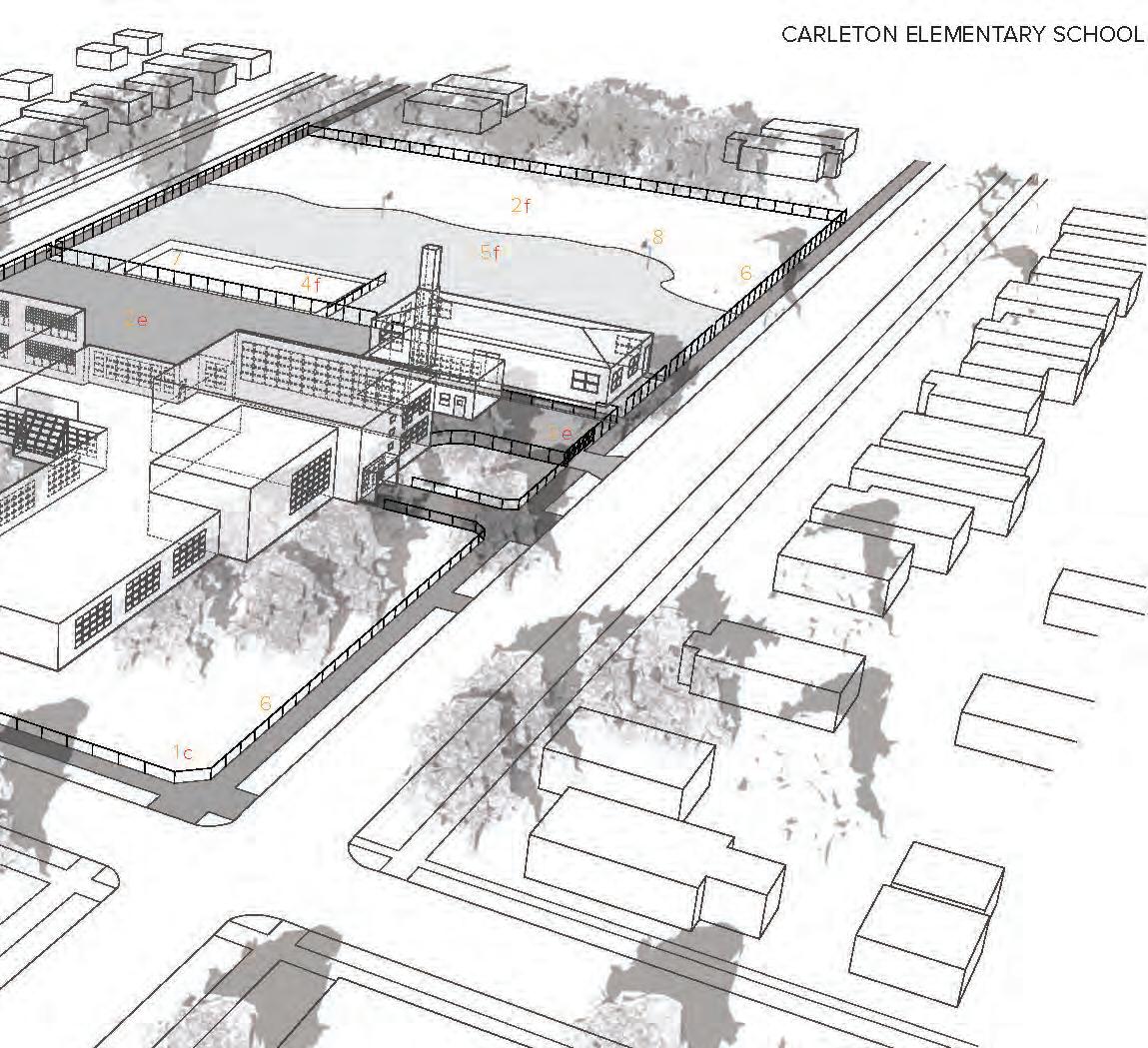

CARLETON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

The construction of the Gardner School was in response to the increasing population of the West Warren section of the city. Originally, the school was 55 by 72 ft. with an area of 6,072 ft2 of floor space. It was constructed in 1926 with a capacity of 340 students. The school that cost $102,783.27 was divided into seven rooms and a kindergarten.

In 1929 and 1934 two-room portable buildings were constructed to accommodate increased enrollment. The peak enrollment was 531 students in September 1934. An addition was opened for use in 1951 and was considered complete the same year. The Gardner School has a long history of service to the community.*

*Histories of the Public Schools of Detroit, Volume II, 1967

Analytical Diagrams

Aerial Image

Buildings

Green Space

Paved Areas

CARLETON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

Carleton Elementary School

School Catchment Area

Proposed playground

Historical Neighborhood Unit Boundary

Population under age 14

Units of Analysis

The first Chrysler Elementary School opened in 1959, in one of the town houses in Lafayette Park. The publicity given to the school, conveniently located in the very downtown of Detroit, resulted in the expansion to a new town house. In 1960 an advisory committee appoinnted by the superintendent of schools started discussion for the construction of a new building.

The new school would open in 1961.*

*Histories of the Public Schools of Detroit, Volume II, 1967

Aerial Image

Paved Areas

Green Space

Analytical Diagrams

Historical Neighborhood Unit Boundary

School Catchment Area

Proposed playground

Carleton Elementary School

Units of Analysis

GARDNER ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

The construction of the Gardner School was in response to the increasing population of the West Warren section of the city. Originally, the school was 55 by 72 ft. with an area of 6,072 ft2 of floor space. It was constructed in 1926 with a capacity of 340 students. The school that cost $102,783.27 was divided into seven rooms and a kindergarten.

In 1929 and 1934 two-room portable buildings were constructed to accommodate increased enrollment. The peak enrollment was 531 students in September 1934. An addition was opened for use in 1951 and was considered complete the same year. The Gardner School has a long history of service to the community.*

*Histories of the Public Schools of Detroit, Volume II, 1967

Paved Areas

Analytical Diagrams

Historical Neighborhood Unit Boundary

School Catchment Area

Proposed playground

Carleton Elementary School

Units of Analysis

VERNOR ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

The James Vernor School was opened on December 1st, 1947. The first unit of the building consisted of 10 classrooms and accommodated 400 students, from kindergarten through 6A. The cost of the building was $338,668.45.

James Vernor was one of the original members of the Michigan Board of Pharmacy, formed in 1887, and he also served on the Detroit City Council for 25 years.

A unique feature of the school was glass block construction that increased the amount of natural daylight. It was the first time in a Detroit school that this material was used. Pastel colors, soundproof ceilings and fluorescent lighting were also introduced.*

*Histories of the Public Schools of Detroit, Volume II, 1967

Aerial Image

Analytical Diagrams

Buildings

Green Space

Paved Areas

Topography

Playgrounds as sites for design thinking

A Dozen Playgrounds brings together three collaborators who collectively represent expertise in design methodologies, the science of water and innovative secondary education learning models. Some of our recent research includes design projects examining the interface between landscape and urbanism, with a strong environmental concern, and scholarship devoted to the development of K-12, designthinking based science curricula.

Through our shared interests in the education of future educators, our research initiative has engaged students in the different phases of the process, from documentation and analysis, the playground design, and the future implementation of the lesson plans in the classroom.

Taubman College has a long educational tradition that combines design and technology. Today, it continues to foster a broad view of architecture and urban and regional planning in the context of a major research university where interdisciplinary initiatives are encouraged and supported. Taubman College conducts innovative design and policy research and serves the community, the state, the nation, and the world through outreach and partnerships.

The WKKF-WW Michigan Teaching Fellowship curriculum at U-M prepares exemplary secondary teachers in biology, chemistry, mathematics, and physics to serve diverse learners in high need urban settings. The program is composed

of students who have majored in or have strong professional experience in math or science, and have the desire to understand how to engage students in exploring these subjects using best practices in pedagogy and learning with a focus on innovation. Fellows develop knowledge and skills needed for the complex environment present in twenty-first century schools.

Innovation in pedagogy can be defined as creativity combined with action where innovative pedagogical ideas get value from their successful application to solving a classroom problem. Design thinking represents a structured way of innovating as it incorporates a process that involves identified roles, techniques, environments, and tools. This process allows teachers to address instructional problems using a human centered design orientation that includes a bias towards action and the use of rapid prototyping to try out new ideas.

Learning from this approach, the next stage of our applied research will take us to the elementary schools in Detroit to teach design thinking through the sciences. Though our collaboration with Clinical Professor R. Charles Dershimer, we have created lesson plans using design thinking to teach geometry though play. By introducing simple geometries and design operations to the students, we will also gain their feedback on the initial designs presented in previous pages.

Lesson Focus Question:

How do Architects and Urban Planners use geometric shapes to design better places to live and play?

State Objectives:

Content Expectation/s Geometry (Common Core):

Grade K-3 - Reason with shapes and their attributes.

Grade 4 - Draw and identify lines and angles, and classify shapes by properties of their lines and angles.

Grade 5 - Classify two-dimensional figures into categories based on their properties.

Arts Education – Visual Arts (Michigan Merit Curriculum):

Grade K-5 - Apply skills and knowledge to create in the arts.

Michigan Career and Employability Skills- Career Planning (Michigan Department of Education):

Elementary- All students will acquire, organize, interpret, and evaluate information from career awareness and exploration activities… to identify and to pursue their career goals.

Lesson Objectives:

Mathematics: (Based on Common Core Curriculum Standards)

• Students will draw and identify lines and angles, and classify shapes by properties of their lines and angles.

• Students will classify two and three dimensional objects based on attributes (e.g. rectangles have four, parallel sides).

• Students will investigate, describe, and reason about decomposing and combining shapes to make other shapes.

• Students will develop a foundation for understanding geometric shapes by building, drawing, and analyzing two- and three-dimensional shapes in relation to a playground.

Arts: (Based on Michigan Merit Curriculum)

• Students will apply critical thinking strategies through the art making process at an appropriate developmental level.

• Students will develop confidence with their creative ability to represent their ideas using two and three-dimensional materials.

Career: (Based on Michigan Career and Employability Skills)

• Students will be able to describe how an Architect and an Urban Planner design better places for people to live and play.

Vocabulary/Word Wall

• Architecture, Urban Planning, Design

• Lines, planes, ruled surfaces, rectangles, parallelograms, rhombuses, squares, quadrilaterals, cubes, pentagons, hexagons, triangles, pyramids, circles, cylinders, spheres

• Prototype, Model, Scale

Materials:

• Multi-color construction paper (rough), multi-color smooth paper

• Pipe cleaners, basswood sticks

• Clay

• Scissors, tape, glue sticks

• Poster paper

Classroom Visit Timeline and Activity Details

Follow the 5 E’s when lesson planning: ENGAGE, EXPLORE, EXPLAIN, ELABORATE, EVALUATE

ENGAGE

Tap prior knowledge, Focus learners’ thinking, Spark interest in the topic

Step 1: The UM Architects/Urban Planners will introduce the project and explain the goal of the project (5 minutes):

“We are going to explore an architectural idea where we work with different materials that have different qualities to help you express your ideas about playgrounds. This is what architects and urban planners do- we work with different materials to make different kinds of things to help solve problems to make people’s lives better.”

“Can you all tell us something that an architect/urban planner might design and build?”

“As architects and urban planners we are going to design a new playground for the community. We want to learn from you and your creativity. We want you to imagine something that you that you like that you have not seen in a playground before, to help us understand what you would want to have in your playground.”

“To help us imagine with you, we are going to have you make your ideas. When you are done we will ask you to describe what you created and describe how you and your friends would play on what you created. Here is what makes this fun- we don’t want you to use playground words to express your ideas...for example, you can’t say ‘build a swing set’ instead you would say ‘build something that moves back and forth and up and down, and goes really fast!’ ”

Step 2: The UM Architects/Urban Planners will introduce the creative thinking activity to get students engaged with expressing their ideas (5 minutes):

“We are going to pass out these carpet squares. After we pass these out we want you to do three things to help us all think about what it is like to use a playground for fun and to help us practice describing what you do on a playground.”

Action #1 – Stand or sit on the square. You will keep your body on this square at all times.

Action #2 – Think about the different ways that you move on a playground.

– Think about what your arms, hands, legs, feet, head, body do when you ‘play’ on a playground.

– Act out your playground motions while you stay on your square.

Action #3 – When you hear ‘freeze!’ everyone will stop moving.

– We will call on someone to have you tell us what you are doing.

– You will need to laugh if it is funny. When we say “go!” you will start moving again.

PLAN

EXPLORE -HANDS-ON!/ Provide learners with common, concrete, experiences with phenomena EXPLAIN -MINDS-ON!/ Encourage students to explain concepts in their own words. Ask for justification ELABORATE -HANDS-ON! + MINDS-ON!/ Apply concepts and skills in a new context resulting in deeper and broader understanding

Step 1: Creative Build Activity. UM Architects/Urban Planners introduce the task (30 Minutes total):

Step 1.1: Individual Activity: Students are provided with “build bag” and a handout showing different geometric shapes. Each student will use the materials and geometric shapes to create something new for a playground (10 minutes):

“What would you do with your shape in a playground?”

Learn: How the student describes and thinks about the play activities for each kind of shape.

“How does your playground shape feel and look? Soft, Hard, Bumpy, Smooth, Open, Closed, Slippery, Sticky, Bouncy, Solid?”

Learn: About the choice of materials for each kind of shape.

Observe: Make note of the kinds of words students use to describe their activities and choice of materials.

Manage: Work to support the task completion for each student.

Step 1.2: Team Activity: Students are combined into groups of four and asked to organize their shapes together in an empty space model. Each group member must explain his/her shape to each other and how the shape is used for play. Then, as a team, the group describes how they and their friends would use all of the shapes together (10 Minutes):

“How do your shapes interact and what can kids do in between the shapes?”

Learn: Find out how students think about and describe each other’s shapes.

Observe: Record student choice of words and use a camera to photograph student work.

Manage: Support team work to place shapes and listen about how their ideas connect within the empty space model.

Step 1.3: Large Group Share Out: Have one person from each team describe their plan. Have teams share out the words that they use to describe their activities and to describe the materials (10 Minutes):

“How do your shapes interact with each others? Use descriptive words or act out the motions that you would use to play.” Observe: Record student comments on two posters: One poster is labeled “activities” and the other is labeled “materials.”

Manage: Ensure that each team gets to share. Encourage playful but supportive responses to each other’s work.

Step 2: Large Group Share Out Analysis and Elaborate task: Have the students, in their teams, verbally summarize what shapes were common and what shapes were not commonly used in the playground models. Have them provide a reason why they think different shapes were used or not used. Have each team verbally share out their ‘claims’ and their reasons to support their claims, encourage use of proper vocabulary (10 minutes):

Step 3: Wrap Up Task: Thank the students for sharing their ideas. Collect the projects from each team and pass out the UM architectural materials and design “goodie bags.” Explain the different materials being left in the classroom (10 minutes): College of Architecture Poster, Dimensions Magazine (student publication that describes the work and projects architecture and urban planning students), Poster with pictures of different Geometric Shapes and Materials found in playgrounds around the world, “goodie bag” with design construction materials and UM stickers.

EVALUATE -Assessment Task to determine if objective was mastered

Evaluation 1: The 3D materials produced in Step 1.2 will be used to examine the application of different shapes.

Evaluation 2: The Analysis task in Step 1.3 will be used to document the correct use of vocabulary and the ability to apply geometric reasoning to their design.

Homework: -To continue/expand learning at home

Students will be asked to visit the UM website for the Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning to learn more about being an architect and urban planner. The website can be found at www.taubmancollege.umich.edu

MEASURE RADIUS

MEASURE RADIUS

DRAW THE CIRCLE BY ROTATING AROUND THE CENTER POINT

DRAW THE CIRCLE BY ROTATING AROUND THE CENTER POINT

DIVIDE THE CIRCLE INTO SEGMENTS BY ROTATING THE DIAMETER

MEASURE DIAMETER

MEASURE DIAMETER

DIVIDE THE CIRCLE INTO SEGMENTS BY ROTATING THE DIAMETER

CONSTRUCTED GROUND STUDIES

CIRCLE BY ROTATING AROUND THE CENTER POINT

DRAW A STRAIGHT LINE 16 FT

ROTATE 90 DEGREES

DRAW ANOTHER STRAIGHT LINE

DRAW A STRAIGHT LINE 16 FT

DIVIDE EACH LINE INTO EIGHT EQUAL SEGMENTS

BEGIN CONNECTING THE POINTS

ROTATE 90 DEGREES

CONSTRUCTED GROUND STUDIES

DRAW ANOTHER STRAIGHT LINE DIVIDE EACH

BEGIN CONNECTING THE POINTS