A Continuation of The Greatest of These Is Charity

The Masonic Homes at 125

A Continuation of The Greatest of These Is Charity

1 The Rebirth: Modernizing the Masonic Homes p. 14

2 Evolving Youth Services: The Childrens Program and MCYAF p. 30

3 Extending Their Reach: Masonic Outreach Services p. 54

4 Leading the Field: Memory Care at the Masonic Homes p. 76

5 A Transformative Gambit: Acacia Creek p. 94

6 Opening the Gates: Community Relations p. 112

7 Retirement 2.0: Technology at the Masonic Homes p. 130

8 Form and Function: The Campus Master Plan p. 150

Milestones Introduction: Across the Years p. 10

Where History Lives On p. 26

When Destiny Chose Walter Wilcox p. 50

A Dark Day in the East Bay Hills p. 74

The Wandering Statue p. 90

Amid the Glory of Nature p. 108

It’s in the Soil p. 126

Beneath the Foundation, Solid Bones p. 144

Intelligent Design p. 148

For more than a century, Masons’ commitment to care has remained firm—even as everything else has changed.

Since 1898, the Masonic Homes of California has stood as a testament to compassion, support, and brotherly love.

For 125 years, it has embodied the commitment that every Mason makes to his brothers and their families. And for 125 years, whenever a Mason has walked through the doors of the Masonic Homes, they’ve found a place of respite and relief.

The Masonic Homes originally grew out of a statewide effort that Masons made to respond to the great cholera outbreak in Sacramento and San Francisco of 1850. That led to the creation of one of the first public hospitals in the state, the Odd Fellows and Masons’ Hospital in Fort Sutter. Three Sacramentoarea lodges shouldered the majority of that burden, contributing more

than $31,000 in direct funds and hospital costs during the outbreak. In today’s dollars, that amounts to something like $15,000 per member. It was a staggering amount, and a powerful symbol of California Masons’ commitment to their fellow members and their community. Half

The Masonic Homes opened in 1898 in Decoto, now Union City.

a century later, Masonic relief in California was centralized through the Masonic Widows and Orphans Home, which we now know as the Masonic Homes of California.

Although a great deal has changed since then—the name of the town it called home, Decoto, became Union City in 1959—the Masons’ commitment to care for one another has remained the bedrock upon which our organization is built. And it is still the generosity of the Masons of California that makes it possible.

One hundred and seventy years after that cholera outbreak spurred the fraternity into action, another pandemic swept through. And again, the Masons of California responded.

Through the Masonic Homes, they were able to ensure that their fellow members, their families, and the most vulnerable in their communities were able to access lifesaving health care, finances, mental health services, advice, and social support. The form that relief took could hardly have been any different than it was in 1850. But the same spirit of generosity and responsibility to those around them was evident.

As we celebrate our sesquicen-

tennial this year, we have a special opportunity to reflect on 125 years of making history—and look to an even brighter future. The story of the Masonic Homes is one of evolution and change, guided by an unwavering commitment to care. And look how far we’ve come!

Of course, this isn’t the first time our history has been committed to print. In 1987, the Grand Lodge of California published The Greatest of These Is Charity, an overview

of the first century of the Masonic Homes, from its founding through the opening of the first Adults Home in Covina. That’s an important dividing line in the organization's history, marking a clear expansion of the Masonic Homes’ services and the evolution of the Covina childrens’ program into what is now

the Masonic Center for Youth and Families. In the 36 years since then, we’ve built new structures dedicated to new services. We’ve launched entirely new divisions dedicated to new models of care, aimed at new groups of people.

So we’ll begin this chapter of the story at that moment, in the late 1980s. In Union City, the Lorber building, home of the skilled-nursing program, is under construction, as is the new Siminoff Center and lodge room. In Covina, the adult program is just getting off the ground. The programs that would become Masonic Outreach Services and the Masonic Center for Youth and Families are still years away. The “new” Masonic Homes of California is still in its infancy. So much change is yet to come.

I’ve had a front-row seat for much of it—as a member of the fraternity, later as a member of the Masonic Homes board of trustees, and ultimately as president and CEO of the organization. I’m unbelievably proud of all that we’ve accomplished since then. And it’s thanks to the Masons of California that we’ve been able to do it. Across the generations,

Masons have given their time, money, and energy to build this magnificent haven of relief. And in so doing, they’ve made a profound difference in the lives of those around them. Now, 125 years in, we have an obligation to preserve this treasure for the Masons of the future and their families. It will be our gift and our legacy.

On behalf of our residents, clients, and staff, and for the thousands of Masons, family members, widows,

and orphans who have walked up our steps and through our doors, I thank you for your support and generosity. The jewel in the crown of Masonry shines as brightly as ever.

— Gary Charland President and CEO, Masonic Homes of California

Siminoff Daylight No. 850

Destiny No. 856

Acalanes Fellowship No. 480

A century-old organization plans for the future.

Inthe middle of the 1980s, leaders at the Masonic Homes of California were worried.

Left: Leaders of the Masonic Homes cut the ceremonial ribbon at the Acacia Apartments at Union City on September 29, 1984. Right: Three years later, ground was broken on a new hospital wing.

“As we draw closer to the 21st century, the need for the Masonic Homes becomes ever more apparent,” wrote Paul Boyar, the Union City administrator at the time. “With the graying of America … we will find ourselves in the midst of a senior housing crunch as never felt before.” Boyar proved prescient. And it was that warning that in many ways drew a line down the middle of the organization’s history, between what

had been the first version of the Masonic Homes—a nearly centuryold (at that time) home for aged Masons and their widows—and the modern, multi-campus health care organization it would soon become.

Consider: Since Boyar first raised the alarm about the urgent need to modernize the Masonic Homes, the organization has updated both of its residential campuses, in Union City and Covina; reshaped its clientele; opened a nationally ranked shortterm care clinic; and constructed new buildings dedicated to services

like memory care and assisted living it had never before offered. Further, it reenvisioned its model for youth and family services. It created brandnew support programs for members of all ages. It embraced new forms of health technology before everyone else, and pioneered new approaches to successful aging.

Boyar was right about the need to upgrade the Masonic Homes of California. What he couldn’t have imagined, however, was how encompassing that work would be.

More than three decades later, it’s clear that the Masonic Homes hasn’t just kept up with the changing times. The organization has fundamentally rethought how to fulfill its mission to provide support and relief to the fraternity and their families.

Across two different campuses (plus Acacia Creek, its not-forprofit sister community), multiple offshoots and service providers, comprising nearly 400 staff members and serving almost 2,000 clients throughout the state, there’s virtually no inch of the Masonic Homes that hasn’t been re-thought since then. Boyar was right. He just had no idea how right he was.

The change from the “old” homes to the “new” can fairly be said to have begun in 1987, with two themes: more space and more specialization.

The first of those modernization efforts was the construction in Covina of new living quarters for 116 senior residents. Prior to that, the Covina Masonic Home had for six decades been a children’s-only campus. But with the shrinking need for permanent housing for kids—and the swell of demand for senior housing that had the Northern California campus practically bulging at the seams—the decision was made to transition the Covina property into a multigenerational community.

“Today we not only turn this first shovel of earth, but we signify a new beginning for Covina,” Masonic Homes board president Kermit A. Jacobson announced at the groundbreaking. “This will be one of America’s most innovative living environments. Soon the wisdom of the elderly, the strength and vitality

The Siminoff Masonic Center and Lorber building were both constructed in 1987, a turning point in the Masonic Homes’ history.

of children, and the beauty of them both will adorn this Masonic Home.”

The first 12 Covina seniors, dubbed “the pioneers,” moved in on January 8, 1990. “I feel compelled to let you know how happy and satisfied we are with everything here!” wrote one of them just two weeks later.

“If we had any doubts concerning the wisdom of our decision to make the move to the Home, they have all been dispelled as everything has far exceeded anything we had anticipated!”

The other major modernizing update was the new Hugo Lorber building in Union City, providing 120 beds to residents in need of highly skilled nursing care. Boyar called the building—along with the adjacent Siminoff Masonic Center, home to

the campus’s first-ever on-campus lodge room, and built around the same time—“regal testaments to the fraternity’s undying commitment to bring the best to its members, wives, and widows.”

Perhaps less visible a change, but no less significant, also occured the same year. That’s when the Masonic Homes received a new state designation as a life care facility. In other words, it was no longer a place where seniors simply lived. It could also be counted upon for progressive health services.

Clockwise

1989.

“Our Home’s rehab department can be considered one of the leaders in the field,” wrote Boyar. “We have evolved as a community that offers a full range of housing, residential, and health care services. Our goal is to serve our residents over time as their physical and mental needs change.”

In 1991, Boyar told the board of trustees that he hoped to make the Masonic Homes the best such provider in California. “Their retort,” he noted, “was they wanted it to be the best in the nation.”

By the time Larry Adamson was coming up the Grand Lodge line in the 2000s, the Masonic Homes was already close to his heart.

“In my mind, the Masonic Homes is the North Star of all Masonic charity,” says Adamson, who now serves as board chairman. “It’s what makes Freemasonry so special—the fact that our ancient brothers took a similar oath to care for one another.”

What really solidified his feelings, though, was when his parents moved in at Union City, a few years prior to his becoming grand master. Shortly before the move, his mother was diagnosed with Lou Gehrig’s disease. Her doctors thought she would only survive six to nine months. Instead, she lived at the Masonic Homes for two and a half years.

“I got to see my mother thrive for a period of time when the doctors told her she couldn’t,” says Adamson. “My entire family credits the care she received here for those extra years we got with her.”

For more than a century since its founding in 1898, the Masonic Homes provided compassionate housing to elderly Masons and their widows (and, through the Children’s Home, to orphans and needy youth) with limited means or few other options. In the 2000s, though, the Masonic Homes started seriously expanding on its basic suite of offerings. That included developing entirely new memory care services, like the ones that would help Adamson’s mother. It also included the birth of Masonic Outreach Services, which launched new programs to support elderly members and their family members at home, and later expanded to include members of all ages in need of support. The children’s program went through a series of transitions, resulting in a new community health model designed to serve as many California youth and families as possible in the ways they need most. And on campus, the Masonic Homes opened

The Masonic Homes’ pharmacy underwent significant upgrades as part of the 2020 campus master plan.

its services to the general public for the first time, welcoming non-Masons to the Acacia Creek Retirement Community, the Transitions shortterm rehabilitation clinic, and, in 2021, the Pavilion memory care and assisted-living community.

Since 2013, under the helm of president and CEO Gary Charland, the Masonic Homes has completed its transformation. Above and beyond the brick-and-mortar residences, it has become a statewide hub for

health care and support.

“The last 10 years have been a period of tremendous change within our organization,” Charland says. “It’s like going zero to 60. Not only did we construct and build on our campuses, but we created programs that have gained national attention. The Masonic Homes is out in the world on multiple fronts.”

Says Adamson, “Today, the Masonic Homes is not just about senior care. It’s about care, period. If

I look at where we were a decade ago and where we are today, I think it’s a real credit to the Masonic Homes’ leadership. They’re not afraid to test programs, to take risks, to move things forward. That’s how an organization grows.”

In 1998, the centennial of the Masonic Homes of California’s founding, Past Grand Master and Masonic Homes president Stanley M. Cazneaux put it simply: “The Masonic Homes exemplifies all that is best in

Freemasonry.” In the 25 years since, that’s been proven time and again.

“We have more to go,” Adamson says. “This is an evolution. Health care is changing. Senior health care is really changing. We’re not afraid to say, alright, where do we fit?”

In its new chapter, the Masonic Homes has become a lifeline for Masons, their families, and their communities, in more ways than early Masons could ever have imagined. In the years to come, Charland and Adamson see that trend only growing.

“My vision is that we’re the first call of choice when people need help,” Adamson explains. “Members have loved ones who may or may not be Masons. They have to make decisions about their families’ care, and they don’t know where to turn. We should be their first call.”

That, leaders say, has always been true of the fraternity.

“Think about how central that commitment is to Masonry,” Charland says. “You don’t have to go it alone in the world.”

For more than a century, the Siminoff Temple has been one of the state’s most important Masonic sites.

Even with several lifetimes spent in Freemasonry, one day stands out in the Adamson family’s fraternal history. It was early 2008, and Larry Adamson was several months into his term as grand master of California. Together with his brother Richard, he’d traveled to the Masonic Homes campus in Union City, where their father, Doc, lived with their mother. That day, the Adamson brothers would lead the installation of their dad as the new master of Siminoff Daylight Lodge No. 850, inside the Siminoff Temple, surrounded by family and a standing-room-only group of their closest friends, neighbors, and Masonic brothers.

“My father wasn’t a real talkative guy, but that day he looked at me and said, ‘Thank you for doing this,’” Larry Adamson recalls. “That was a special moment for me, and probably the most sincere moment I ever had with him.”

It wasn’t just the familial nature of the event that made it memorable, Adamson says. It was also the setting: the Masonic Homes’ Siminoff Temple, just steps from where Adamson’s parents lived for more than a dozen years. As a result, the Masonic Homes remains deeply important to the family—so much so that Adamson later became chairman of its board of trustees. There, in the Masonic Homes’ lodge room, which in its various iterations has hosted Masonic events for more than 100 years, the family was able to celebrate not just a father and his sons, but multiple generations spent in Freemasonry.

Bathed in the colored light of its stained-glass windows and surrounded by Masonic antiques and relics going back to the earliest days of the state fraternity, the Siminoff lodge room in Union City is one of the most important places in California Masonry—and one where that feeling of tradition is palpable. Its history goes back almost to the founding of the campus itself.

In 1902, just four years after the first residents were admitted to the Masonic Widows and Orphans Home in Decoto, a wealthy San Francisco Mason named Morris Siminoff presented a gift of $30,000—more than $1 million in today’s dollars—to erect a Masonic temple there. Siminoff, a Russian immigrant who’d become a successful textile manufacturer in the Bay Area, was a member of Fidelity No. 120 in San Francisco (now named San Francisco

No. 120) and belonged to each of the chapters of the Scottish Rite. Not much else is known about Siminoff, although at one point he was recorded as having donated a shipment of musical equipment, band uniforms, and coats for the young orphans. Siminoff died suddenly in 1907, at the age of 44, likely as a result of injuries he suffered when he fell from a horse during a parade of the Knights Templar in San Francisco.

Siminoff’s gift, made alongside his wife, Emma, paid for the construction of a “splendid temple,” as it was described by the grand master at the time. The temple contained the lodge room, an assembly hall, and 16 new bedrooms for elderly residents. The addition of those rooms allowed the home to convert a former dormitory into its first widows’ quarters. The donation also funded the installation of a 350-pipe, electric-powered organ.

The cornerstone for the Siminoff Temple was laid on April 22, 1903; six months later, the building was formally

dedicated by Grand Master Orrin S. Henderson. More than 3,000 Masons made the trip to the East Bay hills to witness the event. On November 14, Eucalyptus No. 243 of Hayward conferred the first Masonic degree inside the temple; Sequoia No. 349 of Oakland and Alameda No. 167 of Centerville (now part of Fremont) would soon use it for third-degree conferrals of their own.

Yet for more than 100 years, no lodge permanently called the temple home. That wasn’t the original plan: In 1903, Grand Master Henderson “endorsed and advocated for the many advantages, too numerous to mention, that are to be derived” by forming a lodge at the Home. He even went so far as to suggest a name: Preston Lodge, in honor of Past Grand Master Edwin Preston (1895), who had died earlier that year.

It’s unclear why that lodge never came into being, but for more than a century, the Siminoff Temple remained a sort of Masonic home away from home, with no group meeting there regularly. By 1976, the temple had fallen into disrepair and was shuttered by state officials for failing to meet earthquake-safety standards.

For the next decade, the campus was without a Masonic lodge, culminating in the demolition of the original temple in 1986. That same year, though, an ambitious new construction plan for the Masonic Homes brought the old temple back to life—sort of. As part of a $16 million development that included construction of the 120-bed

skilled-nursing facility named for benefactor Hugo Lorber, plans included building a new Masonic lodge room, to be housed alongside the campus chapel. Ground was broken on the project in 1987, and the new Siminoff Masonic Center, comprising the lodge room, foyer, and chapel, was dedicated by grand lodge officers on May 7, 1989.

The new facility was built from scratch, but designers went to great lengths to include elements of the original Siminoff Temple. Bricks from the 1903 structure were salvaged to construct the face of the new building, while the original altar was repurposed and reconditioned. The elaborate gas-powered chandelier that once hung in the temple’s entryway was unearthed by past grand masters Ronald Sherod and Alvin Weis, refurbished, and made electric. It now hangs above the lodge room.

However, the design flourish that commands the most attention is the expansive set of stained-glass windows. Its 56 panels, each measuring 4 by 4.5 feet, were fabricated by Judson Studios, and depict Masonic symbols including the square, plumb, and anchor. In addition to being so near the Masonic Homes’ chapel room, the colored windows lend the lodge room a special feeling of reverence.

Despite having a brand-new space available, it wasn’t until 2006 that the first seeds of a permanent lodge finally began to sprout. That year, a group of senior Masons living on campus began meeting to practice the Masonic degree conferral, “contributing where we could and sharing our expertise,” according to Bobby Joe McCain, one of the

original members of the group.

Recognizing an opportunity to make real a dream that at that point was 103 years old, the Grand Lodge in 2006 issued a dispensation to the group to meet as Siminoff Daylight Lodge, and on October 6, 2007, it received its formal charter.

In the 15 years since, the lodge has grown from 67 to 105 members. The lodge isn’t just for residents and staff, either: Just over 40 percent of its members live off campus. And an additional dozen of them are residents of Acacia Creek who had not previously been Masons—meaning the lodge has more than a few 50-year veterans as well as several newbies. For many, it’s the lodge building itself that inspired their initial curiosity about Freemasonry. Says McCain, “I think we have a very impressive-looking lodge room. It’s quite a draw.”

For emphasis, McCain points to a pair of murals on the lodge walls hand-painted by John Dahle Jr., a member of the lodge and a Masonic Homes resident who for years worked as a commercial artist. The murals on the north and south walls depict scenes from the building of King Solomon’s temple and feature old west typography, echoing the large mural Dahle painted several years ago in his home lodge, Nevada No. 13. “They’re gorgeous,” McCain says of the Siminoff pieces. “They both incorporate a lot of the teachings of Freemasonry. They’re more than just a piece of artwork in the building.”

To Adamson, who as a member of the Masonic Homes board visits the Siminoff lodge often, the space still holds a special place in his heart. “It’s a beautiful complex,” he says. “But it’s not just that. It’s really an experience. It’s an experience to go and see the history that’s there.”

CHAPTER TWO: THE CHILDREN’S PROGRAM AND MCYAF

CHAPTER TWO: THE CHILDREN’S PROGRAM AND MCYAF

Everything started, in a way, with 16 Masonic orphans.

That was the first cohort, six girls and 10 boys, accepted into the Masonic Home for Widows and Orphans in 1899. From the earliest discussions of a centralized form of Masonic relief, there was the belief in an obligation for the fraternity to fill the shoes of deceased members. That included providing for the families they’d left behind—both young and old.

Looking across the Masonic Homes of California’s original campus now, it’s hard to see many traces of that early commitment to children. But for more than a century, children’s care was among the most important elements of the Masons’

charity program. Today, Masons continue that legacy of support through the Masonic Center for Youth and Families, a full-spectrum mental health and wellness provider for children, teens, and families, itself an extension of the Children’s Assistance Program that grew out of the early orphans project.

From little Walter Wilcox, the “Masonic orphan” sent by rail from New Orleans to Oakland with a tag around his neck and adopted by the Grand Lodge of California, to the team of counselors guiding teens through the pandemic via Zoom, the form of that support could hardly be more different today. But the motivation remains the same.

Despite how central children were to the planning and execution of the first Masonic Home, they weren’t there very long. Upon its opening in Decoto in 1899, 19 boys and six girls joined five women and 16 elderly men in the Masonic Home’s inaugural class. A decade later, the number of children had doubled, and it was decided that they should have a space of their own.

That space, it turned out, was about 350 miles away.

There, in the Southern California town of San Gabriel, an association comprising Masons and members

of the Order of the Eastern Star, a women’s Masonic organization, had purchased a 100-room former tourist hotel on 10 acres, with designs on converting it to a home for elderly members of the Eastern Star. Instead, in 1909, the title to the building was transferred to the Masonic Homes of California, and 26 children with an average age of 12 moved in. For five years, the San Gabriel orphans’ home provided as many as 60 children with room, board, and all manner of social and cultural programs. The Southern Pacific Railway offered a special railcar and crew to transport them to Camp Wells, in the Angeles National Forest north of Azusa, for a summer vacation. The former hotel underwent significant upgrades in 1912, but twice suffered damage as a result of major flooding. (This was prior to the channelizing of the San Gabriel River.)

With the site still reeling from the damage and unable to accommodate further growth, in 1916 the board of the Masonic Homes relocated its wards to a new property on 35 acres of retired citrus ranch, just east of the town of Covina in the San Gabriel Valley. Its opening was

a true spectacle, with thousands of Southern California Masons on hand to witness the dedication. Past Grand Master Samuel Burke spoke grandly of the fraternity’s new forever home for children and the commitment it represented: Home, it is said, is Cupid’s resting place. There he practices his most cunning wiles.... There hope is cherished, charity nurtured. There the zephyrs smell the sweetest, there the waters are purest, there the stars shine the brightest. Every woodland path is but a Milky Way leading to the shrine of love and across yon brink of time fair lips whisper, Home, Sweet Home.

At Covina, the children lived in four dormitory buildings, divided by age and gender, and ate their meals in a large cafeteria. They grew up around horses and farm animals, chicken coops, and rabbit hutches. They played sports, formed a marching band, and, in 1923, founded a Boy Scout troop. They attended public schools by day— typically Charter Oak School—and

once a week gathered for movie night. They learned professional skills in an on-campus domesticscience college and manual-training building. In 1927, there were 183 children living on the grounds and an additional 25 supported outside the campus.

But in the 1950s and 1960s, orphanages were being closed in favor of licensed group homes. So the fraternity made an investment: In 1969, it demolished the four dormitory buildings and in their place commissioned the midcentury architects A. Quincy Jones and Frederick Emmons to build eight cottages, each able to house up to 10 children. The new dwellings mimicked typical Southern California suburban homes—albeit in Jones’ elevated, hallmark style of open spaces.

More change was on the horizon. In 1987, responding to the needs of an aging population, the Masonic Homes broke ground on senior residences at the Covina campus. By then the Children’s Home had cared for more than 1,800 kids. Now—in an echo of the organization’s earliest days—they would have company.

Children and house matrons in Covina sit down to a group meal in this undated photo.

Children and house matrons in Covina sit down to a group meal in this undated photo.

“Bringing the elderly and children in close proximity on this property is an innovative and generally nontraditional approach to adult living,” said Past Grand Master Kermit A. Jacobson, then president of the board of trustees.

“We can envision children and older adults fishing on the banks of our lake in Rainbow Park.”

The campus was renamed the Masonic Home at Covina, and children and senior residents were soon woven into one another’s lives. Senior residents attended graduation of the Home’s high school students and cheered on their baseball and football teams. They shared kitchen and dining areas—although the seniors were served restaurant-style while the kids ate family-style, a distinction “based on the truism that ‘children eat and adults dine,’” joked campus administrator John A. Rose.

In the world beyond the Covina campus, the times were changing.

During the ’80s and ’90s, the federal government steadily ramped up social services for children and families, and as a result the number of children requiring residential care tapered off. In 1997, with only a handful of kids left, the fraternity voted to open the residential program to children with no Masonic affiliation.

Not long after, they reinvented it again.

In 2000, with about 48 children still living at the Home, the board of the Masonic Homes embraced a new model, reflecting the latest research about child development and behavioral intervention. (In 2001, Girls and Boys Town—the organization that created the model—accredited the Covina children’s program as one of the “premier family teaching models in the country.”) As part of the shift, the Homes constructed eight new cottages, dedicated in 2002. There, Children gather inside the senior girls’ rumpus room at the Masonic Homes’ Covina campus (undated).

the children lived under the same roof with “house parents,” who were also family specialists.

“This new arrangement emphasizes family life, with its accompanying joys and responsibilities,” said Barbara Ten Broek, the director of children and community services, at the time. “It allows them to flourish as they learn social and academic skills, and acquire a host of other traits that will enable them to succeed.”

A few years later, the fraternity decided to take what the Girls and Boys Town model had shown them and build on it.

“From 2003 to 2009, we reshaped the program,” says chief strategic officer Sabrina Montes, who was then assisting with the children’s initiative. “We developed our own program based on values similar to Masonry and a belief that children belong with their families when they can safely be reunited. It was no longer a place where kids were dropped off and left behind. Children had the stability of a family environment, but parents and caregivers had to actively participate in the program.”

For the first time, the children’s

project became a short-term residential program, aimed at supporting family reunification over a period of about two years. Around the same time, the fraternity opened the Family Resource Center in Covina, a brick-and-mortar resource for families to get tutoring help, access support services, take parenting classes, learn about substance abuse treatment, and more. By 2008, when a project led by then–Grand Master Richard Hopper expanded its scope, the children’s program and the FRC had served more than 100 families and successfully reunited 35 of them.

“It was an amazing program,” Montes says. “We were getting families the tools they needed to be the healthiest, best families they could be.” Amid these successes, though, demand for residential programs—even on a short-term basis—continued to dwindle.

“We started with eight beautiful houses. Then we went down to six. Then five,” Montes recalls. By 2009, the residential program served just 15 children; only three had a Masonic connection.

So in 2009, the fraternity made an emotional decision: After 110 years, it was time to end residential care for kids and focus on the communityfacing work of the Family Resource Center.

“I truly believe that when we closed the residential program, we had perfected it,” Montes says. “But we knew that if kids had the right treatment early on, or their families got therapy, maybe it would never get to the point they had to be placed outside their homes in the first place.”

“Different times require different responses,” said then–Grand Master Larry Adamson and David Doan, the Masonic Homes’ board president, in a letter sent to the fraternity.

“The Masonic Homes of California has the potential, and the fraternal obligation, to do much more.”

The children’s program formally concluded in 2009.

The Masonic Center for Youth and Families opened its doors in February 2011, based in a house in the San Francisco Presidio. The goal was to take a thoughtful, in-depth approach to understanding the struggles faced by children and their families—and then bring together every specialist they needed under one roof.

“We are taking leadership in a difficult, complex, and fragmented area of psychological services,” said Stephanie Kizziar, then vice president of youth and community services.

MCYAF’s range of offerings and single-point-of-service model stood out in the field. The center quickly earned recognition from the American Psychoanalytic Association. In its first five years, MCYAF provided mental health services to more than 300 children and their families.

It was a good start. But the fraternity’s core reason for closing its residential program persisted: a desire to reach more children and families. By 2015, the Masonic

Homes board decided to evolve MCYAF’s model to one framed by the principles of community health.

“Rather than hanging up a shingle that says this is what we do, you start by looking at the surrounding community and assessing its needs. Then you design programs to meet those needs,” explains Kimberly Rich, who became executive director in 2015.

MCYAF would still offer child, family, and group therapies, along with learning assessments and other kinds of support that kids and families desperately needed. But it would do a lot more to insert itself into the community so those families could find it in the first place.

It started by expanding MCYAF’s physical reach—and delving into its past. In December 2016, MCYAF opened a second clinic to serve the southern part of the state, housed in one of the old children’s group homes at the Masonic Home at Covina.

“We brought the kids back to Covina,” Rich says.

Stephanie

The location also set MCYAF up well for an important partnership. Across the street on the Covina campus, in another former group home, was the Children’s Advocacy Center. The center is run by law enforcement and conducts traumainformed forensic interviews with children who have experienced or witnessed abuse.

The partnership with MCYAF fit like a hand in a glove. When a CAC interview is over, social workers often recommend mental health services for the child and their family members. This can be a tall order, since families still reeling from trauma must take on the burden of finding a provider and getting their child to an appointment. With MYCAF’s new clinic in Covina, child and family therapists were literally across the street. Childrens Advocacy Center founder John Pomroy, who previously served as a house parent at Covina’s old residential children’s program, even painted footsteps

leading out the CAC’s door and right to MCYAF.

Says Rich, “At CAC, they do all the investigating and prosecuting to get this criminal out of this child’s life. Then, when the child walks across the street, that’s when the healing begins.”

Over the next couple of years, MCYAF launched yearround workshops for schools and communities, including anti-bullying presentations for the Masonic youth orders, and a student workshop about stress management. In fall of 2019, about 100 teachers in the Southern California city of Alhambra attended a self-care workshop at MCYAF. In Northern California, parents and teachers learned how to support students with attention and learning difficulties. MCYAF partnered with the Covina Police Department on a program called the Youth Accountability Board, providing early intervention—and an alternative to detention—for

first-time juvenile offenders with a minor offense.

Those efforts had a salutary effect. Community referrals began pouring in from a variety of organizations: the CAC, local school districts, private schools, police departments, pediatricians, psychiatrists, and education specialists.

Between 2015 and 2019, MCYAF expanded the number of clients it served by 940 percent.

When the pandemic struck, it exacerbated a youth mental health crisis that was long in the making. As lockdowns swept the nation, community providers went dark, unable to see patients because of the in-person models they relied on. MCYAF, meanwhile, had a solution ready to go. Back in 2017, it had begun piloting a telehealth

program, enabling clients to meet with counselors over a secure video connection from home. At the time, MCYAF clinician Jenna Kemp declared it “the wave of the future.” Neither she nor anyone else realized how quickly that future would arrive.

When pandemic lockdowns began in March 2020, “all the other community mental health providers went months and months without seeing clients,” Rich explains. “We closed our in-person clinics on Friday, March 13. By Monday, all of our clients were hooked up with telehealth.”

Before 2020, according to the National Institute of Mental Health, one in five youths in the U.S. had a mental health condition. By 2022, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, that number had doubled. MCYAF’s mental health services were crucial, providing a lifeline to youth dealing with isolation and grief on top of the usual challenges of growing up.

Of course, it wasn’t just young people.

“The pandemic impacted all of us differently, but no one was spared,” Rich says.

Seniors were, and remain, a particularly vulnerable age group. At the Masonic Homes, where rigorous measures were keeping COVID-19 infections at bay, both residents and staff members were feeling the strain, too.

MCYAF and the Masonic Homes’ senior campuses joined forces. Using Zoom, MCYAF clinicians made hundreds of calls to check in on residents and staff members. Some led to online therapy sessions. Others simply offered a bright spot and a bit of social interaction during a lonely time. Since then, senior services have become an increasingly big part of the clientele.

In 2022, MCYAF earned its Staff at MCYAF are now able to meet with clients around the state virtually—a trend that grew during the pandemic.

Medicare certification, and today each campus of the Masonic Homes has a full-time MCYAF clinician on site. Rich hopes to expand therapeutic services for seniors beyond the Masonic Homes’ campuses soon. In the wake of the pandemic, a robust program has emerged. Far from being merely an offshoot of a long-since-shuttered orphans’ home, the Masonic Center for Youth and Families provides thousands of clients each year with affordable, confidential services for children and their families, both in person and online, within the fraternity and outside it. In addition to the senior residents of the Masonic Homes, the center offers support for Masons and their family members at every age and stage of life, from individual and family therapy to couples counseling.

In 2022, the center added Pomona Unified School District to its growing list of community partners. Schools throughout the state now refer students in need of mental health services to MCYAF. And MCYAF staff members travel onto campuses to meet students there. It’s a simple model—and amid a public shortage of mental health providers and a youth crisis of mental health, it’s nothing short of life-saving. Over 125 years of perfecting its programming, the Masonic Homes of California has arrived again with a program offering services that children and their families need most.

“No other community provider has the ability to do what we do,” Rich says. “It’s because of the charitable funding, and the vision, of the Masons of California. It is a rare thing in the field of child therapy and a point of great pride within our team.” Now as then, she says, “We put families first.”

How a network of Masons assured the future of a young orphan—and helped inspire a century of children’s care.

On October 3, 1878, 4-year-old Walter Cary Wilcox was aboard a Louisiana train headed for Chicago and then Oakland, California. A packing ticket tied around his neck stated his plight: “The bearer of this is Walter Wilcox, who has been orphaned by the epidemic which has pervaded this city… I bespeak for him, on the part of railroad men between New Orleans and Chicago, every possible attention, looking to his comfort and protection.”

When Wilcox’s mother died of yellow fever in New Orleans, the funeral arrangers discovered a watch with a Masonic emblem among her belongings. They sent a petition for the orphan’s case to the Grand Lodge of Louisiana, which in turn purchased Wilcox’s train ticket to Oakland, where his grandmother lived.

Following his arduous journey, Wilcox received a warm welcome from the Masons of California, including Grand Master Nathaniel G. Curtis. Their empathy for his plight was so strong that the Grand Lodge of California offered to pay for his care. A special $20-per-month endowment was established to fund the effort. Famously, he became known as the “Masons’ Boy” in the press.

Just a decade later, Wilcox’s grandmother passed away, and Wilcox was again orphaned.

In stepped Nathan Spaulding. Spaulding, who’d made his fortune pioneering an adjustable saw blade at his mill in Amador County, was a six-term master of Oakland Lodge No. 188 and the grand treasurer of Masons in California. He was also mayor of Oakland in 1871–73 and, in 1888, a delegate to the Republican National Convention. Spaulding owned a mansion in the east Oakland neighborhood of Highland Park, was a trustee

of Stanford University, and was director of the Industrial Home for the Adult Blind.

Spaulding offered to adopt Wilcox and raise him as his own, and in October 1888 he was named the boy’s legal guardian. The Grand Lodge of California voted to increase the stipend for his care to $25 per month, which

Spaulding asked to be discontinued in 1890, since by then he’d accrued sufficient funds to cover the boy’s education. Writing to the Grand Lodge in 1891, Spaulding reported:

When I became his guardian I found him a bright, sensitive, active and kind boy, with no bad habits, but with poor health, and I learned that on account of his sickness, and other reasons, he had not attended school for many months, and that in his studies he was far behind other boys of his age, and so backward in this respect that to return him then to the public school, in the grade he would only be able to sustain, would have a tendency to discourage and dishearten him; and believing that it would meet with the approval of this Grand Lodge, and having a desire to do by the fatherless son of a Master Mason as I would like to have done to my own under like circumstances, I placed him in one of the best private schools in Oakland, where extra care was given him until he was far enough advanced to reenter the Grammar School, from which he graduated last May, with Honors.

Set against the backdrop of early deliberations over what would become the Masonic Home for Widows and Orphans, the story of the Masons’ Boy was a powerful reminder of the real-world impact that Masonic charity can have. A decade later, the first Masonic Home for Orphans opened just 20 miles south of Wilcox’s new home. And in 1895, Wilcox followed his mentor’s example, joining Oakland Lodge No. 188.

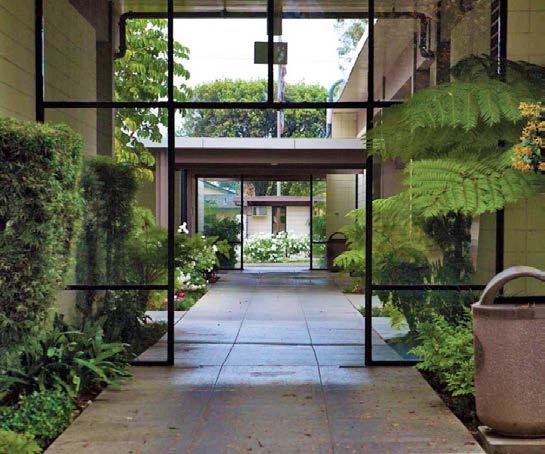

If the simple lines, walls of glass, and low-slung design of the Masonic Homes in Covina seem quintessentially California modern, well, that’s because they are.

Designed by midcentury architect Archibald Quincy Jones, the former dean of the architecture department at USC (and designer of the famous Sunnylands estate in Rancho Mirage belonging to Walter Annenberg), Quincy was hired by the Masonic Homes board of trustees in 1968 to execute the campus master redevelopment plan. Between 1968 and 1973, that included the construction of eight new family-style cottages, in which children lived with house parents (rather than in the dormitories they’d previously occupied); a central community building that includes the cafeteria, library, and administration offices; plus new roadways and landscaping.

While the Covina project is not often listed among Jones’s most iconic designs, it features many of his work’s most distinctive features, from the high ceilings, angled rooflines, and post-and-beam construction to the emphasis on connective greenbelts. In that regard, his legacy is a lasting one. Though Jones was largely overshadowed by his more famous architectural contemporaries (and collaborators) Joseph Eichler and Richard Neutra, he did much to raise “the level of the tract house in California from the simple stucco box to a structure of beauty and logic,” wrote the architect Cory Buckner.

How the Masonic Homes looked outward to deliver relief to a changing fraternity.

Freemasonry reached its 20thcentury zenith in the wake of World War II, a time when the fraternity was growing by 9 percent every year. In 1944, close to one in 20 eligible men in the state belonged to one of the Grand Lodge of California’s constituent lodges. By 1965, the fraternity counted nearly a quartermillion members.

Three decades later, that growth had long since stalled out. California’s Masonic rolls had been halved—while the state’s population had nearly doubled. An even more pressing concern, however, was the graying of the fraternity. The swell of young men who’d joined in the mid-century were approaching retirement age. Leaders of the Masonic Homes braced for that wave to crash onto its shores.

In 1988, then–Grand Master Leo B. Mark addressed the issue directly:

“Due to the advances in modern medicine and the increasing age of our membership, the needs of our dependent elderly continue to grow.”

Even with the Covina campus preparing to admit 100 seniors to what had previously been a home for children, and with the Union City campus at its 400-person capacity, the Masonic Homes struggled to scale up to meet increasing demand from its aging clientele. The organization needed to find new ways to respond to the need—and fulfill the Masons’ obligation to provide aid and relief to “distressed worthy brothers.”

The brick-and-mortar campuses of the Masonic Homes could provide only so much of that relief. To meet the increased call for aid, it would have to deliver services beyond its own walls. Stained glass at the Masonic Homes in Union City. Previous: Members of El Segundo Lodge No. 421 celebrate with Masonic Outreach Services staff in 2019.

As far back as the 1920s, the Masonic Homes had set aside money earmarked for “nonresident assistance.” Typically, that fund was used either to help those on the Masonic Homes waiting list cover in-home care or other expenses until they were able to move in, or to supplement lodge relief funds to support gravely ill or permanently disabled members ineligible for residency at the Homes.

In 1936, the Masonic Homes reported allocating just over $40,000 to these “outside relief” cases, including more than 85 clients in Northern California. By 1990, the old nonresident assistance program had grown to $316,000 and expanded to assist elderly members to age

in place. “In such cases they can retain their independence and the cost is less for the Homes to provide assistance,” wrote then–Grand Master Roy J. Henville.

In 1988, Philip Nichols was named the organization’s first director of outreach services, a position designed to work with lodges and applicants for Masonic assistance, along with their families, to arrange care for those better served beyond the Masonic Homes’ campuses. The nonresident assistance fund was folded into a new department: Masonic Outreach Services.

That same year, the department produced a Resource Guide for Seniors handout, which was distributed to lodges throughout the state. The guide included 38 subjects, including how to obtain transportation, in-home health care, and Meals on Wheels delivery. The intention was clear: The new Masonic Outreach Services team would connect more Masons with existing services. That would include those offered directly through the Masonic Homes, and also through public and state agencies in their own towns and communities.

In subsequent years, that messaging came into even greater focus: Connecting members with community-based care would be an equivalent option when it came to the question of providing relief—not just admission to the Masonic Homes. “Not all those who are distressed and in need can and should be helped at the Homes,” wrote Henville, then president of the board of trustees, in 1992. In many cases, he noted, it was preferable to both the individual and the organization to provide assistance right where members lived. “Understanding the system and what’s out there and how to access it, is the issue.”

In other words, the Masonic Homes was zeroing in on three crucial elements of what would become its approach to fraternal outreach: information, financial support, and lodge partners.

“It was a really proactive approach,” says Sabrina Montes, chief strategic officer of the Masonic Homes of California and the head of Masonic Outreach Services. “In a way, it was a template of what was to come.”

In the new millennium, as the nation’s large population of baby boomers entered their senior years, two trends became clear: Compared with previous generations, boomers wanted to age at home. And many were running out of money.

“The financial resources that would have been sufficient to provide for them into their 70s can run out as they enter their 80s, 90s, and beyond—just at the time that their need for assistance is greater than ever,” wrote George Geanoulis, then a member of the board of trustees, in his board report.

The new Masonic Outreach Services program was the Masonic Homes’ best tool for confronting those challenges. MOS, as it came to be known, combined the financial support of the nonresident assistance program with resource sharing and access to centralized services, Residents board the Masonic Homes’ bus at the Covina campus.

a monthly case-management clinic at the Paradise Park Masonic community in Santa Cruz. “Our programs and services have changed and evolved over our history in response to the changing needs of our fraternity and the changing face of our society,” wrote Past Grand Master Allen B. Gresham, then president of the board. “They’ve had to.”

By 2009, MOS was firmly established. Every month, it provided financial assistance to about 185 seniors in the fraternal family, and referral or case-management services to another 200. Theodore and Mollie Berman were among them. That September, they wrote an open letter to the staff of MOS.

As MOS expanded, the economy was crashing. Between December 2007 and June 2009, the United States went through its longest, and by many measures worst, economic recession since the Great Depression. Entire industries all but shut down: the finance market, real estate, construction, lending. Some 8.7 million Americans lost their jobs. More than 1.2 million lost their homes. Many of them were Masons.

was reinvented as the Masonic Assistance Line, a one-stop source of information about Masonic Outreach Services programs for members and family of all ages. With one phone call, they were connected to information and referrals within their own communities—and, if needed, applications to the Masonic Homes or MOS.

The challenge, as always, was getting the word out about the expanded services. In August 2009, the Masonic Homes’ trustees dispatched Montes and other MOS staff to do just that.

When the fairs were completed, the trustees asked MOS what they’d found. “We told them: Our Masons need jobs and they need money,” Montes recalls. They pitched an outreach program for younger Masons, to complement the one that existed for seniors.

including annual physical exams and medical alert systems. In 2002, the program served 74 clients. That grew to 100 the following year, at a rate of about $75 per person per day. At one point in 2004, demand for MOS services rose by a third in just four months. That year, the fraternity raised more than $650,000 for it.

Fundraising and planning around the Masonic Homes’ 2003 strategic plan centered on the growth of Masonic Outreach Services, which by then had established community partnerships for clients in need of assisted-living services and increased its staff of case managers statewide. The department briefly established

“Never did I think it possible that I would not be able, on my own, to provide shelter, food, medical, and daily needs for my wife and myself,” Theodore Berman wrote. “To say that we were in deep despair would be the understatement of the century. We were at our very end.… You enabled us to keep our dignity and self respect.”

Little did they—or anyone— know, an entirely new population was about to need the same support.

“It was a scary time,” says Montes, who in 2009 had just taken on the role of head of Masonic Outreach Services. “These are Masons around 45 to 55 years old, with kids in college, who’ve been a realtor or a broker their whole life. In some families, it was both the Mason and his wife who lost jobs. People were losing their homes because they couldn’t pay their mortgages.”

Around the same time, thanks to a grand master’s project that began as the Family Resource Center, the Masonic Homes’ intake hotline

Over three months, MOS held six Masonic resource fairs up and down California, from Redding to San Diego. They handed out applications and information on unemployment benefits, affordable utilities programs, housing programs, food stamps, and general relief. They also asked members what else they needed.

In October 2009, the fraternity introduced what’s now known as Masonic Family Outreach Services: financial and nonfinancial case management for members and their families under the age of 60. The board had just one caveat: Financial support for Masons under 60 was limited to one year or less.

“The board said, ‘You cannot let a Masonic family become homeless. You have to do everything in your power,’” Montes says. “We were tasked with this huge responsibility to quickly get people in action and moving forward.”

The entire outreach team consisted of half a dozen care

“Masonic

saved my life.”

managers. In addition to their senior clients, they began meeting with under-60 Masons to help problemsolve their way, in a year or less, out of what often seemed like impossible situations.

“It took the most creative planning imaginable,” Montes says. “We were telling people in their forties, ‘You’re going to need to reinvent yourself. Could you do retraining through the state of California? Could you get a license to drive a bus? Is there a trade you could get into in six to nine months in a field that’s hiring?’” If a Mason found a job in another state, MOS would help cover the costs of the move.

For Craig Wood, a 59-year-old member of Anaheim Lodge No. 207, MOS changed everything. In the span of a few years, he’d lost his job, his home, and then his health. The same day he called MOS, he was assigned a care manager who helped him apply for food stamps, petition and eventually win a Social Security disability claim, and connect with emotional support. Without all that, he said, he’d be homeless.

“I’ll tell you what,” he said, “Masonic Outreach saved my life.”

2010s

As the economy clawed its way back, the need for support among Masons under 60 gradually declined. While the MFOS program would remain in place, the referral and case-management elements came to dominate the financialassistance arm. “We are finding that providing good guidance, support, encouragement, and referrals is sufficient for many Masons, who need just that level of help to navigate the sometimes-confusing system,” wrote David Doan, then president of the board, in 2012. But among the fraternity’s older population, the need for outreach services continued to grow. Housing and health care costs were persistently rising, while the value of the dollar was steadily dropping. By 2013, according to a survey by the Federal Reserve System, about a The entryway to the Masonic Homes’ Union City campus, headquarters of Masonic Outreach Services.

quarter of all people over 60 years old were struggling with “major financial stress.”

In other words, older Masons and their widows were hurting. Lodges for many years offered charitable programs to assist elderly members, often outside the auspices of Masonic Outreach Services. In San Diego, one member in particular had been working the phones. Joe Jackson, of Joseph L. Shell Daylight Lodge No. 837 and Heartland Lodge No. 576, was known for reaching out to members and widows on a weekly basis to check on their well-being. As the MOS program ramped up, Jackson became one of its biggest evangelists, often recommending that members he spoke to apply for services.

By 2011, he and fellow Masonic division leaders John Heisner (who would go on to be elected grand master in 2016–17) and Jim Kurupas had a growing appreciation for the power of MOS. Jackson and the group approached Montes with a question: Could MOS train them in the basics of social work?

“We said, ‘Yeah, sure—Joe acts like he works for us anyway,’” Montes recalls with a laugh.

In August 2012, after nearly a year of preparation, 13 Masons arrived at the Masonic Homes’ Covina campus for their first training session. They walked away with an armful of outreach resources, new relationships with neighboring lodges, and advice for every Mason interested in helping out. “By the end, we had a training binder essentially built by Masons for Masons,” Montes says. “We could offer it to lodges and say: If you want to do outreach, this is how you can do it more effectively.”

In 2014, MOS took that show on the road. Over the next six years, the department rolled out the newly minted Lodge Outreach Program at quarterly meetings in every part of the state. Along the way, MOS and local lodges partnered on several truly remarkable feats. In one such instance, they rescued an elderly Mason who had been living in his car for years. In San Luis Obispo, they helped a member pay rent and afford medication. They secured a stable living situation for a member in La Mesa who could no longer care for his ailing wife.

By 2020, the Lodge Outreach Program trainings had been rolled

out to every part of California, wrapping up in the Central Valley. It’s now an ongoing initiative for lodges, a powerful source of member engagement, and, most important, a safety net for the fraternity’s most vulnerable members. The San Diego vision is a statewide reality. “We had to have Grand Lodge backing, we had to have services available, and then we had to have the lodges and the leadership promote it, teach it, instill it in the leaders,” Heisner says. “Now it’s here to stay.”

Jackson passed away in 2012. In honor of his commitment to serving the needs of his fellow members, the Grand Lodge created the Joe Jackson Award in 2014, given each year to the lodge that best exemplifies his spirit of outreach.

As the Lodge Outreach Program was unfolding throughout the state,

MOS was also growing in its ability to offer other crucial—and often lifesaving—programs. In 2017, to help members navigate the confusion of community-based services, it introduced the Masonic Value Network. The network was, in essence, a listing of local senior care services and providers that had been vetted by MOS staff. In 2018, the MVN grew to include a prescription-drug discount program.

Masonic Outreach also played a role in more acute crises. During the devastating Woolsey and Carr fires, MOS staff organized an allhands-on-deck task force to check on Masons and widows in the fire zones and offer support or connect them to local services. In three days, the task force made nearly 1,400 phone calls. As California’s megafires spark with increasing frequency, MOS has

become the fraternity’s primary point of contact for affected members.

In June 2019, with real estate prices soaring in California, MOS welcomed its first residents to a new program called Shared Housing. Located in two of the unused former children’s homes on the Covina campus of the Masonic Homes of California, the initiative provides affordable co-housing for up to 14 Masonic seniors age 62 and over who are able to live independently. John Parcher, then a 64-year-old artist and actor, was among the first cohort to move into the home, which offered a private bedroom and bathroom, plus a shared living room, dining area, kitchen, and outdoor space. “Those

of us with modest means have few options,” he said. “But here’s a beautiful, affordable home that provides privacy and community.”

This marked a successful, energizing chapter in MOS history. Yes, there were new challenges, especially for the fraternity’s aging population. But with innovative programming and steady charitable support, MOS was rising to meet them.

Then the pandemic hit.

For the Masonic Homes of California, the COVID-19 pandemic was an epochal crisis. Senior homes were among the hardest-hit communities anywhere in the country, and the restrictions put in place to curb the spread made life on campus a grind for both residents and staff.

But it wasn’t just on campus that the pandemic upended things. Much like in 2009, during the Great Recession, the Masonic Outreach Services line was inundated with calls for help from members suddenly

out of work or unable to access care and services from shuttered state agencies. “This was worse, because nothing was open,” Montes says. “People needed money yesterday.”

That was in March 2020, months before unemployment benefits and other government relief kicked in. The Grand Lodge of California, the California Masonic Foundation, and the Masonic Homes together made a swift decision. A new crisis fund would provide one-time financial assistance for any lodge member or their spouse. Even Masons from other states who were living in California would be eligible. The name of the effort, echoing the language of the obligation Masons take in their second degree, was the Distressed Worthy Brother Relief Fund. No sooner had the plan come together than the phone started ringing. Within 48 hours of the first email blast announcing the creation of the fund and calling for donations to it, MOS had feverishly pulled together a program to access

and distribute financial support.

By mid-May, it had fulfilled about 100 formal requests for financial assistance and fielded countless calls, offering information and referrals. It connected jobless Masons with companies that were hiring, helped families access state and federal aid, and informed them about protections and community support. Throughout 2020, MOS served an additional 100 people each month with financial support and case management.

Todd Tei, a Burbank Mason with a 6-year-old daughter, was one of them. When the pandemic struck, his events business went under. A few months later, the replacement job he’d miraculously secured vanished when that company, too, was forced to close. With Tei unable to pay rent, his landlord threatened eviction. From MOS, he received legal advice about his rights as a renter, help creating payment plans for his utilities and cell phone bills, and financial assistance from the fund that helped get him back on his feet.

“This crazy situation has shown me that these brothers are truly like the family I never had,” Tei said.

“The Distressed Worthy Brother Relief Fund really gets to the heart of what it means to be a Mason,” said Doug Ismail, vice president of the California Masonic Foundation, which raised more than half a million dollars in the first six months of the campaign. “During a time of uncertainty, brothers find that they can count on each other.”

During one of the most chaotic, challenging, and frightening times in memory, Masons were able to live up to their highest ideals of caring for the people around them. And they did it through Masonic Outreach Services.

Far from simply supplementing the “meager pensions or incomes” of seniors as they awaited entry into the Masonic Homes, as Henville had written in 1990, MOS has grown into the main apparatus by which the organization delivers relief to its statewide membership.

Looking forward, MOS will

continue to provide for members and their families during moments of crisis and everyday struggles, for every age and stage of life. Along the path of Masonic relief, it has become a crucial channel, flowing outward to meet fraternal family where they are—figuratively and literally. “MOS has no boundaries,” Montes says. “We go wherever we need to go.” One care manager described it as a magic wand they get to wave over members’ and families’ lives. “People are amazed when they finally call and learn what MOS can do for them. We’re here for all of life’s challenges,” they said.

For MHC president Gary Charland, Masonic Outreach Services is the distillation of what the Masonic Homes is all about. “When we make that commitment to take care of each other, they’re not just empty words,” he says. “Through MOS, we do it. We absolutely do it.”

Workers sift through the rubble of the destroyed DC-6 aircraft.

When United Flight 615 crashed just above the Masonic Homes, it was the worst air disaster in state history.

It was a cool, cloudy early morning in the East Bay on August 24, 1951. Low clouds from the marine layer were interlaced in the hills above Union City. At 4:28 a.m., a booming crash was heard just behind the Masonic Homes of California, waking up area residents as far away as Hayward. One witness recalled that it sounded like thunder coming from the hills.

As residents stumbled outside to see what was happening, a second explosion was heard, and the amber glow of a grass fire could be seen along the ridge. It marked the crash site of United Flight 615. All 44 passengers, including two infants, along with six crew perished. “It’s terrible. I’m almost sick from the sight of it,” Chief Roland Bender of the Decoto Fire Department said at the time. “No one could have lived.… There is nothing left of that plane but a few pieces of jumbled metal.”

The crash, which occurred just over a mile from the campus, is little more than a footnote in the history of the fraternity—it wasn’t even mentioned in the Proceedings of the Grand Lodge for 1951. But at the time, the event rocked the Tri-City area to its core and represented the worst air disaster in California history. (In 2023, it remains the fifth worst.) Wreckage from the crash was found more than half a mile from where the DC-6 plowed into the eastern side of Tolman Peak before cartwheeling over the top of the hill and into the canyon below. The fuel tanks exploded on impact. The cause of the crash was confusion involving the plane’s instrument landing system. As the plane approached the Oakland airport, just 14 miles away, the pilot’s radio was tuned to a beacon in the nearby town of Newark; meanwhile, the first officer’s was tuned to the Hayward beacon. As a result, the plane had veered three miles off course. Rather than descending into Oakland from above the flats next to the bay, it did so over the East Bay hills, still partially obscured by cloud cover. The aftermath of the crash was a scene of chaos and agony, with first responders struggling to reach the remote site. According to a history prepared by Timothy Swenson of the Washington Township Museum of Local History:

Horses were used to move the bodies from the ravine, down the creek and to a number of jeeps waiting at the end of the bulldozed road. The jeeps carried the bodies to a farm

house, where they were loaded into hearses and taken to the auditorium of Decoto Elementary School… One of the deputies said this about the crash site, ‘The best way to describe it was like you had thrown a ripe fruit against a Hayward Daily newspaper, had just come back from Korea. He described the scene this way: ‘...In my whole time in Korea, I

Today, there’s little left to commemorate the disaster. The local history museum held a 50th-anniversary exhibition dedicated to the event, but by and large, its memory has evaporated like the early-morning mist.

However, even to this day, intrepid hikers who make the five-mile trek along the Tolman Peak Trail to the crash site often find scraps of metal debris lying innocuously among the tall, gently waving grass.

“The piano had always been there. But having that time to focus, and having that chance to hear a particular song, somebody inside her woke up.”

Betsy rarely spoke anymore.

When she arrived as a resident at the Masonic Homes of California’s Union City campus, she required help with many of the basic activities of daily living. Most of the time, she couldn’t recall the simplest details of her life, which had been long and rich.

But one afternoon, listening to classical music in the parlor with her memory care group, she rose from her seat, walked to the piano, and began to perform.

“Nobody knew she could play,” recalls Christina Drislane, the campus’s director of memory care.

To an outsider, a moment like this seems like a miracle. But to the memory care staff at the Masonic Homes, it’s the result of an approach that has been decades in the making. Today, dementia is often talked about as an epidemic. Every 65 seconds, someone in the U.S. develops Alzheimer’s or another memory-loss condition. It’s estimated that one in three seniors dies with some form of the disease.

Back in 1981, when golden age movie star Rita Hayworth was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, she became a public face for memory loss. The world had little awareness of such diseases, and even less of an idea of how they were treated. That changed quickly: By 1994, Left: A resident of the Masonic Homes shows off her watercolors, part of the Compass Club memory care program. Previous: The interior of the new Pavilion at the Masonic Homes, which specializes in memory care services.

when former U.S. president Ronald Reagan shared that he, too, had been diagnosed, Alzheimer’s and dementia had become household terms. Researchers began exploring special support for memory care, like living environments that prevented residents from wandering away.

At the Masonic Homes, the challenges of memory care have been well-known for some time. In 1990, the Union City campus completed construction on a secure, dedicated dementia unit within its newly built skilled-nursing facility, known as the Lorber building. A little more than a decade later, it had increased staff training and developed an entirely new memory care program, called Traditions, to serve as many as 16 residents in the assisted-living ward.

At a time when there were still more questions than answers surrounding memory care, Traditions got a lot right through sheer compassion. Its success wasn’t just about providing a dedicated space for residents with severe dementia. It was about surrounding

“The Masonic Homes is extremely forward-thinking about these interventions.”

them with a supportive network. As part of their mission, Traditions staff “let residents know they’re there for them,” explains director Jeanette Jones. They focused on promoting social interactions and staving off the isolation that often accompanies and exacerbates memory-loss conditions. Staffers fondly referred to their work as the “best friends approach” to Alzheimer’s care.

Early results were encouraging, but it was only the start. By the midaughts, the Masonic Homes was looking for new ways to nudge the field of memory care forward. That included saying yes to researchers like Nidhi Mahendra and her team from Cal State East Bay, who approached the Masonic Homes with an unusual idea. At the time, most experts assumed that people with

dementia were at the mercy of an unrelenting disease. Mahendra’s team suspected otherwise. “Administrators at other places still treated us with some amount of suspicion and cynicism,” Mahendra said. “But the Masonic Homes is extremely forwardthinking about these interventions and the potential benefits for the residents.”

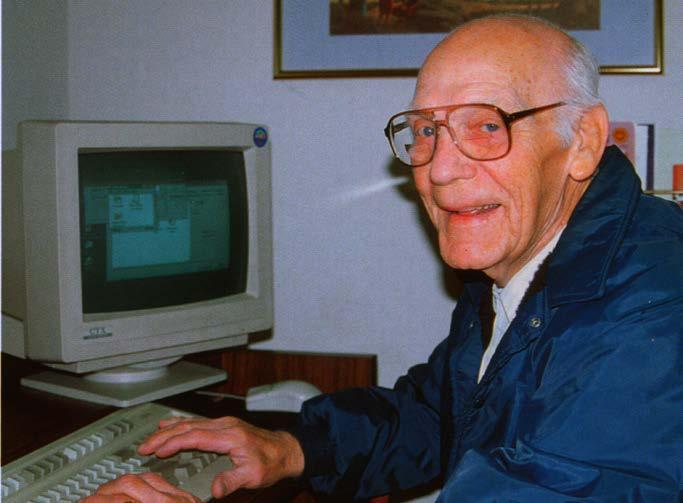

From 2007 to 2011, Mahendra and her team worked with 40 residents at the Union City campus, including several from the Traditions unit. They helped a former lounge singer regain the confidence to perform. They taught a resident who had been struggling with technology how to master the microwave. In other words, they proved that individuals with memory loss can regain lost skills and even acquire new ones.

It signaled a new era in memory care. Diagnosis was no longer the end of the story.

Thanks to clinical researchers like Mahendra, by the end of the decade the world had a new understanding of memory care. In the right kind of environment, supported by expert caregivers, a person with dementia could continue to enjoy a substantial quality of life.

It was hopeful news. But for care communities, it was also complicated. Keeping up with new discoveries meant rethinking everything, from facilities design to program execution. Not everyone was ready for that kind of transformation.

But the Masonic Homes was. And in 2011, it laid out a strategic objective to develop state-of-the-art memory care protocols.

“The Masonic Homes is committed to be a leader in this field,” wrote Past Grand Master David R. Doan, then president of the Masonic Homes board of trustees, in 2012.

“We are looking at new ideas on how to slow down the loss of memory, how to keep a person with memory issues with their family and in their home longer, and how to help them maintain their dignity and quality of life despite their condition.”

By 2013, both campuses offered access to brain-boosting computer programs in collaboration with experts like T.J. McCullen, a psychological sciences researcher at Case Western Reserve University. With the help of a memory care design professional, the Union City campus totally reengineered the Traditions unit in 2014, knocking down walls, redesigning visual cues, and turning the former dining area into a gathering space. Outside the first-floor Grider gym and physical therapy area, staff transformed an abandoned juice bar into the Blue Zone Café, a hub for social activities

that offered a menu focused on foods associated with brain health.

All these changes were leading to an even bigger one. Rather than wait for someone to come up with a cutting-edge memory care program, the Masonic Homes decided to create its own. It was ready, as Doan had promised, to be a leader in the field.

In 2015, the organization turned to Joseph Pritchard, now the Masonic Homes’ chief operating officer, who at the time had just been appointed director of memory care. Pritchard and his team immersed themselves in the available research.

“We updated our activities. We brought in better training for staff. And more importantly, we expanded our focus: What happens before you develop dementia?” Pritchard recalls.

By the end of the year, the Union City campus had launched a brand-new memory care program, called Stepping Stones, designed to diagnose memory loss and create interventions for residents

throughout the campus, not just those in the Traditions program. Stepping Stones was a progressive, campuswide model that aimed to support residents during four distinct stages of brain health.

The first step of the program is designed for residents still in their cognitive prime. The approach is proactive: Residents have access to computer programs in a Brain Fitness Gym; the healthy food and social outlet of the Blue Zone Café; and a slew of activities designed to enhance memory and cognitive health, from art to music to gardening.

The second step is for residents who are still physically independent but beginning to experience early symptoms of memory loss. To support residents at this crucial stage, Pritchard and his team created something no one else had thought of: a day program they named the Compass Club. For a few hours daily, participants are guided through carefully designed activities with the help of highly trained staff.

The program has several innovative features, such as its mobile format, which utilizes various areas around the campus, making the most of space restrictions and keeping participants connected to the wider community. It is therefore able to meet each resident’s challenges and strengths, with staff ready at every turn to emphasize activities that spark joy.

“It’s really important to be flexible with a program like this. You’re adapting to the individual journey that each person goes through with memory loss,” Drislane says. “We’ve learned that there are constructive ways to do that.”

As dementia reaches more advanced stages, individuals benefit from being in a single familiar space.

Phase three of Stepping Stones calls for moving residents into the Traditions assisted-living unit, which was redesigned in 2014 according to a “neighborhood” model—a best practice for adults struggling with memory loss. The fourth and final

phase provides memory care in a skilled-nursing setting, for the most severe stages of dementia.

Even at these final stages of memory loss, residents’ days are organized around the routines and activities that mean the most to them. That can be different things for different people. For instance, staff might make sure that a resident never parts with a beloved doll. For another resident, there might be repeat viewings of a favorite World War II–era film. Caregivers know which songs help resident rest and which help them engage.