THEN AND NOW

like Bakersfield, Masons from all walks are working closely together.

For the first time in its 125-year history, the Masonic Homes of California is now open to Prince Hall Masons.

In Prince Hall Masonry, the appendant and concordant bodies are part of a tight-knit Masonic family. 36 YOUR HONOR

On the bench and in lodge, John Waller preaches fairness.

Drummer Trevor Lawrence puts Masonry in the spotlight.

A lover of history, Aaron Washington brings the lessons of the past to life.

As one of the first Black attorneys in Sacramento, Gary Ransom broke barriers.

Meet Robert J. Eagle Spirit Sr., the next grand master of California Prince Hall Masons.

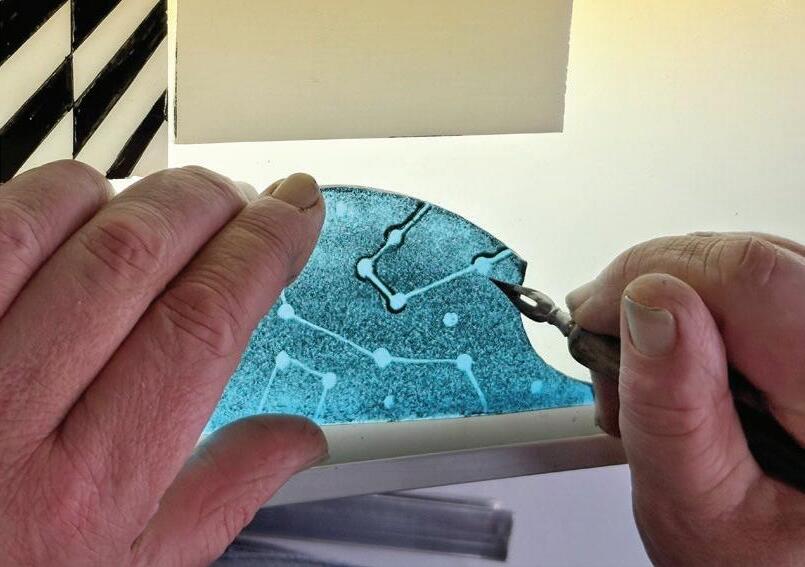

Stained-glass artists

Armelle Le Roux and Ariana Makau (shown here) of Nzilani Glass Conservation used both modern and traditional techniques to create an original stained-glass portrait of Prince Hall, complete with Masonic emblems and symbols.

How do you go about creating an image of someone who was never photographed or painted in his lifetime? For the makers at Nzilani Glass Conservation in Oakland, that was the challenge—and the opportunity—behind this edition’s cover image. Here, Ariana Makau, the studio president, offers her artist’s statement:

“As a Black, female owner of a stainedglass fabrication and preservation company, I was honored and excited to be asked to create this month’s cover. We are constantly seeking opportunities to celebrate people who have contributed to communities yet may have previously been overlooked.

EDITORIAL STAFF

Emily Limón Executive Editor

Ian A. Stewart Editorial Director

Pete Ivey Creative Director

Isabelle Guérin Managing Editor

J.R. Sheetz Multimedia Editor

Justin Japitana Assistant Editor

John Dale Online Editor

PUBLICATION COMMITTEE

G. Sean Metroka Grand Master

Russell E. Hennings Editor-in-Chief and PM, Saddleback Laguna № 672

Allan L. Casalou Grand Secretary and PM, Acalanes Fellowship № 480

Ian E. Laurelin South Pasadena № 290

Dagoberto Rodriguez PM, South Pasadena № 290

Emanuel A. Rose PM, Humboldt № 79

James L. Tucker PM, Logos № 861

OFFICERS OF THE GRAND LODGE

Grand Master: G. Sean Metroka

Nevada Lodge № 13

Deputy Grand Master: Arthur L. Salazar Jr., Irvine Valley Lodge № 671

Senior Grand Warden: Garrett Chan California № 1

Junior Grand Warden: Ara Maloyan

Santa Monica-Palisades № 307

Grand Treasurer: Charles P. Cross Metropolitan № 352

Grand Secretary: Allan L. Casalou

Acalanes Fellowship № 480

Grand Lecturer: Ricky L. Lawler

Elk Grove № 193

CALIFORNIA FREEMASON

ISSUE 03 VOLUME 72 SUMMER 2024

USPS #083-940 is published quarterly by the Masons of California. 1111 California Street, San Francisco, CA 94108-2284. Periodicals

“No definitive image of what Prince Hall looked like exists, yet his influence is still prevalent. To depict this, we used a layering effect with a base of colored glass pieces and frit to build out the contours of his face. As a person of color, it was important to me not to use just browns and tans, but instead use a larger palette which reflects various facets of his personality. An overlayer of clear glass with linework, inspired somewhat by block printing, was a nod and tie back to the late 1700s. It also added definition to the features.

“I personally was impressed to learn about Prince Hall’s accomplishments. I hope the final piece engages the viewer and prompts one to learn more about this fascinating, multi-faceted historical figure. We certainly are richer from doing this project.”

Thirty years ago, leaders from the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of California and the Grand Lodge of California, the two largest Masonic organizations in the state, sat down around a conference table at the Oakland Airport Marriott. The meeting was long overdue. In a series of sessions spread over a five-year period, the groups set the conditions for mutual Masonic recognition.

Postage Paid at San Francisco, CA and at additional mailing offices.

Postmaster: Send address changes to California Freemason, 1111 California Street, San Francisco, CA 94108-2284.

Publication dates are the first day of March, June, September, and December.

Subscriptions: California Freemason is mailed to every member of this Masonic jurisdiction without additional charge. Others are invited to subscribe for $12 a year or $15 outside the United States.

Permission to reprint: Permission to reprint original articles in California Freemason is granted to all recognized Masonic publications with credit to the author and this publication.

Phone: (800) 831-8170 or (415) 776-7000

Fax: (415) 776-7170

Email: editor@freemason.org

FIND US ONLINE

» californiafreemason.org

» facebook.com/MasonsofCalifornia

» twitter.com/MasonsofCA

» youtube.com/CaliforniaMasons

» instagram.com/MasonsofCA

» tiktok.com/@CaliforniaMasons

As bureaucratic as that sounds, its impact was real. For 150 years, Prince Hall Masons and Masons of the Grand Lodge of California had existed side by side in an awkward coexistence, as neither partners nor antagonists.

In 1930, the Grand Lodge of California’s official proceedings referred to Prince Hall Masonry as having “a sort of qualified standing with our Grand Lodge.”

The following year, a Grand Lodge of California report stated that Prince Hall Masons in the state “have been unofficially aided in various ways by officers of the Grand Lodge of California, though no recognition has been or can be extended to them either as a Masonic body or individually.” In 1936, as a show of “cordial feelings” between the two grand lodges, Prince Hall Grand Master Theodore Moss gifted a copy of his organization’s proceedings dating back to 1904 to the Masonic Library of Southern California. “Relations between this Grand Lodge and the white Masons of the state [are] as close as same could be without recognition, and apparently that relationship is satisfactory to both sides,” he said.

That was not the case everywhere. In 1948, the Grand Lodge of Texas’s constitution reflected the hardline stance that many states did regarding Prince Hall Masonry, stating that it did “not recognize as legal or Masonic any body of negroes working under any character of charter in the United States” and that it “regard[s] all negro lodges as clandestine, illegal, and un-Masonic.”

TEstablishing formal Masonic recognition, then, was not simply a matter of procedural legalese. By allowing Masons from both groups to sit in lodge together, recognition was an important tool for laying the groundwork for a partnership that has, in many ways, served as an example for rest of the country’s Masons. It also reinforced that as an international fraternity, Freemasonry is bigger than any one grand lodge. (In California alone, there are at least six other Masonic organizations, including Iranian, Latino, co-ed, and women’s groups that meet regularly.)

As California Prince Hall Grand Master David San Juan explains as part of a sit-down with the leaders of the two fraternities on page 20, there are important historical traditions that are best preserved by keeping the two groups distinct. But by working more closely together with Masons from across jurisdictional lines, we not only strengthen our fraternity, but present a united public front for Masonry in this state. Or as Chernoh Sesay, the Black colonial history and antebellum scholar, writes in his survey of Prince Hall’s legacy (page 6), “Prince Hall Freemasonry is Freemasonry.”

That it took almost a century and a half to get to that point is a sad and regrettable reflection of the legacy of racism in this country. It is up to today’s California Masons—all of them—to undo that precedent and live out the values of harmony and cooperation that are at the heart of Freemasonry.

This issue of California Freemason, we hope, lives up to its name by highlighting and celebrating the history and people of California Prince Hall Masonry. It’s our sincere wish that by sharing these stories, we can introduce all Masons to this important heritage and remind everyone that regardless of race, ethnicity, or background, we are all California Freemasons.

Pulling iPhones out of their 18th-century waistcoat pockets, a who’s who of Prince Hall Masons gathered in April for the 11th biennial reopening of African Lodge № 459 in Boston, the lodge founded by Prince Hall in the 1780s. Masonic leaders from around the country, including Massachusetts Grand Master Justin E. Perry (center, dressed as Prince Hall) and California’s David San Juan (fifth from right), participated as line officers in the ceremonial reopening of the lodge dressed in period-appropriate garb. The event also included a rare public display of the African Lodge charter—the basis for all of today’s Prince Hall Masonry.

LARGELY OVERLOOKED BY HISTORIANS, PRINCE HALL REMAINS

A TOWERING FIGURE OF MASONIC—AND AMERICAN—HISTORY.

Almost 250 years ago, approximately 15 Black men, some perhaps African and the rest probably North American–born, traveled under the cover of night across Boston Harbor. Their destination was Castle Island, where the 38th British Foot Infantry was stationed and where, within it, operated a Masonic lodge of the Irish Registry, known as Lodge № 441. The traveling group, all free men, would have been on high alert: For one thing, fraternizing with British soldiers would invite allegations of loyalism. But also, the group was there for another, practically unheard-of reason: They wanted to become Freemasons.

Today that fateful trek across the harbor does not loom as large in the public mind as Washington’s crossing of the Delaware or Paul Revere’s midnight ride, to name two other colonial moments with Masonic connections. And yet its ramifications were, in many ways, every bit as significant. Centuries later, they continue to resonate all around the globe.

It was there, in Boston, under the supervision of the lodge master (likely a man named John Batt), that the first group of African American men were initiated into Freemasonry. Within a decade, they had formed the first Black lodge in the country (and presumably the world), from which a vast network would emerge connecting some of the most important figures of their time. Those men, in turn, would help shape and drive the movements for the abolition of slavery, for Black education, and for civil rights, establishing the Masonic lodge as a crucial institution in colonial Black American history—and American history writ large.

In forming an all-Black lodge, the group altered the course of Masonic history. The African Lodge, as it was

BY CHERNOH M. SESAY, JR.

originally known, became the first formal and publicfacing institution of African-descended people in all of North America, predating even the founding of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia. This was enormously consequential in its own time, with ramifications that continue to be felt today.

Within the story of African Lodge, one man stands out: Prince Hall. His leadership was essential not just for

the founding of the lodge, but also for its development into a lattice of Black Masonic lodges stretching across the United States and much of the globe.

To be clear: Prince Hall Freemasonry is Freemasonry. It is essentially no different in terms of ritual or form from conventional Masonry. (To borrow a bit of fraternal lingo, it is widely considered “regular.”) However, a complex and difficult racial history has meant that while Prince Hall Freemasonry is recognized today as legitimate within the craft, its history and development took place outside of and in parallel to mainstream American Masonry. In that way, the stories of African Lodge and Prince Hall reflect major issues not only in Masonic history, but also in American and transatlantic history. African Lodge shaped and was shaped by major historical themes including slavery and racism, abolition, the American Revolution, and the growth of free Black communities. And from that, it birthed generations of Black leadership and activism. And behind that immense legacy, there is the man. Prince Hall is one of the most important figures of the 18th century. And yet historians have not fully acknowledged the centrality of Hall or the African Lodge in understanding freedom and citizenship during the Revolutionary era. Hall is, in many ways, one of the overlooked founding fathers of this country. Both within the fraternity and outside it, he continues to cast a long shadow.

So, who was Prince Hall? Relatively little is known about his life before he rose to prominence as a public leader. His death was widely publicized in newspapers, so we know that he passed in 1807 at the age of 72. We know that other men living in Boston who were of African descent shared his name; however, several can be removed from consideration as Prince Hall the Mason due to their age or the date of their death. At the same time, Hall’s biography remains frustratingly opaque. This is both unsurprising and significant. Anyone who has performed genealogical research for people of African descent who lived during slavery will attest to that difficulty.

Hall’s biography, or really the lack of it, illustrates this challenge. For example, we know where Hall was buried, but not where he was born. The important Masonic historian William H. Grimshaw, writing at the turn of the 20th century, claimed that Hall was born in Barbados and traveled to North America in 1765. This suggestion, while tantalizing and frequently repeated by historians, was never attributed to any documentation. Despite the possibility of Hall’s Caribbean origins, historians still have not found clear evidence of his birthplace. It is very probable that an

enslaved man named Prince, who was freed in 1770 after 21 years of ownership by William and Margarett Hall of Boston, was the man who would eventually help found African Lodge. William Hall had worked as a leather dresser, and so too did Prince Hall, who was later noted as such by public authorities and recorded as having furnished leather drumheads to the Continental Army. (Some scholars have inferred that Prince Hall might not have been enslaved, but rather that he was apprenticed to William Hall.)

Prince Hall had a family, but here again, genealogical records raise more questions than they answer. Probate records detail definitively that Hall the Mason left his estate to his final wife, Sylvia Hall (listed as Zilpha in some instances, maiden name Johnson). Hall was one of just a few Black people in late-18th-century Massachusetts who left a will and a small amount of probated wealth. He listed his Masonic apron among his possessions, and he made Sylvia the executor of his estate. Marriage records suggest that Hall was married more than once and that he last wed in 1804. He had at least one child, Primus Hall; however, Primus remembered that when he was born, in 1756, his father was free and that his mother, Delia Hall, was enslaved. Primus’s memory of his father having been free conflicts with William and Margarett Hall’s manumission statement that they had owned Prince as early as 1749.

Despite these biographical gaps and unanswered questions, we know that at the age of 42, just after establishing African Lodge and during the Revolutionary War, Prince Hall emerged onto the public scene. In January 1777, Hall and seven other men penned an abolitionist petition to the Massachusetts House of Representatives. Three of the signees—Hall, Peter Bestes, and Brister Slensen (Slenser in some records)—were by 1777 already members of African Lodge. A fourth, Lancaster Hill, joined just after. This appeal was the last in a series of addresses begun in 1773 and sent by a Black-led interracial group to the Massachusetts government. This campaign was the earliest of its kind in the history of American abolitionism, and the fact that it was led by the first Black American Freemasons has not received its just and proper attention. Black people in colonial America had always resisted their enslavement, but prior to the letter-writing campaign, that resistance had typically been expressed on personal terms or by invoking the particular treatment of an individual. Hall and the other Black petitioners stridently criticized the morality and legality of slavery, echoing the ideas of human equality and natural rights found in Masonic ritual and the Declaration of Independence. They also created direct political

ties with white legislators and the broader Massachusetts public. As power shifted from loyalists to patriots, Hall demonstrated astute political instincts as he called out the hypocrisy of a rebellion that condoned slavery, while also culling favor among whites sympathetic to emancipation.

It’s also important to remember that this abolitionist movement conjoined with several judicial anti-slavery cases brought by the enslaved, as well as examples of owners personally emancipating their enslaved people in the context of expanding abolitionist sentiment. Because the campaign aligned with these other anti-slavery actions, it helped shape the debate about equality. For example, an early draft of the Massachusetts state constitution, adopted in 1780, denied the vote to any person of African descent. The broader public rebutted this proscription, and the final version declared unequivocally that all people were equal. Interestingly, the state constitution also allowed each town to decide its own rules for Black suffrage. Despite the limits and ambiguities of slavery’s end in Massachusetts, Freemasons of color led the charge to guarantee political rights for the state’s emancipated population.

From 1777 forward, Prince Hall’s name appeared time and again in connection with protests for equality. To that end, he exercised determined leadership on two fronts: He led several efforts for Black people’s rights, and he worked tirelessly to gain full Masonic recognition for African Lodge. Masonic recognition was no small matter. Hall was aware that Revolutionary-era frictions between loyalists and patriots created deep divisions among American Freemasons (often political elites), and also that the contingencies of racism might lead white Masons to question the legitimacy of an all-Black lodge—thereby severing a pipeline into middle-class respectability. So Hall approached white Masonic leaders in both America and England. Despite differing accounts, we know that Hall had gained a provincial charter for African Lodge № 1 from John Rowe, who by 1768 had been made the provincial grand master of North America by English Masons. At least as early as 1779, Hall also began a correspondence with English Masons, and it was just after the war’s end, in 1784, that Hall formally petitioned the Grand Lodge in London to convey a full charter to African Lodge. In 1787, African Lodge № 1 received its warrant from London and became listed on official Masonic rolls as African Lodge № 459. (After Hall’s death, African Lodge took his name and, together with a small network of other Black lodges in Philadelphia and the Northeast, declared itself the seat of a Prince Hall Grand Lodge.) Outside the lodge, Hall developed into one of the era’s most important voices. As an abolitionist, Hall was an ambivalent American patriot, simultaneously hopeful and cynical. As a leader among a generation of people who had

successfully won their freedom, he imagined and worked for a future of equal and nonracial citizenship. Masonry inspired his optimism. Hall believed deeply in the sacred history of the craft and in Masonry’s emphasis on universal brotherhood. This spoke to his concerns about ending slavery and supporting Black education. For Hall, Masonic learning represented fundamental knowledge, and Masonic ritual provided an institutional framework for building leadership and demonstrating interracial equality. However, he was also hesitant because he recognized the difference between emancipation from enslavement and full acceptance into American society.

The tensions between Hall’s optimism and his realism were reflected in a series of seemingly conflicting decisions.

In the winter of 1786, Hall pledged the support of African Lodge to Gov. James Bowdoin to help quell the unrest of farmers in western Massachusetts. The following January, having just flexed their newfound political muscle, Hall and 73 other Black men signed a petition asking for state support to help them “Return to Africa, our native country … where we shall live among our equals, and be more comfortable and happy, than we can be in our present situation.” A few months after that, Hall and 35 other men of color solicited

the board of the Boston selectmen (the town’s governing body), asking that the education of Black people be supported by public funds. Hall and his co-signers bemoaned the contradiction of having to pay taxes while Black children were kept out of public schools. These seemingly disconnected moves were not the result of Hall and his cohort’s indecision. Rather, he was a principled pragmatist. Deeply aware of political realities, Hall labored to give Black people a voice, to find or create an environment where they would be seen as capable and deserving citizens, and to emphasize the power of Black people’s intellect.

By the turn of the 19th century, Hall had successfully created a vibrant space within Freemasonry that has thrived all the way to the present.

It was in Prince Hall’s African Lodge that the leaders of Boston’s antislavery movement came to prominence. A century and a half later, Prince Hall lodges in the American South helped produce and organize many of the 20th-century leaders of the civil rights movement. Indeed, several of the towering figures in Black American history, from Duke Ellington to Thurgood Marshall to John Lewis, were proud Prince Hall Masons. Prince Hall lodges provided an avenue into professional circles where previously there had been none. From Prince Hall Freemasonry also emerged the Order of the Eastern Star, a significant sororal auxiliary organization. The connections made in lodge and the accessibility of assistance and relief for those in need have made Prince Hall Masonry, together with the various Black churches and later Black fraternal traditions, among the most important institutions of Black America. Creating all this was no mean feat, as Hall constantly had to navigate perilous and intersecting spaces of racism, hardship, and inter-Masonic conflict. Because of Hall’s tireless advocacy and immense achievement, it is fitting that all those lodges that trace their history back to the African Lodge recognize themselves within the tradition of “Prince Hall Freemasonry.” Hall’s efforts have certainly benefited Black people in America, but his historical impact has also resulted in the global spread of Prince Hall Freemasonry. Just as important, Hall’s determination to establish African Lodge № 459 serves as a testament to the fundamental principle of Masonic universal brotherhood that initially inspired him.

For nearly 170 years, Prince Hall Masonry in California has provided its members with a place of belonging, even as those same people fought against and suffered discrimination in many other parts of their lives. The lodge has been—and still is—a venue to come together for personal betterment, for mutual aid, and for community. That legacy is a proud one—and yet practically every history of Prince Hall Masonry begins not with its contributions to Civil Rights and the progress of Black people in America, but with something else entirely: the matter of its Masonic “regularity.”

For that reason, Prince Hall Masonry has two parallel histories: One in which it has played an important role in the civic lives of its members and Black communities more broadly, and another within the insular world of Freemasonry, in which it has been forced to advocate for its legitimacy.

For more than a century, that issue of regularity lingered over Prince Hall Masonry, used as a cudgel by those looking to denigrate the institution and deny Prince Hall Masons the benefits of membership in a worldwide fraternity. In California, for many years, the story was the same. Partly, that is a reflection of the legacy of racism in this country that endures to this day. It is also partly due to the complicated history of 18th and 19th century Masonry, with its many schisms and reunifications (which occurred among both Black groups and not). In fact, the very founding of what would become known as the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of California, back in 1855, came out of one such split among the descendants of Prince Hall’s African Lodge № 459. Still, the matter hangs over it like a cloud. As a result, virtually every history of the organization is required to include some attempt to trace its lineage back to African Lodge and ultimately to the Grand Lodge of England.

With that said, historians and Masonic scholars have already done this work and the result is clear: Prince Hall Freemasonry is considered “regular” and legitimate by practically every Masonic body in the world, including the United Grand Lodge of England and the Grand Lodge of California. Our state’s Prince Hall grand lodge is recognized by jurisdictions around the globe. The question of regularity is moot. (Read more about Prince Hall Masonry’s origins on page 6.)

FSo, setting that to rest, we find that the history of Prince Hall Masonry in California is a fascinating one, and one that reflects the changing dynamics and positions of Black people in California. Through the development of Prince Hall Masonry here, we see a reflection of the advancement of civil rights, the Black community, and how it has endured through changing times and socioeconomic conditions.

As with so much else, that story begins in 1849 with the Gold Rush. Just as the Grand Lodge of California began in the campsite lodges formed by miners, so too did Black Freemasonry begin in the shadow of the Sierra foothills. The most important figure in this history was Philip Buchanan, the founder of Hannibal Lodge № 1 in San Francisco and the man who chartered the first three Prince Hall lodges in California. Buchanan had been made a Mason in Pennsylvania before emigrating to California in 1850. He received his charter from what was then called the National Grand Lodge (which oversaw several state-level grand lodges of what we now call Prince Hall Masonry) to form Hannibal Lodge on June 15, 1852. The following year, the same National Grand Lodge issued charters for Philomathean

№ 2 in Sacramento and Victoria № 3 in San Francisco.

Between June 19 and 23, 1855, representatives of the three lodges met in San Francisco to form a state grand lodge. Buchanan was elected as first grand master.

Meanwhile, three other lodges, Olive Branch № 5, Wethington № 7, and Mosaic № 11, had received charters from the African Grand Lodge of New York and were also working in California as the Conventional Independent Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons. It wasn’t until June 24, 1874, that the two groups were united under the name of the Most Worshipful Sovereign Grand Lodge of Colored Masons of California. This followed the dissolution of the National Grand Lodge, opening the door to reconciliation among the country’s Black lodges. (Nearly 20 years later, in 1893, a Prince Hall committee officially established that the California grand lodge would

recognize the 1855 date as its inception.) In 1947, the name of the body was changed again to honor Prince Hall, a move made in collaboration with other state grand lodges. That struggle to get established lasted well into the 20th century—thanks in part to persistent territorial fights with “clandestine,” or spurious, Masonic groups, some of which were little more than shams designed to defraud members out of their dues and charity dollars. In 1888, when St. John’s Lodge № 16 (later № 5) became the first subordinate Prince Hall lodge in Los Angeles, there were just eight constituent lodges and 126 total members in the state. The 1906 earthquake nearly wiped that out, destroying practically all of the grand lodge’s belongings and destroying its headquarters. (The organization did not carry insurance, and Grand Master R.C. Marshall refused offers of aid.)

Still, the organization persisted, and eventually began to grow during the years of World War I. From 1909 through 1929, the grand lodge chartered 25 new lodges, many of which were in the fast-growing southern part of the state, but also as far north as McCloud, in Siskiyou County (Pride of the West № 30), and even Portland, Oregon ( Excelsior № 23 ). Membership rose from just 182 men in 1901 to 1,687 by 1921. In 1926, the grand lodge moved into its new temple on East 50th Street in Los Angeles.

But the real membership boom came in the wake of World War II, a period during which the African American population in California nearly quintupled. From 1941 to 1951, the number of Prince Hall Masons in California rose from 1,790 to 6,109. Thirty-eight new lodges were chartered between 1943 and 1954, including Puuloa № 51 and Cosmopolitan № 82, both in Honolulu. In 1951, the total assets of the grand lodge were reported at $205,036—a nearly tenfold increase from a decade prior.

As with nearly all Masonic groups in the United States, the midcentury represented the fraternity’s zenith. Women’s auxiliaries like the Order of the Eastern Star and youth groups including the Junior Masons and Order of the Knights of Phythagoreas were established throughout the state. With that, the organization’s ambitions grew. In 1931, Grand Master Theodore Moss approved the purchase of a 32-acre parcel just outside Tulare to be developed into a home for the fraternity’s aged and infirm, much like the Masonic Homes of California, and to establish a summer camp for children. That project ultimately languished, and the land was eventually sold off; however, the vision for a permanent apparatus for Masonic relief demonstrates the scale of the organization’s aims.

In addition to the network of mutual support that lodges offered one another, Prince Hall Masonry also took steps to formalize money lending. In 1952, the Rev. D.D. Mattocks helped lead the launch of the first Prince Hall Credit Union, which would eventually grow into a network of six such institutions throughout the state, each established to lend money to lodges and members of the fraternity at a time when many Black Americans did not have equal access to banking and lines of credit. These credit unions continued until 1989, when they were dissolved and placed into liquidation.

By the late 1960s, the fraternity had even turned to home-building: Using financing secured under the

1. Three men pose in an undated photo outside the Prince Hall “homesite,” in rural Tulare County, that was purchased in 1932 and intended to be developed into a retirement home and children’s summer camp. The land was eventually sold.

2. Members of a special committee launch a fundraising drive for “Prince Hall City,” a planned Masonic center in Los Angeles open to Prince Hall lodges and other related orders. The drive began in 1958.

3. Grand Master Herbert A. Greenwood, of Angel City № 18 in Los Angeles, who served from 1957–1960 speaks during the organization’s 1957 convention in Sacramento.

4. An undated photo shows a group of Little Leaguers posing for a team photo. For many years, Prince Hall lodges sponsored Prince Hall Masons’ Athletic Leagues in basketball and softball for boys between 12 and 14 in and around Los Angeles.

5. A photo shows men in Masonic attire during a joint constitution ceremony held October 25, 1952, in Woodland with mayor Frank Heard (second from right). At that event, three new lodges were constituted: Jerusalem № 52 of San Francisco, Monument № 74 of Woodland, and Monarch № 73 of Oakland.

National Housing Act, the fraternity funded and constructed the Euclid Avenue Apartments in San Diego and the 92-unit Prince Hall Apartments in San Francisco’s Fillmore District, which broke ground in 1970—one of the signature projects of the infamous redevelopment of San Francisco’s Western Addition. As the historically Black neighborhood was systematically razed and rebuilt, the fraternity helped ensure a toehold for Black residents in the Fillmore. The project is now managed by Bethel AME, one of the longest-running Black churches in the neighborhood, and a close partner of Prince Hall Masonry.

The grand lodge’s interest in business endeavors like banking and home-building wasn’t simply financial. It also reflected the fraternity’s essential role in supporting the community it served and filling holes in the social safety net.

That work has led to a degree of political involvement within Prince Hall lodges that’s atypical of other Masonic organizations.

Particularly in the U.S. South, Prince Hall Masonry is inextricably linked to the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Amos T. Hall, the longtime Prince Hall Grand Master of Oklahoma, and Thurgood Marshall, later to serve as U.S. Supreme Court Justice, were both lawyers with the NAACP, and through them and their connection to the Conference of Prince Hall Grand Masters, Prince Hall lodges throughout the country funneled more than $1.75 million in donations over a decade to the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund to help argue several court cases, including Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, which ended school desegregation.

In 1960, Prince Hall grand lodges pledged to support and defend “every nonviolent demonstrator who requested our aid.” That statement, published in the California Prince Hall Bulletin, further read: “Our position as Free and Accepted Masons is, by belief and obligation, to work with the civil magistrates, local and federal, and, although from time-to-time we do not receive all that we feel and know our Constitution guarantees, we have that confidence that through Legal redress and within the framework of good government, in our time First Class Citizenship shall be attained.”

Locally, the fraternity also cast its eye on political matters where they concerned civil rights. In 1978, Grand Master Jessie B. Thompson was quoted by the Fresno Bee at the Prince Hall annual communication, saying, “In the past Masons have said, ‘Don’t get involved in

politics.’ However, I feel we should get behind anyone who will champion our cause. The time has come when we must become more involved in the issues that affect us.” He cited upholding affirmative action and the appointment of Black judges to federal benches as two such matters.

That has led Prince Hall Masons both in California and elsewhere to more vocally support the candidacy of like-minded politicians. Certainly there has been a close connection between Prince Hall Masonry and some of California’s elected Black leaders. For instance, Tom Bradley, the former mayor of Los Angeles and the first Black mayor of a major U.S. city, was a Prince Hall Mason and spoke at the group’s annual communication in 1970. And Willie Brown, the longtime speaker of the state assembly and the first Black mayor of San Francisco, is a member of Hannibal № 1.

As both a vehicle for advocacy and a powerful network of support, Prince Hall lodges have helped make the voices of their members heard and felt.

As membership in the fraternity declined during the 1980s and 1990s, that visibility began to wane. However, Prince Hall Masonry remains vibrant and is well-positioned to remain so into the future.

One of the most significant developments in its recent history came in 1995, when the Grand Lodge of California and the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of California made Masonic history by passing resolutions formally recognizing each other’s fraternal sovereignty. That move, which was several years in the making, allowed Masons from both groups to visit one another’s lodges and sit in on degree conferrals. It also put an end to what had been a century and a half of disunity.

Further, that effort, led by Prince Hall Grand Masters Herbie Price, Harold Mure, Joseph V. Nicholas, and Ronald Robinson, and California Grand Masters Charles Alexander, Stephen Doan, William Stovall, and Ron Sherod, opened the door to a closer level of cooperation outside the lodge than the groups had ever known.

Since then, Prince Hall and Grand Lodge of California Masons have stood side by side, proudly demonstrating the universality of Freemasonry.

These days, the fraternity is much changed from its halcyon era, but thanks to partnerships like that and the unbroken chain linking members today to those of the past, its history and legacy live on for generations of Masons to come.

Even among the thousands of photographs, papers, and news clippings that make up the Royal E. Towns Prince Hall archive at the African American Museum and Library of Oakland, one black-andwhite image catches the eye: eighteen men in dark suits, arranged behind the altar, the checkerboard floor visible beneath them and Masonic rods, banners, and flags peeking out from either side of the group. It’s a pose that’s been re-created hundreds of thousands of times by lodges all around the world. Dated 1954, it’s an almost archetypal formal portrait of a Masonic lodge.

Latino, Native American, and Filipino members.

The first all-Filipino Prince Hall lodge was formed December 3, 1943, in Vallejo, near Mare Island, then home to one of the largest Naval bases on the West Coast. Vallejo at the time was a center of the Filipino American community—by 1942, there were more than 1,500 Filipinos employed at the shipyard. (The U.S. Navy offered a pathway to American citizenship for Filipino nationals.)

And yet this one stands out, as much for what isn’t there as for what is. The lodge, Jerusalem № 72 of San Francisco, was made up entirely of Filipino Masons. Notably, for a Prince Hall lodge, there wasn’t a single Black member. That isn’t the only curiosity. Today, there’s no trace of Jerusalem Lodge left, nor are there any other Filipino lodges within California Prince Hall Masonry. A Google search reveals nothing about the group.

The image tantalizes with mystery. It may be a perfectly typical lodge photo, but in its utter conventionality, it contains a story that tells us much not only about the history of interracial Masonry in California, but also how and where ethnic subcultures were welcomed into a statewide fraternity—and the tragic undoing of that era. In short, there’s lots more there than meets the eye.

EPrince Hall Masonry is often described as a Black fraternity, but its ranks have never been closed to members of other races. (In fact, the second grand master of Prince Hall Masons, following Prince Hall, was Nero Price, a Russian Jew.) In California, that has included white,

That Masonry would take root there is no surprise. Freemasonry has a long history in the islands and was seen as central to the revolutionary movement that ousted the Spanish in 1898. Many of the country’s preeminent historical figures, including José Rizal, Andrés Bonifacio, and Manuel Quezon, were proud Masons. In 1912, the Anglo-led Grand Lodge of the Philippines was chartered by the Grand Lodge of California, with leadership of the group initially alternating between white and Filipino grand masters. Despite that connection to California Masonry, Filipino immigrants were not typically welcomed into the larger state fraternity.

Rather, many Filipino immigrants who arrived in California formed their own Masonic and quasi-Masonic organizations. Among those were the Gran Oriente Filipino, the Grand Lodge of the Philippine Archipelago, the Legionarios del Trabajo, and the Caballeros de DimasAlang. Groups like these provided essential networking opportunities, as well as housing and a social safety net for men who, especially prior to the War Brides Act of 1946, almost always arrived stateside without family.

The first Filipino Prince Hall lodge, Amicus № 48, was founded by Pedro G. Tolentino, who served as its first master. In 1946, he would go on to organize yet another group, alongside Prince Hall Grand Inspector D.D. Mattocks, called Philadelphus № 54 , headquartered in

Stockton (home to another large Fil-Am population). It was from that lodge that Jerusalem № 72 was born. From the remaining Prince Hall archives, it isn’t clear where or when the charter members of those lodges were initiated, whether in Prince Hall lodges or elsewhere. (New lodges typically require 13 Master Masons, including the sponsorship of a past master.) One theory is that the membership of Amicus may have already belonged to an “irregular,” or unrecognized, Masonic group, and simply petitioned the Prince Hall Grand Lodge for recognition en masse. That kind of thing certainly happened: For instance, Golden West № 83 renounced its affiliation in 1954 with an unrecognized grand lodge

(named for George Washington Carver) in order to secure a new charter under the Prince Hall grand lodge. In any case, on February 16, 1952, a past member of Philadelphus, Stanley H. Manzano, joined with four other members of the Stockton group to form the Filipino Club of San Francisco. Led by Rosendo F. Hadloc, another past master of Philadelphus, the club petitioned the Prince Hall Grand Lodge to form their own lodge, which was granted the next month. Jerusalem № 72 was chartered on October 25, 1952, along with Monarch № 73 and Monument № 74, in a joint ceremony held near Sacramento by Grand Master Starling J. Hopkins and Grand Marshall Stanley Y. Beverly.

That wasn’t the extent of the Filipino presence in Prince Hall: In 1953, another Pinoy lodge, Rising Sun № 75, was constituted in Santa Monica. And the following year, yet another, Zephaniah № 86 of Delano, in Kern County, received its charter. By 1955, an incredible five Prince Hall lodges served almost entirely Filipino constituencies.

Seventy years later, traces of that legacy are hard to find. None of those Filipino lodges remain—the result of an overall membership decline, but also of larger changes within the diaspora.

There were also local misfortunes. Amicus № 48, the first Filipino lodge, attempted to purchase land for a new meeting hall in Earlimart (Tulare County), a plan that it seems never come to fruition. In time, that lodge was consolidated into today’s Firma № 27 (Vallejo).

Perhaps the most unfortunate case, however, is that of Jerusalem № 72. In 1959, three members of the lodge were involved in a fishing boat accident on the San Joaquin River a mile east of the Antioch Bridge.

According to a UPI report carried in several California newspapers, Andres DeLaCruz, 65, a veteran of both world wars, lost his balance trying to net a fish and fell overboard. Another member of the lodge, Oscar Vitan, 40, dove in after him, upsetting the skiff and sending a third member, Ruperto L. Gamboa, 70, in as well. Gamboa had been a charter member of the lodge and served as its first tyler. DeLaCruz and Vitan were both swept away in the fast-moving current as their boat sank; Gamboa was the only survivor. Vitan’s body was discovered April 18, DeLaCruz’s a week later. An obituary in the San Francisco Examiner April 28, 1959, listed DeLaCruz’s death as occurring “accidentally near Antioch.” It also gave the name of his wife, Dionissia, and mentioned his many fraternal affiliations, including Menelik Temple № 36

(Shrine), Victoria Consistory № 25 (Scottish Rite), and Jerusalem № 72, which officiated his funeral.

The incident seems to have cast a pall over the lodge, which appears less frequently in the archival records in subsequent years. It may well have been the beginning of the end for Jerusalem Lodge. In 1971, the group formally surrendered its charter, with the reason given that the lodge could not recruit new members and that existing members were unable to meet regularly.

As for the other Filipino Prince Hall lodges, within a decade each had either folded or been consolidated. At the same time, the first Filipino lodge associated with the Grand Lodge of California, Tila Pass № 797, was chartered in 1960. Over the ensuing decades, Filipino membership in the Grand Lodge of California grew and today makes up one of the largest ethnic subgroups in the fraternity. Where once Filipino Masons had turned to Prince Hall, they began to find acceptance in the Grand Lodge of California.

Ultimately, the Filipino flash in the Prince Hall pan was short-lived, but as a phenomenon it underscored the interracial unity that fraternity fostered. That much is evident in the Prince Hall records, which paint a picture of progressive racial coalition-building. At a time when much of the country remained segregated, Prince Hall lodges were not only a haven for Black Americans, but also for all ethnicities.

Ironically, that was perhaps best seen far away from the shores of the Golden State. From 1943 through 2000, the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of California governed three lodges in Hawaii. The second of those, the aptly named Cosmopolitan № 82, was described by the Honolulu Star-Bulletin in 1954 thusly: “The unique feature of this lodge is the multi-racial membership. It is composed of Portuguese, Chinese, Japanese, Puerto Rican, Caucasian, Hawaiian, Negro, Filipino, [and] Korean ancestries and also others of mixed racial extractions.”

Writing just five years later, the lodge explained its worldview: “The name Cosmopolitan as applicable to our lodge means a brotherhood of men of multiple racial origins or social backgrounds, who ignore local or racial prejudices, attachments, and peculiarities or any of the many shortcomings of humanity by demonstrating to the world that the equality of the human race is a practical solution to many of our problems.”

Almost 80 years later, the local “peculiarities” of the fraternity have shifted, but that same animating spirit remains.

How many members are active in Prince Hall Masonry today?

As with other Masonic organizations, it’s practically impossible to say for sure. But estimates put the number of Prince Hall Masons in the United States at around 100,000, and perhaps up to half a million worldwide. Similarly to all Masonic groups, that number has ebbed and flowed over time, peaking in the postwar years of the mid-20th century. In those U.S. states with the largest Prince Hall presence, you’ll often find up to 20,000 members. In California, there are around 3,000 members.

How many Prince Hall lodges are there in California?

There are currently 58 Prince Hall lodges in California, ranging from Marysville in the north to San Diego in the south. Unsurprisingly, lodges are clustered in the Bay Area (three in San Francisco, six in Oakland, plus others in Berkeley, Vallejo, El Cerrito, and the South Bay) and Los Angeles (14 lodges in L.A., plus another 15 in the greater Southland). Across the country, there are nearly 1,000 Prince Hall lodges, with Louisiana, Texas, Alabama, Florida, and Washington, D.C. having the most.

Is Prince Hall Masonry found in other countries?

Yes, there are Prince Hall lodges all across the Caribbean, Africa, Asia, Europe, and Australia. The United Grand Lodge of England recognizes 36 Prince Hall jurisdictions in the United States (including California), as well as the Prince Hall grand lodges of the Bahamas, the Caribbean, and the province of Ontario.

What philanthropic issues are the Prince Hall Masons of California known for?

Together with the California Masonic Foundation, the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of California awards the C.E. Towne Scholarship Fund to high school graduates to help them afford college, as well as the Prince Hall Memorial Education Scholarship for low-income students and deserving children of Prince Hall Masons. This spring, as part of their support for students, Prince Hall Masons donated 250 pairs of boots to students pursuing career technical training education in Sacramento.

MOST FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS ABOUT THE HISTORIC BRANCH OF THE FRATERNITY.

What is the connection between Prince Hall Masonry and the civil rights movement in the U.S.?

Many of the most important figures of the civil rights movement were closely associated with Prince Hall Masonry, including Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall and the late Rep. John Lewis. Lewis was one of the organizers of the 1963 March on Washington and, in 1965, the famous march from Selma to Montgomery that helped lead to the passage of the Voting Rights Act. Prince Hall Masons from around the country gather each year on March 7 to commemorate the “Bloody Sunday” crossing of the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Through Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, Prince Hall Masons also helped support the landmark 1954 school desegregation Supreme Court case.

How similar or different is the Prince Hall Masonic ritual?

Prince Hall Masons, like the Grand Lodge of California, confer the first three degrees of Masonry according to the Rite of Emulation. In terms of ritual, it is extremely similar to other California lodges, although the performance often includes song. Since ritual is governed at the state grand lodge level, it can vary slightly from one jurisdiction to the next.

Are there any other differences between Prince Hall Masonry and the Grand Lodge of California?

The most notable difference concerns dual or plural membership. Prince Hall Masons in California can belong to only one blue lodge (although they can be made honorary members of another). As a result, a Mason cannot belong to both a Prince Hall lodge and a Grand Lodge of California lodge. Beyond that, grand lodge officers serve in three-year terms, rather than single years.

Prince Hall Masonry is a historically Black fraternity. Do you have to be Black to join?

No. Although Prince Hall Masonry was founded by and largely for African Americans, it has always been open to men of all ethnicities and nationalities.

What are the requirements for membership?

All Freemasons are held to the same standard and must be of good character and reputation to become and remain a member. Additionally, to join Prince Hall Masonry in California, you must first meet the following criteria:

• Be a male at least 18 years old

• Be a California resident for at least six months

• Be prepared to profess a belief in a deity

• Be of good reputation as a man of honor and integrity

• Be recommended by two members of the lodge you wish to join

Does Prince Hall Masonry include appendant and concordant bodies?

Yes. In California, Prince Hall Masonry includes several other Masonic organizations, including the Prince Hall Order of the Eastern Star, the Scottish Rite’s Robert W. Brown Council of Deliberation (organized under the Southern Jurisdiction of the United States, Prince Hall Affiliation), and the Grand Chapter of Holy Royal Arch (York Rite), including the relevant bodies within those groups. Unlike in the Grand Lodge of California, the grand master of Prince Hall Masons in California also leads those groups. (For more, see page 30).

Members of the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of California and the Grand Lodge of California gathered at the San Joaquin Regional Transit District headquarters in Stockton this February for the unveiling of a Rosa Parks–themed bus wrap. The wrap was the brainchild of Prince Hall Masons, intended to honor the legacy of the civil rights pioneer.

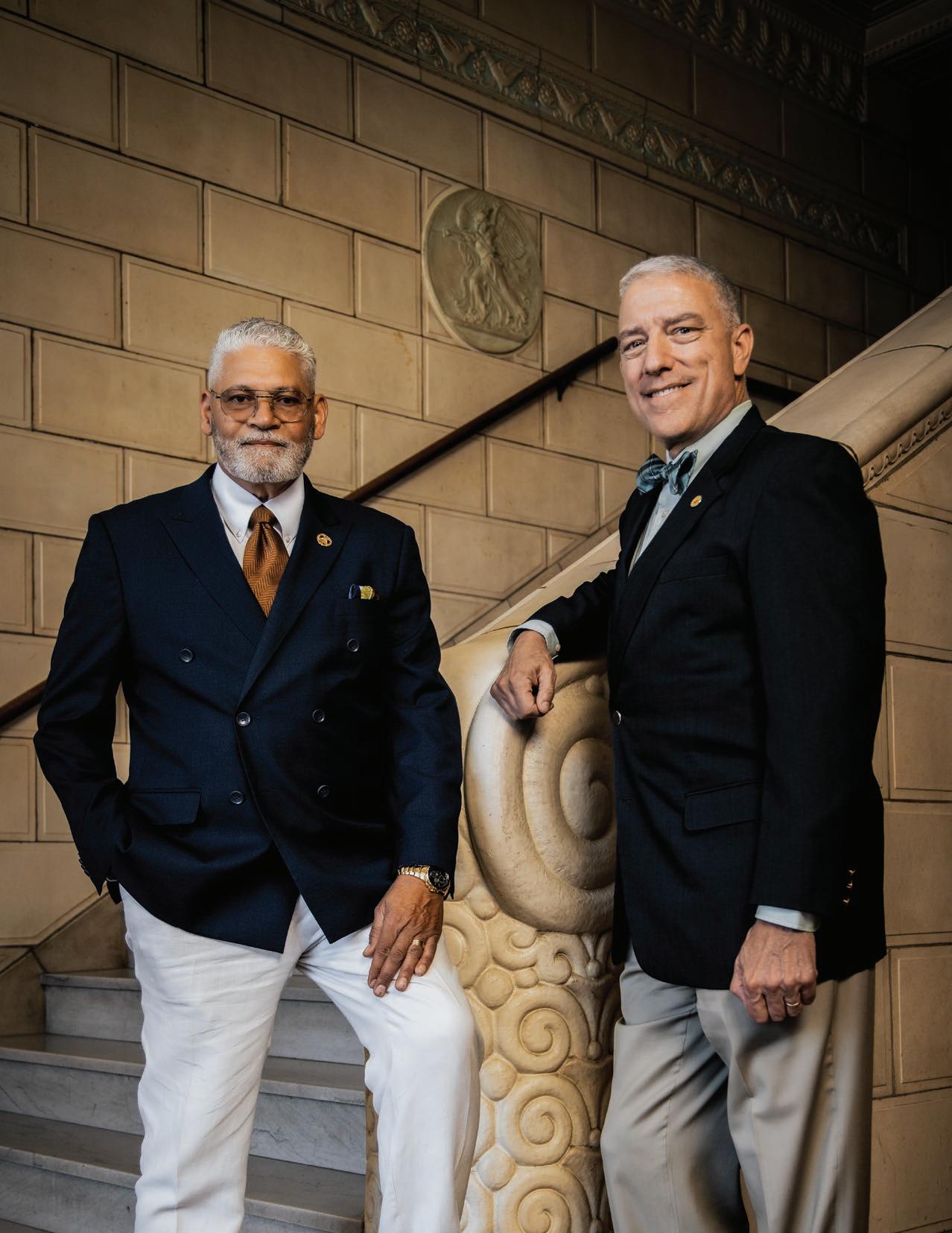

For all the pomp and ritual that defines Freemasonry, the hard work of guiding the fraternity was happening with decidedly less spectacle on a recent May afternoon. Rather, it was happening over a medium pizza at the end of a long table strewn with paper plates inside the Sacramento Masonic Temple. That’s where grand masters David San Juan, of the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of California, and his counterpart, G. Sean Metroka of the Grand Lodge of California, were sitting down for what has become a monthly lunch meeting between the two leaders. It’s a fitting setting, given that the historic temple on J Street is home to lodges from both groups. On the day’s agenda was a proposed partnership between the organizations to support vocational education in Sacramento schools and some preliminary talks about establishing a grand lodge liaison program. There were also plenty of asides about Masonry and history, and more than a few laughs.

GRAND

forward to seeing that progress. I think we can do a lot together that we would not be able to do separately.

For two organizations that until just a generation ago rarely worked together, meetings like this represent major progress. Beginning in 1995, when the two groups mutually recognized each other, Prince Hall Masons and those from the Grand Lodge of California have partnered on several philanthropic initiatives and stood side by side at public events. Still, the leaders say, there’s room for more. Here, the two grand masters—each nearing the end of his term—reflect on what has become a historic partnership, ways to deepen the relationship, and how to confront the challenges facing both organizations.

How can our two organizations work together to achieve each of your goals?

FG. Sean Metroka: We have lodges around the state that do a lot together. Not only do they meet in the same buildings, but when there’s a parade or an event in the community, they often come together. I think that those opportunities, when they arise, are beautiful to take advantage of. But [David San Juan] and I are always talking about other ways we might collaborate for the benefit of Masonry and the communities in which we live. We had a conversation today about how we might come together to assist programs in the Sacramento city schools. And I’m looking

David San Juan: I agree with that 100 percent. And you know what, Sean, this is the thing: Over the years, we have developed a friendship. So it’s about more than just doing the work of what Masons do. It’s about the friendships we’ve developed over these years, from one grand master to the next. I’ve been fortunate to be around a whole lot of your grand masters. It’s enriching to see us come together not only at the highest level but also in our subordinate lodges to support each other’s programs. It’s something that was a long time coming. Whenever we talk about what we’re doing within our jurisdiction or what we’re trying to improve, you’ve been just a phone call away. And I only see that building in the future.

Why continue to have two grand lodges rather than join as one? Why is it important to maintain the traditions of Prince Hall Masonry?

DSJ: That’s a very interesting question. Why is Prince Hall Masonry important? And why do we want to continue to keep our sovereignty and our history? Think about what we’ve had to endure not just to be Masons, but to be citizens who have the right to vote. That’s a very important part of our history. And the fact that we stayed together, held together through all of slavery, the Jim Crow laws, and so forth—that was very difficult. So we’re proud of our history, and we don’t want to change that whatsoever. We want to maintain not just our sovereignty, but our history.

GSM: One of the things that strikes me when I’m asked this question is that even though we are similar in almost every respect, we do have differences that have developed over the years, and I think there is value in maintaining them. I think we would lose more than we would gain if we were to try [to join]. I don’t see a pressing reason to combine them, but I see many reasons not to. And it is

my hope that both of our traditions in Freemasonry will continue side by side, enjoying each other’s fellowship, and working together when it makes sense to.

What are the challenges you each see facing your organizations?

DSJ: What I know from being at the Conference of Grand Masters recently is that we are all facing the same obstacles. If you look at the numbers, the average age of an Entered Apprentice might be around 45, but the average age of a Master Mason is closer to 60. Somewhere along the line, we missed an entire generation. Plus, we’ve had the challenge of covid -19. We have an opportunity now to do what we haven’t always done well enough, and that is to teach people how to live better. You know, there was a time when Masons got together and helped each other buy a home. Or they would buy a car from another Mason. At some point, we need to get back to that.

GSM: Another challenge is that, because of the wide variety of traditions in Freemasonry that are becoming more commonly known, some of our members think the tradition they were brought up in should be what’s practiced elsewhere. But the fact is, our practice of this institution varies widely. So we have a challenge to find a way to become more welcoming to people and also to express the importance of letting our traditions develop organically.

How can your grand lodges work together to address these kinds of challenges?

DSJ: One of the things that we have to improve on—and that we can very easily admit—is that we don’t let the public know all the good things we do. Whenever they do see us out in public, there’s a big mystery about what we’re all about. We need to do better about that. GSM: I think the issue of the incredible variety of traditions in Freemasonry and whether we will ever be seen as a cohesive entity is a real issue, but it’s going to take a long time to make headway on it. We are very old, and in some of our grand lodges, we’re very much stuck in our own ways. So, for example, I think most of us freely acknowledge that there have been women in Freemasonry for hundreds of years, and there’s lots of evidence to support that. Does that make it a problem to acknowledge that there are women Freemasons practicing a regular form of Freemasonry? It’s not a problem, it’s just a change. A part of the way we deal with that is to start to acknowledge one another more openly. It’s kind of like the association between our two jurisdictions: Initially, there was a lot of concern, perhaps unfounded, but it was because that level of trust had not been established. It has been established now, and the concerns, for the most part, have gone by the wayside. I think the same will happen as we reach out to other Masons.

DSJ: We have to understand who we are and that we are different. We bring something a little bit different to Freemasonry. You can hear that in our music, in our literature, even in our speech. But in the end, it’s all Freemasonry. That’s not well understood because we haven’t done what we’re doing right now, and that’s telling our own story so that it’s better understood by not just your Masons [in the Grand Lodge of California], but also by our side as well.

What do you view as the future of Freemasonry in California?

GSM: I am hopeful that 10 years from now, Freemasonry in the state will not be viewed as some great unknown, or some mystical organization that people always wonder about and tend to view as if it were some sort of a conspiracy. And I think that the best way to do that is to continue on the path we’re on now, where we are more open about who we are, what we do, and why we are so devoted to this ancient craft.

Mostly, I am hopeful that in 10 years, people will see Freemasonry for what it has always been: an organization for the good of humanity, to help people live better lives, and to help those in need.

fraternity to take, and work toward that. One year is not sufficient to move an organization of this size to any point. But you can take steps to make progress toward those objectives. I would also suggest that my successors not get mired in the day-to-day. There are lots of challenges that come uniquely to the grand master. It can be difficult not to allow them to take over your existence. Don’t get stuck on those things. Look at the good and expand on that.

What’s one of your favorite memories from your time in Masonry?

“The sky’s the limit as far as what we can do together.”

DSJ: I agree. For us, 10 years down the line is not that long, because our tenure [in the grand line] is three years. So our junior warden, nine years from now, will be the grand master. So we’re all on the same page. This started back in 1995 [with official recognition]. And it has blossomed from there. But with the direction and the momentum that we have right now, I believe we’ll be able to keep that going. The sky’s the limit as far as what we can do together. As I’ve been told so many times, many hands make light work.

You’re both coming up on the end of your terms as grand master. What advice do you want to pass along to your successors?

DSJ: Well, mine is straightforward. The first thing is to prioritize what you intend to do during your tenure and see it through. Secondly—and this I have to give credit to my wife for—she said now that you’re grand master, you have a platform. You have a voice. You need to use that platform to do good and to spread goodwill. You have to actually help your community. And then third, and maybe most importantly, you have to build trust within the community you serve. Whatever you do, don’t break that trust. Because when you do, it’s almost impossible to get it back.

GSM: As I approach the end of my tenure, if I were to give advice, it would include a suggestion that you keep your eye on the bigger picture, well beyond the end of your term. Think about the general direction you want the

DSJ: For me, my dad was my hero. He still is my hero, though he passed away many years ago. When I was a kid, he had a bar in his home that he and all his Masonic buddies would pull up to and talk about solving the world’s problems. And I’d be at the end of the bar until they kicked me out. So when I became a Mason in the lodge that my dad was raised in, Stanley Y. Beverly Lodge № 108 in Suisun City, it was very emotional. I was just thinking about all that talking behind the closed doors my dad was doing with his friends. I remember the feeling that I had as a 13-year-old, feeling as though I was in a village and that I was loved and secure. And here I am now. Who would have ever thought that I would become the grand master of all of that?

GSM: I’ve had many wonderfully fond memories of my time in Freemasonry, but I would have to say, the greatest joys for me are the friendships. I have been blessed with some wonderful friendships because of my association with this fraternity. That’s by far the thing I value the most.

What final message would you like to send to the fraternity?

DSJ: I want to say, Sean, you’re my friend. You’re my brother. You’ve been a wonderful Mason and you’ve made yourself available even in times when it was difficult. Being the grand master, you’re expected to be in a lot of different places at the same time. But you’ve made yourself available. You helped to make my tenure a wonderful one. So I appreciate you.

GSM: Thank you, my brother, I appreciate that. And I appreciate your willingness to go down this rabbit hole with me, because as I was preparing to take office, I gave a lot of thought to what I wanted to accomplish. And chief among my objectives was to work together with you to strengthen the relationship between our grand lodges, and you willingly went along and we’ve managed to get our large organizations working together. And I’m grateful to you for that. I am especially grateful to you for your friendship, and it means a tremendous amount to me. So thank you.

“This is the whole basis of what our fraternity is supposed to be about,” begins Ruben Soto, growing more and more animated as he describes the unique Masonic culture that’s developed in his hometown of Bakersfield. “It’s about brotherly love. Having each other’s back. Pushing each other forward.”

Those are heady words, considering that what Soto is describing is the “Burn-n-Brew”—a casual annual backyard barbecue to which local Masons and their families are invited. And yet to the Masons of Green Dragon Fellowship Lodge № 857 and the Prince Hall–affiliated San Joaquin Lodge № 11, the event is more than an excuse to overindulge in burnt ends and bourbon. It is, he explains, emblematic of a partnership that transcends jurisdictions and exemplifies what’s best about the fraternity.

For two organizations that have not always enjoyed a perfectly simpatico relationship, the Grand Lodge of California and the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of California have in recent years grown closer, blurring what for generations had been a bright line between the groups by working together on a slew of philanthropic endeavors, scholarships, and social gatherings. Much of that movement has happened at the state level, but increasingly—and perhaps most profoundly—it’s between local lodges that such partnerships have emerged. And nowhere is that more evident than in Bakersfield, where the Prince Hall and Grand Lodge of California Masons have become each other’s greatest supporters. “We’re more than close—we’re beyond family,” Soto says. “They have shown me the essence of what it is we’re all about. That may be a cliché, but it’s the truth.”

Stephen Hubble, the master of Green Dragon Fellowship № 857, agrees wholeheartedly. “We’re like-minded,” he says. “The one thing we all share is brotherly love.”

While the annual cookout, held each year at the home of Gary Jackson, a founding member of Green Dragons, may be one of the highlights of the lodges’ crosstown partnership, their fraternization runs much deeper than just that. In fact, the Dragons’ relationship with the local Prince Hall group predates their own chartering. In 2015, as Green Dragon was being formed from members of several Kern County lodges, it was San Joaquin № 11 that opened its hall doors to the nascent group, who were charged a paltry $50 a month in rent. That helped the group get off the ground.

“Our lodge got started out of a lot of adversity, so I guess you’d say we were drawn together,” Jackson explains.

“There’s no us and them. This is us. We're Masons, on the square, hanging out.”

ACROSS THE STATE, CALIFORNIA MASONS ARE REACHING OUT ACROSS LODGE LINES. BY IAN A. STEWART

Over time, that bond grew stronger: The groups have since joined up on efforts to feed the homeless, commandeered a section of the Bakersfield VillageFest to table together and raise money for local charities, and joined one another to assist elderly members of both lodges. A monthly roundtable meeting, dubbed the Smoke-n-Joke, provides a venue for members of both lodges to propose new charitable projects, raise funds, and simply stay up to date on each other’s activities. They’ve come together to restore a Masonic memorial at the local cemetery, partnered on children’s toy drives, and assisted with Children’s Advocates Resource Endowment programs. And of course there’s the Burn-n-Brew, which the grand masters of both orders have attended, and where funds are raised for the local bethel of Job’s Daughters.

That kind of cooperation is intensely local—but also a reflection of many years of hard work at the state level between the two grand lodges. That’s something leaders say had been a long time coming.

In 1995, the Grand Lodge of California and the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of California formally recognized each other, an important Masonic procedure that ultimately allowed for members of both fraternities to sit and work together in lodge, even though members cannot belong to both jurisdictions simultaneously.

For Jason Sevier, a district inspector in San Diego and a member of the Prince Hall Fidelity Lodge № 10, even after the recognition was formalized, there remained a sense of trepidation about what intralodge activities would be like. “I was kind of skeptical, like, I wonder if we’ll be received there,” he recalls. But a visit to Santa Maria № 580 for a third-degree conferral put those concerns to rest. “Once we got there, I’ve never seen the kind of respect and love we were shown,” he says. “It was like we’d been friends forever.”

That kind of response has led the two groups to join together on projects outside the lodge hall, too. Since 2012, that’s included teaming up on the Masons4Mitts fundraising drive, for which Masons from both groups gather for yearly Masons’ Night at the Ballpark events with their Major League Baseball partners. In 2014, more than 400 members of the two groups gathered to ceremonially bless the cornerstone of what is now the Golden 1 Center basketball arena in downtown Sacramento. The following year, the groups again congregated to lay the cornerstone for Willie L. Brown Jr. Middle School in San Francisco, alongside its namesake (himself a Prince Hall Mason with Hannibal № 1). Since 2019, the California Masonic Foundation has partnered with the Prince Hall Grand Lodge to administer the C.E. Towne Scholarship Fund, which has awarded $710,000 for higher education to more than 100 deserving students.

Beyond that, leaders of both organizations are now frequent guests at one another’s gatherings, presenting a unified face for Masonry in California. Never was that more clearly or dramatically on display than at the 2015 World Conference on Freemasonry in San Francisco, when the grand masters of the Grand Lodge of California, the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of California, and the Grand Lodge of Iran in Exile (headquartered in Los Angeles) shared the stage as co-hosts.

On that occasion, the partnership was a powerful demonstration of Masonic cooperation—a reminder that despite their different histories and a legacy rooted in racial discrimination, California Masons of all stripes share an essential bond.

But it isn’t on convention hall stages where that bond is put into practice. Rather, it’s in places like Oakland, where Prince Hall’s Eli Baker № 62 and Oakland № 61 gather each year for a joint St. John’s Day festive board. Or in Temecula, where the members of Temecula–Catalina Island № 524 and the Prince Hall Smooth Ashlar № 119 have held joint toy drives and homeless outreach efforts. Says Maurice Paschall, the Prince Hall senior grand deacon and a member of Smooth Ashlar, “When we’re together and people ask us what we’re doing, we’re just Masons hanging out. There’s no us and them. This is us. We’re Masons, on the square, hanging out.”

And it’s there in places like San Diego, where four Prince Hall lodges and their Grand Lodge of California counterparts visit one another’s degree conferrals and hold an annual golf tournament. Where the Bakersfield groups are concerned, that kind of fellowship can be found in Jackson’s backyard, meat on the grill and ice clinking in glasses.

Soto says the relationship has become more meaningful to him than he ever imagined it would. A few years ago, when he lost his job, Hubble called him with an invitation: “‘Come to work with me, I need you,’” Soto recalls. “I showed up. He gave me a truck with tools, and said, ‘I need you to repair some doors on this house. I know you, I trust you. Let’s get to work.’ In all my years in Masonry, I’d heard stories about things like that. But for it to happen to me, it blew my mind.”

When George Garlington, a member of the Prince Hall Stanley Y. Beverley Lodge № 108 in Suisun City, first laid eyes on the Masonic Homes retirement campus in Union City, he was stunned: Here was a 267acre village in the rolling hills of the East Bay, erected over a century ago for the care of Masons and their families, standing as a living testament to Masonic values of brotherly love, relief, and truth. “There’s really something here for almost everyone, no matter how old you are or what your needs are,” he marvelled.

And now, finally, it was here for him, too. Thanks to changes in eligibility announced in 2023, for the first time in its 125-year history, the Masonic Homes of California is now open to Prince Hall Masons, as well as their spouses, parents, and parents-in-law—providing access to Masonic

relief services to more California Masons than ever before.

That includes entry into the Masonic Homes’ retirement communities in Union City and Covina. Says Prince Hall Grand Master David San Juan, who accompanied Garlington on the spring tour, “I couldn’t be more excited.”

The partnership is an important step in bringing the two fraternal organizations closer together. It’s also serving an immediate need: The average cost of senior housing rose more than 5 percent nationwide in 2023, an

almost five-fold increase in the historic year-over-year costs. Through the Masonic Homes’ communities, which include independent living for those 60 and up, as well as assisted living and skilled nursing (including memory care for those with dementia and memory loss), Prince Hall Masons and their families now have access to senior living that’s affordable and, for many, close to home. But the Masonic Homes is more than just a retirement community. The organization also includes Masonic Outreach Services, a statewide program that provides Masons and their family members with connections to in-home care options and other local benefits, as well as case management and, for eligible applicants, one-time emergency funds. In fact, Masonic Outreach serves more clients each year than do either of the two retirement communities. There’s also the Masonic Center for Youth and Families, which is also now available to Prince Hall Masons. MCYAF offers mental health services, educational assessments, and therapy for families, couples, and people of all ages both online and in person at its San Francisco and Covina offices. At a time when

[Masons of CA Logo]

[Job’s

[Masons of CA Logo]

teenagers are experiencing what’s been described as a mental health crisis—and when mental health care providers are either prohibitively expensive or impossible to access— MCYAF ensures Masons and their families will never be turned away for lack of funds. Taken together, these services provide California Masons from both fraternities with the ability to tap into a powerful resource and offer members an incredible safety net—something that’s been the backbone of California Masonry for more than a century. By coming together around the Masonic Homes, the two grand lodges are embodying a model that Grand Master San Juan says he’s eager to have serve as an inspiration for others. “What I’d like to see is what we’re doing here leading the way for jurisdictions all over the United States,” he says. “And that they, too, would come together as brothers, hand in hand, arm in arm, shoulder to shoulder.”

[Masons of CA Logo]

[Masons of CA Logo]

[Masons of CA Logo]

[Masons of CA Logo]

[Job’s Daughters Logo]

[Job’s Daughters Logo]

[Job’s Daughters Logo]

[Job’s Daughters Logo]

[Rainbow Assembly for Girls Logo]

[Rainbow Assembly for Girls Logo]

[Masons of CA Logo]

[DeMolay Intl Logo]

[DeMolay Intl Logo]

[Job’s Daughters Logo]

[Rainbow Assembly for Girls Logo]

[DeMolay Intl Logo]

[Rainbow Assembly for Girls Logo]

[DeMolay Intl Logo]

[DeMolay Intl Logo]

[Masons of CA Logo]

[Masons of CA Logo]

[Job’s Daughters Logo]

[Job’s Daughters Logo]

[Job’s Daughters Logo]

[Rainbow Assembly

[Rainbow Assembly for Girls Logo]

[Rainbow Assembly for Girls Logo]

[DeMolay Intl Logo] The Next Generation of Masonic Leaders Needs YOU!

[DeMolay Intl Logo] The Next Generation of Masonic Leaders Needs YOU!

[Masons of CA Logo]

[Masons of CA Logo]

[Job’s Daughters Logo]

[Job’s Daughters Logo]

[Rainbow Assembly for Girls Logo]

[Rainbow Assembly for Girls Logo]

[Rainbow Assembly for Girls Logo]

[DeMolay Intl Logo]

[DeMolay Intl Logo]

[Job’s Daughters Logo]

[Rainbow Assembly for Girls Logo]

[DeMolay Intl Logo]

[Masons of CA Logo]

[Job’s Daughters Logo]

[Rainbow Assembly for Girls Logo]

[DeMolay Intl Logo]

The Next Generation of Masonic Leaders Needs

The Next Generation of Masonic Leaders Needs

The Next Generation of Masonic Leaders Needs

FORALLSHASTACOUNTYMASONICFAMILYANDFRIENDS

As the day’s program for the 2023 Annual Communication of the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of California inched closer, the hotel convention hall’s floor began to fill. Men in black suits with white gloves and embroidered aprons worked their way toward the front, while women in white lace dresses, purple and gold sashes draped over their shoulders, found their seats. All around, a mash-up of members in other regalia—white dinner coats, red fez caps with gold embroidery, striking blue blazers—jockeyed for position.

“It’s like one big family,” explains Marilyn Carney. Carney is currently the grand worthy matron of the Golden State chapter of the Prince Hall Order of the Eastern Star, making her the highest-ranking member of the women’s group. (Within the parlance of Freemasonry, it’s known as a concordant body.)

That spectrum of colors, representing a constellation of satellite groups, is a hallmark of Prince Hall Masonry— as it the tight-knit atmosphere. This is partly because, unlike the Grand Lodge of California, the organization’s concordant and appendant bodies fall under the authority of the Prince Hall grand master. In California, that includes not only the Eastern Star, but also the various bodies of the York and Scottish rites (the latter of which is known within California Prince Hall Masonry as the Robert W. Brown Council of Deliberation). There also exists a California desert (or jurisdiction) of the Prince Hall Shrine, which boasts 10 temples throughout the state. (The Scottish Rite is made of several consistories; the York Rite includes eight active chapters.) Additionally, many of those groups include women’s auxiliaries, such as the Order of the Amaranth and the Imperial Court Daughters (formerly known as the Daughters of Isis). In the latter case, there exists one court, or branch, in

California: Egyptian Temple № 5 in Los Angeles. Other states also have women’s groups unique to Prince Hall Masonry, such as the Order of Cyrene Crusaders, the Heroines of Jericho, and youth orders including the Knights of Pythagoras.

This arrangement can create a dizzying array of logos and acronyms at big events. (AEAONMS is the full name of the Prince Hall Shrine, for instance.) But, as Carney says, “It’s all under one umbrella.”