WINTER 2021-22

CALIFORNIAFREEMASON.ORG

WINTER 2023–24

WINTER 2021-22

CALIFORNIAFREEMASON.ORG

WINTER 2023–24

offers an opportunity to stimulate your mind, friends, strengthen your body, and eat well. As the Center for Successful Aging in the region, we leading research to redefine what it means to age.

WINTER

2 SNAPSHOT

The California Masonic Foundation goes back to school for a high-tech update on shop class.

4 EXECUTIVE MESSAGE

Grand Master Sean Metroka reflects on his hopes for the year to come.

5 THE MOSAIC

For 77 years, the Chinese Acacia Club has provided a home away from home [page 5] ; meet a tattoo artist specializing in Masonic ink [page 8]; why do Masons celebrate two Saints John? [page 9]; at an Oakland lodge, Burns Supper is a big date on the fraternal calendar [page 10]; how a new gift is reshaping vocational education in San Diego [page 12]; a new exhibition explains the groundbreaking illustrations in a 300-year-old manuscript [page 13]; how a century-old lodge boom is still reverberating today [page 14]; a Masonic trip to Hungary forges connections across borders [page 15]; and more.

33 MASONIC ASSISTANCE

Don Goldberg and Santa Barbara № 192 have an uncommon commitment to Masonic outreach.

36

How a love of the outdoors inspires one SoCal Mason to give back.

22

The political fights that dominate so much of daily life are conspicuously absent from Masonic lodge rooms. But can the lessons of Freemasonry be replicated in the outside world?

24 WHAT’S IN A NAME

29 BAND OF BROTHERS

expert on “manliness” explains how to discuss these tricky topics.

When a monument to his grandfather came under newfound scrutiny, one Bay Area Mason used the opportunity to shine a light on a lesserknown familial legacy.

How a Native American Masonic degree team forges bonds across cultures—and keeps a heritage alive.

IN EVERY ISSUE

DONOR PROFILE

ON THE COVER ILLUSTRATION BY FRANK STOCKTON

2023–24 72 01 VOL NO BLAZE NEW 34400 Mission Blvd., BLAZE NEW 34400 Mission Blvd., 34400 Mission Blvd., Union City, CA 94587 RCFE 015601302 COA #246 Available on an assignment of assets or entry fee contracts. PHOTO BY WINNI WINTERMEYER

and

TALKING SHOP Politics, religion,

money: An

16

acaciacreek.org | (877) 902-7555 acaciacreek.org | (877) 902-7555 acaciacreek.org | (877) 902-7555 Call now to schedule your complimentary lunch and tour of our bay-view apartment homes. Masons, wives, and widows receive a 10 percent discount on monthly fees and entrance fees. acaciacreek.org | (877) 902-7555

Available on assignment of assets or pay-asyou-go basis.

SNAPSHOT 10/09/2023 | 10:56 A.M.

Getting Schooled

WHEN CALIFORNIA MASONIC FOUNDATION president Douglas Ismail arrived at Madison High School to announce a new $390,000 gift from the Foundation to the San Diego Unified School District to expand its building trades and automotive repair programs, he’d prepped for questions about the nature and mechanics of the grant. He just hadn’t expected them to come from the TikTok generation, as happened when he was interviewed by the school’s broadcast news team. No matter. He and fellow leaders from the fraternity and the school district were happy to explain the transformative potential of the gift, which will help expand the district’s college, career, and technical education programs. “Having access to CCTE programs as a part of a high school curriculum enables students to understand that there is a strong pathway to a stable, living wage outside of a four-year-college program," Ismail said. Read more about the grant on Page 12. —IAN A. STEWART

CALIFORNIA MASONIC FOUNDATION PRESIDENT DOUGLAS ISMAIL ANSWERS QUESTIONS FROM STUDENT JOURNALISTS AT MADISON HIGH SCHOOL IN SAN DIEGO DURING AN EVENT ANNOUNCING A NEW THREE-YEAR, $390,000 GIFT TO EXPAND ITS COLLEGE, CAREER, AND TECHNICAL EDUCATION PROGRAMMING.

PHOTO BY MATHEW SCOTT

EXECUTIVE MESSAGE

WHAT REALLY MATTERS

Finding common ground in a turbulent time.

I’m very excited to share my first message as Grand Master.

As many of you know, I served in the Marines for 32 years, including in Iraq and Kuwait. In that time, I met people from all around the world—different backgrounds, religions, and beliefs. Despite our many differences, I found that we all shared some basic similarities. We all want the best for our families. We all want to be safe. We all want happiness.

Over the years, I’ve found many similarities between my military service and Masonry. One of them is that bond of friendship. When I returned from my last deployment in Iraq, I was able to have conversations with my lodge brothers that just weren’t possible outside the lodge. As in the military, we’d come there from different walks of life, but that shared sense of trust and respect made the lodge a special space. When we’re in lodge, we know we’re among brothers who want to work together, improve ourselves, and better our community.

This issue of California Freemason is dedicated to the common ground that Masons find in lodge—and how the lodge provides the unique context in which our relationships can bloom. When we take things like politics and religion off the table, we find what we really have in common. That’s not to say that politics and religion don’t matter; only that Freemasonry shows us one way of reaching beyond them and seeing what we share with people who may not seem very much like us. Is that something we can replicate outside the lodge? I like to think so. The principles of Freemasonry shouldn’t be confined to just the lodge room. Finding common ground with people who hold different beliefs is a powerful tool for fostering understanding and building a more harmonious world. It’s how we can build a world in which people coexist peacefully, respecting each other’s differences while working together for the greater good.

I think that’s one of the most important lessons of Masonry, and one I hope we can all spend some time thinking about. Margaret and I wish you and your family a healthy and happy holiday season and a wonderful new year.

G. Sean Metroka Grand Master of Masons in California

G. Sean Metroka Grand Master of Masons in California

EDITORIAL STAFF

Emily Limón, Executive Editor

Ian A. Stewart, Editorial Director

Isabelle Guérin, Managing Editor

Pete Ivey, Creative Director

J.R. Sheetz, Multimedia Editor

Justin Japitana, Assistant Editor

John Dale, Online Editor

PUBLICATION COMMITTEE

G. Sean Metroka, Grand Master

Russell E. Hennings, Editor-in-Chief and PM, Saddleback Laguna № 672

Allan L. Casalou, Grand Secretary and PM, Acalanes Fellowship № 480

Ian E. Laurelin, South Pasadena № 290

Dagoberto Rodriguez, PM, South Pasadena № 290

Emanuel A. Rose, PM, Humboldt № 79

James L. Tucker, PM, Logos № 861

OFFICERS OF THE GRAND LODGE

Grand Master: G. Sean Metroka, Nevada Lodge № 13

Deputy Grand Master: Arthur L. Salazar Jr., Irvine Valley Lodge № 671

Senior Grand Warden: Garrett Chan, California № 1

Junior Grand Warden: Ara Maloyan, Santa Monica-Palisades № 307

Grand Treasurer: Charles P. Cross, Metropolitan № 352

Grand Secretary Allan L. Casalou, Acalanes Fellowship № 480

Grand Lecturer: Ricky L. Lawler, Elk Grove № 193

CALIFORNIA FREEMASON

ISSUE 01 • VOLUME 72 • WINTER 2023–24

USPS #083-940 is published quarterly by the Masons of California. 1111 California Street, San Francisco, CA 94108-2284. Periodicals Postage Paid at San Francisco, CA and at additional mailing offices.

Postmaster: Send address changes to California Freemason, 1111 California Street, San Francisco, CA 94108-2284.

Publication dates are the first day of March, June, September, and December.

Subscriptions: California Freemason is mailed to every member of this Masonic jurisdiction without additional charge. Others are invited to subscribe for $12 a year or $15 outside the United States.

Permission to reprint: Permission to reprint original articles in California Freemason is granted to all recognized Masonic publications with credit to the author and this publication.

Phone: (800) 831-8170 or (415) 776-7000

Fax: (415) 776-7170

Email: editor@freemason.org

FIND US ONLINE

» californiafreemason.org

» facebook.com/MasonsofCalifornia

» twitter.com/MasonsofCA

» youtube.com/CaliforniaMasons

» instagram.com/MasonsofCA

MEMBERS OF THE CHINESE ACACIA CLUB AT A MONTHLY MEETING AT TAI WU RESTAURANT IN MILLBRAE.

PHOTO BY WINNI WINTERMEYER

A Legacy Overlooked

FOR 77 YEARS, THE CHINESE ACACIA CLUB HAS CREATED A SPACE FOR MEMBERS OF A HISTORICALLY UNDERREPRESENTED GROUP. BY BRIAN ROBIN

O ne hundred and one years ago, the first plans were drawn up to form a lodge for Chinese American Masons in California. At the time, there were at least 20 members of Chinese ancestry living in the Bay Area, and the idea to band together into their own lodge was raised at the highest levels of the fraternity. However, rather than form a brand-new “ethnic lodge” (as the French La Parfaite Union № 17 had in 1852, the German-speaking Hermann № 127 had in 1858, and Loggia Speranza Italiana № 219

had in 1872), leaders including Grand Master William A. Sherman instead proposed a plan to affiliate Chinese members en masse with an existing lodge, Educator № 554. Once enough Chinese Masons had joined to fill the officers’ ranks, the plan was for the charter members of the group to withdraw from the lodge.

Given the time and place, it was a bold plan. From their arrival in the mid-19th century, Chinese immigrants in California, and particularly in San

5 4 WINTER 2023–24

▼

Covering California Freemasonry

S E O H

HISTORY

Francisco, experienced profound discrimination. That included having their testimony disallowed in court, enduring frequent police raids targeting low-paid laborers, and suffering the exclusion act that prohibited almost all immigration and naturalization for more than 50 years.

The plan for a Chinese lodge, as it turned out, was perhaps too far ahead of its time. The rules of Masonry have always stipulated that candidates cannot be denied membership on the basis of their race or religion, but the reality is that the fraternity has always reflected the world around it.

(The first Hispanic lodge in California wasn’t formed until 1959, almost 40 years later; the first Filipino lodge came a year after that.) Unsurprisingly, then, when the 1922 Chinese plan was reviewed by Grand Lodge inspectors, “It met too much criticism and had to be abandoned,” according to John Whitsell’s history of the fraternity.

A century later, there still isn’t an explicitly Chinese lodge in California. In its place, though, another kind of fraternal home has emerged: the Chinese Acacia Club. Decades after the Educator

“So many of the members when I was younger were like grandparents to me.”

Lodge matter seemed to close that door, another one opened. It began as many social organizations do: as a response to not having a place of one’s own—a chance to build your own house.

Today, the Chinese Acacia Club stands as a testament to the history and contributions of Chinese and Chinese American Masons in California, and also as a gathering place for members who remain part of a demographic minority within the fraternity. “It’s an extended family,” says Garrett Chan, a member of California № 1, the current senior grand warden of the Grand Lodge of California and an active member of the club. “I can call any one of our brothers to take care of my family. They’re

later, the 30 charter members met at the Shanghai Low Café, where the stated purpose of the club was read as part of the bylaws: “To promote and foster a true and sincere Masonic spirit of good fellowship, of mutual helpfulness, of closer relationship among its members and the maintenance of a degree team to further exemplify the great ideals and precepts of Freemasonry.”

What wasn’t spelled out there— but has always been central to the group—was to provide a network of support for the relatively small cohort of Chinese Masons.

always there to help and you can talk to them about anything—if you need advice, if you need a shoulder to cry on, if you need someone to bounce ideas off.”

The club was formed in 1946, initially as a special traveling team trained to confer degrees on fellow members of Chinese descent. The group held its first meeting at the Universal Café in San Francisco on April 12, 1946. It staged a rehearsal after dinner and, 10 days later, raised Wilbur D. Yee to the sublime degree of Master Mason at Justice № 547.

Soon, the club took on a more formal structure. On May 7, 1946, the club’s officers were elected and a constitution was drafted, with Dr. Chang Wah Lee chosen as its first president. A month

As a matter of fact, California and China do share some Masonic DNA. (Although, somewhat confusingly, members of the longstanding San Francisco Chinatown club known as the Chee Kung Tong are often referred to as Chinese Masons, although they have no connection with the fraternal order.) Before the 1930s, the few Masonic lodges to operate in China tended to be organized among American and European expats; in later years, a group of six Chinese lodges came under the jurisdiction of the Grand Lodge of the Philippines—which had received its own charter from the Grand Lodge of California. In 1943, a group called Fortitude Lodge, made up of American servicemen and Chinese nationals, received a dispensation from California to organize in Chungking, though it folded just two years later. In 1949, the former Philippine lodges reorganized in Shanghai as the Grand Lodge of China. That continues to operate today, although it has experienced periods of darkness and operated underground during the

Cultural Revolution. Stateside, the number of Chinese members has grown in California lodges. (Today, an estimated 9 per cent of California members are of East Asian descent.) The Chinese Acacia Club has evolved, too. These days, it counts two past grand masters as current or former members: Leo B. Mark, grand master in 1987, and Frank Loui, in 2011. Chan, as a current Grand Lodge officer, could soon be the third. In 1985, like his father and brother before him, he was raised as a Mason by the club’s traveling degree team. “So many of the members when I was younger were like grandparents to me,” Chan says. “Sometimes there were things either in business or life that I needed someone to ask about, and there was always someone there.” They’ve also made a point of being there for their neighbors. Since 1982, the club has given out yearly college scholarships to high school seniors—gifts that have grown to become the club’s main purpose and legacy. Along

ALL MEN ARE BROTHERS.”

with excellent grades, Chan says recipients are chosen for their community service. “Even putting aside their scholastic achievements, they’re volunteering to help needy kids or needy elders. These kids are pouring out their souls to help others, and we want to make sure they are rewarded for their efforts.”

Service. Purpose. Legacy. Those values still define the Chinese Acacia Club. While the group has shrunk from a high of 350 members to today’s roster of about 50, little else about it has changed. Members still meet once a month at the Scottish Rite Valley in San Francisco, enjoy periodic social events, and pay a princely $12 a year in dues. “We haven’t raised that in a while,” says Loui with a chuckle.

While the meetings remain simple, “The real fun is what happens afterward,” he says—often a group meal at a Chinese restaurant. “That’s where the bonding occurs.”

Chan says that bonding is the key to the club’s existence—it’s what unlocked those doors so many years ago and has turned into a legacy of service. Says Loui, “We’ve been in existence 77 years and we’re still going. We’re still doing our part.”

6

MEMBERS OF THE CHINESE ACACIA CLUB OVER THE YEARS. TODAY THE GROUP NUMBERS ABOUT 50 MEMBERS.

A SCROLL FEATURES THE NAME OF THE CHINESE ACACIA CLUB AND THE PRESIDING GRAND MASTER. IT READS: “WITHIN THE FOUR SEAS,

WINTER 2023–24 S E O H M T A C I COURTESY OF CHINESE ACACIA CLUB 1,500 1,000 500 7 IT’S A PARTY! TOTAL REGISTRANTS FOR THE 173RD ANNUAL COMMUNICATION IN 2023. THAT’S THE HIGHEST ATTENDANCE SINCE 1996. 2023 2022 2019 2017 2015 2013 2021 2018 2016 2014 2012

1,757

Rene Ceniceros

California Freemason: I understand you’re an expert on Masonic tattoos.

Rene Ceniceros: I’ve been tattooing for 16 years; I’m mostly known for my black and gray and fineline work. During the pandemic, I started my own clothing line, Sanctum Secretum, with a lot of my Masonic tattoo designs and imagery. One of the reasons I like doing Masonic tattoos for brothers is that since I’m a Mason, they don’t have to explain these symbols’ meaning to me or give away any secrets. I’ve even corrected some Masonic tattoos where there’s a missing detail or something’s pointed the wrong direction.

CFM: What are the most common Masonic tattoos you’ve done?

RC: Square and compass tattoos are the most popular, but I try to grease it up—add my own design. I’ve also done a few sleeves with allegories from the first, second, and third degrees. I’ve done some Shriner tattoos, some sacred geometry designs. I’ve also tattooed people with their lodge logos, and I’ve even helped create logos for a few lodges. I made a design for Martinez № 41. Apparently, it’s the home of the martini, so the design had a martini glass in it.

CFM: Do you see a connection between Masonry and your artwork?

RC: I think tattoos are like a rite of passage. You’re going to be a Mason as long as that tattoo is around. We see them as a reminder, too—a representation of something greater than us. Also, if you’re a brother and you see someone with an obscure Masonic tattoo, you give them a nod or a look.

CFM: And I’ve heard you’ve even given some tattoos in Masonic lodges, right?

RC: Yes, in September our lodge hosted a Tiki Tattoo social event. We had three tattoo artists, including me, from different lodges come out. We created some Masonic designs in advance, people chose one, and we’d tattoo them on the spot. I didn’t

expect it to take off, but it did. We probably tattooed 20 people that day. And since it was open to families and friends, we even tattooed some of the wives.

CFM: What would you say was the goal of those events?

RC: Besides bringing brothers together for a good time, these events are our way to engage with a younger crowd. By hosting really unique events, we break the stigma that Masons are just stuffy older guys. I even designed the flyers. When people see a cool event that’s out of the ordinary, or even a curious-looking flyer, they’re more likely to show up.

“Square and compass tattoos are the most popular, but I try to grease it up—add my own design.”

CFM: What’s it like knowing your designs are going to be on someone’s body permanently?

RC: Tattooing is a very personal interaction, especially as it’s a profession where you’re allowed to touch another human. It lowers a person’s walls. I get to hear their whole life story, and not just through Masonry. It’s always awesome to tattoo a brother—and yeah, it’s also nerve-racking.

CFM: How did you first learn about Freemasonry?

RC: I’ve known about the craft since I was a child. I think I was 12 when I first saw that episode of The Simpsons about the Stonecutters. At my grandfather’s funeral I noticed his Masonic ring, and I asked my uncle about it. He told me to ask him again when I turned 18. So Masonry was always in the back of my head. It turns out my family in Tijuana is actively involved in Masonry, so I plan to visit some lodges there when I get the chance.

CFM: What do you most enjoy about being a Mason?

Dear Johns

WHY DO MASONS RECOGNIZE THE TWO SAINTS JOHN?

FREEMASONRY HAS MANY unexplained mysteries in its ritual, one of which is the reference to the “Holy Saints John,” whom Masons around the world recognize as their patron saints with feast days on June 24 and December 27. But why St. John? And why two?

There isn't a single answer. One theory is that in John the Baptist (the “forerunner” of Jesus) and the apostle John (called the “Evangelist” for his authorship of the Gospel of John in the New Testament), the figures embody the dual nature of Masonry: the passion of the baptist and the faith of the apostle. (Underscoring that duality, their feast days align closely with the summer and winter solstice.)

RC: A little bit of everything. The camaraderie, the teachings, the esotericism. As a parent raising two young men, Masonry has helped teach me patience and understanding. Also, being with like-minded people, I’m able to connect with brothers who are also parents, and it’s great to share insight with them about parenting and ultimately how to raise our kids to be better than us. —Justin

Other people say the custom came from the practice of Masons taking their obligations on a Bible opened to the first chapter of the Gospel of John. The “word of God” referred to in that chapter echoes the “Mason word” referenced in the ritual. In tilers’ registers from the 18th century, some members even referred to themselves as “St. John’s Masons.” From that, we can assume that the connection to the “Holy Saints John” in the Masonic ritual originated with St. John the Evangelist. And we can assume that the reference to St. John the Baptist as the second patron saint of Freemasonry came later. None of this can be proven, of course. But I think it’s as good a guess as any.

—JOHN COOPER, PGM

Japitana

WINTER 2023–24 8 9 S E O H M T A C I

Islands No 214

since 2015 Tattoo artist and clothing designer MEMBER PROFILE

Channel

Member

PHOTOS BY MATHEW REAMER ABOVE RIGHT: COURTESY OF MUSEO NACIONAL THYSSEN-BORNEMISZA

RENE CENICEROS AT WORK IN HIS LOS ANGELES STUDIO.

Watch Online SEE A VIDEO FEATURE ON ST. JOHN’S FEAST DAY.

SYMBOLOGY

“Most People Treat It Like a Dare”

HARMONY AND HAGGIS AT A MASONIC BURNS NIGHT SUPPER.

It may be the star of the meal, but even at the yearly Burns Supper at Oakland’s Academia Lodge № 847, where members gather to remember the legendary poet, Scottish national hero, and proud Freemason Robert Burns, master Ben Brookshire admits that there are some who approach the haggis with a bit of skepticism. “Most people treat it like a dare,” he says of the infamous dish.

Haggis aside, the members of Academia № 847 (led by the late Arthur Porter, seen at far right) have wholeheartedly embraced Burns Night as a special date on the fraternal calendar. Burns, who was raised in 1781 in St. David’s № 174 in Tarbolton, in South Ayrshire, Scotland, is recognized by Scots around the world on January 25 each year with a feast that bears a great

resemblance to a Masonic festive board. From the ritual piercing of the haggis to recitations of classic Burns songs and poems like “A Red, Red Rose” and “Auld Lang Syne,” the classic dinner program follows a wellworn itinerary. Here, Brookshire explains how the lodge recognizes the poet laureate of the lodge.

—Ian A. Stewart

PIPING IN THE GUESTS

Traditionally, attendees are welcomed into the event with music from a bagpiper.

“We do have a piper, but the tradition at Academia is that it’s always kind of a disaster,” Brookshire says with a laugh.

“He’s always late, or sick, or something else is wrong. You know how people say, ‘What if it rains?’ Our joke is, ‘What if something goes wrong with the piper? Oh, it will.’”

ADDRESS TO A HAGGIS

The haggis, the centerpiece of the meal, is marched in as special guest recites the poem “Address to a Haggis.”

“Finding haggis is tricky. For years, I’d drive up to Dixon to the legendary Alex Henderson of the Scottish Meat Pie Company, before he passed away. He used to include the ‘full tuck.’ That’s part of the sheep’s lung. Anyway, that’s my standard. Now I use a shop in Berkeley. That’s as close as I’ve come to Alex’s.”

THE SELKIRK GRACE

The event host welcomes and introduces guests and reads a short Scots prayer to usher in the meal.

“Acting as the chairman of the Burns Night is sacred for me.

I’m proud of being master of the lodge, of being a 32nd degree, but one of the things I’m most proud of is being chairman of the dinner.”

culinary end up in his wheelhouse. He takes the food very seriously. For the cock-a-leekie, he puts a sort of classic, Eastern European Jewish spin on it. It’s really delicious and very much in the spirit of the thing. For people who don’t want the haggis, we’ve had venison or different things, too. Sometimes salmon—a good Scottish fish.”

ENTERTAINMENT

Guests recite Burns’s poems and songs, often including “To a Mouse,” “Tam o’Shanter,” and others.

“We usually have someone read ‘Green Grow the Rashes.’ I like ‘A Man’s a Man for a’ That.’ We’ve never had anyone read any of Burns’s Masonic poems, such as ‘A Farewell to the Brethren of St. James Lodge,’ or ‘The Mason’s Apron.’ We should, though.”

TOAST TO THE LASSIES

Traditionally, a male guest recognizes the women in attendance with a good-natured and humorous speech.

“It’s not exactly Toastmasters, but people show their wit and usually live up to the occasion.

THE MEAL

A traditional Burns Supper includes, along with the haggis, “neeps and tatties” (mashed turnips and potatoes), “cock-a-leekie” (chicken soup), and more—with generous helpings of whisky.

“We are blessed at Academia to have a self-described foodie in Jonathan Hirshon, who runs a blog called the Food Dictator. He’s a true gourmet. So all things

For Academia, we’re not one of those lodges where families are involved all the time. It’s the one big night where our families come out, so for us it’s special.”

AULD LANG SYNE

The event closes with the singing of Burns’s most famous song—a staple of New Year’s and Masonic gatherings around the world.

“Even before that, we always sing ‘Scot’s Wha Hae,’ then we go into ‘Auld Lang Syne.’ Everyone holds hands around the horseshoe table. Ironically, we do the Chain of Union at our lodge meetings and at the end of degrees, but not at Burns Night. Maybe we will this year.”

11 WINTER 2023–24 10

S E O H M T A C I REFRESHMENT

PHOTOS COURTESY OF JONATHAN HIRSHON; ILLUSTRATIONS: ALAMY

IN

OF THE LATE

MEMBERS OF ACADEMIA № 847 INSIDE THE LODGE ROOM. THE GROUP HOSTS AN ELABORATE ANNUAL BURNS SUPPER EACH JANUARY, HELD

HONOR

ARTHUR PORTER (ABOVE).

All Revved Up

A NEW GIFT FROM THE MASONS IS HELPING KIDS GO UNDER THE HOOD. BY

IAN A. STEWART

As Grand Master Randy Brill spoke this October to the crowd of teachers, school administrators, and students gathered to celebrate a major new gift from the Masons of California to the San Diego Unified School District, all eyes kept turning to the giant blue and yellow rocketship parked just behind him.

Well, not a rocketship, exactly. “Little Giant,” as the vessel is known, is the current electric landspeed record holder, at 353 mph. Working through a novel automotive technology program at Madison High School, more than 100 students have been busy rebuilding the behemoth, which is powered by more than 1,100 prismatic lithium-ion batteries.

The race car was a fitting visual reminder that this isn’t your grandpa’s shop class. Thanks to the district’s College, Career, and Technical Education program, students at Madison High can get

Symbolic Gesture

A NEW EXHIBITION SHINES A LIGHT ON A HISTORIC MASONIC ARTWORK CHOCK-A-BLOCK WITH FRATERNAL MEANING.

If a picture’s worth a thousand words, then what’s a never-before-seen glimpse into the symbology of a secret and mystical fraternal order worth? That’s the question at the heart of a new exhibition from the Henry Wilson Coil Library and Museum of Freemasonry, Illustrations of Masonry. The exhibition breaks down the illustrated engravings by artist John Pine that adorn the frontispiece of James Anderson’s 1723 Constitutions of Free-Masonry, the first-ever rulebook for the organization. Before its printing, these symbols had never been seen before.

On the 300th anniversary of its publication, museum director Joe Evans explains these depictions were so groundbreaking. IAS

THE SUN GOD APOLLO IN CHARIOT

“APOLLO IS THE REPRESENTATION OF CLASSICAL LITERATURE AND KNOWLEDGE. YOU COULD ARGUE THAT, AT THAT TIME, THE MASONIC LODGE WAS ONE OF THE ONLY PLACES THAT KNOWLEDGE WAS BEING KEPT. AT THE END OF THE RENAISSANCE, THAT WAS REALLY ATTRACTIVE TO PEOPLE.”

hands-on training in automotive, mechanical, and building trades, including cutting-edge and emerging fields like electric vehicle repair.

And now they’ll be able to bring even more of that career-readiness programming to students throughout the region. The California Masonic Foundation in September pledged $390,000 over three years to the district to expand its CCTE program. That includes launching a five-week Saturday program focused on automotive systems, diagnostics, and repairs, as well as a five-week summer course. The grant will also help fund additional staffing for the program.

The curriculum is intended to show students that there’s more than one path to a well-paid career, says California Masonic Foundation president Doug Ismail. “Many people still have the antiquated view that the only way to have a successful career is through a four-year-college program,” Ismail says. “Having access to CCTE programs enables students to understand that there is a strong pathway to a stable, living wage outside of a four-year program.”

According to local projections, San Diego County expects 190,000 job openings in the construction and automotive trades through 2030.

TWO FIGURES AT CENTER

JOHN, THE SECOND DUKE OF MONTAGU (GRAND MASTER 1721–22), WITH HIS DEPUTY AND WARDENS HANDING THE CONSTITUTIONS TO HIS SUCCESSOR, PHILLIP, DUKE OF WHARTON (GRAND MASTER 1722–23).

“THIS IS WHERE THE FRATERNITY MOVES INTO THE ARISTOCRATIC REALM, AWAY FROM THE GUILDS AND TRADESPEOPLE. ONCE THE FIRST GRAND LODGE WAS ESTABLISHED IN 1717, YOU SAW ELITES COMING IN AND THAT BECAME ATTRACTIVE TO OTHER ELITES; THAT’S HOW YOU GET YOUR PHILOSOPHERS AND PROFESSIONALS INTERESTED. THAT’S WHY SEEING THESE FIGURES IS SO IMPORTANT.”

MAN CARRYING APRONS

“THIS BOOK’S PUBLICATION REPRESENTS THE FIRST TIME ANYONE HAS SEEN MASONIC REGALIA DEPICTED LIKE THIS. BUT PEOPLE WOULD RECOGNIZE THAT THIS IS ABOUT RITUAL AND SPECIAL REGALIA. IT’S A BIG DEAL IN THE 17TH AND 18TH CENTURY— IT TELLS PEOPLE YOU BELONG TO A SPECIAL GROUP.”

COLUMNS REPRESENTING THE ORDERS OF ARCHITECTURE

“MASONS WHO’VE GONE THROUGH THEIR INITIATION WILL RECOGNIZE THIS FROM THE LECTURE IN THE SECOND DEGREE. THEY GO IN DESCENDING ORDER: DORIC, IONIC, CORINTHIAN, TUSCAN, COMPOSITE.”

THE 47TH PROPOSITION OF EUCLID

“THIS IS WHERE THE GEOMETRY PART COMES IN. IT’S ONE OF THE REASONS MASONRY WAS ATTRACTIVE TO PEOPLE DURING THE AGE OF REASON. THE MASONS WERE SOME OF THE ONLY PEOPLE WHO’D MASTERED THESE LIBERAL ARTS. WITHIN A LODGE, MASONS WERE TEACHING APPRENTICES ABOUT GEOMETRY, MATHEMATICS, HOW A PLUMB WORKS—IT WAS LIKE GOING TO SCHOOL. NOT A LOT OF PEOPLE REALIZE THAT’S WHY LODGES WERE SO ATTRACTIVE.”

COURTESY OF THE HENRY WILSON COIL MUSEUM & LIBRARY OF FREEMASONRY

13 WINTER 2023–24 12 S E O H M T A C I

PHILANTHROPY

PHOTO BY MATHEW SCOTT

MASTER RANDY BRILL ANNOUNCES A NEW GIFT FROM THE CALIFORNIA MASONIC FOUNDATION TO THE SAN DIEGO SCHOOL DISTRICT.

GRAND

ON DISPLAY

Centennial Salute

A SURGE OF NEW LODGES 100 YEARS AGO CONTINUES TO REVERBERATE TODAY.

BY IAN A. STEWART

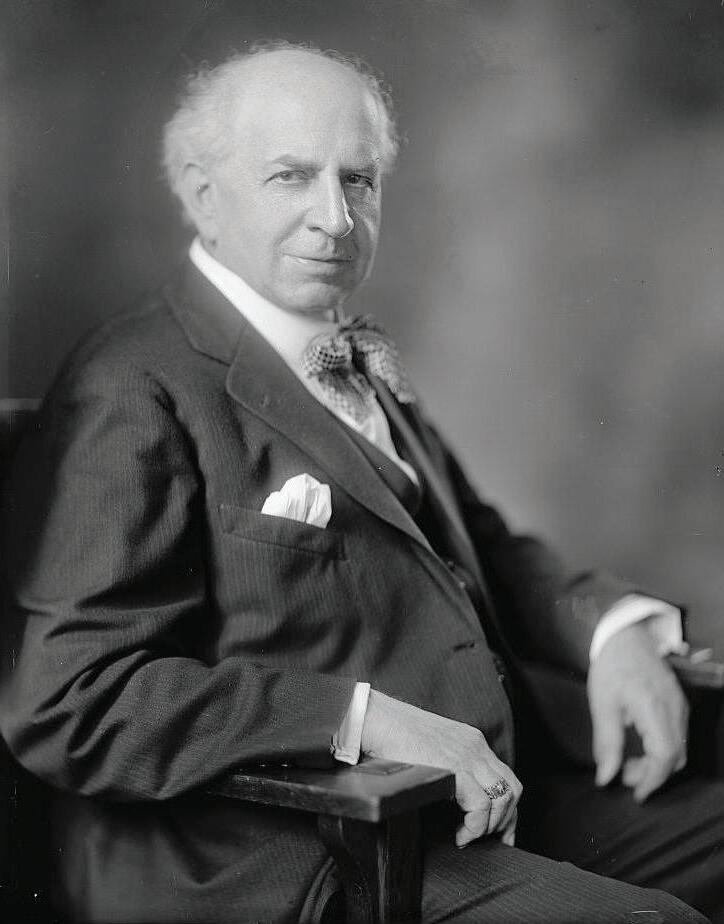

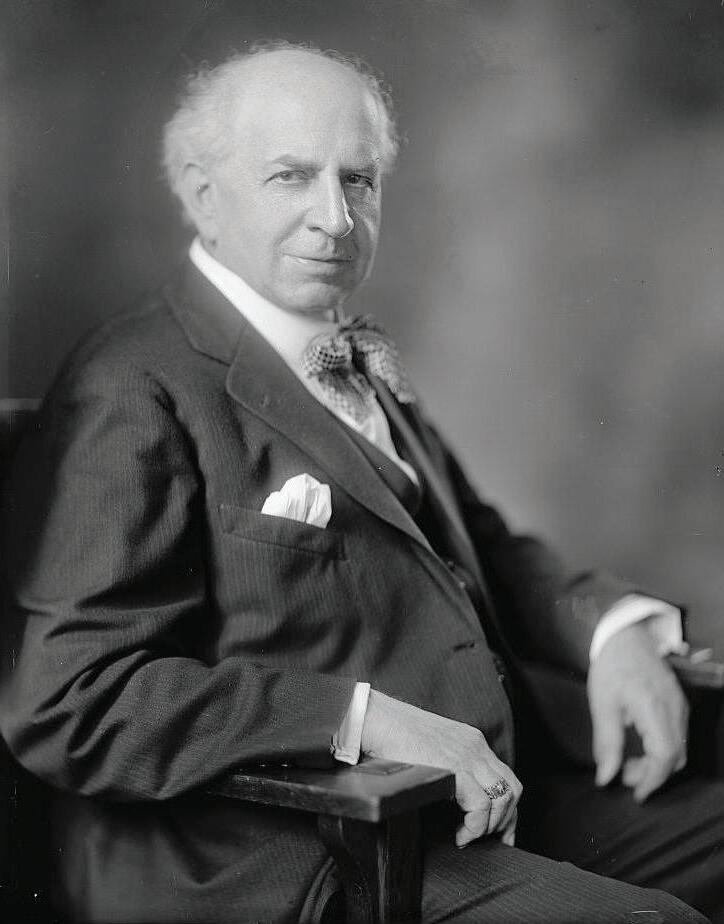

A s his term as Grand Master of California came to a close in the fall of 1923, Arthur Saxe Crites tallied up his travels for the year: In all, he’d logged some 38,000 miles, the result of so many trips around the state for cornerstone events, officers’ installations— and especially new lodge openings. That year, Crites granted a whopping 39 charters to newly formed lodges. In 1924, his successor would grant another 30. Of those, 54 are either still active or part of a consolidated lodge.

A century later, the fraternity is still feeling the ripple effect from that eruption of Masonic activity, in the form of almost nonstop centennial celebrations. Consider: In October 2023 alone, Pacific Rim № 567, Sunnyside № 577, Crow Canyon № 551, and Ross Valley № 556 all recognized 100th anniversaries.

That’s because new lodge development in California peaked in the years between 1922 and 1925, the result of an influx of new members during the

interwar years and a concerted effort by the Grand Lodge to promote new and smaller lodges.

“The smaller lodge … encourages a greater proportion of attendance,” wrote Grand Master David Reese in 1924.

California Masons today may detect a note of familiarity there, as small, intimate lodges have come back into vogue. It’s not the only way in which the echoes of time are ringing out, says Bob Jackson, secretary of Harding San Juan № 579. Over the summer, his group recognized the 100th anniversary of Warren J. Harding Lodge in Sacramento with a celebration and the publication of a lodge history. Many of the challenges facing Masons

a century ago weren’t so dissimilar from today’s, he says— not the least of which was the recovery from the great influenza epidemic.

Emmanuel Rafisura, master of Crow Canyon № 551, chaired his group’s centennial this fall, for which the lodge also produced a history booklet. (Like many lodges today, Crow Canyon is an amalgamation of eight consolidated East Bay outfits; two of those, Lakeshore № 551 and Chateau Thierry № 569, were chartered in 1923.) He, too, marveled at the ways in which Masons a century apart expressed concerns about similar issues—membership, ritual quality, community relations—while acknowledging that his lodge often meets in the decidedly 21stcentury forum of Zoom.

Driving that theme home, as part of the lodge’s centennial, members of Crow Canyon opened a time capsule that had been placed in the Castro Valley Masonic Center when that temple was built in 1985. In it, they found newspapers, correspondence from the Masonic youth orders, and several Susan B. Anthony coins.

Looking forward, Rafisura says the lodge plans to replace the capsule, with a few modern additions. “We’ll add some c ovid tests,” he says with a chuckle.

More Online

Behind the Iron Curtain, a Masonic Brotherhood

A MASONIC TOUR TO BUDAPEST SHOWS MASONRY STEPPING OUT OF THE UNDERGROUND.

WHAT BEGAN AS A CHANCE encounter turned into a trip of a lifetime this summer for a traveling team of California Masons.

In September, a Masonic tour group from South Pasadena № 290, Alhambra № 322, Wisdom № 202, and Pasadena № 272 traveled to Budapest, Hungary, to meet with brothers from a world away. For most of the past 100 years, Freemasonry there has existed underground, having only been legalized in 1989. Today the Symbolic Grand Lodge of Hungary comprises 17 lodges and 400 members.

The seed for the trip was planted a year earlier, during a tour to England, during which District № 717 inspector Paul Bazerkanian and others were introduced to the current Grand Master of Hungary, Andor Àkos Szilágyi, who invited them to visit a degree conferral in Budapest.

So this year they did just that, sitting in on a first-degree conferral led by Iván Kamarás of Kazinczy Lodge № 15. (Interestingly, Kamaras was raised as a Mason at South Pasadena № 290.) The California delegation also staged a third-degree exemplification for their Hungarian hosts. The visit concluded with a symposium led by Attila Pók, a Mason and historian at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences; and representatives from the grand lodges of Croatia, Slovenia, Romania, Austria, the Czech Republic, and Colombia.

Esteban Lopez, a member of the tour group, was impressed by the commitment to Masonry on display. “Even under all current circumstances, people are still willing to come together to practice Masonry,” he says. Bazerkanian says his party forged relationships he expects will last a lifetime. “They’re already talking about going back,” he says. —JUSTIN JAPITANA

WINTER 2023–24 14 HISTORY

PHOTOS BY WINNI WINTERMEYER RIGHT: COURTESY OF ESTEBAN LOPEZ

MEMBERS OF CROW CANYON № 551 CELEBRATE THEIR LODGE’S CENTENNIAL IN OCTOBER, INCLUDING OPENING A TIME CAPSULE FROM 1985.

A CENTURYOLD BOOM

30 40 20 10 1919 1920 1921 1922 1923 1924 1925 1928 1926 1927 1929

New lodge openings peaked in the middle of the 1920s.

S E A C I O H M T 15

VIDEO HIGHLIGHTS OF THE CENTENNIAL CELEBRATION.

TRAVELODGE

FROM LEFT: PAUL BAZERKANIAN, IVÁN KAMARÁS (MASTER OF KAZINCZY LODGE № 15 IN HUNGARY), HUNGARIAN GRAND MASTER ANDOR ÀKOS SZILÁGYI, DENNIS YEN, AND RON LEWIS.

The world is an increasingly bitter and divisive place. Can Masonry hold the key to unlocking a new paradigm?

BY TONY GILBERT

BY TONY GILBERT

17 ILLUSTRATION BY FRANK STOCKTON

RIVING TO LODGE dinner, the news playing on the car radio is focused on the conflict in Israel and Gaza. There are also updates on Ukraine, book bans, and protests on college campuses. National strikes, gas pipeline development, housing battles, a debate over rising crime. Then there’s the election, for which the lodge will transform into a neighborhood polling place in less than a year’s time.

None of that comes up during the dinner. The Masons gathered here shake hands, smile, and exchange pleasant banter about their kids, an upcoming lodge barbecue, and the football season. At the end of the night, everyone piles back into their cars to drive home, the airwaves full again of nonstop news coverage.

One of the most famous—and famously difficult— maxims of Freemasonry is that politics and religion shouldn’t be discussed in lodge. The benefits are obvious: preserving a sense of harmony and cooperation among people from a wide range of backgrounds and with a diverse set of beliefs. But in a world in which nearly everything, from your pronouns to your vaccine status, has become a political statement of sorts, the question stands: Can anyone really avoid politics? Should they?

It’s now taken for granted that politics have become hyper-partisan , polarized , and, perhaps worst of all, all-encompassing. A simple conversation today can feel like navigating a minefield, in which erstwhile neutral topics have taken on new dimensions of divisive connotation. Given that reality, can Masons really live up to their ideal any longer? And if so, is there a secret to Masonic engagement that might be replicated outside of the lodge?

For Russ Charvonia, the answer to both is a resounding yes. Charvonia, a past grand master and member of Channel Islands № 214, has taken this issue on directly, launching the Civility Project, a series of talks, resources, and conferences aimed at helping people communicate across political divides. Since 2011, he has led civility workshops for more than 100 lodges and Masonic organizations, and his 2021 book, The Civility Mosaic, uses the framework of Freemasonry—with its working tools symbolizing patience, tolerance, and respect—to describe a new paradigm for how we can “have rational and productive discussions about hard subjects.”

To Charvonia, Masons shouldn’t avoid uncomfortable topics for the sake of politeness. “If our

Masonic forefathers had that attitude, we wouldn’t have a United States as it’s designed today,” he says. In Masonry, there’s a perfect scaffolding to help members engage in precisely those kinds of challenging conversations. “We as Masons are better equipped than any other organization or society that I can think of, including religious organizations, to do this work.”

Anyway, Masons can hardly claim to exist outside the reach of politics. Consider: Among the many issues that the Masons of California line up behind is support for public schools. And yet public schools today are ground zero for many flashpoints in the so-called culture wars, from bathroom bills to critical race theory, to say nothing of larger debates around charter schools, private school vouchers, and historical curricula.

And of course individual Masons have just as deeply held stances on these topics as anyone. So why don’t lodge discussions of Public Schools Month devolve into riotous sideshows? To Charvonia, it’s because Masonry incorporates elements of reasoned debate into its core lessons. “Freemasonry, in its lowest common denominator, is a means of teaching us to treat others with dignity and respect,” he says. “All the tools, the language, how we operate a lodge room, how we respect and transfer authority—it all boils down to treating others with dignity and respect.”

Marshall Goodman, of Lakewood № 728 in Long Beach, has seen that firsthand. As mayor of La Palma, he presided over contentious local debates that ran the gamut from police funding to ordinances over the color of city-approved housepaint (really). When he arrived at lodge, there was no hiding his position on those matters—they were a matter of public record.

And yet his fellow Masons didn’t try to shout him down, as can sometime happen at city council meetings. The lodge existed as a totally separate space— and it is. Because there are a different set of rules.

SO HOW IS IT that Masonry is able to set aside the kinds of vicious political fights that seem to dominate every other part of our lives? It isn’t just about preserving the peace; when it comes to the prohibition against political talk in lodge, there’s a particular historical context to it.

The rules around political and religious talk are a distinctly British Masonic phenomenon. (The United States and many other jurisdictions are derived from the English tradition, and in fact Masonic lodges in many other countries take on a much more distinctly political bent.) When the United Grand Lodge

of England was formed in the early 18th century, the English Civil Wars were still a relatively recent memory. There was clearly an appetite to tamp down political rhetoric within the craft.

In the United States, an additional reason to limit lodges’ political visibility was the rise of the antiMasonry movement and the Anti-Masonic Party in the 1820s and 1830s. Many of America’s earliest leaders were Masons, including many of the Founding Fathers and framers of the Constitution, but that point of pride for the fraternity eventually soured into distrust of the fraternity. For nearly two decades, Anti-Masonry was a powerful third political party and membership in many Masonic lodges plummeted. In that atmosphere, limiting political chatter wasn’t just about polite behavior; it was a matter of basic survival.

To contemporary Masons, there’s a simpler reason to put a lid on such talk: because politics are divisive. “Politics, like religion, divide rather than unify,” says Peter Coe Verbica of Mt. Moriah № 292. Verbica has a somewhat unusual perspective on the issue: He’s a rancher, financial planner, and published poet, and in 2022 he was a candidate for the state Board of Equalization. He is currently chair of his party’s county central committee, a state delegate, and part of his state party’s executive and proxy committees. While his

“Freemasonry, in its lowest common denominator, is a means of teaching us to treat others with dignity and respect.”

political platform is available for anyone to read on his campaign website, he tries to leave that behind when sitting in lodge. “As a practice, Masonry is at its best when politics are set aside and the hand of friendship and brotherly love is extended,” he says.

Or as Maynard Edwards, the host of the Tyler’s Place podcast, puts it, “The minute you’re in the lodge room, the door’s closed and we have a gentleman’s agreement not to discuss those things that are going to divide us. We put those things aside and we show up for the purpose of improving ourselves and our communities.”

The chain of union bonds Masons together. In the absence of such rituals, can members re-create their lessons outside the lodge?

That silence has echoes in the Masonic ritual. Before they take their degrees, new initiates are given time alone to meditate or ponder, in what Masons in some countries still refer to as a chamber of reflection. The initiate quiets his mind and clears a calm space, far away from the mundanities and noise outside the lodge room. The ensuing drama encapsulates the profound beauty and poetry that Freemasonry has to offer. In so many words, it marks the boundary between the profane and the sacred. Why then would we allow something so profane as politics to intrude upon our sacred inner temple?

IF THE INHARMONIOUS topics of politics and religion are verboten in the lodge room, what about the lodge parking lot? Or on the lodge Facebook page? There are clearly practical reasons for keeping distractions to a minimum during lodge meetings and focusing on the business at hand. But Masons interact as much outside the four walls of the lodge as within them.

Charvonia is adamant that Masonry’s strength isn’t in simply making politics taboo. In fact, he encourages Masons to have more difficult conversations, not fewer. “When we get to a point where we bristle at talking about anything that could be politically interpreted, we’re potentially missing out on important conversations,” he says. By opening ourselves to opinions and experiences that are different from our own, we give ourselves the capacity to grow, he says.

19 WINTER 2023–24 18 PHOTO BY MATTHEW REAMER

Masonry provides a useful template for engaging with others outside of the black-and-white (or redand-blue) framework. By taking the structure and strictures of Masonry and re-creating them in the outside world, Charvonia says Masons have a unique opportunity to usher in a new era of civil dialogue. “When I talk to Masons about how we deal with each other upon the square or how we use the compass to keep our passions within due bounds, they agree these are concepts that can work for non-Masons, too,” he says. “We should share these not in the name of Masonry, but because it’s the right thing to do.”

So how can we re-create the Masonic ideal of harmony in the outside world while recognizing that each of us still have our own set of views, values, and experiences that we feel passionately about? Charvonia lays it out like this.

First, set ground rules

Charvonia, who works as a mediator outside of Freemasonry, often jokes with fellow Masons about how much easier life would be if you could carry a gavel around with you and call order to conversations that were getting out of hand. But while that’s probably not going to happen, there are ways to establish rules of decorum regarding emotionally fraught issues. First, he says, suggest that parties agree to certain ground rules in order to maintain productive dialogue. Allow both parties to add more as they see fit. “Most people, if their motives are pure, tend to abide by them,” Charvonia says.

So what are the rules of engagement? Use Masonry as a model: Listen patiently and don’t interrupt. Avoid framing dialogue as an argument. Allow and welcome counterpoints. Keep your passions within due bounds.

Establish shared goals

Verbica, the rancher turned candidate, points out that there’s a wide swath of unclaimed territory between the two political extremes where most people share common ground. In his political life, he says, “Rather than argue with reflexive presumptions, I try to have conversations around economic issues.” That takes the emotional sting out of thorny topics. It also allows people to start from a baseline of shared values. For instance, we all want safe and supportive schools for our children. We may disagree about how to achieve that, but if our North Star is building toward that shared goal, our conversation is building toward something concrete and not simply rehashing partisan points of conflict.

See the person, not just their politics

There is humanity behind someone’s politics, a face behind the mask, an individual within the group, and a name beyond the label. Politics are actually quite transitory. Platforms peter out, adjust, and swing all the time. People change and switch sides. And the causes that people were willing to die for yesterday might be forgotten tomorrow. (Try to pick a fight today about “free silver” and you won’t find nearly as many takers as you might have in 1895.) A person’s politics and worldview will be influenced by their surroundings and circumstances. So perhaps when our first reaction is to disagree with someone’s politics, we should at least recognize that what we are witnessing is the totality of that person’s experiences and perceptions, which can change.

“A lack of empathy is typically the culprit for societal and political stalemates, and we seem to have many components within our society trading empathic approaches for self-serving ones,” Goodman, the ex-mayor, says.

In Masonry, members presume a level of decency in their fellow brothers, Charvonia point out. “For millennia, people have survived by making judgements about people in certain situations. But we need to flip that on its head and assume that people we’re in contact with are decent people. Occasionally, we’ll be proven wrong. But I want to be proven wrong occasionally rather than assume everyone’s a jerk.”

Focus on service

Masonry has much to teach us about servant leadership, says Frank Udvarhely, a member of Eureka № 16 in Auburn. Udvarhely is the district representative for an elected member of the Placer County board of supervisors. Before that, he served with numerous volunteer groups in his community, including the Greater Auburn Area Fire Safe Council, Leadership Rocklin, Municipal Advisory Council for Placer County, Rotary Club of South Placer, and Stand Up Placer. “It’s about service above self,” he says. “That means I’m doing something wholeheartedly for the benefit of somebody else, with no expected gain.”

Within a Masonic lodge, officer’s positions and the elevated titles that come with them, like worshipful master, aren’t about praise and plaudits. They’re about an obligation to act in service of the group. Plus, by placing others at the forefront of our thoughts and actions, people can transcend the issues that divide

them. As Charvonia says, “If we’re engaged in the service of others, it’s just harder to be a schmuck.”

Goodman says the world of politics needs to take a cue from Masonry on that score.

“Politics can get in the way of public service,” he says. “I think party affiliation should be kept out of local government, because these are nonpartisan positions. There is too much important groundwork to be done to let any party matters or political strategizing get in the way of serving constituents.”

Take action

Masonry and Masonic lodges provide an opportunity for members to take on the problems they see in their own community, often without the baggage of national politics attached to them. (Whatever you think about the curriculum of your local schools, we can usually agree that handing out school supplies to kids is a good thing.) Lodges give us a forum to do that, locally and statewide through the California Masonic Foundation. That kind of public service isn’t partisan.

And, not for nothing, it feels good: “We feel better about ourselves when we do for others,” Charvonia says. “Feeling like you’re part of the solution is liberating. If you can do some good, taking action matters.”

Charvonia recalls his time as grand master, during which he would organize a day of public service to accompany every visit he made for a cornerstone

ceremony or golden veteran’s award. Almost a decade later, he can’t recall many of the particulars about those Masonic events, but he remembers the beach cleanups, the soup kitchen volunteering, and the tree plantings. In fact, he still gets messages from Masons with photos of some of those trees and a note about how much they’ve grown. “That’s your common ground,” he says. “That’s working for a greater good.”

GEORGE WASHINGTON may be the most famous Mason in American history, and Masons have gone to great lengths to highlight the bond between him and his brotherhood. So perhaps they should look to him when thinking about how to approach handling politics in their own lives.

Washington did not belong to any political party— he’s the only American president not to. In fact, Washington was quite clear about his stance on partisanship in his Farewell Address, published in 1796.

[T]he spirit of Party [...] serves always to distract the Public Councils and enfeeble the Public Administration. It agitates the Community with ill founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot & insurrection. It opens the door to foreign influence & corruption, which find a facilitated access to the government itself through the channels of party passions. [Parties] are likely, in the course of time and things, to become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the Power of the People, & to usurp for themselves the reins of Government.”

Curiously, Washington’s fears for the young nation were not necessarily existential threats, but rather internal threats within people’s hearts and souls. He speaks about “jealousies,” “animosity,” and “riot,” which all come about when passions run wild.

Sound familiar? Learning to subdue one’s passions and to seek harmony are precisely Masonic virtues, and the restraint and self-mastery that are extolled in Masonry stand in contrast to the hubris and blustering Washington warned against. Each of us individually can choose to subdue with restraint our raw emotions or allow these to smolder into allconsuming flames. Almost 230 years later, that admonition is as relevant as ever. Just ask a Mason.

21 WINTER 2023–24 20

PHOTO BY WINNI WINTERMEYER

Members of Crocker Lodge No. 212 socialize at a recent New Officer Installation ceremony in San Francisco.

Past Grand Master Russ Charvonia hosts a series of civility conferences, including one in 2018 held at the George Washington National Masonic Memorial in Alexandria, Virginia.

IS IT MANLY TO TALK ABOUT POLITICS <Religion>

POLITICS <Religion> sMONEY ?

BY BRETT M c KAY

YOU’VE PROBABLY heard it said that you should never discuss religion, money, or politics with people.

In terms of discussing these “charged” topics with good friends you’ve known a while, this adage is overly cautious. While you should probably proceed with caution when it comes to talking about money (it can produce ripple effects and reactions that are more visceral

The following article was reprinted with permission from The Art of Manliness. Brett McKay is a member of Lodge Veritas № 556 in Norman, Okla., and an expert on “manliness.”

Read more at artofmanliness.com.

than one anticipates), conversations on politics and religion are too interesting and enjoyable to give up. These are some of the most animating parts of life, after all.

But when it comes to avoiding the topics of politics, religion, and money with new acquaintances— folks you’ve just met—there’s a reason this piece of advice is so timeworn. The introduction of these “controversial” subjects can lead to a conversation getting overly heated, create misunderstandings, cause people to take offense, and end a relationship before it’s even begun.

The difference between discussing charged topics with old and new friends rests on the fact that among the former, you’ve already built a relationship of trust and respect that allows them to disagree

with you civilly. They know the whole context of your life. They can say that even if they disagree with you on a certain issue, they love you anyway. They know that your opinions on certain topics represent just one part of who you are.

With someone new, however, all they know about you is limited to what you’ve said in the last half hour. The little slice of yourself you’ve presented is all they have to go on, and they’ll take it as indicative of your entire life. They don’t have the context to say, “We disagree on X, but we still have enough in common to build a great relationship.”

So while it’s tempting to let it all hang out with everyone, all of the time, it’s best to move into dicier stuff gradually—to first build a supportive scaffolding of trust and respect. Yet even though this is generally the wisest, and certainly the safest route, taking it needn’t be a hard and fast rule.

For all the above being said, charged topics not only have the greatest potential for division, but also carry the greatest possibility for bonding. And they can in fact be talked about with someone new, as long as you do so with care, intelligence, and an open mind, following these guidelines:

INTRODUCE A CHARGED TOPIC GENTLY AND GRADUALLY RATHER THAN STRONGLY AND OVERTLY

For example, rather than suddenly asserting, “I’ve long believed that religion is the opiate of the masses,” ask, “Are you religious?” or “Do you go to church regularly?”

FEEL OUT THEIR INTEREST.

If you float a controversial topic into conversation and the other person doesn’t bite, don’t force it. Move on to something else.

DON’T ASSUME SOMEONE SHARES YOUR CONVICTIONS BEFORE THEY’VE SAID SO

For example, if you want to talk about politics, rather than saying, “Trump’s a real clown, eh?” ask, “Did you watch Trump’s latest press conference?” From their answer, you’ll usually be able to assess their feelings on an issue and decide how to couch what you say next.

“For all the above being said, charged topics not only have the greatest potential for division, but also carry the greatest possibility for bonding.”

HAVE A DISCUSSION RATHER THAN AN ARGUMENT

What’s the difference? A wise writer put it this way: “In discussion you are searching for the truth, and in argument you want to prove that you are right. In discussion, therefore, you are anxious to know your neighbor’s views, and you listen to him. In argument, you don’t care anything about his opinions, you want him to hear yours, hence, while he’s talking you are simply thinking over what you are going to say as soon as you get a chance.”

Instead of trying to convert someone you’ve just met to your side, aim to understand how they’ve arrived at their convictions, where your positions differ, and the common ground you share.

ASK “WHAT” QUESTIONS RATHER THAN “WHY” OR “HOW” QUESTIONS

Questions like, “How can you feel that way?” and “Why do you believe that?” make the other person feel attacked and create defensiveness. Instead, pose “what” questions that show your interest in understanding their position: “What makes you feel that way?” “What has led you to come to that conclusion?”

KEEP CALM

At little bit of heat keeps things interesting, but too much animosity can repel. Avoid inflammatory language and try to keep the conversation friendly and fun. If things are veering toward the acrimonious, change the subject, rather than continuing to hit your new acquaintance over the head with your opinions.

Any topic of conversation can be on the table as long as you handle it in a tactful way. All you really have to remember is this: stay kind and curious.

23 WINTER 2023–24 22

When Sandy Kahn’s family’s legacy was questioned amid a bitter historical reckoning, he did something quintessentially Masonic: He changed the conversation and shone a light on an overlooked figure in his family’s story.

BY IAN A. STEWART

Name

WHAT’S IN A

IN SEPTEMBER 2019, as the San Francisco Recreation and Parks Department officially unveiled the new name for what’s now Presidio Wall Playground, the event went off with little fanfare. A modest delegation of representatives from community groups were on hand as a new sign was revealed by workers in orange reflective vests. They applauded politely and were soon on their way. No one made any remarks. The ceremony took less than 10 minutes. A century earlier, when the park opened in honor of 12-term congressman Julius Kahn, it was planned as a major event, with bands, children’s games, and all kinds of festivities. Perhaps ominously, that grand opening was rained out. ¶ Nearly 100 years later, the park was again the focus of the city’s attention, swept up in a larger debate about the ways in which cities honor certain historical figures— especially those whose legacies are being rethought “as part of a nationwide call to stop glorifying slave traders, antisemites, racists, and imperialists,” according to the San Francisco Chronicle. That effort included Congressman Kahn, the park’s namesake, who was the city’s first Jewish representative in Washington in 1899, but who was also responsible for helping pass an extension of the Chinese Expulsion Act, which prevented nearly all Chinese immigrants from gaining citizenship and many basic rights. In 2018, a resolution was brought to the city’s

PHOTO BY MARTIN KLIMEK WINTER 2023–24 24

While the legacy of his grandfather Julius Kahn has been debated, Sandy Kahn says it’s his grandmother, Florence Prag Kahn, who looms largest in the family's history.

board of supervisors to strip Kahn’s name from the park. Then-supervisor Norman Yee said, “Julius Kahn’s anti-Asian policies during the early 1900s did not espouse the values that San Francisco stands for today.”

Julius “Sandy” Kahn III, a member of Oakland Durant Rockridge № 188 and the grandson of Congressman Kahn, disagrees vehemently with Yee. For many people, the movement to grapple with the history of racism in America has presented some tricky dilemmas and emotionally thorny issues, as oncerevered figures have come under new scrutiny. Especially for Masons, this has led to a conundrum. For 250 years, the fraternity has pointed with pride to its association with the Founding Fathers and other civic leaders like Kahn (a member of St. Cecile № 568 in New York)—in many cases, the very figures being wrenched from their historic pedestals. For Kahn, it was personal, too.

But rather than engage in what appeared to be an unwinnable fight, Kahn, who lives at the Acacia Creek Retirement Community in Union City, chose another tack. He remains proud of his connection to one of San Francisco’s most influential politicians, not to mention one of the most important Jewish families on the West Coast. But he is more apt to use his grandfather’s memory as a launching point for a conversation about early San Francisco history than for an impassioned defense of his grandfather’s character.

Julius Kahn, a 12-term congressman from San Francisco, was the city’s first Jewish representative in Washington.

That, says the younger Kahn, who worked as an estate-planning attorney for nearly 60 years in the Bay Area, is also by design—and a reflection of his half-century membership in the fraternity. Rather than remain at loggerheads over an emotionally charged issue, Masonry compels its members to find shared values around which to work. In doing so, Kahn invokes one of the most profound lessons of Masonry—and something Kahn believes is missing from contemporary political argument. That is summarized in the Masonic degrees, in which the tool of the compass is said to represent the ability to “circumscribe our desires and keep our passions within due bounds.” In doing so, one demonstrates restraint and control, the basis for morality and wisdom.

And so, rather than argue on behalf of the man who introduced the Selective Service Act, secured the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Expo of San Francisco, and served as ranking chairman of the powerful Military Affairs Committee, Kahn pulls out a fading leather binder full of family photos and starts to talk about someone else entirely.

FROM KAHN’S PERSPECTIVE, the good to come out of the debate over his grandfather’s memory is that it’s afforded him an opportunity to shine a spotlight on another member of his family who has been largely overlooked. In fact, it isn’t Julius Kahn that looms largest in the family history at all. It’s his wife. And in many ways, Florence Prag Kahn’s legacy not only rivals that of her better-known husband but it eclipses it.

While largely unknown today, Florence Prag Kahn stands as one of the most important and influential women in local history. Upon her husband’s death in 1924, Prag Kahn was tapped in a special election to finish his term in office, making her the first Jewish woman in Congress. However, Prag Kahn did more than just fulfill a so-called widow’s term. A former teacher whose own mother had served on the

Masonry compels its members to find shared values around which to work.

San Francisco Board of Education, and one of only nine women in her graduating class at the University of California in Berkeley, she proved to be a natural for the job. Not only did she fulfill Kahn’s term, but she was elected five more times after that, in the process becoming one of the most powerful women in the country.

“She was such a compelling figure,” Sandy Kahn says of his grandmother, whom he knew well as a child. “For as important as she was, at home she was sweet and loving, just a real family-oriented person.”

She was also her own woman. Though she advocated for expanded military budgets and pushed a hardline Republican defense position in Congress, as her husband had, she carved her own path on many issues. Like her husband, she was hawkish on military issues—she was even named to the same Military Affairs Committee Kahn had once chaired. But she also pushed many progressive social reforms, including campaigning to repeal the Volstead Act prohibiting the sale of alcohol, opposing federal censorship laws, and fighting against “blue laws” forcing certain businesses to close on Sundays. “Running through all her legislation is a thread of concern for women’s rights and interests,” writes Alice Wentzell, who penned a biography

Workers unveil the new sign for Presidio Wall Playground, formerly Julius Kahn Playground.

of Prag Kahn in 1984. “She introduced legislation for nurses and supported benefits for wives, widows, and children to better their lives.”

While never recognized as a leading suffragette, Florence Kahn through her actions and words stood as a kind of early feminist leader, Wentzell says, and in later years she encouraged women not only to vote but to elect women to political office. Among her chief accomplishments were protecting the Mare Island naval shipyard from closure, securing the funding for the Alameda Naval Base and Hamilton Air Force Base, and helping bring the Golden Gate International Expo of 1939 to Treasure Island. She also carried the legislation that led to the construction of the Bay Bridge and the Golden Gate Bridge. In his history of Jewish San Francisco, Cosmopolitans, historian Fred Rosenbaum writes, “Though she represented a relatively conservative district in the northern part of the city, she was, after all, a San Francisco politician, prounion and broad-minded on social issues.”

Florence Prag Kahn served five terms in Congress from 1925 to 1937.

More than that, Florence Kahn was a revered figure in Washington—a quick wit who became an “overnight hit on the congressional stage,” according to Hope Chamberlin in A Minority of Members. Her success, on the heels of her husband’s, “gave many Bay Area Jews a relative sense of security that lasted well into the 1930s, even while other American Jews were feeling more vulnerable than ever,” Rosenbaum writes.

WINTER 2023–24 26

TOP LEFT: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS; TOP CENTER: COURTESY OF SFRP VIA INSTAGRAM RIGHT: COURTESY OF THE BANCROFT LIBRARY, UC BERKELEY

In 1929, Prag Kahn was appointed to the powerful Congressional Appropriations Committee, making her the first woman named to that body. It was there that she helped increase funding for the nascent Federal Bureau of Investigations, which led J. Edgar Hoover to lovingly refer to her as the “mother of the FBI.” Upon her death in 1948, Hoover served as a pallbearer at her funeral.

Sandy Kahn never met his grandfather, but he remembers Florence well. Despite her elevated standing—Sandy recalls seeing some of the biggest names in politics, from Hoover to Governor Earl Warren (the grand master of Masons in California in 1935), drop by her apartment on Nob Hill in her later years— he says she remained down-to-earth and matronly. “It wasn’t until much later on that I became aware of how important the Kahn family was,” he says.

SANDY KAHN HAD HOPED that in the wake of the renaming debate at Julius Kahn Playground, city leaders might use the opportunity to recognize his grandmother. In her, they had an influential San Francisco leader; one of the first elected women in Washington (and perhaps the first to wield significant power); and the first Jewish woman to serve in Congress. She also offered a link to the influential Kahn family and to a golden era of Jewish history in San Francisco—without the same baggage that attended her husband. Rosenbaum points out that Prag Kahn championed

legislation to provide citizenship to immigrant wives of Chineseborn U.S. citizens, and birthright citizenship for the children of Chinese and Japanese families living here. “Her attitude toward the Indigenous and Chinese was very progressive for her time,” Rosenbaum says.

Still, for all that, she is hardly a household name. Despite her immense popularity during her life, she “has been largely forgotten by the press, historians, and even the people,” Wentzell writes.

Sandy Kahn, a longtime Bay Area lawyer, is intent on keeping his family legacy alive—especially that of his grandmother, Florence Prag Kahn.

None of the physical testaments to her work—the Bay Bridge, Moffett Airfield, the Alameda Naval Base—acknowledge her contributions. Her name does not appear on any parks, buildings, streets, or public monuments. “She deserves more attention than she’s gotten,” Rosenbaum says. “I’m not sure why she hasn’t gotten it. She’s worth much more.”

So, while her name was floated for the renamed playground, in the end it wasn’t to be.

A group from the Pacific Heights Residents Association considered a dozen suggested names for the park, which it winnowed down to three. Only one person’s name made the final cut, alongside West Pacific Playground and Presidio Wall Playground. That was Rhoda Goldman Playground, for the benefactor who funded the playground’s clubhouse. The group decided against even that.

“This is a neighborhood that is devoted to families and children, and it became clear to me, watching what was eliminated and what rose to the top, that because this is a playground for children, it should not get itself involved in large controversies,” Charlie Ferguson, the head of the neighborhood group, told the Richmond Review. “A playground should remain mainly a playground, without controversy associated. And for that reason the names that may sound rather blah rose to the top.”

For Sandy Kahn, it was a missed opportunity— but not the final word. That, he says, will belong to him and his children, ideally delivered while thumbing through the well-worn family scrapbook as they describe the good and the bad, the public statements and the private moments, that made up his grandparents’ lives. That legacy, he says, lives on.

BAND OF BROTHERS

In Oklahoma, an Indian degree team is preserving the legacy of Native American Freemasonry.

PHOTO BY MARTIN KLIMEK WINTER 2023–24 28

29

N SUMMARIZING the role of Masonry in Native American history, there’s a tendency to simplify. In her book Native American Freemasonry: Associationism and Performance in America, Joy Porter points to the seemingly endless supply of stories from the American frontier in which a white soldier is saved from imminent death by flashing a Masonic sign to a Native American attacker. Citing the Masonic writer William Denslow, she writes, “Such stories were so plentiful that… If you had not crossed the western plains without being assaulted by Indians, giving a Masonic distress sign, and finally saved, you were an exception to the rule.” In repeating these “mythohistoric facts,” Masonic historians have presented Masonry as a crucial instrument in smoothing relations between white and Native Americans in the 19th century, not to mention between warring factions in the Indian Territories.

While it’s true that Masonry’s particular role in Indian-Anglo relations has perhaps been romanticized in certain retellings, it’s also true that Native American Masonry has a long and distinguished

Members of the Oklahoma Masonic Indian Degree Team performed the third degree at St. Albans No.56 in Baldwin, New York, this fall.

history, particularly in places like Oklahoma, where Masonic lodges have played an instrumental role within Native communities for more than 150 years. (In 1909, the grand lodges of the Indian Territories and the State of Oklahoma merged into one.) Many of the most influential Native leaders there belonged to local lodges, and through those lodges helped establish colleges, charities, and other enduring civic institutions. Writes Porter, “Examining Indian-Masonic fraternal relationships tends to paint a picture of, if not rosy cooperation, then at least genuine and mutually enabling interaction. Reading Masonic records, we get a positive picture of interethnic brotherhood providing a basis for growth in the west.”

These days, Native influence on Masonic life in the region is practically ubiquitous, as many lodges retain names associated with tribes and feature significant Native American membership. Nowhere is that more in evidence than through the Oklahoma Masonic Indian Degree Team, an interlodge club formed in the 1960s that stages degree exemplifications while dressed in tribal regalia and

incorporating elements of Native American dance, songs, and prayer into the Masonic ritual.

California Freemason spoke with David Dill, the current secretary of the degree team and a member of Coweta № 251, about preserving that cultural history through Masonry. —Ian A. Stewart

CFM : There’s a long history of Native American Masonry in Oklahoma. Is that something you’re trying to consciously acknowledge through the Indian Degree Team?

David Dill: Yes, we are, and yes there’s a very long history of Indian Masonry in Oklahoma. Many of the most famous tribal leaders were all Masons, including the famous Cherokee leader and the founder John Ross, who belonged to Federal Lodge № 1. He also started Cherokee Lodge № 10 in Tahlequah. If you go there, they have pictures of all the past masters going back to the mid-1800s, and most of them were Native. I’m sure at some point in the past, Cherokee was the main language spoken at that lodge.

CFM : And the degree team represents many different tribes, is that right?

DD: The Oklahoma Masonic Indian Degree team is a representation of all of Oklahoma Masonry—and there are a lot of Native Masons here. All of our members belong to lodges in Northeast Oklahoma, mostly in the Tulsa area. I am Muscogee Creek, and I live in the Muscogee Creek jurisdictional boundary. There’s also Ottawa, Pawnee, Apache, Seminole, Choctaw. There are probably seven or eight tribes represented, all from the northeast part of the state. At the same time, it’s hard to recruit members. They need to have the regalia—the dance clothes—all of which is handmade. It’s not like you can go to a store and buy it. So you have to find members who can make the outfits and who are free to travel and take time off work, and they also need to know the ritual work. So finding brothers who can do all three can be a challenge. But we keep it going.

CFM : What can you tell me about the performance itself?

DD: We do the Master Mason degree according to the Oklahoma ritual. And we add a little bit to that, which our Grand Lodge allows us to. All the language is there—everything that’s required to be raised as a Master Mason is there. But we add some words here and there. For example, in the Oklahoma ritual, at several points there is music or a song, and we’ve replaced

“The Oklahoma Masonic Indian Degree team is a representation of all of Oklahoma Masonry.”

A member of the Oklahoma Masonic Indian Degree Team at a degree ceremony in Grapevine, Texas, with the Grand Master of Texas in 2022.

those with native prayer songs. Two of them are Ponca, one is Kiowa. Then the second section—which is usually why people come to see us, when we put on our native regalia—that’s the main draw. I can’t get into too much detail, but if you know the third degree, we never do it the same way twice. We’re allowed to ad-lib a little bit based on the crowd, so we put our own spin on it. That’s the best way to describe it.

CFM : And you have a dance performance, too?

DD: That’s not part of the degree, but yes, we usually have a dance program prepared that we put on,

WINTER 2023–24 30

PHOTOS COURTESY OF DAVID DILL

which is also a chance for members’ families and kids to see us as well. It’s more like an educational program and demonstration of dances you’d see at an Oklahoma powwow. The outfits we wear are the same ones we’d wear to a powwow. They’re real eagle feathers, real buckskin leggings, real beadwork.

CFM : Are most of the degrees you perform for Native American candidates?

DD: It kind of depends. Sometimes we’ll get a candidate who’s full-blood native and the lodge will request it. We also perform at lots of other big events where the lodge will ask us to come. We do a lot of 100th anniversaries and big outdoor degrees. At this point, most people in Oklahoma have seen us; they’re kind of used to it now. But when we have an out-of-state event, we can draw a pretty big crowd.

CFM : What’s a big crowd?

DD: In 2022, we were in Delaware and had 800 people at a degree.

CFM : Wow. Where else have you performed?