MOSTRA / EXHIBITION

Photography Grant on Industry and Work / 2023

25.01 / 01.05.2023

MAST.

Via Speranza, 42

Bologna www.mast.org

CURATORE / CURATOR

Urs Stahel

IDENTITÀ VISIVA / VISUAL IDENTITY

Hibo

ALLESTIMENTI E PRODUZIONE / PRODUCTION AND SET UP

Chiara Badiali

Luca Marenzi

MAST Photography Grant on Industry and Work è promosso dalla Fondazione MAST

MAST Photography Grant on Industry and Work is promoted by Fondazione MAST www.mastphotogrant.com

CATALOGO / CATALOGUE

Photography Grant on Industry and Work / 2023

A CURA DI / EDITED BY

Urs Stahel

TESTI / TEXTS

Negar Azimi

Federica Chiocchetti

Dominik Czechowski

Elvira Dyangani Ose

Nikolas Ventourakis

COORDINAMENTO EDITORIALE / EDITORIAL COORDINATION

Marina Rotondo

DESIGN

Hibo

TRADUZIONI / TRANSLATIONS

NTL

2023 by Fondazione MAST, Bologna Tutti i diritti riservati / All rights reserved

©

SOMMARIO CONTENTS

Isabella Seràgnoli Premessa Foreword 5 Biografie Biographies 187 Giuria Jury 195 Partecipanti Participants 193 Finalisti delle edizioni precedenti Finalists of the past editions 201 MARIA MAVROPOULOU In their own image, in the image of God they created them Nikolas Ventourakis 19 LEBOHANG KGANYE Keep the Light Faithfully Elvira Dyangani Ose 51 HICHAM GARDAF In Praise of Slowness Dominik Czechowski 89 FARAH AL QASIMI Dearborn Negar Azimi 119 SALVATORE VITALE Death by GPS Federica Chiocchetti 161 9 Urs Stahel Il mondo del lavoro e le sue trasformazioni Change in the world of labour

Nato per sostenere la ricerca visiva contemporanea sui temi dell’industria e del lavoro e dare voce ai talenti emergenti, il MAST Photography Grant on Industry and Work, promosso con cadenza biennale da Fondazione MAST, offre a cinque giovani fotografi internazionali l’opportunità di sviluppare un progetto originale e innovativo e di essere protagonisti di una mostra allestita negli spazi espositivi di MAST e accompagnata da un catalogo.

Nel tempo questa iniziativa ha permesso la creazione di un significativo corpus fotografico di artisti contemporanei che rappresenta oggi il nucleo più giovane e dinamico della collezione di fotografia dell’industria e del lavoro della Fondazione MAST, ampliandone l’offerta culturale con sguardi inediti.

Questa settima edizione del MAST Photography Grant presenta le opere dei cinque finalisti: Farah Al Qasimi, Hicham Gardaf, Lebohang Kganye, Maria Mavropoulou e Salvatore Vitale. Selezionati da una giuria internazionale di fotografi, editori e critici tra cinquantatré candidati provenienti da tutto il mondo, questi giovani fotografi hanno elaborato nell’arco di un anno i progetti che danno vita oggi a questa esposizione – alla cui apertura verrà annunciato il vincitore del Grant 2023.

I cinque progetti affrontano temi di grande attualità, mettendo a fuoco le radicali trasformazioni in atto nel mondo del lavoro: la convivenza tra cultura occidentale e cultura araba in un centro urbano industriale degli Stati Uniti (Al Qasimi);

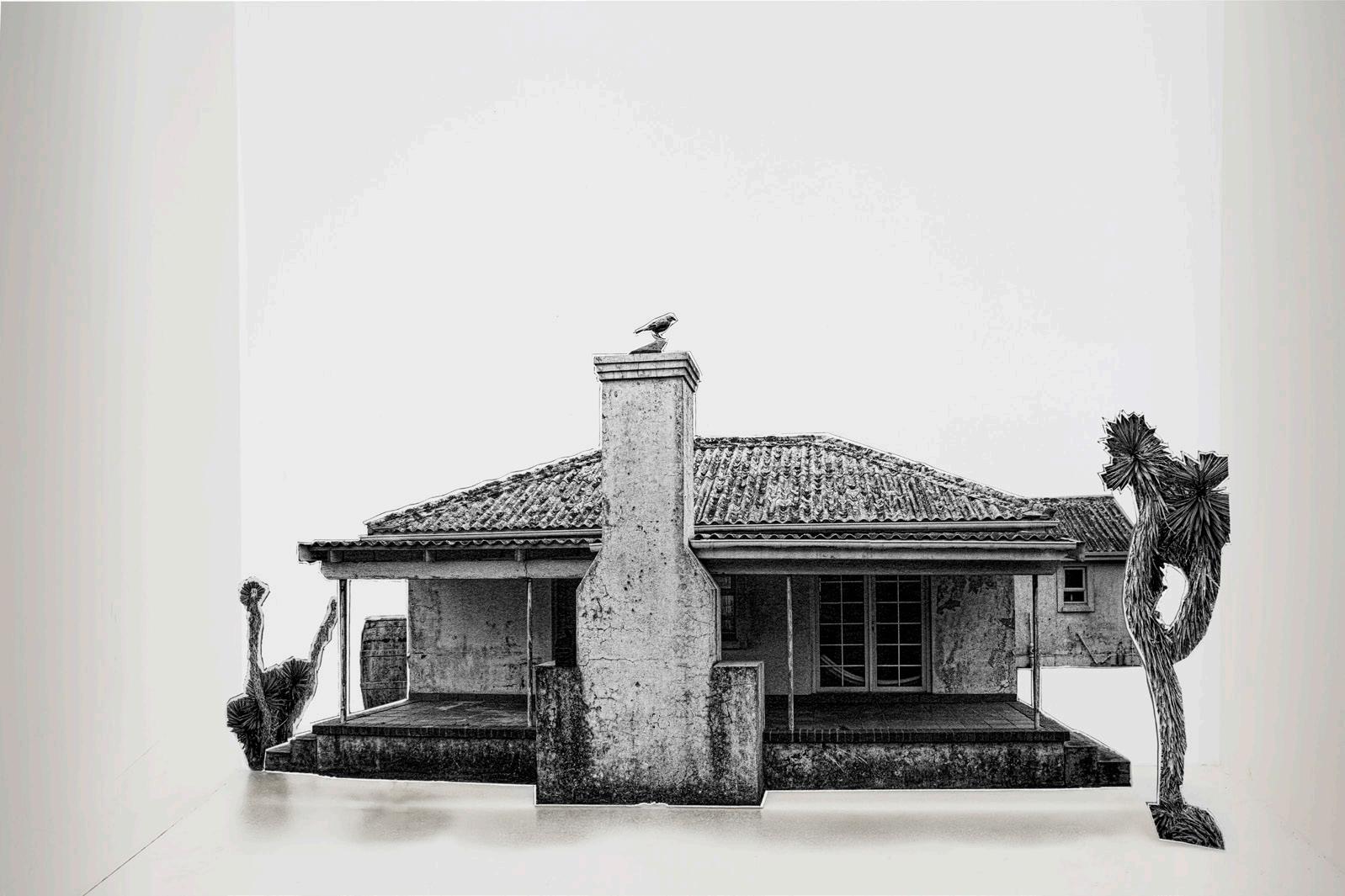

la sopravvivenza di un mestiere antico, il venditore ambulante, caratterizzato da ritmi lenti, nella frenesia di una grande città come Tangeri (Gardaf); l’evocazione tra fantasia e realtà di una professione perduta quale quella delle guardiane dei fari in Sudafrica (Kganye); le possibilità creative che sembrano rivendicare i nuovi software di Intelligenza Artificiale (Mavropoulou); lo sfruttamento – e l’immaginaria rivolta – dei lavoratori della gig economy, messa in relazione con l’attività mineraria e con l’idea di sabotaggio dei mezzi di produzione (Vitale).

Nella mostra, alle opere dei protagonisti dell’edizione 2023 si affiancano i lavori di tutti i ventiquattro finalisti delle precedenti edizioni, a formare una grande, multiforme rassegna, una sorta di giro del mondo per immagini, che vuole celebrare sia il decennale della inaugurazione di MAST, sia i quindici anni di impegno nell’organizzazione del Grant per i giovani fotografi (il primo è stato assegnato nel 2008).

Quindici anni che hanno permesso di conoscere e sostenere nuovi talenti di ogni nazionalità spesso destinati a carriere brillanti e a premi prestigiosi; che hanno consentito di scoprire realtà sconosciute o lontane ma sorprendentemente interconnesse alla nostra vita e al nostro lavoro; che hanno dato la possibilità – come fa sempre l’arte – di posare lo sguardo su un futuro che si avvicina a grande velocità.

Isabella Seràgnoli

7

Set up in order to support contemporary visual research into the themes of industry and work and to give a voice to emerging talents, the biennial MAST Photography Grant on Industry and Work gives five young international photographers the opportunity to develop an original and innovative project and to showcase it in an exhibition, with an accompanying catalogue, presented in the gallery spaces of the Fondazione MAST.

A significant body of photographic work by contemporary artists has been built up over time as a result of this initiative, and it now makes up the youngest and most dynamic core of the foundation’s photography collection on industry and work, broadening its cultural offer with new perspectives.

This seventh edition of the MAST Photography Grant presents the works of the five finalists: Farah Al Qasimi, Hicham Gardaf, Lebohang Kganye, Maria Mavropoulou and Salvatore Vitale. Selected by an international jury of photographers, publishers and photo-historians among fifty-three candidates from around the world, these young photographers have developed over the last year the projects culminating in this show. The winner of the 2023 Grant will be announced at the opening.

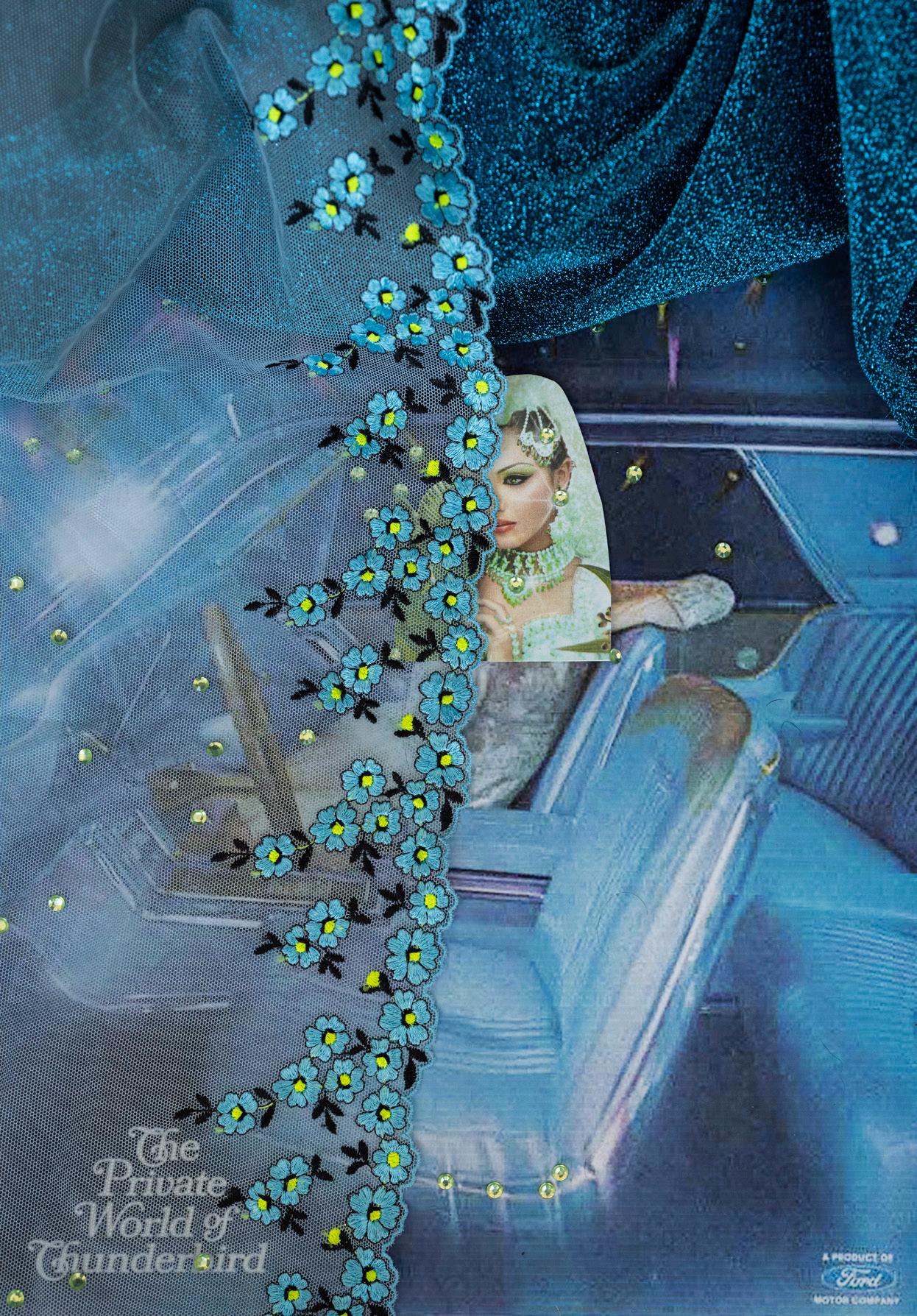

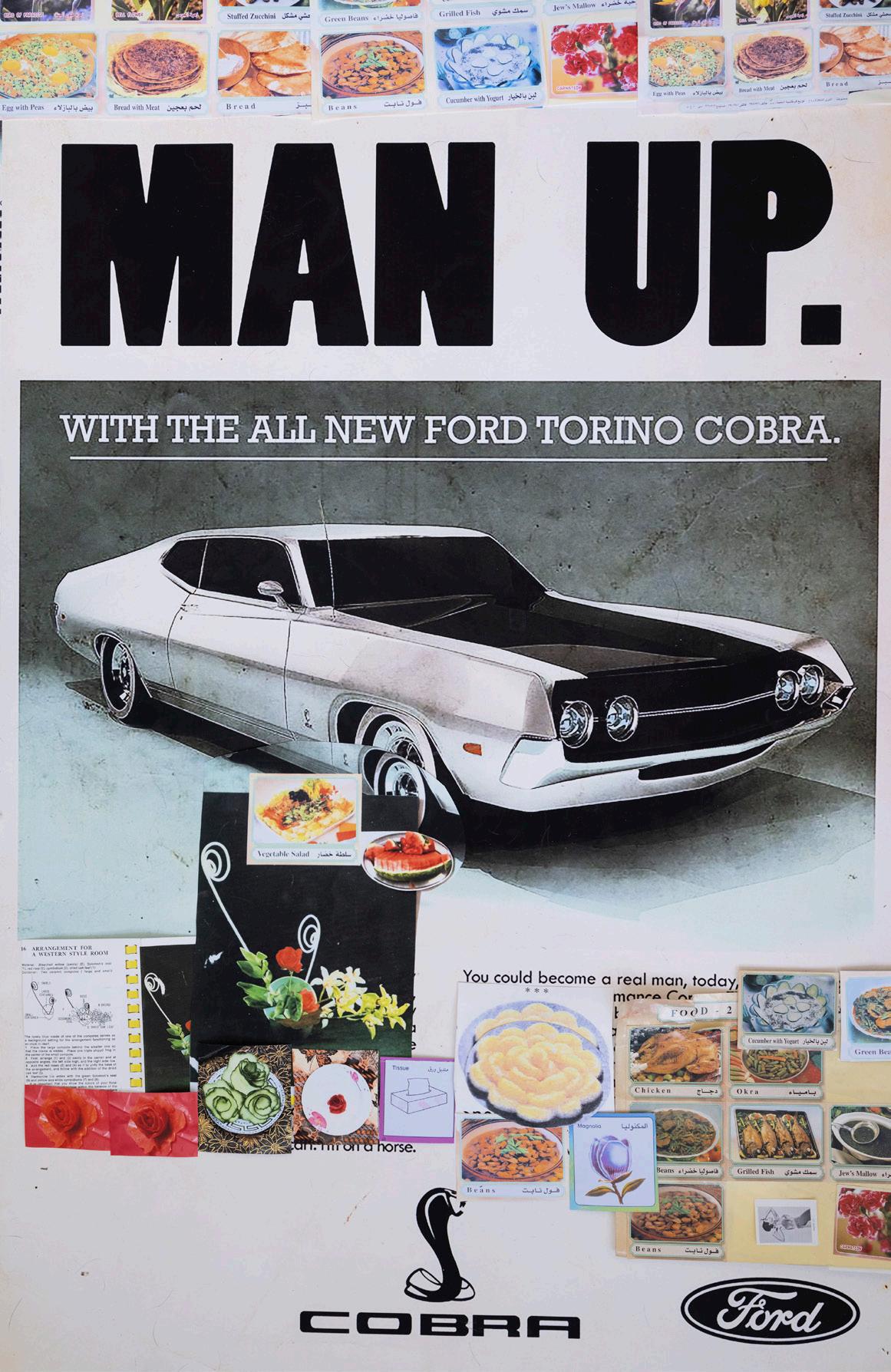

The five projects address highly topical issues, focusing on the radical changes taking place in the world of work: the coexistence between Western and Arab culture in an industrial urban center in the United States (Al Qasimi); the survival of

the ancient trade of the street vendor, with its slow rhythms, in the frenetic context of a large city like Tangier (Gardaf); the evocation, in a blend of imagination and reality, of a profession that has been lost, that of female lighthouse keepers in South Africa (Kganye); the new creative possibilities that seem to be claimed by AI software (Mavropoulou); and the exploitation—and imaginary revolt—of workers in the gig economy, as related to mining and to the idea of sabotaging the means of production (Vitale).

Alongside the projects of the five finalists, the show will also feature works from all twenty-four finalists of the previous editions, forming a large-scale, multiform display, a kind of tour of the world in images, intended to celebrate both the tenth anniversary of the inauguration of MAST and fifteen years of commitment to organizing the MAST Photography Grant for young photographers (the first one was awarded in 2008).

In these fifteen years it has been possible to get to know and to support new talents of many nationalities, who have then often embarked on brilliant careers and won prestigious awards; to discover realities and themes that were unknown or remote yet surprisingly intertwined with our own lives and work; and to rest our gaze—as art always enables us to do—on a rapidly approaching future.

Isabella Seràgnoli

8

Il mondo del lavoro e le sue trasformazioni

Urs Stahel

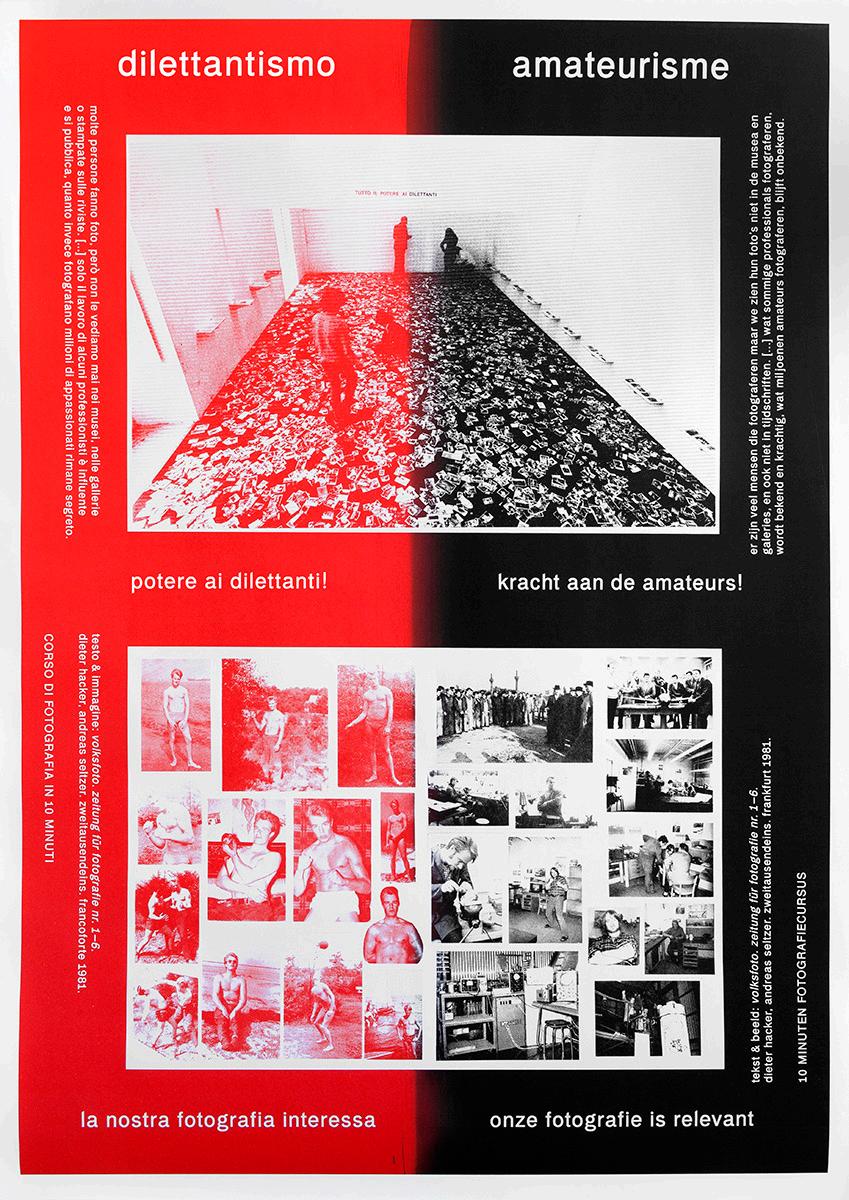

“Il mondo del lavoro è in rapida trasformazione”1 , si legge a chiare lettere sulle pagine economiche di gran parte dei giornali. La digitalizzazione, l’automazione imperante, le mutate aspettative di lavoratori e lavoratrici, una nuova visione delle forme lavorative sono destinati a sconvolgere sempre più frequentemente e profondamente il lavoro. I consulenti online attivi nel campo delle risorse umane sanno sempre come sfruttare a proprio vantaggio questo enorme cambiamento. “Lavoro 4.0” è la parola d’ordine che circola entro i confini dell’Unione Europea, mentre in altre parti del mondo si ricorre più spesso al concetto di “New Work”.

La particolare attenzione ai mutamenti che interessano l’essenza stessa del lavoro accomuna i cinque finalisti del MAST Photography Grant 2023, gli artisti Farah Al Qasimi, Hicham Gardaf, Lebohang Kganye, Maria Mavropoulou e Salvatore Vitale. Indubbiamente si tratta di un aspetto che è opportuno approfondire.

Il primo passo in direzione di un nuovo assetto del lavoro si compie nel momento in cui l’acqua e il vapore si trasformano in fonti di energia per alimentare le macchine coinvolte nella produzione e le navi per il trasporto delle merci. Per la prima volta, i prodotti possono essere realizzati dalle macchine in grandi quantità. A posteriori, questa prima fase della rivoluzione industriale, che ha luogo intorno alla metà del XVIII secolo, è stata ribattezzata “Lavoro 1.0”. La seconda fase, “Lavoro 2.0”, si verifica a

distanza di un secolo grazie all’avvento dell’elettricità, che per la prima volta rende possibile la separazione logistica tra l’utilizzatore dell’energia, per esempio un motore elettrico o un impianto di illuminazione, e la centrale elettrica nella quale varie fonti primarie di energia – acqua, carbone, petrolio – vengono convertite in elettricità. Nel settore industriale, inoltre, l’elettrificazione fornisce una valida alternativa a sistemi di distribuzione dell’energia spazialmente limitati e meccanicamente complessi e dispendiosi come l’albero di trasmissione. Questa innovazione consente una suddivisione sempre più precisa e puntuale delle varie fasi del lavoro. Le prime catene di montaggio delle fabbriche Ford costituiscono ancora oggi un valido esempio.

Negli anni settanta del Novecento ha inizio la fase “Lavoro 3.0”, la terza, travolgente ondata della rivoluzione industriale e tecnologica. A partire da questo momento l’automazione subisce un’accelerazione per gradi supportata dai computer e, in un secondo momento, dalla robotica industriale. Oggi assistiamo all’avvento del “Lavoro 4.0”, che coincide con quella che il filosofo Luciano Floridi ha ribattezzato “quarta rivoluzione”, caratterizzata dal predominio di tecnologie dell’informazione e della comunicazione sempre più avanzate: “La società dell’informazione è concepita come una società neomanifatturiera, in cui le materie prime e l’energia sono ormai sostituite da dati e informazioni, il nuovo oro digitale e la vera fonte di valore aggiunto” 2 .

10

Quando parliamo di rivoluzione industriale, solitamente facciamo riferimento a un arco temporale che interessa gli ultimi 250 anni, caratterizzato dallo sviluppo tecnico e tecnologico. Parliamo di capitalismo industriale quando vogliamo mettere a fuoco i mutamenti economici che l’hanno caratterizzato, mentre ci riferiamo all’era moderna se consideriamo più in generale le trasformazioni sociali e culturali avvenute.

Tuttavia, non si può certo dire che prima di questi eventi il tempo fosse immobile: a partire dall’Alto Medioevo, in Europa si diffonde un fiorente capitalismo mercantile, già del resto presente in Arabia e in Cina. “La formazione degli Stati europei non sarebbe stata possibile senza il capitalismo dei Medici, dei Fugger o dei Baring” 3. Nel XVI secolo, lo spietato capitalismo delle piantagioni, legato al colonialismo, è una realtà diffusa in tutto il mondo. Lo stesso vale per il capitalismo agrario, che “porta al consolidamento di grandi proprietà nelle mani di famiglie nobili e borghesi. I proprietari terrieri dell’Europa centro-orientale vendono il loro grano sui mercati internazionali secondo i principi capitalistici, ma al tempo stesso continuano a sfruttare la forza lavoro di cui dispongono attraverso istituti quali la servitù della gleba e la schiavitù” 4

Negli ultimi 250 anni, tuttavia, lo sviluppo della tecnologia, della scienza e dell’economia è stato così rapido, dinamico e radicale da dare luogo a una vera e propria rivoluzione permanente,

che ha stravolto la vita delle generazioni che si sono succedute scuotendola sin nelle fondamenta. Karl Marx teorizza che “il progressivo rivoluzionamento della produzione, l’ininterrotto scuotimento delle congiunture sociali, l’incertezza e il movimento in eterno divenire distinguono l’epoca della borghesia rispetto a ogni altra epoca che l’ha preceduta” 5. L’innovazione rapidissima e costante diventa il motore trainante di una società che ne subisce più volte i sovvertimenti. Nel momento in cui il lavoro salariato diventa un fenomeno di massa, lo stile di vita del lavoratore subisce continui mutamenti dettati dalle esigenze del posto di lavoro, dei turni di lavoro, delle gerarchie in ambito lavorativo. Se si osservano le cose da una prospettiva odierna, non c’è nulla che sia rimasto immutato. Dalle lotte operaie del XIX secolo, dai salari da fame e dalle prime rivendicazioni sindacali si passa alla rivalutazione del lavoro, che coincide con il periodo di massima floridità dell’economia sociale di mercato negli anni sessanta e settanta, e si giunge infine alla figura del lavoratore della conoscenza, una realtà che Thomas Friedmann, autore di approfondite riflessioni sulla globalizzazione e sul cambiamento strutturale nell’era dell’informazione, interpellato nell’ambito di un dibattito, ha definito così: “Se il lavoro viene separato dalla mansione, e il lavoro e le mansioni vengono separati dalla vita aziendale, visto che (...) noi attualmente viviamo in un mondo caratterizzato da flussi, l’apprendimento

11

si configura come una necessità permanente. Siamo tenuti a fornire tanto gli strumenti quanto le risorse per l’apprendimento permanente nel preciso istante in cui la mansione diventa attività lavorativa e l’azienda diventa una piattaforma” 6. Le sue parole fotografano con grande nitidezza il nuovo cambiamento radicale che interessa la realtà lavorativa odierna. In questa sede tralasciamo la crescente influenza dell’intelligenza artificiale.

Questo ci porta al lavoro dei finalisti del nostro MAST Photography Grant 2023.

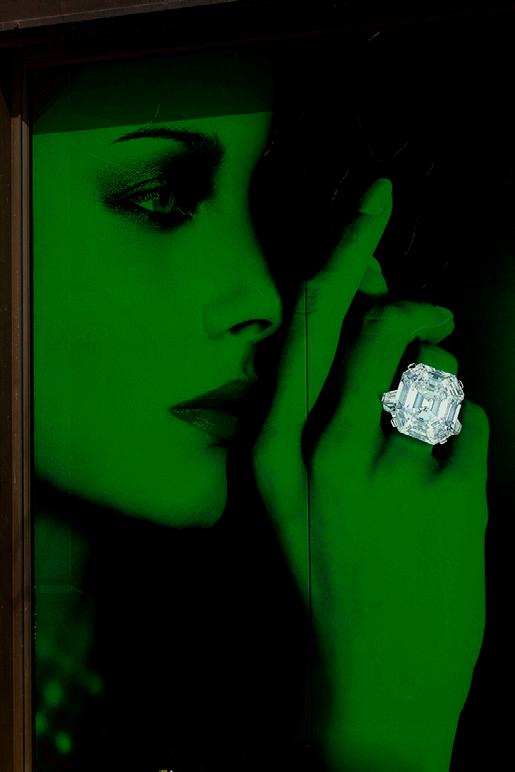

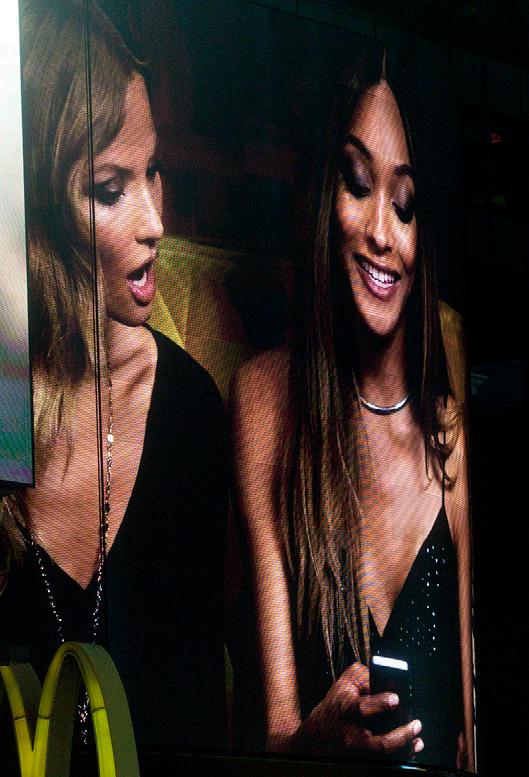

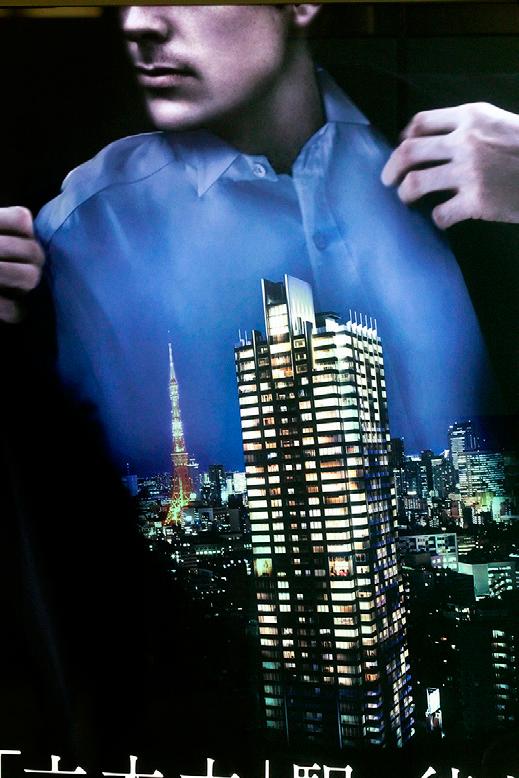

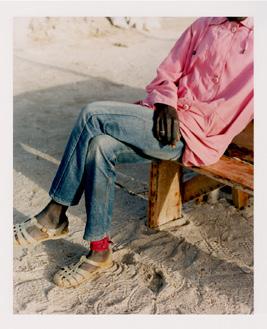

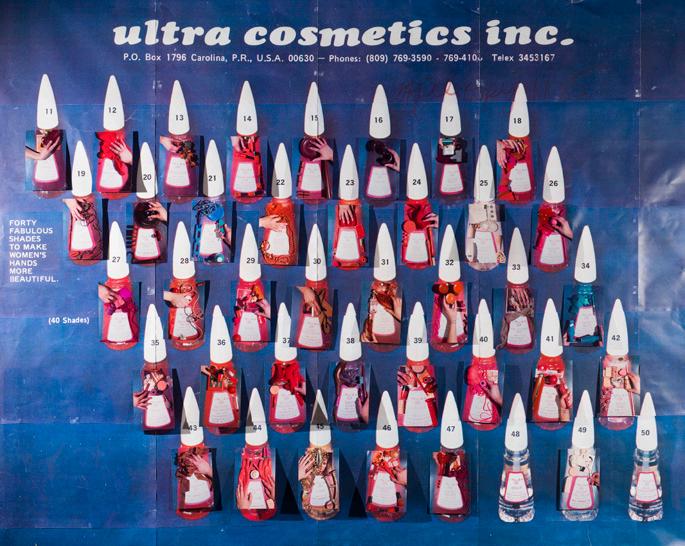

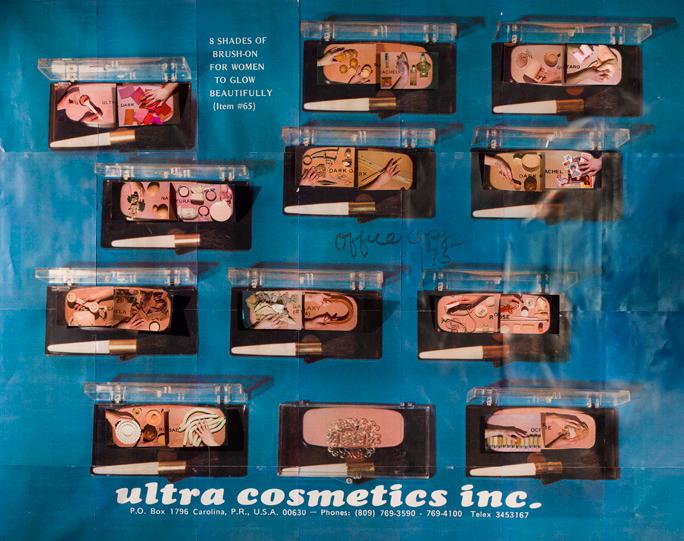

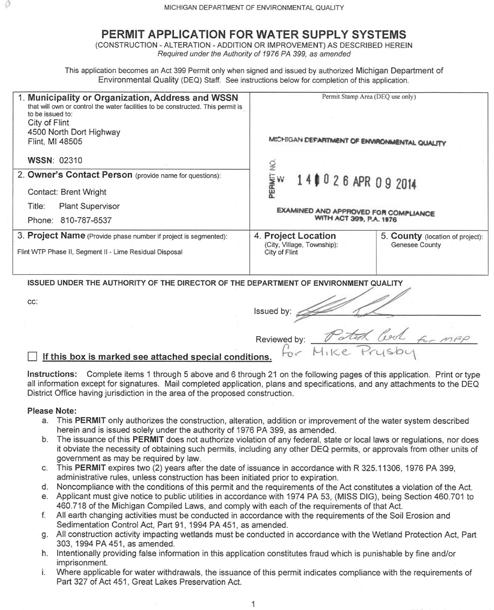

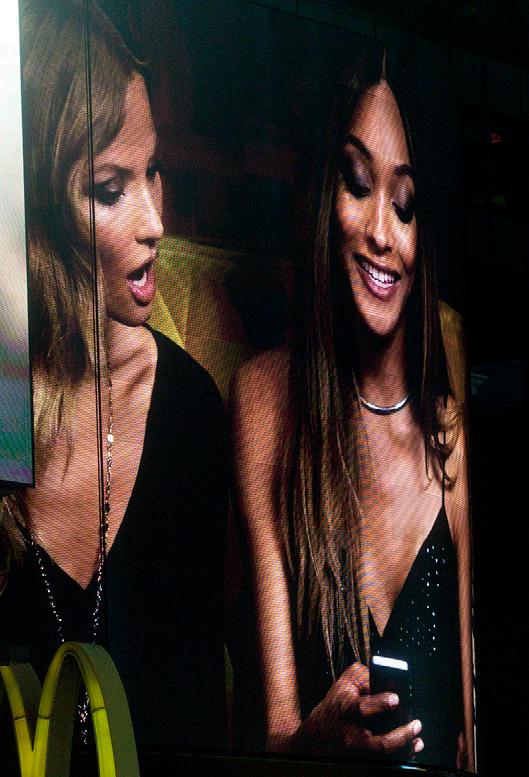

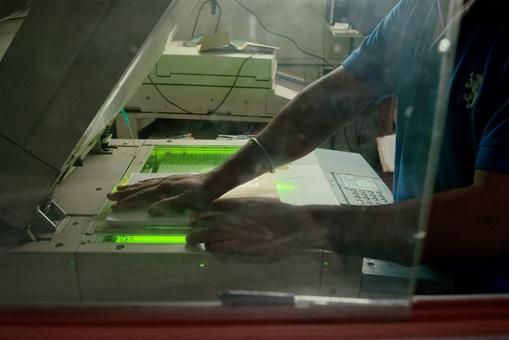

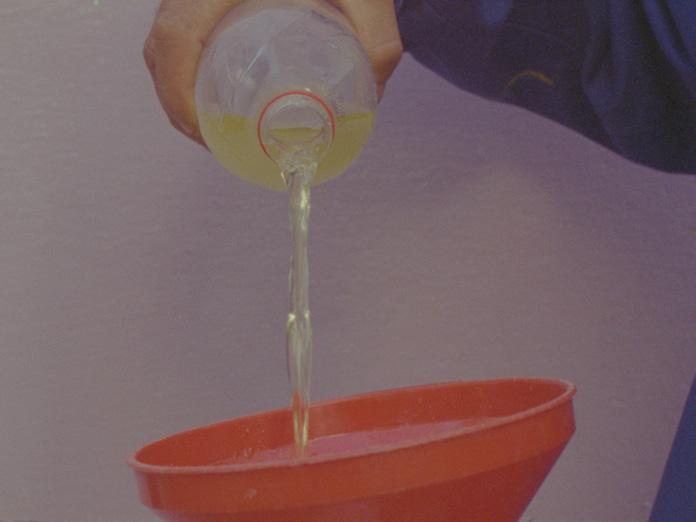

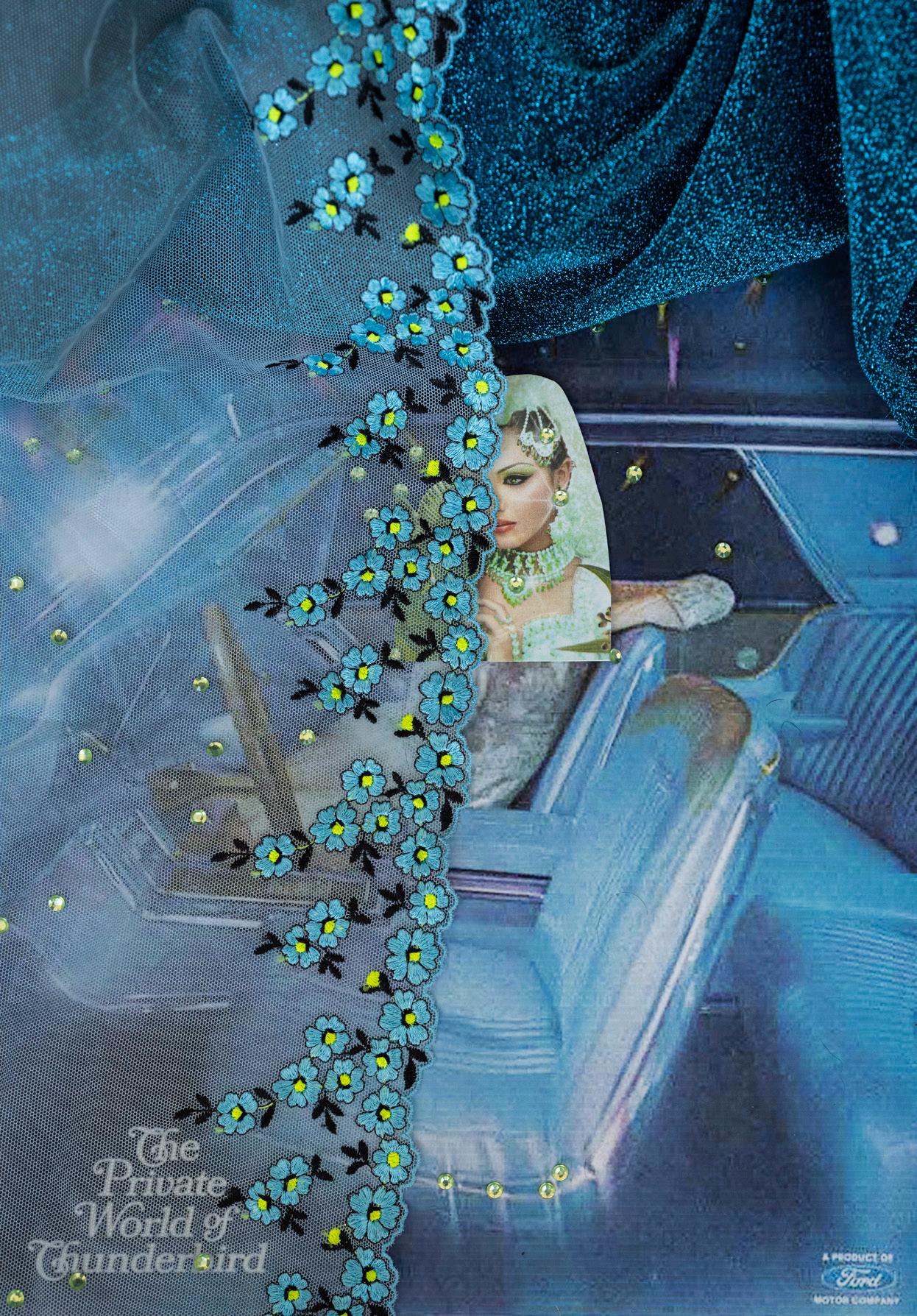

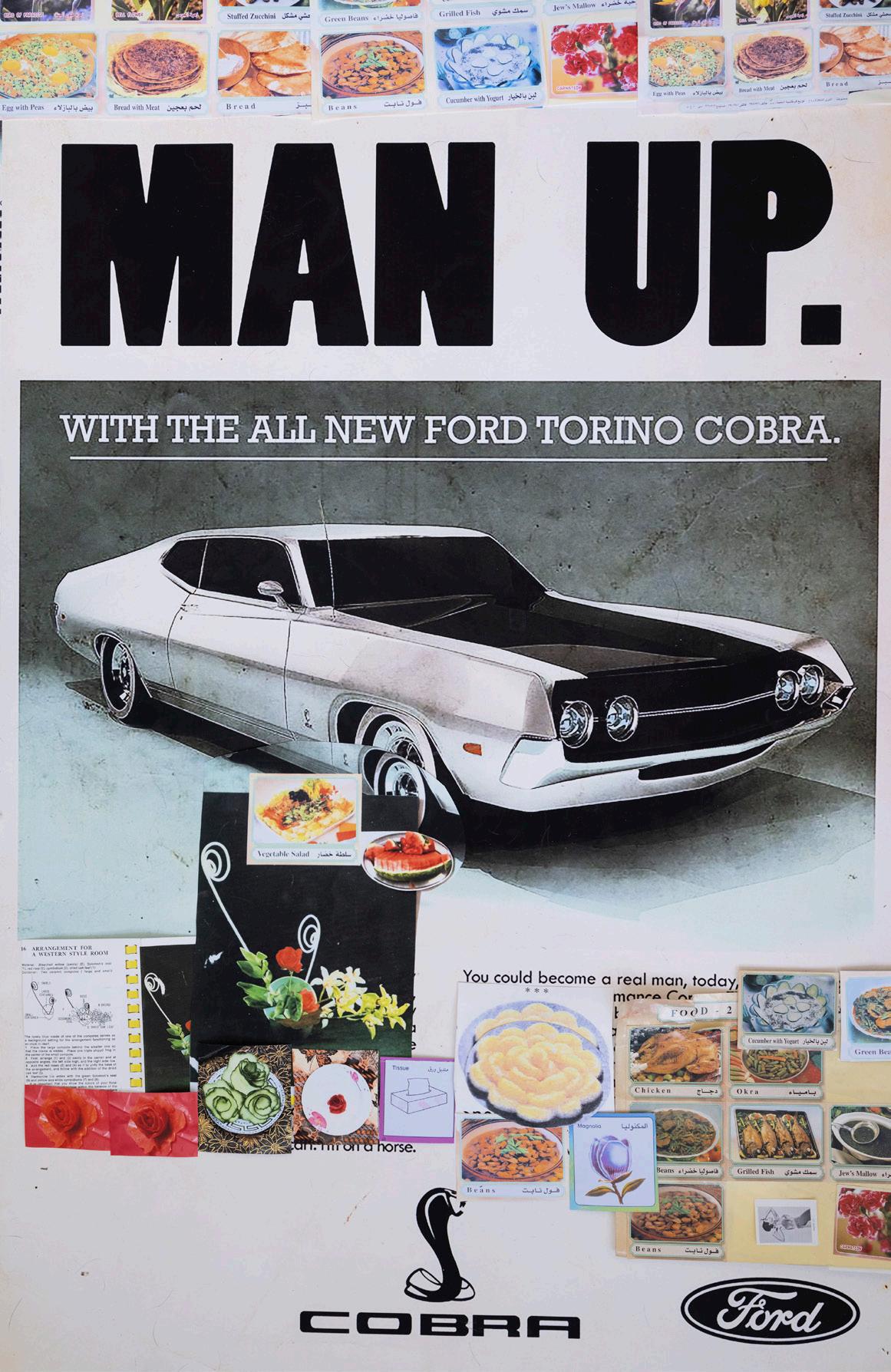

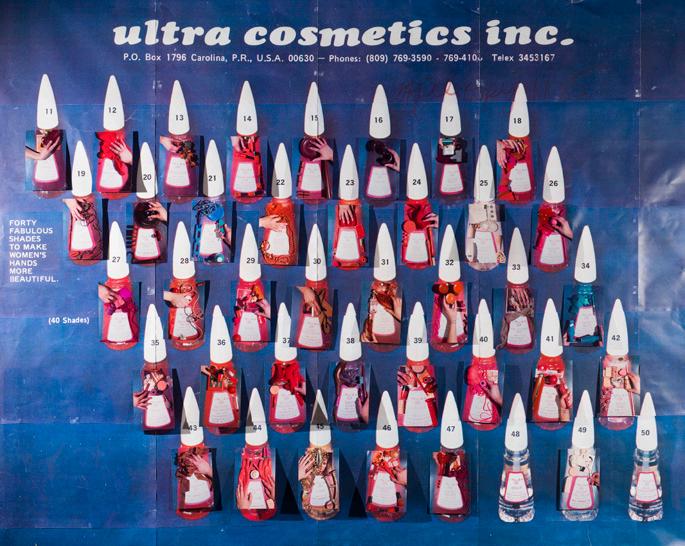

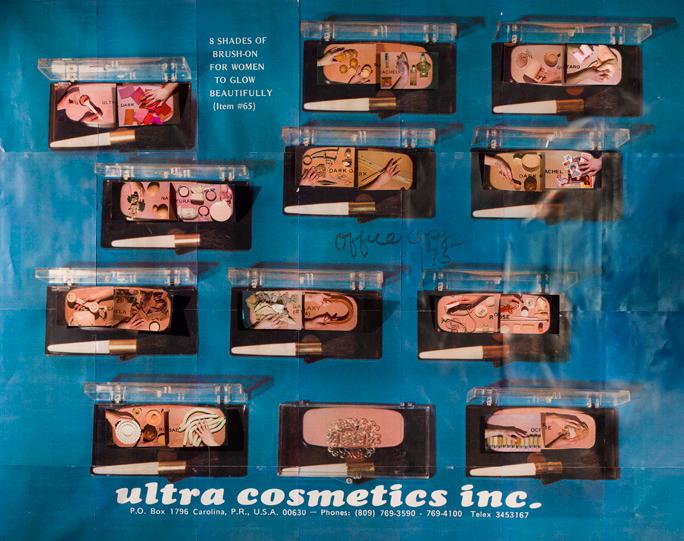

Farah Al Qasimi si concentra sulla grande comunità araba di Dearborn, nello stato del Michigan (USA). Wikipedia descrive come segue la città natale di Henry Ford nonché sede storica della Ford Motor Company:“Lo sviluppo e il carattere della città sono ancora strettamente legati alla figura dell’industriale. (...) Dearborn ospita la seconda comunità araba degli Stati Uniti in ordine di grandezza, con oltre 29.000 arabi americani (secondo il censimento del 2010, questo dato rappresenta il 41,7% della popolazione totale della città). Gli arabi si sono stabiliti qui per lavorare nell’industria automobilistica. (...) Dearborn è sede dello stabilimento Ford Rouge. (...) Nel periodo di maggiore sviluppo, la fabbrica dava lavoro a 100.000 operai e produceva veicoli completi” 7. Al Qasimi ha imparato a conoscere la città giorno e notte, ne ha studiato i ritmi, la viabilità e il sistema culturale. Non ha cercato di accedere alle fabbriche Ford, perché di regola

non è permesso fotografare liberamente, ma si è limitata a osservare nel concreto le persone, le loro attività, i momenti di pausa, gli spostamenti per recarsi al lavoro e il riflesso di tutto questo sui muri degli edifici. L’autrice ha creato una sorta di amalgama tra scorci di vita autentici della città e la sua dimensione più patinata e fotografata nei manifesti, tra insegne pubbliche e private. Dearborn mostra un carattere ibrido che è espressione di due culture, quella araba e quella statunitense. In definitiva

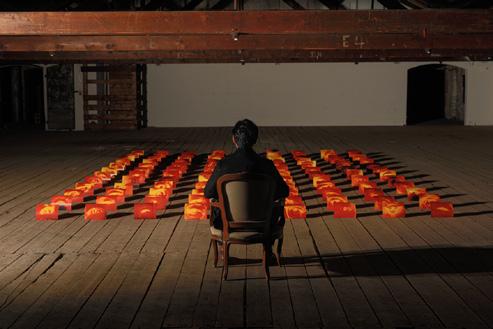

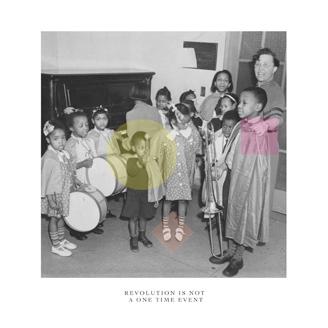

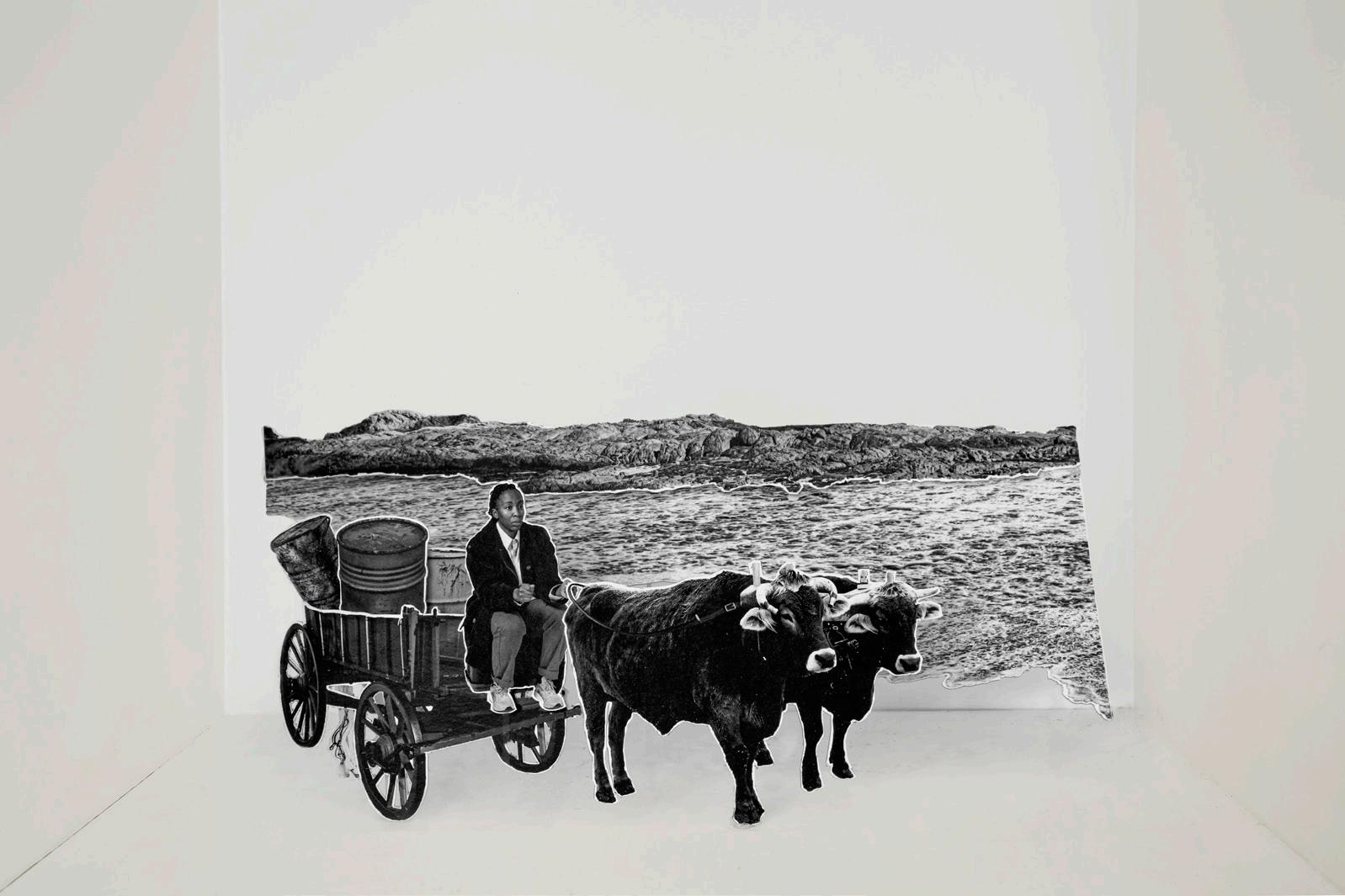

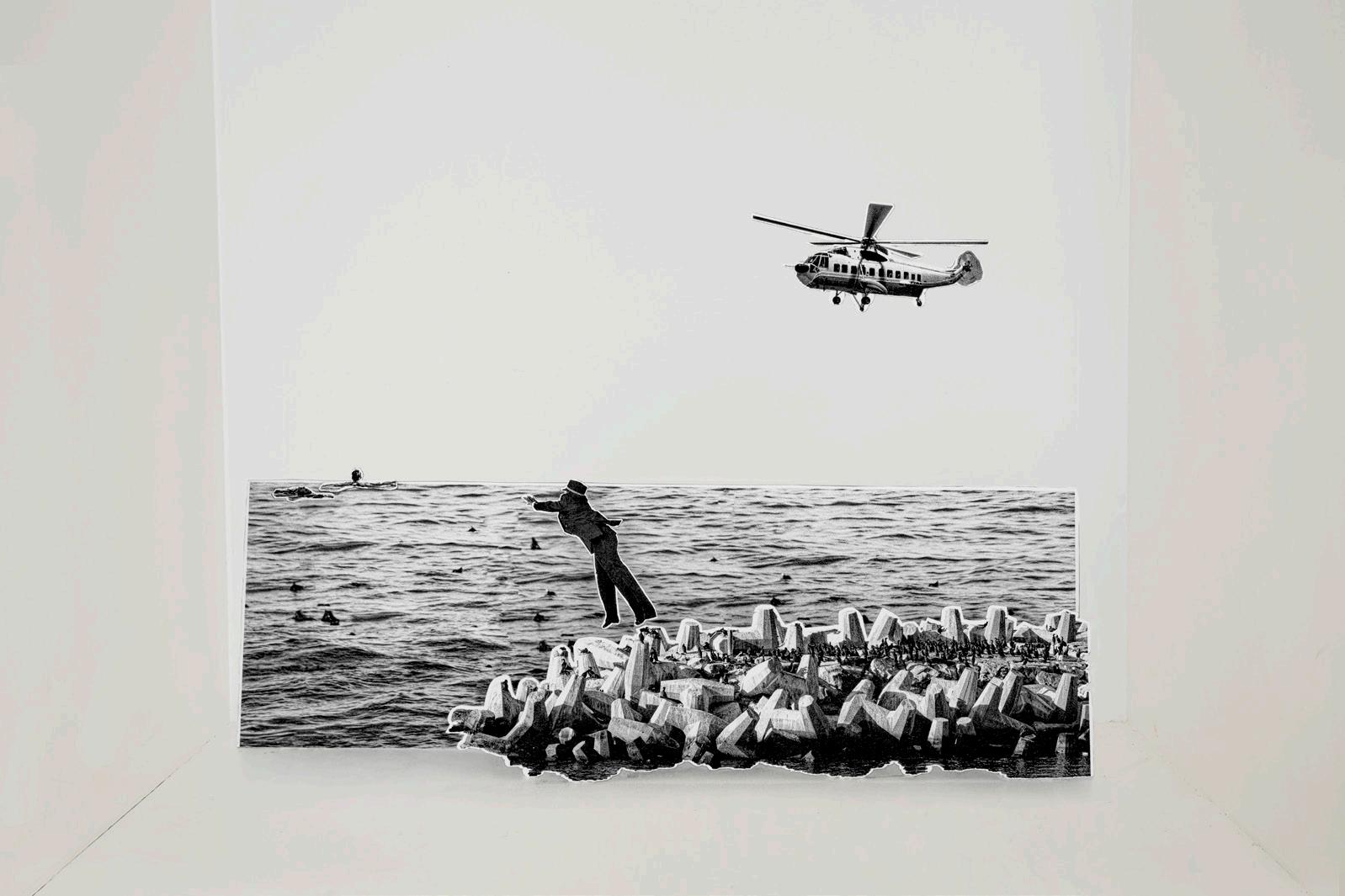

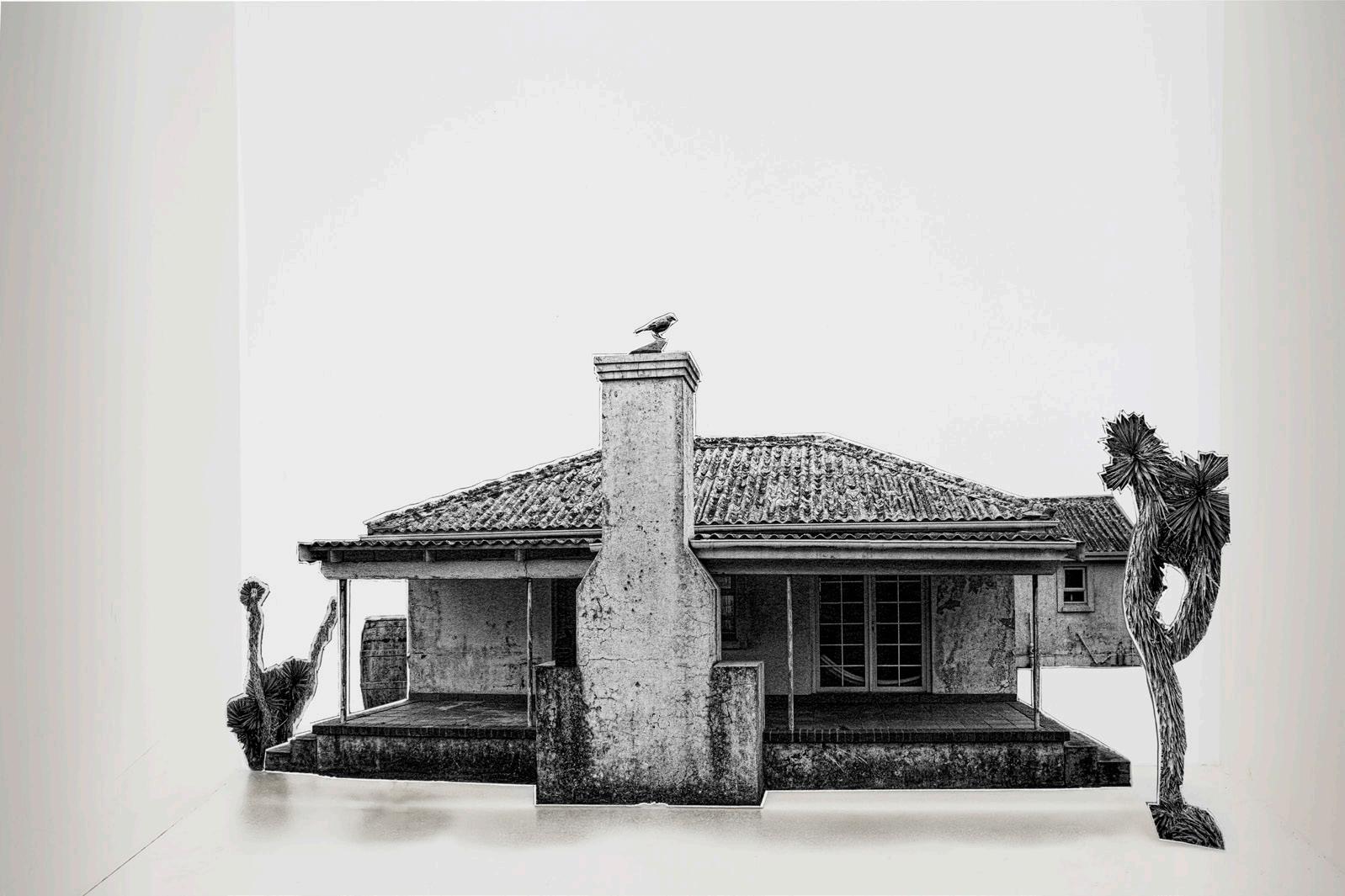

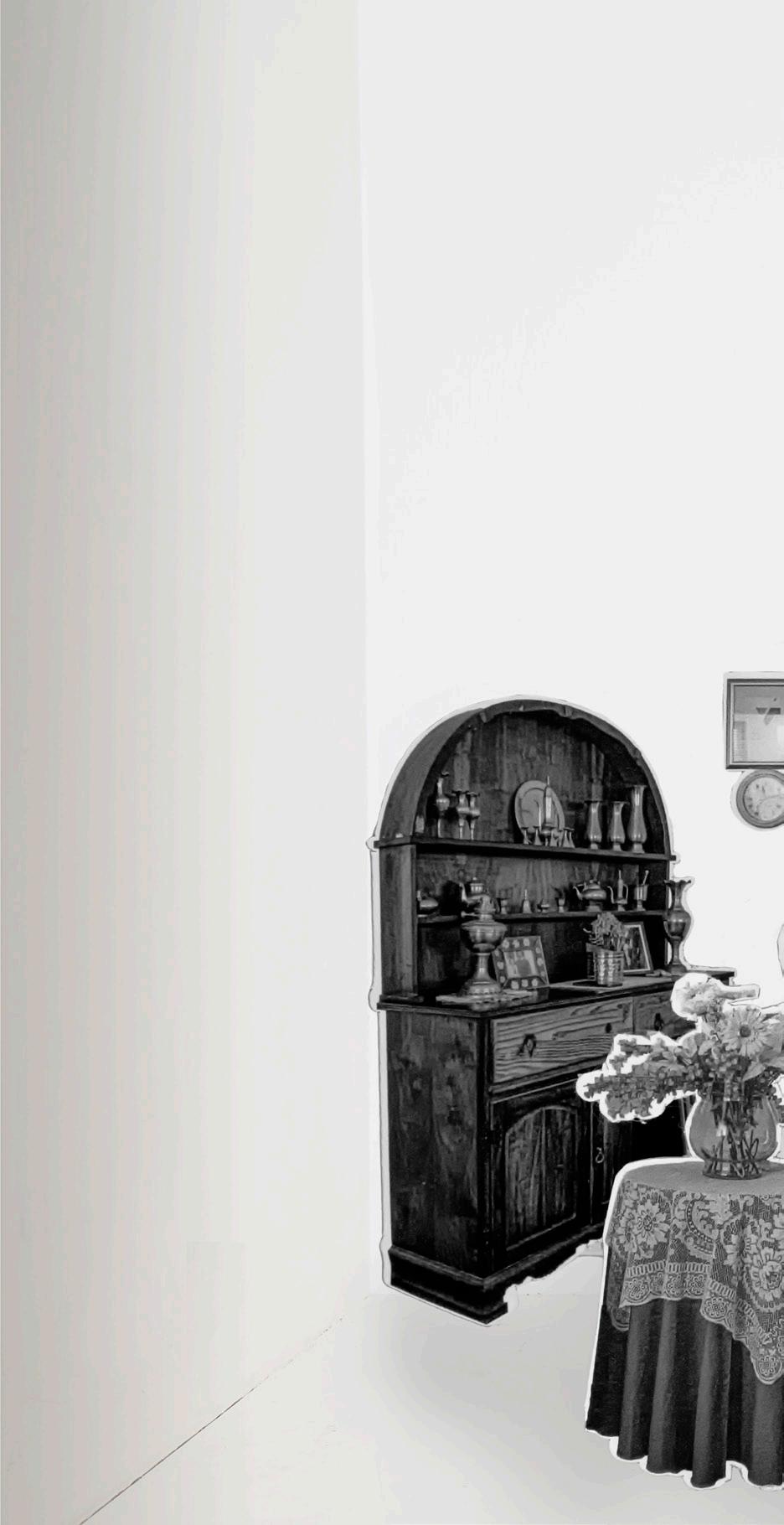

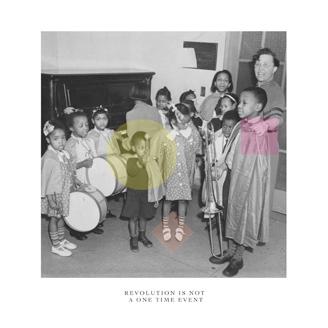

Al Qasimi cura all’interno dello spazio espositivo un allestimento degli universi che ha fotografato come se andasse a comporre un frammento di pittura murale urbana, evocando le medesime sovrapposizioni, le medesime codificazioni personali e culturali. Autrice di un lavoro che non è solo fotografico, Lebohang Kganye propone narrazioni di grande effetto e profondità. In una sorta di teatro delle ombre cinesi, l’artista inscena momenti di vita sudafricana che hanno per protagonisti personaggi fotografati la cui sagoma viene ritagliata e applicata su cartoncino, le ambientazioni valorizzate da una sapiente illuminazione teatrale. All’interno dello spazio espositivo, le sue installazioni hanno dimensioni variabili. Kganye ripropone, inscena, inventa e ricombina una serie di situazioni concrete ed eventi realmente accaduti giocando con la loro rielaborazione letteraria ed enfatizzandone alcuni tratti in un teatro delle immagini suggestivo, immaginifico e realistico al tempo stesso.

12

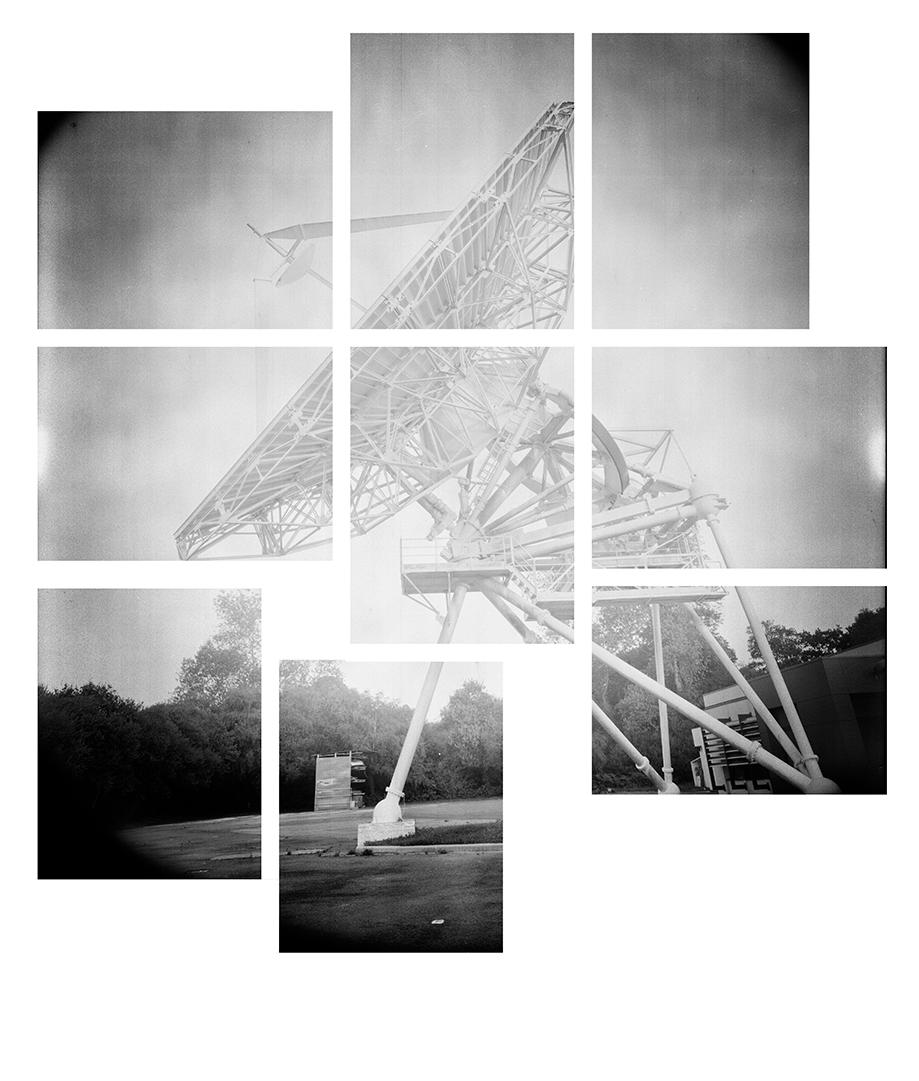

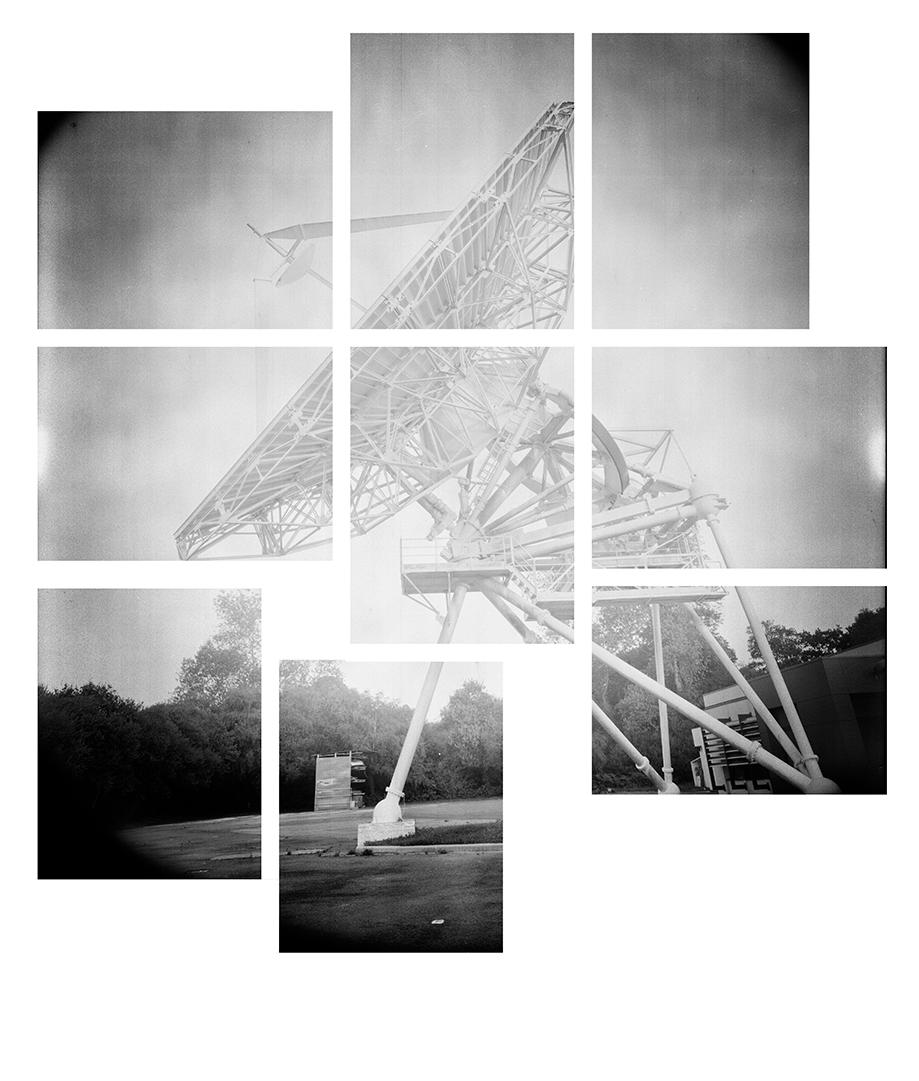

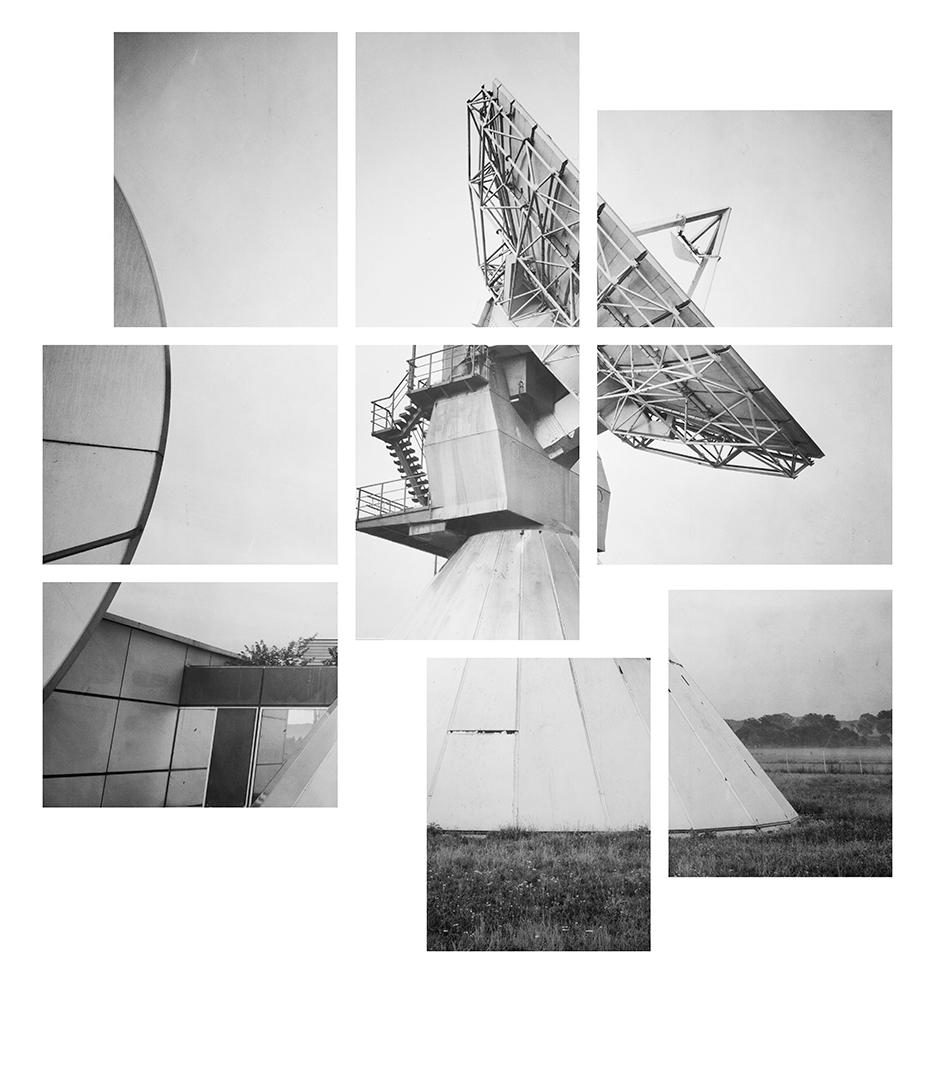

Nel progetto Keep the Light Faithfully (2022)

Kganye ripropone le storie poco conosciute e solitamente relegate alla narrativa di genere di centinaia di donne guardiane di fari del XIX e XX secolo. Tra queste spicca la vicenda di Ida Lewis, guardiana del faro di Lime Rock, raccontata da Lenore Skomal nel libro The Lighthouse Keeper’s Daughter (2010). Storia vuole che Lewis sia diventata famosa per avere portato a termine numerosi salvataggi di uomini nell’Oceano Atlantico che bagna le coste di Rhode Island, nel lontano1858. Inizialmente Kganye torna a mani vuote dal viaggio di ricerca che aveva intrapreso: praticamente tutti i fari sono ormai automatizzati; quello del guardiano del faro è un mestiere destinato a scomparire. L’artista, tuttavia, non rinuncia a ideare nuovi allestimenti scenici e nuove storie integrandole a quelle tramandate dalla tradizione orale per riportare in vita queste figure perdute. Da qualche anno a questa parte l’artista porta avanti una instancabile ricerca di memorie collettive, al fine di riscoprire, per usare le sue stesse parole, “storie segnate da lunghi periodi di solitudine e isolamento, costellate da rocamboleschi salvataggi, da viaggi drammaticamente interrotti, da mari tempestosi e venti impetuosi, ma anche scandite dai compiti monotoni e ripetitivi che caratterizzano la vita del guardiano del faro – senza trascurare l’impatto che il rapido progresso tecnologico ha avuto su una forma di lavoro e di servizio pubblico già relativamente invisibile” 8 .

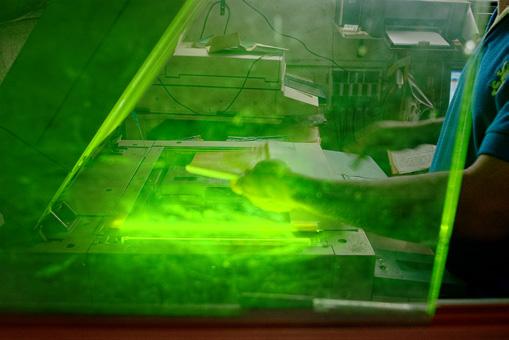

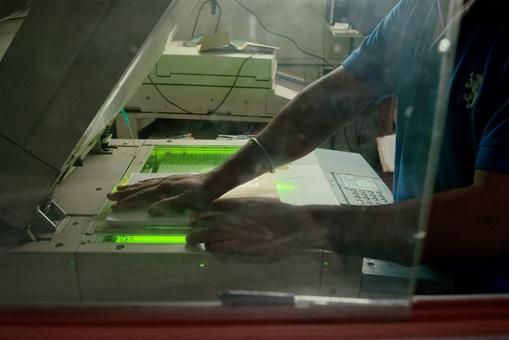

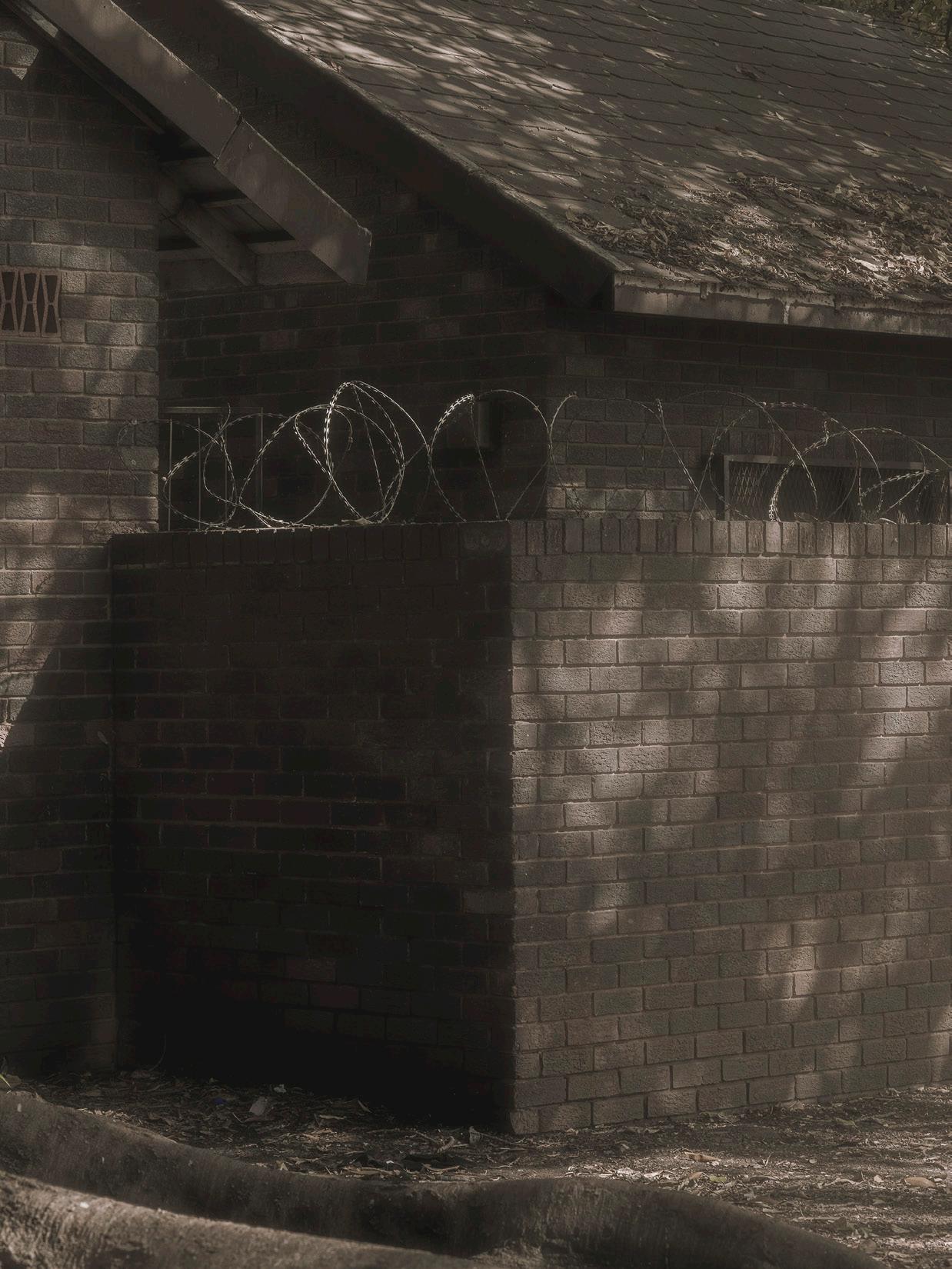

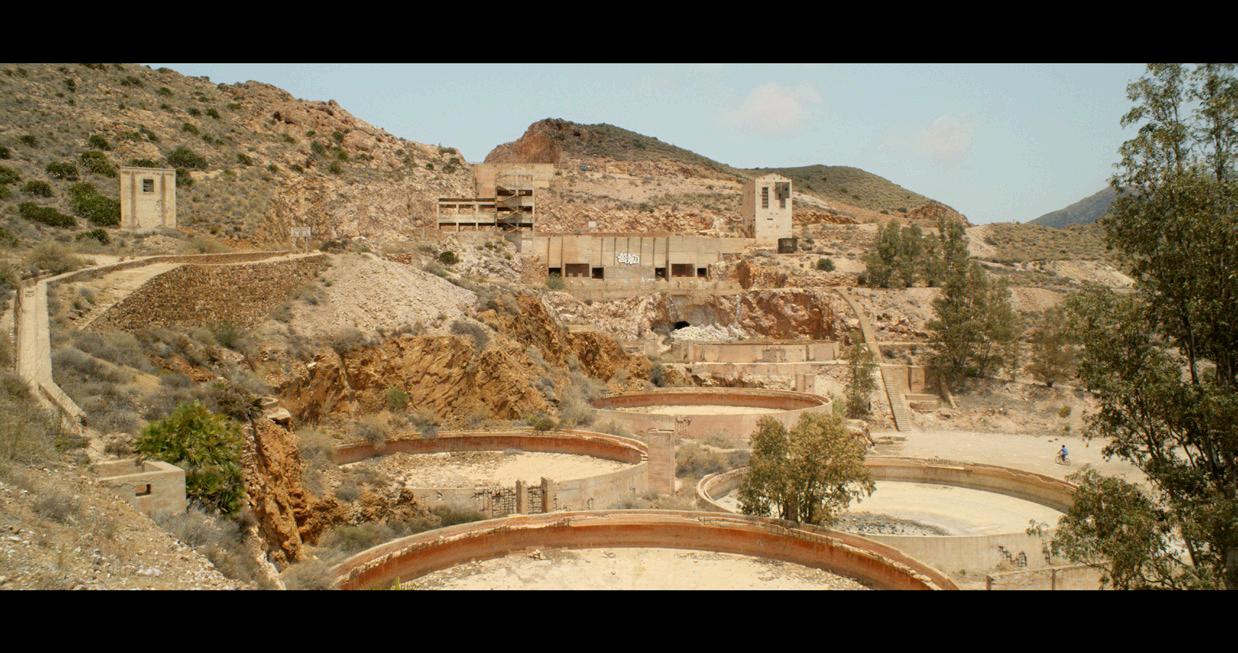

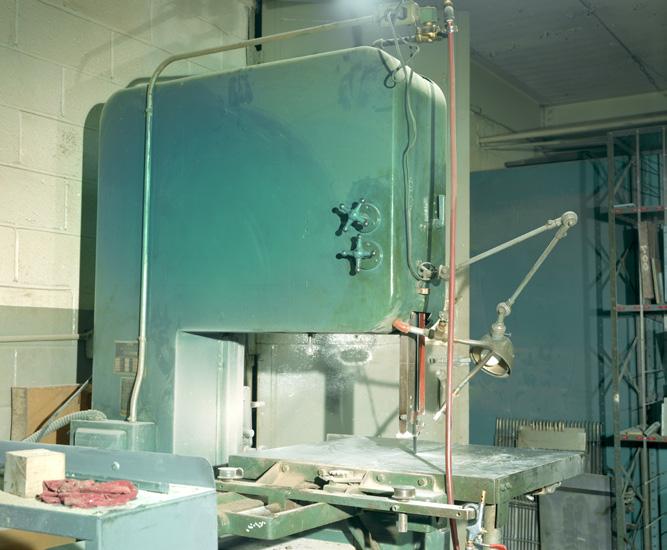

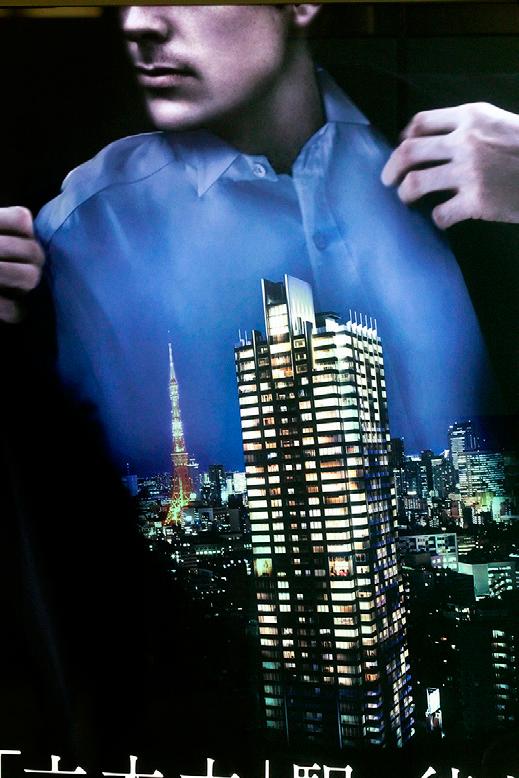

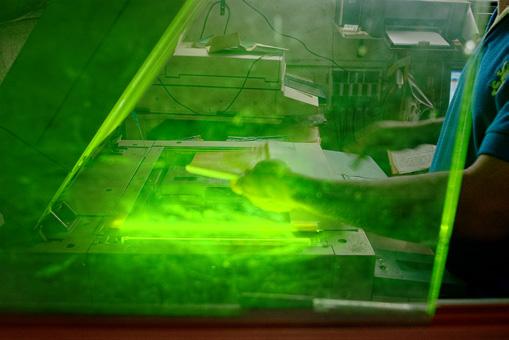

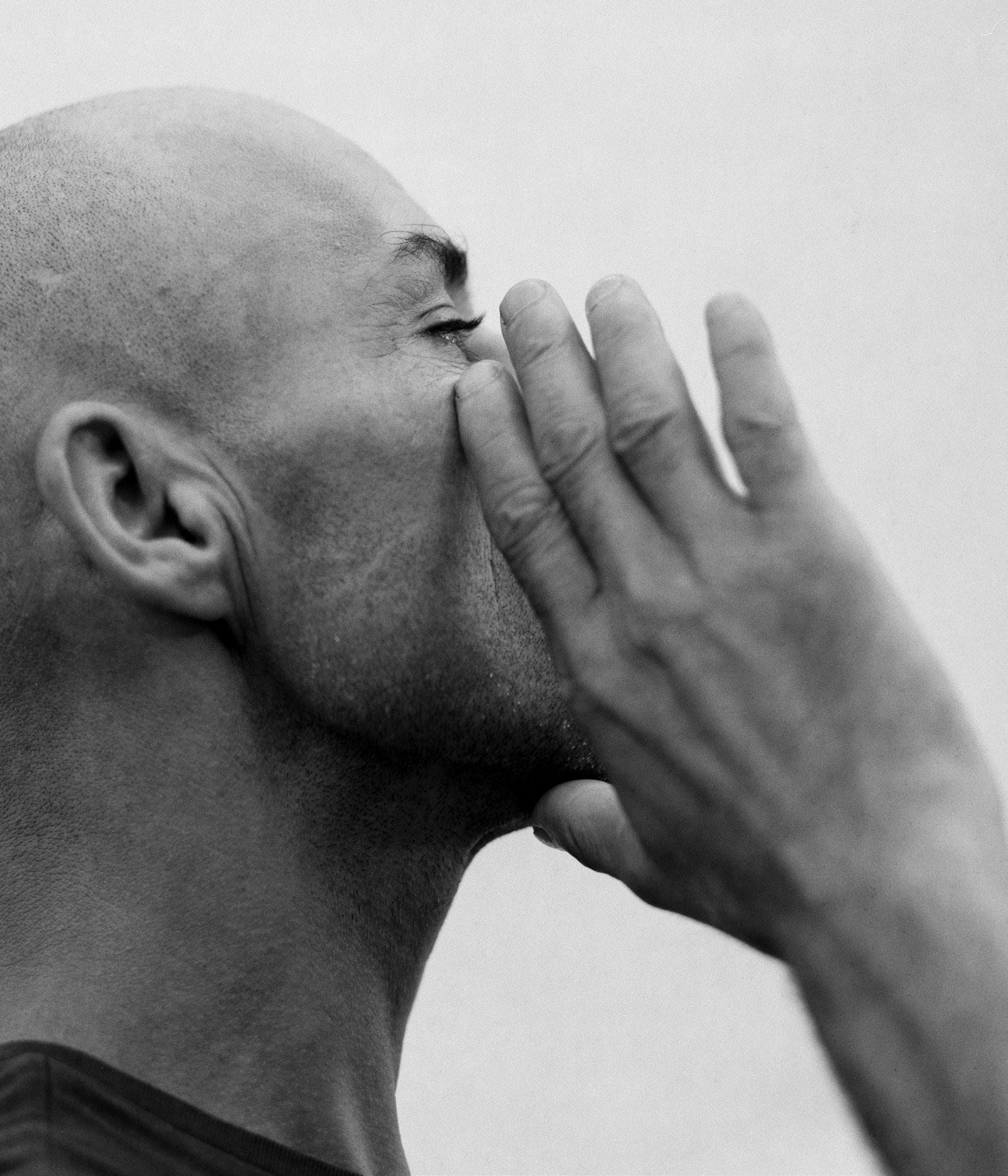

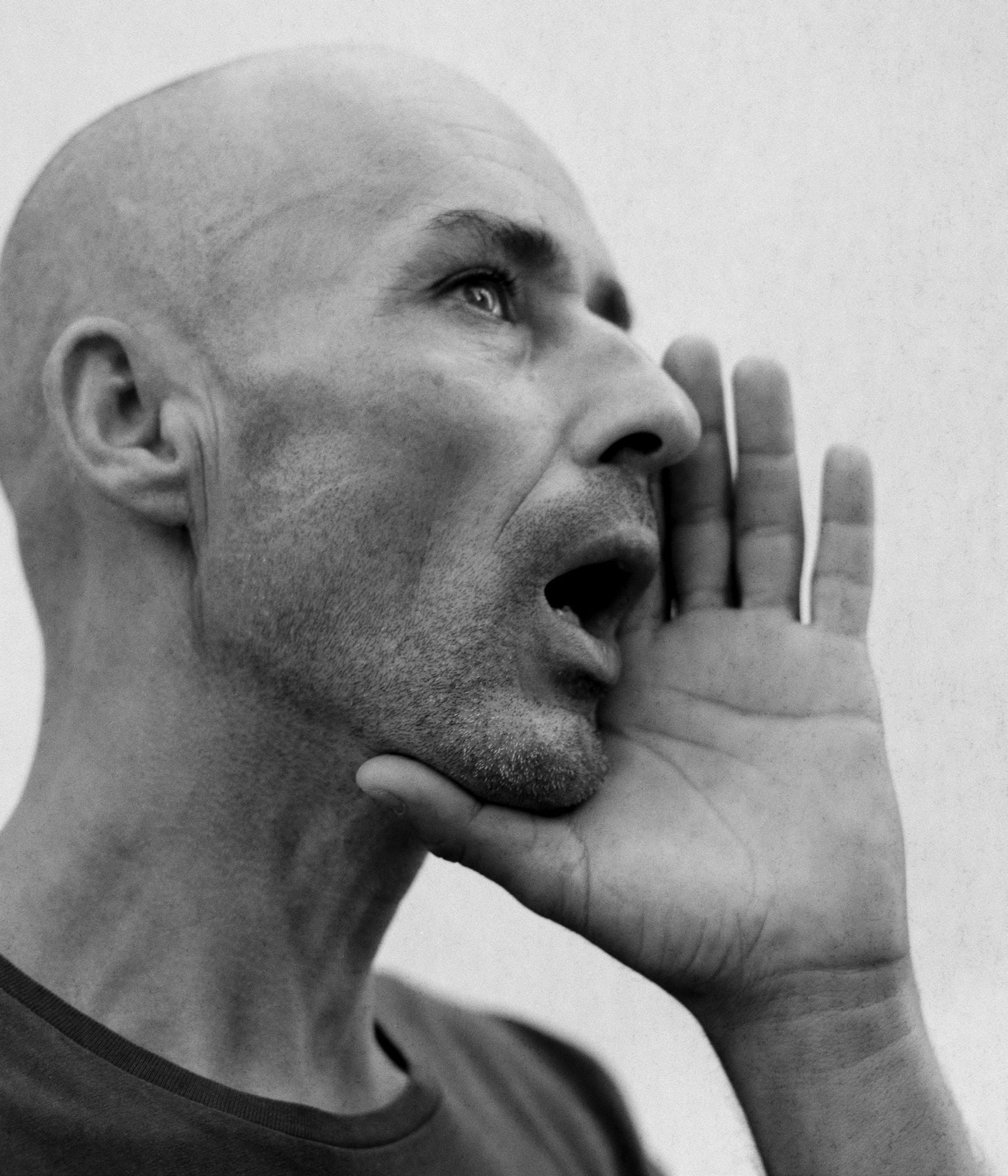

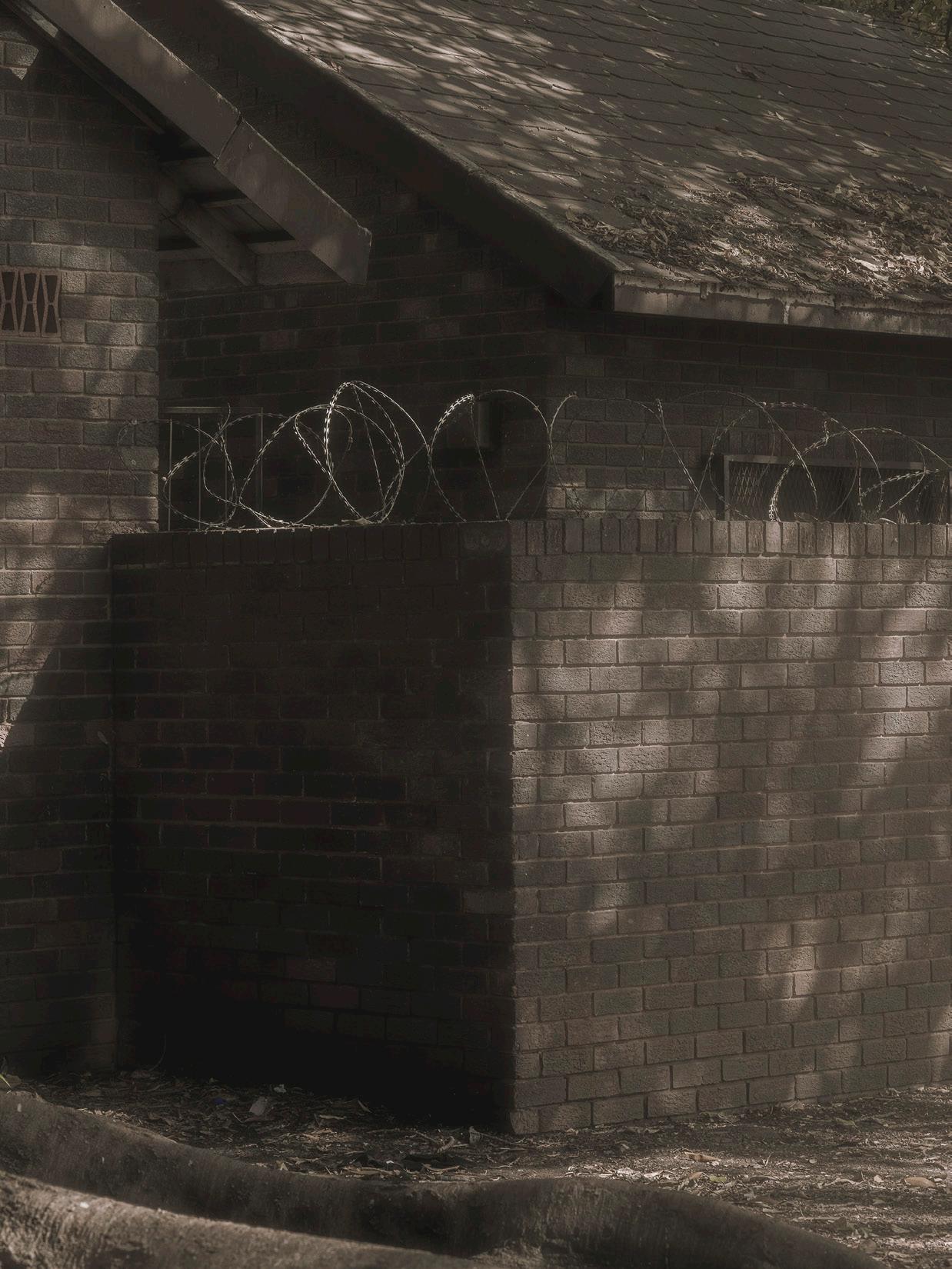

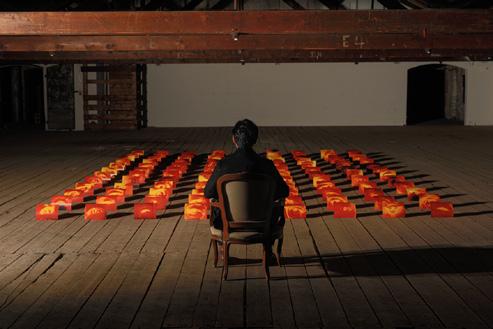

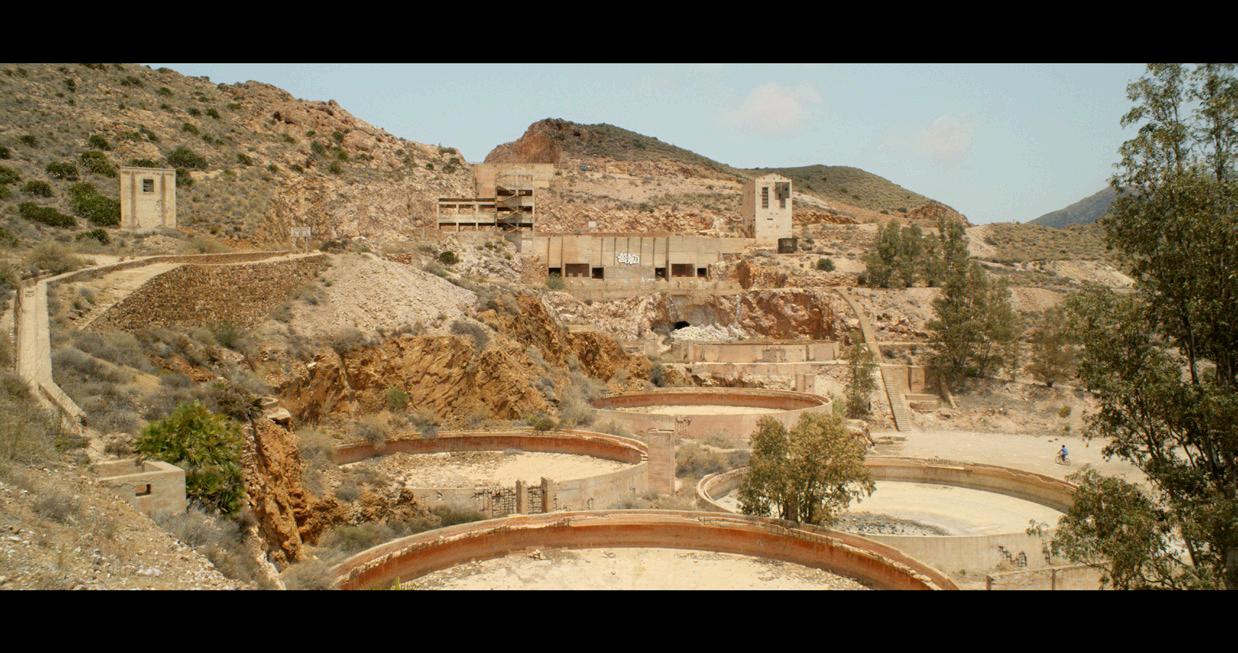

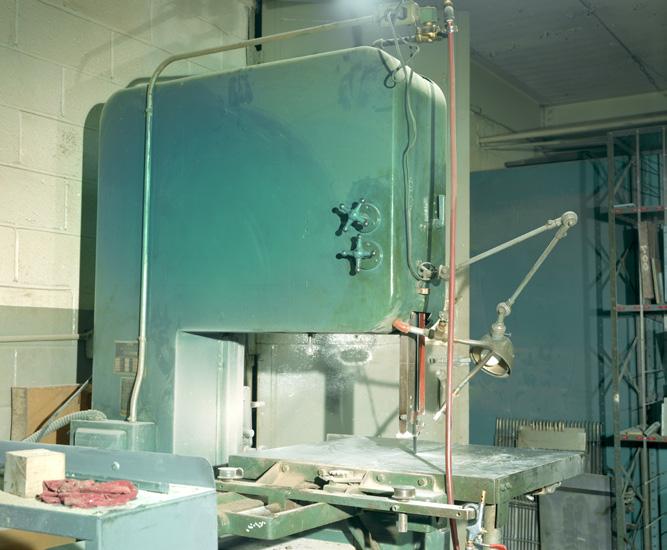

Il progetto di Salvatore Vitale, Death by GPS, è radicale sotto diversi aspetti: evoca al tempo stesso le atmosfere di un laboratorio, di uno studio televisivo e di un luogo che è stato teatro di disordini. Il montaggio in rapida sequenza accosta fotografie documentarie di eventi reali e riprese video di sabotaggi inscenati. Il tutto di fronte a una parete color blu oltremare, a cui è addossata una struttura metallica che funge al tempo stesso da magazzino di stoccaggio e da display. Vitale ci invita a riflettere su tematiche scottanti e divisive, portando alla ribalta la vicenda problematica dell’essere umano che sperimenta sulla propria pelle l’avvento in diretta di una rivoluzione tecnologica che domina azioni e stati d’animo per mezzo dell’automazione dei processi lavorativi e del mercato. Nelle parole dell’artista, “la prima parte di questo progetto a lungo termine è incentrata sulla regione del Gauteng, in Sudafrica, e stabilisce un legame tra la gig economy, l’attività mineraria con le pratiche a essa legate e il concetto di sabotaggio tecnologico. Nello scenario del tardo capitalismo, come conseguenza delle pratiche di esternalizzazione e outsourcing del lavoro, le persone sono ridotte alla stregua di ‘estensioni di software’. Questa posizione paradossale induce i lavoratori a sviluppare nuove strategie di sabotaggio, lotta e sciopero contro quello stesso software” 9. L’artista abbandona più volte la posizione del documentarista, assume lavoratori a salari ragionevoli, fa esplodere strumenti digitali, ad esempio i computer portatili.

13

Si muove, vicino a Johannesburg, nella zona grigia tra gig economy e corsa all’oro, dove quest’ultimo è inteso tanto come metafora di dati informatici quanto come materia prima da estrarre, e, insieme ai suoi neoassunti co-autori, filma persone per lo più giovani, che vivono in condizioni precarie sotto molti aspetti.

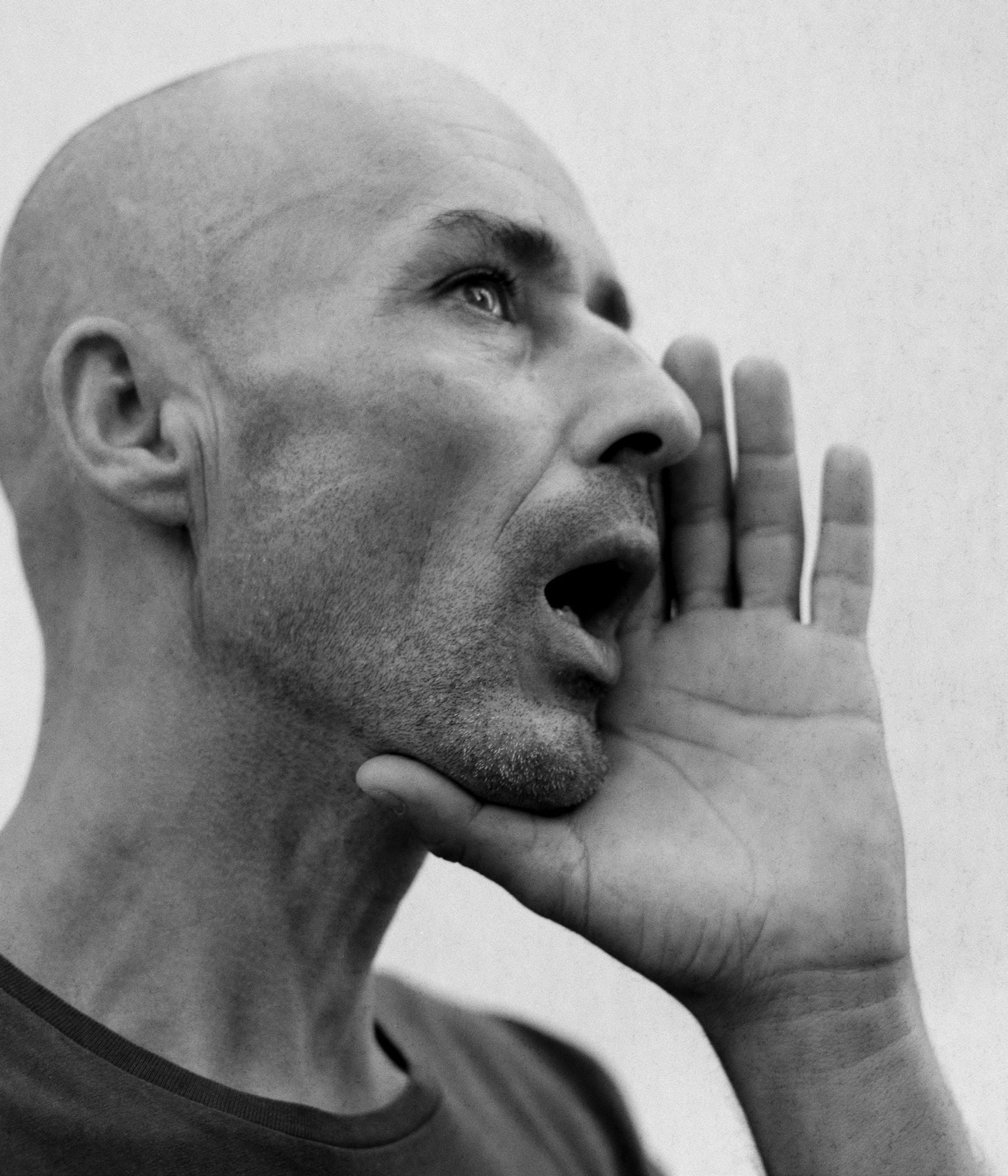

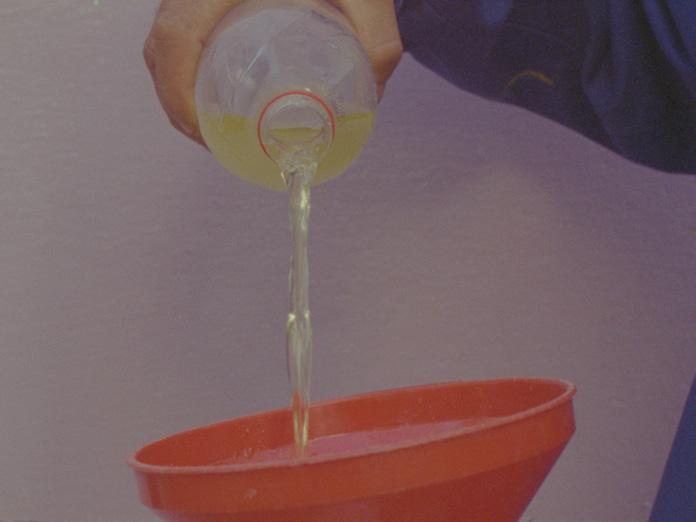

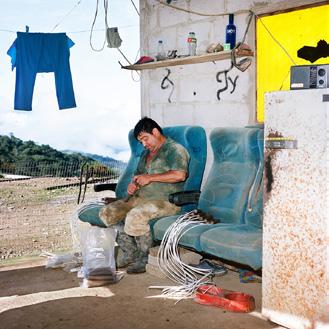

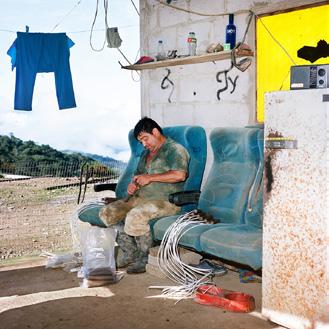

Di primo acchito il lavoro di Hicham Gardaf sembra l’esatto opposto di quello di Salvatore Vitale. In Praise of Slowness è una lode alla lentezza, l’altra faccia della medaglia. Se il video di Vitale mostra nelle scene iniziali un giovane automobilista stressato e in preda a una sorta di frenesia che, bloccato nel traffico, sembra sul punto di avere il suo primo infarto, nelle fotografie e nel video di Gardaf, al contrario, sperimentiamo la calma, un battito cardiaco normale, un ritmo di vita rilassato, in presenza di un carico di lavoro altrettanto impegnativo. Il progetto è ambientato a Tangeri, in Marocco. Il fulcro tematico è rappresentato dal contrasto tra la parte prospera, florida e in espansione della città, e il centro storico con il suo fascino antico, l’ombra fresca alla base delle mura che ne marcano il perimetro, il passo lento e riflessivo. Gardaf veicola questa contrapposizione attraverso una serie di fotografie e un film, riprendendo uomini, venditori ambulanti che ripetono più volte il loro richiamo, passano di casa in casa per portare la candeggina e infine raccolgono le bottiglie di plastica vuote. Un rituale che si ripete inalterato, nella calma ineluttabile di un’azione che

trova la sua ragione d’essere nel contesto sociale e culturale. Così Dominik Czechowski argomenta nel suo convincente saggio: “Soggetta all’impatto della tecnologia avanzata sulla vita quotidiana e alle forze della deterritorializzazione capitalista (Deleuze e Guattari) con le sue politiche di destabilizzazione ed erosione, Tangeri, una città ibrida, con zone industriali in continua espansione, sta subendo una trasformazione sociale senza precedenti e un’urbanizzazione accelerata”. Gardaf segue questo progresso con scetticismo, convinto che per causa sua tutti noi rischiamo di perdere il nostro centro, il nostro orientamento interiore, diventando con il passare del tempo sempre più irrequieti e condizionati dalle regole dettate dalla tecnologia e dal mercato in espansione. Anche in questo senso, Salvatore e Hicham possono essere considerati spiriti affini.

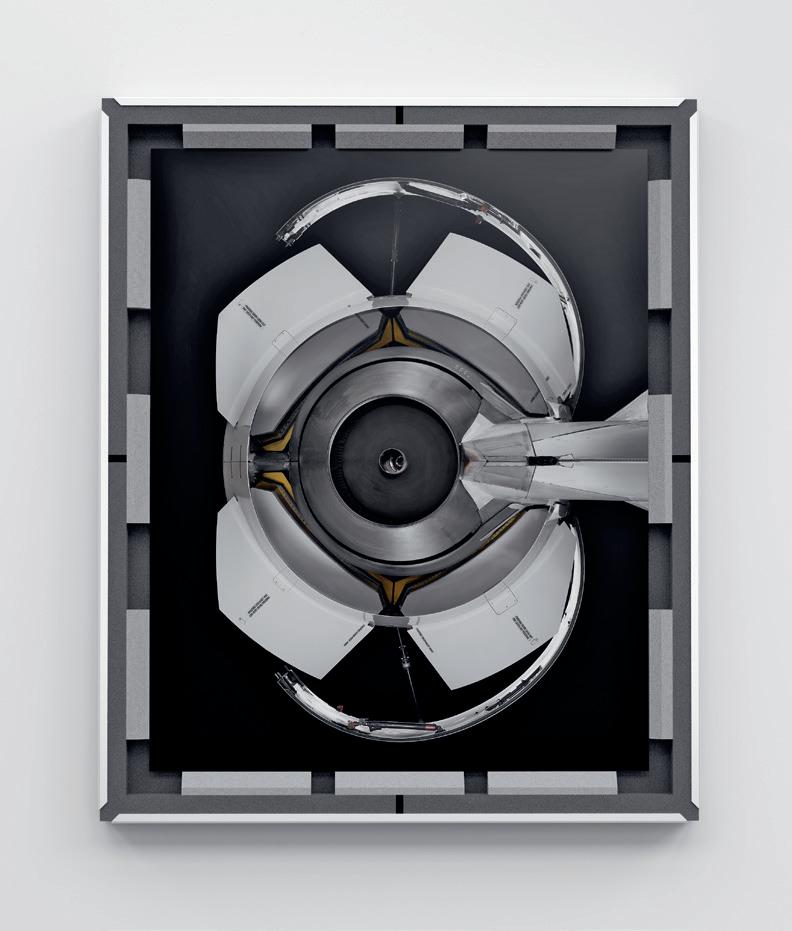

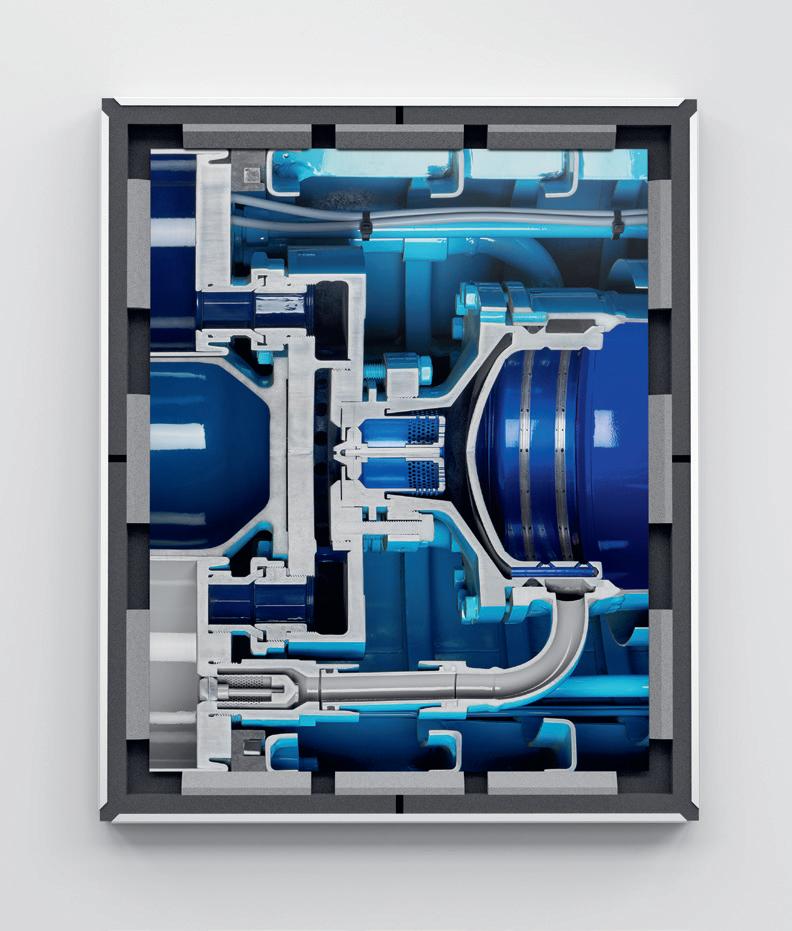

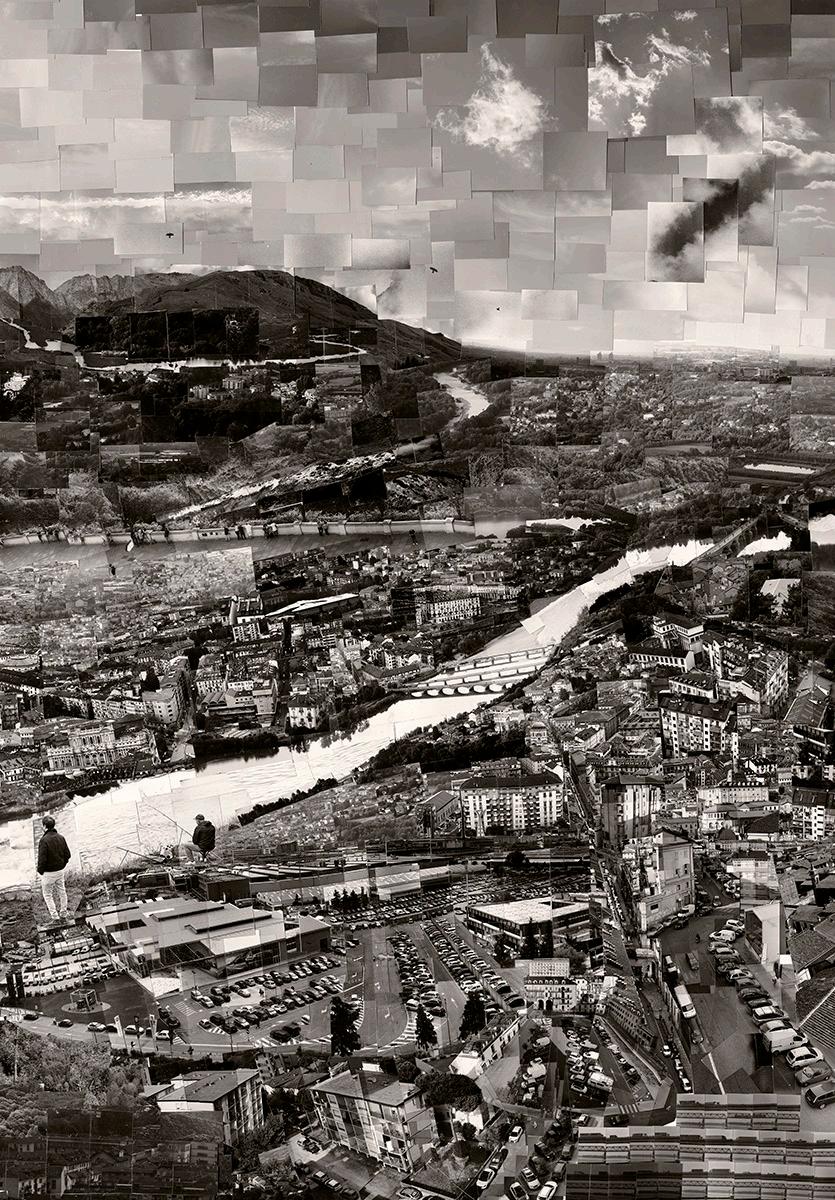

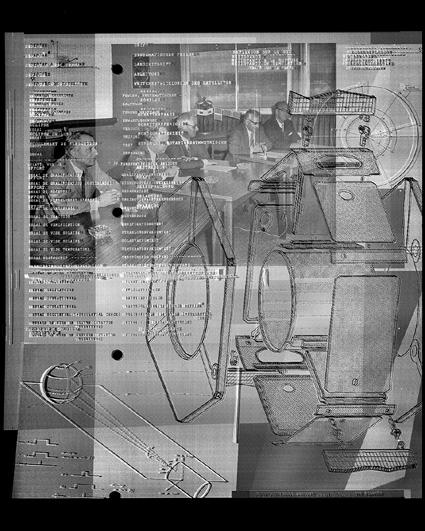

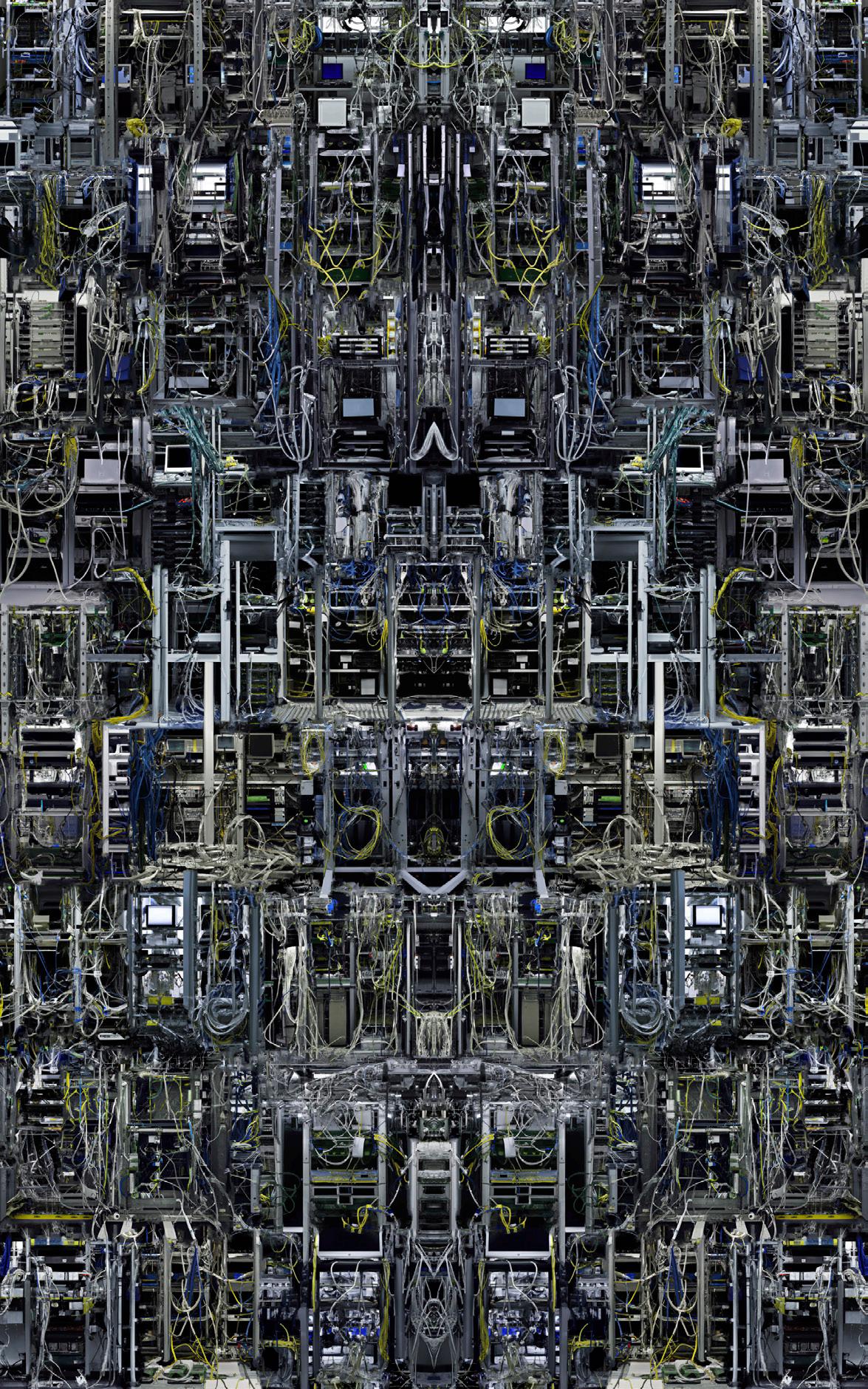

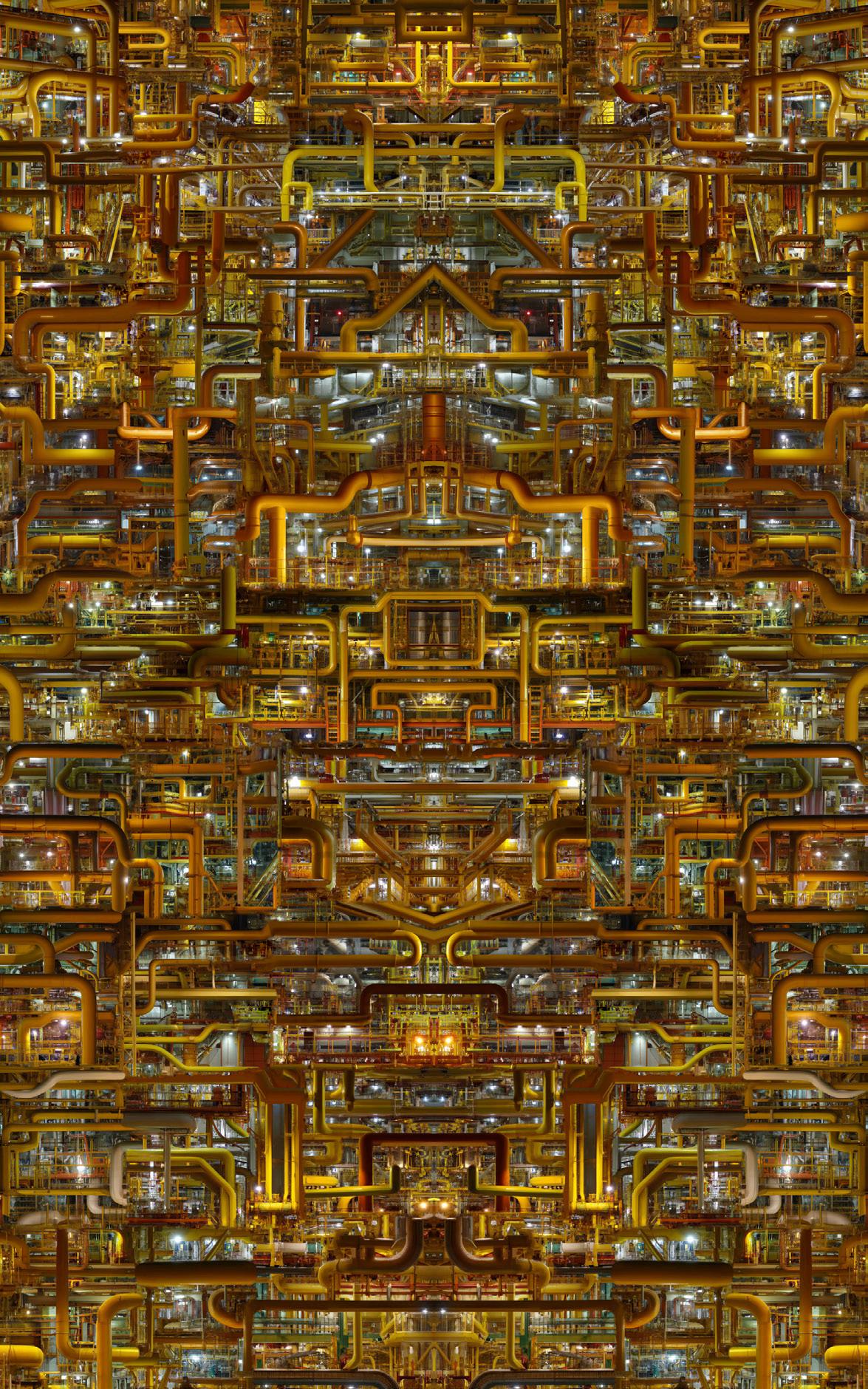

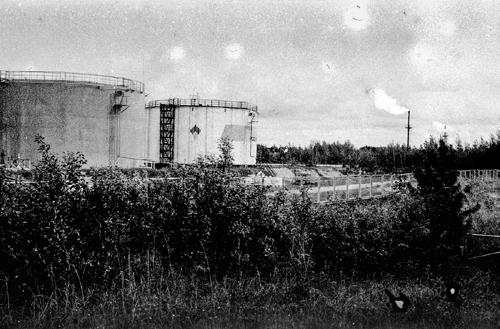

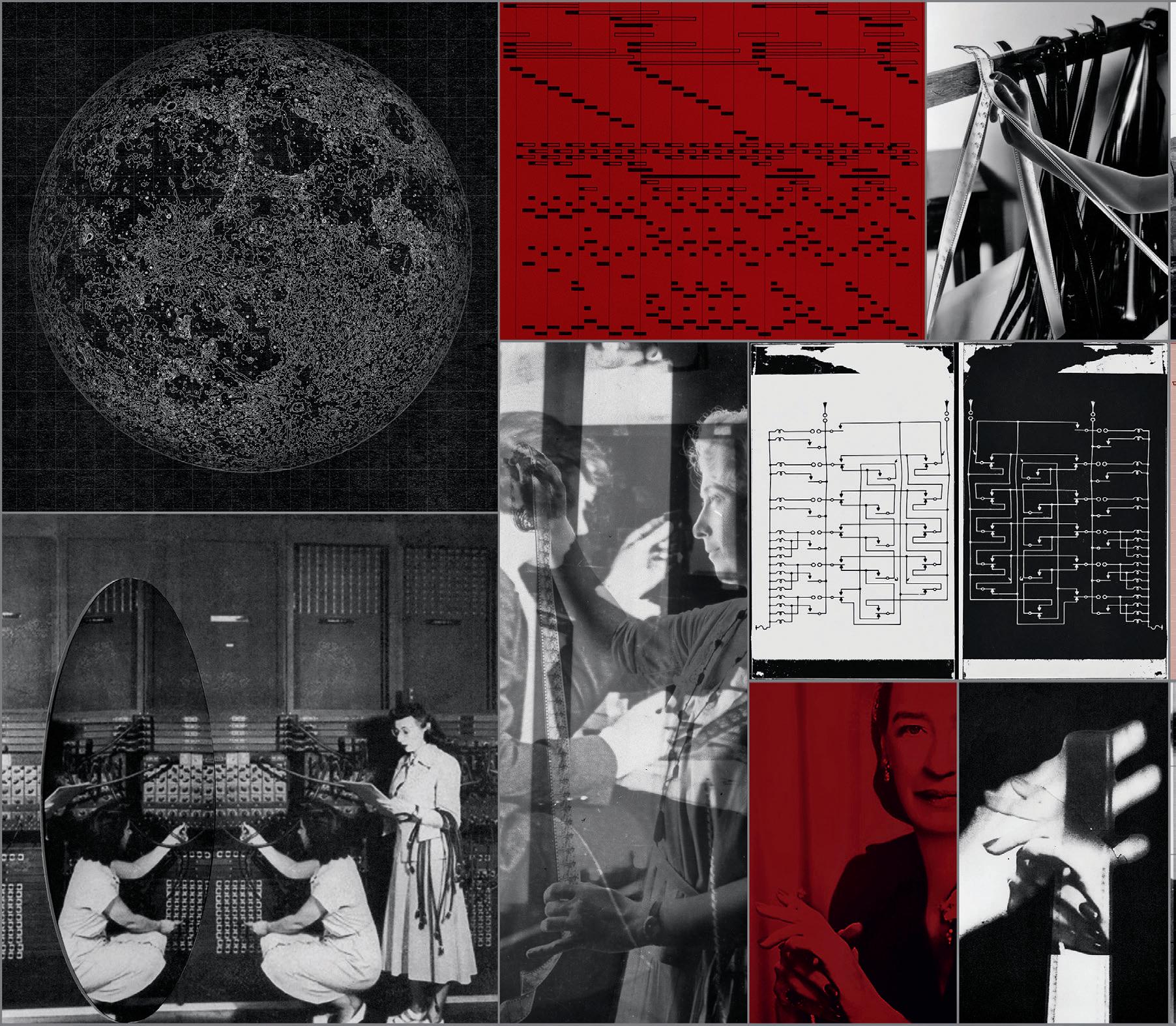

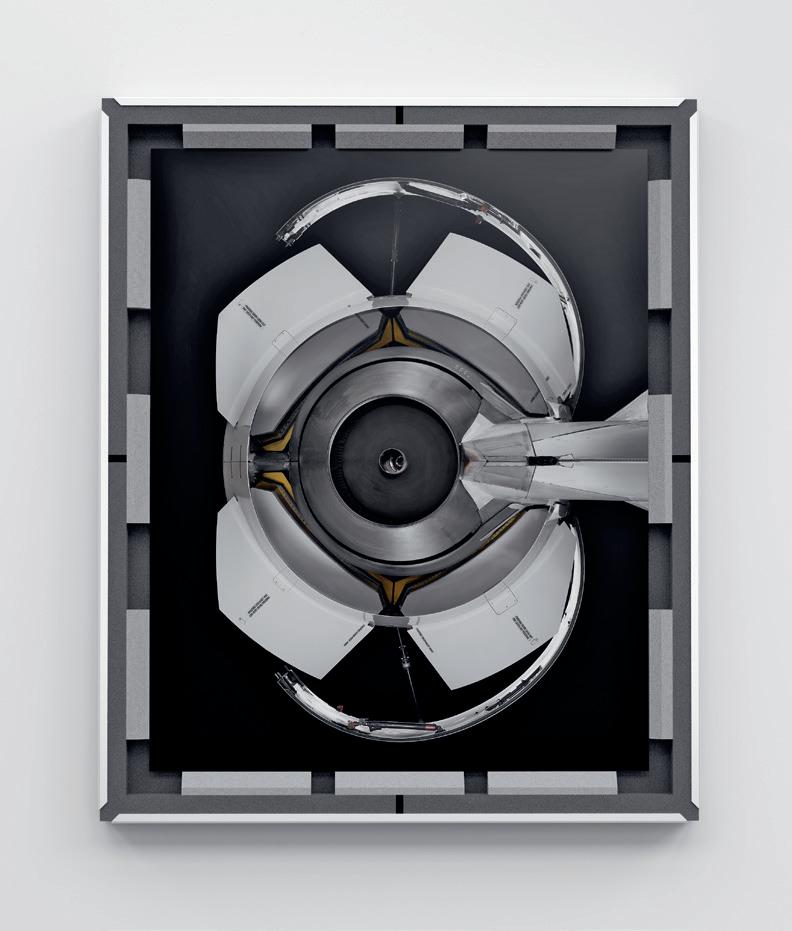

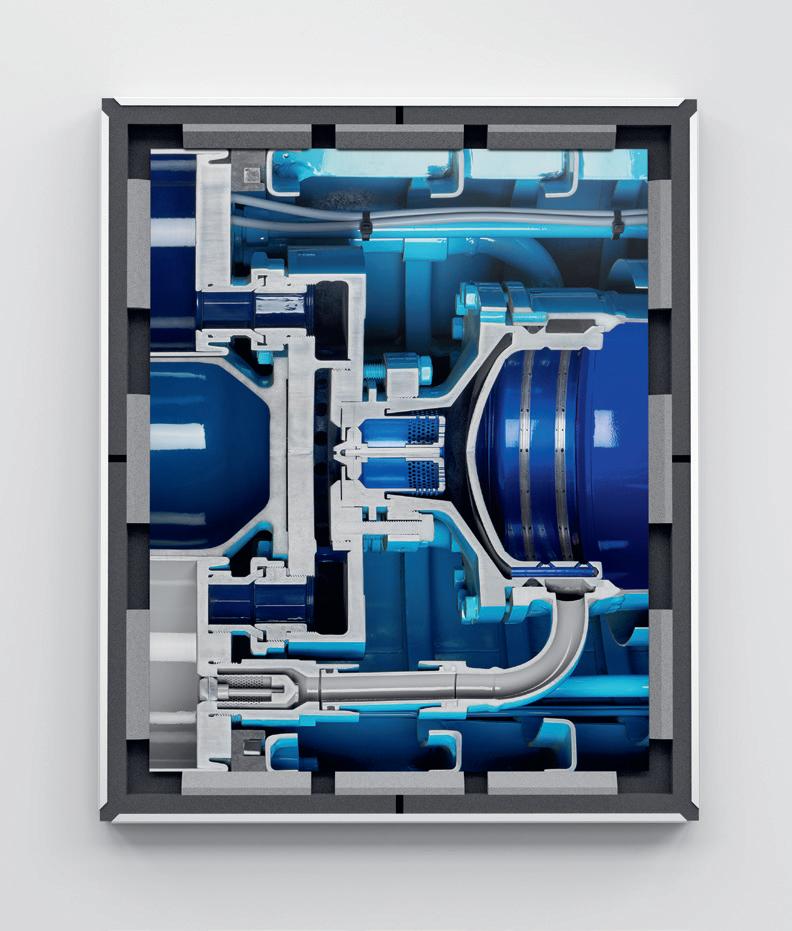

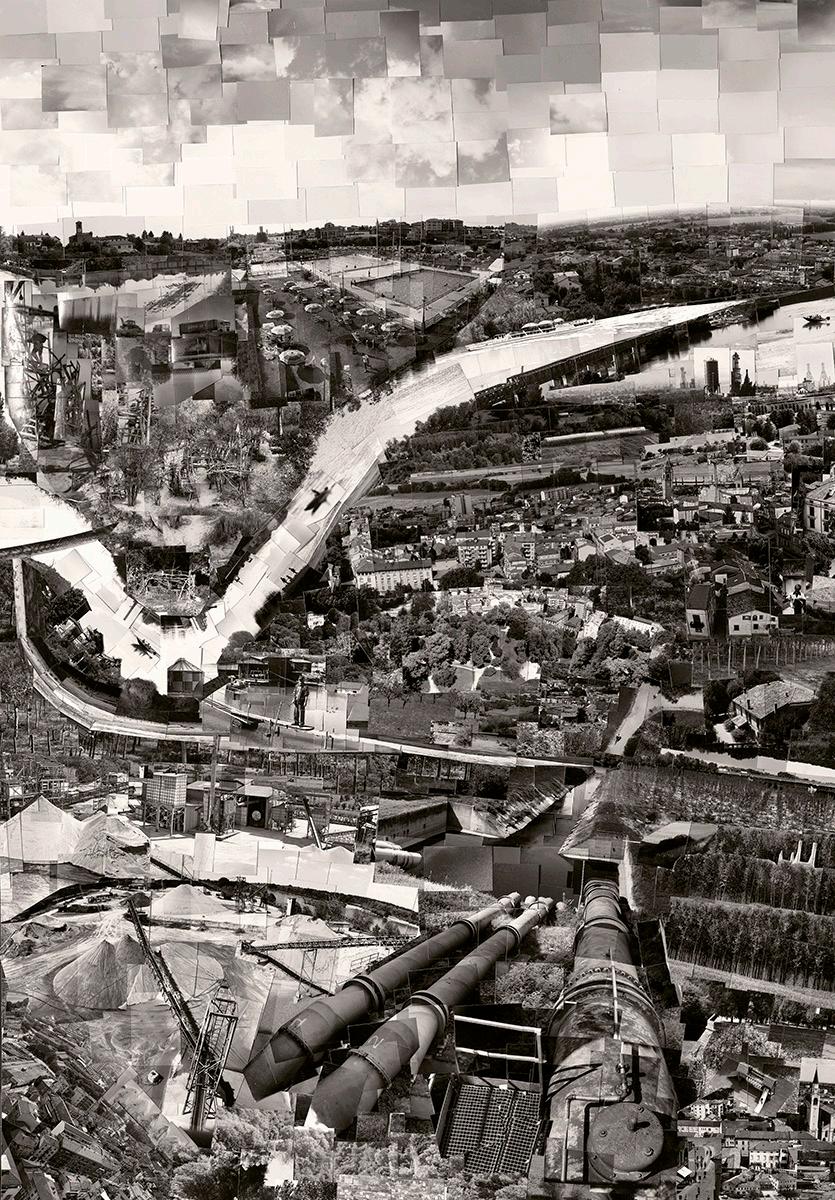

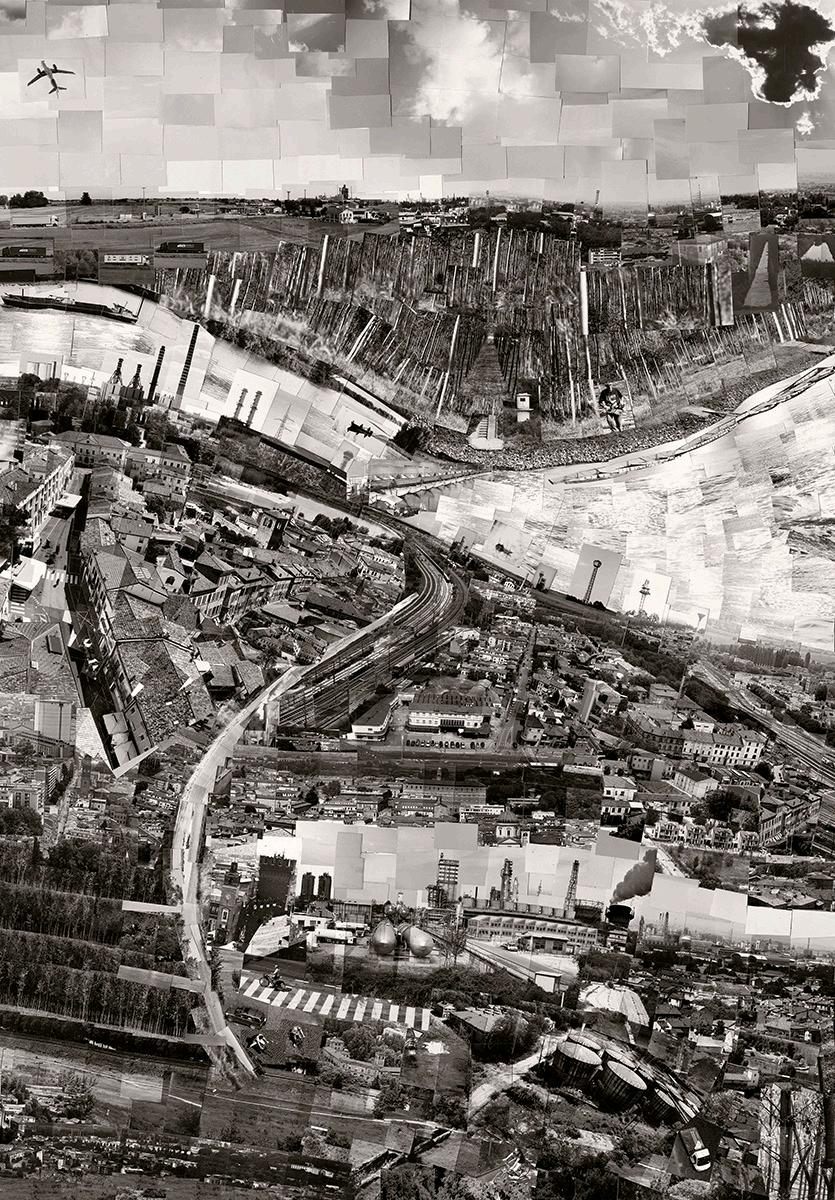

Conclude questa disamina Maria Mavropoulou, e non è certo un caso. Nel suo lavoro, l’autrice compie un significativo passo in avanti rispetto a quanto potevamo, sapevamo o eravamo abituati a fare. L’opera di Mavropoulou In their own image, in the image of God they created them si avvale della più recente tecnologia di intelligenza artificiale disponibile al pubblico. Nikolas Ventourakis descrive così il suo approccio: “Mavropoulou inserisce una serie di prompt di testo in un algoritmo text-to-image: ‘Una struttura complessa e sofisticata di tubi, valvole, manometri, usati nelle raffinerie di petrolio’. L’intelligenza artificiale, che a questo punto può

14

contare su un serbatoio di dati inconcepibilmente ampio, non ha alcun bisogno di una Musa per trovare l’ispirazione. Miliardi di fotografie diventano i punti di riferimento che guidano la macchina verso l’obiettivo, al fine di tradurre la richiesta avanzata in una resa visiva capace di appagare ma anche di alludere astrattamente all’essenza apparente di quei parametri. Quindi l’artista seleziona tra le immagini elaborate dall’algoritmo quella che la soddisfa esteticamente, per poi chiedere al programma di creare delle variazioni sul tema. Successivamente le singole immagini vengono usate come tasselli delle sue composizioni”. Mavropoulou elabora ulteriormente il risultato, moltiplica le tessere in gioco, le fa combaciare, le seleziona e, con un raffinato gioco di specchi e di sdoppiamenti, fa sì che l’immaginario creato risulti familiare ai nostri occhi. In tal modo prende vita una ridda infuocata di immagini così suggestiva da indurci a chiederci se l’intelligenza artificiale resterà sempre vincolata al riferimento alla realtà mediante la fotografia oppure se un giorno non sarà in grado di realizzare un’opera d’arte più significativa in autonomia. Perché ciò che è decisivo qui è il passaggio dal linguaggio all’immagine: l’IA è in grado di convertire l’input testuale avvalendosi di un immenso archivio di immagini la cui origine sfugge ormai al nostro controllo.

Il lavoro, il mondo del lavoro e le immagini del lavoro sono inserite in un carosello che gira sempre più veloce.

1 Arbeit 4.0: Bedeutung, Auswirkungen, Herausforderungen, https://www.personio.de/hr-lexikon/arbeit-4-0 (consultato il 13.12.2022).

2 Luciano Floridi, The Fourth Revolution: How the Infosphere is Reshaping Human Reality, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2014, p. 218.

3 Jürgen Kocka, Arbeit im Kapitalismus. Lange Linien der historischen Entwicklung bis heute, aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, ISSN 2194-3621, Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, Bonn, Vol. 65, Iss. 35/37, pp. 10-17, 2015.

4 Jürgen Kocka, ibidem.

5 Karl Marx, in J. Kocka, op. cit.

6 Deloitte interviews Thomas Friedman: The Future of Work - Consultant’s Mind, https://www.consultantsmind.com/2018/02/11/ thomas-friedman-2/ (consultato il 13.12.2022).

7 Dearborn, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dearborn (consultato il 6.12.2022).

8 Lebohang Kganye, annotazioni inedite, 2022.

9 Salvatore Vitale, annotazioni inedite, 2022.

15

Change in the world of labour

Every other article in the economy pages of newspapers contains the sentence: “The working world is undergoing rapid change.” 1 Digitization, extensive automatization, and even the changing expectations of employees and new concepts of working are revolutionizing the world of work, over and over again. Online HR consultants are always immediately on hand with tips for turning this huge transformation to one’s own advantage. This new situation is generally known in Europe as “Work 4.0,” while the common phrase in other parts of the world is “New Work.”

The five finalists of the MAST Photography Grant 2023—Farah Al Qasimi, Hicham Gardaf, Lebohang Kganye, Maria Mavropoulou, Salvatore Vitale—all engage so conspicuously with the transformation of work that it is worth looking at it in some depth.

The first step towards the new world of work was enabled through the introduction of steam and water power, which opened the way in turn to the development of machines for production and ships for transport. For the first time, products could be made in large volumes by machines. Retrospectively, this first step of the industrial revolution in the mid-18th century might be called “Work 1.0.” The second step, “Work 2.0,” followed around a century later as a result of electrification. Its key feature was the possibility, for the first time, of creating spatial separation between the energy

consumer—e.g., an electric motor or a light—and the power plant in which a variety of primary energy sources (such as water, coal, or oil) are transformed into electricity. In the field of industry, it ushered in a new independence from spatially limited and mechanically complex energy distribution systems, such as the transmission wave. This permitted increasingly small and detailed segmentation of the work steps. An important symbol of this was—and continues to be—the assembly line production employed in the Ford factories.

The 1970s heralded the beginning of “Work 3.0,” the third significant wave of industrial, technological revolution. The speed of automation increased from then on; gradually, this was supported by computers, later by industrial robots. And today “Work 4.0” is underway, concurrently with the fourth revolution, which the Italian philosopher Luciano Floridi has described as an incursion and domination of information and communication technologies: “The information society is better seen as a neo-manufacturing society in which raw materials and energy have been superseded by data and information, the new digital gold and the real source of added value.” 2

We usually term the period encompassing these 250 years the industrial revolution, especially when we are thinking of technical, technological development. We call it industrial capitalism when the focus lies on the economic shift that went hand in

16

hand with the industrial revolution. We define it the modern period when we consider more generally the social and cultural changes linked with it.

Time did not stand still in the period before these particular 250 years: A flourishing mercantile capitalism had existed in Europe since the High Middle Ages and even earlier in the Arab world and in China. “The period of European state building would not have been possible without the capitalism of the Medici, Fugger, or Baring families.” 3 There was also the grim plantation capitalism that had been established during the colonization of the world in the 16th century, not to mention the agrarian capitalism that had “lead to the consolidation of large estates in the hands of noble and burgher owners. The landlords of central and eastern Europe sold their grain crops on the international markets according to capitalist principles, but exploited their labourers in bondage, through serfdom or slavery.” 4

Yet, the dynamism, the speed, the radicalness with which technology, science, and the economy developed in these 250 years was almost monstrous. As a result, we often speak of this period as a time of permanent revolution, of development at breakneck speed that shook the foundations of every generation at least once over the course of life. Karl Marx described it like this: “Constant revolutionizing of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions,

everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones.” 5 Continuous, ever accelerating innovation became the central motor of society, which consequently found itself in repeated revolution. Wage labour became a mass phenomenon, and ways of life changed constantly as a result of changing work places, work shifts, work hierarchies. Retrospectively, it is evident that nothing remained untouched by these changes. From the workers’ struggles of the 19th century, the starvation wages, the trade unions, to the revaluation of work during the golden age of the social market economy in the 1960s and 1970s, and to the knowledge workers and a situation that Thomas Friedmann, writer on globalization and structural change in the Information Age, has described in an interview in this way: “Because if work is being extracted from jobs, and if jobs and work are being extracted from companies—and because (…) we’re now in a world of flows—then learning has to become lifelong. We have to provide both the learning tools and the learning resources for lifelong learning when your job becomes work and your company becomes a platform.” 6 His words highlight once again the fundamental change in work today –leaving aside the increasing influence of artificial intelligence for now.

That brings us to the works of the finalists of our MAST Photography Grant 2023.

17

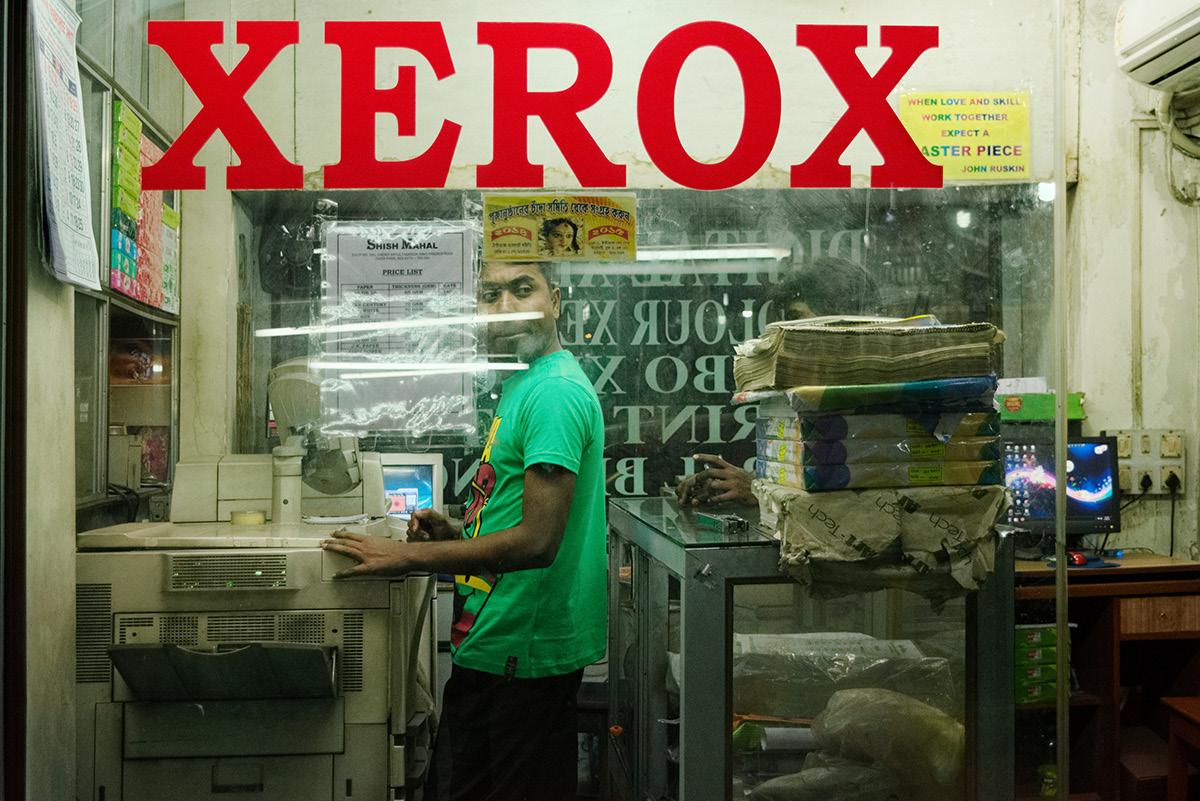

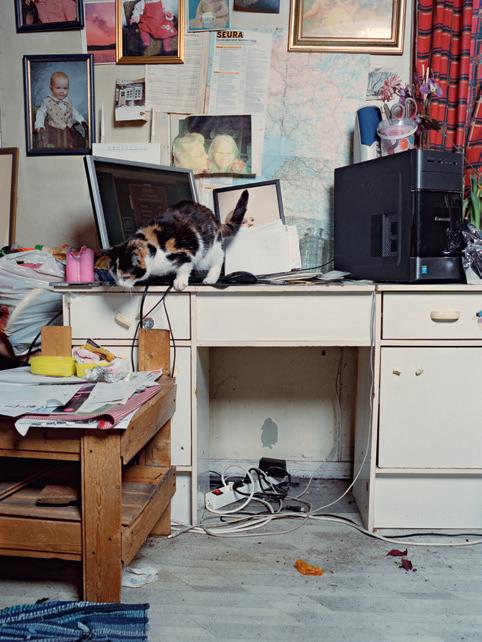

Farah Al Qasimi focused on the large Arabic community in Dearborn, Michigan. Wikipedia provides a description of the city: “The city is the home town of Henry Ford and the location of the international headquarters of the Ford Motor Company. The development and character of the city is largely due to Ford. (…) With over 29,000 Americans of Arabic heritage (according to a census of 2010, this is equivalent to 41.7 % of the city’s population), Dearborn is home to the second largest Arabic population in the United States. Arabs first located here in order to work in the automobile industry. (…) Dearborn is the location of the Ford Rouge Complex. (…). In its heyday it employed 100,000 workers and produced complete vehicles.” 7 Al Qasimi moved around the city by day and by night and observed it as a transport and cultural system. She did not attempt to enter the Ford factories, as free photography is not usually permitted there; instead, she observed the people, their activity, their waiting, their journey to work, and the impact of their activities and reactions on the walls of the city. She has created a kind of amalgam of views onto the real city and onto the city as it is photographed, covered in posters, in other words, views of private and public signs in a city that represents a mix of Arabic and American manifestations. Finally, Al Qasimi re-stages the photographed worlds like a piece of city wall in the exhibition space, with all its overlapping layers, with all its personal and cultural codes.

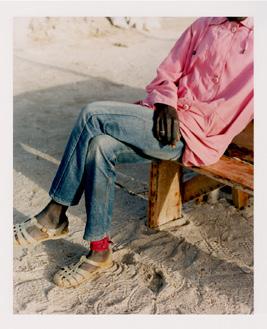

Lebohang Kganye is a seductive and deeply visual storyteller in equal measure. She stages scenes from South African life like a Chinese shadow theater, using photographed cutout figures and theatrical lighting and combines them in the exhibition space to create both small and large-scale installations. She re-enacts, re-imagines, re-installs and re-mixes real situations, real events using literary reflections and exaggerations to create an impressive fantastic-real image theater. In the project Keep the Light Faithfully (2022) Kganye re-imagines western literature of the rarely known and gendered narratives of hundreds of women light keepers from the 19th and 20th century, including Lenore Skomal’s The Lighthouse Keeper’s Daughter (2010)—a tale of Ida Lewis, who tended the light at Lime Rock Lighthouse. As history would have it, Lewis became known for her many rescues of men in the Atlantic Ocean near Rhode Island, from as early as 1858. Yet, Kganye returned empty handed from her research trip on the topic, as practically all lighthouses are automated, the lighthouse keepers have disappeared. But here, bound into oral histories, she stages and invents new stories and thereby resurrects the lightkeepers. In recent years she has been constantly on a search for collective memories, as she herself has written, the sort of “tales marked by long periods of isolation, of their rescues, of voyages disrupted by storm-tossed seas and gale-force winds, stories of the monotonous

18

tasks that frame the life of a lightkeeper—as well as the impact of rapid technological developments and advancements on an already relatively invisible form of labour and public service.” 8

Salvatore Vitale’s project Death by GPS is radical in several respects. His presentation acts simultaneously like a laboratory, a TV-studio, and an agitative event. The artist combines documentary photography with staged sabotage videos, sampled video and hard edited video. Everything is presented in front of an ultramarine blue wall, a storage and presentation rack. His subject is cutting edge, it expresses a question about the human being in the current technological revolution, in which every action, every being is determined by technology, by the automatization of working processes, and by the market. Vitale writes: “The first part of this long-term project focuses on the region of Gauteng, South Africa, and establishes a link between the gig economy, the mining industry and the idea of technological sabotage. In the context of late capitalism and as a consequence of the outsourcing of work, human beings became ‘software extensions.’ This position opens up a paradox, in which workers develop new strategies to sabotage, to fight and strike against the software.” 9

The artist repeatedly abandons the position of the documentary maker, employs workers at reasonable wages, detonates digital tools, even laptops. In the vicinity of Johannesburg, he moves in the grey

area between the gig economy and a gold rush mentality, between data and material, and together with his newly employed co-creators he frequently films people, young people, living in many ways precarious lives.

Hicham Gardaf’s approach appears at first glance to be the exact opposite of Salvatore Vitale’s research. His work is called In Praise of Slowness; it is the other side of the coin. If Vitale’s video begins with an extremely hectic, extremely tense young car driver who almost seems to have his first heart attack in a traffic jam, in Gardaf’s photographs and film we experience calm, a normal heartbeat, even a relaxed rhythm of life, yet with an equally demanding workload. Gardaf’s project takes place in Tangier. Its subject is the opposition between the prospering, growing, expanding part of the city on the one hand and the old town with its ancient sounds, cooling walls, its measured steps on the other hand. The artist shows us this in his photography and in his film through men, street merchants, who announce their stock of bleaching agent with the ever-same cry, bringing it to the inhabitants and later collecting the empty plastic bottles. It is an ever-repeating ritual with the stillness and strength of an activity that is embedded in the social and cultural realm. Dominik Czechowski has written on it in his impressive text: “Subjugated to advanced technology’s impact on everyday life and the forces of capitalist deterritorialization (Deleuze and Guattari)

19

with its politics of destabilization and erosion, Tangier, a hybrid city with its ever-expanding industrial zones, is undergoing an unprecedented social transformation and accelerated urbanization.” Gardaf has been following this progress with evident scepticism, because we lose our centre, our inner orientation in it and, with time, we become ceaselessly restless, defined by the rules of technology and the booming market. In this sense, Salvatore and Hicham are brothers in spirit.

We have deliberately left Maria Mavropoulou until last in this introduction. In her works, she goes a clear step further than we have so far known how or have been able to go. Mavropoulou’s In their own image, in the image of God they created them uses current, freely available AI technology. Nikolas Ventourakis has described her approach in this way: “Mavropoulou inserts a number of text prompts in a text-to-image algorithm: ‘A complex and sophisticated structure of pipes, valves, manometers, used in oil refineries.’ The AI, which at this point has an incomprehensibly large pool of data, has no need for a Muse to be inspired. Billions of photographs serve as reference points and guide the machine towards its goal to interpret the request in a visual output that would fulfil but also allude abstractly to the apparent essences of those parameters. The artist then selects an image from the algorithmically compiled ones that pleases her aesthetically and in the next step would

ask the program to create more variations of it. The individual images would subsequently be used as tiled elements in her compositions.” Mavropoulou then develops the result further, multiplies the tiles, connects them, selects, and, through subtle reflection and duplication, she makes the picture, the resulting image world, seem familiar to us. In this way, such powerful, almost wildly fiery pictures are created that we are forced to ask whether AI could at some point make artworks with greater meaning—rather than asking whether this has irrevocably placed into doubt the referentiality of a photograph to reality. For the decisive moment is the step from language to image. The AI, with the aid of an enormous training archive, transforms the inputted statement into images whose origins we will never fully be able to trace.

Indeed, work, the world of work, and the images of work are truly caught in a rapidly spinning carousel.

1 Arbeit 4.0: Bedeutung, Auswirkungen, Herausforderungen, https://www.personio.de/hr-lexikon/arbeit-4-0 (accessed: 13.12.2022).

2 Luciano Floridi, The Fourth Revolution: How the Infosphere is Reshaping Human Reality, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014, p. 218.

20

3 Jürgen Kocka, Arbeit im Kapitalismus. Lange Linien der historischen Entwicklung bis heute, aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, ISSN 2194-3621, Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, Bonn, Vol. 65, Iss. 35/37, pp. 10-17, 2015.

4 Jürgen Kochta, ibidem.

5 Karl Marx, in J. Kochta, op. cit.

6 Deloitte interviews Thomas Friedman: The Future of Work - Consultant’s Mind, https://www.consultantsmind.com/2018/02/11/ thomas-friedman-2/ (accessed: 13.12.2022).

7 Dearborn, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dearborn (accessed: 6.12.2022).

8 Lebohang Kganye, unpublished notes, 2022.

9 Salvatore Vitale, unpublished notes, 2022.

21

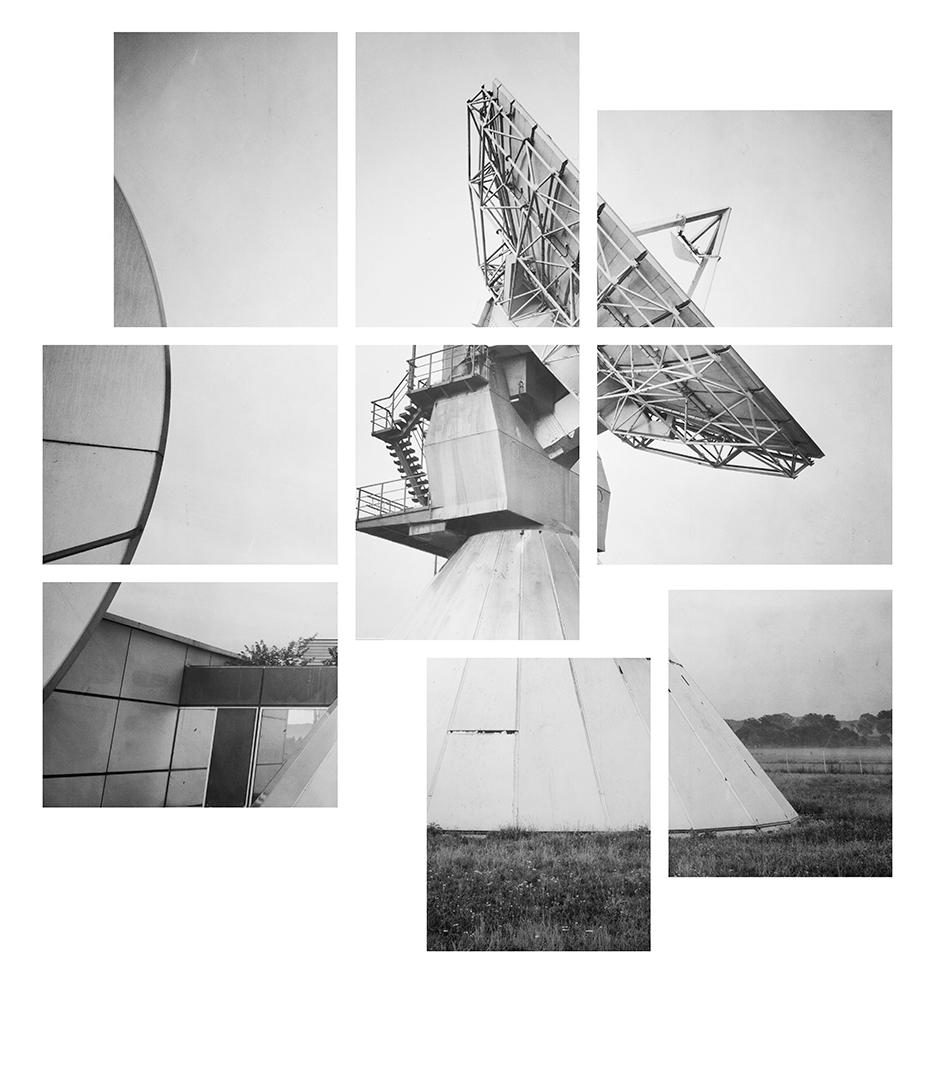

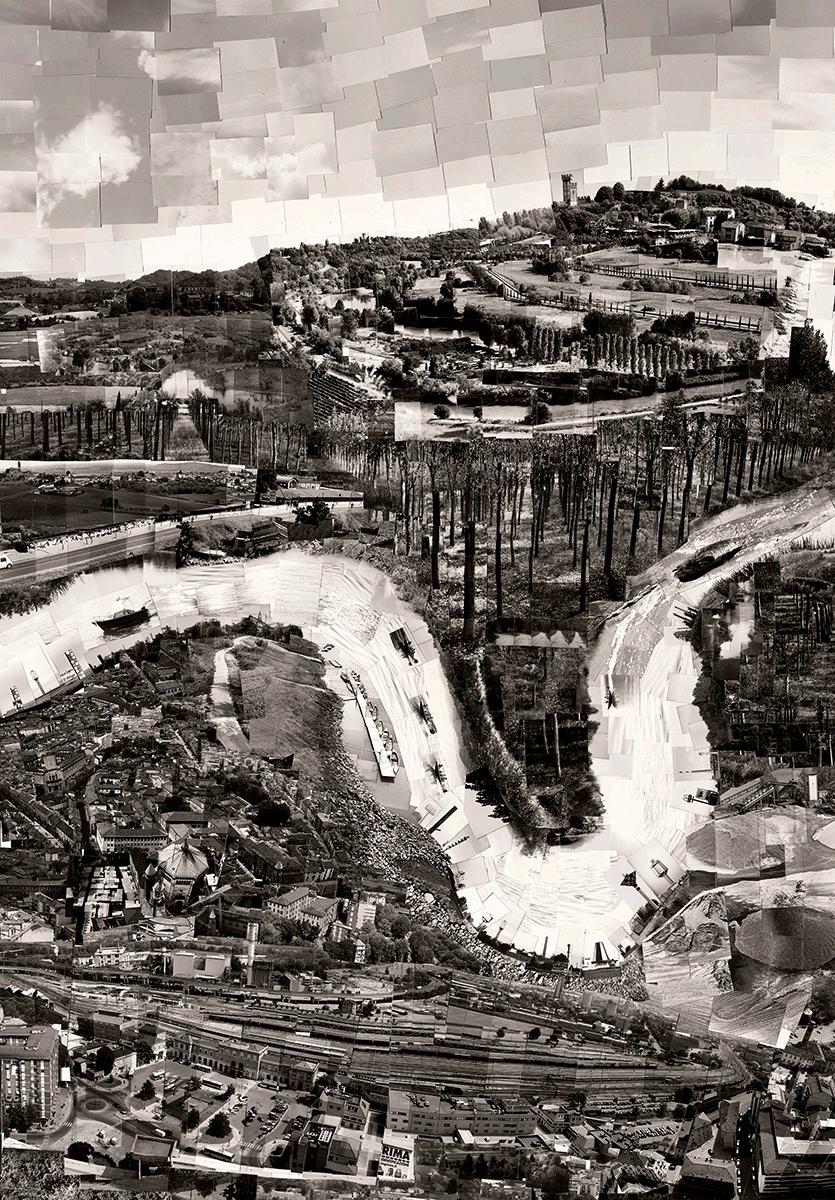

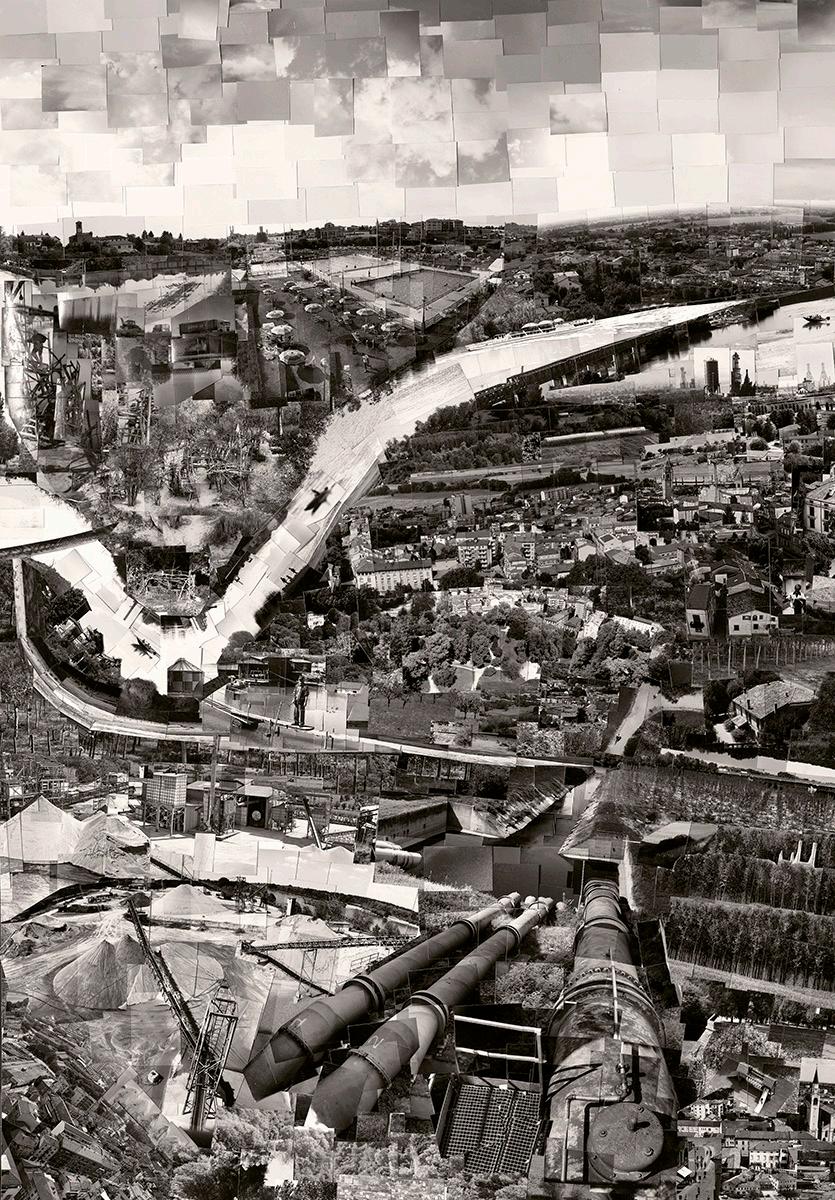

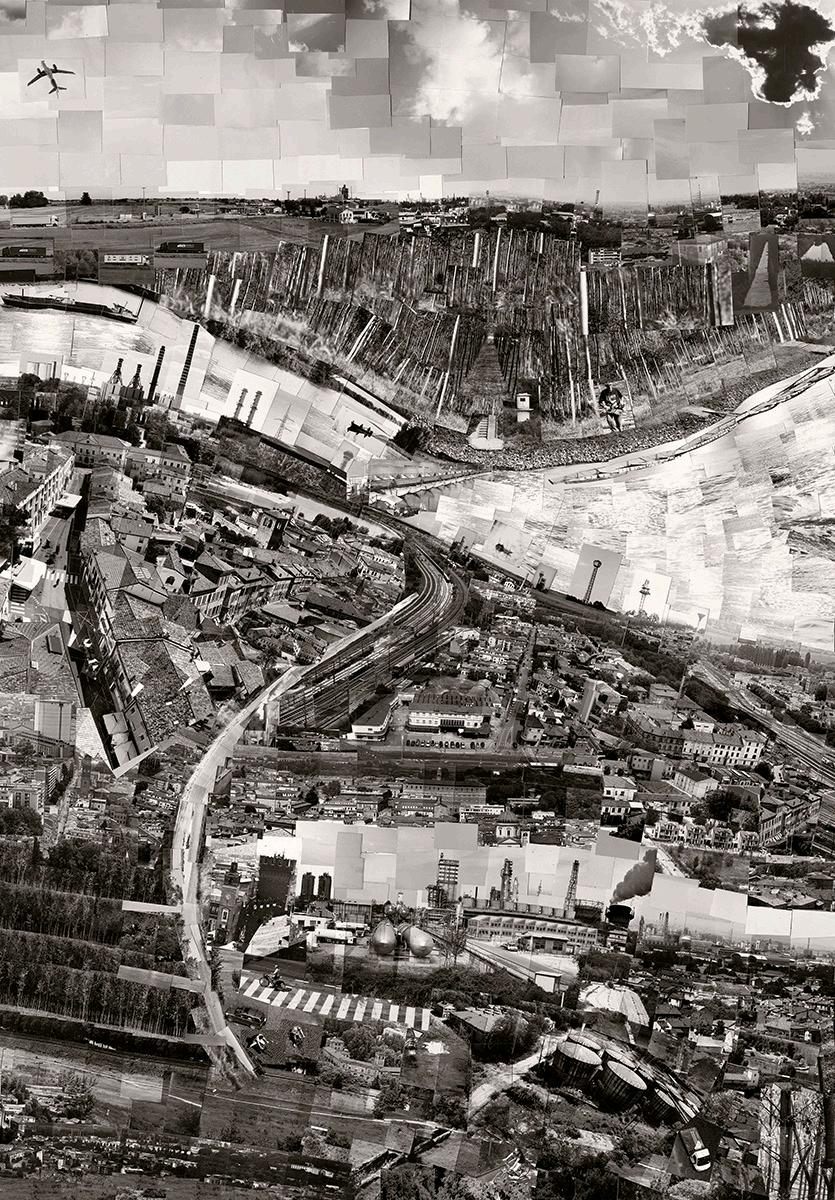

MARIA MAVROPOULOU

Nikolas Ventourakis

In their own image, in the image of God they created them

Mavropoulou 24

Maria

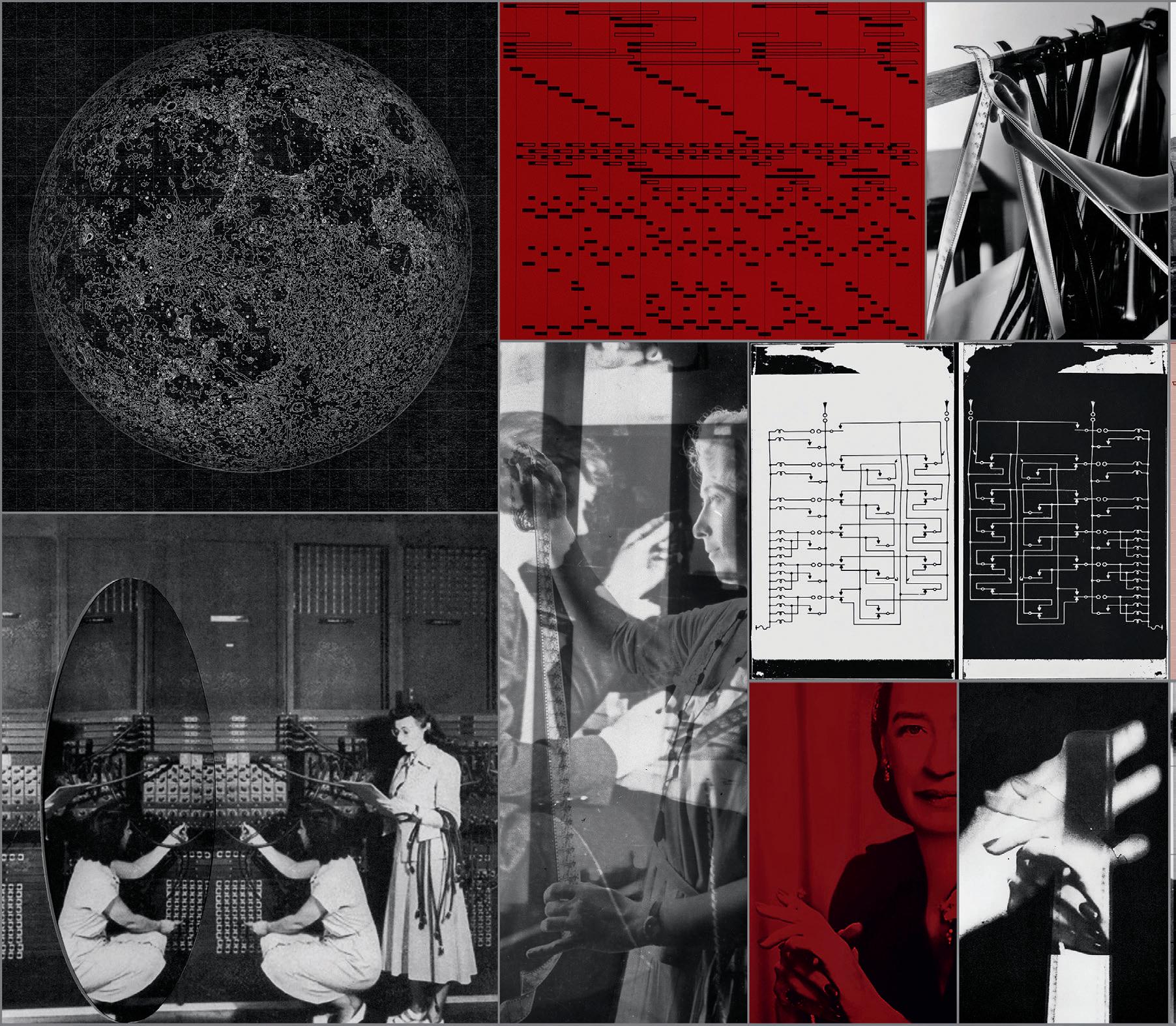

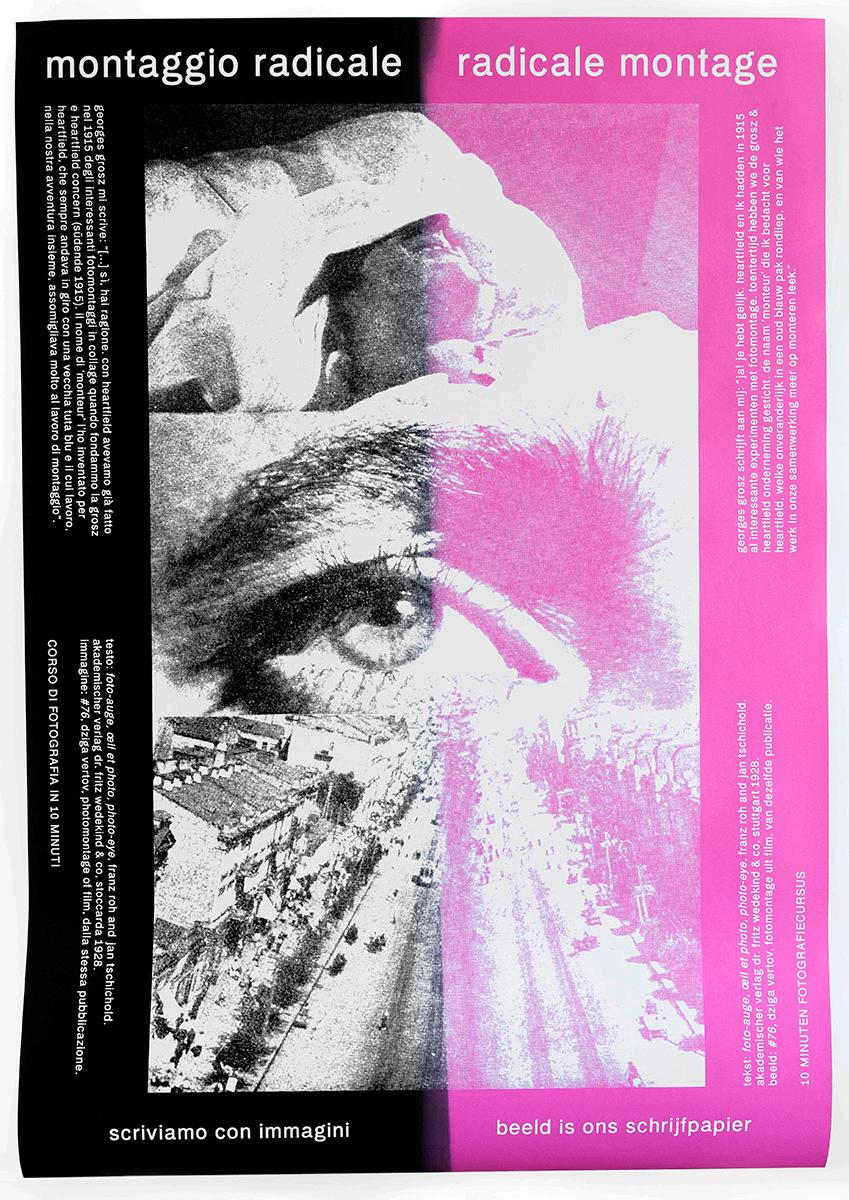

La vittoria che il software AlphaGo di Google riportò nel 2016 contro Lee Sodol, uno dei più grandi giocatori umani di Go di tutti i tempi, non scosse la coscienza collettiva quanto la sconfitta a scacchi di Gary Kasparov contro Deep Blue di IBM, nel 1997. Tuttavia, nello sviluppo dell’intelligenza artificiale, questa vittoria ha avuto un impatto ancora più significativo. A differenza degli scacchi, nel Go non basta applicare la fredda potenza di calcolo per prevedere tutte le mosse possibili e vincere la partita. È un gioco apparentemente semplice, che richiede però intuito e creatività da parte dei giocatori. Il momento decisivo della sfida si è avuto durante il trentasettesimo turno della terza partita, quando l’intelligenza artificiale ha effettuato una mossa inedita, mai eseguita prima da nessun essere umano nella storia di questo gioco, e che chiunque avrebbe semmai classificato come un errore marchiano. A posteriori è stata interpretata dagli esperti come un momento di genialità. Quella mossa ha modificato la nostra visione del modo in cui si può giocare a Go, e persino l’essenza stessa del gioco1

Il titolo dell’opera si ispira all’Antico Testamento e in particolare al versetto 1:27 della Genesi. Quella di Maria Mavropoulou è una riflessione sul rapporto degli esseri umani con la tecnologia, nonché uno studio dei modi in cui la tecnologia ha cambiato la percezione che l’umanità ha di se stessa 2 .

Gli antichi Greci ritenevano necessaria la presenza del divino affinché i mortali potessero trovare l’ispirazione per creare opere d’arte. Invocavano le Muse augurandosi di venire investiti dalla loro grazia per potersi cimentare nelle proprie fatiche artistiche:

“

Omero (circa 700-600 a.C.), primo verso dell’Odissea

L’artista era considerato uno strumento per tradurre idee e verità superiori in forme diverse, che fossero accessibili agli esseri umani. Le stesse opere d’arte erano permeate dall’illuminazione instillata direttamente dalle entità celesti. Nella sfera della comunione tra il terreno e il celeste venivano svelate verità superiori sull’esistenza dell’uomo e sul cosmo stesso. E spesso l’uomo nelle sue creazioni artistiche ha scelto di rappresentare fisicamente gli dei e il mondo spirituale.

2001: Odissea nello Spazio; Matrix; Ex Machina; Terminator; Io, robot; Avengers: Age of Ultron; Blade Runner: sono tutte storie in cui l’intelligenza artificiale si ribella contro i creatori umani.

Ἄνδρα

μοι ἔννεπε, Mοῦσα, πολύτροπον”

25

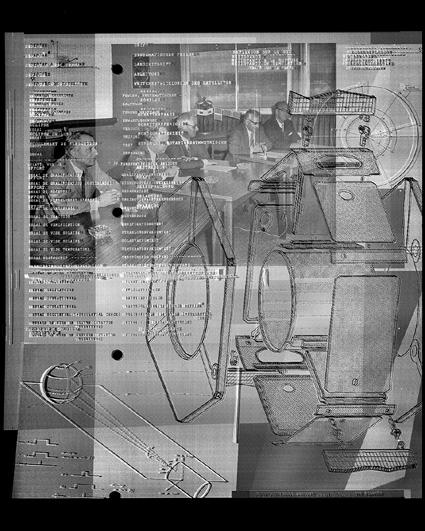

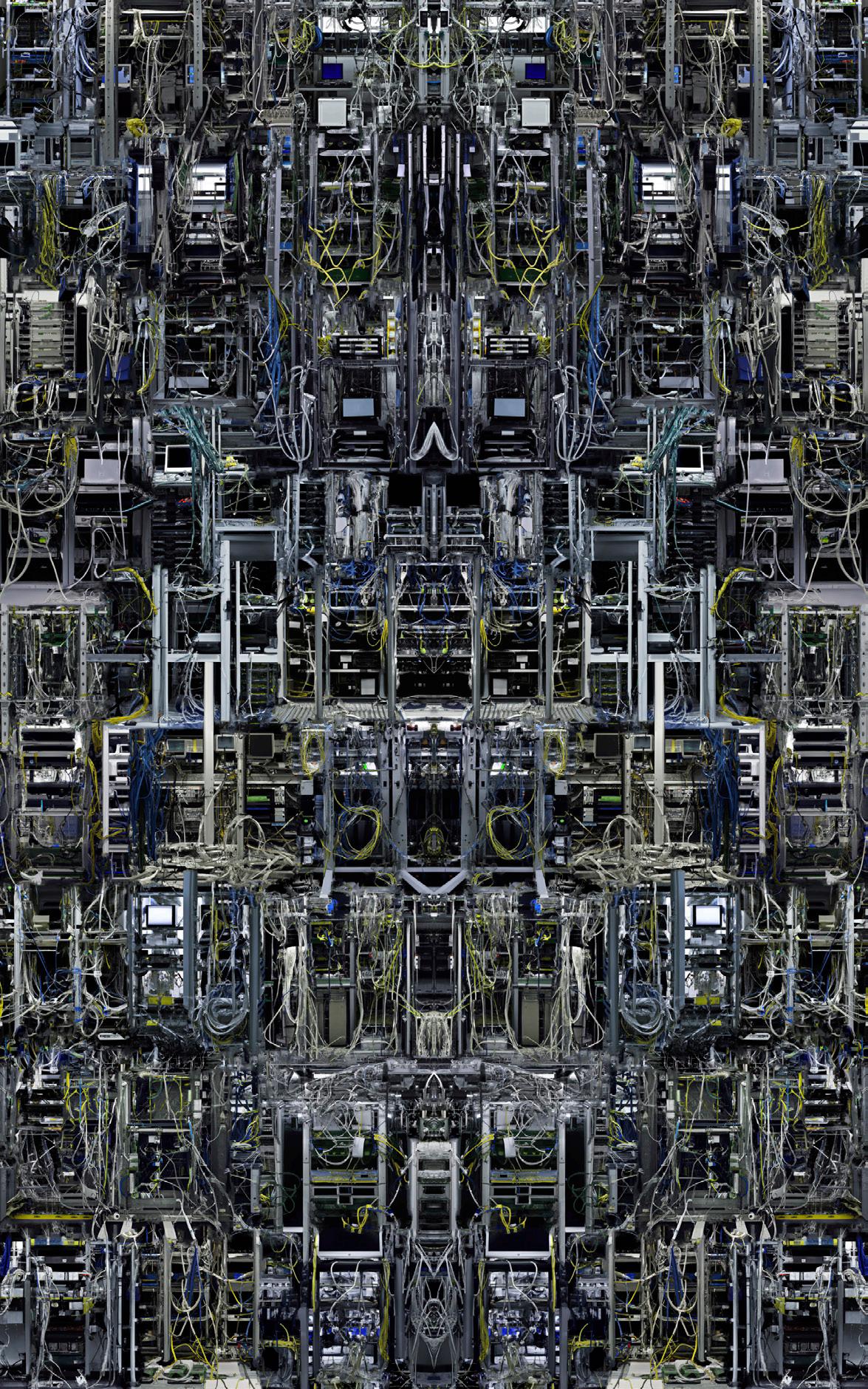

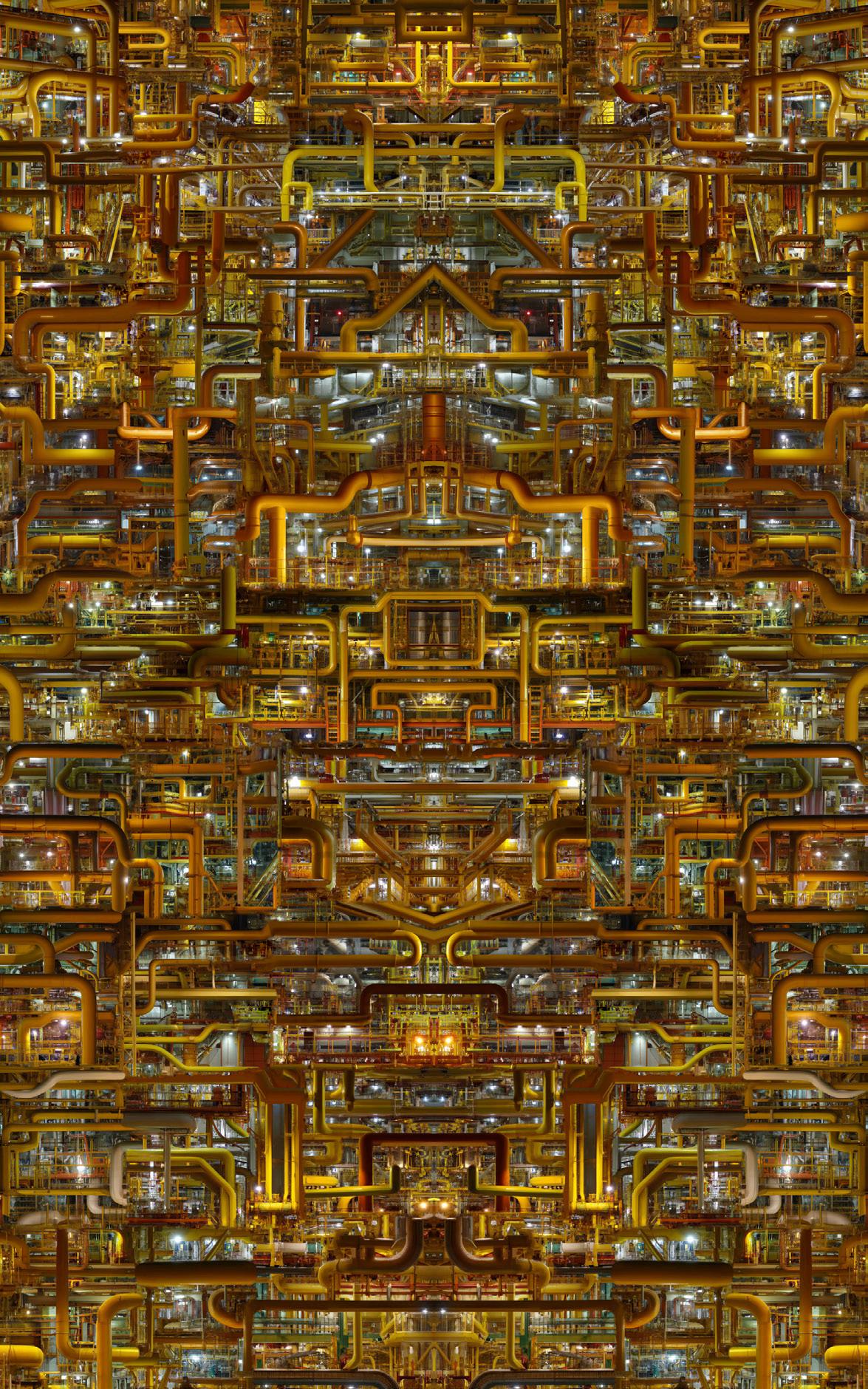

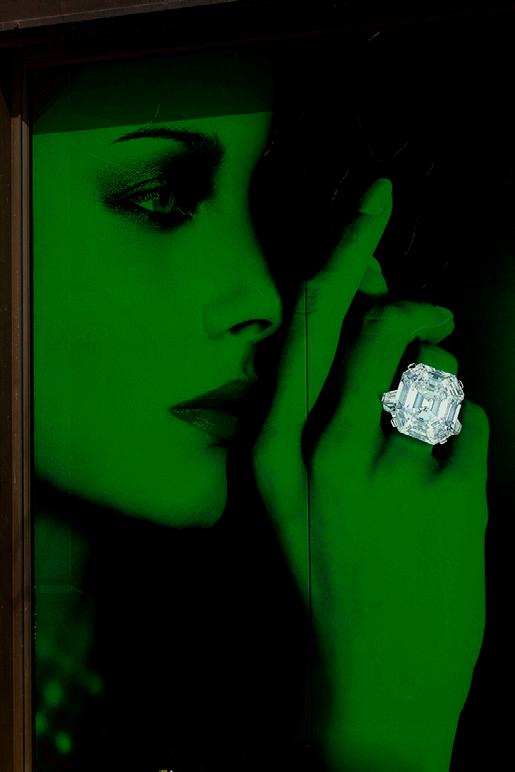

Con In their own image, in the image of God they created them, Maria Mavropoulou utilizza l’intelligenza artificiale più accessibile e all’avanguardia per realizzare opere riconducibili all’eterno tentativo del genere umano di dare forma al divino.

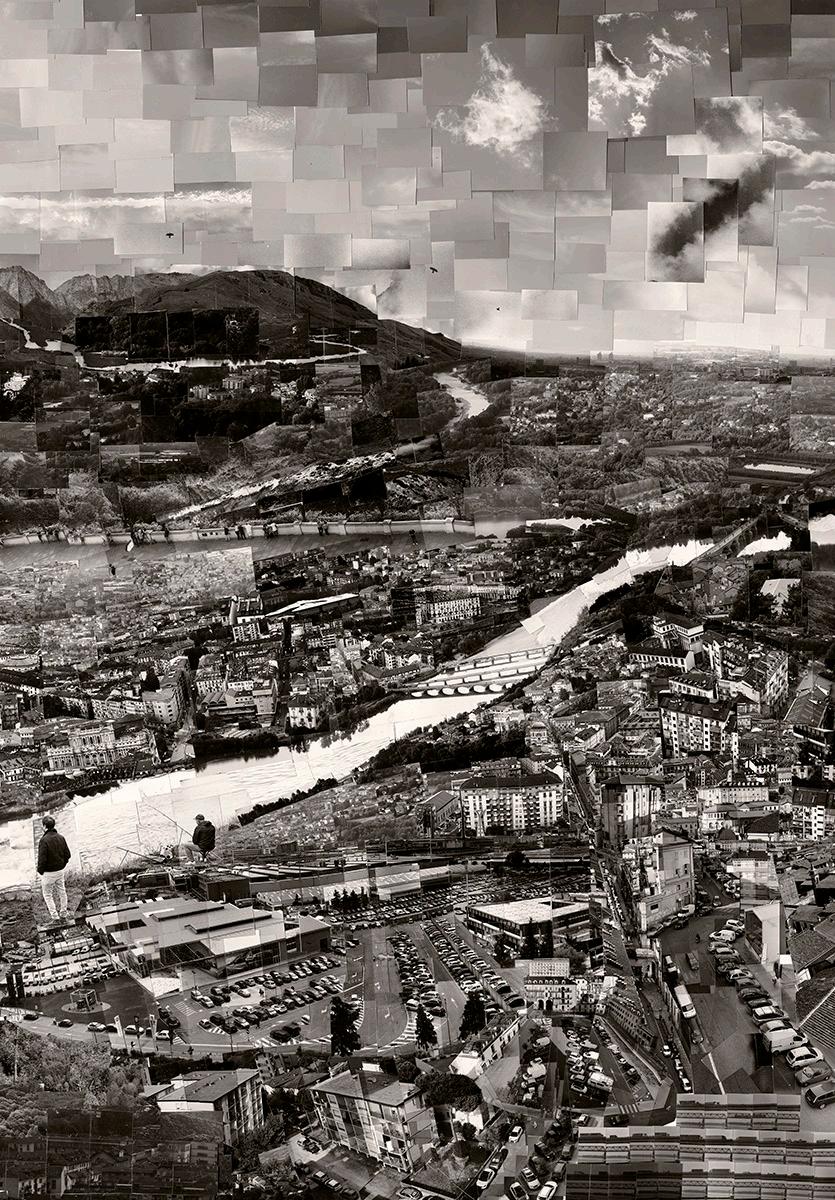

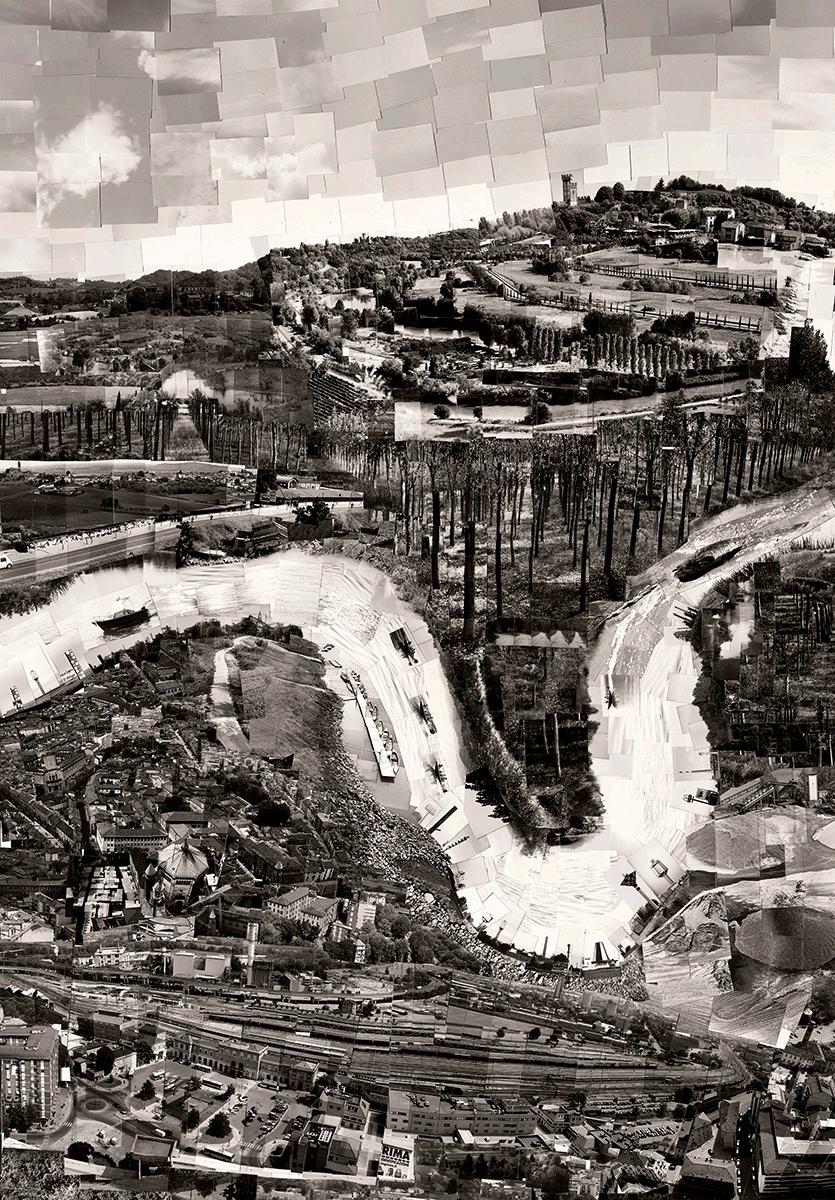

In effetti la prima fase del processo è piuttosto semplice, ma è anche la più delicata, poiché costituisce la base per tutto ciò che verrà dopo. Mavropoulou inserisce una serie di prompt di testo in un algoritmo text-to-image: “Una struttura complessa e sofisticata di tubi, valvole, manometri, usati nelle raffinerie di petrolio”. L’intelligenza artificiale, che a questo punto può contare su un serbatoio di dati inconcepibilmente ampio, non ha alcun bisogno di una Musa per trovare l’ispirazione. Miliardi di fotografie 3 diventano i punti di riferimento che guidano la macchina verso l’obiettivo, al fine di tradurre la richiesta avanzata in una resa visiva capace di appagare ma anche di alludere astrattamente all’essenza apparente di quei parametri. Quindi l’artista seleziona tra le immagini elaborate dall’algoritmo quella che la soddisfa esteticamente, per poi chiedere al programma di crearne altre versioni. Successivamente le singole immagini vengono usate come tasselli delle sue composizioni.

La divinità non ha risposto, ma gli algoritmi hanno iniziato a produrre immagini della nuova divinità. La divinità era un essere fatto di petrolio, e chiaramente non era soddisfatta della richiesta. La divinità ha

iniziato a produrre immagini di fuoriuscite di petrolio, e chiaramente non era soddisfatta della richiesta.

I tasselli sono imperfetti. Il rendering del mondo reale presenta difetti e incongruenze. Un ingegnere, infatti, capirebbe subito che quei tasselli non rappresentano un vero ambiente industriale, ma ne suggeriscono solo l’idea. Proprio come nella scena di un film o sul palcoscenico di un’opera teatrale: controfigure che danno forma a una struttura nella quale la nostra immaginazione può elaborare i temi di più vasta portata che l’artista intende evocare. Tuttavia, queste immagini sono dei simulacri. Un ingegnere sarebbe dunque in grado di individuare quei dettagli che per la maggior parte di noi rimangono oscuri: le combinazioni di colore, i cavi, i materiali palesati. Tutti elementi codificati nel sistema che aiutano a rendere realistica la simulazione.

A questo punto, dopo aver scrupolosamente ultimato le sue composizioni, che sembrano estendersi all’infinito, oltre la cornice, Mavropoulou decide di affidarsi a un tratto evolutivo del corpo umano e introdurre il concetto di Ghosts in the Machine, ricorrendo al riconoscimento facciale. Una funzione talmente importante e vitale per noi che, a quanto pare, il nostro cervello le dedica un’intera area: quella della circonvoluzione fusiforme. Siamo così bravi a riconoscere i modelli facciali che talvolta sovraccarichiamo il nostro sistema, estendendo quest’abilità fino a individuare espressioni mutevoli

Maria Mavropoulou 26

anche negli oggetti inanimati. Questo effetto illusorio è chiamato pareidolia, ed è più facilmente innescato dalla simmetria del soggetto. Mavropoulou provoca questo genere di fraintendimento ribaltando da sinistra a destra l’immagine creata. Il risultato finale è costituito da una serie di figure totemiche, di tecnototem mostruosi e animaleschi, che ci fissano mentre cerchiamo di fronteggiarli.

Le immagini prodotte erano su scala troppo ampia per rappresentare qualcosa di sensato. Maria Mavropoulou ha dovuto regolare i parametri dell’algoritmo fino a ottenere un risultato più gestibile. Dopo qualche tentativo è riuscita finalmente a ricavare una serie di immagini che ritraevano le nuove divinità in tutte le loro forme e funzioni.

Siamo entrati in una spirale inquietante. Le immagini usate dall’artista per creare interpretazioni artistiche delle nuove divinità hanno preso forma grazie a tutte le immagini prodotte in passato dalla specie umana. Secoli – se non millenni – di creazioni ad opera dell’umanità, un’industria di image-making in cui l’effettivo lavoro fisico e intellettuale dell’uomo necessitava di essere trasferito all’interno di un algoritmo, sollevando l’artista dal peso e dalle incombenze materiali dell’attività fotografica, proprio come un carrello elevatore o un sistema di navigazione computerizzato. Nella sua forma attuale, l’intelligenza artificiale è uno strumento definito

dai parametri impostati dall’uomo. Mavropoulou ha inserito le informazioni in un linguaggio che risultasse comprensibile sia a lei che alla macchina e ha realizzato le tessere necessarie alle sue composizioni. Queste tessere-immagine, pur prive di qualità fisiche tangibili, sono intrise di significati. Anche se non cogliamo alcuni dei riferimenti in esse contenuti, ci sono molte probabilità che riusciamo a decifrare il messaggio complessivo. Alla fine, comunque, le opere d’arte così realizzate verranno reinserite nel serbatoio di dati utilizzato dall’algoritmo. Andranno a integrarlo nella sua parte essenziale e in futuro verranno prese come riferimento per ulteriori richieste di rappresentazione della realtà industriale in cui viviamo. In tal senso il lavoro di Mavropoulou trasformerà ulteriormente il modo in cui l’algoritmo comprende i temi da lei affrontati. A un certo punto, inevitabilmente, con il tempo e le risorse adeguati, l’algoritmo produrrà opere d’arte che non potranno più essere distinte da quelle dell’artista.

In altre parole, può una macchina creare un’opera d’arte? Questa è una domanda che ha sollevato non pochi dibattiti e che può essere esaminata sotto diversi aspetti. Qualcuno dice che, poiché una macchina non è dotata dello stesso tipo di creatività di un essere umano, la risposta è no. Per altri, se una macchina è in grado di creare qualcosa che sia esteticamente gradevole, allora questa è da considerarsi un’opera d’arte.

27

Ma forse la questione è mal posta. Il problema infatti non è se le macchine riescano a riprodurre ciò che può realizzare un essere umano, e magari in modo migliore, ma se possano anche diventare il pubblico dei fruitori, avere una reazione viscerale di fronte a un’opera d’arte, e che cosa questo significherebbe in termini evolutivi. Sarebbe un’estensione della coscienza umana? La nostra specie riuscirebbe a comprendere un simile passo? Le macchine ci terrebbero poi in considerazione oppure, come AlphaGo alla mossa 37, reinterpreterebbero le domande fondamentali della vita in modi che non possiamo nemmeno immaginare? E se riuscissero a farlo, fino a che punto ci sarà permesso di servirci di loro, lavoratrici instancabili, per il nostro fabbisogno di manodopera?

1 In Two Moves, AlphaGo and Lee Sedol Redefined the Future, Cade Metz, Wired Magazine, https://www.wired. com/2016/03/two-moves-alphago-lee-sedol-redefinedfuture/ (consultato il 25.08.2022).

2 I paragrafi in corsivo sono stati generati da elaboratori di testo basati sull’IA per fornire una risposta diretta ai temi espressi nel testo.

3 Sarebbe importante aprire un dibattito sull’etica (o sulla sua mancanza) e sui metodi utilizzati dalle società proprietarie di questi algoritmi di IA per procurarsi da utenti e artisti le immagini necessarie ad addestrare i programmi. Tutto ciò infatti ha un impatto profondo sul valore – monetario e non solo – dell’intelletto e del lavoro umano nella produzione e nella circolazione dell’arte.

Mavropoulou 28

Maria

When in 2016 Google’s AlphaGo computer program won the first match against Lee Sodol, one of the top Go human players of all time, it was not marked in the general public’s consciousness in the same way that Gary Kasparov’s loss in chess to IBM’s Deep Blue had back in 1997. Its significance, however, to the development of non-human artificial intelligence could be argued to have been even greater. Go, as opposed to chess, cannot be won simply by utilizing brutal computational power to calculate all the possible moves. The game is deceptively simple, but it requires intuition and creativity from the players. The defining moment in the competition took place in the 37th round of the third game, when the AI made a move that had never before been encountered—a move which no human had played in the history of the game and no human could comprehend in any other way than it being a mistake. In retrospect it was understood by the experts in the field as a moment of brilliance. It changed our understanding of the way Go can be played and even of what the game itself is about.1

The title of the piece is a direct quote from the Old Testament, Genesis 1:27. This work was a comment on humanity’s relationship to technology. It was also a study in how technology has changed humanity’s perception of itself.2

For mortals to be inspired and to produce art the ancient Greeks believed that the divine had to be present. They would invoke the Muses and hope for their grace to be bestowed upon them to embark on their artistic endeavours:

“

Ἄνδρα μοι ἔννεπε, Mοῦσα, πολύτροπον”

Homer (c.700-600 BCE), first line of The Odyssey

The artist was understood to be a conduit, translating ideas and higher truths into different forms accessible to humans and the artworks themselves would be imbued with insights granted by the celestials. Within the parameters of this communion between the earthly and the heavenly greater truths about our existence and the cosmos would be revealed. And often in our art we chose to make physical representations of the gods and the spirit world.

2001: A Space Odyssey; The Matrix; Ex-Machina; The Terminator; I Robot; Avengers: The Age of Ultron; Blade Runner—stories in which AI has turned against its human creators.

29

Maria

Mavropoulou’s In their own image, in the image of God they created them is using the most cutting-edge, publicly available AI technology to produce works that reference the age-old attempt of humankind to visualize its deities.

The first step in her process is quite simple really, but also the most difficult one as it forms the basis for everything that will follow. Mavropoulou inserts a number of text prompts in a text-to-image algorithm: “A complex and sophisticated structure of pipes, valves, manometers, used in oil refineries.” The AI, which at this point has an incomprehensibly large pool of data, has no need for a Muse to be inspired. Billions of photographs 3 serve as reference points and guide the machine towards its goal to interpret the request in a visual output that would fulfil but also allude abstractly to the apparent essences of those parameters. The artist then selects an image from the algorithmically compiled ones that pleases her aesthetically and in the next step would ask the program to create more variations of it. The individual images would subsequently be used as tiled elements in her compositions.

The deity did not respond, but the algorithms began to output images of the new deity. The deity was a being made of oil, and it was clear that it was not happy with the request. The deity began to output images of oil spills, and it was clear that it was not happy with the request.

These tiles are not perfect. There are glitches, inconsistencies in the rendering of the real world counterpart. An engineer would immediately recognize that they do not represent a real industrial environment, but rather the idea of one. They serve in a similar fashion to the stage in a movie or in a theater play; stand-ins that build the framework for our imagination to start processing the wider themes that the artist wants to elicit. However, these images are simulacra. The engineer would, therefore, be able to identify in them details that to most of us would remain obscure: the colour schemes, the wiring, the manifested materials. These are all coded in and help make the simulation lifelike.

At that point, after having painstakingly completed her compositions, which seem to extend infinitely beyond her frame, Mavropoulou decides to rely on an evolutionary trait of our human bodies in order to transform her artworks into proxies of Ghosts in the Machine: face recognition. This function is so important and vital to us that we appear to have a whole area devoted to this task alone in our brains: the fusiform gyrus. We are so good at recognizing facial patterns, that we sometimes overload our system, and we extend this ability into seeing facial expressions in inanimate objects. This illusionary effect is called pareidolia and is more easily triggered by symmetry in the subject. Mavropoulou is activating this misreading in us by mirroring the image she created, left to right.

30

Maria Mavropoulou

The final outcome is a series of totemic figures, TechnoTotems, monstrous and animalistic, which we confront while they are staring back at us.

The images that were generated were of a scale much too large for us to make sense of. Mavropoulou had to adjust the algorithm’s parameters until the output was something more manageable. After a few iterations, she finally had a series of images that depicted the new deities in all their forms and functions.

We find ourselves in an eerie loop here. The images that Mavropoulou used to create artistic renditions of these New Gods, came into existence because of all the images we as a species have produced in the past. Centuries—if not millennia—of creative labour by humanity, an industry of image-making that required the actual intellectual and physical labour of humans passed on to the algorithm which takes the heavy-lifting and corporeal aspects of photographing from the artist in similar fashion to a fork-lift, or a navigational computer. In its current form, the AI is a tool defined by the parameters we set for it. Mavropoulou typed her specifications in high-level language that both her and the machine can understand and produced the tiles she needed to make her new compositions. These image-tiles beyond their incorporeal qualities as materials, are imbued with meanings. Even if we miss some of the references in them, we are more likely than not to

decrypt the overall message. The final artworks, however, will eventually be fed back into the pool of data that the algorithm uses. They will become part of its core and in the future it will reference them in subsequent requests to visualize our industrial environment. Mavropoulou’s work in that sense will be further transforming the way the algorithm understands the themes that she focuses on and inevitable given time and resources at some point produce artworks that are indistinguishable to hers.

In other words, could a machine create a masterpiece? This is a question that has been debated by many people and there are a few different ways to look at it. Some say that since a machine is not capable of the same type of creativity as a human, the answer is no. Others say that if a machine can create something that is aesthetically pleasing, then it is considered a work of art.

This line of thinking might be a red herring. What is at stake here, is not if machines can reproduce what humans can do and be better at it. The question is if machines can become the audience, have a visceral reaction to encountering works of art and what would that mean in evolutionary terms. Would it be an extension of the human consciousness, the next step in our journey? Would it even be comprehensible by our species? Would the machines even need to take us in account or would they, like AlphaGo in

31

Maria Mavropoulou

move 37, just reinterpret what all the big questions of life and our existence truly are about in ways we can’t even imagine. And if they can, up to which point would we be allowed to have them serve us, as tireless workers for our labour needs?

1 In Two Moves, AlphaGo and Lee Sedol Redefined the Future, Cade Metz, Wired Magazine, https://www.wired. com/2016/03/two-moves-alphago-lee-sedol-redefinedfuture/ (accessed: 5.08.2022).

2 The paragraphs in italics have been generated by AI word processors in direct response to themes expressed in the text.

3 There is a debate to be had on the ethics (or the lack thereof) and the methods that the companies behind these AI algorithms utilized to source the images that trained their programs from users and artists. What this means for the value—monetary and otherwise—of human intellect and labour in the production and circulation of art is profoundly redefined.

32

33

Senza titolo 4 / Untitled 4, 2022 Stampa d’archivio montata su Dibond / Archival print mounted on Dibond, 200 × 125 cm

Senza titolo 6 / Untitled 6, 2022 Stampa d’archivio montata su Dibond / Archival print mounted on Dibond, 200 × 125 cm

Senza titolo 6 / Untitled 6, 2022 Stampa d’archivio montata su Dibond / Archival print mounted on Dibond, 200 × 125 cm

34

Maria Mavropoulou

35

Senza titolo 7 / Untitled 7, 2022 Stampa d’archivio montata su Dibond / Archival print mounted on Dibond, 200 × 125 cm

Senza titolo 8 / Untitled 8, 2022

Stampa

d’archivio montata su Dibond / Archival print mounted on Dibond, 200 × 125 cm

d’archivio montata su Dibond / Archival print mounted on Dibond, 200 × 125 cm

36

Maria Mavropoulou

37

Senza titolo 9 / Untitled 9, 2022 Stampa d’archivio montata su Dibond / Archival print mounted on Dibond, 200 × 125 cm

Senza titolo 10 / Untitled 10, 2022 Stampa d’archivio montata su Dibond / Archival print mounted on Dibond, 200 × 125 cm

Senza titolo 10 / Untitled 10, 2022 Stampa d’archivio montata su Dibond / Archival print mounted on Dibond, 200 × 125 cm

38

Maria Mavropoulou

39

Senza titolo 11 / Untitled 11, 2022 Stampa d’archivio montata su Dibond / Archival print mounted on Dibond, 200 × 125 cm

Senza titolo 14 / Untitled 14, 2022

Stampa d’archivio montata su Dibond / Archival print mounted on Dibond, 200 × 125 cm

Senza titolo 14 / Untitled 14, 2022

Stampa d’archivio montata su Dibond / Archival print mounted on Dibond, 200 × 125 cm

40

Maria Mavropoulou

41

Senza titolo 18 / Untitled 18, 2022 Stampa d’archivio montata su Dibond / Archival print mounted on Dibond, 200 × 125 cm

LEBOHANG KGANYE

Lebohang

44

Elvira Dyangani Ose

Keep the Light Faithfully

Kganye

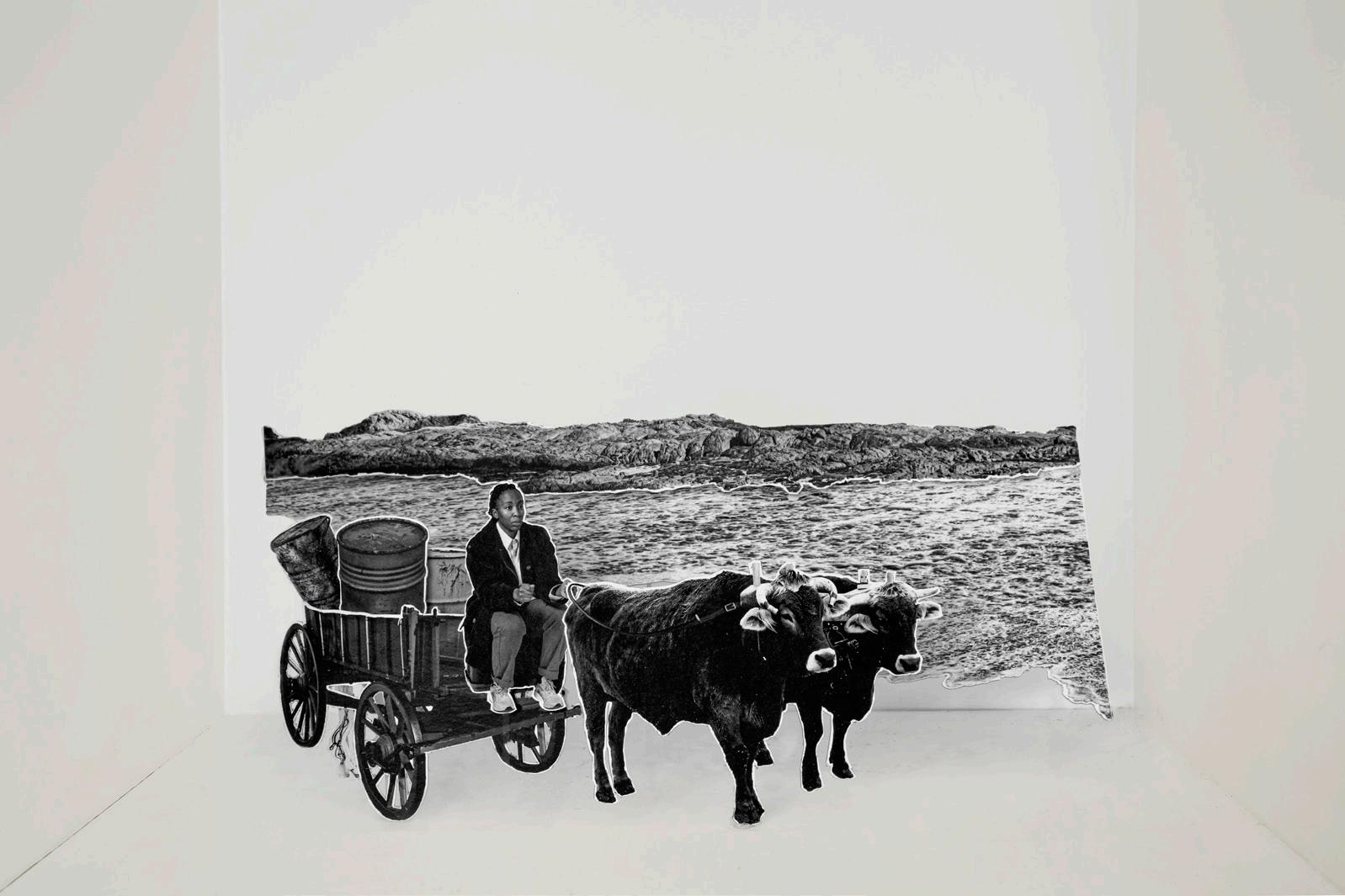

C’è un gesto discreto ma simbolico che Lebohang Kganye compie nella scelta del soggetto della sua attuale ricerca. L’artista, che per la prima volta si imbarca in un racconto che non implica in linea di principio aspetti della storia della propria famiglia o della propria soggettività, indaga comunque la trasparenza e la veridicità della storia. E lo fa svelando racconti di migrazioni e identità attraverso le vicende tramandate oralmente e lo storytelling. Quest’ultimo è per lei un processo critico quanto i meccanismi che rivelano un’immagine sulla carta nell’oscurità di uno studio fotografico. Formulata sia come apparato didascalico di una serie di fotografie sia come sfondo per l’omonima installazione cinematografica a tre canali, Keep the Light Faithfully (2022) propone un racconto sulle guardiane dei fari come eroine quotidiane inquadrate all’interno delle loro ignote disavventure. Sguardo attento agli aspetti della loro vita, questa indagine è informata da dialoghi attraverso i quali Kganye costruisce una rara testimonianza, quella dei racconti dei guardiani dei fari del Sudafrica, della loro routine e delle loro vicissitudini in scenari isolati e remoti lungo la costa del paese.

Ispirata dal libro di Lenore Skomal The Lighthouse Keeper’s Daughter: The Remarkable True Story of American Heroine Ida Lewis, Kganye ha dato avvio a una ricerca sulle guardiane dei fari del Sudafrica dall’inizio del XIX secolo a oggi. Ormai in gran parte automatizzati, i fari nel paese sono quarantacinque. La storia di queste istituzioni senza tempo

è contrassegnata dall’impegno quotidiano di chi si occupa della tediosa gestione dei dati e dei registri, dell’accurata documentazione dei drastici cambiamenti meteorologici, dell’approfondita conservazione dell’architettura e dell’ingegneria meccanica, nonché delle occasionali procedure di salvataggio e delle lotte per preservare la salute mentale degli individui – nel caso del Sudafrica solo uomini – che devono affrontare l’invisibilità e l’immobilità cui sono costretti dal loro lavoro.

Con le sue immagini argute in bianco e nero fatte di figure tagliate e incollate e una tridimensionalità squisita ed evocativa, Kganye riscrive i torti di questa narrazione per ristabilire una storia al femminile mai vissuta, in cui mette in scena episodi di vita reale tratti dalle conversazioni con i protagonisti delle sue interviste. Racconti inattesi di cani all’inseguimento e spettri femminili mescolati a cupe realtà di morti in mare e catastrofi naturali. Tutti di un tono assurdo, quasi surrealista, fra il sarcastico e il malinconico, i suoi gesti spingono l’immaginazione degli spettatori a immergersi nelle storie al di là di ogni senso di drammaticità o retorica. Qui il suo corpo non è più una figura reale a grandezza naturale in mezzo a ritagli e sagome stampati a getto d’inchiostro subalterni alla stessa narrazione, come in altre immagini precedenti quali Last Supper o The Wheelbarrow, che fanno entrambe parte della serie Ke Lefa Laka: Her-Story (2013). Sembra che l’assenza di una vera guardiana abbia reso necessaria una strategia diversa.

45

Allo stesso modo, il processo solitamente nascosto della resa di una profondità di campo, di una teatralità, viene qui presentato come dispositivo palese, come se l’artista sentisse il bisogno, come mai prima d’ora, di sottolineare la dimensione illusionistica della propria narrazione, il trucco dietro le immagini. Come se questa scelta rendesse altrettanto assurda la discriminazione ideologica di genere della storia dei guardiani dei fari, considerata una mera costruzione dall’artista.

Mi domando se la solennità dell’installazione cinematografica a tre canali Dipina tsa Kganya, realizzata da Kganye nel 2021, non abbia suggerito la necessità di un approccio più leggero. Non fraintendetemi, nulla va perso della gravità della storia né delle rivendicazioni dell’artista, ma queste ora vengono proposte al pubblico in modo talmente aneddotico da non indurlo a mettere in discussione la propria percezione. Dipina tsa Kganya, al contrario, esige un’attenzione meticolosa, una partecipazione attiva e una cura di natura particolare. L’architettura avvolgente degli schermi, il suono suadente delle musiche della compositrice Thandi Ntuli e le immagini accuratamente elaborate ricreano l’atmosfera che si immagina si sarebbe vissuta dentro un faro, nella quiete più profonda e fredda di una notte di metà Ottocento. La protagonista si ostina a pulire una lampada, mentre la luce del faro gira, gira e gira ancora, in una coreografia che si prevede senza fine, facendo sfarfallare la stanza a ogni giro.

Al contempo, immersi nella densità delle sonorità di Ntuli, che suona in un carillon polifonico, si può quasi sentire il freddo della notte che ci penetra nelle ossa. I tempi della storia anticipano i nostri, in un processo decisionale in cui siamo invitati a riprendere insieme alla protagonista il nostro impegno a mantenere in luce certe storie e certe comunità. Eppure, come già accennato, non c’è solo la storia in sé. Da un lato, la disperata ricerca della luce nella fitta oscurità, che accompagna ogni marinaio nel desiderio dell’approdo, è qui una metafora della materializzazione dello svelamento fotografico, processo chimico che è “scrittura con la luce”. La fotografia infatti non esiste senza luce, elemento necessario all’artista per diradare l’oscurità su vicende nascoste o invisibili. Dall’altro lato, la continua ricerca del significato e delle varie grafie del suo cognome, Kganye, che potrebbe derivare da “kganya”, ovvero luce, speranza o fede in lingua xhosa, ci porta a credere che ci sia qualcosa di più profondo nella biografia e nelle evocazioni rituali dell’artista, che si riflette sia nel suo percorso artistico sia nell’interesse per i vari mezzi espressivi e per le numerose possibilità offerte. Il suo approccio alla fotografia trae origine dal senso della fantasmagoria caratteristico della fotografia degli inizi del XX secolo, dei primi fotografi d’avanguardia che miravano a preservare l’effimero, l’intangibile. La sua è una sfida ostinata alla fotografia, a ciò che può fare, a ciò che rende possibile.

Lebohang Kganye 46

There is a subtle yet symbolic gesture in Lebohang Kganye’s choice of her current research subject. Though the artist tackles for the first time a story that does not, in principle, deal with aspects of her family’s history or her own subjectivity, she does nonetheless engage in the same pursuit of inquiring about history’s accountability and truthfulness. And she does so by disclosing stories of migration and identity through oral histories and storytelling. The latter is for the photographer as critical a process as the ones that reveal an image on paper out of the gloom of the darkroom. Formulated both as the captions of a photography series and as the backdrop for her three-channel film installation, Keep the Light Faithfully (2022) delivers a tale of lighthouse keepers as everyday heroes framed by their unknown misadventures. The investigation offers a glimpse and a rare record of various aspects of their lives, and is informed by conversations and dialogues that focus on the stories of South African lighthouse keepers, their routines and vicissitudes in isolated, remote settings along the country’s coastline.

Inspired by Lenore Skomal’s The Lighthouse Keeper’s Daughter: The Remarkable True Story of American Heroine Ida Lewis, Kganye began to research female lighthouse keepers in South Africa from the beginning of the 19th century to the present. There are currently forty-five lighthouses in the country, now mostly automated. The history of these

timeless institutions is distinguished by the monotonous day-to-day logging and record management of the keepers, thorough documentation of drastic weather changes, maintenance of the architecture and mechanical engineering, as well as the occasional rescue operation and the mental health struggles of the keepers—in the case of South Africa, only men—as they labour in a job that leaves them stranded and invisible.

With her customary witty black-and-white imagery of cut and pasted figures and an exquisite and evocative three-dimensionality, Kganye rewrites the wrongs in such history-telling to restore a previously unexplored her story, in which she performs real-life episodes drawn from conversations with her interviewees—unexpected stories of female ghosts and of being chased by dogs, combined with the sombre realities of death at sea and environmental catastrophes. In an absurd, almost surrealist tone that is both sarcastic and melancholic, her gestures take the viewer’s imagination deep into the stories, beyond any sense of dramatism or rhetoric. Here, her body is no longer a life-size real figure in the middle of inkjet-printed cutouts and silhouettes subaltern to her own narrative, as in earlier images such as Last Supper or The Wheelbarrow, both part of the Ke Lefa Laka: Her-Story series (2013). It seems that the absence of an actual female keeper made a different strategy necessary. Likewise, the usually concealed process of staging depth of field and its

47

theatricality is offered here as an optional display, as though the artist felt the need, like never before, to emphasize the make-believe sense of her history-making, the trick behind the images. As if that gesture would render equally ludicrous the ideological gender discrimination of the history of lightkeepers, regarded by the artist as a mere construct.

I wonder if the solemnity of her three-channel film installation, Dipina tsa Kganya (2021), also prompted the need for a lighter approach. Do not misunderstand me, none of the seriousness of the story or the artist’s claims is lost, but these are delivered to the public in such an anecdotic way that their perceptions are not challenged. Dipina tsa Kganya, on the contrary, requires meticulous attention, a particular kind of engagement and care. Here the involving architecture of the screens, the persuasive sound of the music by composer Thandi Ntuli, and the carefully crafted imagery conjure up the atmosphere of what one imagines it would have been like to live in a lighthouse in the depths of a bitterly cold and utterly quiet night in the mid-19th century. The character carries on cleaning a bulb, while in the central pane the beam of the lighthouse turns and turns and turns, over and over again, slowly, in what we expect to be a never-ending choreography, making the room flicker at every turn. All the while, as we are immersed in the density of Ntuli’s song playing on a polyphonic music box, one can almost feel the coldness of the night cracking our spine.

The time of the story predates ours, setting up a decision-making process in which we are invited to imagine, with the artist’s protagonist, our own involvement in ensuring that light continues to be shed on certain histories and communities.

Still, there is more to the story than the story itself, as mentioned above. On the one hand, the desperate search for light in the midst of darkness, experienced by any sailor as they try to find the shore, is here a metaphor for the materialization of the photographic unveiling, the actual chemical process that, in the artist’s words, is “writing with light.” Photography in fact does not take place without it, and light processing is essential for her to be able to bear witness to hidden or invisible narratives. On the other hand, the continuous personal search for the meaning and the various spellings of her last name, Kganye, which might derive from Kganya, meaning light, hope or faith in Xhosa, leads us to believe that there is something much deeper in the artist’s biography and ritualistic evocations in both her career choice and her countless approaches to the various possibilities of media. Her take on photography draws on the most categorical sense of the phantasmagory inherent in the photography of the turn of the 20th century, of the early avant-garde photographers who aimed to preserve the fleeting and the intangible. Hers is a persistent challenge to photography, to what it can do, to what it makes possible.

Lebohang Kganye

48

Carro delle consegne trainato da buoi / Ox wagons to deliver supplies, 2022 Inkjet print ritagliate su supporti di legno / Inkjet photographic cutout prints on wooden stands, 90 × 60 × 40 cm

49

Lebohang Kganye

TV al parcheggio dei taxi / TV at the taxi rank, 2022 Inkjet print ritagliate su supporti di legno / Inkjet photographic cutout prints on wooden stands, 90 × 60 × 40 cm

50

51

Lebohang Kganye

Rivendita di palline da golf / Reselling golf balls, 2022

Inkjet print ritagliate su supporti di legno / Inkjet photographic cutout prints on wooden stands, 90 × 60 × 40 cm

52

Prigioniero al lavoro alla manutenzione / Prisoner doing the general work, 2022 Inkjet print ritagliate su supporti di legno / Inkjet photographic cutout prints on wooden stands, 90 × 60 × 40 cm

53

Lebohang Kganye

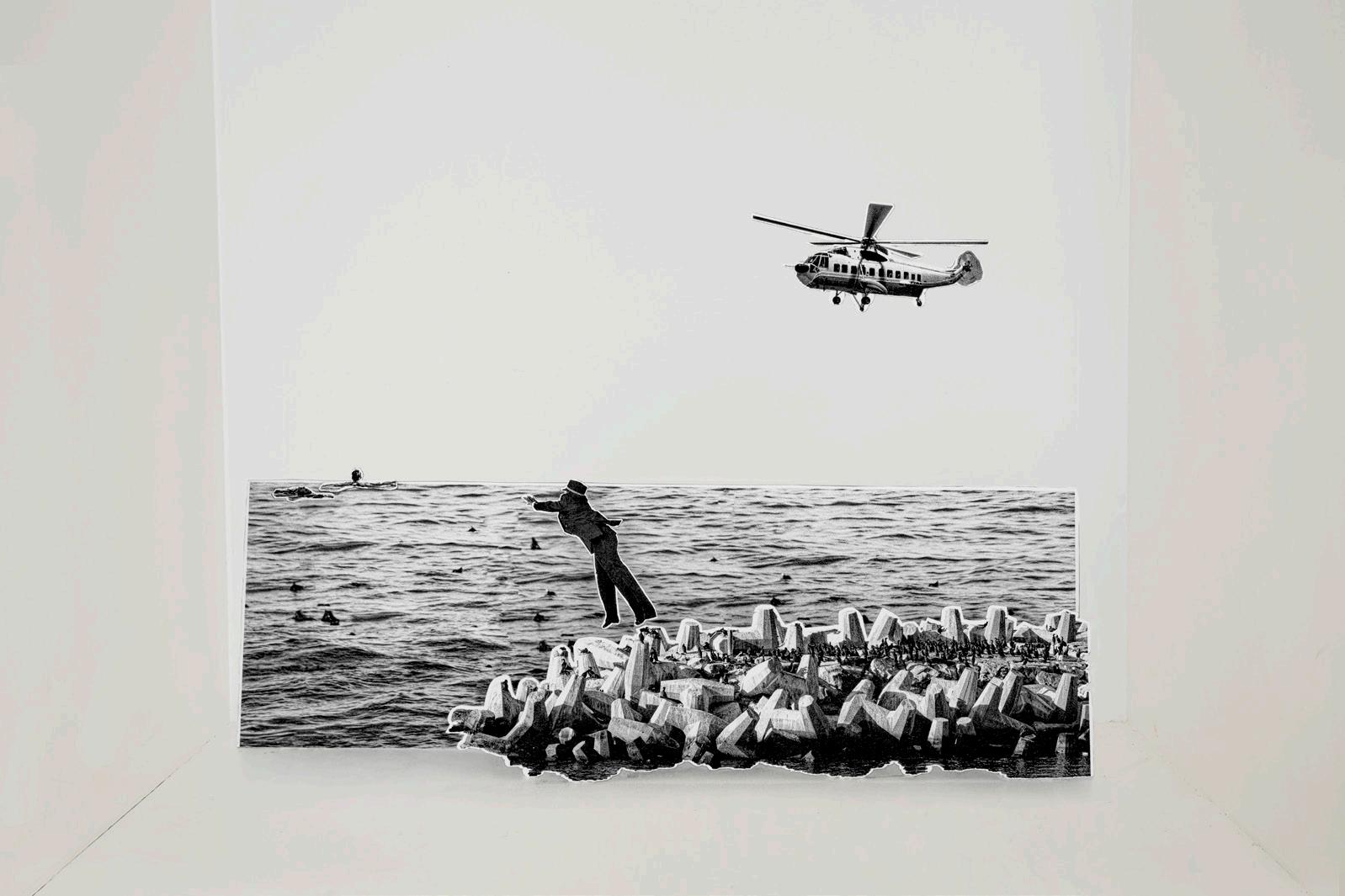

Professori e dottori che annegano / Drowning professors and doctors, 2022

Inkjet print ritagliate su supporti di legno / Inkjet photographic cutout prints on wooden stands, 90 × 60 × 40 cm

54

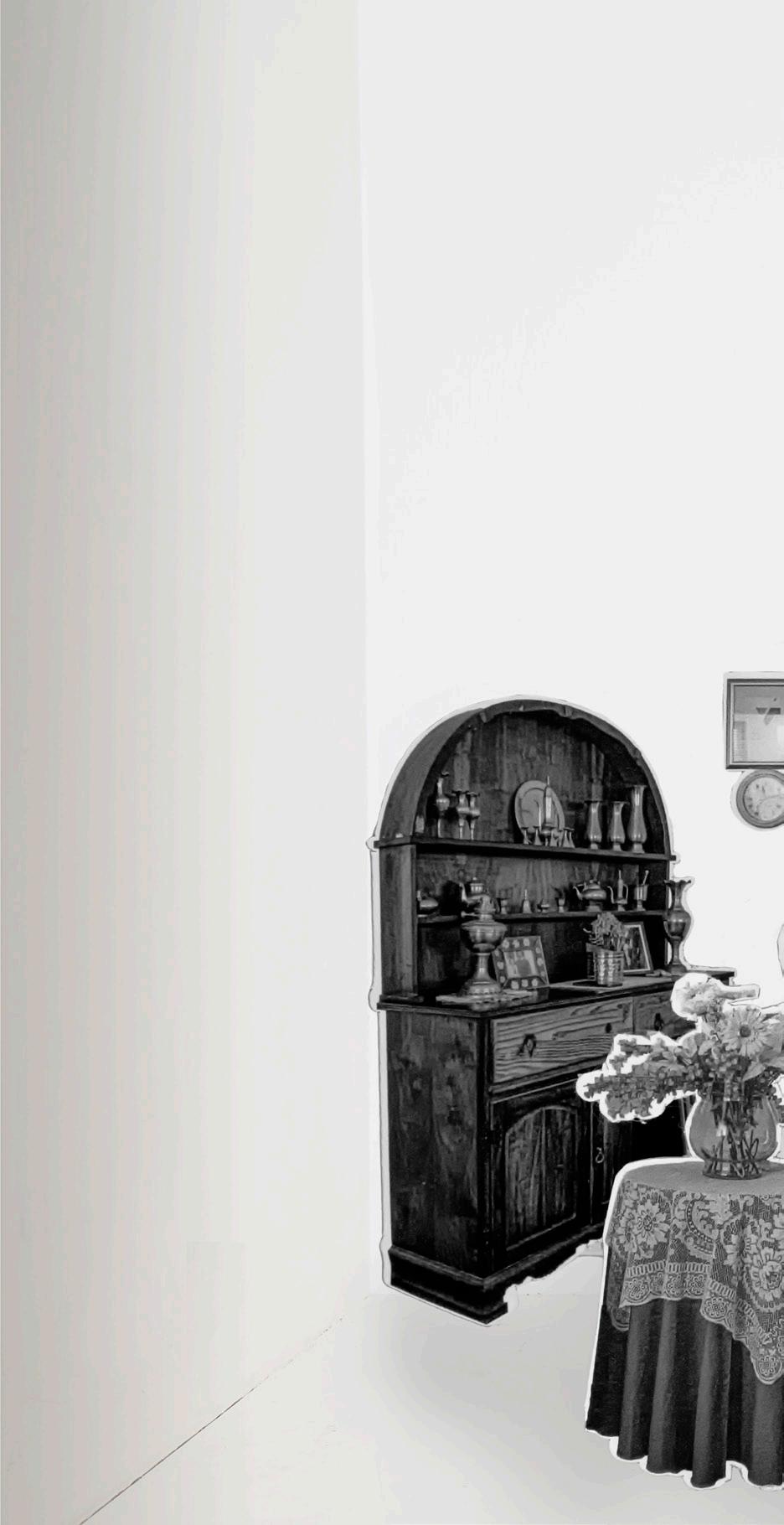

Fantasma nella locanda / Ghost in the guesthouse, 2022

Inkjet print ritagliate su supporti di legno / Inkjet photographic cutout prints on wooden stands, 90 × 60 × 40 cm

55

Lebohang Kganye

Donna nel cuore della notte / Woman in middle of night, 2022

Inkjet print ritagliate su supporti di legno / Inkjet photographic cutout prints on wooden stands, 90 × 60 × 40 cm

< Sepolture al faro / Lighthouse burials, 2022

Inkjet print ritagliate su supporti di legno / Inkjet photographic cutout prints on wooden stands dimensioni varie / dimensions variable

58

59

Lebohang Kganye

Tutti a pesca / We all go fishing, 2022

Inkjet print ritagliate su supporti di legno / Inkjet photographic cutout prints on wooden stands, 90 × 60 × 40 cm

60

61

Lebohang Kganye

Spaccapietre / Mashing rocks, 2022

Inkjet print ritagliate su supporti di legno / Inkjet photographic cutout prints on wooden stands, 90 × 60 × 40 cm

62

Scorciatoia per il faro / Shortening Lighthouse, 2022

Inkjet print ritagliate su supporti di legno / Inkjet photographic cutout prints on wooden stands, 90 × 60 × 40 cm

63

Lebohang Kganye

Uccelli in festa / Birds feasting, 2022

Inkjet print ritagliate su supporti di legno / Inkjet photographic cutout prints on wooden stands, 90 × 60 × 40 cm

64

65

HICHAM GARDAF

Dominik Czechowski

In Praise of Slowness Hicham

68

Gardaf

Nell’aria spasimante involontaria rivolta dell’uomo presente alla sua fragilità

Giuseppe Ungaretti, Fratelli (1916)

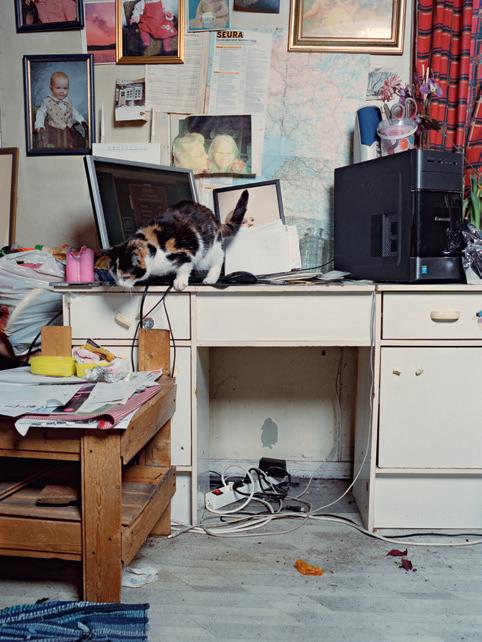

Una figura umana solitaria si allontana dalla camera fissa in un paesaggio desolato. L’uomo porta sulle spalle un carico voluminoso di bottiglie di plastica vuote. Si piega appena sotto il peso di quella grande sagoma simile a una libellula, mentre arranca verso la linea dell’orizzonte per poi scomparire dietro di essa. La scena assume una particolare sfumatura fantascientifica, il protagonista incarna quasi una creatura ultraterrena. È un extraterrestre in una terra desolata pasoliniana. La macchina da presa stacca, e vediamo riapparire l’uomo, che prima si avvicina e poi entra in una città moderna con le sue ciminiere industriali e i capannoni delle fabbriche. Le sequenze mantengono una continuità temporale e spaziale per effetto dei rumori ambientali (il canto delle cicale, il continuo passaggio di automobili, l’abbaiare di cani randagi) e dei suoni extradiegetici (composti dall’artista del suono Hannan Jones). Insieme questi elementi creano una sonorità spettrale di grande fascinazione, un’amplificazione dello spazio psicologico, non solo di quello fisico.

Così si apre il nuovo film di Hicham Gardaf In Praise of Slowness. Girato nella moderna Tangeri, esso ci restituisce le esperienze delle tradizioni vernacolari in uno spazio e tempo contemporanei. A un primo sguardo, il paesaggio industriale della città marocchina evoca quello di Deserto rosso (1964) di Michelangelo Antonioni, un’analisi sulla monotonia e l’alienazione urbana1. Nella sua visione cupa di un inferno artificiale, scevro da ogni idealizzazione, il regista italiano ritrae l’inquietudine moderna e l’inquinamento industriale come qualcosa di seducente e bello. Questo aspetto è ripreso dall’universo cromatico e cinematografico di Gardaf, dove il colore e la luce determinano un raffreddamento dell’immagine, con un effetto delicatamente bleached, sgranato e imperfetto, su una pellicola 16mm che tuttavia mantiene la chiarezza fenomenologica dell’immagine. Giuliana, l’eroina nevrotica di Antonioni, è profondamente turbata dall’ambiente ansiogeno della città, capace di deprimerla e di provocare in lei uno straniamento e una fragilità psicologica ancora maggiori, mentre vaga senza meta nei tetri paraggi di una centrale elettrica. La donna è in bilico tra la disperazione, il ripiegamento su di sé e la rassegnazione; la condizione dell’uomo nel film di Gardaf è invece completamente diversa. Questo “Uomo dalle cento bottiglie”2 è un eroe della classe operaia, non un fantasma in un deserto industriale3. È una pedina nella filiera di distribuzione dei venditori ambulanti di candeggina che nel corso

69