5 minute read

Exploring Oxidation-Resistant Materials for Hypersonic Structural Application Manufactured using Laser Powder Bed Fusion

Source: Michael Ives, Ma Qian, Simon Barter, Raj Das

The aerospace industry has been at the forefront of modern-day innovation. From humble beginnings, aerospace technology now boasts space rockets that can re-land safely back on earth [1], advanced fighter jets, and hypersonic vehicles capable of breaching the sound barrier 5 times over (and even greater). Hypersonic technology currently covers advanced high-speed systems that will offer significant technological advancement in both military and commercial use if certain engineering obstacles currently limiting the technology are overcome.

Speeds such as Mach 5 and Mach 10 may be easy to say; but understanding the sheer magnitude of such speeds can be hard to conceptualise. Designing structural components for hypersonic flight poses additional design hurdles to subsonic flight, due to the variance in major flight principles. The physical nature of the airflow over the flight vehicle changes as the Mach number increases. At great speeds, the shock layer (the flow layer that forms between the shock and the vehicles body) becomes very thin, hot, and dense. The challenge faced here is at the stagnation point that forms at the leading edges of the body, which can experience temperatures exceeding 2250 °C at Mach 10. Few materials can survive such conditions while maintaining structural integrity, which is a design criterion that is crucial to maintain the aerodynamics and flight control of the vehicle.

In addition to a temperature that will melt most materials, hypersonic flight within the atmosphere exposes these edges to an oxygen rich environment resulting in elevated rates of oxidation. Oxidation is accelerated due to the high temperatures since the oxygen molecules are chemically excited to the point of dissociation [2], thus becoming very reactive. The build-up of oxide scales often leads to both deteriorated strength and resistance to thermal loads, which when occurring at high speeds leads to the surface oxide that is formed ablating and chipping, leaving an uneven surface that is further exposed to reaction with the oxygen [3]. The outer structure of high-speed vehicles, the part that will be directly exposed to such extreme conditions, is referred to as the thermal protection system (TPS). The material selection process for TPS’s is vital in mitigating the effects of oxidation. The hypersonic environment provides consistently high temperatures and pressure conditions, where only a few material compositions can resist oxidation while maintaining structural integrity [4]. The current solution is to coat the structures with non-reactive, oxidation resistant materials.

Ultra-high temperature ceramics (UHTC) are known for their good high-temperature properties and oxidation resistance, and thus popular candidates for this application. Research undertaken through RMIT University aims to integrate such materials into the outer surface of a multi-material structure capable of being manufactured through laser powder bed fusion (LPBF).

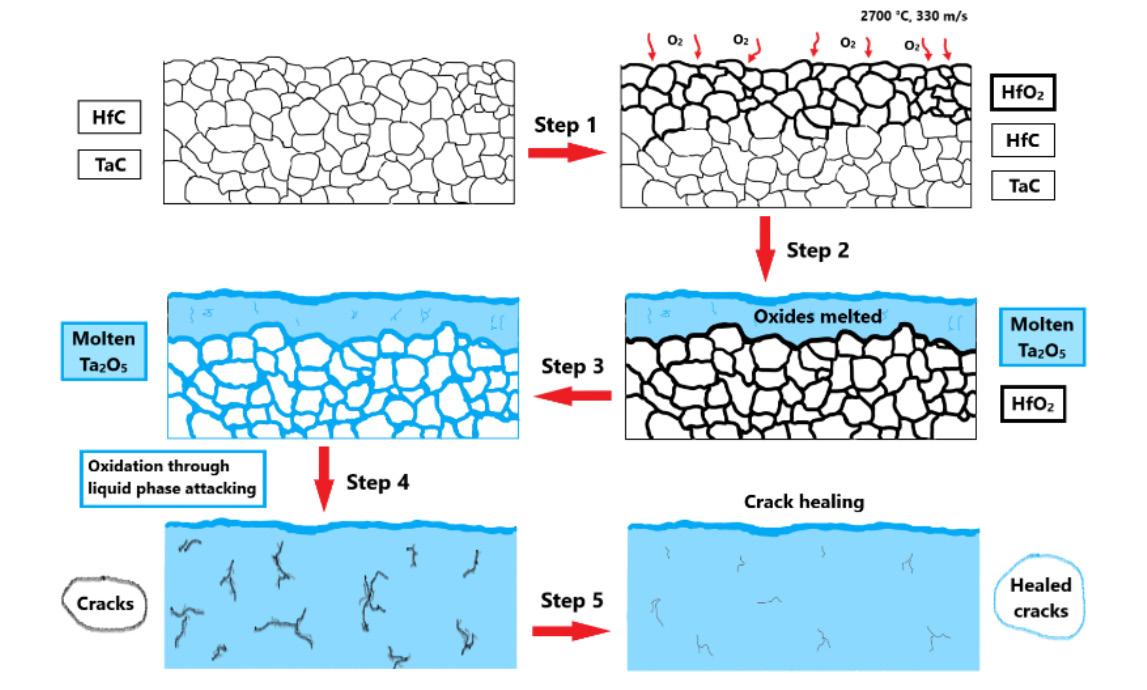

The oxidation resistance of most UHTC's is effective, however a certain solid solution between two of the leading ceramics stands alone. A study [5] observed the oxidation of tantalum carbide (TaC), hafnium carbide (HfC), and TaC-HfC solid solutions under the extreme temperatures and oxygenrich environments produced by a plasma torch to be exceptional. While the pure samples of TaC and HfC showed high resistance to oxidation, having an oxide layer thickness of 305 and 190 μm respectively after 300 seconds of plasma exposure, it was found that combining the materials to form a 50:50 TaC:HfC solid solution resulted in a much reduced oxide layer of only 28 μm after 300 seconds [5]. When HfC oxidises due to the penetration of its grain boundaries the HfO2 formed is porous and is easily ablated (Figure 1). However, with the addition of TaC, Ta2O 5 forms a molten layer. When combined with the porous HfO2 , the liquid Ta2O 5 reforms a solid oxide layer that experiences cracking, which is alleviated through crack healing due to the liquid phase reforming (Figure 2), preventing oxygen from further penetrating the scale.

So why aren’t UHTC’s, especially TaC:HfC in use for such applications?

Well, despite its clear advantages, a structure made entirely of a UHTC would prove more similar to the ceramic tiling of a spacecraft rather than an atmospheric aerospace leading edge. As such, internal base structures are being explored to be manufactured in-situ with the UHTC surfaces. The materials being explored are refractory metals, which refer to a group of metals sharing multiple key properties, including extremely high melting temperatures (>2000 °C), high density, and high hardness. The leading candidate for this application being none other than tantalum (Ta).

Both UHTC and refractory metals have properties that make them ideal candidates to be integrated into hypersonic leading-edge applications. However, on the other hand, both have significant drawbacks that need to be addressed. UHTC’s are limited by their processing ability, in particular their high melting temperatures, extreme hardness, and varying viscosity, all of which add complexity during additive manufacture (AM). For example, the thermal stresses induced in the UHTC during manufacture through melting and re-solidification can often lead to a failed print due to cracking. Conversely, refractory metals have proven manufacturability via AM. However, refractory metals have poor oxidation resistance at high temperatures, thus the necessity to incorporate a UHTC material to coat the structure.

Cermet materials that combine UHTC’s and metal’s show promise for hypersonic applications. Multimaterial structures can often be utilised to combine the preferred properties and characteristics from a range of materials, while alleviating the negative effects of single materials. Implementing such compositions into muti-material sandwich structures offers a potential high temperature, oxidation resistant structure that can minimise both oxidation and thermal stress gradients, as well as alleviate such drawbacks as a high mass, through the implementation of additively manufactured lattice structures. Currently laser powder bed fusion (LPBF), a common AM technique, holds the potential to produce such structures, especially when coupled with a high-temperature build platform such as the Aconity3D system recently installed at the RMIT Centre for Additive Manufacturing. Suitable manufacturing capabilities and an understanding of the impact of relevant process parameters will be required, but if such a technique is found feasible, not only will multiple gaps within the AM of ultra-high temperature materials be addressed, but alternative designs will also be readily available for both hypersonic and other extreme high temperature applications.

The use of LPBF to fabricate UHTC’s such as HfC and TaC does not seem to have been attempted before and no studies have been reported in this area so far. However, that’s not to say that the technique is not viable. Both TaC and HfC have been extensively tested at high temperature as either bulk materials or as specific compositions, however the manufacturing technique always employed has been spark plasma sintering [6]. A laser melting study investigating materials with the highest melting temperature explored various compositions of TaC-HfC, and showed the viability of melting such compositions using a similar laser power to those found on LPBF machines [7]. Further, a proposed method to produce TaC:HfC compositions (while alleviating the chance of increased thermal stresses induced on the part) is to additively manufacture Ta metal powder with added HfC powder, and through the melting process, allow the carbonrich HfC to carburise the Ta to form a TaC-HfC composition solid material. This reaction has been reported to be feasible during the manufacture of HfC powder combined with both a Ta fibre net and also a Ta foil [8]. This concept will be explored throughout the project and developed if initial feasibility testing indicates the viability of such a technique.

The future of using AM techniques to produce hypersonic components is unknown, exciting, and may be inevitable. LPBF offers a unique opportunity to produce cermet materials with exceptional properties that can be applied in hypersonic applications, and still allow the manufacture of detailed and complex structures, unlike current methods. The LPBF technique is novel in this context, nevertheless, time will tell if it proves feasible. But if it is, an entirely new technique of producing ultrahigh temperature, oxidation resistant, complex structures will be opened for exploration.

About the authors: Michael Ives, PhD candidate, Ma Qian, Distinguished Professor, Simon Barter, Professor, and Raj Das, Professor, are all with the Centre for Additive Manufacturing, School of Engineering of RMIT University.