26 minute read

Feature - Powering The Future: Materials Science Paving the Way Towards Net Zero

Powering The Future: Materials Science Paving the Way Towards Net Zero

Australia is in the grips of its greatest transformation into the energy sector since the 1950s.

Traditional energy sources like coal and gas account for approximately 70% of all electricity produced onshore. Meanwhile, natural gas is the third largest energy source and is widely used by power stations, factories, workplaces, and homes. These non-renewable sources are running out of steam, as the world grapples with rising temperatures and sea levels, which are driven by these unsustainable forms of energy production. As such, there are a host of opportunities on the horizon as Australia seeks to decarbonise and shift towards renewable energy sources. In fact, renewables remain the cheapest new-build electricity generation option in Australia.

“Across the energy system we are seeing a significant increase in renewable-generated electricity, combined with an increase in electricity requirements such as in transport, buildings, manufacturing and mining,” said Dr John Ward, who is the Energy Systems Research Director at CSIRO. “The cost of renewable energy is no longer the challenge—integrating renewable energy securely and efficiently into our electricity systems, and ensuring we have the right operational tools and capabilities in place, is what we need to solve,” he added.

Australia produced more clean energy last year than ever before. In fact, the Clean Energy Council has found around 35.9% of renewable energy was generated from wind, which led to 11.7% of all electricity. These changes are driven by economic, environmental, and engineering factors. However, there is also a strong push from consumers and corporate organisations who are seeking to transform Australia’s reliance on supply and use.

“Businesses will drive this change, so we must avoid unintended consequences that hold up transition driving projects, investments in new and existing industries, or make it more difficult secure the capital needed to keep our economy growing,” said Jennifer Westacott, who is the Chief Executive Officer at the Business Council of Australia.

This transformation was recently legislated by the Federal Government, which is seeking to reduce emissions by 43% from 2005 levels by 2030, and then become net zero by 2050. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said the legislation will pave the way for a new era of Australian innovation and sustainability. “It will help open the way for new jobs, new industries, new technologies and a new era of prosperity for Australian manufacturing,” he said. With the Federal Government's recent climate change push, research institutions are ready to launch into a world of opportunity and capitalise on Australia’s renewables-rich environment.

But materials science and industry need to work together transform this plan into a reality.

Where Does Our Electricity Come From?

Australia’s electricity production comes from a range of non-renewable and renewable sources. For example, coal is burned in a large power plant, which then produces electricity. This is transferred through distribution networks that convert voltage to a lower form through local poles, which then feeds into powering homes and workplaces. The National Electricity Market is the backbone of Australia’s electricity supply. It accounts for 80% of all electricity produced in the country, apart from the Northern Territory and Western Australia. In addition, Australia relies on gas fields that can be detrimental to human health and the surrounding environment.

These power sources are unsustainable and according to the Chief Executive Officer at the Climate Council Amanda McKenzie, time is running out to act. “Australia has paid a heavy price for more than a decade of climate inaction from the previous Government, with a “poor and deteriorating” outlook for our irreplaceable environment, ecosystems and species,” she said. The Climate Council is pushing for the Federal Government to stop all new coal, gas projects, and eliminate the country’s reliance on fossil fuels. “Rapid and deep cuts to global greenhouse gas emissions can help protect our environment,” said Ms McKenzie.

“Australia’s high greenhouse gas emissions are contributing to the decline of our environment. After almost a decade of ‘lost years’ of inaction, there is no more time to waste. We must rapidly drive down emissions this decade and immediately stop the expansion of new coal and gas projects,” she added. As the Federal Government works with the private sector to reduce Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions, materials scientists are ready to launch into a new world of opportunity.

A Renewed Focus For The Renewables Journey

Innovative materials that boast functionality, sustainability and productivity can activate a new era in Australia’s shift towards renewables. This comes in many forms: from powering the energy grid, to smarter batteries for electric vehicles.

Researchers are working across a range of areas like wind and solar photovoltaics (PV), which have become the cheapest forms of new electricity generation, and battery storage and thermal energy capacity to drive the nation’s renewable energy generation into the future.

The University of Melbourne

The Engineering Materials Research Program brings some of the sharpest minds together to discover and optimise new materials for energy applications. Together, these scientists and researchers have their sights on hydrogen, solar energy consumption, lighting and conversion, and energy generation and storage. These research capabilities tie together to provide real-world impact to: • Reduce energy consumption of separation processes • Develop organic and earth-abundant inorganic thin film solar photovoltaic technologies • Reduce cost of anode materials in batteries

• Design computational materials for lightweight structural components in electric vehicles

In addition to their research, the program collaborates with industry partners to bring this research to life. “In order to seamlessly integrate large volumes of affordable renewable energy at both centralised and distributed levels, we need the right suites of technical and market solutions and mechanisms in place,” said Professor Pierluigi Mancarella, who is the Chair of Electrical Power Systems at the University of Melbourne. Researchers and industry alike are working to alleviate the stress of transitioning from non-renewable energy sources to renewables. “Just imagine, suddenly you have thousands of customers selling electricity in a market designed for 100 large scale power plants. Commercially, it's completely disruptive. We need to develop completely new concepts around distributed energy,” Professor Mancarella said.

The University of Melbourne has worked with between AusNet Services, Mondo Power, and the Australian Energy Market Operator on Project EDGE—a blueprint for distributed energy sources, which can work with the wholesale market.

In addition, researchers are also working with the Ford Motor Company to design structural components for batteries in their new range of electric vehicles.

Deakin University

Thirty PhD students and 80 postdoctoral researchers are working on the next generation of materials science at any given time at the Institute of Frontier Materials (IFM). The facility is based at Deakin University and connects likeminded peers with a suite of opportunities to address materials challenges in energy. Professor Jenny Pringle and her colleagues are paving the way for new electrolytes for the next generation of batteries. “A more sustainable future relies on better battery technology. But we can’t develop better batteries without better materials, and that’s where the world class researchers and facilities at Deakin University come in,” she said. Through IFM’s advanced facilities, researchers study reliable energy solutions to ensure Australia’s transition to net zero and renewables is successful.

At the state-of-the-art the BatTRIHub, scientists prototype new battery technologies. Through this, they have made advances into new electrolytes and alternative battery technologies, including metal-air batteries and sodium.

Batteries are crucial for mobile phones and electric vehicles. However, Professor Pringle said they also benefit Australia’s road towards net zero.

“Improving station batteries is also vital to help mitigate climate change by reducing emissions through the use of sustainable materials and allowing us to store renewable energy from wind and solar farms,” she said.

Ionic thermal electrolytes are also part of the equation when it comes to energy capture and storage. These devices are a gamechanger for Australia’s thermal energy approach, which involves a complex chemical reaction to produce heated temperatures.

“We’re also looking at incorporating our solid electrolyte materials into membranes that can be used to separate carbon dioxide from industrial waste gas streams to reduce emissions. Collaboration with our valuable industry partners is essential to this work, and we’re looking forward to collaborating with future partners to achieve even more in this field,” Professor Pringle said.

UNSW Sydney

UNSW physicists are one part of the Australian Centre of Excellence, where a dedicated group of professionals work towards a sustainable future.

Together, with FLEET research initiatives, UNSW brings together over 100 Australian and international experts with the goal of developing a new generation of ultra-low energy electronics in a range of fields: • Advanced electronic materials and devices

• Semiconductors for energy applications • Nanoiionic materials • Hydrogen storage and battery technology Up to 8% of global electricity demands energy used in computation, and this figure is doubling with every decade. In fact, society’s increasing need for extra computing requires new developments and more efficient processes to help power the future. “For computing to continue to grow, we need a new generation of electronics that dissipates much less wasted energy,” said Professor Alex Hamilton, who is FLEET’s Deputy Director. For example, FLEET researchers at UNSW are tackling the operation of electronic devices with a range of recent research that investigates highfrequency and smaller devices. “This new all single-crystal design will be ideal for making ultra-small electronic devices, quantum dots, and for qubit applications,” Professor Hamilton said.

There are around 12 billion transistors in the postage-stamp sized central chip of modern smartphones. However, this new research could power highfrequency phones, radar, radio and satellite communications.

Similarly, at the Hydrogen Storage and Battery Technology Group, physicists work on the development of nano and microstructure novel materials for greater use in energy storage systems. Hydrogen has immense opportunities, but its development has been clouded when it comes to putting research into practice. As such, UNSW researchers are seeking to develop safe and effective strategies for hydrogen storage material to ensure that it can power Australian homes and businesses into the future.

Monash University

Functional and energy materials are they a focus for Monash University scientists. Led by Professor Kiyonori Suzuki and Dr Julie Karel, the team of researchers have a keen focus on materials for photovoltaic technologies. These devices convert sunlight into

electricity and are seen as the next era for Australia’s electricity generation. For instance, buildings in the City of Melbourne could be up to 74% selfsustainable when it comes to their own electricity needs when solar technology is used in walls, windows, and roofs.

These window-integrated photovoltaics, alongside other solar technologies, are the first of their kind at a city scale. “By using photovoltaic technology commercially available today and incorporating the expected advances in wall and window-integrated solar technology over the next ten years, we could potentially see our CBD on its way to Net Zero in the coming decades,” said Professor Jacek Jasieniak. The research team believes the widespread deployment of these emerging, highly efficient solar windows and photovoltaic technology could be a gamechanger for building facades. “We began importing coal-fired power from the LaTrobe Valley in the 1920s to stop the practice of burning smoginducing coal briquettes onsite to power our CBD buildings, and it’s now feasible that over one hundred years later, we could see a full circle moment of Melbourne’s buildings returning to local power generation within the CBD, but using clean, climate-safe technologies that help us meet Australia’s Net Zero 2050 target,” Professor Jasieniak said. As the world transitions towards a net zero future, these energy solutions are expected to drive rapid market growth and reduce the overall carbon footprint of high-rise buildings. The findings were recently published in Solar Energy.

CSIRO

Australia's national science agency, CSIRO is leading the charge towards an energy-efficient future. At the Materials for Energy and the Environment Group, scientists solve industrial challenges and reduce the environmental impacts of materials production. The team seeks to develop marketbased materials across the energy sector to drive Australia's position towards net zero.

CSIRO SME Collaboration Lead Dr George Feast said business-led innovation was a key part of Australia’s energy transition, but businesses were often unsure how to get involved with research and development (R&D). “The energy sector in particular will see continued change over the coming years and there are huge opportunities for businesses to be part of the country’s energy transition, in areas such as EV (electric vehicle) charging, household solar, energy storage and other low emission technologies,” Dr Feast said. The CSIRO Kick-Start program and Innovation Connections scheme turns research into practice across several key areas:

• Metal organic frameworks • Nano-porous materials • Catalysis and membranes • Electrospinning • Rapid automated materials and processing • Conservation grade painting resin More than 1,700 businesses have worked with CSIRO to develop modern technologies and ideas, including many in the energy sector. “We want small and medium-sized businesses around the country to be part of the action, so we are looking for people who are sitting on ideas but need more guidance to refine and explore them further,” Dr Feast said.

ANSTO

Alternate energy sources are a big part of ANSTO's work through the Energy Materials stream. This provides the platform for researchers to advance energy technologies across five key areas:

1. Hydrogen production 2. Gas-storage materials 3. Fuel cell research

4. Lithium conducting materials for lithium battery applications 5. Semiconductor materials for dyesensitised solar cell applications As part of the hydrogen production stream of research, neutron-scattering techniques are used to derive benefit from hydrogen generated reactions. This paves the way for sustainable hydrogen production, which could form the key to Australia’s net zero future. ANSTO researchers have access to state-of the-art facilities and equipment, including the gas-dosing rig. This device samples neutron-scattering techniques and hydrogen storage capabilities through the iconic ECHIDNA and WOMBAT equipment. Researchers are also engaged in hydrogen storage techniques, which involves complex chemical reactions (chemisorption) to successfully store the molecule, physisorption. For example, ANSTO researchers are synthesising and developing highly porous new materials to capture hydrogen gas and use them to boost storage capacity and function of storage cylinders. This can produce low-cost materials for mid- to large-scale hydrogen storage applications. “We can assess the uptake of hydrogen under high pressure and other conditions because of equipment that was purposely built for these tasks,” said Professor Vanessa Peterson, who leads the Energy Materials Research Project at ANSTO. “It is not extreme high pressure, but it is at a level that is not available in the university setting,” she added. Part of the overall hydrogen economy challenge is generating enough supply to meet demand.

While H2 is sourced from hydrocarbons and coal, it fails to consider its reduction in carbon emissions gained. However, researchers can use a range of renewable fuels as a source of H2 to fill the power generation gaps.

Turning Waste Silk Into Battery Electrodes

Source: Sally Wood

Energy researchers recently achieved exciting results with battery electrodes prepared from waste silk textiles. The new material showed outstanding performance, with the potential for creating high-energy-density batteries. Issues of sustainability have become increasingly important for battery manufacturers in the face of dwindling lithium reserves. However, new battery technologies should also be competitive in terms of performance and cost. Unlike standard electrodes used in lithium ion batteries (LIBs), which require binders, conductive additives, and toxic solvents to prepare the electrode, the silk-based electrodes are free-standing. According to lead researcher, Dr Jenny Sun from Deakin University’s Institute for Frontier Materials (IFM), this research has the potential for widescale utilisation across a range of industries. “This is a big advantage. It means we don’t need to use any additives, making them more costeffective and sustainable.”

The researchers have also tested the electrodes in sodium ion batteries (NIBs), which are a promising alternative for LIBs. “The great abundance of sodium makes them very price competitive,” Dr Sun said. “And unlike LIBs, NIBs can be stored and transported safely in a fully discharged state.” As they share a similar working chemistry with LIBs, NIBs can also be considered a drop-in technology for existing LIB battery manufacturing lines. However, to expand their commercialisation, further electrode and electrolyte development is required. The project team used an ionic liquid electrolyte developed by storEnergy researchers. StorEnergy is a trailblazer in renewable energy research and engineering solutions, with a key focus on streamlining industrial processes. IFM textile researchers, led by Prof Xungai Wang, had previously shown that a free-standing carbonised silk fabric can be prepared by a one-step heating process. Dr Sun and her colleagues used samples of this material as electrodes in coin cells and tested their performance, including cycling and rate capability. The electrode showed high capacity retention (close to 100 per cent after 100 cycles) and initial coulombic efficiency of 75%. This means the battery retained its capacity after being charged and discharged 100 times, and the capacity did not decline. The team has also worked with Associate Professor Nolene Brown on other waste materials, such as cotton fibre, pitch, and food waste as precursor material for sodium ion batteries.

Deakin University’s IFM is a catalyst for change in materials science. The research hub brings a range of focus areas together including: • Advanced alloys and infrastructure materials • Electro and energy materials • Fibres and textiles • Carbon fibres and composites Researchers work across materials challenges and offer solutions that save energy, transform designs and society. IFM is led by Professor Sally McArthur, who has used engineering principles to improve human wellbeing. "IFM has always been an exemplar for how research organisations can build and lead a culture of impact and industry collaboration within a university and a region," said Professor McArthur.

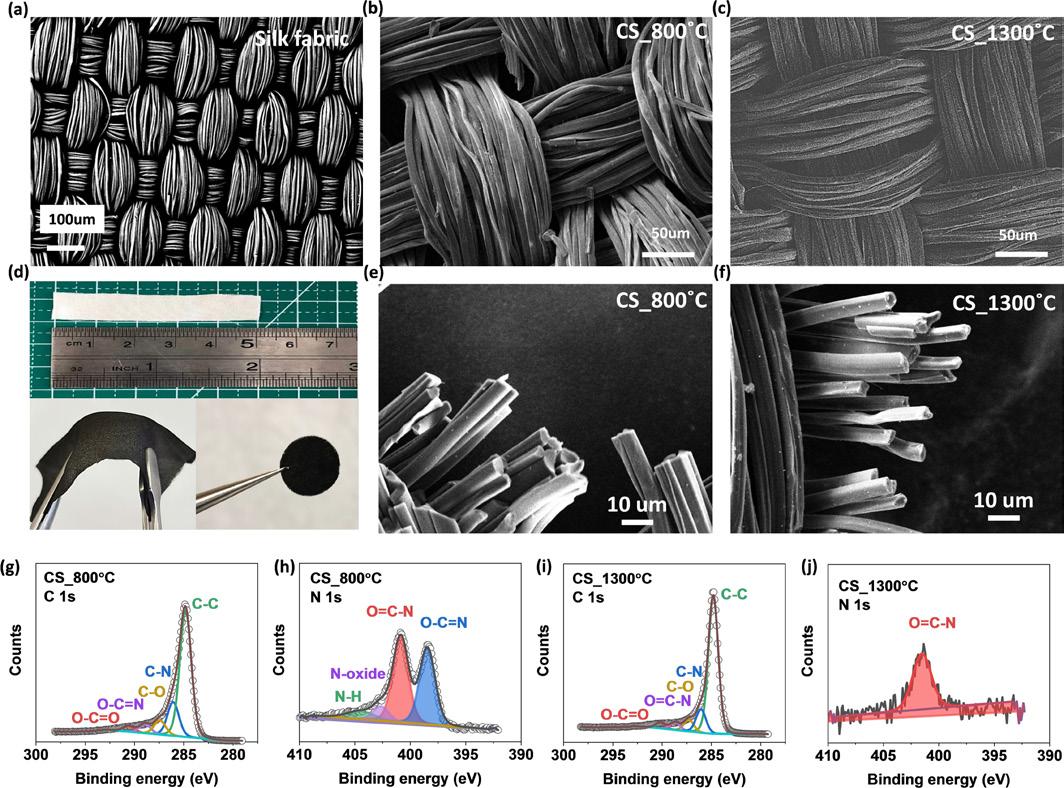

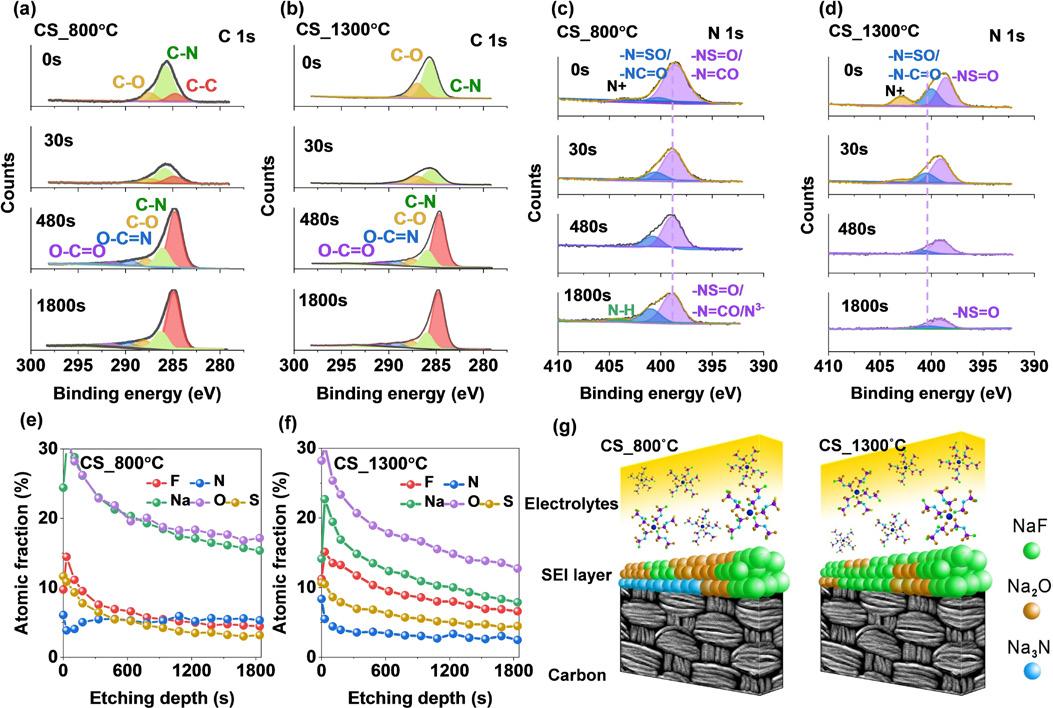

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and optical images of (a) untreated silk fabric, (b) CS_800 °C, (c) CS_1300 °C, and (d) Optical images of untreated silk fabric and CS_1300 °C. The magnified images of the silk fabric for (e) CS_800 °C, and (f) CS_1300 °C. C 1s and N 1s XPS spectra of (g, h) CS_800 °C and (i, j) CS_1300 °C. XPS spectra of the cycled carbonised silk electrodes (5 cycles, 0.01–2 V). C 1s and N 1s spectra for (a, c) CS_800 °C electrode and (b, d) CS_1300 °C electrode at different etching depth (0, 30, 480, and 1800 s). Atomic concentration of different elements on the surface of cycled (e) CS_800 °C and (f) CS_1300 °C electrodes. (g) Schematic illustration of SEI layer on CS_800 °C and CS_1300 °C electrodes.

New Hybrid Electrolyte Enables Fast Charging Of Li Batteries Without Catching Fire

Source: Sally Wood

A new type of battery that has the potential to service an untapped multi-million-dollar market has been developed by researchers at Deakin University. The Sythlett Cells, which were founded by Dr Ali Balkis and Dr Hiroyuki Ueda, who are based at the Institute for Frontier Materials’ Battery Technology Research and Innovation Hub, hope to sell slower-degrading, lightweight, non-flammable batteries to the aviation sector.

They were recently named as national finalists in the ClimateLaunchpad competition—the world’s biggest cleantech and green business ideas competition. The opportunity grants early-stage cleantech and ‘green’ start-ups the chance to take part in bootcamps, workshops and other support with industry leaders to help them translate their idea into a scalable business.

“We originally looked at batteries for e-bikes but there are already a lot of good e-bikes with great designs and there are a lot of companies already doing that,” Dr Balkis said. “When we investigated the aviation sectors, there was not a lot being done—practically only one start-up in Silicon Valley called Cuberg that are making batteries for drones and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and that is it. Our idea is a completely new idea,” he added. The aircraft battery market opportunity in the Asia-Pacific region has been priced at $18 million, while the global aircraft battery market is priced at $785 million. The Sythlett Cells team identified the unique requirements of the aviation battery market to design their battery, which utilises pure lithium metal chemistry for a lighter, safer and more flexible battery. “We’re using these batteries for aviation because the chemistry is lithium metal, so the anode, utilises a lithium metal anode.”

“For aviation, if you can have a battery that’s 50 per cent lighter than the traditional lithium-ion battery, longer lasting and with more performance—it will work really well for the aviation sector compared to lithium-ion,” Dr Balkis said. The Sythlett Cell battery can also have an energy density greater than 450 Wh/kg, which is ideal for drones and UAVs when compared to a lithium-ion battery. “With graphite, you cannot do that. If you try to bend, it will just crack and break. This why our batteries suit the aviation sector because you can place it anywhere along the aircraft, so with the fuselage where there’s curves, you can bend the battery which allows vehicle designers to produce radical designs,” Dr Balkis said. In a similar project, researchers have developed a new hybrid electrolyte, which shows excellent performance when used in lithium batteries. Deakin research fellow Urbi Pal worked with storEnergy researchers from Monash University and the University of California San Diego on the novel ionic liquid-based electrolyte for Li-metal batteries. The conventional battery electrolyte uses the lithium metal in these batteries quite poorly. But Ms Pal’s studies have shown the ionic liquid-based hybrid electrolyte does not allow accumulation of this dead lithium. This allows stable cycling of the lithium battery for hundreds of cycles without risk of short circuiting and catching fire.

Sythlett Cells, founded by IFM's Dr Ali Balkis and Dr Hiroyuki Ueda, is a start-up that hopes to sell slower-degrading, lightweight, non-flammable batteries for aviation.

Tech Breakthrough Could Make Oil Refineries Greener, Hydrogen Safer

Source: Sally Wood

Deakin University researchers have recently made a breakthrough that could help address one of the biggest barriers preventing the widespread adoption of hydrogen energy—safe storage and transport. Hydrogen is increasingly being touted as one sustainable solution to Australia’s gas crisis. But finding a material that can store enormous quantities of gases for practical applications remains a major challenge. However, recent research from Deakin University could offer an answer.

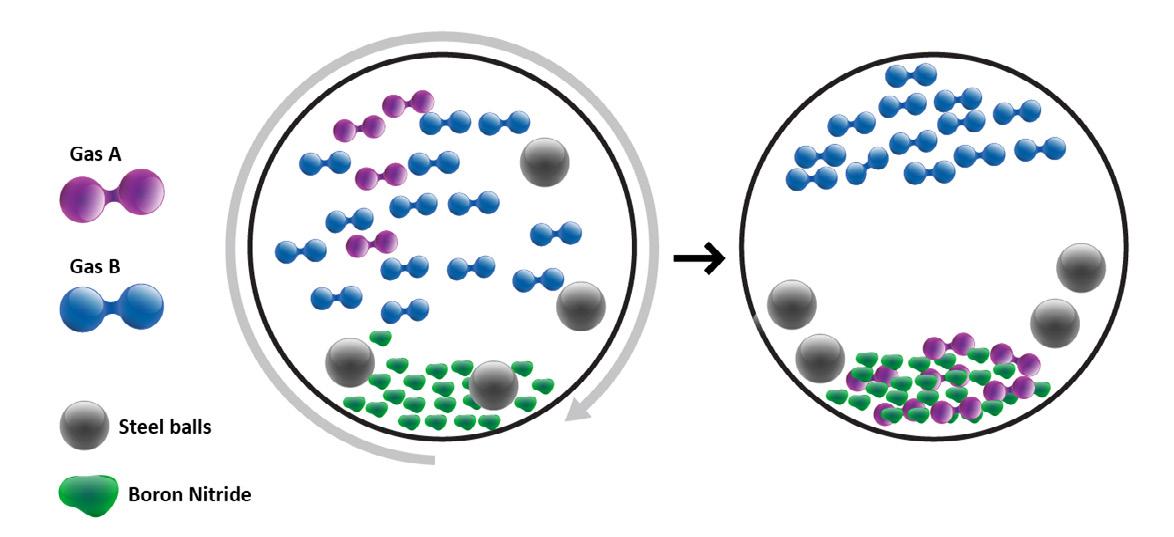

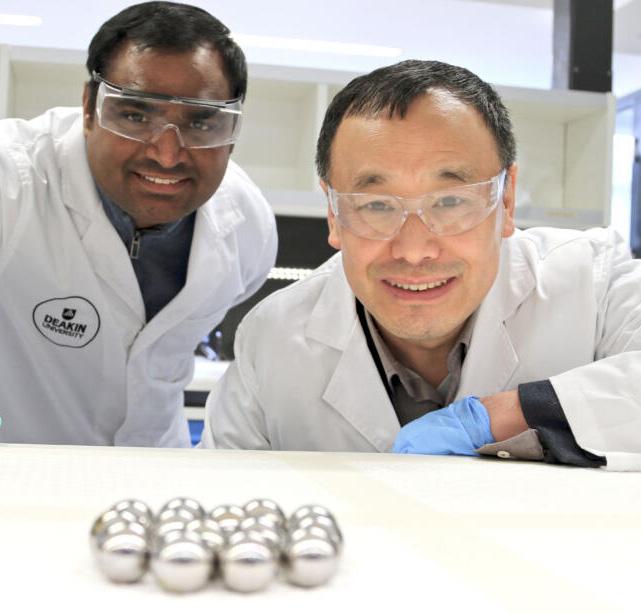

The new process was first described by nanotechnology researchers from Deakin’s Institute for Frontier Materials (IFM) in the prestigious journal Materials Today. It offers a novel way to separate, store and transport huge amounts of gas safely, with no waste. “Right now, Australia is experiencing an unprecedented gas crisis and needs an urgent solution,” said Professor Ying (Ian) Chen, who is IFM’s Chair of Nanotechnology. “More efficient use of cleaner gaseous fuels such as hydrogen is an alternative approach to reduce carbon emissions and slow global warming.” Traditional oil refinery methods use a high-energy ‘cryogenic distillation’ process to separate crude oil into the different gases used by consumers, such as petrol or household gas. This process makes up around 15 per cent of the world’s energy use. However, IFM research outlines a completely different mechanochemical way of separating and storing gases, which uses a tiny fraction of the energy and creates zero waste. The breakthrough is so significant—and such a departure from accepted wisdom on gas separation and storage—that lead researcher Dr Srikanth Mateti said he had to repeat his experiment 20 to 30 times before he could truly believe it himself.

“We were so surprised to see this happen, but each time we kept getting the exact same result, it was a eureka moment,” Dr Mateti said. The special ingredient in the process is boron nitride powder, which is known for absorbing substances because it is so small, yet has a large amount of surface area for absorption. “The boron nitride powder can be re-used multiple times to carry out the same gas separation and storage process again and again,” Dr Mateti said. “There is no waste, the process requires no harsh chemicals and creates no by-products. Boron nitride itself is classified as a level-0 chemical, something that is deemed perfectly safe to have in your house. This means you could store hydrogen anywhere and use it whenever it’s needed.” During the process, the boron nitride powder is placed into a ball mill—a type of grinder containing small stainless-steel balls in a chamber—along with the gases that need to be separated. As the chamber rotates at a higher and higher speed, the collision of the balls with the powder and the wall of the chamber triggers a special mechanochemical reaction resulting in gas being absorbed into the powder. The ball-milling gas absorption process consumes 76.8 KJ/s to store and separate 1000L of gases, which is roughly equivalent to the energy needed to power the average electric vehicle 200 miles.

“We need to further validate this method with industry to develop a practical application,” Professor Chen said.

Lead researcher Dr Srikanth Mateti and Alfred Deakin Professor Ying (Ian) Chen, IFM’s Chair of Nanotechnology.

Faster, Cleaner, Longer: Lithium Battery Breakthrough To Improve Lifetime Performance

Source: Sally Wood

Imagine buying an electric vehicle that only needed to be charged once a week. Think about how the battery was also clean to produce and made in Australia. Monash University researchers have taken a giant leap towards claiming this holy grail of renewable energy by creating a new lithium-sulfur battery. Researchers redesigned the heart of the battery to promote exceptionally fast lithium transfer and improved lifetime performance. “It’s world-leading,” says Professor Matthew Hill, who is the Deputy Head of the Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering at Monash University. “A lot of our research has been about making the battery more stable and lasting longer, so this particular discovery is really exciting,” he explained. As the world charges towards cleaner and greener energy, swapping dirty fossil fuels for emissions-free electrification, lithium batteries are playing an increasingly vital role as storage tools to facilitate energy transition. They are becoming the go-to choice to power everything from household devices such as mobile phones, laptops and electric vehicles to major industries such as aviation and marine technology. But until now, long-duration storage has been somewhat elusive.

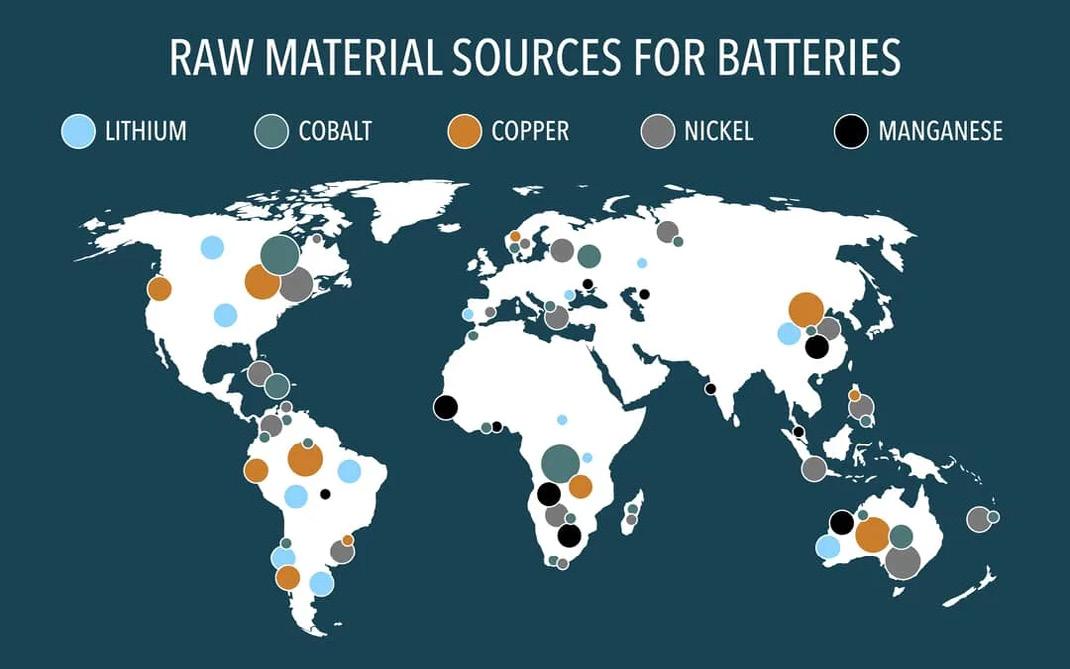

They offer higher energy density and reduced costs when compared to the previous generation of lithium-ion batteries, and they can store two to five times as much energy by weight. Previously, the electrodes in lithium-sulfur batteries deteriorated rapidly and the batteries broke down. However, the new interlayer developed by Professor Hill, Dr Mahdokht Shaibani, Professor Mainak Majumder and PhD candidate Ehsan Ghasemi Estahbanati from the Faculty of Engineering solved that problem. “The interlayer stops polysulfides, a chemical that forms inside this type of battery, from moving across the battery; polysulfides interfere with the anode and shorten the battery life,” Professor Hill said. “It means the battery can be charged and discharged hundreds of times without failing,” he added. Lithium-ion batteries rely on metals such as cobalt, nickel and manganese, which have finite reserves and are often mined in countries known for poor mining practices and reliance on child labour.

But the price of green energy has been a well-documented challenge. Currently, about 60 per cent of the world’s cobalt supply comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo, where large numbers of mines are unregulated, and the use of child labour is common.

In some cases, children as young as seven have been used to mine unstable tunnels, breathing in cobalt-laden dust. By contrast, the mineral sulfur is in abundant supply in Australia and almost considered a waste or by-product, and Australian mining practices are among the world’s best. “We needed to find a better way,” says Professor Hill, “and these batteries are not dependent on minerals that are going to lack supply as the electrification revolution proceeds.” Researchers believe the key to this latest discovery was going against the accepted norms and conventions of lithium battery construction. “It’s ground-breaking technology, because in a regular lithium battery there’s about half a dozen components that make up the battery,” Professor Hill said.

Carbon Neutral 'Spaceplane' Parts To Be Manufactured At Sydney

The Sydney Manufacturing Hub will develop and manufacture components for a green hydrogen-powered launch vehicle capable of deploying small satellites into low earth orbit.

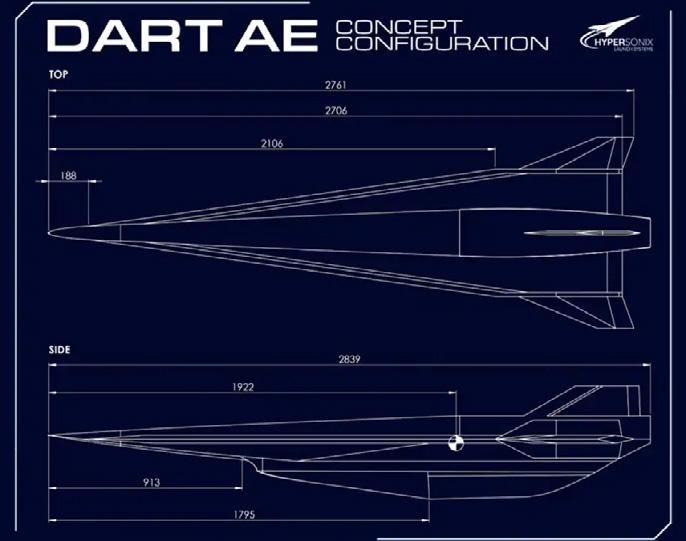

As part of a collaboration agreement with the aerospace engineering startup Hypersonix Launch Systems, the University of Sydney will research and manufacture the components of zero emissions, hypersonic spaceplane. This vehicle will be capable of deploying small satellites into low earth orbit.

Named Delta Velos, the vehicle will be powered by four green hydrogenfuelled scramjet engines, enabling carbon neutral propulsion. It will also include the world's first 3D printed fixed geometry (no moving parts) scramjet engine in Australia, and completed under the Australian Commercialisation grant awarded to Hypersonix in August 2020. University of Sydney researchers will use next generation additive manufacturing technology to develop flight-critical components, further versions of the scramjet engine, and the vehicle’s fuselage at the University’s Sydney Manufacturing Hub. The research team will be led by Professor Simon Ringer, who is an engineer and expert in materials development for additive manufacturing at the University of Sydney. Professor Ringer’s team will work alongside Hypersonix Chief Technology Officer Dr Michael Smart. “We are delighted to be working alongside such an innovative, deep technology company like Hypersonix using advanced 3D printing processes and world-class additive manufacturing facilities for such an important challenge,” Professor Ringer said. “Additive manufacturing is making the previously impossible, possible. This includes the proposed manufacture of satellite-launching spaceplane components right here at the University of Sydney's Darlington campus, situated in the very heart of Tech Central,” he added. Hypersonix Managing Director David Waterhouse said the company had received a lot of interest for its recently announced DART AE project, and would possibly involve the University of Sydney in that project too. “We are pleased to have found such 3D additive engineering facilities in Sydney and are impressed with the capabilities of Simon Ringer’s team,” Mr Waterhouse said.

“We are aiming to launch DART AE in the first quarter of 2023. It is good to be busy, right?” The DART AE project is a technology demonstrator and small version of Delta Velos, which is powered by one single SPARTAN scramjet engine. Delta Velos is a sustainable and reusable space launch vehicle that flies at hypersonic speeds with zero CO2 emissions.

Hypersonix Launch Systems is an Australian engineering, design and build company specialising in scramjet engines and hypersonic technology. Meanwhile, the Sydney Manufacturing Hub is a manufacturing-focused research facility that works alongside industry leaders to deliver cuttingedge research and development in additive manufacturing. The Hub is geared to enable conceptto-production demonstration capabilities, and includes advanced pre- and post-processing of materials. This user-facility supports researchers and companies to leverage 3D printing of metals, ceramics and polymers.

The hub is in the Engineering precinct of the University of Sydney's Darlington campus, which is in the heart of the state’s technologyfocused research area.

DART AE concept configuration visual. Credit: Hypersonix.

Hypersonix Launch Systems and Romar Engineering team, with Professor Simon Ringer. Credit: Hypersonix Launch Systems