2. 五彩魚藻文壺

「大明嘉靖年製」銘

高 23.4 cm 胴径 24.3 cm

来歴

嘉納治兵衛(1862〜1951年) 井上恒一(1906〜1965年)

出展

「中国陶磁 元明名品展」日本橋高島屋, 1956年, no. 130. 「アジアアフリカ展」東京高島屋, 1958年.

所載

座右寶刊行會編『世界陶磁全集 第11巻 元明篇』河出書房, 1955年, 図版105上.

座右寶刊行會編『世界陶磁全集 第十一巻 中國 元明篇』河出書房新社, 1961年, 図版105上.

藤岡了一『陶器全集 明の赤絵 第27巻』平凡社, 1962年, 図版20.

繭山龍泉堂『龍泉集芳 第一集』便利堂, 1976年, 図版825.

矢部良明『中国陶磁の八千年 乱世の峻厳美・泰平の優美』平凡社, 1992年, 挿図V-65.

JAR WITH FISH AND WATER PLANTS DESIGN

Porcelain with underglaze blue and overglaze wucai polychrome enamels

Inscription: “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi”

H. 23.4 cm Torso Dia. 24.3 cm

PROVENANCE

Kanō Jihei (1862-1951)

Inoue Tsuneichi (1906-1965)

EXHIBITED

Exhibition of Yüan and Ming Ceramics, Nihonbashi Takashimaya, Tokyo, 1956, no. 130.

Asia Africa Exhibition, Tokyo Takashimaya, 1958.

LITERATURE

Zauhō Kankōkai (eds.), Yüan and Ming Dynasties Vol. 11 from the series Catalogue of World's Ceramics, Kawade Shobo, 1955, pl. 105 upper.

Zauhō Kankōkai (eds.), Collection of World’s Ceramics Vol. 11, Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 1961, pl. 105 upper.

Fujioka Ryōichi, Min no Aka-e [Ming Polychrome Ceramics], Vol. 27 from the series Tōki Zenshū [Collected Works of Ceramics], Heibonsha, 1962, pl. 20.

Mayuyama & Co., Ltd., Mayuyama, Seventy Years, Volume One, Benrido, 1976, pl. 825.

Yabe Yoshiaki, Chūgoku Tōji no Hassennen: Ransei no Shungenbi, Taihei no Yūbi [8000 Years of Chinese Ceramics], Heibonsha, 1992, fig. V-65.

「大明嘉靖年製」銘

高 18.2 cm 胴径 10.9 cm

来歴

繭山龍泉堂, 1939年12月21日.

GOURD-SHAPED VASE WITH HOSOGE FLOWER AND SCROLL DESIGN

Porcelain with overglaze wucai polychrome enamels

Inscription: “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi”

H. 18.2 cm Torso Dia. 10.9 cm

PROVENANCE

Mayuyama & Co., Ltd., Tokyo, 21 December 1939.

4. 五彩宝相華唐草文瓢形瓶

「大明嘉靖年製」銘

高 23.3 cm 胴径 14.8 cm

GOURD-SHAPED VASE WITH HOSOGE FLOWER AND SCROLL DESIGN

Porcelain with overglaze wucai polychrome enamels

Inscription: “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi”

H. 23.3 cm Torso Dia. 14.8 cm

5. 緑地紅彩宝相華唐草文瓢形瓶

「大明嘉靖年製」銘

高 21.5 cm 胴径 13.1 cm

来歴

ペラム家(チチェスター伯爵)旧蔵(ラベルによる).

GOURD-SHAPED VASE WITH HOSOGE FLOWER AND SCROLL DESIGN

Porcelain with overglaze red and green enamels

Inscription: “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi”

H. 21.5 cm Torso Dia. 13.1 cm

PROVENANCE

Pelham family (Earl of Chichester) Collection (according to an attached label).

6. 黄地青花紅彩牡丹唐草文瓢形瓶

「大明嘉靖年製」銘

高 19.4 cm 胴径 11.4 cm

来歴

Sotheby’s ロンドン, 1963年5月21日, lot 39. Bluett & Sons Ltd., ロンドン.

出展

「Exhibition of Ming Polychrome Porcelain」The Oriental Ceramic Society, 1950年, no. 151. 「中国美術展シリーズ5 明清の美術」大阪市立美術館, 1980年, no. 1〜71.

所載

長谷部楽爾, 林屋晴三編『中国古陶磁 下』毎日新聞社, 1971年, 図版 88. 佐藤雅彦・中野徹『陶器講座 第7巻 中国III 元・明』雄山閣出版, 1971年, 図版124, 125.

藤岡了一『陶磁大系 明の赤絵 第四三巻』平凡社, 1972年, 図版62.

繭山龍泉堂『龍泉集芳 第一集』便利堂, 1976年, 図版826.

大阪市立美術館編『明清の美術』平凡社, 1982年, 図版100.

GOURD-SHAPED VASE WITH PEONY AND SCROLL DESIGN

Porcelain with underglaze blue and overglaze yellow and red enamels

Inscription: “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi”

H. 19.4 cm Torso Dia. 11.4 cm

PROVENANCE

Sotheby’s London, 21 May 1963, lot 39. Bluett & Sons Ltd., London.

EXHIBITED

Exhibition of Ming Polychrome Porcelain, The Oriental Ceramic Society, 1950, no. 151.

Chūgoku Bijutsuten Shirīzu 5 [Chinese Art Exhibitions Series No. 5], Minshin no Bijutsu [Arts of the Ming and Qing], Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts, 1980, no. 1-71.

LITERATURE

Hasebe Gakuji, Hayashiya Seizō (eds.), Chinese Ceramics VolumeⅡ , The Mainichi Newspapers, 1971, pl. 88. Satō Masahiko and Nakano Tōru, Chūgoku Ⅲ, Gen Min [China III, Yuan-Ming], Vol. 7 from the series Tōki Kōza [Lectures on Pottery], Yuzankaku Shuppan, 1971, pls. 124, 125.

Fujioka Ryōichi, Min no Aka-e [Ming Polychrome Ceramics], Vol. 43 from the series Tōji Taikei [Great Lineage of Pottery], Heibonsha, 1972, pl. 62. Mayuyama & Co., Ltd., Mayuyama, Seventy Years, Volume One, Benrido, 1976, pl. 826.

Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts (eds.), Minshin no Bijutsu [Art of the Ming and Qing], Heibonsha, 1982, pl. 100.

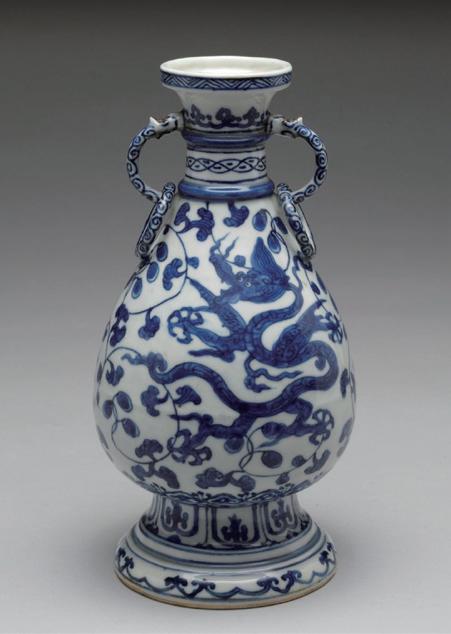

7. 青花応龍仙人文瓢形瓶

「大明嘉靖年製」銘

高 32.7 cm 胴径 16.0 cm

GOURD-SHAPED VASE WITH SQUARE LOWER SECTION AND YINGLONG FLYING DRAGONS AND DAOIST

IMMORTALS DESIGN

Porcelain with underglaze blue

Inscription: “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi”

H. 32.7 cm Torso Dia. 16.0 cm

「大明嘉靖年製」銘

高 7.8 cm 口径 15.2 cm

SQUARE BOWL WITH DRAGONS AND LONGEVITY CHARACTER DESIGN

Porcelain with underglaze blue and overglaze yellow enamel

Inscription: “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi”

H. 7.8 cm Mouth Dia. 15.2 cm

「大明嘉靖年製」銘

高 20.5 cm 胴径 21.5 cm

来歴

C. T. Loo & Co., パリ. Emil Hultmark(1872 〜1943年)およびその子孫旧蔵.

出展

「International Exhibition of Chinese Art」Royal Academy of Arts, ロンドン, 1935 〜1936年, no. 1949.

「Emil Hultmarks Collection」The Royal Swedish Academy of Arts, ストックホルム, 1942年, no. 413.

所載

L. Reidemeister『Ming-Porzellane in Schwedischen Sammlungen』Walter de Gruyter & Co., 1935年, 図版30.

『Catalogue of The International Exhibition of Chinese Art』Royal Academy of Arts, 1935 〜 1936年, 図版1949.

大河内正敏, 横河民輔, 奥田誠一編『陶器圖錄 第八巻 支那篇(下)』雄山閣, 1938年, 図版43.

『Emil Hultmarks Collection』The Royal Swedish Academy of Arts, 1942年, no. 413.

JAR WITH PAIRED DRAGONS DESIGN

Porcelain with overglaze yellow, red and black enamels

Inscription: “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi”

H. 20.5 cm Torso Dia. 21.5 cm

PROVENANCE

C. T. Loo & Co., Paris.

Emil Hultmark (1872-1943) and his descendants Collection.

EXHIBITED

International Exhibition of Chinese Art, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1935-1936, no. 1949.

Emil Hultmarks Collection, The Royal Swedish Academy of Arts, Stockholm, 1942, no. 413.

LITERATURE

L. Reidemeister, Ming-Porzellane in Schwedischen Sammlungen, Walter de Gruyter & Co., 1935, pl. 30.

Catalogue of The International Exhibition of Chinese Art, Royal Academy of Arts, 19351936, pl. 1949.

Ōkouchi Masatoshi, Yokogawa Tamisuke, Okuda Seiichi (eds.), Tōki Zuroku [Illustrated Ceramics Catalogue], Vol. 8, Shina hen (ge) [China Pt. 2], Yuzankaku, 1938, pl. 43.

Emil Hultmarks Collection, The Royal Swedish Academy of Arts, 1942, no. 413.

「大明嘉靖年製」銘

高 9.2 cm 口径 20.5 cm

WHITE PORCELAIN BOWL WITH INCISED PAIRED DRAGONS DESIGN

Inscription: “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi”

H. 9.2 cm Mouth Dia. 20.5 cm

「大明嘉靖年製」銘

高 3.5 cm 径 17.9 cm

DISH WITH PAIRED DRAGONS DESIGN

Porcelain with on-biscuit purple, green, yellow and black enamels

Inscription: “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi”

H. 3.5 cm Dia. 17.9 cm

「大明嘉靖年製」銘

高30.7 cm 胴径 39.8 cm

LACQUER BOX AND COVER WITH DRAGONS IN CLOUDS DESIGN

Carved polychrome lacquer

Inscription: “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi”

H. 30.7 cm Torso Dia. 39.8 cm

嘉靖帝と陶磁器

新井崇之

はじめに

嘉 かせいてい

靖帝(1507 ~ 67)(挿図 1)というとどのようなイメージを 思い浮かべるであろう。歴史の文脈では、嘉靖帝は道教を狂信し、 政治をおろそかにし、明朝衰退の原因になったと語られることが 多いと思う。しかし、これは後の明朝の滅亡を知っているからこ そ、歴史を簡単に語るために嘉靖帝の負の側面が強調されやすい が、それはあくまで後世からの視点でしかない。同時代の眼で見 た場合、彼はどういう人物だったのか。そして、嘉靖帝は明朝歴 代皇帝の中でも、とくに多くの陶磁器を景徳鎮官窯に注文した。 果たしてどのような考えをもって、これほど素晴らしい陶磁器を 作らせたのであろうか。本稿では、嘉靖帝の生涯を概観した上で、 彼が陶磁器に込めた想いについて考えてみたい。

挿図1 明世宗坐像 国立故宮博物院(台北)蔵 出典:NPM Open Data

1.嘉靖帝の生涯

(1)即位

正 せいとく 徳 16 年(1521)3 月、明朝第 11 代皇帝であった正 せいとくてい 徳帝(1491 ~ 1521)が 31 歳の若さで崩御した。正徳帝は中国史上まれに見 る奇人皇帝として有名であり、政治の実権を宦官に委ね、自らは 遠征と称して軍装で外遊旅行を楽しんだり、チベット仏教や回教 に傾倒して秘技の研究に明け暮れたりと、享楽の限りを尽くした。

むしろ皇帝としての自覚はあまりなかったようで、自らのことを 軍事に長けた大将軍や、チベット仏教の指導者である法王などと 称していた。さらに困ったことに、正徳帝には兄弟も後継ぎもい

なかった。そこで時の内閣は次の皇帝を決めるにあたって、皇室 の系図を正徳帝の父 弘 こうちてい 治帝 まで遡り、その弟 興 こうけんおう 献王 のさらに嗣子 である朱 しゅこうそう 厚熜を選出した。

厚熜は長江の畔に位置する湖北安陸府(現在の湖北省鍾祥市)の生まれであ る。父親の興献王は成 せいかてい 化帝の第四子であったが、明朝には皇帝の兄弟を親王と して地方に冊封することで、皇室による中央集権を強固なものにするという制 度があり、興献王は湖北の地で興王府を築いていた。厚熜は幼い頃から父の下 で経書を読み、修身治国の方法を学んでいた。また、領地の近くには道教の聖 地である武当山があり、厚熜は父と共に玄天上帝を祀る儀礼に参加し、道教に も馴れ親しんでいた。

だが、正徳 14 年(1519)に父興献王は病で逝去する。厚 熜 は喪に服し、王 府の主を継承したちょうどその矢先に、正徳帝が崩御したのである。厚熜は急 ぎ北京に召喚され、皇帝として即位することになった。これが明朝第 12 代皇 帝となった世宗嘉靖帝である。

嘉靖帝が即位した時は 15 歳であった。政治は汚職と腐敗にまみれ、地方で 反乱が多発し、国庫の銀を消耗した状態であり、彼の治世はマイナスからのス タートであった。先帝時代の悪政を正すためには、明朝政治の中枢である内閣 と、皇帝に助言する大学士の支えが必須であった。時の大学士は楊 ようていわ 廷和(1459 ~ 1529)という人物で、成化・弘治・正徳と三代にわたって皇帝に仕えた重 臣であり、厚熜を皇帝に選んだまさにその人であった。本来であれば、まだ知 識も経験もない嘉靖帝を補佐し、明朝の立て直しを図るはずであった。しかし、 楊廷和と嘉靖帝の関係は、ある事件をきっかけに亀裂が入る。

(2)大礼の義

明朝の礼制では、従弟は皇位を継承することができないため、正徳帝から従 弟の嘉靖帝に皇位が移るのは本来であればあり得ない。このため、嘉靖帝を選 んだ楊廷和は、明王朝の系図を書き換えることを提案した。弘治帝に対して 「皇 こうこう

考」、つまり在位中の皇帝が亡くなった先代皇帝を呼ぶ際の尊称を用いるこ とで、嘉靖帝を弘治帝の嗣子、正徳帝の弟にしてしまおうというのである。

そうなると、嘉靖帝の実父である興献王は「 皇 こうしゅくふ 叔父 」、つまり叔父というこ とになってしまう。無論、これに嘉靖帝は強く反発した。自分の敬愛する父母 を、それも父に至っては 2 年前に亡くなったばかりで、いきなり叔父だと偽る よう強要されたのである。嘉靖帝は父である興献王にこそ皇帝の称号を与える よう強く求めた。しかし内閣は嘉靖帝の意見を聞き入れなかった。楊廷和に至っ ては、皇帝が反発するたびに辞表を提出する始末であった。皇帝と内閣が真っ 向から対立したこの事件を「大 たいれい 礼の義 ぎ 」と呼ぶ。

嘉靖帝からすると、実の父母を敬うのは当たり前のことであり、その存在を

捻じ曲げろと言う人たちこそが異常である。そもそも儒教でいう孝の教えにも 反している。わずか 15 歳で慣れない北京に呼び出されて、意味の分からない 理屈を押し付けられた嘉靖帝は、徐々に宮廷の中で孤独を感じるようになる。 このような状況の中、内閣官僚であっても張 ちょうそう 璁(1475 ~ 1532)や桂 けいがく 萼(1478 ~ 1531)は皇帝を支持したため、嘉靖帝は大いに喜び、実績がない二人を皇帝 の補佐役である翰 かんりんいん

林院学士に任命してしまう。また宦 かんがん 官の崔 さいぶん 文は、嘉靖帝に道 教の教理を丁寧に教え、道教の道士を紹介する。道士たちとの交流は、かつて 父と行った武当山の記憶をよみがえらせたのかもしれない。徐々に道教に傾倒 していく皇帝に対して、内閣給事中の張 ちょうちゅう 翀(1478 ~?)は「崔文は陛下を翻弄し、 政治に関与し、邪な者たちを宮廷に引き込んでいます」と進言したが、嘉靖帝 は聞く耳を持たなかった。

嘉靖 3 年(1524)、嘉靖帝は度々出されていた楊廷和の辞表を受理し、宮廷 から追放する。なおも皇帝に反対する官僚たちは、紫禁城の左順門前で抗議活 動を行ったが、嘉靖帝はついに堪忍袋の緒が切れたのか、皇帝大権を発動し、 関係者を杖打ちの刑に処した。その中には、かつて諫言を述べた張翀の姿もあっ た。これを「左順門事件」と呼び、3 年にも及ぶ大礼の義はここに幕を閉じた。

結果的に、嘉靖帝の意見が押し通され、父である興献王が「興献帝」となり、 弘治帝が「皇 こうはくこう 伯考」ということになった。だがこの事件以後、進んで嘉靖帝に 諫言を述べる臣下はいなくなり、皇帝に取り入ろうとする佞臣ばかりが集まる ようになった。

(3)礼制改革

嘉靖帝は大礼の義を通じて明朝に対する不信感が募り、「そもそも明の礼制 が間違っている」と考えるに至った。そこで、嘉靖帝の考えが正しかったこと を示すために、礼制の在り方について論じた『明倫大典』を 3 年かけて編纂さ せ、全国にある教育機関に配布した。

だが嘉靖帝は、即位以後毎年のように旱魃が起こっていることを激しく憂慮 していた。というのも、中国の皇帝は「天子」と呼ばれるように、天の意志によっ て統治を任されている存在であり、そこで災害や飢饉などが発生するというこ とは、天が自分の統治に不満の意を示していると考えた。天候異常などで問題 が起こると、官僚が皇帝の代理として祭祀を行うのが常だが、嘉靖 8 年(1529) には北京で旱魃が発生したことで、嘉靖帝は自ら祭壇に赴いて祭祀を執り行 なった。この効果があったのかはわからないが、この年の華北地域は比較的豊

挿図2

紅釉豆 御窯廠(御器廠)遺跡出土 出典:『明清御窯瓷器』故宮出版社, 2016年, p. 167より転載

挿図3

素焼豆(低温釉を施す前の状態) 御窯廠(御器廠) 遺跡出土

出典:『明清御窯瓷器』故宮出版社, 2016年, p. 169より転載

作になったようである。

さらに嘉靖帝は、昔の記録を調べたことで、明朝初代皇帝である洪 こうぶてい 武帝(1328 ~ 98)の時代は皇帝自らが祭祀を行っていたこと、さらには天地を一緒に祀 らずに個別の祭壇を設けていたことを知った。そこで嘉靖 9 年(1530)、嘉靖 帝は北京に置かれていた天地壇を分けて、天壇・地壇・日壇・月壇を設置した。 この際には各壇に置く祭器にもこだわっており、『大明会典』の記録によると、 天壇(円丘)に青、地壇(方丘)に黃、日壇に赤、月壇に白の磁器を置くこと まで定めている。洪武帝の時代にはこのようなカラフルな陶磁器はなく、窯業 技術が進んだことで可能となった嘉靖帝によるオプションである。この時に色 違いで注文されたと考えられる「豆 とう 」という祭器が、景徳鎮官窯の遺跡から出 土している(挿図 2・3)。

嘉靖帝は他にも様々な礼制を変更したが、国家祭祀のやり方を変えるのは 皇帝だけに許された特権でもある。それを存分に発揮したことから、自身が中 華を統治するのにふさわしい皇帝であるという強い意志が感じられる。そして その際に、初代皇帝が定めた制度に立ち返ることは、他の皇帝よりも明朝本来 のやり方を理解しているとアピールする意味を持つ。明朝において洪武帝の制 度を大きく変えたのは、嘉靖帝以外に、第 3 代皇帝の 永 えいらくてい 楽帝(1360 ~ 1424) だけであった。奇しくも永楽帝は、靖難の変というクーデターによって帝位に ついた皇帝であり、正統ではない負い目から礼制改革を行った点がよく似てい る。彼ら 2 人の皇帝にはもう一つ、道教を強く信仰したという共通点もある。

(4)道教への傾倒

嘉靖 3 年(1524)、大礼の義により宮廷内で孤立していた嘉靖帝は、宦官・ 崔文の勧めで道士・邵

しょう 元 げんせつ

節を北京に呼び寄せた。邵元節が祈祷を行うと、実際 に雨が降ったようで嘉靖帝は驚いた。天候不順は嘉靖帝が頭を悩ませていた懸 案であったが、道士がいとも簡単に解決したことで、道教の効果を確信したの であった。

また、長らく世継ぎに恵まれなかった嘉靖帝は、邵元節に祈祷を頼んだ。そ の効果があったのかは不明だが、嘉靖 15 年(1536)に息子・載 さいえい 壡が生まれたため、 嘉靖帝は完全に道教に心酔した。この年、邵元節の地位は揺るぎないものにな り、道士として初めて最高位の官員である礼部尚書に任ぜられた。

道を修めた道士たちは、不思議な術を使って雨を降らせ、病を癒し、富を増 やし、人々を豊かにする。そして仙薬を用いることで不老長寿となり、仙人と なって昇天し、天帝の下に仕える。実際に中国の伝説的な帝王である神農や黄

帝は、神仙の列に名を連ねている。自身の皇帝としての資質に不安を覚えてい た嘉靖帝は、道士たちに超人的なカリスマ性を感じ、現状を打開してくれる唯 一の存在に思えたのであろう。道教の力に頼れば、自分も名君となって国を建 て直し、万民に幸福をもたらすことができるかもしれない。そんな期待を抱い たとしても不思議ではない。

宮廷内における道教の地位の向上に伴い、官僚たちの中にも道教を利用する 者が現れた。道教の儀礼では、天帝に対して読み上げられる祝詞のような文言 があり、青藤紙の上に書かれたことから「青 せいし 詞」と呼ばれた。科挙を突破して きた官僚たちは、政策立案を行う上奏文を書くのに長けていることはもちろん だが、その文才を生かして青詞を書き、嘉靖帝を悦ばせるものが現れた。なか でも 厳 げんすう

嵩(1480 ~ 1567)は、上奏文よりも青詞を書くことに熱中し、それに より内閣の最高位である首輔に上り詰めたため、人々から「青詞宰相」と揶揄 された。

また嘉靖帝は紫禁城の西側に位置する西苑内に、道教の思想を体現するかの ような壮麗な離宮の建築を行った。西苑はモンゴル族が統治した元代(1271 ~ 1368)に宮廷の庭園として造営され、明の永楽帝が改修して短期間だけ使用し ていた。嘉靖帝はそれを自身の離宮として大幅に改築し、道教の修行を行う道 場などを建てた。無論、これらの建築にも莫大な費用がかかったわけで、不足 していた国庫の銀の消費に拍車をかけた。

(5)隠居

ここまで見てくると、嘉靖帝は政治を全く顧みない皇帝であったように思え てしまうが、実は優れた改革をいくつも行っていた。即位直後から正徳帝時代 の悪弊を正すため、皇帝におもねっていた宦官や、皇室との縁故により官職に 付いていた者を宮廷から一掃し、皇室が専有していた農地を民衆に返還し、税 制の大幅な改革を行った。これにより、宮廷内部の政治は一定の正常化を見せ、 国の税収は増加した。嘉靖帝によるこれら一連の政治改革は、「嘉靖新政」と 呼ばれる。

このまま改革を続け、中国全土に波及させることができれば、明朝の立て直 しは実現したかもしれない。しかし嘉靖 21 年(1542)、宮廷を揺るがす大事件 が起こった。皇帝の寝所に宮女十数名が押し入り、なんと寝ている嘉靖帝の首 に縄をかけて絞め殺そうとしたのである。この事件の動機は不明だが、嘉靖 帝は宮女たちから相当な恨みを買っていたようである。結局は未遂に終わり、 嘉靖帝は一命をとりとめたが、関わった宮女はほぼ全員が処刑された。この

「 壬 じんいんきゅうへん

寅宮変 」と呼ばれる事件以降、嘉靖帝は完全に人間不信となり、西苑に引 きこもってしまう。

この後、嘉靖帝は宮廷で政務を執ることはなく、子どもたちにも会わず、ひ たすらに西苑で道教の修行に明け暮れた。その間の政務は、先述した青詞宰相 の厳嵩に壟断されることになり、宮廷では醜い権力闘争が繰り広げられたが、 嘉靖帝はもはや興味を持たなかった。道教には、賢人は世に出ることを好まず、 社会に背を向け隠遁するという思想があるが、まさに皇帝の身でありながら道 教的厭世を実践した状態である。

そして嘉靖 44 年(1565)、道士の王金が献上した丹薬を飲んだ嘉靖帝は異 変を感じ、「体が熱く治まらない」と言い、床に臥せってしまう。嘉靖 45 年 12 月 14 日(1567)、ついに嘉靖帝は危篤に陥り、すぐに紫禁城内の乾清宮に運 ばれ、そこで崩御した。皇帝としてせめて最後は紫禁城で、という臣下たちの 配慮であった。嘉靖帝には世宗という廟号が与えられ、その遺体は明朝歴代皇 帝と並び、陵墓郡の一つである永陵に葬られた。

ここまで嘉靖帝の生涯について見てきたが、どうだったであろう。後世の歴 史が言うように「道教に溺れ、明朝を衰退させた皇帝」という一言では片づけ られないのではないだろうか。明代における嘉靖帝の評価と影響を考える上で、 張 ちょうきょせい 居正(1525 ~ 82)の話を挙げておきたい。嘉靖帝崩御の 6 年後、張居正は 幼い万暦帝(1563 ~ 1620)を補佐して大改革を行い、明朝を立て直した。そ の内の重要な政策は、実は嘉靖新政を継承したものであった。張居正が嘉靖帝 について述べた言葉が残っており、「世宗皇帝はその知恵と賢明さで皇位を継 承し、これまでの悪政をすべて正し、祖法を復活させた。……生来聡明な方で、 即位後二十年間、熱心に統治と研鑽に努め、その知恵と判断力は歴代皇帝の及 ばないものであった」と高く評価している。歴史は一面だけでは評価できない と改めて考えさせられる。 2.嘉靖帝の官窯

嘉靖帝の生涯を踏まえた上で、ここからは嘉靖官窯で作られた陶磁器につい て見ていきたい。明代には景徳鎮に官窯が置かれ、最高品質の陶磁器が作られ たことはよく知られている。ただ一つ注意しておきたいのが、景徳鎮官窯では 皇帝の奢侈のために陶磁器が生産されたといわれるが、これは半分正確ではな い。というのも、奢侈品=必要な程度を超えて作られた贅沢品ということにな

るが、景徳鎮官窯の磁器は多くが必要だから作られたのである。はじめに、嘉 靖年間に至るまでの明代景徳鎮官窯の沿革について簡単に述べておく。

(1)明代景徳鎮官窯の沿革

明代初代皇帝の洪武帝は、国家体制を整えていく過程で、祭礼の重要性を認 識していた。そこで天下を平定した後、すぐに各地から儒者を集めて礼制の在 り方について研究させたのである。とくに祭器については、洪武 2 年(1369) の段階ですべて磁器を用いるように定めた。古の聖王たちの時代に陶が祭器と して用いられていた故事を挙げ、陶磁器が儒教の貴ぶ質朴さに適った素材であ ると判断したのである。そして磁器を生産する場所として、前の王朝である元 代に祭器を生産していた景徳鎮が選ばれた。

永楽帝の時代には、宮廷内部での祭祀や宴会で磁器が多用されるようになっ た。さらに宦官・ 鄭 ていわ 和(1371 ~ 1434)の大航海による朝貢圏の拡大に伴い、 多くの国が中国に対して磁器を下賜するように求めたのであった。そこで、景 徳鎮の中心には宮廷直轄の磁器生産機関である「御 ぎょきしょう 器廠」が築かれた。御器廠 の設置年代には諸説あるが、筆者は永楽帝が即位した頃であると考えている。

実際に、御器廠遺跡から出土する官窯磁器の量は、永楽年間から急増しており、 宮廷での需要に応えつつ、厳格な品質管理の下で磁器を生産したのであろう。

御器廠の成立後、宮廷では磁器が必要になるたびに注文を出していたが、時 代を経るにつれてその数は増加し、次第に御器廠だけでは磁器の生産が追い付 かなくなった。『明史』には成化年間(1465 ~ 87)の官窯の状況について、「宦 官を派遣し浮梁景徳鎮に行かせた。御用の磁器を焼造させることが、最も多く かつ長く、費用も計算できないほど膨れ上がった」とある。嘉靖帝が即位した 頃の状況についても、「弘治(1488 ~ 1505)より以来、焼造のいまだ終わらな いものが三十数万器あった」と書かれており、生産が終わらずに繰越され続け た磁器が膨れ上がっていたのである。

嘉靖年間の官窯も、当初は正徳年間と同じく宦官によって監督されていたが、 後に撤回された。『江西省大志』巻 7、「陶書」によると、「先に官窯は中官(宦 官)1 員が専ら監督した。嘉靖 9 年(1530)に取りやめ、饒州佐貳官 1 員に銭 糧の不正を管理させ、分守道と分巡道(地方官)の管轄に属させた」とあり、 嘉靖 9 年に宦官の派遣をやめ、代わりに地方官によって磁器の生産が監督され るようになった。嘉靖帝は大礼の義の決着後に嘉靖新政に乗り出していたこと は、先に見たとおりである。その際に正徳帝の時代に蔓延していた宦官の悪弊 を正していたが、これまで宦官に任せていた磁器生産を地方官に委ねるという

挿図4

青花八吉祥文香炉 「大明成化年製」銘 故宮博物 院(北京)蔵

出典:『明代成化御窯瓷器』故宮出版社, 2016年, pp. 58-59より転載

挿図5

青花八吉祥文香炉 「大明嘉靖年製」銘 国立故宮 博物院(台北)蔵 出典:NPM Open Data

政策も、その一環であったと考えられる。

さらに嘉靖年間には、磁器の注文件数が多かった場合に、官窯だけで生産す るのではなく、一部を民間に委託して生産させる「官 かんとうみんしょう 搭民焼」という方法が採 られるようになる。具体的な内容は前掲『江西省大志』「陶書」に、「およそ部 限磁器(通常の注文)であれば、平常通り焼造し、民窯に委託することはない。 ただ欽限磁器(皇帝の注文)であれば、数が多く期限も短いため、一時にまと めて処理し、及ばなければ、民窯に割り当てて作らせ、質が用いるのに足るも のを選んで集めて送らせる」と記されている。

民窯に委託生産を行わせるのは、あくまで注文数が多い場合のみの臨時措置 であった。しかし、民間に委託して焼かせるのは恒常化していたようで、景徳 鎮市内で発掘された民窯である観音閣窯址と落馬橋窯址では、商品として作ら れた大量の製品と一緒に、「大明嘉靖年製」銘が書かれた磁器の破片が確認さ れている。民窯で生産された磁器は政府によって買い上げられることになって おり、これが徹底されたならば民窯の職人に不都合はないはずである。そのう え、官窯製品のレベルに準ずるものを作るため、民間では相当な技術開発が行 われた。

以上、嘉靖年間の官窯では宦官の弊害を排除し、地方官に任せた監督体制が 敷かれた。その際に採られた官搭民焼制により、景徳鎮官窯では一部を民間委 託することで多くの注文を処理できるようになり、官窯の技術が民間にも普及 したことで、景徳鎮窯業全体の技術向上につながった。嘉靖年間の景徳鎮では 様々な問題もあったが、現在私たちが見ることができる嘉靖官窯の名品は、こ れらの改革によって生み出されたのである。

(2)嘉靖官窯の製品

明代の御器廠は中央政府による統制を受けた官窯であり、そこでは内府など の中枢機関が磁器のデザインを完全に指定していたため、官窯磁器には嘉靖帝 の意向が如実に反映されていたと考えられる。嘉靖官窯で作られた磁器を分析 した結果、その特徴はおおよそ①皇帝としての正当を示すもの、②天の祝福を 表すもの、③道教の世界観を表すものの 3 種類に分類できると考えられる。

①皇帝としての正当を示すもの

傍系から皇帝となった嘉靖帝は、さらに大礼の義を経て、自身の血統につい てコンプレックスがあったようである。ここで官窯の磁器を見ると興味深い傾 向がある。嘉靖官窯には、直系の祖父である成化帝の官窯を写したタイプが多

くあり(挿図 4・5)、文様と器形の完全な再現を目指しつつも、銘はしっかりと「大 明嘉靖年製」と入れている。一方で、自分とは別の系統となる弘治帝と正徳帝 の官窯磁器については、少なくとも意図的に写そうとしている作例は見当たら ない。ここから、嘉靖帝は成化帝を継承していることを示しつつも、自分の存 在を銘によって主張していた可能性が考えられる。

また、嘉靖帝は礼制の改革を行った皇帝であり、祭祀を通じて天に国家の安 寧を求めるのは、皇帝として為すべき重要な職務だと考えていたため、祭器へ のこだわりが非常に強い。先述した様々な色の豆もそうだが、他にも爵 しゃく ・尊 そん な ど青銅器に由来する器物が多く作られた(挿図 6・7)。青銅器は紀元前から中 国の祭祀で用いられていた礼器であり、そこに洪武帝が定めた祭器をすべて磁 器で作るという規定を当てはめることは、中華の伝統を継承しつつ、明王朝の 祖訓を遵守していることになる。

そして磁器の文様にも皇帝権力を象徴するものがあり、とくに顕著に表れて いるのは龍文である。しかし龍にも多数の種類があり、中でも皇帝の象徴たり 得るのは、皇帝の着る服、通称「 龍 りゅうほう 袍 」と同タイプの龍であると考えられる。 つまり、丸い鼻、二本の角、五本の爪、細長い尾の特徴を持った龍である(挿 図 8)。この龍は鳳凰と対になって描かれる場合や(挿図 9)、龍二匹が円を描 きながら宝珠を追いかけるデザインとして多用される(挿図 10)。同様の龍文は、 宮廷で製造された漆器に描かれることもあり(挿図 11)、当時は漆器が陶磁器 と並んで皇室を象徴する重要な器物であったことを示している。ちなみに、嘉 靖年間には皇室のために作られる漆器にも優品が多く、磁器と同様に複数の色 を用いた鮮やかな作品が特徴である。

その他の種類の龍には、蝙蝠のような羽が生えていたり(挿図 12)、爪が四 本以下であったり(挿図 13)、魚のような尾をしていたりする(挿図 14)。こ れらの龍は皇室の象徴たる龍とは異なるが、それぞれに特別な意味を持ってい る。例えば、蝙蝠のような羽の生えた龍は「応 おうりゅう 龍」と呼ばれ、伝説の聖王であり、 道教の神として天界に君臨する黄帝の象徴である。爪が四本であれば「蟒 ぼう 」と 呼ばれ、皇帝が臣下に下賜する龍の文様として使われることが多い。また、魚 のような尾が付いている場合は「飛 ひぎょ 魚」と呼ばれ、とくに海を象徴する場合も ある。

ここで重要なのは、嘉靖官窯にこれらの龍のバリエーションが非常に多いこ とにある。中国では古くから聖人は霊獣と親しむことができ、とくに帝王は様々 な龍を使役できると信じられていた。嘉靖官窯の磁器に様々な龍が描かれ、そ れを皇帝が日常生活で用いることは、彼が帝王としての資質を備えているとい

挿図6

藍釉爵 「大明嘉靖年製」銘 故宮博物院(北京)蔵 出典:『明代嘉靖隆慶万暦御窯瓷器』故宮出版社, 2019年, p. 255より転載

挿図7

礬紅釉尊 故宮博物院(北京)蔵 出典:『明代嘉靖隆慶万暦御窯瓷器』故宮出版社, 2019年, p. 336より転載

挿図8

青花龍文盤 「大明嘉靖年製」銘 国立故宮博物院(台北)蔵 出典:NPM Open Data

挿図10

青花双龍文盤 「大明嘉靖年製」銘 東京国立博物館蔵 出典:ColBase

挿図12

青花応龍文瓶 「大明嘉靖年製」銘 国立

故宮博物院(台北)蔵 出典:NPM Open Data

挿図9

青花龍鳳文盤 「大明嘉靖年製」銘 国立故宮博物院(台北)蔵 出典:NPM Open Data

挿図11

彫彩漆龍鳳文大盒子 「大明嘉靖年製」銘 故宮博物院(北京)蔵 出典:「故宮博物院蔵文物珍品大系 元明漆器」上海科学技術出 版, 2006年, p. 175より転載

挿図13

青花蟒文杯 「大明嘉靖年製」銘 国立故宮博物院 (台北)蔵 出典:NPM Open Data

挿図14

青花飛魚文碗 「大明嘉靖年製」銘 国立故宮博物院 (台北)蔵 出典:NPM Open Data

うことを暗示していた可能性が考えられる。

さらに磁器に絵付けする顔料についても面白い傾向が見える。かつて鄭和の 大航海によって朝貢圏を拡大させた永楽帝と宣 せんとくてい 徳帝の官窯では、鮮やかな発色 の蘇 そまり

麻離青 せい

と呼ばれる西アジア産のコバルトを用いていた。しかし、明代中期 の官窯では枯渇しており、青花を描く際には薄い発色の国産コバルトを用いて いた。これが嘉靖帝の時代には再び回 かいせい 青と呼ばれる西方産のコバルトを用いる ことができるようになり、その紫を帯びた鮮烈な発色はおそらく嘉靖帝が望ん で実現させたものであった(挿図 15)。遠い異国から貴重な物品が献上される のは、まさに皇帝の徳が遠方に及んでいることの表れであり、その鮮やかな青 花の実現が永楽・宣徳以来の快挙であることは、嘉靖帝にとって誇りとなった であろう。

嘉靖官窯の色についてさらに触れると、黄釉を施した上から赤い顔料で絵付 けをするタイプがあり、龍文や魚文の作品が知られている(挿図 16)。これは 純粋に色の重厚感を出すという目的かもしれないが、一説には「黄上紅(黄色 の上の紅色)」と「皇上紅(皇帝の紅色)」が同じ発音であることから、皇帝専 用の特別な紅彩を演出したとも言われている。また青花と黄釉を合わせた「黄 地青花」も流行しており(挿図 17)、これは嘉靖官窯の主力製品である青花に、 皇帝の色であった黄色釉を施した、皇帝専用の特別な配色であった。

②天の祝福を示すもの

中国には皇帝が優れた治世を行うと、天が何か不思議な現象を起こして、祝 福の意を表すという思想がある。これは天と人が繋がっているためであり、逆 に地震や落雷などが起こると、皇帝は天の怒りと恐れ、自身の行動を省みるの である。このような考え方は「天 てんじんかんのうせつ

人感応説」と呼び、それで起こるめでたい兆 しの事を「瑞 ずいちょう 兆」と呼ぶ。皇帝によって世の中がうまく治められている状態と は、世の中の陰陽や五行の気が調和している状態であり、そうなると五色の瑞 雲が発生したり、鳳凰が現れたりする。明代の官窯磁器は知識人がデザインに 関わっているためか、天人感応説の思想に則した図案が多く、とくに嘉靖官窯 はその傾向が強い。

例えば気の調和について述べると、鳳凰と龍が対で描かれる場合(前掲挿図 9)、鳳凰は陽の象徴、龍は陰の象徴であるため、二匹で陰陽の調和を表す。た だ、龍はそれ自体に陰陽双方の意味も含まれるため、龍を対で描くこと自体が 陰陽の調和を示す(前掲挿図 10)。その際に、昇る龍と降る龍を描いたり、手 を上げた龍と下げた龍を描いたりすることで、さらに陰陽を強調する場合もあ る(挿図 18)。

挿図15

青花龍文罐 「大明嘉靖年製」銘 故宮博物院 (北京)蔵

出典:『明代嘉靖隆慶万暦御窯瓷器』故宮出版社, 2019年, p. 215より転載

挿図16

紅地黄彩龍文罐 「大明嘉靖年製」銘 国立故宮博 物院(台北)蔵 出典:NPM Open Data

挿図17

黄地青花龍文盤 「大明嘉靖年製」銘 故宮博物院 (北京)蔵

出典:『明代嘉靖隆慶万暦御窯瓷器』故宮出版社, 2019年, p. 215より転載

挿図19

青花八宝龍文碗 国立故宮博物院(台北)蔵 出典:NPM Open Data

挿図20

青花鳳鸞鶴文瓶 「大明嘉靖年製」銘 故宮博物 院(北京)蔵

出典:『明代嘉靖隆慶万暦御窯瓷器』故宮出版 社, 2019年, p. 77より転載

挿図18

青花龍文方壺 「大明嘉靖年製」銘 東京国立博物館蔵 出典:ColBase

また、1 つの空間に複数種類の花文が描かれている場合があり、明 代の文献では「四季花」の文様と記されている(挿図 19)。これは現 実世界では起こり得ないことであるが、これは四季の気の調和、季節 の安定的な循環、さらには皇帝の世の永続性を表したと考えられる。 嘉靖官窯の磁器を鑑賞する時は、どのくらい気の調和が図られている かを考えながら見ると面白い。

さらに嘉靖官窯では、複数の色で磁器を装飾する五彩が多く作られ た。五彩というのは、五色の彩という意味ではなく、五行思想の考え 方に近い。例えば、霊鳥である鳳凰は五色の羽を持ち、鸞 らん は五種の声 で鳴くといわれるが、これは 2 種の鳥の神聖さを表している。陶磁器

の五彩とは、ある種の色彩的な完全性を表しており、絵付けの色数が 4 色や 6 色であっても五彩と呼ぶ。したがって、五彩で雲を描くことは、 めでたい兆しである五色の瑞雲を表し、五彩で龍や鳳凰を描くことは、 青花よりもさらに高次元の吉祥性を備えたと考えられる。

くわえて、皇帝の徳が天に届いた時には、特別な動物が現れるとさ れた。例えば漢代の文献である『淮南子』には、聖王として名高い殷 の高宗が統治を始めると、「人の気が天に働き、それにより景星が現 れ、黄龍が下り、祥鳳が至った」とある。他にも、鶴の飛来はよく見 られる瑞兆であり、嘉靖帝の前に鶴が現れた際には大喜びしたそうで ある。それを反映してか、嘉靖官窯では鶴の文様が多用されただけで なく、最高位の瑞鳥である「鳳・鸞・鶴」の 3 種を同時に描いた欲張 りな文様もある(挿図 20)。

特別な魚の出現もまた、瑞兆として史書に現れる。民間の思想で

も、「魚 yu 」と「余 yu (生活にゆとりがある)」は同じ発音であり、魚を描くことで 豊かな生活への願いを表現する。さらに水の中を自在に泳ぐ魚は、何物にも捉 われない自由な精神の象徴でもあり、嘉靖官窯に魚文の磁器が多いことは(挿 図 21)、あたかも嘉靖帝がそれを求めていたようでもある。

③道教の世界観を表すもの

嘉靖帝は治世の中で度重なる困難に直面し、道教にすがってなんとか国を良 くしようと試みた。しかし、嘉靖 21 年(1543)以降は世を憂い、国政に背を向け、 西苑に引きこもって道教の世界に浸りきったとされる。その際に、生活空間の 中で道教の世界観を演出する際に、磁器は大きな役割を担ったと考えられる。

まず注目すべきは、嘉靖官窯で多く作られた瓢形の瓶である(挿図 22)。瓢 箪は中国語で「葫 Hu Lu 蘆」というが、この発音は「福 Fu Lu 禄」と似ているため、瓢箪の 題材がそのまま福禄を表す。また、蔓の上で連綿と実る様は、子孫繁栄を象徴 している。このような吉祥の意味のほかにも、仙人が持つ特別な道具としての 役割もある。

『神仙伝』の有名な話に、後漢の時代に 費 ひちょうぼう 長房 という者がいて、薬売りの老 人が軒先に吊るしてあった壺の中に入るのを見た。彼は老人を問いただし、壺 の中に入れてもらうと、別の世界が広がっており、壮麗な宮殿で仙人たちが豊

挿図22

黄地青花瓢形瓶 「大明嘉靖年製」銘 故宮 博物院(北京)蔵

挿図21 五彩魚藻文罐 「大明嘉靖年製」銘 故宮博物院 (北京)蔵

出典:『明代嘉靖隆慶万暦御窯瓷器』故宮出版社, 2019年, p. 355より転載

館蔵 画像:遠山記念館 かな生活を送っていた。費長房は老人が 仙人だとわかり、弟子入りし、最後は仙 人になったという。この故事は「壺中天」 の言葉の由来となったが、古代中国語で 「壺」と「葫」は同じ意味として用いられ る字であり、ここでいう壺とは瓢箪の事 である。 つまり、瓢箪は理想世界への入 り口であり、自由な精神の象徴でもあった。 嘉靖官窯の瓢形瓶には、上が丸く、下 が四角く形成されたものもあるが(挿図 23)、これはおそらく古代中国の世界観で ある天は円形で、地は方形であるという 思想が反映されている。まさに瓢は世界 そのものを表し、現実世界から遠く離れ た仙界を表現するのに最適なモチーフで あった。

出典:『明代嘉靖隆慶万暦御窯瓷器』故宮 出版社, 2019年, p. 215より転載

挿図24

黄地緑彩方盤 「大明嘉靖年製」銘 東京国立博物館蔵 出典:ColBase

挿図25

青花八仙文碗 「大明嘉靖年製」銘 国立故宮博物院 (台北)蔵

出典:NPM Open Data

嘉靖官窯には四角い器物も多いが(挿図 24)、これもまた天円地方の考え を反映させたものであろう。丸い器物が天を表すならば、地を表す方形の 器物も必要だと考えたのではないだろうか。方形の器物には道教的な文様 が多いことから、道教の祭器として作られた可能性が高い。

道教を極めようとする嘉靖帝にとって、生来は人でありながら昇天した 仙人たちは模範であり、憧れの存在であった。中国で仙人というと八仙が 有名で、風体と持物を見れば八仙と認識できるほど人口に膾炙していた (挿図 25)。なお、八仙それぞれの名前と対応する持物は、 李 りてっかい 鉄拐:瓢箪、 漢 かんしょうり 鍾離:芭蕉扇、呂

りょどうひん 洞賓:剣、藍 らんさいわ 采和:花籃、韓 かんしょうし 湘子:笛、何 かせんこ 仙姑:蓮花、 張 ちょうかろう 果老:魚鼓、曹

挿図26

青花仙鶴文盤 「大明嘉靖年製」銘 故宮博物院(北京)蔵 出典:『明代嘉靖隆慶万暦御窯瓷器』故宮出版社, 2019年, p. 189より転載

そうこくきゅう 国舅:玉板である。嘉靖官窯でも八仙図はよく描かれたが、 八仙のメンバーが他の仙人と入れ替わっていることもあり、人物の特定が 難しい場合もある。

さらに、道教の目標の一つに不老長寿があり、それを端的に表す言葉は 「寿」である。道教には言葉に出すと想いが叶うという思想があり、嘉靖官 窯ではことさら寿の字を陶磁器に書く傾向がある。中には道教のお札であ る「符 ふろく

籙」の文字風に書かれる場合もあり(挿図 26)、陶磁器自体が符籙の ようにお守りとしての役割をしたと考えられる。またこれに付随して、桃 や霊芝など長寿を意味する植物文様も多用され、器物を飾るだけで長寿に 近づけそうなおめでたい文様が多く見られる。道教を実践していた嘉靖帝 にとって、道教世界を具現化させた官窯の磁器は、道教のイメージを駆り 立て、少しでも奥義に近づきたいという皇帝の願いを具象化させる役割を 担ったと考えられる。

おわりに

以上、嘉靖帝の生涯の軌跡を踏まえた上で、嘉靖官窯の磁器に込められた意 味を考えてきた。即位した直後から理不尽な状況に直面し、明朝の命運を背負っ て奮闘するも、心身ともに疲れ果て、最後には精神世界の中で生きた皇帝が、 自身の願いと理想を磁器に求めたと言えるのではないだろうか。官窯磁器はそ れに応え、嘉靖帝が正統な皇帝であることを視覚的に示し、時には天の祝福を 見せることで励まし、現実世界に仙境を現出させることをやってのけた。嘉靖 官窯の磁器は単なる工芸品ではなく、生涯を通じて嘉靖帝を精神的に支えた特 別な存在だったのだろう。

(あらい たかゆき)

1 (明)『明世宗実録』

2 (明)『(万暦)大明会典』

3 (明)王宗沐纂修・陸万垓増修『(万暦)江西省大志』

4. (明)王圻『三才図会』

5. (明)張居正著・張嗣修・張懋修編『張太岳文集』

6. (清)王鴻緒等『明史稿』

7 (清)張廷玉等『明史』

8 本田済・澤田瑞穂・高馬三良訳『抱朴子・列仙伝・神仙伝・山海経 中国 の古典シリーズ 4』平凡社、1973 年

9 岩見宏『明代徭役制度の研究』同朋舎、1986 年

10 王健華「故宮博物院藏嘉靖朝瓷器概况及芸術風格」『故宮博物院院刊』 1987 年第 3 期

11 小島毅「嘉靖の礼制改革について」『東洋文化研究所紀要』117 冊、1992 年

12 林延清「論明世宗打撃和裁抑宦官」『史学集刊』1994 年第 4 期

13. 楊静栄『故宮博物院蔵文物珍品大系 顔色釉』上海科学技術出版社、1999 年

14. 佐久間重男『景徳鎮窯業史研究』第一書房、1999 年

15. 大石隆夫「明代嘉靖初年の密掲政治について」『人文論究』52 巻 2 号、 2002 年

16. 大石隆夫「明代嘉靖朝の西苑再建」『人文論究』53 巻 3 号、2003 年

17 胡凡『嘉靖伝』人民出版社、2004 年

18 彭涛「明代宦官政治与景徳鎮的陶政」『南方文物』2006 年第 2 期

19 中国国家博物館編『中国国家博物館館蔵文物研究叢書 瓷器巻(明代)』 上海古籍出版社、2007 年

20 知切光歳『仙人の世界』国書刊行会、2008 年

21 劉偉『帝王与宮廷瓷器』紫禁城出版社、2010 年

22. 王熹「明世宗与道教浅論」『故宮学刊』2011 年第 1 期

23. 曲水建編著『北京出土瓷片断代与鑑賞』文物出版社、2011 年

24. 寥宝秀『釉色与紋飾 明代青花瓷』国立故宮博物院(台北)、2016 年

25 故宮博物院・景徳鎮市陶瓷考古研究所『明清御窯瓷器 故宮博物院与景徳 鎮陶瓷考古新成果』故宮出版社、2016 年

26 故宮博物院・景徳鎮市陶瓷考古研究所『明代成化御窯瓷器 景徳鎮御窯遺 址出土与故宮博物院蔵伝世瓷器対比』故宮出版社、2016 年

27 新井崇之「明代における景徳鎮官窯の管理体制―工部と内府による 2 つの 系統に着目して―」『明大アジア史論集』第 21 号、2017 年

28 宮崎法子『花鳥・山水画を読み解く 中国絵画の意味』筑摩書房、2018 年

29 岩本真利絵『明代の専制政治』京都大学学術出版会、2019 年

30 故宮博物院・景徳鎮市陶瓷考古研究所『明代嘉靖隆慶万暦御窯瓷器 景徳 鎮御窯遺址出土与故宮博物院蔵伝世瓷器対比』故宮出版社、2019 年

31 新井崇之「明初期における官窯体制の変遷と御器廠の成立年代に関する考 察」『中国考古学』第 19 号、2019 年

32 高憲平「明嘉靖時期祭祀用瓷新探」『文物』2020 年第 11 期

33 新井崇之「明代の官窯瓷器に表された「気」の概念―回転する龍鳳文様を 中心に―」『中国考古学』第 21 号、2021 年

34 新井崇之「明代官窯磁器に見られる龍文とその象徴に関する研究」『鹿島 美術財団年報』第 38 号、2022 年

35 香港芸術館編『浮華・仙境 嘉靖皇帝的虚擬世界』懐海堂出版、2023 年

The Jiajing Emperor and Ceramics

Arai Takayuki

Fig. 1

Seated Portrait of Shizong (Emperor Jiajing) (detail), National Palace Museum, Taipei

Source: NPM Open Data

What image comes to mind when you think about the Jiajing Emperor (1507-1567, fig. 1)? In the current view of history he is seen as a fanatical believer of Daoism who is often said to have been a negligent ruler who caused the downfall of the Ming dynasty. And yet, isnʼt this nothing more than the hindsight of later generations who were aware of the later fall of the Ming and thus easily emphasized his faults as part of their simplified discussion of history? When we consider the Jiajing Emperor from the vantage point of his contemporaries, what kind of person was he? Even among the generations of Ming emperors, the Jiajing Emperor is noteworthy for the particularly large number of ceramics he commissioned from the official kilns at Jingdezhen. In this article I will provide an overview of the Jiajing Emperorʼs life and then focus on his thoughts on ceramics.

1. The Life of the Jiajing Emperor

1) Accession

In the third month of 1521 (Zhengde 16), Emperor Zhengde, the 11th Ming dynasty emperor, died at the young age of 31. The Zhengde Emperor is renowned in Chinese history as a particularly strange emperor. Entrusting the eunuchs with real political authority, he enjoyed dressing up in military garb and setting off on overseas trips that he dubbed “ expeditions.” He was interested in Tibetan Buddhism and Islam, pursuing the study of secret rites from dawn to dusk as he led a

profligate lifestyle. Indeed, he seems to have been barely aware that he was the emperor, and rather thought of himself as a great general adept at martial pursuits or the sacred leader of Tibetan Buddhism. Further complicating matters, the Zhengde Emperor had neither brothers nor children to succeed him. That meant the government cabinet of the time decided who should be his successor. They examined the imperial household lineage back to The Zhengde Emperorʼs father the Hongzhi Emperor, and chose Zhu Houcong, heir of Hongzhi ʼs younger brother Prince Xian of Xing.

Houcong was born in Hubei Anlu Fu (present-day Zhongxiang city, Hubei province). His father was the fourth child of Emperor Chenghua. During the Ming dynasty, the emperorʼs brothers were set up as regional rulers to thereby solidify the central authority of the imperial household. This meant that Prince Xian formed Xingwangfu (興王府), literally the region of Prince Xing, in Hubei. From a young age Houcong read Confucian scriptures under his father, learned self-cultivation and how to rule his land.

The Wudang Mountains, a site sacred to Daoism, was close to the family domain, and Houcong became familiar with Daoism as he participated in his fatherʼs rites honoring the Daoist deity Xuandi.

But then his father Prince Xian fell ill and died in 1519 (Zhengde 14). Houcong went into mourning, and right after he was to succeed his father as head of the principality, the Zhengde Emperor died. Houcong was quickly summoned to Beijing and there ascended the throne. Houcong became the 12th Ming emperor, known as the Jiajing Emperor.

The Jiajing Emperor was only 15 years old when he ascended the throne. The government was riddled with corruption and malpractice, riots were erupting in various regions and the Treasury was running dry. Thus his reign was off to a rough start. The support of the cabinet, which served as the core of Ming dynasty government, and the Grand Secretary was essential for righting the bad governance of the preceding emperor ʼ s reign. Yang Tinghe (1459-1529) was the Grand Secretary at the time, a senior vassal who had served three emperors, Chenghua, Hongzhi and Zhengde. He was the person who chose Houcong as emperor. His true intent was to assist the as yet inexperienced and unknowledgeable Jiajing Emperor in righting the course of the Ming dynasty. And yet, certain events led to fissures in the Jiajing Emperorʼs relationship with Yang Tinghe.

2) Great Rites Controversy

The Ming dynastyʼs imperial system did not allow cousins to succeed to the rank of emperor. This essentially meant that Zhu Houcong could not succeed his cousin the Zhengde Emperor. As a result, Yang Tinghe, who had chosen Houcong as the successor, proposed rewriting the Ming imperial genealogy. He suggested naming emperor Hongzhi as huang kao (皇 考), thus using the honorific for the predecessor emperor employed when the reigning emperor dies. This would make Zhu Houcong Hongzhi ʼ s heir and the younger brother of the Zhengde Emperor.

In that process, the Jiajing Emperorʼs real father, Prince Xian of Xing, would become his uncle, and in the imperial line, his “ imperial uncle.” Needless to say Zhu Houcong, newly named Jiajing Emperor, strongly opposed this idea. He stated that it was wrong to name his revered father and mother, only two years after his father ʼ s death, as his uncle and aunt. The Jiajing Emperor firmly asserted that an imperial name be conferred upon his father Prince Xian of Xing. But the cabinet refused to hear the Jiajing Emperorʼs views. Yang Tinghe ended up submitting his resignation, declaring his opposition to the emperor. The direct confrontation between the emperor and the cabinet in this instance came to be known as the Great Rites Controversy.

The Jiajing Emperor naturally revered his birth mother and father and felt that those who sought to manipulate their existence were wrong. Such actions were also contrary to the filial teachings of the Confucianism. Summoned to Beijing at the young age of 15 and compelled to accept reasoning he did not understand, the Jiajing Emperor gradually felt isolated in the imperial court.

Amid such circumstances, cabinet officials such as Zhang Cong (1475 -1532) and Gui E (1478 -1531) supported the new emperor, to his great delight. This led him to appoint these two inexperienced men to the secretariats of the Hanlin Academy of imperial advisors. The eunuch Cui Wen kindly explained the teachings of Daoism to the Jiajing Emperor and introduced him to Daoist practitioners. The Jiajing Emperor ʼ s interactions with these Daoists may have led him to recall going with his father to the Daoist site, the Wudang Mountains. He gradually turned to Daoism and lent a deaf ear to condemnation by the court official Zhang Chong (1478 - ?), who said, “Cui Wen is toying with you and getting involved in politics by bringing evil people into the imperial court. ”

In 1524 (Jiajing 3), the Jiajing Emperor finally accepted the oft-submitted resignation of Yang Tinghe and banished him from court. Officials who opposed the emperor

protested in front of the Zuoshunmen Gate of the Forbidden City. Seemingly at the end of his patience with the process, the emperor invoked imperial prerogative and ordered the caning of those involved. Zhang Chong, who had previously warned the emperor, also appeared in this situation. This so-called Zuoshunmen Gate Incident marked the end of the three-year-long Grand Rites Controversy. In the end, the Jiajing Emperorʼ s opinion was overridden, his birth father Prince Xian of Xing was named Xingxian Emperor (興献帝) and the Hongzhi Emperor called Huangbokao (皇伯考). And yet, after these incidents, there were no officials willing to admonish the Jiajing Emperor and he surrounded himself with only those ministers who had flattered him.

3) Ritual Reforms

The Great Rites Controversy led the Jiajing Emperor to distrust the Ming dynasty in general and he came to question the Ming rites. In order to demonstrate the veracity of his thoughts on this matter, he had scholars spend three years preparing the Minglun dadian (明倫大典) on how rituals were conducted, and had the book distributed to teaching organs nationwide.

However, droughts seemed to occur almost annually after the Jiajing Emperor ascended the throne and this led to horrific suffering. And given that the Chinese emperor was called the “son of heaven” and thus was considered to rule by the will of the heavens, catastrophes, droughts and famines were thought to be the heavens showing their dissatisfaction with his rule. Court officials normally conducted rites on behalf of the emperor when natural disasters and other problems occurred, but when a drought struck Beijing in 1529 (Jiajing 8), the Jiajing Emperor himself conducted the rites at the sacred altar. Whether or not as a result of such actions, that year northern China had a relatively fruitful harvest.

The Jiajing Emperor also knew from ancient records that the emperor himself performed rites during the reign of the first Ming Emperor Hongwu (1328 -1398), who had further established separate altars for heaven and earth, not worshiping them together. In 1530 (Jiajing 9), the Jiajing Emperor divided the altar to heaven and earth in Beijing, establishing instead an altar to heaven, one to earth, one to the sun and one to the moon. He also was particular about the altar implements placed on each altar. The Daming Huidian (大明会典) stated that different colored porcelain utensils were to be placed on the altars, with blue for the heaven altar (yuanqiu 円丘), yellow for the earth altar ( fangqui 方丘), red for the sun altar, and white for the moon altar. There

2

Dou with Red Glaze, excavated from an official kiln site (yuqichang)

Source: Reproduced from Ming Qing Yuyao Ciqi [The Porcelain of Imperial Kiln in Ming and Qing Dynasties], The Forbidden City Publishing House, 2016, p. 167.

Fig. 3

Biscuit-fired Dou, excavated from an official kiln site (yuqichang)

Source: Reproduced from Ming Qing Yuyao Ciqi [The Porcelain of Imperial Kiln in Ming and Qing Dynasties], The Forbidden City Publishing House, 2016, p. 169.

were no colorful porcelains of this type during the Hongwu Emperorʼs reign, but kiln technology had advanced by the Jiajing Emperorʼs reign, making these colors possible. The dou (豆) ritual vessel is thought to have been commissioned in various colors, and examples of these wares have been excavated at the site of the Jingdezhen official kilns (figs. 2 and 3).

The Jiajing Emperor also made changes to various other rituals, and the authority to change national rituals rested solely with the emperor. We can get a sense of the Jiajing Emperorʼs strong will and belief that he himself was suited to govern China. His return to a system set by the first Ming emperor also favorably implied that his understanding of the Ming dynasty was better than that of other emperors. Other than those by the Jiajing Emperor, the major changes to the Ming dynasty systems set up by the Hongwu Emperor only occurred during the reign of the third Ming emperor, Yongle (1360 -1424). Strangely enough the Yongle Emperor was also brought to the throne by a coup known as the Jingnan Rebellion. The ritual changes made during his rule, also made from a negative view given that he was not an orthodox heir, closely resembling those made by the Jiajing Emperor. These two emperors share another point in common, their firm belief in Daoism.

4) Daoist Tendencies

At the behest of the eunuch Cui Wen, the Jiajing Emperor, who was isolated at court in 1524 (Jiajing 3) due to the Great Rites Controversy, called the Daoist practitioner Shao Yuanjie to Beijing. The Jiajing Emperor was amazed when the rains started after Shaoʼs prayers. Inclement weather was a major worry for the emperor, and his belief in the efficacy of Daoism was confirmed by this Daoistʼs simple solution to that problem.

The Jiajing Emperor had also been long troubled by the succession and asked Shao for prayers. While the results of those prayers are unknown, the Jiajing Emperorʼs son Zairui (載壡) was born in 1536 (Jiajing 15) and the Jiajing Emperor became a whole-hearted Daoist. That year Shao Yuanjie ʼs position became unassailable, and he was the first Daoist entrusted with the highest court official rank, bushangshu

Daoist practitioners used strange techniques to make the rains fall, cure illness, increase riches and make people wealthy. Through the use of elixirs of the

Fig.

Immortals they brought about immortality and ascended to heaven as Immortals that served under the Highest Deity. In fact, legendary Chinese emperors such as Divine Farmer and Yellow Emperor are also considered to be part of the Daoist Immortal lineage. Doubting his own qualities as an emperor, the Jiajing Emperor sensed the supernatural charisma of the Daoists, and considered they were the only ones that could break through his current situation. He may have felt that by relying on the power of Daoism and himself becoming a virtuous ruler, he would be able to rebuild the country and bring prosperity to the masses. Considering what he had been through, such aspirations are not at all strange.

Along with the rising position of Daoism within the imperial court, there also appeared officials who used Daoism. Poetic prayers read to the Highest Deity, similar to Shinto incantations, were used in these Daoist rituals. When these prayers were written on a type of blue formal paper they were called qingci (青詞), literally blue prayer. Officials who had passed the government exams were of course adept at writing government policy texts, but those who were particularly talented writers began to write qingci and thus please the emperor. Among these figures, Yan Song (1480 -1567) was more passionate about his writing of qingci than policy papers, and thus rose to the highest rank within the cabinet, to the point where he was ridiculed as a “qingci premier.”

The Jiajing Emperor built a splendid imperial villa as a personification of Daoist thought in West Garden, a district within the western section of the Forbidden City. West Garden was first built as an imperial garden when the Mongol people ruled China as the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368), and was renovated by the Ming Emperor Yongle and briefly used. The Jiajing Emperor greatly revised the structures there as his own imperial villa, and he built additional structures for Daoist practices. Naturally, these construction projects were extremely costly and hastened the draining of the already under stress national coffers.

5) Seclusion

The description above may make it seem as if the Jiajing Emperor was a ruler completely uninterested in government, when in fact, he executed superb political reforms. Immediately after assuming the throne he began to rectify the evil practices of the Zhengde Emperorʼs reign. He banished from court the eunuchs who had flattered the emperor, as well as the officials at court who had attained their positions due to connections with the imperial household. He returned farmland that had been for the sole

use of the imperial household to the commoners, and revised the taxation system. These efforts brought about a certain normalization of the internal politics of the court and national tax collection increased. This series of political reforms by the Jiajing Emperor are referred to as the Jiajing Reforms.

If he had been able to continue this reform process across all of China he may have been able to revive the Ming dynasty. However, a terrible event hit the court in 1542 (Jiajing 21). A dozen or so palace women entered the emperorʼs sleeping chamber and tried to strangle him. Their motive is unclear, but it seems that the palace women held considerable grievances against him. The plot failed, the Jiajing Emperor survived, and all of the palace women involved were executed. After this incident known as the Palace Plot of Renyin Year, or the Palace Womenʼs Uprising, the Jiajing Emperor lost all trust in people and shut himself up in West Garden.

From then on he conducted no government work in the palace, did not meet his children, and spent everyday immersed in Daoist practices within West Garden. The previously mentioned “qingci premier” Yan Song abused his power over official practices and the palace was awhirl with ugly power struggles, but the Jiajing Emperor remained uninterested. Daoism contains the belief that wise men shun the ordinary world, turn their backs on society and live in seclusion. Even though he was emperor, he appears to have actually realized this Daoist rejection of society.

Then in 1565 (Jiajing 44), the Jiajing Emperor felt strange after taking an elixir presented by the Daoist Wang Jin. He said, "My body burns, unquenchably," and lay prostrate on his bed. On the 14th day of the 12th month of Jiajing 45 (1567) the Jiajing Emperor became critically ill, was immediately carried to the Palace of Heavenly Purity (Qianqinggong) in the Forbidden City, and there died. As emperor, his vassals felt that he must breath his last within the Forbidden City. The Jiajing Emperor was given the posthumous temple name Shizong (世宗) and was buried in Yongling alongside the generations of other Ming dynasty emperors in the Ming tombs.

What do you think of what you have read above of the life of the Jiajing Emperor? Can it be simply summarized, as later histories did, as, “ The emperor was fanatical about Daoism and led to the fall of the Ming dynasty”? Here I would like to note comments made by Zhang Juzheng (1525 -1582) as we consider the Ming dynastyʼ s own evaluation of the Jiajing Emperor and his lasting influence. Six years after the Jiajing Emperorʼs death, Zhang Juzheng assisted the infant Wanli Emperor (1563 -1620), enacted major reforms and revived the Ming dynasty. One of the important policies enacted

was in fact a continuation of the Jiajing Emperorʼs reforms. Zhangʼs comments on the Jiajing Emperor remain for us today. He highly praised him, stating, “Emperor Shizong [Jiajing] assumed the imperial throne and through his wisdom and sagacity righted all of the preceding bad governance, and revived the ancestral law. ... Intelligent by nature, in the twenty years after ascending the throne he worked diligently at governance and study, and his wisdom and discernment was unparalleled among the generations of emperors. ” These words remind us that history should not be unilaterally assessed.

2. The Jiajing Emperor’s Official Kilns

With the above biography of the Jiajing Emperor in mind, I would now like to consider the ceramics he had made at the official Jiajing kilns. The Ming dynasty had their official kilns at Jingdezhen. Their production of the highest quality ceramic wares is well known. However, I would like to note one thing, it is only half true that the ceramics were produced at the Jingdezhen official kilns for the emperorʼs own luxurious use, shechi (奢侈). In other words, these shechi wares were sumptuous wares that were made to standards that exceeded what was necessary for use. However, in fact, many of the porcelains produced by the Jingdezhen official kilns were made from necessity. First I would like to briefly note the history of the Ming dynasty official kilns at Jingdezhen prior to the Jiajing Emperorʼs reign.

1) The History of the Official Ming Dynasty Kilns at Jingdezhen

The Hongwu Emperor, the first Ming dynasty emperor, was aware of the importance of rituals as he organized the nationʼs structures and systems. After he stabilized his country, he immediately gathered Confucians from all regions and ordered them to research ritual methods and practices. Specifically regarding the vessels to be used in ritual practice, in 1369 (Hongwu 2), he ordered that all must be made of porcelain. Citing the old stories which state that ceramic vessels were used in the ancient period of sacred kings, he determined that ceramic is a material suited to the refined simplicity of Confucianism. He then selected Jingdezhen, site of the ritual wares production of the preceding Yuan dynasty, as the site where these porcelains would be produced.

Large numbers of porcelain wares came to be used for rituals and banquets held in the imperial court during the Yongle era. Further, the great sea voyages of the eunuch Zhenghe (1371-1434) expanded the imperial tribute area, and many countries

sought porcelains from China. This led to the establishment of a system of yuqichang (御 器廠) porcelain production facilities directly operated by the imperial court, primarily at Jingdezhen. Today there are various theories regarding when this yuqichang system was establish, but I believe that it was established around the reign of the Yongle Emperor. In fact, the number of official kiln porcelains excavated from yuqichang sites suddenly increased in the Yongle era, and thus it seems that porcelains were produced in response to demand from the court, and under its strict quality management.

After the establishment of the yuqichang, the imperial court would order porcelains as required. As time passed the number ordered increased, and gradually the yuqichang alone could not satisfy the demand. The history of the Ming dynasty, Mingshi , has the following comment on the state of the official kilns during the Chenghua era (1465 -1487). “Eunuchs were dispatched to Jingdezhen in Fuliang. Production orders for porcelains for imperial use have grown so numerous and the firing process so lengthy that the costs have ballooned out to unimaginable amounts.” Similarly regarding the situation during the Jiajing Emperorʼs reign, Mingshi states, “ Since Hongzhi (1488 -1505), and still counting, some 300,000 vessels have been back-ordered.” Production could not keep up with the orders and the back-order list kept on growing.

The official Jiajing era kilns were at first supervised by eunuchs as they had been during the Zhengde era, but later that supervision system was revoked. According to volume 7 “ Taoshu” (陶書) of Jiangxisheng dazhi (江西省大志), “Previously one eunuch was assigned the sole duty of supervising the official kilns. That was stopped in 1530 (Jiajing 9), and one governor of Raozhou (饒州佐貳官) was assigned to manage tax irregularities under the direction of the regional ministers (地方官).” Thus the dispatch of a eunuch from court was stopped in 1530, and instead regional ministers were put in charge of porcelain production. After the Jiajing Emperor settled the Great Rites Controversy, he began what would become known as the Jiajing Reforms, as previously noted. During that process he rectified the bad practices of the eunuchs that developed during the Zhengde era, and the policy of shifting porcelain production management from the eunuchs to the regional ministers can be seen as one element of those reforms.

The Jiajing era also saw the introduction of the guanta minshao (官搭民焼) system. This system called for some production to be entrusted to non-official kilns to supplement the official kilnsʼ production when large numbers of porcelains were commissioned. The details of this process are noted in the previously cited Jiangxisheng dazhi volume 7 “ Taoshu.”

“ So normal procedures were used to fire standard amounts of commissioned porcelains, and this production was not entrusted to non-official kilns. However, when a large number of wares was commissioned by the emperor for production in a short time period, if they could be produced en mass, normal procedures were followed. If they could not be, then non-official kilns were assigned to produce some of them. Those of sufficient quality were selected, assembled and shipped.”

Thus contracted production by non-official kilns was a temporary measure used only in instances when large numbers were commissioned. And yet, it seems that contracting non-official kilns to produce works became normalized. Excavations conducted at the sites of two non-official kilns in Jingdezhen city, Guanyingeyao (観音閣 窯) and Luomaqiaoyao (落馬橋窯), have confirmed shards of wares bearing the Jiajing era date inscription “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi ” (大明嘉靖年製) found alongside a large number of wares produced as non-official items. The porcelains produced at non-official kilns were purchased by the government so non-official kiln workers were satisfied with the system. Further, this system meant the non-official kilns were producing works to the same standards as those of the official kilns, and thus a considerable amount of technological advancement was brought to the non-official operations.

As seen above, during the Jiajing era the official kilns shed themselves of the eunuchsʼ malpractices, and a management system run by regional ministers was established. The official Jingdezhen kilns were able to handle a large number of commissions by entrusting some of the work to non-official operations through the use of the guanta minshao production method. This meant that the official kilnʼs technologies spread to non-official producers, which can be linked in turn to the technical improvement of the Jingdezhen kilns overall. There were of course all manner of problems in Jingdezhen during the Jiajing era, but today we can see that the masterpieces of the Jiajing official kilns were created from these successful reforms.

2) Products of the Jiajing Official Kilns

The Ming dynasty yuqichang were official kilns controlled by the central government, and given that central bureaus such as the imperial household agency fully supervised porcelain design, it is thought that the official kiln wares faithfully reflected the Jiajing Emperorʼs intentions. An analysis of the porcelains produced by the official Jiajing kilns led to the hypothesis that they can be divided into three types, namely: ① items that indicate the emperor ʼs legitimacy; ② items that show the blessings of the heavens; and ③ items that reflect the Daoist world view.

Fig. 4

Incense Burner with Eight Auspicious Design in Underglaze Blue, “Da Ming Cheng Hua Nian Zhi” inscription, The Palace Museum, Beijing Source: Reproduced from Mingdai Chenghua Yuyao Ciqi [Imperial Porcelains from the Reign of Chenghua in the Ming Dynasty], The Forbidden City Publishing House, 2016, pp. 58-59.

Fig. 5

Incense Burner with Eight Auspicious Design in Underglaze Blue, “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi” inscription, National Palace Museum, Taipei

Source: NPM Open Data

① Items that Indicate the Emperor’s Legitimacy

The Jiajing Emperor, who ascended the throne from a collateral line and further went through the Great Rites Controversy, seems to have had a complex about his own bloodlines. It is extremely fascinating to note how this complex can be seen in porcelains produced by his official kilns. The Jiajing official kilns produced many works (figs. 4 and 5) that copied types produced by his official lineage grandfather, the Chenghua Emperor. Even though these works are complete replications of the designs and vessel shapes of the earlier works, their inscriptions firmly state, “Made during the great Ming reign of Jiajing” (大明嘉

靖年製). Conversely, there are no examples to be found of intentional copies of official kiln works produced during the reigns of the Hongzi Emperor and the Zhengde Emperor, two emperors from a different lineage from his own. Thus we can consider that these works might have been meant to indicate that he considered himself a descendent of the Chenghua Emperor and further assert his own existence through their inscription content.

The Jiajing Emperor was also the one who reformed the official rites. Given that the Jiajing Emperor considered the seeking of peace and prosperity for the nation from the heavens by conducting specific rituals as one of his important official functions as emperor, he was extremely particular about the ritual vessels used on those occasions. The previously noted different colored dou vessels were produced, as well as other vessel shapes based on bronze vessels, such as the jue (爵) and zun (尊) (figs. 6 and 7). Bronze vessels were used in Chinese rituals from before the Christian era onwards, and the Hongwu Emperorʼs decree that all ritual vessels be made of porcelain was a continuation of Chinese tradition probably reflecting his determination that the Ming dynasty would obey the ancestral precepts.

The designs on porcelains also symbolize imperial authority, most strikingly dragon motifs. And yet, there are many types of dragons, and it is thought that among those the longpao (龍袍) type seen on the emperorʼs garments is the one type that symbolizes the emperor. The longpao type is characterized by its round nose, two horns, five claws and long narrow tail (fig. 8). There are many designs which pair this dragon type with a phoenix (fig. 9), or those that show a pair of such dragons pursuing a sacred jewel (fig. 10). These same dragon motifs

were also depicted on the lacquer wares produced for the court (fig. 11), which indicates that both lacquer and porcelain wares were important vessel types that symbolized the imperial household at the time. There were a large number of superb lacquer works made for the imperial household during the Jiajing Emperorʼ s reign, and like the porcelains of the period, many are characterized by the vivid use of polychrome.

Other dragon types include those with bat-like wings (fig. 12), four or fewer claws (fig. 13) and those with fish-like tails (fig. 14). These dragons differ from those symbolizing the imperial household and each has its own specific meaning. For example, the dragon with bat-like wings is called yinglong (応龍) and symbolizes Huangdi, the legendary sacred emperor who ascended to heaven as a Daoist deity. The four-clawed dragon is called mang (蟒) and is frequently seen on items that the emperor presented to his vassals. The dragon with a fishlike tail is called feiyu (飛魚) and is often used to symbolize the ocean.

The important point here is the particularly large number of dragon type variations found on Jiajing official kiln wares. From antiquity onwards immortals and saints were the familiars of sacred beasts, and it was specifically believed that the emperor could use these various dragon types. Numerous dragons were drawn on the porcelains produced at the Jiajing official kilns, and their use in the everyday life of the emperor may have also alluded to the fact that he was qualified to be the emperor.

There are also interesting trends in the pigments used to depict designs on these porcelains. The official kilns of the Yongle Emperor and Xuande Emperor, who both expanded Chinaʼs imperial tribute relationships through Zhenghe ʼ s great sea voyages, had begun to use cobalt from West Asia. This pigment type called sumali qing (蘇麻離青) produces a vibrant blue when fired. But supplies of that West Asian pigment were soon depleted and the mid-Ming official kilns kept using domestic cobalt, which produced a paler color, for their underglaze blue designs. Then in the Jiajing era, the kilns began to once again use a cobalt from West Asia called huiqing (回青), thereby realizing the vibrant purplish-toned blue that was most likely the color sought by the Jiajing Emperor for his wares (fig. 15). Receiving precious goods from distant foreign lands clearly showed how the virtues of the emperor had spread far and wide, and the Jiajing Emperor was probably proud that his kilns were able to achieve this vivid underglaze blue for

Fig. 6

Jue with Blue Glaze, “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi” inscription, The Palace Museum, Beijing

Source: Reproduced from Mingdai Jiajing Longqing Wanli Yuyao Ciqi [Imperial Porcelains from the Reign of Jiajing Longqing Wanli in the Ming Dynasty] The Forbidden City Publishing House, 2019, p. 255.

Fig. 7

Zun with Red Glaze, The Palace Museum, Beijing

Source: Reproduced from Mingdai Jiajing Longqing Wanli Yuyao Ciqi [Imperial Porcelains from the Reign of Jiajing Longqing Wanli in the Ming Dynasty] The Forbidden City Publishing House, 2019, p. 336.

Fig. 8

Dish with Dragon Design in Underglaze Blue, “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi” inscription, National Palace Museum, Taipei

Source: NPM Open Data

Fig. 10

Dish with Paired Dragons Design in Underglaze Blue, “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi” inscription, Tokyo National Museum

Source: ColBase

Fig. 12

Vase with “Yinglong” Design in Underglaze Blue, “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi” inscription, National Palace Museum, Taipei

Source: NPM Open Data

Fig. 9

Dish with Dragon and Phoenix Design in Underglaze Blue, “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi” inscription, National Palace Museum, Taipei

Source: NPM Open Data

Fig. 11

Carved polychrome Lacquer Box and Cover with Dragon and Phoenix Design, “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi” inscription, The Palace Museum, Beijing

Source: Gugong Bowuyuan Zang Wenwu Zhenpin Daxi Yuan Ming Qiqi [The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum: Lacquer Wares of the Yuan and Ming Dynasties], Shanghai Scientific and Technical Publishers, 2006, p. 175.

Fig. 13

Bowl with “Mang” Design in Underglaze Blue, “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi” inscription, National Palace Museum, Taipei

Source: NPM Open Data

Fig. 14.

Bowl with “Feiyu” Design in Underglaze Blue, “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi” inscription, National Palace Museum, Taipei

Source: NPM Open Data

the first time since the days of the Yongle Emperor and the Xuande Emperor.

Considering the colors used by the Jiajing official kilns, there are some works which have red pigment designs painted on top of yellow glaze, with dragon design and fish design works known of this type (fig. 16). This layering of two colors technique was probably intended to give the weighty feel of each pure color, but one theory states that given that since the Chinese phrase for “red on yellow ” (huangshanghong 黄上紅) has the same pronunciation as “ emperor ʼs red ” (huangshanghong 皇上紅), it presents a special red color reserved for use by the emperor. A combination of underglaze blue and yellow glaze called huangdeqinghua (黄地青花) was also popular (fig. 17), and this special color combination reserved for use by the emperor combined Jingdezhenʼs signature underglaze blue ware type with the imperial color yellow glaze.

② Things that Show the Blessings of the Heavens

A belief system in China states that when the emperor sagely rules his empire, there is some strange manifestation from the heavens, which is considered to have auspicious meaning. Because of this connection between the heavens and humanity, conversely, when earthquakes, lightning strikes or other calamities hit, the emperor knows the heavens are angry, these calamities condemn his actions. This doctrine is called the Interactions between Heaven and Mankind theory (tianren ganying shuo 天人感応説), and the manifestations or signs of auspicious occurrences are called ruizhao (瑞兆). The state in which the emperor is skillfully ruling the world is a state in which the yin and yang of the world (yinyang 陰陽) and the five phases of energy (wuxing 五行) are harmonized. In this state, five-colored auspicious clouds arise or the phoenix appears. Possibly because intellectuals were involved in the designing of Ming dynasty official kiln porcelains, many of the designs on those wares are aligned with this theory. This tendency was particularly strong at the Jiajing official kilns.

For example, in terms of the harmonization of the energies, the previously noted fig. 9 depicts a phoenix and dragon pair. In this imagery, the phoenix is the symbol of yang, positive energy, while the dragon is the symbol of yin, negative energy. Thus this pair represents the harmonization of yin and yang. However, the dragon itself is also a symbol of the yin/yang pair, and the depiction of a pair of dragons also stands as a symbol of yin/yang harmony (op. cit. fig. 10). In such pairings one dragon will be shown ascending, the other descending, or

Fig. 15

Jar with Lid with Dragon Design in Underglaze Blue, “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi” inscription, The Palace Museum, Beijing

Source: Reproduced from Mingdai Jiajing Longqing Wanli Yuyao Ciqi, [Imperial Porcelains from the Reign of Jiajing Longqing Wanli in the Ming Dynasty] The Forbidden City Publishing House, 2019, p. 215.

Fig. 16

Jar with Lid with Clouds and Dragons Design in Overglaze Yellow and Red Enamel, “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi” inscription, National Palace Museum, Taipei

Source: NPM Open Data

Fig. 17

Dish with Dragon Design in Underglaze Blue and Overglaze Yellow Enamel, “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi” inscription, The Palace Museum, Beijing

Source: Reproduced from Mingdai Jiajing Longqing Wanli Yuyao Ciqi [Imperial Porcelains from the Reign of Jiajing Longqing Wanli in the Ming Dynasty] The Forbidden City Publishing House, 2019, p. 215.

18

Square Jars with Dragons Design in Underglaze Blue, “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi” inscription, Tokyo National Museum

Source: ColBase

Fig. 19

Bowl with Eight Treasures and Dragon Design in Underglaze Blue, National Palace Museum, Taipei

Source: NPM Open Data

one dragon with leg raised, one with leg lowered to further emphasize the yin/yang concept (fig. 18).

Ming dynasty texts call a design made up of various different flowers all depicted within a single space sijihua (四季花), literally flowers of the four seasons (fig. 19). Such cross seasonal blooming does not occur in the real world, but such designs are thought to symbolize the harmonization of the energies of the four seasons, the stable rotation through the four seasons, and the eternal continuation of the emperorʼ s rule. When we look at the porcelain wares of the Jiajing official kilns, it is fascinating to consider what degree of energy harmonization they were calculating in their design choices.

There were also numerous wucai polychrome wares created at the official Jiajing kilns. We might think that wucai (五彩), literally five colors, refers to different colors, but in fact, it is close in concept to wuxing, the five phases doctrine. For example, the mythical bird, phoenix, has five-colored wings, the luan , another mythical bird, has five different types of song, and these five elements convey the sacredness of these two types of birds. Wucai in porcelain refers to a complete color palette, and sometimes four or six colors are actually used, not just the titular five.

Fig.

They are still called wucai , literally five colors. Further, when clouds are created in wucai enamels, they are the five-colored auspicious clouds conveying felicitous meaning. When dragons or phoenixes are depicted in wucai , they convey an even greater sense of auspiciousness than those depicted in underglaze blue.

In addition, when the emperorʼs virtue is conveyed to heaven, a special animal is said to appear. For example, the Han dynasty text Huainanzi (淮南子) states that at the beginning of the reign of the Gaozong Emperor of the Shang dynasty, revered by later generations as a saintly ruler, “ When human energy approached the heavens, an auspicious star appeared, the yellow dragon descended and the phoenix arrived.” The arrival of a crane is also often seen as an auspicious event, and it seems that when a crane appeared before the Jiajing Emperor, he was quite thrilled. Possibly reflecting such feelings, not only were crane motifs frequently used at the Jiajing official kilns, there is one type of motif in which the three most auspicious birds all appear, the phoenix, luan and crane (fig. 20).

Historical texts also record that the appearance of a special type of fish was considered an auspicious event. Fish are auspicious in folklore. The character for fish (魚) and the character for ample means in life (余) are both pronounced yu , and this meant that depictions of fish were seen as prayers for a bountiful life. Fish, which can freely swim in the sea, are also seen as symbols of a free, unburdened spirit, and there are numerous fish motifs on the porcelains produced by the Jiajing official kilns (fig. 21). It would seem that the Jiajing Emperor sought such imagery.

③ Things that Reflect the Daoist World View

The Jiajing Emperor was confronted with repeated troubles throughout his reign, and this meant he latched onto Daoist beliefs to somehow improve conditions in his realm. And yet, from the 21st year of his reign, when the Palace Plot of Renyin Year occurred, onwards, he became world-weary and turned his back on governing. Instead, he sequestered himself in West Garden and immersed himself in the Daoist realm. As part of this process it is thought that the porcelains he used played a major role in enacting the Daoist worldview in his living spaces.

The first noteworthy example is the many gourd-shaped vases created at the official Jiajing kilns (fig. 22). In Chinese a gourd is called hulu (葫蘆), and

Fig. 20

Vase with Three Auspicious Birds (Feng Luan He) Design in Underglaze Blue, “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi” inscription, The Palace Museum, Beijing

Source: Reproduced from Mingdai Jiajing Longqing Wanli Yuyao Ciqi [Imperial Porcelains from the Reign of Jiajing Longqing Wanli in the Ming Dynasty] The Forbidden City Publishing House, 2019, p. 77.

Fig. 21

Jar with Lid with Fish and Water Plants Design in Overglaze Wucai Polychrome Enamel, “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi” inscription, The Palace Museum, Beijing Source: Reproduced from Mingdai Jiajing Longqing Wanli Yuyao Ciqi [Imperial Porcelains from the Reign of Jiajing Longqing Wanli in the Ming Dynasty] The Forbidden City Publishing House, 2019, p. 355.

Gourd-shaped Vase with Design in

Ming

and Overglaze Yellow

this pronunciation resembles that of good fortune fulu (福禄). This meant that gourd themes themselves express good fortune. The fact that gourds grow in succession on a vine is seen as symbolizing prosperous future generations. In addition to this felicitous meaning, gourds also functioned as one of the tools used by Daoist Immortals.

A famous tale in the Shenxian zhuan (神仙伝) hagiography recounts that an Eastern Han dynasty personage named Fei Zhangfang saw an old herbal medicine seller get into a jar suspended from the eaves. Fei asked the old man about this, and when the old man also put him in the jar, a separate realm spread before him, and there Immortals lived luxurious lives in splendid palaces. Fei then understood that the old man was an Immortal himself, became his disciple, and is said to himself become an Immortal in the end. This tale is the source of the Chinese phrase, “ heaven in a jar” (huzhongtian 壺中天), and given that in ancient Chinese the characters 壺 and 葫 are synonymous, the 壺 read as jar in this instance is actually a gourd (葫). In other words, the gourd is an entrance to utopia, a symbol of a free spirit.

inscription, The Palace Museum, Beijing Source: Reproduced from Mingdai Jiajing Longqing Wanli Yuyao Ciqi [Imperial Porcelains from the Reign of Jiajing Longqing Wanli in the Ming Dynasty] The Forbidden City Publishing House, 2019, p. 215.

Some of the gourd-shaped vases made at the Jiajing official kilns have round ). This combination of shapes can prob -

ably be thought to reflect the ancient Chinese worldview that the heavens are a sphere and the earth is a cube. Indeed, a gourd represents a world itself, and thus it is the most appropriate motif for expressing the immortal realm far from the real world.

The Jiajing official kilns produced numerous square vessels (fig. 24), and they too can probably be thought to reflect the heaven = circle, earth = square concept. If round vessels represent the heavens, then wouldnʼt they think that they needed square vessels to represent the earth. Since many of these square vessels have Daoist imagery designs, it is also highly likely that they were used as Daoist ritual vessels.

Fig. 22

Underglaze Blue

Enamel, “Da

Jia Jing Nian Zhi”

with Dragon, Scroll and Figure Design in Underglaze Blue, “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi” inscription, Toyama Memorial Museum Photo: Toyama Memorial Museum

24

Square Dish with Design in Overglaze Green and Yellow Enamel, “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi” inscription, Tokyo National Museum

Source: ColBase

Fig. 25

Bowl with Eight Immortals Design in Underglaze Blue, “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi” inscription, National Palace Museum, Taipei

Source: NPM Open Data

As the Jiajing Emperor began to focus on Daoism, the Immortals who lived as humans and then ascended to the heavens were his models and desired existence. In China the Eight Immortals are a renowned group of Daoist Immortals, so famous that everyone can recognize which Immortal is indicated simply by seeing a depiction of that Immortal ʼs specific appearance and attribute item (fig. 25). The Eight Immortals and their respective attributes are: Li Tieguai (gourd); Han Zhongli (banana leaf fan); Lu Dongbin (sword); Lan Caihe (flower basket); Han Xiangzi (flute); He Xiangu (lotus blossom); Zhang Guolao (fish-shaped drum); and Cao Guojiu (jade tablet). The Jiajing official kilns often created works with Eight Immortals imagery, but there some instances where different Immortals are substituted for regular members of the Eight Immortals group and sometimes it is difficult to identify who is actually represented. Longevity was also one of the goals of Daoism, and the word shou (寿) was used as a simple expression of this concept. Daoism is a belief system in which the uttering of a word manifests that thought. The official Jiajing kilns tended to write the shou character on ceramic vessels. Some of these works depict the shou character in the special writing style used on Daoist talisman incantations called fulu (符籙) (fig. 26). Thus the ceramic vessel itself is thought to have functioned as a fulu -like talisman. The Jiajing kilns also often used plant motifs that symbolized longevity and immortality, such as peaches and reishi mushrooms. Simply by adorning vessels with these celebratory designs they hoped to approach longevity and immortality. For the Jiajing Emperor who sought to realize a Daoist life, the official kiln porcelains he had made as manifestations of the Daoist realm

Fig.

Fig. 26

Dish with Immortal Cranes Design in Underglaze Blue, “Da Ming Jia Jing Nian Zhi” inscription, The Palace Museum, Beijing

Source: Reproduced from Mingdai Jiajing Longqing Wanli Yuyao Ciqi [Imperial Porcelains from the Reign of Jiajing Longqing Wanli in the Ming Dynasty] The Forbidden City Publishing House, 2019, p. 189

can be thought to have functioned as the manifestations of the emperorʼ s belief that by cultivating Daoist imagery he was at the very least approaching the inner mysteries of Daoism.

Conclusion

Above we have considered the course of the Jiajing Emperorʼ s life and the meanings incorporated in the porcelains created by the Jiajing official kilns. Confronted with non-ideal circumstances immediately after ascending the throne, and struggling with the burden of the Ming dynastyʼ s fate exhausted the Jiajing Emperor both physically and mentally. Canʼ t we thus say that this emperor who in the end lived out his life in a spiritual realm sought porcelain wares that expressed his own desires and ideals? The official kiln porcelains were the response to those desires. They were visualizations of the Jiajing Emperorʼs legitimacy as emperor, at times they were encouragements that revealed the blessings of the heavens and allowed him to manifest the realm of the Immortals in the real world. Thus the porcelains of the Jiajing official kilns were not simply decorative arts, canʼt they be seen as a special presence that spiritually supported the Jiajing Emperor throughout his life.

(Arai Takayuki)

Select Bibliography

1 Ming text, Ming Shizong Shilu [Ming Veritable Record of Jiajing Emperor].

2 Ming text, Da Ming Huidian [Collected Statutes of the Ming Dynasty], Wanli edition.

3 Ming text, Wang Zongmu and Lu Wangai (eds.), Jiangxisheng Dazhi [Great Chronicle of Jiangxi Province], Wanli edition.

4 Ming text, Wang Qi and Wang Siyi (eds.), Sancai Tuhui [Assembled Pictures of the Three Realms].

5 Ming text, Zhang Juzheng, author; Zhang Sixiu and Zhang Maoxiu (eds.), Zhangjiajie Wenji [Complete Works of Zhang Taiyue].

6 Qing text, Wang Hongxu et al., Mingshigao [Draft History of the Ming Dynasty].

7 Qing text, Zhang Tingyu et al., Mingshi [History of the Ming Dynasty].

8 Honda Wataru, Sawada Mizuho, and Takama Mitsuyoshi, (trans.), Hōbokushi, Ressenden, Shinsenden, Sengaikyō [Baopuzi, Liexianzhuan, Shenxianzhuan, Shanhaijing] Vol. 4 from Chinese Classics Series, Heibonsha, 1973

9 Iwami Hiroshi, Mindai Yōeki Seido no Kenkyū [Studies on the Statute Labour System in the Ming Dynasty], Dohosha, 1986

10 Wang Jianhua, “Gugong bowuyuan cang Jiajingchao ciqi gaikuang ji yishu fengge ” [Overview of Jiajing Period Porcelain Collection and Its Artistic Style in the Palace Museum], Palace Museum Journal , Issue 3, 1987

11 Kojima Tsuyoshi, “Kasei no reisei kaikaku ni tsuite ” [Reform of the Ritual System in the Jiajing Period], The Memoirs of the Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia No. 117, 1992

12 Lin Yanqing, “Lunming shizong daji he caiyi huanguan” [A study of Emperor Shizong of Ming Dynasty's criticism and restraint of eunuchs], Shixue Jikan , Issue 4, 1994.

13 Yang Jingrong, Gugong Bowuyuan Cang Wenwu Zhenpin Daxi, Yanseyou [The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum: Color Glazes], Shanghai Scientific and Technical Publishers, 1999.

14. Sakuma Shigeo, Keitokuchin Yōgyōshi Kenkyū [Research on the History of the Jingdezhen Ceramic Industry], Daichi Shobō, 1999.

15. Ōishi Takao, “Mindai Kasei shonen no mikkei seiji ni tsuite ” [A Study of "mijie (密掲)" in the "Jiajing" era], Humanities Review: The Journal of the Literary Association of Kwansei Gakuin University, Vol. 52 No. 2 , 2002

16. Ōishi Takao, “Mindai Kaseichō no Seien saiken” [Reconstruction of West Garden during the Ming Jiajing era], Humanities Review: The Journal of the Literary Association of Kwansei Gakuin University, Vol. 53 No. 3, 2003.

17. Hu Fan, Jiajing Zhuan [Biography of the Jiajing Emperor], Peopleʼs Publishing House, 2004.

18. Peng Tao, “Mingdai huanguan zhengzhi yu Jingdezhen de taozheng” [The eunuch system of the Ming dynasty and the ceramic industry management of Jingdezhen], Nanfang-wenwu , Issue 2 , 2006

19. National Museum of China (eds.), Zhongguo Guojiabowuguan Guancang Wenwu Yanjiu Congshu Ciqijuan (Mingdai) [Research on Cultural Properties in the National Museum of China, Ceramics Volume (Ming Dynasty)], Shanghai Classics Publishing House, 2007

20 Chigiri Kō sai, Sennin no Sekai [The Realm of the Immortals], Kokusho Kankokai, 2008

21 Liu Wei, Diwang Yu Gongting Ciqi [The Emperor and Ceramics for the Court], The Forbidden City Publishing House, 2010

22 Wang Xi, Ming Shizong Yu Dao Jiao Qianlun [A Brief Study on Ming Shizong and Taoism], Journal of Gugong Studies, Issue 1, 2011

23 Qu Shuijian (ed.), Beijing Chutu Cipian Duandai Yu Jianshang [Dating and Appreciation of Ceramic Shards Excavated in Beijing], Cultural Relics Publishing House, 2011

24 Liao Baoxiu, Youse Yu Wenshi: Mingdai Qinghuaci [Decorative Motifs and Glazes: Ming Underglaze Blue Porcelains], National Palace Museum, Taipei, 2016.

25 The Palace Museum and Jingdezhen Ceramics Archaeology Institute, Ming Qing Yuyao Ciqi: Gugong Bowuyuan Yu Jingdezhen taoci kaogu xinchengguo [The Porcelain of Imperial Kiln in Ming and Qing Dynasties - The New Achievement on Ceramic Archaeology of the Palace Museum and Jingdezhen], The Forbidden City Publishing House, 2016

26. The Palace Museum and Jingdezhen Ceramics Archaeology Institute, Mingdai Chenghua Yuyao Ciqi: Jingdezhen Yuyao Yizhi Chutu Yu Gugong Bowuyuan Cang Chuanshi Ciqi Duibi [Imperial Porcelains from the Reign of Chenghua in the Ming Dynasty: A Comparison from the Imperial Kiln Site at Jingdezhen and Imperial Collection of the Palace Museum], The Forbidden City Publishing House, 2016.

27 Arai Takayuki, “Mindai ni okeru keitokuchinkanʼ yō no kanri taisei: K ōbu to naifu ni yoru futatsu no keitō ni chakumoku shite ” [Management Systems at the Jingdezhen Official Kilns in the Ming Dynasty – Focusing on the Two

Systems by the Ministry of Works (Gongbu) and the Imperial Household Department], Meiji University Journal of Asian History No. 21, 2017.

28. Miyazaki Noriko, Kachō-sansuiga wo Yomitoku Chūgoku Kaiga no Imi [Interpreting Bird and Flower and Landscape Paintings – The Meaning of Chinese Painting], Chikuma Shob ō, 2018.

29. Iwamoto Marie, Mindai no Sensei Seiji [Ming Dynasty Autocracy], Kyoto University Press, 2019.

30. Palace Museum and Jingdezhen Ceramics Archaeology Institute, Mingdai Jiajing Longqing Wanli Yuyao Ciqi: Jingdezhen Yuyao Yizhi Chutu Yu Gugong Bowuyuan Cang Chuanshi Ciqi Duibi [Imperial Porcelains from the Reign of Jiajing Longqing Wanli in the Ming Dynasty: A Comparison of Porcelains from the Imperial Kiln Site at Jingdezhen and the Imperial Collection of the Palace Museum], The Forbidden City Publishing House, 2019

31 Arai Takayuki, “Min shoki ni okeru kanʼ yō taisei no hensen to gyokishō no seiritsu nendai ni kansuru kō satsu ” [A study on the transition of the official porcelain production system and establishment date of yuqichang in the early Ming period], Chūgoku Kōkogaku [Chinese Archaeology], No. 19, 2019.

32 . Gao Xianping, “Ming Jiajing shiqi jisiyongci xintan” [A new investigation into the ritual porcelain from the Jiajing period of the Ming dynasty], Wenwu [Cultural Relics], Issue 11, 2020.

33. Arai Takayuki, “Mindai no kanʼ yō jiki ni arawasareta ʻ ki ʼ no gainen – kaiten suru ry ū ho monʼ yō wo chū shin ni ” [The 'chi' concept expressed on Ming dynasty Imperial porcelains – Focusing on the circling dragon and phoenix designs], Chūgoku Kōkogaku [Chinese Archaeology], No. 21, 2021

34 Arai Takayuki, “Mindai kanʼ yō jiki ni mirareru ry ū mon to sono shō chō ni kansuru kenky ū [Research on dragon motifs and their meaning in Ming dynasty official kiln porcelains], Kajima Foundation for the Arts Annual Repor t No. 38, 2022

35 Hong Kong Museum of Art (eds.), Fuhua Xianjing: Jiajing Huangdi De Xuni Shijie [Eternal Enlightenment: The Virtual World of Jiajing Emperor], Huaihaitang, 2023.

Notes

- Japanese and Chinese personal names are presented in family name, personal name order, with Chinese names given in Pinyin.

- Where possible, published English versions of book and article titles are used. When no such published version is available, new English versions have been prepared for this volume.

2024年10月10日(木) 〜 10月19日(土)

会場 / Venue

Mayuyama & Co., Ltd

〒104-0031東京都中央区京橋2-5-9

TEL 03-3561-5146

2-5-9 Kyobashi, Chuo-ku, Tokyo, 104-0031, JAPAN

TEL 03-3561-5146

https://www.mayuyama.jp

E-mail: mayuyama@big.or.jp