14TH TO 23RD OCTOBER 2022

MAYUYAMA & CO., LTD.

ごあいさつ

北斉から隋にかけての鉛釉の流行を基盤として、初唐、そして盛唐期に全盛期を迎 えることとなる三彩は、北朝文化の終着点とも云えます。白という色を尊んだ北朝の 人々は、隋において白磁を完成させ、隋から初唐にかけての白磁隆盛を生み出します。 その裏側で鉛釉陶器も漢以来の興隆をみせることとなります。

一般に三彩は武則天の治世より盛んになったと云われていますが、北斉の時点で完 成しているとも云え、そこから盛唐、武周の最盛期までには、百年以上の時が横たわっ ております。唐三彩は仏教と密接に関わっていた可能性が指摘されており、これは仏 教を重んじた武則天によるその擁立と三彩の流行が、時を同じくしていることからも 明らかかと思われます。従って、初唐、高宗の治世下で武照(武則天)が皇后となっ た655年を仏教及び唐三彩隆盛の起点とみることが可能ではないでしょうか。

本展には、そういった初唐後半のものと推定される作品に加え、北朝から隋、そし て初唐前半に至るまでの作品も出展されております。これにより北斉から盛唐に至る 三彩及び鉛釉の推移を把握する一助になればと思っております。

また器種においても、多種多様な作品を出陳いたします。中でも梅瓶、燭台、建築 明器類などは極めて珍しい作例と云えるでしょう。その他の作品も、同様の作例の中 で美的に秀抜なものを選びました。本展に出品される作品の殆どは、1910年代から 戦前期までに市場に出たと推察されるものです。これは本展を催すにあたってとくに

3

拘った点でもあります。 唐三彩のイメージはその発見より百年以上の時を経て、だいぶ固定化し形骸化して いるようにも思われます。個々の鑑賞者が感受性の扉を開き、自己の中に瑞々しい感 動と新たな可能性を見出す契機となれば幸いです。 令和4年10月 繭山龍泉堂

4 略年表 北周 隋 557 577 550 705 684 700 750 600 初 唐 盛 唐 550 535 西魏 東魏 北魏 534 - 655 武照(武則天)皇后となる - 659 長孫無忌ら自殺。武則天の権力確立 - 712 玄宗即位。開元の治始まる - 740 楊玉環(楊貴妃)、玄宗の後宮に入る - 751 タラス河畔の戦いでアッバース朝に大敗 - 651 サーサーン朝滅亡 - 627 玄奘三蔵、仏教の真理を求めインドへ - 645 玄奘帰国。翌646年に『大唐西域記』完成 - 682 洛陽を神都とする - 755 安史の乱起こる 618 隋煬帝討たれる。 李淵(高祖)、隋恭帝の禅譲を受け唐を建国 690 武則天即位。国号を周とする 梁 557 陳 587 554 756 武周 617 581 楊堅(文帝)、北周静帝の禅譲を受け隋を建国 仏教の復興に努める 589 陳 滅び隋中華統一 唐 中唐 650 628 北斉

Message

Sancai three-colored ceramics reached a golden age during China's Early Tang to High Tang eras, building from the basis of lead-glazed ceramic trends in the Northern Qi to Sui dynasties. Tang sancai wares are considered the final form of Northern Dynasties cultural expression. The color white was revered during the Northern Dynasties era. Sui dynasty potters perfected white porcelain technology, which ushered in the golden age of white porcelain from the Sui to Early Tang. Lead glazed ceramics constituted the flip-side of these porcelain developments and flourished from the Han dynasty onwards.

In general, sancai wares are thought to have been popular from Wu Zetian's reign onwards, while other theories think the ware type matured during the Northern Qi dynasty. Such dating would mean that sancai ware technology matured more than a century before the High Tang when Wu Zetian was at the height of her powers. A possible close connection between Tang sancai and Buddhism has also been noted. The simultaneous growth of Buddhism under Wu Zetian, a devout Buddhist, and the burgeoning sancai ware trend seems to further indicate such a connection. Thus we can suggest the year 655 when Wu Zhao (Zetian) was named empress consort during the reign of Gaozong as the pinnacle of both the flourishing of Buddhism in China and the Tang sancai trend.

In addition to works attributed to the latter half of the Early Tang era, this exhibition presents an array of items dating from the Northern Dynasties through the Sui and first half of the Early Tang. We hope this variety will provide visitors with an understanding of the changes that occurred in sancai and lead glazed wares from the Northern Qi through the High Tang.

We are also pleased to present a varied selection of vessel types and shapes in this exhibition, some rarely found in sancai, such as meiping jars, candlesticks and

5

architectural model grave goods. These examples and those of other vessel forms were all selected as particularly beautiful examples of their type. Most of the works displayed are thought to have appeared in the marketplace from the 1910s through the pre World War II era, and indeed, this provenance timing was another factor we considered when deciding which works to display in this exhibition.

The Tang sancai image has become all the more fixed and stereotypical over the century or more since its discovery by the modern world. It is our greatest hope that this exhibition will provide an opportunity for all visitors to fully discern the true beauty of Tang sancai, and through that experience, discover within themselves vibrant new sensations, new potential.

October 2022 Mayuyama & Co., Ltd.

6

Liang

Northern Wei

Western Wei Eastern Wei Chen

Chen state collapses, China unified under the Sui.

Northern Zhou Northern Qi

Northern Zhou emperor Jing abdication. Yang Jian (Emperor Wen) founds Sui dynasty. Buddhism promoted.

Emperor Yang of Sui defeated. Sui dynasty Gong abdicates. Li Yuan (Gaozu) founds Tang dynasty.

627 Xuanzhuan Sanzang to India seeking Buddhist truths.

Early Tang High Tang Middle Tang

645 Xuanzhuan returns to China. His travel record Datang xiyuji published in 646.

651 Southern Dynasties end.

655 Wu Zhao (Wu Zetian) made empress.

659 Suicide of Zhangsun Wuji. Wu Zetian solidifies power.

682 Luoyang named imperial capital.

Wu Zetian made Zhou dynasty empress regnant.

Sui Wu ZhouTang

712 Emperor Xuanzong named, Kaiyuan era begins.

Yang Yuhuan (Yang Guifei) becomes Xuanzong's concubine.

Tang forces defeated by Abbasid Caliphate at the Battle of Talas.

755 An Lushan Rebellion.

7 Brief Chronology

557 577 550 705 684 700 750 600 550 535 534 -

-

-

- 740

- 751

-

-

-

-

-

618 690

557 587 554 756 617 581 589 650 628

1. 緑釉杯

北朝〜隋(6〜7世紀)

高6.0 cm 口径8.5 cm 来歴

Sotheby & Co., ロンドン, 1955年5月24日.

Robert Stanley Hope Smith(1910〜1979年)旧蔵.

GREEN GLAZED CUP

Northern Dynasties - Sui dynasty (6th - 7th centuries) H. 6.0 cm Mouth Dia. 8.5 cm

PROVENANCE

Sotheby & Co., London, 24 May 1955.

Robert Stanley Hope Smith (1910-1979) Collection.

8

9

2. 三彩同心円文杯

隋〜初唐(7世紀)

高6.0 cm 口径7.6 cm

Alfred Clark(1873〜1950年)旧蔵. Alfred Clark夫人(1890〜1976年)旧蔵.

Spink & Son Ltd., ロンドン, 1975年.

「The Arts of the T’ang Dynasty」The Oriental Ceramic Society, ロンドン, 1955年, no. 113.

SANCAI CUP WITH CONCENTRIC CIRCLE DESIGN

Sui dynasty - Early Tang (7th century) H. 6.0 cm Mouth Dia. 7.6 cm

PROVENANCE

Alfred Clark (1873-1950) Collection. Mrs. Alfred Clark (1890-1976) Collection. Spink & Son Ltd., London, 1975.

EXHIBITED

The Arts of the T'ang Dynasty, The Oriental Ceramic Society, London, 1955, no. 113.

10

来歴

出展

11

3. 三彩梅

cm 胴径22.4 cm

Gian Francesco Giaquili Ferrini旧蔵.

Mario Prodan『La Poterie T’ang』Arts Et Métiers Graphiques, 1960年, 図版

SANCAI MEIPING JAR

Sui dynasty - Early Tang (7th century) H. 31.5 cm Torso Dia. 22.4 cm

PROVENANCE

Gian Francesco Guiquili Ferrini Collection.

LITERATURE

Mario Prodan, La Poterie T'ang, Arts et Métiers Graphiques, 1960, Pl. Ⅵ

12

めいぴん 瓶 隋〜初唐(7世紀) 高31.5

来歴

所載

Ⅵ

13

4. 三彩花文燭台

初唐(7世紀)

高23.3 cm 径24.5 cm

Russell M. Tyson(1867〜1963年)旧蔵. The Art Institute of Chicagoに寄贈, シカゴ, 1951年.

弓場紀知『中国の陶磁 第三巻 三彩』平凡社, 1995年, 挿図65.

SANCAI LAMP WITH FLORAL DESIGN

Early Tang (7th century) H. 23.3 cm Dia. 24.5 cm

PROVENANCE

Russell M. Tyson (1867-1963) Collection. Gift to the Art Institute of Chicago, 1951.

LITERATURE

Yuba Tadanori, Sansai [Three-color ware], vol. 3 from the series Chūgoku no Tōji [Chinese Ceramics], Heibonsha, 1995, fig. 65.

14

来歴

所載

15

16

17

SANCAI ELEPHANT RHYTON

Tang (7th century)

EXHIBITED

Heisei Gannendo Tokubetsuten, Inki - Hai, Wan, Taku [Heisei 1 Special Exhibition Drinking Vessels − Cups, Bowls, Cup/Bowl Stands], Kuboso Memorial Museum of Arts, Izumi, Osaka, 1989, no. 123.

LITERATURE

Kamei Akinori, Research on Chinese Ceramic History, Rokuichi Shobo, 2014, p. 153, pls. 1-5a, 5b.

18 5. 三彩象形角杯 初唐(7世紀) 高7.2 cm 長10.7 cm 出展 「平成元年度特別展示 飲器−杯・碗・托−」和泉市久保惣記念美術館, 1989年, no. 123. 所載 亀井明徳『中国陶瓷史の研究』六一書房, 2014年, p. 153, 図版1-5a, 5b.

Early

H. 7.2 cm L. 10.7 cm

19

SANCAI ELEPHANT RHYTON

Tang (7th century)

cm L. 10.4

PROVENANCE

Box inscription by Sugimura Yūzō (1900-1978)

EXHIBITED

Heisei Gannendo Tokubetsuten, Inki - Hai, Wan, Taku [Heisei 1 Special Exhibition Drinking Vessels − Cups, Bowls, Cup/Bowl Stands], Kuboso Memorial Museum of Arts, Izumi, Osaka, 1989, no. 123.

20 6. 三彩象形角杯 初唐(7世紀) 高6.8 cm 長10.4 cm 来歴 杉村勇造(1900〜1978年)箱書. 出展 「平成元年度特別展示 飲器−杯・碗・托−」和泉市久保惣記念美術館, 1989年, no. 123.

Early

H. 6.8

cm

21

7. 三彩有蓋丸壺

初唐(7世紀)

高6.5 cm 胴径7.6 cm

Robert Stanley Hope Smith(1910〜1979年)旧蔵.

SANCAI ROUND JAR WITH LID

Early Tang (7th century) H. 6.5 cm Torso Dia. 7.6 cm

PROVENANCE

Robert Stanley Hope Smith (1910-1979) Collection.

22

来歴

23

8. 三彩騎象胡人燭台

初唐(7世紀) 高15.8 cm 長11.1 cm

SANCAI LAMP WITH WEST ASIAN FIGURE ON ELEPHANT

Early Tang (7th century) H. 15.8 cm L. 11.1 cm

24

25

9. 三彩加彩胡児

初唐(7世紀)

高30.0 cm

PAINTED SANCAI WEST ASIAN BOY

Early Tang (7th century) H. 30.0 cm

26

27

28 初唐(7世紀) 高4.3 cm 幅9.8 cm 来歴 Timmer-Kerkhoven夫人旧蔵, 1930〜1950年代に入手. 10. 三彩印花葡萄唐草文杯

29

SANCAI FOLIATE CUP WITH STAMPED GRAPES AND ARABESQUES DESIGN

Early Tang (7th century)

H. 4.3 cm W. 9.8 cm

PROVENANCE

Mrs. Timmer-Kerkhoven Collection, acquired 1930s-1950s.

30

31

32 11. 三彩印花円珠文杯 初唐(7世紀) 高4.0 cm 口径9.7 cm 来歴 Wilfrid Fleisher(1897〜1976年)旧蔵.

SANCAI CUP WITH IMPRESSED DOT DESIGN

Early Tang (7th century) H. 4.0 cm Mouth Dia. 9.7 cm

PROVENANCE

Wilfrid Fleisher (1897-1976) Collection.

33

34 12. 三彩印花花弁文杯 初唐(7世紀) 高4.0 cm 口径9.9 cm 来歴 Wilfrid Fleisher(1897〜1976年)旧蔵.

SANCAI CUP WITH IMPRESSED FLOWER PETAL DESIGN

Early Tang (7th century) H. 4.0 cm Mouth Dia. 9.9 cm

PROVENANCE

Wilfrid Fleisher (1897-1976) Collection.

35

36 13. 三彩印花花文杯 初唐(7世紀) 高3.8 cm 口径9.8 cm

SANCAI CUP WITH STAMPED FLOWER DESIGN

Early Tang (7th century) H. 3.8 cm Mouth Dia. 9.8 cm

37

三彩貼花鳳首瓶 重要美術品

初唐(7世紀)

cm 胴径16.6 cm

1930年代.

「東京帝室博物館復興開館記念陳列」東京帝室博物館, 1938年, 8室14函.

1960年, no.7.

1961年, no.7.

唐宋名陶展」白木屋, 1964年, no. 1.

「中国陶磁 美を鑑るこころ」泉屋博古館分館, 2006年, no. 10. 所載

『陶器圖錄 第七巻 支那篇[上]』雄山閣, 1938年, 図版31.

『陶磁』第十巻第五號, 東洋陶磁研究所, 1938年, p. 4. 奥田誠一, 広田不孤斎, 田中作太郎, 林屋晴三編『中国の陶磁』東都文化出版, 1955年, 挿図79. 座右寶刊行會編『世界陶磁全集 第9巻 隋唐篇』河出書房, 1956年, 図版53.

小山冨士夫編『中国名陶百選』日本経済新聞社, 1960年, p. 39.

座右寶刊行會編『世界陶磁全集 第九巻〈中國 隋唐篇〉』河出書房新社, 1961年, 図版53.

『陶説』日本陶磁協会, 133号, 1964年, 図版1.

『陶説』日本陶磁協会, 135号, 1964年, 図版1. 水野清一『陶器全集 第25巻 唐三彩』平凡社, 1965年, 図版1.

小山冨士夫編『日本の美術 第76号 三彩』至文堂, 1972年, 第90図.

三上次男「唐三彩鳳首パルメット文の水注とその周邊−唐三彩の性格に關する一考察−」『國華』國華 社, 960號, 1973年, 挿図6. 繭山龍泉堂『龍泉集芳 第一集』便利堂, 1976年, 図版225. 繭山順吉『美術商のよろこび』便利堂, 1988年, PLATE 11. 矢部良明『日本の美術 第408号 唐三彩と奈良三彩』至文堂, 2000年, 第6図. 矢部良明, 今井敦編『やきもの名鑑[6]中国の陶磁』講談社, 2000年, p. 17.

亀井明徳『中国陶瓷史の研究』六一書房, 2014年, p. 194, 図版4-41.

38 14.

高37.7

来歴 繭山龍泉堂,

森村義行(1896〜1970年)旧蔵. 出展

「中国名陶百選展」日本橋髙島屋,

「中国名陶百選展」大阪・なんば髙島屋,

「中国古陶磁

39

SANCAI PHOENIX HEAD EWER WITH APPLIQUE DESIGN Important Art Object

Early Tang (7th century)

H. 37.7 cm Torso Dia. 16.6 cm

PROVENANCE

Mayuyama & Co., Ltd., Tokyo, 1930s. Morimura Yoshiyuki (1896-1970) Collection.

EXHIBITED

Tokyo Teishitsu Hakubutsukan Fukkō Kaikan Ki'nen Chinretsu [Display Commemorating the Restoration of the Tokyo Imperial Museum], Tokyo Imperial Museum, Tokyo, 1938, Room 8, Case 14.

Chinese Ceramics, A Loan Exhibition of One Hundred Selected Masterpieces from Collections in Japan, England, France, and America, Nihonbashi Takashimaya, Tokyo, 1960, no. 7.

Chinese Ceramics, A Loan Exhibition of One Hundred Selected Masterpieces, OsakaNanba Takashimaya, Osaka, 1961, no. 7.

Chūgoku Kotōji, Tō Sō Meitōten [Chinese Antique Ceramics, Tang, Song Ceramic Masterpieces Exhibition], Shirokiya, Tokyo, 1964, no. 1.

Chinese Ceramics, Enlightening through Beauty, Sen-oku Hakukokan, Tokyo, 2006, no. 10.

LITERATURE

Shina Hen (jō) [China Pt. 1], vol. 7 from the series Tōki Zuroku [Ceramics Illustrated Catalogue], Yuzankaku, 1938, pl. 31.

Oriental Ceramics Vol. Ⅹ , No. 5, Institute of Oriental Ceramics, 1938, p. 4. Okuda Seiichi, Hirota Fukosai, Tanaka Sakutaro, Hayashiya Seizō, (eds.), Chūgoku no Tōji [Chinese Ceramics], Tōto Bunka Shuppan, 1955, fig. 79.

Zauhō Kankōkai (ed.), Zuitō hen [Sui-Tang], vol. 9 from the series Sekai Tōji Zenshū [Ceramic Art of the World], Kawade Shobo, 1956, pl. 53.

Koyama Fujio (ed.), Chinese Ceramics, A Loan Exhibition of One Hundred Selected master pieces from collections in Japan, England, France, and America, The Nihon Keizai, 1960, p. 39.

Zauhō Kankōkai (ed.), Sui-Tang, vol. 9 from the series Collection of World's Ceramics, Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 1961, fig. 53.

The Tosetsu, The Japan Ceramic Society, No. 133, 1964, pl. 1.

The Tosetsu, The Japan Ceramic Society, No. 135, 1964, pl. 1. Mizuno Seiichi, Tōsansai [Tang three-color ware], vol. 25 from the series Tōki Zenshū [Complete Collection of Pottery], Heibonsha, 1965, pl. 1.

Koyama Fujio, ed., Sansai [Three-color ware], vol. 76 from the series Nihon no Bijutsu [Arts of Japan], Shibundo, 1972, pl. 90.

Mikami Tsugio, "A T'ang Three-color Ewer with Applied Palmette Medallions and the Character of T'ang Three-color Ware", Kokka, No. 960, 1973, fig. 6.

Mayuyama & Co., Ltd., Mayuyama Seventy Years Vol. Ⅰ, Benrido, 1976, pl. 225.

Mayuyama Junkichi, The Joys of an Art Dealer, Benrido, 1988, pl. 11.

Yabe Yoshiaki, Tōsansai to Narasansai [Tang three-color ware and Nara three-color ware], Vol. 408 from the series Nihon no Bijutsu [Arts of Japan], Shibundō, 2000, pl. 6.

Yabe Yoshiaki, Imai Atsushi, (ed), Chūgoku no Tōji [Chinese Ceramics], vol. 6 from the series of Yakimono Mēkan [Ceramic Directory], Kodansha, 2000, p. 17.

Kamei Akinori, Researches on Chinese Ceramic History, Rokuichi Shobo, 2014, p. 194, pl. 4-41.

40

41

15. 三彩万年壺

初唐〜盛唐(7世紀)

高13.1 cm 胴径18.5 cm

C. T. Loo & Co., パリ. Marie-Rose Loo旧蔵.

Gian Francesco Giaquili Ferrini旧蔵.

SANCAI JAR

Early Tang - High Tang (7th century) H. 13.1 cm Torso Dia. 18.5 cm

PROVENANCE

C. T. Loo & Co., Paris. Marie-Rose Loo Collection.

Gian Francesco Giaquili Ferrini Collection.

42

来歴

43

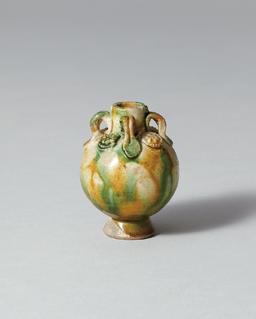

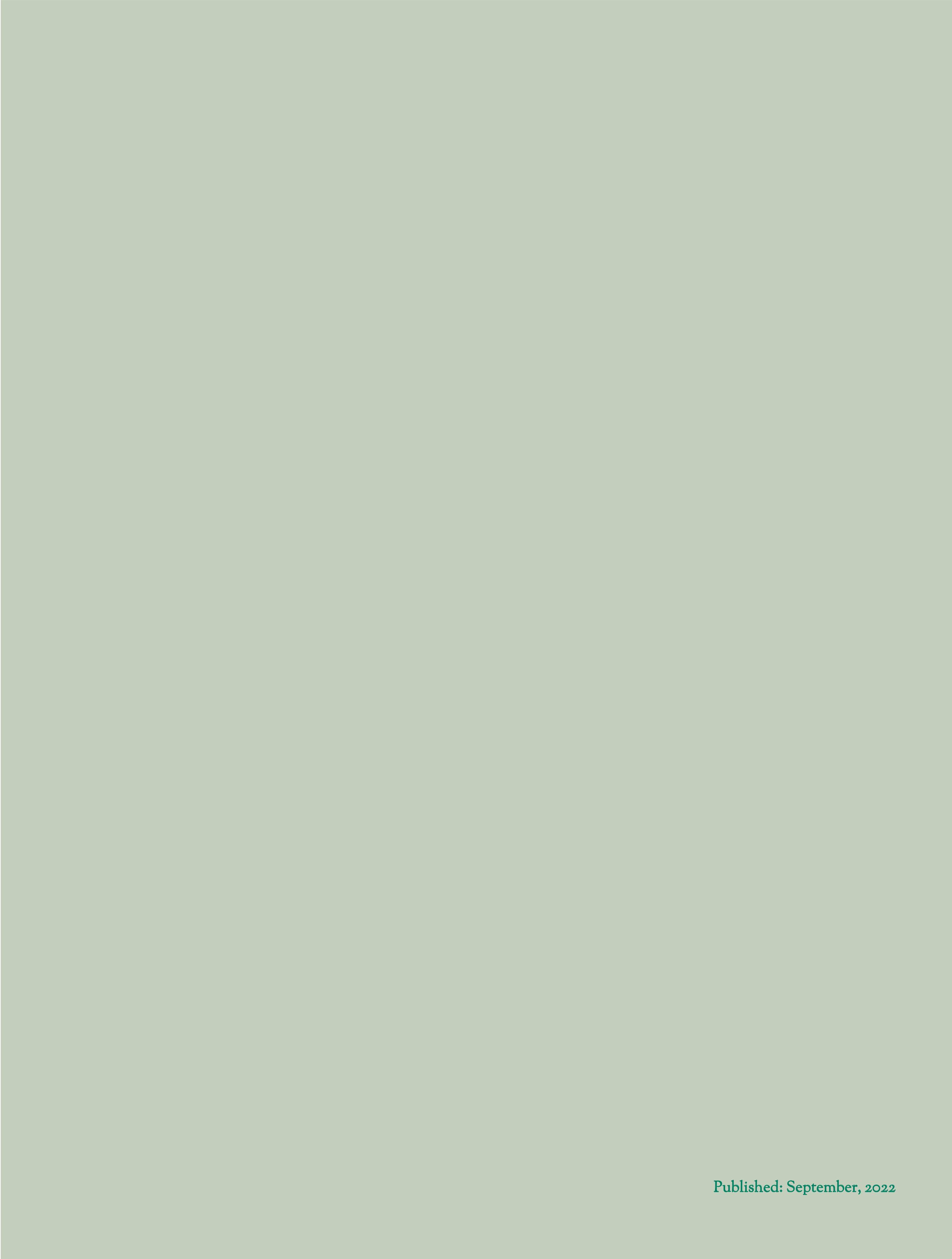

16. 三彩兔耳壺

初唐〜盛唐(7世紀)

cm 幅20.3

Gian Francesco Giaquili Ferrini旧蔵.

Mario Prodan『La Poterie T’ang』Arts Et Métiers Graphiques, 1960年, 図版

2014年, p. 185, 挿図3-22.

SANCAI JAR WITH RABBIT LUGS

Early Tang - High Tang (7th century) H. 18.5 cm W. 20.3 cm

PROVENANCE

Gian Francesco Guiquili Ferrini Collection.

LITERATURE

Mario Prodan, La Poterie T'ang, Arts et Métiers Graphiques, 1960, pl.

Kamei Akinori, Researches on Chinese Ceramic History, Rokuichi Shobo, 2014, p. 185, pl. 3-22.

44

高18.5

cm 来歴

所載

ⅩⅩⅩ 亀井明徳『中国陶瓷史の研究』六一書房,

ⅩⅩⅩ

45

17. 三彩把手杯

初唐(7世紀)

高6.3 cm 幅9.7 cm

SANCAI CUP WITH HANDLE

Early Tang (7th century) H. 6.3 cm W. 9.7 cm

46

47

18. 三彩丸壺

cm

SANCAI ROUND JAR

Early Tang - High Tang (7th century) H. 7.5 cm Torso Dia. 11.0 cm

PROVENANCE

Kochukyo, Tokyo. Sugiyama Tōjudō, Tokyo.

48

初唐〜盛唐(7世紀) 高7.5 cm 胴径11.0

来歴 壺中居. 杉山陶樹堂.

49

19. 三彩五足炉

初唐〜盛唐(7世紀) 高8.4 cm 幅14.4 cm

SANCAI INCENSE BURNER WITH FIVE ANIMAL-SHAPED LEGS

Early Tang - High Tang (7th century) H. 8.4 cm W. 14.4 cm

50

51

20. 三彩五足炉

初唐〜盛唐(7世紀) 高9.8 cm 口径15.1 cm

Stephen Junkunc Ⅲ(1904〜1978年)旧蔵.

SANCAI INCENSE BURNER WITH FIVE ANIMAL MASK LEGS

Early Tang - High Tang (7th century) H. 9.8 cm Mouth Dia. 15.1 cm

PROVENANCE

Stephen Junkunc Ⅲ (1904-1978) Collection.

52

来歴

53

21. 三彩杯及び承盤

初唐〜盛唐(7世紀)

盤:高5.0 cm 径24.8 cm 杯(大):高4.0 cm 口径7.5 cm

繭山龍泉堂, 1950年代.

SANCAI CUPS AND TRAY

Early Tang - High Tang (7th century)

Tray: H. 5.0 cm Dia. 24.8 cm

Cup (Large): H. 4.0 cm Mouth Dia. 7.5 cm

PROVENANCE

Mayuyama & Co., Ltd., Tokyo, 1950s.

54

来歴

55

56 22. 三彩弁口水注 初唐〜盛唐(7世紀) 高9.0 cm 胴径6.5 cm SANCAI EWER WITH PETAL-MOUTH Early Tang - High Tang (7th century) H. 9.0 cm Torso Dia. 6.5 cm

23. 三彩貼花四耳壺

初唐〜盛唐(7世紀)

高5.6 cm 胴径4.3 cm

SANCAI JAR WITH FOUR HANDLES AND APPLIQUE DESIGN

Early Tang - High Tang (7th century) H. 5.6 cm Torso Dia. 4.3 cm

24. 三彩丸壺

初唐〜盛唐(7世紀)

高5.3 cm 胴径7.7 cm

SANCAI ROUND JAR

Early Tang - High Tang (7th century) H. 5.3 cm Torso Dia. 7.7 cm

57

初唐〜盛唐(7世紀) 高11.2 cm 幅16.6 cm

Bluett & Sons, ロンドン. Gian Francesco Giaquili Ferrini旧蔵.

58 25. 絞 こうたいふく 胎

来歴

59

MARBLED CLAY FU TRIPOD VESSEL

Early Tang - High Tang (7th century) H. 11.2 cm W. 16.6 cm

PROVENANCE

Bluett & Sons, London.

Gian Francesco Giaquili Ferrini Collection.

60

61

黄釉絞

胎象嵌花文枕

1988年, no. 45.

1963年, no. 64.

1966年, no. 57.

1976年, no. 1-165.

第9巻 隋唐篇』河出書房, 1956年, 図版96下.

座右寶刊行會編『世界陶磁全集 第九巻〈中國 隋唐篇〉』河出書房新社, 1961年, 図版96下. 繭山龍泉堂『龍泉集芳 第一集』便利堂, 1976年, 図版304.

大阪市立美術館編『隋唐の美術』平凡社, 1978年, 図版148 (B).

佐藤雅彦『中国陶磁史』平凡社, 1978年, 挿図 113.

亀井明徳『中国陶瓷史の研究』六一書房, 2014年, p. 236, 挿図2-25.

YELLOW GLAZED MARBLED CLAY PILLOW WITH INLAID FLOWER DESIGN

High Tang (7th century) H. 5.1 cm L. 10.7 cm

PROVENANCE

Moriya Kōzō (1876-1953) Collection. Mayuyama & Co., Ltd., Tokyo.

EXHIBITED

Chūgoku Sōdai Tōchinten [Chinese Song dynasty ceramic pillows], Kanagawa Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, Kanagawa, 1963, no. 64.

Chūgoku Tōji Meihōten Shiri-zu II Sansai [Chinese Ceramic Treasures II Three-color ware], The Gotoh Museum, Tokyo, 1966, no. 57.

Zuitō no Bijutsu [Arts of the Sui and Tang], Osaka City Museum of Fine Art, Osaka, 1976, no. 1-165.

Tang Pottery and Porcelain, Nezu Institute of Fine Arts, Tokyo, 1988, no. 45.

LITERATURE

Zauhō Kankōkai (ed.), Zuitō Hen [Sui-Tang], vol. 9 from the series Sekai Tōji Zenshū [Ceramic Art of the World], Kawade Shobo, 1956, pl. 96, lower.

Zauhō Kankōkai (ed.), Sui-Tang, vol. 9 from the series Collection of World's Ceramics, Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 1961, pl. 96, lower.

Mayuyama & Co., Ltd., Mayuyama Seventy Years Vol. Ⅰ , Benrido, 1976, p. 304.

Osaka City Museum of Fine Art (eds.), Zuitō no Bijutsu [Arts of the Sui and Tang], Heibonsha, 1978, pl. 148 (B).

Satō Masahiko, Chūgoku Tōjishi [History of Chinese Ceramics], Heibonsha, 1978, fig. 113. Kamei Akinori, Researches on Chinese Ceramic History, Rokuichi Shobo, 2014, p. 236 pl. 2-25.

62 26.

こうたいぞうがん

盛唐(7世紀) 高5.1 cm 長10.7 cm 来歴 守屋孝蔵(1876〜1953年)旧蔵. 繭山龍泉堂. 出展 「中国宋代陶枕展」神奈川県立近代美術館,

「中国陶磁名宝展シリーズII 三彩」五島美術館,

「中国美術展シリーズ3 隋唐の美術」大阪市立美術館,

「唐磁」根津美術館,

所載 座右寶刊行會編『世界陶磁全集

63

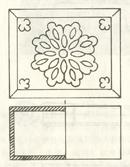

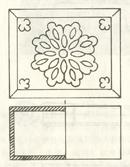

27. 三彩印花花文枕

SANCAI PILLOW WITH STAMPED FLOWER DESIGN

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries) H. 5.2 cm W. 10.9 cm

PROVENANCE

Mayuyama & Co., Ltd., Tokyo, 1958.

LITERATURE

Zauhō Kankōkai (ed.), Zuitō hen [Sui-Tang], vol. 9 from the series Sekai Tōji Zenshū [Ceramic Art of the World], Kawade Shobo, 1956, fig. 107. Zauhō Kankōkai (ed.), Sui-Tang, vol. 9 from the series Collection of World's Ceramics, Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 1961, fig. 107. Mizuno Seiichi, Tōsansai [Tang three-color ware], vol. 35 from the series Tōji Taikei [Great Lineage of Pottery], Heibonsha, 1977, pl. 89.

64

盛唐(7〜8世紀) 高5.2 cm 長10.9 cm 来歴 繭山龍泉堂, 1958年. 所載 座右寶刊行會編『世界陶磁全集 第9巻 隋唐篇』河出書房, 1956年, 挿図107. 座右寶刊行會編『世界陶磁全集 第九巻〈中國 隋唐篇〉』河出書房新社, 1961年, 挿図107. 水野清一『陶磁大系 第三五巻 唐三彩』平凡社, 1977年, 図版89.

65

28. 緑釉象

嵌花文枕

盛唐(7〜8世紀) 高5.0 cm 長10.9 cm

GREEN GLAZED PILLOW WITH INLAID FLOWER DESIGN

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries) H. 5.0 cm L. 10.9 cm

66

ぞうがん

67

三彩象

SANCAI GLAZED PILLOW WITH INLAID FLOWER DESIGN

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries) H. 5.6 cm L. 11.6 cm

PROVENANCE

Kochukyo, Tokyo.

EXHIBITED

Chūgoku Sōdai Tōchinten [Chinese Song dynasty ceramic pillows], Kanagawa Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, Kanagawa, 1963, no. 63.

68 29.

ぞうがん 嵌花文枕 盛唐(7〜8世紀) 高5.6 cm 長11.6 cm 来歴 壺中居. 出展 「中国宋代陶枕展」神奈川県立近代美術館, 1963年, no. 63.

69

30. 三彩花文枕

盛唐(8世紀)

高5.6 cm 長12.2 cm

SANCAI PILLOW WITH FLOWER DESIGN

High Tang (8th century) H. 5.6 cm L. 12.2 cm

70

71

31. 褐釉絞

胎枕

盛唐(7〜8世紀) 高6.6 cm 長12.8 cm

1959年, 香港にて購入.

AMBER GLAZED MARBLED CLAY PILLOW

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries) H. 6.6 cm L. 12.8 cm

PROVENANCE

A previous owner purchased in Hong Kong, 1959.

72

こうたい

来歴

73

32. 三彩屋舎

盛唐(7〜8世紀) 高23.6 cm 幅25.6 cm

Collins & Moffat Chinese Antiques, シアトル, 1954年. John Yeon(1910〜1994年)旧蔵.

74

来歴

75

SANCAI HOUSE

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries) H. 23.6 cm W. 25.6 cm

PROVENANCE

Collins & Moffat Chinese Antiques, Seattle, 1954. John Yeon (1910-1994) Collection.

76

77

33. 三彩穀倉

1961年, 挿図152. 水野清一『陶器全集 第25巻 唐三彩』平凡社, 1965年, 図版49上.

佐藤雅彦『中国の土偶』美術出版社, 1965年, 図版153.

水野清一『陶磁大系 第三五巻

1977年,

SANCAI GRANARY

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries) H. 13.8 cm L.14.2 cm (including a stand)

PROVENANCE

Hosokawa Moritatsu (1883-1970) Collection. Kochukyo, Tokyo.

LITERATURE

Otsuka Minoru, Catalogue of Old Chinese Clay Wares and Images, Part 6, Ohtsuka Kogeisha, 1938, pl. 57 center left.

Zauhō Kankōkai (ed.), Zuitō hen [Sui-Tang], vol. 9 from the series Sekai Tōji Zenshū [Ceramic Art of the World], Kawade Shobo, 1956, fig. 152.

Zauhō Kankōkai (ed.), Sui-Tang, vol. 9 from the series Collection of World's Ceramics, Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 1961, fig. 152.

Mizuno Seiichi, Tōsansai [Tang three-color ware], vol. 25 from the series Tōki Zenshū [Complete Collection of Pottery], Heibonsha, 1965, pl. 49 upper.

Satō Masahiko, Chūgoku no Dogū [Chinese Figurine], Bijutsu Shuppansha, 1965, pl. 153.

Mizuno Seiichi, Tōsansai [Tang three-color ware], vol. 35 from the series Tōji Taikei [Great Lineage of Pottery], Heibonsha, 1977, fig. 41.

Mikami Tsugio, Chūgoku Ⅰ , kodai [China 1, Antiquity], vol. 5 from the series Tōki Kōza [Lectures on Pottery], Yuzankaku Shuppan, 1982, pl. 118 center.

78

盛唐(7〜8世紀) 高13.8 cm 幅14.2 cm(台含む) 来歴 細川護立(1883〜1970年)旧蔵. 壺中居. 所載 大塚稔『支那古明器泥像圖鑑 第六輯』大塚巧藝社, 1938年, 図版57中左. 座右寶刊行會編『世界陶磁全集 第9巻 隋唐篇』河出書房, 1956年, 挿図152. 座右寶刊行會編『世界陶磁全集 第九巻〈中國 隋唐篇〉』河出書房新社,

唐三彩』平凡社,

挿図41. 三上次男『陶器講座 第5巻 中国Ⅰ 古代』雄山閣出版, 1982年, 図版118中.

79

三彩 舂

図版49下.

第三五巻 唐三彩』平凡社, 1977年, 図版95.

1982年, 図版118上.

SANCAI CHONGCHU THRESHING EQUIPMENT

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries) H. 6.4 cm L. 17.9 cm

LITERATURE

Zauhō Kankōkai (ed.), Zuitō hen [Sui-Tang], vol. 9 from the series Sekai Tōji Zenshū [Ceramic Art of the World], Kawade Shobo, 1956, fig. 155.

Zauhō Kankōkai (ed.), Sui-Tang, vol. 9 from the series Collection of World's Ceramics, Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 1961, fig. 155.

Mizuno Seiichi, Tōsansai [Tang three-color ware], vol. 25 from the series Tōki Zenshū [Complete Collection of Pottery], Heibonsha, 1965, pl. 49 lower.

Mizuno Seiichi, Tōsansai [Tang three-color ware], vol. 35 from the series Tōji Taikei [Great Lineage of Pottery], Heibonsha, 1977, pl. 95.

Mikami Tsugio, Chūgoku Ⅰ , Kodai [China 1, Antiquity], vol. 5 from the series Tōki Kōza [Lectures on Pottery], Yuzankaku Shuppan, 1982, pl. 118, upper.

80 34.

しょうしょ 杵 盛唐(7〜8世紀) 高6.4 cm 長17.9 cm 所載 座右寶刊行會編『世界陶磁全集 第9巻 隋唐篇』河出書房, 1956年, 挿図155. 座右寶刊行會編『世界陶磁全集 第九巻〈中國 隋唐篇〉』河出書房新社, 1961年, 挿図155. 水野清一『陶器全集 第25巻 唐三彩』平凡社, 1965年,

水野清一『陶磁大系

三上次男『陶器講座 第5巻 中国Ⅰ 古代』雄山閣出版,

81

SANCAI WELLHEAD

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries) H. 5.7 cm W. 9.7 cm

PROVENANCE Kochukyo, Tokyo.

LITERATURE

Zauhō Kankōkai (ed.), Zuitō hen [Sui-Tang], vol. 9 from the series Sekai Tōji Zenshū [Ceramic Art of the World], Kawade Shobo, 1956, pl 130 upper.

Zauhō Kankōkai (ed.), Sui-Tang, vol. 9 from the series Collection of World's Ceramics, Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 1961, fig. 130 upper.

Mizuno Seiichi, Tōsansai [Tang three-color ware], vol. 25 from the series Tōki Zenshū [Complete Collection of Pottery], Heibonsha, 1965, pl. 48 upper.

Satō Masahiko, Chūgoku no Dogū [Chinese Figurines], Bijutsu Shuppansha, 1965, pl. 153.

Mizuno Seiichi, Tōsansai [Tang three-color ware], vol. 35 from the series Tōji Taikei [Great Lineage of Pottery], Heibonsha, 1977, pl. 96.

82 35. 三彩井 せいらん 欄 盛唐(7〜8世紀) 高5.7 cm 一辺9.7 cm 来歴 壺中居. 所載 座右寶刊行會編『世界陶磁全集 第9巻 隋唐篇』河出書房, 1956年, 図版130上. 座右寶刊行會編『世界陶磁全集 第九巻〈中國 隋唐篇〉』河出 書房新社, 1961年, 図版130上. 水野清一『陶器全集 第25巻 唐三彩』平凡社, 1965年, 図 版48上. 佐藤雅彦『中国の土偶』美術出版社, 1965年, 図版153. 水野清一『陶磁大系 第三五巻 唐三彩』平凡社, 1977年, 図 版96.

SANCAI WELLHEAD

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries) H. 6.7 cm W. 9.3 cm

PROVENANCE Kochukyo, Tokyo.

LITERATURE

Zauhō Kankōkai (ed.), Zuitō hen [Sui-Tang], vol. 9 from the series Sekai Tōji Zenshū [Ceramic Art of the World], Kawade Shobo, 1956, pl. 130 lower.

Zauhō Kankōkai (ed.), Sui-Tang, vol. 9 from the series Collection of World's Ceramics, Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 1961, fig. 130 lower.

83 36. 三彩井 せいらん 欄 盛唐(7〜8世紀) 高6.7 cm 一辺9.3 cm 来歴 壺中居. 所載 座右寶刊行會編『世界陶磁全集 第9巻 隋唐篇』河出書房, 1956年, 図版130下. 座右寶刊行會編『世界陶磁全集 第九巻〈中國 隋唐篇〉』河出 書房新社, 1961年, 図版130下.

84 37. 黄釉褐彩鴨 盛唐(7世紀) 高8.9 cm 幅9.0 cm 来歴 Wilfrid Fleisher(1897〜1976年)旧蔵. AMBER PAINTED YELLOW GLAZED DUCK High Tang (7th century) H. 8.9 cm L. 9.0 cm PROVENANCE Wilfrid Fleisher (1897-1976) Collection.

38. 褐釉犬

盛唐(7世紀)

高11.8 cm 幅5.2 cm

来歴 Wilfrid Fleisher(1897〜1976年)旧蔵.

AMBER GLAZED DOG

High Tang (7th century) H. 11.8 cm W. 5.2 cm

PROVENANCE

Wilfrid Fleisher (1897-1976) Collection.

39. 褐釉猪

盛唐(7世紀)

高4.6 cm 長12.8 cm 来歴 Wilfrid Fleisher(1897〜1976年)旧蔵.

AMBER GLAZED WILD BOAR

High Tang (7th century) H. 4.6 cm L. 12.8 cm

PROVENANCE

Wilfrid Fleisher (1897-1976) Collection.

85

40. 黄褐釉加彩騎馬胡人

盛唐(7世紀) 高37.0 cm 長32.0 cm

Gian Francesco Giaquili Ferrini旧蔵.

Gian Francesco Giaquili Ferrini『Dal Neolitico al Sung』1976年, 図版 Ⅷ

PAINTED YELLOW AND AMBER GLAZED WEST ASIAN FIGURE ON HORSEBACK

High Tang (7th century) H. 37.0 cm L. 32.0 cm

PROVENANCE

Gian Francesco Giaquili Ferrini Collection.

LITERATURE

Gian Francesco Giaquili Ferrini, Dal Neolitico al Sung, 1976, pl. Ⅷ

86

来歴

所載

87

41. 褐釉白斑文馬

盛唐(7〜8世紀)

高52.5 cm 長47.5 cm

Joseph Winterbotham Jr.(1878〜1954年)旧蔵. The Art Institute of Chicagoに寄贈, シカゴ, 1954年.

AMBER GLAZED AND WHITE SPOTTED HORSE

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries) H. 52.5 cm W. 47.5 cm

PROVENANCE

Joseph Winterbotham, Jr. (1878-1954) Collection. Gift to the Art Institute of Chicago, 1954.

88

来歴

89

42. 黄釉褐彩駱駝

盛唐(7〜8世紀)

高51.3 cm 長35.0 cm

Wilfrid Fleisher(1897〜1976年)旧蔵.

Alf Liedholm「Tokio-Stockholm. Hos Mr Och Mrs Wilfrid Fleisher」『Svenska Hem och Trädgårdstidningen』Nr 3, Årg. 44, 1956年, pp. 61-63.

YELLOW GLAZED AMBER PAINTED CAMEL

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries) H. 51.3 cm L. 35.0 cm

PROVENANCE

Wilfrid Fleisher (1897-1976) Collection.

LITERATURE

Alf Liedholm, "Tokio-Stockholm, Hos Mr Och Mrs Wilfrid Fleisher", Svenska Hem och Tradgardstidningen, Nr. 3, Arg. 44, 1956, pp. 61-63.

90

来歴

所載

91

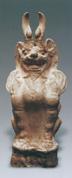

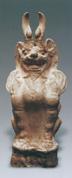

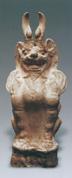

43. 三彩鎮墓獣

盛唐(7世紀)

高95.0 cm 幅31.0 cm

Bertha Palmer Thorne(1911〜1974年)旧蔵.

Pauline Palmer Wood(1917〜1984年)旧蔵.

The Art Institute of Chicagoに寄贈, シカゴ, 1970年.

92

来歴

SANCAI TOMB GUARDIAN BEAST

High Tang (7th century) H. 95.0 cm W. 31.0 cm

PROVENANCE

Bertha Palmer Thorne (1911-1974) Collection. Pauline Palmer Wood (1917-1984) Collection. Gift to the Art Institute of Chicago, 1970.

94

95

44. 三彩馬

96

97

44. 三彩馬

SANCAI HORSE High Tang (7th - 8th centuries) H. 68.0 cm L. 79.0 cm

PROVENANCE

Matsuoka Family Collection, Kanazawa. The Chinese Ceramics Museum, Oita.

EXHIBITED

Kaikan 5shūnen Kinen, Chūgoku no Yakimono - Kan, Tō, Sō, Min [Exhibition Commemorating 5th Anniversary of the Museum Opening, Chinese Ceramics - Han, Tang, Song, Ming], Ishikawa Prefectural Museum of Art, Ishikawa, 1964, no. 17.

LITERATURE

Chūgoku Tōji Bijutsukan Zōhin Senshū [Selected Works from the Chinese Ceramics Museum Collection], The Chinese Ceramics Museum, 2005, pl. 21. −Yō, Tō, Ka− Kanzō Yūhin Senshū [Figurines, Ceramics from Song to Yuan, and Porcelain from Ming to Qing, Selected Masterpieces from the Museum Collection], The Chinese Ceramics Museum, 2005, pl. 7.

98

盛唐(7〜8世紀) 高68.0 cm 長79.0 cm 来歴 松岡家(金沢)旧蔵. 中國陶瓷美術館. 出展 「開館5周年記念 中國のやきもの 漢・唐・宋・明」石川県立美術館, 1964年, no. 17. 所載 『中國陶瓷美術館蔵品撰集』中國陶瓷美術館, 2005年, 図版21. 『−俑・陶・華− 館蔵優品撰集』中國陶瓷美術館, 2005年, 図版7.

99

100 45. 三彩女子 盛唐(7世紀) 高29.8 cm 来歴 繭山松太郎(1882〜1935年)が1920年代に北京にて購入. 杉山陶樹堂. 繭山龍泉堂.

101

SANCAI FEMALE FIGURINE

High Tang (7th century) H. 29.8 cm

PROVENANCE

Purchased by Mayuyama Matsutarō (1882-1935) in Beijing, 1920s. Sugiyama Tōjudō, Tokyo. Mayuyama & Co., Ltd., Tokyo.

102

103

46. 三彩胡服童子

盛唐(8世紀)

高42.8 cm

Gian Francesco Giaquili Ferrini旧蔵. John Sparks Ltd., ロンドン.

SANCAI YOUTH IN WEST ASIAN DRESS

High Tang (8th century) H. 42.8 cm

PROVENANCE

Gian Francesco Giaquili Ferrini Collection. John Sparks Ltd., London.

104

来歴

105

47. 三彩洗

SANCAI BASIN

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries) H. 2.6 cm Dia. 15.1 cm

PROVENANCE Kochukyo, Tokyo.

EXHIBITED

Chūgoku Bijutsuten Shiri-zu 3 [Chinese Art Exhibitions Series No. 3], Zuitō no Bijutsu [Art of the Sui and Tang], Osaka City Museum of Fine Art, Osaka, 1976, no. 1-123.

LITERATURE

Mizuno Seiichi, Tōsansai [Tang three-color ware], vol. 35 from the series Tōji Taikei [Great Lineage of Pottery], Heibonsha, 1977, pl. 61.

Osaka City Museum of Fine Art, eds., Zuitō no Bijutsu [Art of the Sui and Tang], Heibonsha, 1978, pl. 21.

106

盛唐(7〜8世紀) 高2.6 cm 径15.1 cm 来歴 壺中居. 出展 「中国美術展シリーズ3 隋唐の美術」大阪市立美術館, 1976年, no. 1-123. 所載 水野清一『陶磁大系 第三五巻 唐三彩』平凡社, 1977年, 図版61. 大阪市立美術館編『隋唐の美術』平凡社, 1978年, 図版21.

107

48. 三彩洗

盛唐(7〜8世紀)

SANCAI BASIN

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries) H. 4.2 cm Dia. 21.6 cm

PROVENANCE

Kochukyo, Tokyo.

Inoue Tsuneichi (1906-1965) Collection.

108

高4.2 cm 径21.6 cm 来歴 壺中居. 井上恒一(1906〜1965年)旧蔵.

109

盛唐(7〜8世紀)

高4.7 cm 径18.9 cm

Bluett & Sons, ロンドン.

Robert Stanley Hope Smith(1910〜1979年)旧蔵.

SANCAI TRIPOD TRAY WITH HŌSŌGE FLOWER DESIGN

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries)

H. 4.7 cm Dia. 18.9 cm

PROVENANCE

Bluett & Sons, London.

Robert Stanley Hope Smith (1910-1979) Collection.

110 49. 三彩宝相華文三足盤

来歴

111

三彩印花宝相華文洗

盛唐(7〜8世紀)

高5.7 cm 径23.5 cm

Rose Movius Palmer(1909〜2003年)旧蔵. The Art Institute of Chicagoに寄贈, シカゴ, 1976年.

SANCAI BASIN WITH STAMPED HŌSŌGE FLOWER DESIGN

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries)

H. 5.7 cm Dia. 23.5 cm

PROVENANCE

Rose Movius Palmer (1909-2003) Collection. Gift to the Art Institute of Chicago, 1976.

112

来歴

50.

113

高5.6 cm 径28.4 cm

Rose Movius Palmer(1909〜2003年)旧蔵. The Art Institute of Chicagoに寄贈, シカゴ, 1976年.

SANCAI TRIPOD TRAY WITH STAMPED FLYING BIRDS AND LOTUS LEAVES DESIGN

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries) H. 5.6 cm Dia. 28.4 cm

PROVENANCE

Rose Movius Palmer (1909-2003) Collection. Gift to the Art Institute of Chicago, 1976.

114 51. 三彩印花飛鳥蓮葉文三足盤 盛唐(7〜8世紀)

来歴

115

52. 三彩印花鴛

盛唐(7〜8世紀) 高2.6 cm 径14.9 cm

鴦連珠文洗

Kate Sturges Buckingham(1858〜1937年)旧蔵. The Art Institute of Chicagoに寄贈, シカゴ, 1928年.

SANCAI BASIN WITH STAMPED MANDARIN DUCKS AND PEARL CIRCLE DESIGN

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries) H. 2.6 cm Dia. 14.9 cm

PROVENANCE

Kate Sturges Buckingham (1858-1937) Collection. Gift to the Art Institute of Chicago, 1928.

116

えんおう

来歴

117

53. 三彩万年壺

盛唐(7〜8世紀)

高20.1 cm 胴径17.8 cm

Rolf Cunliffe(1899〜1963年)旧蔵. 出展

「Wares of the T’ang Dynasty」The Oriental Ceramic Society, ロンドン, 1949年, no. 26. 「The Arts of the T’ang Dynasty」The Oriental Ceramic Society, ロンドン, 1955年, no. 98.

The Oriental Ceramic Society『The Arts of the T’ang Dynasty』1955年, 図版7-h99.

SANCAI JAR

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries)

H. 20.1 cm Torso Dia. 17.8 cm

PROVENANCE

Rolf Cunliffe (1899 – 1963) Collection.

EXHIBITED

Wares of the T’ang Dynasty, The Oriental Ceramic Society, London, 1949, no. 26. The Arts of the T’ang Dynasty, The Oriental Ceramic Society, London, 1955, no. 98.

LITERATURE

The Oriental Ceramic Society, The Arts of the T’ang Dynasty, 1955, pl. 7-h99.

118

来歴

所載

119

54. 三彩有蓋万年壺

盛唐(8世紀)

cm 胴径21.6 cm

第15巻

1956年, 図版10.

1961年, 図版10.

1961年, 挿図79.

第一集』便利堂, 1976年, 図版248.

1977年, 図版43.

挿図94.

SANCAI JAR WITH LID

High Tang (8th century) H. 27.0 cm Torso Dia. 21.6 cm

LITERATURE

Zauhō Kankōkai (ed.), Zuitō hen [Sui-Tang], vol. 9 from the series Sekai Tōji Zenshū [Ceramic Art of the World], Kawade Shobo, 1956, pl. 10.

Zauhō Kankōkai (ed.), Sui-Tang, vol. 9 from the series Collection of World's Ceramics, Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 1961, pl. 10. Chūgoku (4) Zui Tō [China (4) Sui Tang], vol. 15 from the series Sekai Bijutsu Zenshū [Art of the World], Kadokawa Shoten, 1961, fig. 79. Mayuyama & Co., Ltd., Mayuyama Seventy Years Vol. Ⅰ , Benrido, 1976, pl. 248. Mizuno Seiichi, Tōsansai [Tang three-color ware], vol. 35 from the series Tōji Taikei [Great Lineage of Pottery], Heibonsha, 1977, pl. 43. Satō Masahiko, Chūgoku Tōjishi [History of Chinese Ceramics], Heibonsha, 1978, fig. 94.

120

高27.0

所載 座右寶刊行會編『世界陶磁全集 第9巻 隋唐篇』河出書房,

座右寶刊行會編『世界陶磁全集 第九巻〈中國 隋唐篇〉』河出書房新社,

『世界美術全集

中国(4)隋・唐』角川書店,

繭山龍泉堂『龍泉集芳

水野清一『陶磁大系 第35巻 唐三彩』平凡社,

佐藤雅彦『中国陶磁史』平凡社1978年,

121

55. 三彩万年壺

盛唐(8世紀)

高20.7 cm 胴径21.0 cm

Neill Malcom(1869〜1953年)旧蔵.

SANCAI JAR

High Tang (8th century) H. 20.7 cm Torso Dia. 21.0 cm

PROVENANCE

Neill Malcolm (1869-1953) Collection.

122

来歴

123

56. 褐釉弦文壺

盛唐(7〜8世紀)

高14.9 cm 胴径13.3 cm

Gian Francesco Giaquili Ferrini旧蔵. John Sparks Ltd., ロンドン.

AMBER GLAZED JAR WITH SHOULDER RIDGE

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries) H. 14.9 cm Torso Dia. 13.3 cm

PROVENANCE

Gian Francesco Guiquili Ferrini Collection. John Sparks Ltd., London.

124

来歴

125

57. 緑釉有蓋万年壺

盛唐(7〜8世紀) 高18.4 cm 胴径17.0 cm

GREEN GLAZED JAR WITH LID

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries) H. 18.4 cm Torso Dia. 17.0 cm

126

127

58. 藍釉洗

盛唐(7〜8世紀)

高3.4 cm 口径10.6 cm

Bluett & Sons, ロンドン.

A. Lionel Despointes旧蔵.

Sotheby & Co., ロンドン, 1954年, lot 6. Robert Stanley Hope Smith(1910〜1979年)旧蔵.

「Exhibition of Wares of the T’ang Dynasty」The Oriental Ceramic Society, ロンドン, 1949年, no. 116.

BLUE GLAZED BASIN

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries)

H. 3.4 cm Mouth Dia. 10.6 cm

PROVENANCE

Bluett & Sons, London.

A. Lionel Despointes Collection.

Sotheby & Co., London, 1954, lot 6. Robert Stanly Hope Smith (1910-1979) Collection.

EXHIBITED

Exhibition of Wares of the T'ang Dynasty, The Oriental Ceramic Society, London, 1949, no. 116.

128

来歴

出展

129

59. 三

彩

盛唐(7〜8世紀)

高7.2 cm 幅9.5 cm

C. T. Loo & Co., パリ, 1949年4月10日.

Bluett & Sons, ロンドン, 1949年6月9日.

Rolf Cunliffe(1899〜1963年)旧蔵.

「The Arts of the T’ang Dynasty」The Oriental Ceramic Society, ロンドン, 1955年, no. 101.

SANCAI FU TRIPOD VESSEL

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries) H. 7.2 cm W. 9.5 cm

PROVENANCE

C. T. Loo & Co., Paris, 10 April 1949.

Bluett & Sons, London, 9 June 1949.

Rolf Cunliffe (1899-1963) Collection.

EXHIBITED

The Arts of the T'ang Dynasty, The Oriental Ceramic Society, London, 1955, no. 101.

130

ふく

来歴

出展

131

FU TRIPOD VESSEL WITH BLUE PIGMENT

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries) H.

cm

PROVENANCE Kochukyo, Tokyo.

LITERATURE

Zauhō Kankōkai (ed.), Zuitō hen [Sui-Tang], vol. 9 from the series Sekai Tōji Zenshū [Ceramic Art of the World], Kawade Shobo, 1956, pl. 72 lower middle.

Zauhō Kankōkai (ed.), Sui-Tang, vol. 9 from the series Collection of World's Ceramics, Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 1961, fig. 72 lower middle.

Mizuno Seiichi, Tōsansai [Tang three-color ware], vol. 25 from the series Tōki Zenshū [Complete Collection of Pottery], Heibonsha, 1965, pl. 44e.

132 60. 藍 ふく 彩 盛唐(7〜8世紀) 高7.0 cm 幅9.0 cm 来歴 壺中居. 所載 座右寶刊行會編『世界陶磁全集 第9巻 隋唐篇』河出書房, 1956年, 図版72下中. 座右寶刊行會編『世界陶磁全集 第九巻〈中國 隋唐篇〉』河 出書房新社, 1961年, 図版72下中. 水野清一『陶器全集 第25巻 唐三彩』平凡社, 1965年, 図 版44e.

7.0 cm W. 9.0

Sparks, Ltd., ロンドン.

M. Sackler(1913〜1987年)旧蔵.

Sackler(1913〜2000年)旧蔵.

Years of Chinese Art: Ceramics from the Arthur M Sackler Collections」Israel Museum, エルサ レム, 1987年.

FU TRIPOD VESSEL WITH BLUE PIGMENT

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries)

5.5 cm W. 7.0 cm

PROVENANCE

John Sparks, Ltd., London. Arthur M. Sackler (1913-1987) Collection. Else Sackler (1913-2000) Collection.

EXHIBITED

3500 Years of Chinese Art: Ceramics from the Arthur M. Sackler Collections, Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 1987.

133 61. 藍 ふく 彩 盛唐(7〜8世紀) 高5.5 cm 幅7.0 cm 来歴 John

Arthur

Else

出展 「3500

H.

Giaquili

AND COVER WITH BLUE PIGMENT

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries)

4.5 cm Dia. 9.5 cm

PROVENANCE

Gian Francesco Giaquili Ferrini Collection.

134 62. 藍彩盒子 盛唐(7〜8世紀) 高4.5 cm 径9.5 cm 来歴 Gian Francesco

Ferrini旧蔵. BOX

H.

135 63. 藍釉盒子 盛唐(7〜8世紀) 高2.7 cm 径6.9 cm BLUE GLAZED BOX AND COVER High Tang (7th - 8th centuries) H. 2.7 cm Dia. 6.9 cm

64. 三彩盒子

盛唐(7〜8世紀) 高2.7 cm 径7.5 cm

壺中居.

SANCAI BOX AND COVER

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries) H. 2.7 cm Dia. 7.5 cm

PROVENANCE Kochukyo, Tokyo.

136

来歴

137

65. 藍彩碗

盛唐(7〜8世紀)

高4.6 cm 口径10.6 cm

Kate Sturges Buckingham(1858〜1937年)旧蔵. The Art Institute of Chicagoに寄贈, シカゴ, 1924年.

BOWL WITH BLUE PIGMENT

High Tang (7th - 8th centuries)

H. 4.6 cm Mouth Dia. 10.6 cm

PROVENANCE

Kate Sturges Buckingham (1858-1937) Collection. Gift to the Art Institute of Chicago, 1924.

138

来歴

139

高3.3 cm 径5.7 cm

SANCAI BOX AND COVER High Tang (8th century) H. 3.3 cm Dia. 5.7 cm

140 66. 三彩盒子 盛唐(8世紀)

JAR WITH HANDLE

141 67. 三彩把手壺 盛唐(8世紀) 高6.5 cm 胴径6.0 cm 来歴 小林一三(1873〜1957年)旧蔵. SANCAI

High Tang (8th century) H. 6.5 cm Torso Dia. 6.0 cm PROVENANCE Kobayashi Ichizō (1873-1957) Collection.

68. 三彩華盤

盛唐(8世紀)

高5.1cm 幅17.4 cm

Russell M. Tyson(1867〜1963年)旧蔵.

The Art Institute of Chicagoに寄贈, シカゴ, 1951年.

SANCAI FOLIATE TRAY

High Tang (8th century) H. 5.1 cm W. 17.4 cm

PROVENANCE

Russell M. Tyson (1867-1963) Collection. Gift to the Art Institute of Chicago, 1951.

142

来歴

143

どのミニチュアは、玩具類あるいは装飾のための置物類に含めることができ るかもしれない。墓誌を伴った子どもの墓は極めて稀だが、河南沁陽の唐天宝

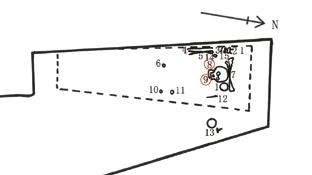

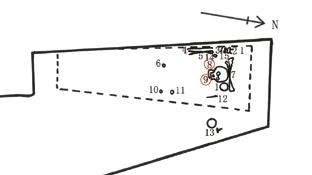

145 唐代(618 907 年)の鉛釉陶器として、いわゆる唐三彩が最も広く知られて いる。造形によって分類するならば、唐三彩は大きく俑類、建築模型類、器皿 類に分けることができる。そのうち、人物、馬、駱駝、鎮墓獣などの俑類や、 家屋、築山、棚などの広い意味での模型類は、主に墓に入れて副葬に用いる明 器に含まれる。もちろん、わずかながら例外もあり、一概に論じることは難し い。そのなかでも、あどけない男女の童俑、コミカルな牛車、鞍を置いた馬な

十四年(755 年)墓は、わずか 5 歳で夭折した李洪鈞が埋葬されており、三足鍑 (高 3 8㎝)、緑釉水注(高 6 5㎝)などのミニチュアが出土している 1。目下確認 されている小型三彩陶の中でも、この度の『唐三彩』展に出品されている環状 把手杯(図版 17)、弁口水注(図版 22)、四耳貼花小壺(図版 23)、三足鍑(図版 59、60、61)などのミニチュアは、もしかしたら児童用の玩具に属するもので、 子どもの墓に明器として副葬されたものかもしれない。しかしながら、目下の 考古資料を見る限り、大型製品を含む唐三彩の器皿類は、おそらくすべてが副 葬用の明器であったというわけではなく、人々が使用するための什器であった 可能性も考えられる。 1. 初唐の三彩 唐三彩の器皿類について検討するためには、まず器皿類が唐三彩の中で最も 早く出現したグループであることに留意する必要がある。これまでに発見され た、副葬に用いる明器の俑類の早い考古遺物の例としては、洛陽の則天武后期 垂拱三年(687 年)王雄誕夫人魏氏墓まで遡ることができる 2。これより早い時 代の出土例として、陝西省の上元二年(675 年)李 りほう 鳳墓出土の彩 さいとう 榻[寝台の意味] (挿図 1) 3 があり、検討の余地が残っているが、これ以外の唐高宗期(650 683 年)の三彩陶は、いずれも広い意味で器皿類に含まれている。水野清一氏はか つて唐詩の 4 分期になぞらえ、唐三彩を初唐(618 684 年)、盛唐(684 756 年)、 中唐(756 827 年)、晩唐(827 907 年)に区分している 4。この分期に従うと、 唐三彩雑感 謝 明良 挿図1 三彩榻 中国陝西省献陵 唐上元二年(675)李鳳墓出土 長さ25cm

たものだと考えられる。河南鞏義窯の区域を跨いだ広大な流通範囲は、非常に 驚くべきものがある。

唐三彩の酒杯の器形は多様で、著名な杯のタイプとしては、李白(701 762 年)が『襄陽歌』に詠んだ「鸚鵡杯」が思いつく。鸚鵡の頭部は写実的で、腹 部は杯の形をしており、頭が腹部を向いている。また、首を体に向けた川鵜の 姿を模した鵜首角杯や、龍首角杯、さらには巻貝を半分に切ったような三彩螺 杯もある。後者の造形は法螺貝を模したもので、文献の記載によると、法螺貝

の殼の尾部の尖った箇所には段ができており、一つの空間が貫通しているだけ なので、酒器として用いると一気に飲み干すことができず、宴会などで罰杯と して用いるのに最適であった。そのほかにも、祖型が西方のリュトン(Rhyton) と関連する杯のタイプもあり、各種の獣首角杯のほかにも、長い鼻を反らせて

146 現在までに確認されている初唐の三彩は、ほぼすべてが器皿類に含まれる。 正式な発掘により初唐の墓葬から出土した三彩器には、型で成形された印花 の杯が比較的多く見られる。山東省陵県の咸亨二年(671 年)東方合夫婦墓 5 や、 遼寧省朝陽の咸亨三年(672 年)勾龍墓から出土した印花杯(挿図 2) 6、そして 今回の『唐三彩』展に出品されている 12 弁の菱形杯(図版 10)、半円形の杯(図 版 11、12、13)など、印花で成形された杯のスタイルは、いずれも西方の金銀 器を模倣している。後者は、日本の三重県 縄 なお 生 廃 はいじ 寺 遺跡の塔基で発見された、 舎利容器の上部を覆っていた唐三彩印花杯とよく似ている。上原真人氏が廃寺 遺跡出土の瓦をもとに作った編年を見ると、縄生廃寺はおよそ 7 世紀末から遅 くとも 8 世紀初期までに建立されており 7、舎利を安置する空間に置かれてい た三彩杯の年代は、当然それよりも早いと見るべきである。さらには、河南省 鞏 きょうぎこうや 義黄冶窯跡からこのタイプの印花杯を造るための陶器製の型が見つかってい ることから、7 世紀中後期に流行した三彩印花杯の多くは、鞏義窯で生産され

環状にした、耳付きの印花象首杯ないしは獣首杯がある。西安唐墓(挿図 3) 8 、 洛陽唐墓 9、湖北省鄖県の嗣聖元年(684 年)李徽墓などでも、このタイプの三 彩獣首杯と角杯(挿図 4)が出土している 10。これ以外には、下に承盤が付属す る多子杯もあり、例えば洛陽咸亨元年(670 年)張文惧墓からの出土例が確認で 挿図2 印花杯 中国遼寧省朝陽市咸亨三年(672)勾龍墓出土 直径12cm 挿図3 三彩象首杯 中国陝西省西安南郊唐墓出土 高さ7cm 挿図4 中国湖北省嗣聖元年(684) 李徽墓出土唐三彩(実測図)

く用いられた技法であったと判断できる。『唐三彩』展に出品されている梅瓶(図 版 3)や、二段の燭台(図版 4)もまた、その一例である。前者の梅瓶は、中国

147 き(挿図 5)、今回の『唐三彩』展でも類品(図版 21)が出品されている。承盤 内に置く小杯の数は決まっていないが、それらが取り囲む盤の中央には、高足 盤や口がすぼんだ盂などが置かれることもあり、いくつかのバリエーションが 確認されている。このタイプの多子盤は盤の中心に一つの杯(あるいは盂など) を置き、その周囲に六つの小さい杯を置くことが多いため、「七星盤」という 名称で呼ばれることがある。なお、杯の数が少ない場合や、あるいは 7 個以上 が置かれた唐代の多子杯盤であっても、この名称が用いられる。 以上のように、現在までに発見された考古資料から判断すると、初唐(618 684 年)の三彩器はみな広い意味での器皿類に含まれ、専ら副葬に用いる陶俑 などの明器は今のところ確認されていない。このため、唐三彩の出現は唐代の 人々が厚葬を好んだために起こったというよく聞く学説は、考古出土状況と合 致しないのである。 陝西省で見つかった上元二年(675 年)の李鳳墓出土の三彩榻(前掲挿図 1)や 三彩瓢形有足盤、さらにはその他の初唐の三彩器の施釉技法を見ると、線描あ るいは点を繋げて線を表す方法によって、緑色や褐色の釉を素地の上に施して いる。このように、鉛釉が流れる効果を活かした施釉方法は、初唐の三彩でよ

での出現時期が北朝まで遡る器物で、陝西省の隋大業四年(608 年)李静訓墓か らは、墨緑ガラスの小梅瓶(挿図 6)が出土している。二段の燭台は隋唐期の響 銅など金属器によく見られ、河南省鞏義市の芝田二電廠唐墓(M4)からも、こ のタイプの三彩燭台(挿図 7)が確認されている。 2. 唐三彩器皿類の用途 高火度焼成で造られる堅牢な炻器と比べて、陶胎上に鉛釉を施して低火度焼 成を行う唐三彩などの鉛釉陶は、どうしても柔らかく粗製になってしまう。一 部の器皿類は、高火度で素焼した後に釉をかけ、低火度で二次焼成を行ってい るとはいえ、やはり液体を入れるのには向いていない。さらには鉛釉陶器を使 用することで、慢性的な鉛中毒を引き起こし、ひどい場合には死に至ると認識 されていたという説も聞く。もっとも、鉛の毒性は近代における公衆衛生の発 展によって明らかになったことであり、鉛や水銀などが有毒金属だという現代 人の考え方を、それらが不老長寿の仙薬の材料だと信じていた古代中国の人々 に当てはめることはできない。 一方で学術界においては、墓葬以外の遺跡からも唐三彩が出土することが、 挿図5 三彩杯と承盤 中国河南省洛陽市咸亨元年(670)張文倶墓出土 直径25cm 挿図6 墨緑ガラス梅瓶 中国陝西省隋大興四年(608)李静訓墓出土 高さ16cm 挿図7 三彩燭台 中国河南省鞏義市芝田二電廠唐墓(M4)出土 高さ24cm

唐三彩の器皿に仏教儀物が含まれていたかを証明することは困難だが、以下 にいくつかの寺院遺跡から出土した唐三彩の資料を列挙することで、唐三彩が 仏僧たちに受容されていたのかについて簡単に示したい。例えば、陝西省臨潼

慶山寺の舎利塔の下で見つかった釈迦如来舎利精室には、石門の両側に護法の ための三彩獅子(挿図 9)が 2 匹安置されていただけでなく、石製の舎利宝帳の 前方には、1 列に並んだ三彩供盤が 3 件置かれていた。真ん中の盤には三彩の 南瓜(挿図 10)が供えられており、その他の

148 徐々に認識されるようになってきた。出土する唐三彩の器形は、玩具とおぼ しき小型俑像や仏像(羅漢)の破片等を除き、圧倒的多数は器皿類に属してい る 11。この状況は、唐三彩の器皿類のある一群が、実用器物として供されてい た可能性を実証している。このため、本稿では唐三彩の器皿類を観察すること で、いったいどのように「実用」されていたのかを検討し、それらが消費され た文脈を整理してみたい。 唐三彩の製品には、まれに浄瓶(挿図 8)などの仏教用具に関する器種が確認 できるうえ 12、仏教遺跡からも少なからず唐三彩が出土している。筆者はこの 類の三彩浄瓶が確実に仏僧によって使用されていたのか、あるいは陶工が寺院 の金属器などの象徴的な器物を模して作ったのか、実証することはできない。 しかしながら、唐三彩の器皿類と仏教儀物との間には、興味深い関連性がある。

2 件の盤には、それぞれガラス製 の供物が数件ほど置かれていた。共伴した「上方舍利塔記」の石碑には、下の 方に「翰林内供奉僧貞干詞兼書」銘と「大唐開元廿九年(741 年)四月八日」の 紀年銘が彫られていた 13。他の例として、唐長安城太平坊実際寺遺跡からは、 口径が 30㎝にもなる折沿盆(挿図 11)が出土し 14、陝西華陽西岳廟遺跡からは、 装飾が極めて美しい蓋付きの三彩盒子が見つかっている 15。江蘇省揚州では、 日本からの留学僧であった円仁が仏法を求めて入唐した際に住んだ龍興寺の遺 跡からも、三彩の資料が出土している 16。さらに、唐長安城新昌坊東南に位置 する密教の中心的寺院であった青龍寺からは、念珠を手に携えた三彩羅漢像(挿 図 12)が出土している 17。同じ造形の三彩羅漢の残欠(挿図 13)は、陝西省西安 の旧飛行場で、かつての長安城醴 れいせんぼう 泉坊内に比定される地点からも出土している。 近くには三彩窯跡が見つかっていることから、羅漢像はこの窯で焼造された製 品であったと推定されている 18 。 西安旧飛行場の三彩窯跡は、唐代には長安城醴泉坊に位置しており、窯場は 挿図8 三彩浄瓶 中国陝西省西安三橋鎮出土 高さ26cm 挿図9 三彩獅子 中国陜西省臨潼慶山寺塔基出土 高さ18cm 挿図10 三彩南瓜 中国陜西省臨潼慶山寺塔基出土 南瓜:直径 14cm 盤:直径24cm 挿図11 三彩折沿盆 中国陝西省唐長安城太平坊実際寺遺跡出土 直径30cm

14)は、専ら寺院のために焼造した物であった

造した窯場が見つかっている。この窯の位置は、唐代前後には白馬寺の領域で

年)に比定

149 挿図12 三彩羅漢残部 中国陝西省西安唐青龍寺遺跡出土 高さ4cm 挿図14 三彩磚 唐長安醴泉坊窯跡出土 挿図15 三彩枕の実測図 中国江西省瑞昌県唐墓出土 左:高さ5cm 右:直径20cm 長さ11cm 街道を隔てて醴泉寺と隣接していたため、報告書ではその窯が寺院に関連して いたと判断し、醴泉寺窯と名付けている。確かに、この窯跡で見られる三彩 羅漢像や宝相華文の磚(挿図

19 。 この他にも、河南省洛陽の白馬寺からも、唐三彩の盆、盂、豆など器皿類を焼

あり、その北側で唐代に修建された寺院の遺跡も発見された。報告書ではさら に関連する文献史料を対照させ、窯の創業時期を武周垂拱初年(685

している。くわえて、薛 せつかいぎ 懐義が白馬寺の住持であった時に、白馬寺が勅命で修 建されたことと密接に関わっていたと判断し、この窯が「官窯」であったと述 べた上で、共伴した三彩資料はおそらく白馬寺院で使用した器物であったと指 摘している 20。上述の西安醴泉坊窯と洛陽白馬寺窯の 2 箇所の三彩窯場は、寺 院に所属するものであったのか、あるいは寺院と関連があったのか、証明する ことは難しい。しかし、醴泉坊窯で焼造された三彩羅漢像が寺院で使用されて いたこと自体は、考古発掘によってすでに実証されたと言えるだろう。 寺院遺跡から出土した唐三彩資料について、個々の三彩窯場が寺院によって 運営されていた可能性を考える以外に、1980 年代に江西省瑞昌県で唐三彩枕 形器が出土した遺跡は、報告書によって「僧人墓」であると比定されており、 注目に値する。この瑞昌県范鎮郷朱家村唐墓は、墓室が完全に破壊されており、 形状も不明であったが、三彩枕形器(報告書では「脈枕」と書かれている)(挿 図 15)の他にも、青銅鍍金塔式頂盒子、青銅鍍金瓶鎮柄香炉、青銅鉢が共伴し ていたようである 21。近年の調査によって明らかになったが、仏具として造ら れたであろうこの瓶鎮柄香炉は、実際には范鎮八都村の畑から出土しており、 挿図13 三彩羅漢残部 唐長安醴泉坊窯跡出土 高さ7cm

范鎮朱家村から出土した三彩枕形器とは全く関係が無かった 22。しかし青銅鍍 金盒子と青銅鉢は、確かに三彩枕形器と共に出土しており、日本の正倉院に収 蔵されている内部に香などを入れた高足銅盒子とも類似している 23。さらには、 洛陽永泰元年(765 年)荷澤神会身塔の塔基から共に出土した銅盒と手炉の組み 合わせを想起させる 24。ここから、瑞昌范鎮朱家村の盒子は、本来は手炉と組 み合わせて使用する仏具であった可能性があり、これによりその墓主が仏僧で

彩枕形器は、仏教に関連した什器であった可能性が高い。

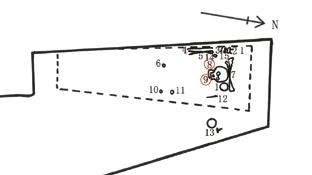

『唐三彩』展には、器形が異なる多くの枕形器ないしは磚形器が出品されて いる(図版 26、27、28、29、30、31)。だが、この類の作例が本当に枕であっ たのかという問題が存在し、学術界でも意見が分かれている。先行研究を見る と、その用途として頭枕、脈枕、書枕、頸枕、明器枕、および台座、文鎮など の諸説が提示されている。日本の奈良県の大安寺講堂遺跡から出土した、復元 すると約 30 〜 40 個体になる三彩枕形器を見ると、このタイプの作品が仏教に 関わる什器であった可能性が高いように思える 25。またこの用途に関する事例 として、陝西省銅川新区西安変電廠一号墓(M1)は未盗掘墓であり、ここから 出土した三彩枕は、墓主の頭骨の下に置かれていた(挿図 16)26。その墓の年代 は遅くとも中唐期(756 827 年)であり、盛唐期の三彩枕形器が、頭の下に置く 枕として使われていた可能性を考える上での重要な事例となる 27 。

150

あった可能性が高まった。以上のように、青銅盒子などの仏具と共出した唐三

挿図16 図中の8は三彩枕、9は「開元通宝」(口に含む) 中国陝西省銅川新区西安変電廠一号墓 平面図

墓獣」という俗称で呼ばれるが、実はこれは近代の人が命名し

年代に河南省鞏義唐墓から出土した、

151 3. 陶俑および明器としての模型 7 世紀後期から 8 世紀中期、すなわち則天武后の大周年間か ら、玄宗皇帝の開元〜天宝年間は、唐朝が最も繁栄した時代で あり、唐三彩の副葬用陶俑の生産が始まり、発展のピークを迎 えた段階に当たる。この時期には唐三彩陶が共伴する墓葬の例 が極めて多く、河南省洛陽と陝西省西安の唐代両都が置かれて いた地区に集中している。本章では、未盗掘で発見されたため に保存状態が良好で、なおかつ墓主の身分と埋葬年代が明らか な洛陽孟津西山頭唐墓(M64)出土の唐三彩を例に見ていきた い 28。この墓の墓主である屈 くっとつきさつ 突季札は、銀青光禄大夫燕郡公で あった屈突詮の子であり、天授二年(691 年)に洛陽 北 ほくぼうざん 邙山 に埋 葬された。出土した三彩陶は、鎮墓獣、天王俑、文武官俑、騎 馬俑、男女立俑、動物俑などを含んでおり、そのうちの三彩鎮 墓獣(挿図 17a)、男騎俑(挿図 17b)、三彩犬(挿図 17c)の造形は、 『唐三彩』展の出展作品(図版 38、40、43)を見る上での参考資 料となる。河南洛陽の景龍三年(709 年)安国人定遠将軍安菩夫 婦墓から出土した三彩女俑(挿図 18)は、髪形と衣服のスタイ ルが今回出品されている女俑(図版 45)のそれとよく似ている。 単角人面と双角獣面の 2 件が 1 組で組み合わされる俑は、「鎮

た呼称である。1980

1 件 の双角獣面陶製鎮墓獣の背中には、墨書で「祖明」という字が 書かれていた(挿図 19 a、b)29。唐開元二十七年(739 年)の『唐 六典』によれば、副葬品として墓に入れる類の「四神」には、「当 壙、当野、祖明、地軸」があると記載されていることから、こ の獣面鎮墓獣は四神の一つである「祖明」であったと考えられ る。 前述した通り、これまでに確認されている副葬品として墓に 入れられた三彩陶俑は、最も早い例が洛陽垂拱三年(687 年)王 雄誕夫人魏氏墓である。そして、今回の『唐三彩』展に出品さ れた南海地域(唐代には 崑 こんろん 崙 と呼ばれた)の人を象った三彩俑 (図版 9)は、大英博物館にも類品がある他、その造形が陝西禮 泉麟徳元年(664 年)右武衛大将軍鄭 ていじんたい 仁泰墓から出土した灰陶加 彩俑とおおむね一致している(挿図 20)30。鄭仁泰墓は盗掘に 挿図17a 三彩鎮墓獣 左:通高62.5cm 右:通高69cm 中国河南省洛陽天授二年(691) 屈突季札墓出土 挿図17b 三彩男騎馬俑 通高39cm 中国河南省洛陽天授二年(691) 屈突季札墓出土 挿図17c 三彩犬俑 高さ14.4cm 中国河南省洛陽天授二年 (691)屈突季札墓出土 挿図18 三彩女俑 中国河南省洛陽景龍三年(709) 安菩夫婦墓出土 高さ33cm

あっているが、墓中には白地コバルト藍彩蓋鈕の破片(挿図 21)が 1 件残され ており、唐三彩鉛釉陶の器皿類の最も早い製作年代は、660 年代まで遡る可能 性が考えられる。くわえて、造型が良く似ている鄭仁泰墓灰陶加彩俑と前述の 三彩南海人物俑の製作された年代も注目に値する。二つの俑が似ている要因と して、同一類型の陶俑を成形する「型」が長い期間にわたって使用されたため、 三彩俑の副葬が流行した

7 世紀後期においても、数十年前のスタイルの俑や像 が造られたのか。あるいは、7 世紀中期にすでに三彩釉を施した俑や像が造ら れていたのか。さらに深く検討する必要があるだろう。

ここで一度、鄭仁泰墓出土の藍彩を施した蓋の鈕について見てみたい。良く 知られたことではあるが、この藍彩は中国陶磁史上初めてコバルト藍釉を用い て加飾した事例である。かつて行われた唐代鉛釉陶藍彩の化学分析によると、 そのコバルト顔料は鉄分が多く、マンガンが少ないことが明らかにされている。 中国産のコバルト顔料は、マンガンが多く鉄が少ないため、この藍彩には輸入 顔料を使用していたと考えられ

152

31、外来のコバルト藍ガラスを加工していた可 能性もある。コバルト藍彩を帯びた唐代鉛釉陶器は、多くが凝った作りになっ ており、レベルも比較的高く、それは今回の『唐三彩』展の作品からも感じる ことができる。なお、最も有名な考古出土例としては、唐垂拱三年(687 年)に 副葬された河南恭陵の太子妃 裴 はい 氏(諡号は哀皇后という)墓から出土した、コ バルト藍釉双龍耳瓶(挿図 22)等の作品を挙げることができる 32 。 『唐三彩』展には、藍彩を施した作品も多く出品されており、前掲の小型の 鍑(図版 59、60、61)の他、盒子(図版 62、63)、洗(図版 58)、印花の連珠平 盤(図版 52)、碗(図版 65)、4 弁の輪花盤(図版 68)、双耳壺(図版 16)がある。 後者の壺はいわゆる「万年壺」のスタイルであり、この類の器物にはもともと 挿図19a 陶鎮墓獣 中国河南省鞏義市唐墓出土 高さ30cm 挿図19b 図19aの背面「祖明」墨書 挿図20 中国陝西省昭陵麟徳元(664) 鄭仁泰墓出土 高さ30cm 挿図21 藍彩蓋鈕 中国陝西省昭陵麟徳元年(664)鄭仁泰墓出土 高さ3cm 挿図22 濃緑釉龍耳瓶 唐垂拱三年(687) 中国河南省偃師市恭陵哀皇后墓出土 高さ32.2cm 洛陽博物館蔵

153 蓋が添っており、前述した鄭仁泰墓の藍彩鈕(前掲挿図 21)が、まさに このような器物に乗せる蓋の鈕部分であった。このほか、出品された 胡服童子(図版 46)の衣服には、黄褐釉と藍釉が施されている。その姿 勢は、よく見られる駱駝を引く胡人馭駝俑と共通している。『唐三彩』 展に出品された明器の模型にもまた、藍釉を施したタイプがあり、四 方の舂杵(図版 34)や井戸(図版 35)を挙げることができる。唐墓では、 このように陶製の井戸と舂碓を副葬することが度々見られる。例えば、 前述の洛陽孟津天授二年(691 年)屈突季札墓では、陶製の井戸、舂碓、 かまど等が見つかっており、洛陽景龍三年(708 年)宣州宣城令李敬彝 墓からは、黄褐釉を施した陶製の井戸が出土している(挿図 23)33。偃 師県長寿三年(693 年)張思忠墓からは、三彩陶の舂碓と井戸が共伴し ている他、同時に盤中央に 1 件の白磁杯を置き、その周囲に 8 件の三 彩小杯を並べた多子盤も確認されている 34 。 三彩家屋の例はやや少ないが、陝西省銅川あるいは西安中堡村唐墓 から出土した三彩邸宅模型は、良く知られた名品である。邸宅建築模 型は、大門、房舎、亭、築山、および井戸、磨臼、人、馬等を含んでおり、 唐代邸宅の建築と生活空間の構造を反映している(挿図 24)。その中で も、中堡村唐墓から出土した懸山式の方形屋根の建物は、中央の扉が 開き、扉の両側には格子窓が付き、屋根はコバルト藍釉が施されてい る。家屋全体は彩色され 35、建築様式は『唐三彩』展の緑褐釉家屋(図 版 32)とよく似ている。ほかにも、出品されている藍褐釉倉(図版 33) もまた、盛唐期の北方で見られた糧倉の様式を模している。倉には扉 がなく、わずかに倉の一面の高い所に、通風口を兼ねた方形の窓が開 いており、これもまた唐代の木造倉の特徴を忠実に模倣しているので ある。 (しゃ めいりょう/國立台灣大學 藝術史研究所 講座教授) 挿図23 中国河南省洛陽景龍三年(708) 李敬彝墓出土褐釉井欄 長さ13.4cm 挿図24 三彩建築群 中国陝西省西安市西郊中堡村唐墓出土

の年代をもとに判断している、ただ山田寺は奈良時代に補修した時にも、 同じ「型」を用いて製造していた。そのうえ、山原寺式瓦は 8 世紀に下る 例も確認されている。このため、縄生廃寺の年代は必ずしも 7 世紀とは言 いきれない」と指摘している(同氏「奈良三彩の起源と唐三彩─技術 / 意 匠の系譜について」『美術フォーラム 21』4, 2001 年, p. 55)。いずれにせよ、 三彩印花杯のスタイルなどを見ると、その相対的な年代は 7 世紀後期だと 考えられる。あるいは、亀井明徳教授が主張したように、

154 註 1 李志軍等「河南沁陽唐代李洪鈞墓発掘簡報」『洛陽考古』2015 年 1 期 , pp. 30 〜 34 2 洛陽市文物考古研究院(陳誼等)「洛陽唐代王雄誕夫人魏氏墓発掘簡報」『華 夏考古』2018 年 3 期 , pp. 15 〜 29 洛陽市文物考古研究院編『唐・王雄誕夫 人魏氏墓』鄭州:中州古籍出版社 , 2016 年. 3 富平県文化館等「唐李鳳墓発掘簡報」『考古』1977 年 5 期 , pp. 313 〜 326 4 水野清一『唐三彩』陶器全集 25, 東京:平凡社 , 1965 年, pp. 8 〜 9 5 亀井明徳「日本出土唐代鉛釉陶の研究」『日本考古学』第 16 号, 2003 年, p. 153,『人民網』2002 年 3 月 21 日より引用 魏訓田「山東陵県出土唐《東 方合墓誌》考釈」『文献』2004 年 3 期 , pp. 89 〜 97 を参照。カラー図版 は、柴晶晶編「“東方朔係陵県人”的有利佐証」を参照。http://www. dezhoudaily.com/news/dezhou/folder136/2012/11/2012 11 04400444.html (閲覧日:2013 年 7 月 25 日) . 6. 朝陽市博物館(李国学等)「朝陽市郊唐墓清理簡報」『遼海文物学刊』1987 年 1 期 , 図版 2 2. 7. 上原真人「縄生廃寺の舍利容器」『仏教芸術』188 号, 1990 年, p. 119 〜 131. このほか、尾野善裕氏は、「縄生廃寺の年代は、山田寺式と山原寺式の瓦

7 世紀第 3 四半 期の可能性もある(亀井明徳「陶範成形による隋唐の陶瓷器」『出光美術館 館報』106, 1999 年, p. 84)。 8 陳安利主編『中華国宝:陝西珍貴文物集成』第 2 冊・唐三彩巻 , 西安:陝 西人民教育出版社 , 1988 年, pp. 20 〜 21 9 洛陽市博物館編『洛陽唐三彩』北京:文物出版社 , 1980 年, 図 114 10. 湖北省博物館(全錦雲等)「湖北鄖県唐李徽・閻婉墓発掘簡報」『文物』1987 年 8 期 , p. 32, 図 2 8, 11, 13, 14, および図版 4 2 〜 4 関連する先行研究とし ては、孫機「瑪瑙獣首杯」(同氏著『中国聖火─中国古文物与東亜文化交 流中的若干問題』瀋陽:遼寧教育出版社 , 1996 年, pp. 178 〜 197 所収)を参 照。 11 謝明良「唐三彩の諸問題」(成城大学)『美学美術史論集』5, 1985 年, pp. 178 〜 179,「表一:墓葬以外遺跡出土唐三彩」

155 12. 前掲註 8, 陳安利主編『中華国宝:陝西珍貴文物集成』第 2 冊・唐三彩巻 , pp. 80 〜 81. 13. 臨潼県博物館(趙康民)「臨潼慶山寺舍利塔基精室清理記」『文博』1985 年 5 期 , p. 13, および図 4 3, 4. 14. 劉瑞「西北大学出土唐代文物」『考古与文物』1999 年 6 期 , 裏表紙の図版 . 西北大学文博学院『百年学府聚珍:西北大学歴史博物館蔵品選』北京:文 物出版社 , 2002 年, 図 138. 実際寺の歴史沿革とその他の出土文物について は、柏明主編『唐長安城太平坊与実際寺』(西安:西北大学, 1994 年)を参 照のこと。 15 「陝西華陽岳廟遺址」(国家文物局『1998 中国重要考古発現』(北京:文物 出版社 , 2000 年, pp. 81 〜 83 所収) 16 南京博物院(羅宗真)「揚州唐代寺廟遺址的発現和発掘」『文物』1980 年 3 期 , p. 31 17 中国社会科学院考古研究所西安工作隊「唐青龍寺遺址発掘簡報」『考古』 1974 年 5 期 , p. 306, 図版 12 4 18 小林仁「西安・唐代醴泉坊窯址の発掘成果とその意義―俑を中心とした考 察」『民族藝術』21 号, 2005 年, pp. 118 〜 119 19 陜西省考古研究院『唐長安醴泉坊三彩窯址』北京:文物出版社 , 2008 年, p. 9 20. 中国社会科学院考古研究所洛陽漢魏故城隊(銭国祥等)「河南洛陽市白馬寺 唐代窯址発掘簡報」『考古』2005 年 3 期 , pp. 45 〜 54 21. 何国良「江西瑞昌唐代僧人墓」『南方文物』1999 年 2 期 , pp. 8 〜 10. 22. 加島勝「柄香炉と水瓶」『日本の美術』540 号, 東京:至文堂 , 2011 年, p. 46. 23. 毛利光俊彥『古代東アジアの金属製容器』Ⅰ(中国編)奈良文化財研究所 , 2004 年, p. 73. 24. 洛陽市文物工作隊(余扶危等)「洛陽唐神会和尚身塔塔基清理」『文物』1992 年 3 期 , pp. 64 〜 67, 75. 25. 日本出土の唐三彩枕形器に関する諸説については、以下の文献を参照のこ と。謝明良「日本出土唐三彩及其有関問題」『中国古代貿易瓷国際学術研 討会論文集』(1994 年)初出。後に、『貿易陶瓷与文化史』(北京:三聯書店 , 2019 年, pp. 3 〜 27)に採録。亀井明徳「三彩陶枕と筺形器の形式と用途」, 同氏著『中国陶瓷史の研究』(東京:六一書房 , 2014 年, pp. 221 〜 241)所収。 26 銅川市考古研究所(董彩琪)「陝西銅川新区西南変電站唐墓発掘簡報」『考古 与文物』2019 年 1 期 , pp. 37 〜 45

156 27. 詳しくは、謝明良「再談唐代鉛釉陶枕」『故宮文物月刊』437 期 , 2019 年初 出 ,『陶瓷手記 4:区域之間的交流和影響』(上海:上海書画出版社 , 2021 年, pp. 27 〜 39)再録。 28. 301 国道孟津考古隊(王炬等)「洛陽孟津西山頭唐墓発掘報告」『華夏考古』 1993 年 1 期 , pp. 52 〜 68. 29. 張文霞等「隋唐時期的鎮墓神物」『中原文物』2003 年 6 期 , p. 69, 図 7. カラー 図版は, 鄭州市文物考古研究所『中国古代鎮墓神物』(北京:文物出版社 , 2004 年)図 161 を参照 30. 陝西省博物館等唐墓発掘組「唐鄭仁泰墓発掘簡報」『文物』1972 年 7 期 , 図 版 10 3 31. 陳尭成等「歴代青花瓷器和青花色料的研究」『硅酸塩学報』6 巻 4 期 , 1978 年, pp. 225 〜 241 「河南鞏県黄冶窯唐代藍彩器研究」(羅宏傑等編『古陶瓷 科学技術 7:国際討論会論文集』上海:上海科学技術文献出版社 , 2009 年, pp. 319 〜 328 所収) 32 朝日新聞社等編『唐三彩展 洛陽の夢』(大広 , 2004 年, p. 51, 図 21)等、多 数の書籍に収録 33 洛陽市文物考古研究院(司馬国紀)「洛陽市唐代李敬彝墓清理簡報」『華夏考 古』2019 年 3 期 , p. 36, 図 17 1 カラー図版は , 何娟等「大唐望族・三彩風 華 洛陽唐代李敬彝墓出土三彩器物浅述」(『典蔵』古美術 , 345 期 , 2021 年, p. 98)図 27 を参照 . 34 偃師県文物管理委員会(王竹林)「河南偃師県隋唐墓発掘簡報」『考古』1986 年 11 期 , p. 999, 図 8 6, 10, および図版 6 5. 35 前掲註 8, 陳安利主編『中華国宝:陝西珍貴文物集成』唐三彩巻 , p. 99

Miscellaneous Thoughts on Tang Sancai

Hsieh Ming-liang

Today Tang sancai , or tri-colored ware, is the best-known, lead-glazed ceramic ware of the Tang dynasty (618 907). In terms of vessel shape, Tang sancai can be largely divided into figurines, architectural models and dish ware. Of those, the figurines, whether people, horses, camels, tomb guardian mythical beasts, or object and architectural miniature models, from houses to mountain-like landscape miniatures and household furnishings, were primarily made as grave goods to be interred with the deceased. Of course, there were some rare exceptions of other uses, but they are not commonly found. Of those exceptions, we might consider that some of the miniatures, such as adorable boy or girl figurines, comical ox carts or saddled horses, may have been made as toys or decorative objects. Tombs for children with burial detail steles are extremely rare, but various miniatures, including a tripod fu (H. 3.8 cm) and a green-glazed ewer (H. 6.5 cm), have been excavated from a tomb built in Qinyang, Henan province, in 755 (Tang Tianbao 14) for Li Hongjun who died at the young age of 5 1 Among the confirmed miniature sancai ceramic types known today, the miniatures included in this Tang Sancai exhibition -- such as a cup with circular handle (pl. 17), a ewer with pinched spout (pl. 22), a small jar with four handles and applique designs (pl. 23) and the tripod fu (pls. 59, 60, 61) -- are all types that could have been toys for children, and as such, may have been grave goods for children's tombs. However, to the degree I have found in archeological materials, some Tang sancai dishware, including large works, may have been used as practi cal everyday goods, while others were burial goods.

1. Early Tang Sancai

In a consideration of Tang sancai dishware types, first we must keep in mind that dishware was the earliest vessel category that appeared in Tang sancai ware. At present the earliest excavated examples of figurines used as burial goods date back to the tomb of Wei, wife of Wang Xiongdan, buried in 687 (Chuigong 3)

157

Fig. 1

Sancai Platform Bed, excavated from the tomb of Li Feng (675, Tang Shang Yuan 2) Xian Mausoleum, Shanxi province, L. 25 cm.

in Luoyang during the reign of the female emperor Wu Zetian.2 An earlier ex cavated example can be seen in the painted sleeping platform (fig. 1) 3, excavated from the tomb of Li Feng, buried in 675 (Shangyuan 2) in Shanxi province. While there is some room for further examination, Tang Gaozong period (650 683) sancai wares, except for the sleeping platform, are all dishware in the broad sense of the term. Mizuno Seiichi has previously likened sancai periods to the four periods of Tang literature, namely Early Tang (618 684), High Tang (684 756), Mid Tang (756 827) and Late Tang (827 907)4. In line with that chronology, almost all confirmed Early Tang sancai examples are dishware.

Fig. 2 Cup with Impressed Floral Designs, excavated from the tomb of Gou Long (672, Xianheng 3), Zhaoyang city, Liaoning province, Dia. 12 cm.

A relatively large number of mold-formed cups with impressed designs can be seen in the sancai wares that have been properly excavated from Early Tang tombs. The cups with impressed designs (fig. 2) excavated from such tombs as those of Dong Fanghe and his wife dated 671 (Xianheng 2)5 in Ling district, Shandong province, or the Goulong tomb dated 672 (Xianheng 3)6 in Chaoyang, Liaoning province, or among the works exhibited here, the 12-petal, lozenge-shaped cup (pl. 10), and the semi-spherical cups (pls. 11, 12 , 13), are all examples of cups formed with impressed designs, and all imitate West Asian gold and silver wares. The semi-spherical cup closely resembles a Tang sancai im pressed design cup that was found on top of the reliquary buried at the base of the pagoda in the grounds of the Naohaiji temple ruins in Mie prefecture. Looking at the chronology Uehara Mahito created on the basis of the tiles excavated at Naohaiji sites, Naohaiji was probably established at the end of the 7th century or at the latest, the beginning of the 8th century7, and thus the sancai cup placed in the reliquary enshrining space should naturally be considered to predate that period. Given that molds for the production of this type of cup with impressed designs have been found at the Gongyi Huangye kiln site, Henan province, the majority of the sancai cups with impressed designs popular in the middle and late 7th century can be thought to have been made at the Gongyi kilns, and indeed, the broad distribution range of the objects made in that kiln district is truly impressive.

Tang sancai wine cup vessel shapes vary widely and remind us of the famous yingwu (鸚鵡杯, parrot cup) type heralded by Li Bai (701 762) in his Xiangyang Song (Xiangyang ge). In this cup type a realistically formed parrot's

158

Fig. 3

Sancai Elephant Head Rhyton, excavated from a Tang tomb in the southern suburbs of, Xi’an city, Shanxi province), H. 7 cm.

Fig. 4

Archaeological Drawing of a Tang Sancai Work, excavated from the tomb of Li Hui (684, Sisheng 1), Hubei province.

head is attached to the bird's body which constitutes the cup section, with the head turned back towards its body. There are also horn-shaped cups with cormorant neck forms turned back towards the cup body, or dragon-headed horn-shaped cups and sancai snail-shell cups that look like coiled shells cut in half. The latter was made to look like a conch shell. According to textual records the pointed protruding tail section of a conch shell cup had internal steps, and since only a single hollow space extended through the whole shell, a drinker cannot drain the cup in a single draught when such cups are used as a wine vessel. This made them the most appropriate vessel type for the cups used by those who lost bets at banquets and other such events. There were also cup shapes related to the West Asian rhyton form, horn-shaped cups with various types of animal head handles and cups with various beasts, such as the impressed design elephant head cups with their long trunks turned back into a circular form. These types of animal head cups and horn-shaped cups (fig. 4) have been excavated at various tombs, including the Xi ʼan Tang tombs (fig. 3)8, Luoyang Tang tombs,9 and Li Hui tomb dated 684 (Sisheng 1) in Yun district, Hubei province.10 Other than these types there are also examples of sets of cups with accompanying trays, such as the example (fig. 5) excavated from the Zhang Wenju tomb dated 670 (Xianheng 1) in Luoyang and a similar example (pl. 21) exhibited here. A range of variations have been confirmed for such sets, with no set number of little cups placed on the trays. Often a tall footed tray (高足盤) or round jar with a small mouth (盂) is placed in the center of the tray. This type of cup and tray set in which a single cup or yu was placed in the center of the tray and then surrounded by six smaller cups, came to be known as "seven star trays" (qi xing pan 七星盤). Even if the number

Fig. 5

Sancai Tray and Cups Set, excavated from the tomb of Zhang Wenju (670, Xianheng 1), Luoyang city, Henan province, Tray dia. 25 cm.

159

Fig. 6

Blackish Green Glass Meiping Jar, excavated from the tomb of Li Jingxun (608, Sui Daxing 4), Shanxi province, H. 16 cm.

of surrounding cups was actually more or less than six, this was the name used for these cup and tray sets.

As seen above, judging from the currently excavated materials, the sancai wares from the Early Tang (618 684) were dishware in the broad sense of the term, and at present there are no known examples of works, such as figurines, specifically made as grave goods from that time period. This indicates that the frequently heard scholarly theory that Tang sancai wares appeared because of the Tang preference for elaborate funerary practices does not accord with the state of archaeological excavation evidence.

If we look at the glazing techniques used on the sancai platform bed excavated from the 675 tomb discussed above as fig. 1, a footed gourd-shaped tray, and other Early Tang sancai , we notice that drawn lines or continuous lines of dots of green and amber glaze were applied directly to the unglazed clay surface. This indicates that the glazing method which completely activated the flowing effect inherent in lead glaze was fully used in Early Tang sancai . Two works in this Tang Sancai exhibition, the meiping jar pl. 3 and the two-tier lamp pl. 4, are also examples of this fact. The meiping jar is a vessel type which appeared in China from the Northern Dynasties onwards. A small blackish green glass meiping jar (fig. 6) was excavated from the Li Jingxun tomb dated 608 (Sui Daye 4) in Shanxi province. The two-tier lamp is a shape often found in Sui and Tang copper-alloy (響銅) wares, and a sancai example (fig. 7) of this type can be confirmed from the Zhitian Erdianchang Tang Tombs (M4) (芝田二電廠唐墓) in Gongyi city, Henan province.

2. How Tang Sancai Dishware Was Used

Fig. 7

Sancai Lamp, excavated from Zhitian Erdianchang Tang Tomb (M4), Gongyi city, Henan province, H. 24 cm.

Compared to strong, high-fired stoneware, iron-glazed pottery such as Tang sancai in which iron-based glaze was applied directly to the clay body and fired at a low temperature was by nature a rougher, softer pottery form. Even if some of the dishware was bisque-fired at a high temperature, glazed, and then refired at a lower temperature, those works were not suitable for use with liquids. Further, we also sometimes hear the explanation that prolonged use of lead-glazed pottery causes chronic lead poisoning, and in worst case scenarios, death. But it wasn't until the modern era and its development of public health systems that the poisonous nature of lead came to be understood. We cannot

160

view the ancient Chinese through a modern looking glass assuming that lead, mercury and other minerals were poisonous, notwithstanding their belief that such metals were materials used by the immortals to bring about eternal youth and longevity.

On one hand, the scholarly world has gradually come to recognize that Tang sancai wares have been excavated from sites other than burial sites. With the exception of the toy-like miniature figurines or fragments of Buddhist sculptures (Arhats), dishware is the overwhelmingly commonly found excavated Tang sancai vessel type.11 This proves the possibility that a group of Tang sancai dishware type works were for actual use. For that reason, in this article, I would like to examine Tang sancai dishware types, consider how they were actually used, and get a sense of the context in which they were consumed.

While rare, some vessel types used as Buddhist equipment, such as the jingping ( jōhei , kundika, 浄瓶) ewer type (fig. 8), have been confirmed among Tang sancai products,12 and a considerable number of Tang sancai works have been excavated from Buddhist sites. I cannot prove whether or not this type of sancai jingping ewer was actually used by Buddhist priests or whether the ceramic versions were made as symbolic copies of the metalware examples of those forms held by the Buddhist temples. And yet, there is a fascinatingly close connection between Tang sancai vessel types and Buddhist ritual equipment. While it is hard to prove that Tang sancai dishware was included in Buddhist ritual equipment, I would like to use the following listing of the Tang sancai materials that have been excavated from several temple sites to show how Tang sancai was received by Buddhist priests. For example, in the Sakyamuni relic chamber discovered beneath the reliquary stupa at Qingshansi, Lintong, Shanxi province, not only were there two sancai lions (fig. 9) placed as guardian figures on either side of the stone gate, three sancai offering trays were lined up in front of the stone-carved, building-shaped reliquary (舎利宝帳). A sancai pumpkin (fig. 10) was placed as an offering on the middle tray, and offerings made of glass were placed on the other two trays. The lower section of the accompanying stone stele is carved with a dedicatory statement composed and brushed by Zhenyu (貞干), a high-ranking priest in the Hanlin organization "

Neigongfengseng Zhenyu Cijianshu] and the date, 8th day of the 4th month of

Kaiyuan

Fig. 8

Sancai Kundika Ewer, excavated from the Sanqiaozhen site, Xi’an city, Shanxi province, H. 26 cm.

Fig. 9

Two Sancai Lions, excavated from the base of the pagoda at Qingshansi, Lintong, Shanxi province, H. 18 cm.

Fig. 10

Sancai Pumpkin with Tray, excavated from the base of the pagoda at Qingshansi, Lintong, Shanxi province, Pumpkin: Dia. 14 cm, Tray: Dia. 24 cm.

161

翰林内供奉僧貞干詞兼 書" [Hanlin

741, (Datang

29, 大唐開元廿九年(741年)四月八日).13 Other

Fig. 11

Sancai Bowl, excavated from the site of Taipingfang Shijisi, Tang Chang'an castle, Shanxi province, Dia. 30 cm.

examples include the 30 cm mouth diameter deep bowl (fig. 11) excavated at the site of the Taipingfang Shijisi temple, Tang Chang'an castle,14 or the sancai box and cover with extremely lovely decoration found at the site of the Xiyue mausoleum, Huayang, Shanxi province.15 In Yangzhou, Jiangsu province, sancai materials have also been excavated from the site of Xingsi, the temple where the Japanese priest Ennin sought training in the Buddhist dharma.16 A sancai Arhat figure holding prayer beads (fig. 12) has been excavated from the site of Qinglongsi, a major Esoteric sect temple located in the southeast section of Xinchangfang, Tang Chang'an castle. A sancai Arhat figure of the same formation (fig. 13) has also been excavated at an old airport in Xi

an, Shanxi province, which is thought to be within the Liquanfang area of Chang'an castle.17 Given that a sancai kiln site has been discovered nearby, it can be surmised that these Arhat figures were fired at this kiln.18

Fig. 12

Fragment of a Sancai Arhat Figurine, excavated from the Tang Qinglongsi site, Xi’an city, Shanxi province, H. 4 cm.

Fig. 13

Fragment of a Sancai Arhat Figurine, excavated from the Liquanfang kiln site, Tang Chang'an, H. 7 cm.

an airport sancai ware kiln site was located in Liquanfang, Chang'an castle, and given that the kiln site was positioned just across a road from Liquansi temple, excavation reports concluded that the kiln was related to the temple and thus they named it Liquansi temple kiln. Originally the sancai Arhat figures and bricks and tiles (zhuan) with hōsōge designs (fig. 14) would have been created for the sole use of the temple.19 Kiln sites that fired Tang sancai dishware types, such as trays, jars and stemmed trays, have been found at Baimasi in Luoyang, Henan province. These kilns were located in the Baimasi area before and after the Tang dynasty and a site where a temple was built during the Tang dynasty has been discovered to the north of that area. The archaeological reports were cross-checked with related historical documents, and they surmised that the kilns were established in 685 (Wuzhou Chuigong 1). These reports determined that these kilns were closely connected to the imperial decree to construct Baimasi when Xue Huaiyi was Baimasi head priest, and thus stated that these kilns were “official kilns," and indicated that the sancai materials excavated from the kiln sites were probably vessels used at Baimasi.20 It is hard to prove whether the two sancai kiln sites, namely the above noted Liquanfang kiln in Xi ʼan and the Baimasi kiln in Luoyang, were part of the temples or related to temples. However, archeological excavation evidence proves that the sancai Arhat figurines produced at the Liquanfang kiln were used in a temple.

During the Tang dynasty, the former Xi

162

ʼ

ʼ

Regarding the Tang sancai materials excavated from temple sites, along with the possibility that the individual Tang sancai kilns were operated by temples, it is noteworthy that the excavation report for the site where Tang sancai pillow-shaped works were excavated in the 1980 s in the Ruichang district of Jiangxi province, identifies the site as "priest graves." The tomb chambers of these Tang tombs in Fanzhenzhujia village, Ruichang district were completely destroyed and hence their original shape is not clear, but the materials excavated from the site included not only a sancai maizhen pillow used for pulse assess ment (脈枕, fig. 15), they also report a gilt bronze covered box and stupa-shaped finial, a gilt bronze long-handled censer, and a bronze bowl.21 Recent surveys have clarified that this long-handled censer probably made as Buddhist ritual equipment and excavated from a field in Fanzhenbadou village was completely unrelated to the sancai pillow excavated in Fanzhenzhujia village.22 And yet, the gilt bronze covered box and bronze bowl were definitely excavated with the sancai pillow and those bronze works resemble the bronze covered box with high foot that contained incense which is today in the Shō sōin collection in Japan.23

They also are reminiscent of the bronze box and censer with handle combination that was excavated from the heart stone area of the Hezeshenhuishenta pagoda dated 765 (Yongtai 1) in Luoyang.24 This means that the gilt bronze incense box at Ruichang fanshenzhujia was likely used as a Buddhist ritual implement with the long-handed censer, which in turn would suggest the strong possibility that the tomb occupant was a Buddhist priest. It is highly likely that the Tang sancai pillows excavated with the bronze incense box and other Buddhist implements were originally used in some connection with Buddhism.

This Tang Sancai exhibition displays several pillows or brick-shaped works (pls. 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 and 31), albeit their shapes vary. It is still uncertain whether or not these kinds of works were actually pillows and scholarly opinion is divided on this matter. Looking at earlier research we can see that various explanations have been offered for their use, whether as head pillows, pillows for pulse assessment, book rests, neck pillows, grave good pillows, pedestals, or scroll weights. Looking at the sancai fragments -- which could, if reassembled, form approximately 30 to 40 sancai pillow-shaped works -- that have been excavated from the site of the Daianji lecture hall in Nara prefecture, we can consider it highly likely that examples of this type of work were furnishings used in some

Fig. 14

Sancai Brick and Tile Shards, excavated from the Liquanfang kiln site, Tang Chang'an.

Fig. 15

Archaeological Drawings of a Sancai Pillow excavated from a Tang tomb, Ruichang district, Jiangxi province, Left: H. 5 cm, Right: Dia. 20 cm, L. 11 cm.

163

Fig. 16

Sancai Pillow (8 in the drawing) and the "Kaiyuan Tongbao" coin placed in the mouth of the deceased (9 in the drawing), Ground plane of Xi'an Biandianchang Tomb No. 1, Tongchuan Xinqu, Shanxi province.

connection with Buddhism.25 Another example related to this type of usage can be found in an unlooted tomb, the Xi ʼan Biandianchang, Tongchuanxinqu, Shanxi province Tomb 1 (M1). The Tang sancai pillow excavated from this tomb was found beneath the skull of the tomb occupant (fig. 16).26 That tomb is dated at the latest to the Mid Tang dynasty (756 827), and thus it is an im portant example when considering the possibility that High Tang dynasty sancai pillow-shaped works were used as pillows placed beneath the head.27

3. Ceramic Figurines and Object Replicas as Burial Goods

The Tang dynasty's most flourishing period occurred across the late 7th century through the mid 8th century, in other words, from the Dazhou era of empress Wu Zetian through the Kaiyuan and Tianbao eras of emperor Xuanzong. The production of Tang sancai figurines for burial good use began during this period and their development reached their peak. A massive number of burials accompanied by Tang sancai goods have been confirmed from this period, primarily concentrated in the two Tang capitals, namely Luoyang in Henan province and Xi ʼan in Shanxi province. In this chapter I will discuss the Tang sancai excavated from Tang Tomb (M64) at Mengjin Xishantou, Luoyang (洛陽孟津西山頭唐墓). Tomb M64 is noted both for its good state of preservation thanks to its unlooted state and the fact that the deceased's identity and burial date are known.28 The deceased, Qutu Jizha, was the son of Qutu Quan, who was Yinqing Guanglu Dafu, Yanqungong (銀青光禄大夫燕郡公). Jizha was buried at Beimangshan, Luoyang in 691 (Tianshou 2). Sancai objects excavated from

164

this tomb include various figurine forms, including guardian beasts, heavenly kings, scholarly officials, riders on horseback, standing men and women, and animals. Of those, the forms of the sancai guardian beast figurine (fig. 17a), man on horseback figurine (fig. 17b) and the sancai dog (fig. 17c) are good reference materials for a consideration of works displayed in this Tang Sancai exhibition (pls. 38, 40, 43). In terms of hairstyle and garment style, the sancai female figurine (fig. 18) excavated from the tomb of An Pu from Anguo, Dingyuanjiangjun (安国人定 遠将軍安菩夫婦墓) dated 709 (Jinglong 3) in Luoyang, Henan province, closely resembles a work (pl. 45) exhibited here. The term "tomb guardian figurines" is commonly used to describe a pair of figurines one single-horned with human head and one two-horned animal headed but this terminology is actually a modern not traditional naming. The characters "zu ming" (祖明) were written in ink on the back of one two-horned animal-faced ceramic tomb guardian figure excavated in the 1980 s at a Tang tomb in Gongyi, Henan province (河南省鞏義唐墓) (fig. 19 a, b).29 The Tangliudian published in 739 (Kaiyuan 27) noted that "Dang Kuang, Dang Ye, Zu Ming and Di Zhuo" (当壙、当野、 祖明、地軸) were the type of "four deities" (四神) figures to be put in a grave as grave goods, and thus this animal-faced tomb guardian figure can be thought to be the Zu Ming of those four deities.

As noted above, the earliest example of a confirmed san cai figurine placed in a tomb was excavated at the tomb of Wei, wife of Wang Xiongdan, buried in 687 (Chuigong 3) in Luoyang. The sancai figurine exhibited here as pl. 9, depicting a person from Southeast Asia, referred to in the Tang dynasty as Kunlun (崑崙), resembles a work at the British Museum. Its form accords with that of a painted gray pottery figurine (fig. 20) excavated from the tomb of Zheng Rentai, Youwuwei Dajiangjun (右武衛

大将軍鄭仁泰) dated 664 (Linde 1) in Liquan, Shanxi.30 Zheng's tomb had been looted, and thus only one fragment (fig. 21) of a

Fig. 17a

Sancai Tomb Guardian Beasts, excavated from the tomb of Qutu Jizha (691, Tianshou 2), Luoyang city, Henan province.

Left: Overall H. 62.5 cm, Right: Overall H. 69 cm.

Fig. 17b

Sancai Man on Horseback, excavated from the tomb of Qutu Jizha (691, Tianshou 2), Luoyang city, Henan province, H. 39 cm.

Fig. 17c

Sancai Dog Figurine, excavated from the tomb of Qutu Jizha (691, Tianshou 2), Luoyang city, Henan province. H. 14.4 cm.

Fig. 18

Sancai Female Figurine, excavated from the tomb of An Pu and his wife (709, Jinglong 3), Luoyang city, Henan province, H. 33 cm.

165

Fig. 21

Pot Finial with Blue Pigment, excavated from the tomb of Zheng Rentai (664, Linde 1), Zhao Mausoleum, Shanxi province, H. 3 cm.

Fig. 19a

Ceramic Tomb Guardian Beast, excavated from a Tang tomb in Gongyi city, Henan province, H. 30 cm.

Fig. 19b

The characters "Zuming" written on the back of the work at Fig. 19a.

Fig. 22

Dark Green Glazed Amphora with Dragon Head Handles, excavated from the tomb of Empress Ai (687, Tang Chuigong 3), Gong Mausoleum, Yanshi city, Henan province, H. 32.2 cm, Luoyang Museum.

Fig. 20

Foreign Boy Figurine, excavated from the tomb of Zheng Rentai (664, Linde 1), Zhao Mausoleum, Shanxi province, H. 30 cm.

white ground, cobalt blue painted lid finial remained, suggesting the possibility that the earliest production date for Tang sancai lead glazed pottery dishware type works may be pushed back to the 660 s. In addition, the production dates of two works that closely resemble each other the Zheng tomb painted gray pottery figurine and the sancai Southeast Asia person figurine are also noteworthy. The elements of the two that resemble each other suggest that the molds used to create a single type of figurines may have been used over a long time period, and that the latter half of the 7th century, when sancai figurine grave goods were popular, may have seen the production of figurines and images in a style from several decades earlier. Or were sancai glazed figurines and images already in production in the mid 7th century? Further study is needed to answer these questions. Here I would like to consider the lid finial painted with blue pigment which was excavated from the Zheng Rentai tomb. As is well known, this blue pigment use is the earliest known example of cobalt blue glaze decoration in the history of Chinese ceramics. Chemical analysis of Tang dynasty lead glazed blue painted ware pigments has confirmed that this cobalt pigment contained a large amount of iron and a small amount of manganese. Chinese-produced cobalt pigment, conversely, has a large amount of manganese and small amount of iron, and thus this blue pigment is thought to be an imported pigment31 which may have been a reworked byproduct of imported cobalt glass. Most of the Tang lead-glazed ceramic wares with cobalt blue pigment are highly refined, well-made wares, characteristics also seen in works displayed in this Tang Sancai exhibition. The most famous archaeologically excavated items of this type include the blue

166

glazed amphora-style vase with dragon head handles (fig. 22) that was excavated from the tomb of Princess Pei (posthumous name: Empress Ai, 太子妃裴, 哀皇 后), buried in 687 at Gong Mausoleum, Henan province.32