airworthiness MARTYN COOK National Airworthiness Officer

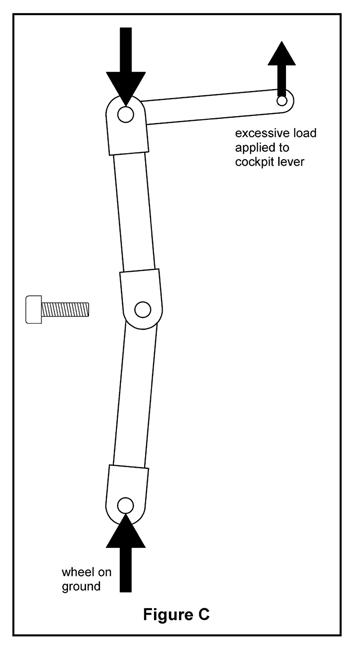

actuating linkage. If the linkage deflected further the load on the linkage would keep increasing, leading to a runaway situation and failure of the linkage. See Fig C. Now the wheel would have collapsed.

Why Did the Undercarriage Collapse? It happened while outlanding on a difficult contest day. The two-seat glider touched down normally, then for a brief moment became airborne as it jumped over a concealed ditch. When the wheel touched for a second time the undercarriage collapsed and the glider slithered to a halt on the long grass. It wasn't a heavy landing. Back at the hangar the undercarriage parts were laid out on the floor and the helpers gathered around, offering a range of opinions. The undercarriage itself was undamaged. But the actuating linkage was twisted and bent out of shape. How could this happen? The actuating linkage is designed to move the wheel up and down, but not to carry any load from the glider sitting on its wheel. To understand this, we need to know a little more about over-centre latches. These devices are very common in daily life – google if you don't know what they look like. They can transmit a large load with the application of a very

small closing force. But they have some quirks in certain dynamic situations. When loaded in compression (the normal state) they do carry very high loads, and if the load increases the latch locks even more firmly. In a glider, even a heavy landing would never transmit any extra load to the actuating linkage. See Fig A. Now consider what happens when tension is applied to the latch. This could happen when the wheel suddenly dangled free, such as during a bumpy ground roll. The latch would now be pulled towards the neutral position, as shown in Fig B. Normally the actuating linkage would push the latch firmly back into its locked position and all would be well. But if the tension was applied as a sharp impulse and there was some flexibility or free play in the actuating linkage, the latch could flick past the 'neutral' point, even if just for a brief moment. And what if – at the exact moment the latch was on the 'wrong' side of neutral – the wheel touched down firmly? A sudden load would now be applied to the

This mode of failure requires a momentary load reversal at a specific frequency. Timing is everything! The undercarriage has to be loaded up, unloaded then loaded again. In the above example this 'vibration' happened at a frequency determined by the width of the ditch and the speed the glider was travelling. How could this be prevented? Firstly, if the amount of over-centre is adjustable, there is no advantage in going too far past the 'neutral' position. Although this will make the connection more stable in compression, it will make it more prone to unlatching under strong vibration, when tension forces also arise. Secondly, it is important that the actuating linkage holds the over-centre latch firmly in the down-and-locked position. I have seen several instances where this has not been the case and the undercarriage has collapsed on a normal landing. And don't trust the factory settings on a new glider – I know of two new gliders of the same type arriving in NZ, both with sloppily-adjusted undercarriage linkages. One was picked up by a sharp-eyed engineer before any damage occurred. The other was discovered the hard way!

February–April 2017

43