11 minute read

Ingrid Periz — Looking seaward, and elsewhwere

Looking seawards and elsewhere

Ingrid Periz

Advertisement

I saw LANDSEASKY on a wet and blustery winter’s day in August 2014, when the exhibition was installed at the National Art School Gallery in Sydney. Housed in the old Darlinghust Gaol, the gallery is part of a campus clad in Sydney sandstone, or yellowblock, a Triassic period sedimentary stone that undergirds the entire Sydney area as well as marking the city’s colonial architecture. Inside the gallery however, all markers of location and of history large and small, seemed temporarily abandoned. As orchestrated by curator Kim Machan in the gallery’s large upstairs space the show’s confuence of video images of waves and water, shifting shorelines, and tilted or reversed horizon lines marked out a site where orientations changed and few points appeared fxed. The one fxed point, digitally produced in João Vasco Paiva’s Forced Empathy of a buoy resolutely stationary in Hong Kong waterways served to heighten, by contrast, this illusion of disequilibrium.

LANDSEASKY has appeared in different iterations with an occasionally variable roster of artists. In addition to Sydney the exhibition traveled to Shanghai, Brisbane, Guangzhou, and Seoul, where it was hosted across six venues. As several of the texts gathered here point out, each location produced its own effect. Sunjung Kim likens the experience in Seoul of strolling from one venue to another to a promenade in a scroll painting. Judith Blackall, National Art School Gallery manager and curator, recalled in conversation that some students regularly spent their lunch hours in front of favourite works and Naomi Evans, writing of the two venues hosting the exhibition in Brisbane notes the potency of interstitial states alluded to in both the title and a number of the works.

Central to any experience of the exhibition was Jan Dibbets’ Horizon – Sea (1971) Series I, II and III, a work comprising seven projections, shown simultaneously for the frst time in the exhibition. Installed as a three-part suite of paired, tripled, and fnally paired projections, the work shows a series of maritime horizons, aligned vertically, horizontally and diagonally. In the frst pair, vertical waves roll horizontally into the center of the screen; in the second triptych, horizontal waves roll vertically to the bottom of the screen (much as they appear to do at the beach); and in the fnal pair, diagonal waves on left and right roll into the center diagonally. Complicating this is Dibbets’ use of a pivoting camera. Thus, the vertical horizon lines of the frst projected pair shift horizontally, the horizontal horizon lines of the centre group shift vertically, and the diagonal horizontal lines of the last projected pair move diagonally. While the camera movement is uniform within any single one of the seven projected “views,” the speed of movement varies from view to view.

Confronting the work of course, any spectator probably intuits Dibbets’ procedure in less time than it would take to read the above description; nevertheless, one of the initial pleasures of the work is the mental recreation of this process. (1) Dibbets’ work arrests, in large part because the sideways and oblique movements of the horizon line disturbs the assumed verticality of the viewing body. To this extent the work is anti-illusionistic; the screen space is fattened, treated in the frst and last diptychs as a surface for a series of what look like cinematic wipes. Horizon – Sea extends the investigation into the nature of perception and representation that Dibbets initiated in his Perspective Corrections, begun in 1968. Here he photographed a series of lawns, studio foors and walls onto which a single trapezoidal shape had been drawn. The perspective of the camera confronting the surface made this shape look like a square in the resulting photographs. In subsequent series Dibbets collaged together photographed land- and seascapes to produce a uniform horizon line, showing how the latter is both a structuring principle of photographic representation as well as a subjective element in viewing.

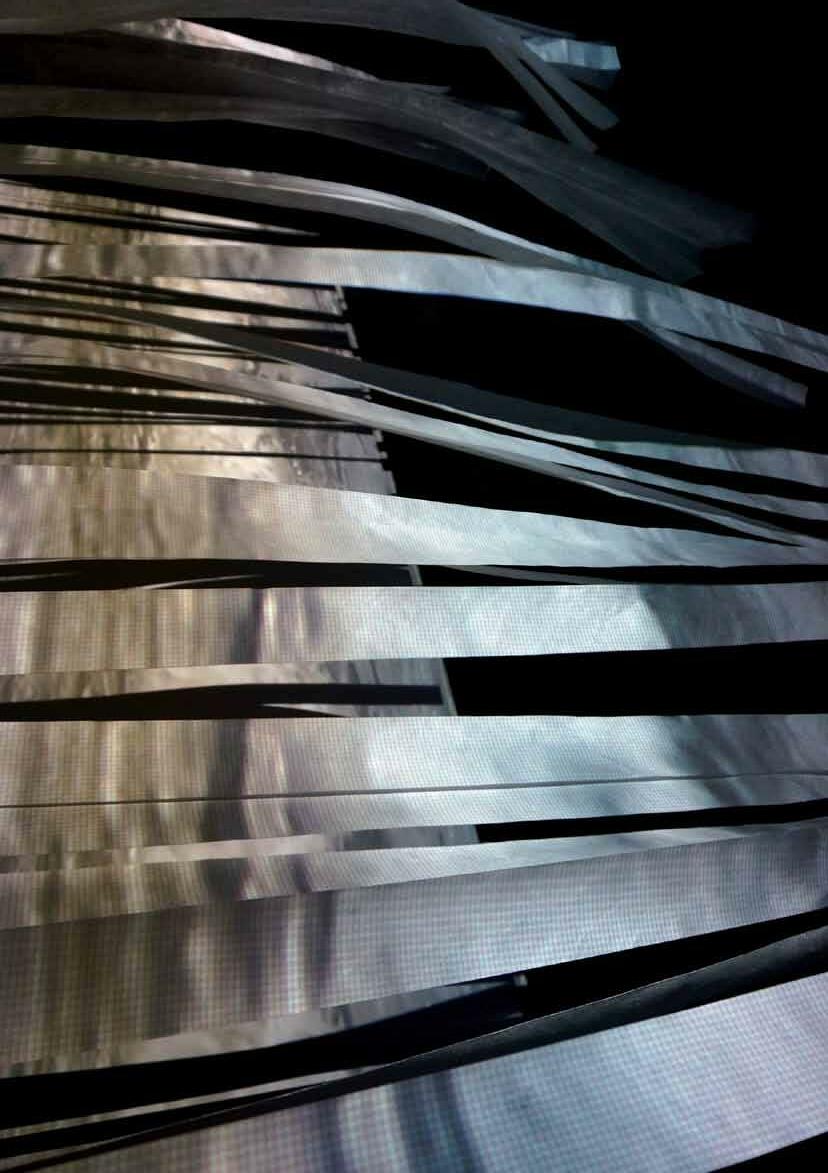

Dibbets has called the horizon a straight line in three dimensions. Horizon – Sea brackets the horizontal in the experience of the horizon: the seas run sideways, the breaker line appears to bounce up and down. That this is not a discomfting viewing experience may be due to the Newman-esque zips in each of the work’s three sections, the interstitial vertical lines marking where the edge of each image meets the next. (2) These zips provide a vertical orientation point. In Sydney,Horizon – Sea was fanked by Derek Kreckler’s Littoral (2014) which projected footage of breaking waves onto a regularly incised screen, the resulting curtain of strips nudged gently by an oscillating fan placed behind it. At times the swells of airborne strips echoed the waves’ breaks and swells, their gently regular unpredictability undoing the projected image on the fapping screen to reveal a second, intact one directly behind. A little joke on illusionism with its homely apparatus of fan and strip curtain, Littoral’s apparent simplicity recalled the appeal of early cinema’s plethora of images of waves and seashores.

Machan’s idea of a universal “looking to the shoreline” was given very specifc infections in work by Shilpa Gupta and Kimsooja, installed in Sydney with the work by Dibbets, Kreckler and Vasco Paiva. Gupta’s 100 Hand drawn maps of India (2007–08) shows the coastline of the Indian sub-continent drawn and redrawn by 100 adults, the boundaries of the country changing, its coastline in its particularities almost as elastic as its eastern and western-most boundaries. Shorelines are borders too, marking cartographic boundaries, and with them constructs of national identities. Gupta’s work suggests both the fantasmatic dimension of this ideological operation as well as its bloody working out in imperial and post-imperial history. Kimsooja’s Bottari—Alfa Beach (2001) is an inverted view of the eponymous Nigerian beach from where slaves were shipped. As sombre in its historical reference as 100 Hand Drawn Maps of India, the work’s reference remains invisible. The horizon line produced by the inversion of sea and sky yields nothing now except perhaps a kind of abyssal space of horror. (3)

Dibbets’ “straight line in three dimensions” operates in historical time as well as space, as Gupta and Kimsooja make plain. Indeed the initial placelessness of that large Sydney room, it might be argued, was the result of specifc aesthetic strategies rather than any universal meaning of the horizon line, particularly the maritime one. As Alain Corbin argues in The Lure of the Sea: The discovery of the seaside 1750–1840, the shoreline and with it the sea has a history of meanings, produced through a range of aesthetic and discursive practices. (4) Corbin shows how the Western seaside is a post-Enlightenment, and specifcally Romantic project, underwritten as well by the new science of geology and the history of Dutch landscape painting. In his account the meanings accruing to the practice of looking to the sea–girt horizon are inseparable from this web of discursive and aesthetic representations. Thus, when we speak now of the spaces of LANDSEASKY, of the different forms of spatiality that are “revisited” in and by the works selected, as Paul Bai and Andrew McNamara’s deeply suggestive essays make clear, we do so through the languages of modernist aesthetic practice. (5)

Outlining what he calls the Third Spatial Position, an “other than” to the familiar binary of inside/outside, Bai alludes to the phenomenologically–infected thrust of Minimalism’s interest in the spatiality of the viewer. He writes of minimalism making the ‘spatial turn’ to ‘connect artwork to its surrounding space,’ a project undertaken in a different register by Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau as McNamara recounts in his history of spatial art and early modernism. McNamara writes of Schwitters’ debt to artist Erich Buchholz who planned a spatial art of mobile screens and imagined the possibility of walk-in pictures. That these goals might be realized in “immersive” technologies, let alone the more prosaic bounds of a video installation, seems in this instance beside the point; as McNamara notes, a perennial theme of spatial art was movement.

Bai asks: What would be the precondition of spatial construction, the “no space” that exists, unmarked by up/down, left/right, inside/outside, before space? Perhaps amniotic space offers a model for this kind of ur-space, a space also experienced from within the movements of the sea. Corbin hints as much when glossing Novalis’ Disciples at Saïs. He writes of diving into the sea and “experiencing the coenesthetic harmony that exists between the movements of the sea and those of the original waters carried within the human body.” (6)

Untitled (Wind Charm) (2013), Bai’s installation in LANDSEASKY, suggests a different way of fguring this space. Instead of a sensory combination, the work proposes an analysis of sensory terms in Bai’s deceptively simple doubled projection of a spiraling wind chime. The chime’s movement is ambiguous; structured like a screw, it is diffcult to establish whether it moves up/down or left/right, an effect that helps destabilize a viewer’s orientation in front of the work. In addition to this suspension of the viewer’s compass bearings, Bai de-realizes the illusion of the screen surface which leans against the wall behind it. (Leaning is itself a minimalist trope, a way of intruding into the viewing space so that space becomes experiential, while emphasizing the weighted materiality of the viewed surface.) In spite of these interventions, the apparent regularity of the chime’s turn makes this a meditative work that invites a lengthy, stilled contemplation.

By way of contrast Barbara Campbell’s interactive close, close (2014) retains the shoreline orientation, showing footage of migratory shorebirds in their habitat, and demands activation by the viewer whose movement to and from the screen controls the aperture of a horizontal slice of the image which moves up and down the screen. Up close to the screen, this activation leaves the viewer ‘submerged’, a sensation cued as well by sound. Campbell plays on the blinds used by bird watchers and hunters to hide themselves while observing their quarry. Inverting this scenario by making the viewer activate the unfolding scene, the work withholds any complete perceptual feld, subtly undoing the illusion of spectatorial agency.

Like close, close, Wang Gongxin’s The Other Rule in Ping Pong (2014) creates an illusory space, created

by the peregrinations of a ping pong ball which is spat, ricochets, and fnally swatted at over three screens set up in a triangular arrangement. The ball moves unpredictably; a viewer might want to duck whenoccupying the same space as its trajectory. Eschewing any reference to a vertical or horizontal horizon line, the work illustrates precisely Dibbets’ dictum that the horizon exists in three dimensions, “activated” here by synchronized video legerdemain. Zhu Jia’s It’s beyond my control (2014) similarly addressed video’s capacity to confgure spatiality. Positioned in a corner, the work shows a hand holding a pencil outlining the edges of the corner by marking the junctions of wall and foor. In Sydney the projection was almost exactly co-extensive with the corner into which it was projected, the hand’s action doubly demarcating illusionistic and real space and undoing their difference.

LANDSEASKY offered no single conception of spatiality in its concatenation of moving images designed to be addressed by moving bodies. That “sea between us,” in Machan’s words, is multiple and if it offers the possibility of a coenesthetic Romantic immersiveness, it is equally the ground for formal invention, refexivity, and historical reckoning.

Notes:

1. Dibbets is most frequently called a conceptual artist, but this work complicates that designation. Writing of the earliest phase of Postminimalism, a term he coined, Robert Pincus-Witten notes, “the virtual content of the art became that of the spectator’s intellectual re-creation of the actions used by the artist to realize the work in the frst place.” PincusWitten calls this frst phase, which peaked in the United States 1968-70, “painterly.” (Dibbets trained as a painter.) Robert Pincus-Witten, “Introduction”, Postminimalism into Maximalism: American Art, 1966-1986, (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1987), p.11. 2. Barnett Newman used thin vertical strips of colour to separate large areas of colour, giving his mature paintings spatial defnition and unity. Additionally, according to Yves-Alain Bois, the zip also served as a command to the beholder to “stand here [with the zip] ...and you will know exactly where you are.” Bois adds that Newman’s greatest wish was to give the beholder a sense of place. See Yves-Alain Bois, “Newman’s Laterality”, in Melissa Ho ed., Reconsidering Barnett Newman: A Symposium at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2002), p.33. 3. Other photographers producing work that documents sites of historical atrocities where all markers of the event have disappeared include Ricky Maynard and Tomoko Yoneda. Kimsooja’s inversion however is singular. “Horror” is only one of several possible responses. 4. Alain Corbin, The Lure of the Sea: The discovery of the seaside 1750-1840, Jocelyn Phelps trans., (London: Penguin, 1994). 5. Thus Dibbets’ “painterly” (in Pincus-Witten’s terms) concerns with horizontality and the picture plane might usefully be discussed with reference to Mondrian’s versions of Pier and Ocean (1914/1915). 6. Corbin, op. cit., p.178. Coenaesthesia can be defned as the general sense or feeling of existence that arises from the sum of bodily impressions.

Littoral . Installation detail of Derek Kreckler’s

29德里克·克雷克勒参展作品《沿海》的局部照。