6 minute read

Reflux-induced respiratory disease

Reflux of gastric contents into the oesophagus may occur during intermittent relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS). Occasionally there is free reflux through an incompetent LOS, sometimes associated with a hiatus hernia.

Reflux into the lower oesophagus when upright is cleared readily by swallowing, peristalsis, gravity. Local mucosal factors help protect against intermittent acid injury (epithelial lining fluid and saliva, carbonic anhydrase). Reflux symptoms (regurgitation, belching, heartburn) are common and not necessarily pathological. However, recurrent reflux can result in chronic aerodigestive disease. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is usually considered an oesophageal disease, affecting about 20% of the population, but may also present with upper and lower respiratory manifestations (Table 1). Most reflux-induced airway and lung injury occurs as a result of high reflux and micro-aspiration during sleep. While sleeping, there is reduced oesophageal sphincter tone, increased evening acid production, delayed gastric emptying, impaired oesophageal

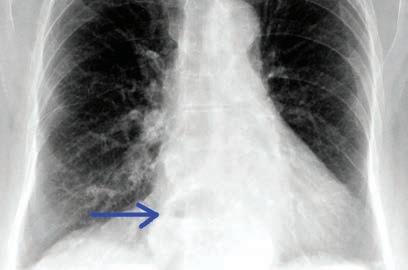

Fig 1. Penetrated PA chest x-ray demonstrating a retrocardiac opacity with air fluid level (blue arrow): moderate hiatus hernia.

clearance of acid and reduced swallowing and saliva production. Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is a key risk factor for nocturnal reflux due to increased transdiaphragmatic pressure. Acid and pepsin are additive in causing respiratory mucosal injury. Barium swallow and upper GI endoscopy are useful when positive but have limited sensitivity. Oesophageal pH studies are more useful for oesophageal disease. Measurement of pepsin or bile acids in respiratory secretions are generally diagnostic, but not yet readily available. The best ‘diagnostic test’ is response to combination therapy.

Table 1: Extra-oesophageal disorders secondary to gastro-oesophageal reflux.

Location

Oropharyngeal

Laryngeal

Bronchopulmonary Disorders

dental erosion postnasal irritation chronic rhinitis

Globus sensation Frequent throat clearing Dysphonia

Chronic cough Chronic bronchitis Recurrent respiratory infections otalgia sleep disordered breathing

Paroxysmal reflex laryngospasm Subglottic stenosis Laryngeal carcinoma

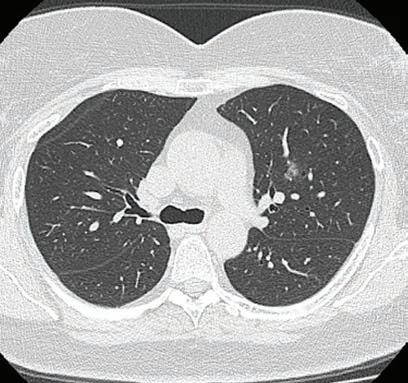

Chronic bronchiolitis Community-acquired pneumonia Aspiration pneumonia, abscess Acute lung injury Exacerbation of chronic lung disease Anecdotally, single interventions tend to be less effective than combination therapy, however, there are no randomised controlled trials. Combination therapy includes proton pump inhibitors (PPI) at night, H2R blocker, promotility agent, dietary modification (avoid eating late, small evening meal, avoid certain food groups), raised head of bed, weight loss. Case study A 45-year-old woman has a fiveyear history of gradually increasing cough, initially dry, and more recently productive of mucoid sputum. Her cough tended to be worse in the morning, sometimes caused sleep disturbance and, rarely, she woke from sleep with a choking sensation. Weight increased 18kg in the past decade, recently her voice was hoarse, and she noted wheeze and shortness of breath, unresponsive to overthe-counter salbutamol. She complained of waking unrefreshed in the morning and daytime sleepiness. There was a history of snoring but not asthma. On examination, she was overweight (BMI = 32), had noticeable dysphonia, mild pharyngeal erythema and reduced pharyngeal volume (Malampatti class IV). Respiratory examination: wheeze on forced expiration. Spirometry demonstrated moderate volume loss with no bronchodilator response. Chest x-ray showed a moderate hiatus hernia (Fig 1). This is a typical presentation of reflux induced cough and asthmalike symptoms in an adult. A sleep study demonstrated severe OSA which responded to CPAP. Prior to commencing CPAP, she was treated with PPI, pro-motility agent at night and dietary modification and her cough, wheeze and dysphonia resolved over three weeks.

Author competing interests – nil

Lung cancer staging – a snapshot of diagnostic pathway

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer death in Australia with the five-year survival rate remaining at a disappointing 18%. Morbidity and survival outcomes are highly dependent on early diagnosis. The National Lung Cancer Optimal Pathway endorsed by state and federal governments recommend six weeks as the time from initial identification of potential lung cancer to complete staging and diagnosis and receiving first treatment. It can be challenging to meet this. The current recommended staging pathway (see below) is a stepwise approach. First step is a wholebody 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET scan (can be omitted if baseline CT has already identified metastatic disease) to identify whether the patient has locally advanced disease (stage I-III) or systemic disease (stage IV). If stage IV disease is identified (approximately 40% incidence), Key messages

Lung cancer survival outcomes highly depend on early diagnosis First step is a whole-body 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET scan staging (unless metastatic disease identified on baseline CT chest) EBUS-TBNA significantly increases mediastinal lymph node staging accuracy.

it is generally advised that histopathological tissue diagnosis is obtained from distant metastatic sites (where most accessible and least invasive to obtain), either via ultrasound or CT-guided biopsy. A positive biopsy of the primary lung lesion on its own will not answer the question of whether the distant metastatic deposits are from lung origin or in the offchance, might have arisen from a separate synchronous malignancy.

Lung nodule/mass suspected to be lung cancer – with no evidence of metastasis disease on baseline CT-chest

18F-FDG PET scan

Negative nodes on PET/CT with small peripheral lesion N2/N3 enlarged nodes on CT or positive on PET Normal N2/N3 nodes on CT/ PET but central, large tumour (3cm) or N1 positive node Stage IV on PET

Lowest risk diagnostic procedure (navigational bronchoscopy, CT biopsy, or excisional biopsy) Mediastinal lymph node staging with EBUS-TBNA bronchoscopy Least invasive tissue biopsy Whereas tissue diagnosis from other metastatic sites can be traced back to lung where it exhibits typical immunohistochemical markers (i.e. TTF-1). If no distant metastatic disease site is identified on staging scan and the disease is found to be stage IA (primary tumour size <3cm and no suspicious node was identified on FDG-PET scan – approximately 10% incidence), it is generally advised that the histopathological tissue diagnosed is obtained directly from the primary site via navigational bronchoscopy or CT-guided biopsy. Where a larger tumour or suspicious node is identified on staging scan, a diagnostic bronchoscopy with linear endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) transbronchial needle aspirate (TBNA) is recommended. This is a minimally invasive technique to biopsy mediastinal lymph node. Staging scan alone cannot accurately stage the disease, given associated high false positive (FP) and false negative (FN) rates. In radiographically identified N2/N3 nodal disease (metastasis involving lymph nodes beyond mediastinal or subcarinal in location), 40% FP rate is associated with CT and 15% FP and 25% FN with PET.

Conversely, in cases of large central tumours (>3cm) with only radiographical positive N1 nodal disease and negative N2/N3 disease, a 25% FN rate of lymph node metastasis is associated with CT and PET; and 15% FP with PET. EBUS-TBNA significantly increases the accuracy of mediastinal lymph node staging (specificity 100%, sensitivity 93%). Once appropriate staging has been performed, each lung cancer case should be referred to a lung cancer multidisciplinary meeting for complete optimal discussion on staging and treatment options.

Author competing interests – nil relevant disclosures.

Your sleep health experts with heart

ResSleep Western Australia is a leading sleep health clinic. For over 20 years, we have been providing professional, outcome-focused care for the treatment of snoring, sleep apnea and more. Every day, we earn our reputation by putting our patients first. With our team of friendly, knowledgeable staff and a comprehensive range of products, we are ready to help your patients achieve healthy sleep. We’re also proud to be a ResMed Authorised Dealer for the Department of Veteran’s Affairs and an NDIS affiliate.

What we offer:

CPAP therapy equipment and support Alternative sleep health products Telehealth and sleep coach services After hours phone support Bi-level and ASV equipment trials One-on-one education sessions CPAP Rescue Program Commercial driving management program

We’ll look after your patients

At ResSleep, helping ensure patients have all they need for therapy is our key priority. Our virtual hub, PlaceofDreams.com.au, for example, enables them to book virtual consults, browse all our products and even read the latest sleep health advice online. And if you have patients who have trouble staying on CPAP therapy, please ask us about our CPAP Rescue Program. We’ll be glad to help them get back on track.