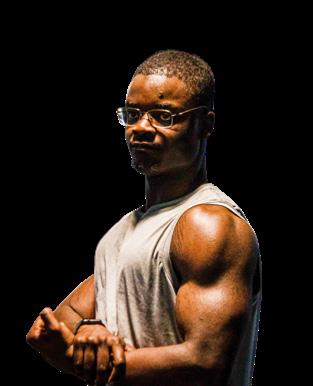

‘Alawo Dudu’ is Yoruba term for a ‘person of colour.’ This piece is of a trilogy graphical representation of a young black male’s photographs in different arrival, departure and ascension poses that capture the baptismal ruling of water in cleansing the racial still-livingness of the young male model. Ranging from an aquatic exodus stance (of which this artwork is), to homecoming, then the sacrificial stance of being put against a white background and/ American flag: as typical racial plots of many-a-helpless Black males; self-fulfilling clairvoyants. From the historical instance of Emmet Till to today’s media witness of Ahmaud Arbery to lots more minor-natured misfortunes of underage males of colour in the umpiring hands of privileged Americans. This piece is inspired from my poetic ideation of a piece in ‘Gills:’

“To stay above. the water and bond with a god in one’s own image, free to make a renaissance mistake of living on just nostrils & the remaining share of biblical breadcrumbs” […]”-Bills

Ayomide Bayowa is an award-winning Nigerian Canadian poet, actor, and filmmaker. He holds a B. A in Theatre and Creative Writing from the University of Toronto. Bayowa started in 2018, on the shortlist for the Christopher Okigbo Inter-University Poetry Prize, then on the longlist for the Nigerian Students Poetry Prize. He is currently the poet laureate of Mississauga, Ontario, Canada (2021-24), a top-ten gold entrant of the 9th Open Eurasian Literary Festival U.K, a long list of the Unserious Collective’s Fellowship and the 2021 Adroit Journal Poetry Prize. He won first place in the 2020 July Open Drawer Poetry Contest, the June/ July 2021 Edition of the Bi-monthly Brigitte Poirson Poetry Contest (BPPC). He evolved second place in the 2021 K. Valerie Connor Poetry Prize’s Student Category. His play ‘Recyclable Chairs’ was the second runner-up of the Arojah Students Playwriting Prize’s maiden edition. He currently reads poetry for Adroit Journal.

During Black History Month, in Canada, we recognize the legacies of the Black communities who have contributed to creating a diverse country and continue to shape Canada’s prosperity. This creates a space for education and conversation on Black history. February 1, 2023, marks the start of Black History Month, during which the International Education Centre (IEC) has several interactive events planned for all University of Toronto Mississauga (UTM) students.

In an email interview with The Medium, the IEC team expresses that: “[For Black History Month], in the spirit of our office’s mandate to advance global and intercultural perspectives within the UTM community, the IEC will roll out events and social media campaigns as per previous years.”

On February 15, 2023, the IEC, alongside the International Student Centre at the University of Toronto Scarborough and the Centre for International Experience at the University of Toronto St. George, will be hosting a tri-campus event titled Our Stories: Black History Month. During the event, Black students will be sharing their stories and experiences with the U of T community.

Additionally, on February 16, 2023, the IEC will be partnering with the Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Office at UTM to host

a “Black History Month Social Hour open to all members of the UTM community.”

Throughout the month of February, the IEC will also be featuring posts on its social media that are “geared toward celebrating the achievements of prominent Black Canadians; telling the stories of UTM students, faculty, and staff self-identifying as Black; commemorating the dark history of slavery, racism, discrimination, and subjugation faced by the Black community around the world; and reflecting on how such institutional racism and discrimination in the Canadian context still continue today.”

As UTM is home to many international students and communities, the IEC recognizes the importance of curating a welcoming, knowledgeable, and supportive atmosphere for different cultures and backgrounds. In planning Black History Month’s events, the IEC seeks to celebrate and inform. “Professional staff and studentstaff self-identifying as Black within the IEC are the ones curating and guiding the direction of [their] initiatives,” the centre outlines.

Black History Month events hosted by the IEC are open to all members of the UTM community. The IEC looks forward to the Black History Month celebrations and encourages all members of the UTM community to participate in the events. This will broaden intercultural perspectives and increase awareness of the importance, origin, and development of Black history.

The International Education Centre prepares to celebrate Black History Month as it rolls out honorary and informative events for the UTM community.

OnJanuary 1, 2023, Professor Charmaine C. Williams started a five-year term as Dean of the Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work (FIFSW). She is the first Black woman to hold the position of dean at the FIFSW, and the second Black professor to do so after the previous dean, Professor Dexter Voisin.

Professor Williams completed her Master of Social Work and PhD at the FIFSW, later joining U of T as a faculty member in 2002. She has held various positions within U of T, such as associate dean, academic of the FIFSW from 2009 to 2014, and most recently, vice dean of students at the School of Graduate Studies from 2018 to 2021. Professor Williams works as a social worker in mental health and conducts research on social work and healthcare, investigating health equity in relation to groups that already face systemic discrimination, such as women of colour, and the 2SLGBTQI+ community.

Outside of U of T, Professor Williams has served on panels addressing Canadian social issues, with a focus on racial and health equity. An example is her position on the Public Health Agency of Canada’s panel for their Mental Health of Black Canadians Ini-

tiative—a project that explores the inequalities and challenges experienced by Black Canadians regarding mental health support and develops programs to tackle these issues.

In addition to her appointment as dean, Professor Williams is the Sandra Rotman Chair in Social Work. In this role, she focuses on researching emerging trends in the social work profession. Professor Williams’ interests lie in the new trend of social workers choosing to practice outside of traditional social work organizations in favour of initiating and leading independent organizations. “Before, there were standard places you expect social workers to practice, for example, they’d be in hospitals, child and family services, or they’d be in a school board,” says Professor Williams in conversation with The Medium. “But what’s changing is that more social workers are establishing private practices or standalone social service organizations outside of the system.”

She hopes to find the causes behind this change and its relationship with institutional oppression.

“I first noticed this happening with our Black and Indigenous graduates, who were setting up systems and organizations that were independent because they felt the system was too broken to meet the needs of their community,” shares Professor Williams. These independent social work services are being used to develop effective strategies and resources that specific communities can utilize, instead of institutions that were not historically built for them.

Professor Williams also has many goals she hopes to attain and explore as dean, a main one being diversity in social work. “Social work is more diverse than it’s ever been before,” says Professor Williams, “but as we become more representative of different populations, we have to change the way that we do social work.” Citing the multiculturalism of Toronto, Professor Williams acknowledges U of T’s and the FIFSW’s responsibility to be “culturally responsive, across the spectrum of identities, and also responsive to the fact that we are practicing social work in a globalized environment.”

Diversity and inclusion are important in academia—where members belonging to a minority, particularly Black students and academics, have a history of experiencing discrimination. Professor Williams references her own experiences as a Black woman in academia, saying, “I can think of many incidents that showed people were surprised to see me in that space, and I felt that my ambitions were undermined by people’s low expectations.” She explains research that shows systematic discrimination against racial minority faculty members, such as lower course evaluations or higher service loads.

To combat this, Professor Williams encourages finding a community and forming relationships with others that understand these struggles, such as student associations. Additionally, joining committees aimed to find solutions for such problems empowers students and faculty members to have their voice heard and contribute their own perspectives.

On February 6, 2023, the Anti-Racism and Cultural Diversity Office will hold the Black History Month Symposium from 1:00 p.m. to 3:00 p.m. The event will take place on Zoom, and students can join to learn about anti-Black racism and how attitudinal barriers affect Black communities in general and in post-secondary environments. Professor Williams will be giving the opening remarks, and there will be a panel discussion with Black leaders in Canadian academia.

InJuly 2020, a small team of Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics, Medicine and Health (STEMM) professionals gathered to address the ongoing disparity in education and opportunities for Black people in STEMM fields. This spurred the creation of the Canadian Black Scientists Network (CBSN), which has now grown to over 500 members. The group is comprised of academics across disciplines, including professors, researchers, practitioners, and students.

The CBSN’s annual BE-STEMM conference, a four-day event showcasing the diversity and breadth of STEMM excellence amongst Black Canadians, will be held at the University of Toronto Scarborough (UTSC) from February 1 to 4, 2023. The conference includes virtual and in-person events, featuring keynote speeches from established and rising Black STEMM scholars; contributing speeches from scholars, practitioners, students, and educators; as well as discussion panels.

The virtual career and science fairs will offer opportunities for Black students and early-career scientists to enter their fields. Students can attend the conference free of charge.

The primary purpose of the conference is to elevate Black students, address disparities in education for Black youth, and create a platform for underrepresented Black professionals in STEMM fields. CBSN president, Maydianne Andrade, a pro-

fessor from the Department of Biological Sciences at UTSC, explained to a CityNews reporter that “there’s a problem with Black youth being excluded from academic streams.”

While the event celebrates the strides Black people have made in STEMM across Canada, the CBSN emphasizes the need for continued advocacy and innovation. “Deliberate, tailored interventions for Black communities are required to remove the long-standing discrimination, exclusion, and oppression,” stated Andrade in a presidential message in August 2021. Inequities that exist in schools, colleges, and universities reflect the disparities in many other areas of life, such as the workplace, the doctor’s office, and the courtroom. Historically, these disparities were “created to justify slavery,” explained Andrade. “Those structures and stereotypes still manifest in systematic anti-Black racism in the lives of Canadians.”

As dismantling systemic discrimination is a hefty, long-term endeavor, the CBSN stresses the importance of speaking up. To address anti-Black racism in education, people must continue to advocate for equitable treatment in their fields and institutions, and to carry these values with them outside of school.

From February 1-4, 2023, the University of Toronto Scarborough will be hosting the Canadian Black Scientist Network’s BE-STEMM 2023 conference—an event aiming to create a welcoming and uplifting environment for Black individuals in STEMM fields.

BE-STEMM 2023

Another contributing factor to the theme has to do with hair. “Black hair and textured hair have been stigmatized for a very long time, and we loved the idea of comparing hair to a crown,” shares Roopnarine.

to have a good time and enjoy Black art and music. Performers can sign up through a form available on the UTMSU Instagram page (@ myutmsu), as well as that of the Black Literature Club (@black_literature).

WithBlack History Month in February, the Black History Month Committee— consisting of members from the University of Toronto Mississauga Students’ Union (UTMSU), the African Students Association, the Somali Students Association, the Black Literature Club, Caribbean Connections, and the Black Students Association—has organized several events to raise awareness of Black history and success.

The Medium spoke with the UTMSU vicepresident of equity, Reagan Roopnarine, about this year’s Black History Month.

Roopnarine shares that the theme for Black History Month 2023 is “Black Royalty,” explaining that it was chosen due to numerous reasons. “Black history tends to be told from the perspective of suffrage and struggle—we wanted to switch the narrative and make Black history more about triumph, and more about overcoming barriers,” explains Roopnarine.

The committee recognizes that the African continent is home to many monarchs and empires that are often not highlighted in history.

There are five major events planned for Black History Month.

On February 2, 2023, the Buy Black event will take place at the Student Centre from 12:00 p.m. to 4:00 p.m. Many Black-owned businesses will be setting up stalls. Students will be able to purchase products and learn about the various Black business owners by visiting the booths.

On February 6, 2023, the 12 Jurors event will be held at the Student Centre’s presentation room from 6:00 p.m. to 8:00 p.m. Everyone is welcome to participate as a member of a mock jury, returning a verdict to a real case that has gone through the judicial system.

On February 9, 2023, an open mic night will take place at the Blind Duck Pub from 7:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m. The event will be open to anyone looking

On February 15, 2023, the day after Valentine’s Day, Caribbean Connections will be leading an annual love, sex, and relationships event from 6:00 p.m. to 8:00 p.m. in the presentation room of the Student Centre. The event provides a closed space for Black students to have an open discussion about everything relating to relationships. “It gets super spicy and really fun,” remarks Roopnarine. This event is open to Black students only.

Finally, on February 17, 2023, Nuit Noire will take place from 7:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m. in the Blind Duck Pub. It is open exclusively to Black students, where they can enjoy cultural food, gain insights from a presentation, and have a celebratory end to Black History Month.

Recognition of Black history goes beyond just one month of events. Since the Covid-19 pandemic, there have been more equity-based events hosted at the UTMSU, creating more opportunities to engage with racialized students. Roopnarine highlights the Black Mentorship program, which was launched partially in January 2023, and is created by Black students, for Black students. “We’ve already collected a group of really passionate mentors and will be reaching out to mentees shortly,” shares Roopnarine. “Any first- or second-year student who wants to get connected with an upper year student, get career advice, more communication, understand the grad school [or] law school process, or whatever they need—they can do that [through the mentorship program].” Interested students can register through the UTMSU Instagram page (@ myutmsu).

“The Black community on campus is growing; it’s very strong and it’s full of a lot of very talented students,” states Roopnarine. “I want people to take away that [Black History Month] is also about celebration, recognizing the innovation that comes out of the Black community, the endless contributions to academia, and the Black people who have influenced history positively.”

CEO Janice Pancho highlights the importance of Black representation in retail and shares the organization’s successes, challenges, and future goals.

Angelina Jaya Siew Staff WriterThe Canada Black Owned Marketplace is an e-commerce and in-person platform that sells products and goods from Blackowned vendors. Established in 2019, the marketplace currently has physical stores at Erin Mills Town Centre, Pickering Town Centre, and Bramalea City Centre (temporarily closed since December 28, 2022), operating alongside its virtual shopping site.

In conversation with The Medium, CEO of the Canada Black Owned Marketplace, Janice Pancho, explains that the marketplace initially launched as an e-marketplace during the Covid-19 pandemic. Due to high demand, physical stores opened with a “multi-vendor” concept. She states that a large number of Black entrepreneurs lack the opportunity to open a brick-and-mortar store to sell their product. This is where the Canada Black Owned Marketplace comes in—being a place “to feature local business owners’ products to clients,” akin to “a mall within a mall.”

“We [the Black community] believe that we are faced with barriers [in society],” says Pancho, highlighting her prime reason for launching the Canada Black Owned Marketplace. “We want to build wealth within our own community,” she explains, outlining her hope for the Canada Black Owned Marketplace to help minimize the wealth gap between the Black community and others in Canada. Pancho and her team created the organization to “bring everyone together in a cohesive platform to collaborate.” She adds that “divided, we are not strong, but together, we are strongest.”

Pancho says that “[The Canada Black Owned Marketplace’s] mission is to help Black entrepreneurs to build wealth, to be great business leaders, to manage finances, [and] to live a comfortable life.” The organization assists Black entrepreneurs as young as 15

years old in areas such as business plan creation, so that they can launch successful businesses.

A wide variety of goods from numerous Black-owned businesses are offered at the Canada Black Owned Marketplace. Pancho outlines that “The items that we have are hand-made, hand-crafted, and curated by our Black vendors.” Vendors produce candles, skincare products, art, jewelry, clothing, and food items—such as pepper and ginger beer, all reflecting African and Caribbean culture. Additionally, Black ancestry publications by local authors are sold. The marketplace is constantly expanding, and all Black entrepreneurs are welcome to start the application process through the company’s website if they would like to register as a vendor for the Canada Black Owned Marketplace.

Pancho remembers the challenges the Canada Black Owned Marketplace encountered in securing start-up funding, as no financial support was offered to the organization during its set up. All expenditures were paid “out of pocket” by the organization’s founders.

Therefore, to improve Black representation in the local retailing industry, Pancho believes that more state funding is imperative. Many Black entrepreneurs require financial help to successfully launch their businesses. Additionally, Pancho emphasizes the importance of hav-

ing workshops that focus on business plan creation and building financial literacy accessible to aspiring Black business owners.

Apart from financial support, the Canada Black Owned Marketplace has also encountered other barriers. “We have encountered people that are surprised to see us,” remarks Pancho, who contends that there were negative responses to the marketplace since some thought it was restricted to the Black community. However, Pancho refutes this claim, emphasizing that “Our store is open to everyone.” Prospectively, she hopes to change the public’s perception that “Black-owned” means “Black only,” and asserts that the Canada Black Owned Marketplace welcomes all ethnicities, ages, and races.

Nevertheless, the positive reactions garnered by the organization, particularly within the Black community, far outweigh any negative outlooks. Pancho notes that the Black community enjoys shopping from the Canada Black Owned Marketplace as they feel more connected to their Caribbean and African roots. The strong support from customers motivates Pancho and her team to “keep going” and “keep pushing.”

The organization has several plans to celebrate Black History Month. Among them is a Celebrating Black Excellence in Entrepreneurship event taking place at the Pickering Library on February 4, 2023, where Pancho will be discussing her experiences in entrepreneurship. There will also be a “Children’s Story Time Session” at one of the physical stores to educate youth about the importance of Black History Month.

“We are here to stay, and [we] appreciate the support that the community has given us,” affirms Pancho. In the long term, she hopes that the organization can open more outlets in different provinces, thus enabling more of Canada’s Black population to enjoy a wide variety of products and feel represented in the retail industry.

The UTMSU and various Black student clubs will be organizing numerous events to celebrate Black History Month, focusing on “triumph” over “struggles.”

Lily Yu Contributor

Editor-in-Chief Elizabeth Provost editor@themedium.ca

Managing Editor Juliana Stacey managing@themedium.ca

News Larry Lau news@themedium.ca

Opinion Kareena Kailass opinion@themedium.ca

Features Prisha (Maneka) Nuckchady features@themedium.ca

A&E Julia Skoczypiec arts@themedium.ca

Sports Alisa Samuel sports@themedium.ca

Photo Samira Karimova photos@themedium.ca

Design Manjot Pabla design@themedium.ca

Copy Aidan Thompson aidan@themedium.ca

River Knott river@themedium.ca

Social Belicia Chevolleau social@themedium.ca

Podcast Kareem Al-Sawalmeh message@themedium.ca

Emily Rogers, News

Mihail Cubata, News

Dalainey Gervais, Features

Olga Fedossenko, Features

Megan Freedman, Arts

Maja Tingchaleun, Arts

Melody Yang, Sports

Radhia Rameez, Sports

Beatriz Simas, Photos & Design

Natalie Ng, Photos & Design

Sabrina Mutuc, Photos & Design

TO CO NTRI BU TE & CONNECT: themedium.ca/contact

@themediumUTM @themediumUTM

@themediumUTM @themediumUTM

@themessageUTM @humansofUTM_

Editor | Kareena Kailass opinion@themedium.caInrecent years, the “Black Excellence” hashtag has gained widespread attention on social media. Every day, there seems to be a prodigal Black kid absolutely crushing records in science, academics, or even in sports. And you know what? Good for them! In a society that mocks the Black identity only to steal from it, we need positive images of Black people.

For centuries, media representations of Blackness were demeaning, belittling and, well, racist. These images not only perpetuated negative stereotypes but impeded on our community’s ability to break the glass ceiling and to exist in realms of excellence and prestige. As a response to those offensive depictions, #BlackExcellence serves as an alternative. The hashtag shows Black people earning respect in such spaces of excellence by being exceptional.

“The hashtag shows Black people earning respect in such spaces of excellence by being exceptional.”

But here’s the thing with #BlackExcellence: when we emphasize achievement as the primary way of empowerment, we pressure Black people into unrealistic standards of exceptionality. We teach Black children that they must display superhuman qualities in order to be seen or heard. Despite its initial intentions of empowerment, #BlackExcellence has become sort of an expected standard for the Black community.

During this Black History Month, I want to shed light on the negative effects of positive Black representation on the Black community. And if you find that previous statement counterintuitive, please bear with me.

faces, the women at the forefront of #BlackGirlMagic have become beauty standards of their own. What about the Black girls who do not have these physical attributes? Not that most Black women aren’t stunning (from what I’ve seen on the University of Toronto Mississauga campus, trust me, they are), but most Black women should not have to look like supermodels for you to pay attention.

Second, #BlackExcellence content perpetuates white supremacy. Yes, you read that right. It teaches us that our worth is measured by how well we integrate into white spaces. In addition, #BlackExcellence content shows achievement but only through white metrics of success. A Nobel Prize. A Grammy. An Ivy League School. All of these institutions are, at their core, Eurocentric, and have routinely shunned Black people. This is where #BlackExcellence supposedly comes in; it shows us that Black people have the potential to enter such spaces. And to that, I say: duh! Black people have been displaying talent, brilliance, strength, and ability for millennia. There’s nothing new here, there really isn’t.

The first downside of #BlackExcellence affects Black women and their relation to beauty. The #BlackGirlMagic movement—an undercurrent of #BlackExcellence—is a good example of this. This hashtag started off with an inspiring wave of content representing stunning Black women, and stunning Black women only. From large afros and hourglass shapes to oiled-up skin and modelesque

The problem with #BlackExcellence is its subconscious adherence to white supremacy. By promoting the belief that Black talent must be recognized by white institutions, #BlackExcellence fails to actually define excellence on our own terms.

Lastly, #BlackExcellence content makes space for privileged Black people—those who are educated, well-spoken, and wellread. Yet, by limiting Black representation to Black people in academia, in sports, and in entertainment, #BlackExcellence content forgets about those who cannot exist in those spaces. What about unemployed Black people? Black college dropouts? Don’t they deserve the same hype Black doctors receive? That is, in my opinion, the biggest downside of #BlackExcellence—it sometimes tends to be classist and only empowers Black voices of a certain standing. Although it is important to encourage social mobility in our community, we should not define success through an elitist point of view. We already deal with systemic racism, and we certainly do not need another ladder to climb.

That said, #BlackExcellence content still comes from a genuine desire for community empowerment. I cannot sit here and deny that. When I have children of my own, I hope to expose them to positive representations of Black people doing amazing things. But I also want my children to know that I will love them with all my heart, even if they do not make it into history books.

“From large afros and hourglass shapes to oiled-up skin and modelesque faces, the women at the forefront of #BlackGirlMagic have become beauty standards of their own.”

“By promoting the belief that Black talent must be recognized by white institutions, #BlackExcellence fails to actually define excellence on our own terms.”

Allowing Black people to be normal is real allyship.

on social media can be a good way to get people to learn about social issues, such as discrimination, and engage many people in conversation. However, raising awareness alone is not enough to bring real change.

ness in those engaging, making them completely disregard posts regarding social movements.

Performative Activism

Noun.

“Defined as activism that is done to increase one’s social capital rather than because of one’s devotion to a cause.”

Performative activism has become more popular in recent years, mainly due to the increased use of social media. Sharing certain posts, using hashtags, and changing profile pictures have become incredibly trendy. Fundamentally, social media platforms can be powerful tools for organizing and spreading information, helping to amplify the voices and stories of marginalized groups, and bringing attention to issues that may not have received mainstream media coverage. However, with performative activism, these platforms can be a distraction from the organizing, planning, and participating in real-world actions that can have tangible impact. Clicking a re-share button offers an easy method of support, but also takes away the commitment necessary to take significant actions. Raising awareness about a cause

While there are many individuals who genuinely care about and actively work to address social issues, there are also those who use the disguise of social consciousness for personal gain or to build a favorable reputation—especially in environments such as digital platforms, schools, universities, and the workplace, where individuals are concerned with how they are perceived by others. It is important to note that while there is nothing inherently wrong with expressing support for a cause on social media, it is crucial to make sure that it’s a part of a larger, meaningful effort, and not the only form of engagement.

On the other hand, the consistent flow of information and the pressure to be constantly engaged with the news can also lead to feelings of burnout, fatigue, and helpless-

Being stuck in both extremes can be dangerous when it comes to creating a genuine commitment to minority cultures, and in recognizing and honouring their contributions, struggles, and experiences throughout history. Performative activism can truly hold us back from acknowledging the past justly and from working towards a more equitable future. Let us not allow performative activism to detract from the true purpose of Black History Month. Let us strive to remember the perseverance and contributions of those who came before us as they deserve.

The Medium strives to be a place that moves far past performativity, using our platform to create tangible change and uplift your voices. Without you, The Medium would not be here. Take this space to be open and accepting. To be a place to stand on what you believe in. To stand on what matters most. To make your voice heard.

Vanessa Bogacki Contributor

Vanessa Bogacki Contributor

Along with the rise of social media, many of us have found ourselves using labels in our everyday language. After all, once one makes their Instagram account public, they must decide if they are a “business,” “comedian,” “sex therapist,” or “waterpark,” amongst many other options, but whatever you chose to have in your biography introduces you to the world with a label.

We get to pick how we are labelled, so what’s the harm? Well, many new advocates believe it takes away from promoting equality and causes barriers for those who aim to achieve notoriety within the corporate world.

Inequality and injustice are two of the many negative factors that individuals within the Black community have been forced to face time and time again. These issues have been studied historically, and continue to be explored, hence the rise in protests to promote change—recently seen with the 2020 Black Lives Matter movement.

During the digital era, which further expanded during Covid-19, individuals quickly saw the increase in influencers and learned the power of voice. This allowed for the development of labels within cinemas, music, businesses, and more. Several activists have seen an increase in labelling businesses designed and started by Black individuals as “Black-owned businesses.” The debate has sparked a lot of attention towards these labels, and more importantly, whether they ultimately harm or benefit Black business owners.

Using the “Black-owned business” label for new business owners may also be responsible for pushing away consumers, as racism is unfortunately still a problem in our society. Labelling one’s company as a “Black business” might be responsible for a decrease in sales, as certain individuals may turn away from a business which publicly promotes their racial background within their title. This idea may be applied to cinema, clothing, food, or music, simply based on the inequalities present within society. In addition to this, the label itself promotes inequality naturally, as the business is put at a disadvantage by being labelled as something different. This pushes society further back instead of forward by causing segregations within the corporate world. Furthermore, labels may form the view of this business being different because it can only appeal to the Black community, which is simply a false statement. Consumers from all ethnicities are welcome to purchase these products and further promote them to increase popularity, resulting in higher sales.

Another factor that should be explored due to these labels is the stereotypes which may come hand in hand with the idea of strictly “Black” organizations. Many individuals may shy away from supporting the business because they feel as if they are not represented and heard within the community This can be dissected in the regions of cinema as well, as individuals may not purchase tickets to a movie they feel as if they “cannot relate to it.” Just because one cannot relate to the subject proposed does not mean it should not be studied or brought into light. Topics that cause controversy or uncomfortable emotions tend to be repressed which results in individuals being uneducated.

By: Reid FournierThere is a further belief that these labels cause harm simply because they take away from the business aspect of the company. They discuss the downfalls which these labels bring, as they tend to appeal more to a certain group of consumers as opposed to the general public. In addition, these labels may cause individuals to believe they must refrain from consuming a product as it does not suit their needs. This phenomenon is exemplified by the finding that certain shampoos may only be for certain hair types if it is promoted by a “Black business.”

When looking at the label of “Black businesses,” many can argue as to why they believe this is morally correct or incorrect. The conclusion is not necessarily if one believes in this action, but how society can come together to further educate tomorrow’s leaders regarding finding more support for the Black community.

It must be taught that supporting the Black community is not something which should only be done during Black History Month, but every day of the year. We must face the problem to begin fixing it. Being silent about injustice causes individuals to ignore the problem but, as Martin Luther King Jr said, “our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.”

In a

creating a dependency on domestic slave birth. The results? A drive for medical innovation and the birth of gynecology as a field in North America. James Marion Sims, an unpleasantlycelebrated American physician, set to experiment his “brilliant

Many of us have come across that TikToker who has compiled a list of “cons” to pregnancy. When videos of women showing the reality of motherhood find their way onto our For You Pages, people flood comments calling for the “girl with the list.” Through the media, we are often provided with reasons to not have children. There are 350 reasons, according to @yuniquethought’s page. While we have come to an understanding that pregnancy is, undeniably, dangerous, this reality is amplified in the experience of Black women—specifically in the West.

Pregnancy-related death rates are concerning, but the mortality rate of pregnant Black women is both alarming and frightening. In the United States, for instance, Black women “are three times more likely to die from pregnancyrelated causes than white women,” more likely to experience preventable maternal deaths, and more likely to undergo maternal health complications. In the United Kingdom, as of 2020, Black women are four times more likely to die during childbirth than their white counterparts. Yet, all stand true regardless of socio-economic status, access to health care systems, and insurance coverage. The horrific pregnancy stories of Beyoncé and Serena Williams are two examples of many.

In Canada, data is scarce. As public health specialist Dr. Onye Nnorom states, Canada’s “current [medical] practices are hurting Black Canadians, because there is little to no health care data or research that is specific to race or ethnicity.”

This inhumanity finds its roots in slavery. In 1808, the United States declared a federal ban on the importing of slaves,

Rola Fawzy Staff WriterIcouldn’t tell you the details of why my 13-year-old-self stomped angrily into my house that day. I couldn’t tell you what the girls on the street said to bother me. All I can remember is that they directed a snide, racially-motivated remark at me, were surprised when I clapped back in Arabic, and pushed me into a rage that brought all my previous hurt to the forefront.

Upon seeing the force with which I shoved the door, my parents urged me to tell them what was wrong. After repeating “I am just done with these people” some 10 times, I obliged and recounted what happened. I waited for comfort from my parents. To my surprise and—at the time—dismay, my father broke into guffaws. My father’s guffaws became shouts. Then he held me by the shoulders and directed his shouts to snap me from my rage-infused stupor. “Some stupid girls called you some stupid name and you get this upset? Do you know how many people called me names? Do you know how many people hated me just because I was Black? Do you think you would be living in this nice house going to your nice school if I kept on crying about it? Stop being dumb!”

Growing up, I knew two sides of my father.

I knew the angry man. I knew a man so intense that schoolteachers were afraid to have parent-teacher meetings with him. A man who valued diligence and righteousness above anyone else’s feelings. It became clear to me that this is the way the world perceived him: an imposing and intimidating figure. I remember once I had a conversation with a person who didn’t know that he was my father and identified him in conversation as the “big Black man.” For the sake of irony, my father is a man of medium build, not taller than 5’6”.

But he was a lot more than what people made him out to be. I knew him as a man who fascinated me with all the facts and cul-

achievements” on Black women. Like many other physicians in the 1830s, Sims’ work was fueled by a source of pernicious biological folk and weaponized faith: one claiming that Black people were not capable of experiencing pain. Some may dictate this to be trivial history, but the disparities in the health care system continue to haunt the contemporary world. When medical institutes echo the teachings of these baseless and racist ideas, the pillars of health care in the West curate a systemic injustice that directly targets Black women. It reinforces a past we struggle to detach from, a past we claim to have learned and evolved beyond.

In 2021, a medical illustration created by Chidiebere Ibe, a Nigerian medical student at the Kyiv Medical University, consumed the internet. Its reason for going viral was simple: it featured a pregnancy diagram of a Black mother and fetus. While the majority of the general public stood in awe of the illustration, it was the reaction of medical specialists that defined the state of the health care system—it was the first time for many to interact with a medical diagram depicting a Black woman. Concerning, to say the least.

So, the first step toward change is simple—we must acknowledge the existence of the disparities. Whether that is done within your community or if we direct it to the education system, it is critical for reality to be put on display. But our duties should lie beyond that. Black women’s voices need to be centralized. When we chant that Black women have gone unheard, we do not merely refer to the social sphere. Black women are actively silenced and ignored in our hospitals, clinics, and birth centres.

So, the next time you comment on a post calling for “that girl with the list,” make sure it is for one last reason: the health care system.

ture he knew. I knew him as a man who told many stories about the world, little about his life, and just wanted me to know more. I knew him as a man who sometimes got teary-eyed. I knew him as a slightly funny, certainly impulsive man with hopes that he would leave his children more prepared for the world than his father did.

But my father did not know how to have conversations with me about anger, nor did he know how to have conversations about being Black. Still, being angry and Black was a label that I felt swallowed me for much of my life. A label that made me feel like a pariah, an untouchable of sorts.

When I was a child, my Blackness was not something that I realized for myself. Rather, it was something that the world made me aware of. My Blackness was something that I learned through being othered, both subtly and outwardly. On the basis of taking after my mother’s beige skin, my siblings did not understand my experience, nor did my mother. It became isolating, so I learned to fall on my rage like my dad fell on his.

My dad’s anger was a law of nature that I did not question. But I did try to infer what it meant to be Black growing up. When I would try to decipher what his experience was growing up Black and working class in Egypt, my father would be mostly quiet, sometimes agitated that I pestered him a little too long for his liking. “Things were okay, why are you asking?”

But as my father grew older, he mellowed. And his lips loosened. In sporadic spurts, my father gave me tidbits of his younger years as a Black man. When I told him I couldn’t land a waitressing job, he told me that it was similar for him too; when he worked at a restaurant, they did not allow their Black staff to work as servers. On another service job that he took up during university, people often treated him with inferiority just because of his skin. Perhaps this is why he felt strongly against me getting anything “lower” than a desk job. One day, my father talked to me about the importance of having mentors in my career. Unprovoked, he admitted, “oddly enough, none of [my mentors] were Arab or Egyptian.” When I asked him why that was, he said, “I guess they just found me too angry, and they didn’t understand why.”

My father released me from his grip, and I would soon be in my room. Tears were still in my eyes. My shock surpassed my anger. At that moment, because my father did not give me the comfort that I wanted, I thought he did not understand. How could he let his anger overtake his duty to soothe my pain? Although he couldn’t communicate it, my father did understand. He just wanted to prepare me for the world that he knew. And the world my father knew would not care for my feelings.

A reflection on the coupling of Blackness and anger.

“Black like her father”Yasmine Benabderrahmane Contributor BEATRIZ SIMAS/THE MEDIUM ROLA FAWZY/THE MEDIUM Editor | Prisha (Maneka) Nuckchady features@themedium.ca

In2020, Frank Castle, known as The Punisher from the self-titled Netflix series (2017-2019), became the new warrior logo of the American police. Law enforcement officers were spotted wearing the Punisher skull as a statement of their power over regular citizens during protests against police brutality following the murder of George Floyd.

In her recent paper, “Violence in the American Imaginary: Gender, Race, and the Politics of Superheroes,” Menaka Philips, an assistant professor of Political Science at the University of Toronto Mississauga, talks about how the American police twisted the meaning of The Punisher’s emblem. She writes that Punisher’s actions in the series are meant to critique the failure of the state, not support its violence. “In the comic book, they have cops coming up to Punisher and saying, ‘We love you, you’re awesome’. And he loses it. He’s like, ‘I’m not on your side. You’re part of the corruption, you’re part of the problem,’” shares Professor Philips in an interview with The Medium

Professor Philips believes nothing can justify the desire of American police officers to reclaim a sense of authority. Although Punisher’s murderous violence is always excused in the series, this should not be the case in real life. “This cannot be a response to that kind of movement. It should be disturbing that it is,” observes Professor Philips.

Then how did this vigilante icon gain such an immense fol-

lowing among American—and even Canadian—police? “Punisher’s appeal lies in his unrestricted relationship to violence—a relationship guaranteed by his status as a white man,” wrote Professor Philips in her article for Political Violence At A Glance.

The character’s background makes his vigilantism acceptable to many audiences. In the 2004 action film, Punisher, an FBI agent transforms into a vigilante after criminals murder his family. He represents a loss of power, which creates the perfect excuse for his response to his tragedy.

Professor Philips calls the type of violence the character uses “unrestricted” because of how brutal it is on screen. And yet, his actions are always rationalized, not only by the people but also by the state. He has full access to such cruelty because he does not fear being judged or arrested for his killings.

last resort. On Cage’s part, violence always remains reluctant, as if he has to suffer to gain permission for it. “He’s always in the position of loss, in order for the audience to recognize his violence as valid,” comments Professor Philips.

The third and final type of violence that Professor Philips identifies in her paper is “vulnerable.” When it comes to Marvel movies, female superheroes and their abilities are often overlooked. A potential reason for this is that their aggression is almost always defensive.

vulnerable and a victim.”

As an example of this type of violence, Professor Philips talks about Marvel’s Jessica Jones (2015-2019). Jones is a superheroine who possesses super strength and durability, as well as flight and mind control. The audience never sees her being violent as a response to rage. The TV series about Jones provides a constant reminder that she is vulnerable and a victim. That is why she needs violence to protect herself. “These gendered and racialized norms are filtered into the American context,” claims Professor Philips. “They are reproduced over and over again, even in texts or films that are trying to raise difficult questions about racial politics or gender.”

Professor Philips mentions that the bigger question here is about how much violence should be put on display in superhero films and who should be allowed to use it. However, while she does not have the answer, she knows that even in the most progressive Marvel movies, violence remains restricted in many ways for women and people of colour—so much so that they would rather sacrifice themselves than hurt anybody else.

The rationalization of violence granted to Punisher is rarely granted to minority heroes in the superhero universe. For example, in TV series Luke Cage (2016-2018), Cage, a Black Marvel superhero with super strength and unbreakable skin, approaches violence with caution. Despite also experiencing great trauma in the past, the way he is allowed to respond to his suffering is very different from Punisher.

“In his violence, Luke Cage is always contained. It’s rarely explosive. It’s almost never bloody. You never see him hurt anyone too much,” explains Professor Philips. The main difference between him and Punisher is that Cage is never forgiven by the state, despite actually doing good for the community rather than focusing on his personal agenda.

In her paper, Professor Philips calls Cage’s violence “sacrificial.” The superhero never engages in brutal fights unless it is his

“Punisher’s appeal lies in his unrestricted relationship to violence—a relationship guaranteed by his status as a white man.”

“In his violence, Luke Cage is always contained. It’s rarely explosive. It’s almost never bloody. You never see him hurt anyone too much.”

“The audience never sees her being violent as a response to rage. The TV series about Jones provides a constant reminder that she is

she says allows Black academics to have a sense of community and rely on each other as a resource for scholarship. This is a model she hopes to see adopted by other institutions as well.

“Growing up, my parents, as immigrants, [...] always raised me to be hyper-aware of the meaning of my Blackness in the bigger matrix of my identity,” shares University of Toronto Mississauga Sociology professor, Camisha Sibblis. She explains that her experience and awareness as a Black woman naturally led her to learn more about how “Blackness shapes our realities and shapes our opportunities or lack thereof.”

Dr. Sibblis is also an adjunct professor at the University of Windsor’s School of Social Work, and is currently the Co-Investigator of a project funded by Social Science and Humanities Research Council, titled “Sealing the Leaky Pipeline: Constructing Mentorship Best Practices for Racialized Graduate Students in the Academy.”

Dr. Sibblis has worked extensively with marginalized youth within the public school system as a social worker and as a clinician, assessing the mental health of convicts who are dealing with anti-Black racism. One of the most important learning experiences for Dr. Sibblis while working with Black people dealing with discrimination within the criminal justice system is a phenomenon she calls “the ubiquity of carcerality.” Carcerality refers to methods of social control, including but extending beyond prison incarceration, that systematically discriminates against racialized communities. Having spoken to convicts, through their stories she learned that “it’s really evident how […] the carceral is implicated at every stage of their life.”

ness means, and I think that in itself is a tool of containment,” she adds.

When it comes to preventing systematic forms of oppression within academia, Dr. Sibblis emphasizes the importance of working toward the redistribution of power. She argues that while it is a positive step to have more Black and racialized professors in assistant and associate positions, “we don’t see a whole lot in full professorships, […] as deans, as provosts.” Dr. Sibblis stresses that it is important for the entire institution and organization of academia to reflect the diversity of society.

Dr. Sibblis explains that Black people who have been convicted often deal with carcerality earlier in life, either due to being firstgeneration immigrants, or through their school system, child welfare, or the medical field. She emphasizes that as a result of their experiences dealing with hyper-surveillance within these institutions, Black people’s construction of their identity is heavily affected. “All of that I find very carceral because it’s this inability to transcend what their Black-

Dr. Sibblis’ current research project, which is piloted through the Canadian Sociological Association Black Caucus, emphasizes the importance of building community by connecting students to people working within academia. “There is a kinship that we don’t take for granted, and we can be candid around what our common struggles are,” she notes. Dr. Sibblis points out that through this community building, mentors enlighten their mentees on how to navigate academia and ensure that they are excelling within the academic institution. When asked what she hopes to gain from this project, Dr. Sibblis says that she hopes for “more critical numbers of Black and racialized faculty in academia,” so that not only are students of colour better represented, but the Eurocentric nature of academia can change.

Having worked with children and youth as a social worker, Dr. Sibblis draws connections between the public-school model and post-secondary education. Addressing the reality of systematic forms of oppression, she says that the Ministry of Education has

recently started to deal with the streaming issue, whereby Black students have been streamed into tracks that do not lead to postsecondary education. Dr. Sibblis shares that she has witnessed similar patterns within academia: “Black undergrads and Black graduate students [are] not actually ushered and put into advantageous roles and positions by their superiors.” She further explains that through reviewing applications for incoming graduate students, she has noticed that white students are often groomed for success in ways that Black students are not.

Dr. Sibblis acknowledges that she has noticed positive changes with academia. For example, Dr. Sibblis says that universities taking action to hire more Black and racialized academics is a step in the right direction. However, she states that more can be done, as in certain instances, many Black academics are scattered across multiple faculties and departments. “So, they still end up being the one token Black educator in the faculty or in the department […]. It’s a very isolating and alienating position,” she adds.

Dr. Sibblis praises the University of Windsor for starting a Black Studies Institute, which

For sociology students who are interested in studying and pursuing work that deals with racial identity and anti-oppressive frameworks, Dr. Sibblis encourages them to take courses in social work. She mentions that given her background as a social worker, she makes sure to bring that lens to her sociology and criminology classes. “My advice is to do work outside of sociology and to gain a critical lens,” she shares. She explains that through this, students will be able to make the shift from recognizing statistics and theory to humanizing the experiences of people in the real world. She adds that it is important to be reflective and reflexive: “Ask yourself how is it that you are implicated, know that we can never really be separate from our object of study,” Dr. Sibblis explains.

For Dr. Sibblis, Black History Month is a bittersweet occasion. She shares that it can feel peripheral in the importance it is given. “I think it should be Black History every day. It should be completely integrated,” she stresses. She further elaborates that she thinks “Black History” is a misnomer, “it kind of separates us from the greatness that we are achieving today,” she says. Dr. Sibblis argues that perhaps “Black Heritage” could be more accurate, as it is important to not just engage with the past, but the present and future as well.

“Growing up, my parents, as immigrants, [...] always raised me to be hyper-aware of the meaning of my Blackness in the bigger matrix of my identity.”

“Blackness shapes our realities and shapes our opportunities or lack thereof.”

“Black undergrads and Black graduate students [are] not actually ushered and put into advantageous roles and positions by their superiors.”

“It is important for the entire institution and organization of academia to reflect the diversity of society.”

Dr. Camisha Sibblis shares how discrimination shapes Black individuals’ perceptions of identity and how academia should create more inclusive practices.

Mahera Islam ContributorCAMISHA SIBBLIS Cristina Pincente Writer

so I’m making the decision for you. I am giving you three months to get yourself together and go to Japan, or I’m going to fire you.” She needed this push to apply to an agency that hired ESL teachers in Japan.

Jackson, a guest speaker for the Hart House series Laugh, Cry, Cringe, is a traveller, educator, and storyteller. From backpacking across Asia and doing a four-day hike up Machu Pichu, to volunteering with a start-up in Cape Town and camping in the national parks of Southern Africa, Jackson has travelled to 37 different countries spread across 5 continents.

Jackson shared that she wants to show people they can travel just like she has because she believes that “especially to people of colour, travel is one of the greatest gifts you can give yourself because travel is the key to discovering ourselves.” Jackson started her talk by asking us to keep this question in mind: “How has a lack of representation affected the decisions you’ve made in your life?”

Growing up in the Jane and Finch neighbourhood as a child of Jamaican immigrant parents who were working class, Jackson shared that “school was not a priority, surviving was. [My parents] didn’t get a lot of education, but they still managed to come to Canada and make a living.” They preached those same values to her, hoping she would own a house with a white picket fence and one big happy family living inside it.

You can imagine Jackson’s overwhelming emotions when she got off the plane at the airport. “I knew I wouldn’t blend in but preparing for the onslaught of attention you receive in certain countries is hard,” she shared. During her first month in Japan, people stared, pointed, and moved away from her. Jackson’s students, however, she adds, were a treat: “we had amazing cultural exchanges.” They wanted to know everything about her, and she wanted to know everything about them. But outside the classroom, it was not a pleasant experience. Every day, she went home and cried.

But on the fourth weekend, she had an epiphany. She looked in the mirror at her sewnin extensions and didn’t feel like herself. She cut off the extensions and expressed that she felt like “a new person had appeared again, and that day I also knew I needed to change my mindset about the situation.”

Jackson understood that locals had little experience with foreigners. She had to understand that she was there to learn about them, but they also wanted to learn about her. She said, “I was chasing geishas, and they were chasing me.” Instead of getting upset, she tried to interact with people. If they pointed out her hair, she asked them if they had seen hair like hers before; some would rub her skin, and she asked them if they had seen skin like hers before. Jackson learned to make friends in Japan by reaching her hand out first.

Jackson was fascinated with exploration from a young age. She loved to take the bus or the train by herself and discover Downtown Toronto. She was also passionate about Asia and discovered that native English speakers would teach English in places like South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan, through the organization Dave’s ESL Cafe—an international hub for English second language (ESL) teachers. “I quickly noticed that many of these sites I was obsessing over never featured anyone who looked like me. Some of the job postings that I would see as a 16-year-old girl explicitly said they were looking for a white, blonde male or a white, blonde woman because that is what the parents of the students wanted,” she noted. The summer after graduating from York University in 2007, Jackson got a certification in teaching English as a second language—a credential required for anyone interested in teaching overseas.

The idea of being halfway across the world, in a place that may not accept her, gave her cold feet. So, she decided to move to Montreal in the middle of the winter to teach English. “I wasn’t happy. I wasn’t in alignment with my heart,” Jackson confessed. After eight months, she was back teaching ESL at a school in Toronto, where she met Christina, her boss. Jackson was still apprehensive, so she made safer trips, like a road trip across Cuba with a small group tour. She went to Vancouver, and when she came back, Christina said, “Lotoya, you are going to ruin your life with regret,

She discovered the field of e-learning during a free period in her class. Two boys were huddled in the corner on little devices, and she asked them what they were doing, and they said they were taking a law class online. It was a lightbulb moment for her.

In 2013, she completed a Master’s in Education at University of Toronto’s Ontario Institute for Studies in Education. “Before I graduated, I had my first e-learning developer job at Pearson, the world’s biggest education company. It was a full-time corporate job, the opposite of what I wanted for my life,” she explained.

So, she booked a trip to Brazil for a Carnival. On this trip, Jackson bought a book that she claims changed her outlook. The four-hour work week by Tim Ferriss is “an amazingly detailed blueprint for escaping the 9-to-5,” she explained. Drawing from the book’s principle of liberation, she met with her boss to discuss her plan to work remotely since most of her clients were in the US. But her boss declined, and she resigned immediately. The next day her boss called her back and said she wanted her back, not as an employee but on contract for a 30 per cent pay hike.

This was a pivotal moment for Jackson. She had realized the benefit of taking rest and following her heart, so she began five years of checking off all the places she had wanted to go on her bucket list. She spent summers in Europe on a one-way ticket. She chased wa-

terfalls in Iceland. She stayed on a Columbian farm milking cows. “I allowed myself to wander,” she explained. A travel tip Jackson stresses is the beauty of boutique hostels. She says that hostels have a terrible reputation, but it’s not like it is in the movies. They can be as cheap as $30 a night, which is perfect for someone travelling on a budget. Safety is the biggest concern. She shares that you can check in with ID. You don’t have to stay in a dorm. You can ask for a private room; there’s a lot of flexibility. There are lockers for your valuables, and the community aspect is the best.

Now, Jackson is trying to balance being a mom and a traveller. She’s aware that her daughter’s needs must be prioritized, but not in the way people think. She knows that she can forge a path where her and her daughter can have the best of both worlds. Travelling gave her a depth of education. Although her daughter is starting school this year, Jackson hopes they will be able to travel. “Travelling with her and seeing her reaction to things is the best joy I didn’t know I needed,” she confessed.

“I allowed myself to wander.”

Jackson is inspired by The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho. The book is about understanding that everyone is self-obligated to achieve their “personal legends.” In other words, discover their purpose, follow their hearts, take risks, and follow the omens—or signs—that will lead them to find their personal legends and achieve their destinies. Jackson says that being young with few commitments is the ideal time to experiment with life. “If you’re interested in shaking up your world perspective, gaining new perspectives, and hitting the reset button, I challenge you to see how travel can do that for you,” she concluded.

“Especially to people of colour, travel is one of the greatest gifts you can give yourself because travel is the key to discovering ourselves.”Staff

During the Laugh, Cry, Cringe storytelling series, Lotoya Jackson shares her desire to inspire, encourage, and empower women of colour to travel.

Lotoya Jackson shares how she escaped the 9-to-5 and created a life focused on travel, remote work, entrepreneurship, and parenthood

Editor | Julia Skoczypiec arts@themedium.ca

Editor | Julia Skoczypiec arts@themedium.ca

In this age of fast paced and career-oriented living, we often get caught brushing over life’s deeper meanings in shallow ways. We hear but we don’t listen. We swim but we don’t float. Often, we forget to remember the hands that raised us and those that continue to pave our futures.

Ayomide Bayowa is an award-winning Nigerian-Canadian poet, filmmaker, and actor. He is a recent graduate from the University of Toronto Mississauga and currently serves as Mississauga’s Poet Laureate. This spring, Bayowa is publishing a poetry collection titled Gills—a refined version of his first collection Stream of Tongues; Watercourse of Voices. In an interview with The Medium, Bayowa shared insight about Gills and its connection to concepts like survival and socio-economical injustices.

Growing up in Nigeria, Bayowa began his journey as a poet at the University of Ibadan in Oyo, Nigeria. He became inspired by the writings of his teachers and friends. “The first poem I ever wrote [was written for] a friend of mine who is now late,” said Bayowa. “His name is Akinfolarin Pojo, [and he] died of sickle cell anemia in 2017.”

Later in the interview, Bayowa explained that Gills is in part dedicated to Pojo. While most of his writing stems from his own life and the experiences of those that he calls friends, Bayowa aims for Gills to speak to a vast audience. According to the book’s publisher, Wolsak & Wynn, the collection aims to depict the lives of “millions of immigrants” through “dramatic and quip lyrical” language that plays with aquatic and bodily images.

“[The word] gills will give you an impression of a fish—its skin is its natural component for survival,” said Bayowa. “If you, like

me, ever feel like a fish, [your] scales are like bubble wrap, exposing [you] to the regular bones of [societal] conditions.”

Relating this analogy to people of colour, Bayowa continued, “Immigrants, like me, are the souls and the palms in Gills. Our presence depends on our skin—for survival or misfortune.”

Through his poems, Bayowa aims to unravel the immigrant experience. His work places Black individuals at the centre, reliving silenced life lessons that many should hear. While poets often write about identity, Bayowa’s words steer away from concepts of the self. His writing speaks for the hearts and the lives of those that have shaped him and those that continue to suffer.

Reflecting on how his Nigerian roots inspired his poetic tongue, Bayowa told a story of a time in Bodija, a Nigerian town, where he and his friends ran from gang members that pursued them—what he described as a “near-death experience.” His friend and colleague, Molawa Davies, wrote a song about this forsaken town titled “Bodija.”

“When I left Nigeria, I listened to this ‘Bodija’ song. I seemed to listen to this song less [after] I wrote a poem titled ‘The Little I Remember.’ I was able to pour out this cycle of feelings that I couldn’t tell [I had],” Bayowa explained.

It is through writing poetry and learning about theatre arts that Bayowa found his voice. By analyzing and “scaffolding” the styles and sounds of other writers and artists, Bayowa learned to fearlessly express his own feelings. He emphasized that poetry writing is using one’s “voice that you use to read in silence”—the only voice that matters.

As we reflect on and celebrate Black culture during the month of February, Bayowa reminds us of the importance of survival— a theme that circulates through Gills. “Gills is about staying above the water. [It is about] survival. And to me, survival is the present and continuous condition of dying,” said Bayowa.

He reminds us that this month is “one for the Black community to have space, reflect, and re-live” the injustices that continue to plague society. Through his poetry, Bayowa aims to educate readers on the barriers that Western ideologies continue to create for marginalized groups.

To conclude the interview, Bayowa left me with a quote to remember: “Consider Blacks your customers. They are always right in their own status,” he said.

For more information on Gills, visit Wolsak & Wynn. To keep up with Bayowa’s poetry and other works, follow him on Instagram @_officialayomi.

Iamnot an avid reader. For a long time, graphic novels with fantastical illustrations were the only stories I found worth reading. When I started high school, I thought it was time to give more reading a try. So, I decided not to leave my reading experience in the hands of my English teachers, and I visited my high school library.

I read Chinua Achebe’s novel Things Fall Apart and became familiar with the names Okonkwo, Nwoye, and Ikemefuna. But after I returned the book to the library, I felt somewhat deprived. For me, Black history usually started with the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, but in his novel, Achebe shared stories of pre-colonial life in Western Africa. As a place populated with tribes all bearing different languages, customs, and traditions, I

was rarely given the chance to explore West African culture outside of Achebe’s words. His story wasn’t a fictious work to me, in my mind it must have always existed. Reading it made me realize all that I had been missing.

In another trip to the library, I found James Baldwin’s Nobody Knows My Name. I discovered how effective well-crafted essays can be. Baldwin’s words rung as a deep analysis of the American psyche—in ways that are more complex than any history or psychology class put together. “No one is more dangerous than he who imagines himself pure in heart: for purity, by definition, is unassailable,” he writes. His words are profoundly relevant as checking our biases becomes more of a common practice.

My reading journey continued with Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, a novel that explores the vastness of the diasporic experience. Then, I time-travelled to the Antebellum South in Kindred, a sci-

ence-fiction story only Octavia Butler could think of. And finally, after letting go of what was weighing me down, I learned how to fly with Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon Black literature taught me everything I know about literature. I will always cherish the emotions these novels evoked and the ideas they left me with. I often wonder: would I have ever discovered these authors within a school’s curriculum? Black literature exists outside of the bounds of Black history month. With this, I think about books banned from the shelves of countless libraries around the world.

So, to writers like Baldwin, Achebe, Morrison, Butler, Adichie and all the rest I am left to discover—thank you for telling me how you see the world. Thank you for showing me that amid pain and destruction, there is also love and wonder. To readers like myself, I hope you find the value in literature—especially in the pages that

you haven’t discovered yet. The new Black perspectives, experiences, and tales that we read educate us on individual human experiences that will forever bind us. The more time we take to understand each other, the better off we will be.

WOLSAK & WYNNTrigger warning: This article mentions sexual assault.

History allows us to reflect on the paths that paved the ways to our futures. By learning the stories of those who came before us, we are encouraged to develop our own understandings and shape our world views. History is crucial to Black History Month.

Based on true events, Gina Prince-Bythewood’s The Woman King (2022) follows the African Kingdom of Dahomey. Specifically, the film showcases the historical, allfemale group of highly trained and wellrespected soldiers known as the Agojie. Up until watching this film, I had never heard of the Agojie—let alone a group of soldiers composed only of women.

History suggests that the Agojie came to be around the 1700s. Some even believe the Agojie originated from a group of elephant

hunters. As one of the few female armies documented in history, being in the group required extensive training—ranging from hand-to-hand combat and musket training, to relentless exposure to pain. The Woman King highlights these aspects of the group, along with many others.

The film also focuses on the roots of the slave trade. Often, the media repre-

sents slavery in a “post transaction” kind of way—we see enslaved individuals but do not understand how they became slaves. The Kingdom of Dahomey played a large role in the Atlantic Slave Trade; the Europeans used their peoples as a large outlet for slaves. In one of the opening scenes of the film, a group of men sit around a fire and hear a rustle in the bushes. Nansica (Viola Davis), the Agojie General, reveals herself—followed by her group of soilders. She lets out a war cry and the Agojie charge, proceeding to raid the village. A gruesome battle ensues, and we find out that the village they raided was holding Dahomey people and other nations captive.

This scene was quite shocking. This film shows that greed comes in any colour. Throughout the plot, we are introduced to the Oyo Empire—a group that have allied with the Europeans in the slave trade. Historically, the Oyo was a dominant kingdom known for their ties in the Atlantic Slave Trade. They were highly militarized and profited off of slaves—as the Europeans allowed them to expand their empire. In the

film, the Oyo raid villages and take captives who they then sell to the Europeans. They were willing to sell their own African peoples just to satisfy their need for wealth and power.

Another aspect of the film that stood out to me was its display of empowerment. Amid the gruesome fight scenes, the women of the Agojie remind us that strength can be found in vulnerability. While the main character, Nanisca, is known for her resilience and bravery, she also has a secret. She too was once sexually assaulted by the now leader of the Oyo empire. When he comes back into her life, she begins to relive the traumatic events she endured. But, by facing her fears head on, she accepts her past and uses it as fuel to move forward.

Black culture is represented quite beautifully in this film. This was refreshing to see, as there are few films that allow us to envison Black history in this perspective. I think that everyone should add The Woman King to their watchlist. It is these kinds of films that pave paths for Black representation in Hollywood.

Kuicmar Phot Staff Writer

Kuicmar Phot Staff Writer

In the past few decades, Hollywood film productions have made efforts to feature stories about racial minorities who were once excluded from the film industry. The number of films containing Black leads and plotlines has significantly increased— in an attempt to create Black representation. Unfortunately, films about the Black experience are often centred around some form of trauma—such as slavery, police brutality, the civil rights era, and more.

Accurate portrayals of the grim reality of Black history are necessary. In my opinion, the issues that remain in many Black-centred films come from the oversaturation of heavy and dark themes. It’s become apparent that Hollywood will not prioritize Black films unless racism or violence are the pinnacle of the plotlines.

See You Yesterday (2019), directed by Stefon Bristol, is a film about two Black teenage geniuses who invent a time machine to get college scholarships. At first glance, the movie sounds like a wholesome, coming-of-age sci-fi film—until the main character’s brother is wrongfully murdered by police. The teens spend the entirety of the film going back in time, hoping to save the main character’s brother. As they time travel, the movie constantly shows the character’s brother being murdered, repeatedly.

Travon Free’s and Martin Desmond Roe’s film Two Distant Strangers (2020) is a film about a Black man trying to get home to his dog. However, in the process, he gets wrongfully murdered by police. Similar to Bristol’s film, the main character must then live the same day over and over again until he finds a way to survive.

Unlike many Hollywood love stories, the ones that portray Black individuals always contain inevitable struggle. In the

coming-of-age romance movie The Sun Is Also A Star (2019), directed by Ry Russo-Young, the main character’s picturesque love life is dampened by her family’s deportation to Jamaica. Melina Matsoukas’s Queen & Slim (2019) starts off as a romance, but the main character’s first date gets derailed when a cop tries to wrongfully murder the Black pair. They spend the rest of the movie as outlaws trying to escape the police and their own deaths.

While all of these fictional movies are promising due to their diverse genres and Black representation, all of their plots are tangled in a web of wrongful violence, racism, and death. In imaginary worlds where characters can have magical powers or dragons, why is racism considered a necessity?

Movies are meant to be an escape—an art form in which everyone should get the opportunity to see characters that look like themselves in creative and important roles. They aim to educate audiences with unique worlds and untold stories. Unfortunately, the abundance of Black trauma, and the lack of wholesome Black movies, hardly offers an escape for

Black viewers. While others get to identify with characters and experience entertaining sci-fi, thriller, comedy, and romance plots, Black viewers are subjected to watching characters that look like them experience the same violence that occurs in their daily lives.

Having to watch your own people suffer in reality and fiction is draining. Films like Selma (2014), 12 Years a Slave (2013), and Hidden Figures (2016) are absolutely essential, as they portray real stories that our Black ancestors have lived through. But only being offered movies where Black people must overcome violence and racism is a form of racism itself.

Films about Black trauma are typically well-received by Hollywood’s award machine— which is far from a bad thing. However, there is a fine line between wanting to commemorate forgotten stories for the sake of showcasing Black history and exploiting Black trauma for entertainment purposes. It often feels like we’re being told that our stories and representation are only worth showing when we’re being graphically brutalized. As racism affects Black people significantly to this day, the grim realities of the Black experience should be highlighted—but they should not be our only representation.

Black people deserve wholesome, real romance films and fun coming-of-age movies. They deserve sci-fi, fantasy, fairies, vampires, even objectively cringey movies. Just like any other racial group, Black people are not a monolith. We live complex lives and have intricate experiences. We are not just figures of trauma. We are people, and we deserve films that represent us as people.