IN WITH THE NEW

MEDIUM MAGAZINE

The cover of the “In With The New” Medium Magazine was created using Midjourney, an artificial intelligence (AI) platform that generates images from textual prompts.

We wanted Midjourney to take the lead in our cover design—to show us the full potential of AI-generated art; so, we simply entered the title of our magazine and let the interface use its imagination. The image of our choosing was subsequently manipulated in Procreate to fit our cover format.

“And in the evening After the fire and the light One thing is certain: Nothing can hold back the light Time is relentless And as the past disappears We’re on the verge of all things new”

― Billy Joel, “Two Thousand Years”

4 MEDIUM MAGAZINE

IN WITH THE NEW

MM 5

MAGAZINE

MEDIUM

Masthead

Editor-in Chief

ELIZABETH PROVOST

Managing Editor

JULIANA STACEY

Director of Design

MANJOT PABLA

Copy Editors

AIDAN THOMPSON

Writers

KAREENA KAILASS

ELIZABETH PROVOST

AIDAN THOMPSON

JESTINA HAJJAR

RADHIA RAMEEZ

JULIANA STACEY

EMILY ROGERS

ROLA FAWZY

SAMIRA KARIMOVA

RIVER KNOTT

AIA JABER

OLGA FEDOSSENKO

RIVER KNOTT Published

ERIN DELANEY

www.themedium.ca

All content printed in Medium Magazine is the sole property of its creators and cannot be used without consent. Opinions expressed in this publication are exclusively of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Medium Magazine

Printing by Master Web Inc.

6 MEDIUM MAGAZINE

by Medium II Publications

Mississauga

N., Student

3359

Rd.

Center, Room 200 Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6

Dear Future You, You Are Art: A Letter in Four Parts / Kareena Kailass

Painting Love: A Reflection on Love and Museums / Elizabeth Provost

Pop Culture is Dead—But It’s Probably for the Best / Aidan Thompson

Performance Anxiety: The Pressures of Performing Queerness / Jestina Hajjar

The New Meaning of Octobers / Radhia Rameez

Holding Hands with Grief / Juliana Stacey

Renew Through Life / Emily Rogers

I Am Not My Sister’s Mother / Rola Fawzy

Brushworks of Tomorrow / Samira Karimova

MM 7

Compulsions,

Crashes

Mind | Body | Soul / Aia Jaber Love Me, Love Me Not / Olga Fedossenko What Happens Next is Up to You / Erin Delaney

11 13 19 23 27 33 39 45 49 55 59 63 69

Concussions,

and Car

/ River Knott

Table of Contents

Editor’s Note

“Out With The Old,” the first Medium Magazine of Volume 49, welcomed you into the world of nostalgia. Now, with “In With The New,” we’re ready to look towards the future.

Writing about “the new” meant pondering over what is to come, what happens next, and what might be. Nothing for certain. Nothing definitive.

However, the new is not always synonymous with what has yet to be experienced. The new can be a fresh perspective, or a different understanding. It can be the exciting, the dreaded, or the unimaginable. It can be anticipated or unprecedented—something we’ve waited our whole lives for or something we wish had never surprised us.

This magazine unveils innovation, art, family, friendship, and the self in a meditative experience of change. We hope “In With The New” serves as a reminder that change is healthy, because it steers us towards our futures.

Kareena’s piece, “Dear Future You, You Are Art: A Letter in Four Parts,” ties this magazine together. Read it as a letter to your future self, and allow yourself to be transported into a world that embraces a new you.

We have divided “In With The New” into three chapters. The magazine welcomes you with observations of

the world around us with Liz, Aidan, Jestina, and Radhia’s pieces. Liz and Jestina inspect their personal experiences and understandings of love while reflecting on the unexpected threads that keep relationships together. Radhia re-defines Octobers and all the beautiful changes she’s welcoming into her ever-evolving universe. In his analytical essay, Aidan investigates how the digital revolution challenged pop culture by promoting individualism and supporting niche interests.

The second chapter explores the destabilizing effects of family and loss. Juliana writes a heart-wrenching account of her encounters with Grief, while Emily shares her coming-of-age story, where she grapples with her father’s addiction. Rola gives us insight into the life of a caregiver, showcasing the importance of healing our relationships with ourselves and with those around us. In her photo essay, Samira explores how the roots of trauma that take hold in one’s childhood can still produce blossoms of hope when given the right care and attention.

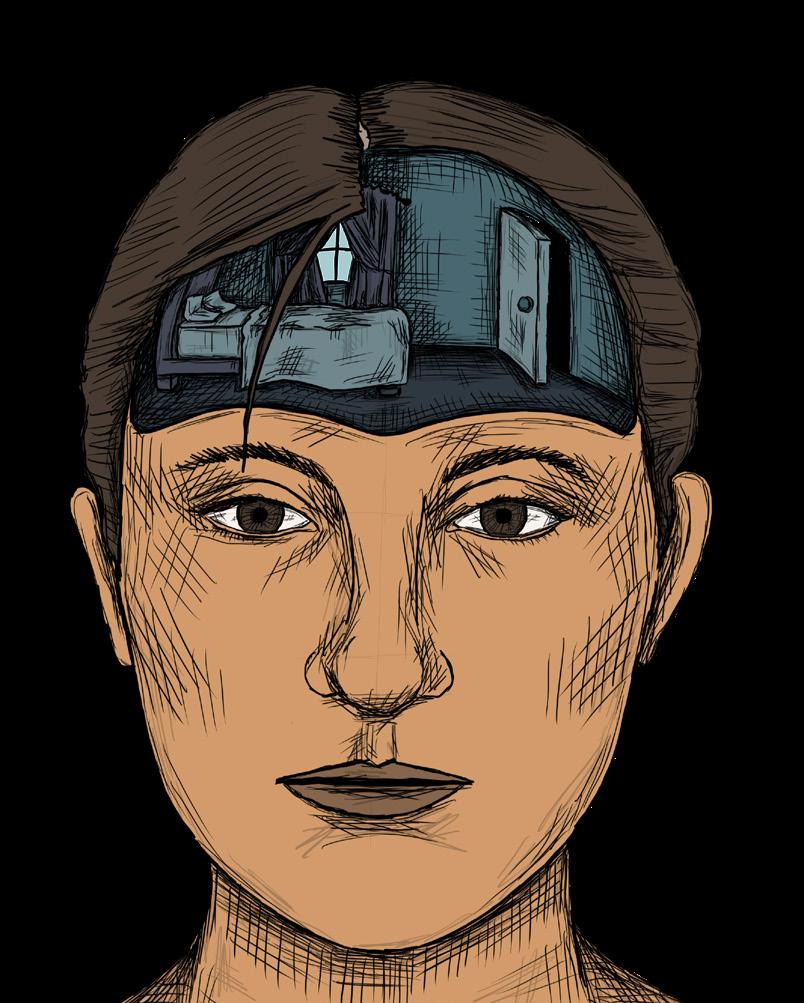

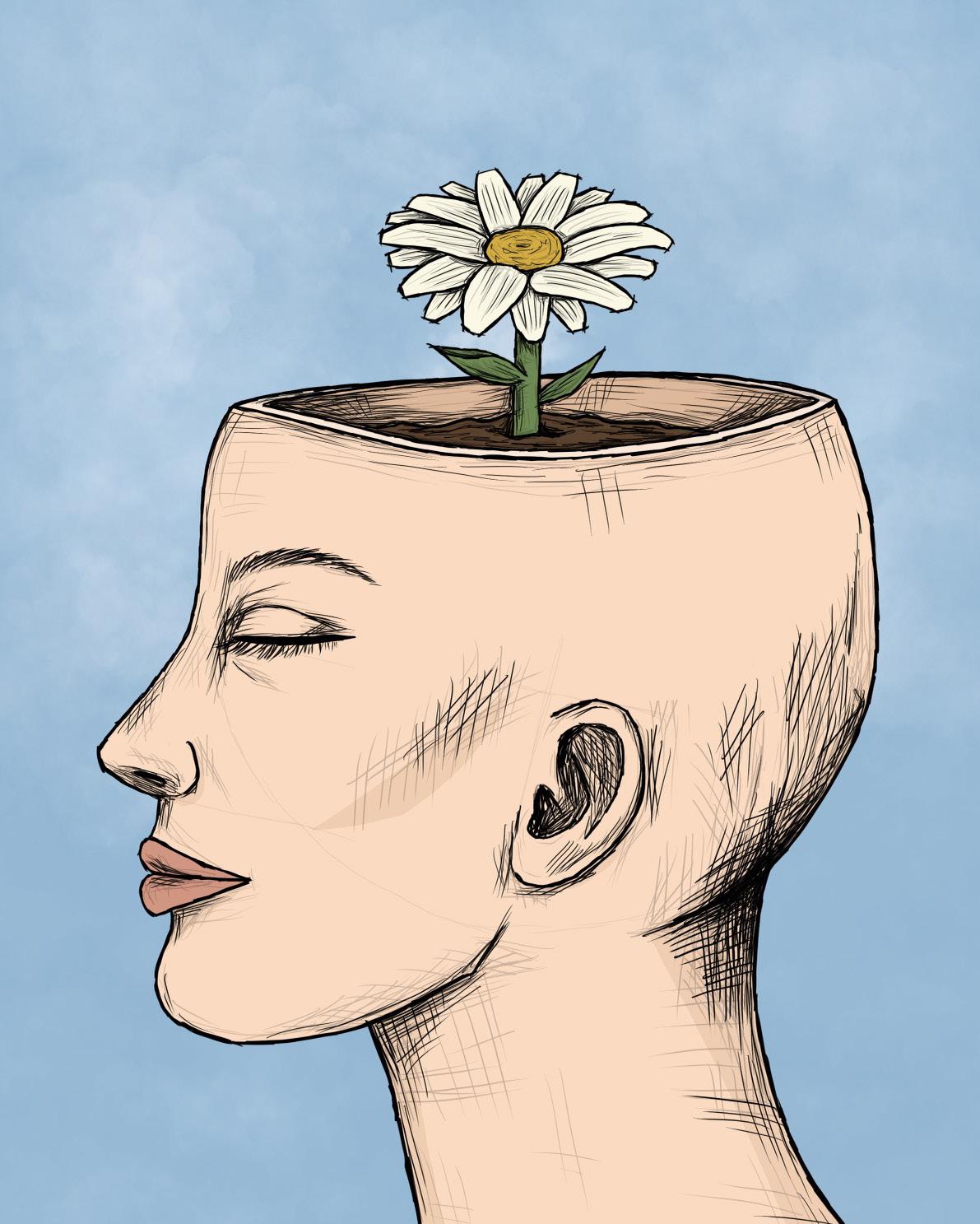

In the final chapter of “In With The New,” we spotlight relationships with the self. With threads of self-love, self-understanding, and self-growth, this final portion invites you to think about your place amongst the noise of the world. River shows us how a traumatic accident can lead to a deeper understanding of oneself. Aia shares a beautiful reflection on the crippling effects of anxiety, demonstrating to readers that we can persevere, even when our own minds become our adversaries. Olga teaches us how to accept and grow into our own skin. And Erin, in her deeply personal essay, shows us that even the most hurtful and unexpected changes can lead to truth and freedom, as we mend what was broken into something beautiful.

As The Medium says farewell to Volume 49, we hope you take inspiration from each of our unique stories. We hope you take a few moments to stop and contemplate your own relationships with the world, your family, and yourself. We hope our experiences help you see that change should be welcomed, rather than feared. Remember: what happens next is up to you.

Editor-in-Chief & Managing Editor, Volume 49

MM 9

10 MEDIUM MAGAZINE

Dear Future You, You Are Art: A Letter in Four Parts

Kareena Kailass

Dear future you,

You are art.

Each intricate detail—every thought, belief, expression, and movement—sculpts who you are. With each brushstroke on your canvas, gliding in pure harmony and smoothness, your masterpiece awaits.

So, who are you?

The painting. The sculpture. The sketch. The visions in your mind that you rework a thousand times. The minute details and edges you clean up as you stray from your graphite boundaries.

You are unique, even as you change and envelop yourself in the warmth of new skin. As you transform, so does the world around you, and you realize that change transcends time. There will always be another detail, another touch-up, another colour.

But why?

Well, that’s the odd thing about life—as it persists, pieces within us move around, rearrange, and settle into different shapes. They shatter and coalesce. Rend and mend. Diffuse and merge.

When people admire you, asking what you choose to title your piece, you stop and think. You release your pent-up breath. For now, the piece is Untitled, not ready for its final touch.

MM 11

Painting Love: A Reflection on Love and Museums

Elizabeth Provost

exist not as individuals, but as threads in an interconnected web of relationships—some nourishing, others deleterious and disheartening. Every relationship has its own purpose, sometimes evident in the moment, sometimes long after you’ve removed their contact from your phone and vowed to never speak to them again. Relationships—romantic or otherwise—rely on the emotional capacity of those involved. Love is not a 9-to-5. It’s a 9-to-5 followed by a 5-to-9. When I am single, I prioritize being emotionally available to myself; that is how I heal. When in relationships, I ask myself four questions: Are you willing to be vulnerable? Are you able to be a better person tomorrow than you are today? Can you listen when you would rather speak? Will you water the flowers even if they are weeds?

Shortly before the first time I fell in love, we were standing in front of Alex Colville’s Soldier and Girl at Station. The couple was in embrace. He and I faced the painting, hand-in-hand, my thumb comfortably curled inside his palm. “He threw his bag to the side to catch her in his arms, he’s obviously arriving,” I argued, letting go of his tender grip and taking a step back for a new perspective. He argued that the soldier was leaving.

I went back to see the painting at the Art Gallery of Ontario many times during and after our relationship. It became familiar—my soldier came and left too. He was in the marines, and I was delusional. I quickly learned that love is flawed because we, as human beings, are flawed. Some flaws I’m actively working on, others I’ve accepted. For example, I enjoy taking the last piece of food on a communal appetizer plate and I fall in love too easily. Love can be a smile in the morning, an “I love you” at the end of each phone call, or a shared cup of coffee—but love is also accepting your partner’s flaws just as much as yours. I was under the impression that love was perfect. I was wrong.

Religion, ambition, distance, and timing—so far, those seem to have been the reasons I haven’t found an eternal love. Heartbreak forced me to realize that we

Before all else, I fell in love with art in 2014 while in St. Petersburg. My mother, an artist, brought me to a painting lesson off the Avtovo metro station. This was the first day that I noticed that art had always been all around me. Coming onto the platform from the train, I faced a crystal palace. We walked around the pavilion; the ceiling of the underground station was supported by 46 columns—30 lined with marble, 16 lined with molten glass. My mother told me the station was built and decorated to commemorate the end of the German siege of Leningrad during the Second World War. It was the first station of the second operational metro system of the country. A mosaic panel titled Victory adorned the far wall. A woman and a child.

The painting instructor, Igor, asked my 13-year-old self what my favourite painting was. He told me that I would paint it. This was an easy task for the last-minute addition of a teenager who was too old to be babysat but too young to explore the city on her own. I looked over at my mother, her eyes were fixed on the unlimited supply of oil paints. In the small art studio on the third floor of a Soviet-style apartment building, the unfamiliar Russian women were busy unpacking the chocolate candies, home-made pastries, and tea they’d brought to share with others. They made sure I was fed.

The only painting I could remember was from a postcard I’d seen at a gift shop a few days before. The back read “Pierre-Auguste Renoir.” French, like my father, I

MM 13

“Will you water the flowers even if they are weeds?”

thought. Igor passed me his tablet and I searched the artist’s name. It was the first image that appeared in the results—Two Sisters (On the Terrace).

“Ah, Renoir, great choice,” Igor chirped. For the rest of the day, he spoke the artist’s name like one does to a baby, over-enunciating the vowels in a higher pitched, diminutive voice and smiling with his front teeth. “Renoir-chick,” he called him. He treated me with care, as if his own child was finally discovering the magnificence of the passion he loved deeply. He was delicate, both with the master’s piece and with my poor rendition. The picture was patient with him, and he was patient with it. I didn’t know you could love and respect art. Nor did I know that love was an art either; one that could also be learned, taught, and experienced with time. I would soon know this too.

I had never liked art museums before. In each new city we visited, my mother would bring me to these large, bright buildings with confusing floor plans. I always carried the map. When I was ten years old, she dragged me to the basement of the Hermitage. As we scurried past crowds of tourists with cameras bearing elongated lenses, she kept looking back at me, my hand in hers, saying “I’m going to show you Rembrandt, just you wait.” I stood next to her as she contemplated The Return of the Prodigal Son. I tugged at her pant leg, wanting to leave. She tried

to explain the painting before us. The son kneeled at his father’s feet in repentance, pleading for forgiveness.

In my formative years, my mother endeavored to edify me with art; I, rather, was interested in eating gelato and building sandcastles. After my lesson with Igor, art became a material and medium with which to think, affording new octaves, new registers. The paintings and sculptures that drew my eye weren’t the ones that made it onto postcards—although those showed me beauty in all its forms; rather, I became captivated by art’s power to repair and resist.

Understanding art relies on an ability to be open and enter and engage in conversation. I asked Georgiana Uhlyarik, curator of Canadian art at the Art Gallery of Ontario, what role museums play in making art active in society. She answered, “Art is part of everybody’s daily life—whether they know it or recognize it or not.” The soft patterns of paws in fresh snow, the geometry of street signs, the varied textures of asphalt, and the lattes at your favourite coffee shop. Toronto’s Victorian homes, billboards, engines, and people coming together. The human body, bread, love, sex, and tears.

Uhlyarik recalled art movements at the turn of the twentieth century that worked to break down the hierarchies between textile work, furniture, painting, fashion, and ceramics, rather defining visual expression and art as a “communal and fundamental way of communicating that is preverbal.”

MM 15

“I became captivated by art’s power to repair and resist.”

Museums are still trying to disrupt these outdated orders by acknowledging that the rest of the world does not exist in hierarchies as we traditionally understand them—nor is society framed only in a white, Eurocentric moulding, she shared. “The future is, at least, the aspiration is, to create very welcoming, very active, very socially engaged spaces, but also to continue to be a space of communion.”

In The Future of Museums, Gerald Bast, rector of the University of Applied Arts Vienna, outlined that futurists argue that museums are cemeteries to which we take a pilgrimage once a year at most. They also argue that the fate of museum objects is akin to that of wild animals transported to the zoo. Bast explained this by comparing the reactions of an elderly couple with that of a child when presented with Baroque art. The Massacre of the Innocents by Peter Paul Rubens at the Art Gallery of Ontario depicts the execution of all male children in the vicinity of Bethlehem under the order of Herod the Great. Bast posed that with sight of such a painting, the elderly couple will admire the aesthetic beauty of the bare bodies and the technical perfection of the artist’s work, while the child, frightened, will want to leave the gallery upon spotting tied, bloodied, gagged, green-faced babies scattered across the canvas. Ruben’s intent was neither of those outcomes—the painting was completed as a reflection on the massacres taking place in Antwerp, Belgium during the Dutch Revolt. It was meant to elicit dread, acting as a weapon of counter-reformation.

In the text, Bast asked: “Why are the visitors in a museum generally left alone with the superficial aesthetic effect of an artwork? Why is

art in the museum so rarely experienced as an analysis of life reality and so rarely seen as a contribution to the development of social ideas?” Museums are moving to reframe our experiences to address these questions.

“What is great about a museum, in addition to getting to see the art, is that it’s a very contemplative space.” As a philosopher, Diana Raffman, a professor at the University of Toronto, deems the museum to be a natural space that simulates an experience akin to doing philosophy. The sensory, perceptual modality of art—one that doesn’t exist in literature, for example—places us in dialogue with the artist.

In my opinion, what art, especially good art, asks of us, is a response. It draws us in, connecting us to its fibres, its material, its composition, and its subject. It asks us to inquire about what we see—to ask questions and to seek answers. Of course, acknowledging how well one paints, the history of a piece, and its provenance can allow us to determine its value, but for me, the value lies in the response. Does the piece move me? How does it move me? Why does it move me? Raffman explained to me that the purpose of an artistic image is “not simply to prompt action, or to communicate a message, or to be a beautiful object, or to be aesthetically apprehensible;” rather, art pushes us into this “other” space where instead of acting, we contemplate.

The importance of humans and art across generations has been mutually inclusive—one does not exist, nor can it be valued, without the other. We have left our marks on caves, placed script on paper, and laid brushstrokes on canvas to show the life we have borne. Art is a mirror in which we have revealed

our turmoil and our grief in painted faces and sculpted bodies—sometimes appearing tenderly, sometimes grotesquely. Art captures what is fleeting, making us feel alive despite being stains and fading letters in the library of history. Art is beauty, and beauty is the antidote to our suffering.

The last time I visited my father in Montreal, we attended the Museum of Fine Arts. We walked through the exhibits slowly. I savoured the rare moments I shared with him, and the rare moments I shared with art. The museum didn’t feel like a cemetery, more like an eternal field of blooming tulips in the spring. I returned to it because it made me feel alive, injecting meaning and light into my veins. With each visit, even standing at the feet of the same works of art, I found new understanding. What was unclear—love, loss, sadness— became clear. The museum became my playground and my teacher.

The star exhibit at the Museum of Fine Arts was Nicolas Party’s—a contemporary Swiss visual artist—“L’heure Mauve (Mauve twilight).” The installation presented the indivisible unity of humans and nature in a colourful meditation. Party’s watercolours, pastels, and sculptures were set against works from the museum’s collection. The exhibit’s title referenced Ozias Leduc’s oil painting of oak branches fallen in the snow. In the winter scene, a purple glow reflects off the white landscape, set in the transitory moment between day and evening. It reminded me of the leap from action to acceptance—when the body and mind welcome the result. When the self acknowledges that what is meant to be isn’t always what is wanted. When I finally let go of the hope that what once was will come back.

My father was once a director, strengthening his love for the arts in visits to art museums. He and I shared a few breaths in front of Leduc’s L’heure Mauve. The artist’s

16 MEDIUM MAGAZINE

name felt familiar, I told him. He reminded me of his documentary on Leduc—one of Quebec’s first Symbolist painters of portraits, landscapes, still lifes, and decorator of churches—he’d shown me a few months prior. I knew very little of what my father did, but then I knew a little more. In her work Collecting Piece II, Japanese multimedia artist Yoko Ono wrote, “Break a contemporary museum into pieces with the means you have chosen. Collect the pieces and put it together with glue.” That day at the museum, I did just that—I broke the exhibit down and glued it with the slivers of what I knew about my father. The picture was now different.

To love my father meant to engage with him. To give into his flaws, his imperfections, his demands, and to remember that he is human. To answer his emails and to show up at his door. In his book The Art of Loving, German psychologist Erich Fromm wrote, “Love is an activity, not a passive affect; it is a ‘standing in,’ not a ‘falling for.’ In the most general way, the active character of love can be described by stating that love is primarily giving, not receiving.” We often worry about how to be loved, or how to be lovable, rather than choosing to learn how to love. Love is not easy—it does not come without fail or effort. It can feel effortless—that is good— but it requires effort. Ultimately, love is a choice. It’s easy to love when the sun is shining, but real love involves bringing an umbrella when it rains.

There are very few lived experiences that start with tremendous hope and prospect, yet fail so regularly, as love. Overcoming the failure of love involves realizing that love is an art that can be learned and nurtured with time and experience. Van Gogh once said, “I feel that there is nothing more truly artistic than to love people.” That may be why most impactful artworks are about love, in one way or another. It is also why the recipe for loving one person will not be the same as for loving another, or for loving that same person tomorrow. Van Gogh’s oil paints were predictable—he knew how the colours would behave when he used certain brushes or painted on certain canvases. But

people are imperfect and unpredictable, so loving them is a far greater endeavour than painting.

I’ve learned that understanding art and love in the modern day requires letting go of the conventions of both. Boundaries, limits, and expectations cannot be set; love and art are boundless. They exist beyond our capabilities and even our understanding of them. In many ways, love will always be passion, strength, care, and beauty. Art will continue to be a love letter through colours, pictures, and lines. The familiar memory of sending an image across the ocean with a “This made me think of you” was a love letter, revealed in the way the brush strokes touched the canvas, immortalizing that which I could not explain with words.

In his 1991 memoir-in-essays, Close to the Knives, American artist and activist David Wojnarowicz details his story in fragmented acts and sights. The final essay, “The Suicide of a Guy Who Once Built an Elaborate Shrine Over a Mouse Hole,” retells the life of a friend through interviews of mutual acquaintances. The essay is a meditation on death, and art’s ability to speak on the artist’s behalf. Wojnarowicz struggles to reach a conclusion; he fears that his own death will silence his voice. “I am glad I am alive to witness these things; giving words to this life of sensations is a relief. Smell the flowers while you can,” he ends. Smelling the flowers means finding the courage to commit to pleasure despite the forces competing for our health and for our love. It’s realizing that the only way forward, is through. With courage, with care, with passion, and with love.

MM 17

“Boundaries, limits, and expectations cannot be set; love and art are boundless.”

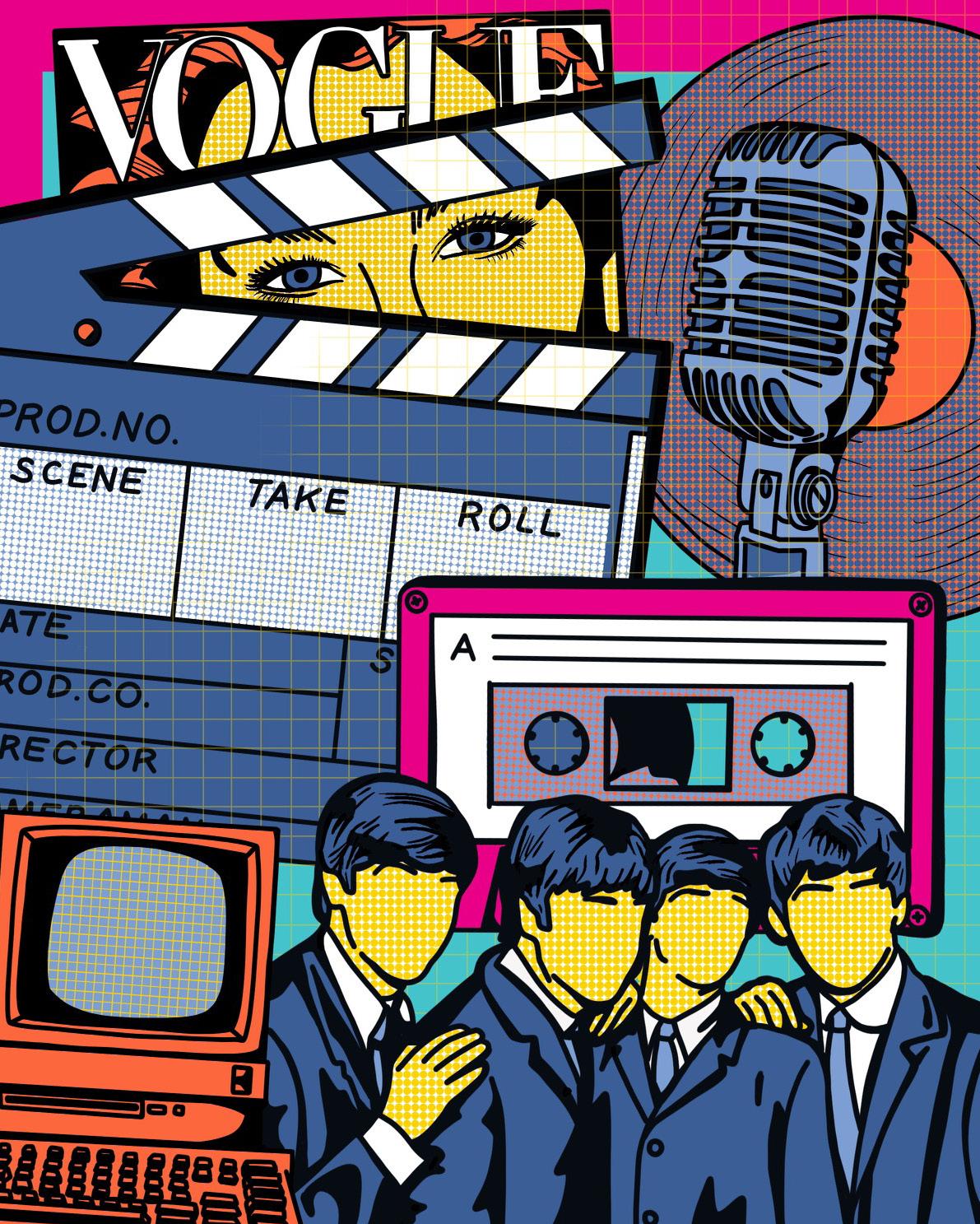

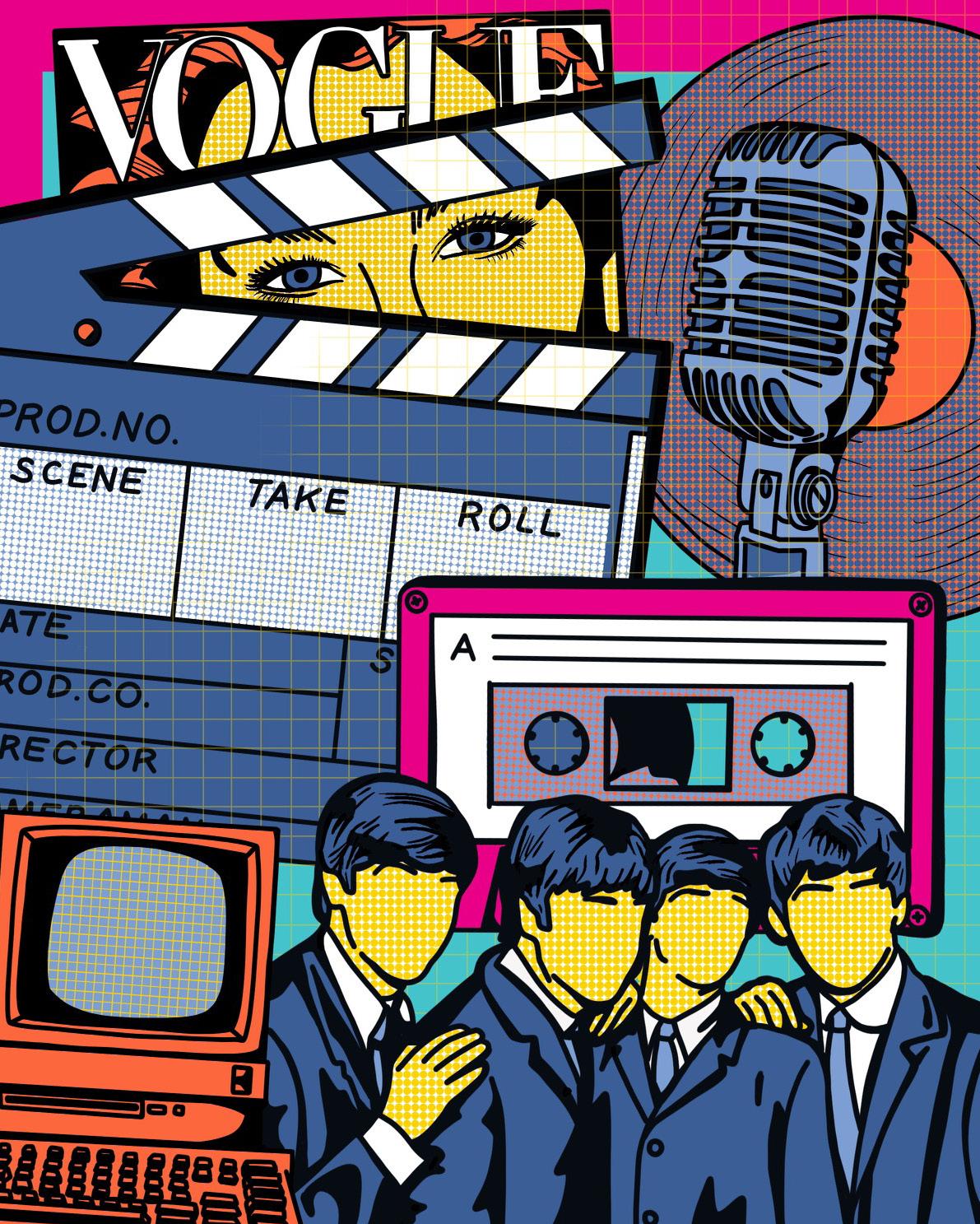

Pop Culture is Dead—But It’s Probably for the Best

Aidan Thompson

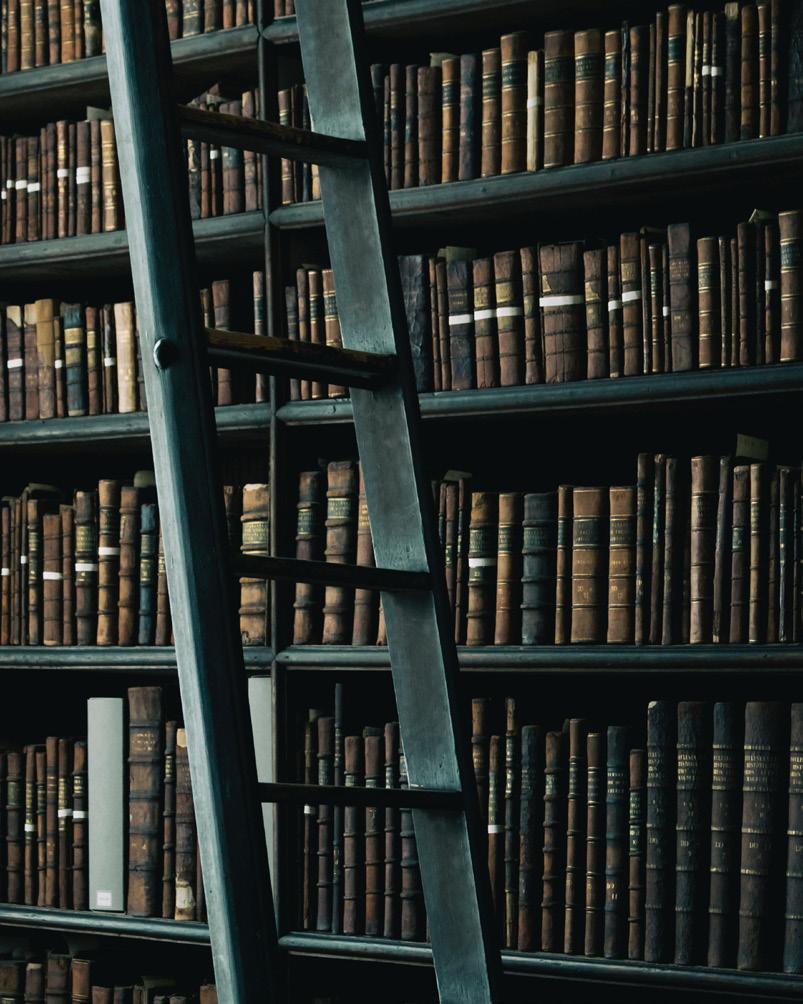

No modern band receives more undivided praise than The Beatles did in the 1960s. No fashion trend decorates the current cultural landscape like hairspray and high-waisted jeans did in the 1980s. No music genre dominates popular interest like rock ‘n’ roll did in the 1970s. In fact, even trying to define a genre now is a chore that generally provokes more arguments than agreements. Today, trends disappear from popular discourse as quickly as they arrive, often leaving no lasting cultural impact beyond mere entertainment. Pop culture is in a crisis, but should we mourn its dissolution or celebrate it?

As Marcel Danesi, a professor of semiotics at the University of Toronto, explains in his book, Popular Culture: Introductory Perspectives: “Whereas once a single style or genre dominated, today, everything from rock and jazz to classical and gospel have

their own niche audiences, each with [their] own recording artists, radio stations, websites, [and] accompanying fan blogs.” The same is true for almost every creative discipline. The internet diversified popular media. But is this a modern phenomenon or did the internet just help to pronounce and legitimize existing diversities in individual interests?

We remember the culture of the 1960s as radically bohemian and drug-inspired, but yet this cultural movement to “turn on, tune in, and drop out,” was predominantly representative of educated, middle-class youth in the Western world. It’s important to realize that although it would have made for engaging history classes, senior citizens weren’t abandoning nursing homes in the 1960s and retreating to communes in Southern California, just as middle-aged men in rural Texas weren’t

growing their hair out and practicing mindfulness. In other words, pop culture demands a certain generalization. Particular trends define a particular era by outweighing other less-popular ones. As a result, we marginalize certain communities and trends when we define pop culture.

But in the 21st century, the internet makes generalizing about cultural trends more complicated. Social media maintains niche fanbases that would otherwise be disconnected or overlooked. For example, in the 1970s, a dedicated fan of Captain Beefheart—an avant-garde musician and long-time friend of Frank Zappa—would have had to hang out in underground record stores or dingy concert venues in hopes of meeting someone with even a slight interest in his obscure artistry. Now they can visit www.beefheart.com and instantly connect with thousands of fellow fans. This capacity of the internet legitimizes the popularity of hundreds of overlooked artists and audiences and continues to testify for the breadth of cultural interest.

Likewise, changes in how we discover content diversified individual interests. For a long time, popular magazines, radio stations, or television shows informed people about new music, movies, or fashion trends. In this sense, media standardized content discovery; people received a lot of the same information and encountered similar trends and ideologies. This isn’t the case anymore. People don’t listen to the radio to check in with the music industry or discover a new artist; they listen

MM 19

“Pop culture is in a crisis, but should we mourn its dissolution or celebrate it?”

to the radio when they’re stuck in an Uber, or their aux cord isn’t working. Now, companies like Spotify and Netflix individualize content discovery based on a user’s unique preferences—they recommend particular artists or movies based on your digital footprint.

This intent of digital media, while slightly invasive, is of incredible value to the individual. People whose tastes don’t conform to the masses now have the freedom to explore themselves and connect with others who share their passions. If you have a credit card and some free time (or even just a willingness to venture into the seedier parts of the internet) you can watch any movie, listen to any song, or read any book, and do so without ever having to change your posture. We have the luxury of choosing what we attend to, but in consequence, the spectrum of individual interest broadens. If you want to see this reality for yourself, ask strangers what kind of music they listen to and count how many people respond with, “a little bit of everything.”

Compounded on this diversity is the advent of digital streaming and home-recording technology, which dramatically increased the amount of available content. According to Rachel Newman, the global head of editorial at Apple Music, in the 1960s, 5,000 new albums were released each year. If we leaned towards a generous estimate and assumed each album had 15 songs on it, that would mean around 75,000 songs were released in a year. Admittedly, that’s a lot. If you wanted to cover them all, you’d have to be listening to 200 songs a day. That’s 10 hours. But at an industry conference in September 2022, the CEOs for the Warner Music Group and the Universal Music Group confirmed that over 100,000

songs are uploaded to various digital streaming platforms every day. If you started listening the second you were born and took enough stimulants to give an elephant a seizure, you’d need 205 years to sample all the songs that were released in 2022.

So, to recap, digital media has diversified cultural interest by individualizing content discovery and supporting niche fan bases. Simultaneously, with the advent of on-demand streaming and home-recording, the entertainment industry has become so overwhelmingly productive that trying to sort through it feels like a small battalion of 12-year-olds is throwing tabloids and vinyl records at your face as you try to browse a labyrinth of unlabeled shelves and disorganized CDs. In consequence, it’s almost impossible to get people to look at the same thing. When digital media freed creativity from the dimly-lit, windowless basement of corporate America and invited every artist with an idea and a smartphone to publish their

20 MEDIUM MAGAZINE

“People whose tastes don’t conform to the masses now have the freedom to explore themselves and connect with others who share their passions.”

work, the notion of collective identity—one reliant on fixed ideologies and cultural trends—disappeared.

Perhaps the only creative industry to resist this broader trend away from monoculture is Hollywood. Amidst the digital revolution, which propelled the music industry towards strange and interesting genres, Hollywood decided that the most profitable line of course was to squeeze every penny from existing cinematic franchises. By analyzing box office scores, consumer reports, and hundreds of other data sets, the entertainment industry discovered that audiences react predictably to familiar content. So, when Universal Studios is

holding a $90 million cheque and deciding whether to invest it into a period piece starring an unknown actor or an 18th Despicable Me movie, they will pick the one with an existing fan base and a predictable box office return. This is why in the last eight years, the highest charting films have almost all extended existing franchises: the top 10 highest grossing films of 2022 included four Marvel films, four blockbuster sequels, and a 14th Batman movie. Likewise, in 2014, the top 10 highest grossing films included four Marvel movies, four blockbuster sequels, and a Disney spinoff. This is why much of what is “popular” in the 21st century, particularly

in the film industry, feels distinctly un-cultural. Blockbusters are often devoid of any honest ideological convictions, instead settling for socially soluble themes and conservative characters which can peacefully exist in the lucrative middle ground of cultural interest. As analytics regulate popular media, production studios pour out generic, homogenous, profit-hungry products that lack any specific representation. With so much diversity in creative content, what appeals to the lowest common denominator becomes most popular. Hollywood’s desire to appeal to the largest audience and protect their investments regulates the industry into a predictably boring state of complacency.

This is the perfect example of why we should celebrate the passing of pop culture. Before the internet disturbed the corporate colonization of popular media, every creative industry surrendered to executive authority. As Danesi explains, “The birth of pop culture in the 1920s was made possible by a partnership that it contracted with the mass media and the business world.” Exposure on television or radio determined popularity, but those platforms were protected by industry executives. The internet changed this. Now, anyone with an internet connection and a willingness to confront culture’s worst critics can release their creative projects, and with the advent of digital platforms like TikTok, YouTube, and Spotify, have a chance at finding popularity. So, if the consequence of equality is diversity, I hope we never go back.

MM 21

“Before the internet disturbed the corporate colonization of popular media, every creative industry surrendered to executive authority.”

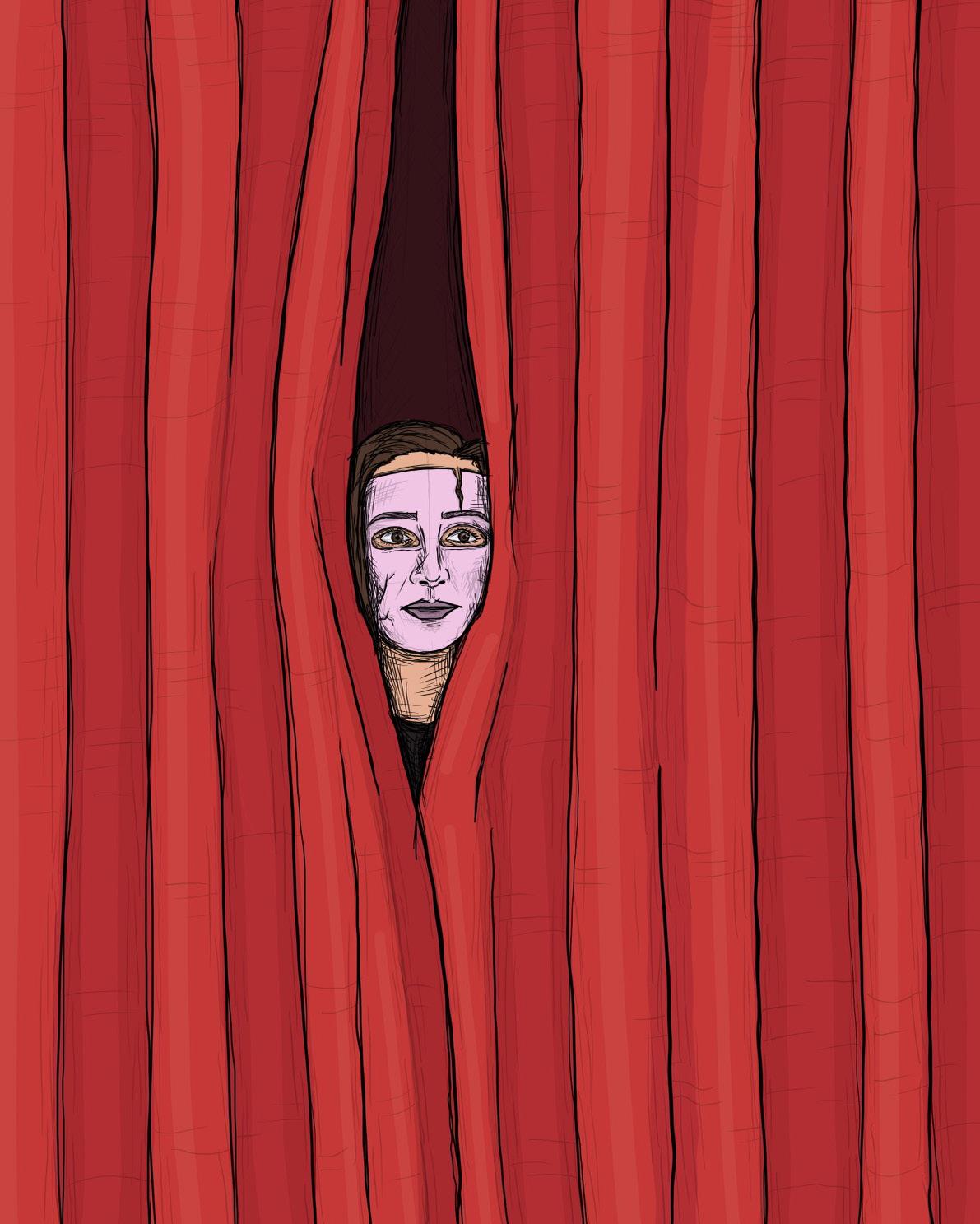

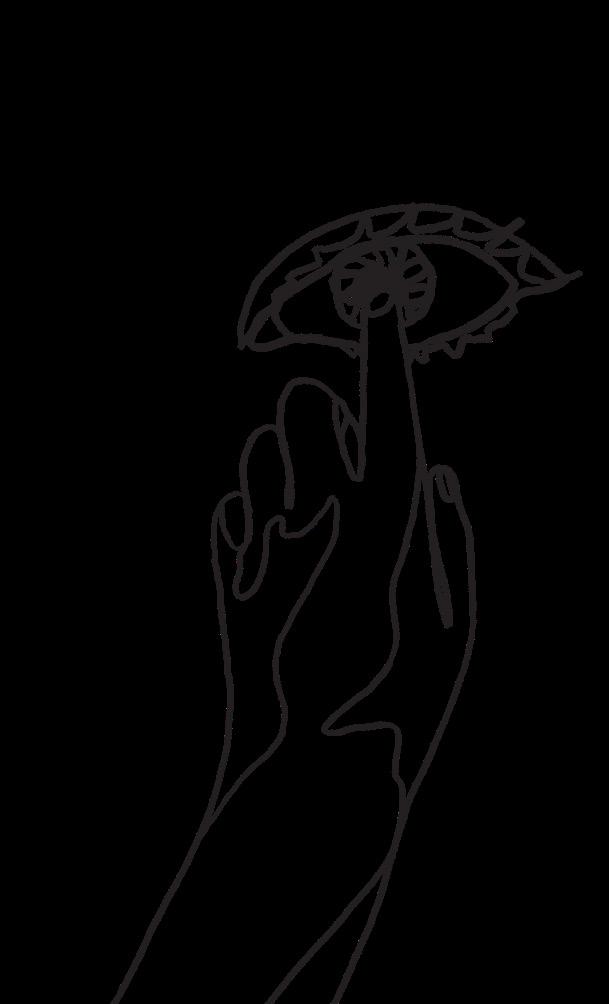

Performance Anxiety: The Pressures of Performing Queerness

Jestina Hajjar

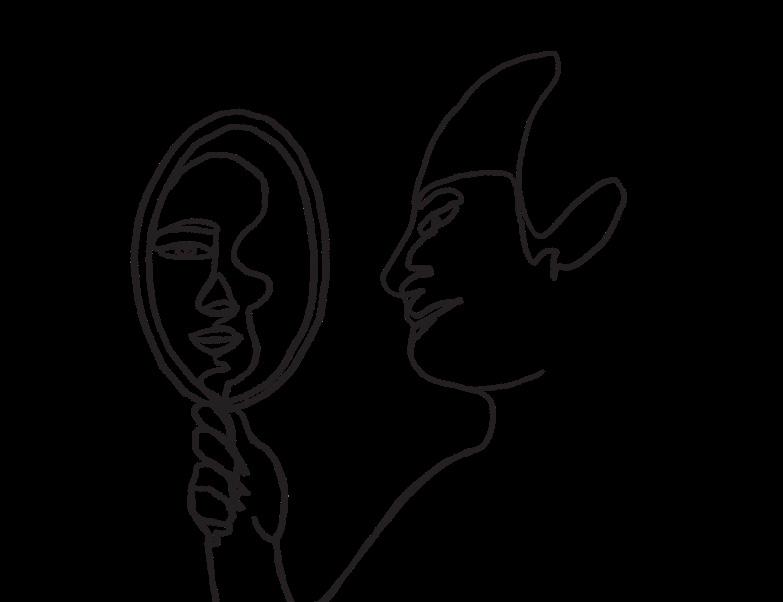

Performing queerness is an unending endeavour. It always seems to creep its way into my mind. It starts when I open my eyes and catch a glance at myself in the mirror and concludes with the final glimpse of my raw cuticles clutching my pillow right before my eyes shut. My life is a constant array of performances. As a queer woman, I was not given the chance or privilege to discover myself in a linear manner. Before I acknowledged my queerness, all that dwelled in my mind was confusion and placelessness. Following my sexual awakening was a flood of every version of queerness that I believed I should project. The most important thing that drowned in that flood was not my fairytale ending, not the respect of those around me, not my sense of belonging, not even my safety—it was myself.

As I discovered my identity as a queer person, the former began to consume the latter—the person I wanted to be was lost to the character I was forced to play. There was no correct way for me to express myself because the very skin I was in was a stranger to me. Queerness is deconstructing and reintroducing an image of oneself, to both you and those who perceive you, that is lost under the ill-fitting layers of straightness. Imagine yourself playing pretend, but an afternoon turns into a year, a year turns into two, and two becomes ten—suddenly, the game of pretend is all you know of yourself. The problem comes with taking the costume off and getting to know the girl behind the mask.

I presented myself in an extremely feminine manner during my teenage years. I had long hair that flowed down to the small of my back, acrylic nails, and I refused to wear any scent that could be mistaken as androgynous. During my senior prom, I wore a tight, corset-style, blush princess gown. It was so long, tight, and itchy that it prohibited me from acting in any sort of natural or comfortable way—that was what performing heterosexuality felt like. I stubbornly clung to my femininity like a person who knew they had lost a fight but refused to surrender—it was all that was left of my identity, and I had such a hard time letting it go. When I finally did, I realized that the “comfort” feminine performance provided me was not comfort at all, it was hiding, and hiding is not living.

I didn’t know how to be queer enough, feminine enough, masculine enough—I never felt like anything I did was enough. Either I presented a hyperfeminine image of myself, draped in blush and gold-specked highlight on the tip of my nose, or a masculine version, which involved an array of arrogance and confidence that I simply did not have. Queerness became another costume—it was not about who I was, but rather what I did. Because queerness, like all other things, is examined through a heteronormative lens; there is no way to be

MM 23

“Queerness became another costume— it was not about who I was, but rather what I did.”

queer—at least, not in any way that will satisfy the gaze of

queer—at least, not in any way that will satisfy the gaze of one’s observers. Heteronormativity views queerness, specifically sapphic queerness, as one of two things: tragic or dreamlike. For queerness is not afforded the luxury of being an individualistic experience; it is instead attached to meaningless tropes and expectations. For queer people, normalcy is a dream that can only be achieved through a painful degree of denial.

I, as a queer woman, am unable to feel any sense of normalcy in romantic situations. They must involve an ounce of tragedy: a sad coming out story, a jealous ex-boyfriend, homophobic friends, homophobic parents, a love interest that struggles with compulsory heterosexuality—the list goes on. There is no room for happiness in the heteronormative depiction of queerness because it is seen as boring, without substance, and missing something—that something is a person’s impression of what queer performance must look like. However, one is not allowed to be completely happy either; if tragedizing is not present, then overly

romanticizing most definitely is. People seem to have an impression that lesbian relationships are without any sort of conflict or turmoil, as queer performance has created the idea that two women, if involved romantically, simply stare into the abyss of each other’s eyes as they discuss their birth charts and eat chocolate-covered strawberries in an open field that is rid of any bugs. Though I do know how to fill a wicker basket with French bread, jam, and various artisan cheeses, and spread a patterned blanket over a grassy knoll with a perfect view of the sunset, my relationship has conflict just like any other would. This constant clarification does not seem to stop the age old “I hate men, I wish I was a lesbian” phrase that quite literally makes me want to pluck my eyeballs out. I agree, misogyny is awful; however, as male privilege exists, as does heterosexual privilege. Queer performance not only involves the slippery slope that is finding the way queerness fits into one’s identity, but also knowing when to stop the performance altogether and begin a new one. Queer performance is far

24 MEDIUM MAGAZINE

one’s observers.”

beyond wearing Dr. Martens loafers and Dickies (though they are fundamental aspects of the practice). Not only is it a complicated process to come to terms with how I perceive myself, but also how others will perceive me. Sometimes, it is in compromising my own comfort and perception of myself that I maintain safety and security. The sadness is in that first look in the mirror after I put on an outfit. The uncertainty that comes with any choice is enough to make me want to scream. A pair of pants that falls over my legs and a shirt that makes my waist completely indiscernible from my hips. Do I look like too much of a dyke in this?

This area of performance is the most complicated of all. Do I dress masculinely and risk outing myself to the wrong people as I walk down the street? Or do I feminize myself and be forced to watch men’s vile attempts at trying to “turn me,” or worse, delegitimize my relationship by acting as if, by mere coincidence, he didn’t see her clutching my hand? Either way, performance is everything and has quite the way of making you feel like nothing all in the same shallow breath.

Is there a light at the end of all this? Is progress being made? I must tell myself, “Yes,” to salvage enough energy, wake up each day, and keep trying. If it means a better world for those who come after me, then I will break myself into a million pieces through performing, unperforming, and reperforming until there is nothing left. That road will be paved even if it is through our blood and tears. I can only hope that there will come a day when sexuality need not be anything beyond itself—a sexuality.

Butterflies, tears, heartbreak, shy smiles, side glances, brushes of the arm—that is all it will be. It will be nothing that requires a strong will; all one will need is an open heart, an open mind, and an open set of arms, waiting to comfort and be comforted. That is all anyone wants when we are put to rest. I just want to close the curtain, thank the audience, and send everyone home. I hope you enjoyed the show. I pray there will not be another.

MM 25

“For queer people, normalcy is a dream that can only be achieved through a painful degree of denial.”

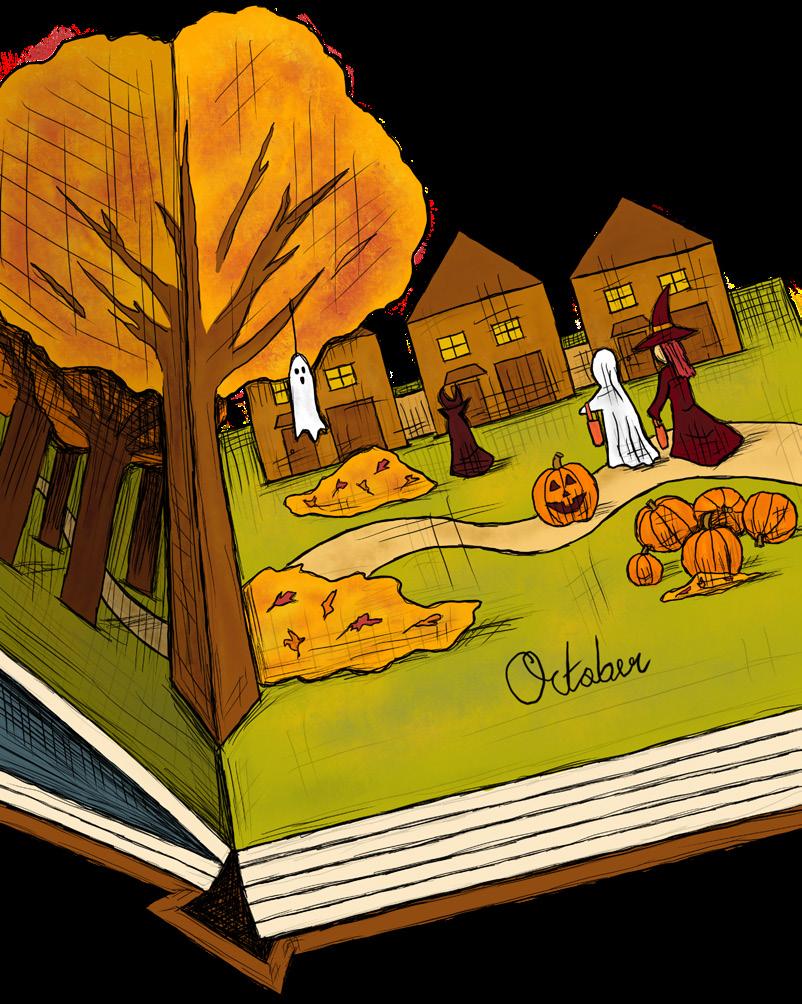

The New Meaning of Octobers

Radhia Rameez

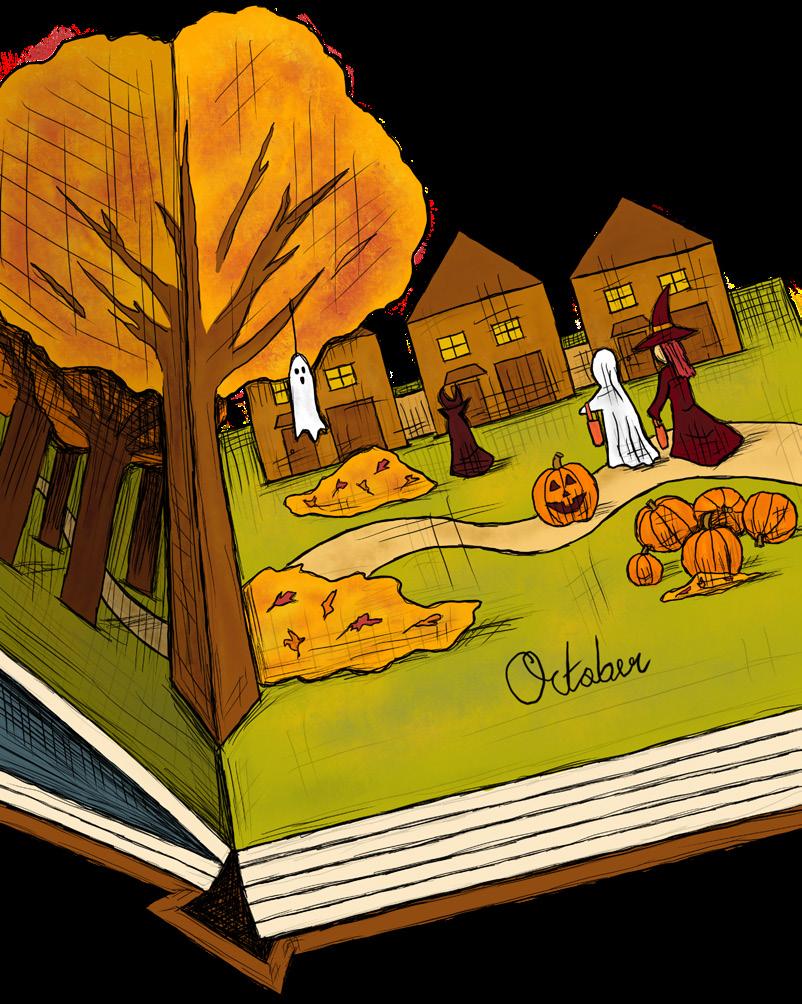

Octobers have a new meaning for me now. I realized this when I answered “October” to a work meeting ice-breaker question, “What is your favourite month of the year?” When, I wondered afterwards, had October become my favourite month? Four years ago, Octobers, to me, meant the monsoon—cool, drizzly days interspersed with angry thundershowers, lightening splitting the sky, and rain drumming heavily against windowpanes. They meant mossy paths and paper boats and wild, verdant ferns bursting out of creviced walls. But with two annual monsoons, each of which lasted about two to three months, a rainy day was just another day, and Octobers had never been a particular favourite of mine. Here, however, in this country of four seasons, Octobers stand out. They mean trick-or-treating and picture-book trees and piles of leaves made for jumping in. They mean Halloween pop-ups and chilly breezes. Somewhere in between 2019—when I left my home in Sri Lanka—and today, I realized that Octobers had

The New Meaning of Strength

Walking away. Looking truth in the face. Feeling your feelings instead of beating them down.

Asking the questions you’re most afraid of: Is my heart safe here? Am I happy? Do I deserve this?

Realizing your worth.

Realizing your power.

changed for me. And so had several other matters—like cottages and koi ponds, black cats, and bookshops. Strength. Writing. Joy. Self-Love.

It’s an odd thing about life—as it persists, pieces within us move around, rearrange, and settle into different shapes. They shatter and coalesce. Rend and mend. Diffuse and merge. To quote a tired platitude, there is one constant of existence—change. A relentless conveyer belt of out-with-the-old, in-with-the-new. Outwith-the-old, in-with-the-new. A mantra as old as time.

The last few years have been a strange, ever-shifting time for me, with page after new page, chapter after new chapter, flicking in a high wind—the close of a five-year relationship, the move to a new country, the discovery of snow, the realization of hard truths, the beginning— and approaching end—of an undergraduate degree. In a few more years, Octobers will probably mean something else yet again. But for now, I try to come to terms with life as it is.

Realizing that closure should stem from within and not without. Putting your trust in deeds; it is easy to fall for honeyed words and flamboyant promises, harder to face the truth behind actions.

Making friends with your solitude.

Making friends with your grief.

Getting out of bed on dark, snowy days when ghosts from the past whisper and weep and weigh you down. Taking steps to heal from the staccato slaps littering your childhood like broken glass.

Listening to your heart.

Picking yourself up again… and again… and again.

MM 27

The New Meaning of Writing

Catharsis.

The consequence of a brief flash of a possibility; a skeleton of a story; a hint of a tune; a fleeting glimpse of poem or picture in the mundane clutter of everyday.

Running words through fingers, like sand. Turning grief into muse.

Turning joy into inspiration.

Truth-telling.

Soul-searching.

Solidifying the abstract. Making sense of heartbreak. Making sense of identity. Self-reflection.

Self-care.

The craft you turn to when something cannot be grasped or sung or painted or danced to.

The immortalization of stories.

The immortalization of truth. Truth.

The New Meaning of Joy

Dappled tree-shadows. Quiet woodland paths. Meandering creeks.

Willows weeping over still ponds.

The first crunchy leaf.

The first snowfall.

The first spring buds.

Little signs of life—

fuzzy caterpillars on stems, blue robin eggs, bright-eyed squirrels.

Pebbles on a beach, as countless as stars.

Sunny dandelions.

The first jacketless day of the year.

Bundles of letters tied together with a shoelace bursting with love and laughter echoing across the intervening years.

Old keepsakes breathing quietly in dusty memory boxes waiting to be stumbled upon.

The smell of new books.

Ink-spattered fingers, fine-tipped pens, and crisp paper.

The possibilities of a blank page.

The sharp edges of an A+.

The first morning without heaviness.

The first laughter after leaving.

Relics from childhood— a little stuffed blue donkey, a tattered copy of Winnie-the-Pooh, a crude crayoned note from a once-little sibling.

Long-distance calls.

Quiet moments on a velvet prayer mat.

28 MEDIUM MAGAZINE

The New Meaning of Self-love

Nights out with new roommates. Spontaneous trips.

Affirmations: You are worthy. You are loved. You are complete. Kind conversations with yourself. Saying no.

Asking for help.

Making your bed each morning.

Acknowledging difficult days.

Acknowledging pain.

Acknowledging possibilities.

The comfort of furry blankets, hot chocolate, and dog-eared library books.

Reveling in aloneness.

Reveling in aliveness.

Building dream-towers, splendid accretions of visions and wishes and ambitions.

Scalding showers.

Warm mugs of coffee.

Balsam-scented candles and home-made face masks. Realizing you are storm and steel, ocean and inferno. Realizing you are enough.

The New Meaning of Octobers

Sunbeams and tree-shadows.

Leaves crunching underfoot.

The best time to take photographs.

The best time to take walks.

Leaves of fire and gold.

The sudden loneliness of chilly winds.

The absence of an arm around a shoulder.

Grey-skied, gloomy days, when drops of water line eaves and forlorn robins peck hopelessly for worms.

Damp asphalt reflections.

The smell of pumpkin spice.

Cuddly days and fuzzy robes.

Fingers constantly aching to curl around a hot mug.

Windblown leaves, scudding dryly along sidewalks, or swooping and swirling, redolent of dreams.

Salmon runs.

New horror movies.

The ache of missing someone.

The ache of someone faraway. New beginnings.

MM 29

Dear You, You Are Art (2/4)

Kareena Kailass

Sometimes, you will hesitate to call your art beautiful. Defining something—that in your eyes is a mess—takes more pride than you thought.

Words too are like the brushstrokes on a canvas, painting vivid portraits of the soul and the past.

In each brushstroke, you, more than anyone, will see the life and love, the grief and loss.

They will hold your free hand while you brush your teeth. They will sit in the passenger seat while you drive to school. They will flip the pages of every book you read.

Your masterpiece is a collaboration; between redefining your muse and finding yourself, you draw from the inspiration of others you seldom get to choose.

You may not want their touch on your canvas, but their mark is permanent. The most you find yourself capable of is letting the ink fade and painting over it. But sometimes, you want to be reminded of them. You wish that their touch will never wither, tracing it gently with your finger.

But remember, what is most important is your relationships with yourself. Allow yourself to face your reflection, define your worth, and live on your own terms. This life was made for you.

This is for all the years you did not see yourself. This is for all those years you thought you’d only be able to be happy with someone or because of someone. Now, let yourself be happy just as you are, with all of your awkwardness and differences, but never despite them.

Your piece is different each time you look at it. You’ll discover a new jagged edge you didn’t noticed before peeking through. A vibrant hue inviting your gaze. An added dimension that’s found comfort in the fibres of your canvas.

MM 31

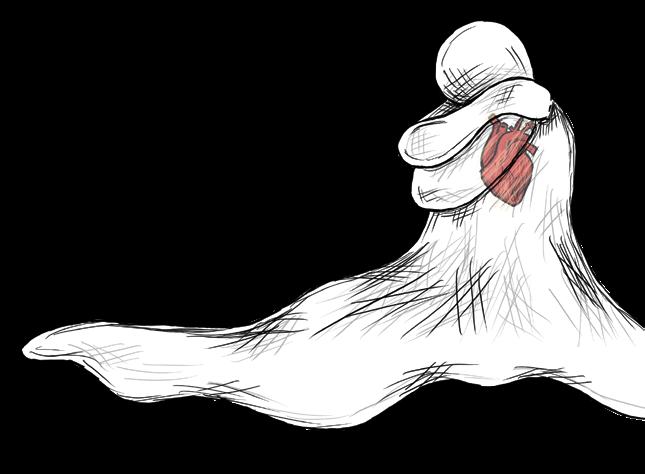

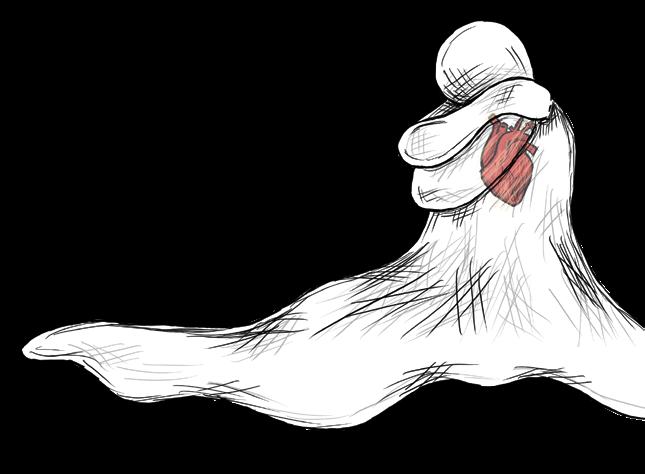

Juliana Stacey Holding Hands with Grief

Funerals have never really fazed me. From the age of eleven, I remember packing up my violin, slipping on a black dress, and marching my way over to the church. I would tune my instrument, adjust my microphone, and arrange my sheet music on the stand. My fingers would glide up and down the neck of my violin. My eyes glazed over, staring at the pages in front of me but not really digesting them. I knew every line of every piece by heart, and I had the timing of a Catholic funeral completely memorized. My cues were now instincts. I didn’t have to listen to anything that was happening. My brain chanted: You don’t know them. You’re getting paid. It’s almost over. Funerals were a job. That was that.

I only dreaded the ends of funerals, when the family of the deceased would gather at the back of the church in a receiving line, making it nearly impossible for me to exit the building without interacting with them. It was always the wails of the widow or the cries of the children that made my arm hair stand on edge, rather than the closed casket sitting just a few feet away. Besides, in the few times I attended the visitations, I always found that the dead radiated a sort of eerie peace, as if they were finally getting the rest they so desperately craved.

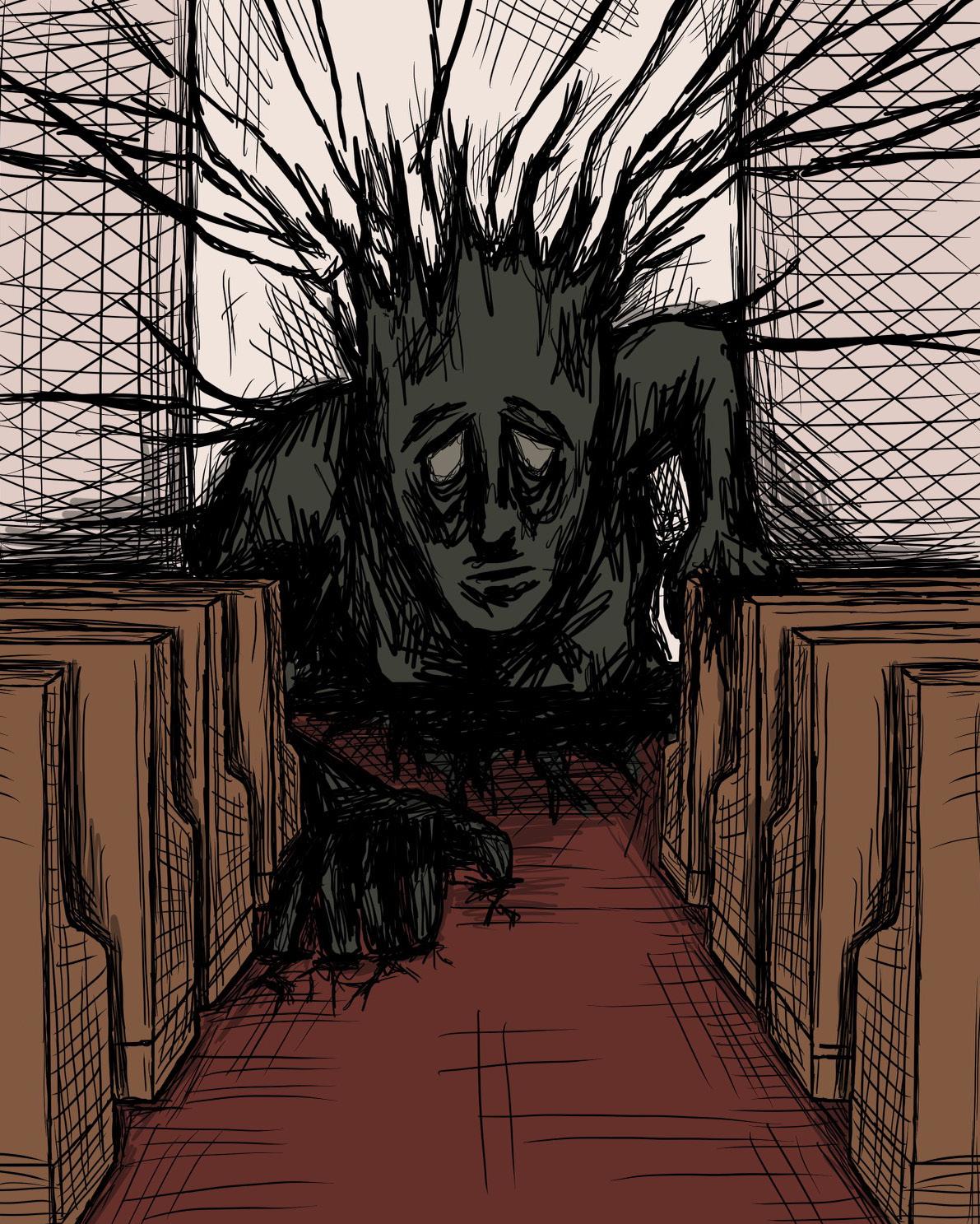

It was also helpful that I had never really come face-to-face with Grief. It lurked between the pews—you could always feel its frigid breath and beady eyes tracing the back of your neck—but in the church the creature stayed, while I went home after every service.

Though Grief did pay a brief visit to the Stacey household. In the

“My eyes glazed over, staring at the pages in front of me but not really digesting them.”

eighth grade, I lost my best friend of twelve years—my chihuahua, Chica. She was a small, peppy dog, with jet-black hair and a white stripe running down her forehead (I called it her skunk stripe). Pictures of me as a child almost always include her; from the time I was born, I had a personal security detail, except this guard occasionally took time off to unravel an entire roll of toilet paper, or to use the bathroom underneath

my parents’ bed. I went to school one day and returned to an empty crate—she didn’t make it home from the vet. Sadness seeped in and left me crying in a ball on my bathroom floor. But the next morning brought clarity: she was 16, a monumental age for any dog, and her heart was giving out. She wasn’t with us, but she also wasn’t in pain anymore. My 12-year-old brain made sense of this quickly, and the puppy we had just

MM 33

gotten was enough of a distraction from my pain. Grief’s stop on my front porch was over as rapidly as it had begun.

Grief kept to the walls of the church for a long time afterwards. I caught glimpses of its presence, shedding the occasional tear when I made unintentional eye contact with a grieving loved one. Don’t look up. But the blinders grew larger with time, and I became an expert at avoiding Grief as it stalked its way down the centre aisle, following every footstep of the deceased’s family. Just another paycheque

Grief visited my home one more time before it decided to take up permanent residence. In the summer of 2021, Mom’s father passed away after battling dementia for some time. I didn’t know him very well—Mom’s family lives in New Brunswick, so we don’t visit often. The person I knew was gone long before he passed, withered down from a man who used to build Lego houses with my brother, Alex, in the basement or wake up at 6 a.m. to work in the backyard, to a man who didn’t recognize his family’s faces. I had already made peace with his condition. I winced when family members or friends passed on condolences—they were constant reminders that I had lost someone, that everyone expected me to be in pain. You should be hurting

The day Grief came to stay was August 22, 2022. Grief called Dad during the second intermission of an Imagine

Dragons concert. He stood up, reassuring Alex and I that he would be back, and walked to the main lobby of the Rogers Centre. Alex and I joked around and took selfies—it was his first concert, and I wanted him to have pictures to look back on. I’ve deleted those pictures since.

Dad came back halfway through “Believer.” The strobe lights and smoke didn’t let me see his face clearly, but I caught a tear welling up in his left eye. I had never seen Dad cry. Years of stubbed toes and stomach surgeries barely elicited reactions, apart from scrunched-up faces and an occasional curse word. Now I watched his eyes water as Dan Reynolds jumped around the stage shirtless, singing about perseverance and hope.

We exited the building the moment the concert finished, rushed back to the car, and merged onto the highway. Dad said nothing. Alex droned on about how great the concert was. We drove home with Grief in the backseat and Dad hoping it would go unnoticed.

Dad retreated to his office in the basement as soon as we walked through the door. Alex gobbled up a couple of Eggos—the double-patty burger with a large side of fries that he devoured before the concert was apparently not enough for his 13-year-old stomach—and made his way to bed.

“What’s going on?” I asked Mom from across the kitchen table, her face buried in her phone.

“Ask your father. This isn’t for me to tell you.”

I took the basement stairs one at a time, my fingers clenching the railing. Dad was slumped over on his desk. His back vibrated with each sob. When he looked up at me, the whites of his eyes were gone, replaced by intricate pathways of angry blood vessels.

“The call was about your grandfather. He isn’t expected to make it through the night, and if he does, he’s chosen to go ahead with Medical Assistance in Dying in the morning.”

My grandfather suffered from Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) for more than 20 years.

COPD is an umbrella term for a collection of conditions that cause breathing issues— specifically chronic bronchitis and emphysema. As the disease worsens, most patients end up requiring constant oxygen therapy. There is no cure for COPD, only tools that aim to make life a little more comfortable.

34 MEDIUM MAGAZINE

“Grief kept to the walls of the church for a long time afterwards.”

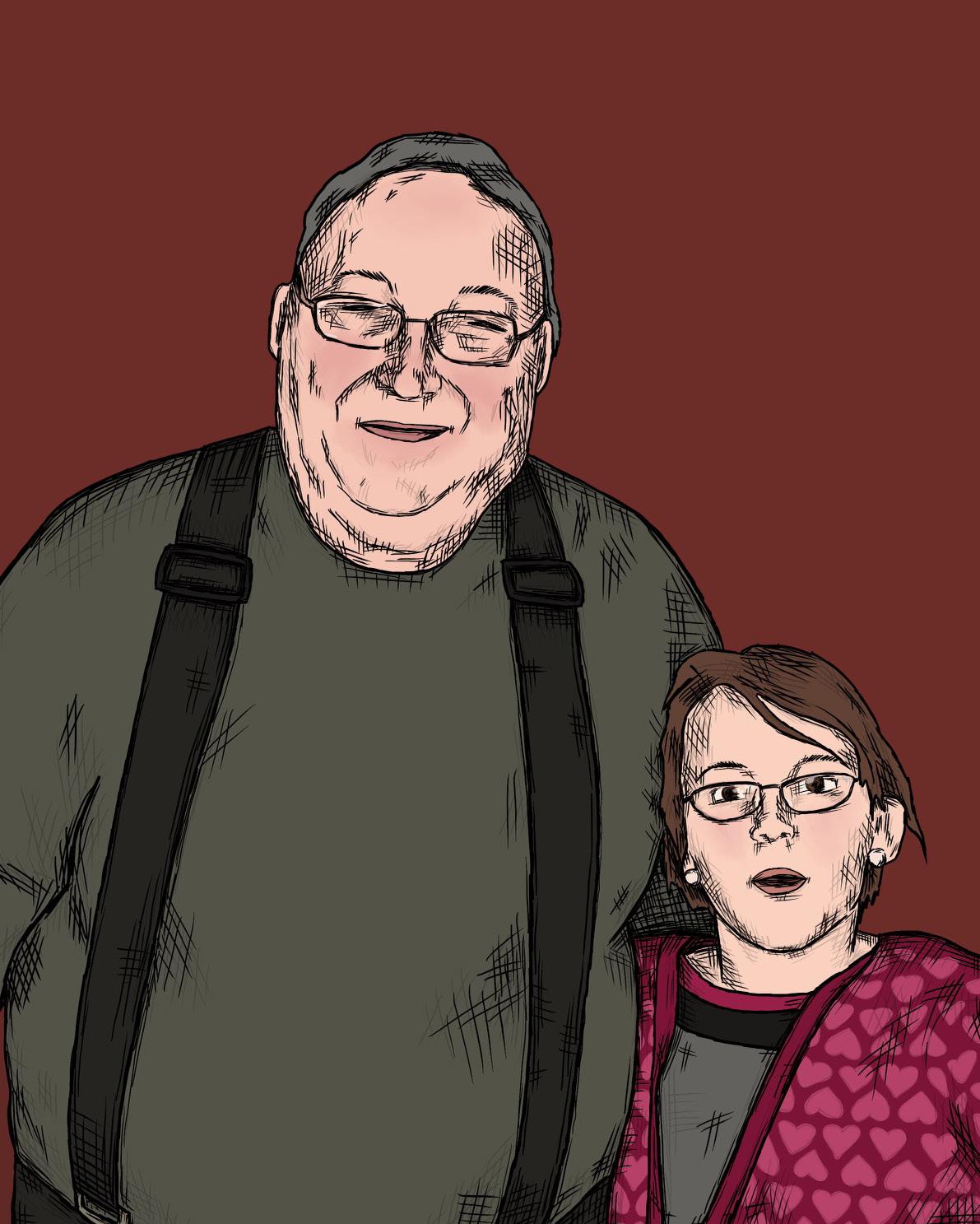

Early memories of my grandfather involve spending time in his backyard, riding around the two-acre property on the back of his tractor-mower, and playing badminton, using my grandmother’s clothesline as our net. As his COPD progressed, my grandfather’s lung function dwindled. The oxygen tank appeared when I started elementary school. At first, my grandfather only used the tank when he had to leave the house, although it was recommended that he used his oxygen at home as well. He always said that the hose got in the way; he didn’t want a leash holding him back. My grandfather never lived tethered to the rules or recommendations of others.

By the summer of 2022, my grandfather could no longer walk from the living room to the kitchen—20 steps—without needing 20 minutes to catch his breath. His oxygen machine was replaced, with his new machine providing double the oxygen saturation of the last. His lungs reached critically low levels of function and sent him into frequent breathing attacks, where his chest filled with thick mucus, and he would sputter and wheeze and gasp for air.

He slept for more than 18 hours a day, waking up only to eat small meals and go back to sleep again.

There was no quality to the life he was living. He was forced to watch his body fail while his mind remained crisp. He only felt pain.

We left early the next morning. Dad and I quickly packed a few days worth of clothes, then began the four-hour drive to my grandparents’ home just outside of Sudbury. Grief was folded neatly in my suitcase, waiting for the right time to unzip the bag and climb onto my lap.

We arrived to find my grandfather sitting at the kitchen table, peeling a tangerine. He smiled when he saw me, and I gave him the best hug I could. Tears slipped out as I took a seat next to him.

“You don’t need to cry sweetheart. It’s okay. I just hope you understand why I’ve chosen this.” His eyes always had this magic to them—a sparkle that danced across his pupils whenever he made a joke or

asked you if you knew a certain song (it didn’t matter if you did or not; you were about to hear it).

That sparkle was gone.

I did understand, in the adult sense of understanding things. I knew that he was in pain, that he wasn’t able to breathe, that choosing Medical Assistance in Dying would be a much more peaceful way to end his life than waking up in the middle of the night and choking to death. But the little girl who played X’s and O’s or Battleship with him at the kitchen table; who looked forward to every birthday just because he would always call and always sing “Happy Birthday,” even though he couldn’t breathe and she truly hated that song; who was always excited to tell him about the latest movie she watched or the newest album she was loving; who spent hours listening to his stories about his time as a sergeant in the Royal Canadian Air Force—that little girl didn’t want to let go.

“I do.”

MM 35

“That little girl didn’t want to let go.”

The procedure was scheduled for one week later— an expedited process, but one filled with hours of paperwork. I was asked to write the obituary ahead of time, so there was less to worry about after. I sat at the kitchen table and pulled out my laptop, looking to scrounge together something comprehensible. A blank Word document stared back at me for a long time.

My grandfather was a Not was. He’s still here. He is. He still is.

My eyes stung. I couldn’t write his obituary. Not here. Not now. Not while he was getting ready to walk over to the table and read it over my shoulder. Not while he was still cracking jokes in the other room. Not while I could still hear him laughing.

Obituaries are for the dead.

I would not write his death into existence.

On August 31, 2022, I woke up in the basement of my grandparents’ home. Sleep came in short spurts throughout the night. My grandparents’ room was directly above mine, so frantic footsteps and constant coughing kept me awake, staring at the clock on my phone, counting each minute, figuring out how long we had left.

The procedure was scheduled for 1:30 p.m. I woke up early, hoping to catch as much time with my grandfather as possible. By the time I made my way upstairs, the medications had already taken effect. My grandfather stirred in and out of consciousness, occasionally asking me to turn up the TV or telling me how much he loved us all.

I had no plans of being in the room when it happened. Dad and I had talked this through several times: we were

going to excuse ourselves and go sit in the trailer outside the house. We would not partake in the procedure.

But when the doctor arrived and the nurse showed up and everyone was trying to get everything ready, I found myself huddled in the doorway of my grandparents’ bedroom, holding Dad as tightly as I could. Grief had now checked in.

I watched the doctor explain which medications she was giving him.

“Safe journeys,” she said, then started the procedure.

I watched as his breathing slowed, then stopped.

There was no sense of peace this time. The air was empty.

I spent my 21st birthday sitting by the phone. I knew he wasn’t going to call He couldn’t call. But I still wanted him to. It wasn’t a birthday without hearing my grandfather belt “Happy Birthday” as loud as his lungs would let him. Sometimes, he would stop in the middle of a line, panting and coughing between syllables, but he never stopped singing until the song was over.

Now the song is finished. There will be no more Happy Birthdays. There will be no call on my graduation day. There will be no conversations about engagements or weddings or kids or promotions.

Instead, Grief whispers “Happy Birthday” into my ear as I blow out the candles. Grief holds my free hand as I brush my teeth. Grief sits in the passenger seat while I drive to school. Grief turns the pages of every book I read. Grief guides my fingers as I type each word on this page.

MM 37

“Grief is a part of me now. It always will be.”

Renew Through Life

Emily Rogers

Heavy footsteps fall down the hallway and stop at the end, where three closed doors lead into three bedrooms: the twins’ rooms and mine. Leaning back against my headboard in the dark, balancing a Sleepytime Tea on my closed laptop, I forgo further movement. He is standing outside my room. It’s midnight and I leave for the airport at 5 a.m. It’s his last chance to talk to me.

The tell-tale fingernail tap-ti-ti-tap-tap sounds through my wooden door, followed by a singsong “entre vous?”

Like some sort of joke, he begs entry.

“Come in,” I reply, an incorrect response to the meaning of the French phrase. Neither of us speak the language, but according to Google Translate it actually means “between you.”

My dad steps through and squeals, “Emilyyyy, you’re leaving us,” in a fake whine and plops onto my twinsized bed.

I flick on my iPhone’s flashlight to see him bare his toothy grin in the white underlighting, like a campfire storyteller.

“Yeah, I know,” I say, forcing a smile that is weak in comparison.

“Come on, aren’t you going to miss me?” He pouts down at me.

“Yeah,” I say. “Of course.”

I wait for a comment about how I’m giving him a “hard time,” but I don’t have another response stored in my back-of-head-small-talk-rolodex.

“Well,” he pats my knee through the bedsheet, causing my laptop to wobble with my tea. “I just wanted to thank you for your kind words in the car the other day.” My throat drops to my stomach. “I know that was probably hard for Ashley and Haley to hear, and, y’know, it’s a bummer we didn’t get to talk about it as a family. I’m sorry about that.”

I resist the urge to dig my nails into the cavern between my shoulder and collarbone and tear off the skin in frustration. He’s wrong in so many ways.

By “the other day,” he meant Christmas Day. The twins and I spent Christmas Eve, the Norwegian Christmas celebration, with my mom at her twin sister’s house, where we ate lefse and sushi, and cookies with coffee.

Christmas Day was always for our dad’s parents. As usual, this year we opened excessive amounts of presents and when conversation ran dry, discussed world affairs. My dad’s sister told me I need to be more open-minded when I expressed distaste towards Joe Rogan. We laughed. Despite disagreeable politics, my family enjoyed that I talked a lot and sounded smart, which reflected nicely on them. According to my dad, though, they could do without my tattoos.

Once my sisters and I were exhausted, we got in my dad’s car to go home. While pulling out of the

MM 39

“It’s his last chance to talk to me.”

driveway, he put on a big smile and opened his pre-planned argument: “So, it isn’t often that I get the three of you alone.” My sisters, in the boot, were glad they let me sit shotgun.

“And—I wanted to discuss this as a family, but apparently Mom told you—I don’t know what her and her sister are planning, but she let you know that after the two of you graduate,” he gestured back at the twins, “she plans to move on from us.”

My sisters’ lack of response gripped the back of my shoulders.

“I just want you guys to know, I didn’t do anything wrong. Like, I didn’t cheat or anything.”

Beat of silence.

I cringed. “We know, Dad, don’t worry,” I said, now wondering why this was his first concern. “You’re still our dad and she’s still our mom. That won’t change.”

I didn’t want to affirm that he did nothing wrong, but it seemed too cruel to tell him off on Christmas.

“And I got my sixteen year chip a few days ago. I’ve gone sixteen years without any drugs or alcohol. So, I just want you guys to know you can come to me about anything,” his tune changed with a sharp left turn. Over a decade was impressive—every day was

impressive for an addict in theory. But I had been his daughter for 20 years, and I knew when he was lying.

My sisters nodded. He drifted around the roundabout onto the main road. The large country-club houses shrunk to ramblers. Twinkling lights flickered on the windowpane. The colours clashed like fireworks in my weary eyes.

“Yeah, that’s great, Dad,” I said.

“C’mon, it’s cool!” He leaned back and held up his chip over the centre compartment. “Do you guys want to hold it?”

One of the seventeen-year-old twins took it. He’d never spoken to them about this side of himself. Educating them about the risks of drugs and alcohol was my mom’s job. They shared a silent glance between one another in the rearview mirror.

“I still have the first ones you gave me,” I said blankly, providing conversational fuel.

My dad looked at me, “Wow! Oh my gosh, you remember?”

the Minneapolis Skywalk. Your arm stretched up diagonally to clutch your mom’s hand, which effortlessly dangled at your height. Her spare grip pushed a double stroller, carrying the twins. Strangers passed by and remarked, “Boy, do you have your hands full,” with friendly Midwestern smirks. Your mom, who already knew her hands were full, offered a glib nod back.

You were going to visit your dad in the hospital, and earlier you had been excited. You’d never visited anyone in the hospital. Before you left the house, your mom handed you a token to give to him, which she told you was for spending 24 hours getting better. She told you the shiny coin was special because you were going to give it to him.

She lifted you into the backseat of her minivan and told you to raise your arms in the car seat. Somewhere along the way you lost the coin. It took a few minutes before you noticed your hands were empty and remembered they shouldn’t have been. Your tummy twisted with an awful feeling.

In your earliest memory, you were walking at your mom’s side, hopping building to building above streets, safe inside the warmth of

In the bright white hospital room, you held your tears in your throat, telling your dad how you were sorry you lost his coin. “It’s okay, it’s okay,” he laughed, crouched down, and slighted his fist to reveal

40 MEDIUM MAGAZINE

another token between his index and his thumb. You gasped, your awful feeling melting. He pushed it towards you, and you grabbed it with all five fingers.

“Is this a magic coin?” you asked.

Both your mom and dad chuckled and decided “Why not?” Dad said you could keep it.

There was a sentence, inscribed in all uppercase letters, popping out of the smooth surface. You touched the letters beneath your pointer-fingertip and read them out loud. “Re…new……th-RUG?” You did not know that word, but you knew the next. “Life. New life new life new life,” you repeated under your breath.

“Renew through life.” Your mom ran her fingers beneath the words, reading them out for you. You closed your fingers around the rim. Your dad placed his ginormous hand gently against your small back. Not for the last time, you felt golden.

none; you had just left your school’s social work program, where your anxiety manifested socially. The school documented your clinical lack of popularity, which was mortifying. You weren’t stupid—the claw gripping your chest wasn’t ignorable, but you were on a mission to take your shame to the grave.

The night after races, you could never sleep; endorphins kept you up. But, after killing yourself in each race, you laid in bed with your eyes shut anyway. Your little sisters tore through the house in thuds of dancing leaps and shockingly—annoyingly—talented belting. You shifted from your stomach to your side to your stomach, and the noise grew quieter, until just your parents talking in the stove-fan light remained. You heard your name and tuned in, still as a statue gathering dust. It was barely discernible, but you heard your mom suggest medication. Your dad whispered “no” much too loud, because “it’s weird.”

Without reluctance, you nodded slightly in agreement.

“It doesn’t matter,” I meet his eyes, icy-blue, swallowing his pupils in the phone flashlight’s glow. The fluffy blanket suffocates my crisscrossed legs. I wiggle my toes around beads of sweat. “We already knew.”

“But that’s the problem,” his forehead crinkles. The light from below exaggerates the shadows and highlights of his wrinkles, making me feel too young. “We didn’t get to tell you as a family.”

“No, Dad, we already knew.” He scrunches his eyelids, but I keep my best poker face. I feel like an RPG protagonist and “force kindness” or “monotone” are the only options dangling above my head. I normally choose the former, but now I’m tired and have a flight the next morning and we’re sitting on my childhood bed in my childhood bedroom and it’s midnight, my alone time. “Before Mom told us, we knew. We’re fine with it. We don’t care.”

Years later, the echoes of middle school gossip and coaches shouting “On the thirty!” slipped out of your reality when you plunged, streamlined, through the greenblue pool water. You discovered by honing endurance that your pain became currency transferable for pride. Swimming felt like the closest to flying a girl could get.

Every once in a while, though, you remembered it’s much closer to drowning. This thought emerged when you hit the cool water at the Minnesota State Swimming Competition. You were just sitting on the bleachers, watching your scrawny figure windmill its arms stupidly. The summer sun glinted blindingly on the surface. You choked, and when your head breached the surface at the backstroke bars, you heard the pity clap.

On the car ride home, your mom tried to talk to you about your anxiety. You, however, claimed to have

MM 41

“You discovered by honing endurance that your pain became currency transferable for pride.”

You spend high school in bed, growing stale. It was a shame that no one liked you, but you wanted to be alone. “I want to be alone,” you screamed again, most often following a terse “get out of my room.”

The mirror was your greatest source of pain. At the sight of your face, that petrifying pain swelled your tongue. Your body turned to stone. You could only stare into your cold icy-blues in disbelief that you were you. Repulsive you. You were ugly and vain for caring about it and selfish for indulging in such vanity.

You remembered a child-psychologist, back in grade school, calling you “well-intentioned”: what people say when you’ve done something wrong. You laid awake on popcorn crumbs, keenly aware of the MacBook slumbering at your side. You opened up for no one, except for solitude. Her, you treated like a house guest. You conversed with her for hours, pacing up and down your room. The stream of consciousness eroded all your poise, and the stone of your statuesque persona ground to a pebble, whisked up in the rapids. For dinner, you offered her your pain for free.

Inside your drawer, in a shiny purple box, you hid your blade under your dad’s old coins. He didn’t remember them, and they gave you no comfort, so what were they even for now?

“But it wasn’t fair to me,” Dad whines, the same way I used to when I was a little kid. The typical response, of course, was that “life’s not fair.” I hated to hear this but couldn’t argue.

“I don’t care,” I say. My limbs shake, sweat pooling under my arms. I long for five minutes ago—for comfort.

He frowns deeply. “I care.”

It strikes me that this is the first time I’ve told him how I feel. Then, it strikes me that he’s never asked. He’s never asked the twins, who still live under the same roof. My blood runs fast, hard, almost painful. Begging for freedom I won’t grant.

“But I don’t.”

“Oh,” he says.

The conversation is over.

He replasters his grin. “Well, it was sooooo great having you home, Em!” and pulls me into an awkward hug. “I’ll miss you so much. Okay, goodnight.”

“Goodnight.”

He waves with a whole flat hand, not dropping his bared teeth until the door fully shuts behind him.

I touch my phone to turn off the torch. My room is

cloaked in a dark grey, not quite black to my now adjusted eyes. My rabbit heart pumps like it’s on the clock, over and over. Eyes shut, head on my arm, knees curled up, I go through the steps of sleep. For five hours, I lie awake, tired, and sweating. I want to get up to distract myself but can’t. I have to wake up early for my flight. I can’t risk sleeping in.

My mom, my best friend in my emerging adulthood, comes into my room at five, like I asked her to the night before. She brings me an espresso in a cute little cup. Wordlessly, the two of us putz around the house, handing hairbrushes and utensils to each other intuitively.

She drives me to the airport in the dark. She’s already started her day, but to me it’s just a late night. On the radio, a Christian pop group sings a ballad. Mom lets out a breathy nasal sigh, a habit that always makes me squirm in the passenger seat. It feels uncomfortably cliché: the stoic mother listens to worship songs while the melodramatic daughter sulks in resentment. My mom and I are supposed to be different.

“I have depression,” I say factually, running my nail along the plastic interior panel. “But I am happy, like right now. But I always have it.”

“Totally,” she smirks, keeping her eyes on the road. “It’s stupid that people expect people’s lives to be perfect for them to be happy. You know what I mean?”

She always ends statements with that question, and I always answer “yeah” because she’s never wrong. But, if anyone deserves a perfect life, it’s her. If addicts get a new life, a renewed life, why can’t she? After decades of fixing our messes, winning bread, and making mortgage payments, the praises others sing for her never seem to materialize.

I tell her about Dad coming into my room hours before. She snorts and rolls her eyes, saying he does that on purpose, starting serious conversations when you’re relaxed, your guard unwound. So he can stay in control. So he only has to reveal what he wants to.

“It’s just like when he made amends to me,” she elaborates. “All he said was ‘I was wrong.’ That’s it.”

She’s always keeping everything together and being told she’s amazing for it, but no one, not even her partner, ever lets her be human. She might not be “an addict,” but she still deserves a break.

“Things are looking up,” Mom tells me. “Let’s not think about it anymore.”

“Agreed, no more thinking,” I say—because I’m a liar, I guess.

MM 43

I Am Not My Sister’s Mother

Rola Fawzy

March 2021

I did not want to be in the emergency room of Trillium Hospital, but I had to be.

Hand in hand, Haidi and I entered the waiting area. I had already told her of the Covid-19 protocols; I asked her to sanitize her hands, draped a mask on her face, and answered the hospital’s questionnaire on her behalf. Mom trailed behind— close enough to intervene if needed, far enough to keep Haidi at ease.

Haidi scanned the room, then quietly stated A’yza chocolata (“I want chocolate”), as she headed towards a vacant seat by the vending machine.

“Dooda, wouldn’t it be better to sit over there?” I gestured to the reception desk. She wouldn’t budge. I didn’t have her attention; songs from her favourite Spotify playlist blasted through her headphones.

“Dooda, Dooda,” I repeated, hoping to catch her attention, but her expression remained vacant. “I’m going to check us in. I will speak with a nurse for a few minutes. Please stay here. Please don’t speak to anyone until I’m back. Listen to your music.” I repeated my instructions again. I hoped that she would follow.

I shuffled to the front desk. My eyes did a three-step dance: nurse, Haidi, exit door. Nurse, Haidi, exit door. With every rotation completed, I found it harder to breathe.

At the desk, I handed the nurse Haidi’s health card. I confirmed my sister’s birth month and year—May 2003. The nurse did not look at me; her eyes were affixed to the form she was filling on the computer.

She shot her first question at me: “What brings you to the hospital?”

“My sister is on the spectrum. She has been having a lot of meltdowns, and we needed a psychiatrist to see her, possibly to change her medicine,” I answered.

“Are you her guardian?” Another question, spoken with disdain.

“No ma’am,” I replied, trying my best to keep my calm.

“Well, where is her mother?” The nurse retorted, finally raising her eyes to meet mine. In regular circumstances, I would bite down on my teeth so hard that they could chip. I would allow my anger to fizzle. As I stood, I did not have the energy to avenge my bruised pride. All my energy was going towards the dance that my eyes were doing.

I inhaled and allowed my eyes to soften. A tear or two emerged.

“Ma’am, her mother does not speak English. I understand that this is frustrating. But my sister just had a violent meltdown before we got here. She got physically aggressive, and she’s at risk of running away. Please, try to understand,” I pleaded, knowing that my attempt to win her over could backfire.

“Okay,” she acknowledged. “I’ll talk to the nurses and try to get someone to see her quickly.”

I returned to Haidi. I was ahead of a war I did not want to fight. I closed my eyes and tried to think of the online lectures I missed and the upcoming finals season. But instead, I found myself frantically praying that Haidi continued to be seated or, at worst, stimmed nondisruptively. I breathed what little air my lungs could ingest.

Haidi’s name was called, and I spotted a procession of blue scrubs. They steered us into a different room. They asked me questions about Haidi’s condition.

“How were the past few days?”

“When angry, how did Haidi behave?”

“What is the name and dose of her medication?”

After going through the door, Haidi slowed down. Before us were rooms that locked from the outside and had windows for onlookers to peer into. We were in the psychiatric unit. Haidi squatted down and clung onto the leg of the nurse who was peppering me with questions. The nurse froze. Haidi was trying to calm herself by moving the nurse’s leg, dragging it forward and back, forward and back. The nurse panicked, and called her male colleague, who called security. Haidi would not budge. She dug her

MM 45

“I was ahead of a war I did not want to fight.”

“Like lost children, we wailed in the hallway.”

nail into the nurse’s legs. A river of red dripped to her socks. I couldn’t breathe.

Shy from one nurse who monitored the other patients, every staff member in the unit was now trying to wrestle Haidi off the nurse’s leg. Everything and everyone before me turned into silhouettes as I hyperventilated. After some sharp breaths, my eyes focused again, and I found Haidi on a stretcher. As they pinned her down, the staff formulated a plan: they had to sedate Haidi. They communicated in sporadic bursts, knowing that Haidi’s kicks, punches, and shrieks could not afford them the luxury of uninterrupted speech anytime soon.