Caring Campus

Las Positas College is implementing the Caring Campus Initiative which is designed to create a college environment that increases students’ sense of connectedness and belonging and, in turn, completion of each student’s educational goals.

Rankings & Recognitions

Rankings are based on the strength of academic quality, graduation rate, affordability, available student resources, and overall students’ experiences.

LeTTer

from The edITor

What began as a brainstorming ses- sion on whiteboards has finally come to fruition: Naked’s 17th edition. Produced by a team of six students, a mentor and two advisors, we proud- ly bring you the outcome of many long days’ work. This edition covers streaming platforms, a rising per- former, and even daylight savings. We hope you, reader, enjoy this magazine as much as we have.

Strzemp Editor-in-Chief

Jude

Jude

Instructors enliven burgeoning writers

Words by Peter Zimmer

by Naked Staff

Words by Peter Zimmer

by Naked Staff

The Tutorial Center is lit with large, hanging fixtures and the natural glow from full-length windows. Attendees occupy the room’s many rows of chairs and small round tables for the spring 2022 Literary Arts Festival. They look on with anticipation as published writer Kevin O’Brien takes the grand podium. He wears a red shirt, blue jeans and has his brown hair cut short. O’Brien is one of the guest authors in the spring 2022 publishing ceremony for the Journal of Arts and Literature: Havik. He is also a non-verbal quadriplegic who communicates using a speech-generating device.

O’Brien responds to Raymond Carver’s story “Cathedral” with honest, analytical reflections on the short stories’ ableism. The prejudice raised red flags for O’Brien, who experiences discrimination on a daily basis.

“During my research, I found a lot of Ph. D. doctors who didn’t have a disability to overcome. Although they had a good idea of it, they don’t know what it’s like to have an individual treat you differently because you’re disabled,” O’Brien says.

A wash of tears flows over audience-members.

O’Brien’s performance exemplifies Havik’s mission

statement for the spring 2022 semester: Everyone has a story to tell. And Havik aspires to be a platform for authors and artists to express and discover themselves.

Debuting in 2021, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Literary Arts Festival began gathering seasoned writers for workshops, a poetry slam and networking at Las Positas College.

It may not seem probable, but this suburban school is a haven for one of humanity’s greatest gifts: poetry, the economy of language and loftiness of thought. The genre may feel dead since poets are no longer social giants, and people don’t speak in stanzas like they once did, but Las Positas College showcases how poetry is far from dead. It breathes and transforms. It is historic and modern, remaining relevant even if not particularly mainstream.

It makes sense that this hilly terrain just off the I-580 freeway, where painted skies and plush vineyards offer prose for the eyes, would be a home for poetry. This campus is indeed an incubator for a time-honored storytelling curated with linguistic mastery and ideology. In this place, effort on behalf of professors and students ensures the liveliness of poetry.

On Tuesdays and Thursdays, tucked in one of the older Southwestern-inspired buildings, Toby Bielawski, in whispery tones, inspires creativity through words in The Craft of Poetry class. She gives students the space to experiment with form, structure and different strategies of imagery.

No matter the student’s background, no matter their skill set, all students are welcome to take this

class in spring. Bielawski’s inclusivity piques students’ interest in poetry and even helps produce new poets.

She constructs each writing exercise with imagery and sound in mind, so students can learn to wield these literary techniques. It’s all about evoking a response in readers. Bielawski gets down to the nitty-gritty of how consonants and vowels elicit different responses in readers and listeners. “(I guide students through) thinking about the sounds that we have to make, physically, with our mouths and throats to make the words and how those sounds affect the listeners,” she said.

Bielawski has been involved in poetry since elementary school. Her first grade teacher, John Oliver Simon, introduced her to the craft. “I was just so enthralled by the poems that he had us write,” Bielawski said. “And so that’s really where I got my start.”

Her enthusiasm has not wavered. She excitedly returns the favor to emerging poets, teaching them the complex craft.

Alongside Bielawski, English professor and former Poet Laureate of Pleasanton Jim Ott uses his poetic expertise to teach his English 1A classes.

He prioritizes editing poems, cutting out the “telling” to get to the “showing.”

“I enjoy offering block text, like prose, and inviting students to edit down the sentences as much as possible,” Ott said.

Doing this work, students prepare for their careers, as many poets start as editors.

Another professor, Kisha Turner, teaches hip-hop lyricism in English 1A, noting its poetic quality: rhythm.

Turner teaches hip-hop lyricism to engage students in social justice dialogue and to champion poetry’s modern relevance.

“Some rap music or musicians have shouted out their neighborhoods, have described their lives in those communities, what the culture is like there, how they celebrate, what the dance is, what the lingo is, what the language is like,” Turner said. “It brings visibility, and perhaps conversation, and cultural richness to our world.”

Cross-genre teachers at Las Positas encourage student writers, helping develop future poets.

Fiction writer Chris Delameter is one of these students at Las Positas who’s gained interest in poetry. It allows him to flex his creative muscles.

Under the guidance of Las Positas faculty Steven Budd, Delameter learned about the potential sources of inspiration.

“One of the greatest lessons that my poetry teacher has taught me this semester is that (inspira-

tion) doesn’t have to be some glorious, cerebral or deep message,” Delameter said. “Just find inspiration in everyday benign things: washing the dishes, going to school, talking to a friend on the phone, talking to a parent on the phone, anything. You can find inspiration in all kinds of things that you wouldn’t normally think of as inspirational.”

Delameter, who learned to love poetry and finds inspiration in unexpected places, is just one of many students who enliven poetry at Las Positas.

So, while the hilly campus near highway I-580 may seem like a quiet and sleepy corner of Livermore, California, it actually contains a thriving poetry department of burgeoning poets and passionate instructors. In and out of class, with events like the Literary Arts Festival, the school welcomes poetry and all its crafters.

Poetry is not dying at Las Positas College. It is operating on hyperdrive.

Photograph from Express archives.

Few things were as fun as sitting on the carpet with my mother. Thanks to child glee and giddy, it didn't matter that I was sitting criss-cross applesauce on a grungy carpet, no longer beige thanks to a collection of stains.

What mattered was being on that carpet meant my mother was reading to me. Her gentle voice, strained by asthma, transported me to other worlds. Of princesses, tree houses and outer space.

It wasn’t long before the stories were coming from my Dora the Explorer boombox, with musical backgrounds and sound effects. My mother had a tower of books on CD, kid’s books where characters like Strawberry Shortcake detailed their cartoon lives.

Eventually, Hooked on Phonics — created in 1987 and a staple by my toddler years in the early 2000s — became one of my favorite toys, doubling as a learning program. It unveiled a world where Laura’s little house on the prairie was my home, and Junie B. Jones became my best pal.

So by the time I got to elementary school in the Central Valley, holding the book catalog by Scholastic was like Christmas at my fingertips. Every academic season, we were allowed to shop for imagination in a catalog plastered with popular series and rainbow colors. We were being raised as bookworms, seized by adventure and creativity.

The culture of reading seemed to perfectly blend the fantastical with the practical, teaching children how to read and developing a habitual use of books, while percolating our sense for inventiveness and originality.

Eventually, the universe we once inhabited with our minds would be altered. A threat to the culture of reading was growing and would forever transform our relationship with stories and fantasies. That threat was the internet.

In spite of the efficiency and swiftness of the internet, Las Positas English professor and writer, Martin Nash, pushes for his students to maintain reading and writing skills.

“(Reading) is necessary for the communications that keep us human,” Nash said

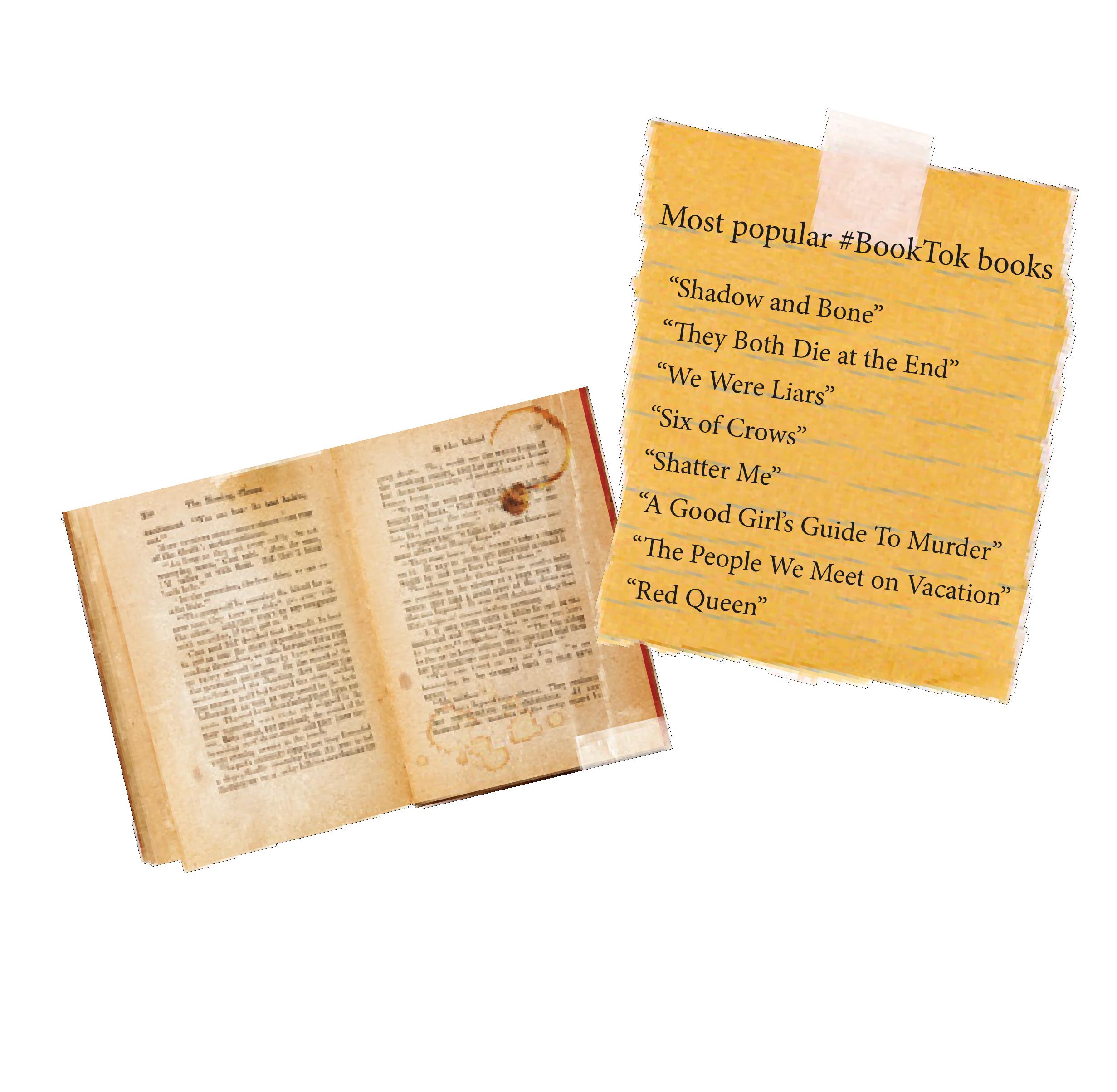

From buying novels off of book orders to #BookTok, a reader-oriented group in the TikTok app, modern youth have rekindled their relationship with reading through their digital addiction.

Though its existence can be traced back to 3500 B.C., reading significantly declined throughout the 2000s compared to the 20th century, according to “The New Yorker”. Hobbies have changed as America swapped its reading glasses for Netflix subscriptions and social media accounts.

With the prevalence of short and speedy content following a decline in consumers’ attention spans, the nature of literature has gradually changed. In turn, fictional novels have shied away from long-form slow burners to rapid page-turners.

Through apps like TikTok, viewers can discover authors like Colleen Hoover and Holly Black without the burden of papyrus and bookshelves. BookTok is one of the many offspring of the reading revival, with movements like its push for daily reading leading a generation toward intellectual growth.

“I've noticed that with the internet — that whole headline phenomenon: you know, where people are trying to get clicks — writers are trying to get people's attention more quickly,” Nash said.

“So I think that the way we read has evolved as well, at least in my experience. I think in our day and age (reading has) kind of evolved to become more immediately captivating, ” Nash said.

Accessibility to electronics, paired with such headline phenomena, has put reading at risk. The National Endowment for the Arts concluded that the percentage of adult Americans reading literature has dropped over 10% over between 1982 and 2002.

Though this drop has affected nearly all Americans, “the steepest decline in literary reading is in the youngest age groups.” The survey attributes this to the insurgence of non-reading media such as television, internet and web-apps.

The National Endowment for the Arts stated, “The trends among younger adults warrant special concern, suggesting that –– unless some effective solution is found –– literary culture, and literacy in general, will continue to worsen. Indeed, at the current rate of loss, literary reading as a leisure activity will virtually disappear in half a century.”

In the words of LPC professor and published author Nolan Higdon, “To read well is to think well.”

Though with #Booktok garnering over 103.4 billion views, print book sales and the publishing industry are being brought back to life.

The notoriety surrounding up-and-coming cult favorites, inadvertently affects big-name retailers like Barnes and Nobles.

“BookTok gets excited about it, the retailers pay attention, merchandise it, other people find it, other retailers start to find it because the numbers start to go up, and it takes off,” NPD BookScan executive director Kristen McLean said.

According to Forbes, readers bought 825 million copies of print books in the U.S. in 2021, leading to an increase in the book market of 9% since 2020. McLean attributes this rise to TikTok, specifically due to the popularity of #BookTok.

“It starts with BookTok, and then it just ripples out

from there,” McLean said.

While book influencers have played a massive role in shaping the market, at the root of the community, above all else, is connection.

“Without reading, we don't really know each other more than, you know, what we see on TV or in the news,” Nash said.

He continued, “In a broader sense, (reading and writing) just allows us to interact with many more people than we would obviously, if we didn't have a way of reaching them.”

It took me a while to reach the same discovery. But first-grade was a start. I would often be asked by the teacher to read to my peers and sound out letters they struggled with. Every time we lined up in a reading circle alongside Mrs.Campbell, I sat in anticipation of finishing each chapter book. I couldn’t wait until I learned how the story ended. I couldn’t wait for another to begin.

It’s easy to forget that feeling. The feeling of curiosity eating at your stomach after finishing the first “Fablehaven.” The feeling of the world opening up for the first time.

Most of us learned early on that the pages are a portal to a world of difference. A place where pens became wands and stuffed animals became friends.

It all started with stringing vowels together, with simple communication from author to reader.

While social media breeds a different form, it exists for a similar purpose.

It’s a way for adults to connect with the magic of words. A way to get back to the domain we once ran as kids.

So the next time you sit down, feet tucked under blankets and pillows beneath your head, remember those moments. It may lead you to a pathway back there. And when you discover that that’s what you’ve been missing — explore.

A crisis of streaming

Words by Lauren Cavalieri Illustrations by Jude StrzempCNET, a website dedicated to product reviews for consumers, ran an op-ed on Aug. 7, 2015. It was titled: “Resistance is Futile: Streaming TV is the future - now.” Caitlin Petrakovitz, the article’s author, rejoiced in streaming’s convenience. It was a kind she could only imagine as a child, back when she had to memorize the air times of “Sesame Street” and “Star Trek: The Next Generation.” She loved TV back then. Streaming made her love it more. She wrote, “Everything you could want to watch is so readily available.” Streaming is a dream come true for Petrakovitz, writing “Fifty years ago, watching TV on public transportation felt like a sci-fi dream; now, I watch sci-fi on the train every day. And that’s progress, baby.”

Petrakovitz’s excitement, the glorious utopia she anticipated, makes sense. Film and TV are two of Western culture’s most valued forms of storytelling. Yet, historically, access to these mediums have been

limited. Films were only viewable in a theater, where they’d play for a few months before archival or destruction. TV episodes aired at a specific time — missing them meant waiting years for the reruns. This lack of access would be squashed by videotape, which proliferated in the 1980s and gave people the power to watch what they wanted, when they wanted. In the 2000s, the internet suggested another revolution in media access, actualized in the form of Netflix.

Netflix became the great equalizer, offering thousands of movies and shows under one digital roof, all instantly available, for a small monthly fee.

It was unprecedented. Netflix became an unparalleled force of the entertainment industry. Those that tried to imitate their reign failed. But about a decade later, Hollywood studios charged the streaming world with powerhouses like Hulu and, especially, Disney+, before Netflix’s Godzilla-sized jaws ate them alive.

Where does that leave streaming? Embroiled in war.

Once it was a revolutionary medium. Now it is a nuisance: a laundry list of expensive services, ever-changing libraries and deleted content. As a result, subscription numbers are plummeting. Streaming companies are scrambling to steady declining profits.

“The world of streaming can be highly frustrating,” says Chuck Barney, a former TV critic for the Bay Area News Group. “Not only are the number of services — and shows — overwhelming, it’s often difficult to understand where and why certain content is located.”

Yet as ugly as streaming looks now, it could get uglier.

When the Coronavirus shut down the globe in 2020, many people were stuck at home with little to do but binge-watch. Companies took full advantage, understanding they’d need to make their services seem irresistible in this crucial time. Their digital platforms became life rafts for movies that planned to debut in theaters. Once theaters began to open back up, Warner Bros. decided to premiere their 2021 slate of movies on HBO Max and in theaters at the same time. Disney made a similar move with “Black Widow.” Its star, Scarlett Johansson, filed a lawsuit against Disney for allegedly cutting her out of her share of box office profits. The suit also claimed ”the decision to (release “Black Widow” in theaters and on Disney+ the same day) was made at least in part because

Disney saw the opportunity to promote its flagship subscription service.” Sure enough, Disney+ and other services saw their subscriber numbers explode. Streamers celebrated lofty earnings and eagerly invested them back into content. Disney began releasing a continuous stream of Marvel and Star Wars shows, bringing in huge audiences due to these franchises’ past success. Disney+ soon began to rival Netflix in subscriber count. Then, in March 2022, the Apple TV+ movie “CODA” made history as the first streaming film to win an Oscar for Best Picture. There was seemingly no limit to the heights streaming could reach, no slowing of the mountainous growth.

But a problem was brewing. The volume of streaming content overwhelmed subscribers. A 2022 study by Nielsen Data found over the last three years, unique programing has increased by 20%. They claimed 46% of viewers felt overwhelmed by the overall number of services. This customer frustration was snowballing, rapidly.

A month after “CODA’s” big win, that snowball plundered downhill. In April of 2022, Netflix announced it lost more subscribers in one fiscal quarter than it gained, which hadn’t happened since 2011. Disney declared a net loss of $1.47 billion in its streaming division, over its third quarter. CNBC noted that NBCUniversal, owner of Peacock, received an ominous note from a Bank of America investor

in October 2022 that read, “we worry that Peacock may struggle to hit engagement figures of 10 hours a month.” Engagement is industry-speak for watch time, and 10 hours a month is really, really low. When asked about this note in an interview, NBCUniversal CEO Jeff Shell quickly changed the subject.

As per usual, the consumer eventually paid the price.

The concept of on-demand video streaming was introduced by Netflix, founded in 1997 by Reed Hastings and Marc Randoph. Blockbuster was the biggest name in home entertainment then. They were notorious for charging customers late fees. Hastings, per CNBC, wound up paying $40 after returning a copy of “Apollo 13” past the due date, and the idea for Netflix was born. Randolph, though, via The Washington Post, said this was “convenient fiction.” The real spark, he said, was when the two decided to create “the Amazon.com of something” (Amazon was only selling books at the time). Whatever the case, the two decided to build a website where they’d sell DVDs in bright red envelopes.

The lure was irresistible. No late fees. DVDs were brand new tech, and sleeker than Blockbuster’s VHS tapes. Best of all, the movies were delivered. No more trips to a brick and mortar. No more lines. Eventually, Netflix would take convenience to another level. Utilizing the streaming technology made famous by YouTube, they created a service where people could stream shows and movies instantly for a monthly fee of $5.99. Launching in 2007, it came at

just the right time.

Cable TV was getting unruly, especially as bundles forced customers into buying hundreds of channels they’d never watch.

Ditching cable seemed a no-brainer, which led to the “cord-cutting” trend. Hundreds of Blockbusters closed throughout the late 2000s and, in 2010, the video giant filed for bankruptcy. Streaming was the future. Established entertainment companies soon realized they’d have to adapt.

Despite their debut on cable, old shows like “the Office” and “Friends” thrived on Netflix. Even though creator companies profited from licensing, they disliked sharing. Barney argued this was what fueled them to make their own services. “The feeling was, ‘Why should Netflix be benefiting from our content? We should be controlling our own content.’”

Early attempts to take on Netflix were largely a saga of failures.

Remember YouTube Red? Youtube hoped it would turn its biggest creators into movie stars, which backfired when many of them got into scandals, notably Logan Paul, whose mockery of a dead body led to his resignation from YouTube completely. In 2018, the service dissolved. NBC invented Seeso, a comedy-focused platform, in 2016 but it lasted just two years. Perhaps Netflix’ most successful competitor was Hulu, which was available to the public in 2008. Yet, it’s always lagged in subscribers and original content.

The pioneering legacy of Netflix gave it a special place in online culture. Shows like “Orange Is The New Black” and “House of Cards” raised the stan-

Blockbuster. Photograph orginated from South Durham, North Carolina. Photograph by Angelo Yape.dard for quality TV. They became an essential part of modern dating through the infamous phrase “Netflix and Chill.” Following its debut in 2016, the success of “Stranger Things” was stratospheric.

Disney would finally become the first competitor to make Netflix really sweat. On Aug. 4, 2017, Netflix released “Icarus” (their first feature-length film to win an Oscar). Four days later, Disney announced it would pull all of its content from Netflix and launch its own streaming service. They would call it Disney+, and it would host a century’s worth of iconic movies and shows for its fiercely loyal consumer base. Its launch in November 2019 shook the industry. Meanwhile, WarnerMedia was preparing to launch HBO Max, NBCUniversal was gearing up to release Peacock, and Discovery was setting Discovery+ for liftoff.

The streaming war was on for real. Just a few months later, a bomb dropped that would raise the stakes tenfold.

While the pandemic was devastating for most industries, streaming flourished. “We weren’t going to restaurants. We weren’t going to movie theaters, or to see plays or concerts. So our time spent with streaming services was bound to increase,” Barney explained. As the pandemic raged, streaming also provided comfort. “(It) was a welcome alternative to all the grim news we were seeing on television.”

The Coronavirus gave new streaming companies the opportunity to get aggressive with self-promotion. Suddenly, customers were getting stretched thin by a seemingly endless number of services that all demanded loyalty.

There’s an issue I noticed one night in September 2022 when my brother and his friends were looking for something to watch together. They went to Netflix and couldn’t find anything, so they headed to Prime Video, then to HBO Max then to Hulu. Useless exertion before finally deciding they’d watch YouTube.

This problem is called fragmentation.

In 2020, the average American subscriber, according to the accounting firm Deloitte, has four streaming subscriptions, a result of content being stratified across a large number of services. These platforms are experts at convincing users to stay subscribed.

“People don’t want to miss out on the new seasons,” said Brody Price a freshman and computer science major at Las Positas. Another student, Rachel Dayton: “There’s been times where I’ve been like, ‘Dang, I should really delete HBO.’ But my boyfriend’s

watching ‘House of The Dragon’ right now and I don’t want to wait.“

Adding to customer stress is the scheme of expiring content. America’s favorite shows are becoming like milk with a “Best By” date.

Per the site What’s On Netflix, more than 90 titles left Netflix in the U.S. on Nov. 1, 2022. This might sound like a lot, but this is a standard monthly rotation for Netflix. Streaming platforms rotate their licensed content to ensure subscribers are always satiated.

Jenna Heke, a San Ramon resident who considers herself a TV lover, takes issue with this. She uses Emby, a media server which downloads and stores her content from many services.

“(It’s) kind of like how you would have a library of all your DVDs,” said Heke, who pays for the service’s monthly subscription. “I can go to Emby and it’s all there.”

The service can save treasured shows from being completely erased, atleast on a small scale.

August 2022, HBO Max culled 20 original shows as part of Warner Bros.’ plan to save $3 billion, before merging with Discovery. According to streaming analyst Julia Alexander, deleting shows helped avoid “residuals to casts and crews of a production,” residuals being monthly payments after a title has been released.

Some of the shows, such as “Infinity Train,” are available to rent on iTunes and Amazon. Others, like “Aquaman: King of Atlantis,” are plain gone. And along with them, that ol’ unlimited options, kid-in-a-candystore feeling Perkowitz raved about.

Barney suggests this could become a trend, as studios realize it’s not financially viable to preserve content. “I think we will see a lot more culling,” he stated. “...We’ve been accustomed to thinking shows/ movies will permanently reside on these platforms. I think we’ll steadily adapt when we realize this isn’t always the case.”

However, the TV business already tried this. It ended up backfiring.

Before the 70s, TV networks practiced “junking,” which involved erasing and reusing tape recordings to save money. BBC did this with Doctor Who, vaporizing more than a hundred episodes, 97 of which are still missing. Fans are disappointed. Even now, there’s online forums dedicated to finding the lost episodes.

When the HBO Max purge happened, many subscribers took to social media to rant, so much so that

Zaslav’s name trended on Twitter’s home page. Their anger was reminiscent of the kind “Doctor Who” fans likely felt decades ago. Fans enjoy the ability to watch and rewatch. There’s security in knowing content will always be available.

As it has turned out, streaming isn’t the holy grail of entertainment it once seemed. Corporate power has seemingly reduced streaming to a labyrinth of exclusive and temporary content, locked behind growing paywalls.

At once democratizing how people watched, it now features financial barriers that create different levels of access. Helmed for how easy it was to navigate, it’s now difficult to keep up with the shifting libraries. And perhaps most jarring: movies and TV are no longer mediums that exist perpetually in the present. Now they are ephemeral, temporary forms, trashable unless they meet the right engagement metrics.

It was a sci-fi dream 50 years ago to watch a show on a train. Nowadays, it’s an everyday thing. What audiences from both periods have in common, and from every period in between, is being sabotaged in the name of corporate interest. People believed they’d finally reached the point of unlimited opportunity, but that fantasy has come and gone. But pendulums swing hard, and maybe one day these companies will realize how much they’ve alienated customers. How much money they’ve lost. How much trust they have crushed. And all for what? Winning the content war.

“I think you’ll see some services wither and die, simply because the landscape is so overwhelming and oversaturated,” Barney observed. That’s not to say streaming itself is going anywhere.” Barney continued,“It will evolve and morph in various ways. But overall, streaming isn’t going to ddisappear.”

Olan Rogers introduced the animated series “Final Space” in 2018. It’s a comedy-drama centered on an astronaut working off a prison sentence who bonds with an alien named Mooncake. Together they embark on a space adventure to unlock the mystery of where the universe ends. The response was so encouraging it graduated from TBS to the more popular Adult Swim for the second season.

“Final Space” developed a sort of cult following. Beloved by fans around the world the show was acclaimed with the likes of the insanely famous “Rick and Morty.” This was a hit.

But in September 2021, Rogers tweeted the third season would be the last. Not even a year later, in July 2022, he took to social media to announce that “Final Space” might disappear. Forever.

“You could wake up,” Rogers said on his Instagram, getting a tad choked up, “and it could be gone.”

How could this happen? How could a show just disappear? After its final season on Adult Swim, the series was housed on HBO Max in America and Netflix internationally. But on June 30,

2022, HBO Max dropped Final Space, and in 2023 Netflix International will drop it too.

So “Final Space” can no longer be discovered in the states. Its fans can’t dive into old episodes. A new audience won’t discover its influence or its innovation. It can’t even be purchased in its entirety. It’s just … gone.

And since it’s an animated show, that seems to be fine.

HBO Max removed 25 animated shows and movies, in August 2022. The next month, Netflix fired 30 animation employees. Netflix has also been canceling animated shows including a few that were already in production.

It’s getting more difficult to see why people would want to join the animation industry. As an aspiring animator myself I’ve questioned my own career choice. It once felt so desirable, so profitable and so productive. Now the allure is gone.

For years, corporate studios kept a ceiling on the potential of animation. Studios have a history of erasing queer storylines and not funding experimental projects, prioritizing profits over storytelling and progressing animation

as a medium

For years, corporate studios kept a ceiling on the potential of animation.

These studios have a history of erasing queer storylines and not funding experimental projects, prioritizing profits over progressing animation as a medium.

But the industry’s constraints are producing a silver lining: independent animation. In fact, it’s a force that may help the animation endure. Recently, many indie studios have been gaining traction. Fueled by Patreon and Indie Go-Go campaigns, many studios have been empowered to produce content outside the suffocating contraints of big corporations. While much less lucrative, the indie studios give animators one thing corporations don’t: freedom.

The industry’s failings left artists with nothing to do but rebuild. The result could be something much better than what has ever existed for this audience and its artists.

Mistreating animators is nothing new.

In 1941, Disney animators went on strike to protest how little they were paid and the lack of screen credits they received for their work. They protested outside the studio for weeks.

As animation’s golden child, Disney did a lot to keep this from tarnishing their reputation. Their solution to the strike was to print a letter in Variety that described the supposed “Communist agitation, leadership and activities” behind the strike.

According to author Nathalia Holt, in the

following deal, Disney laid off the majority of studio employees in exchange for doubling the salary of full-time employees who remained. Additionally, the studio agreed to take “a more equitable approach to screen credits,” wrote Holt. In 2021, animators took to the internet with #NewDeal4Animation to fight for better pay for industry employees. The campaign cited the success of animated streaming shows as a reason that animators deserved fair compensation.

At the same time, #PayAnimationWriters, another popular rallying cry, hoped to bridge the gap of “41 to 52 cents on the dollar per week” that animation writers make “compared to live-action writers,” according to the Animation Guild (TAG).

On May 26, 2022, an agreement was made between TAG and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers. After what TAG called “some of the most focused and member-led negotiations in the Guild’s history.” According to TAG they were able to negotiate “retroactive wage increases, significant gains for animation writers” and more.

This negotiation was historic for animation, but there are still a lot of ways that corporations are taking advantage of animators.

Netflix, for a time, was viewed as one of the best streaming services for animators. They have a history of making groundbreaking animated content like “The Mitchells vs. The Machines,” “Klaus” and “Wendell and Wild.”

In March 2022, after “The Cuphead Show”

announced news of a second season,“ storyboard artist for the show, Nick Lauer, tweeted in response.

“Nothing was ‘renewed.‘ All the episodes were made as one season and Netflix is dropping them in batches,” Lauer tweeted.

According to Lauer, Netflix is ordering episodes in bulk and splitting them up into seasons, allowing them to pay workers less. This comes as bad news to animators because their salaries usually increase when shows are renewed for more seasons.

“Animation—and by extension content and storytelling in general—are really great mediums to visually convey very hard-to-verbalize things,” said Sarah Ligatich, Assistant Editor of “Wendell and Wild” in regards to trans representation in the film.

Queer stories are being written. In March 2022, Pixar employees wrote a letter in response to Disney’s financial backing of the controversial Don’t Say Gay Bill. “(We’ve) witnessed beautiful stories, full of diverse characters...shaved down to crumbs of what they once were,” Pixar employees wrote. They continued, “(Disney) cuts nearly every moment of overtly gay affection...”

There is no shortage of queer stories proposed in animation. There is no lack of audience for queer animation. There are only shamelessly riskaverse corporations refusing to bring these stories to life.

“The main consequence of this, in my opinion, is that it causes creativity to be very ‘cookie cutter’ and very repetitive,” said “Star Wars: The Clone

Wars” story artist Spyros Tsiounis. Independent Studios are fighting for animation. In June 2022, Studio Heartbreak began working on their new animated story, “The Lovers.” A sapphic love story about a “seafood chef and a mermaid, set in the Philippines.” “The Lovers,” is precisely the kind of thing big studios don’t fund.

The problem is Studio Heartbreak depends on Patreon, a service that lets people pay for exclusive access to their favorite artists’ behind-thescenes content. Patreon is not a significant income source, meaning everyone working for the studio is likely doing so pro bono.

This leaves animation artists with a choice: money or passion.

If they choose money, they will be faced with a barely livable wage, corporate oversight on stories and the constant threat of layoffs or their show being locked in a vault.

If they choose passion, they’re forced to be starving artists and must work a day job to live. But they will have the freedom of artistic expression.

That was animation’s original promise: a storytelling medium without limit.

As of November 2022 there has been no progress on the #RenewFinalSpace front. Rogers laments to his fans, “Your memory of Final Space will be the only proof it ever existed.”

However, Rogers has promised fans “I will never stop fighting for Final Space. If it takes years, then so be it!”

“Gobelins Student Films”

WHAT TO WATCH: WHAT TO WATCH: 1

Every year the graduating class of animators at Gobelins L’ecole de L’image, a university in Paris, France, collaborate to produce stunning animated shorts. The 2022 year’s films were “Last Summer,” “Go Fishboy,” “Magnifica,” “Gloire Amere 40000,” “Funeral at Nine,” “Hotel Nuit Noire,” and “La Quete de L’Humain.” Most of these films are in different languages but have English subtitles. The variety in animation styles and storylines make these student films one of my yearly highlights.

“Walter”

“Walter” by Lorenzo Fresta is a charming film about a gardening frog and his dandelions. This film includes no dialogue, instead building its atmosphere with whimsical character design and beautiful visuals. Fresta made this as his senior film at The California Institute of the Arts. Since graduating has worked on “Klaus” and “Luca,” two full-length animated films.

The 2022 Oscar winner for Best Short Film (Animated), “The Windshield Wiper,” directed by Alberto Mielgo, explores the question: What is love? This 15-minute film is an excellent introduction to the world of experimental animation, meaning non-narrative, animated content. This film explores love with exquisite visuals, making it an unforgettable piece. This short features explicit language, some nudity and adult content like sex and implied suicide.

“The Windshield Wiper”

“Pear Cider and Cigarettes”

From the mind of animation legend Robert Valley, “Pear Cider and Cigarettes,” is the story of Techno Stype’s downward spiral, as told from the perspective of his childhood friend. Based on a true story from Valley’s life, this film’s unique style tells an exciting tale of loyalty, thrill-seeking and consequences. This film features nudity and mature themes.

“I Can’t Spare Another Moment: 48 Hour Animated Anthology,” features 28 films based on the title’s prompt. It’s one of my favorites. 48-hour film contests are frequently hosted online and at animation colleges. Participants collaborate or work individually to create a short from scratch in 48 hours.Watching winners of “48-hour film” contests on Youtube is a great way to discover upand-coming artists and animation students.

“48 Hour Films / Film Anthologies”

Drawn to life: A tribute to Eric Jones

Words by Peter Zimmer Artwork by Eric JonesEmpowering young girls. Standing up for underprivileged youth. Championing that the next generation of artists are needed in this world. Eric Jones spearheaded change. The loss of that voice, that spark, that energy rumbles through the art community and beyond.

He was the comic book artist behind “Supergirl: Cosmic Adventures in Eighth Grade,” “Little Gloomy,” and many more. But his legacy stretches beyond the pages of his impressive portfolio. Eric will be remem-

bered as family: Caring son of LPC professor Ernie Jones, loving older brother of Ian Jones, cherished husband of Erin Jones and dedicated business partner to fellow artist Landry Walker.

On Saturday, Sept. 10, 2022, Eric died unexpectedly in his Oakland, California, home. He died in his sleep. His passing struck the Bay Area art community, hard.

While Eric might be gone, his legacy will live on at Chapter 510, an Oakland-based arts and writing

organization for youth. This organization supports Black, Brown and Queer youth in writing freely and confidently.

“Chapter 510 was near and dear to his heart,” Ernie said.

So even following his death, he work went towards supporting Chapter 510. On Nov. 5, 2022, Walker and Erin coordinated a charity auction of Eric’s artwork. His longtime friend and local pizza chain owner, Jon Guhl, hosted the event at The Star on Grand in Oakland, California. The intimate restaurant setting brought together loved ones and admirers to connect over Eric’s art and his memory.

“They sold everything,” Ernie said. “There was one

huge wall, and they just covered it in Eric’s art,” Ernie said.

The auction amassed over $10,000 dollars, which was donated to Chapter 510 and the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund. The nonprofit organization protects the First Amendment rights of comic book artists in classrooms, courtrooms, conventions and libraries all around the United States.

Eric was born on May 27, 1971, in Walnut Creek, California to Ernie and Mary Jones. Within mere years, Eric proved himself a burgeoning artist.

“He started drawing really early in recognizable things, even before he was age two,” Ernie said. “I

came home from work one day when he was probably about three, and he was all excited,” said Ernie as he laughed. “He wanted to show me something and took me into his bedroom. He had drawn this big mural on the wall. It was just this big kid’s drawing.”

The mural invoked neither shame nor punishment. Instead Eric’s composition maintained its place on the bedroom wall until the family moved out.

As a child, Batman’s adventures and Star Wars galaxies emblazoned their artistic influence on Eric. His passion for art soared in the rich pop culture of the time. He continued to improve his craft through adolescence, even garnering public attention at 14 years old for his art. He submitted his artwork to an art show contest, hosted by comic book artist and creator or “Mr. Monster,” Michael T. Gilbert. Eric won an art show contest in Berkeley, California.

It was the first triumph in his young career, hitting the accelerator on his career.

At the age of 15, Eric joined The Advocate newspaper at Contra Costa College as an artist. Eric joined the newspaper by his uncle, Gary Barker’s recommendation. Barker was editor of The Advocate, which was considered one of the country’s most prestigious college newspapers at the time. Despite the newspaper’s shining reputation, it was in desperate need of an

artist.

“His Uncle Gary said, ‘Well, you know, my nephew is really good,’” Ernie said. They brought him in, and he became a staff artist.”

During his time at The Advocate, Eric rose through the ranks in the newspaper, as his adviser Paul DeBolt considered him to be an especially skilled staff artist.

At the age of 16, Eric was building his portfolio, big time. Green Day in its early days, big time. He drew the band’s flyer for their first show in 1987. Long before the band’s mainstream success, then drummer, John Kiffmeyer, was on staff on The Advocate. Eric’s connection with the band carried through the years and he submited artwork for the cover of the band’s “American Idiot” album. His design for the album cover, while not the final artwork, was one of the pieces sold at the Nov. 5 event.

Creative partnership can come at surprising times, cultivating new possibilities for projects. This is exactly what happened to Eric and Walker, who met after a failed party.

“Eric and Landry happened to be at a party when they were both 18,” Ernie said. “They found out the party was a dud, and they came over to the house. It was about 10:30, and I got up saying ‘What’s going on?’ Landry said ‘Well, the party wasn’t any fun.’ That’s where they connected.”

It was a serendipitous meeting of two like-minded artists. Walker, a writer, wanted to pursue his craft and

create comics. Eric, an artist, had similar goals.

They’d known each other since high school, but this pivotal night proved the two’s artistic compatibility.

Walker was awestruck by Eric’s capabilities. “He could draw, and he was exceptional for his age,” Walker said. “But mostly what struck me was trying to get a comic project off the ground with a couple of other friends. He was drawing full (sequences).”

The two began their artistic partnership, pursuing their mutual interest in creating comics. It was a fruitful friendship.

“(Comics) were escapism when we became fans of comics,” Walker said. “Then they’d slowly become our job.”

In 1996 they published their first comic underground: “Filthy Habits.” Shortly after, Eric and Walker began submitting their work to children’s magazines. Their comic, “Little Gloomy,” was published in the now-defunct magazine “Disney Adventures” in October 1999.

“Little Gloomy” emerged from the creative minds of Eric and Walker on a simple drive from San Jose. “We were driving back from a meeting with our publisher,” Walker said. “I had always been a fan of (old comics like) Hot Stuff, Casper, Richie Rich and Little Dot. One of us said, ‘Little Gloomy like feeling,’ and we spun off of it because it is a comic book trope for Harvey comics.”

He is a founder of the film production company 1492 Pictures and director of popular films like “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone,’’ and “Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets,” film adaptations of J.K. Rowling’s novels by the same title.

1492 Pictures partnered with Largardere Animation (which involved the international productions company OuiDO! Production, AKA Timoon Animation) to create a 7 million dollar TV adaptation of “Little Gloomy,” first airing in France in 2012. The show was adapted into “Scary Larry” and ran for more than thirty episodes.

Eric and Walker had reached an international audience, a huge victory for them, as the two had published “Little Gloomy” more than a decade prior.

“When we were there, there was a three-story building dedicated completely to the concept of ‘Little Gloomy,’” Walker said.

“The basement level was the animators working on all these computers.”

In light of their success with “Little Gloomy,” the two creatives kept at their craft, working together to produce more content.

“Supergirl.” Illustrated by Eric Jones, 2015. (Cintiq tablet).

The idea ballooned into a full-fledged comic, geared towards a young audience, about a girl’s adventures in a monster town.

“One of the big successes was when they came out with ‘Little Gloomy,’” Ernie said.

“Little Gloomy” attracted attention from Hollywood. In particular, the attention of Chris Columbus.

Eric turned his artistic attention to social justice, specifically the empowerment of young girls. He aimed at creating an inclusive world of superheros, one that welcomed pre-adolescent girls. He wanted to change the comic industry, one where superhero worlds often excluded women. He made a simple but powerful reply to defy industry norms. He created female superheroes. “Supergirl” and his final project, “Pepper Page Saves the Universe,” are two of these gamechangers

Pepper Page is not a traditional hero, having no desire for public heroism. “What we both liked about

the character was that she really had no interest in being a hero,” Walker said.

“She is a superhero for her(self),” Landry said. She saves herself with comic books, which she uses as an escape from reality.

The public raved about Pepper Page.“They got feedback from parents of pre-adolescent girls that thanked them for producing something where you had a positive female character,” Ernie said.

Praise for Pepper Page illustrates the impact of Eric and Walker’s empowering comic.

Being a passion project, “Pepper Page Saves the Universe” remains unfinished by Eric’s hand.“He had drawn almost half of (Volume 2) when he died,” Ernie said.

Eric’s legacy lives on.

Friends, fans, and family have much to remember Eric by, whether it’s “Supergirl: Cosmic Adventures in Eighth Grade,” “Batman,” “Pepper Page Saves the Universe” or “Little Gloomy.” But his work transcended artistry. He was a devout champion for underprivileged youth and pre-adolescent girls and a community advocate in the Bay Area.

What a legacy Eric Jones leaves. An inspiration to all.

NATALIE HAWKINS

Words by Sophia Sipe and Jude StrzempTHE JOURNEY OF A RISING STAR

Photograph by Sophia Sipe

Photograph by Sophia Sipe

The art of singing is an extensive production, requiring the labor of so much more than a pair of vibrating bands of muscles in the throat. It involves the larynx and pharynx. The tongue and the soft palate. The diaphragm, lungs and rib cage. Abdominal and back muscles.

But the physical components of singing are not the most critical. They certainly aren’t what makes Natalie Hawkins special. The spiritual ones set her apart.

The soul pouring out.

The psyche molding her sounds.

The passion manipulating her volume.

The wisdom shaping her why.

She embodies the sentiments of Jewish-American writer Esther Broner when she said, “The total person sings, not just the vocal cords.” Hawkins’ voice has become her backbone, the foundation for what by most accounts is a promising future. More than a nice voice, she can inflict a world of agony or joy. She can evoke a rush of despair or even fun. She can because her life has touched most corners of the heart. Hawkins, 33, has enough pain to relate to the broken. Enough jubilance to capture the spirit of adolescence. Enough soul to front a gospel choir. Enough range to do justice to classics.

Makes one wonder, who is this woman?

Amy Mattern, dean of Arts and Humanities at LPC, contemplated as much after attending a winter vocal concert in 2021.

“She started to sing,” Mattern said, “and I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, who is that? What is that voice?’”

Her voice is velvety strong, both soft in delivery but unbreakable, comforting and sturdy. She can give it a breathiness evoking the depths of being dumped or summon piercing octaves placing listeners on the edge of a proverbial cliff. She can dig deeper, belt even more, until her passion pours through speakers and reveals the heart beneath her voice. She can hold notes and dance on melodies with incredible control. The enunciation of a school teacher. The emotion of a teenager in love. The power of a single mom determined to keep going.

Mattern was moved enough to approach the director of the concert and rave about the Hawkins’ solo she experienced.

“Her voice really was incredible,” Mattern said, praising Hawkins during a Zoom interview in December. “So she really stood out. We have beautiful singers, wonderful. And her voice just stood out as being so powerful.”

But living through music can be draining. Harnessing her potential for stardom doesn’t come without demands. Pouring out such affection requires allowing herself to connect with some deep emotions.

This gift of hers, which has the power to stir sentiments and reach cores, comes with its own curse. Talent is hardly a deterrent to trauma. Hers is fed by hardships. The pain she can unfurl from her lips, the sadness she can conjure in her tenor — even the escalating power of her soaring runs — are enhanced by struggles. They aren’t visible on the surface, instead hidden behind her glow.

Hawkins is on her way, somewhere big it seems. To choreograph the next phase, she returned to Livermore. Not just to sharpen her vocal tool belt, but to recuperate on the prosperous web of friends, mentors and loved ones she’s sewn together over the years. Here, she can be encouraged in her pursuit of the impossible. To have her cup refilled and, in the spirit of reciprocity, to fill the cups of others.

She might sell a million records someday. She may perform a world tour and become a household name. If she does, it will be because she came home. To the awaiting embrace of arms and voices and energy. To the roots that keep her strong. To Las Positas College.

“Where I am today, it’s taken so much love,” Hawkins said between sips of iced coffee inside Panama Bay Coffee Co. on a sunny December afternoon in downtown Livermore.

“So many helping hands to pull me out of those depressive periods. Angels in the form of people guide you to the next thing and show up.”

The 14 members of the acapella choir Vocal East moved in such sync they appeared to be gliding onto the stage. In black suits and dresses, stylized with green scarves, they lined up in a crescent beneath a white banner reading “Cuesta Vocal Jazz Festival” in black letters. Festival goers flowed in and out of the dimly lit Harold J. Miossi Cultural and Performing Arts Center, on the campus of Cuesta Community College in San Luis Obispo. But a crowd of 100 or so eager listeners, many of them musicians themselves, settled into their seats once the ensemble began.

Their performance opened with harmonizing of the quick one-two, one-two beat from the song “Happy Talk” over the bubbly chimes of a piano.

Doot-daht. Doot-daht. Doot-daht. Doot-daht. Doot-daht. Doot-daht. Doot-daaaaht.

Hawkins, her green ascot shimmering under the spotlight, eventually strutted forward from the arc

of Vocal East performers. Finesse marked her movements. Her knees bent with cadence and her arms swung rhythmically like a graceful painter. She smiled into her lyrics.

Hap-py talk, keep talk-in’ Hap-py talk

Talk about things yoooou’d like to do. You gotta have a dreeeam. If you don’t have a dreeeam. Oh, how ya gon-na have a dreeeeam Come true?

Hawkins’ voice cascaded through the theater, and it wasn’t the microphone. The power she brought revived the 1961 Rodgers and Hammerstein classic. Groove unbroken, she danced back to her leftmost spot in the arc.

“She was a very strong singer and she had a really wonderful stage presence,” said Christine Guter, director of the vocal jazz program at Cal State Long Beach and a clinician for the fall 2022 Cuesta festival. “Really lovely quality of voice, clear voice, and certainly a very talented individual. She seemed very sure of herself, which is awesome to see. A real maturity and confidence.”

Presence. Quality. Maturity. Confidence. They’re common descriptors affixed to Hawkins by peers and experts. But they’ve been earned, accumulated through decades of inspiration, formal training and diverse experiences. Her grooming began as a toddler being serenaded by her mother’s singing. Her mother has been a champion to Hawkins, a supporter and devoted friend. Someone who’s mention brings tears of love to Hawkin’s eyes.

kins breaks out into laughter at the memories. She was so determined to sing it just like Judy Garland. She even put her hair in pigtails like Dorothy.

Once, Hawkins asked her uncle to learn the “Wizard of Oz” classic on his guitar. Quickly, too, because she wanted to sing while he played. Hawkins could recite the lines to the song without fail. But uncle and his guitar couldn’t keep up.

“Call me when you learned it,” the frustrated niece barked. He laughed at her impatience. No wonder her grandpa nicknamed her little “Velhinha,” which means “old lady” in Portuguese. It stuck.

Hawkins was in the third grade when her mother, Liz, got her own place in the pastured hills of Livermore, decorated with windmills and grazing cattle. Music moved with them. She also continued acting in Livermore, performing alongside her brother in plays. But trials came in her teenage years. And did they ever come down hard.

Hawkins joined the theater program at Livermore High which turned out, according to Hawkins, to be a hostile community. She said some parents and students bullied her relentlessly. They called her names, doubted her potential and harshly critiqued her body. She said they tore at her from every direction, for reasons she could never grasp. Peers began avoiding her like mold.

“I was starting to be blackballed from schools, several where parental bullying was happening towards me,” Hawkins said before recalling some of the comments. “She has the face of a horse, the body of a cow, no tits, zits, and she’ll never make it.”

Hawkins said the unwelcoming theater community at Livermore High prompted her to fall back from performing. The stage became a platform for ridicule, thus, a hazard. Which meant one of the avenues to joy and self-expression was suddenly gone. Battles with overwhelming sadness and loneliness followed.

Photograph by Sophia SipeHer parents divorced before her fourth birthday. Hawkins spent her early years living with her mom and brother in Fremont with her grandparents, Hilda and Manuel. Her theater roots began in that house, which always had music playing. She fell in love deeply and fast, performing at Glenmore Elementary School in Fremont. Hawkins and her brother, Nathan, with whom she was especially close, sang “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” together at family functions. Haw-

Back then, conversations about mental health were scarce. What she knows now is she was suffering from

"

She seemed very sure of herself, which is awesome to see. A real maturity and confidence.”

Photograph by Asia Alpher

Photograph by Asia Alpher

extreme ostracization. At the time, she was considered to be suffering from an overblown ego.

“I was a kid that had all of this music and all of this energy inside me,” Hawkins said. “And to not have a stage to do it on … I was like, ‘Where do I go? What do I do? How do I make music if no one will give me a chance, and no one will give me a stage?’”

The answer was a guitar.

At 15, she learned the six strings from her uncle and began listening to music production with more intentionality. Hawkins found a supportive choir teacher at Livermore High in Art Gagnier. She ate lunch in his office daily, and they talked about music. As a senior, with Gagnier’s encouragement, Hawkins took part in an original capstone project — transcribing, arranging, composing and teaching a choir of about 65 students the music of Rufus Wainwright. This was revelatory for Hawkins, her first time trying her hand at scoring and music composition.

As she stacked notes and constructed melodies, she also rebuilt her confidence. It ignited her resolve. An emboldened 17-year-old, Hawkins returned to theater her senior year at Livermore High, no longer allowing the bullying and cruelty to keep her off the stage.

“It was somewhat validating in a way,” she said. “Because, for a while, I thought that maybe I just had no talent, and it was strictly my inability or something that was keeping me off the stage. But I also remember returning to the stage feeling a lot more defensive and self-preserving than I ever had before.”

Not long after Hawkins graduated high school in 2007, she bought a microphone and low-quality webcam and took her talents to social media. Her bedroom became her stage. Her first post was in October 2007, a reenactment of the song “Popu-

lar” from the musical “Wicked.”

She went on to captivate hundreds of thousands of viewers with her combination of girl-next-door cuteness, booming voice and convincing authenticity. Her theater friends grilled her about why a talent with Tony Award potential was posting performances on YouTube in the early 2000s. For one,

Hawkins said, it was fun not to take herself so seriously. She revived her full character bit of “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” pigtails and all. Her eyes traced the arc of an invisible rainbow as she nailed the yearning in a ballad 50 years older than her. She ramped up the energy for an on-point rendition of Michael Jackson’s “Leave Me Alone.”

She was having a blast.

Plus, she was investing in her craft. Listening to herself on recordings, editing and tweaking her performance, proved to be a more productive form of self-criticism. She grew as an artist by reviewing her own work in this way. Also, it worked.

“Through YouTube,” Hawkins said, “things started to happen. Opportunities started to come. And then all the theater kids stopped questioning.”

In 2008, she caught news of an online singing competition put on by a Broadway composer named Jason Robert Brown. He wanted singers to upload a performance of one of his songs and get people to vote for them.

So at 19 years old, Hawkins recorded herself singing Brown’s “I’m Not Afraid of Anything” over a piano track and became one of four who won a chance to perform in New York City.

Just like that, Hawkins went from covering songs on the edge of her bed in Livermore to singing at a jazz club in New York City.

Birdland, where she performed, has been played by a laundry list of legends including Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis and John Coltrane. This opportunity marked a vital point in her career, one which aligned with her family’s lineage.

Liz was a professional vocalist who graced many stages. She was in a band called Black Pearl with her friend

Photograph by Rodriguez Cruzana

"

YOU'VE GOT TO FOLLOW YOUR HEART, EVEN IF IT DOESN'T MAKE SENSE”Photograph by Jude Strzemp

Howard. They used to serenade little Natalie to sleep. Some of Hawkins’ earliest memories are falling asleep to images of her mom on stage under the lights.

“Those are core memories,” Hawkins said, a tear gradually rolling down her cheek. “Those are good times. Sweet times.”

Her mother is the blueprint. Her uncle played the guitar, which he mastered simply for the love of it. He illustrated early for Hawkins the purity of artistic passion. And she’s heard stories about the old days when family members harmonized on the porch, passing time with songs full of melodies and jokes.

It goes even deeper. Her grandmother, Hilda, was such a good singer she earned a full ride to The Juilliard School in Manhattan. Two generations later, her granddaughter was on stage in New York.

“I’ve waited for this moment all my life,” Hawkins said, recalling the memory with snappy speed and in present tense. She told it as if she was back in that moment just before stepping on stage at Birdland, as if she could still feel the bad case of laryngitis strangling her voice.

“I’m 19 years old. I’m scared to death. I’m sitting in a room in New York full of people in the middle of fall. It’s turning to winter. It’s cold, and I feel like dog shit. I have stars in my eyes looking at all these people. And I’m about to get up and make an ass of myself. Please don’t let it be.”

When she hit that stage, and the lights came on, she did the venue honor. With Brown on piano, Hawkins sang “I’m Not Afraid of Anything” with trained fluctuation between melody and speech. She was present, refusing to overthink the surreality of it all.

The standing ovation the crowd lavished on her snapped her back to reality. The moment felt high. Her purpose was suddenly tangible. New York seemed to offer everything of which she’d dreamed.

But it was a one-night gig with a one-night high. The low would come.

Hawkins wound up jobless and overwhelmed. New York quickly became intimidating. One of the few highlights was getting to see Ariana Grande perform in the musical “13” on Broadway in 2008. Getting to chat with Grande fueled Hawkins’ desire to work with talented stars. Getting there would be tough, though, as her social anxiety was escalating.

“I got scared,” Hawkins said, bluntly, like a confession. “Sometimes you have to follow that… You have to follow your intuition at all times. You’ve got to follow your heart even if it doesn’t make sense.”

Hawkins’ heart tends to overflow with raw emotion, fully experiencing the highs and lows of life. She tears up when talking about her family. She speaks glowingly of fellow musicians and performers, of their talent and kindness. She responds to hundreds of complimentary comments on her YouTube channel.

“What’s your business is that you got on the stage, and you were vulnerable and real and authentic,” she said following her performance with Vocal East at Cuesta College. “And you poured your heart out, and you gave people something real, in a world where so much feels like an illusion and where so much feels like we’re putting on a show.”

As a result, her heart doesn’t just break, not like a pencil snaps cleanly into two parts. Hers shatters like an iPhone screen, a collage of cracks forming a mosaic of brokenness.

Like when Nathan gave up theater, taking away her long-time stage partner.

Like when her grandpa, Manuel, passed away. Like when tragedy struck close enough to shake her up.

In June of 2016, after performing for a crowd in Orlando, Florida, YouTube star Christina Grimmie was shot four times at her post-concert meet and greet. The 22-year-old rose to national prominence when she appeared on the hit TV show “The Voice.” She was impressive enough to receive high praise from Adam Levine, Selena Gomez and Justin Bieber.

Grimmie’s shocking death would prove to be a significant turning point for Hawkins. One that would lead her to LPC.

It’s taken a village to get here. Angels, she calls them: one teacher who gifted home-recording equipment during the pandemic, leaving it on her porch in the pandemic; another teacher who hired her and became a major industry resource; an unrelentingly supportive family whose mention chokes her choked; a plethora of mentors and supporters have been instrumental in shaping the career growing from Hawkins’ mellifluous sound.

In 2012, she took a music technology course at Chabot College. Instructor Bryan Matheson, trying to surmise the talent he was working with, asked

for volunteers to sing a song. Any song.

Hawkins raised her hand and, when called upon, revealed her choice: Lady Gaga’s “Edge of Glory.” Matheson was surprised, and a bit concerned. It’s a vocally challenging song. He obliged with hesitation.

“First take — pow. Nailed it,” Matheson said, reenacting his original shock, dropped jaw and all, as he recalled the memory. “Killer, right out of the box.”

Matheson found a prized student. Hawkins found a mentor. He offered her an internship at Skyline Studio, his state-of-the-art recording studio in Oakland. The duties began basic — getting sandwiches, running copies, setting up microphones, welcoming in customers. Her aspiration to become a recording artist bubbled.

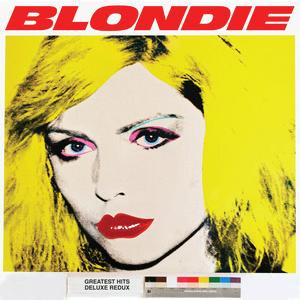

She got a break when legend Jeff Saltzman, producer of The Killer’s “Hot Fuzz,” made Skyline Studio his home. He asked Hawkins if she wrote music. He had a track from Blondie’s guitarist Chris Stein, it just needed lyrics and a voice. That broom flew out of Hawkins’ hand quicker than a toupee in a hurricane.

Lyrics came for her the way numbers do for a math genius. She earned her first professional gig making songs for Blondie, beginning with the first song she co-created with Saltzman and others. She co-wrote seven songs on their album “Ghosts of Download,” part of the 2014 double-CD “Blondie 4(0) Ever.”

It was also at Skyline Studios where Hawkins met Steven Rezza.

They began a professional relationship. Musically, they were an interesting pair. Rezza’s background was in rock and metal while Hawkins’ was in musical theater. But pop influence was a connector.

Soon, they started dating, becoming more than just a musical partnership.

The pair relocated to Los Angeles in October 2013 with only their talent, a dream and a few friends. They slipped into writing and producing their own EDM tracks. They produced work for other musicians, too, including Grimmie. Hawkins and Rezza built a reputation as dependable producers.

The hustle was real. She lived at the studio. Going home to sleep was a faux pas. She kept pushing, laboring day after day, bellowing out-of-range lyrics for clients, cranking out lines and verses and hooks. She pushed so hard because she could still hear criticism from her past. How she was crazy to pursue this. How she was too old and it was too late for her. How she was good but not good enough. Eventually, her obsession became all-enveloping. She wasn’t sleeping, nor was she taking care of her mental health. She lost her voice for a whole year. Burned out.

“I spent the majority of my time in LA not really

living, and mostly working,” she said. “I was kind of feeling like a dead battery.”

Still, in 2015, Hawkins was contacted by a label called Bump into Genius Music, an extension of Warner Chappell Music. The publisher connected Hawkins and Rezza with up-and-coming artists and watched the two do their thing. Hawkins and Rezza churned out work, refusing to sacrifice quality despite the quantity.

Nearly a year later, Bump into Genius Music drew what Hawkins deemed “a good, entry-level contract.” She said they kept the rights to the majority of their music.

But her and Rezza, which had been such a productive relationship, became a Hollywood cliche.

“Ultimately, I feel like we were songwriting friends first, lovers second,” Rezza said in a Zoom interview. “We were best friends for years who were just writ-

ing amazing music consistently. And I feel like, obviously, there’s an attraction with somebody who you’re doing amazing things with consistently, right?”

With romance came struggle. They’d come together as a dynamic tandem. They had a chemistry that produced magic. But as overburdened as they were, it was taking a toll. Things changed between them. Ego and emotion took over. All that advice her mom gave suddenly felt so prescient. The importance of working out, stretching, hydration and vocal warmups. Mom also warned Hawkins about being careful on the road, being “extremely mindful of your health.” Getting sleep, eating regularly and “really having boundaries.”

“Two artists dating each other is delicate,” Hawkins said, “and something that I haven’t perfected yet.”

This Hollywood love didn’t survive. The added weight of intimacy was too much. After tirelessly walking a tightrope of passion and production, they made the decision to split as spring 2016 rolled into summer.

“She’s amazing,” Rezza said. “But, you know, if you write too long with somebody, sometimes you could use a break.”

She folded up the hurt and tucked it beneath her ambition. Until Grimmie was murdered and she couldn’t compartmentalize anymore.

The death of her industry peer was all over the national news and social media. The articles, commentaries and takes were everywhere. Hawkins couldn’t escape.

Grimmie’s death hit home. Not only had their paths crossed professionally, but she was on a path similar to Hawkins’. Grimmie, too, put in years of work on her craft, also had a booming voice and a magnetic presence. And she was making it big. In the end, making it only exposed Grimmie to the ultimate danger.

Hawkins grappled with meaning, questioning the purpose about which she was once so certain. Did she want to make it big and be famous? Was this the right path for her? Who was she, really? This existential crisis came on the heels of the breakup.

Rezza, her ex who was dating Grimmie at the time of her death, grief-stricken ex was mourning. So Hawkins’ heart and career plans needed mending. Her future knelt at the foot of a giant question mark.

She hung on in Los Angeles for a while after that, songwriting and doing about a dozen sessions. But her mental health had deteriorated.

Traumatized and emotionally spent, Hawkins withdrew from the hustle and bustle of LA in December

Photographs by Jude Strzemp2016. The plan: retreat to a safe boundary and grow again. After all, the singer found herself needing more formal education and compositional skills. As strong a songwriter and powerful a vocalist as she is, Hawkins learned what was missing from her repertoire.

But most importantly, she needed salve for her wounded soul. She thought of her mother’s embrace. The warmth. The tight squeeze. The shoulder on which her head can rest. Her reservoir of love had run empty. She required the comforts that make her feel safe, the moments that sharpen her perspective. So she hauled up Interstate 5, speeding through the grapevine, then a winter wonderland of icy mountains and crispy air.

After replanting in the Bay, Hawkins reconnected with Saltzman from Skyline Studios. He linked her with drummer Thomas Pridgen, and they frequented the Bay Area jazz scene for a couple of years. Hawkins was hesitant to perform again. She was content spending time listening and rebuilding her love for sound. That was enough at the time.

On other days, she rolled herself burrito style into a pile of warm blankets and binge-watched “Gilmore Girls.”

“And, you know, I didn’t make much of it,” she said. “I just wanted to be around it to remind myself even

"Killer, right out of The box”

though it’s a hard industry, I love it. Music is healing and beautiful. Sometimes you just appreciate it, which is how it started for me.”

She was hired in 2019 as a vocalist working at Mastro’s Steakhouse in San Francisco’s Union Square. It was her first recurring professional gig — that is until the pandemic canceled all shows in 2020.

Stuck at a standstill prompted by COVID-19, Hawkins made the decision to finish her degree. Where to go was an easy choice because LPC’s performing arts program was extensive. She enrolled in a slew of music courses, such as piano pedagogy and music theory, to fill the hole in her repertoire.

“She didn’t have much formal background, and having more knowledge can only help,” said LPC music professor Daniel Marshak, who encouraged Hawkins to become a vocal major. “This idea of being adaptable, especially these days, is really key.”

Hawkins said the LPC teachers have been critical to her growth. She said Grammy-nominated conductor Ash Walker, choral director for the Oakland Symphony, and Ian Brekke, LPC’s then director of choral and vocal studies and co-coordinator of the music department, helped her realize who she was after grueling burnout from L.A. Performing arts professor Dyan McBride took Hawkins under her advisory.

Photograph by Sophia SipeYes, her penchant for theater reemerged, too.

McBride could instantly see the pupil was serious about music and equally serious about performing. Hawkins has the goods, McBride is sure. The key is for Hawkins to once again own that truth.

She pointed Hawkins toward the stability of theater.

“She was in the slog of life,” McBride said, “and I told her ‘You know, there is a path forward in this industry.’ Freelancing is a hard gig. The songwriting world feels like ‘Does anybody see me? Does anybody know?’ But in the theater world, it’s like ‘Of course they do.’ ”

For the first time in 12 years, Hawkins returned to the stage. A year after enrolling at Las Positas, she performed in “High Fidelity” in March of 2022. She played Laura in the campus production of the musical based on the 1995 Nick Hornby novel.

Hawkins has been finding her groove ever since. In addition to singing with LPC’s Vocal East jazz vocal ensemble, she tours with Terror Jr. as a background vocalist and is part of the Pacific Edge Voices choir, which helps her study her voice. She joined a new student-led ensemble on campus called Early Birds, featuring five performers with music arranged by Lorenzo Roblesent.

Hawkins is also currently working on a musical in development and aiming for Broadway. “Can You Hear Me Baby?” is about a young millennial couple on the rise in their careers but pregnancy, while on the brink of success, brings up a host of issues. A Matheson connection set up the opportunity for Hawkins. She is working closely with Emmy Award-winning composer and producer Gary Malkin, who is collaborating on the project with composer and playwright Lisa Rafel.

Hawkins is still planning to release an EP of original songs. She described it as “Folk-Americana country” and is being produced in Pleasanton. She’s also recorded music for a film trailer. The surprise opportunity came from reconnecting with Rezza.

In November of 2022, Rezza contacted Hawkins, in part, to share with her they’d been released from their publishing contracts.

“He reached out to me in the most selfless way,” she said, “which is really the only way it would have worked. I feel really grateful that we’re reconnected now. Things are good. It’s brought a lot of peace to us both, I think.”

Despite the six years apart, their work relationship still produces quality. Their current project is shrouded in secrecy. She won’t reveal the name of the film or

the song because the trailer has not been finalized.

In the meantime, LPC serves as an epicenter of joy and growth. The kind of replenishment home brings was on display during a November photoshoot at the Barbara Mertes Center for the Arts, which on this night was livened by a throng of students participating in a variety of rehearsals. Hawkins — sparkling in a red, long-sleeved sequin dress gently hugging her curvy 5-foot-7 frame — was showered with adoration. Classmates and friends took turns depositing affection. Passersby lit up at the sight of her. She was bombarded with hugs and compliments at every turn, greeted by faces painted with their widest grins. Fellow singers, actors and students yelled her name, affirmed her greatness, gushed at her beauty. They all shared giggles and comforting words.

This was why she returned. Restoration. And why she is loved and supported here was evident the next day during a performance with the Early Birds in LPC’s theater.

Dressed in all black, the ensemble soaked in yellow backlighting with towering white boards behind them and curling over their heads. Crisp white lights projected from below. A crowd of over 100 people sat in silence and listened. The snapping of one performer set the pace. The five slid into a chilling symphony, their voices were clear, sweet and longing as they harmonized the lyrics of “Run To You.” The overhead lights turned purple, and the ensemble built to a resonant ring. That’s when Hawkins’ voice broke through.

It was high, skating the upper limits of the ensemble’s vibrant chants. She clenched her fist as her voice scaled to another peak. Her sound was full, stuffed with hope and loss, with talent and trauma, with buoyancy and fear. Because Hawkins sings with her whole person.

Goosebumps swept through the crowd like a gust of wind. Everyone here knows she’s on her way.

“I know how it feels when you’re surrounded by community,” Hawkins said, “and that’s how I feel when I sing. And it’s totally warm and beautiful and loving and terrifying and exhilarating.”

Her eyes water. Her voice begins to crack. This flooding emotion isn’t hurt. The tears welling up aren’t from pain. They’re from the fulfillment that comes with being home, from the gratitude she feels for making it back here.

“I mean this whole year has been like a shift from feeling alone before this year to just so much community. So much support and so much love.”

Photograph by Sophia SipeSisterly love

Origins of the Cheer Squad