Paintings

THE PAINTINGS OF Baltimore Country Club

Written by John Voneiff II

Art by Sam Robinson

Book Design by Rachel Upton

Editing & Production by Mary Brunk

Concept by Martin P. Brunk

Copyright © 2022 by Baltimore Country Club

All Rights Reserved

The First Clubhouse

The Winter Serenity of Roland Park

The 1932 Clubhouse

Grand Clubhouse

The Olivier Mansion at Five Farms

Under the Elms

The Beginning of Tennis 13

The Tennis Championships

Transformation of Five Farms

The Roland Park View Corridor 19

William Dunn’s 1898 Roland Park Course 21

The First Tee 23

The Match 25

#10 East The Pond Hole 27

Francis Ouimet at #1 East 1932 U.S. Amateur 29

#9 and #10 East The Turn 31

Chick Evans at #6 East The Barn Hole 33

#13 East A Tiny Gem 35

The Course Beautiful 37

Foreword

Dear Fellow Members,

We have been on a journey that began with a vision and now culminates with a beautiful new clubhouse for all to enjoy. In commemoration of our Grand Reopening, I am excited to present this special publication, The Paintings of Baltimore Country Club.

There are many people that made this expansion and renovation project possible through their hard work and dedication. First and foremost, I extend much gratitude to our volunteer members serving on the Planning & Capital Improvement Sub Committee, Finance Committee, Interior Design Charrette Committee, and Archive Committee. Your expertise and dedication to Baltimore Country Club and this project were instrumental to its success.

To our Club leadership and staff, we recognize and commend you for your commitment to this project. Thank you for navigating the logistics of serving two locations while remaining undaunted by the Five Farms construction site. To our consultants and contractors, thank you for your expert advice and excellence of your craft.

To our membership, I am especially thankful. You shared your opinions, observations, and suggestions to assist us in the creation of Phase 1 of the Lifestyle Facilities Master Plan. You demanded excellence and supported the construction of our wonderful new Clubhouse.

To our Board of Governors, whom I have served with as a member and as Club President, you have given much of your personal time to this undertaking. I thank you for your passion, collaboration, and support of this project and your dedication to the welfare of Baltimore Country Club.

During the interior design planning, we were presented with a unique opportunity that would allow us to honor our rich heritage through art. We made the decision to commission Maryland artist Sam Robinson to paint a series of impressionistic oils and gouaches that captured selected scenes of Baltimore Country Club’s storied history. Sam’s beautiful canvases are displayed throughout the Five Farms Clubhouse and are captured here in print for your enjoyment.

For this special publication, John Voneiff II, Baltimore Country Club historian emeritus, has penned 19 original stories to accompany the images of the paintings. It is through his eloquence of word that we are transported back in time to relive the history of Baltimore Country Club. I thank John for sharing his vast knowledge of our Club’s heritage and his tireless work with the publication.

To my wife Mary, I give you my heartfelt thanks. Your passion, dedication, and tireless work behind the scenes has been indispensable not only to this project but to my term as President. I am deeply grateful for all of your support along this journey.

It has been an honor to serve as your 37th President. I hope you enjoy our new Clubhouse, the wonderful artwork, and this special publication—The Paintings of Baltimore Country Club. ◆

Sincerely, Martin P. Brunk 37th President, Board of Governors

The First Clubhouse

ON NOVEMBER 18, 1896, with Edward H. Bouton as its President and Charles H. Grasty and James Richard Edmonds as principal investors, the Roland Park Company established the Roland Park Golf Club as a community amenity. In 1897, Scottish professional William Dunn, Jr. was hired to layout the golf course. The architectural firm of J.B. Noel Wyatt and William Nolting was engaged to design the clubhouse.

Bouton was confident that a signature clubhouse where people could gather, dine, host events, read the newspapers, play cards, and escape the daily grind, would entice residents, who preferred the private comfort of downtown clubs, to consider moving their families north. Wyatt and Nolting proposed a 55,000 square foot three-story shingled and gabled American cottage style clubhouse that overlooked the Jones Falls River Valley and fronted Club Road.

In January 1897, when construction of the golf course and clubhouse was underway, a group of prominent Baltimoreans, headed by Lawrason Riggs, formed what they called a provisional committee with the idea of transforming the community based Roland Park Golf Club into a private country club centered on the game of golf. Bouton, Grasty, and Edmonds eventually agreed. On January 13, 1898, Baltimore Country Club of Baltimore City, Inc. was officially launched into an approaching and unbridled new century.

Sam Robinson’s majestic painting shows the western façade of the Roland Park Clubhouse from a location downhill from the 18th green. The rounded three-story veranda, called the Ladies’ Gallery, was added in 1904. The old clubhouse, with its turn of the century dark paneled interior, stood for 33 years until it was destroyed by fire on January 5, 1931. ◆

FROM BCC ARCHIVES

The photograph above is of a golfer putting on the 18th green with the original Roland Park Clubhouse circa 1899 in the background.

Postscript: Sam Robinson’s painting of the clubhouse was inspired by a note card that was part of a set given to all members in 1973 as a gift commemorating Baltimore Country Club’s 75th anniversary.

of Roland Park

THERE IS SOMETHING SERENELY beautiful about an evening snowfall, especially at Christmas time. It is winter’s gift, billions of icy crystals settling across an already blanketed landscape. In 1904, Lucille Bouton, wife of Roland Park Company President and Baltimore Country Club founding Board Member, Edward H. Bouton said, “Christmas in Roland Park is always magical-especially when it snows.”

Sam Robinson’s panoramic scene captures the quiet splendor of a winter snowfall viewed across the eastern incline of the Jones Falls River Valley-westward to a misty horizon. Sometime during the winter of 1905, the photograph that inspired Robinson’s painting was snappedpossibly by a lodger staying in one of the clubhouse’s third floor guest rooms. Whoever it was, the photographer was standing on the second floor level of the rounded veranda. The first tee is in the right forefront. The small snow covered box, visible on the back edge of the tee, is where caddies would collect sand to form a tee for their golfing patron. To the immediate right, just down the hill between the 1st and 18th fairways, is the caddie house (known as the Shack). Until World War II, golfers were required to use caddies. Most were boys from Hampden. 50 cent bag haulers, as young as

twelve, would walk or ride bicycles up Roland Avenue to the Club where they could count on a round-maybe two.

In the distance, through the trees, to the left of Robinson’s canvas, the snow covered lawn tennis grounds and its little clubhouse are visible. This five acres of flatland, chiseled from the steep hillside around 1885, had been the home of the Mount Washington Cricket Club. Because of the increasing popularity of lawn tennis, the Club purchased the property in 1903. Baltimore Country Club fielded its own cricket team until 1909, when the five acres of flatland was fully transformed into 24 lawn tennis courts.

The blanketed first green is centered in the foreground 40 yards east of the Falls Turnpike-354 yards west and 130 feet below the tee. Barely recognizable in Robinson’s painting, the Falls Turnpike follows the distant tree line north from Baltimore City. ◆

The 1932 Clubhouse

DURING THE NIGHT OF January 5, 1931, Club President Heyward Boyce and other members, gathered on the front lawn of 10 Club Road just across the street from the clubhouse and watched the wind driven inferno progressively engulf the shingled and gabled structure as torrents of freezing water flooded Club, Hillside, and Edgevale Roads-clogged with fire hoses and trucks. For Baltimore Country Club, suffering through the third year of the Great Depression where more than 1,000 members had resigned, the destruction of its 1898 Roland Park Clubhouse was a bitter blow.

The new clubhouse, designed in the classic Georgian style by the architectural firm of Edmonds and Hyde, was underpinned by the foundation of the original building. When it opened, in September 1932, 700 members, along with newspaper reporters and Baltimore Mayor Howard W. Jackson, toured the facility. The eagerly awaited clubhouse was heralded as being grander than anyone could have imagined. The following night, five hundred members and guests attended a gala dinner dance-the first of countless celebrations to follow.

Edmonds and Hyde designed the classical structure to be as fire proof as possible. The building is primarily concrete, brick, steel, slate, and stone rather than wood. The main floor features vaulted hand-crafted plaster arches that complement 20 corresponding radius windows. A porch, now enclosed, extends the full north-south length of the western façade, on either side of a Greek Revival columned portico that overlooks the Jones Falls River Valley. Sam Robinson patterned his painting from a 1991 ink rendering sketched from the lawn of 10 Club Road where Heyward Boyce and his fellow members watched the old building burn to the ground. ◆

FROM BCC ARCHIVES

A. Aubrey Bodine, a world renowned photographer and photojournalist who worked for The Baltimore Sun for 50 years, photographed our Roland Park Clubhouse in 1932. He shot a series of four photographs including this image of the Falls Road side of the clubhouse with a few golfers walking down #1.

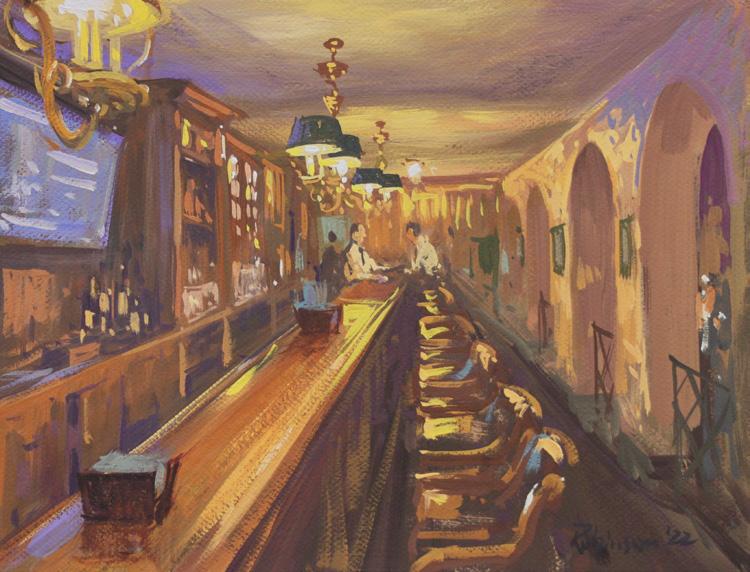

A Grand Clubhouse

WHILE THE 1898 AMERICAN cottage style clubhouse destroyed by fire in 1931 reflected the Victorian Era of American architecture that was popular between 1837 and 1914, the architectural firm of Edmonds and Hyde designed the 1932 clubhouse in the grand classical style that signaled the rise of American prosperity following the First World War. Sam Robinson visited the Georgian style Roland Park Clubhouse to capture the beautiful interiors. From the magnificent archways that grace each side of the Georgian Room to the cozy library that looks out over the Club Road porte cochere to the comfortable and inviting bar and fireplace of the 1898 Grille, which still retains the stone arches from the original 1898 Grille, the Clubhouse is truly grand.

FROM BCC ARCHIVES

A. Aubrey Bodine photograph from his 1932 photographic series of the interior vaulted arches gracing the Falls Road side of the clubhouse.

at Five Farms

BY 1920, WITH MEMBERSHIP approaching 3,000, the Roland Park course overwhelmed with play and too short to qualify for a second USGA or PGA championship, Club President Dr. Joseph Sweetman Ames and his Board of Governors began searching for a track of land, north of the city, suitable for a second golf course. Three years later, the New Property Committee was still looking.

Stuart Olivier arrived in Baltimore in the early 1900s to manage The Baltimore Evening News, which Frank Munsey purchased from its publisher and owner, Charles H. Grasty. Grasty, a major investor in the Roland Park Company and founding member of Baltimore Country Club, sponsored Olivier for membership. By 1915, Olivier was building his wealth through investments in real estate, oil, and banking. One of Olivier’s favorite acquisitions was a 125-acre farm seven miles north of the city that included a gracious mansion house, swimming pool enclosed within a circular pavilion, stables, barns, gardens, and orchards. In subsequent years, Olivier enlarged the house, built additional barns and stables, and bought adjoining property. It was this larger estate that Olivier named Five Farms, totaling 390 acres, that in the summer of 1923, he offered to Baltimore Country Club. In January 1924, Dr. Ames announced that the Club was finalizing the purchase of Stuart Olivier’s Five Farms property.

Stuart Olivier’s 9,800 square foot mansion, preserved in Sam Robinson’s painting, was located just west of the Club’s Mays Chapel Road entrance and directly south of the first tee. Members and guests gathered on the lawn, before or after golf to socialize, enjoy a drink, or have lunch. The mansion served as the Five Farms Clubhouse for almost 40 years. Robinson’s canvas reflects a Post War Era when, after being closed from 1941 to 1945, life at Five Farms began anew. ◆

Postscript: The Baltimore Evening News was also referred to as The Baltimore News, The News, The Evening News, and the evening Baltimore News.

FROM BCC ARCHIVES

Aerial photograph of the Olivier Mansion before the golf courses were constructed.

Under the Elms

RELAXING IN AN ADIRONDACK chair with friends and family on a balmy evening, after golf, or before dinner, it’s hard to imagine a more splendid setting. But for almost 40 years, this bit of Elm shaded landscape was a parking lot. When the Club purchased Stuart Olivier’s property in 1924, the plan was to build a second golf course at Five Farms. Olivier’s big house, with a few alterations, would do just fine as a summer clubhouse. Roland Park was the Club’s north star—not Five Farms.

Gradually, things began to change. A swimming pool complex was built across the driveway just south of the Olivier Mansion in 1957. Then, in 1961, the Club sold the land just west of Falls Road, ending 64 years of golf at the historic Roland Park golf course. A second golf course at Five Farms, already underway, opened in 1962. There was talk about building a larger more accommodating clubhouse or expanding the mansion, but recent projects had exhausted reserves. A new clubhouse or expansion of the old clubhouse would have to wait.

Then in 1963, there was a fire in the kitchen of the Olivier Mansion that gutted much of the interior. The Baltimore County Fire Department condemned the building as uninhabitable. Add to this, the Club was awarded the 1965 Walker Cup. It would be the biggest event since the 1932 U.S. Amateur. Five Farms would be the focus of international golf. Thousands were expected. The decision was made to construct a modern 40,000 square foot clubhouse. The parking lot between the courses was the perfect spot.

In 1998, the building was redesigned in a country style. The interior was refurbished. Porches were added. But the stately Elms and broad lawn remain, as they were when the United States Team and Great Britain and Ireland Team gathered here, for a farewell photograph, 57 years ago. ◆

FROM BCC ARCHIVES

The Beginning of Tennis

LAWN TENNIS WAS INTRODUCED to North America during the second half of the 19th century, about the same time as the game of squash racquets. The genesis of all racquet sports, real or court tennis, racquets, squash, various forms of handball, modern tennis, and even paddle tennis, can be traced back to medieval times, in 12th century France, where monks began hitting some form of ball, with their bare hands, against and along the walls of their monasteries over some kind of obstacle. Eventually, leather gloves softened the blow and by the 16th century, gloves gave way to racquets. Lawn tennis is most closely derived from “Real Tennis,” now court tennis, where a tightly wrapped hard cloth ball is hit back and forth, along a roof line, against walls, to targets over a net with a racquet.

Between 1859 and 1865, the first form of lawn tennis, played against a wall with racquets, took place on a croquet lawn. In 1873, on his estate in Wales, Major Walter Clopton Wingfield went one step further. For the amusement of his guests, Wingfield, based on a simplified version of Real Tennis, added a net and invented the sport that has grown into the game played today. He filed a patent naming his newfound pastime “sphairistike”

or “lawn tennis.” Four years later, in 1877, the first Wimbledon tournament was played.

The American craze for tennis took hold quickly, as the first U.S. National Singles Championship for men was held in 1881.

In 1900, when Baltimore Country Club opened its first two courts, lawn tennis had been officially played for less than a quarter century. The courts were built 70 yards north of the shingled and gabled clubhouse just south of Edgevale Road. They were cut into the northern portion of the manicured lawn that was used for relaxation, dining, weddings, parties and lawn sports like croquet. Beginning in 1900, the lawn was also a place to watch tennis. A nine-foot high “terraced” wall, built in 1899 separated the lawn from Club Road.

In 1903, the Club purchased the Mount Washington Cricket Club. For a time, both lawn tennis and cricket were played. In subsequent years, as lawn tennis became ever more popular, it became difficult to field a cricket team. In 1909, cricket was dropped as a Club sport. The cricket green was transformed into 24 lawn tennis courts. The two courts, highlighted in Sam Robinson’s canvas, launched a storied century of lawn tennis at Baltimore Country Club. ◆

Postscript: The U.S. National Singles Championship for men was the precursor to the modern day U.S. Open.

FROM BCC ARCHIVES

Ladies wearing “tennis white” dresses were a requirement of the time.

Championships

SAM ROBINSON’S PAINTING IS based on a photograph published in The Baltimore Sunday Sun on July 16, 1939, during the singles final of the Maryland State Open Tennis Championship held at BCC. The match was viewed by a packed gallery, gathered on bleachers, in front of the Tennis House. 1939 was the 34th year that the qualifying championships were played on Baltimore Country Club’s grass courts. Ninety players, from across the United States, entered the singles and doubles divisions. On a steamy July afternoon, Howard Surface from Kansas City, Missouri defeated Edward Alloo of San Francisco, California. 18-year-old Jack Kramer, who in 1948 would become #1 in the world, and his 19-year-old partner Sidney Welby Van Horn of Los Angles, California took the doubles title. The following year in 1940 was the first time the tournament included women. Having the best women in the United States side by side with the best men, captivated an immense following. The world’s number one players Bobby Riggs and Alice Marble came to Baltimore.

From 1906 through 1934, thousands of spectators were lured to Baltimore Country Club’s grass courts to watch the United States Davis Cup Team qualifying matches. One of the most renowned Davis Cup team members was Wimbledon Doubles Champion and BCC member Charles Stedman Garland.

In 2007, with only 15% of play on grass, tennis relocated to Five Farms ending a remarkable and wonderful century when lawn tennis was the game to watch at Baltimore Country Club. ◆

FROM BCC ARCHIVES

Spectators watch the Maryland State Open Tennis Championship on the grass courts at Roland Park.

Postscript: The tournament was renamed the Maryland State and Middle Atlantic States Championship.

FROM BCC ARCHIVES

THE TRANSFORMATION OF Five Farms

IN 1989, THE BOARD of Governors and Capital Planning Committee began to formulate changes that would begin the makeover of Five Farms. The first undertaking was to redesign the West Course. Golf course architect Robert E. Cupp collaborated with Hall of Famer Tom Kite to turn the West Course into a low impact challenge that would be fun to play and alleviate pressure on the East. This project led to a long term Master Plan that addressed ever increasing needs.

Over half of the membership lived north of the city. The swimming pool and golf facilities were inadequate. The clubhouse, built in 1963 to replace the Olivier Mansion, was dull and outdated. With the guidance of architect Jack Reinhart, the Five Farms campus was gradually transformed into a farmland setting.

The new swimming pool complex, with its pitched roof pavilion, covered terrace, three pools, and broad lawn opened in the spring of 1996. That same year, the golf maintenance facilities and barns were restored. In May 1997, the ribbon was cut for the Golf House with expanded cart and bag storage, enhanced pro shop, and offices. And in 1998, the clubhouse, was transformed into a country manor. For planning reasons, construction of the tennis house, locker rooms, fitness facility, and 10 state-of-art courts was delayed until 2006.

Sam Robinson’s painting commemorates Saturday, September 8, 2007, when hundreds gathered to celebrate the opening of tennis at Five Farms. ◆

FROM BCC ARCHIVES

View Corridor

ALL THESE YEARS SINCE the Club’s founding in 1898, the western setting from the Roland Park Clubhouse still offers a glorious, if not nostalgic, panoramic vista. It’s a mirage, of course. The golf course is long gone. The first fairway, once a sea of trimmed rye grass, has surrendered to the encroaching purples and yellows of unchecked wildflowers. Abandoned bunkers, where fox and gnawers dig to escape the winter chill, mark the skeleton of the ancient green where Willie Smith began his unanticipated charge to win the fifth U.S. Open on September 14,1899.

Sam Robinson’s beautiful landscape, based on an early photograph, hints at the awesome challenge facing Willie Smith and all turn of the century golfers who paused for a moment and look westward, before driving their ball toward the distant horizon. Smith, a Scotsman who immigrated to the United States to be the professional at Midlothian Country Club near Chicago, won that early U.S. Open championship by 11 strokes. It was a margin of victory that was not surpassed until Tiger Woods won by 15 strokes in 2000. Smith returned to Midlothian with a gold medal, about the size of a quarter, and $150 in cash.

Following the 1899 U.S. Open, golfers from all parts of the country came to Baltimore for a chance to play the Roland Park course. Over the next decade, Club membership ballooned. Baltimore Country Club became recognized as one of America’s great private clubs. It is a lasting reputation that began on this little first tee all those years ago. ◆

A photo of Willie Smith, winner of the fifth U.S. Open hosted at Baltimore Country Club on September 14, 1899.

Roland Park Course

USING SIX VINTAGE TURN of the century photographs, Sam Robinson captures the rustic beauty of Roland Park. The grasses on fairways and greens were less refined. Roughs could be entangled with ditches, risky embankments, high fescue, and prickly scrubs. While 19th century courses were generally nine holes or less, the Roland Park course began as 18 dissimilar holes laid out within the confines of a two mile stretch of the Jones Falls River Valley. Totaling 4,876 yards, given the golf clubs and balls of the time, it was a tough test of golf. The best single round score in the 1899 U.S. Open was 77. Dunn’s course echoed the rugged unforgiving windswept links of Scotland when compared to Tillinghast’s Five Farms East Course.

When Edward Bouton and Charles Grasty hired William Dunn, Jr. to design the Roland Park course in 1897, Dunn was already a wellknown professional champion of Scottish heritage, golf ball and club maker, and course designer. He first came to America in 1893 under the patronage of William K. Vanderbilt who met and took golf lessons from Dunn while vacationing in Biarritz, France. Dunn spent his first year in America

giving lessons to the grandees at Newport Country Club. The following year, he became the professional at Ardsley Country Club in Ardsley, New York, where he designed the course and started his club making business.

Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., the landscape architect hired to layout Phase II of Roland Park, the land west of Roland Avenue, had already specified the 150 acres reserved for the course. It would be the first 18-hole golf course south of Philadelphia. Within its perimeter, Dunn was given a free hand with two exceptions—the location of the first tee box and 18th green. When the course was completed in the spring of 1898, the United States Golf Association rated Dunn’s bold layout exceptional and soon after awarded Baltimore Country Club the fifth U.S. Open Championship. Dunn, who played in the 1899 U.S. Open, came in 33rd. Baltimore Country Club became internationally known as a place to play championship golf. Within 20 years, it was the largest private club in America.

Willie Dunn died at the age of 88 in August 1952. He is buried in the family plot in Putney, London, England. ◆

FROM BCC ARCHIVES

The First Tee

THE POSITION OF THE American cottage style clubhouse, designed by the architectural firm of Wyatt and Nolting in 1897, was based on the location of the first tee. At the same time terrain was being excavated for the building’s foundation, masons were at work using stones from Rusty Rocks, the old quarry immediately south, constructing the rounded wall of the diminutive hallmark of Baltimore Country Club golf.

The photograph Sam Robinson used to commemorate the first tee of the first 18 hole golf course in Maryland, is thought to be the earliest image in the Club’s archives. The picture was taken before the erection of the multi-story rounded observation porch that was completed in 1904. It could be any of those years that predate the observation porch-later called the Ladies’ Gallery.

One and one-quarter centuries later, the first tee remains pretty much as it was in the fall of 1899. Lewis I. Turner used his hickory driver to launch a guttapercha golf ball 240 yards into the center of the fairway-130 feet below. At the conclusion of 36 holes, Lewis Turner defeated T. Courtney Jenkins to become Baltimore Country Club’s first champion.

Even after the Roland Park course closed in 1961, the first tee has been maintained. Through 64 years of play, site of the fifth U.S. Open, generations of members and guests, the famous, the nostalgic, and the curious, have driven a ball from this notable spot of American golf history. ◆

At the base of the Ladies’ Gallery, built in 1904, golfers and caddies look on as a golfer tees off at the first tee.

The Match

IN THE 1920S, THE most recognized and sought after players were the great amateurs. These celebrated golfers, through events like The Amateur Championship, The Open, and The Walker Cup, became stars of the game. If they weren’t playing in a major, they would compete in local championships like Baltimore Country Club’s Maryland Cup or to raise money for some benevolent cause.

At the request of General Douglas MacArthur, President of the U.S. Olympic Committee, who was a BCC member, and Club President Dr. Joseph Sweetman Ames, four of the greatest came to Baltimore to raise money for the 1928 United States Olympic Team. Four thousand golf enthusiasts, from as far away as New York City and Atlanta, Georgia, showed up. The Match was played on the Club’s Roland Park course on Sunday, April 29, 1928.

Forty-year-old B. Warren Corkran, Baltimore Country Club’s most distinguished golfer, would be the oldest participant. His partner, twentyone year-old Roland MacKenzie, a Walker Cup Team member from Washington, D.C., would be the youngest. In 1928, 26-year-old Robert Tyre “Bobby” Jones, Jr. was the greatest golfer in the world—amateur or professional. When Jones received a call from General MacArthur and Dr. Ames requesting he come to Baltimore,

Jones accepted straightaway. He would bring his college pal, Watts Gunn. Had it not been for Bobby Jones, the charismatic Gunn, also a member of the 1928 Walker Cup Team, would have gone down as Georgia’s greatest golfer.

The visitors from Atlanta lost two of the first three holes. Bobby Jones countered with back-toback birdies. When the players reached the ninth tee, Jones and Gunn were two up. The two teams played even until MacKenzie eagled the long 515 yard 15th, cutting Jones and Gunn’s lead to one. They halved 16 and 17. As the players walked to the 18th tee, the gallery raced ahead to gain positions on both sides of the steep 18th fairway. All four players reached the green in regulation. The immense swarm of fans, encircled the green and the high ground beyond.

Jones’, Gunn’s and Cockran’s tries for birdie fell short. It had been a long, damp, and gusty fivehour day and here on the 18th was the last chance to make a difference. MacKenzie would take his time. A miss would send his ball a good way beyond. But Roland didn’t miss. The thousands that hiked the length of the course, start to finish, let loose with thunderous applause, not just for Roland’s great effort or that the Match was played to a draw, but for the championship golf they had witnessed and the four men who delivered it.

Postscript: Details of this match were reported in The Baltimore Sun on April 30, 1928.

Sam Robinson’s painting captures Bobby Jones leading Roland MacKenzie, Watts Gunn, B. Warren Cockran, their volunteer caddies who were Club members, and police escorts, surrounded by a multitude of fans, heading south toward the second green where the Poly-Western complex is today. Falls Road is immediately east, on the other side of the hill, crowned with spectators, scrambling to catch up. ◆

FROM BCC ARCHIVES

Bobby Jones, Watts Gunn, B. Warren Cockran, and Roland MacKenzie at BCC’s Roland Park course on April 29, 1928.

The Pond Hole

IN THE MAY 1974 edition of The Golf Journal, Frank Hannigan, USGA Executive Director, penned an article titled “A.W. Tillinghast -Golf’s Forgotten Genius.” He wrote, “Tillinghast was a superb, not a good or very good, but a superb golf course architect.” By then (1974) Hannigan continued, “35 national championships or international matches of the USGA or PGA of America will have been played on 19 different Tillinghast courses.” Among them is our Five Farms East Course. Hannigan went on to write, “Tillinghast’s greatest assets were his rich intelligence, imagination and sense of aesthetics. He could and did build beautiful golf holes. It is no accident that the prestigious USGA Green Section Award ‘for distinguished service to golf through work with turf grass’ is surfaced by a cast bronze impression of a Tillinghast hole—the lovely willowed 10th of the East Course of Baltimore Country Club at Five Farms.”

“A natural pond, lake, or running stream,” Tillinghast once said, “is a gift of the Gods.” He found it on #10 East. Writing about the Pond, Tillinghast biographer Philip Young wrote, “#10 is brilliantly designed, with demands especially on the skills of the more accomplished players; and yet the use of water creates a hole whose beauty and charm will thrill beginner and great players alike.”

Sam Robinson’s scenic interpretation of Baltimore Country Club’s most photographed and famous golf hole accents the timeless beauty that Tillinghast imagined nearly a century ago. ◆

FROM BCC ARCHIVES

Postscript: In 2015, A.W. Tillinghast, Dean of American Born Golf Course Architects, was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame.

Golfers at #10 East in 1928.

1932 U.S. Amateur

IF BOBBY JONES WAS the most beloved golfer in America, Francis Ouimet, the reigning U.S. Amateur Champion, was the most revered. Nineteen years earlier, at The Country Club in Brookline, Massachusetts, the shy 20-year-old son of working-class immigrants, stunned the golfing world by winning the 18th U.S. Open in a three-way playoff against two of golf’s professional titans, Britain’s Ted Ray and Harry Vardon. Ouimet’s improbable upset aroused a national interest that inaugurated the Golden Age of Golf in America. When he showed up at Five Farms on September 9, 1932, to defend his U.S. Amateur title, he was captain of the United States Walker Cup Team that had just defeated the Great Britain and Ireland Team, also at Brookline.

Nearly 600 golfers applied to enter the 36th U.S. Amateur Championship. The 167 who qualified traveled to Baltimore, Maryland to compete on Baltimore Country Club’s challenging 6,595 yard, par 70, Five Farms East Course–September 12-17, 1932.

Ouimet’s chance of winning two U.S. Amateurs in a row ended in the semifinals when he was defeated by Johnny Goodman. Canada’s Ross Somerville defeated Goodman, on the 35th hole, to become the 1932 U.S. Amateur Champion.

Francis Ouimet passed away on September 2, 1967. He was the first nonBriton elected captain of the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St. Andrews and was the first winner of the Bob Jones Award, the highest honor bestowed by the USGA, in recognition of distinguished sportsmanship in golf. Ouimet has a room named after him in the USGA Museum where he is venerated as the Father of Amateur Golf in America. ◆

FROM BCC ARCHIVES

The Turn

IT MAY NOT SEEM important to the average golfer but A.W. Tillinghast considered the TURN, between the front and back sides, a transition of careful thought. There are few better examples than Five Farms. Tillinghast laid out the front nine finish to be a thought-provoking uphill par 3 where the entire bunkering scheme brings reward to judgment of distance, wind, and accuracy of stroke… No matter the level of play, the ninth can engender joy or anguish. Then, regardless of outcome, there is the chance to begin anew. Just eastward—down the slope, sits the teeing ground to #10—long ago named the Pond. Nestled within a pristine stream fed orchard valley, Tillinghast designed the 10th to be a pleasant break in the course where the beauty of the surroundings pleases the eye—masking the perils beyond. Sam Robinson borrowed images from photographs to paint impressions of golfing championships hosted at Five Farms. ◆

FROM BCC ARCHIVES

IN TILLINGHAST’S OWN WORDS…

#9 – 197 Yard - Par 3

The last hole on the way out has a spectacular uphill carry. The hole is unique, deceptive, and one of the most beautiful on the course. The green is fair sized, undulating, and well-guarded by sand traps right, left, and front. Because of slope and contour, able putting is a requisite for par.

IN TILLINGHAST’S OWN WORDS…

#10 – 378 Yard – Par 4

From the tee, which is surrounded by orchards on three sides, a stream paralleling the fairway on the left, and an apple orchard along the right, one must make a drive straight and long in order to get an easy shot to the green, which is surrounded by possibilities for grief on all sides—water, high bunkers, rough, and woodland.

FROM BCC ARCHIVES

The Barn Hole

CHARLES E. “CHICK” EVANS, JR. was no stranger to Baltimore Country Club. He often played at Five Farms with close friends who were BCC members. Sam Robinson’s painting depicts Evans driving toward the barn from the sixth tee on September 15, 1932, during the third match-play round of the 36th U.S. Amateur Championship. A.W. Tillinghast planned for the corner barn to be a risk-reward element of this testing 590 yard par five. He wrote: “Distance and accuracy are the challenges of the second longest hole on the course.” Evans, always confident he could clear the barn, was paired against former Amateur Champion Jesse Gilford.

In 1916, Chick Evans was the first amateur to win the U.S. Open and U.S. Amateur in the same year. He won the U.S. Amateur again in 1920, competed in a record 50 consecutive Amateurs and was runner up three times. Always playing with the same seven hickory-shafted clubs, Evans was selected to be on the United States 1922, 1924, and 1928 Walker Cup teams.

In 1960, the USGA presented Chick Evans with its highest honor, the Bob Jones Sportsmanship in Golf Award. In 1975, Evans was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame. Despite his prodigious fame for earning 54 victories, he viewed his greatest accomplishment as the success of what began as his mother’s remedy for putting his golf earnings to a worthwhile purpose, the little charity that grew into the Evans Scholarship Foundation.

Chick Evans once said during an interview shortly before his death in 1979, “Getting to meet the young people who have been able to benefit by becoming Evans Scholars has been my greatest thrill in golf.”

Postscript: Baltimore Country Club is a member of the Western Golf Association and a patron of the Evans Scholars Foundation.

Tiny Gem

TILLINGHAST WROTE, “THIS IS the shortest hole on the course, but by no means the most easily played. Because of its deceptiveness, it is believed that there are fewer pars laid here than anywhere else on the course. A keen pitch shot possessing direction, full carry, and plenty of back spin is required to hold the green.”

Approaching a century of tournament play, Tillinghast’s prophecy for #13 has proved true. Even for the majors-1928 PGA Championship, 1932 U.S. Amateur, 1965 Walker Cup, 1988 U.S. Women’s Open, and three Senior Players Championships 2007-2009, little #13—strategically placed between the only right elbow hole and the longest hole on the East, has played havoc on the score card. “It seems to me”, Tillinghast once said, “that he who plans a hole for golf, should have two aims: first to produce something that will provide a true test of the game, and then consider every conceivable way to make it as beautiful as possible.”

Sam Robinson’s impressionistic interpretation of this challenging golfing gem cannot convey the dangers lurking about the green but it shares the beauty that Tillinghast imagined within this tiny wooded hollow. ◆

FROM BCC ARCHIVES

The Course Beautiful

PHILIP YOUNG, A.W. TILLINGHAST’S biographer, wrote: “If one had to put into as few words as possible the design philosophy of Albert Warren Tillinghast, his own phrase, “The Course Beautiful,” best describes what he was consistently trying to create. A golf course for him was more than a place to play; it was the defining character of his person, the essence of all he held dear and admired.”

Tillinghast believed that most golfers are “keenly appreciative” of the striking beauty of a picturesque hole. But “there are others,” he said, “that do not care a rap about their surroundings, so absorbed are they in hard play.” The magic of Tillinghast was the ability to imagine and create beautiful golf holes, that in his own words, “add much to the pleasure of golf without detracting in the least from its qualities as a test.” It was this inspired talent that earned him the tribute: Dean of American Born Golf Course Architects.

Although he laid out 98 original courses and renovated over one hundred more, the mark of his most celebrated masterworks, in the end, according to A.W. himself, came down to the superiority of the land. On a snowy day in February 1924, he found exactly what he was looking for at Five Farms. In a letter to the Club President Joseph Ames, Tillinghast wrote: “Please take strongly into account the fact that I am not given to over-optimism in rendering an opinion. It is seldom that I am able to give immediately such a very favorable report, but I have found nothing unfavorable. I observed many natural greens and a number of strikingly obvious holes. The property is worthy of the upmost you will bestow upon it.”

Masked within his remarks but crystal clear in his imagination was the chance to create something uniquely singular on this unspoiled high slope of the Piedmont Plateau that had been the 390acre farmland estate of Stuart Olivier. On Sunday afternoon, May 25, 1924, at a joint meeting of the New Property Committee and Board of Governors, it was decided that Albert Warren Tillinghast would be engaged to design contiguous golf courses on the Five Farms property. The East Course opened for play in the Spring of 1926. It was soon after acknowledged as a Tillinghast masterpiece—a golfing gem. A.W. considered the East at Five Farms one of his best.

Sam Robinson’s enchanting southwest panorama, for what is often a golfer’s left approach to the eighth green, captures the timeless majesty of Five Farms. It is a parkland prospect little changed since the Grand National Steeplechase crossed over Olivier’s open fields. Robinson could have chosen any one of the many vistas that Tillinghast understood, a century ago, as the perfect place to conjoin the playing challenges and visual splendor he called—The Course Beautiful. ◆

Sam

SAM ROBINSON WAS BORN in New York City, September 29, 1953. He moved to South Korea in 1960 where his parents served as missionaries. Gifted with artistic talent, his first instructions were in Korean Ink Brush painting, imparting a preference for strong brushwork-so prevalent in the wonderful paintings displayed in this special publication of The Paintings of Baltimore Country Club and framed within the newly renovated Five Farms Clubhouse. Sam and his wife Barbara, a landscape and garden designer, live in the Green Spring Valley.

Sam attended the Maryland Institute College of Art, graduating Magna Cum Laude in 1978 with a BFA, majoring in painting. After graduation, he founded The Valley Craftsmen, Ltd., a decorative painting company well known throughout Maryland. In 2007, Sam returned to Fine Arts. Often leaving Valley Craftsman and the four walls of his studio behind, Sam set out to paint the landscape, in the open

air plein air style, favored by early French Impressionists who found that working outdoors, in natural color and light, rewarded their canvases with illuminating distinctions. The scenic images Sam was commissioned to paint for Baltimore Country Club reflect the ephemeral qualities of en plein air Robinson is nationally famous for his spectacular paintings of Maryland and Virginia steeplechase panoramas and portraits. His paintings have been featured in magazines including Atlantic Thoroughbred, Equestrian Living, Equestrian Style, and Piedmont Virginian. Through his picturesque interpretations, at Roland Park and Five Farms, Sam has preserved a slice of Baltimore Country Club’s enduring heritage.

INDEX OF PAINTINGS

The Oil Paintings

Bobby Jones and Gallery at Roland Park

FIG. 23

Chick Evans at #6 East The Barn Hole FIG. 28

The Course Beautiful FIG. 30

The Elms and the Adirondacks FIG. 11

The First Clubhouse FIG. 1

The First Tee at Roland Park FIG. 22

Francis Ouimet at #1 East 1932 U.S. Amateur FIG. 25

Lawn Tennis at Roland Park FIG. 12

The Maryland State Open Tennis Championship FIG. 13

The 1932 Clubhouse FIG. 3

The Olivier Mansion at Five Farms FIG. 10

The Pond Hole #10 East FIG. 24

The Roland Park View Corridor FIG. 15

The Tennis and Fitness House at Five Farms FIG. 14

The Winter Serenity of Roland Park FIG. 2

The Gouache Paintings

The Bar FIG. 8

Crossing the Jones Falls River East from #7 FIG. 19

The 1898 Grille FIG. 7

The First Tee FIG. 16

The Fireplace FIG. 9

The Georgian Room FIG. 5

Golfer Putting #9 East Course FIG. 26

Golfer Putting #10 East The Pond Hole FIG. 27

Golfers on #18 Roland Park FIG. 20

The Library FIG. 6

North Lawn at Roland Park in 1898 FIG. 21

Teeing Off #11 Roland Park FIG. 18

A Tiny Gem #13 East FIG. 29

A Vaulted Gallery FIG. 4

View Across Jones Falls River Valley FIG. 17

Paintings