P FOR PROSTATE

Prostate Health Made Easy

Prostate cancer affects 1 in 4 black men and 1 in 8 white men

Our website:

MEN’S HEALTH FORUM

The Men’s Health Forum’s Man Manuals contain easy-to-read information on a wide range of men’s health subjects. Founded in 1994, the MHF is the independent voice for the health and wellbeing of men and boys in Great Britain. Our goal is the best possible physical and mental health and wellbeing for all men and boys.

P For Prostate © Men’s Health Forum

Written and edited by Jim Pollard (jimpollard.co.uk) with cartoons by John Byrne.

Thanks to the advisory team:

> Dr John Chisholm (Men’s Health Forum chair)

> Dr Su Wang (Men’s Health Forum trustee)

> Sara Richards (Men’s Health Forum trustee)

> Dr Annette Fenner (Chief Editor, Nature Reviews Urology and Men’s Health Forum trustee)

> Prof. Alan White (Men’s Health Forum patron)

Our shop:

Men’s Health Forum, 7-14 Great Dover St, London SE1 4YR 0330 097 0654

Registered charity number 1087375

Company limited by guarantee number 4142349 – England

> Prof. Roger Kirby (President, Royal Society of Medicine)

> Jonathan Kay (Prostate Cancer UK)

> Paul Campbell (Cancer Black Care)

and all those who helped with the booklet. Names of some case studies have been changed.

First published: June 2024 • Next revision: June 2027

You’ll find all our Man Manuals and books at: shop.menshealthforum.org.uk

A full list of references is available at: menshealthforum.org.uk/ MMreferences

The MHF encourages your feedback at: menshealthforum.org.uk/ MMfeedback

All rights reserved. You must not reproduce or transmit any part of this booklet in any form or in any way without written permission from the Men’s Health Forum. This includes photocopying or scanning it.

Printed in the UK. ISBN: 978-1-906121-47-1

www.menshealthforum.org.uk

2

P FOR PROSTATE CONTENTS

Plus men talking prostates: John F, Paul, Winston, Nick & John W

In 2024, when King Charles III announced that he had a prostate problem, millions of people went online to look it up.

No wonder. According to a survey by our friends at Prostate Cancer UK, almost half (44%) of men in the UK do not know where their prostate is and threequarters (74%) aren’t sure what it does.

Whatever your age, you need to know.

P FOR PROSTATE will explain everything you need to be aware of in one easy-to-read booklet:

> How it works

> What can go wrong

> Signs and symptoms

> Tests and examinations

> All aspects of prostate health.

What The Hell Is A Prostate? 4 Know The Signs 8 A Growing Problem? 12 Prostate Cancer 16 Testing, Testing 24 Be Good To Your Prostate 27 Living With Prostate Issues 32 Men’s Health Info 35

Prostate cancer affects 1 in 4 black men and 1 in 8 white men

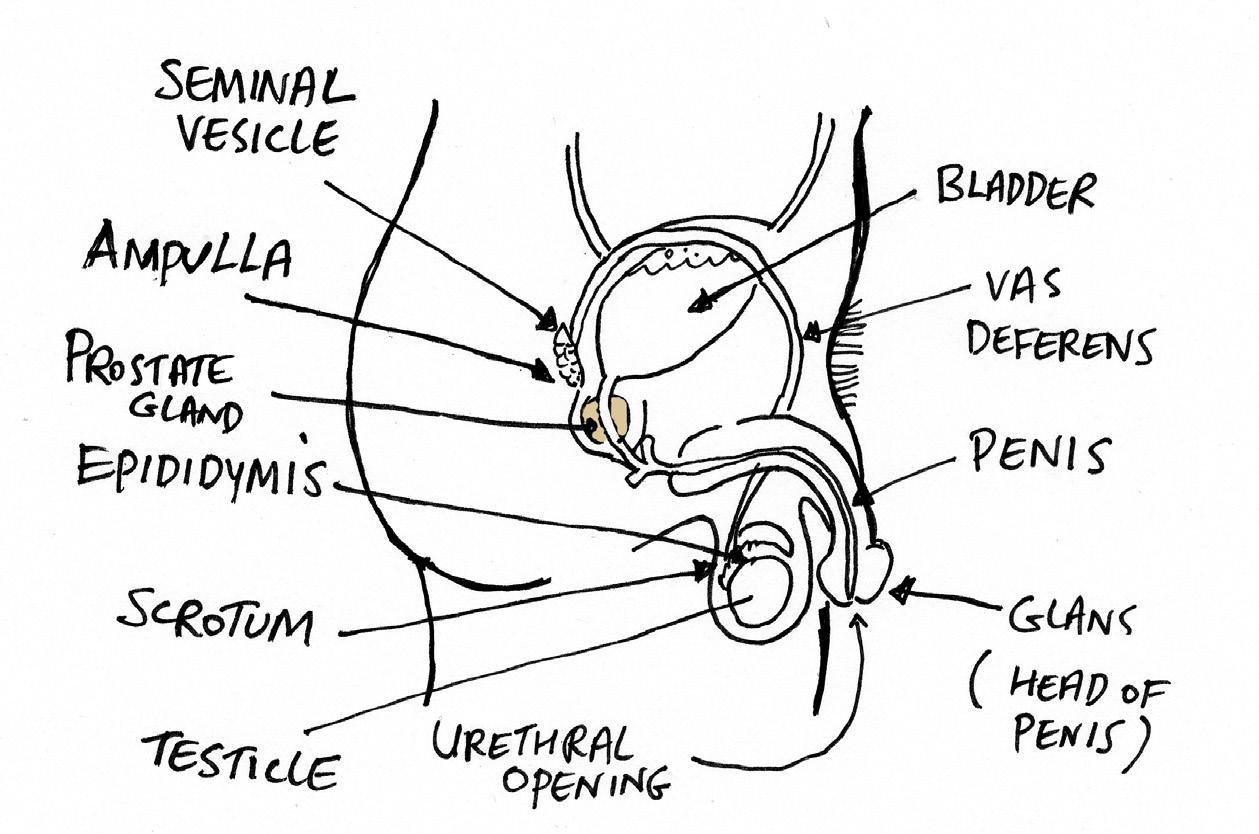

WHAT THE HELL IS A PROSTATE?

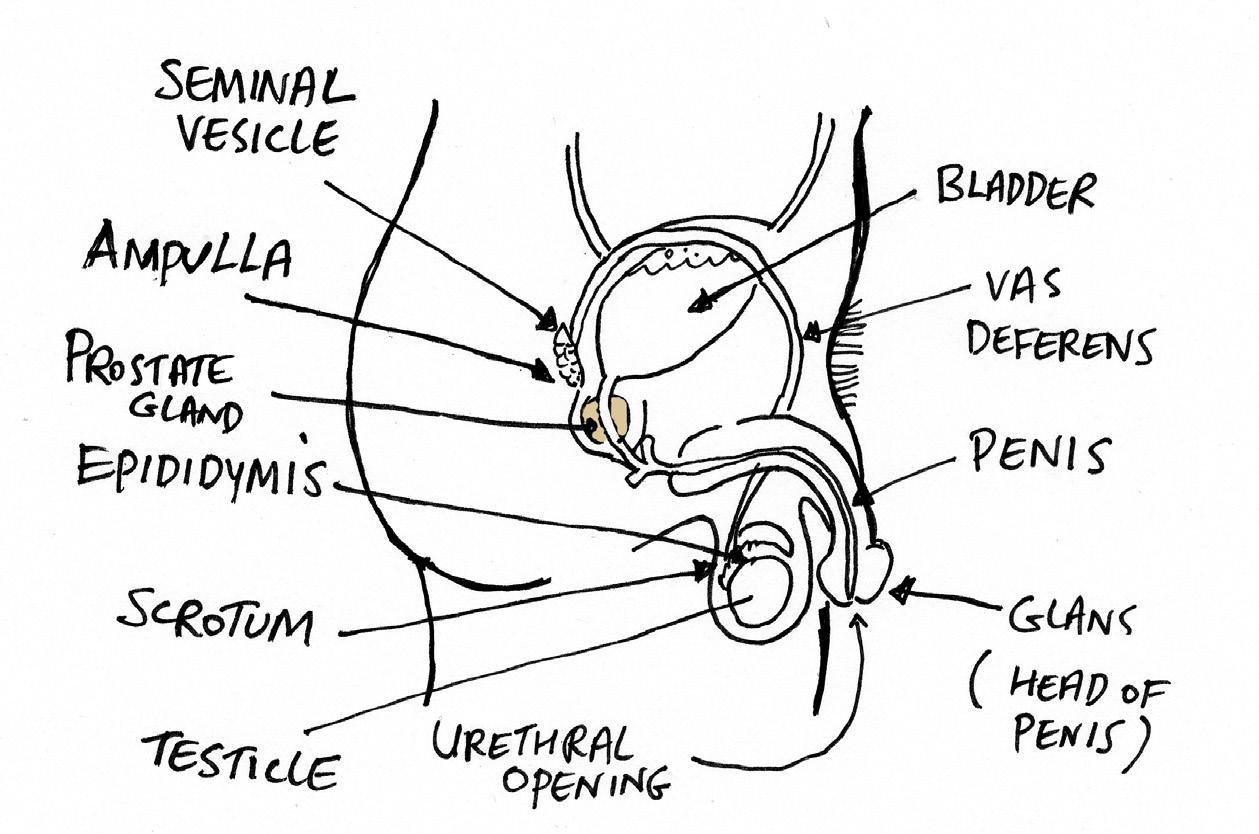

All men (plus trans women and some non-binary people) have a prostate.

It’s a small, rubbery gland about the size and shape of a walnut that sits below your bladder and above the base of the penis, between your pubic bone and your rectum. It encircles the urethra (the tube through which urine passes from the bladder).

The prostate isn’t essential for a man to stay alive but it is necessary if he wants to have children. During orgasm, contraction of the prostate facilitates ejaculation. The prostate also provides part of the fluid that makes up semen. In order to fertilise the female egg, male sperm needs protection from bacteria and other pathogens it might encounter on the way. Enzymes and other substances from the prostate provide this protection. Without zinc, citrate, energy-giving fructose and other protective substances from the prostate, the sperm might not survive the journey.

4

In short, the prostate is a sex organ. But, in this case, small is beautiful.

WHY IS SMALL BEAUTIFUL?

In newborn boys the prostate is about the size of a pea. It grows very slowly until puberty when it increases in size dramatically to about the size of a walnut. When a man reaches his 40s it begins to increase in size again and can become as large as an apple. This growth can cause various health problems.

WHY DOES IT GROW?

Various hormones are involved in the prostate. The most important is the male sex hormone, testosterone.

In the prostate gland, testosterone is broken down into the related hormone dihydrotestosterone, which appears to be involved in both baldness and the enlarged prostate. This doesn’t mean that high or low levels of testosterone cause prostate enlargement or prostate cancer (or baldness, for that matter). It’s more about the way your body reacts to a normal amount. Most men’s prostates grow to some degree with age. This doesn’t necessarily cause any problems but more than a third of men over 50 will be aware of some symptoms of prostate enlargement.

WHAT PROBLEMS CAN THIS CAUSE?

The easiest way to think about this is to imagine standing on a hosepipe. This restricts the flow of water. An expanding prostate will press against the urethra in a similar way, making peeing more difficult or more frequent, for example. Usually – and this is a key point – the growth is not caused by cancer, but in some cases it can be cancerous.

It’s important therefore for men to be prostate-aware, particularly once we get over 50 or – in the case of Black men – once we get over 45.

5

IS PROSTATE CANCER INCREASING?

Globally, the number of new cases is expected to double between 2020 and 2040.

In the UK, prostate cancer is the most common type of cancer in men. Over 50,000 new cases are diagnosed every year. Cancer Research UK reckons that rates will go up by 15% in the UK between 2023-25 and 2038-40.

Throughout this century, the total number of prostate cancer deaths recorded in the UK has been rising. The risk of cancer goes up with age so this increase is partly because men are living longer. Men are also coming forward earlier and having cancers caught sooner as awareness grows, increasing the number of deaths recorded as caused by prostate cancer. However, the number of cases among younger men is also increasing so other factors might well be involved. There’s also a strong family link. Your risk of prostate cancer may be linked to cancers in both male and female relatives. (See ‘Am I at risk?’ on page 16 for more detail.)

Prostate cancer often has no symptoms, so it makes sense to talk about your risk with your GP. See the section on prostate cancer on page 16.

ARE BLACK MEN AT MORE RISK?

Compared with White men, incidence rates for prostate cancer are generally higher in Black men. That’s why Black men need to be prostate-aware at an even younger age. (See Paul’s story on page 10.) They are generally lower in Asian men than White men although rates do vary considerably across Asia.

John F, age at diagnosis: 60

DON’T PUT IT OFF UNTIL YOU CAN’T PEE AT ALL!

“

I play golf and usually need a pee during a round. But I was finding it wasn’t so easy. I was dashing into the woods two or three times. It took ages to start and I was having to stop to catch the lads up.

After say four years, I saw my GP. I was told I had a very enlarged prostate but no sign of cancer. So I left it another year. One day, I had a long meeting and left it too long. When I finally went to pee, I was desperate but couldn’t go at all. It was awful. The internet told me it was acute retention and to get to the doctor immediately. Fifteen minutes later, the doctor was fitting a catheter in my penis. I’d been healthy all my life and suddenly a woman was sticking a plastic tube up my willy so as to empty my bladder. It was traumatic. It’s not even embarrassing because you’re in so much pain, you just want something done. The relief as you finally feel the bladder begin to empty is enormous despite the catheter pain.

The catheter came out after two weeks but I had acute retention again. This time they couldn’t get the catheter in. It was so painful. I had to go to the hospital 45 minutes away. I knew this wasn’t going to solve itself with drugs. I’d been put on the usual treatment, alpha-blockers, but had side-effects like headaches and dizziness.

I knew I needed a surgical solution. I looked at several. I didn’t like the idea of lasers and possible ejaculation and erection problems. In the end I chose the prostate arterial embolisation (PAE). This blocks some of the blood supply to the prostate preventing growth.

For the first four years after the PAE, things were great - it rolled back the clock 20 years and is a better solution than the more invasive options in my opinion. A year ago, I noticed a slight deterioration in the ability to pee easily, as the consultant radiologist said might happen. I’m considering having the PAE again, as he suggested I could do, but it’s manageable so I’m waiting to see for now. I’m not too worried.

I’d say to anyone with peeing problems, see your GP. It may well finish in acute retention unless you do something. I was in denial. I hoped the problem would go away or not get worse. The PAE hardly inconvenienced me at all but the acute retention was the worst.

7

KNOW THE SIGNS

IS MY PROSTATE GROWING?

Signs of an enlarged prostate include:

> Weakness – a weak, slower flow when you pee

> Intermittency – a flow that stops and starts

> Hesitancy – having to wait before you start to go

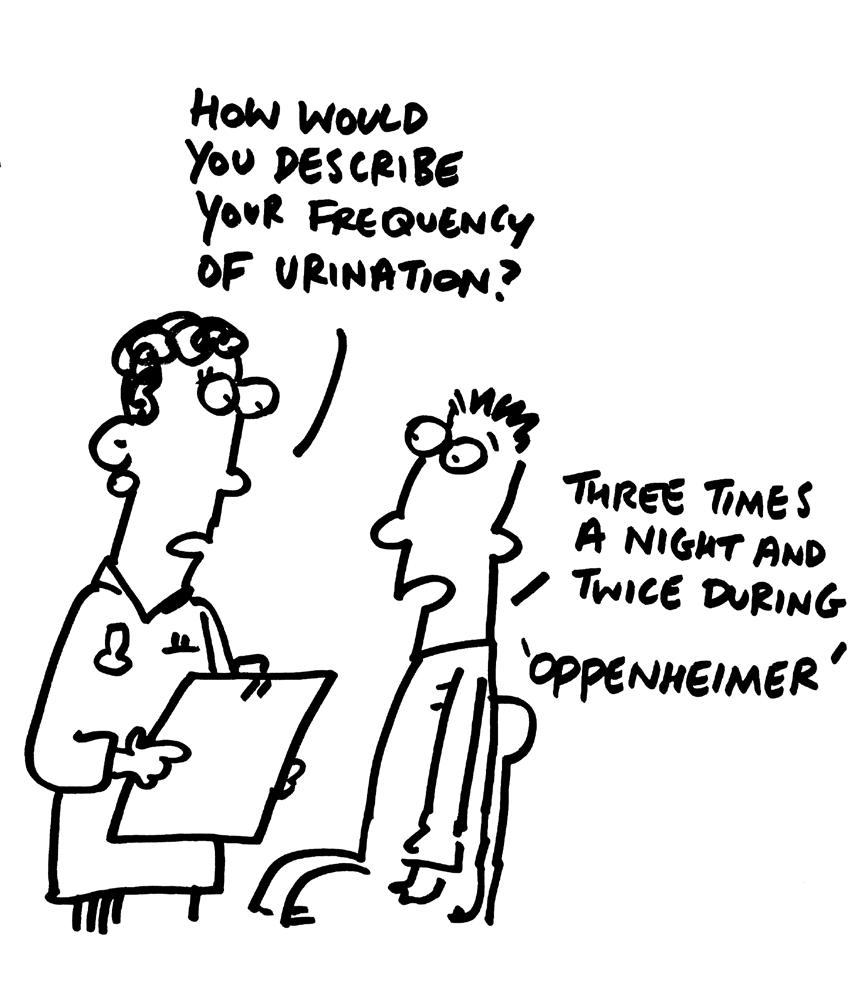

> Frequency – having to urinate more often than previously

> Urgency – finding it difficult to postpone urination

> Nocturia – having to get up at night to urinate.

IS IT ALWAYS THE PROSTATE CAUSING THIS?

These symptoms are usually – but not always – related to the urinary system. They might be caused by a tight or enlarged bladder neck or an overactive bladder or perhaps a narrowing in the urethra known as a stricture. But it’s also quite likely to be a prostate issue.

There are generally three conditions that affect the prostate:

> benign (non-cancerous) prostate enlargement (BPE) - sometimes referred to as benign prostatic hyperplasia or hypertrophy (BPH)

> inflammation of the prostate gland (prostatitis)

> prostate cancer.

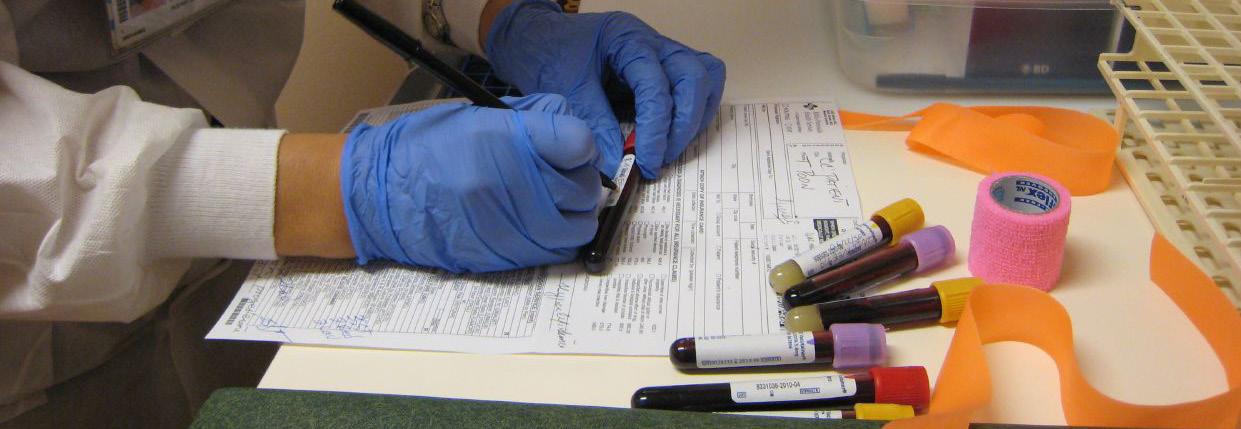

You’ll need urine and blood tests and perhaps some other tests to check which one is affecting you. There’s more on the tests in the section beginning on page 24.

8

TALKING TO A HEALTH PROFESSIONAL

If you have any concerns, ask yourself these questions. (These are the sorts of questions a GP will ask if you go to discuss your prostate symptoms.)

> how often do you have a sensation of not emptying your bladder completely after you finish urinating?

> how often do you have to urinate again less than two hours after you finished urinating?

> how often do you stop and start again several times when you urinate?

> how often do you find it difficult to postpone or delay urination?

> how often do you have a weak stream of urine?

> how often do you have to push or strain to begin urination?

> how many times a night do you typically get up to urinate (from the time you go to bed until the time you get up in the morning)?

If you’re answering ‘often’ to one or more of these questions or getting up frequently at night, you have what are sometimes called LUTS (lower urinary tract symptoms). There are several possible causes of LUTS. A problem with your prostate is one of the most likely so you may want to talk to your GP.

LUTS can affect all aspects of your life - sleep, work, travel, leisure, sex. It can feel like peeing – thinking about it, planning for it, feeling the need to do it and the act of doing it – has taken over your life.

Regardless of your precise answers to the questions above, it’s also worth asking yourself how you feel about your urinary symptoms. If you were to spend the rest of your life with your urinary condition the way it is now, how would you feel about that? If the answer is dissatisfied or unhappy, again, it is worth talking to your GP.

There’s a full checklist on page 34.

9

Paul, age at diagnosis: 49

HAD I NOT BEEN ASSERTIVE AT THE START, IT’S

POSSIBLE I WOULD NOT BE

HERE

I was aged 42 when I saw an advert for men over 40 to have an NHS health check. I went to my GP but was turned down because I was not unwell. They didn’t want to do the check. Having seen the ad on the TV, I insisted. They wanted to dissuade me. I dug in my heels. The TV had talked about the risks once men reach 40. They found out I was diabetic. Both my father and my brother had it. Because of the diabetes, I then continued to have regular blood tests and they noticed an elevated PSA.

I wasn’t having any other prostate symptoms but my PSA continued to go up. I was referred to hospital for further checks.

Eventually, I had a biopsy even though the only symptom was the very high PSA. This was stressful. I had opted for a general anaesthetic but on arrival at the hospital, I was told only local anaesthetic was available which wasn’t what we’d agreed pre-op.

After the biopsy, the consultant who told me the result looked very worried. We’d been friendly but he delivered the news terribly.

‘Oh my God,’ he said, and got up and hugged me. He was more disturbed than I was. I already thought I had prostate cancer. He said it was aggressive. He offered me a number of treatment options and asked me to choose. I was shocked at the request as I was the least qualified person in the room to make that decision.

The MRI was nerve-racking – waiting to see if the cancer had spread. The surgeon told me that if it was him he’d have a prostatectomy (removal of the prostate) so I did. On the day of the surgery, I remember the anaesthetist telling me to raise my legs and next thing I’m waking up in the recovery room. It was tough being in a room full of people who had had cancer operations. Some were getting bad news.

I didn’t have pain but I was uncomfortable. I hated the catheter. I had to inject myself to prevent blood clots. Two months in bed. The incontinence wasn’t too bad - not as bad as I’d been led to believe it might be. I wore nappies maybe about six times.

10

“

“When my son picked me up I was on crutches with a catheter. For a while, it was hard for my sons seeing me vulnerable. They withdrew. They said ‘we don’t know what to say’. I say you don’t have to know what to say. Just being there watching TV together is fine.

After surgery, my PSA wouldn’t come down. More blood tests. I was told there were cells in the prostate bed so I had radiotherapy and hormone therapy. It was peak lockdown. Life wasn’t good anyway. The happy jolliness of the nurses was sometimes difficult to deal with. It was a place you didn’t want to be. I felt crap for weeks after the radiotherapy. I had pain and it was difficult to sit down. Hormone therapy left me feeling empty. It was the worst time.

I am still sexually active – a surprise given the treatment I’ve had –but it’s different compared to before. It’s a difficult subject. Men put their idea of masculinity ahead of their health and, if you don’t feel ill, I can understand why you might. But we have to drum the message home, especially to black men: this is serious and can kill.

My brother’s also had prostate cancer. We were fit and healthy. I’ve since lost my father to prostate cancer but he never told me. I didn’t know until I saw the meds on his bedside. My sister’s had cancer and she’s younger than me. The family is having genetic testing.

I’ve done talks to rooms full of black men and they’re amazed, they sit in silence, they just don’t know anything about the prostate or cancer. We need to raise awareness among black men. I never saw the statistic that ‘1 in 4 black men get prostate cancer’ anywhere before I was diagnosed. Some men request a test and are told no - it’s not right that they they have to exaggerate to get a test done. Yes, I have a family history. Yes, I have symptoms. Black men also need to be included more in the clinical trials.

Since cancer, my body’s not the same, my energy’s not the same. I’m not the same. The journey doesn’t end with the end of treatment.

Had I not been assertive at the very start, it’s possible I would not be here. Now I wear a prostate badge all the time and people ask about that. I tell everyone I know to get checked out – family and friends. My message though is not just to get a check for prostate but to make sure you go for an NHS health check - even if they don’t invite you.

Paul is now CEO of Cancer Black Care, a charity providing support for all those living with and affected by cancer with an emphasis on black people and people of colour.

11

A GROWING PROBLEM?

This section looks at non-cancerous prostate conditions. The next section on page 16 looks at prostate cancer.

WHAT IS BPE?

BPE is benign prostate enlargement which is non-cancerous growth of the prostate. (It’s also often referred to as BPH or benign prostatic hyperplasia.)

It is a very common condition in men over 50 and by the age of 70, some 80% of men are affected.

Treatment depends on how severe your symptoms are. Initially, for mild symptoms, you’ll probably be advised to make some simple lifestyle changes including reducing alcohol, caffeine, fizzy drinks and artificial sweeteners, taking more exercise, eating more fibre and reducing fluid intake at night. (There’s more on smart lifestyle changes in the section beginning on page 27.)

Make sure your GP knows all the medications you’re taking, as some can make LUTS worse. BPE can also increase the risk of a urinary tract infection.

For moderate symptoms you might need drugs to relax the bladder, improve the flow of urine or reduce the size of the prostate.

Sometimes, for more severe symptoms, more invasive measures might be suggested. There are a wide range of these to discuss with your health professional. We mention some of the procedures here just so you’re familiar with the various terms and techniques:

> Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) - removing part of the prostate using a surgical instrument (a resectoscope) that's passed down the urethra

> Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP) - using a laser inserted via the urethra to remove part of the prostate

12

> Water ablation - using water pressure or steam to reduce the prostate size, again performed via the urethra

> Greenlight XPS - a newer type of laser that can destroy prostate tissue, again via the urethra

> Prostatic urethral lift (PUL) implants - implants that hold the prostate away from the urethra, sometimes known by the brand name UroLift

> Prostate artery embolisation (PAE) - injecting tiny particles into the blood vessels that supply the prostate to reduce its blood supply and therefore its size, via a catheter inserted into an artery in your groin or wrist

> PLASMA system - surgery placing electrodes into the prostate through the urethra to cut out prostate tissue

> Bladder neck incision (prostatotomy) - cutting the neck of the bladder to enable you to pee more easily. Again entry is through your urethra

> Open prostatectomy - removing the part of the prostate gland obstructing the urethra through surgery, possibly as a keyhole (laparoscopic) procedure.

There are pros and cons to all of these. Some are more suitable for larger prostates, some for smaller, others for when other treatments haven’t worked. Of course, none of them sound much fun when described in just one line as above, but millions of men have had them and they can give you your life back.

Discuss these options with your doctors.

13

WHAT IS URINARY RETENTION?

This is when you cannot empty your bladder fully. A weak flow, a feeling of not emptying your bladder or leaking pee at night can be signs of retention. With time, this can weaken your bladder muscle.

Most concerning is acute urinary retention when you cannot empty your bladder at all. This is usually accompanied by abdominal pain and the feeling of a swollen bladder. If you experience symptoms like this, go to A&E immediately. (See John F’s story on page 7.)

WHAT IS PROSTATITIS?

Prostatitis is a condition where the prostate gland becomes inflamed (red and swollen). Symptoms include many of those we’ve already discussed on page 8 plus often a stinging or burning pain when peeing. The cause may be a bacterial infection (treated with antibiotics) or it may not. Prostatitis can become long-term (chronic). Chronic non-bacterial prostatitis is sometimes called Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome.

In men under 50, prostatitis is a not uncommon cause of LUTS, but it also occurs in older men. Some 10-15% of men will have prostatitis at some time.

CAN AN ENLARGED PROSTATE CAUSE ERECTION PROBLEMS?

Certainly, the two can go together. It’s not clear whether there is a direct physical link but obviously having waterworks problems is unlikely to help you to feel relaxed or create the right mood. Some BPE treatments, such as finasteride, can cause erectile dysfunction (ED). On the other hand, some ED treatments can help to relieve the symptoms of an enlarged prostate.

All sorts of things can cause erection problems including heart disease, depression, diabetes and multiple sclerosis. If you just treat the ED, the underlying cause won’t be identified and, therefore, cannot be treated.

GPs are used to discussing erection problems so if this is an issue for you, have a word. There is much that can be done.

14

Winston, age at diagnosis: 63

THE PROSTATE IS AN INNOCUOUS LITTLE ORGAN BUT

CAN DO A LOT OF DAMAGE WHEN IT GOES

WRONG

As an academic working in health, I’d been advised to know my numbers so I knew my PSA. When I started getting up more at night, I got it checked again. It wasn’t very high (5.9) but it was higher than before and, on retest, it was higher still (6.11).

An MRI scan revealed four probable tumours. The biopsy confirmed they were malignant but that the cancer was contained within the prostate. I had a bone scan which helped to be certain on this. I was then ‘fast-tracked’ but it was still weeks between each stage. It took over 8 months for treatment to start from the first PSA.

I wasn’t keen on surgery. Professionally, I’d read the research and knew the risks of surgery and possible side-effects. I was also in a new relationship – my new partner had moved in just as the whole business started – and the idea of urinary and sexual problems concerned me a lot. Loss of ejaculation is quite a thing for a man.

Because the cancer was contained in the prostate, it was suitable for radiotherapy but because there were four sites it wasn’t suitable for brachytherapy. It was a choice between conventional radiotherapy or the more localised stereotactic body radiation therapy, sometimes called Cyberknife. The latter was just coming off clinical trial but the trial had been a success so it was offered to me. You have 5 sessions over 5 days compared to 20 or more sessions over a month for conventional radiotherapy. It’s highly-focused radiotherapy using a precision robotic tool and also using ultrasound alongside to examine the prostate as it goes.

Radiotherapy is very tiring physically and psychologically so 5 days is a lot better than 20. I had some explosive bowel movements and urinary problems at first but it settled down. I still have some increased urgency but that’s really the only long-term urinary issue.

Erections are fine though ejaculation is more difficult and takes longer. That can be an issue for both the man and his partner. Both need to understand what’s going on. I think psychosexual counselling should be far more widely available.

15

“

PROSTATE CANCER

In the UK, about 1 in 8 men will get prostate cancer. Every day nearly 150 men are diagnosed with the disease.

That sounds scary and, yes, it is a serious disease that kills more than 12,000 men every year in the UK. But treatments are improving considerably and, at the time of writing, there are nearly half a million men in this country living with or after prostate cancer. That’s a lot of blokes.

In other words, if you’re concerned, it makes sense to speak to your GP as soon as possible. There is much that can be done, especially if the cancer is caught early. Research suggests that prostate cancer treatment at the earlier stages of cancer (stages one and two) has a near 100% survival rate compared with around 50% at stage four.

The 2022 Prostate Cancer National Audit for England and Wales found that prostate cancer had already spread elsewhere in 17% of men diagnosed in 2020-21 compared with 13% the previous year. This was a significant increase of nearly a third – in part because of Covid-related delays.

There is also a serious North-South divide in the UK when it comes to prostate cancer detection. In Scotland, one man in three (35%) is detected too late for the cancer to be cured. In London, it is far lower at one in eight (12.5%).

AM I AT RISK?

Most diagnoses are in men in their 70s but diagnoses in younger men are increasing. In the USA about 10% of diagnoses are in men under 55.

As we said earlier, prostate cancer can run in families. Your risk of prostate cancer is more than doubled if you have an affected brother or father, and it increases still further the more male relatives you have with the disease.

16

But it’s not just prostate cancer. If you have relatives who have had breast cancer or ovarian cancer, your risk of hereditary prostate cancer may be higher.

Make sure your GP is aware if you have relatives who have had any of the cancers mentioned here.

Mutations in some genes – for example, the BRCA genes – can affect your risk and be associated with familial prostate cancer.

BRCA gene variants are rare (around 1 in 300 to 400 people have one) but if you have a family history or come from certain ethnic groups you may be offered gene testing. For example, people from an Ashkenazi Jewish background have a higher risk – about 1 in 40 carry a BRCA gene variant.

As we’ve said, Black men are at particularly increased risk of prostate cancer from a younger age. Prostate Cancer UK has calculated that 1 in 4 Black men will get prostate cancer in their lifetime.

Men of mixed Black ethnicity are also likely to be at higher risk than a white man although we don’t know by how much. We don’t know whether it makes a difference if it’s your mother or father who is Black.

Having said all that, anyone with a prostate is at risk of prostate cancer whatever their age, genes or family history.

17

HOW IS PROSTATE CANCER DIAGNOSED?

Traditionally there have been two main prostate tests in the doctor’s armoury: DRE and PSA. Nearly all diagnoses of prostate problems whether benign or cancerous begin this way.

> DRE (digital rectal examination) involves nothing more than having a finger stuck up your bottom to feel the size and texture of your prostate.

> PSA (prostate-specific antigen) was discovered in 1979. It is a particular protein in the blood that is produced in the prostate and can be measured with a simple blood test. Higher levels are associated with prostate disorders including cancer. PSA is usually measured in nanograms per millilitre of blood (ng/ml).

Doctors may also:

> test your flow rate - the ‘speed’ at which you pee

> measure your prostate volume - using ultrasound and gel (the technique is similar to a pregnancy scan)

> check how empty your bladder is after peeing - again, using ultrasound

> test so-called ‘free PSA’ - this is a variant on the standard PSA test. The two PSA tests together may give a better guide as to what is causing your prostate growth.

If your symptoms and the various tests raise concern in your doctors, they may suggest further ‘urodynamics’ (tests to check the bladder and urethra) and/or take an MRI scan which uses magnetic fields and radio waves to generate detailed images of the prostate. These can be assessed for the likelihood of cancer.

18

But the final diagnosis will usually require a biopsy. This involves a thin needle to remove small tissue samples from the prostate (under local or general anaesthetic). These samples are then checked under a microscope for cancer. The needle may be inserted through the wall of the back passage (a transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy) or through the skin between the testicles and the back passage (a transperineal biopsy). The latter is generally favoured as infection is much less likely. The area to be biopsied may be identified through an MRI scan. This provides a target within the prostate for the doctor to aim for.

The biopsy will be given what is called a grade group (on a scale of 1-5) or a Gleason score (on a scale of 1-10). They’re not quite the same thing but generally the higher your grade group or Gleason score, the more aggressive the cancer and the more likely it is to spread.

Your doctors will explain all this. If they don’t, ask.

DOES PROSTATE CANCER ALWAYS HAVE SYMPTOMS?

Often prostate cancer does not come with the typical LUTS symptoms listed on page 8. (See John W’s story on page 30.) In fact, prostate cancer often starts to grow in the outer part of the prostate, which is why it can sometimes be felt during a DRE, but it also means it is less likely to press on the urethra and cause LUTS symptoms.

However, you might spot other symptoms such as blood in your urine or semen; bone pain, especially in the back, hips or pelvis; erection problems; or unexpected weight loss. Of course, these symptoms could be caused by something other than prostate cancer, so you need to talk to your GP to be sure.

THE DIGITAL RECTAL EXAM (DRE)

If you’re putting off going to the GP because you’re worried about the DRE, don’t. It’s over in seconds, you’ll barely feel it and it won’t affect you or your masculinity in any way at all, honestly. Millions of men have had one. You may not even need one anyway.

19

HOW IS PROSTATE CANCER TREATED?

Prostate cancer treatment is getting more and more effective. Survival rates have tripled in the last 50 years in the UK. In the 1970s, barely a quarter of men diagnosed with prostate cancer were still alive ten years after diagnosis (25.2%). By the 2010s it was more than four-fifths (83.8%).

Treatment is also getting less unpleasant with fewer side-effects for the men treated.

Which treatment is best for you depends on:

> how far the cancer has spread. Is it only in the prostate? Has it spread outside? Has it spread to other parts of the body? (The process of identifying how far a cancer has spread is called staging)

> how quickly it is growing

> the pros and cons of each treatment including the possible side-effects

> practical matters such as how close you live to the hospital and how often you will need to go there

> your thoughts about the treatment options

> how the treatment you choose now could affect future treatment options if the cancer comes back

> your general health and life-expectancy.

The different treatment options are listed in the box. It’s beyond the scope of this booklet to go into them all in detail but again we will introduce the terms and techniques so you can better discuss the options with your health professionals.

20

PROSTATE CANCER TREATMENTS

Treatments for cancer that is only in the prostate (called localised prostate cancer) include:

> Watchful waiting - this involves simply keeping an eye on symptoms. If a cancer is slow-growing and not causing problems it might not need treatment. Watchful waiting is often supervised by your GP.

> Active surveillance - this involves closer monitoring of the cancer including regular tests and is usually supervised by the consultant.

> Surgery - a radical prostatectomy involves the removal of the prostate, generally using keyhole surgery. It may be carried out with robot assistance.

> Radiotherapy - high-energy X-ray beams targeted at the prostate from outside the body to damage the cancer cells and stop them growing and spreading. There are various types of radiotherapy including newer more focused techniques such as stereotactic ablative radiotherapy or SABR. (See Winston’s story on page 15.)

> Brachytherapy - this too is radiation but it is applied from within. Tiny implanted devices filled with radioactive materials (sometimes called seeds), which provide a dose of radiation, are inserted into the prostate over a few months.

For cancer that has spread outside the prostate but not to another part of the body, you might be offered surgery, radiotherapy or brachytherapy and also:

> Hormone therapy - to stop your body from making testosterone or to stop testosterone from reaching the cancer cells. This can cause the cancer to shrink.

If you have more advanced cancer which has spread to another part or parts of the body, you may be offered any of the above and/or

> Chemotherapy - regular doses of anti-cancer (cytotoxic) drugs to kill cancer cells.

Obviously, there are pros and cons to all of these and possible side-effects. You’ll want to discuss them with your health team and your family.

The Prostate Cancer UK website includes excellent detailed information on all the treatments mentioned and on new ones as they are approved. Treatments are being improved and added to all the time. You may be offered the chance to take part in a clinical trial of a new treatment.

21

Nick, age at diagnosis: 60

SURGERY HAS IMPROVED SO MUCH

I’m a nurse and early on in my career, I worked in A&E. I witnessed a guy in acute retention. I saw it several times and inserted the catheter myself on occasion. I think that trauma haunted me.

This encouraged me to keep an eye on my PSA. But even with my increased levels of concern, I normalised the number of times I found myself going to the loo - especially at night. I was like Private Godfrey in Dad’s Army but I underscored my own symptoms (see page 34) and found reasons not to do anything. One evening my daughter said ‘you just need to ring them up’.

My PSA was slightly up. The doctor said the DRE suggested the prostate was mildly enlarged but soft and so probably benign. Then I had urodynamics which was, to coin a phrase, a watershed. None of my tests were impressive. Flow was slow and there was significant residual urine in my bladder after I thought I’d finished. That made me question the apparent reassurance of the DRE.

Next, they did a free PSA test. Online, I found a matrix plotting regular and free PSAs tests against your age - my relatively high PSA but relatively low free PSA suggested something malignant. This added to my concern but nobody was sure. I was going on a short cycling break to Italy so they prescribed alpha-blockers for me. I came back to a phone call telling me I was on the ‘cancer pathway’. I protested - ‘I’m not on the cancer pathway’ - but I was.

The subsequent MRI showed a worrying shadow but again nothing specific. I think I was about 80% sure now that it was malignant but held out some hope until I had a transperineal biopsy under general anaesthetic and they gave me a Gleason score.

I had a consultation with the urology team during the Covid lockdown. I was given three options: active surveillance, radiotherapy or surgery. My wife was so important at this point - supporting me through the blind panic of my worst fears.

I spoke to the radiographer first, then the surgeon. He explained his approach: a robot-assisted radical laparoscopic prostatectomy. He also explained that tissue was damaged by radiotherapy and so difficult to operate on if you needed surgery subsequently.

22

“I dithered for a couple of days. I spoke to health professionals at work. Radiotherapy was attractive but I was reassured by the surgeon’s experience and confidence in his proposed surgery. Before surgery, I exercised more including my pelvic floors. I made sure I was as fit as possible. It was frightening going in even though I’m a nurse. They only mention side-effects as you’re about to go into theatre! I remember the robot and the narrow operating table.

Back in the 80s, a radical prostatectomy meant at least two weeks in hospital and going home in a wheelchair. But things have changed so much. All the same, you wake up with 5 or 6 tubes in you and bags. They inflate your abdomen - it takes about 24 hours to fully deflate. It was still during Covid and since I could handle my own catheters and injections - I’d done it many times for other patients - they let me go after just the one night. You go home with an indwelling urinary catheter for 10-14 days afterwards.

I use Squeezy for Men (see page 28). You rely on your pelvic floors because surgery affects your urinary sphincter. Initially, drinking beer and walking would lead to dribbling which you get neurotic about. Now I might wear a small pad if having a beer and walking.

When I came back for the catheter removal, I knew it wouldn’t be nice. The nurse told me they’d prescribe (erectile dysfunction drug) tadalafil but he didn’t really explain about the sort of sexual problems I’d have. He didn’t say and I didn’t ask.

I had nocturnal emissions which were worrying but in a way reassuring. Tadalafil works. It makes you realise you’ve still got a cock. But it gives me gastric burning so I need to take (acid reflux drug) omeprazole alongside. Freud has a lot to say about penises and clearly this is important to us men. I can get a bit obsessive about it. A prostatectomy is a big operation and does have an impact on you but it’s not curtains for sexual activity.

I’m on six-monthly PSA tests now and it remains very low. I’ve had a couple of phone conversations with the consultant but haven’t seen one since the op. I keep comms open with the nurses.

The key thing for me to stress as a nurse is the massive change in the technology for this operation that has taken place during my career. In fact, that’s true of the treatment of prostate problems more generally. It is incredible. I’m in my 60s yet I walked out of the ward within hours of the surgery which is quite remarkable. I was also back on my bike within three months of surgery.

23

TESTING, TESTING

Having read this far you’ll probably be wondering why men aren’t screened for prostate cancer in the same way as women are screened for breast or cervical cancer.

It’s a good question because in 2018, prostate cancer killed more people than breast cancer for the first time. This is in part because breast screening works to reduce deaths associated with the disease. The evidence currently does not show such a benefit for prostate cancer screening but, as research continues, this may change in the future.

WHAT PROSTATE TESTS DO WE HAVE?

We’ve already mentioned the PSA blood test and the DRE.

Both tests, especially if they’re repeated over time, can help a professional get a rough idea of what’s going on with your prostate but neither have been accurate enough predictors on their own or together to roll out to all men.

Indeed, since the introduction of PSA testing in the 1980s, there has, according to the European Association of Urology, been considerable overdiagnosis and overtreatment of prostate cancer. Lives have been saved but many others have been damaged with unnecessary procedures for

cancers that might not have caused any effects and so didn’t need treating.

WHAT’S WRONG WITH THE DRE?

If the prostate feels hard or lumpy this could be a sign of cancer. But this is a very inexact science and there might be another cause.

What’s more, the health professional can’t feel your whole prostate, only the part nearest your rectum. There may be cancer elsewhere or in parts of the prostate that the professional can’t feel.

WHAT’S WRONG WITH THE PSA TEST?

There is no ‘normal’ PSA. NHS guidelines suggest different ‘normal’ levels depending on age and ethnic group: ‘normal’ varies from man to man and levels increase as you get older.

Research suggests that three quarters of men with a raised PSA level will not have cancer while around 1 in 7 men with a ‘normal’ PSA result do have prostate cancer. PSA can be high in some other non-cancerous prostate conditions such as BPE or prostatitis. PSA can also be raised by a urinary tract infection or even vigorous sex or cycling. It can also be lowered by some medicines.

Moreover, prostate cancer does not always need active treatment. That’s why sometimes doctors will recommend watchful waiting or active surveillance. They do this to try to distinguish between ‘tigers’ (cancers which grow quickly and can kill) and ‘pussycats’ (which don’t and won't). The PSA is not much help in determining which cancers need treatment.

25

SO, WE’LL NEVER SEE PROSTATE CANCER SCREENING?

Never say never. There is research going on in Europe to try to develop an algorithm which will use a PSA test as a starting point and then use a number of other tests to minimise overdiagnosis. These include a risk assessment based on family history, possibly a simple ultrasound scan similar to those used in pregnancy to measure the prostate’s volume plus assessment of urinary symptoms and other risk factors. Those men who are still identified as at risk will have an MRI scan that will also be scored on the likelihood of cancer being present. Only at that point might a biopsy be taken.

In the UK, researchers supported by Prostate Cancer UK and the NHS are examining the types of scan used. For example, MRI scans generally use a contrast dye (gadolinium) but research suggests that skipping this stage may be quicker, cheaper and just as effective.

A risk-based approach should minimise over-diagnosis while still catching prostate cancer relatively early. It is possible that this research will lead to the introduction of prostate cancer screening in Europe by the late 2020s.

In the meantime, we need to be prostate-aware and watch out for symptoms.

It’s fair to say that, because of the variety of examinations and treatments for enlarged prostates, the approach and what is offered varies across the NHS depending on the surgery, hospital or doctor. If you’re concerned about how your case is being handled, do talk to your GP.

26

BE GOOD TO YOUR PROSTATE

If you haven’t got a prostate issue, the ideas in this section will help you keep it that way. If you have got an issue, they will help with your self-management and may reduce the need for other interventions.

IS THERE A PROSTATE-FRIENDLY DIET?

There’s no magic bullet or super food. You probably know what a good, balanced diet should look like and a prostate-friendly diet is pretty similar:

> more fresh fruits and vegetables - particularly cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli, cabbage, kale, cauliflower and sprouts, and berries such as such as strawberries, blackberries, blueberries and raspberries

> more lycopene (the antioxidant found in tomatoes, especially tomato paste, sauce, juice and sun-dried tomatoes)

> whole grain versions of bread, pasta and rice

> legumes and pulses (such as bean and lentils)

> healthy fats from sources such as olive oil, nuts (almonds, walnuts, pecans, peanuts), seeds and fish, especially fish with high levels of Omega-3s like salmon, sardines, herring, trout and mackerel

> moderate amounts of seafood

> go easy on dairy and red meat, especially processed meat

> cut back on salt and sugar

> avoid ultra-processed foods (UPFs) as far as possible. (UPFs are best defined as factory-made foods that you can’t recreate in your own kitchen)

> drink plenty of fluids, especially earlier in the day but cut right down on fizzy drinks, alcohol and drinks that contain caffeine (tea, coffee and cola). These may well irritate the bladder. Green tea is a good alternative.

Try to maintain a healthy weight. Obesity is linked to several prostate issues, including cancer.

WHAT ABOUT EXERCISE?

You should definitely exercise regularly: aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate exercise a week, the sort of thing that makes you slightly breathless like brisk walking, jogging etc. There is even research suggesting exercise may delay disease progression in low-risk cancers.

Pelvic floor exercises are specific movements that might be good for prostate health. They may help bladder control and erections. You can find your pelvic floor muscles by imagining you’re urinating and then tightening the muscles as if to stop mid-flow. There’s advice on the Prostate Cancer UK website about how to do these exercises or you could check out the NHSrecommended app Squeezy for Men. Don’t overdo it though.

WHAT ABOUT SUPPLEMENTS?

Various ‘natural’ supplements have been suggested for the prostate but there’s not a lot of evidence for any of them. If you have a diet like that outlined

28

above, you should also be getting all the vitamins and minerals you need.

Vitamin D may help. Boost the benefit by getting out into the sun as often as possible (safely, of course). Vitamin D supplements might help if you are at risk of having low levels.

Vitamin E supplements are best avoided as in high doses they may actually increase the risk of prostate cancer.

Obviously if you have any concerns, speak to your GP.

ANYTHING ELSE?

The usual, really. Don’t smoke and try to avoid stress, quack therapies and monetised social media advice!

And, because we can’t stress this enough, make sure you know your family history. The Prostate Cancer Foundation in the USA reckons that of the major cancers, prostate cancer is one of those most driven by genetic factors. If you have close relatives (brother, father) who have had prostate cancer you are at considerably increased risk, especially if they were diagnosed young.

You may also be at increased risk if you have a strong family history of other cancers including female-specific cancers. Find out your family cancer history and make sure your GP is aware of it.

29

John W, age at diagnosis: 46

HAVING YOUR PROSTATE REMOVED IS NOT THE END OF THE WORLD. IT’S OVER TWENTY YEARS SINCE MY SURGERY.

“

As every man knows, cancer is one of the numerous illnesses or diseases in the world that only affect other people.

I believed prostate cancer was something old men got and, anyway, I didn’t have any symptoms. Wrong! I had symptomless prostate cancer.

That was 2002 and I was just 46 years old. My wife played a major role in my getting the diagnosis. She pushed me into having the initial PSA test. My GP thought I was too young, so if I’d taken his advice I might not be here. Fortunately, I persisted. And here we are.

When cancer was diagnosed, I had a radical prostatectomy. After I recovered, I decided to get as fit as I could. I was playing five-a-side football twice a week until very recently. I had to stop because of my knees – nothing to do with my diagnosis. So, one positive of developing prostate cancer was it galvanised me into getting myself fit.

I’m an optimist by nature, so I never thought I’d simply slide down a tunnel and expire. I thought there’d be some good out of it eventually. It’s been an irritation, but everyone’s got irritations. Say you’re a footballer and injury ends your career before it’s started, that’s worse, isn’t it? I’m fully recovered from my operation and cancer-free. Even the scar has vanished.

Having a catheter in the bladder was worse than the operation itself. It was a pain finding somewhere comfortable to sit with it in place. I used to go and sit in the car. I went back to work very quickly. Mentally speaking, it was the right thing for me to do.

As far as sex is concerned, the little pills are available. I get them on the NHS. Your desire in this area diminishes a bit as you get older but, if the mood takes me, they work. I just have to be careful at my age. I don’t want a bad back to go with my dodgy knees.

30

“Loss of erection was a consequence of the surgery, but you have to strike a balance between shall I hang on and perhaps the cancer will get worse or should I do something about it now?

It might have been a different story, I suppose, if I hadn’t been happily married. Me and my wife discussed it forensically and looked at the alternatives. But for me at the time it was really a no-brainer. Dying is permanent; erection problems can be solved.

I think we need to do more about male screening, but right now there isn’t really a reliable testing method. I know things are coming through now to make it better. The trouble is that as men we worry more about our ability to perform sexually than we do about death. Add in the fact that we can’t be bothered with going to the doctor, and I wonder how many men would take up screening were it offered? We’d rather not know.

The assumption is still that if you have prostate cancer, that’s it. Game over. I’m proof that that’s not true. It’s over twenty years since my surgery. More than two decades. I’m semi-retired now. I’ve had a really busy life and still do. A radical prostatectomy is not the end of the world. It’s something that can be overcome.

I’ve been a Manchester City fan for more than fifty years. At the time of my diagnosis, it wasn’t an easy job; we’d not long ago been in the third division. But as I say, I’m an optimist and look what’s happened since. I’ve been able to watch the team win the premier league many times. And no, I’m not bored with it.

Below, John celebrates yet another Manchester City triumph with his granddaughter Niamh.

LIVING WITH PROSTATE ISSUES

As we’ve said, there are nearly half a million men in the UK living with prostate cancer. Millions more if you add in benign conditions.

Prostate growth and the treatment for it can affect peeing, bowel function, sex, feelings and emotions, sleep and fatigue and various practical issues related to daily life like work and money. It makes sense to ask what the long-term effects might be when discussing potential treatments for a prostate issue.

Remember, however, that as with treatments for the cancer itself, treatments for these after-effects continue to improve, so if you have a question, ask.

TELL ME MORE ABOUT THE IMPACT ON SEX

Prostate issues, treated or untreated, can affect both how you feel about sex and the mechanics of it.

They can affect libido, penis sensation, size, orgasms, fertility and erections. All of these will, of course, affect relationships too.

Again, there is treatment and support available for you and your partner through your health team and/or charities and voluntary organisations. For example, there are a number of erection treatments available including tablets (PDE5 inhibitors), vacuum pumps, injections, pellets, gel, implants and testosterone replacement therapy. They work in different ways and which works best for you depends on various factors including the prostate issue you have, the treatment you’ve had or are having for it, your overall health and your age.

Psychosexual counselling may be available for you and your partner to help manage any issues but again you may need to ask.

32

IS CANCER A DISABILITY?

Equality legislation in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland includes people with cancer. The law can protect your rights in many walks of life, including work. People who have had cancer and are now cancer-free are still protected.

WHERE CAN I FIND OUT MORE?

There are many organisations out there helping with prostate issues. Cancer Research UK has an excellent list which also includes organisations that can help with side-effects and after-effects.

Stick to trusted information sources (NHS, Prostate Cancer UK, Cancer Research UK, Men’s Health Forum). There is a lot of nonsense online and in social media. Both our partners on this publication can provide individual support:

> As well as its website (www.prostatecanceruk.org), Prostate Cancer UK has a specialist nurse service on 0800 074 8383

> Black Cancer Care provide support for all those living with and affected by cancer with an emphasis on Black people and people of colour (www.cancerblackcare.org.uk)

FINAL THOUGHT

Nobody would pretend that any of the tests or treatments outlined here are fun. But neither is prostate cancer. A little discomfort now is better than a lot of discomfort and death later.

Don’t procrastinate. Know your prostate.

33

SCORE YOUR SYMPTOMS

1. Incomplete Emptying

Over the past month how often have you had a sensation of not emptying your bladder completely after urination?

2. Frequency

Over the past month how often have you had to urinate again less than two hours after you have finished urinating?

3. Intermittency

Over the past month how often have you found you stopped and started again several times when urinating

4. Urgency

Over the past month how often have you found it difficult to postpone urination?

5. Weak stream

Over the past month how often have you had a weak urinary stream?

6. Straining

Over the past month how often have you had to push or strain to begin urination?

Not at all Less than one time in 5 Less than half the time About half the time More than half the time Almost always Your Score

7. Nocturia

Over the past month how many times did you typically get up each night to urinate from the time you went to bed until the time you got up in the morning?

Total I-PSS Score

If you were to spend the rest of your life with your urinary condition just the way it is now, how would you feel about that?

This is the International Prostate Symptom Score (I-PSS). You can use it to score your urinary symptoms on 7 scales from 0-5 giving a total score out of 35. Although there is no standard grading, doctors tend to classify as follows: 1-7 = mildly symptomatic; 8-19 = moderately symptomatic; 20-35 = severely symptomatic. Doctors may use the last question on quality of life as a starting point for discussing your symptoms.

If you’re concerned, talk to your GP. (The I-PSS is particularly helpful for benign prostate conditions but remember prostate cancer does not always have these symptoms.)

0 1 2 3 4 5

0 1 2 3 4 5

0 1 2 3 4 5

0 1 2 3 4 5

0 1 2 3 4 5

0 1 2 3 4 5

0 1 2 3 4 5

None Once Twice 3 times 4 times 5 or more

Score Delight -ed Pleased Mostly satisfied Mixed Mostly unhappy Unhappy Your Score

Your

Quality of life due to urinary symptoms

MEN’S HEALTH INFO

OUR WEBSITE

www.menshealthforum.org.uk

Hundreds of pages of health information by men for men.

OUR MAN MANUALS

FEELING DESPERATE?

Samaritans

Emotional support 24/7

www.samaritans.org

The Man Manual www.menshealthforum.org.uk/MM Beat Stress, Feel Better www.menshealthforum.org.uk/BSFB Eat Drink, Don’t Diet www.menshealthforum.org.uk/EDDD Man MOT www.menshealthforum.org.uk/MOT Man MOT For The Mind www.menshealthforum.org.uk/MMM Man To Man www.menshealthforum.org.uk/MTM Serious Drinking www.menshealthforum.org.uk/SD Wanna Bet? www.menshealthforum.org.uk/WB Porn Free www.menshealthforum.org.uk/PF

OTHER USEFUL ORGANISATIONS

www.menshealthforum.org.uk/links

116 123

On our website are links to other useful organisation. (The NHS website is nhs.uk)

SMALL PRINT: The authors and the publisher have taken care to make sure that the advice given in this edition is correct at the time of publication. We advise you to read and understand the instructions and information included with all medicines and to carefully consider whether a treatment is worth taking. The authors and the publisher have no legal responsibility for the results of

treatments, misuse or overuse of the remedies in this book or their level of success in individual cases. The authors and the publisher do not intend this book to be used instead of advice from a medical practitioner, which you should always get for any symptom or illness.

PHOTO CREDITS: Thanks to Julian Mason, tableatny, Knight Foundation, Rodnae Productions, Garry Knight,

Isengardt, Sascha Kohlmann, edenpictures, Forest Service USDA, Mikael Häggström, Ewen Roberts Josef Laimer, Abhijit Tembhekar, sheesalt. Jules, Jim Champion, Dave Crosby and Captain Chim who were all kind enough to make images available through the Creative Commons. (If this is not the case, please contact us.) Full credits, links etc at: menshealthforum.org.uk/ MMreferences

35

P FOR PROSTATE

The prostate is a small organ that can have a big impact on a man’s life. It’s important for sex, for a start. But it can also create health challenges. For example, prostate cancer affects 1 in 4 black men and 1 in 8 white men.

Whatever your age, P FOR PROSTATE will explain everything you need to know in one easy-to-read booklet.

> Where it is and how it works

> What can go wrong

> Signs and symptoms

> Tests and examinations

> Self-help for prostate issues

> All aspects of prostate health

Don’t procrastinate. Know your prostate.

The prostate: a sex organ you need to know more about.

WARNING: Reading this booklet could seriously improve your health.

ISBN: 978-1-906121-47-1

www.menshealthforum.org.uk