For NGC, our focus on sustainability is not just a passion. It is a pledge to our planet that we will be mindful of our impact. It is a plan to help realise the potential of our people. It is a promise to our children that we are thinking of tomorrow.

NGC – PURSUING SUSTAINABILITY AT THE FOREFRONT OF ENERGY.

NGC – PURSUING SUSTAINABILITY AT THE FOREFRONT OF ENERGY.

rfhl.comemail@rfhl.com

Season’s greetings to you and your loved ones, as we come to the close of another year. And what a year it has been!

With the support of our shareholders, our valued customers, and a steely resolve from our team, we stepped into 2022 committed to REsetting expectations. Aware both of forecasted travel hesitancy and your desire to see family and friends, we set out to REconnect you with your loved ones and REignite the passion for travel.

We listened to your feedback and set out to add value to your travel experience in ways that would tangibly impact you.

We expanded Caribbean Layaway — our interest free payment plan, where you pay down for travel and complete payment within an agreed time.

We introduced the game-changing Boeing 737-8 jets to our fleet — enabling us to provide a superior in-flight experience. As the year progressed, we reintroduced many of your favourite routes.

One of the most popular additions to our service was the introduction of pre-order inflight meals, so that you can select from a range of authentic Caribbean cuisine including doubles, jerk, macaroni pie, and pepper pot. Our inflight snack service Caribbean Café also returned.

In September, after months of dedicated work by our team, we reopened the

upgraded Caribbean Club Lounge at the Piarco International Airport — an impressive 3,062 square foot space with a sleek, contemporary design, where Club Members can relax and unwind before your flight; do business; enjoy great refreshments; and bring a guest, as we’ve reintroduced the complimentary guest pass for all Club members.

For the very first time, we’ve also included a children’s playroom — a safe space where your children can play and have fun.

If you’re not yet a Club Member, not to worry — you can buy a day pass to enjoy the amenities of the Caribbean Club. Other benefits include priority check-in and boarding; waivers on date change penalty fees; air travel perks; and retail discounts with our partners.

This flagship lounge experience created at Piarco will be replicated in other locations soon. We look forward to you, your family, friends, and business associates signing up.

In the coming weeks, the new kiosk outside the Piarco lounge also will be activated, so that Caribbean Club members can conveniently purchase duty-free items. Our staff will then deliver your items at the gate just before boarding.

What’s more, very soon you will be able to visit D’ Caribbean Shop, where you

can buy a range of quality merchandise online — including Caribbean Airlines keepsakes, branded clothing, jewellery, souvenirs, and lots more. Purchases are then delivered to your door via JETPAK, our redefined courier service

D’ Caribbean Shop is being rolled out in phases and will begin in Trinidad. The products will also be available at the Caribbean Airlines Duty Free Store at Piarco.

Registering for a FREE JETPAK account (jetpak.caribbean-airlines.com/#/signup) means you receive a United States address, which can be used to shop online. Items purchased are then delivered to the US address; and Caribbean Airlines will transport them to Trinidad, clear the pack ages with customs, and deliver them safely to your door. There’s real time tracking, so you always know where your packages are!

It has been a year of recovery, but with your support and the dedication of our teams, we made it! 2023 looks promising — and we have some awesome activities planned! More on this in the next issue.

For now, we wish you continued good health and best wishes for this wonderful season!

Regards, Garvin14 EvEnt buzz

Festivals and events around the region

20 Fashion buzz

Tobago-born, US-based designer Trishelle Leacock

22 music & book buzz Reviews by Nigel A Campbell and Shivanee Ramlochan

cookup

One fOr all Vaughn Stafford Gray maps out how those with dietary restrictions — and those hosting them — can enjoy the festive season together

28 DiD you know fOOd fOr thOught

Jo-Anne S Ferreira shares some insights on the fascinating origins of some of our favourite festive foods

snapshot BrOadway BOund

After decades delighting audiences in Trinidad & Tobago and Great Britain, Melanie (Hudson) La Barrie makes her Broadway debut. Caroline Taylor learns more

36 DiscovEr the tOwn Beneath the sand

Archaeologists in Dominica are unearthing an abandoned town which, explains Paul Crask , may fundamentally change our understanding of Dominica’s history

40 portFolio Making Mas with the Messiness Of histOry Andre Bagoo profiles the award-winning Guyanese-British contemporary artist Hew Locke, whose latest commission is on show at the Tate Britain

44 inspirE daring tO dance Dance has brought Gina Mayers through devastating personal loss and a Multiple Sclerosis diagnosis — and to stages from Barbados to New York, writes Shelly-Ann Inniss

48 travEllErs’ talEs Of lOvers and pirates Aisha Sylvester spends a magical day in Charlotteville, Tobago

50 GrEEn cariBBean natiOns sOund the alarM On cliMate change

Erline Andrews explains why Caribbean leaders are taking a much tougher stance at COP27 and beyond

54 on this Day the Black BOlshevik James Ferguson profiles Jamaican poet and revolutionary Claude McKay, whose landmark collection Harlem Shadows was published a century ago

puzzlEs

Editor Caroline Taylor

Designer Kevon Webster

manager Halcyon Salazar

Editorial assistant Shelly-Ann Inniss

manager Jacqueline Smith

director Joanne Mendes

Publisher Jeremy Taylor

Business Development Manager, Tobago and International Evelyn Chung T: (868) 684–4409 E: evelyn@meppublishers.com

Business Development Representative, Trinidad Tracy Farrag T: (868) 318–1996 E: tracy@meppublishers.com

Media & Editorial Projects Ltd.

Prospect Avenue, Long Circular, Maraval 120111, Trinidad and Tobago T: (868) 622–3821/6138 E: caribbean-beat@meppublishers.com Websites: meppublishers.com • caribbean-beat.com

Caribbean Beat is

year for Caribbean Airlines by Media & Editorial Projects Ltd. It is

Airlines 2022. All rights reserved. ISSN 1680–6158.

the written permission of

advertisers. The views of the

represent

Website: www.caribbean-airlines.com

in any way.

Innovation is one of the most tossed around terms in global business today, yet what it actually means can still be nebulous.

From my perspective, innovation can be anything that adds value to the bottom line of the company — a new product, service, re-engineered process, or simply taking an already existing idea or product and applying it in a new way.

New products and services innovation can be groundbreaking and revolutionary, resulting from major new technologies (3D printing, nanotechnology or augmented reality); from small, simple changes (like turning a ketchup bottle upside down or putting mayonnaise into a “spouch”); or updating product colours or design.

Innovations can also involve taking something long enjoyed in one market — such as a food or face cream — and introducing it to a market that has never seen it.

From a consumer perspective we’ve been primed to look for and want what’s new, best, fastest, more convenient, or more fashionable.

Some companies even use a “vitality index” with regard to product life cycles — measuring what percent of a company’s sales can be attributed to new products or services that did not exist two years ago (they’re then removed from the index after two years, and replaced with new ones).

Look for insights by methodically and systematically scrutinising three areas: a valuable problem to solve, a technology that enables a solution, and a business model that generates money from it.

Companies that effectively collect, synthesise, and “exploit” these have the highest probability of success. Hint: talk to your customers and suppliers. They will lead you to business-model innovations that change the economics of the value chain, diversify profit streams, and/or modify delivery models.

Eat your own lunch, or someone else will Hugely successful companies fail when they are reluctant to risk tampering with their core business model until it’s visibly under threat — but by then it is too late.

Leading companies establish funding vehicles for new businesses that don’t fit into the current structure, and they constantly re-evaluate their position in the value chain — carefully considering business models that might deliver value to priority groups of new customers.

Antibodies undermine innovation In many companies, the very same process we put in place to protect the company (cautious governance processes) also make it easy to find reasons to halt or slow innovation; we get in our own way. Obviously, a balance must be maintained between entrepreneurial flare and bureaucracy.

Managers across functions — from marketing, to legal and IT — with the right knowledge, skills, and experience can achieve this by making crucial decisions in a timely manner, so that innovation continually moves through an organisation without exposing a company to unnecessary risk.

Why is innovation important? We are at a crossroads in the Caribbean. Creating a culture of innovation means taking some calculated risks — but it is also one mechanism by which we can break the chains that bind us. As we move forward, we must develop a passion for new knowledge and bold ideas, while allowing creativity to guide and chart a new course for our future.

In the words of Peter Drucker: “The best way to predict the future is to create it.” The choice is ours.

Anthony Ali is the Managing Director of Goddard Enterprises Limited

“Large corporations welcome innovation and individualism in the same way the dinosaurs welcomed large meteors.”

Turners Beach — near Johnson’s Point on Antigua’s southwest coast — is a stunner...and delightfully accessible. Though it’s popular on Sundays, it’s much quieter during the week. You’d be forgiven for wanting to just laze — enjoying the cooling breezes; soft, sparkling white sand; and calm, clear ocean waters that are mesmerising shades of blue. It makes for wonderful snorkelling. Back on land, there are the ruins of a small fort to investigate, plus lots of good food, drink, and accommodation options nearby.

Essential info about what’s happening across the region in November and December!

On Boxing Day (26 December) and New Year’s Day, the irresistible, rhythmic sounds of drums, whistles, cowbells and brass instruments accompany exuberant dance routines at the Junkanoo “rush” through downtown Nassau. Along the parade route, popular rival bands like The Saxons, One Family, Roots and Valley Boys playfully call to each other as masqueraders revel in the spirit and pulsating energy of Junkanoo. It’s a bucket list Caribbean festival experience — and a mustdo in The Bahamas!

During Sint Maarten’s Culinary Month (November), participating restaurants design a special prixe fix menu of either three courses or one, highlighting their wide-ranging specialties — a perfect reason to dine out and try new places with family and friends.

Ahoy matey! Previously hosted as Cayman Pirates Week, the inaugural Cayman Pirates Fest celebrations began in September and culminate 4–27 November. Enjoy signature events like the mock pirate “invasion”, Heritage Days, undersea treasure hunts and a steelpan competition. With 160 pirates around, be on guard for a surprise or two.

For approximately 26.2 miles across the five boroughs of New York, scores of runners will test their stamina in the new york City Marathon (6 November), encouraged by cheerleading onlookers along the route.

In the following weeks, the kärcher Coral Estate Classic (13 November) and kärcher Duo Xtreme Mountain Bike Race (20 November) will challenge legs and lungs across the hills and salinas of Bandabou in northwest Curaçao.

Garifuna settlement Day (19 November) usually begins at dawn, with locals re-enacting the arrival of the Garifuna people on Belize’s shores 220 years ago. The re-enactment — which includes lots of drumming, music, and food — takes place on a beach in Stann Creek District, Dangriga.

Myriad deliciously decadent lobster dishes are served up at the Anegada Lobster Festival (25–27 November) in the British Virgin Islands. It kicks off with an island-wide scavenger hunt and opportunities to enjoy not just lobster but other fresh fish, meats and more.

The Gemonites Moods of Pan event (26–27 November) brings music lovers together in Antigua through the melodious, rhythmic strains of steelpan and more. The National Choir of Antigua & Barbuda, Ebony Steelband (London), Arturo Tappin (Barbados), New Dimensions (Grenada), Andy Narell, and Women of Steel (both from New York) are some of the acts to have graced the stage.

Recreational runners from across the globe make a dash for the scenic courses of the Run Barbados Marathon (10–11 December), enjoying the island’s friendly local culture, beauty, and history along the way.

The period between Christmas and New Year’s is extra sweet at st kitts sugar Mas (2 December–3 January) and Montserrat Carnival (17 December–2 January). Cherished experiences like J’Ouvert, Soca Monarch, folkloric storytelling, and many fetes keep the atmosphere pumping. It all climaxes with dazzling costumes on Parade Day.

Trinidad & Tobago Bioblitz (3–4 December) is a treasure hunt for nature lovers. Explore the islands’ rich biodiversity with the T&T Field Naturalists’ Club while documenting and cataloguing your findings. Maybe you’ll even discover new species!

In St Lucia, a parade of lanterns, a variety show, and a fireworks display in Castries symbolise the start of the Christmas season. The island’s Festival of Lights (13 December) honours Saint Lucia or Saint Lucy — the patron saint of light — and represents renewal, good overcoming evil, and light triumphing over darkness. Traditionally, St Lucians hang the lanterns, made of natural and recycled materials, in their doorways to light the way.

In Trinidad, it’s parang season! Paranderos — especially in the communities of Paramin, Lopinot and Arima — serenade neighbours and visitors with the lively sounds of parang. It’s the island’s traditional Christmas music — derived from Venezuelan folk music, sung in Spanish, and brought to life by cuatro, guitar, mandolin, maracas and box bass. The season extends from Parang History Month in September through early January. And if you love parang, make sure also to check out the Carriacou Parang Festival (16–18 December).

All year, the neighbourhoods of San Salvador and El Carmen in Cuba secretly plan innovative ways to outdo each other and present the most spectacular light show during Las Parrandas de Remedios (usually 16–26 December). The communities compete fiercely with elaborate floats, street bands, and pyrotechnics to create a scintillating showcase — and lots and lots of noise!

At the nine Mornings Festival (16–24 December), communities across St Vincent awake before 4am for (you guessed it!) nine mornings before Christmas to indulge in family-friendly activities, including a Christmas light-up, fun games, fetes, street concerts, sea baths, and more.

In Suriname, owru yari (31 December) sees out the old year in the capital city Paramaribo — not at midnight but midday! Live bands and throngs of people fill the streets in a carnival atmosphere. And at noon, celebrants set off lengthy garlands of firecrackers (paragas) — with the street party then continuing the rest of the afternoon into the night.

Tobago-born, US-based designer Trishelle Leacock — a former national track and field athlete — has sprinted into the world of fashion design. And she’s already turning heads, earning recognition in Marie Claire and Essence magazine earlier this year. She shares more about her brand (Kaiso. Swim), and her new collection, VOYAGE. — as told to Shelly-Ann Inniss

I discovered another meaning of the word “kaiso”, which is “ka” (go), “iso” (forward) — so my mantra is “go forward”. The name Kaiso. Swim is rooted in the idea of continually breathing life into our stories and heritage through our pieces, and also being inspired by the new generation who are now writing their own. It also highlights some of our central values of continually growing, evolving, and innovating as a brand.

The process [of creating VOYAGE.] came from a flood of emotions on a trip home to Tobago. It felt extra special. I knew then what I wanted to do with my life and brand, and that my first resort collection should reflect that shift. So the DISCOVERY. print has elements from different areas of the island, areas I grew up visiting

often: Parlatuvier Bay, Pigeon Point, and Argyle Falls.

The BLOOM. print is a little selfexplanatory as it shows the result of me finding myself and the legacy I

want to create. I know I still have a way to go, but getting to this point has been fun.

This collection is very near to my heart as it signifies an extreme growth phase for me. This brand has always been my outlet to share my creativity and tell stories based on my life and heritage, so being able to do that through clothing has been a blessing.

VOYAGE. relates to life’s constant journey. Part one signifies discovery as she found herself, and part two illustrates purpose — she bloomed. Sharing this phase of my life has brought me so much joy and peace throughout the creative process, and I hope this collection resonates with anyone who comes into contact with it, as they are on their VOYAGE. of self-discovery.

We are currently online, but the goal is to get it in boutiques around the Caribbean and major department stores worldwide. I want to venture into Carnival wear. I’m excited to be able to get a little crazier with the designs.

Reviews by nigel A. Campbell

Reviews by nigel A. Campbell

Reggae music offers perspectives on Caribbean realities that often resonate globally. One initial catalyst that “brought reggae to the world” was the 1972 film The Harder They Come, starring Jimmy Cliff as Ivan Martin — a country boy who came to town seeking reggae stardom, only to end up as a wanted criminal. Fifty years later, the iconic Cliff is still at the forefront of keeping reggae in the international consciousness. His new album balances a variety of love songs with some thought-provoking anthems. The title song — a collabora tion with Haitian-American star Wyclef Jean — reflects an upsurge in recognition of refugees’ status, and shines “a light on people forced to flee”, identifying the histori cal plight of refugees that is a continuing tragedy of human existence. Thirteen songs showcase a voice that thrilled in the 1970s and now signi fies what majesty sounds like, having kept the flame alive when others passed on. An important keepsake of a career milestone.

Haitian stories are some times tinged with a kind of tragedy that can either arouse rage and anger, or inspire a type of creativity that repairs our perceived hopelessness and helpless ness. Haitian-American Leyla McCalla developed a multimedia theatre piece on Jean Dominque — the owner of the pioneering Kreyòl-language Radio Haiti, and an outspoken critic of the callous and corrupt Baby Doc regime — who was assassinated by stillunknown, but possibly retaliatory, criminal foes. This album arises out of that project, with 15 tracks of originals, remade folk songs, and audio excerpts in both Kreyòl and English that sublimely capture the story’s pathos, intrigue and gloom. McCalla’s voice, once described as “disarm ingly natural”, renders the threads of this ugly episode as songs to be heard and understood. Cello and banjo become her lead instruments as she revisits the legacy of a martyr and invites us to learn. Epic!

M.O.A.M. [Man On a Mis sion] (Tad’s Records)

Hezron (Clarke) says that this — his new album — “in its truest sense, is a mission to bring back great Jamaican music and musicianship to the mainstream … It’s a reminder of where reggae is supposed to be in the world.” And with that mission statement, Hezron croons his way through the 16 tracks here, in the style of Beres Hammond and Denis Brown, to reinforce the idea that beyond conscious lyricism, reggae singing had American soul and R&B as original influences — and now the new poster-boy for these jams is alive and kicking. The title track tells us he is the ideal man for the job: I don’t know ‘bout dem, yuh know / Anybody who tell meh so meh can’t do it / Meh told dem meh go harder. In other words, I will prove the doubt ers wrong. With love songs and inspirational tunes bub bling with a modern produc tion aesthetic, harking back to the days of lovers rock dominance of the genre, this album is a happy reminder of why reggae is universally appealing.

Blue Dew (Repopulate Mars) • Single

American producer and DJ Lee Foss has tapped the currency and vocal magic of Trinidadian roots-pop singer Annalie Prime to enhance this house music thumper. Prime — whose popular 2021 sophomore album Nine was rewarded for its fresh take of island realities — has been on the lips of a new genera tion of local influencers and music fans looking for new and original expressions of Caribbean-ness. She also got the ear of movers and shakers in the wider music industry for her unique timbre and vocal flow. On this single, Foss made a smart choice by pairing her child-like vocal tone with lyrics that read on paper as a heady account of love, full of trepidation: Closed my eyes, feels like I am falling / Too soon, mountain blues, I heard the sunset calling / Save me mountain dew, I don’t want to fall / I’m scared of falling for you, for you / My heart beats in two, one for me, one for you / Blue dew, blue dew. Hallmarks of a hit here.

Reviews by shivanee Ramlochan, Book Review Editor

Reviews by shivanee Ramlochan, Book Review Editor

by Alake Pilgrim (Knights Of, 200 pp, ISBN 9781913311292)

Narnia has nothing on the imaginative pathways of Alake Pilgrim. In her middlegrade debut, the two-time Caribbean region winner of the Commonwealth Short Story Competition flexes her creative muscles, imbu ing a fantastical world with all the colourful commotion of a Trinidadian thriller for young readers. Our pro tagonist Zo is both intrepid and resourceful: a blueprint for parents seeking to instil progressive mettle in their children, and the forerun ner of a generation which must (as the novel gently prompts) be concerned about a burgeoning climate crisis. Descriptive prose swirls around generous nods to traditional Caribbean storytelling — but these are no rehashed symbolisms, no paper cut-outs of horned protectors or river spirits. Zo and her troupe of friends, each of them uniquely suited to survival in a very real Trinidad & Tobago, are bound to inspire endlessly.

neruda on the park by Cleyvis Natera (Bal lantine Books, 336 pp, ISBN 9780593358481)

Can you be a good immi grant when the walls you were forced to build start crumbling? The Guerreros have made Upper Manhat tan their home for many years, toiling to solidify their status as respectable Dominican-Americans, working in service of their community. Nothar Park has become their modest but indisputable dominion — a security that shatters as soon as the first high-priced condominium is advertised, and the threats of moving vans roll onto their streets. Luz, her mother Eusebia, and father Vladimir each react to the looming axe of gentrification with revolv ing resignation and revolt, creating a tapestry of intergenerational responses to the encroaching pillars of capitalism and racism. Natera’s debut has been 15 years in the making; Neruda on the Park shows a pro digious care for the Carib bean diaspora enclaves so instrumental in defining the United States.

the drowned forest by Angela Barry (Peepal Tree Press, 272 pp, ISBN 9781845235376)

An ancient cedar root is retrieved from the watery deep in a place where once no seawaters rose. Drawing from this real-life envi ronmental marvel, Angela Barry animates the past and present faces of Bermudian society in a potent, historymired novel. Genesis Smith — a youth offender caught in the crosshairs of systemic violence and cyclical aban donment — finds a cohort of disparate yet well-inten tioned figures who make her rehabilitation their concern. In each of their voices, Barry allows a portal to open — a pathway into what being Bermudian means, and all the stations of class, respectability, defiance and dreaming it embodies. As attuned to the nation’s contradictions as she is to its astonishing beauty, Barry crafts a space for the novel as eco-witness, semaphor ing critical attention on how we might collectively heal a fragmented archipelago. These storytelling roots hold fast.

Matters arising by Kenneth Ramchand (Royards Publishing Company, 244 pp, ISBN 9789768303711)

How do you take the pulse of a nation? The key to writing about a people — our people — is a steadfastness of gaze, as the essays in Matters Arising prove. Pro fessor Emeritus of English at the University of the West Indies Kenneth Ramchand puts the life of the public intellectual to the test of the page in non-fiction observations that both sear and soar — cutting in their conclusions but generous in their ambit. These news paper columns, originally published in the Trinidad & Tobago Guardian, represent a fine cross-section of Ram chand’s originary thought from 1987 to 1998. Notable contemporary essays have been added too, contem plating these Covid times and our regional place in them. Hewn with thought fulness, wit, picong, and a sly scattering of mauvaiselangue, these reflections don’t seek to redefine us to ourselves, but to attend us, faithfully.

Christmas and the holidays can be challenging for people with dietary restrictions — and for those hosting them. But they don’t have to be. With a dash of his trademark humour and a healthy helping of sage advice, Vaughn stafford Gray shows how

We all have that one relative (or friend) at whose house we fear going to dinner. Stop pretending. You know it’s true. Whether they are known to serve dry ham, overcooked and bland macaroni pie, or badly burnt black cake, suffering through dreadful holiday meals creates bad memories instead of moments that we can fondly reminisce about.

So, imagine being a person with dietary restrictions who is rarely accom modated at a gathering. Could you forgo a delicious-smelling meal and sip pipe water while everyone else pats their bellies and belches? Trust me, this happens.

Let me share a story with you.

There we were around the dinner table anticipating the main course. The

host was a popular chef, and this was the first big holiday dinner party after pandemic restrictions were lifted. As the servers entered the dining room with plates of deliciousness, the person to my right dipped into her handbag for a Tupperware container. She shyly inverted the contents onto her plate. The beige meal indicated that she had dietary restrictions. As a former chef, this is something I can easily recognise. After asking, she confirmed.

She said that she didn’t want to miss the party as she craved human connection. But after speaking

with the host, she decided it was easier to bring her own meal. The reality is, what she brought along was a pared down and lesser seasoned version of our meal. The host didn’t even offer to warm it up. Talk about bush league hosting. I haven’t spoken to him since, and she and I regularly share a meal together. It can be done.

You see, (most) people don’t adopt a restrictive diet or forego alcohol to be difficult or for style. Yes, you may still kiss your teeth whenever you think of that “vegan-keto-paleo” friend — OK, that’s me trauma-dumping — but for others, it’s terrifying to eat outside the home. Certain foods make it difficult to breathe (we need air, right?), will send them running to the toilet (not fun at a party), or land them in the hospital (in this economy?).

In addition to well-known health issues such as celiac disease (can’t have gluten) and lactose intolerance (no dairy), there are autoimmune diseases like Mixed Connective Tissue Disorder that mean you can’t eat garlic, processed foods, sugar or salt. There are many as well who don’t have full-blown allergies, but still have a range of food sensitivities.

Here are some facts. There are over 160 foods that can cause allergic reactions, and food allergies affect approximately 220 million people globally. In the United States, someone is admitted to the emergency room for food-induced anaphylaxis every two to three minutes.

Any food can cause allergic reactions, but sci entists have identified eight that are most trouble some: shellfish, tree nuts (almonds, pistachios, cashews etc), dairy, peanuts, eggs, fish, wheat and soy. If that’s not restrictive enough, I have Caribbean-born friends who will break out in a rash or blisters if they eat ackee, anything curried, thyme, ginger, onions and hot peppers. Talk about an affliction!

Though it requires some juggling, you can host a holiday dinner/party that considers people with restrictive diets or who are abstaining from alcohol. Here are a few tips so you can be the MVH (most valuable host) this holiday season.

Ask. Create a WhatsApp group of all the invitees…or, if your family or circle is known to incite drama, send an email with all the guests in the bcc line. Ask if they have dietary restrictions, allergies, or need to avoid alcohol, pork, or shellfish for health or religious reasons. Ask them if they are OK with other guests consuming them in the same space. If they aren’t, consider food and drink that everyone can enjoy.

Educate. Sober doesn’t mean boring. Whether your guests are in recov ery, pregnant, religiously devout, diabetic, or just don’t want to partake, offer a selection of alcohol-free beverages. Make batches of sorrel with no rum (you’ll manage) and fresh unfermented ginger beer. There’s something about the holidays and hot “cocoa tea”. Create a nostalgic moment by serv ing traditional Caribbean hot chocolate laced with nutmeg.

Request. Ask guests with the most severe dietary restrictions to give you recipes or bring a dish. Inviting them to participate in steering the meal makes them know how much they’re valued and that the event won’t be the same without them. Name the dish after them and let every one broaden their horizons through empathy.

Plan. Don’t attempt recipes you’ve never tackled before. This is not Chopped ! Do a couple of test runs in the weeks leading up to the event. Write out the to-do list and be sure to thoroughly clean surfaces and utensils between the preparation of each dish. On the day of the event, have some antihistamines and an EpiPen on hand.

Cater. If you’re not confident in your skills to create a tasty dairy- and sugar-free cake or a gluten-free vegan dish, call up a chef, restaurant or caterer specialising in free-from dishes.

Conceptualise. Consider a theme. This may take some convincing, especially if you’re hosting dinner on 25 December. But serving menu items that satisfy many diets without sacrificing flavour is the way to go. Why not serve Ital or Thai food (dishes are dairy-free) or host a vegetar ian Indian Christmas feast (many of these dishes are gluten-free)?

Create. Serve sugar-free or no-sugar-added desserts. Many Caribbean families have diabetic members and it’s about time we include them in the final course of the evening. After all, most of us have the urge for something sweet after dinner, but no sense in losing a foot over a slice of pound cake. Suitable items include in-season fruit and cakes baked with honey or coco nut sugar. If you’re a skilled baker, try sweet potato pudding/pone or conkie/ dukunoo which can rely on the natural sweetness of their ingredients.

And finally…

Respect. Let folks know they should be on their best behaviour. No need to comment on people’s weight or what they are not eating or drink ing. Set boundaries. Maybe it’s time we banish that inappropriate uncle to the back verandah under the watchful eye of your no-nonsense cousin.

Caribbean festivities, especially holiday feasts, aren’t without their pickles, and our culture bonds by eating together — it is deeply symbolic. Most tradi tions are rooted in food rituals, and there are numerous physical and spiritual benefits of eating together. But being fed isn’t the same as being nourished. And there’s immense value in listening, understanding, and respecting those whose needs and experiences differ from our own.

Our history is rooted in listening; after all, griots were revered walking encyclopaedias. Holiday food rituals are important, but human connected ness matters most. Listening builds trust, deepens relationships, and helps eliminate conflict. And according to acclaimed Jamaican-American poet Claudia Rankine, we can “listen someone back to life.” n

The Caribbean is full of words with fascinating origins and histories — including those for our favourite festive foods. University of the West Indies linguistics lecturer Dr Jo-Anne S Ferreira shares some insights, and why what some consider linguistic “corruptions” are really preservations and innovations — as told to Caroline Taylor

Jamaica, Antigua & Barbuda, and other parts of the region.

Ponche crema is a drink that comes from Venezuela — where it is said to have been created in 1871 by Eliodoro gonzález P.

At

We can probably trace the history of food names like guava, pawpaw/papaya, cocoa as among the earliest that the Spanish encountered in the Americas and spread to their fellow Western Europeans. Others like banana came from West Africa; while mango came from India (Tamil and other languages).

French Creole heritage unites Dominica, grenada, St Lucia, Trinidad & Tobago, Martinique, guadeloupe, French guiana, Haiti, and parts of Brazil, Venezuela and the United States; while Bhoj puri/Hindustani heritage unites guyana, Suriname, and Trinidad. So there’s plenty variation in our words for foods (and flora).

garlic pork — popular at Christmas — was called calvinad age or carvindage in Trinidad, or vinadosh in St Vincent & the grenadines, coming from carne vinha d’alhos of Madeira.

Pastelle — another Christmas favourite — is from pastel (used across the Spanish-speaking Caribbean) but spelt a Frenchified way in Trinidad & Tobago.

Paime — an ever-popular popular dessert — is another Patois word, probably meaning corn bread, and also known as conkie, blue drawers, dukanoo (an Akan word), tie-a-leaf in Barbados,

Like many other Spanish and other names and words in Trini dad (like bachaco, planazo, sapato, caimito and the pronunciations of San Juan and Farfán), ponche crema became French Creolised or Patois-ified to punch a creme ( ponch a krèm or punch a krem in the formal Patois spelling).

Those with Spanish influence or background will say ponche crema, and those with more French Creole/Patois exposure will say punch a creme (with perhaps an anglicised pronunciation).

Some want to spell it as French as possible (with accents) or English, even though ponche crema is Spanish. There is also ti punch in the French West Indies, and ti ponch in Haiti — but a different drink.

I can’t say where ponche de creme has come from other than someone trying to use some knowledge of non-native French and Spanish.

The bottom line is that language contact causes language change and the development of lexicon. All these words — barbe cue, canoe, cassava, cay, guava, hammock, hurricane, mangrove, potato, savannah and tobacco — came into English via Spanish during colonisation, and are respected because these are useful names for concepts that mostly didn’t exist in Europe.

Yet we have English words, straight from England — like hoss, mines, onliest, to carry (someone), to full, to grater (to grate), to learn (to teach), to out (a light), to loss, to leff (to leave), and to study (to ponder) — which are considered lowly, archaic/obsolete and/or regional elsewhere in the English-speaking world.

We think those are Caribbean “corruptions”. We preserve, innovate and borrow, like all language users. I guess it depends on who is doing the borrowing... n

Through tufts of clouds, Barbados begins to come into view — one of my favourite sights in the world. The corners of my mouth gleefully stretch almost to my ears, savouring each moment as the aircraft slowly descends. I see azure waters, fringed with white foam, lapping against the golden sand. I see familiar places and think about the memories made on my last trip, while imagining new ones. It seems like the plane will touch the sea but no, this is a gallery view of smiling sea bathers waving their hands enthusiastically welcoming us to their beloved island. I glance at the other passengers, wondering if I’m the only one whose heart is skipping a beat.

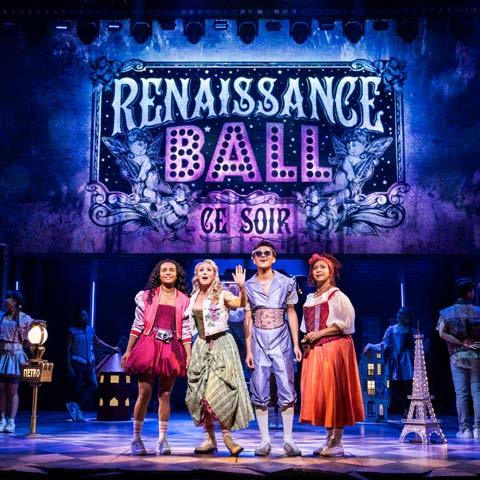

Shelly-Ann InnissShe was a household name in her native Trinidad, with hit songs like “I will (always be there for you)”. Since then, she’s spent two decades delighting theatre audiences in the West End and across Great Britain. And now, she makes her Broadway debut. Caroline Taylor learns more

Photography by Mathew Murphy courtesy Grapevine PR nyIt’swhat the Independent called “a gloriously silly, unexpectedly poignant” jukebox musical that — using the music of grammy-winning songwrit er and super-producer Max Martin — envisions a world in which Shakespeare’s Juliet actu ally survived. Shakespeare’s wife Anne Hathaway has insisted on a rewrite, you see.

The result is & Juliet , and among its stellar cast is a talent many from Trinidad & Tobago are sure to remember — former radio personality, calypso and soca singer Melanie La Barrie (née Hudson).

La Barrie originated the role of Angelique or Nurse in the West End production of & Juliet in 2019, and now makes her Broadway debut as the show — which began pre views last month — prepares to open on 17 November at New York’s Stephen Sondheim Theatre.

Achild star in Trinidad, La Barrie has been in the public eye for 40 years. Her 1990 song “I’ll always (be there for you)” — co-written by calypso legend David Rudder — received heavy rotation both on radio and television, with its Banyanproduced music video.

“My first foray onto the stage was at the age of eight, as a calypsonian. I sang the music of Carnival, hung out at the mas

camps, played in strips of fabric, glitter and glue,” she said in 2015, ahead of the premiere of Trinidad-born playwright Mustapha Matura’s Play Mas at London’s Orange Tree Theatre.

“I have had my music played by a few 100-strong steel orches tras and performed in front of audiences of tens of thousands all waving flags and partying,” she remembers. “I have sung for eight hours on a music truck accompany ing the costumed revellers. Trinidad Carnival is in my blood, as much a part of my genetic make-up as the language.”

Her first major foray into theatre was in Trinidad: a 1998 staging of the play Clear Water by Trinidad-born playwright Christopher Rodriguez. She was 24 at the time, and it was then she realised just how good she was at comedy.

“For a long time I wanted to be a serious actor, but I do comedy better. It’s more fun!” she told Official London Theatre in 2008, as she took on one of musical theatre’s most treasured comedic roles — Madame Thénardier in Les Misérables

Her life would change when London’s Oval House Theatre sought to mount a production of Clear Water in 2000, with a mix of Trinidadian and British talent — and in which she and her then-husband were cast. It was, in effect, a rare Trinidad to London theatre transfer.

What began as a three-month stint in the United Kingdom for the production became a permanent move to London, a place she’s described as her “spiritual home” full of rich cultural life, myriad professional opportunities…and refreshing anonymity.

“You can entertain over 1,000 people nightly, get cheered mightily at the curtain call, then take the train home with the very audience who appreciated you,” she says. “You can even eavesdrop while they talk about you, even as you are sitting right there. I’ve heard many interesting things about what people think of me on the train!”

She’s entertained a great number of audience members since moving to the UK, amassing a slew of impressive theatre credits. She’s originated roles in hits like Matilda , Mary Pop pins, & Juliet, and Daddy Cool (she can be heard on the original London cast recordings for all, as well as the Broadway equivalent for & Juliet ); and appeared in iconic productions on and off the West End — from Les Misérables and Wicked, to Fiddler on the Roof, and Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom . She’s also had television roles in the long-running Casualty and EastEnders series.

In some of those performances, she’s been able to draw heav ily on her Caribbean roots, as in the role of Mama Euralie in Once on this Island, a musical inspired by the novel My Love, My Love: or The Peasant Girl — a Caribbean-set retelling of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, and written by TrinidadianAmerican author Rosa guy.

“I rely heavily on my own Caribbean-ness to fuel my per formance,” she told WhatsOnStage during the show’s 2009 run. “And the beautiful thing about theatre is that we can introduce the unfamiliar to a wider audience.”

She has also been able to bring her West Indian roots to roles like Mrs Corry in Mary Poppins , and her current role as Angelique

in & Juliet. Both characters have infectiously familiar Caribbean accents, cadences, and humour.

Irresistible comic timing has become one of La Barrie’s trademarks, along with powerful vocals and commanding stage presence. And she gets to show them all off to full advantage in & Juliet.

The show’s score features many of Max Martin’s hits — ones he’s worked on for stars like Britney Spears, Kelly Clarkson, Bon Jovi, Katy Perry, Justin Timberlake, Demi Lovato, the Weeknd, Ariana grande, the Backstreet Boys, and others.

La Barrie’s shining moments come with renditions of bops like Spears’ “Oops I did it again”, Lovato’s “Confident”, Robyn’s “Show me love”, and Pink’s “F---in’ Perfect” — in turns playful, profound, and powerful.

Much like she did in Clear Water, La Barrie now makes the transfer across the ocean — in another role she originated — as new North American opportunities await.

& Juliet completed a pre-Broadway run in Toronto last sum mer — picking up eight Dora award nominations, including one for La Barrie in the category of Best Performance in a Featured Role (Angelique had also earned her a 2019 WhatsOnStage Awards nod for Best Supporting Actress in a Musical).

“While I’ve made several original West End shows, many of which transferred to Broadway, I never in my wildest imagination thought that I would one day be here,” she posted to Instagram in late August as she began rehearsals in New York. “I cried, at every step I cried. So grateful for the opportunity. I promise to always do my very best and to work hard. That’s the very least I can do. Broadway debut, here I come!”

And it seems certain New York audiences are set to fall in love with La Barrie — just as Trinbagonian, British, and Canadian audiences did before them. n

She has been able to bring her West Indian roots to roles like Mrs Corry in Mary Poppins, and her current role as Angelique in & Juliet

La Soye field sessions were undertaken by

and

here, the team has

a

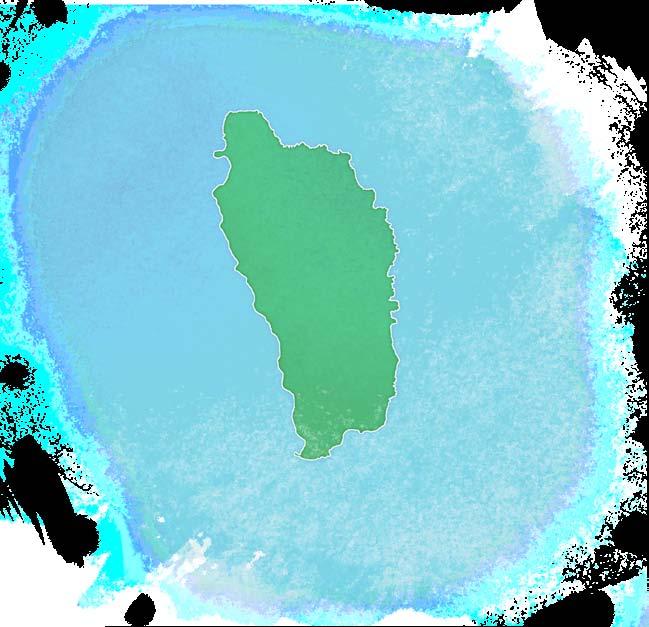

Archaeologists in Dominica are unearthing an abandoned town — once home to the Kalinago, and possibly the island’s first European settlement. Their fascinating findings may fundamentally change our understanding of Dominica’s history, explains Paul Crask

Several months after hurricane Maria ravaged Dominica in 2017, local historian Dr Lennox Honychurch was strolling along the beach near his home at Woodford Hill, in the northeast of the island, when he made a tantalising discovery.

Beach erosion, caused by high tidal surges, had exposed curious pottery frag ments. Intriguingly, they appeared to be from different cultures and time periods. Some of the ceramics were Amerindian — possibly Cayo — and others European, possibly French or Dutch.

Honychurch contacted Mark Hauser, Associate Professor of Anthropology at Northwestern University; he had been visiting Dominica for around 10 years on

various field seasons to study colonial estate sites at Bois Cotlette, Sugarloaf, and Morne Patates.

Keen to understand the effects of the hurricane on Dominica’s historical legacies, he was more than happy to investigate Honychurch’s discovery.

What Hauser learned on that first exploratory trip was enough for him to organise a small team of experts to return to Dominica to examine the location in more detail.

The area first appears on an anony mous map of 1760 as a settlement called La Soye, but no known historical records shed any light on who may have lived there, for how long, why it was so named (“la soye” is French for “silk”), or why it was eventually abandoned.

With its mountainous terrain, thick forest, and occupation by a formidable population of Kalinago, Dominica was the last island in the eastern Caribbean to be colonised by Europeans seeking their fortunes; they’d regarded it as too inaccessible and inhospitable.

The first recorded European settle ment was in the early 1700s, when French lumbermen from Martinique arrived and set up camp on the south coast in an area now known as grand Bay. given the lack of information about the La Soye commu nity, the only way to understand its story would be through archaeology.

The first test excavation holes at the La Soye site on Woodford Hill beach certainly caused a stir. Not really knowing what they might find, Hauser’s team unearthed a wealth of diverse artefacts from a very small sample area.

They included glassware, clay pipes, ceramics of Amerindian and European legacy, trade items such as trinkets and beads, ironware such as nails and a tool for making musket shot, and even a perfect little sewing thimble. It felt as if they had chanced on a storeroom or warehouse, but what real meaning could be learned from these relics?

The first real surprise was the date. The discovery of scores of Dutch Delft blue pottery fragments suggested the early 1600s — a century before the first records of any kind of European occupa tion of Dominica.

This was later verified by carbon dating charcoal fragments (related to cooking or blacksmithing) from the same soil strata. The trinkets, beads, and Cayo pottery fragments suggested contact, interaction, and probably trade between the island’s Indigenous people and the newcomers.

We know that expeditions had called at the island during this period. Sir Fran cis Drake’s logs state that, with the help of Kalinago, he had provisioned his ship in Prince Rupert’s Bay on the island’s west

coast as early as 1565. It’s also known that, for a time, Europeans traded with the Kalinago of other eastern Caribbean islands, seeking tobacco and cotton — valuable commodities in Europe.

This was an era and a region of fortune seekers, pirates, and privateers. It was also a time when the indigenous Kalinago — and the island resources they had long depended upon — came under serious threat.

There’s evidence of numerous Kali nago settlements along Dominica’s northeastern coastline, while the island of Marie- galante — an important foraging ground that would soon be taken by the French — is located directly across the water. Should La Soye reveal itself as an early trading outpost, it would be a new entry in Dominica’s historical record.

With his interest piqued, Hauser and his colleagues — including Diane Wall man, Associate Professor of Anthropol ogy at the University of South Florida; and Douglas Armstrong, Professor of Anthropology at Syracuse University — managed to secure funding from the National g eographic Society and the National Science Foundation for addi tional studies (interrupted only by the pandemic) to further develop the curious story of La Soye.

The latest, and penultimate, field season was in July 2022. Several special ist teams collaborated, blending different areas of expertise and technologies — including soil and botanical sampling, lidar, and magnetronomy.

This resulted in a rough map of the coastal land that suggested around a dozen stone buildings and a couple of stone roads had once existed there.

Hauser speculated that the settlement may well have extended from the beach into the bay, with rising sea levels perhaps eventually covering as much as half of it.

With a theoretical plan of the settle ment on their laptops, the team set about excavating small test pits to verify what the technology was indicating — a pro cedure that’s known as ground truthing.

The excavations did indeed reveal the stone foundations of buildings and road, but they also surprised the team with evi dence of wooden post holes — something the technology didn’t capture. Wooden post holes would have supported framed structures, possibly belonging to an earlier Kalinago presence. One building on top of another suggested succession or displacement.

Should La Soye reveal itself as an early trading outpost, it would be a new entry in Dominica’s historical recordLa Soye Portsmouth Roseau D o MI n ICA 17th and 18th century european pottery recovered from the site

When the team returns in the summer of 2023, it will be with the aim of excavating as much of the hidden village as possible. There will also be further efforts to understand the significance of Kalinago material culture as well as the possibility of an even earlier Amerindian presence.

So far, the story of La Soye seems to begin with an Amerindian settlement that was certainly Kalinago but may have existed even earlier. In the late 1500s and early 1600s, European vessels arrived in the bay — probably at the end of their transatlantic voyages, perhaps to undertake essential careenage and provisioning.

We can imagine first contact with the island’s indigenous Kalinago may have included basic trade for fresh water and food that developed into a more com mercial (though unrecorded) exchange dealing in tobacco and cotton.

At some point, that outpost became a village, and that village eventually displaced the Indigenous people who had been there before. (It’s thought by

some experts that the Kalinago were already beginning to move to higher ground from coastal margins.) And then at an unknown later date, the village was entirely abandoned.

Although the picture is becoming clearer, many questions remain unan swered. Was La Soye the domain of pirates and privateers, or perhaps the

trading outpost of a French settlement in nearby Marie- galante? How well did the European settlers and the Kalinago engage with each other? Why the name La Soye? And what predicament resulted in its abandonment?

With any luck, a final field season will shed more light on this enigmatic town beneath the sand. n

Andre Bagoo introduces us to the awardwinning Guyanese-British contemporary artist Hew Locke, whose subversive and provocative work — including a commission currently on display at the Tate Britain — is richly infused with Caribbean cultural influences

As you enter the room, you are confronted by them. At first glance, they seem life-sized, these four horsemen. But then you realise they are miniatures that have been placed on pedestals. Immediately, through this trick of scale and this gesture of placement, Hew Locke invites us to question the idea of what is “monumental”. Who gets to be immortalised? Which figures make it onto the plinth? Why?

But The Ambassadors (2021) is also a series of objects very much concerned with other subversions. Each is covered with materials, colours, and textures that both reinforce and undercut their connotations of power.

They are laden with strings of fake pearls, Mardi gras beads, plastic flowers, mesh, doilies, two-dimensional sculptural forms, wooden boxes, and tattered regalia. Toy-like and monumental, earthly and mystical, they seem to gallop right out of the febrile imagination of Wilson Harris — a writer who, like Locke, voy aged between guyana and Britain.

“They come from some empire, some imaginary state,” Locke says of his horsemen in a note in a room at London’s Hayward gallery, where The Ambassadors was on display last summer.

The series, among the artist’s most recently shown pieces in the United Kingdom, was part of In the Black Fantastic , an Afrofu turist exhibition curated by Ekow Eshun, which also included British artist Chris Ofili and American artist Kara Walker.

Locke was born in Edinburgh, Scotland in 1959, the eldest son of guyanese sculptor Donald Locke and British painter Leila Locke (née Chaplin). The family moved to guyana by boat when he was five, triggering Locke’s enduring interest in the relics of voyaging, colonialism, and nationhood.

As a child living in the tropics — that inspired the yellow ochre tones in his mother’s paintings and the modernist forms of his father’s pieces — he witnessed guyana’s independence in 1966.

“I saw the flag being designed,” Locke recently recalled. “We were allowed to stay up at night to watch the handover from the British to the guyanese government. And that had quite an impact on me. It gave me a lifelong interest in how nations are formed and what they choose as their symbols of nationhood.”

After the rise of Forbes Burnham, the family moved back to Britain in 1980, during Margaret Thatcher’s reign. But Locke did not leave behind his roving spirit.

That spirit — which this year has garnered wider attention in the UK and internationally — is infused with the charge of Caribbean cultural influences, arguably including Trinidad’s

theatrical Carnival, guyana’s colourful Mashramani, and The Bahamas’ rhythmic Junkanoo.

In the same room of the Hayward gallery this summer was a series of older, life-sized photographs by Locke called How

Do You Want Me? The artist is featured in each image, but is — deliberately — barely visible: he is overladen with a profuse cornucopia of objects.

In “Saturn” (2007), he stands in front of a famous silhouette of the late Queen Elizabeth II. He holds a royal staff while being completely encumbered by silk flowers, dollies, plastic mangoes, toy crowns, ribbons, and beads.

Locke began the series wishing to mock the appetite of the met ropolitan art world for the latest “exotic” thing. But the pageantry here also pokes fun at the history of portraiture more generally, particularly its association with the wealthy and the powerful.

While Locke is somewhat agnostic when it comes to the institution of the monarchy (“my political position is neither republican nor monarchist”, he once declared) he nevertheless brings a tongue-in-cheek sensibility to ideas of royalty — a sensibility that is straight out of Caribbean ole mas and picong.

“It’s all about messing around with all this cheap tat but trying to elevate it to something much higher,” Locke says. “I make work in which there is a lot of difficulty … maybe defiance, maybe conflict.”

In these images, which in a way refract and echo The Ambas sadors , the ludicrousness of claims to power is laid bare, while that same power is re-apportioned elsewhere — and, in the process, rehabilitated.

Scale is crucial in Locke’s work. The Procession — a commission currently on display in London at the Tate Britain — feels at once epic and intimate. A parade of colourful costumed figures stretches before us through a grand gallery space. Some are life-sized, but some seem diminutive: possibly children or, as in The Ambassadors, miniatures.

g olden and flamboyant materials rub against each other in a collage of rough textures, flags, and strips of custom-made fabric — some of which has been hand painted by the artist. The Trinidadian figure of the Pierrot g renade — a traditional Carnival character who spouts verse and wears colourful strips of cloth — looms large.

But whereas the Pierrot speaks, these figures are silent. Whereas the Pierrot wields a rod and even dances, these figures — as much as they suggest movement — are still, much like the oddly impassive figures of The Kingdom of the Bling, shown at London’s Institute of International Visual Arts in 2008.

The effect creates a kind of productive claustrophobia. The artist has crowded the space but, in the process, invites us to have intimate engagements in a journey from one point to the next.

“I think of The Procession as an epic poem,” Locke says. “How this piece is perceived over time will change and evolve.”

That sense of evolution is key to Foreign Exchange, a tempo rary installation at Birmingham’s Victoria Square also staged earlier this year, coinciding with the city’s hosting of the Com monwealth games.

In a previous show — Here’s the Thing, a 2019 retrospec tive held at Birmingham’s Ikon gallery — Locke hung several miniature boats in space alongside busts of Queen Elizabeth II. But here, a statue of Queen Victoria is encased in a single boat sculpture. And that boat is filled with several replicas of the Victoria statue. The move suggests the multiple understandings of history that emerge with different perspectives.

“It’s about complexity, it’s about the messiness of history,” Locke says.

And yet the stasis of both works raises the idea of something trapped in a moment in time: a calm before the storm. Exuber ance and optimism meet fear and stuntedness. Each piece in the procession of the artist’s increasingly ambitious output may well be a portrait of the yearning of the artist — of the artist himself.

“It’s about hope,” Locke says of what he is doing. “It is a posi tive movement of people. They are moving into another life.” n

Locke began the series wishing to mock the appetite of the metropolitan art world for the latest “exotic” thingHew

In classical ballet, there’s a position called attitude. The dancer stands on one leg with the other lifted — either in front or behind, slightly bent at the knee. It’s a pose dancer and educator gina Mayers holds with incredible poise — one that belies the challenges of balancing a dynamic dance career and living with Multiple Sclerosis (MS).

“Dancing defines my spiritual being. It’s physi cal, it’s complicated, it brings great joy,” says g ina. “It allows me to be vulnerable in a way that is impossible in everyday life. I can be myself without fear of self-judgement.”

gina started ballet classes at age six in her homeland, Barbados. That joyful journey was tragically interrupted by her father’s sudden death five years later.

“When my father died, we were unable to afford dance classes, as we only had one income,” she remembers. It forced her mother Ingrid Mayers to

make the excruciating decision for gina and her sister to stop training.

It was a massive blow, as gina was already struggling to work through her father’s passing. “While everyone cried during the grieving process, gina was numb — unable to cry,” says Ingrid.

A year later, g ina — a “daddy’s girl” — still hadn’t shed a single tear. She refused to talk about her father’s passing. So Ingrid tried one more thing: she re-enrolled g ina at Dance Place under a scholarship provided by then principal Elizabeth Bayley.

Understandably, gina struggled with technique during her first year back, leading them to defer her Royal Academy of Dance (RAD) exam. “When that happened, a fire in me ignited,” she says with bright eyes. “I got a copy of the recorded music for grade 4, and every night I practised the entire class on the grass outside with my stereo. My barre was my patio ledge.”

For dancer and educator

Gina Mayers, writes shelly-Ann Inniss, dance has been a Godsend. It has seen her through devastating personal loss and a Multiple Sclerosis diagnosis, while igniting a passion that’s taken her from stages in her homeland of Barbados to New York and beyondPhotography courtesy Gina Mayers

It was a turning point for her. “As I was building my artistic performance and technique, I didn’t realise dance was changing me,” she says.

One evening when she got home after class, she finally began to cry. “Dance allowed me to tap into my deepest feelings of grief … it was a form of therapy that didn’t require talking.”

One year later, gina entered the grade 4 RAD exam, earning distinctions at that and each exam through grade 8. She made a lasting impression on Bayley and the current Dance Place principal Adonia Evelyn, as well as on her fellow alumnae Simonne Cumberbatch and Dr Tamica Lawrence. They describe g ina as “fearless, determined, dream-seeking and deeply caring”.

It was no surprise gina would pursue dance professionally. But no one anticipated her journey. In 2009, when she was finishing her BFA in Creative Arts: Dance & Film at the University of the West Indies, Cave Hill, she experienced blurred vision and memory loss. She was 23 at the time.

She was admitted to the hospital after a visit to an eye specialist and a neurologist. Her vision had deteriorated rapidly, leading to blindness in one eye. The diagnosis? Optic Neuritis. Steroids helped her regain most of her sight, but it never fully returned.

MRI scans showed lesions around her brain, and doctors told her she was high risk for MS. She experienced crippling nerve pain, severe memory loss, and consistent exhaustion — but wasn’t prescribed any medication.

“You’re always hurting with body pain. Your nerves are over-firing, so there is electric pain radiating down your arms,” says gina. “Stiff neck, depression, lack of balance and hand-eye coordi nation are also symptoms.”

She saw two more neurologists, receiving inconclusive results each time. So she took a leap of faith — enrolling at The Ailey School at the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre in New York.

“I figured if this will continuously get worse, I might as well do what I truly want to do on a larger scale,” she says.

Over the years, gina has been able to perform at numerous festivals and events, in music videos, film and television, and across a range of styles — jazz, ballet, West African, modern and contemporary.

She danced and choreographed a solo for the first annual Summer Bricolage in New York (2017), executive produced by renowned Broadway star and actor Taye Diggs. Ten years earlier, she’d performed at the Barbados Music Awards, sharing the stage with acts like Rihanna. She also repre

sents Barbados as an official US-based Cultural Ambassador in Dance.

But it hasn’t always been an easy road. In 2014, she finally received an MS diagnosis — five years after her first symptoms. The trajectory of her promising dance career completely changed.

With her hand-eye coordination affected, turns, pirouettes, and even balancing on one leg some times became nearly impossible. At one point, she experienced numbness in both legs and had to ask her friend if her toes were pointing. Short term memory difficulties made retaining choreography a challenge; she now relies heavily on muscle memory.

“I missed performances and rehearsals because I was ill or blind, and was terminated because I was constantly sick,” she remembers.

opposite page gina performs in “Season of the woman” with the Asha dance Company, new york

Below “All that Jazz” performance at the dance place Barbados’ Just Dance show

Early treatments also caused a range of side effects, including depression, and steroid injec tions caused significant weight gain. “Dance being an aesthetic sport, [it] caused me to be unconsid ered for roles because I no longer had the ideal body type,” she says.

But she’s now on a new course of medication and much happier with the results.

“With dance, [there’s also] a way in which my aesthetic — being a dark-skinned Black woman — would impact roles I had the technical and artistic ability to get,” she says. “Once I found where I fit in, I was embraced there,” she says.

In 2019, gina was handpicked as a choreographer and teacher at the prestigious Dwana Smallwood Performing Arts Center, whose founder Dwana Smallwood was proclaimed “one of the greatest modern dancers” by Vogue. gina was also a teaching assistant at The Ailey School and a dance specialist and choreographer with the South Asian Youth Action (SAYA) dance programme, among others.

“My favourite part is performing in large venues and the reactions from the audience — specifically children,” she says.

In 2017, gina developed the movement com ponent of the Shadow Box Theatre’s One Foot in One Foot Out curriculum workshop at Children of Promise — an organisation that nurtures the children of incarcerated parents. She also was

commissioned to write and develop a dance syl labus based on the New York Times ’ acclaimed The Earth and Me musical.

gina’s positive attitude — choosing to live life passionately, and without regrets — touches the children she teaches, and is palpable in all her interactions. “Bite into life, take everything you can from it — the manna, the nectar. Live in the present!” she urges.

Every day, gina takes inspiration from trailblaz ers like Aesha Ash, Lauren Anderson, Hope Boykin, Misty Copeland, and the Trinidad-born Pearl Pri mus — all of whom overcame tremendous adver sity, breaking barriers for Black women in dance and contributing immeasurably to the artform.

Their achievements inspire gina to keep trying — working every day to do what brings her joy, and to impact the lives of young dancers for the better. And always, with attitude.

MS is one of the most common causes of disability in adults in their 20s, 30s, and 40s. It is two to three times more common in women than men.

“Dance allowed me to tap into my deepest feelings of grief … it was a form of therapy that didn’t require talking.”gina dances on the Chamberlain Bridge in Bridgetown, as part of the Bajan Ballerina project photo Series by Jared niles-Morris

FVisitors to Tobago often stay in its beautiful southwest, missing the opportunity to discover the charms of its northern towns, including Charlotteville. The area is part of the Northeast Tobago Biosphere Reserve, under the UNESCO Man & the Biosphere Programme. Aisha sylvester takes us off the beaten path to two of its most beautiful and unforgettable beaches

I’ve accumulated many memorable moments over the years in Tobago. One of my top highlights is spending the day serenely ensconced in the scenic solitude of Charlotteville.

Quite possibly my favourite village on the island, this sleepy hamlet serves up some of the most idyllic stretches of coastline, and one day we visited two of them — Lovers’ Bay and Pirate’s Bay.

We cruised effortlessly across blue waters, past caves, over reefs, and around many dramatic rock formations. With every passing second, I felt more in awe of Tobago’s raw, unadulterated beauty.

Charlotteville seemed to be showing off that day because the water at Lovers’ Bay was the clearest and calmest I’d ever seen it. Dubbed Pink Sand Beach due to the pinkish hue the sand takes on when wet, the tiny beach also presented many different spots for photo ops. I split my time doing two of my favourite things: swimming and snap ping pics.

We then moved on to Pirate’s Bay, where we set up camp for the rest of the day. Literally. We pitched a spacious tent and created our own little comfort zone in an alcove at the far end of the beach.

From within that clear-topped cocoon, we could see the sky up above and hear the waves just

outside. And while we shared the beach with a few other people that day, for the most part, it felt like we were the only ones there.

I’ve had more beach days than I can count and logged more countryside excursions that I can recall, but this day was by far one of the most perfect I’ve spent in Tobago. n

Aisha is obsessed with Trinidad Carnival, lives to travel, loves to write and dabbles in amateur photography. She shares her travel insights, tips and tricks on her blog islandgirlintransit.com

Boats on the beach at pirate’s Bay, tobago opposite page Aerial view of Charlotteville, part of the northeast tobago Biosphere Reserve

threat.

Anyone regularly watch ing or reading news reports about the impact of the climate crisis on the Carib bean would have heard those words ad nauseam.

But with the release of the latest Inter governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report in the last 18 months, gov ernment leaders, activists and scientists in the region have even more reason to use those words.

The report warned that the continued increase in greenhouse gas emissions means that if urgent steps aren’t taken, global warming will go far beyond the goals set in the 2015 Paris Agreement

— causing devastating natural disasters, accelerated degradation of the environ ment, and widespread loss of life and livelihoods.

Small island developing states (SIDS) like those in the Caribbean are among the most vulnerable because of our size, income levels, and location.

Following disappointment with the out come of COP26 in glasgow (the last inter national meeting on climate change) and the findings of the IPCC report, Caribbean leaders organised a meeting in advance of COP27 (6–18 November in Egypt).

An initiative of Bahamian prime min ister Phillip Davis, the meeting was the first of its kind — and one Caricom hopes to make a regular part of its schedule.

Leaders, representatives of international organisations, and other stakeholders met for two days in Nassau last August.

“The time for action is now. The time for talking needs to cease,” Davis said at a press briefing at the start of the meeting.

The Bahamas is still recovering from Hurricane Dorian, one of the most destruc tive storms ever to hit the region. Storms of increased intensity are one of the climate crisis’ most significant impacts.

The Office of the Prime Minister’s YouTube channel uploaded a video — Upclose: The Courage to Rebuild — a few weeks after the meeting to mark Dorian’s third anniversary. It showed a woman, Baronette Thomas, weeping as she vis ited where the home she shared with her husband and three children once stood.

All four of them were killed, along with 74 other people across The Bahamas. Hundreds more went missing. Tens of thousands lost homes, businesses, or jobs. The storm caused almost US$4 billion in damage — or about a quarter of The Bahamas’ gDP.

“Dorian ruined my life,” said Thomas.

As global decision-makers gather for COP27 — with the planet now on the brink of several climate tipping points — Erline Andrews explains why Caribbean leaders are taking a much tougher stance on the crisis to compel critical action

The impact of Dorian and other storms likely contributed to the tougher stance Caribbean leaders are now adopting.

“Regrettably, there has been too little attention paid to planet, to people, and to poverty by those countries who have been motivated by profit,” said Barbadian prime minister Mia Mottley at the meeting’s clos ing press briefing. “It’s time for the world to stand up and say enough is enough.”

Barbados has been trying to cope with persistent drought, a longstanding problem made worse by climate break down. In 2019, the island experienced its most severe drought in decades. Drought reduces farm yields and occasionally taps run dry in parts of the island.

Dominican president Roosevelt Skerrit said he had wondered if Caricom should boycott the COP meetings to show their dissatisfaction with how little the gather ings benefited the region. Eventually he concluded, “We have to go and let our voices be heard. Because our forebears who fought for independence and eman cipation — had they given up, where

would we be today? We have a duty and an obligation to fight for the survival of future generations.”

In 2017, the category five Hurricane Maria flattened much of Dominica. The losses amounted to more than 225% of the country’s gDP. Skerrit has since vowed to make the island “hurricaneproof” by 2030.

g renadian prime minister Dickon Mitchell seemed to take the position of gaston Browne — Antigua & Barbuda’s prime minister and former Caricom chair — that small islands should explore the possibility of climate change lawsuits.

“I think the issue of climate change

has gone beyond that of a moral issue,” said Mitchell. “It’s a justiciable issue. I think that as islands that have borne the brunt of the proven loss and damage aris ing from the greenhouse gases, we are entitled to compensation.”

He spoke of plans to build a wall to protect the Carenage, a 300-year-old waterfront area on the outskirts of St g eorge’s that is popular with tourists, and being encroached on as sea levels rise. Eventually he hopes to make the capital a “climate smart” city. All of this, of course, requires immense amounts of money.

Caricom’s focus at COP27 and beyond is getting industrialised countries to live up to their Paris Agreement commitment to give US$100 billion a year to countries affected by the climate crisis — but who had little to do with causing it.

One idea discussed at the meeting was a loss and damage fund maintained using 1% or more of the revenues derived from the sale of fossil fuels, the burning of which is one of the main sources of greenhouse gas emissions.

To make accessing loans and other funding easier, Davis is asking for a change in how national income is mea sured. The Bahamas’s gDP per capita has been deemed too high to qualify for certain aid facilities. Davis is asking that a vulnerability index be used instead of gDP per capita in determining a country’s need for financial assistance.

Caricom’s focus at COP27 and beyond is getting industrialised countries to live up to their Paris Agreement commitment to give US$100 billion a year to countries affected by the climate crisis — but who had little to do with causing it

need to pay attention to climate change. Because of climate change you may not have any islands left to even think about tourism,” she said.

climate scientist Adelle Thomas said Caricom countries have been pushing for these things for a long time, but have been especially focused after COP26.

“Since COP26, Caribbean countries have really been proactive in coming up with what they want from the interna tional community as it relates to climate change,” she said.

Thomas has been part of the move ment to make the climate change-induced loss and damage sustained by vulnerable countries a bigger part of the conversation.

“Since the development of the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) back in 1992, the primary focus has been on mitigation. What can we do to reduce greenhouse gas emissions?” Thomas says.

“As small island countries, we in the Caribbean emit less than 1% of those global emissions,” she continued. “What we really need to be focussing on is how we deal with the impacts of climate change. And that’s adaptation. If we expe rience those impacts, how do we recover from them — and that’s loss and damage.”

Thomas works with the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) and the Santiago Network, which was established in 2019 by the UNFCCC — the body behind the COP meetings and assessment

reports — to give countries technical support about loss and damage. She was a lead author in the IPCC report.

She said Caricom has a number of obstacles to getting its demands met.

“We do OK at saying this hurricane caused this much damage. What we need to do more of is assessing the other effects, particularly slow onset,” she said.

“We know that sea levels are rising but we’re not really tracking where we’re experiencing coastal erosion, where are we seeing loss of land,’’ she continued. “One of the challenges that we then face at the international level is that without that assessment of all of the impacts of climate change that we are experiencing now, it’s difficult to say we need this much money to deal with it,” she said.

At the COP meetings, the delega tions from Caricom countries are small compared to those of the bigger countries — two or three people compared to hundreds.

“We are spread very thin in the negotiating rooms. This is why AOSIS is so important. It allows the voices of small islands to be heard in the different negotiating rooms,” she said.

At graduate school, Thomas intended to specialise in sustainable tourism but was persuaded to choose climate change.

“My dissertation advisor said you

Like most people in The Bahamas, she has personal experience with the effects of hurricanes. “My earliest recollection is Hurricane Andrew in 1992, having to seek shelter in our bathroom. Because that was the one room that had concrete all around it,” she said.

Her grandparents’ home was com pletely destroyed by Dorian. Friends and other family members also lost their homes. “So it’s a very personal connec tion with climate change impacts and with loss and damage. When you are experiencing it yourself you have that much more of a commitment to make sure that this is dealt with,” she said.

She said there’s reason for optimism about the Caribbean’s prospects in deal ing with climate change. “When I came back to The Bahamas in 2012 after finish ing my studies, people were still arguing with me as to whether or not climate change was real. I was just flabbergasted by that. Then 10 years later, people are like, ‘This is real. This is a huge threat for us. And we need to do something about it.’

“There has been progress. Even though it’s been slow,” she said. “We can’t give up. It’s not an option to give up.”

Her words echoed a comment made by Prime Minister Mitchell at the press brief ing in August. He and the other leaders at the meeting saw it as a positive sign that g renadian Simon Stiell was appointed executive secretary of the UNFCCC the day before the meeting started.