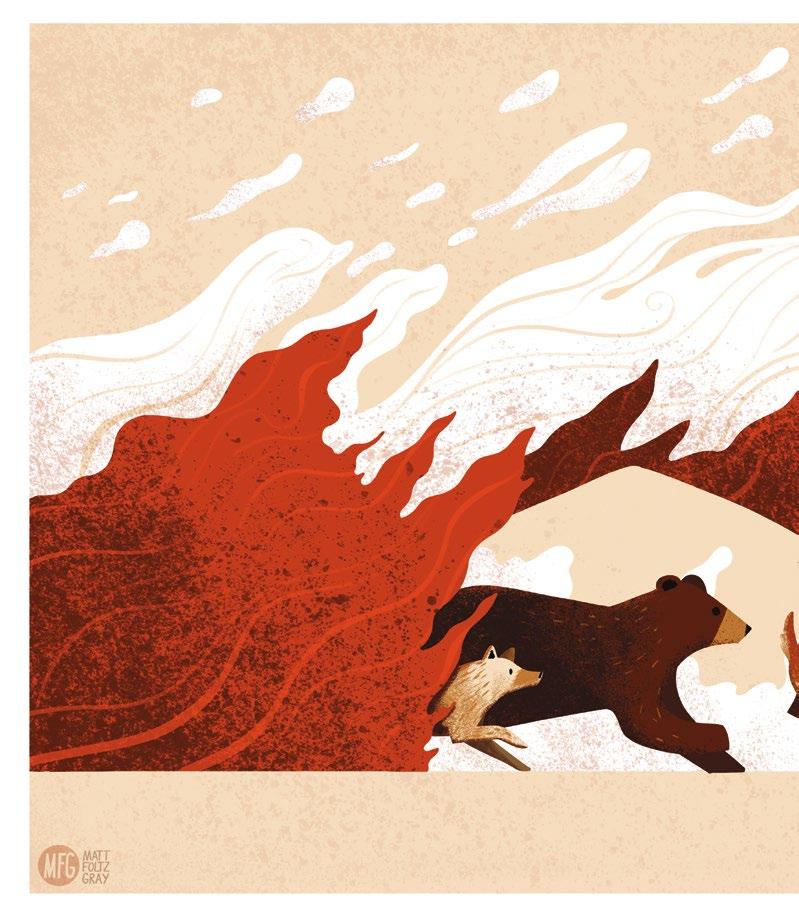

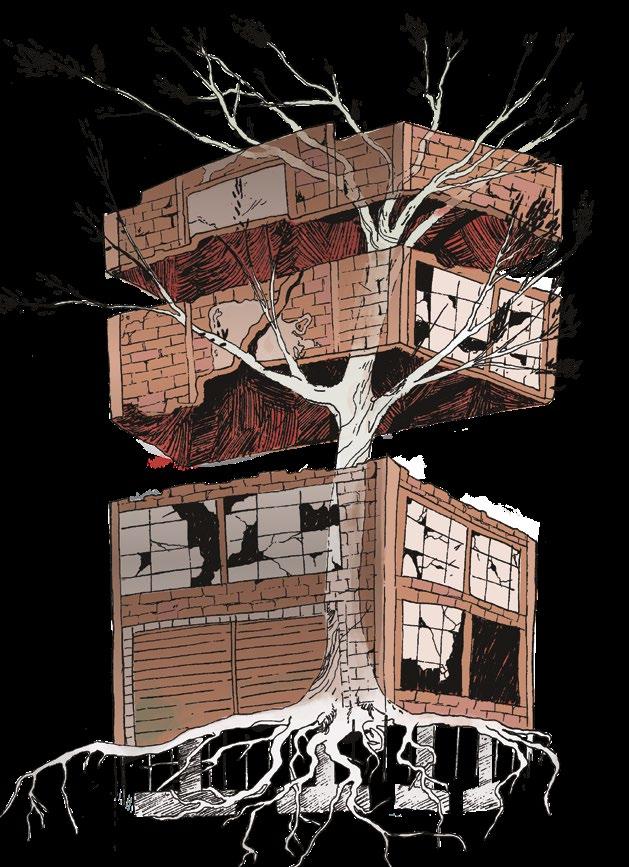

HILLBILLY ECOLOGIES AFTER THE APOCALYPSE

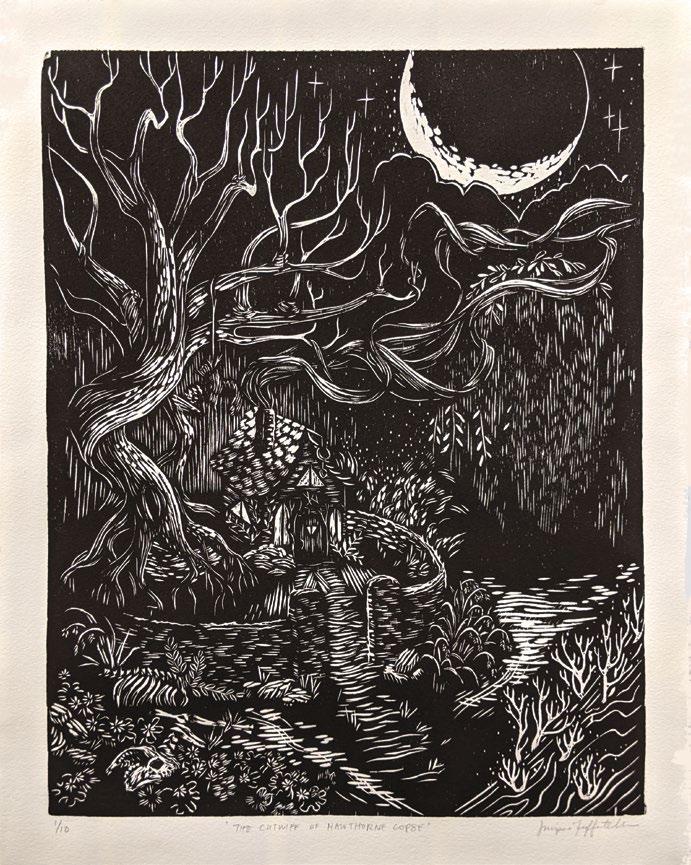

original cover photo taken by Kelsey Adler, cover art collage by Emily Hoffman. Frog art unknown; Sorrel cut it out of a fantasy novel many moons ago.

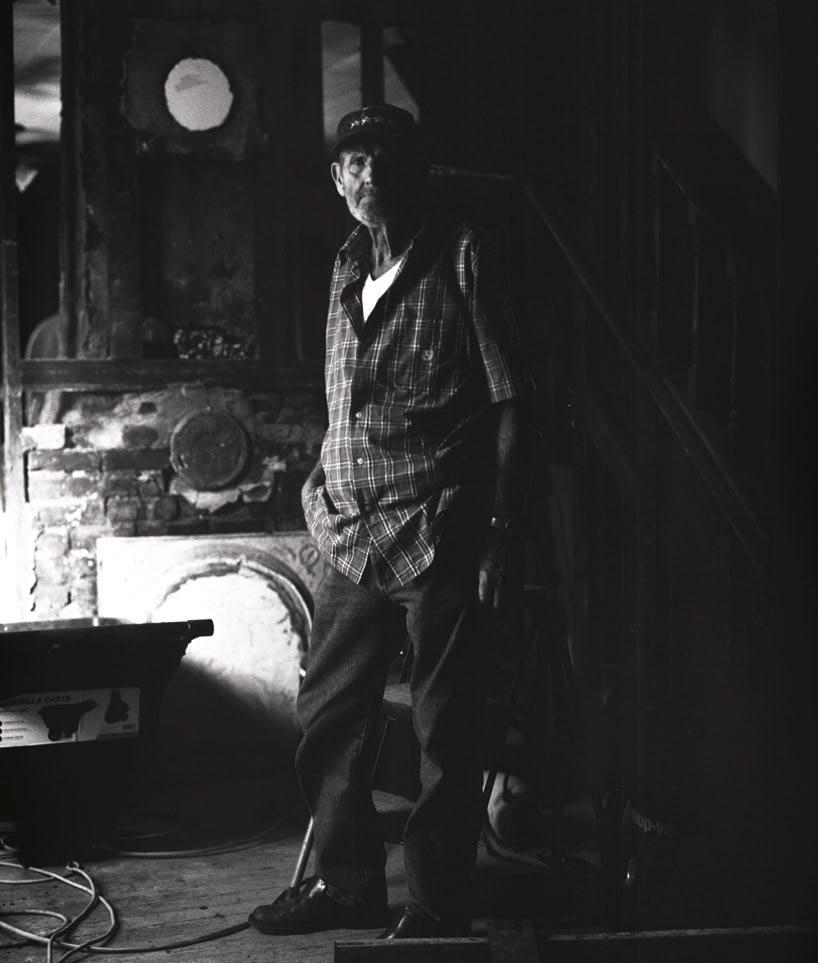

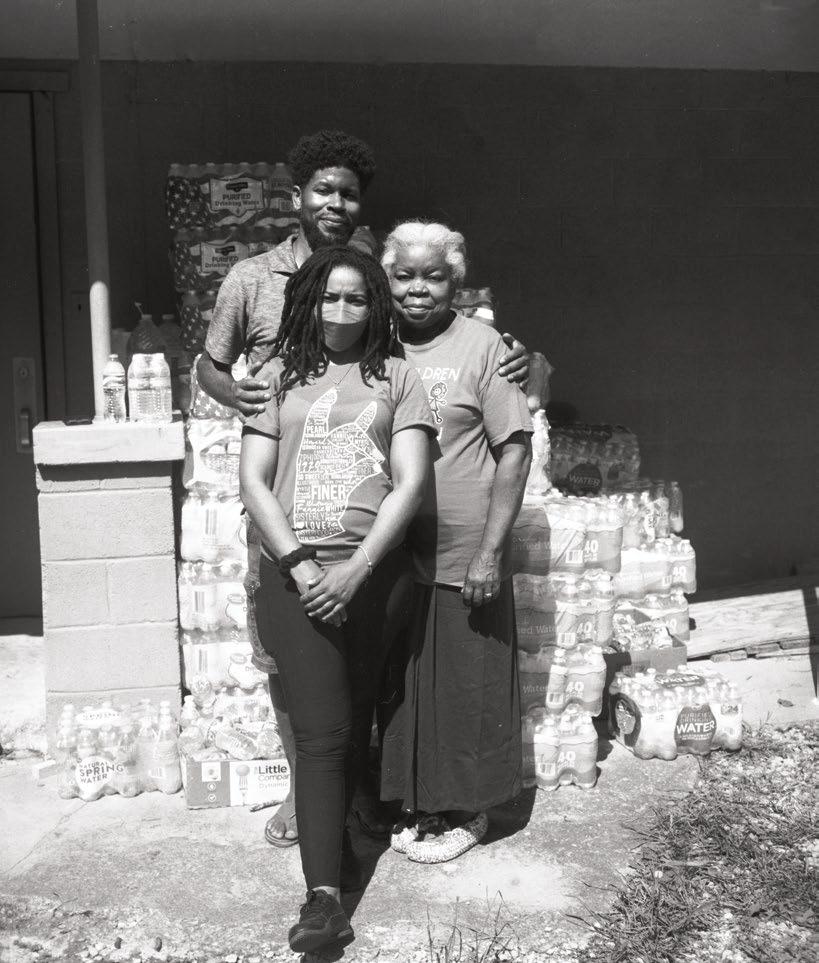

Photo by Derek Wheaton

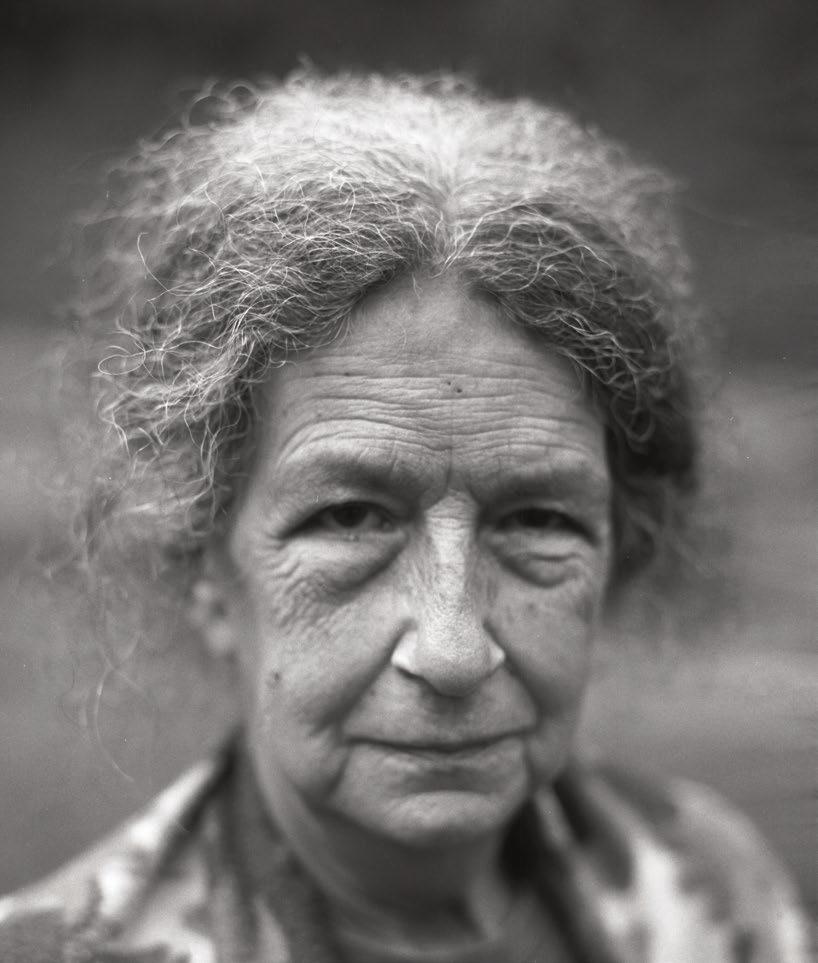

Photo by Derek Wheaton

Once there were brook trout in the streams in the mountains. You could see them standing in the amber current where the white edges of their fins wimpled softly in the flow. They smelled of moss in your hand. Polished and muscular and torsional.

On their backs were vermiculate patterns that were maps of the world in its becoming. Maps and mazes. Of a thing which could not be put back. Not be made right again. In the deep glens where they lived all things were older than man and they hummed of mystery.

—Cormac McCarthy, The Road

—Cormac McCarthy, The Road

Mergoat Magazine is a quarterly magazine published out of Knoxville, Tennessee. The best way to support our work is to become a subscriber at mergoat.com. mergoat.mag

Dear Reader,

There is a sense in which I am astonished that we are here together. There is another sense in which I am not surprised at all. During my brief existence, I have been forced many times to consider the fragility of life. Life has also handed me opportunities, occasionally against my will, to consider its resiliency. This ambivalent sense of surprise may resonate with you.

Life has a way of remaining—even as moments of bleakness, desolation, and violence wash over it. Through it all, we also learn that life has a way of remaining, even after death.

The issue you hold in your hand is the result of life ending time and again, and life remaining.

Southern Appalachia is rich in diverse and interwoven ecologies, cultures and histories. This reality is often forgotten or misconstrued in pop culture, industrial practices, and general public perception. The cultural flattening of Appalachia left many of us feeling alienated from birth, unable to find ourselves in the projected narratives. The picture painted never matched our life experience and often portrayed something of a contradiction or a fragmentation. Our ecologies reflect this fragmentation, as industrial extraction, the introduction of invasive species, suburban development and fossil fuels continue shattering our once unified ecological networks. As a result, many of us arrive at this/historical moment in pieces, wondering how to find ourselves whole in this wounded place.

Through these reflections, we can dive further in our inquiry of this place. What makes the Appalachian region distinguishable from another? How is it we ended up here? At Mergoat, we believe a true record of Appalachian ecologies must account for the ways that cultures, institutions, and political bodies have shaped and been shaped within our unique ecological environs. There is no dichotomy between human society and nature. Rather, they exist as an inextricable unity, for good or ill. I do not mean that nature is a container—a place, if you will—wherein society resides. Rather, society is a component, or feature, within the network of ecological relations. This magazine aims to expound upon this reality through a long and collective exploration of the unfolding ecological situation in Southern Appalachia.

In the West, the unity of society and nature was erased and confounded over many centuries. The severance of society from nature was initiated by Plato and perpetuated by the neo-platonists and the early church. Eventually, the binary between society and nature was galvanized by Descartes and the totality of the Enlightenment epoch. At this point, however, we find ourselves at a veritable inflection point. We find ourselves standing on the catastrophic precipice of climate change and extinction largely as a result of the societal practices that stem from the nature/society binary at the heart of our status quo ideological structures. Can we suture our severed and profoundly binary minds? We think so.

It is our firm belief that in order to preserve the possibility of a future, any future at all, we must begin to reimagine human society as an ecologically embedded phenomenon. We must depart from our inherited anthropocentric ideological paradigms in order to make collective decisions for the benefit of all species and for life itself.

In the coming years, Mergoat Magazine will provide a record of Southern Appalachian ecologies and cultures, as they unfold on the horizon of history and futurity. This work is momentous. This publication has very little interest or investment in upholding the utopian futures described in the eschatological paradigms of most religious or political thought. Rather, we seek to hold space for the possibility of a future in its most basic sense, that is, the possibility of any future at all, other than apocalypse.

We have learned from many diverse cultural and intellectual traditions, born out of oppressive and life threatening conditions, that our ability to see a future is what fuels our capacity to affirm life and to will its continuation. Thus, with the examples of our ancestors close at hand, we hold hope in one hand and grief in the other; rage in one hand and compassion in the other; fear in one hand and determination in the other.

I am so incredibly proud of our team, who have worked tirelessly on this project for months leading up to its release. This first issue, our charter issue, is also largely a reflection of our team’s passionate commitment to the material within these pages. Our team has invested hundreds of hours in pursuit of this collaborative goal even in the early stages of developing revenue streams to support our work. Many of you reading this have buttressed our work by subscribing before we printed this first issue, and we could never thank you enough for trusting and supporting us!

I would like to give special thanks to my team: Kathryn Gruszecki, Emily Hoffman, Alex Bonner, and Aaron Searcy. These people have executed their work at a remarkably high standard. There is no sense at all in which what you hold in your hands would exist without them. I would also like to mention a few people who offered unwavering support to my personal work in the years leading up to this point: Rosemary Saczawa, Jimmy Tucker, Janis Smith, and Peter Andreae. These folks have been an absolute cornerstone of support for me as I worked to establish Mergoat Land Design and Restoration. My personal work building that business provided the impetus for this publication. As it stands, this publication is the theoretical wing of Mergoat, working in tandem with the landscape design company, which is the praxis wing.

Welcome to our work! We hope you find nourishment in the contents. We hope, too, that you will join us. Suck out the Poison, Sorrel

Dear Reader,

This issue, Mergoat Magazine’s charter issue, aims to reflect on Southern Appalachian ecologies and the effects of an array of cataclysmic events that have struck the region. As citizens of the anthropocene, we continuously live in an era of apocalypse. Undoubtedly,

current ecological devastations in the area are a testament to this reality. Apocalypse can be thought of as a moment of chaos and disorder. The inauguration of the anthropocene also revealed the limitations of capitalism as a sustainable, global economic model. After years of ignoring these limitations, mass-doubt in capitalism’s ability to successfully and immediately address the emergent chaos of unpredictable and unprecedented disasters saturates the minds of the populus.

The global collision of climate change, pandemics, and economic collapse demands that we reevaluate the ability of our social systems to effectively address manmade ecological disturbance and prevent its continuation. As the ineptitude of our social institutions and economic models continues to unravel, we are challenged to strengthen the ties within our communities. As these systems are eroded, we relearn how to rely on each other. Like a quilt, stitch by stitch, we have the opportunity to strengthen our reliance on one another. We pick up the pieces strewn about by corporations and inefficient governmental bodies, patching them together by pieces.

Apocalypse, though, is often misconstrued as an absolute ending. While it certainly invokes the imagery of an end, an end to how things were before, it also opens an opportunity for new understanding and reconstruction. After the flood, we joined hands with our neighbors and rebuilt. The same floods that form canyons also shape the consciousness of our communities.

Many of the contributors in our charter issue focus on the communal efforts of restoration, looking beyond apocalypse for solutions and reclaiming our roots in the earth. However, this is done in motion with grief and without the glorification of tragedy. As we mourn the loss of material history and the sense of stability offered by the holocene, we find strength and beauty in the bonds of community.

As editor of our charter issue, I find solace in the community of Mergoat Magazine and welcome each of our readers to join.

In solidarity, Kathryn Gruszecki

Executive Editor

Mergoat Magazine

Below is a list of people who we have given the title of Founders. These generous people provided the startup capital for Mergoat Magazine by subscribing at the solidarity level prior to us printing a single word. We owe each of these folks an enormous debt of gratitude for trusting us with their investment. Your support has not only provided a material benefit in support of this project, but also a source of encouragement during the malaise of self-doubt and fear leading up to printing this first issue. Thank you all!

I’m detaching all the time now Supine in the living area of my polydrug mind A bee maneuvering depressed air towards ripening trees How is it that I melt away from my feet upwards, through micro-plastic landscapes? Dropping my little protests as I go

Dr. Beverly Collins is a botanist and associate professor of ecology at Western Carolina University in Cullowhee, North Carolina, specializing in old-growth forests, disturbance, and understory herb communities in Southern Appalachia and the eastern US.

Our interview with Dr. Collins was conducted in September 2022 via email.

Where is home for you? Can you tell me about the land there?

i grew up in southeastern kentucky, specifically about halfway between Whitesburg and Jenkins in Letcher County. The holler I grew up in backs up to Pine Mountain, which is the transition between the Cumberland Plateau and Mountains and the head of the Kentucky River watershed. The hills are steep, valleys are narrow, and slopes are covered with high-diversity mixed-mesophytic forest.

I can’t tell you how much I love to hear “holler” and “mixed-mesophytic forest” in the same breath. Only a few weeks ago, that very area around Pine Mountain and southeastern Kentucky experienced some catastrophic flooding. Have you been back home since?

yes, I went back the week after the flood and have been back just about every weekend since. This was a catastrophic and truly tragic event that will have long-lasting ecological effects and consequences for people’s lives. In Letcher County, I saw streams that drain from the hills completely blown out and scoured to bedrock, with feet-deep piles of sediment, rocks, and even boulders and coal from old mines washed into the road, creek, and sometimes people’s houses.

I now understand how the Grand Canyon formed! There were landslides and trees that had come down onto the road, creek, powerlines, and sometimes buildings. Farther downstream, I saw houses that had been almost completely underwater, buildings washed off their foundations, and vehicles and people's furnishings in the river.

I also saw places where floodplains had 'done what they are supposed to' ecologically—that is, give the water a place to spread out, slow down, and drop sediment and debris. This tragedy could have a silver lining if we can build back sustainably, so that floodplains function and people have homes that are less at risk of future floods.

According to FEMA data, Kentucky has seen more flood-related disaster declarations than any other state between 2000 and 2022. If anyone figures out how to cope with floods, it might be your neighbors in those eastern Kentucky hollers. Who do you see leading your community in the recovery on the ground?

i hope those neighbors you mentioned will lead the way. By this I mean, the community can best navigate its own way to a more sustainable long-term recovery. And the community is taking the first steps.

An article from in my hometown newspaper (The Mountain Eagle) by Jim Branscome and Tom Bethell called for a ‘homegrown recovery’ that works with, rather than against, nature. Ideas included accelerating land reclamation with native species, purchasing buildable land out of the floodplain, developing building designs that resist flooding, investigating strategies for mitigating future flooding, and developing sustainable farming practices that provide food self-sufficiency and a food-export economy.

A crucial next step is to bring experts with relevant knowledge to the table and ensure they have sufficient funding to actually implement these ideas. Perhaps history could be reversed and Southern Appalachia could lead the way in turning recovery into a bright future. Disturbance, as you’ve described it, clearly brings about an opportunity for change. What opportunities do you see opening up across Southern Appalachia as those extractive industries start to wane and leave gaps in the canopy so to speak?

Transitioning from large-scale extractive industries brings an opportunity to invest in new land uses that fit the local community and restore the Southern Appalachian landscape.

abandoned mine land brings the opportunity to scale-up what we’ve learned from smaller landslide studies and re-establish native forest succession. Mine land could also be used to develop sustainable housing and non-extractive industry, like forest-farmed botanicals. Logging on private and industrial lands brings an opportunity to regenerate forests that have high native species diversity, applying what we’ve learned from public forest management and research.

In thinking about long-term recovery, it's important to plan for 'enough' natural area; by that I mean large, contiguous blocks of forest, natural openings such as balds, watershed headwaters, riparian zones, and floodplain. We need to make a commitment to conserve or expand natural areas even in the face of all the factors that threaten them— e.g., increasing disturbances, loss of land due to ocean rise, human population growth and urban expansion. We need large, contiguous blocks of natural area for ecological reasons—to maintain biodiversity, ecosystem functions and services—but also for their recreational and aesthetic value.

I think the key, as you mentioned, is that disturbances bring opportunities. We can develop these lands into a new, sustainable version of an Appalachian holler.

How would you describe our present ecological situation in Southern Appalachia?

i think southern appalachia is at an ecological decision point.

The Southern Appalachian landscape, including our forests, has been used by people for centuries. Historically, as the demand for Southern Appalachian resources grew (e.g., coal, timber, copper, farm products), land-use practices became more intense or widespread, and forest land was increasingly converted or broken up.

Climate change is driving 'species shuffling' and intensifying pressure from 'invasive' species. These are mostly non-native species that outcompete native plants and animals—especially in waterways, along roadsides, and in forest openings caused by natural disturbances or forest-management practices. And this can have cascading effects on biodiversity, ecological food webs, and ecosystem processes.

At the same time, demand for some extractive resources, including coal, is decreasing, and some areas have been 'mined out', creating opportunities to restore these lands or re-think how we use them. The future depends on our choices.

There are laudable ongoing restoration, conservation, and 'future proofing' efforts on many public, conservation trust, agency, and private lands. However, since much of the region is privately owned by individuals or companies, such as timber or coal companies, widespread ecological education and commitment is needed to create an ecologically sustainable, resilient future in Southern Appalachia.

In your own research focused on plant communities closer to home, do you see the spread of invasive plants as the most significant threat to native Southern Appalachian plant ecology?

i certainly see the loss of biodiversity especially the loss of key species—as a significant threat to Southern Appalachian forests and waterways. We all know about kudzu, but there are many other invasive species that can quickly become dominant and sometimes even a near monoculture.

On my last trip to Letcher County, I found hundreds of Japanese knotweed plants coming up where the flood had broken apart and spread pieces of rhizomes. This plant has been called the 'world's worst invasive' because it has spread to almost every continent and forms dense stands along streams. In the Southern Appalachians, it’s often mixed with other invasives such as privet, multiflora rose, and autumn olive.

In upland forests, native tree species have been lost or are threatened by non-native pests and diseases. My mom could remember picking up American chestnuts, but there were no living trees in our area by the time I was born; they had been killed by an invasive fungus. Chestnut was a dominant tree in Southern Appalachian forests used by wildlife as a food source and by people as a food source and building material. Now, we’re losing

ash trees to the emerald ash borer and hemlocks to the hemlock woolly adelgid. A number of fruit and forest trees are also at risk due to the spotted lanternfly, which is spreading quickly.

Even among ecologists, opinions about how to respond to the increasing invasive species load vary widely, from 'no action needed because communities are always changing' to 'remove all invasives and restore native communities no matter the financial cost.' It sometimes comes down to whether an invasive [species] enhances or disrupts ecosystem services or processes.

For example, honeybees are a non-native species that can escape cultivation and are pretty much ubiquitous in the Southern Appalachians. They can enhance pollination and biodiversity in some cases but usually displace native pollinators and thus lower biodiversity. They illustrate the tradeoff between maintaining native biodiversity and accepting a non-native species that enhances an ecosystem service (pollination and honey production).

In general, though, most non-native invasive species have few positive effects in forests, and we are ecologically better off without them.

Even among ecologists, opinions about how to respond to the increasing invasive species load vary widely.

Restoring our native plant communities entirely—even if we all agreed it was a goal worth working toward—seems like an impossible task at this stage. That knotweed really is everywhere. But doing nothing doesn’t feel right either. How do you navigate that middle ground when you’re pulling weeds, or not, in your own backyard?

navigating the middle ground is tricky, and there’s no guarantee we’ll get it right. I think one key is to encourage middle-ground efforts across scales—from individuals through large corporate or public lands.

At the individual scale, for example, choosing to plant native bittersweet, Virginia creeper, or a native holly rather than Oriental bittersweet in your yard will still provide fall color and winter berries while replacing an invasive with native species. Reclaiming industrial land with hybrid or genetically modified chestnuts—along with a suite of native species rather than non-native invasives—is a great example of a larger-scale middle-ground solution because it requires little extra effort and is more sustainable.

At the largest scale—public and private forest lands and watersheds in Southern Appalachia—removing invasives completely may very well be impossible. But individual landowners and volunteer groups can make a dent at individual locations, and replanting with natives might prevent or slow invasives from re-establishing. For example, students and faculty at my university turned out to help pull invasives on Earth Day and cleared about an acre.

None of these efforts can work by itself, but putting them all together might be a middle ground.

disturbances are natural (not human-caused) or human-caused events or phenomena that remove biomass or disrupt ecological processes. For example, a windstorm might break or knock over one or more trees in a forest, or loggers might cut a patch of trees.

Over the region as a whole, Southern Appalachian forests have weathered natural disturbances, including windstorms, droughts, wildfire, native pests, landslides, and floods, and human-caused disturbances, including clearing, logging, invasive pests, human-set fires, and mining.

Historically, there were occasional windstorms, droughts, floods, and wildfires. Although droughts and floods could affect large areas, wind and wildfire disturbances were more often localized within forests or forest patches.

Historical human-caused disturbances included small-to-largescale clearing and farming in the valley bottoms and lower slopes; widespread logging at the turn of the twentieth century (throughout the region); human-set fires that ranged from ground fires to canopy fires; mining that ranged over time from underground mines to strip mines and mountaintop removal mining; and invasive pests like the chestnut blight, balsam woolly adelgid, and hemlock adelgid that kill key tree species. Disturbances can also include longer-term ‘presses’ such as acid rain caused by industrial pollutants in the atmosphere. These atmospheric pollutants have had long-lasting effects, especially on high-elevation forests like spruce-fir forests. Today’s forests reflect the suite of disturbances they have weathered over time.

You’ve spent years studying plant responses to environmental disturbance in Southern Appalachian forests. What exactly is a disturbance, and what kinds of disturbance have the forests of Southern Appalachia weathered in their time?

That’s a lot of disturbance! Even without the anthropogenic disturbances—which do seem substantial—it sounds like disturbance is almost the rule rather than the exception. When you say that Southern Appalachian forests reflect those disturbances, what are some of the clues that you look for when you’re in the woods that might tell you something about the deeper history of a place?

there are many clues to a forest’s past. You might see ‘pits and mounds,’ which are left behind when a tree is uprooted by wind or rain. The tree leaves behind a pit, or hole, where the roots were in the ground next to a mound of dirt when soil falls off the uprooted roots.

The downed log is a great place for some tree species, such as yellow birch, to establish. Those are called nurse logs. If you see a yellow birch that looks like it grew on top of something that’s no longer there, it probably established on a nurse log that has decayed. Other clues to past disturbances are lightning or fire scars on trees, broken crowns from wind or ice damage, and, of course, standing dead trees, which might have died from a fire, pest, or disease.

Looking up, you might see gaps in the canopy or patches of younger, smaller trees growing toward the canopy. Some tree species, such as tulip poplar, birches, maples, and oaks, grow faster or establish from seed in the canopy gaps that are made when a disturbance breaks or kills one or more trees. As these trees grow taller, the gap fills in. Old forests are usually ‘uneven aged’ due to repeated canopy gap-forming disturbances. An ‘even aged’ forest, in which all the canopy trees are about the same size (diameter), is a clue there was a large stand-replacing disturbance or logging.

Some invasive species can also be a clue to the forest’s past. For example, princess trees are established after fire (as well as on forest edges and along roads) in some Southern Appalachian forests.

A thick leaf litter and organic material, or duff, layer on the ground is a clue that the forest hasn’t experienced fire in a while; even ground fires will burn duff.

In short, disturbance is definitely the rule rather than the exception, and the forest is a product of its disturbance history.

“

Disturbance, as you’ve described it, clearly brings about an opportunity for change. What opportunities do you see opening up across Southern Appalachia as those extractive industries start to wane and leave gaps in the canopy so to speak?

transitioning from large-scale extractive industries brings an opportunity to invest in new land uses that fit the local community and restore the Southern Appalachian landscape.

Abandoned mine land brings the opportunity to scale-up what we’ve learned from smaller landslide studies and re-establish native forest succession. Mine land could also be used to develop sustainable housing and non-extractive industry, like forest-farmed botanicals. Logging on private and industrial lands brings an opportunity to regenerate forests that have high native species diversity, applying what we’ve learned from public forest management and research.

In thinking about long-term recovery, it's important to plan for 'enough' natural area; by that I mean large, contiguous blocks of forest, natural openings such as balds, watershed headwaters, riparian zones, and floodplain. We need to make a commitment to conserve or expand natural areas even in the face of all the factors that threaten them—e.g., increasing disturbances, loss of land due to ocean rise, human population growth and urban expansion. We need large, contiguous blocks of natural area for ecological reasons—to maintain biodiversity, ecosystem functions and services—but also for their recreational and aesthetic value.

I think the key, as you mentioned, is that disturbances bring opportunities. We can develop these lands into a new, sustainable version of an Appalachian holler.

How quiet it will be when the morning cicadas & scissor-grinder cicadas tuck their instruments & retire for the season. This poem is the only silent thing. It rests unblinking on the page, so still, like a dead fish. & all the rest of us, shouting, murmuring, clapping with sudden hoots of laughter, while our children run screaming among our legs.

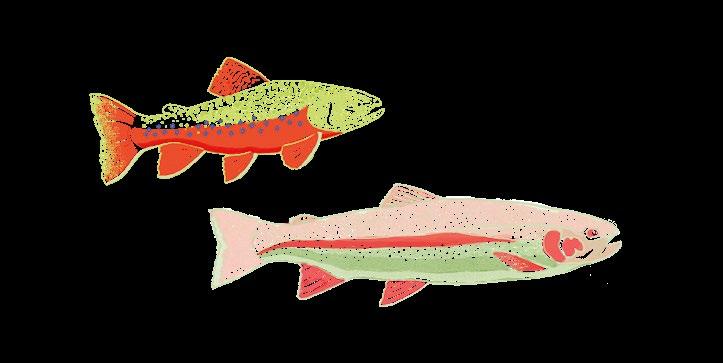

A bullet-shaped fish rarely exceeding eight inches, the southern brook trout exhibit a distinct red-orange belly and white-edged fins. Their dorsal side is washed in olive tones with a wormlike pattern of lighter shades cutting through. Their flank is adorned in red, blue, and yellow speckles, lending them their regional nickname “speck.”

In sufficiently forgotten places, far up the holler, under the shade of hemlocks and hickories, you may find a small fish speckled with gems and a flaming red chest. You join a long line of peoples who have loved this fish, perhaps the first moment you spot one. It is a fish adored by the Indigenous peoples of the Southeast who used it to feed their communities, the mine workers who used them as body-fuel to gain the strength to strike back against the dominant power structure, and the modern angler devoted enough to seek out this increasingly rare animal. This fish, the brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis), is the only native trout species in the Southeastern United States.

Unlike the more popular intruders—like rainbow trout, which come from the Oncorhynchus genus of western North America, and brown trout, which belong to genus Salmo largely found in Europe—the brook trout comes originally from the northern Salvelinus group. They share the genus with other notable species like arctic char and lake trout. It’s odd to think of a species that is most closely related to animals that are largely restricted to cold climates as a native resident to the hot and humid Southern Appalachians, but when you begin to dig into their evolutionary history, it makes sense.

During the Wisconsin glaciation, the last major ice age, brook trout took advantage of the cold glacial flows running all the way to the eastern seaboard by becoming anadromous, meaning they migrated from salt water to fresh water throughout the year. Jumping from one coastal river to the next, brook trout ranged much farther south than their sibling species. However, as the glaciers began to recede roughly 11,000 years ago, these rivers became too warm, forcing them inland. They chased the freezing glacial meltwaters, following them to higher altitudes and more northern latitudes.

As the ice sheets continued to work their way towards the arctic circle, their flows dissipated, breaking up the oncemassive cold-water rivers into smaller, warmer streams. With less continuity of habitat, brook trout were unable to continue migration north and were forced to march even farther upstream. These montane, spring-fed creeks that they found were much less biologically productive and ecologically diverse than the oceans they had previously lived in, forcing them to decrease in size and become dependent on insects as the bulk of their diet.

This evolutionary history creates the next wrinkle in our story. As the glaciers receded and brook trout moved into ever smaller and less connected streams, they

anadromous Migrating upstream from salt water to fresh water, like salmon do, to spawn.

the five major clades

Salters or sea-run brook trout

Coasters or Great Lakes brook trout

Upper Mississippi or Driftless Region brook trout

Southern Appalachian brook trout or specks

Northern Appalachian brook trout

became genetically isolated. This has led to a massive amount of differentiation from one stream to the next, but most people working with these animals try to lump these diverse groups into five major clades. “Salters,” or sea-run brook trout, are found in so-called New England and Canada. They are most reminiscent of the historic brook trout, living anadromously and growing much larger than their landlocked siblings. “Coasters,” the variety found in the Great Lakes, are only slightly more derived from their ancestors. Instead living potamodromously, they swapped out the ocean for the lake and the coastal streams for small tributaries.

feeds almost exclusively on the insects found in clear, clean, and cool mountain creeks, often small enough to step across.

potamodromous

Moving and completing their lifecycle entirely within fresh water

driftless region

A topographical area in the Midwest bypassed by the last continental glacier redd A brook trout’s nest

The Upper Mississippi has its own unique kind of brook trout, although they do not have a special name. They are one of the smallest trout and spend their lives in the unique groundwaterfed meadow streams in between the bluffs of the Driftless Region. This is a small part of the north woods that was spared the ravages of glaciation and served as a refuge for many animals displaced by the pulse of the ice. Then, there is the most well-known and widespread of the brookies, the Northern Appalachian strain. These fish are intermediate in size and able to inhabit larger rivers. Lastly, we have the fish of particular interest to the people of the Southeast, the Southern Appalachian brook trout. This fish rarely exceeds twelve inches in length and

This particular population has undergone significant range restrictions since European colonization. First, the great forests of the Southeast were clear-cut, warming the waters, creating massive erosion, and scouring the headwaters of their sediments—a crucial component of a brook trout’s nest, also known as a redd. If that wasn’t enough, state and federal wildlife agencies, working with anglers associations, saw an open niche where southern brookie populations were decimated. Instead of working to repair the habitats to give them a chance to recover, they began mass producing the northern strain. This strain was much more tolerant of hatchery conditions and more desirable to sportsmen for their larger size. These fish, in combination with invasive brown and rainbow trout, which were similarly stocked by the same groups for the same reasons, wreaked havoc on these finely balanced ecosystems. All three of these animals are much more reliant on fish as a source of food compared to the native strain, severely reducing the populations of minnows, darters, and daces in smaller waters.

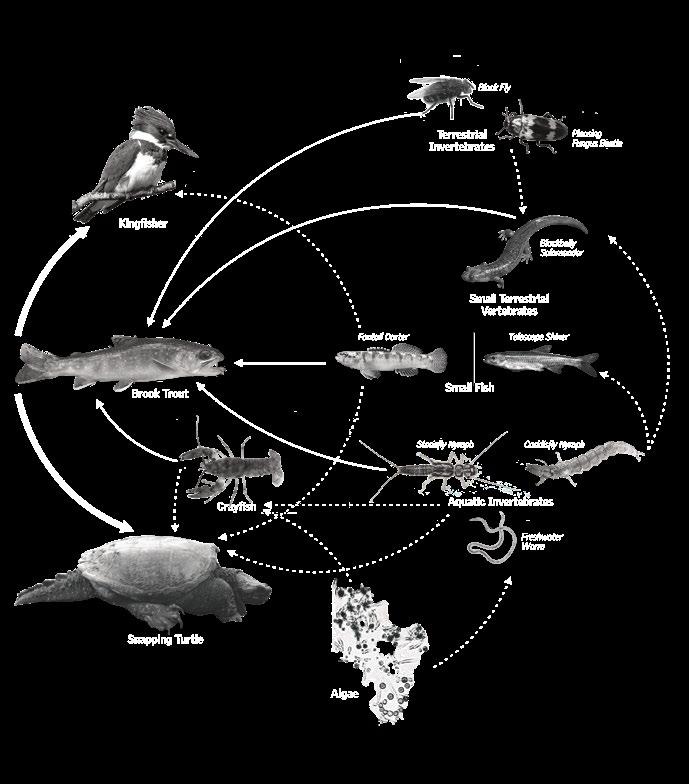

food web Neither primary consumers nor apex predators, brook trout are situated at the intersection of a dynamic food web. Like most ecosystems, this food web is built upon algae and other aquatic plants as primary producers. Energy generated through photosynthesis is consumed by primary consumers such as herbivorous aquatic invertebrates. Brook trout feed primarily upon these invertebrates, but will consume smaller vertebrates opportunistically. When young, and sometimes adult size, they do fall prey to predators; including snapping turtles, water snakes, kingfishers, otters, and even larger fish.

Before the last Ice Age, the ancestors of brook trout existed in waters of the northern hemisphere. This ancestral species would eventually go on to diverge into five distinct subspecies of brook trout following the Ice Age. While exact habitat range is unknown, brook trout would have existed in the area between present day New Jersey and Hudson Bay.

glaciation Dropping global temperatures resulted in vast ice sheets traveling south across the North American continent. Deep depressions were carved into the landscape from the sheer mass of glacial movement. Over the course of the Pliocene, the brook trout’s habitat range shifted south, following melt water off traveling glaciers.

postglaciation & colonization New water bodies were born by receding glaciers’ meltwater filling in depressions. These depressions are the direct result of the same glaciers advancing many thousands of years before. Brook trout populations settled into habitats along the Northeastern United States, into Canada where temperatures were still amenable to their needs. Scattered across separate bodies of water, the Brook Trout slowly underwent small divergences resulting in the sub categorizations used today; Upper Mississippi, Great Lakes, Salters, Northern and Southern Appalachian brookies.

Introduction of invasive species combined with habitat destruction has led to decline and fragmentation of brook trout populations. Present day populations have only continued to exist in spring fed mountain streams where temperatures are cooler and oxygen levels higher.

However, the very things that gave them the advantage in the past will likely come back to hurt them as our forests recover and mature. Although these introduced fishes still persist and reproduce, they are fundamentally unsuited to the unique conditions of montane, old-growth Southern Appalachian woods. The places that have entirely lost native southern genetics will be left lacking a key part of their ecosystems when the canopy closes in, the waters cool, large foods become less abundant, and the invaders lose their grip.

The story of these fish mirrors many other aspects of the region. Whether it is coal, lumber, culture, or agricultural products, the peoples and resources of the Southeast are routinely exploited and exported for the benefit of those who will never face the consequences of their loss. The final step in this theft is consistently marked by an attempt by the robbers to return a pale imitation of what was taken. It can be seen in the non-native trout swimming in our streams, the microplastics from polyester clothes polluting our drinking water, or the new “Nashville” sound playing through the radio.

Today, several groups are working to restore Southern Appalachian brook trout to their historic range. The Eastern

The places that have entirely lost native southern genetics will be left lacking a key part of their ecosystems when the canopy closes in, the waters cool, large foods become less abundant, and the invaders lose their grip.

Band of Cherokee Indians as well as the National Park Service, the United States Forest Service, and several state agencies are focusing on streams with natural or man-made barriers to trout movement in the form of cascades, dams, culverts, and reservoirs. If the habitat is suitable, these groups will work to remove any existing invasive or introduced trout. Once they are certain that the stream is clear, they will go to a healthy population of true southern brookies and collect eggs and sperm from adults during their fall spawn—manually combining them and rearing the tricky larvae in specialized hatcheries. Once they are of a sufficient size, they are released to the stream. Although they can’t immediately replicate the massive genetic diversity of the populations that were once found throughout the Southeast, the hope is that time and natural selection will slowly get us closer to that lost past.

These projects, despite their major importance to the Southeast, receive a fraction of the funding and community support of their western counterparts.

Over the last several decades, the salmon and trout along the Pacific Coast have received billions of dollars in conservation funding, and yet there is little to show for it. Many of their populations are restricted from reaching their spawning grounds by large hydroelectric and irrigation dams. Instead of the money going towards the destruction of those walls

of death, it funds teams of trucks and nets, capturing the fish below the impediments, driving them upstream, and dumping them back in the river to complete their fossil-fuel-dependent migration. Then, they lay their eggs and die, rotting on the stream bed as their larvae float downstream and try their best to avoid being ground to a pulp in the turbines.

In a time of imminent ecological and systems collapse, the hubris of this disparity is particularly foul. The moment the gas stops flowing and the trucks stop running, western searun salmonid populations will almost entirely collapse. Meanwhile, as long as the forests stand and the streams keep flowing, the brookies left in our temperate rainforest will continue on in the way they had been since the ice left and they first learned the ways of mountain life.

What does it mean to identify with, or belong to, contemporary Appalachia? This is no simple question. To find an answer, we might begin by working to understand the trope of the “hillbilly,” a label with debated origins used, in turns, to both vilify and idolize the people of Appalachia.1

At the heart of the hillbilly has always been the practice of preservation. It pervades everyday life to the point that what is preserved is often less important than the practice itself. For our ancestors, preservation was a means of survival, but it is shortsighted to assume that hillbilly tactics served them in a purely physical sense. Whether it be canning for the promise of peaches in winter or composing scraps of fabric to create a quilt, equal parts warm and beautiful, communities held space for pleasure, aesthetics, and even gossip

alongside survival. The crisis we face now is the loss of such communities with which a culture of preservation is created and maintained.

The antidote is neither nostalgic pastiche nor a move toward homogeneity and erasure; but rather, a more nuanced, critical approach.

Looking more deeply into the evolution of the hillbilly, and using the humble quilt as a symbol of community and our shared histories, the next step might become clearer. Quilts express love and pass along generational knowledge and skills. For centuries in our region, they have been given as gifts for a wide array of important events in someone’s life, from birth to burial. The tedious hours of craftsmanship and curation that go into creating a quilt indicate the care of the quilter(s). By studying both the qualities of the quilt as an artifact of memory, as well as the mechanics of the quilting process, we can find tactics

for rebuilding the communities we so desperately need.

For generations, our identities have been repeatedly borrowed, bastardized, and redefined. From the violent uprooting and subsequent sequestering of Native Americans to the silencing of immigrant groups, the region has seen scores of communities shepherded through the various rinse cycles imposed upon them by the powers that be. This includes the subjugation of folks through slavery and servitude, required service in wars that demanded allegiance at all costs, and societal expectations to create nuclear family units as general assimulation into the ideal of modern American life. As a result, regardless of the wide breadth of opinion and belief within the Appalachian region, we all share the same hunger for a sense of belonging.

The Appalachian Mountains we call home are known to be among the oldest in the world. But the concept of

Appalachia as a distinct region inhabited by a distinct population, characterized by culture and not just geographic location, did not formally exist until the 1900s. In the decades leading up to the twentieth century, various explorations by local-color writers uncovered “exotic ‘little corners’” of the Appalachians.2 Writers depicted these corners as untamed wildernesses, in but not of America. They painted the mountain dwellers as more of a threat to the American ideal than anything else.3

The man credited with “inventing” Appalachia as an accepted region of America was William Goodell Frost, president of Berea College in Kentucky from 1892 to 1920.4 Frost solidified the image of Appalachia as the last American frontier, announcing to a group of peers in 1895, “We have discovered a new pioneer region in the mountains of the central South just as our western frontier has been

lost in the Pacific Ocean.”5 Frost’s embrace of his “contemporary ancestors” effectively served to frame Appalachia and the hillbilly as both an icon and a charity case—the poster child of the lost American pioneer spirit but also an isolated population in need of “systematic benevolence,” from education, culture, and home missionaries to infrastructure and regulation.6 These ideas would later come to fruition throughout the early twentieth century in the form of government-led programs like the Tennessee Valley Authority and the Appalachian Regional Commission. Meanwhile, the caricature of the hillbilly remained just as “exotic” in the collective American consciousness as it did in the 1870s.7

The most advantageous option available to the evolving hillbilly, especially throughout decades of wars, was to assimilate into a thoroughly patriotic American lifestyle—thus, reflecting only on one’s Appalachian roots through nostalgia and kitsch. The prosthetics8 of the old ways remained draped over the backs of armchairs and archived in tourist-trap dinner theaters, but the wisdom baked into our Appalachian relics became increasingly hidden as we reached for progress. As mechanization and mass production made our lives faster and more efficient, the quilt became an antique, symbolizing a time too slow to be relevant, too imperfect to be modern.

One quality of Appalachia that seems to have permeated American identity

the most is the projection put upon it by Frost and his contemporaries: rugged individualism, the ability to survive through self-sufficiency and without help from a support network, government-run or otherwise.9 However, the self-sufficiency witnessed in the Appalachian people was falsely equated to the individualism of western frontier settlers. Where frontiersmen were migratory and often solitary, mountain men were stationary and connected; although the mountains can be isolating, a network runs through them. It wasn’t that there was a lack of community in Appalachia, it was just invisible to the eyes of outsiders.

In his book Appalachia on our Mind, Henry Shapiro explains this misrepresentation and subsequent rise in folk culture in

Appalachia was characterized not so much by the absence of community as the absence of a realized community. The work of benevolence then became one of bringing this preexistent community to the level of consciousness . . . by establishing among the mountain people a sense of their own Appalachianness and of their participation in the distinct if not unique patterns of mountain culture. In its most prevalent form, it involved the special definition of the Appalachian community as a folk community, and the inauguration by the agents of benevolence of programs designed to instruct the mountain people in the usages of their own culture.10

While admiring the Appalachian people for their perceived individualism, the

systematic benevolence efforts of the early 1900s still saw them as needy, requiring a community visible and tangible enough to be commodified.

After a century of modernization, industrialization, globalization, and the resulting shift toward nuclear families and urban density, the most recent iteration of Appalachian identity has morphed into a parody of itself, leaving the rugged individual, which sounds remarkably like freedom at first blush, as the only viable moniker one might adopt to be taken seriously. The load once carried by a community is now shifted onto the shoulders of one person, producing burnt-out and resentful subjects struggling to make ends meet. Although widely celebrated, this shift has been the wedge that has driven Appalachia apart. Modern hillbillies are at a loss for how to reconcile their rich regional history with their twentyfirst-century lives. It may seem that the options at hand are either to purchase admission to a caricature of the past, repackaged in a mason jar with synthetic apple flavor, or to reject it entirely in favor of a nondescript, late-postmodernappropriate persona.

There may be gold in the cracks of our regional identity, though. We need not reject the advantages offered by our highly digital, ultra-global existence. In fact, these advantages can be co-opted

into the work of rebuilding the invisible support networks once relied upon by our hillbilly predecessors. The strategy of the quilt illustrates this simply but effectively. Like many artifacts of Appalachia, the quilt performs not only physically and economically but also socially and emotionally.11 Quilts were an intimate link to ancestors and to identity, with certain patterns often behaving like a coat of arms within a family. Heritage, however, can also be painful and exclusionary. How can one of the most potent effects of this Appalachian relic still be relevant today, particularly in the midst of the adoption of the rugged individual identity?

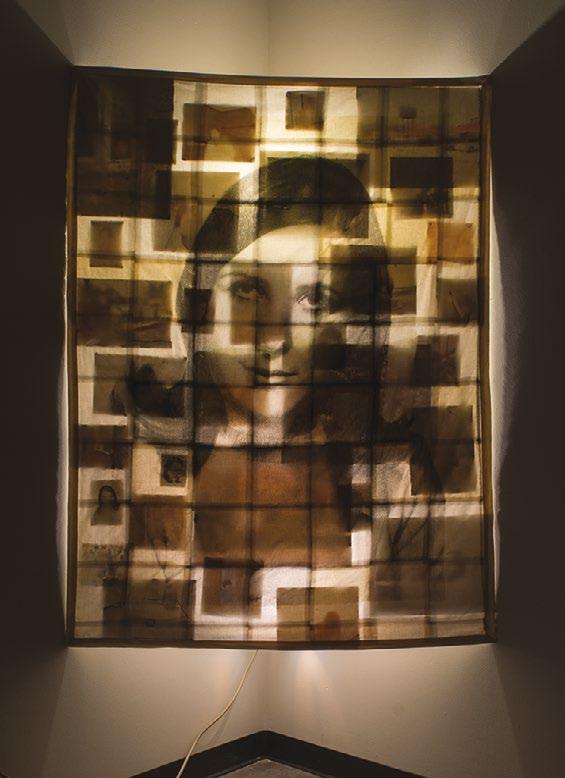

Artist and quilter, Megan G. King, explores the connection between the medium of quilting and the preservation of memory. This is done by using vintage photography to invoke an awareness of the past in her series Like a Woman. While the images are static, many of the quilts are unfinished, suggesting a feeling of being in-process. In the effort to redefine an Appalachian identity, this serves as a useful metaphor. How we move forward will be in slow, sustainable stitches, pieced together one at a time. The stories we choose to preserve will not be carved into stone but more like a temporal, projected image, loose threads hanging from the edges.

Quilts were an intimate link to ancestors and to identity, with certain patterns often behaving like a coat of arms within a family.

the idea of heritage is still available to the modern hillbilly in the form of shared community histories. Part of rebuilding our communities is holding space for those histories to be heard collectively. Just as quilting bees or community quilts were historically both a venue for women to build friendship and share this kind of support and also a way to pool labor in order to produce better results, our digital infrastructures offer us the opportunity to share resources and create in ways we could not achieve alone. An example of this can be found in the monumentsized NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt conceived in 1985 by activist Cleve Jones, which is still growing and

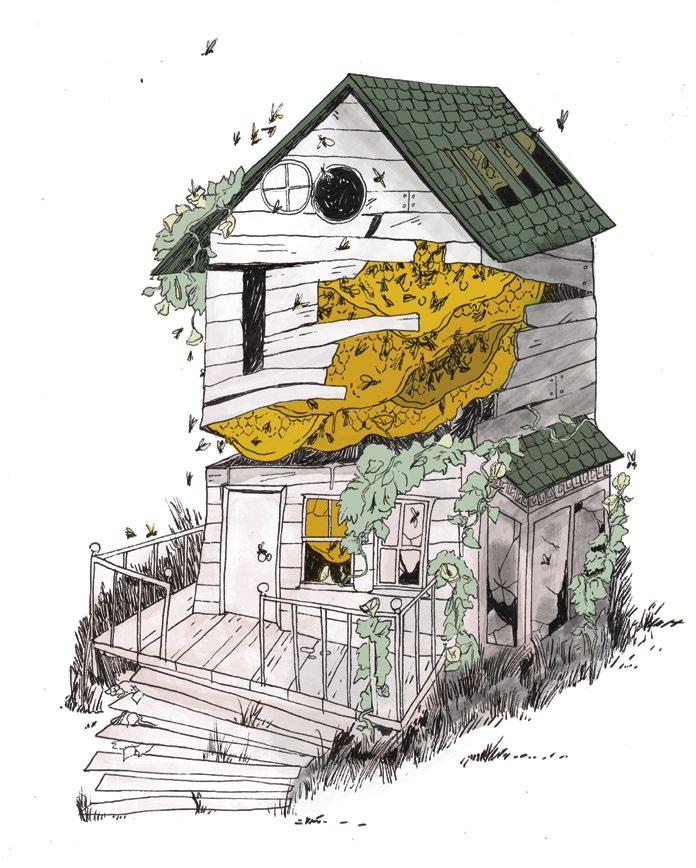

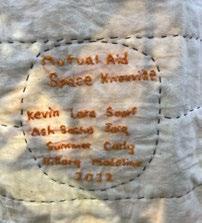

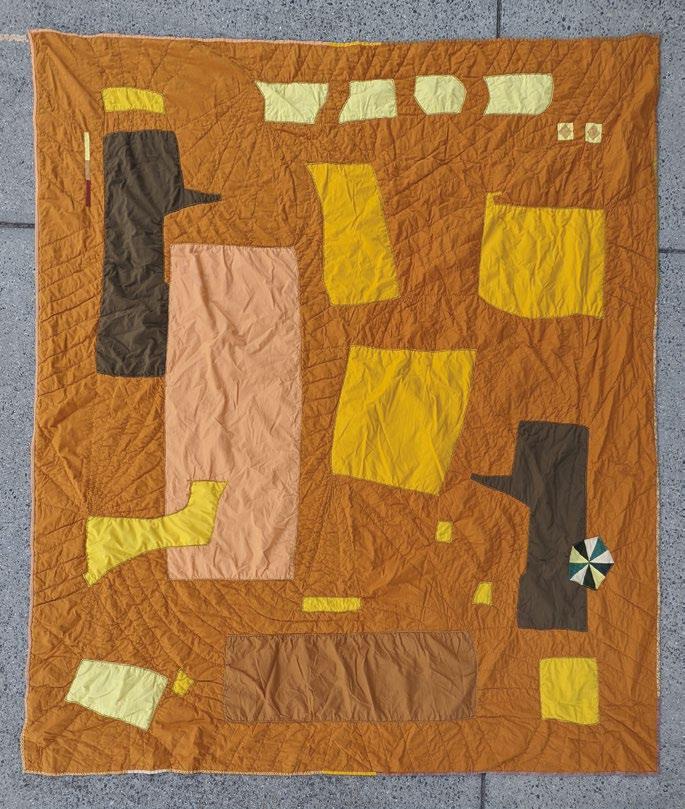

community-led. Similarly, the mutual aid quilt (pictured above), recently created by Soorf Carman, was completed by crowdsourcing quilt squares which then raised money for Mutual Aid Space Knoxville (MASK) by raffling the final quilted piece. This project is a symbol of how economic praxis, along with community, is still present in the act of quilting.

Ali Homan’s work (undoing., big yellow.) illustrates how this new approach to an old methodology can produce unexpected yet still beautiful outcomes. With more diversity and an infinitely wide range of information, symmetry has space to break down, creating a more complex composition than was possible before.

HILLBILLY ECOLOGIES

AFTER THE APOCALYPSE

mutual aid space knoxville quilt

Soorf Carman et al.

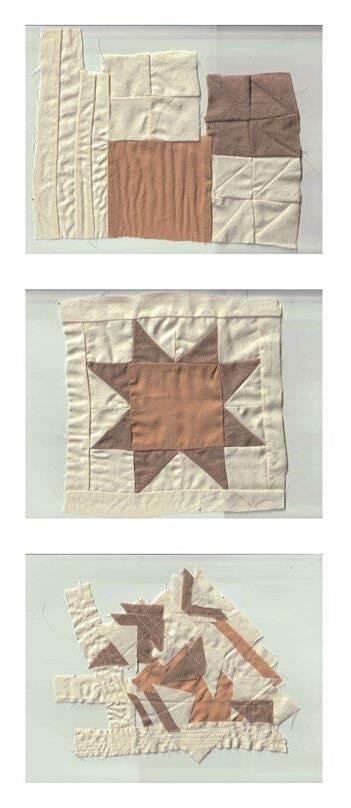

clark griffin Quilt Triptych

HILLBILLY ECOLOGIES

AFTER THE APOCALYPSE

mutual aid space knoxville quilt

Soorf Carman et al.

clark griffin Quilt Triptych

As shown in Quilt Triptych by Lindsay Clark Griffin, the same resources can be reconfigured to create very different compositions. Where systems built to classify, quantify, and compare start to fail, a strategy of ad hoc asymmetry and amplified diversity offers a fresh perspective. Such a strategy is best implemented not through large-scale, sweeping overhauls but from grassroots efforts. We cannot wait for caregivers; we must start giving the care we see a need for now, with whatever we have at hand. The old Appalachian saying, “use it up, wear it out, make it do, do without,” is a radical sentiment in a culture of next-day delivery.

ali homan big yellow. (left) undoing. (above)

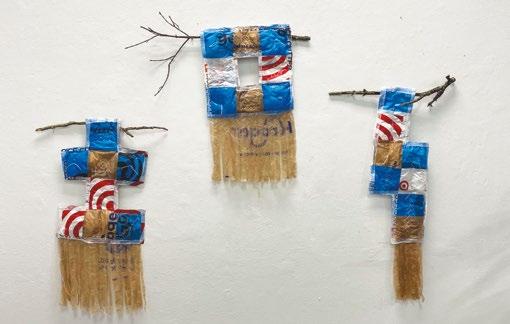

we can reclaim the wisdom of the hillbilly by opening our eyes to the abundant resources around us. Griffin Nordstrom captures this tactic by reimagining the feed-and-flour-sack quilts of the Depression Era in the more twenty-first-century medium of a plastic grocery bag. This quilt serves as a double act of preservation, one that is in direct relation to the hillbilly identity: preservation of resources, particularly those that are abundant, and preservation of the quilting tradition itself. What would it mean to translate other hillbilly strategies into our modern parlance? Would the process shed light on our hidden strengths and help us identify our blindspots?

The quilt shows us that a scrap doesn’t need to be perfect to contribute to a

beautiful composition. The strength of the quilt is not singularly found in its inherent uniqueness, precision, or pragmatism but in the amalgamation. On its own, a quilt is a massive undertaking, but it becomes accessible as each skilled hand at the table compliments the next. Both beauty and efficiency are prioritized in equal measure. As we look for ways to benefit from our global connectedness, we should acknowledge Appalachia’s natural capacity for facilitating invisible community networks. In this chapter of the region’s history, we know better than to believe the individualist myth, and we’re more equipped than ever to operate collaboratively. As modern hillbillies, we have both the roots from which to draw and the habitat in which to thrive.

We can reclaim the wisdom of the hillbilly by

abundant

griffin nordstrom Single Use Quilt, 2021 plastic, cotton, thread (top)

Permutations of Eight, 2021 plastic and thread (below)

1. Anthony Harkins, Hillbilly: A Cultural History of an American Icon (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003).

2. Henry Shapiro, Appalachia On Our Mind (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1978), 11.

3. Shapiro, Appalachia On Our Mind, 114–16.

4. Berea College Special Collections and Archives Catalog. Abstract, William Goddell Frost Papers. RG 03/3.03. https://berea.libraryhost. com/index.php?p=collections/ findingaid&id=250&q=hc+09

5. Shapiro, Appalachia On Our Mind, 120.

6. Shapiro, Appalachia On Our Mind, 121-3.

7. Shapiro, Appalachia On Our Mind, 213-43.

8. Mark Wigley, “Prosthetic Theory: The Disciplining of Architecture,” Assemblage 15 (1991): 6.

9. Lawrence M. Eppard, Mark Robert Rank, and Heath E. Bullock, eds., “In Conversation,” in Rugged Individualism and the Misunderstanding of American Inequality (Bethlehem, PA: Lehigh University Press, 2020).

10. Shapiro, Appalachia On Our Mind, 215-16.

11. Amei Wallach, “Fabric of Their Lives,” Smithsonian, October 2006, https://www.smithsonianmag. com/arts-culture/fabric-of-theirlives-132757004/.

The lines in the Roberto Bolaño poem: every insect egg was alive and dreaming i thought: now / i’m going to be alone forever, of which there is no title; only a Catalan epilogue that translates: just the front door of your beautiful likeness by Jordi de Sant Jordi entered my forehead on the bus terminal escalator. And I felt tilted toward a kind of earnest, life-affirming tenderness

estranged in the world. A neutral, collective space where blood could circulate again without unpaid data harvests, without pesticide coupons.

there were papers strewn all up and down the asphalt as we walked down Madison Street. In the still-glistening and gelatinous mud, you could see, crumpled up, a nonlinear chronology of assorted things that had happened over the past fifty years. Old concert posters and such. Gospel records by enormous talents that probably no one outside of eastern Kentucky had ever heard of bobbed beneath bridges. Broken banjos lay across stones in the river. Spools of film, each moment preserved in negative, decayed before our eyes. In the archive that spilled its guts out onto Madison street, were the photographs. The solemn bespectacled eyes of grandfathers, black and white and matte, peeked between gobs of mud. The river had liberated history from the basement of the archives and then immediately pounded it into oblivion with everything else, laying it out at the feet of the people of Whitesburg, Kentucky.

The archives at Appalshop and the Hindman Settlement School were both caught in the record flood of July 28, 2022. The Appalshop archivist told the Kentucky Courier-Journal that there was enough film in the building’s basement to make a long, thin road to Nashville—4,000 hours of footage. First and foremost, the building was founded as a film workshop, and the film in it reflected a people’s history of Appalachia: raw tape that children took of their mothers cooking dinner; tape that mothers took of their children playing in the yard; Sunday baptisms and rowdy Appalachian funerals; striking coal miners hollering themselves hoarse as scabs replaced them at work; hours of women sweating over the night shift at a local burger chain; teenagers playing basketball. The flood with its greasy fingers flipped through handwritten diaries of children of the coal camps. The flood reached for 3,600 original photographs, many of them by a man called Pictureman Mullins, who took photographs all over Letcher County; 80 percent of these were damaged, tangled in tree branches and strewn across the road.

So, too, were pieces of the past that echo the present. In the mud were tapes containing recordings of the local radio station’s once-preeminent DJ personality, Jim Webb, who is now deceased, talking about his involvement in a communityoriented disaster response to the Tug Fork flood of 1993. Unspooling on

the sidewalk were reels from a film about the Buffalo Creek flood of West Virginia on February 26,1972. On that day, a rainstorm burst a coal slurry impoundment dam managed by Pittston Coal, which referred to the incident in its legal filings as an Act of God. Out of 5,000 people in the community, 125 were killed and over 4,000 left homeless.

All these are pieces of life—reminders that the questions you are asking today have been asked before, things that made you see everything precious to you has been precious to someone before. All these artifacts had been living quietly in air-conditioned basements, where you could look at them if you asked.

The archivists often discussed releasing these historical records to the public in a more deliberate way. It takes a long time to digitize collections and make them searchable and more money than anybody, particularly any nonprofit in the Mountain South, really has. History is material, or what’s left of it is. It is things. It is stuff. And there’s a lot of it.

After the flood, my mind is broken, and some of it, I think, will not come back. All I can engage with is the reality of what it is, right now and three months ago, the way it felt and smelled and tasted.

how big was the flood? Nobody knew on the first day. Hollerwide flooding is common enough that most of us woke up assuming that, even though we had it bad, it was probably fine across the mountain. But it was big. For a time, it was too big to really comprehend. Hardly anywhere within a huge, sixcounty swath of eastern Kentucky had been spared. I suppose I had known this was coming, but you never think it will come today—tomorrow—yesterday.

We didn’t know it, but forty people had been swallowed by the water that night. As we slept, the creeks all at once had come roaring down the narrow hollers, where there’s one way in and one way out. The only place to go was up a mountainside, or let the water take you away. Some would tell me it was twenty feet high, that they clung to treetops, curled up on roofs, scrambled with dogs and babies and grandmas for higher ground. All through the cities of Hindman, and Neon, and Whitesburg, the home of the Appalshop Archive, water surged maybe twelve feet high,

with the strength of an EF-4 tornado, blowing out windows and collapsing buildings.

I had spent the night sleeping half an hour from the place where I live, in the town of Whitesburg, after attending a writing workshop and poetry reading the night before. Many of us had traveled far to be there, and so the cabin, one of several, was full. Other writers were all around me, sharing rooms, rising in the night. The night before we had all laughed and drank bourbon and watched the latest of many wild storms blow in. As it blew our bourbon cups into brick walls and forked endless lightning like I’d never seen, the writers said, “Lord willing and the creek don’t rise!” like it was a joke and not the product of generations of anxiety on nights like this.

When we woke in the morning, some of the writers, bless their hearts, said, “Writers trapped on a hill in a flood with nothing but pretzels and yesterday’s liquor! I can’t wait to write a story about this.”

The floods are in the language people speak, and writers recognize that and we love it, sometimes to a fault. This go round, we all made wry jokes with one another that we could no longer say we were “in deep water” or “up the creek without a paddle” or “come what may, hell and high water.” The memory of bad rains doesn’t have to terrify you for you to worry about them as a constant inconvenience. Friends of mine who live up rutted dirt-and-gravel drives will simply cancel plans when there’s a hint of bad weather, for fear they won’t be able to go home.

On the very first day, I woke up on a hill in the town of Hindman surrounded by water. At least, that was what I thought as I stumbled out of bed to grab hundred-year-old dulcimers and mandolins from the long-dead poet James Still’s cabin. That is what I thought as I made my way through the early morning mist to the lapping edges of the swollen Troublesome Creek and saw, unbelievably, around ten entire cars turned on their sides in the middle of the water. That is what I thought as I heard what others described to me, that I had been lucky enough, on high ground, to sleep through: the infernal rushing in the dark, the sounds of not just water but all that it carried, the things and the stuff, the detritus of lives in Knott County tumbling down a cold torrent.

I went into emergency mode. The power’s out. How much food do we have? Do we have a head count? Do we know each other’s names? What medical supplies do we have? Does everyone have their medication? I set about taking all this information mostly to keep myself from wringing the other writers’ necks. Then, I let them be. We all reacted humanly to this thing, just in our own way, and I was too tense to hold a conversation; I wouldn’t act right, I would be unkind for no good reason. Besides, there were a few famous writers here; those of us nobodies would be safe by the grace of their presence, and the people who’d come after them. Some of the writers were from here; they’d go home when they could to see what happened. Some would soon pile into their cars and dip out of eastern Kentucky history for the moment. Around ten of them would soon discover their own vehicles had been swallowed in the night. Surrounded by last night’s bourbon, some wild-eyed from lack of sleep and the sound of the rushing water, they would have to figure out what to do.

I drifted away, walked down the hill towards Troublesome Creek. I am also a reporter, and I work for a community radio station in Whitesburg, and I had a job to do. I had to go and see what on earth was going on, so that I could tell you.

troublesome creek is called Troublesome Creek for a reason. It swells quickly. In Knott County, the mountains are rugged and steep. Poets love that name, Troublesome, because of the abstract sense of mischief it represents. The Troublesome gives the gift of life and then drags it away. Musician Doug Naselroad, who lives in downtown Hindman, wrote a song about love and violence and rain on the Troublesome.

. . . when the creek came up at the break of day, He drowned himself taking me away, Down Hindman town, Hindman town, Where the mountains ring you all around. Hindman town, Hindman town, where the rain comes down with a troublesome sound . . .

Everything was upside down that morning: fire trucks wedged beneath bridges, cars flung into houses, houses in the road, entire hollers trapped by fallen trees. We heard later that the fire department said it couldn’t reach its own vehicles. The fire chief sat despairing in the dark and thought, It’s up to them now, they have to save themselves. We’ll see them in the morning.

The creek had left its mark in lines of mud on the courthouse and the library. Every gutter was stuffed full of a loathsome mix of tree branches and shredded plastic. It continued down into Hindman town, about a mile long from the pizza place, to the courthouse, to the vape shop, to the left turn onto Highway 80 towards Prestonsburg. Normally Hindman is quiet, and you don’t see many people out, but that day everyone was outside. It wasn’t even eight in the morning yet, and everyone was standing around with our hands lifted slightly from our sides, not limp, almost supplicating, or just helpless. One man stood by the road with a hatchet, which had presumably been used to hack apart tree limbs that blocked the road but now just hung useless by his side. The haggard-eyed volunteer firefighters directed traffic around the trees and bits of rubble that were in the road. The water was still up all through town, though it had receded since the dark hours of the morning. The water was slick on top with oil and milky brown. It swirled around the cars it had eaten in

the night. Dulcimers and banjos from the community luthiery lay broken across stones. All around was the acrid smell of gasoline.

“What happened?” asked those of us who had slept through the night.

“Never seen anything like it,” we were told by a couple of women. “Water twenty feet high all through downtown Hindman.”

The Troublesome took hours to go down. It was a long wait. There was a total blackout with cell towers, internet, and power. I idly watched a quartet of white geese waddle back and forth across the parking lot, occasionally stop to nibble at something on the side of my car. When a bar of cell service came back, I gave the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet a call to ask which roads were intact so that we could get back home; they were unsure. We heard from somebody who’d tried to get out, that there was a mudslide in the way. We heard state highway 80, in the other direction, was a puddle. A friend and I

spent four hours debating what to do before we decided to chance the road to Pikeville, which would take us, in a two-hour roundabout trip, all the way back to Whitesburg. The trip is normally about thirty minutes across Carr Fork Lake. One of the rocky cliffs that was once blasted apart to create the road, that bleeds red from mine drainage, had collapsed. You can’t see from the road, but about two-thirds of Knott County mountaintops are mined out, the useable coal taken and the raw mountaintop or empty shaft left behind. The lake, which was created long ago to control the river’s course to Lexington and prevent floods downstream, filled up like a bathtub. To create Carr Fork Lake, the Army Corps of Engineers moved a whole town, including its cemetery. One of the engineers says he looked inside a coffin and found a woman perfectly preserved, her nails and hair longer than when she was buried. He said he hasn’t slept a full night since.

now they say that, when it storms, we are time traveling in a way. As we see the effects of coal and gas burned in years past, the history is written upon the landscape. Coal encircles us; we begin and end with it. It births the gasses that trap heat in the atmosphere, and when the rain comes, the slag and silt ponds burst their seams and head towards the valleys where the people live.

The Appalachian world has ended many times over. The first time this world ended, when the settlers arrived, they set about ending this world again almost instantly. The Shawnee and Cherokee were sent on foot and wagon to Indian Territory in Oklahoma. Settlers stripped the hills of trees and shipped them on river barges to the coasts. The soil degraded, and farming became difficult. In 1820, the first coal mine in Kentucky opened.

Coal reshaped Appalachia like putty. Kentucky mountaintops were cleaved off for the Tennessee Valley Authority and for the cities to burn. Roads were

built here, but they spidered away from the country and towards the city rather than connecting country places to one another. The infrastructure existed to ferry coal and capital into populated places, not to carry people towards one another. The Environmental Protection Agency estimates that valley fills have buried over 2,000 miles in headwater streams. From the 1980s onward, coal industry employment has declined steadily, which has been blamed on any number of things, mostly hippies, but is truly the result of mechanization, closure of coal plants, and cheaper, more plentiful gas, among other economic factors. Towns that once had cinemas and operas and grocery stores have shrunk to a few families. The older generation bemoaned the loss of the region’s youth, feeling that its future was trickling away.

The line of people leaving eastern Kentucky stretches for a hundred years. Communities followed the boom-andbust cycle of the coal industry, rising and falling with coal’s fortune. In particular, the steep decline of coal in the 2010s took the carpet out from the economy. Thirteen percent of Letcher County hit the road that decade. Annual regional economic conferences and nonprofit summits are always discussing how to retain the youth. Usually they say better internet and cute downtowns will do it. Maybe a factory, if any company would come in here. Or a prison. Anything, some parents beg—anything for my baby to come back to me.

Young people who left Whitesburg returned to help clean their parents’ ruined homes, some of them staying for weeks and months at a time when they could. At Summit City, the Whitesburg bar, the region’s adult children could be heard yearning over a whiskey to stay longer, to put in more sweat, to roll up their sleeves and fix it all. But many of them had to leave eventually, back to jobs and families and homes with better water and sewer lines and broadband. The young people who remain aren’t convinced that the place is ever really coming back from this.

My friend and I drank in the afternoons at Summit City, the sun drawing sweat into our eyes, leaving muddy footprints all over the deck. He’s a photographer and was helping folks take pictures of their houses so FEMA could help them.

He came in every day with haunted eyes, repeating the same stories over and over. A family had lost four children; it was on the news. They were from Knott County, and he knew them. He heard how they clutched the trailer as it spun apart in the torrent, grabbed for one anothers’ shirts only to lose their grip in the whitewater. The flood aimed to reduce you, shrink you and erase you, tear away all the possessions that you’ve gathered, the people who remember who you are, the home you’ve built, leave you with nothing but your body to rely on and the animal fear in your mind. The flood would have you blank and empty as that awful July dawn, when the

sun rose on a world without four Knott County children in it. ” He would talk about that, and then would lean in close and say, shaking his head, in a low voice, “Honestly, I just think people are gonna leave. It’s already starting.”

In 2019, a study by the Army Corps of Engineers showed massive disturbance by strip mining across the Big Sandy and Kentucky River watersheds of the Ohio Valley and a projected increased rainfall of up to 35 percent. Though the place is relatively safe from hurricanes and wildfire, the annual rainfall has ballooned and is likely to continue.

As the mud hardened and the water receded, people found themselves linking these little ends of the world to one another. In Millstone, the people cannot prove it, but they are certain the mine waste retention ponds busted and gushed water six- and eight-feet high across their property. People up and down the holler all swear it. They say that the water was black, that there is no other reasonable explanation for the sudden gush that left them rushing to the roof, dogs in hand, to wait out the night.

In Breathitt County, an hour west, sixty plaintiffs in the Lost Creek area are suing Blackhawk Mining for their strip-mining practices. They say the dam that keeps the mine’s silt ponds burst and knocked their homes from their foundations. The plaintiffs say they knew because strange, massive orange

carp live in the silt ponds, and the day after the flood, they saw dozens of carp wiggling and gasping under their single-wides.

things in eastern kentucky have a way of dissolving and reforming, of disappearing and reappearing. Entire towns cease to exist only to be brought back to life in the ensuing decade. In the old coal-camp town of Blackey, it was the flood of ’57 that brought an era to heel. Blackey was officially dissolved as a town as of July. I reported on the dissolution at the time, speaking with a woman named Denise Bates, who grew up in Blackey, as did her mother before her. When I sat with her on her second-story porch, she drew a map for me of where things in town used to be. The corner store grocery, the gas station, the train depot, the school. The coal industry decline—one of many— struck Blackey a blow early, in the 1930s. Things tipped into decline, and the ’57 flood overtook the iron bridge and spilled into Blackey. After that, businesses moved out, saying the flood would come again.

There had been a flood in ’27, which made everybody assume that the sevens were unlucky years, but they were wrong. The floods didn’t come back to Letcher County for a long time. Even so, pieces of Blackey fell away over the years—the Caudill country store where people gathered to play music and talk politics, the teenagers with dreams of moving to the city.

When I was in Blackey speaking with Denise, her grandchildren came to the porch to look out over the town’s pretty green hills. “I don’t want Blackey to not be a place anymore,” said the grandson. “It’s still a place,” said Denise. Her grandkids thought Blackey was the best place on earth.

There was once a Bible school in Breathitt County that got taken by the flood of ’39. Students and staff died holed up in the boiler room. There remained a dorm, a gym, and a stone chapel. Visitors said children’s laughter and speech could be heard echoing through the halls. Some have even said they see red, glowing eyes upstairs. The basement, they say, was filled with black

mud. The building was demolished in 2006. And then, in the town of Hardburly, they say a child drowned by the flood still cries out. I consider ghosts to be a historical record. I did not disbelieve in ghosts before I moved to eastern Kentucky, but I did not believe in them either. But too many have seen too much; I have to believe them. I imagine they are there to preserve the emotions of a particular time and place, to remind themselves and make sure that we never forget.

Water has washed repeatedly in and out of Breathitt County over the decades. In 1957, 1972, 1977, and 1984, record flooding came to the area. The county sits trapped between the North Fork and the Middle Fork of the Kentucky River, and all throughout it are the creeks, the Quicksand, the Shoulderblade, the Bear, the Bloody, and of course, the old Troublesome. Places with names like Quicksand Road come up in the old records repeatedly, as does the Panbowl Dam, which in the past couple of years alone has threatened to burst open. In 2020 and 2021, the Panbowl has been

“I don’t want Blackey to not be a place anymore,” said the grandson. “It’s still a place,” said Denise.

evacuated. I talked to a woman last year who was still living in a camper in her yard five months after the 2020 flood; I don’t know where she is now. I don’t know if my little radio story did her justice. There’s a limit to what the medium can do, at least the soft-voiced, NPR-style radio story. Fury and grief become sound bites.

The 1972 flood, at least, was documented in song and story, not really by newspapers but by local storytellers whose fury comes through in their recollections. Rich Kirby, a songwriter and storyteller who still makes his way around the region’s festivals and radio stations, recalled it in a piece he wrote titled simply, “The Flood.”

He recounts it:

“One person got out of every family—one living person got out of every house and every family that went, one person got out.”

And later, a conversation between family members:

nell: My grandmother was warned of this, and she told them, back in May. My grandfather’d come to her [in a dream—he was some years dead] told her he was happy and this and that, and when he started to leave she called him back, and he says, “I’ll come get you at the fourth.” My brother was hear Mother singing out there in down here on the fourth, and he the lane, “Dear Friends Farewell” says “Well, Grammaw,” he said, and all those songs… “he fourth is about gone and nothing’s happened yet,” and what did she say?

nan: “The Lord is never a minute too late or a minute too soon.”

nell: And at 2:30 the next morning she left this world and warned—it come out in the papers, she went and warned there was going to be a great destruction. She’d tell it in church, tell it anywhere she went. She said, “After the fourth of July you’ll find out, around the fourth.” And sure enough it did happen.

Kirby describes the flood, which was small in scope but incredibly violent: “The post offices at Stevenson and Rousseau were washed away . . . scenes of utter desolation in the Frozen Creek valley. The villages of Wilhurst, Vancleve, and Puckett were washed away . . . nothing is left now but silt-covered ground.”

Kirby points the finger at the lumber industry, saying that while a connection couldn’t be proven, everybody seemed in agreement that the deforested slopes and

strip mines bare of soil had obviously led to a quicker and more savage flood. “No one in authority proposes to control floods by eliminating strip mining,” he says. Above the Lost Creek community in Breathitt County, where the carp washed in, are strip mines; above Neon strip mines; above Millstone strip mines; above Hindman, strip mines. To this day, it’s insisted by certain people in power that the connection between flooding and strip mines can’t be exactly proven, that the floods are a natural outgrowth of a rugged landscape and the victims simply foolish people who had not left yet. Floods are regular. Floods are normal. Nothing can be done. “Mountain communities are subject to floods—‘acts of God,’ it seems—that are not worthy of recording,” says Kirby.

government would come here to help. The only person who’ll help you is the weirdest old man up the holler you ever saw, who wore aviator sunglasses and an American flag bandana around his head and rode a side-by-side around the broken roads to deliver groceries and conduct wellness checks. Or somebody to remain unnamed who stole his work bulldozer and got to moving debris with it. That’s who comes through in the end.

After a disaster the people are in a dream. And after the dream, the people begin to wake up and do what must be done. We begin to understand that everything cannot remain in pieces forever. The cars wrapped in tree branches must come down. The fire truck must be dredged from the creek. Community centers push aside their tables, cancel their programming, and begin to solicit clothes, canned food, water, camping supplies for the people they serve.

up the hollers everybody felt forgotten. In the weeks after the flood, Susannah was trapped up the holler by fallen trees. Susannah said she always knew nobody was coming because nobody ever comes. She and her neighbor laughed at the idea the