Mergoat Mag

emma oxford

Beard Cane Mountain digital 2016

artist statement

The red-cockaded woodpecker (named for the small red streak present on males’ heads) is an endangered species that historically inhabited the northwestern area of Great Smoky Mountains National Park but has not been sighted in the park since the 1970s. The reason for their disappearance is understood to be the loss of preferred habitat: the longleaf pine forest that was heavily logged in the beginning of the twentieth century. Additionally, red-cockaded woodpeckers are suited to forests that burn frequently, which clears the understory and keeps predators like arboreal snakes from breaching the resin barriers the birds build around their nest cavities. The fire management strategy deployed by the National Park Service for many years—to suppress any and all fires—was likely another factor that contributed to the drop in population.

Woodpeckers perform vital ecosystem services, turning dead trees into suitable habitat for other life. At least twenty-seven species have been documented using red-cockaded woodpecker cavities, including other birds, insects, snakes, lizards, squirrels, and frogs.

Ecologists now understand that fires caused by natural forces like lightning are an important part of forest health, and the National Park Service has embraced the use of controlled burns (which many Indigenous groups have employed for centuries). The red-cockaded woodpecker, too, still hangs on in isolated pockets throughout the Southeast. Time will tell if this will be enough for the birds to join the ranks of elk, river otters, and peregrine falcons in successful reintroduction to the park or whether they will become another ghost of the Smokies.

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 005

ECOGRIEF

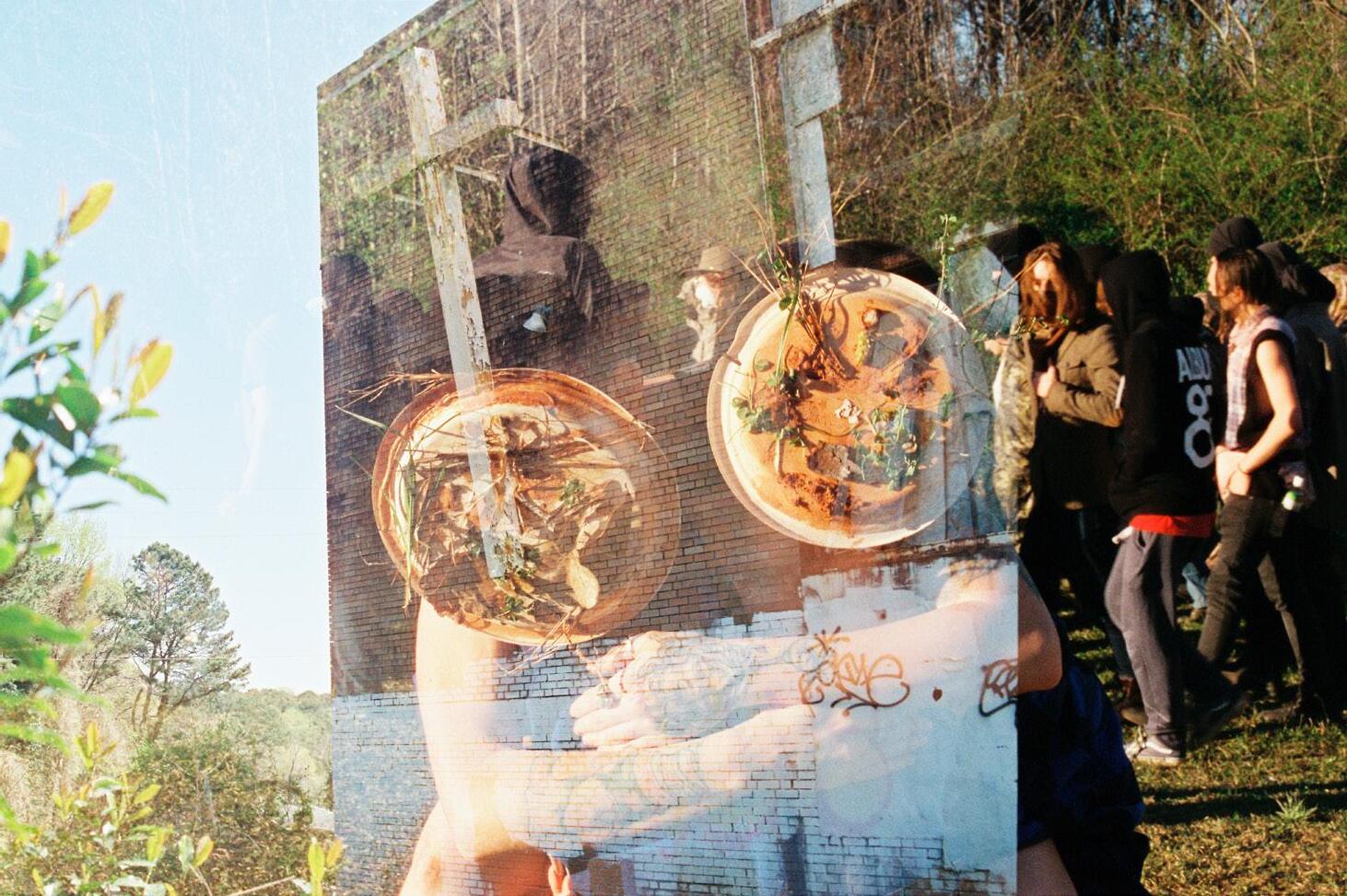

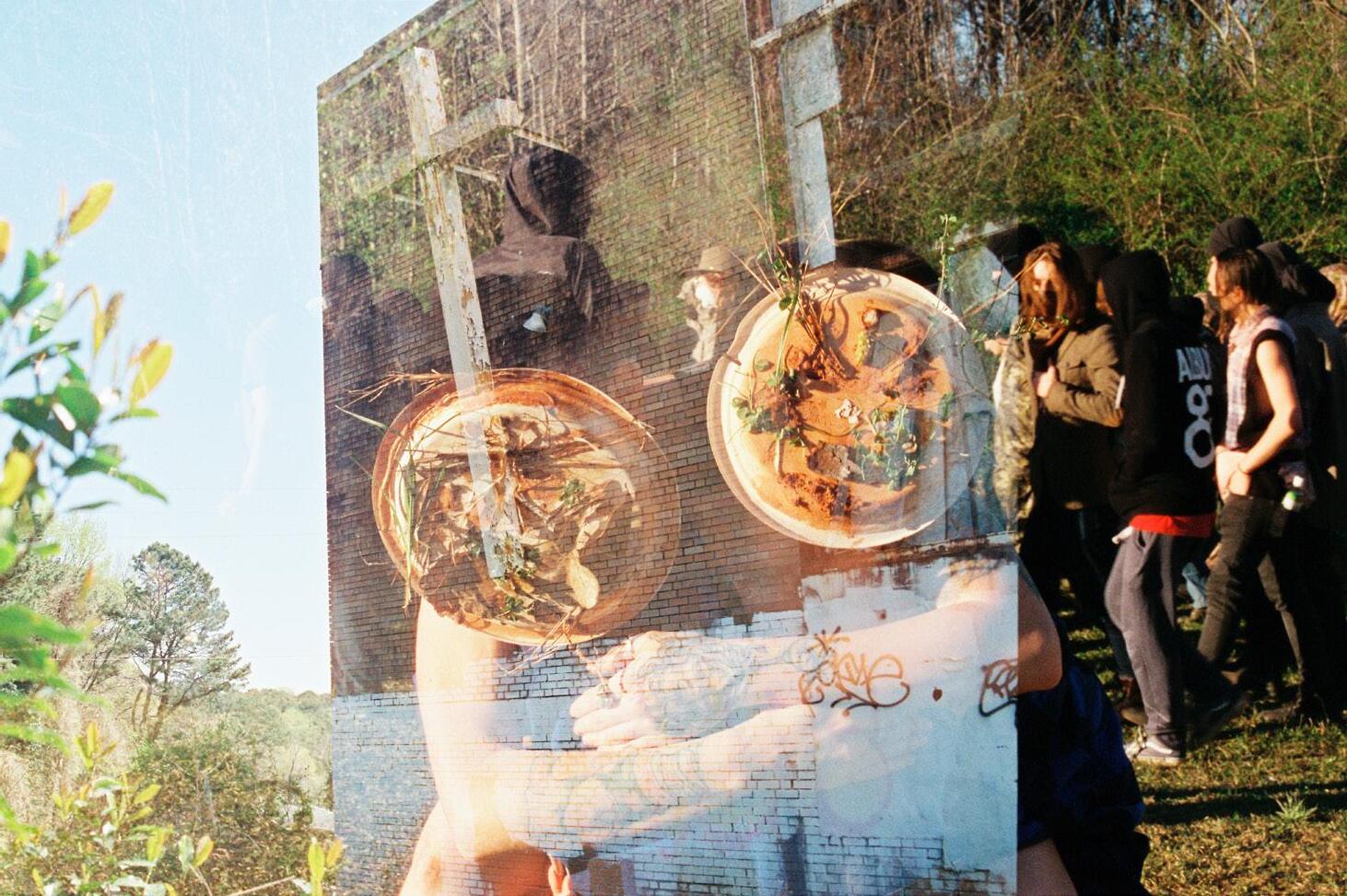

Photo by Bryce Wade

Poems of lamentation allow the melancholic loss that never truly disappears to be given voice. Like a slow solemn musical refrain played again and again, they call us to remember and mourn, to know again that as we work for change our struggle is also a struggle of memory against forgetting.

—bell hooks, Appalachian Elegy: Poetry and Place

Mergoat Staff

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE 008 ECOGRIEF

publisher & editor Sorrel Inman executive editor Kathryn Gruszecki creative director & designer Hazel Hoffman illustrator & designer Alex Bonner interviewer & copyeditor Aaron Searcy This text is illuminated throughout with illustrations by the illustrious Dayna Walton of Solstice Handmade.

Mergoat Magazine is a quarterly magazine published out of Knoxville, Tennessee. The best way to support our work is to become a subscriber at mergoat.com.

mergoat.mag

writing

Jessie Crow Mermel

Kerry Leigh

Jonathan Cox

CrimethInc.

Aidan Duir

Kathryn Kolb

Jacqueline Echols

Kamau Franklin

Scott Cave

Mila Roeder

featured poets

Lily Someson

Amelia Brady

cover art by Alex Bonner

art & photography

Emma Oxford

Bryce Wade

Dayna Walton (Solstice Handmade)

Eniko Ujj

Julianne Nash

Summer Wagner

Alex Bonner

Hazel Hoffman

Michael Arpino

Jonathan Cox

Huck Reyes

Black In Appalachia

Mila Roeder

Ryan McCown

Noah Grigni, ANI, + Mirina

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 009

From the Editor

Dear Readers,

We are in a constant state of grief. We grieve for the future we may not have. We grieve for those both near and far who are routinely killed while protecting the environment. We grieve for those who died at the hands of the police—an endless list. We grieve for poisoned lands and waters. And we grieve for non-human species at risk, endangered, and extinct. With this issue of Mergoat Magazine, we make a monument to our grief.

It is important to begin by acknowledging that environmental catastrophe has no political borders. When ice caps melt, ocean levels rise on each and every shoreline of the globe. When it comes to environmental activism, there can not be an ‘outside agitator.’ There is no outside nature. Mergoat Magazine is dedicated to Southern Appalachia, but we welcome those from elsewhere to share in our rage and grief at environmental catastrophe. The environmental catastrophe here means catastrophe everywhere.

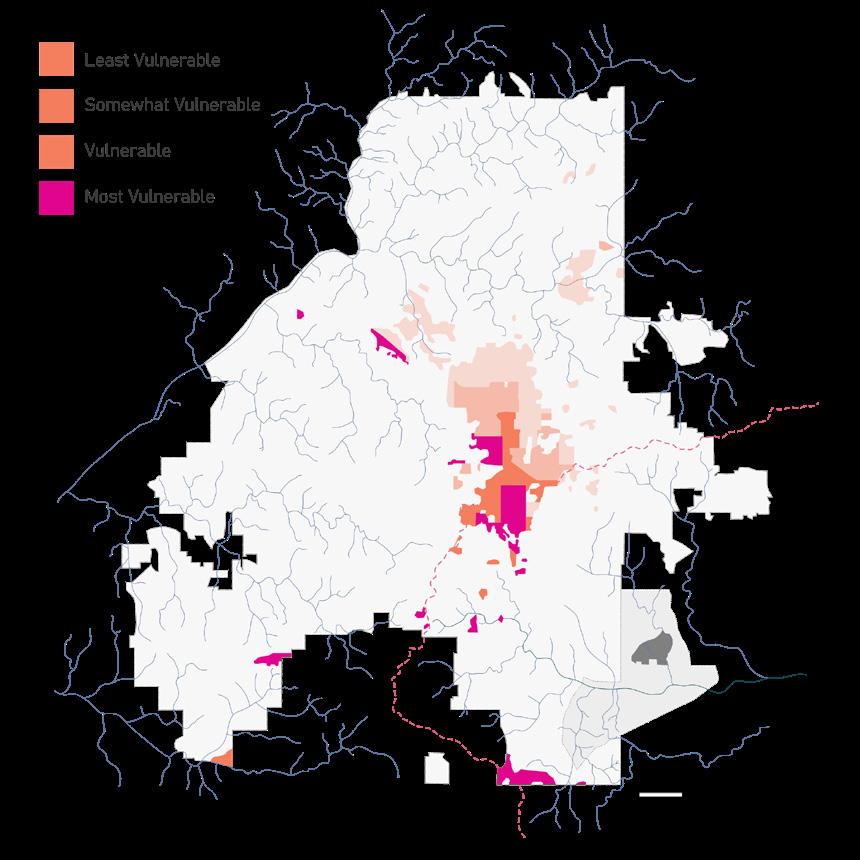

Over the last several months, the rhetoric of the outside agitator, once used to delegitimize the civil rights movement, has resurfaced yet again to dismiss Atlanta’s Stop Cop City movement. But when we consider the floods that may come if Atlanta’s Weelaunee Forest is not protected, and when we think of the violent tactics that will be bestowed upon local, national, and international police forces at this training site, the irrelevance of political borders is clear.

Stop Cop City is a movement that arose out of grief. It draws attention to the many connections between ecological grief and environmental racism; simultaneously we are seeing the destruction of a forest and the racist ideology that justifies its destruction. As plans arose to build a stateof-the-art police training facility in a predominantly Black community, protesters rebelled by actively occupying the forest to halt construction. The movement that began in 2021 continues to this day, despite attempts to charge protestors as domestic terrorists and the death of beloved environmental activist Tortuguita.

Many had warned of escalating police violence against forest protectors in the months leading up to Tortuguita’s death. As Stop Cop City protesters held a press conference on December 14, 2022, one month before the incident, Marlon Kautz of the Atlanta Solidarity Fund looked into the camera and stated:

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE 010 ECOGRIEF

The Atlanta Police Department is using plastic bullets and pepper spray against unarmed nonviolent political protesters. I’ll say that again, the Atlanta Police Department is using chemical weapons against unarmed non violent political protesters. This is not normal. This is not normal in Atlanta. This should not be normal anywhere.

Why is it happening? Well we’ve seen over the past year or so, during the course of the movement against Cop City . . . that the police have been engaging in a deliberate campaign to demonize this particular protest movement. They’ve made an effort in the press to associate this protest movement with fires, the governor . . . at one point calling the Stop Cop City protest movement terrorists.

But I want to be clear. The people that the police are attacking with plastic bullets, with chemical weapons, as recently as yesterday, these people were not involved with threatening anybody. They were not involved in endangering anybody. They were sitting passively in trees trying to express their political position . . . for sitting in trees trying to conduct a nonviolent protest they were attacked by police . . . arguably tortured with chemical weapons.

So we can see the Atlanta police are engaging in a clear campaign of an escalation of tactics over the past year. When the Stop Cop City movement began, police tried to use intimidation to dissuade activists to try to get them to go home and end their movement.

When that didn’t work, they began making baseless arrests, which the Atlanta Solidarity Fund has documented and is providing legal support to defend people in those cases. When the baseless arrests failed to discourage people from speaking out about the problems that they saw with Cop City, we got to where we are now. . . .

Protesters are continuing to speak out. . . . What’s changing is the police response. And it’s clear that if the public doesn’t respond, if the public doesn’t do something about this, that escalation is going to continue.

Are we going to end up in a situation where police are murdering protestors in order to advance, not public safety, but their particular political agenda, in building a Cop City?

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 011

When the news of Tortuguita’s death was released, corporate media outlets echoed a narrative spun by the police, promoting uninformed and irrelevant claims of outside agitators and highlighting films of fires to associate the movement with violence and destruction. But environmental activists had an entirely different narrative. Their narrative showed the insistent and brutal rage of the Atlanta police officers against those protecting the forest from becoming a militarized police playground.

At the heart of these contradicting stories, one dominated the airwaves more than the other. One being an institution more concerned with maintaining its power than the health of communities and the environment that maintains the health of those communities.

As I write this letter, news has broken about the autopsy of Tortuguita. Their hands were raised, and they were seated in surrender to the police at the time of their death. Both of Tortuguita’s hands were pierced by bullet wounds as they were raised openly, without a weapon, and without residue. Additionally, police can be heard on video footage of the aftermath stating that they may have been the ones to harm their own state trooper—the justification used to murder Tortuguita. This proves the deceit within the narrative spun around Tortuguita’s death and the movement itself.

Backed by concrete evidence and witness statements, it is clear which narrative is the truthful one and which we are obliged to report.

This issue is dedicated to the irreplaceable life of Tortuguita, all those who have died at the hands of the police, and all those who have died defending the earth.

Sincerely,

Kathryn Gruszecki Executive Editor Mergoat Mag

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE 012 ECOGRIEF

Support our work

Here is a breakdown of our sliding-scale payment structure. We have made it possible to subscribe for as little as $4.58/ month. With this in mind, we ask those who have the means to subscribe at the solidarity level. Not only are solidarity subscribers a huge support as we start this project, but you are also helping to subsidize discounted subscriptions!

DISCOUNTED RATE

This price level is intended to serve working class, queer, disabled, and BIPOC folx.

PRINT & DIGITAL $75/year -or- $20 every 3 months

DIGITAL ONLY $55/year -or- $15 every 3 months

STANDARD RATE

This is retail price: what you would pay at the bookstore.

PRINT & DIGITAL $90/year -or- $25 every 3 months

DIGITAL ONLY $75/year -or- $20 every 3 months

SOLIDARITY RATE

This price is for subscribers who wish to invest in the longevity of our project.

PRINT & DIGITAL $150/year -or- $40 every 3 months

DIGITAL ONLY $120/year -or- $30 every 3 months

Want to carry our magazine at your store?

Message hello@mergoat.com for wholesale inquiries.

mergoat.com

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 013

Bell Bowl Prairie Blues

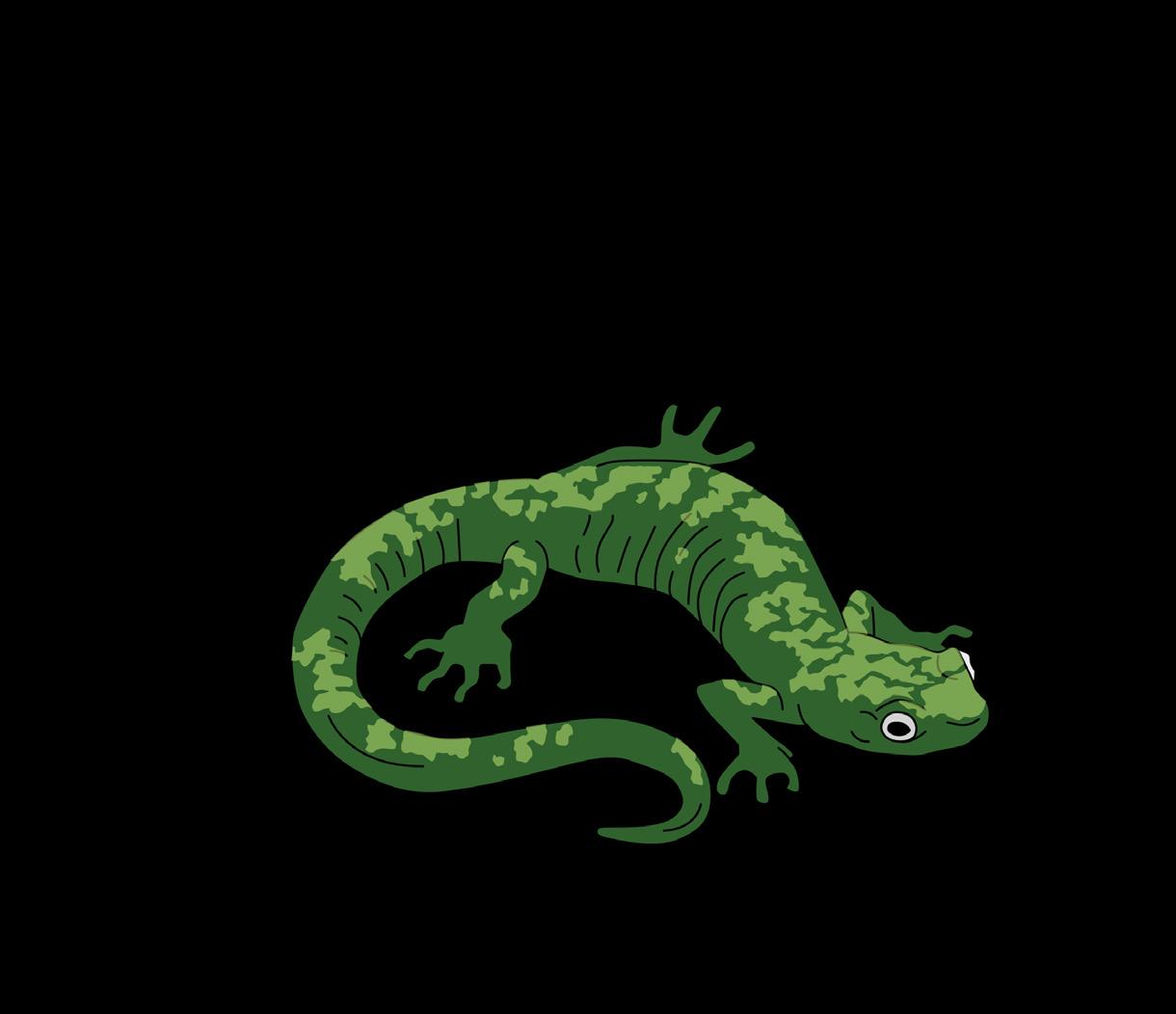

Species Feature: Green Salamander

Stop Cop City: A Timeline

Turtle-Shaped Sunbeam

Voices from Atlanta

Project Feature: Citizens Cemetery

Bloodroot and Honoring Grief

Coloring Sheets + Contest Featured Poets

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE 014 ECOGRIEF

TABLE

OF DISCONTENTS

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 015 Jessie Crow Mermel Kerry Leigh Amelia Brady Lily Someson Aidan Duir Kathryn Kolb Jacqueline Echols Kamau Franklin Scott Cave Mila Roeder illustrations by Ryan McCown CrimethInc. Jonathan Cox photography by Summer Wagner + Jessie Crow Mermel photography by Huck Reyes photography by Huck Reyes art by Mila Roeder art by Eniko Ujj art by Michael Arpino illustrations by Dayna Walton of Solstice Handmade illustrations by Alex Bonner photography by Bryce Wade + Jonathan Cox 20 36 50 60 76 134 150 160

eniko ujj

L’Inconnu de la forêt (The Unknown of the forest) pit-fired ceramic 2022

artist statement For this installation I take raw ceramic slabs and make prints of individual endangered longleaf pine needle trees from an area around Pensacola that is under development. I then pit fire the pieces with collected fallen debris from storms in the longleaf pine ecosystem to help with the prescribed burn process. All of these trees will end up being cut down. The title references "L'Inconnue de la Seine" and the tradition of a death mask as a memento of the deceased. The resulting prints and process of firing leave a haunting impression.

Pensacola has a long and important history connected to longleaf pine needle trees. This area was heavily logged and had a thriving turpentine industry. The town was practically built with pine trees. Due to this deforestation and overharvesting, only about 3 percent of the original longleaf pine forest remains. However, efforts are being made to restore longleaf pine ecosystems to within their natural range. More than thirty endangered and threatened species, including red-cockaded woodpeckers and indigo snakes, rely on longleaf pines for their habitat. Additionally, these trees are more resilient to the negative impacts of climate change than other southeastern pines. They can withstand severe windstorms, resist pests, tolerate wildfires and drought, and capture carbon pollution from the atmosphere. A number of nonprofits, government agencies, and private landowners are collaborating to restore longleaf pine forests.

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE ECOGRIEF 016

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 017

A group of starlings is called a murmuration

I run teeth first to the riverbank, hair streaming like tears flowing in worship I weep, mourning murmurations, starlings in the wind like all my hands sweeping you over. Grief like great flocks. I telescope my hand to see all the wonders I was born too late for: earthworms, yarnflesh beauties, dancing upwards in the hundreds through red earth while all kinds of birds fill the air, enough to sing a symphony—every frequency lovetuned to beautiful sex and baby making, enough food to go around, insects galore, rubbing their legs together, and did you know there used to be parrots in North Carolina? In that world, I have children. I name my daughter Viscera, tell her, darling girl, this was not made, it was grown.

—Amelia Brady

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE ECOGRIEF 018

eniko

L’Inconnu de la forêt (The Unknown of the forest) pit-fired ceramic 2022

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 019

ujj

Bell Bowl

THE DRUMMING HEART

Jessie Crow Mermel

Jessie Crow Mermel and Kerry Leigh explore how their fight to save an ancient, 8,000-year-old dry gravel prairie and its endangered rusty patched bumble bee led them through hope, then a deep grief, to a re-membering of how we can hold one another—and the earth—in a sacred embrace, even in this period of great social and ecological crises.

Jessie Crow Mermel (she/her) is passionate about the intersectionality of rewilding the land and rewilding ourselves. She has been an agroecology educator at Angelic Organics Learning Center since 2008 and a master naturalist since 2012. A longtime activist, artist, and ceremonialist, she cultivates community healing through land-led ecological restoration, women’s circles, grief work, and deep ecology programs and ceremonies.

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE 020 ECOGRIEF

Prairie Blues

INVITING GRIEF IN Kerry Leigh

Kerry Leigh (she/her) currently works as the executive director at the Natural Land Institute, a 501(c)3 conservation land trust located in northwest Illinois. With over thirty years of experience in ecosystem restoration, water resources, land protection, and land management, she has been a key strategist in policy development, advocacy, and land planning and has focused on building partnerships and teams. She also works to create a community for healing of both land and the human spirit in a reciprocal way that honors the life force and interdependence of every living thing.

photography by Summer Wagner unless otherwise noted

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 021

THE DRUMMING HEART

Jessie Crow Mermel

Holding vigil with Bell Bowl Prairie on the eve of its destruction felt akin to how I imagine holding hands and praying with someone about to face execution might feel. Even though this rare prairie ecosystem was one of the last of its kind in the so-called “Prairie State” of Illinois, and despite it being a critical habitat for the federally endangered rusty patched bumble bee (Bombus affinis), the FAA, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Department of Natural Resources sentenced this prairie to death. The prairie was a sacrifice zone for an international cargo airport expansion, specifically a road to a parking lot that the Chicago Rockford Airport was unwilling to move. There was to be no eleventh-hour call from the governor with a stay of execution. As was proven in the case of Bell Bowl, so many of these laws that we think are meant to protect species or habitats exist simply to regulate their destruction.

After eighteen months of the advocates stalling the destruction, the advocates of the remnant dry gravel prairie were out of options. The Chicago Rockford Airport was poised to move fast once the FAA approval came in.. Construction was to resume on March 9 to ensure that the road was carved before March 15, the date that the rusty patched bumble bees might be seen emerging from their nests to begin foraging. According to the Endangered Species Act, if the bees were to be seen foraging, it would force the construction to stop. They are only allowed to kill the bee while she sleeps in her hibernaculum amidst the deep roots and stirring seeds of the prairie. Out of sight, out of mind.

However, the beings of Bell Bowl Prairie were on the advocates’ minds, and the prairie was deeply rooted in our hearts. After a rally at the Rockford courthouse on March 8, 2023, where the last motion to stop the prairie was denied that day, a group of us moved on to the airport, as close to the prairie as security would allow. We gathered in a circle under the darkening sky, just after sunset, and shared poems and songs of lament. A version of Joanna Macy’s “Bestiary” poem was read, calling out the rare, threatened, and endangered species that find refuge in Bell Bowl Prairie. The drum pounded a heartbeat rhythm for each species named. Deep grief was expressed, as was rage and frustration for a system so broken that it failed to protect something so precious and rare.

022

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE

ECOGRIEF

Some left after the ceremony, while others stayed to hold vigil for the prairie. A handful of us created a circle of intention by walking a six-and-a-half-mile circuit around the airport campus, which was developed between the confluence of the Kishwaukee and Rock rivers on land that had been sacred to the original Indigenous inhabitants (Potawatomi, Sauk, Fox, Ho-Chunk, Peoria, Miami, Kickapoo along with others). I stayed out that night to watch the nearly full moon emerge briefly and disappear back under the cloudy skies, drumming as a form of prayer. I wanted the prairie to feel my loving presence, even if I could do nothing else.

The sky was still dark when the birds began to sing, and I was briefly filled with hope that nothing had happened to the prairie in the night.

Shortly after, a sheriff’s car pulled in to join the security forces whose headlights had been shining on me all night. I had an ominous feeling upon the increased police presence. Other prairie advocates began to join me in the early morning. At 6 a.m., the headlights of a single bulldozer crest the hill of the prairie and began carving its way down through this ecosystem that was both long-enduring and so fragile. We stood in horror, many of us feeling the bulldozer

photo by Anonymous

photo by Anonymous

tear through us as we watched it tear the body of the earth. We carried out the large ceremonial drum and stood around it. Pounding our pain, our impotent rage, our grief, and our love for the prairie through the drum, we gave physical presence and voice to all of these feelings coursing through us. We watched the bulldozer make pass after pass while the tears rolled down our faces. We beat the drum with all the force of our hearts. We held one another. We bore witness and held a loving presence for the prairie as Bell Bowl was being dismembered. Yet even as that was happening, there was also a re-membering of how we can hold one another—and the earth—even in this period of great social and ecological crises.

Joanna Macy, a scholar and teacher of Buddhism, deep ecology, and systems thinking, reminds us that “the most radical thing any of us can do at this time is to be fully present to what is happening in the world.” As painful as it was to stay present with the destruction, it was our way of attending to this ecocide with hearts wide open in the active practice and cultivation of compassion.

Our society makes little space for grieving and rarely honors the ecological pain that is held both individually and collectively. Yet it’s imperative to take time to honor the grief and to share it with others as a form of solidarity and community healing. Even as I felt the profound grief inside my heart that day, as well as the palpable weight of the grief of so many who fought for the prairie, I also felt a profound sense of love and wonder at the capacity of the human heart to hold so much at once. What is grief if not part of the natural life cycle of love? When we take time to create a ceremony for our grief and not look away, we allow the grief to move and alchemize. Like a river, grief wants to move. When properly attended, the grief becomes compost for the next season of the garden of the heart. In this garden, this despair is transformed into inspired collaborative action. The rhythm of the drum that morning of mourning at Bell Bowl Prairie will forever beat in my heart reminding me to keep loving and keep fighting.

024

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE

ECOGRIEF

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 025

photo by Jessie Crow Mermel

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE 026 ECOGRIEF

photo by Jessie Crow Mermel

INVITING GRIEF IN Kerry

Leigh

The destruction of an ancient, 8,000-year-old gravel prairie remnant that hosted the federally endangered rusty patched bumblebee by the Rockford International Airport in Illinois this March was the deeply disturbing culmination of 18 months of legal battles and an incredible grassroots movement across the state and the country. Poets, artists, and musicians were inspired to compose and express love for this unique prairie, a love that became a reflection of our love for each other. High school students advocated to our elected representatives and to the regular people going about their daily lives who stopped to sign postcards and petitions to send to our elected representatives pleading with them to save the prairie. Thousands of them. The prairie was written about in the local, national, and international press, with TV and radio interviews. This outpouring of love held an element of fear, as we no longer see nature as separate from us but a part of us. The sixth great extinction includes us.

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 027

Being involved in the day-to-day protection activities, however, was time-consuming and exhausting. Potentially losing this exquisite, ancient living being was a reality too difficult to deeply contemplate. Our hope was strong. Our faith in our elected leaders was strong. Our faith in our state and federal legal protections and the courts was strong. Our faith in the wisdom of the airport authorities was not.

So when the legal protections failed, the courts refused our petitions, the elected officials turned their backs, and the bulldozers were at the ready, we gathered to pay witness. We had been the voice of the prairie for so long—the land itself and its creatures, plants, and endangered species that were denied protection. That night, before the bulldozers that lay in waiting awoke in the dawn to complete their destruction, to my surprise, the sobs were heaving in my body. I had not been able to tap into my grief. I was too busy, too focused, and too fearful that, if I allowed that grief to well up in me, its depth would be overwhelming. Only now did I invite the grief in, to wash over and through me, feeling despair. My grief was also for the awareness that the environmental legal protections we thought we had are not nearly adequate for the twenty-first-century environmental issues that confront us—the habitat fragmentation, invasive species, climate challenges, and more. Then, in its depth, I realized that my grief was also for the people so disconnected from their inner wisdom that they could not see. Our elected representatives were, in fact, unwilling to do the right thing.

028

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE

ECOGRIEF

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 029

Blocking my grief in the past had led to a stuckness, a deep blockage of vision and creativity. I had created a mask of an intellectual person who was in control. This time, I recognized my grief was a part of me, not something to be healed but something to be honored, treasured, and transformed.

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE 030 ECOGRIEF

Blocking my grief in the past had led to a stuckness, a deep blockage of vision and creativity. I had created a mask of an intellectual person who was in control. This time, I recognized my grief was a part of me, not something to be healed but something to be honored, treasured, and transformed. It could bring me peace with my past as long as I didn’t hide it or deny it. The expression of my grief was unseemly and messy. Yet I no longer cared. I wanted to care for my grief, whatever it looked like. Many thousands are grieving; even the security guard at the airport board meeting after the destruction was sobbing.

This incredible campaign to save an ancient prairie has brought a sense of peace to my grief. Knowing that I was not alone, and that my passion and awareness was shared by so many, has been deeply comforting. It has been comforting to know that the awareness and caring at the heart of this grassroots campaign was not centered around environmentalists but regular, everyday people who cared and who had perhaps never given the prairie a thought before its imminent destruction for an unnecessary road. The fact that we ran a respectful campaign stressing that we could have both the airport expansion and the prairie was important to me. Conservationists are no longer working in the old paradigm of one or the other, economic development or respecting and honoring nature. We are in a time of realizing we can have both economic development and also save our unique and irreplaceable natural world that supports our lives on earth. We just need to have the

will and release an ego need to be right. The airport, the City of Rockford, and the US Fish and Wildlife Service should be deeply ashamed that this is their legacy.

We are living in a time of planetary upheaval that is deeply disturbing on many levels. In this transitional time of cleansing old ways of being, forces are being brought up to be healed. Our world needs all of us, the career environmentalists and the everyday people, to hold the light for the unfolding awareness of our deep connection to nature, even as the dark rages around us. Those of us who were witnesses to this destruction can also be the inspirational and fierce healing force that works synchronistically with all life on earth. We will continue to nurture the healing energies of the planet, and of its people. It is a way of transforming our grief into action so that it is not a fruitless effort. We can step up and own our newly realized power to be the voice for our living world. This has taught us how deeply connected to the earth and its energies we are. Inviting in and allowing space for grief, for me, begins a new way forward to action in community that cuts through all the darkness and brings me joy.

My grief formed a desire to create a community for healing of both land and the human spirit in a reciprocal way so that we no longer feel alone, exhausted, or overwhelmed. This will be different for each of us, yet we can hold each other and the earth in a sacred embrace. Please join me in releasing your grief and fill that space with hope and compassionate action.

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 031

Rust Belt Pastoral

A snap of ice beneath boot. Bloodroot, road that coils under highway overpass.

Control-fire dunes, black with soot. Dead grass, winter’s imprint the color of evening goldenrod. Blue-collar hands—city cleaved from finger with tweezers from the medicine cabinet.

Growing up wading in waste ponds, big sisters on the lawn haloed in sticker burrs. A home is associative logic—

imagined light in the peripherals. City as UFO sighting, disappearing like our Jäger-breathed fathers in after-work bar crawls.

Knowing the fields by their structure of sound, corn husks languished by the early frost. The blue gill of my heart—

my city is airplane parts, steel mecca, seaweed brain. Midwest as necromancy, the past re-imagined. Blight of sun hitting

oil ribbons floating to the white-knuckled shore. Strip clubs pinching the highway on either side, truckstop jubilee

quilting the infrastructure. Outlet malls lolling in knapweed, an economy of metal and rust. I have come to understand this skeleton of buildings, this

smoke-stack sky, fire collapsing through my open window. The factory of my want, thermal in nature. The ways fate has decided who is under the car, on the conveyor line, wielding blow-torches until snow turns to steam. Vacancy of self, like the tinny sound of January, lawnchairs and windchimes on an abandoned porch. We pray to the industrial God, who examines our weakness of will, blows helicopter leaves until they sing their yearly whistle. It is freeing, sometimes, to be forgotten. To live liminally. Zest of lemon in the pie window, smell of iron crowding the lungs.

—Lily Someson

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE 032 ECOGRIEF

In my Father’s House, there are Many Rooms acrylic on canvas 2020-2021

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 033

michael arpino

“The Most Miserable Place in America”

“We used to be the murder capital of the US, but now there’s hardly anybody left to kill.”

—A drug-enforcement officer in Gary, Indiana. Business Insider, 2019

Screaming damsel tied tight to railroad tracks. Hands bonded in silent-film fashion, body fastened onto steel death trap. She cries out look, if one of you could just

untie me. Camera pans to 70,000 people—state government, legislatures, white families with well-mannered wristwatches, audience collected like colosseum crowd around her inevitable end, fork in the tracks growing too close, switch to pull away the armored animal

untouched. Crowd cackles, throws money in bets to guess how long it will take to see her die. It’s like that, only now remember that the scene has replayed itself

since the 1960s. It’s like that, only now remember the damsel is Black. Her screaming, once comical to the crowd, becomes too melancholic. They sigh, begin

to leave the stadium and flock to neighboring communities. We couldn’t have helped her, you know—she should have helped herself. They turn their bodies from her, left on the tracks baking in midwestern humidity. We don’t do handouts, the governor says, his pockets overfilled. Her desperation is being tied to the tracks and seeing the faces of those who knew she was doomed and still left. How no one asked who tied her in the first place. It’s like that, but the damsel is a city. She’s a tax bracket.

Specter of a steel mecca, white flight when the jobs dried up.

—Lily Someson

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE 034 ECOGRIEF

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 035

michael arpino

Deep Calls out to Deep acrylic on canvas 2020-2021

Species Feature Jonathan Cox

COMMON NAME

Green salamander

SCIENTIFIC NAME

Aneides aeneus

FAMILY

CONSERVATION STATUS

Plethodontidae (lungless salamander) Vulnerable Moist crevices along rock outcrops, often sandstone, within Cumberland Plateau and Appalachian cove forests

HABITAT

FOOD < 10 years

LIFESPAN

Insects

THREATS

Pathogens, deforestation, and climate change

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE 036 ECOGRIEF

Green Salamander 02

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Greens are lanky salamanders with proportionally long limbs stretching from their slender body. Their feet have obviously square-tipped toes, which assist with clinging to their rocky habitat. Typically, green salamanders are no more than five inches long including their dextrous prehensile tail. Their dorsum is mottled with chartreuse green blotches giving them the appearance of lichen or moss. Their eyes are golden, appearing as if they were wrapped in gold leaf, and bulging above their head like many other amphibians.

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 037

Photo by Bryce Wade

Crouched, you struggle through a tangle of rhododendron branches dotted with white blooms. You follow in the heavy footsteps of a black bear that carved this tunnel of living wood searching for berries and grubs and emerge from this ‘hell of slick and lettuce beds,’ as the Appalachian mountaineers termed the shrubby thickets, at a rocky impasse. A wall of gritty sandstone looms ahead, illuminated by your headlamp. Shadowy fingers sway on the canvas of stone, projected from the limbs of American beech and eastern hemlock. Lichenous growth radiates across the surface of the towering cliff face, and

lichen, grasps the rock with its prehensile tail and square-tipped toes as it searches for a sheltering crevice. This cryptic amphibian is not often seen in the wild, due in part to its camouflage and nocturnal lifestyle. This salamander is one of only a few known species fully adapted to life in the moist and shaded rock outcrops of Appalachia, typically found in cove forests tucked into hollers and the walls of gorges.

GORGE-OUS SALAMANDERS

Green salamanders are relatively rare even though their ideal habitat is relatively common throughout the foothills of

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE 038 ECOGRIEF

lifestyle. During the Miocene Epoch, when the tree line shifted in exchange for grasslands, green salamanders became geographically isolated in upland gorges, where cove forests remained near rocky bluffs.

As glaciers moved south and pushed the tree line in the late Miocene and early Pliocene, populations of green salamanders took refuge in these rock crevices. This arboreal theory may be supported by other members of the Aneides genus, many of whom live in redwoods and Douglas fir on the West Coast of the US.

Over the millennia, the remaining disjunct populations began to undergo allopatric speciation, giving rise to unique genetic lineages. Recently, a new species of green salamander was described, the Hickory Nut Gorge green salamander (Aneides caryensis), which is found only within Hickory Nut Gorge in North Carolina. Other unique lineages of green salamanders adapted to

this niche habitat can be found on the Blue Ridge Escarpment and both the northern and southern Cumberland Plateau.

Wherever you find a green salamander clinging to a rock face, you will likely find the oddly circular web of a large spider nearby. Upon closer inspection, it may look as if a spider has woven together a miniature lampshade. The lampshade spiders (Hypochilus spp.) don’t just share their habitat with green salamanders; they also share some evolutionary history. Just as the newly described Hickory Nut Gorge green salamander is confined to the boundaries of North Carolina’s Hickory Nut Gorge, so too is a microendemic lampshade weaver species. This fascinating link between seemingly unrelated animals could help us find new populations of genetically unique green salamanders, or relocate lost ones, by comparing range maps of both species.

miocene epoch An era between 23 and 5.3 million years ago that is marked by the intense diversification of mammals that preceded many of the extant families.

pliocene epoch During this short period between 5.3 and 2.6 million years ago, the Panamanian Land Bridge connected the Americas while the global climate became more temperate due to the formation of polar ice caps.

allopatric speciation

A process by which one species diverges into two or more separate species due to geographic isolation.

square-tipped toes

The green salamander’s square-tipped toes allow it to cling to rocky surfaces. They are a defining characteristic of this species.

2023 039

MERGOAT MAG SPRING

SMOKY MOUNTAIN MYSTERY

While we continue to deepen our understanding of green salamanders, there remains plenty of mystery. In 1929, the study of salamander ecology was booming in the Southern Appalachians. Several scientists were publishing notes, articles, theses, and books on these small diverse amphibians within the region and paying particularly close attention to the Great Smoky Mountains. One such scientist was Ralph E. Dury of the Cincinnati Natural History Museum.

Dury would frequently travel into Gatlinburg, Tennessee, and up to an area known as Cherokee Orchard to access the trail that leads to Mount LeConte. In Dury’s time, much of this land was privately owned by the Voorheis family. The surrounding mountainscape held other large estates, farms, orchards, and the recent scars of logging, but since 1934, this area has been owned by the US National Park Service and served as one of many entrances to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. What was once the Voorheis estate is now a successional forest—even aged tulip poplar dominates the canopy with other cove species filling in the midstory of the hollers and oaks and pines lining the ridges once ruled by American chestnut. Although, you don’t have to hike far into the LeConte Creek watershed to find old-growth silverbell and poplar intermixed with the skeletons of ancient hemlock.

Dury traveled to the Smokies to collect salamander specimens for his museum and describe any species he caught to Western science. On one of these trips, he collected

a salamander species that no one has found in the area since—a slender lichenous green salamander, with square tipped toes, discovered under a log on the trail to Mount LeConte. To confirm his species identification, Dury sent the specimen to his nineteen-year-old pupil, Worth Hamilton Weller, who made the following note:

I identified it as Aneides aeneus, but, having no specimens on hand to compare it with, I sent it to Dr. Thomas Barbour, of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, and later to Prof. Emmett Dunn of Haverford College … for a confirmation of my identification. The latter informed me that it had never before been taken in the Smoky Mts.

In the midst of this period of discovery, Dury and his team may not have been surprised to find a salamander that apparently had never been found in the Great Smoky Mountains before. But despite their best efforts over the last century, herpetologist research teams, citizen scientists, and National Park Service staff have not been able to relocate green salamanders in the Smokies.

Many scientists and park staff today believe that this species may have never actually been found in the park and was simply a mistake by Dury, citing the unusual habitat where the specimen was reportedly collected. The salamanders could also have disappeared due to commercial logging and the near extinction of the American chestnut from the invasive chestnut blight. Others think that green salamanders might still be in the Great Smoky Mountains hiding in rocky crevices tucked in one cove of the 800 square miles of national park. Regardless, the apparent fate of the Smoky Mountain green salamander raises conservation concerns and questions for this vulnerable species across its range.

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE 040 ECOGRIEF

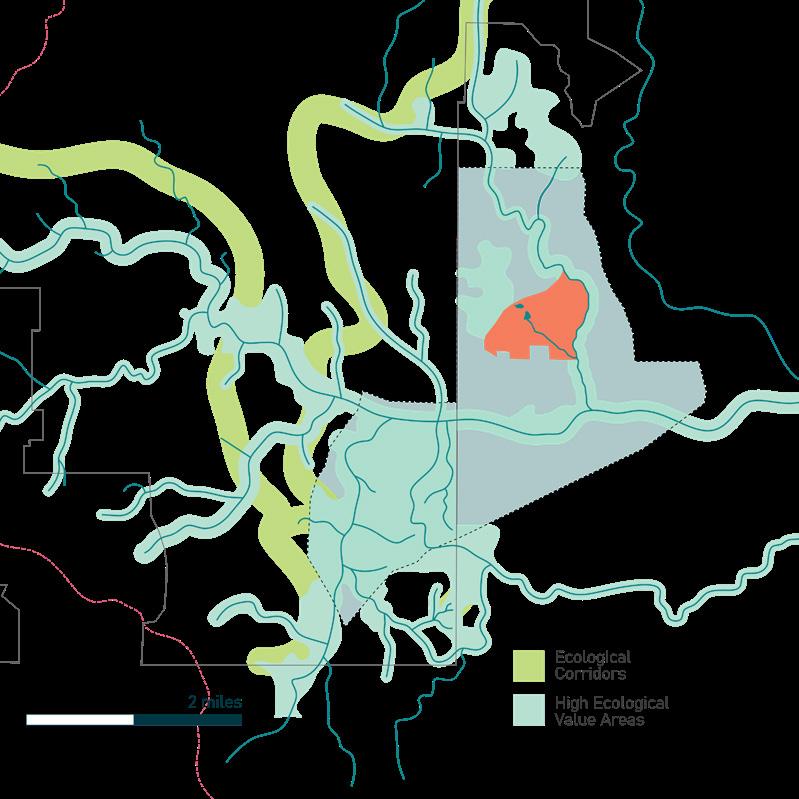

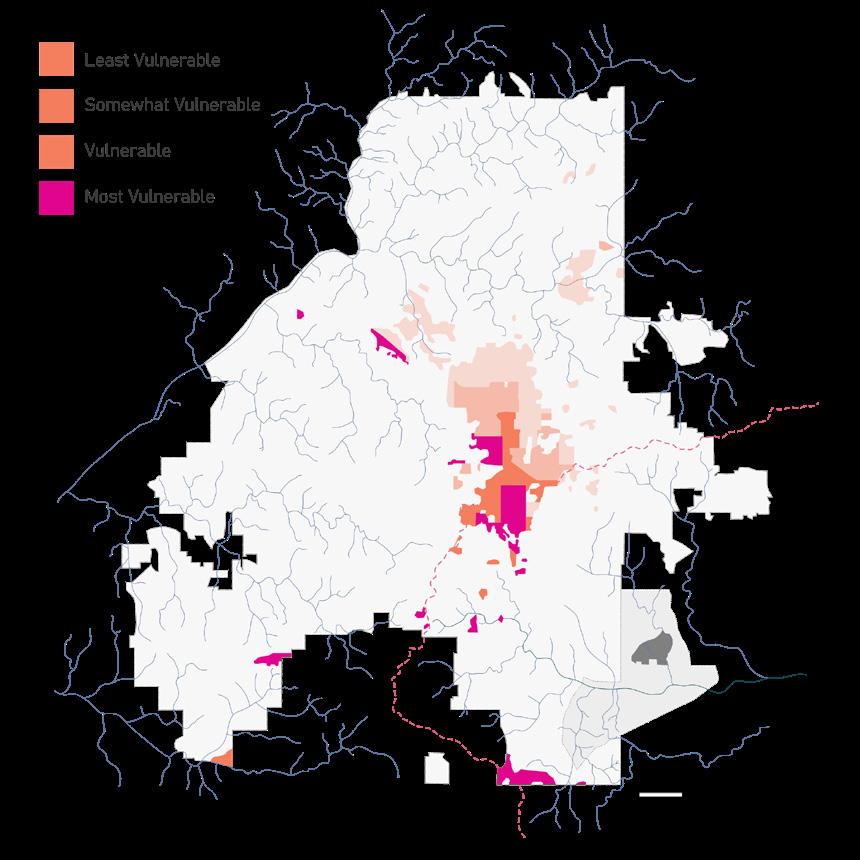

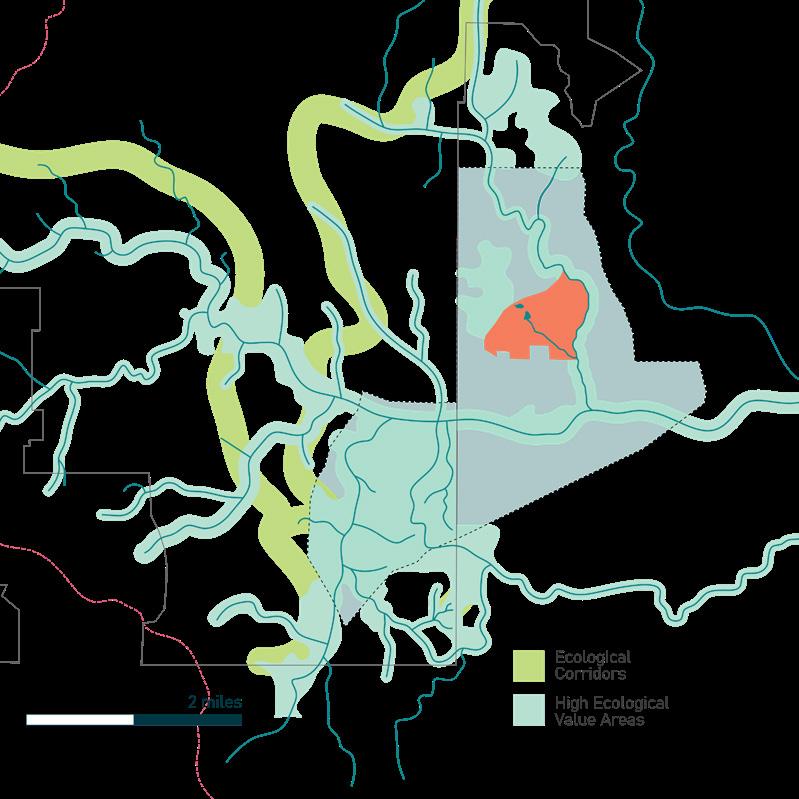

green salamander distribution The north-to-south distribution along the Appalachian Mountain range reflects the green salamander’s dependence on the niche conditions found in rocky crevices. The green salamander relies on the geology and climate of the gorges and mountain coves woven into the Appalachian region. A. Cherokee Orchard in the Great Smoky Mountains B. The Hickory Nut Gorge green salamander is confined to the boundaries of North Carolina’s Hickory Nut Gorge.

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 041

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE 042 ECOGRIEF

Photo by Jonathan Cox

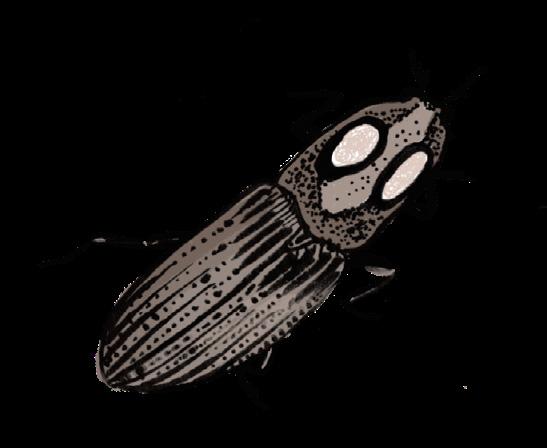

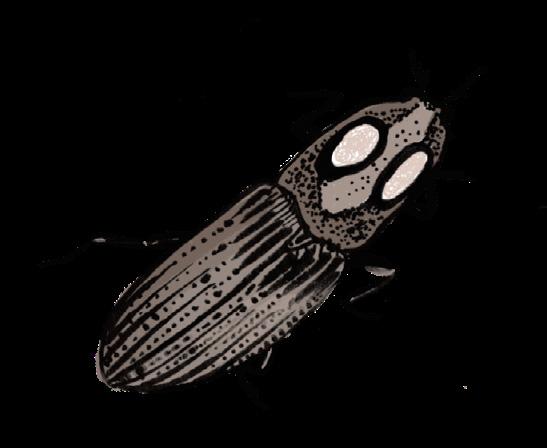

food web Green salamanders can live in the same rock face as multiple other species but have limited interaction due to their ability to secure habitat higher up. Species like the Cumberland Plateau and northern slimy salamander are more often found lower on outcroppings, reducing competition for food.

Insects

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 043

Ring-necked snake

Arachnids

Common garter snake

Snails and slugs

Allegheny Mountain dusty salamander

Cumberland Plateau salamander

Northern slimy salamander

Green salamander

Golden net-wing beetle

Mite

Batacholandros magnavulgaris

*predates upon juvenile green salamanders

IT’S NOT EASY BEING GREEN

Forty years after Dury collected his salamander in the Smokies, populations of green salamanders elsewhere across their range experienced a large-scale collapse. Scientists aren’t exactly sure what caused this decline beginning in the 1970s, but some speculate that it could have been due to a decline in air quality or forest disturbance from invasive species and logging. This would have increased rocky outcrops’ exposure to sun and reduced the availability of tree trunks to climb and forage upon.

The green salamander’s unique lineages compounded by its uncommon habitat and sensitive physiology raise a multitude of conservation concerns. As a result, green salamanders are listed as critically imperiled to vulnerable across their range. To fully understand the threat these salamanders are facing, it’s important to understand how their bodies interact with their environment.

Salamanders, and most amphibians, are thought of as bioindicators or species whose disappearance from an ecosystem signals environmental degradation. You can think of them as the canaries Appalachian coal miners would take underground to alert them of dangerous conditions. Salamanders have fascinating physiologies, which make them sensitive to shifts in temperature,

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE 044 ECOGRIEF

Salamanders, and most amphibians, are thought of as bioindicators or species whose disappearance from an ecosystem signals environmental degradation. You can think of them as the canaries Appalachian coal miners would take underground to alert them of dangerous conditions.

moisture, water quality, and habitat degradation. Green salamanders and all species in the family Plethodontidae are lungless and consequently rely on air and soil moisture to effectively respire via their permeable skin. Their skin also allows for the transfer of water to and from their environment, meaning a change in air or soil moisture could put them at risk of desiccation. Greens are also ectothermic, meaning they can’t physiologically regulate their own body temperatures and must therefore do so by traveling to and from ideal conditions. Additionally, green salamanders are presumed to have a relatively small home range, which means they may not be able to escape a changing environment. These factors put them at risk of population collapse, particularly if an area is logged or invaded by forest pests that threaten the canopy, thereby changing the climate of that habitat.

Given their physiology, it’s easy to see how greens would be impacted by climate change and the vast logging of the Southern Appalachian forests in the late 1800s and early 1900s. This was quickly followed by the invasion of forest pests and pathogens decimating American chestnut, eastern hemlock, and ash. While greens, and most

amphibians, are facing an existential threat from these factors and pathogens, there is hope in their conservation.

Some federal, state, and nonprofit agencies are working towards conserving their habitat and populations either directly or indirectly. The Amphibian and Reptile Conservancy (ARC), North Carolina Wildlife Resource Commission, and the University of Tennessee, Knoxville’s Center for Wildlife Health are some of the groups actively working towards monitoring green salamander populations and unraveling amphibian pathogen transmission and impacts. Other federal and state land management agencies such as the National Park Service, US Forest Service, and state natural resource groups protect Southern Appalachian land from development and actively research and manage forest pests and pathogens. While the fate of greens and other amphibians is uncertain, it’s important to look to those people and agencies that are passionate about ensuring their survival through the Anthropocene. I’m hopeful that those of us who are motivated by our love for the other species we share this planet with can solve these complicated conservation quandaries through action. As a gentle reminder, nature has and will always carry on despite humankind’s best efforts.

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 045

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE 046 ECOGRIEF

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 047

Photo by Bryce Wade

Deadsquirrel Roadside Shrine

Silly to weep for this, deadsquirrel roadside shrine, bowing low, head on the concrete, face hissing like an egg frying, worshiping roadkill because I killed it. I am you, dead on impact, bursting into slow motion bloodrain. Shapeless strewnbody pavement, teeth in a pile of guts, cooked, flat, enroute. Makes me sad, you know, for being another littlegod, human delivered death at your door, shameshrill screaming. Shhhh, baby.

I’m sorry.

It’s all going to be okay.

—Amelia Brady

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE ECOGRIEF 048

eniko ujj

L’Inconnu de la forêt (The Unknown of the forest) pit-fired ceramic 2022

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 049

The following introduction and timeline was created from excerpts by two anonymously written articles at CrimethInc. ex-Workers’ Collective. The first article is titled: “The City in the Forest: Reinventing Resistance for an Age of Climate Crisis and Police Militarization.” The other, “The Forest in the City: Two Years of Forest Defense in Atlanta, Georgia.” You may find the entirety of those articles at crimethinc.com.

Our society is at a crisis point. Decades of escalating economic pressure have created rampant inequality and desperation. Rather than addressing the root causes of these, politicians across the political spectrum continue channeling more and more money to police, relying on them to suppress unrest by force alone. This dependance has enabled police departments and their allies to consume a vast amount of public resources. Meanwhile, driven by the same economic pressures, catastrophic climate change is generating hurricanes, forest fires, droughts, and widespread ecological collapse.

Introduction

050

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE

ECOGRIEF

In this context, starting in April 2021, a bold movement set out to defend a forest in Atlanta, Georgia, where local politicians and corporate profiteers want to build a police training compound and a soundstage for the film industry. The training compound, known as Cop City, would be the largest police training facility in the United States. It would devastate the South River Forest, also known as Weelaunee Forest in honor of the Muscogee Creek people who lived there until they were deported in the Trail of Tears.

The movement to defend the Weelaunee Forest has drawn together a wide range of groups and strategies. Legal defense organizations like the South River Forest Coalition, which is bringing a lawsuit against the Dekalb County government, work parallel to groups like the SRY Campaign, an anonymous collective of researchers who publicize the home and office addresses of those who seek to destroy the forest. While abolitionists and radical environmentalists have established encampments and tree houses in the forest, a network of pre-schools and parents has built community gardens and hosted public outreach events. Still others have organized raves and cultural events in the forest, connecting the most ambitious artists with the irrepressible spirit of the movement.

Among those who wish to see Cop City built are the Atlanta Police Foundation (APF), mayor Andre Dickens, and the various corporations that stand to profit on the development. At the same time, thanks to a back-room deal with the city government, real estate mogul and film industry executive Ryan Millsap is preparing to destroy a public park on an adjacent land parcel within the same forest.

Behind the scenes, Cop City has the support of the Atlanta Committee for Progress, a business association involving the region’s most powerful industrial and bureaucratic cliques. Alex Taylor, the former chairman, is also the acting president of Cox Enterprises, which owns various Atlanta media outlets and is among the leading funders of the Atlanta Police Foundation. In order to create a veneer of democratic process and local support, the APF and their supporters have contrived the Community Stakeholders Advisory Committee (CSAC), comprised of members of the Police Foundation and a few residents of Southwest Dekalb. When one of the initial members of CSAC spoke out against the project, she was removed from her position.

These are the forces that are facing off over the forest. On one side, some of the wealthiest and most institutionally powerful figures in the state of Georgia. On the other, a network of local activists and their friends.

some of the corporations

funding cop city

Nationwide Bank of America

Home Depot

UPS

Delta Airlines

Merrill Lynch

Truist Bank

Cadence Bank

Wells Fargo

Target Chase Bank

AT&T Chik-fil-a

some of the contractors planning to build cop city

Brasfield & Gorrie

Brent Scarbrough & Co.

LS3P

For more detailed information and to contact these entities, please visit stopcopcitysolidarity.org/ targets and srycampaign.org.

MERGOAT

2023 051

MAG SPRING

april-may 2021

Activists and local ecologists uncover a plan by the Atlanta Police Foundation to transform the land known as the Old Atlanta Prison Farm at Key Road and Fayetteville Road into a massive police training compound.

may 17, 2021

According to an anonymous statement on Abolition Media Worldwide, seven machines left unguarded on the land parcel owned by Blackhall—chiefly tractors and excavators—are vandalized. Their windows are broken, their tires cut, and they are set on fire. The statement connects the sabotage to the destruction of the forest:

spring-summer 2021

The City of Atlanta, in partnership with Blackhall Studios, approves the swap of Dekalb County public lands at Intrenchment Creek Park for a parcel of land currently owned by the movie studio. The land deal is conducted in a semi-secretive series of board meetings and hearings.

may 15, 2021

Over 200 people gather at Intrenchment Creek Park

june 10, 2021

Three more excavators are burned on the parcel of land owned by Blackhall Studios. Neither action appears in local news media, although photographic evidence of the damage circulates on social media.

june 23-26, 2021

The first week of action brings hundreds of people into the movement.

october 18, 2021

A small group of rapid-responders disrupt the surveying and clearing of grounds at Old Atlanta Prison Farm. A surveillance tower is destroyed.

june 2021

Notices appear affixed in the forest notifying passersby that trees in the area have been “spiked,” with the consequence that cutting them could damage saws and possibly injure those utilizing them.

june 16, 2021

On the night that the Atlanta City Council is to vote on the construction ordinance for the “Cop City,” a handful of activists protest outside of the private residence of City Councilperson Joyce Shepherd, the sponsor of the ordinance.

september 2021

City Council meetings, held on Zoom because of coronavirusrelated restrictions, are repeatedly flooded with hours of objections to the project. Votes on the ground-lease ordinance are repeatedly delayed because of these objections and demonstrations at the homes of Atlanta Chief Operations Officer Jon Keen and City Councilperson Natalyn Archibong.

We don't need a soundstage for entertainment. Everything we need is already there. We don't need police training facilities. We demand an end to policing... Any further attempts at destroying the Atlanta Forest will be met with similar response. This forest was here long before us, and it will be here long after.

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE 052

ECOGRIEF

november 12, 2021

A demonstration takes place at Reeves Young Headquarters. Intelligence gathering by activists indicates that Reeves Young Construction has been contracted to destroy the forest and build the Cop City development. About thirty people converge at the company headquarters in Sugar Hill, Georgia, holding banners and demanding that the company sever their contract with the Atlanta Police Foundation.

november 27, 2021

A group of Muscogee (Creek) people return to their ancestral lands at the current site of Intrenchment Creek Park in the South River Forest, which, in Creek, is called Weelaunee. The Muscogee delegation calls on everyone to defend the land from the Cop City and Blackhall developments.

december 17, 2021

A dozen protesters march to the entrance gate of Blackhall Studios on Constitution Road and block the main entrance, chanting slogans. Shortly after, a large contingent of police raids the forest, evicting the protest camp established there.

december 20, 2021

According to an anonymously-written statement republished on the website Scenes from the Atlanta Forest, banners are hung in the backyard of the private residence of Dean Reeves, chairman of Reeves Young. Reportedly, Dean Reeves was among the board members present at the November 17 action and personally shoved and assaulted protesters.

january 18, 2022

In order to begin “boring” the land, a process necessary for determining the construction supplies needed for laying foundation, Reeves Young and a representative of the Atlanta Police Foundation enter the woods near Key Road and use a bulldozer to knock down many trees. Construction is stopped when protesters demand that they leave. The bulldozer remains at the scene; it is subsequently vandalized, losing its windows.

november 10-14, 2021

A wide range of cultural events, info-nights, bonfires, and meetings occur during a second week of action. This coincides with the establishment of an encampment in the forest; it lasts for six weeks.

november 20, 2021

Two more bulldozers burn in the forest. According to an anonymous statement republished on the Unoffensive Animal website, anonymous forest defenders

This equipment was located on the land-swap parcel currently owned by Blackhall Studios, the planned future location of “Michelle Obama Park.”

january 19, 2022

Several people climb into tree houses in the forest near the previous day’s confrontation, announcing their intention to remain there in order to delay further destruction.

...burnt two bulldozers in the south Atlanta forest. No Cop City, No Hollywood dystopia. Defend the Atlanta Forest.

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 053

january 28, 2022

Sixty forest defenders march into South River Forest near the Old Atlanta Prison Farm to stop the boring and soil sample collection. Dekalb County Police attack the protesters, arresting four—the first arrests inside the forest in the context of the movement.

Forest defenders light smoke bombs and flares on their way to meet the tractors on January 28, 2022.

may 2022

Across the country, at least twenty acts of direct action followed the police raid of May 2022.

At least half a dozen tree houses were constructed on the Old Atlanta Prison Farm and a section of Intrenchment Creek Park in late May 2022.

january 25-27, 2022

Long Engineering resumes surveying Old Atlanta Prison Farm, accompanied by the Atlanta Police Foundation, Atlanta police officers, and Dekalb County sheriffs.

march 1, 2022

According to another communiqué, five large Long Engineering trucks used to do survey work to help delineate destruction in the South Atlanta Forest were destroyed in solidarity with ecodefenders currently protecting the forest from being clear-cut to build cop city and more Hollywood infrastructure for Black Hall Studios.

march 19, 2022

Six machines owned by Reeves Young, including two large excavators and a bulldozer, are destroyed in Flowery Branch, Georgia.

The online communiqué reads:

Unless your company chooses to pull out of the APF's Cop City project of its own volition, we will undermine your profits so severely that you'll have no choice but to drop the contract.

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE ECOGRIEF 054

may 8, 2022

Hundreds of people poured into the forest: anarchists, environmentalists, abolitionists, and other direct action-oriented groups bringing tents, hammocks, sleeping bags, and food. Some arrived prepared to operate a field kitchen. Small encampments emerged everywhere, some adopting names for themselves. Clusters of tents and canopies appeared in a patchwork on both sides of the South River—some organized by affinity group, others by chance. It is difficult to take a head count in the forest, as the opponents of the movement have probably also noticed. The kitchen crews estimated that a minimum of 200 people were sleeping in the forest at night; on some days, considerably more people joined the occupation.

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 055

Move back!

may

9, 2022

Several dozen people marched to the suburban home of Shepherd Long, the CEO of Long Engineering, a subsidiary of Atlas Technical Consultants and a subcontractor of Brasfield & Gorrie. This was the first of several such actions during the Third Week of Action.

may 12, 2022

Around eighty people in hoodies and camouflage descended on the Brasfield & Gorrie regional office in The Battery. Demonstrators chanted “Stop Cop City” while some in the crowd painted graffiti and shot fireworks at the façade of the building. After breaching the lawn of the facility, a few determined people began throwing paint balloons and stones at the building, cracking the plate glass windows. Others continued lobbing fireworks. After several minutes, the crowd dispersed into the surrounding streets.

june 6, 2022

A convoy of police officers accompanied a work crew on Key Road.

june 10, 2022

A few days later, the Dekalb County Government posted a “Stop Work” order at the entry gate to the Old Prison Farm, likely because of phone calls to various departments and commissions.

may 9, 2022

On the first day of the Week of Action, forest defenders awoke to the sound of falling trees. At the behest of Ryan Millsap, a small construction crew and a group of Dekalb County Sheriffs working as private security were making their way into the tree line from the Radio Control (“RC”) club on the southeast side of Intrenchment Creek Park. A number of determined people responded immediately, repelling the bulldozers with a few stones before linking arms and chanting “move back” in unison at the police officers further afield. One courageous person approached an officer and explained to him that the construction crew was engaging in illegal activity. Later, Dekalb County issued a “Stop Work” order, ostensibly following a flurry of calls by lawyers and neighborhood groups tipping them off about the illegal work.

may 11, 2022

A small crowd gathered outside the suburban home of Keith Johnson, regional President of Brasfield & Gorrie. Protesters scaled the fence and banged on drums early in the morning, chanting “Drop the contract!” Johnson is invested with the authority to make decisions for Brasfield & Gorrie—and he is compensated handsomely for this responsibility, judging by the size and location of his multi-house estate.

may 11,

2022

The frustration and bitterness of the police, which had accumulated for a week, was unleashed on those living in the Old Atlanta Prison Farm. In the early morning, dozens of police vehicles, helicopters, and drones encircled the forest. Atlanta Police Department, Dekalb County Sheriffs, the Department of Homeland Security, Department of Natural Resources, the Atlanta Bomb Squad, the Joint Terrorism Task Force, and possibly other agencies mobilized their forces and prepared to raid.

For the next six months, no work took place inside the perimeter of the forest without considerable police protection.

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE ECOGRIEF 056

july 23, 2022

The Week of Action launched with a ribboncutting ceremony that drew over 100 people. A lovely official-looking sign was planted in the ground reading “Weelaunee People’s Park” on one side and “South River Forest Park” on the other. After cutting the ribbon, the assembled crowd chanted “People’s park, people’s park!” while cars and equipment began loading in. By afternoon, hundreds of people filled the area.

july 30, 2022

On the final day of the Week of Action, campers woke up to shouting:

june and july

Throughout June and July and continuing well into fall, police began carrying out ritualistic “sweeps” of the forest, specifically the Old Atlanta Prison Farm.

july 28, 2022

The music festival began on July 28. The promotional materials promised three days of “Peace, Love, and Anarchy.”

Around 8 a.m., Ryan Millsap and a colleague of his arrived at Weelaunee People’s Park with a tow truck pulling an excavator atop a flatbed trailer, accompanied by a small cohort of Dekalb County police he had hired as private security. In Georgia, you can legally hire offduty police, who are permitted to bring their service weapons, uniforms, and city-owned vehicles with them while fulfilling a private contract. This is unusual in other parts of the Global North, but common enough elsewhere in the Americas.

Millsap did not venture far from his car, but his colleague, Anthony Wayne James, approached forest defenders who were seated beneath a gazebo in the middle of the parking lot. James began using the excavator to hit the roof of the gazebo, despite the potentially lethal risk that this posed to those beneath it. At this point, the cops-for-hire intervened, notifying James that it was not acceptable for him to attempt to risk killing people in front of them. Frustrated, he began screaming at them to arrest people:

august 3, 2022

A large operation did indeed occur around the forest. On Bouldercrest Road, Key Road, Fayetteville Road, Constitution, and Old Constitution—all of the streets adjacent to the section of forest that was occupied—construction workers and utility companies initiated work, accompanied by police officers and security guards.

december 13, 2022

Following weeks of propaganda, a massive interagency raid encircled the forest on December 13. By the end of the day, five people were under arrest. All of them were slapped with felony charges including “Domestic Terrorism.”

"Do your jobs!"

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 057

"They are going to tow your car! Everybody wake up! A tow truck is here! Get to the parking lot!"

december 16, 2022

The Dekalb County government denied the “Land Disturbance Permit” required to begin the destruction of the Old Atlanta Prison farm. This was the fourth time that an application for the permit was denied. The next day, 200 people gathered in East Atlanta Village. At that point, this was one of the biggest local protests in the context of the movement.

december 21, 2022

A week after the raid, Ryan Millsap and his henchman entered Weelaunee People’s Park. Nearly eight months after his attempt to destroy the area during the third Week of Action, he finally had a free hand.

december 22, 2022

The next day, the contractors returned. This time, they demolished the parking lot with heavy machinery and tore up a large segment of the paved bicycle path.

They brought bulldozers and heavy machinery into the area through the entrance of the Radio Control club. Reportedly, the Georgia Bureau of Investigations requested this for the explicit purpose of denying anarchists the ability to operate freely in the forest. They knocked down dozens of trees along the paved bicycle path, overturned the park gazebo, and cut down a large number of saplings and bushes. By midday, they had destroyed substantial swaths of the forest near the parking lot and trailhead, creating clear lines of sight at ground level.

january 18, 2023

january 18, 9:04 am

Some thirty or more shots rang out in the forest.

The Georgia State Patrol had killed Manuel Páez Terán, a Venezuelan anarchist of Tomoto-Cuica heritage who went by the name Tortuguita in the forest.

In the early hours of January 18, police established an operations control center in the parking lot of Gresham Park. Dozens of police vehicles from metroAtlanta agencies began amassing there. Across the forest, other agencies spearheaded by Atlanta Police Department began amassing on Key, Fayetteville, Woodham, and adjacent streets. Helicopters were circling overhead. Forest defenders could hear the sounds of police drones hovering near their tree houses and tents. K9 units arrived with dogs. The bomb squad was stationed nearby, while all-black SUVs parked alongside Constitution Road near Shadowbox Studios. For the first time, the Georgia State Patrol entered Weelaunee People’s Park.

Continue to Crimethinc.com for more recent updates on Stop Cop City.

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE ECOGRIEF 058

Turtle -shaped Sunbeam

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE 060 ECOGRIEF

Duir

Aidan

Grief

Nonlinear Entrapping

Today sad and cold

Tomorrow a spot of sun

Night falls and sorrow’s way is won one day bleak, the next day rage

The next day a spot of joy; despite it all

I am alive

Too many have fallen

Too many people

Too many trees

I still feel the sun on my skin

And I laugh because I love you

Like I cry because I love you

Nature’s way of knowing itself; Ecology

We are part of it too

We could be

We would be

If they could let us be

Industrial man can’t build an oldgrowth forest

Can’t

Can’t be braver than nature

Brave is nature

Can’t be still as the trees

Swaying, gentle The industrial man hopes to preclude That nature can Tort lived outside Away with industry’s man

As much as they could

As much as any of us could try They believed

Weelaunee called and Tort answered Their smile the day they first shared the ink

Shaped like a flag

Above their heart

Flesh-bound with their love of the forest of that great oak tree

“Nobody had to die for this”

We say that all the time

Forgetting that powerful capitalists

Truffle hogs ever-sniffing

Believe someone should die, blood on their face for another dime

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 061

Ecological grief is in all of us; knowing that everything is connected, that all of living relates to the next. One small portion of the world and life in the world is part and parcel to the largest thing you could possibly imagine—to the sea, to the sky, to the sweeping lands. The same factors that ecology is up against, that mother earth is up against, are the factors that oppress us socially.

We are just as bound by our grief as we are bound to this earth.

Before the raids, there was a sense of love, beauty, community, and culture. What doesn’t make sense is how anyone could murder someone because of this, even when considering the police. They killed a climate activist? They killed my friend? How could they come into the forest and not notice that what we were building was love? And I pause to remind myself that love is their greatest threat. I see why, to them, destruction is the only way forward in knowing the abundance we grew within the community of the Weelaunee Forest. But to them I decry: you can’t destroy love—not with bulldozers, not with arrests, not with guns.

A morning dove coos, a kestrel cries. I think of you, Tortuguita.

The sun greets my skin, and beside me I see Tortuguita’s spirit. I hear their contagious laugh, I see their brimming smile. The sunbeams twist and bounce as their curls did. I remember the light that surrounded them. The light that infected us all. I feel it on my skin. Warm, hopeful, brave.

Affirming that I am here, I am one leg of the millipede that is this movement. Crawling, determined, one with the earth. Easily perceived to be harmful by those in power. Those unable to witness beauty were it held like a rose beneath their nose.

As they continue their destruction, somehow in our grief we strengthen. Our empathy for each other grows. Our cleverness is required. But in this tailspin of loss, where do I look for the right words to encapsulate something as buoyant and radical and illustrious as the life of our friend Tortuguita?

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE ECOGRIEF 062

I look to the trees of the Weelaunee, who stand still and protect the loss. Protect the memories.

I look to my friends, comrades, who chat on the phone. Tort had the funniest Signal names: three raccoons in a trenchcoat, as I first knew them. At least two smiles per joke, relieving us even here as we grieve you. We laugh, we feel you tug at our humor through the veil. We feel you here as we howl into the night, candles burning for you, tears flowing for you, wails roaring for you. We gather to fathom that you could be gone and then that you are. We feel you here as we throw caution to the wind, smoking another cigarette.

I look to the earth, where across its unmatched beauty people are crying for you, Tort. As they cry for this earth, for Tyre Nichols, for all those taken and murdered by the police. For doing nothing. Or for being too beautiful, too impactful in their love.

As we cycle through waves of grief after waves of grief with each tree, mountain, water source we lose to greed, to power, to hate and control we cry.

But for us, knowing what is at stake, we remember there are two ways to cry. The cries that clog our throats and grip our spirits as we mourn and the cries of that sorrow’s dear brother, anger, that rip across our tongues loud enough to reach the next realm:

WE WILL CONTINUE YOUR FIGHT YOUR MEMORY WILL NEVER DIE NOR WILL THE FOREST NOR WILL THE FOREST!

I remember talking with Tortuguita. We were sitting along the barricades, pushed aside by ants, at the mouth of Weelaunee People’s park. It was a hot late summer’s day. They strode up to me, their camo shirt flapping open, curls dancing in the wind, their laughter encapsulating the furthest reaches of their aura, giving sound to something almost unseeable.

We talked about community we talked about trust. How do we truly find ways to connect when security culture and the state posture their tactics to sow fear for each other in our hearts.

Tort gave me a wry smile. We must believe we can trust each other. With trust comes happiness, joy, ideations, feelings that can change the world.

Just as easily as the stress can poison, we can heal. We heal with trust. And in my experience with Tort, a dose of sunshine, an easysmoked spliff and a moment with the piano in the gazebo could build a bridge in under thirty minutes. Welcome to the forest, comrades.

This spirit of Tort changed the dynamic of the forest. All of a sudden we were hustling not only to defend the forest, but to create the world we believe we deserve for our collective gain and our respective joys. Imagine how many people we could feed if we had a big kitchen? Imagine if we had enough art out here that nobody feared the police destruction? And so we created. And so we built, and now we hold a movement full of more trust and more love.

As Tort would have felt for any of us, we feel rage. As we all feel for each tree we remember rage is a useful feeling. May it show us what we truly love. May the grief, which perhaps is love with nothing visible to attach to, teach us that what we value most is each other. That the trees, too, are our families. That they are the true conductors of the land. Knowing it. Being it. In Tort’s name we must continue to protect it.

MERGOAT MAG SPRING 2023 065

We wouldn’t be here without you, Tort.

I trust you still. Through the facade of life and death, I feel you trust me too. In dark hours, as we grieve, the smallest turtles appear. They flop off a log, they reappear on the next, they show us they are not one but many. A multiplicity of Tortuguitas. You are all in our spirits now. If the bonds weaken, may you puppet that we trust each other again. May you remind us we are strong. May we never forget to love like you did. To share like you did. Abundantly, without judgment, with the hopes of a better world overwhelming the hate icons in each curse-ed greenback.

While I yearn for recourse from grief, it is nowhere to be found. Instead, I fight. I cry. I scream. I search for ways to integrate my grief with my peace. All this pain and death met with such frigidity such hate. The city says they’ll keep razing the forest even though it’s illegal. There is no room for surprise in our watery eyes. They are not here for us. I hold the hands of my friends as they cry mighty tears. I am my own friend as I am yours.

I am those I love, as empathy holds us entwined with loss.

Gathering grieving comforts from those who spend each day believing … may we need to grieve just a little less.

Protect the forest. Protect our future. Protect our community from 382 acres of grief. Protect us from violence expanded, from hate compounded, fascism rewarded.

Protect us like the trees do.

Back in December, the grief for the trees was enough for us. The grief of the camps, the rhythms, the spirit of the first go. It was enough. We were holding each other in that grayness. Plucking thru piles, plucking thru dust.

Torn apart because it could be. Because the state plays vicious games. Nothing alive is sacred. Only property to them holds value. So the police came and slashed each tent and tarp and flag. They came back with loaded guns.

They surrounded a small sleeping turtle resting between actions, of slow, assured success.

066

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE

ECOGRIEF

And they opened fire

They opened fire

They opened fire

They opened fire

They opened fire

They opened fire

They opened fire

They opened fire

They opened fire

THEY OPENED FIRE

THEY OPENED FIRE

THEY OPENED FIRE

THEY OPENED FIRE

THEY OPENED FIRE

To be sure they had murdered our friend.

When we ask of the lessons of the movement, of the trees, who better could answer in more lightness, hope, and meaningful context and creativity than our fallen comrade Tortuguita?

MERGOAT

2023 067

MAG SPRING

Could these robots of the state have possibly known what martyr they chose? Was it their brown skin that made the trigger that much easier to pull? Did they look at them before they shot them? Or did they murder, blindly, through the thin walls of their tent? Was it their racism that killed them? Sent to the forest with the imperative to kill? Autopsy results say Tort was sitting, legs crossed, hands raised. The police shot them 57 times anyway.

The forest defender skirts the status quo asks questions that force our movement to grow. The mainstream attacks these caught ones for being from another state: colonial reasoning. This “state” is my home; I’m tangled up in every corner. Spooling in love and loss and history. I don’t have the peace to sit in those woods. But my far-traveled friends in the forest, the nomad comrades, met the needs of the Weelaunee. Searching for a place for their purpose as our woods, this home, searched for guardians. As we, the people of Atlanta, take moments to recharge. Grateful for the shift in guards.

All my brave forest friends, teaching patience, weathering storms. Never letting fear stop them from the joy of their forest home.

And we yield, we are burnt out on grief. Shot 57 times at least.

Seated, hands raised.

Horror unending, horror unyielding.

This city I’ve loved for my mom, my mom’s mom, my father who can’t fully walk it.

City I’d never depart.

Bureaucratically unanimous, each mouth reaches back to the same circuit board.

Ungrounded, static, fraying, sparks: senselessness. Unyielding. Deliberate.

Destruction like theirs has to be planned. Closed doors with such blindness they think we cannot see, but the stench escapes by the crack in the door. It wretches us: guts full of poison when we consume this as if it may become reality.

Tortuguita knew better, knew we may always dream of a better way. The power of the creative: revolutionary. In the face of darkness: a powerful light.

BLUE HOLLERS IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLOCENE 070

ECOGRIEF

A friend far away grieves with me. Voice messages across the seas:

If your country sees it

If your country sees it

We know this boastful city doesn’t truly care of its people nor of its trees.

Nearby the collective supports the grief: a song, a dance, a bodywork ritual.

We memorialize! We fight! We find peace in naught but the earth and the souls that walk it.

We dig out holes for our loved ones, for the creatures we knew.