KINDLY OF A QUEER NATURE

creative director & designer

design support

editorial support + photography

Mergoat Magazine is a quarterly magazine published out of Knoxville, Tennessee. The best way to support our work is to become a subscriber at mergoat.com.

mergoat.mag

writing

Margaret Spalding

Josefine Parker

Hazel Hoffman

Hillbilly Gothic / Clover

Rachel Milford

Andreas Bastias

Benjamin Titeras

Margaret Killjoy

Cate O'Connell-Richards

L. Hartsock

Flip Zang

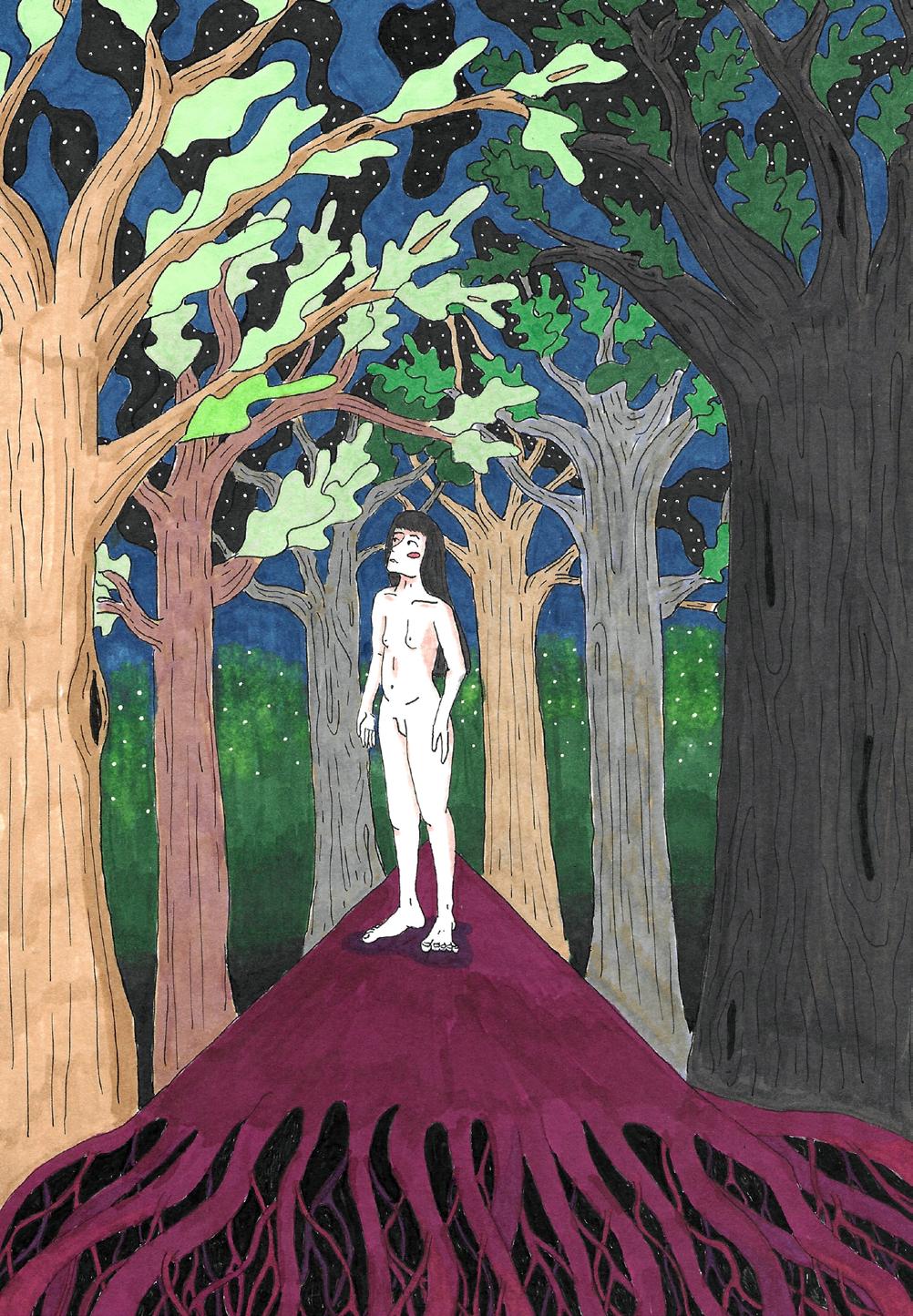

cover art by Ryan McCown

art & photography

Rine Bloom

David Michael

Danielle Calibird Fernandez

NASA / James Webb Telescope

Madison Tunnicliff

Evan Poellinger

Mad Bishop

Keara Giannotti

Cate O'Connell-Richards

Alex Bonner

Hazel Hoffman

Ryan McCown

Kat Smith

Adam Mescher

Kym Mackinnon

August 1, 2023

Centuries of anthropocentric thought have led to the development of a binary: humans and nature. This binary has since solidified a misunderstanding that humans and nature are not one and of the same but two distinct and separable categories. Through the misconception of nature as being outside of humanity, nature became both a destination (a place to venture into) and a resource (a place to exploit). The most detrimental ideology of nature is precisely this.

A nature that is separate from humanity and to serve humanity causes a sense of indifference towards its overuse, manipulation, exploitation, and destruction. It is this precise ideology that has led to prairies being turned into lawns, oceans into fisheries, forests into deserts, and shale rock into fracking mines.

Just like the gender binary, distinctly either male or female, the ecological one has been created by man to perpetuate particular political and economic systems. There is nothing natural about it.

Nothing makes this binary more of a farce than the current mass extinction event and climate disaster. It is precisely this understanding of nature that has led to these events and many peoples’ denial. Although, we will inevitably realize the inseparability of ourselves and the earth as we experience the consequences of this ideology.

With a focus on futurity, Mergoat Mag denounces any understanding of nature as a binary. Mergoat Mag solely acknowledges Mother Earth as trans.

Transness destroys any form of polarity. Through queer and feminist thought we’ve developed this critique in regards to gender. With the application of queer theory to ecology, we work to eliminate the binary of humanity and nature — one that is artificial, inaccurate, and catastrophic. It is through trans-identity we can understand our positionality as within nature and not in opposition to it.

In this issue, we explore the concept of transecology and feature queer and trans writers and artists.

We welcome you to our queer nature.

Sincerely,

Kathryn Gruszecki Executive EditorYes! Come in! Come in! The transition ceremony starts in just a few pages. We’re waiting for some others to arrive, but the transition will begin momentarily…

“Transition” is not an unfamiliar word for anyone who has spent their life in Southern Appalachia. The nonprofit industry has saturated our communities with the rhetoric of “a just transition” for many years. Even so, the federal government continues to use our region as a negotiating chip and sacrifice zone for big coal and oil, approving and fast-tracking disastrous projects like the Mountain Valley Pipeline and the TVA fossil fuel swap from coal to natural gas. What’s more, our state and local governments continue to fail us over and over again when it comes to our ecological health, and the corresponding health of ourselves and communities.

This year, we are laying a conceptual foundation from which to build new strategies in the fields of politics, science, and conservation in our region and beyond. With this issue on transecologies, we arrive at the crux point in our first year as a publication.

To start this year, in issue no. 1, Hillbilly Ecologies After the Apocalypse, we acknowledged that Southern Appalachia has undergone a multitude of apocalypses. We rejected the notion that an apocalypse is some abstract long-awaited future event. Rather, we have already seen the absolute death of nature as we once understood it. In issue no. 2, Blue Hollers in the Shadow of the Holocene, we grieved. We grieved the loss of wilderness as something wholly other than human society, a romantic ideal that characterized Western society throughout the Holocene epoch. We grieved the loss of idealized nature, uninfluenced by industrial society. We also grieved the loss of specific ecologies and of the beloved forest defender, Tortuguita.

We do not understand transition as an abandonment of grief. Rather, grief itself is a portal for ecological transition. The wound itself becomes a threshold, a threshold we may or may not cross.

Ecological transition is not only a slippery concept but also a process that often feels completely futile. It isn’t futile, though. We believe it is worth asking again: What does it mean to transition? What does it take to transition? How can we transition? Science alone is not equipped to answer this question. Science provides observations and data sets that are integral for developing the mechanics of transition. Nevertheless, if we are unwilling to collectively implement science-based practices, science is dead—nothing but observations and data sets.

Science must be wed to a political practice that takes seriously the connection between ecological collapse, industrial capitalism, and imperial governance. Thus, a transition is not simply mechanical scientific knowledge, but also a psycho-social operation. Transition is not simply a set of facts, but an epistemological movement. How do we grasp this movement?

We believe a profound store of transitional wisdom saturates the marginalized lived experience of trans people in our region, and we seek to magnify that wisdom for the benefit of all beings in this issue of Mergoat Magazine.

In her seminal 1985 essay, Cyborg Manifesto, Donna Haraway says:

Contemporary science fiction is full of cyborgs-creatures simultaneously animal and machine, who populate worlds ambiguously natural and crafted. Modern medicine is also full of cyborgs, of couplings between organism and machine, each conceived as coded devices, in an intimacy and with a power that were not generated in the history of sexuality. . . . By the late twentieth century, our time, a mythic time, we are all chimeras, theorized and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism-in short, cyborgs. The cyborg is our ontology; it gives us our politics. The cyborg is a condensed image of both imagination and material reality, the two joined centers structuring any possibility of historical transformation. In the traditions of "Western" science and politics -the tradition of racist, male-dominant capitalism; the tradition of progress; the tradition of the appropriation of nature as resource for the productions of culture; the tradition of reproduction of the self from the reflections of the other-the relation between organism and machine has been a border war. The stakes in the border war have been the territories of production, reproduction, and imagination. This essay is an argument for pleasure in the confusion of boundaries and for responsibility in their construction. It is also an effort to contribute to socialist-feminist culture and theory in a postmodernist, non-naturalist mode and in the utopian tradition of imagining a world without gender, which is perhaps a world without genesis, but maybe also a world without end. The cyborg incarnation is outside salvation history.1

Haraway’s work is a ringing bell throughout this issue. We are familiar with the tired use of words like monster, abomination, and robot by right-wing pundits to refer to trans people, suggesting they are somehow unnatural. They lob aspersions, feigning to mediate the judgment of one deity or another. We affirm again what our executive editor, Kathryn Gruszecki, stated so well in our last issue: There is no outside nature. The proposal of something being unnatural is based on a flawed understanding of the material world. Rather, nature, and everything within it, is a constantly evolving set of relations— wind to rock, water to soil, insect to plant, one genome to another, predator to prey, mind to matter, individual to society. It is our task, now, to comprehend together what makes some relations healthy and others necrotic. To say it again using Haraway’s vocabulary: in the sense that all of nature is the product of one state of matter acting on another resulting in a variable product, all of nature is a cyborg. In a post-industrial society, as we watch the necrosis of industrial capitalism begin to take deep root in our winds, watersheds, oceans, forests, and society, we must rethink how we negotiate our relationship within the broader context of relations that we call “nature.”

We can also think of the cyborg discourse as a discourse on the plasticity of matter. Trauma studies in recent years have unearthed a massive amount of rich data exploring the plasticity of the human mind, making it possible to conceive of new models for alleviating the distress caused by various forms of traumas—ranging from single event trauma, the trauma of war, complex family trauma, and even addiction. Similarly, transitional medical practices have revealed an enormous amount of rich data on the plasticity of anatomical expressions of sex, whether it is through the use of supplementary hormones or surgical interventions. We believe the earth itself also exhibits this capacity for plasticity and recovery. While capitalists have used the earth’s plasticity in the form of development and

extraction to pad their profit margins, contemporary science affirms that we can collaborate with landscapes and nonhuman species to rebound the stability of our ecologies. Throughout this issue, we propose that a dying world is not dead and that the wrong relations that rot our world from the inside out can be corrected.

Last June, when we were mapping out this year’s conceptual arc, we knew the theme of transecologies would be the apex of our exploration. What we did not know is how violently our governing bodies would turn against queer people, particularly our trans siblings. Since we started planning this publication, we have been thrown into a wave of legislative violence against trans people, alongside a host of hate crimes committed against trans individuals. We have also borne witness to the state-sponsored murder of Tortuguita, a trans activist of color and forest protector in Atlanta.

In this moment, we each have a decision to make: we can either look or look away as mass extinction sweeps across our lands and waters. We can either look or look away as the existence and well-being of trans people are threatened in our society. We are choosing to not only look toward our trans siblings as they share their lived experience with us but also to listen and magnify their voices as leaders in the movement for ecological transformation.

Transition! Transition! We must transition! Once a strategy, now a demand: Just transition!! Appalachia deserves clean energy! Appalachia deserves biodiversity! Appalachia deserves justice for all species!

And let us begin…

In solidarity, Sorrel Inman

Here is a breakdown of our sliding-scale payment structure. We have made it possible to subscribe for as little as $4.58/ month. With this in mind, we ask those who have the means to subscribe at the solidarity level. Not only are solidarity subscribers a huge support as we start this project, but you are also helping to subsidize discounted subscriptions!

This price level is intended to serve working class, queer, disabled, and BIPOC folx.

PRINT & DIGITAL $75/year -or- $20 every 3 months

DIGITAL ONLY $55/year -or- $15 every 3 months

This is retail price: what you would pay at the bookstore.

PRINT & DIGITAL $90/year -or- $25 every 3 months

DIGITAL ONLY $75/year -or- $20 every 3 months

This price is for subscribers who wish to invest in the longevity of our project.

PRINT & DIGITAL $150/year -or- $40 every 3 months

DIGITAL ONLY $120/year -or- $30 every 3 months

Want to carry our magazine at your store?

Message hello@mergoat.com for wholesale inquiries.

mergoat.com

Rites of Transition

WSKJ: When Sorrow Kills Joy

Project Feature: Cattywampus

The End of Man

An Interview with Hillbilly Gothic Puppet Council

The Limp Wrist and the Anthropological Machine

I Used to Be a Boy Named Margaret

Homecoming

Craft, Queerness, and Hopefulness

Species Feature: Skunk Cabbage Into the Rift

In January of 2023 a land disturbance permit for the police training facility was approved by DeKalb County. Clear-cutting of the site began immediately after approval.

Land disturbance on the property of Cop City in the Weelaunee Forest violates state and federal environmental laws. Attorney Jon Schwartz represented plaintiffs Amy Taylor and Edward “Ted” Terry in submitting an appeal to the DeKalb Zoning Board of Appeals regarding the building permit and

Dthe subsequent filing for injunctive relief when work continued despite the appeal. Taylor serves on the City’s infamous SCAC committee while Terry is Commissioner of DeKalb super district 6 in which the former Atlanta Prison Farm and proposed site of Cop City is located.

The plaintiffs waited 3 weeks to receive an official ruling from the Zoning Board of Appeals (ZBA) before an appeal of Land Disturbance Permit (LDP) could even be filed.

In February, Fulton County Judge Thomas A. Cox, Jr. denied the injunctive request to halt land disturbance at the site, despite DeKalb County law which requires

work to stop during the appeals process. Judge Cox cited that no irreparable harm was being done.

APRIL 2023

By April of 2023 the appeal was rejected. The rejection in April came after DeKalb County hired former

When an appeal is filed in DeKalb County, work on the site is required to stop. However, the Atlanta Police Foundation was allowed to bulldoze ahead with clear cutting and land clearing.

Chief Justice of GA Supreme Court, Leah Ward Sears, to defend DeKalb’s approval of the Land Disturbance Permit. In subsequent weeks, the Atlanta Police Foundation leveled no less than 85 acres of greenspace and forest.

FIntrenchment Creek and South River. Both waterways are on Georgia Environmental Protection Division’s 303-d list of impaired waters and are protected under the Clean Water Act and Georgia Water Quality Control Act. Despite the law, the permit issued by Dunn authorizes sediment pollution and allows for the violation of federal and state laws.

Ogathered from hundreds of area residents, indicating that the pursuit of environmental justice is a primary concern. In late February of 2023 the Atlanta Regional Commission (ARC) released the report: South River Forest Community Development Action Plan (SRF Plan).

The South River Watershed Alliance (SRWA) appealed the issuance of the Land Disturbance Permit to state Superior Court on behalf of plaintiff DeKalb County Commissioner Ted Terry.

SRWA is continuing to challenge the “all purpose” stormwater permit issued by Georgia Environmental Protection Division (EPD) Director, Richard Dunn, which authorizes the discharge of sediment pollution from the clear cut site into

EOver a one-year period in 2022, the ARC conducted a community engagement process in southeast Atlanta in support of the South River Forest – a vision to create a conservation area including the 296acre former Prison Farm property. SRWA leadership, Jackie Echols and Margaret Spalding, served on the Project Management and Steering Committees. Public input was

By March 2023, Mayor Andre Dickens announced the formation of a Task Force in an attempt to merge the South River Forest Conservation Plan with Cop City. This attempt outright ignored the will of residents who, within the SRF Plan, stated

STconservation as their primary concern. Atlanta Mayor Dickens commandeered the SRF Plan upon its release with the formation of a Task Force to merge the 85-acre Police and Fire Training Center development with the SRF Plan. This was a blatant attempt to advance his own political agenda.

In early March, The Atlanta Community Press Collective (ACPC) won a free press battle over demands for documents from lawyers representing DeKalb County and Blackhall Studios (Ryan Millsap). The documents were demanded by the plaintiff’s attorneys in discovery phase of the civil case that contests the legality of the exchange of 40 acres of public land at Intrenchment Creek Park to a private entity, Blackhall Studios. The suit was filed in February of 2021 by the South River Watershed Alliance, the South River Forest Coalition and several residents of DeKalb County. The land-swap case is now in the postdiscovery phase.

Also in March, an independent autopsy report for Manuel Esteban Paez Terán, also known as Tortuguita, was released. The report stated that Teran was seated with both their hands raised at the time of death— proving they surrendered and were not a threat to the arresting officers. In April of 2023, the DeKalb County autopsy report was released. This report showed that no gun residue

was found on Teran, disproving the police report’s claim that Teran was engaging in crossfire.

On March 20th, Rose Scott, host of “Closer Look” on WABE radio, interviews attorney Alex Joseph who debunks city council’s claims that nothing can be done to reverse the lease of the former prison farm property to the Atlanta Police Foundation. Shortly after, on March 23, Rose Scott interviewed Liliana Bakhtiari who admitted the majority of her constituency is opposed to the development of Cop City.

On March 24, 2023, DeKalb County CEO, Michael L. Thurmond, issued an executive order closing Intrenchment Creek Park due to “contraption traps.” Images released by the county show wooden boards with nails in them.

On April 10, 2023, Dr. Bernice A. King, daughter of Martin Luther King and CEO of The King Center, wrote Higher Ground, an open letter to Atlanta about Cop City. In the letter she states:

Atlanta’s division is a disheartening dichotomy of institutions against individuals and corporations against communities. Reasoned discourse for the collective good is hampered by insidious thirsts for power, control, and unilateral triumph. We are caught in a spiral of chaos, confusion, and confrontation, with a tale of two cities at odds about what ails us and what remedies will cure us. The reality is, we have yet to create models where ‘police reform’ is not simply a recommitment to the status quo in another form. Criminal justice system transformation and improving public safety must coexist, especially during a time marked by rising crime.

On April 1, 2023, Angela Davis vocalized her support in the Stop Cop City movement. “I urge people everywhere to join the campaign to stop Cop City,” Davis proclaims.

CIn late April, the South River Watershed Alliance and other environmental groups submitted a letter to the Chair of Soil and Water Conservation District supervisors to enforce state law. This happened after supervisors for the DeKalb County Soil and Water Conservation District (DCSWD), the agency responsible for enforcing Georgia’s Erosion and Sedimentation Act regulations, admitted in a meeting that they should conduct a review. Despite being state-sanctioned, DeKalb County did not allow DCSWD supervisors onto the property to inspect the site. In an

April DCSWD meeting, supervisors discuss the problem and state that the site is indeed a point source for sediment pollution—exceeding the legally allowed limit (TMDL: total maximum daily load) of pollution into Intrenchment Creek.

On April 25, 2023, the DeKalb County Commission deferred any decision to reopen Intrenchment Creek Park for 30 days despite a petition to reopen the park signed by nearly 900 people and supported by DeKalb County Commissioner Ted Terry.

On May 24, 2023, Atlanta City Council finance Committee approved $31 million in funding for the Cop City project.

On May 31, 2023, Atlanta Police and the Georgia Bureau of Investigation raided the home of Atlanta Solidarity Fund organizers Marlon Kautz, Savannah Patterson, and Adele Maclean. All three were arrested and charged with money laundering and charity fraud.

JUNE 2023

AOn June 2, 2023, Bail was granted to Kautz, Patterson, and Maclean.

On June 5, 2023, Atlanta Council began hearing public comments from hundreds of constituents. Public comments continued through the night and into the early hours of June 6th.

of a website, CopCityVote.com, and a citizen-led campaign to collect the signatures needed to put the referendum on the ballot.

On June 21, 2023, the proposal for referendum was approved by the Atlanta Municipal Clerk’s office. To get the referendum on the ballot, organizers must collect approximately 70,000 signatures in support of the proposed referendum in 60 days. If successful, the campaign will put the referendum on the November ballot and will read:

MAY 2023

On May 11, 2023, it is reported that the United States Geological Survey had recently and quietly shut down the monitoring device, located on Intrenchment Creek at Constitution Rd, that collects data on various types of pollution including sediment and sewage occuring in the waterway. USGS monitoring devices are key to collecting the data necessary to enforce state and federal environmental law.

At approximately 5:30 am on June 6, 2023, Atlanta City Council approved funding in an 11-4 vote for the development of Cop City. The vote approved $31 million in funding for the construction of the sprawling 171-acre development plan.

On June 7th, a broad coalition of activists announced an effort to force a ballot referendum that would allow City of Atlanta residents to vote to approve or repeal the ordinance authorizing the lease of 381-acres to the Atlanta Police Foundation. The announcement included the launch

Shall the City of Atlanta Ordinance 21-O0367 authorizing the ground lease of 381 acres of forested land to the Atlanta Police Foundation for the construction of a $90 million police training facility be repealed.

JULY 2023

On July 2, 2023, @stopcopcity began Week of Action 6. This week of action included rallies, abolitionist workshops, and a music festival within the Weelaunee Forest.

Invocation

You who courses through twisting galaxies, planetary landscapes, churning civilizations, and our ever-altering bodies —this element we call transition— we ask to glimpse your wisdom, nestled in the mystery that is life in these times.

Photo by the NASA James Webb Space Telescope

Photo by the NASA James Webb Space Telescope

While this rite is designed for use across faith traditions and secular contexts, it is based in traditions of expansive Christian liturgy tradition, like that of the Enfleshed Liturgy Library. Please adapt this text to your own community’s needs.

Clover Lynn is a trans banjo player known as Hillbilly Gothic on both Instagram and TikTok. She plays in the Laurel Hells Ramblers, a bluegrass band hailing from the southern Blue Ridge Mountains. We met through social media earlier this year; our interview was conducted in June 2023 via Zoom.

hazel: Clover, you are a widely known banjo player on Tiktok, with nearly 300,000 followers. Many of your most popular videos feature comical banjo playing interrupting the noise of right-wing speakers. How did that surge in popularity happen and what was that like?

clover: I was never trying to be a TikTok influencer. I was only trying to make funny videos. My initial goal was actually to raise money for laser hair removal for my beard. I heard TikTok was good for crowdfunding, so I made videos to go along with that, or videos that I thought were fun. I ended up raising $5,000, and then it kept getting bigger and bigger.

h: So you didn't start off posting banjo videos?

c: Yes and no. Actually, the first semi-viral video I made got 270,000 views. There was a trend at the time meant to show the “boys my parents expected me to date” versus the boys I actually dated. I thought it was incredibly funny, and decided to turn the trend on its head by showing the boy my family expected me to be growing up in the mountains versus who I actually became, a trans woman with my banjo.

I wasn't really playing at the time, but people started asking if I played, because of my profile picture. I immediately regretted choosing that picture, because where I grew up there are so many talented musicians. In my mind, plucking out a few chords on a banjo did not translate to “playing music.” The folks from my home play music; I just have an instrument.

h: Where did you grow up? Are there specific figures you remember who influenced you from the area?

c: I'm from a small place between Boones Mill and Callaway, Virginia, right off the Blue Ridge Mountains. We’re right there, nestled in the hills. Part of my family is from Franklin County and part of my family is from Floyd County.

If y'all know anything about Floyd County, then you have heard of places like the Floyd County Country Store or the Crooked Road, which is a traditional music heritage trail starting in Franklin County then looping all the way down to the bottom half of Southwest Virginia, eventually hooking back upwards into Dickenson County on the West Virginia and Kentucky border. So much music has come out of that trail—people like the Stanley brothers, and the Carter family. You've also got countless fiddlers like Peg Hatcher, whose grandson now fiddles for the Twin Creek String Band, once known as the Dry Hill Draggers. You've also got the Lonesome River Band from Patrick County, which is just south of us, and The Lost and Found, which was an influential bluegrass band in the 80s and 90s. These folks are from Franklin County; even my great uncle used to run around with one of them—if I remember correctly it was the banjo player Gene Parker, but my great uncle passed away 10 or 15 years ago now.

h: Did your family play music too?

c: As far as publicly, no. I have a working theory that Papa played privately, but he refuses to talk about it. I can't pinpoint it, but he has a strong vested interest in my banjo playing. Maybe it is because the banjo is an important element of our culture that he was raised with, but there is also one specific thing he does that I have only ever seen banjo players do: he'll bounce his thumb to the beat when he listens to me play. That's a very drivey thing. If you are doing that, you have probably played something. That generation, I think, had a very similar thought process to mine, though. Just because someone could pick a bit didn’t mean they were a musician. To people who are not from the region, though, if you can pick even a little bit, well, that's part of you.

h: Do you feel like you were forced to consider yourself a musician as a result of your visibility to the public as a musician?

c: I only started considering myself a musician over the last year, though I've been playing for three and a half years now. Over the last year or so I arrived at a place where I can comfortably say, “I'm a musician. I can play music.” I can keep up with other musicians, and I feel competent that way.

h: What drew you to the banjo over other instruments?

c: I had moved away from home, and was feeling very homesick after spending time with my family during Thanksgiving. I got to see a bunch of live music while I was at home for the holiday. When I got back to my new residence, I missed home, and I missed the region. So I decided to pick up an instrument. I didn't know what to pick up until I remembered that all the songs from Crooked Road were played on banjo.

h: So the choice to play banjo was connected to your southern identity?

c: Absolutely. With the banjo, there are so many different styles. It is easier to show than to talk about, so I'll play some tunes to demonstrate. I'm gonna need to retune a little bit because I'm in a traditional tuning right now, do you play banjo by chance?

[Clover asked this as she took out her banjo to demonstrate the regional characteristics of the banjo playing from her home.]

Not only is my identity connected to the banjo itself, but my style also comes from the way I was raised. Many modern, progressive players have a very specific style which is not my style at all. It is a newer way of playing. Bill Keith started that whole trend, but it's taken hold in more progressive bluegrass, like Béla Fleck and Tony Trischka.

I started learning progressive bluegrass at some point. When I went to show my Granny and Papa a progressive song, Béla Fleck's “Vertigo,” they responded by politely saying, “That’s nice.” Then my Papa followed up with, “Do you know Clinch Mountain Backstep?”

The moment he asked that question, it occurred to me that the reason I play this music is because I listened to the Stanley Brothers with Granny and I listened to Flatt and Scruggs with Papa. We'd go to the county fair or a fiddler's convention, and that was the music I heard growing up. When I started developing my own style, I stopped focusing on which cool licks I could play and started focusing on what would make my grandparents happy. For me, being from a region and a culture is not just about being a self, it is also about being part of a community. So I can't really separate myself from my community when I'm playing music, and the music that comes out most naturally is traditional to my community. If my Granny and Papa don't want to dance to it, or I don't see Papa bouncing his thumb, why bother?

h: Sounds like playing banjo is a way of connecting to your community and your family. Has your family been supportive of your transition?

c: It depends. My direct family, like Mom and Dad, have been very supportive, especially in recent years. It took a bit, but it has been an absolute blessing to see their journey to acceptance. When I first came out, my dad kicked me out. He wasn't happy, and he didn't like it. It has been such a blessing to see him grow and to see us grow together.

We used to butt heads when I was growing up, fighting all the time. Growing closer to him is something I didn't think I would get to experience. When I was first kicked out, I thought that was it. Then when I got away from the region, I realized how important family was. I never cut them off completely while I was away, but I didn't talk to my dad for almost a year and a half. Now I'm living at home before we go on tour, and I see him every day. We talk and he's really supportive.

He also learned to ask certain questions in better ways. For instance, he's a public school teacher. The other day he received his class list and said, “Oh, I've got one of them ‘they’ kids.” I responded, ”Oh, you mean a nonbinary kid?” And he said, “Yeah, a ‘they’ kid.” So, he doesn't always have the right language, but there’s never ill intent. There's no hate behind it.

My granny and Papa are the best examples of acceptance, though. When I go over to spend time with them at their home, they still call me “he” and they still call me by my dead name. I'm okay enough with that, especially from them, because they give me a special type of acceptance.

For instance, when I go hang out with Granny and Papa, we work on the truck, work in the garden, or break beans and shuck corn—activities that I don't need to dress up for. I don't wear much makeup over there. On one occasion, though, I was on my way to a gig and needed to stop by and see them beforehand. I was wearing a bodycon dress and a pair of fishnets. My papa looked at me and said “Now, [Deadname], I don't care that you dress like a girl, but in my house please don’t dress like a hussy.” Someone else might hear that as aggression, but, to me, that was the most loving thing I’d ever heard him say.

h: When you came out to your family and your dad kicked you out, is that when you left home? Did you feel like you needed to leave the region to find yourself?

c: I was away from home for about four years. It wasn't that I was trying to find myself, per se. I'll be honest: growing up, I hated being from here. I used to hide my accent as much as possible. I even used to shun the music. When I was eighteen, one of my proudest moments happened while I worked at a coffee shop in Roanoke. A guy asked, “Where are you from? You don't sound like you are from here.” At the time, I was so happy that someone didn't think I was from the area. Now, I would hate that.

h: Your chosen name is Clover, a beautiful name that carries a botanical reference. How did you choose that name?

c: I chose about fifteen different names over the course of two years or so. Eventually, I narrowed it down to either Clover or Chamomile, and I finally chose Clover. It was the name my friends gravitated towards, and everyone liked it. As much as I'd like to say that I thought of it while laying in a field of clover, that isn’t the case. Now, I was listening to “Dixieland Delight” by Alabama at the time, and there's a line that says “White-tail buck deer munching on clover…” and I thought to myself, “Clover. That would be a pretty name.” It was also right around the time Chris Stapleton had released “Starting Over,” where he sings a line that says, “I can be your lucky penny, and you can be my four leaf clover.” So as much as I would love for it to be connected to botanicals, it was just music. For me, everything is connected back to music.

h: And the name of your band also contains a botanical reference, right?

c: That one is very intentional. My fiddler came up with the name originally because she likes laurel hells. Do you know what a laurel hell is? It’s more of an East Tennessee word, from the greater Smokies area. People would get lost in these thickets of mountain laurel, and they would go mad or die. She thought we could use the name Laurel Hells Ramblers because we're wandering and trying to figure out some things our own way.

As I was putting together our first packet of promotional material, I found out that Mitski had actually released an album called Laurel Hell. People also asked her why she used the name Laurel Hell, and she said that she thinks there is something interesting about being lost in something that is so beautiful but can also kill you. No matter how beautiful it is, staying there may ultimately lead to your death. Sometimes, trying to escape will also lead to your death. I related strongly to that. The fact that we are a band with two Appalachian trans femme people at the core, there is something resonant about the analogy of a laurel hell. There is something resonant about being queer in the rural South and being caught up in your love for a place, even though it can be dangerous at times.

As an aside, I want to be clear that I'm not saying that I think our region is more transphobic than others. On a personal level, I think I've actually experienced more acceptance from people in Franklin County, Virginia than I have anywhere else in the world—including cities like New York, Chicago, and San Francisco. The level of acceptance I've experienced from cis people in Franklin County is different from what I have experienced with cis people outside the region. I don't exactly know how to word it, but it's much like my granny or my papa.

I wouldn’t want to be trans and from New York City. I love that I'm from Southwest Virginia, from the Blue Ridge Mountains. Even when they don't get it, I think people here are more accepting and willing to stick up for you. People in metropolitan places will say they support you, but they're not always willing to stick up for you. They're not willing to actually sacrifice anything themselves. Here, if someone says they are on your side, even if they notice something is different about you, they are always there.

There is something interesting about being lost in something that is so beautiful but can also kill you. No matter how beautiful it is, staying there may ultimately lead to your death. Sometimes, trying to escape will also lead to your death. I related strongly to that. The fact that we are a band with two Appalachian trans femme people at

Photo by Hazel Hoffman

Photo by Hazel Hoffman

the core, there is something resonant about the analogy of a laurel hell. There is something resonant about being queer in the rural South and being caught up in your love for a place, even though it can be dangerous at times.

h: I also think there is often an innocence to how people here approach the topic—as if seeing something for the first time. Instead of having a preconceived notion about what it means to be queer or trans, they just don't know. And so, in a way, they experience it more directly.

c: You are 100% onto something. People always ask me why I have more tolerance for people saying something kind of hurtful here than I do in other places. A lot of times when someone meets me, especially in Franklin County, there's a very good chance I'm the first out-of-the-closet trans person they've ever met. Some people don't even realize I am trans until later on, then they have some ignorant stuff to say. When I say “ignorant” I don't mean they are being intentionally mean or hurtful. I mean it more in the sense that they naively ask inappropriate questions. I’ll entertain them a bit, but I take the opportunity to gently suggest that they shouldn’t go around asking other trans people questions like that. I allow myself to be the person who they can have those conversations with. I would hate for their view of trans people to be influenced by the media, or even by another trans person who might be fed up and snap at them for saying the wrong thing. Right or wrong, in a situation like that the country person probably does not understand why the trans person just snapped. So if I can be the person who has those conversations as much as possible with rural southwest Virginians, then, you know, that seems like a positive way to educate these folks.

h: Do you think being trans in the South has given you a unique perspective into the world of banjo playing?

c: I think there's a lot of interconnection there. First and foremost, most people in bluegrass circles, to my knowledge, don't know that I'm trans. I'm very lucky to be cis passing. You know, I'm 5’5” and I weigh 110 pounds. I am very lucky that I have a body that people can easily categorize as “woman”. No one has ever clocked me for my height. No one has ever clocked me for my weight, or my structure, or anything. I have a fairly feminine face, my voice isn't easily read as either male or female. So I think my experience in bluegrass and old-time circles is quite different from someone who might not pass as easily. To take it a step further, most people see me not only as a woman, they see me as a white woman. I experience traditional misogyny from time to time, and that sucks, but I've never been told I don't belong at a jam or a show. I know that is not the case for other trans people and other minorities in bluegrass and old time.

h: Given the history of the banjo, it's interesting how much the world of banjo playing has been co-opted by white men. Could you tell us a little bit about what you know about the history of the banjo?

c: Something I hear mentioned frequently that I think needs to be slightly clarified is the idea that the banjo came over with slaves on the ships. I think that does a disservice to those who were enslaved because it implies that the people who ran the transatlantic slave trade allowed slaves to bring an instrument. This is not true. The instrument came over in the minds of the enslaved people. It was not by some small grace of the slave owners. Rather, Black folks recreated the banjo from within a place of suffering, as a way to connect to their home, their spirit. They created the banjo based on an African instrument which was called the akonting. It was a gourd instrument with a hide head. I think they were typically three or four-string instruments, but the thing that was unique was the high, shortened drone string. You still see that today with five-string banjos.

The banjo was seen as a plantation instrument for the longest time, and then it started to intermix with other musical forms. It was taken up by minstrels, then it made its way into the mountains. From there, it moved into these hollers and people would play both modern and traditional music, be it Scotch-Irish fiddle tunes, German fiddle tunes, or music that they made up on the spot.

There's no way to talk about the history of bluegrass, or even American music in general, without talking about minstrels. A lot of surprising tunes like “Angeline the Baker” came from minstrel shows. I don't know that I'm the person to say whether or not we should do anything about that, but I think it is an important reality to be aware of.

h: Are you familiar with artists like Rhiannon Giddens and Don Flemmons, or the Black Banjo Reclamation Project?

c: Yeah, absolutely! Speaking of Rhiannon and Dom, the first time I got to see old-time music on stage was The Carolina Chocolate Drops. That was in 2015 or 2016. It was the first time I saw someone play old-time music who was not local to my part of Virginia.

h: How do you envision the future of banjo music and its role in promoting inclusivity and diversity within the southern musical landscape? Country and hillbilly music are often the last places people think to look when discussing queer inclusion, but we've seen something of a queer renaissance in country music. I am thinking of the emergence of powerful queer artists in our region, like Orville Peck or Adeem the Artist.

c: I love Adeem! There are so many others right now, too, like Sam Gleaves and Tyler Hughes. Locally, there's a band called Palmyra. They are from various parts of Virginia, but their front person, Sasha, is from Texas Holler—a place on the western end of Roanoke County. I could talk for days about the state of queer representation in country music. Willie Carlisle also comes to mind. There are also many people in the scene who I know are queer but have not come out publicly.

Don’t get me wrong: country music has always been queer. But there is a scene emerging in alt-country that is queer to the core, and a lot of that music is from right here in Appalachia. People like Adeem the Artist (Knoxville, TN), Palmyra (Virginia), Newport Transplant (Athens, GA), Tyler Hughes (Southwest Virginia), and Sam Gleaves (Southwest Virginia). Willie Carlisle is not from Appalachia, but he is from the Ozarks. There is a lesbian couple who plays folk music under a couple of different band names in Southwestern Virginia. They are from Patrick County. There are almost too many to talk about.

Of course, queer musicians play an important role in building diversity. I think a lot of queer musicians grew up rejecting our culture like I did. When they come back into it, they are often out and proud of who they are. I think it reflects the need to show off who we are in our fullness because for so long we have rejected one part of our identity for the other. It is an integration of those parts.

h: Can you tell us about your Instagram and Tiktok handle, @hillbillygothicc? It also seems like a fusion of two different cultural identities.

c: One of the first radio stations to play Bill Monroe and other early bluegrass music was a station out of Indiana called WJKS, Where Joy Kills Sorrow. I always thought it would be cool to have a goth bluegrass album titled WSKJ: Where Sorrow Kills Joy. When I brought this up to a friend, they asked if I knew anything about minor keys, and suggested I transpose some songs. At the time, I had no idea how to go about doing that. He gave me some tips, and the first song I transposed to a minor key was Cripple Creek.

I had grown up listening to the Stanley brothers, Flatt and Scruggs, The Lonesome River Band, and other acts like these. As I got older, I rejected a lot of that. I started moving toward bands like My Chemical Romance, Black Sabbath, Iron Maiden, and Cradle of Filth. Later I would listen to more punk, like The Dead Kennedys, and The Velvet Underground.

Eventually, I found folk punk. There has been a kind of Nickelbackification of folk punk. There are plenty of really bad folk punk bands, and I am implicated in many of the jokes directed toward that genre. I still love bands like Apes of State or Days and Daze—it’s fun. But, more than anything, folk punk gave me a way back into traditional mountain music. For instance, there was a folk-punk cover of Mountain Dew. When I first heard that cover, I recognized it immediately because I listened to the Stanley brothers growing up. So folk punk gave me the opportunity to go back and explore the music I grew up with. Combining alternative influences with traditional music is basically what my band does now. We take inspiration from everything.

h: There is a book by David Haskell that came out recently, entitled Sounds Wild and Broken, that explores the evolution of sound. As he tells it, the story begins with these microscopic critters that barely make any sound at all, because to do so would be to alert predators to their location. These critters only communicated through sight and touch. Once these ancient bugs started developing adaptations that allowed them to escape or protect themselves from predators, they also developed more sound-making apparatuses and eventually vocalization to communicate with each other. I find this to be a beautiful parallel to feeling safe enough to use our voices in the modern era—to feel safe enough to come out or to share our transition on the internet for instance.

c: That is a really interesting comparison to the queer experience and learning how to feel safe enough to share ourselves with society. I think you put that beautifully.

h: You became well known on Tiktok for using your banjo playing to silence the tired mansplaining of misogynists and incels. In the face of ongoing trans exclusion and the political challenges that we're surrounded by, how does your music and banjo playing serve as a form of expression within and against these oppressive forces?

c: I think there is a lot to be said about a band of queer women playing old-time music. We've changed certain lyrics here and there to explore that theme. For instance, the original lyrics to the song Greasy Coat say, “I don't drink, and I don’t smoke, and I don’t wear no greasy coat.” This song has some floating verses that bands change from time to time. So if a straight person is singing, they may change a line to something like, “I don't dip, and I don't chew, and I don't run with girls that do.” But we changed the lyric to “I don't dip, and I don't chew, but, boy, I love the girls that do.” I think that line is a celebration of rural queerness, because, even if you're in an urban area where they more readily accept you as trans or queer, they might not accept the fact that you chew tobacco or hunt.

I had a recent flirt who could not handle the fact that I hunt. This is nothing against them, but I believe we need to learn to celebrate both the ruralness and the queerness of rural queers. I think Laurel Hells Ramblers' music is a place where that celebration can happen.

I’ve been working on a special project for about a year and a half, and it's almost done. It is a song that I've always wanted to write—a murder ballad about my own transition. I don’t want to spoil too much, but I am also the first-person narrator, singing the song as the perpetrator of the murder. The central line goes, “Oh, tell me, sister, what have I done? I've gone and I’ve killed daddy’s firstborn son.” That'll be released sometime... hopefully… eventually.

A challenge I am working to address now is the reality that Tiktok is a finicky platform where some things just don’t do well. It can be really discouraging as a creator. So whenever I feel done with the platform, I don’t want people to think I'm done with them. I would love for people to support me on Instagram, and I’ll also continue posting on Tiktok. But sometimes, with the algorithm, I feel like it doesn’t work unless I'm playing the same song and dance, quite literally in this case. Like most artists, I'm fairly multifaceted.

There is also another side of it, too, where I don't want to sell out my Appalachian identity or my roots in the rural South as a way to get a couple of extra followers on TikTok. I love telling my stories, and I don’t mind—but I don't want to become a caricature of the region.

One of my biggest pet peeves—and this is no fault of any individual—is to go on Spotify and search for Appalachia. Many of the top results are things like “the haunted woods of Appalachia” or “Don't whistle at night.” Those are fun stories that get passed down, but there is so much other history and culture that we can fall on. Why do we reduce Appalachia to

This all brings me back to a common question: What is Appalachia? I believe, at the end of the day, there are many Appalachias. The idea that we can only be portrayed as kitsch or scary stories is strange. Historically, we have heard, “Oh, there are terrible people up in the mountains who will kill you or eat you.” Others go the opposite direction, idealizing our ancestors as people with some profound, unreachable wisdom. Don't get me wrong, there is a lot of old knowledge to be had here. I just feel like no matter what we do, people from outside of the region reduce us to a stereotype.

You have to remember, though: we're just people. The gentrification that is happening in the region, and has been for a long time now, is concerning. We've had gentrification in my county since the 1960s when the lake flooded—and I'm sure y'all in Tennessee know all about that. Appalachian Power flooded a system of hollers up in the northeastern part of Franklin County. My papa and his family lived up there for a while, sharecropping in a place called No Head Hollow. That place is now flooded, and the house where he grew up sharecropping is now a multimillion-dollar lakefront property. They never got to see any of that wealth. They never owned that property, because they were sharecroppers. They were tenant farmers. So, gentrification is not a new thing in Appalachia. It looks different from generation to generation, but I think we're gonna see an uptick as a result of climate-related migration.

I'm not a climate scientist, and I'm not going to pretend to know everything about it. I know that there are going to be migrants coming to America because of climate change. I also suspect that there will be a group of hyper-wealthy individuals who come to the region, especially Southern Appalachia. They're going to try to settle in those places because they're supposedly “climate-proof.” I don't know if I believe that, or if someone's just trying to make a buck off of land.

"Oh,

PROJECT NAME

Various titles

CONDUCTED BY

Cattywampus Puppet Council

PROJECT TYPE

Parades, street parties, and performance art with giant puppets

HOMEBASE

DATE STARTED

Knoxville, TN 2014

MATERIALS

Trash and other found objects, paper-mâché, scrap foam, magic

SERVICES PROVIDED

Programs in giant puppet making, community-based theater, and storytelling

Parading up to its 10th year of existence, cattywampus Puppet Council is a living, breathing, dancing, shouting, honking, banging, transformative, magical party. Currently, the giant puppets rest in the 1400 Building on 6th Avenue in Knoxville, Tennessee, after a whirlwind yearand-a-half-long partnership with the Big Ears Music Festival and a spring collaboration with Yo-Yo Ma and his project entitled Our Common Nature: An Appalachian Celebration.

The essence of the Cattywampus Puppet Council is humanity. It is an expression of the deepest yearnings we all feel for connection and meaning in times of suffering, illness, loneliness, and despair. Our ancestors understood that living could be hard and often cruel. Nevertheless, in every wisdom tradition, we find the pursuit of joy. We find celebration, pleasure, and play as tools for resilience and survival. Cattywampus is a project rooted in this knowledge and the life-giving practices of creating, playing, and dreaming together.

When she first began imagining Cattywampus, Rachel Milford, the Council’s Executive, and Artistic Director, was profoundly ill and intuitively turned toward her background in giant puppetry and community-based art as a source of healing. She was suffering from environmental illness brought on by black mold poisoning and a family history rooted in the radioactive catastrophe that is Oak Ridge, TN. Rachel’s work as an herbalist, an artist, a performer, an organizer, and a storyteller, both then and today continues to be deeply and foundationally informed by her experience of chronic illness and the well of resilience we can tap into through joy and play.

On a warm fall evening amidst the patinated brick of Knoxville’s Old City, our first puppets, Grandma and Grandpa, casually made their debut—unannounced and arm-in-arm. As Grandma and Grandpa strolled among clusters of First Friday aesthetes, some people took a pause and giggled, while others took the opportunity to dance with the larger-than-life characters. Captivated onlookers found a surreal joy and life-giving excitement in these tender and absurd characters. They were funny. They were relatable. They were feeble yet vital, silly, and unexpected. Grandma and Grandpa became regulars in Knoxville’s downtown. As more attention was drawn to their spectacle, more friends and community members were recruited into The Council to make and play alongside us—leading to the emergence of characters like Possum, Raven, and a sixteen-foot-tall Big Dolly Parton. Thus, the Cattywampus Puppet Council was born.

Cattywampus continued to grow, with the search for ever larger containers for ever more diverse and intergenerational community participation leading to the first giant puppet parade in the spring of 2017. The parade marked a shift towards the transformative; centering justice, relationship building, raising joy and power together, and using art and play as vehicles for envisioning the worlds we want to create. Going on seven years, the parade and street party have entered the realm of tradition.

Core to these celebrations is the following community-based art programs that take place in the months leading up:

8 week-long youth arts residencies with community partners such as Centro Hispano, Canvas Can Do Miracles, the Boys and Girls Club; A paid Youth Intern Squad (which trains high schoolers to be teaching artists and cultural organizers); The Knoxville Honkers and Bangers, a new, raucous, hot pink, and inclusive community brass band project; Open Studio Days, Giant Puppet Making Workshops, and more!

Collaboration and deep partnerships continue to be the core values of Cattywampus and our work. A wildly successful example of this is the 2018 collaboration between Cattywampus and The Good Guy Collective, a Knoxville-based hip-hop community, to create the play What the Water Tells Me—a coming-of-age, environmental justicecentered theatrical puppet, dance, hip-hopera. Nearly 50 community artists had their hands in bringing this innovative play to life, resulting in many lasting relationships and partnerships. Five years later, we find ourselves working with One World Circus to create our newest community-based theater piece: Solastalgia, an outdoor circus of ritual and pageantry exploring grief, hope, and world-building in the context of societal unraveling and climate chaos.

In both of these productions, we’ve discovered again and again the power of puppetry as a form of magical realism. As a way to create containers for exploring pain, trauma, and injustice together and find pathways towards healing. As a method for opening up space to share our own stories of harm and imagine different, more life-giving worlds that we might create together.

from a technical perspective, there is nothing new here. Large-scale papier-mache traditions can be found all over the world. In our studio, the process begins by mixing water and cornstarch to adhere strips of brown paper grocery bags on a clay, cardboard, or crumpled paper armature. After a couple of layers have dried, depending on the desired scale and effect, these paper-mâché creations will get paint, “bones,” and bodies made out of what is inexpensive and readily available (not unlike ourselves). Helmet-style puppets get filled with scrap foams. Old bed sheets can be dyed and hung between bamboo poles to create a largerthan-life character. Sometimes, a scrap external frame backpack is used as the platform for the puppet, as seen with Cattywampus’s own Bear and Big Dolly.

In the studio, we see the artistry and creativity of making the puppet look spectacular, look fabulous. Then there is the puppeteering. The puppeteer lends soul, agency, agenda, and life to their puppet. The puppeteer, with their subjective experience and history, comes into a rapturous, synergistic, swilling dance (metaphorical and often literal) between the character, the audience, and the self. The elements coalesce, producing the life and essence of the character as it comes to know and experience itself. There is a porousness and selflessness in this dance. The lines between self and other—or, self and puppet—are blurred. Puppeteering, in this sense, can be understood as a form of drag.

In their brilliant, illustrated proposal Bloodtide: a New Holiday for Horseshoe Crabs, Eli Nixon, a trans puppeteer “clown who doesn’t like makeup,” writes beautifully on the practice of naturedrag through puppetry. In their book, Nixon describes feeling at once both drawn to the transcendent performance and joyful community of the drag world, while simultaneously feeling uncertain and frustrated by the “queer-but-binary” imposed in traditional drag. Distinct from the often hyper-binary expressions found in traditional drag culture, Nixon found their place in drag performance as neither “drag king nor queen, but more-than-human, a royalty of sorts but accessible to anyone with a body: drag kin.” By expanding their understanding of the transformative process at the heart of drag performance, Nixon demonstrates the profound opportunity for interspecies kinship at the heart of puppeteering. Nixon names this practice: naturedrag.

Nixon draws heavily on Una Chaudhuri’s concept of “boundary work” when exploring their idea of naturedrag. Nixon describes boundary work as “the use of animality to configure human subjectivity in performance.” Nixon takes this to mean “our ability to see and know ourselves in new/old ways by activating the space between ourselves and more-than-human creatures.” Naturedrag betrays the binary of traditional drag culture for a more expansive exploration: “[taking] on [the] body-plan of another life form activates feelings of being both a more and less human part of the ‘natural world,’ awake to an impulsive porousness as a beast among fellow beasts.”

When Nixon crafts and then dons a giant cardboard horseshoe crab, they expand the rich tradition of drag culture into naturedrag. This practice is timely and relevant, expanding the liminality of the queer zeitgeist. Naturedrag invites us into a nonbinary, interspecies experiment that is less “between” and more “among.”

We also find ancestral resonance in the practice of naturedrag. Many Indigenous communities include ceremonies that call for participants to ritually inhabit the forms of our more-thanhuman kin. In Restoring the Kinship Worldview: Indigenous Voices Introduce 28 Precepts for Rebalancing Life on Planet Earth, we find wisdom in dialogues between Wahinkpe Topa (Four Arrows) and Darcia Narvaez, Ph.D. In identifying the 28 precepts, they contextualize and converse at length on 28 writings, powerful excerpts of works representing a diverse cross-section of Indigenous leaders. In this visionary collection, we see the deep vein Nixon has tapped into, particularly among the precepts of Respect for Gender Role Fluidity, Nonanthropocentrism, Humor as Essential, and Ceremony as Life Sustaining.

In the chapter on Ceremony as Life Sustaining, we encounter the following wisdom from Linda Hogan, “We remember that all things are connected. Remembering this is the purpose of the ceremony. [...] We speak. We sing. We swallow

water and breathe smoke. By the end of the ceremony, it is as if skin contains land and birds. The places within us have become filled. Inside the enclosure of the lodge, the animals and ancestors move into the human body, into skin and blood. The land merges with us. The stones come to dwell inside the person. [...] We who easily grow apart from the world are returned to the great store of life all around us, and there is the deepest sense of being at home here in this intimate kinship”.

Similarly, in the 1988 collection Thinking Like a Mountain, Pat Flemming and Joanna Macy recount their experience with a ritual they created for activists called the Council of All Beings. This ritual invites participants to make a mask and embody the voice and wisdom of a river, plant, mountain, or animal. To accomplish this, participants must reject anthropocentricity and enter into a place of empathy and co-occurrence with the more-than-human world. This practice fits within the larger body of Macy’s “The Work that Reconnects”, a transformative framework merging spiritual practice and systems thinking to equip us with the tools to creatively and constructively respond to the interconnected global crises we face.

The ritual space for Cattywampus Puppet Council is the parade. Parades are a powerful act of collective self-determination and self-expression, a taking up of space and of streets to communicate something about who we are and who we want to be. We draw inspiration from other community giant puppet parades that have come before us, such as the “May Day Parade” in Minneapolis, hosted annually by In the Heart of the Beast Puppet and Mask Theatre, as well as Philadelphia’s “Peoplehood Parade” organized by our dear friends and mentors Spiral Q, and many others.

Parade day is an exuberant and chaotic scene, lively and electric. Parade crews of 3 and sometimes as many as 100 children and adults gather with giant puppets and other creations to share with the community. Giant flora and fauna can be found dancing alongside mythical creatures (such as queer dragons and colossal alebrijes), social-justice-themed art (like giant power fists, factory smokestacks,

and portraits of beloved transcestors), stilt walkers, West African drums, and everything in between.

At the center of it all, or at the front, whichever is required, Rachel can often be found in her finest circus ringleader ensemble, complete with a flowery top hat lovingly crafted by Council member and milliner Mindy Cooper. Each parade has a theme sourced from the community (Past examples: I See You; Our Roots, Our Power; and Our Wildest Dreams), and in that theme, the intention of the ritual and the inspiration for the parade art are found.

On parade day, the spell is cast in the performance itself, with the music, shouting, and revelry. After so many hours with hands in goop, so many floors littered with glitter and craft paper scraps, the ritual objects of love and play and creativity form a critical mass of exuberant joy and imagination, breaking us free from the trance of the everyday and the mundane, allowing us to inhabit a space of unforetold possibilities.

Rachel first learned the art of giant puppets and parades 14 years ago while interning with Paperhand Puppet Intervention in North Carolina. Paperhand’s founders, Jan Burger and Donovan Zimmerman, follow in the lineage of their teacher Peter Schumann, of the legendary Bread and Puppet Theater in Vermont. They, too, inhabit an ecosystem of countless far-flung puppeteers who converge at sites of profound harm and injustice to practice the transformative magic and spellcasting of demonstration puppetry. These grassroots practitioners believe, as do the Cattywampus Council members, that these humble means and materials are all you truly need to change the world. We are made of “trash,” playfully and intentionally making art out of “trash”, in community with one another to communicate a transformative message of radical love, solidarity, resilience, and joy.

This is the transformative and subversive magic in which Cattywampus invites us all to participate.

THIS MAGIC IS RECURSIVE. IT IS ITERATIVE. IT IS EMERGENT AS ADRIENNE MARIE BROWN DEFINES THAT TERM. IT IS DIALECTICAL AND DIALOGICAL. IT IS ART, AND IT IS CREATIVE PROBLEM-SOLVING. IT IS A PRACTICE OF COLLECTIVE MEANING-MAKING. IT IS AN OPPORTUNITY TO BUILD COMMUNITY WHEN WE FEEL ISOLATED AND ALONE. IT IS GENTLE ENCOURAGEMENT TO CONNECT WHEN EVERY FIBER OF OUR BEING TELLS US TO DISSOCIATE. IT IS A WELL OF INSPIRATION WHEN THE CHALLENGES WE FACE ARE OVERWHELMING AND SEEM INSURMOUNTABLE. IT IS CARVING OUT SPACE TO BE WILD AND UNRULY, AUTHENTIC AND MESSY IN A WORLD OBSESSED WITH PRESENTING ITSELF AS LOGICAL, RATIONAL, AND PROFITABLE. IT IS QUEER AND TRANS IN A WORLD INCREASINGLY OBSESSED WITH AND CONSTRUCTED ON BINARIES. IT IS A LIFELINE FOR OUR DEEPLY SENSUAL AND SENSORY NATURES IN AN INCREASINGLY DIGITAL, IMPERSONAL WORLD. IT IS A REMINDER OF OUR CONNECTION TO THE EARTH AND OUR AGENCY IN CO-CREATING THIS WORLD THAT OTHERS WOULD HAVE US BELIEVE WE HAVE NO BUSINESS IN SHAPING AND BEING SHAPED BY. AS A POWERFUL AND RESOUNDING REBUTTAL, AS A TACTILE AND JOYFUL INVITATION INTO POSSIBILITY, WE ARE HERE. WE PLAN TO PARADE INTO AND THROUGH THESE UNRAVELING TIMES—WITH YOU, BESIDE YOU.

In 2012, Pastor Sean Harris from Fayetteville, North Carolina made headlines following a controversial sermon in which he advocated using violence to correct young boys who exhibit “girlish” behavior. Pastor Harris taught his congregation that effeminate boys must be “squashed like a cockroach.”1 The comparison Harris makes between a limp-wristed boy and a cockroach is fascinating as a rhetorical device. A complex and latent discourse about sexuality, misogyny, gender, and the human species are all tucked neatly into

this single analogy. Not only should the boy be squashed like a cockroach, but “the second you see your son dropping the limp wrist,” he says, mimicking the offending gesture, “you walk over there and crack that wrist. Man up. Give him a good punch. Ok?” In the footage of the sermon,

the audience murmurs back with noncommittal laughter. The media descended upon an otherwise unremarkable Baptist pastor with such intense scrutiny that Harris was forced to apologize for preaching violence against children. What could possibly be so offensive about the “limp wrist” in question?

The limp wrist is a mysterious gesture with no definite origin. Some have suggested the limp wrist first became a point of contention in the Roman Republic, where public speakers were encouraged to

have wrists as firm and solid as their arguments. Others suggest the limp wrist may have emerged during the height of late 18th century Victorian fashion, in which women’s garments were so constricting that only their hands were free enough to gesticulate. While none of these speculations can be verified historically, we can say with certainty that the limp wrist is a stereotypical signifier of a gay man in contemporary society. The physiognomic posturing of the “gay wrist” is most recognizable when a gay man’s wrist falls limp, forming a 90-degree angle to the vertical forearm. The limp hand may also flick about involuntarily as the gay man explicates, laughs, or critiques. So, beyond its actual structure as a pose, it is, of course, the telltale sign of a big fag.

We can derive at least two strands of thought from historical accounts like these regarding the limp wrist phenomenon. The primary strand, or the Sean Harris model, suggests that the limp wrist stands for human degeneracy. In this line of thought, the limp wrist, in its flimsiness and infirmity, presents the lameness of humanity. The limp wrist is the type of gesture that threatens to drag humanity down into the undifferentiated abyss of “nature,” a nature in which the human form is contorted into grotesque angles, and from which people like Harris envision themselves as distinct, or separate. The second strand, or the dandy model, posits the limp wrist as a leftover gesture of the transcendent bourgeois class. As a denial of our all-too-human animal impulses, the dandy limp wrist emphasizes aesthetic values and social order over cruel reality. This hand is not one that grasps and manipulates its way through the morass, but is one that softly waves away any notion of struggle. Unaffiliated with the unstoppable horror of the abyss, the dandy lets his wrist dangle as he affirms his central place within the universe.

In his work Notes on Gesture, Giorgio Agamben explains how certain gestures are so loaded with social code and political meaning—that the very existence of these gestures imply an ascension above common nature, and thus beyond animality. This particular function of the limp wrist as a gesture reveals what Agamben refers to as the “anthropological machine.” The anthropological machine is the ever-present system in which the line between man (using Agamben’s term here) and “animal” is contested and constructed. As human society begins to recognize the arbitrariness of the boundary between human and animal, anthropological machines produce new distinctions, which work to affirm the existence of man—in all of his

problematic, convenient, medical, or genocidal causes—as a being that is distinct from animals. The anthropological machine functions as “an ironic apparatus that verifies the absence of a nature proper to Homo, holding him [man] suspended between a celestial and a terrestrial nature, between animal and human—and, thus, being less and more than himself.”2

In Agamben’s words, exhibiting a limp wrist reveals the contours of the “anthropological machine.” Indeed, our “homo” in question is devoid of an essence; he is neither natural nor transcendent. On one hand, he is an absolute degenerate, disrupting the functioning of human society. On the other hand, he is a myopic lover of culture. The gesture of the limp wrist has opened two distinct anthropological deductions: one suggesting that Homo is inhuman, and one suggesting that Homo is superhuman. In both cases, the limp wrist signifies something undesirable, but from what vantage point and to what end?

The Inhuman Agamben traces the origin of this tension between Homo and animal through Darwin’s seminal text The Origin of Species. Recognition of the common ancestry of humans with apes caused a major crisis in our understanding of Homo, and we have developed methods to mask the fragility of our supposedly exceptional humanity.

The anthropological machine, Agamben writes, “is an optical machine constructed of a series of mirrors in which man, looking at himself, sees his own image always already deformed in the features of the ape.”3 Like a form of trans-species dysphoria, we can imagine the anthropological machine as the means through which we resolve the unheimlich anxiety of witnessing our own human form bend into something grossly inhuman, yet fundamentally the same. By catching a glimpse of ourselves as inhuman, a convenient reaction is to reaffirm our humanity. Ultimately, the difference between us and what we see in the mirror remains slim.

We must return once again to the remarkable and influential pastor, Sean Harris, urging his community to break the wrists of young girly boys. The anthropological machine is a convenient tool to avoid psychoanalyzing Pastor Harris, the method queers often use to tackle homophobic politicians who seem to know all too well the kind of things homosexuals do. We will not characterize Pastor Harris as a closeted homosexual, although he is.

Instead, with Agamben, we can accuse him of blatant anthropocentrism (which is certainly worse!). Harris peered into the anthropological funhouse and saw something not so different from himself in the contorted mirrors, a cockroach. In Clarice Lispecter’s vivid text The Passion According to GH, the titular character GH is confronted by the broken body of a cockroach after crushing it. This single event triggers GH’s descent into another dimension, wherein she undergoes a long crisis of depersonalization. She is enamored by the body of the dead cockroach, hypnotized by the life she has just taken. She slowly begins to forget her own name, and the names of others who are in her life. Language slips from her, as she begins to speak nonsense. The limits of her humanity break at the seams, and she is forced into a realm of absolute neutrality, where the distinction between Homo and animal vanishes. She is no longer quite human. She asks herself, “Before I entered the room, what was I?... I was what others had always seen me be, and that was the way I knew myself.”4 In a moment of radical disavowal at the height of her mystical mania, GH rejects the reality of binary oppositional positions, consuming the oozing flesh of the cockroach she just smashed. She “adores” the unity of the cockroach’s flesh to her tongue, as it sheds her humanity, becoming-cockroach.

We can see the outline of Agamben’s anthropological machine—which is always lubed, intact, and running—in Lispecter’s text. GH’s fear and indifference to the life of the cockroach led her to kill it, thereby asserting her superhuman domination over the inhuman. After squashing the cockroach, the mystical trip begins, allowing GH to enter the representative space that Agamben calls the “empty center” of the anthropological machine.5

Anthropological machines function “only by establishing a zone of indifference at their centers, within which… the articulation between human and animal, man and non-man, speaking being and living being, must take place…”6 Here, within the “zone of indifference,” GH sees beyond the funhouse mirror of the anthropological machine. The crisis provoked by the death of the cockroach is indeed the crisis of the anthropological machine itself, as GH sees beyond the anthropological machine and peers into the unity of human and animal. GH has penetrated the “absent center,” the zone of neutrality, wherein Agamben says “the truly human being who should occur there is only the place of a ceaselessly updated decision in which the caesurae and their re-articulation are always dislocated and displaced anew.”7 Lispecter has dislocated GH into a realm of communication and unity with the cockroach, and in the end, a new type of human emerges in conjunction with the cockroach from the absent realm.

To see oneself in the worst of all creatures, the cockroach, necessitates a response. In the Sean Harris model, limp-wristing is becomingcockroach, to become an unwanted pest, and to infest the community at large. Like GH’s initial impulse to squash the cockroach, Harris advocates for the exclusionary principle of the Anthropological Machine, in which “isolating the nonhuman within the human….” affirms a human to compare it against.8 In communities where gender roles are rigid, an errant boy who mixes coded signals of gender is a risk and liability to the community. For the community to understand the boy as a risk, he must be animalized, turned into something other than what he is—the inhuman. He is produced by “the exclusion of an inside,” so to speak.9 A crisis is provoked when we enter the “absent center,” or the uncanny valley of recognizing our unity with the other.

A boy’s limp wrist signifies a threat to the very functioning of the propagation of the species. The hand, as it dangles from the erect forearm shows a certain vulnerability to the forces of the world. Whether corroborated or not by homosexual activity, the limp-wristed has no interest in reproductive capability. It has tasted the cockroach and “adored it,” in Lispecter’s terms.10 It has merged with the inhuman, turning its back to the generative principle of the human project. It allies with the sodomite, with incest, or with bestiality over its commitment to its own species. It is a degeneracy, the retardation of the species, and a plug to its own continuity. These are the unique properties of the Sean Harris model of the limp wrist.

There is a kind of parasite different from the cockroach: the bourgeoisie. According to Agamben’s timeline, advances in imaging technologies in the late 19th century marked a considerable shift in the Western bourgeoisie’s understanding of gesture’s relevance to selfhood. Following Agamben’s thought, Deborah Levitt argues that “the Western bourgeoisie… are dispossessed of gestures that have historically worked both to constitute individuality per se and to allow individuals to relate to one another through a set of legible psycho-physiological postures…”11 Agamben similarly claims that “the mythical fixity of the image has been broken, and we should not really speak of images here, but of gestures.”12 We can argue from this basis that any articulation of the limp wrist today stems from a bourgeois gesturality. Contrary to the Sean Harris model of the limp wrist gesturing degenerately toward the collapse of Homo into the inhuman, this alternate interpretation of the limp wrist suggests that it gestures toward a class of human above and beyond the vulgarity of Homo. To understand this claim more completely, we must look at the limp wrist in its modern context.

In homophobic discourse, the limp-wristed homosexual curls his hand into the pose when he is appraising someone. We can imagine an individual with a limp wrist as he slightly adjusts flowing fabric on a mannequin, as he looks over a piece of stunning modern art, or when he critiques the interior decor of his wealthy girlfriend’s home. Ultimately, the limp wrist is detached from the feral barbarity of the world. The limp wrist offers instead a discriminating gesture that signifies femininity, and is associated with an understanding of class and taste. In this model, the limp-wristed person is the taste-maker, a trusted opinion on culture, someone who knows which colors match, and someone who practices ikebana.