By DARCY DOUGHERTY MAULSBY

JEFFERSON — As concerns about drought loom over many parts of Iowa this spring, more farmers are keying in on ways to manage soil moisture more effectively.

Cover crops and reduced tillage (strip till or no-till) can be part of the solution. These practices require smart management, rather than lots of inputs or high-dollar attachments or accessories.

“I’m cheap, so I don’t like to buy anything I don’t have to,” said Bill Frederick, a Greene County farmer who co-owns Iowa Cover Crop, a fullservice cover crop business based in Jefferson.

Frederick and his fellow cover croppers value the erosion control, weed suppression and nutrient scavenging that cover crops provide on their acres. Some of these growers (as well as farmers who are just getting started with cover crops) gathered at Iowa Cover Crop on March 12 for the “Planter Settings to Plant Into Cover Crops” workshop sponsored by the Iowa Soybean Association (ISA). About 15 farmers and other ag professionals gathered to discuss planter settings to ensure a good stand after a cover crop.

“When you’re planting green, you swear that the people passing by your field are going to drive into the ditch,” said Pete Bardole, a Greene County farmer who has extensive experience with cover crops. “They can’t believe what they’re seeing.”

Other farmers at the meeting who have experience planting green could relate. Some common themes came

See PLANTER, Page 2C

“When

you’re planting green, you swear that the people passing by your field are going to drive into the ditch. They can’t believe what they’re seeing.”

PETE BARDOLE

Greene County farmer who has extensive experience with cover crops

up during their discussions, including the general agreement that soybeans are more adaptable to planting green than corn.

“Get comfortable with soybeans first,” Frederick said.

Both Iowa Cover Crop and Practical Farmers of Iowa (PFI) have been studying the best ways to help farmers plant green. They offered these five tips:

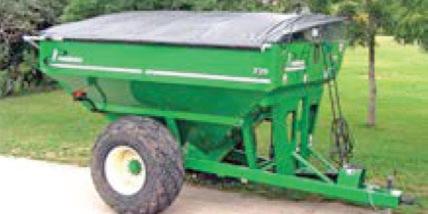

1. Simplify planter set-up. Jason Russell, who farms near Monticello in eastern Iowa, has experience planting corn and soybeans in living cereal rye. To plant soybeans into a cover, Russell’s planter set-up includes sharp, double-disk openers and Yetter Twister closing wheels. For corn, he uses Precision Planting CleanSweep to engage SharkTooth row cleaners from the cab, on the go, according to PFI. The row cleaners sit on 1.5-inch-wide treader wheels to prevent the row cleaners from going too deep.

2. Check for planting depth. It’s vital to account for cover crop thickness when planting. When he’s planting into a dense rye cover, Russell lowers the planter depth settings down a notch. He points out that, cover or not, planting depth is field-specific. “It’s important to get out of the cab and dig to check depth.”

3. Pay attention to down pressure. One of the biggest issues to pay attention to when planting into a cover crop is down pressure. Proper down pressure ensures consistent seed depth and good seed-to-soil contact. “Especially when conditions are dry, it takes a lot of down pressure to get the seed in the ground,” said Frederick, a no-tiller who plants with a Case 1245 planter. “When you’re planting into cover crops, increase the down pressure on the closing settings.”

4. Fine-tune timing with termination. Frederick recommends planting into either dead cover crops or bright green cover crops. A partially terminated cover crop creates lots of complications. “Don’t get stuck somewhere in between,” Frederick said. “I’d rather plant into green rye than brown soil.”

Tim Bardole, a fifth-generation farmer from Rippey, agreed. “Planting into rye is more forgiving than planting into tilled soil,” said Bardole, a past president of ISA and a United Soybean Board director whose family has used no-till since 1993. The timing of terminating a cover crop depends, in part, on weather conditions, added Frederick, who grazes cattle on cover crops. “I bump the termination date up on my cereal rye if conditions are dry,” he said.

Russell relay-intercrops a lot of rye with soybeans. When he terminates the rye as a cover crop, he will often wait until the rye is at pollen-shed to spray. Then he’ll roll the rye to create a weed-suppressing mat and to stimulate soybean branching. Later termination helps with mid-season moisture conservation and weed suppression, noted PFI.

5. Don’t be surprised by lower weed pressure. While it can be scary to plant green, one thing isn’t scary — seeing fewer weeds during the growing season. “Weed pressure is way less with this system,” Frederick said. “In my fields where the cover crop was thick, it helped choke out weeds. Where the rye was thin, there was waterhemp.”

Now that he’s seen the benefits of incorporating cover crops onto his acres year after year, Frederick can’t imagine farming without cover crops. “Not using cover crops would be like not combining in the fall. It’s just part of my farming program. There’s no reason not to do this.”

The March 2025 World Ag Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) report released recently shows that while the average trade expectation was for decreased 2024-2025 U.S. corn ending stocks and slightly higher soybean ending stocks, the USDA held both estimates steady month-overmonth.

U.S. wheat ending stocks, however, increased more than expected.

“The outlook for 2024-2025 U.S. wheat this month is for larger supplies, unchanged domestic use, lower exports and higher ending stocks,” the USDA said in the report.

For 2024-2025 global corn and soybean ending stocks, the USDA lowered estimates more than the average trade expectation. For wheat, the USDA went higher, though the average trade expectation was for a slight decrease.

Chad Hart, Iowa State University Extension economist, said that the expectations are to plant more corn this year, which is being driven by two factors.

Looking at the acreage from 2023 to what the USDA projects for 2025, it’s almost “on top of that.”

“The agronomics idea is to plant more corn, less beans, but no matter which crop I look at, if we get trendline yields, we’ll produce more of both crops than we use, and that will lead to higher stocks and lower prices,” Hart said.

“Let’s face it, as we look at corn prices, they’ve held up better than soybean prices, especially over the past six months. There’s financial pressure to plant more corn,” Hart said. “Farmers usually have a corn-soybean rotation and they’ve indicated that they’re going to follow that.”

The idea being pushed in Washington, D.C., is to use all commodities domestically, but that can’t always happen, leaders note.

“It seems the president doesn’t necessarily understand the specific markets we’re in,” Hart said. “It’s a general statement, but it doesn’t fit corn and soybeans.”

Wheat’s been performing in between corn and soybeans, Hart said, and

there’ll be a bit more winter wheat planted this fall.

“I was kind of concerned because winter hasn’t had the best conditions to protect (the wheat). Hopefully, things are looking good with wheat,” Hart said. “The idea is that they’re not having quite as bad of a problem in overproduction. … There’s demand that’s close, but not like corn and soybeans.”

By KRISTIN DANLEY GREINER Farm News writer

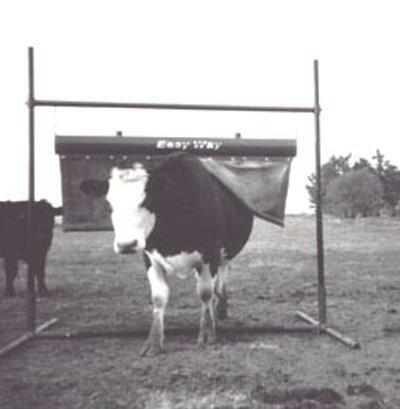

Drought conditions across the western U.S. and into the Northern Plains will remain a considerable factor in 2025 on herd expansion and cattle prices due to the pressure on pasture and grazing availability.

Meteorologist Matt Makens spoke during the CattleFax Outlook Seminar at CattleCon 2025 last month to talk about the cattle industry. He said it seems the beef cowherd has entered a stabilization phase after years of contraction.

Chad Hart, Iowa State University Extension economist, confirmed that the cattle herd continues to shrink, which likely will continue until 2026.

“The problem is that it’s not that it wouldn’t be valuable to start building the herd back up, but the drought out West will hamper efforts to grow the herd back up. That heifer is still more valuable as steak than she is a momma cow,” Hart said. “Given that, we continue to see the cattle herd shrink. There are some incredibly high prices for feeder cattle.”

The hog market is behaving much like corn and soybeans, Hart said.

“We’re probably going to overproduce again. If you look at pigs-per-litter productivity, it’s through the roof,” he said. “Farmers are doing a great job of producing a lot of pork. The problem is that they need export markets to absorb all that pork.” Then there’s the wild card egg industry.

“For as long as this problem has been here, this disease is not going to go away. It continues to hit wave upon wave,” Hart said. “It’s like a stream eroding a streambank along an oxbow that erodes and collapses. The eggs are eroding, the industry collapsed and prices went through the roof.”

Kevin Good, vice president of market analysis at CattleFax, reported during CattleCon that the U.S. beef cow herd is expected to see the cycle low to start 2025 at 28 million head, 150,000 head below last year and 3.5 million head from the

2019 cycle highs.

“We expect cow and bull slaughter to continue declining in 2025, with overall numbers down by about 300,000 head to 5.9 million head total.

Feeder cattle and calf supplies outside of feedyards will also shrink by roughly 150,000 head, while cattle on feed inventories are starting the year slightly below 2024 levels at 11.9 million head,” Good said.

“With a tighter feeder cattle supply, placement pace will be more constrained, leading to a

projected 700,000-head drop in commercial fed slaughter to 24.9 million.

“After modest growth in 2024, beef production is expected to decline by about 600 million pounds to 26.3 billion in 2025, ultimately reducing net beef supply per person by 0.8 pounds.”

Beef prices continued their upward trend in 2024, averaging $8.01 a pound, the secondhighest demand level in history. While demand may ease slightly in 2025, retail prices are still

expected to rise to an average of $8.25 a pound. Wholesale prices will follow suit, with the cutout price projected to reach $320 per hundredweight (cwt.), reported the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association.

“Retail and wholesale margins are historically thin, making strong consumer demand essential to maintaining higher price levels,” Good said.

“While opportunities for further leverage gains are limited, the market remains favorable for producers.”

Mike Murphy, CattleFax chief operating officer, forecasted the average 2025 fed steer price at $198/cwt., up $12/cwt. from 2024. All cattle classes are expected to trade higher, and prices are expected to continue to trend upward. The 800-pound steer price is expected to average $270/cwt., and the 550-pound steer price is expected to average $340/ cwt. Utility cows are expected to average $140-/cwt., with bred cows at an average of $3,200/ cwt.

“While the cyclical upswing in cattle prices is expected to persist, the industry must prepare for market volatility and potential risks,” Murphy said. “Producers are encouraged to adopt risk management strategies and closely monitor developments in trade policy, drought conditions, and consumer demand.”

By DARCY DOUGHERTY MAULSBY Farm News writer

LAKE CITY — There’s nothing like a new crop of lambs to make a farm come alive. When Dwight Dial walks out to his barn this time of year, a lively chorus of high-pitched bleats — mixed with the occasional lowerpitched baa — greets him.

“I’ve always enjoyed raising sheep,” said Dial, 75, whose flock includes 60 Suffolk and Polypay ewes. By mid-March, more than half of his ewes had lambed, and there were seven sets of triplets. “This year I’m running about 10% triplets, 20% singles and 70% twins,” Dial said. Dial’s interest in sheep production started when he was a sophomore at Lake City High School. “I didn’t go out for basketball after my freshman year, and my dad said, ‘You’re not just going to sit around,’” noted Dial, whose father, Gerald, raised cattle, hogs and crops.

Dial needed an FFA project, so he decided to try sheep. In October 1964, he bought 15 purebred Suffolk ewes and 10 commercial (crossbred) ewes at Bill Goins’ farm sale at Lake City. A member of the Jackson Pioneers 4-H Club and the Lake City FFA chapter, Dial showed sheep at the Calhoun County Fair in Manson, the Rockwell City Expo, the Sac County Fair and the Iowa State Fair. Today, Dial is still raising sheep, along with hogs, corn and soybeans, in the Lake City area. In the 1980s, he played a key role in creating the

Calhoun County Sheep Producers Association. For 14 years, he also assisted with a replacement ewe sale that was held at the Lake City Sales Pavilion during Labor Day weekend.

“That sale attracted people from all over,” Dial said.

Dial also promoted the sheep industry at the state and national levels through the Iowa Sheep Industry Association (ISIA) and the American Sheep Industry Association. “In the 1980s and 1990s, 500 to 700 people would attend the ISIA’s state symposiums in Ames, Des Moines and Cedar Rapids,” Dial said.

Big changes have re-shaped the sheep industry

Throughout the years, Iowa has often ranked among the top 10 sheep-producing states in America. Sheep flocks help diversify farming operations and offer a viable business for young producers with ample labor and limited facilities and capital, according to the Department of Animal Science at Iowa State University.

“The farm where I’ve lived for years doesn’t have a lot of pasture, so sheep make sense here,” Dial said.

While the peak of Iowa’s sheep industry occurred in the 1800s, when demand for wool was strong, sheep production endures in Iowa. The inventory of all sheep and lambs in Iowa as of Jan. 1, 2025, totaled 161,000 head, up 6,000 head from 2024, according to the National

See DIAL, Page 7C

Continued from Page 6C

Agricultural Statistics Service’s Sheep and Goats report. Total breeding stock (at 117,000 head) was 6% higher than the previous year.

Dial remembers when there were more than 1,000 ewes at various farms in his rural neighborhood 30 to 40 years ago. “I was running about 300 ewes back then,” he added.

In years past, Dial sold his sheep to a packing plant in Hawarden, Iowa. “We used contracts to lock in prices with them,” Dial said.

While that processing plant in Hawarden is gone, lambing time remains a rite of spring. It starts in early March on Dial’s farm. “I’m done lambing when it’s time to head to the field for planting,” he said.

Lambs typically weigh 7 to 8 pounds each in multiple births (twins and triplets), while single lambs usually weigh 10 to 12 pounds.

“I raise the sheep to about 140 pounds,” said Dial, who markets his sheep during special sales at the livestock auction in Gowrie.

From a business standpoint, wool production has become one of the most challenging aspects of modern sheep production.

“When I started raising sheep, wool brought 70 to 85 cents a pound,” said Dial, who noted that wool goes for a nickel a pound today.

An average black-faced sheep will produce 5 pounds of wool, he added. It costs Dial $4.50 per head to shear his sheep.

The demand for wool has changed dramatically through the years, he said. While wool used to be a primary fiber for suits, hats, coats, military uniforms and more, the rise of synthetic fabrics changed everything.

Also, China has become a

See DIAL, Page 8C

KANAWHA 641-762-8261

player in wool processing and manufacturing, with a large number of woolen mills and a significant share of the global textile industry. There are just a handful of woolen mills left in America, including the Faribault Woolen Mill in Minnesota and the Pendleton Woolen Mills in Portland, Oregon, Dial noted.

“I’ll keep raising sheep as long as I’m able”

Despite all these changes, livestock production remains a key part of Dial’s farm. In the spring of 2022, Dial received the Wergin Good Farm Neighbor Award, which is coordinated by the Coalition to Support Iowa’s Farmers (CSIF).

Wergin Good Farm Neighbor winners must be a family farm operation, be active in their community, produce livestock or poultry to the highest animal care standards, and be dedicated to conservation and environmental stewardship on their land.

“I was really humbled to receive this award,” Dial said. “It ranked right up there with some of the most memorable, meaningful accomplishments in my life.”

Iowa Secretary of Agriculture

Mike Naig presented Dial with the Wergin award during a 2022 ceremony at the Community Memorial Building in Lake City. “Since Dwight started farming in 1978, he has worked to make his operation more sustainable for future generations through the implementation of conservation practices,” Naig said. “Dwight is a great example of someone who takes pride in caring for his pigs and sheep, while recognizing the importance of caring for his land and being involved in his local community.”

Gretta Irwin, executive

director of the Iowa Turkey Federation, became acquainted with Dial in the 1990s when she served as executive director of the ISIA.

“Dwight has a strong commitment to the Iowa and U.S. sheep industry,” said Irwin, who noted that Dial was a dedicated leader on the ISIA board, plus he served on the American Sheep Industry Association’s first executive board from 1989 to 1993. He also received the Iowa Master Lamb Producer award in 1994.

“Dwight’s smile and charisma made board meetings better,” Irwin added. “He enjoyed connecting with other farmers, talking about sheep and educating himself on sheep health. Promoting lamb products was also a passion for Dwight.”

Dial has no plans to quit raising sheep anytime soon. “I’ll keep raising sheep as long as I’m able.”

9-18-9, 3-18-18

By DARCY DOUGHERTY MAULSBY Farm News writer

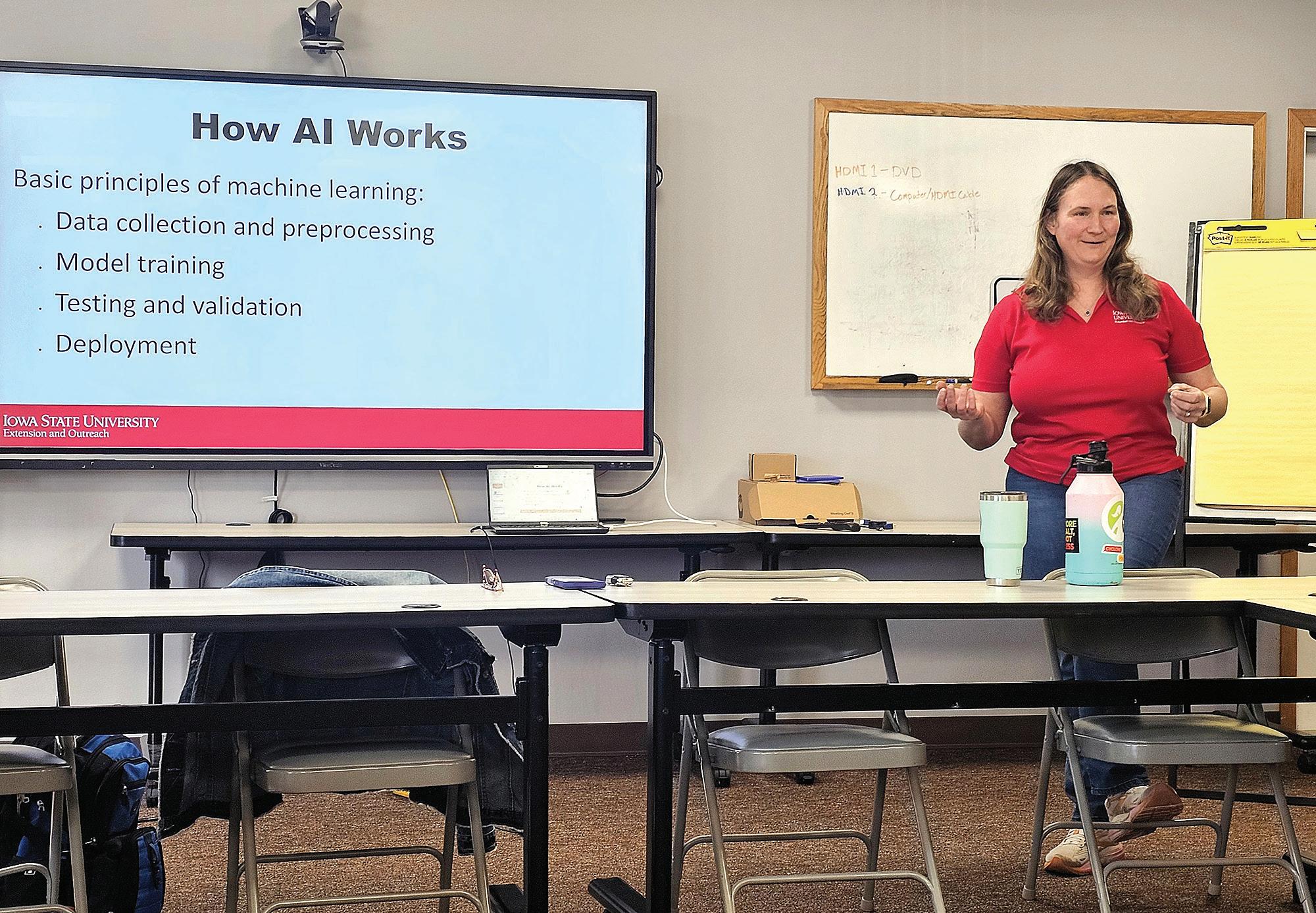

JEFFERSON — Take a guess — how many artificial intelligence (AI) tools are available commercially?

While it’s hard to pin down a definitive, official count, the number exceeds 30,000, by some estimates.

“This number just keeps growing,” said Alexis Stevens, a farm management specialist for Iowa State University Extension.

This technology is moving fast. In 2023, 60% of ag was already using an AI tool in some form. “That means you’re probably using AI and may not even realize it,” Stevens said.

One of the most visible examples of AI’s evolving impact on farming is precision ag. As the technology utilizes data from satellites to sensors, AI algorithms offer intricate insights into farmers’ acres.

“I’m really excited about AI’s potential to take precision ag and soil health to the next level,” Stevens said. “The technology can handle jobs that humans can do but often don’t have the time or labor to cover.”

This technology includes soil sensors that can help with crop management, from agriculture to horticulture.

“If a grower is using drip irrigation, for example, the technology can be really useful for not over-irrigating or underirrigating the crop,” Stevens said.

During a monthly Ag Coffee chat on March 14 at the Greene County Extension office in

IN

Jefferson, Stevens answered common questions regarding AI and cybersecurity in ag.

“These are important issues, especially since data is vital to modern agriculture and the food system.”

She offered the following insights to help farmers and other ag professionals navigate the opportunities and challenges of AI and cybersecurity:

How does AI work?

Think of AI as a prediction machine. It can’t think for itself, and it doesn’t have feelings.

“It tries to determine what’s the next most likely thing,

based on the data we put into it,” Stevens said. “It’s like teaching a kid.”

It’s also an example of “garbage in, garbage out,” a concept in computing that incorrect or poor-quality input will produce faulty output. (That’s why ethical issues matter when these systems are designed, Stevens said.) The results that AI generates also depend largely on the questions that users ask AI.

“It will give you much different results if you say, ‘Tell me about corn,’ versus ‘tell me about peer-reviewed scientific papers focused on Zea mays,’”

she noted.

What are some of the biggest potential benefits of AI in ag?

AI helps take the human error out of the equation and can make precision ag more precise, Stevens said. This is especially true with crop scouting. With a drone, AI can key in on fine detail and detect potential problems sooner than humans can. It can identify diseases like tar spot or pinpoint areas in the field where weeds are growing.

The Landus SkyScout system, for example, uses AI-powered insights to help

“I’m really excited about AI’s potential to take precision ag and soil health to the next level. The technology can handle jobs that humans can do but often don’t have the time or labor to cover.”

ALEXIS STEVENS Farm management specialist for ISU Extension

growers and agronomists determine each field’s specific needs in a timely manner.

“AI can do all this so much faster and cover a bigger area more quickly than a human can,” Stevens said. “After the technology gathers this data, AI makes recommendations to the agronomist, who reviews the information to determine a course of action. It’s all about ‘trust but verify.’”

Is AI cost effective?

It depends on a variety of factors. The University of Missouri (MU) recently looked into this question regarding drone technology. In March 2025, MU published the report “Economics of Drone Ownership for Agricultural

See AI, Page 11C

Spray Applications.”

introduced

applications.

The findings suggest that for farmers spraying 1,000 acres annually, the total cost per acre for drone applications is approximately $12.27. The study found that custom rates are typically around $16 per acre. Based on these calculations, owning a drone could be cost-effective for farms spraying at least 980 acres annually. For custom operators spraying 4,000 acres annually, the cost per acre is around $7.39, MU noted.

How can AI foster more conservation in ag?

AI can help optimize farming practices. This can give farmers more opportunities to improve their crop yields, reduce waste, manage crop nutrients more effectively, improve water quality, boost soil health and increase their profit potential, Stevens said.

Is there anything AI can’t do?

“AI isn’t good at all at predicting black-swan events,” said Stevens, referring to those rare, highly impactful events that lie outside the realm of regular expectations. “Humans are much better at this.”

Since no technology is foolproof, what do you recommend to protect data?

Don’t keep your data strictly in the cloud or in an electronic form.

“Print out your soil maps, for example, and other key records,” said Stevens, who reminds farmers that electricity

can go out, and internet connections can go down. “You want to have access to this data when you need it.”

Think these old-school solutions are overkill? It doesn’t take much to show just how fragile a digital world can be.

In May 2024, a solar storm exposed a critical vulnerability in farming’s high-tech systems. These solar flares (also known as geomagnetic storms) occur periodically and disrupt the earth’s magnetic field, specifically the ionosphere — the layer of the atmosphere responsible for transmitting GPS signals from satellites to the earth. When that layer becomes turbulent, it distorts signals from GPS satellites, causing technologies like auto steer to lose their connections.

These technological failures can affect so many facets of modern agriculture, Stevens added.

“If the co-op’s computers get hacked, they have to use paper scale tickets, for example. What will you do when you don’t have access to your computer?”

Where does cybersecurity fit into all this?

Conversations about AI must go hand-in-hand with conversations about cybersecurity, Stevens said.

“In general, the ag industry doesn’t have a really good grasp of cybersecurity,” she said. Cybersecurity isn’t just something big companies need to worry about, she added. “Assume that a cyberattack will happen to you.”

An attack can be as simple as an electronic request to pay a fraudulent invoice that arrives via email. “I’ve seen this scam rob people of thousands of dollars,” Stevens said.

urges farmers to create their own cybersecurity plan for their farm before trouble strikes. “In the military, you have a plan, and then you practice it, so you know how it works.”

Not sure where to start? ISU Extension offers a variety of farm-focused cybersecurity resources at extension.iastate. edu/agdm/info/cybersecurity. html.

As promising as modern technology can be, AI and other advances can’t replace the uniquely human skills that have defined farming for generations, Stevens added.

“Trust still matters the most,” she said. “Going forward, good communication skills and trust will become even more important in agriculture.”

Taking soil samples will be key following 2024 summer flooding

By KAREN SCHWALLER Farm News writer

Soil sampling will be the name of the game following historic flooding in June of 2024 that ravaged areas all around northwest Iowa, and moved river sand into fields, and topsoil into and out of fields, according to Iowa State University Extension agronomists.

Flooding last summer was the result of nearly a year’s worth of rain in a matter of weeks, and levees that could not withstand the pressure. Those rivers included the Little Sioux and Rock Rivers, along with the Ocheyedan River and other tributaries into which these rivers flowed.

Gentry Sorenson, an ISU Extension field agronomist based out of Clay County (Spencer), said he saw the gamut when he surveyed fileds following the flood.

“I saw field ponding in Dickinson, Palo Alto, Clay, Emmet, Buena Vista, Pocahontas, Hancock, Kossuth and Winnebago counties in my area,” he said. “Flooding or whole-field flooding occurred next to rivers and streams in many of the counties.

“Last year, many fields experienced ponding. In some fields, areas dried up; and in areas where ponding caused crop damage, the crops were able to be planted again, only to have substantial rainfall cause ponding again, causing crop loss in the same area again.”

Sorenson said attempts were made to replant until it was too late to proceed with either corn or soybeans. He said many farmers planted cover

Some of the buildings we’ve constructed in this area are shown here. Since 1976, Tom & Debbie Witt have made a commitment to live up to the highest standards for falmess, honesty, superior workmanship and service. We’re dedicated to designing the most innovative and cost-effective buliding solutions for our valued customers. Call Tom or Debbie today for a free quote on your next building project! Tom & Deb Witt, Newell, IA • 712-272-4678

crops later in the season to help with weed control and soil health.

Leah Ten Napel, an ISU Extension field agronomist based out of Plymouth County (Le Mars), said she saw widespread damage in her ninecounty area of northwest Iowa.

“I’m right along the western border of the state, so we saw a lot of damage — especially in Lyon, Sioux (Rock Valley) and Monona (Oto, Correctionville) counties, with two different rivers there,” she said.

Flood waters and field flooding moved top soil off of some fields and into others, and even moved river sand into fields if they were located near rivers that went out of their banks.

Ten Napel said crop damage last

summer directly correlated to the amount of time the water remained in the field, and also the force behind the water that created much erosion.

“A guy I talked to who farms near Oto had (in the worst parts of his field) almost four feet of sand, so when they go to take that out, it will have a huge impact,” she said.

“I don’t think very many areas had it that extreme, but it will still have a major impact on his field for a long period of time because that field is never going to be the same.”

Ten Napel said that Oto farmer removed as much river sand as he could last fall, but he is planning to switch around his crop rotation to

Continued from Page 1D

give him more time to clean up this spring before planting.

“He also applied extra fertilizer last fall to help build up what had been taken away,” said Ten Napel.

She said soil sampling will be important in areas where heavy flooding occurred because there is no way of knowing what’s out there. Ten Napel added that producers will need to get a baseline measurement of what their soil looks like now.

“Some of these areas may have more fertility,” she said, explaining that flood waters moved soil out of some fields and moved it into others. “Farmers may want to go out and fill in where some of those fertility gaps might be from what was taken away.”

She said landscapes also changed with the velocity of water movement during the flood, and that soil make-up could have also been changed, with the possibility of diseases and chemicals being transferred with flood water. Ten Napel said with the change in soil make-up and landscape from flooding, fields may hold onto water differently than they have before.

“I haven’t heard as many people being worried about diseases as I’ve heard concerns about chemicals,” said Ten Napel. “We can’t just test for that, so when it comes to testing for chemicals in the soil or in a plant, you have to have an idea of what you’re looking for, such as wondering if there is dicamba in a plant; or for any kind of carry-over this growing season.”

Soil sampling this year will be best suited to measure soil fertility, such as nutrient levels in soil. She said much of the good soils had more clay and silt, and those may have been washed away and replaced with sand, which has low nutrient value.

“That farmer near Oto could have lost 10 years’ worth of nutrient value that he could have been building up,” said Ten Napel. “… and yet, his soil may have gone somewhere else, and someone else’s soil may have gone into his field and replaced some of the soil nutrients lost. So I would really recommend

people soil sample in those areas.”

Ten Napel said tight profit margins may encourage soil sampling.

“We don’t really want to be putting fertility out there that we may not need,” she said. “So sampling would be a minimal cost when you think about a check you could be writing to put fertility out there; I wouldn’t be putting that out there without some answers first with soil samples.”

Sorenson said crop diseases due to flooding and long-term ponding would have occurred in last year’s crops if there were any new ones present.

“If cover crops were planted in situations where planting of corn and soybeans were too late in the season, the cover crops may have helped with fungi recolonization in the soil, which is important for the crops; and the crop will benefit from the nutrient uptake that would be increased from the interaction and the relationship,” he said.

Summarized By KAREN SCHWALLER Farm News writer

ISU Extension has issued a link with some guidelines for incorporating river sand into field soil, which states:

n Soil testing separately from areas with different amounts of sand incorporation may be appropriate to account for nutrient levels of the sand, and adding organic matter may be beneficial where large amounts of sand are incorporated. Soil microbiology can also change during and after flooding, and producers can look up discussions on that topic on the ISU Extension website (www.iastate.edu), and search for “Flooded Soil Syndrome.”

n Loss of soil structure may cause effects similar to soil compaction, and prolonged exposure to water and wave action may destroy soil structure. Submerged soils may develop a layer of dense consolidated silt that is resistant to water infiltration and plant root penetration. If the layer is only one or two inches thick, tillage and subsequent weathering and biological activity should return the soil structure in time. Severe cases may require deep tillage.

n Moisture condition of soils should be evaluated before beginning tillage or moving sand in order to reduce or avoid compaction.

n Plant debris (without other trash) less than four inches deep can most likely be incorporated into soil with tillage. If debris is deeper than four inches, it may need to be spread out before incorporating, and more nitrogen may be demanded due to decomposing plant debris in the soil.

n The State of Iowa prohibits pushing flood debris back into rivers. Farmers should consult with their local NRCS office to discuss where to take river sand.

“Sand may be moved to field border areas, but water quality rules prohibit pushing sand back into a river,” ISU Extension officials state.

n Allowable sand depth for mixing into the soil depends on underlying soil

types and tillage methods. Local USDA offices would have county soil surveys to determine soil types.

n Sand less than two inches deep can be incorporated into soil normally.

n Sand two to eight inches deep can be incorporated with a chisel plow, moldboard plow or other aggressive tillage tool. “The goal is to achieve a modified soil that still has adequate water holding capacity in the root zone. Because the sand is likely in drifts, use a front-end loader to spread the piles to decrease the depths to four inches, then till across the piles to twice the depth, several times,” ISU Extension advises.

ISU Extension also said for silty clay loam soils, tilling sand to a depth at least 1.5 times the original sand depth is recommended. For example, use a nineinch tillage depth for a six-inch layer of sand.) ISU Extension said sandy soils may require tillage to a depth of twice the

sand depth or more.

n Sand eight to 24 inches deep should be spread to areas with a sand depth of less than four inches, if possible. If there is too large of an area of sand that depth, farmers should evaluate the cost of moving the sand to waste or stockpile areas, and consider relative costs of moving the sand and of abandoning the crop area.

“When the flood subsides, there is often a thick layer of clay over all the land, and when it dries out it will cake and lift up at the edge. This layer needs to be tilled into the soil to restore the water movement of the soil below,” said ISU Extension officials.

n Deep tillage tools are available for inverting soils to depths deeper (four to five feet) than reached by moldboard plows. ISU Extension says the cost and availability of such equipment may make sand removal more practical than extra

deep tillage.

n Erosion may have occurred in areas where water velocity was higher. Shallow erosion of less than one foot may be repaired with tillage on deep river bottom soils. Deeper erosion repair may require earth moving equipment, but farmers should be cautious about using debris sand to fill deep erosion channels unless an adequate depth of quality soil can be placed over the top of the sand fill, keeping in mind water holding capacity of the finished soil.

ISU Extension goes on to say that severely eroded areas may be too expensive to repair, and that selective abandonment of small areas may be a more logical choice.

Further and more detailed Information can be found in this ISU Extension link: https://crops.extension.iastate. edu/cropnews/2019/03/managementconsiderations-post-flooding-soils.

By CLAYTON RYE Farm News writer

AMES — With winter ending and the arrival of spring, farmers are making their final plans for the new crop year. These decisions involve seed, fertilizer, herbicides, machinery readiness, and more.

Crop insurance coverage decisions have been made and, after the March 17 deadline, those decisions will be final for the 2025 crop year.

So what about the weather?

For all their planning, every farmer knows that weather will have the last word in determining a good or bad outcome for the growing season. Sub-soil moisture and rainfall combine to determine water availability for the growing crop. The drought monitor map will be watched warily for months to come.

Madelynn Wuestenberg is an agricultural climatologist in the Agronomy Department at Iowa State University. As a climatologist, she takes the long view of weather, using weather records that go back 140 years, paying particular attention to the temperature of the Pacific Ocean currents as they change off the coast of Peru. These ocean currents affect the temperature of the atmosphere, and that is where our weather begins.

The ocean water temperature is recorded continuously and categorized into normal, below normal, and above normal. The data is compiled into the ENSO, the El Nino Southern Oscillation index.

A normal ENSO index gives us the weather we are accustomed to. Water

temperatures below normal result in La Nina conditions, and temperatures above normal result in El Nino weather conditions.

La Nina weather conditions are typified as more extreme in temperature and precipitation. El Nino weather is milder and more favorable to crops and people. These weather conditions take months to go through their cycles.

What does Wuestenberg have to say about weather for 2025?

She says that as of now, a

mild La Nina period is ending, with the water temperatures off the coast of Peru below normal. She described the La Nina conditions we are under as “pretty weak.”

While La Nina provided the cold temperatures, Wuestenberg attributed the lack of snow cover this past winter due to abnormally dry air of the polar jet stream that lacked the moisture necessary for snow. This past winter had a snowfall deficit of 15 to 20 inches.

For the approaching months

-Submtted graphic

of March, April, and May, Wuestenberg said there is a 66% chance of a transition to neutral weather with May and June going to 70%. For June, July, and August, there will be a 60% chance of a normal ENSO index.

At the 2025 year’s end for September, October, and November, there will be a 45% chance of neutral weather conditions, a 30% chance of La Nina, and a 20% chance of El Nino weather.

“I am a lot more optimistic

about 2025,” Wuestenberg said, comparing 2024 to 2025.

The drought monitor map had its beginning in 2000 and, according to Wuestenberg, there has been a drought occurring somewhere in Iowa every year since its start.

From last year’s drought monitor to this year’s drought monitor, she said, “Compared to last year, we are sitting on less drought severity.”

The March 2025 drought monitor, when compared to March 2024, shows a shortterm drought with improving shallow soil moisture.

“In 2025 we have to make sure we have those timely rainfall events,” she said. “These rainfall events will be important for soil moisture to rebound.”

Iowa State University records weather as it happens and it is posted to Iowa State’s website as Iowa Environmental Mesonet.

On the home page, there is a heading called “Ag Weather,” which will provide current and past weather information. Much information is available that includes air temperature, rainfall, soil moisture, soil temperature, growing degree days and more.

A search feature is available to show local weather. For example, a search for weather departures since Jan. 1 for Spencer, showed 42 days above normal and 28 days below, indicating the drastic temperature swings so far this year. At drought.gov, NOAA provides drought information available nationally and searchable down to state, county, and town.

By KRISTIN DANLEY GREINER Farm News writer

AMES — Spring at Iowa State University’s sheep farm means adorable little lambs scampering about, kicking up the dirt as they gain control of their wobbly little legs. Spring at the sheep farm also means students are gaining valuable handson experience in spring lambing.

Caitlin Sliger is in her second year of working toward her master’s degree in animal breeding and genetics. She earned her bachelor’s degree from ISU in animal science.

She grew up on a livestock farm in northern Iowa with a cow-calf operation and sheep herd. She currently serves as the grad student assistant overseeing Iowa State’s sheep farm, which was established in 1865 and spans around 60 acres.

“We got our sheep at the family farm when I was 12 years old for a 4-H project. I recently got a border collie, and the more you work hands-on with the sheep patterns, you realize they’re actually smarter than you think,” Sliger said. “They learn quickly and can more easily move between different pastures and paddocks for rotational grazing during the summer.”

However, sheep are quite hard on fences, Sliger said. They have a barn for the sheep to lamb in and paddocks for grazing.

At Iowa State, there are two breeds raised: Hampshires and Polypays.

Sliger said there are clear differences in lambing between the two breeds, which have been raised at Iowa State for at least 20 years.

“I really don’t prefer lambing out the Hampshire flock. They aren’t the best moms. But then we follow that up with the Polypays and they’re really great moms. Lambing starts out stressful then turns easier,” Sliger said. “The Hampshires don’t have the strongest maternal instincts and aren’t great milk producers compared to the Polypays. They’re also more high strung. They’ll drop a lamb and walk away from it.”

The Polypays rotational graze with their lambs after they’re born in April and are on pasture all summer long. The Hampshires lamb in January and February in the barn. There are 75 Hampshire breeding ewes and 150 Polypay breeding ewes. Each spring, the farm sees close to 300 lambs born.

“I have four undergrads who work out here with me for lambing season. The advanced sheep class does night checks in teams, staying at the farm. That helps us all not lose as much sleep,” Sliger said. “I do love lambing and I love when the lambs bounce around on all four feet and bounce up in the air.”

The Hampshire breed is terrific for studying their genetic makeup, evaluating them and other learning activities, however. Having two totally opposite breeds exposes students to the differences in managing and

See FARM, Page 8D

1705 North Lake Ave • P.O. Box 67 Storm Lake, IA 50588 Office (712) 732-4811

General information: BioEmpruv is a biological fermentation extract containing a host of di erent substances that accomplish numerous actions within a corn plant. BioEmpruv contains biologically derived extracts, enzymes, vitamins, minerals, natural growth regulators and simulators, antioxidants, amino acids and bases and more. It also contains natural phytoalexins to boost the corn plants’ immune system and to increase the resistance to disease and pathogens as well as to environmental stresses. BioEmpruv contains natural and biodegradable ingredients. No chemicals or residues. BioEmpruv will be your best line of defense against Goss’s Wilt and other bacterial leaf diseases. Curative & very systemic. Much wider application window. Developed by PhD biochemist Dr Awada, Logan, UT. Bio-Empruv * Commercially applied to spuds, sweet and eld corn since 2014. It has increased corn yields from 10-90 Bu/A, depending on application timing and infection rate. Keeps plants green and lling until natural maturity (BL) is reached. Drydown with normal senescent plants let the healthy ears dry faster and earlier than corn and grain from a die down plant.

Foliar Application

• Produces a systemic e ect in the plant. For best result apply 8 oz at V6 to VS and 24 oz at V12 to V14 before the plants get too tall. Apply along with a high quality surfactant like Argosy at 1 qt/100 gals to prevent wash-o and prolong e ect. 2.5 to 3 months activity.

• Compatible with most pesticides and can be applied with other fertilizers, minerals, herbicides,

Farm Continued from Page 6D

handling them, too.

Several ISU classes utilize the sheep farm, Sliger said.

Animal Science 101 students tour the farm both semesters, and then the sheep will travel to the Hansen Agriculture Student Learning Center a couple times a semester. The sheep also travel to an anatomy lab and a meats lab. There are two sheep classes that students interested in cattle, goats, sheep or companion animals tend to take, Sliger said.

“The 101 students get to watch our sheep shearer, and he lets them help with the Australian blow, which is the pattern most used with show sheep where you put them on the stand and clip them. Then they learn how to halter break a sheep. We also do average daily gains on the lambs, band cut the testicles and ear tag them to process them,” Sliger said. “With the daily gain tracking, by the end, they know which sheep they would keep or cull based on genetic values and phenotypes.”

There’s also a cookery lab where the sheep is sold to the meat lab, then it’s bought back and prepared.

“I get to judge along with others, so I enjoy that,” Sliger said. “Other things we do here at the sheep farm — we do a dog demonstration with the border collies to see how the sheep move with the dogs versus humans. I’ll do a live carcass evaluation with all the meat classes and they’ll do a health hoof trimming, practice giving shots with saline and other activities.”

To help keep the sheep herd safe, Zeus the livestock guardian dog patrols the Iowa State farm.

Viking alfalfa product manager Matt Helgeson pays close attention to the what makes for a strong alfalfa around here. Get a closer look at these high-performing alfalfas.

Highest Combination of Yield & Quality

• Highest quality for 4- or 5-cut system (FD4.0)

Next generation of 372HD, winner of 2022 Forage Super Bowl!

• See yield comparisons from Southern Wisconsin Forage Trial on page 26 Lignin levels comparable to other highly digestible varieties

• Aphanomyces race 1 & 2 resistance and branch root trait = strong persistence and productivity on wetter soils

Available with ApexTM Green HydroLoc coating or OMRI-approved inoculant

Max Yield. Every Inch. Every Field.

• 1st place dry matter tons/acre in 2023

Michigan State University Trial (Seeded 2022, Chatham, MI)

Best disease resistance available, including Aphanomyces Races 1, 2, and 3

• Extremely high forage yield and great quality

FD 4.3; suitable for 4 to 5-cut systems

High expression of branch root trait and sunken crown trait

• Exhibits some tolerance of saline soils

• Available with ApexTM Green HydroLoc coating or OMRI-approved inoculant

Got Leafhoppers? No problem!

• Built-in potato leafhopper protection with glandular hairs

Higher expression of glandular hairs than many other competitor leafhopper resistant varieties

• Outstanding yield and forage quality

Excellent fit in a 3- to 4-cut harvest system

• ApexTM Green HydroLoc coating (OMRI)

Connect with your local dealer, visit alseed.com, or call 800.352.5247 to put Viking non-GMO alfalfa to work on your farm.