2022 Respites • Roamings • Retreats the north bay & beyond PUBLISHED BY THE BOHEMIAN AND PACIFIC SUN

Drop

tune

in and

out.

Voted Top 5 Best Roadside Motel by USA Today 10Best Readers 2021, The Sandman is a charming motor lodge inspired by the Spanish Mission Revival buildings found throughout the state. Playful, yet refined, our modern throwback serves as an ideal launch pad for exploring Sonoma County’s renowned wine country, plus a host of outdoor activities. Located one hour north of the Golden Gate Bridge and minutes away from Charles Schulz Airport in Santa Rosa. 3421 Cleveland Avenue, Santa Rosa, CA 95403 more at sandmansantarosa.com.

Discover

California Bohemian Flair

Rosemary

PRODUCTION

MANAGER

Sean George

Phaedra Strecher

SENIOR

Jackie Mujica

ADVERTISING DIRECTOR

Lisa Marie Santos OFFICE

Michael Giotis

Daedalus Howell

Lisa Summers

Jane Vick

Liz Alber ADVERTISING

3 2021 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY the north bay

e

& EXECUTIVE EDITOR

Pulcrano PUBLISHER

& beyond

2022 CEO

Dan

Olson EDITOR

EDITOR

Daedalus Howell COPY

Mark Fernquest CONTRIBUTORS

Christian Chensvold

OPERATIONS

PRODUCTION MANAGER

DESIGNER

MANAGER

ACCOUNT MANAGERS

Danielle McCoy,

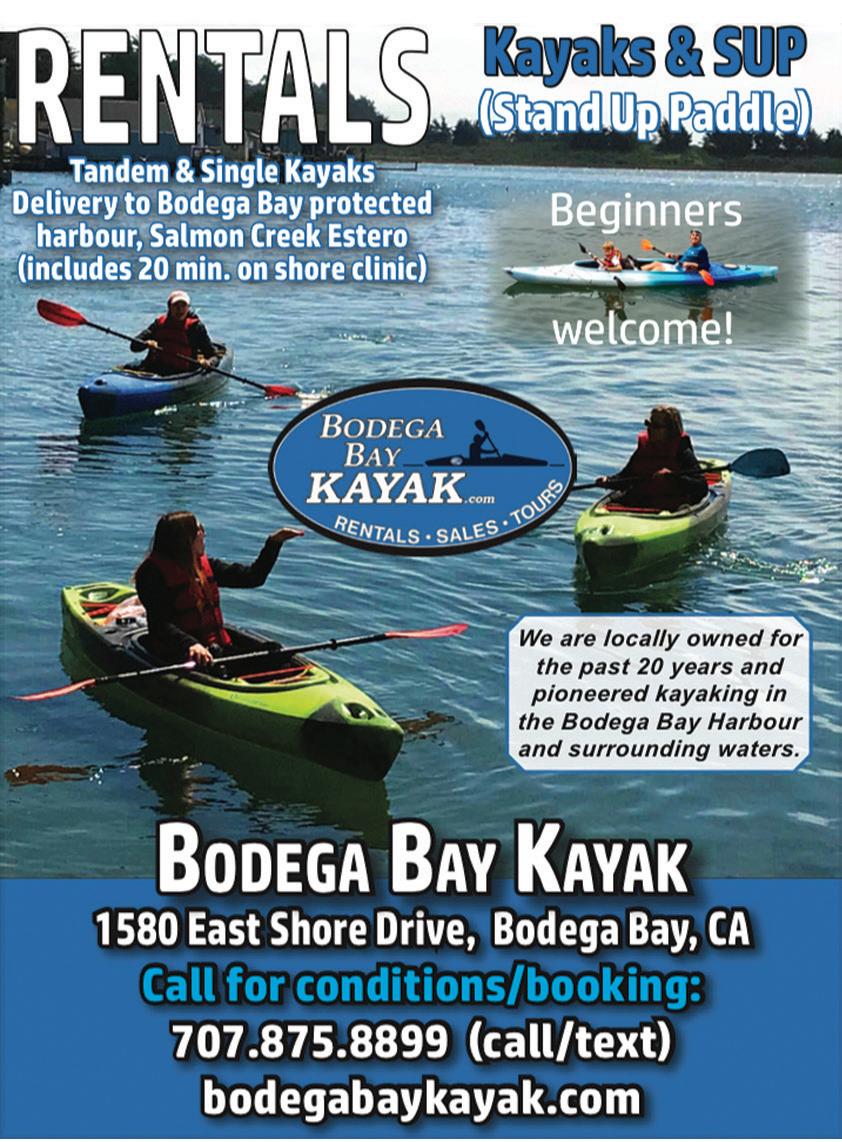

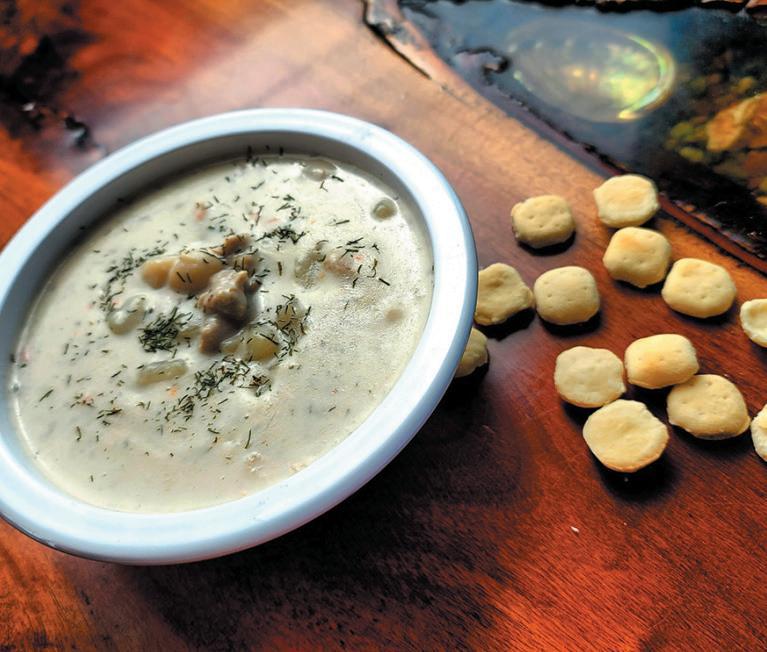

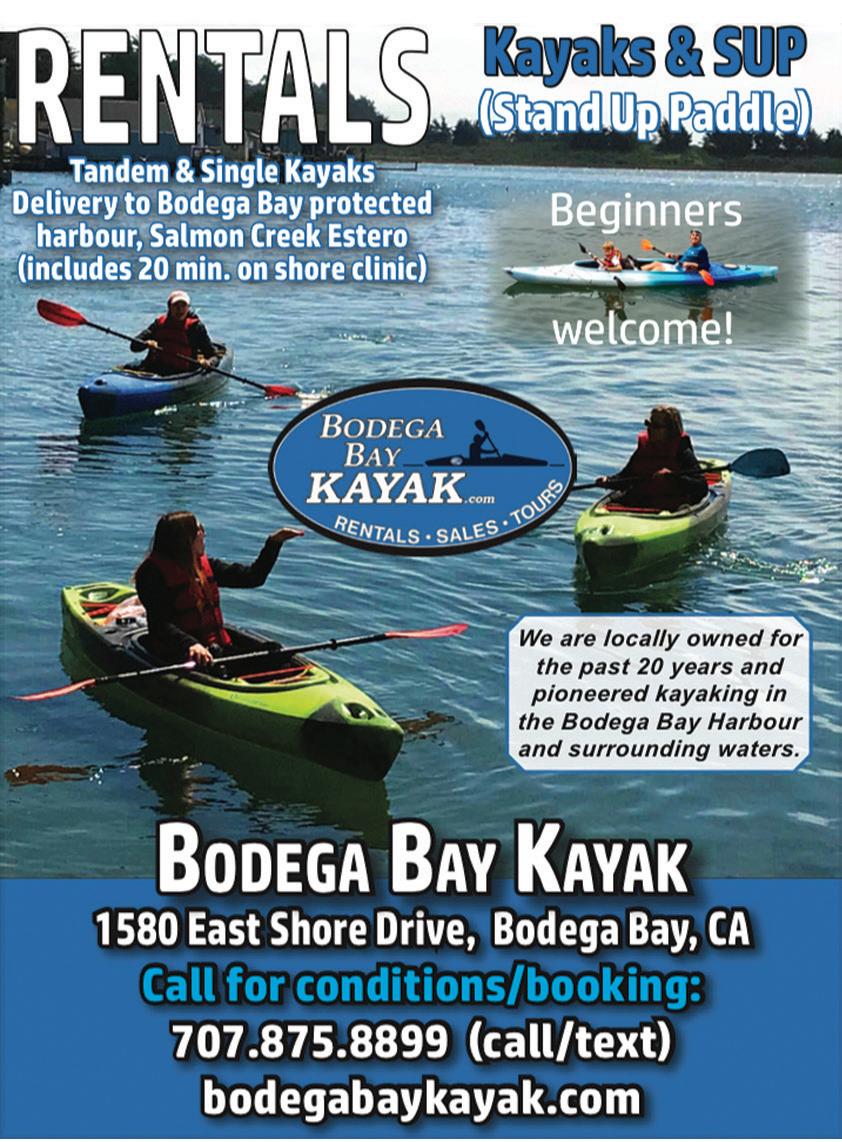

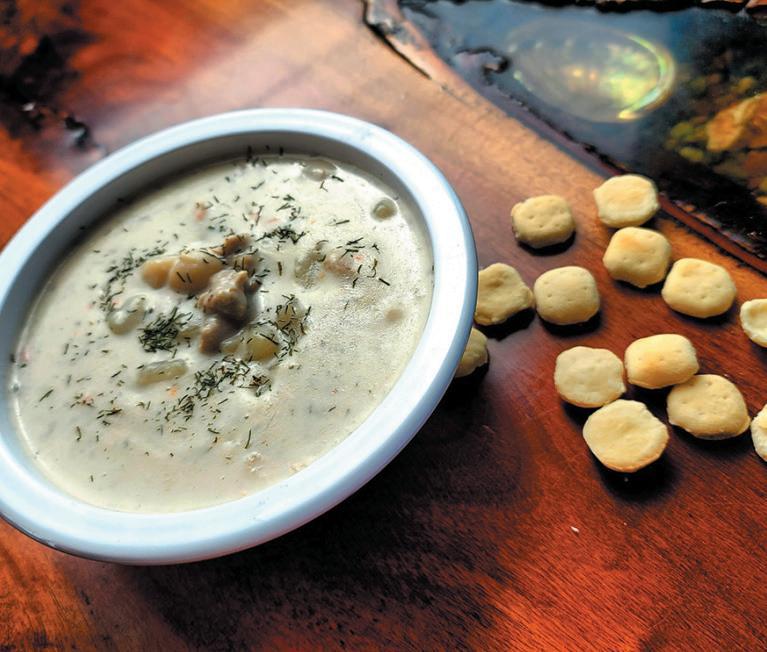

Lynda Rael 445 Center Street, 4C Healdsburg, CA 95448 Phone: 707.527.1200 bohemian.com 1020 B Street San Rafael, CA 94901 Phone: 415.485.6700 pacificsun.com PUBLISHED BY THE BOHEMIAN AND PACIFIC SUN A LETTER FROM OUR EDITOR All Roads Lead to ‘Roam’ 4 STRAIGHT ARROW Northwoods Bowmen’s Club 6 FREEDOM IN FREESTONE The Osmosis Day Spa Sanctuary 10 NATURE NURTURES The majesty of local hikes 16 HUNTING THE HIDDEN Letterboxing Has a Moment 28 RIDE THE LIGHTNING Rent E-bikes at Mad Dogs & Englishmen 36 WHY HITCHCOCK WOULD MURDER FOR A MEROT Bodega is still for ‘The Birds’ 42 A COSPLAY CAMP ENCOUNTER The Wild ‘Ponies’ of Middle Lion 46 Cover: Sonoma County Regional Parks Come & pick up some of Carol’s World Famous Award Winning Clam Chowder It’s made fresh daily. BEWARE! It is addicting! © COPYRIGHT 2018 JOHN HERSHEY PHOTOGRAPHY. All RIGHTS RESERVED | .jhersheyphoto.com There is only “One” SPUD POINT CRAB CO. We are open 7 days a week from 9–5 for takeout and dining at our outdoor tables 1910 Westshore Road, Bodega Bay, CA Let us know if you have any questions! 707.875.9472 | spudpointcrabco.com

Sue Lamothe,

Mercedes Murolo,

IF

The spirit of exploration

As I take to the backroads of Sonoma, Marin and Napa in a car he manufactured, I’m compelled to remind Musk that the North Bay takes that same spirit of exploration but bottles it. Like, literally, as wine. Vineyards quilt hillsides in every county and every turn reveals more.

The evolution of our area into Wine Country was so gradual that I can scarcely remember when and where it began. Some argue that it technically started in

France, imported here as a clipping in a vintner’s suitcase. Others will point to thirsty missionaries in need of gallons of sacramental wine. My own awareness of our Wine Country started at a 7-11 in an ill-gotten jug of Carlo Rossi vin rose circa 1989. My palate has since matured, ditto our viticulture but that wanton wanderlust I had as a young person persists in me today. I suspect it might be the same for you, dear reader. So, this is what you do—cue up the B-52s on Spotify and “Roam if you want to, without anything but the love we feel.”

— Daedalus Howell, Editor

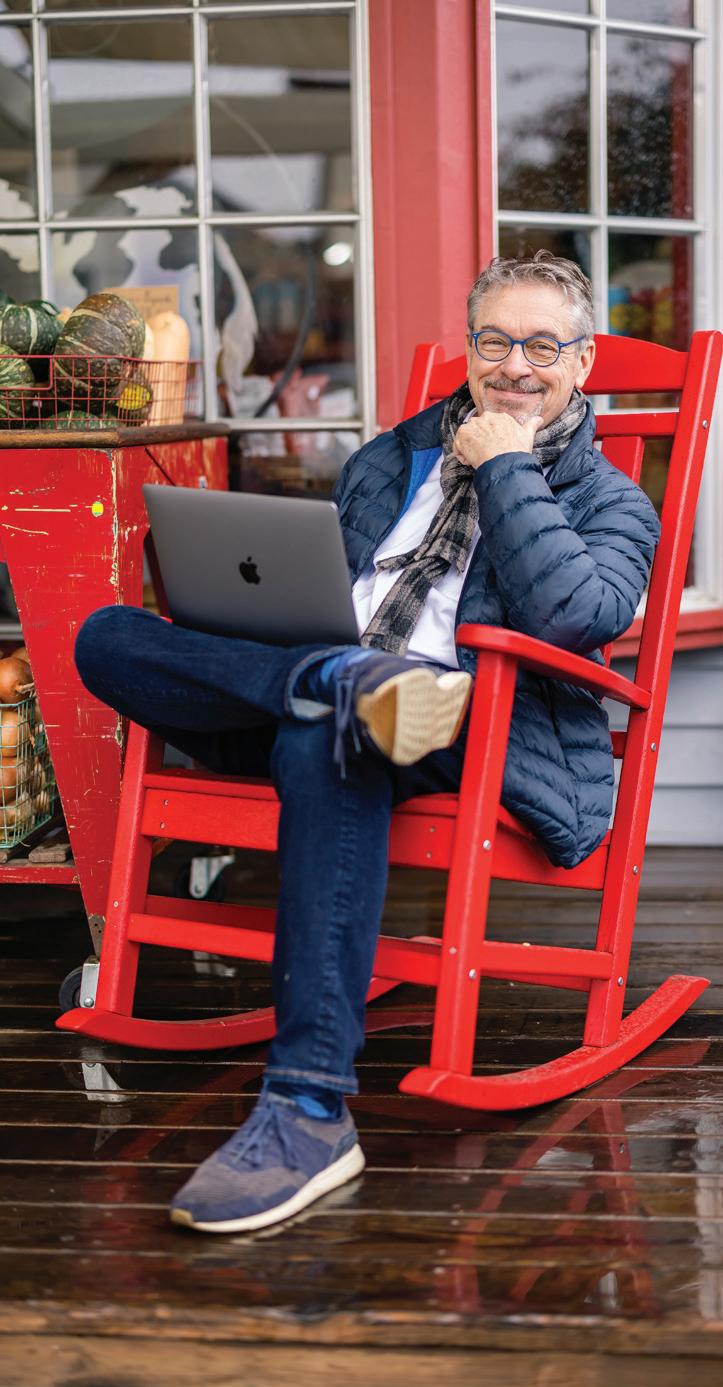

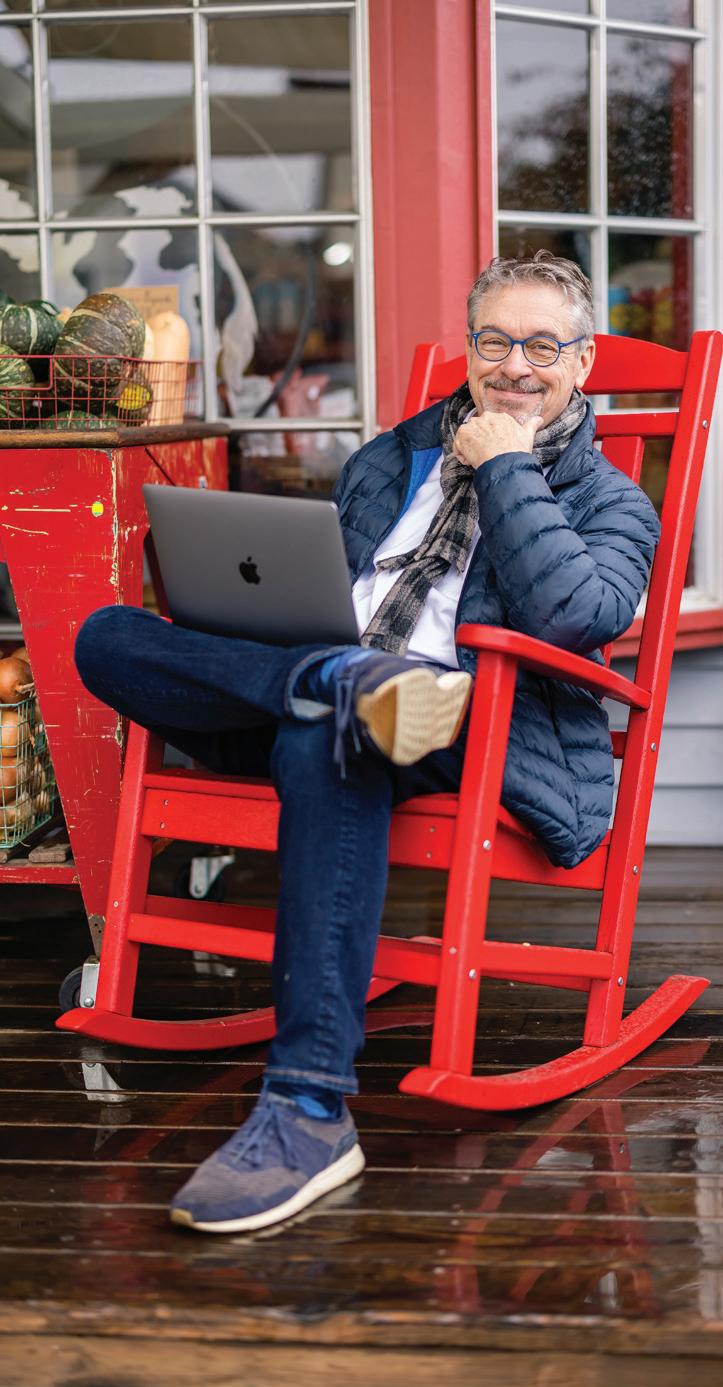

Christian Chensvold writes the “Spirit” column for the North Bay Bohemian and the Marin Pacific Sun, blogs about the wisdom tradition at trad-man.com and provides astrological readings.

Michael Giotis contributes to the Marin Pacific Sun, the North Bay Bohemian and the East Bay Express. His most recent book of poetry, Daybreak, explores existential quandaries and the vagaries of love in the postmodern era. Editor Daedalus Howell is the writer-director of the feature film Pill Head and the author of the novel Quantum Deadline. He’s also the editor of the North Bay Bohemian and the Marin Pacific Sun

Lisa Summers has contributed to the North Bay Bohemian and the Marin Pacific Sun and is the author of the novel The Green Tara, the story collection Vlkodlak and the poetry books Star Thistle and Ogygia

Jane Vick is an artist and writer based in New York, New Mexico and California. Her main fields of research include neuropsychology, psychology and the nature of the divine. She has written for the Marin Pacific Sun and the North Bay Bohemian

4 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY 2022

AD

As Elon Musk observed, “America is the spirit of human exploration distilled.”

DRIVE The backroads beckon. 12301 Sir Francis Drake Blvd., Inverness Park 415.663.1491 • InvernessParkMarket.com breakfast, lunch, dinner. Local, Organic, Delicious MARKET: Mon through Sat 8:00–8:00 Closed Sunday TAP ROOM: Tues through Sat 4:00–9:00 Closed Sunday and Monday

ROAM

WANT TO YOU SASAN HEZARKHANI

1.415.332.4843 www.seaplane.com See the Golden Gate, Alcatraz, the San Francisco Skyline and more, all from the air! ROUTE ONE BAKERY & KITCHEN 27000 HIGHWAY 1, TOMALES, CALIFORNIA The Place for the Best Oysters and Much More 1922 5 S TAT E ROUTE 1 M A RSH A L L , C A 415. 6 6 3 -13 3 9 THEMARSHALLSTORE.COM Mon: 8–2pm urs: 7:30–5pm Fri–Sat: 7:30–6pm Sun: 7:30–5pm BREAD urs–Sun 11am–till we run out! BAKERY IN THE MORNING PIZZAS IN THE AFTERNOONS

NOTCHED ARROW AT NORTHWOODS NORTHWOODS

Novato’s Archery Club is a hidden gem worth discovering

BY JANE VICK

BY JANE VICK

NOT JUST FOR ROBIN HOOD

We’ve all seen Robin Hood— and yes, I am referring to the cartoon version, where Robin is a fox and we couldn’t explain why, but we all had a crush on him. It’s a phenomenal film—and the archery scene stands out. Not only because Little John—a large bear—is disguised as a stripedpantaloon-wearing baron and cozies up to the nefarious Prince John while Robin wins first place. All those arrows flying, all those bullseye shots … are exhilarating.

There’s something sexy, something powerful—we can leave the cartoon animals behind here—about notching an arrow into one’s bow, feeling one’s arm and shoulder muscles contract as they pull it back, and then, with a discerning and certain eye, letting it loose to fly straight for the desired target. I mean, woof! And hear this: archery isn’t just for cartoon foxes, or any other iteration of Robin Hood. All of us, good sportspeople, can fill our quivers and make that journey towards our destinies at the center of the target.

The question then becomes, where? Archery might not be the most readily available pastime these days. As a young

7 2022 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY »»

PHOTO PROVIDED BY VINCE FLEMING

Take time off from your regular sporting routine to stretch the bowstring back.

«« girl, my parents sent my siblings and I to camp every summer in Canada where, among other things, we practiced archery. I was a rather good shot, actually. My brother was so taken with the sport that during his teenage years he bought a bow and quiver and set up a target in the backyard at home. But the good news is, those not planning a two-week stay in Canada next summer— shout-out to Ontario Pioneer Camp—don’t have to, because I have the solution to the archery conundrum no one realized they had until roughly two paragraphs ago.

NORTHWOODS—BULLSEYE

I did some research and found an archery opportunity that I would describe, if committed to one adjective, as adorable. It’s called Northwoods Bowmen’s Club— don’t be put off by bowmen, it’s open to everyone. Located in Novato and founded in 1954, Northwoods Bowmen’s Club has nearly a century of recreational archery under its belt, and its cute range—with 3D animal-shaped targets that give the feel of a miniature-golf course—is complemented by its dedicated and skilled staff, who can teach even the most timid neophyte to fire arrows in one evening.

Northwoods is tucked into the forest off Novato Boulevard, down a road called Oliva Court. At the end of this road sits a gate, which members have the key for … this is an incentive to become a member, by the way! For newcomers who arrive during regular hours, the gate is already open. Once inside the Northwoods Bowmen’s Club, guests can review their options regarding how they want to get their archery on.

THE NORTHWOODS MENU

Northwoods offers informal shoot nights on Monday evenings, which any and everyone is welcome to attend. On their website they list the types of music they like to shoot to, which include classical and classic rock. Personally, I’d happily learn to wield a bow and arrow to the tunes of Vivaldi or Pearl Jam. Show up on a Monday evening, and they’ll provide the equipment, and see what Bach’s cello suite no. 2 inspires in terms of target accuracy. For those looking for a longerterm experience, Northwoods also offers a four-week introduction to archery classes, held on the first Tuesday and Thursday of each month, as well as a league which

meets Wednesdays at 7pm and archery workshops which are several weeks long.

Northwoods also offers novelty shoots— described to me as “fun nights with wacky targets.” They recently held a Halloweenthemed novelty shoot, where the targets were outfitted with blacklights and rendered like zombies and ghouls. For added spice, the shooting was done in the dark, with flashlights. I cannot lie—this slightly concerns me.

Northwoods has both indoor and outdoor ranges, and provides equipment, which includes traditional longbows with cedar arrows, as well as compound bows with sites, mechanical releases and stabilizers. This is where I get nervous about the flashlight novelty shoot, though I’m sure it’s all perfectly secure.

While not the dashing-through-the woods, looking-like-a-rough-and-tumble morally heroic outlaw experience I’d initially imagined, Northwoods still proved to be an awesome place to try a less-wellknown sport. Watch Robin Hood, take a trip to Novato and shoot an arrow.

8 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY 2022

Personally, I’d happily learn to wield a bow and arrow to the tunes of Vivaldi or Pearl Jam.

BE S T EVER

SBBQ

We use only fresh, local ingredients and the finest brisket, pork, ribs and chicken available. Come and give us a try!

Follow u s on I n sta gram @piginapickleb b q nd piginapickleb e er for up date s Find o ur r otating craf t b e er menu on untapp d

Follow u s on I n sta gram @piginapickleb b q and piginapickleb e er for up date s

Find o ur r otating craf t b e er menu on untapp d

C orte M ade r a To wn C e n te r | 4 15.891.326 5 Emery v ill e Public M ar k e t | Sold-Out Ho tline: 51 0 .922.890 2 piginapickl e . c o m

SANCTUARY SANCTUARY

SANCTUARY SANCTUARY

BY JANE VICK

BY JANE VICK

Contemporary culture has begun to appreciate the spa experience in a new way; no longer considered just a luxury, massage, bodywork and other body treatments are now understood as a valuable and rewarding addition to overall health and wellness. To this end, there is a particular spa in Sonoma County that has long been a cherished destination of mine: Osmosis Day Spa Sanctuary. Osmosis is one of the more unique spas in the country, and a must-visit destination for deep rejuvenation.

If coming from out of town, rent a car or borrow a friend’s, and head up Highway 12 towards Bodega Bay. Not only does this drive end with an unparalleled spa day, it is also nothing short of resplendent;

11 2022 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY »» PHOTO PROVIDED BY PRISCILLA FRAIRE

CEDAR ENZYME FOR THE SOUL

Osmosis Day Spa Sanctuary is the only place on the continent that o ers a cedar enzyme bath.

A day at Osmosis Day Spa will renew a sense of reverence and provide a new lease on life

meandering through green rolling hills, sharp gray clusters of rock, flowering orange poppies—depending on the season, of course—and Breugel-esque black-andwhite cows. I often, on my drive out, like to see how many hawks I count sitting meditatively on the telephone wires. The most I ever counted was eight.

Follow Highway 12 until it intersects Bohemian Highway, and make a right turn. The spa is a few hundred yards past the turn, but prior to the first treatment there are a few destination options. Wild Flour Bread, on the immediate left, has some of the more delicious pastries and bread in a 50-mile radius. There is almost always a line, so be prepared to wait or arrive early— the coffee and pastries are well worth it.

Wild Flour Bread recently added an online ordering option, so to skip the line, order ahead and pick up upon arrival. The area surrounding Wild Flour is beautiful—there’s a dilapidated old barn across the street that I never tire of gazing at—and there are picnic tables where one can enjoy treats before treatments.

Alternatively, for a full breakfast and a perpetuation of the scenic drive, continue down Bohemian Highway, through breathtaking and dense old-growth redwood trees. Stop at the tiny town of Occidental, at the one-and-only Howard’s Station Cafe. This cafe is legendary—I can’t say how many times in my teenage years friends and I started a day at the coast with a Howard’s breakfast. The strawberry-peanut

butter shake—a dream in liquid form—the banana pancakes and the Denver omelette are all must-haves.

After breakfast, wherever it may have been, pull into the gravel driveway of Osmosis Day Spa Sanctuary, and let the rejuvenation begin.

OSMOSIS DAY SPA SANCTUARY

Osmosis has a beautiful and meaningful history, which enhances the experience of the sanctuary all the more. The founder of Osmosis, Michael Stusser, was a student at UC Santa Cruz in the 1960s and felt a deep calling toward ecological and spiritual harmonization in the budding of the environmental protection movement.

12 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY 2022 »»

««

After breakfast, wherever it may have been, pull into the gravel driveway of Osmosis Day Spa Sanctuary, and let the rejuvenation begin.

Stusser studied and practiced organic gardening, and established two horticultural training centers that are still in operation. After graduation he became interested in meditation, and after studying Zen and traditional Japanese landscaping in Kyoto, Japan—during which time he discovered the traditional cedar enzyme baths which are now a signature feature of the Sanctuary—he returned in 1984 to share his findings with the Western world.

His first cedar enzyme bath was a prototype—built on a friend’s ranch in Sebastopol—which suddenly and quickly garnered attention from the San Francisco Chronicle and the New York Times. People soon began flocking to Sebastopol to experience the phenomenon. In 1988 Stutter bought five acres of land and, over a period of years, together with fellow apprentice Robert Ketchell and Zen-priest Steve Stucky, envisioned and designed Osmosis Day Spa Sanctuary, a space dedicated to optimal healing, vitality and transformation, and designed to create and foster an expansive

sense of timelessness and tranquility. Walk through the front garden—which is full of sweet, resounding wind chimes— and check in for treatments. A kimono and slippers are provided, and if the first treatment is a Cedar Enzyme Bath, guests are sent to await their attendant in the Japanese Tea Garden—a beautiful space that integrates inside and outside with careful landscape and water architecture to promote tranquility and reflection. There is a flowing pond full of koi, where one may sit with tea to contemplate the water and mentally prepare for treatment.

The Cedar Enzyme Bath at Osmosis Day Spa Sanctuary is found nowhere else on the continent, and is unlike any other treatment I’ve experienced. It is a bathing ritual in which the recipient is immersed in fermented, warm ground cedar and rice bran, rich with living enzymes that stimulate metabolic activity inside and out. The cedar’s soft, weighted warmth and rich, spicy aroma are so relaxing that I am often transported into a deep meditation

and sleep. As the warmth from the bath is organic—generated by the enzymes at work rather than by an artificial heater—one’s body is able to deeply absorb it, allowing it to truly permeate to the center, stimulate core organs and allow deep healing from within. The release of tension and stress is unparalleled by any other spa treatment I have received—it feels much like returning to the womb.

The bath lasts for an hour or so—during which time an attendant periodically provides water and a cold towel. I highly recommend a massage afterwards. Osmosis offers a wide variety, from deep-tissue to Swedish.

After treatments are complete, take some tea to the Meditation Garden—a Kyotostyle garden that offers a quiet place for contemplation amid a labyrinth of plants, water and stones. Sit quietly. Experience the sounds and the bodily sensation of reverence. Integrate the effects of the cedar and the massage, and truly be nourished by the experience. This is 0.

14 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY 2022

««

Give the Gift of Restaurants Buy the perfect gift and support Sonoma County restaurants. Shop restaurant gift cards at SoCoRestaurantWeek.org Sleep well. Live well. @JaneDispensaryCalifornia @JaneDispensaryCalifornia www.JANEdispensary.com 2074 Armory Drive, Santa Rosa, CA C10-0000861-LIC VISIT US TODAY IN SANTA ROSA! FIRST TIME GUESTS RECEIVE 20% OFF PURCHASE JOIN OUR LOYALTY REWARD PROGRAM Become a VIP and get a coupon for your first purchase!

CALL OF THE WILD

Rediscovering nature’s rhapsody in the Age of Pandemic

BY CHRISTIAN CHENSVOLD

BY CHRISTIAN CHENSVOLD

16 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY 2022

RETURN TO SELF Nature’s magic surrounds us in the North Bay, providing a respite from Covidinduced limitation.

It was one of those same spontaneous compulsions that grabbed me like it did in childhood, when something deep inside dared me to take on a challenge. I’d just begun a hike along the perimeter of Spring Lake Park when I caught sight of a strange trail, or perhaps something disguised as a trail in order to tempt those prone to quixotic adventure. The incline was so steep that it was less of a trail and more of a ladder, with exposed roots and rocks as rungs. Before I knew what I was doing, I was down on all fours commencing my ascent. »»

2022 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY 17

PHOTO PROVIDED BY SONOMA COUNTY REGIONAL PARKS

What followed was seven minutes of manic climbing improvisation driven by pure determination and a hunger for spontaneous adventure. Roots and branches were quickly tested to make sure they would hold. The soil was dry and loose, and the primary danger was sliding. If sliding feet first, I’d likely just get scraped a bit before my splayed legs and groin were stopped by a tree trunk. The main fear was of feet catching on something, throwing my body weight into a summersault resulting in a cracked skull. When I finally reached the summit and gazed down, it looked as though I’d scaled something of skyscraper height, level with the eagles that glided over the valley below.

It was not some foolhardy lust for danger that propelled me to that vantage point but, alas, more of a parched thirst to explore—the title, in fact, of this very publication—places where people seldom go, to get off the beaten track even if cars and voices are still within earshot.

Since the start of the pandemic I’ve devoted myself entirely to the rediscovery of nature and the endless nuances to be found in a world that is primordial rather than virtual. I closed my decade-long chapter in New York right before Covid struck, ready to fulfill the lifelong dream of living in a charming New England town— not having yet realized I’d left my heart near San Francisco. Winter in Newport, Rhode Island, brought with it walks in the falling snow at night, where I got lost on slender streets lined with colonial buildings, each marked with the year it was built. Then the third week of March struck, and everything shut down. There was nothing to do but hike the nature preserves and rocky coast. When summer finally came and the ocean climbed to a balmy 70 degrees, I felt a certain freedom I’d never known, pulling over my bicycle, kicking off my canvas sneakers and just walking into the sea and swimming to some distant rock. No sand, no beach, no one else around—just me and the

salty waves of Narragansett Bay.

When I returned to Sonoma County, I brought with me this longing for unsupervised play, untamed spaces and the endless variations experienced in the natural world. My lifelong love of Annadel Trione Park was rekindled in a completely new way as I took to long meditative hikes rather than blazing through it on a mountain bike. The golden twilight reflected on humble Lake Ralphine in Howarth Park was a sight for screen-sore eyes. The freshly filled creek running alongside St. Helena Road, just 10 minutes outside my old home in Rincon Valley, had me feeling like one of the pioneers and prospectors who crossed the Sierra Nevada mountains. The Sonoma Botanical Garden provided an afternoon of reveries, while Jack London State Park seemed to have somehow escaped my entire life spent in Sonoma County, and I had no idea that just a few minutes from the brown hills of Highway 12 stands an archetypal »»

18 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY 2022

««

When I returned to Sonoma County, I brought with me this longing for unsupervised play, untamed spaces and the endless variations experienced in the natural world.

#AbsolutelyABX | ABX.org AbsoluteXtracts CDPH-10004584 CDPH-10002270 It’s time to say:

redwood forest where one can fancy meeting Robin Hood.

In a cold and honest assessment of the way we live now, we must concede that modern life is completely unnatural and a development that, in the grand scheme of things, happened about five minutes ago in human history. From the dawn of time until just recently, mankind lived within a cosmos; a world of lands, seasons, sky and weather. Culture grew organically from this primal experience of being a created being in a created world. When Coleridge and Wordsworth wanted to share their latest poems exalting the sublime feelingstates found in nature, they each walked 10 miles across the Lake District to see their friend. And 19th-century art is replete with scenes from antiquity, in which a group of young girls in ancient Greece would walk down to the sea to look at the sunset together, presumably because that’s what they actually did before the invention of “entertainment.”

Even before Covid struck, this naturehunger was slowly gnawing at my innards, no doubt from my time spent living in New York City. Having exhausted its museums and concert halls, I found myself spending summer in Tarzan-mode, possessed by a wild man within and walking shirtless and barefoot across the entire length of Central Park. In autumn a sudden gust of wind would cause the trees to release a thousand leaves of golden vermillion, a sight of pure enchantment that would only last for a few ecstatic moments, but hold my spirits up for hours.

But there’s no place like home and this chosen spot in the world as far as nature is concerned, as Luther Burbank so wisely stated.

As fearsome as this era is, I will be forever grateful for the pandemic’s shock to my system, jolting me into a mode of life in which pleasure is found merely by stepping outside. We needn’t go far to find such wonders as a heron patiently hunting fish,

a squadron of squawking geese speeding towards a hot-pink sunset, the smell of a misty dawn, a raccoon that rises on its hind legs to inspect us while we gaze at the stars, the smell of a distant fireplace and the sound of church bells.

It’s still possible to live an archetypal life in tune with the forces of nature; all we have to do is take the “forest passage.” The term was coined by German writer Ernst Junger in his 1951 book of the same name, which called for escape from the creeping powers of conformity and materialism through an alternate frame of mind possible even in a dense city, for the forest is a metaphor for the deepest part of a person, where one reconnects with natural rhythms and rediscovers forgotten powers. Writes Junger:

“In all epochs there will be powers that seek to force a mask on him, at times totemic powers, at times magical or technical ones. Rigidity then increases, and with it fear. The arts petrify, dogma becomes »»

20 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY 2022

««

As fearsome as this era is, I will be forever grateful for the pandemic’s shock to my system, jolting me into a mode of life in which pleasure is found merely by stepping outside.

Sarah Butler 415.265.5070 DRE# 01258888 OceanicRealty.com STINSON BEACH’S # 1 REAL ESTATE TEAM Listed At $4,500,000 26 Calle Del Resaca 3 Beds | 1 Bath | 1,235 SF Stinson Beach, CA Oceanic Realty Stinson Beach

absolute. Yet, since time immemorial, the spectacle also repeats of man removing the mask, and the happiness that follows is a reflection of the light of freedom.”

Utilizing techniques gleaned from meditation and tapping the soul’s resonant frequency—the place of imagination where dreams are bred—it’s possible to conjure up that most primal experience of mankind:

walking through the natural world, and its ever-shifting terrains and conditions, while knowing one has the innate nobility of a divinely decreed place in it. Those whose souls soar with the eagles, unwired but connected to something greater than anything that can be seen on a screen, can think of themselves as a new kind of aristocracy, one that traces its lineage back

to creation itself. When we pass a fellow wanderer, their demeanor says it all. We may pass each other in silence with only a subtle nod of acknowledgement, but we know we’ve encountered a kindred spirit who knows what so many others have forgotten, and who, like us, can be counted among those who are truly alive. »»

22 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY 2022

««

SUBLIME Nature’s rhythms reconnect us with our own innate powers.

SKIP THE LINE, ORDER ONLINE! FISHETARIANFISHMARKET.COM OPEN 7 DAYS A WEEK 11AM–7PM Enjoy all of your coastal favorite dishes while embracing the “True Bodega Bay Experience!” We’ve got it all! Fresh and Locally caught! Covered, Outside, & Beachfront dining available! COME VISIT US IN THE “BUMMER FREE ZONE!” GO LOCAL Sonoma County www.golocal.coop 1407 Lincoln Ave., Calistoga | 707.942.4231 Open Wed through Sun, 12–6 pm or by arrangement. Facebook: sofiecontemporaryarts | Website: sofiegallery.com

Images: Will Ashford Photo: Marcel & Meher Photography Contemporary • California • Calistoga Best Art Gallery Napa County

W hat Is Art?

ENCHANTMENT Landscape and metaphor interweave in the psyche of the spiritual aspirant.

TAYLOR MOUNTAIN

The limpid pool, reflecting the image of those who come to gaze upon it, has come to symbolize the dark and murky realm of the unconscious. The raging ocean can lead one to an enchanted isle or a maelstrom of doom, while the forest may hide a hoard of gold, yet is populated with the watching eyes of bears and wolves, witches and ogres—and the treasure, if we can find it, is guarded by a dragon.

»»

««

So it should be no surprise that of all natural landscapes, the verdant valley is said to be most pleasing to the human eye, kindling deep ancestral memories of security and abundance, of flowers and fruit and trout-filled streams.

The mountains, however, quite literally tower over all of these places, their height conveying rarified realms inaccessible to ordinary humans, the abode of the gods and heroes. Throughout the world’s cultures the mountain represents the summit of knowledge, the spot where heaven and earth meet and where revelation is transmitted, as with wise Moses, who received the Ten Commandments atop Mount Sinai. In Norse mythology there is Valhalla, while Montsalvat is the resting place of the sacred chalice in the legend of the Holy Grail. The legendary Mount Meru, in the Himalayas, is said to be where the Hindu god Shiva went to meditate, exemplifying the association of remote mountain peaks with spiritual realization.

Those who have scaled the true apex of the world—Mount Everest—have earned the right to carry in their eyes a gaze that is different from others who cannot understand why one would risk one’s life to climb it, nor fathom all that is implied in the oft-quoted quip “Because it’s there.”

But one can get a small taste of the mountain-scaling experience atop Santa Rosa’s Mount Taylor, which I climbed on an ill-chosen day when the trails were still muddy, where every step in the grass forced me to contend with rocks or holes. Taylor Mountain Regional Park and Open Space Preserve is how it’s known officially; it’s part of Sonoma County Regional Parks and is accessed at 3820 Petaluma Hill Rd. The park currently consists of seven miles of trails and a master plan to increase that to 17. The summit is an 1,100-foot elevation gain—so hikers should make sure it hasn’t rained recently and wear boots with good traction. In addition to the threat of backache, there is the chance of a rolled ankle or twisted knee,

and the ascent, though not steep, taxes the calf muscles on the way up and the thighs on the way down.

But even a 30-minute ascent provides a vast view and can encourage states of mind not experienced in everyday life in the city below. The sense of closeness to the clouds, of beholding their shadows covering miles below, was palpable. The most deeply satisfying sight was the horizon, with all the other mountains in the distance, and the blue sky where they met. Here one can easily imagine the silent majesty of sacred mountains in truth and legend, and the inner states they conjure—a sense of being and eternity that quiets all inner agitation carried, like a burdensome pack, from our lives down below. The mountain’s lofty height and the spiritual elevation it inspires blend together, the inner and outer world fusing and allowing a privileged glimpse into the momentous and mysterious workings of ourselves and the world.

26 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY 2022

««

The legendary Mount Meru, in the Himalayas, is said to be where the Hindu god Shiva went to meditate, exemplifying the association of remote mountain peaks with spiritual realization.

packing your suitcase… and experience some of the classic tastes of Rocco’s Marin.

gift certificates available online millvalleymassage.com Hepa13 Air Filters in Each Room Medical Grade Medical Grade pH Neutral Disinfectant Thorough Cleaning Before Every Appointment Our Safety Protocols All Therapists are Vaccinated Voted Best Of Marin 13 Years

most delicious pizza in Marin County!

The

Sandwiches made to order Mon-Sun: 11:00am to 9:00pm 711 E Blithedale Ave, Mill Valley, CA 415.388.4444 info@roccosmarin.com roccospizzamillvalley.com

We use fresh ingredients and make our own pizza dough from scratch everyday! We also offer generous portions at affordable prices. We take always look into quality, and consistency of delicious, homemade Italian cuisine. So enjoy the flavors of Italy without

HIGH ADVENTURE

Letterboxing brings with it delight, community and exercise—give it a try sometime.

THINKING INSIDE THE BOX

Letterboxing bridges generations

BY MICHAEL GIOTIS

The history of letterboxing is both present and personal as I walk three growing boys among creeks and trees hidden along the edges of ballparks, following the clues that make letterboxing so much fun for any age.

The suburban roams that letterboxing leads to are even perfect for a grandparent or uncle looking for a way to spend time with their young loved ones that does not involve Marvel, but is still physically possible when a hike or fishing trip is out of the question.

Like its more well-known cousin, geocaching, letterboxing spread far and wide with the rise of the world wide web. Unlike geocaching—which arose because of the emergence of GPS technology— letterboxing has a much longer history and is pre-technological.

Both experienced a resurgence in the Pandemic Age as people sought new ways to connect with each other and with nature, and to get out of the house.

Letterboxers follow written clues on a hunt to find a box hidden in a public space. Letterboxing up and down the coast of California while on trips with the boys

over the years uncovered boxes hidden in you-pick orchards, on hiking trails and even on the underside of a metal bookshelf in a library, the box fastened upside down with a magnet.

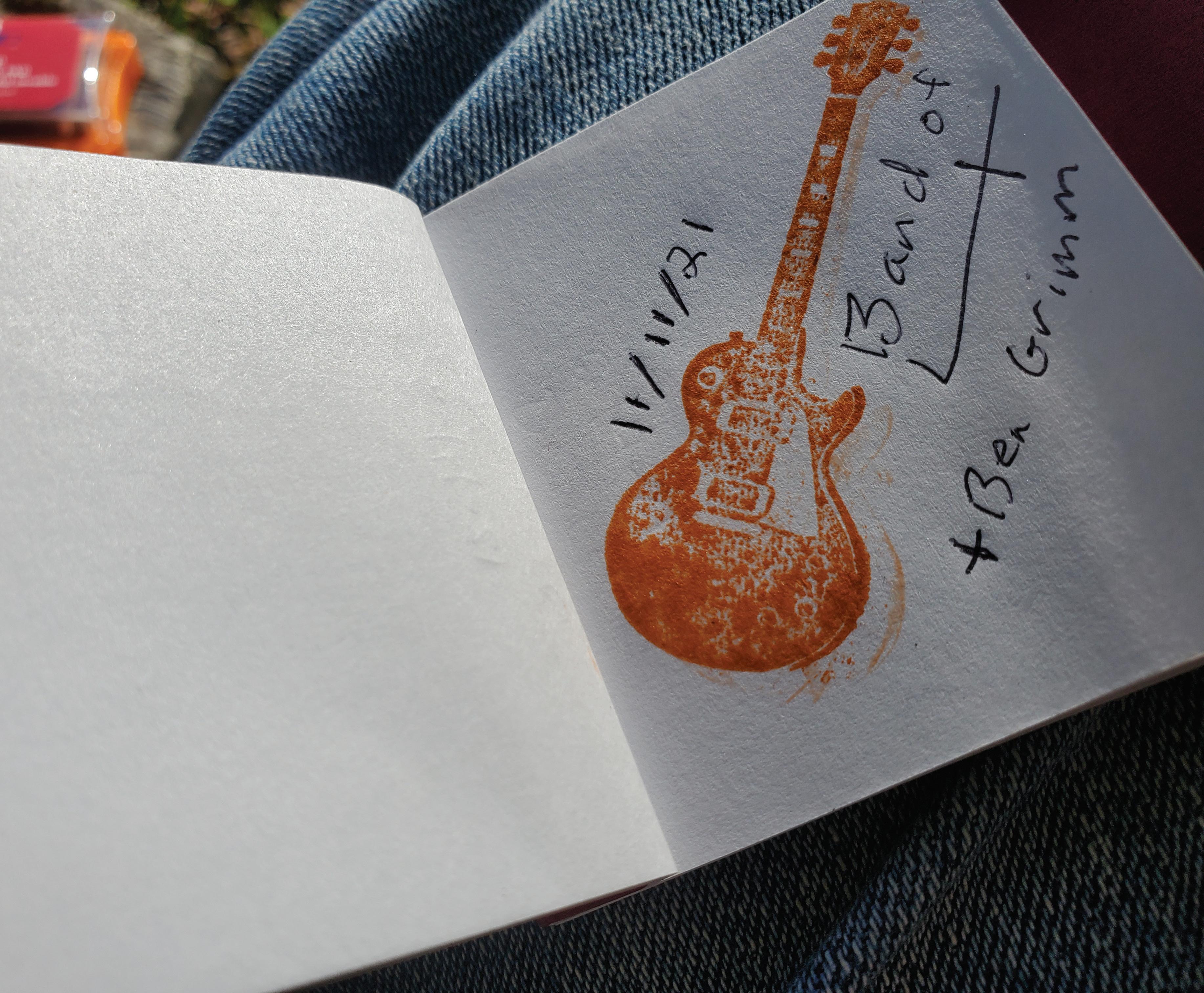

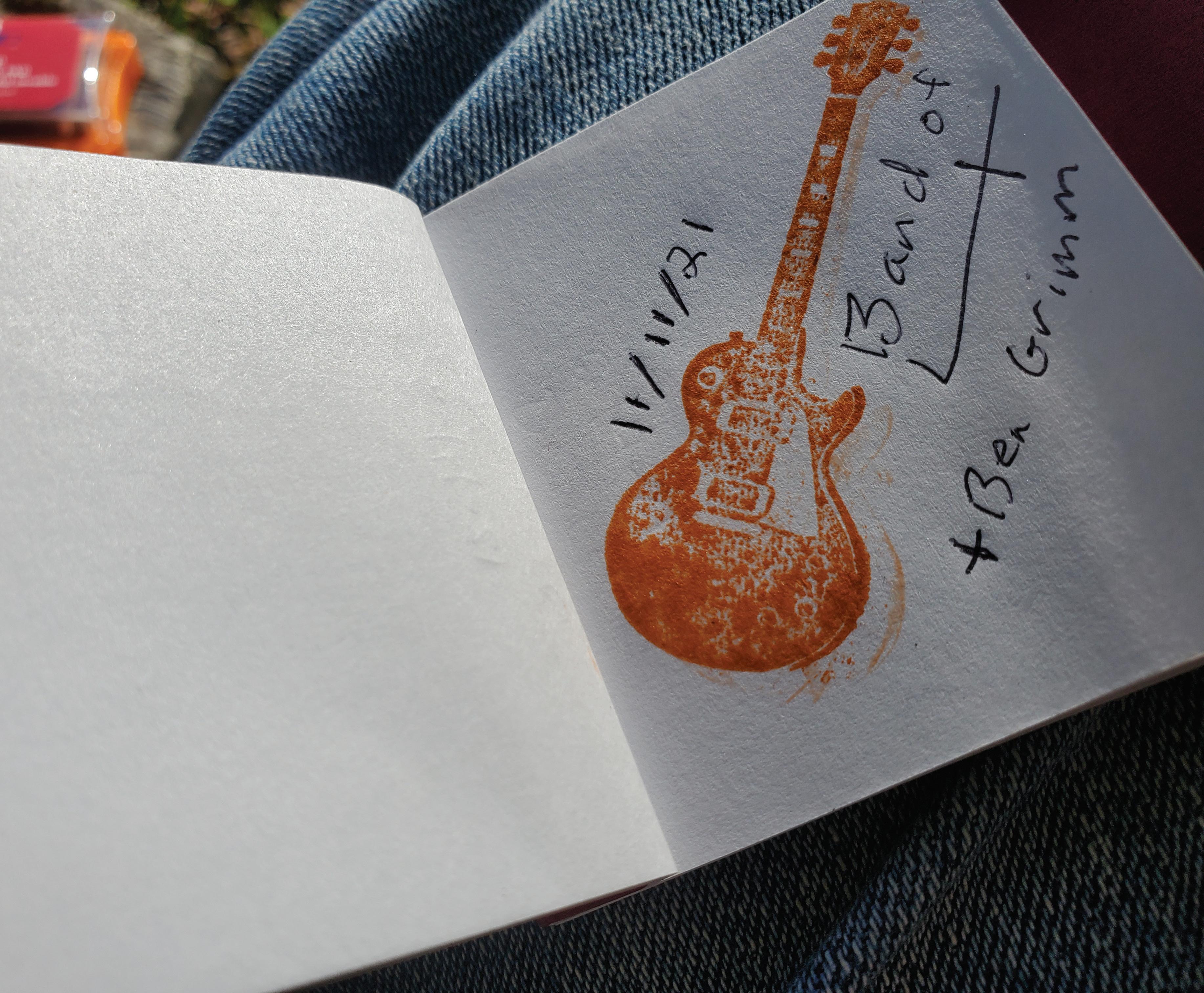

Inside each of these boxes is a booklet and a unique stamp. Letterboxers carry their own unique stamp and logbooks, and they stamp and sign the box’s book, then stamp and record the finding in their book. The process brings joy—it’s that simple.

Yet our finds were some time ago; the boys are much older now. In Covid’s nearly two years thus far, the idea of going on the hunt for letterboxes again arose »»

29 2022 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY

PHOTOS BY MICHAEL GIOTIS

more than once. As the clocks fell back and bigger hikes became too muddy and treacherous for my temperamental knees, I brought it up again—and this time the family was game, eager for something different.

Historically, we hunted as the “Band of Four”—the two boys, my wife and myself. With my wife down with sciatica, we needed a fourth. Enter “Ben Grimm,” taking as a pseudonym the character in Marvel’s Fantastic Four. Having played with the boys since infancy, Grimm was a perfect fit. Adventurous, clever and funny, we needed him as much as he needed us.

Grimm needed this, all right. He was dealing with some pretty serious family health issues, which were especially acute

the day we decided to take him into the woods on the hunt. In fact, we all needed a reset, each for our own reasons.

Letterboxing has changed significantly since it was established in 1854. Still, the sense of adventure that started the hobby will live forever in the heart of letterboxers.

According to AtlasQuest.com, one of the most popular sites for letterbox listings, the hobby started when James Perrott of Dartmoor, in England, planted a glass jar in a remote location as a way of enticing hikers to the difficult—yet rewarding—journey along the Cranmere Pool.

At first, letterboxing spread around the Dartmoor area as a local curiosity, evolving slowly as the decades went by. Then, in the 1970s, the hobby got a boost with the

creation of a detailed map of the by-then 15 Dartmoor letterboxes. Suddenly the hobby took off, with thousands of letterboxes being listed by the 1980s, all still in and around Dartmoor. When Smithsonian magazine wrote about the phenomenon in 1998, American hobbyists took on the tradition, moving onto the internet and organizing as Letterboxing North American (LbNA). Atlas Quest, the site we used for our recent hunt, was founded in 2004.

Letterboxers follow some written and unwritten rules. When the situation in Dartmoor began to get out of hand, with some placements causing damage, a code of conduct was written to address the problem.

My favorite line from the Code is, “Boxes should not be sited in any

30 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY 2022

»» ««

When the situation in Dartmoor began to get out of hand, with some placements causing damage, a code of conduct was written to address the problem.

The Caviar Co.

is the sister-founded and San Francisco-based purveyor of fine caviar, opening your palate to one of the finest delicacies in the world.

We have the optimal selection of caviar to suit your needs, whether you’re in need of some domestic caviar to kick-start your week, or you’re planning a date night and would like to try one of our imported caviars. We have the perfect caviar for every night of the week!

Visit our retail store in San Francisco and allow our caviar concierge team to assist you in selecting the perfect caviar for your party or to enjoy at home. You could also join us in our newly opened Caviar and Champagne Tasting Room and Marketplace for specially curated caviar bites and flights paired perfectly with champagne. Don’t miss out on shopping in our marketplace to take home your favorite caviar and bubbly!

thecaviarco.com

Champagne & Caviar Tasting Room 46 A Main St., Tiburon, CA 94920 Wed–Sun, 12–7pm 415.889.5168 Retail Store 1954 Union St., San Francisco, CA 94123 Mon–Fri, 10am–6pm; Sat, 11am–6pm 415.580.7986 Lunch, Dinner & Weekend Brunch | 9900 Sonoma Highway (CA12), Kenwood | 707.833.6326 | saltstonekenwood.com | Reservations: resy.com Dine in Sonoma Wine Country’s most spectacular vineyard setting. Will Bucquoy Photography Will Bucquoy Photography Voted Best Restaurant with a View Best Outdoor Dining

kind of antiquity, in or near stonerow, circles, cists, cairns, buildings, walls, ruins, peatcutters’ or tinners’ huts, etc.”

I love the contrast of this anachronistic language with the reality that letterbox listings on an online database get people out into the world to hunt.

The Band of Four circled up for a gooooteam—“‘Four’ on 4. Ready, 1, 2, 3, 4, FOUR!”— before leaving the car and heading out on foot across a bridge and following a creek along the tree-lined trail.

While the site of the original letterbox in England was an arduous, nine-mile journey over uneven ground, today’s letterboxes are much more forgiving. Yet the love of the journey is still evident. Our path took us along a creek and over bridges, sneaking

along the edges of parks and back down into the creek path, where trees and brush overflowed with life from the recent rains.

Our walk took us less than 20 minutes on a path accessible to walkers of all different mobility levels. The four of us, following clues along the way, moved with care, always looking at the places we passed through for a pole or a tree described by the instructions. When we found the box, it took the whole team.

The day was more than a mere hike together. We had vowed to find the box together and there it was, uncovered, waiting since the last visitor stamped its booklet four months before. Our sense of accomplishment was palpable, and we felt alive, buzzing at having taken some control

over our lives, if only for an afternoon. I saw, in my sons’ eyes, the confidence that comes with knowing what to do and then doing it.

The letterboxers’ Code prevents me from disclosing more details about our hunt. Just rest assured that finding our box required some perseverance, but never any physical strain. We shared the joy of inscribing the record of our hunt in the two journals. Even now, somewhere in Sonoma County, a stamped image of a Les Paul guitar is drying, framed by the date and the words, “Band of Four + Ben Grimm.”

To find a letterboxing adventure near you, check out atlasquest.com

32 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY 2022

««

Our sense of accomplishment was palpable, and we felt alive, buzzing at having taken some control over our lives, if only for an afternoon.

Cucina Rustica

RED HILL Shopping Center

High Tech Burrito www.hightechburrito.com Hot Wok Chinese Food 415.454.0877

Jillie’s Wine Bar and Shop jillieswine.com • 415.521.5500

JOLT! • www.joltgifts.com

Safeway

www.safeway.com • 415.458.1170

Kitty Corner • 415.747.8322

www.marinhumanesociety.org

Lark Shoes

www.larkshoes.com • 415.258.9954

Mathnasium of San Anselmo mathnasium.com/SanAnselmo

628.400.4002

Peet’s Coffee & Tea www.peets.com • 415.306.0310

Pet Food Express • 415.455.8888

www.petfoodexpress.com

Pizzalina

www.pizzalina.com • 415.256.9780

Precision 6 Haircutting 415.457.5340

Red Hill Cake & Pastry

415.457.3632

Red Hill Holiday Cleaners

415.457.9992

Sophie’s Nail Spa

sophiesnailspasananselmo.com

415.459.6868

Subway • 415.456.1170 • subway.com

Swirl Frozen Yogurt

SwirlSA.com • 415.457.7947

Bella • 415.457.1066

www.bellamarin.com

West America Bank

www.westamerica.com

LoCoco’s is everything an Italian restaurant should be— boisterous, busy, fun, with excellent authentic food of the best quality: fresh seafood, meats and pasta.

707.523.2227

Lo Coco’s

Bay

Gift CertifiCates vailable | l oC oC os.net bestof bestof bestof bestof the bohemian’s the the north bay 2005 the north bay 2005 the bohemian’s the bohemian’s the north bay 2005 the north bay 2005 r ated INSIDE & PATIO DINING DINNER Tues–Sun ~ Takeout Available

a familiar place to shop, dine and unwind.

www.chase.com

Serving Lunch & Dinner hiStoric r aiLroa D Square 117 Fourth Street, Santa roSa 2021—Voted Best Italian restaurant of the North Bay —North

Bohemian

The center of it all Introducing

Chase Bank

• 415.453.4306 CVS • www.cvs.com • 415.456.9900

Get

www.getinshapeforwomen.com

The Hub • 415.785.4802

in Shape for Women

415.521.5984

ALL COVID-19 PROTOCOLS FOLLOWED

Letterboxing Code of Conduct:

Boxes should not be sited in any kind of antiquity, in or near stonerow, circles, cists, cairns, buildings, walls, ruins, peatcutters’ or tinners’ huts, etc.

Boxes should not be sited in any potentially dangerous situations where injuries could be caused.

Boxes should not be sited as a fixture. Cement or any other building material is not to be used.

—Source AtlasQuest.com

OUT AND ABOUT Letterboxers carry their own unique stamp and logbooks, and they stamp and sign the box’s book, then stamp and record the finding in their book.

34 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY 2022

Target, Costco, Nordstrom Rack, and over 50 other stores, restaurants and services Rowland Blvd Exit, Highway 101 ShopVintageOaks.com AL FRESCO SHOPPING & DINING FURNISHINGS TO FUZZY SLIPPERS AND SO MUCH MORE FR O M

EASY

RIDE IN

E-STYLE

E-bike rentals get couture

BY MICHAEL GIOTIS

To the list of advantages that come with e-bikes, now add style. Mill Valley’s Mad Dogs & Englishmen e-bike shop oozes with post-hipster ur-style just like the bikes that can be bought or rented at the Mill Valley Lumber Yard location.

The advantages of an e-bike are many, and worth reviewing.

“[Riding an e-bike provides] a distinct advantage,” says shop manager Mike Penfield. “The fitness levels of riders are distinctly different.” The e-bike motors support any fitness level, making big rides more accessible. “And then you have riders in good shape who [e-bikes] are good for as well, and that’s the one thing, they allow

you to go further, longer distances … but you still get a great workout.”

“There are so many different riders out there right now, especially with Covid,” Penfield said. “It really showed that people wanted to get out and do something.”

Importantly, the new opportunity opened up the market for dazzling innovation in e-bike design.

Among the loveliest on display at the shop were a pair of black Serial One cargo bikes emblazoned with the words “powered by Harley Davidson.”

Penfield gushed as he talked about the way the “gearing in the back hub uses torque sensors to sense your rate of peddling,” because riders look for that steady cadence of peddling for best stamina.

“You like this one the best don’t you?” I teased, pointing out the obvious.

37 2022 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY

PHOTO BY MICHAEL GIOTIS

RIDER When in Mill valley, make like the locals and take a scenic bike ride through the redwoods, to a view.

»»

The trails of Mount Tamalpais start not far

“I’m impressed with them,” Penfield said. “They have one of the better motors, the better batteries and the [Enviolo AUTOMATiQ intelligent automatic transmission] is really unique.”

Serial One, the original motorcycle built by the Harley Davidson company back in 1903, was little more than a bicycle with an engine. Now it is exactly that again, this time built by a separate company in partnership with Harley Davidson. The end result is a cool Danish-bike look—a work-aday machine and a true classic. Add to that Silicon Valley–influenced innovations such as brake lights that flash when you lay the bike down.

Mad Dogs & Englishmen was born to bring high-quality electric bikes to “some of the most scenic cycling destinations on the West Coast,” according to the company website.

Here are the rental options one can expect in Mill Valley, looking first at mountain bikes, then at cruisers.

MOUNTAIN BIKE RENTALS

The trails of Mount Tamalpais start not far from here, offering some of the best

mountain biking in the world on the very inclines where the sport was born. The main rental bike is the Specialized Turbo Levo Comps mountain e-bike.

“Specialized is one of the leaders in the e-bike space,” Penfield said. “They’ve done such a great job with their motor/battery pairing and their mission control; you can set up and customize things like how you want to pedal [and] how much usage you want to get out of your battery, and you can conserve your battery usage that way as well. And you can track all kinds of data like routes you’ve been on, routes you are going on.”

As Penfield said when we first started talking, “we just do e-bikes here, basically.” Clearly.

CRUISER BIKE RENTALS

The main rental road bike is the Specialized Como, which has pedal-assist up to 20 mph. It is known to be user friendly and is available for rent in both stepthrough and step-over models.

People who rent the cruisers tend to ride to Sausalito and on to Tiburon. Down the road from the shop riders get on the

dedicated bike path that eventually leads them to a choice to go toward Sausalito or over the bridge.

I asked Penfield if he had ever ridden across the bridge.

“I never have,” he said, laughing. “I’ve walked, but I’ve never ridden. I need to do that.”

To see the bridge, he rides the Marin Headlands up and over Mount Tam, and over Muir Woods.

“What about the Richmond Bridge?” I asked. I have always wondered who in the world rides the bike lane on that bridge.

He told me he definitely has not, but that groups such as the Marin Bike Coalition ride across the Richmond Bridge together.

Another popular destination is the Paradise Loop in Tiburon, which draws riders with its dedicated bike path and views of wetlands along the Bay. The wide path and long, flat picturesque stretches make the loop perfect for a ride on cruiserstyle bikes like the Como.

Penfield started to say that the trip took three hours, when I interrupted. “Three hours if I am with my wife, or just me? Because that is a very different speed.”

38 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY 2022

»» ««

from here, offering some of the best mountain biking in the world on the very inclines where the sport was born.

• Four local wine-makers featuring over 30 different wines. • Specialty organic juice elixirs for our non-alcohol-drinking patrons. Extraordinary Wines, Specialty Food Items & Gorgeous Views Join us for good vibes with LIVE MUSIC and fine, local wines! 10439 Hwy 1, Jenner, CA | tastingbythesea.com | 707.520.6060 • Wine by the glass, the bottle and the case. • A tasting room for our winemakers offering tastings of your choice for $3 per taste! 707.377.4238 Mon–Sun, 11am–6pm 1850 Bay Flat Rd Bodega Bay, CA fishermanscovebodegabay.com ALWAYS SERVING LOCAL OYSTERS FROM TOMALES BAY Breakfast & Lunch on the Bay Clam & Scallop Chowder Award Winning Clam & Scallop Chowder, Crab Sandwich, Fish Tacos, & Brisket 1410 Bay Flat Road, BODEGA BAY WED–SUN 9am–3pm Visit us on and ginochioskitchen.com Open for Indoor Dining and on our 2 Waterfront Patios

He said four hours with a stop for lunch, then recommended, “Do the whole thing.”

RESIDENTIAL RIDES

There are plenty of opportunities to ride right in town.

“Some people actually just go up [the streets here] in Mill Valley because it’s Mill Valley,” Penfield said. “You get to see a lot of really cool homes, and the redwood trees are awesome. We get a fair amount of tourists that come and stay and just want to dayride.”

The paved residential streets are very accessible and suitable for any rider. And the payoff is huge, Penfield said. “You can also get pretty high up on the mountain and get some vista views of the Bay.”

The bike rentals at the shop start at about $90 per day for the e-cruiser or $125 for mountain e-bikes. The shop also rents out the hot new fat tire-style e-bike, the Super73.

“You dooo?” was all I could say as I looked at the beautiful machine, which costs just over $100 per day.

Return rental customers earn a 20% discount. For those who rent for more than one day in a row, the cost goes down by 50% on the second day, until the bike is returned. Bikes come with a charger, a lock and a phone holder.

For Mad Dogs & Englishmen customers with dogs on their agenda and no price limit, perhaps the most famous offering is the vintage-style sidecar cargo bikes. Custom-assembled for each customer, these beautiful machines boast a motorcycle-style

sidecar strong enough to safely carry a dog or child up to 100 pounds.

According to the company website, Mad Dogs & Englishmen launched their first shop in Carmel specifically because it is a dogfriendly town. Because cycling with their dogs is important to their customers—who expect “5-star cycling experiences”—the redand-chrome, leather-seat sidecar-and-e-bike marriage was inevitable.

“Our very special bicycle sidecars are made to order and handcrafted in Europe … . [You can also] buy the sidecar separately and hook it up to your own bicycle,” the website says.

Still, 100 pounds means only two out of the four kids and/or pets in my house can join the ride—it seems the cat, who is not likely to appreciate a ride anywhere, will have to stay at home.

40 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY 2022

««

WOOF Mad Dogs & Englishmen launched their first shop in Carmel specifically because it is a dog-friendly town.

Reservations Requested 5700 River Road, Santa Rosa • Thursday – Sunday, 11 – 4 woodenheadwine.com • 707.887.2703 Friendly, Artisan Winery Toast with bubbles then roll into the reds …they’ll leave you coming back for more! Point Reyes Arabian Adventures • Horseback Riding • Horse Trail Rides • Horseback Riding Lessons 11925 CA-1, Point Reyes Station, CA 94956 707.477.7181 | svrowsell@aol.com pointreyesarabianadventures.us

HITCHCOCK BY THE BAY

‘The Birds,’ Bodega and wine

BY DAEDALUS HOWELL

BY DAEDALUS HOWELL

HITCHED The iconic Alfred Hitchcock looms large over Bodega Bay.

HITCHED The iconic Alfred Hitchcock looms large over Bodega Bay.

When we think of filmmakers and wine, it’s likely in this order of appearance that they come to mind: Francis Ford Coppola, Orson Welles and Alexander Payne. Why? Coppola has long had a flourishing wine brand under his own name, Welles promised to sell no Paul Masson wine “before its time” in his famed TV commercials and, of course, Payne directed Sideways, which instantly sent sales of merlot plummeting— whilst elevating pinot noir a few price points. The oenophile director who doesn’t get mentioned much, and should be, is Alfred Hitchcock.

The stylish master of suspense flirted with wine throughout his storied career. He owned a vineyard in the Santa Cruz mountains—now known as Armitage Wines at Heart O’ The Mountain—and his 1946 spy thriller, Notorious, finds Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman as spies working against Nazis, uranium and a lot of wine. This is an explosive combination on any day but perhaps more so with a plot point contained in a rare bottle of 1934 Grands Vins de Bourgogne – Pommard Francois Penot & Cie.

Interestingly, Hitchcock also made more than a few visits to—not to mention movies in—our own local Wine Country. Shadow of a Doubt was shot in Santa Rosa and perhaps more notoriously, his ode to avian terror, The Birds, was shot in and around the oceanadjacent village of Bodega and the bay that shares its name.

Vestiges of the 1963 film remain in the area, the most prominent being the iconic Potter School House, which is still located 17110 Bodega Lane, Bodega. It’s a stone’s throw from the fantastic local eatery The Casino and crests a hill that overlooks a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it town of about 220 people total.

Built in 1873, prior to the The Birds, Potter School had been abandoned, but the film’s art department readied it for its close-up by repairing its facade. Sometime in the aughts, I led a tour of Producers Guild of America members through Wine Country, and this particular stop was an obvious favorite. Naturally, I couldn’t resist embellishing the school’s history with some improvised Hitchcockian intrigue—something about bodies in the basement; but don’t quote me.

It’s unclear to me what inspired the parking job, but I have my suspicions that it came from a bottle and didn’t contain Nazi uranium. I’ll refer you to a second-season episode of the television show, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, in which we find Hitch addressing the audience from a wine cellar:

“Good evening,” Hitchcock says. “I came down here because I understand that the current year is a very good year for wine. For drinking it, that is.”

That year was 1957, and Hitch was doing his usual droll introduction for an episode entitled A Bottle of Wine. In it, an older, insufferably pedantic judge is concerned that his younger wife is about to run off with a man her own age. The judge invites her paramour to a glass of wine and explains the bottle was purchased during a honeymoon in Spain. The young man drinks the wine after which the judge announces it’s poisoned, but ha!, it actually isn’t. In his resulting panic, the young man manages to kill the judge. When the wife returns, he tells her about the Spanish wine only to learn—spoiler alert—that she’s never been to Spain.

Should schedules align, across the street at the Sea Gull Antiques store, passersby may encounter a lifesize statue of Hitchcock himself. The likeness is something of a herald, signifying that the store is actually open—otherwise, I recommend calling ahead.

Inside, one will find a bevy of treasures, including a rack of postcards featuring the The Birds and its star Tippi Hedren, which I spied through the shop’s window—it was closed the Monday I visited. Also closed was the beloved Bodega Country Store one door down, which has been shuttered since late August after some cretin swerved their jeep off Bodega Highway and parked inside of it. A GoFundMe campaign has been established to aid its reopening.

What this Sartrean irony betokens is anyone’s guess, but it captures something of the experience of the director’s films themselves from the requisite whimsy to the twist of fate that is, if not macabre, at least mercurial. Notably, no wine was harmed during the production—not even fictionally, which, for my money, underscores an abiding reverence for the juice.

There is a photograph of Hitch, most recently seen on the cover of Stockholm University cinema-studies professor Jan Olsson’s tome, Hitchcock à la Carte, that depicts the director seated at a table, a roast chicken before him and a carving knife in his back. The weapon doesn’t seem to bother the director, who stares dolefully at the camera—and even if it did, he looks like he’s about to anesthetize himself with a very full glass of white wine.

The label on the bottle is illegible to the naked eye but, aided with a magnifying

43 2022 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY

AGUILAR.

PHOTO BY MERITT THOMAS. GRAPHIC BY MON

»»

JUICE The stylish master of suspense flirted with wine throughout his storied career.

THE BIRDS Hitch’s seminal movie has a cafe named after it, but alas, Turner Classic Movies Wine Club, the licensee of the Hitchcock wines, has yet to produce a wine in its name.

glass, I ascertained it likely reads “Pouilly-Fuissé,” which means it’s probably a chardonnay because, according to the company’s website “Chardonnay is the only voice through which the various Terroirs of the Pouilly-Fuissé are expressed.” Well, then.

A few years ago, Reed Brand Management, the firm that manages the Hitchcock brand for the erstwhile director’s estate, licensed the production of a series of wines named after his TV show. They were notably all red—no chardonnay in sight— including a popular 2013 zinfandel with a label reminiscent of the famous Vertigo

titles by Saul Bass. The romance copy declared that “Like the Master of Suspense, this idiosyncratic grape produces some of its finest work on location in California.” The grapes in question hailed from the Alexander Valley as well as—to bring it all home—Sonoma County.

Somehow, inexplicably, Turner Classic Movies Wine Club, the licensee of the Hitchcock wines, missed the golden opportunity to produce a wine for The Birds, with grapes sourced from the Sonoma Coast appellation. And, in keeping with Hitch’s burgundian predilection, the wine, ahem, without a shadow of a doubt, would have

been a pinot noir. Moreover, it could have been served in every restaurant up and down the coast, especially at … drumroll, please … The Birds Cafe Bodega Bay!

But, alas.

A bottle of “Alfred Hitchcock Presents Zinfandel 2013” will have to suffice; if you can find one. I recommend pairing it with the fish and chips from The Birds—in fact, its menu is almost entirely composed of fish, prawns, oysters and fries except the chicken strips—a faint gustatory nod to its cinematic namesake.

44 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY 2022

««

A few years ago, Reed Brand Management, the firm that manages the Hitchcock brand for the erstwhile director’s estate, licensed the production of a series of wines named after his TV show.

The Most Pet-Friendly Winery

45 2021 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY

GO FORTH Beauty beckons at the edge of Hitchcock Country.

Shop til you drop in our pawfect tasting room…indulgence at its best… come slurp, chomp & ru !

WINE TASTING | GIFT SHOP | DOG FRIENDLY | HOUND LOUNGE

JOURNEYING

The wild ponies of Middle Lion

BY LISA SUMMERS

My parents took my sister and I to Disneyland when we were little—but only once, and it wasn’t the happiest place on Earth. Neither of them could sustain happiness for longer than it took to smoke a cigarette. I was young, maybe third grade, my sister in kindergarten. We still lived in San Francisco, but my father’s sister lived in Downey, in her personal plastic paradise not far from Anaheim. I think it was the one and only time we visited her. I remember the Astro Turf in the living room and her daughter, my cousin Wendy, who flinched every time my aunt spoke. She was younger than us and already had a flat affect. Wendy never stood a chance.

»»

46 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY 2022

PHOTO BY LISA SUMMERS

ALL IN A DAY No Southern California road trip is complete without a stop at Salvation Mountain.

“Store with Confidence” O pen 7 Da y s a Week • Free Park ing Open 7 Days a Week Easy Parking 24 Bellam Blvd., San Rafael • 415.454.1983 www.bellamstorage .com Moving? Need More Space? We’ve Got You Covered! Celebrating Our 14th Solar Anniversar y! Best Place for Boxes and Supplies • Best Prices in Town “Store with Confidence” The first Green-Cer tified, 100% Solar Powered Self Storage in California. Unmatched, personalized ser vice with fantastic convenience , quality and security Come by for your free consultation and book on how to store properly! “Store with Confidence” We feel for tunate for all the positive response on our ser vices , staff and building Yes , we feel our building is alive with the positive energy from our tenants and customers and that enables us to concentrate on ser vice We thank you! “The facilities are safe and clean. I never worr y about my belongings . ” —E.McC (Visit our website for more testimonials .) BEST GREEN BUSINESS BEST SELF STORAGE 186 N Main St #230, Sebastopol | 707.861.3434 | blissorganicdayspa.com BEST SKIN CARE SPA Wellness and Beauty, In Balance GIFT CARDS AVAILABLE Step into Bliss!

We arrived in Downey in my father’s 1972 Camaro, which had no seat belts and only ran on airplane fuel, or that’s what he told everyone. It was the kind of thing he liked to say—a macho, short-guy lie. Maybe it did run on airplane fuel, but it was still up on cinder blocks most of the time. It had an 8-track cassette player and we listened to Yes and Crosby, Stills and Nash until the speakers blew. My father smoked dope and drank in the car, and my mother just slept so she didn’t scratch his eyes out. They had

both grown up in suburban Maryland, but my father used to tell people who didn’t know him well that he “hailed from North Texas.” His sister, on the other hand, was straight out of John Waters’ Baltimore with an orange bouffant, orange shorts, orange lipstick, aquamarine eyeshadow, white high-heeled sandals and a voice like Victoria Jackson.

I don’t recall anything about our day at Disneyland. I’m not sure why I forgot the fun parts—maybe there weren’t any. Here’s

what I do remember: My father refused to buy food, and my sister and I were both starving by the time we left. I had heat exhaustion and threw up in the car. The night that followed our visit to the Magical Kingdom was profoundly unmagical. We left Anaheim in the evening. My father was too cheap or too mean to get a motel room, so he decided we would camp on the way back to San Francisco. I know we drove to Los Padres National Forest because I always remembered the name— »»

48 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY 2022

««

DESERTS AND DRAGONS

Exploring the California wilds leads to adventures and misadventures alike.

ROAD TRIP ESSENTIALS TAKEOUT ORDERS • MAKE YOUR OWN PIZZA KITS BEER TO GO & DELIVERY • PIZZA DELIVERY TIL 3AM BEST: FOOD DELIVERY & DINING AFTER 10PM 70 7. 52NYPIE 707.526.9743 NEW-YORK-PIE.com 65 Brookwood Ave, Santa Rosa First Saturdays 3840 Finley Ave., Bldg 32, Santa Rosa 707.695.1929 First Saturday Nov. 6/21 11am to 4pm With West side Artists Lourdes Medina Daniel Howard Anna Rybat Gale McKee Art is alive and well at The Studio Santa Rosa Jazz & Blues are Back! �Sundays 2–5pm BEST BBQ & BEST TAKE-OUT time after time BUSTERS BARBECUE | CATERING | OUTDOOR PATIO 707.942.5605 | WWW.BUSTERSSOUTHERNBBQ.COM 1207 FOOTHILL BLVD, CALISTOGA, CA /busterssouthernbbq

Los Padres—like a whisper from God. It was dark when we arrived, and we had only a rented army-surplus tent and a thin cotton blanket between the four of us. It’s strange to think back on how poor we were then. My father was a resident or an intern—I can’t remember that, either. Now that he’s gone, I can’t ask him any more questions about the misadventures that led to his career as a successful headand-neck surgeon—his favorite subject—at the expense of his wife and children—my mother’s favorite subject. We couldn’t afford snacks at Disneyland or sleeping bags or water or a motel. I think that was supposed to build character in all of us, but it really just called into question his own.

As if the trip hadn’t been a disaster enough—staying with my aunt in Downey and then freezing in the tent—we woke up in Los Padres surrounded by a herd of grazing cows, just yards away from a firing range. My mother walked off towards the mountains and refused to get in the car. My father brought beer and Spam, and we were out of gas. He thought this was hilarious. I

think this was his way of telling us never to ask to go to Disneyland again. And we didn’t. Even then I sensed divorce was inevitable.

I went back to Los Padres this year with my husband, Scott. We were supposed to be empty nesters, but then Covid hit and we both had cabin fever.

Los Padres National Forest is huge, stretching across almost 220 miles of the Central Coast. Scott and I wanted to see Piedras Blancas after a tour at Lotus Land and before heading to Joshua Tree, where we were to meet our son and his girlfriend for Instagram moments among the fan palms and chollas. From there we were headed to Mecca, East Jesus, Salvation Mountain, the Salton Sea and into Anza Borrego to drive the Devil’s Drop Off—all very Old Testament, angry-father-sounding places.

We reserved a night at Middle Lion Campground about a half hour outside of Ojai, but it was for Sunday, not Saturday. In the fog of Covid time, I had gotten the days mixed up. I called the ranger station and the ranger told me where dispersed camping

was allowed inside the forest—just walk through the campground and across the creek, where we’d see a flat grassy area. That was our spot. Watch out for bears.

When we arrived at Middle Lion, the campground was occupied by a group. The people seemed normal enough—there was a toddler and a very round lab with a spiky collar who ran up to greet us. And, oddly, a pony cart. The dog’s owner, a woman I guessed to be in her early-to-mid-60s, in very tight-fitting activewear, approached us. “Don’t worry,” she said. “Queen Oliver is friendly. He’s just very interested in food, aren’t you Ollie?”

“I can see that,” I said. “Me, too.”

The dog had to execute a three-point turn to have his rump scratched.

It was already late in the day, so we needed to scout out the site where we were to sleep, and it wasn’t immediately obvious.

“Are you looking for a campsite?” the woman asked. “Because our friends had to leave early. You can have their site if you want.” She had a very distinctive way of stretching out her vowels and dropping

50 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY 2022

»» ««

It was dark when we arrived, and we had only a rented army-surplus tent and a thin cotton blanket between the four of us.

made local 2421 Magowan Drive, Santa Rosa in Montgomery Village 707.583.7667 | madelocalmarketplace.com WHISTLESTOP ANTIQUES Open 11am–5pm Daily • 130 4th Street • Historic Railroad Square • Santa Rosa 707.542.9474 • Whistlestop-Antiques.com Voted Wine Country’s BEST ANTIQUE STORE 24+ years Voted BEST PRIVATE SCHOOL 4 YEARS IN A ROW! Sonoma County’s oldest independent K–12 school WALDORF SCHOOL AND FARM Enjoy the beauty of San Francisco Bay aboard the traditionally rigged tall ship Matthew Turner. Board the ship in lovely Sausalito, at the Bay Model Visitors Center. You can lend a hand sailing the ship or relax and enjoy the views of Angel Island, Golden Gate Bridge and marine wildlife. Explore the Bay and learn about Maritime Heritage. callofthesea.org 415.331.3214

Inset photo by John Skoriak Background photo by Benjamin Spillman

her jaw for exaggerated annunciation, which I associate with people from L.A. I explained my mistake, and we gratefully accepted the offer.

“I book the whole campground once a year for our annual event. Not everyone can stay the whole weekend.” She smiled and seemed to size us up for a moment. “I mean, I need to tell you who we are, you know, to understand what we do—full disclosure about our kink.”

Scott’s eyes opened wide. “Oh?”

“Yes, we are the L.A. Chapter of Ponies and Critters. I am the founder.”

“What?” I asked. “The L.A. Chapter of what?”

“It’s a consensual role-play group,” she said. “Basically, we dress up as ponies and pull each other around on the pony cart. There’s more to it than that, other roles to play, of course. We have several play dates throughout the year.”

On the picnic table at our site was a clear plastic tube of streamers and pompoms. Inside her camper I could see a few leather bridles.

“Does Ollie participate?” I asked. “Only if he wants to.”

I had questions. Scott was just so stoked to be there.

We talked for a while about the campsite and what there was to see in the area, as we unloaded the car. The woman told me she had discovered Middle Lion in the ’70s while she was making bondage films. She put a few images in my head that I can’t unsee.

We made dinner in the dark and hid in our tent where we could eavesdrop inconspicuously. Two of the members were middle-school teachers—one was in tech, and one was in diapers. One of the men was an avid through-hiker who had discovered the PCH late in life. He spent the better part of an hour talking shop about boots and backpacks and GPS trackers with another guy who had also arrived late to the campground hoping to score an empty site. We had clearly missed the best of the revelry.

In the morning, Ponies and Critters cleared out. Staring at us on the picnic table

was the plastic box of props. Scott wanted to deliver the box, since we would be driving through L.A. “L.A. is an event horizon,” I protested. I called my daughter, who called her friend in Virginia to find out more about Ponies and Critters. “You should open the box, Mom.”

We left it. I finally succumbed to curiosity and looked them up.

“All pony and critters are welcome in the club, as well as trainers and handlers. The diversity of the club enables us to exchange ideas and possibilities and to be welcoming to all individuals regardless of their level of involvement or interest levels. We have some unowned critters and trainers looking for their pets and we aim for all critters and trainers to get some experience in their role, so even if you do not have an owner or a pet, you are very welcome in our club.”

Somehow Ponies and Critters seemed a reasonable proposition compared to trips with my father. Memories of our childhood camping trips with him came into sudden and painful focus.

52 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY 2022

»» ««

The woman told me she had discovered Middle Lion in the ’70s while she was making bondage films. She put a few images in my head that I can’t unsee.

15 Annual GINGERBREAD HOUSE TOUR & COMPETITION Dec. 1–31 Download a map & Vote for Your Favorite! @SausalitoGingerbreadhouses #SausalitoGingerbreadHouse Support Sausalito Business Buy Local, Shop Local, Dine Local! Stop in to our new Visitor Center and see some of our businesses Gingerbread Houses on display! 22 El Portal Avenue, Sausalito, 415-331-7262 www.VisitSausalito.org www.Sausalito.org Tour Sponsors THE 222 Healdsburg’s New Performing Arts Venue THE222.ORG JAZZ CLASSICAL CONTEMPORARY Experience the arts like never before CHORAL Our Barn Shop & Cantina are ready to welcome in the holiday season with everything you need. Celebrate with Cheese COWGIRLCREAMERY.COM | @COWGIRLCREAMERY

On the way down the mountain, we passed a firing range. I was never sure whether or not the firing range was one of his embellishments, and my mother is no longer alive to vet his stories. He had taken me to Kings Canyon when I was five, where we slept on an old mattress in a Ford Econoline, ate ham from a can and he played the one song on the guitar he knew: “Stewball.” On the way home he let me sit on his lap to drive, and I drank beer, too. Another time he took my sister and I to Big Sur, where he broke all the speed limits on Highway 1, drank more beer and picked up hitchhikers stumbling out of the redwoods. He listened to “Dream Weaver” and “Free Bird” while we got car-sick in his smokefilled Camaro with some random tweaker

in the front seat. Then there was the time he took us to the Sierras in late spring and made us sleep out in the middle of the raging Stanislaus on a boulder. I learned to drive in that ridiculous car on the winding roads of Mount Tam—a near-death experience—and I wasn’t allowed to shift gears using the clutch. He wasn’t overly concerned about the carbon monoxide problem, either.

When I had to pick a place to scatter his ashes last year, the obvious choice was Hetch Hetchy, where he had taken my sister and I to swim—illegally—and dropped the keys to his Camaro into the abyss. We watched him swim down until he disappeared between the submerged boulders, still wearing his jeans, and resurface, miraculously, with the keys.

Maybe he was most terrified, as a troubled young father and doctor, of becoming what was expected of him, and wanted us to experience both the awe and the fear that he felt—and a lot of loathing. Who knows. I have re-visited all those places since his death last summer, with the sole exception of Downey. It’s hard to know what to make of it all; California’s wild places are so overrun, and the people so unafraid.

Leaving Los Padres, I felt I had failed, in some sense, to step into the role of the hungry lion, a coyote, a free bird—an unowned critter—at least once in my life. Maybe that’s the lesson the cart pony teaches us.

54 EXPLORE THE NORTH BAY 2022

««

BLEAK Father was too cheap or too mean to get a motel room, so he decided we would camp on the way back to San Francisco.

Best Thai Restaurant My Thai Restaurant • 415-456-4455 1230 4th Street • San Rafael Open 7 Days a Week • Lunch 11–3 • Dinner 5–9:30 mythai.com Mill Valley • Lush plants & lovely things 5 Fourth Street, Petaluma 707.971.7666 flourishbayarea.com @flourishbayarea 132 N Main Street, Sebastopol 707.827.8294

848 B St. San Rafael, California | californiagoldbar.com We are open 7 days a week: Sunday–Wednesday 4PM–12AM | Thursday–Saturday 4PM–2AM Golden Hour: 4PM–6PM Daily Best Bar Best Cocktails

BY JANE VICK

BY JANE VICK

BY JANE VICK

BY JANE VICK

BY CHRISTIAN CHENSVOLD

BY CHRISTIAN CHENSVOLD

BY DAEDALUS HOWELL

BY DAEDALUS HOWELL

HITCHED The iconic Alfred Hitchcock looms large over Bodega Bay.

HITCHED The iconic Alfred Hitchcock looms large over Bodega Bay.