Where do you believe the soul is housed? Is it in your mind, your heart, or even your stomach, tucked away behind some nook or cranny that medicine can neither define nor see? Is it the people we hold dear, the food we make to nourish ourselves, the quiet before we drift off into sleep?

In the time that this publication has existed as Nova, we moved from the celestial bodies above us to the dreams that defy our material reality. This year’s edition examines what we define as Soul. Inspired by Plato’s tripartite division, we looked beyond what the work of our contributors could be on their own and crafted three books to reflect aspects of our definition of the soul.

Does your soul search for order? Your consciousness, constantly looking for answers in a chaotic world, may crave an unsolvable set of questions, the measured ticking of a metronome, or the glint of a mirror that reflects the inner self.

Does your soul strive for greatness? Honor is found in the legacy of your passions, ambitions, and desires; the soft brush of a laurel wreath rests easily upon your brow.

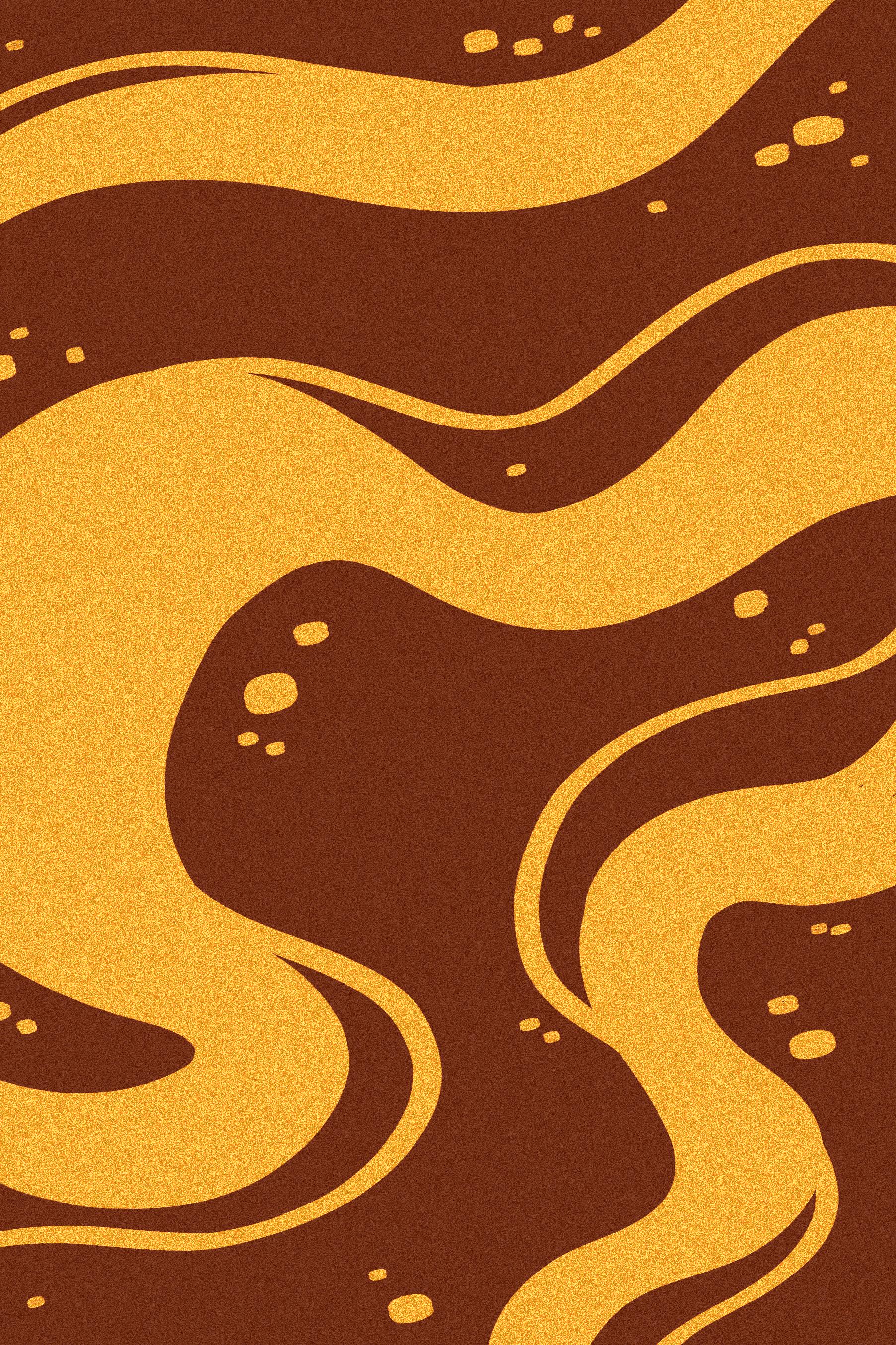

Does your soul savor earthly comforts? You may find joy– or a guilty pleasure– in the glint of gold under the summer sun, the soft glow of burning embers, and the heat of two hands held together in winter snow.

I encourage you to try to find pieces of your soul between the pages of this magazine. Our work is the truest reflection of our souls in standstill moments of time, snapshot images of what we cling to as dearest and regard as curious and awe-inspiring. Look for the moments that bring you to a halt, for what your own soul recognizes as art from a kindred spirit.

Where do you believe the soul is housed? As to my answer, I believe it lies in the stillness of a keyboard after the frenetic movement of fingers, in the clatter of a brush against a palette exhausted of its color, in the moment after a pen leaves the page for the final time. I believe it is here, in the pages of issue 55.

As our submission process has evolved over time, so too have our procedures regarding the selection of pieces. In 1998, we formalized our review and introduced an external jury of judges composed of UNC Charlotte faculty across multiple disciplines and departments. While the size of this panel and its membership has differed from volume to volume, it has been an essential component of our operations for over twenty years.

However, with this year’s issue, we’ve made the difficult decision to remove the external panel from our submission process. We feel Charlotte’s community and our readers deserve to know why we made this decision.

Our submission pool has grown exponentially since we introduced our digital portal in 2013. As the workload for each juror has increased, asking our judges to review and give individual feedback to each piece has become unsustainable.

As the majority of our contributors are Charlotte students or alumni, there is a non-zero possibility that jury members will have seen student work before the judging period. This introduces bias that cannot be accounted for.

All other aspects of production are handled in-house. We want to unify our operations and allow our editors to gain experience and take ownership of the final product.

The integrity of our review is not affected by this change. Each submission is reviewed independently by each editor over three rounds, and each piece is stripped of identifying information, ensuring that they are judged by their merits alone and not by their author.

Jeffery Alfier: JC Alfier’s (they/them) most recent book of poetry, The Shadow Field, was published by Louisiana Literature Press (2020). Journal credits include The Emerson Review, Faultline, New York Quarterly, Notre Dame Review, Penn Review, Southern Poetry Review, and Vassar Review.

Chris Allard: Chris is a Senior currently getting his BFA in Digital Media. He has a passion for Animation, Digital Art, and Photography. In his work, Chris has an interest in capturing and engaging with characters and moments as a way to tell a greater story.

Sydney Carmer: Sydney Carmer (she/they) is a senior in the Art & Art History Department at UNC Charlotte. She is pursuing a BFA in Art with a double concentration in Digital Media and Illustration. She is also double minoring in Psychology and Art History and is a part of the Arts & Architecture Honors Program. After college, they hope to find a career in postproduction.

Uma Chavali: Uma Chavali, an undergraduate student at UNC Charlotte, is pursuing a major in Business Analytics alongside other academic disciplines. Beyond her studies, she aspires to be a wildlife photographer and artist, driven by a passion for capturing the beauty of nature through a lens and creating art that reflects her unique perspective.

Kelli Crockett: Kelli Crockett is a multimedia artist who graduated with a BFA in Art from UNC Charlotte in December 2023. She has concentrations in painting and digital media and a minor in Art History. Crockett’s work focuses on themes of identity, memory, and the unreality of human emotions. Once she graduates, Crockett will continue exhibiting her developing body of work, pursuing local residencies, and her education with an MFA.

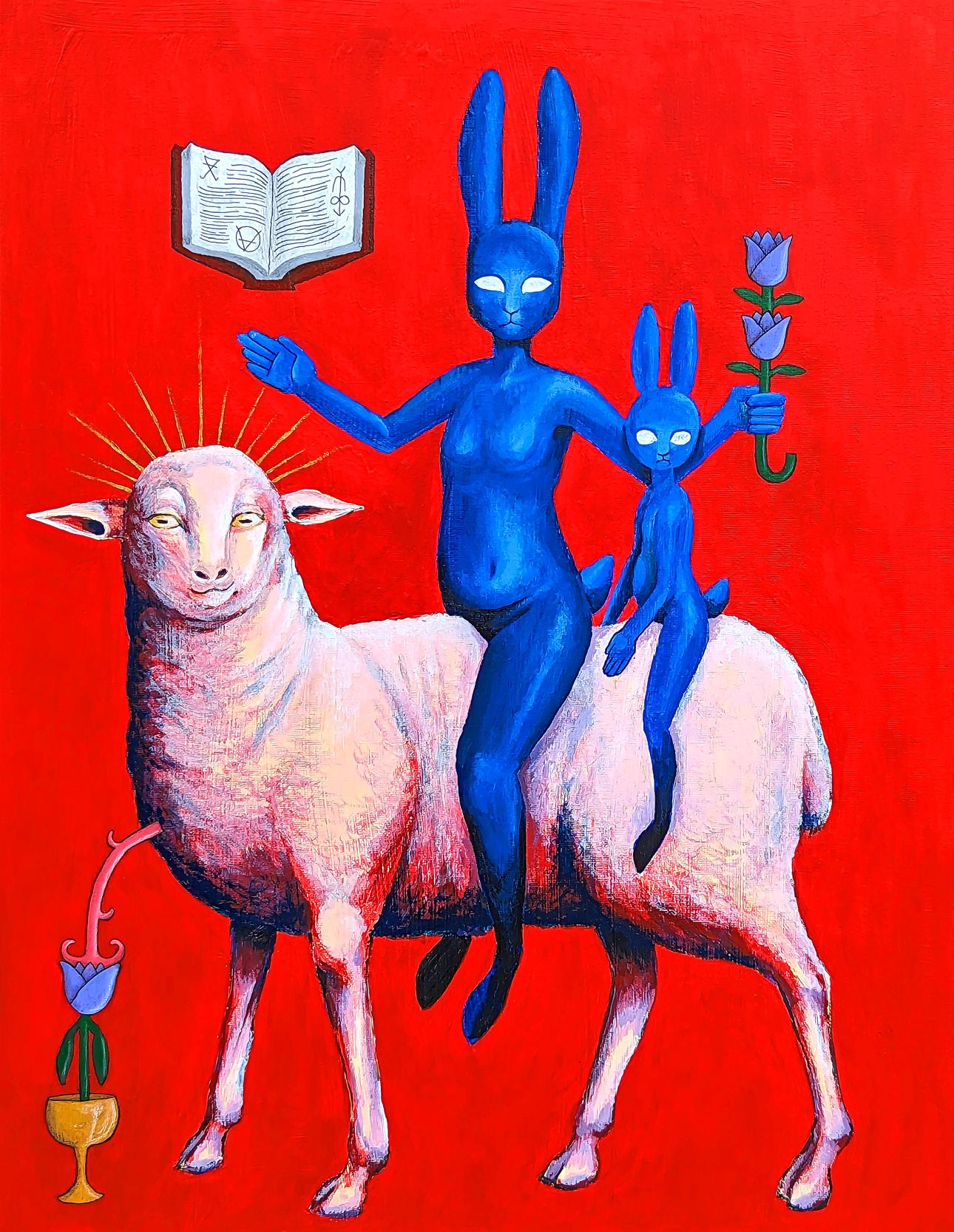

Cadaver Doe: Cadaver is a UNC Charlotte Alumni now living in Asheville, NC. She earned her Bachelors in Fine Arts back in 2018. Out of her home studio, she creates paintings, blockprints, and costumes primarily featuring rabbits. Her most prominent body of work is the “Red Series.” Cadaver uses rabbits as her most prominent motif. They are an ironic fertility symbol referring to the artist’s struggle to conceive children.

Olivia Hedrick: Olivia Hedrick is a multimedia fine artist in her final semester of pursuing a Bachelor of Fine Arts with a concentration in Education at UNC Charlotte. Her art focuses on better understanding our pasts and our present to create a better future, and on creating whimsical art that reimagines the mundane.

Titania Hunter: Titania Hunter is a Charlotte, NC-based multidisciplinary visual artist. She obtained her Associate of Arts degree from CPCC in 2020 and is graduating with her BFA in Painting from the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She received the Roderick MacKillop Memorial Painting Merit Scholarship Award (2023-2024). You can view more of her work on Instagram @titaniahunterart or on her website at www.titaniahunterart.com.

Maya Hutagalung: Maya Hutagalung is a current art student at UNCC. Maya has always enjoyed drawing and painting. Nature is her favorite muse. Often, she will paint or draw landscapes, either live at the scene or from a photo she took at the scene. If not, her artwork is often inspired by stories she’s made up.

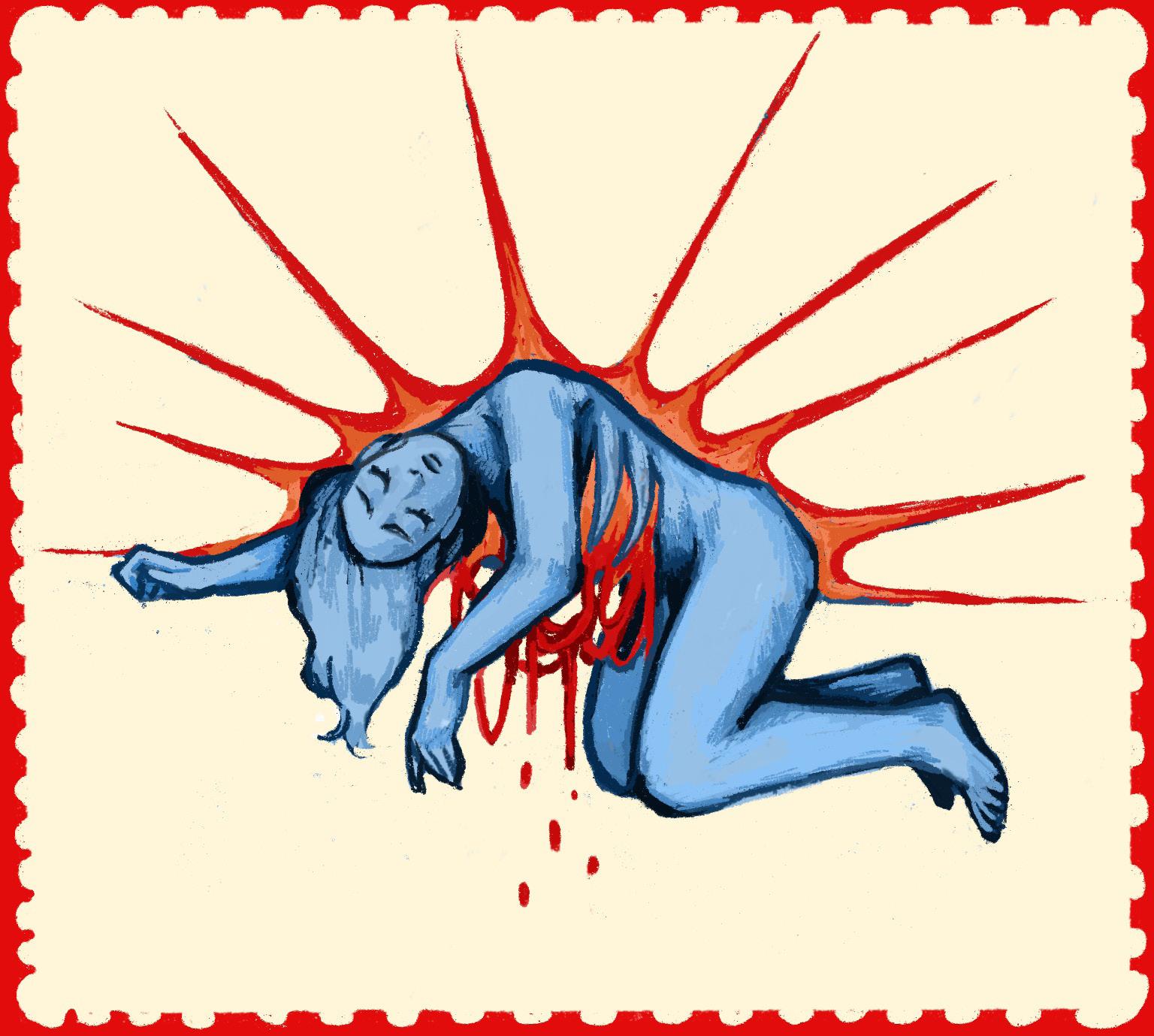

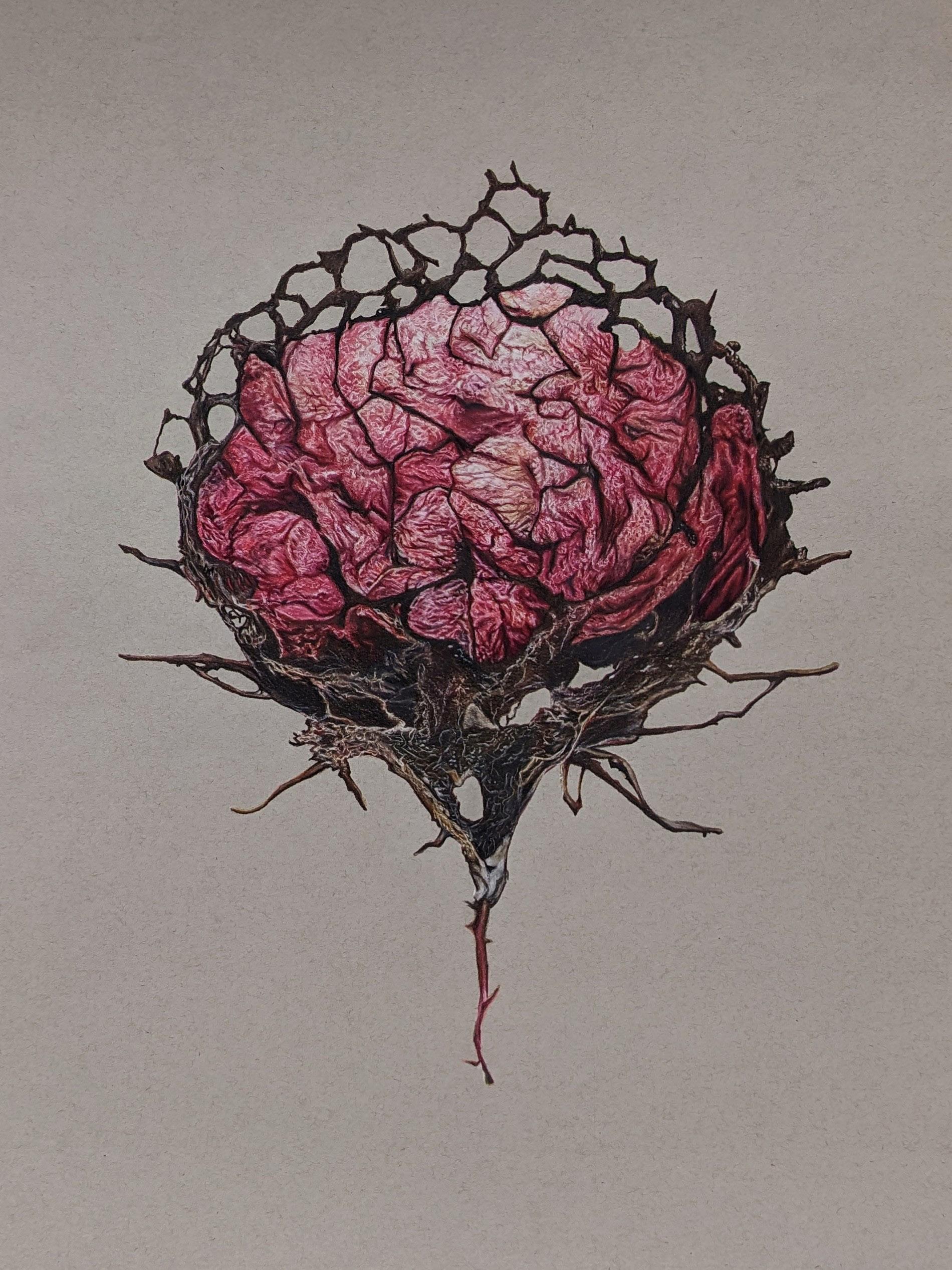

Simon Lane: Simon Lane is a full-time Illustration student. A principal theme in their work is exploring different facets of the human experience, often drawing on the body and the macabre.

M.A: As a queer and trans-Honduran, M.A explores facets of their identity through their visual works. They use varied mediums to express subjects from their experiences, such as growing up in a Honduran household or growing into their gender identity and gender expression. From crochet to gouache, they are unbound by the mediums they use and never stick with just one.

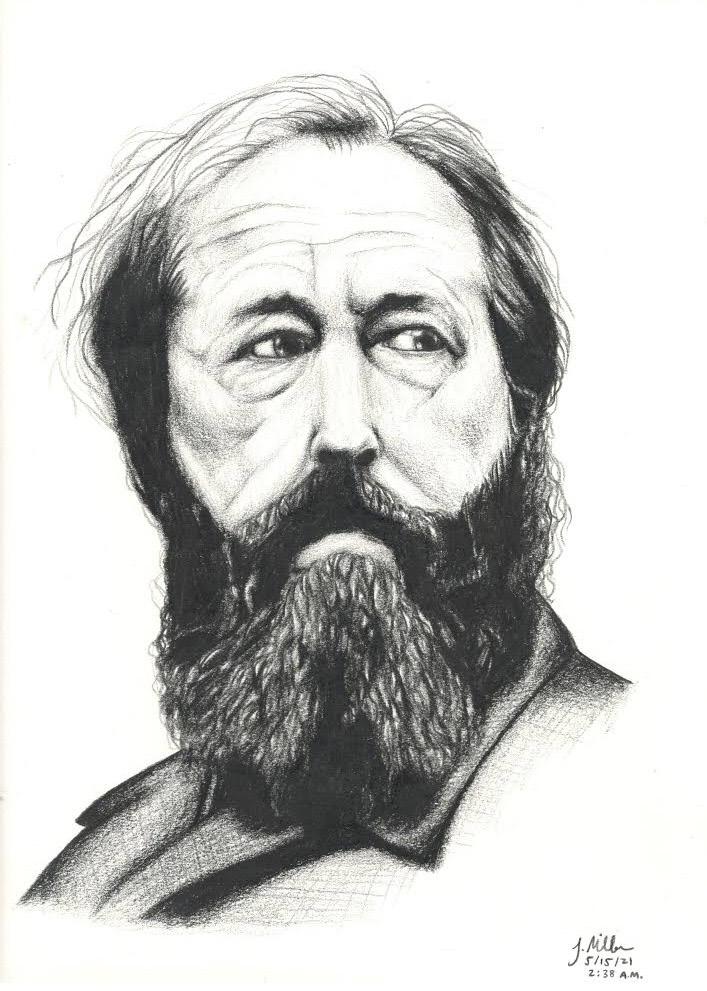

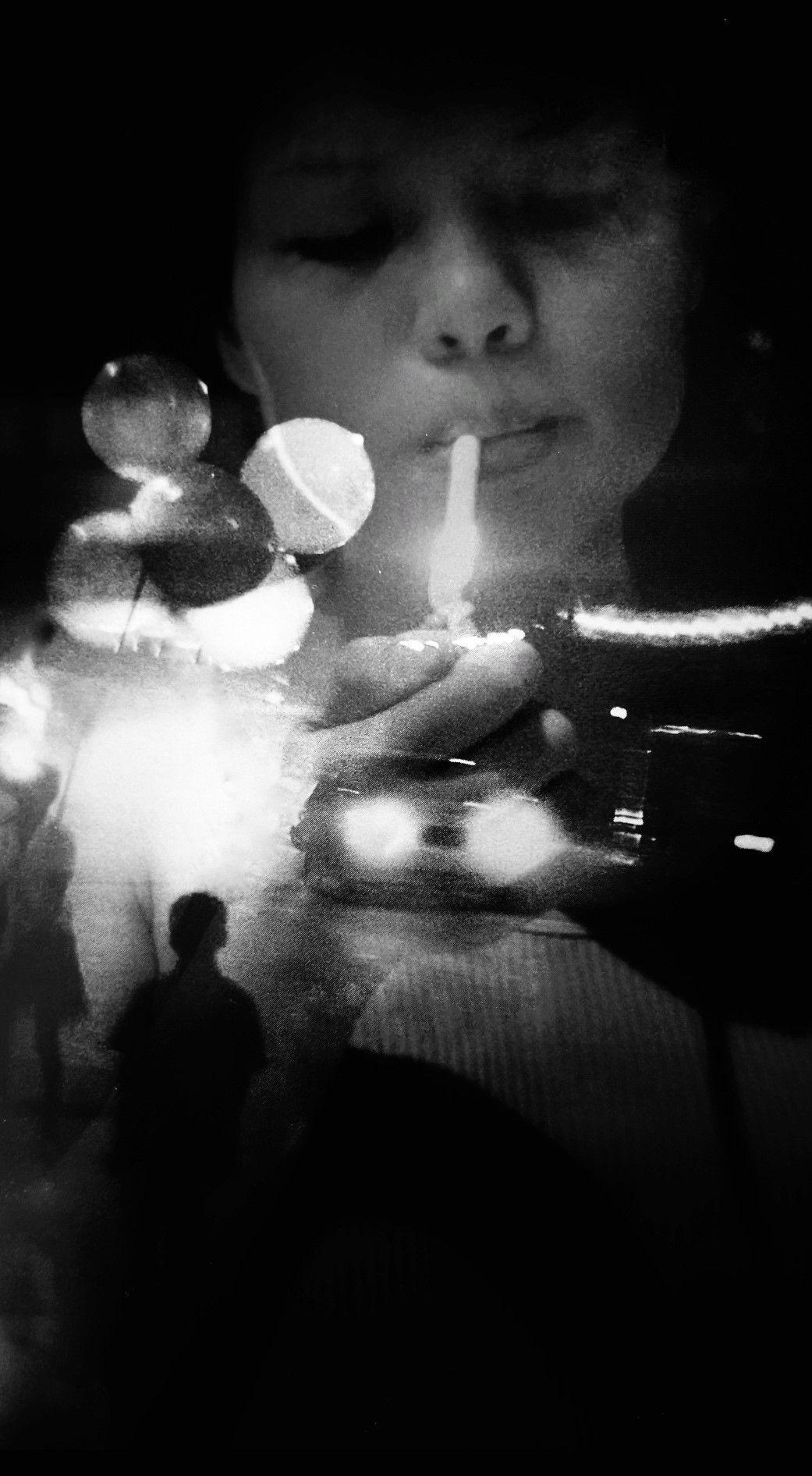

Jessica Miller: Jessica is a Ph.D. student in Epidemiology at UNCC. She loves to train jiu-jitsu in her free time and hang out with friends on the weekends. She is an avid movie watcher and reader when she has the time. Although she mainly creates black-and-white art pieces, she is constantly trying to create pieces outside of her comfort zone.

Lisa Mirisola: Lisa is a BFA student with a concentration in Painting at UNCC. She is graduating in December 2023. After graduation, she plans to continue her interest in art by exploring her interests in graphic design, gallery, and curatorial work.

Katie Moua: Katie Moua is a student at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte majoring in Graphic Design. She was born and raised in southern California and is currently living in North Carolina. She likes to travel and take photos. She favors 2D and digital art, as well as photography, and aspires to be a graphic designer working for magazines.

Richard Nuzzo: Richard Nuzzo Jr, an emerging artistic force who passionately captures the world through the lens of their camera. As a self-taught photographer, their unique perspective blends creativity and technical skill, producing captivating visual narratives. With an eye for detail and a heart for storytelling, Richard invites viewers into a realm where every frame tells a vivid and personal story.

Sami Pacitto: Sami Pacitto is a photographer based in Charlotte, North Carolina. She received her Bachelors in Fine Arts in Photography in the Fall of 2023. Her BFA group exhibition, titled Collected Fragments, featured eight of her rural landscape photographs focused on documenting the fences of local farms.

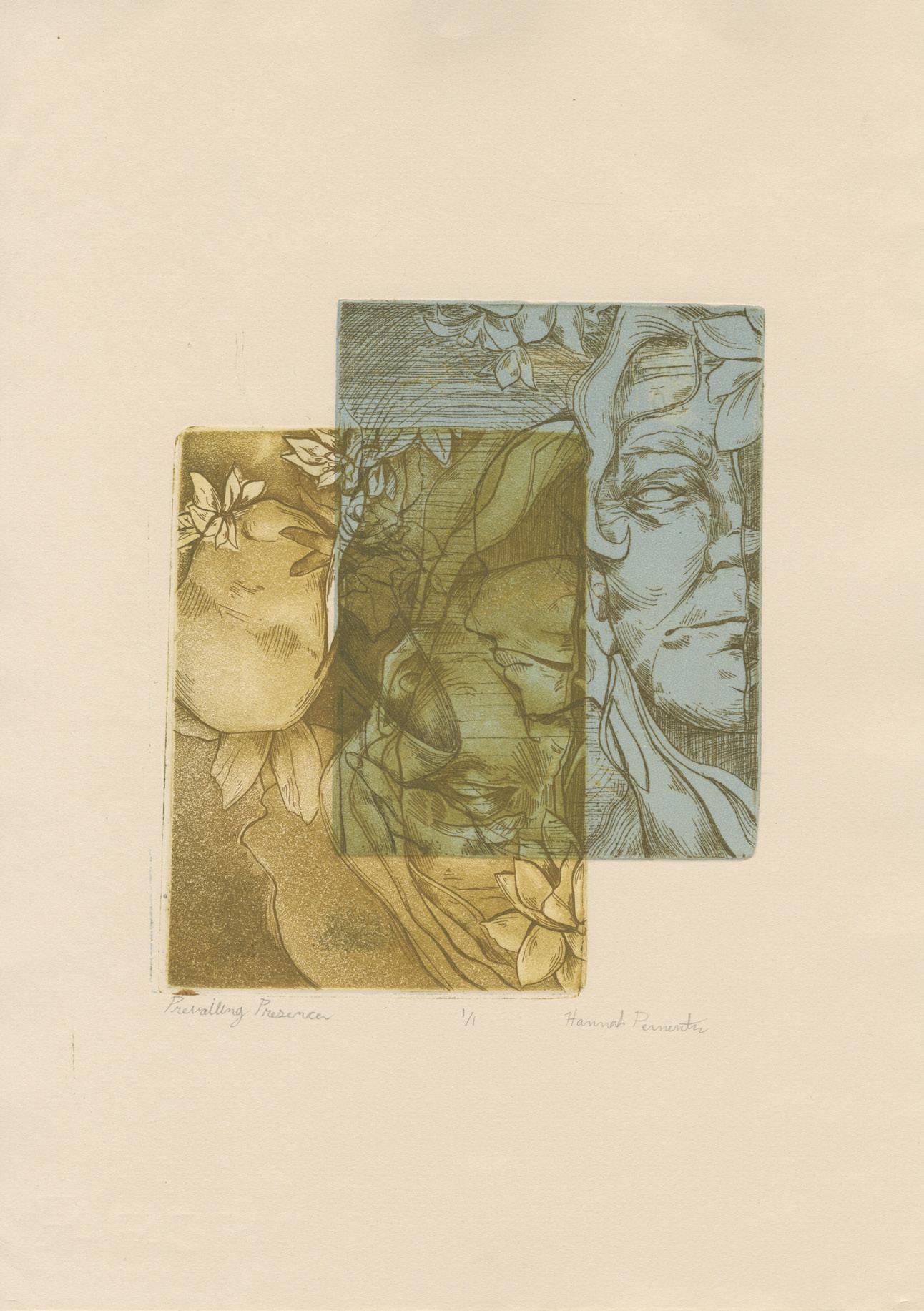

Hannah Permenter: Hannah Permenter is an illustrator currently pursuing a BFA at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Her goal as an artist is to make work that brings value and joy to other people, be that through telling a story or by making someone smile. Hannah’s main mediums of choice include watercolor, colored pencil, and digital painting.

McKenzie Perry: McKenzie Perry is a young adult painter, who primarily works with acrylic. She started painting in 2020 and has since started selling her pieces internationally through Etsy. She has also taken commissions.

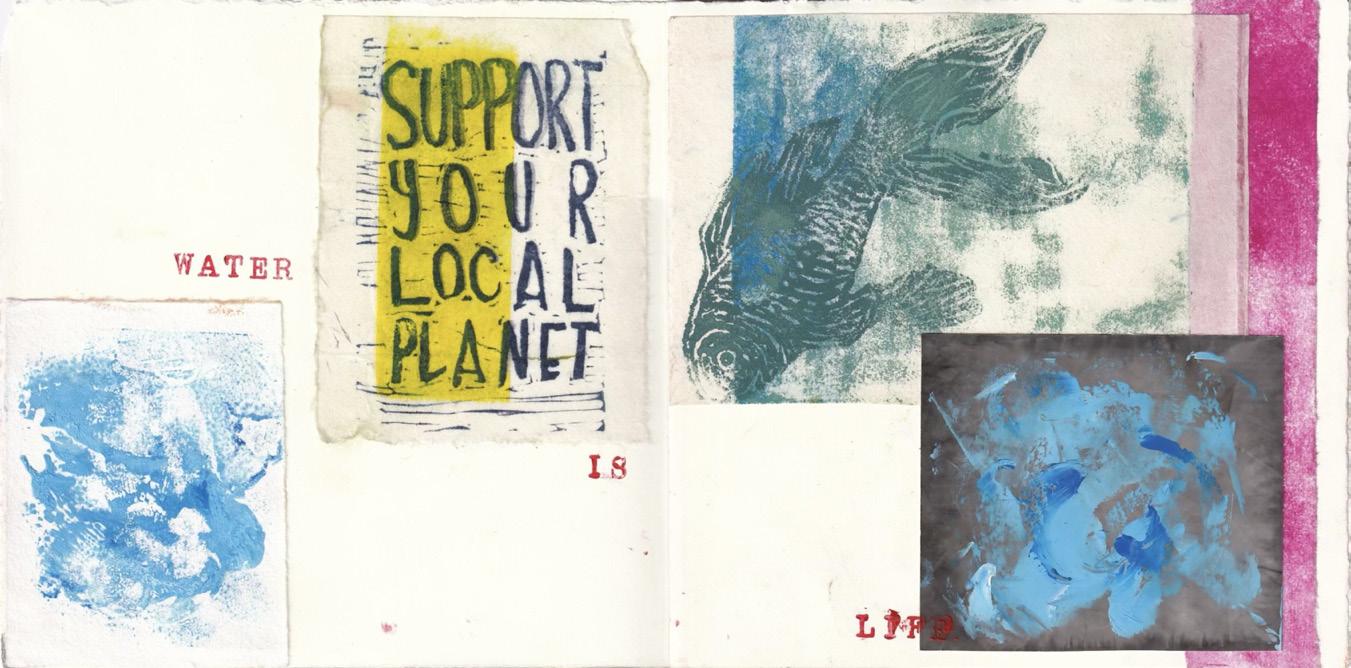

Constance Sartor: Constance “Coco” Sartor is an artist with a background in marine science. She is currently pursuing her Masters in Architecture degree at UNCC. Her artwork is inspired by the natural world and she aims to promote environmental stewardship through her artwork which includes illustrations, murals, and analog collages.

Jade Suszek: Jade always has her camera on her to capture life’s moments. Nothing stays the same forever and she manages to preserve the fleeting moments in life. Her favorite genres to photograph are portraiture, landscapes, and concerts.

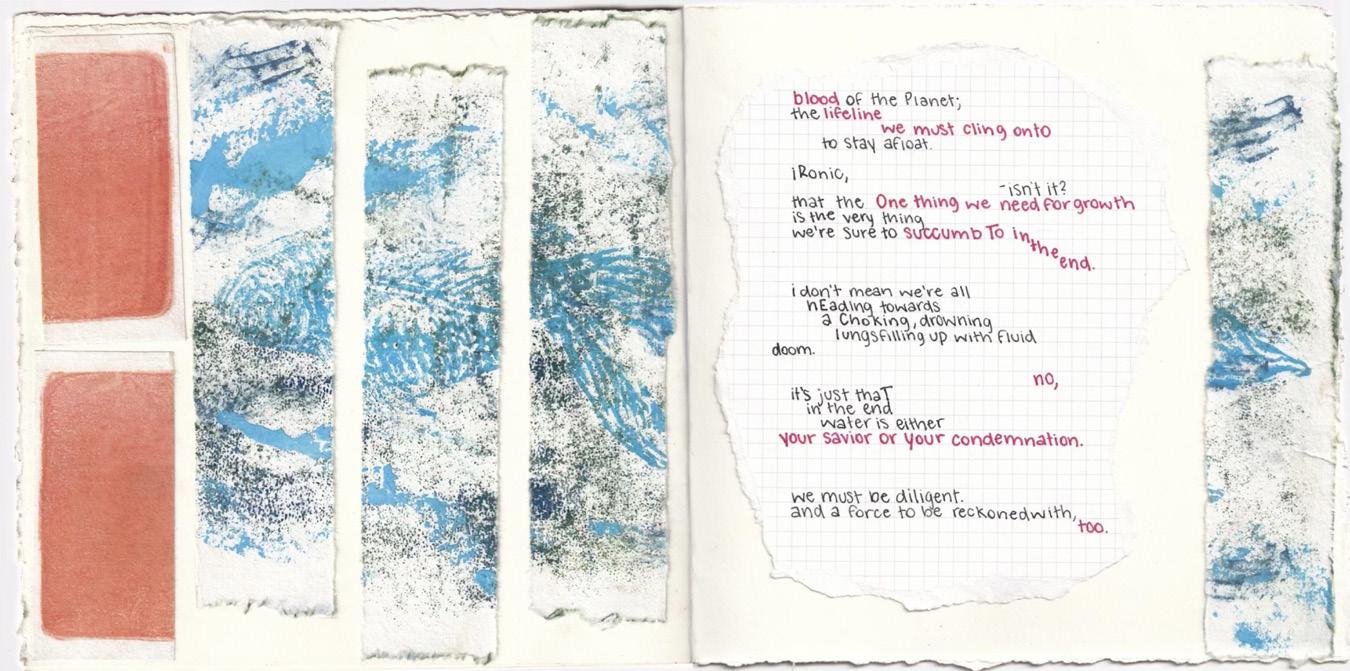

Zoe Turner: Zoe Leigh Turner (she/her) is a student at UNCC, and will receive her BFA in Art with a concentration in Print Media in Fall 2024. Painting, photography, and printmaking are her mediums of choice, with topics of environmentalism and social justice being her main focuses. Zoe is also a writer, thespian, lifeguard instructor, dog lover, and dedicated napper. You can see more of her work at zoeleigh.com.

Angel Uy: Angel is a UNCC student who works with various mediums of art to express life experiences and tell stories. She hopes her art can inspire people and connect to the world so that others can take meaning from what she creates.

Barbara A. Meier: Barbara A Meier is a writer living in Lincoln, KS. She loves walking where her grandparents walked, watching baseball where her dad played, and sitting in the same church where her great-grandfather preached. She loves all things ancient. She works in a second-grade classroom and in her free time she likes to drive the dirt roads around Lincoln.

Matthew Caskey: Matthew Caskey is an English major with a concentration in Creative Writing and a minor in History. He is from Monroe, NC, and he has a cat named Sailor.

Timothy Dodd: Timothy Dodd is from Mink Shoals, WV. He is the author of the short story collections, Fissures, and Other Stories (Bottom Dog Press), Men in Midnight Bloom (Cowboy Jamboree Press), and Mortality Birds (Southernmost Books, with Steve Lambert), as well as poetry collections, Modern Ancient (High Window Press) and Vital Decay (Cajun Mutt Press). He is also a visual artist who primarily exhibits in the Philippines. Sample his artwork on Instagram @timothybdoddartwork. His website is timothybdodd.wordpress.com.

William Doreski: William Doreski lives in Peterborough, New Hampshire. He has taught at several colleges and universities. His most recent book of poetry is ‘Venus, Jupiter’ (2023). His essays, poetry, fiction, and reviews have appeared in various journals.

Jonathan Doughty: Jonathan Doughty is a graduate of UNC Charlotte. His writing has appeared in Little Patuxent Review, Chiron Review, and a host of joyless academic journals. Send him ideas at yonatandoughty@yahoo.com.

Maya Osaka: Maya Osaka is a junior at UNC Charlotte majoring in English (Creative Writing) and Philosophy, and minoring in Holocaust, Genocide & Human Rights Studies. Outside of writing poetry, she ends up watching terrible reality TV with her roommates and waiting for the New York Times crossword.

Gerard Sarnat: Poet/Aphorist Gerard Sarnat is a widely-published physician who’s built/ staffed homeless/disenfranchised/prison clinics, particularly for monolingual Spanish speakers, and worked as a Stanford professor and healthcare CEO. He belongs to the longestrunning U.S. Jewish-Palestinian dialogue group, has served on New Israel Fund’s International Board, devotes energy and resources to global justice, and serves as a Climate Action Now board member. He has been married since 1969 and has 9 grandkids. He looks forward to future granddaughters. Gerardsarnat.com

Jackson Stover: Jackson is an English Major at UNCC. He grew up in King, North Carolina, just outside of Winston Salem, and has always had a love for any type of art form. He has always enjoyed writing fiction, alongside poetry and lyrical writing.

Heaven Carter Williams: Heaven Carter Williams is a third-year student at UNC Charlotte. She is an English major with a minor in Diverse Literature and Cultural Studies. Whether it be love, joy, grief, or anything in between, Heaven’s literary works are always inspired by personal life experiences. Her poetic works in particular are very dear to her, but she looks forward to the opportunity to be able to share them with others.

Kathryn Worley: Kathryn Worley is an undergraduate English student at UNC Charlotte. When she is not writing for school or herself, she is walking her dog, trying new recipes, or finding a new hobby.

Alessio Zanelli: Alessio Zanelli is an Italian poet who writes in English. His work has appeared in over 200 literary journals from 17 countries. His sixth collection, titled “The Invisible”, was published in 2023 by Greenwich Exchange (London). For more information please visit www. alessiozanelli.it.

Grace Yochem is a senior studying English with minors in Data Science and Communication Studies. She is currently working on her undergraduate thesis and staying sane. She loves going on midday coffee runs with the Nova staff, playing DnD or Fortnite with her friends, and listening to the same three albums obsessively.

Associate Editor

Skylar Hatch is a junior studying English with a concentration in Creative Writing. She has two minors in Technical & Professional Writing and Journalism. Skylar spends her time reading, journaling, studying at local coffee shops with her friends, and battling writer’s block. She dabbles in music and art by writing songs on her ukulele and painting with watercolors in her dining room. Add her @skyghatch on Instagram.

Lead Designer

Landry Hutchens is a sophomore studying Graphic Design and Marketing. Landry has over ten million victory royales in Fortnite. Out of office, you can find her at Caribou Coffee poring over her newly developed film photos. Check them out @landry.hutchens.

Zachary Jenkins is an undergraduate studying English and Computer Science. He is a constant presence in the Student Niner Media offices: phantom-like and incorporeal, he wanders about, yellow Red Bull in hand, muttering to himself. His fiction has appeared in several journals, and he is at work on more of it. You can reach him by email at znjenki@gmail.com.

ZACHARY JENKINS Content Editor

Content Editor

Hannah Yarrington is a senior majoring in English with a concentration in Language and Digital Technology and a minor in Technical & Professional Writing. Whenever she isn’t hanging out with friends or listening to music, Hannah likes to curl up on her couch to read a good book, prompting her roommate to ask if she’s moved or eaten that day. You can reach her on Instagram @513hny.

HANNAH YARRINGTON

George Stern is a junior in the Graphic Design program. He once strangled a bear with a rubber band but brought it back to life with a can of Coca Cola. He dedicates all his efforts in the Nova Literary Arts department to his grandma. "Love you grandma."

GEORGE STERN Graphic Designer

Ben Stadler is an undergraduate in the Graphic Design program. He is a big fan of PC hardware. He is a big movie guy. He does digital art and renders too. Contact him @ben.stadler with music that sounds bad. That's his favorite type.

BEN STADLER Graphic Designer

Jonathan Revoir is a junior studying Computer Science with a concentration in Data Science. When Jonathan isn't hiding out in a small tunnel he constructed under the desks in the Nova office, you can find him idling around UNCC campus in search of a free drink from the Red Bull truck. He also enjoys listening to hyper-pop, playing video games, and theorizing about what he would do if he were a horse. You can reach him on Instagram @jonathan_revoir.

JONATHAN REVOIR Website Manager

Ashani Pendleton is a junior majoring in English and Theater and minoring in Chinese. When she’s not spending an unhealthy amount of time obsessing over her favorite books and movies, Ashani can be found adding to her rapidly growing mug collection or attempting to work on one of her many story ideas.

ASHANI PENDLETON Promotions CoordinatorCopyright 2024

Nova Literary-Arts Magazine and the Student Media Board of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without permission of the copy holder.

iTek, Charlotte, NC

2000 copies of each magazine for Nova Literary-Arts Magazine were printed on 100lb Silk Text. Each cover was printed on 80lb Silk Cover. This magazine contains 16 pages, with a trim size of 6 x 9 inches. The other three magazines contain 30 pages, with a trim size of 6 x 9 inches. 2000 box containers were printed on 24.00 pt Tango C1S with an AQ Soft Touch Coating and clear foil on one side. They have a size of 9.25 x 6.25 x .625. inches.

Typography

Cushion Family

Neuton Family

Appropriated

Adobe Creative Cloud 2024

Google Workspace

iMac Computer (24” 4.5k Retina Display, Apple M1 Chip, 2021, Silver and Mint Green)

Zoom Cloud Meetings

Fortnite Zero Build

Meowing

Panera Charged Lemonades

Disco Elysium

Plato’s Theory of Soul

The Multitudes You Contain

Credits

Book Casing and Cover Designs: Landry Hutchens

Layout Design: Landry Hutchens, Ben Stadler, George Stern, & Alex Schauble

Interior Illustrations: Landry Hutchens & Ben Stadler

Staff Photography: Landry Hutchens

Copy Editing: Skylar Hatch, Zachary Jenkins, Hannah Yarrington, & Ashani

Pendleton

Jury Removal Explanation: Grace Yochem & Zachary Jenkins

Submission Guidelines

Please visit novacharlotte.com to view past issues, submission forms, and general requirements.

“The mind is not a vessel to be filled, but a fire to be kindled.”

- Plutarch

You can’t have me there.

—El MiguelDraw me the wind if you can—I asked. Here it is—he replied, after dragging the pencil across the blank sheet without leaving a mark. We looked into each other’s eyes— his face turned serious, but he snickered inside.

Crouching next to the glass, I take photos of a mottled frog pressed up against the tank. My father reads the placard for me— Ishikawa’s frog, from the tropical archipelagos of the Okinawa islands. They are found tucked into the streams and rocks of the Yanbaru forest, settled into the mosses that blend with their spotted green skin. A quiet companion of the islands. When my father tells me they are endangered, now a rare find between slaughtered trees and polluted rivers, he does so in crumpled words roughly translated for my English tongue. The two of us have never had reason to name something like this– to call forth the word “extinction.” And I imagine now how this pressed down on my father, caught in the unblinking gaze of Ishikawa’s frog, to see his language dying in his daughter’s mouth.

They say the world is sick, its blood corrupt, its breathing labored, and— it is our fault, truly solely ours. I am convinced of that—more than something’s not quite right, and our hand’s in it.

I am not sure to what exact extent we are to blame. In fact—that’s not so important. What really matters is all we do know—nobody dares ignore, no more.

As for me, I only hope I’ll be able to see the hoarfrost again, before I—too—have to call it quits. I mean—the dress of homeland as it used to be, when the world was sound.

The shiny-white blades of grass, shivering in the liquid light of early morning, and the spectral-silver trees, silhouetted in the goldening haze of late afternoon.

For days and days on end—once more—in the silence of subdued light, in the slow flow of midwinter. I walked in by it, a child of cold. I’d like to walk off on it, a man of old.

Boxed In Jessica Miller

What you think are glacial boulders are fossilized eyeballs of titans. Press your ear to one and hear moss and lichen murmuring, arguing about priorities. Kiss the gnarled surface and taste

the history of massive beings self-extinguished when their bodies required impossible fodder. Now that elephants and whales are tottering toward extinction, we’re the largest creatures in sight

Of course great underground fungi snicker at our cultural pretense. And horses and cattle regard us with disinterest and surly disdain. But since we don’t keep horses and cows and since our farming neighbor sent his belted steers to the slaughterhouse our savvy and bulk go unchallenged, except by our resident porcupine. Waddling through our back yard she rattles her quills to warn us that design and cunning trump bulk.

Also, the white-faced hornets nesting under our eaves suggest that neoliberalism has finished and now sleeps with the titans. Go ahead, stroke a boulder and fill yourself with images of that battleground of giants Keats invoked in Hyperion. He didn’t know that New England was strewn with their fossil remains, so much of their matter surviving without a trace of fossil brain.

On the library steps, face to glass gives dark reflection, all the wars and ancient Greeks locked inside napping in a void of holiday cheer, print all the more inconsequential now to festive minds. Even streets are calm, cars quieted in lit favors of living room squawk and meaty dinner tables. But from the outside I peer in on postponed utility, old ideas still new, forgotten features once carved in marble. An earlier search for immortality is unhidden but unwanted. You cannot blame the species living these occasions of the moment any more than you can blame me for hearing a silent reverberation, wanting to be let in.

“ hT e os u l t a kes flig ht to t he world itaht s i n v is i blebutthere arriving sh e i s s foeru blissandforever swel l

Static on the radio. Snow sliding off the roof, metallic piano notes struck and interspersed. You’ve withdrawn to bed; your old complaint complaining. I’m another old complaint, but I’m silent. The static speaks for me. The snow speaks for someone else. The piano notes speak for God. Although I believe in snow, I don’t believe in pianos anymore. I used to. Once, I performed in public. I played a famous sonata. I struck every note squarely without hesitation. Beethoven might have approved, or maybe he would have wrapped me in his deafness and smothered me. I’d ask you what you think, but you’re prowling a book I’ve never read, a sociological study of a town in Alabama famous for its frights and racial overtones. The radio never reports the news because I keep it tuned to innocence. Sometimes, Harvard students interrupt the music to chat about sports. They’re knowledgeable and charming, so I don’t mind. You dislike them. You’d send them to Alabama for a good licking. Beethoven would surely approve.

Here— touch my body see how it has become an open wound, salted.

How could you ever call my body idle?

Mine is a cradle of ecology, the column of my vertebrae a nest for the soft hagfish,

the fullness of my flesh rendered to particulate under the chewing kiss of the sleeper shark.

Dip your fingers into the swell of my eye—

you are not the first to feel the hollow crest of the socket.

Feel it anyway.

Jade Suszek

when i was young, i was not ashamed to be the child of a hell flame and a gambling man.

my mother burns through the night, the moon spilling over, staining her pale cheeks. i watch her sway to the holy song of a hazy sky, cassandra chanting at the river’s edge.

my father loves my mother, devoured by the smoke of her wind-wild hair, gasping for the air of her wine-stained fingertips. his soul, the boundless forest she calls home.

i met him some months and a lifetime ago, found him in the woods, sated by the fire. his voice– my first taste of bleeding devotion–led my tripping feet across tangled roots.

i met her last night, eyes flutter-shut on the damp moss. i pressed my nose to hers, lashes laced until she pulled me from this body into the water to be born again.

they are made of myths and magic. evergreen resurrections unearthed through the hollows of my headphones, the closest i’ll get to common tongues.

i wonder how many sunsets it took for them to meet each other here again; how many lifetimes before i knew to exist and not by accident.

Memories don’t abide among the ruins and the pathways. Nothing belongs to the place; the place belongs to nothing. Screechy-winged mammals rule. The precipitous rocky spur the houses are squeezed upon commands the gorge below while bowing to the sky. The dry creek coils around its base like a dormant wyrm Everything has left here— man, legend, space, time. And the water that’s chased them away.

I crawl into the hollowed-out roadside T-72 tank, honey wine on my lips.

Floating in ancient scripts, crippled men trail curiosity like mountain smoke. Hyena and healing hustlers scaffold saints and sky’s pageantry,

swinging on deep coffee, cow carcasses and piles of qat. Dollar bed

welcoming drops of rain, devil dreams in a star pulse most ancient.

He walks out of the storm, dust, rain, hail, and wind forming a curtain to mark the grand entrance from the dugout. Dragging his lightning bat, furrowing the dust, this sultan of storms in a southwest swing, snaps out stadium lights in left field. Mamutas pocketing his face, puckering up his lips to blow, delighting in the smoke rings of dust and chalk, sweeping the ball between the shortstop’s feet.

The lightning bat poking holes in the sky as he twirls it ‘round and ‘round.

A curveball of hail, a spitball of rain, a knuckleball of thunder, he sweeps the field. Each swing, the front advances lightning, gravitating to the bat. The eye of the storm in the doubleheader game ending in a pickle between 2nd and 3rd. His booming chuckle thundering across the night sky.

Looming black beside the railroad, the Scitico water tower shaded and shielded my childhood from too much sun and puberty. Dreaming of a railroad life, obsolete before I was born, kept me pleasantly infantile. The water tower bled water fed by a pipe from the Scantic, dammed for a former woolen mill now a plastics research firm. The water didn’t drip but poured for years, eroding the roadbed. The dark old steel-banded staves bulged like an errant pregnancy. In summer, I stood near the leak to cool myself while waiting for the daily train to Springfield.

A few boxcars, a huffing diesel, a brakeman flagging down traffic. No one saw me hop the freight with a dollar for a bus ticket home at the close of the workday. My railroad life ended when

the water tower burst in the night, the flood slopping back to the river. Then, I became too self-aware to daydream about the railroad and followed the pattern of my peers— sweating for fifty cents an hour

hanging shade tobacco in sheds, then lazing with friends in the dusk. Like the obsolete water tower, I leaned into the world and gasped as the runoff flowed unabated, obliquely dragging me along.

Five-hour drive isn’t bad on a usual day, but I haven’t done it in years. There really wasn’t anything holding me there when I left except for Fisher and the sea. Then Anna came along, and I found something easier, so we ended up moving.

I’ve known Fisher since we were little guys. We used to run all around the island after school, causing trouble: jumping off the dock naked, stealing peaches from Mr. Zolack’s store, and even letting Mrs. Borders’ dog loose to chase the pelicans. Dumb thing seemed to forget they could fly. Fisher was always my buddy. You wouldn’t find me without him.

Ninth grade is when we started changing. Fisher liked his books. I liked the ladies. Stonewall riots had me asking him if he was a queer. Boy turned his head around faster than a minnow near a splash, locked his blues onto my browns, and said, “So what if I was?” To this day, I’ve never felt my face get so hot. I backed off, but after that, things were weird. I saw something in him that I had too, made me nervous. There wasn’t a single queer on the island; well, none brave enough to back themselves.

We went separate ways til junior year took us. Prom was a dirty night. I bumped into Fisher outside, and he scoffed at me, shrugged his shoulders, and rolled his eyes. I swear, I don’t know if it was the drinks or what, but the shit infuriated me. I pulled my fist back and decked him in the left eye. It was a shiner, too. A couple of days later, the guilt was stinging me. Usually, I wouldn’t care too much about this kind of thing, but this was Fisher I’d hit. I took care to go and pay him a visit and apologize.

He was docking the boat when I found him. I wasn’t planning on some grand gesture, just a chat. He avoided my eyes and told me to leave, but I didn’t. Even tried to shove me off the dock, but I grabbed him; we both ended up wet. When we came up, my body wailed. I stole his face and mashed it into mine. It felt like there were smores in my belly, except the fire was in there, too. After that, the only thing he was mad about was his gazelles; he never took them off. That day, I knew it was right, never mind what Mama and Daddy said.

Five years; forbidden and free-falling, but I’ve never been so happy to be around. When it came time to settle down, get real jobs, and start making something of ourselves, I couldn’t do it anymore. I met Anna on a little ferry heading to the mainland and wound up marrying her about a year later. Girl didn’t deserve any of this; loving was sweet. I’ve never seen Fisher like when I told him I was going.

We were standing on the shore at the furthest point from the lighthouse. He went there when his house wasn’t all that peaceful; sadly, that was often. He showed it to me the day after I kissed the guy; really is a great spot. Sun meets the sea like laying down for bed. The shells are always in their full form, and the air is as crisp and fresh as the Provision Company’s filet. I told him we weren’t meant to go long, just something buddies did. We both knew I was spitting bull.

When he wrote me to come back, I damn near tore the roof off the house. Anna found it first, which is probably what killed us. She hated Fisher, and I’m sure she always knew. She called me a coward and told me to leave; seemed like she’d been waiting for the day. I’d never seen someone so ready, and boy, was it ugly. Didn’t even care about the kids, woke them and everything. She said she wanted nothing to do with me anymore, and if I didn’t want the police to handle it, then I’d best be on my way. So, I said bye to the girls; that was the worst part. Five and three, and Daddy’s a faggot.

Now I’m driving. To what, I’m not sure, but he said he wanted to see me when he wrote, and if there’s one thing I’ve learned over the years, it’s that I’m not myself without him.

Pulling up to the spot seems different, but I know he’s here, even six years down the line. I know it in my marrow that he’s here, I’m shaking like a box car, and my heart sounds like Daddy’s first Scout’s motor. It’s 5:53 am, and the air still smells the same. The water’s doing its wishing and washing, and the sky’s dressed in blue and pink. As my right foot slides into the sand, I hear my body wailing again, and I sail.

Now I see.

Stained laces.

Grubby soles.

Three stripes.

A note underneath.

Dear Ander,

You got a new life. I never thought about leaving until recently, so above all, I need you to know that. If there is anything that you take with you, it should be that.

I wanted you to come because I thought I could wait, but I think I overestimated myself again. I’ve lost hope that you’ll come. I feel that all my life’s been a consistent overbearance of “I thought.” I thought you’d stay here. I thought you’d come back. I thought I could fix things. I thought you’d leave her. I thought we’d wrinkle together. I thought I’d be able to forgive you. I thought you always had love for me.

I believe that, at times, you did love me, but my heart collapsed when you left. You were my only companion, and you were stolen from me. She took your eyes from me. When your gaze no longer fell on me, I lost my blaze. I didn’t mean to, but I’m barely flickering if you’re not there to keep me lit; that’s what I know now. I never thought of myself to be someone that needs anyone. Even when Papa would rage, I could handle it. No matter what, I knew I could get through it because there was always something keeping me up. I thought it was me, but in all the searching, I found it was you.

I hope she’s giving you all of the love that I couldn’t, and I hope that what you feel for her is strong enough to erase me. If you can go on, then do it, but don’t come back here again. This is where I’ve always been. I showed it to you because you’re the only person I thought worthy of sharing it with.

It’s a lonely world, Ander. You don’t need me to make it up for you because you’ve already laid down in it. If you didn’t come, then I guess this letter is for the ocean, but I had to write it down, nevertheless.

I’ll love you from the sea now.

Fisher

You had tiny, tangly wires taped to your chest when the nurse quietly laid you into the sweater-clad crook of my arm, your beeping machine keeping time with the beating of your tiny heart.

I watched you closely, eyeing the inconsistent rising and falling of your wooly, knit blanket. You weighed nothing, but your circumstances came with an unforgettable heaviness.

The worry that you’d sense the cloud hanging over my head and take the rain personally forced my mind and body into submission.

So there I sat, filled with quiet fear and immense awe at your strength, pride swelling in my heart at your willingness to fight. And in that moment, we made a silent promise. My unwavering protection in exchange for your survival.

“Love is simply the name for the desire and pursuit of the whole.”

- Plato

Jeffrey Alfier

Jeffrey Alfier

Inca Trail sherpas hauled humongous gringo

This’s-and-thats on their backs up and down the Andes

To and from magnificent old Machu Picchu...while their hearts

Exploded from high-altitude pulmonary hypertension.

Straight out of the eye of Indiana Jones’ Egyptian needle,

For six hundred years, precisely at midday

On both equinoxes, a narrow laser of light shone

Through the Intihuatana Stone, the Hitching Post of the Sun.

My teenage son (now a doctoral student in evolutionary biology) and I

Spent a hallowed sunrise almost alone there in silent holiness before

The day’s first train of tourists arrived in loud sticky teeming packs

From the funky hippy town of Aguas Caliente down below.

We’d just puddle-jumped to Cusco after two weeks backpacking,

Cavorting with and riding on capybaras in the Amazon River to the north, Before then heading south into the eco-protected Manu Biosphere, which Made the more developed Amazon Basin rainforest seem like Manhattan.

It was there that I was turned on to “holes in the ozone layer”

By hardy Australian birders

Who were covered head to toe

And amply sun-screened despite the 100-degree, 100% humidity.

The highland’s dry cool night

Offered a welcome short respite

Until we dived back into the wet sea level hundred degree, Hundred percent humidity, XXXX killer-mosquito malarial environment.

Nevertheless, my boy relished our escapades in the dense evergreen

Haven to millions of animal and plant species, especially when each night

He’d scare the heebie-jeebies out of me, shining his beam on scorpions

The size of giant Harlem rats — right before I’d inadvertently stomp on ‘em.

Lubricated by indigenous, legal coca leaves and Angel’s Trumpet we dried

On bare electric bulbs in our room; we preferred wilderness under the canopy,

Drifting in canoes, birdwatching, spearing piranha, gazing at the Southern Cross — to Lima’s ghetto kids ripping the glasses off our heads on the bus.

Sadly, the big city’s most notable (and totally empty) museum was chock

Full of medically trephined skulls and nifty irrigation/agriculture systems

That were painfully more sophisticated during their Incan heyday

Four hundred years ago than those currently serving the peasants.

A decade past — stirring memories beginning to dissolve in the liquid vat of my mind

— Recontouring, nailing our high adventure, the cosmopolitan highlight of our epic trip

Was taking in Willem Dafoe in The Last Temptation of Christ: controversial enough in this Devoutly Catholic country that the movie theater had more security guards than customers.

After Manu we crossed over from Peru to Bolivia, making it

Down to La Paz, a colorful poor sweet aboriginal town where we feasted

On street popcorn and six-course meals costing twenty cents, and made

Fun of the palace’s El Presidente-of-the-moment before the next coup.

It was so steamy in our windowless cheap fourth-floor digs, that reading

The Grapes of Wrath to each other, even buck-naked, we couldn’t fall

Asleep ‘til Boychick devised an ingenious cooling system of cascading Plastic garbage cans filled with water underneath Jerry-rigged fans.

Ten years later, my inner chimp wonders if folks who were so good to us — Tolerating all our antics — would have a different attitude now, what with Colonialist Bush leading El Norte, and Evo Morales, anti-imperialist Venezuelan boss Chavez’s buddy, the first Indian to run their big show?

By ten o’clock that Friday night, nearly all the nineteen expected guests— along with a few invited others who had not pleased to reply—had arrived at Ned’s excruciatingly modest basement apartment for his end-of-term holiday party. The previous two Decembers, Ned had attended the Christmas social hosted by his university’s History department, where he worked as a teaching assistant when not tapping away, three pages a day at the pace of a sap drip, on his dissertation (“A Genealogy of Whiteness in Modern China,” its seventh tentative title). But this year, Ned decided to forego the stuffy pageantry of the drunk-and-tenured and instead spend the time socializing with his own students. Ned welcomed these opportunities to decrease the formal distances between teachers and students, knowledge producers alike, by socializing on level grounds. Grades were in for the term, and all present seemed quite chuffed by what they had received.

It was one of those years where Hanukkah and Christmas coincide, so to compound the holiday joy, Ned had hung a few paper menorahs from the ceiling of his living room. The room was a minimalist wood-floored space containing at its center a tea table with six puffy seat cushions; a spindly, candy caneladen artificial Christmas tree; a recliner draped by a blanket stained in illegible Chinese calligraphy; and a record player stereo system that, at the moment, was spinning Run-D.M.C.’s “Christmas in Hollis.” Ned’s finical flatmate, Benton, had earlier vacated the premises to visit his family in Vancouver and would not be returning to pick nits until after the New Year. (His absence was itself a fine holiday gift.) Out of social practicality, Ned had converted Benton’s bedroom into the evening’s bar. A collapsible table that functioned as the self-service area was stocked with an economy-priced (but far from rotgut) fifth of each of the major spirits, a Rehoboam of serviceable red, and a clean, ice-filled plastic trash can that kept its many bottles of Steam Whistle and Blue drinkably chilled. But few were drinking any of the beverages Ned had purchased out of his own distressingly low stipend; instead, they were opting for substances illegal and nominally illegal in Canada. Smoking was permitted, Ned had cautioned, as long as it was done outdoors—and most indulgers who inhaled seemed to be vaping, anyway. A few were going on with great enthusiasm about something called Phenibut, which apparently got one drunk and horny without compromising clarity of thought or libidinal activity of the body. “Soviet cosmonauts used it back in the day!” Dominique Beauvais told Ned as he offered him some of the gritty granulated white powder from a plastic baggie.

The doorbell, barely registering above the music and laughter and thick atmosphere warmed by so many bodies, rang its two-pitched ding-dong. Ned excused himself and opened the door. It was Jamie Starnes—his quietest, but no less analytically sharp, student. Visually and aurally evaluated, Jamie was of indeterminate gender, something that had intrigued Ned over the past four months. Student personal information files were available only to Administration, and on more than one occasion Ned had wanted to inquire, directly but politely, of Jamie’s androgyny—if for nothing but the sake of appropriate pronouns. (Jamie’s middle name—Taylor—was of no identifying help either.) Now that school had recessed and he was physically off-campus, Ned could speak less fearfully; but just as that innocent will-to-know returned, a small fairy, looking much like a Judith Butler bobblehead, rematerialized on Ned’s shoulder and yapped something about privilege. Ned warmly greeted Jamie and indicated coats could be left in the closet. Then he went to visit his bathroom, which had seemed long occupied. And—it still was. The four beers he’d already consumed would have to continue awaiting dismissal.

A finger poked the center of Ned’s back. Ned turned to see little Ruthie Birnbaum—though nineteen, she looked barely out of middle school—smiling as politely as when she would raise her hand in tutorial. “Is Mark going to be here?” she asked Ned.

Mark Pombrosa was the other teaching assistant for the Modern Chinese History course and Ned’s chief strategic competitor for departmental funding. “Mark is likely at the faculty party,” Ned told her. Ruthie’s eyes dropped a little in disappointment. Ned filled the conversational silence by drinking his beer until it was gone.

(But what would be going on at that faculty party, presently being held in the History department, up on the thirteenth floor of the university’s library and a mere four blocks’ distance from Ned’s? All-in-all, it was likely a fine local specimen of a gigantic human centipede. There would be a few dozen professors and lecturers, the possessive holders of great intellectual capital, as well as a sprinkling of the long-term sessional scrapers-by, together joined by scores of solicitous graduate students hoping to avoid at all costs the professional disentitlement, or misplaced positionality, or just plain rotten luck of the latter. By now, Mark had likely finished his mandatory rounds of effusive faculty jawing, the formalities of congratulations on articles recently published and monographs going to press, and was moving on toward the pretty M.A. candidates, who, in their less-guarded tipsy states, were silently questioning how Mark could suddenly seem so attractive. Of course, Mark would be aggressively cock-blocked by Vanessa Dariotis, the newest Ph.D. student to reach candidacy, who would be working to maximize the slightest hint of bisexuality from this same pool of girls. Ned’s advisor, the recently tenured Yorick Kondracki-

Sanchez, was likely dilating to all nearby ears about his newest vanity project, a book of photography documenting the rise, fall, and unsteady resurrection of China’s automobile industry. [Several of its photographs, enlarged and framed, adorned the reception lounge of the History department. They were terribly depressing to look at and unfit to welcome all but the department’s most unwelcome guests.]

Through the shadowy assemblage of youthful bodies crowding in his living room, Ned could almost sense Shijin Zhang, the distinguished co-appointment with Peking University, looking as uncomfortable as any good atheist CCP cadre should while celebrating anything nominally Christian. Over his stereo, Ned could hear Rita Thigbath, obnoxiously loud and still riding the discreetly concealed professional high that had come earlier in the year when her rival for tenure, D. Vernon Ding, had put a bullet in his mouth upon concluding his afternoon lecture on Mao’s Great Leap Forward. [Ned himself was TA’ing for Ding at the time, and had worked, with a makeshift leather belt tourniquet and very limited success, to control the fountains of Ding’s hot blood until police and paramedics arrived.] The truth was, no one in the department was a friend, or, outside of the peer-review process, even close to an actual peer.)

“Colleen’s blowing cashews out her nose!” someone shouted. A tiny object on a curved trajectory whizzed by Ned’s increasingly rosy face. He walked into Benton’s bedroom and poured a small quantity of bourbon into his plastic cup, and swallowed the entirety without gag or cough, though it did sting an incipient cold sore on his lower lip. Then he grabbed a couple ice cubes from the beer tub and dropped them into his cup, which he filled with more bourbon. He suddenly needed some cold, fresh air, and stepped outside into his yard, where the dusting of snow that had begun falling at sundown had risen to a good half-foot. Erratic shifts in the wind were piling small drifts in seemingly random spots.

Mo Ismat and Sid Robatham sat on the porch steps, sharing a hash joint and snickering. Mo looked up at Ned and offered him the flimsy paper cylinder. “It’s not haram!” Mo joked.

Ned smiled weakly and shook his head. “No thanks. Merry Christmas.”

“Always a happy time, Isa’s birthday,” Mo said, the thick sweet smoke rising from his mouth.

Ned looked over the rooftops toward the misty lighting downtown. The firmament was equal parts black space and dull snow specks. The campus purlieu always stayed so quiet and dark at night that the noises and spotty light pulsing from Ned’s seemed to suggest activities criminal or at least morally suspect; and yet, on this night, all the neighbors were either away, or else they were simply too Canadian to complain. “Isn’t it pleasant to be able to actually say ‘Merry Christmas?’” Ned observed. “Back home in the States, a person risks being sued if—”

“—I gotta say,” Sid interrupted him, “yours was the best class I had all term. And I’m not even a History major. You are fucking awesome, Ned.” The smoke was laryngitical on his throat.

The burning cannabacco irritated Ned’s sinuses. He made some space for himself, turned his head, and coughed hard enough to satisfy any physician who might have poked his hanging gonads. “You earned it, Sid,” he said. “Congratulations.” Ned turned again and spat phlegm into the snow.

“I’m just curious, but why aren’t you at the faculty party?” asked Sid. “I think it’s awesome you’d rather spend time with your students, though.”

“I don’t really wanna be part of that party,” Ned said.

Sid and Mo each had another chokey drag. “How’s your thesis coming along?” Mo asked.

Ned was staring upward toward the university library. The thirteenth floor was lit and lively. “Honestly? It’s seeming more and like a Common Core way of performing a common sense operation.”

“Huh?” said both students.

Ned went back inside and was promptly pulled aside by Thomas Wooten. “Your place has killer feng shui!” he yelped at Ned and wiped a suspiciously sniffly nose with an index finger. The apartment’s staid air actually felt congealed, and it had begun to smell as if a gaggle of heavily made-up girls had been perspiring there for a long while—which, indeed, was very much the case.

Ned reached up and opened the front window an inch-high crack. In times of warmer weather, it offered a fine view of the ground outside, something now almost completely occluded by the snow. “I don’t believe in feng shui,” he told Thomas. “I lived in China for three years and got sick every other month.” But the music was too loud for Thomas to really hear Ned, and besides, he seemed more interested in the activity of Cilla Hopkins and Melissa Barnett, who, with the assistance of some bass-heavy music and an enthusiastic audience, were simulating a very aggressive doggystyle coitus. Ned gradually realized that the music playing now wasn’t his. He peered through the denseness of bodies and saw that someone had attached a digital music device to the speakers, which were now booming lyrically crude Top 40. Ned thought of reconnecting his record player, but let it pass and sipped his bourbon instead. He checked the bathroom once more, but again found it occupied. He rapped loudly on its door. Someone tapped Ned on the shoulder and he turned around.

“Hey Ned, I’m just curious,” said wide-eyed Carl Roundthwaite. “I have a question—just a personal question. I’m not trying to be offensive. Are you Jewish?” Ned could sense an unwanted bobblehead on Carl’s shoulder, too. Someone must have taught him that even the purest of his intents are inevitably situated.

Ned belched before he responded. His lagers, though passing swiftly to his bladder, were leaving behind some terribly gaseous gut residue. A chicken shawarma, his customary evening meal, can only provide so much digestive ballast. “Uh—I proudly wear both a large nose and a gorgeous circumcised cock, but no. It’s my nose, isn’t it?” He laughed quite heartily.

Carl was stunned by Ned’s candor. It had, after all, just come from the same mouth that regularly dripped honey during lecture, whether explaining the finer points of the Qing’s colonial project in Central Asia or gently, expertly coaxing smallgroup participation from the most under-confident of first-year students. “Uh... it’s just all these Hanukkah candle decorations I keep walking into,” he explained, flipping the nearest with a middle finger.

Ned was distracted. He’d just noticed that, on the doorhead between the kitchen and living room, someone had taped plastic mistletoe. “Uh—I’d’ve hung up some Kwanzaa banners too if there were any black students in the class.” He smiled and turned back to Thomas. “Kujichagulia.”

“Uh...xie xie!” Carl said atonally, but with the small pride of an au courant stripling who can express basic greetings and simple thankfulness in most major foreign languages.

There was an abrupt, uneven undulation in the crowd. The lights dimmed, and Ned instinctively stepped back. Somebody behind him placed their hands over his eyes, and he felt someone’s lips press against his. After that initial scene of blind excitement, and then the small panic that the exchange was likely being caught on cellular phones for perpetual future iterations, Ned felt very bad for whoever was kissing him. He didn’t fight it, but hoped it was at least a female student—Carrie Murdock, or Trina Volovich, perhaps? Those two, in particular, had always delighted in casting schoolgirly eyes and coquettishly worded suggestions during office hours, though he had always been careful never to contravene any of Human Resources’ stone-set mitzvot (the unchiseled first of which was, he constantly reminded himself: “You are a resource. Like gas and manure.”) When the hands parted from his eyes, Ned found himself surrounded by grinning faces. He didn’t bother turning around to wager a guess at whose hands they had been. Someone muted the stereo, and all present—even the customarily silent Jamie Starnes, who was actually laughing—broke out into a spirited rendition of “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow.” Ned tongued his cold sore while he accepted the serenade, through all its jumbled registers, with gracious patience. A few people tried, unsuccessfully, to initiate a round. Ned smiled and murmured thanks, bowed at the waist as naturally as he could, and then escaped outside, this time to the backyard. He felt loose and unsolid, and hoped the freeze might initiate within him a more concrete change of state. And, he desperately needed to pee.

Concealed under a series of maple branches that hung low against the snow, Ned unzipped and extended his member. Ever since his childhood in the North Carolina foothills, he’d always enjoyed penning messages (occasionally vulgar) and drawing pictures with his bladder’s ink during wintry times. And now, with an almost artisanal care, amidst the starts and stops of strangury, he proceeded to reproduce none other than the Confederate Stars-and-Bars. It was a surprisingly accurate two-tone rendition that, if seen aerially and in a better light, would have actually quite popped. He stepped back and used a tiny keychain light emblazoned with Edward Snowden’s anemic mug to admire his work, this frozen whiteness collapsed by yellow heat. But then, as he cleared the final weak dribbles from his now-relaxed bladder, his sphincter panicked. His stomach commanded him, with diminishing patience, to attend to it as well. He was still going to have to somehow visit that toilet after all.

*

Inside the living room, Dominique Beauvais was performing some standup comedy. After swallowing whatever beverage had been in his plastic cup, he lowered the receptacle to waist level, pivoted to a profile, and proceeded to drop his ice cubes, one after another, onto the floor. “Inuit piss,” he punctuated the maneuver, to riotous, stoned laughter all around. Ned sifted through the crowd, dodging bodies, an anonymous guided missile working to avoid an early explosion at all costs. He found the bathroom door still locked. He banged on it, again without effect.

Anger mixed with nausea and together they surged through him. On a final desperate impulse, Ned grabbed the key atop the doorpost and forced it into the doorknob. He twisted the key and, with a commanding force, threw open the door. There, on the bathroom floor, he found a bottomless, spread-legged Jamie Starnes— who appeared to be receiving a sexual favor from Thomas Wooten.

No door slams shut like a vagina.

A terrible commotion ensued, and Butler’s bobblehead (which, truthfully, never quite left Ned’s shoulder) exploded. Bodies caromed off each other, and it was impossible to distinguish angry shouts from happy laughter. Ned managed to reach the safety of Benton’s bedroom, where for quite some time the searing post-image frozen in his mind blinded him. He poured a good shot-and-a-half bourbon into his glass, made it disappear, and slipped back outside to the sanitorium of brisk, steadying, and now-still night air. Snow was falling perfectly vertical. Sid Robatham was again out on the porch, but now he was sound asleep, propped up in the corner and wrapped snugly in his pea coat, an ushanka pulled down over his eyes. Someone’s shattered beer bottle had left crunchy spalls spread underfoot.

Ned battled a series of wet burps and glanced over toward the campus. The thirteenth floor of the library was still very active. It was too distant to make out what

the bodies inside, and those out on the wrap-around balcony, were doing, but Ned could easily imagine a likely scene: Kondracki-Sanchez, alone, drunk, and admiring his photography on the wall; Shijin Zhang, Asian-flushed in the extreme, chain-smoking his tarry Zhongnanhai cigarettes and flicking the butts over the balcony railing onto the snowy ground far below; Thigbath taking candid video and snapshots of passed-out faculty members with her smartphone; and Vanessa Dariotis, in turn, cunt-stunted by Mark Pombrosa, feeding herself into a state of temporary comfort with the last of the catered hors d’oeuvres—mounds of Christmas cookies, speared cold cuts, and cup after cup of spicy glühwein ladled from a massive punch bowl. Mark, meanwhile, had retreated to the privacy of his carrel for some intimate exchanges with the most intoxicated of the pretty M.A. candidates. Might someone be surveilling Ned’s tiny beacon from that thirteenth floor? Or did he remain safe and unmissed?

Ned looked over toward the unconscious Sid. “Why do I work so hard for a group of people I neither like nor even respect,” he declared, rather than asked. In the immediate clarity of that alcoholic moment, he began to sense how the sum of his work over the past three years was nothing more than a vain addiction, an inglorious habit that refused exhaustion. He wondered what becomes of such slyly extracted surplus labor. Ned suddenly felt no longer liquid but all belly, a pure combustion ballooning in the cold darkness of space. His mouth salivated with a canine abandon. His stomach, he realized in panic, was as inflated as the grades he’d turned in the week before.

Ned fell back against the house and into a snow drift between some holly bushes. No longer able to keep pace with this crapulous behavior, he surrendered to the moment’s emergency and allowed his guts to empty, at both ends, while he sat concealed in the shrubbery. The temperature of his loins surged from cold to hot and back to cold, and he felt helplessly infantile. When the smell became overpowering, he packed himself from the waist down in snow. He ate some of the frozen wetness to chill the sour taste from his tongue and to soothe the burning sore on his lip. He resolved to sit patiently, obscured in the frosty shrubbery, until the final guest had left. The cold on his thighs and buttocks became a heavy numbness. He closed his eyes, bowed his head, and pretended he was not anywhere. *

Inside, an awareness that Ned was no longer around gradually seeped through the crowd, who, in their manifold altered states, took their time in making an erratic egress. Someone had the foresight to turn off the stereo, which left the entire block in silence. The abruptness of that quiet awakened Ned.

The last guests left shortly after one o’clock. Ned couldn’t help detecting their concerned susurance echo along the street. He listened to the voices disappear

and thought of the year ahead—its promise of parturition, the daily renewals of its incandescence, and its prospects, however deep-veined and hidden, for agency and autonomy. He thought of the sacrality of good will and the undergirding of a washed conscience. He thought of how his parents, from his earliest memories, had taught him to take good care of himself—to eat sensibly, to exercise daily, to manage his money wisely, and to speak truthfully. For several minutes, he attempted to force himself to cry, but his body’s dehydration refused the indulgence. Then the exigencies of everyday life silently returned, and he remembered that he hadn’t locked his bedroom door, and that he’d better get back inside to see if anyone had stolen anything else from him.

fractured self reflected in red shattered stained glass spitting my name muffled and misshapen. scar on her brow where hair won’t grow, there, a moment of recognition.

doll-sized bed frame broken, splintered wood snapped from a rush of anger. anger analyzed in a red college-ruled notebook asking how can I be angry when anger is selfish?

i like the taste of vinegar on my tongue, of words spitting past my teeth. words so easily spoken to my mother get stuck. a row of sad red stickers marking seven imperfect days.

strong arms to comfort lay at your side unstretched, holding your bible with its worn leather cover, thin pages painted by green and yellow. red words you live by.

words understood but never spoken fade red anger into the pink of your sunday tie. my doll-sized bed frame repaired. broken glass glued back together. band-aid for my bloodied brow.

I’ve started breaking into people’s houses again. It’s not a big deal or anything. It’s just something I do to pass the time.

I try to approach each house on its own merits. I’m in the tree line, or I’m across the street, or I’m on the curb in my car. I watch the families until I’m pretty sure of their routines. I don’t take pictures. I write down what I can in a notebook, and I repeat it to myself at night when I’m alone in bed, when I’m brushing my teeth, when I’m sitting on my couch downstairs. Then, I try to make a plan. This takes about a week or two. Sometimes, I’m not able to figure out a way in, not even hypothetically, and I have to throw out my hard work. Other times, I get to the house with my plan perfect and something goes wrong; someone stayed in, the door has a tough lock, there’s a dog I didn’t see, whatever. If anything like that happens, I’m out, hands in my pockets, walking away. I never return. No skin off my back. I’m not in it for the money anymore.

The easiest ones are when there’s only one person living there. You know, less variables at hand. I remember, I wonder if you do too, there was this one twostory brick Georgian building that must have been built in the 1800s. It looked like it had held its own for a while, but it was starting to lose its fight with time. Kudzu vines had stretched up to the upper windows where the curtains were always closed, and they had wrenched a white wrought-iron balcony on the left free from its bolts so it was just hanging a slant from its door. The right side of the house was missing its balcony, pale stretch marks left where it once was, where the rain missed the brick. It was surrounded by a brick fence with black spikes about my height. The entrance from the road was a big metal gate chained shut, and the driveway leading towards the house was overgrown with weeds. It didn’t look like anybody lived there. I probably would have thought nobody did if I hadn’t seen a lit window on the bottom floor. I tried to spy with my binoculars, but the curtains were closed.

I decided that I would go in through the back. It was a populated neighborhood, sure, but trees were spread between the houses and woods stretched out behind the home. I took a walk out there. There was an old plastic slide that had been sucked up by the ground. Some other old toys, a ball, a few other things I couldn’t make out in the dark from over the fence. I looked around for any way in. The back door was old, and I could definitely pick the lock, but by this point, I had been watching the house for four days, and the person downstairs had never come out. I’d have to climb up to the windows. Which wasn’t a big deal.

I got off work at the chicken plant one night, it was around seven or eight, and I decided I had to break in. It’s a gut feeling I get sometimes when I know I have

to get inside. Maybe something will tear out of me if I don’t. Do other people feel that way? Do you?

Regardless, I went back home, microwaved myself a Lean Cuisine, the kind with spaghetti and meatballs, put some parmesan on it, and then I listened to music for an hour. I was really into In the Zone at the time. I remember that the plastic of the bowl was warped. I don’t know why. I remember that I left the empty container on my coffee table, and then I got my tools and I headed out.

When I arrived, I parked down the street and took into the woods then came around the back with my things. I put a bucket top-down next to the fence and used it to climb over, and then I walked through the backyard. I looked down at the toys I couldn’t see before and saw they were tiny little action figures, GI Joe’s maybe, or some other newer toy I wasn’t privy to in adulthood. I walked past them, watching the dark windows for movement, and then I climbed onto the sill of one and used the window hood to pull myself up further. Then I climbed onto the second-story window. I was up at the cornice, my hands grabbing the shingles, asphalt grains spilling onto my face, when I heard someone shriek inside. I pulled myself onto the roof and listened for a while. But there wasn’t anything else. Nobody came out. I crawled on my hands and knees to one of the dormer windows and tried to open it. It wasn’t locked, but it was stuck pretty bad. I was pushing on it so hard that one of the shingles came loose and fell, and I thought I was gonna fall down with it, but I was fine. As you can probably tell.

After I opened it, I climbed in. It was pretty dusty in there. Big attic, it looked like, all the insulation spilling out of the rafters, a bunch of old cardboard boxes full of clothes and decorations. I turned on my flashlight and took off my shoes, stepping towards a little square of light in the floor between the clutter, a folded ladder stuck to it. It was the hatch. I put my ear to the door and listened. When I was satisfied there was no one below me, I decided to go through everything. Lots of wreaths, lots of sweaters, ornaments. There was a big old Christmas tree in one of the boxes. There wasn’t anything valuable anywhere, so I went back to the hatch and opened it, dropped the ladder down as slow as I could, and then I came into the house itself. I was in a hallway. It was all dark, but I had turned off my flashlight at this point. Didn’t want anyone to know I was coming. I saw a light up ahead and as I found myself around, touching the wall to guide me, I saw some railing and the light below it. There you were, sitting on your couch, the rough cloth thing, your cheek on a cushion. You were sobbing, I think. I saw that you were an old woman but you were bald and there was all this medical equipment around, and I slunk back into the hallway and thought She won’t miss a thing that I take. I still feel guilty for that.

I crept past the railing and the stairs while you were crying and then I came to a door with a bronze knob, and I went in and shut it behind me. I turned on my flashlight and took a look around. It was a mess. Little wicker statues all over a wooden dresser, a dusty mirror I couldn’t see into. There was this big, upholstered bed frame but I never thought for a second that anyone slept in here. It was neatly made, sure, but there were boxes and photos all over the covers and I wondered

what the hell you even had an attic for. I remember a black and white photo of a man, more a boy, in a fancy army uniform and hat and a couple of medals. Then another one, the picture in color but still old, with a shirtless man standing outside of a helicopter in the jungle. A little girl in black and white. A woman with a bunch of snot-nosed, sideways-looking kids out by a lake. It didn’t mean much to me back then. I drew a smiley face with my finger on the mirror and hoped it would scare you. Sorry again.

I went on to the next room and God if it wasn’t the same thing. Clutter, clutter, clutter! You had Bibles everywhere, Bibles of all English translations it seemed like. You loved those porcelain boys out fishing too, the kind you were supposed to turn into bird baths, but you had ’em all inside. You had those wicker statues like I said before, most of them were angels, and I wondered if you made them, but I saw a price tag on one and made up my mind. There were these candle holders that looked bronze, the sticks still in them, but I touched them and realized they were plastic. Worthless. Anything of value was downstairs with you.

I was walking out, frustrated and mindless, when I bumped into a dresser in the hallway and the little glass trinkets on top of it shook and clinked together. I heard something shuffling downstairs. And then I heard you calling, your voice so timid and strange. “Hello? Hello?” And then you were silent for a moment. I was up against the wall, scared out of my fucking wits. “Is someone there?” you said, and I didn’t respond. Of course, I didn’t. Then there you went, crying again. Your sobs all muffled. A wall and a floor between us, and I could picture your face in the pillow. I wanted to punch you until you shut up. You had valuable shit down there and you were crying and it pissed me off. I’m sorry I thought that.

I came around the corner where the railing and the stairs were, and I looked down just to see you were gone. I was scared, but I was thinking that if you saw me I could just run and never come back and no one would find me. It’s not like you ever left that place anyways. I came down, and I had never done anything like this, you know, so I was shaking a little bit, no one had ever seen me before, but I didn’t give a shit. I was still wanting to hit you over the head. I went through the living room and saw the magazines on the coffee table, shit like Reader’s Digest, Good Housekeeping, and TV Guide. There were crossword and word search puzzle books, worn and torn, the spines cracked, and pens were scattered through the pages and papers. There was a big TV, and it was still on, just muted, and I watched the closed captions go on for a long time. They were talking about a woman’s dead son. Then I thought about it a little bit, and it all freaked me the fuck out because I was thinking you muted the TV so you could hear me better. That made me remember where I was. I heard a creaking from the kitchen, and when I walked over, there you were, your back to me, your arms shaking while you went into one of the upper cabinets. You reached your feeble little hands out, all wrinkled and stretched over with skin, and you slid a panel open in the back. I couldn’t see what was back there; just that you were holding it. If you had looked back then you would have seen me but by the time you were done, I was climbing back down your walls.

A week later, I was sitting in the woods outside your house. I don’t even know why. I saw two different cars that would pull up, one of them a guy dressed in a raincoat and a ballcap, always bringing you groceries. Another was a guy in scrubs. I guess your nurse. You remember him? It was a long time ago, I know. Squirrelly kind of guy. His hair in a bun, back when that was just starting to get popular. When they left, I’d come in through the back and stand on the second floor and listen. I’d hear you crying or talking to someone sometimes. Making food. I never heard the TV. I was breaking all of my rules just to listen to you pity yourself. Back then I told myself I was waiting for you to go to sleep. But I couldn’t make it down there anymore.

I did this every night after I got off work at the chicken plant. Cutting meat all fucking day at that assembly line, all I could think about was getting out of my car and climbing up the wall of your house. I’m okay with being alone, mind you. That’s just a natural sort of state of things, isn’t it? I mean, it didn’t seem like you could accept it. Not that it matters what you think anymore. But sure, maybe I liked hearing from someone who couldn’t look at me. Judging me from where they were, thinking that they knew what was best for anyone and everything. Sure. I liked hearing you cry.

It was a month in when it happened. I went into the attic, and I didn’t hear a thing. Didn’t think a thing of it. I opened the ladder, went downstairs, closed the ladder back up, the usual. Still nothing. I sat in the dark of the hallway by the railing and when I peeked over the railing I saw you sitting still. But you weren’t making any noise. Your TV was still playing. There was a plate of food on the coffee table before you. Think it was collard greens. Some frozen kind, that you put in the bag, you know, the kind you put over your bruises when you can’t afford an ice pack. I sat for probably an hour and still hadn’t heard anything. I started getting upset. I was pacing around in that stretch of shadow before the wall turned into railing, and I got so mad I stomped on the floor and waited for a response. But you didn’t say a thing. I went to the stairs and looked down at you.

“Hey,” I whispered. I didn’t talk much. My voice sounded weird and my throat hurt.

I came down the steps one at a time. Real slow. And then when I got to the bottom I walked up into the living room, definitely in your peripheral, if you had such a thing left, and I rounded the couch and stood behind you. When I saw how still you were, something in me croaked, but I still touched your shoulder and watched you fall into your armrest, stiff. I burned most of my smell out at the plant but the stench in that room was so awful I couldn’t think of anything else. Until I did, of course. That’s how things go. The TV had a main menu of a DVD on it, a black and white movie called Europe ‘51. I recognized the lady in the background from when I came down here last. I found your remote. Hit the play button. I only watched it for about ten minutes. I thought it was kind of boring, but I can see why you liked

it. I don’t really remember much about that night. That’s weird, I assume. People should remember things like that. I just remember that I dialed 911 on your landline and left the phone on the couch next to you.

It’s not like I left you behind there. I came back the next day and watched. Waiting for some family to come by. None did. I took a break for a while, but I swung back around after a week and there was a lady in a pantsuit with some big guy in a plaid shirt and khakis there. Real estate people, I guess. On my days off I started doing drive-bys and saw a big moving crew out there taking all your things out. I spent eight months not feeling that burn to break in anywhere else. I just sat on my couch and stared at the wall or watched some TV. Tried to watch Europe ‘51. I take it back. I don’t know how you could like that kind of movie.

One day when I was driving past I saw a sign outside that said “FOR SALE.” So I went and tidied myself up. Got on my best shirt, the one I didn’t wear to the plant or in someone else’s house. Called the number on the sign, set up an appointment with Mrs. Maynard, and met her the next day for a tour. She was pretty nice. She was showing me the house and everything had gotten cleaned out. It was kind of amazing how they did it. All your magazines, all your decorations, all your books, all your fucking Bibles and wicker angels, all gone. No plates. No TV. No Europe ‘51, certainly. All your pictures too. I wonder if anyone took any souvenirs?

Anyways.

I saw that your carpets had been stolen and so had your bed. The mirror with my mark wasn’t there. Just a bunch of places where dust should be but instead there was just some gleam, some vague smell of Pine-Sol. I could smell that, too, I guess. She was telling me about the hardwood floors, the fact that the house faced south, whatever that meant, the open floor plan, the height of the ceiling, the new windows they had just installed, some good insulation in the walls they had been working on, a bunch of stuff you have to pretend to care about even if you don’t know. You know how it is. Or maybe you don’t.

I asked Mrs. Maynard if I could have a look through the cabinets in the kitchen, and she gladly acquiesced. I went straight for your cabinet. Saw the panel back there. You did a good job hiding the thing. I would never have known a thing if you hadn’t stuck your arms into it. It was the same color and material as the rest of the interior cabinets, and when I ran my fingers along the back until I found the crack in the wall I felt like I had just thrown a brick through a window. It was great. I moved the panel open, smiling on the inside, grinning, Mrs. Maynard blabbing about how the cabinets were all original but still in great shape, whatever, and I was poking my head into the cabinet to get a better look, and then I saw that there was nothing in there. Not a damn thing. I pulled my head out of the cabinet. Thanked her for her time, probably in a half-hearted way, and stepped out. I was walking through the

garden when I came to the mailbox and saw a piece of old paper lying in the grass near it. I bent down to pick it up and had to scrape it out with my hands it was so stuck in there. It’s this electrical bill. You never got it. I remember I shoved it in my pocket then threw it on my table when I got home and it got lost somewhere here and there. Well, it took me six years but I found it again. Then I went and found you.

That’s pretty much all there is to it. I just wanted to ask you how you were doing. Not that you can respond. So many graves out here, just a huge fucking field of them, and all the grass is too green. Too shiny. At least they had the dignity to give you a marker. I suppose you had some sort of policy for that at least. There are no flowers up here, and I don’t plan to bring any either. I’m too busy with my hobbies. I got into a family of four’s house last week. They’re never ever home. I like to trace my fingers over their dressers, their drawers, their photos, their fridge. Maybe one of them will notice I’m there, eventually. But probably not. I’m good at staying hidden.

I’ve been wondering if you got to Heaven, too, recently. It’s not a big deal or anything. Just something I do to pass the time.