THE AT SIXTY

The Unlikely Rise of America’s Most Surprising Opera Company

The Unlikely Rise of America’s Most Surprising Opera Company

In memory of Wesley Balk, for whom life—and the lives he created on many stages—was both an adventurous journey and an expression of love

In appreciation for Lucy Rosenberry Jones, whose generosity and vision made capturing this history a dream come true

The MN Opera at Sixty © copyright 2025 by Michael Anthony. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form whatsoever, by photography or xerography or by any other means, by broadcast or transmission, by translation into any kind of language, nor by recording electronically or otherwise, without permission in writing from the author, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in critical articles or reviews.

ISBN 13: 978-1-63489-737-2

Library of Congress Number: 2024924333

Printed in Canada

First Printing: 2025

29 28 27 26 25 5 4 3 2 1

Design by Cindy Samargia Laun

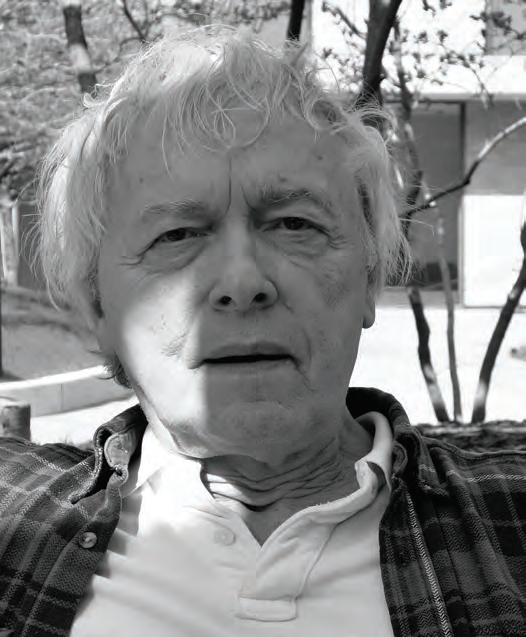

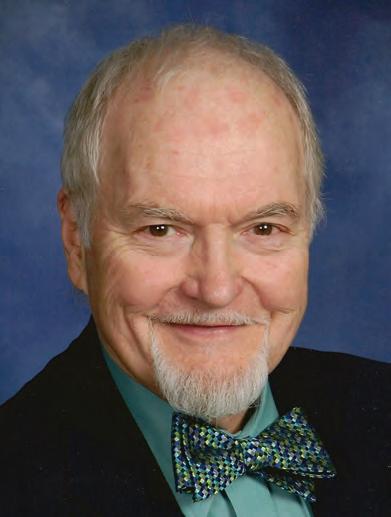

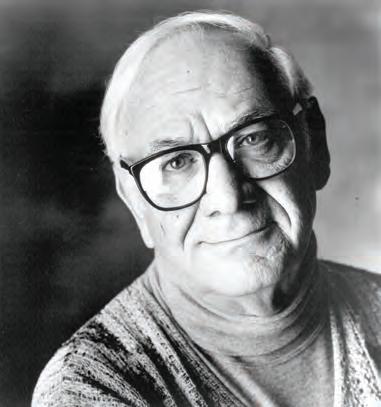

Author photo by John Mihelic

Edited by Steve Woodward

Production editing by Victoria Petelin

Proofread by Elizabeth Farry and Abbie Phelps

Wise Ink PO Box 580195 Minneapolis, MN 55458-0195

Wise Ink is a creative publishing agency for game-changers. Wise Ink authors uplift, inspire, and inform, and their titles support building a better and more equitable world. For more information, visit WiseInk.com.

To order, visit ItascaBooks.com or MNOpera.org. Reseller discounts available.

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

Productions 4

Foreword 12

Prelude 14

A Tale of Two Cities 17

The Sixties 23

The Seventies 85

The Eighties 131

The Nineties 195

The Aughts 237

The Teens and Early Twenties 287

The Future 380

Acknowledgments 382

Index 384

Author Biography 392

2022—2023

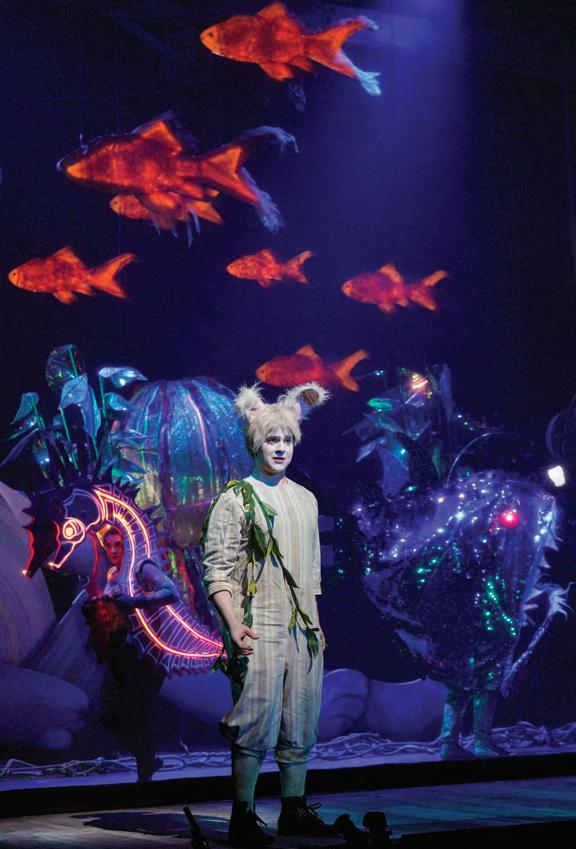

Edward Tulane (Prestini)

Rinaldo (Handel)

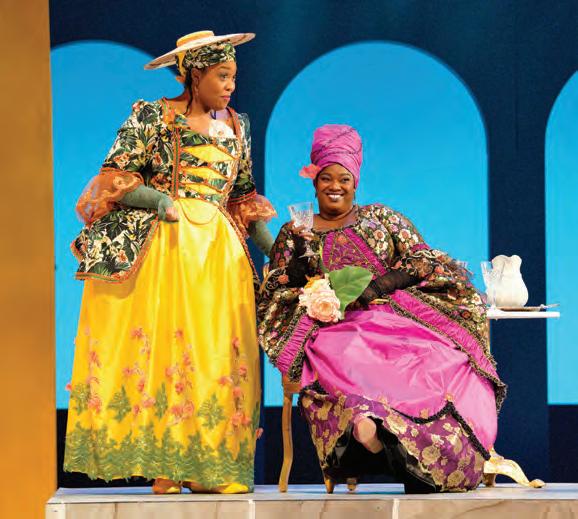

The Daughter of the Regiment (Donizetti)

The Song Poet (Hagen)

Don Giovanni (Mozart)

2021—2022

Opera Afuera

The Anonymous Lover (Bologne)

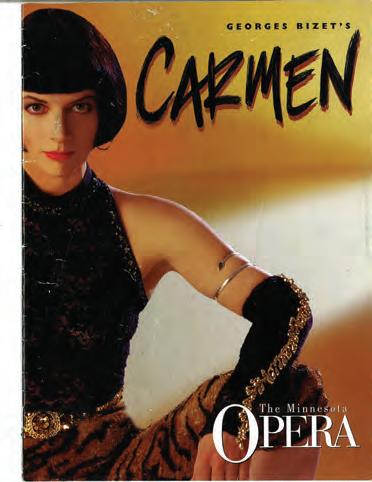

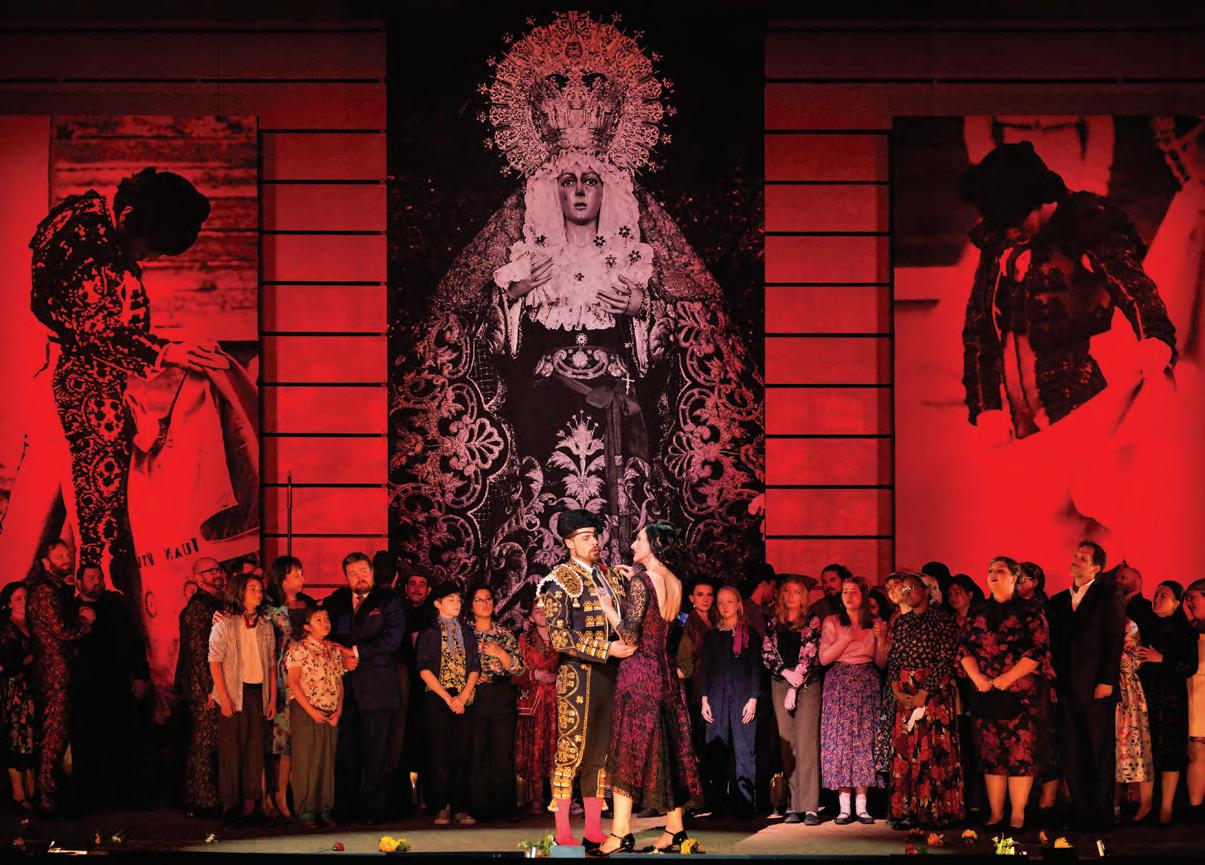

Carmen (Bizet)

LEGEND

World Premiere/Commission

American Premiere

Tour Production/Education Production

Concert Version/Semi-Staged

New Music-Theater Ensemble Production

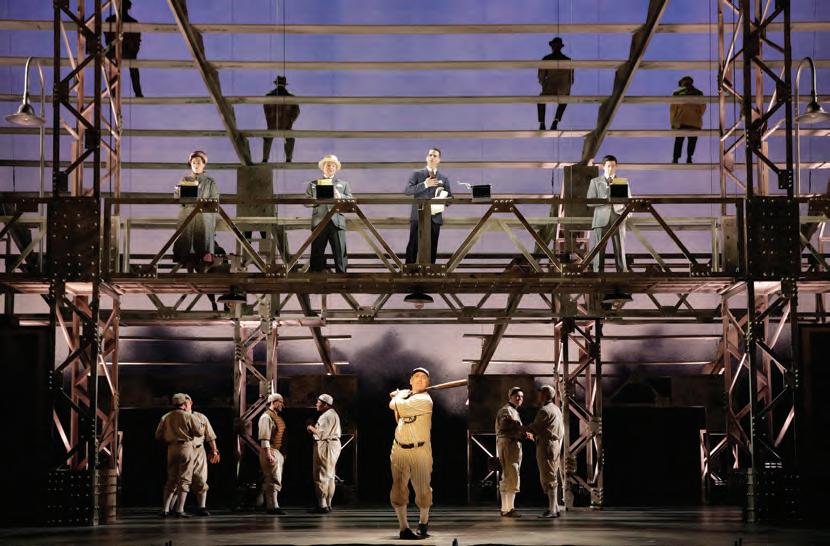

Opera in the Outfield

Albert Herring (Britten)

2019—2020

Elektra (Strauss)

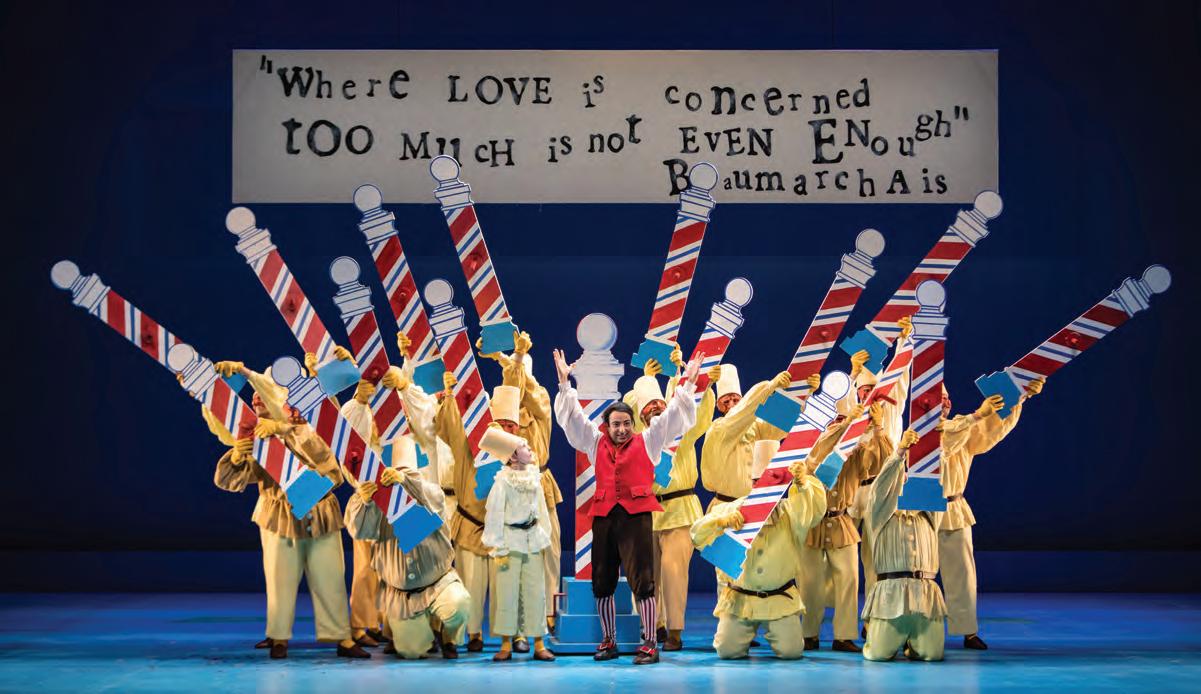

The Barber of Seville (Rossini) Flight (Dove)

2018—2019

La rondine (Puccini)

Silent Night (Puts)

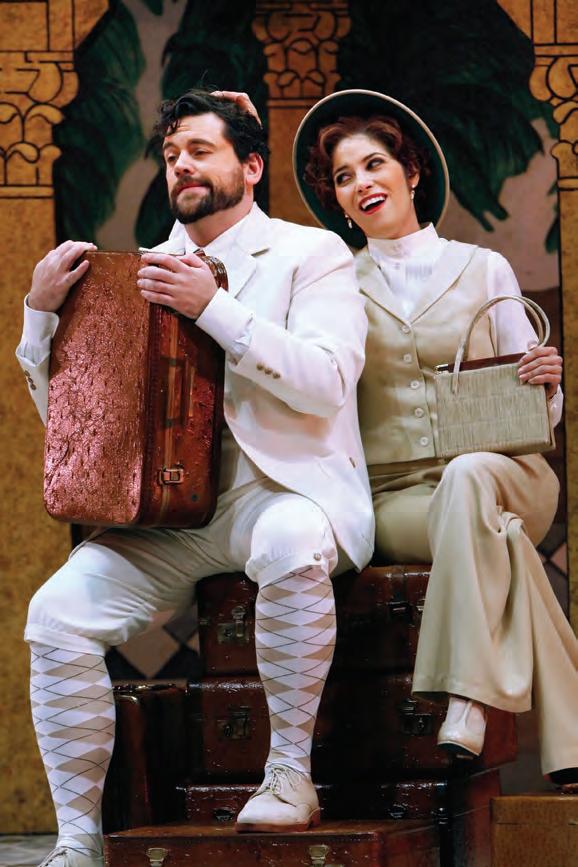

The Italian Straw Hat (Rota)

The Fix (Puckett)

La traviata (Verdi) NOOMA

The Gondoliers (Sullivan)

Brundibár (Krása)

2017—2018

Don Pasquale (Donizetti)

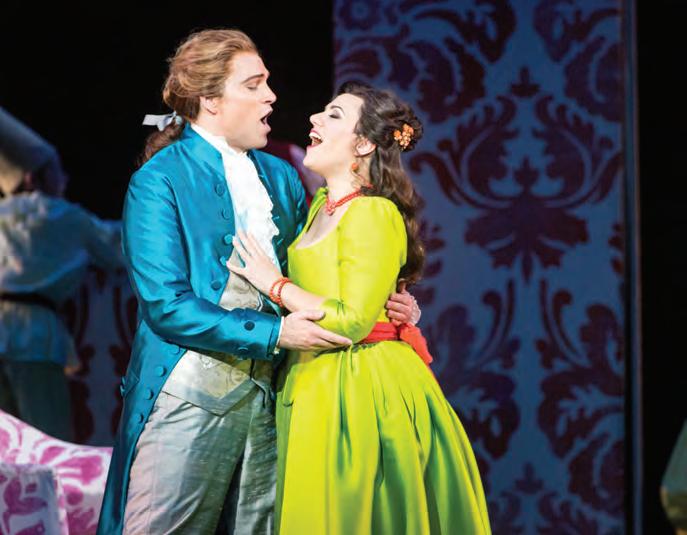

The Marriage of Figaro (Mozart)

Dead Man Walking (Heggie)

Rigoletto (Verdi)

Thaïs (Massenet)

Fellow Travelers (Spears)

Odyssey (Moore)

2016—2017

Romeo and Juliet (Gounod)

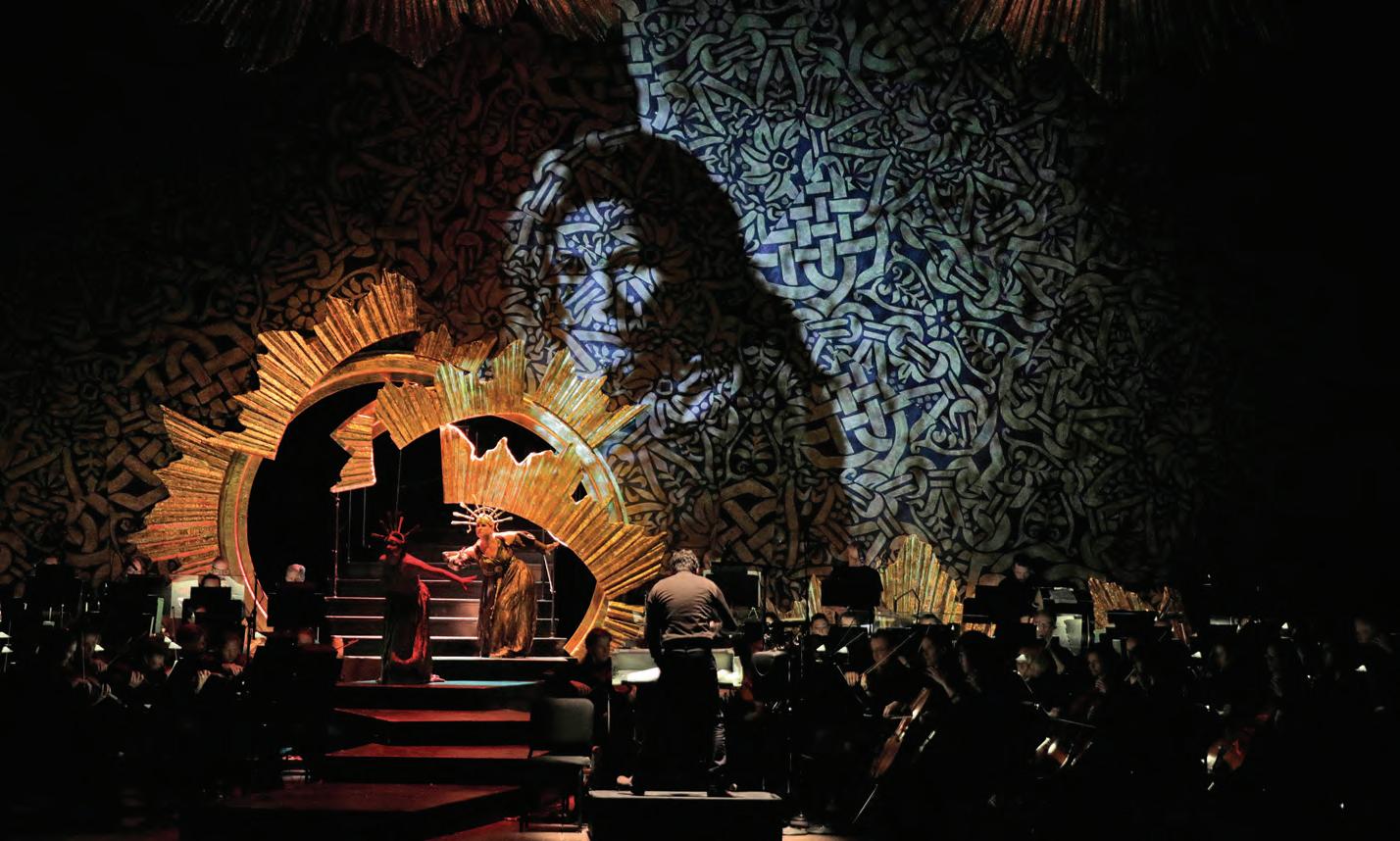

Das Rheingold (Wagner)

Diana’s Garden (Martín y Soler)

Dinner at Eight (Bolcom)

La bohème (Puccini)

The Nightengale (Raminsh)

2015—2016

Ariadne auf Naxos (Strauss)

The Magic Flute (Mozart)

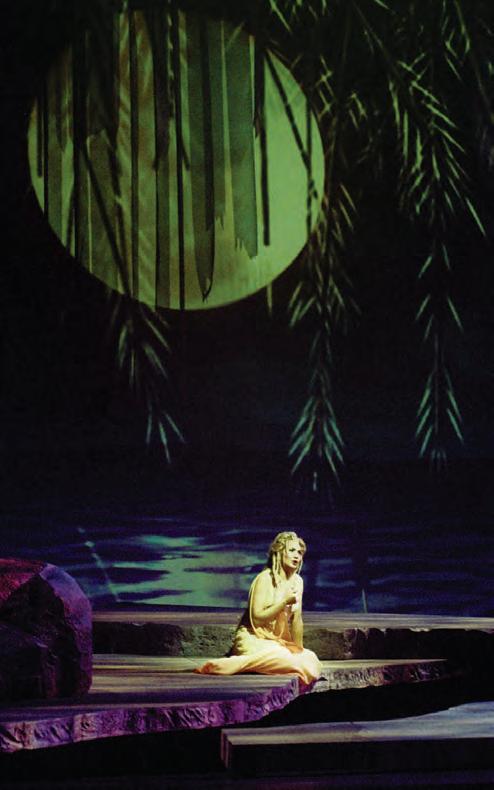

Rusalka (Dvořák)

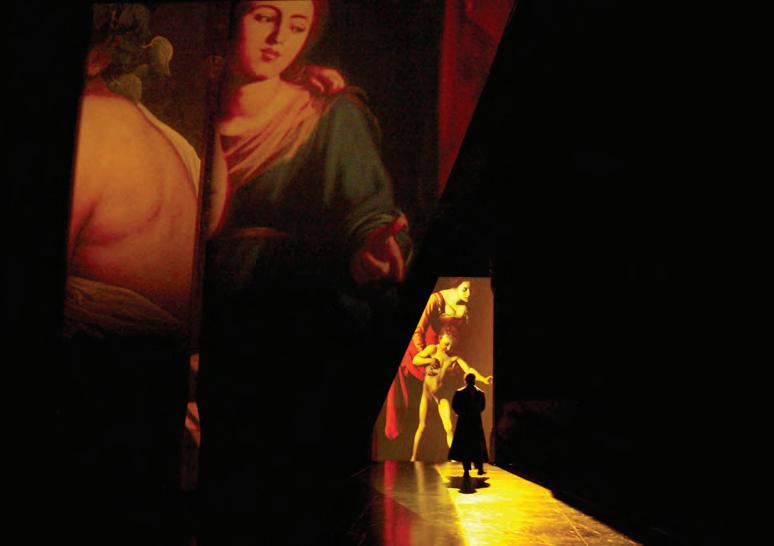

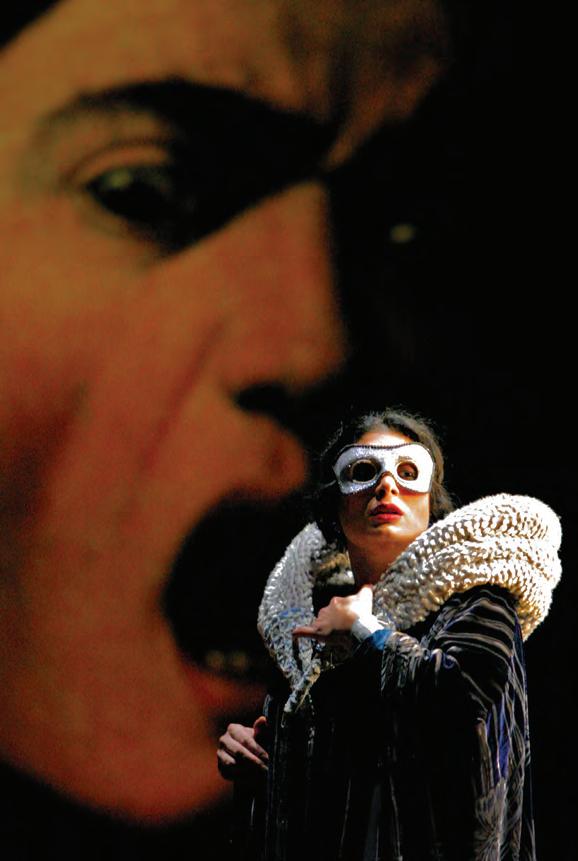

Tosca (Puccini)

The Shining (Moravec)

Memory Boy (Moya)

2014—2015

La faniculla del West (Puccini)

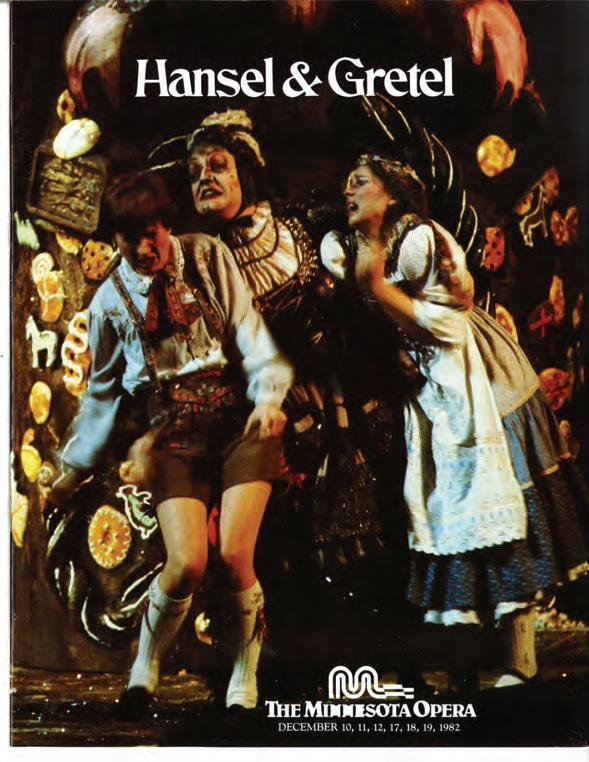

Hansel and Gretel (Humperdinck)

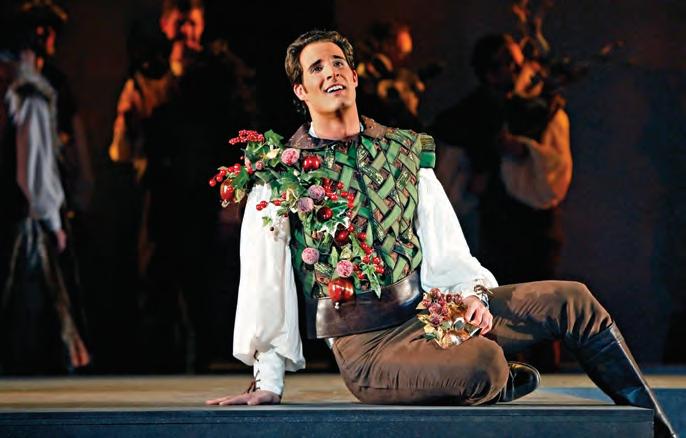

The Elixir of Love (Donizetti)

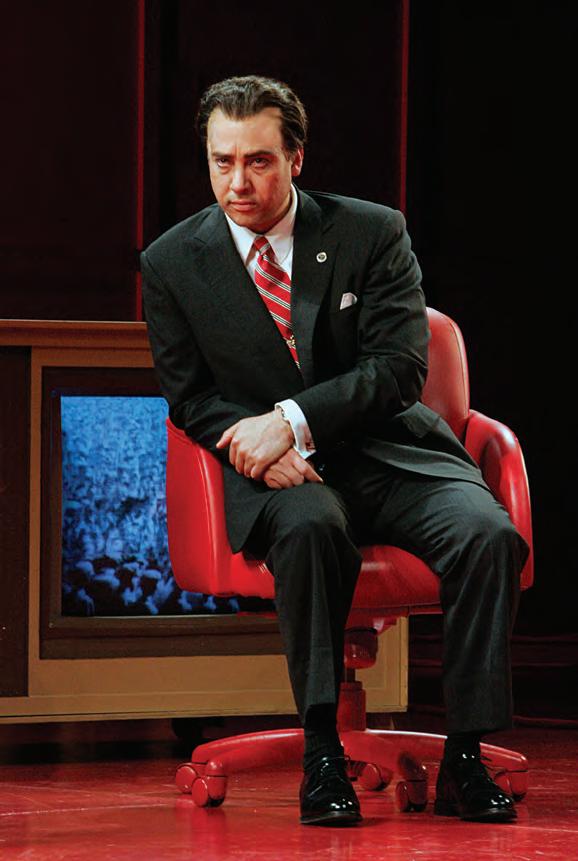

The Manchurian Candidate (Puts)

Carmen (Bizet)

2013—2014

Manon Lescaut (Puccini)

Arabella (Strauss)

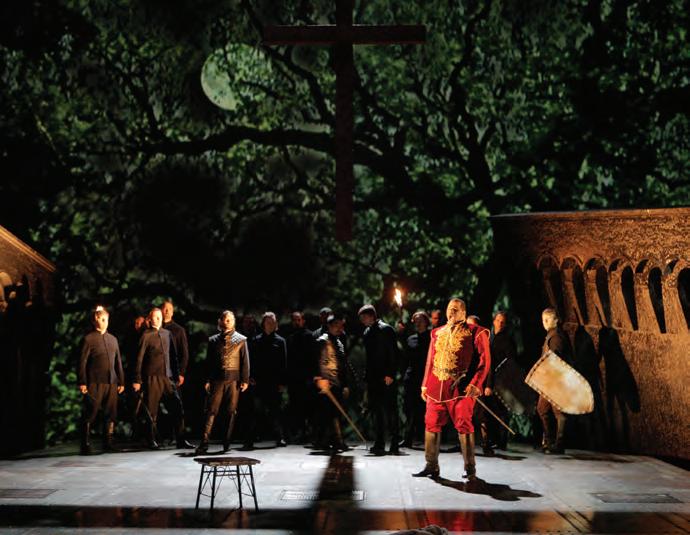

Macbeth (Verdi)

The Dream of Valentino (Argento)

The Magic Flute (Mozart)

Griffelkin (Ross)

2012—2013

Nabucco (Verdi)

Anna Bolena (Donizetti)

Doubt (Cuomo)

Hamlet (Thomas)

Turandot (Puccini)

Noye’s Fludde (Britten)

Down in the Valley (Weill)

Shoes for the Santo Niño (Paulus)

2011—2012

Così fan tutte (Mozart)

Silent Night (Puts)

Werther (Massenet)

Lucia di Lammermoor (Donizetti)

Madame Butterfly (Puccini)

The Giver (Kander)

2010—2011

Orpheus and Eurydice (Gluck)

Cinderella (Rossini)

Mary Stuart (Donizetti)

La traviata (Verdi)

Wuthering Heights (Herrmann)

2009—2010

The Pearl Fishers (Bizet)

Casanova’s Homecoming (Argento)

Roberto Devereux (Donizetti)

La bohème (Puccini)

Salome (Strauss)

Tom Thumb (Werner-Henze)

2008—2009

Il trovatore (Verdi)

The Abduction from the Seraglio (Mozart) Faust (Gounod)

The Adventures of Pinocchio (Dove)

The Barber of Seville (Rossini)

Brundibár (Krása)

Iolanthe (Sullivan)

2007—2008

A Masked Ball (Verdi)

The Italian Girl in Algiers (Rossini)

Romeo and Juliet (Gounod)

The Fortunes of King Croesus (Keiser)

Rusalka (Dvořák)

The Nightengale (Stravinksky)

2006—2007

La donna del lago (Rossini)

The Tales of Hoffmann (Offenbach)

The Grapes of Wrath (Gordon)

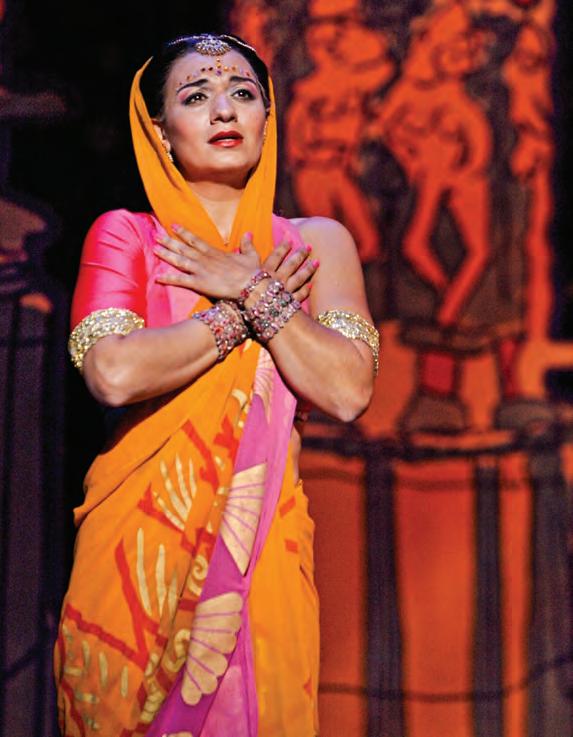

Lakmé (Delibes)

The Marriage of Figaro (Mozart)

Ruddigore (Sullivan)

LEGEND

World Premiere/Commission

American Premiere

New Music-Theater Ensemble Production l l l l l

Tour Production/Education Production

Concert Version/Semi-Staged

2005—2006

Tosca (Puccini)

Don Giovanni (Mozart)

Orazi and Curiazi (Mercadante)

Joseph Merrick, the Elephant Man (Petitgirard)

Hansel and Gretel (Humperdinck)

2004—2005

Madame Butterfly (Puccini)

Maria Padilla (Donizetti)

Carmen (Bizet)

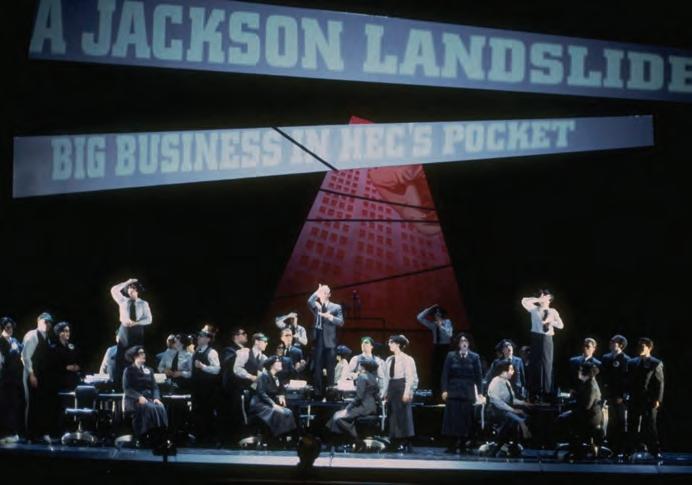

Nixon in China (Adams)

2003—2004

Rigoletto (Verdi)

Lucrezia Borgia (Donizetti)

Passion (Sondheim)

The Magic Flute (Mozart)

2002—2003

The Merry Widow (Lehár)

Norma (Bellini)

The Flying Dutchman (Wagner)

La traviata (Verdi)

The Handmaid’s Tale (Ruders)

2001—2002

Lucia di Lammermoor (Donizetti)

La clemenza di Tito (Mozart)

La bohème (Puccini)

Little Women (Adamo)

Don Carlos (Verdi)

2000—2001

Turandot (Puccini)

The Capulets and the Montagues (Bellini)

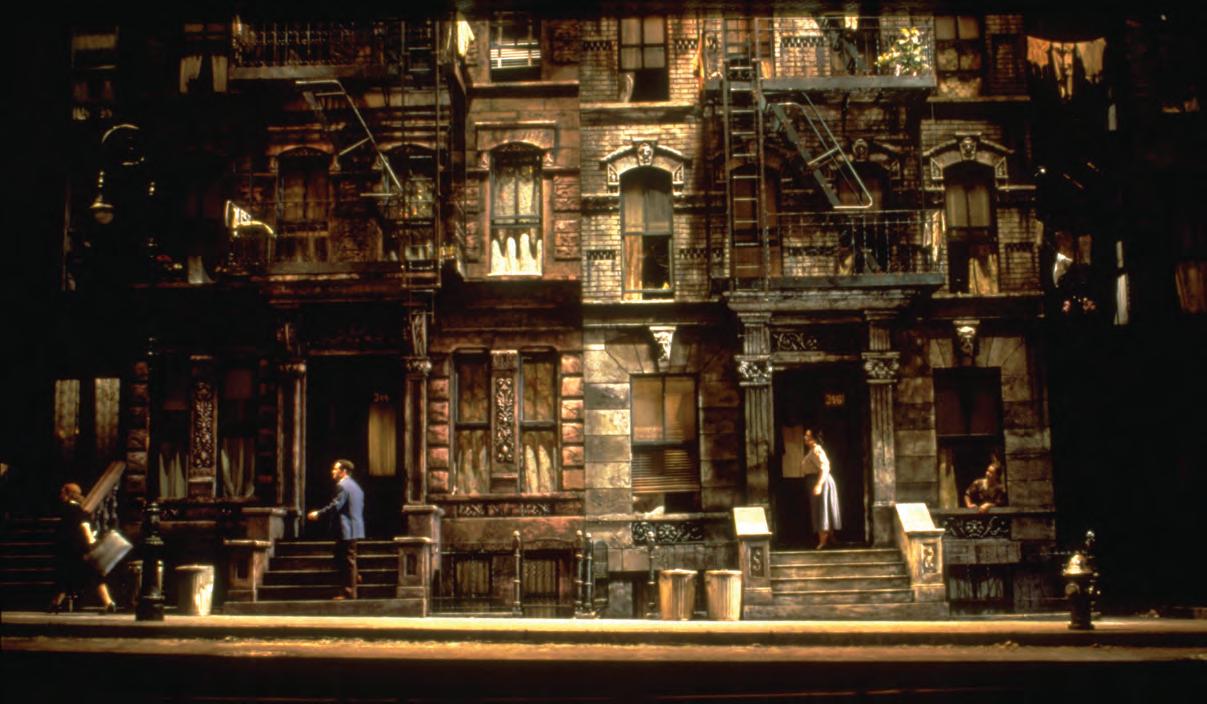

Street Scene (Weill)

The Barber of Seville (Rossini)

Pagliacci/Carmina burana (Leoncavallo/Orff)

The Barber of Seville (Rossini)

The Birds, the Beasts, and the Ball Game (Alcorn)

1999—2000

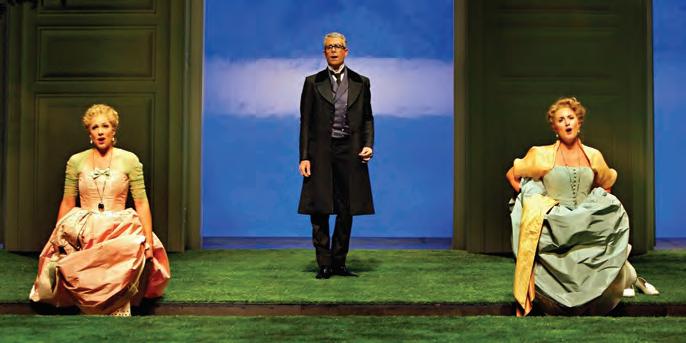

Der Rosenkavalier (Strauss)

Macbeth (Verdi)

Semiramide (Rossini)

The Marriage of Figaro (Mozart)

The Marriage of Figaro (Mozart)

The Cat That Walked By Himself (Alcorn)

1998—1999

Otello (Verdi)

Madame Butterfly (Puccini)

The Turn of the Screw (Britten)

Faust (Gounod)

Madame Butterfly (Puccini)

How the Camel Got His Hump (Alcorn)

1997—1998

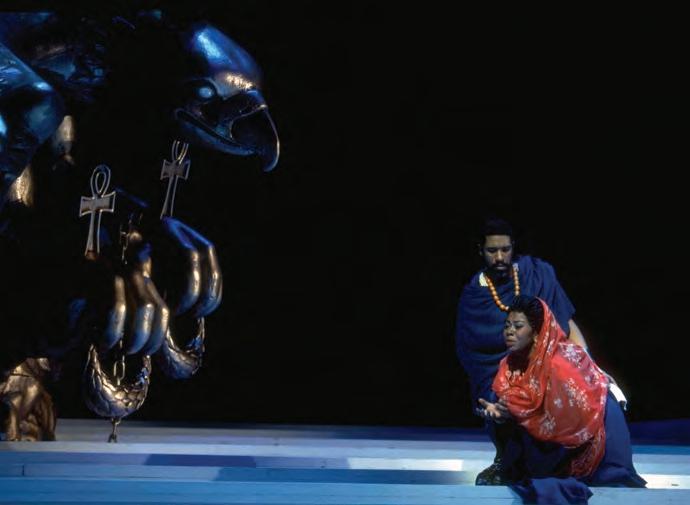

Aida (Verdi)

Cinderella (Rossini)

Transatlantic (Antheil)

Tosca (Puccini)

Cinderella

1996—1997

La traviata (Verdi)

The Magic Flute (Mozart)

The Rake’s Progress (Stravinsky)

Carmen (Bizet)

Carmen (Bizet)

1995—1996

La bohème (Puccini)

Don Giovanni (Mozart)

Pelléas and Mélisande (Debussy)

The Tales of Hoffmann (Offenbach)

The Bohemians (Puccini)

1994—1995

Turandot (Puccini)

The Barber of Seville (Rossini)

Rigoletto (Verdi)

Bok Choy Variations (Chen & Simonson)

Figaro’s Revenge (Rossini, Paisiello)

1993—1994

Julius Caesar (Handel)

Diary of an African American (Peterson)

Il trovatore (Verdi)

The Merry Widow and The Hollywood Tycoon (Lehár)

Don Giovanni (Mozart)

1992—1993

The Flying Dutchman (Wagner)

Armida (Rossini)

Madame Butterfly (Puccini)

The Pirates of Penzance (Gilbert & Sullivan)

1991—1992

Tosca (Puccini)

The Pearl Fishers (Bizet)

The Marriage of Figaro (Mozart)

From the Towers of the Moon (Moran & La Chiusa)

The Magic Flute (Mozart)

Carousel (Rodgers & Hammerstein)

1990—1991

Norma (Bellini)

The Aspern Papers (Argento)

Carmen (Bizet)

Così fan tutte (Mozart)

Così fan tutte (Mozart)

Swing on a Star (Winkler)

1989—1990

La bohème (Puccini)

A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Britten)

Romeo et Juliette (Gounod)

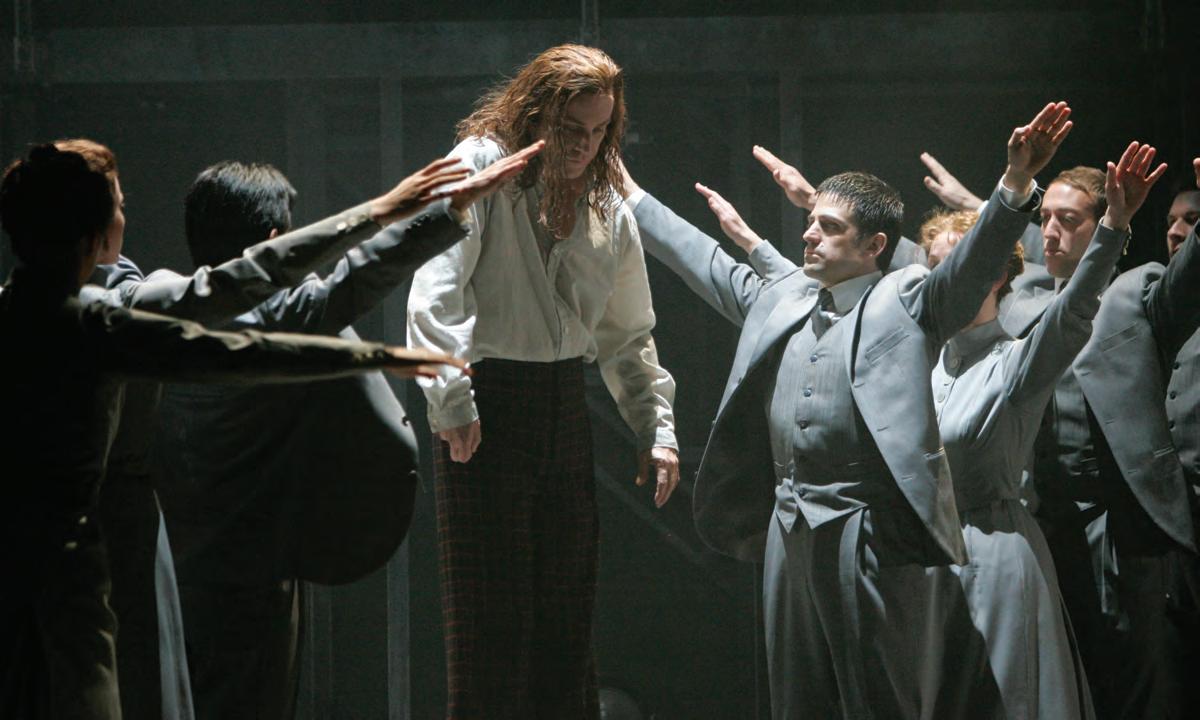

Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus (Libby Larson)

My Fair Lady (Lerner & Loewe)

Snow Leopard (Harper & Nieboer)

Madame Butterfly (Puccini)

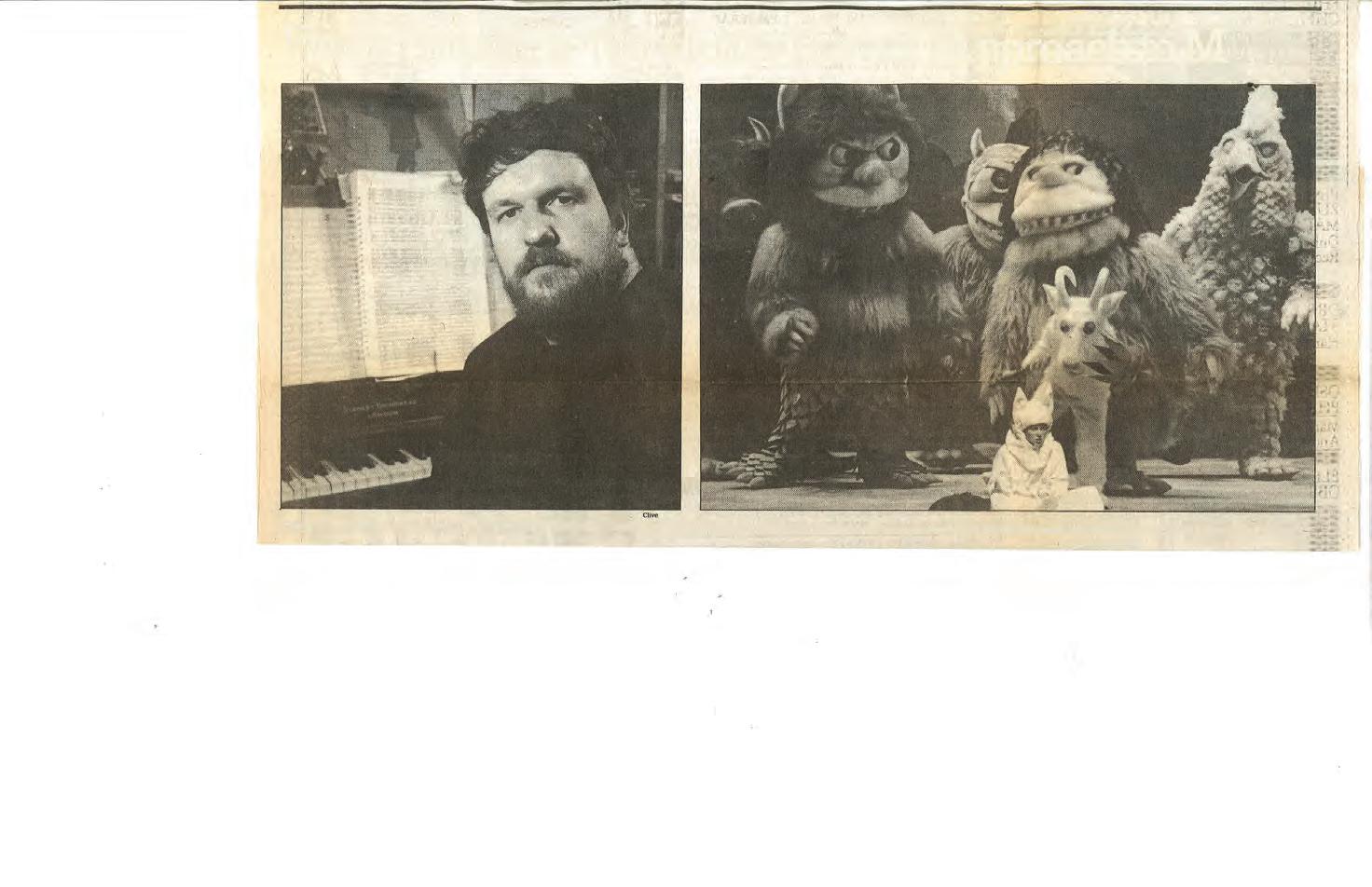

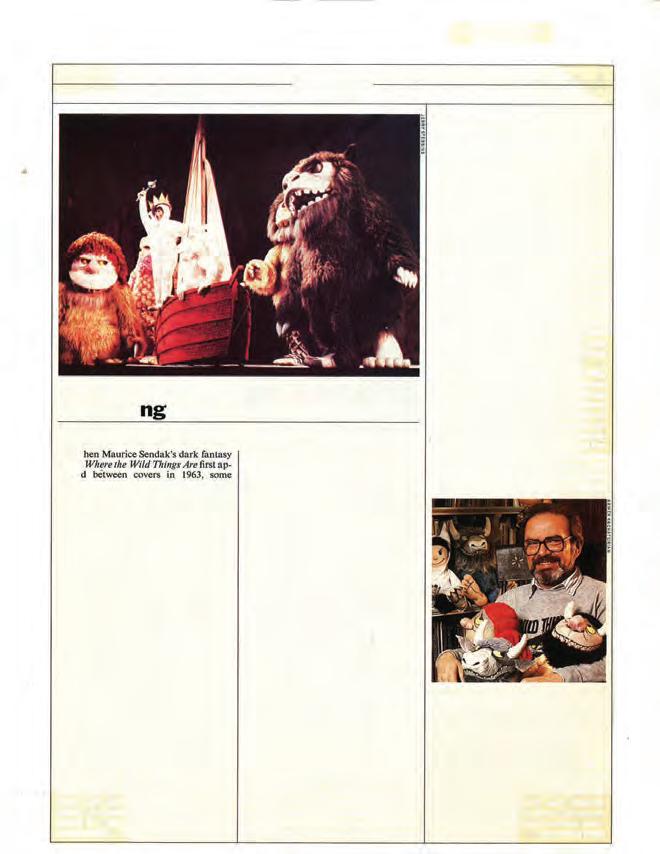

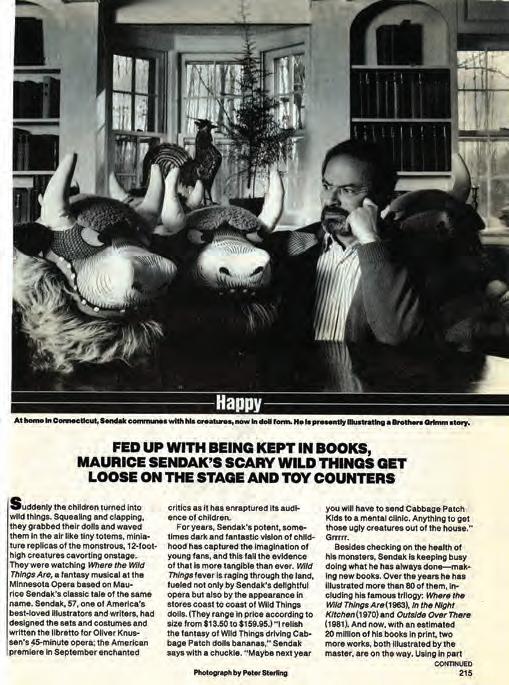

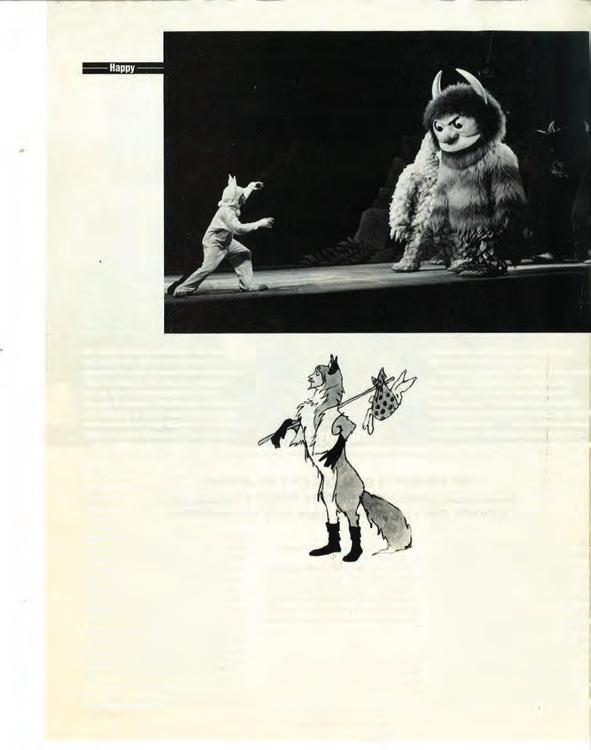

Where the Wild Things Are (Sendak & Knussen)

1988—1989

Don Giovanni (Mozart)

Salome (R. Strauss)

The Mikado (Gilbert & Sullivan)

The Juniper Tree (Glass & Moran)

Show Boat (Kern & Hammerstein)

Without Colors (Wellman & Shiflett)

Red Tide (Selig & Sherman)

Newest Little Opera in the World (Ensemble)

Cinderella (Rossini)

Tintypes (Kyte, Marvin, Pearle)

LEGEND

World Premiere/Commission

American Premiere

New Music-Theater Ensemble Production l

Tour Production/Education Production

Concert Version/Semi-Staged

Die Fledermaus (J. Strauss)

Rigoletto (Verdi)

Rusalka (Dvorak)

Cowboy Lips (Greene & Madsen)

Fly Away All (Hutchinson & Shank)

Book of Days (Monk)

Oklahoma! (Rodgers & Hammerstein)

Carmen (Bizet)

Jargonauts, Ahoy! ( McKeel)

1986—1987

The Pearl Fishers (Bizet)

The Postman Always Rings Twice (Paulus)

Ariadne auf Naxos (R. Strauss)

South Pacific (Rodgers & Hammerstein)

Hansel and Gretel (Humperdinck)

Jargonauts, Ahoy! (McKeel)

1985—1986

Where the Wild Things Are/Higglety Pigglety Pop! (Knussen & Sendak)

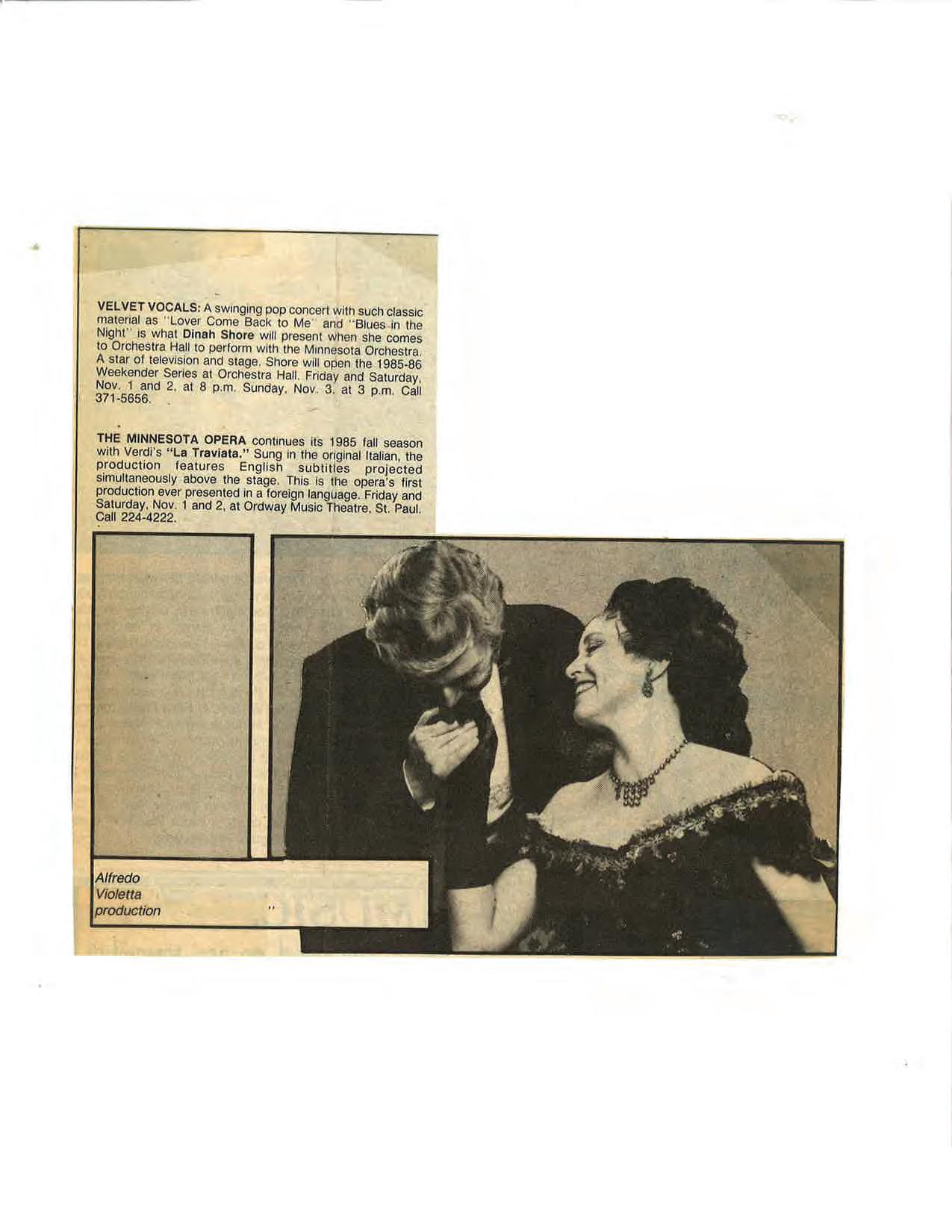

La traviata (Verdi)

The Elixir of Love (Donizetti)

The King and I (Rodgers & Hammerstein)

Opera Tomorrow

The Fantasticks (Schmidt)

The Magic Flute (Mozart)

The Music Shop (Wargo)

1984—1985

Animalen (Werle)

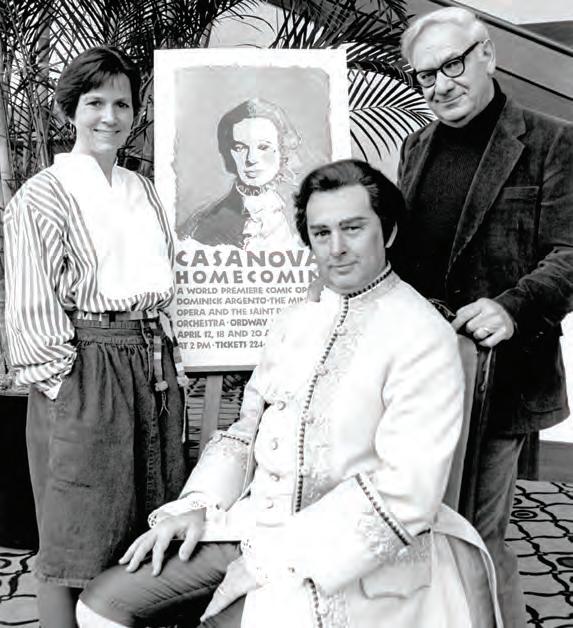

Casanova’s Homecoming (Argento)

The Magic Flute (Mozart)

La bohème (Puccini)

Meanwhile, Back at Cinderella’s (Arlan)

1983—1984

Hansel and Gretel (Humperdinck)

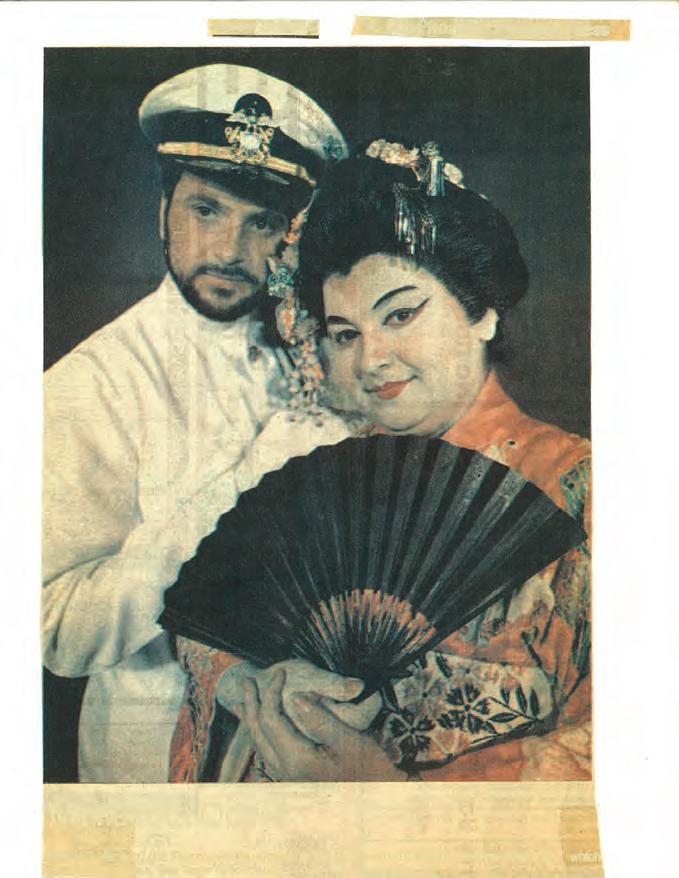

Madame Butterfly (Puccini)

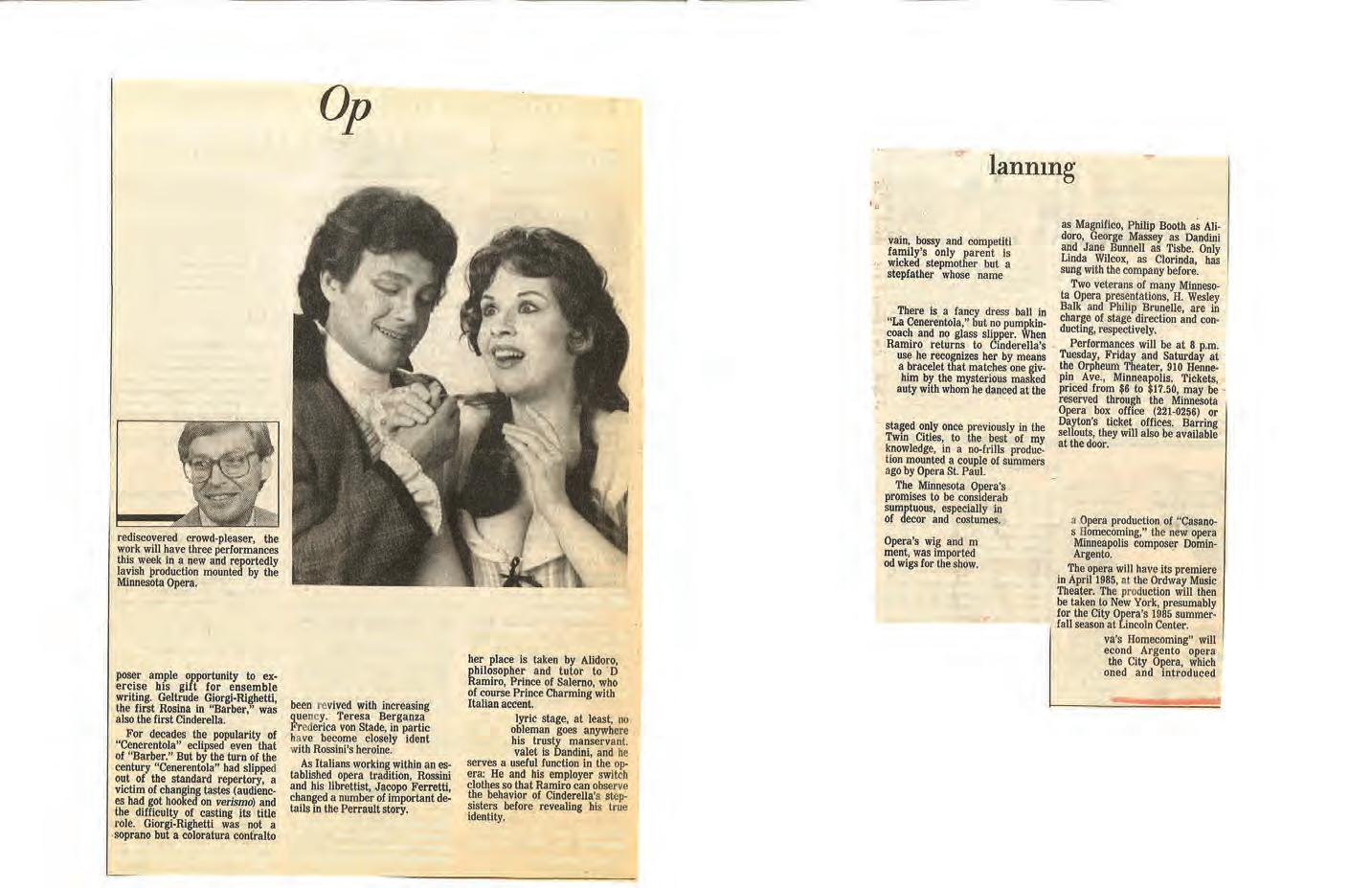

La cenerentola (Rossini)

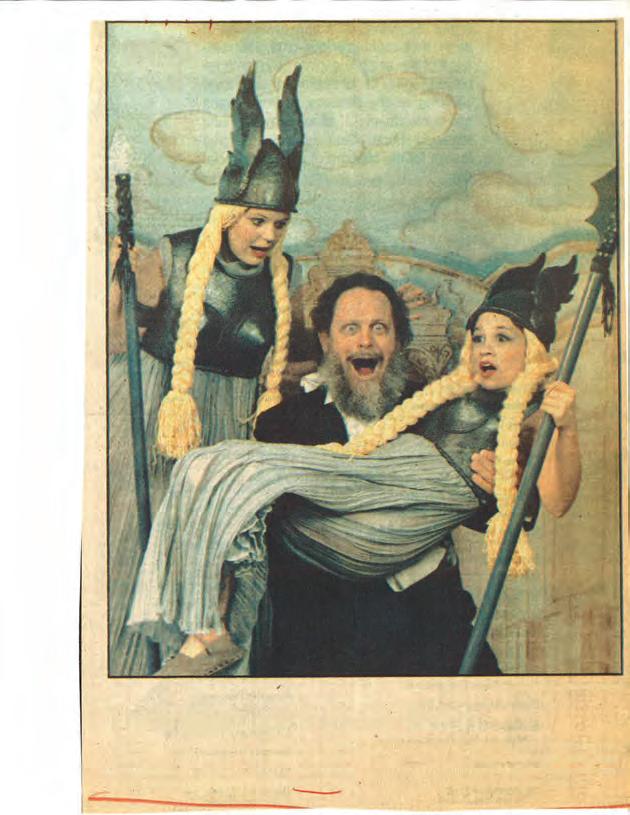

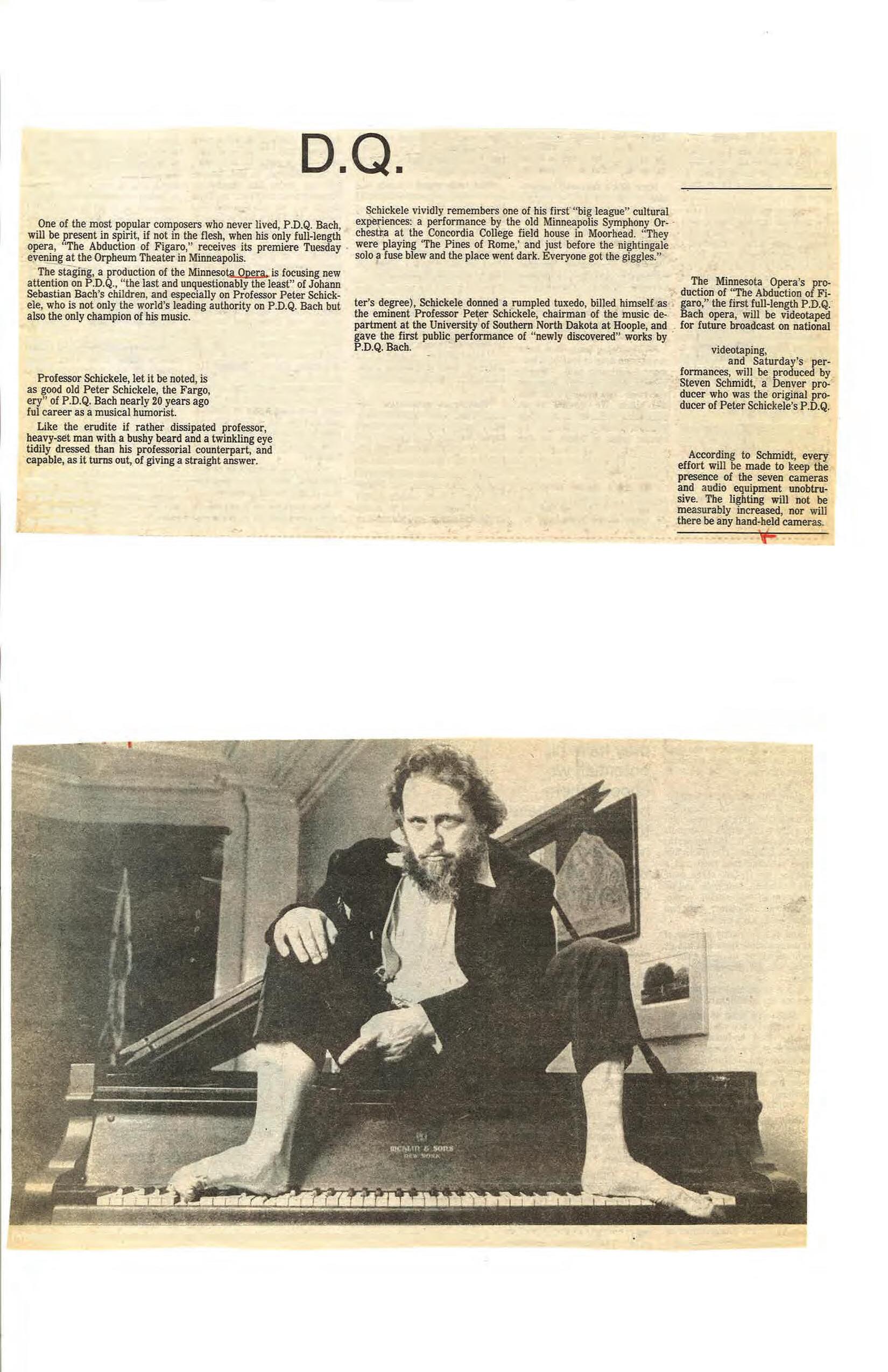

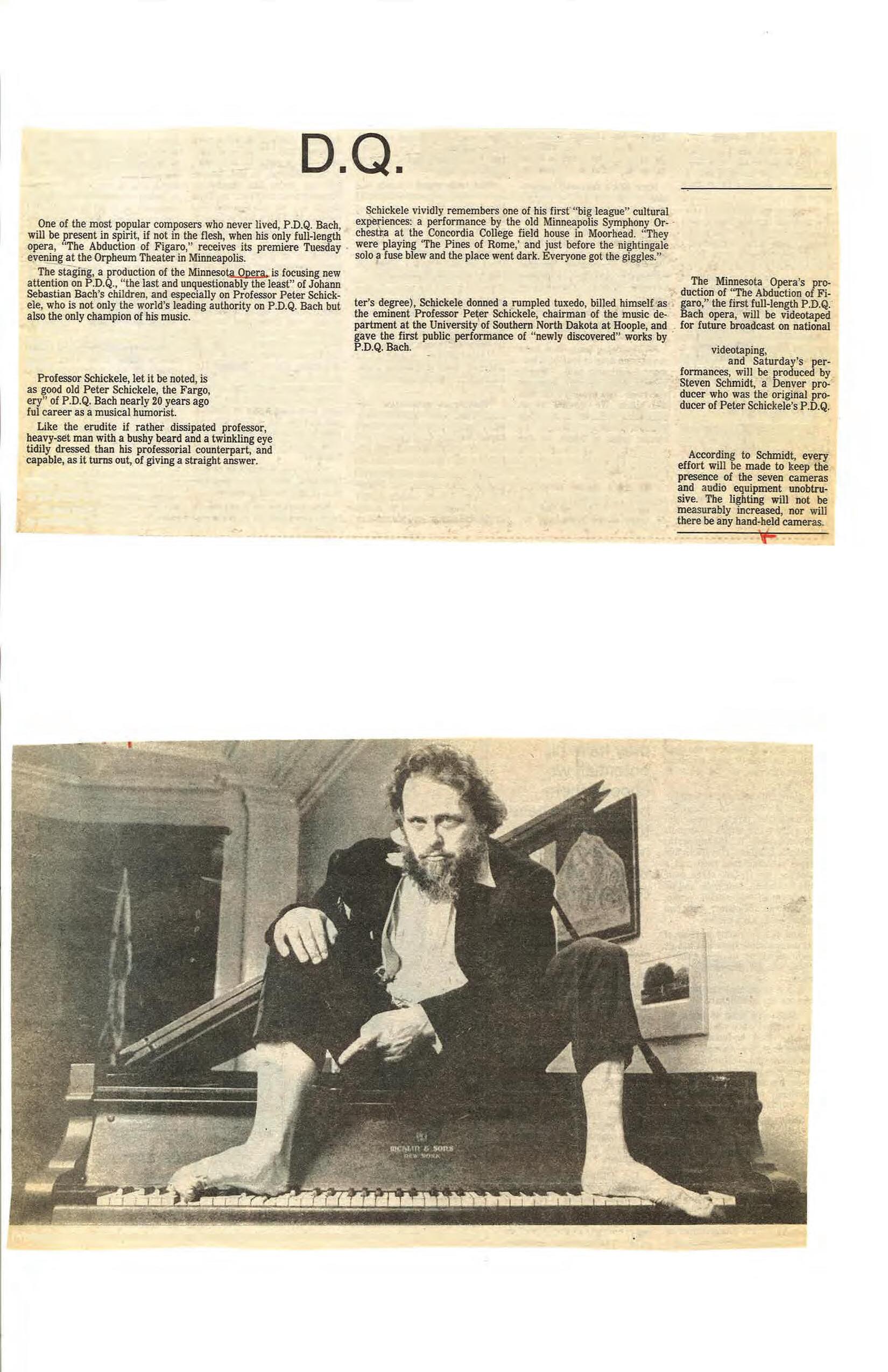

The Abduction of Figaro (PDQ Bach)

The Boor (Argento)

Chanticleer (Barab)

Don Pasquale (Donizetti)

1982—1983

Hansel and Gretel (Humperdinck)

Lucia di Lammermoor (Donizetti)

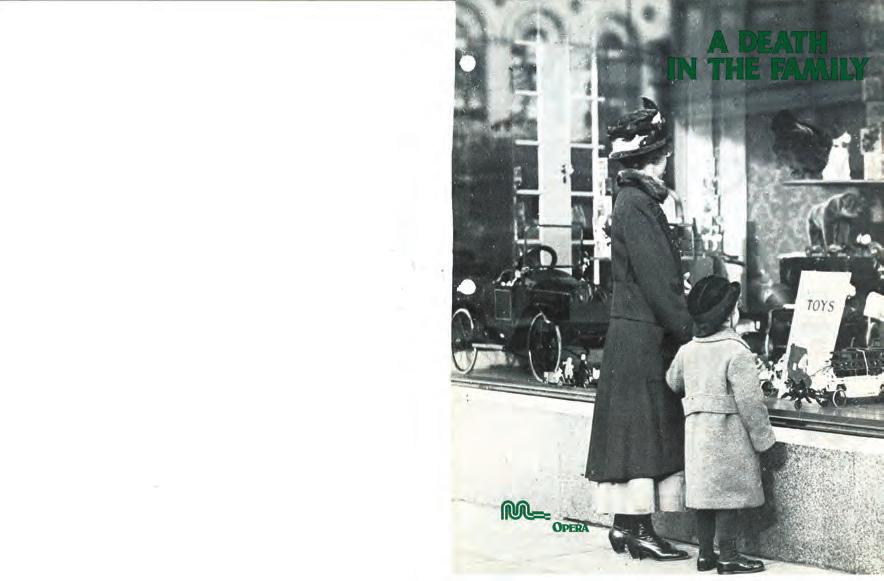

A Death in the Family (Mayer)

Kiss Me, Kate (Porter)

The Barber of Seville (Rossini)

The Frog Who Became a Prince (Barnes)

Zetabet (Barnes)

1981—1982

Hansel & Gretel (Humperdinck)

The Village Singer (Paulus)

Gianni Schicchi (Puccini)

The Barber of Seville (Rossini)

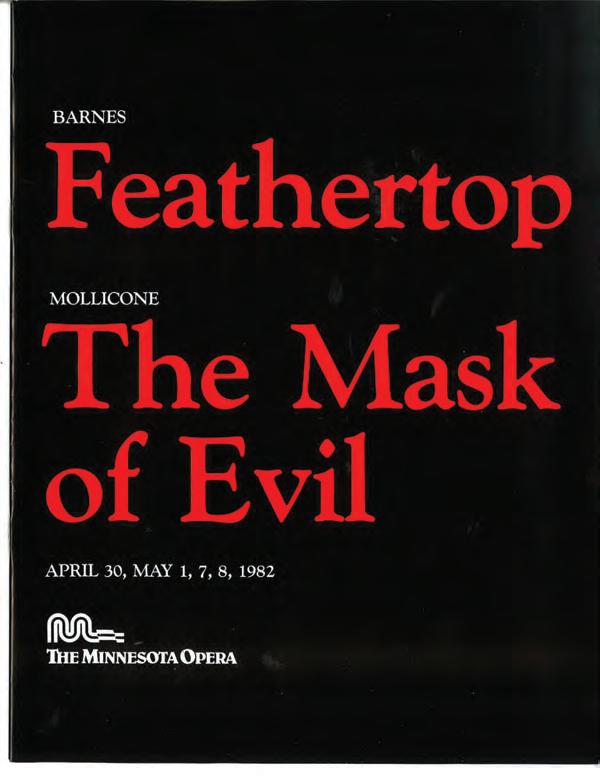

Feathertop (Barnes)

The Mask of Evil (Mollicone)

Hansel and Gretel (Humperdinck)

Rosina (Titus)

1980—1981

The Merry Widow (Lehar)

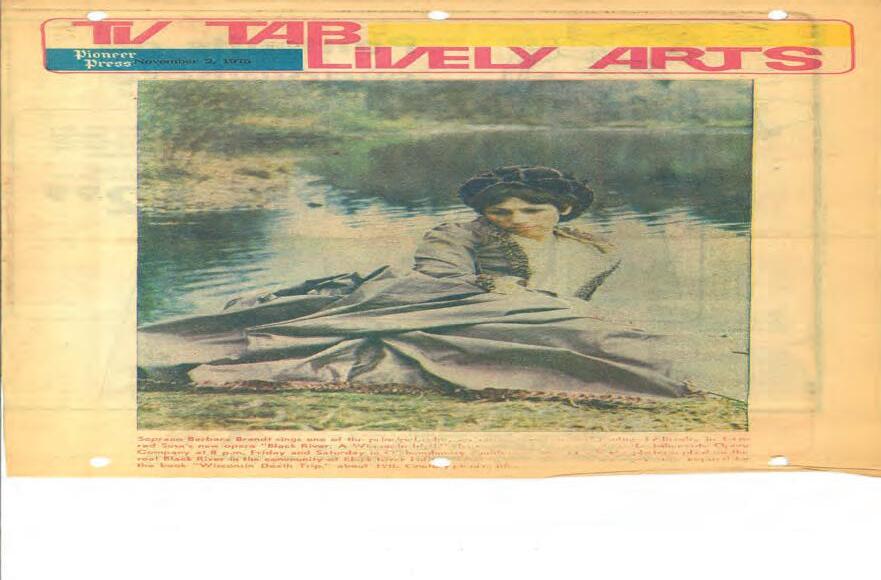

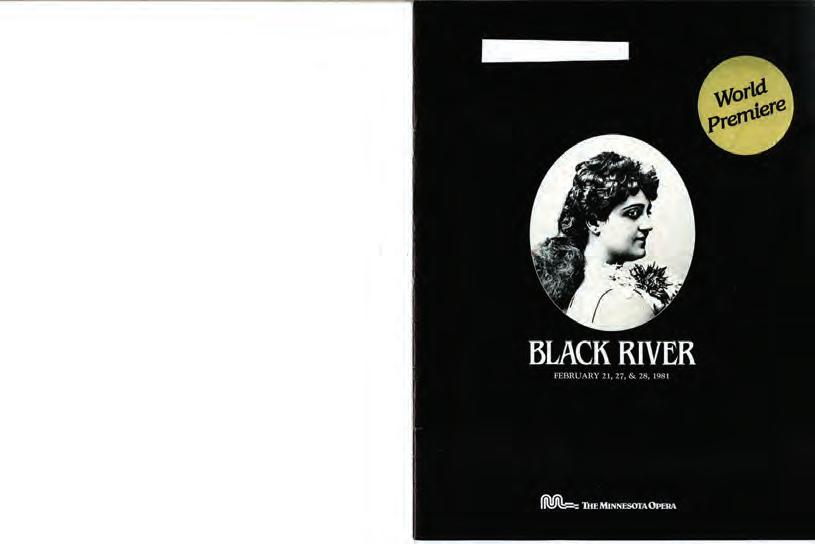

Black River (Susa)

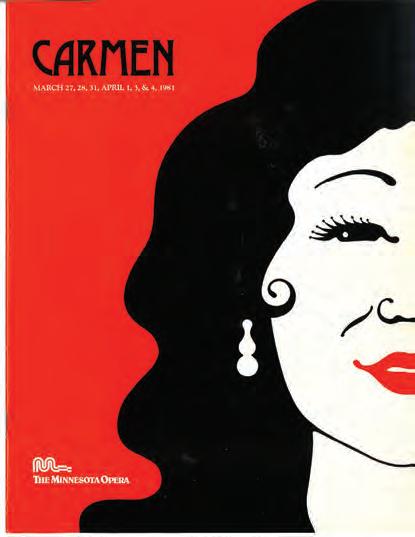

Carmen (Bizet)

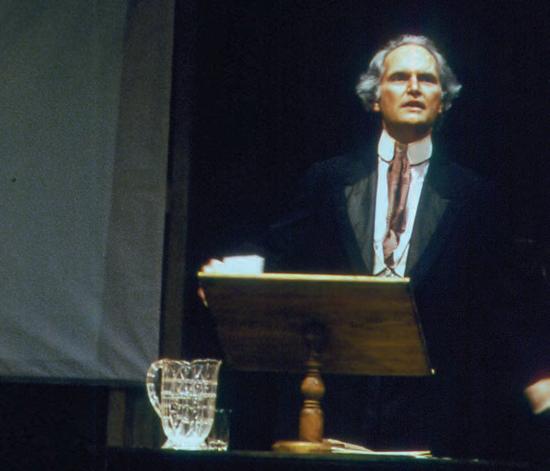

A Water Bird Talk (Argento)

Miss Havisham’s Wedding Night (Argento)

The Marriage of Figaro (Mozart)

The Threepenny Opera (Weill)

1979—1980

The Abduction from the Seraglio (Mozart)

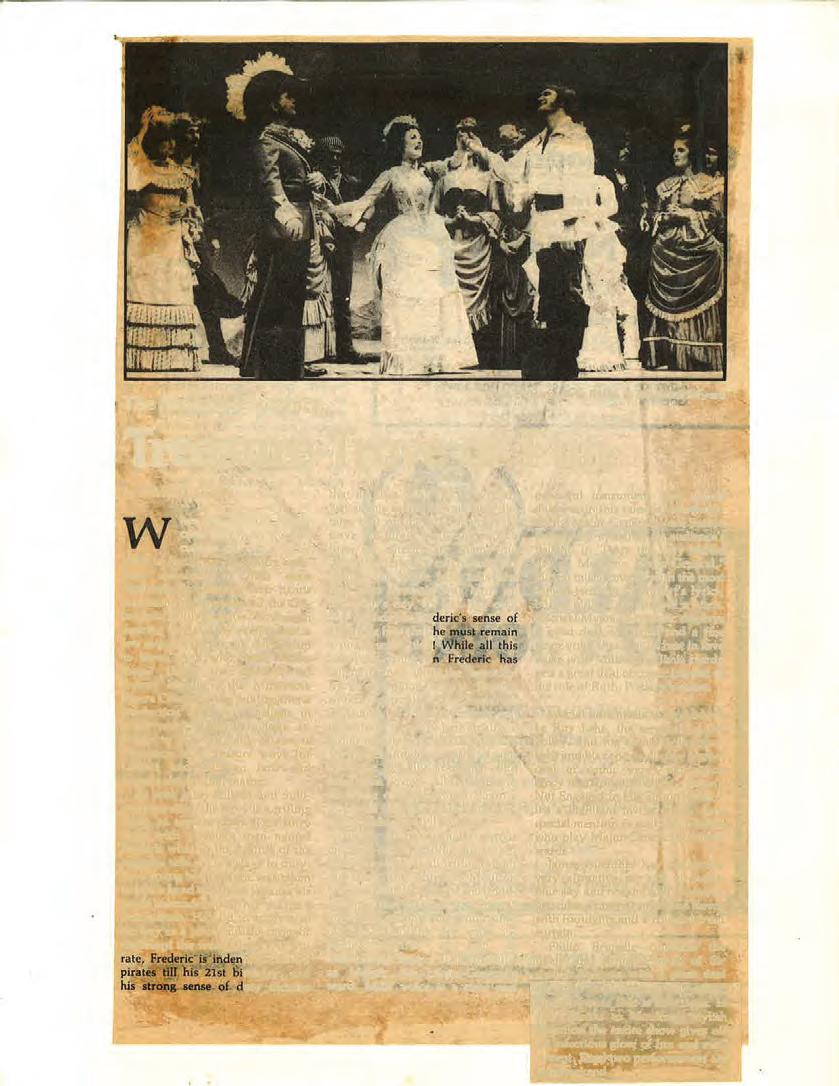

The Pirates of Penzance (Gilbert & Sullivan)

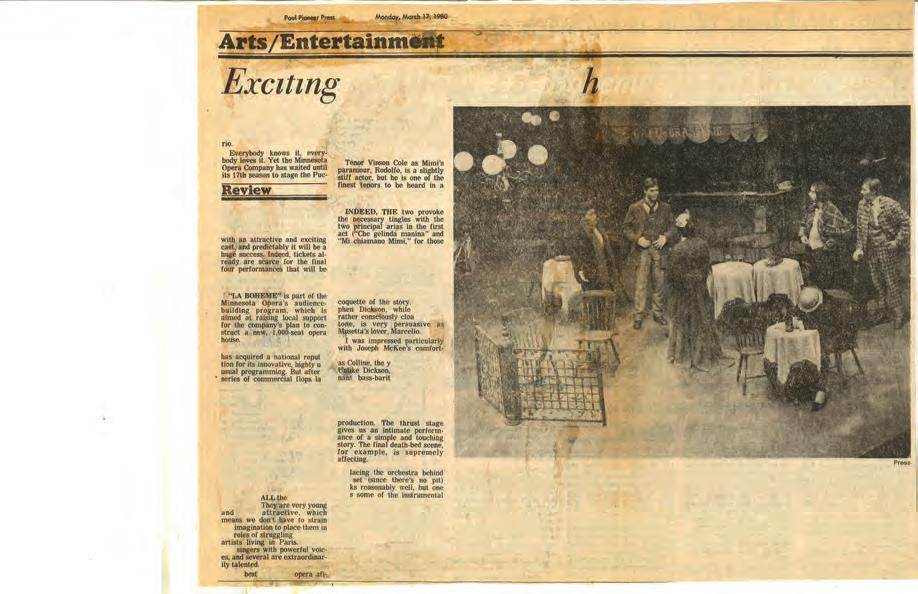

La bohème (Puccini)

Rosina (Titus)

A Christmas Carol (Sandow)

1978—1979

The Love for Three Oranges (Prokofiev)

The Jealous Cellist (Stokes)

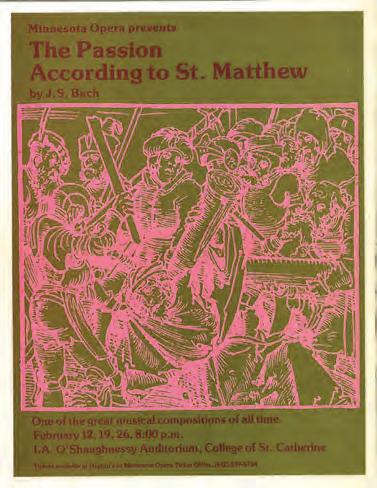

The Passion According to St. Matthew (J.S. Bach)

La traviata (Verdi)

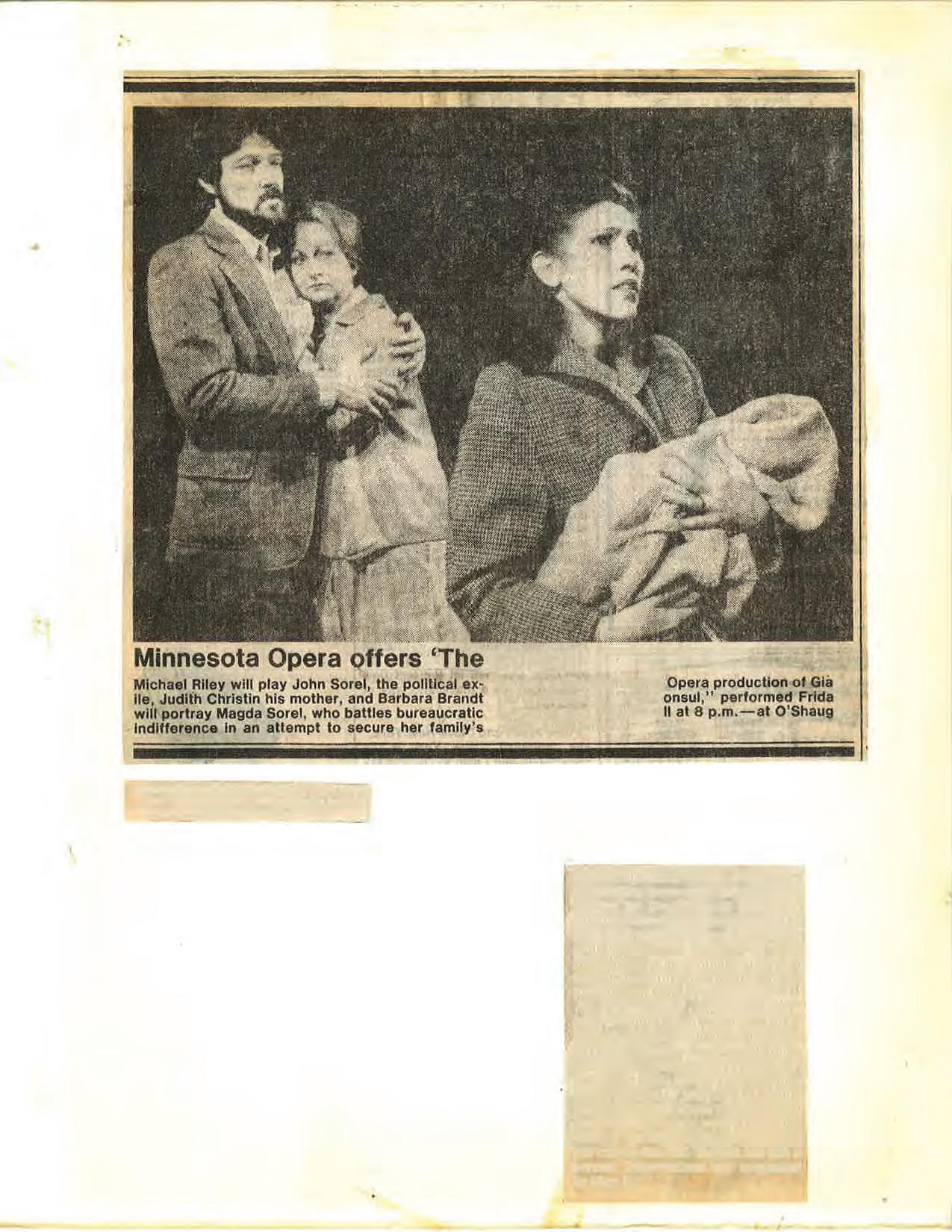

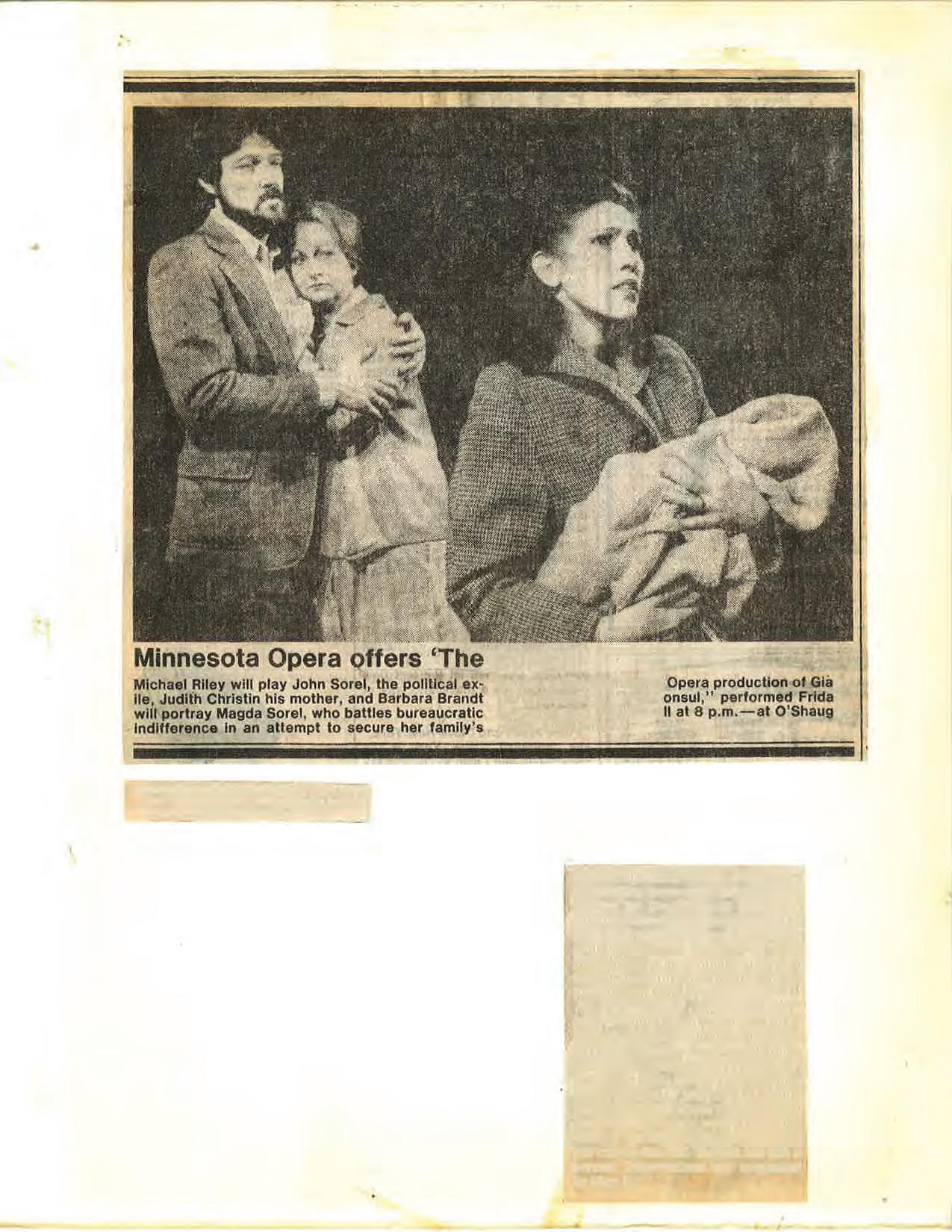

The Consul (Menotti)

Viva la Mamma (Donizetti)

1977—1978

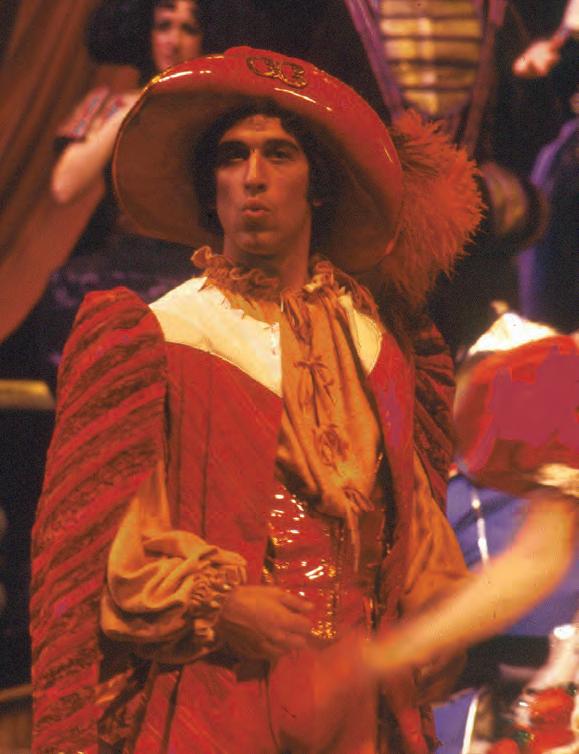

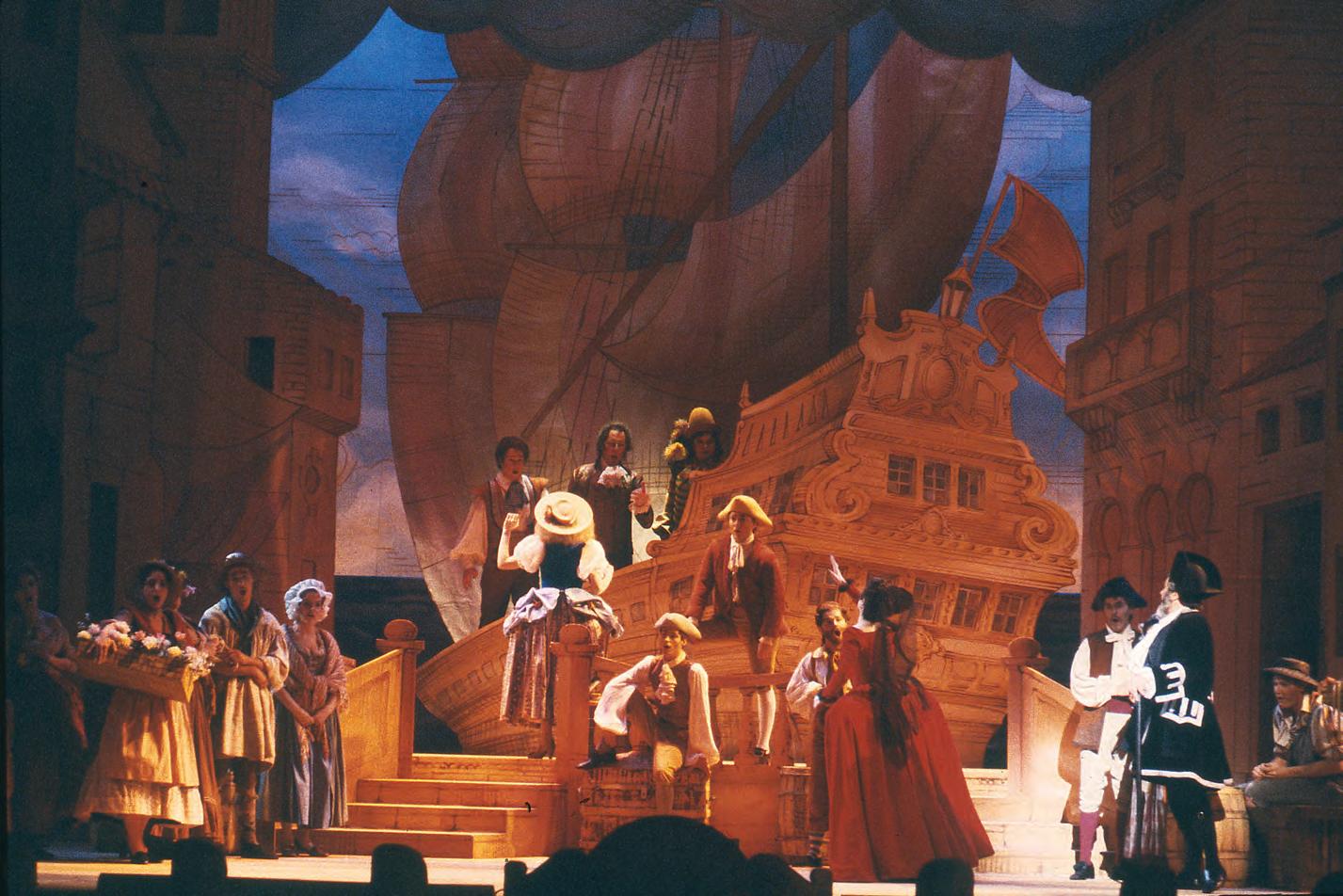

Christopher Columbus (Offenbach)

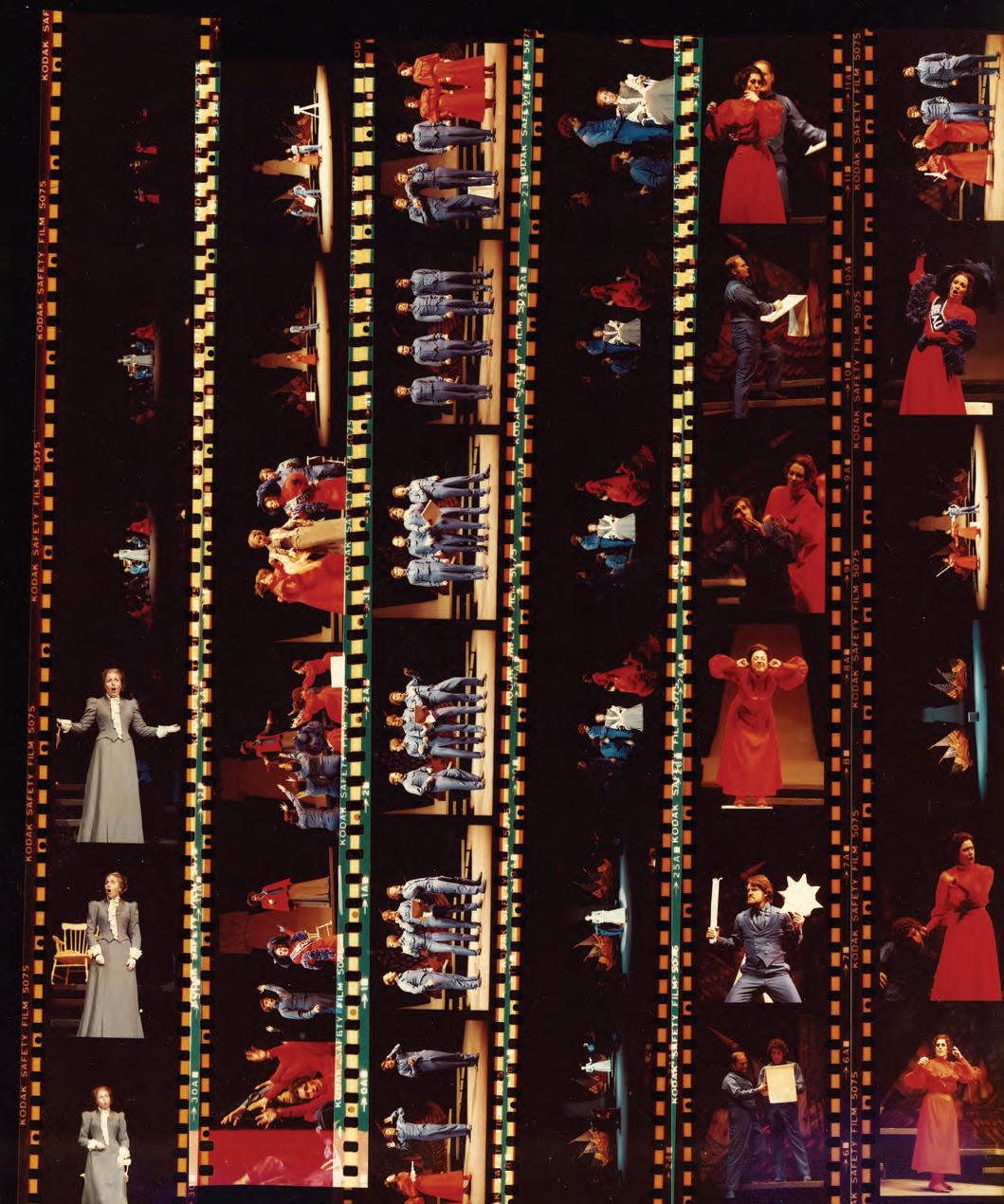

The Mother of Us All (Thomson)

The Marriage of Figaro (Mozart)

Claudia Legare (Ward)

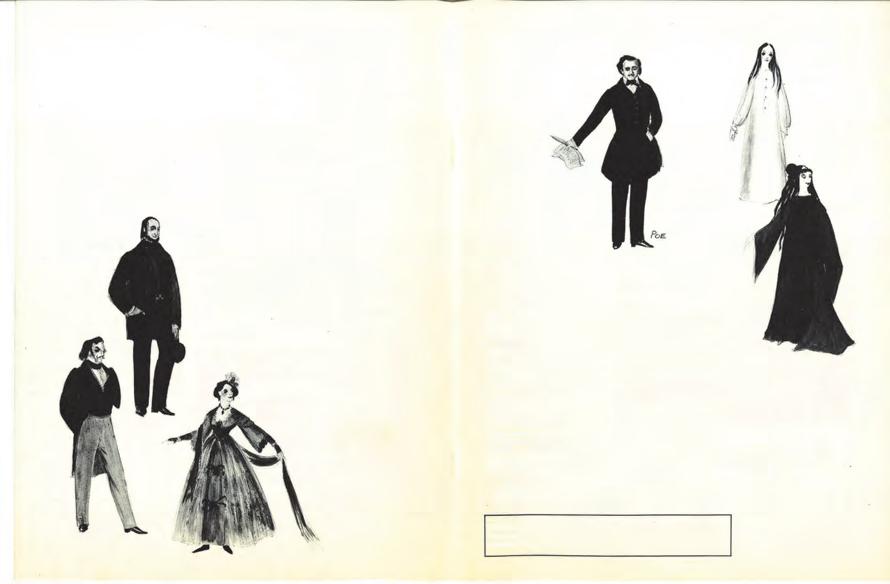

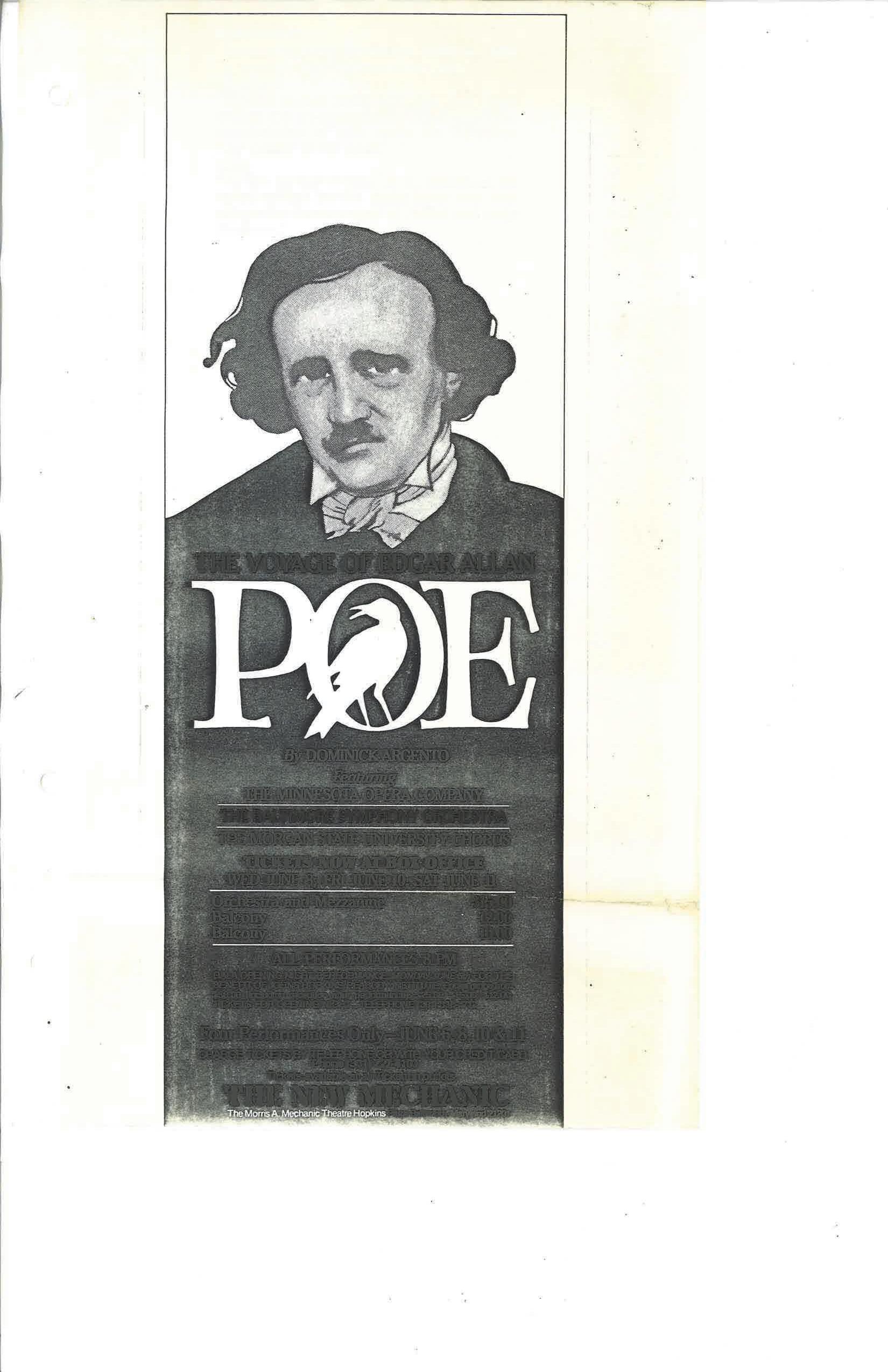

The Voyage of Edgar Allan Poe (Argento)

1976—1977

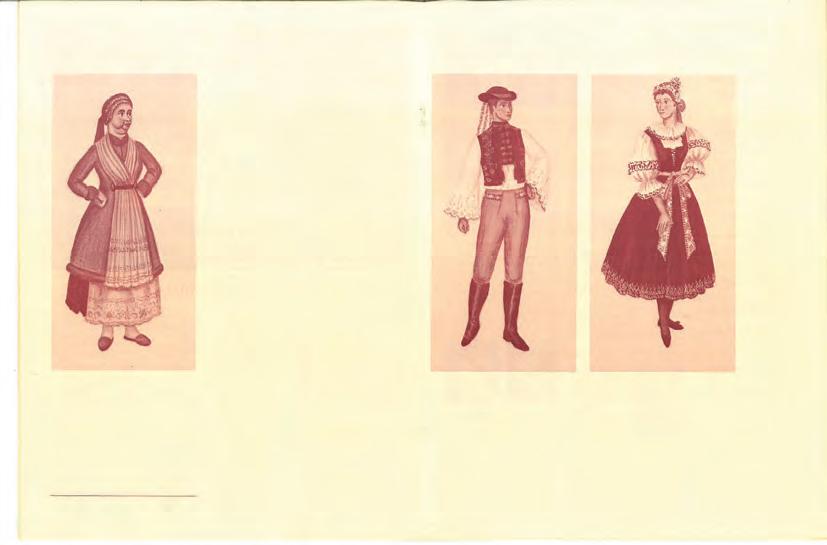

The Bartered Bride (Smetana)

The Passion According to St. Matthew (J.S. Bach)

Candide (Bernstein)

Mahagonny (Weill)

1975—1976

Black River (Susa)

El Capitan (Sousa)

Così fan tutte (Mozart)

The Voyage of Edgar Allan Poe (Argento)

1974—1975

Gallimaufry (Minnesota Opera)

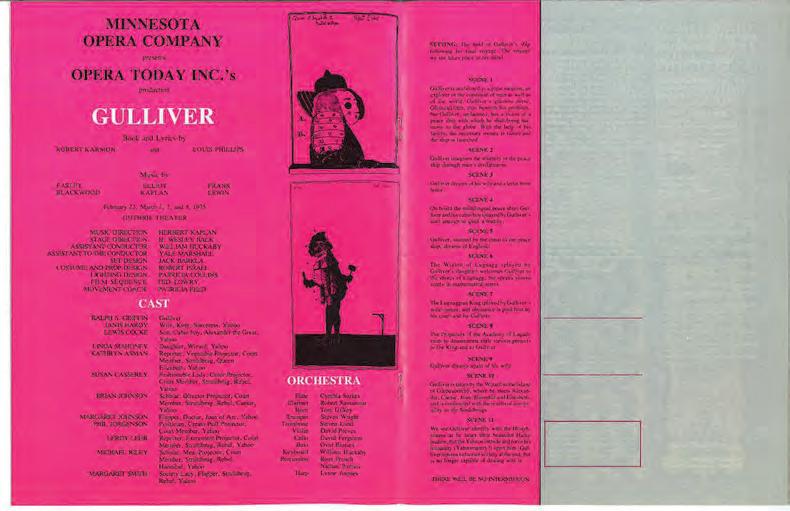

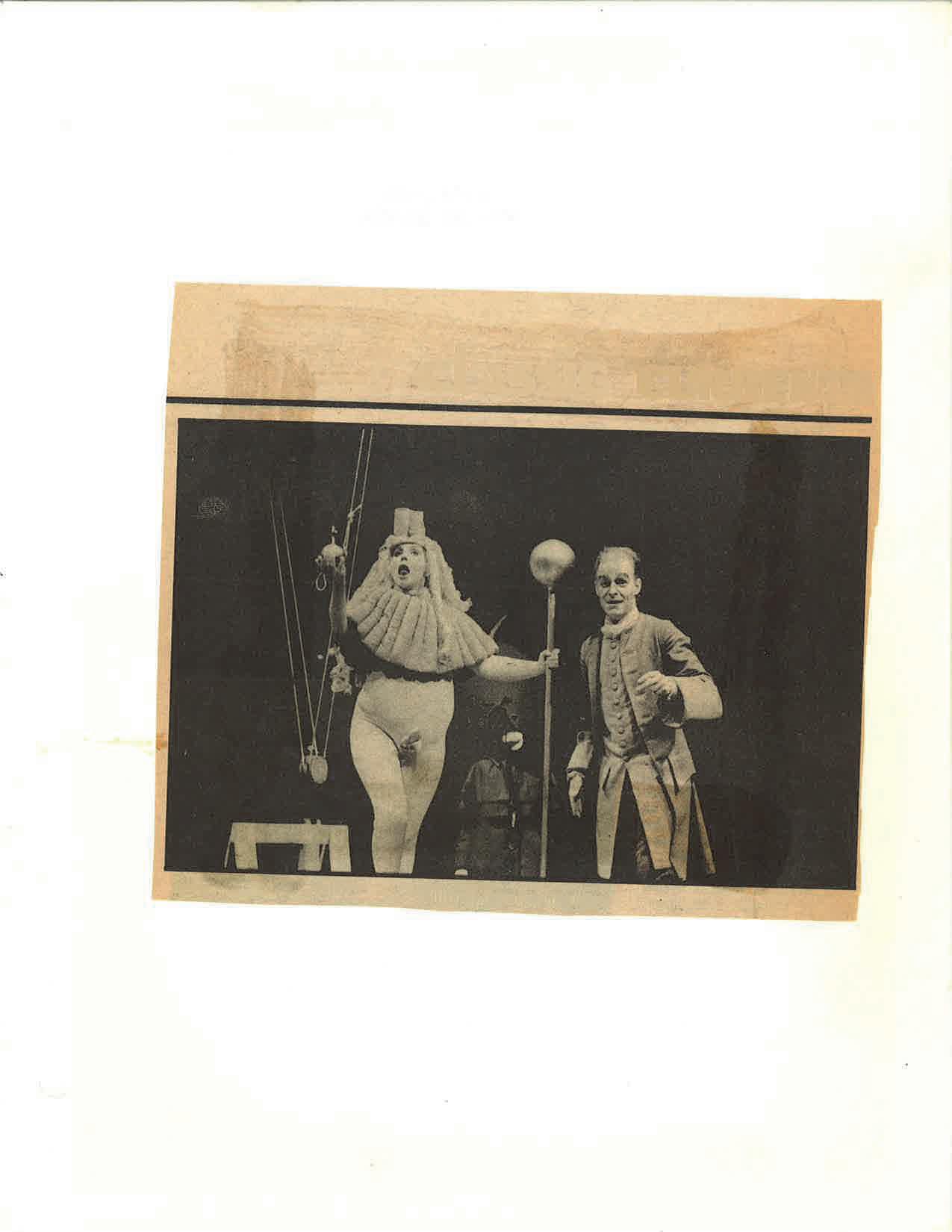

Gulliver (Blackwood, Kaplan, Lewin)

Eight Songs for a Mad King (Davies)

Music from the Court of George III

The Magic Flute (Mozart)

Albert Herring (Britten) Transformations (Susa)

1973—1974

El Capitan (Sousa) Transformations (Susa)

Don Giovanni (Mozart)

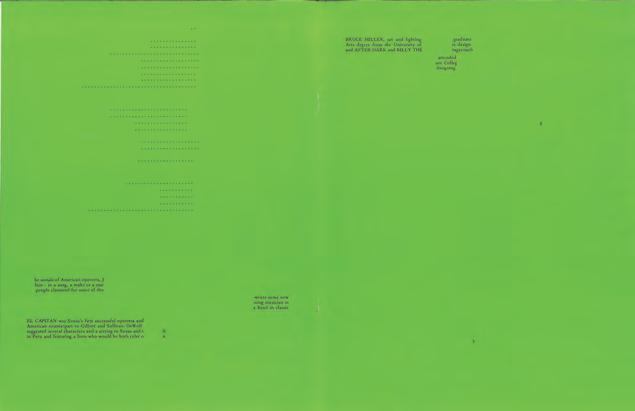

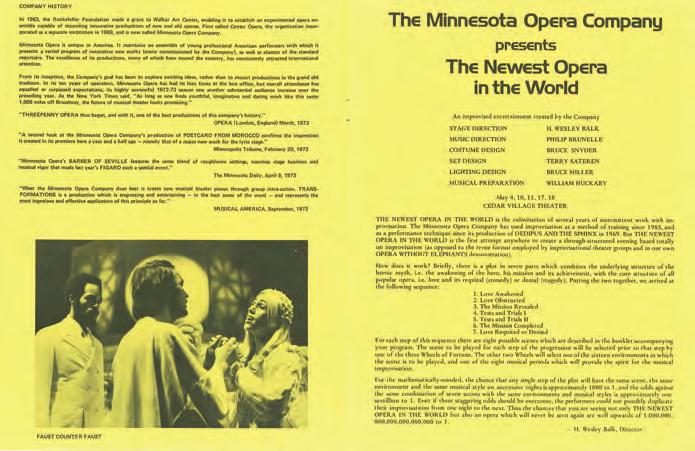

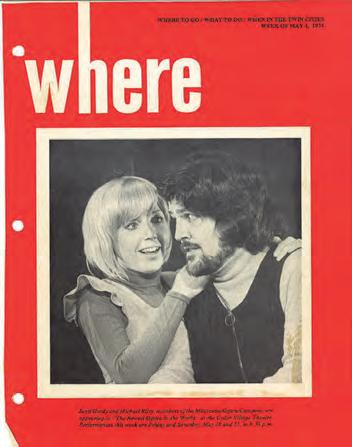

The Newest Opera in the World (Minnesota Opera)

1972—1973

The Threepenny Opera (Weill)

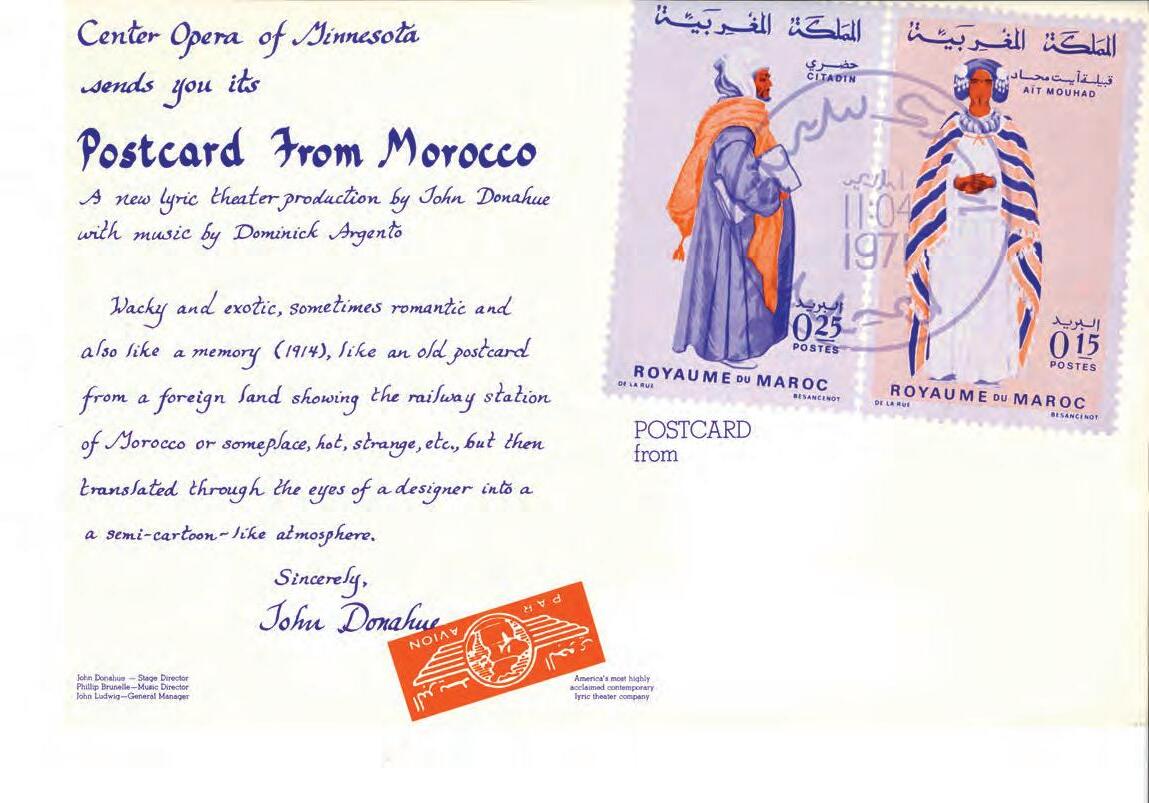

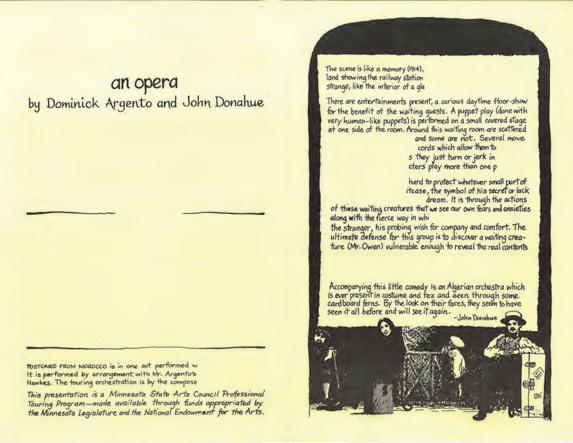

Postcard from Morocco (Argento)

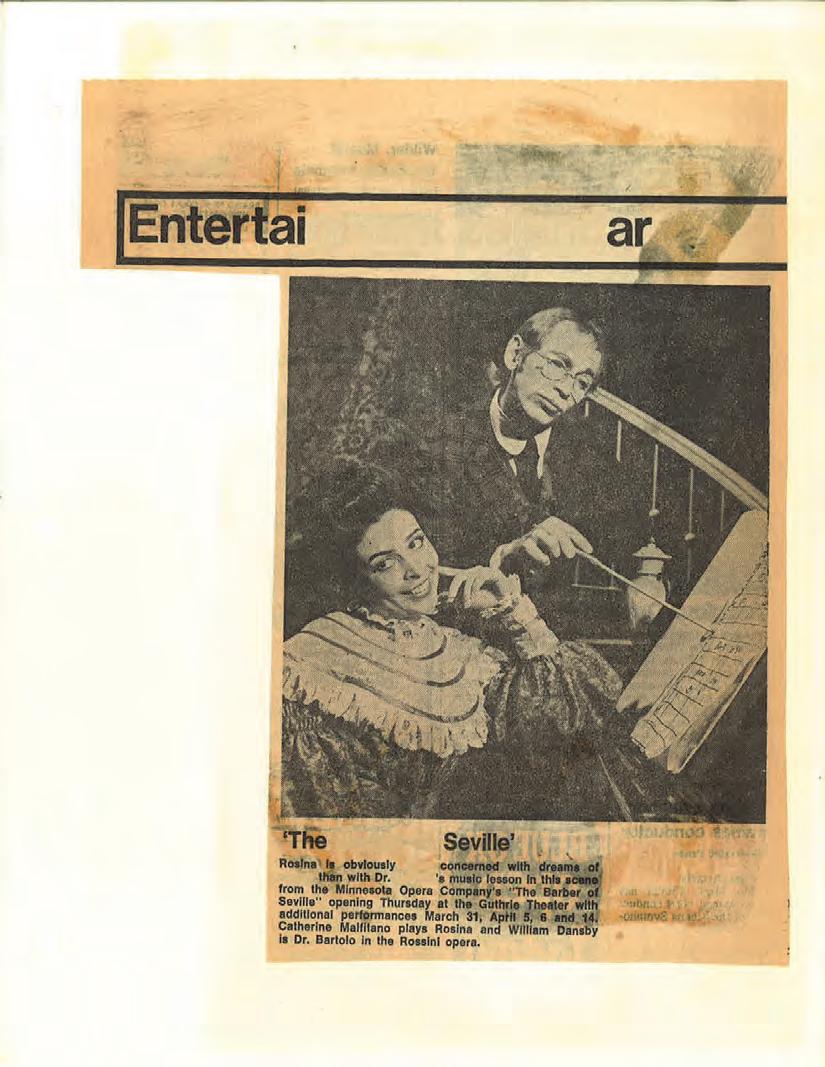

The Barber of Seville (Rossini) Transformations (Susa)

Postcard from Morocco (Argento)

LEGEND

World Premiere/Commission

American Premiere

New Music-Theater Ensemble Production l l l l l

Tour Production/Education Production

Concert Version/Semi-Staged

AS CENTER OPERA COMPANY

1971—1972

Postcard from Morocco (Argento)

The Business of Good Government (Marshall)

The Rake’s Progress (Stravisnky)

Four Saints in Three Acts (Thomson)

The Good Soldier Schweik (Kurka)

The Marriage of Figaro (Mozart)

Postcard from Morocco (Argento)

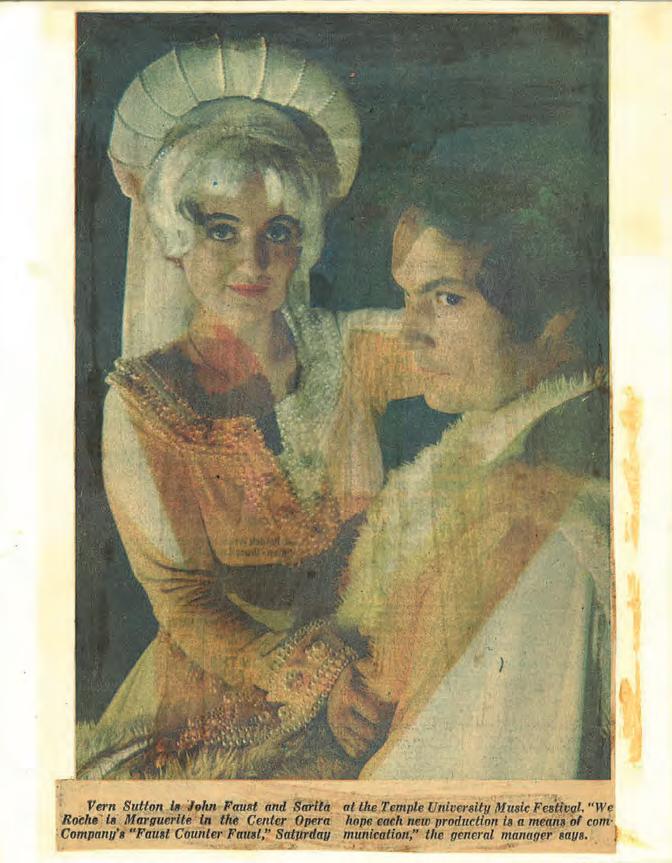

Faust Counter Faust (Gessner)

1970—1971

Sir John in Love (Vaughan Williams)

Christmas Mummeries and Good Government (Marshall)

Faust Counter Faust (Gessner)

The Coronation of Poppea (Monteverdi)

The Mother of Us All (Thomson)

Faust Counter Faust (Gessner)

The Mother of Us All (Thomson)

1969—1970

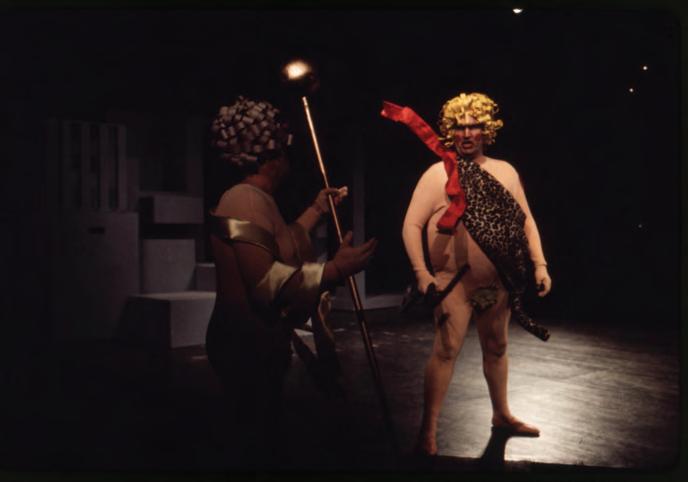

Oedipus and the Sphinx (Marshall)

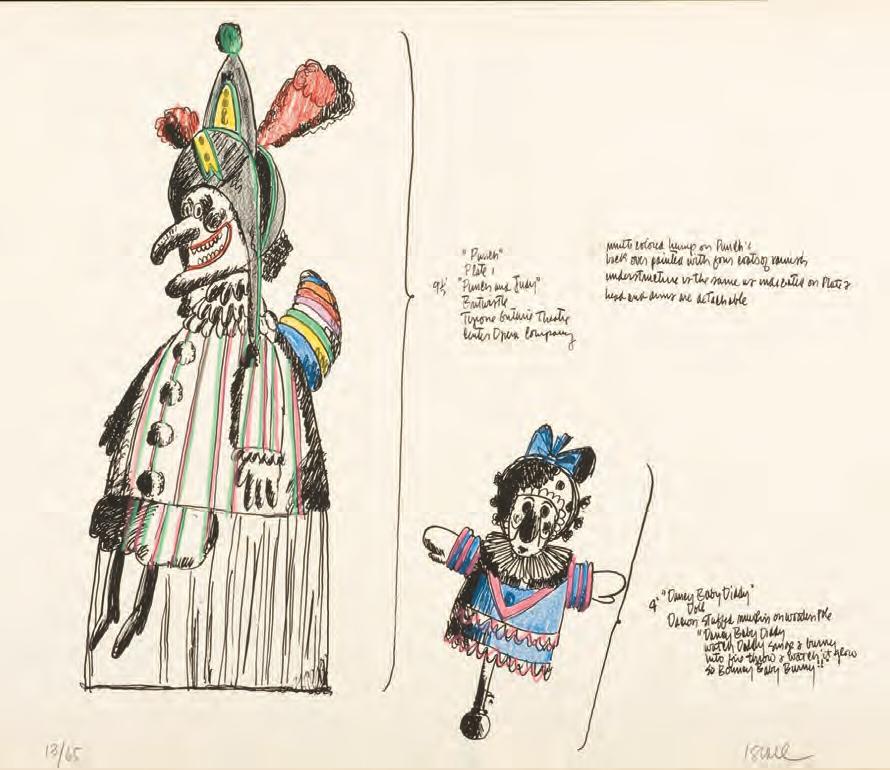

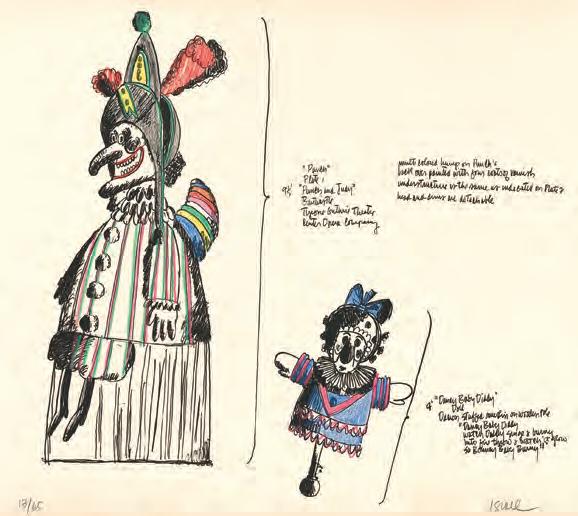

Punch and Judy (Birtwistle)

17 Days and 4 Minutes (Egk)

The Wanderer (Paul & Martha Boesing)

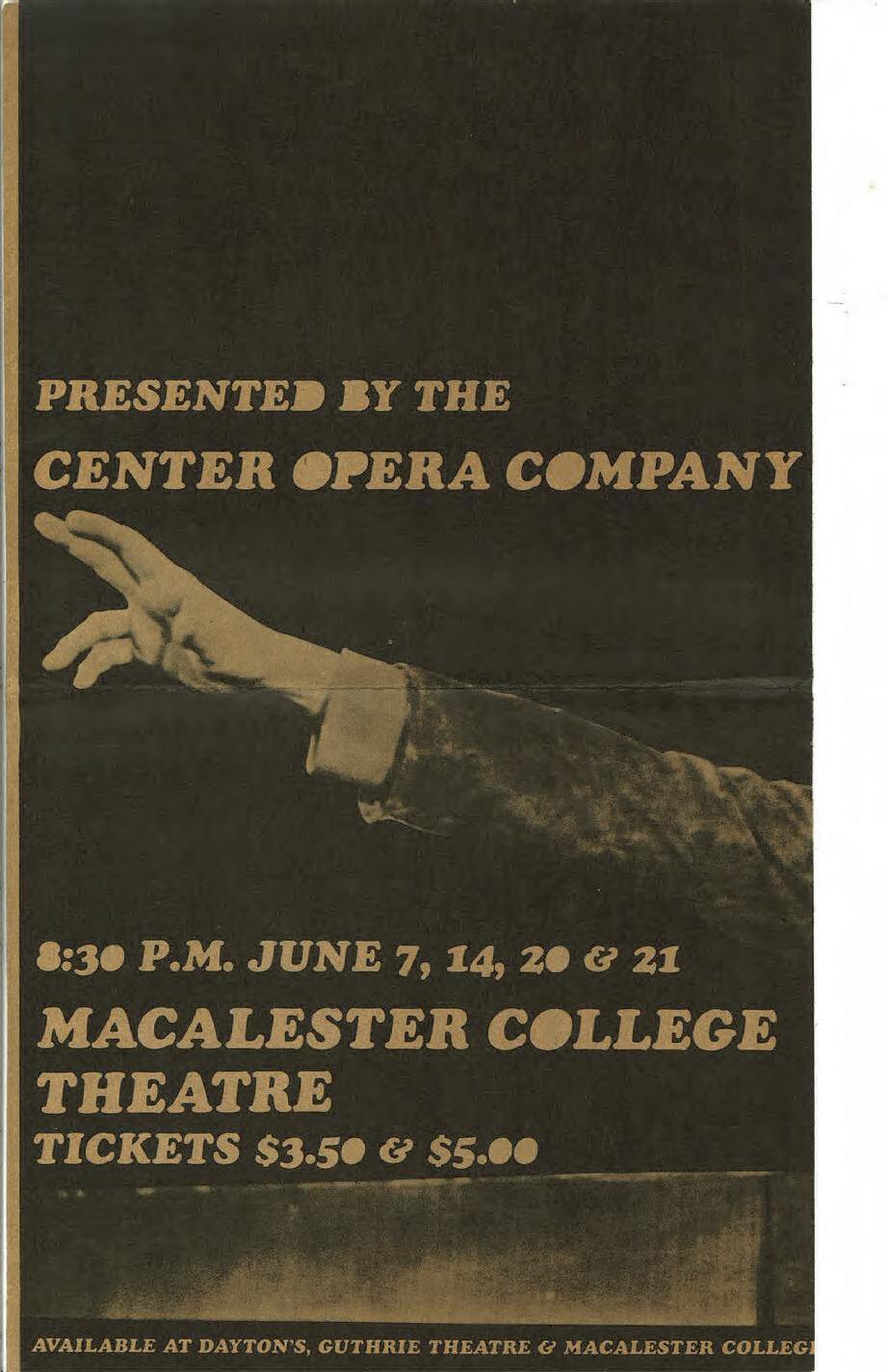

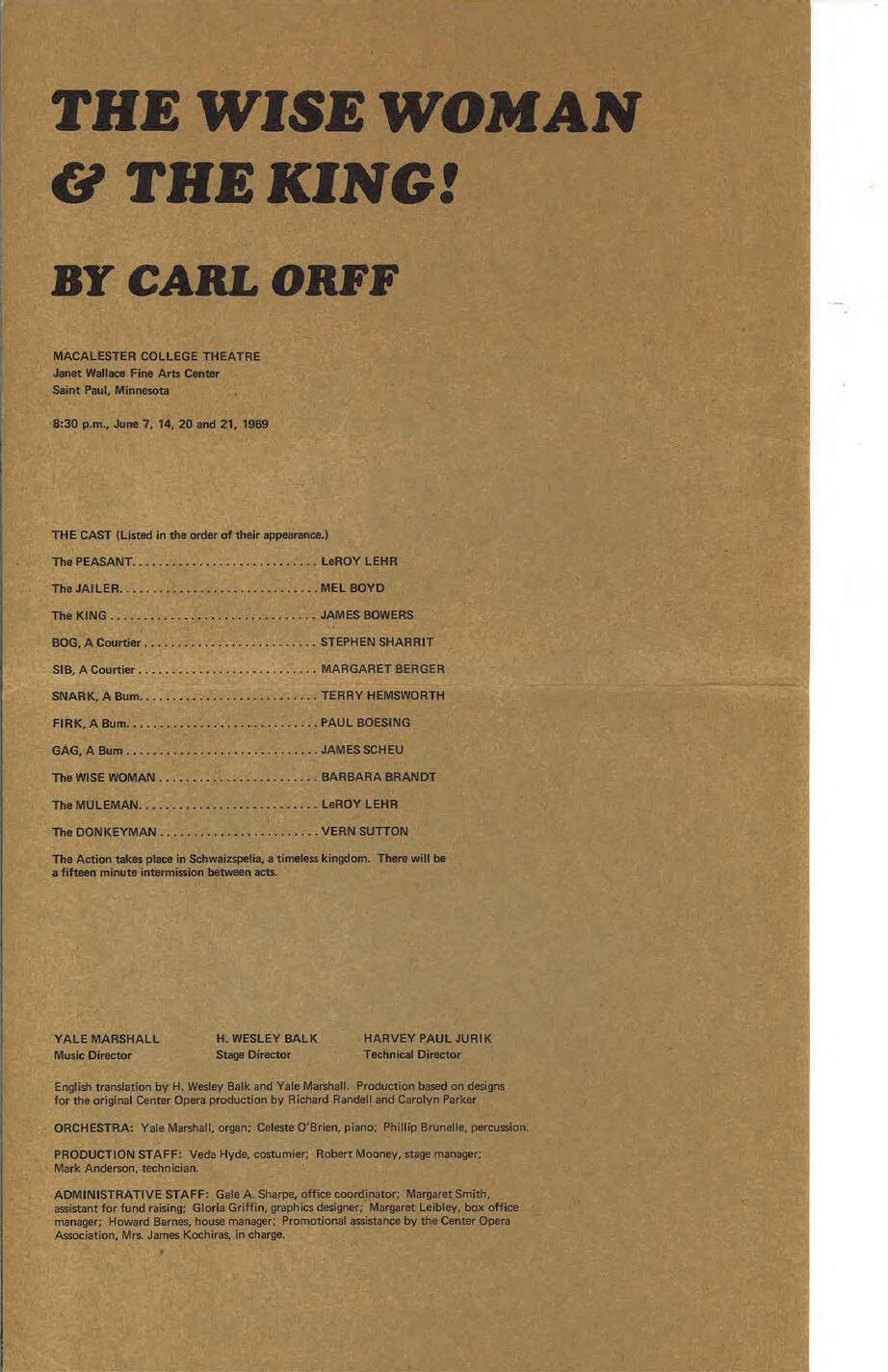

1968—1969

Così fan tutte (Mozart)

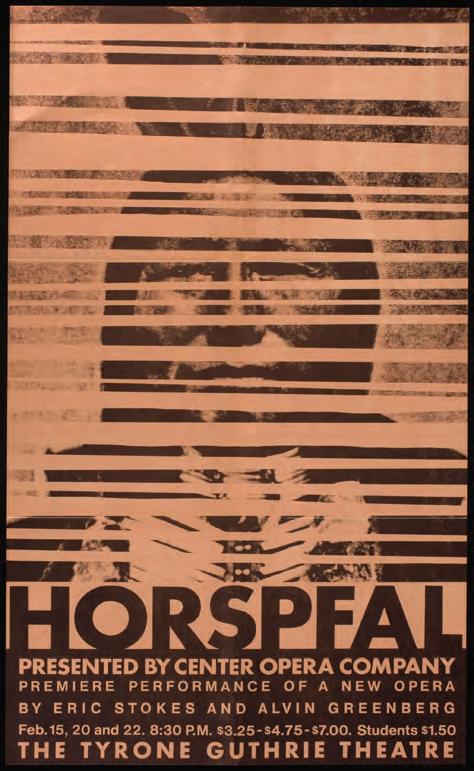

Horspfal (Stokes)

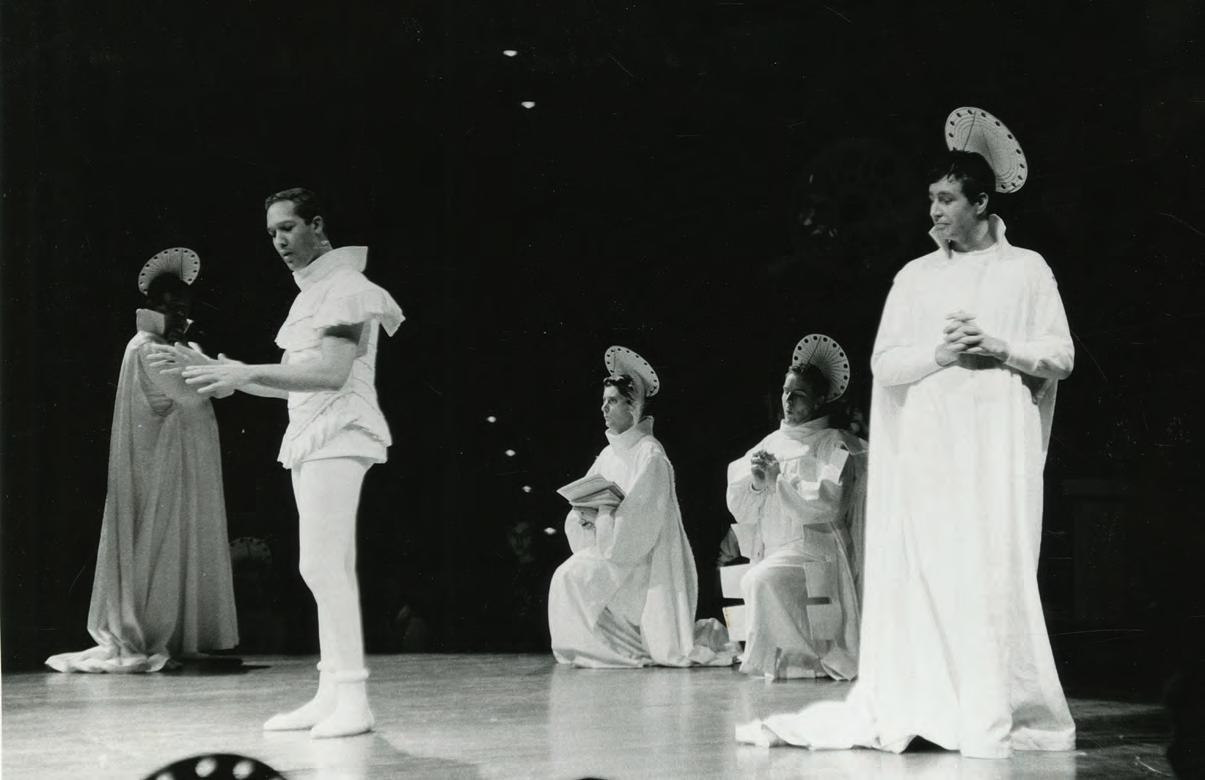

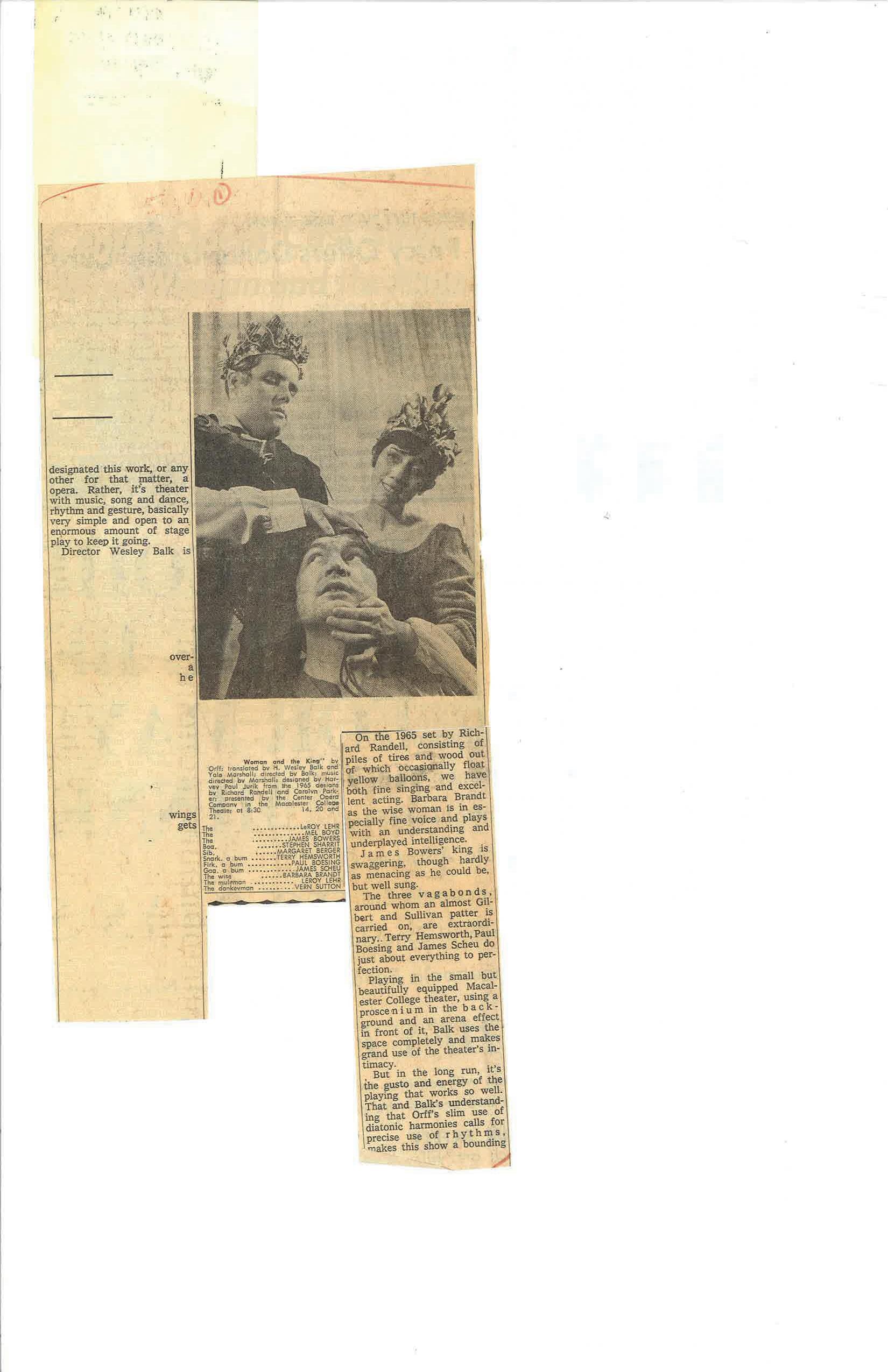

The Wise Woman and the King (Orff)

Bluebeard’s Castle (Bartok)

L’heure espanole (Ravel)

1967—1968

The Magic Flute (Mozart)

The Man in the Moon (Haydn)

A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Britten)

1966—1967

Opera Without Elephants

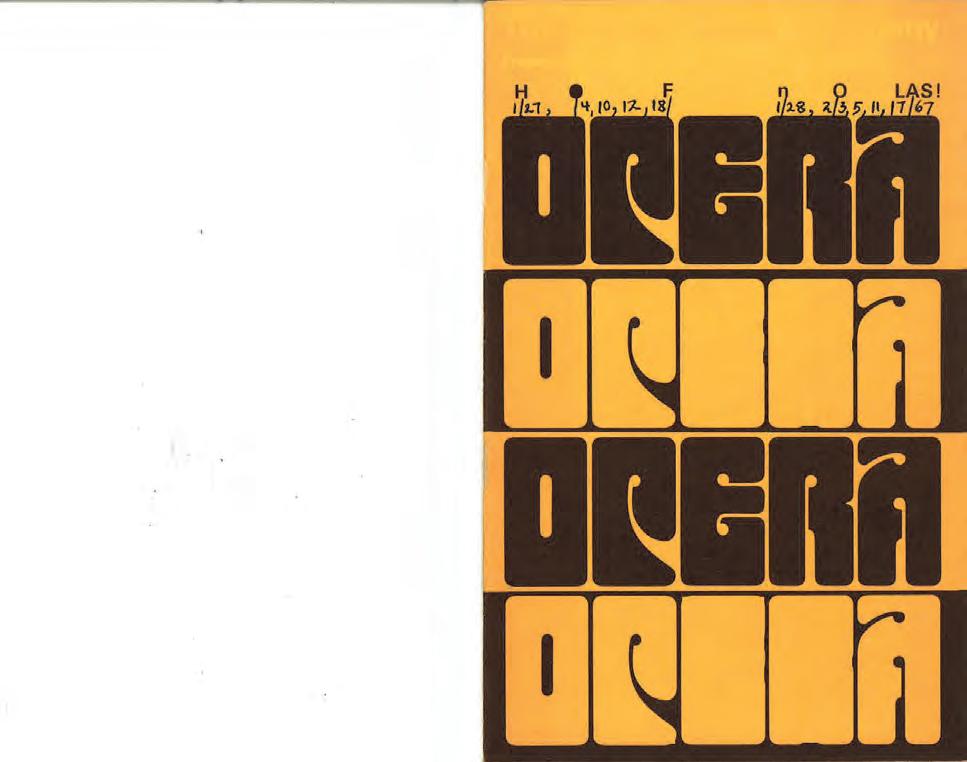

The Mother of Us All (Thomson)

To Hellas

-The Sorrows of Orpheus (Milhaud)

-The Harpies (Blitzstein)

-Socrates (Satrie)

Three Minute Operas (Milhaud/Hoppenot)

-The Rape of Europa

-The Abandonment of Ariadne

-The Liberation of Theseus

The Gondoliers (Sullivan)

1965—1966

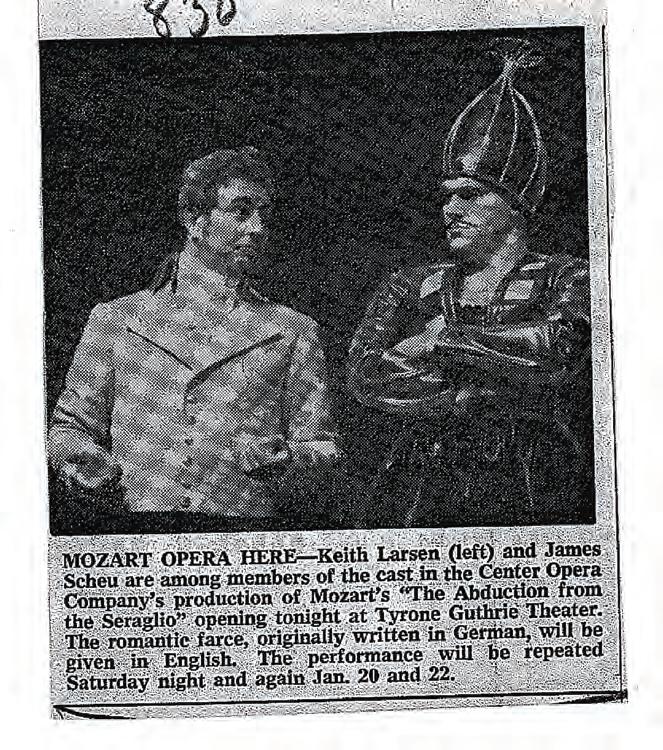

The Abduction from the Seraglio (Mozart)

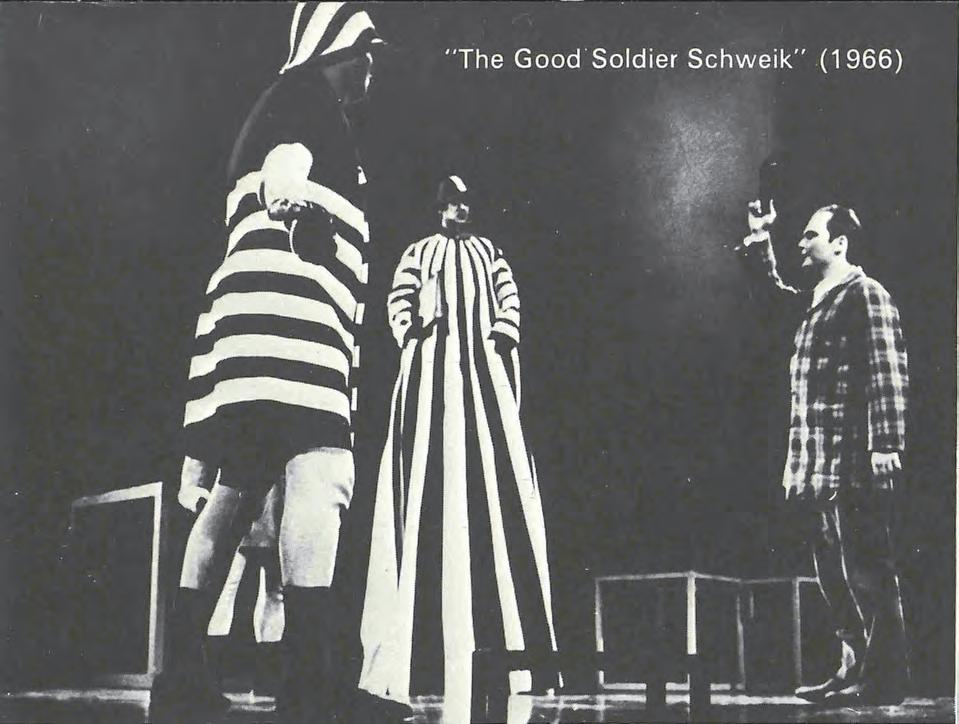

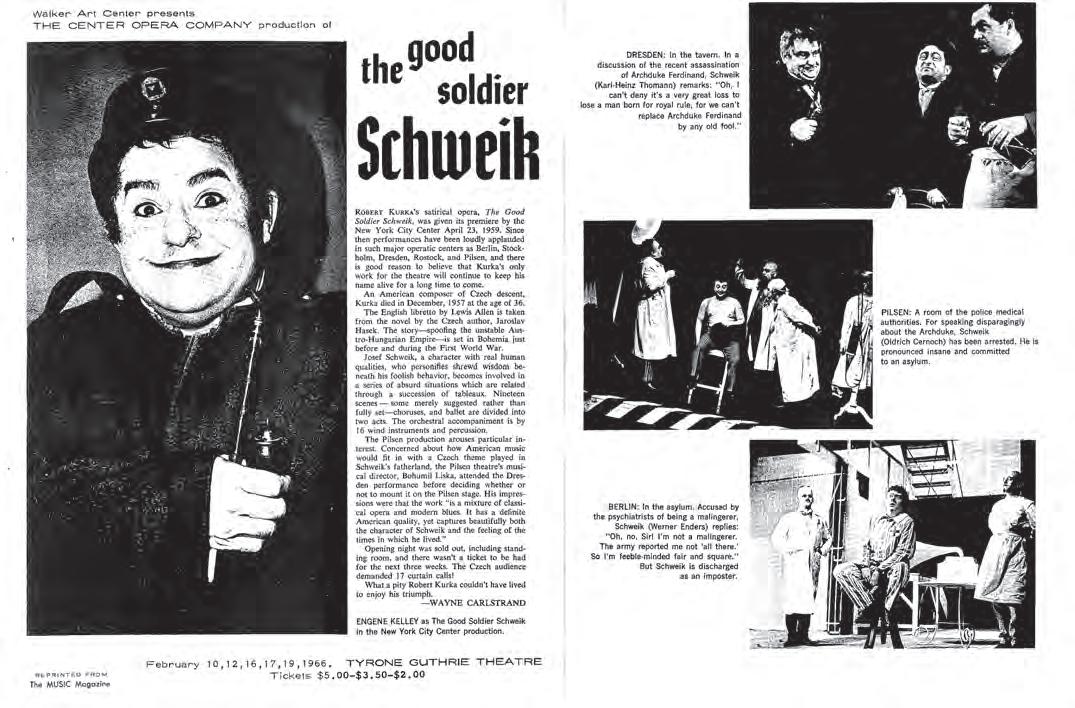

The Good Soldier Schweik (Kurka)

1964—1965

The Rape of Lucretia (Britten)

The Wise Woman and the King (Orff)

1963—1964

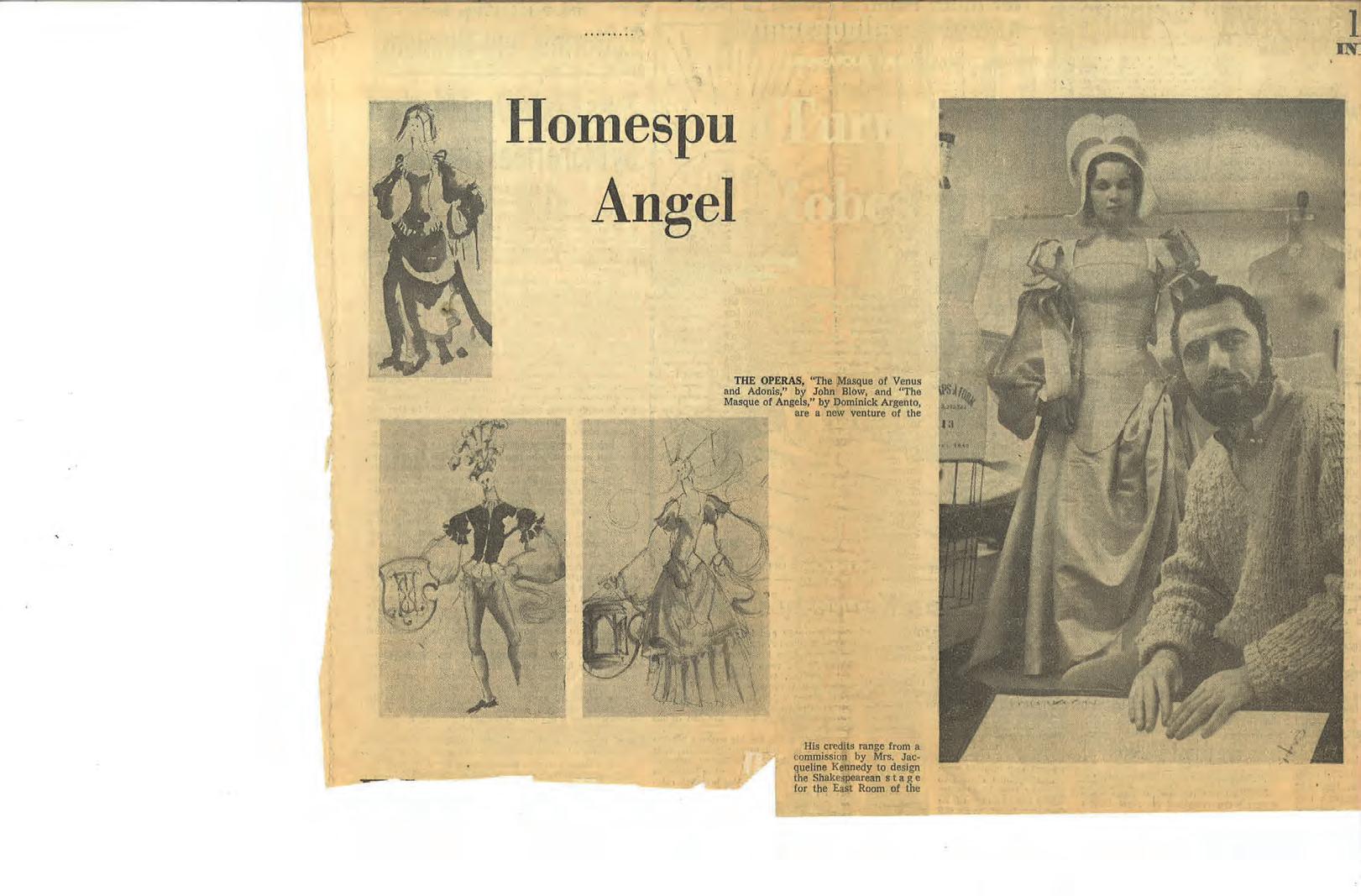

The Masque of Angels (Argento)

The Masque of Venus and Adonis (Blow)

Albert Herring (Britten)

On a cold night in January 1964—when Center Opera made its debut at the Guthrie Theater, premiering a witty new work by Dominick Argento paired with a Baroque one-act by the English composer John Blow—Harold Schonberg, chief music critic of the New York Times, was in the audience. “There are very few groups who engage contemporary opera with such flair, gusto, and imagination,” said Schonberg. Over the years he returned to Minneapolis several times to see the creation of this unlikely avant-garde offshoot of the Walker Art Center, a company whose unconventional productions were designed not by theater professionals but by young painters and sculptors hired for the boldness of their imagination.

Center Opera eventually became Minnesota Opera, which celebrated its sixtieth season with two new works— Edward Tulane and The Song Poet—bringing the company’s number of world premieres so far to fifty. In its inspiring and implausible history over the years since its formation, Minnesota Opera has charted an unusual path through the landscape of opera production. This is perhaps most notably marked by its championing of new works, but also by its training and

development of artists, its artistic philosophy rooted in bel canto (“beautiful singing”), and its commitment to equity, diversity, and inclusion. We’re proud to say that the company has not only survived but prospered, attracting an increasingly diverse and engaged audience and building on its legacy of presenting new and seldom-heard works that remains without parallel among opera companies in North America.

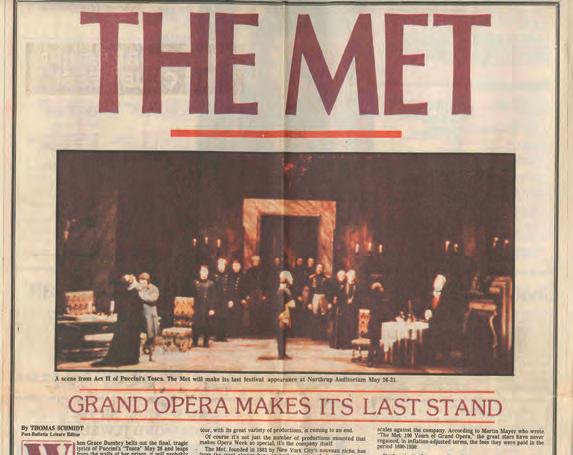

The tale of how Minnesota Opera became the company it is today is one worth telling. It’s a story that traces the growth of opera in the Upper Midwest, from the raggedy touring ensembles of the late nineteenth century to the formation of civic opera associations and the eventual rise of professionally managed local opera companies. It explores the impact of the annual weeklong visits to Northrop Auditorium by the Metropolitan Opera from the years 1945 to 1986 and articulates the opposing ways in which the performing arts developed in the cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul under their distinct ethnic and religious differences. It’s a story energized by large personalities, by conflicts and crises, and—of course— by unforgettable performances.

No one volume could capture every nuance of this epic journey, which includes countless performers, audience experiences, supporters, community and education initiatives, and points of view. However, this account by Michael Anthony, a close observer and longtime participant in the company’s history, is an illuminating account of the origin and growth of our company, offering never-before-published insights, information, and perspectives regarding Minnesota Opera’s leaders, performances, and evolution into one of America’s most forward-facing opera companies.

As we reflect on these untold stories from our past, we become aware that Minnesota Opera’s innovative, imperfect, and inspiring sixty-year history sets the bar for continued artistic exploration, growth, and expansion. It is now our challenge and our joy to imagine alternative visions of the future. Please join us in celebrating all that we’ve accomplished. We look forward to seeing you again at Minnesota Opera as we write the next chapter of our history together.

—Nadege Souvenir, MN Opera Board Chair

—Ryan Taylor, MN Opera President and General Director

As we reflect on these untold stories from our past, we become aware that Minnesota Opera’s innovative, imperfect, and inspiring sixty-year history sets the bar for continued artistic exploration, growth, and expansion.

One afternoon in 2002, I began my day at the Star Tribune in the usual manner: opening the mail and listening to phone messages, most of which required no immediate attention.

The sixth message was different.

“Hey, Mike, this is Wes Balk.”

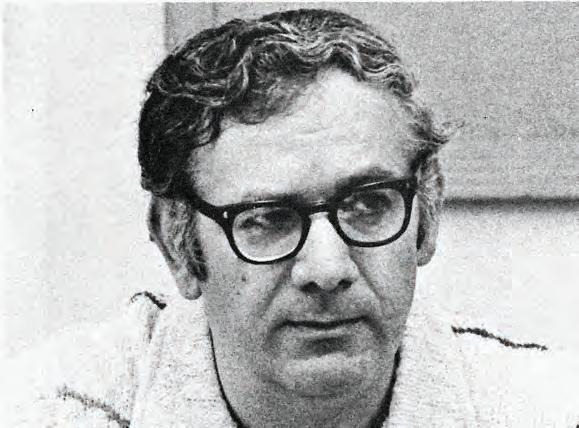

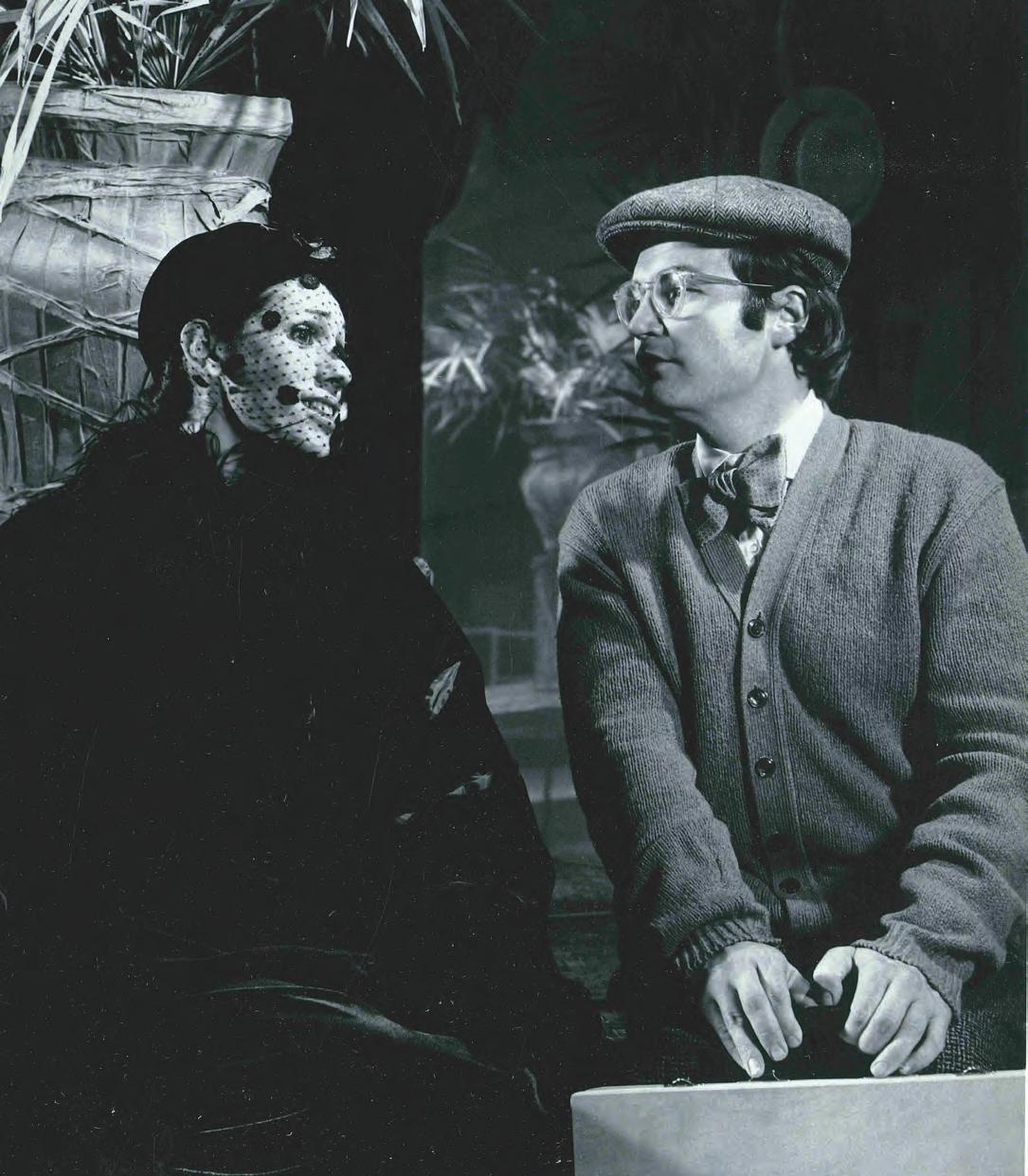

The voice was frail, but I recognized it: H. Wesley Balk, a large figure in the opera and theater world, both locally and around the country. A stage director of singular wit and imagination, an author and teacher whose novel insights into the training of actor-singers influenced at least two generations of performers, Balk directed more than sixty productions for Minnesota Opera over the course of seventeen years, serving as resident director, co–artistic director, and finally as director of artistic planning. In later years, though he was suffering from Parkinson’s disease, he served as director of performer development for the New MusicTheater Ensemble, which became Nautilus Music-Theater.

“They tell me you mentioned me in a review,” he said. “You still remember me.”

Wesley, I wanted to say, no one ever forgets you.

He had enemies as well as friends, and he seemed to relish both. His iconoclasm wasn’t an act. He really did hate convention and tradition, especially in opera, where those qualities had ruled for so long. Reviews of his own work, especially from out-of-town critics, were usually raves. More conservative operagoers were often puzzled and irritated by his productions.

I knew Wesley first as a teacher. While I was doing graduate work at the University of Minnesota, where Wesley was a professor of theater arts from 1966 to 1993, I managed, though I wasn’t a theater major, to be admitted into his main course, Acting for the Lyric Stage. Students alleged this course was so hard to get into that no one was ever admitted. Not true, of course. The atmosphere that Wesley created in the classroom—a room with a tiny stage at one end—was like a party with everyone contributing, offering ideas, and trying things out. Everybody had a scene or a song they were working on and were eager to show the class. Wesley loved putting dissimilar things—and idioms—together. Mary Corrigan, who went on to become a speech teacher of international renown,

did a duet with me from the Off-Broadway musical You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown, as if Noel Coward had written it. We were a hit.

Just a few years later, I was interacting with Wesley by reviewing his shows for the Star Tribune. What Wesley was referring to in the message was a comment I had made about him in a review of Minnesota Opera’s production of Lucia di Lammermoor that had just opened.

The audience on opening night had responded at the end with a standing ovation. While we know at this late date in our cultural evolution that just about everything gets a standing ovation, there was no doubt that the 2002 production, directed by James Robinson, was greeted more favorably than the Lucia Wesley directed during the 1982–83 season. Wesley’s was a high-concept production that turned the story into a therapy session wherein a young soprano is encouraged to sever her dangerous identification with the character of Lucia. The opening night audience booed Wesley when he walked onstage to take a bow with the cast.

I made light of this. Here was an audience of Lutherans— mostly—who had been instructed all their life to avoid drawing attention to themselves and certainly never to express disapproval in public, and they were booing lustily.

Considering the difference in audience reaction, I offered three explanations: (a) Wesley was ahead of his time, (b) the new production was simply better than the old one, and (c) opera audiences are nutty and impossible to figure out.

Going back to Wesley’s phone message, he said, “I’m in a nursing home. Can you get me a computer? I have so many ideas I want to write down.” I called some people at Minnesota Opera, explained the situation, and was told they could probably spare a computer. I called Wesley and left a message, saying a computer was on its way.

Wesley died six months later, on the morning of March 21, 2003. The cause was complications from Parkinson’s disease.

This book is dedicated to the memory of Wesley Balk, for whom life—and the lives he created on many stages—was both an adventurous journey and an expression of love.

—Michael Anthony

Fortune magazine went on an expedition to the Twin Cities in the early months of 1936 and took a long, hard look at the residents of these two towns. It’s possible that the writer— or writers—of the lengthy Fortune article were led astray by the citizens of St. Paul and Minneapolis, dozens of whom are quoted directly or indirectly, though much of what they wrote rings true.

Under the subheading “A Practical Guide to the Twin Cities,” the article provides advice on varied topics:

CLIMATE: Tough on strangers. Summers are burning hot, winters stinging cold. Last summer the temperature hit 104 degrees. Last winter it dropped to 33.5 degrees below zero. Psychologists have observed that such extremes make for emotional instability.

HOTELS (in order of quietude): The St. Paul has put in a cocktail room, but it is still stuffy. The Nicollet in Minneapolis is a typical Western hotel, better than the average. The bar is crowded and you may speak to unattended ladies. In the Radisson a few blocks away, they may speak to you.

AMUSEMENT: Minneapolis has three legitimate theaters in which, last winter, you could see anything from

Blossom Time to Tobacco Road. It has one grandiose cinema palace, the Minnesota, [and] many good cinema theaters. The excellent Minneapolis Symphony plays twice a week at the university. St. Paul has one legitimate theater, a few mediocre cinema houses. St. Paul uses its municipal auditorium for hockey, basketball, prize fights, opera, ice carnivals.

WHAT TO REMEMBER: The Twin Cities hate each other.

Concerning this last piece of advice, surely by the third decade of the twenty-first century the two cities—which were never Twins in any sense of the word—have more or less buried the hatchet. War’s over. There seems to have been, nonetheless, a certain amount of rivalry between the cities that continues. The rivalry at times was fierce, as when the 1890 US Census led to the two cities allegedly arresting and/ or kidnapping each other’s census takers to keep either city from outgrowing the other.

At other times the competition was genteel. Irma Wachtler, a prominent St. Paul arts administrator and enthusiast, once recalled, “Our father forbade us to have charge accounts at stores in Minneapolis, saying, ‘If you can’t find it in St. Paul, you don’t need it.’”

Sometimes it was simply a matter of who could put up a building faster. The St. Paul Grand Opera House, at Wabasha between Third and Fourth Streets, was dedicated on February 22, 1867. The Pence Opera House in Minneapolis was dedicated in June of the same year. After St. Paul completed its ornate cathedral in 1915, Minneapolis followed up with the Basilica of St. Mary in 1926. With opera the picture is more complicated. Which of the two is an opera town? For decades, the answer was St. Paul. John K. Sherman, veteran arts critic of the Minneapolis Star, said it in a review in the April 1967 issue of Musical America

Until four years ago, Minneapolis had never had much success in building up its own operatic ensembles; the town’s musical interest, money, and pride largely turned toward the sixty-year-old symphony orchestra. The spring visits of the Metropolitan Opera apparently slaked our opera thirst in one feverish week per year, usually drawing capacity crowds from the Twin Cities and the surrounding region. If Minneapolis wanted opera between times, they could drive across the river and attend the St. Paul Civic Opera, which offers operas and musicals.

Surely there is some demographic support for this. St. Paul, we’re told, was influenced by its early French, Irish, and German Catholic immigrant roots, while Minneapolis drew chiefly on its Scandinavian and Lutheran heritage. If, in the most general sense, St. Paul has been Catholic and Minneapolis Protestant, this ancestry links St. Paul to the Catholic countries of Europe—among them France and Italy— that have a long history of operatic expression, whereas in the Protestant countries of Northern Europe, opera has often been a hard sell. Concerning England, it’s common for historians to say that opera, meaning the homegrown variety, took time out for a couple of centuries, leaving a sizable gap between Henry Purcell and Benjamin Britten.

Protestants have often dismissed opera or at least shown that they can live without it. Theodore Thomas, the great German American conductor of the nineteenth century, said, famously, “A symphony orchestra shows the culture of a community, not opera.” (Perhaps he had relatives in Minneapolis.)

In Thomas’s view, orchestral music of the second half of the nineteenth century, especially German music, was not just good music. It was edifying. Listening to it makes you a better person. “The masterworks of instrumental music are the language of the soul,” he said. Opera was different. It was frivolous, and worse—it was decadent. And it certainly didn’t make anybody a better person. Opera houses were, at least metaphorically, on the dark side of town, where people flirted and made dates for after the show.

John Dizikes, in his excellent book Opera in America, recalls the Presbyterian pastor in Nashville who reminded his listeners that opera is “sinful, in league with hell and abetting Satan.” Bostonians thought opera to be a “showy hybrid,” a “breathless, exotic, passing excitement” while they took “the pleasures of the concert hall tranquilly, morally, and steadily.” Here’s John Sullivan Dwight, America’s first influential music critic: “Opera is inferior to pure instrumental music. Opera moves the feelings, not the mind.” And even worse, as time went on, opera became not just sinful but elitist.

We hear an echo of that censorious tone in the attitude of people connected to the young and feisty Center Opera toward that company’s competitor on the other side of the river, St. Paul Opera. “I never really knew anything about St. Paul Opera, and I’m sure I wouldn’t have been caught dead there,” said a former Center Opera board member, looking back on those early days. “It was that uptight crowd. They got all dressed up. They put on their pearls, and the women probably wore long gloves, whereas the Walker [Art Center] people were much more sophisticated. They were really smart. It was wild and wooly. It was really out there, and everybody loved it.”

To the Center Opera/Walker Art Center crowd, St. Paul Opera symbolized not just old-fashioned, empty-headed traditional opera and opera production but a way of life that the Center Opera audience with their graduate degrees and horn-rimmed glasses were trying to get away from. St. Paul Opera was Squaresville. It was “Ozzie and Harriet.” It was all about parties and dressing up and expensive dinners. In contrast, Center Opera people dressed down and, we would imagine, took dinner after the show so they could spend hours discussing it. To them opera was music theater, not

just singing. They didn’t even like the word “opera.” That was their poster: “Help stamp out opera!” Whatever it was they were doing, the critics loved it. Center Opera, wrote Bernard Jacobson in the Chicago Daily News, “has acquired a reputation as the most innovative, intellectually alive opera company in America.”

Opera in the old style—the St. Paul Opera style—could no longer be called sinful. (Sin itself was an unpopular subject by the 1970s.) But it could be brushed off as frivolous and wasteful, a pastime for the idle rich. That was the way Center Opera manager John Ludwig characterized the two companies— and their respective cities—in an article in Newsweek. St. Paul Opera was older and richer. Its annual budget was $750,000 compared to Center Opera’s measly $140,000. “They get more diamonds and furs,” said Ludwig. “We get the hip: beads and vinyl.”

To be sure, some of this was promotional rhetoric. St. Paul Opera, though it loved its candlelight dinners, was never as old-fashioned in its choices of repertoire as its detractors maintained. During its short life, 1969 to 1974, the company offered an occasional bold venture—George Antheil’s Venus in Africa , Carl Nielsen’s Maskarade , Carlyle Floyd’s Of Mice and Men —and in 1971 it gave the premiere of Lee Hoiby’s tender Summer and Smoke in a staging by Frank Corsaro, a work based on the play by Tennessee Williams with a libretto by a young Lanford Wilson, who would go on to become one of the nation’s major playwrights. (Williams showed up on opening night and pronounced the opera “beautiful.”)

It was odd, too, for St. Paul Opera to be thought of as the wealthy company. It was always underfunded, and just five years after its manager George Schaefer proclaimed “the New Era of the St. Paul Opera,” the company folded, owing $300,000 and canceling its 1975 season. (Orchestra members refused to play the last performance of the company’s final production, Wagner’s Siegfried, unless they were paid in advance—in cash.)

The following year, St. Paul Opera’s parent company, the St. Paul Civic Opera Association, paid off its offspring’s debt, which had risen to almost $600,000, and then went into a deep sleep, never to awaken. In an effort to expand its fundraising opportunities into the darker and wealthier regions

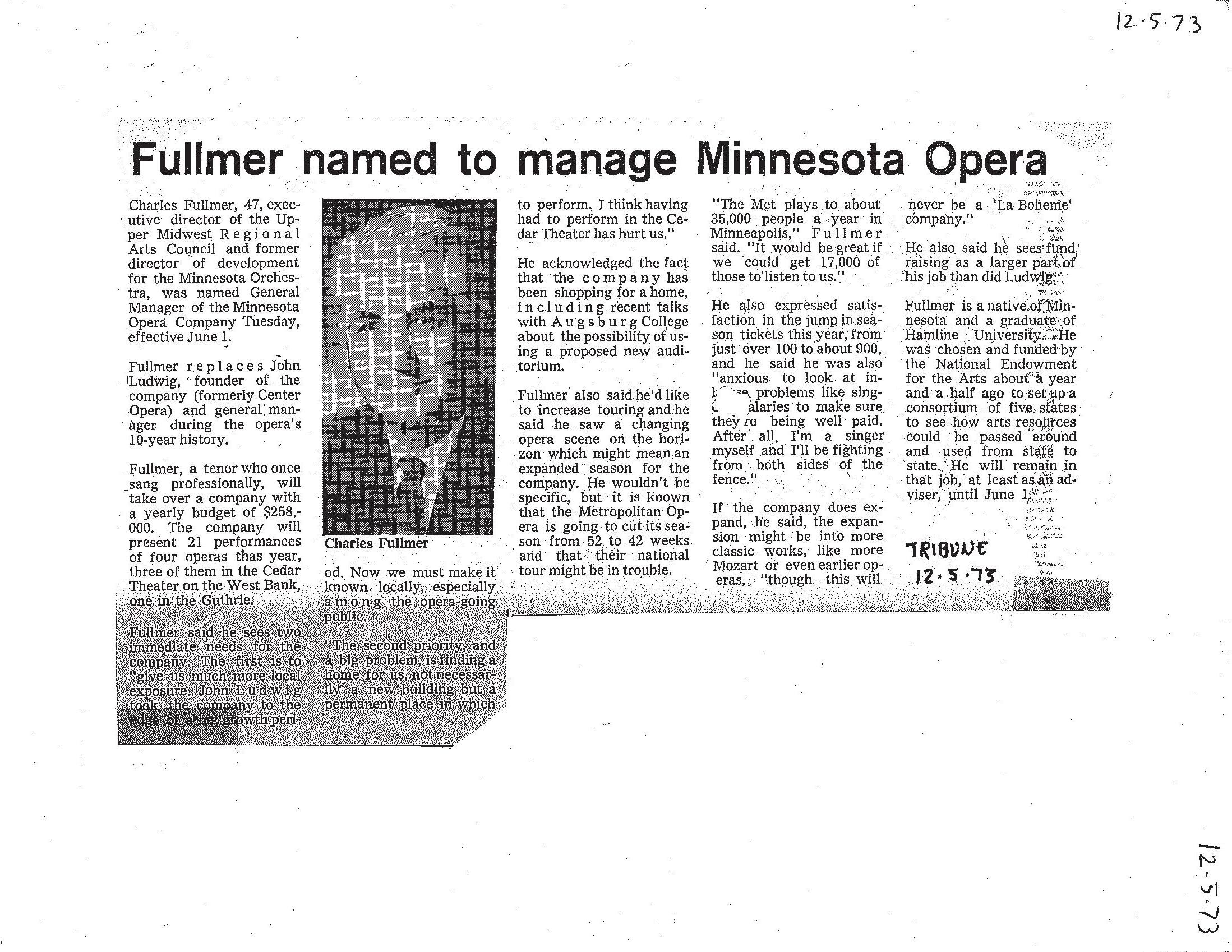

of St. Paul, Minnesota Opera, formerly Center Opera, invited a dozen or so board members of the now-defunct St. Paul Opera onto its own board. Certain people, chiefly residents of St. Paul, proclaimed this invitation a merger of the two companies—which was, of course, false. You can’t merge with a dead company, said Charles Fullmer, manager of Minnesota Opera. Whether the invitation actually brought in some extra funds from the eastern side of the Mississippi River has never been revealed.

The question remains: why were the two companies so different? St. Paul Opera and Center Opera were different, both onstage and backstage. If you liked one, you probably didn’t like the other. Karen Bachman, former board chair of Minnesota Opera and an experienced arts patron, traces the differences back to the founding of the two companies and to the founders themselves. “Center Opera and Minnesota Opera were founded and led by artists,” she said. “St. Paul Opera was founded, in my understanding, by volunteers. A lot of artistic organizations were founded by volunteers. The Metropolitan Opera was created by a group of wealthy people, Mrs. August Belmont, people like that, and then gradually they became more professional. Whereas with Minnesota Opera, it was, you know, Martin Freedman and Wesley Balk and Philip Brunelle and Kevin [Smith] and Dale [Johnson]. There was professional artistic direction, and I don’t think that was the case with the St. Paul Opera or Civic Opera.”

As it was, the entire episode—the death of St. Paul Opera, and the resulting “merger” that wasn’t—caused a resentment on both sides of the river that has never gone away. The complaint of the St. Paulites is that those board members who joined the Minnesota Opera board were treated as second-class citizens of the newly enlarged board. Their second beef: if this was really a merger, then Minnesota Opera should date its start in 1933 when the St. Paul Civic Opera put on its first show. Answer: there was no merger. Case closed. The complaint from Minnesota Opera regulars was that board members from St. Paul pushed Minnesota Opera toward more standard, “safer” repertoire and away from all that avant-garde stuff that many St. Paulites, at least those on the board, couldn’t tolerate. Answer: could be. But there were other reasons.

In 1980, a small company, Opera St. Paul, grew out of the ashes of St. Paul Opera but had little connection to the earlier organization, except that some of the same people were involved. In 1986, Opera St. Paul became North Star Opera, a small but lively company under the direction of the indefatigable Irma Wachtler that specialized in operettas. North Star Opera eventually became Skylark Opera.

Until 1964 when Center Opera began putting on shows at the Guthrie Theater, John K. Sherman had it right. If you wanted to see an opera in the Twin Cities, you had to go to St. Paul, to the St. Paul Auditorium or later to O’Shaughnessy Auditorium or the Crawford-Livingston Theater (eventually the History Theater)—that is, to one of the offerings of the St. Paul Civic Opera Association, which for more than four decades put on respectable productions featuring large casts of mostly local amateur performers. Some 3,000 people showed up for the company’s debut at the St. Paul Auditorium on December 8, 1933, a production of Samson and Delilah sung in English and featuring, according to the advertising, one hundred voices and forty dancers. Ticket prices ranged from 25 cents to $1.

The company was part of the “civic opera movement” that spread to many cities around the country. According to the articles of incorporation, the organization was formed “for the general promotion of civic and public interest in music, musical education, and culture, and the sponsoring and production of musical entertainments, operas and the like, thereby providing education and recreation for all classes.”

Performances continued at the St. Paul Auditorium, which was remodeled in 1936, just in time for the season-opener, Robin Hood, a popular comic opera by Reginald De Koven. Leo Kopp and Phil Fein, both from Chicago, were hired as the regular conductor and director. When attendance began to dwindle, the company reversed its policy of casting only local singers and began to hire stars—the first being soprano Rosa Tentoni to sing the lead in Madame Butterfly. And they also began to present light operas and musicals mixed in with the standard fare of grand opera.

After several financial crises, the City of St. Paul stepped in and agreed in the summer of 1955 to help support the company with an annual grant of $10,000. Glenn Jordan was named to the post of general director in 1961, the first year the company had a year-round, full-time executive.

When Jordan resigned in 1967, the board hired George Schaefer to replace him. Schaefer, who had been director of the St. Paul Arts and Science Center, charted a new course for the company. He dropped the musicals and returned the repertoire to opera and occasional contemporary works. He moved to professionalize the staff and to drop the word “civic” from the company’s title, as he thought the term connoted amateurism. And as conductor he replaced Leo Kopp with Ray Cutting, which forced the board to give Kopp $5,000 in severance. Schaefer’s first season, 1969–70, comprised six grand operas at the St. Paul Auditorium and four chamber operas at the Crawford-Livingston.

It worked for a while. Grants started coming in—$100,000 from the Gramma Fisher Foundation to do a new English version of the Danish opera Maskarade Summer and Smoke brought the company much-needed attention. But then, soon enough, it didn’t work, and it was all over. Schaefer resigned in January 1975. Most of the board members didn’t know the company was broke. No one had told them.

Meanwhile, across the river, in the opera sweepstakes, Minneapolis tried to catch up—and failed, mostly. The city had the Met, of course, performing at Northrop Auditorium for a week each year in May, and that went on until 1986. But as far as homegrown opera, the attempts were failures until Center Opera, under the aegis of Walker Art Center, began presenting avant-garde productions at the newly built Guthrie Theater.

The major player on the Minneapolis side of the river during these years was the Twin Cities Civic Opera Association, which made its debut with a program of excerpts from The Bohemian Girl at the Minneapolis Auditorium on October 4, 1933, just two months before its competitor, if we can call it that, the St. Paul Civic, made its debut with Samson and

Delilah at the St. Paul Auditorium. The company had been the dream, we’re told, of Mrs. Henry W. Jones, president of the Ladies' Thursday Musicale. The goal of the organization, according to its promotional material, was “to produce opera of real professional merit at popular prices. Only local directors, singers, and musicians will be employed. The company must be self-sustaining. The association is modeled after the European state theater and opera house.”

The similarity unfortunately didn’t include the heavy government subsidy the European opera houses were accustomed to, which made the Twin Cities Civic an especially ambitious undertaking and one that had to be well organized. Among the vice presidents of the board was Minnesota Chief Justice John P. Devaney. And despite its name, the organization was clearly a Minneapolis endeavor. No performances in St. Paul are documented. Offerings during the remainder of the first season were Faust, the standard pairing of Pagliacci and Cavalleria Rusticana, and Aida, all given at the Minneapolis Auditorium.

In 1935 the company began putting on shows at Lake Harriet, either at the bandshell or at some other facility nearby. The lineup for that summer offered a new show every week: Martha (July 9), H.M.S Pinafore (July 16), The Bohemian Girl (July 23), Lelewala or The Maid of Niagra (July 30), Blue Bandits (August 6). The season wrapped up with Rapunzel, A Fairy Extravaganza by Percy S. Williams, featuring “a colorful ensemble of one hundred artists and an orchestra of twentysix pieces.”

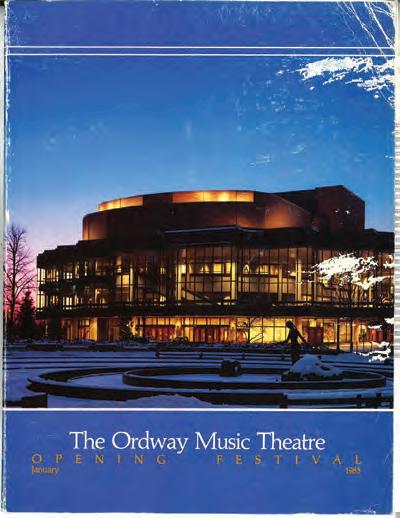

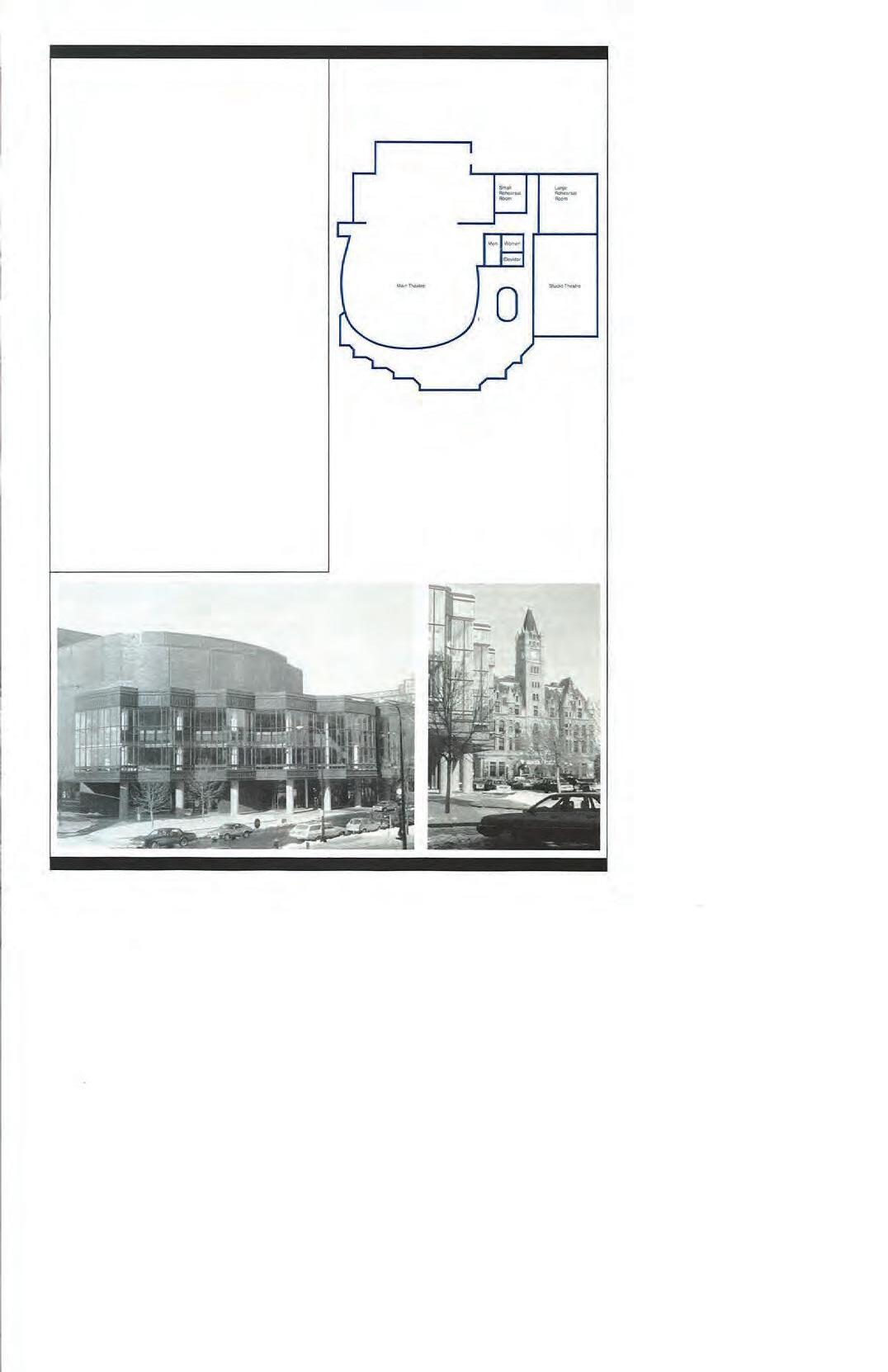

The company repeated some of these productions at Lake Harriet in the autumn of 1938, and then disappeared. There was apparently room for only one civic opera association at that time. Some forty years later, the same message appeared, as if written in the sky with diamonds: the Twin Cities couldn’t support two professional opera companies. One of them had to go, and that was St. Paul Opera. By 2021, this tale of two cities had shifted course more than once. St. Paul finally got an opera palace of its own in 1985, the Ordway, an edifice that promised to ease the city’s

lingering dismay and self-doubt over the failure of its own opera company a decade earlier. With the completion just a few years later, in 1990, of its Opera Center, Minnesota Opera now had feet planted firmly in both cities—a set of offices in Minneapolis and a production stage in St. Paul. And then in 2019 the company bought the Lab Theater (since renamed the Luminary Arts Center), a versatile space next door to the Opera Center. The Lab Theater would be a suitable environment for smaller, perhaps experimental productions aimed at an audience different from the company’s regular Ordway audience. In doing so, with productions going on in both cities, the question was no longer which one was the opera town. By now, they both were, and contrary to Fortune magazine, they no longer hated each other.

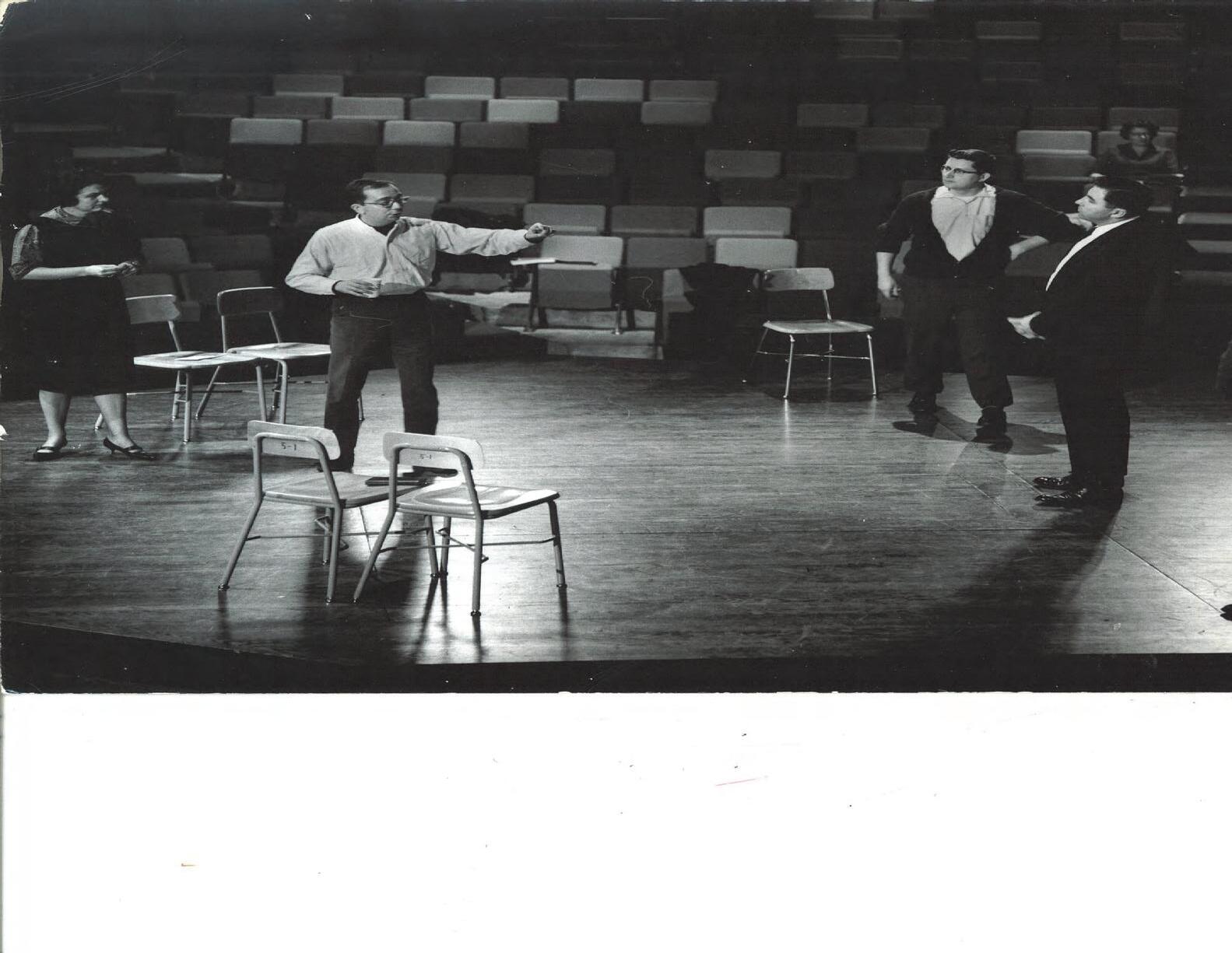

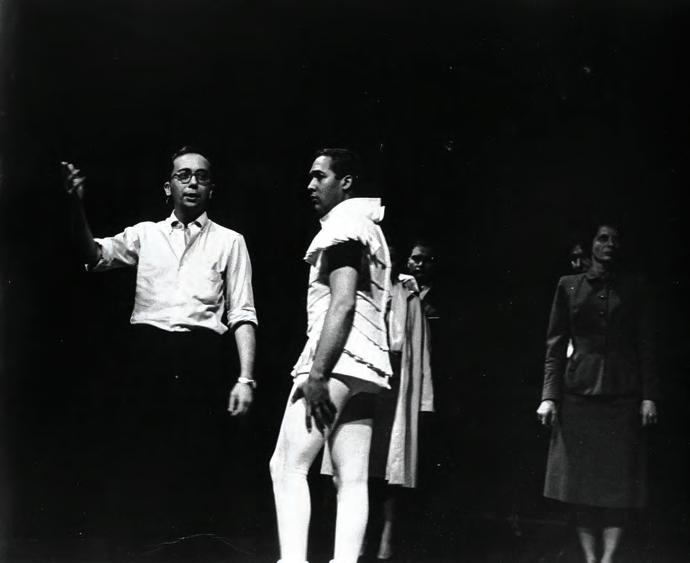

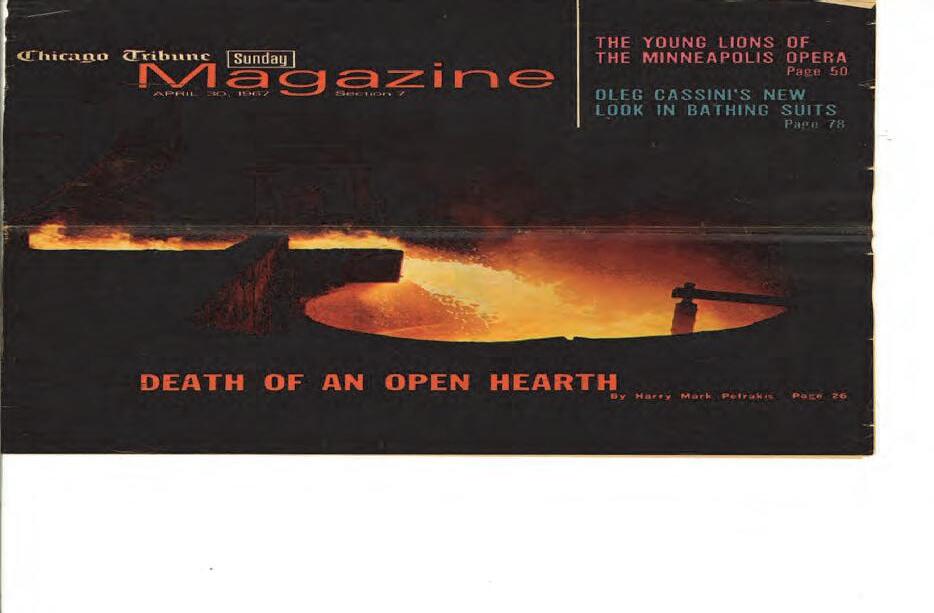

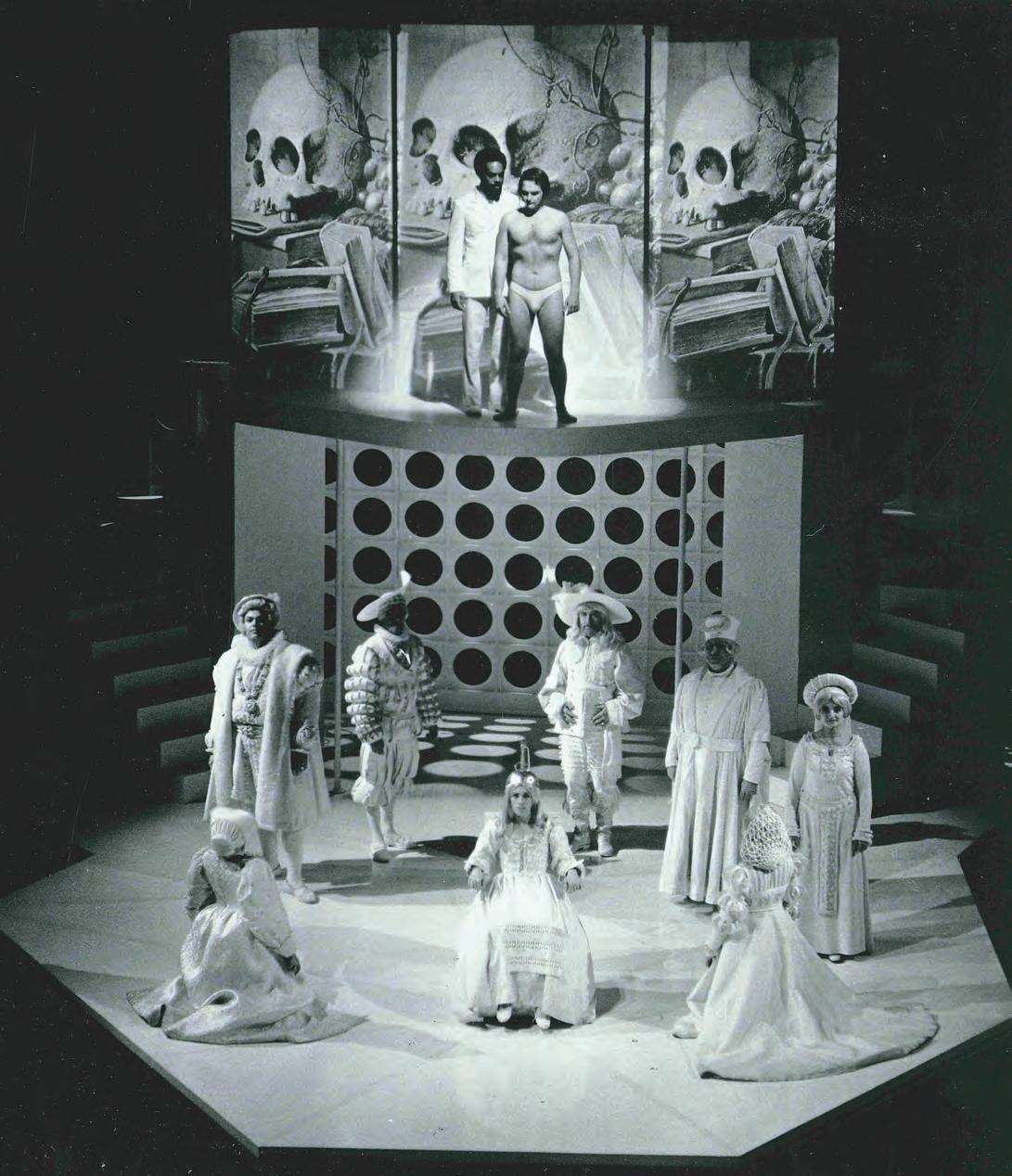

ON A COLD NIGHT in January 1964, Minneapolis, to quote the Chicago Tribune, finally got an opera company of its own. Center Opera, which would eventually become Minnesota Opera and would often be called America’s most innovative opera company, made its debut at the Tyrone Guthrie Theater, offering as a statement of artistic intention two one-act operas, one of them shiny and new, the other a littleknown gem from the seventeenth century.

Reviews the next day in both the Star and the Tribune, two separate and competing newspapers back then, were more than respectful; they were jubilant. “A consummate work of art” was the way the Tribune ’s Dan Sullivan described the new work, The Masque of Angels by the thirty-six-year-old Minneapolis composer Dominick Argento, who would go on to be widely acclaimed as the most important American opera composer of his generation. There was praise, too, for the work’s witty libretto devised by John Olon-Scrymgeour, who also directed the production. The story, which concerns a band of angels who contrive a romance between two young humans, nicely avoids being an operatic version of the ’40s movie Going My Way, as Sullivan pointed out. The companion

piece, The Masque of Venus and Adonis by the English composer John Blow, was lauded by the Star ’s Edwin L. Bolton for its “baroque charm and touching sentiment.” The success of the evening—a third performance was added to accommodate the demand for tickets—sparked an extra quotient of civic pride. How often does a city’s major daily paper publish an editorial commending the debut of an opera company and then go on to explain, probably for the first and last time, the differences between baroque opera and the later varieties?

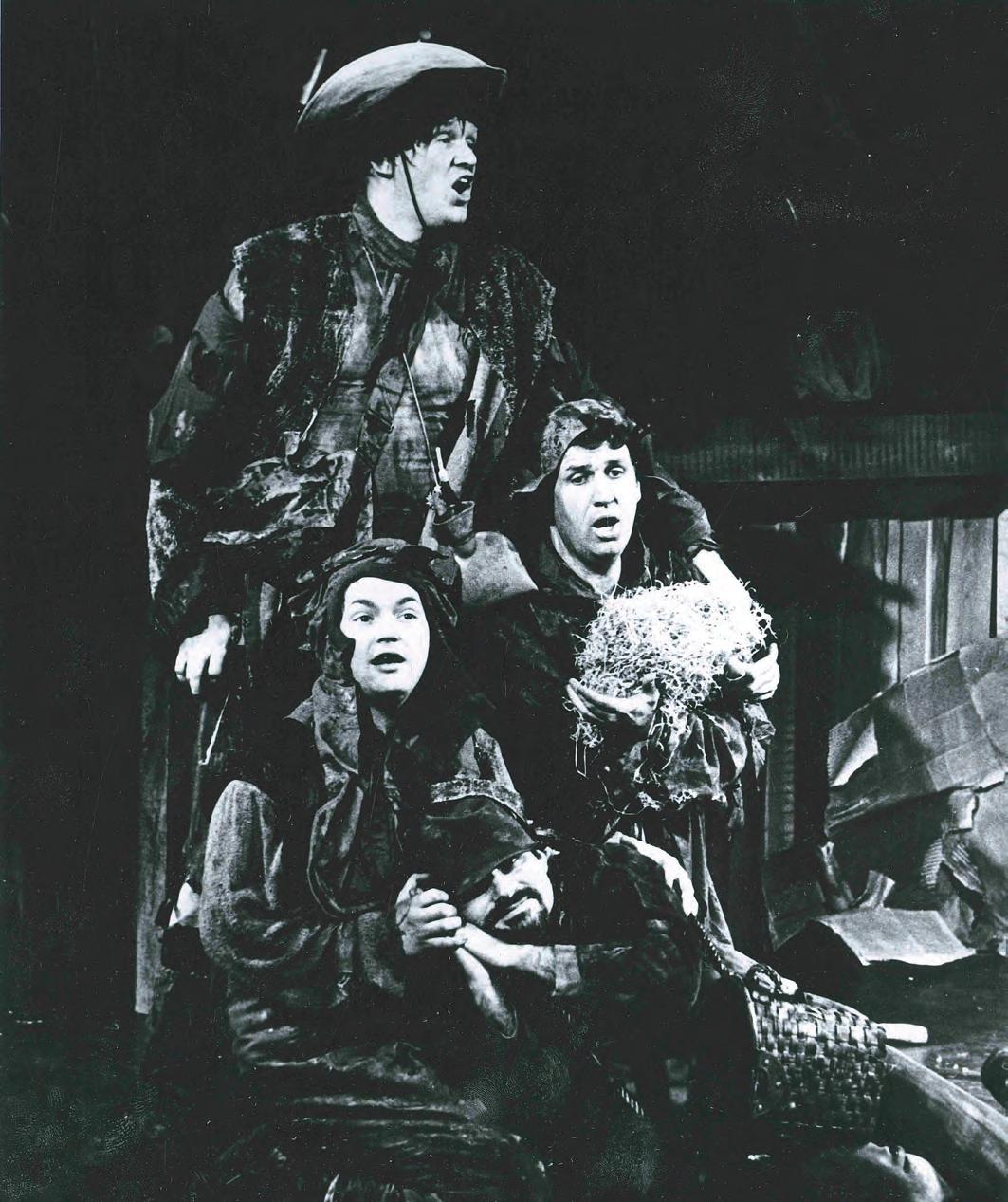

The city was coming of age culturally. Minneapolis had been able to boast for quite some time about its major art museums, and the Minneapolis Symphony had been making important recordings since 1924. The city’s theater scene, on the other hand, was pallid, consisting chiefly of touring companies and amateur playhouses. But all that changed in May 1963, when the Guthrie Theater opened, and scores of correspondents and critics pounced on Minneapolis to report on what the Washington Post called “the year’s most exciting theatrical event.” It can’t be said that Minneapolis became an opera town the following January. The audience, first of all, was a fraction of the Guthrie’s audience. However, its reputation around the country as a center of operatic experiment and innovation was solidified by the third season, or even

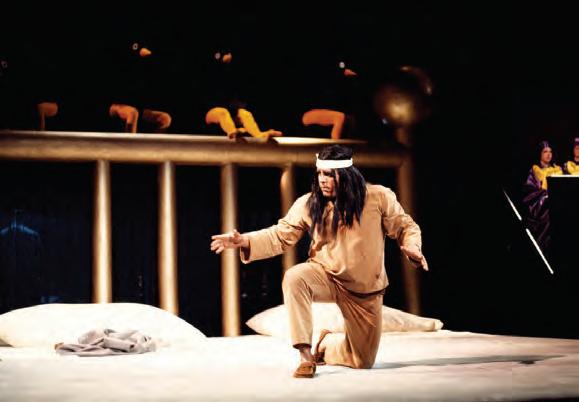

earlier, with its production of Carl Orff’s The Wise Woman and the King, concerning which TIME magazine devoted a full page. That production also boosted the career of its director, H. Wesley Balk, who as co–artistic director would dominate the company and establish its performance style until the early ’80s.

Small as the company was in its first decades, its significance was undeniable. It offered local audiences an alternative to the tradition-bound, star-oriented Metropolitan Opera, which presented seven productions at Northrop Auditorium in the spring of each year, during “Met Week,” as it was called, and to the St. Paul Civic Opera Association, which became a professional company, St. Paul Opera, in 1968 and followed the same aesthetic principles as the Met. What Center Opera offered was almost the opposite: small-scale productions that emphasized dramatic values as much as musical, meticulously rehearsed and sung in English. Surely there was some overlap in audience, but each company attracted its own crowd. And as it happened, Center Opera—which became Minnesota Opera in 1971—eventually had the field all to itself. St. Paul Opera folded in 1975, and the Met stopped touring in 1986.

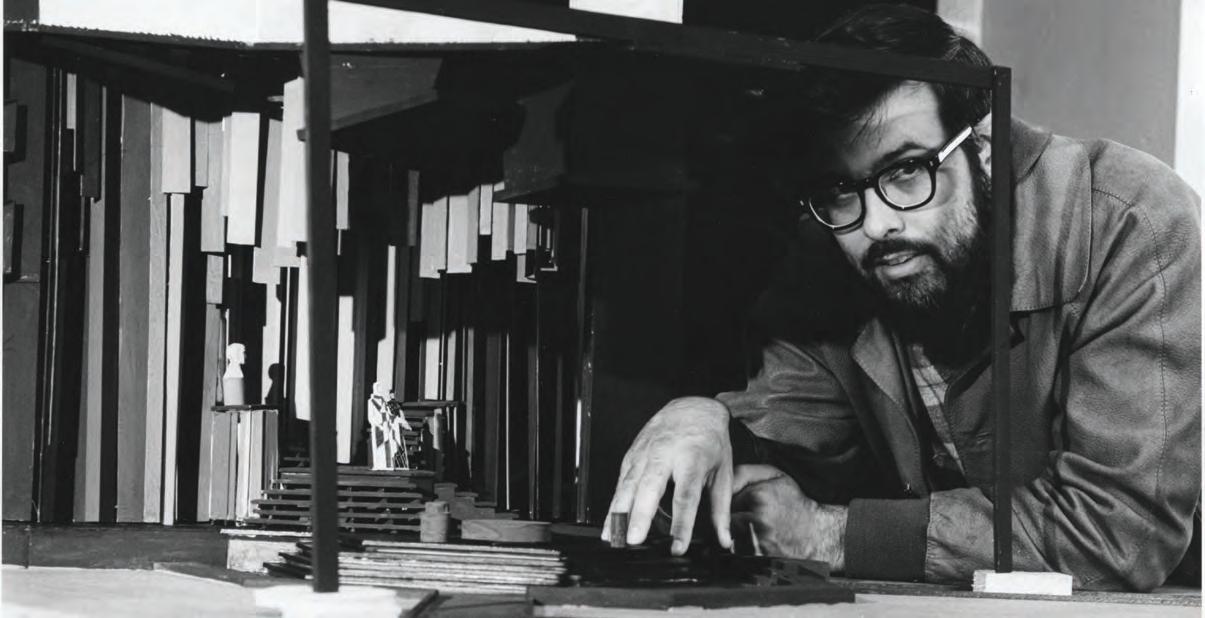

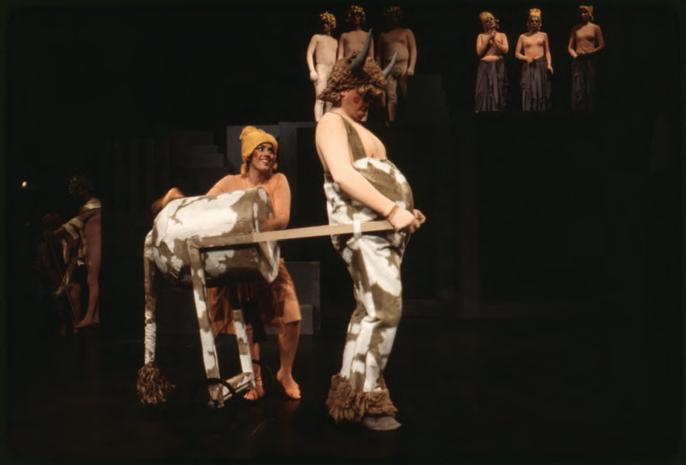

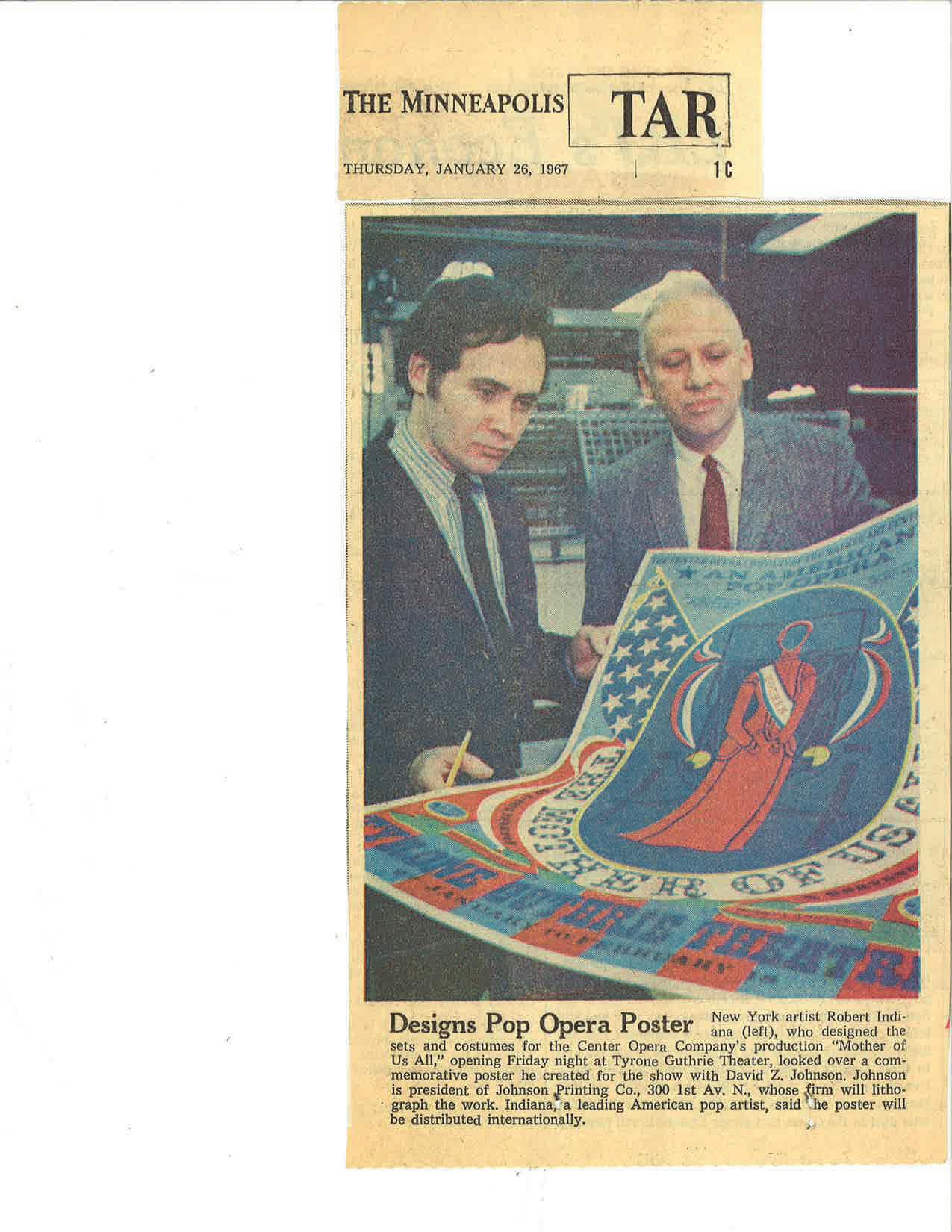

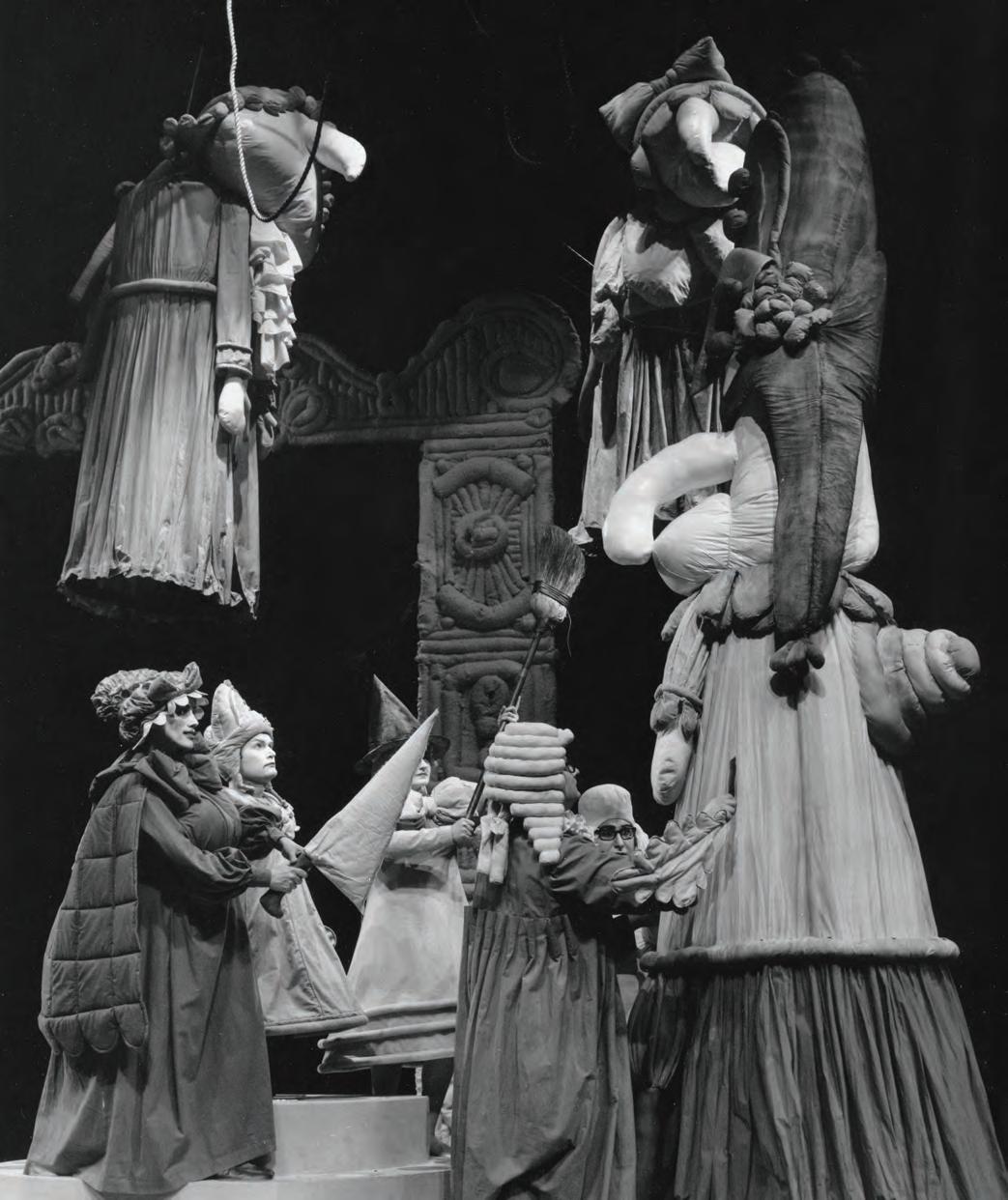

Center Opera, right at the start, was unique. It was the only opera company sponsored by an art museum, the Walker Art Center. It was the only company at that time performing chamber operas in English on a thrust stage. And while there was precedent for it—Picasso designed sets for the 1917 production of Erik Satie’s Parade —it was the only opera company at this time to engage painters and sculptors rather than theater artists to design its productions. Though the company abandoned that practice in 1969 when it separated itself from the Walker, it can be said that for five seasons Center Opera offered its audiences visual experiences of a most singular nature: bizarre, confounding, otherworldly, and at times strikingly beautiful.

More than two centuries ago, Samuel Johnson famously described opera as an “exotic and irrational entertainment.”

Dr. Johnson might have conceived that definition while observing Minnesota Opera’s unpredictable journey through the dark forest of modern opera production during the ensuing five decades. Years of high accomplishment followed periods of frustration and despair. The company at times seemed to lose its way, having somehow forgotten—or lost—its mission and the knowledge of how it’s possible to hold in balance artistic and financial success. The company almost folded in the early 1980s. Its devotion up to the present time to new work remains impressive—fifty world premieres. To be sure, not all of these were successes. A few of them were bombs of generous proportion. Others found favor and have entered the repertoire. In 2012 an opera titled Silent Night, which the company commissioned and premiered, received the Pulitzer Prize.

This is how it all began.

SOME SAY ONE OF THE NATION’S MOST innovative opera companies was born in Arnold and Helen Walker’s house in the Kenwood area of Minneapolis on a humid summer night in 1962. Walker, the sonorous voice for many years at KUOM radio and the host for almost as many at the Lake Harriet bandshell concerts—he led the children’s march at every concert—was also a singer, a baritone in the mold of Nelson Eddy. His wife, Helen Rice Walker, was an accomplished soprano who had given a well-received recital at Carnegie Hall and had played small parts in the original Broadway production of Wonderful Town starring Rosalind Russell.

Recalling the event some thirty years later, Walker said:

We were having a party of Center Arts Council people, and we were bemoaning the fact that there was such a limited outlet for local singers here. My wife and I were looking for opportunities to sing, as were other singers we knew. We didn’t have a good opera company available to us. Now when I look back on it, we sounded like Mickey Rooney shouting, “Let’s make an opera company.” Lo and behold, Norton Hintz was there, and he jumped up and said, “By God, we’re going to form an opera company.” The seeds of it, in other words, were planted that night. And the seeds kept growing because the fertile ground of the Center Arts Council was there.

The creation of an opera company was, in fact, a bee that had been buzzing around in Hintz’s bonnet for quite some time. A man of many parts—a nuclear physicist with a doctorate from Harvard, an accomplished photographer whose landscapes and urban scenes were in considerable demand, and a man who remained an avid and agile ballroom dancer well into his eighties—Hintz was born in Milwaukee and raised in Los Angeles. On leaving Harvard in 1951, he spent the next year on a postdoctoral fellowship at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, England, and the following year he accepted a position at the University of Minnesota, where he helped build the university’s proton accelerator and taught physics until his retirement in 1991.

Hintz had become interested in opera in 1959 during a year spent in Copenhagen on a fellowship. “There are two opera houses in Copenhagen,” he said, “and during the season both of them were doing shows six nights a week. It was like the way people here go to movies—or used to. So I saw a lot of opera, small and large, all sung in Danish. I came to like it a lot.”

On returning to Minneapolis in 1960, Hintz began talking to friends about forming a company to produce chamber operas—works requiring a small number of singers and instrumentalists. There was no sense, he thought, in trying to produce opera on the scale that the Metropolitan Opera

offered each spring at Northrop Auditorium nor even what the St. Paul Civic Opera had been presenting on a semiprofessional basis since the early 1930s. “We had no desire to compete with that, nor did we think we’d ever have the resources to do so,” he said.

Others began to share his enthusiasm for creating a small company, among them the conductor Tom Nee, the oboist Warren Cheston, and several faculty members from the music department at the University of Minnesota, among them George Houle, James Alifaris, and the composer Dominick Argento. Most were members of the Center Arts Council, a volunteer organization aimed at promoting cultural activities in the community that complemented Walker Art Center’s program of exhibitions and events.

Looking back many years later, Suzanne Weil said, “The Center Arts Council was one of the most amazing things that ever happened in Minneapolis—or anywhere. It was a volunteer organization, but you were a member only by invitation. Martin Friedman, who ran the Walker, gave it some money each year, but the council was very independent, though it was obviously in the spirit and aesthetic of the Walker Art Center.”

The council’s mission was to present events and sponsor activities—lectures, plays, and concerts of all types of music. Members worked on committees. There was a dance committee, a drama committee, other committees for folk music and jazz, another for architecture and design. Suzanne headed the jazz committee and later served as vice president of the council’s board.

Formed in 1952 by Walker director H. Harvard Arnason, the council’s two hundred or so members focused their efforts on the new and the unusual, though they didn’t shy away from traditional works such as a staging of Under Milkwood by council member Connie Goldman that was presented in the Walker gallery. The director was Michael Lessac, a young theater artist who later produced an album of songs titled Sleep Faster, We Need the Pillow.

More often, Goldman took a walk on the wild side. When the council invited Allan Kaprow to come to Minneapolis to stage one or more of his controversial Happenings, Connie was his assistant. A distinctly freewheeling ’60s phenomenon, Happenings were serious and yet whimsical theatrical events composed of a seemingly illogical collection of elements in which performers interacted with audience members in what was often a nontheatrical environment.

“I was totally enchanted with this crazy project,” Goldman recalled in an interview in 1995. She continued:

I loved experiments and breaking up theatrical forms. I did a lot of driving around looking for strange things. Allan wanted huge numbers of boxes that would fall down right in front of people and scare them half to death. One time we had the audience walk around in the mushroom caves by the river in St. Paul. The audience reaction was mixed. Some had a wonderful time and thought it was wild and adventurous and crazy and fun and, thank goodness, here was something different to do on a Saturday night. Others were deeply offended. “This is art?” I remember people stomping out and saying terrible things about Martin [Friedman]. They blamed him.

As a member of the council’s drama committee, Goldman hosted a symposium titled “How to Make Theater Seats More Uncomfortable,” which put forth the idea that theater ought to agitate and provoke. One year, she brought playwrights from around the country to the Walker, asking them to do whatever they wanted to do. Some read their plays to an audience.

One of them was actor and playwright Sam Shepherd, then unknown. “Somebody had said to me, ‘This guy’s hot. He’s really innovative,’ Goldman recalled. “He must have thought we were a bunch of dilettantes because he walked onstage, opened a box, and pulled out a bunch of balloons. He blew them up and let them go, and they flew up to the ceiling. That was his play. I got a lot of flak on that one. I thought Martin [Friedman] was going to kill me. But we all felt that we had a mission to nurture new artists and that that was what the Center Arts Council was set up to do.”

Norton Hintz, who was invited to join the council in 1955, saw the council as “a mix of fun things involving intelligent people interested in the arts and putting on programs and that allowed you to espouse some of your favorite ideas.” Hintz ended up being chairman of the music committee. The committee brought in people such as Arnold Dolmetsch, the early-music expert, and at one point put on an evening of songs by Hindemith with the soprano Helen Rice with Richard Zgodava at the piano.

Center Opera was CAC’s biggest and most expensive project—a little more than $40,000 for its first season. The company gave its first performances at the then-new Guthrie Theater in January 1964, and five seasons later it separated from the Walker and went off on its own, eventually changing its name to Minnesota Opera.

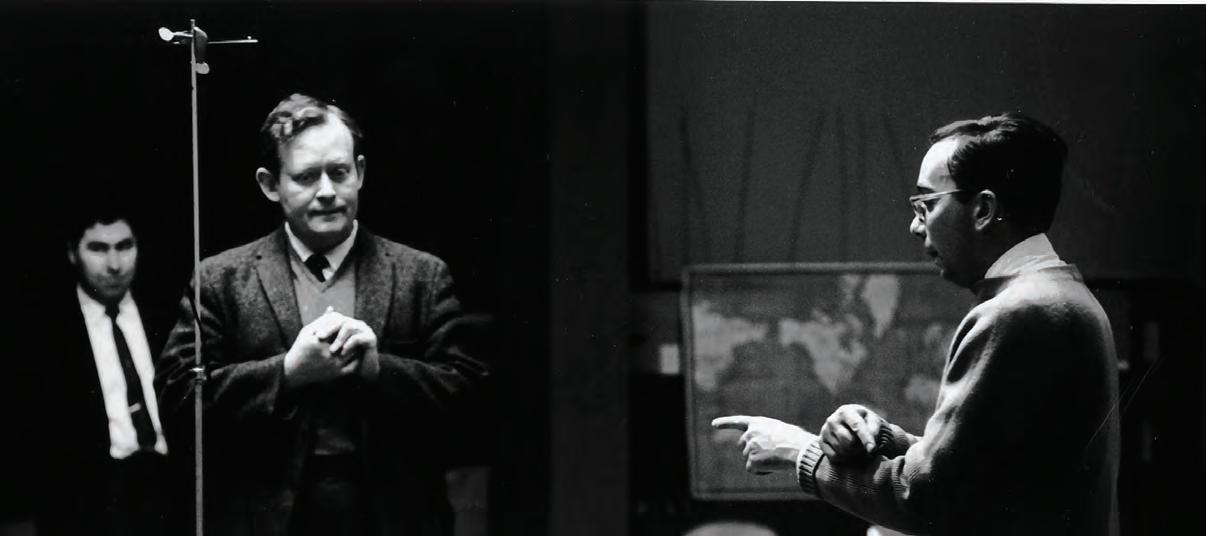

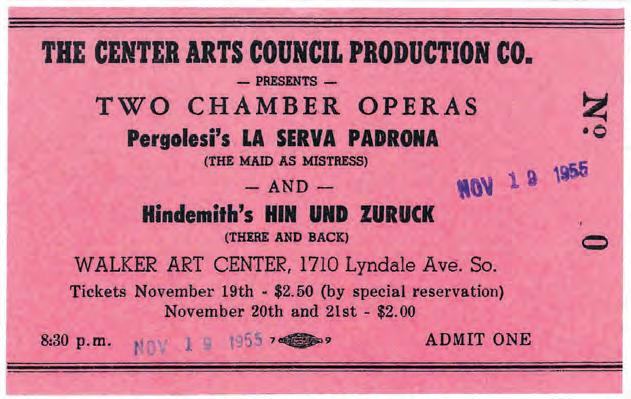

There had, in fact, been earlier efforts at opera production by the CAC. In November 1955, the council presented, for two nights, a double bill of chamber operas: a comedy from the eighteenth century by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, The Maid as Mistress (La serva padrona) and a brief work from the twentieth century by Paul Hindemith, There and Back (Hin und Zuruck). The large staircase at the front end of the Walker lobby served as a stage. The audience sat on the stairs and in the balconies. James Alifaris conducted and George Amberg staged the two works. Alifaris and Amberg resumed their collaboration three years later in another double bill that included Menotti’s The Unicorn, the Gorgon, and the Manticore, a madrigal fable, as the composer described it, scored for chorus and an orchestra of nine players.

The choice of repertoire in these offerings was relatively bold. Clearly, the CAC wasn’t aiming at a mass audience. What this repertoire suggests instead is the sensibility manifest in Center Opera, just a few years in the future, an uncompromising stance that said: we think these works—and the way we interpret them—are clever and smart, we hope you like them, and if you don’t, come back again—or don’t. This essentially aristocratic point of view would successfully guide the company during its first decade.

By the start of the 1970s the CAC was fading. “The CAC was unique in its time,” said Connie Goldman. “I’m not aware of any situation like that, where a visual arts museum develops an elaborate performing arts program. [. . .] I think what we did made a difference to people.”

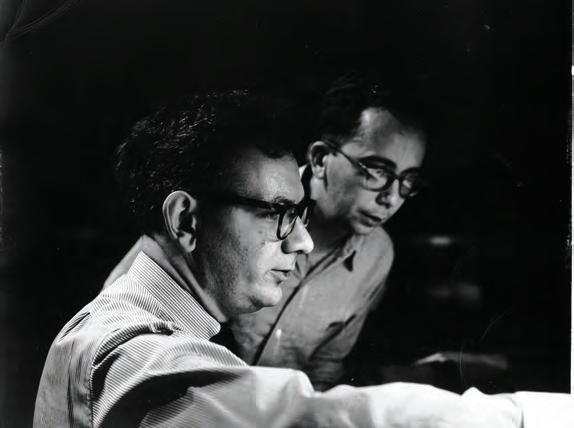

IT SHOULD BE NOTED that there are other versions of this creation story. Argento’s version starts early that same year at a concert given by the Civic Orchestra of Minneapolis that he and his librettist, John Olon-Scrymgeour, attended. Recalling the story in 2018, just nine months before he died at the age of ninety-one, Argento said that after the concert the two of them went backstage, where he introduced OlonScrymgeour to Nee, after which the three of them repaired to a nearby boîte for a restorative beverage or two.

“Benjamin Britten was the big thing in those days,” Argento recalled. “We all said, ‘We’ve got to do Albert Herring here.’ I had been looking at the score. ‘It’s such a great opera,’ I said, ‘but how can we do it?’ Tom said, ‘You get a sponsor like, say, the Walker. They might let us do it.’ I said, ‘You know anybody connected to the Walker?’ Tom said, ‘Norton Hintz is interested in doing something musical. I’ve talked to him about Kafka.’ So we sounded out Norton, and Norton joined our group. He said he would present the idea to the Walker Art Center board. So he did.”

In yet another version of the story—Martin Friedman’s— Hintz first sought the approval not of the Walker Art Center board but of the Center Arts Council, of which he was a prominent member and chairman of the council’s music committee. Hintz’s pitch to the council was that it sponsor a twoproduction season at the Guthrie Theater, which was scheduled to open in May of 1963. The council said yes, after which, in the fall of 1962, a delegation from the council—among them Nee, Argento, and Hintz—paid a call on Friedman, the

museum’s director, to seek the Walker’s blessing—and sponsorship—of at least an initial season of opera productions and perhaps more after that.

The Walker, it turned out, was not a complete stranger to opera performance. Under the aegis of the Arts Council the museum had presented two one-act operas in 1955— Pergolesi’s La serva padrona and Hindemith’s Hin und Zuruck staging them in the Walker lobby for two nights. Three years later the council offered, in the same modest circumstances, with colored slides projected onto the walls of the lobby, Menotti’s The Unicorn, the Gorgon, and the Manticore, which the composer described as a madrigal ballet. These were modest, low-budget productions that cried out for a theater. In just a few years there would be one next door.

DURING HIS TWENTY-NINE YEARS as director of the Walker Art Center, Martin Friedman, a Pittsburgh native who died in 2016 at the age of ninety, pulled more than a few rabbits out of his hat. Remembered for his sharp wit and compulsive attention to detail, Friedman exhibited Picasso’s private art collection before it debuted in New York, and he developed an eye-catching new public space across the street from the museum, the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden. Over the years he presented the best in contemporary art, gradually transforming the Walker from a regional museum into an internationally respected center of innovation. And in 1963 he did something slightly crazy, something museums don’t normally do: he formed an opera company. And it wasn’t your average

opera company. Its aim, to quote a slogan from later years, was to present “opera without elephants.” The programming would consist of chamber operas featuring small casts— chiefly local singers—backed by a small orchestra, and the focus was to be on new and unusual repertoire.

When the delegation from the Center Arts Council presented its case, Martin was dubious but intrigued by the idea of a museum helping to bring another artistic entity into existence. And there was an added—and rather enticing—factor that everyone present was aware of. The Walker would have use of the Guthrie Theater for up to a third of each year because the T. B. Walker Foundation, the museum’s main benefactor, had contributed $400,000 to the theater’s construction fund. The Guthrie’s acting company would use the theater the rest of the year for its own productions. According to the terms of the foundation’s gift, the theater would belong to the museum because it, too, would be on land owned by the foundation. Though he had little desire to involve himself in a bigger, more expensive performing-arts program than the one the museum already had, Martin had to admit that the Guthrie would be a promising venue for these chamber operas, which could be anything from Mozart to Benjamin Britten and perhaps new works as well. Opera at the Guthrie made sense. The theater’s seating capacity of 1,400 and its thrust stage would likely turn opera-going into an intimate experience. The downside was that the theater wouldn’t have an orchestra pit, which for opera is like a car without wheels or, at the very least, a car without shock absorbers. Either way, it was going to be a bumpy and perhaps exhilarating ride.

Warming to the idea, Martin said the Walker would participate if two conditions were met. One was that the museum would oversee the opera company’s finances and would work with the Center Arts Council on the company’s budget and on obtaining both public and private support. The other was that the Walker reserved the right to select painters and sculptors to design the sets and costumes in consultation with the new company’s managing and artistic directors, yet to be named. The involvement of visual artists, Martin thought, would go a long way toward explaining to the public why a museum of contemporary art would get involved in something so foreign to its mission, and surely the artists themselves would benefit from the collaboration. He brought those justifications up a couple of weeks later when he presented the Center Opera proposal to the Walker board. The board backed the idea with the stipulation that the project not interfere with the museum’s other programs. Martin said he swallowed hard and agreed.

“They suggested that the Walker use some of its time in the Guthrie to present chamber opera. And what exactly might that be, I asked warily?”

—Martin Friedman, Director, Walker Art Center

HAVING RECEIVED A GREEN LIGHT, the first step was to assemble a team capable of, first, putting an opera company together, and second, of putting on an actual opera production from time to time, something that audiences might enjoy. They had fourteen months to do it, and none of them had ever done anything like this before. The team was quickly agreed upon. Hintz would be company manager; Argento the artistic advisor (though he was listed as “artistic director” in an early news release); Yale Marshall, a local singer and composer, would be executive producer; and Tom Nee the music director. Nee, an associate professor of music at Macalester College who grew up in Albert Lea, Minnesota, and later studied conducting in Zurich and at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, was an obvious choice for the position. A champion of new music and a conductor much respected by local musicians, Nee, among his colleagues at the new opera company, was the chief proponent of Center Opera’s commissioning of new works. It was a loss to both the company and the city when, after four seasons of exceptional work with the company, Nee said goodbye to Minnesota winters and accepted a position on the faculty of the University of California, San Diego. He died in 2008 at the age of eighty-seven.

At the time of the agreement the only work under discussion was Britten’s comic opera Albert Herring, which would be staged in March of 1964. John Olon, also known, depending on his mood, as John Olon-Scrymgeour, would direct. The official sponsor would be the Center Arts Council, though it was clear that the Walker would pay the bills—minus whatever the Arts Council could raise on its own.

“We had a small amount of money to put it all together,” Argento said. “The truth is we were too ignorant to know we had to pay a hefty royalty to do an opera like Albert Herring We talked about financing the whole thing, and it got to be difficult, but we were committed to doing it. If they were going to let us do an opera at the Guthrie, it was too great an opportunity to pass up.”

The initial plan was that the company would make its debut in January of 1964 with Albert Herring. Then came a cautionary thought: perhaps a new, untested company shouldn’t start out with so complicated and delicate a work as Britten’s comic masterpiece. Perhaps that should be tackled in March. The premiere of the company could be something simpler that needed a chorus, since there are so many good choruses in this city. So what would that be?

Argento recalled:

I don’t remember who suggested it—maybe it was Tom or Norton—why don’t I write an opera for the occasion? I talked to John [Olon-Scrymgeour]. He said we could probably do a chamber opera. I said, "I know one that would be perfect for this. It’s by John Blow, The Masque of Venus and Adonis."

John said, "Well, for your work, I have this idea about angels." I wrote most of the music that summer at a cottage my wife and I rented in northern Minnesota. The John Blow opera didn’t cost any money to produce. There were no royalties, and I think they gave me $500 to compose the piece. So it was a double-bill, and John would direct.

Said Hintz:

One of the earliest bits of advice Martin gave us was to form a ladies’ auxiliary. Of course, nowadays, it wouldn’t be called that. But we needed an association, an opera guild. And he said, "I’ve got just the person for you. She has tons of energy that’s not being used, namely, Alice Smith, wife of Justin Smith." We approached her and she said, "Sure, great idea." She was a dynamo. She had been a prime mover in organizing what was originally called the Chamber Opera Guild. And they immediately started raising money, which was what we had in mind.

Guild membership was secured by buying a season ticket and contributing $7 or more. Ticket prices were low. Single tickets were available at $2, $3.50, and $4.50. Season tickets were $3, $5, and $7. The biggest funding success was announced just a few days before the debut season opened: a grant of $14,250 from the Rockefeller Foundation. The grant specified the formation of a chamber-opera company that would feature local singers in performances at the Guthrie Theater. The productions were to be guided by a guest director, two acting and singing coaches, and a choreographer, all from New York. As director, John Olon-Scrymgeour fit the bill. He was from New York. The acting coach turned out to be Mark Gordon, who died in 2010 at the age of eighty-four after a long, eventful career as an actor in television, film, and the stage. In 1973 Gordon made television history by portraying Chuckles the Clown in a famous episode of The Mary Tyler

Moore Show, which is set in Minneapolis.

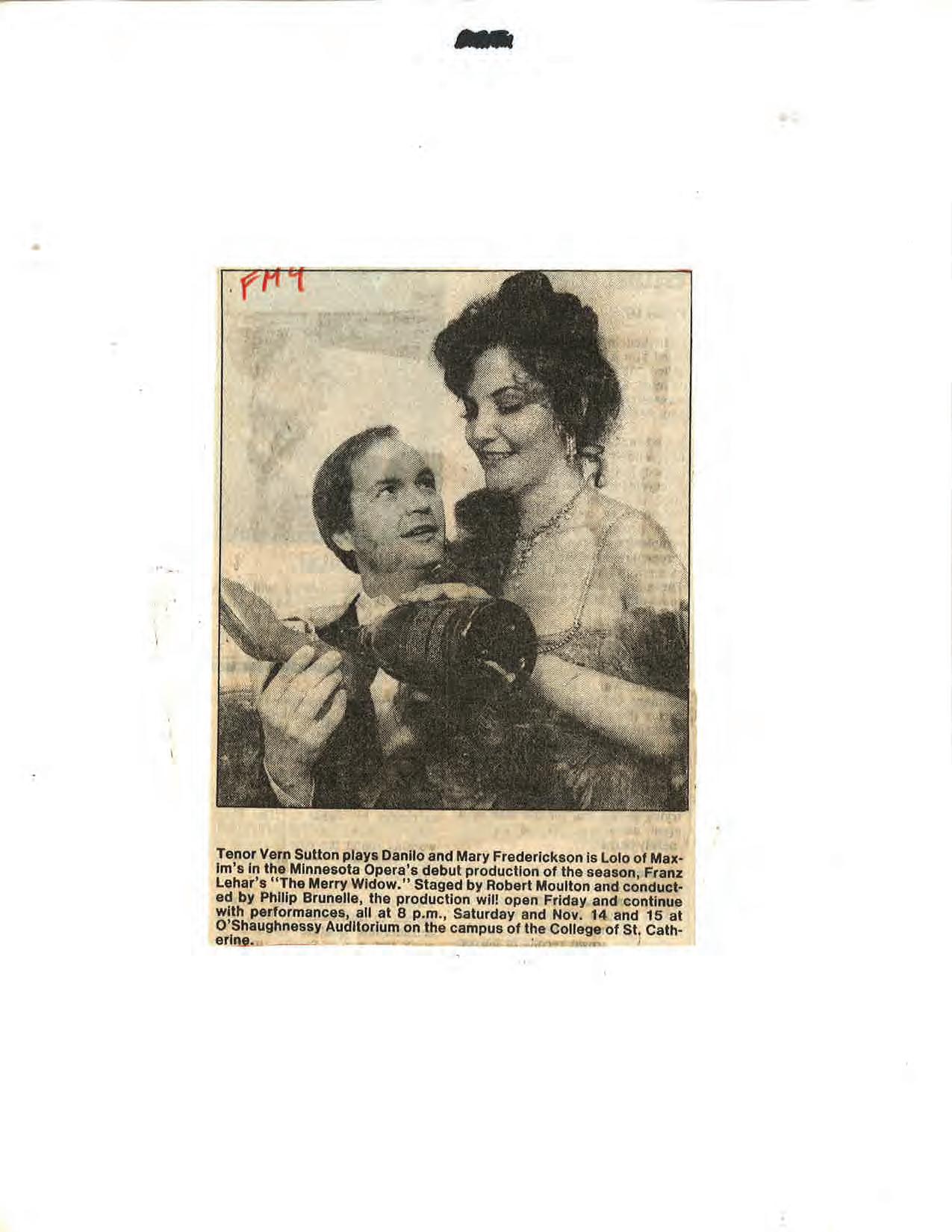

The search for a cast began in the fall of 1963 when a call went out for singers in the Twin Cities interested in helping form an opera company. Several dozen singers showed up in the green room of the Guthrie. One of them was Vern Sutton, a tenor who would soon become the company’s most prominent and admired performer, appearing in nearly four dozen productions until 1985 when the company stopped hiring him. A year earlier, Sutton had sung a role in Argento’s Christopher Sly at the University of Minnesota, where he was

pursuing a doctorate in musicology. By then acquainted with Sutton’s characteristic light, flexible voice, Argento wrote a part for him in Masque of Angels.

“Dominick encouraged me, and the company sounded like a great idea,” Sutton said in 2018. “We were told there was no guarantee we would be paid, but they were going to charge admission, and if they made any money after paying expenses, they were going to divide it up among the singers, so we agreed to do it. And after we opened, they did divvy up the money. It wasn’t a lot, but it was fun.”

A good tenor is always in demand. In the case of Vern Sutton, the demand was so intense that a radical solution had to be devised. In the fall of 1969 Sutton was double-booked in Minneapolis and St. Paul on a Saturday night, and there was no way the trip could be made by car. So, as any sensible opera company would have done, the St. Paul Opera rented a helicopter, and within twenty minutes Sutton was standing in a dressing room at the St. Paul Auditorium putting on his costume.

Growing up in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, Sutton came to Minneapolis in 1960 to do graduate study in voice at the University of Minnesota, and over the decades he successfully balanced two full-time careers, one as a performer and another as an educator, while earning acclaim as a director, staging more than 115 productions for the University Opera Theater, and becoming a widely recognized expert in the creation of concert staging or “semi-staging” of musical theater works. His lead roles as a member of the Stagecoach Players in Shakopee, Minnesota, especially his extravagant, almost Baroque-style villains—giving some 1,200 performances during the ’60s—remain the stuff of theatrical legend.

Sutton was a rather exotic bird, one not often sighted during the ’60s though perhaps not so uncommon today: a singer who can act. Sutton’s twenty-plus years with Minnesota Opera, first as a lead performer and then as a member of the company’s ensemble, sit on the top shelf of this busy man’s accomplishments. Sutton sang in the company’s first production in 1964, the premiere of The Masque of Angels by Dominick Argento, and twenty-one years later he performed his farewell, a role in Casanova’s Homecoming, the premiere of another work by Argento. And then, in a command performance, he returned in the spring of 2013 to sing the brief but challenging role of the Emperor in a production of Turandot, the occasion being two birthdays, the company’s fiftieth and Sutton’s own seventy-fifth.

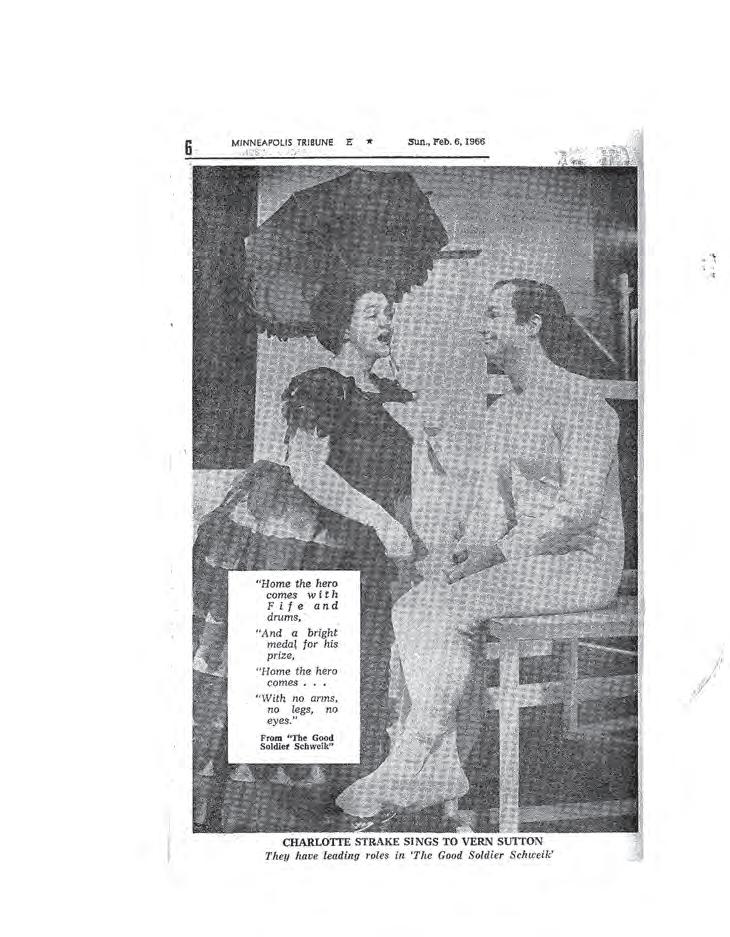

Between these years Sutton produced a gallery of indelible characterizations: the innocent and oblivious Schweik in Robert Kurka’s antiwar opera The Good Soldier Schweik (1966, ’71), the menacing and murderous Punch in Harrison Birtwistle’s Punch and Judy (1969), the paranoid and terrified Mr. Owen in Argento’s Postcard from Morocco (1971, ’72), the demented King George III in Peter Maxwell Davies’ Eight Songs for a Mad King (1974), and, as an example of Sutton’s skill playing comedy, his portrayal of the wily Don Medigua in John Phillip Sousa’s El Capitan. Mezzo-soprano Janis Hardy, who joined the company in 1970 and over the years was Sutton’s most frequent singing partner, recalled seeing Sutton in Eight Songs at the Walker Art Center auditorium. “It was the most spellbinding performance I’ve ever seen,” she said. “He finished it by walking up the steps of the auditorium and out the door, giving out this haunting semi-scream. No one in the audience moved for a long time afterwards.”

John Ludwig, who was general manager of Center Opera during its first decade, recalled seeing his first Center Opera production in 1964: Albert Herring. “The first person I saw in rehearsal was Vern Sutton,” Ludwig said. “The quality of his acting and musicianship was fantastic.”

This is high praise for a singer who claims he never had an acting lesson. Sutton’s musical training came early, however. As is the case with most professional singers, he started out as a boy soprano. By the time he got to Minnesota, having graduated magna cum laude from Austin College in Sherman, Texas, his experience in musical theater had been chiefly in musical comedy, though he does recall a youthful portrayal of a dancing bear in The Bartered Bride.

Nonetheless, it wasn’t until 1963 that Sutton sang in an actual opera production in the Twin Cities, Christopher Sly, an opera by Dominick Argento based on Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew. The production initiated a long and fruitful composer-singer relationship. Argento ended up writing a part for Sutton in his next opera, his fifth, The Masque of Angels, and he continued creating roles large and small for Sutton in operas (Postcard from Morocco, Waterbird Talk, The Voyage of Edgar Allan Poe, Casanova’s Homecoming) and concert works (Jonah and the Whale, The Revelation of Saint John the Divine, Letters from Composers).

Once Center Opera got underway, the renown of both the company and its singers spread quickly. Sutton was surprised to find that conductors, performers, and vocal coaches in Europe knew who he was, as early as the late ’60s, when he studied voice in Italy. “I mentioned my name,” he recalled, “and they said, ‘Oh, yes, you’re the tenor with the Center Opera company.’ They had read in the national and international publications my name associated with the company. We were better known in Europe than in the Twin Cities.”

Sutton named two roles as his favorites: Albert Herring and Mr. Owen in Postcard from Morocco. “And I loved Schweik too,” he said. “And, you know, to have composers write things specifically for me, I really liked that, though I’ve been cursed by other tenors because they have to do what was written for me—what was in the score—and they can’t all do what I do, especially in the case of Mr. Owen.”

By 1985, the year the company moved into the Ordway Center, Minnesota Opera was planning its twenty-second season and looking toward the future, which meant, in the view of some people close to the company, shutting the door on the past. Most of the performers associated with the company’s first two decades—the Balk-Brunelle era—were no longer being cast in the productions. Conspicuously absent were Sutton and Janis Hardy. Sutton, at any rate, continued performing in various venues and capacities throughout the ’90s and beyond. Sutton’s performing schedule is less frantic today than in earlier times. (No helicopter rides are scheduled.) Now in his early eighties—he has been a widower since 1998—he spends his winters in a condominium in Palm Springs.

A COMPANY OF THIRTY-EIGHT SINGERS was formed. Frederick Hilary, a veteran choral conductor, was appointed chorus master, and Hilary’s own ensemble, the Minneapolis Madrigal Singers, was enlisted to sing the choral parts in both operas. Apart from Sutton, two of the singers performed in numerous later productions: tenor Yale Marshall and bass LeRoy Lehr, who eventually spent nineteen years singing solo roles at the Metropolitan Opera until his retirement in 2010. Peter Wexler, a twenty-seven-year-old designer who had earned acclaim in New York, was engaged to design the sets, costumes, and lighting. Argento’s wife, the soprano Carolyn Bailey, would sing the role of Venus and would be much praised for her interpretation of the poignant aria that concludes the work. The dancers in both operas were to be the members of the First Chamber Dance Quartet, alumni of the New York City Ballet.

Rehearsals began in early December, and most were held on the Guthrie stage. “That’s how we got to meet the Guthrie people,” said Sutton. “They came in to start their own rehearsals as we were finishing our season. I’ll never forget when I met Tyrone Guthrie in the green room. He had been observing some of our rehearsals for Albert Herring. I came in and he said, ‘Oh, you’re Mr. Sutton, aren’t you? Hello, I’m

Tony Guthrie. I must tell you how much I admire your work.’ He actually became a fan of mine.”

Opening night—January 9, 1964—was, for the most part, a rousing success. Onstage everything proceeded smoothly, both the singing and the dancing. Backstage, however, was pandemonium. For the designer, Peter Wexler, the set, being minimal and easy to assemble, was not a challenge. The costumes were another matter. There were eighty of them. They were nearly ready, but as opening night drew near, many of the costumes still needed sewing and ironing. A desperate call for help went out to members of the Arts Council and assorted friends. The legend, it turns out, is true: on opening night, costumes for act two were being sewn while act one was being performed on stage. Martin Friedman and his wife Mildred were members of the ad-hoc sewing committee, as was the city’s First Lady, Frances Naftalin, wife of Minneapolis Mayor Arthur Naftalin. A mad scramble during intermission got everyone into the right costume.

The small orchestra, positioned backstage, played well. Tom Nee conducted wearing earphones that were attached to microphones that picked up the singers’ voices. The situation was awkward. Singers and orchestra weren’t always in sync.

Nee always worked well with musicians. “Tom was a wonderfully supportive conductor,” said Cynthia Stokes, who played principal flute in the company’s orchestra off and on for several decades, including on opening night. “I think people really enjoyed playing for him. He was careful to give us notes at the start of each rehearsal. He knew how to get the most out of people.”

Buoyed up by enthusiastic audiences and favorable reviews, the little company soon began preparing for the second production, Britten’s Albert Herring. Great new comic operas were underrepresented in the twentieth century, perhaps because it was such a grim time. Albert Herring ranks high on anyone’s list, and by all accounts, Center Opera’s production, which closed the company’s first season (and

was revived in 1975) was close to perfect. There were several reasons for this high praise, but Vern Sutton’s impeccable performance in the title role was probably at the top of the list. That performance was, as Edwin L. Bolton put it in his review in the Star, “a show-stopper” in “a beguiling production, smart and well-paced.” Albert is a virtuous young grocery clerk who, despite his protests, is declared May King

when no suitably virginal Queen can be found in the village. Albert was the twenty-six-year-old Sutton’s first big showcase in the Twin Cities, and it led to further engagements. Shortly after the Center Opera production closed, Sutton was invited to repeat the role of Albert that spring at the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore, Maryland, and at the Long Island Summer Festival at Hofstra University. Another plus was

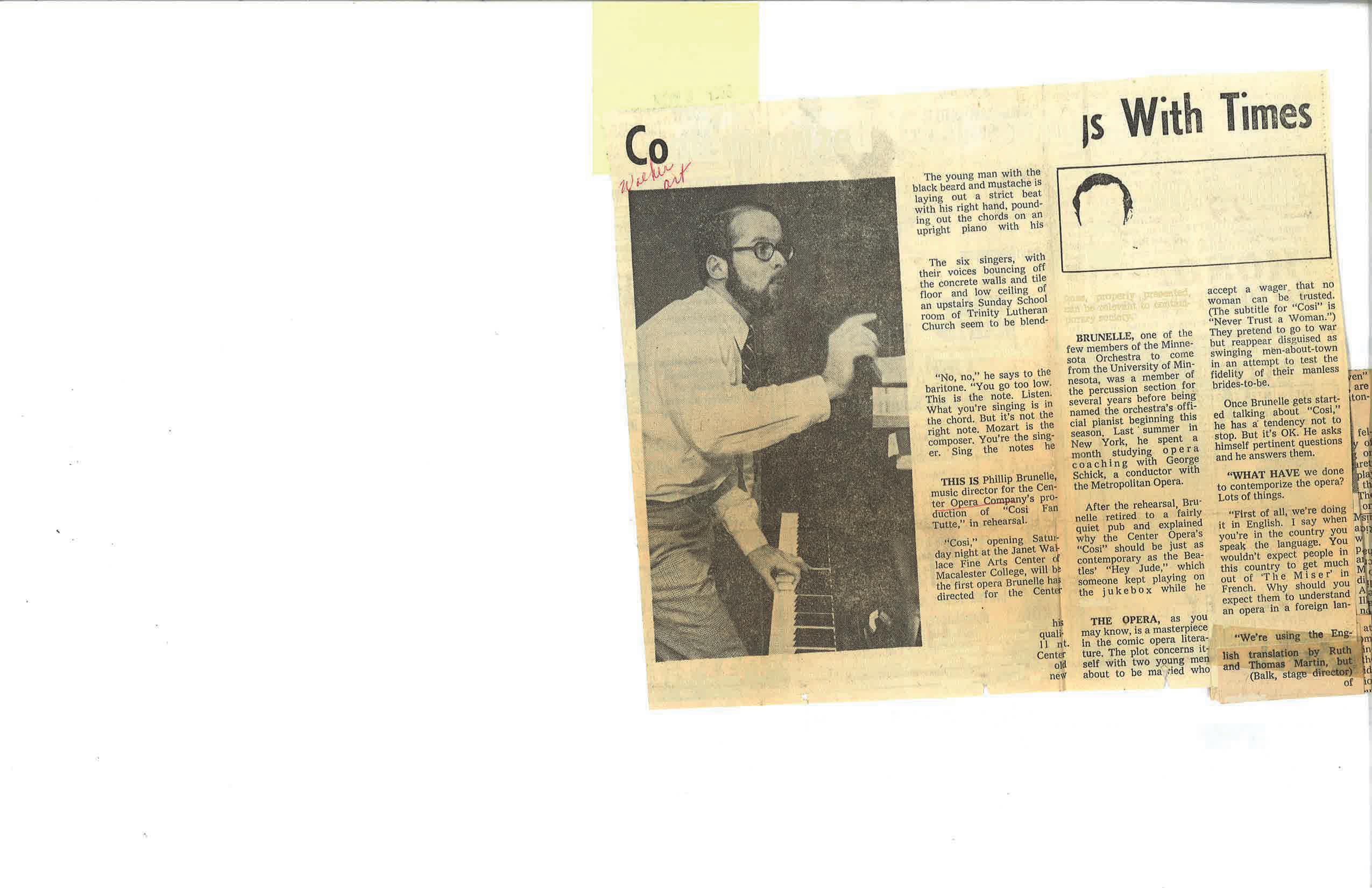

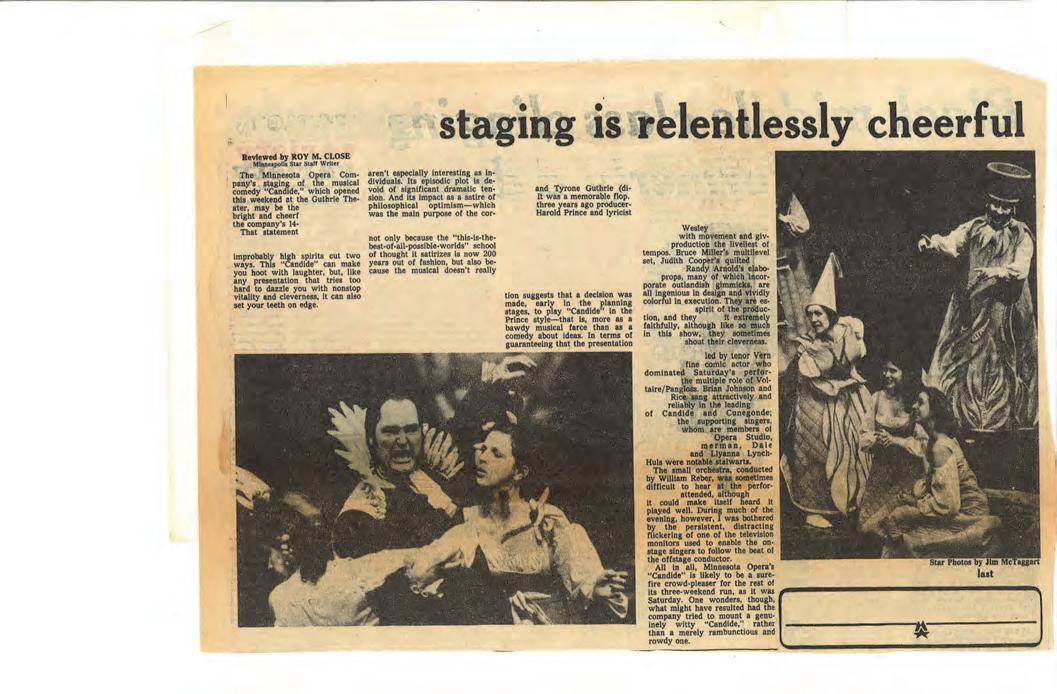

the colorful performance by soprano Ellen Faull, the only import in the cast, who portrayed Lady Billows, the town’s one-woman morals squad. Faull, a veteran of the New York City Opera, was a shrewd choice. She had played the part in the first US production in 1949. John Olon-Scrymgeour’s directing was much praised once again, as was Tom Nee’s conducting.