COME & PLAY

COME & PLAY

NEW carpet collection, Pattern Play, where you make the rules.

NEW carpet collection, Pattern Play, where you make the rules.

LAUNCHING SPRING 2025

LAUNCHING SPRING 2025

NEW carpet collection, Pattern Play, where you make the rules.

NEW carpet collection, Pattern Play, where you make the rules.

LAUNCHING SPRING 2025

LAUNCHING SPRING 2025

42 28 48

12 Upfront Projects, products and people through a future-centric lens.

22 Things I’ve learnt Olga Gomez, partner at Squire & Partners, shares her advice on following your instincts and learning not to postpone your happiness.

24 The height of design Writer, curator and commentator Priya Khanchandani on the object she feels represents the pinnacle of timeless, great design.

26 View from the outside Architect, curator and urbanist Madeleine Kessler presents a new vision for the high street.

28 In conversation with: Sevil Peach Design pioneer Sevil Peach talks chance, opportunity and challenging the norm.

&4 In conversation with: Ido Garini Studio Appétit founder Ido Garini discusses building a multi-disciplinary career and feeding creativity.

40 Designing for di erence Shawn Adams on our duty to support the next generation of creatives.

42 Case study: Lazari Investments

MoreySmith creates a workspace tailored to the client on London’s Savile Row.

48 Case study: MEplace Nursery

In King’s Cross, O!ce S&M devises a colour-"lled home for burgeoning nursery brand MEplace.

54 Case study: Riverstone Heights Build-to-rent brand Way of Life champions community engagement for a more ‘mindful’ take on gentri"cation.

60 Case study: Caravan Manchester

Channelling New Zealand’s all-day co ee culture, Other Side brings laid-back Kiwi charm to Caravan’s Manchester outpost.

1'8

66 Case study: The Waterman With e Waterman, Fathom Architects and Fettle create a Clerkenwell workspace "t for today, but proud of its past.

74 The Ask Tina Norden asks: are we "nally living in a posttrend world?

76 Positive Impact

Looking ahead to tomorrow’s design landscape, we gather a cohort of A&D’s leading names to chart their ambitions for %&%'.

82 Fast Forward Designer and engineer Duncan Carter explores why the power of digital tools is all in the way we use them.

90 Paradoxically speaking Neil Usher examines the ‘one size "ts all’ mantra and the concept of workplace elasticity.

92 Mix Roundtable with 2tec2

100 Mix Roundtable with Elevate Spaces With Elevate, we delve into the di erent pillars of sustainability, exploring how businesses can balance pro"t with purpose.

108 Mix Talking Point Matter of Form founder Anant Sharma asks: have we chased e!ciency at the expense of meaning?

In partnership with 2tec2, we discuss what constitutes meaningful innovation and whether technical advancement is at odds with naturedriven design principles.

114 Material Matters

Johannes Karlström and Kristo er Fagerström, partners at Swedish practice Note Design Studio, share the futureforward materials in their rotation.

115 Material Innovation

Interdisciplinary studio Matter

Forms looks to the sea for a bioalternative to concrete.

116 Final Word

Mike Walley on the cyclical ebb and (ow of design trends.

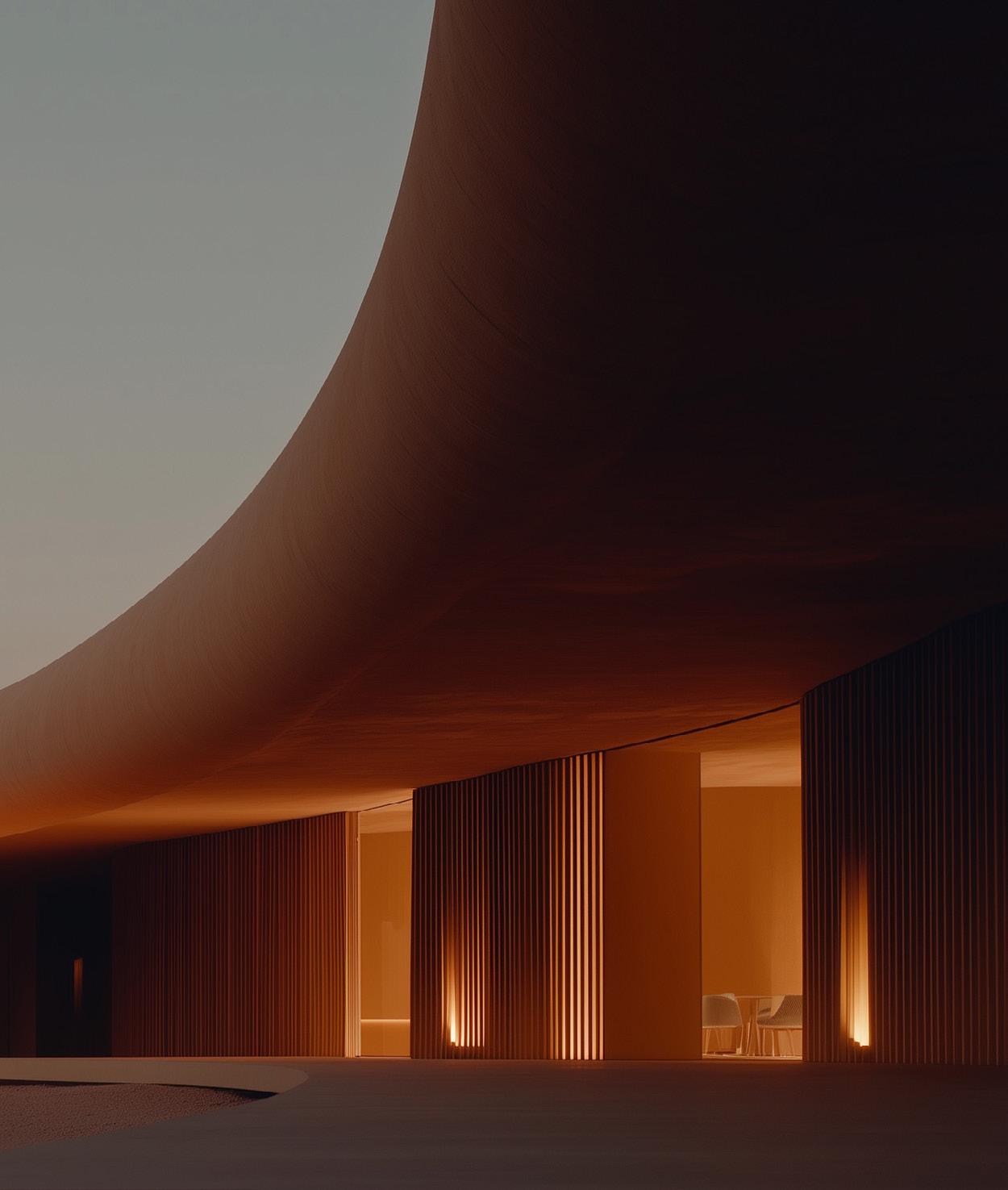

Gensler’s brand studio creates spatial experiences that connect people and place. By using key shapes within Milliken's design, we represent the variety of environments, spaces, scales, brands and sectors in which we work. All uniquely di erent, all with their own purpose, all with a story to tell.

gensler.com

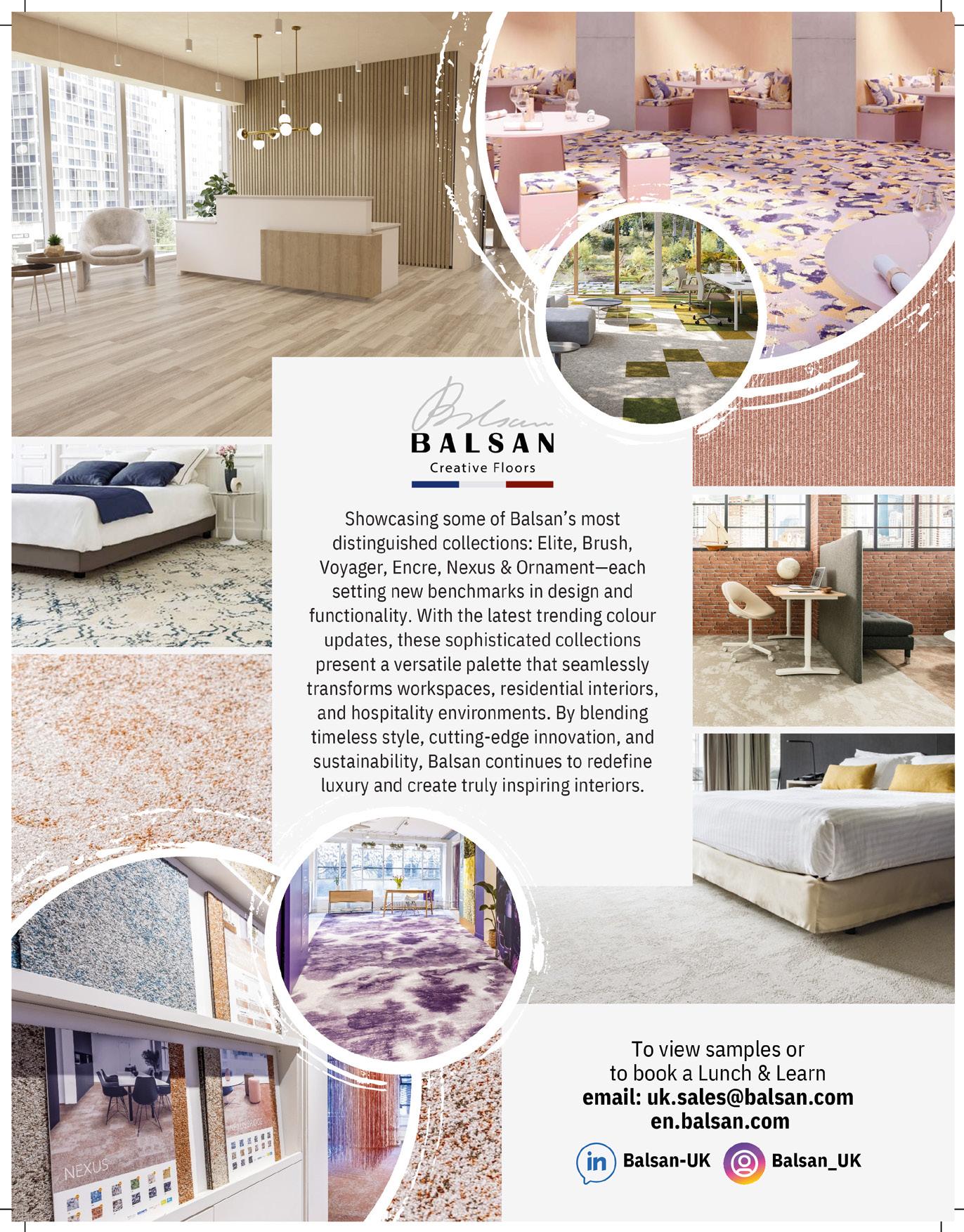

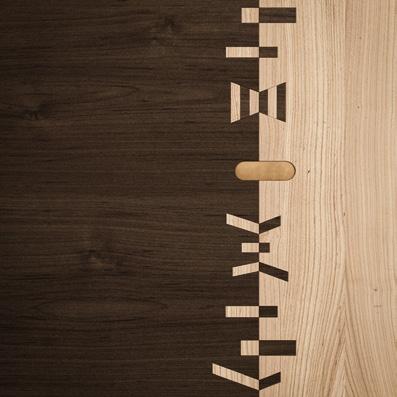

Inspired by e New London Fabulous Movement, Pattern Play is a bold carpet collection combining pattern, colour and texture, showcasing Milliken’s propriety Millitron technology. A joyous celebration of pattern and colour with something for everyone, from a softly textured neutral combination of designs to a bold statement of impactful shapes and colours, pick and mix to build your own design statement. milliken.com

Managing Editor Harry McKinley harry@mixinteriors.com

Deputy Editor

Chloé Petersen Snell chloe@mixinteriors.com

Editorial Assistant Charlotte Slinger charlotte@mixinteriors.com

Editorial Assistant

Ellie Foster ellie@mixinteriors.com

Managing Director Leon March leon@mixinteriors.com

Account Manager Stuart Sinclair stuart@mixinteriors.com

Account Manager

Patrick Bowley patrick@mixinteriors.com

Account Manager Gaia Cafarella gaia@mixinteriors.com

Marketing Manager Paul Appleby paul@mixinteriors.com

Head of Operations Lisa Jackson lisa@mixinteriors.com

Advertising and Events Operations Manager Maria Da Silva maria@mixinteriors.com

Art Director Marçal Prats marcal@mixinteriors.com

Founding publisher Henry Pugh

To ensure that a regular copy of Mix Interiors reaches you or to request back issues, call +)) *&+ ,-, ',. )/'& or email lisa@mixinteriors.com

Annual Subscription Charges UK single £)' '& Europe £,0' (airmail) Outside Europe £,-' (airmail)

Unit % Abito, /' Greengate, Manchester M0 1NA

Telephone +)) *&+ ,-, ',. )/'& editorial@mixinteriors.com www.mixinteriors.com

Instagram @mix.interiors LinkedIn Mix Interiors

by

I’d hope that innovation is a common thread within every issue. After all, what use retreading ground already wellworn? But this issue feels particularly imbued with a sense of radicalism – with themes and ideas that feel especially worldchanging and mould-breaking.

On AI, perhaps the most vigorous topic of discussion in design currently, Matter of Form’s Anant Sharma asks if we’re chasing e!ciency at the expense of meaning, in our regular Talking Point, while Duncan Carter presents his own manifesto on using digital tools with care, in our Fast Forward feature. AI is also the basis of a Mix Roundtable with %tec%, in which we explore how revolutionary technological advancements can sit alongside engagement with the natural world and a commitment to sustainability.

On sustainability then, the most worn of well-worn ground at this point, we seek to push the conversation further, asking how we break out of siloed thinking to address our impact on people and planet – in another Mix Roundtable, with Elevate. We

also tap the expertise of some of the industry’s leading lights, in a special Positive Impact piece traversing their ultimate sustainability aspirations for %&%'. And we aim to address sustainability beyond the environmental and push into the social – Madeleine Kessler positing a bold new vision for the high street that places community and culture "rst, and Shawn Adams explaining why meaningful social impact means supporting young talent.

Our lead interviews also feature two wildly disruptive, abundantly creative thinkers: with Sevil Peach discussing remaking the world of work through design, and Studio Appétit’s Ido Garini candidly re(ecting on the ‘hustle’ of building his own practice and being an unconventional person in an often conventional world.

As our "rst entirely new issue of %&%', it feels "tting that these pages are fundamentally outward-looking in content –concerned with the future and the forces shaping it. Enjoy.

Harry McKinley Managing Editor

A deep-rooted heritage in soft seating manufacturing.

Since 1901, we have proudly designed high-quality wall and floor tiles, preserving our rich history and heritage in the heart of the Potteries, Stoke on Trent. What sets us apart is our experienced in-house design team, who travel the world seeking inspiration and sourcing on trend ceramic and porcelain tile collections to bring to market. Our extensive product portfolio has been featured in interior design projects globally, including residential spaces, education facilities, hotels, hospitals, leisure facilities and commercial developments.

We don’t just design and supply the finest quality products; we also deliver exceptional service. With our unrivalled stock availability, next day delivery, first class customer experience and technical support, you can trust that our 120+ years of expertise ensure all our products and services meet the highest quality standards. We also remain committed to providing sustainable materials and ensuring all partnering factories hold the same values and principles.

Incara is a range of functional, ergonomic wiring devices dedicated to any modern, flexible workspace, from o ice to hotel, café, airport or any other shared working environment.

First revealed at the 1968 Milan Triennale, Gino Sarfatti’s Model 600 lamp rose to fame for its distinctive lead pellet-" lled base and stitched leather upholstery, making for a lighting solution that was high-functioning and visually intriguing in equal measure. Made on behalf of his brand, Arteluce, Sarfatti would go on to design more than 600 lighting products over the course of his lifetime, fusing technological advancements with a humanistic approach, and becoming one of the greatest Italian lighting designers of his time.

Fashion house Bottega Veneta and Flos may seem an unlikely pairing for the reimagining of the Model 600, but it was in 1966 that the Model 600 went to market, the same year the fashion house was born in the neighbouring city of Vicenza. Several years later, Sarfatti would sell Arteluce to fellow Venetian lighting company Flos, and the rest is history.

Launched in late %&%), Bottega Veneta’s creative director, Matthieu Blazy, oversaw the renaissance of the Model 600, remaining faithful to the charm of the original design but infusing Bottega Veneta’s craft sensibility. In close collaboration, Flos has rendered the leather base in two styles using the

fashion brand's signature woven leather – Intrecciato and Intreccio Foulard. e former follows a simple plaiting of leather strips, whereas the latter sees the leather ruched before weaving to create a more voluminous shape and overall sense of movement.

Dependent on the angle of its "lleted re(ector, the new collection throws both direct and indirect light, marrying the ingenuity of the original design with the latest Flos LED technology. Available in small and large editions, Model 600 now comes in a variety of shades, including sleek black, lipstick red, industrial grey and Bottega Veneta green.

flos.com

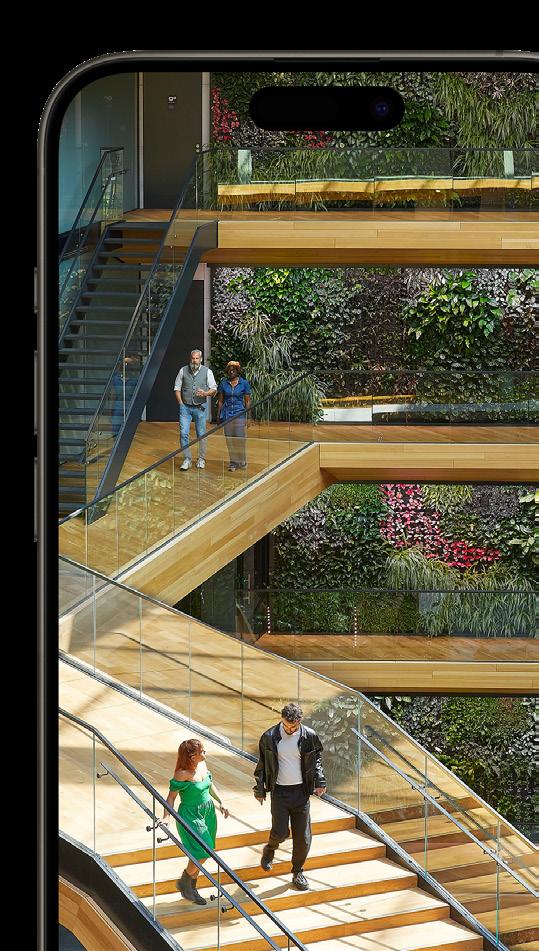

A dramatic overhaul of Calton Square has received the go-ahead from Edinburgh City Council, the major refurbishment by Sheppard Robson cleverly complying to the curtails of the neighbouring Calton Hill – a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Edinburgh’s new town.

Commissioned by Ardstone Capital Ltd (UK), the landmark o!ce campus will retain 88% of its structural frame, meanwhile a 50,000 sq ft expansion will join the building to the city’s vibrant core. A new main entrance, complete with step-free access, cultivates an energetic dynamism on arrival, thanks to its scattered arrangement of co-working spaces, punctuated by various relaxation zones and café outlets for refreshments. Glazed frontage will improve connectivity to Leith Street – a triple-height atrium, located in an underutilised internal courtyard, set to activate the public realm though its comprehensive events programme.

Further features include a series of stacked terraces, accessible only to private tenants, as well as a communal green space for inter-business gathering. Wildlife planting, brown habitat and PV panels are part of plans to achieve BREEAM ‘Outstanding’, NABERS '* and WELL Platinum criteria, ful"lling environmental credentials whilst improving sta wellbeing.

From the outside, the new design echoes traditional Edinburgh architecture through its broken-up vertical bays, where sandstone façades further root the building into its historic context. Together, sawtooth parapets and biophilic integration form a green, crown-like beacon overhead, providing an aesthetic, air-purifying addition to Edinburgh’s skyline.

Home to 3.4 million residents, Busan is the second largest city in South Korea and an important maritime city. As (uctuating sea levels engulf more coastal communities, UN-Habitat and blue tech company OCEANIX elected Busan to host the world’s "rst (oating metropolis, following a string of talks at New York’s UN Headquarters starting in %&,..

A project of gargantuan scale, OCEANIX founders, Itai Madamombe and Marc Collins Chen, nominated architectural engineers SAMOO to lead the build process with Denmark’s BIG Architects to design. e hope: to trial breakthrough technologies in a fully operational prototype by EXPO %&0&.

Proposed by BIG, a 15.5-acre expanse of interconnected pontoons, tethered to land with link-span bridges, have been divided into three distinct zones, comprising living, research and lodging. Designed to house around 12,000 people, the living division has the potential to accommodate 100,000 further residents, through hitching mechanics between tessellated platforms. Characterised by soft lines, low-rise buildings feature terraces that spill out onto approximately 40,000 sq m of outdoor space and mixed-use amenities for fostering community and public engagement.

Powered by photovoltaic energy alone, six integrated systems have been devised to ensure the safe and sustainable future of OCEANIX Busan: zero waste

and circular systems, closed loop water systems, food, net zero energy, innovative mobility and coastal habitat regeneration. Similarly, each neighbourhood will treat and replenish its own water, reduce and recycle resources and provide innovative urban agriculture through greenhouses.

With 90% of mega cities worldwide being vulnerable to rising sea levels, (ooding is destroying billions of pounds-worth of infrastructure, but more pressingly, creating millions of climate refugees.

ough OCEANIX-endorsed dwelling looks futuristic in appearance, is waterborne urbanism closer than we think?

oceanix.com

Better known as London Olympia, Olympic Events is the £1.3 billion redevelopment of the 19th century event space, located in West London’s Hammersmith and Fulham. e reimagined venue is set to o er a multifunctional arts space, theatre, fourscreen cinema and a myriad of cafes, putting itself on the map as a new go-to destination. Upon the completion of Heatherwick Studio’s dramatic glass canopy in %&%), Olympic Events has additionally announced hotels, a music arena, theatre and a conference centre as part of its ongoing plans.

Central to the wider development will sit citizenM’s London Olympia outpost, marking the brand’s "fth opening for the city. With interior architecture by SPPARC and EPR, the 146-key hotel, slated for summer %&%', will bring a playful spirit to the soon-to-be cultural hotspot, mixing the brand’s signature tech-forward ethos with thoughtful nods to its historic surroundings. e Apex Room, a part of the original 1886 structure, will be unveiled as a hotel lounge, its sensitive redesign enhancing socialising and public engagement. Further to this, workers can bene"t from three societyM meeting rooms which have been con"gured with creative collaboration, brainstorming sessions and team workshops "rmly in mind.

Pioneering the notion of a ordable luxury, the hotel will present guests with elevated hospitality at a lower price point, as well as direct access to the plethora of Olympic Events’ amenities beyond its doors. Primed for visitors attending shows, dinner reservations or exploring the capital at large, citizenM’s position within the public regeneration scheme aims to provide convenient and considered short stays for all.

By industrial designer Jenny Nordberg, e Executive series is an exploration of innovative furniture reuse, more speci"cally, the reappropriation of second-hand furniture into FF&E fit for commercial use. Together with Swedish furniture specialist, Soeco, the team’s shared goal was to utilise the least desirable facets, mechanisms and frameworks of recyclable pre-owned o!ce furniture that had become faulty or surplus to requirement.

roughout the series, Nordberg had deliberately chosen not to use parts for their most obvious duties nor follow the conspicuous design paths their shapes immediately suggest. To dissociate form

with function, she treated the objects as a catalogue of items, viewing them as pristine raw material or ‘a library of possibilities’, as the designer likes to call it. By doing so, the material is viewed with optimism and opportunity, and sheds its past association with redundancy or, indeed, ‘waste’.

Once unsellable, sound absorbing insulation has been transformed into comfortable sofas, where a countertop o cut has been dissected and reassembled into a new co ee table. From adjustable desks, damaged supports have been taken and combined with whiteboard pen holders to create contemporary lighting solutions. Each new object, imagined for use in the o!ce

of an ‘executive’ "gure, is a jigsaw pieced together through the unbiased lens of the Swedish designer.

In collaboration with Soeco’s skilled craftsmen in Lund, the series exempli"es how manufacturers can become a material pool for high-calibre design projects, working as a recycling point for individual designers and producing new product lines in the process. Individual pieces from e Executive will be available to purchase on a made-to-order basis following the collection’s debut at Stockholm Design Festival %&%'.

jennynordberg.se

soeco.se

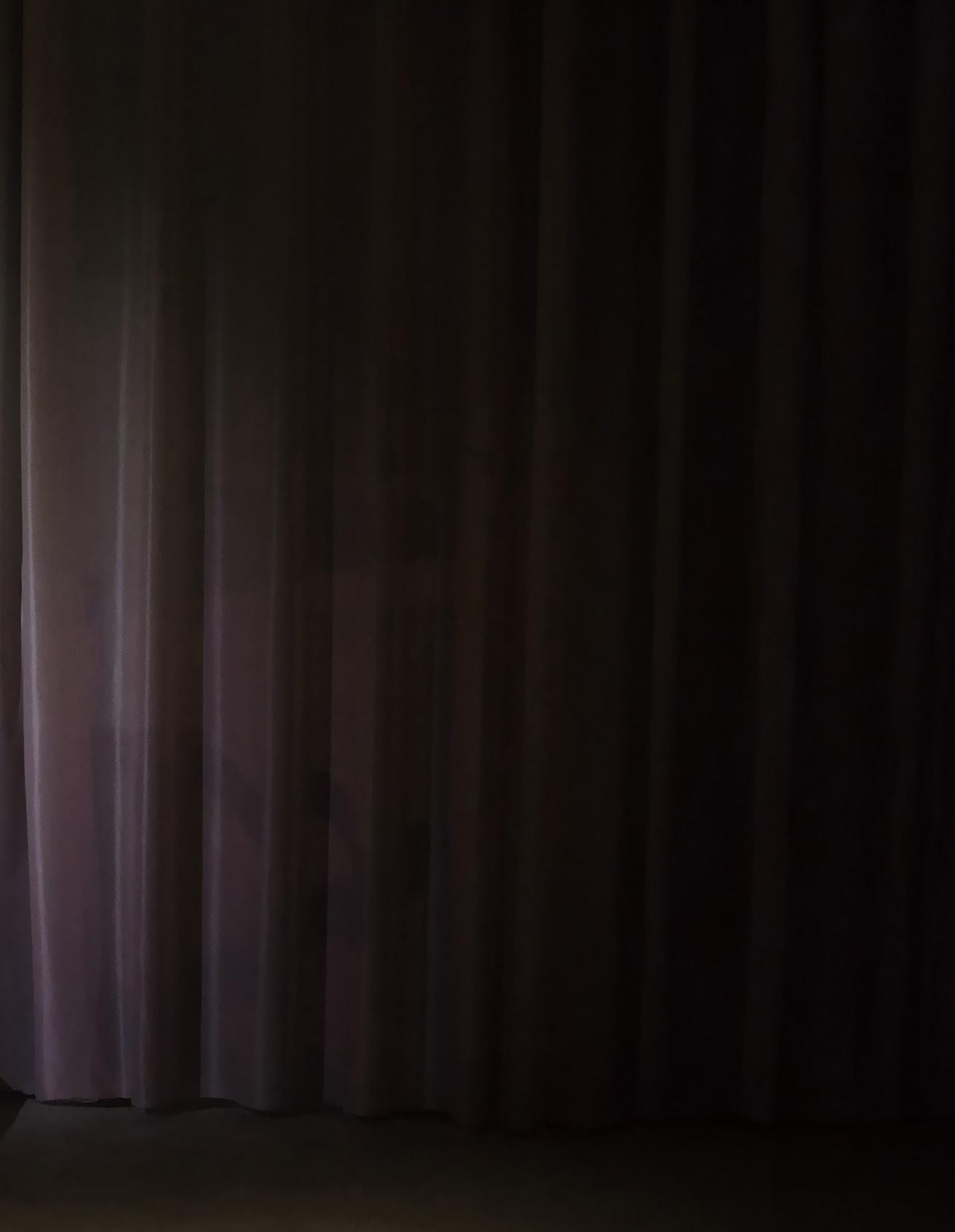

Imagine a space where inspiration can run free. A world that tells your own story, every single day. At RAK Ceramics we help create the perfect living space, for you and your loved ones. Imagine your space.

Olga Gomez is a partner at Squire & Partners and has been responsible for many of the practice’s prestigious international projects, from London to Abu Dhabi.

squireandpartners.com @squirepartners

Avoid perfection and don’t get overly attached to ideas.

I remember crying when my tutor tore my very "rst drawing apart at university, but I also remember what he said: “the drawing is not important. e important thing is that you can now redraw it anytime you want.” Designing is a process and ideas may need to change and adapt for a variety of reasons during a project’s lifetime. e key to successful design is to recognise this and "nd a range of solutions accordingly. Try not to become "xated on one idea as it may end in disappointment.

Work for someone you admire. is will avoid frustration and you’ll bene"t from having a free mentor. Your career is all about continual professional development and in the design world we are constantly learning new things, so surround yourself and engage with people that can teach you and share a lifetime of experience and knowledge with you.

Respect your personal and private time.

It’s important to help others, but don’t spread yourself too thin. It’s important to learn to say ‘no’ at the right time in order to ensure balance and avoid detriment to your own goals and wellbeing. It’s so easy to get lost in project deadlines and competitions and burn out as a result. As an industry we’re becoming increasingly aware of this danger. Make sure that you know your own limits and don’t obsess over work.

Follow your instincts and dreams but make sure you distinguish between passion and talent.

Be honest with yourself and identify these clearly. Sometimes we get caught up in the things that we aren’t as successful at and reject areas that we have a (air for, which may lead to missed opportunities further down the line. Talent combined with passion equals success.

Don’t postpone your happiness. is is perhaps a cliché, but it is true. Try to feel happy with routine and the more boring tasks. ey make up 85% of your life and it is better to do them well and with a smile. e most boring project can be beautiful because you chose to design it that way – even a dustbin! at is what makes us great designers. It’s not just about designing museums and constantly winning competitions. Be proud of, and happy with, your designs even if they are humble and simple.

Priya Khanchandani

is a writer, curator and commentator specialising in contemporary design and visual culture, curating international biennales and until recently working as the Head of Curatorial at the Design Museum.

@hiyapriya

The item

Footed bowl with a manganese glaze and sgra!to decoration by Lucie Rie.

The why

is bowl is not explicitly trying to be the height of anything, but that is what’s so extraordinary about it. It feels like a form that has achieved its fullest potential, in its sculptural quality. e manganese glaze draws you in with its depth, while the sgra!to lines cut into slightly soft clay after glazing add a sense of energy. It manages to transform something as humble as a bowl into an object of profound preciousness –proof that beauty doesn’t have to be grand.

The inspiration

What inspires me about the work of Lucie Rie is that she overcame scepticism over her work and established herself as an independent female potter in a male-dominated "eld. Born in Vienna, she studied pottery at the Vienna Kunstgewerbeschule, a school of arts and crafts. In 1937, she won a silver medal at the Paris International Exhibition and soon after, Rie moved to London to (ee Nazi Austria. Her modernist aesthetic wasn’t appreciated in Britain at a time when ceramics were dominated by the more rustic approach of potter Bernard Leach in St Ives. With the encouragement of fellow immigrant Hans Coper, a young potter who became a partner in her studio, Rie evolved a strong sense of form and an awareness of texture that de"ned her practice.

The impact

is bowl challenges how we think about craft. Rie taught us that a bowl isn’t just a bowl – it’s a meditation, a re(ection of its maker and its place in time. Her work helped bridge the gap between craft and art, making greater space for ceramics in galleries and museums and in(uencing the trajectory of craft which was conventionally perceived as relevant only in the domain

of the domestic. But perhaps its greatest impact is that it shows us how to live with objects and "nd signi"cance in the ordinary. e craftsmanship of this bowl honours imperfection. e glaze is never uniform and the hand of the maker is always there, yet it’s that humanity that makes it extraordinary. e idea of objects existing both to be used and to have lives of their own is something that informs my own work.

The personal connection

I’ve never held this bowl in my hands, so I can only imagine its touch. When I encounter Rie’s work in a book or gallery, as I did most recently at the Hepworth Wake"eld as part of the exhibition e Art of the Potter: Ceramics and Sculpture from 1930 to Now, it feels like a conversation – a reminder to slow down, to look closely, to appreciate the e ort behind the smallest line. In an era of mass-production, consumption and throwing away, I aspire to be surrounded by objects like this, not as possessions but as companions.

High streets have long been at the heart of towns and cities, not just as places of trade but as spaces where communities gather and everyday life unfolds. In the UK, 'High Street' is the most common street name, re(ecting its historic role in commerce and community. But in recent decades, high streets have struggled, leaving many as empty voids at the centre of our towns and cities.

e pandemic accelerated this decline, with lockdowns reducing footfall and forcing widespread closures. Across the UK and Europe, there are hundreds of vacant public buildings and disused spaces, many in prime locations, sitting empty despite their potential to support and engage communities. In her 'Dead Spaces' report, Sian Berry MP highlights the scale of this issue, identifying over 400 publicly owned sites across London alone. ese spaces hold opportunities to support culture, community and public life, yet many remain restricted by policy barriers, underinvestment or bureaucracy. is isn’t helped by recent planning reforms, which have made it easier to convert commercial properties into housing. While originally intended to address housing

shortages, this shift prioritises residential use over public function. So can we encourage high streets to become sites for cultural production, social exchange and experimentation? And what role do architects, policymakers and local communities play in shaping this transformation?

As an architect, curator, and educator, I’m interested in the potential for participatory installations and performances to bring people together to test ideas and inform longterm change. is was an approach we tested in Filling the Void in Karlsruhe, where students curated a series of live projects bringing together the community, city planners and the university to turn abandoned shopfronts and street-space into places for play, contemplation and gathering – spatially testing ideas to bring di erent groups together to question the future of the city and inform strategies for the future of the high street. We have been testing similar strategies in Bournemouth, where we are working with the artist Stuart Semple on bringing culture to a series of abandoned spaces along the high street.

Addressing the sheer number of vacant spaces

means rethinking what high streets can be. Examples such as GIANT Gallery in Bournemouth, the largest artist-led space in the UK, which transformed a former Debenhams department store into a major cultural venue, and Camden Collective in London, which turned vacant buildings into creative workspaces, show what is possible, but also highlight the challenges of making these interventions sustainable. GIANT, for example, became a vibrant hub for contemporary art, attracting around 240,000 visitors and providing vital access to culture and creative opportunities. Yet despite its impact, it was forced to close, highlighting the "nancial pressures that threaten such initiatives. Without sustained policy, "nancial backing, and long-term planning, such e orts remain fragile.

Without action, our high streets will continue to decline. rough policy reform, grassroots initiatives, creative design and spatial practice, we can reclaim these spaces as places of connection, culture, and community. It’s time to rethink and reclaim our high streets. Not as relics of the past, but as vibrant, diverse, evolving spaces that serve our communities into the future.

Words: Chloé Petersen Snell

.mages: courtesof SPGA

Sevil Peach on chance and oppo,unit-, challenging the norm and putting people at the hea, of things.

Being a pioneer in the design industry is more than creating something new, it’s the courage to forge a path where none existed before. And while many are quick to claim the ‘innovator’ mantle, there are a handful that stand apart as true trailblazers – creating an impact that resonates beyond their time and shapes the future of design. Driven by personal vision over a desire for accolades, Sevil Peach has quietly created the humancentered concepts we know today over the past three decades – long before pandemics and muted Zoom calls.

Born in Turkey, 16-year-old Peach and her sister arrived in London on the Orient Express in the 1960s – “it was all groovy, e Beatles and e Rolling Stones” – and soon set her sights upon interior design, eventually arriving at Brighton University. After a rambunctious few years there, kicked out for protesting and de"antly returning to academic success, Peach cut her teeth at Frederick Gibberd & Partners and eventually became design director at London-based practice YRM.

“We wanted the users to work wherever the- wanted in this homelatmophere – something never seen before.”

Most noted nowadays for revolutionary workplace projects for the likes of Microsoft, Novartis, co-working innovator Spaces and a long-term relationship with Vitra, it’s surprising to hear that o!ces were historically Peach’s least favourite projects. “In the /&s and .&s they were very formulaic and hierarchical, grey and miserable. At the time I dreaded designing an o!ce, as I didn’t know how I would approach it –I avoided them as much as I could.”

Disillusioned with the management-driven style of many big practices, Peach and architect Gary Turnbull established SPGA in ,..), “rolling up their sleeves” to create human, design-led spaces that responded to client and users’ needs. “I left [YRM] without a project in my back pocket, so I was prepared to see how things would develop, but only after I'd had a good rest.” She smiles. “So of course when we set up on our own, the "rst project that came along was an o!ce, right?"

No rest for the wickedly creative, and a short time later Peach arrived to meet a former client, Barclay’s property director, in a hotel restaurant she had worked

Left: Artek’s Helsinki o/ce

Below: Flexible workspace and bespoke ‘ 0exiboxes’ at Barclay’s Kennedy Tower

Right: Vitra o/ces, Weil am Rhein

on early in her career. Enquiring about a tapestry she had designed that was missing from the wall, the hotel manager eventually interrupted the conversation to inform her that it had been acquired by the V&A for their collection. “ is obviously impressed my host,” Peach laughs, “who already liked my work and so asked me to design the reception of one of their o!ces, where they were trying non-territorial work and wanted to re(ect their new work spirit. I was excited by the the idea of this new way of working, which was so rare at the time.”

Visiting the o!ce, Peach was unimpressed – “no di erent from the norm; a sea of desks and dreary and not representative of this dynamic work” –and told the client as much, then invited to renovate the group’s Birmingham o!ce as a pilot, which would become the studio’s breakout project.

e resulting workspace was a lesson in mould-breaking and bold originality – open plan with varied spaces for choice and (exibility, a café, sofas to work from, focus rooms and smaller, touch-down desks. e studio couldn’t "nd the tools and products

they needed for this approach and began to craft their own, creating ‘(exiboxes’ from builders’ toolboxes for sta to carry their belongings to wherever they wanted to work, and residential-style trolleys to carry "les instead of under-desk storage. “We were making up products out of nothing in order to ful"ll this project,” Peach muses. “We wanted the users to work wherever they wanted in this homely atmophere –something never seen before.”

e studio’s design centred on the human; creating non-hierarchical spaces with the feeling of ‘home’ – something we take as standard now, but at the time a radical new concept. Did it come as second nature to design in this new and exciting way?

“At the time we were working from home and enjoying the pleasures of doing so,” Peach recalls, “gathering around the kitchen table, both to work as well as to socialise, cook and eat together; working and having a barbeque in the garden on nice days, working by the "re on a sofa. All this meant that the only room in the house that was sacrosanct was my daughter's bedroom – every other room was "lled with people, desks equipment and "les, including a photocopier in the attic! e

upshot was that we realised that you did not need your own desk to be productive, and not being trapped by your desk made work both more interactive and pleasurable, allowing you the opportunity to re-set during the course of a day.”

Specifying Vitra’s recently launched Ad Hoc desks throughout the Barclays project, word of the o!ce reached then-CEO Rolf Fehlbaum, who shared his excitement about the concept and invited SPGA to redesign their o!ces on the Vitra campus in Germany. “I could not believe my ears and hurried back to our o!ce – and of course no one believed me,” Peach remembers. And yet in 1997 the project in Weil am Rhein began; a ‘breathing’ o!ce that could adapt to evolving work styles and showcase and rigorously test Vitra furniture in a real-world o!ce environment. A raised timber platform was introduced, with two outdoor patios punctuating the deep space, around which the various teams were organised.

A social avenue was created along the facade for everyone to share and enjoy the views to the cherry orchard beyond, which linked the communal areas, informal meeting spaces, focus booths and non-territorial touchdown workplaces and support facilities, including focus booths and desks.

Before the Weil project had "nished, Fehlbaum was asking SPGA to design part of Vitra’s Birsfelden HQ, “and it went from there” as she describes, Peach and her team leaving an indelible mark on the manufacturer’s ways of working and indeed, creating – designing showrooms, exhibitions, more workplace concepts and even consulting on product design. e relationship is clearly special to Peach, one that continues now, 27 years on.

“We entered each project with an open mind. Each had their own challenges, but equally with their own rewards. It’s fair to say we were inspired by them and they were inspired by us.”

“.t was our ambition to destro- the norm of ‘sea of desks and grave-ard lookalike o/ces’.”

Below: Kvadrat’s Ebeltoft o/ce. Photography: Gillbert McGarragher

Right: Vitra’s LA showroom

is extensive work for Vitra opened the (oodgates, leading to a long list of transformative workplace concepts across Europe and beyond, each with a distinctly human touch that is individual to each project.

“It was our ambition to destroy the norm of ‘sea of desks and graveyard lookalike o!ces’ – not many people had thought about doing this before,” she says. “Now, these concepts are everyday conversations, and if we have in anyway helped to inspire these discussions, well, good on us. But, my feeling is we are not yet there in terms of manifestation.”

ere’s a lot of humility and bittersweet sentiment in Peach's re(ection on the impact of her studio’s work; while the concepts have spread, the original heart and intention behind them sometimes lost in translation. “People are always looking for a meaning – what does human design mean? What does homely design mean? – so they can recreate it. Sometimes I think like we've created a

monster,” she laughs. “Sometimes I can’t see the genuine feeling, as thought it’s treated like a menu. Every single project we’ve done is with a really open heart. It was never about making money or getting big, so we’ve always remained small. It’s about our love of people.”

Our conversation happens virtually from across the continent, Peach sipping on Turkish co ee in sunny Istanbul, where she splits her time with London. Nowadays, life is – slightly – less busy, her and Turnbull taking on a more ad-hoc consultative approach and passing work to former colleagues. For Peach, it’s another chapter in her long relationship with design. “It's been a hard adjustment at times, but rewarding and even occasionally frustrating, as we have lived our lives over the last 30 years at a very fast rate. Now, I am excited about designing our house, it’s about time – cobbler’s children syndrome! –and to become more involved with some philanthropic projects. And of course, there is the book, if we ever get round to it.” ,,

Studio Appétit founder .do Garini discusses building a multi-disciplinar- career, feeding creativit- and surreal experiences.

Words:

Harr- McKinle-

Photograph-: courtes- of

Studio Appétit

Ido Garini is sat on the (oor of his new son’s nursery, in his home in the Hague. Somewhere in the background his husband is keeping said son occupied –at least for so long as needed for Garini to have a conversation about his journey in the creative industries and his boundarybreaking work. It makes a change, I’m told, from talk of sleeping patterns and feeding times. It isn’t, perhaps, the typical setting for such a chat – Garini cross-legged in front of a fetching, animal-themed wall mural – and yet it neatly encapsulates this new chapter in his life, one involving balancing the professional with parenting.

Even when there wasn’t a baby competing for his attentions, Garini’s career has always been a balancing act, sometimes even a ‘hustle’ as he describes it –a sentiment that will resonate with anyone who’s carved their own path or created a business from scratch. And as the founder of Studio Appétit, a wildly creative practice that works on experiential design projects with global clients, Garini is one of the industry’s bona "de self-starters. His portfolio is a brightly coloured jewellery box of assorted treasures –everything from devising a design-led afternoon tea for Rosewood Hotels

and a towering sculptural installation with Conran and Partners, to productcentric collaborations with brands including Laufen, Raw Finnish and Petite Friture. He’s also partnered with some of the world’s most prestigious creative institutions and is a crowd-rousing speaker on sensory design – including for the V&A and TED Talks.

“Of course, I wanted to be a lawyer,” he laughs, re(ecting on his own childhood ambitions. “But it was based on what I’d seen in "lms, so mostly for the out"ts and the monologues. Although you could say that was when I realised I was interested in storytelling; the theatre of it.”

Garini was born and raised in Tel Aviv, Israel, and credits his parents for both instilling within him a can-do attitude and for encouraging him in the pursuit of his passions. ough art, as an academic discipline, wouldn’t be his forte, his mum nonetheless ferried him to afterschool drawing classes, as well those for puppetry, drama, dance and ceramics – in those formative years then, already

exploring how to express himself through di erent mediums and channelling his ADHD into charting new interests and building skills. “Looking back, it’s almost a microcosm of my adult life; the bouncing around between di erent creative areas. Still today, I have an appetite for everything.”

e ability to funnel radically diverse in(uences into his work, to connect dots in a way that others cannot, is something of a hallmark of Garini’s work; ‘openness’ a quality he believes anyone in design should learn to cultivate.

“If you’re creative by nature, then engaging with di erent forms of expression is like fuel, and understanding that inspiration is all around us is something I’ve carried forward since childhood,” he notes. “I always have a notebook in my bag. Sometimes I’m inspired by something I see on the shelf of a supermarket; sometimes I’m captured by part of a conversation I overhear on a bus, or the way a building looks in a certain moment of weather.”

“Understanding that inspiration is all around us is something .’ve carried forward since childhood.”

Yet growing up in the Middle East, and even gaining a degree in Industrial and Product Design, Garini quickly realised that plugging himself into the global design industry would be tricky if he remained on home turf. He didn’t ultimately leave because he wanted to, but because he felt he had to, if his aspirations were to become reality at least. Again, it’s a familiar tale for those who’ve sought to parlay their potential into a profession, and throws up age-old questions around barriers to entry and access to opportunity.

“I had a lot of con"dence. It wasn’t necessarily that I thought I was a very good designer, but I did believe in myself, and that’s a lot to do with the way I was raised; that anything is possible and it isn’t helpful to always second guess yourself,” he explains. “I was also taught to do things all the way through; to do them properly and with care. at way, when you're done, you know that you did a good job and if somebody wants to see your receipts, you haven’t taken shortcuts. I think that helps with selfdoubt too, which is a big issue in the

creative world. But, ultimately, I would look at counterparts and friends in other countries, those graduating from more established and connected design schools, and wonder, would my life and career be di erent if I were on that path – would I have to hustle so much? But looking back, I think at least I had that challenge, a problem some others didn’t have, because it taught me how to navigate it.”

Garini would relocate to the States, commuting to ‘regular’ day jobs in New York City from leafy Connecticut, all the while thinking: “OK, I’m planning on being this designer, but knowing that I’d probably have to create my own job.” He’d take on classes in sugar blowing and casting; he’d develop his skills in carpentry.

“I was always coming up with ideas. Some connected with food, others design or hospitality broadly,” he details.

“But I knew that I wanted to work in a way that is rooted in physical interaction between people. So I didn’t want to just design a chair, I wanted to design a chair for an experience.”

Landing a conceptual project in New York meant ‘o!cialdom’ and Studio Appétit was born: “ e name came quite fast, because I liked the word appetite a lot. You have an appetite for a lot of di erent things – for life, for time, for learning. It really resonated with me.”

ough Garini was resigned to a career in which he’d have to create his own successes, combining his talents with sheer chutzpah, it was serendipity that would give him ‘the break’; a project that solidi"ed the studio as a solid proposition.

“I was in Milan for Design Week, just information gathering and walking more than I’d ever walked in my life,” he laughs. “At the end of the trip I just wanted to celebrate, by myself. So I went for a drink at a very nice restaurant in the Galleria, part of a hotel, and got chatting to the maître d’. He asked about my time in

Milan and my studio, and the next thing I’m being introduced to the owner, who was also sitting in the restaurant.”

at owner was Alessandro Rosso, hotel heavyweight and founder of Seven Stars Galleria – at the time widely called the world’s only seven-star hotel. He asked Garini to stick around in Milan to work with him on a lavish, design-led dining experience for various dignitaries, including the city’s mayor.

“ e whole thing was surreal,” re(ects Garini. “I had to check out of my hotel and didn’t even know if I’d have anywhere to stay – then I’m being o ered a suite with a butler, touring the market for inspiration and creating woodwork in my room. It was a huge success and a real con"dence boost. It helped me realise that there are a few ways to get to my destination. Not all of them are open for

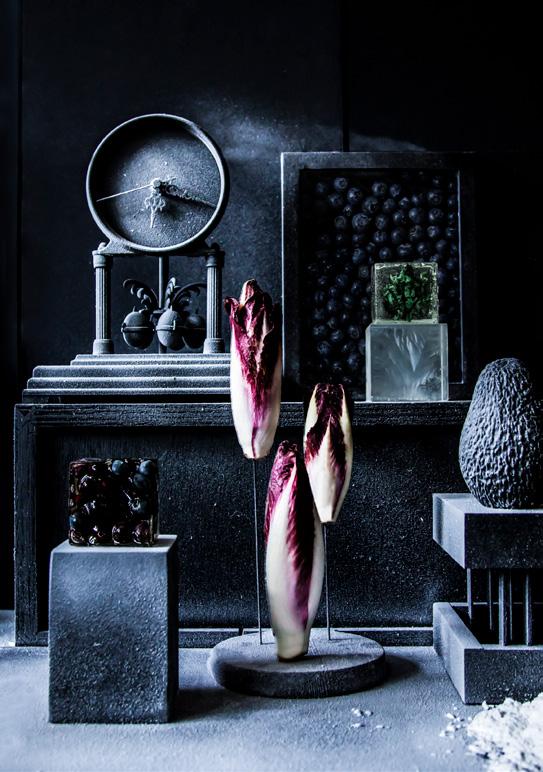

Top left: Studio Appétit for Laufen

Top centre: Studio Appétit for Gaggenau

Top left: Studio Appétit product design

Right: Studio Appétit with Conran and Partners at German

me of course, so I learnt I have to be a bit of a cowboy, because I'm working in an interdisciplinary "eld and I don't have a built in network. I also asked myself, where can I have the most impact? And from there I gravitated towards those conceptual projects.”

Garini describes his career as a bit like brick laying, sometimes building upwards, sometimes length wise – a foundation for things to come. Subsequent years would bring professional milestones: his "rst self-concepted show for Milan Design Week and his collaboration with Conran & Partners, that saw a monumental totem pole installed at London’s German Gymnasium.

“ at was a commercial but conceptual project that brought together all of the parts of Studio Appétit,” he says of the latter. “It was a six-metre shrine, unveiled during London Design Festival. With

that installation, in such a huge space that feels like a church, you walked in and were just in awe. You felt small; it was overwhelming and it was beautiful. at was a very meaningful moment in my career and by then I was no longer hustling, I was just working.”

For Garini the key to delivering highconcept work that lands, is in moderating the familiar and the unexpected. Whether it’s branding, product design or the creation of a radical experience, the ‘completely new’ breeds discomfort, but “if you work in a language people understand, then you can twist and surprise; create emotional connections; tap into a logic and a meaning that is recognisable and then knock people out with something they didn’t see coming.”

Fatherhood, on the other hand, is something Garini saw coming – even if this particular non-professional milestone

has also thrown up its own occasional surprises. “He’s another chapter in creativity,” he jokes, “and I’m seeing new perspectives through his eyes.”

I wonder what lessons Garini might have to impart then, on creativity or carving a path to success? “Well, being multidisciplinary doesn't always work well with jobs, because people need you in a box,” he explains. “So if you come with a bag of boxes, then it's on you to "gure out how you "t places. But that doesn’t mean you should limit yourself to just the one box. After all, where’s the fun in that?”

Ido Garini joined us on ings I’ve Learnt, the new podcast from Mix Interiors, to discuss success, failure and his views on design. Listen to the episode and subscribe to the series on Spotify and Apple Podcasts, and watch in video at mixinteriors.com.

We have a duty to support the next generation of creatives. Young designers can bring fresh ideas, unique perspectives and innovative approaches to the creative industry. With their boundless energy and fearless attitudes, they are often unafraid to challenge norms and experiment with unconventional concepts. eir familiarity with new tools and technologies, such as AI-driven design, parametric modelling and use of social media platforms, positions them as key drivers of innovation. By investing in young talent, we can nurture a pipeline of diverse viewpoints and pioneering solutions for critical current and future global issues.

By inviting emerging talent to networking events, we are enabling them to build professional connections, exchange ideas, and gain exposure to di erent companies. Mentorship is also a powerful way for professionals to support young talent. Mentors can provide insights into industry practices, decision-making processes and e ective project management techniques, which are crucial for the professional growth of mentees.

16-18 that teaches teenagers about city making, architecture and the built environment. rough workshops delivered by leading industry professionals, students gain valuable knowledge and experience.

poorcollective.com

Experienced practitioners can help young minds by providing them with work experience opportunities, mentoring sessions and inviting them to sector-speci"c events. Work experience is a vital component of a young professional's development. By providing work placements, established experts allow emerging talent to apply their academic knowledge in realworld settings. is exposure helps them understand industry practices, work(ows and challenges that cannot be fully grasped through studying alone. Work experience also gives students the chance to re"ne their technical skills and learn the nuances of e ective collaboration.

Mentorship is a mutually bene"cial relationship that goes beyond a one-way exchange. While industry professionals can provide guidance and experience, emerging talent bring new perspectives and an adaptive mindset. Mentoring not only supports the growth of mentees but also revitalises mentors, reigniting their passion and motivation –encouraging experienced professionals to rethink their approaches, embrace new trends and continuously evolve their practices, making mentorship a powerful vehicle for mutual growth.

Programmes like Londonbased charity Open City’s 'Accelerate', and the Design Museum’s 'Ardagh Young Creatives' aim to support young talent by providing resources, mentorship and opportunities to develop their skills. Accelerate is an award-winning education programme for ages

Similarly the Ardagh Young Creatives programme provides an enriching platform for young designers to develop their skills. Each year, it supports London-based individuals aged 14–16 from underrepresented backgrounds through structured mentorship, hands-on workshops and collaborative live projects.

Nurturing the next generation of designers is both a responsibility and an opportunity for the design industry. By o ering mentoring and work experience opportunities, we not only facilitate the transfer of knowledge but drive innovation. Initiatives like Open City’s Accelerate and the Design Museum’s Ardagh Young Creatives play a pivotal role in providing essential resources, helping young designers gain the skills, experience and networks they need to succeed. As the industry continues to evolve, the collaboration between experienced professionals and emerging talent will tackle global challenges such as climate change, and shape a resilient, forward-thinking built environment.

More-Smith creates a workspace tailored to the client on London’s Savile Row.

Words: Helen Pa,on

Photograph-: Bill- Bolton

“I was really keen to make it glamorous,” begins Linda Morey-Burrows, describing %0 Savile Row, the project her practice MoreySmith recently completed. “I just thought it’d be fun to have people come in and feel good.” In keeping with a street synonymous with high-end style, there is a feeling of quiet luxury, achieved through the choice of colours and textures throughout the ground (oor façade, main ground (oor space, the atrium and the lift lobbies that overlook it.

“It was just a bit tired; it didn’t have a lot going on in it,” explains Andrew McCann, MoreySmith’s creative director, painting a picture of what it was like before. “ e client was very keen to have something in

here, like a bar that made it usable space, because it's quite a large reception,” adds Zoe Bailey, the "rm’s senior associate, “It's so prominent on the street, and on a prominent street as well, the vision was de"nitely to have something almost retail-like and it’s got that hospitality feel too, that sort of draws the eye in.” McCann gives yet further context: “Trying to act to give more back to their tenants is what most landlords are doing, adding all this additional hospitality to spaces is happening a lot.” e client in this instance is Lazari Investments, with whom MoreySmith successfully collaborated previously at CBRE’s headquarters at Henrietta House, also in London’s West End.

Image on previous page and above: The Hera bar features bespoke geometric tiled 0ooring

Right: The sage green reception desk contrasts with concrete panels

Below right: Bespoke velvet banquette seating

Stepping back onto the street momentarily, McCann continues, “ e idea was to try and push the façade forward, make it a bit bigger and make it more relevant to the area. e bronze casement framing to the windows harks back to more Art Deco detailing on nearby buildings.” Pyrolave glazed stone external walls and stone (ooring outside, with the address spelled out, complete the material palette here, “and then as you come in, it's mostly stone and concrete creating soft forms,” he adds. Corrugated concrete and battened timber wall panelling exude exceptional craftsmanship. To the left, an understated sage green suede reception desk sits in front of the concrete panels, with a Holly Hunt glass pendant hanging above.

One of the most noticeable patterns is the bespoke geometric tiled (oor with honed Grigio Carnico and Arabescato marble. And as we head back to some dark grey velvet banquette seating, a bespoke MoreySmith design located at the rear right section of space; the (ooring provides zoning, going from patterned to a solid grey.

e 'Hera' bar is undoubtedly the design hero of the reception, crafted from pro"led smoked oak panelling and a double-curved Arabescato marble bar top, with a customised Coppibartali luminaire by Viabizzuno creating a halo of light above the bar. An adjacent "vemetre-high glass brick wall epitomises quiet practicality, serving to obscure the existing staircase.

e word Hera is a key part of this project. “It’s the goddess and protector of the family, and Lazari is a family business,” McCann explains. e space features three specially commissioned works, curated in collaboration with Patrick Morey-Burrows of ArtSource. In the right-hand window, Zachary Eastwood-Bloom’s work is a marble depiction of Hera. And above the glass wall, hangs a Daniel Chadwich sculpture, representing the topography surrounding the temple of Hera and Greece’s Mount Olympus. ere’s a sense of family – of community and coming together – in this building as the midmorning queues form around the bar.

e remaining artwork is SASSE/SLUICE, a piece crafted by Kate MccGwire, located on the left as you enter the space, integrated into the bespoke concrete panelling and ingeniously crafted from thousands of pigeon feathers. ese are intended to symbolise the ethos of renewal; that sense of a building transformed by MoreySmith. One of the most signi"cant areas of structural intervention is the atrium at the rear of the reception. Here a ‘pod’ extending over two tenant (oors has

“You spend so much time and e1o, creating an environment, it’s about making sure it sits together.”

Left: Material details in the lobby

Below: SASSE/SLUICE by Kate MccGwire is integrated into the concrete panels

Right: Daniel Chadwich’s sculpture The Temple of Hera is inspired by Mount Olympus

been created. “We’re trying to create di erent pockets of seating – the pod puts a ceiling of sorts over the banquette seating,” says Bailey.

MoreySmith also designed a new internal balcony on the third (oor, giving tenants there a view to the reception and a sense of visual context: the monochrome geometric (ooring, the clusters of chairs and tables and the top of the bar, as well as getting up close to that beautiful Daniel Chadwick piece. e lift lobbies further encapsulate MoreySmith’s approach to materiality with timber panelling, warm lighting, new marble (ooring and brass balustrading.

MoreySmith’s attention to detail even extends to working with the building management team on the security sta ’s

uniforms, “picking out the suits and the fabrics and helping with styling them; we were also involved with the catering sta ’s uniforms too, to make sure they were consistent. You spend so much time and e ort creating an environment, it’s about making sure it sits together,” says Zoe Bailey. It’s no surprise then to see her, on our site visit, painstakingly rearrange the objects on the Kops co ee table by Van Rossum situated near the front window exactly as the design scheme intended.

“I think we were one of the "rst people to put a co ee bar in a landlord’s building,” says Morey-Burrows, re(ecting on a key element of the practice’s 30-plus years in workplace design and one that makes this space so successful, “giving people what they need and getting them back in the building.”

.nKing’sCross, O/ceS&Mdevisesa colour-2lledhomeforburgeoningnurserbrand,MEplace.

Photograph-: Megan Ta-lor

Words: NatashaLev-

Image on previous page: Each zone follows a distinct colour scheme of blue, green, lilac or pink for a clear sense of place

Left: Cross-laminated timber features on ceilings and support columns

Below: Cushioned cork guards line the wall corners

Right: The planted terrace

Over the course of more than 20 years, King’s Cross has been entirely reborn. While the area was previously populated by dilapidated warehouses and disused railway yards leftover from the capital’s industrial heyday, it’s presently home to upscale stores for the stylish, swanky hotels for (eeting tourists, and o!ces for tech giants. Now there’s something for little Londoners too: a new MEplace nursery with colour-rich interiors devised by architecture practice O!ce S&M.

MEplace was founded by entrepreneur Vlada Bell who, after struggling to "nd the right nursery for her own son, wanted to set up a holistic childcare space that nurtured mental and physical wellbeing in equal measure. e inaugural two branches opened in East London’s trendy Hackney Wick neighbourhood in %&%& and %&%% and went on to (ourish, but Bell eventually came to feel that the locations didn’t visually re(ect MEplace as a brand. So to develop the King’s Cross branch, the nursery asked O!ce S&M to step in. “We had a series of workshops at the MEplace o!ce with Vlada and her key management team, as well as practitioners that were going to be

working in the space with di erent age groups, so we were able to get voices from lots of areas of experience,” explained the practice’s co-founder Hugh McEwen.

Set within a mixed-use building completed just last year by architecture "rm Haptic, the nursery features three core care spaces charmingly named Caterpillars, for tots aged under two; Butter(ies, for twos to threes; and Dinosaurs, for those aged three to four. ese rooms are all located on the "rst (oor, accessed via spacious cloakrooms where parents can seamlessly set down kids and their belongings in the mornings (instead of doing a (ustered drop-o at the front door). At this level

“Space is thirdthe teacher.”

there’s also a sequence of service rooms, as well as a planted terrace where the children can play on days with fair weather – a feature that feels like a real treat when in the dense heart of central London. Down on the ground (oor is another room that serves as an after-school club, as well as an o!ce, meeting space and extra toilet facilities for MEplace sta . Before they moved in, McEwen and his team had to make some changes to the shell to help it feel more inviting; cross-laminated timber now lines the ceilings and upper half of all support columns, while the lower halves have been "tted with cushiony cork corner guards. Eggshell-coloured paint has also been used to create dados across the three-metre-high walls, helping the interior appear less imposing to its tiny occupants. Finally, a non-slip vinyl (oor with subtle terrazzo-esque (ecks has been installed, along with adjustable lighting, water "ltration systems and air ventilators.

Fixtures and furnishings throughout the nursery are meant to act as learning tools in themselves, an approach O!ce S&M say was largely in(uenced by the philosophies of 20th-century Italian physician and educator Maria

“We see colour as reallimportant because it can be a lot about representation, and children seeing themselves withinaspace.”

Left: A bubblegum-pink scheme plays out in the skirting, doors and shelving units

Below: Di1erent sink heights correspond to di1erent age groups

Right: The lilac zone

Flooring

Forbo

Montessori, whose teaching methods are still championed in childcare today. “ ere was a quote from her about how ‘space is the third teacher’, and that really resonated with how we were thinking about spaces and the ways in which they can help the development of children,” recounts McEwen. Sinks in the toilets, for example, have been specially crafted to correspond to the height of the age group they’re for so that the kids feel con"dent enough to use them independently. Timber tables and chairs produced by Community Playthings are also scaled appropriately for the respective rooms. No stranger to using vibrant hues in their residential projects, O!ce S&M has additionally ensured that components of each care room follow a distinct colour scheme of blue, green, lilac or bubble-gum pink so that children can easily identify where they belong. e colours – which match the jolly palette of MEplace’s website – play out across the shelving units, miniature sofas, doorframes and skirting boards. “ e nursery has a really strong

online-"rst presence, and sometimes the translation of digital colours into physical colours is not direct. So it took quite a bit of back-and-forth with MEplace and their graphic designer to synthesize that into something which was deliverable,” adds McEwen. “We see colour as really important because it can be a lot about representation, and children seeing themselves within a space.”

Parents will no doubt be pleased to hear that O!ce S&M has already begun working on another MEplace nursery in Angel, north London, due to open summer this year. And though the site (an old dance studio) is completely di erent in style, McEwen says establishing the aesthetic of the King’s Cross location has prepared the practice for whatever comes its way: “We've got to the point where we have a kit of parts that shows, if we continue to use these elements, how any new MEplace space will look and feel in the future.”

Furniture

Tylko and Community Playthings

Surfaces

Grestec

Dulux

Lighting

Ovia

FF&E

Dulux

Hoppe

Studio Swade

Words: Charlotte Slinger

Photograph-: Ben Anders

Completing its 23h London prope,-, build-to-rent operator Wa- of Life champions communitengagement and o1ers a more ‘mindful’ take on gentri2cation.

Image on previous page: Event space on the 27th 0oor

Left: First-0oor coworking area

Above: Residents’ shared lounge

Right: Bookable kitchen and dining room

With a population of nine million and growing, London is already one of the most diverse, rapidly expanding cities in the world. And while Central London has been home to global "nance giants and luxury residences for some decades now, this a3uence has also been trickling into the capital’s many boroughs – including those which, until recently, had not been home to Canary Wharf high(iers, but rather to families or students on the lower end of the income spectrum. is process of gentri"cation inevitably comes with a well-warranted debate about what value these developments bring to the local area; something Way of Life was conscious of when unveiling its "fth London location, Riverstone Heights.

“The focus is increasingl- on designing spaces that go be-ond basic functionalit-.”

Joining a total of eight properties across the UK, Riverstone Heights cuts a tall "gure in Bromley-by-Bow, a district in one of the city’s most swiftly developing boroughs, Tower Hamlets. As a buildto-rent brand whose USP is nurturing connection in an increasingly disconnected world, Way of Life is striving to root this latest property "rmly within its surroundings and contribute positively to the local area. rough its Community Life programme, Riverstone Heights has begun an ongoing partnership with the Bromley-by-Bow Centre, a charity that o ers everything from employability support and English classes to adult social care and "nancial advice. ese workshops and classes are now held pro bono in the building’s swish event space and promoted across social media and Way of Life’s resident app, with ticket sales raising valuable funds and awareness.

Day-to-day, tenants can also engage in weekly yoga and comedy nights hosted by the local pub, and on their arrival were gifted welcome packs with food from local vendors (including co ee from sustainable, women-owned brand Hey Sister). “We believe that the desire to belong – to a family, a community or a larger group – is a fundamental human need,” explains hospitality heavyweight Aaron David Clarke, whose eponymous studio ADC Atelier led the interiors. “At Riverstone Heights, the design was carefully crafted to encourage connection and the formation of bonds among residents. is re(ects a clear shift in today’s BTR market, where the focus is increasingly on designing spaces that go beyond basic functionality.” is combination of connection and convenience also informed the property’s accessible location, with Canary Wharf, LCF Library and UCL all just a short tube ride away.

Stepping into the spacious reception with its double height atrium, one feels instantly removed from the roadside tube station less than a minute away and immersed in an eclectic yet elegant hotel lobby. No surprise, considering Clarke’s tenures directing both Soho House and Martin Brudnizki Design Studio. “For us, the most important aspect of any space is that it feels welcoming, inviting

Flooring

Jodul

Gancedo

Guell La Madrid

Furniture

Parla

PolsPotten

Lighting

Milan Iluminación

Audo

“We were also drawn to the clean lines and functional la-outs of 1970s British architecture.”

people to stay, relax and feel at ease,” he muses. “Whether it's a residential project or one in the hospitality sector, our goal is to convey these feelings of comfort by carefully considering every detail, from how we distribute the spaces to the materials we use.” ese details extend to sensory elements, including ambient music that drifts through integrated speakers and an omnipresent fragrance from hidden scent di users.

Clarke cites one of his design inspirations as the nearby Lea Valley, re(ected by the palette of rich, earthy hues and abundant planting. In the two-storey atrium, glossy tiled columns are encased in metal latticework, where well-tended plants supplied by Hackney-based Conservatory Archives sprout forth. Decked in the same meticulous tiling that reappears throughout, these columns pool into central islands where residents can perch with a co ee or a laptop; alternatively, they can sink into one of the lounges underneath the central staircase, or in the library nook, with its trendy co ee table books, sculptural side tables and large, scalloped pendants by Audo Copenhagen.

Well-versed in creating luxury coworking spots thanks to his involvement in Soho Works, Clarke employed textured, segmented ceilings, vintage-inspired light "xtures and dark wood panelling across the in-house coworking (oors. Soft, organic shapes reappear throughout, in the form of bulbous table lamps in deep red and cobalt blue and sumptuous bubble armchairs. Tiled banquette seating curves into private seating booths, leading to a kitchenette with blush sintered stone countertops – chosen as a more sustainable alternative to marble. Using the app, residents can book this entire (oor for presentations and conference calls, as well as reserve the private dining room, fully equipped kitchen and outdoor terrace on the 27th (oor. According to sta , these luxury amenities are becoming a big draw for residents who create content online, who often use these sleek spaces to "lm or host PR events.

e Barbican Centre was another key touchpoint: “Its unique blend of bold geometry and seamless integration of nature into urban spaces became a key in(uence on our design,” reasons Clarke. “We were also drawn to the clean lines and functional layouts of ,.1&s British architecture, and the way modernist principles were harmoniously blended with natural materials.” ese clean lines and classic aesthetics continue into the pet-friendly apartments, where occupancy rates sit at a healthy 95%. Units are sold with a furniture pack containing a dining table, sofa, TV unit and a co ee table, while the bedrooms boast fulllength windows and the fully equipped kitchens, a walk-in pantry. Alongside the 202 long-term apartments, guest suites can also be let out for short stays, a move trialled at Way of Life’s (agship property, e Gessner, in Tottenham Hale – and with no plans to stop, the brand has two more locations in the pipeline for %&%'.

Other Side brings laid-back Kiwi cool to Caravan’s Manchester outpost.

Words: Chloé Petersen Snell

Photograph-: Mariell Lind Hansen

One of London’s favourite all-day dining spots has landed in Manchester; Caravan’s "rst regional site outside of the capital now o ering another brunch nirvana for the northern city’s large young professional demographic. Founded by New Zealanders Chris Ammerman, Miles Kirby and Laura Harper-Hinton, who felt London missed the laid-back co ee house culture so popular in their home country, the inaugural Exmouth Market spot opened in 2010 and has grown to be a bit of a London institution, popping up across the city from Covent Garden to Canary Wharf.

A "nely tuned collaboration, this is the third Caravan designed by Other Side –a fresh challenge to translate the brand’s London-centric DNA to both a new city

and a newly developed area within it, explains founder Gavin Mayaveram, adding an industrial character without being a caricature like many over-styled spaces in the city. “[Caravan has] always believed in placemaking – helping to create vibrant, creative communities in areas that are developing, as they’ve done with King’s Cross, Bankside and e City in London,” he notes. “Manchester is perfect for this ethos. ere’s a creative buzz here, a real sense of inclusivity and a strong connection to craft and community. is resonated with Caravan and played a big role in their decision to make Manchester their "rst location outside of London. is space embodies that spirit – fresh, inspiring and built to bring people together.”

As such, “authentic” Mancunian touches are incorporated – more literally in the zinc-topped bar, concrete ceiling and exposed services, and more "guratively in the 4-metre-long communal tables, crafted in wany natural wood, that re(ect the city’s community-centric spirit.

Naturally, Other Side found inspiration in Kiwi heritage and craftsmanship too: using raw, honest materials and a laid-back attitude with a mix of zones for cosy co ee dates, larger events and more formal dining – building upon the brand’s ethos of ‘no boundaries.’

“Designing with no boundaries is about creating spaces that welcome everyone,” Mayaveram details. “Caravan’s concept is naturally democratic – it’s about o ering a space where you can grab co ee, share a meal with friends, or host a private event, all without feeling con"ned to any particular ‘rules’ about how the space should be used.”

Timber dividers, bespoke banquettes, over(owing planters and a doublefronted brick "replace delineate the areas, without detracting from the (ow of the 6,600 sq ft, purpose-built building –ensuring the space would feel warm and approachable even at quieter times, notes Mayaveram. Guests can hire multiple, (exible spaces for events; including a ‘listening room’ with decks and bespoke pine shelving stacked with vinyl for small gatherings, and a dining area that can be opened up via folding doors depending on the number of guests.

Layers of tactile textures ensure it’s di!cult not to touch every surface of the space. New Zealand’s trail huts and wool sheds provided a material muse – guiding the central bar’s timber framework and rustic terracotta tiles, a quarry-tiled (oor by Ketley Brick and a palette of natural timbers, warm oranges and mustards that connect and add warmth to the di erent

Image on previous page: Natural timber tables and leather pendants in the main restaurant

fireplace delineates the space

“Caravan’s concept is naturall- democratic, without feeling con2ned to any pa,icular ‘rules’ about how the space should be used.”

Left: Timber panelling and open kitchen

Above: The laid-back private dining room

Right: Hemp wall panels and textured upholstery create a tactile experience

spaces. “Everything in the design was chosen with durability and sustainability in mind – reclaimed materials, organic hemp for acoustic and aesthetic purposes, and furniture that’s both beautiful and practical,” notes Mayaveram. “We also avoided ‘trendy’ design choices that would quickly feel dated. Instead, we leaned into Caravan’s DNA and built a space that can stand the test of time as though it’s been there a few years and, in doing so, created that familiar, neighbourhood vibe that welcomes all guests.”

e bar acts as the central stage in the theatre of the space, the mirrored backbar warmly lit to contrast with the grey concrete and matching skies outside. Extensive and thoughtfully layered lighting further adds to the ambiance – from handmade leather pendants hanging above the communal tables to the glowing glass wall pendants in each toilet cubicle, which

dim in sync with the rest of the restaurant as the day passes. Outside, ready for bright days and Manchester’s (perhaps surprisingly) popular outdoor café culture, an emphasis on New Zealand’s ‘indooroutdoor’ living is re(ected in extensive, fully-retractable shopfront windows.

Mayaveram and the team hope these details will position Carvan as a standout destination in a crowded market and struggling hospitality industry. “One of the big challenges in hospitality is staying relevant while remaining operationally e!cient,” he says. “Guests expect more these days – they want experiences, not just spaces. Hospitality spaces today need to connect with people, tell a story and contribute to the community. In Manchester, this meant taking a huge footprint in an emerging part of the city and transforming it into a loved part of the community.”

Flooring

Broadleaf Timber

Ketley Tiles

Furniture

Forest to Home

Contract Chair

Dodds and Shute

Atlas

Surfaces

A.M. Contract

Curtain Services

Solus Ceramics

Grestec

Material Assemble

Lighting

DCW

TedWood

With The Waterman, Fathom Architects and Fettle create a workspace 2t for toda-, but proud of its past.

Words: Harr- McKinle-

Photograph-: Martina Ferrera

Image on previous page:

Coworking space with natural lighting

Below:

Soft seating with views of the street

London’s Clerkenwell has a wild and storied history. What is now the Farringdon station-adjacent Turnmill Street was once described, in the era of Shakespeare, as ‘the most disreputable street in London, a haunt of thieves and loose women’. In fact, the whole neighbourhood was infamous for its brothels, its unruly tenements and its cluster of decrepit prisons. In the early and mid-1900s it was a centre of radical leftist politics, at one time home to the headquarters of Britain’s "rst socialist

party, as well as Vladimir Lenin – who resided on Percy Circus and who was said to have met a young Stalin at the Crown and Anchor Pub, now e Crown Tavern.

Today the district is a tad more respectable, rooted in the business of design and home to more design studios, architecture practices and manufacturer showrooms per square mile than anywhere else in the world. As for the bawdy drinking dens, well, stroll the streets by evening during Clerkenwell Design Week and, on that front, you’d be forgiven for thinking not much has changed.

For all its patchiness, it’s worth recognising the area’s vivid history – for the simple fact that its built environment is increasingly one of polished, even soulless, modernity. Not so at e Waterman, one of Clerkenwell’s largest heritage retro"t projects. Once a series of four Victorian warehouses, the property has been combined to create 70,000 sq ft of swish workspace. And though it features a slew of contemporary amenities, and some seriously modish styling, there’s a healthy respect for the past – an embracing of the building’s story, in all its cracked brickwork and chipped plaster glory.

Fathom Architects led on the reimaging of the property, originally designed by Alfred Waterman in 1894, after whom the building is now named. e brief was a simple-in-theory, tricky-in-practice one: bring what were still four separate buildings together into one cohesive whole, with a uni"ed identity and a commitment to sustainability.

“Heritage and sustainability were linked from the outset,” explains Fathom associate Tom Bulmer. “ e ultimate ambition was to reimagine the existing warehouses for the 21st century workplace, unlocking the value added by their historic character. Incremental conversions over the years had left the buildings with a confusing array of tenancies, housed within an ine!cient, leaky envelope.”

For Fathom the key, from the outset, was in recognising that the buildings – though complex and well over a century old –would have to be worked with, not fought against; their quirks and wrinkles part of their charm and not imperfections to be smoothed over or scrubbed out. In discussing the project, Bulmer uses one word recurrently: honesty.

e initial priority was connectivity, to create “large light-"lled (oorplates encompassing the entire footprint and as close to ‘open-plan’ as possible,” he details.

“Working closely with the client (BGO) and design team, we formed multiple new connections across the Victorian load-bearing masonry structure to create large, bright workspaces. [We] uncovered the Victorian bones of the structure by delicately stripping back added layers, with large and small openings across the (oorplates, exposed servicing and honest expression of new [interventions] allowing the heritage to shine through.”

Above: Stairs leading to further workspaces

Below left: Collaborative workspace with high stool seating

“Rather than erase traces of the past, we allowed the warehouses to celebrate each of their lives.”

e result is six (oors of workspace, starting from the "rst (oor up, which includes a ‘replacement’ "fth (oor –taking its design cues from the original brick facades – and a new recessed sixth (oor, which leads out onto a 2,900 sq ft communal roof garden, with thoughtful planting and bug habitats to encourage biodiversity.

“ e thermal envelope needed to be improved and spaces recon"gured for contemporary models of working,” explains Bulmer, “moving away from narrow cellular o!ces to o er more openplan, collaborative spaces.”

ese generous spaces beg the question as to why stark uniformity is so sought after –occasionally discordant (oor plates, connected by steps or sweeping gangways, adding interest and personality. Materials throughout are handsome and robust: glazed tiles, exposed brick, painted steelwork and recycled timber (ooring. Layers of history on proud display.

“ e building’s EPC rating improved from a C to an A rating, no mean feat with a building of this age and scale,” continues Bulmer. “Where new openings were formed in party walls, original bricks

were kept and re-used throughout the project – approximately 5,000 bricks. When new lift shaft openings were created, existing timber (oorboards were carefully salvaged for re-use in the ground (oor reception, sanding and treating them on site. And 360 original windows didn’t meet the high insulation standards required, so new double-glazed units were speci"ed to reduce energy consumption – paying back the embodied carbon from replacing them within six years.”

Rather than simply disposing of the redundant windows, three tonnes of glass was sent o to Diamik Glass in Leeds, where it was repurposed as the terrazzo-like Ecorok and, rather marvellously, speci"ed as countertops throughout the building.