No other magazine brings together confessional Lutheran, Anglican, Reformed, and Baptist representatives to discuss the significant biblical and cultural issues of our day. We’re committed to helping you hone your theological thinking and share your insights effectively with others. Your support allows Modern Reformation to keep this conversation going strong.

I.

Modern Reformation

July/August 2023

Vol. 32, No. 4

RETRIEVE 08 REFORMATION OUTTAKES | Guillaume Farel

Dies Another Day | by Zachary Purvis

II.

CONVERSE 14 INTERVIEW | Being Human at the Intersection of Embodiment and Technology: An Interview with Jens Zimmermann | by Brannon Ellis

20 ESSAY | The Material Is Not Immaterial

| by T. David Gordon

III.

PERSUADE 32 BIBLE STUDY | Something Beautiful: Blessed with Bodies—and Technology

| by J. D. “Skip” Dusenbury

38 ESSAY | Going Upstream of Streaming Worship: Embracing Creaturely Limits in an Age of Autonomy and Disembodiment

| by Joshua Pauling

IV.

ENGAGE 50 ESSAY | Music and Technology

| by William Edgar

56 ESSAY | The Medium Is the Mania: Anxiety as a Feature, not a Bug, of Digital Media

| by Caleb Wait

65 BIBLIOGRAPHY | Media Ecology: A Brief Annotated Bibliography | by T. David Gordon

Endsheet illustration by Raxenne Maniquiz

Since Modern Reformation appreciates a full theological conversation, we’d like to hear your thoughts about what you’re reading in the magazine. So please write to us at letters@modernreformation.org. Due to limited space, please keep your letter under 400 words (letters may be edited for length and clarity). Letters will be published two issues later. We look forward to hearing from you!

Maybe sitting on your couch at home or looking at your phone on a walk. But what if we try to get more specific? Where are you, your self—the unique location of your personal consciousness and agency? If we know our Bibles, we might point to our chests and say we’re our hearts. (We might even point to our “bowels”— if we’re reading 1 John 3:17 in the King James— and say we’re also our feelings!) Christians sensitive to modern materialism might say our true selves are our spirits or souls. But most people nowadays, if you ask us to get that technical about it, will point to our heads. Really, your brain is where you are. Modern people know that everything we think, want, and feel happens between our ears.

Or does it? Here’s something that may seem counterintuitive: Many of the best artificial intelligence researchers have realized for decades that the main challenge confronting the development of true AI is the fact that thinking requires embodiment.* Try perceiving without senses. Try making wise decisions without context or constraints.

In this issue, we’re exploring the fascinating themes at the intersection of embodiment and technology and what these can teach us about God and ourselves. Many philosophers over the centuries have taught that the unique location of personal consciousness and agency is the immaterial soul. This seems directly contradictory to the modern view that we are simply the precise configuration of chemicals and proteins in our brains. But is the true self as soul so different, in practical terms, from the true self as mind ?

*See, for example, Hubert Dreyfus’s classic What Computers Can’t Do: A Critique of Artificial Reason (New York: Harper & Row, 1972), and more recently, the critiques in Alva Nöe, Out of Our Heads: Why You Are Not Your Brain, and Other Lessons from the Biology of Consciousness (New York: Hill and Wang, 2010). For a fascinating study in how our body size and position affect our senses, see Laurence R. Harris et al., “How Our Body Influences our Perception of the World,” in Frontiers of Psychology vol. 6 (2015).

Either way, you remain a hidden, inner reality. This disembodied notion of human identity seems even more plausible nowadays with so many digital alternatives to real presence. All the while, we’re asked to ignore the obvious fact that we’re still sitting here, every one of us living, breathing bags of mostly water, thumbing sheets of printed paper or poking slabs of polished glass. We are undeniably, astonishingly— even embarrassingly—bodily. And that’s good because God’s word says so. “Very good,” in fact (Gen. 1:31).

It’s not only good to be bodily; it’s essential to the good news. The gospel isn’t a spiritual idea, but a flesh-and-bone fact. The eternal Son of God took on our flesh. The location of your redemption was a desecrated hill outside Jerusalem. Blood smeared upon a splinter-ridden cross. Being embodied is now inseparable from who Jesus is, sitting triumphant at the right hand of the Father, coming again in glory to judge the living and the dead.

Your self is where you are, body and soul. And it’s true that you’re also hidden—but not within your inner self. You’re hidden with Christ in God (Col. 3:3), and one day, where he is, there you will be also.

Brannon Ellis Executive EditorOUTSIDE THE CATHOLIC VICAR-GENERAL’S HOUSE in Geneva, a large mob of priests congealed in the thin sunlight one autumn morning in 1532. Inside, Guillaume Farel, the French Protestant missionary who had stopped in Geneva, was summoned to answer the accusations of ten canons of the cathedral chapter. “Tell us,” said the canons, “have you been baptized, you ugly devil? Why do you travel here and there, unsettling the whole world? . . . Who invited you to preach?” One of the canons drew a sword. An attendant took aim at Farel and pulled the trigger of his gun, a pistol, or an arquebus (reports vary). What happened next was chaos: the weapon exploded in the attendant’s hand, Farel declared that he cowered before no popgun, the mob grew vicious in the street, and the city council expelled Farel and his little entourage of “Lutheran” Reformers. 1 The Frenchman escaped death—barely.

The gears and flywheels of the Reformation’s machinery often turned anything but smoothly. No one knew this more than Farel, who worked to a large extent in a particularly fascinating setting: the world of early religious reform among the French-speaking Swiss. Eventually, he became the leading preacher in Geneva from 1534, remonstrated successfully with a young John Calvin to join the cause in Geneva in 1536, and pastored in Neuchâtel from 1538 until his death in 1565. Someone—perhaps the Strasbourg Reformer Wolfgang Capito— dubbed Farel the “Apostle of the Alps.” For a decade at least, he remained far more influential, with much greater stature in the church, than Calvin. Before any critic of the Reformed hurled the epithet “Calvinist” as a term of abuse, “Farellista” was in common parlance.2

Educated in Paris and influenced by the great humanist and Bible reader Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples, Farel had taught briefly at the Collège du Cardinal Lemoine. Then he joined an illustrious circle of Luther sympathizers in Meaux on the River Marne before clashing briefly with Desiderius Erasmus in Basel. In 1526, the Council of Bern authorized him to teach and preach in French-speaking towns under the canton’s considerable religious and political control. The next year, the Bernese Council added that he not be harmed in his duties.3 In hindsight, the comment seems unpleasant—a premonition of future dangers in his endeavors as a first-generation Reformer under the cross.

Farel poured inexhaustible energy into his task. Though he traveled with a stamp of approval from the Bernese Council, he experienced remarkable frustration. In fact, the episode at the vicar-general’s house in Geneva in 1532 was typical—one chapter in a harrowing itinerant mission, especially from 1529— structured around Farel’s fiery sermons against idolatry. 4 His conflicts seemed never-ending. When he spent the night in Saint Martin de Vaud in the winter of 1529–30, the Catholic clergy accused him of being a heretic and a devil. The vicar flung a cooking pot at his head. 5 Farel moved on. A few months later, the Bernese Council received information that a priest had assaulted one of Farel’s associates with a knife, and that elsewhere some priests’ concubines had tried to stone Farel. 6 In August 1530, Farel ranged near the town of Valangin, a few miles outside Neuchâtel. Some twenty priests and women tried to force him to kneel before a statue of the Virgin Mary and beg her for absolution. When he refused, the group beat him, leaving him severely bloodied. 7 In February 1531, at the request of the Bernese Council, Farel traveled to Orbe, the birthplace of the eloquent Pierre Viret, whom Farel would soon recruit as a fellow preacher. Farel tried to enter the pulpit in the church, but hostile congregants blocked the path. For everyone’s safety, a bailiff escorted Farel to his room at the inn. Undeterred, he tried again in vain several times to enter the church, berated by clergymen and laymen alike. 8 So, he left the town and passed through Yverdon, where he was again demonized. One of his co-laborers escaped an attempted drowning. 9

In the spring of 1531, Farel arrived in Grandson, on the southwest tip of Lac de Neuchâtel. He tried to enter the Benedictine monastery to preach. The chaplain of the priory pulled out a knife that he had concealed under his habit and thrust it at Farel, who managed to break free. 10 On June 18, 1531, Farel was refused entry into the church in Payerne, so he preached outside in the adjacent cemetery. Some hundred men gathered in protest, and when Farel would not stop, they threatened to cast him into the River Boye. The assistant bailiff had to sneak him into the prison for protection.11 After that, the Bernese Council arranged for the statesman Hans Jakob von Wattenwyl, Lord of Columbier, to provide Farel with a security detail. On June 25, 1531, von Wattenwyl personally escorted Farel to the Grandson monastery to attend the service. The Grandson religious, however, anticipated Farel’s arrival and refused to let him in. Von Wattenwyl’s servant pushed aside one of the monks, who revealed a hatchet hidden under his garment. Farel entered the building and interrupted the preacher anyway.12 For months, Farel and company continued to agitate in Grandson to stop celebration of the Mass. It seems easy, and natural, to connect “fiery Farel” with the squalid, violent side of the sixteenth century. 13 He left no real theology, after all, and made considerable trouble for himself and others. But this is a one-sided caricature. Farel championed frequent Communion, psalm singing, and catechesis before most of his generation. He was known and esteemed by contemporaries for his homiletic gifts. Calvin’s successor in Geneva, Theodore Beza, commented, “No one could

“Let all . . . whether priests or preachers, have respect to the great shepherd Jesus Christ, who gave his body and his blood for the poor people. Let us prefer to be nothing, if only the poor sheep, gone so far astray, may find the right way, may come to Jesus and give themselves to God.”

Farel quoted in J. H. Merle D'Aubigne, History of the Reformation

listen to Farel’s fervent prayers without feeling almost as it were carried up to heaven.”14 Farel even recovered the ancient sursum corda, “lift up your hearts,” and introduced it into Reformed liturgy: “If Christ is in heaven and is to be worshipped there, then the church’s worship must involve more than God coming down to be in the midst of the church; the church must also ascend to the heavens by the power of the Holy Spirit.”15

So, how did Farel feel about such violent rejection and repeated assassination attempts—which, after the first or second occasion, might have been at least somewhat predictable and therefore avoidable? Perhaps he himself did not know but merely trudged forward. Still, he left clues in a few striking passages he composed on what seems to have been his favorite subject. “Praying,” wrote Farel, “is an ardent speaking with God from whom man asks and begs that which he has promised; that is, to aid his people, delivering them, forgiving them, saving them. In prayer, man declares God’s power and magnifies his name and reign.”16 This theme remained central to Farel’s life. In prayer, he had a foot in heaven already, as it were, which displaced and relativized his fears on earth. Convinced of the new understanding of the gospel and confident that God would hear and answer him in any distress, he threw himself into the reform of the church. Prayer reoriented his desires. In the end, Farel did see most of the French-speaking Swiss cities become Protestant, and usually he was at the center of the change. Like the psalmist, Farel made his fundamental appeal to God in Christ: “Will I die without hearing your holy word preached openly?”17

1. Details combined from Charles Borgeaud, “La conquête religieuse de Genève,” in Guillaume Farel, 1489–1565: Biographie nouvelle (Neuchâtel, 1930), 304 (hereafter Biographie nouvelle); Aimé-Louis Herminjard, Correspondance des réformateurs dans les pays de langue français, 9 vols. (Geneva, 1866–1897), 2:451; Paul Henry, Das Leben Johann Calvins des großen Reformators, 3 vols. (Hamburg, 1835–1844), 1:146–48; Abraham Ruchat, Histoire de la Réformation de la Suisse, 6 vols. (Geneva, 1727–1728), 3:175–79; Michel Roset, Les chroniques de Genève, ed. Henri Fazy (Geneva, [1560] 1896), 165; and Antonie Froment, Les actes et gestes merveilleux de de la cité faicte lan 1534 (Geneva, [1550] 1854), 5–9.

2. Pierre Caroli, Refutatio blasphemiae farellistarum in sacrosanctam Trinitatem (Metz, 1545).

3. Biographie nouvelle, 175–76.

4. Frans P. van Stam, “Piety in Tumultuous Times: Farel the Flamboyant Herald of Reformed Belief,” in Between Lay Piety and Academic Theology, ed. Ulrike Hascher-Burger, August den Hollander, and Wim Janse (Leiden: Brill, 2010), 289–307.

5. Herminijard, Correspondance, 2:223.

6. Aktensammlung zur Geschichte der Berner-Reformation, 1521–1532, ed. Rudolf Steck and Gustav Tobler, 2 vols. (Bern: Wyss, 1923), 2:1271, no. 2832.

7. Herminijard, Correspondance, 2:269–70, 275–76; Biographie nouvelle, 242–44.

8. Biographie nouvelle, 250.

9. Aktensammlung, 2:1344, no. 2988.

10. Herminijard, Correspondance, 2:486–87; cf. Herminijard, Correspondance, 2:370–76; 6:413–14.

11. Aktensammlung, 2:1364 (nos. 3029–30).

12. Aktensammlung, 2:1365–69 (nos. 3031–37).

13. See, e.g., Carter Lindberg, The European Reformations, 2nd ed. (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), 247.

14. Ioannis Calvinia opera omnia quae supersunt, ed. G. Baum, E. Cunitz, and E. Reuss, 59 vols. (Brunswick: Schwetschke, 1863–1900), 21:132.

15. Theodore Van Raalte, “Apostle of the Alps: Guillaume Farel and the Reforming of Geneva,” in A Companion to the Reformation in Geneva, ed. Jon Balserak (Leiden: Brill, 2021), 72.

16. Guillaume Farel, Sommaire c’est une brieve declaration [ . . . ] (Geneva, 1552), 113.

17. Guillaume Farel, Oraison tresdevote [ . . . ] (Strasbourg, 1542), b7v, quoted in Jason Zuidema and Theodore Van Raalte, Early French Reform: The Theology and Spirituality of Guillaume Farel (Farnham: Ashgate, 2011), 83.

Exploring perspectives from the present

Jens Zimmermann is the J. I. Packer Professor of Theology and director of the Houston Centre for Humanity and the Common Good at Regent College in Vancouver, British Columbia. He’s written or edited numerous works, including Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Christian Humanism (Oxford, 2019) and Incarnational Humanism: A Philosophy of Culture for the Church in the World (IVP, 2012). This conversation is edited for length and clarity. Listen to an extended version at modernreformation.org/human.

Jens, in your conclusion to Incarnational Humanism, you say that one of your main goals is to help others see “the enormous theological, philosophical and social implications of the incarnation.” Why is the incarnation so central, not just for Christian doctrine but for Christian thinking?

I believe this occurred to me when I started reading the church fathers, particularly Irenaeus. But think about it: What is the gospel? How does God save the world? It’s by becoming human. It’s actually through humanity that all creation is reconstituted, renewed, and saved. (Whereas today, if we want to save the planet, we usually think we need to get rid of humanity or diminish it because we’ve so rapaciously exploited the world.) If the incarnation is at the heart of the gospel, then obviously it must be totally central for all our thinking.

It was quite a mundane occasion that triggered my interest in Christian humanism as a philosophy that rehabilitates the value of creation and embodiment, built on the good news that God became human so that we could become fully human by becoming Christlike. I was teaching undergraduate English classes at a Christian liberal arts college, and I was confronted with a deep-seated dualism in student’s attitudes to learning. I kept getting business and professional students who didn’t want to read poetry. The basic issue for them was a perceived gap between “real stuff”—you know, real knowledge that business conveys or the natural sciences—and the “airy fairy” stuff that literature and poetry convey. So, I had to come up with a defense, a way of saying, “Well, if you dismiss poetry, you’re also dismissing your own faith. You’re dismissing theology.” My defense of literature as real knowledge was the incarnation as the unifying center for all human knowing. The integration of all things starts with the incarnation, with the apostle Paul’s statement in Colossians that Christ is the center of all reality: “In him all things hold together” (1:17). And

“all things” means all things, including the arts. Sometimes it’s good to read the Bible literally!

As we think about the relationship between modern digital technology and personal identity, what are the dangers we should be sensitive to—especially as those who believe the fullness of human being and flourishing is Jesus himself, glorified at the right hand of the Father?

In the ancient world, a “person” fundamentally meant somebody’s social status. The idea of personhood that we have nowadays—that it’s my deepest interiority, who I am with my feelings and convictions, possessing irreplaceable dignity and worth—that idea is new in relation to all the millennia of human history prior to the biblical tradition. It arose through Judaism and Christianity. We believe in a Creator God who has made all things and is therefore the ground of everything, which makes him awesome and unknowable. Yet, as Jewish philosopher Martin Buber pointed out so well through the story of the burning bush, this personal Creator God addresses us and calls us to respond. This personal relationship between the transcendent God and individual human beings is totally, radically new in philosophy and theology. This Creator God, who is the ground of everything (even the very ground of Moses thinking about him), singles out Moses as a person and addresses him as a person. The Bible is the beginning of human dignity and personhood in that sense.

We can apply this insight to the dangers of technology. The person whom God addresses and dignifies is body and soul. The early church fathers were often accused of being body-hating Platonists. What is often overlooked, however, is that they recognized—based on Christ’s bodily resurrection—that you’re incomplete without your body. We also have personal identity and value because we’re made in the image of God, and not because we possess certain capabilities (like rationality or freedom). You can’t reduce the person to mental or physical capacities. A person has to reveal him or herself, just like God has to reveal himself. There’s a secret depth and opacity that we can never fathom.

We’ll never get to the point in the new heavens and earth where we say, “Okay, I guess I’m done growing in my knowledge and experience of the Lord.” No, not at all. This is what Gregory of Nyssa called “constant expansion.”

Can it be that in glory I expand every day and God fills me every day with a little more? There’s so much more—infinitely more! We can’t even imagine that. So, the question for any technology, particularly the digital technologies we have now, is whether it supports this rich biblical notion of the embodied and dignified person or diminishes or atrophies our imagination of what a person is and what we’re made for.

Transhumanists are fundamentally gnostic, in the sense that they want to get beyond the limits of the body to engineer humanity into a new species no longer reliant on this flesh. . . . For

Christians, transhumanism isn’t a cool creative reimagination of life but a violation of what nature actually is.

In the broadest sense, everything we’ve ever invented to accomplish a goal is a technology—from the alphabet to the airplane. Some technologies have been wonderful and some destructive. Most of them are both, depending on whose hands they’re in. So, what’s distinctive (and perhaps distinctively problematic) about recent developments in digital technology?

When we reflect on technology, it’s important to distinguish between the idea of devices or tools we employ to make life easier and the idea that technologies may change our worldview and even our self-understanding, and therefore change the way we interact with one another. Technology is never neutral; it always changes how we perceive reality. Some technologies do so more than others. Martin Heidegger, for example, in his famous essay “The Question of Technology,” says that modern technology frames our relation to the world in terms of commodities. We no longer consider the mystery of life as something we need to surrender to or conform to. It’s not something we need to explore in awe and wonder with an openness that says, “You teach me. Let me see.” With technology, our comportment changes; our framing of nature and reality changes. We increasingly look at nature as a huge warehouse of commodities available for our projects—the trees are made for chairs, that kind of stuff. Eventually, we start looking at each other in the same objectifying, commodifying way.

Another good example of this comes from Gabriel Marcel, a French Christian philosopher, who said that technology frames our thinking about reality in a way that replaces mystery with problem solving. Life, including human life, now becomes a problem to be solved by technological means. We see this today in a movement called “transhumanism,” a movement mainly founded by computer scientists and engineers. Here humanity is conceived in completely functionalist terms. You and I are sophisticated machines. Our brains are basically computers. We can be reverse engineered, and our consciousness can be uploaded onto a digital platform. What is consciousness? Simply the accumulated patterns of emotional and behavioral activity inscribed into our memories. Transhumanists are fundamentally gnostic, in the sense that they want to get beyond the limits of the body to engineer humanity into a new species no longer reliant on this flesh. So, with this technological mindset, we move in our imagination from the paradigm of incarnation to digitization.

For Christians, transhumanism isn’t a cool creative reimagination of life but a violation of what nature actually is. My point is that this reimagination of reality through technology is a metaphysic. That sounds pretty abstract, but this metaphysics is present in the gadgets that are conceived and built in order to instantiate the metaphysics that transhumanists believe. The use of our smartphones every day, or being on Zoom rather than meeting with others in person–these things are hugely powerful for how we think about reality. Our imagination is being changed by our use of these technologies. It’s the most powerful influencer, I think, that humanity has ever experienced en masse.

Is there any silver lining to these tensions for a Christian approach to identity and personhood? Is this pushing us in any good directions?

One simple point to be made is that technology should be our servant and not our master. That technology can be helpful is without question. I’m old enough for my parents to have experienced the end of the Second World War. In postwar Europe, there was so much displacement; people had to find their families across Europe by posting notes on Red Cross bulletin boards, hoping that somebody would see it. Sometimes it worked. Sometimes people didn’t locate their families for decades. If they’d had WhatsApp or even a cell phone, it would’ve taken seconds. What misery that would have saved!

Yes, technology can be helpful if we can use it in such a way that we preserve our souls. One of my favorite tech writers is Steve Talbott, who wrote Devices of the Soul He’s a former computer programmer who asks, How do we use technology without being suckered into the framing of technology? Think about when people say things like, “Oh, this new online service (ChatGPT) wrote an essay for me.” Nobody wrote an essay for you. What happened is that an algorithm capable of sifting through an enormous amount of data in nanoseconds is playing a statistical game of finding the appropriate parts to put together into sentence patterns. What’s the endgame here? As I tell my students, you would have this algorithm write your essay for you, then my algorithm would grade it for you, then another would create the grade report for you. And meanwhile, have you learned how to write? Have you learned how to think?

Toward the end of Incarnational Humanism, you say something that starts to get at our answer as believers to some of these issues: “The social imagination of the early Christians was filled with this vision of Christ as the first true human being, to whose image we are molded by the work of God’s Spirit, a Spirit that does not deny our own efforts.” And then you end with the Lord’s Supper: “This is the heart of incarnational humanism, into which we’re drawn every time the Lord invites us to the Eucharistic table.” Please reflect on that.

You have to believe in a real presence; otherwise, this doesn’t work. And I can accommodate the Calvinistic spiritual presence—that’s all good, as long as it’s a full presence! If it’s Christ, the new creation, a Person who is really there, and we really are feeding on his flesh and blood in that spiritual yet real sense that Jesus talks about in John 6:53–59, then we are ingesting life and being sustained by it. The Christ in whom all things were created, in whom all things hang together, is there! So, when you come to the table, what you experience is the materiality of the new creation. That new reality has come, and it’s there in our midst. We’re tasting all that is good, true, and beautiful. It connects you to your activity as a poet, as an artist, as a scientist, businessperson, or pastor, whatever your mission is, whatever your work is, because here is the transforming power that gives your mission its energy. This is the origin and the completion of all that we are given to be and to do.

When you come to the table, what you experience is the materiality of the new creation. That new reality has come, and it’s there in our midst. We’re tasting all that is good, true, and beautiful.

As I get older, I pray that God will make that reality more real to me than the desk I’m sitting at and the world I’m experiencing, because that’s where we’re all going. That’s what sustains us. If I have that, then why would I fear death? The absence of the fear of death is what set the early church apart. If you read Athanasius’s On the Incarnation, he says, in effect, “I have presented my argument for the incarnation. But if you want real proof, look at us Christians: we’re not afraid of death.” Unlike the transhumanists, who attempt to find a technological way of overcoming death without the body, Christianity embraces death because Christ made it the gateway to life.

And at the table is where I should learn not only who I am but also what my relationship with my smartphone should be.

As Rowan Williams has said, when you take the elements, you should see the glory of the new creation dripping from the bread and the wine, knowing that you’ve been drawn into that reality. It’s not the minister you see. It’s Christ you see. You’re truly eating life.

IF THERE WERE A SILVER LINING to the dark cloud of the recent COVID-19 restrictions, it would be that we were compelled to think about our bodies: what to put on them, what to put in them, how proximate to other bodies to place them. COVID forced us to come to terms with our embodiment and to manage our physical exile and segregation from others by using (settling for?) various digital media to preserve some sense of communion and communication with others when embodied communion was either unsafe or unlawful.

We’ve been wrestling with deep theological and philosophical questions about human communion, and mediated communion, long before COVID. God prohibited entirely the making or using of visual media in worshiping him.1 Socrates famously expressed concerns about oral cultures becoming manuscript cultures (ironically preserved for us in the manuscripts of his disciple, Plato). 2 Medieval popes and cardinals were concerned that the printing press might provide a standard by which the deliverances of the church could be critically assessed. Marshall McLuhan (and his disciples) regarded the visual and electronic media of the twentieth century to have placed humans in a new, virtual universe, referring to the previous four-plus centuries as “The Gutenberg Galaxy.”

McLuhan’s protégé Neil Postman credited McLuhan with inventing and naming the discipline now known as Media Ecology. Media ecologists look at cultures similarly to the way cultural anthropologists and archaeologists do: analyzing a culture, in large part, by its tools. The tacit assumption of all three disciplines has been to ask not merely what a tool does for us but what it does to us. 3 Put differently, we make our tools and then our tools make us. Three decades ago, we added a room to our house and I decided to build a deck next to it. When my wife looked out into the backyard, saw me digging away, and asked me what I was making, I replied, “Calluses.” What the shovel did for me was make a hole for a foundation; what the shovel did to me was give my hands calluses. This isn’t a value judgment about rough hands; handball players, for example, develop calluses intentionally, because the ball comes off of a harder surface faster than off of a softer surface. A callused hand is a type of tool. Every material tool affects the material human who uses it, since humans are material beings. This material reality is not in itself negative; to the contrary, it can be quite positive (as handball players realize). At each stage in the Creation account, God describes the various material realities he has made as “good” (tov) : light, water, a heavenly expanse, dry land, vegetation, plants bearing seeds, trees, sun, moon, planets, fish, birds, livestock, beasts, even “creeping things.” Then God made human beings in his image, expressly distinguished in two kinds materially as “male and female” (Gen. 1:27). After so doing, he looked at all that

Every material tool affects the material human who uses it, since humans are material beings.

Fallen humans . . . have always attempted not merely to extend but to transcend our human nature— especially in our desire to be more “like God” than we already are as his image.

he had made and affirmed that it was, by his own divine standard, “ very good” (Gen. 1:31).

The goodness of our material nature was affirmed even more emphatically in Genesis 2, in which we discover that Adam was created “of dust from the ground” (v. 7). Indeed, Genesis 2 contains twenty references to stuff of the earth in some form or another: land/eretz (5), ground/adamah (5), garden/gan (5), field/sadeh (4), and dust/afar (1).

If we add the fifteen references to “Adam,” an obvious derivative of ground/ adamah , that makes thirty-five references. We can safely say that Genesis 2 is the dirtiest passage in the Bible! It’s no wonder Paul refers to Adam as the “man of dust,” whose image we have as truly borne as that of the “man from heaven” (1 Cor. 15:47–49). From its first two chapters until Christ’s apostles wrote their letters, the Bible embraces human materiality.

One of McLuhan’s books is titled Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. 4 McLuhan regarded various media as “extensions” of some aspect of being human. The telephone extended the human voice a far greater distance; the manuscript or book extended one’s communications into the future. Fallen humans, however, have always attempted not merely to extend but to transcend our human nature— especially in our desire to be more “like God” than we already are as his image. The serpent cultivated this yearning to transcend our created order by saying to Eve, “For God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil” (Gen. 3:5). We human beings, already dignified by being the only creature made in the image or likeness of God, were not content to remain so; we desired to transcend human creatureliness, to be “like God.” The Bible suggests, therefore, that obedient, grateful humans may very well extend their human capacities to serve God or others (by wearing glasses or using an X-ray machine, for example), while disobedient, ungrateful humans will be enticed to use the same capacities to transcend our created human nature and its God-given constraints.

***

Harold Innis, a political economist at the University of Toronto, argued that all human media (technologies of whatever sort) have biases, or emphases inherent in their form, that permit us to extend ourselves in either time or space.

Media that emphasize time are those that are durable in character, such as parchment, clay, and stone. The heavy materials are suited to the development of architecture and sculpture. Media that emphasize space are apt to be less durable and light in character, such as papyrus and paper.5

Grave markers, carved in stone, are time-extenders and last for many centuries; tweets and emails are space-extenders, permitting us to communicate with

people anywhere on earth. But these space-extenders also tend to be ephemeral (though the NSA probably has copies of them all), merely a hard-drive crash or a cloud-hack away from disappearing altogether. Interestingly, the media of ancient religions (including Christianity) have an inherent bias toward time-extending media. We regard some truths and realities as being timeless; we regard the ancient God of Abraham as our God still today, and the content of our beliefs derives from ancient documents that are at least two millennia old. Space-biased media serve us as instrumental goods—for example, by permitting us to disseminate the gospel more broadly than ever before—but our time-extending media roots run deep.

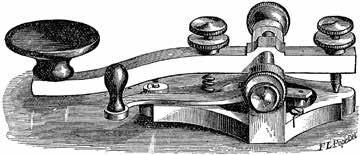

In contrast, electronic media, from the telegraph to Instagram, are inherently space-biased, and usage of such media has tended to shape us in ways that do not merely extend but also attempt to transcend our material nature. With the telegraph, the cultural impact on the typical individual or family was somewhat inconsequential. Telegrams were expensive, and one had to travel to a Western Union office in order to send or receive a message. 6 Then with each new development in electronic media (radio, telephone, television), the process of transcending our material nature accelerated. Via television, for instance, noncombatant Americans saw televised news of the war in Vietnam on the evening news—something that only military personnel had previously witnessed. By 1969, we could sit in our living rooms and watch the Apollo 11 team walk on the moon. With social media, we can not only communicate with those who are physically distant, but we can reach hundreds or even thousands with a single tweet. It seems a little like God, who can hear a million prayers simultaneously or be adored and worshiped by millions simultaneously. But does the quest to capture the attention of hundreds (or more) followers at a time seem a properly modest expectation for a mere creature, or is it an effort to transcend our material nature? Rereading Cicero’s essay on friendship recently, I was struck by his observation that few individuals had more than a single friend, perhaps two.7 Contemporary users of Facebook, Instagram, or other platforms may have thousands of connections— though, too often, no real friends in Cicero’s sense of the term.

Of course, people corresponded through letters before the electronic age, and these are a form of space-extending media. But when I write a letter, I do not feel in any sense as though I myself am present when and where the letter arrives. When speaking on the phone, I sense that I am actually, in some sense, with the other person on the line. Analog media like letters remind us of the material distance from our correspondent; electronic media tend to disguise the material distance. Yet this material human nature is part of our humanity, part of the humanity that God described as “very good,” and perhaps for good reason.

Analog media like letters remind us of the material distance from our correspondent; electronic media tend to disguise the material distance.

If the Christian doctrine of Creation honors the material human body as very good, then surely the doctrine of the incarnation does so!

What space-biased media do for us is permit us to influence and be influenced by those who are physically distant from us; what they do to us is harder to assess. According to media ecologists, media probably alter our sense of self, particularly our sense of our embeddedness in a particular physical environment. Some observers regard the matter as even more severe: Space-extending media cultivate a degree of contempt for place, enabling us to evade and avoid those who are present while attending to those who are absent, relativizing and obscuring the very definitions of “present” and “absent.” McLuhan noticed this long before the digital era and referred to such space-ignoring consciousness as “discarnate.”

The discarnate user of electronic media bypasses all former spatial restrictions and is present in many places simultaneously as a disembodied intelligence. This puts him one step above angels, who can only be in one place at a time. Since, however, discarnate man has no relation to natural law (or to Western linearity), his impulse is towards anarchy and lawlessness.8

McLuhan’s Christian faith informed his vocabulary, and I believe he coined the term “discarnate” as an intentional (and sarcastic?) inversion of “incarnate.” If the Christian doctrine of Creation honors the material human body as very good, then surely the doctrine of the incarnation does so!

McLuhan was not the first Christian to wrestle with issues of media, nor the first to be suspicious of space-biased, “discarnate” media. The apostle Paul was very aware of his material location, perhaps especially when he wrote his prison epistles. He was also aware, not merely of his physical captivity, but also of his painful absence from the congregations he had founded and served:

For God is my witness, whom I serve with my spirit in the gospel of his Son, that without ceasing I mention you always in my prayers, asking that somehow by God’s will I may now at last succeed in coming to you. For I long to see you, that I may impart to you some spiritual gift to strengthen you—that is, that we may be mutually encouraged by each other’s faith, both yours and mine. I want you to know, brothers, that I have often intended to come to you (but thus far have been prevented), in order that I may reap some harvest among you as well as among the rest of the Gentiles. (Rom. 1:9–13)

I wish I could be present with you now and change my tone, for I am perplexed about you. (Gal. 4:20)

But now that Timothy has come to us from you, and has brought us the good news of your faith and love and reported that you always remember us kindly and long to see us, as we long to see you . . . as we pray most earnestly

night and day that we may see you face to face and supply what is lacking in your faith. (1 Thess. 3:6, 10)

As I remember your tears, I long to see you , that I may be filled with joy. (2 Tim. 1:4)

But since we were torn away from you, brothers, for a short time, in person not in heart, we endeavored the more eagerly and with great desire to see you face to face, because we wanted to come to you—I, Paul, again and again—but Satan hindered us. (1 Thess. 2:17–18)

This Pauline preference for face-to-face communication is both ironic and remarkable. It is remarkable because Paul not only strongly preferred in-person communication but, at least in the case of the Thessalonians, he also attributed his absence from them—an absence that necessitated the second-best available substitute medium, a written letter—to diabolical interference.

It is ironic because the only Paul we know is the Paul who wrote thirteen epistles and who appears in Luke’s account in Acts. The apostle, whom we know primarily by his letters, routinely expressed that he would have preferred to have been personally and physically present with his addressees rather than writing to them. We are forever grateful to have Paul’s letters, which are richly edifying to us; but it seems that Paul would have preferred if we as his brothers and sisters in Christ knew him only in person. This ancient lament from Paul should give Christians pause as we consider our relationship with space-biased electronic and digital media today. ***

The rapidity of media changes in the third millennium has made it difficult to assess what these media do to us, as well as what they do for us. I am not prepared to offer normative counsel on such matters, but I believe we should at least be wary of how our circumstances amplify the concerns Paul expressed. As limited beings, we should beware the trade-off between quality and quantity of communication and its consumption—only for God is this not an issue.

Our new media are called, even by their most avid proponents, “information technologies.” Implicit in “information technology” is the value judgment that what we need is more information. But the Bible—alongside other sage guides, ancient and modern—suggests that few human problems are due to a lack of information.

Too much in formal education has to do with quick response, with coughing up information quickly, and not enough leeway is allowed for reflection and brooding in the thoughtful way that serious subjects require.9

We are not brains on sticks, whose primary way of loving and serving others is to dispel information.

In an address he gave in Germany a decade before the third millennium, Neil Postman noticed the same reality when he said:

If you and your spouse are unhappy together, and end your marriage in divorce, will it happen because of a lack of information? If your children misbehave and bring shame to your family, does it happen because of a lack of information? If someone in your family has a mental breakdown, will it happen because of a lack of information? 10

We are not brains on sticks, whose primary way of loving and serving others is to dispel information. Our most important human concerns are not informational; we attempt to make sense of our own internal conflicts and of our conflicts with those around us. These important issues in life do not, in the first place, require information. They require understanding and wisdom: understanding of the human condition, of the internal conflict we all experience, and understanding of others, whose conflicts, fears, and aspirations differ from our own.

In prolific author Mortimer Adler’s book A Guidebook to Learning: For a Lifelong Pursuit of Learning , he observed that all educational systems from the ancient world through the early part of the twentieth century conceived of education as having four progressive steps: information, knowledge, understanding, and wisdom. Information, for Adler, is merely an observation about some specific thing (e.g., a frog); when that thing has properties similar to other things (e.g., salamanders), he calls this “knowledge.” When we understand the properties common to reptiles, amphibians, mammals, marsupials, and so

1. “You shall have no other gods before me. You shall not make for yourself a carved image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. You shall not bow down to them or serve them, for I the Lord your God am a jealous God” (Exod. 20:3–5).

2. Plato, Phaedrus, trans. Benjamin Jowett, The Project Gutenberg Ebook Phaedrus, 274–77, https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/ epub/1636/pg1636-images.html.

3. “In The Second Self, I traced the subjective side of personal computers—not what computers do for us but what they do to us, to our ways of thinking about ourselves, our relationships,

our sense of being human.” Sherry Turkle, Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other (Philadelphia: Basic Books, 2011), 2. She followed this book with Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age (New York: Penguin, 2015).

4. Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994).

5. Harold Innis, Empire and Communications (1950; repr., Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1972), 7.

6. While the cultural impact of the telegraph was minimal, astute observers were wary about it. Henry David Thoreau famously said, “We are in great haste to construct a magnetic

on, we call this “understanding.” But the goal of all learning is wisdom: What do you do with a frog? What is it for ? How does it fit in an ecosystem where it plays a significant role? Should we study it? Should we fry its legs and eat them? Should we protect it?

At the turn of the millennium, the digital world was largely well received, and many of its early boosters spoke almost messianically of the potential of digital devices and the “information superhighway” (which quickly became the commercial cul-de-sac). Such fervor has largely waned now, and much of the cultural conversation revolves around how best to manage the disruptive, distracting, discarnating, dehumanizing nature of our beloved digital devices.

The material order that God made is “good,” and when God completed that order by making the human in his image, he declared that this entire material order, and the material human, was “very good” (Gen. 1:4, 10, 12, 18, 21, 25, 31). In the economy of redemption, God’s holy Son entered this material world in a material body, and he lived and died sinlessly in that material body. We who are benefactors of the incarnate work of Christ should be wary of the discarnate nature of electronic and digital media, and we should celebrate both his and our material humanity whenever circumstances permit.

T. David Gordon (PhD) is a retired professor of Religion and Greek at Grove City College. He has contributed to a number of books and study Bibles, published scholarly reviews and articles in various journals and periodicals, and his books include Promise, Law, Faith: Covenant-Historical Reasoning in Galatians (Hendrickson, 2019).

telegraph from Maine to Texas; but Maine and Texas, it may be, have nothing important to communicate. . . . We are eager to tunnel under the Atlantic and bring the old world some weeks nearer to the new; but perchance the first news that will leak through into the broad, flapping American ear will be that Princess Adelaide has the whooping cough.” Henry David Thoreau, Walden (Boston: Riverside, 1957), 36. Mark Twain was even less desirous of electronic media: “The Bermudians are hoping soon to have telegraphic communication with the world. But even after they shall have acquired this curse it will still be a good country to go to for a vacation, for there are charming little islets scattered about the enclosed

sea where one could live secure from interruption. The telegraph boy would have to come in a boat, and one could easily kill him while he was making his landing.”

7. Cicero, Treatises on Old Age, on Friendship and on Divination, trans. W. A. Falconer, Loeb Classical Library No. 154 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1923).

8. “Laws of Media,” in Essential McLuhan, ed. Eric McLuhan and Frank Zingrone (Philadelphia: Basic Books, 1995), 370.

9. Joseph Epstein, A Literary Education and Other Essays (Edinburg, VA: Axios Press, 2014), 9.

10. Neil Postman address given at Gesellschaft für Informatik in Stuttgart, Germany, on October 11, 1990.

At time’s first dawn, the Godhead shone in glory deep and splendor great. Enwrapt with beauty, mankind owned the praise of God inviolate.

‘Till in that sin of unbelief man sped to his eternal grief.

Then Eden fell, and, with it, joy as God His face from man withdrew. In desp’rate longing earth employed the scourge of sinners yet anew. Yet fleeting pleasures ne’er could fill the sightless void that lingered still.

From Cain to Judas horror swept across the dying realm of earth. In drunken blindness mortals crept away from joy, and love, and mirth. Take heart! The cross, though cloaked in pain shall guide man to their God again.

At death’s last night, a cloudless bliss shall gather ‘round the gates of heav’n. What glory deep and splendor this!— pure sight of God, all purged of leav’n. No cloud of sin shall e’er arise to dim man’s thrice-adoring eyes.

A crushed spirit dries up the bones. (Prov. 17:22) He himself bore our sins in his body on the tree. (1 Pet. 2:24)

TECHNOLOGY’S TRIUMPH OVER SPACE , its power to entertain and distract, its promise of enabling us to construct not only our own virtual identities but our own realities—all this can seem to render our bodies problematic, even superfluous in the digital age. One legitimate response to such mythical thinking is that it’s patently false. After all, we must access these technologies with our eyes and ears and manipulate them with our fingers and voices. But here I want to explore together several deeper realities that give the lie to the myth of digital disembodiment and underscore both the importance and goodness of being flesh and bone. ***

One inescapable reality that underscores our embodiment is suffering. It comes, as we do, in as many shapes and sizes. Some kinds of suffering are overtly physical: for example, cancer, COVID-19, toothaches, and broken bones. Others are more mental and emotional. But can we ever really separate any form of suffering from our bodies? Can you suffer cancer with no mental and emotional consequences? Even “immaterial” pains like guilt, shame, anxiety, grief, bitterness, and depression manifest themselves in physical ways. Anyone who has experienced mental and emotional anguish can testify to the very real and very bodily tears, loss of appetite, overeating, insomnia, or excessive fatigue. As Proverbs 17:22 says, “A crushed spirit dries up the bones.”

Medical technology may provide healing or relief for many overtly physical pains. It may also provide some relief for mental and emotional pains. But no technology or technique can eliminate suffering from human experience, and many pains are so acute that technology can do little or nothing to ease their effects. Whether directly or indirectly—and especially when it is acute—suffering underscores the inescapable fact that we are physical beings. All suffering involves our bodies, but our bodies don’t explain all suffering. So suffering also drives us to the

further truth that in the unity of every human person, the material and the immaterial are inextricably united and interrelated: the body and the soul or spirit. ***

This brings us back to the fundamental, historical reality of human nature as created by God. Genesis 1–2 is clear that our existence is not the result of random natural processes but of the specific, intentional actions of our all-wise Creator, who showed a special interest and involvement in creating human beings in his image. Adam’s creation included both forming his physical body and breathing life or spirit into him. Our physicality or embodiment is no more superfluous to who we are than our souls. This body and soul unity is the express plan of God himself, and therefore, most wise and good. From the beginning, we were designed to glorify and enjoy him in the setting of his “very good” material universe and equipped with bodies to enable us to fulfill his calling to be fruitful and exercise dominion.

Far from being the prison house of the soul (as Plato and others have suggested over the centuries), the human body is the soul’s proper and permanent home, the good gift of our all-wise Creator. But, of course, that inevitably raises the question of suffering’s existence or the problem of pain. Here again, the Scriptures have a clear and satisfying answer if we are willing to hear it: While suffering profoundly affects our bodies and our souls, they are not suffering’s true source or cause. For that, we must look to Satan’s deception, Adam’s fall, and God’s righteous curse.

Genesis 3 connects those dots for us as it records Satan’s use of the serpent to deceive Eve (Gen. 3:1–6, 13; 2 Cor. 11:3; 1 Tim. 2:13),1 Adam’s willful disobedience in eating the fruit (Gen. 3:6–12; Rom. 5:12, 14), and the Lord’s consequent curse upon not just these three parties but the entire creation (Gen. 3:17–19; Rom. 8:20–22). In this brief passage, we find the word cursed twice, pain three times, and other suffering-related words—e.g., afraid (fear), naked (shame), and return to dust (death)—all underscoring sin’s sad effects upon formerly perfect creatures and creation. Yet amid those painful realities, the text (Gen. 3:15) also points us to another glorious confirmation of our embodiment: Christ’s redemption! ***

By pointing us to our need for Christ and his salvation, suffering further underscores our embodiment in profound and powerful ways. The Bible teaches that in order to be our covenant head and atone for our sins, Christ had to become like us in every way, except for sin (Heb. 2:14; John 1:14); and in that likeness, he had to live a sinless human life and bear our sins “in his body on the tree” (1 Pet. 2:24). Christian theology describes this as the eternal Son assuming or joining to his person our complete human nature. He became incarnate—enfleshed in

Adam’s creation included both forming his physical body and breathing life or spirit into him. Our physicality or embodiment is no more superfluous to who we are than our souls.

Jesus’ incarnation was no mere theophany in which he simply appeared to have a body; it is his actual and permanent embodiment, because having a body is an essential aspect of our human nature, the nature Christ fully assumed in order to redeem us.

a real human body together with a “reasonable soul” (as the Definition of Chalcedon puts it). When the Son of God came into this world to redeem us, he did not come in his divine glory or even as a disembodied spirit, but as the Word made flesh (John 1:14). In that flesh, he suffered—supremely on the cross, but also throughout his life. Having come in “the likeness of sinful flesh” (Rom. 8:3), Jesus was subject to the same bodily trials that we face. He was hungry and thirsty (Matt. 4:2; John 4:7; 19:28), he was tired to the point of exhaustion (John 4:37–38), and he was subject to physical agony and death (Mark 15:37, 42–45). His body was conceived by the Spirit in Mary’s womb (Matt. 1:20–23; Luke 1:34–5); his newborn body was laid in a manger in Bethlehem (Luke 2:12, 16); his body sweated in a carpenter shop in Nazareth (Mark 6:3); his body walked the hills of Galilee and Judea (Mark 7:9–10); his body bled under Pilate’s scourge (Matt. 27:26); his body died upon Calvary’s cross (Mark 15:37, 42–45); his body was laid in the garden tomb (Matt. 27:57–60); his body was raised in glory on the third day (Luke 24:1–12); his resurrected body was seen and touched by a host of witnesses (Luke 24:14–43; 1 Cor. 15:4–8); and his glorified body now sits at the Father’s right hand in glory (Luke 24:51; Heb. 1:3; 10:12; 12:2). As my former professor Dr. Robert Reymond loved to say, “The reins of the universe are in the hands of a man—the nail-scarred hands of the God-man, Jesus Christ.” Ruling from heaven, he sympathizes with his suffering people on earth as he builds his church before he returns in the same glorified body in which he ascended (Acts 1:9–11; Rev. 19:11–16). Until that return, we feast at the table with elements, at his command, that underscore his embodiment: “This is my body. . . . This is my blood” (1 Cor. 11:23–25).

Jesus’ incarnation was no mere theophany in which he simply appeared to have a body; it is his actual and permanent embodiment, because having a body is an essential aspect of our human nature, the nature Christ fully assumed in order to redeem us. To say that Jesus accomplished all these things in his body is to say in the most profound way that he accomplished them.

***

Reflecting on the gracious work of redemption our Savior accomplished in the body leads to another classic Christian affirmation of our embodiment that we often lose today: the stress that Scripture places on our glorious hope, which is not to be set free from our bodies but to be glorified in our bodies. The separation of body and soul that occurs at death is not regarded in Scripture as a blessing, but as an unusual, temporary state (2 Cor. 5:4–8). While Paul says that “to be absent from the body is to be present with the Lord,” and that it is “far better” than life in this present fallen age (2 Cor. 5:8; Phil. 1:23), he also comforts and encourages believers by assuring us that at the resurrection our redeemed souls will be reunited with our glorified bodies (1 Cor. 15). Paul’s ultimate hope, as well as ours, is not to be “unclothed” or disembodied but “further clothed” (2 Cor. 5:4).

This isn’t just the hope of each individual Christian, but the hope of the cosmos. We will enjoy many “withouts” in the new heavens and new earth, which will be without sin, without death, without pain, without mourning, and without tears—but not without bodies! ***

As we await this glorious hope, the present reality of suffering also calls us to minister to the hurting, and all the various aspects of such ministry further underscore our embodiment. As mentioned above, given the unity of our persons, even nonphysical suffering manifests itself in our bodies. Whether or not suffering stems from our bodies, it involves our bodies. Jesus experienced this himself. In Gethsemane, as our Lord agonized at the prospect of the cross, he acknowledged his profound spiritual and emotional suffering accompanied by sweat like drops of blood: “My soul is deeply grieved, to the point of death” (Matt. 26:38a). As we contemplate this fearful mystery, we must not miss how in the midst of this experience Jesus sought comfort from his disciples in a physical way: “Remain here and keep watch with me” (Matt. 26:38b).

This is an example of what has been called by some “the ministry of presence”: the simple physical presence of a loved one can have a powerful soothing effect upon both physical and emotional sufferers. For all that they got wrong, Job’s three friends ministered well to him when they traveled to his home and sat with him in silent sympathy for a week (Job 2:11–13). Paul also alludes to the ministry of presence when recounting an episode from his missionary journeys: “For even when we came into Macedonia, our bodies had no rest, but we were afflicted at every turn—fighting without and fear within. But God, who comforts the downcast, comforted us by the coming of Titus” (2 Cor. 7:5–6). Simply “being there” can be a tremendous comfort and blessing to sufferers, and that blessing—the reality that I am here and I am with you must be imparted and received in the body.

Sadly, Job’s friends discredited their ministry once they opened their mouths, but that need not always be the case. The blessing of bodily presence can be greatly enhanced by well-spoken words, as was the case with Titus and Paul in the rest of the episode recounted above:

God, who comforts the downcast, comforted us by the coming of Titus and not only by his coming but also by the comfort with which he was comforted by you, as he told us of your longing, your mourning, your zeal for me, so that I rejoiced still more. (2 Cor. 7:7)

Unlike Job’s friends, Titus’s words were an additional source of comfort to Paul as he brought a good report concerning the Corinthians’ repentance and their love for Paul. This reminds me of the Book of Common Prayer’s description of

Simply “being there” can be a tremendous comfort and blessing to sufferers, and that blessing—the reality that I am here and I am with you—must be imparted and received in the body.

the verses to be read in the assurance of pardon: these gospel promises are “comfortable words.” Whether read, quoted, or sung, “comfortable words” embodying God’s wise and gracious word out loud are a rich source of blessing to sufferers. Isn’t it also fascinating that though Jesus could heal with only a thought or a word, he also frequently touched those he was healing? Physical touch—a hug, a kiss, an arm around the shoulder, shared tears—can be a vital encouragement in the midst of suffering.2 Note how Paul and the Ephesian elders mutually comforted one another at the painful thought that this was the last time they would be together in person:

When [Paul] had said these things, he knelt down and prayed with them all. And there was much weeping on the part of all; they embraced Paul and kissed him, being sorrowful most of all because of the word he had spoken, that they would not see his face again. And they accompanied him to the ship. (Acts 20:36–8)

These wonderful and important ways to minister to sufferers—and many others I haven’t mentioned—have one thing in common: embodiment. Even ministry through recorded words or music or a written letter must be made and received by means of the eyes, ears, and hands. Not just the nature of suffering, but the nature of ministry to sufferers underscores the reality and significance of embodiment. Comfort is simply impossible for human beings to give or to receive apart from our bodies.

I previously mentioned the Bible’s seminal book of beginnings, Genesis 1–2, in connection with humanity’s creation as an “enfleshed soul.” In its revelation of the image of God and the dominion mandate, Genesis also reveals the origin of technology.

My favorite basic definition of technology is Merriam-Webster’s: “applied science,” or “the application of knowledge to practical purposes.”3 Given our creation in the Creator’s image, and his mandate to “rule” or “subdue” the earth, humanity also received what might be called the “technology mandate,” which Genesis reveals as being fulfilled very early in human history. Beginning with Cain, we read in quick succession of the development of agriculture, animal husbandry, architecture, and construction or “city-building,” musical instruments, and metalworking (Gen. 2:15; 4:2, 17, 20–22).

Yet Cain’s involvement gives us a hint at the mixed nature of this technological progress: technology, like everything else, is affected by man’s fall and God’s curse and simultaneously expresses our dignity and our depravity. So throughout human history, technology has been used for good and evil, and this too is inseparable from the reality of our embodiment. Like everything related to fallen humanity, technology is the proverbial two-edged sword. It has been used to

inflict great suffering but also to alleviate pain and promote healing. Besides its medical and other wonderful achievements, when we cannot be with needy sufferers in person, or touch them, or cook for them, modern technology enables us to see, hear, and share words of comfort and encouragement with them from halfway around the world.

Nevertheless, to the extent that technologies isolate us from other people and deceive us into imagining we can create our own identities and realities (including denying or diminishing our embodiment), they are harmful. Let me put a sharper point on this as it applies to suffering: If any technology shapes us to be so isolated, self-centered, or numbed that we fail to minister to those who are hurting, then it is destructive and idolatrous. This failure also includes minimizing our ministry to sufferers: we must not substitute a text, a tweet, a photo, or even a phone call when we should visit, talk, touch, and take a meal. ***

Someday, in that glorious new world in which righteousness dwells, technology will no longer be a double-edged sword. In that perfect environment, sinless men and women in deathless bodies will use human insight in practical ways to glorify God fully and bless neighbors perfectly. But we will not use our bodies or our technology to bless sufferers: that ministry will be fulfilled because pain will have been banished forever, along with mourning, crying, and death.

Our bodies will be glorified because the one who fashioned our bodies took a body to himself, and in that body he lived and worked, using technology with perfect wisdom and righteousness in a humble carpenter’s shop. In ministering to other sufferers, he suffered greatly to “abolish death and bring life and immortality to light” (2 Tim. 1:10) by bearing our sins “in his body on the cross” (1 Tim. 2:24). Until that eternal Day breaks, may we be properly grateful for our redemption through his body, and may our own bodies, who are “members of Christ” (1 Cor. 6:15), glorify him as living sacrifices and holy temples (1 Cor. 6:19–20; Rom. 12:2). And as members of his “body,” the church, we are his hands and feet, obliged and privileged to minister in his name to fellow sufferers. As we do, may we steward the double-edged gift of technology wisely, never letting it distract us or undermine our physical ministry of grace and comfort to other embodied souls.

J. D. “Skip” Dusenbury (DMin, Westminster Theological Seminary) is a retired pastor who continues serving the Lord and his church through preaching, teaching, and writing.

Our bodies will be glorified because the one who fashioned our bodies took a body to himself, and in that body he lived and worked, using technology with perfect wisdom and righteousness in a humble carpenter’s shop.

1. All scripture quotations are from the English Standard Version unless otherwise specified.

2. There is a lot of data to show that physical touch is absolutely essential for healthy human development in the first place: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/infant-touch/.

3. Merriam-Webster.com. Britannica.com offers a somewhat fuller definition along the same lines: “Technology is the application of scientific knowledge to the practical aims of human life or, as it is sometimes phrased, to the change and manipulation of the human environment” (my italics).

IN

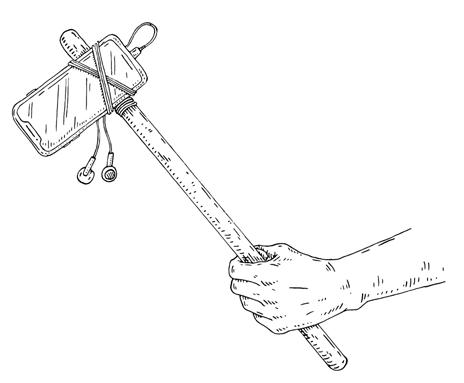

NLINE WORSHIP . Zoom church. Streaming services on Facebook Live (if you can get it to actually work). We’re all used to this strange new world by now. But it can get stranger: how about entirely virtual churches in the Metaverse?1 This latest development should remind us that even though we’ve become used to digital versions of Christian community over the last couple of years, we should still find it all strange (if no longer quite so new). Now that there is sufficient distance from the COVID-19 pandemic, it is time for more intentional theological thinking about these matters. We can now ask—or revisit—some important questions: How are our experiences of the past few years to be understood in light of God’s word and Christian teaching? And what should we do moving forward? I want to begin this process of theological reflection by going upstream from online worship to explore its headwaters. What we find there is more complex than the strategic pros and cons or potential uses and abuses of worshiping via streamed or recorded media. Instead, at the wellspring, we discover age-old dilemmas: questions of human autonomy and embodied limitations, questions of the relationship of mind to body and of man’s nature in relation to God.

These are not new questions, but in the digital age, the church’s practices are mixing with new cultural and technological accelerants, which makes for an especially volatile combination—and makes clear theological thinking even more crucial. Once we explore the environment upstream, then we can more clearly navigate the downstream challenges the digital revolution has brought to the church, to bodily life, and specifically to the worship life of local congregations. ***

In Transhumanism and the Image of God, Jacob Shatzer suggests that technologies “train and disciple us in certain ways . . . drawing us further into a technological liturgy of control.” 2 Byung-Chul Han similarly notes how constant technological engagement functions as a “liturgical gesture” that catechizes us to conclude that “I have the world firmly in my grip. The world has to accord with my desires.”3 My phone stands always at the ready, to serve my every whim. My fingers effortlessly control the world. I click, I get; I swipe, I see. Both Shatzer and Han put their finger on the connection between our East-of-Eden desire for autonomy and the nonstop nudges in that direction from our technological surroundings. What results is a self-reinforcing loop: our disordered desire for control fed by the technological prowess at our fingertips, which in turn feeds our technological mastery.

Screen-based and internet-connected devices easily morph from capable tools with specific purposes to all-encompassing reality-mediating mechanisms through which we encounter one another and the world.

I don’t mean to suggest that we should consider digital technology to be categorically different from previous forms of technology. All technologies—from a plow to a pencil, from a calculator to a computer—impact our perception of ourselves and our world. Rather, we need to see that our deep impulse toward autonomy, which first arose in that primordial garden in response to the Serpent’s temptation that “ye shall be as gods,” is now intensified by advanced technologies that enable the effortless expression of such desires with the swipe of a finger or push of a button—or even, like God, by simply speaking.4 Screen-based and internet-connected devices easily morph from capable tools with specific purposes to all-encompassing reality-mediating mechanisms through which we encounter one another and the world. They are seamless habitats in ways that technologies like shovels, excavators, or electric toasters are not.5 You cannot be immersed in a toaster in the same way you can be immersed in an online world or a social media platform—unless, perhaps, you are a piece of bread.

To be clear, my argument here is not that each activity of, say, scrolling a news feed, posting on social media, checking a weather app, or taking a selfie are theologically suspect or harmful to our spiritual health in and of themselves. My point is that these undeniably convenient aspects of modern life are not neutral. Today’s digital milieu is filled with technological accelerants that excite our pre-existing tendency toward the illusion of self-sufficiency. The accumulation of such practices and habits—reinforced in countless small daily rituals—makes it seem as if everything that really matters is under our direct control, consumed, constructed, and curated when and how we choose. As Han says, “Through all my swiping, I submit the world to my needs. The world appears to me under the digital illusion of total availability.”6 Humanity’s essence is no longer one of being a creature dependent on God and others, but one of self-creation and autonomy— what Carl Trueman describes as “a world in which it is increasingly easy to imagine that reality is something we can manipulate according to our own wills and desires, and not something that we necessarily conform ourselves to or passively accept.”7 Seeing myself and so many others breaking our backs hunched over our screens, I can’t help but think of Augustine’s understanding of fallen humanity being curved in on ourselves: incurvatus in se smartphone style.

***

Running in stride with this increasing sense of technologically fueled autonomy is an intensified sense of digital disembodiment, what Charles Taylor calls “excarnation.” This is a wordplay on incarnation: while the Son of God purposefully took on our flesh, we often try our best to escape it. In the process, we become “alienated from our anchoring in the world, in fleshy reality; which we can only recover access to through the lived body, whose testimony is being distortively shaped or even denied by ‘virtual’ reality.”8 By treating “the body as extrinsic to the person,” Nancy Pearcey explains, the inner self can impose its own inter-

pretations and desires on the physical body, resulting in a form of person-body dualism: the person is defined as the authentic self, constituted in the mind or heart, while the body is relegated to a secondary position with significance but no inherent meaning.9 Today’s cultural and technological conditions make it more possible, plausible, and palatable to reject the limits of bodily life in favor of such self-constructed identity and reality.

Such temptations toward disembodiment cluster around two main trajectories. For one, in the digital world we are nudged toward being thinking things, or as James K. A. Smith puts it, “brains on a stick.”10 We send messages and hot takes, consume endless information and images, perform our cultivated online identities, but all at a distance, seemingly without bodily involvement with the real world and in-person engagement with real people. Second, behind the screen, we are nudged toward being feeling things, or hearts on a stick. In a “race to the bottom of the brain stem,”11 digital and especially social media easily feed our basest instincts. In consuming, we are in turn consumed by sentiment, fed by algorithms through the frictionless allure of the swipe and the click. In both trajectories, disembodiment reigns. Screen and phone win out over skin and bone. ***

The upstream currents explored above are increasingly infiltrating the church’s downstream worship life. We frequently treat worship not as a communal set of practices but as an intellectual activity for God in our individual heads or an emotional activity for God in our individual hearts.12 In Disruptive Witness, Alan Noble warns of the consequences of a brain-on-a-stick approach to worship: “The weekly gathering together of saints is only justified if attending church is about much more than intellectual growth. In this sense, excarnation is not only a deviation from historical Christianity. It also renders regular church attendance obsolete.” 13 The heart-on-a-stick outlook fares no better. In it, “we experience worship much like we experience a concert. It becomes an individual, emotional, and spiritual exercise wherein I try my best to think about the words and praise God. But even though I am surrounded by the saints, I remain comfortably in my own head.” 14

Mind you, Noble offered these warnings before COVID-19. Such trends have only accelerated since the pandemic and the online turn. Digital technology disembodies: Why bother coming to church when online sermons and songs enable mind and heart work to be done anywhere, and with better musicians and preachers, and while in your pajamas to boot? And this technology accelerates our pursuit of personal autonomy: The church becomes just another content provider offering its product to consume or ignore. I choose which sermons and songs to listen to. I can turn them on or off at will.

Certainly, listening to sermons or songs online can be educational and edifying. But virtual presence cannot be confused with real presence, and the church’s use of digital technologies must not unintentionally undercut the very

Why bother coming to church when online sermons and songs enable mind and heart work to be done anywhere, and with better musicians and preachers, and while in your pajamas to boot?

message of Christ made flesh, Christ crucified, and Christ risen from the dead— an embodied message delivered through God-ordained means. We turn now to the natural embodied limits of creaturely reality and how they should inform our understanding of Christian worship in the digital age.

We are meant to touch, smell, taste, see, and hear the physical world with our actual physical bodies. The inbuilt limits of bodily life are purposeful and for our good. As modern life becomes increasingly digitized and mediated by technological layers, however, L. M. Sacasas wonders at what point humans will cross “a threshold of artificiality” beyond which our “capacity to flourish as human beings is diminished.”15 In an environment teeming with accelerants toward disembodiment and autonomy, we do well to recover the role of bodily limits in human flourishing. The body binds us to one physical location at a time, placing us within humanely scaled and manageable frameworks that direct our attention toward its proper ends. Such boundaries are what make the world navigable and meaningful.

Limits are part of God’s good design for human creatures. Kelly Kapic encourages us to “celebrate the goodness of being a creature of the God who loves what he made. God delights in our finitude: he is not embarrassed or shocked by our creatureliness.”16 Bodily limits are lovely to God and should also be to us. Recognizing the God-given limits of your body, according to Alan Noble, helps you also embrace “that you belong to your family . . . to the church . . . [and] to the place where you live.”17 Physical limits are a feature, not a bug, of the human experience.